CELL COVERAGE LAYER

See where you can dial 911 or explore completely off the grid with Gaia GPS.

Get Your Local Running Newsletter

Plan your week with local routes, events, and weather.

Powered by Outside

8 Performance Science Takeaways From The Men’s Tour de France

The tour de france is the world’s best field experiment for endurance performance. what did we learn in 2022.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Reddit

New perk! Get after it with local recommendations just for you. Discover nearby events, routes out your door, and hidden gems when you >","name":"in-content-cta","type":"link"}}'>sign up for the Local Running Drop .

Cycling is the greatest endurance experiment. Millions of people hop on bikes as kids. A few hundred thousand might start pushing themselves harder and harder. Tens of thousands of those athletes might notice that they have an elite talent to put sustained power into the pedals. Thousands become professional racers. Just under 200 start the Tour de France.

That funnel to the highest level of sport is not unique to cycling. But what sets cycling apart is what happens to distill thousands of world-class athletes into the final 200. Those thousands have already proven their talent and their work ethic. And then they are all thrown into the meat grinder of professional cycling training.

We’re talking 25-30+ hours a week, most of the year, with tons of racing. Unlike running, they are not limited by impact and rarely limited by overuse injuries. Unlike triathlon, they don’t have to balance multiple movement patterns with different demands. Unlike swimming and skiing, form doesn’t play a huge role. Hulk smash pedal, multiplied by something approaching infinity.

So at the men’s and women’s Tours de France, we’re seeing the best of the best at the very limits of human physiology’s capabilities. You can see why doping is a huge issue, since everyone trains wildly hard (within a few percent), and the talent differences are marginal at the top level (within a few percent). You don’t need to be a nihilist or an asshole to become a skeptic, you just need to have a cursory understanding of statistics and history.

If you take any random sample of the best in the world, pushing themselves to the maximum, and assume a few are doping, it’s likely that at least some of the champions will be doping unless drug testing catches everyone and/or doping is less powerful than marginal differences in talent/training.

All that said, I am still a massive cycling fan. Life is too short to be governed by skepticism or statistics (I prefer a cocktail of hope and belief that has hints of naive optimism). And whether PEDs (performance-enhancing drugs) are prevalent or not (most insiders say not, but they always say that out in the open air), there is still so much to learn from the pointy end of what happens when elite physiology gets stuffed into the meat grinder.

These eight takeaways are lessons that my co-coach/wife Megan and I flagged while watching the 2022 Men’s Tour de France ( we talk about it more on our podcast ). Because we are not bike coaches and we have that nagging fear of doping, we tried to focus less on the stated justifications for riders pushing pants-crappingly high watts per kilogram, and more on patterns across the peloton and performance psychology. Let’s do this!

One: You don’t need to have a “win at all costs” mentality to be a champion.

Jonas Vingegaard won this year’s race with a story made for Disney. In 2018, he worked part-time in a fish-packing plant (a plant where they put adorable backpacks on consenting salmon). On a training trip in Spain with his continental team (the minor leagues of European cycling), he set a Strava record on a 13-minute climb. World Tour team Jumbo Visma got wind of the record, and they did some quick calculations to estimate that Jonas pushed 6.7 watts per kilogram for the segment. That would be like a runner averaging around 4:15 minutes per mile grade-adjusted pace on a similar climb. The team signed him within a few months.

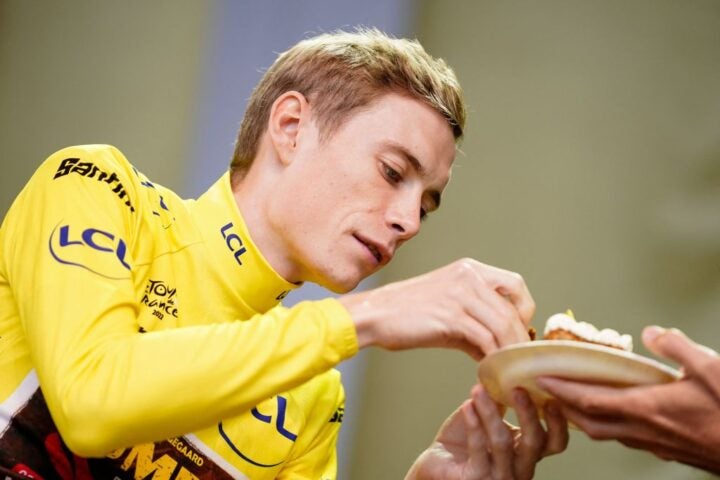

For me, there were two enduring moments from this year’s Tour. The first was in stage 19, when race favorite and 2-time defending champion Tadej Pogačar crashed as he was trying to drop Vingegaard on a descent. Vingegaard sat up and waited for Pogačar to get back on his bike and catch up. When they reunited, they grabbed hands. We were just a steady rain and a little tongue away from The Notebook 2.

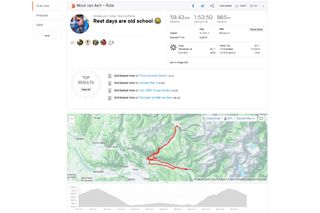

Then on the Stage 20 time trial, Vingegaard was close to the fastest time ahead of teammate Wout Van Aert. With the yellow jersey fully secured, in the final 500 meters, he visibly stepped off the gas, ensuring his teammate would win. Van Aert stepped toward the finish line and gave Jonas a slap on the back before bursting into joyous tears.

Some Tour champions of the past were worshipped as bosses who dripped toxic masculinity along with EPO. I think that many assumed that their take-no-prisoners, show-no-love approach was part of the reason for their successes. Vingegaard and Pogačar both showed throughout this Tour that you can be kind and be a champion. Maybe in the future, we shouldn’t excuse athletes for being assholes just because they end up on top of a podium.

Two: What appears to be an endurance limitation can sometimes be a fueling limitation.

The conventional wisdom starting this year’s Tour was that Pogačar was invincible. If NASA needs to get back to the moon, they could do away with the rockets and just have Tadej time his glute engagement just right. And the first 10 stages confirmed that wisdom–he not only won different styles of stages, he seemed to do it with ease.

The turning point of the Tour was Stage 11, when Vingegaard broke away from Pogačar on the final climb. It was shocking! At the bottom of that final climb, Pogačar flashed that movie star smile and looked ready to make one giant clench for mankind. Over the next few days, he confirmed the speculation on the cycling message boards. It was a “hunger flat,” or a bonk, caused by underfueling.

RELATED: 6 Inspirational (Or Not) Quotes From The Tour De France Announcers

According to online estimates, he still pushed 5+ watts per kilogram after he was dropped, but Vingegaard was up in the mid-6s! You can’t put out massive power without massive power reserves , and in a moment that determined the outcome of the Tour, Pogačar’s fueling was not adequate. All the fitness in the world won’t mean much without mid-event fueling to match. Many riders are now taking in 90-120 grams of carbs per hour on intense stages, backed up by scientific studies on cyclists ( 2011 review in the Journal of Sport Science ) and runners ( 2021 study in Frontiers of Physiology ). And let’s not even get started with ketone supplementation .

Three: Avoiding spikes in output can conserve glycogen stores and prevent excess fatigue.

While that Stage 11 drop-heard-round-the-world decided the Tour, the most dramatic part of the race happened earlier on the same day. At the base of the majestic Col du Galibier climb, Vingegaard’s teammate Primož Roglič attacked. Pogačar responded. Then Vingegaard attacked. Pogačar responded. Every time Pogačar got back into the draft, he’d be attacked again. Whoever wasn’t attacking sat on Pogačar’s wheel, meaning that they were doing significantly less effort.

This offset may have determined the hunger flat on the final climb. Every time Pogačar shot up toward 1000 watts, his body rapidly depleted glycogen from leg muscles, replenishing that from overall stores and whatever calories he could throw into the full-gas incinerator. He was exceeding his critical power (think an effort an athlete can sustain for 30-40 minutes) so often that he needed to do absolutely everything right on the rest of the stage–and be stronger than Vingegaard. Everyone assumed that Vingegaard needed a miracle, when all he needed was 90% science and 10% luck.

Four: Just because you can play through pain doesn’t mean you should play through pain.

Roglič played a huge part in Vingegaard’s win with those faux attacks. Pogačar respected Roglič as a rival for the overall win, so he responded to each one when it would have been a wiser physiological move to let Roglič tire himself out off the front. It was a two-wheeled version of Muhammad Ali’s rope-a-dope. And the whole time, Roglič must have been in excruciating pain.

He dropped out of the race after Stage 14. Commentators ripped him to shreds. “Get to the finish for your team!” some screamed. A few days later, it came out that Roglič had been riding with two fractured vertebrae in his back after a crash on Stage 5. How did he ride up and down those mountains so fast with a broken back? The simple answer is that cyclists are insane in the membrane. The complex answer is that athletes can tell themselves that toughness is a virtue of devotion. But when the mask of race-day toughness is removed, they may find out that what looked like devotion is actually self-destruction.

Yes, what Roglič did showed courage, and that courage should be celebrated. But we should be careful about elevating courage over health. We’ll see how his season unfolds from here. Hopefully a couple weeks of courage doesn’t contribute to a couple years of health struggles.

Five: Cooling strategies are key even before it gets hot.

What do the world’s best runners and world’s best cyclists have in common? Fashion! Namely, ice vest chic. Before and after almost every stage, you could spot these stars in ice vests to lower core temperature just like they were at the Foresthill Aid Station of the Western States 100 . And during stages, they were never far from ice packs to put on the back of their necks, and water to douse themselves with. I cringed every time they sprayed themselves, worried that their chains would get rusty if they forgot to clean their bikes post-stage. THINK ABOUT YOUR CHAINS, MEN!

Three weeks of the hardest racing in the world can spur physiological supercompensation. But even more than that, three weeks of vulnerability can spur psychological growth that shifts the understanding of what is possible.

My favorite innovation was from Team Ineos, long known as the team that leverages every exercise science study to its advantage. Prior to the final time trial, Geraint Thomas had his hands in “cooling mitts.” Some research (e.g., 2018 study in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine ) shows that one of the most effective ways to lower core temperature is via the hands and lower wrists, so Thomas was keeping his paws nice and frosty.

Coming to an aid station near you: ICE GLOVES. We’re going to be like Curley in Of Mice And Men, keeping our hands soft and cold for performance. That reference is for 5 readers at most. To them, I say, knowing wink .

Six: Tech giveth, and tech taketh away.

In the final time trial, top contender Stefan Bissegger’s bike erroneously went into “crash mode,” preventing shifting. That’s also what I call it when I run down technical trails. He had to change bikes, and his new bike didn’t have a water bottle, leading him to limp to a tough finish.

I am sure crash mode has a number of benefits. But it demonstrates how tech advances also come with sometimes unforeseen, often low-probability risks that need to be considered. For example, in running, I am concerned about how the proliferation of carbon-plated shoes may impact foot, achilles, and ankle injuries given changing impact forces . Yeah, they may be fast. However, it’s hard to be fast in a walking boot.

Seven: Drafting is important even at slower cycling speeds (and faster running speeds).

Every year in the mountains, it’s a battle for the best slipstream. If Pogačar couldn’t ride Vingegaard off his wheel with an attack, he sat up and waited for another opportunity. And they both had American teammates that dictated the pace on some of the steepest climbs (Brandon McNulty for Pogačar, Sepp Kuss for Vingegaard). All cyclists know the value of the draft. But for some reason, we barely think about it in running.

True, running is much slower. But on some of these steep climbs, Pogačar and Vingegaard are going slower than fast runners (you’ll often see normal people run right beside them for a bit). So what gives?

I think runners might just be missing a major opportunity. A July 2022 study in the Journal Of Applied Physiology found that in a 2-hour marathon, drafting can save between 3:42 and 5:29! Those numbers will be much less at slower paces, but no matter what the exact benefit, it can be magnified around physiological thresholds. Even if the draft effect is a fraction of a percent, when an athlete is at the margins of their capabilities, that fraction could be the difference between bonking and finishing strong.

Eight: Output under 1 hour strongly correlates with output over 21 days.

I think that we sometimes complicate ultra training in particular, creating entirely different frameworks to excel in long trail events. But as the Tour shows, in terms of our aerobic output, speed is speed . Or to put it another way, critical power and/or lactate threshold (output on efforts between ~30 minutes and 1 hour) will correlate strongly with performance at longer distances.

In the final time trial, the winner was Van Aert, who may be the star of the entire Tour. Even though he wasn’t going for overall place, he won a few stages and was voted the most aggressive rider. 2-3-4 in the ~50-minute time trial were 1-2-3 in the whole race (Vingegaard, Pogačar, Thomas). That makes sense with what we know about physiology–combine a formula for maximal aerobic power with equations for fatigue resistance, and you can get pretty close to predicting who has the most potential in longer events.

RELATED: How Sport Sampling Can Unlock Your Running Potential

Fatigue resistance studies have been pioneered in cycling, showing that what separates the best of the best from the thousands of elite athletes that don’t reach that level has to do with how their power curve deteriorates after a few thousand kilojoules of work.

But the prerequisite for fatigue resistance to be the differentiating factor is that the power curve is close-to-optimized on the top end. A runner or cyclist that isn’t working on their speed is making an unreasonably heavy bet on their fatigue resistance. And over time, they will lose that bet relative to their genetic potential.

Big Takeaway

The 2022 Tour de France was one of the best races ever, and I couldn’t get enough of it. Reading rider reflections, a persistent theme stood out: doing the Tour changes you. Three weeks of the hardest racing in the world can spur physiological supercompensation. But even more than that, three weeks of vulnerability can spur psychological growth that shifts the understanding of what is possible.

Think back to your own history. When did you make yourself the most vulnerable, in situations where you may win, but way more likely you will be spit out of the back of the peloton? For me, my breakthrough as a writer came from writing a book. Long before that, I supercharged my toughness in the misery of football two-a-days. Between those moments, a summer doing the Trial of Miles made me realize that my endurance limits were far beyond what I assumed.

That book I wrote was OK, but not great. I ended up quitting football as a freshman in college. As a runner, I’m finding new limitations every year. But I wouldn’t trade those experiences for anything because they shaped me as a person and athlete. My character was forged in discomfort, and that’s why I’m resilient.

Every Tour rider goes through that and more. Three weeks of discomfort, of doubts, of vulnerabilities. The rider that finishes (or DNFs) the Tour is different than the rider who started, and always will be. What’s your personal Tour de France? What’s the big, scary thing that makes your self-doubt scream so loud that you can’t hear Bob Roll in the announcer’s booth?

Whatever that thing is, attack it like you’re Tadej Pogačar. The point isn’t whether you win or not. The point is to get vulnerable and find out that your suitcase of courage is actually a warehouse, with so many more aisles to explore.

David Roche partners with runners of all abilities through his coaching service, Some Work, All Play . With Megan Roche, M.D., he hosts the Some Work, All Play podcast on running (and other things), and you can find more of their work (AND PLAY) on their Patreon page starting at $5 a month.

Popular on Trail Runner Magazine

Join Outside+ to get access to exclusive content, 1,000s of training plans, and more.

© 2024 Outside Interactive, Inc

- Couch to 5K

- Half Marathon

- See All ...

- Olympic/International

- IRONMAN 70.3

- Road Cycling

- Century Rides

- Mountain Biking

- Martial Arts

- Winter Sports

ACTIVE Kids

Sports camps, browse all activites, race results, calculators, calculators.

- Running Pace

- Body Fat Percentage

- Body Mass Index (BMI)

- Ideal Weight

- Caloric Needs

- Nutritional Needs

- Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR)

- Kids' Body Mass Index (BMI)

Running Events

- Half Marthon

Running Articles

- Distance Running

- Trail Running

- Mud Running

- Training Plans

- Product Reviews

Triathlon Events

- Super Sprint

Cycling Events

Triathlon articles, cycling articles.

- Cyclo-Cross

Fitness Events

- Strength Training

- Weight Lifting

Fitness Articles

- Weight Loss

Sports Events

Outdoor events.

- Book Campground

Sports Articles

- Water Sports

- Snowshoeing

Nutrition Articles

- Supplements

Health & Injury Articles

- Health & Injury

- Physical Health

- Mental Health

- Injury Prevention

Kids & Family

- Infants (0-1)

- Toddlers (2-4)

- Big Kids (5-8)

- Tweens (9-12)

- Teens (13-18)

- Cheerleading

- Arts & Crafts

- Kids Fitness

ACTIVE Kids Articles

Active works®.

From marketing exposure to actionable data insights, ACTIVE Works® is the race management software for managing & marketing your events.

How to Train Like a Tour de France Cyclist

- By Marc Lindsay

While you might not be able to line up next to Chris Froome and Peter Sagan at this year's race, that doesn't mean you can't train like a pro. Whether it's rolling hills, crosswinds, sprint finishes or a Hors Categorie climb, to make it to the finish line in Paris, Tour de France riders have to be able to do it all. Include these three workouts that mimic the challenges of the famous race, so you can become a more well-rounded rider.

Saint Girons to Foix

Length: 100km Skills needed: Conquering steep gradients; Descending The stage: A new trend in pro cycling stage racing is the short mountain stage where anything can happen. While the Latrape, Cold d'Agnes and the Mur de Peguere aren't terribly long, they are some of the steepest gradients Tour riders will face. The final 3.3km of the Mur will feature gradients in the double digits, reaching into the 20-percent range on occasion. Even though this will undoubtedly be the biggest challenge, to reach the finish cyclists will need to stay sharp on the long 27km descent into Foix.

- You'll need plenty of power to tackle steep pitches. Since 20-percent gradients will require maximum effort, you'll need to include a few high-power output hill repeats into your weekly workouts.

- Find a hill that is at least one to two miles long. If you don't have any hills in your area, you can do this workout on an indoor trainer.

- To mimic the distance of the Mur de Peguere, which is about six miles, you'll need to complete four to six of these hill repeats depending on the length of the climb you're training on.

- If you're training with a power meter, the pace you'll want to begin the repeat with is threshold. If not, ride at a rate of perceived exertion (RPE) of about 8 or 9 out of 10.

- During each 1- to 2-mile interval, ride for 15 seconds as hard as you can (RPE-10/10) two times with a short recovery between each effort. Your two 15-second efforts will mimic those really steep 20-percent gradients you'll need to crest.

- Recover for one to two minutes in between each interval or the time it takes you to get back down to the bottom. Remember to practice your descending skills on the way down, since you'll need to be a good descender to reach the finish line first.

Briacon to Izoard

Length: 178km Skills needed: Ascending monster climbs The stage: There are only three summit finishes in this year's Tour, and this one on the 14.1km Izoard promises to be the most decisive. In addition to this Hors Catgorie climb, cyclists will also need to ascend the challenging Col de Vars beforehand, which is 9.3km at 7.5 percent gradient.

To get to the top of a really long climb, you'll need to find your sweet spot. This means maintaining a consistent effort for a fairly long duration. Pacing is key so you have enough energy to reach the top.

- If you're using a power meter, these efforts should be just below your functional threshold power or FTP. If you're using RPE to gauge your effort, you should ride these intervals at about a 7/10. This means continuous conversation should be difficult but you can still talk throughout these efforts.

- Begin with a 15-minute warm up, spinning easy at a cadence higher than 90 revolutions per minute.

- Complete three sets of 20-minute sweet spot intervals. If you have a long gradual climb near you that takes 20 minutes to get to the top, consider yourself lucky. If not, try these on an indoor trainer with your front wheel raised.

- During each of your three intervals, stand out of the saddle and sprint for 5 to 10 seconds every 3 to 4 minutes. This will help you deal with any gradient changes on the course.

- In between each interval, recover with 15 minutes of easy spinning.

- Cool down for 10 minutes in a high cadence.

Marseille Time Trial

Length: 23km Skills needed: Sustained power The stage: This short, individual time trial will take place in Marseille for the first time in the Tour's history. The course is flat except for one lone climb up the Notre-Dame-de-la-Garde cathedral.

While you can expect most Tour riders to be well under the 30-minute mark, this effort will probably take you at least 35 minutes if you're in good shape. The duration of your time trial intervals should be slightly more than this amount of time.

- Do these intervals on a flat road where you won't have to stop very often. You can also do these on an indoor trainer. If possible, try to do one of the four interval sets below on a moderate climb or by raising your front wheel on the indoor trainer.

- Begin with a 15- to 20-minute warm up, spinning easy.

- For the main set, complete three to four 12-minute intervals at race pace with 3 minutes of easy spinning in between each interval. If you're using a power meter, these efforts should be at or just above lactate threshold. If you're using RPE, your effort should be in the 8/10 range. Try to keep your effort level as even as possible for each interval.

- Cool down with 15 to 20 minutes of easy spinning.

Next Gallery

The 7 Wildest Tour de France Stories You'll Never Believe

About the Author

Marc lindsay.

Marc writes gear reviews, training, and injury prevention articles for Active.com. He is also a contributor to LAVA Magazine, Competitor Magazine, and Gear Patrol.com. He is a certified Physical Therapy Assistant (PTA) and earned his M.A. in Writing from Portland State University. Marc resides in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Share this article

Discuss this article, cycling events near you, trending articles, 10 essential strength training exercises for cyclists, 8 core exercises every cyclist should do.

3 Cycling Workouts to Help You Conquer Hills

6 essential yoga poses for cyclists, 16 cool cycling tattoos.

More Cycling Articles

Connect With Us

Add a family member, edit family member.

Are you sure you want to delete this family member?

Activities near you will have this indicator

Within 2 miles.

To save your home and search preferences

Join Active or Sign In

Mobile Apps

- Couch to 5K® View All Mobile Apps

Follow ACTIVE

© 2024 Active Network, LLC and/or its affiliates and licensors. All rights reserved.

Sitemap Terms of Use Copyright Policy Privacy Policy Do Not Sell My Personal Information Cookie Policy Privacy Settings Careers Support & Feedback Cookie Settings

- Get Your 3rd Race FREE

- Up to $10 off Event Fees

- Get $50 off New Running Shoes

- FREE pair of Pro Compression Socks

- Up to 15% off GearUp

- VIP Travel Discounts

...and more!

- Subscribe to newsletter

It's going to be so great to have you with us! We just need your email address to keep in touch.

By submitting the form, I hereby give my consent to the processing of my personal data for the purpose of sending information about products, services and market research of ŠKODA AUTO as well as information about events, competitions, news and sending me festive greetings, including on the basis of how I use products and services. For customer data enrichment purpose ŠKODA AUTO may also share my personal data with third parties, such as Volkswagen Financial Services AG, your preferred dealer and also the importer responsible for your market. The list of third parties can be found here . You can withdraw your consent at any time. Unsubscribe

Getting Ready for the Tour de France

How do the pros prepare for one of the hardest races in cycling? The 109 th edition of the Tour de France is just around the corner and professional riders are putting the finishing touches on their year long journey to the pinnacle of cycling. What do they train in each of the distinct training stages leading up to the Tour? Let’s take a closer look.

Tour de France 2022

This year’s Tour will span 3328 km inside the classic 21 days of racing. There will be 6 mountain stages, 2 individual time-trials, and plenty of flat stages for breakaways and exciting sprint finishes. Stage 7 will be the longest with 220 km while stage 11 will take riders to the highest point at the top of Col du Galibier, a breath taking 2607 metres above sea level. If last year is anything to go by, then the winner will be expected to maintain an average speed of 41,17 kilometres per hour over nearly 83 hours of racing. It’s clear that every competitor will have to be in the shape of their life.

😍Ahead of the #TDF2022 Grand Départ from Denmark, @Letour is meeting the "golden generation" of Danish cycling Today: 🇩🇰 @Mads_Pedersen ⤵ pic.twitter.com/F6tVUkcEHj — Tour de France™ (@LeTour) June 22, 2022

It takes the whole season

Competing at the Tour de France is the highlight of every cyclist’s season, if not their whole career. That’s why most pros plan their season with the main goal to peak just as the Tour kicks off. The preparation often starts around 7 months before the Tour and includes several training macro-cycles. They will be building an aerobic base, adding high-intensity, doing race-specific training, and tapering. Let’s take a closer look at each of these training stages.

Building a base

The Tour is set to start on the 1 st of July which means that most rider initiated their base-building phase late November or early December of last year. Their main focus is on long, low-intensity rides to build up the basic aerobic endurance required. It also includes some flexibility and strength training on top of that. The riders typically do something like 20-30 hours of training each week.

Adding intensity

Come February, or about 5 months before the start of the Tour, cyclists start adding more tempo, sub-threshold, and threshold rides. Threshold tempo is the hardest effort that you can sustain for an hour which means they will be spending more and more time at high intensity. This training phase is also where they start working on their nutrition on and off the bike. They need to get used to consuming a lot of food on the bike. Their digestion needs to be conditioned to handle up to 90 g of carbs per hour while cycling.

This is also the time when the pros start to peak with their body weight. They start early because steady weight loss is the best way to avoid sacrificing performance. There is a general rule of thumb that they shouldn’t lose more than 0,5 % of their bodyweight per week.

Race-specific training

Right around the beginning of April, Tour competitors will refocus on race-specific training. They will reduce their strength work and use actual races as some of their training. There is no substitute to racing. Certain skills can only be gained while amidst a race. The Ardennes Classics or the Giro D’Italia are often used for this purpose.

This is also the time when cyclists include training camps. These are typically 10-day training blocks of structured cycling where every day is planned out. Training camps often include altitude training and adapting to riding in the heat. The specific schedule depends on the type of rider. Climbers will spend more time in the mountains doing lots of long, steady climbs while others might work on high-intensity speedwork elsewhere.

Tapering means reducing training load to be fresh at the starting line. During this process riders will go from riding 5-6 hours a day to riding about 1 hour or not at all. About 2 weeks before the Tour, riders will start shortening their training blocks and adding ample rest in between. They would do their last long ride the weekend before the Tour. There might be a short speed workout mid-week to practice bursts of power and picking up pedalling cadence. They will also have a session on the time trial bikes during the last week.

They take recovery as seriously as training

A crucial part of getting ready for the Tour de France is recovery. It’s present in every phase of training and riders know that they can’t cut any corners there. Recovery is a continuous process that includes post-ride shakes, massages, stretches, and quality sleep. Especially sleep is what most professionals focus on as the bedrock of recovery. They go to bed and wake up at the same time, sleep in a cool and dark room, and avoid blue light an hour before sleep.

The riders give it a better part of a year to get ready for the Tour, let’s cheer them on as they compete for glory on this 21-stage Grand Tour!

Articles you might like

How to Find the Right Coach? Use These 5 Questions

Working with a coach is the best way to reach your body-composition, dietary and athletic goals. But finding a good coach is hard! Getting a recommendation can help a lot but it’s not enough. You have to know how to judge whether a coach will…

Understanding Your Limits: Balancing Discomfort and Endurance in Long-Distance Cycling

For seasoned cyclists who regularly go beyond the 100 km mark, the primary challenge shifts from building leg strength and endurance to balancing one’s level of comfort. Once you’ve reached a certain degree of fitness and can manage longer distances, discomfort in the neck, hands,…

Half of All Deaths Linked to Lifestyle Factors You Can Change

A new study adds evidence that your lifestyle plays a major role in how likely you are to develop serious diseases such as cancer. And it’s not just about smoking. Let’s take a look at what other behaviours are impactful and how you can improve.

Energy Deficit in Athletes – Negative Impacts on Health

Energy deficits commonly used for managing weight are reaching better power-to-weight ratios in cycling. But they can come at a cost. Being in an energy deficit is hard on the body and sports science shows it can have substantial negative effects on health.

- Strava Guides

- What's New

- English (US)

- Español de América

- Português do Brasil

Get Started

Pro Training: What Does it Take to Race the Tour de France?

, by Chris Case

We take a closer look at the demands of the most famous grand tour, and how the pros train for three weeks of intense racing.

For three weeks each July, we watch as the best bike racers in the world tear themselves apart for five-plus hours per day at the Tour de France .

Over 21 stages, nearly 200 incredible athletes race an event that would shatter most of us in just one day. But then they also have to contend with answering reporter’s questions, pleasing sponsors, transferring between hotels, trying to eat enough food to cover the day’s expenditures, and, finally—and perhaps most importantly—trying to get quality sleep.

It’s a feat that’s hard to comprehend. In this brief review, we’ll explore what it takes to race the Tour—physiologically and psychologically. We will look at the Tour from a numbers perspective—and describe why the numbers really don’t tell the tale. Then we’ll dive into how the riders train for the Tour before discussing what amateur riders should and shouldn’t take away from how Tour riders train.

Vive le Tour!

RELATED: The Beginner's Guide to the Tour de France

The tale of the Tour in numbers

Compared to what everyday cyclists do, the raw numbers of a Tour de France effort are staggering. Over the course of three weeks, riders will average around 100 hours of racing. And that doesn’t include anything extra that they might do: warming up, cooling down, or rest-day rides.

On a course that averages around 3,500 kilometers, Tour riders will expend about 5,000 to 7,000 calories per day, or over 120,000 calories over the three weeks. The true number depends on things like rider size, their role on the team, and so on.

Interestingly, when you look at the average power over the 21 stages, it can be as low as 170 watts for some light climbers who are in protected roles and who spend a lot of the time off the front of the peloton. It’s just that they will also need to produce those sudden moments of very high power outputs.

RELATED: Preview: An Unusual Tour de France Route

“It doesn’t sound like much, but it’s a lot if you’re holding that for 110 hours,” says Ciaran O’Grady, a sport scientist and lead coach at Israel-Premier Tech professional cycling team. “It’s going to certainly add up in terms of physiological load. It’s absolutely astonishing what these guys go through over those 21 stages.”

According to O’Grady, 70 percent of the time the riders spend, on average, during the race is in zone 1 (in a three zone model). So it’s a prolonged sub-threshold pace. Above threshold? For most of the riders, it’s around 10 to 15 percent of the total time.

On a course that averages around 3,500 kilometers, Tour riders will expend about 5,000 to 7,000 calories per day, or over 120,000 calories over the three weeks.

“Again, it doesn’t sound like much on paper, but when you add it up over the course of 21 stages, it’s a fair old physiological whack,” O’Grady proclaims.

Training a Tour engine

The first thing to appreciate about riding the Tour is the sheer volume—over 100 hours of pedaling. So, one of the first training considerations is, no surprise, pure volume on the bike.

During the base phase of a pro rider’s training program, they will have months where the training load is 100 or more hours, to mimic the conditions of the race. Once they’ve built that ability to handle the volume, then they work on their ability to produce explosive, intense efforts.

RELATED: The 10 Hardest Climbs in Tour de France History

That said, most of the riders who race the Tour, or any grand tour, will have been a professional for several years. Their endurance engine is already very well developed. So the bulk of those 100 hours may have fairly low average power. When they do training blocks, they’ll strategically add intensity to that high volume.

“This is what I call dirty intervals: you go out and ride for three hours at tempo pace, burn maybe 2,500 to 3,000 kilojoules, and then start the intervals,” O’Grady says. “It’s all about making sure that the body is able to work when it is fatigued.”

After doing that day by day by day, with the proper recovery to allow for the adaptive process, you create the engine to perform in a grand tour environment, according to O’Grady. This assumes the athlete already has the genetic predisposition to do so.

A study that analyzed six years of training data from Pierre Rolland, a former Tour de France GC rider, confirms this approach.

In short, his five-second power, 30-second power, and one-minute power didn’t change much over the course of those six years, as he developed into a top-10 finisher at the Tour. However, his training volume over those six years increased 79 percent. The development was focused on the aerobic engine, and on the ability to resist fatigue.

FEELING INSPIRED? Build Back Stronger with a Cycling Overload Block

At the start of the six-year study, he managed to do only three big training blocks filled with extremely stressful, big volume, big intensity workouts. However, by the time he finished in the top 10 at the Tour de France, he was completing 11 of those training weeks in a year.

The focus was never about building huge power. It was much more about that ability to resist the grind.

For the mortals among us (that’s you!)

It goes without saying: these guys are professionals, so what they do is not usually what a recreational rider should do.

This [type of training] would probably set us mortals back more than it would drive us along. We’re just not able to assimilate those adaptations that are being made by the stresses.

“This [type of training] would probably set us mortals back more than it would drive us along,” O’Grady says. “We’re just not able to assimilate those adaptations that are being made by the stresses that we would be putting our body under.”

If you had a week off from work, you could do a huge amount of volume in that week . But then to make quality adaptations from that, it’s going to be extremely difficult without the proper recovery.

It’s always important to be mindful of your limitations. Don’t try to replicate the rides of the pros, particularly if you work full-time.

RELATED: Low Risk, High Reward: The Polarized Training Method for Cyclists

However, one aspect of their training is highly relevant. The so-called polarization of their training—spending most of the time at a relatively low intensity, and then doing very specific hard efforts only sparingly—leads to the biggest gains with the smallest risks.

This is the type of training you see time and time again from the bulk of the professional peloton. It takes time, it takes discipline, but if their efforts at the Tour are any indication, it works very well.

Related Tags

More stories.

Lael Wilcox Becomes Fastest Woman to Cycle Around The World

Cyclocross: A Fun & Effective Way To Maintain Winter Fitness

How to Go Bikepacking in Iceland

Currently Trending:

We’ve selected the 44 best dumbbell exercises for building muscle and strength

This dumbbell-only leg workout is my go-to session for busy gyms

Our pick of the best resistance band exercises for every body part

How to use metabolic resistance training to transform your physique

Transform your physique with our six-week fat-loss plan

Advertisement

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Home » Features » How Do Tour de France Riders Train, Eat & Recover?

How Do Tour de France Riders Train, Eat & Recover?

The Tour de France is one of the world’s toughest, and certainly most iconic, endurance events, with over 180 elite riders covering 3,383km and tackling 30,000m of vertical ascent.

During the three-week race, which is divided into 21 stages across June and July, each rider will burn more than 140,000 calories.

This summer, Britain’s 2018 Tour winner Geraint Thomas is hunting his second victory with INEOS Grenadiers (formerly Team Sky), the all-conquering British team that has won seven of the last nine Tours.

But in order to get race-ready, the squad has endured months of hard training, backed up by smart nutritional plans and intelligent sports science.

Here INEOS Grenadiers’ coach Conor Taylor and nutritionist Javier Gonzalez reveal how the riders arrive at the start line in peak condition.

Team INEOS on a training ride before the Tour starts on 26 June

The importance of low-intensity exercise

To build an elite endurance engine, pro riders prioritise low- to moderate-intensity training.

“Around 75-85 per cent of our riders’ total training time is spent doing long, continuous, low- to moderate-intensity cycling,” explains Taylor.

“Only 20 per cent of their training is of a high-intensity nature. Those low-intensity rides are typically at 65-70 per cent of their maximal heart rate and can last four to seven hours.”

This high-volume, low-intensity approach triggers adaptations within the riders’ cardiovascular, metabolic and neuromuscular systems, which help them better endure longer rides.

“One of the primary adaptations is that our riders become more efficient,” explains Taylor. “At that intensity and volume, you’re predominantly using fat, instead of carbohydrate, as a fuel source.

“We’ve all got ample fat stores in the body, so we are just trying to train the body to utilise that fat, because carbohydrate can only be stored in relatively small quantities.

“A cyclist with high efficiency will always use less oxygen than a cyclist with poor efficiency, when they both cycle at the same given power output or speed.”

Stick to real food

To fuel up for this huge volume of training, the riders take a ‘food-first’ approach, relying mainly on nutritious ‘real’ food, with supplements used sparingly. Breakfast is usually a protein-rich omelette with a portion of energy-dense rice.

“The amount of carbohydrate in something like porridge is relatively low compared to rice,” explains Gonzalez.

During rides, the cyclists fuel up with homemade rice cakes flavoured with cream cheese or cinnamon.

“They are not the kind of crispy rice cakes you buy in shops, they are more like a solidified risotto,” explains Gonzalez. “Rice is very easy to digest and easy on the stomach.”

A post-ride lunch is typically tuna steak with quinoa and tomato salad. And dinner might be salmon and rice with an Asian broccoli salad.

“During training periods the riders eat more veg, too, as the nutrients support health and immunity,” adds Gonzalez.

Varied training forces positive adaptations

Riders begin their winter training in October and steadily accumulate volume as the weeks go by.

“It is very individual, but as a guide if you increase your weekly volume by ten per cent that is a good starting point to safely progress your training programme and ensure overload,” explains Taylor.

As the riders get closer to races, they start layering on higher-intensity work.

“You don’t need many high-intensity sessions to get the desired training effect,” he adds. “It’s about doing high-quality work to develop the power and speed that could enable a race-winning move.

“A typical high-intensity session might be four lots of eight-minute efforts at 90 per cent HRM, with four minutes’ recovery. But we are constantly playing with the duration and the intensity and the recovery.

“One of the key training principles we work to is variation. We all adapt very quickly to a training stimulus, so you need a constantly novel stimulus to keep the body guessing.”

Watch the weight

Power to weight ratio is hugely important for endurance athletes, with Geraint Thomas stripping down from 74kg, when competing in the team pursuit on the track at the London 2012 Olympics, to 67kg when racing over mountains at the Tour de France.

But what is the optimal way to lose weight without compromising your training?

“One of the key factors is slow and steady weight loss, and a general rule of thumb is 0.5 per cent of bodyweight per week as a maximum,” explains Gonzalez.

“So six months out before the Tour, we will start the rider ona nutrition plan to gradually achieve their optimal body composition at the Tour, rather than suddenly trying to achieve it two months before.”

The secret is to be good at food maths. “The great thing about cycling is we can quantify the energy our riders burn and consume,” says Gonzalez. “Of course, to lose weight, we need a small energy deficit, but you can track that relatively easily.”

Some riders weigh their food; others use the LIBRO app by Nutritics – a bit like MyFitnessPal – which helps them to track their daily calories, protein and sugar input to improve their body composition over time.

Protein matters for endurance athletes, too

One of the challenges for endurance athletes is working out how to lose weight while maintaining lean muscle mass. The key is to drip-feed protein into your body.

“Our riders are aiming for an even distribution of protein throughout the day,” explains Gonzalez. “Typically, that is 30g of protein at each eating occasion, for breakfast, lunch, dinner and for an extra snack. That helps the riders to retain muscle mass, even as they’re losing weight.

“But protein also facilitates the reconditioning of the muscles after training. Studies on endurance athletes show that protein helps the mitochondria – the parts of the muscle where the energyis generated – to better adapt to training.”

Don’t neglect strength training

Endurance riders may be super lean, but they still lift weights.

“The use of resistance training at INEOS has grown,” explains Taylor. “It improves efficiency on the bike, it may improve bone mineral density, which can be low in non-load-bearing sports like cycling, and it can help with your maximal power output.”

However, riders need to build raw strength without packing on unwanted bulk to carry around the mountains.

“Cycling can be seen as a weight-making sport, in a similar way to boxing,” says Taylor. The secret is to stick to low repetitions (3-6 reps), low volume (3-5 sets), and low frequency (2-3 sessions per week), but with maximal intent in each session.

“This helps to increase the rate of force development and power, but limits muscle hypertrophy to keep the riders light but powerful,” adds Taylor.

“The exercises mainly consist of single and double leg presses, split squats, glute bridges and lunge variations: so lateral, forward and reverse lunges.”

Incorporate spiked training sessions

“‘Spiked sessions’ – essentially undulations in power during training – create additional metabolic stress within the muscles that the body needs to deal with,” explains Taylor.

“As a result, they drive specific adaptations within the muscle and cardio-respiratory system that help to buffer and accelerate the clearance of this additional stress.”

These sessions can therefore help you to cope with any ‘spikes’ – or changes in pace and power – during races.

Spiked sessions can be completed in different ways.

“You can include spikes or sprints within your longer rides, such as 15-20-second maximal sprints every 20-30 minutes,” suggests Taylor.

“Or they can be included within a longer effort, such as short, out-of-the-saddle accelerations within a sustained seated effort. For example, performing five to ten-second accelerations every two minutes within a longer ten to 20-minute sustained, hard effort.”

Take recovery as seriously as training

At the end of hard training days, riders recover quickly using a nutrition-first approach.

“Recovery involves a post-ride shake and a pre-prepared mini meal, which is usually rice, potatoes or pasta in a pot with some salmon or chicken,” says Gonzalez.

Although riders have massages and perform stretches, their main recovery protocol involves quality sleep.

“We provide them with as much good sleep hygiene advice as possible,” says Taylor. “Everything from going to bed and waking up at a set time, to trying to refrain from looking at bright lights and blue lights in the hour before bed.

“Massage balls and yoga can aid recovery, but for endurance athletes nothing beats a quality night’s sleep.”

A breakaway group tackles the ascent of Bisanne during the 2018 Tour de France | Photography: Jeff Pachoud

ANATOMY OF A TDF RIDER

- 60-67kg: the average weight

- 5-15%: body fat percentage

- 70-90: typical V02 max score

- 30-50: resting heart rate

- 4,500-9500: calories burned per day

Words: Mark Bailey

MF editor Isaac combines close to a decade’s experience in fitness publishing with a keen interest in all things exercise and sport. Although strength training is his primary passion, he's also an occasional ultramarathon runner, with one particular career high/lowlight being a 24-hour 'race' around Tooting Bec Athletics Track (never again).

You may also like...

10th September 2024

Dominic Taylor explains what it takes to conquer the world’s toughest one-day endurance event

by Rob Kemp

4th September 2024

From emphasising the eccentric to exposing yourself to heavier loads, we asked a panel of strength specialists for their favourite get-strong protocols

by Isaac Williams

From how long each workout should last to turning fat into muscle

by Laurence McJannet

Powered by Outside

Tour de France

Fueling the tour de france: inside a grand tour rider’s gut-buster diet, we speak to worldtour chefs and nutritionists to reveal the mega-carb menus that power the race for the yellow jersey..

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Reddit

Don't miss a moment of the 2024 Tour de France! Get recaps, insights, and exclusive takes with Velo's daily newsletter. >","name":"in-content-cta","type":"link"}}'>Sign up today! .

What does it take to fuel three weeks of racing the Tour de France ?

Mountains of rice, fistfuls of energy gels, and plates pitifully short of vegetables, that’s what it takes.

The 21 stages of this year’s Tour de France could see riders like Tadej Pogačar and Jonas Vingegaard pedal through up 80,000 calories-worth of work.

- From altitude camp to taper, how riders train for the Tour de France

- Why running, psychology sessions, and food apps are part of the peloton’s Tour de France preparation

Add to that the metabolic demands of breathing, digesting, and the rest of the body’s basic functions, and riders are constantly chasing for a break-even level of energy.

The only way to keep on keel?

Mammoth menus and a fast-flowing stream of carbs.

“These guys look skinny, and they’re tiny when you see them for real. But they sure know how to eat. They have huge appetites,” EF Education-EasyPost nutritionist Will Girling told Velo .

‘Riders eat a lot of rice … like, kilos of it’

When they’re not pedaling or sleeping, riders are probably eating – and it’s most likely to be carbohydrates on their plate.

Carbs are the endurance kings of macronutrients, with basic staples like rice, pasta, potatoes, and bread the jewels in their crown.

They’re the energy-giving fuels that power bunch sprints and drive mountaintop victories.

And in the modern pro peloton, rice is increasingly becoming the carbohydrate of choice.

“Riders eat a lot of rice … like, kilos of it. It’s sort of boring, but it works,” Trek-Segafredo chef Bram Lippens told Velo . “We add sauces like tomato or pesto to keep it interesting, but it is essentially still just rice!”

A rider is never far from their next meal when at a grand tour.

Around three hours before a stage, riders will scarf down a breakfast banquet of rice, eggs, oatmeal, pancakes, and toast.

When riding through stages that can burn as many as 5,000 calories, legs are kept turning via carb-laden drinks, energy gels, bars, and team-made rice cakes. The demands of modern racing require riders to eat as often as three to four times per hour in what is an open pipeline of fuel.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Science in Sport (@scienceinsport)

And once a stage is done, a carb-based snack and recovery shake act as a mere stopover before another gut-busting meal in the evening.

The nighttime feast makes for a starchy double-serve that both boosts recovery from the day’s stage and refuels for the rigors to come.

“The night before a big race or stage we keep it simple with maybe chicken and rice, or salmon and rice,” Girling said. “It’s nearly always white rice we serve, because it’s so easy to consume and it’s low fiber.”

The rice-rich diet of the modern Tour de France rider defies the belief that the peloton pedals on pasta.

“Rice is more energy dense than pasta. So for the same volume, you got more carbohydrate from rice. Plus it’s gluten-free. So theoretically it’s more digestible than pasta,” Jayco-AlUla nutritionist Laura Martinelli told Velo .

“Pasta is OK if it’s the correct type and cooked properly, and we don’t stop riders from eating it. But if I had to recommend one or the other I’d 100 percent always say rice.”

High energy, locally sourced

The entourage of any pro team has expanded exponentially in recent decades.

In-house nutritionists and chefs like Martinelli, Girling, and Lippens are now as common as the soigneurs, mechanics, and masseuses that have long had their seats in a grand tour team bus.

Jayco-AlUla staffer Martinelli oversees the diets of Tour-bound riders like Simon Yates, Dylan Groenegen, and U.S. all-rounder Lawson Craddock.

One of Martinelli’s daily on-race functions is to plan out what each individual needs to eat, based on the demands of the stage to come. Bodyweights and expected expenditures make part of a series of calculations that ensure riders match the huge energy output of the Tour de France with a similarly staggering caloric input.

For a relatively straightforward sprint stage like this year’s seventh stage into Bordeaux, Martinelli’s riders would be tasked with taking down around five grams of carbohydrate per kilo of bodyweight.

For the kingmaker mountain stages through the Pyrénées and the Alps, that multiplies up to almost beyond-belief bucketloads of carb. On the Tour’s toughest days, a rider like Craddock might force down up to 18 grams of carbs per kilo of his mass.

At around 69 kilograms (152 pounds), the Texan would be facing more than 1,200 grams of carbohydrate over the course of a day’s meals, shakes, and on-bike nutrition.

For context, that’s the equivalent of around four kilos of prepared white rice or a similar amount of white pasta.

“Toward the final week when there are more big days in the mountains and riders are getting more tired, eating so much can become more difficult,” Martinelli said.

“We try to make things easier by preparing energy-dense food and minimizing the total volume. So we choose the most carb-rich sources we have and use carb drinks and smoothies. When a rider is fatigued, they typically find it easier to drink than to eat.”

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Owen Blandy (@owenblandy_)

Professional chefs like Trek-Segafredo’s Lippens work out of kitchen trucks or hotel facilities to prepare menus that would be worthy of a five-star restaurant.

Meat, fish, and vegetables freshly sourced from local shops and markets come together with a deep traveling storecupboard to create meals that are about a lot more than just fuel.

“When they’re eating so much, we need to maximize the flavors we serve and keep it quite varied. But it needs to be simple at the same time,” Lippens said. “Some things like the carbs, we have to serve. But we try to change the sauces, chicken, salmon, whatever as much as we can or riders will lose interest.”

The question of ‘watts per kilo’

A healthy racer who’s following an appropriate meal plan should have both the fuel to recover from the past stages, and the energy to power the days to come, all the while keeping a steady bodyweight.

Riders check their weight on a daily basis and report back to staffers to ensure they’re on a level.

Although the watts-per-kilo equation is crucial for climbing speed, lost mass comes at the risk of muscle wastage or hormonal malfunction.

As with sports like running and gymnastics, body mass is a big metric in the pro peloton. And in an environment where disordered behaviors could easily become commonplace, teams use weigh-ins to ensure riders aren’t toying with long-term health problems.

“We always would prefer they eat a little more than a little less, within reason,” Martinelli said.

Intriguingly, some riders finish a three-week race like the Tour de France heavier than they started.

Younger riders or grand tour rookies might mistakenly over-fuel for fear of getting dropped. Others report water retention resulting from long days of travel or the impact of glycogen storage.

“A bigger rider can gain two to three kilos in water weight, very quickly,” Martinelli said. “We can manage that by changing the distribution of when in the day they eat carbohydrates. That should manage their insulin response and prevent more fluids. But it’s difficult to get perfect.”

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Bram Lippens (@bram_cooking_stuff)

Carbohydrate isn’t the only thing carefully monitored in the Tour de France diet.

Protein intake is supercharged to help maintain muscle mass and to speed post-race recovery; healthy fats like olive oil, avocados, and nuts are a must-have due to their contribution to hormonal health and vitamin absorption.

There is one food group that does take a hit however.

Fiber is drastically reduced on hard mountain stages or days expected to be particularly intense, such as this Tour’s climb-filled grand départ .

The so-called “low G.I. protocol” ensures riders take the next day’s start line with empty stomachs and low water weight.

“Before all hard and heavy races, they skip salads and almost all the raw fruits and vegetables,” chef Lippens said. “I may put out a few veggies, like just one or two pieces of broccoli. They basically eat like teenagers.”

The booze, burgers, and brownies of balance

However, the daily diet of a Tour de France racer isn’t all carefully calculated carbohydrate quantities and the leanest cuts of meat.

Staffers appreciate the need for balance.

Desserts like brownies, cheesecakes, and fruit tarts are served daily, and the night before a rest day will see teams allow riders to let off some nutritional steam. Barbecues, or homemade pizzas, burgers, or lasagna are cited as the most-frequent pre-rest-day treats served to the multinational peloton.

And, of course, victories are celebrated with something a little more appetizing than another carb drink or high-vitamin shake.

“We’re lucky at Jayco-AlUla,” Martinelli said. “Our owner [Jerry Ryan] owns amazing wineries in Australia, so we always have good wine with us.

“We mainly have red, but sometimes white. The guys only get one glass, but it’s better to have one very good glass rather than a whole bottle of a bad one. The occasional glass – that’s recovery for the mind!”

Popular on Velo

What’s it like to be an American cyclist living in France? Watch to get professional road cyclist Joe Dombrowski’s view.

Related content from the Outside Network

One way south, mountain bikers react to their first taste of non-alcoholic craft beer, video review: bmc urs 01 two gravel bike, kiel reijnen vuelta video diary: the painful decision to abandon.

Pre-register now for the 2025 edition!

Extra services

- Presentation

- Host cities

- The comitted étape

- Etape series

- Regulations

- Starting / Arrival areas

- Tour Operators

- Photos / videos

Training plans

- Road captains

- My first Étape

- Village infos

- Collect race number

- Mechanical assistance

TRAINING PLANS WILL BE COMMUNICATED TO YOU LATER. STAY CONNECTED.

The secret to achieving your cycling goals lies in determination and preparation. There are no shortcuts, but by giving yourself the necessary means, you can achieve your goals.

That's why, in collaboration with the FFC (French Cycling Federation), we're offering you a detailed training plan for the last 3 months before L'Étape du Tour de France. These 12 weeks will give you the peace of mind you need to be in top form on D-day.

We've divided your preparation into 3 blocks of 4 weeks, with each block focusing on a specific aspect: velocity, strength and power. We believe in the equation power = strength x velocity.

TRAINING PLAN "THE CLASSIC PROGRAM"

- "Finisher goal": dedicated to insiders and those who don't have much time, with 3 outings a week.

- "Chrono goal": 5 outings a week for those who want to push their limits.

TRAINING PLAN "THE LADIES, IT'S YOUR TURN TO PLAY!"

Plan dedicated to women and taking into account menstrual cycles.

- "Finisher goal": 3 outings per week for those who want to discover a training plan that integrates their lifestyle rhythm.

- "Chrono goal": 5 outings per week for those who are aiming to race!

Want to go further and get a personalized coaching ?

Go here on the NOLIO platform to find the FFC Coach plans.

You'll be able to export your sessions on your GPS bike computer, monitor your improvements, validate your feelings and get in touch with the FFC coaches who'll be delighted to support you!

Your goal: be at your best for L'Étape du Tour de France 2025!

FAQs of the Tour de France: How lean? How much power? How do they pee mid-stage? All that and more explained

Ever wondered why riders have such veiny legs? Do riders share rooms? How does a 60km ride count as a rest day? We take a look at the burning questions and those you never thought to ask

- Sign up to our newsletter Newsletter

The 2024 edition of the Tour de France is not far away - and if you’ve watched previous editions, there’s probably quite a fair few points that might have piqued your curiosity. That is to be fully expected - a lot is left going on behind the scenes that the cameras aren’t capturing.

Google's autocorrect can provide us with a wealth of information around the general public's deepest thoughts about the pros. For instance, it seems there are enough people desperately searching for ‘how do cyclists pee whilst racing the Tour de France?’ that the search engine is serving up this suggestion for everyone.

Naturally, we couldn’t leave them hanging, and our answer to how exactly cyclists do pee during top level races can be found here. There’s an almost dizzying array of other questions, too, which we'll get fully stuck into here.

We will take a look at Tour de France performance trends and, continuing past the finish line, we’ll also reveal what the riders get up to in their team buses and talk more about how the pros deal with the hotel-to-hotel life that makes up the three weeks of a Grand Tour.

Why are Tour de France cyclist’s legs so veiny?

We’ve all got veins in our legs quite near to the skin surface, but they are hidden by a layer of fat just under the skin.

Tour de France cyclist's legs appear to be uber-veiny for two main reasons: firstly, they have much less body fat than ‘ordinary’ people, and secondly, their veins and arteries have adapted to carry more blood around their bodies. The cardiovascular adaptations are numerous, but a large increase in vein and artery diameter is one of them. You can read more about the science behind why Tour de France rider’s legs are so veiny here.

A post shared by Tomasz Marczyński 🅻🅾🅲🅾 (@tmarczynski) A photo posted by on

What do Tour de France riders do on their rest days?

They ride, and not just a little amble around the streets. Most will be on their bikes for two hours and some even more.

In the early days of Team Sky, Russell Downing found out why after the first rest day of his Grand Tour debut in the 2011 Giro d’Italia: “It was a hard race, the weather was bad and by the first rest day I was really tired. The others asked if I was going with them, but it was cold and raining and I said I’d go on the turbo in the hotel basement instead. I did that for about 45 minutes, just very easy, then went back upstairs to lie down. Next day I was nailed for the whole stage, just hanging on. I was okay the day after, but I’d learnt my lesson and rode with the boys on the next rest day. If you don’t ride reasonably hard on the rest day , your body thinks you’ve stopped and switches off ready for deep recovery. You’ve got to keep it firing for the whole three weeks.”

What is a soigneur in cycling and what are their duties during the Tour de France?

Soigneur is the French word for ‘carer’, and basically soigneurs care for riders. They prepare them for each stage, looking after them at the finish and back the hotel, with massage and rehab therapies. And they care in other ways too.

Dirk Nachtergaele, a Belgian pro team soigneur for over 40 years says: “A soigneur is also like a priest. We are the one who riders can confide in, confident that anything they tell us goes no further. They can complain about another rider, the sports director even; they can talk about problems at home – anything. They know we will not tell anyone what they said. That role as confidante is as necessary in a team as being a skilled therapist.”

How light and lean are the Tour de France climbers?

Double Tour de France stage winner, and now retired Irish pro rider Dan Martin was a climbing specialist. His racing weight was 62kg, which is light for his 5ft 9in height, but some shorter climbers weigh under 60kg. However, being super-light is no longer the preserve of the pure climbing specialists. Defending Tour champion Pogacar is the same height as Martin and only slightly heavier at around 66kg, while 2019 winner Egan Bernal , also 5ft 9in, is a true featherweight at just 60kg.

The riders mentioned start the Tour de France with body fat percentages well below 10 per cent, but nutritionists are careful not to allow ‘cutting’ to go too far.

In fact, it can be better to offload a little muscle, as Dr Rob Child, a performance biochemist who worked with several World Tour teams, explains: “It’s sometimes worth losing a bit of muscle to reduce weight because very low body fat has health implications. Tour de France performance is governed by the cardiovascular system, not by the maximum force applied to the pedals. Pro riders don’t need huge amounts of muscle to pedal at 400 watts for 20 or 30 minutes, and that’s often the key to performing well overall in the Tour. They need a highly developed cardiovascular system, not big muscles.”

Why do Tour de France riders drink Coca-Cola?

Most team nutritionists would rather the riders didn’t drink coca cola, and some teams even forbid it.

That said, there’s also always one small can of coke in the musettes Trek-Segafredo gives its riders. Drinking a regular fizzy drink such as a cold can of coke after a stage is good for morale – and preserving positivity in a brutal three-week race is vital.

Of course, the most important nutritional consideration for riders is getting enough calories to meet the extreme demands of the race. If you’re wondering how they achieve that, here we look into what exactly goes into fuelling the riders of the Tour de France .

What do Tour de France riders do to recover between stages?

The standard of hotels used by the Tour has improved a lot in recent years, so that helps with sleep and recovery . Even so, teams provide further ‘home comforts’ by carrying all their own bedding, including mattresses and pillows. They also have their own washing machines in the team buses and equipment trucks. Everything is done to promote good sleeping habits and hygiene.

Riders generally do room-share, partly through tradition but also because it’s good to have company. Pairings are decided diplomatically, though.

Why and how do riders warm up before each stage?

The ‘why’ is explained by double Tour stage winner Steve Cummings: “There are two races in every stage: the first is to get a breakaway established, and the second is to win the stage. If I saw a stage that suited me, one where a break might stay away and give me a chance to win, I’d focus on the first hour to 90 minutes, nothing else. Typically it was attack after attack right from the start, then a huge effort to get the break established. You had to be fully warmed up for that.”

As to the ‘how’, a Tour warm-up is usually done on a turbo trainer, allowing the whole team to warm-up in one compact space, everyone controlling their effort. Ineos-Grenadiers’s deputy team principal Rod Ellingworth says: “The idea is to prepare the rider’s energy systems for a fast start. They ride steady but progressively harder for at least 20 minutes, then do five minutes of capacity work to open everything up. After that they pedal easily and try to stay loose.”

How much do riders have to eat to meet energy demands?

Riders can burn twice or even three times their usual calorie requirement during a hard day at the Tour. Nigel Mitchell, a nutritional consultant who worked extensively with WorldTour cycling teams, says: “At a Grand Tour, riders can burn more than 5,000kcal on a single stage, depending on the terrain, and that means consuming a huge amount, both off the bike at meal times and on it during the race, in the form of energy drinks, bars and gels.” To put 5,000kcal into perspective, it is roughly equivalent to four large McDonald’s BigMac meals.

What do the riders eat after each stage?

Does each rider have their own bespoke meals? Who does the cooking?

Three questions, but they are related and so are the answers, which come from a former Tour de France rider, UAE Team Emirates former sports director and current race analyst Allan Peiper. The man who oversaw Tadej Pogačar’s first Tour de France win in 2020 told us: “Each rider has a bespoke meal plan based on any needs flagged up by team doctors and physiologists, and on any personal physiological quirks such as intolerances or allergies. The medics talk with nutritionists, and the nutritionists tailor meals to meet specific needs. Each team also has its own chef who works with the nutritionist to prepare tailor-made meals.”

How heavy are the heaviest riders in the race, and how do they get over the mountains inside the time cut?

There are very few riders of over 80kg in the Tour de France nowadays. The limiter when climbing mountains is power-to-weight ratio, and if a rider is too bulky they cannot overcome the disadvantage, no matter how mighty their power output. The heaviest Tour de France rider since 2000 was the Swede Magnus Backstedt, who says: “I had to be the lightest I could be for the Tour, which was around 90kg, and as fit as I could be. But at my weight, every hill is steep, and the mountains were a real challenge. On mountain stages, I’d hang on to the peloton for as long as possible, then look for a good grupetto – that’s what we call the groups of non-climbers who ride together to get inside the time limits. Once in a grupetto with experienced riders, it was just a case of digging deep, sometimes very deep, and hanging on.”

Grit and stubbornness get heavier riders up the mountains, but they have an advantage to deploy on the other side, going down. Tour stage winner Sean Yates was a tall, well-built rider, and he says: “You have to get good at descending if you are bigger. You can’t regain all the time you lost going up, but you can get some of it back by really going for it on the descents.”

What’s the relationship between rider age and Tour de France performance?

It used to be that riders developed into Tour contenders gradually over many years. Those youngsters who did take part would be expected to help the team and gain experience, and possibly even drop out after the first week. That’s all changed. Tadej Pogačar was just 21 when he first won in 2020, and Egan Bernal was 22 when he won in 2019. Pogačar’s coach Inigo San Millan has this to say about his rider’s prodigious ability: “He has extraordinary physiological characteristics, and the correct mental attributes, so he was already good enough to win at 21.”

Until Bernal’s win four years ago, it was thought that riders reached their peak in terms of physiology, psychology and skill at around 26 or 27. According to Allan Peiper: “This may still be true, we just don’t know what the young winners we have now will be like when they are 27 or 28. Will they still be winning, or will the next generation have surpassed them?” At the other end of the scale, the oldest Tour winner of modern times was Cadel Evans in 2011, at the age of 34.

What do the riders’ musettes contain?

Nothing very surprising, just a re-supply of the gels, drinks and energy bars. Musettes were more interesting in times gone by, when they contained cakes and tarts for energy, small ham and cheese baguettes for protein, and all manner of delights. The food was individually wrapped and packed by the soigneurs. The first female soigneur Shelley Verses, who worked for US team 7-Eleven in the 1980s, used to wrap her riders’ food in pages from Playboy magazine. “It was good for their morale,” she commented.

Do Tour de France riders drink alcohol during the three weeks?

Yes, but not much. Stage wins might be celebrated with a glass of champagne, and sometimes a small glass of red wine is taken with the evening meal, but that’s as far as it goes. Teams have tried total bans on alcohol, but most allow small amounts to protect morale.

All rather sensible – not like Tour riders from previous eras. In the early days of the race, riders drank wine and beer during stages because it was less of a threat to health than the contents of some of the primitive water supplies. Right up to the 1960s, some riders enjoyed a mid-Tour tipple or two. One of the most notorious stories is about the 1964 Andorran rest day when race leader Jacques Anquetil went to a party and indulged to such an extent he was hungover the next day and almost lost the race.

How do Tour de France riders stay hydrated through sweltering long stages?

Nigel Mitchell tells us: “I get riders to start drinking as soon as they wake. I mix water with a little fruit juice in a big bottle, because that makes it more interesting than plain water, and I ask them to finish it before breakfast. They drink fruit juice with breakfast for the electrolytes, and another bottle of diluted fruit juice travelling to the stage start.

“During the stage, they drink from two bottles on the bike, one plain water and one energy drink, and they keep getting fresh bottles from the team car or support motorbikes. They get more fluid in a protein shake after the stage, and an electrolyte drink if it’s been hot. I also provide rice cakes, which contain quite a lot of moisture from the water absorbed by the rice during cooking.

“Even then, we still check on hydration by checking the rider’s weight each morning. If they are well hydrated, they will stay at pretty much the same weight throughout the Tour.”

What’s the role of the bottle-carrying domestiques in the Tour de France?

The cycling community uses a lot of French words, with domestiques being one of them. Transporting bottles from the team car to team-mates in the peloton is just one of many duties carried out by domestiques.

This supply chain is overseen by the sports directors, as Allan Peiper explains: “The sports directors have real-time information in the team cars on each rider’s performance metrics. They can tell if anyone is having a bad day, and they won’t ask that rider to drop back to the team car and pick up bottles, because it could just push them further into the red.”

Each team has several domestiques and their role, although complicated in execution, is straightforward in mission. It’s to put the team’s leader (or leaders) in the best position to challenge for victory.

That could involve riding at the front to control the peloton’s pace, leading riders who’ve punctured back to the action, chasing when a breakaway needs to be brought back, leading out sprinters at the end of stages, setting the pace in the mountains, and many other jobs. They even perform a very unglamorous function in comfort stops.

Find definitions of the French cycling terms you hear during the Tour de France , such as domestiques, over here.

In terms of FTP and watts per kilo, what does it take to be a GC contender at the Tour de France?

In 2020 the power meter supplier to Team UAE Emirates, Stages, released the following information on Tour de France winner Tadej Pogačar’s performance metrics from Stage Nine, a mountainous stage in the Pyrenees:

Time: 3:58:16

Average power: 301W (4.5W/kg)

Normalised power: 351W (5.4W/kg)

Peak 5min power: 473W (7.2W/kg)

Peak 20min power: 429W (6.5W/kg)

To put these figures in context, good amateur racers (i.e. cat two) are capable of five-minute power in the region of 4-5W/kg and 20-minute power of 3.5-4.1W/kg. Even for committed amateurs who train hard, a huge gulf in performance separates them from the likes of Pogačar.

Do Tour de France riders use dietary supplements. If so, which ones?

They need lots of protein to help recover, so they drink recovery drinks and eat protein bars to augment the protein they get from food. They sometimes consume vitamin and mineral supplements too. Dr Rob Child says: “I try to meet a rider’s needs through well-cooked, nutritious foods, but I always know what their nutritional state is in detail. We take regular blood tests, and I can use supplements to make good any deficiencies.”

Do riders pee during the Tour de France?