Unveiling Eons: Where Myths Breathe and Legends Live — Dive into the heart of ancient tales, explore mythology from across the world, and discover the legends that have shaped our past and continue to inspire our future.

The Hero’s Journey in Greek Mythology

- Post author: MythologyWorldwide

- Post published: February 15, 2024

- Post category: Blog

Table of Contents

Greek mythology is replete with tales of heroism, gods, and epic quests that have inspired countless stories over the centuries. In many of these ancient myths, we find the recurring theme of the hero’s journey – a transformative adventure that reveals strength, courage, and ultimately, self-discovery. Let’s delve into the essence of the hero’s journey in Greek mythology and explore some of its iconic examples.

What is the Hero’s Journey?

The hero’s journey, as outlined by Joseph Campbell, is a universal narrative structure found in myths, stories, and legends across cultures. In Greek mythology, this archetype is prevalent in the narratives of heroes like Hercules, Perseus, and Odysseus. The journey typically consists of stages such as the call to adventure, facing trials and challenges, and returning home transformed.

Key Stages of the Hero’s Journey in Greek Mythology

1. The Call to Adventure: The hero receives a challenge or quest that sets them on their journey. This could be a divine mandate, a revelation, or a personal yearning for exploration or growth.

2. Threshold Crossi ng: The hero leaves the familiar world behind and enters the unknown, facing initial challenges and uncertainties.

3. Trials and Tribulations: Along the way, the hero encounters various obstacles, enemies, and tests of character that push them to their limits.

4. Abyss: The hero confronts their greatest fear or faces a near-impossible challenge that tests their resolve and inner strength.

5. Transformation and Atonement: Through decisive action or self-realization, the hero undergoes a profound change, acquiring wisdom and power to overcome the final obstacle.

6. Return with the Boon: The hero returns home, bringing knowledge, a gift, or a transformative experience that benefits their community or loved ones.

Examples of the Hero’s Journey in Greek Mythology

– Hercules: Known for his Twelve Labors, Hercules battles numerous foes and completes seemingly impossible tasks to prove his heroism and achieve redemption.

– Perseus: Armed with a sword and shield from the gods, Perseus faces Medusa and a host of other challenges to save Princess Andromeda and fulfill his destiny.

– Odysseus: The cunning hero of the Trojan War, Odysseus navigates a decade-long journey filled with mythical creatures, temptations, and divine interventions on his quest to return home to Ithaca.

Understanding the hero’s journey in Greek mythology not only enriches our appreciation of these timeless tales but also reflects the timeless human experience of growth, resilience, and transformation. These legendary stories continue to resonate with audiences, serving as a reminder of the enduring power of myth and the hero’s eternal quest.

FAQ: The Hero’s Journey in Greek Mythology

What is the hero’s journey in greek mythology.

The Hero’s Journey in Greek Mythology is a common narrative pattern found in ancient Greek myths. It typically involves a hero undertaking a quest or adventure, facing challenges, overcoming obstacles, and ultimately achieving a goal or gaining wisdom.

What are the key stages of the Hero’s Journey in Greek Mythology?

The Hero’s Journey in Greek Mythology often includes stages like the Call to Adventure, Crossing the Threshold, Allies and Mentors, Tests and Trials, the Ordeal, Rewards, and the Return. Each stage contributes to the hero’s growth and transformation.

Can you provide an example of the Hero’s Journey in Greek Mythology?

One famous example is the story of Odysseus in Homer’s epic poem, “The Odyssey.” Odysseus faces numerous challenges and temptations on his journey home from the Trojan War, showcasing the classic elements of the Hero’s Journey.

Why is the Hero’s Journey important in Greek Mythology?

You Might Also Like

The Influence of Norse Mythology on Norse Music and Dance

The Role of Magic in Slavic Mythology

Understanding the Concept of Dharma in Hindu Mythology

Shortform Books

The World's Best Book Summaries

5 Hero’s Journey Examples in Classic Mythology

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "The Hero with a Thousand Faces" by Joseph Campbell. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What are some good hero’s journey examples? What can these examples of the hero’s journey demonstrate about the hero’s journey?

Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces is an exploration of the power of myth and storytelling, from the ancient world to modern times, and spanning every human culture across the world. We’ll cover hero’s journey examples for the departure stage of the journey and explore how the themes of myth remain consistent across the globe.

Hero’s Journey Examples

All peoples, and indeed, all individuals, make sense of the world they live in and grapple with the experience of living by telling stories . Myths are the foundation of all human physical and intellectual pursuits , be they religious, economic, social, or cultural, because these myths tell us who we are and what destinies we are here to fulfill. Let’s look at some hero’s journey examples for the departure stage.

Hero’s Journey Example, Departure Stage #1: The Call to Adventure

In the first part of the monomyth , we meet our hero, our “man of destiny,” and witness their call to adventure . The call to adventure can come about through chance, even a mistake or blunder, which introduces the hero to a hidden world of possibility, guided by mysterious forces which the hero will come to understand through the course of their journey.

A frequent device employed in mythology is that of the herald or conjurer , the (often unlikely) figure who reveals the hero’s destiny and spurs them to action. The herald represents our subconscious, wherein all of our darkest fears are hidden. They are forcing us to confront things that we do not want to. As such, the herald is frequently a grotesque or unpleasant-looking figure, like a frog or a beast , or otherwise some veiled, mysterious, or unknown figure.

King Arthur and the Hart

In the hero’s journey example of Arthurian legend , King Arthur encounters a great hart (an archaic Old English term for a deer) in the forest. He gives chase to the animal, vigorously riding his horse until it dies from exhaustion. Arthur then comes to a fountain, where he sets down his dead horse and becomes lost in deep thought.

While he’s sitting at the forest fountain, he hears what sounds like dozens of hounds coming toward him. But, it is not hounds—instead, it is some strange beast, the likes of which the King had never seen before. The noise of 30 hounds barking and snarling emanate from its stomach, although there is no noise while the beast drinks at the fountain. Arthur marvels at this sight: this is his herald, his signal to begin his quest.

Hero’s Journey Example, Departure Stage #2: Refusal of the Call

A common feature of the monomyth is the hero’s refusal of the call , an initial reluctance to follow the steps of their destiny. In folk tales and myths across the world and throughout history, this refusal amounts to a selfish impulse to give up one’s narrow, immediate interests in the pursuit of spiritual awakening or even the salvation of the universe. In psychoanalytic terms, the refusal represents the clinging to infantile needs for security . Thus, the mother and father are the figures preventing true growth and transformation as the ego fails to develop and embrace the world outside the nursery.

Prince Kamar al-Zaman and Princess Budur

This concept is well illustrated in the hero’s journey example of the Arabian Nights tale of Prince Kamar al-Zaman and Princess Budur. In it, the prince has rejected his father’s demands that he take a wife, citing his desire to commit his life to Allah and avoid the pleasures (and sins) of the flesh.

The sultan is advised to broach the subject with his son in the presence of a great council of state, the rationale being that the prince will surely be goaded into accepting marriage under these conditions of immense social pressure. But Kamar al-Zaman again refuses his father and insults him in front of his great ministers and viziers. Enraged, Kamar al-Zaman’s father has him imprisoned in a decrepit tower, where he is to reflect upon the injury and shame he has brought upon his family.

Simultaneously, in distant China, Princess Budur—the beautiful daughter of the emperor—is similarly refusing marriage to all suitors her father presents to her. She even threatens to kill herself with a sword if he brings up the subject of matrimony again. Like the sultan, the emperor locks his daughter up and appoints ten old women to guard her. He then sends messengers to all the kingdoms of Asia, telling the rulers that Princess Budur has gone mad.

Both the hero and the heroine have taken the negative path and refused the call of destiny. They are a predestined match, but it will take a miracle to bring them together.

Hero’s Journey Example, Departure Stage #3: Supernatural Aid

Some heroes respond to the call immediately. They are then guided along the path of adventure by a supernatural helper , as part of their first steps along the hero-journey. This helper is the personification of destiny. Often, this figure takes the form of an old man or old woman, like the fairy godmother, wizard, shepherd, smith, or woodsman figures of European fairy tales . But it can also take on other forms, like that of the Virgin Mary in many Christian saints legends from the Middle Ages. In the ancient mythology of Egypt and Greece, this figure was the boatman or ferryman, the conductor of souls to the afterworld—Thoth in Egyptian lore and Hermes-Mercury in Greek legend.

We see the supernatural aid theme as we return to the story of Kamar al-Zaman and Budur , another hero’s journey example. A shape-shifting figure named Maymunah crawls out of an old well in the tower where Kamar al-Zaman has been locked up by the sultan (the well symbolizes the unconscious and Maymunah the flowing up of unconscious thoughts into the realm of the conscious).

Finding the prince sleeping, she is awed by his physical beauty. Flying away, Maymunah encounters another supernatural being called Dahnash, who declares that he has just returned from China, where he has laid eyes on the most beautiful woman in the world—none other than Princess Budur. The two spirits argue about which royal youth is fairer. Each of them brings the other to their preferred candidate’s resting-place, but they cannot decide who is more beautiful unless they see them lying side-by-side.

Thus, these two otherworldly helpers begin the process of uniting the two fated youths , without either the prince or princess exerting any conscious will. The helpers are moving the hand of destiny.

Hero’s Journey Example, Departure Stage #4: Crossing the Threshold

With this aid and guidance in hand, the hero sets off on their adventure until they come to a point where they are further away from the world of comfort and familiarity than they have ever been before. Ahead of them lies the danger of the unknown. On an individual level, this aspect of the heroic monomyth parallels the dangers and uncertainties of growing out of childhood and away from the protection of one’s parents .

It is at this point that the hero meets the guardian of the threshold , who stands between the worlds of the known and the unknown. This guardian is often a fearsome and monstrous figure, who represents our fears of leaving our comfort zone and stepping out into the world beyond. The hero must overcome this obstacle, just as we all must overcome our fears of the unknown if we are to thrive and grow as human beings in the great adventure of life . Only those with competence and courage can overcome the danger.

The Greek god Pan is perhaps the best-known of this type of border guard in hero’s journey examples. He instilled a wild, irrational fear into those who dared to cross into his realm (this is where the word “panic” comes from). To some, Pan would frighten his victims to death. But to those who paid him proper respect and homage, Pan would bestow bounty and wisdom.

Hero’s Journey Example, Departure Stage #5: Belly of the Whale

Next comes one of the most potent symbols of the hero’s death and rebirth—the common motif of the hero being inside the belly of the whale . This belly symbolizes the womb (also a temple); the darkness within represents death; and the hero’s emergence parallels the act of birth (or rebirth).

The Greek hero Heracles sees the city of Troy being sacked by a monster that had been sent by the angry god of the sea, Poseidon. The king ties his daughter to the sea rocks as a sacrificial offering, hoping to appease the angry deity. Heracles agrees to rescue the girl and dives into the monster’s gaping mouth. He is digested, and manages to kill the beast by hacking his way out and emerging from the belly.

Other swallowing-and-reemerging motifs occur in mythological traditions across the world. The Irish hero Finn MacCool is swallowed by a monster known as a peist ; in the German fairy tale of Red Ridinghood, the heroine is devoured by a wolf; on the other side of the world, in Polynesia, Maui is consumed by his great-great-grandmother.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read read the rest of the world's best summary of "the hero with a thousand faces" at shortform . learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less ..

Here's what you'll find in our full The Hero with a Thousand Faces summary :

- How the Hero's Journey reappears hundreds of times in different cultures and ages

- How we attach our psychology to heroes, and how they help embolden us in our lives

- Why stories and mythology are so important, even in today's world

- ← Extremistan: Why Improbable Events Have a Huge Impact

- Supernatural Aid: The Hero’s Journey, Stage 3 (Explained) →

Amanda Penn

Amanda Penn is a writer and reading specialist. She’s published dozens of articles and book reviews spanning a wide range of topics, including health, relationships, psychology, science, and much more. Amanda was a Fulbright Scholar and has taught in schools in the US and South Africa. Amanda received her Master's Degree in Education from the University of Pennsylvania.

You May Also Like

How to Start Meditating: Tips for Beginners

How Regulatory Agencies Enabled Racism in Housing

Edward Snowden: Stolen NSA Files Prove His Story

Karma by Sadhguru: Insights on Karma from a Yogi

The Legacy of the United States Caste System

What Is the Hero Archetype—and Who Is His Evil Twin?

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Libraries Home

- Research Guides

Classical Mythology - Greek

- The Hero's Journey

- Reference Resources

Electronic Resources

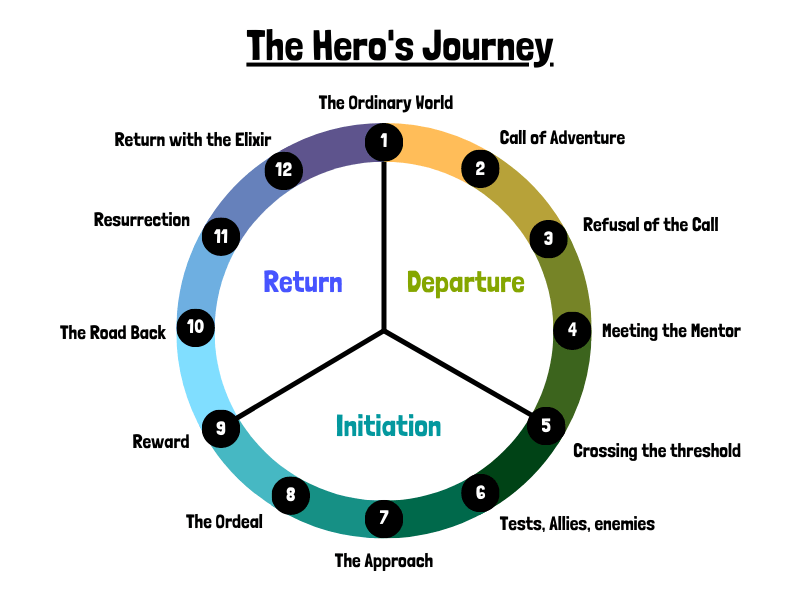

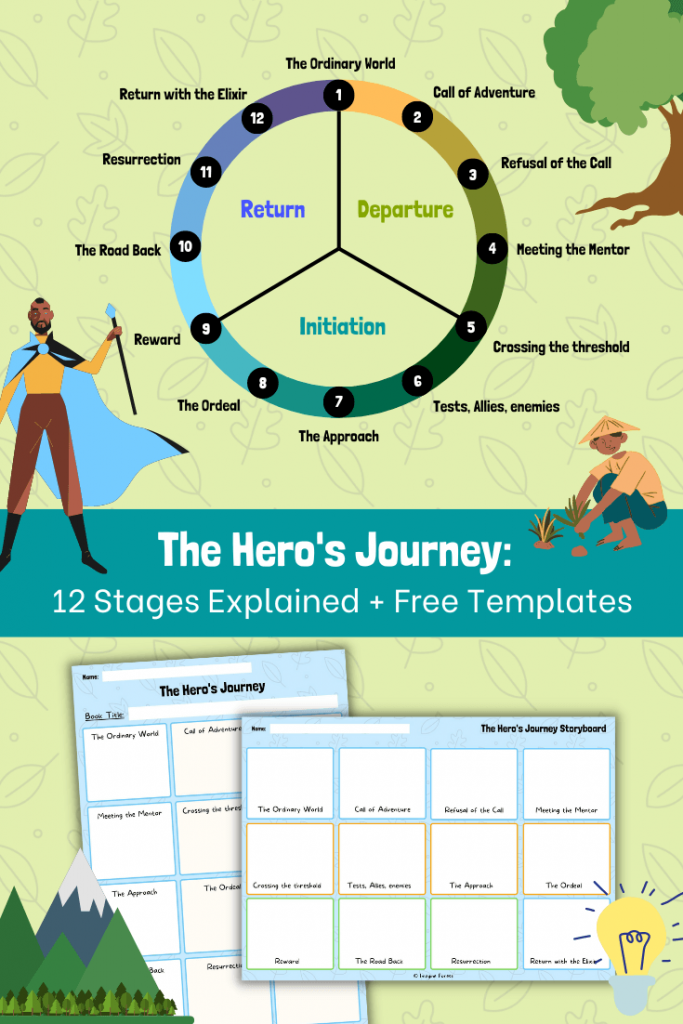

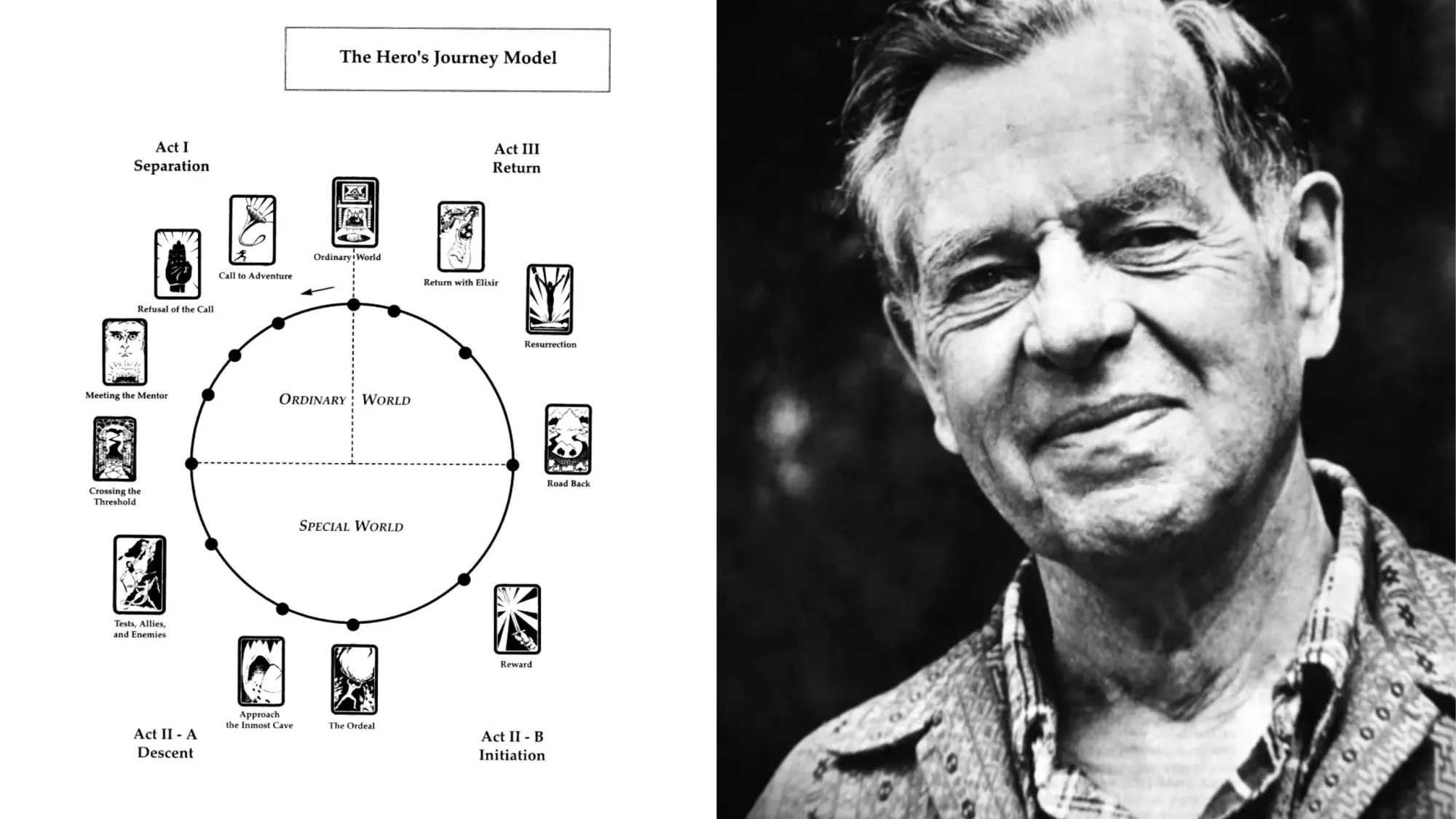

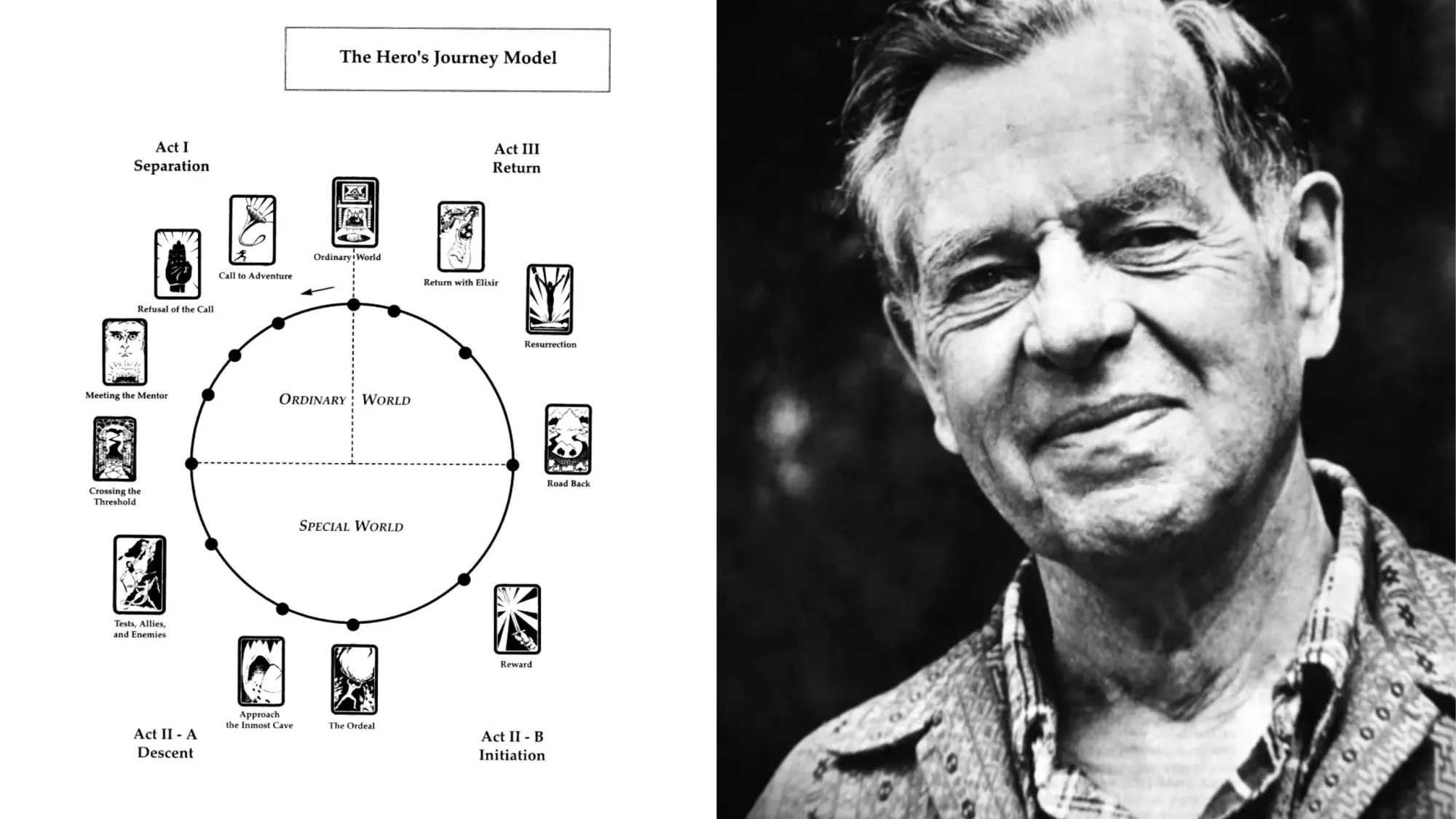

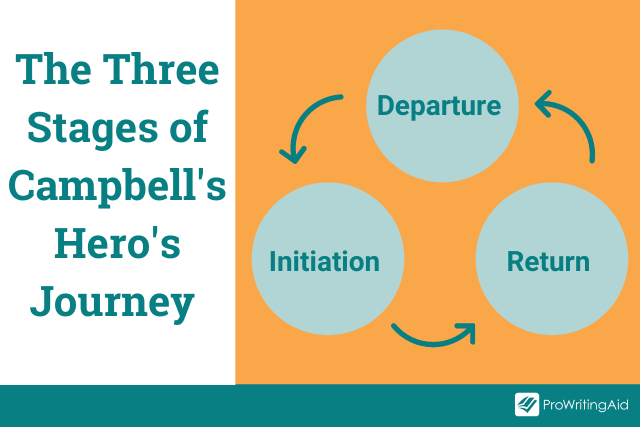

The monomyth, or Hero’s Journey, was first recognized as a pattern in mythology by Joseph Campbell, who noticed that heroes in mythology typically go through the same 17 stages in their journey toward hero-dom.

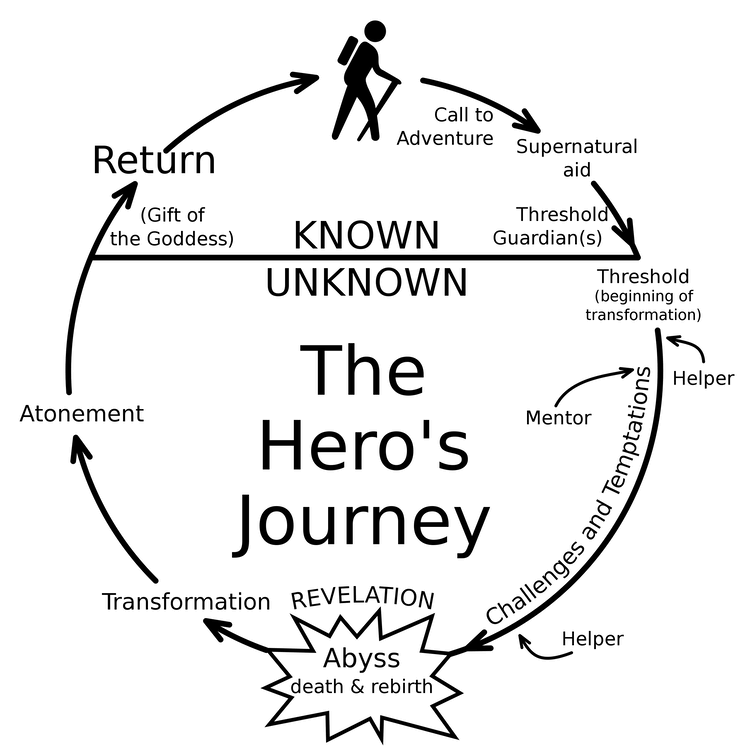

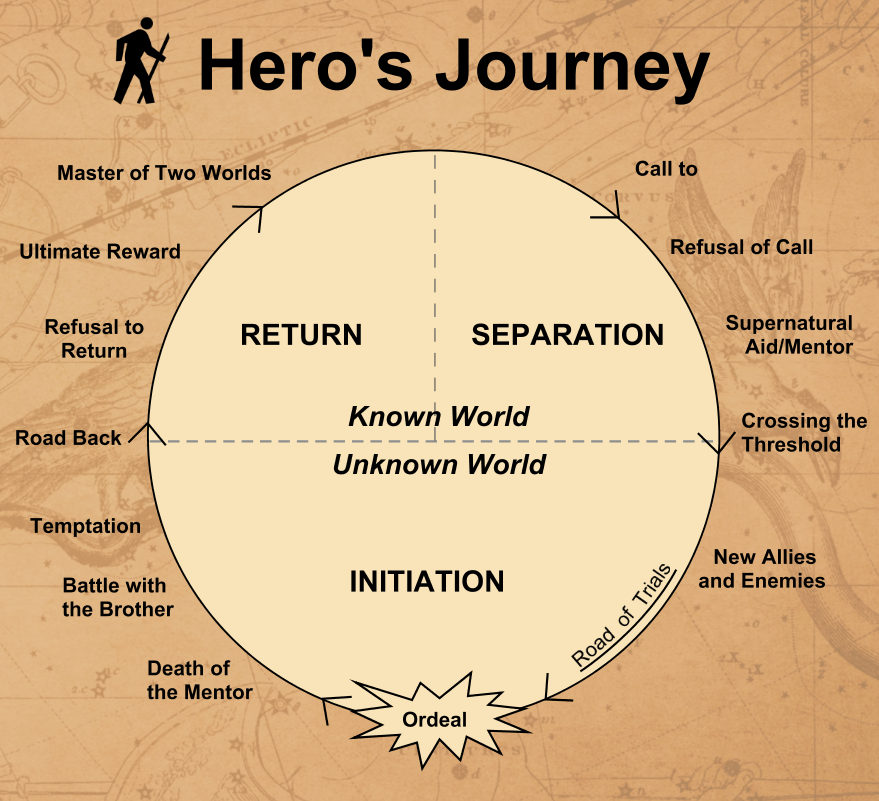

The Hero’s Journey follows a path which is represented by a circle in which the hero travels into the unknown and is faced with many trials only to come full circle, returning to the known world. The path includes but is not limited to the following segments:

- Call to Adventure

- Supernatural Aid

- Cross the Threshold into the Unknown

- Mentors / Helpers

- Transformation

- Return from the Unknown

- Return to a Normal Life

A popular interpretation of the Hero’s Journey is Luke Skywalker’s journey toward Jedi Knighthood in the original Star Wars films. George Lucas found tremendous inspiration in the monomyth when creating the original trilogy. Fans will notice how closely the films mirror the monomyth pattern. Luke’s call to the rebellion, his aid of the force, the assortment of guides and companions, the many trials he faces along the way, his confrontation with Vader, the temptations of power, the destruction of the Empire, and the freedom of the galaxy from the Emperor’s evil tyranny. Several documentaries and books have been published on Campbell’s influence on the Star Wars films.

Model of the Monomyth

The Monomyth, or Hero's Journey, is a path commonly represented by a circle. Along this path the hero encounters numerous stages which he must overcome in order to progress.

Library Print & Media

- The Mythology of Star Wars An interview with George Lucas about the influence of his mentor, Joseph Campbell and his explanation of the Hero’s Journey. Available through Films on Demand.

- Wikipedia - Monomyth

- << Previous: Electronic Resources

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 10:18 AM

- URL: https://guides.stlcc.edu/classical_mythology

- My Library Account

- Articles, Books & More

- Course Reserves

- Site Search

- Advanced Search

- Sac State Library

- Research Guides

World Mythology and Folklore

- The Monomyth; the Hero's Journey

- Finding Books

- Journal Articles and Databases

- General Mythology Websites

- Characters and Places

- Art, Literature, Music

- Classical Mythology (Greece and Rome)

- Africa (includes Egypt)

- The Americas

- Asia and the Middle East

- Australia and Oceania

- Writing Guides and Citing Sources

The Monomyth or the Hero's Journey

"In narratology and comparative mythology , the monomyth, or the hero's journey, is the common template of a broad category of tales that involve a hero who goes on an adventure , and in a decisive crisis wins a victory , and then comes home changed or transformed." ("Monomyth." Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia . Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 15 February 2016. Web. 12 April 2016. < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monomyth>

Wikipedia has an excellent article which provides an overview of the Monomyth or the Hero's Journey. Click here to read the complete article.Read the Wikipedia article here :

This image outlines the basic path of the Monomyth , or " Hero's Journey " and is loosely based on Campbell (1949) and (more directly?) on Christopher Vogler, "A Practical Guide to Joseph Cambell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces" (seven-page-memo 1985).

Campbell's original diagram was labelled "The adventure can be summarised in the following diagram:" and had the following items:

- Call to Adventure

- Threshold of Adventure: Threshold crossing; Brother-battle; Dragon-battle; Dismemberment; Crucifixion; Abduction; Night-sea journey; Wonder journey; Whale's belly

- 1. Sacred Marriage; 2. Father Atonement; 3. Apotheosis; 4. Elixir Theft

- Threshold of Adventure: Return, Resurrection, Rescue, Threshold

This image is from Wikipedia article on MONOMYTH (4/11/2016) : scan from an unknown publication by an anonymous poster, in a thread, gave permission to use it. Re-drawn by User:Slashme

Books and Websites

- The American monomyth Available at 2 SOUTH E 169.12 J48 1988

- The hero's journey : Joseph Campbell on his life and work ; collected works of Joseph Campbell Available at 2 SOUTH BL 303.6 C35 A3 1999

- The hero : myth/image/symbol Available at 2 SOUTH BL 815 H47 N67 1990

- The hero with a thousand faces Available at 2 SOUTH BL 313 C28 1972

- The myth of the birth of the hero, and other writings Available at 2 SOUTH BL 313 R263

- The Myth of the Birth of the Hero, by Otto Rank From Sacred Texts website

- The mythological foundations of the epic genre : the solar voyage as the hero's journey Available at 3 NORTH PN 56 E65 F69 1989

- Mythology : the voyage of the hero Available at 2 SOUTH BL 311 L326 1998, ebook also

- Outlaw heroes in myth and history e-book

- The power of myth by Joseph Campbell Available at 2 SOUTH BL 304 C36 1988

- Superheroes and gods : a comparative study from Babylonia to Batman Available at 2 SOUTH BL 325 H46 L63 2008

- << Previous: Characters and Places

- Next: Art, Literature, Music >>

- Last Updated: Jul 12, 2023 2:54 PM

- URL: https://csus.libguides.com/c.php?g=768332

What is Hercules Hero’s Journey? 12 Stages

Wondering how Joseph Campbell ’s monomyth narrative structure applies to this well-known Greek myth ? Read on to discover the Hercules hero’s journey .

Hercules – also known as Heracles – and his twelve labors, are one of the staples of Greek mythology . The story has even been transformed into a Disney movie and plenty of big-budget action-adventure fantasy films over the years.

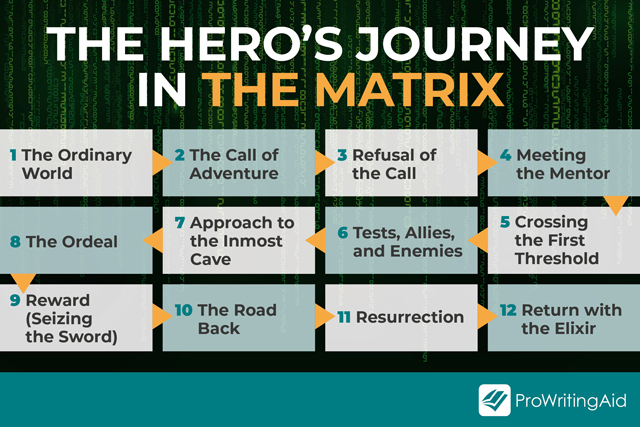

The hero’s journey structure can be clearly identified in the tale. We can see the twelve stages, from The Ordinary World through to The Return with the Elixir in Hercules’s story, as his adventures take him from an ordinary town in Greece to the Temple of Zeus.

Return with Elixir: Hercules Becomes a God-Like Hero

Stages of the hero’s journey in hercules.

To prepare this analysis, we’ve read through many of the best books about greek mythology and also applied the hero’s journey framework to the legend of Hercules .

The Ordinary World: Hercules in the Human World

Hercules , the demigod son of Zeus, grew into a mighty warrior in the human world. He was well-respected and generally adored in his hometown of Thebes in Greece. Despite his lofty heritage, Hercules was a mortal. This background may not scream ‘ordinary world’, but it was business as usual for Hercules . You can also check out our guide on hero’s journey archetypes .

The Call to Adventure: Hercules Goes To War

Now for the next stage of the hero’s journey . Every year the people of Thebes were compelled to pay homage to the king of the Minyans, Erginus. Hercules isn’t happy about this state of affairs and, encountering some Minyans by chance, takes matters into his own hands, cutting off their noses, ears, and hands.

King Erginus is not impressed and subsequently declares war on Thebes – and Hercules in particular. The king’s army is no match for the demigod, though, and he dispatches it in short order. As a symbol of gratitude, the king of Thebes allows Hercules to marry his daughter, Megara.

Refusal of the Call: Hercules Goes Insane

Hercules happens to be Zeus’s illegitimate son, and this infuriates the jealous Hera, Zeus’s wife. She decides to drive him insane, and is so successful in her endeavors that Hercules goes seriously off the rails, even killing his three children.

For some, this represents the initial refusal stage of the hero’s journey as it represents Hercules’s refusal to take on the role of hero, becoming the dark reflection of the hero, instead. Even if he had a little help with this decision.

Meeting the Mentor: Hercules Visits the Oracle of Delphi

Hercules , recovering from the temporary insanity, is devasted at what he has done. He decides that a visit to the Oracle of Delphi is needed to help him figure out what to do. The Oracle was a high priestess, serving in the sanctuary of Apollo, with powerful prophetic abilities.

Here, the Oracle advises him that the best way to atone for his terrible actions is to serve King Eurystheus.

Crossing the First Threshold: Hercules Undertakes Ten Labors

King Eurystheus accepts Hercules’s service offer but tells him he’ll need to undertake ten labors successfully. And that’s not a typo; there were initially ten rather than twelve labors. Hercules agrees – he is the son of Zeus, after all, so he has a level of confidence that we mere mortals may struggle to muster when faced with ten near-impossible endeavors.

Tests and Meeting Allies and Enemies: Hercules Meets Athena and Chiron

Hercules completes nine of the ten tasks. These missions include the Nemean Lion’s slaying, the Hydra’s vanquishing, capturing the Cretan Bull, and retrieving Hippolyte’s belt.

Some of the allies that Hercules meets on his adventures are Athena and the centaur Chiron, but it wasn’t all plain sailing, even with a ton of supernatural aid. The Greek god Poseidon’s sons and Sarpedon (another of Zeus’s offspring) were just a few of the characters that cause trouble for the erstwhile hero during his quest. But being Hercules , he vanquishes them all.

Approaching the Inmost Cave: Hercules Travels to The Edge of The World

For his tenth labor, Hercules has to travel to the very edge of the world, Erytheia, sailing across the Atlantic Ocean to do so. His mission is to retrieve the Red Cattle of Geryon. This part of the hero’s journey concerns the approach to the inmost cave.

According to Joseph Campbell , who wrote widely on this structure , this part of the journey represents a pause before a shift: the hero’s mindset may change. He or she may be approaching unchartered territory, either physically or spiritually, and must draw on new energy to continue.

The Ordeal: Hercules Recovers the Golden Apples of Hesperides

Those allies we mentioned above who gave Hercules a helping hand in his quest? King Eurystheus wasn’t best pleased with the intervention and stated that two of the ten labors that had been assigned were, therefore, invalid. The king subsequently set two additional tasks – bringing the total to twelve labors.

These extra missions were to bring back the golden apples of Hesperides and to fetch Cerberus from Hades. When Hercules successfully completes these two extra tasks, he becomes a bona fide Greek hero.

The Reward: Hercules Enters Olympus

It was never about treasure. By completing the twelve labors, Hercules is seen as atoning for the murder of his children and is now ready to join the godly world of his father in Olympus . But the hero’s journey doesn’t end there…

The Road Back: Hercules Returns to Earth

According to the Disney version of this Greek myth , Hercules isn’t satisfied with life in Olympus and returns to the ordinary world to live as a mortal with his beloved Meg (Megara). However, this isn’t exactly what happens, according to Greek mythology .

In the original legend, Hercules gives his wife to his friend Iolaus (okaaaay) and decides to live out his life as a heroic wanderer on Earth.

The Resurrection: Hercules is Reborn Immortal

Zeus granted Hercules immortality after successfully undertaking his twelve labors. According to some versions of the tale, this happened immediately after he returned from Hades with Cerberus in tow, and in others, it occurred at a later point. Either way, Hercules’s rebirth as an immortal is clearly the Resurrection stage of his journey .

As well as gaining God status and access to Mount Olympus, Hercules is now able to use the lessons he has learned throughout the hero’s journey to heal his past wounds and be a true hero. He is triumphant in every sense of the word, has atoned, and gained spiritual freedom.

Hero’s Journey Archetypes

When it comes to main characters, there are several archetypes. Hercules is generally considered an example of the Warrior archetype, as he primarily uses his physical skills and strength to overcome challenges and trials.

However, the character in Disney’s Hercules can be categorized differently. In Disney’s retelling of the tale, Hercules is cast in the Orphan role, cast adrift in the Ordinary World and needing to discover himself and his powers to gain fulfillment. The role of the hero does not sit quite comfortably at first; think Peter Parker in Spiderman , another Orphan archetype.

This shift of Hercules’s character from Warrior to Orphan archetype tells an interesting story about general cultural shifts that have occurred over time and the nature of our understanding of the ‘hero’ role and its mentality.

If you enjoyed this analysis, check out our guide to movies that follow the hero’s journey .

- Story Writing Guides

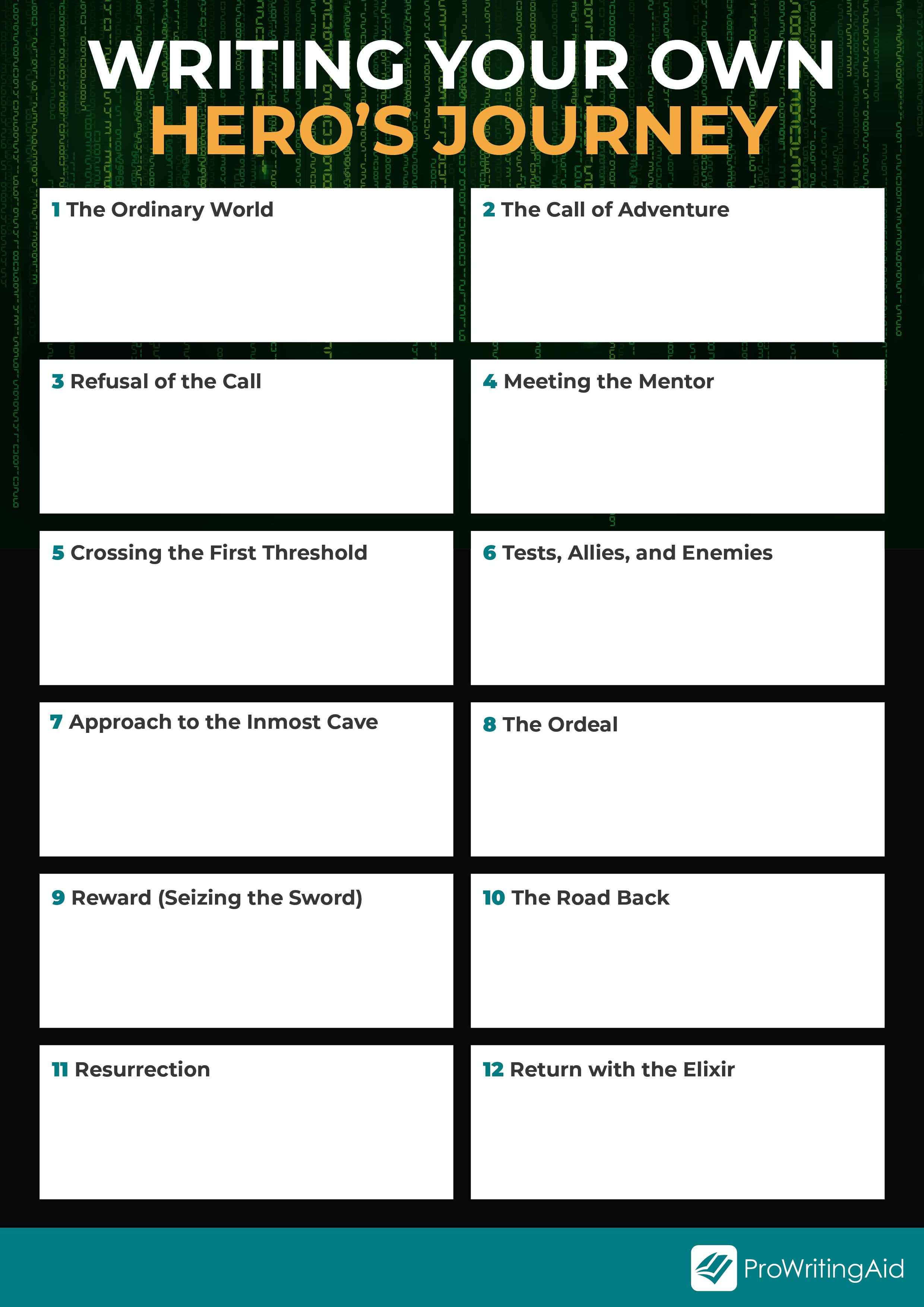

12 Hero’s Journey Stages Explained (+ Free Templates)

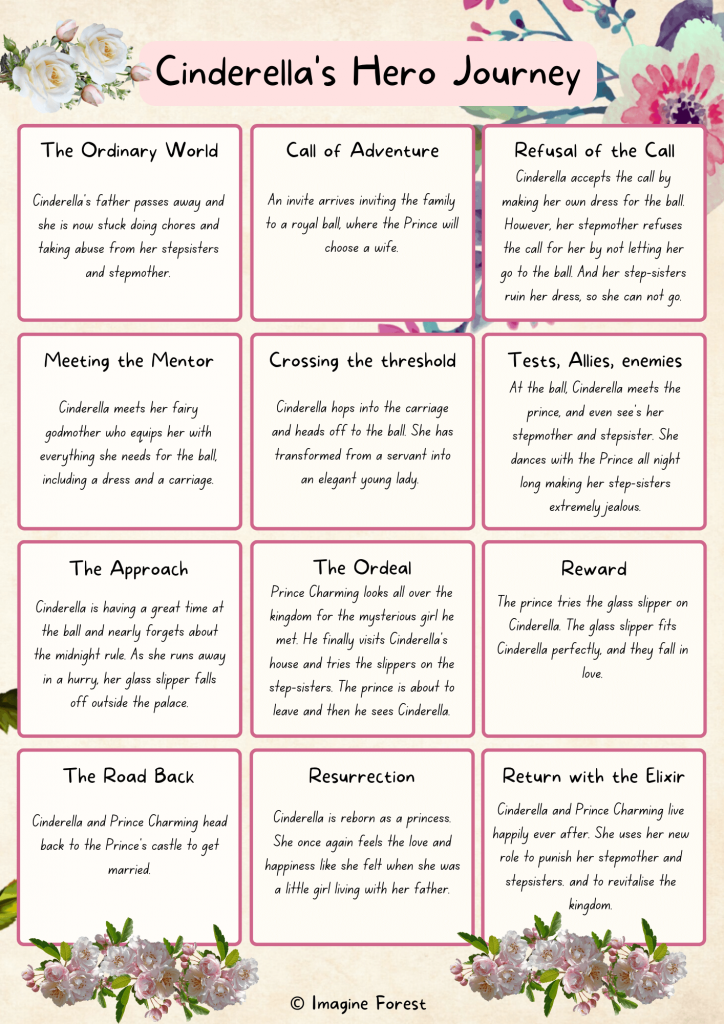

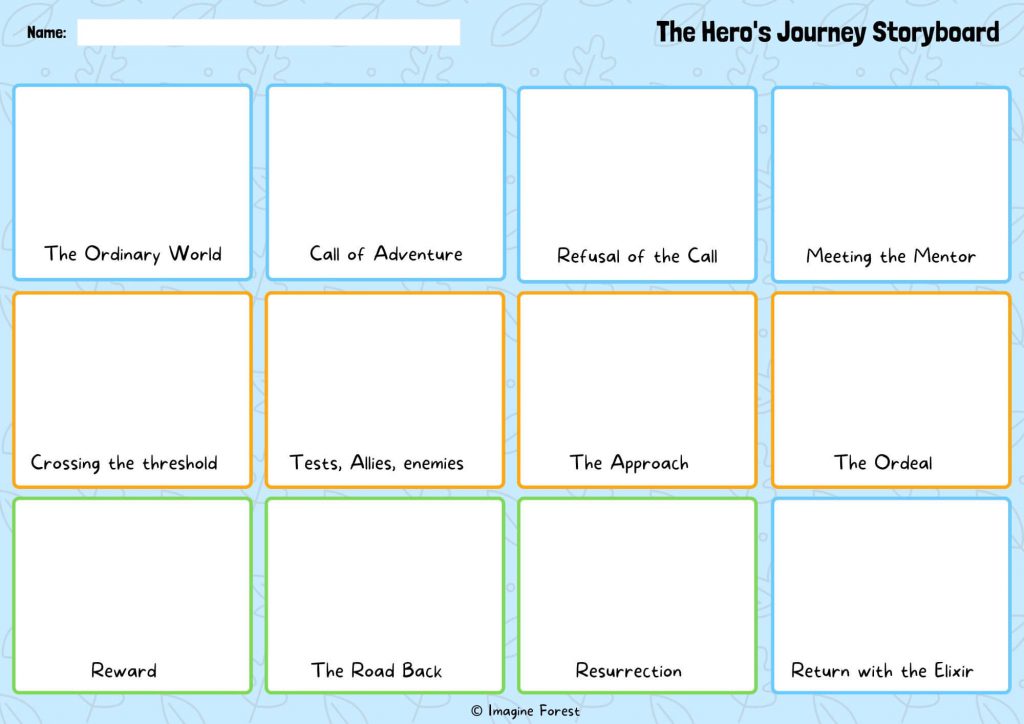

From zero to hero, the hero’s journey is a popular character development arc used in many stories. In today’s post, we will explain the 12 hero’s journey stages, along with the simple example of Cinderella.

The Hero’s Journey was originally formulated by American writer Joseph Campbell to describe the typical character arc of many classic stories, particularly in the context of mythology and folklore. The original hero’s journey contained 17 steps. Although the hero’s journey has been adapted since then for use in modern fiction, the concept is not limited to literature. It can be applied to any story, video game, film or even music that features an archetypal hero who undergoes a transformation. Common examples of the hero’s journey in popular works include Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, The Hunger Games and Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.

- What is the hero's journey?

Stage 1: The Ordinary World

Stage 2: call of adventure, stage 3: refusal of the call, stage 4: meeting the mentor, stage 5: crossing the threshold, stage 6: tests, allies, enemies, stage 7: the approach, stage 8: the ordeal, stage 9: reward, stage 10: the road back, stage 11: resurrection, stage 12: return with the elixir, cinderella example, campbell’s 17-step journey, leeming’s 8-step journey, cousineau’s 8-step journey.

- Free Hero's Journey Templates

What is the hero’s journey?

The hero’s journey, also known as the monomyth, is a character arc used in many stories. The idea behind it is that heroes undergo a journey that leads them to find their true selves. This is often represented in a series of stages. There are typically 12 stages to the hero’s journey. Each stage represents a change in the hero’s mindset or attitude, which is triggered by an external or internal event. These events cause the hero to overcome a challenge, reach a threshold, and then return to a normal life.

The hero’s journey is a powerful tool for understanding your characters. It can help you decide who they are, what they want, where they came from, and how they will change over time. It can be used to

- Understand the challenges your characters will face

- Understand how your characters react to those challenges

- Help develop your characters’ traits and relationships

In this post, we will explain each stage of the hero’s journey, using the example of Cinderella.

You might also be interested in our post on the story mountain or this guide on how to outline a book .

12 Hero’s Journey Stages

The archetypal hero’s journey contains 12 stages and was created by Christopher Vogler. These steps take your main character through an epic struggle that leads to their ultimate triumph or demise. While these steps may seem formulaic at first glance, they actually form a very flexible structure. The hero’s journey is about transformation, not perfection.

Your hero starts out in the ordinary world. He or she is just like every other person in their environment, doing things that are normal for them and experiencing the same struggles and challenges as everyone else. In the ordinary world, the hero feels stuck and confused, so he or she goes on a quest to find a way out of this predicament.

Example: Cinderella’s father passes away and she is now stuck doing chores and taking abuse from her stepsisters and stepmother.

The hero gets his or her first taste of adventure when the call comes. This could be in the form of an encounter with a stranger or someone they know who encourages them to take a leap of faith. This encounter is typically an accident, a series of coincidences that put the hero in the right place at the right time.

Example: An invite arrives inviting the family to a royal ball where the Prince will choose a wife.

Some people will refuse to leave their safe surroundings and live by their own rules. The hero has to overcome the negative influences in order to hear the call again. They also have to deal with any personal doubts that arise from thinking too much about the potential dangers involved in the quest. It is common for the hero to deny their own abilities in this stage and to lack confidence in themselves.

Example: Cinderella accepts the call by making her own dress for the ball. However, her stepmother refuses the call for her by not letting her go to the ball. And her step-sisters ruin her dress, so she can not go.

After hearing the call, the hero begins a relationship with a mentor who helps them learn about themselves and the world. In some cases, the mentor may be someone the hero already knows. The mentor is usually someone who is well-versed in the knowledge that the hero needs to acquire, but who does not judge the hero for their lack of experience.

Example: Cinderella meets her fairy godmother who equips her with everything she needs for the ball, including a dress and a carriage.

The hero leaves their old life behind and enters the unfamiliar new world. The crossing of the threshold symbolises leaving their old self behind and becoming a new person. Sometimes this can include learning a new skill or changing their physical appearance. It can also include a time of wandering, which is an essential part of the hero’s journey.

Example: Cinderella hops into the carriage and heads off to the ball. She has transformed from a servant into an elegant young lady.

As the hero goes on this journey, they will meet both allies (people who help the hero) and enemies (people who try to stop the hero). There will also be tests, where the hero is tempted to quit, turn back, or become discouraged. The hero must be persistent and resilient to overcome challenges.

Example: At the ball, Cinderella meets the prince, and even see’s her stepmother and stepsister. She dances with Prince all night long making her step-sisters extremely jealous.

The hero now reaches the destination of their journey, in some cases, this is a literal location, such as a cave or castle. It could also be metaphorical, such as the hero having an internal conflict or having to make a difficult decision. In either case, the hero has to confront their deepest fears in this stage with bravery. In some ways, this stage can mark the end of the hero’s journey because the hero must now face their darkest fears and bring them under control. If they do not do this, the hero could be defeated in the final battle and will fail the story.

Example: Cinderella is having a great time at the ball and nearly forgets about the midnight rule. As she runs away in a hurry, her glass slipper falls off outside the palace.

The hero has made it to the final challenge of their journey and now must face all odds and defeat their greatest adversary. Consider this the climax of the story. This could be in the form of a physical battle, a moral dilemma or even an emotional challenge. The hero will look to their allies or mentor for further support and guidance in this ordeal. Whatever happens in this stage could change the rest of the story, either for good or bad.

Example: Prince Charming looks all over the kingdom for the mysterious girl he met at the ball. He finally visits Cinderella’s house and tries the slippers on the step-sisters. The prince is about to leave and then he sees Cinderella in the corner cleaning.

When the hero has defeated the most powerful and dangerous of adversaries, they will receive their reward. This reward could be an object, a new relationship or even a new piece of knowledge. The reward, which typically comes as a result of the hero’s perseverance and hard work, signifies the end of their journey. Given that the hero has accomplished their goal and served their purpose, it is a time of great success and accomplishment.

Example: The prince tries the glass slipper on Cinderella. The glass slipper fits Cinderella perfectly, and they fall in love.

The journey is now complete, and the hero is now heading back home. As the hero considers their journey and reflects on the lessons they learned along the way, the road back is sometimes marked by a sense of nostalgia or even regret. As they must find their way back to the normal world and reintegrate into their former life, the hero may encounter additional difficulties or tests along the way. It is common for the hero to run into previous adversaries or challenges they believed they had overcome.

Example: Cinderella and Prince Charming head back to the Prince’s castle to get married.

The hero has one final battle to face. At this stage, the hero might have to fight to the death against a much more powerful foe. The hero might even be confronted with their own mortality or their greatest fear. This is usually when the hero’s true personality emerges. This stage is normally symbolised by the hero rising from the dark place and fighting back. This dark place could again be a physical location, such as the underground or a dark cave. It might even be a dark, mental state, such as depression. As the hero rises again, they might change physically or even experience an emotional transformation.

Example: Cinderella is reborn as a princess. She once again feels the love and happiness that she felt when she was a little girl living with her father.

At the end of the story, the hero returns to the ordinary world and shares the knowledge gained in their journey with their fellow man. This can be done by imparting some form of wisdom, an object of great value or by bringing about a social revolution. In all cases, the hero returns changed and often wiser.

Example: Cinderella and Prince Charming live happily ever after. She uses her new role to punish her stepmother and stepsisters and to revitalise the kingdom.

We have used the example of Cinderella in Vogler’s hero’s journey model below:

Below we have briefly explained the other variations of the hero’s journey arc.

The very first hero’s journey arc was created by Joseph Campbell in 1949. It contained the following 17 steps:

- The Call to Adventure: The hero receives a call or a reason to go on a journey.

- Refusal of the Call: The hero does not accept the quest. They worry about their own abilities or fear the journey itself.

- Supernatural Aid: Someone (the mentor) comes to help the hero and they have supernatural powers, which are usually magical.

- The Crossing of the First Threshold: A symbolic boundary is crossed by the hero, often after a test.

- Belly of the Whale: The point where the hero has the most difficulty making it through.

- The Road of Trials: In this step, the hero will be tempted and tested by the outside world, with a number of negative experiences.

- The Meeting with the Goddess: The hero meets someone who can give them the knowledge, power or even items for the journey ahead.

- Woman as the Temptress: The hero is tempted to go back home or return to their old ways.

- Atonement with the Father: The hero has to make amends for any wrongdoings they may have done in the past. They need to confront whatever holds them back.

- Apotheosis: The hero gains some powerful knowledge or grows to a higher level.

- The Ultimate Boon: The ultimate boon is the reward for completing all the trials of the quest. The hero achieves their ultimate goal and feels powerful.

- Refusal of the Return: After collecting their reward, the hero refuses to return to normal life. They want to continue living like gods.

- The Magic Flight: The hero escapes with the reward in hand.

- Rescue from Without: The hero has been hurt and needs help from their allies or guides.

- The Crossing of the Return Threshold: The hero must come back and learn to integrate with the ordinary world once again.

- Master of the Two Worlds: The hero shares their wisdom or gifts with the ordinary world. Learning to live in both worlds.

- Freedom to Live: The hero accepts the new version of themselves and lives happily without fear.

David Adams Leeming later adapted the hero’s journey based on his research of legendary heroes found in mythology. He noted the following steps as a pattern that all heroes in stories follow:

- Miraculous conception and birth: This is the first trauma that the hero has to deal with. The Hero is often an orphan or abandoned child and therefore faces many hardships early on in life.

- Initiation of the hero-child: The child faces their first major challenge. At this point, the challenge is normally won with assistance from someone else.

- Withdrawal from family or community: The hero runs away and is tempted by negative forces.

- Trial and quest: A quest finds the hero giving them an opportunity to prove themselves.

- Death: The hero fails and is left near death or actually does die.

- Descent into the underworld: The hero rises again from death or their near-death experience.

- Resurrection and rebirth: The hero learns from the errors of their way and is reborn into a better, wiser being.

- Ascension, apotheosis, and atonement: The hero gains some powerful knowledge or grows to a higher level (sometimes a god-like level).

In 1990, Phil Cousineau further adapted the hero’s journey by simplifying the steps from Campbell’s model and rearranging them slightly to suit his own findings of heroes in literature. Again Cousineau’s hero’s journey included 8 steps:

- The call to adventure: The hero must have a reason to go on an adventure.

- The road of trials: The hero undergoes a number of tests that help them to transform.

- The vision quest: Through the quest, the hero learns the errors of their ways and has a realisation of something.

- The meeting with the goddess: To help the hero someone helps them by giving them some knowledge, power or even items for the journey ahead.

- The boon: This is the reward for completing the journey.

- The magic flight: The hero must escape, as the reward is attached to something terrible.

- The return threshold: The hero must learn to live back in the ordinary world.

- The master of two worlds: The hero shares their knowledge with the ordinary world and learns to live in both worlds.

As you can see, every version of the hero’s journey is about the main character showing great levels of transformation. Their journey may start and end at the same location, but they have personally evolved as a character in your story. Once a weakling, they now possess the knowledge and skill set to protect their world if needed.

Free Hero’s Journey Templates

Use the free Hero’s journey templates below to practice the skills you learned in this guide! You can either draw or write notes in each of the scene boxes. Once the template is complete, you will have a better idea of how your main character or the hero of your story develops over time:

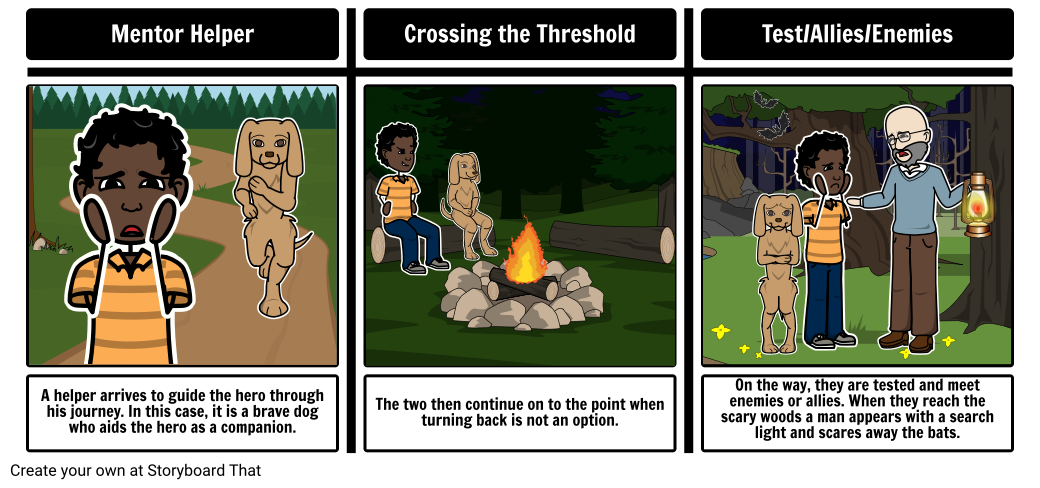

The storyboard template below is a great way to develop your main character and organise your story:

Did you find this guide on the hero’s journey stages useful? Let us know in the comments below.

Marty the wizard is the master of Imagine Forest. When he's not reading a ton of books or writing some of his own tales, he loves to be surrounded by the magical creatures that live in Imagine Forest. While living in his tree house he has devoted his time to helping children around the world with their writing skills and creativity.

Related Posts

Comments loading...

Holiday Savings

cui:common.components.upgradeModal.offerHeader_undefined

The hero's journey: a story structure as old as time, the hero's journey offers a powerful framework for creating quest-based stories emphasizing self-transformation..

Table of Contents

Holding out for a hero to take your story to the next level?

The Hero’s Journey might be just what you’ve been looking for. Created by Joseph Campbell, this narrative framework packs mythic storytelling into a series of steps across three acts, each representing a crucial phase in a character's transformative journey.

Challenge . Growth . Triumph .

Whether you're penning a novel, screenplay, or video game, The Hero’s Journey is a tried-and-tested blueprint for crafting epic stories that transcend time and culture. Let’s explore the steps together and kickstart your next masterpiece.

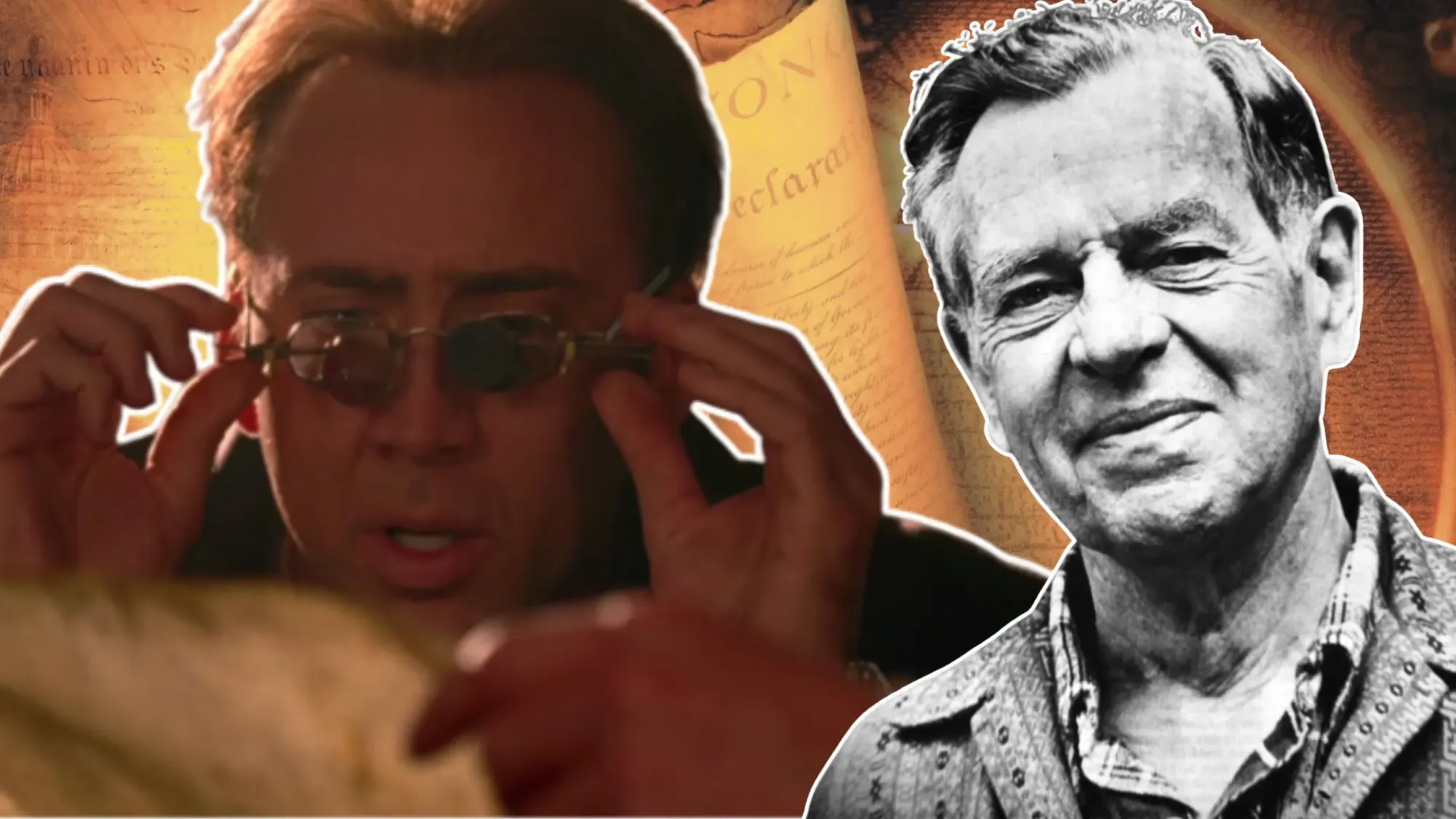

What is the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey is a famous template for storytelling, mapping a hero's adventurous quest through trials and tribulations to ultimate transformation.

What are the Origins of the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey was invented by Campbell in his seminal 1949 work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces , where he introduces the concept of the "monomyth."

A comparative mythologist by trade, Campbell studied myths from cultures around the world and identified a common pattern in their narratives. He proposed that all mythic narratives are variations of a single, universal story, structured around a hero's adventure, trials, and eventual triumph.

His work unveiled the archetypal hero’s path as a mirror to humanity’s commonly shared experiences and aspirations. It was subsequently named one of the All-Time 100 Nonfiction Books by TIME in 2011.

How are the Hero’s and Heroine’s Journeys Different?

While both the Hero's and Heroine's Journeys share the theme of transformation, they diverge in their focus and execution.

The Hero’s Journey, as outlined by Campbell, emphasizes external challenges and a quest for physical or metaphorical treasures. In contrast, Murdock's Heroine’s Journey, explores internal landscapes, focusing on personal reconciliation, emotional growth, and the path to self-actualization.

In short, heroes seek to conquer the world, while heroines seek to transform their own lives; but…

Twelve Steps of the Hero’s Journey

So influential was Campbell’s monomyth theory that it's been used as the basis for some of the largest franchises of our generation: The Lord of the Rings , Harry Potter ...and George Lucas even cited it as a direct influence on Star Wars .

There are, in fact, several variations of the Hero's Journey, which we discuss further below. But for this breakdown, we'll use the twelve-step version outlined by Christopher Vogler in his book, The Writer's Journey (seemingly now out of print, unfortunately).

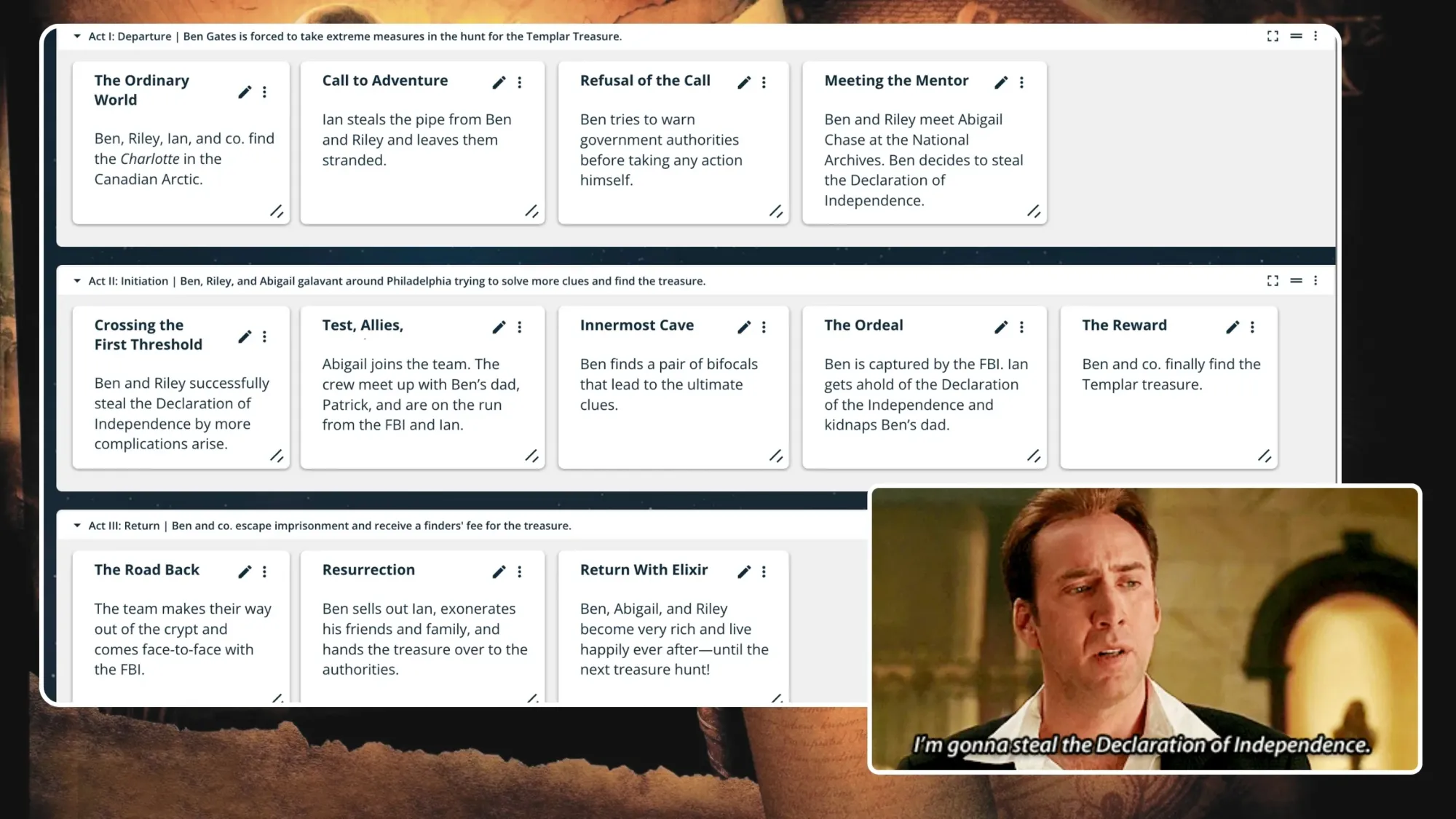

You probably already know the above stories pretty well so we’ll unpack the twelve steps of the Hero's Journey using Ben Gates’ journey in National Treasure as a case study—because what is more heroic than saving the Declaration of Independence from a bunch of goons?

Ye be warned: Spoilers ahead!

Act One: Departure

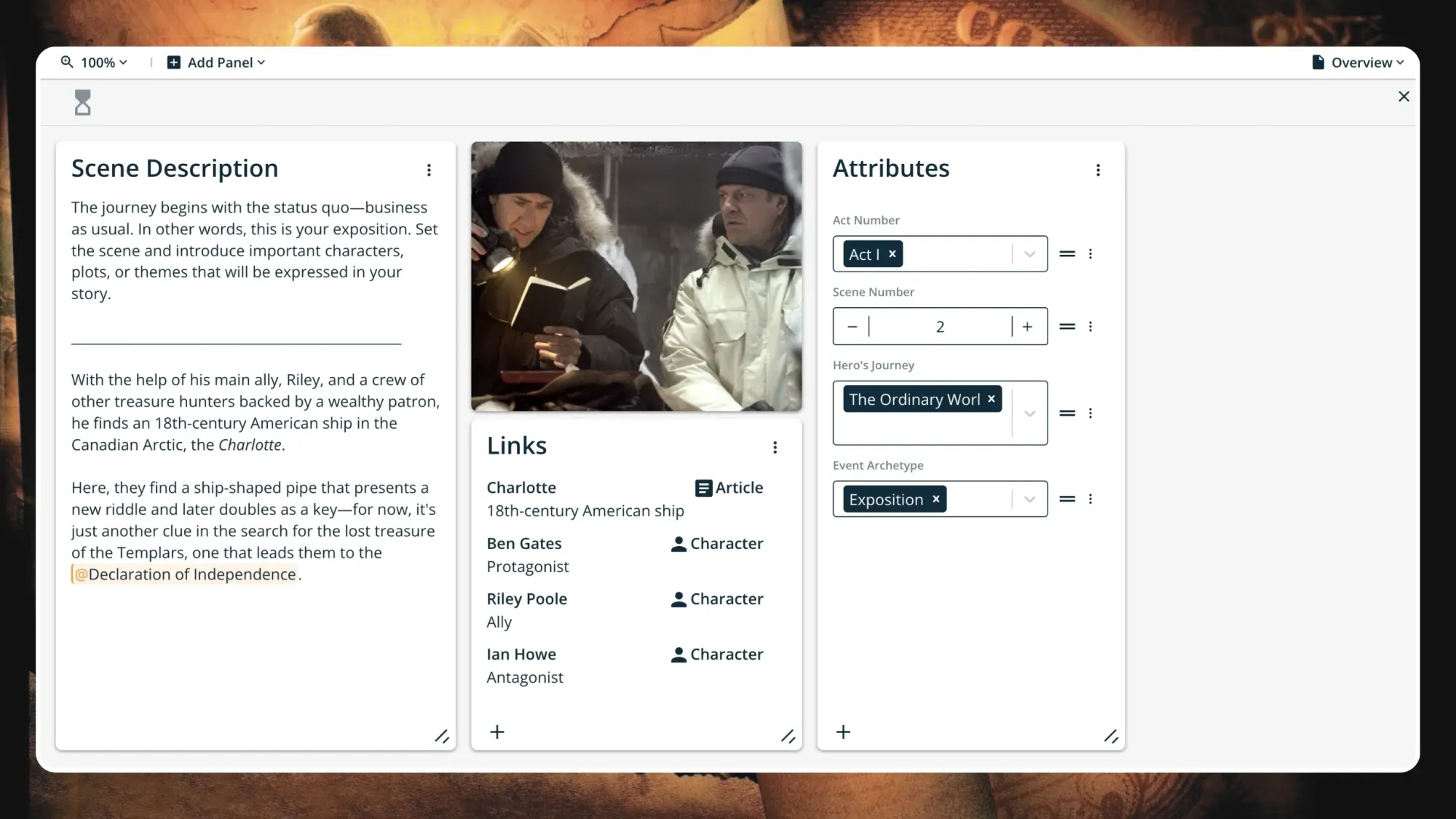

Step 1. the ordinary world.

The journey begins with the status quo—business as usual. We meet the hero and are introduced to the Known World they live in. In other words, this is your exposition, the starting stuff that establishes the story to come.

National Treasure begins in media res (preceded only by a short prologue), where we are given key information that introduces us to Ben Gates' world, who he is (a historian from a notorious family), what he does (treasure hunts), and why he's doing it (restoring his family's name).

With the help of his main ally, Riley, and a crew of other treasure hunters backed by a wealthy patron, he finds an 18th-century American ship in the Canadian Arctic, the Charlotte . Here, they find a ship-shaped pipe that presents a new riddle and later doubles as a key—for now, it's just another clue in the search for the lost treasure of the Templars, one that leads them to the Declaration of Independence.

Step 2. The Call to Adventure

The inciting incident takes place and the hero is called to act upon it. While they're still firmly in the Known World, the story kicks off and leaves the hero feeling out of balance. In other words, they are placed at a crossroads.

Ian (the wealthy patron of the Charlotte operation) steals the pipe from Ben and Riley and leaves them stranded. This is a key moment: Ian becomes the villain, Ben has now sufficiently lost his funding for this expedition, and if he decides to pursue the chase, he'll be up against extreme odds.

Step 3. Refusal of the Call

The hero hesitates and instead refuses their call to action. Following the call would mean making a conscious decision to break away from the status quo. Ahead lies danger, risk, and the unknown; but here and now, the hero is still in the safety and comfort of what they know.

Ben debates continuing the hunt for the Templar treasure. Before taking any action, he decides to try and warn the authorities: the FBI, Homeland Security, and the staff of the National Archives, where the Declaration of Independence is housed and monitored. Nobody will listen to him, and his family's notoriety doesn't help matters.

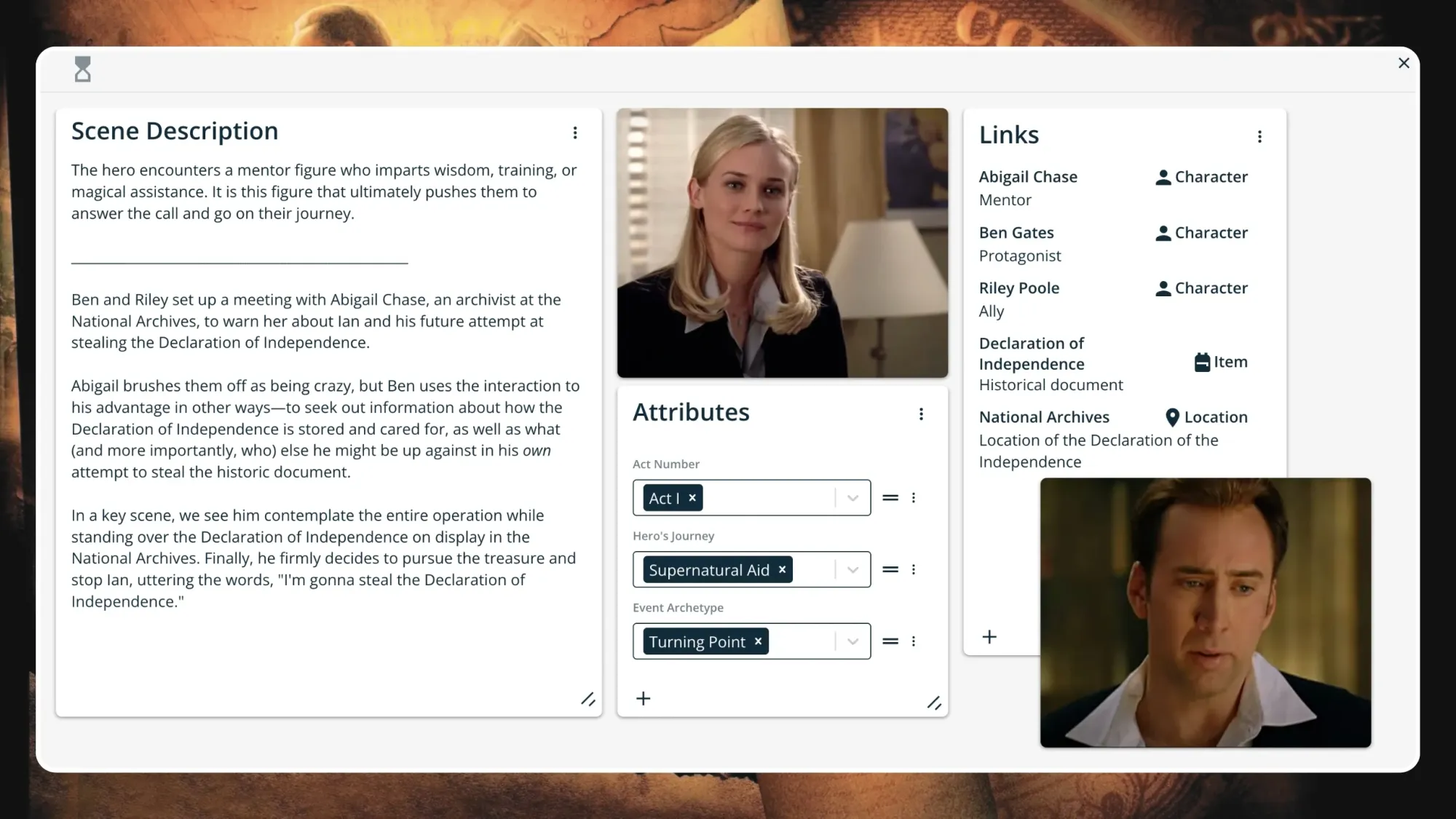

Step 4. Meeting the Mentor

The protagonist receives knowledge or motivation from a powerful or influential figure. This is a tactical move on the hero's part—remember that it was only the previous step in which they debated whether or not to jump headfirst into the unknown. By Meeting the Mentor, they can gain new information or insight, and better equip themselves for the journey they might to embark on.

Abigail, an archivist at the National Archives, brushes Ben and Riley off as being crazy, but Ben uses the interaction to his advantage in other ways—to seek out information about how the Declaration of Independence is stored and cared for, as well as what (and more importantly, who) else he might be up against in his own attempt to steal it.

In a key scene, we see him contemplate the entire operation while standing over the glass-encased Declaration of Independence. Finally, he firmly decides to pursue the treasure and stop Ian, uttering the famous line, "I'm gonna steal the Declaration of Independence."

Act Two: Initiation

Step 5. crossing the threshold.

The hero leaves the Known World to face the Unknown World. They are fully committed to the journey, with no way to turn back now. There may be a confrontation of some sort, and the stakes will be raised.

Ben and Riley infiltrate the National Archives during a gala and successfully steal the Declaration of Independence. But wait—it's not so easy. While stealing the Declaration of Independence, Abigail suspects something is up and Ben faces off against Ian.

Then, when trying to escape the building, Ben exits through the gift shop, where an attendant spots the document peeking out of his jacket. He is forced to pay for it, feigning that it's a replica—and because he doesn't have enough cash, he has to use his credit card, so there goes keeping his identity anonymous.

The game is afoot.

Step 6. Tests, Allies, Enemies

The hero explores the Unknown World. Now that they have firmly crossed the threshold from the Known World, the hero will face new challenges and possibly meet new enemies. They'll have to call upon their allies, new and old, in order to keep moving forward.

Abigail reluctantly joins the team under the agreement that she'll help handle the Declaration of Independence, given her background in document archiving and restoration. Ben and co. seek the aid of Ben's father, Patrick Gates, whom Ben has a strained relationship with thanks to years of failed treasure hunting that has created a rift between grandfather, father, and son. Finally, they travel around Philadelphia deciphering clues while avoiding both Ian and the FBI.

Step 7. Approach the Innermost Cave

The hero nears the goal of their quest, the reason they crossed the threshold in the first place. Here, they could be making plans, having new revelations, or gaining new skills. To put it in other familiar terms, this step would mark the moment just before the story's climax.

Ben uncovers a pivotal clue—or rather, he finds an essential item—a pair of bifocals with interchangeable lenses made by Benjamin Franklin. It is revealed that by switching through the various lenses, different messages will be revealed on the back of the Declaration of Independence. He's forced to split from Abigail and Riley, but Ben has never been closer to the treasure.

Step 8. The Ordeal

The hero faces a dire situation that changes how they view the world. All threads of the story come together at this pinnacle, the central crisis from which the hero will emerge unscathed or otherwise. The stakes will be at their absolute highest here.

Vogler details that in this stage, the hero will experience a "death," though it need not be literal. In your story, this could signify the end of something and the beginning of another, which could itself be figurative or literal. For example, a certain relationship could come to an end, or it could mean someone "stuck in their ways" opens up to a new perspective.

In National Treasure , The FBI captures Ben and Ian makes off with the Declaration of Independence—all hope feels lost. To add to it, Ian reveals that he's kidnapped Ben's father and threatens to take further action if Ben doesn't help solve the final clues and lead Ian to the treasure.

Ben escapes the FBI with Ian's help, reunites with Abigail and Riley, and leads everyone to an underground structure built below Trinity Church in New York City. Here, they manage to split from Ian once more, sending him on a goose chase to Boston with a false clue, and proceed further into the underground structure.

Though they haven't found the treasure just yet, being this far into the hunt proves to Ben's father, Patrick, that it's real enough. The two men share an emotional moment that validates what their family has been trying to do for generations.

Step 9. Reward

This is it, the moment the hero has been waiting for. They've survived "death," weathered the crisis of The Ordeal, and earned the Reward for which they went on this journey.

Now, free of Ian's clutches and with some light clue-solving, Ben, Abigail, Riley, and Patrick keep progressing through the underground structure and eventually find the Templar's treasure—it's real and more massive than they could have imagined. Everyone revels in their discovery while simultaneously looking for a way back out.

Act Three: Return

Step 10. the road back.

It's time for the journey to head towards its conclusion. The hero begins their return to the Known World and may face unexpected challenges. Whatever happens, the "why" remains paramount here (i.e. why the hero ultimately chose to embark on their journey).

This step marks a final turning point where they'll have to take action or make a decision to keep moving forward and be "reborn" back into the Known World.

Act Three of National Treasure is admittedly quite short. After finding the treasure, Ben and co. emerge from underground to face the FBI once more. Not much of a road to travel back here so much as a tunnel to scale in a crypt.

Step 11. Resurrection

The hero faces their ultimate challenge and emerges victorious, but forever changed. This step often requires a sacrifice of some sort, and having stepped into the role of The Hero™, they must answer to this.

Ben is given an ultimatum— somebody has to go to jail (on account of the whole stealing-the-Declaration-of-Independence thing). But, Ben also found a treasure worth millions of dollars and that has great value to several nations around the world, so that counts for something.

Ultimately, Ben sells Ian out, makes a deal to exonerate his friends and family, and willingly hands the treasure over to the authorities. Remember: he wanted to find the treasure, but his "why" was to restore the Gates family name, so he won regardless.

Step 12. Return With the Elixir

Finally, the hero returns home as a new version of themself, the elixir is shared amongst the people, and the journey is completed full circle.

The elixir, like many other elements of the hero's journey, can be literal or figurative. It can be a tangible thing, such as an actual elixir meant for some specific purpose, or it could be represented by an abstract concept such as hope, wisdom, or love.

Vogler notes that if the Hero's Journey results in a tragedy, the elixir can instead have an effect external to the story—meaning that it could be something meant to affect the audience and/or increase their awareness of the world.

In the final scene of National Treasure , we see Ben and Abigail walking the grounds of a massive estate. Riley pulls up in a fancy sports car and comments on how they could have gotten more money. They all chat about attending a museum exhibit in Cairo (Egypt).

In one scene, we're given a lot of closure: Ben and co. received a hefty payout for finding the treasure, Ben and Abigail are a couple now, and the treasure was rightfully spread to those it benefitted most—in this case, countries who were able to reunite with significant pieces of their history. Everyone's happy, none of them went to jail despite the serious crimes committed, and they're all a whole lot wealthier. Oh, Hollywood.

Variations of the Hero's Journey

Plot structure is important, but you don't need to follow it exactly; and, in fact, your story probably won't. Your version of the Hero's Journey might require more or fewer steps, or you might simply go off the beaten path for a few steps—and that's okay!

What follows are three additional versions of the Hero's Journey, which you may be more familiar with than Vogler's version presented above.

Dan Harmon's Story Circle (or, The Eight-Step Hero's Journey)

Screenwriter Dan Harmon has riffed on the Hero's Journey by creating a more compact version, the Story Circle —and it works especially well for shorter-format stories such as television episodes, which happens to be what Harmon writes.

The Story Circle comprises eight simple steps with a heavy emphasis on the hero's character arc:

- The hero is in a zone of comfort...

- But they want something.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation...

- And adapt to it by facing trials.

- They get what they want...

- But they pay a heavy price for it.

- They return to their familiar situation...

- Having changed.

You may have noticed, but there is a sort of rhythm here. The eight steps work well in four pairs, simplifying the core of the Hero's Journey even further:

- The hero is in a zone of comfort, but they want something.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation and have to adapt via new trials.

- They get what they want, but they pay a price for it.

- They return to their zone of comfort, forever changed.

If you're writing shorter fiction, such as a short story or novella, definitely check out the Story Circle. It's the Hero's Journey minus all the extraneous bells & whistles.

Ten-Step Hero's Journey

The ten-step Hero's Journey is similar to the twelve-step version we presented above. It includes most of the same steps except for Refusal of the Call and Meeting the Mentor, arguing that these steps aren't as essential to include; and, it moves Crossing the Threshold to the end of Act One and Reward to the end of Act Two.

- The Ordinary World

- The Call to Adventure

- Crossing the Threshold

- Tests, Allies, Enemies

- Approach the Innermost Cave

- The Road Back

- Resurrection

- Return with Elixir

We've previously written about the ten-step hero's journey in a series of essays separated by act: Act One (with a prologue), Act Two , and Act Three .

Twelve-Step Hero's Journey: Version Two

Again, the second version of the twelve-step hero's journey is very similar to the one above, save for a few changes, including in which story act certain steps appear.

This version skips The Ordinary World exposition and starts right at The Call to Adventure; then, the story ends with two new steps in place of Return With Elixir: The Return and The Freedom to Live.

- The Refusal of the Call

- Meeting the Mentor

- Test, Allies, Enemies

- Approaching the Innermost Cave

- The Resurrection

- The Return*

- The Freedom to Live*

In the final act of this version, there is more of a focus on an internal transformation for the hero. They experience a metamorphosis on their journey back to the Known World, return home changed, and go on to live a new life, uninhibited.

Seventeen-Step Hero's Journey

Finally, the granddaddy of heroic journeys: the seventeen-step Hero's Journey. This version includes a slew of extra steps your hero might face out in the expanse.

- Refusal of the Call

- Supernatural Aid (aka Meeting the Mentor)

- Belly of the Whale*: This added stage marks the hero's immediate descent into danger once they've crossed the threshold.

- Road of Trials (...with Allies, Tests, and Enemies)

- Meeting with the Goddess/God*: In this stage, the hero meets with a new advisor or powerful figure, who equips them with the knowledge or insight needed to keep progressing forward.

- Woman as Temptress (or simply, Temptation)*: Here, the hero is tempted, against their better judgment, to question themselves and their reason for being on the journey. They may feel insecure about something specific or have an exposed weakness that momentarily holds them back.

- Atonement with the Father (or, Catharthis)*: The hero faces their Temptation and moves beyond it, shedding free from all that holds them back.

- Apotheosis (aka The Ordeal)

- The Ultimate Boon (aka the Reward)

- Refusal of the Return*: The hero wonders if they even want to go back to their old life now that they've been forever changed.

- The Magic Flight*: Having decided to return to the Known World, the hero needs to actually find a way back.

- Rescue From Without*: Allies may come to the hero's rescue, helping them escape this bold, new world and return home.

- Crossing of the Return Threshold (aka The Return)

- Master of Two Worlds*: Very closely resembling The Resurrection stage in other variations, this stage signifies that the hero is quite literally a master of two worlds—The Known World and the Unknown World—having conquered each.

- Freedom to Live

Again, we skip the Ordinary World opening here. Additionally, Acts Two and Three look pretty different from what we've seen so far, although, the bones of the Hero's Journey structure remain.

The Eight Hero’s Journey Archetypes

The Hero is, understandably, the cornerstone of the Hero’s Journey, but they’re just one of eight key archetypes that make up this narrative framework.

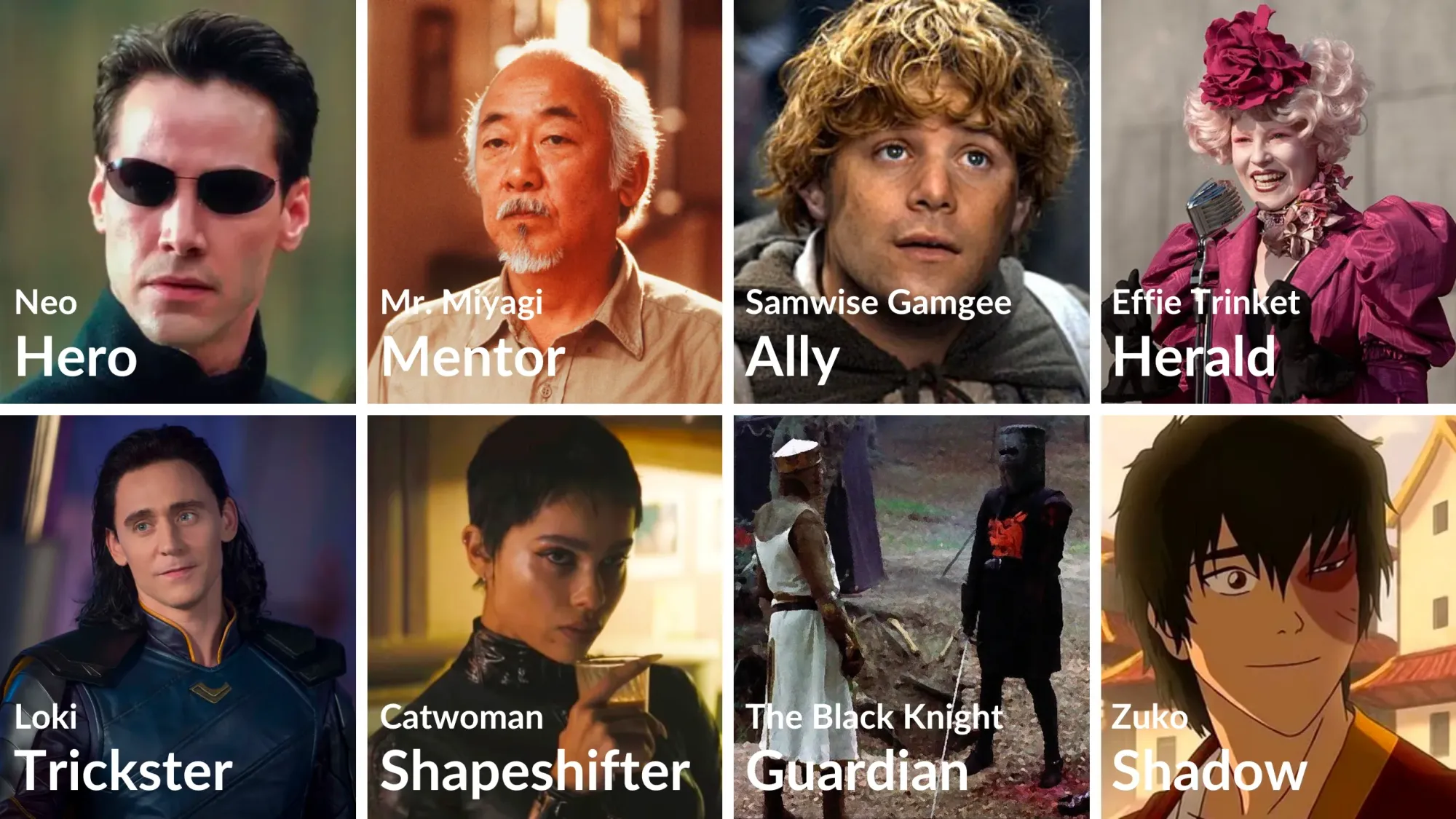

In The Writer's Journey , Vogler outlined seven of these archetypes, only excluding the Ally, which we've included below. Here’s a breakdown of all eight with examples:

1. The Hero

As outlined, the Hero is the protagonist who embarks on a transformative quest or journey. The challenges they overcome represent universal human struggles and triumphs.

Vogler assigned a "primary function" to each archetype—helpful for establishing their role in a story. The Hero's primary function is "to service and sacrifice."

Example: Neo from The Matrix , who evolves from a regular individual into the prophesied savior of humanity.

2. The Mentor

A wise guide offering knowledge, tools, and advice, Mentors help the Hero navigate the journey and discover their potential. Their primary function is "to guide."

Example: Mr. Miyagi from The Karate Kid imparts not only martial arts skills but invaluable life lessons to Daniel.

3. The Ally

Companions who support the Hero, Allies provide assistance, friendship, and moral support throughout the journey. They may also become a friends-to-lovers romantic partner.

Not included in Vogler's list is the Ally, though we'd argue they are essential nonetheless. Let's say their primary function is "to aid and support."

Example: Samwise Gamgee from Lord of the Rings , a loyal friend and steadfast supporter of Frodo.

4. The Herald

The Herald acts as a catalyst to initiate the Hero's Journey, often presenting a challenge or calling the hero to adventure. Their primary function is "to warn or challenge."

Example: Effie Trinket from The Hunger Games , whose selection at the Reaping sets Katniss’s journey into motion.

5. The Trickster

A character who brings humor and unpredictability, challenges conventions, and offers alternative perspectives or solutions. Their primary function is "to disrupt."

Example: Loki from Norse mythology exemplifies the trickster, with his cunning and chaotic influence.

6. The Shapeshifter

Ambiguous figures whose allegiance and intentions are uncertain. They may be a friend one moment and a foe the next. Their primary function is "to question and deceive."

Example: Catwoman from the Batman universe often blurs the line between ally and adversary, slinking between both roles with glee.

7. The Guardian

Protectors of important thresholds, Guardians challenge or test the Hero, serving as obstacles to overcome or lessons to be learned. Their primary function is "to test."

Example: The Black Knight in Monty Python and the Holy Grail literally bellows “None shall pass!”—a quintessential ( but not very effective ) Guardian.

8. The Shadow

Represents the Hero's inner conflict or an antagonist, often embodying the darker aspects of the hero or their opposition. Their primary function is "to destroy."

Example: Zuko from Avatar: The Last Airbender; initially an adversary, his journey parallels the Hero’s path of transformation.

While your story does not have to use all of the archetypes, they can help you develop your characters and visualize how they interact with one another—especially the Hero.

For example, take your hero and place them in the center of a blank worksheet, then write down your other major characters in a circle around them and determine who best fits into which archetype. Who challenges your hero? Who tricks them? Who guides them? And so on...

Stories that Use the Hero’s Journey

Not a fan of saving the Declaration of Independence? Check out these alternative examples of the Hero’s Journey to get inspired:

- Epic of Gilgamesh : An ancient Mesopotamian epic poem thought to be one of the earliest examples of the Hero’s Journey (and one of the oldest recorded stories).

- The Lion King (1994): Simba's exile and return depict a tale of growth, responsibility, and reclaiming his rightful place as king.

- The Alchemist by Paolo Coehlo: Santiago's quest for treasure transforms into a journey of self-discovery and personal enlightenment.

- Coraline by Neil Gaiman: A young girl's adventure in a parallel world teaches her about courage, family, and appreciating her own reality.

- Kung Fu Panda (2008): Po's transformation from a clumsy panda to a skilled warrior perfectly exemplifies the Hero's Journey. Skadoosh!

The Hero's Journey is so generalized that it's ubiquitous. You can plop the plot of just about any quest-style narrative into its framework and say that the story follows the Hero's Journey. Try it out for yourself as an exercise in getting familiar with the method.

Will the Hero's Journey Work For You?

As renowned as it is, the Hero's Journey works best for the kinds of tales that inspired it: mythic stories.

Writers of speculative fiction may gravitate towards this method over others, especially those writing epic fantasy and science fiction (big, bold fantasy quests and grand space operas come to mind).

The stories we tell today are vast and varied, and they stretch far beyond the dealings of deities, saving kingdoms, or acquiring some fabled "elixir." While that may have worked for Gilgamesh a few thousand years ago, it's not always representative of our lived experiences here and now.

If you decide to give the Hero's Journey a go, we encourage you to make it your own! The pieces of your plot don't have to neatly fit into the structure, but you can certainly make a strong start on mapping out your story.

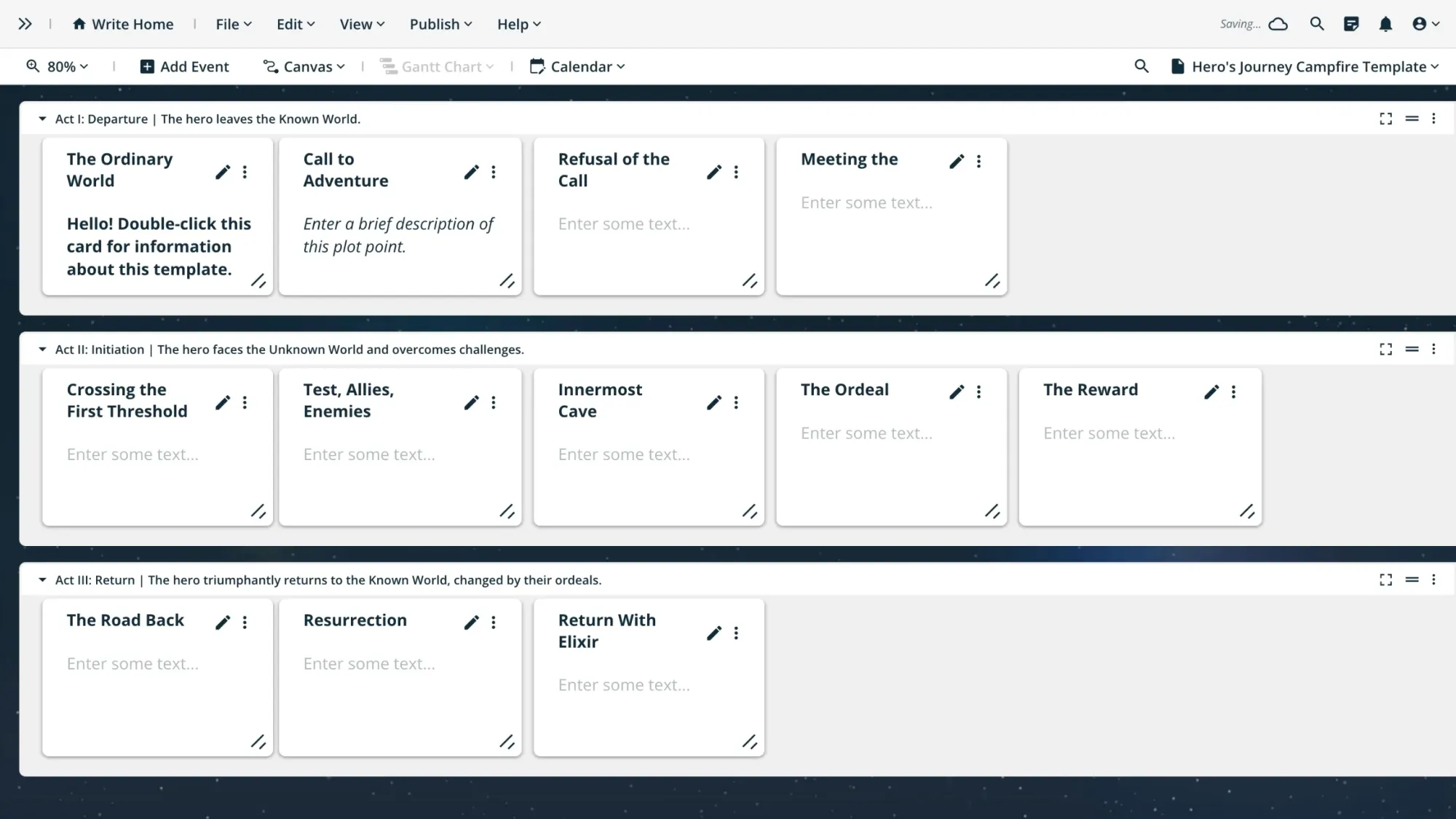

Hero's Journey Campfire Template

The Timeline Module in Campfire offers a versatile canvas to plot out each basic component of your story while featuring nested "notebooks."

Simply double-click on each event card in your timeline to open up a canvas specific to that card. This allows you to look at your plot at the highest level, while also adding as much detail for each plot element as needed!

If you're just hearing about Campfire for the first time, it's free to sign up—forever! Let's plot the most epic of hero's journeys 👇

Lessons From the Hero’s Journey

The Hero's Journey offers a powerful framework for creating stories centered around growth, adventure, and transformation.

If you want to develop compelling characters, spin out engaging plots, and write books that express themes of valor and courage, consider The Hero’s Journey your blueprint. So stop holding out for a hero, and start writing!

Does your story mirror the Hero's Journey? Let us know in the comments below.

- My Storyboards

The Hero’s Journey

What is the Hero's Journey in Literature?

Crafting a heroic character is a crucial aspect of storytelling, and it involves much more than simply sketching out a brave and virtuous figure. The hero's journey definition is not the typical linear narrative but rather a cyclical pattern that encompasses the hero's transformation, trials, and ultimate return, reflecting the profound and timeless aspects of human experience. The writer's journey in this endeavor goes beyond the external actions of the hero and delves into the character's inner world. The hero arc is the heart of the narrative, depicting the character's evolution from an ordinary person to a true hero.

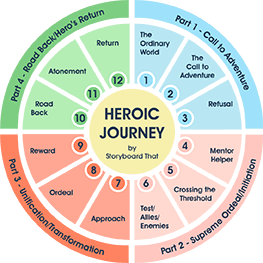

Narratology and Writing Instructions for Heroic Characters

Related to both plot diagram and types of literary conflict , the ”Hero’s Journey” structure is a recurring pattern of stages many heroes undergo over the course of their stories. Joseph Campbell, an American mythologist, writer, and lecturer, articulated this cycle after researching and reviewing numerous myths and stories from a variety of time periods and regions of the world. He found that different writers take us on different journeys, however, they all share fundamental principles. Through the hero's trials, growth, and ultimate triumph, the narrative comes full circle, embodying the timeless pattern of the hero cycle. Literature abounds with examples of the hero cycle, illustrating how this narrative structure transcends cultural boundaries and remains a fundamental element of storytelling. This hero cycle in literature is also known as the Monomyth, archetype . The most basic version of Joseph Campbell's Monomyth has 12 steps, while more detailed versions can have up to 17 steps. His type of hero's journey diagram provides a visual roadmap for understanding the various stages and archetypal elements that protagonists typically encounter in their transformative quests. The wheel to the right is an excellent visual to share with students of how these steps occur. Hero's journey diagram examples provide a visual roadmap for understanding the various stages and archetypal elements that protagonists typically encounter in their transformative quests. Exploring the monomyth steps outlined by Joseph Campbell, we can see how these universal narrative elements have shaped countless stories across cultures and time periods.

Which Story Structure is Right for You?

The choice of story structure depends on various factors, including the type of story you want to tell, your intended audience, and your personal creative style. Here are some popular story structures and when they might be suitable:

- The Hero's Journey: Use this structure when you want to tell a story of personal growth, transformation, and adventure. It works well for epic tales, fantasy, and science fiction, but it can be adapted to other genres as well.

- Three-Act Structure: This is a versatile structure suitable for a wide range of genres, from drama to comedy to action. It's ideal for stories that have a clear beginning, middle, and end, with well-defined turning points.

- Episodic or Serial Structure: If you're creating a long-running series or a story with multiple interconnected arcs, this structure is a good choice. It allows for flexibility in storytelling and can keep audiences engaged over the long term.

- Nonlinear Structure: Experiment with this structure if you want to challenge traditional narrative conventions. It's suitable for stories where timelines are fragmented, revealing information gradually to build intrigue and suspense.

- Circular or Cyclical Structure: This structure is great for stories with recurring themes or for tales that come full circle. It can be particularly effective in literary fiction and philosophical narratives.

Ultimately, the right story structure for you depends on your creative vision, the genre you're working in, and the narrative you want to convey. You may also choose to blend or adapt different structures to suit your story's unique needs. The key is to select a structure that serves your storytelling goals and engages your target audience effectively.

What is a Common Theme in the Hero's Journey?

A common theme in the hero's journey is the concept of personal transformation and growth. Throughout the hero's journey, the protagonist typically undergoes significant change, evolving from an ordinary or flawed individual into a more heroic, self-realized, or enlightened character. This theme of transformation is often accompanied by challenges, trials, and self-discovery, making it a central and universal element of hero's journey narratives.

Structure of the Monomyth: The Hero's Journey Summary

This summary of the different elements of the archetypal hero's journey outlines the main four parts along with the different stages within each part. This can be shared with students and used as a reference along with the hero's journey wheel to analyze literature.

Part One - Call to Adventure

During the exposition, the hero is in the ordinary world , usually the hero’s home or natural habitat. Conflict arises in their everyday life, which calls the hero to adventure , where they are beckoned to leave their familiar world in search of something. They may refuse the call at first, but eventually leave, knowing that something important hangs in the balance and refusal of the call is simply not an option.

Part Two - Supreme Ordeal or Initiation

Once the hero makes the decision to leave the normal world, venture into the unfamiliar world, and has officially begun their mysterious adventure, they will meet a mentor figure (a sidekick in some genres) and together these two will cross the first threshold . This is the point where turning back is not an option, and where the hero must encounter tests, allies and enemies . Obstacles like tests and enemies must be overcome to continue. Helpers aid the hero in their journey.

Part Three - Unification or Transformation

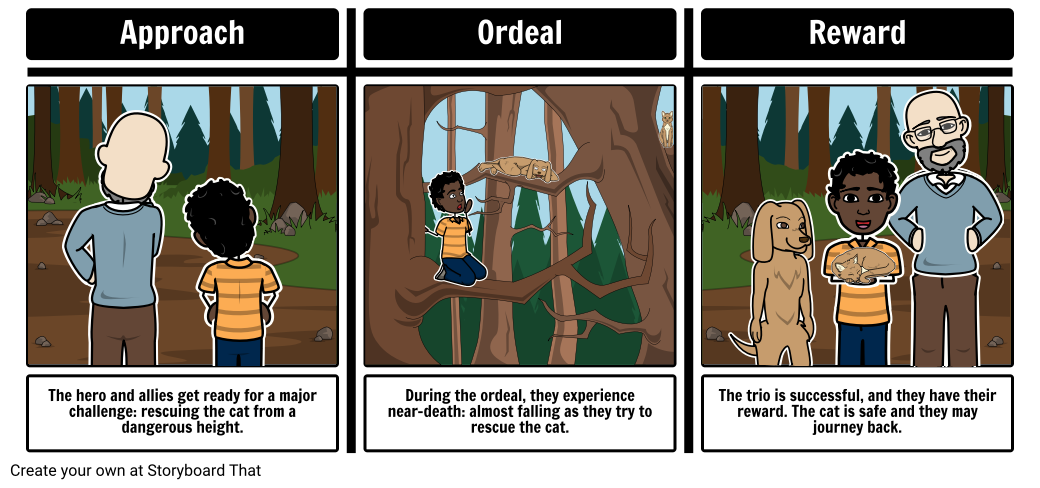

Having overcome initial obstacles, in this part of the heroic cycle, the hero and their allies reach the approach . Here they will prepare for the major challenge in this new or special world. During the approach, the hero undergoes an ordeal , testing them to point near death. Their greatest fear is sometimes exposed, and from the ordeal comes a new life or revival for the hero. This transformation is the final separation from their old life to their new life. For their efforts in overcoming the ordeal, the hero reaches the reward . The hero receives the reward for facing death. There may be a celebration, but there is also danger of losing the reward.

Part Four - Road Back or Hero's Return

Once the hero achieves their goal and the reward is won, the hero and companions start on the road back . The hero wants to complete the adventure and return to their ordinary world with their treasure. This stage is often referred to as either the resurrections or atonement . Hero's journey examples that showcase the atonement stage often highlight the protagonist's inner turmoil and the difficult decisions they must make to reconcile with their past and fully embrace their heroic destiny. The hero becomes "at one" with themselves. As the hero crosses the threshold (returning from the unknown to their ordinary world), the reader arrives at the climax of the story. Here, the hero is severely tested one last time. This test is an attempt to undo their previous achievements. At this point, the hero has come full circle, and the major conflict at the beginning of the journey is finally resolved. In the return home, the hero has now resumed life in his/her original world, and things are restored to ordinary.

Popular Hero's Journey Examples

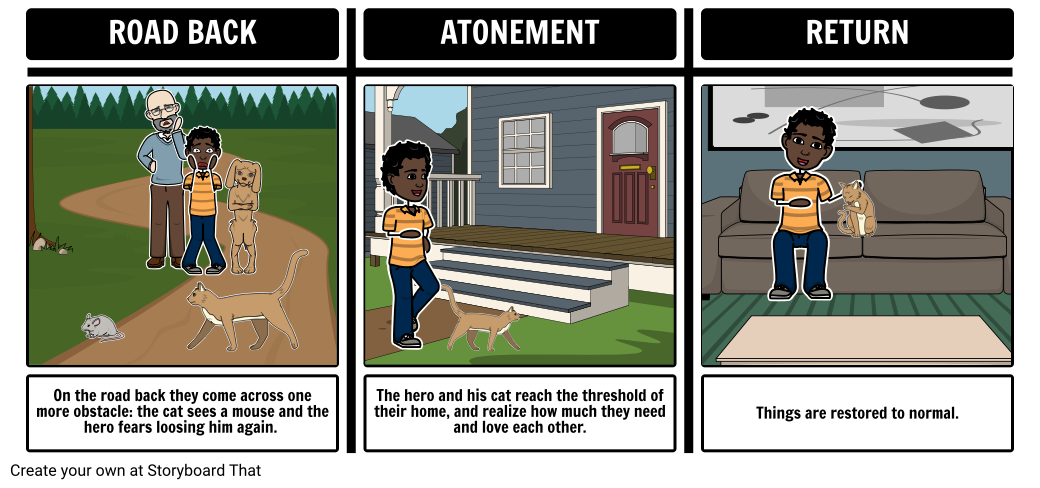

Monomyth example: homer's odyssey.

Monomyth examples typically involve a hero who embarks on an adventure, faces trials and challenges, undergoes personal transformation, and returns home or to society with newfound wisdom or a significant achievement, making this storytelling structure a powerful and timeless tool for crafting compelling narratives.

The hero's journey chart below for Homer’s Odyssey uses the abridged ninth grade version of the epic. The Heroic Journey in the original story of the Odyssey is not linear, beginning in media res , Latin for “in the middle of things”.)

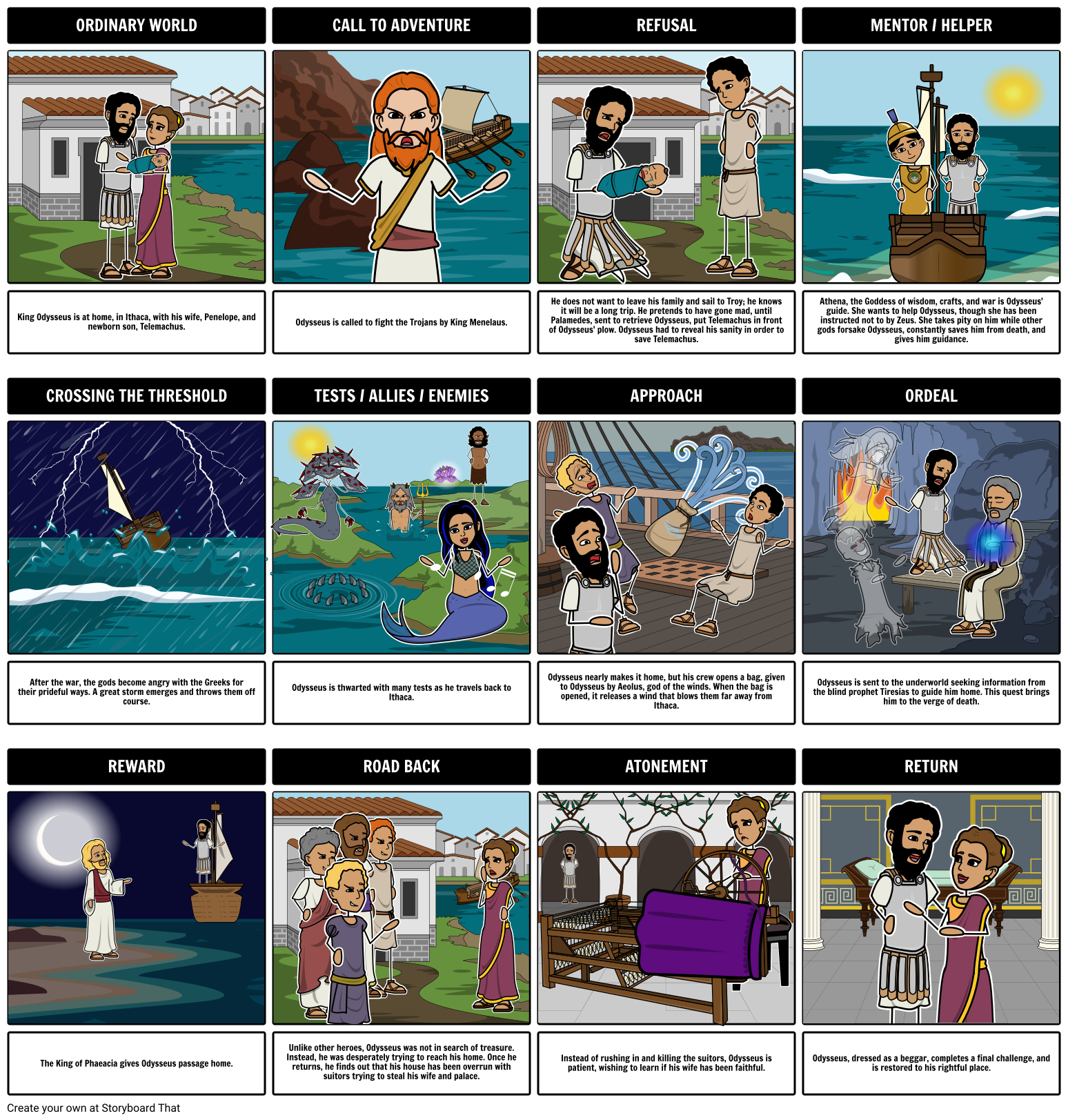

To Kill a Mockingbird Heroic Journey