1981 Springbok Tour drove New Zealand to the 'brink of civil war'

Share this article

Reminder, this is a Premium article and requires a subscription to read.

They came to play rugby – but the 1981 Springboks' presence in New Zealand resulted in a torrent of violent protests never previously seen in New Zealand. Neil Reid looks at the Barbed Wire Boks' unhappy place in sporting history

For Errol Tobias, the 1981 Springbok tour to New Zealand should have been a career highlight – a chance to make a global statement for black and coloured South African rugby players.

But just weeks into the tour, the trail-blazing midfielder was ready to pack his bags and fly home.

Then aged 31, Tobias was the only non-white player selected to tour.

Prior to the team's arriving in New Zealand, his selection had been labelled by both New Zealand critics of the South African's racist regime and also by white South Africans who backed the apartheid system as a cynical move from South African rugby officials to try and placate anger from the anti-tour protest movement.

And as he was to find out during the tour which divided our nation so violently, members of the team management - including manager Professor Johan Claassen - several team-mates and also some South African media covering the tour were also of the opinion that his selection wasn't based on his ability.

The issue came to a head when Tobias – who had impressed right from the start of the tour - missed selection for the first test against the All Blacks; being overlooked for midfield rival Willie du Plessis who was struggling with a hamstring injury.

"I seriously considered packing my bags and returning home to [my wife] Sandra who was pregnant with our twins," Tobias reveals in his autobiography, Pure Gold.

"I phoned my wife and poured out my heart about the demonstrators and violence, and our unfeeling, ineffective team management. Sandra immediately said that if I felt unsafe, I should rather ask to come home."

Tobias said in his book – which has never been released in New Zealand in hardcopy form – that he told his wife: "In the current situation no Springbok can feel safe".

After some soul-searching he backtracked on thoughts of quitting the tour from hell.

"I realised it would encourage Professor Claassen in his efforts to keep the Springbok team lily-white," he said in his book.

After the omission he could understand why touring South African reporters gave his strong form "very little coverage".

Tobias – who now serves his church as a lay preacher – also decided to refuse to pray with his team-mates, confiding he "didn't feel up to praying with people who believed only white people were worthy of wearing the green and gold".

Tobias revealed he first felt a "very negative attitude" towards him before the Springboks even arrived in New Zealand.

Claassen didn't make eye contact with him when they met for the first time. He added coach Nelie Smith was also "strangely evasive".

"My sixth sense had never let me down and I immediately had the feeling a very unpleasant time would be ahead of us," he wrote in Pure Gold.

The only person he confided in was friend, team-mate and Springbok great Rob Louw; another player Claassen didn't want on tour and who would also be ostracized by some within the squad while in New Zealand for his friendship with Tobias.

Before boarding their flight to New Zealand, the team received impassioned speeches from South African Rugby Board president Danie 'Doc' Craven and South African Rugby Football Federation president Cuthbert Loriston.

Craven's final words was that the Boks of 1981 would lay the "groundwork" for South Africa to host a Rugby World Cup in 1990. Loriston said he hoped the tour would "pave the way" for the Springboks' readmission to the international rugby fraternity.

Both statements were optimistic – and by the time the Springboks departed New Zealand on September 13, they couldn't have been further from the truth.

No idea of what awaited them

Speaking to the Herald from his home in Stellenbosch, in South Africa's Western Cape province, former Springbok star Theuns Stofberg said when he boarded the plane to New Zealand he was totally unaware of what awaited.

"We were just a group of guys who came to New Zealand to play against the best in the world," he said.

Six years earlier he had made his test debut against the All Blacks on their tour of South Africa. In 1980 he had captained the Boks against the South American Jaguars; an honour he would have again in the first test against the All Blacks at Lancaster Park.

"Playing the All Blacks . . . that is the highlight of any South African, especially on their home field," Stofberg said.

"I got the opportunity in 1976 to play against the All Blacks. Five years later it was my chance to go to New Zealand and it was going to be the highlight of my playing career."

Tobias initially thought the same.

He recalled rugby officials said there was no need "to be concerned" about demonstrators disrupting tour matches.

Among items to be given out by the tourists to members of the rugby community and public during their stay were stickers featuring a Springbok leaping through a silver fern with the wording: "A rugby friend is a friend indeed".

But their unpopularity quickly sunk in during a stop-over in New York on their travels here.

The Boks had to fly via the US after Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser refused to allow their plane to land and refuel in Australia.

Waiting for them were protestors with banners telling them to "Go Home".

And their arrival here proved to be anything but welcoming.

Protestors awaited the Springboks when they finally touched down at Auckland International Airport on July 19, three days out from the tour opener against Poverty Bay.

He described the atmosphere on arrival as "unfriendly".

"Many of the [demonstrators] . . . wanted to know how I could be on the side of such a despicable bunch of racists . . . 'Errol, what are you doing with these racists? They don't belong here'," Tobias wrote in Pure Gold.

"On the one hand, these words hurt me deeply, but on the other hand, it was the best possible motivation to play even better."

More concerning was learning days later of pamphlets from a section of the anti-tour movement offered instructions on how to make firebombs, and also urging them to collect broken glass "by the bucketful" to spread over grounds to host the Springboks.

Tobias was one of the stars of the Boks' first up 24-6 win over Poverty Bay.

But his desire that the "entire New Zealand could experience first-hand that I deserved my position on the team" received a "rude awakening" from management, including Claassen.

"A 'non-white' player wasn't welcome in this Springbok team, not to mention a 'non-white' assistant manager with the tact of Abe Williams," Tobias wrote.

Very early in the tour Williams told media: "As rugby players there's nothing we can do about apartheid because it's the law. Maybe we should rather see this tour as the beginning of a new era for South African rugby. In our team we have Errol Tobias who was selected for the team purely on merit and not because he is coloured.

"This your own scout [an un-named All Black scout] can vouch for, who saw him in action in the second test against Ireland and thought he posed a bigger threat for the All Blacks than Danie Gerber'."

They were the last words Williams spoke at a press conference during the tour.

New Zealand was on the "brink of civil war"

Springbok captain Wynand Claassen fully realised his team were in for a "tough" time after the protests on the day of the Poverty Bay game.

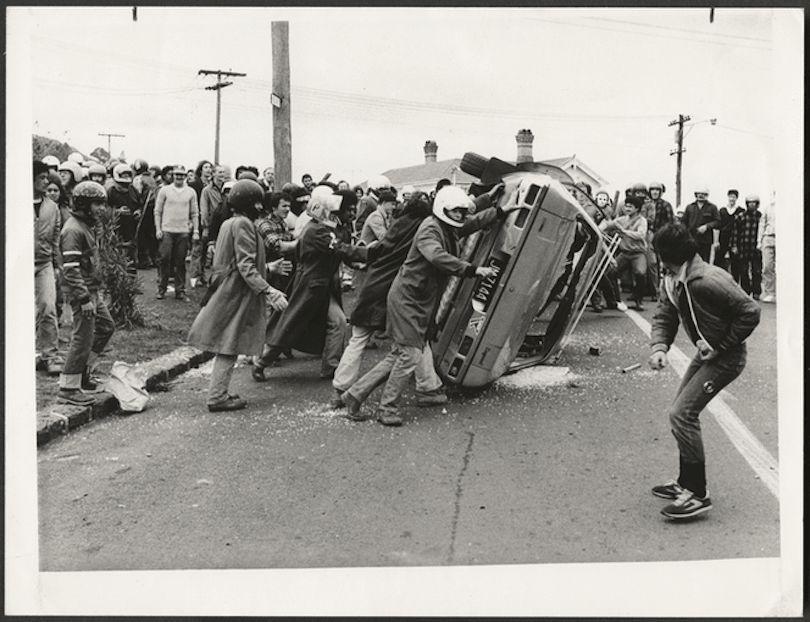

But by the end of what should have been the second match day of the tour – when the scheduled clash against Waikato had been abandoned after a mass pitch invasion and fears a stolen plane would be crashed into Hamilton's Rugby Park – he had upgraded his description the atmosphere the Boks were operating in as "like a war at times".

"Protestors tore down a wire fence and stormed the field. While the police were grappling with those on the field, we rushed back to the change-room where we stood on benches to look out the back window to see what was going on," Claassen recalled in Springbok – The Official Opus.

"I remember seeing a group of protestors overturn one of those big trailers, and then turning and coming towards the change-room."

The charge towards where the Boks had taken sanctuary was halted by police.

Tobias also remembers protestors "bashing" against the windows of his side's dressing room.

The fears by senior police that the stolen light plane was going to crash into the ground if the match wasn't cancelled was also passed onto the Springboks.

"It was now a full-scale war with real blood being shed," Tobias wrote.

"For me, it was equally shocking and tragic to see how the Kiwis were fighting each other, how friendships and families were ripped apart, for example, where one part of the family was waving placards in the streets, while other family members had to protect the Springboks as part of the police force."

While the match was cancelled, the tour continued.

Temporary fortifications were put up around match venues, including heavy shipping containers and thousands of metres of strategically laid barbed wire to keep protesters out; the latter saw the team being dubbed the 'Barbed Wire Boks'.

The police's new anti-riot group - the Red Squad – followed the Springboks everywhere. And the team was not allowed to travel from their hotels in small groups in team gear without the threat of potential violence.

"It was beyond my comprehension how not even the bloodshed in Hamilton could open the eyes of the team management and make them realise that the world was not going to accept a white Springbok team anymore," Tobias said.

"It was one of the largest campaigns of civil disobedience in New Zealand's history and drove the country to the brink of civil war."

Tobias said as the tour progressed it became a "bizarre, never-ending nightmare".

Players had mirrors shone in their eyes from protestors who managed to get into match venues.

Noisy protests were also held outside hotels the team stayed in through the early hours of the morning.

The increasing targeting of hotels saw the Springboks being housed in function rooms at both Athletic Park and Eden Park prior to the second and third tests respectively. The team dubbed those new arrangements as the 'Grandstand Hotel'.

"Don't you have an air force in New Zealand?"

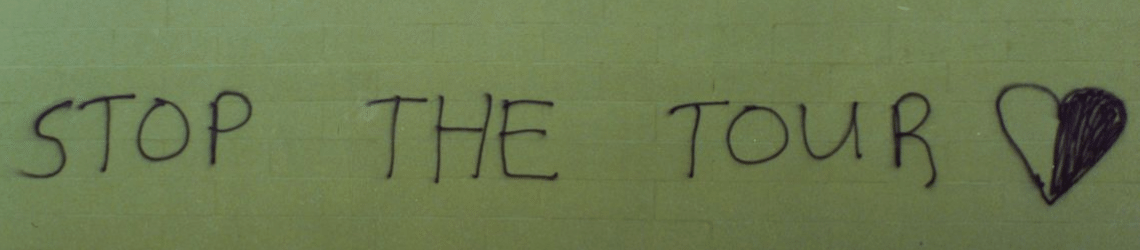

New Zealand witnessed protest scenes with the intensity and violence never seen previously here during the Springboks' 56-day stay here.

None were as shocking as those around Eden Park on September 12, 1981; the day of the third test against the All Blacks.

For several hours, protestors wearing a myriad of protective gear, and some using cricket bats, softball bats and fence palings as weapons, clashed violently with police.

Inside the stadium, crazy scenes were also played out as 50,000 rugby fans watched a pulsating test which went on to be dubbed the 'Flour Bomb Test'.

A light plane piloted by Marx Jones completed numerous low-level passes of Eden Park. Flares, anti-tour pamphlets and flour bombs – one which felled All Black prop Gary Knight – rained down on the playing surface.

After Knight was hit by the flour bomb, Wynand Claassen asked those around him: "Don't you have an air force in New Zealand?'."

"We were under enough pressure as it was and with all this going on around us, it was important – but equally tough – to keep the guys focused," the captain later said.

"I just kept telling them that we should think of the people back home and that we simply must win this test."

Stofberg said the antics of Jones was the extreme end of protests the Springboks never imagined to experience in New Zealand.

By the time they walked onto Eden Park for the final test the team vowed to use the spite directed towards them as a motivating factor.

"When you see the barbed wire [around the field and stadiums] and the plane, it was more of a motivation to play and do the best in the game."

Latest from New Zealand

Focus: Flooding in Glen Innes

Flooding signs have been placed on Elstree Ave in Glen Innes overnight after heavy rain caused surface flooding. Video / Hayden Woodward

Māori law expert says tikanga progress in the judicial system is unstoppable

NZDF plane breaks down: Air NZ flight diverted for delegation; Defence Minister talks to Hosking

Top Hawke's Bay Surf Life Savers honoured

Lawyer’s quest to reduce suicides

Springbok tour research: how does history interpret?

This weekend marks 40 years since the notorious flour-bomb incident at Eden Park during the 1981 Springbok tour.

Violence erupted outside the stadium grounds as protesters and police faced off, while others threw flour bombs and flares on the field to stop the game.

Although apartheid was a major factor behind the unrest, protesters were also actually critiquing wider New Zealand society, says sports historian Sebastian Potgieter .

- Download as Ogg

- Download as MP3

- Play Ogg in browser

- Play MP3 in browser

- Check out RNZ's collection of audio about the 1981 Springbok Tour

Dr Sebastian Potgieter is a South African who moved to Dunedin to conduct a PhD on the Springboks tour.

Back in 1981, the general public in South Africa wasn't too familiar with what was going on in New Zealand yet the Springbok tour of that year negatively affected the team's ability to play internationally, Dr Potgieter tells Kathryn Ryan.

"The South African government had a very strict information policy in place, which means that a lot of information, particularly that which was critical of the apartheid government, didn't actually make it through to the general public.

"In the wake of that tour, South African rugby came to be seen as somewhat of a symbolic liability and a lot of countries didn't want to play against South Africa.

"They felt that if the '81 tour is anything to go by, there was a likelihood of very extreme protests taking place in those countries which did host South Africa."

Dr Potgieter found it interesting to hear how vividly New Zealanders remembered the tour as it's not often spoken about in South Africa.

"We sort of know about incidents like the 'flour-bomb' test, but in general, South Africans don't know too much about this tour.

"It's still a matter which polarises opinions, so people have a lot to say about the tour, and have a lot to say about where they were, what they were doing during that tour."

Dr Sebastian Potgieter Photo: Supplied

It wasn't just apartheid that people were upset about in 1981 - protesters were also taking a stand against the deportation of Pacific Islanders and overstayers and the annexed Māori lands, Dr Potgieter says.

"We very selectively remember the past. It's impossible to remember the past in its entirety ... so certain parts of the past become elevated and contemporarily what we see in New Zealand.

"If you go back and look at some of the recollections of protesters who are writing shortly after the tour, we see that they say yes, apartheid was a problem, it was certainly what mobilised protests.

"But in the process of protesting a lot of people ... linked the protests to a lot of the racial discrimination that was happening in New Zealand at that time.

"It's more complex than simply saying this was an anti-apartheid protest and the anti-apartheid side of things is what's elevated at the moment, but it certainly doesn't define what those protests were about."

The demonstrations were also used as a platform to discuss the problematic aspects of rugby culture such as violence, gender stereotyping and alcoholism, he says.

People also need to remember that many New Zealanders supported the tour, Dr Potgieter says.

"Every single stadium during that entire tour was sold out and that there were large numbers of New Zealand television audience who tuned in to watch every game.

"We also see that a lot of New Zealand's far right and extremist groups actually have their biggest sort of phase of public acceptance or public profile when the question of South African tours cropped up in New Zealand.

"When those tours became put into jeopardy, these extremist groups or far right groups - whatever one wants to call them - received tremendous support in New Zealand."

Dr Sebastian Potgieter is a teaching fellow at the University Of Otago's school of physical education, sports and exercise sciences.

- Sebastian Potgieter

- anniversary

To embed this content on your own webpage, cut and paste the following:

<iframe src="https://www.rnz.co.nz/audio/remote-player?id=2018811821" width="100%" frameborder="0" height="62px"></iframe>

See terms of use .

Recent stories from Nine To Noon

- The week that was Irene Pink and Elisabeth Easther

- Sports commentator Sam Ackerman

- Music reviewer Grant Smithies

- Around the motu: Peter de Graaf in Northland

- Book review: Margo's Got Money Troubles by Rufi Thorpe

Get the RNZ app

for easy access to all your favourite programmes

Subscribe to Nine To Noon

Podcast (MP3) Oggcast (Vorbis)

'Both countries learnt a lot' – Springbok remembers 1981 tour 40 years on

The third Test of the 1981 capped two months of civil unrest and division that left its mark on this country and South Africa.

Eden Park, regarded as the All Blacks' fortress for their dominant record there, actually looked like one on September 12, 1981. Flares smoked out the sidelines and flour bombs fell from a light plane buzzing the ground.

The third Test capped two months of civil unrest and division over the controversial Springbok rugby tour from apartheid South Africa.

The former Springbok captain Wynand Claassen remembers the game well. "That was bizarre. When you ran on to the field and that small plane circling, you know, I don't know how many times, somebody said about 110 times," Claassen said from his home in Pretoria.

But this was the series decider and the Springboks had a job to do.

"We couldn't bother about the plane because the All Blacks are a handful, so we've got to worry about the All Blacks and trying to win the Test," he said.

Keith Quinn commentated on the series. He said he found the Auckland match distressing as he watched the plane buzz the ground from the commentary box.

"My voice in the commentary is downbeat. It's not an upbeat commentary voice because I was anxious, if not scared, in some parts of that game," he said.

He also didn't agree with the tour going ahead and said so at the time. Consequently, the sports commentator was called "the enemy of rugby" by a top New Zealand rugby official. "I had been to South Africa in the 1976 tour and when I came home, I went on TV and said I would never go back to that place again."

Senior All Blacks from the 1981 tour declined or weren't available for interviews, not unlike 40 years ago. "We didn't hear much from the All Blacks on that tour. They were well looked after and there was a distance created," Quinn said.

He said he's since spoken to some All Blacks about 1981. "I think most of them were in favour of the tour."

The final match was narrowly won by the All Blacks, but it was overshadowed by the violence on the streets outside Eden Park.

It was the climax of weeks of demonstrations involving 150,000 people across 28 centres. Claassen said the Boks were not prepared for that level of opposition to the tour.

He recalled a news conference in Gisborne where he and other South African rugby officials got “hammered” with "not one rugby question". He said he thought they should have handled it differently. "We should have been open about South Africa and the problems we had," he said.

The protests also highlighted problems in New Zealand. Donna Awatere Huata was a member of the Patu squad, an anti-tour group led by Māori activists that aimed to put the spotlight on racism at home.

"And to that end we were partly successful. Not totally but we did make some gains," said Awatere Huata. She said gains were made shortly after the tour in education and the police, but "by and large they were very small”.

"The legacy of the tour is that we have a long way to go. We made a minor dent in the colonial attitudes but what we are left with now is still a colonial bureaucracy, a colonial government that still hasn't made the changes that need to be made to honour the Treaty," she said.

In South Africa, the 1981 protests put the pressure on for political change. Claassen said it marked the "beginning of the end" of apartheid.

He sees the tour as a part of history. “It’s a strange way of looking at it, but we were. Both teams, both countries… I think both countries learnt a lot from each other.”

More Stories

'Vile backlash' online to decision to fund marae upgrades

Whanganui's nearly 20 marae will be able to apply for marae development grants from a $500,000 pool each year for seven years.

Fri, Jun 14

Funeral director says MSD grant application process 'archaic'

Kaiora Tipene of Tipene Funerals wants the Funeral Grant process reviewed, highlighting "inconsistencies" between MSD's website and application form for confirming the death of a loved one.

Thu, Jun 13

Programme looks to help address undiagnosed dyslexia among offenders

Wed, Jun 12

Rotorua emergency housing motel cut the 'first step' - MP

Woman loses use of legs after 'nangs' overdose

The ins and outs of sex etiquette while flatting

How much money will you need in retirement?

Severe thunderstorms bring a wet start to the week — MetService

12 mins ago

A history of PM plane problems as latest trip runs into turbulence

Dutch tourist found dead, four other tourists missing on Greek islands

More people divorcing in midlife – some of them are happier than ever

Body found in search for missing Auckland woman - police

18 mins ago

Data shows more serving prison time before being found not guilty

23 mins ago

German police shoot man wielding an axe ahead of Euros match

38 mins ago

Princess Kate marks Father's Day with new photo of William, children

44 mins ago

Scotty Stevenson: On The Sidelines - June 17

Toyota unveils new Hilux, Land Cruiser Prado models with hybrid tech at Fieldays

Sponsored by Tyota

More from Entertainment

Ellen DeGeneres 'needed time to recover' after the end of her show

A close friend of the 66-year-old comedian said she "needed to make a comeback to the limelight".

Gordon Ramsay 'lucky to be alive' after bruising bike crash

The 57-year-old chef took to social media to remind his followers of the importance of wearing a helmet.

Sean 'Diddy' Combs returns key to NY City after Cassie video

Jurgen Klopp returns to Anfield for first time since stepping down

Saturday 9:00pm

Hit Tongan rugby movie Red, White and Brass turned into stage play

Saturday 8:15pm

Chris Brown left dangling mid-air as gig stunt goes wrong

The Spinoff

Ātea December 28, 2021

Three things you didn’t know about the 1981 springboks tour.

- Share Story

Summer read: This year marked the 40th anniversary of the rugby tour that divided a nation. While countless books and articles have been written about that time, some important details have faded with age. Leonie Hayden looks back at three of them.

First published July 22, 2021

Merata Mita’s documentary Patu! opens with a group collecting signatures on the street in Auckland to petition the government to stop the upcoming Springboks’ tour of New Zealand. A young passer-by starts arguing with the organisers, asking how would they feel if a group of “wogs” or “Blacks” came over here. One group member explains that she’s married to a Black South African man. Undeterred, the man continues his tirade about what would happen if “they” were in charge.

It’s 1981 and Mita’s grainy film footage captures one of those most divisive periods in our history since the New Zealand Wars. It was a battle that played out on the rugby field, in the streets, within the halls of parliament and at kitchen tables all over the country. But the fight for New Zealand to take a stand against South Africa’s apartheid regime was far from new.

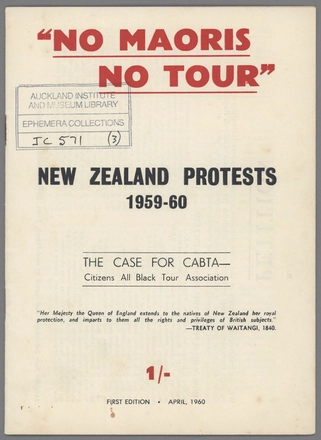

The New Zealand Rugby Football Union had left rugby legend George Nēpia and other giants of the game at home in 1928 to conform with South Africa’s segregation laws. In 1959, the Citizens’ All Black Tour Association had tried to demand “No Maoris, no tour” when Māori players were excluded from the team’s 1960 visit. They weren’t successful then, but Māori players would go on to tour South Africa as “honorary whites” in 1970 and then in 1976 – the same year as the Soweto uprising that saw hundreds of children and student protestors murdered by police.

While Robert Muldoon campaigned on sports and politics being kept separate, deftly side-stepping the Commonwealth members’ Gleneagles agreement , the world had very much decided the two were connected. Black African nations boycotted the 1976 Montreal Olympics in protest of our ongoing engagement with South Africa. New Zealand was becoming a pariah.

And so when the 1981 tour was announced, anti-apartheid groups such as Halt All Racist Tours (HART), Citizens Association for Racial Equality (CARE) and the Patu Squad (led by Hone Harawira, Donna Awatere, Josie Keelan and Ripeka Evans) began a national campaign to stop it in its tracks.

Ultimately, the demonstrations and petitions to Muldoon’s government – plus a national poll showing only 46% public support for the tour – fell on deaf ears and the South African team were officially welcomed to New Zealand at Te Poho-o-Rawiri marae in Gisborne on July 19, 1981.

Tā Graham Latimer’s wero

It was a pōwhiri with teeth.

The welcome for the Springboks took place at the same time as Māori activists were spreading glass across Gisborne’s Rugby Park ahead of the first game. The speakers that evening comprised Te Poho-o-Rawiri kaumātua, dignitaries of the Tairāwhiti Māori council, and the president of the New Zealand Māori Council, the late Sir Graham Latimer .

To many the welcome would have looked like a sign of a generational divide – conservative assimilationists on the marae versus activists on the field – but Latimer ensured the pōwhiri wasn’t an occasion that ignored or played down what was at stake. In fact, he very politely told Springboks captain Wynand Claassen and his team they wouldn’t be welcome again while apartheid remained in South Africa.

Per tradition, it was Latimer’s role as the New Zealand Māori Council president to extend a greeting to any international group being welcomed onto a marae. The speaker before him, Tom Fox, had emphasised with some pride, and to much applause, that the Tairāwhiti branch was the only Māori council that actively supported the tour.

Latimer, however, was less effusive. “I am fully conscious of the fact that I do not have a complete mandate to make this welcome,” he began. “Seven out of the nine district councils that make up the New Zealand Māori council are opposed to the tour, and one is undecided.” A long pause, silence from the crowd.

“Fifty-four per cent of the general public of New Zealand has expressed opposition to your tour. That’s in a poll. The last time such a tour was mooted, only 16% were against the tour. That you have come has been seen by some as a major victory but it must be recognised that if there were only another 6% against the tour, there would be neither a political party not a rugby union game enough to extend an invitation to you.”

He continued: “There can be no doubt in my mind that we will not be making another such welcome on a Māori marae – I emphasise that point – unless your government can show it is prepared to change its policies on apartheid. We hope we can look forward to a time in the not too distant future when you could be welcomed on any marae. It would be a pity if this could be looked upon as the last international tour by South Africa.”

Latimer finished by giving an especially warm mihi to Errol Tobias, the first player of colour to tour with the Springboks. “I believe he represents hope for 18 million South Africans, for whom there appears to be little hope.”

The genius of Latimer’s challenge was in its statesmanlike delivery. While much of his speech was received with (presumably) shocked silence, he was still rewarded with a huge round of applause at its conclusion, even though he had just told those gathered they would not be welcome in future under the same circumstances. The extraordinary recording of that evening, housed in the Ngā Taonga archive , captures a mild-mannered assassin executing an entire squad with diplomacy.

Naturally we have no way of measuring the effects of that speech on either the Springboks or apartheid. But it may have been the last time the issue was discussed politely.

Police violence was far worse than they’d like you to remember

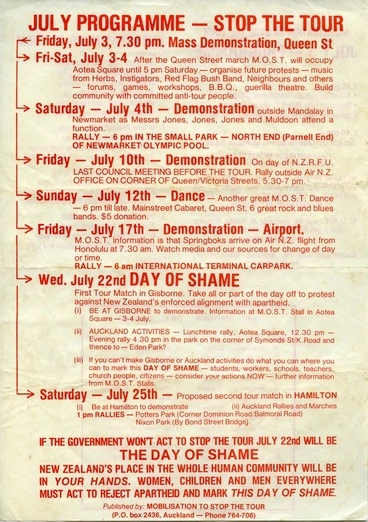

Nicknamed the Day of Shame, July 22 saw the Springboks’ opener against Poverty Bay. Three hundred protestors marched to Rugby Park in Gisborne via a nearby golf course and attempted to breach a fence. Rugby fans jumped into action and a brawl broke out between the two groups. Police arrived to break up the fighting, and only two men managed to run onto the field. Thirteen were arrested and many were hurt in the resulting brawl, but it was nothing compared to the violence that was to come.

Over the course of the next two months, police, in particular the infamous Red and Blue riot control squads, would become more and more comfortable with using extreme violence against unarmed protestors, causing serious and sometimes permanent injuries. Pro-tour rugby fans were also brutal in their retaliation.

Singer and journalist Moana Maniapoto, then a first-year law student at the University of Auckland, remembers when the fence came down at the second game in Hamilton on July 25. “Everyone’s leaning on it, pushing and pushing it, and then the next minute the fence came down and you just heard this ‘Run!’ You’re just swept along. So then I’m in the middle thinking, ‘what am I doing here? They’re gonna kill us!'”

She recalls looking up at thousands of angry faces in the stands. “They were totally rabid. Screaming, yelling and throwing cans of beer at us.

“The police arrived, just the ordinary cops, not the Red Squad, and I actually thought, ‘oh this is good, surely they’re not gonna let us get murdered’. Then the commissioner came on and said the match has been called off and there was this huge roar from the crowd. At first it was like, ‘yay!’ and then ‘oh my god. How the hell are we gonna get out of here?’”

Maniapoto, along with land protector Eva Rickard and another friend, managed to escape into the surrounding streets. “The cops were sporadically placed so you had to make a run for it to the gate. Then the cops recognised Eva and they were abusing the shit out of her. But we got out, and we were very lucky, my friend’s father heard on the radio that the match had been cancelled and he circled until he found us. A lot of people got attacked.”

Marx Jones and Grant Cole flour bomb Eden Park in a hired Cessna.

She would go on to attend protests in Rotorua and at the third test in Auckland – the latter resulting in a violent clash between police, protestors and rugby fans on the streets of Mount Eden. “Red Squad came out of nowhere and nutted off at everyone. I was with the least militant bunch when they charged. We were just standing there. Couldn’t believe it. I was batoned, kicked by heavy police boots while on the ground. Shock for a young freshie like me. They just smashed into us and left people lying on the ground in their wake.”

For further proof you need only watch the violence through Mita’s lens. The dull thud of police batons hitting flesh and human skull, and the wails of the injured, some of them young teenagers, is the haunting soundtrack for nearly half the film.

Maniapoto scoffs at the selective memory that it was “New Zealand” who took a stand against apartheid. “It’s held out as a landmark, framing New Zealand as a global social justice advocate. It wasn’t New Zealand; it was people power. It was activists, people from across all walks of life, and there were far fewer of us than there were in the stands.”

She talks abut the Nelson Mandela exhibition hosted at Eden Park in 2019 – a strange venue considering the violence that played out on the surrounding streets 38 years earlier. She says at the launch none of the speakers from the New Zealand Rugby Union came close to admitting they’d been wrong, or offering an apology. Instead everybody spoke proudly about the stand taken by the protestors. Says Maniapoto: “They’re starting to rewrite the history!”

The good bishop saves the Patu Squad

It was at the last test at Eden Park on September 12 that a young Hone Harawira, one of the leaders of the predominantly Māori and Pasifika Patu Squad, was finally caught.

Harawira and a handful of others had been arrested at Waitangi earlier in the year, and although they had been denied bail, they were turfed out of the cells for causing a ruckus and told when to attend their court date. They didn’t show up.

The group had outstanding warrants for their arrest before the tour even began.

“It must have got out to the police that we were all going to be involved in the tour, and one by one we were all picked up. One of the brothers, they got him before it started! So he spent the whole of the tour in Mt Eden,” Harawira chuckles.

Harawira says he was caught early on after the test that ended with Marx Jones’ aerial flour bomb attack , so hadn’t been involved in the upturning of a cop car, or the violence that erupted on an unprecedented scale outside Eden Park. Nevertheless, Harawira was charged with the assault of a police officer who’d had both collar bones broken.

“It wasn’t me but they wanted someone to pin it on so they pinned it on me.”

He says he had seven charges against him. “They were serious charges. Three charges of participating in a riot and four charges of assault with intent to cause grievous bodily harm. Which all carried a total of something like 98 years.”

Justice being neither blind nor in a hurry, Harawira wouldn’t stand trial for another two years, alongside many others who he notes were mostly brown, despite the vast majority of protestors being Pākehā. “Most of them were members of the Patu Squad.”

As he had many times before, Harawira planned to defend himself in court. He’d had University of Auckland law lecturers Jane Kelsey and David Williams to rely on for advice, but this time he wasn’t sure it going to be enough.

“The day before my court date, I’m sitting out the back in the cells thinking ‘jeez, what am I gonna do?’ Then the brain wave came to me. Bishop Desmond Tutu had been invited over by the Anglican church to come and do a speaking tour. Interest was still very high in apartheid South Africa. My mum knew George and Jocelyn Armstrong, who were part of the organisation that brought him over.

“So I rang my mum and said look, I want Bishop Tutu as a witness. She said, ‘He wasn’t there!’. I said, ‘that doesn’t matter! I want him for my witness’. So she said ‘OK when is it?’ And I said ‘Tomorrow! I’m gonna need him by about 10.30.’”

The next day Harawira and 10 others prepared to stand trial.

When the time came for him to give his defence, his star witness wasn’t there. “I read my statement. I’d come to the very end and I was dragging it out. I didn’t want to get out of the dock ‘cos I knew it hadn’t been enough to get me off. Then the door burst open, and someone looked at me with a big smile and just nodded and I knew then. So I asked the judge: ‘Can you please call my witness?’”

Harawira still laughs at the memory of the stunned faces of the judge, prosecution and jury as as the now-Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in his signature dark suit and purple cleric’s shirt, walked into the courtroom.

“And then I’m thinking, ‘What the fuck, now what do I do?’

“So he takes the stand and I go, ‘Could you please tell the court your name?’ And then I said, ‘Can you please tell the court your address?’ And he gave an address in Soweto. Instantly, if the room wasn’t already charged, everyone was completely wide-eyed now.

“And then I said, ‘Can you please explain to the court what apartheid is?’. And away he went. He must have spoken for 20 minutes. It was absolutely stunning. You could have heard a pin drop.”

He says that after Tutu had finished, neither he nor the prosecution could think of any more questions.

“As Bishop Tutu stepped out of the dock, all 11 defendants, we all stood up. Then our lawyers stood up, then the public, the screws from Mount Eden, the police stood up, then the jury stood up. Half of them were in tears. If was one of those moments. I knew right then and there we were gonna get off.” He crows in delight at the memory.

The group were acquitted of all charges.

“It’s kind of hard to believe but it’s all true. Meeting Nelson Mandela himself and going to his tangi, that’s another story.”

We are here thanks to you. The Spinoff’s journalism is funded by its members – click here to learn more about how you can support us from as little as $1.

Important note about COVID Red Settings:

At Orange our libraries are open with face masks required. Vaccine passes are no longer required. Please stay home if you are unwell. Learn more about visiting our branches at Orange .

Service update:

Miramar Library will reopen at 2pm — maintenance related to last night's stormy weather is now complete. Thank you for your patience.

Service note:

Wadestown Library will close early on Thursday 12 August at 5:30pm for a community meeting.

Wellington City Libraries

Te matapihi ki te ao nui, te haerenga a ngā piringa pāka ki aotearoa i te tau 1981 the 1981 springbok tour of new zealand.

Other heritage topics

- Architecture |

- The sinking of the Wahine |

- Wellington waterfront |

- Earthquakes in Wellington |

- More heritage resources

The rivalry between the Springboks and the All Blacks is one of the longest and most enduring between two sporting nations. In the past, generations of rugby players and enthusiasts from both countries viewed a series victory over the other nation as being the pinnacle of achievement in the sport. Alongside the history of fierce competition went a tradition of hospitality towards the visiting side.

In 1956 and 1965 when the South African rugby team toured New Zealand, they were showered with warmth and generosity wherever they went. Yet 25 years later, the 1981 Springbok tour became one of the most divisive events in New Zealand history.

Its impact went far beyond the rugby ground as communities and families divided and tensions spilled out onto the streets and into the living rooms of the nation. What were the events that made this tour so significant? What motivated ordinary Kiwis to take such extraordinary action against one another?

Although things had been far from perfect between my parents, the Springbok tour caused such tension and stress that we could not live together in the same house and function as a family unit. An example of the increase was when we, as a family, watched the evening news. Often one side would raise their voices in abuse and offensive name calling towards public figures. Later the abuse was turned in an indirect way on individual family members. This was done by blaming the chaos and disruption to rugby games in individual family members, their friends and associations. As the tour went on and the turmoil increased, the negative feelings intensified to such as degree that feelings of dislike, anger and incomprehension dominated our home. It's Just a Game (anon), in, The New Zealand Experience : 100 Vignettes, collected by B. Shaw & K. Broadley, 1985 .

From Digital NZ

Central library closure — collection availability.

Unfortunately much of our heritage collection is currently not available through our online catalogue — because of the closure of the Central Library, much of this collection is in storage. We hope to make it available again soon, but in the meantime, we suggest visiting the National Library of New Zealand in Thorndon (Corner Molesworth & Aitken St) to access these book titles and newspaper resources.

- Visiting the National Library

- Using the National Library Catalogue

Newspaper articles

Unfortunately, contemporary newspaper accounts of the Springbok Tour from 1981 fall into a time period where newspapers are generally not even indexed for searching, let alone available in full text online — see our finding historical Wellington newspaper articles resource.

That being said, information about (and sometimes the full text of) many anniversary accounts (10 years, 20 years later etc.), can be found online (see Online databases below) — and contemporary accounts can be accessed on microfilm if you know approximate dates (we've provided a table of key dates below).

Finding Historical Wellington Newspapers

Tip: Remember that many reports will not appear in newspapers until the following day.

Magazines — online databases

Our online databases can also be used to access a large number of articles about the tour which have previously been published in magazines . Though the databases do not go back as far as 1981, they do contain many retrospective articles written since then.

- Magazine databases

- New Zealand databases

- Newspaper databases

To access contemporary accounts of the Springbok Tour in magazines, we recommend visiting the National Library on Molesworth Street (see collection note above).

To find magazine titles of interest, have a read of the article below:

Story — Magazines and periodicals in New Zealand

Heritage Links (Local History)

The Springbok Tour

A DigitalNZ Story by Hana McIntyre

A digitalNZ story by Hana McIntyre

The springbok tour of the 1980’s was the largest civil disturbance New Zealand had seen in thirty years. The whole of New Zealand was divided over the tour, this division of the country lasted over fifty days. The Springbok tour was a real factor in the way New Zealand grew as a county. The outcomes that arose from the tour has led New Zealand to find and express our identity as people and as nation.

Maori take a stand

A group of maori protesters stand together with helmets on as police with baton smarch behind them.

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

The beginning

This pamphlet was given out in the 1960's in an effort to have maori included in the tour.

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

Together as a nation

All people of NZ came together to protest the tour, despite the debate on NZ racism, people of all backgrounds joined.

The tour was a useful tool as it helped to kick start the discussion of New Zealand's identity. For many decades New Zealand was in a limbo, we had the fundamentals of a culture events, people and objects all people could relate to. This is prominent in the source of the tour, rugby. Such a staple in ‘kiwi culture’, rugby is a thing everybody could enjoy no matter their race, age or gender. Rugby was a nationwide spot that the rest of the world knew as kiwi culture. However, this all changed when the announcement was made that the All Black would be taking am ‘all white’ team to play the springbok tour in South Africa.

Police resistance

Police and protesters in 1981

Children joined the fight

The tour did not only see adults who fought and protested, but it also saw young children protesting with their familie.

NZ Police 1981

Police where given 'night sticks' to keep protesters under control.

A nation always slightly confused about where the line of culture stood between Maori natives and the pakeha. This was an event that would change the way Maori people saw themselves and their culture within New Zealand's culture. People started to stand against the tour, peaceful marches where organized, rallies with children were held. People even boycotted games in an effort to bring awareness to the fact that an ‘all white’ team was unacceptable in a country where its native people would not be included in such a prominent activity that defined the nations sporting culture.

The riot squad posing for a picture in 1981. They where a step up for NZ police and a shock for NZ people.

Peaceful protesters fight against the Springbok tour and for the recognition of NZ's own faults.

The uncle of the of the captain of the NZ Maori team stood with the NZ Police in napier in 1981

Alexander Turnbull Library

Maori and Pacifica people started to express their identities more, “people started to realize you can’t protest against racism 6,000 miles away when it’s right here in your country” - John Minto This quote from John Minto clearly sums up the thoughts of many people at the time. How are we as a country supposed to find a collective identity if we cannot even see the own blatant racism that happens daily in New Zealand.

The New Zealand Police force are not known to be aggressive or violent. However, the springbok tour bought out the worst in the Police of New Zealand. On the night of the 21st of July 1981 Police brought down their ‘nightsticks’ onto a crowd protester’s who refused to ‘halt’, leaving many people with injuries. This is a prominent event within the Springbok tour. However, New Zealand does not let this define our police nor do we let it impact our culture in a manner where we lost all of the good relations between police and the New Zealand public. This however did tend to complicate the traditional depictions of kiwi culture, as we now had to reinvent the culture of NZ Police.

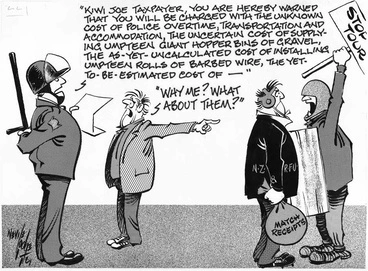

Public opinions

The tour effected everyone, the people who had a voice in society often used it in many ways this time a comic was drawn

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

![[Springbok Tour - Auckland street protest] Image: [Springbok Tour - Auckland street protest]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2Fd3085a739ec91232075a008722345e591fec81aa%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

Police vs Civilians

The tour of 1981 hindered civilians relations with NZ Police.

Police force

Police men and women get ready to face another encounter with protesters.

The tour tells us many things about how kiwis expressed their identities in the past. New Zealand has never been a violent country, new Zealanders have tended to express and convey their feeling through actions and speech. This is a part of kiwi identity in itself, we don’t identify as aggressive people or a nation who is an aggressive world party. This alone reinforces the idea of traditional ‘Kiwi Culture’. We are known as a people of fierce warriors but also known as a nation of respect and understanding.

Springbok Tour protest programme

School children protesting, 1981 Springbok tour

Furthermore, this event deepened our Maori populations identity within New Zealand. The tour made many people realize how poorly our own native people has been treated within our society. This was a catalyst for the change that we see today. Over the past thirty years New Zealand’s identity has become much more inclusive of Maori and all their traditional customs. Maori have become a large part of Kiwi identity and a larger part of ‘kiwi culture’. While the tour was a confusing time for many New Zealanders its consequence of the highlighting of Maori injustice helped to confirm what we see now as ‘traditional kiwi culture’.

New Zealand has always been a proud country, we like to think that we have always had each other's backs and continue to do so even through the toughest of times. The springbok tour was a major exception to this belief. However, this tour ended up adding value and lessons to which became some of New Zealand's most important values and morals. These have now become what we call ‘Kiwi culture’.

Peaceful Protest 1981

The people of New Zealand banded together for peaceful protests against the tour in Wellington 1981

Bibliography

References:

M. (2014, August 5). 1981 Springbok tour. Retrieved from https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/1981-springbok-tour

T. (2006, July 16). Springbok Tour Protests 'Good For Maori'. Retrieved from http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PO0607/S00145.htm

M. (2018, July 20). Police baton anti-tour protesters outside Parliament. Retrieved from https://nzhistory.govt.nz/police-baton-anti-springbok-tour-protestors-near-parliamentv

Listener, T. (2016, November 21). Inside the 1981 Springbok tour. Retrieved from https://www.noted.co.nz/archive/listener-nz-2011/inside-the-1981-springbok-tour/

Wellington City Libraries. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.wcl.govt.nz/heritage/tour.html

Roughan, J. (2017, August 25). NZ memories: Protests during the Springboks tour. Retrieved from https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10830511

http://www.aucklandmuseum.com/collection/object/am_library-ephemera-11756

https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22905580?search%5Bi%5D%5Bcollection%5D=Dominion+post+%28Newspaper%29%3A+Photographic+negatives+and+prints+of+the+Evening+Post+and+Dominion+newspapers&search%5Bi%5D%5Bprimary_collection%5D=TAPUHI&search%5Bi%5D%5Bsubject%5D=Police&search%5Bpath%5D=items

New Zealanders protest against Springbok rugby tour, 1981

Time period, location description, methods in 1st segment, methods in 2nd segment, methods in 3rd segment, methods in 4th segment, methods in 5th segment, methods in 6th segment, additional methods (timing unknown), segment length, external allies, involvement of social elites, nonviolent responses of opponent, campaigner violence, repressive violence, classification, group characterization, groups in 1st segment, success in achieving specific demands/goals, total points, notes on outcomes, database narrative.

Halt All Racist Tours (HART) was organized in New Zealand in 1969 to protest rugby tours to and from South Africa. Their first protest, in 1970, was intended to prevent the All Blacks, New Zealand’s flagship rugby squad, from playing in South Africa, unless the Apartheid regime would accept a mixed-race team. South Africa relented, and an integrated All Black team toured the country.

Two years later, the Springboks arranged a tour of New Zealand. HART held intensive planning meetings, and, after laying out their nonviolent protest strategies to the New Zealand security director, he was forced to recommend to the government that the Springboks not be allowed in the country. Prime Minister Kirk, though he had promised not to interfere with the tour during his election campaign, canceled the Springbok’s visit, citing what he predicted would be the “greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known.”

HART remained active in the anti-apartheid community, continuing to protest the Springboks, and helping to organize a boycott of the 1976 Montreal Olympics. The International Olympic Committee had not banned New Zealand after the All Blacks had toured South Africa, and many African countries saw this failure as a tacit endorsement of Apartheid. In 1980, New Zealand again attempted to bring the Springboks to New Zealand.

The Springboks arrived on July 19, 1981. Though they were officially welcomed by the New Zealand government, there was a sense of dread and anticipation that surrounded their arrival – perhaps, some thought, the 1981 tour should have been cancelled like the tour in 1972 was. The government officials could not anticipate, however, that the country was about to fall into “near-civil war.” In response to HART, pro-rugby groups like Stop Politics in Rugby (SPIR) organized in an effort to help the Springbok’s tour succeed. Both sides tended to be easily identified by armbands that made their affiliation clear. In particular, HART activists wore their armbands for the entire length of the tour, subjecting themselves to constant ridicule and the threat of violence, despite their commitment to nonviolent protest only.

The Springboks played their first game on July 22 in Gisborne. An anti-Springbok rally took place that day, near the rugby pitch. When the campaigners arrived at the arena, they were confronted by pro-rugby demonstrators. Because Gisborne, like most cities in New Zealand, was close-knit, demonstrators on both sides knew each other, and were not afraid to call each other out for supporting the wrong side, whichever they believed that was. The pro-rugby demonstrators did not restrict themselves to words, even throwing stones at the other side. The anti-Springbok protesters could not stop the match that day. Though they were able to break through the perimeter fence, and engage the pro-tour demonstrators face to face, they were prevented from occupying the field. Though both sides reported that they were uneasy with the clashes between fellow New Zealanders, neither side was easily swayed.

Three days later, the Springboks were scheduled to play in Hamilton. Anti-Springbok planners had circulated a strategy that would hopefully allow them to tear down the fence, invade the field, and disrupt the match. Protesters had also secured more than 200 official tickets to the match, to make sure that their presence was felt, even in the event that they could not storm the pitch. Despite the presence of more than 500 police officers and a sizable pro-rugby contingent, the anti-Springbok march would prove unstoppable. 5000 anti-Springbok protesters descended upon the Hamilton pitch, and more than 300 made it onto the field, forcing a match cancellation. Protesters chanted that the whole world was watching. Many of the demonstrators were arrested, and those on the pitch endured a constant bombardment of bottles and other objects from rugby fans in the stands. This entire situation was captured on live TV and shown around the world.

With tensions in New Zealand reaching astronomical proportions, the Springboks were next scheduled to play four days later, on July 29. The anti-Springbok protesters were largely absent from the match, but had instead planned a march on the South African consulate in Wellington, New Zealand. Despite police declaring that a march was not permitted, the protesters marched right up to the police line on Molesworth Street. The police began to stop the marchers with their batons, violently forcing them away from the consulate building. The marchers, stunned and bloodied, turned towards the police station, chanting “Shame, shame, shame.” When they arrived, the accosted marchers pressed assault charges on the police that had attacked them. Though the charges were dismissed, the policing of the tour protests had taken a turn for the worse. From this point on, protesters were careful to carry shields and wear crash helmets in order to protect themselves from attacks.

Protests would continue for the entire length of the Springbok’s stay in New Zealand. Only one more match was cancelled, in Timaru. However, there were a few more notable encounters. In Christchurch, on August 15, protesters failed to occupy the pitch in time for the game to be cancelled. The police cordon around the arena held, and several observers believe that the police saved the lives of many protesters. The attacks of rugby supporters were growing more and more violent, The Christchurch incident was characterized by flying blocks of cement and full beer bottles. Had the anti-Bok protesters succeeded in reaching the field, the attacks would certainly have been even more dangerous.

The final match of the tour was in Auckland on September 12. Not only was the match important as a final chance for protesters to demonstrate their opposition to the Springboks, it was the deciding third meeting between the Springboks and the All Blacks. Doug Rollerson of the 1981 All Blacks recalled that it seemed very important for the All Blacks to win the match, to show that a mixed team was superior to the segregated Springbok side. When the All Blacks won, the sense of victory in New Zealand was similar to the US victory over the Soviet Union in 1980 – the triumph of righteousness over the evil empire. However, for most observers around the world, the off-field events were far more important. Though the protesters were generally non-violent, there were many others that joined in the marches – HART characterized them as opportunists that simply wanted to fight with police. Though eruptions of violence had taken place throughout the campaign, they were largely viewed by the protesters as third-party actions, and HART consistently distanced themselves from violent attacks. More memorably, Max Jones and Grant Cole commandeered a prop plane, and proceeded to drop flares and flour bombs on the pitch during play in an attempt to stop the game. Though the game continued, the actions of the protesters were again the primary news story in New Zealand and throughout the world.

Though the anti-Springbok protests were largely unsuccessful in that the vast majority of the planned contests took place, they were able to raise an incredible amount of awareness for the anti-Apartheid movement. Nelson Mandela recalled that when the game in Hamilton was cancelled, it was “as if the sun had come out.” HART would continue protesting until the fall of the Apartheid regime.

Influenced and influenced by anti-Springbok protests in other countries like Australia, Britain (see "Australians campaign against South African rugby tour in protest of apartheid, 1971" and "British Citizens Protest South African Sports Tours (Stop the Seventy Tour), 1969-1970") (1,2).

This campaign was also influenced by the New Zealand Waterfront Strike (1951) (1).

Additional Notes

Name of researcher, and date dd/mm/yyyy.

COMMENTS

1981 Springbok tour Page 1 - Introduction. A country divided. For 56 days in July, August and September 1981, New Zealanders were divided against each other in the largest civil disturbance seen since the 1951 waterfront dispute. More than 150,000 people took part in over 200 demonstrations in 28 centres, and 1500 were charged with offences ...

Police officers guarding a barbed wire perimeter around Eden Park near Kingsland railway station.. The 1981 South African rugby tour (known in New Zealand as the Springbok Tour, and in South Africa as the Rebel Tour) polarised opinions and inspired widespread protests across New Zealand.The controversy also extended to the United States, where the South African rugby team continued their tour ...

Support for the Springbok tour was particularly strong in rural and small-town New Zealand. In the Taranaki dairy town of Eltham, 50 protesters were showered with eggs and bottles as they marched up the street one Friday night. In the 1981 general election National retained power because it held on to marginal provincial seats such as Gisborne ...

Read a story about the 1981 Springboks rugby tour. The 1981 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand caused social ruptures within communities and families across the country. With the National government backing the tour, protests against apartheid sport turned into confrontations with both police and pro-tour rugby fans — on marches and at matches.

The controversial 1981 Springbok tour, which divided NZ, began 30 years today. Relive the memories. Image 1 of 14: New Zealand Prime Minister Sir Robert Muldoon commenting on the forthcoming tour ...

In 1981 the Springbok rugby team toured New Zealand which led to public protests. Those against the tour objected to South Africa's apartheid policies, whilst those supportive of the tour thought politics and sport shouldn't mix. The game against Waikato at Hamilton's Rugby Park on 25 July was called off when several hundred anti-tour ...

Video / Chris Tarpey, Merata Mita, NZ On Screen, Getty. People were left bloodied and bruised, friendships ended and civil unrest hammered our nation during the Springboks 1981 tour. But 40 years ...

The 1981 Springbok tour schedule (map) T he Springboks started their tour with a comfortable 24-6 victory over Poverty Bay in Gisborne. Anti-tour protestors pulled down perimeter fences in an attempt to disrupt the game. Police and rugby fans prevented a full-scale pitch invasion. Step through to find out what happened at different games when ...

The 1981 Springboks' only non-white player Errol Tobias said his side's presence put New Zealand on the verge of "civil war". Photo / AP. Tobias said as the tour progressed it became a "bizarre ...

The 1981 Springbok Tour. From Sports History NZ, 5:02 am on 9 May 2024. Share this. Protesters opposing the Springbok tour in 1981 march through the streets of Wellington. Photo: Duncan Miller Gallery. Listen to Sports History NZ: The 1981 Springbok Tour 27′ 08″. Add to playlist.

Check out RNZ's collection of audio about the 1981 Springbok Tour; Dr Sebastian Potgieter is a South African who moved to Dunedin to conduct a PhD on the Springboks tour. Back in 1981, the general public in South Africa wasn't too familiar with what was going on in New Zealand yet the Springbok tour of that year negatively affected the team's ability to play internationally, Dr Potgieter tells ...

In South Africa, the 1981 protests put the pressure on for political change. Claassen said it marked the "beginning of the end" of apartheid. He sees the tour as a part of history. "It's a strange way of looking at it, but we were. Both teams, both countries…. I think both countries learnt a lot from each other.".

Throughout 1981, plans by the New Zealand Rugby Union to host a rugby tour from apartheid South Africa faced growing public opposition (New Zealand prime minister. Despite calls for the tour to be scrapped, the all-white Springbok team arrived in July. The anti-apartheid demonstrators responded by mobilising a mass protest movement to disrupt the tour.

Springbok Tour 1981. Protests against the South African rugby team touring New Zealand divided the country in 1981. Discover the reasons behind this civil disobedience, as well as the demonstrations, police actions and the politics of playing sports. SCIS no. 1809122. Filter by media type. Images.

This year marks the 30th Anniversary of the 1981 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand. Due to on-going public interest, including a recent formal request made under the Official Information Act 1982 (OIA) by an historian, the NZSIS has decided it is appropriate to release some of its historical information surrounding the Springbok tour, and is making 10 documents available.

Right: a protestor in Gisborne, July 22, 1981. Baton-weilding police and anti-tour demonstrators clash in Molesworth Street, Wellington, July 30 1981. (Photo: Ian Mackley/Alexander Turnbull ...

The Springbok rugby tour brought us to the brink of civil war, as many protested the racial segregation of Apartheid South Africa and made links to racism at home. On the 29th of July, 1981, protesters opposing the Springbok Tour were met by baton-wielding police trying to stop them marching up Molesworth St to the home of South Africa's ...

The anti-tour protest movement included many urban, educated professionals but also enjoyed strong union support. Historian Jock Phillips sees the tour as a clash between the 'old and the new New Zealand', which revealed itself in five main ways: the struggle between baby boomers and war veterans. city versus country.

The Springboks were officially welcomed to New Zealand at Te Poho-o-Rawiri Marae in Gisborne (just as they had been in 1965) on 19 July 1981. Despite all the pre-tour rhetoric and debate, few anticipated that the country was about to descend into near civil war, 'a war played out twice a week' as the Springboks moved from game to game.

Newspaper articles. Unfortunately, contemporary newspaper accounts of the Springbok Tour from 1981 fall into a time period where newspapers are generally not even indexed for searching, let alone available in full text online — see our finding historical Wellington newspaper articles resource.. That being said, information about (and sometimes the full text of) many anniversary accounts (10 ...

The Springbok Tour. The springbok tour of the 1980's was the largest civil disturbance New Zealand had seen in thirty years. The whole of New Zealand was divided over the tour, this division of the country lasted over fifty days. The Springbok tour was a real factor in the way New Zealand grew as a county. The outcomes that arose from the ...

The conflict within New Zealand over sporting contacts with apartheid South Africa reached a peak in the protests against the 1981 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand. Here police and protesters confront one another at Palmerson North on 1 August 1981, when South Africa played Manawatū. Because it was three days after police had used batons ...

In 1980, New Zealand again attempted to bring the Springboks to New Zealand. The Springboks arrived on July 19, 1981. Though they were officially welcomed by the New Zealand government, there was a sense of dread and anticipation that surrounded their arrival - perhaps, some thought, the 1981 tour should have been cancelled like the tour in ...