- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Outpatient Therapy: What It Is and Is It Effective?

Dr. Amy Marschall is an autistic clinical psychologist with ADHD, working with children and adolescents who also identify with these neurotypes among others. She is certified in TF-CBT and telemental health.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/HeadShot2-0e5cbea92b2948a1a2013271d90c2d1f.jpg)

Dr. Sabrina Romanoff, PsyD, is a licensed clinical psychologist and a professor at Yeshiva University’s clinical psychology doctoral program.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/SabrinaRomanoffPhoto2-7320d6c6ffcc48ba87e1bad8cae3f79b.jpg)

Alihan Usullu / Getty Images

What Outpatient Therapy Can Help With

- Effectiveness

Things to Consider

How to get started.

Outpatient therapy is defined as any psychotherapy service offered when the client is not admitted to a hospital, residential program, or other inpatient settings. Outpatient therapy is a resource for individuals seeking support for mental health concerns who do not require round-the-clock support or safety monitoring.

Outpatient therapy can be offered through hospitals, in doctor’s offices that employ therapists, group practices, or private practice.

Psychologists, clinical social workers, counselors, and certain medical professionals can offer outpatient therapy . Interns and students working towards degrees or licensure in mental health may also offer outpatient therapy with supervision and oversight from a qualified, licensed professional.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, BetterHelp, and ReGain. Find out which option is the best for you.

Press Play for Advice On What to Do When Therapy Isn't Enough

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast , featuring life coach Mike Bayer, shares other treatment options if you find that therapy isn't enough. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts / Amazon Music

Types of Outpatient Therapy

Outpatient therapy can take many forms , depending on the client’s needs. Individual therapy, group therapy , family therapy, and couple’s therapy can all be provided in an outpatient setting. Sessions can range in frequency, including weekly, twice per week, every other week, and monthly, depending on the individual client’s need and progress in treatment.

Therapists offering outpatient services can practice from many different theoretical orientations depending on the therapist’s personal style and training background. Most orientations taught in clinical and counseling programs can be implemented in an outpatient setting, including:

- Adlerian therapy : A brief therapy approach that emphasizes setting and achieving specific goals, as well as psychoeducation about mental health.

- Behavioral therapy : A form of therapy aimed at changing problem behaviors by reinforcing preferred behaviors.

- Cognitive therapy : A typically short-term therapy approach that explores how one’s thoughts affect feelings and behaviors.

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy : A form of therapy aimed at helping individuals identify the connection between maladaptive thoughts, behaviors, and emotions and make positive changes to these patterns.

- Humanistic therapy : An approach to mental health that helps clients identify their “true self” and determine how to live their most authentic life.

- Psychoanalysis : A long-term talk therapy approach that involves exploring how one’s unconscious mind impacts thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

- Psychodynamic therapy : A long-term therapy approach involving deep exploration and understanding of emotions and thoughts through talk therapy.

- Strengths-based therapy : An approach to therapy that emphasizes clients’ already existing strengths and helps the client identify and use these strengths in their life.

Techniques of Outpatient Therapy

Therapy techniques will vary based on the therapist’s theoretical orientation as well as the client’s individual needs. All orientations include talk therapy , which helps the client articulate their needs and treatment goals and allows the therapist to determine which interventions might be most helpful.

Because outpatient therapy consists of sessions with time in between, many outpatient therapists will assign homework in between sessions. Assignments might include tracking thoughts and emotions, mindfulness or meditation exercises, or trying different communication styles or conflict resolutions.

Because outpatient therapists have the flexibility to pull from a variety of theoretical orientations and techniques, outpatient therapy can help with a wide variety of mental health concerns.

Therapists can use outpatient therapy to help with many diagnoses, including depression , anxiety , trauma , and stress .

Benefits of Outpatient Therapy

Therapy in an outpatient setting allows clients to schedule sessions based on their availability, and they can choose frequency and treatment goals based on their needs and priorities.

Outpatient therapy allows anyone to seek therapy services and support for their mental health while allowing them to live their lives in between sessions. Many clients can continue to work or go to school while receiving outpatient therapy services.

Since many different types of outpatient therapy exist, clients can find a therapist who meets their individual needs and preferences. Outpatient therapy can also be conducted via telehealth , so clients living in rural areas do not have to travel to receive services.

Effectiveness of Outpatient Therapy

“Outpatient therapy” can refer to many different techniques and therapy approaches, which vary in their empirical support and evidence-based data about effectiveness. However, outpatient therapy can reduce an individual’s risk for needing a psychiatric hospitalization or inpatient mental health services.

Research has shown that various outpatient services can provide symptom relief for diagnoses from depression and anxiety to borderline personality disorder . In addition, outpatient therapy is an important resource and support for clients following discharge from the hospital, including improving treatment outcomes and reducing the need for additional hospitalizations.

If you are struggling with your mental health but are able to live independently, outpatient therapy might be a good resource for you.

Individuals who require ongoing therapeutic support, need to be seen daily, or who are unable to live independently may require residential or inpatient treatment. If you experience active suicidal ideation , you might need a higher level of care to ensure your safety.

When exploring options for outpatient therapy, contact your insurance company to get information about your coverage and what therapy services might cost you. You can also talk to your employer about whether you have an Employee Assistance Program that provides a limited number of free sessions.

If you are having suicidal thoughts, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

If you feel like you would benefit from outpatient therapy, you can find a therapist whose training and style fit your needs and preferences.

Your first therapy session will likely include providing information about your personal history, family history, and symptoms. When you first start therapy , it can take time to build trust and rapport with your therapist, and you might find yourself exploring emotions you had not previously addressed. You may also have to try out more than one therapist before you find a provider who is a good fit.

You and your therapist will work together to develop a treatment plan and goals that fit your needs and address your specific symptoms. Starting outpatient therapy can be stressful, but it allows you to continue living your life while you receive support for your mental health needs.

Eskildsen A, Reinholt N, van Bronswijk S, et al. Personalized psychotherapy for outpatients with major depression and anxiety disorders: transdiagnostic versus diagnosis-specific group cognitive behavioural therapy. Cogn Ther Res . 2020;44(5):988-1001.

Ellison WD, Levy KN, Newman MG, Pincus AL, Wilson SJ, Molenaar PCM. Dynamics among borderline personality and anxiety features in psychotherapy outpatients: An exploration of nomothetic and idiographic patterns. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment . 2020;11(2):131-140.

Teixeira C, Rosa RG. Post-intensive care outpatient clinic: is it feasible and effective? A literature review. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Intensiva . 2018;30(1).

By Amy Marschall, PsyD Dr. Amy Marschall is an autistic clinical psychologist with ADHD, working with children and adolescents who also identify with these neurotypes among others. She is certified in TF-CBT and telemental health.

Mental Health-Related Outpatient Visits Among Adolescents and Young Adults, 2006-2019

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

- 2 Department of Psychiatry, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts.

- 3 Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

- 4 Computational Health Informatics Program, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

- 5 Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

- PMID: 38451523

- PMCID: PMC10921253

- DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.1468

Importance: Concerns over the mental health of young people have been increasing over the past decade, especially with the rise in mental health burden seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. Examining trends in mental health-related outpatient visits provides critical information to elucidate contributing factors, identify vulnerable populations, and inform strategies to address the mental health crisis.

Objective: To examine characteristics and trends in mental health-related outpatient visits and psychotropic medication use among US adolescents and young adults.

Design, setting, and participants: A retrospective cross-sectional analysis of nationally representative data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, an annual probability sample survey, was conducted from January 2006 to December 2019. Participants included adolescents (age 12-17 years) and young adults (age 18-24 years) with office-based outpatient visits in the US. Data were analyzed from March 1, 2023, to September 15, 2023.

Main outcomes and measures: Mental health-related outpatient visits were identified based on established sets of diagnostic codes for psychiatric disorders. Temporal trends in the annual proportion of mental health-related outpatient visits were assessed, including visits associated with use of psychotropic medications. Analyses were stratified by age and sex.

Results: From 2006 to 2019, there were an estimated 1.1 billion outpatient visits by adolescents and young adults, of which 145.0 million (13.1%) were associated with a mental health condition (mean [SD] age, 18.4 [3.5] years; 74.0 million females [51.0%]). Mental health-related diagnoses were more prevalent among visits by male (16.8%) compared with female (10.9%) patients (P < .001). This difference was most pronounced among young adults, with 20.1% of visits associated with a psychiatric diagnosis among males vs 10.1% among females (P < .001). The proportion of mental health-related visits nearly doubled, from 8.9% in 2006 to 16.9% in 2019 (P < .001). Among all outpatient visits, 17.2% were associated with the prescription of at least 1 psychotropic medication, with significant increases from 12.8% to 22.4% by 2019 (P < .001).

Conclusions and relevance: In this cross-sectional study, there were substantial increases in mental health-related outpatient visits and use of psychotropic medications, with greater overall burden among male patients. These findings provide a baseline for understanding post-pandemic shifts and suggest that current treatment and prevention strategies will need to address preexisting psychiatric needs in addition to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- COVID-19* / epidemiology

- Cross-Sectional Studies

- Mental Health*

- Outpatients

- Retrospective Studies

- Young Adult

Routine Psychiatric Assessment

- Mental Status Examination |

- More Information |

Patients with mental complaints or concerns or disordered behavior present in a variety of clinical settings, including primary care and emergency treatment centers. Complaints or concerns may be new or a continuation of a history of mental problems. Complaints may be related to coping with a physical condition or be the direct effects of a physical condition on the central nervous system. The method of assessment depends on whether the complaints constitute an emergency or are reported in a scheduled visit. In an emergency, a physician may have to focus on more immediate history, symptoms, and behavior to be able to make a management decision. In a scheduled visit, a more thorough assessment is appropriate.

Routine psychiatric assessment includes a general medical and psychiatric history and a mental status examination. (See also the American Psychiatric Association’s Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults Quick Reference Guide, 3rd Edition and American Psychiatric Association : Practice guideline for the psychiatric evaluation of adults.)

The physician must determine whether the patient can provide a history, ie, whether the patient readily and coherently responds to initial questions. If not, information is sought from family, caregivers, or other collateral sources (eg, police). Even when a patient is communicative, close family members, friends, or caseworkers may provide information that the patient has omitted. Receiving information that is not solicited by the physician does not violate patient confidentiality. Previous psychiatric assessments, treatments, and degree of adherence to past treatments are reviewed, and records from such care are obtained as soon as possible.

Conducting an interview hastily and indifferently with closed-ended queries (following a rigid system review) often prevents patients from revealing relevant information. Tracing the history of the presenting illness with open-ended questions, so that patients can tell their story in their own words, takes a similar amount of time and enables patients to describe associated social circumstances and reveal emotional reactions.

The interview should first explore what prompted the need (or desire) for psychiatric assessment (eg, unwanted or unpleasant thoughts, undesirable behavior), including how much the presenting symptoms affect the patient or interfere with the patient's social, occupational, and interpersonal functioning. The interviewer then attempts to gain a broader perspective on the patient’s personality by reviewing significant life events—current and past—and the patient’s responses to them (see table Areas to Cover in the Initial Psychiatric Assessment ). Psychiatric, medical, social, and developmental histories are also reviewed.

A review of systems to check for other symptoms not described in the psychiatric history is important. Focusing only on the presenting symptoms to the exclusion of past history and other symptoms may result in making an incorrect primary diagnosis (and thus recommending the wrong treatment) and missing other psychiatric or medical comorbidities. For example, not asking about past manic episodes in a patient presenting with depression could result in making an incorrect diagnosis of major depressive disorder instead of bipolar disorder. Review of systems and past medical history should include questions about new or recent physical symptoms, diagnoses, and current drugs and treatments to identify potential physical causes of mental symptoms (eg, COVID-19 as a possible cause of anxiety or depression).

The personality profile that emerges may suggest traits that are adaptive (eg, openness to experience, conscientiousness) or maladaptive (eg, self-centeredness, dependency, poor tolerance of frustration) and may show the coping mechanisms used. The interview may reveal obsessions (unwanted and distressing thoughts or impulses), compulsions (excessive, repetitive, purposeful behaviors that a person feels driven to do), and delusions (fixed false beliefs that are firmly held despite evidence to the contrary) and may determine whether distress is expressed in physical symptoms (eg, headache, abdominal pain), mental symptoms (eg, phobic behavior, depression), or social behavior (eg, withdrawal, rebelliousness). The patient should also be asked about attitudes regarding psychiatric treatments, including drugs and psychotherapy, so that this information can be incorporated into the treatment plan.

The interviewer should establish whether a physical condition or its treatment is causing or worsening a mental condition (see Medical Assessment of the Patient With Mental Symptoms ). In addition to having direct effects (eg, symptoms, including mental ones), many physical conditions cause enormous stress and require coping mechanisms to withstand the pressures related to the condition. Many patients with severe physical conditions experience some kind of adjustment disorder, and those with underlying mental disorders may become unstable.

Observation during an interview may provide evidence of mental or physical disorders. Body language may reveal evidence of attitudes and feelings denied by the patient. For example, does the patient fidget or pace back and forth despite denying anxiety? Does the patient seem sad despite denying feelings of depression? General appearance may provide clues as well. For example, is the patient clean and well-kept? Is a tremor or facial droop present?

Mental Status Examination

A mental status examination uses observation and questions to evaluate several domains of mental function, including

Emotional expression

Thinking and perception

Cognitive functions

Brief standardized screening questionnaires are available for assessing certain components of the mental status examination, including those specifically designed to assess orientation and memory. Such standardized assessments can be used during a routine office visit to help screen patients; such screening can help identify the most important symptoms and provide a baseline for measuring response to treatment. However, screening questionnaires cannot take the place of a broader, more detailed mental status examination .

General appearance should be assessed for unspoken clues to underlying conditions. For example, patients’ appearance can help determine whether they

Are unable to care for themselves (eg, they appear undernourished, disheveled, or dressed inappropriately for the weather or have significant body odor)

Are unable or unwilling to comply with social norms (eg, they are garbed in socially inappropriate clothing)

Have engaged in substance use or attempted self-harm (eg, they have an odor of alcohol, scars suggesting IV drug abuse or self-inflicted injury)

Speech can be assessed by noting spontaneity, syntax, rate, and volume. A patient with depression may speak slowly and softly, whereas a patient with mania may speak rapidly and loudly. Abnormalities such as dysarthrias and aphasias may indicate a physical cause of mental status changes, such as head injury, stroke, brain tumor, or multiple sclerosis.

Emotional expression can be assessed by asking patients to describe their feelings. The patient’s tone of voice, posture, hand gestures, and facial expressions are all considered. Mood (emotional state reported by the patient) and affect (patient's expression of emotional state as observed by the interviewer) should be assessed. Affect and its range (ie, full vs constricted) should be noted as well as the appropriateness of affect to thought content (eg, patient smiling while discussing a tragic event).

Thinking and perception can be assessed by noticing not only what is communicated but also how it is communicated. Abnormal content may take the form of the following:

Delusions (false, fixed beliefs)

Ideas of reference (notions that everyday occurrences have special meaning or significance personally intended for or directed to the patient)

Obsessions (recurrent, persistent, unwanted, and intrusive thoughts, urges, or images)

The physician can assess whether ideas seem to be linked and goal-directed and whether transitions from one thought to the next are logical. Psychotic or manic patients may have disorganized thoughts or an abrupt flight of ideas.

Cognitive functions include the patient’s

Level of alertness

Attentiveness or concentration

Orientation to person, place, and time

Immediate, short-term, and long-term memory

Abstract reasoning

Abnormalities of cognition most often occur with delirium or dementia or with substance intoxication or withdrawal but can also occur with depression .

More Information

The following is an English-language resource that may be useful. Please note that THE MANUAL is not responsible for the content of this resource.

American Psychiatric Association : Practice guideline for the psychiatric evaluation of adults

Copyright © 2024 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

- Cookie Preferences

- Conclusions

- Article Information

The period 2007-2009 is prior to implementation of the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA), 2010-2013 is the period after implementation of MHPAEA but prior to implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), and 2014-2016 is the period after implementation of many provisions of the ACA. The MHPAEA “prevents group health plans and health insurance issuers that provide mental health or substance use disorder (MH/SUD) benefits from imposing less favorable benefit limitations on those benefits than on medical/surgical benefits.” 4 The ACA requires “that most individual and small employer health insurance plans, including all plans offered through the Health Insurance Marketplace, cover mental health and substance use disorder services.” 5 Pursuant to ACA implementation, 15% of Americans had no insurance in 2013, vs 9% in 2015. 2 If psychiatrists accepted insurance, increased insurance coverage should reduce the percentage of patients who self-pay and the percentage of psychiatrists predominantly paid by patients directly for office-based psychiatric care. Visit-level analysis uses visit-level weights and is based on response of yes to the statement “expected source of payment: self” by the clinician. Physician-level analysis uses clinician-level weights. Metrics are based on a response of “more than 75%” to the question “Roughly what percent of your patient care revenue comes from patient payments?”

See More About

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Others Also Liked

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Benjenk I , Chen J. Trends in Self-payment for Outpatient Psychiatrist Visits. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(12):1305–1307. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2072

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Trends in Self-payment for Outpatient Psychiatrist Visits

- 1 University of Maryland School of Public Health, College Park

Even though insurance coverage for mental health has greatly improved over the last 10 years in the US, 1 , 2 many patients continue to struggle to find psychiatrists willing to accept their insurance and need to pay upfront for their psychiatrist visits. 3 This is a hurdle that many patients cannot surmount, even if a portion of that payment is eventually paid by insurance. This study aimed to explore patterns in self-payment for office-based psychiatric services and changes over time, particularly with the passage of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act and the Affordable Care Act. 4 , 5

This study used 10 years of data (January 2007 through December 2016) from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), 6 which is a random sample of outpatient visits made to a nationally representative random sample of physicians who are nonfederally employed, younger than 85 years, and treating outpatients. Patients seen in hospital units, nursing homes or other extended care institutions, or the patient's home were not included. This dataset also does not include telephone visits. Of note, prior to 2012, the NAMCS included community health centers in their primary sampling frame. Starting in 2012, these were sampled separately. As a result, they are excluded from this analysis.

The study accounted for complex survey design to describe the characteristics of patients who self-paid (submitting either self-payment or upfront payment that the patient later submitted to their insurance for at least partial reimbursement) and clinicians who were reimbursed predominantly (>75%) by self-payment for office-based visits. We also compared payment trends for psychiatrist visits with payment trends for primary care clinician visits using logistic regression with group by time interaction. The NAMCS has a waiver of consent from the National Center for Health Statistics’ Research Ethics Review Board because it used secondary data and posed minimal risk to participants. Institutional review board approval was waived because the NAMCS data set is publicly available. Data analysis was completed from December 2019 to February 2020 with StataIC version 15 (StataCorp), with a significance threshold set at a 2-tailed P < .05.

After we excluded visits to community health centers, there were 16 464 psychiatrist visits in the sample (mean [SE], 20.1 [13.7] visits per psychiatrist), of which 15 790 had expected source of payment information. There were 127 500 primary care visits in the sample (mean [SE], 26.4 [13.4] visits per primary care clinician), of which 119 749 had expected source of payment information. There were 816 psychiatrists in the sample and 750 with information on predominant source of revenue. There were 4842 primary care physicians in the sample and 4294 with information on the predominant source of revenue.

Of the psychiatrist visits, 3445 (21.8%; weighted, 22.0%) were self-paid by patients, compared with 4336 primary care clinician visits (3.6%; weighted, 3.6%). One hundred forty-six psychiatrists (19.5%; weighted, 23.5%) were reimbursed predominantly by self-payment, compared with 69 primary care clinicians (1.6%; weighted, 1.7%).

As shown in the Figure , the percentage of visits to psychiatrists that patients self-paid has trended upward (from 18.5% in 2007-2009 to 26.7% in 2014-2016), while the percentage of visits to primary care clinicians that patients self-paid has trended downward (from 4.1% in 2007-2009 to 2.8% in 2014-2016). The percentage of psychiatrists who work in predominantly self-pay practices has trended upward (from 16.4% in 2007-2009 to 26.4% in 2014-2016), while the percentage of primary care clinicians who work in predominantly self-pay practices has not changed significantly (from 1.5% to 1.7%).

At the visit level, we found that self-payment for psychiatrist visits was significantly more common among white patients (white patients, 3082 of 12 732 [24.2%; weighted, 24.2%]; black patients, 97 of 1191 [8.1%; weighted, 9.7%]; Hispanic patients, 173 of 1193 [14.5%; weighted, 12.2%]; P < .001) and male patients (1587 of 6952 men [22.8%; weighted, 24.5%]; 1858 of 8838 women [21.0%; weighted, 20.2%]; P < .001) and not significantly different across age groups (<18 years, 353 of 2318 individuals [15.2%; weighted, 16.8%]; 18-64 years, 2765 of 11 832 individuals [23.4%; weighted, 23.5%]; >64 years, 327 of 1640 individuals [19.9%; weighted, 19.3%]; P = .08). Self-paid visits were a mean (SE) of 38.3 (1.1) minutes in duration, as opposed to 28.8 (0.7) minutes for visits paid directly by third parties ( P < .001). Patients who were self-paying had a mean (SE) of 18.3 (2.1) visits in the 12 months prior to the current visit compared with 9.4 (0.6) visits for patients with third-party payers ( P < .001).

We found that psychiatrists who are reimbursed predominantly by self-payment were more likely to work in solo practices (mean [SE], 30.5% [2.8%]) than group practices (8.3% [2.3%]; P < .001) and were less likely to care predominantly for pediatric patients (mean [SE], 6.6% [4.3%]) than adult patients (25.4% [2.3%]; P = .01). Compared with those receiving fewer self-payments, psychiatrists reimbursed predominantly by self-payments saw fewer total office-based outpatients per week (mean [SE], 21.0 [0.8] visits vs 15.0 [1.2] visits; P < .001), had a greater mean percentage of white patients (mean [SE], 77.6% [0.1%] vs 87.3% [1.8%]; P < .001), had longer mean appointment times (mean [SE] minutes, 31.6 [0.7] vs 40.5 [1.6]; P < .001), and saw patients more frequently (mean [SE] visits per patient in the last 12 months, 10.3 [0.7] vs 20.4 [2.2]; P < .001) ( Table ).

Despite the small sample of psychiatrists in the NAMCS and the associational design of this study, this study appears to find that many patients continue to self-pay for psychiatrist visits and many psychiatrists continue to only care for patients that can self-pay. Psychiatrists may be more likely to rely on self-payment models than other specialties because of low insurance reimbursement rates, particularly for psychotherapy, as well as a demand for psychiatric services that outstrips supply. Our findings begin to highlight a 2-tiered system for outpatient psychiatrist care, which presents potential issues of health equity. Patients who choose to or must rely on third-party payment for psychiatrist appointments may be receiving only psychopharmacology, while those who can self-pay may be able to receive psychotherapy as well.

Accepted for Publication: May 12, 2020.

Corresponding Author: Ivy Benjenk, BSN, MPH, University of Maryland School of Public Health, 4200 Valley Dr, School of Public Health Building, Ste 2242, Room 3310, College Park, MD 20742 ( [email protected] ).

Published Online: July 15, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2072

Author Contributions: Ms Benjenk had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: All authors.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Benjenk.

Drafting of the manuscript: Benjenk.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Benjenk.

Obtained funding: Chen.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Chen.

Supervision: Chen.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Funding/Support: Dr Chen is supported by grants from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01MD011523) and the National Institute on Aging (1R56AG062315-01).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Inpatient vs. Outpatient Services

At Seven Counties Services, we offer both inpatient and outpatient services. The main difference between these services is if a patient will need to stay overnight at one of our facilities to receive the care they need.

Inpatient

Inpatient care is provided in a facility where you stay overnight, sometimes for several nights, depending on your health condition and needs. During your stay, our dedicated healthcare professionals will be by your side, providing necessary medicine, care, monitoring, and medical treatment. When your doctor decides you are ready for discharge, you will receive comprehensive instructions, including follow-up with your doctor, medication management, and the possibility of receiving outpatient services if needed.

Outpatient

Outpatient care is a service you receive that you don’t have to stay overnight. The benefits of receiving outpatient care are the flexibility and freedom of scheduling appointments, virtual options, and the ability to continue with daily life while receiving treatment. Some examples of services include:

- Mental health services

- Substance use treatment

- Physical therapy

- Appointments and consultations

- Emergency care that doesn’t require hospitalization

- Bloodwork and lab tests

- Attending group or peer support meetings

Support Through Seven Counties Services

Inpatient and outpatient programs, although different from one another, provide effective treatment and ensure you receive the level of care you need. If you or a loved one are facing challenges with mental or behavioral health concerns, Seven Counties Services is here to help. We offer both inpatient and outpatient services for children and adults. Visit sevencounties.org to request an appointment online or call (502) 589-1100.

Reviewed by Kayti Michel LPCC-S, Unit Manager, at Seven Counties Services.

Blog Professional Training Institute Regional Prevention Center Frequently Asked Questions Glossary Trustworthy Sites

Schedule Appointment

Seven Counties Services serves everyone regardless of diagnosis or insurance status. We ensure that getting started on your journey to recovery is as easy as possible. To schedule your first appointment, you can call directly or complete an online appointment request.

Helpful Resources

Educating individuals, parents, caregivers, and the community through specialized content provided by industry-leading experts.

Get Started

Mental Health Substance Use Developmental Schedule Appointment Make a Referral

Quick Links

Patient Portal Pay Bill Online Careers Locations Media Center Contact

Seven Counties Services Newsletter

Funding is in whole or in part from federal, Cabinet for Health and Family Services, or other state and local funds.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 20 November 2021

Adolescent psychiatric outpatient care rapidly switched to remote visits during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Emma M. Savilahti ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5419-0485 1 ,

- Sakari Lintula 1 ,

- Laura Häkkinen 1 ,

- Mauri Marttunen 1 , 2 &

- Niklas Granö 1

BMC Psychiatry volume 21 , Article number: 586 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

1209 Accesses

6 Citations

Metrics details

The COVID-19-pandemic and especially the physical distancing measures drastically changed the conditions for providing outpatient care in adolescent psychiatry.

We investigated the outpatient services of adolescent psychiatry in the Helsinki University Hospital (HUH) from 1/1/2015 until 12/31/2020. We retrieved data from the in-house data software on the number of visits in total and categorized as in-person or remote visits, and analysed the data on a weekly basis. We further analysed these variables grouped according to the psychiatric diagnoses coded for visits. Data on the number of patients and on referrals from other health care providers were available on a monthly basis. We investigated the data descriptively and with a time-series analysis comparing the pre-pandemic period to the period of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The total number of visits decreased slightly at the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in Spring 2020. Remote visits sharply increased starting in 3/2020 and remained at a high level compared with previous years. In-person visits decreased in Spring 2020, but gradually increased afterwards. The number of patients transiently fell in Spring 2020.

Conclusions

Rapid switch to remote visits in outpatient care of adolescent psychiatry made it possible to avoid a drastic drop in the number of visits despite the physical distancing measures during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Peer Review reports

World Health Organization (WHO) declared on 3/11/2020 that the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID-19, had spread to a pandemic. The pandemic with the ensuing physical distancing measures has drastically impacted social life, economic circumstances and personal freedom. Adolescents are especially vulnerable to the disruptions given their dependence on their care-givers and their developmental tasks that may be severed by lack of adequate social, emotional and educational stimuli and support [ 1 , 2 ]. Research on mental health during the pandemic was first published predominantly on adult populations, but data on children and adolescents have begun to emerge. Few studies have, however, reported on how adolescent psychiatric services have adapted to the unprecedented circumstances.

Numerous studies based on self-assessment surveys have reported signs of poor mental health in adult general populations during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic [ 3 , 4 ]. In contrast, a Dutch longitudinal study observed no significant increase in depressive and anxiety symptoms in 3/2020 compared with 11/2019, but did find a slight decrease in symptoms in 6/2020 compared with both previous time points [ 5 ].

Although studies on mental health of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic are far fewer than on adult populations, they have reported nuanced observations. A German nationwide survey of 7–17-year olds showed that compared to pre-pandemic results from another nationwide cohort study, subjects had more mental health problems than before the pandemic based on both their own and their parents’ reporting [ 6 ]. Two studies from the USA observed that mental health symptoms in adolescents increased in Spring 2020 during the first wave of the pandemic and then subsided towards the Summer, when the pandemic and ensuing restrictions eased [ 7 , 8 ]. In a Canadian study on both community and psychiatric clinical populations, the majority (70%) of parents reported in 4–6/2020 that the mental health of their 6–18 year old child had deteriorated with stress related to social isolation, whereas 20% of parents reported improvement in their child’s mental health [ 9 ].

Mental health services are challenged during the pandemic by physical distancing measures as well as potential changes in demand. In contrast to the reports that mental health indicators have deteriorated at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, studies on mental health care have observed sharp decreases in demand of services [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Psychiatric emergency visits in the early stage of the pandemic (Spring 2020) were fewer than before the pandemic according to seven studies recently reviewed [ 11 ] and in a study on children and adolescents (under 18 years of age) with data from ten countries [ 12 ]. In a French study on adults, the proportion of referrals due to psychosis and on involuntary basis increased, whereas visits due to anxiety disorders and first psychiatric contacts were lower than in 3–4/2019 [ 13 ]. In primary health care in the UK in 4/2020, the incidence of depression and anxiety disorders had reduced by nearly half, and the rate of referral to mental health services was less than a quarter compared with expected rates based on data from previous 10 years [ 10 ]. By 9/2020, however, the incidence of several mental health problems had increased to expected levels in England, while elsewhere in the UK rates remained around a third lower than expected [ 10 ]. In secondary mental health care services the overall number of registered patients decreased from 4/2020 to 9/2020 compared with pre-pandemic period, whereas the number of underaged patients slightly increased [ 14 ]. The total number of clinical contacts for underaged patients in Spring 2020 reduced less than for adults, and while in-person visits decreased, remote visits increased [ 14 ].

Our aim was to investigate how adolescent outpatient psychiatric care in Helsinki University Hospital has changed during the pandemic from its onset until the end of year 2020 compared with previous 5 years. We are aware of only one previous study reporting on adolescent outpatient psychiatric care during the pandemic [ 14 ], and no previous studies have, to our knowledge, investigated whether changes in adolescent outpatient psychiatric care differed between diagnostic groups. The extant research on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic provides discordant basis for hypotheses: psychiatric symptoms increased, whereas visits to health care services for psychiatric reasons decreased. Firstly, we hypothesized that the overall number of outpatient visits in adolescent psychiatry dropped during the first lockdown in Spring 2020, consistent with the changes reported in the UK primary health care [ 10 ] and in psychiatric emergency visits in several countries [ 12 , 13 ]. Secondly, we expected visits to increase after Spring 2020 to attain the previous or possibly an even higher level, considering that in specialized adolescent psychiatric services most of the patients suffer from mid- to long-term problems and that other studies indicate that mental health has deteriorated in both adult [ 3 , 4 ] and underage [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ] populations during the pandemic. Thirdly we further expected an increase in remote visits and a decrease in in-person visits during the pandemic especially concomitantly with the lockdown in Spring 2020. Finally, we hypothesized most changes in the number of visits to be in the diagnostic group of depressive and anxiety disorders and least in psychotic disorders due to the severity of these disorders, and based on observations from a French study [ 13 ].

In Finland, the spread of the virus started later than in many other European countries. Finnish health officials recommended physical distancing measures starting in 3/2020. The first lockdown started on 3/16/2020. Primary and secondary schools were operating remotely 3/17–5/13/2020 except for some pupils with special needs. High schools and vocational schools operated remotely from 3/17/2020 until the end of the semester (beginning of June). The second wave in Autumn/Winter 2020–2021 resulted in less severe restrictions. Primary and secondary schools did not move to remote learning, but high schools and vocational schools operated remotely from 11/30/2020 to Spring 2021.

The department of adolescent psychiatry of the Helsinki University Hospital (HUH) is responsible for the publicly funded specialized psychiatric services for 13–17-year old residents ( n = 92,677 in 2020) of the Uusimaa district (population 1.71 million in 2021) in Southern Finland. Due to the physical distancing measures nationally installed to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in Finland, HUH adolescent psychiatry moved to supplying outpatient services predominantly remotely from 3/17/2020 onwards. After the lockdown from 3/16/2020 to 5/13/2020, remote services were still recommended except in emergency situations, but patients had a subjective right to choose in-person visits. Wearing of masks at in-person visits became mandatory in HUH clinics from 9/1/2020 onwards.

The study was approved by the research administrative board of the department of psychiatry at HUH (decision number HUS/153/2021), and conducted at the division of adolescent psychiatry, HUH, Finland. Since we did not gather or analyse any identifiable patient data, review by an ethical board was not necessary.

We investigated outpatient visits and referrals in the division of adolescent psychiatry of HUH from 1/1/2015 until 12/31/2020. We chose to retrieve the data starting on 1/1/2015 in order to have a relatively long reference period preceding the pandemic. We retrieved data from the in-house hospital data software (called HUS Total) on a daily basis on the number of visits in total as well as separately categorized as in-person visit or remote visit (phone calls and video calls over internet) and on a monthly basis on the number of persons in outpatient care.

We further analysed these variables according to the psychiatric diagnoses coded for each visit. Psychiatric diagnoses were coded in the system by clinicians according to ICD-10. For analyses, we combined diagnoses into the following broad four groups: 1) psychotic disorders (F20-F29), 2) depressive and anxiety disorders (“neurotic” F32, F33, F40–48, F93.0, F93.1, F93.2, F93.80, F93.9), 3) ADHD and conduct disorders (F90, F91, F92), and 4) all other psychiatric diagnoses not included in the previous categories. Primary, severe eating disorders in HUH are treated in a specialized unit affiliated to adult psychiatry, and are thus not in the data on adolescent psychiatric outpatient care. Eating disorders in our data are included in the category of other diagnoses. We aggregated the daily data to weekly time series data.

Data on referrals to adolescent psychiatric out-patient care from other health care providers (mostly from primary health care) were available on a monthly basis. The data on referrals did not include referrals or visits to emergency services.

Based on the public statements and regulations of the Finnish government and health care authorities, we defined the start of the COVID-19 pandemic period with widely implemented physical distancing measures at 3/16/2020 and the lockdown period 3/16/2020–5/18/2020.

Data analyses

We investigated the data descriptively and with regression models and time-series analyses with emphasis on comparing the pre-pandemic period (in Finland 1/1/2015–3/15/2020) to the period of the COVID-19 pandemic (from 3/16/2020 until the end of study period 12/31/2020).

The regression analysis of our count data was done using quasi-Poisson regression to account for overdispersion. In the regression models, seasonality was accounted for using flexible cubic splines [ 15 ] (7 evenly distributed internal knots in weekly data, 5 in monthly data, and boundary knots at the first and last week/month of the year), separate dummy -variables were included to account for clearly observed overall inactivity annually during July and in the last week of every year, and possible secular trend by using an integer vector from 1 to the number of weeks/months included in the data [ 16 ].

The hypothesized immediate step-wise change of the COVID-19 lockdown period was modelled by including a dummy variable from 3/16/2020 (or 3/2020 in monthly data) to the end of the year. A separate ascending integer vectorer was included, starting from 5/18/2020 (or 5/2020 in monthly data), to model the hypothesized delayed slope-change after Spring 2020 in the variables of interest [ 15 ]. The validity of the regression models was inspected using autocorrelation functions, partial autocorrelation functions and residual plots. Two-sided significance tests and confidence intervals were calculated for the parameters of interest.

We also made counterfactual predictions based on our estimated models to demonstrate the (estimated) continuation of time series without the effects of COVID-19. All the statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.0.3 [ 17 ].

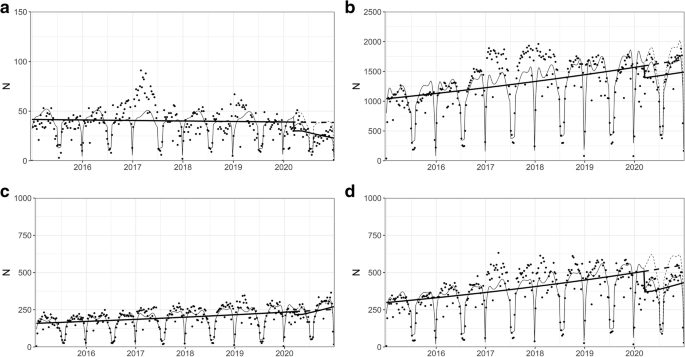

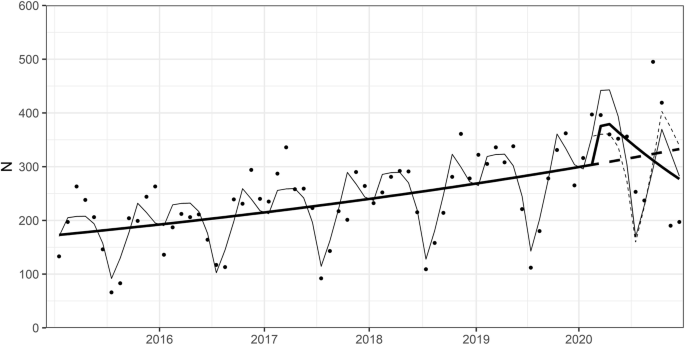

The total number of visits showed a mild decrease in Spring 2020 (step change of − 16, 95% CI -24- -6.4%, p < 0.002), whereas later change in slope was not significant, compared with the predicted counterfactual outcome (Fig. 1 a). In-person visits decreased in Spring 2020 significantly (step change of − 73, 95% CI -77- -68%, p < 0.0001), and after the Spring a significant increase in slope was observed (change with weekly increase of 3.2, 95% CI 2.3–4.1%, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1 b). Remote visits sharply increased starting in 3/2020 (step change of 412, 95% CI 370–460%, p < 0.0001), and after 5/2020, a significant decrease in slope was observed (weekly change of − 2.5, 95% CI -2.9- -2.1%, p < 0.0001); thus, after Summer 2020 remote visits were at a lower level than in Spring, but still at a higher level than predicted based on pre-pandemic data (Fig. 1 c). The portion of remote visits of all outpatient visits was 47% during year 2020, whereas in previous 5 years (2015–2019) it was 10–12% (Online Resource, Fig. S 1 a). Remote visits comprised predominantly of phone calls before the pandemic and at the very early stage of the pandemic (3–4/2020), when they increased significantly (step change of 201, 95% CI 179–225%, p < 0.0001), whereas video calls peaked a little later in Spring 2020 (step change of 469, 95% CI 319–697%, p < 0.0001) (Online Resource, Fig. S 1 b). Both modes of remote visits decreased after Spring 2020 (weekly change for phone calls − 2.3, 95% CI -2.7 - -1.9%, p < 0.0001, and for video calls − 2.4, 95% CI -3.9 - -0.8%, p < 0.003), but remained at a much higher level than in previous years (Online Resource, Fig. S 1 b).

Outpatient visits 2015–2020 (weekly data). a ) The total number of visits. b ) The number of in-person visits. c ) The number of remote visits. The dots denote weekly data points, the fine line denotes the fitted line and the fine dashed line denotes the predicted counterfactual line based on the model (based on data from years 2015–2019). The thick line denotes the trend over time when controlling for seasonality, and the thick dotted line denotes the counterfactual prediction when controlling for seasonality, based on previous 5 years (2015–2019). X-axis shows the time from Jan, 1, 2015 to Dec, 31, 2020, ticks denote the start of each year. Y-axis shows the number of visits

When we stratified the data according to psychiatric diagnoses coded for the visits, the results mainly conformed to the observations in the aggregate data (Fig. 2 a-d). However, in the group of psychotic disorders, the decrease in in-person visits of Spring 2020 was similar, but it was not followed by any significant change in slope unlike in other diagnostic groups (Online Resource, Fig. S 2 a-d). Changes in remote visits were similar in all diagnostic groups and consequently similar to the changes observed in the aggregate data: rapid increase in Spring 2020 and slow gradual decrease afterwards (Online Resource, Fig. S 2 d-f).

Outpatient visits 2015–2020 in different psychiatric diagnostic groups (weekly data). a ) psychotic disorders (F20–29). b ) depressive and anxiety disorders (F32, F33, F40–48, F93.0, F93.1, F93.2, F93.80, F93.9). c ) ADHD and conduct disorders (F90, F91, F92). d ) all other psychiatric diagnoses. The dots denote weekly data points, the fine line denotes the fitted line and the fine dashed line denotes the predicted counterfactual line based on the model (based on data from years 2015–2019). The thick line denotes the trend over time when controlling for seasonality, and the thick dotted line denotes the counterfactual prediction when controlling for seasonality, based on previous 5 years (2015–2019). X-axis shows the time from Jan, 1, 2015 to Dec, 31, 2020, ticks denote the start of each year. Y-axis shows the number of visits. NB. The scale of Y axes varies between figures

The number of subjects in adolescent outpatient care on a monthly basis showed a slight but significant decrease in Spring 2020 (step change of − 10, 95% CI -17- -2.9%, p < 0.01), and no significant change in slope during the rest of the year 2020 (Online Resource, Fig. S 3 ).

Referrals to HUH adolescent psychiatry outpatient clinic from other health care providers (mostly from primary health care) did not significant change in Spring 2020 compared with previous 5 years, but decreased towards the end of 2020 (weekly change of − 4.7, 95% CI -8.8- -0.5%, p = 0.03) (Fig. 3 ).

Referrals to HUH adolescent psychiatry outpatient clinic from other health care providers 2015–2020 (monthly data). The dots denote monthly data points, the fine line denotes the fitted line and the fine dashed line denotes the predicted counterfactual line based on the model (based on data from years 2015–2019). The thick line denotes the trend over time when controlling for seasonality, and the thick dotted line denotes the counterfactual prediction when controlling for seasonality, based on previous 5 years (2015–2019). X-axis shows the time from Jan, 1, 2015 to Dec, 31, 2020, ticks denote the start of each year. Y-axis shows the number of referrals

Our main finding was that the number of visits at HUH adolescent psychiatry outpatient care at the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic only slightly decreased compared with counterfactual prediction based on previous 5 years, as rapid increase in remote visits compensated for the steep drop in in-person visits. After Spring 2020, in-person visits began to gradually increase, but the proportion of remote visits of all visits remained at a higher level than before the pandemic. In-person visits of adolescents with psychosis diagnosis did not, however, show any positive gradual change unlike those observed in the aggregate data and other diagnostic groups.

Our result that the total number of visits slightly decreased at the early stage of the pandemic supported our hypothesis, which was based on the assumption that physical distancing measures would interfere with accessing care and on studies reporting a drop in visits during Spring 2020 in primary mental health care [ 10 ] as well as in psychiatric emergency visits in adults [ 11 ] and in underaged subjects [ 12 ]. The change was, however, much smaller in magnitude than the ones reported in the afore mentioned studies, which is explained by the swift transition to offering care remotely. Similar transition in response to the pandemic was reported in secondary outpatient mental health care in the UK especially among underaged patients [ 14 ]. The rapid transition from in-person to remote psychiatric outpatient care during the pandemic has been predominantly positively received according to a qualitative study that interviewed psychiatrists [ 18 ].

We did not observe any significant increase in visits nor in referrals to adolescent psychiatric outpatient care later during the pandemic, despite many studies reporting increased mental distress during the pandemic in both adult [ 3 , 4 ] and underaged populations [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ] and our consequent hypothesis that demand for adolescent psychiatric care would increase during the second half of year 2020. The current study spans up until the end of the year 2020. One possible explanation is that adolescents and their families do not seek help for mental health issues, or primary health care is not able to properly respond to their needs, until after the acute phase of the pandemic has subsided. All in all, any change in psychiatric morbidity in the general adolescent population often affects the demand for secondary and tertiary care in adolescent psychiatry, which is our study setting, with a lag, and thus the potential effect of the pandemic may not yet appear in our study period. Another perspective is that some longitudinal studies have observed mental health to rebound after the restrictions on everyday life ease both among adults [ 5 ] and adolescents [ 7 , 8 ]. Some parents have even seen their child’s mental health improve during the pandemic [ 9 ], and adults surveyed during a lockdown expressed the situation to entail diverse positive aspects for mental health [ 19 ].

Our observation that outpatient in-person visits gradually returned near to the expected levels after lockdown is in line with data on secondary outpatient mental health care in the UK [ 14 ]. From June, 2020, onwards HUH recommended remote visits in outpatient care, but patients were allowed to opt for in-person visits based on subjective preference. Our result would thus suggest that in-person visits were preferred over remote visits in our study population, contrary to findings of an Australian study where adolescents attending mental health services rated high satisfaction with telehealth and expressed interest in continuing its use after the pandemic [ 20 ]. Research on adult populations shows that telephone and video-delivered synchronous interventions in mental health care are as effective as in-person care [ 21 ], whereas research on adolescents lags behind [ 22 ]. Both quantitative and qualitative research in adolescent populations on remote mental health care addressing issues like the effectiveness of care, participants’ satisfaction and best practices would be most welcome in order to improve the flexibility of services without sacrificing quality.

The result in our study that raises concern and opposes to our hypothesis is that in-person visits of adolescents with a diagnosed psychotic disorder remained at a low level during the pandemic after Spring 2020 contrary to other diagnostic groups. Remote visits in this patient group increased in Spring 2020, but like among most patients, they later gradually decreased. In clinical practice, adolescents with psychosis and their families would need, in the light of our results, more support than other patients in accessing care during a pandemic. Research on adults shows that remote care is feasible and effective in assessing and treating patients with psychosis [ 23 ], but research on underaged patients with psychosis is lacking [ 22 ]. A further research topic could be how adolescents with psychosis, and their families, experience return to in-person visits after a lockdown and what kind of support they might need.

Strength of the study is the relatively long time period of 5 years we compared the pandemic period to, and also the relatively long time span, in comparison to other studies published so far, of the pandemic from the onset until the end of year 2020. A limitation is that the study is based on one organization only, but on the other hand HUH adolescent psychiatry is the largest secondary mental health care unit for adolescents in Finland. The data inevitably reflect some organizational issues such as variation in personnel resources and rare events such as the transition to a new clinical software in 2019–2020. We sought to compensate these limitations with the rather long comparison period of 5 years. The number of visits by adolescents with a psychotic disorder was low and the results are not as robust as in other diagnostic groups with more patients and visits. Our study was set in secondary and tertiary adolescent psychiatric care, and thus not directly comparable to studies on primary or mixed level mental health care. In our statistical analyses, we sought to model the dynamics of the pandemic period by including both step and slope change, but we recognise that interpreting statistical significance of such analyses may be problematic [ 24 ]. Finally, a rapid switch to remote care such as the one we observed requires high level of internet access and acceptability of online services as well as confidence in health care service providers, which are features of the Finnish society. Our results should be compared with caution to observations from societies that differ in these aspects.

Our results demonstrate that mental health services need to be flexible and responsive in how care is delivered in the event of a disruptive and evolving phenomenon such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Special attention should be given to most vulnerable and severely ill patients such as those with a psychotic disorder. Longitudinal studies on mental health outcomes and care reaching over to the post-pandemic period will show whether access to care and effectiveness of (mainly remote) treatments have been sufficient during the pandemic. Given that adolescence is such a critical developmental stage where social relationships are key, both clinical and research efforts need to specifically address this age group during the pandemic and its aftermath.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Coronavirus disease of 2019

Helsinki University Hospital

International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision

World Health Organization

Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, Reynolds S, Shafran R, Brigden A, et al. Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2020;59(11):1218–1239.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009 .

Article Google Scholar

Orben A, Tomova L, Blakemore SJ. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(8):634–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30186-3 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kunzler AM, Röthke N, Günthner L, Stoffers-Winterling J, Tüscher O, Coenen M, et al. Mental burden and its risk and protective factors during the early phase of the SARS- CoV-2 pandemic: systematic review and meta-analyses. Glob Health. 2021;17(1):34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00670-y .

Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, Hatch S, Hotopf M, John A, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7(10):883–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4 .

van der Velden PG, Hyland P, Contino C, von Gaudecker HM, Muffels R, Das M. Anxiety and depression symptoms, the recovery from symptoms, and loneliness before and after the COVID-19 outbreak among the general population: findings from a Dutch population-based longitudinal study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(1):e0245057. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245057 .

Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Erhart M, Devine J, Schlack R, Otto C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2021;25:1–11. Epub ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01726-5 .

Hawes MT, Szenczy AK, Olino TM, Nelson BD, Klein DN. Trajectories of depression, anxiety and pandemic experiences; A longitudinal study of youth in New York during the Spring-Summer of 2020. Psychiatr Res. 2021;298:113778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113778 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Breaux R, Dvorsky MR, Marsh NP, Green CD, Cash AR, Shroff DM, et al. Prospective impact of COVID-19 on mental health functioning in adolescents with and without ADHD: protective role of emotion regulation abilities. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2021;62(9):1132–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13382 .

Cost KT, Crosbie J, Anagnostou E, Birken CS, Charach A, Monga S, et al. Mostly worse, occasionally better: impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2021 Feb;26:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01744-3 .

Carr MJ, Steeg S, Webb RT, Kapur N, Chew-Graham CA, Abel KM, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on primary care-recorded mental illness and self-harm episodes in the UK: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(2):e124–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30288-7 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Munich J, Dennett L, Swainson J, Greenshaw AJ, Hayward J. Impact of pandemics/epidemics on emergency department utilization for mental health and substance use: a rapid review. Front Psychiatr. 2021;12:615000. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.615000 .

Ougrin D, Wong BH, Vaezinejad M, Plener PL, Mehdi T, Romaniuk L, et al. Pandemic-related emergency psychiatric presentations for self-harm of children and adolescents in 10 countries (PREP-kids): a retrospective international cohort study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2021:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01741-6 .

Pignon B, Gourevitch R, Tebeka S, Dubertret C, Cardot H, Dauriac-Le Masson V, et al. Dramatic reduction of psychiatric emergency consultations during lockdown linked to COVID-19 in Paris and suburbs. Psychiatr Clin Neurosci. 2020;74(10):557–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13104 .

Patel R, Irving J, Brinn A, Broadbent M, Shetty H, Pritchard M, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on remote mental healthcare and prescribing in psychiatry: an electronic health record study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e046365. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046365 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bhaskaran K, Gasparrini A, Hajat S, Smeeth L, Armstrong B. Time series regression studies in environmental epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):1187–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt092 .

Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299–309. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. https://www.R-project.org/ . Accessed from Dec 2020 to March 2021

Google Scholar

Uscher-Pines L, Sousa J, Raja P, Mehrotra A, Barnett ML, Huskamp HA. Suddenly becoming a "virtual doctor": experiences of psychiatrists transitioning to telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(11):1143–50. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000250 .

Jenkins M, Hoek J, Jenkin G, Gendall P, Stanley J, Beaglehole B, et al. Silver linings of the COVID-19 lockdown in New Zealand. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(4):e0249678. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249678 .

Nicholas J, Bell IH, Thompson A, Valentine L, Simsir P, Sheppard H, et al. Implementation lessons from the transition to telehealth during COVID-19: a survey of clinicians and young people from youth mental health services. Psychiatr Res. 2021;299:113848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113848 .

Payne L, Flannery H, Kambakara Gedara C, Daniilidi X, Hitchcock M, Lambert D, et al. Business as usual? Psychological support at a distance. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2020;25(3):672–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104520937378 .

Hollis C, Falconer CJ, Martin JL, Whittington C, Stockton S, Glazebrook C, et al. Annual research review: digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems - a systematic and meta-review. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2017;58(4):474–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12663 .

Donahue AL, Rodriguez J, Shore JH. Telemental health and the management of psychosis. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2021;23(5):27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-021-01242-y .

Bernal JL, Soumerai S, Gasparrini A. A methodological framework for model selection in interrupted time series studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;103:82–91.1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.05.026 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Henna Haravuori, Dr. Pekka Närhi and Dr. Klaus Ranta for their valuable contributions that helped in designing the study.

This work was supported by the Helsinki University Hospital Research funding. The funding institution was not involved in any stage of the study i.e. not in the study design, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report nor in the decision to submit an article for publication.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Adolescent Psychiatry, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital, PO BOX 660, 00029 HUS, Helsinki, Finland

Emma M. Savilahti, Sakari Lintula, Laura Häkkinen, Mauri Marttunen & Niklas Granö

Mental Health Unit, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland

Mauri Marttunen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ES, SL, MM and NG contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection and analysis were performed by SL. The first draft of the manuscript was written by ES and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Emma M. Savilahti, MD, PhD, is an adolescent psychiatrist currently working at the adolescent psychiatry unit in HUH and a clinical research scientist at the University of Helsinki. Sakari Lintula, M. Sc, is a clinical psychologist currently working at the adolescent psychiatry unit in HUH. Laura Häkkinen, MD, PhD, is an adolescent psychiatrist currently working as the head of department of the adolescent psychiatry unit in HUH. Mauri Marttunen, MD, PhD, is an adolescent psychiatrist and professor emeritus of adolescent psychiatry at the University of Helsinki. Niklas Granö, PhD, is currently working as the chief psychologist at the adolescent psychiatry unit in HUH and is a research scientist at University of Helsinki.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Emma M. Savilahti .

Ethics declarations

Consent publication.

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable: The manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:.

Fig. S1. Outpatient in person and remote visits on annual level, and division of remote visits to phone calls and video calls. a) Annual number of outpatient visits and the proportion of in-person (blank) and remote (shaded) visits 2015–2020. X-axis shows the year and Y axis the number of visits. b) Remote visits (thick line) comprised of phone calls (dashed line) and online video calls (fine line). X-axis shows the time from Jan, 1, 2015 to Dec, 31, 2020, ticks denote the start of each year. Y-axis shows the number of visits.

Additional file 2:

Fig. S2. Outpatient in person and remote visits 2015–2020 in different psychiatric diagnostic groups. a) In person visits in the group of psychotic disorders (F20–29). b) In person visits in the group of depressive and anxiety disorders (F32, F33, F40–48, F93.0, F93.1, F93.2, F93.80, F93.9). c) In person visits in the group of ADHD and conduct disorders (F90, F91, F92. d) In person visits in the group of all other diagnoses. e) remote visits in the group of psychotic disorders (F20–29). f) remote visits in the group of depressive and anxiety disorders (F32, F33, F40–48, F93.0, F93.1, F93.2, F93.80, F93.9). g) remote visits in the group of ADHD and conduct disorders (F90, F91, F92). h) remote visits in the group of all other diagnoses. The dots denote weekly data points, the fine line denotes the fitted line and the fine dashed line denotes the predicted counterfactual line based on the model (based on data from years 2015–2019). The thick line denotes the trend over time when controlling for seasonality, and the thick dotted line denotes the counterfactual prediction when controlling for seasonality, based on previous 5 years (2015–2019). X-axis shows the time from Jan, 1, 2015 to Dec, 31, 2020, ticks denote the start of each year. Y-axis shows the number of visits. NB. The scale of Y axes varies between figures.

Additional file 3:

Fig. S3. The number of subjects in adolescent outpatient care 2015–2020 (monthly data). The dots denote monthly data points, the fine line denotes the fitted line and the fine dashed line denotes the predicted counterfactual line based on the model (based on data from years 2015–2019). The thick line denotes the trend over time when controlling for seasonality, and the thick dotted line denotes the counterfactual prediction when controlling for seasonality, based on previous 5 years (2015–2019). X-axis shows the time from Jan, 1, 2015 to Dec, 31, 2020, ticks denote the start of each year. Y-axis shows the number of subjects.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Savilahti, E.M., Lintula, S., Häkkinen, L. et al. Adolescent psychiatric outpatient care rapidly switched to remote visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry 21 , 586 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03580-w

Download citation

Received : 24 June 2021

Accepted : 03 November 2021

Published : 20 November 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03580-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.