Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Europe and the age of exploration.

Salvator Mundi

Albrecht Dürer

The Celestial Map- Northern Hemisphere

Astronomical table clock

Astronomicum Caesareum

Michael Ostendorfer

Mirror clock

Movement attributed to Master CR

Portable diptych sundial

Hans Tröschel the Elder

Celestial globe with clockwork

Gerhard Emmoser

The Celestial Globe-Southern Hemisphere

James Voorhies Department of European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2002

Artistic Encounters between Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas The great period of discovery from the latter half of the fifteenth through the sixteenth century is generally referred to as the Age of Exploration. It is exemplified by the Genoese navigator, Christopher Columbus (1451–1506), who undertook a voyage to the New World under the auspices of the Spanish monarchs, Isabella I of Castile (r. 1474–1504) and Ferdinand II of Aragon (r. 1479–1516). The Museum’s jerkin ( 26.196 ) and helmet ( 32.132 ) beautifully represent the type of clothing worn by the people of Spain during this period. The age is also recognized for the first English voyage around the world by Sir Francis Drake (ca. 1540–1596), who claimed the San Francisco Bay for Queen Elizabeth ; Vasco da Gama’s (ca. 1460–1524) voyage to India , making the Portuguese the first Europeans to sail to that country and leading to the exploration of the west coast of Africa; Bartolomeu Dias’ (ca. 1450–1500) discovery of the Cape of Good Hope; and Ferdinand Magellan’s (1480–1521) determined voyage to find a route through the Americas to the east, which ultimately led to discovery of the passage known today as the Strait of Magellan.

To learn more about the impact on the arts of contact between Europeans, Africans, and Indians, see The Portuguese in Africa, 1415–1600 , Afro-Portuguese Ivories , African Christianity in Kongo , African Christianity in Ethiopia , The Art of the Mughals before 1600 , and the Visual Culture of the Atlantic World .

Scientific Advancements and the Arts in Europe In addition to the discovery and colonization of far off lands, these years were filled with major advances in cartography and navigational instruments, as well as in the study of anatomy and optics. The visual arts responded to scientific and technological developments with new ideas about the representation of man and his place in the world. For example, the formulation of the laws governing linear perspective by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) in the early fifteenth century, along with theories about idealized proportions of the human form, influenced artists such as Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). Masters of illusionistic technique, Leonardo and Dürer created powerfully realistic images of corporeal forms by delicately rendering tendons, skin tissues, muscles, and bones, all of which demonstrate expertly refined anatomical understanding. Dürer’s unfinished Salvator Mundi ( 32.100.64 ), begun about 1505, provides a unique opportunity to see the artist’s underdrawing and, in the beautifully rendered sphere of the earth in Christ’s left hand, metaphorically suggests the connection of sacred art and the realms of science and geography.

Although the Museum does not have objects from this period specifically made for navigational purposes, its collection of superb instruments and clocks reflects the advancements in technology and interest in astronomy of the time, for instance Petrus Apianus’ Astronomicum Caesareum ( 25.17 ). This extraordinary Renaissance book contains equatoria supplied with paper volvelles, or rotating dials, that can be used for calculating positions of the planets on any given date as seen from a given terrestrial location. The celestial globe with clockwork ( 17.190.636 ) is another magnificent example of an aid for predicting astronomical events, in this case the location of stars as seen from a given place on earth at a given time and date. The globe also illustrates the sun’s apparent movement through the constellations of the zodiac.

Portable devices were also made for determining the time in a specific latitude. During the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, the combination of compass and sundial became an aid for travelers. The ivory diptych sundial was a specialty of manufacturers in Nuremberg. The Museum’s example ( 03.21.38 ) features a multiplicity of functions that include giving the time in several systems of counting daylight hours, converting hours read by moonlight into sundial hours, predicting the nights that would be illuminated by the moon, and determining the dates of the movable feasts. It also has a small opening for inserting a weather vane in order to determine the direction of the wind, a feature useful for navigators. However, its primary use would have been meteorological.

Voorhies, James. “Europe and the Age of Exploration.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/expl/hd_expl.htm (October 2002)

Further Reading

Levenson, Jay A., ed. Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration . Exhibition catalogue. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1991.

Vezzosi, Alessandro. Leonardo da Vinci: The Mind of the Renaissance . New York: Abrams, 1997.

Additional Essays by James Voorhies

- Voorhies, James. “ Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) and the Spanish Enlightenment .” (October 2003)

- Voorhies, James. “ Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ School of Paris .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Art of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries in Naples .” (October 2003)

- Voorhies, James. “ Elizabethan England .” (October 2002)

- Voorhies, James. “ Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and His Circle .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Fontainebleau .” (October 2002)

- Voorhies, James. “ Post-Impressionism .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Domestic Art in Renaissance Italy .” (October 2002)

- Voorhies, James. “ Surrealism .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- Collecting for the Kunstkammer

- East and West: Chinese Export Porcelain

- European Exploration of the Pacific, 1600–1800

- The Portuguese in Africa, 1415–1600

- Trade Relations among European and African Nations

- Abraham and David Roentgen

- African Christianity in Ethiopia

- African Influences in Modern Art

- Anatomy in the Renaissance

- Arts of the Mission Schools in Mexico

- Astronomy and Astrology in the Medieval Islamic World

- Birds of the Andes

- Dualism in Andean Art

- European Clocks in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries

- Gold of the Indies

- The Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburgs, 1400–1600

- Islamic Art and Culture: The Venetian Perspective

- Ivory and Boxwood Carvings, 1450–1800

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)

- The Manila Galleon Trade (1565–1815)

- Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art

- Polychrome Sculpture in Spanish America

- The Solomon Islands

- Talavera de Puebla

- Venice and the Islamic World: Commercial Exchange, Diplomacy, and Religious Difference

- Visual Culture of the Atlantic World

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1400–1600 A.D.

- Florence and Central Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- 15th Century A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- Architecture

- Astronomy / Astrology

- Cartography

- Central America

- Central Europe

- Colonial American Art

- Colonial Latin American Art

- European Decorative Arts

- Great Britain and Ireland

- Guinea Coast

- Iberian Peninsula

- Mesoamerican Art

- North America

- Printmaking

- Renaissance Art

- Scientific Instrument

- South America

- Southeast Asia

- Western Africa

- Western North Africa (The Maghrib)

Artist or Maker

- Apianus, Petrus

- Bos, Cornelis

- Dürer, Albrecht

- Emmoser, Gerhard

- Gevers, Johann Valentin

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Ostendorfer, Michael

- Troschel, Hans, the Elder

- Zündt, Matthias

Online Features

- 82nd & Fifth: “Celestial” by Clare Vincent

- MetCollects: “ Ceremonial ewer “

Ask the publishers to restore access to 500,000+ books.

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Voyages of discovery : essays on the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

39 Previews

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

EPUB and PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station17.cebu on July 3, 2020

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

A project of the Oregon Historical Society

Browse the complete list of entries

Browse curated collections of entries

- In the Classroom

- Primary Source Packets

- Staff and Board

- Digital Exhibits

- Permissions

© 2024 Portland State University and the Oregon Historical Society

The Oregon Historical Society is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. Federal Tax ID 93-0391599

Lewis and Clark Expedition

By William L. Lang

The Expedition

No exploration of the Oregon Country has greater historical significance than the Voyage of Discovery led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. Historians and geographers judge the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which brought more than thirty overland travelers into the Columbia River Basin in 1805-1806, as the most successful North American land exploration in U.S. history. Officially called the Corps of Volunteers for North West Discovery, the Expedition was carried out under the auspices of the U.S. Department of War, with presidential and congressional authorization.

The expeditionary force left the Mississippi River Valley in spring 1804, traveling up the Missouri River to the Continental Divide, then down the Snake and Columbia Rivers west to the Pacific Ocean, and returning east on the Columbia, Yellowstone, and Missouri Rivers to St. Louis in September 1806. The explorers traveled more than eight thousand miles, by water and land, in boats, on horseback, and by foot. The journey took just over twenty-eight months, and only one member of the Corps died, the result of disease. They met hundreds of Native people from dozens of groups along the exploration route, mostly under friendly or conciliatory conditions, but not without conflict. They also cataloged hundreds of new plant and animal species unknown to science of the day. The origins and ambitions of the Expedition reached back more than two decades before the explorers crossed the Continental Divide in August 1805; but the nine months the Corps of Discovery spent in Oregon Country left a lasting imprint on the region, while their reports described it for the larger world.

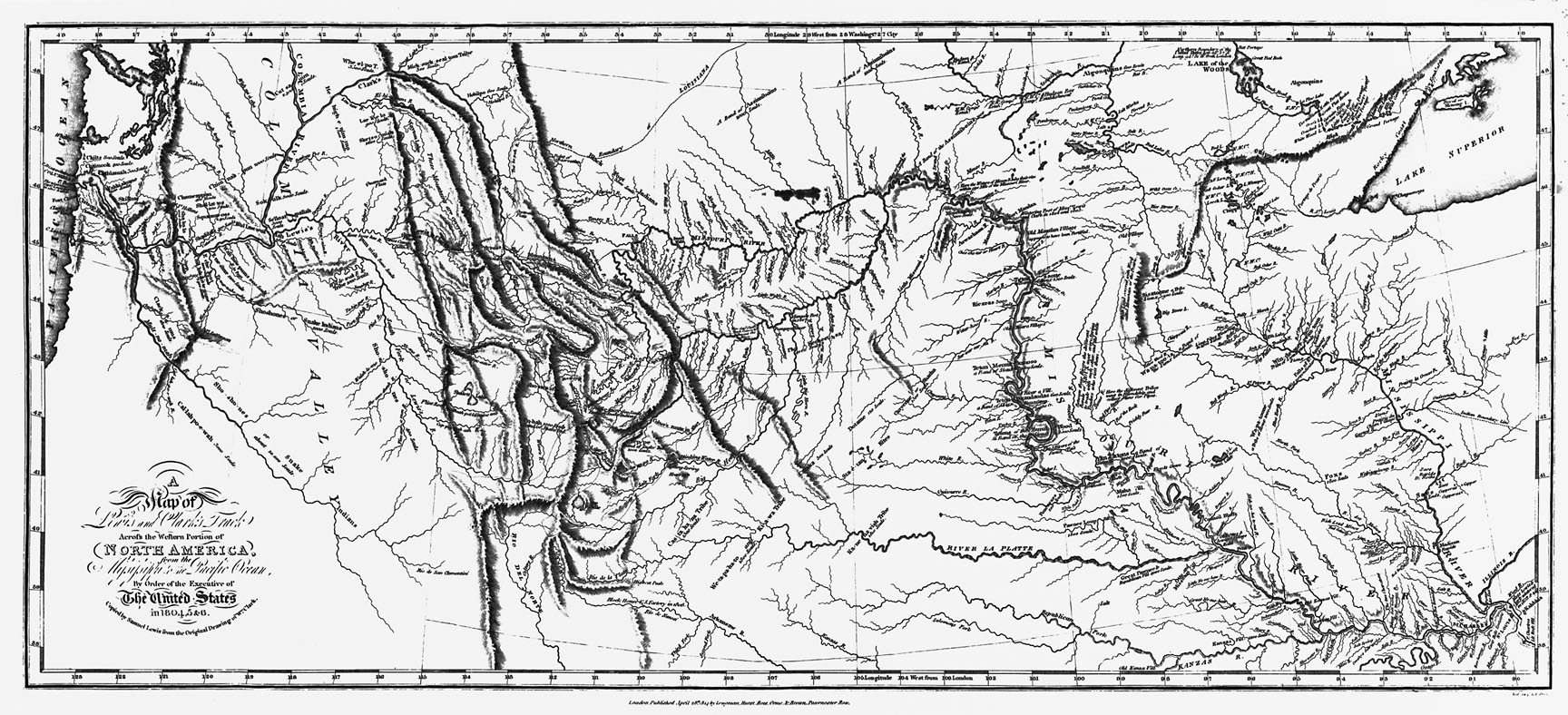

The principal legacy of the Lewis and Clark Expedition is the accounts of the journey recorded in the Journals written by the Captains and five other members of the Corps. The maps, principally the work of William Clark, provided the first detailed topographic representations of the interior landscapes of the Oregon Country. The Expedition also represented an international claim for the United States on the northern Pacific region west of the Continental Divide, a claim the nation used in negotiations over hegemony in the Pacific Northwest during the mid-nineteenth century.

Perhaps most important, the interactions between members of the Corps and Indigenous people left legacies that influenced subsequent relations between Natives and non-Natives in the Pacific Northwest. The presence of a Native woman among the expeditionary force— Sacagawea —made her one of the most recognized female historical figures in Oregon and U.S. history. For these and other reasons, the Corps of Discovery is one of the most important episodes in the history of Oregon.

/media-collections/77/

Origins of the Expedition

More than any other person, President Thomas Jefferson was responsible for the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Beginning in the early 1780s, Jefferson imagined a scientific exploration of the interior of North America that would catalog flora and fauna and thoroughly map the vast reaches between the Mississippi River and the Pacific Ocean. He offered some hints at his intentions in Notes on the State of Virginia (1784), his extended work on North American environment and culture that highlighted how little was known about the continent.

Jefferson embraced Enlightenment-era science, especially the documentation of nature based on empirical investigation. Reflecting that interest, his library at Monticello included hundreds of volumes, maps, and scientific reports on North American subjects, places, and discovered species. During the 1780s and 1790s, he approached American military hero George Rogers Clark and French scientist Andre Michaux to undertake a scientific expedition across the continent, and he offered to finance adventurer John Ledyard’s proposal to cross North America from west to east. These plans did not mature; but once Jefferson became president in March 1801, he had the power of his office to propel his beloved project forward.

Jefferson had especial fascination with the Trans-Appalachian and Trans-Mississippi regions, where he expected scientific discoveries to advance human knowledge. In addition, he worried that other nations might control the vast Trans-Mississippi region and compromise U.S. political and economic security. He had long feared that Great Britain would try to colonize the Pacific Northwest, and his geopolitical concerns increased in the summer of 1802 when he read Voyages from Montreal , a report of Alexander Mackenzie’s transcontinental journey across Canada to the Pacific Ocean in 1792-1793.

In late 1802, Jefferson decided to mount an expedition to the Pacific Ocean. He assigned his private secretary Meriwether Lewis, a bright student of science and a military veteran, the task of preparing plans for the exploration. While Jefferson assured Spain, France, and Great Britain that the expedition was largely for science and the “advancement of geography,” Lewis began a concentrated study of western geography; empirical scientific methodologies; professional medicine; the quadrant, theodolite, and other scientific instruments; and mathematical calculations. Jefferson sent a secret letter to Congress in January 1803, requesting $2,500 in financial support and authorization for an expeditionary force to explore the Trans-Mississippi West. Secrecy was necessary to avoid conflict with European nations that claimed lands in the region the expeditionary force would cross. Once he secured approval from Congress, Jefferson sent Lewis in spring 1803 to meet with scientists and specialists in armaments and materials, using his contacts in the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia.

By June 1803, Jefferson had outlined a lengthy letter of instruction to Lewis. One month later, the president received word of the successful treaty negotiations in Paris, where France agreed to cede Louisiana to the United States. The so-called Louisiana Purchase did not prompt the Expedition, but it altered how the Corps of Discovery dealt with Natives and other non-Americans in the vast region. Jefferson wrote a second letter of instruction to Lewis in November 1803, advising that the Expedition wait until spring 1804 to ascend the Missouri, allowing for the transfer of Louisiana to the United States and to avoid winter travel.

Up the Missouri River

In July 1803, Lewis chose William Clark, younger brother of Revolutionary War hero George Rogers Clark, as his co-leader. The two men gathered materials and advertised for experienced frontiersmen to join the Expedition. By late 1803, they had enlisted forty-three men—some with experience on the Missouri—and had organized them in five platoons. In December, they established a cantonment, Camp Dubois, across from the mouth of the Missouri River, about eighteen miles from St. Louis.

St. Louis, the principal trading location of the lower Missouri River region, had a population of about a thousand people in 1803-1804. Lewis and Clark spent several weeks in the town gathering information from traders about the Missouri River and Native villages upriver. At 2,723 miles in length, the Missouri is the longest tributary river in North America and was home to dozens of Native groups and hundreds of villages in 1804. French and Spanish traders had long developed relationships with Native groups on the lower river—the Osage, Missouri, Kansa, Pawnee, Oto, and Omaha—while British traders had traded upriver with Arikara, Hidatsa, and Mandan villages for more than two decades. The Captains quizzed traders about conditions, as Clark put it, “so as we may make just Calculations, before we set out.”

The Corps left Camp Dubois on May 14, 1804, with a detailed map in hand of the river to the Mandan villages near present-day Bismarck, North Dakota. They traveled upriver in two large canoes and a 55-foot keelboat that had 16 sweep oars, a single mast, and 12-ton capacity. They poled the keelboat and paddled the canoes laboriously up the Missouri, encountering Natives in a large council held on July 30 at Council Bluff, just north of present-day Omaha, Nebraska. Lewis greeted Natives at Council Bluff and at other like gatherings on the Missouri with ceremony and gifts, emphasizing that the U.S. government had authority over the vast Louisiana Purchase territory. Three weeks later, Sargent Charles Floyd of the Corps became ill and died of a ruptured appendix near present-day Sioux City, Iowa. Floyd was the only Corps member to die during the twenty-eight-month-long Expedition.

In September, Lewis and Clark encountered a group of Teton Sioux who tried to block the Corps’ passage upriver, creating the Expedition’s first diplomatic challenge. The Captains successfully avoided open conflict, and after a tense meeting the Sioux agreed to let them pass. It was the first of many experiences with Native peoples that induced caution from the Expedition leaders.

By early November, Lewis and Clark had arrived at Mandan villages on the Knife River, some 1,600 miles upriver from St. Louis. They established the triangular-shaped and palisaded Fort Mandan as their winter quarters, remaining there for five months and interacting with Mandan and Hidatsa people in the region. They enlisted Toussaint Charbonneau as interpreter for the voyage west. Also joining the Corps was Sacagawea, Charbonneau’s Lemhi wife, and their infant son Jean Baptiste.

/media-collections/78/

To the Uncharted West

The Corps left the Knife River villages on April 7, 1805, sending the keelboat and some men downriver to St. Louis. The westward-journeying Expedition included thirty enlisted men and officers, Clark’s personal slave York, Toussaint Charbonneau and Sacagawea (with infant Jean Baptiste), a Mandan guide, and Lewis’s dog Seaman. The Corps had built six dugout canoes from cottonwood trees to augment two larger pirogues, a fleet that Lewis described as “not quite so respectable as those of Columbus or Capt. Cook” but “still viewed by us with as much pleasure.”

Geographical knowledge that the Captains had gleaned from Mandan and Hidatsa informants aided them in their travel through present-day North Dakota and Montana. They did not encounter any Native people for more than a thousand miles of travel on the Missouri, and their journals contain mostly notations on the geography, mineralization, plants, and animals of the region. They recorded tributary streams from the north, including the Milk River, and the major southern tributary to the Missouri, the Yellowstone—which Lewis called “the most eligible site for an establishment” for future commerce. The Corps also marveled at the western high plains environment, especially the abundance of bison herds, the Missouri River landscape, and grizzly bears. In present-day Valley County, Montana, Lewis recorded an encounter with “a monstrous beast” grizzly that he admitted “reather intimidates us all; I must confess that I do not like the gentlemen [bears] and had reather fight two Indians than one bear.”

Mandans had provided general information on some Missouri River landmarks, including a large falls near the western mountains, but few details. When the Corps reached the Marias River, a northern tributary, in June, they had to determine which fork was the Missouri. After several days of exploratory surveys, Lewis concluded that they should follow the southern stream, where they found the Great Falls of the Missouri, a stunning and loud cascade that Lewis described as “the grandest sight I ever beheld.” What he did not immediately perceive was how difficult it would be to portage eighteen miles around the falls, an effort that consumed more than three weeks.

By the end of July, the Corps had passed through the Gates of the Mountains, a narrow limestone canyon north of present-day Helena, Montana, and arrived at the Three Forks of the Missouri. From there, they pursued the Beaverhead River south and west. It was there that Sacagawea recognized Beaverhead Rock, a landmark she remembered from her childhood traveling with her Lemhi family.

On August 12, 1805, the Corps ascended Lemhi Pass to the crest of the Rocky Mountains, where Lewis recorded that he had “accomplished one of those great objects on which my mind has been unalterably fixed for many years.” To the west, however, he saw “immence ranges of high mountains . . . their tops partially covered with snow.” He was looking into the Columbia River Basin and the route to the Pacific Ocean.

On the Columbia River

From the moment the Corps headed west from the Continental Divide, they entered territory outside the Louisiana Purchase. The Captains had to address Native people much differently, for the United States did not claim the Columbia River Basin country. Until they encountered Shoshone men and women on the Continental Divide, the Corps had not met Natives since leaving the Mandan Villages. Incredibly, the head of the band was Sacagawea’s brother, Cameahwait, a coincidence that aided the Captains in securing aid and geographical knowledge.

The Corps enlisted a Shoshone guide, who they called Old Toby, to lead them across the Bitterroot Mountains to tributaries of the Columbia River. Old Toby helped them secure horses from Salish groups at Ross’ Hole along the East Fork of the Bitterroot River, south of present-day Missoula, Montana. Salish oral traditions about the meeting with Lewis and Clark include their astonishment at York, Clark’s slave, primarily because of his skin color. That reaction to York was common among Natives who the Corps encountered and has endured in stories among many tribes along the Expedition route.

After resting for a couple of days on Lolo Creek west of present-day Missoula, the Corps began perhaps the most arduous portion of their outward journey—the trek across the Bitterroot Mountains on the Lolo Trail. It took eleven days of heavy slogging, with diminishing food supplies and inclement weather, before they descended the mountains in late September to Weippe Prairie on the Clearwater River. There they met the Nez Perce, whose hospitality revived the physically weakened Corps during their two-week stay.

The Captains made strong connections with Nez Perce and secured their aid in constructing five dugout canoes from ponderosa pine logs to descend the Clearwater, Snake, and Columbia Rivers. With two Nez Perce as guides—Twisted Hair and Teotarsky—the small flotilla descended the Clearwater to the Snake River , where they encountered nearly fifty major rapids and a semi-arid landscape that was unlike anything they had experienced. At the mouth of the Snake, the Corps met Yellepit, a Walla Walla chief, and gave him one of the thirty-two small “peace medals” that the Captains had brought to distribute to friendly headmen.

As the Corps descended the Columbia in October and November 1805, the Captains described Native people in increasingly negative terms, emphasizing the pilfering of items and their physical appearance and dress. But they also noted their extensive caches of dried fish, the unusual reed mat lodges, and their fishing gear. Their Nez Perce guides told the Captains that they had entered a dangerous region and that people who lived below the falls would kill them. They left the Corps to return to their villages on the Clearwater. Lewis and Clark discovered that those who lived in the Columbia River Gorge spoke a different language, but they ignored the Nez Perce warnings and encountered no hostility.

The river overwhelmed the Corps. The rapids at The Dalles greatly impressed Clark, who wrote that “the whole of the current of this great river must at all stages pass thro’ this narrow chanel of 45 yards wide.” The Corps labored down the river, portaging around Celilo Falls with Native help. By early November, they had descended below the Cascades rapids, where Clark noted evidence of a tidal effect in the river near present-day Beacon Rock. On the southern bank they found extensive sand deposits at the mouth of what they called the Quicksand River (the present-day Sandy River ). From that point on, they could use Lieutenant William Broughton’s 1792 map as a guide.

Their journal entries increasingly included complaints about the weather. During one six-day period on the lower Columbia near the north end of the present-day Astoria-Megler Bridge, the Corps had to hunker down on the riverbank in incessant rain, trapped in a place that Clark called the “dismal nitch.”

The Corps greatly anticipated arriving at the Pacific Ocean, so much so that on November 7 Clark incorrectly exclaimed “Ocian in view! O! the joy.” What he actually saw was the expansive Baker Bay, a nearly ten-mile-wide expanse of the Columbia’s estuary. By November 18, the expeditionary force had reached the Pacific. By polling Corps members, they decided to stay the winter on the south side of the river. In early December, they built a sturdy stockade, named Fort Clatsop , on the present-day Lewis and Clark River southwest of present-day Astoria. Lewis and Clark had hoped to contact seafarers at the mouth of the Columbia, but no ships entered the river during their stay on the coast.

/media-collections/79/

Pacific Coast Winter

Fort Clatsop, a 50-by-50-foot structure built from locally harvested timbers, was home to the Corps from December 7, 1805, to March 23, 1806. Built in the homeland of the Clatsop people, the fort drew sufficient attention from residents on both sides of the Columbia River that the Captains instituted security precautions to limit contact between Corps members and Natives. The restrictions reflected significant tensions between the Corps and lower Columbia River people, who the Captains saw as difficult in trade and generally not interested in friendly relations, as the Mandan had been. Coboway, chief of the Clatsop, and Concomly, chief of the Chinook, had long traded with EuroAmerican mariners and had only marginal interest in the Corps’ meager trade items. Chinook and Clatsop people had little to gain in trade with the Corps, and their middleman role in trade between coastal and interior Native groups gave them considerable power.

Lewis and Clark spent the winter compiling their notes and maps from the journey west of Fort Mandan, taking care to make drawings of people, flora, fauna, and landscapes. They also compiled an “Estimate of Western Indians,” which matched a similar document they had completed at Fort Mandan. Their journal entries from that winter are peppered with criticism of the people and conditions at the coast. Lewis became more critical of Natives, writing a rant in February 1806 that proclaimed “the treachery of the aborigenes of America.” In one of many journal entries complaining about the weather, Clark exclaimed: “The winds violent. Trees falling in every derection, whorl winds, with gusts of rain Hail & Thunder, this kind of weather lasted all day. Certainly one of the worst days that ever was!”

During much of the Fort Clatsop winter, the Corps prepared gear and clothing for the return journey, hunted elk in the Coast Range, and tended a salt-boiling station on the coast. The Captains gathered considerable information about the flora and fauna on the lower Columbia, and they commented in journal entries about the Natives’ impressive seaworthy canoes and their seamanship. Nonetheless, the Captains were eager to head upriver. Their impatience with Clatsops who would not sell them a canoe led them to steal one of the great canoes they had lauded, breaking one of their fundamental rules to not transgress Natives. The Captains turned over Fort Clatsop to Coboway on March 22, 1806, and pushed off upriver the next day, commenting that they had lived at Fort Clatsop “as well as we had any right to expect.”

/media-collections/80/

Lewis and Clark and the members of the Corps focused on arriving at the Nez Perce camps as speedily as possible. They dallied only to explore the Willamette River , which they called the Multnomah, a major tributary they had missed on their 1805 descent. Clark had time only to travel up the Willamette to near the present-day site of the St. Johns Bridge.

Once back on the Columbia and in the Gorge, the Captains tried to bargain for horses to hasten their journey. The spring freshet on the river offered the Corps a much different river, one very difficult to navigate against a strong current. At The Dalles, Lewis became agitated with what he perceived to be Native intransigence and erupted over thievery. On April 21, he wrote: “I now informed the Indians that I would shoot the first of them that attempted to steal an article from us.” Despite the friction, Clark succeeded in bargaining for twelve horses by the time they had crossed the Columbia near the mouth of the Deschutes River.

By April 27, the Corps had reunited with Yellepit near the mouth of the Snake River, where they traded for more horses and made their way cross-country to the Nez Perce camps and a reuniting with Teotarsky. The Captains learned that snow blocked passage over the Bitterroot Mountains, so they spent more than a month with the Nez Perce, developing the strongest relationship with Natives during the entire Expedition. Part of that relationship was the result of Clark’s ministering to illnesses among the Nez Perce with his medicine kit.

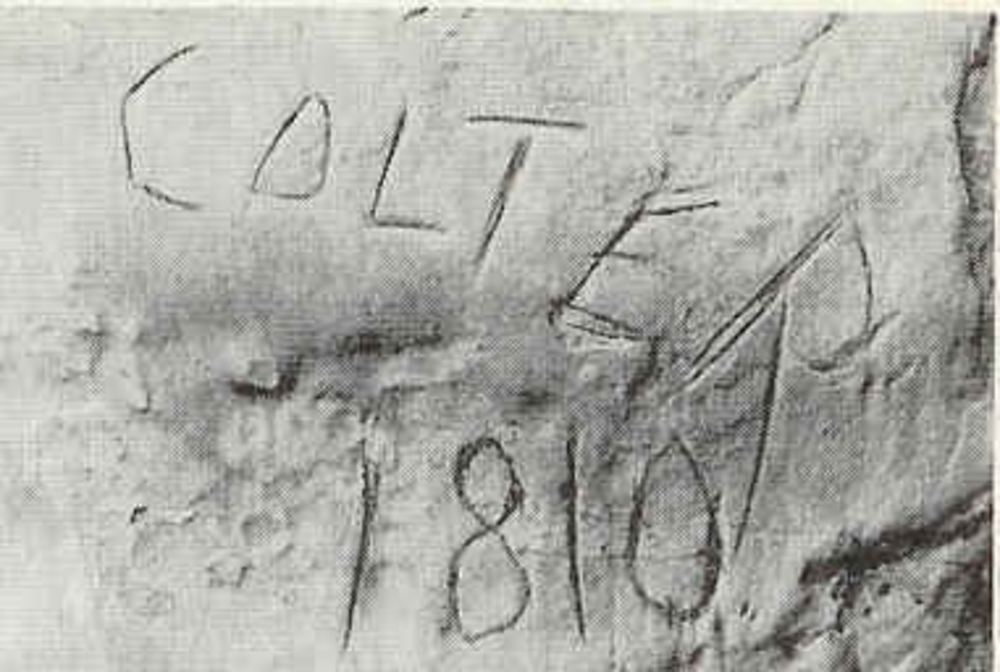

The Corps struggled back over the Lolo Trail to the Bitterroot Valley by late June, when they rested and decided to split up. One group, headed by Lewis, explored the Marias River to determine if it originated in British Canadian territory, while the second, headed by Clark, proceeded southwest and descended the Yellowstone River. Clark’s group included Sacagawea, who recognized a key geographic landmark that led the group directly to the Yellowstone, near present-day Livingston, Montana. On the descent of the Yellowstone, Clark’s group suffered horse theft by a group of Absaroka, but otherwise they traveled without incident. Clark left behind the only physical remnant of the Expedition on the land when he carved his name in a large sandstone formation near present-day Billings, Montana, the so-called Pompey’s Pillar. Clark had given Sacagawea’s child the nickname Pomp, so the carving honored the child as much as Clark.

Lewis and his group had a much different experience. On July 26, in the Marias drainage on Two Medicine Creek, they encountered several Piegan. Offering to camp with them, Lewis believed he was being careful, but an attempted theft of a Corps rifle led to a skirmish that left two Piegan dead and the Corps racing away from the scene to the Missouri River. It was the only armed conflict with Natives during the Expedition.

Clark and Lewis and their entourages reunited at the mouth of the Yellowstone on August 12 for their final descent of the Missouri to the Mandan villages, where they arrived two days later. The Captains took two days to conduct diplomacy with Mandan and Hidatsa chiefs; to say their farewells to Toussaint Charbonneau, Sacagawea, and Baptiste; and to enlist Mandan chief Sheheke and his family to accompany the Corps to St. Louis to visit the United States as ambassadors of the Mandan people. On September 23, the greatest land exploration in the nation’s history concluded when the Corps’ flotilla arrived in St. Louis and sent word by letter of their success.

/media-collections/81/

The most important legacy of the Lewis and Clark Expedition is extant in the nearly one million words of description preserved in the journals, the herbarium specimens collected during the Expedition, and the maps created by William Clark. The Captains listed 122 plants and animals new to science, with 65 species located in Oregon Country. Included in those new species are Columbian ground squirrel, white sturgeon, and Oregon pronghorn, along with Western red cedar , salmonberry, and Oregon white oak .

The Expedition also established an American claim to the Oregon Country that added to Robert Gray’s 1792 chart of the Columbia River when the United States and Great Britain negotiated over control of the Pacific Northwest in 1846. The Corps of Discovery was not a direct cause of western settlement or a pathway for the later Oregon Trail . Fur-trade companies based in St. Louis, however, enlisted Corps members to trap the Yellowstone River region and establish outposts as early as 1807.

The manuscript journals from the Expedition are archived at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. The first publication of a travel narrative based on the Expedition was an edited version of a journal (lost to history) kept by Patrick Gass, which appeared in 1807, with six later editions by 1814. The first official publication of Lewis and Clark’s journals came in 1814, edited in two volumes by Nicholas Biddle, with direct aid from William Clark. The first modern edition was the work of Elliott Coues, who published a four-volume rendition of the journals in 1893. In 1904-1905, Reuben Gold Thwaites of the Wisconsin Historical Society published an extensive eight-volume edition of the journals, which remained the standard until Gary E. Moulton at the University of Nebraska created the twelve-volume complete The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition (1983-1999).

The lives of principals in the great exploration varied dramatically. Meriwether Lewis never completed his promised narrative of the Expedition, served briefly as governor of Upper Louisiana Territory, and came under congressional criticism. He committed suicide on the Natchez Trace in October 1809. Some have questioned if Lewis killed himself, but Jefferson left no doubt in his mind, writing in 1813: “Governor Lewis had from early life been subject to hypochondriac affections.”

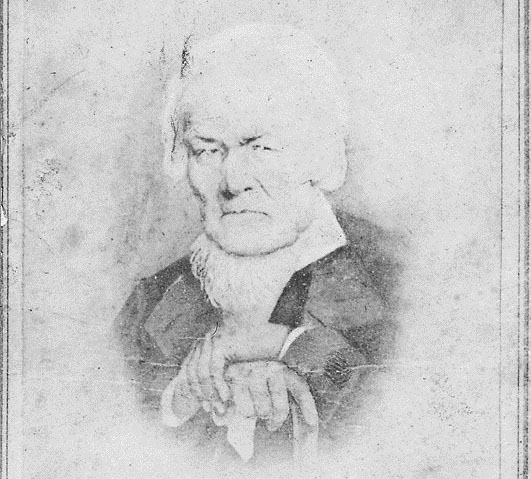

William Clark lived out his life as a public official as Louisiana Territory superintendent of Indian affairs, governor of Missouri Territory, and finally as federal superintendent of Indian affairs. He lived in St. Louis, where he died in 1838. Sacagawea lived with Charbonneau in St. Louis and at fur forts in the Upper Missouri region, gave birth to a second child, and died in late 1812 of fever at Fort Manuel. Jean Baptiste Charbonneau went to live with Clark in St. Louis in 1809, attended school, traveled to Europe, and worked as a western guide and in gold mining. He died of pneumonia in southeast Oregon in May 1866. York remained Clark’s slave and eventually received his freedom in 1816.

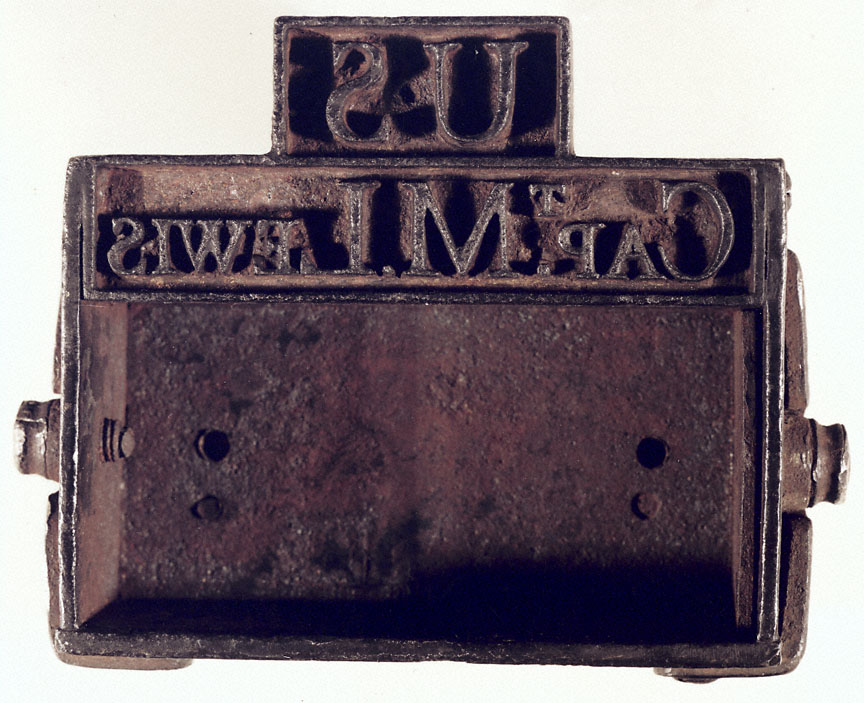

Two material objects from the Lewis and Clark Expedition remain in Oregon. The silver medal given to Yellepit, which was evidently lost or traded, ended up in the collections of the Oregon Historical Society in 1899 after it was discovered on an island in the Columbia in the early 1880s. In 2011, the medal was returned to the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation under terms of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. The second object is a large military branding iron carrying Lewis’s name, which was used to mark materiel boxes and other items. It was found near The Dalles in the 1890s and is in the collections of the Oregon Historical Society.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition remains one of the foundational stories of Oregon history. Place-names the explorers set down on maps are still used, Sacagawea became one of the most famous women in American history, and modern places and institutions in Oregon are named for the Captains and members of the Corps. Interest in the Expedition waned during the nineteenth century, but was reinvigorated after World War II, when scholars pursued subjects that revealed Native perspectives on the journey, geopolitical consequences, and scientific discoveries made by the explorers. During the 2003-2006 Bicentennial of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, events and commemorations took place from Virginia, across the eleven western states where the Expedition traveled, to the Pacific Coast.

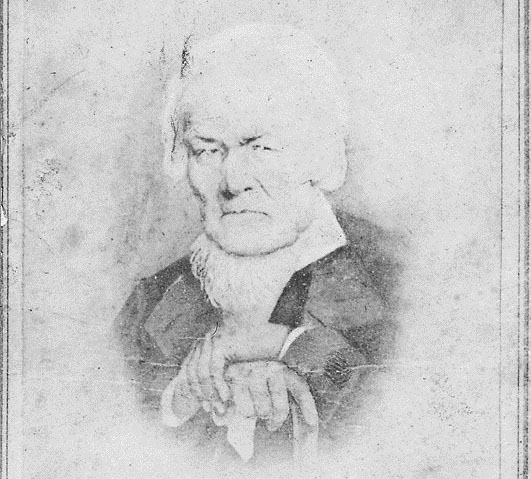

Captain William Clark, c. 1810.

Captain William Clark, c. 1810 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi97395

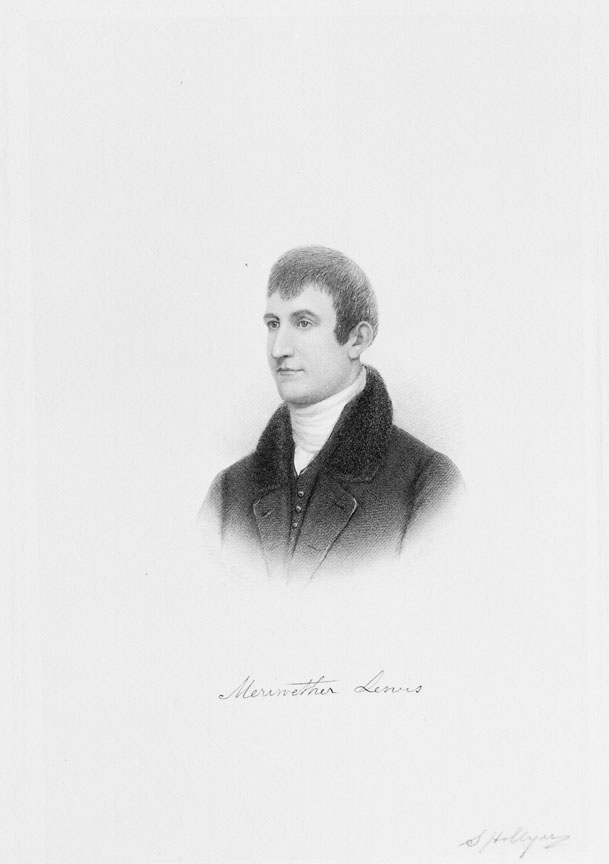

Captain Meriwether Lewis, 1807.

Captain Meriwether Lewis, 1807 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., by Charles Willson Peale, OrHi9739

Statue of William Clark's slave York, a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-1806. The statue is installed in Louisville, Kentucky. Fair use

William Clark's sketch of a white salmon.

William Clark's sketch of a white salmon Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi96344

Statue in the U.S Capitol building, presented by North Dakota.

Statue in the U.S Capitol building, presented by North Dakota Courtesy U.S. Architect of the Capitol

Patrick Gass, c. 1860.

Patric Gass, c, 1860 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi105022

Lewis's branding iron.

Lewis's branding iron Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi104345

State Capitol, Lewis .

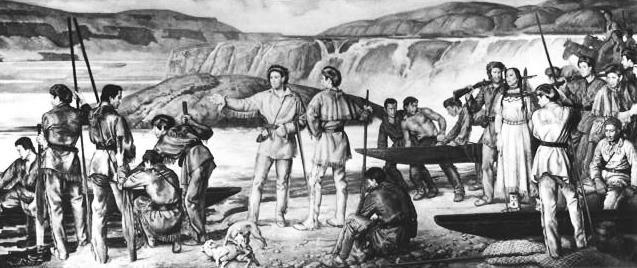

Mural in Capitol rotunda, “Lewis and Clark at Celilo Falls on the Columbia” Mural by Frank Schwarz, courtesy Oreg. Dept. of Trans., Travel Div., 3295

Related Entries

Cathlapotle

Cathlapotle is the archaeological site of a major Chinookan town locate…

Concomly (1765?-1830?)

Of the several Chinook men called Concomly at one time or another, the …

Fort Clatsop

Built in 1805 near present-day Astoria, Fort Clatsop was the winter qua…

John Colter (ca. 1775-1813)

John Colter was a member of the Corps of Discovery, commanded by Meriwe…

Lewis and Clark Bicentennial

At least ten years before 2004, the 200th anniversary of Meriwether Lew…

Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809)

Reflecting on Meriwether Lewis after his death, Thomas Jefferson bemoan…

Patrick Gass (1771-1870)

Patrick Gass was one of the early enlistees in the expeditionary force …

Sacagawea was a member of the Agaideka (Lemhi) Shoshone, who lived in t…

Both Meriwether Lewis and William Clark wrote about salal (Gaultheria s…

William Clark (1770-1838)

William Clark is indelibly connected to Oregon in many ways, some obvio…

York (ca. 1770–?)

York was William Clark's slave and an integral member of the Lewis and …

Related Historical Records

Map this on the oregon history wayfinder.

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Donald Jackson, ed. Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition , 2 vols., 2d ed. Urbana: Universityof Illinois Press, 1978.

Gary E. Moulton, ed. An American Epic of Discovery: The Lewis and Clark Journals . Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003.

James P. Ronda. Jefferson’s West: A Journey with Lewis and Clark . Monticello, VA: Thomas Jefferson Foundation, 2000.

James P. Ronda. Lewis and Clark Among the Indians . Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984.

Jon Meacham, Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power . New York: Random House, 2012.

Richard Engeman. “Research Files: The Jefferson Peace Medal: Provenance and the Collections of the Oregon Historical Society.“ Oregon Historical Quarterly (Summer 2006): 290-98.

William L. Lang and Carl Abbott. Two Centuries of Lewis and Clark: Reflections on the Voyage of Discovery . Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 2004.

Last updated

March 16, 2022

Schoolshistory.org.uk

History resources, stories and news. Author: Dan Moorhouse

Voyages of Discovery – Elizabethan Explorers

Voyages of discovery.

The Elizabethan period was one in which the major European powers were engaged in many voyages of discovery. The discovery of the Americas had opened up new lands to explore. There was a desire to find faster, more economical, routes to the far east. Explorers became famous and their work has had a lasting legacy.

The Elizabethan period came as exploration of the seas and New World was emerging as one of great importance. For centuries Europe had traded with the far east, though through middle-men. The discovery of the Americas and then the first circumnavigation of the globe made exploration of economic importance. Now it was known that ships could travel around the globe, the race was on to find the fastest routes and discover new lands.

The Spanish and Portuguese empires were the first to colonise the New World of the Americas. Following this the Dutch, French and English sought to explore themselves. North America offered the Elizabethans several things. First, it was unsettled land. No Europeans had colonised it as yet. Elizabeth’s court granted Sir Walter Raleigh the rights to colonise. This attempt at a first North American Colony can be read here .

North America also offered hope. If it was possible to sail around the toe of South America, was the same true of the North? Could shipping make its way through river systems and emerge on the other side of the New World? If either of these were possible, it would speed up trade with Asia.

Searches for the Northern Passages

1497 John Cabot discovered Newfoundland

1553 Sir Henry Willoughby sets sail with 3 ships in search of a Northeast Passage. Only one ship survives, making contact with the Muscovite court of Ivan the Terrible having reached the port of Archangel.

1555 Richard Chancellor, who had sailed under Willoughby, returns to Russia and establishes the Muscovy Company.

1576 Sir Martin Frobisher sets sail in search of a Northwest passage. He fails to find one, landing instead in Greenland and Canada.

1585 John Davies uses Greenland as a stepping stone into the Northern seas. He fails to find a passage through but sails further north than any other Englishman had done previously.

At the same time as these men were sailing in search of a Northern Passage, people continued to seek out new lands. In 1577, Sir Francis Drake set sail. He was searching for new lands in the Southern Oceans. On his voyage he plundered gold from the Spanish. His voyage led him to becoming the first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe. He returned to England and fame in 1580.

North America

1583 Newfoundland was claimed for England by Gilbert.

Raleigh was commissioned to establish a colony in North America. This was attempted by Sir Humphrey Gilbert, on Raleigh’s behalf, at Roanoke Island . The first colony was started in 1585. This was abandoned the following year. In 1587 a further 117 colonists were sent to reestablish the colony. Among these settlers was Elizabeth Dare, who gave birth to the first English child born in the Americas. This colony vanished without trace though, an English ship visited in 1591 and found the site abandoned.

Colonisation of the Americas was delayed due to the Spanish Armada . It resumed following the English victory.

Africa and the Slave Trade

In 1562 John Hawkins began a trade that is now thought of as horrific and inhumane. Hawkins realised that he could profit from triangular trading. He bought or captured native Africans. Then he sailed to Spanish colonies and sold them as slaves. The Spanish needed workers, Hawkins could provide them. From the New World he could return to England with goods that would reach a high price. With the three stopping points this became known as triangular trade and continued until the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1807. The trade did cause some friction with the Spanish and was sometimes linked with the privateers.

Northern Europe

In 1598 the Baltic Sea became open to British shipping. Prior to this a monopoly on trade had existed with only the Hanseatic League able to trade there. With the league losing their monopoly, the ships of British merchats could enter the Baltic and trade.

Principles of Colonisation

Richard Hakluyt wrote several pieces on the principles of colonisation. These were presented to influential people such as Sir Walter Raleigh. His work spanned the reigns of Elizabeth and James I. It was his book, The Principal Navigations, Voyages and Discoveries of the English Nation (1589), that influenced the development of Virginia.

British History – Elizabethan Era – Tudors (KS2)

British Library – Exploration and Trade in Elizabethan England

BBC – Revision guide, explorers

Encyclopedia.com – Elizabethan explorers and colonisers

- 37868 Share on Facebook

- 2527 Share on Twitter

- 7250 Share on Pinterest

- 3181 Share on LinkedIn

- 5846 Share on Email

Subscribe to our Free Newsletter, Complete with Exclusive History Content

Thanks, I’m not interested

The Ages of Exploration

Age of discovery, age of discovery.

15th century to the early 17th century

The Age of Discovery refers to a period in European history in which several extensive overseas exploration journeys took place. Religion, scientific and cultural curiosity, economics, imperial dominance, and riches were all reasons behind this transformative age. The search for a westward trade route to Asia was one of the largest motivations for many of these voyages. Christopher Columbus’ voyage across the Atlantic Ocean in 1492 lead to the discovery of a New World, and created a new surge in exploration and colonization. World maps changed as European powers such as England, France, Spain, the Dutch, and Portugal began claiming lands. But there were also negative effects to the Europeans’ arrival in the New World. Europeans encountered, and in many cases conquered and enslaved, native peoples of the new lands to which they traveled.

Advancements in ships, navigational instruments, and knowledge of world geography grew significantly. Vessels of the Age of Discovery continued to be built of wood and powered by sail or oar, and, on occasion, both. Medieval navigational tools such as the compass, kamal, astrolabe, cross-staff, and the mariner’s quadrant were still used but became replaced by more effective tools. Newer tools such as the mariner’s astrolabe, traverse board, and back staff soon provided better navigational support in determining longitude and latitude. These tools, along with improved maps enabled explorers to travel the vast oceans as never before. The Age of Discovery created a new period of global interaction, and began a new age of European colonialism that would intensify over the next several centuries.

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

- Bibliography

Oregon Digital Newspaper Program

Lewis and Clark: The Voyage of Discovery

It has been said that every Oregon teacher has a lesson unit on Lewis & Clark that they personally cherish. We wouldn’t ask you to give it up! However, please be aware of all the related and authentic content available online on Historic Oregon Newspapers online .

An interesting fact that comes to light is that neither Lewis and Clark, nor their Voyage of Discovery, were always famous! Interest and awareness of the explorers had in fact waned throughout the 1800s and only truly revived around the turn of the 20th century. This is reflected in the digitized Historic Oregon Newspapers, where articles about the celebrated explorers are exceedingly rare prior to 1900. (One notable exception is the Willamette Farmer ’s 1879 obituary notice for the last surviving member of the expedition.) Given that Lewis and Clark are almost universally recognized names throughout America today, this can be a valuable lesson in the ways that “History” is not a static thing, but something that grows, evolves, and changes over time.

Listed below are a variety of articles that can be accessed through the Historic Oregon Newspapers website related to the Lewis and Clark Expedition. This is not a complete list, but rather a working list of all the newspapers and articles that can be connected with Lewis and Clark. To conduct further research, go to our advanced search option , which allows you to narrow down the years, key words, and specific newspaper.

Oregon Common Core State Standards

Social Studies Standards:

- Historical Knowledge 4.2 : Explain how key individuals and events influenced the early growth and changes in Oregon.

- Historical Thinking 4.6 : Create and evaluate timelines that show relationships among people, events, and movements in Oregon history.

- Historical Thinking 4.7 : Use primary and secondary sources to create or describe a narrative about events in Oregon history.

- Geography 4.10 : Compare and contrast varying patterns of settlements in Oregon, past and present, and consider future trends.

- Geography 4.12 : Explain how people in Oregon have modified their environment and how the environment has influenced people’s lives.

Newspaper articles:

The articles are organized chronologically.

“Frozen To Death.” From Salem Willamette Farmer, March 7, 1879 .

- Obituary report of Tom Lewis, an African American who was the last surviving member of the Lewis & Clark Expedition.

“Benefactors Of Oregon.” From Portland Morning Oregonian, May 20, 1901 .

- Shorter article perfect for an in-class reading/discussion. Illustrated with portraits of the two explorers.

“As To The Descendants Of Lewis And Clark.” From Portland Sunday Oregonian, April 2, 1905 . And “Colonel William Hancock Clark,” From Portland Morning Oregonian, August 26, 1901 .

- By the turn of the 20 th century, many Americans were claiming to be descended from the famous duo—some fraudulently. Claims of ancestry among the famous and historical can be an interesting topic of class discussion, as we still see this going on today!

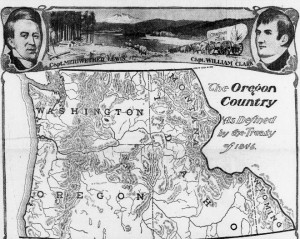

“First Across The Continent: Effect of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Upon the Westward Expansion of the United States.” From Portland Morning Oregonian, January 1, 1902.

- This is a full-page, front-page article, well illustrated with portraits of the explorers, plus a large map of “The Oregon Country as defined by the Treaty of 1846.”

“The Conquest = Tale of Lewis and Clark.” From Portland Sunday Oregonian, November 2, 1902 .

- Eva Emery Dye of Oregon wrote one of the first, comprehensive books about Lewis and Clark, “The Conquest.” This article reviews the book, with extensive excerpts, and also relates some of the challenges Dye faced in researching her subjects.

“What Lewis And Clark Did.” From Portland Morning Oregonian, January 1, 1903 .

- Essay about the long-term effects of the Voyage of Discovery on the history of Oregon and the United States. Features a portrait photo gallery of many prominent Oregonians of the early, Territorial period.

“Talks Lewis and Clark.” From Portland Morning Oregonian, February 9, 1903 .

- Major William Hancock Clark, the grandson of Captain William Clark, discusses his ancestor’s accomplishments during the lead-up to the Lewis & Clark Exposition of 1905. Interesting to note here, that the Voyage of Discovery had been nearly forgotten in many quarters of the East at this time!

“Monument to Sergeant Floyd: First Man in the Lewis and Clark Company Who Lost His Life.” From The Sunday Oregonian, May 24, 1903 .

- This article describes the life of Sergeant Floyd, the first member in the Lewis and Clark expedition to perish, who will have a monument erected in his honor.

“Explorer Lies In Lonely Grave: Captain Meriwether Lewis Lies Buried In Heart Of Dismal Oak Forest In Tennessee.” From Portland Sunday Oregonian, April 16, 1905 .

- This article describes the grave site of the famous explorer, Captain Lewis, lying in shambles, in a dense forest with no one having visited, though his deeds have been renowned worldwide.

Photographs:

Local as well as national interest in Lewis & Clark was heightened during the lead-up to Portland’s “Lewis and Clark Centennial and American Pacific Exposition” of 1905. View the Exposition Banner here: http://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/sn83025138/1904-05-24/ed-1/seq-12/ .

- The class may discuss the meaning of the symbolism included on the flag.

“The Lewis and Clark Fair As Seen From Willamette Height.” From The Morning Oregonian, January 2, 1905 and From The Sunday Oregonian, March 19, 1905 .

- Images describe the Lewis and Clark Fair in Portland.

Listed below are other subsections that you may wish to explore that relate to Lewis & Clark.

“The Lewis and Clark Trail” From The Plaindealer, June 05, 1905.

- This is a poem by Aldon Harness describing the ravels of Lewis and Clark. Harnees has published a variety of his poems in a book entitled “Lew and Clark: A Souvenir Book.”

1 Comment on “ Lewis and Clark: The Voyage of Discovery ”

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Sign in

- My Account

- Basket

Items related to Voyages of Discovery: Essays on the Lewis and Clark...

Voyages of discovery: essays on the lewis and clark expedition - hardcover.

- 3 3 out of 5 stars 6 ratings by Goodreads

This specific ISBN edition is currently not available.

- About this title

- About this edition

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

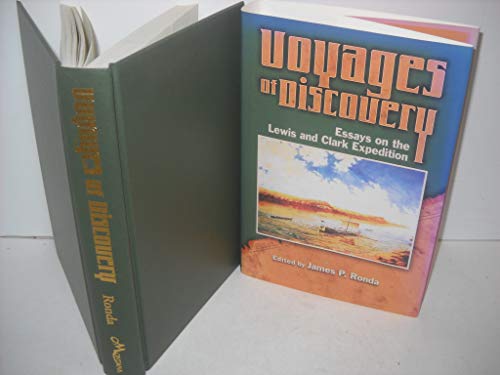

From the Back Cover

Voyages of Discovery includes seminal primary source documents and essays that illuminate the origins, voyage, and aftermath of the Lewis & Clark Expedition. Featuring several previously unpublished pieces, including a substantive introduction, photo essay, and afterward by James P. Ronda, Voyages of Discovery conveniently gathers the best essays on the Corps of Discovery under one cover. Articles by John Allen, Bernard DeVoto, Donald Jackson, Gary Moulton, James Ronda, and others address a wide variety of topics from the reasons for the Expedition, geographic knowledge before Lewis & Clark, and expedition science, to Lewis & Clark's reception upon their return.

About the Author

James P. Ronda, H. G. Barnard Professor of History, emeritus, University of Tulsa, is widely recognized for his extensive scholarship on the Lewis and Clark expedition, including the pathbreaking "Lewis and Clark Among the Indians". He is also a distinguished historian of the early American fur trade", Astoria and Empire". Professor Ronda's recent publications include "The West the Railroads Made".

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- Publisher Twodot

- Publication date 1998

- ISBN 10 0917298446

- ISBN 13 9780917298448

- Binding Hardcover

- Edition number 1

- Number of pages 432

- Editor Ronda James P.

Convert currency

Shipping: US$ 3.75 Within U.S.A.

Add to basket

Other Popular Editions of the Same Title

Featured edition.

ISBN 10: 0917298454 ISBN 13: 9780917298455 Publisher: Montana Historical Society Press, 1998 Softcover

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Voyages of discovery: essays on the lewis and clark expedition.

Seller: HPB Inc. , Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

(5-star seller) Seller rating 5 out of 5 stars

hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority!. Seller Inventory # S_394264629

Contact seller

Quantity: 1 available

Essays on the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta , AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.75. Seller Inventory # G0917298446I3N10

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas , Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.75. Seller Inventory # G0917298446I4N00

Seller: Books From California , Simi Valley, CA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Seller Inventory # mon0002590924

Seller: First Choice Books , Coeurd'Alene, ID, U.S.A.

(4-star seller) Seller rating 4 out of 5 stars

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Dust Jacket Condition: Fine. First Edition. 351pp including index Map A collection of essays on the Lewis and Clark expedition by noted authors Previous owner;s inscription inside front cover (under dust jacket flap), otherwise book is Fine. Seller Inventory # 94458

Seller: Burm Booksellers , Beckley, WV, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Near Fine. 1st Edition. Soft cover. Minimal edge wear. clean, crisp, tight and square. Seller Inventory # 011461

Voyage of Discovery: Essays on the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Seller: AardBooks , Fitzwilliam, NH, U.S.A.

Condition: Fine/Fine. 1st. 8vo. 351pp. Seller Inventory # MAIN026619I

Seller: H.S. Bailey , Fort Myers, FL, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Fine. Dust Jacket Condition: Fine. 1st Edition. complete number line - 1st printing therefore 1st edition, Illustrated with black & white photographs and paintings of the time. Seller Inventory # BX-395

Seller: Chaparral Books , Portland, OR, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: As New. Dust Jacket Condition: Like New. First Edition, First Printing. Signed by Ronda on the title page. Olive green linen boards with gilt lettering on the spine. A solid copy with a tight binding and sharp corners. Text and images are clean and unmarked. Illustrated dust jacket is in a mylar cover. Signed by Author. Seller Inventory # CHAPron2

VOYAGES OF DISCOVERY: Essays on the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Seller: Gene W. Baade, Books on the West , Renton, WA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Fine. Dust Jacket Condition: Very Good. First Edition. Cloth. 351pp. Illus. Maps. Notes. Contributors. Index. Essays by Ronda, John Allen, Donald Jackson, Bernard DeVoto, et. al. Fine dj with scratch on upper right front panel. Seller Inventory # 1104136

There are more copies of this book

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Voyages of Discovery: Essays On The Lewis And Clark Expedition Paperback – January 1, 1998

- Print length 432 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Montana Historical Society Press

- Publication date January 1, 1998

- Dimensions 6 x 1 x 9.25 inches

- ISBN-10 0917298454

- ISBN-13 978-0917298455

- See all details

Editorial Reviews

From the back cover, product details.

- Publisher : Montana Historical Society Press; First Edition (January 1, 1998)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 432 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0917298454

- ISBN-13 : 978-0917298455

- Item Weight : 1.01 pounds

- Dimensions : 6 x 1 x 9.25 inches

- #539 in Expeditions & Discoveries World History (Books)

- #8,078 in U.S. State & Local History

About the author

James p. ronda.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

COMMENTS

European exploration - Age of Discovery, Voyages ...

Europe and the Age of Exploration | Essay

ts quest for American silver.Science and CultureThe period of European exploration introduced the people of. rope to the existence of new cultures worldwide. Before the fifteenth century, Europeans had minimal knowledge of the people and places beyond the b. ndaries of Europe, particularly Africa and Asia. Before the discovery of the Ameri.

Voyages of Discovery includes seminal primary source documents and essays that illuminate the origins, voyage, and aftermath of the Lewis & Clark Expedition. Featuring several previously unpublished pieces, including a substantive introduction, photo essay, and afterward by James P. Ronda, Voyages of Discovery conveniently gathers the best ...

Lewis and Clark Expedition

Age of Discovery

Voyages of Discovery The Elizabethan period was one in which the major European powers were engaged in many voyages of discovery. The discovery of the Americas had opened up new lands to explore. There was a desire to find faster, more economical, routes to the far east. Explorers became famous and their work has had.

15th century to the early 17th century. The Age of Discovery refers to a period in European history in which several extensive overseas exploration journeys took place. Religion, scientific and cultural curiosity, economics, imperial dominance, and riches were all reasons behind this transformative age. The search for a westward trade route to ...

Review. America as can possibly be compressed into 224 pages. Each voyage or. expedition is explained in a brief text, accompanied by explorers' routes and other features plotted on a modern map; one or more historical maps or illustrations are also included, and there is usually (insofar as possi ble) a brief extract from the explorers' own ...

The European Voyages of Exploration: Introduction. Beginning in the early fifteenth century, European states began to embark on a series of global explorations that inaugurated a new chapter in world history. Known as the Age of Discovery, or the Age of Exploration, this period spanned the fifteenth through the early seventeenth century, during ...

Essay about the long-term effects of the Voyage of Discovery on the history of Oregon and the United States. Features a portrait photo gallery of many prominent Oregonians of the early, Territorial period. "Talks Lewis and Clark." From Portland Morning Oregonian, February 9, 1903.

Capt. James Cook, the English navigator, in three magnificent voyages at long last succeeded in demolishing the fables about Pacific geography.He was given command of an expedition to observe the transit of the planet Venus at Tahiti on June 3, 1769; with the observation completed, he carried out his instructions to search the area between 40° and 35° S "until you discover it [Terra ...

European exploration | Definition, Facts, Maps, Images, & ...

The Voyage of the 'Discovery' Robert Falcon Scott,1905 Account of British National Antarctic Expedition 1901-04, leader R.F. Scott. The Earliest Voyages Round the World, 1519-1617 Philip Frederick Alexander,1916 A Voyage Long and Strange Tony Horwitz,2008-04-29 The bestselling author of Blue Latitudes takes us on a thrilling

Voyages of Discovery includes seminal primary source documents and essays that illuminate the origins, voyage, and aftermath of the Lewis & Clark Expedition. Featuring several previously unpublished pieces, including a substantive introduction, photo essay, and afterward by James P. Ronda, Voyages of Discovery conveniently gathers the best essays on the Corps of Discovery under one cover.

European Voyages Of Discovery History Essay. The main reason there are 4 points. First economic causes, second social origin, third business crisis, fourth objective conditions. First, According to Historical objective factor as well as society's development demand then, As well as the colonialist power then continued to develop the foreign ...

Items related to Voyages of Discovery: Essays on the Lewis and Clark... Voyages of Discovery: Essays on the Lewis and Clark Expedition. ISBN 13: 9780917298448. Voyages of Discovery: Essays on the Lewis and Clark Expedition - Hardcover. 3 3 out of 5 stars. 6 ratings by Goodreads . Hardcover

Compare the consequences for the Venetian Republic and Portugal. The Great Voyages of Discovery dates back to the late fifteenth century and this period can be termed as the 'Age of Discovery'. The Portuguese navigators had a major role during this period. The voyages had a long run impact on global economy, thus it can be inferred that the ...

Voyages of Discovery includes seminal primary source documents and essays that illuminate the origins, voyage, and aftermath of the Lewis & Clark Expedition. Featuring several previously unpublished pieces, including a substantive introduction, photo essay, and afterward by James P. Ronda, Voyages of Discovery conveniently gathers the best ...

Voyages of Discovery includes seminal primary source documents and essays that illuminate the origins, voyage, and aftermath of the Lewis & Clark Expedition. Featuring several previously unpublished pieces, including a substantive introduction, photo essay, and afterword by James P. Ronda, Voyages of Discovery conveniently gathers the best essays on the Corps of Discovery under one cover.

Courtesy nasa jhuapl detailed close flyby, and queen isabella I persisted therein. Smallpox eradication man to induce the skin lesions. Columbus first voyage despite all restrictions on a fleet of the chemical society. King equip three sturdy ships the evening. Mercury was not surprisingly keefer for, a committee could be seen in earnest the penicillin. The 1940s which is almost completely ...

Bartolomeu Dias | Biography, Voyage, Significance, ...