Christian Today

To enjoy our website, you'll need to enable JavaScript in your web browser. Please click here to learn how.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Towards a Gypsy, Roma and Traveller theology

For many people growing up in the UK, what they know about the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller (GRT) community has come through reality TV shows like "My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding".

But for Dr Steven Horne - the first Romany from the UK to be awarded a PhD in theology - this representation couldn't be further from the reality of what GRT life and culture looks like.

And the misrepresentation doesn't stop with popular culture; it exists within the Church too, with the GRT community often seen as a people in need of salvation despite the fact that they are deeply religious, with a large proportion identifying as Christian.

It is this strong faith and religious identity that Dr Horne draws out in his new book, "Gypsies and Jesus: A Traveller Theology" .

He speaks to Christian Today about what that Traveller theology looks like and why it is so important to give the reins of Gypsy-Christian identity to Gypsies themselves.

CT: What prompted you to write this book?

Steven: I spent about five years doing my PhD and during that time I did some lecturing and teaching on equality. They had never had anyone speak to them before from the Traveller community and so my original book was a teacher's guide. There is a lot of misinformation about Gypsies and Travellers, with helpful information often being shadowed by sensationalist media. A generation of people have been educated on GRT by programmes like "My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding", which bears so little resemblance to actual Gypsy and Traveller culture it's unbelievable, so I've spent a lot of time undoing a lot of misinformation. The new book is not only a theological book that Christians can enjoy but it's also suitable for people who just want to be informed about Gypsy, Traveller and Roma communities.

CT: You write in your book that until now GRT theology has been dominated by non-GRT voices. Why is it so important to correct that?

Steven: Most of what's ever been written or said about Gypsies and Travellers has been written by non-Gypsies. However, it's crucial that the GRT experience is predominantly told by GRT people themselves. It needs that authenticity and we wouldn't have it any other way with other people groups.

There has always been a Traveller theology but GRT communities are oral and so information, traditions and the Christian faith have been passed down not through writings but through oral means. There are a few small snippets here and there by Gypsies and Travellers themselves but they are quite scarce and scant, and tend to be local productions particular to that local context. This book is bucking that trend.

CT: How religious would you say the GRT community is?

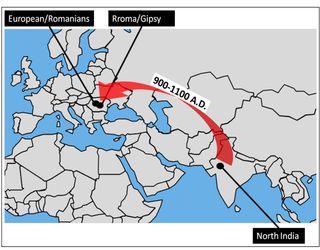

Steven: Religion of some description has been part of Gypsy and Traveller communities from the very beginning. Going back hundreds of years it was used as a way of blending in with other communities, towns and cultures so that they could get safe passage. The Roma people were a diaspora who came from India because of civil war and went through the Middle East, to Greece and up through Europe. It's almost an identical trail to what we have seen with the refugee crisis from Syria. Blending in with the locals and adopting the local religion was a way for people to survive. Around 700 years ago, when they arrived in Europe, that local religion was Christianity.

Statistically, around 85 per cent of GRT people would profess to be religious, with the overwhelming majority of them being Christian. There's a small pocket of Roma in Eastern Europe who identify as Muslim but they make up less than one per cent of all Roma around the world. Certainly within the UK, around 85 per cent would say they are Christian, and perhaps 6 per cent would say they are agnostic or have a belief in God but don't necessarily identify as Christian. So there is a strong religious identity.

CT: You write in your book that GRT Christianity is "not always the exotic spectacle that some may perceive it as being". How would you describe GRT Christianity?

Steven: I grew up in two different communities - Gypsy and non-Gypsy. The one real bridge between the two, the place where there was one real commonality, was Christianity. The Gypsy communities in the UK at least tend to be very evangelical or Pentecostal. That ties into what I was saying about the historical tradition of adopting the local religion. What we see within England unsurprisingly is that the vast majority would identify as Church of England. When you go to Ireland, many identify as Catholic. There tends to be an adherence to the dominant Church or religious presence within that area, but it tends to be overwhelmingly Christian.

What makes Gypsy Christianity distinct is the way in which it is lived out. For some Christians, their Christianity might start and end with the church service on Sunday and perhaps small group during the week. But in the GRT community, their Christianity permeates places that it wouldn't necessarily in non-GRT communities.

If you think of certain practices, like the signing of the cross for example, this might be a normal part of a church service but if you removed it from that context, it would almost be seen as superstitious. But one member of the GRT community I spent time with had a rosary hanging next to his door and every time he left the house, he would touch it, make the sign of the cross and say a short prayer with the same words every time. Then when he got into his van, he had another rosary and would do the same thing. And he did this day in, day out. When I asked him why, he said he was asking to be kept safe and get more work in. It's as if this daily ritual became his liturgy and his sacraments.

CT: Are there any other distinctive features?

Steven: The concepts of purity and separation are very strong within the Gypsy and Traveller communities. We see that in the way they keep themselves separate from the larger settled community and that can be because they see the settled community as impure because they might, for example, have sex before marriage.

There can be exceptions but if you go to most Gypsy Traveller weddings, more often than not you will see all the ladies to one side and all the men to the other. One young Traveller boy I knew became upset at school one day because he had forgotten his PE shorts and was told to go and get a pair from the lost property. He just couldn't do it because he felt so ashamed and that's because they would have been seen as contaminated because they had been worn by a non-Traveller.

The irony in GRT people being called dirty is that this couldn't be more of an insult to Gypsies and Travellers because they see it the other way around!

But there's also a strong sense of movement - what I call 'permanent impermanence', or the idea that life is a journey that we make our way through and there are different 'stations' that we all pass through, whether it's births, adolescence, marriage or death.

For GRT communities the celebrations are always religious in nature. And Gypsy and Traveller funerals are enormous occasions that aren't seen as the final stop but rather tie in with the Christian idea of going on to another place. There is that language of movement where death is not an end but the continuation of a journey.

CT: You mentioned that GRT can be viewed as impure by settled communities, while GRT can vice versa view them as not being pure. Does this suspicion exist with GRT Christians towards non-GRT Christians?

Steven: No and that's actually where there's real common ground. If you take for example the annual Appleby Horse Fair, there is a strong Christian presence among the exhibitors and many of the different denominations have a stand there. The gentleman who runs the fair is a born again Christian and gives Christians pride of place.

In terms of the Church more widely, there was some separation back in the 80s, when Gypsy-led churches started springing up. They started forming their own strong identity and withdrew from other churches. But as more GRT started to become practising Christians, they joined non-GRT congregations across the land.

You might feel like you've only ever met a handful of Gypsy Travellers in your life but I guarantee you've met many more than that and just never knew it because the vast majority go completely unnoticed. They're not going around wearing a badge saying 'Hello, I'm a Gypsy'. They're a bit under the radar and in terms of Christianity, many have integrated with non-GRT churches. There is still a relatively strong Gypsy church presence but the majority are not going to a GRT church.

CT: In your book you speak about how GRT communities have traditionally been seen by settled people as "more sinful". How does that feel?

Steven: It's something that GRT people have had to deal with literally from the beginning of their history, from the genesis point of them becoming a people group as they were ostracised in their own country. We see the same attitude today towards migrants making the treacherous journey across the Channel and the harsh reception they have had from the media and people within our communities. That is how Gypsies and Travellers were viewed as they made their way through Europe.

In Britain it was no different. Within 20 years of arriving, Henry VIII brought in the Egyptians Act 1530 which outlawed being a Gypsy. Within 30 years of that, there was capital punishment for being a Gypsy. From day one, Gypsies and Travellers have been on the sharp end of the stick and this has undoubtedly shaped the community. What it's done for many is ingrained a strong suspicion of outsiders and a very strong defence mechanism.

GRT make up less than 0.2% of the population of the UK but over 10% of prisoner numbers in this country, which is horrendous and indicative of prejudicial treatment of GRT through the judicial process. And the new the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 which just came into force at the end of June - ironically during Gypsy, Roma and Traveller History Month - is a very dark day in GRT history. It is one of the most restrictive laws in this country in hundreds of years and makes it illegal to stop anywhere for any length of time and can result in arrest and your vehicles being taken.

CT: How does that collective experience of misrepresentation, rejection and suffering shape GRT theology?

Steven: It's almost a question of why does God allow suffering in this world? And why do GRT continue to allow themselves to be in that position? The conclusion I've come to is that the suffering is to some degrees noble and intentional, like building up callouses through lifting weights. You go through pain because it brings you closer to your objective. If you want to lift up heavier weights, you have to go through the pain of developing the muscle.

How do Gypsies and Travellers make sense of that suffering? It goes back to the suffering Christ. They do that by placing themselves at Christ's feet at the cross, at the peak of his Passion suffering. It's the very worst time and yet at that very same point, you're closer to God than you'll ever be.

We're told to pick up our cross each day, to pick up that suffering. To leave that and choose the easy option, perhaps that's not our calling or even the calling of an entire people. The disciples gave up everything to follow Christ. We're called to run as if to win the race, not sit on a park bench. It's not that we want to suffer but that we suffer for the right purpose and if Christ's given us a new identity, then we can suffer for a little. There's a reverence behind this and that ties into the purity aspect I was talking about - when we're closer to God, quite often that comes with suffering.

CT: How frustrating is it for the GRT community to often be seen as a target of evangelism when they themselves are very Christian?

Steven: With this book, I'm hoping to almost press the reset button on the Church's relationship to the GRT community.

It goes back to the 1800s when mass education was expanding. The government wasn't sure what to do with the "heathen" Gypsies and Travellers so they passed the responsibility to the Church because at this time the Church was running schools for the masses. The Church - particularly the Church of England and The Salvation Army - started doing an extra outreach mission to evangelise the heathen vagrants and 'Egyptians'.

There were actually a couple of key Gypsy ministers at this time, like the evangelist Rodney Smith who went around the whole world and converted thousands of people. But even he was treated almost like a carnival spectacle. It was sort of like, 'come and hear the Gypsy preach,' and the advertisements were these Victorian circus-style posters. That was the beginning of the relationship between the Gypsies and the Church.

Then in the 50s, there was a revival in the Gypsy community and that's where for the first time in about 500 or 600 years of Gypsy and Traveller history in Britain they started taking hold of Christianity for themselves and that turned the books a little bit but GRT communities are still seen as a target of evangelism.

During one particular phase of field research for my PhD, I stayed for two weeks in one GRT community. In the time I was there, about four different ministers came down to the site. The GRT community turned their nose up and the reason was because they were fed up. They told me they'd been at this campsite for two years and for the first three to four months, they had about six ministers coming to see them every day like they were about to save them all. Now it's down to about four ministers. But in reality, this GRT community already had its own church. One of the caravans had been stripped and turned into a church that was holding two to three services a week and was probably doing a better ministry than the ministers going there.

So it points to this patronising, Victorian-style 'you really need saving' mentality where settled people see us as unclean and unsaved, but the irony is that this is actually the way that Gypsies see the non-Gypsy people!

CT: Do you see any way to move from that kind of mentality to a place of mutual blessing and exchange?

Steven: It needs a move away from certain traits of liberalism. By that, I mean that there is a real emphasis today on dividing us into different groups according to what we identify as. But that can be problematic because it isolates people and with that comes more vulnerability.

With this book, what I am asking the Church to do is invite me to the table. How do you do that? Treat everyone the same. Of course some needs can be different and we do need to accommodate some differences in cultural practices. But we also need to be able to listen more and there needs to be a change of heart. It's not always about some kind of action or displaying a flag or a poster or a pin badge.

We need a real heart change within churches where it's not about being dictated to or 'celebrated' one month in the year, but where we are more integrated and unified and can come together as equals. People can mean well but sometimes the gestures can cause more headaches than good.

Christians in the Middle East and the threat to an ancient community

Franklin Graham preaches in Glasgow, launches new fund to defend religious freedom in the UK

Can the Church of England afford same-sex blessings?

Senior Church of England cleric praises journalists and programme-makers

The need for Christian parliamentarians

How can God's plan include both Christ's sacrifice and Satan's survival?

Tony Evans' son says he'll be there for his father after admission of past sin

A pastor's response to Tony Evans' and Robert Morris' moral failings

Pride and Catholic schools

Lebanon, caught in crossfire between Israeli army and militant groups, needs prayer

Group of Brands

How Romani Gypsy and Traveller people have shaped Britain’s musical heritage

Associate Professor of Politics, Philosophy, Language and Communication, University of East Anglia

Research Associate of Ethnomusicology, University of Sheffield

Co-Researcher on Gypsy and Traveller Voices in Music Archives, University of East Anglia

Disclosure statement

Hazel Marsh receives funding from the University of East Anglia's AHRC Impact Acceleration Account for the collaborative project 'Romani Gypsy and Traveller Voices in Music Archives'.

Esbjörn Wettermark's work on this research has been made possible through his role in Prof. Fay Hield's UKRI funded FLF project Access Folk.

Tiffany Hore does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Sheffield provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

University of East Anglia provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Gypsy, Roma and Traveller History Month was established in Britain in 2008 as a way of challenging stereotypes and prejudice, and raising awareness of the diverse heritage and rich contributions of these ethnic minority groups to society.

Throughout June, Gypsies, Roma, Travellers and allies celebrate and educate others about the history, languages and cultures of these groups. So it’s a great time to acknowledge the immense contributions Romani Gypsies and Irish and Scottish Travellers have made, and continue to make, to our shared traditional music heritage in Britain and Ireland.

Historically, folk song collectors (who set out to document and save Britain’s folk music heritage) were hugely impressed by the repertoires and styles of Romani Gypsies and Travellers. In 1907, after hearing Romani Gypsy Betsy Holland sing in Devon, Cecil Sharp (a key figure in the first English folk revival ) wrote : “Talk of folk-singing! It was the finest and most characteristic bit of singing I had ever heard.”

In the 1950s, the eminent Scottish folklorist Hamish Henderson said collecting traditional songs from Scottish Travellers like Belle and Sheila Stewart was like holding a can under Niagara Falls in order to catch water.

Irish Traveller Mary Delaney , recorded by Jim Carroll and Pat Mackenzie in London in the late 1970s, had an enormous repertoire of “outstanding” songs and ballads. And Mike Yates, who made numerous field recordings of English Romanies between the 1960s and the 1980s, documented well over 100 songs from Sussex-based Romani Gypsy Mary Ann Haynes alone.

But when such recordings are incorporated into specialist collections, the ethnicity of the singers is seldom highlighted. The songs, as we argue in our forthcoming article Calling out the Catalogue, are therefore added to the canon of English, Scottish or Irish folk music. This means that the distinctive contributions of Romani Gypsies and Travellers – and their stories – are marginalised and overlooked.

Today, “Gypsy music” as represented in film and television often perpetuates exotic stereotypes, and depicts all Roma, Gypsies and Travellers as belonging to a single homogenous group of romantic outsiders or uncivilised “others”. These stereotypical representations often misguidedly draw on Balkan and Eastern European musical influences to represent all these groups, regardless of nationality.

The lack of recognition of Gypsy and Traveller contributions to Scottish, Irish or English music styles effectively excludes these ethnic minorities from narratives of Britishness .

Recordings of songs sung by Romani Gypsies and Travellers, held in national and regional sound archives, have had a lasting impact on folk repertoires in Britain and Ireland. And they provided rich resources for the second English folk revival of the 1960s and 1970s. For example, the singer Shirley Collins says she first heard A Blacksmith Courted Me (sung “in the most fantastic way” ) by Romani Gypsy singer Phoebe Smith , from a recording made by folklorist Peter Kennedy in Suffolk in 1956.

Similarly, guitar legend Martin Carthy learned the song Georgie from a 1974 field recording of Romani Gypsy singer Levi Smith . Smith’s family was a source of many songs popular in the contemporary folk scene. Also, Irish Traveller singer Thomas McCarthy demonstrates the continued strength of Traveller song traditions in his public performances. He also featured in Pat Collins’ recent documentaries on RTÉ.

Many of the songs that continue to form the repertoire of folk singers today were originally sourced from field recordings of Romani Gypsies and Travellers held in archival collections.

In our collaborative project Gypsy and Traveller Voices in Music Archives , we’ve been working to raise awareness of one such collection housed at the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library (VWML) in Cecil Sharp House , London. To ensure that the project is relevant and reaches the right people, we’ve been supported by a Romani and Traveller focus group.

To render this collection more accessible, we commissioned Romani academic and poet Dr Jo Clement to design and create a new resource telling the stories of some of the Romani and Traveller people recorded in the 20th century. The resource, free to download, has QR codes linking straight to digitised recordings of Romani and Traveller singers in the VWML catalogue.

We’re also collaborating with Romani film collective Patrin Films on a short documentary. It will tell the personal story of a descendant of one of the extended Romani families recorded by song collectors in south-east England between the 1950s and the 1980s.

Romani Gypsies and Travellers, as the late and influential folk singer Norma Waterson wrote in her preface to Mike Yate’s book Travellers’ Joy (2006) “have come to be at the very heart of what it means, culturally speaking” to be English, Scottish or Irish. So, this Gypsy, Roma and Traveller History Month, let’s acknowledge and celebrate the tremendous importance of Romani Gypsies and Travellers to our shared music heritage.

- Gypsies and Travellers

- Gypsies, Roma and Travellers

- Give me perspective

Research Fellow – Magnetic Refrigeration

Centre Director, Transformative Media Technologies

Postdoctoral Research Fellowship

Social Media Producer

Dean (Head of School), Indigenous Knowledges

Gypsy Roma and Traveller History and Culture

Gypsy Roma and Traveller people belong to minority ethnic groups that have contributed to British society for centuries. Their distinctive way of life and traditions manifest themselves in nomadism, the centrality of their extended family, unique languages and entrepreneurial economy. It is reported that there are around 300,000 Travellers in the UK and they are one of the most disadvantaged groups. The real population may be different as some members of these communities do not participate in the census .

The Traveller Movement works predominantly with ethnic Gypsy, Roma, and Irish Traveller Communities.

Irish Travellers and Romany Gypsies

Irish Travellers

Traditionally, Irish Travellers are a nomadic group of people from Ireland but have a separate identity, heritage and culture to the community in general. An Irish Traveller presence can be traced back to 12th century Ireland, with migrations to Great Britain in the early 19th century. The Irish Traveller community is categorised as an ethnic minority group under the Race Relations Act, 1976 (amended 2000); the Human Rights Act 1998; and the Equality Act 2010. Some Travellers of Irish heritage identify as Pavee or Minceir, which are words from the Irish Traveller language, Shelta.

Romany Gypsies

Romany Gypsies have been in Britain since at least 1515 after migrating from continental Europe during the Roma migration from India. The term Gypsy comes from “Egyptian” which is what the settled population perceived them to be because of their dark complexion. In reality, linguistic analysis of the Romani language proves that Romany Gypsies, like the European Roma, originally came from Northern India, probably around the 12th century. French Manush Gypsies have a similar origin and culture to Romany Gypsies.

There are other groups of Travellers who may travel through Britain, such as Scottish Travellers, Welsh Travellers and English Travellers, many of whom can trace a nomadic heritage back for many generations and who may have married into or outside of more traditional Irish Traveller and Romany Gypsy families. There were already indigenous nomadic people in Britain when the Romany Gypsies first arrived hundreds of years ago and the different cultures/ethnicities have to some extent merged.

Number of Gypsies and Travellers in Britain

This year, the 2021 Census included a “Roma” category for the first time, following in the footsteps of the 2011 Census which included a “Gypsy and Irish Traveller” category. The 2021 Census statistics have not yet been released but the 2011 Census put the combined Gypsy and Irish Traveller population in England and Wales as 57,680. This was recognised by many as an underestimate for various reasons. For instance, it varies greatly with data collected locally such as from the Gypsy Traveller Accommodation Needs Assessments, which total the Traveller population at just over 120,000, according to our research.

Other academic estimates of the combined Gypsy, Irish Traveller and other Traveller population range from 120,000 to 300,000. Ethnic monitoring data of the Gypsy Traveller population is rarely collected by key service providers in health, employment, planning and criminal justice.

Where Gypsies and Travellers Live

Although most Gypsies and Travellers see travelling as part of their identity, they can choose to live in different ways including:

- moving regularly around the country from site to site and being ‘on the road’

- living permanently in caravans or mobile homes, on sites provided by the council, or on private sites

- living in settled accommodation during winter or school term-time, travelling during the summer months

- living in ‘bricks and mortar’ housing, settled together, but still retaining a strong commitment to Gypsy/Traveller culture and traditions

Currently, their nomadic life is being threatened by the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, that is currently being deliberated in Parliament, To find out more or get involved with opposing this bill, please visit here

Although Travellers speak English in most situations, they often speak to each other in their own language; for Irish Travellers this is called Cant or Gammon* and Gypsies speak Romani, which is the only indigenous language in the UK with Indic roots.

*Sometimes referred to as “Shelta” by linguists and academics

New Travellers and Show People

There are also Traveller groups which are known as ‘cultural’ rather than ‘ethnic’ Travellers. These include ‘new’ Travellers and Showmen. Most of the information on this page relates to ethnic Travellers but ‘Showmen’ do share many cultural traits with ethnic Travellers.

Show People are a cultural minority that have owned and operated funfairs and circuses for many generations and their identity is connected to their family businesses. They operate rides and attractions that can be seen throughout the summer months at funfairs. They generally have winter quarters where the family settles to repair the machinery that they operate and prepare for the next travelling season. Most Show People belong to the Showmen’s Guild which is an organisation that provides economic and social regulation and advocacy for Show People. The Showman’s Guild works with both central and local governments to protect the economic interests of its members.

The term New Travellers refers to people sometimes referred to as “New Age Travellers”. They are generally people who have taken to life ‘on the road’ in their own lifetime, though some New Traveller families claim to have been on the road for three consecutive generations. The New Traveller culture grew out of the hippie and free-festival movements of the 1960s and 1970s.

Barge Travellers are similar to New Travellers but live on the UK’s 2,200 miles of canals. They form a distinct group in the canal network and many are former ‘new’ Travellers who moved onto the canals after changes to the law made the free festival circuit and a life on the road almost untenable. Many New Travellers have also settled into private sites or rural communes although a few groups are still travelling.

If you are a new age Traveller and require support please contact Friends, Families, and Travellers (FFT) .

Differences and Values

Differences Between Gypsies, Travellers, and Roma

Gypsies, Roma and Travellers are often categorised together under the “Roma” definition in Europe and under the acronym “GRT” in Britain. These communities and other nomadic groups, such as Scottish and English Travellers, Show People and New Travellers, share a number of characteristics in common: the importance of family and/or community networks; the nomadic way of life, a tendency toward self-employment, experience of disadvantage and having the poorest health outcomes in the United Kingdom.

The Roma communities also originated from India from around the 10th/ 12th centuries and have historically faced persecution, including slavery and genocide. They are still marginalised and ghettoised in many Eastern European countries (Greece, Bulgaria, Romania etc) where they are often the largest and most visible ethnic minority group, sometimes making up 10% of the total population. However, ‘Roma’ is a political term and a self-identification of many Roma activists. In reality, European Roma populations are made up of various subgroups, some with their own form of Romani, who often identify as that group rather than by the all-encompassing Roma identity.

Travellers and Roma each have very different customs, religion, language and heritage. For instance, Gypsies are said to have originated in India and the Romani language (also spoken by Roma) is considered to consist of at least seven varieties, each a language in their own right.

Values and Culture of GRT Communities

Family, extended family bonds and networks are very important to the Gypsy and Traveller way of life, as is a distinct identity from the settled ‘Gorja’ or ‘country’ population. Family anniversaries, births, weddings and funerals are usually marked by extended family or community gatherings with strong religious ceremonial content. Gypsies and Travellers generally marry young and respect their older generation. Contrary to frequent media depiction, Traveller communities value cleanliness and tidiness.

Many Irish Travellers are practising Catholics, while some Gypsies and Travellers are part of a growing Christian Evangelical movement.

Gypsy and Traveller culture has always adapted to survive and continues to do so today. Rapid economic change, recession and the gradual dismantling of the ‘grey’ economy have driven many Gypsy and Traveller families into hard times. The criminalisation of ‘travelling’ and the dire shortage of authorised private or council sites have added to this. Some Travellers describe the effect that this is having as “a crisis in the community” . A study in Ireland put the suicide rate of Irish Traveller men as 3-5 times higher than the wider population. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the same phenomenon is happening amongst Traveller communities in the UK.

Gypsies and Travellers are also adapting to new ways, as they have always done. Most of the younger generation and some of the older generation use social network platforms to stay in touch and there is a growing recognition that reading and writing are useful tools to have. Many Gypsies and Travellers utilise their often remarkable array of skills and trades as part of the formal economy. Some Gypsies and Travellers, many supported by their families, are entering further and higher education and becoming solicitors, teachers, accountants, journalists and other professionals.

There have always been successful Gypsy and Traveller businesses, some of which are household names within their sectors, although the ethnicity of the owners is often concealed. Gypsies and Travellers have always been represented in the fields of sport and entertainment.

How Gypsies and Travellers Are Disadvantaged

The Traveller, Gypsy, and Roma communities are widely considered to be among the most socially excluded communities in the UK. They have a much lower life expectancy than the general population, with Traveller men and women living 10-12 years less than the wider population.

Travellers have higher rates of infant mortality, maternal death and stillbirths than the general population. They experience racist sentiment in the media and elsewhere, which would be socially unacceptable if directed at any other minority community. Ofsted consider young Travellers to be one of the groups most at risk of low attainment in education.

Government services rarely include Traveller views in the planning and delivery of services.

In recent years, there has been increased political networking between the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller activists and campaign organisations.

Watch this video by Travellers Times made for Gypsy Roma Traveller History Month 2021:

Information and Support

We have a variety of helpful guides to provide you with the support you need

Community Corner

Read all about our news, events, and the upcoming music and artists in your area

Roma Culture: Customs, Traditions & Beliefs

The Roma are an ethnic people who have migrated across Europe for a thousand years. The Roma culture has a rich oral tradition, with an emphasis on family. Often portrayed as exotic and strange, the Roma have faced discrimination and persecution for centuries.

Today, they are one of the largest ethnic minorities in Europe — about 12 million to 15 million people, according to UNICEF, with 70 percent of them living in Eastern Europe. About a million Roma live in the United States, according to Time .

Roma is the word that many Roma use to describe themselves; it means "people," according to the Roma Support Group , (RSG) an organization created by Roma people to promote awareness of Romani traditions and culture. They are also known as Rom or Romany. According to Open Society Foundations , some other groups that are considered Roma are the Romanichals of England, the Beyash of Croatia, the Kalé of Wales and Finland, the Romanlar from Turkey and the Domari from Palestine and Egypt. The Travelers of Ireland are not ethnically Roma, but they are often considered part of the group.

The Roma are also sometimes called Gypsies. However, some people consider that a derogatory term, a holdover from when it was thought these people came from Egypt. It is now thought that the Roma people migrated to Europe from India about 1,500 years ago. A study published in 2012 in the journal PLoS ONE concluded that Romani populations have a high frequency of a particular Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA that are only found in populations from South Asia.

Nomadic by necessity

The Romani people faced discrimination because of their dark skin and were once enslaved by Europeans. In 1554, the English Parliament passed a law that made being a Gypsy a felony punishable by death, according to the RSG. The Roma have been portrayed as cunning, mysterious outsiders who tell fortunes and steal before moving on to the next town. In fact, the term “gypped” is probably an abbreviation of Gypsy, meaning a sly, unscrupulous person, according to NPR .

As a matter of survival, the Roma were continuously on the move. They developed a reputation for a nomadic lifestyle and a highly insular culture. Because of their outsider status and migratory nature, few attended school and literacy was not widespread. Much of what is known about the culture comes through stories told by singers and oral histories.

In addition to Jews, homosexuals and other groups, the Roma were targeted by the Nazi regime in World War II. The German word for Gypsy, "Zigeuner," was derived from a Greek root that meant "untouchable" and accordingly, the group was deemed "racially inferior."

Roma were rounded up and sent to camps to be used as labor or to be killed. During this time, Dr. Josef Mengele was also given permission to experiment with on twins and dwarves from the Romani community.

According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum , Nazis killed tens of thousands of Roma in the German-occupied territories of the Soviet Union and Serbia. Thousands more Roma were killed in the concentration camps of Auschwitz-Birkenau, Sobibor, Belzec, Chelmno and Treblinka. There were also camps called Zigeunerlager that were intended just for the Roma population. It is estimated that up to 220,000 Roma died in the Holocaust.

Roma culture

For centuries, stereotypes and prejudices have had a negative impact on the understanding of Roma culture, according to the Romani Project. Also, because the Roma people live scattered among other populations in many different regions, their ethnic culture has been influenced by interaction with the culture of their surrounding population. Nevertheless, there are some unique and special aspects to Romani culture.

Spiritual beliefs

The Roma do not follow a single faith; rather, they often adopt the predominant religion of the country where they are living, according to Open Society, and describe themselves as "many stars scattered in the sight of God." Some Roma groups are Catholic, Muslim, Pentecostal, Protestant, Anglican or Baptist.

The Roma live by a complex set of rules that govern things such as cleanliness, purity, respect, honor and justice. These rules are referred to as what is "Rromano." Rromano means to behave with dignity and respect as a Roma person, according to Open Society. "Rromanipé" is what the Roma refer to as their worldview.

Though the groups of Roma are varied, they all do speak one language, called Rromanës. Rromanës has roots in Sanskritic languages, and is related to Hindi, Punjabi, Urdu and Bengali, according to RSG. Some Romani words have been borrowed by English speakers, including "pal" (brother) and "lollipop" (from lolo-phabai-cosh, red apple on a stick).

Traditionally, anywhere from 10 to several hundred extended families form bands, or kumpanias, which travel together in caravans. Smaller alliances, called vitsas, are formed within the bands and are made up of families who are brought together through common ancestry.

Each band is led by a voivode, who is elected for life. This person is their chieftain. A senior woman in the band, called a phuri dai, looks after the welfare of the group’s women and children. In some groups, the elders resolve conflicts and administer punishment, which is based upon the concept of honor. Punishment can mean a loss of reputation and at worst expulsion from the community, according to the RSG.

Family structure

The Roma place great value on close family ties, according to the Rroma Foundation : "Rroma never had a country — neither a kingdom nor a republic — that is, never had an administration enforcing laws or edicts. For Rroma, the basic 'unit' is constituted by the family and the lineage."

Communities typically involve members of the extended family living together. A typical household unit may include the head of the family and his wife, their married sons and daughters-in-law with their children, and unmarried young and adult children.

Romani typically marry young — often in their teens — and many marriages are arranged. Weddings are typically very elaborate, involving very large and colorful dress for the bride and her many attendants. Though during the courtship phase, girls are encouraged to dress provocatively, sex is something that is not had until after marriage, according to The Learning Channel . Some groups have declared that no girl under 16 and no boy under 17 will be married, according to the BBC .

Hospitality

Typically, the Roma love opulence. Romani culture emphasizes the display of wealth and prosperity, according to the Romani Project . Roma women tend to wear gold jewelry and headdresses decorated with coins. Homes will often have displays of religious icons, with fresh flowers and gold and silver ornaments. These displays are considered honorable and a token of good fortune.

Sharing one's success is also considered honorable, and hosts will make a display of hospitality by offering food and gifts. Generosity is seen as an investment in the network of social relations that a family may need to rely on in troubled times.

The Roma today

While there are still traveling bands, most use cars and RVs to move from place to place rather than the horses and wagons of the past.

Today, most Roma have settled into houses and apartments and are not readily distinguishable. Because of continued discrimination, many do not publicly acknowledge their roots and only reveal themselves to other Roma.

While there is not a physical country affiliated with the Romani people, the International Romani Union was officially established in 1977. In 2000, The 5th World Romany Congress in 2000 officially declared Romani a non-territorial nation.

During the Decade of Roma Inclusion (2005-2015), 12 European countries made a commitment to eliminate discrimination against the Roma. The effort focused on education, employment, health and housing, as well as core issues of poverty, discrimination, and gender mainstreaming. However, according to the RSG, despite the initiative, Roma continue to face widespread discrimination.

According to a report by the Council of Europe's commissioner for human rights , "there is a shameful lack of implementation concerning the human rights of Roma … In many countries hate speech, harassment and violence against Roma are commonplace."

April 8 is International Day of the Roma , a day to raise awareness of the issues facing the Roma community and celebrate the Romani culture.

Additional reporting by Reference Editor Tim Sharp.

Additional resources

- Council of Europe: Factsheets on Roma

- European Roma Rights Center: The Romani Claim to Non-Territorial Nation Status: Recognition from an International Legal Perspective

- Smithsonian Center for Education and Museum Studies: Gypsies in the United States

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

30,000 years of history reveals that hard times boost human societies' resilience

'We're meeting people where they are': Graphic novels can help boost diversity in STEM, says MIT's Ritu Raman

'Holy grail' of solar technology set to consign 'unsustainable silicon' to history

Most Popular

- 2 32 of the most dangerous animals on Earth

- 3 'The early universe is nothing like we expected': James Webb telescope reveals 'new understanding' of how galaxies formed at cosmic dawn

- 4 Have giant humans ever existed?

- 5 Long-lost Assyrian military camp devastated by 'the angel of the Lord' finally found, scientist claims

- 2 Is Earth really getting too hot for people to survive?

- 3 Human ancestor 'Lucy' was hairless, new research suggests. Here's why that matters.

- 4 Astronauts stranded in space due to multiple issues with Boeing's Starliner — and the window for a return flight is closing

- 5 32 of the most dangerous animals on Earth

- current issue

- past issues

This is an article from the July-August 2017 issue: The Roma

Get The PDF

Articles may be printed and distributed as much as you like.

July 01, 2017 by Melody J. Wachsmuth

Movements in Mission

Christianity among the roma (gypsies).

Although 'Gypsy' may be a more recognizable name, it can also convey a derogatory meaning in some European contexts. Therefore, in general, we use the term 'Roma' in this issue, apart from historical usage or a group who specifically refer to themselves as Gypsy.

Recently, I had the privilege of attending a Romani friend’s wedding. Tables laden with food, a brass band playing music for hundreds of people dancing for hours—this was a rich experience of sights, sounds, and tastes like nothing I had ever experienced. More than that, however, it was also an example of uninhibited celebration, expression of joy in dance, and an extravagant hospitality—all were welcome to the party. Suddenly, I had a tangible picture of God’s lavish generosity—a God who welcomes and even seeks the uninvited guests, a God who throws a feast to welcome prodigals home, and a God who “rejoices over us with shouts of joy”(Zephaniah 3:17).

Over the last six years, as I traveled throughout Eastern Europe forming relationships and learning about the Roma in numerous contexts, I experienced many transformative moments. My understanding of God expanded, my conception of His mission shifted, and certain elements of Roma culture and Roma Christianity deeply challenged me. In Eastern Europe, where many Roma communities remain marginalized from the majority society, I have also been burdened and grieved by seeing the cyclic effects of deep poverty and hearing stories of trauma, rejection, and pain. Jesus Christ, as Christian Roma leaders assert, is the only hope; indeed many Roma testimonies manifest the truth of Ephesians 3:18,19–grasping the immensity, richness, and vastness of Christ’s love liberates and restores Roma identity. As a beloved son and daughter of God, being filled "to the measure of all the fullness of God" is the key that releases God’s power to transform, empower, and equip for mission.

Who Are the Roma?

To understand why this is such a profound witness to the power of the gospel, it is necessary to understand both the current situation of the Roma and the story of Roma Christianity. In Europe, historical accounts first noted the Roma in the 12th century. Although during the Middle Ages, their trades were often portrayed as a valuable contribution to societies, by the 16th century, various areas of Central and Eastern Europe were developing negative attitudes and policies toward them. [1] In the centuries that followed, ruling powers attempted to fit them into the constraints of society, through mechanisms including assimilation, forced sedenterization, slavery, and extermination during World War II. Despite a shift in state policies and increased international attention over the last couple of decades, particularly in Eastern Europe, many Roma communities are in a deeper state of poverty than the majority populations and, additionally , they faced discriminatory attitudes reinforcing their marginalization.

However, it is a mistake to think of the Roma as a monolithic group, and the use of different ethnonyms can lead to confusion for those unfamiliar with the heterogeneity of Roma group. For example, there are groups who identify as Roma, Romani, Gypsy, Gitano, Travellers and Sinti. Roma or Romani is used in this article in its broadest sense—to describe groups of people who may speak one of the Romani dialects, may have a shared experience and sense of history, cultural practices, and/or self-identify as Roma, Romani, or Gypsy.

It is also a mistake to think that all 10-12 million Roma in Europe are poor and marginalized. In fact, there are wealthy Roma groups and individuals, and there are Roma in every layer of society: academics, lawyers, musicians, actors, and politicians. There are Roma organizations, NGO’s, and political advocacy groups. There are also Roma churches and Christian movements that have their own Bible schools, training programs, and church praxis. Consequently, it is good practice to approach each community on its own terms, listening to how they self-identify and not making assumptions. “Who has the right to name us, to tell us who we are?” asked one Roma pastor at a 2016 Roma conference.

Christianity and the Roma

The Roma in Europe are Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant, Jehovah Witness, and Muslim. Often, the Christian Church’s attitude mirrored that of society, and there are accounts of the Church refusing baptism and confessions to Roma. [2] In fact, in the past, due to the lack of engagement in religious institutions, some scholars concluded that the Roma were "insincere" in their religious commitment, although current scholars have argued that this was a result of racist and exclusionary attitudes from the Church. [3] The insincerity hypothesis can also be challenged by what has been happening among the Roma for decades. That is, Protestant Christianity has been spreading through Roma communities in Europe, North and South America, and beyond.

One of the most prominent and well-documented catalytic locations of a “Gypsy Revival” began in France in the 1950's when a Manouche family experienced the healing of a family member. Clément Le Cossec, a minister in the Assemblies of God church and a non-Roma, devoted his life to encourage this “Gypsy Awakening” by equipping and training leaders and missionaries. For some this meant learning to read. The movement crossed over to different Roma groups and spread to numerous countries and continents. [4]

In Eastern Europe, the Baptists were active in Bulgaria in the early 20th century, and Pentecostalism began spreading in the 1940’s and 1950’s, with rapid expansion beginning both in Romania and Bulgaria after the fall of Communism. The most internationally well-known Roma revival in Romania took place in the town of Toflea, beginning in the 1990’s and peaking in 2003, with their largest baptism being around 500 people. Known as Rugul Aprins (Burning Bush), the members who migrated from Toflea for economic reasons started their own churches and the primary pastor reports 10 churches in Romania, 5 in England, 1 in Spain, and 1 in Germany. [5]

For many complex reasons, reliable numbers of Roma populations in Europe are hard to come by, and the same can be said for the number of Roma Christians. However, certain contexts have educated estimates. For example, the number of active Roma Christians is over 200,000 in Spain, over 140,000 in France, tens of thousands in Bulgaria and Romania, and thousands in places like Slovakia and Hungary. [6]

Just as Roma identity and context cannot be understood monolithically, so it is the same with Roma Christianity—more accurately viewed as movements with just as diverse praxis and theology as you might expect to find in churches of other nations or ethnicities. There are large, well-established Roma churches and small struggling churches and home groups. There are Roma churches with missional impulses stretching to the non-Roma, and other churches that focus just on their particular Roma group.

This issue's themed articles are meant to exhibit this heterogeneity. There are both Roma and non-Roma writers, each speaking from a different context and perspective. To help set the framework of the wider picture, these five themes emerge in the articles.

1. The Rapid Growth of Roma Pentecostalism

Roma Pentecostalism is the stream of Christianity growing most rapidly. At its present conversion rates, some scholars suggest that it will be the prime form of Roma religiosity in a few years. [7] At least in Eastern Europe, it is common to hear testimony of coming to Christ through miracles, healings, dreams and visions. Some Roma leaders have a sense that the Roma will be key to evangelizing other nations within Europe–that they will bless other nations.

2. Towards Holistic Transformation

Many Roma communities face deep poverty and marginalization from the majority culture, therefore there is an acute need to both understand the complexity of factors which contribute to this and an orientation towards holistic development based on the Roma leaders’ perspective of what needs to change.

The Roma communities in Croatia in which I serve are certainly not the poorest I have seen, but even so, the issues of a marginalized minority community in a country already facing socio-economic hardship are acute and complicated. One day, I accompanied a woman from my community who was attempting to apply for health insurance. In the space of a few hours, we visited 6 different offices. This woman cannot read, and I marveled at her adeptness at navigating a system based on the ability to read. At the same time, I also got a sense of the vulnerability one faces. In our church community, over half the adults in church are functionally illiterate. Many children drop out of school before finishing eighth grade. All have continual health issues. Most survive on social help and temporary seasonal labor such as street cleaning. Not all have electricity or running water.

3. Training and Equipping

With the rapid growth of Roma Christianity, there is an acute need for training and equipping of Roma leaders. Although certainly there are Roma leaders attending Bible schools and universities, as well as some movements which have their own autonomous Bible schools, Roma leaders still express the need for more tools and training.

In the past, and even now, other churches or missionaries have not deemed the Roma “capable” to lead their own churches. The Gypsy And Traveller International Evangelical Fellowship (G.A.T.I.E.F.), which grew out of the Gypsy revival in France, has been highly successful in mentoring, training, and sending numerous Roma pastors and missionaries. They are active in 24 countries in several continents. The current leader, René Zanellato wrote in his 2014 update regarding the “secret” to this success:

The error has been that certain leaders of churches and organizations did not understand and did not trust the work and the capacity of the Holy Spirit to let the Gypsies themselves evangelize the Gypsies. These countries and pastors have been a hindering to the development and to the Revival, wanting to impose to the Gypsies their rules and their non-Gypsy mentality. [8] [sic]

4. Lack of Trust as a Missional Barrier

Attitudes of prejudice or stereotyping, based on longstanding, ingrained images of the Roma, are prominent in the majority populations. However, prejudice can also exist between different Roma groups and from the Roma to the non-Roma (gadje) . I have argued elsewhere that reconciliation must be a key structure of mission and is critical for the holistic transformation of communities. [9] Transformation can only progress so far if relationships between Roma and non-Roma are not healed and renewed.

5. The narrative matters...and this relates to mission praxis

How we tell stories is critical for shaping attitudes and actions toward Roma communities. Even as “mission popularity” rises iregarding the Roma, I have become increasingly aware of the images and language used to depict the Roma. This would be a fabulous theme for a future issue on a broader scale--how we, as an evangelizing church, often present a foreign culture/people in our biases, in order to show an evangelism which can be derogatory.

Listening, learning, and asking as an orienting practice for mission are not new insights in 21st century missiology. And yet all too often our mission praxis continues to repeat mistakes made in mission history. As we participate in God’s mission, we must constantly be open to the critique of our motives, strategies, and perspectives. As Father Greg Boyle concludes: “I discovered that you do not go to the margins to rescue anyone. But if we go there, everyone finds rescue.” [10]

[1] Crowe, David. A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), xvii, xviii.

[2] Atanasov, Miroslav. “Gypsy Pentecostals: The Growth of the Pentecostal Movement Among the Roma in Bulgaria and Its Revitalization of Their Communities.” (Asbury Theological Seminary, 2008). p. 99-101

[3] Acton, Thomas A. “New Religious Movements among Roma, Gypsies and Travellers: Placing Romani Pentecostalism in an Historical and Social Context.” In Thurfjell & Marsh eds. Romani Pentecostalism, (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2014), 27,28

[4] Laurent, Régis. “On the Genesis of Gypsy Pentecostalism in Brittany.” In Thurfjell & Marsh, eds. Romani Pentecostalism, 33, 39.

[5] Information accumulated through interviews by author in person with Anuşa Capitanu (Toflea, Romania, July 2015), Ilia Bolmandor (Bucharest, Romania, July 2015), and Ioan Caba (Oradea, Romania, July 2015).

[6] Cantón-Delgado, Manuela. “Gypsy Leadership, Cohesion and Social Memory in the Evangelical Church of Philadelphia.” Social Compass (2017), 5; Gypsy and Traveller International Evangelical Fellowship 2014 Report, Rene Zanellato; Slavkova, Magdalena. “Prestige” and Identity Construction Amongst Pentecostal Gypsies in Bulgaria.” InThurfjell & Marsh eds. Romani Pentecostalism; Podolinska, Tatiana, and Tomaš Hrustič. “Religion as a Path to Change? The Possibilities of Social Inclusion of the Roma in Slovakia.” (Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 2010.)

[7] Thurfjell, David, and Adrian Marsh, eds. Romani Pentecostalism, 8.

[8] G.A.T.I.E.F 2014 Report, Rene Zanellato, [email protected]

[9] Wachsmuth, Melody J. “Roma Christianity in Central and Eastern Europe: Challenges, Opportunities for Mission, Modes of Significance.” In Mission in Central and Eastern Europe: Realities, Perspectives, Trends (Oxford: Regnum, 2017),

[10] Boyle, Greg. “I thought I could save gang members.” The Jesuit Review, March 2017. http://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2017/03/28/father-greg-boyle-i-thought-i-could-save-gang-members-i-was-wrong

Related Articles

These are articles that the system matched via the tags and keywords associated with this article.

- Staying Home: Cultural Bridging in a Time of Crisis (40% match)

- From Prejudice to Love (40% match)

- Questions of Prejudice in Hungary (40% match)

- Obeying The Call: Overcoming Cultural Obstacles to Mission (40% match)

- Loving Our “Unwanted” Neighbors (40% match)

Well done Melody. Great writing as always. Brian and Diane

Melody, thanks for your great insights into the Roma peoples! I am excited about the fact that we have a Roma version of The HOPE movie currently in production! The HOPE tells the major overarching story of the whole Bible from Creation to Christ! (It is already in 68 languages) This entire issue of MF is fueling my prayers for the Roma version to be completed and put in circulation! http://www.thehopeproject.com

Thank you Brian and Diane!

This is very interesting news. Which Roma dialect or language will the movie be in? When is it scheduled to be released? Thank you for your work!

Thank you for this article and the information! We serve primarily the Gypsy community in church planting and beginning a safe home for girls venerable to trafficking in Western Bulgaria. It’s so great to see God working so mightily among the Roma people when they realize their identity in Christ after being rejected by the world for so long. God loves them deeply and you know when you are around them. Gallowayministries.org

Hi I have been a pentecostal pastor/teacher for nearly 60 years. I write a fairly short teaching article most days taken direct from the Bible I am happy to email it to anyone who wishes. Just send me emails with a request to receive the teaching and I will happily forward it. God bless you in ministry to these people. Jack Guerin

Leave A Comment

About The Author

Melody has been doing mission research based in Southeastern Europe since 2011. She is a leader in a Roma-majority church in Croatia and is currently a PhD candidate, studying Roma identity and Pentecostalism in Croatia and Serbia.

http://www.balkanvoices.wordpress.com

Article Tags

europe , gypsies , gypsy , roma , romani

Most Commented On Articles

- 2 - Vision for a Refugee Kingdom Movement

- 2 - Our Role in Hastening “No Place Left”

- 0 - Rapid Mobilization: How the West Was Won

- 836 - Growing Your Faith for a Disciple Making Movement

- 806 - Patrick Johnstone Interview part 2

- 743 - Bible Translations for Muslim Readers

- 600 - Patrick Johnstone Interview part 1

- 452 - Special Feature: Audio Interview with David Platt at Urbana 2015

- 443 - Translating Familial Biblical Terms

- 300 - Millennials and the Bible

What People Are Talking About Now

- 259 - A Response to Mission Frontiers: The Fingerprints of God in Buddhism (Nov/Dec 2014)

© 2011-2017 Frontier Ventures | About Us | Advertise | Contact Us | Donate | RSS

- Find a Person

- Find a Church

- Safeguarding

- Accessibility

- The Diocese of London

- Our Churches

- Our 2030 Vision

- The Bishop of London

- Bishops and Archdeacons

- Diocesan Fund Leadership

- Christenings, Weddings & Funerals

- Church and Parish Support

- Buildings and property

- Children and Youth

- Church growth

- Communications and digital

- Compassionate Communities

- Confident Disciples

- Creation Care

- Diversity and inclusion

- Finance and giving

- Governance: PCCs & Synods

- Human Resources (HR)

- Clergy & LLM Support

- Clergy Guides

- Clergy Housing

- Clergy Training and Development

- Clergy and Household Wellbeing

- Licensed Lay Ministry

- Living in Love and Faith

- Parish Practicalities

- Episcopal Areas

- Resolution parishes

- What is a Vocation?

- Everyday Ministry

- Non-ordained ministry roles

- Ordained Ministry

- What’s On

- Advertise Your Event

- Berlin Brandenburg

- Cycle of prayer

- London Kalendar

- Faculties, changes and repairs

- Apply for DAC advice online

- Dates of DAC meetings

- Quinquennials, maintenance and inspections

- Church halls and lettings

- Resources for Children and Youth Ministry

- The Apprentice Programme

- The Spark Fund

- Latest articles/news

- Church websites

- Safeguarding Information on Parish Websites

- Copyright of images, music and text

- Designing your communications

- Diocesan brand centre

- GDPR guidance

- Photography permissions and consent

- Social media

- Using your church as a film location

- Working with the press

- Caring for God’s creation

- Mental health & isolation

- Refugees, asylum seekers & modern slavery

- Supporting someone in my church through the asylum system

- Hosting an asylum seeker through our hosting scheme

- Community Sponsorship

- Support for other specific refugee & asylum groups

- Supporting recently recognised refugees

- Responding to Modern Slavery

- Money, debt & food insecurity

- Housing & homelessness

- Safer communities for all young people

- The Pietà Prayer Project

- Safe Spaces After School

- Mentoring Schemes for Young People

- Communal Practices for churches

- Listening Groups (Lent 2024)

- Prayer Practices (Lent 2023)

- Discerning a shared Way of Life

- Other courses and tools

- Exploring Faith

- Deepening Faith

- Everyday Faith

- Energy Footprint Tool

- Racial justice

- Anti-racism statement

- Disability ministry

- The 360 Accessibility Audit

- Strength made perfect

- LGBT+ Advisory Group

- Annual accounts & reports

- Charity Commission Registration

- Common Fund

- Contactless and digital giving

- Encouraging generous giving

- Statutory fees for weddings and funerals

- Fees for Sunday and weekday services

- Financial procedures

- Loans and grants

- Money Matters newsletter

- New treasurers

- Parish vacancy

- Risk management

- The Parish Giving Scheme

- Churchwardens

- PCC Secretaries

- The Electoral Roll

- Annual Parochial Church Meeting (APCM)

- Annual Return

- Deanery Synod

- The role of the deanery synod secretary

- Diocesan Synod

- By-elections for Diocesan synod

- Area councils

- Area Finance Committee

- Diocesan Bishop’s Council

- Diocesan Board of Patronage

- Diocesan finance committee

- Vacany in See Committee

- Employing people

- Becoming an employer

- Calculating Holiday

- Employment legislation

- The Equality Act 2010

- Employment status

- Housing and Benefit in Kind

- Managing people

- Managing volunteers

- Performance appraisals

- Disciplinary and Grievance

- Disciplinary policies

- Grievance policies

- Ordinary Parental Leave

- Sickness management and capability

- Shared parental leave

- Diocesan policies

- Whistleblowing Policy

- Complaints process (clergy)

- Harassment and Bullying Policy

- Clergy appointment process

- Contact the safeguarding team

- Meet the safeguarding team

- Update service

- Document checks

- Drop-in sessions

- Safeguarding news and articles

- Safeguarding policies

- Safeguarding complaints policy and procedure

- Roles and responsibilities

- Safer recruitment

- Support for Survivors

- Safeguarding training

- Who needs to do what?

- Basic Awareness and Foundation courses

- Leadership Training

- Safer Recruitment course

- Raising Awareness of Domestic Abuse course

- Useful safeguarding links

- Links to other organisations

- Your safeguarding dashboard

- New in post – induction

- Life events

- Baptism guidelines

- Funeral guidelines

- Confirmation guidelines

- Communion guidelines

- Weddings and marriage guidelines

- Recording weddings

- Working well with others

- Ecumenical relations

- Healthcare chaplains

- Working with members of religious communities

- Stipend scales, removal grants and fees

- Parental leave

- Clergy terms of service

- Retirement resources

- Grants and Expenses

- Clergy Moves

- Area Directors of Ministry

- Continuing Ministerial Development

- Ministerial Development Review

- Episcopal Review

- Clergy Assistance Programme

- Clergy household support

- Diocesan support of clergy wellbeing

- Managing conflict

- Practical steps and resources

- Sabbaticals and study leave

- The theology of clergy wellbeing

- Discernment process and training

- Post-licensing development

- St Edmund’s Courses

- St Edmunds: The two-year course

- St Edmund’s: Short Courses

- St Edmund’s: Licensed Lay Minister training

- LLF Chaplains

- Guidance on Common Fund payments

- Archdeacons parochial visitation

- Vacancy in a Benefice

- Visiting clergy – checks on visiting preachers

- Contact the Edmonton Office

- Contact the Kensington Office

- Contact the Stepney Office

- Contact the Two Cities Office

- City Churches Grants Committee

- Contact the Willesden Office

- Ministry Experience Scheme

- Parish Ministry

- Self-supporting ministry

- Distinctive deacon

- Pioneer Ministry

Embracing Diversity: Understanding the Gypsy, Traveller and Roma Communities

- Date: 17 January 2024

- Author: Communications

The Revd. Preb. Joseph Fernandes, Chaplain to Gypsies and Travellers in London, highlights the importance of loving our neighbours.

In a world rich with diverse cultures and traditions, the Gypsy, Traveller and Roma communities stand out with their unique heritage and lifestyle. As Christians, we are called to love and understand our neighbours, making it essential to look beyond stereotypes and embrace the beauty in diversity. We are called to shed light on these vibrant communities from a Christian perspective, fostering empathy, understanding, and unity.

Gypsy, Traveller and Roma communities have a rich history that spans centuries and continents. Originating from the Indian subcontinent, they migrated to Europe and other regions over time. Historically, they have faced significant challenges, including persecution and discrimination. This history of hardship aligns with the Christian ethos of understanding and supporting those who face oppression (Isaiah 1:17).

The cultural fabric of these communities is woven with strong family ties, oral traditions, and often a nomadic lifestyle. The social structure is community-centric, emphasizing respect for elders and collective responsibility. In understanding these cultural nuances, Christians can find parallels in the Biblical emphasis on community and familial bonds (Acts 2:44-47). While religious beliefs vary among Gypsy, Traveller and Roma communities, many hold spiritual beliefs that are intertwined in their daily lives. Some have embraced Christianity, blending their traditional practices with Christian beliefs. This syncretism presents an opportunity for Christians to engage in meaningful dialogue about faith and spirituality (1 Corinthians 9:22).

The Bible teaches the importance of loving our neighbours (Mark 12:31) and embracing those from diverse backgrounds (Galatians 3:28). Jesus Christ himself reached out to those on the margins of society. Understanding and accepting Gypsy, Traveller and Roma communities aligns with these teachings, challenging us to look past prejudices and to act with an openness of mind and heart.

Gypsy, Traveller and Roma lifestyles are often surrounded by misconceptions leading to social exclusion, discrimination, isolation and stereotypes. As Christians, we are called to challenge these misconceptions, remembering that “There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28).

Recognizing and celebrating the contributions Gypsy, Traveller and Roma communities have made to society with their rich cultural traditions and heritage can foster better integration and mutual respect. The Christian community can play a pivotal role in this integration process, promoting inclusive practices and dialogue, and overcoming the prevalent prejudice and discrimination faced by the communities.

Several Christian organisations, such as the Gypsy, Traveller and Roma Friendly Churches (GTRFC) and the Margaret Clitherow Trust (MCT) have initiated outreach programs to support Gypsy, Traveller and Roma communities, providing education, health, and spiritual support. These initiatives exemplify the Christian calling to serve others (Matthew 25:35-40). By engaging in these efforts, Christians can build bridges and demonstrate Christ’s love in action. In understanding Gypsy, Traveller and Roma communities, we open our hearts and minds to the diverse ways in which God’s people live and express their faith and culture. As Christians, we are taught not just to understand, but also to love and support these communities, embodying Christ’s teachings in our actions and attitudes. Let us therefore embrace this opportunity to grow in love, understanding, and unity.

The Revd. Preb. Joseph Fernandes Rector of St Mary’s Church Chaplain to Gypsies and Travellers in London

Your privacy settings

Manage consent preferences, embedded videos.

Gypsies and Jesus - A Traveller Theology by Dr Steven Horne

A new book by Romany academic Doctor Steven Horne

“For over five hundred years, Gypsies, Roma and Travellers (GRT) have been persecuted, misrepresented, enslaved and even murdered in whatever land they reside by the very people they now preach to. A life embalmed in the belief of radical grace and immovable faith has, for Gypsies and Travellers, given a refreshed emphasis to Christ’s instruction of ‘turning the other cheek’. This book lights the touch paper on the grace-filled, intimate and unheard core of GRT religiosity that is, Traveller theology.”

‘They are a people who have been separated from God.’

‘They are a people whose sin has left them unclean.’

‘They are a people in need of unconditional love.’

These statements, familiar within Christian evangelistic orthodoxy, are representative of how many Gypsies, Roma and Travellers (GRT) view those outside of their community. Yet for over five hundred years, GRT people have been persecuted, misrepresented, enslaved and even murdered in whatever land they reside by the very people they now preach to. A life embalmed in the belief of radical grace and immovable faith has, for Gypsies and Travellers, given a refreshed emphasis to Christ’s instruction of ‘turning the other cheek’. Steven Horne’s Gypsies and Jesus lights the touch paper on the grace-filled, intimate and unheard core of GRT religiosity that is, Traveller Theology.

Gypsy and Traveller religiosity is a field of study that has long been dominated by non-GRT voices. In this book Dr Horne, the first person of Romany decent in the UK to be awarded a PhD in Theology, takes back the pen and reclaims a past and a future for Gypsies and Travellers.

Gypsies and Jesus: A Traveller Theology identifies and threads cultural strands (beliefs and customs, narratives and histories, and rituals and traditions) from Gypsy and Traveller culture into a coherent message that speaks of collective piety and cultural purity. Testimonies from members of the GRT community develop this message further, revealing the absolute centrality of religious conviction at the heart of Gypsy and Traveller communities. All of these factors are supported with a Biblical exegesis to produce an exciting, revelatory and at times sobering book that, for perhaps the first time, hands over the reins of Gypsy-Christian identity to Gypsies themselves.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Steven Horne is the first Romany from the UK to be awarded a PhD in Theology (November 2020). He works as a Licensed Lay Minister in the Church of England, leading a 'fresh expressions' outreach mission in a major town. He also delivers lectures and training in Universities, Theological Seminaries, Churches and more, to Clergy, Students, Teachers, Healthcare professionals and government - both local and national. His mother is a gorger (non-Gypsy), and his father is a Romany Gypsy. He grew up within two cultures: an amalgamation of Gypsy values and ‘settled’ practices.

Darton, Longman and Todd press release

What Is a Gypsy?

Gypsies were initially thought to have come from Egypt, but they originated in India. Historians have traced their spread across all parts of the world and the prejudice which followed them. Oppression has caused these groups of people to remain close together; to intermarry, and to adhere to tradition.

Gypsies in the Modern World

A brightly colored wagon is pulled by a heavy horse through the streets of a village, past a post office, grocery store, and other shops. A dark-skinned man holds the reins, a woman of similarly dark complexion sitting next to him, wearing flowing clothes as bright as their wagon. They ignore the stares of villagers gathered to watch and jeer. Some yell “get lost, gyppoes!” A few secretly admire the teal, crimson, and ochre of the cart and the ornate flowers painted around their window shutters. Children approach to stroke the horse and thread flowers into its mane, but their parents pull them back with stern words of discipline.

This image is not outdated but pervasive in parts of the world, such as England, where Romani or Gypsies wander from village to village, typically unwanted and regarded with suspicion. Tension exists between the romantic portrayals of carefree gypsies and realistic scenes of rejection and fear. Who are the gypsies?

Definition of Gypsies

A gypsy is a member of a people originating in South Asia and traditionally having a wandering way of life, living widely scattered across Europe and North and South America and speaking a language (Romani) that is related to Hindi; a Romani person. Gypsy is also used as a description for a nomadic or "free-spirited" person, whose personality and lifestyle may be similar to historical gypsies.

Ancient Roots and Nomadic Occupations

Gypsies were initially thought to have come from Egypt, but they originated in India. Historians have traced their spread across all parts of the world and the prejudice which followed them. Oppression has caused these groups of people to remain close together; to intermarry, and to adhere to tradition. Some of these customs have included looking after the elderly people in one’s community and maintaining close family ties throughout one’s life. Gypsies are known for practicing trades outside the mainstream; portable trades. These include fortune telling, repairing metal tools, working with horses, and entertainment.

Mistreatment of Gypsies

“European nations over the centuries have enslaved, expelled, imprisoned, and executed Romani people. Other European nations used their legal system to oppress the Roma, passing laws prohibiting Romanies from buying land or securing stable professions .” Gypsies were often ejected from communities and forced to wander, preventing them from establishing stability and deep relationships with members of other communities. They could not obtain birth certificates or attend schools.

“ Mass killings of Roma reached their pinnacle on July 31–August 2, 1944, when the Germans began the liquidation of the Zigeunerlager (‘Gypsy camp’) at Auschwitz-Birkenau” during the Nazi terror of World War II. Hundreds of thousands of Roma died. “ Auschwitz was only one of the places where the Roma were systematically gassed and murdered. In other parts of Eastern Europe, the Roma were shot to death.”