- location of the visitor¡¦s home ¡¦ how far they traveled to the site

- how many times they visited the site in the past year or season

- the length of the trip

- the amount of time spent at the site

- travel expenses

- the person¡¦s income or other information on the value of their time

- other socioeconomic characteristics of the visitor

- other locations visited during the same trip, and amount of time spent at each

- other reasons for the trip (is the trip only to visit the site, or for several purposes)

- fishing success at the site (how many fish caught on each trip)

- perceptions of environmental quality or quality of fishing at the site

- substitute sites that the person might visit instead of this site

- The value of improvements in water quality was only shown to increase the value of current beach use. However, improved water quality can also be expected to increase overall beach use.

- Estimates ignore visitors from outside the Baltimore-Washington statistical metropolitan sampling area.

- The population and incomes in origin zones near the Chesapeake Bay beach areas are increasing, which is likely to increase visitor-days and thus total willingness to pay.

- changes in access costs for a recreational site

- elimination of an existing recreational site

- addition of a new recreational site

- changes in environmental quality at a recreational site

- number of visits from each origin zone (usually defined by zipcode)

- demographic information about people from each zone

- round-trip mileage from each zone

- travel costs per mile

- the value of time spent traveling, or the opportunity cost of travel time

- exact distance that each individual traveled to the site

- exact travel expenses

- substitute sites that the person might visit instead of this site, and the travel distance to each

- quality of the recreational experience at the site, and at other similar sites (e.g., fishing success)

- perceptions of environmental quality at the site

- characteristics of the site and other, substitute, sites

- The travel cost method closely mimics the more conventional empirical techniques used by economists to estimate economic values based on market prices.

- The method is based on actual behavior¡¦what people actually do¡¦rather than stated willingness to pay¡¦what people say they would do in a hypothetical situation.

- The method is relatively inexpensive to apply.

- On-site surveys provide opportunities for large sample sizes, as visitors tend to be interested in participating.

- The results are relatively easy to interpret and explain.

- The travel cost method assumes that people perceive and respond to changes in travel costs the same way that they would respond to changes in admission price.

- The most simple models assume that individuals take a trip for a single purpose ¡¦ to visit a specific recreational site. Thus, if a trip has more than one purpose, the value of the site may be overestimated. It can be difficult to apportion the travel costs among the various purposes.

- Defining and measuring the opportunity cost of time, or the value of time spent traveling, can be problematic. Because the time spent traveling could have been used in other ways, it has an "opportunity cost." This should be added to the travel cost, or the value of the site will be underestimated. However, there is no strong consensus on the appropriate measure¡¦the person¡¦s wage rate, or some fraction of the wage rate¡¦and the value chosen can have a large effect on benefit estimates. In addition, if people enjoy the travel itself, then travel time becomes a benefit, not a cost, and the value of the site will be overestimated.

- The availability of substitute sites will affect values. For example, if two people travel the same distance, they are assumed to have the same value. However, if one person has several substitutes available but travels to this site because it is preferred, this person¡¦s value is actually higher. Some of the more complicated models account for the availability of substitutes.

- Those who value certain sites may choose to live nearby. If this is the case, they will have low travel costs, but high values for the site that are not captured by the method.

- Interviewing visitors on site can introduce sampling biases to the analysis.

- Measuring recreational quality, and relating recreational quality to environmental quality can be difficult.

- Standard travel cost approaches provides information about current conditions, but not about gains or losses from anticipated changes in resource conditions.

- In order to estimate the demand function, there needs to be enough difference between distances traveled to affect travel costs and for differences in travel costs to affect the number of trips made. Thus, it is not well suited for sites near major population centers where many visitations may be from "origin zones" that are quite close to one another.

- The travel cost method is limited in its scope of application because it requires user participation. It cannot be used to assign values to on-site environmental features and functions that users of the site do not find valuable. It cannot be used to value off-site values supported by the site. Most importantly, it cannot be used to measure nonuse values. Thus, sites that have unique qualities that are valued by non-users will be undervalued.

- As in all statistical methods, certain statistical problems can affect the results. These include choice of the functional form used to estimate the demand curve, choice of the estimating method, and choice of variables included in the model.

- GolfSW.com - Golf Southwest tips and reviews.

- VivEcuador.com - Ecuador travel information.

- TheChicagoTraveler.com - Explore Chicago.

- FarmingtonValleyVisit.com - Discover Connecticut's Farmington Valley.

Richard T. Melstrom

RESOURCE ECONOMICS AND POLICY

Zonal travel cost method of nonmarket valuation

Carson Reeling and I recently published a paper describing a new method to measure the value of outdoor recreation areas to visitors. The method works off a model that identifies trip patterns using aggregate data, such as visitor counts and census populations . This contrasts with traditional approaches that use individual trip information collected via surveys, which tend to be costly and time-consuming. Either way, it is this trip information (and the cost thereof) that conveys the value of recreation experiences.

The paper shows the proposed and traditional approaches produce similar estimates in a couple of applications with real-world data. One of these applications compares publicly available hunting data, available here , to individual trips numbering in the 100,000s (which is proprietary data from the Indiana DNR). While there are some differences, there are more similarities, and we find the our proposed approach produces even more similar results when we account for the fact that the residential location of hunters is more rural than the (census) population as a whole. So, overall, this suggests the method provides a practical, cost-effective and accessible alternative to measuring the economic value of recreation sites.

Our work builds on a large amount of earlier research. The travel cost method originated in a letter written to the U.S. National Park Service by Harold Hotelling in 1947. This letter described measuring the economic value of a visit in a linear demand framework using data on travel costs and per capita visitation rates from concentric zones around a park. Over time, economists and other researchers moved away from this simple design toward more utility-theoretic methods. One thing I liked about this project is learning how to use utility theory to infer individual from aggregate behavior (although this paper is far from the first to do that; see here ).

Recent Posts

Not quite an R.O.U.S.

Northern Michigan

Incorporating ecosystem service values into benefit cost analysis

Eli Fenichel recently shared official U.S. guidance on how to include ecosystem services in benefit cost analysis. Including these values has been a goal of economists for many decades. To be sure, ma

Environmental Justice Organisations, Liabilities and Trade

Mapping environmental justice.

- Nuclear Energy

- Oil and Gas and Climate Justice

- Biomass and Land Conflicts

- Mining and Ship Breaking

- Environmental Health and Risk Assessment

- Liabilities and Valuation

- Law and Institutions

- Consumption, Ecologically Unequal Exchange and Ecological Debt

Travel-cost method

The travel-cost method (TCM) is used for calculating economic values of environmental goods. Unlike the contingent valuation method, TCM can only estimate use value of an environmental good or service. It is mainly applied for determining economic values of sites that are used for recreation, such as national parks. For example, TCM can estimate part of economic benefits of coral reefs, beaches or wetlands stemming from their use for recreational activities (diving and snorkelling/swimming and sunbathing/bird watching). It can also serve for evaluating how an increased entrance fee a nature park would affect the number of visitors and total park revenues from the fee. However, it cannot estimate benefits of providing habitat for endemic species.

TCM is based on the assumption that travel costs represent the price of access to a recreational site. Peoples’ willingness to pay for visiting a site is thus estimated based on the number of trips that they make at different travel costs. This is called a revealed preference technique, because it ‘reveals’ willingness to pay based on consumption behaviour of visitors.

The information is collected by conducting a survey among the visitors of a site being valued. The survey should include questions on the number of visits made to the site over some period (usually during the last 12 months), distance travelled from visitor’s home to the site, mode of travel (car, plane, bus, train, etc.), time spent travelling to the site, respondents’ income, and other socio-economic characteristics (gender, age, degree of education, etc). The researcher uses the information on distance and mode of travel to calculate travel costs. Alternatively, visitors can be asked directly in a survey to state their travel costs, although this information tends to be somewhat less reliable. Time spent travelling is considered as part of the travel costs, because this time has an opportunity cost. It could have been used for doing other activities (e.g. working, spending time with friends or enjoying a hobby). The value of time is determined based on the income of each respondent. Time spent at the site is for the same reason also considered as part of travel costs. For example, if respondents visit three different sites in 10 days and spend only 1 day at the site being valued, then only fraction of their travel costs should be assigned to this site (e.g. 1/10). Depending on the fraction used, the final benefit estimates can differ considerably.

Two approaches of TCM are distinguished – individual and zonal. Individual TCM calculates travel costs separately for each individual and requires a more detailed survey of visitors. In zonal TCM, the area surrounding the site is divided into zones, which can be either concentric circles or administrative districts. In this case, the number of visits from each zone is counted. This information is sometimes available (e.g. from the site management), which makes data collection from the visitors simpler and less expensive.

The relationship between travel costs and number of trips (the higher the travel costs, the fewer trips visitors will take) shows us the demand function for the average visitor to the site, from which one can derive the average visitor’s willingness to pay. This average value is then multiplied by the total relevant population in order to estimate the total economic value of a recreational resource.

TCM is based on the behaviour of people who actually use an environmental good and therefore cannot measure non-use values. This method is thus inappropriate for sites with unique characteristics which have a large non-use economic value component (because many people would be willing to pay for its preservation just to know that it exists, although they do not plan to visit the site in the future).

The travel-cost method might also be combined with contingent valuation to estimate an economic value of a change (either enhancement or deterioration) in environmental quality of the NP by asking the same tourists how many trips they would make in the case of a certain quality change. This information could help in estimating the effects that a particular policy causing an environmental quality change would have on the number of visitors and on the economic use value of the NP.

For further reading:

Ward, F.A., Beal, D. (2000) Valuing nature with travel cost models. A manual. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

Ecosystem valuation [ www.ecosystemvaluation.org/travel_costs.htm ]

This glossary entry is based on a contribution by Ivana Logar

EJOLT glossary editors: Hali Healy, Sylvia Lorek and Beatriz Rodríguez-Labajos

One comment

I quite like reading a post that will make people think. Also, thanks for allowing me to comment!

Browse by Theme

Browse by type.

- Presentations

- Press Releases

- Scientific Papers

Online course

Online course on ecological economics: http://www.ejolt.org/2013/10/online-course-ecological-economics-and-activism/

Privacy Policy | Credits

Advertisement

The travel cost method: a valuable tool for organizers quantifying the economic value of environmental education—a case study from Oklahoma

- Research and Theory

- Published: 19 March 2024

Cite this article

- Tiffany A. Legg ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7265-5503 1 , 2 ,

- Jason R. Vogel 1 , 3 &

- Jeri Fleming 4

69 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Environmental education (EE) and training is integral to public involvement in environmental stewardship. Although entities supported by grants and public funding provide a range of benefits, determining the economic value of the EE delivered is essential in quantifying the scope of its benefit. Data on this subject are limited; this study aims to address this gap. As a non-market good, evaluating education requires a non-traditional economic approach. An approach offering a methodological value to evaluate EE is the travel cost method (TCM), which is a non-market valuation approach in the field of environmental economics. Conventionally, TCM has been used to assess the economic value of recreational sites. For this study, the TCM is applied to indirectly value EE by using the costs of travel as a proxy for what consumers pay to travel to educational events and what they would be willing to pay (WTP) in addition to the same educational experience if higher travel costs were to be incurred. This study also considers the feasibility of TCM as a method for evaluating the value of EE, particularly for EE event organizers. Data collected via the distribution of surveys at EE events within the state of Oklahoma were incorporated into an econometric model and used to observe demographic predictors associated with a willingness to travel farther to access EE. To quantify the value of EE, the difference between the actual costs and WTP was assessed. This expressed valuation of EE is intended to assist in informed decision-making on allocation of monetary resources for agencies supported by grants and public funding.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Rural–nonrural divide in car access and unmet travel need in the United States

What Makes Congestion Pricing a Successful Landing in Indian Cities? Identification of Motivators, Insights, and Inferences for Policy Formulation

Evidence-based guidelines for greener, healthier, more resilient neighbourhoods: Introducing the 3–30–300 rule

Data availability.

Data supporting this study will be made available from the authors upon request. Data will be openly available and linked to the future publication of this work.

Ardoin NM, Bowers AW, Gaillard E (2020) Environmental education outcomes for conservation: a systematic review. Biol Cons 241:108224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108224

Article Google Scholar

Arnocky S, Stroink M (2010) Gender differences in environmentalism: the mediating role of emotional empathy. Curr Res Soc Psychol 16:9

Bogner FX (1998) The influence of short-term outdoor ecology education on long-term variables of environmental perspective. J Environ Educ 29(4):17–29

Bureau of Labor Statistics (n.d.) State occupational employment and wage estimates. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_ok.htm . Accessed 1 Oct 2019

Galetzka M, Pruyn A, Hagen M, Vos M, Moritz B, Gostelie F (2018) The psychological value of time. Transpo Res Procedia 31:47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2018.09.045

Galobardes B, Demarest S (2003) Asking sensitive information: an example with income. Soc Prev Med 48(1):70–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s000380300008

Graves PE (2013) Chapter 15 environmental valuation: the travel cost method. In: Environmental economics: an integrated approach. CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/b15404

Greene W (2008) Econometric analysis, 6th edn. Pearson Education Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey

Google Scholar

Hutcheson WP, Hoagland, Jin D (2018) Valuing environmental education as a cultural ecosystem service at Hudson River Park. Ecosyst Serv 31(C):387–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.03.005

Iftekhar MS, Polyakov M, Ansell D, Gibson F, Kay GM (2017) How economics can further the success of ecological restoration: economics and Ecological Restoration. Conserv Biol 31(2):261–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12778

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Imbur BO (2009) Cultivating hope: the emotional side of environmental education. Master's Thesis, Prescott College. https://www.proquest.com/docview/305148426

Ireland TR (1999) Opportunity cost vs. replacement cost in a lost service analysis. J Forensic Econ 12(1):33–42

Krasny ME, Kalbacker L, Stedman RC, Russ A (2015) Measuring social capital among youth: applications in environmental education. Environ Educ Res 21(1):1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.843647 . (Accessed December 18, 2019)

Kudryavtsev A, Stedman RC, Krasny ME (2012) Sense of place in environmental education. Environ Educ Res 18(2):229–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2011.609615 . (Accessed March 3, 2020)

La Rosa D, Spyra M, Inostroza L (2016) Indicators of cultural ecosystem services for urban planning: a review. Ecol Ind 61:74–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.04.028

Leclerc F, Schmitt B, Dubé L (1995) Waiting time and decision making: is time like money? J Consum Res 22:110–119. https://doi.org/10.1086/209439

Mayor K, Scott S, Tol RSJ (2007) Comparing the travel cost method and the contingent valuation method: an application of convergent validity theory to the recreational value of Irish forests. Working Paper No. 190. The Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI), Dublin

Milcu AI, Hanspach J, Abson D, Fischer J (2013) Cultural ecosystem services: a literature review and prospects for future research. Ecol Soc 18(3):44. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05790-180344

Milfont TL, Sibley CG (2016) Empathic and social dominance orientations help explain gender differences in environmentalism: a one-year Bayesian mediation analysis. Personal Individ Differ 90:85–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.044

National Conference of State Legislatures State Minimum Wages (2020) Minimum Wage by State. Available at: https://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/state-minimum-wage-chart.aspx . Accessed March 1, 2020

Na-Yemeh DY, Legg TA, Lambert LH (2022) Economic value of a weather decision support system for Oklahoma public safety officials. Ann Am Assoc Geogr 113(2):549–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2022.2108747

Oklahoma State Department of Education (n.d.) School personnel salary information. Available at: https://sde.ok.gov/state-minimum-teacher-salary-schedule . Accessed 5 Oct 2019

Parsons GR (2003) Chapter 6 The travel cost model. In: Champ PA, Boyle KJ, Brown TC (eds) A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 269–329

Chapter Google Scholar

Parsons GR (2017) Chapter 6 Travel cost models. In: Champ PA, Boyle KJ, Brown TC (eds) A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation. Springer, Netherlands, pp 187–233

Poor PJ, Pessagno KL, Paul RW (2007) Exploring the hedonic value of ambient water quality: a local watershed-based study. Ecol Econ 60(4):797–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.02.013 . (Accessed July 11, 2019)

Sarukhán J, Whyte A (eds) (2005) Ecosystems and human well-being: synthesis (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment). Island Press, World Resources Institute, Washington, D.C., USA

Schuman H, Presser S (1979) The open and closed question. Am Sociol Rev 44(5):692. https://doi.org/10.2307/209452

Sharpe DL, Abdel-Ghany M (1997) Measurement of the value of homemaker’s time: an empirical test of the alternative methods of the opportunity cost approach. J Econ Soc Meas 23(2):149–162. https://doi.org/10.3233/JEM-1997-23203

Smith SJ (1983) Estimating annual hours of labor force activity. Mon Labor Rev 106(2):13–22

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Turrell G (2000) Income non-reporting: implications for health inequalities research. J Epidemiol Community Health 54(3):207–214. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.54.3.207

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

U. S. Census Bureau (n.d.) American FactFinder - Community facts. Available at: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml . Accessed 12 Dec 2019

US EPA (2012) What is environmental education? [Overviews and Factsheets]. US EPA. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/education/what-environmental-education . Accessed 14 Jun 2019

Workforce Profiles (2019) Oklahoma Department of Commerce. Available at: https://www.okcommerce.gov/doing-business/data-reports/workforce-profiles/ . Accessed 1 Dec 2019

Zelezny LC, Chua PP, Aldrich C (2000) New ways of thinking about environmentalism: elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. J Soc Issues 56(3):443–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00177

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible by the Oklahoma Water Survey and the numerous government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and other entities across the state of Oklahoma that distributed surveys at their environmental education events. The authors thank Dr. Jadwiga Ziolkowska for her guidance on this project.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Oklahoma Water Survey, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA

Tiffany A. Legg & Jason R. Vogel

Environmental Studies Program, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA

Tiffany A. Legg

School of Civil Engineering and Environmental Science, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA

Jason R. Vogel

Grand River Dam Authority, Langley, OK, USA

Jeri Fleming

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tiffany A. Legg .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing interest.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Legg, T.A., Vogel, J.R. & Fleming, J. The travel cost method: a valuable tool for organizers quantifying the economic value of environmental education—a case study from Oklahoma. J Environ Stud Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-024-00898-1

Download citation

Accepted : 15 February 2024

Published : 19 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-024-00898-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Ecosystem services

- Environmental education

- Environmental economics

- Non-market valuation

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Travel Cost Method (TCM)

Some amenities do not have a direct cost associated with them. For example, recreational sites may be free to enter. In order to apply a value to these types of amenities a value is often derived from a good or service which is complementary to the consumption of the free amenity. One method of estimating a value is therefore to collect data on the travel costs associated with accessing the amenity or recreational site. This is commonly referred to as the travel cost method of estimating the value of an amenity.

The travel cost method involves collecting data on the costs incurred by each individual in travelling to the recreational site or amenity. This ‘price’ paid by visitors is unique to each individual, and is calculated by summing the travel costs from each individuals original location to the amenity. By aggregating the observed travel costs associated with a number of individuals accessing the amenity a demand curve can be estimated, and as such a price can be obtained for the non-price amenity.

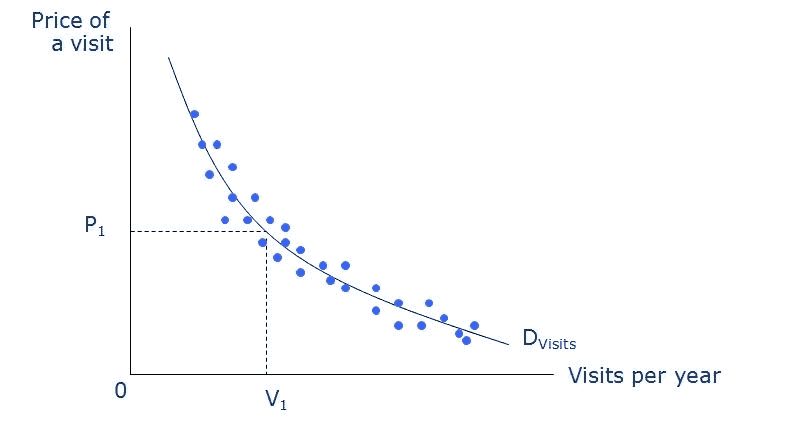

We can show this method of using observed or revealed preferences using a diagram as shown below.

D(Visits) shows the overall trend between travel costs and visit rates at a particular asset or site. To generate an estimate of the recreational value for the site, estimates are needed for the average visitors (V1) total recreational value for the site. This is then multiplied by the total number of visitors per annum giving the total annual recreational value of the site or asset. For a more complete explanation continue to the flash example .

Zonal Travel Cost Method Example

Using the zonal travel cost method a researcher can estimate the value of an asset by exploring the actual visitors or users of a site or asset, rather than potential visitors or users. The level of analysis focuses on the zones in which people live compared to the location of the asset. The researcher is required to specify the zones from which the site users travel to the asset.

Consider an example of valuing a country park. In this example four zones have been designated by the researcher. Zone A has an average travel time of 1 hour, and a distance of 25km. Zone B has an average travel time of 1.5 hours and a distance of 40km. Zone C has an average travel time of approximately 2 hours and a distance of 80km. Finally, zone D has an average travel time of 4 hours and a distance of 120km. The admission cost for all users is the same, and is equal to £10. The number of visits per year has been observed by the researcher for each zone. Zone A has an average of 10,000 visits per year. Zone B has an average of 12,000 visits per year, zone C has 8,000 visits, and zone D has 4,000 visits. This information is shown in the table below.

To calculate the value of the asset (V) for a single visit the researcher now uses the simple equation as follows:

V = ((T x w ) + (D x v ) + Ca) x Va

T = travel time (in hours) w = average wage rate (£/hour) D = distance (in km) v = marginal vehicle operating costs Ca = cost of Admission to asset Va = average number of visits per year

Using the country park example, the value of the asset can be calculated using this formula. It is important that the researcher provides an accurate measure for the average hourly wage rate, and also for the marginal vehicle operating costs. A common value for the operating costs is around £0.16p per km. This is the equivalent of around £0.40p per mile, a standard value given for vehicle operating costs in calculating expenses claims within firms and organisations.

In the example the average hourly wage rate is £10, and marginal vehicle operating costs are calculated at £0.16p per km. The researcher can now calculate the value of the country park for each zone to get an overall value for the asset. This is shown in the table below.

Limitations of the TCM

There are a number of limitations associated with the travel cost method of value estimation. These are as follows:

(1) Difficulties in measuring the cost of visiting a site.

It may actually be quite difficult to measure the cost of accessing a site or amenity. This is because of the opportunity cost associated with the travel time. If the opportunity cost of all individuals is the same then the estimated price will be accurate. If, however, the opportunity cost of individuals accessing the site varies, which is more likely, then the measure will be inaccurate.

For example, one individual’s opportunity cost of the travel time spent accessing a recreational site is equivalent to one hours wage equalling £35. However, another individual’s opportunity cost for an hours wage is only £8. This is problematic to the TCM as if individual’s opportunity costs differ including the costs of time spent at the site, this would change the price faced by different individuals by different amounts.

(2) The estimation of willingness to pay used in the TCM is for entire site access rather than specific features.

As the TCM only provides a price or value relating to the cost of accessing the amenity or recreational site, it does so for the whole site. It may, however, be the case that we wish to value a certain aspect of the site in our project appraisal. For example, we do not wish to value a whole park, but instead the fishing ponds within it.

(3) The exclusion of the marginal cost of other complementary goods.

The travel cost method does not account for the costs involved in purchasing complementary goods which may be required in order to enjoy accessing the amenity. For example, individuals accessing a park area may take a football with them, or a picnic. Alternatively, individuals accessing a recreational site may take walking equipment and tents with them. The marginal costs of using this equipment should be included in the price estimated.

(4) Multi-purpose or multi-activity journeys.

Individuals may visit an amenity or recreational site in the morning, but then visit another site or enjoy some other activity in the afternoon. The travel endured to access the amenity was also undertaken to enable access to the afternoon activity. In this case the cost incurred in travelling to the amenity does not represent the value the individuals place on the amenity, but that which they place on both the amenity they visited in the morning and the one which they visited in the afternoon.

(5) Journey value.

It may be the case that the journey itself has a value to the individual. If this is true then some of the cost incurred in travelling to the amenity should not actually be applied to the individual accessing the amenity, and as such should be removed from the estimation of the amenities value.

(6) Assumed responses to changes in price.

The TCM method assumes that individuals respond to changes in price regardless of its composition. For example, TCM assumes that individuals will react consistently to a £10 increase in travel cost as they would to a £10 increase in admission costs.

Search CBA Builder:

- What is CBA?

- Costs/Benefits

- Environ. Assess.

- Impact Assess.

- Quantification

- Shadow Pricing

- Revealed Pref.

- Hedonic Pricing

- Life and Injury

- Discounting

- Discount/Compound

- Horizon Values

- Sensitivity Analysis

- Comparing NPV and BCR

- CBA Builder

- Worksheets/Exercises

- 1: Discounting

- 2: Multi-year Discounting

- 3: Multi-year Discounting

- 4: Shadow Pricing

- 5: NPV and BCR

- 6: CBA Builder

- Useful Texts

- Journals: Concept.

- Journals: Applic.

Quick Links

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License .

This resource was created by Dr Dan Wheatley. The project was funded by the Economics Network and the Centre for Education in the Built Environment (CEBE) as part of the Teaching and Learning Development Projects 2010/11.

COMMENTS

The zonal travel cost method is applied by collecting information on the number of visits to the site from different distances. ... A cross-sectional analysis of travel cost data collected from 484 people at 11 public beaches was used to impute the aggregate willingness to pay for a 20% increase in water quality, which was assumed to be ...

On the other hand, the mobile phone data used in this study had several challenges for their application to the travel cost method. First, the data were not applicable to the individual or multi-site travel methods which are considered more advanced methods than the zonal travel cost method (Haab and McConnell, 2002, Parsons, 2017). Unlike the ...

In this study, we successfully replicated the methods of Mayer and Woltering (2018) but the simple zonal travel cost techniques presented here could be further developed and extended to explore more sophisticated forms of travel cost modelling such as the individual travel cost model or multi-site models using random utility methods, which can ...

The travel cost method (TCM) may be used to estimate the recreation use value of natural resources or a recreation site. ... 5 It is possible to conduct a simple zonal travel-cost approach—using mostly secondary data, with some simple data collected from visitors—to estimate the recreation use value of a site. The researcher uses ...

Travel cost would be computed for each zone based on travel to ... Although the zonal method sees some use in current practice (Moeltner 2003), in the 1970s most modeling transitioned from aggregate zonal data to individual-based data as the unit of observation (Brown and Nawas 1973). The transition

The travel costs method was first applied in the US in 1959 to value the recreational use of nature. There are basically two different types of travel cost methods; one based on a valuation of a single site and one based on choices between multiple sites. In this overview the use and requirements for these two methods are described separately.

In particular, the study adopts the zonal method starting from secondary data. According to the literature, this approach is more suitable and should be preferred when only secondary data are available. Data from the year 2021 were used. ... An application of the zonal travel cost method. Water SA 2010, 36.

The earliest travel cost models, dating from the late 1950s and into the 1960s, used "zonal" data and followed a method proposed by Hotelling . Geographic zones were defined around a single recreation site. The zones might be concentric or otherwise spatially delineated but varied in their distance from the site.

Eight TC models were derived using as regressors the zonal travel cost and selected picking and socio-economic variables. The resulting demand curves produce an estimate of the average site value per trip that ranges from 9 to 22€/visit considering the onsite data, and from 21 to 47 €/visit for zonal TC implemented on the online data.

We initially apply this idea in the zonal travel cost method (ZTCM) and conduct the valuation research for Hoi An, Vietnam. ... Data of the Number Visitors and Travel Costs (Appendix 3) shows that there are three groups of tourists with different demand curves. It is necessary to simulate the demand curves of these three groups according to the ...

Big data have the potential to improve nonmarket valuation, but their application has been scarce. To test this potential, we apply mobile phone data to the zonal travel cost method and measure ...

The method of individual travel costs aims to eliminate the limitations of the zonal model and uses data about visitors rather than about the recreational area . A structured questionnaire was applied to identify the factors that influence the tourists' willingness to visit the historical center of Bucharest.

This article, using the zonal version of the travel cost method (ZTCM), provides the first economic valuation of recreational trips to Mont-Saint-Michel (MSM). The MSM was designated as United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization World Heritage Site in 1979, and is the most visited coastal site in France.

in Kasibu Nueva Vizcaya was estimated using the zonal travel cost method, a revealed preference ... Data were collected through on-site and online visitor surveys with a total of 429 respondents. Regression analysis using the different functional forms of data was explored to estimate the demand function of the site. Results show that ...

spend resources (time and money) to travel to the site. The travel activity is a reflection of the use value this service has to people. The travel costs method was first applied in the US in 1959 to value the recreational use of nature. There are basically two different types of travel cost methods; one based on a

Travel cost data transformation to their different . functional forms was explored in this study to find better . ... This paper, using the zonal travel cost method, estimates the recreational use ...

The coefficient of travel cost revealed that a peso increment would increase the number of visits in the lake by ~0.0011%. The estimated use-value of Lake Pandin was based on tourists' perceptions ...

This paper applies the Travel Cost (TC) method to estimate the value of mushroom picking in three forest areas in the region of Catalonia, Spain. In particular, the main objective is to contrast different sampling strategies (online vs. onsite data collection) when used to build zonal Travel Cost models. ... Zonal Travel Cost - online data ...

Carson Reeling and I recently published a paper describing a new method to measure the value of outdoor recreation areas to visitors. The method works off a model that identifies trip patterns using aggregate data, such as visitor counts and census populations. This contrasts with traditional approaches that use individual trip information collected via surveys, which tend to be costly and ...

The travel-cost method (TCM) is used for calculating economic values of environmental goods. ... In zonal TCM, the area surrounding the site is divided into zones, which can be either concentric circles or administrative districts. ... This information is sometimes available (e.g. from the site management), which makes data collection from the ...

The value of recreation services generated by the caving activity in Capisaan Cave System (CCS) in Kasibu Nueva Vizcaya was estimated using the zonal travel cost method, a revealed preference ...

Data on this subject are limited; this study aims to address this gap. As a non-market good, evaluating education requires a non-traditional economic approach. An approach offering a methodological value to evaluate EE is the travel cost method (TCM), which is a non-market valuation approach in the field of environmental economics.

The travel cost method involves collecting data on the costs incurred by each individual in travelling to the recreational site or amenity. This 'price' paid by visitors is unique to each individual, and is calculated by summing the travel costs from each individuals original location to the amenity. ... Zonal Travel Cost Method Example.