Starting at $5, these customer-loved Amazon products will help kickstart summer

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Concert Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

- TODAY Plaza

Patients now have access to doctor's visit notes: A guide to what's inside

What does your doctor really think about your condition and health concerns? For more than a year now, patients have been able to access and read the observations doctors write down about them during a visit.

The clinical notes can come with surprises. Patients may be amused to find out they’re described by their physician as “well-nourished,” “well-groomed,” “pleasant” or “normal-looking.”

“’He is not ill-appearing or toxic-appearing.’ That’s the best review I’ve ever received,” one man wrote on Twitter after reading his doctor’s notes.

But patients may also be taken aback by comments referring to them as “obese” or mentioning their marijuana use. One woman was shocked when she saw her doctor wrote down that she “seemed overly dramatic,” she complained on Reddit .

As of April 2021, healthcare providers must give patients access to all of the health information in their electronic medical records as part of the 21st Century Cures Act . That includes your doctor’s written comments about your physical condition during a visit, along with any symptoms and what the treatment should be.

The rules don’t apply to psychotherapy notes made during counseling sessions or when doctors believe a patient would harm another person or themselves after reading the information, according to OpenNotes , a non-profit organization based at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston that advocates for greater transparency in healthcare.

Doctors have been both supportive and cautious of the movement. In a 2020 survey of 1,628 clinicians, 74% agreed note sharing was a good idea.

“It does give the patient a lot more ownership of their medical condition because they can see what we’re thinking about, they understand our thought processes a little bit more, and they can see what the options are,” Dr. Sterling Ransone, Jr., a family physician in Deltaville, Virginia, and chair of the American Academy of Family Physicians, told TODAY.

But knowing that patients can now read his notes, Ransone finds he self-censors himself to avoid sounding critical or judgmental of a patient.

“It’s difficult because sometimes you have to leave a note to yourself what your concerns are, but they can cause anxiety with the patient,” he noted. “I can say that it really has changed the way that a lot of physicians write their notes.”

That means more accessible language, less jargon and more caution with certain terms that might offend or upset a patient.

Ransone no longer uses the abbreviation “SOB,” which stands for “short of breath” and instead writes out the full term in his notes. Same with “FU,” which stands for “follow up.”

The American Academy of Family Physicians has also urged doctors to write “patient could not recall” instead of describing them as a “poor historian;” “patient declines” instead of “patient refuses;” and “patient is not doing X” instead of describing them as “non-compliant.”

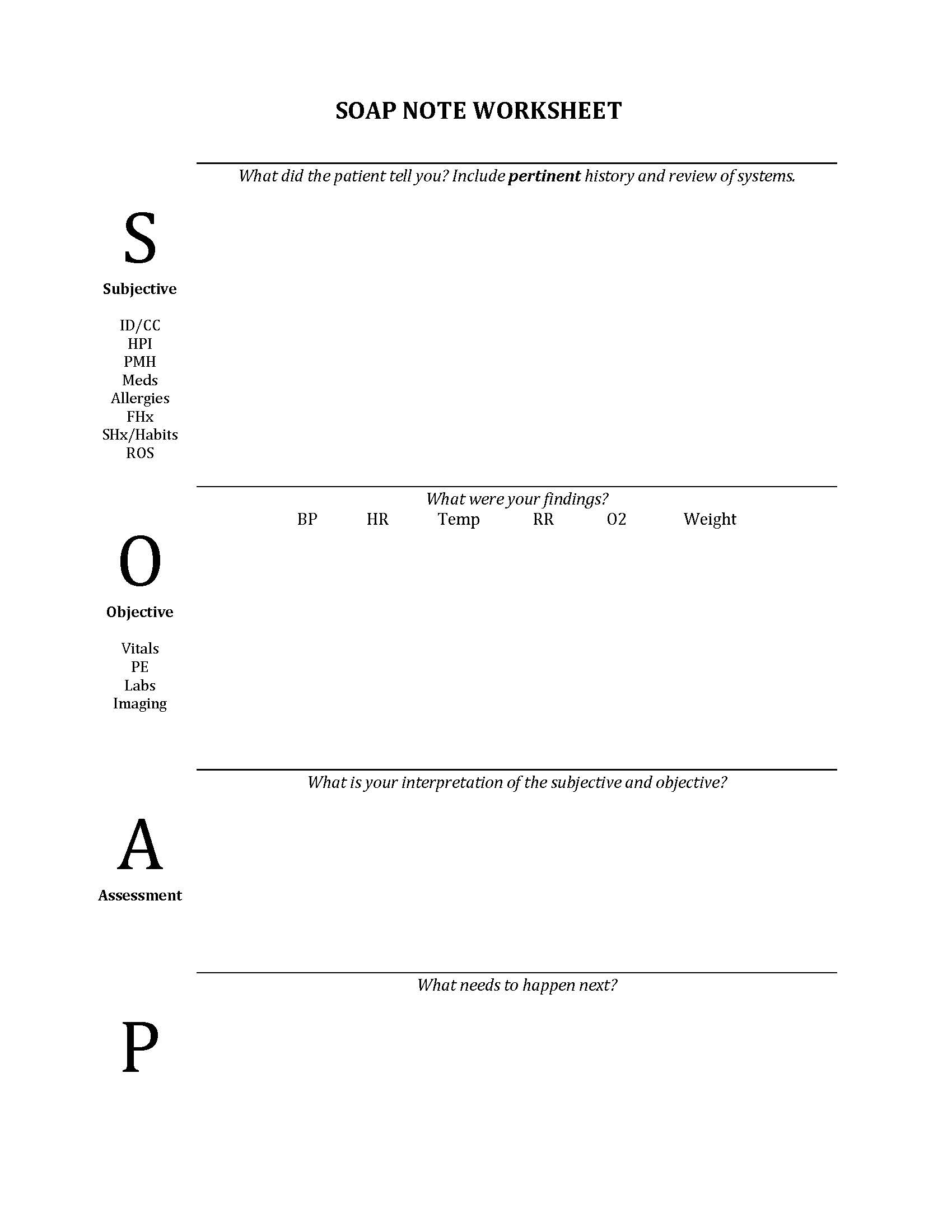

A guide to your doctor’s note:

The medical note has traditionally included four parts, Ransone said: The subjective findings, or what a patient said they were concerned about; the objective findings, or what the doctor actually observed during the visit; the physician’s assessment after evaluating the patient and the treatment plan.

Doctors are used to jotting down any observations that can offer clues to what’s going on. So writing down that a patient “seemed overly dramatic” can mean the person’s complaint wasn’t consistent with the degree of their symptoms and something else might be the reason for their visit that day, he noted.

Here are other descriptions patients may find in their doctor’s notes:

Well-groomed or pleasant: This can indicate mental status. “If someone comes in and they’re somewhat disheveled, it leads you to wonder why and what do I need to look into?” Ransone said. “Pleasant” means the patient was communicative and responded to social cues, he noted. Patients who are upset or sleepy could have a substance abuse disorder or another reason why they’re having trouble interacting.

Well-developed or well-nourished: “A lot of times when people look at open notes and they’ll say, ‘Well, of course I am. What does this mean?’” Ransone said. “It just means that we checked in our mental checklist… (that) those aren’t things that we need to worry about.” If a person isn’t well-nourished, it might mean they don’t have access to food or their teeth might be in such bad condition that they can’t chew and get nutrition.

Unremarkable: This is a good thing. “Unremarkable is exactly what you want to be when you see a physician,” Ransone said. “I joke with my patients all the time: You want to be the most boring patient that I’ve seen today, because that means we haven’t seen anything that is abnormal that we need to chase down.”

Obese : To a physician, the term means the patient is of a certain weight for their height and frame, which comes with a certain constellation of medical concerns, Ransone said. “There’s a stigma to obesity in society and a lot of patients really don’t want to have that on their charts… but it’s a very important piece of the puzzle for me as I’m trying to help a patient get healthier,” he noted.

Substance use: This isn’t necessarily bad. Doctors will note a patient has an occasional glass of wine, for example, to give them an idea of the person’s alcohol consumption habits. “The way that our society looks at, say, marijuana use has changed a lot over the years, but a lot of people don’t want that included in the medical record,” Ransone said. “I’d like to know if someone is smoking weed because it could affect the medications that I should give them for their health condition.”

Other health observations patients frequently don’t want on their chart include mental health issues such as depression, anxiety or bipolar disorder, he noted.

Some patients have called Ransone to ask that he change something in their note because they see it as a pejorative or they disagree with his assessment, but that doesn’t mean he’s wrong, the doctor noted.

One guide for physicians suggested telling the patient: “I’m sorry you disagree with my assessment. While I can’t change my medical opinion, if you’d like I can add that you disagree with it.”

Patients pointing out factual errors — such as noticing the note referenced a problem in the right knee rather than the left — is a completely different issue. If there's anything inaccurate in your chart, bring it to your doctor's attention.

In fact, patients who read their doctor’s notes may play an important role in finding errors in their records, a 2020 study published in JAMA found.

Ransone encouraged patients who are reading their doctor’s notes to keep the lines of communication with their physician open.

“Don’t necessarily assume the worst when they read things. Realize that a lot of the things that they read are open to interpretation,” he advised.

A. Pawlowski is a TODAY health reporter focusing on health news and features. Previously, she was a writer, producer and editor at CNN.

This 1 trick can help you feel happier in 20 seconds, happiness expert says

Mind & body.

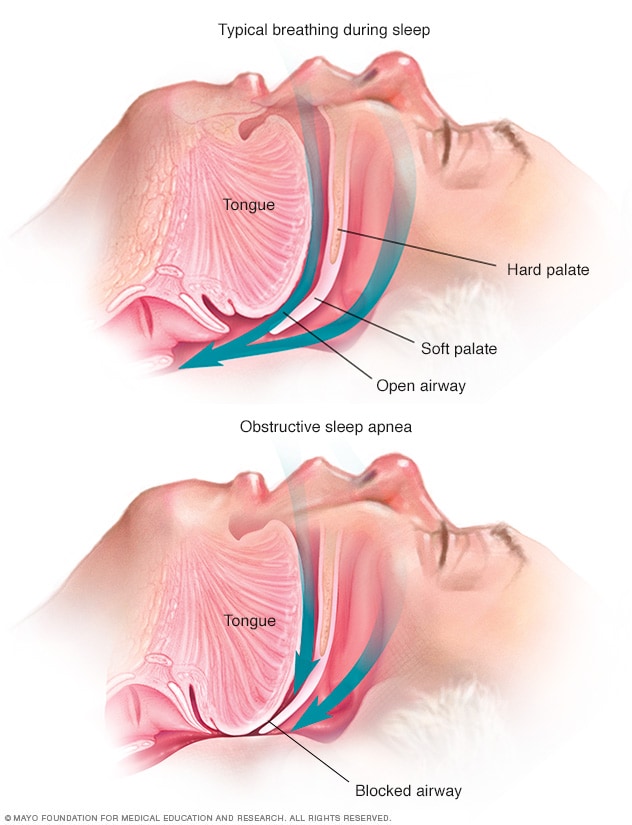

Woman, 39, driven crazy when mystery whooshing noise suddenly starts in her ear

Women's health.

‘American Idol’ singer Mandisa died of class III obesity, autopsy reveals

I was eating myself to death before losing 200 pounds without weight-loss drugs

Diet & fitness.

Train yourself to fall asleep in 2 minutes with this viral sleep hack

What is a ‘hyperfixation meal’ and why does it happen? Mental health specialists explain

Do you struggle to cry? Here’s what that says about your health

Psychotherapist and mom of 4 recalls her biggest source of 'mom guilt'

EXCLUSIVE: John Green recalls how OCD struggles as a teen inspired ‘Turtles All the Way Down’

Selena Gomez's lupus and other health issues: Singer opens up in new TODAY interview

Select Your Interests

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

What to Consider When Reading Your Medical Notes

- 1 Associate Editor, JAMA

Shared medical visit notes are notes written by clinicians that are made available (“open”) to patients in electronic health records.

Clinicians add medical notes to a patient’s electronic health record following clinical encounters such as office visits. There is no difference between the notes that patients can view and those that clinicians keep on file.

In 2021, new legislation was introduced in the US that required almost all medical notes to be shared with patients. These notes include

History and physical notes

Progress notes

Consultation notes

Procedure notes

Discharge summary notes

Imaging narratives

Laboratory report narratives

Pathology report narratives

There are a few exceptions. Some medical notes that do not need to be shared with patients include psychotherapy notes that are separated from the rest of the medical record, written by any health care professional; information related to a civil, criminal, or administrative action or proceeding; and any note that a doctor perceives may cause harm or danger to a patient.

The goal of note sharing is to increase transparency between clinicians and patients. Some studies have shown that shared medical notes may help patients feel more engaged in their health care, better understand their medical conditions and care plans, and take their medications properly.

Approach to Reading Medical Notes

Patients are typically able to access their notes through a patient portal to their electronic health record. The notes are there for a patient’s consideration and are optional, not required, reading. The main purpose of medical notes is to communicate information among health care professionals, not between doctors and patients. A patient can avoid reading their medical notes if they find that the information causes them too much worry.

When patients do choose to read their medical notes, it is important to approach them in the right way—not as a clinician, but as a patient. You can discuss with your doctors whether or not you plan to read your notes, which may help them put more patient-directed information (such as follow-up instructions) directly in the notes. If you identify anything in your note that concerns you, discuss that information with someone on your health care team.

For More Information

Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology www.healthit.gov/curesrule/

OpenNotes www.opennotes.org/

To find this and other JAMA Patient Pages, go to the For Patients collection at jamanetworkpatientpages.com .

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Source: Delbanco T, Wachenheim D. Open Notes: new federal rules promoting open and transparent communication. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2021;47(4):207-209. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2021.02.004

See More About

Jin J. What to Consider When Reading Your Medical Notes. JAMA. 2021;326(17):1756. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.16493

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Patient Access To Medical Records Is Set To Become Mandatory

Westend61 / Getty Images

Key Takeaways

- Starting in April 2021, the United States' government will require health organizations to share medical records with patients electronically, free of charge.

- Once the mandate goes into effect, patients will be able to see doctors' notes and other information in their electronic medical record.

It’s soon going to be easier to read your doctor's notes from your last visit thanks to a measure to improve patient record transparency. Starting in April 2021, all medical practices will be required to provide patients free access to their medical records. The concept of sharing medical notes is known as OpenNotes.

Under the 21st Century Cures Act , consumers will be able to read notes that recap a visit to the doctor’s office as well as look at test results electronically.

In the past, accessing your doctor's notes could require long wait times and fees. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) made it legal to review medical records, but it didn't guarantee electronic access.

More than 250 healthcare organizations in the U.S. (including multiple locations within a single system) are already sharing notes with patients digitally.

What Is OpenNotes?

With OpenNotes , doctors share their notes with patients through electronic health records (EHR). Practices and hospitals use various kinds of software for EHRs, such as MyChart. Once the mandated medical transparency measure goes into effect, patients will be able to log in and see their notes.

The mandate was supposed to begin on November 2, 2020, but in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the deadline was extended to April 5, 2021.

Doctor’s notes will include consultations, imaging and lab findings, a patient's medical history, physical exam findings, and documentation from procedures.

Cait DesRoches , executive director of OpenNotes (a group advocating patient note access), explains that patients will have two ways to get their notes. Either the organization will put the notes on the portal automatically or a patient can request that notes be added to the portal.

“The notes are full of great information for patients,” DesRoches tells Verywell. Viewing the notes can help patients recall what they discussed with their doctors during a visit as well as remind them of what they’re supposed to do after an appointment.

“My hope is that organizations will implement this in a really robust way,” DesRoches says. “That’s when the health system will get to the place where they’re seeing the benefits.

What This Means For You

Being able to see notes in an electronic portal also provides patients with the opportunity to ensure that their medical records are accurate. Before the mandate goes into effect in April 2021, talk to your doctor about how you will be able to access your medical record.

Downsides of Data Sharing

The ability to view documentation from medical care sounds like a great opportunity for patients, but some worry that it could create confusion. For physicians, there's also the potential for an increased workload, as they might need to respond to questions that arise when patients see—and question—what's in their notes.

UC San Diego Health launched a pilot program using OpenNotes for primary care patients in 2018. Marlene Millen, MD , a professor and doctor in the UC San Diego Health , told MedicalXpress that she did not see an increase in inquiries from patients when their notes were available.

What To Know About Doctors’ Notes

There are some cases when a doctor does not have to share medical notes with patients. These scenarios are different state by state, as privacy laws vary.

Doctors can withhold medical records if they think releasing the information will lead to physical harm, such as in the case of partner violence or child abuse.

Providers also do not have to share information regarding certain diagnoses that are considered protected, and psychotherapy documentation is not shared. However, other mental health services outside of talk therapy—such as talking to your primary care doctor about depression—are included in the notes.

Depending on the state you live in, DesRoches explains that parents can also view notes of their teen’s doctor visits. Parents might not have access when teens turn a certain age, based on the state. However, the rules don’t supersede state laws on privacy for adolescents.

Evaluating OpenNotes

OpenNotes.org reports that reading doctors' notes benefit patients in many ways and may lead to better health outcomes. According to OpenNotes, patients who are able to review their doctors' notes:

- Are more prepared for visits with their providers

- Can recall their care plans and adhere to treatment, including medication regimens

- Feel more in control of their care

- Have better relationships with their physicians

- Have a better understanding of their health and medical conditions

- Take better care of themselves

Several studies have assessed OpenNotes. A study published in the journal BMJ Open in September 2020 found that medical transparency is a right that is viewed favorably among people in different countries including Canada, Australia, Japan, Chile, Sweden, and the U.S.

Another study published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine in July 2020 found that patients typically understand their doctor's notes and that the information in their record is accurate. However, there were several notable disparities, and participants in the study had suggestions for improving the quality of access.

The researchers found that if patients didn’t understand a note or found inaccurate information in their notes, they had less confidence in their doctors.

According to a report in NEJM Catalyst, the ability to exchange information—including requesting information from patients before a visit—has been instrumental during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to sharing notes with patients after a visit, doctors were able to send a pre-visit questionnaire to patients that enabled them to gather more detail before the visit.

“We suspect, for example, that patients and care partners may recall even less of telemedicine encounters than they do after face-to-face office visits," the authors noted. "As a result, they may turn more often to reading their OpenNotes online."

The researchers concluded that once there are patient- and clinician-friendly mechanisms in place for record-sharing, "inviting patients to contribute directly to their records will both support patient engagement and help clinician workflow.”

Advantages and Disadvantages

Wayne Brackin, CEO of Kidz Medical Services , tells Verywell that it is “fair and reasonable” to expect patients would have access to doctors' notes. However, Brackin is concerned that doctors could “moderate their description in a manner that might affect care,” if they know that the patient or family will have access to records.

Wayne Brackin

To have a layperson, with a more limited vocabulary, or who has English as a second language, read the notes in isolation could lead to misunderstandings.

“This could be particularly sensitive with behavioral health issues," Brackin says, adding that a medical interpreter of sorts could help avoid misunderstandings during the initial record review. The language, abbreviations, and terminology in physician notes can be difficult for trained medical colleagues to interpret, let alone patients.

“To have a layperson, with a more limited vocabulary, or who has English as a second language, read the notes in isolation could lead to misunderstandings,” Brackin says.

Suzanne Leveille, RN, PhD , a professor of nursing at the University of Massachusetts and a member of the OpenNotes.org team tells Verywell that patients are generally enthusiastic about having online access to their office visit notes, but many providers initially expressed concerns that giving patients access to their notes could cause more worry than benefits.

"Our large surveys across health systems have not shown this to be the case. Very few patients report they became worried or confused from reading their notes," says Leveille, who also authored one of the OpenNotes' studies. "Overwhelmingly, patients report they benefit from note reading, for example, that it’s important for taking care of their health, feeling in control of their care, and remembering their plan of care."

While concerns about misunderstandings are not unwarranted, most patients report they are able to understand their notes, and that they have benefitted from viewing them. In cases where patients have been able to spot—and correct—mistakes, they feel not just more empowered, but safer.

"Open notes can improve patient safety," Leveille says. "About 20% of patients pick up errors in the notes and some report the errors to their providers."

Medical Xpress. More US patients to have easy, free access to doctor's notes .

Salmi L, Brudnicki S, Isono M, Riggare S, Rodriquez C, Schaper LK, et al. Six countries, six individuals: resourceful patients navigating medical records in Australia, Canada, Chile, Japan, Sweden and the USA . 2020. BMJ Open. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037016

Leveille SG, Fitzgerald P, Harcourt K, Dong Z, Bell S, O’Neill S, et al. Patients evaluate visit notes written by their clinicians: a mixed methods investigation . 2020. J Gen Intern Med. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06014-7

Kriegel, G, Bell S, Delbanco T, Walker J. Covid-19 as innovation accelerator: cogenerating telemedicine visit notes with patients . May 12, 2020. NEJM Catalyst. doi:10.1056/CAT.20.0154

By Kristen Fischer Kristen Fischer is a journalist who has covered health news for more than a decade. Her work has appeared in outlets like Healthline, Prevention, and HealthDay.

Visit Note Documentation Guide- Best practices for co-signing visit notes

This is a best practice guide on how non-physician practitioners and practitioners can co-sign visit note documentation. apr 29, 2022 • knowledge, who needs to co-sign visit notes, npp flags specific visit notes, the supervising physician selects visit notes, creating the visit note template for attestation, completing the encounter, using templating software to facilitate co-signing.

If your practice employs non-physician practitioners (NPPs), a supervising physician is responsible for reviewing the work, records, and practice of the NPP to ensure that appropriate treatment is rendered and appropriate directions are given and understood as applicable to the law. Supervising physicians are required to note that they reviewed an NPP's work or include their name/signature in the clinical documentation for proper legal documentation purposes. Each state has different co-signature requirements that need to be followed. Elation currently allows one provider-level user to sign each visit note which then captures one signature in a 'structured' manner in the visit note. The physician/practitioner that signs the visit note is typically the provider you are billing the encounter under. Then, to capture a co-signature, there are subsequent workflows that can be completed depending on how you plan to bill:

- The NPP performs the visit, and the visit is billed under the NPP's NPI number. There must be documentation that the supervising physician reviewed a certain percentage of encounters.

- The NPP performs the visit, and the visit is billed under the supervising physician's NPI number. There must be documentation of which NPP saw the patient and who rendered the encounter.

Direct Billing

For Direct Billing, the NPP is billing under their own NPI number. Different states require a different percentage of a NPP's encounter documentation to be reviewed by their supervising physician for clinical appropriateness. The co-sign workflow in Elation can be divided into two main steps:

- Identifying the visit notes that a supervising physician needs to review

- Documenting that a review was completed

Identifying visit notes for review

- The NPP can flag specific visit notes for the supervising physician

- The supervising physician can randomly select visit notes themselves

- The NPP locates a signed visit note in the patient's chart

- The NPP clicks "Actions" >> "Send: Office Message" at the top of the visit note

- The NPP enters the supervising physician's name in the "To" field and enters a short message in the "Body" (ex. 'Please review' or 'Please review & sign')

- The NPP clicks "Send"

- The supervising physician then checks their "Office Messages" inbox daily for messages from the NPP

- The supervising physician clicks on the patient's name to open the chart to view the visit note and review the documentation

- The supervising physician then replies to the office message to close the loop (ex. 'Review complete' or 'Approved') and clicks "Send and Sign Off".

- There is now documentation in the patient's chart that states the supervising physician reviewed a specific visit note signed by the NPP.

- Note : This workflow requires the NPP to enter billing information for each visit note prior to the NPP signing off on the visit note.

- Click on the "Billing" button at the top of the Practice Home

- Click "Reports" >> "Billing Report" at the top of any page in Elation

- the "Signed Visit Notes Not Yet Billed" section for customers who do not have a Practice Management System (PMS) integration with Elation

- the "Visit Notes with Bills Pending Sync to PMS" section for customers who have a Practice Management System (PMS) integration with Elation

- User Tip : If the supervising physician needs additional clarification from the NPP about any contents of the encounter, they can send an Office Message to the NPP for additional clarification before signing off on the visit note draft.

- Click "Actions" >> "Send: Office Message" at the top of the visit note they reviewed

- Enter the NPP's name or their own name (depending on preference) in the "To:" field

- Enter a short message in the "Body" (ex. 'Review complete' or 'Approved')

- Click "Send"

- Locate the message in the Requiring Action section of the patient's chart & click "Sign" at the top of the message

- Click "Notes" >> "Non-Visit Note" at the top of the patient's chart after reviewing the NPP's visit note

- Enter a short message in the body of the Non-Visit Note (ex. 'I reviewed the visit note for Date of Service 04/01/2022' or 'I reviewed the visit note for Date of Service 04/01/2022 and sign off on the work.')

- Click "Sign Note"

Incident-To Billing

Incident-To Billing means the non-physician practitioner (NPP) sees the patient and documents the encounter and is billing under their supervising physician's NPI number. The documentation must capture the NPP's name in order to meet a requirement about documenting who saw the patient and who rendered the encounter.

We recommend the NPP uses a Visit Note Template to capture their name and statement in regards to seeing the patient and rendering the encounter. For example, the statement can be 'Visit was rendered and documented by Jane Doe, NP and completed under supervising physician James Hibbert, MD'.

- Click the "Visit Note Templates" button at the top of any visit note draft

- Click "Templates" >> "Visit Note Templates" at the top of any patient's chart

- Click the "+New Template" button at the top of the Visit Note Templates management window

- Enter a name for the template in the "Template Name" field (ex. 'Visit Attestation')

- Select a section for storing your attestation. We recommend the Procedure section because it usually stores actions taken during the encounter.

- Enter your attestation language in the Procedure section of the Visit Note Template. (ex. 'Visit Attestation: Visit was rendered and documented by Jane Doe, NP and completed under supervising physician James Hibbert, MD'.)

- Click "Save Template"

- The NPP completes documentation of the encounter in the visit note draft

- The NPP clicks the "Visit Note Templates" button at the top of any visit note draft

- The NPP clicks the "Export to Note" button next to the visit attestation template to export the visit attestation template into the visit note draft

- The NPP changes the provider at the top of the visit note draft to the supervising physician's name

- The NPP clicks "Save as Draft & Close" to drop the visit note draft in the supervising physicians's "Draft Notes" inbox

- The supervising physician then checks their Practice Home "Draft Notes" inbox daily for visit notes to review

- The supervising physician clicks on the patient's name to open the chart and clicks on the 'In Progress...' visit note

- that the NPP rendered a visit

- that the NPP is requesting their supervising physician to review a visit note they signed

- that the supervising physician reviewed the encounter and is co-signing a visit note

Related Articles

- Office Message Feature Guide

- Practice Home Guide- Checking for requiring action items

- Templates Guide- Using templating softwares with Elation

Do You Have Access to Your Doctors’ Notes About You?

Here’s why you should request access to what your physician writes in your charts.

Do You Have Access to Your Doctors’ Notes About You?

If you’re like most patients in the U.S., you haven’t a clue what your doctor writes about you in your health record .

Despite a move toward more transparency in medicine, only about 3 percent of the U.S. population currently has ready access to notes written in their charts. And most physicians polled are still resistant to the idea. “Two-thirds of doctors still do not feel comfortable in giving access to the notes of their visit to the patients,” says Dr. Eric Topol , a cardiologist and professor of genomics at The Scripps Research Institute, a nonprofit medical research organization based in La Jolla, California.

HIPAA, or the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, gives patients the legal right to review their medical record. This includes doctor's notes, though not notes kept separate from the medical record, as mental health observations sometimes are. But only a fraction of patients have access to their doctors' notes online, like through medical organizations' patient portals, which increasingly offer patients a way to access their lab test results or other information about their care online.

However, a not-for-profit national initiative called OpenNotes has sought to make it easier for patients to gain access to notes – and for doctors to share them. As a result, today, about 80 health care institutions, from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston – a site where the concept was first tested – to Cleveland Clinic and the Veteran’s Health Administration allow patients access to their clinicians' notes about them online. In total, approximately 12.7 million patients now have access to OpenNotes, says Catherine DesRoches, executive director of OpenNotes, which is funded by philanthropic grants.

[See: 12 Questions to Ask Before Discharge .]

DesRoches and OpenNotes co-founder Dr. Tom Delbanco have set a goal of ensuring 50 million patients have access to their clinicians’ notes through the initiative by 2020.

There’s no reason for doctors to write notes about patients without a patient being privy to what's written, since patients can benefit by seeing what their physicians write and being fully informed , says Delbanco, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Managing the Power Dynamic Between Doctors and Patients

Lisa Esposito May 13, 2014

Based on early research done when the concept was still being tested – surveying patients a year after they’d begun using OpenNotes – most patients reported they felt more in control of their care, were more educated and better prepared for future visits. “They certainly remembered what happened in the visit better,” Delbanco says. That’s of no small consequence, since it’s well-documented that patients tend to forget or misremember the majority of information doctors share in person during medical visits. Experts say giving patients full access to their medical records and doctors’ notes can improve both patient engagement and follow through, as well. And 70 percent of surveyed patients who’d been using OpenNotes and who were on medicine said they were actually doing better at taking their medications as prescribed, Delbanco says.

Meanwhile, doctors’ concerns about sharing their notes – ranging from whether patients questioning notes would increase physician workload to whether reading doctors' notes would contribute to patient anxiety – have been systematically, carefully studied and found not to be at issue. Yet most physicians are still reluctant to share notes, Topol says. “Doctors still feel it’s their property – that they created the notes, and that the patients aren’t entitled to the notes – and this is an outgrowth of paternalism – medical paternalism” – as well as the unfounded fears related to sharing the notes, he says.

The lack of transparency misses another important opportunity, he adds, by keeping patients from being able to set their medical records straight. “Office notes are riddled with mistakes that could be easily cleaned up by patients. They know what medicines they’re taking, largely, and they know what conditions [they have],” he says. Research has found that often information in medical records and physicians notes is incorrect. “Notes are fraught with errors when they’ve been audited,” Topol says. “So why not have the patients involved? It’s their care, it’s their body. They paid for the visit one way or another. But yet they have no work product.”

[See: HIPAA: Protecting Your Health Information .]

Mary Ellen Sexton of Jefferson Township, Pennsylvania, says she hasn’t had to suggest any changes or corrections to her notes, but along with her husband, Lynn, she appreciates being able to see doctors’ notes through OpenNotes. The Sextons go to primary care provider Dr. Richard Martin, a family physician at the community clinic Geisinger Mt. Pleasant in Scranton, Pennsylvania, which is part of Geisinger Health System, an early adopter of OpenNotes.

Lynn, 84, who had a heart attack decades ago, says being able to access details through his medical record and OpenNotes post-visit improves the overall understanding he and his wife have of what’s going on with his care. “If we go to the cardiologist, everything is on there. The [tests] that he’s had, echocardiograms or stress tests – everything’s one there,” adds 81-year-old Mary Ellen; that includes an explanation of what the test was for and the cardiologist’s notes. “Even if Dr. Martin isn’t in and we have to go to somebody else, because Lynn has an emergency, all those notes are on there, too – exactly what they did or what they ordered or new medication,” she says. “It’s fantastic.”

The notes can help with recall following medical visits, particularly for older patients who have multiple chronic conditions that require much to be covered in a short office visit, Martin says “If somebody’s diabetic and their blood sugars aren’t well-controlled, I’ll get specific about things they need to avoid in their diet,” Martin says. “They may not remember everything I tell them. So they can go back to my note, and refresh their memory.”

For patients who don’t have ready access to their doctors’ notes online, experts say it’s still worth putting in a request for those notes. “ Ask your doctor for a copy. Doctors have been giving patients copies of notes for many years on a one-by-one basis,” Delbanco says. “Encourage your doctor to give it to you, and tell him or her if he doesn’t, you’ll go somewhere else for care.”

Gaining full access to your health record may require going through a health organization’s patient records department, which can take time. Patients may even be charged administrative or copying fees. But it's worth putting in the effort, even if patients shouldn't have to do that, experts say. Request electronic transmission if possible. “There are certainly practices throughout the country where patients are very comfortable and they routinely get their notes from the doctor, whether it be by email or hard copy, for their files,” Topol says. “There’s just very few – that’s the problem,” he says. “Every patient should have their notes as far as I’m concerned."

[See: 5 Common Preventable Medical Errors .]

Delbanco agrees. Though the vast majority of patients still don’t see their doctors’ notes, he’s encouraged that the growth of OpenNotes means an increasing number of patients are able to read what their doctors write about them. “There’s no question in my mind that it will become the standard of care over time,” he says. “It’s only a matter of when – not if.”

What Your Doctors Wish You Knew

Tags: patient advice , patients , medical records , medical quality , health care , doctors

Most Popular

Patient Advice

health disclaimer »

Disclaimer and a note about your health ».

Your Health

A guide to nutrition and wellness from the health team at U.S. News & World Report.

You May Also Like

Do blue light glasses work.

Paul Wynn June 7, 2024

Protein During Pregnancy: How Much?

Kelly LeBlanc June 6, 2024

How to Make Friends as an Adult

Karin Vandraiss June 5, 2024

Apple Cider Vinegar Benefits

Janet Helm June 4, 2024

Why Are Younger People Getting Cancer?

Paul Wynn May 31, 2024

12 Best Superfoods for Older Adults

Christine Comizio and Elaine K. Howley May 30, 2024

Healthy Barbecue Ideas and Recipes

Lon Ben-Asher May 23, 2024

Plant-Based and Vegan Protein Powder

Annika Urban May 22, 2024

What to Eat – and Avoid – on Semaglutide

Lisa R. Young May 22, 2024

Factors Contributing to Weight Loss

Vanessa Caceres May 21, 2024

New and Noteworthy

The physician visit note.

December 2018

Bobby Green, MD

This post was originally published on LinkedIn .

The physician visit note is many things to many people.

To the patient, they contain their personal health story.

To the clinicians who create them, they are the result of hours of work, day after day, year after year.

To the clinic, they become legal documents that must be preserved for years.

They are filled with fancy words, often with a little Latin thrown in.

They are long. Painfully long. Agonizingly difficult to read. Repetitious.

They are also, far too often, useless.

I live on both sides of the aisle. I am tortured having to sort through the abominably long and relatively devoid of important information monoliths created by my physician colleagues. But, to be fair, I create them too.

It was Dr. Lawrence Weed , exactly half a century ago, who set the revolutionary framework for the problem-oriented medical record (POMR), as a way to record and monitor patient information. To be fair, these written notes had their fair share of problems. Before computers, physician notes on paper were often illegible and held hostage — trapped in the physical confines of the paper chart. A distracted colleague could throw the day into chaos by accidentally putting a chart in the wrong bin on the ward. Spilled coffee could effectively and permanently delete important information. But at least they sometimes said something useful.

We assumed that technology would eventually make things better, and in some ways it has — my visit notes don't have weird stains from unidentifiable beverage spills. I rarely interact with hole punchers anymore (unless I want to throw one at a computer). I can sit in one chair and access all of my patients' records, instead of endlessly walking around searching for the right chart.

But go talk to a doctor. Any doctor. Ask them what they think of the physician visit note in this modern era of artificial intelligence, machine learning, self-driving cars. You will not get one positive response, not one.

I am an oncologist. I take care of cancer patients. That's what I do. And I think I'm reasonably good at it. And one of the main reasons I'm good at it is because that's my core area of focus. I stay away from other things. I don't take care of patients with arthritis. I don't read and interpret pathology slides. I don't perform surgery. As healthcare becomes more complex, it's increasingly important that clinicians specialize in the problem for which they are trained. For oncologists, that's cancer. I rely on my expert colleagues for help in areas beyond my expertise.

But here's the challenge. Unlike clinicians, the physician visit note tries to do too many things at once. It's always been a problem, but as the number of documentation requirements has drastically increased over the last decade, the visit note has become a dumping ground — a jack of all trades, but a master of none.

Specifically, today's visit note attempts to solve three wholly different problems:

Document the amount of work a clinician does to justify what they bill. Physicians do things like serve up a long list of negatives in our review of symptoms because it's required — this alone fills up half a page. We do the same thing for our physical exam when we write absurd things like "no splenomegaly" for the twentieth time in a year. You can argue whether this information is relevant and if pertinent negatives are helpful. But the format in which it's captured often obscures what is most critical. Two pages of a negative review of systems shouldn't hide that the patient was having 8/10 pain.

Serve as the clinician's source of truth and our main reference point. I need to know certain things about my patients in order to take good care of them. This includes which chemotherapy treatments they've previously had if they have a targetable EGFR mutation. I need to know that I ordered a CT scan to review next week. I should remember that they have a spouse sick at home that they care for which impacts their ability to come in for regular treatment. But EHRs don't create a framework to easily retrieve this information, instead functioning only as digital filing cabinets.

Communicate with other clinicians who also care for the patient. My colleagues don't need a full patient history summary or all of my negative physical exam findings every time I send them a note. When Mrs. Jackson receives a blood transfusion for her MDS, it's the blood transfusion that's important. They need to be able to see the important things without getting lost in details. The time clinicians spend digging through notes from referring doctors to find that one nugget of useful information is an epic waste.

Our notes do many things, and none of them well. But it doesn't have to be this way.

Imagine a world where the visit note serves as a framework for how we input and share information, where it isn't actually a physical note, but a framework for how we input and disseminate information.

Imagine the long list of negatives that have to be documented for a ROS or PE, or the data point that gets entered for the 10th time that the lifetime non-smoker hasn't started smoking again; imagine that these things never clutter up what my referring doctor has to see when she reads my note.

Imagine that I can enter staging and genomic information and then that information becomes easily retrievable and relevant.

Imagine that the abnormal physical exam findings are what I see highlighted, but not the normal negatives.

Imagine I'm prompted to make sure that "port in left chest wall" on my exam doesn't stay in my note years after the port is removed.

Imagine that I can spend 50 percent less time on my computer, and 50 percent more time with patients.

I do believe that there is a world in which the visit note actually gets better. We need to advocate for a reduction in documentation requirements, and kudos to CMS for finalizing a policy that starts to do this. And technology must play a role. Surely in a world where rockets can land themselves, we can build a better visit note. As someone who works at a health tech company, I am inspired by what engineers, designers, product managers and many of my other talented colleagues can do. As we strive to solve problems that matter, this, without question, matters. All of us who build EHRs for physicians have an obligation to make things better. An obligation to, as Dr. Weed wrote , create an environment where "...the art of medicine will gain freedom at the level of interpretation and be released from the constraints that disorder and confusion always impose." Stay tuned.

- Point of care

- Flatiron stories

More to explore

- Value-based care

- Customer interviews

- Clinical decision support

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Outpatient SOAP Notes

In the outpatient clinic, SOAP is the traditional note structure: S ubjective, O bjective, A ssessment, P lan. Although electronic health records may structure notes differently, this is still the information that you would enter at a problem focused or chronic disease management visit.

You may see some providers move the Assessment and Plan to the top of the note in this this order-APSO. Due to the amount of information automatically included in many electronic notes some providers chose to bring attention the the assessment and plan first.

This section begins with ID/CC ( the reason for the scheduled visit) and includes the history of present illness plus any other pertinent history. This pertinent history is often a combination of what may have been elicited from the patient and/or information you’ve confirmed from the medical record.

If you address more than one problem at the visit, the subjective section of the note should be organized by problems, with separate paragraphs for each issue addressed. At times you will be addressing multiple and both acute and chronic medical conditions at the same visit. How to address this in the note will be discussed below.

Use the appropriate medical terms for each problem so that future readers can quickly review its history by glancing at past visit notes. Remember that most patients have access to their medical records electronically and will be reading and reviewing chart notes and telephone encounters. Be mindful about the language you use in your documentation and remain patient-centered .

If there is a separate medication list, discuss with your preceptor if you, a nurse, or the preceptor should update this. If there is not a separate medication list, the patient’s current medications should be documented in the note. Use generic names if possible and indicate strength of medication and how often patient is to take medication. This can be placed at the end of the subjective section. Remember to review allergies in case you need to prescribe any medications during the visit.

The objective section should include:

- vital signs

- your findings on physical exam, organized by system

- results of lab tests or imaging studies performed since the last visit.

For most visits you will perform a focused physical exam based on the problem(s) the patient is presenting with. Performing a complete physical exam in the outpatient setting usually occurs during establish care visits and occasionally during wellness visits (more often the exam is tailored to appropriate preventive health measures. e.g. pelvic exam if cervical cancer screening due, skin exam if at higher risk for skin cancer, etc). Report the presence or absence of findings pertinent to the visit’s concerns, keeping in mind your differential diagnosis. This will almost always include vital signs, general appearance and findings from more than one organ system.

This section includes your interpretation of the information you presented in the subjective and objective sections. For an acute problem, it will be a differential diagnosis, which should include at least 2-3 reasonable possibilities. For a chronic disease visit, it should include your assessment of current control, adherence, and/or complications and any gaps or needs that were identified.

This section includes what you are going to do. When more than one problem has been addressed, many physicians write the assessment and the plan together for each one. The problems in the “assessment/plan” section correspond to those listed in the subjective section. A specific plan for follow up should be included in every note. On every note, indicate the name of your supervising physician (“seen with Dr. Jones”).

Link to SOAP note worksheet.

SOAP worksheet only

The patient has come in for a yearly wellness visit?

Update the past medical history, family, social, sexual, health related behaviors, allergies and medication list. Be familiar with the preventive health and wellness measures that are relevant based on the patient’s age, sex assigned at birth and other medical conditions or risk factors. Review any relevant screening questionnaires that may be part of the wellness visit. Often patients will bring up other acute and chronic medical conditions they would like to discuss during the wellness visit. Use agenda setting early on to identify these concerns and negotiate what can be accomplished during the visit. You may need to plan for a follow up visit to address other concerns.

The visit addresses multiple issues?

Follow the ID/CC with a statement of other issues raised by the patient or addressed by you. “Mr. Jones is a 63 year old man with hypertension and diabetes who presents today with an acutely swollen and painful left big toe. He also requests refills on his diabetes medications and a referral for massage for low back pain.”

Organize the Subjective, Assessment, and Plan sections by problem. The first paragraph under S would address the first problem, the next would address the second problem, and so on. The assessment and plan should address each of these problems individually. In this case, the subjective and assessment sections would address:

- Acute L big toe swelling

- Low back pain

- Hypertension

The visit includes follow-up of a known problem(s)?

ID/CC should include the reason for follow-up “Mr. Jones is a 63 year old man recently diagnosed with gout in the L great toe who returns for follow-up and discussion of prevention.”

The subjective section should include for each problem:

- Interval history: what’s happened since the last visit

- History of an current status of the problem

- Current therapy, adherence and how well it is working

- Any side effects or concerns about therapy

- Any monitoring that’s due

The Foundations of Clinical Medicine Copyright © by Karen McDonough. All Rights Reserved.

- Become a Member

- Everyday Coding Q&A

- Can I get paid

- Coding Guides

- Quick Reference Sheets

- E/M Services

- How Physician Services Are Paid

- Prevention & Screening

- Care Management & Remote Monitoring

- Surgery, Modifiers & Global

- Diagnosis Coding

- New & Newsworthy

- Practice Management

- E/M Rules Archive

June 7, 2024

CMS Update on Medical Record Documentation for E/M Services

The world as we knew it

Summary of changes described in this article

In 2018, CMS changed the requirements for using medical student E/M notes by the attending physician. In the 2019 Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule, CMS stated its desire to reduce the burden of documentation on practitioners for E/M services, in both teaching and non-teaching environments. They stated that a clinician no longer had to re-document the history and exam, but could perform those and “review and verify” information entered by other team members, or entered in prior notes. In 2019, CMS updated the section of the Medicare Claims Processing Manual that addressed E/M services in teaching settings, allowing a nurse, resident or the attending to document the attending’s presence during an E/M service. In 2020, CMS made a radical change to documentation requirements, adopting this as a policy,

“Therefore, we proposed to establish a general principle to allow the physician, the PA, or the APRN who furnishes and bills for their professional services to review and verify, rather than re-document, information included in the medical record by physicians, residents, nurses, students or other members of the medical team.” [1]

- CMS has made significant changes in E/M notes to reduce burden on practitioners in the past years.

- CMS is now allowing clinicians to “review and verify” rather than re-document the history and exam. The details are below.

Want unlimited access to CodingIntel's online library?

Including updates on CPT ® and CMS coding changes for 2024

“Copy-Pasting. Copy-pasting, also known as cloning, enables users to select information from one source and replicate it in another location. When doctors, nurses, or other clinicians copy-paste information but fail to update it or ensure accuracy, inaccurate information may enter the patient’s medical record and inappropriate charges may be billed to patients and third-party health care payers. Furthermore, inappropriate copy-pasting could facilitate attempts to inflate claims and duplicate or create fraudulent claims.” [2]

Read the OIG report

CMS responded that it agreed that additional guidance was needed and that it intended to work with its contractors in the development of effective guidance. To my knowledge, that guidance was never released.

- The OIG expressed concern about copy/paste and over-documentation in 2014, but this did not lead to CMS standards about the practice.

- Commercial payers are largely silent, as well.

2019 Easing the burden of documentation

“We proposed to expand this policy to further simplify the documentation of history and exam for established patients such that, for both of these key components, when relevant information is already contained in the medical record, practitioners would only be required to focus their documentation on what has changed since the last visit or on pertinent items that have not changed, rather than re-documenting a defined list of required elements such as review of a specified number of systems and family/social history. Practitioners would still review prior data, update as necessary, and indicate in the medical record that they had done so. Practitioners would conduct clinically relevant and medically necessary elements of history and physical exam, and conform to the general principles of medical record documentation in the 1995 and 1997 guidelines. However, practitioners would not need to re-record these elements (or parts thereof) if there is evidence that the practitioner reviewed and updated the previous information.” [3]

That long-winded paragraph says that a practitioner would not need to re-record history and exam for established patients that they had reviewed and verified from a prior note.

This was verified by a letter from CMS head Seema Verma . Ms. Verma’s letter went further. It said that effective 1-1-2019, not only could the clinician review and verify history and exam, but for both new and established E/M services, specifically,

“Clarify that for both new and established E/M services, a Chief Complaint or other historical information already entered into the record by ancillary staff or patients themselves may simply be reviewed and verified rather than re-entered” [4]

- In 2019, CMS said that for a new or established patient, the billing clinician could “review and verify” information entered into the record by ancillary staff or patients, rather than re-document.

- CMS included “history and exam” as components that could be reviewed from prior entries and verified, not re-documented.

- Section from 2019 rule and letter from Ms. Verma attached to this article

2020 Expanded “Review and verify”

Perhaps the most shocking change came in the Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule in 2020. CMS noted that stakeholders were questioning whether “students” described in the Medicare claims processing manual referred only to medical students, or if that also referred to nurse practitioner and physician assistant students. Advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) and physician assistants (PAs) told CMS that they wanted to use the same rules for precepting their students as physicians used when precepting medical students. CMS agreed with them. But, they went farther.

“Therefore, we proposed to establish a general principle to allow the physician, the PA, or the APRN who furnishes and bills for their professional services to review and verify, rather than re-document, information included in the medical record by physicians, residents, nurses, students or other members of the medical team. We explained that this principle would apply across the spectrum of all Medicare-covered services paid under the PFS. We noted that because the proposal is intended to apply broadly, we proposed to amend regulations for teaching physicians, physicians, PAs, and APRNs to add this new flexibility for medical record documentation requirements for professional services furnished by physicians, PAs and APRNs in all settings.” [5]

Read that section in it’s entirety

- In the 2020, CMS established a general principal to allow the physician/NP/PA to review and verify information entered by physicians, residents, nurses, students or other members of the medical team.

- This principle applies broadly for professional services furnished by a physician/NP/PA.

Codes 99202–99215 in 2021, and other E/M services in 2023

In 2021, the AMA changed the documentation requirements for new and established patient visits 99202—99215. Neither history nor exam are required key components in selecting a level of service. This further reduces the burden of documenting a specific level of history and exam. The 2021 CPT book says this regarding history and exam.

“The care team may collect information and the patient or caregiver may supply information directly (eg, by portal or questionnaire) that is reviewed by the reporting physician or other qualified health care professional. The extent of history and physical examination is not an element in selection of office or other outpatient services.” [6]

- In 2021, for visits reported with codes 99202—99215, history and exam will not be used to select the level of E/M services. This framework was extended to other E/M services in 2023.

What about teaching physicians

CMS began changing the teaching position rules in 2018, with the stipulation about student documentation. The citation from the CMS manual that changed is below.

B. E/M Service Documentation Provided By Students

“Any contribution and participation of a student to the performance of a billable service (other than the review of systems and/or past family/social history which are not separately billable, but are taken as part of an E/M service) must be performed in the physical presence of a teaching physician or physical presence of a resident in a service meeting the requirements set forth in this section for teaching physician billing. Students may document services in the medical record. However, the teaching physician must verify in the medical record all student documentation or findings, including history, physical exam and/or medical decision making. The teaching physician must personally perform (or re-perform) the physical exam and medical decision making activities of the E/M service being billed, but may verify any student documentation of them in the medical record, rather than re-documenting this work.” [7]

What this says is the teaching physician must still do the work. But, the teaching physician doesn’t have to re-document the work. It saves re-documentation on the part of the attending, in the same fashion as the attending doesn’t need to re-document all of the resident’s work.

Documentation performed by medical students, advance practice nursing students and physician assistant students:

“Therefore, we propose to establish a general principle to allow the physician, the PA, or the APRN who furnishes and bills for their professional services to review and verify, rather than re-document, information included in the medical record by physicians, residents, nurses, students or other members of the medical team. This principle would apply across the spectrum of all Medicare-covered services paid under the PFS.”

- Now, physician assistant and nurse practitioner students are treated the same way as medical students for documentation purposes.

- Any physician or NPP who bills a service can “review and verify” rather than re-document.

- Includes “information included in the medical record by physicians, residents, nurses, students or other members of the medical team.”

The new rules allow the attending, the resident or the nurse to document the attending’s participation in the care of the patient when performing an E/M service. CMS said they were going to do this in the 2019 Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule, released in November of 2018, but the transmittal wasn’t released until April 26, although there is an effective date of January 1, 2019 and an implementation date of July 1, 2019. The transmittal does not include any of the examples of linking statement that were in the manual for so many years. It is brief—here is the section on E/M.

100.1.1 – Evaluation and Management (E/M) Services (Rev. 4283, Issued: 04- 26-19, Effective: 01-01-19, 07-29-19) A. General Documentation Requirements

Evaluation and Management (E/M) Services – For a given encounter, the selection of the appropriate level of E/M service should be determined according to the code definitions in the American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) book and any applicable documentation guidelines.

For purposes of payment, E/M services billed by teaching physicians require that the medical records must demonstrate:

- That the teaching physician performed the service or was physically present during the key or critical portions of the service when performed by the resident; and

- The participation of the teaching physician in the management of the patient.

The presence of the teaching physician during E/M services may be demonstrated by the notes in the medical records made by physicians, residents, or nurses.

These are significant changes for all practices, including those in academic settings. We hope that our MACs are paying attention to CMS’s intentions and that other payers follow suit.

[1] CMS 2020 Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule

[2] CMS and Its Contractors Have Adopted Few Program Integrity Practices to Address Vulnerabilities in EHRs, January 2014 OEI-01-11-00571.

[3] CMS 2019 Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule, page 572

[4] CMS letter from S. Verma, 2019

[5] 2020 Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule, p. 380

[6] AMA, CPT E/M codes, 2021

[7] Medicare Claims Processing Manual, 100-04, Chapter 12, Section 100

Last revised May 21, 2024 - Betsy Nicoletti Tags: compliance issues

CPT®️️ is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association. Copyright American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

All content on CodingIntel is copyright protected. Any resource shared within the permissions granted here may not be altered in any way, and should retain all copyright information and logos.

- What is CodingIntel

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

Our mission is to provide up-to-date, simplified, citation driven resources that empower our members to gain confidence and authority in their coding role.

In 1988, CodingIntel.com founder Betsy Nicoletti started a Medical Services Organization for a rural hospital, supporting physician practice. She has been a self-employed consultant since 1998. She estimates that in the last 20 years her audience members number over 28,400 at in person events and webinars. She has had 2,500 meetings with clinical providers and reviewed over 43,000 medical notes. She knows what questions need answers and developed this resource to answer those questions.

Copyright © 2024, CodingIntel A division of Medical Practice Consulting, LLC Privacy Policy

Do You Really Want to Read What Your Doctor Writes About You?

You’re now allowed to see everything physicians say about you in their notes. It’s complicated.

You may not be aware of this, but you can read everything that your doctor writes about you. Go to your patient portal online, click around until you land on notes from your past visits, and read away. This is a recent development, and a big one. Previously, you always had the right to request your medical record from your care providers—an often expensive and sometimes fruitless process—but in April 2021, a new federal rule went into effect , mandating that patients have the legal right to freely and electronically access most kinds of notes written about them by their doctors.

If you’ve never heard of “ open notes ,” as this new law is informally called, you’re not the only one. Doctors say that the majority of their patients have no clue. (This certainly has been the case for all of the friends and family I’ve asked.) If you do know about the law, you likely know a lot about it. That’s typically because you’re a doctor—one who now has to navigate a new era of transparency in medicine—or you’re someone who knows a doctor, or you’re a patient who has become intricately familiar with this country’s health system for one reason or another.

When open notes went into effect, the change was lauded by advocates as part of a greater push toward patient autonomy and away from medical gatekeeping. Previously, hospitals could charge up to hundreds of dollars to release records, if they released them at all. Many doctors, meanwhile, have been far from thrilled about open notes. They’ve argued that this rule will introduce more challenges than benefits for both patients and themselves. At worst, some have fretted, the law will damage people’s trust of doctors and make everyone’s lives worse.

A year and a half in, however, open notes don’t seem to have done too much of anything. So far, they have neither revolutionized patient care nor sunk America’s medical establishment. Instead, doctors say, open notes have barely shifted the clinical experience at all. Few individual practitioners have been advertising the change, and few patients are seeking it out on their own. We’ve been left with a partially implemented system and a big unresolved question: How much, really, should you want to read what your doctor is writing about you?

The debate about open notes can be boiled down to a matter of practicality versus idealism. You’d be hard-pressed to find anyone, doctor or otherwise, who argues against transparency for patients in principle . At the same time, few people I spoke with for this article believe that the new rule has been put in place all that smoothly. For care providers, the primary concern has been the trouble that can come with writing notes for a new audience. Notes, generally scribbled in shorthand incomprehensible to the unknowing eye, have traditionally served doctors, and doctors alone. They allowed physicians to stay up to date on their patients and share information with colleagues for input on cases.

Some doctors told me they worry that open notes could result in distress for patients who read something they don’t understand, and that highly technical language could make something sound worse than it is. Oncology, for instance, can involve an onslaught of potentially concerning terminology . (Psychotherapy notes are exempt from the new rule.) Other doctors fear that valuable information can be lost if they go too far in de-jargonizing notes to make them patient-friendly. Or that de-jargonizing notes is simply unfeasible. “Let’s say you came to me with pain and pointed to your mid-clavicular line. I’d just put ‘MCL,’” says Aldo Peixoto, a nephrologist at Yale. “But if I were writing for you to understand, I’d have to say ‘pain on the top-right portion of her abdomen in the line that runs from the middle of her clavicle,’ and so on. Rather than writing four lines of prose, I could’ve used literally three letters.”

If that sounds quibbling, consider the trade-offs. Less time for doctors can translate into less time for patients. Many clinicians already write notes well into the evening. Certainly, the pandemic hasn’t helped . Some doctors told me that if they find themselves in a dilemma of either writing notes in less-efficient, plain language or fielding worried patient calls and messages, exhausted practitioners will face yet another burden. And then there’s the matter of trust. Jack Resneck, the president of the American Medical Association, the nation’s largest professional group of doctors and medical students, told me that doctors can need time and space with patients to get them to open up and be receptive to guidance through difficult situations. If these patients were to see notes too soon, Resneck said, they might “immediately flee and not come back to see you.”

Read: Why health-care workers are quitting in droves

As doctors have spent more time dealing with open notes, many have eased off their strongest objections. Some, including Resneck and the AMA, have warmed up to the new rule as certain exceptions have been granted, such as allowing doctors whose patients have parents or partners with access to their notes to omit certain details from their write-ups for privacy reasons. Other physicians seem to be coming to a somewhat awkward realization: On a practical level, many concerns about how this change affects patients are irrelevant, because most patients don’t yet know they have instant access to their notes in the first place. Every doctor I spoke with for this story told me that their patients were largely unaware. Many doctors and hospitals are not going out of their way to inform people about the new rule, so unless patients are particularly on top of shifting rules within our convoluted health-care system, they’re unlikely to encounter the notes on their own. Kerin Adelson, an oncologist at Yale, admitted she didn’t know how to find notes in her own patient portal. She spent several minutes with me on the phone fumbling through different tabs to locate them.

Fans of open notes are frustrated that there is not a greater push for awareness. Even acknowledging that the new system has its shortcomings, many argue that the only way to make things better is to get people invested in the access they’ve recently been granted. Lydia Dugdale, a primary-care doctor at Columbia University, worries about ensuring equity. “Things like socioeconomic status, education, literacy: All of those issues affect the degree to which any given patient is going to want to read and correct and interrogate his or her health record,” she told me. Tom Delbanco, a Harvard doctor and one of the co-founders of OpenNotes, an initiative that spearheaded the push for access to doctors’ notes in the U.S., believes that the effort required to refrain from using “bad words” in notes is minor, and that it shouldn’t make any significant demands on clinicians’ schedules. Doctors who are now taking more time to write notes because of the change, he told me, “probably ought to because they’ve been writing lousy notes.”

Open notes can be valuable for people with chronic conditions and their caregivers, who need to stay in the know. Liz Salmi, the communications and patient-initiatives director at OpenNotes, told me about pulling her full medical record eight years into dealing with brain cancer, before notes were easily and freely available. The document was 4,839 pages. To get a PDF, she said, she had to pay $15 for each DVD it was uploaded to, and her records spanned multiple discs. But the information was worth it: Having access to the record gave Salmi a way to remember all of the crucial bits of information she’d gotten piecemeal from various doctors.

The fact that many people have no idea open notes exist doesn’t change the deeply personal questions at stake in the debate about whether the notes do more good or harm—questions that everyone must confront in one way or another in dealing with America’s medical system, whether or not they fully realize it. How much information do you truly want about your health, and how much do you trust your doctor to deliver it to you? What is a doctor’s role in informing people about their health?

Read: Following your gut isn’t the right way to go