- Português Br

- Journalist Pass

Alzheimer’s and dementia: Understand wandering and how to address it

Dana Sparks

Share this:

Wandering and becoming lost is common among people with Alzheimer's disease or other disorders causing dementia. This behavior can happen in the early stages of dementia — even if the person has never wandered in the past.

Understand wandering

If a person with dementia is returning from regular walks or drives later than usual or is forgetting how to get to familiar places, he or she may be wandering.

There are many reasons why a person who has dementia might wander, including:

- Stress or fear. The person with dementia might wander as a reaction to feeling nervous in a crowded area, such as a restaurant.

- Searching. He or she might get lost while searching for something or someone, such as past friends.

- Basic needs. He or she might be looking for a bathroom or food or want to go outdoors.

- Following past routines. He or she might try to go to work or buy groceries.

- Visual-spatial problems. He or she can get lost even in familiar places because dementia affects the parts of the brain important for visual guidance and navigation.

Also, the risk of wandering might be higher for men than women.

Prevent wandering

Wandering isn't necessarily harmful if it occurs in a safe and controlled environment. However, wandering can pose safety issues — especially in very hot and cold temperatures or if the person with dementia ends up in a secluded area.

To prevent unsafe wandering, identify the times of day that wandering might occur. Plan meaningful activities to keep the person with dementia better engaged. If the person is searching for a spouse or wants to "go home," avoid correcting him or her. Instead, consider ways to validate and explore the person's feelings. If the person feels abandoned or disoriented, provide reassurance that he or she is safe.

Also, make sure the person's basic needs are regularly met and consider avoiding busy or crowded places.

Take precautions

To keep your loved one safe:

- Provide supervision. Continuous supervision is ideal. Be sure that someone is home with the person at all times. Stay with the person when in a new or changed environment. Don't leave the person alone in a car.

- Install alarms and locks. Various devices can alert you that the person with dementia is on the move. You might place pressure-sensitive alarm mats at the door or at the person's bedside, put warning bells on doors, use childproof covers on doorknobs or install an alarm system that chimes when a door is opened. If the person tends to unlock doors, install sliding bolt locks out of his or her line of sight.

- Camouflage doors. Place removable curtains over doors. Cover doors with paint or wallpaper that matches the surrounding walls. Or place a scenic poster on the door or a sign that says "Stop" or "Do not enter."

- Keep keys out of sight. If the person with dementia is no longer driving, hide the car keys. Also, keep out of sight shoes, coats, hats and other items that might be associated with leaving home.

Ensure a safe return

Wanderers who get lost can be difficult to find because they often react unpredictably. For example, they might not call for help or respond to searchers' calls. Once found, wanderers might not remember their names or where they live.

If you are caring for someone who might wander, inform the local police, your neighbors and other close contacts. Compile a list of emergency phone numbers in case you can't find the person with dementia. Keep on hand a recent photo or video of the person, his or her medical information, and a list of places that he or she might wander to, such as previous homes or places of work.

Have the person carry an identification card or wear a medical bracelet, and place labels in the person's garments. Also, consider enrolling in the MedicAlert and Alzheimer's Association safe-return program. For a fee, participants receive an identification bracelet, necklace or clothing tags and access to 24-hour support in case of emergency. You also might have your loved one wear a GPS or other tracking device.

If the person with dementia wanders, search the immediate area for no more than 15 minutes and then contact local authorities and the safe-return program — if you've enrolled. The sooner you seek help, the sooner the person is likely to be found.

This article is written by Mayo Clinic Staff . Find more health and medical information on mayoclinic.org .

- Answers to common questions about whether vaccines are safe, effective and necessary Consumer Health: Treating and living with HIV and AIDS

Related Articles

Call our 24 hours, seven days a week helpline at 800.272.3900

- Professionals

- Younger/Early-Onset Alzheimer's

- Is Alzheimer's Genetic?

- Women and Alzheimer's

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

- Dementia with Lewy Bodies

- Down Syndrome & Alzheimer's

- Frontotemporal Dementia

- Huntington's Disease

- Mixed Dementia

- Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

- Posterior Cortical Atrophy

- Parkinson's Disease Dementia

- Vascular Dementia

- Korsakoff Syndrome

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

- Know the 10 Signs

- Difference Between Alzheimer's & Dementia

- 10 Steps to Approach Memory Concerns in Others

- Medical Tests for Diagnosing Alzheimer's

- Why Get Checked?

- Visiting Your Doctor

- Life After Diagnosis

- Stages of Alzheimer's

- Earlier Diagnosis

- Part the Cloud

- Research Momentum

- Our Commitment to Research

- TrialMatch: Find a Clinical Trial

- What Are Clinical Trials?

- How Clinical Trials Work

- When Clinical Trials End

- Why Participate?

- Talk to Your Doctor

- Clinical Trials: Myths vs. Facts

- Can Alzheimer's Disease Be Prevented?

- Brain Donation

- Navigating Treatment Options

- Lecanemab Approved for Treatment of Early Alzheimer's Disease

- Aducanumab Discontinued as Alzheimer's Treatment

- Medicare Treatment Coverage

- Donanemab for Treatment of Early Alzheimer's Disease — News Pending FDA Review

- Questions for Your Doctor

- Medications for Memory, Cognition and Dementia-Related Behaviors

- Treatments for Behavior

- Treatments for Sleep Changes

- Alternative Treatments

- Facts and Figures

- Assessing Symptoms and Seeking Help

- Now is the Best Time to Talk about Alzheimer's Together

- Get Educated

- Just Diagnosed

- Sharing Your Diagnosis

- Changes in Relationships

- If You Live Alone

- Treatments and Research

- Legal Planning

- Financial Planning

- Building a Care Team

- End-of-Life Planning

- Programs and Support

- Overcoming Stigma

- Younger-Onset Alzheimer's

- Taking Care of Yourself

- Reducing Stress

- Tips for Daily Life

- Helping Family and Friends

- Leaving Your Legacy

- Live Well Online Resources

- Make a Difference

- Daily Care Plan

- Communication and Alzheimer's

- Food and Eating

- Art and Music

- Incontinence

- Dressing and Grooming

- Dental Care

- Working With the Doctor

- Medication Safety

- Accepting the Diagnosis

- Early-Stage Caregiving

- Middle-Stage Caregiving

- Late-Stage Caregiving

- Aggression and Anger

- Anxiety and Agitation

- Hallucinations

- Memory Loss and Confusion

- Sleep Issues and Sundowning

- Suspicions and Delusions

- In-Home Care

- Adult Day Centers

- Long-Term Care

- Respite Care

- Hospice Care

- Choosing Care Providers

- Finding a Memory Care-Certified Nursing Home or Assisted Living Community

- Changing Care Providers

- Working with Care Providers

- Creating Your Care Team

- Long-Distance Caregiving

- Community Resource Finder

- Be a Healthy Caregiver

- Caregiver Stress

- Caregiver Stress Check

- Caregiver Depression

- Changes to Your Relationship

- Grief and Loss as Alzheimer's Progresses

- Home Safety

- Dementia and Driving

- Technology 101

- Preparing for Emergencies

- Managing Money Online Program

- Planning for Care Costs

- Paying for Care

- Health Care Appeals for People with Alzheimer's and Other Dementias

- Social Security Disability

- Medicare Part D Benefits

- Tax Deductions and Credits

- Planning Ahead for Legal Matters

- Legal Documents

- ALZ Talks Virtual Events

- ALZNavigator™

- Veterans and Dementia

- The Knight Family Dementia Care Coordination Initiative

- Online Tools

- Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and Alzheimer's

- Native Americans and Alzheimer's

- Black Americans and Alzheimer's

- Hispanic Americans and Alzheimer's

- LGBTQ+ Community Resources for Dementia

- Educational Programs and Dementia Care Resources

- Brain Facts

- 50 Activities

- For Parents and Teachers

- Resolving Family Conflicts

- Holiday Gift Guide for Caregivers and People Living with Dementia

- Trajectory Report

- Resource Lists

- Search Databases

- Publications

- Favorite Links

- 10 Healthy Habits for Your Brain

- Stay Physically Active

- Adopt a Healthy Diet

- Stay Mentally and Socially Active

- Online Community

- Support Groups

Find Your Local Chapter

- Any Given Moment

- New IDEAS Study

- Bruce T. Lamb, Ph.D., Chair

- Christopher van Dyck, M.D.

- Cynthia Lemere, Ph.D.

- David Knopman, M.D.

- Lee A. Jennings, M.D. MSHS

- Karen Bell, M.D.

- Lea Grinberg, M.D., Ph.D.

- Malú Tansey, Ph.D.

- Mary Sano, Ph.D.

- Oscar Lopez, M.D.

- Suzanne Craft, Ph.D.

- RFI Amyloid PET Depletion Following Treatment

- About Our Grants

- Andrew Kiselica, Ph.D., ABPP-CN

- Arjun Masurkar, M.D., Ph.D.

- Benjamin Combs, Ph.D.

- Charles DeCarli, M.D.

- Damian Holsinger, Ph.D.

- David Soleimani-Meigooni, Ph.D.

- Donna M. Wilcock, Ph.D.

- Elizabeth Head, M.A, Ph.D.

- Fan Fan, M.D.

- Fayron Epps, Ph.D., R.N.

- Ganesh Babulal, Ph.D., OTD

- Hui Zheng, Ph.D.

- Jason D. Flatt, Ph.D., MPH

- Jennifer Manly, Ph.D.

- Joanna Jankowsky, Ph.D.

- Luis Medina, Ph.D.

- Marcello D’Amelio, Ph.D.

- Marcia N. Gordon, Ph.D.

- Margaret Pericak-Vance, Ph.D.

- María Llorens-Martín, Ph.D.

- Nancy Hodgson, Ph.D.

- Shana D. Stites, Psy.D., M.A., M.S.

- Walter Swardfager, Ph.D.

- ALZ WW-FNFP Grant

- Capacity Building in International Dementia Research Program

- ISTAART IGPCC

- Alzheimer’s Disease Strategic Fund: Endolysosomal Activity in Alzheimer’s (E2A) Grant Program

- Imaging Research in Alzheimer’s and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Zenith Fellow Awards

- National Academy of Neuropsychology & Alzheimer’s Association Funding Opportunity

- Part the Cloud-Gates Partnership Grant Program: Bioenergetics and Inflammation

- Pilot Awards for Global Brain Health Leaders (Invitation Only)

- Robert W. Katzman, M.D., Clinical Research Training Scholarship

- Funded Studies

- How to Apply

- Portfolio Summaries

- Supporting Research in Health Disparities, Policy and Ethics in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia Research (HPE-ADRD)

- Diagnostic Criteria & Guidelines

- Annual Conference: AAIC

- Professional Society: ISTAART

- Alzheimer's & Dementia

- Alzheimer's & Dementia: DADM

- Alzheimer's & Dementia: TRCI

- International Network to Study SARS-CoV-2 Impact on Behavior and Cognition

- Alzheimer’s Association Business Consortium (AABC)

- Global Biomarker Standardization Consortium (GBSC)

- Global Alzheimer’s Association Interactive Network

- International Alzheimer's Disease Research Portfolio

- Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Private Partner Scientific Board (ADNI-PPSB)

- Research Roundtable

- About WW-ADNI

- North American ADNI

- European ADNI

- Australia ADNI

- Taiwan ADNI

- Argentina ADNI

- WW-ADNI Meetings

- Submit Study

- RFI Inclusive Language Guide

- Scientific Conferences

- AUC for Amyloid and Tau PET Imaging

- Make a Donation

- Walk to End Alzheimer's

- The Longest Day

- RivALZ to End ALZ

- Ride to End ALZ

- Tribute Pages

- Gift Options to Meet Your Goals

- Founders Society

- Fred Bernhardt

- Anjanette Kichline

- Lori A. Jacobson

- Pam and Bill Russell

- Gina Adelman

- Franz and Christa Boetsch

- Adrienne Edelstein

- For Professional Advisors

- Free Planning Guides

- Contact the Planned Giving Staff

- Workplace Giving

- Do Good to End ALZ

- Donate a Vehicle

- Donate Stock

- Donate Cryptocurrency

- Donate Gold & Sterling Silver

- Donor-Advised Funds

- Use of Funds

- Giving Societies

- Why We Advocate

- Ambassador Program

- About the Alzheimer’s Impact Movement

- Research Funding

- Improving Care

- Support for People Living With Dementia

- Public Policy Victories

- Planned Giving

- Community Educator

- Community Representative

- Support Group Facilitator or Mentor

- Faith Outreach Representative

- Early Stage Social Engagement Leaders

- Data Entry Volunteer

- Tech Support Volunteer

- Other Local Opportunities

- Visit the Program Volunteer Community to Learn More

- Become a Corporate Partner

- A Family Affair

- A Message from Elizabeth

- The Belin Family

- The Eliashar Family

- The Fremont Family

- The Freund Family

- Jeff and Randi Gillman

- Harold Matzner

- The Mendelson Family

- Patty and Arthur Newman

- The Ozer Family

- Salon Series

- No Shave November

- Other Philanthropic Activities

- Still Alice

- The Judy Fund E-blast Archive

- The Judy Fund in the News

- The Judy Fund Newsletter Archives

- Sigma Kappa Foundation

- Alpha Delta Kappa

- Parrot Heads in Paradise

- Tau Kappa Epsilon (TKE)

- Sigma Alpha Mu

- Alois Society Member Levels and Benefits

- Alois Society Member Resources

- Zenith Society

- Founder's Society

- Joel Berman

- JR and Emily Paterakis

- Legal Industry Leadership Council

- Accounting Industry Leadership Council

Find Local Resources

Let us connect you to professionals and support options near you. Please select an option below:

Use Current Location Use Map Selector

Search Alzheimer’s Association

- Who's at risk?

Reduce the risk of wandering

Take action when wandering occurs, prepare your home, who's at risk for wandering.

- Returning from a regular walk or drive later than usual.

- Forgetting how to get to familiar places.

- Talking about fulfilling former obligations, such as going to work

- Trying or wanting to “go home” even when at home.

- Becoming restless, pacing or making repetitive movements.

- Having difficulty locating familiar places, such as the bathroom, bedroom or dining room.

- Asking the whereabouts of past friends and family.

- Acting as if doing a hobby or chore, but nothing gets done.

- Appearing lost in a new or changed environment.

- Becoming nervous or anxious in crowded areas, such as markets or restaurants.

- Provide opportunities for the person to engage in structured, meaningful activities throughout the day

- Identify the time of day the person is most likely to wander (for those who experience “ sundowning ,” this may be starting in the early evening.) Plan things to do during this time — activities and exercise may help reduce anxiety, agitation and restlessness.

- Ensure all basic needs are met, including toileting, nutrition and hydration. Consider reducing – but not eliminating – liquids up to two hours before bedtime so the person doesn’t have to use and find the bathroom during the night.

- Involve the person in daily activities, such as folding laundry or preparing dinner. Learn about creating a daily plan .

- Reassure the person if he or she feels lost, abandoned or disoriented.

- If the person is still safely able to drive, consider using a GPS device to help if they get lost.

- If the person is no longer driving, remove access to car keys — a person living with dementia may not just wander by foot. The person may forget that he or she can no longer drive.

- Avoid busy places that are confusing and can cause disorientation, such as shopping malls.

- Assess the person’s response to new surroundings. Do not leave someone with dementia unsupervised if new surroundings may cause confusion, disorientation or agitation.

- Decide on a set time each day to check in with each other.

- Review scheduled activities and appointments for the day together.

- If the care partner is not available, identify a companion for the person living with dementia as needed.

- Consider alternative transportation options if getting lost or driving safely becomes a concern.

As the disease progresses and the risk for wandering increases, assess your individual situation to see which of the safety measures below may work best to help prevent wandering.

Home Safety Checklist

Download, print and keep the checklist handy to prevent dangerous situations and help maximize the person living with dementia’s independence for as long as possible.

- Place deadbolts out of the line of sight, either high or low, on exterior doors. (Do not leave a person living with dementia unsupervised in new or changed surroundings, and never lock a person in at home.)

- Use night lights throughout the home.

- Cover door knobs with cloth the same color as the door or use safety covers.

- Camouflage doors by painting them the same color as the walls or covering them with removable curtains or screens.

- Use black tape or paint to create a two-foot black threshold in front of the door. It may act as a visual stop barrier.

- Install warning bells above doors or use a monitoring device that signals when a door is opened.

- Place a pressure-sensitive mat in front of the door or at the person's bedside to alert you to movement.

- Put hedges or a fence around the patio, yard or other outside common areas.

- Use safety gates or brightly colored netting to prevent access to stairs or the outdoors.

- Monitor noise levels to help reduce excessive stimulation.

- Create indoor and outdoor common areas that can be safely explored.

- Label all doors with signs or symbols to explain the purpose of each room.

- Store items that may trigger a person’s instinct to leave, such as coats, hats, pocketbooks, keys and wallets.

- Do not leave the person alone in a car.

- Consider enrolling the person living with dementia in a wandering response service.

- Ask neighbors, friends and family to call if they see the person wandering, lost or dressed inappropriately.

- Keep a recent, close-up photo of the person on hand to give to police, should the need arise.

- Know the person’s neighborhood. Identify potentially dangerous areas near the home, such as bodies of water, open stairwells, dense foliage, tunnels, bus stops and roads with heavy traffic.

- Create a list of places the person might wander to, such as past jobs, former homes, places of worship or a favorite restaurant.

When someone with dementia is missing

Begin search-and-rescue efforts immediately. Many individuals who wander are found within 1.5 miles of where they disappeared.

- Start search efforts immediately. When looking, consider whether the individual is right- or left-handed — wandering patterns generally follow the direction of the dominant hand.

- Begin by looking in the surrounding vicinity — many individuals who wander are found within 1.5 miles of where they disappeared.

- Check local landscapes, such as ponds, tree lines or fence lines — many individuals are found within brush or brier.

- If applicable, search areas the person has wandered to in the past.

- If the person is not found within 15 minutes, call 911 to file a missing person’s report. Inform the authorities that the person has dementia.

Other pages in Stages and Behaviors

- Care Options

- Caregiver Health

- Financial and Legal Planning for Caregivers

Related Pages

Connect with our free, online caregiver community..

Join ALZConnected

Our blog is a place to continue the conversation about Alzheimer's.

Read the Blog

The Alzheimer’s Association is in your community.

Keep up with alzheimer’s news and events.

Diseases & Diagnoses

Issue Index

- Case Reports

Cover Focus | June 2022

Wandering & Sundowning in Dementia

Preventive and acute management of some of the most challenging aspects of dementia is possible..

Taylor Thomas, BA; and Aaron Ritter, MD

Alzheimer disease (AD) and related dementias are complex disorders that affect multiple brain systems, resulting in a wide range of cognitive and behavioral manifestations. The behavioral symptoms often have clinical analogs in idiopathic psychiatric disorders and are frequently referred to as neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) of dementia. Many therapeutic strategies for NPS are borrowed from treatment of idiopathic psychiatric disorders. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) commonly used to treat major depressive disorder may also be prescribed for depressive symptoms in AD. This strategy has been deemed the “therapeutic metaphor” and has shown varying degrees of success in clinical trials. 1

Clinicians face significant challenges, however, when there is no suitable metaphor to guide treatment for behaviors that emerge solely in dementia. This is particularly problematic for 2 of the most burdensome behavioral manifestations of dementia—sundowning (the worsening of symptoms in the late afternoon and early evening) and wandering. Despite being among the most impactful behaviors in dementia, there is very little research evidence to guide therapeutic approaches. This review provides a brief update of the current literature regarding wandering and sundowning in dementia. Using evidence-based approaches from the research literature, where available, and best practices adopted from our own clinical practice when little evidence exists, we outline a practical treatment algorithm that can be used in the clinic when facing either of these common and problematic behaviors.

Wandering Frequency, Consequences & Causes

Wandering is a complex behavioral phenomenon that is frequent in dementia. Approximately 20% of community-dwelling individuals with dementia and 60% of those living in institutionalized settings are reported to wander .2 Most definitions of wandering incorporate a variety of dementia-related locomotion activities, including elopement (ie, attempts to escape), repetitive pacing, and becoming lost. 3 More recently, the term “critical wandering” or “missing incidents” have been used to draw distinctions between elopement and pacing vs wandering and becoming lost. 4 Critical wandering episodes have a high mortality rate of 20%, placing this symptom among the most dangerous behavioral manifestations of dementia. 5

The risk of wandering increases with severity of cognitive impairment, with the highest rate in those with Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) scores of 13 or less. 6 Individuals who frequently wander (ie, multiple times per week) almost always have at least moderate dementia. Few studies have compared wandering rates among people with different types of dementia. 7 Experience from our clinical practice suggests that wandering is most common in AD—where spatial disorientation and amnesia are common clinical features—but can also occur in moderate to advanced stages of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and Lewy body dementia (LBD). The presence of comorbid NPS (eg, severe depression, sleep disorders, and psychosis) may increase the likelihood of wandering. 8

Causes of wandering are not well understood. Some hypothesize wandering emerges from disconnection among brain regions responsible for visuospatial, motor, and memory functions. A positron-emission tomography (PET) study of 342 individuals with AD, 80 of whom were considered wanderers, found a distinct pattern of hypometabolism in the cingulum and supplementary motor areas among wanderers. Correlations between specific brain regions and the type of wandering (eg, pacing, lapping, or random) were also seen. 9

A relatively larger body of research informs psychosocial perspectives on wandering with 3 scenarios identified in which wandering behaviors commonly emerge, including 1) escape from an unfamiliar setting; 2) desire for social interaction; and 3) exercise behavior triggered by restlessness or lack of activity. Other factors that increase wandering behavior include lifelong low ability to tolerate stress, an individual’s belief that they are still employed at a job, and a repeated desire to search for people (eg, dead family members) or places (eg, a home where they no longer reside). 10

Managing Wandering

There is little empiric evidence to inform treatment approaches to wandering in dementia. Nonpharmaceutical interventions that promote “safe walking” instead of aimless wandering are preferred initial approaches. Several “low tech” options with low associated costs and negligible side effects have some evidence for use, including exercise programs, aromatherapy, placing murals and other paintings in front of exit doors, or hiding door handles. 11 More recently, the explosion of discrete and affordable wearable devices that have global positioning system (GPS) tracking ability have significantly expanded the number of “high-tech” options available to address elopement. These include GPS tagging, bed and door alarms, and surveillance systems. Few have been tested in prospective, placebo-controlled studies, however, making it hard to make firm conclusions regarding efficacy. 12 The ethical implications of using these technologies—including potential infringements on privacy, dignity, and autonomy of individuals—are seldom considered in clinical trials or clinical practice. 13

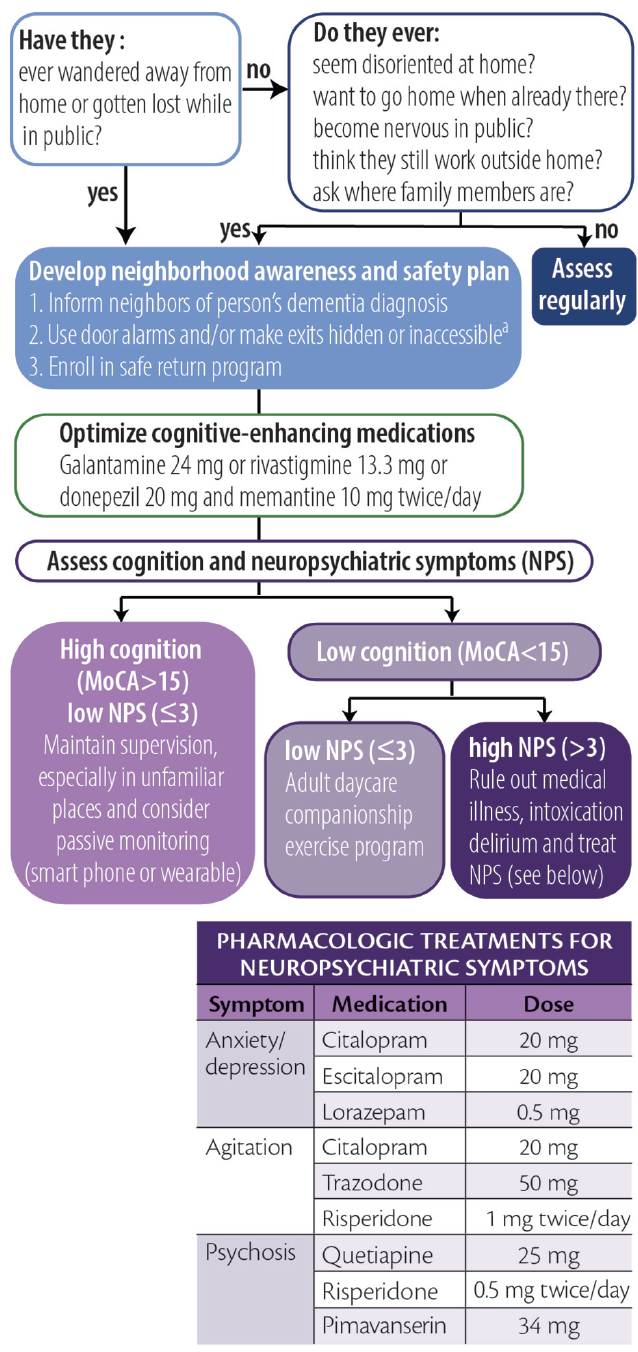

Considering the high prevalence and often deadly consequences associated with wandering, we offer a practical, algorithmic approach to wandering in dementia (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Algorithmic approach to wandering. Abbreviation: MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment. a Persons with dementia should never be left alone behind locked doors.

Click to view larger

Screening for Wandering

To screen for wandering behavior, we ask the following 2 questions of or about all persons with dementia:

1. Have they ever wandered away from their home?

2. Have they ever gotten lost while in public?

If either of these are responded to affirmatively, we make recommendations and stratify risk as described below. If both questions are responded to with “no,” we ask if they:

1. ever seem disoriented at home or in familiar places?

2. ever report a desire to go home even while at home?

3. become excessively nervous while in public?

4. talk about needing to fulfill prior work obligations?

5. ask about the whereabouts of past family or friends?

An affirmative answer to any of these 5 questions may indicate an increased risk for wandering. For those who wander or are at high risk for wandering we provide basic education, recommend increased diligence, and maximize behavioral strategies to improve orientation (eg, display a written calendar and/or a large digital clock with time and date and optimize use of cognitive-enhancing agents when appropriate).

Creating a Wandering Safety Plan

Once a wandering event has occurred, we recommend families develop a neighborhood awareness and safety plan. The Alzheimer’s Association’s website has excellent resources devoted toward developing this plan ( https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/stages-behaviors/wandering ). At a minimum, the safety plan should include notifying neighbors that the person has dementia, keeping a list of places they are likely to wander to, and having a recent photo readily available for emergency medical and other services. We also educate families about the initial steps to take if wandering occurs, including immediately searching areas favoring the direction of the dominant hand, focusing the search within 1.5 miles of the home, and calling 9-1-1 no more than 15 minutes after a person with dementia has been determined to be missing. Additional recommendations include obtaining medical identification jewelry, installing door alarms, and making locks inaccessible (ie, hiding them or placing them out of reach). Families should be encouraged to enroll in a safe return program (eg, MedicAlert, Project Lifesaver, or Silver Alert) if one is available in their area. It is important to note that people with dementia should never be locked by themselves inside a home.

Managing Risk by Stratified Wandering Type

Cluster analyses show people who wander can largely be grouped into 1 of 3 different types based on cognitive and behavioral characteristics. 14 These groupings are useful for tailoring interventions and can be identified for an individual with combined cognitive test scores and behavioral symptom profiles. We use the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) 15 and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Questionnaire (NPI-Q) 16 because they are relatively quick to administer while providing important information and can be simultaneously administered to caregivers (NPI-Q) and patients (MoCA). These assessments can be used to stratify patients as follows.

Group 1: High Cognitive Function, Low Behavioral Disturbances. Individuals who score greater than 15 on the MoCA and have 3 or fewer behavioral symptoms wander infrequently (<1 time/month) and often only in unfamiliar settings. Because wandering is usually triggered by unexpected stressors, the main goal for these individuals is to provide adequate supervision in unfamiliar settings. Those in this group may also still carry a mobile phone with several high-tech options (eg, GPS systems or “find my phone” apps) that may be beneficial.

Group 2: Low Cognitive Function, Low Behavioral Disturbances. Persons with lower cognitive test scores (eg, ≤10 on the MoCA) and fewer than 3 NPS may wander because of boredom or a lack of physical or cognitive stimulation. For this group, we recommend a companion caregiver or adult daycare program to engage the patient in enjoyable activities and incorporate supervised walks or exercise programs during the day. Individuals in this group may benefit from the creation of an outdoor area that may be explored safely.

Group 3: Low Cognitive Function, High Behavioral Disturbances. People in this group require the most proactive approaches because they are likely to be the most frequent wanderers and may be at highest risk for dangerous outcomes. Wandering in this group may be driven by delusions, particularly the persecutory type. 8 We recommend, as a first step, determining whether other factors such as pain, delirium, or intoxication may be contributing to the person’s NPS. If no additional etiologies can be clearly identified, comorbid NPS should be addressed with best clinical practices, borrowing heavily from psychiatry with the “therapeutic metaphor” (See Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Dementia in this issue). Many in this group may require institutionalization or constant supervision from hired caregivers to prevent harm. Nonpharmacologic strategies recommended for this group include taping a 2-foot black threshold in front of each door to serve as a visual barrier, installing cameras and warning alarms for outward facing doors, and installing safety gates around the house.

Sundowning Frequency, Consequences & Causes

Sundowning is the term used to describe the emergence or intensification of NPS occurring in the early evening. This phenomenon, thought to be unique to people with dementia, has long been recognized by researchers and caregivers as being among the most challenging elements of dementia care. 17 Although most frequently seen in AD, sundowning has also frequently been observed in other forms of dementia. Sundowning is among the most common behavioral manifestations of dementia, with rates in institutionalized settings exceeding 80%. 18 The risk of sundowning increases in moderate and severe dementia and because of its close association with sunlight, is more common in the autumn and winter seasons. 19

The impact of sundowning on persons with dementia is immense. Sundowning is among the most common reasons for institutionalization and is associated with faster rates of cognitive decline and increased risk for wandering. 17 Sundowning also increases care partner stress, which, in turn, may increase risk for agitation in patients. 18

The causes of sundowning are likely multifactorial. Sundowning is commonly linked to alterations in circadian rhythms. 19 Autopsy studies of people who had AD show a disproportionate loss of neurons in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which regulates the release of melatonin in response to light. 20 Other research links sundowning to reductions in cholinergic neurotransmission, 21 and at least 1 study showed increased levels of cortisol, which may suggest alterations of the entire hypothalamic-pituitary axis. 21 Sleep disruption, inadequate sunlight exposure, and disrupted routines increase the likelihood of sundowning. 17 Medications with anticholinergic properties and sedatives may also exacerbate sundowning.

Management of Sundowning

The Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold (PLST) model provides a framework for understanding and managing sundowning. 22 In this model, sundowning occurs because diurnal alterations in circadian rhythms temporally correlate with increases in pain, hunger, or fatigue that occur later in the day. Disruptions in emotional regulation emerge when a person’s ability to tolerate such stressors is exceeded.

As with wandering, there is little empiric evidence to guide pharmacologic management of sundowning. Melatonin has been studied in several open-label studies and case series with varying levels of success. 23 Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine reduce agitated behaviors, but have not been studied for management of sundowning. 24 Nonpharmacologic interventions (eg, eliminating daytime naps, increasing sunlight exposure, aerobic exercise, and playing music) can reduce sundowning, 17 but it is difficult to make firm conclusions about the efficacy of these measures because most have not been evaluated in prospective, placebo-controlled studies.

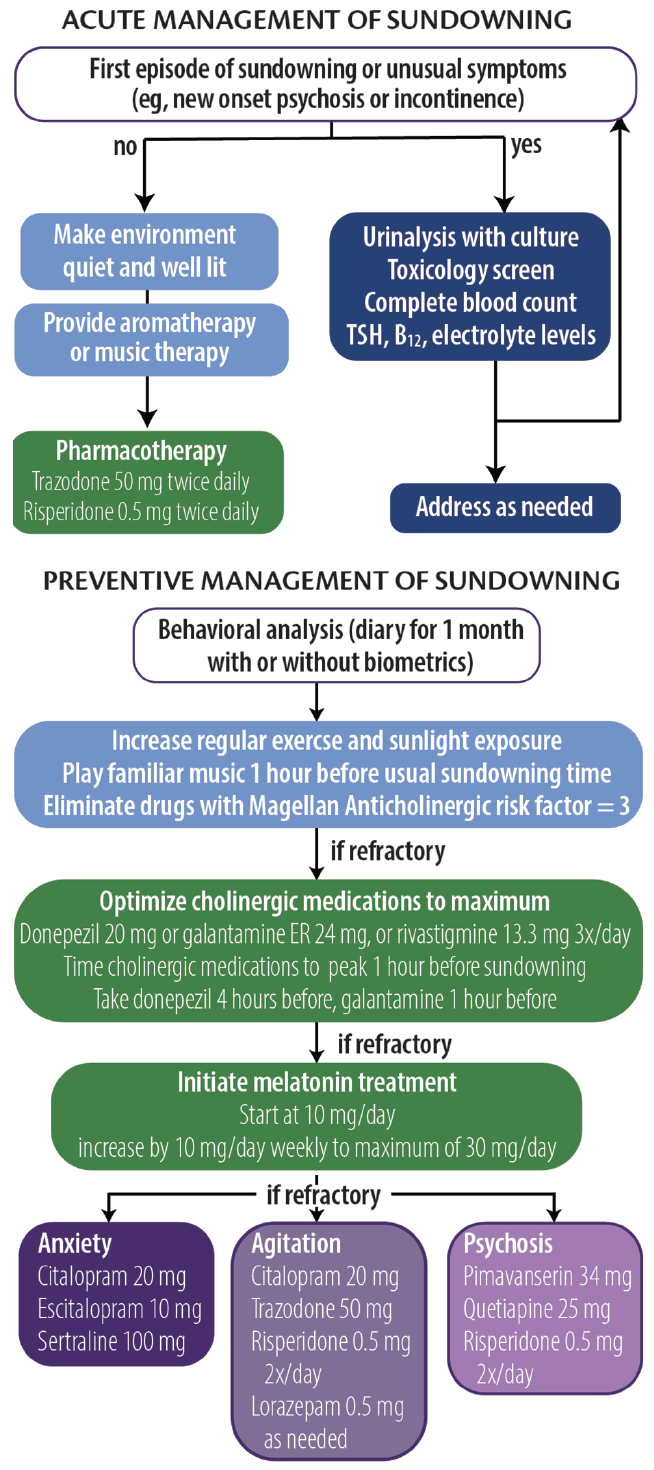

Analogous to headache management, approaches to sundowning can be broadly categorized as acute or preventive (Figure 2). Although preventive approaches may be more effective, caregivers may be able to reduce NPS associated with sundowning when it occurs.

Figure 2. Acute and preventative approaches to sundowning. Abbreviation: TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Acute Management

The PLST model can be used to identify any and all triggers that may contribute to sundowning episodes. For a first or unusual episode, it is recommended that a targeted medical and laboratory evaluation including urine culture, complete blood count, drug toxicology, and levels of electrolytes, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and vitamin B 12 be obtained. During an episode, whenever possible, a quiet, well-lit environment should be provided. Aromatherapy and familiar music at a medium volume may also help reduce anxiety and agitation. For persons at risk of hurting themselves or others, a low-dose psychotropic medication (eg, trazodone 50 mg repeated 1 hour later followed by risperidone 0.5 mg) may be necessary.

Preventive Management

In our clinical experience, prevention strategies may reduce the severity and frequency of sundowning. The first step is to conduct a behavioral analysis of the sundowning behavior. We recommend a daily journal be maintained for at least 1 month to document the types of behavior (eg, agitation, anxiety, psychosis, and disorientation) that occur, time of onset, and any extenuating circumstances that may have contributed to episodes of sundowning. Care partners can also provide information regarding medication administration and sleeping behavior to inform the analysis. The health care professional should analyze the journal, looking for patterns and correlations with other factors (eg, shift changes at care homes or changes to daily routines). The journal can be supported by biometric data from wearable technologies that provide objective measures of physical activity and sleep, which can be helpful in tailoring both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches.

We also recommend increasing the amount of regular exercise and sunlight exposure, preferably in the early afternoon. Caregivers are advised to start playing soothing or familiar music approximately 1 hour before sundowning behavior typically starts. Any medication with Magellan Anticholinergic Risk Scale scores of 3 should be eliminated, which requires scrutiny of medication lists. 25 Optimization of cognitive-enhancing medication doses and timing administration such that mean peak plasma concentrations are reached 1 hour before a person’s typical time of sundowning behavior may be beneficial.

If problematic sundowning behavior still persists, we recommend melatonin supplementation at an initial dose of 10 mg taken at nighttime, followed by a weekly increase by 10 mg to a maximum dose of 30 mg. This regimen is instituted regardless of reported sleep quality. If symptoms persist, the next step is to target NPS based on the individual’s most recent NPI-Q profile. The mantra of “start low and go slow” should guide therapeutic interventions, waiting at least 2 weeks before altering doses. In general, antidepressants are preferred first steps unless safety concerns necessitate more proactive approaches.

1. Cummings J, Ritter A, Rothenberg K. Advances in management of neuropsychiatric syndromes in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Psychiatry Rep . 2019;21(8):79.

2. Cipriani G, Lucetti C, Nuti A, Danti S. Wandering and dementia. Psychogeriatrics . 2014;14(2):135-142.

3. Algase DL, Moore DH, Vandeweerd C, Gavin-Dreschnack DJ. Mapping the maze of terms and definitions in dementia-related wandering. Aging Ment Health . 2007;11(6):686-698.

4. Petonito G, Muschert GW, Carr DC, Kinney JM, Robbins EJ, Brown JS. Programs to locate missing and critically wandering elders: a critical review and a call for multiphasic evaluation. Gerontologist. 2013;53(1):17-25.

5. Rowe MA, Vandeveer SS, Greenblum CA, et al. Persons with dementia missing in the community: is it wandering or something unique? BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:28.

6. Hope T, Keene J, McShane RH, Fairburn CG, Gedling K, Jacoby R. Wandering in dementia: a longitudinal study. Int Psychogeriatr . 2001;13(2):137-147.

7. Ballard CG, Mohan RNC, Bannister C, Handy S, Patel A. Wandering in dementia sufferers. Int J Geriat Psychiatry . 1991;6:611-614.

8. Klein DA, Steinberg M, Galik E, et al. Wandering behaviour in community-residing persons with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry . 1999;14(4):272-279.

9. Yang Y, Kwak YT. FDG PET findings according to wandering patterns of patients with drug-naïve Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Neurocogn Disord . 2018;17(3):90-99.

10. Hope RA, Fairburn CG. The nature of wandering in dementia: a community-based study. Int J Geriat Psychiatry . 1990;5(4):239-245.

11. Neubauer NA, Azad-Khaneghah P, Miguel-Cruz A, Liu L. What do we know about strategies to manage dementia-related wandering? A scoping review. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2018;10:615-628.

12. Neubauer NA, Lapierre N, Ríos-Rincón A, Miguel-Cruz A, Rousseau J, Liu L. What do we know about technologies for dementia-related wandering? A scoping review: Examen de la portée: Que savons-nous à propos des technologies de gestion de l’errance liée à la démence? Can J Occup Ther. 2018;85(3):196-208.

13. O’Neill D. Should patients with dementia who wander be electronically tagged? No. BMJ. 2013;346:f3606.

14. Logsdon RG, Teri L, McCurry SM, Gibbons LE, Kukull WA, Larson EB. Wandering: a significant problem among community-residing individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53(5):P294-P299.

15. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment [published correction appears in J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(9):1991]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

16. Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci . 2000;12(2):233-239.

17. Canevelli M, Valletta M, Trebbastoni A, et al. Sundowning in dementia: clinical relevance, pathophysiological determinants, and therapeutic approaches. Front Med (Lausanne) . 2016;3:73.

18. Gallagher-Thompson D, Brooks JO 3rd, Bliwise D, Leader J, Yesavage JA. The relations among caregiver stress, “sundowning” symptoms, and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(8):807-810.

19. Madden KM, Feldman B. Weekly, seasonal, and geographic patterns in health contemplations about sundown syndrome: an ecological correlational study. JMIR Aging 2019;2(1):e13302. doi:10.2196/13302

20. Wang JL, Lim AS, Chiang WY, et al. Suprachiasmatic neuron numbers and rest-activity circadian rhythms in older humans. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(2):317-322.

21. Weinshenker D. Functional consequences of locus coeruleus degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res . 2008;5(3):342-345.

22. Smith M, Gerdner LA, Hall GR, Buckwalter KC. History, development, and future of the progressively lowered stress threshold: a conceptual model for dementia care. J Am Geriatr Soc . 2004;52(10):1755-1760.

23. Cohen-Mansfield J, Garfinkel D, Lipson S. Melatonin for treatment of sundowning in elderly persons with dementia - a preliminary study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr . 2000;31(1):65-76.

24. Gauthier S, Feldman H, Hecker J, et al. Efficacy of donepezil on behavioral symptoms in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(4):389-404.

25. Rudolph JL, Salow MJ, Angelini MC, McGlinchey RE. The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch Intern Med . 2008;168(5):508-513.

TT reports no disclosures AR's work on this paper was supported by NIGMS P20GM109025

Taylor Thomas, BA

University of Nevada-Las Vegas School of Medicine Las Vegas, NV

Aaron Ritter, MD

Clinical Assistant Professor of Neurology Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health Las Vegas, NV

Treating Dementias With Care Partners in Mind

Dylan Wint, MD

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Dementia

Jeffrey L. Cummings, MD, ScD

This Month's Issue

Nicholas J. Silvestri, MD

Candie Jammal, MD; Iago Pinal-Fernandez, MD, PhD; and Andrew L. Mammen, MD, PhD

Anne Møller Witt, MD; Louise Sloth Kodal, MD; and Tina Dysgaard, MedScD

Related Articles

Abdalmalik Bin Khunayfir, MD; and Brian Appleby, MD

Simon Ducharme, MD, MSc, FRCPC

Sign up to receive new issue alerts and news updates from Practical Neurology®.

Related News

- Older Adults

- Professionals

- Explore NCOA.org

- Get Involved

- Best Hearing Aids

- Best OTC Hearing Aids

- Most Affordable Hearing Aids

- Best Medical Alert Systems

- Best Fall Detection Devices

- Life Alert Review

- Best Portable Oxygen Concentrator

- Best Mattress

- Best Mattress for Back Pain

- Best Adjustable Beds

- Best Walk-In Tubs

Find us on Social

The NCOA Adviser Reviews Team researches these products & services and may earn a commission from qualified purchases made through links included.

The NCOA Adviser Reviews Team researches these products & services and may earn a commission from qualified purchases made through links included. NCOA does not receive a commission for purchases. If you find these resources useful, consider donating to NCOA .

Understanding Wandering Risks With Older Adults

Key takeaways.

- Approximately 36% of people with dementia will wander.

- The top dangers for people who wander include injuries, dehydration, harsh weather exposure, medical complications, drowning, or being hit by a car.

- Understanding and planning for wandering is vital in caring for someone with dementia.

For many of us, staying at home as we age , also known as aging in place, is ideal. In fact, a recent survey shows 90% of adults [1] Gavin, Kara. Michigan News. Most Older Adults Want to ‘Age in Place’ But Many Haven’t Taken Steps to Help Them Do So. April 13, 2022. Found on the internet at https://news.umich.edu/most-older-adults-want-to-age-in-place-but-many-havent-taken-steps-to-help-them-do-so 50 and over say they want to age in place . [2] National Institutes of Health (NIH). Aging in Place: Growing Older at Home. May 1, 2017. Found on the internet at https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/aging-place-growing-older-home But home safety is critical, and for older adults with cognitive decline, wandering is a safety concern you should consider.

Wandering , also known as elopement, is “when someone leaves a safe area or responsible caregiver” and can occur inside or outside the home. [3] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Disability and Safety: Information on Wandering (Elopement). Sept. 18, 2019. Found on the internet at https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandsafety/wandering.html People who wander may not be aware of their safety, which puts them at risk of getting lost, falling, or other accidents with injuries.

“Aging in place can be feasible for some older adults with dementia,” said Sean Marchese , a registered nurse at the Orlando, Florida-based Mesothelioma Center with more than 20 years of direct patient care. “Depending on individual circumstances, familiar surroundings, caregiver support, and dependable routines can reduce the risks of wandering and elopement. Another essential aspect is emotional well-being. A fulfilling environment is crucial to safely aging in place.”

In this guide, we discuss safety precautions to prevent wandering for caretakers whose care recipients are aging in place.

What is wandering risk, and who does it impact?

The risk of wandering is common among people with dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, six in 10 people with dementia will wander at least once. [5] Alzheimer’s Association. Causes and Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease. Found on the internet at https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers/causes-and-risk-factors Caregivers should be aware of this potential safety risk. Wandering can occur when people are:

- At home or alone in public: Those who live alone can wander away from home while shopping or completing errands. If accessible, your care recipient may use a car or other means of transportation to wander off.

- At home or in public with others: People can wander from their homes or while shopping unnoticed, even with family or friends.

Why does wandering happen?

Risk factors for wandering include cognitive impairment, restlessness, agitation, previous wandering attempts, and expressions of a desire to leave. [6] MeetCaregivers. Elopement and Wandering in Seniors. June 27, 2022. Found on the internet at https://meetcaregivers.com/dementia-wandering-prevention-management Wandering off may be intentional or unintentional due to confusion or loss of memory. [7] The Helper Bees. Wandering and Elopement: A Brief Guide. Viewed Aug. 19, 2023. Found on the internet at https://www.thehelperbees.com/families/healthy-hive/wandering-and-elopement-a-brief-guide Intentional incidents may occur when people feel they need to be somewhere, have something to do, or seek something they need. Some common triggers include changes in medication, changes in environment, and feeling overwhelmed.

What are the risks of wandering?

“Older adults with dementia face several risks from wandering and elopement,” said Marchese. “Memory loss, confusion, disorientation, and other impairments can lead to physical harm and forgotten surroundings without a plan of returning home. In some cases, restlessness and communication challenges can exacerbate these issues.”

A review of 325 U.S. newspaper articles describing incidents with people with dementia (PWD) found 40% of PWD who went missing were found dead the next day. [8] BMC Geriatrics. Persons With Dementia Missing in the Community: Is It Wandering or Something Unique? June 5, 2011. Found on the internet at https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2318-11-28 This statistic emphasizes the importance of recognizing the dangers older adults may face after wandering. These dangers include injuries, dehydration, harsh weather exposure, medical complications, drowning, or being hit by a car. [9] ECRI Institute. Continuing Care Risk Management: Wandering and Elopement. April 2014. Found on the internet at https://alnursing.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/WanderingandElopementPacket.pdf And experiencing these dangers could impact the mental and emotional well-being of the older adult and their caregivers.

Physical dangers of wandering

- Exposure to extremes in hot or cold weather can be deadly for someone who has wandered from their safe environment.

- Hurricane exposure increases the risk of death for people with dementia. [10] University of Michigan News. Risk of Death for People With Dementia Increases After a Hurricane Exposure. March 13, 2023. Found on the internet at https://news.umich.edu/risk-of-death-for-people-with-dementia-increases-after-a-hurricane-exposure The confusion and disruption of living conditions in the aftermath may lead to wandering.

- Annually, roughly 300 older adults die from drowning . Wandering may result in encounters with bodies of water when lost, like lakes or rivers. Some drowning also occurs in swimming pools that people may encounter while wandering.

- People who wander may feel they know where they are going , but their cognitive state can lead them to become lost. [11] Sundara Living. Elopement in Dementia. What do I do? July 26, 2021. Found on the internet at https://sundaraliving.com/living-with-dementia/elopement-in-dementia-what-do-i-do

- Falls may occur after a person has wandered away from home. Being in unfamiliar surroundings, medication effects, difficulty walking, and weakness are some contributing factors for older adults who fall . [12] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Facts About Falls. May 12, 2023. Found on the internet at https://www.cdc.gov/falls/facts.html These falls may lead to serious injuries, like head injuries or broken bones.

In the focused review of 325 U.S. newspapers cited above, 74 articles noted that driving was a factor when the person went missing. Of these incidents, 80% drove with their caregiver’s knowledge, and 11% drove without their knowledge. [8] BMC Geriatrics. Persons With Dementia Missing in the Community: Is It Wandering or Something Unique? June 5, 2011. Found on the internet at https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2318-11-28 Results included missing-driver incidents, head-on collisions, and wrong-way driving. Studies have shown older drivers with cognitive impairment have an increased risk of motor vehicle crashes (MVC). Driving too slowly and taking too long turning left at intersections are two big reasons for MVCs in older people . [13] Dementia & Neuropsychologia. Cognitive Impairment and Driving: A Review of the Literature. October 2009. Found on the internet at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5619413

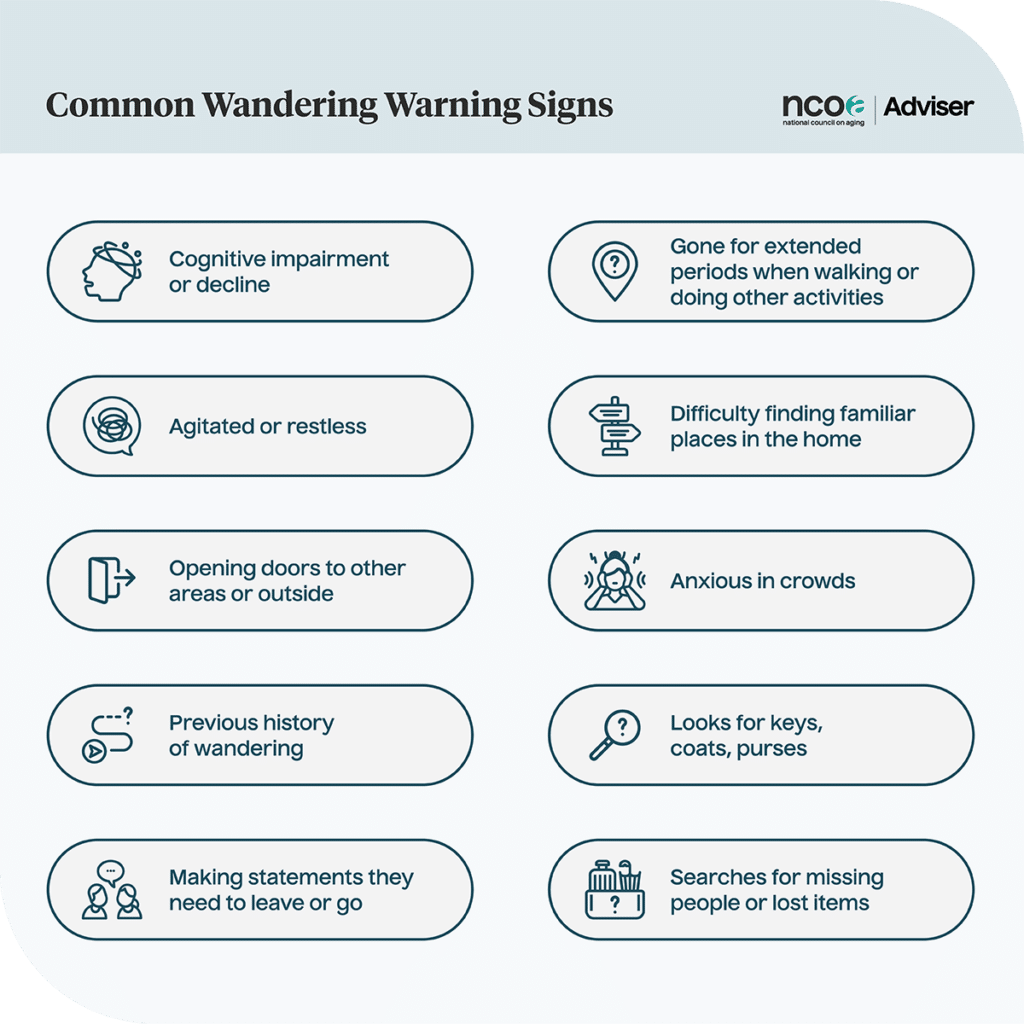

Common wandering warning signs

People with dementia often wander, and it’s estimated that 36% of those diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and living in a community will wander. For people who consistently wander, an estimated 80% will leave their area. [9] ECRI Institute. Continuing Care Risk Management: Wandering and Elopement. April 2014. Found on the internet at https://alnursing.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/WanderingandElopementPacket.pdf It’s important to note that allowing people to walk around their environment will not necessarily lead to wandering. Walking has many benefits, including relieving stress and boredom. [11] Sundara Living. Elopement in Dementia. What Do I Do? July 26, 2021. Found on the internet at https://sundaraliving.com/living-with-dementia/elopement-in-dementia-what-do-i-do

Caregivers should learn to recognize the signs and symptoms that may lead to a wandering incident. These include people who: [6] MeetCaregivers. Elopement and Wandering in Seniors. June 27, 2022. Found on the internet at https://meetcaregivers.com/dementia-wandering-prevention-management [11] Sundara Living. Elopement in Dementia. What Do I Do? July 26, 2021. Found on the internet at https://sundaraliving.com/living-with-dementia/elopement-in-dementia-what-do-i-do [7] The Helper Bees. Wandering and Elopement: A Brief Guide. Viewed Aug. 19, 2023. Found on the internet at https://www.thehelperbees.com/families/healthy-hive/wandering-and-elopement-a-brief-guide

- Have a cognitive impairment diagnosis or cognitive decline

- Become agitated or restless

- Make efforts to open doors leading to other areas or outside

- Have wandered or have left home in the past

- Express a desire to leave their current location (making statements they need to go to work or home)

- Are gone for extended periods when walking or participating in other activities

- Have difficulty finding familiar places in the home

- Become anxious when in crowds, like at a shopping center

- Look for keys, coats, purses, or other items that may reflect an attempt to leave

- Frequently search for missing people or lost items

What caregivers can do about wandering

The Joint Commission International considers wandering a sentinel event , which is an event that can result in temporary, severe, or permanent harm or death. [14] The Joint Commission. Sentinel Event. Viewed Aug. 20, 2023. Found on the internet at https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/sentinel-event Maintaining a safe environment can help prevent wandering and injury.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, as the disease progresses, you can make your home safer with tactics that include making doors the same color as walls to camouflage them, installing monitoring devices above doors to detect when they’re opened, installing or planting fences or hedges around patios and yards, and creating indoor areas that are safe to explore. [4] Alzheimer’s Association. Wandering. Found on the internet at https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/stages-behaviors/wandering

Conduct a wandering risk assessment

A wandering risk assessment evaluates a person’s condition and likelihood of wandering. Several tools can help determine an older adult’s risk of wandering, including the Rating Scale for Aggressive Behavior in the Elderly (RAGE) and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), which measures dementia-related behavioral symptoms . [15] American Psychological Association. Neuropsychiatric Inventory. 2011. Foud on the internet at https://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/neuropsychiatric-inventory

Consider having a risk assessment done by a health provider, so you can be fully prepared for a wandering incident while someone is in your care.

If you’re unsure if a professional assessment is needed, conducting a basic at-home assessment of your care recipient’s habits can help determine if they may be at risk for wandering behavior. Ask yourself questions, like: [6] MeetCaregivers. Elopement and Wandering in Seniors. June 27, 2022. Found on the internet at https://meetcaregivers.com/dementia-wandering-prevention-management [16] Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Elopement. Dec. 1, 2007. Found on the internet at https://psnet.ahrq.gov/web-mm/elopement

- How frequently has your care recipient wandered?

- When was the first time your care recipient wandered?

- Do they tend to wander more during the day or night?

- Are common triggers noise or discomfort?

- When your care recipient wanders, is it random, or does it happen at regular intervals?

- Can you identify a motivation for when your care recipient wanders?

- Does your care recipient have a court-appointed legal guardian?

- Is your care recipient dangerous to you or others?

- Has cognitive decline impacted your care recipient’s ability to make decisions?

These questions are excellent for caregivers to be familiar with, so they’re not caught (completely) off-guard if an incident occurs. Answering these questions may provide a reliable assessment of wandering risk. Once you complete this assessment, it should assist in determining if further assessment is needed.

Check out our Wandering Risk Assessment

Unable to display PDF file.

Understand triggers

Recognizing the behaviors or events that may lead to wandering is one of the most critical factors caregivers need to prevent this from occurring. Examples of potential triggers for missing incidents include: [9] ECRI Institute. Continuing Care Risk Management: Wandering and Elopement. April 2014. Found on the internet at https://alnursing.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/WanderingandElopementPacket.pdf [6] MeetCaregivers. Elopement and Wandering in Seniors. June 27, 2022. Found on the internet at https://meetcaregivers.com/dementia-wandering-prevention-management

- Disorientation from the current location, going off in the wrong direction, and the inability to reorient due to dementia. People may not be able to self-correct, particularly in the later stages of the disease, but someone else with the right approach can often reorient them

- Experiencing feelings of hunger, pain, boredom, anxiety, or urge to use the bathroom

- Exposure to high-traffic areas

- Being near stairwells and elevators, which may prompt them to try to exit the area

- Easily locating suitcases, outdoor clothing, or other items associated with leaving their current location or taking a trip

- Exposure to noise, discomfort, or other distress

Understanding their habits and usual activity time frames can help you be more aware of when their triggers may occur. Watch your care recipient for signs of hunger, boredom, and anxiety, and act quickly when triggered. Be sure to keep your care recipient in an area with easy access to the bathroom and other frequently visited rooms to reduce their risk of wandering. Store suitcases, outdoor clothing, or other travel items, like keys, wallets, and handbags, in an area not usually accessible to your care recipient.

Take preventive steps

Avoiding wandering is crucial to prevent serious injury or death. Some suggestions for prevention include: [9] ECRI Institute. Continuing Care Risk Management: Wandering and Elopement. April 2014. Found on the internet at https://alnursing.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/WanderingandElopementPacket.pdf [6] MeetCaregivers. Elopement and Wandering in Seniors. June 27, 2022. Found on the internet at https://meetcaregivers.com/dementia-wandering-prevention-management [17] Sparks, Dana. Mayo Clinic. Alzheimer’s and Dementia: Understand Wandering and How to Address it. Nov. 30, 2020. Found on the internet at https://newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/alzheimers-and-dementia-understand-wandering-and-how-to-address-it [4] Alzheimer’s Association. Wandering. Found on the internet at https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/stages-behaviors/wandering

- Use a medical alert system that includes GPS tracking . Many new systems available on the market today have wearable GPS devices for older adults in the form of necklaces or smartwatches .

- If there is a risk of wandering by using a car, storing the keys in a location unknown to your care recipient may be beneficial. You can also track someone if wandering occurs in a vehicle using a GPS locator system, like OnStar’s Guardian or Safepoint.

- Provide a stimulating environment. Instances of wandering can begin with the person feeling bored. Keep an eye on your care recipient to prevent overstimulation, which can also trigger wandering.

- Create a safe space where your care recipient may wander without the risk of leaving. Gardens, walking paths, or outdoor lounge areas may serve this purpose.

- Create a schedule of daily activities for your care recipient. Participating in these activities may help them feel a sense of purpose and can prevent boredom.

- Use alarm systems and locks to prevent wandering away from the home.

Make a plan ahead of time

Readying a plan of action can help you find your care recipient sooner. Making sure recent photographs are available can assist authorities in searching for your care recipient, and ensuring they are wearing a medical ID bracelet can help with identification while providing crucial medical information in an emergency. These can be obtained through the Alzheimer’s Association or are available through stores, like Amazon. Additional considerations include: [4] Alzheimer’s Association. Wandering. Found on the internet at https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/stages-behaviors/wandering [18] Alzheimer’s Society. Supporting a Person With Dementia Who Walks About. Found on the internet at https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/symptoms-and-diagnosis/supporting-person-dementia-who-walks-about [9] ECRI Institute. Continuing Care Risk Management: Wandering and Elopement. April 2014. Found on the internet at https://alnursing.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/WanderingandElopementPacket.pdf

- Secure a case number from the police if your care recipient goes missing. Be sure to specify they are diagnosed with dementia or other cognitive deficits.

- Talk to anyone in the surrounding area where your care recipient was last seen to get information regarding their direction of travel.

- Request the police issue a Silver Alert (a public notification system broadcasting missing older adults with Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, or other cognitive decline) to media outlets and other police departments in the area.

- If your care recipient has a cellphone, contact the service provider and see if they can assist you in finding the phone’s location. Apps, like Find My iPhone or Life360 , can help you track your care recipient as long as they have their phone on them.

- Contact nearby hospitals and describe your missing care recipient, including any medical issues they have.

- Check locations your care recipient frequently visits. These locations may include their favorite restaurant or shopping center. Leave missing person signs in these locations if available.

- Maintain a list of up-to-date phone numbers for friends and family, so you can alert them if your care recipient is missing or inquire when they last saw them and where they were headed next.

Coping with wandering

When a care recipient wanders, friends and family may experience many emotional challenges, commonly including anxiety, pain, and grief. [19] Cake End-of-Life Planning. How to Cope When a Loved One is Missing: 11 Tips. May 2, 2022. Found on the internet at https://www.joincake.com/blog/grief-for-missing-persons

Here are five steps to cope with a missing care recipient: [19] Cake End-of-Life Planning. How to Cope When a Loved One is Missing: 11 Tips. May 2, 2022. Found on the internet at https://www.joincake.com/blog/grief-for-missing-persons

- Seek support from friends and family. Ask them to assist with the search or other tasks to help you.

- Take care of yourself physically and emotionally. Avoid isolation.

- Find ways to express your feelings. Denying yourself the expression of grief can cause damage to your physical and emotional health.

- Limit your exposure to news coverage. Ask a friend or family member to share the responsibility of monitoring the news to prevent you from becoming overwhelmed.

- Keep hope alive. Seek out grief or missing person support groups online.

Bottom line

People with dementia benefit from exercise and activity, but caregivers should also be aware of the risk their care recipient will wander.

About six in 10 people with dementia will wander at least once. [4] Alzheimer’s Association. Wandering. Found on the internet at https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/stages-behaviors/wandering Wandering is common among people with dementia, including Alzheimer’s. Serious injury or death can occur when wandering leads to leaving a safe place.

Preventive measures may include monitoring for triggers, like looking for car keys or stating they need to leave for work or home. [6] MeetCaregivers. Elopement and Wandering in Seniors. June 27, 2022. Found on the internet at https://meetcaregivers.com/dementia-wandering-prevention-management Prior planning is essential for quick response and recovery if a care recipient leaves home.

Many options are available to help find your care recipient should they go missing. Modern technology has brought us medical alert systems with wearable GPS locators. Additional location assistance may be available through vehicle GPS services, like OnStar , which can help find people quickly and safely. Consequently, when wandering occurs, anxiety, pain, and grief are common for caregivers and clinicians, so emotional support is critical to helping you cope with these emotions. [19] Cake End-of-Life Planning. How to Cope When a Loved One is Missing: 11 Tips. May 2, 2022. Found on the internet at https://www.joincake.com/blog/grief-for-missing-persons

Have questions about this review? Email us at [email protected] .

- Gavin, Kara. University of Michigan News. Most Older Adults Want to ‘Age in Place’ But Many Haven’t Taken Steps to Help Them Do So. April 13, 2022. Found on the internet at https://news.umich.edu/most-older-adults-want-to-age-in-place-but-many-havent-taken-steps-to-help-them-do-s

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). Aging in Place: Growing Older at Home. May 1, 2017. Found on the internet at https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/aging-place-growing-older-home

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Disability and Safety: Information on Wandering (Elopement). Sept. 18, 2019. Found on the internet at https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandsafety/wandering.html

- Alzheimer’s Association. Wandering. Found on the internet at https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/stages-behaviors/wandering

- Alzheimer’s Association. Causes and Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease. Found on the internet at https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers/causes-and-risk-factors

- MeetCaregivers. Elopement and Wandering in Seniors. June 27, 2022. Found on the internet at https://meetcaregivers.com/dementia-wandering-prevention-management

- The Helper Bees. Wandering and Elopement: A Brief Guide. Viewed Aug. 19, 2023. Found on the internet at https://www.thehelperbees.com/families/healthy-hive/wandering-and-elopement-a-brief-guide

- BMC Geriatrics. Persons With Dementia Missing in the Community: Is It Wandering or Something Unique? June 5, 2011. Found on the internet at https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2318-11-28

- ECRI Institute. Continuing Care Risk Management: Wandering and Elopement. April 2014. Found on the internet at https://alnursing.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/WanderingandElopementPacket.pdf

- University of Michigan News. Risk of Death for People With Dementia Increases After a Hurricane Exposure. March 13, 2023. Found on the internet at https://news.umich.edu/risk-of-death-for-people-with-dementia-increases-after-a-hurricane-exposure

- Sundara Living. Elopement in Dementia. What Do I Do? July 26, 2021. Found on the internet at https://sundaraliving.com/living-with-dementia/elopement-in-dementia-what-do-i-do

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Facts About Falls. May 12, 2023. Found on the internet at https://www.cdc.gov/falls/facts.html

- Dementia & Neuropsychologia. Cognitive Impairment and Driving: A Review of the Literature. October 2009. Found on the internet at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5619413

- The Joint Commission. Sentinel Event. Viewed Aug. 20, 2023. Found on the internet at https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/sentinel-event

- American Psychological Association. Neuropsychiatric Inventory. 2011. Foud on the internet at https://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/neuropsychiatric-inventory

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Elopement. Dec. 1, 2007. Found on the internet at https://psnet.ahrq.gov/web-mm/elopement

- Sparks, Dana. Mayo Clinic. Alzheimer’s and Dementia: Understand Wandering and How to Address it. Nov. 30, 2020. Found on the internet at https://newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/alzheimers-and-dementia-understand-wandering-and-how-to-address-it

- Alzheimer’s Society. Supporting a Person With Dementia Who Walks About. Found on the internet at https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/symptoms-and-diagnosis/supporting-person-dementia-who-walks-about

- Cake End-of-Life Planning. How to Cope When a Loved One is Missing: 11 Tips. May 2, 2022. Found on the internet at https://www.joincake.com/blog/grief-for-missing-persons

Manage Wandering in Dementia

Prevent your loved one from wandering and track them if they’re lost..

Posted December 26, 2023 | Reviewed by Ray Parker

- What Is Dementia?

- Find a therapist to help with dementia

- Write a plan for wandering now; no one can stay calm and think when it occurs.

- Make a stop sign for the door and consider using a door alarm.

- Have your loved one wear identification jewelry and a tracking device.

Wandering is a very serious problem that can result in disorientation, injury, and death. If your loved one exhibits wandering behavior, such as opening the front door or going outside, you should immediately work to prevent wandering. You can introduce measures that could be used to track them should they wander out of the house (or a restaurant or shop) despite your best efforts.

Here's a list of methods that can be used to prevent wandering and help return them home safely if they do.

Understand the triggers that cause wandering; resolve situations calmly

Use the ABCs of behavior change to find the antecedents that lead to wandering and work to eliminate them. Sometimes, simple visual cues are effective, such as a red, octagonal "STOP sign" banner that can be placed on a door or across a doorway, providing a visual clue to your loved ones that they shouldn't go past it.

If you catch them trying to leave the house, use the 4Rs—reassure, reconsider, redirect, and relax —to help them stay safe in the moment. If they are determined to leave the house, sometimes taking a walk around the block with them or giving them a brief ride in the car can resolve the situation with minimal conflict.

Lock the doors

One simple way to prevent wandering is to install locks so the doors cannot be easily opened inside the house. However, you need to make sure that you can open doors quickly in case of a fire. The best locks are fast and easy for you to open but are either out-of-sight or complicated such that your loved one cannot use them.

Often, simple sliding locks on the top and bottom of the door are sufficient. Or you could use a latch at eye level that requires two steps or more to unlock. Some child-proof locks will also work, depending upon the individual and their strength.

Use an alarm

From a simple mechanical bell that will ring when a door is opened (such as in a shop) to a sophisticated home alarm system using a method to signal when a door is approached or opened. It can alert you if your loved one is trying to leave the house.

There are also bed alarms that will alert you when your loved one gets up in the middle of the night—important if that is a time when they wander. Similarly, chair alarms tell you when your loved one gets up out of their favorite chair, and motion alarms can be set to sound when someone is near the door.

Provide supervision

It is simple to say that individuals who could wander should be supervised, but we know it is a much more difficult thing to do. Nonetheless, if your loved one has shown signs of wandering, it may be prudent to have someone with them all the time.

Use respite care and day programs. Enlist family and friends to spend a few hours with them each week. Speak with others in your care team to help you find solutions.

Identification jewelry; use an emergency response service

Because wandering is common in dementia and can lead to such serious problems, we recommend that all individuals with dementia wear identification bracelets or other jewelry that includes their name, diagnosis, and emergency number to call. Some programs allow you to obtain identification jewelry for yourself, which can help to normalize the wearing of such items, especially if you think your loved one may feel stigmatized by it. The Alzheimer's Association has partnered with MedicAlert to create one such service .

Consider tracking devices

We know a few individuals who seem to be magicians at getting out of the house despite their caregivers' best efforts. Some individuals are only in the mild stage of dementia and are not going to wander off but get lost quite frequently.

In either of these cases, a tracking device worn on the wrist can be helpful. For individuals who are used to wearing a watch, wearing a tracking device often feels fine, and, in fact, there are many electronic watches on the market today can be used to track your loved one through GPS (global positioning system), cellular, and Wi-Fi signals.

Some watches are made explicitly for this purpose, while others are smart watches that anyone might purchase. Other types of trackers, such as Apple AirTags, can be worn on the wrist or around the neck or attached to clothing. Some trackers allow two-way communication, and others can be easily hooked into the police system.

Write a plan for wandering, just in case.

When your loved one wanders off, staying calm and thinking clearly is very difficult. That's one reason why it is best to write a plan now, just in case it happens. You might want to include the following information in your plan:

- A list of people to call for help, with their phone numbers.

- You can give a dozen recent photographs of your loved one to police and volunteers.

- A dozen copies of their updated medical information can also be given to police and other emergency personnel.

- Areas in your neighborhood that could pose dangers, such as busy streets, forests, or bodies of water.

- A list of places that you think they might try to get to, whether it is a friend's house, corner store, childhood home, or where they used to work.

© Andrew E. Budson, MD, 2023, all rights reserved.

Budson AE, O’Connor MK. Seven Steps to Managing Your Aging Memory: What’s Normal, What’s Not, and What to Do About It , New York: Oxford University Press, 2023.

Budson AE, O’Connor MK. Six Steps to Managing Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia: A Guide for Families , New York: Oxford University Press, 2022.

Budson AE, Solomon PR. Memory Loss, Alzheimer’s Disease, & Dementia: A Practical Guide for Clinicians , 3rd Edition, Philadelphia: Elsevier Inc., 2022.

Andrew Budson, M.D. , is a professor of neurology at Boston University, as well as a lecturer in neurology at Harvard Medical School.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Your Health

Understanding dementia and 'wandering'.

People suffering from dementia display many common behavioral traits, and one of the hardest to manage and understand is wandering. Correspondent Linton Weeks talks about his recent report for NPR.org entitled "The Mysteries of Dementia-Driven Wandering." The condition can be confusing, frustrating and even fatal.

The Mysteries of Dementia-Driven Wandering

- About dementia

- Types of dementia

- Testing and diagnosis

- Treatment and management

- Dementia facts & figures