Historical travel

- 1 Understand

- 2.2 Antarctica

- 2.3.1 Across Asia

- 2.3.2 Middle East

- 2.3.3 East and Central Asia

- 2.3.4 South and Southeast Asia

- 2.4.1 Pan-European

- 2.4.2 Central and Eastern Europe

- 2.4.3 Nordic countries

- 2.4.4 Northwestern Europe

- 2.4.5 Southern Europe

- 2.5 Oceania

- 2.6.1 Mexico history series

- 2.6.2 United States history series

- 2.7 South America

- 3.1 The great epics

- 3.2 Espionage history

- 3.3 Science and technology tourism

- 3.4 History of justice

- 3.5 Military tourism

- 3.6 Exploration

- 3.7 Philosophy tourism

- 3.8 Political history

Historical travel includes various kinds of destinations, from Stone Age cave paintings to Cold War installations of the late 20th century. History is a central focus for some travellers and some destinations, and almost every traveller in most places will at least have a look at some old buildings or the local museums .

The early history of life on Earth is studied in paleontology , mainly through fossils. The earliest known fossils of the genus Homo date back at least 4.4 million years. Our species, Homo sapiens , is thought to have evolved between one and two hundred thousand years ago. Some homo sapiens migrated from Africa to the Middle East about 100,000 years ago and to Europe about 60,000 years ago. For purposes of this article, anything after 50,000 BCE counts as history. Naturally this overlaps considerably with our archaeology article.

The boundary between paleontology and archaeology , which deals mainly with the study of ancient human artifacts, is not at all well-defined. The oldest known tools made by hominids — Oldowan stone tools excavated in the Olduvai Gorge of Tanzania — are about 2.6 million years old. Australopithecines, of the genus which included direct ancestors of Homo , had cruder stone tools starting at least 3.3 million years ago. Controlled use of fire is apparently at least a million years old.

The boundary between prehistory and history is commonly drawn at the first local written records, which date back to around 3,000 BCE in Ancient Egypt and Ancient Mesopotamia , but as recently as the 19th century in some other parts of the world. Widespread literacy was rare in most of history and even when commoners could read and write, they often had no or limited access to durable material on which to write. As such, the written record is often focused on what the ruling elites deemed noteworthy and what can be learned about the everyday lives of common people is often only revealed indirectly or through archeology. "Oral history" or what was transmitted from generation to generation through poems, songs, legends and other means of storytelling was often dismissed by "Western" historiography but is now seen as a vital source of historical information instead of or in addition to the written record.

The distinction of history and pre-history by the availability of writing alone is not unanimously accepted and other markers are used as well. Pottery, the wheel, the first domesticated animals (dogs), and the first evidence of crop cultivation all appeared between 30,000 and 20,000 BCE. A number of other important developments took place between about 12,000 BCE and 3,000 — the Neolithic revolution transformed some societies from purely hunting/gathering to being based on agriculture, irrigation, cities, metalworking, and domestication of many more animals. During the civilizations of Greece and Rome , historians demonstrated their interest in history with contributions such as the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World , a list of important works of art and architecture in the region.

The line between "historical" and "modern" is arbitrary; some draw it around the time of the European Renaissance or slightly later with the great voyages of discovery starting with Columbus and Vasco da Gama . For the purposes of a travel guide, it can be convenient to draw it at the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries, when cities, industries and railroads began to expand fast, displacing older structures and rural folk culture. Surviving settlements and city districts from before the mid-19th century which were designed before and survived the advent of cars and trains, referred to as old towns , are typically smaller and more compact (and thus walkable) than modern cities. However, during the 19th and 20th centuries, older styles of art , architecture and furnishing were revived and reproduced, so that many buildings that look ancient might be less than 100 years old. There might even be a neo- Gothic train station or an Ancient Greek-style building in the Americas.

Deserted settlements can be archaeological sites or ghost towns . Pioneer villages can be authentic or artificial. In some places you quite literally trip over historical remnants, whereas other historic sites have been painstakingly preserved and restored. While the latter is usually more interesting it may seem "fake", "sterile" or even "artificial" when done badly. Also — with few exceptions — there are fewer lines (if any) for historical places that people actually still live in (like old towns ) or use for their original purpose (like many churches, mosques, synagogues, and temples) than for museums or "theme parks".

Nostalgia tourism aims at recent history, remembered by people alive today (especially the middle-aged and elderly ). As of the 2020s, it includes World War II , as well as postwar United States , Cold War Europe and the Soviet Union .

Some historical sites are threatened, either for natural causes or human-influenced ones like war or neglect. As of the 2020s, coastal cities such as Venice and New Orleans are sinking into the sea, ancient ruins in Iraq and Syria were damaged by wars of the 21st century, and many indigenous cultures around the world have only a handful of survivors left. Future generations are very unlikely to experience these places as they are today, as they will change even if they survive. Responsible travel can provide incentives to save them, or at least their memory.

Continents and regions

Africa is the wellspring of the human race and therefore the site of the oldest finds of human remains, in locations ranging from South Africa to Ethiopia . See paleontology .

Africa was also home to some of the world's oldest civilizations, particularly Ancient Egypt but also Nubia and Ethiopia ; see Ancient African nations for an overview. A bit later in antiquity, Carthage dominated much of North Africa and was then conquered by the Romans , who did major construction projects in their African provinces as they did in all other parts of their empire, leaving behind substantial ruins. In addition, there were great empires in both the Sahel and Southern Africa in the centuries before European colonialism; some of these relics have been vandalized by Salafist extremists in the 21st century, such as those in northern Mali , but a lot is still standing. Perhaps the two most prominent pre-colonial sites in sub-Saharan Africa are Timbuktu in Mali and the Great Zimbabwe in Zimbabwe .

Arab and Berber/Moorish civilization also has left deep and lasting marks on North Africa, and the Arabs, especially the Sultanate of Oman , had far-flung tributary states down the East African coast, also known as the Swahili Coast , notably including Zanzibar , Kilwa Kisiwani and Mombasa . There are also many relics of European colonialism, including slave forts and other forts on the coasts. Locations associated with the trans-Atlantic slave trade , World War II battles , the fights for independence, and the fight against Apartheid in South Africa can also be visited; see 20th-century South Africa for the latter.

- Ancient African nations

- Ancient Egypt

- Churches in Ethiopia

- Great Zimbabwe

- Atlantic slave trade

- World War II in Africa

- 20th-century South Africa

- MV Liemba , built for the Imperial German Navy before World War I, and still in service as a ferry

- Workers’ Assembly Halls

The only unsettled continent has very few traces of human history. Some Antarctic islands, such as the South Georgia Island and South Shetland Islands , have remnants of the whaling industry. The remains of expeditions of the "heroic age" of Antarctic exploration can still be seen and some have been actively preserved or relocated to museums in Europe and elsewhere. Many former research stations have been abandoned to be "swallowed" by snow and ice, and there aren't always many traces visible.

Asia had some of the world's oldest civilizations, including those in Ancient Mesopotamia , the Indus Valley , Persia , Anatolia , Syria , Phoenicia , Israel , the Edomites and Moabites of Jordan , China , India and Java , to name a few. The Middle East contains the world's first cities; some old towns have been inhabited for three millennia or more. The Holy Land is sacred to Judaism , Christianity , Islam and the Baháʼí Faith .

Iran has one of the oldest histories on earth. You may have heard names of emperors like Cyrus the Great or Ardashir I. The Achaemenid Empire was a really big empire which consisted of many states. The Silk Road played a very important role in supporting the economy of empire. The official language of the various Persian empires was usually Persian, but Aramaic and several other languages were also used.

The Asian nation that lacks archaeological relics is much more the exception than the rule. Much has been lost due to iconoclasm, such as in Malaysia several hundreds of years ago, when the relatively new Muslims destroyed Malay Hindu temples; in Saudi Arabia within the last few years, when numerous historical sites were razed in Mecca and other places; in Afghanistan , when statues of the Buddha that were thousands of years old were dynamited by the Taliban; and in Iraq and Syria in the first decade of the 21st century, when the Islamic State group destroyed many of the larger Babylonian and other historical relics they could get their hands on and spirited many of the smaller relics out of the country to sell on the black market.

Across Asia

- Silk Road , an ancient trading route that provided cultural and technology interchange between the East and West from the 2nd century BCE

- On the trail of Marco Polo , who traveled from Venice to China in the 13th century

- Voyages of Ibn Battuta , a 14th-century Muslim who travelled widely in Asia and Africa

- Istanbul to New Delhi overland , the "Hippie Trail" of the 1960s and 70s. Parts of what was the usual route back in the day have become too dangerous, but the journey is still possible using alternative routes.

Middle East

- Fertile Crescent

- Ancient Mesopotamia

- Persian Empire

- Troy , an ancient city famous for the legendary Trojan War recounted in Homer's Iliad

- Pre-Islamic Arabia

- Ancient Israel

- Islamic Golden Age

- Phoenecians

East and Central Asia

- Imperial China — the history of China prior to the establishment of the Republic of China in 1911

- Three Kingdoms — the period that China was tripartite divided into three dynastic states

- Western Xia — a lost ancient Chinese civilization (11th–13th century)

- Mongol Empire (13th–14th century)

- Pre-modern Japan — the history of the Japanese people prior to the Meiji Restoration in 1868

- Pre-modern Korea — the history of the Korean people prior to the Japanese occupation in 1910

- Japanese colonial empire

- Long March — a significant military event during the Chinese civil war in the 1930s that forged the Communist party

- World War II in China — the longest lasting and deadliest front of World War II

- Pacific War — the Second World War in the Asia-Pacific region

- Korean War — the 20th-century conflict at the beginning of the Cold War

- Tibetan Empire — history of the Tibetan people prior to the Qing conquest in the 18th century

- Jomon Prehistoric Sites in Northern Japan

- Minority cultures of China

- Indigenous Taiwanese culture

- Minority cultures of Japan

South and Southeast Asia

- Indus Valley Civilisation

- Maurya Empire

- Ahom Kingdom

- Mughal Empire (16th–early 19th century)

- British Raj (1858–1947)

- Khmer Empire

- Philippine Revolution (1896–1898)

- Indochina Wars

Europe has been more thoroughly excavated by archaeologists than any other continent. Southern Europe has archaeological sites from Ancient Greece , the Roman Empire and other ancient civilizations. Central Europe in particular is filled with medieval castles and early-modern palaces, with Old towns across the whole continent. Historical tourism itself has a long history in Europe; educational journeys such as the Grand Tour have been customary since the 17th century.

Europe's heritage has been scarred by war, especially World War II . The Holocaust was not just a genocidal campaign against the Jews; the Nazis also set out to methodically destroy Jewish heritage. Many beautiful synagogues were destroyed and never rebuilt due to — among other things — lack of a Jewish congregation, lack of funds or personal and institutional continuities. Jewish cemeteries, too, were vandalized. As the Second World War left many cities bombed beyond recognition, many city planners saw their opportunity to replace the "old fashioned" old towns with (in today's eyes) bland 1950s architecture and big streets and overpasses to make these places "ready for the automobile". Although the worst excesses have been turned back, many historical buildings that survived the wars were torn down in this somewhat iconoclastic frenzy.

Pan-European

- Prehistoric Europe

- Medieval Europe

- Protestant Reformation

- Napoleonic Wars

- World War I

- D-Day beaches

- Holocaust remembrance

- Cold War Europe

Central and Eastern Europe

- Austro-Hungarian Empire

- German Empire

- Hanseatic League

- Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

- Russian Empire

- Soviet Union

- Thirty Years' War

- Minority cultures of Russia

Nordic countries

- Danish Empire

- Nobel tourism ; life and works of Alfred Nobel, and the Nobel Prize

- Nordic history (since 1000 CE)

- Stockholm history tour

- Swedish Empire (strictly 1611–1721, the article covers a longer period)

- Vikings and the Old Norse (until 1000 CE)

Northwestern Europe

- Medieval Britain and Ireland

- Early modern Britain and Ireland

- Dutch Empire

- Kingdom of France

- French Colonial Empire

- Industrial Britain

- British Empire

Southern Europe

- Ancient Greece

- Roman Empire

- Byzantine Empire

- Italian Empire

- Medieval and Renaissance Italy

- Al-Andalus , began as an extension of the Islamic Umayyad Caliphate in Iberia

- Armenian Genocide remembrance

- Portuguese Empire

- Spanish Empire

The first humans arrived at New Guinea and Australia 65,000 years ago; this places their indigenous cultures among the oldest known on Earth. Without writing or metalworking, their heritage is sourced from their artwork and oral tradition. See Indigenous Australian culture . The first settlers of the Solomon Islands arrived more than 30,000 years ago. The general term for these ethnic groups is Melanesians .

The rest of Oceania has a relatively short human history, though. The Austronesians began migrating into the Pacific around 3,000 BCE and were the first people to arrive in Polynesia , from 1,000 BCE onwards. They reached Hawaii in the 4th century CE, and New Zealand in the 13th century (see Maori culture ), making the North and South Islands the last major landmasses on Earth to be settled (other than Antarctica). Oceania was also among the last regions to be charted and colonised by Europeans.

- Indigenous Australian culture

- Australian Convict Sites

- Military museums and sites in Australia

- Ned Kelly tourism

- Pacific War

North America

North American prehistory has left behind sites such as the New Mexico Pueblos and Ohio prehistoric sites . In addition, in Mexico and Central America , especially Guatemala , there are very impressive remains of the Mayan civilization , particularly quite a number of pyramids. Civilizations even older than the Maya are studied throughout Mexico, with cave drawing sites and places where civilization advancements such as the development of agriculture or writing systems happened independent of similar advancements in other parts of the world.

Sites associated with written history for the most part begin with early contact between the indigenous peoples of North America and European colonists. Often the indigenous were displaced by European settlers and sometimes killed (for example, the infamous Trail of Tears ). Even when they were not deliberately killed, the settlers frequently decimated indigenous populations by introducing European diseases.

Early colonial sites are often preserved as " old towns " in Atlantic coastal cities such as Quebec City , Havana , San Juan , or St. Augustine . But there are also old cities inland, such as Santa Fe, New Mexico , Guanajuato and Granada (Nicaragua) .

Early settlements that did not develop into major cities are often preserved (or reconstructed) as outdoor museums or " pioneer villages" , like Louisbourg , Plymouth (Massachusetts) , and Williamsburg .

The economic development of the American continent can be experienced by visiting historic plantations in the southern United States, haciendas in Mexico , and historic railroads.

Military tourism on this continent includes the American Revolution , War of 1812 , the Mexican War of Independence , the American Civil War , the Mexican Revolution and the various "Indian Wars" between the colonists and the indigenous peoples.

African-American history includes sites related to the Atlantic slave trade as well as the Underground Railroad : multiple routes for smuggling slaves who had escaped the southern US across the northern states into what later became Canada (at the time British North America) or other non-US territory. Active primarily in the 1850s, when US federal law left slaves who had escaped to free states in immediate danger of recapture by slave catchers unless they left the US entirely.

History-focused itineraries include the Camino Real , the Royal Road linking the 21 Spanish missions of California and the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro , the Royal Road that enabled economic development of New Spain in northwestern Mexico and the southwestern United States; the Lewis and Clark Trail leading across the Western United States, following the route of explorers Lewis and Clark; the Oregon Trail which took settlers to the Pacific coast; the Ruta del Tránsito , the historic route from east to west across North America that passed through Nicaragua ; Route 66 , which existed from 1926-1985 but continues to be marketed for nostalgia tourism; and the American Industry Tour from 17th-century Massachusetts to 20th-century Chicago.

For the politically-inclined there is also the chance to see sites related to the Presidents of the United States .

Mexico history series

Some of these topics overlap a bit with articles in other countries, especially those related to indigenous cultures, which share some stories with Canada , the United States , and Central America (especially Guatemala ). Events during Mexico's Colonial era and the War of Independence often hinge on events in Spain and its empire .

- Indigenous cultures of North America

- Indigenous cultures of Mesoamerica

- Maya civilization

- Colonial Mexico (1492 to 1810)

- Mexican War of Independence (1810-1821)

- Post-Independence Mexico (1821-1910)

- Mexican Revolution (1910-1920)

- Modern Mexico (1920 to today)

United States history series

Note that most of these topics are not exclusive to the United States. Indigenous cultures did not conform to modern boundaries and thus many were equally present in Canada and Mexico. Colonial boundaries were also different to modern ones: British colonial history includes Bermuda and Nova Scotia as much as the "13 colonies" of U.S. school textbooks while the Spanish Empire included all of the southwestern United States. The American War of Independence was partially fought in present-day Canada. Even after the establishment of the modern boundaries, trends and events touched multiple countries; those interested in the Old West will also find cowboy culture in Northern Mexico and the Canadian Prairies .

- New France (1608 to 1763)

- Early United States history (1492 to 1861)

- American Civil War (1861 to 1865)

- Old West (mainly 1865 to 1900)

- Industrialization of the United States (1865 to 1945)

- Postwar United States (1945 to present day)

South America

Many people travel to Peru every year to see the Inca Trail and other historical sites from the Inca Empire. Other historical sites include the remnants of the Falklands War and the history of the Jesuit missions in Paraguay . Beautiful colonial old towns can be found all over the continent, especially in Argentina and Chile , whose mineral wealth made them some of the richest countries in the world during the early 20th century.

- Indigenous cultures of South America

The great epics

Some of the oldest and most famous works of literature are epic poems about great heroes. In all cases there is some dispute among scholars about the historical authenticity of these stories, and about the dates of both the events described and the composition of the text.

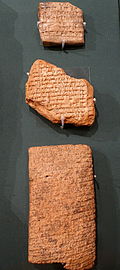

The Epic of Gilgamesh is the oldest known piece of literature. It tells tales of a Sumerian king who probably ruled in the first half of the 3rd millennium BCE and of a great flood. The best-known version was likely written around 1200 BCE. While a surprising number of copies survive for a text of that age, they are not all written in the same language and sometimes disagree significantly on details.

Other great epics were written a few hundred years BCE and describe events around 1000 BCE:

- Homer recounts the story of the Trojan War in two epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey . In Roman times Virgil's Aeneid continues the story, following a warrior from Troy to Italy. Today Troy is an archaeological site which attracts tourists.

- The Mahabarata is a great Indian epic. Perhaps the most famous passage in India literature is the Baghavad Gita , a dialog between the warrior Arjuna and the God Krishna which takes place just before the climactic battle. That battle was fought at Kurukshetra , which now attracts both pilgrims and tourists.

- The Ramayana is another great Indian epic. An epic battle was fought between the forces of the hero, Rama, and the villain, Ravana, on the island of Lanka, which is widely believed to be modern-day Sri Lanka . There is a chain of islands stretching from modern-day India to Sri Lanka, which is believed by Hindus to be the remains of the land bridge to Lanka that Rama and his army built.

- The Shahnameh is Iran 's national epic, written in the late 10th and early 11th centuries by the poet Ferdowsi. It recounts the mythical origins and history of the Persian Empire up until the Muslim conquest in the 7th century. Besides Iran, it is also highly revered in the neighboring countries that were historically influenced by Persia, such as Afghanistan , Tajikistan , and Azerbaijan .

- The Crusades have inspired much epic poetry in medieval Europe . Perhaps the most famous among them is the French poem La Chanson de Roland (The Song of Roland), composed in the 11th century, possibly by a Norman poet called Turold. Other notable ones include the 16th century Italian poems La Gerusalemme Liberata by Torquato Tasso and Orlando Furioso by Ludovico Ariosto, the latter of which inspired numerous operas over the years.

- The Bible is a more complex set of books than can be encompassed by the term "epic", but parts of it are basically Hebrew epics. The Torah (Pentateuch or Five Books of Moses) was first written down in full in the 6th century BCE, with fragments having been found that date to the 7th century BCE. The Exodus of Moses is one of the most famous stories of the Old Testament. See Holy Land , Judaism and Christianity for Biblical destinations.

Various Norse Sagas and Eddas probably originated as oral tradition around 1000 CE and were written down a few centuries later. Other Europeans also had epics, such as the Old English Beowulf or the Middle High German Nibelungenlied .

When reading any epic, keep in mind that most were passed down orally for centuries before being written down. Also, many tended to exaggerate numbers, either just to make a better story or to make rulers look impressive with great army sizes, harem sizes and feats of city building, so the "real deal" when finally verified by archeologists can fall short of the epic scales of the tales.

The equivalent in Chinese historiography is known as the Twenty-Four Histories (二十四史), starting with the compilation of the Records of the Grand Historian (史記/史记) by the Han Dynasty historian Sima Qian in the 1st century BCE. Subsequent official histories were typically compiled by the succeeding dynasty about the dynasty that preceded them. The official history of the Qing Dynasty has yet to be compiled; the Chinese government is attempting to compile it, but progress has been slow.

Espionage history

Espionage has existed since ancient times, and sometimes made or broken the fate of nations.

Science and technology tourism

Science tourism is for those with an interest in science, including science museums as well as live science research centers and exploratory missions. Closely related is industrial tourism , factory tours and museums describing manufacturing in various time periods from the start of the Industrial Revolution to the modern era.

Industrial tourism includes visits to historical or present-day industrial sites and museums. Mining tourism and certain underground works are a subset of industrial tourism. It is often related to the history of transportation, with maritime history , steam power , heritage railways , automotive history , aviation history and space flight sites .

History of organized labor describes the first trade unions and their struggle to improve working conditions.

Nuclear tourism is for those with an interest in the nuclear industry from either a science or military perspective. The locations can either contain live reactors or be otherwise of interest from a historical point of view; see Golden Age of Modern Physics for the preceding research in the first half of the 20th century.

Mathematics tourism includes places which inspired the understanding of numbers, geometry, and mathematical structure.

History of justice

Judicial tourism includes visits to courthouses, police buildings, prisons, crime scenes, and other places related to the legal system.

Military tourism

Military tourism is for those with an interest in current or historical military sites and facilities, including museums, battlefields, cemeteries and technology.

Exploration

Retracing the voyages of the great explorers of old:

- On the trail of Marco Polo

- Voyages of Zheng He

- Voyages of Ibn Battuta

Many famous journeys are from Europe's Age of Discovery :

- Magellan-Elcano circumnavigation

- Voyages of Columbus

- Voyages of James Cook

- Voyages of George Vancouver

- Voyages of Matthew Flinders

Later European explorers:

- Voyages of John Franklin

- Voyages of Roald Amundsen

Philosophy tourism

Philosophy tourism is for those with an interest in the history of philosophy, including historical residences of philosophers, museums, statues and places of burial.

Political history

Monarchies , grand houses , legislative buildings , local governments , history of organized labour and United Nations are some themes for the history of government and politics.

- Archaeological sites

- Grand houses

- Grand old hotels

- Fiction tourism and Literary travel

- Heritage railways

- Legacy food markets and Legacy retailers

- Mining tourism

- National parks

- Official residences

- Old towns and Ghost towns

- Some Tourist trains also focus on a supposed or actual historical connection

- Reenactment and LARP

- Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

- UNESCO Creative Cities

- UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage

- UNESCO World Heritage List

- Articles without Wikipedia links (via Wikidata)

- Has custom banner

- Cultural attractions

- Topic articles

- Usable topics

- Usable articles

Navigation menu

Heritage Tourism

The late Alan Gordon was professor of history at the University of Guelph. He authored three books: Making Public Pasts: The Contested Terrain of Montreal’s Public Memories, 1891–1930, The Hero and the Historians: Historiography and the Uses of Jacques Cartier and Time Travel: Tourism and the Rise of the Living History Museum in Mid-Twentieth Century Canada.

- Published: 18 August 2022

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Heritage tourism is a form of cultural tourism in which people travel to experience places, artifacts, or activities that are believed to be authentic representations of people and stories from the past. It couples heritage, a way of imagining the past in terms that suit the values of the present, with travel to locations associated with enshrined heritage values. Heritage tourism sites are normally divided into two often overlapping categories: natural sites and sites related to human culture and history. By exploring the construction of heritage tourism destinations in historical context, we can better understand how and through what attributes places become designated as sites of heritage and what it means to have an authentic heritage experience. These questions are explored through heritage landscapes, national parks, battlefield tourism, architectural tourism, and the concept of world heritage.

Heritage is one of the most difficult, complex, and expansive words in the English language because there is no simple or unanimously accepted understanding of what heritage encompasses. 1 We can pair heritage with a vast range of adjectives, such as cultural, historical, physical, architectural, or natural. What unites these different uses of the term is their reference to the past, in some way or another, while linking it to present-day needs. Heritage, then, is a reimagining of the past in terms that suit the values of the present. It cannot exist independently of human attempts to make the past usable because it is the product of human interpretation of not only the past, but of who belongs to particular historical narratives. At its base, heritage is about identity, and the inclusion and exclusion of peoples, stories, places, and activities in those identities. The use of the word “heritage” in this context is a postwar phenomenon. Heritage and heritage tourism, although not described in these terms, has a history as long as the history of modern tourism. Indeed, a present-minded use of the past is as old as civilization itself, and naturally embedded itself in the development of modern tourism. 2 The exploration of that history, examining the origins and development of heritage tourism, helps unpack some of the controversies and dissonance it produces.

Heritage in Tourism

Heritage tourism sites are normally divided into two categories: natural sites and sites of human, historical, or cultural heritage. the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) separates its list of world heritage sites in this manner. Sites of natural heritage are understood to be places where natural phenomena such as wildlife, flora, geological features, or ecosystems, are generally deemed to be of exceptional beauty or significance. Cultural heritage sites, which represent over three quarters of UNESCO-recognized sites, are places where human activity has left a lasting and substantial physical impact that reveals important features of a culture or cultures. Despite the apparent simplicity of this division, it is not always easy to categorize individual sites. UNESCO thus allows for a category of “mixed” heritage sites. But official recognition is not necessary to mark a place as a heritage destination and, moreover, some authors point to versions of heritage tourism that are not tightly place-specific, such as festivals of traditional performances or foodways. 3

The central questions at the heart of heritage tourism ask what it is that designates something as “heritage” and whether tourists have an “authentic” heritage experience there. At its simplest, heritage tourism is a form of cultural tourism in which people travel to experience places, artifacts, or activities that are authentic representations of people and stories from the past. Yet this definition encompasses two, often competing, motivations. Heritage tourism is both a cultural phenomenon through which people attempt to connect with the past, their ancestors, and their identity, and it is an industry designed to profit from it. Another question surrounds the source of the “heritage” in heritage tourism. Many scholars have argued that heritage does not live in the destinations or attractions people seek. Heritage is not innate to the destination, but is rather based on the tourist’s motivations and expectations. Thus, heritage tourism is a form of tourism in which the main motivation for visiting a site is based on the traveler’s perceptions of its heritage characteristics. Following the logic of this view, the authenticity of the heritage experience depends on the traveler rather than the destination or the activity. Heritage features, as well as the sense of authenticity they impart, are democratized in what might be called a consumer-based model of authenticity. 4 This is a model that allows for virtually anything or any place to be a heritage destination. Although such an approach to understanding heritage tourism may well serve present-day studies, measuring motivations is more complicated for historical subjects. Long-departed travelers are not readily surveyed about their expectations; motivations have to be teased out of historical records. In a contrasting view, John Tunbridge and Gregory Ashworth argue that heritage attractions are created through marketing: they are invented to be heritage attractions and sold to a traveling public as such. Yet, heritage attractions, in this understanding, are still deemed authentic when they satisfy consumer expectations about heritage. 5 This insight also implies that heritage tourism destinations might be deceptions, and certainly there are examples of the fabrication of heritage sites. However, if motivations and expectations are arbiters of heritage, then even invented heritage can become authentic through its acceptance by a public. While not ignoring the motivations and expectations of travelers, for historians, any understanding of heritage tourism must include the process by which sites become designated as a places of heritage. It must encompass the economic aspects of tourism development, tourism’s role in constructing narratives of national or group identity, and the cultural phenomenon of seeking authentic representations of those identities, regardless of their origins. Such a practice might include traveling to sites connected to diasporas, places of historical significance, sites of religious pilgrimages, and landscapes of scenic beauty or cultural importance.

Scholarly interest in heritage, at least in the English-speaking world, dates from the 1980s reaction to the emergence of new right-wing political movements that used the past as a tool to legitimize political positions. Authors such as David Lowenthal, Robert Hewison, and Patrick Wright bemoaned the recourse to “heritage” as evidence of a failing society that was backward-looking, fearful, and resentful of modern diversity. 6 Heritage, they proclaimed, was elitist and innately conservative, imposed on the people from above in ways that distanced them from an authentic historical consciousness. Although Raphael Samuel fired back that the critique of heritage was itself elitist and almost snobbish, this line continued in the 1990s. Works by John Gillis, Tony Bennett, and Eric Hobsbawm, among others, concurred that heritage was little more than simplified history used as a weapon of social and political control.

At about the same time, historians also began to take tourism seriously as a subject of inquiry, and they quickly connected leisure travel to perceived evils in the heritage industry. Historians such as John K. Walton in the United Kingdom and John Jakle in the United States began investigating patterns of tourism’s history in their respective countries. Although not explicitly concerned with heritage tourism, works such as Jakle’s The Tourist explored the infrastructure and experience of leisure travel in America, including the different types of attractions people sought. 7 In Sacred Places , John Sears argued that tourism helped define America in the nineteenth century through its landscape and natural wonders. Natural tourist attractions, such as Yosemite and Yellowstone parks became sacred places for a young nation without unifying religious and national shrines. 8 Among North America’s first heritage destinations was Niagara Falls, which drew Americans, Europeans, Britons, and Canadians to marvel at its beauty and power. Tourist services quickly developed there to accommodate travelers and, as Patricia Jasen and others note, Niagara became a North American heritage destination at the birth of the continent’s tourism trade. 9

As the European and North American travel business set about establishing scenic landscapes as sites worthy of the expense and difficulty of travel to them, they rarely used a rhetoric of heritage. Sites were depicted as places to embrace “the sublime,” a feeling arising when the emotional experience overwhelms the power of reason to articulate it. Yet as modern tourism developed, promoters required more varied attractions to induce travelers to visit specific destinations. North America’s first tourist circuits, well established by the 1820s, took travelers up the Hudson River valley from New York to the spas of Saratoga Springs, then utilizing the Erie Canal even before its completion, west to Niagara Falls. Tourist guidebooks were replete with vivid depictions of the natural wonders to be witnessed, and very quickly Niagara became heavily commercialized. As America expanded beyond the Midwest in the second half of the nineteenth century, text and image combined to produce a sense that these beautiful landscapes were a common inheritance of the (white and middle-class) American people. Commissioned expeditions, such as the Powell Expedition of 1869–1872, produced best-selling travel narratives revealing the American landscape to enthralled readers in the eastern cities (see Butler , this volume). John Wesley Powell’s description of his voyage along the Colorado River combined over 450 pages of written description with 80 prints, mostly portraying spectacular natural features. American westward exploration, then, construed the continent’s natural wonders as its heritage.

In America, heritage landscapes often obscured human activity and imagined the continent as nature untouched. But natural heritage also played a role in early heritage tourism in Britain and Europe. Many scholars have investigated the connection between national character and the depiction of topographical features, arguing that people often implant their communities with ideas of landscape and associate geographical features with their identities. In this way, landscape helps embed a connection between places and particular local and ethnic identities. 10 Idealized landscapes become markers of national identity (see Noack , this volume). For instance, in the Romantic era, the English Lake District and the mountains of the Scottish Highlands became iconic national representations of English, Scottish, or British nationalities. David Lowenthal has commented on the nostalgia inherent in “landscape-as-heritage.” The archetypical English landscape, a patchwork of fields divided by hedgerows and sprinkled with villages, was a relatively recent construction when the pre-Raphaelite painters reconfigured it as the romantic allure of a medieval England. It spoke to the stability and order inherent in English character. 11

Travel literature combined with landscape art to develop heritage landscapes and promote them as tourist attractions. Following the 1707 Act of Union, English tourists became fascinated with Scotland, and in particular the Scottish Highlands. Tourist guidebooks portrayed the Highlands as a harsh, bleak environment spectacular for its beauty as well as the quaintness of its people and their customs (see Schaff , this volume). Over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, tourist texts cemented the image of Highland culture and heritage. Scholars have criticized this process as a “Tartanization” or “Balmoralization” of the country by which its landscape and culture was reduced to a few stereotypes appealing to foreign visitors. Nevertheless, guidebook texts described the bens, lochs, and glens with detail, helping create and reinforce a mental picture of a quintessential Highland landscape. 12 The massacre of members of the Clan MacDonald at Glencoe, killed on a winter night in 1692 for insufficient loyalty to the monarchy, added romance. Forgotten for over a century, the event was recalled in the mid-nineteenth century by the historian Thomas Babington Macaulay, and quickly became a tragic tale associated with the scenic valley. At the same time the Highlands were being re-coded from a dangerous to a sublime landscape, its inhabitants became romanticized as an untainted, simple, premodern culture. The natural beauty of the landscape at Glencoe and its relative ease of access, being close to Loch Lomond and Glasgow, made it an attraction with a ready-made tragic tale. Highlands travel guides began to include Glencoe in their itineraries, combining a site of natural beauty with a haunting human past. Both natural and cultural heritage, then, are not inherent, but represent choices made by people about what and how to value the land and the past. On France’s Celtic fringe, a similar process unfolded. When modern tourism developed in Brittany in the mid-nineteenth century, guidebooks such as Joanne’s defined the terms of an authentic Breton experience. Joanne’s 1867 guide coupled the region’s characteristic rugged coastlines with the supposedly backward people, their costumes, habitudes, beliefs, and superstitions, who inhabited it. 13 Travel guides were thus the first contributors in the construction of heritage destinations. They began to highlight the history, real and imagined, of destinations to promote their distinctions. And, with increasing interest in the sites of national heritage, people organized to catalog, preserve, and promote heritage destinations.

Organizing Heritage Tourism

Among the world’s first bodies dedicated to preserving heritage was the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), organized in England in 1877. Emerging as a result of particular debates about architectural practices, this society opposed a then-popular trend of altering buildings to produce imaginary historical forms. This approach, which was most famously connected to Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc’s French restorations, involved removing or replacing existing architectural features, something renounced by the SPAB. The society’s manifesto declared that old structures should be repaired so that their entire history would be protected as part of cultural heritage. The first heritage preservation legislation, England’s Ancient Monuments Protection Act of 1882, provided for the protection initially of 68 prehistoric sites and appointed an inspector of ancient monuments. 14 By 1895, movements to conserve historic structures and landscapes had combined with the founding of the National Trust, officially known as the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, as a charitable agency. Much of the Trust’s early effort protected landscapes: of twenty-nine properties listed in 1907, seventeen were acreages of land and other open spaces. 15 Over the twentieth century, however, the Trust grew more and more concerned with protecting country houses and gardens, which now constitute the majority of its listed properties.

British efforts were duplicated in Europe. The Dutch Society for the Preservation of Natural Landmarks was established in 1904; France passed legislation to protect natural monuments in 1906. And in Sweden, the Society for the Protection of Nature was established in 1909, to name only a few examples. Nature was often connected to the spirit of “the folk,” an idea that encompassed a notion of an original ethnic core to the nation. Various European nationalisms of the period embraced the idea of an “authentic” national folk, with each folk considered unique due to its connection with a specific geography. Folklore and the celebration of folk culture offered Europeans links to imagined national heritages in a rapidly modernizing world, as modern, middle-class Europeans turned their attention to the romanticized primitive life of so-called simple peasants and linked notions of natural and human heritage. Through the concept of the folk, natural and human heritage combined to buttress emerging expressions of nationalism. 16

Sweden provides an instructive example. As early as the seventeenth century, Swedish antiquarians were intrigued by medieval rune stones, burial mounds, and cairns strewn across the country, but also saw these connected to natural features. Investigations of these relics of past Nordic culture involved a sense of the landscape in which they were found. This interest accelerated as folk studies grew in popularity, in part connected to nationalist political ambitions of Swedes during the growing tensions within the Kingdom of Sweden and Norway, which divided in 1905. Sweden’s preservation law required research into the country’s natural resources to create an inventory of places. Of particular interest were features considered to be “nature in its original state.” The intent was to preserve for future generations at least one example of Sweden’s primordial landscape features: primeval forests, swamps, peat bogs, and boulders. But interest was also drawn to natural landmarks associated with historical or mythical events from Sweden’s past. Stones or trees related to tales from the Nordic sagas, for example, combined natural with cultural heritage. 17

Although early efforts to protect heritage sites were not intended to support tourism, the industry quickly benefited. Alongside expanding tours to the Scottish Highlands and English Lake District, European landscapes became associated with leisure travel. As Tait Kellar argues for one example, the context of the landscape is crucial in understanding the role of tourism in the German Alps. 18 Guidebooks of the nineteenth and early twentieth century did not use the term “heritage,” but they described its tenets to audiences employing a different vocabulary. Baedeker’s travel guides, such as The Eastern Alps , guided bourgeois travelers through the hiking trails and vistas of the mountains and foothills, offering enticing descriptions of the pleasures to be found in the German landscape. Beyond the land, The Eastern Alps directed visitors to excursions that revealed features of natural history, human history, and local German cultures. 19

Across the Atlantic people also cherished escapes to the countryside for leisure and recreation and, as economic and population growth increasingly seemed to threaten the idyllic tranquility of scenic places, many banded together to advocate for their conservation. Yet, ironically, by putting in place systems to mark and preserve America’s natural heritage, conservationists popularized protected sites as tourist destinations. By the second half of the nineteenth century, the conservation movement encouraged the US government to set aside massive areas of American land as parks. For example, Europeans first encountered the scenic beauty of California’s Yosemite Valley at midcentury. With increasing settler populations following the California Gold Rush, tourists began arriving in ever larger numbers and promoters began building accommodations and roads to encourage them. Even during the Civil War, the US government recognized the potential for commercial overdevelopment and the desire of many to preserve America’s most scenic places. 20 In 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant, designating acres of the valley protected wilderness. This set a precedent for the later creation of America’s first national park. In 1871, the Hayden Geological Survey recommended the preservation of nearly 3,500 square miles of land in the Rocky Mountains, in the territories of Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho. Ferdinand V. Hayden was concerned that the pristine mountain region might soon be as overrun with tourists as Niagara Falls had by then become. 21 The following year, Congress established Yellowstone National Park, the world’s first designated “heritage” site. Yet, from the beginning, Yellowstone and subsequent parks were assumed to be tourist attractions. By 1879, tourists to Yellowstone had established over 200 miles of trails that led them to the park’s most famous attractions. Although thought of as nature preserves, parks were often furnished with railway access, and amenities and accommodations appeared, often prior to official designation. National parks were immediately popular tourist attractions. Even before it had established a centralized bureaucracy to care for them, the United States government had established nine national parks and nearly two dozen national monuments. Canada lagged, but established Rocky Mountain National Park (now Banff) in 1885 to balance interests of resource extraction and conservation. (The world’s second national park was Australia’s Royal National Park, established by the colony of New South Wales in 1879.) By the outbreak of the Great War, Canada and the United States had established fifteen national parks, all but one west of the Mississippi River.

Establishing parks was one component of building a heritage tourism infrastructure. Another was the creation of a national bureaucracy to organize it. The Canadian example reveals how heritage and tourism drove the creation of a national parks service. Much of the mythology surrounding Canada’s national parks emphasized the role of nature preservationists, yet the founder of the parks system, J. B. Harkin, was deeply interested in building a parks network for tourists. 22 Indeed, from early in the twentieth century, Canada’s parks system operated on the principle that parks should be “playgrounds, vacation destinations, and roadside attractions that might simultaneously preserve the fading scenic beauty and wildlife populations” of a modernizing nation. 23 Although Canada had established four national parks in the Rocky Mountains in the 1880s, the administration of those parks was haphazard and decentralized. It was not until the approaching third centennial of the founding of Quebec City (now a UNESCO World Heritage Site) that the Canadian government began thinking actively about administering its national heritage. In 1908, Canada hosted an international tourist festival on the Plains of Abraham, the celebrated open land where French and British armies had fought the decisive battle for supremacy in North America in 1759. The event so popularized the fabled battlefield that the government was compelled to create a National Battlefield Commission to safeguard it. This inspired the creation of the Dominion Parks Branch three years later to manage Canada’s natural heritage parks, the world’s first national parks service. By 1919 the system expanded to include human history—or at least European settler history—through the creation of national historic parks. These parks were even more explicitly designed to attract tourists, automobile tourists in particular. In 1916, five years after Canada, the United States established the National Parks Service with similar objectives.

As in Europe, nationalism played a significant role in developing heritage tourism destinations in America. The first national parks were inspired by the series of American surveying expeditions intended to secure knowledge of the landscape for political control. Stephen Pyne connects the American “discovery” of the Grand Canyon, for example, to notions of manifest destiny following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) that ended the Mexican-American War and ceded over 500,000 square miles of what is today the western United States. Popularized by the report of John Wesley Powell (1875) , the canyon began attracting tourists in the 1880s, although Congress failed to establish it as a national park. 24 Tourism was central to developing the Grand Canyon as a national heritage destination. Originally seen by Spanish explorers as an obstacle, and as a sacred place by the Navajo, Hopi, Hualapai, and Havasupai peoples, the canyon came to mark American exceptionalism. Piece by piece, sections of the canyon were set aside as reserves and finally declared a national park in 1919. By then, the park had been serviced by a railway (since 1901) and offered tourists a luxury hotel on the canyon’s south rim.

Archaeology also entered into the construction of American heritage. Almost as soon as it was annexed to the United States, the American southwest revealed to American surveyors a host of archaeological remains. For residents of the southwest, the discovery of these ancient ruins of unknown age pointed to the nobility of a lost predecessor civilization. By deliberately construing the ruins as being of an unknown age, Anglo-American settlers were able to draw distinctions between the ancients and contemporary Native Americans in ways that validated their own occupation of the territory. The ruins also had commercial potential. In Colorado, President Theodore Roosevelt established Mesa Verde National Park in 1906 to protect and capitalize on the abandoned cliff dwellings located there. These ruins had been rediscovered in the 1880s when ranchers learned of them from the local Ute people. By the turn of the century, the ruins had attracted so many treasure seekers that they needed protection. This was the first national park in America designated to protect a site of archaeological significance and linked natural and human heritage in the national parks system. 25

If, as many argue, heritage is not innate, how is it made? Part of the answer to this question can be found in the business of tourism. Commercial exploitation of heritage tourism emerged alongside heritage tourism, but was particularly active in the postwar years. Given their association with tourism, it is not surprising that railways and associated businesses played a prominent role in promoting heritage destinations. Before World War II, the most active heritage tourism promoter was likely the Fred Harvey Company, which successfully marketed, and to a great degree created, much of the heritage of the American southwest. The Fred Harvey Company originated with the opening of a pair of cafés along the Kansas Pacific Railway in 1876. After a stuttering beginning, Harvey’s chain of railway eateries grew in size. Before dining cars became regular features of passenger trains, meals on long-distance trips were provided by outside business such as Harvey’s at regular stops. With the backing of the Santa Fe Railroad, the company also developed attractions based on the Southwest region’s unique architectural and cultural features. The image capitalized on the artistic traditions of Native Americans and early Spanish traditions to create, in particular, the Adobe architectural style now associated with Santa Fe and New Mexico. 26 These designs were also incorporated into tourist facilities on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, including the El Tovar hotel and the Hopi House souvenir and concession complex, designed to resemble a Hopi pueblo.

Relying on existing and manufactured heritage sites, North American railways popularized attractions as heritage sites. The Northern Pacific Railroad financed a number of hotels in Yellowstone Park, including the Old Faithful Inn in 1904. In 1910, the Great Northern Railroad launched its “See America First” campaign to attract visitors (and new investments) to its routes to the west’s national parks. In Canada, the Dominion Atlantic Railway rebuilt Grand Pré, a Nova Scotia Acadian settlement to evoke the home of the likely fictional character Evangeline from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1848 poem by the same name. In the poem, Evangeline was deported from Acadia in 1755 and separated from her betrothed. By the 1920s, the railway was transporting tourists to Grand Pré, christened “Land of Evangeline,” where reproductions stood in for sites mentioned in the poem. 27 However, following World War I, heritage tourism in North America became increasingly dependent on automobile travel and the Dominion Atlantic eventually sold its interest to the Canadian government.

Conflict as Cultural Heritage

Tourism to sites of military history initially involved side trips from more popular, usually natural, attractions. Thomas Chambers notes that the sites of battles of the Seven Years’ War, Revolutionary War, and War of 1812 became tourist attractions as side trips from more established itineraries, such as the northern or fashionable tours. War of 1812 battlefields, many of them in the Niagara theater of the war, were conveniently close to the natural wonders people already came to see. By visiting the places where so many had sacrificed for their country, tourists began attaching new meaning to the sites. Ease of access was essential. Chambers contrasts sites in southern states with those in the north. In the south, the fields of important American Revolution victories at Cowpens and King’s Mountain were too remote to permit easy tourist access and long remained undeveloped. 28 In a contrary example, the Plains of Abraham, the scene of General Wolfe’s dramatic victory over France that led to the Conquest of Canada, was at first a curiosity. The visit to Quebec, a main destination on the northern tour, was originally based on its role as a major port and the attraction of the scenic beauty of the city on the cliffs, compared favorably to Cintra in Portugal. 29 Ease of access helped promoters convert an empty field near the city into the “hallowed Plains.”

Access to battlefields increased at almost the exact moment that one of the nineteenth century’s most devastating wars, the American Civil War, broke out. Railway travel was essential to both the success of the Union Army in reconquering the rebelling Confederacy, and in developing tourism to the sites of the slaughter. Railway travel made sites accessible for urban travelers and new technologies, such as photography and the telegraph, sped news of victories and defeats quickly around the nation. Gettysburg, the scene of a crucial Union victory in July 1863, became a tourist attraction only a few days later. Few would call the farmland of southeastern Pennsylvania sublime, but dramatic human history had unfolded there. The battle inspired the building of a national memorial on the site only four months later, the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. At the inauguration of the cemetery Abraham Lincoln delivered his “Gettysburg Address,” calling on the nation to long remember and cherish the “hallowed ground” where history had been made.

Gettysburg sparked a frenzy of marking sites of Civil War battles and events. Battle sites became important backdrops for political efforts at reunion and reconciliation after the war and attracted hundreds and later thousands of tourists for commemorative events and celebrations. Ten thousand saw President Rutherford Hayes speak at Gettysburg in 1878 and, for the 50th anniversary of Gettysburg, some 55,000 veterans returned to Pennsylvania in July 1913. What had once been a site of bloody, brutal combat had been transformed into a destination where tourists gathered to embrace their shared heritage, north and south. As the years progressed, more attractions were added as tourists began to see their heritage on the battlefield. 30

The conflict that most clearly created tourist attractions out of places of suffering was the World War I. Soon after the war ended, its sites of slaughter also became tourist attractions. As with the Civil War in America, World War I tourists were local people and relatives of the soldiers who had perished on the field of battle. By one estimate 60,000 tourists visited the battlefields of the Western Front by the summer of 1919, the same year that Michelin began publishing guidebooks to them. Numbers grew in the decades following the war. Over 140,000 tourists took in the sites of the war in 1931, which grew to 160,000 for 1939. Organizations such as the Workers’ Travel Association hoped that tourism to battle sites would promote peace, but the travel business also benefited. Travel agencies jumped at the chance to offer tours and publishers produced travel guides to the battlefields. At least thirty English guidebooks were published by 1921. 31

This interest in a conflict that killed, often in brutal fashion, so many might seem a ghoulish form of heritage tourism. Yet Peter Slade argues that people do not visit battlefields for the love for death and gore. They attend these sites out of a sense of pilgrimage to sites sacred to their national heritage. Organized pilgrimages reveal this sense of belonging most clearly. The American Legion organized a pilgrimage of 15,000 veterans in 1927 to commemorate the decade anniversary of America’s entry to the war. The following year 11,000 Britons, including 3,000 women, made a pilgrimage of their own. Canada’s first official pilgrimage involved 8,000 pilgrims (veterans and their families) to attend the inauguration of the Vimy Ridge Memorial, marking a site held by many as a place sacred to Canadian identity. Australians and New Zealanders marched to Gallipoli in Turkey for similar reasons. 32 As with the sites of the Western Front, Gallipoli and pilgrimages to it generated travel accounts and publishers assembled guidebooks to help travelers navigate its attractions and accommodations. In these episodes, tourism was used to construct national heritage. In the interwar years, tourist activity popularized the notion that sites of national heritage existed on the battlefields of foreign lands, where “our” nation’s history was forged. National heritage tourism, then, became transnational.

Since the end of World War II, battlefield tourism has become an important projection of heritage tourism. Commercial tour operators organize thousands of tours of European World War I and World War II battlefields for Americans and Canadians, as for other nationalities. The phenomenon seems particularly pronounced among North Americans. The motivation behind modern battlefield tourism reveals its connection to heritage tourism. If heritage is an appeal to the past that helps establish a sense of identity and belonging, the feelings of national pride and remorse for sacrifice of the fallen at these sites helps define them as sacred to a particular vision of a national past. The sanctity of the battle site makes the act of consuming it as a tourist attraction an act of communion with heritage.

Built Heritage and Tourism

During the upheaval of the Civil War, some Americans began to recognize historic houses as elements of their heritage worthy of preservation. These houses were initially not seen as tourist attractions, but as markers of national values. Their heritage value preceded their value as tourist attractions. The first major preservation initiative launched in 1853 to save George Washington’s tomb and home from spoliation. Behind overt sectional divisions of north and south was an implied vesting of republican purity among the patrician families that could trace their ancestors to the revolutionary age and who could restore American culture to its proper deferential state. The success of preserving Mount Vernon led to a proliferation of similar house museums. By the 1930s, the American museum association even produced a guide for how to establish new examples and promote them as sites of heritage for tourist interest. Historic houses provided tangible, physical evidence of heritage. Like scenic landscapes attached to the stories of history, buildings connected locations to significant events and people of the past. Architectural heritage came to be closely associated with tourism. Architectural monuments are easily identified, easy to promote, and, as physical structures, easily reproduced in souvenir ephemera. Although the recognition of architectural monuments as tourist draws could be said to have originated with the Grand Tour, or at least with the publication of John Ruskin’s “Seven Lamps of Architecture” (1849), which singled out the monuments of Venice for veneration, twentieth century mobility facilitated a greater desire to travel to see historic structures. Indeed, mobility, especially automobility, prompted the desire to preserve or even reinvent the structural heritage of the past.

A driving factor behind the growth of tourism to sites associated with these structural relics was a feeling that the past—and especially the social values of the past—was being lost. For example, Colonial Williamsburg developed in reaction to the pace of urban and social change brought about by automobile travel in the 1920s. Williamsburg was once a community of colonial era architecture, but had become just another highway town before John D. Rockefeller lent his considerable wealth to its preservation and reconstruction. 33 Rockefeller had already donated a million dollars for the restoration of French chateaux at Versailles, Fontainebleu, and Rheims. 34 At Williamsburg, his approach was to remove structures from the post-Colonial period to create a townscape from the late eighteenth century. By selecting a cut-off year of 1790, Rockefeller and his experts attempted to freeze Williamsburg in a particular vision of the past. The heritage envisioned was not that of ordinary Americans, but that of colonial elites. Conceived to be a tourist attraction, Colonial Williamsburg offered a tourist-friendly lesson in American heritage. Rockefeller, and a host of consultants convinced the (white) people of Williamsburg to reimagine their heritage and their past. America’s heritage values were translated to the concepts of self-government and individual liberty elaborated by the great patriots, Washington, Madison, Henry, and Jefferson. The town commemorated the planter elites that had dominated American society until the Jacksonian era, and presented them as progenitors of timeless ideals and values. They represented the “very cradle of that Americanism of which Rockefeller and the corporate elite were the inheritors and custodians.” 35

Rockefeller’s Williamsburg was not the only American heritage tourist reconstruction. Canada also underwent reconstruction projects for specifically heritage tourism purposes, such as the construction of “Champlain’s Habitation” at Port Royal, Nova Scotia or the attempt to draw tourists to Invermere, British Columbia with a replica fur trade fort. 36 Following World War I and accelerating after World War II, the number and nature of places deemed heritage attractions grew. Across North America, all levels of governments and private corporations built replica heritage sites with varying degrees of “authenticity.” Although these sites often made use of existing buildings and landscapes, they also manufactured an imaginary environment of the past. The motivation behind these sites was almost always diversification of the local economy through increased tourism. Canada’s Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site is perhaps the most obvious example. It is a reconstructed section of the French colonial town, conquered and destroyed in 1758, built on the archaeological remains of the original. Constructed by the government of Canada as a means to diversify the failing resource economy of its Atlantic provinces, the tourist attraction was also designated a component of Canada’s national heritage. The US government also increased its interest in the protection of heritage destinations, greatly expanding the list of national historic landmarks, sites, parks, and monuments. As postwar governments became more concerned with managing their economies, tourism quickly came to be seen as a key economic sector. The language of national heritage helped build public support for state intervention in natural and historic artifacts and sites that could be presented as sacred national places.

In Europe, many historic sites were devastated by bombardment during World War II. Aside from pressing humanitarian issues, heritage concerns also had to be addressed. In France, the war had destroyed nearly half a million buildings, principally in the northern cities, many of which were of clear heritage value. The French government established a commission to undertake the reconstruction of historic buildings and monuments and, in some cases, entire towns. Saint-Malo, in Brittany, had been completely destroyed, but the old walled town was rebuilt to its seventeenth century appearance. Already a seaside resort, the town added a heritage site destination. In the 1920s and 1930s, European fascist states had also employed heritage tourism. In Mussolini’s Italy and Nazi Germany, workers’ leisure time was to be organized to prevent ordinary Italians and Germans from falling into unproductive leisure activities. Given the attachment to racialized views of purity and identity, organized tourism was encouraged to allow people to bond with their national heritage. Hiking in the Black Forest or the alpine Allgau might help connect Germans to the landscape and reconnect them to the traditional costumes and folkways of rural Germany. As Kristin Semmens argues, most studies of the Nazi misappropriation of the past ignore the displays of history aimed toward tourists at Germany’s heritage sites. Many museums and historic sites twisted their interpretations to fit the Nazi present. 37 In ways that foreshadowed the 1980s British left’s critique of heritage, fascist regimes made use of heritage tourism to control society. After the war, a vigorous program of denazification was undertaken to remove public relics of the Nazi regime and in formerly occupied territories, as was a program of reconstruction. In the communist east, blaming the Nazis for the destruction of German heritage was an ideological gift. It allowed the communist regime to establish itself as the true custodian of German identity and heritage. 38 In the capitalist west, tourism revived quickly. By early 1947, thirteen new tourist associations were active in the Allied occupation zone. Tourism rhetoric in the postwar years attempted to distance German heritage from the Nazi regime to reintroduce foreign travelers to the “real Germany.” Despite this objective, Alon Confino notes that traces of the Nazi past can be located in postwar tourist promotions that highlighted Nazi-era infrastructure. 39

Postwar Heritage Tourism

As tourism became a more global industry, thanks in no small part to the advent of affordable air travel in the postwar era, heritage tourism became transnational. Ethnic heritage tourism became more important, and diaspora or roots tourism, which brought second- and third-generation migrants back to the original home of their ancestors, accelerated. Commodifying ethnic heritage has been one of the most distinctive developments in twenty-first century tourism. Ethnic heritage tourism can involve migrants, their children, or grandchildren returning to their “home” countries as visitors. In this form of tourism, the “heritage” component is thus expressed in the motivations and self-identifications of the traveler. It involves a sense of belonging that is rooted in the symbolic meanings of collective memories, shared stories, and the sense of place embodied in the physical locations of the original homeland. Paul Basu has extensively studied the phenomenon of “roots tourism” among the descendants of Scottish Highlanders. He suggests that in their trips to Scotland to conduct genealogical research, explore sites connected to their ancestors, or sites connected to Scottish identity, they construct a sense of their heritage as expatriate Scots. 40 Similar “return” movements can be found in the migrant-descended communities of many settler colonial nations. For second-generation Chinese Americans visiting China, their search for authentic experiences mirrored those of other tourists. Yet, travel to their parents’ homeland strengthened their sense of family history and attachment to Chinese cultures. 41 On the other hand, Shaul Kellner examines the growing trend of cultivating roots tourism through state-sponsored homeland tours. In Tours that Bind , Kellner explores the State of Israel and American Jewish organizations’ efforts to forge a sense of Israeli heritage among young American Jews. However, Kellner cautions, individual experiences and human agency limit the hosts’ abilities to control the experience and thus control the sense of heritage. 42

Leisure tourism also played a role in developing heritage sites, as travelers to sunshine destinations began looking for more interesting side trips. Repeating the battlefield tourism of a century before, by the 1970s access to historic and prehistoric sites made it possible to add side trips to beach vacations. Perhaps the best example of this was the development of tourism to sites of Mayan heritage by the Mexican government in the 1970s. The most famous heritage sites, at least for Westerners, were the Mayan sites of Yucatan. First promoted as destinations by the American travel writer John Lloyd Stephens in the 1840s, their relative inaccessibility (as well as local political instabilities) made them unlikely tourist attractions before the twentieth century. By 1923, the Yucatan government had opened a highway to the site of the Chichén Itzá ruins, and local promoters began promotions in the 1940s. It was not until after the Mexican government nationalized all archaeological ruins in the 1970s that organized tours from Mexican beach resorts began to feature trips to the ruins themselves. 43

Mexico’s interest in the preservation and promotion of its archaeological relics coincided with one of the most important developments in heritage tourism in the postwar years: the emergence of the idea of world heritage. The idea was formalized in 1972 with the creation of UNESCO’s designation of World Heritage Sites. The number of sites has grown from the twelve first designated in 1978 to well over 1,000 in 167 different countries. In truth, the movement toward recognizing world heritage began with the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, which did not limit its activities to preserving only England’s architectural heritage. Out of its advocacy, European architects and preservationists drafted a series of accords, such as the Athens Charter of 1931, and the later Venice Charter of 1964, both of which emerged from a growing sense of cultural internationalism. These agreements set guidelines for the preservation and restoration of buildings and monuments. What UNESCO added was the criterion of Outstanding Universal Value for the designation of a place as world heritage. It took until 1980 to work out the first iteration of Outstanding Universal Value and the notion has never been universally accepted, although UNESCO member countries adhere to it officially. Once a site has been named to the list, member countries are expected to protect it from deterioration, although this does not always happen. As of 2018, 54 World Heritage Sites are considered endangered. This growth mirrored the massive expansion of tourism as a business and cultural phenomenon in the late twentieth century. As tourism became an increasingly important economic sector in de-colonizing states of Asia and Latin America, governments became more concerned with its promotion by seeking out World Heritage designation.

Ironically, World Heritage designation itself has been criticized as an endangerment of heritage sites. Designation increases the tourist appeal of delicate natural environments and historic places, which can lead to problems with maintenance. Designation also affects the lives of people living within the heritage destination. Luang Prabang, in Laos, is an interesting example. Designated in 1995 as one of the best-preserved traditional towns in Southeast Asia, it represents an architectural fusion of Lao temples and French colonial villas. UNESCO guidelines halted further development of the town, except as it served the tourist market. Within the designated heritage zone, buildings cannot be demolished or constructed, but those along the main street have been converted to guest houses, souvenir shops, and restaurants to accommodate the growing tourist economy. Critics claim this reorients the community in non-traditional ways, as locals move out of center in order to rent to foreign tourists. 44 While heritage tourism provided jobs and more stable incomes, it also encouraged urban sprawl and vehicle traffic as local inhabitants yielded their town to the influx of foreign, mostly Western, visitors.