- TPC and eLearning

- What's NEW at TPC?

- Read Watch Interact

- Practice Review Test

- Teacher-Tools

- Subscription Selection

- Seat Calculator

- Ad Free Account

- Edit Profile Settings

- Classes (Version 2)

- Student Progress Edit

- Task Properties

- Export Student Progress

- Task, Activities, and Scores

- Metric Conversions Questions

- Metric System Questions

- Metric Estimation Questions

- Significant Digits Questions

- Proportional Reasoning

- Acceleration

- Distance-Displacement

- Dots and Graphs

- Graph That Motion

- Match That Graph

- Name That Motion

- Motion Diagrams

- Pos'n Time Graphs Numerical

- Pos'n Time Graphs Conceptual

- Up And Down - Questions

- Balanced vs. Unbalanced Forces

- Change of State

- Force and Motion

- Mass and Weight

- Match That Free-Body Diagram

- Net Force (and Acceleration) Ranking Tasks

- Newton's Second Law

- Normal Force Card Sort

- Recognizing Forces

- Air Resistance and Skydiving

- Solve It! with Newton's Second Law

- Which One Doesn't Belong?

- Component Addition Questions

- Head-to-Tail Vector Addition

- Projectile Mathematics

- Trajectory - Angle Launched Projectiles

- Trajectory - Horizontally Launched Projectiles

- Vector Addition

- Vector Direction

- Which One Doesn't Belong? Projectile Motion

- Forces in 2-Dimensions

- Being Impulsive About Momentum

- Explosions - Law Breakers

- Hit and Stick Collisions - Law Breakers

- Case Studies: Impulse and Force

- Impulse-Momentum Change Table

- Keeping Track of Momentum - Hit and Stick

- Keeping Track of Momentum - Hit and Bounce

- What's Up (and Down) with KE and PE?

- Energy Conservation Questions

- Energy Dissipation Questions

- Energy Ranking Tasks

- LOL Charts (a.k.a., Energy Bar Charts)

- Match That Bar Chart

- Words and Charts Questions

- Name That Energy

- Stepping Up with PE and KE Questions

- Case Studies - Circular Motion

- Circular Logic

- Forces and Free-Body Diagrams in Circular Motion

- Gravitational Field Strength

- Universal Gravitation

- Angular Position and Displacement

- Linear and Angular Velocity

- Angular Acceleration

- Rotational Inertia

- Balanced vs. Unbalanced Torques

- Getting a Handle on Torque

- Torque-ing About Rotation

- Properties of Matter

- Fluid Pressure

- Buoyant Force

- Sinking, Floating, and Hanging

- Pascal's Principle

- Flow Velocity

- Bernoulli's Principle

- Balloon Interactions

- Charge and Charging

- Charge Interactions

- Charging by Induction

- Conductors and Insulators

- Coulombs Law

- Electric Field

- Electric Field Intensity

- Polarization

- Case Studies: Electric Power

- Know Your Potential

- Light Bulb Anatomy

- I = ∆V/R Equations as a Guide to Thinking

- Parallel Circuits - ∆V = I•R Calculations

- Resistance Ranking Tasks

- Series Circuits - ∆V = I•R Calculations

- Series vs. Parallel Circuits

- Equivalent Resistance

- Period and Frequency of a Pendulum

- Pendulum Motion: Velocity and Force

- Energy of a Pendulum

- Period and Frequency of a Mass on a Spring

- Horizontal Springs: Velocity and Force

- Vertical Springs: Velocity and Force

- Energy of a Mass on a Spring

- Decibel Scale

- Frequency and Period

- Closed-End Air Columns

- Name That Harmonic: Strings

- Rocking the Boat

- Wave Basics

- Matching Pairs: Wave Characteristics

- Wave Interference

- Waves - Case Studies

- Color Addition and Subtraction

- Color Filters

- If This, Then That: Color Subtraction

- Light Intensity

- Color Pigments

- Converging Lenses

- Curved Mirror Images

- Law of Reflection

- Refraction and Lenses

- Total Internal Reflection

- Who Can See Who?

- Formulas and Atom Counting

- Atomic Models

- Bond Polarity

- Entropy Questions

- Cell Voltage Questions

- Heat of Formation Questions

- Reduction Potential Questions

- Oxidation States Questions

- Measuring the Quantity of Heat

- Hess's Law

- Oxidation-Reduction Questions

- Galvanic Cells Questions

- Thermal Stoichiometry

- Molecular Polarity

- Quantum Mechanics

- Balancing Chemical Equations

- Bronsted-Lowry Model of Acids and Bases

- Classification of Matter

- Collision Model of Reaction Rates

- Density Ranking Tasks

- Dissociation Reactions

- Complete Electron Configurations

- Elemental Measures

- Enthalpy Change Questions

- Equilibrium Concept

- Equilibrium Constant Expression

- Equilibrium Calculations - Questions

- Equilibrium ICE Table

- Intermolecular Forces Questions

- Ionic Bonding

- Lewis Electron Dot Structures

- Limiting Reactants

- Line Spectra Questions

- Mass Stoichiometry

- Measurement and Numbers

- Metals, Nonmetals, and Metalloids

- Metric Estimations

- Metric System

- Molarity Ranking Tasks

- Mole Conversions

- Name That Element

- Names to Formulas

- Names to Formulas 2

- Nuclear Decay

- Particles, Words, and Formulas

- Periodic Trends

- Precipitation Reactions and Net Ionic Equations

- Pressure Concepts

- Pressure-Temperature Gas Law

- Pressure-Volume Gas Law

- Chemical Reaction Types

- Significant Digits and Measurement

- States Of Matter Exercise

- Stoichiometry Law Breakers

- Stoichiometry - Math Relationships

- Subatomic Particles

- Spontaneity and Driving Forces

- Gibbs Free Energy

- Volume-Temperature Gas Law

- Acid-Base Properties

- Energy and Chemical Reactions

- Chemical and Physical Properties

- Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion Theory

- Writing Balanced Chemical Equations

- Mission CG1

- Mission CG10

- Mission CG2

- Mission CG3

- Mission CG4

- Mission CG5

- Mission CG6

- Mission CG7

- Mission CG8

- Mission CG9

- Mission EC1

- Mission EC10

- Mission EC11

- Mission EC12

- Mission EC2

- Mission EC3

- Mission EC4

- Mission EC5

- Mission EC6

- Mission EC7

- Mission EC8

- Mission EC9

- Mission RL1

- Mission RL2

- Mission RL3

- Mission RL4

- Mission RL5

- Mission RL6

- Mission KG7

- Mission RL8

- Mission KG9

- Mission RL10

- Mission RL11

- Mission RM1

- Mission RM2

- Mission RM3

- Mission RM4

- Mission RM5

- Mission RM6

- Mission RM8

- Mission RM10

- Mission LC1

- Mission RM11

- Mission LC2

- Mission LC3

- Mission LC4

- Mission LC5

- Mission LC6

- Mission LC8

- Mission SM1

- Mission SM2

- Mission SM3

- Mission SM4

- Mission SM5

- Mission SM6

- Mission SM8

- Mission SM10

- Mission KG10

- Mission SM11

- Mission KG2

- Mission KG3

- Mission KG4

- Mission KG5

- Mission KG6

- Mission KG8

- Mission KG11

- Mission F2D1

- Mission F2D2

- Mission F2D3

- Mission F2D4

- Mission F2D5

- Mission F2D6

- Mission KC1

- Mission KC2

- Mission KC3

- Mission KC4

- Mission KC5

- Mission KC6

- Mission KC7

- Mission KC8

- Mission AAA

- Mission SM9

- Mission LC7

- Mission LC9

- Mission NL1

- Mission NL2

- Mission NL3

- Mission NL4

- Mission NL5

- Mission NL6

- Mission NL7

- Mission NL8

- Mission NL9

- Mission NL10

- Mission NL11

- Mission NL12

- Mission MC1

- Mission MC10

- Mission MC2

- Mission MC3

- Mission MC4

- Mission MC5

- Mission MC6

- Mission MC7

- Mission MC8

- Mission MC9

- Mission RM7

- Mission RM9

- Mission RL7

- Mission RL9

- Mission SM7

- Mission SE1

- Mission SE10

- Mission SE11

- Mission SE12

- Mission SE2

- Mission SE3

- Mission SE4

- Mission SE5

- Mission SE6

- Mission SE7

- Mission SE8

- Mission SE9

- Mission VP1

- Mission VP10

- Mission VP2

- Mission VP3

- Mission VP4

- Mission VP5

- Mission VP6

- Mission VP7

- Mission VP8

- Mission VP9

- Mission WM1

- Mission WM2

- Mission WM3

- Mission WM4

- Mission WM5

- Mission WM6

- Mission WM7

- Mission WM8

- Mission WE1

- Mission WE10

- Mission WE2

- Mission WE3

- Mission WE4

- Mission WE5

- Mission WE6

- Mission WE7

- Mission WE8

- Mission WE9

- Vector Walk Interactive

- Name That Motion Interactive

- Kinematic Graphing 1 Concept Checker

- Kinematic Graphing 2 Concept Checker

- Graph That Motion Interactive

- Two Stage Rocket Interactive

- Rocket Sled Concept Checker

- Force Concept Checker

- Free-Body Diagrams Concept Checker

- Free-Body Diagrams The Sequel Concept Checker

- Skydiving Concept Checker

- Elevator Ride Concept Checker

- Vector Addition Concept Checker

- Vector Walk in Two Dimensions Interactive

- Name That Vector Interactive

- River Boat Simulator Concept Checker

- Projectile Simulator 2 Concept Checker

- Projectile Simulator 3 Concept Checker

- Hit the Target Interactive

- Turd the Target 1 Interactive

- Turd the Target 2 Interactive

- Balance It Interactive

- Go For The Gold Interactive

- Egg Drop Concept Checker

- Fish Catch Concept Checker

- Exploding Carts Concept Checker

- Collision Carts - Inelastic Collisions Concept Checker

- Its All Uphill Concept Checker

- Stopping Distance Concept Checker

- Chart That Motion Interactive

- Roller Coaster Model Concept Checker

- Uniform Circular Motion Concept Checker

- Horizontal Circle Simulation Concept Checker

- Vertical Circle Simulation Concept Checker

- Race Track Concept Checker

- Gravitational Fields Concept Checker

- Orbital Motion Concept Checker

- Angular Acceleration Concept Checker

- Balance Beam Concept Checker

- Torque Balancer Concept Checker

- Aluminum Can Polarization Concept Checker

- Charging Concept Checker

- Name That Charge Simulation

- Coulomb's Law Concept Checker

- Electric Field Lines Concept Checker

- Put the Charge in the Goal Concept Checker

- Circuit Builder Concept Checker (Series Circuits)

- Circuit Builder Concept Checker (Parallel Circuits)

- Circuit Builder Concept Checker (∆V-I-R)

- Circuit Builder Concept Checker (Voltage Drop)

- Equivalent Resistance Interactive

- Pendulum Motion Simulation Concept Checker

- Mass on a Spring Simulation Concept Checker

- Particle Wave Simulation Concept Checker

- Boundary Behavior Simulation Concept Checker

- Slinky Wave Simulator Concept Checker

- Simple Wave Simulator Concept Checker

- Wave Addition Simulation Concept Checker

- Standing Wave Maker Simulation Concept Checker

- Color Addition Concept Checker

- Painting With CMY Concept Checker

- Stage Lighting Concept Checker

- Filtering Away Concept Checker

- InterferencePatterns Concept Checker

- Young's Experiment Interactive

- Plane Mirror Images Interactive

- Who Can See Who Concept Checker

- Optics Bench (Mirrors) Concept Checker

- Name That Image (Mirrors) Interactive

- Refraction Concept Checker

- Total Internal Reflection Concept Checker

- Optics Bench (Lenses) Concept Checker

- Kinematics Preview

- Velocity Time Graphs Preview

- Moving Cart on an Inclined Plane Preview

- Stopping Distance Preview

- Cart, Bricks, and Bands Preview

- Fan Cart Study Preview

- Friction Preview

- Coffee Filter Lab Preview

- Friction, Speed, and Stopping Distance Preview

- Up and Down Preview

- Projectile Range Preview

- Ballistics Preview

- Juggling Preview

- Marshmallow Launcher Preview

- Air Bag Safety Preview

- Colliding Carts Preview

- Collisions Preview

- Engineering Safer Helmets Preview

- Push the Plow Preview

- Its All Uphill Preview

- Energy on an Incline Preview

- Modeling Roller Coasters Preview

- Hot Wheels Stopping Distance Preview

- Ball Bat Collision Preview

- Energy in Fields Preview

- Weightlessness Training Preview

- Roller Coaster Loops Preview

- Universal Gravitation Preview

- Keplers Laws Preview

- Kepler's Third Law Preview

- Charge Interactions Preview

- Sticky Tape Experiments Preview

- Wire Gauge Preview

- Voltage, Current, and Resistance Preview

- Light Bulb Resistance Preview

- Series and Parallel Circuits Preview

- Thermal Equilibrium Preview

- Linear Expansion Preview

- Heating Curves Preview

- Electricity and Magnetism - Part 1 Preview

- Electricity and Magnetism - Part 2 Preview

- Vibrating Mass on a Spring Preview

- Period of a Pendulum Preview

- Wave Speed Preview

- Slinky-Experiments Preview

- Standing Waves in a Rope Preview

- Sound as a Pressure Wave Preview

- DeciBel Scale Preview

- DeciBels, Phons, and Sones Preview

- Sound of Music Preview

- Shedding Light on Light Bulbs Preview

- Models of Light Preview

- Electromagnetic Radiation Preview

- Electromagnetic Spectrum Preview

- EM Wave Communication Preview

- Digitized Data Preview

- Light Intensity Preview

- Concave Mirrors Preview

- Object Image Relations Preview

- Snells Law Preview

- Reflection vs. Transmission Preview

- Magnification Lab Preview

- Reactivity Preview

- Ions and the Periodic Table Preview

- Periodic Trends Preview

- Chemical Reactions Preview

- Intermolecular Forces Preview

- Melting Points and Boiling Points Preview

- Bond Energy and Reactions Preview

- Reaction Rates Preview

- Ammonia Factory Preview

- Stoichiometry Preview

- Nuclear Chemistry Preview

- Gaining Teacher Access

- Tasks and Classes

- Tasks - Classic

- Subscription

- Subscription Locator

- 1-D Kinematics

- Newton's Laws

- Vectors - Motion and Forces in Two Dimensions

- Momentum and Its Conservation

- Work and Energy

- Circular Motion and Satellite Motion

- Thermal Physics

- Static Electricity

- Electric Circuits

- Vibrations and Waves

- Sound Waves and Music

- Light and Color

- Reflection and Mirrors

- About the Physics Interactives

- Task Tracker

- Usage Policy

- Newtons Laws

- Vectors and Projectiles

- Forces in 2D

- Momentum and Collisions

- Circular and Satellite Motion

- Balance and Rotation

- Electromagnetism

- Waves and Sound

- Atomic Physics

- Forces in Two Dimensions

- Work, Energy, and Power

- Circular Motion and Gravitation

- Sound Waves

- 1-Dimensional Kinematics

- Circular, Satellite, and Rotational Motion

- Einstein's Theory of Special Relativity

- Waves, Sound and Light

- QuickTime Movies

- About the Concept Builders

- Pricing For Schools

- Directions for Version 2

- Measurement and Units

- Relationships and Graphs

- Rotation and Balance

- Vibrational Motion

- Reflection and Refraction

- Teacher Accounts

- Task Tracker Directions

- Kinematic Concepts

- Kinematic Graphing

- Wave Motion

- Sound and Music

- About CalcPad

- 1D Kinematics

- Vectors and Forces in 2D

- Simple Harmonic Motion

- Rotational Kinematics

- Rotation and Torque

- Rotational Dynamics

- Electric Fields, Potential, and Capacitance

- Transient RC Circuits

- Light Waves

- Units and Measurement

- Stoichiometry

- Molarity and Solutions

- Thermal Chemistry

- Acids and Bases

- Kinetics and Equilibrium

- Solution Equilibria

- Oxidation-Reduction

- Nuclear Chemistry

- Newton's Laws of Motion

- Work and Energy Packet

- Static Electricity Review

- NGSS Alignments

- 1D-Kinematics

- Projectiles

- Circular Motion

- Magnetism and Electromagnetism

- Graphing Practice

- About the ACT

- ACT Preparation

- For Teachers

- Other Resources

- Solutions Guide

- Solutions Guide Digital Download

- Motion in One Dimension

- Work, Energy and Power

- Algebra Based Physics

- Other Tools

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Purchasing the Download

- Purchasing the CD

- Purchasing the Digital Download

- About the NGSS Corner

- NGSS Search

- Force and Motion DCIs - High School

- Energy DCIs - High School

- Wave Applications DCIs - High School

- Force and Motion PEs - High School

- Energy PEs - High School

- Wave Applications PEs - High School

- Crosscutting Concepts

- The Practices

- Physics Topics

- NGSS Corner: Activity List

- NGSS Corner: Infographics

- About the Toolkits

- Position-Velocity-Acceleration

- Position-Time Graphs

- Velocity-Time Graphs

- Newton's First Law

- Newton's Second Law

- Newton's Third Law

- Terminal Velocity

- Projectile Motion

- Forces in 2 Dimensions

- Impulse and Momentum Change

- Momentum Conservation

- Work-Energy Fundamentals

- Work-Energy Relationship

- Roller Coaster Physics

- Satellite Motion

- Electric Fields

- Circuit Concepts

- Series Circuits

- Parallel Circuits

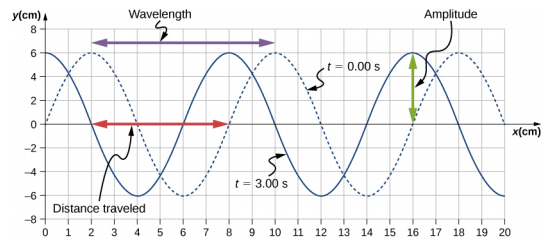

- Describing-Waves

- Wave Behavior Toolkit

- Standing Wave Patterns

- Resonating Air Columns

- Wave Model of Light

- Plane Mirrors

- Curved Mirrors

- Teacher Guide

- Using Lab Notebooks

- Current Electricity

- Light Waves and Color

- Reflection and Ray Model of Light

- Refraction and Ray Model of Light

- Classes (Legacy Version)

- Teacher Resources

- Subscriptions

- Newton's Laws

- Einstein's Theory of Special Relativity

- About Concept Checkers

- School Pricing

- Newton's Laws of Motion

- Newton's First Law

- Newton's Third Law

- The Speed of Sound

- Pitch and Frequency

- Intensity and the Decibel Scale

- The Human Ear

Since the speed of a wave is defined as the distance that a point on a wave (such as a compression or a rarefaction) travels per unit of time, it is often expressed in units of meters/second (abbreviated m/s). In equation form, this is

The faster a sound wave travels, the more distance it will cover in the same period of time. If a sound wave were observed to travel a distance of 700 meters in 2 seconds, then the speed of the wave would be 350 m/s. A slower wave would cover less distance - perhaps 660 meters - in the same time period of 2 seconds and thus have a speed of 330 m/s. Faster waves cover more distance in the same period of time.

Factors Affecting Wave Speed

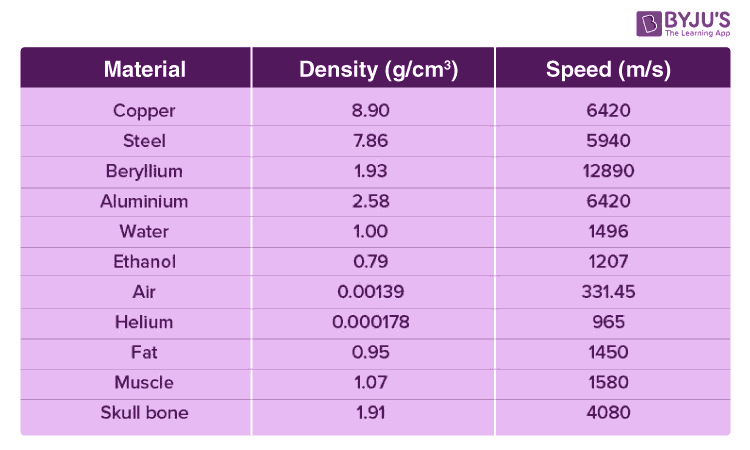

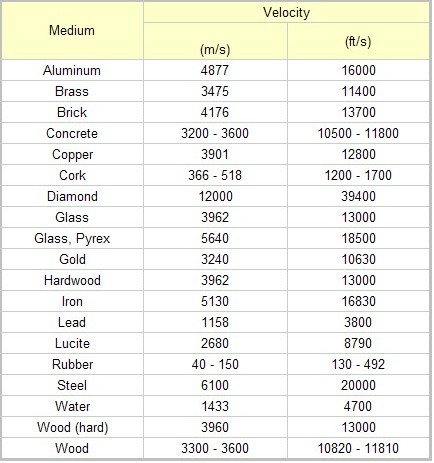

The speed of any wave depends upon the properties of the medium through which the wave is traveling. Typically there are two essential types of properties that affect wave speed - inertial properties and elastic properties. Elastic properties are those properties related to the tendency of a material to maintain its shape and not deform whenever a force or stress is applied to it. A material such as steel will experience a very small deformation of shape (and dimension) when a stress is applied to it. Steel is a rigid material with a high elasticity. On the other hand, a material such as a rubber band is highly flexible; when a force is applied to stretch the rubber band, it deforms or changes its shape readily. A small stress on the rubber band causes a large deformation. Steel is considered to be a stiff or rigid material, whereas a rubber band is considered a flexible material. At the particle level, a stiff or rigid material is characterized by atoms and/or molecules with strong attractions for each other. When a force is applied in an attempt to stretch or deform the material, its strong particle interactions prevent this deformation and help the material maintain its shape. Rigid materials such as steel are considered to have a high elasticity. (Elastic modulus is the technical term). The phase of matter has a tremendous impact upon the elastic properties of the medium. In general, solids have the strongest interactions between particles, followed by liquids and then gases. For this reason, longitudinal sound waves travel faster in solids than they do in liquids than they do in gases. Even though the inertial factor may favor gases, the elastic factor has a greater influence on the speed ( v ) of a wave, thus yielding this general pattern:

Inertial properties are those properties related to the material's tendency to be sluggish to changes in its state of motion. The density of a medium is an example of an inertial property . The greater the inertia (i.e., mass density) of individual particles of the medium, the less responsive they will be to the interactions between neighboring particles and the slower that the wave will be. As stated above, sound waves travel faster in solids than they do in liquids than they do in gases. However, within a single phase of matter, the inertial property of density tends to be the property that has a greatest impact upon the speed of sound. A sound wave will travel faster in a less dense material than a more dense material. Thus, a sound wave will travel nearly three times faster in Helium than it will in air. This is mostly due to the lower mass of Helium particles as compared to air particles.

The Speed of Sound in Air

The speed of a sound wave in air depends upon the properties of the air, mostly the temperature, and to a lesser degree, the humidity. Humidity is the result of water vapor being present in air. Like any liquid, water has a tendency to evaporate. As it does, particles of gaseous water become mixed in the air. This additional matter will affect the mass density of the air (an inertial property). The temperature will affect the strength of the particle interactions (an elastic property). At normal atmospheric pressure, the temperature dependence of the speed of a sound wave through dry air is approximated by the following equation:

where T is the temperature of the air in degrees Celsius. Using this equation to determine the speed of a sound wave in air at a temperature of 20 degrees Celsius yields the following solution.

v = 331 m/s + (0.6 m/s/C)•(20 C)

v = 331 m/s + 12 m/s

v = 343 m/s

(The above equation relating the speed of a sound wave in air to the temperature provides reasonably accurate speed values for temperatures between 0 and 100 Celsius. The equation itself does not have any theoretical basis; it is simply the result of inspecting temperature-speed data for this temperature range. Other equations do exist that are based upon theoretical reasoning and provide accurate data for all temperatures. Nonetheless, the equation above will be sufficient for our use as introductory Physics students.)

Look It Up!

Using wave speed to determine distances.

At normal atmospheric pressure and a temperature of 20 degrees Celsius, a sound wave will travel at approximately 343 m/s; this is approximately equal to 750 miles/hour. While this speed may seem fast by human standards (the fastest humans can sprint at approximately 11 m/s and highway speeds are approximately 30 m/s), the speed of a sound wave is slow in comparison to the speed of a light wave. Light travels through air at a speed of approximately 300 000 000 m/s; this is nearly 900 000 times the speed of sound. For this reason, humans can observe a detectable time delay between the thunder and the lightning during a storm. The arrival of the light wave from the location of the lightning strike occurs in so little time that it is essentially negligible. Yet the arrival of the sound wave from the location of the lightning strike occurs much later. The time delay between the arrival of the light wave (lightning) and the arrival of the sound wave (thunder) allows a person to approximate his/her distance from the storm location. For instance if the thunder is heard 3 seconds after the lightning is seen, then sound (whose speed is approximated as 345 m/s) has traveled a distance of

If this value is converted to miles (divide by 1600 m/1 mi), then the storm is a distance of 0.65 miles away.

Another phenomenon related to the perception of time delays between two events is an echo . A person can often perceive a time delay between the production of a sound and the arrival of a reflection of that sound off a distant barrier. If you have ever made a holler within a canyon, perhaps you have heard an echo of your holler off a distant canyon wall. The time delay between the holler and the echo corresponds to the time for the holler to travel the round-trip distance to the canyon wall and back. A measurement of this time would allow a person to estimate the one-way distance to the canyon wall. For instance if an echo is heard 1.40 seconds after making the holler , then the distance to the canyon wall can be found as follows:

The canyon wall is 242 meters away. You might have noticed that the time of 0.70 seconds is used in the equation. Since the time delay corresponds to the time for the holler to travel the round-trip distance to the canyon wall and back, the one-way distance to the canyon wall corresponds to one-half the time delay.

While an echo is of relatively minimal importance to humans, echolocation is an essential trick of the trade for bats. Being a nocturnal creature, bats must use sound waves to navigate and hunt. They produce short bursts of ultrasonic sound waves that reflect off objects in their surroundings and return. Their detection of the time delay between the sending and receiving of the pulses allows a bat to approximate the distance to surrounding objects. Some bats, known as Doppler bats, are capable of detecting the speed and direction of any moving objects by monitoring the changes in frequency of the reflected pulses. These bats are utilizing the physics of the Doppler effect discussed in an earlier unit (and also to be discussed later in Lesson 3 ). This method of echolocation enables a bat to navigate and to hunt.

The Wave Equation Revisited

Like any wave, a sound wave has a speed that is mathematically related to the frequency and the wavelength of the wave. As discussed in a previous unit , the mathematical relationship between speed, frequency and wavelength is given by the following equation.

Using the symbols v , λ , and f , the equation can be rewritten as

Check Your Understanding

1. An automatic focus camera is able to focus on objects by use of an ultrasonic sound wave. The camera sends out sound waves that reflect off distant objects and return to the camera. A sensor detects the time it takes for the waves to return and then determines the distance an object is from the camera. If a sound wave (speed = 340 m/s) returns to the camera 0.150 seconds after leaving the camera, how far away is the object?

Answer = 25.5 m

The speed of the sound wave is 340 m/s. The distance can be found using d = v • t resulting in an answer of 25.5 m. Use 0.075 seconds for the time since 0.150 seconds refers to the round-trip distance.

2. On a hot summer day, a pesky little mosquito produced its warning sound near your ear. The sound is produced by the beating of its wings at a rate of about 600 wing beats per second.

a. What is the frequency in Hertz of the sound wave? b. Assuming the sound wave moves with a velocity of 350 m/s, what is the wavelength of the wave?

Part a Answer: 600 Hz (given)

Part b Answer: 0.583 meters

3. Doubling the frequency of a wave source doubles the speed of the waves.

a. True b. False

Doubling the frequency will halve the wavelength; speed is unaffected by the alteration in the frequency. The speed of a wave depends upon the properties of the medium.

4. Playing middle C on the piano keyboard produces a sound with a frequency of 256 Hz. Assuming the speed of sound in air is 345 m/s, determine the wavelength of the sound corresponding to the note of middle C.

Answer: 1.35 meters (rounded)

Let λ = wavelength. Use v = f • λ where v = 345 m/s and f = 256 Hz. Rearrange the equation to the form of λ = v / f. Substitute and solve.

5. Most people can detect frequencies as high as 20 000 Hz. Assuming the speed of sound in air is 345 m/s, determine the wavelength of the sound corresponding to this upper range of audible hearing.

Answer: 0.0173 meters (rounded)

Let λ = wavelength. Use v = f • λ where v = 345 m/s and f = 20 000 Hz. Rearrange the equation to the form of λ = v / f. Substitute and solve.

6. An elephant produces a 10 Hz sound wave. Assuming the speed of sound in air is 345 m/s, determine the wavelength of this infrasonic sound wave.

Answer: 34.5 meters

Let λ = wavelength. Use v = f • λ where v = 345 m/s and f = 10 Hz. Rearrange the equation to the form of λ = v / f. Substitute and solve.

7. Determine the speed of sound on a cold winter day (T=3 degrees C).

Answer: 332.8 m/s

The speed of sound in air is dependent upon the temperature of air. The dependence is expressed by the equation:

v = 331 m/s + (0.6 m/s/C) • T

where T is the temperature in Celsius. Substitute and solve.

v = 331 m/s + (0.6 m/s/C) • 3 C v = 331 m/s + 1.8 m/s v = 332.8 m/s

8. Miles Tugo is camping in Glacier National Park. In the midst of a glacier canyon, he makes a loud holler. He hears an echo 1.22 seconds later. The air temperature is 20 degrees C. How far away are the canyon walls?

Answer = 209 m

The speed of the sound wave at this temperature is 343 m/s (using the equation described in the Tutorial). The distance can be found using d = v • t resulting in an answer of 343 m. Use 0.61 second for the time since 1.22 seconds refers to the round-trip distance.

9. Two sound waves are traveling through a container of unknown gas. Wave A has a wavelength of 1.2 m. Wave B has a wavelength of 3.6 m. The velocity of wave B must be __________ the velocity of wave A.

a. one-ninth b. one-third c. the same as d. three times larger than

The speed of a wave does not depend upon its wavelength, but rather upon the properties of the medium. The medium has not changed, so neither has the speed.

10. Two sound waves are traveling through a container of unknown gas. Wave A has a wavelength of 1.2 m. Wave B has a wavelength of 3.6 m. The frequency of wave B must be __________ the frequency of wave A.

Since Wave B has three times the wavelength of Wave A, it must have one-third the frequency. Frequency and wavelength are inversely related.

- Interference and Beats

- Science Notes Posts

- Contact Science Notes

- Todd Helmenstine Biography

- Anne Helmenstine Biography

- Free Printable Periodic Tables (PDF and PNG)

- Periodic Table Wallpapers

- Interactive Periodic Table

- Periodic Table Posters

- How to Grow Crystals

- Chemistry Projects

- Fire and Flames Projects

- Holiday Science

- Chemistry Problems With Answers

- Physics Problems

- Unit Conversion Example Problems

- Chemistry Worksheets

- Biology Worksheets

- Periodic Table Worksheets

- Physical Science Worksheets

- Science Lab Worksheets

- My Amazon Books

Speed of Sound in Physics

In physics, the speed of sound is the distance traveled per unit of time by a sound wave through a medium. It is highest for stiff solids and lowest for gases. There is no sound or speed of sound in a vacuum because sound (unlike light ) requires a medium in order to propogate.

What Is the Speed of Sound?

Usually, conversations about the speed of sound refer to the speed of sound of dry air (humidity changes the value). The value depends on temperature.

- at 20 ° C or 68 ° F: 343 m/s or 1234.8 kph or 1125ft/s or 767 mph

- at 0 ° C or 32 ° F: 331 m/s or 1191.6 kph or 1086 ft/s or 740 mph

Mach Numher

The Mach number is the ratio of air speed to the speed of sound. So, an object at Mach 1 is traveling at the speed of sound. Exceeding Mach 1 is breaking the sound barrier or is supersonic . At Mach 2, the object travels twice the speed of sound. Mach 3 is three times the speed of sound, and so on.

Remember that the speed of sound depends on temperature, so you break sound barrier at a lower speed when the temperature is colder. To put it another way, it gets colder as you get higher in the atmosphere, so an aircraft might break the sound barrier at a higher altitude even if it does not increase its speed.

Solids, Liquids, and Gases

The speed of sound is greatest for solids, intermediate for liquids, and lowest for gases:

v solid > v liquid >v gas

Particles in a gas undergo elastic collisions and the particles are widely separated. In contrast, particles in a solid are locked into place (rigid or stiff), so a vibration readily transmits through chemical bonds.

Here are examples of the difference between the speed of sound in different materials:

- Diamond (solid): 12000 m/s

- Copper (solid): 6420 m/s

- Iron (solid): 5120 m/s

- Water (liquid) 1481 m/s

- Helium (gas): 965 m/s

- Dry air (gas): 343 m/s

Sounds waves transfer energy to matter via a compression wave (in all phases) and also shear wave (in solids). The pressure disturbs a particle, which then impacts its neighbor, and continues traveling through the medium. The speed is how quickly the wave moves, while the frequency is the number of vibrations the particle makes per unit of time.

The Hot Chocolate Effect

The hot chocolate effect describes the phenomenon where the pitch you hear from tapping a cup of hot liquid rises after adding a soluble powder (like cocoa powder into hot water). Stirring in the powder introduces gas bubbles that reduce the speed of sound of the liquid and lower the frequency (pitch) of the waves. Once the bubbles clear, the speed of sound and the frequency increase again.

Speed of Sound Formulas

There are several formulas for calculating the speed of sound. Here are a few of the most common ones:

For gases these approximations work in most situations:

For this formula, use the Celsius temperature of the gas.

v = 331 m/s + (0.6 m/s/C)•T

Here is another common formula:

v = (γRT) 1/2

- γ is the ratio of specific heat values or adiabatic index (1.4 for air at STP )

- R is a gas constant (282 m 2 /s 2 /K for air)

- T is the absolute temperature (Kelvin)

The Newton-Laplace formula works for both gases and liquids (fluids):

v = (K s /ρ) 1/2

- K s is the coefficient of stiffness or bulk modulus of elasticity for gases

- ρ is the density of the material

So solids, the situation is more complicated because shear waves play into the formula. There can be sound waves with different velocities, depending on the mode of deformation. The simplest formula is for one-dimensional solids, like a long rod of a material:

v = (E/ρ) 1/2

- E is Young’s modulus

Note that the speed of sound decreases with density! It increases according to the stiffness of a medium. This is not intuitively obvious, since often a dense material is also stiff. But, consider that the speed of sound in a diamond is much faster than the speed in iron. Diamond is less dense than iron and also stiffer.

Factors That Affect the Speed of Sound

The primary factors affecting the speed of sound of a fluid (gas or liquid) are its temperature and its chemical composition. There is a weak dependence on frequency and atmospheric pressure that is omitted from the simplest equations.

While sound travels only as compression waves in a fluid, it also travels as shear waves in a solid. So, a solid’s stiffness, density, and compressibility also factor into the speed of sound.

Speed of Sound on Mars

Thanks to the Perseverance rover, scientists know the speed of sound on Mars. The Martian atmosphere is much colder than Earth’s, its thin atmosphere has a much lower pressure, and it consists mainly of carbon dioxide rather than nitrogen. As expected, the speed of sound on Mars is slower than on Earth. It travels at around 240 m/s or about 30% slower than on Earth.

What scientists did not expect is that the speed of sound varies for different frequencies. A high pitched sound, like from the rover’s laser, travels faster at around 250 m/s. So, for example, if you listened to a symphony recording from a distance on Mars you’d hear the various instruments at different times. The explanation has to do with the vibrational modes of carbon dioxide, the primary component of the Martian atmosphere. Also, it’s worth noting that the atmospheric pressure is so low that there really isn’t any much sound at all from a source more than a few meters away.

Speed of Sound Example Problems

Find the speed of sound on a cold day when the temperature is 2 ° C.

The simplest formula for finding the answer is the approximation:

v = 331 m/s + (0.6 m/s/C) • T

Since the given temperature is already in Celsius, just plug in the value:

v = 331 m/s + (0.6 m/s/C) • 2 C = 331 m/s + 1.2 m/s = 332.2 m/s

You’re hiking in a canyon, yell “hello”, and hear an echo after 1.22 seconds. The air temperature is 20 ° C. How far away is the canyon wall?

The first step is finding the speed of sound at the temperature:

v = 331 m/s + (0.6 m/s/C) • T v = 331 m/s + (0.6 m/s/C) • 20 C = 343 m/s (which you might have memorized as the usual speed of sound)

Next, find the distance using the formula:

d = v• T d = 343 m/s • 1.22 s = 418.46 m

But, this is the round-trip distance! The distance to the canyon wall is half of this or 209 meters.

If you double the frequency of sound, it double the speed of its waves. True or false?

This is (mostly) false. Doubling the frequency halves the wavelength, but the speed depends on the properties of the medium and not its frequency or wavelength. Frequency only affects the speed of sound for certain media (like the carbon dioxide atmosphere of Mars).

- Everest, F. (2001). The Master Handbook of Acoustics . New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-136097-5.

- Kinsler, L.E.; Frey, A.R.; Coppens, A.B.; Sanders, J.V. (2000). Fundamentals of Acoustics (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-84789-5.

- Maurice, S.; et al. (2022). “In situ recording of Mars soundscape:. Nature. 605: 653-658. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04679-0

- Wong, George S. K.; Zhu, Shi-ming (1995). “Speed of sound in seawater as a function of salinity, temperature, and pressure”. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America . 97 (3): 1732. doi: 10.1121/1.413048

Related Posts

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Physics library

Course: physics library > unit 8.

- Production of sound

- Sound Properties: Amplitude, period, frequency, wavelength

- Speed of Sound

Relative speed of sound in solids, liquids, and gases

- Mach numbers

- Decibel Scale

- Why do sounds get softer?

- Ultrasound medical imaging

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Video transcript

17.1 Sound Waves

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the difference between sound and hearing

- Describe sound as a wave

- List the equations used to model sound waves

- Describe compression and rarefactions as they relate to sound

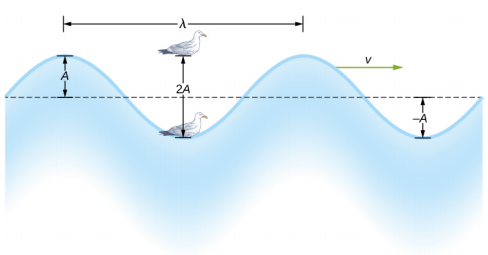

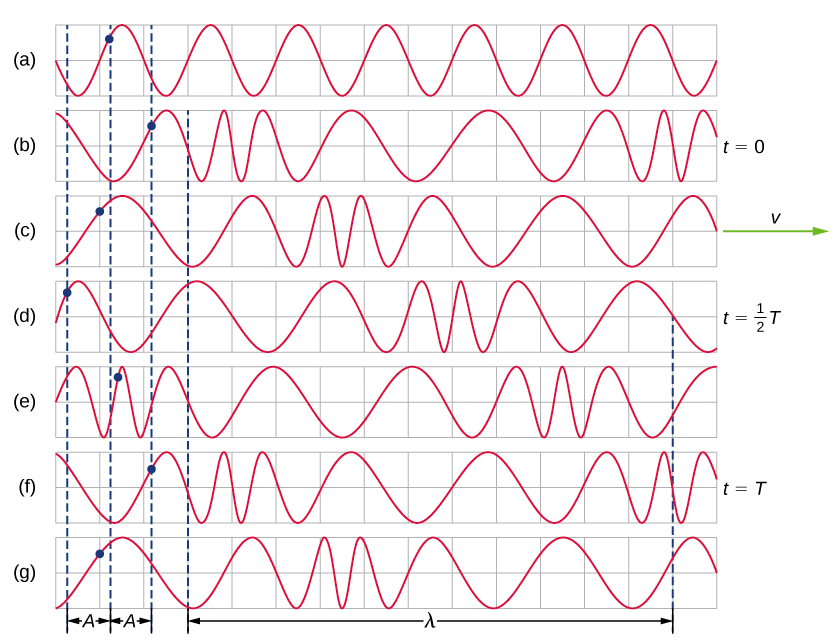

The physical phenomenon of sound is a disturbance of matter that is transmitted from its source outward. Hearing is the perception of sound, just as seeing is the perception of visible light. On the atomic scale, sound is a disturbance of atoms that is far more ordered than their thermal motions. In many instances, sound is a periodic wave, and the atoms undergo simple harmonic motion. Thus, sound waves can induce oscillations and resonance effects ( Figure 17.2 ).

Interactive

This video shows waves on the surface of a wine glass, being driven by sound waves from a speaker. As the frequency of the sound wave approaches the resonant frequency of the wine glass, the amplitude and frequency of the waves on the wine glass increase. When the resonant frequency is reached, the glass shatters.

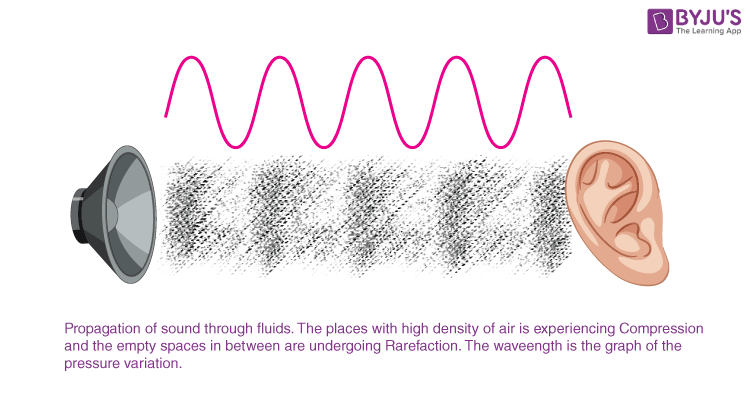

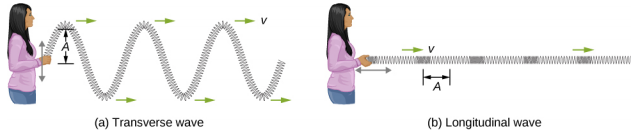

A speaker produces a sound wave by oscillating a cone, causing vibrations of air molecules. In Figure 17.3 , a speaker vibrates at a constant frequency and amplitude, producing vibrations in the surrounding air molecules. As the speaker oscillates back and forth, it transfers energy to the air, mostly as thermal energy. But a small part of the speaker’s energy goes into compressing and expanding the surrounding air, creating slightly higher and lower local pressures. These compressions (high-pressure regions) and rarefactions (low-pressure regions) move out as longitudinal pressure waves having the same frequency as the speaker—they are the disturbance that is a sound wave. (Sound waves in air and most fluids are longitudinal, because fluids have almost no shear strength. In solids, sound waves can be both transverse and longitudinal.)

Figure 17.3 (a) shows the compressions and rarefactions, and also shows a graph of gauge pressure versus distance from a speaker. As the speaker moves in the positive x -direction, it pushes air molecules, displacing them from their equilibrium positions. As the speaker moves in the negative x -direction, the air molecules move back toward their equilibrium positions due to a restoring force. The air molecules oscillate in simple harmonic motion about their equilibrium positions, as shown in part (b). Note that sound waves in air are longitudinal, and in the figure, the wave propagates in the positive x -direction and the molecules oscillate parallel to the direction in which the wave propagates.

Models Describing Sound

Sound can be modeled as a pressure wave by considering the change in pressure from average pressure,

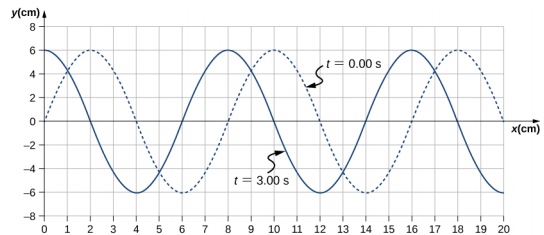

This equation is similar to the periodic wave equations seen in Waves , where Δ P Δ P is the change in pressure, Δ P max Δ P max is the maximum change in pressure, k = 2 π λ k = 2 π λ is the wave number, ω = 2 π T = 2 π f ω = 2 π T = 2 π f is the angular frequency, and ϕ ϕ is the initial phase. The wave speed can be determined from v = ω k = λ T . v = ω k = λ T . Sound waves can also be modeled in terms of the displacement of the air molecules. The displacement of the air molecules can be modeled using a cosine function:

In this equation, s is the displacement and s max s max is the maximum displacement.

Not shown in the figure is the amplitude of a sound wave as it decreases with distance from its source, because the energy of the wave is spread over a larger and larger area. The intensity decreases as it moves away from the speaker, as discussed in Waves . The energy is also absorbed by objects and converted into thermal energy by the viscosity of the air. In addition, during each compression, a little heat transfers to the air; during each rarefaction, even less heat transfers from the air, and these heat transfers reduce the organized disturbance into random thermal motions. Whether the heat transfer from compression to rarefaction is significant depends on how far apart they are—that is, it depends on wavelength. Wavelength, frequency, amplitude, and speed of propagation are important characteristics for sound, as they are for all waves.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-1/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: William Moebs, Samuel J. Ling, Jeff Sanny

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: University Physics Volume 1

- Publication date: Sep 19, 2016

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-1/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-1/pages/17-1-sound-waves

© Jan 19, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Sound Waves

- Speed Of Sound Propagation

Speed of Sound

A sound wave is fundamentally a pressure disturbance that propagates through a medium by particle interaction. In other words, sound waves move through a physical medium by alternately contracting and expanding the section of the medium in which it propagates. The rate at which the sound waves propagate through the medium is known as the speed of sound. In this article, you will discover the definition and factors affecting the speed of sound.

Speed of Sound Definition

The speed of sound is defined as the distance through which a sound wave’s point, such as a compression or a rarefaction, travels per unit of time. The speed of sound remains the same for all frequencies in a given medium under the same physical conditions.

Speed of Sound Formula

Since the speed of sound is the distance travelled by the sound wave in a given time, the speed of sound can be determined by the following formula:

v = λ f

Where v is the velocity, λ is the wavelength of the sound wave, and f is the frequency.

The relationship between the speed of sound, its frequency, and wavelength is the same as for all waves. The wavelength of a sound is the distance between adjacent compressions or rarefactions . The frequency is the same as the source’s and is the number of waves that pass a point per unit time.

Solved Example:

How long does it take for a sound wave of frequency 2 kHz and a wavelength of 35 cm to travel a distance of 1.5 km?

We know that the speed of sound is given by the formula:

v = λ ν

Substituting the values in the equation, we get

v = 0.35 m × 2000 Hz = 700 m/s

The time taken by the sound wave to travel a distance of 1.5 km can be calculated as follows:

Time = Distance Travelled/ Velocity

Time = 1500 m/ 700 m/s = 2.1 s

Factors Affecting the Speed of Sound

Density and temperature of the medium in which the sound wave travels affect the speed of sound.

Density of the Medium

When the medium is dense, the molecules in the medium are closely packed, which means that the sound travels faster. Therefore, the speed of sound increases as the density of the medium increases.

Temperature of the Medium

The speed of sound is directly proportional to the temperature. Therefore, as the temperature increases, the speed of sound increases.

Speed of Sound in Different Media

The speed of the sound depends on the density and the elasticity of the medium through which it travels. In general, sound travels faster in liquids than in gases and quicker in solids than in liquids. The greater the elasticity and the lower the density, the faster sound travels in a medium.

Speed of Sound in Solid

Sound is nothing more than a disturbance propagated by the collisions between the particles, one molecule hitting the next and so forth. Solids are significantly denser than liquids or gases, and this means that the molecules are closer to each other in solids than in liquids and liquids than in gases. This closeness due to density means that they can collide very quickly. Effectively it takes less time for a molecule of a solid to bump into its neighbouring molecule. Due to this advantage, the velocity of sound in a solid is faster than in a gas.

The speed of sound in solid is 6000 metres per second, while the speed of sound in steel is equal to 5100 metres per second. Another interesting fact about the speed of sound is that sound travels 35 times faster in diamonds than in the air.

Speed of Sound in Liquid

Speed of Sound in Water

The speed of sound in water is more than that of the air, and sound travels faster in water than in the air. The speed of sound in water is 1480 metres per second. It is also interesting that the speed may vary between 1450 to 1498 metres per second in distilled water. In contrast, seawater’s speed is 1531 metres per second when the temperature is between 20 o C to 25 o C.

Speed of Sound in Gas

We should remember that the speed of sound is independent of the density of the medium when it enters a liquid or solid. Since gases expand to fill the given space, density is relatively uniform irrespective of gas type, which isn’t the case with solids and liquids. The velocity of sound in gases is proportional to the square root of the absolute temperature (measured in Kelvin). Still, it is independent of the frequency of the sound wave or the pressure and the density of the medium. But none of the gases we find in real life is ideal gases , and this causes the properties to change slightly. The velocity of sound in air at 20 o C is 343.2 m/s which translates to 1,236 km/h.

Speed of Sound in Vacuum

The speed of sound in a vacuum is zero metres per second, as there are no particles present in the vacuum. The sound waves travel in a medium when there are particles for the propagation of these sound waves. Since the vacuum is an empty space, there is no propagation of sound waves.

Table of Speed of Sound in Various Mediums

Another very curious fact is that in solids, sound waves can be created either by compression or by tearing of the solid, also known as Shearing. Such waves exhibit different properties from each other and also travel at different speeds. This effect is seen clearly in Earthquakes. Earthquakes are created due to the movement of the earth’s plates, which then send these disturbances in the form of waves similar to sound waves through the earth and to the surface, causing an Earthquake. Typically compression waves travel faster than tearing waves, so Earthquakes always start with an up-and-down motion, followed after some time by a side-to-side motion. In seismic terms, the compression waves are called P-waves, and the tearing waves are called S-waves . They are the more destructive of the two, causing most of the damage in an earthquake.

Visualise sound waves like never before with the help of animations provided in the video

Frequently Asked Questions – FAQs

What is the speed of sound in vacuum, name the property used for distinguishing a sharp sound from a dull sound., define the intensity of sound., how does the speed of sound depend on the elasticity of the medium, why is the speed of sound maximum in solids, name the factors on which the speed of sound in a gas depends., what is a sonic boom, the below video helps to completely revise the chapter sound class 9.

Stay tuned to BYJU’S and Fall in Love with Learning !

Put your understanding of this concept to test by answering a few MCQs. Click ‘Start Quiz’ to begin!

Select the correct answer and click on the “Finish” button Check your score and answers at the end of the quiz

Visit BYJU’S for all Physics related queries and study materials

Your result is as below

Request OTP on Voice Call

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post My Comment

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

- Random article

- Teaching guide

- Privacy & cookies

by Chris Woodford . Last updated: July 23, 2023.

Photo: Sound is energy we hear made by things that vibrate. Photo by William R. Goodwin courtesy of US Navy and Wikimedia Commons .

What is sound?

Photo: Sensing with sound: Light doesn't travel well through ocean water: over half the light falling on the sea surface is absorbed within the first meter of water; 100m down and only 1 percent of the surface light remains. That's largely why mighty creatures of the deep rely on sound for communication and navigation. Whales, famously, "talk" to one another across entire ocean basins, while dolphins use sound, like bats, for echolocation. Photo by Bill Thompson courtesy of US Fish and Wildlife Service .

Robert Boyle's classic experiment

Artwork: Robert Boyle's famous experiment with an alarm clock.

How sound travels

Artwork: Sound waves and ocean waves compared. Top: Sound waves are longitudinal waves: the air moves back and forth along the same line as the wave travels, making alternate patterns of compressions and rarefactions. Bottom: Ocean waves are transverse waves: the water moves back and forth at right angles to the line in which the wave travels.

The science of sound waves

Picture: Reflected sound is extremely useful for "seeing" underwater where light doesn't really travel—that's the basic idea behind sonar. Here's a side-scan sonar (reflected sound) image of a World War II boat wrecked on the seabed. Photo courtesy of U.S. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, US Navy, and Wikimedia Commons .

Whispering galleries and amphitheaters

Photos by Carol M. Highsmith: 1) The Capitol in Washington, DC has a whispering gallery inside its dome. Photo credit: The George F. Landegger Collection of District of Columbia Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith's America, Library of Congress , Prints and Photographs Division. 2) It's easy to hear people talking in the curved memorial amphitheater building at Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia. Photo credit: Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress , Prints and Photographs Division.

Measuring waves

Understanding amplitude and frequency, why instruments sound different, the speed of sound.

Photo: Breaking through the sound barrier creates a sonic boom. The mist you can see, which is called a condensation cloud, isn't necessarily caused by an aircraft flying supersonic: it can occur at lower speeds too. It happens because moist air condenses due to the shock waves created by the plane. You might expect the plane to compress the air as it slices through. But the shock waves it generates alternately expand and contract the air, producing both compressions and rarefactions. The rarefactions cause very low pressure and it's these that make moisture in the air condense, producing the cloud you see here. Photo by John Gay courtesy of US Navy and Wikimedia Commons .

Why does sound go faster in some things than in others?

Chart: Generally, sound travels faster in solids (right) than in liquids (middle) or gases (left)... but there are exceptions!

How to measure the speed of sound

Sound in practice, if you liked this article..., find out more, on this website.

- Electric guitars

- Speech synthesis

- Synthesizers

On other sites

- Explore Sound : A comprehensive educational site from the Acoustical Society of America, with activities for students of all ages.

- Sound Waves : A great collection of interactive science lessons from the University of Salford, which explains what sound waves are and the different ways in which they behave.

Educational books for younger readers

- Sound (Science in a Flash) by Georgia Amson-Bradshaw. Franklin Watts/Hachette, 2020. Simple facts, experiments, and quizzes fill this book; the visually exciting design will appeal to reluctant readers. Also for ages 7–9.

- Sound by Angela Royston. Raintree, 2017. A basic introduction to sound and musical sounds, including simple activities. Ages 7–9.

- Experimenting with Sound Science Projects by Robert Gardner. Enslow Publishers, 2013. A comprehensive 120-page introduction, running through the science of sound in some detail, with plenty of hands-on projects and activities (including welcome coverage of how to run controlled experiments using the scientific method). Ages 9–12.

- Cool Science: Experiments with Sound and Hearing by Chris Woodford. Gareth Stevens Inc, 2010. One of my own books, this is a short introduction to sound through practical activities, for ages 9–12.

- Adventures in Sound with Max Axiom, Super Scientist by Emily Sohn. Capstone, 2007. The original, graphic novel (comic book) format should appeal to reluctant readers. Ages 8–10.

Popular science

- The Sound Book: The Science of the Sonic Wonders of the World by Trevor Cox. W. W. Norton, 2014. An entertaining tour through everyday sound science.

Academic books

- Master Handbook of Acoustics by F. Alton Everest and Ken Pohlmann. McGraw-Hill Education, 2015. A comprehensive reference for undergraduates and sound-design professionals.

- The Science of Sound by Thomas D. Rossing, Paul A. Wheeler, and F. Richard Moore. Pearson, 2013. One of the most popular general undergraduate texts.

Text copyright © Chris Woodford 2009, 2021. All rights reserved. Full copyright notice and terms of use .

Rate this page

Tell your friends, cite this page, more to explore on our website....

- Get the book

- Send feedback

Noise Control Help Line: 1-800-854-2948 M - F 8a.m. - 5p.m. (Central Time)

Acoustical Surfaces, Inc.

Sound Proofing | Acoustics | Noise & Vibration Control

Speed of Sound: How Sound Travels Through Objects and Materials

Posted by Acoustical Surfaces on 03/14/2024 11:54 am | Leave a Comment

From the snap of a twig to the booming echo of a drumbeat, sound plays an important role in helping us navigate our space. While sound is incredibly important, many people rarely stop to ponder its physical properties.

In physics, sound is defined as an acoustic vibration that sends waves through a medium, such as a solid, liquid, or gas. 1 These mediums’ properties can influence sound’s speed. By understanding the relation between material properties and the speed of sound, you can optimize the acoustics of various spaces, from professional recording studios to company conference rooms.

We’ll be diving into the fascinating mechanics of sound propagation and explain how different objects’ density, elasticity, and temperature all influence the speed of sound (plus how to contain or absorb those fast-moving sound waves).

Table of Contents

What is the Formula for the Speed of Sound?

Many people assume that the speed of sound is a constant number, but this isn’t the case. The materials that transmit sound can influence its speed considerably. Even so, there is a general speed of sound formula, which multiplies the sound’s wavelength by its frequency. 2 In mathematical terms:

In this formula:

- v represents the speed of sound

- f is the frequency of the sound wave

- λ is the length of the sound wave

While this general formula is an excellent baseline, the speed of sound can vary greatly from one medium to the next, depending on its temperature, density, and elasticity.

Speed of Sound: Example Equation

To clarify the connection between the sound’s speed, frequency, and wavelength, let’s take a look at a real-life example.

Let’s say that you’re measuring a sound with a frequency of 261 Hz, also known as middle C or concert pitch. 3 This sound’s wavelength is around 1.3 meters. After plugging these numbers into the speed of sound formula, you can calculate sound using the following equation:

v=(261 Hz)(1.3 m)

v=341.9 m/s

With this equation in mind, let’s take a closer look at the role of various materials’ properties on the speed of sound.

How Does a Material’s Density Impact the Speed of Sound?

Density, which measures the mass per unit volume of a given material, can influence the speed of sound significantly. That’s because density dictates how closely a material’s molecules are packed together.

Since sound is kinesthetic energy that travels by passing from one molecule to the next, materials with more densely packed molecules facilitate faster sound propagation. For this reason, sound travels faster through solids than liquids and faster through liquids than gasses.

Varying Densities of Different Elements

Denser elements often feature heavier molecules, which take more energy to vibrate, subsequently slowing down sound’s speed. As a result, sound can travel through aluminum nearly twice as fast as it moves through gold, due to the differences in the molecules. 4

How Does Material Density Relate to Soundproofing?

If you’re interested in optimizing the acoustics of a space, you’ll likely employ soundproofing solutions at some point. Soundproofing materials add mass to walls and ceilings to prevent sound from escaping.

Since these materials are often quite dense, it begs the question, “Why use dense, solid materials for soundproofing if sound waves travel through them faster?”

When dense materials are thick enough, they contain enough molecules to drain the sound wave of energy before it can reach the other side. That’s why most soundproofing solutions, from double-layer drywall to solid-core doors, are so thick.

How Does a Material’s Elasticity Impact the Speed of Sound?

Another key factor that influences the speed of sound through materials is their elasticity, which refers to a material’s ability to maintain its shape when placed under stress. For example, a rigid material like steel won’t lose its shape as easily as a more flexible material like rubber.

Materials with atoms that are strongly attracted to each other end up being more rigid, due to their powerful internal bonds. The strength of these bonds ultimately determines how quickly a material will return to its original shape.

So, what does this mean for the speed of sound? Particles that quickly regain their shape after an external force will also vibrate at higher speeds. As a result, they enable sound to travel faster than materials with lower elastic properties. 4

Speed of Sound Elasticity Equation

If you want to flex your mathematical muscles, you can calculate the speed of sound while taking into account different material’s elastic properties.

This more complicated formula divides the elastic property by the inertial property and takes the resulting number’s square root, as showcased by this equation 2 :

Here’s a quick breakdown:

- Elastic property is a material’s ability to deform and reform in the face of an external force.

- Inertial property looks at whether a material will stay at rest or in motion in the absence of an external force.

How Does a Material’s Temperature Impact the Speed of Sound?

Many people are often surprised to learn that temperature can influence the speed of sound. Typically, higher temperatures facilitate faster sound travel, especially through gasses.

So, what’s behind this phenomenon? Well, heat is a form of kinetic energy. Increasing the temperature speeds up the vibration of molecules within a material, and causes sound waves to jump from one molecule to the next more quickly.

This explains why room-temperature air has a speed of sound of 346 m/s, while air at water’s freezing point (0°C / 32°F) has a speed of sound of 331 m/s. 4 While this fascinating connection between thermal dynamics and acoustics is often overlooked, it can make a noteworthy difference in a room’s sound quality.

Speed of Sound Formula With Temperature

If you want to measure the average speed of sound for various temperatures, you can use this formula 5 :

v = 331 m/s + 0.61T

Here’s how the equation breaks down:

- v is the speed of sound

- 331 m/s is the speed of sound at 0°C

- 0.61 is a constant that represents the increase in sound’s speed with every additional degree

- T is the air’s temperature in Celcius

What is the Speed of Sound for Common Materials?

Now that you understand the basic components that affect the speed of sound, let’s take a look at how quickly sound moves through the following mediums 2 :

Gasses at 0°C or 32°F

- Air – 331 m/s

- Carbon dioxide – 259 m/s

- Oxygen – 316 m/s

- Helium – 965 m/s

- Hydrogen – 1,290 m/s

Liquids at 20°C or 68°F

- Ethanol – 1,160 m/s

- Mercury – 1,450 m/s

- Freshwater – 1,480 m/s

- Sea water – 1,540 m/s

- Rubber – 60 m/s

- Polyethylene – 920 m/s

- Lead – 1,210 m/s

- Gold – 3,240 m/s

- Marble – 3,810 m/s

- Copper – 4,600 m/s

- Aluminum – 5,120 m/s

- Iron – 5,120 m/s

- Glass – 5,640 m/s

- Steel – 5,960 m/s

- Diamond – 12,000 m/s

As you can see, the effect of these materials’ varying properties on the speed of sound is quite pronounced—sound travels nearly 35 times faster through a diamond than it does through air. 6

Soundproofing Solutions

The speed of sound is a complex and fascinating phenomenon, but thankfully, soundproofing solutions tend to be relatively simple.

Here are some popular soundproofing solutions we offer at Acoustical Surfaces:

- Noise S.T.O.P.™ Vinyl Barrier Mass Loaded Vinyl Barrier

- Noise S.T.O.P.™ Interior Soundproof Glass Window

- SoundBreak XP Acoustically Enhanced Gypsum Boar d

- Green Glue Viscoelastic Damping Compound

- Resilient Sound Isolation Clips (RSICs)

Sound Absorption Solutions

Soundproofing solutions have many valuable applications, but they’re not always right for your acoustical goals. Maybe you want to enhance the acoustics of a space instead, whether that involves dampening distracting echoes and reverberations or balancing the sound within a space. In this case, sound absorption is what you need.

While soundproofing materials isolate sound within a space, sound absorption materials are often soft and foamy, enabling them to soak up excess sound waves like a sponge and stop them from bouncing around, creating an unpleasant cacophony in their wake.

Some of our best-selling sound absorption products at Acoustical Surfaces are:

- Poly Max™ Acoustical Panels

- Envirocoustic™ Wood Wool Cementitious Wood-Fiber Acoustic Ceiling and Wall Panels

- Echo Eliminator Bonded Acoustical Cotton Panels

- NOISE S.T.O.P. Fabric-Wrapped Acoustical Panels

- Flat Faced Open Cell Melamine Acoustical Foam

- WALLMATE® Fabric Wall System

Learn More About Sound With Acoustical Surfaces

From music to meteorology, the speed of sound is an important concept. It’s especially relevant to understand how sound speeds change with varying levels of density, elasticity, and temperature.

By understanding the way sound travels through different materials, you can make smarter acoustical decisions. However, you don’t have to navigate this process alone—just reach out to our team of sound experts at Acoustical Surfaces . We’ve been providing comprehensive sound solutions for over 35 years.

If you want custom sound solutions for your space, whether that’s a classroom, restaurant, recording studio, or home, we can help you select the ideal products. Contact our team today to receive tailored soundproofing or sound absorption support.

- BYJU’s. Sound Waves. https://byjus.com/physics/sound-waves/

- LibreTexts. 17.3: Speed of Sound. https://phys.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/University_Physics/University_Physics_(OpenStax)/Book%3A_University_Physics_I_-_Mechanics_Sound_Oscillations_and_Waves_(OpenStax)/17%3A_Sound/17.03%3A_Speed_of_Sound

- SFU. Wavelength. https://www.sfu.ca/sonic-studio-webdav/handbook/Wavelength.html

- Iowa State University. Sound. https://www.nde-ed.org/Physics/Sound/index.xhtml

- University of Rhode Island. Sound Waves. https://penrose.uri.edu/labs/PHY275/sound_waves/sound_waves.pdf

- Inspirit. Speed Of Sound Study Guide. https://www.inspiritvr.com/speed-of-sound-study-guide/

Additional Resources

Creating better-sounding rooms.

Solutions to Common Noise Problems

CAD, CSI, & Revit Library

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Speed of Sound in Solids

Claudia Tiller, Spring 2023

This page discusses the speed of sound in various solids, how to calculate them, and examples of such calculations.

- 1 The Main Idea

- 2.1 A Mathematical Model

- 2.2 Speeds of Various Compositions

- 3.1 Theoretical

- 3.2 Numerical Example

- 4 Connectedness

- 6.1 Further reading

- 6.2 External links

- 7 References

The Main Idea

The speed of sound can be defines as the distance travelled per a unit of time by a sound wave as it travels through an elastic medium. Elasticity refers to the ability of a body to resist distorting influence and return to its original shape when that influence is removed.

Factors that control the speed that sound travels in solids is measured by the solid's density and elasticity, as they affect the vibrational energy of the sound. Overall, the way the solid is composed determines the sound's speed limit through that solid.

The Structure of Solids and Effects on Sound Travel

Mediums are composed of particles that can be closely knit together or spread apart. Solids are characterized by an arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules, where these components are generally locked in their positions. The particles can also be defined as elastic or inelastic. Particles that are closer to each other allow sound to be transferred quicker through the medium. Since particles that are compressed closer together allow sound to travel faster, it can be reasoned that sound travels slower in air.

With an increase in density, the space between particles in the solid decreases. The smaller distance between particles, or interatomic distance, the higher the speed. With an increase in elasticity of the atoms that make up the object, the lower the speed of sound in the object. Particles that have a high elasticity take more time to return to their place once they received vibrational energy. However, if the solid is completely inelastic then the sound cannot travel through it.

The practicality of this concept is highly applicable. The human ear captures sound waves through the outer cartilage of the ear, called the Pinna. The sound waves then travel up the ear canal and arrive at the ear drum which vibrates from the sound waves. After traveling through the inner ear, the vibrations arrive at the Cochlea. The Cochlea transfers the vibrations into information that auditory nerves can analyze.

A Mathematical Model

The speed of sound in solids [math]\displaystyle{ {V_{s}} }[/math] can be determined by the equation. Young's Modulus is a measure of elasticity of an object, and it can be computed to solve for interatomic values, such as interatomic bond stiffness or interatomic bond length.

[math]\displaystyle{ {V_{s}} = d \cdot \sqrt{\frac{K_{s}}{m_{atom}}} }[/math]

Alternative speed equation:

[math]\displaystyle{ {V_{s}} = \sqrt{\frac{B}{\rho}} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ ρ }[/math] = density

[math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] = Bulks Modulus

Bulks Modulus = [math]\displaystyle{ {\frac {ΔP}{ΔV/V}} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math] = interatomic bond length

[math]\displaystyle{ K_{s} }[/math] = Interatomic bond stiffness

Youngs Modulus = ( [math]\displaystyle{ Y = K_{s}/d }[/math] )

Youngs Modulus: [math]\displaystyle{ Y ={\frac{Stress}{Strain}} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ Stress = {\frac{F_{tension}}{Area_{Cross Sectional}}} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ Strain = {\frac{ΔL_{wire}}{L_{0}}} }[/math]

Speeds of Various Compositions

Theoretical

Two metal rods are made of different elements. The interatomic spring stiffness of element A is four times larger than the interatomic spring stiffness for element B. The mass of an atom of element A is four times greater than the mass of an atom of element B. The atomic diameters are approximately the same for A and B. What is the ratio of the speed of sound in rod A to the speed of sound in rod B?

Solution: In this situation, the ratio of the speed of sound in rod A to the speed of sound in rod B is 1.

Looking at the formula for computing speed of sound in solids, [math]\displaystyle{ {V_{s}} = d \cdot \sqrt{\frac{K_{s}}{m_{atom}}} }[/math] , you see that velocity depends three factors, interatomic stiffness, the mass of one atom, and interatomic bond length. The two rods differences in atomic mass and interatomic stiffness offset each other when the equations are set equal, and the ratio is determined to be 1.

[math]\displaystyle{ d \cdot \sqrt{\frac{4 \cdot K_{s}}{m_{atom}}} = d \cdot \sqrt{\frac{4 \cdot K_{s}}{m_{atom}}} }[/math] After simplification [math]\displaystyle{ V_{s_{1}} = V_{s{2}} }[/math]

Numerical Example

The Young's Modulus value of silver is 7.75e+10, atomic mass of silver is 108 g/mole, and the density of silver is 10.5 g/cm3. Using this information, calculate the speed of sound in silver.

Solution: The key to solving this problem is to realize the micro-macro connection of Young's Modulus. You are given that Young's Modulus is equal to 7.75e+10, and we know that Youngs Modulus = ( [math]\displaystyle{ K_{s}/d }[/math] ). In this situation, we need to calculate the interatomic bond length and use it and our Young's Modulus value to determine our interatomic stiffness.

To solve for d , we use the given density of silver (10.5 g/cm3). Using the basic equation for volume in relation to density and mass ( [math]\displaystyle{ V=m*d }[/math] ), we can find d , since d is equal to the cube root of volume.

Once d is solved for, it can be plugged back into the the equation [math]\displaystyle{ Y = K_{s}/d }[/math] to solve for [math]\displaystyle{ K_{s} }[/math]

Now, we have solved for both interatomic bond length and stiffness. The only quantity in the final speed of sound equation we need is the mass of one atom, which can be determined using Avogardro's number and the atomic mass. [math]\displaystyle{ m_{atom} = }[/math] atomic mass / [math]\displaystyle{ 6.022e23 }[/math]

Now that all variables are solved for, we can substitute values into our [math]\displaystyle{ {V_{s}} = d \cdot \sqrt{\frac{K_{s}}{m_{atom}}} }[/math] equation.

[math]\displaystyle{ {V_{s}} = 1.6 \cdot 10^{-10} \cdot \sqrt{ \frac{78534.7}{1.79 \cdot 10^{-22}}} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ {V_{s}} = 2723 }[/math] m/s

Connectedness

Computing the speed of sound in solids depends on a mass' interatomic properties, such as interatomic bond length. In this specific case, an object's elasticity depends on the interatomic bond length. There are many applications that connect to the ability to compute the speed of sounds.

Seismic and ultrasonic imaging are also fields that benefit greatly from the calculation of sound speeds in solids. Seismic imaging refers to capturing images of the subsurface structure of the Earth. Seismic waves can be generated by earthquakes or other sources. Engineers and scientists can then locate gas and oil reservoirs, monitor activity such as volcano eruptions, and geological formations. In ultrasonic imaging, ultrasonic waves can be sent through the body and have the time it takes to bounce back be measured. This then creates images of internal organs or tissues, used in cases such as prenatal imaging as well as medical diagnosing. In more specific fields such as in Industrial Engineering, these calculations could be applied to questions regarding how to build a soundproof area. It would therefore be optimal to select a solid with a low speed of sound velocity, with a solid that has tightly packed particles. There are many vast applications to this, as an object's ability to block or allow sound waves through it. However, some cases require contractors to build structures that allow sound to travel through. Material testing uses the calculation of sound in solids to determine mechanical properties of such materials. Engineers can then calculate the material's elasticity, stiffness, and other properties. Knowledge regarding how solids are structured and how they correlate with the speed of sounds in those solids are vital to building structures that meet the criteria.

Overall, being able to calculate the speed of sounds in solids has a wide range of applications in engineering, medicine, and science.