The Ages of Exploration

Christopher columbus, age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

He is credited for discovering the Americas in 1492, although we know today people were there long before him; his real achievement was that he opened the door for more exploration to a New World.

Name : Christopher Columbus [Kri-stə-fər] [Kə-luhm-bəs]

Birth/Death : 1451 - 1506

Nationality : Italian

Birthplace : Genoa, Italy

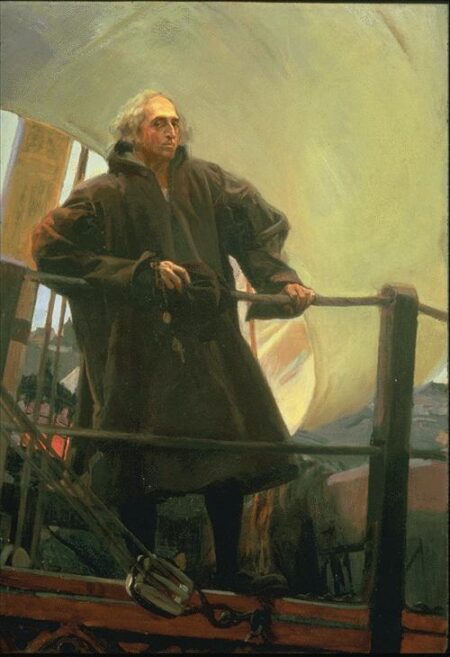

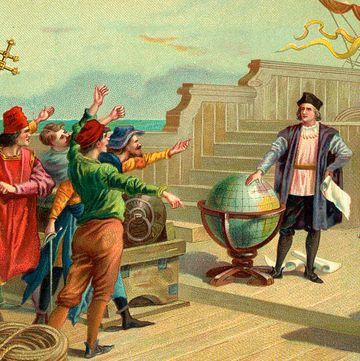

Christopher Columbus leaving Palos, Spain

Christopher Columbus aboard the "Santa Maria" leaving Palos, Spain on his first voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. The Mariners' Museum 1933.0746.000001

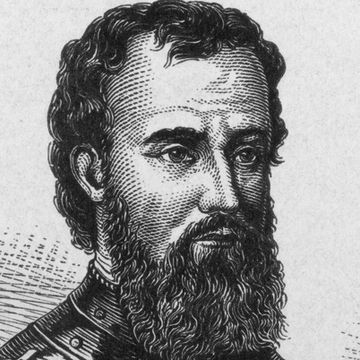

Introduction We know that In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue. But what did he actually discover? Christopher Columbus (also known as (Cristoforo Colombo [Italian]; Cristóbal Colón [Spanish]) was an Italian explorer credited with the “discovery” of the Americas. The purpose for his voyages was to find a passage to Asia by sailing west. Never actually accomplishing this mission, his explorations mostly included the Caribbean and parts of Central and South America, all of which were already inhabited by Native groups.

Biography Early Life Christopher Columbus was born in Genoa, part of present-day Italy, in 1451. His parents’ names were Dominico Colombo and Susanna Fontanarossa. He had three brothers: Bartholomew, Giovanni, and Giacomo; and a sister named Bianchinetta. Christopher became an apprentice in his father’s wool weaving business, but he also studied mapmaking and sailing as well. He eventually left his father’s business to join the Genoese fleet and sail on the Mediterranean Sea. 1 After one of his ships wrecked off the coast of Portugal, he decided to remain there with his younger brother Bartholomew where he worked as a cartographer (mapmaker) and bookseller. Here, he married Doña Felipa Perestrello e Moniz and had two sons Diego and Fernando.

Christopher Columbus owned a copy of Marco Polo’s famous book, and it gave him a love for exploration. In the mid 15th century, Portugal was desperately trying to find a faster trade route to Asia. Exotic goods such as spices, ivory, silk, and gems were popular items of trade. However, Europeans often had to travel through the Middle East to reach Asia. At this time, Muslim nations imposed high taxes on European travels crossing through. 2 This made it both difficult and expensive to reach Asia. There were rumors from other sailors that Asia could be reached by sailing west. Hearing this, Christopher Columbus decided to try and make this revolutionary journey himself. First, he needed ships and supplies, which required money that he did not have. He went to King John of Portugal who turned him down. He then went to the rulers of England, and France. Each declined his request for funding. After seven years of trying, he was finally sponsored by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain.

Voyages Principal Voyage Columbus’ voyage departed in August of 1492 with 87 men sailing on three ships: the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María. Columbus commanded the Santa María, while the Niña was led by Vicente Yanez Pinzon and the Pinta by Martin Pinzon. 3 This was the first of his four trips. He headed west from Spain across the Atlantic Ocean. On October 12 land was sighted. He gave the first island he landed on the name San Salvador, although the native population called it Guanahani. 4 Columbus believed that he was in Asia, but was actually in the Caribbean. He even proposed that the island of Cuba was a part of China. Since he thought he was in the Indies, he called the native people “Indians.” In several letters he wrote back to Spain, he described the landscape and his encounters with the natives. He continued sailing throughout the Caribbean and named many islands he encountered after his ship, king, and queen: La Isla de Santa María de Concepción, Fernandina, and Isabella.

It is hard to determine specifically which islands Columbus visited on this voyage. His descriptions of the native peoples, geography, and plant life do give us some clues though. One place we do know he stopped was in present-day Haiti. He named the island Hispaniola. Hispaniola today includes both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. In January of 1493, Columbus sailed back to Europe to report what he found. Due to rough seas, he was forced to land in Portugal, an unfortunate event for Columbus. With relations between Spain and Portugal strained during this time, Ferdinand and Isabella suspected that Columbus was taking valuable information or maybe goods to Portugal, the country he had lived in for several years. Those who stood against Columbus would later use this as an argument against him. Eventually, Columbus was allowed to return to Spain bringing with him tobacco, turkey, and some new spices. He also brought with him several natives of the islands, of whom Queen Isabella grew very fond.

Subsequent Voyages Columbus took three other similar trips to this region. His second voyage in 1493 carried a large fleet with the intention of conquering the native populations and establishing colonies. At one point, the natives attacked and killed the settlers left at Fort Navidad. Over time the colonists enslaved many of the natives, sending some to Europe and using many to mine gold for the Spanish settlers in the Caribbean. The third trip was to explore more of the islands and mainland South America further. Columbus was appointed the governor of Hispaniola, but the colonists, upset with Columbus’ leadership appealed to the rulers of Spain, who sent a new governor: Francisco de Bobadilla. Columbus was taken prisoner on board a ship and sent back to Spain.

On his fourth and final journey west in 1502 Columbus’s goal was to find the “Strait of Malacca,” to try to find India. But a hurricane, then being denied entrance to Hispaniola, and then another storm made this an unfortunate trip. His ship was so badly damaged that he and his crew were stranded on Jamaica for two years until help from Hispaniola finally arrived. In 1504, Columbus and his men were taken back to Spain .

Later Years and Death Columbus reached Spain in November 1504. He was not in good health. He spent much of the last of his life writing letters to obtain the percentage of wealth overdue to be paid to him, and trying to re-attain his governorship status, but was continually denied both. Columbus died at Valladolid on May 20, 1506, due to illness and old age. Even until death, he still firmly believed that he had traveled to the eastern part of Asia.

Legacy Columbus never made it to Asia, nor did he truly discover America. His “re-discovery,” however, inspired a new era of exploration of the American continents by Europeans. Perhaps his greatest contribution was that his voyages opened an exchange of goods between Europe and the Americas both during and long after his journeys. 5 Despite modern criticism of his treatment of the native peoples there is no denying that his expeditions changed both Europe and America. Columbus day was made a federal holiday in 1971. It is recognized on the second Monday of October.

- Fergus Fleming, Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration (New York: Grove Press, 2004), 30.

- Fleming, Off the Map , 30

- William D. Phillips and Carla Rahn Phillips, The Worlds of Christopher Columbus (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 142-143.

- Phillips and Phillips, The Worlds of Christopher Columbus , 155.

- Robin S. Doak, Christopher Columbus: Explorer of the New World (Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2005), 92.

Bibliography

Doak, Robin. Christopher Columbus: Explorer of the New World . Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2005.

Fleming, Fergus. Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration . New York: Grove Press, 2004.

Phillips, William D., and Carla Rahn Phillips. The Worlds of Christopher Columbus . New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Map of Voyages

Click below to view an example of the explorer’s voyages. Use the tabs on the left to view either 1 or multiple journeys at a time, and click on the icons to learn more about the stops, sites, and activities along the way.

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

The Third Voyage of Christopher Columbus

Artem Dunaev / EyeEm / Getty Images

- History Before Columbus

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Caribbean History

- Central American History

- South American History

- Mexican History

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- Ph.D., Spanish, Ohio State University

- M.A., Spanish, University of Montana

- B.A., Spanish, Penn State University

After his famous 1492 voyage of discovery , Christopher Columbus was commissioned to return a second time, which he did with a large-scale colonization effort which departed from Spain in 1493. Although the second journey had many problems, it was considered successful because a settlement was founded: it would eventually become Santo Domingo , capital of the present-day Dominican Republic. Columbus served as governor during his stay in the islands. The settlement needed supplies, however, so Columbus returned to Spain in 1496.

Preparations for the Third Voyage

Columbus reported to the crown upon his return from the New World. He was dismayed to learn that his patrons, Ferdinand and Isabella , would not allow enslaved people from the newly discovered lands to be used as payment. As he had found little gold or precious commodities for which to trade, he had been counting on selling enslaved people to make his voyages lucrative. The King and Queen of Spain allowed Columbus to organize a third trip to the New World with the goal of resupplying the colonists and continuing the search for a new trade route to the Orient.

The Fleet Splits

Upon departure from Spain in May of 1498, Columbus split his fleet of six ships: three would make for Hispaniola immediately to bring desperately needed supplies, while the other three would aim for points south of the already explored Caribbean to search for more land and perhaps even the route to the Orient that Columbus still believed to be there. Columbus himself captained the latter ships, being at heart an explorer and not a governor.

Doldrums and Trinidad

Columbus’ bad luck on the third voyage began almost immediately. After making slow progress from Spain, his fleet hit the doldrums, which is a calm, hot stretch of ocean with little or no wind. Columbus and his men spent several days battling heat and thirst with no wind to propel their ships. After a while, the wind returned and they were able to continue. Columbus veered to the north, because the ships were low on water and he wanted to resupply in the familiar Caribbean. On July 31, they sighted an island, which Columbus named Trinidad. They were able to resupply there and continue exploring.

Sighting South America

For the first two weeks of August 1498, Columbus and his small fleet explored the Gulf of Paria, which separates Trinidad from mainland South America. In the process of this exploration, they discovered the Island of Margarita as well as several smaller islands. They also discovered the mouth of the Orinoco River. Such a mighty freshwater river could only be found on a continent, not an island, and the increasingly religious Columbus concluded that he had found the site of the Garden of Eden. Columbus fell ill around this time and ordered the fleet to head to Hispaniola, which they reached on August 19.

Back in Hispaniola

In the roughly two years since Columbus had been gone, the settlement on Hispaniola had seen some rough times. Supplies and tempers were short and the vast wealth that Columbus had promised settlers while arranging the second voyage had failed to appear. Columbus had been a poor governor during his brief tenure (1494–1496) and the colonists were not happy to see him. The settlers complained bitterly, and Columbus had to hang a few of them in order to stabilize the situation. Realizing that he needed help governing the unruly and hungry settlers, Columbus sent to Spain for assistance. It was also here where Antonio de Montesinos is remembered to have given an impassioned and impactful sermon.

Francisco de Bobadilla

Responding to rumors of strife and poor governance on the part of Columbus and his brothers, the Spanish crown sent Francisco de Bobadilla to Hispaniola in 1500. Bobadilla was a nobleman and a knight of the Calatrava order, and he was given broad powers by the Spanish crown, superseding those of Colombus. The crown needed to rein in the unpredictable Colombus and his brothers, who in addition to being tyrannical governors were also suspected of improperly gathering wealth. In 2005, a document was found in the Spanish archives: it contains first-hand accounts of the abuses of Columbus and his brothers.

Columbus Imprisoned

Bobadilla arrived in August 1500, with 500 men and a handful of native people that Columbus had brought to Spain on a previous voyage to enslave; they were to be freed by royal decree. Bobadilla found the situation as bad as he had heard. Columbus and Bobadilla clashed: because there was little love for Columbus among the settlers, Bobadilla was able to clap him and his brothers in chains and throw them in a dungeon. In October 1500, the three Columbus brothers were sent back to Spain, still in shackles. From getting stuck in the doldrums to being shipped back to Spain as a prisoner, Columbus’ Third Voyage was a fiasco.

Aftermath and Importance

Back in Spain, Columbus was able to talk his way out of trouble: he and his brothers were freed after spending only a few weeks in prison.

After the first voyage, Columbus had been granted a series of important titles and concessions. He was appointed Governor and Viceroy of the newly discovered lands and was given the title of Admiral, which would pass to his heirs. By 1500, the Spanish crown was beginning to regret this decision, as Columbus had proven to be a very poor governor and the lands he had discovered had the potential to be extremely lucrative. If the terms of his original contract were honored, the Columbus family would eventually siphon off a great deal of wealth from the crown.

Although he was freed from prison and most of his lands and wealth were restored, this incident gave the crown the excuse they needed to strip Columbus of some of the costly concessions that they had originally agreed to. Gone were the positions of Governor and Viceroy and the profits were reduced as well. Columbus’ children later fought for the privileges conceded to Columbus with mixed success, and legal wrangling between the Spanish crown and the Columbus family over these rights would continue for some time. Columbus’ son Diego would eventually serve for a time as Governor of Hispaniola due to the terms of these agreements.

The disaster that was the third voyage essentially brought to a close the Columbus Era in the New World. While other explorers, such as Amerigo Vespucci , believed that Columbus had found previously unknown lands, he stubbornly held to the claim that he had found the eastern edge of Asia and that he would soon find the markets of India, China, and Japan. Although many at court believed Columbus to be mad, he was able to put together a fourth voyage , which if anything was a bigger disaster than the third one.

The fall of Columbus and his family in the New World created a power vacuum, and the King and Queen of Spain quickly filled it with Nicolás de Ovando, a Spanish nobleman who was appointed governor. Ovando was a cruel but effective governor who ruthlessly wiped out native settlements and continued the exploration of the New World, setting the stage for the Age of Conquest.

Herring, Hubert. A History of Latin America From the Beginnings to the Present. . New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1962

Thomas, Hugh. Rivers of Gold: The Rise of the Spanish Empire, from Columbus to Magellan. New York: Random House, 2005.

- What Was the Age of Exploration?

- Biography of Christopher Columbus

- The Second Voyage of Christopher Columbus

- Biography of Christopher Columbus, Italian Explorer

- 10 Facts About Christopher Columbus

- The Fourth Voyage of Christopher Columbus

- The First New World Voyage of Christopher Columbus (1492)

- The Truth About Christopher Columbus

- Biography of Juan Ponce de León, Conquistador

- La Navidad: First European Settlement in the Americas

- Where Are the Remains of Christopher Columbus?

- Biography of Bartolomé de Las Casas, Spanish Colonist

- Biography of Vasco Núñez de Balboa, Conquistador and Explorer

- Biography of Hernando Cortez

- Explorers and Discoverers

- The History of Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : October 12

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Columbus reaches the “New World”

After sailing across the Atlantic Ocean, Italian explorer Christopher Columbus sights a Bahamian island on October 12, 1492, believing he has reached East Asia. His expedition went ashore the same day and claimed the land for Isabella and Ferdinand of Spain , who sponsored his attempt to find a western ocean route to China, India, and the fabled gold and spice islands of Asia.

Columbus was born in Genoa, Italy, in 1451. Little is known of his early life, but he worked as a seaman and then a maritime entrepreneur. He became obsessed with the possibility of pioneering a western sea route to Cathay (China), India, and the gold and spice islands of Asia. At the time, Europeans knew no direct sea route to southern Asia, and the route via Egypt and the Red Sea was closed to Europeans by the Ottoman Empire , as were many land routes.

Contrary to popular legend, educated Europeans of Columbus’ day did believe that the world was round, as argued by St. Isidore in the seventh century. However, Columbus, and most others, underestimated the world’s size, calculating that East Asia must lie approximately where North America sits on the globe (they did not yet know that the Pacific Ocean existed).

With only the Atlantic Ocean, he thought, lying between Europe and the riches of the East Indies, Columbus met with King John II of Portugal and tried to persuade him to back his “Enterprise of the Indies,” as he called his plan. He was rebuffed and went to Spain, where he was also rejected at least twice by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. However, after the Spanish conquest of the Moorish kingdom of Granada in January 1492, the Spanish monarchs, flush with victory, agreed to support his voyage.

On August 3, 1492, Columbus set sail from Palos, Spain, with three small ships, the Santa Maria, the Pinta and the Nina . On October 12, the expedition reached land, probably Watling Island in the Bahamas. Later that month, Columbus sighted Cuba, which he thought was mainland China, and in December the expedition landed on Hispaniola, which Columbus thought might be Japan. He established a small colony there with 39 of his men. The explorer returned to Spain with gold, spices, and “Indian” captives in March 1493 and was received with the highest honors by the Spanish court. He was the first European to explore the Americas since the Vikings set up colonies in Greenland and Newfoundland in the 10th century.

During his lifetime, Columbus led a total of four expeditions to the "New World," exploring various Caribbean islands, the Gulf of Mexico, and the South and Central American mainlands, but he never accomplished his original goal—a western ocean route to the great cities of Asia. Columbus died in Spain in 1506 without realizing the scope of what he did achieve: He had discovered for Europe the New World, whose riches over the next century would help make Spain the wealthiest and most powerful nation on earth. He also unleashed centuries of brutal colonization, the transatlantic slave trade and the deaths of millions of Native Americans from murder and disease.

Columbus was honored with a U.S. federal holiday in 1937. Since 1991, many cities, universities and a growing number of states have adopted Indigenous Peoples’ Day , a holiday that celebrates the history and contributions of Native Americans. Not by coincidence, the occasion usually falls on Columbus Day , the second Monday in October, or replaces the holiday entirely. Why replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day? Some argue that the holiday overlooks Columbus' enslavement of Native Americans—while giving him credit for “discovering” a place where people already lived.

Also on This Day in History October | 12

This day in history video: what happened on october 12.

Silent-film star Tom Mix dies in Arizona car wreck

Uss cole attacked by terrorists, the origin of oktoberfest, ussr leads the space race, terrorists kill 202 in bali.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Conscientious objector awarded Medal of Honor

Racial violence breaks out aboard u.s. navy ships, thomas jefferson composes romantic letter, john denver dies in an aircraft accident, al gore wins nobel prize in the wake of "an inconvenient truth", fire rages in minnesota, matthew shepard, victim of anti-gay hate crime, dies, nikita khrushchev allegedly brandishes his shoe at the united nations, robert e. lee dies.

Columbus’ Confusion About the New World

The European discovery of America opened possibilities for those with eyes to see. But Columbus was not one of them

Edmund S. Morgan

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Christopher-Columbus-631.jpg)

In the year 1513, a group of men led by Vasco Núñez de Balboa marched across the Isthmus of Panama and discovered the Pacific Ocean. They had been looking for it—they knew it existed—and, familiar as they were with oceans, they had no difficulty in recognizing it when they saw it. On their way, however, they saw a good many things they had not been looking for and were not familiar with. When they returned to Spain to tell what they had seen, it was not a simple matter to find words for everything.

For example, they had killed a large and ferocious wild animal. They called it a tiger, although there were no tigers in Spain and none of the men had ever seen one before. Listening to their story was Peter Martyr, member of the King's Council of the Indies and possessor of an insatiable curiosity about the new land that Spain was uncovering in the west. How, the learned man asked them, did they know that the ferocious animal was a tiger? They answered "that they knewe it by the spottes, fiercenesse, agilitie, and such other markes and tokens whereby auncient writers have described the Tyger." It was a good answer. Men, confronted with things they do not recognize, turn to the writings of those who have had a wider experience. And in 1513 it was still assumed that the ancient writers had had a wider experience than those who came after them.

Columbus himself had made that assumption. His discoveries posed for him, as for others, a problem of identification. It seemed to be a question not so much of giving names to new lands as of finding the proper old names, and the same was true of the things that the new lands contained. Cruising through the Caribbean, enchanted by the beauty and variety of what he saw, Columbus assumed that the strange plants and trees were strange only because he was insufficiently versed in the writings of men who did know them. "I am the saddest man in the world," he wrote, "because I do not recognize them."

We need not deride Columbus' reluctance to give up the world that he knew from books. Only idiots escape entirely from the world that the past bequeaths. The discovery of America opened a new world, full of new things and new possibilities for those with eyes to see them. But the New World did not erase the Old. Rather, the Old World determined what men saw in the New and what they did with it. What America became after 1492 depended both on what men found there and on what they expected to find, both on what America actually was and on what old writers and old experience led men to think it was, or ought to be or could be made to be.

During the decade before 1492, as Columbus nursed a growing urge to sail west to the Indies—as the lands of China, Japan and India were then known in Europe—he was studying the old writers to find out what the world and its people were like. He read the Ymago Mundi of Pierre d'Ailly, a French cardinal who wrote in the early 15th century, the travels of Marco Polo and of Sir John Mandeville, Pliny's Natural History and the Historia Rerum Ubique Gestarum of Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini (Pope Pius II). Columbus was not a scholarly man. Yet he studied these books, made hundreds of marginal notations in them and came out with ideas about the world that were characteristically simple and strong and sometimes wrong, the kind of ideas that the self-educated person gains from independent reading and clings to in defiance of what anyone else tries to tell him.

The strongest one was a wrong one—namely, that the distance between Europe and the eastern shore of Asia was short, indeed, that Spain was closer to China westward than eastward. Columbus never abandoned this conviction. And before he set out to prove it by sailing west from Spain, he studied his books to find out all he could about the lands that he would be visiting. From Marco Polo he learned that the Indies were rich in gold, silver, pearls, jewels and spices. The Great Khan, whose empire stretched from the Arctic to the Indian Ocean, had displayed to Polo a wealth and majesty that dwarfed the splendors of the courts of Europe.

Polo also had things to say about the ordinary people of the Far East. Those in the province of Mangi, where they grew ginger, were averse to war and so had fallen an easy prey to the khan. On Nangama, an island off the coast, described as having "great plentie of spices," the people were far from averse to war: they were anthropophagi—man-eaters—who devoured their captives. There were, in fact, man-eating people in several of the offshore islands, and in many islands both men and women dressed themselves with only a small scrap of cloth over their genitals. On the island of Discorsia, in spite of the fact that they made fine cotton cloth, the people went entirely naked. In one place there were two islands where men and women were segregated, the women on one island, the men on the other.

Marco Polo occasionally slipped into fables like this last one, but most of what he had to say about the Indies was the result of actual observation. Sir John Mandeville's travels, on the other hand, were a hoax—there was no such man—and the places he claimed to have visited in the 1300s were fantastically filled with one-eyed men and one-footed men, dog-faced men and men with two faces or no faces. But the author of the hoax did draw on the reports of enough genuine travelers to make some of his stories plausible, and he also drew on a legend as old as human dreams, the legend of a golden age when men were good. He told of an island where the people lived without malice or guile, without covetousness or lechery or gluttony, wishing for none of the riches of this world. They were not Christians, but they lived by the golden rule. A man who planned to see the Indies for himself could hardly fail to be stirred by the thought of finding such a people.

Columbus surely expected to bring back some of the gold that was supposed to be so plentiful. The spice trade was one of the most lucrative in Europe, and he expected to bring back spices. But what did he propose to do about the people in possession of these treasures?

When he set out, he carried with him a commission from the king and queen of Spain, empowering him "to discover and acquire certain islands and mainland in the ocean sea" and to be "Admiral and Viceroy and Governor therein." If the king and Columbus expected to assume dominion over any of the Indies or other lands en route, they must have had some ideas, not only about the Indies but also about themselves, to warrant the expectation. What had they to offer that would make their dominion welcome? Or if they proposed to impose their rule by force, how could they justify such a step, let alone carry it out? The answer is that they had two things: they had Christianity and they had civilization.

Christianity has meant many things to many men, and its role in the European conquest and occupation of America was varied. But in 1492 to Columbus there was probably nothing very complicated about it. He would have reduced it to a matter of corrupt human beings, destined for eternal damnation, redeemed by a merciful savior. Christ saved those who believed in him, and it was the duty of Christians to spread his gospel and thus rescue the heathens from the fate that would otherwise await them.

Although Christianity was in itself a sufficient justification for dominion, Columbus would also carry civilization to the Indies; and this, too, was a gift that he and his contemporaries considered adequate recompense for anything they might take. When people talked about civilization—or civility, as they usually called it—they seldom specified precisely what they meant. Civility was closely associated with Christianity, but the two were not identical. Whereas Christianity was always accompanied by civility, the Greeks and Romans had had civility without Christianity. One way to define civility was by its opposite, barbarism. Originally the word "barbarian" had simply meant "foreigner"—to a Greek someone who was not Greek, to a Roman someone who was not Roman. By the 15th or 16th century, it meant someone not only foreign but with manners and customs of which civil persons disapproved. North Africa became known as Barbary, a 16th-century geographer explained, "because the people be barbarous, not onely in language, but in manners and customs." Parts of the Indies, from Marco Polo's description, had to be civil, but other parts were obviously barbarous: for example, the lands where people went naked. Whatever civility meant, it meant clothes.

But there was a little more to it than that, and there still is. Civil people distinguished themselves by the pains they took to order their lives. They organized their society to produce the elaborate food, clothing, buildings and other equipment characteristic of their manner of living. They had strong governments to protect property, to protect good persons from evil ones, to protect the manners and customs that differentiated civil people from barbarians. The superior clothing, housing, food and protection that attached to civilization made it seem to the European a gift worth giving to the ill-clothed, ill-housed and ungoverned barbarians of the world.

Slavery was an ancient instrument of civilization, and in the 15th century it had been revived as a way to deal with barbarians who refused to accept Christianity and the rule of civilized government. Through slavery they could be made to abandon their bad habits, put on clothes and reward their instructors with a lifetime of work. Throughout the 15th century, as the Portuguese explored the coast of Africa, large numbers of well-clothed sea captains brought civilization to naked savages by carrying them off to the slave markets of Seville and Lisbon.

Since Columbus had lived in Lisbon and sailed in Portuguese vessels to the Gold Coast of Africa, he was not unfamiliar with barbarians. He had seen for himself that the Torrid Zone could support human life, and he had observed how pleased barbarians were with trinkets on which civilized Europeans set small value, such as the little bells that falconers placed on hawks. Before setting off on his voyage, he laid in a store of hawk's bells. If the barbarous people he expected to find in the Indies should think civilization and Christianity an insufficient reward for submission to Spain, perhaps hawk's bells would help.

Columbus sailed from Palos de la Frontera on Friday, August 3, 1492, reached the Canary Islands six days later and stayed there for a month to finish outfitting his ships. He left on September 6, and five weeks later, in about the place he expected, he found the Indies. What else could it be but the Indies? There on the shore were the naked people. With hawk's bells and beads he made their acquaintance and found some of them wearing gold nose plugs. It all added up. He had found the Indies. And not only that. He had found a land over which he would have no difficulty in establishing Spanish dominion, for the people showed him an immediate veneration. He had been there only two days, coasting along the shores of the islands, when he was able to hear the natives crying in loud voices, "Come and see the men who have come from heaven; bring them food and drink." If Columbus thought he was able to translate the language in two days' time, it is not surprising that what he heard in it was what he wanted to hear or that what he saw was what he wanted to see—namely, the Indies, filled with people eager to submit to their new admiral and viceroy.

Columbus made four voyages to America, during which he explored an astonishingly large area of the Caribbean and a part of the northern coast of South America. At every island the first thing he inquired about was gold, taking heart from every trace of it he found. And at Haiti he found enough to convince him that this was Ophir, the country to which Solomon and Jehosophat had sent for gold and silver. Since its lush vegetation reminded him of Castile, he renamed it Española, the Spanish island, which was later Latinized as Hispaniola.

Española appealed to Columbus from his first glimpse of it. From aboard ship it was possible to make out rich fields waving with grass. There were good harbors, lovely sand beaches and fruit-laden trees. The people were shy and fled whenever the caravels approached the shore, but Columbus gave orders "that they should take some, treat them well and make them lose their fear, that some gain might be made, since, considering the beauty of the land, it could not be but that there was gain to be got." And indeed there was. Although the amount of gold worn by the natives was even less than the amount of clothing, it gradually became apparent that there was gold to be had. One man possessed some that had been pounded into gold leaf. Another appeared with a gold belt. Some produced nuggets for the admiral. Española accordingly became the first European colony in America. Although Columbus had formally taken possession of every island he found, the act was mere ritual until he reached Española. Here he began the European occupation of the New World, and here his European ideas and attitudes began their transformation of land and people.

The Arawak Indians of Española were the handsomest people that Columbus had encountered in the New World and so attractive in character that he found it hard to praise them enough. "They are the best people in the world," he said, "and beyond all the mildest." They cultivated a bit of cassava for bread and made a bit of cottonlike cloth from the fibers of the gossampine tree. But they spent most of the day like children idling away their time from morning to night, seemingly without a care in the world. Once they saw that Columbus meant them no harm, they outdid one another in bringing him anything he wanted. It was impossible to believe, he reported, "that anyone has seen a people with such kind hearts and so ready to give the Christians all that they possess, and when the Christians arrive, they run at once to bring them everything."

To Columbus the Arawaks seemed like relics of the golden age. On the basis of what he told Peter Martyr, who recorded his voyages, Martyr wrote, "they seeme to live in that golden worlde of the which olde writers speake so much, wherein menne lived simply and innocently without enforcement of lawes, without quarreling, judges and libelles, content onely to satisfie nature, without further vexation for knowledge of things to come."

As the idyllic Arawaks conformed to one ancient picture, their enemies the Caribs conformed to another that Columbus had read of, the anthropophagi. According to the Arawaks, the Caribs, or Cannibals, were man-eaters, and as such their name eventually entered the English language. (This was at best a misrepresentation, which Columbus would soon exploit.) The Caribs lived on islands of their own and met every European approach with poisoned arrows, which men and women together fired in showers. They were not only fierce but, by comparison with the Arawaks, also seemed more energetic, more industrious and, it might even be said, sadly enough, more civil. After Columbus succeeded in entering one of their settlements on his second voyage, a member of the expedition reported, "This people seemed to us to be more civil than those who were in the other islands we have visited, although they all have dwellings of straw, but these have them better made and better provided with supplies, and in them were more signs of industry."

Columbus had no doubts about how to proceed, either with the lovable but lazy Arawaks or with the hateful but industrious Caribs. He had come to take possession and to establish dominion. In almost the same breath, he described the Arawaks' gentleness and innocence and then went on to assure the king and queen of Spain, "They have no arms and are all naked and without any knowledge of war, and very cowardly, so that a thousand of them would not face three. And they are also fitted to be ruled and to be set to work, to cultivate the land and to do all else that may be necessary, and you may build towns and teach them to go clothed and adopt our customs."

So much for the golden age. Columbus had not yet prescribed the method by which the Arawaks would be set to work, but he had a pretty clear idea of how to handle the Caribs. On his second voyage, after capturing a few of them, he sent them in slavery to Spain, as samples of what he hoped would be a regular trade. They were obviously intelligent, and in Spain they might "be led to abandon that inhuman custom which they have of eating men, and there in Castile, learning the language, they will much more readily receive baptism and secure the welfare of their souls." The way to handle the slave trade, Columbus suggested, was to send ships from Spain loaded with cattle (there were no native domestic animals on Española), and he would return the ships loaded with supposed Cannibals. This plan was never put into operation, partly because the Spanish sovereigns did not approve it and partly because the Cannibals did not approve it. They defended themselves so well with their poisoned arrows that the Spaniards decided to withhold the blessings of civilization from them and to concentrate their efforts on the seemingly more amenable Arawaks.

The process of civilizing the Arawaks got underway in earnest after the Santa Maria ran aground on Christmas Day, 1492, off Caracol Bay. The local leader in that part of Española, Guacanagari, rushed to the scene and with his people helped the Spaniards to salvage everything aboard. Once again Columbus was overjoyed with the remarkable natives. They are, he wrote, "so full of love and without greed, and suitable for every purpose, that I assure your Highnesses that I believe there is no better land in the world, and they are always smiling." While the salvage operations were going on, canoes full of Arawaks from other parts of the island came in bearing gold. Guacanagari "was greatly delighted to see the admiral joyful and understood that he desired much gold." Thereafter it arrived in amounts calculated to console the admiral for the loss of the Santa Maria , which had to be scuttled. He decided to make his permanent headquarters on the spot and accordingly ordered a fortress to be built, with a tower and a large moat.

What followed is a long, complicated and unpleasant story. Columbus returned to Spain to bring the news of his discoveries. The Spanish monarchs were less impressed than he with what he had found, but he was able to round up a large expedition of Spanish colonists to return with him and help exploit the riches of the Indies. At Española the new settlers built forts and towns and began helping themselves to all the gold they could find among the natives. These creatures of the golden age remained generous. But precisely because they did not value possessions, they had little to turn over. When gold was not forthcoming, the Europeans began killing. Some of the natives struck back and hid out in the hills. But in 1495 a punitive expedition rounded up 1,500 of them, and 500 were shipped off to the slave markets of Seville.

The natives, seeing what was in store for them, dug up their own crops of cassava and destroyed their supplies in hopes that the resulting famine would drive the Spaniards out. But it did not work. The Spaniards were sure there was more gold in the island than the natives had yet found, and were determined to make them dig it out. Columbus built more forts throughout the island and decreed that every Arawak of 14 years or over was to furnish a hawk's bell full of gold dust every three months. The various local leaders were made responsible for seeing that the tribute was paid. In regions where gold was not to be had, 25 pounds of woven or spun cotton could be substituted for the hawk's bell of gold dust.

Unfortunately Española was not Ophir, and it did not have anything like the amount of gold that Columbus thought it did. The pieces that the natives had at first presented him were the accumulation of many years. To fill their quotas by washing in the riverbeds was all but impossible, even with continual daily labor. But the demand was unrelenting, and those who sought to escape it by fleeing to the mountains were hunted down with dogs taught to kill. A few years later Peter Martyr was able to report that the natives "beare this yoke of servitude with an evill will, but yet they beare it."

The tribute system, for all its injustice and cruelty, preserved something of the Arawaks' old social arrangements: they retained their old leaders under control of the king's viceroy, and royal directions to the viceroy might ultimately have worked some mitigation of their hardships. But the Spanish settlers of Española did not care for this centralized method of exploitation. They wanted a share of the land and its people, and when their demands were not met they revolted against the government of Columbus. In 1499 they forced him to abandon the system of obtaining tribute through the Arawak chieftains for a new one in which both land and people were turned over to individual Spaniards for exploitation as they saw fit. This was the beginning of the system of repartimientos or encomiendas later extended to other areas of Spanish occupation. With its inauguration, Columbus' economic control of Española effectively ceased, and even his political authority was revoked later in the same year when the king appointed a new governor.

For the Arawaks the new system of forced labor meant that they did more work, wore more clothes and said more prayers. Peter Martyr could rejoice that "so many thousands of men are received to bee the sheepe of Christes flocke." But these were sheep prepared for slaughter. If we may believe Bartolomé de Las Casas, a Dominican priest who spent many years among them, they were tortured, burned and fed to the dogs by their masters. They died from overwork and from new European diseases. They killed themselves. And they took pains to avoid having children. Life was not fit to live, and they stopped living. From a population of 100,000 at the lowest estimate in 1492, there remained in 1514 about 32,000 Arawaks in Española. By 1542, according to Las Casas, only 200 were left. In their place had appeared slaves imported from Africa. The people of the golden age had been virtually exterminated.

Why? What is the meaning of this tale of horror? Why is the first chapter of American history an atrocity story? Bartolomé de Las Casas had a simple answer, greed: "The cause why the Spanishe have destroyed such an infinitie of soules, hath been onely, that they have helde it for their last scope and marke to gette golde." The answer is true enough. But we shall have to go further than Spanish greed to understand why American history began this way. The Spanish had no monopoly on greed.

The Indians' austere way of life could not fail to win the admiration of the invaders, for self-denial was an ancient virtue in Western culture. The Greeks and Romans had constructed philosophies and the Christians a religion around it. The Indians, and especially the Arawaks, gave no sign of thinking much about God, but otherwise they seemed to have attained the monastic virtues. Plato had emphasized again and again that freedom was to be reached by restraining one's needs, and the Arawaks had attained impressive freedom.

But even as the Europeans admired the Indians' simplicity, they were troubled by it, troubled and offended. Innocence never fails to offend, never fails to invite attack, and the Indians seemed the most innocent people anyone had ever seen. Without the help of Christianity or of civilization, they had attained virtues that Europeans liked to think of as the proper outcome of Christianity and civilization. The fury with which the Spaniards assaulted the Arawaks even after they had enslaved them must surely have been in part a blind impulse to crush an innocence that seemed to deny the Europeans' cherished assumption of their own civilized, Christian superiority over naked, heathen barbarians.

That the Indians were destroyed by Spanish greed is true. But greed is simply one of the uglier names we give to the driving force of modern civilization. We usually prefer less pejorative names for it. Call it the profit motive, or free enterprise, or the work ethic, or the American way, or, as the Spanish did, civility. Before we become too outraged at the behavior of Columbus and his followers, before we identify ourselves too easily with the lovable Arawaks, we have to ask whether we could really get along without greed and everything that goes with it. Yes, a few of us, a few eccentrics, might manage to live for a time like the Arawaks. But the modern world could not have put up with the Arawaks any more than the Spanish could. The story moves us, offends us, but perhaps the more so because we have to recognize ourselves not in the Arawaks but in Columbus and his followers.

The Spanish reaction to the Arawaks was Western civilization's reaction to the barbarian: the Arawaks answered the Europeans' description of men, just as Balboa's tiger answered the description of a tiger, and being men they had to be made to live as men were supposed to live. But the Arawaks' view of man was something different. They died not merely from cruelty, torture, murder and disease, but also, in the last analysis, because they could not be persuaded to fit the European conception of what they ought to be.

Edmund S. Morgan is a Sterling Professor emeritus at Yale University.

Get the latest Travel & Culture stories in your inbox.

10 Famous Explorers Whose Discoveries Connected the World

From Christopher Columbus to Marco Polo, these celebrated—and controversial—explorers made groundbreaking journeys across the globe.

Some of these explorers, like Christopher Columbus , are both celebrated and vilified today. Others, like Ferdinand Magellan and Francisco Pizarro , were met with violent and untimely deaths. And some, like Marco Polo , failed to received recognition in their lifetime, only to have their discoveries confirmed centuries later.

Learn more about some of the history’s most famous explorers and what they are remembered for today.

Time Period: Late 13 th century Destination: Asia

Marco Polo was a Venetian explorer known for the book The Travels of Marco Polo , which describes his voyage to and experiences in Asia. Polo traveled extensively with his family, journeying from Europe to Asia from 1271 to 1295, remaining in China for 17 of those years. As the years wore on, Polo rose through the ranks, serving as governor of a Chinese city. Later, Kublai Khan appointed him as an official of the Privy Council. At one point, he was the tax inspector in the city of Yanzhou.

Around 1292, he left China, acting as consort along the way to a Mongol princess who was being sent to Persia. In the centuries since his death, Polo has received the recognition that failed to come his way during his lifetime. So much of what he claimed to have seen has been verified by researchers, academics, and other explorers. Even if his accounts came from other travelers he met along the way, Polo’s story has inspired countless other adventurers to set off and see the world.

Christopher Columbus

Time Period: Turn of the 16 th century Destination: Caribbean and South America

Christopher Columbus was an Italian explorer and navigator. Columbus first went to sea as a teenager, participating in several trading voyages in the Mediterranean and Aegean seas. One such voyage, to the island of Khios, in modern-day Greece, brought him the closest he would ever come to Asia.

In 1492, he sailed across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain in the Santa Maria , with the Pinta and the Niña ships alongside, hoping to find a new route to India. Between that year and 1504, he made a total of four voyages to the Caribbean and South America and has been credited—and blamed —for opening up the Americas to European colonization. Columbus died in May 1506, probably from severe arthritis following an infection, still believing he had discovered a shorter route to Asia.

More about Christopher Columbus

Amerigo Vespucci

Time period: turn of the 16 th century destination: south america.

America was named after Amerigo Vespucci , a Florentine navigator and explorer who played a prominent role in exploring the New World.

On May 10, 1497, Vespucci embarked on his first voyage, departing from Cadiz with a fleet of Spanish ships. In May 1499, sailing under the Spanish flag, Vespucci embarked on his next expedition, as a navigator under the command of Alonzo de Ojeda. Crossing the equator, they traveled to the coast of what is now Guyana, where it’s believed that Vespucci left Ojeda and went on to explore the coast of Brazil. During this journey, Vespucci is said to have discovered the Amazon River and Cape St. Augustine.

On his third and most successful voyage, he discovered present-day Rio de Janeiro and Rio de la Plata. Believing he had discovered a new continent, he called South America the New World. In 1507, America was named after him . He died of malaria in Seville, Spain, in February 1512.

More about Amerigo Vespucci

Time Period: Late 15 th century Destination: Canada

John Cabot was a Venetian explorer and navigator known for his 1497 voyage to North America, where he made a British claim to land in Canada, mistaking it for Asia . The precise location of Cabot’s landing is subject to controversy. Some historians believe that Cabot landed at Cape Breton Island or mainland Nova Scotia. Others believe he might have landed at Newfoundland, Labrador, or even Maine.

In February 1498, Cabot was given permission to make a new voyage to North America. The May, he departed from Bristol, England, with five ships and a crew of 300 men. En route, one ship became disabled and sailed to Ireland, while the other four ships continued on. On the journey, Cabot disappeared, and his final days remain a mystery. It’s believed Cabot died sometime in 1499 or 1500, but his fate remains a mystery.

More about John Cabot

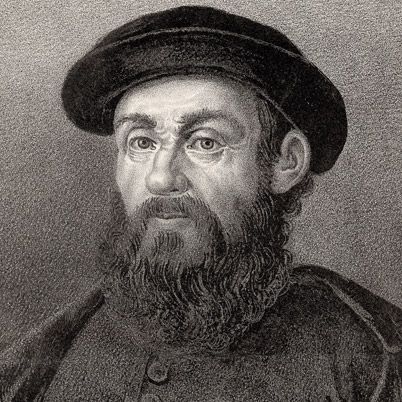

Ferdinand Magellan

Time Period: Early 16 th century Destination: Global circumnavigation

While in the service of Spain, Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan led the first European voyage of discovery to circumnavigate the globe. As a boy, Magellan studied mapmaking and navigation. In 1505, when Magellan was in his mid-20s, he joined a Portuguese fleet that was sailing to East Africa. By 1509, he found himself at the Battle of Diu, in which the Portuguese destroyed Egyptian ships in the Arabian Sea. Two years later, he explored Malacca, located in present-day Malaysia, and participated in the conquest of Malacca’s port.

In 1519, with the support of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (also known as Spain’s King Charles I), Magellan set out to find a better route to the Spice Islands. In March 1521, Magellan’s fleet reached Homonhom Island on the edge of the Philippines with less than 150 of the 270 men who started the expedition. Magellan traded with the island’s king Rajah Humabon, and their bond quickly formed. The Spanish crew soon became involved in a war between Humabon and another rival leader, and Magellan was killed in battle in April 1521.

More about Ferdinand Magellan

Hernán Cortés

Time period: 16 th century destination: central america.

Hernán Cortés was a Spanish conquistador who explored Central America, overthrew Montezuma and his vast Aztec empire, and won Mexico for the crown of Spain. He first set sail to the New World at the age of 19. Cortés later joined an expedition to Cuba.

In 1518, he set off to explore Mexico. Cortés became allies with some of the Indigenous peoples he encountered there, but with others, he used deadly force to conquer Mexico . He fought Tlaxacan and Cholula warriors and then set his sights on taking over the Aztec empire. In their bloody battles for domination over the Aztecs, Cortés and his men are estimated to have killed as many as 100,000 Indigenous peoples. In his role as the Spanish king, Emperor Charles V appointed him the governor of New Spain in 1522.

More about Hernán Cortés

Sir Francis Drake

Time period: late 16 th century destination: global circumnavigation.

English admiral Sir Francis Drake was the second person to circumnavigated the globe and was the most renowned seaman of the Elizabethan era. In 1577, Drake was chosen as the leader of an expedition intended to pass around South America, through the Strait of Magellan, and explore the coast that lay beyond. Drake successfully completed the journey and was knighted by Queen Elizabeth I upon his triumphant return in 1580.

In 1588, Drake saw action in the English defeat of the Spanish Armada , though he died in 1596 from dysentery after undertaking an unsuccessful raiding mission.

More about Francis Drake

Sir Walter Raleigh

Time Period: Late 16 th century Destination: United States

Sir Walter Raleigh was an English explorer, soldier, and writer. At age 17, he fought with the French Huguenots and later studied at Oxford. He became a favorite of Queen Elizabeth I after serving in her army in Ireland. He was knighted in 1585 and, within two years, became captain of the Queen’s Guard.

An early supporter of colonizing North America, Raleigh sought to establish a colony, but the queen initially forbade him to leave her service. Between 1585 to 1588, he invested in a number of expeditions across the Atlantic, attempting to establish a colony near Roanoke, on the coast of what is now North Carolina, and name it “Virginia” in honor of the virgin queen, Elizabeth. Accused of treason by King James I, Raleigh was imprisoned and eventually put to death.

More about Walter Raleigh

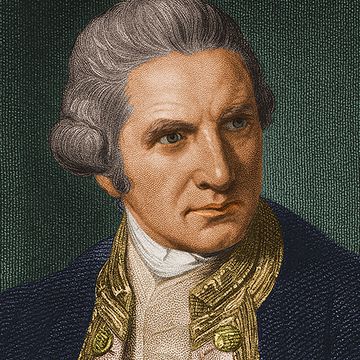

Time Period: Late 18 th century Destination: New Zealand and Australia

James Cook was a naval captain, navigator, and explorer. After serving as an apprentice, Cook eventually joined the British Navy and, at age 29, was promoted to ship’s master. During the Seven Years War that began in 1756, he commanded a captured ship for the Royal Navy. Then, in 1768, he took command of the first scientific expedition to the Pacific.

In 1770, on his ship the HMB Endeavour , Cook charted New Zealand and the Great Barrier Reef of Australia. This area has since been credited as one of the world’s most dangerous areas to navigate . He later disproved the existence of Terra Australis, a fabled southern continent. Cook’s voyages helped guide generations of explorers and provided the first accurate map of the Pacific.

More about James Cook

Francisco Pizarro

Time period: early 16 th century destination: central and south america.

In 1513, Spanish explorer and conquistador Francisco Pizarro joined Vasco Núñez de Balboa in his march to the “South Sea,” across the Isthmus of Panama. During their journey, Balboa and Pizarro discovered what is now known as the Pacific Ocean, though Balboa allegedly spied it first and was therefore credited with the ocean’s first European discovery.

In 1528, Pizarro went back to Spain and managed to procure a commission from Emperor Charles V. Pizarro was to conquer the southern territory and establish a new Spanish province there. In 1532, accompanied by his brothers, Pizarro overthrew the Inca leader Atahualpa and conquered Peru. Three years later, he founded the new capital city of Lima. Over time, tensions increasingly built up between the conquistadors who had originally conquered Peru and those who arrived later to stake some claim in the new Spanish province. This conflict eventually led to Pizarro’s assassination in 1541.

More about Francisco Pizarro

Watch Next .css-avapvh:after{background-color:#525252;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

European Explorers

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Leif Eriksson

Vasco da Gama

Bartolomeu Dias

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Jacques Marquette

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

Self-Paced Courses : Explore American history with top historians at your own time and pace!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

Our Collection

At the Institute’s core is the Gilder Lehrman Collection, one of the great archives in American history. More than 65,000 items cover five hundred years of American history, from Columbus’s 1493 letter describing the New World to soldiers’ letters from World War II and Vietnam. Explore primary sources, visit exhibitions in person or online, or bring your class on a field trip.

At the Institute’s core is the Gilder Lehrman Collection, one of the great archives in American history. More than 85,000 items cover five hundred years of American history, from Columbus’s 1493 letter describing the New World through the end of the twentieth century.

Advanced Search

- Exhibitions

- Spotlighted Resources

- Rights & Reproductions

Morison, Samuel Eliot (1887-1976) Journals and other documents on the life and voyages of Christopher Columbus.

NOT AVAILABLE DIGITALLY Online access and copy requests are not available for this item. If you would like us to notify you when it becomes available digitally, please email us at [email protected] and include the catalog item number.

Gilder Lehrman Collection #: GLC08616 Author/Creator: Morison, Samuel Eliot (1887-1976) Place Written: New York, New York Type: Book Date: 1963 Pagination: 1 v. : xv, 417 p. : illus. col. : maps. ; 31 cm. Order a Copy

Translated and edited by Samuel Eliot Morison. Illustrated by Lima de Freitas. Printed for members of the Limited Editions Club. One of 1500 copies, signed by the artist.

At the time of the first discoveries, Europeans tended to view the New World from one of two contrasting perspectives. Many saw America as an earthly paradise, a land of riches and abundance, where the native peoples led lives of simplicity and freedom similar to those enjoyed by Adam and Eve in the Biblical Garden of Eden. Other Europeans described America in a much more negative light: as a dangerous and forbidding wilderness, a place of cannibalism and human misery, where the population lacked Christian religion and the trappings of civilization. This latter view of America as a place of savagery, cannibalism, and death would grow more pronounced as the Indian population declined precipitously in numbers as a result of harsh labor and the ravages of disease and as the slave trade began transporting millions of Africans to the New World. But it was the positive view of America as a land of liberty, liberation, and material wealth that would remain dominant. America would serve as a screen on which Europeans projected their deepest fantasies of a land where people could escape inherited privilege, corruption, and tradition. The discovery of America seemed to mark a new beginning for humanity, a place where all Old World laws, customs, and doctrines were removed, and where scarcity gave way to abundance. In a letter reporting his discoveries to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain, Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) paints a portrait of the indigenous Taino Indians as living lives of freedom and innocence near the biblical Garden of Eden.

....The people of this island [Hispaniola] and of all the other islands which I have found and seen, or have not seen, all go naked, men and women, as their mothers bore them, except that some women cover one place with the leaf of a plant or with a net of cotton which they make for that purpose. They have no iron or steel or weapons, nor are they capable of using them, although they are well-built people of handsome stature, because they are wondrous timid. They have no other arms than the arms of canes, [cut] when they are in seed time, to the end of which they fix a sharp little stick; and they dare not make use of these, for oftentimes it has happened that I have sent ashore two or three men to some town to have speech, and people without number have come out to them, as soon as they saw them coming, they fled; even a father would not stay for his son; and this was not because wrong had been done to anyone; on the contrary, at every point where I have been and have been able to have speech, I have given them of all that I had, such as cloth and many other things, without receiving anything for it; but they are like that, timid beyond cure. It is true that after they have been reassured and have lost this fear, they are so artless and so free with all they possess, that no one would believe it without having seen it. Of anything they have, if you ask them for it, they never say no; rather they invite the person to share it, and show as much love as if they were giving their hearts; and whether the thing be of value or of small price, at once they are content with whatever little thing of whatever kind may be given to them. I forbade that they should be given things so worthless as pieces of broken crockery and broken glass, and lace points, although when they were able to get them, they thought they had the best jewel in the world.... And they know neither sect nor idolatry, with the exception that all believe that the source of all power and goodness is in the sky, and in this belief they everywhere received me, after they had overcome their fear. And this does not result from their being ignorant (for they are of a very keen intelligence and men who navigate all those seas, so that it is wondrous the good account they give of everything), but because they have never seen people clothed or ships like ours.

Citation Guidelines for Online Resources

Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specific conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law.

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

Home — Essay Samples — History — Christopher Columbus — Christopher Columbus: The Contested Legacy of a Hero

Christopher Columbus: The Contested Legacy of a Hero

- Categories: Christopher Columbus Heroes

About this sample

Words: 643 |

Published: Jun 13, 2024

Words: 643 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

The adventurous spirit, the darker side of exploration, reevaluating heroism.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: History Life

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 877 words

1 pages / 464 words

6 pages / 2701 words

2 pages / 718 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Christopher Columbus

The Columbian Exchange, which occurred following the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Americas in 1492, facilitated the widespread transfer of plants, animals, diseases, and culture between the Eastern and Western [...]

Christopher Columbus, the famed Italian explorer who sailed across the Atlantic Ocean in 1492 in search of a shorter route to Asia, is a figure whose legacy remains deeply contested today. While Columbus's voyages marked the [...]

Christopher Columbus is often celebrated as a pioneering explorer who "discovered" the Americas, leading to an age of exploration and cultural exchange. However, a more nuanced examination of his actions and their consequences [...]

In 1492, Christopher Columbus embarked on a voyage that would forever alter the course of history, leading to the discovery of the Americas. While celebrated for this supposed achievement, the negative effects of Columbus's [...]

Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) was an Italian trader, explorer and navigator. He was born in Genoa, Italy. In 1492, a new world had been founded by this man. Many people in Western of Europe want the shorter way to get to [...]

In the past, European nations ventured to the Americas in pursuit of empire-building and the accumulation of power. This era witnessed fierce competition among European powers, each striving to assert its dominance and enhance [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Christopher Columbus - Audio Biography: The Epic Voyages of an Explorer Embark on a journey through history with "Christopher Columbus - Audio Biography," a captivating podcast that explores the life and legacy of one of the world's most famous explorers. Discover the fascinating story of Christopher Columbus, the Genoese navigator whose voyages across the Atlantic Ocean opened the door to the New World and changed the course of history. Subscribe now to "Christopher Columbus - Audio Biography" on [platforms like Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and Google Podcasts] and set sail on an epic voyage through the life of an explorer who changed the world. Keywords: Christopher Columbus biography, exploration history, New World discovery, Columbus podcast, historical figures, maritime history, voyages of Columbus, historical podcast, biography podcast. for more https://www.quietperiodplease.com/

Christopher Columbus - Audio Biography Biography

- Society & Culture

- MAY 27, 2024

Christopher Columbus Biography

Christopher Columbus, born Cristoforo Colombo in Genoa, Italy, in 1451, is one of the most famous and controversial figures in world history. He is best known for his four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean, which led to the European discovery and colonization of the Americas, a turning point in global history that would have far-reaching consequences for centuries to come. Columbus was born into a middle-class family of wool traders and weavers in the bustling port city of Genoa. His father, Domenico Colombo, was a master weaver and small-time merchant, while his mother, Susanna Fontanarossa, came from a family of weavers. Columbus had three brothers – Bartolomeo, Giovanni Pellegrino, and Giacomo – and a sister named Bianchinetta. As a young boy, Columbus received a basic education in reading, writing, arithmetic, and drawing. He likely attended a school run by the Franciscan order, where he would have been taught Latin, the language of scholars and the Church. From an early age, Columbus showed a keen interest in geography, astronomy, and navigation, subjects that would later become central to his life and career. At the age of 14, Columbus began his maritime career by sailing on Genoese merchant ships in the Mediterranean Sea. He quickly gained experience and expertise in navigation and seamanship, and by his early twenties, he had already sailed as far north as Iceland and as far south as the Gold Coast of Africa. In 1476, Columbus moved to Portugal, which was then a center of maritime exploration and trade. He settled in Lisbon and married Filipa Moniz Perestrelo, the daughter of a prominent Portuguese nobleman and navigator. Through his marriage, Columbus gained access to his father-in-law's charts, journals, and maritime connections, which would later prove invaluable in his own voyages of discovery. In the late 15th century, European merchants and explorers were eagerly seeking new routes to the spice-rich lands of Asia, which were then dominated by Muslim traders. The traditional overland routes, such as the Silk Road, had become increasingly dangerous and expensive due to political instability and the spread of Islam. Meanwhile, the Portuguese were exploring a southern route around Africa, hoping to reach India and the East Indies by sea. Columbus, however, had a different idea. He believed that the shortest and most direct route to Asia was to sail west across the Atlantic Ocean. This idea was based on a number of misconceptions and errors in his calculations. Columbus believed that the Earth was much smaller than it actually is, and that the distance between Europe and Asia was much shorter than it really is. He also believed that there was a large undiscovered landmass between Europe and Asia, which he thought might be the lost continent of Atlantis or the biblical land of Ophir. Despite these errors, Columbus was convinced that his plan was feasible and could bring immense wealth and glory to whoever sponsored his voyage. He spent years trying to persuade various European monarchs to support his plan, including the kings of Portugal, England, and France. However, he was repeatedly rejected and ridiculed for his ideas, which were seen as impractical and even heretical by many of his contemporaries. Finally, in 1492, Columbus was able to secure the support of Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, the rulers of the newly unified Spain. The Spanish monarchs were eager to find new sources of wealth and to spread Christianity to the far corners of the world. They agreed to sponsor Columbus's voyage and granted him the titles of "Admiral of the Ocean Sea" and "Viceroy and Governor of the Indies" in exchange for a share of the profits from any lands he discovered. On August 3, 1492, Columbus set sail from the Spanish port of Palos...

- © Copyright 2024 Quiet. Please

Top Podcasts In Society & Culture

COMMENTS

Captain's ensign of Columbus's ships. For his westward voyage to find a shorter route to the Orient, Columbus and his crew took three medium-sized ships, the largest of which was a carrack (Spanish: nao), the Santa María, which was owned and captained by Juan de la Cosa, and under Columbus's direct command. The other two were smaller caravels; the name of one is lost, but it is known by the ...

The explorer Christopher Columbus made four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain: in 1492, 1493, 1498 and 1502. His most famous was his first voyage, commanding the ships the Nina, the ...

Christopher Columbus (born between August 26 and October 31?, 1451, Genoa [Italy]—died May 20, 1506, Valladolid, Spain) was a master navigator and admiral whose four transatlantic voyages (1492-93, 1493-96, 1498-1500, and 1502-04) opened the way for European exploration, exploitation, and colonization of the Americas. He has long been called the "discoverer" of the New World ...

Columbus's first voyage to America included three ships, the Pinta, the Nina and Santa Maria. When the adventures of Christopher Columbus are studied, the main focus undoubtedly rests on his maiden voyage that occurred in the fall of 1492. The importance of this venture still rings true today, for it was the discovery of the "trade winds" that ...

Christopher Columbus - Exploration, Caribbean, Americas: The gold, parrots, spices, and human captives Columbus displayed for his sovereigns at Barcelona convinced all of the need for a rapid second voyage. Columbus was now at the height of his popularity, and he led at least 17 ships out from Cádiz on September 25, 1493. Colonization and Christian evangelization were openly included this ...

Christopher Columbus (/ k ə ˈ l ʌ m b ə s /; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 - 20 May 1506) was an Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed four Spanish-based voyages across the Atlantic Ocean sponsored by the Catholic Monarchs, opening the way for the widespread European exploration and European colonization of the Americas.

Christopher Columbus, Italian Cristoforo Colombo Spanish Cristóbal Colón, (born between Aug. 26 and Oct. 31?, 1451, Genoa—died May 20, 1506, Valladolid, Spain), Genoese navigator and explorer whose transatlantic voyages opened the way for European exploration, exploitation, and colonization of the Americas.He began his career as a young seaman in the Portuguese merchant marine.