The Ages of Exploration

Quick Facts:

British navigator and explorer who explored the Pacific Ocean and several islands in this region. He is credited as the first European to discover the Hawaiian Islands.

Name : James Cook [jeymz] [koo k]

Birth/Death : October 27, 1728 - February 14, 1779

Nationality : English

Birthplace : England

Captain James Cook

Print of James Cook, famous circumnavigator who explored and mapped the Pacific Ocean. The Mariners' Museum 1938.0345.000001

Introduction Captain James Cook is known for his extensive voyages that took him throughout the Pacific. He mapped several island groups in the Pacific that had been previously discovered by other explorers. But he was the first European we know of to encounter the Hawaiian Islands. While on these voyages, Cook discovered that New Zealand was an island. He would go on to discover and chart coastlines from the Arctic to the Antarctic, east coast of Australia to the west coast of North America plus the hundreds of islands in between.

Biography Early Life James Cook was born on October 27, 1728 in the village Marton-in-Cleveland in Yorkshire, England. He was the second son of James Senior and Grace Cook. His father worked as a farm laborer. Young James attended school where he showed a gift for math. 1 But despite having a decent education, James also wound up working as a farm laborer, like his father. At 16, Cook became an apprentice of William Sanderson, a shopkeeper in the small coastal town Staithes. James worked here for almost 2 years before leaving to seek other ventures. He then became a seaman apprentice for John Walker, a shipowner and mariner, in the port of Whitby. Here, Cook developed his navigational skills and continued his studies. Cook worked for Walker’s coal shipping business and worked his way up in rank. He completed his three-year apprenticeship in April 1750, then went on to volunteer for the Royal Navy. He would soon have the opportunity to explore and learn more about seafaring. He was assigned to serve on the HMS Eagle where he was quickly promoted to the position of captain’s mate due to his experience and skills. In 1757, he was transferred to the Pembroke and sent to Nova Scotia, Canada to fight in the Seven Years’ War.

Cook continued to expand his maritime knowledge and skills by learning chart-making. He helped to chart and survey the St. Lawrence River and surrounding areas while in Canada. His charts were published in England while he was abroad. After the war, between 1763 and 1767, Cook commanded the HMS Grenville , and mapped Newfoundland and Labrador’s coastlines. These maps were considered the most detailed and accurate maps of the area in the 18th century. After spending 4 years mapping coastlines in northeast North America, Cook was called back to London by the Royal Society. The Royal Society sent Cook to observe an event known as the transit of Venus. During a transit of Venus, Venus passes between the Earth and the Sun and appears to be a small black circle traveling in front of the Sun. By observing this event, they believed they could calculate the Earth’s distance from the Sun. In May 1768, Cook was chosen by the Society and promoted to lieutenant to lead an expedition to Tahiti, then known as King George’s Island, to observe the transit of Venus. 2 This begin the first of several voyages that would earn James Cook great fame and recognition.

Voyages Principal Voyage James Cook sailed from Deptford, England on July 30, 1768 on his ship Endeavour with a crew of 84 men. 3 The crew included several scientists and artists to record their observations and discoveries during the journey. They made many small stops at different locations along the way. In January 1769, they rounded the tip of South America, and finally reached Tahiti in April 1769. They established a base for their research that they named Fort Venus. On June 3, 1769, Cook and his men successfully observed the transit of Venus. While on the island, they collected samples of the native plants and animals. They also interacted with some native people, learning more about their customs and traditions. Cook sailed to some of the neighboring islands, including modern day Bora Bora, mapping along the way. After completing the observation of Venus’ transit, Cook was given new orders to sail south, search for the Southern Continent – known today as Australia. On August 9, 1769, the Endeavour departed from Tahiti in search of the Southern Continent. After sailing for several weeks with no sign of land, Cook decided to sail west. On October 6th, land was sighted, and Cook and his men made landfall in modern day New Zealand.

Cook named the place Poverty Bay. They were met by unfriendly natives, so Cook decided to sail south along the coast of this new land. He named several islands and bays along the way, such as Bare Island and Cape Turnagain. At Cape Turnagain, the Endeavour turned around and sailed north along the coastline again and rounded the northernmost tip of the island. They sailed down along the western coast Cook and his men crossed a strait to return to Cape Turnagain, thus completing a circumnavigation of the northern island. This trip proved that New Zealand was made up of two separate islands. The expedition then sailed south along the eastern coastline of the southern island. They stopped at Admiralty Bay on the northern coast to resupply before sailing west into open ocean. In April of 1770, Cook first spotted the northeastern coastline of modern day Australia. He landed in Botany Bay near modern day Sydney. 4 He explored some of the area and coastline including places such as Port Jackson and Cape Byron. The Endeavour then sailed around the northernmost tip of the continent before setting sail east back to England. They soon landed in Batavia, now known as Jakarta, in Indonesia. In Batavia, several of the crew, including James Cook became ill, many dying from diseases. 5 The expedition eventually sailed onward, and reached London on July 13, 1771.

Subsequent Voyages In 1772, Cook was promoted to captain. He was given command of the two ships, the Resolution and Adventure , to look for the Southern Continent. On July 13, 1772, the expedition left England, stopping at the Cape of Good Hope to resupply before sailing south. May 26, 1773, Cook and his crew reached Dusky Bay, New Zealand . They spent the winter anchored in Ship Cove, exploring inland and interacting with the Maori natives. When they departed from New Zealand in October of 1773, the two ships became separated and never reunited. 6 The Adventure returned to England. Cook and the Resolution continued onward exploring various islands throughout the Pacific. While sailing in the Pacific, the Resolution crossed into the Antarctic Circle several times sailing farther south than any other explorer at the time. Several times they got stuck in sea ice. So Cook decided to suspend the search for the Southern Continent. But they did not return to England just yet. They sailed to Easter Island and stayed there for seven months, exploring and mapping the nearby Society Islands and the Friendly Islands. November 10, 1774, the Resolution began its return journey to England.They traveled around the tip of South America and stopped briefly on the Sandwich Islands to claim them for England. Cook finally returned to England on July 30, 1775 and reported that there was no Southern Continent to be found.

Just one year later, Cook was given the Resolution and Discovery to lead yet an expedition to search for the Northwest Passage. The ships left England on July 12, 1776. A storm forced them to stop at Adventure Cove in Tasmania before continuing on to Ship Cove. In December of 1777 the men landed at Christmas Island, now known as Kiritimati. Several weeks later, they made a significant discovery when they came upon the islands of Hawaii. They landed at modern day Kauai and were fascinated by the environment and friendly natives. But Cook still wanted to discover the Northwest Passage so they left two weeks laters. They finally landed at modern day Vancouver Island where they interacted and traded with the native people. Cook continued his search for the Northwest Passage and commanded the expedition to sail northwest along the coastline of what is now Alaska, and throughout Prince William Sound. On August 9th, they reached the westernmost point of Alaska, which Cook named Cape Prince of Wales. From here, Cook sailed farther into the Arctic Circle until he was stopped by a thick wall of ice. Cook named this point Icy Cape. Cook and his men sailed back down the coast of Alaska and back south until they reached the Hawaiian Islands again.

Later Years and Death When first landing in Kealakekua Bay, they were met with angry natives. Cook soon met with the Hawaiian ruler, King Kalei’opu’u. It was a friendly meeting, was given large amounts of food and resources.They left Kealakekua Bay on February 4, 1779 but were forced to return a few days later after the Resolution was damaged in a storm. Once more, they were not greeted with joy by the natives. While the Resolution was being repaired, the crew noticed that the natives were stealing their supplies and tools. On February 14th, Cook attempted to stop the thievery by taking Chief Kalei’opu’u hostage. 7 However, fighting between the crew and native people had already started. When Cook attempted to return to his ship, he was attacked on the shoreline. He was beaten with stones and clubs and stabbed in the back of the neck. Cook died on the shore and his body was left behind as the other men returned to the ship. After making peace with the natives a few days later, pieces of Cook’s body were recovered and buried on February 22, 1779. The next day, the remaining crew left Hawaii to return to England. The ships arrived in England on October 4, 1780 after attempting to search for the Northwest Passage one more time.

Legacy Captain James Cook is known for his incredible voyages that took him farther south than any other explorer of his time. He was not able to prove that a southern continent existed, but he had many other achievements. He was the first to map the coastlines of New Zealand, the eastern coastline of what would become Australia, and several small islands in the Pacific. Cook was also one of the first Europeans to encounter the Hawaiian Islands. His reports on Botany Bay were part of the reason Britain established a penal colony there in 1787. 8 He is still recognized today for creating some of the most accurate maps of the Pacific islands during his time. James Cook helped the south seas go from being a vast and dangerous unknown area to a charted and inviting ocean.

- Charles J. Shields, James Cook and the Exploration of the Pacific (Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2002), 16.

- Richard Hough, Captain James Cook (New York: WW Norton & Co., 1997) 38-39.

- James Cook, The Voyages of Captain Cook, ed. Ernest Rhys (Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Limited, 1999), 11

- Captain James Cook and Robert Welsch, Voyages of Discovery (Chicago: Academy Chicago Publishers, 1993), v.

- Cook and Welsch, Voyages of Discovery , 102-106.

- Cook, The Voyages of Captain Cook , xiv.

- Charles J. Shields, James Cook and the Exploration of the Pacific , 56.

- Cook and Welsch, Voyages of Discovery , v.

Bibliography

Shields, Charles J. James Cook and the Exploration of the Pacific . Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2002.

Hough, Richard. Captain James Cook . New York: WW Norton & Co., 1997.

Cook, James. The Voyages of Captain Cook , edited by Ernest Rhys. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Limited, 1999.

Cook, Captain James, and Robert Welsch. Voyages of Discovery. Chicago: Academy Chicago Publishers, 1993.

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

Captain Cook’s voyages of exploration

Terra Australis Incognita - the unknown southern land. The existence (or not) of this mysterious, mythical place has intrigued philosophers, explorers and map-makers since it was first hypothesised by the ancient Greeks and Romans. The empire-builders of 18th century Britain were just as obsessed with investigating territories below the Equator.

In 1768, when Captain James Cook set sail on the first of three voyages to the South Seas, he carried with him secret orders from the British Admiralty to seek ‘a Continent or Land of great extent’ and to take possession of that country ‘in the Name of the King of Great Britain’.

While each of Cook's three epic journeys had their own aims and significant achievements, it was this confidential agenda that would transform the way Europeans engaged with the Pacific, its lands and inhabitants. The maps, journals, log books and paintings from Cook’s travels are just some of the State Library’s incredible records of this exciting time.

The first voyage

James Cook's first Pacific voyage (1768-1771) was aboard the Endeavour and began on 27 May 1768. Cook’s voyage had three aims; to establish an observatory at Tahiti in order to record the transit of Venus (when the planet passed between the earth and the sun), on 3 June 1769. The second aim was to record natural history, led by 25-year-old Joseph Banks. The final secret goal was to continue the search for the Great South Land.

Cook reached the southern coast of New South Wales in 1770 and sailed north, charting Australia’s eastern coastline and claiming the land for Great Britain on 22nd August 1770.

The second voyage

Cook's second Pacific voyage, (1772-1775), aimed to establish whether there was an inhabited southern continent, and make astronomical observations.

The two ships Resolution and Adventure were fitted out for the expedition. In 1772, before he set out, Cook created a map which showed the discoveries made in the Southern Ocean up until 1770 and sketched out his proposed route for the upcoming voyage. In 1773, accompanied by naturalists, astronomers and an artist, Cook made his first crossing of the Antarctic Circle, claiming that he had been further south than any person. During a voyage of 100,000 km, Cook sailed south of the Antarctic Circle (at 66˚30’S) on three occasions, proving that the southern landmass was neither as large or as habitable as once thought. Cook also discovered several islands along the Scotia Arc, initiating the commercial interest that underpinned much of the focus on Antarctica over the next 150 years.

The third voyage

Cook’s third and final voyage (1776-1779) of discovery was an attempt to locate a North-West Passage, an ice-free sea route which linked the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. Again, Cook commanded the Resolution while Charles Clerke commanded Discovery . Leaving England in 1776, Cook first sailed south to Tahiti to return Omai, a Tahitian man, to his home. Omai had been taken on Cook’s second voyage and had been an object of curiosity in London. It was on this, Cook's final voyage, that he discovered the Hawaiian Islands in January 1778. This major discovery would lead to his death – Cook was killed on a return visit to Hawaii at Kealakekua Bay, on 14 February 1779.

This story has been developed with the support of the State Library of NSW Foundation.

We would like to acknowledge the generosity of the Bruce and Joy Reid Foundation.

- Exploration

Story Contents

- Free general admission

We are no longer updating this page and it is not optimised for mobile devices.

- Browse collection by place

- Browse collection by category

- The collection

- About this site

Cook's voyages to the Pacific

By michelle hetherington.

James Cook’s three Pacific voyages represent the turning point for British ambitions in the South Seas. Prior to these voyages, the Pacific was poorly documented. Inadequate charts left room for surmise and disaster. As navigators could only guess their longitude, islands were discovered, lost and then rediscovered under different names. A poor understanding of nutrition resulted in terrible loss of life on expedition vessels. Access to the rich markets of the Americas, China and the Spice Islands remained out of reach. At the end of Cook’s third Pacific Voyage, the Pacific had been charted from Antarctic waters to the Arctic, contact had been made with island populations, and the huge collections of the natural and ‘artificial’ productions of the region had given rise to scientific studies that would develop into what are now known as anthropology and ethnology. From an Australian point of view, the first voyage in particular has great significance. Eighteen years after Cook mapped much of the east coast and claimed it for the British Crown, the First Fleet arrived and British colonisation of the continent began.

Cook's Pacific Encounters exhibition, National Museum of Australia, 2006. Photo: George Serras.

British interest in the Pacific was of long standing. Spanish claims to exclusive control of most of South America, the south Atlantic and the Pacific had largely stymied British access to the riches of the New World (although her buccaneers and privateers had been bringing home captured cargoes and maps since the 1580s). Taking advantage of the changed balance of power in Europe following the signing of the Treaty of Paris at the end of the Seven Years War, the Royal Navy sent out three vessels between 1764 and 1766 to locate and claim a suitable land base in the Pacific from which to conduct trade. Each ship failed to find the hoped-for Great South Land, but one of them, the Dolphin , returned in May 1768 with news of a hospitable island claimed for the Crown as King George III’s Island, but known to its inhabitants as Tahiti.

The catalyst for Cook’s first Pacific voyage was a petition sent to King George III by the British Royal Society in 1768. 1 The petition requested assistance to send a scientific expedition to the South Seas to observe the transit of Venus across the face of the sun (expected to occur in June 1769), and supplied the King and his navy with a pretext and opportunity to extend British knowledge of a region from which Spain had sought to exclude them for centuries. The need for more accurate astronomical knowledge which underpinned the petition was as old as Britain’s maritime rivalry with Spain, but the more recent originator of the petition was Edmund Halley, who in 1716 encouraged the Royal Society to observe the next transits of Venus, due in 1761 and 1769. Accurate transit measurements could then be used to calculate the distance of the Earth from the Sun and, by extension, the size of the solar system and the universe.

Observations of the 1761 transit were taken from across Europe and in China, India, Réunion Island, Cape of Good Hope, St Helena and Newfoundland. However, with no method for accurately calculating the longitude of most observation sites, no useful results were obtained. Venus was expected to transit the Sun again on 3 June 1769, but if this opportunity was also lost, it would be another 105 years before the transit next occurred and another attempt at recording it could be made.

The Royal Society’s petition, supported by the Greenwich Observatory, sought the sum of £4000 to defray the costs of a Pacific expedition which would, it was stressed, enhance Britain’s imperial ambitions and scientific reputation, and improve navigation and trade. The petition was soon approved. In addition to the requested sum, a further £8235 was spent on the purchase and refitting of a suitable ship, HMB Endeavour . 2 With such a considerable investment at stake, the Lords of the Admiralty rejected the Royal Society’s nomination of a ‘civilian’, Alexander Dalrymple, for captain. 3 Dalrymple refused to join the voyage merely as an observer, and so the Royal Society asked the navy to suggest a ‘proper person’ in his stead.

In May 1768, the Royal Society was informed that Lieutenant James Cook had been appointed expedition commander by the Admiralty. Cook had spent most of his summers for the past decade mapping the Gulf of St Lawrence and Newfoundland, and in addition to perfecting his cartographic skills, had also observed a solar eclipse from the Burgeo Islands on 5 August 1766. 4 The Royal Society was therefore happy to appoint Cook as one of the observers of the transit in Dalrymple’s place. Cook attended the Council of the Royal Society on 19 May 1768 and accepted the sum of 100 guineas as a ‘gratuity for his trouble as one of the Observers’. 5 At the same meeting, Charles Green, assistant to the Astronomer Royal at Greenwich Observatory, was appointed voyage astronomer.

For the 1769 transit, there were 150 observers in locations from Hudson Bay to the Pacific, both north and south of the equator. Dr Nevil Maskelyne, Astronomer Royal and fellow of the Royal Society, had calculated that the best possible vantage point south of the equator was between the Marquesas Islands in the north-east and Tonga in the west. The preferred site within this large area had not yet been determined when the Dolphin returned with news of Tahiti, located almost at the centre of the area identified by Maskelyne. In addition to the pleasant climate, friendly locals and excellent food supply, Tahiti’s longitude had been established by the Dolphin ’s purser, John Harrison, using Maskelyne’s astronomical tables to perform the mathematically complicated but effective method of calculating lunar distances. The following month, the Royal Society informed the Admiralty that Tahiti was its desired site for the observation of the transit, and also requested that naturalist Joseph Banks and his party be permitted to join the expedition. 6

The avowedly scientific purpose of this voyage in a Royal Navy ship, and the inclusion of civilian scientists, naturalists and artists among the Endeavour ’s company, was unprecedented. On 3 June 1769, with a cloudless sky and the thermometer at 119°F, measurements of the transit were taken at Point Venus by Cook, Green and naturalist Daniel Solander; at the islet of Taaupiri by Lieutenant Zachary Hicks; and at the nearby island of Moorea by Lieutenant John Gore. And their readings did not agree. Many years of planning and vast sums of money culminated only in confusion, due to the difficulty of determining exactly when Venus first crossed and last touched the solar disc. The 15 to 20 second variations in the Tahitian readings were repeated around the world. 7

Other scientific aspects of Cook’s first voyage were more successful, especially Banks’s and Solander’s botanical discoveries and natural history collections, although commentators have regretted Banks’s failure to publish. 8 The political and imperial aspects of the voyage, less publicly acknowledged than the scientific rationale, were also a considerable success. Lord Morton, then president of the Royal Society, had supplied Cook with ‘Hints’ outlining the scientific program and desired approach to interactions with the peoples of the Pacific. The Admiralty supplied Cook with secret instructions that required him to search for and claim for the Crown the fabled Terra Australis, or failing that, any other site likely to be valuable as a base for exploration and trade. On leaving Tahiti the Endeavour sailed into southern latitudes in search of a large body of land and, finding none, headed for New Zealand, the west coast of which had been sighted and partially mapped by Tasman in 1642–1643.

The crew of the Endeavour spent from October 1769 to the end of March 1770 circumnavigating and mapping New Zealand, proving conclusively that it was not, as some believed, an outlying promontory of Terra Australis. Cook and his men continued to collect specimens and artefacts, and to record detailed observations, before the decision was made to return home via the east coast of New Holland. Only two stays of any length were made on the Australian coast — one at Botany Bay to take on wood and water, and another to repair their ship at Endeavour River after it struck the Great Barrier Reef. After mapping and claiming a 2000-mile stretch of the coast, Cook sailed for Batavia.

Despite the deaths of many of the ship’s company from illness contracted at Batavia, and the inconclusive results from the observation of the transit of Venus at Tahiti, the Endeavour ’s voyage was considered a great success, and even as he sailed home, Cook was formulating a plan to return to the Pacific to establish irrefutably the existence, or otherwise, of the Great South Land. Lord Sandwich, recently reappointed First Lord of the Admiralty, approved Cook’s suggestion, and planning began for a second voyage along similar scientific and strategic principles to the first.

Many lessons had been learnt from the voyage of the Endeavour , in particular the folly of sending single ships on expeditions into unexplored waters. For the second voyage, two ships were commissioned, and the names initially given to them — the Drake and the Raleigh — made clear Britain’s resolve to defy Spanish pretensions to ‘own’ the Pacific. Banks’s experience of the cramped conditions of the great cabin on the Endeavour also led him to make preparations for his improved comfort on the second voyage, with extra accommodation constructed on the Resolution ’s upper deck at his own expense and the services of a greatly increased retinue of assistants secured.

Upon reflection, the navy chose not to antagonise Spain, and renamed the ships the Adventure and the Resolution . Banks’s plans also suffered alteration when the Resolution nearly capsized during sea trials to test the safety of his additions. They were removed forthwith. Banks expressed his fury and, after a week of intense lobbying, withdrew himself and his retinue from the voyage. In place of Banks, Johann Reinhold Forster and his son Georg were appointed as principal and assistant naturalists to pursue the voyage’s scientific program.

William Hodges was offered the position of voyage artist and, unlike the artists of the first voyage, worked under Cook’s direction.

Reflecting much more closely Cook’s own navigational and geographic interests, the second voyage ventured further south than ever before recorded and finally exploded the myth of the Great South Land. Islands mentioned by previous explorers were located and their positions fixed, and new discoveries were made of New Caledonia, Norfolk Island, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. The effectiveness and reliability of the chronometers on board were thoroughly tested and, learning from his earlier experiences of trade and exchange in the Pacific, Cook accumulated a remarkable collection of cultural items including the highly prized mourning dress from Tahiti. Of equal importance, certainly when considering the reception of this voyage back home, Cook also spent his time writing and polishing his own account, thus escaping the embroideries and misrepresentations of John Hawkesworth’s published account of the first voyage, while securing the financial rewards of publication for himself.

The inclusion of the Forsters had a huge impact on the outcomes of the voyage. Described as ‘gentlemen skilled in natural history and drawing’, the Forsters were not given any official instructions for the voyage. 9 Principally a zoologist, JR Forster’s wealth of knowledge was his greatest asset. 10 Like Cook, he had to rely on his abilities to secure patronage, and like Cook his aim was to exceed the achievements of others in his field. At his own expense, Forster hired Swedish naturalist Anders Sparrman at Cape Town to be his assistant, aware that he and Georg would need extra help to pursue his scientific program of thoroughly documenting the species, elements, productions and phenomena of the Pacific. In 1775 the list of the voyage achievements was excitedly conveyed to Banks by Solander as ‘260 new plants, 200 new animals, 71°10' farthest south, no continent, many islands, some 80 leagues long … no man lost from sickness’. 11 While JR Forster brought great learning to his study of mankind, he was less sure in his dealings with its individual examples. He managed to alienate the very men on board the Resolution and in the navy whose good opinion he most needed to retain. As a result, it was nearly 200 years before a thorough appreciation of his achievements was published in English to replace Solander’s scant list. 12

Cook’s health had suffered during the three years of this voyage, and after his return to England in July 1775 he sought and secured the position of fourth captain at Greenwich Hospital, a sinecure with pension attached that would allow him time to prepare his account of the voyage for publication. Cook won even greater acclaim for his second voyage to the Pacific than he had for the first. He was presented at Court, made a fellow of the Royal Society and was sought after in polite society as a dinner companion. After two such highly successful voyages to the Pacific, the Admiralty was tempted to restart the 200-year-old search for the North-West Passage between the North Pacific and North Atlantic oceans. Should this passage exist, the British would have a trade route to China and the Spice Islands that avoided the traditional southern routes controlled by Portugal and Spain. Despite needing more time to recuperate, Cook was soon prevailed upon to undertake a third voyage to the Pacific, during which he would also return Omai, a young Polynesian man brought to England on board the Adventure in 1774, to Tahiti. 13

The Resolution was repaired and refitted for another voyage, and the Discovery was chosen as consort vessel. No independent scientific party accompanied Cook this time. However, surgeon William Anderson doubled as naturalist and ethnologist, William Bayley served as astronomer and David Nelson was employed to collect botanical specimens for Joseph Banks. The Admiralty appointed John Webber as the voyage artist, and William Ellis also completed drawings and paintings on the voyage. Charles Clerke, who had already made three Pacific voyages, two of them with Cook, was selected as captain of the Discovery. Clerke’s extensive knowledge of the Pacific was typical of many of the crew on board the two ships, large numbers of whom had sailed with Cook before. As a result, there were many who spoke ‘Otaheitian’ with varying levels of competence, and who had established the ties of friendship with islanders that would allow them to acquire and exchange cultural objects for which there was a lucrative market back home.

With such a breadth of Pacific experience among the crew, the success of the expedition must have seemed assured. However, the third voyage was plagued with mischance and difficulty from the start. The departure of the ships was delayed by Clerke’s incarceration for his brother’s debts. The expedition was carrying plant seeds and numerous ‘useful’ animals including sheep, goats and horses with which to stock the Pacific, and the crowded ships had to make frequent landfall for supplies of water and feed to keep the animals alive. Both ships leaked and further delays from bad weather left insufficient time to reach the Arctic Circle during the northern spring. Instead the ships had to wait nearly a year for their next chance to sail north and spent that time cruising the South Pacific with a captain who seemed to have lost his usually strong focus on exploration. 14

With so much time at their disposal, the ships made long stays at the islands visited on earlier voyages. Cook’s journal reveals a growing sense of disillusionment with Polynesian society and concern about the impact of European contact. In declining health, Cook reacted to instances of insubordination and theft with increasingly violent outbursts and punishments, which impaired relations with the islanders and caused discontent and desertions among the crew. The observation of a human sacrifice on Tahiti distressed Cook and his officers, and raised concerns as to whether it was safe to leave Omai on that island as intended. Instead, Omai was installed on Huahine in late 1777, and on 8 December Cook left the Society Islands for the last time.

Six weeks into their voyage towards the North American coast the ships encountered Hawai‘i, which Cook named the Sandwich Islands in honour of the First Lord of the Admiralty. The similarities in language and culture between Hawai‘i and the Society Islands eased communication between the ships and the Hawaiian people. Fresh supplies were taken on board and, after a brief reconnoitre that was hampered by bad weather, the ships resumed their passage north. The islands and their people were fascinating, but no-one wanted to miss the northern spring a second time.

Cook’s instructions required him to make landfall at 45°N, near present-day Oregon. He carried an English version of a map by Gerhard Müller, published in London in 1761. Müller had drawn on information from Spanish maps showing the coastline northwards from California and had indicated the routes taken by Bering and Chirikov’s 1741 exploration of the northern Pacific. Cook was suspicious of the accuracy of a map which contained so many omissions, and exploration was hampered by fogs and poor weather that made approaching the coast dangerous. The ships spent a month at Nootka Sound repairing, restocking and trading with the local people. They also explored a number of inlets that proved not to be the North-West Passage and on 28 June 1778 were finally able to sail through Unalga Pass into the Bering Sea and, via the Bering Strait, into the Arctic Ocean.

The Resolution and Discovery crossed the Arctic Circle and reached 70°41'N before pack-ice blocked their path. Heading west they reached the Russian coast at Cape Shmidta and followed it southwards. Nearly two months were spent in the Arctic Ocean before the expedition headed back towards the unexplored parts of the Alaskan coast to search, without success, for the passage. Cook concluded that if the passage did exist, it must lie beyond the Bering Strait where the freezing conditions that prevailed even in summer would compromise its usefulness as a trade route. With summer nearly over, Cook returned to Samgoonoodha in Unalaska where work began refitting both ships. He made contact with the Russians from Dutch Harbour and they kindly supplied him with a letter of introduction to the Governor of Kamchatka, and better charts of the region, which Cook copied.

In late October the ships finally sailed for Hawai‘i, arriving off Maui on 26 November 1778. Many of the islanders, including King Kalani‘opu‘u and Kamehameha, visited the ships in their canoes, but Cook spent the next six weeks sailing around the islands and refusing to land, despite the parlous condition of his ships and the desperation of his men. When the ships finally anchored in Kealakekua Bay on 17 January 1779, relations with the Hawaiians were cordial. Gifts were exchanged and trade was good. Cook’s journal stops at this date, and so we do not have his reaction to the reverential way in which he was treated by the islanders. However, failure by members of the crew to respect the religious sensibilities of their hosts soured relations, and Cook soon realised it was time to leave. The ships were escorted from the bay on 4 February but, after winds broke a mast on the Resolution , returned again on 11 February to a very different reception.

The tabu placed by the Hawaiian priests upon the ships and their equipment which had protected them from theft was lifted, and shows of respect were replaced with taunts and harassment. A number of brazen thefts occurred which many on board were convinced had been instigated by the chiefs. On the morning of 14 February the Discovery ’s great cutter was discovered stolen. Cook armed the mates and crews and, attended by ten marines, they set off to take the king, ‘Terreeoboo’, hostage in order to secure the speedy return of the boat. Cook had resorted to taking island rulers hostage before, but he made a serious miscalculation this time and was trapped upon a rocky beach by a furious crowd of rock-throwing islanders. Cook, four of the marines and 17 Hawaiians were killed, and their bodies were left on the shore as the rest of Cook’s party retreated to the ships. Amid the shock and distress on board, Clerke assumed command of the expedition, and John Gore, first lieutenant on the Resolution , was made captain of the Discovery .

Until repairs to the Resolution ’s foremast were completed, the ships could not leave, and requests were made to the Hawaiians for the return of Cook’s body. Flesh from his thigh was brought on board on 15 February and on 20 and 21 February bundles of his remains were returned and given burial at sea the following day. Cook’s clothes were sold in the great cabin to the officers of both ships and his papers and effects were reserved for his widow. The final preparations were made for departure, and on 23 February the ships left Kealakekua Bay, although it was not until mid March that the ships finally left Hawaiian waters. They sailed for Kamchatka to complete their mission, as they believed Cook would have wished.

At Kamchatka the Russian governor Behm was preparing to return to St Petersburg and offered to carry with him letters and copies of journals which would be forwarded to the British Admiralty. News of Cook’s death reached London in January 1780, by which time the two ships were finally sailing home. Clerke, who had grown progressively weaker from tuberculosis throughout the third voyage, died at sea on 22 August 1779. Permission was obtained to bury him at Petropavlosk, and Gore became voyage commander in Clerke’s stead. Returning to the Arctic Ocean, they failed to find a north-west passage and the exhausted crews finally reached London in October 1780 after four-and-a-half years at sea. Their arrival had been delayed by six weeks of storms in the English Channel and North Atlantic Ocean.

Lieutenant King, who had been placed in command of the Discovery after Clerke’s death, was given the task of editing the logs and journals for publication, while midshipman Roberts prepared the maps. The voyage account appeared in 1784 and was soon translated into a number of European languages, increasing Cook’s fame. Cook was posthumously awarded a coat of arms and the Royal Society struck a medal in his honour. Poems, a pantomime and an opera were written celebrating his achievements, and paintings and engravings depicting his death in Hawai‘i were produced. Among the more effusive outpourings was an image of Cook being wafted heavenwards by Fame and Britannia above a representation of Kealakekua Bay originally drawn by John Webber. The Apotheosis of Captain Cook captured the popular contemporary view that Cook had become a martyr to Britain’s scientific and territorial advancement.

Cook would serve as the role model for many generations of British explorers, and the wide dissemination of published accounts of his voyages encouraged other nations’ explorers to emulate their remarkable scope and scientific rigour. In the years immediately following Cook’s death, La Perouse, Krusenstern and Malaspina all set out to explore the South Seas and in their wake came countless others. Life in the Pacific was changed utterly and, with it, the scientific and political understanding of the world was transformed.

Michelle Hetherington is a curator at the National Museum of Australia.

1 Joseph Banks’s handwritten records of the Royal Society’s arrangements for recording the 1796 transit are printed in JC Beaglehole (ed.), The Journals of Captain James Cook on his Voyages of Discovery , vols I–IV, Hakluyt Society Extra Series 34–37, The Hakluyt Society, Cambridge, 1968–1972, reprinted by the Boydell Press, Sussex and Hordern House, Sydney, 1999, vol. I, The Voyage of the Endeavour 1768–1771 , pp. 511–514.

2 Another £2000 or so would also be required for wages for the ship’s company. See Richard Sorrenson, ‘The ship as scientific instrument in the eighteenth century’, reprinted in Science, Empire and the European Exploration of the Pacific , ed. by Tony Ballantyne, Ashgate Variorum, Hampshire, 2004, p. 126.

3 Dalrymple had finished his An Account of the Discoveries Made in the South Pacifick Ocean , previous to 1764 in 1767 and a few printed copies were available in autumn that year.

4 Cook’s credentials were helped by the fact that he had sent his observations of the eclipse to Dr John Bevis in England, who read Cook’s paper to the Royal Society in April 1767. In November 1767, Bevis was elected a member of the committee set up by the Royal Society to examine in detail the practical arrangements for the Pacific transit observation. See John Robson, Captain Cook’s World: Maps of the Life and Voyages of Captain James Cook R.N. , Random House Australia, Milsons Point, 2000, p. 19. Other members of the committee were Reverend Dr Nevil Maskelyne, John Short and James Ferguson. See Glyndwr Williams, ‘The Endeavour voyage: A coincidence of motives’, reprinted in Williams’, Buccaneers, Explorers and Settlers: British Enterprise and Encounters in the Pacific, 1670–1800 , Ashgate Publishing Limited, Aldershot, Great Britain and Burlington, USA, 2005, p. 5.

5 Beaglehole (ed.), The Journals of Captain James Cook , vol. I, p. 513.

6 David Turnbull, ‘(En)-countering knowledge traditions: The story of Cook and Tupaia’, in Ballantyne (ed.), Science, Empire and the European Exploration of the Pacific , p. 230.

7 By the end of 1771 over 200 readings had been received by the French Academy of Sciences and the distance of the Earth from the Sun was calculated as being between 87,890,780 and 108,984,560 miles. Subsequent readings in 1874 and 1882 were no more accurate.

8 William T Stearn, ‘A Royal Society appointment with Venus in 1769: The voyage of Cook and Banks in the Endeavour in 1768–71 and its botanical results’, in Ballantyne (ed.), Science, Empire and the European Exploration of the Pacific , p. 94.

9 This lack of direction differed markedly from the detailed instructions given to the two astronomers, William Wales and William Bradley.

10 Forster excelled in subjects as diverse as ancient history and antiquities, oriental and classical languages, geography, chemistry, mineralogy, meteorology, mapping and surveying, and Linnean classification.

11 Forster’s own estimation of what he and his party achieved can be found in the dedication he wrote to Georg in his book Enchiridion historiae naturali inserviens … (Halle, 1788). ‘On this journey we not only saw new and various miracles of nature, but we described them both in word and drawing … It was my particular province … to describe all the animals, to investigate closely the habits, rites, ceremonies, religious beliefs, way of life, clothing, agriculture, commerce, arts, weapons, modes of warfare, political organisation, and the language of the people we met: and also I had to take note of the daily changes in the atmosphere, the winds, increase and decrease in temperature, and whatever was worth noting … About 500 new plants and 300 animals have been sketched with great care. Any understanding person will be amazed that so much work could have been completed by one man and a youth not yet 20, with only one single assistant.’ Michael Hoare, (ed.), The Resolution Journal of Johann Reinhold Forster 1772–1775 , volumes I–IV, The Hakluyt Society, London, 1982, vol. I, p. 77.

12 On their return to England, both Forster and Cook expressed their determination to write the authoritative narrative account of the voyage. The argument which followed led to Lord Sandwich prohibiting Johann Forster from publishing any account of the voyage. His son Georg produced an account instead, racing to beat Cook into print and save his family from financial ruin. See Nicholas Thomas, Discoveries: The Voyages of Captain Cook , Allen Lane, London, 2003, pp. 265–267.

13 Cook’s decision was made easier because the final stylistic and grammatical polishing of his voyage account was now in the hands of Cannon Douglas, and was sweetened by the prospect of a £20,000 reward should the passage be discovered.

14 For more detailed information on Cook’s search for the North-West Passage, see Beaglehole (ed.), The Journals of Captain James Cook , vol. III, The Voyage of the Resolution and the Discovery, 1776–1780 , pp. 292–470; and Robson, Captain Cook’s World , pp. 155–162.

- / Online features

- / Cook-Forster Collection online

- / Background

The National Museum of Australia acknowledges First Australians and recognises their continuous connection to Country, community and culture.

This website contains names, images and voices of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

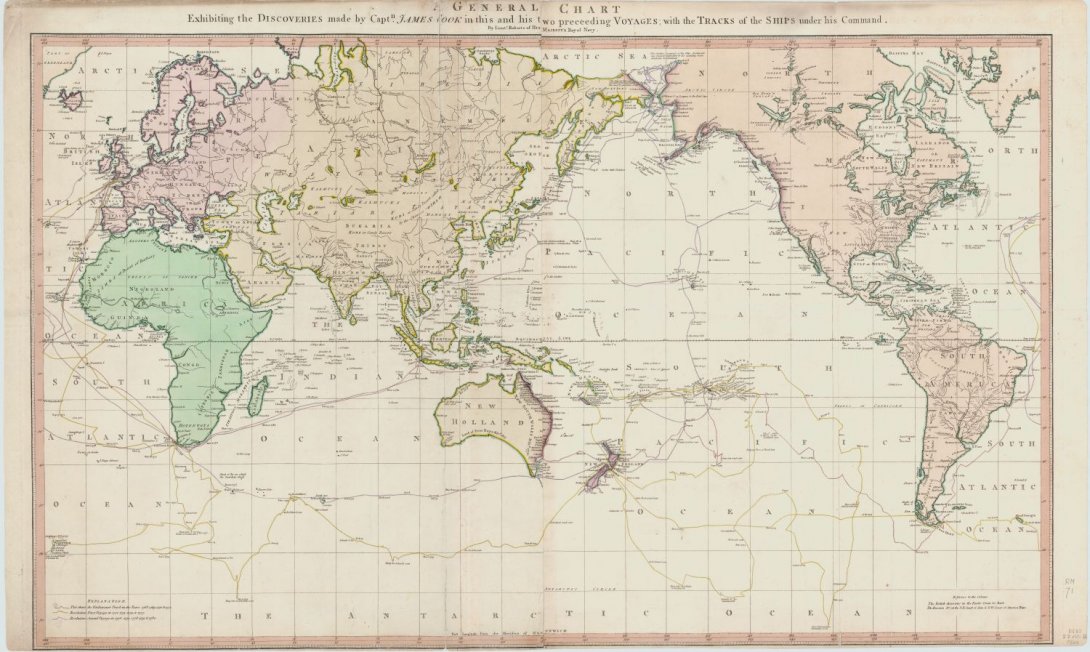

“A General Chart: Exhibiting the Discoveries Made by Captn. James Cook in This and His Two Preceeding Voyages, with Tracks of the Ships under His Command.” Copperplate map, 36 × 57 cm. From the atlas volume of Cook’s A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean . . . (London, 1784). [Rare Books Division]

Cook’s legacy: a revealed world. His world map was the most accurate at its time. During his life, he had explored farther north (70°44′ N) and farther south (71°10′ S) in the Pacific than any previous human being.

James Cook and his voyages

The son of a farm labourer, James Cook (1728–1779) was born at Marton in Yorkshire. In 1747 he was apprenticed to James Walker, a shipowner and master mariner of Whitby, and for several years sailed in colliers in the North Sea, English Channel, Irish Sea and Baltic Sea. In 1755 he volunteered for service in the Royal Navy and was appointed an able seaman on HMS Eagle . Within two years he was promoted to the rank of master and in 1758 he sailed to North America on HMS Pembroke . His surveys of the St Lawrence River, in the weeks before the capture of Quebec, established his reputation as an outstanding surveyor. In 1763 the Admiralty gave him the task of surveying the coast of Newfoundland and southern Labrador. He spent four years on HMS Grenville , recording harbours and headlands, shoals and rocks, and also observed an eclipse of the sun in 1766.

First voyage

In May 1768 Cook was promoted to the rank of lieutenant and given command of the bark Endeavour . He was instructed to sail to Tahiti to observe the transit of Venus in 1769 and also to ascertain whether a continent existed in the southern latitudes of the Pacific Ocean. The expedition, which included a party of scientists and artists led by Joseph Banks, left Plymouth in August 1768 and sailed to Brazil and around Cape Horn, reaching Tahiti in April 1769. After the astronomical observations were completed, Cook sailed south to 40°S, but failed to find any land. He then headed for New Zealand, which he circumnavigated, establishing that there were two principal islands. From New Zealand he sailed to New Holland, which he first sighted in April 1770. He charted the eastern coast, naming prominent landmarks and collecting many botanical specimens at Botany Bay. The expedition nearly ended in disaster when the Endeavour struck the Great Barrier Reef, but it was eventually dislodged and was careened and repaired at Endeavour River. From there it sailed around Cape York through Torres Strait to Batavia, in the Dutch East Indies. In Batavia and on the last leg of the voyage one-third of the crew died of malaria and dysentery. Cook and the other survivors finally reached England in July 1771.

Second voyage

In 1772 Cook, who had been promoted to the rank of captain, led a new expedition to settle once and for all the speculative existence of the Great Southern Continent by ‘prosecuting your discoveries as near to the South Pole as possible’. The sloops Resolution and Adventure , the latter commanded by Tobias Furneaux, left Sheerness in June 1772 and sailed to Cape Town. The ships became separated in the southern Indian Ocean and the Adventure sailed along the southern and eastern coasts of Van Diemen’s Land before reuniting with the Resolution at Queen Charlotte Sound in New Zealand. The ships explored the Society and Friendly Islands before they again became separated in October 1773. The Adventure sailed to New Zealand, where 10 of the crew were killed by Maori, and returned to England in June 1774. The Resolution sailed south from New Zealand, crossing the Antarctic Circle and reaching 71°10’S, further south than any ship had been before. It then traversed the southern Pacific Ocean, visiting Easter Island, Tahiti, the Friendly Islands, New Hebrides, New Caledonia, Norfolk Island and New Zealand. In November 1774 Cook began the homeward voyage, sailing to Chile, Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego, South Georgia and Cape Town. The expedition reached England in July 1775.

Third voyage

A year later Cook left Plymouth on an expedition to search for the North West Passage. His two ships were HMS Resolution and Discovery , the latter commanded by Charles Clerke. They sailed to Cape Town, Kerguelen Island in the southern Indian Ocean, Adventure Bay in Van Diemen’s Land, and Queen Charlotte Sound in New Zealand. They then revisited the Friendly and Society Islands. Sailing northwards, Cook became the first European to travel to the Hawaiian Islands (which he named the Sandwich Islands), and reached the North American coast in March 1778. The ships followed the coast northwards to Alaska and the Bering Strait and reached 70°44’N, before being driven back by ice. They returned to the Sandwich Islands and on 14 February 1779 Cook was killed by Hawaiians at Kealakekua Bay. Clerke took over the command and in the summer of 1779 the expedition again tried unsuccessfully to penetrate the pack ice beyond Bering Strait. Clerke died in August 1779 and John Gore and James King commanded the ships on the voyage home via Macao and Cape Town. They reached London in October 1780.

Acquisition

The earliest acquisitions by the Library of original works concerning Cook’s voyages were the papers of Sir Joseph Banks and a painting of John Webber, which were acquired from E.A. Petherick in 1909. In 1923 the Australian Government purchased at a Sotheby’s sale in London the Endeavour journal of James Cook, together with four other Cook documents that had been in the possession of the Bolckow family in Yorkshire. The manuscripts of Alexander Home were purchased from the Museum Bookstore in London in 1925, while the journal of James Burney was received with the Ferguson Collection in 1970. A facsimile copy of the journal of the Resolution in 1772–75 was presented by Queen Elizabeth II in 1954.

The 18 crayon drawings of South Sea Islanders by William Hodges were presented to the Library by the British Admiralty in 1939. They had previously been in the possession of Greenwich Hospital. The view from Point Venus by Hodges was bought at a Christie’s sale in 1979. The paintings of William Ellis were part of the Nan Kivell Collection, with the exception of the view of Adventure Bay, which was bought from Hordern House in Sydney in 1993. The painting of the death of Cook by George Carter and most of the paintings of John Webber were also acquired from Rex Nan Kivell. The painting by John Mortimer was bequeathed to the Library by Dame Merlyn Myer and was received in 1987.

Description

Manuscripts.

The Endeavour journal of James Cook (MS 1) is the most famous item in the Library’s collections. It has been the centrepiece of many exhibitions ever since its acquisition in 1923, and in 2001 it became the first Australian item to be included on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO’s) Memory of the World Register. While there are other journals of the first voyage that are partly in Cook’s hand, MS 1 is the only journal that is entirely written by Cook and covers the whole voyage of the Endeavour . The early entries in 1768, as the ship crossed the Atlantic Ocean, are brief but the passages describing Cook’s experiences and impressions in Tahiti, New Zealand and New South Wales in 1769–70 are very detailed. The journal, which is 753 pages in length, was originally a series of paper volumes and loose sheets, but they were bound into a single volume in the late nineteenth century. The current binding of oak and pigskin dates from 1976.

Two other manuscripts, also acquired in 1923, relate to the first voyage. The Endeavour letterbook (MS 2), in the hand of Cook’s clerk, Richard Orton, contains copies of Cook’s correspondence with the Admiralty and the various branches of the Navy Board. Of particular importance are the original and additional secret instructions that he received from the Lords of the Admiralty in July 1768. The other item (MS 3) is a log of the voyage, ending with the arrival in Batavia. The writer is not known, although it may have been Charles Green, the astronomer. Other documents concerning the voyage are among the papers of Joseph Banks (MS 9), including his letters to the Viceroy of Brazil in 1768 and the ‘Hints’ of the Earl of Morton, the president of the Royal Society.

The Library holds a facsimile copy (MS 1153) of the journal of HMS Resolution on the second voyage, the original of which is in the National Maritime Museum in London. It is in the hand of Cook’s clerk, William Dawson. It also holds the journal (MS 3244) of James Burney, a midshipman on HMS Adventure , covering the first part of the voyage in 1772–73. It includes a map of eastern Van Diemen’s Land and Burney’s transcription of Tongan music. In addition, there is a letterbook (MS 6) of the Resolution for both the second and third voyages. Documents of the third voyage include an account of the death of Cook (MS 8), probably dictated by Burney, and two manuscripts of Alexander Home (MS 690). They contain descriptions of Tahiti and Kamtschatka and another account of Cook’s death.

The earliest manuscript of Cook in the collection is his description of the coast of Nova Scotia, with two maps of Harbour Grace and Carbonere, dating from 1762 (MS 5). The Library holds original letters of Cook written to John Harrison, George Perry, Sir Philip Stephens and the Commissioners of Victualling. There is also in the Nan Kivell Collection a group of papers and letters of the Cook family, 1776–1926 (MS 4263).

MS 1 Journal of the H.M.S. Endeavour, 1768-1771

MS 2 Cook's voyage 1768-71 : copies of correspondence, etc. 1768-1771

MS 3 Log of H.M.S. Endeavour, 1768-1770

MS 5 Description of the sea coast of Nova Scotia, 1762

MS 6 Letterbook, 1771-1778

MS 8 Account of the death of James Cook, 1779

MS 9 Papers of Sir Joseph Banks, 1745-1923

MS 690 Home, Alexander, Journals, 1777-1779

MS 1153 Journal of H.M.S. Resolution, 1772-1775

MS 3244 Burney, James, Journal, 1772-1773

MS 4263 Family papers 1776-1926

Many records relating to the voyages of Cook have been microfilmed at the National Archives (formerly the Public Record Office) in London and other archives and libraries in Britain. They include the official log of HMS Endeavour and the private journals kept by Cook on his second and third voyages. The reels with the prefixes PRO or M were filmed by the Australian Joint Copying Project.

mfm PRO 3268 Letters of Capt. James Cook to the Admiralty, 1768–79 (Adm. 1/1609-12)

mfm PRO 1550–51 Captain’s log books, HMS Adventure , 1772–74 (Adm. 51/4521-24)

mfm PRO 1554 Captain’s log books, HMS Discovery , 1776–79 (Adm. 51/ 4528-9)

mfm PRO 1554 Captain’s log books, HMS Resolution , 1779 (Adm. 51/4529)

mfm PRO 1555–6 Captain’s log books, HMS Discovery , 1776–79 (Adm. 51/4530-1)

mfm PRO 1561–3 Captain’s log books, HMS Endeavour , 1768–71 (Adm. 51/4545-8)

mfm PRO 1565–70 Captain’s log books, HMS Resolution , 1771–79 (Adm. 51/4553-61)

mfm PRO 1572 Logbooks, HMS Adventure , 1772–74 (Adm. 53/1)

mfm PRO 1575–6 Logbooks, HMS Discovery , 1776–79 (Adm. 53/20-24)

mfm PRO 1580 Logbooks, HMS Endeavour , 1768–71 (Adm. 53/39-41)

mfm PRO 1590–4 Logbooks, HMS Resolution , 1771–80 (Adm. 53/103-24)

mfm PRO 1756 Logbook, HMS Adventure , 1772–74 (BL 44)

mfm PRO 1756 Observations made on board HMS Adventure , 1772–74 (BL 45)

mfm PRO 1756A Logbook, HMS Resolution , 1772–75 (BL 46)

mfm PRO 1756 Observations made on board HMS Resolution , 1772–75 (BL 47)

mfm PRO 1756 Journal of Capt. J. Cook: observations on variations in compass and chronometer rates, 1776 (BL 48)

mfm PRO 1756 Astronomical observations, HMS Resolution , 1778–80 (BL 49)

mfm PRO 4461–2 Ship’s musters, HMS Endeavour , 1768–71 (Adm. 12/8569)

mfm PRO 4462–3 Ship’s musters, HMS Adventure , 1769–74 (Adm. 12/7550)

mfm PRO 4463–4 Ship’s musters, HMS Resolution , 1771–75 (Adm. 12/7672)

mfm PRO 4464 Ship’s musters, HMS Discovery , 1776–80 (Adm. 12/8013)

mfm PRO 4464–5 Ship’s musters, HMS Resolution , 1776–80 (Adm. 12/9048-9)

mfm PRO 6119 Deptford Yard letterbooks, 1765-78 (Adm. 106/3315-8)

MAP mfm M 406 Charts and tracings of Australian and New Zealand coastlines by R. Pickersgill and Capt. James Cook, 1769–70 (Hydrographic Department)

mfm M 869 Letters of David Samwell, 1773–82 (Liverpool City Libraries)

mfm M 1561 Log of HMS Endeavour , 1768–71 (British Library)

mfm M 1562 Journal of Capt. Tobias Furneaux on HMS Adventure , 1772–74 (British Library)

mfm M1563 Drawings of William Hodges on voyage of HMS Resolution , 1772–74 (British Library)

mfm M 1564 Log of Lieut. Charles Clerke on HMS Resolution , 1772–75 (British Library)

mfm M 1565 Journal of Lieut. James Burney on HMS Discovery , 1776–79 (British Library)

mfm M 1566 Journal of Thomas Edgar on HMS Discovery , 1776–79

mfm M 1580 Journal of Capt. James Cook on HMS Resolution , 1771–74 (British Library)

mfm M 1580–1 Journal of Capt. James Cook on HMS Resolution , 1776–79 (British Library)

mfm M 1583 Journal of David Samwell on HMS Resolution and Discovery , 1776–79 (British Library)

mfm M 2662 Correspondence of Sir Joseph Banks, 1768–1819 (Natural History Museum)

mfm M 3038 Letters of Capt. James Cook, 1775–77 (National Maritime Museum)

mfm M 3074 Drafts of Capt. James Cook’s account of his second voyage (National Maritime Museum)

mfm G 9 Journal of voyage of HMS Endeavour , 1768–71 (National Maritime Museum)

mfm G 13 Journal of voyage of HMS Resolution , 1772–75 (National Maritime Museum)

mfm G 27412 Journal of Capt. James Cook on HMS Endeavour , 1768–70 (Mitchell Library)

The only manuscript maps drawn by Cook held in the Library are the two maps of Halifax Harbour, Nova Scotia, contained in MS 5. The map by James Burney of Van Diemen’s Land, contained in his 1773–74 journal, is the only manuscript map in the Library emanating from Cook’s three Pacific voyages.

On the first voyage most of the surveys were carried out by Cook himself, assisted by Robert Molyneux, the master, and Richard Pickersgill, the master’s mate. Cook produced some of the fair charts, but it seems that most were drawn by Isaac Smith, one of the midshipmen. After the voyage the larger charts were engraved by William Whitchurch and a number of engravers worked on the smaller maps. The Library holds nine maps (six sheets) and five coastal views (one sheet) published in 1773, as well as two French maps of New Zealand and New South Wales based on Cook’s discoveries (1774).

Cook and Pickersgill, who had been promoted to lieutenant, carried out most of the surveys on the second voyage. Others were performed by Joseph Gilbert, master of the Resolution , Peter Fannin, master of the Adventure , the astronomer William Wales and James Burney. Isaac Smith, the master’s mate, again drew most of the fair charts of the voyage and William Whitchurch again did most of the engravings. The Library holds 15 maps (10 sheets) published in 1777.

On the third voyage, Cook seems to have produced very few charts. Most of the surveys were carried out by William Bligh, master of the Resolution , and Thomas Edgar, master of the Discovery . Henry Roberts, the master’s mate and a competent artist, made the fair charts and after the voyage he drew the compilation charts from which the engraved plates were produced. Alexander Dalrymple supervised the engravings. The Library holds five maps and five coastal views published in 1784–86.

The Library holds a number of objects that allegedly belonged to Cook, such as a walking stick, a clothes brush and a fork. A more substantial artefact is a mahogany and rosewood fall-front desk that was believed to have been used by Cook on one of his voyages. Other association items are a compass, protractor, ruler and spirit level owned by Alexander Hood, the master’s mate on HMS Resolution in 1772–75.

Three of the medals issued by the Royal Society in 1784 to commemorate the achievements of Cook are held in the Library. Another medal issued in 1823 to commemorate his voyages is also held.

The Library has several collections of tapa cloth, including a piece of cloth and two reed maps brought back by Alexander Hood in 1774 and a catalogue of 56 specimens of cloth collected on Cook’s three voyages (1787).

Captain James Cook's walking stick

Clothes brush said to have been the property of Captain Cook

Captain James Cook's fork

Mahogany fall-front bureau believed to have been used by Captain Cook

Compass, protractor, ruler and spirit level owned by Alexander Hood

Commemorative medal to celebrate the voyages of Captain James Cook (1784)

Medal to commemorate the voyages of Captain Cook (1823)

Sample of tapa cloth and two reed mats brought back by Alex Hood

A catalogue of the different specimens of cloth collected in the three voyages of Captain Cook

The Library holds a very large number of engraved portraits of James Cook, many of them based on the paintings by Nathaniel Dance, William Hodges and John Webber. It also holds two oil portraits by unknown artists, one being a copy of the portrait by Dance held in the National Maritime Museum in London. Of special interest is a large oil painting by John Mortimer, possibly painted in 1771, depicting Daniel Solander, Joseph Banks, James Cook, John Hawkesworth and Lord Sandwich.

There were two artists on the Endeavour : Alexander Buchan, who died in Tahiti in 1769, and Sydney Parkinson, who died in Batavia in 1771. The Library has a few original works that have been attributed to Parkinson, in particular a watercolour of breadfruit, which is in the Nan Kivell Collection. In addition, there are a number of prints that were reproduced in the publications of Hawkesworth and Parkinson in 1773, including the interior of a Tahitian house, the fort at Point Venus, a view of Matavai Bay, Maori warriors and war canoes, mountainous country on the west coast of New Zealand, and a view of Endeavour River.

William Hodges was the artist on the Resolution in 1772–75. The Library holds an outstanding collection of 18 chalk drawings by Hodges of the heads of Pacific Islanders. They depict men and women of New Zealand, Tahiti, Tonga, New Caledonia, New Hebrides and Easter Island. Other works by Hodges include an oil painting of a dodo and a red parakeet, watercolours of Tahiti, Tonga and the New Hebrides, and an oil painting of Point Venus. There are also two pen and wash drawings of the Resolution by John Elliott, who was a midshipman on the ship. Among the prints of Hodges are other heads of Pacific Islanders, a portrait of Omai, the Tahitian who visited England in 1775–76, and views of Tahiti, New Caledonia, New Hebrides, Norfolk Island, Easter Island and Tierra del Fuego.

John Webber, who was on the Resolution in 1776–80, had been trained as a landscape artist in Berne and Paris. Another artist on the expedition was William Ellis, the surgeon’s mate on the Discovery , who was a fine draughtsman. The Library holds 19 of Webber’s watercolours, ink and wash drawings, crayon drawings and pencil drawings of views in Tahiti, the Friendly Islands, the Sandwich Islands, Alaska and Kamchatka. There are also oil portraits by Webber of John Gore and James King. Ellis is equally well represented, with 23 watercolours, ink drawings and pencil drawings of scenes in Kerguelen Island, New Zealand, Tahiti, Nootka Sound, Alaska and Kamchatka. Of particular interest is a watercolour and ink drawing by Ellis of the Resolution and Discovery moored in Adventure Bay in 1777, the earliest original Australian work in the Pictures Collection. The death of Cook is the subject of the largest oil painting in the Library’s collection, painted by George Carter in 1781.

Omai, the first Polynesian to be seen in London, was the subject of a number of portraits, included a celebrated painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds. The Library has a pencil drawing of Omai by Reynolds. A pantomime by John O’Keefe entitled Omai, or a Trip Round the World , enjoyed great success in London in 1785–86, being played more than 50 times. The Library holds a collection of 17 watercolour costume designs for the pantomime, drawn by Philippe de Loutherbourg and based mainly on drawings by Webber. The subjects include ‘Obereyaee enchatress’, ‘Otoo King of Otaheite’, ‘a chief of Tchutzki’ and ‘a Kamtchadale’.

Publications

Bibliography.

Beddie,M.K. (ed.), Bibliography of Captain James Cook, R,N., F.R.S., circumnavigator , Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 1970.

Original Accounts of the Voyages

Hawkesworth, John, An account of the voyages undertaken by the order of His Present Majesty, for making discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere, and successively performed by Commodore Byron, Captain Wallis, Captain Carteret, and Captain Cook, in the Dolphin, the Swallow, and the Endeavour (3 vols, 1773)

Parkinson, Sydney, A journal of the voyage to the South Seas, in His Majesty’s Ship, the Endeavour (1773)

Marra, John, Journal of the Resolution’s Voyage, in 1772, 1773, 1774, and 1775, on Discovery to the Southern Hemisphere (1775)

Cook, James, A voyage towards the South Pole, and round the world: performed in His Majesty’s Ships the Resolution and the Adventure in the years 1772,1773, 1774, and 1775 (2 vols, 1777)

Forster, Georg, A voyage round the world in His Britannic Majesty’s Sloop, Resolution, Commanded by Capt. James Cook, during the years 1772, 3, 4 and 5 (2 vols, 1777)

Wales, William, The original astronomical observations, made in the course of a voyage towards the South Pole, and round the world (1777)

Rickman, John, Journal of Captain Cook’s last voyage to the Pacific Ocean, on discovery: performed in the years 1776, 1777, 1778, and 1779 (1781)

Zimmermann, Heinrich, Heinrich Zimmermanns von Wissloch in der Pfalz, Reise um die Welt, mit Capitain Cook (1781)

Ellis, William, An authentic narrative of a voyage performed by Captain Cook and Captain Clerke, in His Majesty’s ships Resolution and Discovery during the years 1776, 1777, 1778, 1779, and 1780 (2 vols, 1782)

Ledyard, John, Journal of Captain Cook’s last voyage to the Pacific Ocean, and in quest of a North-West Passage Between Asia & America, performed in the years 1776, 1777, 1778 and 1779 (1783)

Cook, James and King, James, A voyage to the Pacific Ocean: undertaken by Command of His Majesty, for making discoveries in the Northern Hemisphere, performed under the direction of Captains Cook, Clerke, and Gore, in the years 1776, 1777, 1778, 1779, and 1780 (4 vols, 1784)

Sparrman, Anders, Reise nach dem Vorgebirge der guten Hoffnung, den sudlischen Polarlandern und um die Welt (1784)

Modern Texts

Beaglehole, J.C. (ed.), The Endeavour journal of Joseph Banks, 1768–1771 (2 vols, 1962)

Beaglehole, J.C. (ed.), The journals of Captain James Cook on his voyages of discovery (4 vols, 1955–74)

David, Andrew (ed.), The charts & coastal Views of Captain Cook’s voyages (3 vols, 1988–97)

Hooper, Beverley (ed.), With Captain James Cook in the Antarctic and Pacific: the private journal of James Burney, Second Lieutenant on the Adventure on Cook’s second voyage, 1772–1773 (1975)

Joppien, Rudiger and Smith, Bernard, The art of Captain Cook’s voyages (3 vols in 4, 1985–87)

Parkin, Ray, H.M. Bark Endeavour: her place in Australian history: with an account of her construction, crew and equipment and a narrative of her voyage on the East Coast of New Holland in 1770 (1997)

Biographical Works and Related Studies

There are a huge number of books and pamphlets on the lives of Cook, Banks and their associates. The following are some of the more substantial works:

Alexander, Michael, Omai, noble savage (1977)

Beaglehole, J.C., The life of Captain James Cook (1974)

Besant, Walter, Captain Cook (1890)

Blainey, Geoffrey, Sea of dangers: Captain Cook and his rivals (2008)

Cameron, Hector, Sir Joseph Banks, K.B., P.R.S.: the autocrat of the philosophers (1952)

Carr, D.J., Sydney Parkinson, artist of Cook’s Endeavour voyage (1983)

Carter, Harold B., Sir Joseph Banks, 1743–1820 (1988)

Collingridge, Vanessa, Captain Cook: obsession and betrayal in the New World (2002)

Connaughton, Richard, Omai, the Prince who never was (2005)

Dugard, Martin, Farther than any man: the rise and fall of Captain James Cook (2001)

Duyker, Edward, Nature’s argonaut: Daniel Solander 1733–1782: naturalist and voyager with Cook and Banks (1998)

Furneaux, Rupert, Tobias Furneaux, circumnavigator (1960)

Gascoigne, John, Captain Cook: voyager between worlds (2007)

Hoare, Michael E., The tactless philosopher: Johann Reinhold Forster (1729–98) (1976)

Hough, Richard, Captain James Cook: a biography (1994)

Kippis, Andrew, The life of Captain James Cook (1788)

Kitson, Arthur, Captain James Cook, RN, FRS, the circumnavigator (1907)

Lyte, Charles, Sir Joseph Banks: 18th Century explorer, botanist and entrepreneur (1980)

McAleer, John and Rigby, Nigel, Captain Cook and the Pacific: art, exploration & empire (2017)

McCormick, E.H., Omai: Pacific envoy (1977)

McLynn, Frank, Captain Cook: master of the seas (2011)

Molony, John N., Captain James Cook: claiming the Great South Land (2016)

Moore, Peter, Endeavour: the ship and the attitude that changed the world (2018)

Mundle, Rob, Cook (2013)

Nugent, Maria, Captain Cook was here (2009)

Obeyesekere, Gananath, The apotheosis of Captain Cook: European mythmaking in the Pacific (1992)

O’Brian, Patrick, Joseph Banks, a life (1987)

Rienits, Rex and Rienits, Thea, The voyages of Captain Cook , 1968)

Robson, John, Captain Cook's war and peace: the Royal Navy years 1755-1768 (2009)

Sahlins, Marshall, How ‘natives’ think: about Captain Cook, for example (1995)

Saine, Thomas P., Georg Forster (1972)

Smith, Edward, The life of Sir Joseph Banks, president of the Royal Society (1911)

Thomas, Nicholas, Cook: The extraordinary voyages of Captain James Cook (2003)

Villiers, Alan, Captain Cook, the seamen’s seaman: a study of the great discoverer (1967).

Organisation

The manuscripts of Cook and his associates are held in the Manuscripts Collection at various locations. They have been catalogued individually. Some of them have been microfilmed, such as the Endeavour journal (mfm G27412), the Endeavour log and letterbook (mfm G3921) and the Resolution letterbook (mfm G3758). The Endeavour journal and letterbook and the papers of Sir Joseph Banks have been digitised and are accessible on the Library’s website. The microfilms have also been catalogued individually and are accessible in the Newspaper and Microcopy Reading Room.

The paintings, drawings, prints and objects are held in the Pictures Collection, while the maps and published coastal views are held in the Maps Collection. They have been catalogued individually and many of them have been digitised.

Biskup, Peter, Captain Cook’s Endeavour Journal and Australian Libraries: A Study in Institutional One-upmanship , Australian Academic and Research Libraries , vol. 18 (3), September 1987, pp. 137–49.

Cook & Omai: The Cult of the South Seas , National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2001.

Dening, Greg, MS 1 Cook, J. Holograph Journal , in Cochrane, Peter (ed.), Remarkable Occurrences: The National Library of Australia’s First 100 Years 1901–2001 , National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2001.

Healy, Annette, The Endeavour Journal 1768–71 , National Library of Australia, Canberra, 1997.

Healy, Annette, ' Charting the voyager of the Endeavour journal ', National Library of Australia News, volume 7(3), December 1996, pp 9-12

Hetherington, Michelle, 'John Hamilton Mortimer and the discovery of Captain Cook', British Art Journal, volume 4 (1), 2003, pp. 69-77

First posted 2008 (revised 2019)

- Preservation

- What's in our collections

- Australians with Indian heritage

- Australian Responses to COVID-19

- 2023 Referendum

- Badja Forest Road Fire oral history project

- Our acquisitions wish list

- Legal deposit

- Digitisation of Library collections

- Australian Web Archive

- Offer us collection material

- Donation FAQs

- Guide to selected collections

- History of the collection

- Describing our collections

- Acquisition methods

- Join Your National Library

- Book a Librarian

IMAGES

COMMENTS

James Cook was a British naval captain, navigator, and explorer who sailed the seaways and coasts of Canada and conducted three expeditions to the Pacific Ocean (1768–71, 1772–75, and 1776–79), ranging from the Antarctic ice fields to the Bering Strait and from the coasts of North America to Australia and New Zealand.

Captain James Cook FRS (7 November [O.S. 27 October] 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, cartographer and naval officer famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and to New Zealand and Australia in particular.

James Cook's third and final voyage (12 July 1776 – 4 October 1780) took the route from Plymouth via Tenerife and Cape Town to New Zealand and the Hawaiian Islands, and along the North American coast to the Bering Strait.

The map shows the three voyages of Captain James Cook. The first voyage is in red, the second voyage is in green and the third voyage is in blue. Following Cook’s death, the route his crew took is in the blue dashed line.

Captain James Cook is known for his extensive voyages that took him throughout the Pacific. He mapped several island groups in the Pacific that had been previously discovered by other explorers. But he was the first European we know of to encounter the Hawaiian Islands.

James Cook's first Pacific voyage (1768-1771) was aboard the Endeavour and began on 27 May 1768. Cook’s voyage had three aims; to establish an observatory at Tahiti in order to record the transit of Venus (when the planet passed between the earth and the sun), on 3 June 1769.

James Cook’s three Pacific voyages represent the turning point for British ambitions in the South Seas. Prior to these voyages, the Pacific was poorly documented. Inadequate charts left room for surmise and disaster.

A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean. Undertaken, by the Command of His Majesty, for Making Discoveries in the Northern Hemisphere, to Determine the Position and Extent of the West Side of North America; Its Distance from Asia; and the Practicability of a Northern Passage to Europe.

The three major voyages of discovery of Captain James Cook provided his European masters with unprecedented information about the Pacific Ocean, and about those who lived on its islands and...

In November 1774 Cook began the homeward voyage, sailing to Chile, Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego, South Georgia and Cape Town. The expedition reached England in July 1775. Third voyage. A year later Cook left Plymouth on an expedition to search for the North West Passage.