A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Risk Factors

- Breast Cancer Resources to Share

- What CDC Is Doing About Breast Cancer

- Advisory Committee on Breast Cancer in Young Women

- MMWR Appendix

- National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program

- Bring Your Brave Campaign

Breast Cancer Basics

- Breast cancer is a disease in which cells in the breast grow out of control.

- There are different kinds of breast cancer.

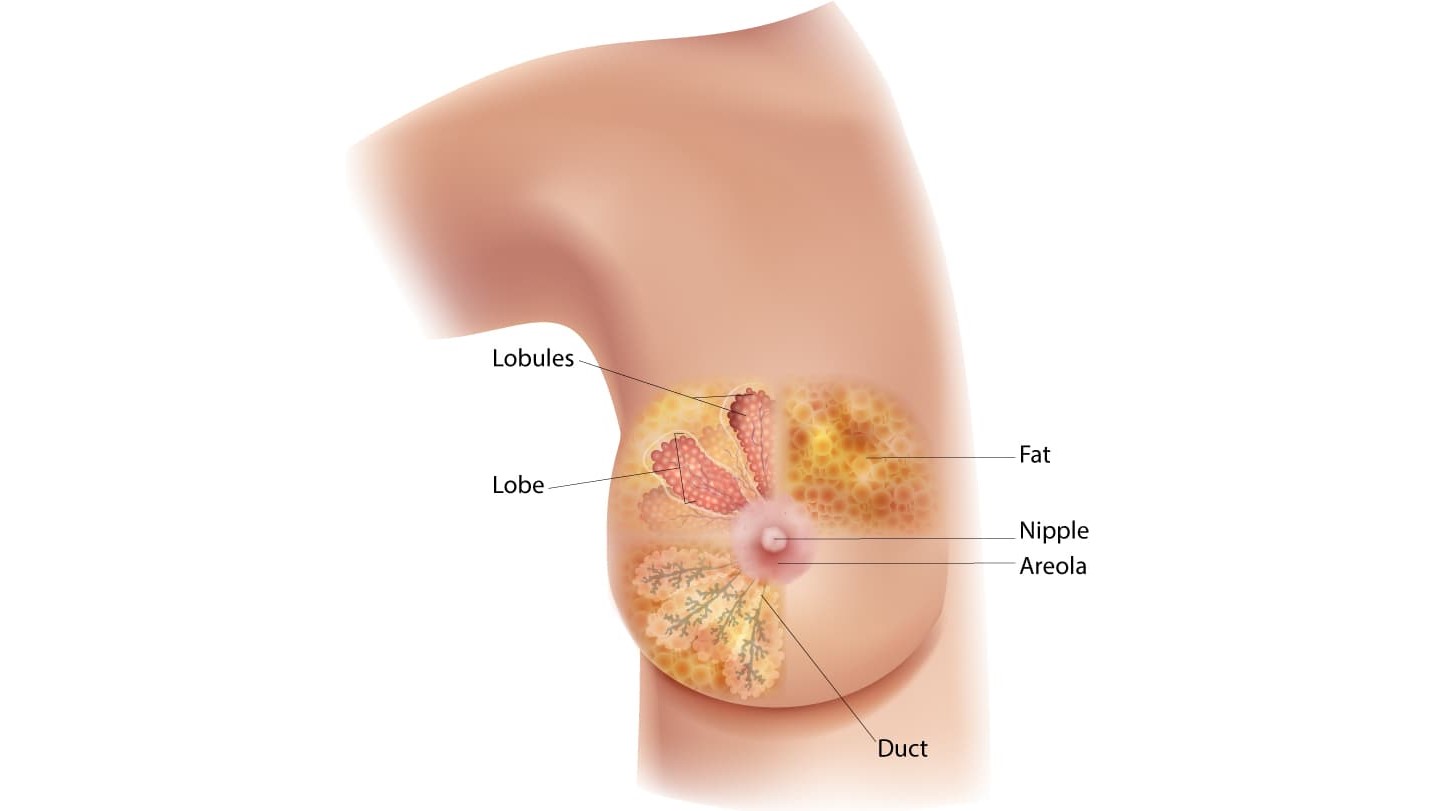

A breast is made up of three main parts: lobules, ducts, and connective tissue. The lobules are the glands that produce milk. The ducts are tubes that carry milk to the nipple. The connective tissue (which consists of fibrous and fatty tissue) surrounds and holds everything together.

Breast cancer is a disease in which cells in the breast grow out of control. There are different kinds of breast cancer. The kind of breast cancer depends on which cells in the breast turn into cancer.

Most breast cancers begin in the ducts or lobules. Breast cancer can spread outside the breast through blood vessels and lymph vessels. When breast cancer spreads to other parts of the body, it is said to have metastasized.

The most common kinds of breast cancer are:

- Invasive ductal carcinoma. The cancer cells begin in the ducts and then grow outside the ducts into other parts of the breast tissue. Invasive cancer cells can also spread, or metastasize, to other parts of the body.

- Invasive lobular carcinoma. Cancer cells begin in the lobules and then spread from the lobules to the breast tissues that are close by. These invasive cancer cells can also spread to other parts of the body.

There are several other less common kinds of breast cancer, such as Paget's disease, medullary, mucinous, and inflammatory breast cancer.

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is a breast disease that may lead to invasive breast cancer. The cancer cells are only in the lining of the ducts and have not spread to other tissues in the breast.

Breast Cancer

Talk to your doctor about when to start and how often to get a mammogram.

For Everyone

Public health.

Breast Cancer Spread to the Brain: What You Need to Know

When breast cancer spreads, or metastasizes, it’s more likely to travel to some parts of the body than others. The most common sites of metastasis include the bones, brain, liver, or lungs.

It’s rare for patients with early-stage breast cancer, which has not spread beyond the breast or adjacent lymph nodes, to develop a brain metastasis: The brain is the first site where breast cancer spreads in fewer than 5% of these patients.

Among patients diagnosed with breast cancer that has already spread, however, between 10% and 50% develop a brain metastasis, depending on the subtype of breast cancer and other factors.

The Program for Patients with Breast Cancer Brain Metastases in the Susan F. Smith Center for Women’s Cancers at Dana-Farber provides care from a team of experts including medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, neurosurgeons, neuro-oncologists, neuroradiologists, and pathologists. Patients receive a personalized treatment plan based on their unique situation and the specific nature of their disease.

What are possible symptoms of breast cancer metastasis to the brain?

Possible symptoms of breast cancer metastasis to the brain can include:

- Headache

- Nausea or vomiting

- Dizziness

- Weakness or paralysis on one side of the body

- Balance problems

- Changes in vision

- Changes in mood or behavior

- Seizures

- Problems with speech

These symptoms can be caused by factors other than breast cancer. If you’re experiencing any of them, it’s important to be examined by a doctor.

How is brain metastasis diagnosed?

To determine if metastasis to the brain has occurred, your doctor will likely order a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. If an MRI isn’t feasible, a computed tomography (CT) scan may be used instead.

What are the major risk factors for brain metastasis?

Scientists do not yet know why breast cancer is more likely to spread to some parts of the body than others, but some factors that increase the risk of spread to the brain have been identified:

- Being diagnosed with breast cancer while relatively young, particularly before age 35.

- Having a breast cancer that has already spread to the lungs.

- Certain subtypes of breast cancer, such as HER2-positive or triple-negative.

How is metastatic breast cancer treated?

Although metastatic breast cancer currently can’t be cured, it can be treatable with hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, biologic targeted treatments, and novel drug combinations.

Treatment for brain metastases — whether originating in the breast or other part of the body — takes a variety of forms, including:

- Surgery

- Radiation therapy

- Systemic treatment such as chemotherapy and/or targeted therapy

Care teams at the Metastatic Breast Cancer Program at Dana-Farber develop personalized treatment approaches for each patient’s specific type of cancer, as well as an individual plan of care and support for them and their loved ones.

What is the prognosis for patients?

The prognosis depends on a variety of factors, including the subtype of breast cancer a patient has. Advances in treatment approaches have led to lengthened survival for many patients, particularly those with HER2-positive breast cancer.

What is some of the latest research in this area?

Dana-Farber/Brigham Cancer Center offers an array of trials for patients with brain metastases, as well as patients who have leptomeningeal disease (LMD, cancer that has spread to the lining of the brain and/or spinal fluid).

Dana-Farber investigators including Nancy Lin, MD , have led studies of the oral drug tucatinib, which targets the HER2 protein. The HER2CLIMB study included patients with HER2-positive breast cancer who had been previously treated with Herceptin ® , Perjeta ® , chemotherapy, and T-DM1 but whose disease had worsened. Participants, including patients with and without brain metastases, received either tucatinib or a placebo in addition to a traditional regimen of Herceptin ® and the oral chemotherapy agent capecitabine. Results of the clinical trial demonstrated that in nearly 300 patients with brain metastases including in the study, the three-drug regimen more than doubled the chance of tumor shrinkage in the brain, extended the length of disease control in both the brain and body, and doubled the overall survival at two years. With these results, HER2CLIMB became the first large, randomized clinical trial to demonstrate that systemic treatment can improve outcomes in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer that has spread to the brain, and the first targeted drug approved by the FDA for the treatment of patients with brain metastases.

Dana-Farber investigators have also led multiple other studies testing new approaches to treating patients whose breast cancer has spread to the brain. Rachel Freedman, MD , reported on a trial that tested the drugs neratinib and capecitabine in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer with brain metastases. About 50% of patients experienced a response to the therapy. In the next part of the study, Freedman found that combining ado-trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla) with neratinib is also an effective therapy in some patients, even those who have previously been treated with ado-trastuzumab emtansine. Ongoing trials are combining antibody drug conjugate medications such as trastuzumab deruxtecan with HER2-targeted oral drugs (such as tucatinib or ZN-A-1041) in patients with or without brain metastases. Finally, Dana-Farber has launched a clinical trial, the BRIDGET study, led by Sarah Sammons, MD , to explore whether adding tucatinib after a course of radiation might have the potential to delay or prevent progression of cancer in the brain.

In laboratory research , Dana-Farber’s Jean Zhao, PhD , in collaboration with Nancy Lin, MD , and Jose Pablo Leone, MD , has tested new targeted regimens in order to identify the most promising regimens to take into clinical trials. Already, two of the regimens that have been tested in the laboratory have been translated into phase 2 clinical trials, and a third is anticipated to enter a clinical study by late 2023.

About the Medical Reviewer

Dr. Lin is a medical oncologist specializing in the care of patients with all stages of breast cancer. Her research focuses upon improving the outcomes of people living with metastatic breast cancer, including a particular focus on the challenge of breast cancer brain metastases. She has led multiple clinical trials which have led to new treatment options for patients with breast cancer that has metastasized to the brain.

Dr. Lin received her MD from Harvard Medical School in 1999. She completed her residency in internal medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital and went on to complete fellowships in medical oncology and hematology at Dana-Farber. In 2005, she joined the staff of Brigham and Women's and Dana-Farber, where she is a medical oncologist and clinical investigator in the Breast Oncology Center.

Skip to Content

- Conquer Cancer

- ASCO Journals

- f Cancer.net on Facebook

- t Cancer.net on Twitter

- q Cancer.net on YouTube

- g Cancer.net on Google

- Types of Cancer

- Navigating Cancer Care

- Coping With Cancer

- Research and Advocacy

- Survivorship

Breast Cancer - Metastatic: Introduction

ON THIS PAGE: You will find some basic information about this disease and the parts of the body it may affect. This is the first page of Cancer.Net’s Guide to Metastatic Breast Cancer. Use the menu to see other pages. Think of that menu as a roadmap for this entire guide.

About metastatic breast cancer

Cancer begins when healthy cells change and grow out of control, forming a mass or sheet of cells called a tumor. A tumor can be cancerous or benign. A cancerous tumor is malignant, meaning it can grow and spread to other parts of the body. A benign tumor means the tumor can grow but will not spread. When breast cancer is limited to the breast and/or nearby lymph node regions, it is called early stage or locally advanced. Read about these stages in a different guide on Cancer.Net . When breast cancer spreads to an area farther from where it started to another part of the body, doctors say that the cancer has “metastasized.” They call the area of spread a “metastasis,” or use the plural “metastases” if the cancer has spread to more than 1 area. The disease is called metastatic breast cancer. Another name for metastatic breast cancer is "stage IV (4) breast cancer” if it has already spread beyond the breast and nearby lymph nodes at the time of diagnosis of the original cancer.

Doctors may also call metastatic breast cancer “advanced breast cancer.” However, this term should not be confused with “locally advanced breast cancer,” which is breast cancer that has spread to nearby tissues or lymph nodes but not to other parts of the body.

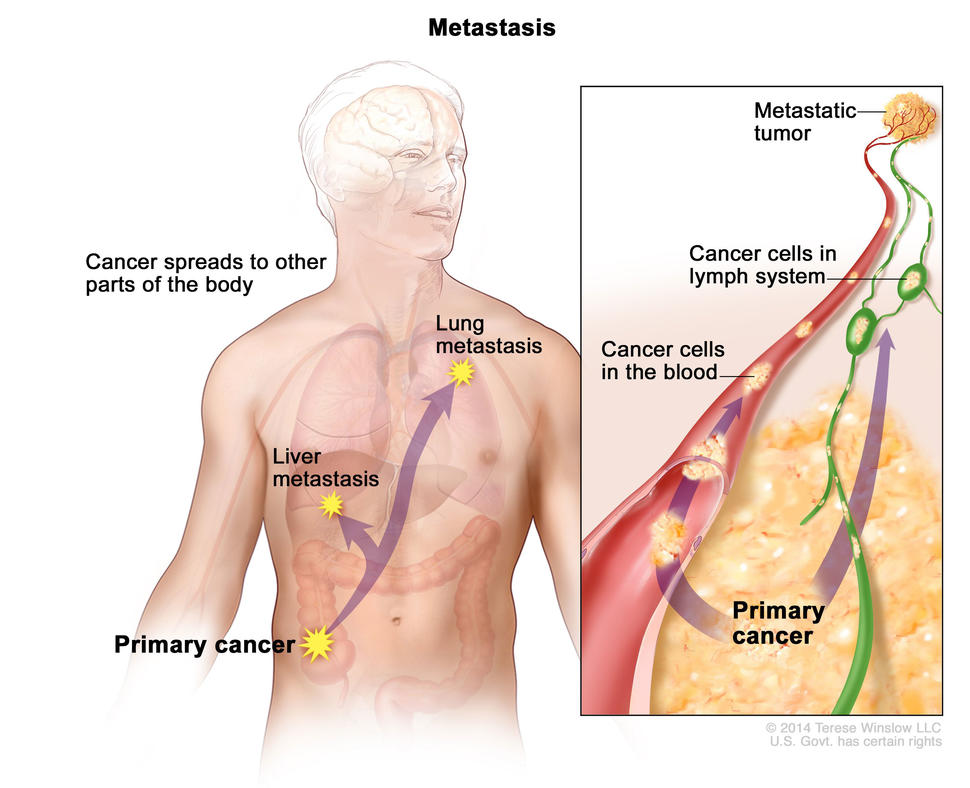

Metastatic breast cancer may spread to any part of the body. It most often spreads to the bones, liver, lungs, and brain. Even after cancer spreads, it is still named for the area where it began. This is called the “primary site” or “primary tumor.” For example, if breast cancer spreads to the lungs, doctors call it metastatic breast cancer, not lung cancer. This is because the cancer started in breast cells.

Metastatic breast cancer can develop when breast cancer cells break away from the primary tumor and enter the bloodstream or lymphatic system. These systems carry fluids around the body. The cancer cells are able to travel in the fluids far from the original tumor. The cells can then settle and grow in a different part of the body and form new tumors.

Most commonly, doctors diagnose metastatic breast cancer after a person previously received treatment for an earlier stage (non-metastatic) breast cancer. Doctors sometimes call this a “distant recurrence” or “metastatic recurrence.” This can happen at any time after someone is diagnosed with breast cancer, even a few decades later. Sometimes, a person’s first diagnosis of breast cancer is when it has already spread to other parts of the body. Doctors call this “de novo” metastatic breast cancer or stage IV breast cancer.

Types of breast cancer

There are several types of breast cancer, and any of them can metastasize. Most breast cancers start in the ducts or lobules and are called ductal carcinomas or lobular carcinomas:

Invasive ductal carcinoma. These cancers start in the cells lining the milk ducts and make up the majority of breast cancers.

Invasive lobular carcinoma. This is cancer that starts in the lobules, which are the small, tube-like structures that contain milk glands.

Some breast cancers are made up of a combination of types of breast cancers. These are sometimes called invasive mammary cancers.

Breast cancer can develop in women and men. However, male breast cancer is rare , accounting for less than 1% of all breast cancers.

Breast cancer subtypes

Breast cancer is not a single disease, even among the same type of breast cancer. When you are diagnosed with breast cancer, your doctor will recommend lab tests on the cancerous tissue. If you have been diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer after being treated for non-metastatic breast cancer, your doctor may want to repeat the tests to see if the tumor’s cells have changed in any way. These tests will help your doctor learn more about the cancer and choose the most effective treatment plan . Metastatic breast cancer is usually not curable, but it can be treatable. Many people continue to live well for many months or years with the disease, and treatments continue to improve.

Tests can find out if your cancer is:

Hormone receptor-positive. Breast cancers expressing estrogen receptors (ER) and/or progesterone receptors (PR) are called “hormone receptor-positive.” These receptors are proteins found in cells. Tumors that have estrogen receptors are called “ER-positive.” Tumors that have progesterone receptors are called “PR-positive.” These cancers may depend on the hormones estrogen and/or progesterone to grow. Hormone receptor-positive cancers can occur at any age. However, they may be more frequent in people who have gone through menopause. Menopause is when the body's ovaries stop releasing eggs. About 60% to 75% of breast cancers have estrogen and/or progesterone receptors. If the cancer does not have ER or PR, it is called “hormone receptor-negative.”

HER2-positive. About 15% to 20% of breast cancers depend on the gene called human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 ( HER2 ) to grow. These cancers are called “HER2-positive” and have many copies of the HER2 gene or high levels of the HER2 protein. These proteins are also called “receptors.” The HER2 gene makes the HER2 protein, which is found on the cancer cells and is important for tumor cell growth. HER2-positive breast cancers grow more quickly. They can also be either hormone receptor-positive or hormone receptor-negative (see above). Cancers that have no HER2 protein are called “HER2-negative.” Cancers that have low levels of the HER2 protein are called “HER2-low.”

Triple-negative. If the breast tumor does not express ER, PR, or HER2, the tumor is called “triple-negative.” Triple-negative breast cancers make up about 15% of invasive breast cancers. This type of breast cancer seems to be more common among younger women, particularly younger Black women. Triple-negative breast cancer may grow more quickly. Triple-negative breast cancers are the most common type of breast cancer diagnosed in people with a BRCA1 gene mutation. This means that you may be more likely to have a BRCA1 gene mutation if you have been diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer. All people younger than 60 with triple-negative breast cancer should be tested for BRCA gene mutations. Find more information on BRCA gene mutations and breast cancer risk .

Looking for More of an Introduction?

If you would like more of an introduction, explore these related items. Please note that these links will take you to other sections on Cancer.Net:

ASCO Answers Fact Sheet: Read a 1-page fact sheet that offers an introduction to metastatic breast cancer. This free fact sheet is available as a PDF, so it is easy to print.

ASCO Answers Guide: Get this free 52-page booklet that helps you better understand breast cancer and its treatment options. The booklet is available as a PDF, so it is easy to print.

Cancer.Net En Español: Read about metastatic breast cancer in Spanish . Infórmase sobre cáncer de mama metastásico en español .

Find a Cancer Doctor. Search for a cancer specialist in your local area using this free database of doctors from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Cancer Terms. Learn what medical phrases and terms used in cancer care and treatment mean.

The next section in this guide is Statistics . It helps explain the number of people who are diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer and general survival rates. Use the menu to choose a different section to read in this guide.

Breast Cancer - Metastatic Guide

Cancer.Net Guide Breast Cancer - Metastatic

- Introduction

- Risk Factors

- Symptoms and Signs

- Types of Treatment

- About Clinical Trials

- Latest Research

- Palliative and Supportive Care

- Coping with Treatment

- Living with Metastatic Breast Cancer

- Questions to Ask the Health Care Team

- Additional Resources

View All Pages

Timely. Trusted. Compassionate.

Comprehensive information for people with cancer, families, and caregivers, from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the voice of the world's oncology professionals.

Find a Cancer Doctor

Together we are beating cancer

About cancer

Cancer types

- Breast cancer

- Bowel cancer

- Lung cancer

- Prostate cancer

Cancers in general

- Clinical trials

- Causes of cancer

Coping with cancer

- Managing symptoms and side effects

- Mental health and cancer

- Money and travel

- Death and dying

- Cancer Chat forum

Health Professionals

- Cancer Statistics

- Cancer Screening

- Learning and Support

- NICE suspected cancer referral guidelines

Get involved

- Make a donation

By cancer type

- Leave a legacy gift

- Donate in Memory

Find an event

- Race for Life

- Charity runs

- Charity walks

- Search events

- Relay For Life

- Volunteer in our shops

- Help at an event

- Help us raise money

- Campaign for us

Do your own fundraising

- Fundraising ideas

- Get a fundraising pack

- Return fundraising money

- Fundraise by cancer type

- Set up a Cancer Research UK Giving Page

- Find a shop or superstore

- Become a partner

- Cancer Research UK for Children & Young People

- Our We Are campaign

Our research

- Brain tumours

- Skin cancer

- All cancer types

By cancer topic

- New treatments

- Cancer biology

- Cancer drugs

- All cancer subjects

- All locations

By Researcher

- Professor Duncan Baird

- Professor Fran Balkwill

- Professor Andrew Biankin

- See all researchers

- Our achievements timeline

- Our research strategy

- Involving animals in research

Funding for researchers

Research opportunities

- For discovery researchers

- For clinical researchers

- For population researchers

- In drug discovery & development

- In early detection & diagnosis

- For students & postdocs

Our funding schemes

- Career Development Fellowship

- Discovery Programme Awards

- Clinical Trial Award

- Biology to Prevention Award

- View all schemes and deadlines

Applying for funding

- Start your application online

- How to make a successful application

- Funding committees

- Successful applicant case studies

How we deliver research

- Our research infrastructure

- Events and conferences

- Our research partnerships

- Facts & figures about our funding

- Develop your research career

- Recently funded awards

- Manage your research grant

- Notify us of new publications

Find a shop

- Volunteer in a shop

- Donate goods to a shop

- Our superstores

Shop online

- Wedding favours

- Cancer Care

- Flower Shop

Our eBay store

- Shoes and boots

- Bags and purses

- We beat cancer

- We fundraise

- We develop policy

- Our global role

Our organisation

- Our strategy

- Our Trustees

- CEO and Executive Board

- How we spend your money

- Early careers

Cancer news

- Cancer News

- For Researchers

- For Supporters

- Press office

- Publications

- Update your contact preferences

ABOUT CANCER

GET INVOLVED

NEWS & RESOURCES

FUNDING & RESEARCH

You are here

How cancer can spread

This page tells you about how cancers can spread. There is information about

Primary and secondary cancer

The place where a cancer starts in the body is called the primary cancer or primary site. Cells from the primary site may break away and spread to other parts of the body. These cells can then grow and form other tumours. These are called secondary cancers or metastases.

How cancer can spread to other areas of the body

Cancers are named according to where they first started developing. For example, bowel cancer that has spread to the liver is called bowel cancer with liver metastases or secondaries. It is not called liver cancer. This is because the cancerous cells in the liver are cancerous bowel cells. They are not liver cells that have become cancerous.

01._diagram_showing_a_primary_and_secondary_cancer.svg

To spread, some cells from the primary cancer must break away. They then travel to another part of the body and start growing there. Cancer cells don't stick together as well as normal cells do. They may also produce substances that stimulate them to move.

The diagram below shows a tumour in the cells lining a body structure such as the bowel wall. The tumour grows through the layer holding the cells in place. This is the basement membrane.

35_diagram_showing_a_malignant_tumour.svg

Spread through the bloodstream

Cancer cells can go into small blood vessels and then get into the bloodstream. They are called circulating tumour cells (or CTCs).

The circulating blood sweeps the cancer cells along until they get stuck somewhere. Often they get stuck in a very small blood vessel such as a capillary.

33_diagram_showing_a_cancer_cell_stuck_in_a_small_blood_vessel_capillary.svg

Then the cancer cell must move through the wall of the capillary and into the tissue of the organ close by. The cell can multiply to form a new tumour if:

- the conditions are right for it to grow

- it has the nutrients that it needs.

42_diagram_showing_how_cancer_cells_get_into_the_bloodstream.svg

This is quite a complicated process and most cancer cells don't survive it. Many thousands of cancer cells that reach the bloodstream. Only a few survive to form a secondary cancer.

Spread through the lymphatic system

The lymphatic system is a network of tubes and glands in the body. It filters body fluid and fights infection. It also traps damaged or harmful cells such as cancer cells.

This 2 minute video is about the lymphatic system.

The lymphatic drainage system

Content not working due to cookie settings.

Read a transcript of the video.

Micrometastases

Micrometastases are areas of cancer spread (metastases) that are too small to see. They are too small to show up on any type of scan.

For a few types of cancer, blood tests can detect certain proteins that the cancer cells release. These are sometimes called tumour markers. These may show that there are metastases in the body that are too small to show up on a scan. But for most cancers, there is no blood test that can say whether a cancer has spread or not.

For most cancers, doctors can only say whether it is likely or not that a cancer has spread. Doctors base this on a number of factors:

- previous experience – doctors collect and publish this information to help each other

- whether there are cancer cells in the blood vessels in the tumour removed during surgery. If they find cancer cells in the blood vessels then the cancer is more likely to have spread to other parts of the body

- whether there are cancer cells in the lymph nodes removed during an operation. If the lymph nodes contain cancer cells this shows that cancer cells have broken away from the original cancer. But there is no way of knowing whether the cells have spread to any other areas of the body.

This information is important in treating cancer. You might have extra treatment if doctors suspect there are micrometastases. This treatment might include:

- chemotherapy

- radiotherapy

The extra treatments might increase the chance of curing the cancer.

Related information

You can read detailed information about:

Cancer, the blood and circulation .

The lymphatic system and cancer

Cancer grading

Where can cancer spread

Next review due: 9 October 2026

Last reviewed

About cancer.

- Spot cancer early

- Talking to your doctor

- How cancer starts

- How cancers grow

- Where cancer can spread

- Why some cancers come back

- Stages of cancer

- Cancer grades

- Genes, DNA and cancer

- Body systems and cancer

- Understanding cancer statistics - incidence, survival, mortality

- Understanding statistics in cancer research

- Where this information comes from

- Find a clinical trial

- Children's Cancers

- How do I check for cancer?

- Welcome to Cancer Chat

Rate this page:

How does cancer spread to other parts of the body?

Senior Research Officer, Blood Cells and Blood Cancer Division, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute

Senior Resarch Officer, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute

Disclosure statement

Sarah Diepstraten receives funding from the Victorian Cancer Agency.

John (Eddie) La Marca is also affiliated with the Olivia Newton John Cancer Research Institute.

View all partners

All cancers begin in a single organ or tissue, such as the lungs or skin. When these cancers are confined in their original organ or tissue, they are generally more treatable.

But a cancer that spreads is much more dangerous, as the organs it spreads to may be vital organs. A skin cancer, for example, might spread to the brain.

This new growth makes the cancer much more challenging to treat, as it can be difficult to find all the new tumours. If a cancer can invade different organs or tissues, it can quickly become lethal.

When cancer spreads in this way, it’s called metastasis. Metastasis is responsible for the majority (67%) of cancer deaths.

Read more: Cancer evolution is mathematical – how random processes and epigenetics can explain why tumor cells shape-shift, metastasize and resist treatments

Cells are supposed to stick to surrounding tissue

Our bodies are made up of trillions of tiny cells. To keep us healthy, our bodies are constantly replacing old or damaged cells.

Each cell has a specific job and a set of instructions (DNA) that tells it what to do. However, sometimes DNA can get damaged.

This damage might change the instructions. A cell might now multiply uncontrollably, or lose a property known as adherence. This refers to how sticky a cell is, and how well it can cling to other surrounding cells and stay where it’s supposed to be.

If a cancer cell loses its adherence, it can break off from the original tumour and travel through the bloodstream or lymphatic system to almost anywhere. This is how metastasis happens.

Many of these travelling cancer cells will die, but some will settle in a new location and begin to form new cancers.

Particular cancers are more likely to metastasise to particular organs that help support their growth. Breast cancers commonly metastasise to the bones, liver, and lungs, while skin cancers like melanomas are more likely to end up in the brain and heart.

Unlike cancers which form in solid organs or tissues, blood cancers like leukaemia already move freely through the bloodstream, but can escape to settle in other organs like the liver or brain.

When do cancers metastasise?

The longer a cancer grows, the more likely it is to metastasise. If not caught early, a patient’s cancer may have metastasised even before it’s initially diagnosed.

Metastasis can also occur after cancer treatment. This happens when cancer cells are dormant during treatment – drugs may not “see” those cells. These invisible cells can remain hidden in the body, only to wake up and begin growing into a new cancer months or even years later.

Read more: How cancer cells move and metastasize is influenced by the fluids surrounding them – understanding how tumors migrate can help stop their spread

For patients who already have cancer metastases at diagnosis, identifying the location of the original tumour – called the “primary site” – is important. A cancer that began in the breast but has spread to the liver will probably still behave like a breast cancer, and so will respond best to an anti-breast cancer therapy, and not anti-liver cancer therapy.

As metastases can sometimes grow faster than the original tumour, it’s not always easy to tell which tumour came first. These cancers are called “cancers of unknown primary” and are the 11th most commonly diagnosed cancers in Australia .

One way to improve the treatment of metastatic cancer is to improve our ways of detecting and identifying cancers, to ensure patients receive the most effective drugs for their cancer type.

What increases the chances of metastasis and how can it be prevented?

If left untreated, most cancers will eventually acquire the ability to metastasise.

While there are currently no interventions that specifically prevent metastasis, cancer patients who have their tumours surgically removed may also be given chemotherapy (or other drugs) to try and weed out any hidden cancer cells still floating around.

The best way to prevent metastasis is to diagnose and treat cancers early. Cancer screening initiatives such as Australia’s cervical , bowel , and breast cancer screening programs are excellent ways to detect cancers early and reduce the chances of metastasis.

New screening programs to detect cancers early are being researched for many types of cancer. Some of these are simple: CT scans of the body to look for any potential tumours, such as in England’s new lung cancer screening program .

Using artificial intelligence (AI) to help examine patient scans is also possible , which might identify new patterns that suggest a cancer is present, and improve cancer detection from these programs.

Read more: AI can help detect breast cancer. But we don't yet know if it can improve survival rates

More advanced screening methods are also in development. The United States government’s Cancer Moonshot program is currently funding research into blood tests that could detect many types of cancer at early stages .

One day there might even be a RAT-type test for cancer, like there is for COVID.

Will we be able to prevent metastasis in the future?

Understanding how metastasis occurs allows us to figure out new ways to prevent it. One idea is to target dormant cancer cells and prevent them from waking up.

Directly preventing metastasis with drugs is not yet possible. But there is hope that as research efforts continue to improve cancer therapies, they will also be more effective at treating metastatic cancers.

For now, early detection is the best way to ensure a patient can beat their cancer.

- Skin cancer

- Cancer treatment

- Cancer screening

- cancer detection

Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Alternatively, use our A–Z index

Scientists discover how breast cancer cells spread from blood vessels

- Study sheds light on how cancer cells leave the blood vessels to travel to a new part of the body

Researchers have identified a protein that controls how breast cancer cells spread around the body, according to a Cancer Research UK-funded study published in Science Signaling and carried out at The University of Manchester.

This study sheds light on how cancer cells leave the blood vessels to travel to a new part of the body, using a technique that allows researchers to map how cancer cells interact and exchange information with cells that make up the blood vessels.

When tumour cells spread, they first enter the blood stream and grip onto the inner walls of blood vessels. The researchers found that the cancer cells control a receptor protein called EPHA2 in order to push their way out of the vessels.

When cancer cells interact with the walls of the blood vessels, EPHA2 is activated and the tumour cells remain inside the blood vessels. When the EPHA2 is inactive, the tumour cells can push out and spread.

The next step is to figure out how to keep this receptor switched on, so that the tumour cells can’t leave the blood vessels – stopping breast cancer spreading and making the disease easier to treat successfully

Dr Claus Jorgensen , who led the research at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and at Cancer Research UK’s Manchester Institute at the University of Manchester, said: “The next step is to figure out how to keep this receptor switched on, so that the tumour cells can’t leave the blood vessels – stopping breast cancer spreading and making the disease easier to treat successfully.”

Nell Barrie, Cancer Research UK ’s senior science information manager, said: “This is important research that teaches us more about how breast cancer cells move.

"Research like this is vital to help our understanding of how cancer spreads, and how to stop this from happening. More research is needed before this will benefit patients but it’s a jump in the right direction.”

Paper: Locard-Paulet M. et al., ‘ Phosphoproteomic analusis of tumor-endothelial signalling identifies EPHA2 as a negative regulator of transendothelial migration ’. Science Signaling , 2016. DOI: 10.1126/scisignal.aac5820

Cancer is one of The University of Manchester’s research beacons - examples of pioneering discoveries, interdisciplinary collaboration and cross-sector partnerships that are tackling some of the biggest questions facing the planet.

#ResearchBeacons

Share this page

Latest news.

- News Archive

- Media Library

Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland, Starting Immediately

Due to the downward trend in respiratory viruses in Maryland, masking is no longer required but remains strongly recommended in Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. Read more .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

Cancer Cells Take Over Blood Vessels to Spread

.@HopkinsKimmel discovers key step in how cancer cells may spread. ›

In laboratory studies, Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and Johns Hopkins University researchers observed a key step in how cancer cells may spread from a primary tumor to a distant site within the body, a process known as metastasis.

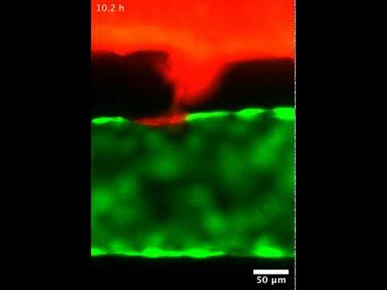

Trying to determine how groups of cells migrate to other parts of the body, the scientists used tissue engineering to construct a functional 3D blood vessel and grew breast cancer cells nearby. They observed the cancer cells reaching out to the blood vessel and taking over a patch of the cell wall. As a result of this attachment to the blood vessel, a cluster of tumor cells were easily released into the bloodstream to travel to distant sites. Cancer cells also were able to constrict blood vessels, cause them to leak, or pull on them.

A description of the work was published online July 14 in the journal Cancer Research .

“We observed that cancer cells can rapidly reshape, destroy or integrate into existing blood vessels,” says senior study author Andrew Ewald, Ph.D., co-director of the Cancer Invasion and Metastasis Program at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and professor of cell biology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine . The work was conducted in close collaboration with the lab of Peter Searson, Ph.D. , the Joseph R. and Lynn C. Reynolds Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, with joint appointments in the departments of biomedical engineering, oncology and physical medicine and rehabilitation.

“Just as people going scuba diving versus ice climbing require different tools, cancer cells bring different equipment depending on the job they intend to perform,” Ewald says. “Determining what that equipment is can help us understand how to stop cancer.” In this case, Ewald and collaborators expected to see groups of eight to 10 cells leaving a tumor, migrating through a protein barrier and squeezing between blood vessel walls to travel.

“We never saw that,” he says. “What we kept seeing instead was that a piece of an existing tumor would take over a neighboring blood vessel wall, putting cancer cells in direct contact with the circulation, and that the cancer cells could do so in a matter of hours. They didn’t have to invade past the blood vessels; they became the blood vessels, and could just release cancer cells there.”

Mosaic Vessel Formation in a 3D Tumor-microvessel Model

The “mosaic” vessels that result — named because they consist of some natural blood vessel cells and some cancer cells — were observed in about 6% of blood vessels in human breast tumors and in a mouse model of breast cancer in this and other studies, Ewald says. They also have been found in deadly brain tumors called glioblastomas, melanoma skin cancers and gastric cancers, he says. Their presence is associated with increased distant metastases.

The 3D model could be adapted to study additional aspects of the tumor microenvironment or to study alternate cancer types, Ewald says.

In addition to Ewald and Searson, other Johns Hopkins researchers included Vanesa Silvestri, Elodie Henriet, Raleigh Linville and Andrew Wong.

The work was supported in part by The Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF019-048), the Metastatic Breast Cancer Network, the Commonwealth Foundation and the National Cancer Institute (grants U01CA217846, U01CA221007, U54CA2101732 and 3P30CA006973).

No authors declared conflicts of interest related to this research under Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine policies.

On the Web:

- How Cancer Cells Spread in the Body

A monthly newsletter from the National Institutes of Health, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Search form

Print this issue

Health Capsule

How Cancer Cells Spread in the Body

Cancer can sometimes be found in several parts of the body. Most of the time, these are not separate types of cancer. Rather, cancer has developed in one organ and spread to other areas. When cancer spreads, it’s called metastasis.

In metastasis, cancer cells break away from where they first formed, travel through the blood or lymph system, and form new tumors in other parts of the body. Cancer can spread to almost anywhere in the body. But it commonly moves into your bones, liver, or lungs.

When these new tumors form, they are made of the same kind of cancer cells as the original tumor. For example, lung cancer cells that are found in the brain don’t look like brain cells. This disease would be called metastatic lung cancer, not brain cancer.

Cancer cells can be sent to the lab for tests to identify the origin of the cells. Knowing the type of cancer and whether it has spread helps the health care team suggest a treatment plan. The goal of treatment is to stop or slow the growth of cancer or to relieve symptoms.

A new animated video, Metastasis: How Cancer Spreads, shows how cancer cells can break off from the primary tumor in one organ, travel through a blood vessel, and invade another organ to form a new tumor. Watch the video and learn more about how cancer spreads at www.cancer.gov/types/metastatic-cancer .

Related Stories

Comparing Side Effects of Prostate Cancer Treatments

Testing an mRNA Vaccine to Treat Pancreatic Cancer

Stop Smoking Early To Improve Cancer Survival

Advances in Childhood Cancer

NIH Office of Communications and Public Liaison Building 31, Room 5B52 Bethesda, MD 20892-2094 [email protected] Tel: 301-451-8224

Editor: Harrison Wein, Ph.D. Managing Editor: Tianna Hicklin, Ph.D. Illustrator: Alan Defibaugh

Attention Editors: Reprint our articles and illustrations in your own publication. Our material is not copyrighted. Please acknowledge NIH News in Health as the source and send us a copy.

For more consumer health news and information, visit health.nih.gov .

For wellness toolkits, visit www.nih.gov/wellnesstoolkits .

Metastatic Cancer: When Cancer Spreads

What is metastatic cancer.

The Challenges of Living with Metastatic Cancer

Survivors describe “scanxiety,” financial concerns, and other issues.

Cancer that spreads from where it started to a distant part of the body is called metastatic cancer. For many types of cancer, it is also called stage IV (4) cancer. The process by which cancer cells spread to other parts of the body is called metastasis .

When observed under a microscope and tested in other ways, metastatic cancer cells have features like that of the primary cancer and not like the cells in the place where the metastatic cancer is found. This is how doctors can tell that it is cancer that has spread from another part of the body.

Metastatic cancer has the same name as the primary cancer. For example, breast cancer that spreads to the lung is called metastatic breast cancer, not lung cancer. It is treated as stage IV breast cancer, not as lung cancer.

Sometimes when people are diagnosed with metastatic cancer, doctors cannot tell where it started. This type of cancer is called cancer of unknown primary origin, or CUP . See the Carcinoma of Unknown Primary page for more information.

How Cancer Spreads

Metastasis: How Cancer Spreads

During metastasis, cancer cells spread from the place in the body where they first formed to other parts of the body.

Cancer cells spread through the body in a series of steps. These steps include:

- growing into, or invading, nearby normal tissue

- moving through the walls of nearby lymph nodes or blood vessels

- traveling through the lymphatic system and bloodstream to other parts of the body

- stopping in small blood vessels at a distant location, invading the blood vessel walls, and moving into the surrounding tissue

- growing in this tissue until a tiny tumor forms

- causing new blood vessels to grow, which creates a blood supply that allows the metastatic tumor to continue growing

Most of the time, spreading cancer cells die at some point in this process. But, as long as conditions are favorable for the cancer cells at every step, some of them are able to form new tumors in other parts of the body. Metastatic cancer cells can also remain inactive at a distant site for many years before they begin to grow again, if at all. ( Audio descriptive and interactive transcript version of video available .)

Where Cancer Spreads

In metastasis, cancer cells break away from where they first formed and form new tumors in other parts of the body.

Cancer can spread to almost any part of the body, although different types of cancer are more likely to spread to certain areas than others. The most common sites where cancer spreads are bone, liver, and lung. The following list shows the most common sites of metastasis, not including the lymph nodes, for some common cancers:

Symptoms of Metastatic Cancer

Metastatic cancer does not always cause symptoms. When symptoms do occur, what they are like and how often you have them will depend on the size and location of the metastatic tumors. Some common signs of metastatic cancer include:

- pain and fractures, when cancer has spread to the bone

- headache, seizures , or dizziness, when cancer has spread to the brain

- shortness of breath, when cancer has spread to the lung

- jaundice or swelling in the belly, when cancer has spread to the liver

Treatment for Metastatic Cancer

There are treatments for most types of metastatic cancer. Often, the goal of treating metastatic cancer is to control it by stopping or slowing its growth. Some people can live for years with metastatic cancer that is well controlled. Other treatments may improve the quality of life by relieving symptoms. This type of care is called palliative care . It can be given at any point during treatment for cancer.

The treatment that you may have depends on your type of primary cancer, where it has spread, treatments you’ve had in the past, and your general health. To learn about treatment options, including clinical trials , find your type of cancer among the PDQ® Cancer Information Summaries for Adult Treatment and Pediatric Treatment .

When Metastatic Cancer Can No Longer Be Controlled

If you have been told your cancer can no longer be controlled, you and your loved ones may want to discuss end-of-life care. Whether or not you choose to continue treatment to shrink the cancer or control its growth, you can always receive palliative care to control the symptoms of cancer and the side effects of treatment. Information on coping with and planning for end-of-life care is available in the Advanced Cancer section of this site.

Ongoing Research

Researchers are studying new ways to kill or stop the growth of primary and metastatic cancer cells. These ways include:

- helping your immune system fight cancer

- disrupting the steps in the process that allow the cancer cells to spread

- targeting specific genetic changes in tumors

Visit the Metastatic Cancer Research page on this site to stay informed of ongoing research funded by NCI .

What are the tell-tale warning signs of breast cancer?

A breast is made up of three main parts - lobules, ducts, and connective tissue. The lobules are the glands that produce milk. The ducts are tubes that carry milk to the nipple. The connective tissue (which consists of fibrous and fatty tissue) surrounds and holds everything together.

There are different kinds of breast cancer. Most breast cancers begin in the ducts. Breast cancer can spread outside the breast through blood vessels and lymph vessels. When breast cancer spreads to other parts of the body, it is said to have metastasized.

Breast cancer can manifest with a variety of signs and symptoms. It's important to note that having one or more of these signs does not necessarily mean one has breast cancer, as these symptoms can be caused by other conditions as well. However, if one notices any of the following warning signs, it's important to consult with a healthcare professional for further evaluation:

READ ALSO: Understanding and addressing infertility in men

- Lumps: A persistent lump in the breast or underarm can be an initial indication of breast cancer. It's important to note that cancerous breast lumps are frequently painless. The majority of lumps in the breast are often noncancerous, with various benign conditions potentially responsible for them like fibroadenomas, cysts or infection and abscesses.

- Pain and sensitivity: Hormonal fluctuation is the commonest cause for heaviness, pain, and increased sensitivity. This is often associated with period cycles but can also happen anytime. While cancerous lumps typically remain nonpainful, some can be associated with pain.

- Swelling: Enlargement in the armpit or close to the collarbone could signify the spread of breast cancer to lymph nodes in that vicinity. Swelling may become apparent even before the detection of a palpable lump.

- Skin dimpling

- Any rash or wound on the nipple or breast that does not settle within 2-3 weeks of routine treatment

- Orange peel: If the skin of the breast feels thicker and looks like an orange peel, have it checked right away.

- Pulls inward

- Develops sores

It is crucial to conduct routine self-examinations of your breasts and become acquainted with their normal appearance and texture to promptly recognize any alterations. Furthermore, women should adhere to the screening recommendations outlined by their healthcare provider, which typically involve mammograms and clinical breast exams. Early detection plays a pivotal role in the successful management of breast cancer. Should you observe any of these cautionary indications, it is imperative to seek consultation with a healthcare expert for a comprehensive assessment and, if deemed necessary, additional diagnostic evaluations.

(Author: Dr Kanchan Kaur, Senior Director - Breast Surgery, Breast Cancer, Breast Services, Cancer Institute, Medanta, Gurugram)

For more news like this visit TOI . Get all the Latest News , City News , India News , Business News , and Sports News . For Entertainment News , TV News , and Lifestyle Tips visit Etimes

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Nih research matters.

October 1, 2019

How cancer vesicles breach the blood-brain barrier

At a glance..

- Researchers discovered how small particles from cancer cells called extracellular vesicles cross the blood-brain barrier to make the brain more hospitable to metastatic tumors.

- A detailed understanding of this process could guide strategies to stop brain metastases as well as methods to deliver drugs to the brain.

The brain is walled off from the rest of the body by the blood-brain barrier. This tightly packed mix of cells sits between the blood vessels that lead to the brain and the brain tissue itself. The blood-brain barrier helps protect the brain from threats like infection. But it can also stop helpful medications from getting to the brain when needed.

Researchers know that the blood-brain barrier isn’t perfect. For example, cancer cells can sometimes get past it and establish metastatic tumors (ones from other locations) in the brain. If scientists could better understand how cancer cells accomplish this crossing, they might be able to develop methods to prevent it.

Many cells, including cancer cells, release tiny sacs called extracellular vesicles (EVs). EVs can affect other cells by transferring proteins and genetic material into them. EVs from tumors, for example, can enter the circulation and alter distant organs to make them more susceptible to metastatic cancer. Because of their ability to alter cells, EVs are being studied as potential therapeutics for cancer and other diseases.

A research team led by Drs. Marsha Moses and Golnaz Morad from Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School investigated whether EVs can cross the blood-brain barrier and play a role in brain metastases. The research was funded in part by NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI). Results were published on September 3, 2019, in ACS Nano .

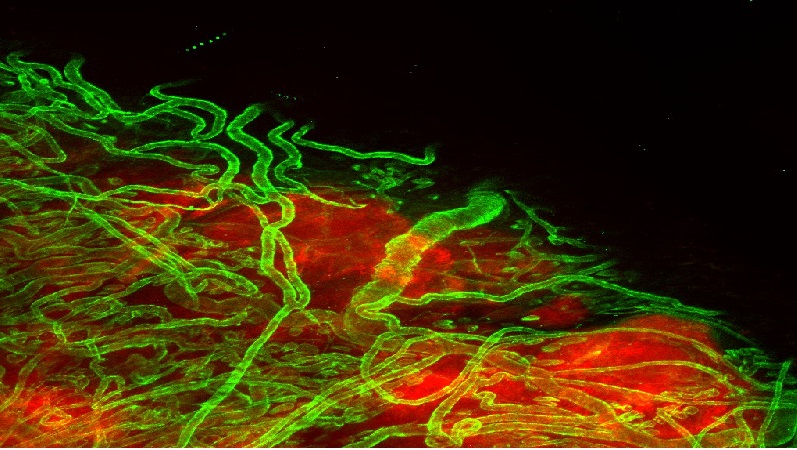

The team first injected mice with EVs released from breast cancer cells known to form tumors in the brain. Mice injected with EVs from these cells developed more and larger brain metastases than mice that received EVs from breast cancer cells that hadn’t turned metastatic. Fluorescent tagging of the EVs showed that they crossed the blood-brain barrier.

The researchers next used their laboratory models of the blood-brain barrier to find out how the EVs crossed into the brain. They found that EVs were able to cross the cells of the blood-brain barrier through a process called transcytosis. They were first engulfed with other materials, then moved through the cell, and finally fused with the cell membrane on the other side to be released. In this way, their contents could pass through the blood-brain barrier to the brain.

Using fluorescent imaging of live zebrafish embryos, the researchers were able to watch EVs travel through cells and fuse with cell membranes to be released on the other side.

The team also showed that EVs from metastatic cancer cells altered blood-brain barrier cells to disrupt their ability to break down vesicles. This would allow more EVs to make their way safely across the barrier cells and into the brain. Once inside, the EVs help make the region more hospitable to metastatic cancer cells.

“EVs can manipulate endothelial cells to facilitate their own transport across the blood-brain barrier,” Morad says. “They hijack the pathways involved in the uptake and sorting of molecules.”

The team is now testing whether EVs could be engineered to deliver anticancer drugs across the blood-brain barrier.

—by Sharon Reynolds

Related Links

- Blood-Brain Barrier Test May Predict Dementia

- Most Tumors in Body Share Important Mutations

- Novel Approach Gives Insights Into Tumor Development

- Genes Help Breast Cancer Cells Invade the Brain

- Metastatic Cancer

- Metastatic Cancer Research

References: Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Breach the Intact Blood-Brain Barrier via Transcytosis. Morad G, Carman CV, Hagedorn EJ, Perlin JR, Zon LI, Mustafaoglu N, Park TE, Ingber DE, Daisy CC, Moses MA. ACS Nano . 2019 Sep 10. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b04397. [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 31479239.

Funding: NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI) and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK); Breast Cancer Research Foundation; Advanced Medical Foundation.

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Chemotherapy Speeds Up Physical Decline in Older Women—But Certain Interventions Can Help

wera Rodsawang / Getty Images

Key Takeaways

- A new study on breast cancer in older women shows that chemotherapy can negatively impact physical functioning.

- Physical, social, and emotional support can improve functioning.

- Women should ask their doctor about a geriatric assessment before beginning chemotherapy to log their physical abilities, health conditions, and medications. This helps the provider and patient make decisions regarding the best treatment option.

A multicenter clinical trial conducted at over a dozen academic medical centers in the U.S. found that chemotherapy can speed up physical decline in older women. However, the researchers say that interventions such as physical therapy and emotional and social support can help reduce the negative effects of the treatment.

The study, published recently in the Journal of Cancer Survivorship, found many older women who had early-stage breast cancer and underwent chemotherapy experienced a significant decline in their ability to perform daily tasks like walking or climbing stairs compared to those who didn’t have chemotherapy and women without cancer who were the same age.

The clinical trial compared the changes in physical function over time in women aged 65 and older. Participants included 444 women with early-stage breast cancer receiving chemotherapy, 98 women with early-stage breast cancer not receiving chemotherapy, and 100 women who did not have cancer.

The researchers found that almost 35% of older adults who received chemotherapy for breast cancer had a significant decline in physical function, compared to 8% of those who didn’t receive chemotherapy and 5% of those without cancer. In women who had a substantial decline, stair climbing, walking a mile, and moderate activity were especially difficult.

The new study is important because doctors have known that older women can face physical challenges when treated for breast cancer, but they weren’t sure whether it was the cancer or the treatment that caused these issues. The new study is the first to compare functional decline in older adults receiving chemotherapy to older breast cancer patients not receiving chemo. This allowed the researchers to see that the physical challenges, in many cases, were linked to chemo.

“The study provides a lens on the impact of common cancer treatment on the health and well-being of our patients, and it raises awareness that we should be doing more to support outpatients so that we can improve both the quantity and quality of their survival,” Mina Sedrak, MD , director of the Cancer and Aging Program at the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center at UCLA and the first author of the study, told Verywell.

The findings don’t necessarily mean you should avoid chemo after a certain age, especially since it can be an extremely effective treatment. The researchers were able to highlight certain interventions that could help improve the difficulties women experience during and after chemotherapy.

A Note on Sex and Gender Terminology

Verywell Health acknowledges that sex and gender are related concepts, but they are not the same. To reflect our sources accurately, this article uses terms like “female,” “male,” “woman,” and “man” as the sources use them.

Geriatric Assessments Are a Crucial Tool for Older Cancer Patients

As part of the trial, all of the participants completed questionnaires about demographics and health status. They also agreed to a geriatric assessment: an evaluation to look at a person’s physical and mental functioning as well as medical conditions, medications, nutrition, and social support, Sedrak said.

Another geriatric assessment was conducted 30 days after women finished chemotherapy and at established points during the study for women who were not having cancer treatment. Updated geriatric assessment guidelines were published by the American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in July of 2023, which the researchers consider to be critical for older adults facing treatment for breast or any other kind of cancer.

“We know that there are significant survival advantages for patients who are evaluated with the geriatric assessment, which enables us to provide interventions to help prevent negative outcomes of cancer treatment,” William Tew, MD , clinical director of the Gynecologic Medical Oncology Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, told Verywell.

The study also noted that given the expected rise in the number of older survivors with breast cancer—projected to reach more than six million by 2040—understanding the mechanisms of accelerated aging and finding ways to prevent it is critical.

Tew said doctors should discuss the risk of decline with patients and family members and let them know what can be done to help alleviate it. Two examples of interventions include physical therapy and encouraging movement to help reduce the risk of neuropathy, or nerve pain.

The research team is continuing their work by looking at the interaction between cancer treatment and the aging processes to identify “mechanisms that can be targeted by drugs to potentially reverse these processes,” Sedrak said.

What Else Can Make Cancer Treatment Manageable?

Breast cancer treatment is quite individualized these days, and may not require chemotherapy at all.

“A woman’s breast cancer may respond to a particular regimen which can make it harder to choose a less toxic therapy [than chemo],” Tew said. But depending on the type of cancer, radiation or other medication may be just as effective, which can help reduce physical decline.

A combination of physical, emotional, and social support can help keep older chemo patients in the best physical condition possible. Especially at an academic cancer center, your doctor is likely to refer you to specialists for social support and physical therapy of some kind. If they don’t, ask them about it, Liz Farrell, LICSW , lead social worker at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, told Verywell. She added that a medical center’s website should list a description of these types of services and a directory for accessing them.

Miranda Zinn, LMSW , a breast care helpline specialist at the Susan G. Komen Foundation, told Verywell she advises women diagnosed with breast cancer to ask if they have access to a social worker or navigator. This person can help them determine what support is available to them, including help with medical costs and transportation.

The researchers are committed to mitigating the physical decline that comes with chemotherapy treatment.

“There is a lot of work being done around the world on this topic, ranging from efforts to find chemotherapy agents that are tolerable to help with decision making around treatment,” study author Rachel Freedman, MD, MPH , founder and director of the Program for Older Adults with Breast Cancer at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, told Verywell. “We’re also exploring early interventions in those who are frail, test exercises in this population as a way to improve outcomes, and ways of making chemotherapy and other treatments more manageable. There is a lot of work being done as well to better understand who needs chemotherapy and who doesn’t.”

What This Means For You

Social, emotional, and physical support are paramount if you’re being treated for cancer, especially if you’re over the age of 65. Resources from the American Cancer Society include:

- Emotional support: Reach to Recovery Program

- Transportation during treatment: Road to Recovery Program

- Lodging during treatment: Hope Lodge and Extended Stay America Partnership

Additionally, social workers staffing the Komen Help Line can help you find a slew of resources for cancer support, ranging from financial aid to online and in-person support groups.

Sedrak MS, Sun CL, Bae M, et al. Functional decline in older breast cancer survivors treated with and without chemotherapy and non-cancer controls: results from the Hurria Older PatiEnts (HOPE) prospective study . J Cancer Surviv . Published online April 28, 2024. doi:10.1007/s11764-024-01594-3

By Fran Kritz Kritz is a healthcare reporter with a focus on health policy. She is a former staff writer for Forbes Magazine and U.S. News and World Report.

- The Star ePaper

- Subscriptions

- Manage Profile

- Change Password

- Manage Logins

- Manage Subscription

- Transaction History

- Manage Billing Info

- Manage For You

- Manage Bookmarks

- Package & Pricing

Lower your cancer risk by controlling these factors

- Women's World

Monday, 20 May 2024

Related News

Eating these foods might help reduce your cancer risk

Our sense of balance is crucial to prevent falls, women still face many barriers when it comes to healthcare.

Although our genes do have an effect on the development of cancer, this disease is more often than not due to external factors like lifestyle choices, pollution, infectious agents and radiation exposure. — Filepic

American biotechnologist Dr Craig Venter highlighted the complexity of human biology after sequencing his own genome.

He emphasised that while genes provide useful information about disease risk, they have limited impact on life outcomes, compared to the intricate interplay of proteins, cells and environmental factors.

Studies indicate that migration to different countries influences chronic illness rates more than genetic predisposition.

For example, identical twins show low concordance rates for diseases like breast cancer, suggesting that non-genetic factors play a dominant role.

Indeed, it is suggested that lifestyle and environmental factors, not genes, contribute 90-95% to the development of chronic diseases like cancer.

Cancer arises from both internal (e.g. inherited mutations) and external factors (e.g. tobacco, diet), with lifestyle choices significantly impacting cancer development.

The modifiability of these external factors suggests that cancer is preventable, emphasising the importance of lifestyle modifications in reducing cancer risk.

Let us take a look at the major external factors that can cause cancer:

Smoking was identified as the primary cause of lung cancer in a 1964 report by the US Surgeon General’s Advisory Commission, and efforts to reduce tobacco use have been ongoing ever since.

Tobacco use increases the risk of developing at least 14 types of cancer and accounts for a significant portion of cancer-related deaths, particularly lung cancer.

The carcinogenic effects of both active and passive smoking are well-documented, with tobacco containing numerous carcinogens.

While smoking has been declining in developed countries, it is increasing in developing countries where most of the world’s population resides.

The exact mechanisms by which smoking contributes to cancer are not fully understood, but it is known to alter cell-signalling pathways and induce inflammation, as evidenced by the activation of NF-kB, an inflammatory marker.

Studies have shown that curcumin, which is derived from turmeric, and other natural phytochemicals can block NF-kB induced by cigarette smoke, potentially reducing the carcinogenic effects of tobacco.

This suggests that dietary agents with anti-inflammatory properties may have chemopreventive effects against smoking- related cancers.

Since 1910, studies have consistently linked chronic alcohol consumption to an increased risk of various cancers, including those of the upper aerodigestive tract (i.e. the oral cavity, pharynx, hypopharynx, larynx and oesophagus), liver, pancreas, mouth and breast.

Notably, heavy alcohol intake is a well-established risk factor for liver and colorectal cancers, with evidence of a synergistic effect with hepatitis C or B viruses (HCV or HBV) in promoting hepatocellular carcinoma.

Alcohol-induced inflammation, mediated partly by the NF-kB pathway, is implicated in carcinogenesis (the formation of cancer).

Ethanol metabolism generates acetaldehyde and free radicals, which damage DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) and proteins, contributing to cancer development.

Other mechanisms include alterations in cell-cycle behaviour, nutritional deficiencies and immune system dysfunction.

Abstaining from alcohol and smoking can prevent up to 80% of upper aerodigestive tract tumours.

Globally, 3.5% of cancer deaths are attributed to alcohol, with variations between countries.

A 1981 report in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute estimated that around 30-35% of cancer deaths in the United States were linked to diet, with the contribution varying by cancer type.

For example, diet is associated with up to 70% of colorectal cancer cases.

The mechanisms by which diet influences cancer risk are not fully understood, but ingested carcinogens like nitrates, nitrosamines, pesticides and dioxins, along with cooking methods, play a role.

Heavy consumption of red meat is a risk factor for several cancers due to carcinogens produced during its cooking and processing.

Food additives, plastic contaminants and arsenic ingestion also increase cancer risk.

Obesity is associated with increased death from various cancers, including colon, breast (for postmenopausal women), endometrium, renal cell, oesophagus (i.e. adenocarcinoma), gastric cardia, pancreas, prostate, gallbladder and liver cancers.

In the US, excess weight or obesity contributes to 14% of cancer deaths in men and 20% in women.

The rise of modernisation and a Westernised diet has led to an increased number of overweight individuals in many developing countries.

Common factors linking obesity and cancer include neurochemicals, hormones (e.g. IGF-1, insulin, leptin), sex steroids, adiposity, insulin resistance and inflammation.

Signalling pathways like IGF/insulin/Akt and leptin/JAK/STAT, along with inflammatory cascades, are implicated in both obesity and cancer.

Hyperglycaemia (high blood sugar levels) activates NF-kB, potentially linking obesity with cancer.

Cytokines produced by adipocytes (fat cells), such as leptin, TNF and IL-1, also activate NF-kB.

The close relationship between energy balance and carcinogenesis underscores the need for research into inhibitors of these pathways to reduce obesity-related cancer risk, likely requiring multi-targeting agents.

Infectious agents

Worldwide, approximately 17.8% of tumours are associated with infections, with the percentage varying from less than 10% in high-income countries to 25% in African countries.

Viruses are the primary infectious agents linked to cancer, with human papillomavirus (HPV), Epstein-Barr virus, Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpes virus, human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV) 1, HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), HBV and HCV posing risks for various cancers.

These include cervical, anogenital, skin, nasopharyngeal, Burkitt’s and Hodgkin’s lymphomas, Kaposi’s sarcoma, adult T-cell leukaemia, B-cell lymphoma, and liver cancer.

In developed countries, HPV and HBV are the most common cancer-causing DNA viruses.

HPV induces mutation via its viral genes E6 and E7, while HBV (and HCV) generates reactive oxygen species through chronic inflammation, leading to indirect mutations.

HTLV also directly causes mutations.

Other microorganisms such as certain parasites ( Opisthorchis viverrini or Schistosoma haematobium ) and bacteria ( Helicobacter pylori ) may also act as co-factors or carcinogens.

The mechanisms by which infectious agents promote cancer are becoming increasingly understood, with infection-related inflammation being a major risk factor.

Most viruses linked to cancer activate NF-kB as do components of H. pylori .

Agents that can block chronic inflammation hold promise for treating these conditions.

It has also been suggested that the SARS-CoV-2 virus might influence the vulnerability of specific organs to cancer due to its ability to infect multiple organs directly or indirectly.

However, the long-term consequences of this virus on cancer development are still being investigated and require further observation over time.

Environmental pollution

Environmental pollution is associated with various cancers.

It encompasses outdoor air pollution by carbon particles containing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs); indoor air pollution from environmental tobacco smoke, formaldehyde, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) like benzene and 1,3-butadiene; and food pollution from additives and carcinogenic contaminants such as nitrates, pesticides, dioxins and organochlorines.

Carcinogenic metals, pharmaceuticals and cosmetics also contribute to pollution-related cancer risks.

Outdoor pollutants like PAHs, especially in fine carbon particles, increase lung cancer risk through inhalation, with long-term exposure in polluted cities associated with elevated lung cancer deaths.

Nitric oxide from pollution also raises lung cancer risk, while motor vehicle exhaust exposure is linked to childhood leukaemia.

Indoor pollutants like VOCs and pesticides increase childhood leukaemia and lymphoma risk, along with the risk of brain tumours, Wilm’s tumours, Ewing’s sarcoma, and germ cell tumours in both children and adults.

Exposure to pollutants while in the womb raises testicular cancer risk, while chlorinated drinking water and nitrates transform to mutagenic compounds, increasing risks of lymphoma, leukaemia, colorectal and bladder cancers.

Radiation – both ionising and non-ionising – contributes to up to 10% of total cancer cases.

Ionising radiation sources include radioactive substances and medical X-rays, leading to cancers like leukaemia, lymphoma, thyroid cancer, skin cancer, sarcoma, lung cancer and breast carcinomas.

Notably, the 1986 Chernobyl incident in the then-Soviet Union underscored the increased cancer risk from radioactive fallout.

Radon exposure, primarily in homes and workplaces, poses a significant risk for gastric cancer.

Medical X-rays, especially during puberty, elevate breast cancer risk.

Patient age, synergistic interactions with carcinogens, and genetic susceptibility, influence radiation-induced cancers.

Non-ionising radiation, notably UV (ultraviolet) rays from sunlight and sunbeds, contribute to skin cancers like basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma.

Ozone layer depletion exacerbates UV exposure risks.

Low-frequency electromagnetic fields from power lines and electrical equipment increase the risk of childhood leukaemia, brain tumours and breast cancer.

Prolonged mobile phone use is associated with an increased risk of brain tumours, as shown in recent meta-analyses.

Datuk Dr Nor Ashikin Mokhtar is a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist, and a functional medicine practitioner. For further information, email [email protected]. The information provided is for educational and communication purposes only, and it should not be construed as personal medical advice. Information published in this article is not intended to replace, supplant or augment a consultation with a health professional regarding the reader’s own medical care. The Star does not give any warranty on accuracy, completeness, functionality, usefulness or other assurances as to the content appearing in this column. The Star disclaims all responsibility for any losses, damage to property or personal injury suffered directly or indirectly from reliance on such information.

Related stories:

Tags / Keywords: Cancer , smoking , tobacco , diet , alcohol , obesity , infectious diseases , pollution , radiation

Found a mistake in this article?

Report it to us.

Thank you for your report!

PTPTN HOSTS APPRECIATION CEREMONY FOR CUSTOMERS

Next in health.

Trending in Lifestyle

Air pollutant index, highest api readings, select state and location to view the latest api reading.

- Select Location

Source: Department of Environment, Malaysia

Others Also Read

Best viewed on Chrome browsers.

We would love to keep you posted on the latest promotion. Kindly fill the form below

Thank you for downloading.

We hope you enjoy this feature!

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

F.D.A. Approves Drug for Persistently Deadly Form of Lung Cancer

The treatment is for patients with small cell lung cancer, which afflicts about 35,000 people in the U.S. a year.

By Gina Kolata

The Food and Drug Administration on Thursday approved an innovative new treatment for patients with a form of lung cancer. It is to be used only by patients who have exhausted all other options to treat small cell lung cancer, and have a life expectancy of four to five months.

The drug tarlatamab, or Imdelltra, made by the company Amgen, tripled patients’ life expectancy, giving them a median survival of 14 months after they took the drug. Forty percent of those who got the drug responded.

After decades with no real advances in treatments for small cell lung cancer, tarlatamab offers the first real hope, said Dr. Anish Thomas, a lung cancer specialist at the federal National Cancer Institute who was not involved in the trial.

“I feel it’s a light after a long time,” he added.

Dr. Timothy Burns, a lung cancer specialist at the University of Pittsburgh, said that the drug “will be practice-changing.”

(Dr. Burns was not an investigator in the study but has served on an Amgen advisory committee for a different drug.)

The drug, though, has a side effect that can be serious — cytokine release syndrome. It’s an overreaction of the immune system that can result in symptoms like a rash, a rapid heartbeat and low blood pressure.

Each year, about 35,000 Americans are diagnosed with small cell lung cancer and face a grim prognosis. The cancer usually has spread beyond the lung by the time it is detected.

The standard treatment is old-fashioned chemotherapy — unchanged for decades — combined with immunotherapies that add about two months to patients’ life span. But, almost inevitably, the cancer resists the treatment.

“Ninety-five percent of the time it will come back, often in a matter of months,” Dr. Burns said. And when it comes back, he added, patients find it harder to tolerate the chemotherapy, and the chemotherapy is even less effective.

Most patients live just eight to 13 months after their diagnosis, despite having chemotherapy and immunotherapy. The group of patients in the clinical trial had already had two or even three rounds of chemotherapy, which is why their life expectancy without the drug was so short.