Our Organisation

Our Careers

Tourism Statistics

Industry Resources

Media Resources

Travel Trade Hub

News Stories

Newsletters

Industry Events

Business Events

THE ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE OF TOURISM

Tourism in Australia continues to be a driver of growth for the Australian economy, with domestic and international tourism spend totalling $122 billion in 2018-19.

Link Copied!

In the financial year 2018–19, Australia generated $60.8 billion in direct tourism gross domestic product (GDP). This represents a growth of 3.5 per cent over the previous year – faster than the national GDP growth. Tourism also directly employed 666,000 Australians making up 5 per cent of Australia’s workforce.

44 cents of every tourism dollar were spent in regional destinations and tourism was Australia’s fourth largest exporting industry, accounting for 8.2 per cent of Australia’s exports earnings.

There are now more than 1.4 billion international travellers globally, spending US$1.5 trillion per year. In 2018-19, 9.3 million international visitors arrived in Australia, an increase of 3.0 per cent compared to the previous year. Australia is currently one of the highest yielding destinations in the world, with international visitors spending $44.6 billion in 2018-19 compared to the previous year, a growth of 5 per cent.

Download our infographic on the economic importance of tourism

International Tourism Snapshot

See the latest arrivals, spend and aviation data all on one page with this handy international tourism snapshot., discover more.

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience. Find out more .

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Acknowledgement of Country

We acknowledge the Traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Owners of the land, sea and waters of the Australian continent, and recognise their custodianship of culture and Country for over 60,000 years.

*Disclaimer: The information on this website is presented in good faith and on the basis that Tourism Australia, nor their agents or employees, are liable (whether by reason of error, omission, negligence, lack of care or otherwise) to any person for any damage or loss whatsoever which has occurred or may occur in relation to that person taking or not taking (as the case may be) action in respect of any statement, information or advice given in this website. Tourism Australia wishes to advise people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent that this website may contain images of persons now deceased.

Australian National Accounts: Tourism Satellite Account

Estimates of tourism’s direct contribution to the economy including GDP, value added, employment and consumption by product and industry

- Australian National Accounts: Tourism Satellite Account Reference Period 2021-22 financial year

- Australian National Accounts: Tourism Satellite Account Reference Period 2020-21 financial year

- Australian National Accounts: Tourism Satellite Account Reference Period 2019-20 financial year

- View all releases

Key statistics

- Tourism gross domestic product (GDP) rose 60.1% to $57.1b in chain volume terms in 2022-23 but remains below the 2018-19 peak of $63.4b.

- Tourism's contribution to economy GDP rose to 2.5% in 2022-23 but remains below the 2018-19 level of 3.1%.

- Domestic tourism consumption rose by $34.9b to $124.9b in 2022-23 while international tourism rose by $17.7b to $23.6b in chain volume terms.

- Tourism filled jobs rose to 626,400 in 2022-23 but remains below the 2018-19 peak of 700,900 filled jobs.

- Download table as CSV

- Download table as XLSX

- Download graph as PNG image

- Download graph as JPG image

- Download graph as SVG Vector image

(a) As the reference period for chain volume measures is 2021-22, chain volume measures and current prices are identical in 2021-22.

Direct tourism

All references to "tourism" are referring to "direct tourism" unless otherwise specified. A direct tourism impact occurs where there is a direct (physical and economic) relationship between the visitor and producer of a good or service. For more information, refer to the Methodology section.

Gross Domestic product

- In current price terms, tourism GDP rose 76.6% to $63.0b in 2022-23 to be above the 2018-19 level of $60.3b. Of this, tourism GVA was $57.2b and tourism net taxes on products $5.7b.

- In chain volume terms, tourism GDP rose 60.1% in 2022-23 but stands at 90.1% of its 2018-19 level.

Consumption

- In purchasers' price terms, domestic consumption increased 53.7% to $138.4b in 2022-23, the highest level in the time series.

- In chain volume terms , domestic consumption increased 38.8% to $124.9b in 2022-23, the highest level in the time series.

- In purchasers' price terms, international consumption increased from $5.9b to $26.1b in 2022-23 but remains well below the 2018-19 level of $39.3b.

- In chain volume terms, international consumption increased from $5.9b to $23.6b in 2022-23 but remains well below the 2018-19 level of $42.5b.

Industry gross value added, current prices

- The accommodation industry's GVA increased to $7.7b in 2022-23 which is 25.5% higher than the 2018-19 level of $6.2b.

- The cafes, restaurants and takeaway food services industry's GVA increased to $7.0b which is 17.6% higher than the 2018-19 level of $5.9b.

- The travel agency and information centre services industry's GVA increased to $6.1b which is 7.8% higher than the 2018-19 level of $5.7b.

- The air, water and other transport industry's GVA increased to $7.1b but remains 9.2% below the 2018-19 level of $7.9b.

- The education and training industry's GVA increased from $1.2b to $3.2b but remains 47.9% below the 2018-19 level of $6.1b.

Tourism employment

- Tourism accounted for 4.1% of the filled jobs in the whole economy in 2022-23 but this is still lower than the 5.1% of filled jobs in 2018-19.

- The greatest increases in filled jobs in 2022-23 occurred in cafes, restaurants and takeaway food services (up 58,100 jobs), retail trade (up 32,500 jobs), accommodation (up 22,900 jobs) and education and training (up 19,600 jobs).

- Increases were recorded in both full-time filled jobs (up 46.0% to 317,600 jobs) and part-time filled jobs (up 37.2% to 308,800 jobs) in 2022-23.

- In 2022-23, filled jobs worked by females increased more than those filled by males with increases of 42.9% to 345,500 jobs and 39.9% to 280,900 jobs respectively.

Key considerations in data interpretation

Tourism estimates.

The International Visitor Survey (IVS) data sourced from Tourism Research Australia (TRA) is one of the key inputs to this account. Due to the COIVD-19 pandemic, IVS interviews were paused from June quarter 2020 to June quarter 2022 and data were imputed. Full sampling interviewing returned from March quarter 2023. Following a review by the TRA of the imputation method and changes to ABS Overseas Arrivals and Departures data used for IVS benchmarking, data for 2021-22 has been revised.

For more information see International Visitor Survey Methodology and Overseas Arrivals and Departures .

Changes in this issue

New process to derive economic measures.

This publication includes a methodological update. This update was undertaken to modernise the processing system and enhance the methodology. Consequently, the estimates for the 2019-20, 2020-21 and 2021-22 periods, which were previously published, have been revised. For an overview of the updated methodology, please refer to the Methodology page.

Status in employment

The term ‘status in employment’ has been changed to full-time and part-time employment to be consistent with Labour Force, Australia .

Updated job distribution in transport

The jobs that were previously reported under rail transport are now included in the air, water, and other transport industry.

Analysis of results

The contribution of tourism to the Australian economy has been measured using the demand generated by visitors and the supply of tourism products by domestic producers.

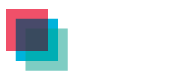

The diagram below provides a graphical depiction of the flow of tourism consumption through the Australian economy in 2022-23. What the diagram highlights is that, unlike traditional ANZSIC industries in the Australian National Accounts, tourism is not measured by the output of a single industry, but rather from the demand side i.e. the activities of visitors. It is the products that visitors consume that define what the tourism economy produces. The diagram shows how the value of internal tourism consumption (as measured by the sum of international and domestic tourism consumption in purchaser's prices, i.e. the price the visitor pays) is disaggregated to either form part of tourism GVA/tourism GDP, is excluded as it forms part of the "second round" indirect effects of tourism, or is output that was not domestically produced.

Flow of tourism consumption through the Australian Economy (a)(b)(c)

A flow chart representing the flow of tourism consumption through the Australian economy, year ending June 2023. Note, totals may not add due to rounding; tourism consumption is measured in purchasers’ prices unless otherwise specified. Other monetary aggregates are measured in basic prices; all figures in this diagram are in current price terms unless otherwise specified. Domestic tourist consumption to the value of $138,423 million is comprised of business and government, to the value of $25,433 million, and household, to the value of $112,990 million. International tourism consumption, to the value of $26,105 million, combines with domestic tourist consumption to create internal tourism consumption, to the value of $164,528 million. Internal tourism consumption splits into three values; internal tourism consumption at basic prices, to the value of $138,492 million; cost to retailers of imported goods sold directly to visitors, to the value of $13,506 million, and net taxes on tourism products to the value of $12,530 million. Internal tourism consumption at basic prices is comprised of cost to retailers of domestic goods sold directly to visitors, including wholesale and transport margins supplied domestically, to the value of $24,667 million; and direct tourism output, to the value of $113,825 million. Direct tourism output flows into two values; intermediate inputs used by tourism industries, to the value of $56,595 million; and direct tourism value added, to the value of $57,230 million. Cost to retailers of domestic goods sold directly to visitors and intermediate inputs used by tourism industries connect to second round (indirect) effects to supplier industries. Net taxes on tourism products flows into two values; net taxes on tourism products (in the case of goods, this will only include the net taxes attributable to retail trade activities), to the value of $5,720 million; and net taxes on indirect tourism output to the value of $6,810 million. Direct tourism value added and net taxes on tourism products combine to create direct tourism GDP, to the value of $62,950 million. Direct tourism value added is used to estimate total tourism employed persons, to the value of 626,400 tourism filled jobs.

Revisions are a necessary and expected part of accounts compilation as data sources are updated and improved over time. This issue includes revisions to tourism aggregates from 2019-20 to 2021-22. Revisions in the 2022-23 release include:

- Revisions to both domestic and international tourism expenditure as a result of the TSA annual balancing and confrontation process. This is particularly the case for tourism products where the estimates have been modelled using a range of source data.

- Replacing modelled 2021-22 net taxes, imports and margins data with the latest issue of Australian National Accounts: Supply Use Tables (available on a T-1 basis) for 2021-22.

- Revisions related to the new process to derive economic measures.

- Revisions to international tourism consumption due to the incorporation of updated 2021-22 data from Tourism Research Australia and updated data from the Survey of International Trade in Services for 2020-21 and 2021-22.

Please note, the revisions to the chain volume level estimates across the time series are an expected part of re-referencing the indexes to 100 in the reference year.

Data downloads

Australian national accounts: tourism satellite account, create your own tables and visualisations.

ABS provide access to a number of other datasets for you to create your own tables and make visualisations. See what's available in Data Explorer .

Caution: Data in Data Explorer is currently released after the 11:30am release on the ABS website. Please check the reference period when using Data Explorer. For information on Data Explorer and how it works, see the Data Explorer user guide .

For further information about these and related statistics, please contact the Customer Assistance Service via the ABS website Contact Us page. The ABS Privacy Policy outlines how the ABS will handle any personal information that you provide to us.

Previous catalogue number

This release previously used catalogue number 5249.0.

Methodology

Do you need more detailed statistics, request data.

We can provide customised data to meet your requirements

Microdata and TableBuilder

We can provide access to detailed, customisable data on selected topics

Check your browser settings and network. This website requires JavaScript for some content and functionality.

Bulletin – December 2022 Australian Economy The Recovery in the Australian Tourism Industry

8 December 2022

Angelina Bruno, Kathryn Davis and Andrew Staib [*]

- Download 940 KB

The Australian tourism industry is gradually recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic that brought global travel to an unprecedented standstill. International tourism fell sharply in early 2020 and has only slowly recovered since restrictions were lifted in the first half of this year. By contrast, domestic tourism spending bounced back quickly as local restrictions eased and is now above pre-pandemic levels. This article outlines the recovery in the Australian tourism industry following the pandemic, the challenges the industry has faced in reopening, and the uncertainties around the outlook for the tourism industry over the next few years.

Introduction

Restrictions to contain the spread of COVID-19 and precautionary behaviour by consumers significantly disrupted the movement of people both domestically and internationally during the pandemic period. This had a devastating impact on many Australian businesses that provided services to domestic or international tourists. Nevertheless, many of these businesses have shown considerable resilience and flexibility, aided by a range of government support packages, and are now expanding to service the recovery.

This article presents a snapshot of the tourism industry through the pandemic, before focusing on the recovery over the past year. While international tourism is recovering only slowly, domestic tourism spending has rebounded strongly – to above pre-pandemic levels – as many Australians have chosen to take domestic rather than overseas holidays. The article draws on information from the Bank’s regional and industry liaison program to discuss the challenges the tourism industry has faced in meeting this sudden increase in demand, and the outlook for tourism activity over the next few years. Many tourism businesses have found it difficult to quickly scale up to meet demand, and these supply constraints have limited tourism activity and led to higher prices. Looking ahead, a continued recovery in tourism activity is expected as supply-side issues are gradually resolved and international tourism picks up further. However, there are a number of uncertainties around the timing and extent of this recovery.

International tourism

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic led to a sharp drop in international tourism, as governments around the world implemented travel and border restrictions (Graph 1). In April 2020, international tourism arrivals declined globally by around 90 per cent and Australia’s international tourist arrivals effectively came to a standstill for several months.

The timing and extent of the recovery in international tourism has been uneven across the world, as national governments removed restrictions at a different pace. Globally, international tourism arrivals picked up to be around three-quarters of their pre-pandemic levels by September 2022. In Australia, international tourist arrivals rose slightly in mid-2021 under the temporary operation of the Australia–New Zealand travel bubble, and also in November 2021 as border restrictions eased in some parts of the country. However, it wasn’t until February 2022 – when Australia removed border restrictions for vaccinated persons – that arrivals began to substantially pick up. Since July 2022, people have been able to travel to and from Australia without being required to declare their vaccination status.

Short-term overseas arrivals to Australia (which include tourists but also those visiting for less than 12 months for business, education and employment purposes) picked up to be around half of pre-pandemic levels by September 2022 (Graph 2). However, short-term departures of Australian residents have picked up more quickly than short-term arrivals of overseas visitors, and so the net outflow of travellers has been larger than pre-pandemic levels in recent months.

Reasons for travel

The recovery in short-term travel to and from Australia has been particularly pronounced among those visiting friends and relatives (VFR) (Graph 3). VFR accounted for just over half of all international visitors’ spending over the year to June 2022, whereas it accounted for just under one-fifth in 2019 (Table 1). Short-term travel for business and education purposes has also picked up. However, the recovery in outbound business travel (including conventions and conferences) has outpaced inbound business travel, with relatively few major business events held in Australia in 2022. Short-term travel for employment reasons has almost fully recovered to its 2019 levels. By contrast, the number of visitors arriving in Australia for holidays has picked up only slightly, to be around one-third of its pre-pandemic level (holiday visitors accounted for only 10 per cent of international visitor spending over the year to June 2022, compared to nearly 40 per cent in 2019).

Working holiday makers and international students who are in Australia for more than a year are not included in the short-term arrivals data, but they make a significant contribution to tourism spending. According to Hall and Godfrey (2019), visitors who state the main purpose of their trip as education stay longer and spend more than leisure and business tourists. International students and individuals on working holiday visas have a high propensity to travel within Australia, and often their friends and relatives come to visit. The number of international students and working holiday visa holders in Australia has risen to be around two-thirds and one-half of their pre-pandemic levels in the September quarter of 2022, respectively.

The recovery in international visitors to Australia has been uneven across source countries, reflecting both travel restrictions and the quicker recovery in VFR relative to other types of travel (Graph 4). The recovery in the number of visitors from India, New Zealand and the United Kingdom has been faster than for other countries, possibly due to the close relationships residents from those countries have with Australian residents (in the 2021 Census, England and India were the top two countries of birth for Australian residents, other than Australia). While there has been a notable pick-up in people from India visiting friends and relatives, there has also been a pronounced recovery in the number of Indian students coming to Australia. By contrast, the number of Chinese visitors remains more than 90 per cent below pre-pandemic levels, due to ongoing travel restrictions to control the spread of COVID-19 in China. This is significant for the Australian tourism sector as, prior to the pandemic, Chinese visitors were the largest source of tourist spending and contributed around 20 per cent of total leisure travel exports in 2019 (or nearly 30 per cent if education-related travel is included).

Domestic tourism

Domestic tourism activity was severely disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, due to the introduction of strict restrictions on household mobility (‘lockdowns’) across the country in March 2020 (Graph 5). At the same time, a number of states and territories implemented interstate border restrictions and quarantine arrangements. As a result, domestic tourist visitor numbers declined sharply. By April 2020, domestic tourist numbers were less than 20 per cent of pre-pandemic levels.

The first lockdown ended for most parts of the country by the end of May 2020, although some restrictions on household activity and state border closures remained in place for an extended period of time. Melbourne re-entered lockdown for much of the second half of 2020. By the end of that year, however, a number of states and territories had eased restrictions and reopened domestic borders, allowing domestic visitor numbers to recover to around 80 per cent of pre-pandemic levels over the 2020/21 summer and the 2021 Easter holidays (Graph 6).

A third major disruption emerged in mid-2021, as a sharp rise in the number of Delta-variant cases led to the reintroduction of lockdowns in New South Wales, Victoria and the ACT. Around half of the Australian population were under significant restrictions for most of the September quarter of 2021 and domestic visitor numbers declined to around 40 per cent of pre-pandemic levels.

Domestic tourism numbers rebounded again during the 2021/22 summer holidays as health restrictions eased once more, but not to the levels of the previous year; the Omicron outbreak in early 2022 tempered activity somewhat. As concerns about Omicron abated, domestic visitor numbers again recovered, and have been around 85 per cent of pre-pandemic levels since Easter 2022.

While domestic visitor numbers remain below pre-pandemic levels, total domestic tourism spending and the average spend per visitor have been above pre-pandemic levels since March 2022. Some liaison contacts report that domestic travellers are staying longer than they did before the pandemic and spending patterns have become more like those on overseas holidays, with domestic tourists spending more on tours and experiences to explore Australia. This higher spending also reflects an increase in domestic travel prices (see below).

The recovery in domestic tourism spending in 2022, to around or above pre-pandemic levels, is evident in all states and territories (Graph 7). Naturally, states that experienced longer and stricter COVID-19 restrictions had much more significant declines in tourism activity over 2020 and 2021. Western Australia experienced the least disruption to the tourism industry, partly due to having fewer restrictions on movement, but also because the closed state border meant that more Western Australians were holidaying in their own state. In recent months, the Northern Territory and Queensland have been the recipients of domestic tourism spending well above 2019 levels, perhaps because these travel destinations are regarded as closer substitutes for overseas holidays.

Travel to regional areas recovered more quickly and fully than travel to capital cities (Graph 8). Regional areas were less affected by lockdowns and liaison suggests that travellers preferred to avoid more densely populated areas. There was also a shift towards driving holidays, which has greatly benefited regions within two to three hours’ drive from capital cities.

Challenges in reopening the Australian tourism industry

While pandemic-related declines in domestic and international tourism weighed heavily on the Australian tourism industry, many businesses have proved resilient and have experienced a strong rebound in demand from domestic tourists in recent months. Nevertheless, many businesses have found it difficult to scale up to meet this demand, and supply constraints have acted to limit tourism activity and led to higher prices.

In 2022, the biggest constraint on the recovery in tourism activity has been difficulty finding sufficient labour to service tourism demand. The tourism industry lost a large number of experienced staff during the pandemic – and so when domestic tourism recovered, the sector had to rapidly hire workers in a tight labour market. Online advertisements for tourism jobs rose to record highs by mid-2022 (Graph 9). These jobs have been difficult to fill. Liaison contacts have suggested that many of the Australians who had worked in the tourism industry prior to the pandemic have since found jobs in other industries. Moreover, many tourism-related jobs had previously been filled by international students and, particularly in regional locations, working holiday makers – many of whom left Australia during the pandemic and have been slow to return. On top of the difficulties in attracting and retaining staff, illness-related absenteeism has been elevated more broadly through 2022.

Tourism businesses in many regional areas have had additional difficulties attracting staff, partly due to a shortage of housing. An increase in net migration to these areas has contributed to very low rental vacancy rates in many popular tourist areas. In response, some holiday accommodation providers have resorted to housing their own staff.

There have also been some changes in consumer behaviour resulting from the pandemic that have made it harder for tourism businesses to plan and have sufficient staff available to meet demand. Trends such as increased working from home and a reduction in business-related day trips have created a larger gap between peak and off-peak periods for many tourism businesses. There are also sharper peaks and troughs in demand because there are fewer international tourists, who often travel at different times to domestic travellers (e.g. filling accommodation mid-week and outside school holidays). Booking lead times substantially shortened during the pandemic, though there is some evidence that perhaps these are lengthening out again. Nevertheless, booking lead times have always been shorter for domestic travel than international travel, so the change in the composition of travellers has made it more difficult for tourism businesses to plan ahead.

While labour has been a constraint across most of the tourism industry, a lack of capital equipment has been an additional constraint for some businesses. Many tourism-related businesses sold off or retired vehicles, boats, aircraft and other equipment during the pandemic when they could not operate and were in need of cash (Grozinger and Parsons 2020). The sudden and stronger-than-anticipated recovery in domestic tourism in 2022, combined with supply chain issues delaying the manufacture and delivery of new equipment and vehicles, has meant that many businesses did not have the capital equipment they need to service the increase in demand.

These supply-side constraints (in both labour and capital) have limited the tourism industry’s ability to ramp up to meet demand. Liaison suggests many tourism operators are operating below their previous capacity – for example, many have had to limit their operating hours because of lack of staff, and some accommodation providers have not been able to offer all their rooms for booking as they do not have enough staff to service them. Labour shortages and supply chain delays have also weighed on aviation capacity and contributed to a decline in domestic airlines ‘on-time performance’ over 2022 (Graph 10).

Similar constraints are also weighing on the recovery in international tourism. Contacts suggest that the recovery has been held back by limited flight availability, the higher cost of travel insurance and, in many cases, the higher cost of flights. Liaison contacts have indicated that delays in visa issuance in 2022 have also been a barrier for those seeking to travel to Australia. Over the past few months, however, visa processing times have shortened somewhat, and visa processing for applicants located overseas – including applicants for visitor, student and temporary skilled visas – have been given higher priority to allow more people to travel to Australia (Department of Home Affairs 2022).

The supply-side constraints in the tourism industry, combined with a strong pick-up in domestic demand and the higher cost of inputs such as fuel, have led to a sharp increase in domestic travel prices (Graph 11). Liaison contacts suggest that consumers have been relatively accepting of price rises for services essential to travel, such as accommodation. However, smaller operators – particularly in highly discretionary services, such as tours – have had less scope to increase their prices, and their margins have been squeezed by the higher costs of inputs such as food, fuel, energy and insurance costs. Prices for overseas travel have also increased significantly in recent quarters, as demand for flights has outstripped capacity, alongside rising jet fuel costs and increases in prices for international tours (ABS 2022).

The outlook

Looking ahead, tourism activity is expected to continue to recover as supply-side issues are slowly resolved and international tourism picks up further. Most liaison contacts suggest a full recovery will not occur until at least mid-2023; many expect it to take a few more years. There are a number of factors that will affect the timing and extent of the ongoing recovery in tourism, including:

- The easing of supply-side constraints : It is unclear how long it may take for some of the supply-side constraints in the industry to ease, including whether planned changes in flight availability will be sufficient to meet changes in demand, and whether the sector will be able to fill more job vacancies over time and as migration returns.

- The return of international students and working holiday visas : Many people have recently had working holiday visas approved and are expected to arrive over the coming year. Liaison contacts also expect international student numbers to increase over the next few years. The return of working holiday and student visa holders will increase demand for tourism services, and will likely alleviate labour shortages as they take jobs in the sector.

- Australians’ preferences for domestic and international travel : Demand for Australia’s tourism services may decline if Australians’ preference for overseas rather than domestic holidays picks up before international inbound tourism demand increases further. It is possible that cost-of-living pressures, combined with the higher cost of international travel, could lead Australian households to continue to prefer domestic holidays for a time. Nevertheless, many households have significant savings and pent-up demand for international travel after planned trips have been deferred over the past few years.

- The global economic outlook : Global economic conditions and the exchange rate affect decisions about whether to travel the long distance to Australia (as they have in the past) (Dobson and Hooper 2015). Financial concerns and the rising cost of living could make expensive, long-haul travel less attractive.

- The timing and extent of recovery in Chinese tourism : As noted above, China accounted for a large share of tourism spending prior to the pandemic. The outlook for Chinese tourism (and international students from China) remains highly uncertain and will depend on a number of factors, including China’s policies to restrict the spread of COVID-19 , the outlook for the Chinese economy and the travel preferences of Chinese tourists more generally.

Restrictions to contain the spread of COVID-19 and precautionary behaviour significantly disrupted the movement of people both domestically and internationally throughout the pandemic. Since restrictions have eased, international travel has been slow to recover, but domestic tourism spending has rebounded to be above pre-pandemic levels and many tourism service providers are currently operating at capacity. Looking ahead, tourism activity is expected to continue to recover, as supply-side issues are slowly resolved and international tourism picks up further. Australia remains an attractive destination for both domestic and international tourists, and the resilience and flexibility demonstrated by Australian tourism businesses in recent years bode well for the opportunities and challenges that lie ahead.

The authors are from the Regional and Industry Analysis section of Economic Analysis Department. The authors are grateful for the assistance provided by others in the department, in particular Aaron Walker and James Holloway. [*]

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2022), ‘Main Contributors to Change’, Consumer Price Index , June.

Department of Home Affairs (2022), ‘Visa processing times’, viewed 14 November 2022. Available at <https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/visas/getting-a-visa/visa-processing-times>.

Dobson C and Hooper K (2015), ‘ Insights from the Australian Tourism Industry ’, RBA Bulletin , March, pp 21–31.

Grozinger P and Parsons S (2020), ‘ The COVID-19 Outbreak and Australia’s Education and Tourism Exports ’, RBA Bulletin , December.

Hall R and Godfrey A (2019), ‘Edu-tourism and the Impact of International Students’, International Education Association of Australia, 3 May.

Advertisement

Wish You Were Here? The Economic Impact of the Tourism Shutdown from Australia’s 2019-20 ‘Black Summer’ Bushfires

- Open access

- Published: 30 January 2024

- Volume 8 , pages 107–127, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Vivienne Reiner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0964-1608 1 ,

- Navoda Liyana Pathirana 1 , 2 ,

- Ya-Yen Sun ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6788-7644 3 ,

- Manfred Lenzen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0828-5288 1 , 4 &

- Arunima Malik ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4630-9869 1 , 5

3581 Accesses

141 Altmetric

20 Mentions

Explore all metrics

Tourism, including education-related travel, is one of Australia’s top exports and generates substantial economic stimulus from Australians travelling in their own country, attracting visitors to diverse areas including World Heritage rainforests, picturesque beachside villages, winery townships and endemic wildlife. The globally unprecedented 2019-20 bushfires burned worst in some of these pristine tourist areas. The fires resulted in tourism shutting down in many parts of the country over the peak tourist season leading up to Christmas and into the New Year, and tourism dropped in many areas not physically affected by the fires. Our research quantified the cost of the short-term shock from tourism losses across the entire supply chain using input-output (IO) analysis, which is the most common method for disaster analysis; to this end, we also developed a framework for disaggregating the direct fire damages in different tourism sectors from which to quantify the impacts, because after the fires, the economy was affected by COVID-19. We calculated losses of AU$2.8 billion in total output, $1.56 billion in final demand, $810 million in income and 7300 jobs. Our estimates suggest aviation shouldered the most losses in both consumption and wages/salaries, but that accommodation suffered the most employment losses. The comprehensive analysis highlighted impacts throughout the nation, which could be used for budgeting and rebuilding in community-and-industry hotspots that may be far from the burn scar.

Similar content being viewed by others

Impacts of disaster on the inbound tourism economy in Kyushu, Japan: a demand side analysis

Conclusion: Practical and Policy Perspectives in Reshaping the Tourism and Hospitality Industry Post-COVID-19 Industry

Economic impact of tourism in Cabo Verde: a CGE analysis

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Australia’s 2019-20 bushfires were unprecedented globally, burning through more than one-fifth of its temperate broadleaf and mixed-forest biome (Boer et al. 2020 ) over several months, and including every State and Territory. Starting in what was then Australia’s hottest and driest year on record (Norman et al. 2021 ), in a nation used to increasing extremes (Gergis 2018 ), the fires killed or displaced an estimated three billion animals (van Eeden et al. 2020 ) in addition to at least 33 people (Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements 2020 ). At its peak, Australia’s worst fire, the Gospers Mountain mega-fire that formed from the convergence of six fires, was one day away from spreading from bushland to the built-up Sydney suburb of Hornsby (McDonald 2020 ), where 20,000 homes lie within 100 m of the bush (Hannam 2016 ). The ferocity of the fires has also raised questions about cumulative or irreversible damage, for example to rainforest dating back to the Jurassic Period, including cultural heritage (Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Water and Environment 2020 ); animals (Murphy and van Leeuwen 2021 ) such as the koala becoming endangered in New South Wales (NSW), Queensland (QLD) and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) (Dalton 2022 ); and potentially climate targets as a result of greenhouse gases emitted from the fires (van der Velde et al. 2021 ). The fires resulted in about 830 million tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent emissions (Australian Government Department of Industry 2020 ), which is one-and-a-half times Australia’s annual emissions for the previous year to March 2019, of 538.9 Mt C0 2 -e (Australian Government Department of Industry & Resources 2019 ). The Australian government (2020) noted that bushfires tend to result in a carbon sink in future years as a result of regrowth, however, concerns have been raised regarding the extent of Australia’s 2019–2020 fires in terms of post-fire recovery (Boer et al. 2020 ).

The bushfires (also called wildfires) started in mid-2019; in the nation’s north, what became known as the Queensland bushfires between September to December 2020, marked the start of a catastrophic season. The QLD fires affected a number of tourism areas, including the World Heritage Lamington National Park, where the historic Binna Burra Lodge was destroyed, along with Parks and road infrastructure (Binna Burra 2022 ; Queensland Government 2020 ). A State of Emergency had been declared briefly in November. In December the fires intensified in NSW, VIC and South Australia (SA) in the lead-up to Christmas and in the early New Year period, disrupting the peak tourist season, with many tourists stranded, evacuated or cancelling trips. A “Tourist leave zone” was set up in NSW, extending 500 km from Batemans Bay along the coast to the VIC border in the first week of January. The Rural Fire Service warned of upcoming weekend fires “the same or worse” than the devastating New Year’s Eve fires and encouraged holiday-makers to get out of harm’s way and allow emergency workers to focus on protecting the local communities (BBC 2020 ). Tourism Australia paused its advertisement Matesong , which focused on celebrity Kylie Minogue (Bourke 2020 ) and an image of the spots of bushfires over a month on a map of Australia was Tweeted by singer Rhianna and went viral, giving the impression that the whole of the country was on fire simultaneously (Rannard 2020 ). In Australia’s 4th -most visited island, SA’s Kangaroo Island, catastrophic conditions resulted in evacuations and the death of two people before the fires were brought under control in late January (Kangaroo Island Council 2020 ). With conditions improving in some areas such as the NSW Blue Mountains, Australia’s capital, the ACT became the worst-hit region in February (Tourism Research Australia 2020a , b ), experiencing the most hazardous air quality in the world (Norman et al. 2021 ). Melbourne was also affected by hazardous air-quality levels and smog from the fires made its way across the globe (Rodriguez 2020 ), before the bushfire season ended in March 2020.

In some regions directly affected by fires, business takings were reduced by more than 70% in the important summer holiday period; in addition to losses from tourism, residents also spent less because of safety- and supply-chain disruptions (Indigo Shire Council 2020 ; McIlwain 2020 ). Research showed that at its peak, awareness about the fires was close to 100% across all markets (Tourism Australia 2020 ), and the government’s export arm noted that tourism and education was its most-impacted industry (Austrade 2020 , p. 2).

The federal government provided an AU$76 million Rebuilding Australian Tourism package and among other initiatives, Tourism Australia executed a successful “Holiday here this year” campaign after some of the worst of the fires, in January, encouraging Australians to return to bushfire-affected areas and support local communities across the country. In February an international campaign was launched, called “There’s still nothing like Australia”, building on a pre-fire campaign, “There’s nothing like Australia”; however, all marketing was stopped because of increasing coronavirus travel restrictions, and Australia comprehensively closed its international borders on 20 March 2020.

What has been referred to as Australia’s “Black summer” could be a sign of things to come (Canadell et al. 2021 ; Handmer et al. 2018 ; Norman et al. 2021 ; Van Oldenborgh et al. 2021 ) in a continent already subject to heatwaves and drought, which is being exacerbated by climate change (Gergis 2018 ). In particular, bushfires have been increasing their share compared to other natural hazards; this trend has been noted in Australia as well as globally (Handmer et al. 2018 ; Swiss Re 2021 ).

This is, to our knowledge, the first supply-chain analysis of the cost of the 2019-20 bushfire tourism damages on the Australian economy and is based on the popular technique input-output (IO) analysis. Drawing on surveys by Tourism Research Australia about the direct impact of the bushfires, we calculate losses across the entire supply chain, uncovering hotspots in particular sectors and regions.

This paper is set out as follows: Brief overviews of IO analysis, as well as the IO disaster analysis stream and its application to this study are detailed in the Methods section. Key findings are set out in the Results, risks to long-term tourism as well as future research recommendations are outlined in the Discussion, and we then conclude.

Overview of Input-Output Analysis

This study draws on input-output (IO) analysis, a methodology that is globally standardised and enables impact analysis along the entire supply chain. In comparison to production-based accounting, where impacts are relegated to the producer or territory responsible, IO underpins consumption-based accounting because it traces the impact of intermediate industry demand in addition to the impact of final demand from the consumption of a good or service (Afionis et al. 2017 ). In this way, IO analysis facilitates comprehensive impact analysis such as carbon footprints that include all scope-3 emissions. Furthermore, IO analysis facilitates researcher and policy expert insights, through the ability to provide highly disaggregated information at the sectoral and regional levels and across a wide range of indicators (Wiedmann 2009 ); outputs range from headline figures on gross domestic product (GDP) and environmental impacts to a breakdown of employment impacts in specific regions or sectors.

IO analysis was developed by economist Wassily Leontief during the 1930s and 1940s to enable practitioners to quantify the relationship between inputs into, and outputs of economic activity, including pollution (Leontief 1936 ). With the methodology demonstrating the relationships between consumption and production and enabling the identification of supply-chain hotspots (Leontief 1966 ), IO analysis increased in popularity during the 1970s oil shocks, winning Leontief a Nobel Prize (The Nobel Prize 1973 ).

Because it is based on the economic structure of nations, Leontief’s prize-winning formula overcomes barriers such as data collection from indirect suppliers faced in traditional life-cycle assessment (LCA). Traditional LCA tends to be limited to direct (on-site) impacts or else typically does not extend beyond direct suppliers or suppliers of direct suppliers. However, hybrid IO-LCA studies can make use of LCA’s bottom-up data while benefitting from the calculation of higher orders of production via IO’s top-down approach. The structure of IO analysis additionally lends itself to numerous applications related to economic activity (Wiedmann 2009 ), extending to environmental and social indicators and answering complex and novel research questions (for a recent example, see Malik et al. ( 2022 ).

Multi-region input-output (MRIO) models were expanded globally by research collaborations (Lenzen et al. 2017a , b , 2013 ; Malik et al. 2019 ; Tukker and Dietzenbacher 2013 ). These developments were supported by increased data availability and improvements in high-performance computing that enables the analysis of billions of supply chains.

Global, multi-regional analysis, also referred to as GMRIO draws on data issued regularly by more than 100 statistical agencies around the world and is routinely employed by organisations such as the OECD, the European Commission and the World Bank. Recently, IO analysis was used to build an open-access database on behalf of the UN for the measurement of countries’ economic, social and environmental indicators against the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), for standardised reporting and hotspot analysis (Lenzen et al. 2022 ).

IO analysis draws on input-output tables (IOTs) from countries’ statistical agencies as part of the almost universal System of National Accounts 2008 framework (European Commission et al. 2009 ). IO analysis also draws from international data providers such as Eurostat and sources such as UN Comtrade, the data from which can be used to build inter-country supply-and-use-tables that form the basis of IOTs. Just as the System of National Accounts has facilitated international comparisons across significant economic activities, so too has IO and its extended environmental, social and disaster analysis facilitated comparisons of impacts across companies, industries and regions; IO analysis is governed by standards set by the United Nations (UN Statistics Division 1999 ).

In this study, negative entries in the final-demand and value-added blocks of the pre-disaster MRIO tables were removed by mirroring, as described in Sect. 4 of Lenzen et al. ( 2014b ).

Disaster Analysis Sub-Stream of IO

Research focusing on quantifying the impacts of disasters was not common until a string of disasters in the decade from the 1990s, including the Kobe earthquake in 1995, the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami in 2004 and Hurricane Katrina in 2005 (Okuyama 2007 ). The need for routine, effective and efficient quantification of economic impacts, in order to adapt and mitigate against catastrophic disasters, is now considered urgent (Okuyama and Santos 2014 ). An increasing focus on quantifying disasters, assisted by increased data availability has led to the development and advancement of empirical research methodologies including econometric models, social accounting matrix (SAM), computable general equilibrium (CGE) and IO disaster analysis as well as hybrid models (for example, as proposed by Oosterhaven ( 2017 ). The relative strengths and applicability of various approaches have been well-discussed in the disaster analysis literature; CGE and IO models are commonly used (Galbusera and Giannopoulos 2018 ; Steenge and Bočkarjova 2007 ; Zhou and Chen 2021 ), with IO analysis increasingly popular in recent years (Bočkarjova et al. 2004 ; Li et al. 2013 ; Schulte in den Bäumen et al. 2015 ) to become the most commonly employed method for disaster impact analysis (Okuyama and Santos 2014 ). For example, IO analysis has been used recently to quantify the impacts of cyclone Debbie in Australia (Lenzen et al. 2019 ), earthquakes in Taiwan (Faturay et al. 2020a ), COVID-19 (Lenzen et al. 2020 ) and the Venezuelan energy crisis (Li et al. 2022 ).

With IO models previously established as the major tool of impact analysis that assesses more than one region (Richardson 1985 ), this methodology plays a crucial role in tracing the indirect, flow-on effects from large-scale disasters in an increasingly globalised world (Steenge and Bočkarjova 2007 ). IO post-disaster analysis calculates impacts from direct damages data rather than relying on expected future trends as inputs to the model. In addition to its universality, IO disaster assessment because of its relatively straightforward structure, has also enabled integrative approaches where IO is incorporated with other models to enable them to assess higher-order (indirect) effects, such as for CGE (Koks et al. 2016 ; Rose 1995 ) and transportation networks (Okuyama 2007 ). In comparison, CGE’s approach in simulating future states is more flexible, which can be a weakness. In a meta-analysis of CGE studies, Zhou and Chen ( 2021 ) concluded that variability in results because of practitioner assumptions inherent in the modelling remain a challenge. An assumption that the market produces optimal outcomes and the economy re-adjusts towards equilibrium over the longer term can provide an underestimation of losses, particularly where a large disruption occurs in a short timeframe (less than a year), which typifies natural hazards (Rose 2004 ). Oosterhaven ( 2022 ) details a new approach, which has been referred to as IO/SU non-linear programming and allows for substitutability, as well as price rises, which minimise business disruption; however, it may be less suitable for quantifying the impacts of complex disasters where shortages are common, along with business shutdowns. Recognising the imbalance that exists in the aftermath of a disaster and the new situation the economy faces as a result of spillover impacts along supply chains, Steenge and Bočkarjova ( 2007 ) built on the concept of a basic equation, using IO analysis, to describe the pre- and post-disaster economies, with the idea that governments can use the model to determine market interventions and analyse alternate pathways to the desired post-catastrophe equilibrium.

We follow the approach by Steenge and Bočkarjova to determine the short-term post-disaster loss for the economy, which has been built on in recent studies to improve the disaster model. Limitations of IO disaster analysis have included the fact that the rigid structure requires constant prices and does not take account of real-world behaviour such as substitution of goods and services; however, advances have gone some way to addressing several limitations. Steenge and Bočkarjova described a “basic equation” that can be represented as \(\stackrel{\sim}{\mathbf{x}}=\left(\mathbf{I} -\widehat{\varvec{\upgamma }} \right)\mathbf{x}\) – where the potential maximum production of each sector of the impacted economy \(\stackrel{\sim}{\mathbf{x}}\) takes into account the event matrix of losses placed on the diagonal, gamma hat ( \(\widehat{\varvec{\upgamma }}\) ), of proportionate production losses that shinks the pre-disaster economy \(\mathbf{x}\) , so that losses in total output are the difference between this new output level and the initial output (Bočkarjova et al. 2004 ; Steenge and Bočkarjova 2007 ). Total output is determined according to standard IO anaysis: \(\mathbf{x}={(\mathbf{I} -\mathbf{A})}^{-1}\mathbf{y}\) , where \(\mathbf{I}\) is an identity matrix of 1’s on the diagonal and 0’s elsewhere; the \(\mathbf{I}\) matrix is the same dimensions as the direct requirements matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) to which it relates, which is a “production recipe” of the selected sector groupings comprising the economy, with the inputs into each sector are a fraction adding up to $1 (or other monetary unit as relevant) worth of production; \(({\mathbf{I} -\mathbf{A})}^{-1}\) being the famous Leontief inverse \(\mathbf{L}\) that includes the entire supply chain, and demand from end-consumers \(\mathbf{y}\) (also referred to as final demand or consumption) being equal to \(\left(\mathbf{I} -\mathbf{A}\right)\mathbf{x}\) . A relaxation of Steenge’s approach is described by Schulte in den Bäumen et al. ( 2014 ). Developed to be used in instances when the “unbound” constant production recipe approach results in negative final demand ( \(\mathbf{y}\) ) values, this method assumes that very small, marginal inputs to production, in the \(\mathbf{A}\) matrix, are substitutable, meaning intermediate demand can shoulder some of the shock to ensure no negative final demand in order to reflect better the real world. To achieve this, marginal inputs in \(\mathbf{A}\) are reduced to zero to ensure the post-event final demand sectors in \(\mathbf{y}\) are either zero or positive.

An alternative to removing marginal inputs in \(\mathbf{A}\) was developed by Faturay et al. ( 2020a ) because small values may nonetheless be important in complex supply-chain interactions; this approach uses optimisation coding in MATLAB to determine the maximum total output losses. Given the disaster “basic equation” \(\stackrel{\sim}{\mathbf{x}}=\left(\mathbf{I}-\widehat{\varvec{\upgamma }} \right)\mathbf{x}\) , with \(\mathbf{x}={(\mathbf{I}-\mathbf{A})}^{-1}\mathbf{y}\) , the optimisation approach to determining the post-disaster economy enables changes in intermediate demand ( \(\mathbf{A}\) ), final demand \(\mathbf{y}\) and total output ( \(\mathbf{x}\) ) in order to meet the constraints of no negative values in final demand ( \(\mathbf{y}\) ). This model was used in a comprehensive footprint of the first COVID-19 lockdown (Lenzen et al. 2020 ) and more recently in projections of climate impacts on the Australian food system (Malik et al. 2022 ). A new “minimum-disruption” approach to modelling the post-disaster transition has also been proposed by Li et al. ( 2022 ), who apply priority weights to essential sectors to guard against the economic shock. In this novel study of the tourism impacts of Australia’s 2019-20 mega-fires, we use the optimisation approach developed by Faturay et al. ( 2020a ) described above, because of its application to numerous recent disasters.

Data Collection

Tourism Research Australia (TRA) published a range of data in the National Visitor Survey ( 2020b ) and International Visitor Survey ( 2020a ); in order to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the losses from the bushfires, TRA provided, upon request, quarterly expenditure including day trips (personal communication, 31 August, 2022). Only data from January-March 2020 was used because expenditure only started falling in that quarter. By the following quarter, the fires had been brought under control and it would not be possible to determine if any bushfire tourism losses flowed through to the following quarter because non-essential travel was banned because of the coronavirus pandemic. TRA also provided the underlying data from surveys that sought to determine the proportion of tourists who were impacted by the bushfires (personal communication, 10 & 14 June, 2022). These percentages were applied to the March quarter losses to ensure no losses because of the coronavirus were included. In order to disaggregate losses by sector, the proportionate representation of tourism- and tourism-related sectors from TRA’s 2018-19 State Tourism Satellite Accounts (TSA) (Austrade & Tourism Research Australia 2020 ) was applied to the 2019-20 losses (Austrade & Tourism Research Australia 2021 ). The UN World Tourism Organization and Australian Bureau of Statistics definitions of tourism relate to expenditure by visitors to an area where the visit is for less than a year; TSAs, which comprise expenditure on tourism and related activities of nations, include business- and education-related travel, in other words, any visits, as opposed to long-term moves. Online Resource 1 SI 2.7 provides further details about the calculations of direct damages.

The Event (Gamma) Matrix

Losses were divided across eight regions (each State and Territory) and 39 sectors, which included the most-affected sectors as well as other key primary, secondary and tertiary sectors. The post-disaster losses were then compared with the pre-disaster total output for the year, for the relevant sectors and regions in the MRIO and converted into a proportion. A separate gamma matrix of capital damages was also compiled, with the treatment of infrastructure, including depreciation, following the approach described in previous IO disaster studies (Faturay et al. 2020a ; Lenzen et al. 2019 ) (see Online Resource 1 SI 2.6 for details); added together, these make up the final gamma matrix of proportionate losses for the economy. For example, 0.02 for South Australian Accommodation means that income in the accommodation sector in SA reduced 2% for the year; areas where no known direct damage occurred are 0. Table 1 shows the final gamma matrix ( \(\varvec{\upgamma }\) ) of direct losses and capital damages.

As can be seen in Table 1 , no losses were recorded for Tasmania (TAS) because that State recorded increased tourism expenditure (of $1.1 million). This study quantified the total impact from direct losses, across the supply chain, but did not quantify the impact of gains (in Tasmania); in the same way, insurance paid out can be seen as an economic stimulus, as can hospitalisations in providing money for the healthcare sector; these are also not included in IO disaster-analysis calculations. In this way, a standardised approach is followed in quantifying the short-term economic cost of the losses from each impacted sector.

MRIOs are based on countries’ input-output tables (IOTs) in the National Accounts so the aggregated sectors were selected from 1284 sectors in the Australian Industrial Ecology Virtual Laboratory ( http://www.ielab.info/ ), which are based on the Input-Output Product Classification in the Australian National Accounts (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2009 ). The States and Territories were aggregated from the 2214 Statistical Area level 2 (SA2) regions (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011 ). A concordance matrix to aggregate the sectors and regions was converted into a MRIO of the Australian economy in the IELab. The IELab developed at the University of Sydney (Lenzen et al. 2014a ) was Australia’s first such collaborative cloud-based platform for IO analysis. Such platforms overcome the time-consuming nature of MRIO compilation through an open-source approach, with the source data updated regularly. IELabs have now been built for Indonesia (Faturay et al. 2017 ), Japan (Wakiyama et al. 2020 ), Taiwan (Faturay et al. 2020a ), China (Wang 2017 ) and the United States (Faturay et al. 2020b ), and the Global MRIO Lab infrastructure was used to build GLORIA on behalf of the UN International Resource Panel as the database for the open-access global Sustainable Consumption and Production Hotspot Analysis Tool (Lenzen et al. 2022 ).

Indicators for Impact Analysis and Unravelling supply Chains Through Production Layer Decomposition

The satellite account attached to the tailored MRIO was selected during the MRIO compilation in the IELab, with matrix calculations then carried out in MATLAB. In this study, the satellite account employment (in addition to the related indicator, income) was selected as an indicator for impact analysis, to be quantified along with the post-event total output ( \(\mathbf{x}\) ) and final demand ( \(\mathbf{y}\) ).

The change in final demand ( \(\varDelta \mathbf{y})\) is used to calculate the employment and income impacts of the disaster using the formula \(\mathbf{q}\mathbf{L}\mathbf{y}\) , where \(\mathbf{q}\) is the multiplier derived by dividing the desired indicator by pre-disaster total output \(\mathbf{x}\) , and \(\mathbf{L}\) represents the entire supply chain \({(\mathbf{I}-\mathbf{A})}^{-1}\) . Income data is extracted from the first row of the value-added block of the MRIO ( \(\mathbf{v}\) ), while the aggregated total employment data is contained in the 24th row of the employment satellite account in the IELab. In both instances, the \(\mathbf{q}\) matrix is calculated using element-wise multiplication so that the intensity sectors/multipliers align with the final demand sectors, enabling production layer decomposition (PLD) for a disaggregated view of impacts. The entire impact \(\mathbf{q}\mathbf{L}\mathbf{y}\) is unravelled at each production layer through the following decomposition:

where \(\mathbf{q}\mathbf{y}\) is the direct impact (first layer in the PLD), \(\mathbf{q}\mathbf{A}\mathbf{y}\) is the additional impact from direct suppliers involving the \(\mathbf{A}\) matrix of direct requirements, \(\mathbf{q}{\mathbf{A}}^{2}\mathbf{y}\) is the impact from suppliers of the direct suppliers and so on, to infinite (n) layers/orders of production i.e., direct suppliers as well as all indirect suppliers.

Limitations

Our results may be conservative because it is possible that tourists would have spent even less than anticipated in the Tourism Research Australia surveys on which this bushfire research is based, had it not been for the first COVID-19 lockdown, which then became the primary reason for slashed tourism expenditure. We calculated bushfire-related tourism expenditure losses from the National Visitor Surveys and International Visitor Surveys that were carried out from 21 January to 15 March (personal communication, 15 & 17 June, 2022), which asked tourists about the extent to which their changed behaviour occurred because of the bushfires. Had it not been for the pandemic, the bushfire impact on tourism may have measured more post-fire, without being mixed up with losses from concurrent disasters, meaning we would have identified potentially higher bushfire losses. As well, direct bushfire damages data were only available for regions, not sectors, apart from tourism-related infrastructure. Although sectoral expenditure is available in the 2019-20 ABS Tourism Satellite Account, this period included COVID-19; therefore, assumptions had to be made about bushfire-specific direct sectoral losses, based on the usual proportionate representation of tourism spend, which were then used to calculate total losses including indirect impacts (see Online Resource 1 SI 2.7 for details about the calculation of the direct damages data).

From the Tourism Research Australia quarterly data and bushfire surveys, we calculated direct losses in tourism expenditure of $1629.9 million nationwide, in addition to $112.6 million in depreciated infrastructure (in other words, $1742 million direct losses for the year, including infrastructure). In terms of regional breakdown, these direct losses (including infrastructure) were: NSW - $760.5 million, VIC - $347 million, QLD - $343.7 million, SA - $113.8 million, Western Australia (WA) - $135.6 million, TAS - $0, ACT - $22.2 million and Northern Territory (NT) $19.7 million. This triggered losses across the entire supply chain totalling $2801.6 million in total output, $1561.8 million in consumption, $809.4 million in income, and employment losses of more than 7292 full-time equivalent (FTE), which impacted sectors and regions in different ways. Taking the total output losses into account as a proportion of the pre-fire total output, in 2018-19, the losses were worst in NSW, closely followed by SA, which experienced significant fires not only in the Adelaide Hills winery and day-trip region near the State’s capital but also in Kangaroo Island, where almost half the island burned (Kangaroo Island Council 2020 ). Next in terms of proportionate losses was NT, despite the fact that this region did not suffer catastrophic fire conditions.

Geographic Distribution of the Employment Losses

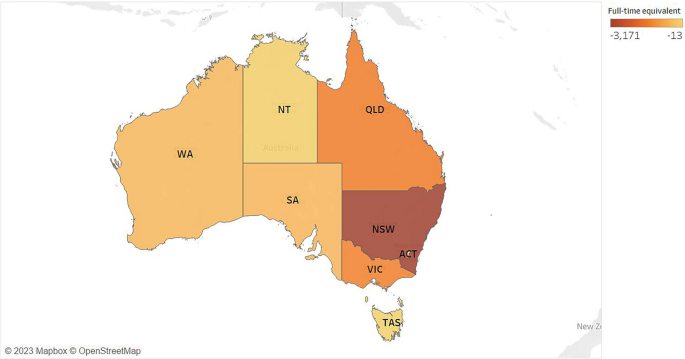

The geographical spread of losses in employment are similar to losses in the other indicators measured in this study. Figure 1 shows that almost half of the 7292 jobs lost were experienced in NSW, the most populous State, which is also where the fires were worst.

Losses in full-time equivalent (FTE) jobs across Australia resulting from the tourism losses because of the 2019-20 fires. The most populous State, New South Wales (NSW), suffered about twice as many losses in employment as its neighbouring eastern States, equivalent to 3171 full-time jobs. The Northern Territory (NT), although not suffering catastrophic fires, nonetheless lost 75 jobs from the short-term shock. Nationwide, more than 7292 jobs were lost. Other regions: Victoria (VIC), Queensland (QLD), South Australia (SA), Western Australia (WA), Tasmania (TAS), Australian Capital Territory (ACT)

Figure 1 shows that although most of the employment losses were concentrated around Australia’s east-coast States that also suffered the most direct tourism losses, spillovers were experienced across the nation. QLD and VIC suffered about half as much job losses as NSW, at 1499 and 1430 respectively, and SA experienced about one sixth of NSW’s losses, at 516, followed by WA at 479. Tasmania, despite not suffering direct tourism damages, lost 13 jobs because of supply-chain impacts resulting from the contraction in consumption. The ACT lost substantially more jobs (110), closely followed by the NT (75 jobs).

Sectoral and Regional Hotspots

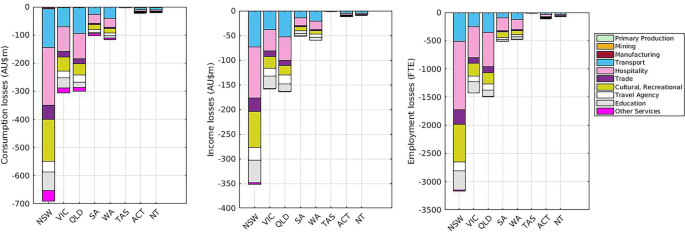

As can be seen in Fig. 2 that compares losses in consumption (final demand) and related income and employment, from an industry perspective, hospitality and transport were the worst hit overall, with the recreation and educational sectors also significantly impacted.

Losses in consumption, income and employment, across Australia’s eight States and Territories and disaggregated by broad sector groupings, because of the tourism shutdown from the 2019-20 bushfires. Hospitality and transport suffered the most losses. Regional abbreviations: New South Wales (NSW), Victoria (VIC), Queensland (QLD), South Australia (SA), Western Australia (WA), Tasmania (TAS), Australian Capital Territory (ACT), Northern Territory (NT)

The “Accommodation” and “Cafes, restaurants and take-away” study sectors, which make up our aggregated hospitality grouping, together suffered the most losses in the consumption, income and employment indicators. However, disaggregating into our 39 individual sector groupings in this study, the aviation-led “Air, water and other transport” sector was the worst-hit in consumption and income (but not in employment, where “Accommodation” dominated), losing $292 million and $159 million respectively.

NSW shouldered the most losses, including 44% of both consumption and income impacts; NSW differed somewhat from the other regions in that the single most-impacted sector, out of the 39 sector groupings in this study, was “Cultural and recreational services” across consumption, income and employment (reducing by $148 million, $73 million and 662 jobs respectively), although when considering “Accommodation” and “Cafes, restaurants and take-away” together as hospitality, the hospitality industry dominated NSW consumption, income and employment losses. The particularly large NSW losses in “Cultural and recreational services” is in part a reflection of the destruction of more than $200 million in Crown Lands and National Park infrastructure, (which was then depreciated - see Methods ). These impacts including on areas such as the World Heritage Blue Mountains National Park (where approximately 82% was burnt (Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment 2020 ) would also have resulted in flow-on impacts to the local community, as well as more broadly, in areas such as reduced consumption of lodgings, restaurant meals and transport. Differences can also be seen between indicators for regions that suffered similar total losses. These include: VIC suffered more losses than QLD in consumption but the reverse was the case for related income and employment, with a key driver being greater losses in VIC’s consumption of education and training ($37 million loss compared to $20 million). As well, WA experienced more losses than SA in consumption ($118 million compared to $102 million) and income ($60 million compared to $52 million) but not in employment (479 jobs lost compared to 516), where SA suffered particularly more losses in hospitality (229 jobs compared to 179. SA hospitality losses included from the Kangaroo Island destination the Southern Ocean Lodge, which was destroyed by the fires and for which the rebuild was estimated at $50 million (Boisvert 2022 ). From a per-capita perspective, the NT was particularly impacted; for example, the NT had the smallest population in Australia in March 2020, at 245,400 people, which was more than half the TAS population of 539,600 (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2020 ), however, the NT lost more income, at $9.3 million compared to $1.4 million. The underlying data on losses is in Online Resource 1 .

Chain Reactions Along Supply Chains

In the following analysis, we discuss the impact on income and employment, which was triggered by the contraction in consumption.

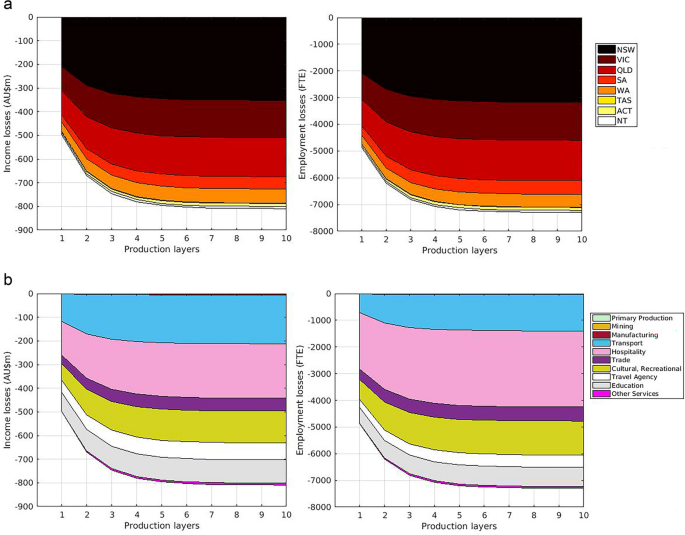

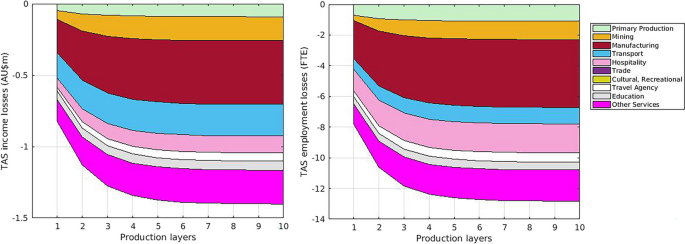

Figure 3 shows that almost all the impacts were felt within about six or seven layers in the upstream supply chain, after which the additional losses per layer particularly start to level off.

Production layer decomposition (PLD) of regions ( a ) and broad sector groupings ( b ). Layer 1 represents the impact from the direct tourism losses, layer 2 represents the impact from direct suppliers and so on, with the cumulative losses up to 10 layers depicted, which represent most of the losses. Employment losses measured in full-time-equivalent (FTE) jobs. Regions: New South Wales (NSW); Victoria (VIC); Queensland (QLD); South Australia (SA); Western Australia (WA); Tasmania (TAS); Australian Capital Territory (ACT); Northern Territory (NT)

The least-impacted regions tended to have a longer tail of losses because of supply-chain spillovers. In comparison, the most-impacted regions, the eastern States of NSW, VIC and QLD, experienced more losses directly or within a few orders of production.

Similarly, key industries such as transport and hospitality experienced more losses earlier on, while “Other services”, which includes sectors not directly impacted such as “Finance, property and other business services”, continued to experience significant losses further along the supply chain.

Regional Case Studies

Losses in the most-impacted State, NSW, followed a similar trend to the national results so in this section we highlight examples of divergence from the aggregated results, in the Australian Capital Territory and Tasmania. Additional disaggregation for regions and sectors and the underlying data are in Online Resource 1 SI 4 .

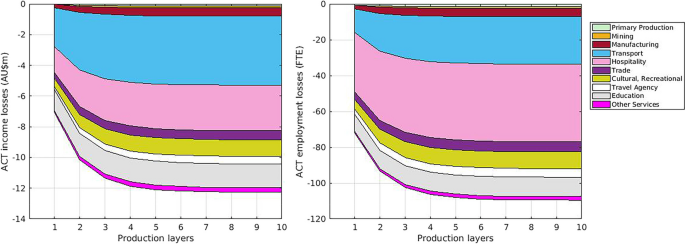

The dominance of losses in accommodation and the aviation-led transport sector in Australia’s capital may in part be explained by the “fly-in-fly-out” economy (Fig. 4 ).

Production layer decomposition of the impact of tourism losses from the 2019-20 bushfires in the Australian Capital Territory, for income and full-time equivalent (FTE) employment in broad sector groupings. Although the number of upstream supply-chain interactions is theoretically infinite, results are illustrated for up to 10 orders of production, which comprise most of the losses

The ACT experienced the biggest income impact in the transport industry, led by the “Air, water and other transport” sector, which lost $3.4 million. These losses are in part because of the extreme bushfire smoke that the ACT’s capital Canberra experienced, which resulted in the airport being closed for hours on one of the worst days (Foster 2020 ). “Accommodation”, as part of the hospitality industry, experienced substantially more employment losses than other sectors, equivalent to 30 jobs.

Despite Tasmania not experiencing an overall loss in direct tourism expenditure, losses from other regions flowed throughout Tasmania’s economy.

Production layer decomposition, across 10 broad sector groupings, of the impact of tourism losses from the 2019-20 bushfires in Tasmania. The losses are illustrated in terms of income and full-time equivalent (FTE) employment, up to 10 orders of production

As Fig. 5 shows, the losses from elsewhere in Australia flowed through Tasmania across the primary, secondary and tertiary sectors, with significant losses continuing to accumulate in upstream layers of production, particularly in the services sectors. TAS’s employment indicator is notable because although the manufacturing industry in aggregate was substantially impacted in TAS, out of the 39 sectors in this study, the “Accommodation” hospitality sector suffered the most, experiencing 2 job losses in TAS.

Tourism has been a critical driver of economic output and risks damage from climate change, particularly in countries such as Australia that are vulnerable to disasters. Tourism spend in the year prior to the fires was more than AU$120 billion, being responsible for the employment of 5% of Australians overall and 8.1% in rural areas, or almost one in 12 people (Tourism Australia n.d. ), and the bushfires burned worst outside of major cities because of tree cover. From a global perspective, Australia was one of the highest-yielding tourism destinations in 2018-19, with international visitors spending $44.6 billion (Tourism Australia n.d. ). Education-related travel services was Australia’s fourth-biggest export in 2018-19 and, when combined with personal travel, was beaten only by iron ore and coal and was responsible for more export income than natural gas (Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade 2020 , p. 19); in fact, the federal export arm Austrade reported that its two most-impacted industries from the bushfires were tourism and education ( 2020 , p. 2). It should be noted that tourists are defined as any visitors who will stay for less than a year; standardised tourism satellite accounts (TSA) of tourism and related activities of nations include business- and education-related travel, meaning the official tourism statistics include not only holidaymakers but also the large and growing area of air travel generally. In Australia prior to the bushfires, “Air, water and other transport” was the main component of tourism travel, responsible for expenditure of $23.278 billion (compared to just $1.090 billion for rail transport, $1.252 billion for taxi transport, $1.854 billion for other road transport and $1.839 for motor vehicle hiring (Austrade & Tourism Research Australia 2020 ).

With bushfires/wildfires increasing compared to other natural hazards (Handmer et al. 2018 ) and natural hazards generally projected to intensify under climate change (IPCC 2022 ), it is important for countries such as Australia to quantify the economic impact of disasters as part of routine practice, that take account of supply-chain spillovers. As our research demonstrates, by including the entire supply chain, using IO analysis, total output losses identified were a 61% increase on top of the direct damages.

Our highly disaggregated results enabled us to identify differences in impacts along supply chains, which was important because the impacts were unevenly distributed. For example, in addition to the key industries of transport, hospitality and cultural and recreational services, the education sector was significantly impacted. Therefore, universities and other providers could consider planning for potential cuts to expenditure on their services in the longer term if major shutdowns to tourism become more commonplace because of increasing natural hazards in particular regions or perceptions that Australia may be unsafe. As well, although we found that the hospitality industry was the most affected overall, with “Accommodation” experiencing the most job losses, followed by “Cafes, restaurants and take-away”, in terms of consumption and income, the aviation-led “Air, water and other transport” sector suffered the most out of the 39 sectors that we studied, indicating that different approaches may be taken by the government depending on policy priorities, for example in terms of jobs or income. From a regional perspective, although the States that were declared bushfire catastrophes also instigated State inquiries to help guide responses, we found that some other regions suffered significant impacts compared to their pre-fire total output. As well, supply-chain spillovers rendered some smaller regions more vulnerable to shouldering the impacts from a per-capita perspective, and this was particularly the case for the remote NT, which has the smallest population. These disaggregated results may help decision-makers in investigating certain hotspots, not only for re-building post-fire but also in terms of preparing for the next disaster.

It is also worth considering the losses suffered by “Cultural and recreational services”, largely because of extensive infrastructure destruction, and spillover impacts, in National Parks that are key drawcards for tourists, for example to the World Heritage Blue Mountains in Greater Sydney. From infrastructure damage and destruction before even accounting for supply-chain impacts, we identified $275 million in losses, although these direct damages were then depreciation for the purposes of our impact analysis (see Online Resource 1 SI2.6 Summary of infrastructure damage). These infrastructure losses are borne by the State governments and their repair, which would be paid by public funding, is an investment in tourism in addition to nature-based recreation generally. However, similar damages in poorer countries could be much more difficult to rectify efficiently ahead of upcoming holiday seasons, particularly in developing nations with weak local municipalities. Therefore, natural hazards may increase economic inequalities, with the burden of climate adaptation and mitigation adding to the costs of governments already struggling under business-as-usual.