- South America

- How To Visit One Of...

How to Visit One of Brazil’s Indigenous Amazonian Tribes

Aside from its incredible diversity of flora and fauna, one of the great allures of the Amazon are the indigenous inhabitants who call the region home. Although the most remote and traditional tribes have not opened their homes to visitors, there are some interesting ethno-tours that can be experienced by the curious traveler. Read on to discover how to get a slice of traditional Amazonian culture on your next trip to Brazil.

The center of ethno-tourism in Brazil is Manaus . Right in the heart of the Amazon, this far-flung city of two million people has no direct road access to much of the country, requiring visitors to arrive by boat or by air. Yet despite the logistical challenges, travelers flock here to relish the beauty of the world’s largest ecosystem, with visits to an indigenous tribe known as Dessana included in many rain forest tours.

A few decades ago, a contingent of the Dessana tribe founded a settlement just 15 miles (24km) from Manaus in an area known as the Tupé Sustainable Development Reserve. These people—whose ancestral home is some 600 miles (965km) away in the dense remote jungle of northwestern Brazil—migrated to Tupé in the hopes of finding a better life as subsistence farmers and fishermen. As the years went by, the Dessana began benefiting from tourist who were curious to see their ancient traditions.

Countless Amazon tours depart from Manaus each day, all offering a similar experience; a boat ride to see the Meeting of the Waters where the dark Rio Negro and the muddy Amazon River collide, a hike through January Ecological Park to admire those incredibly large water lilies, and perhaps a swim with dolphins or a spot of piranha fishing along the way. As a bonus, many visit Tupé to watch a ritualized dance on the way home.

Dressed in feather headdresses and covered in body paint, the Dessana display their ancestors’ traditions. Though they currently live only a short distance from a booming metropolis with modern luxuries such as cellphones and satellite TV, the tribe keeps their preserved culture alive in spite of global modernization.

On a typical visit, travelers are invited into a traditional thatched-roof building and take a seat as they wait for the show to start. Suddenly, the performers jump to their feet, playing maracas and percussion instruments as they chant Amazonian songs, later beckoning visitors to join in as the show picks up steam. An explanation of their history and culture is provided at the end, followed by a Q&A session which allows visitors to directly interact with the tribespeople and purchase souvenirs.

According to a BBC article of 2015, most tour companies don’t actually pay the Dessana for the spectacle, forcing the villagers to attempt to sell jewelry and handicrafts in order to make ends meet. The government and local NGOs have labelled the unfair practice as exploitation, and they seek to enact regulation requiring payment from the tour companies. For this reason alone, it’s helpful for visitors to buy some of the tribe’s beautiful handmade wares.

Become a Culture Tripper!

Sign up to our newsletter to save up to $1,395 on our unique trips..

See privacy policy .

The experience provides an insight into how Amazon jungle tribes traditionally lived. These tribespeople offer to display their rituals both as a way to make ends meet and a way to remember and sustain their cultural inheritance. Their customs, music and dance are an authentic look at times past.

Day trips from Manaus covering the region’s best sights and a visit to Tupé start at just US$57.

Guides & Tips

The best private trips to book for your dance class.

The Best Private Trips to Book for Reunions

Places to Stay

The best resorts in brazil.

See & Do

Everything you need to know about rio’s pedra do telégrafo.

The Most Beautiful Botanical Gardens in the World

The Best Campsites and Cabins to Book in Brazil

The Most Beautiful Sunsets on Earth

The Best Hotels to Book in Brazil for Every Traveler

The Most Beautiful Coastal Cities to Visit With Culture Trip

The Best Destinations for Travellers Who Love to Dance

The Best Villas to Rent for Your Vacation in Brazil

Food & Drink

The best brazilian desserts you need to try.

Culture Trip Summer Sale

Save up to $1,395 on our unique small-group trips! Limited spots.

- Post ID: 1485744

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

All the Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon Rainforest

Amazonian indigenous peoples sometimes range across borders, inhabiting two or three countries without regard for geopolitical boundaries. Examples include the Yanomami between Venezuela and Brazil, and the Achuar between Peru and Ecuador. Because they were there before the Spanish conquest, they do not belong to any single nation state.

This article presents a list and description of the main tribes or peoples that inhabit the different countries of the Amazon jungle and basin , their history, origins, how many are left (population), and the dangers they face today.

Editor’s Note

Amazonian peoples by country

Indigenous people of the bolivian jungle.

In the Bolivian Amazon there are about 100,000 indigenous people, divided into 24 ethnic groups: Tucana, Araona, Chiman, Moseten, Machineri, Yaracare, Yaminahua, Yuquinmojeno, Motiva, Reyesano, Siriono, Guarayo, Cavineño, Ese Ejja, Pacuahara, More and Aymara. -Quechua.

Brazilian jungle tribes

Some 125,000 indigenous people live in the Brazilian Amazon, which is equivalent to only 0.78% of the region’s total population.

Among them, the Guaran í are notable with some 51,000 individuals, followed by the Tikuna with a little over 40,000, and the Yanomami , with 19,000 people scattered in the north of the Amazon.

These indigenous ethnic groups are subjected to constant harassment from illegal miners ( garimpeiros) , drug traffickers, smugglers, plantation owners, and large-scale cattle ranchers.

September 14, 2022

The silence of the indigenous people – Dying languages in the Brazilian Amazon

Rafael Cartay

July 14, 2022

Ayahuasca retreats in Brazil

Gerson Alvarado

June 4, 2022

Asurini do Xingu – Amazonian Rainforest People from Brazil

María Liliana Quintero

May 21, 2022

Karitiana – Amazon Rainforest People from Brazil

May 3, 2022

Tourist Attractions Brazil

Manaus: a gastronomic and cultural experience

February 17, 2020

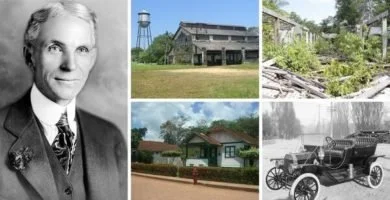

Fordlandia: Ford’s Amazon Rainforest Dream

An American-style city, created by the genius Henry Ford, as if it were located in Michigan, and not in the middle of the jungle. why did it fail?

Amazonian peoples of Colombia

Between 80,000 and 150,000 indigenous people live in the Colombian Amazon , grouped into 64 ethnic groups, which correspond to about 10% of the total population of the region.

Most numerous are the Curripaco, Puinaba, Piaroa, Piapoco, Tucano, Desano, Cubeo, Uitoto, Ticuna, Macú, and Siona.

August 26, 2022

Cofán, an indigenous people between Colombia and Ecuador

Ayahuasca Retreats in Colombia

May 7, 2022

Siona – Colombian Amazon Rainforest People

December 7, 2020

Tourist Attractions Colombia

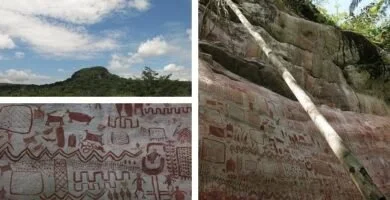

Awesome Ice-Age Cave Paintings in Colombia – Serranía de la Lindosa

Cave paintings in the Colombian Amazon, Cave art, Serranía de la Lindosa, Chiribiquete National Park, photos, What paintings are there?

November 28, 2020

Tabatinga is a Brazilian city located in the extreme west of the Amazonas state of Brazil, on the left bank of the Solimões River and forms part of the shared border with Colombia and Peru located in the so-called Amazon Trapeze.

November 26, 2020

Sanctuary of Medicinal Plants Orito Ingi Ande

Orito Ingi Ande Medicinal Plants Flora Sanctuary: protected ancestral territory, dominant flora, ancestral plants, fauna.

November 24, 2020

Aguas Claras Wildlife Reserve

Aguas Claras Nature Reserve: location, ecotourism and permitted activities, gastronomy and typical dishes.

November 21, 2020

Puerto Nariño, Colombian Amazon Rainforest

Puerto Nariño (Department of Amazonas – Colombia) where it is, map, geographical location, what to do, PHOTOS + VIDEO

November 19, 2020

Santander Park (Leticia)

The indigenous settled in the Putumayo river basin suffer the ongoing consequences of armed conflicts, deforestation, the effects of oil extraction, and contamination of rivers, all of which cause their displacement.

Indigenous from Eastern Ecuado r

In the Ecuadorian Amazon there are between 130,000 and 146,000 indigenous people, making up 20% of the regional population. They are distributed among ten ethnic groups; the seven most populous include the Kichwa, Shuar , Achuar , Shiwar, Cofán, Siona-Secoya and Huaorani ( Waorani ). The Kichwa and Shuar-Achuar together make up 83% of the regional indigenous population.

June 21, 2022

Oil exploitation in the Ecuadorian Amazon

May 28, 2022

Shiwiar – Amazon Rainforest People from Ecuador

Amazonian peoples in peru.

According to the 2007 indigenous census, there was a total of 332,975 individuals in the Peruvian Amazon . This was equivalent to nine percent of the Peruvian Amazonian population (3,675,292), and was distributed among 65 indigenous groups. In the Loreto region alone there were 105,900 indigenous people, distributed among 16 towns and 75 communities. The four largest ethnic groups are Awajún or _ Aguaruna (45,000), Shipibo-Conibo (20,178), Chayahuta (13,717) and Cocama-Cocamilla (10,705).

June 30, 2022

Asháninka – Amazon Rainforest People From Peru

December 29, 2020

Tourist Attractions of Peru

Aguaytía: settlers and native communities, the exploitation of rubber, places of tourist interest. Gastronomy and typical dishes.

December 26, 2020

The Father Abad Canyon (SPN: Boquerón del Padre Abad)

Father Abad Canyon: location, origin, geographical characteristics, permitted leisure activities.

December 24, 2020

Chachapoyas

Chachapoyas: History, how is the city. Cultural Heritage of Peru. Tourist places of the city.

December 22, 2020

Kuelap Fortress

Kuelap Fortress: archaeological discovery, researchers, location, description, access routes.

December 19, 2020

Laguna de las momias (lagoon of the mummies)

Lagoon of the condors or lagoon of the mummies (Leimebamba – Chachapoyas, Amazonas Peru): location, activities, fauna, mausoleums, photos

December 17, 2020

Yarinacocha Lagoon

Yarinacocha Lagoon: location, characteristics, Tourism, aquatic activities, animals and plants of the lagoon

December 15, 2020

Pitaya petroglyphs

Pitaya Petroglyphs: Scientific research, description, location, how to get there.

December 13, 2020

Well of Yanayacu

Yanayacu well: location, miraculous origin, myths and legends. The source of love. Tourism in Chachapoyas.

Amazonian communities in Venezuela

Some 100,000 people live in the Venezuelan Amazon , of which 40,000 are indigenous, divided into 20 ethnic groups, which make up some 500 communities, including Yanomami , Piaroa , Jivi, Curripaco, Bare, Piapoco, Baniba, Warquena, Yeral, Yekuana .

February 20, 2023

The Yanomami and the Garimpeiros

July 2, 2022

Are the Yanomami a Violent people? Napoleon Chagnon Review

May 19, 2022

Illegal mining and mercury contamination in Venezuela

April 30, 2022

Pemon – Indigenous People from Venezuela – Language, Location and Tribe Traditions

April 28, 2022

Uranium in the Venezuelan Amazon

Of all the ethnic groups in Venezuela, the Yanomamu and the Piaroa stand out, and together represent 48% of the total indigenous population. They are distributed in the states of Amazonas and Bolívar.

Indigenous people of Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana.

A little more than 42,000 indigenous people live in the Amazon regions of these three nations. There they are sometimes known as “Amerindians,” to differentiate them from the population that originated in India.

Indigenous communities found in the nation of Guyana include the Arawak, Akawaio, Arekuna, Carib, Hakushi, Patamona, Wapichan, Warau, and Wai Wai.

French Guiana is home to the Pahikweneh, Lokono, Kari’na or Kali’na, Wayampi, Teko and Wayana tribes, and Suriname has communities of the Akurio, ayarekuie, Trio, Warao and Wayana.

This total is distributed as follows: Cooperative Republic of Guyana (former British Guyana): 3,000 indigenous people divided into nine groups. Suriname (former Dutch Guiana): 20,344 indigenous people in five groups. French Guiana: 19,000 indigenous people in six groups.

Indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation (PAV)

It is hard to count the indigenous population that is in contact with other inhabitants of the Amazon basin. But it is even more difficult to estimate figures on the number of PAV ( población aislada voluntaria, or Indigenous Peoples in Voluntary Isolation) who live there. Some estimate that there may be as many as 100 true PAV groups, numbering probably 5,000 individuals. As its name suggests, a PAV is an indigenous group that avoids contact with other groups, and goes into the jungle to avoid it. The PAV are hunting and gathering peoples who live in the jungle without changing their customs, their lifestyles, or their harmonious relationship with nature.

The Coordinator of the Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA) mentions the existence of 66 PAVs in the Quito Declaration of 2018, but there are certainly many more. Specialists estimate that there may be about 145, of which 80 have been studied. Of this total, about 100 are scattered throughout the vast territory of the Brazilian Amazon, and there are about 25 in the Peruvian Amazon. Some of them are the Piripkura, K awahiva , Korubo, and Kuikuro in Brazil ; the Nahua, Nauti, Masco-piros and Cohibo in Peru ; and the Yuri and Nukak in Colombia .

History of the indigenous peoples of the Amazon

To understand the indigenous peoples of the Amazon, with all their great linguistic diversity and distinctive cultural traits, it is first necessary to understand their history: how they got there and how they became what they are today.

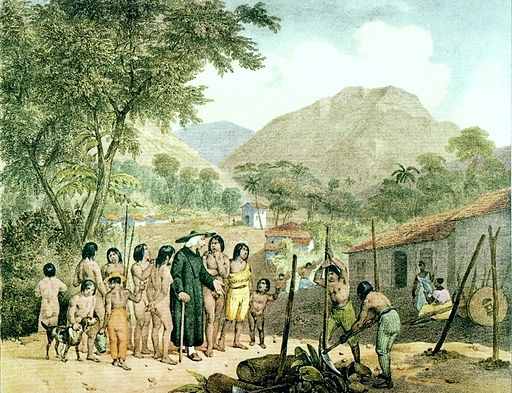

The Amazon basin began to be noticed by foreigners beginning in the 19th century. Political and religious efforts to establish colonies in these almost impregnable jungle areas did not make much progress, despite the great dedication of the religious orders involved, largely Jesuits and Franciscans .

These orders founded many settlements to concentrate the indigenous people in “reductions,” particularly in the Upper Amazon, but their progress was very limited. The Amazon Basin also continued to be an attractive location for naturalists and explorers throughout the 19th century.

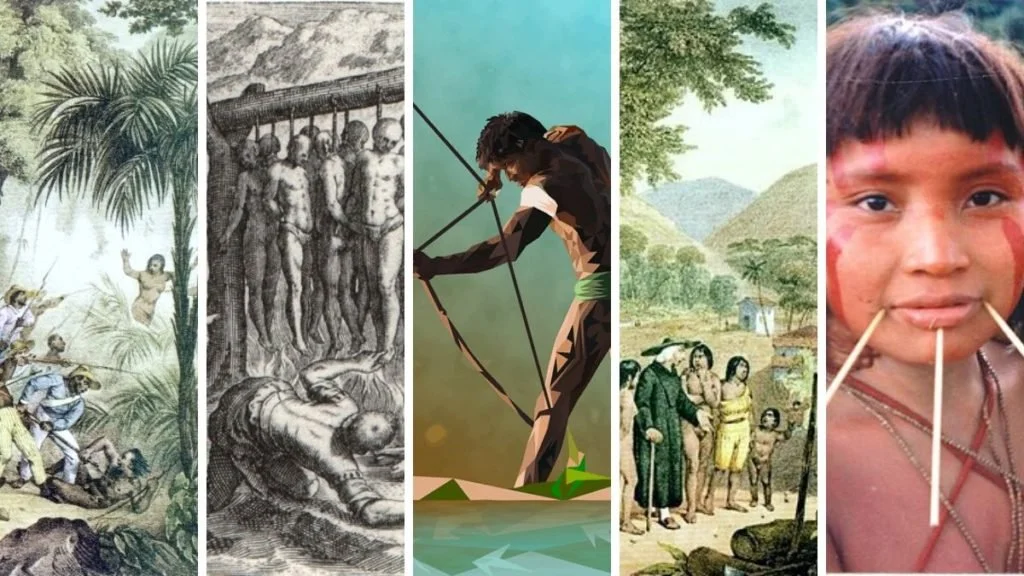

Indigenous genocide

Rubber exploitation (species Hevea brasiliensis ) started in 1879. This inaugurated a time of great economic prosperity for the rubber barons , who became very wealthy by collecting and exporting their product. However, this booming business also led to genocide and enormous suffering for the native Amazonian communities.

This was effectively a new, voluntary genocide, which followed the armed genocide by the Spanish and Portuguese conquerors and colonizers, and the involuntary genocidal effect of contagious diseases against which the indigenous people had no defenses.

This has been called epistemicide : the destruction of indigenous knowledge bases. Through this, the perpetrators sought to eliminate indigenous religious practices, cosmology , languages , and general ancestral knowledge. Fortunately, this effort was not a complete success.

How did the indigenous people get to the jungle?

The Amazon basin has been home to humans for more than 10,000 years (Roosevelt 1994). The residents were initially hunter – gatherers who settled in the eastern and southern part of the basin. Then around 5,400 to 3,200 BCE, they began to settle in the central and lower Amazon regions, with migrations from the Caribbean or the Andes, arriving in the lowlands from the high forest or the edge of the jungle.

The first settlers of the jungle were likely attracted by its extraordinary wealth of resources, especially plants and animals.

Indigenous population in South America before the arrival of the conquerors.

Although it is not certain, historians conservatively estimate that at the time of the arrival of the Europeans around 1500, there were between 13 and 17 million inhabitants in North, Central, and South America. However, other historians, (Spinden and the Berkeley School) estimate the indigenous population of the continents at more than 70 million. Estimates of the population in South America range between 7 and 20 million. In the 7 million square kilometers of the Amazon basin, population estimates vary between 5 and 7 million, distributed among some 2,000 indigenous tribes.

As a result of the European conquest, these peoples slowly transformed, changing their ways of life as a result of contact with foreigners and the cultural patterns of settlements and urban life. European-based politicians, economic groups and city dwellers considered the indigenous to be primitive peoples that opposed development. Thus, plans were made to conquer the jungle territory, and in the process, its natural resources were harmed or destroyed. Expansion followed, with increasing deforestation of the agricultural and livestock frontiers, along with increased logging and mining activities.

Current indigenous population of the basin

The current population of the entire Amazon basin is estimated at about 20 million. Of these, close to a million, or five percent of the total, are indigenous, and belong to about 400 different ethnic groups.

By “ethnicity” we mean a human community that shares a set of socio-cultural elements (language, religion, institutions, organizational forms, values, and customs), in addition to having common ancestors. The vast majority of the current inhabitants of the Amazon are mestizo (mixed indigenous and European) settlers, or landless peasants, who have come from other non-Amazonian regions. The figures and information above differ according to the source, and the authors’ political affiliations.

Indigenous organizations (COICA)

The Coordinator of the Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA), based in Quito, was created in 1995. Its members come from nine countries in the basin: Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela, Guyana, French Guiana, and Suriname.

In the Declaration of Quito of March 2018, COICA indicates that in the Amazon basin there are 390 indigenous groups, of which more than 66 are in voluntary isolation. There are more than 2.5 million indigenous individuals in all.

Dr. Rafael Cartay is a Venezuelan economist, historian, and writer best known for his extensive work in gastronomy, and has received the National Nutrition Award, Gourmand World Cookbook Award, Best Kitchen Dictionary, and The Great Gold Fork. He began his research on the Amazon in 2014 and lived in Iquitos during 2015, where he wrote The Peruvian Amazon Table (2016), the Dictionary of Food and Cuisine of the Amazon Basin (2020), and the online portal delAmazonas.com, of which he is co-founder and main writer. Books by Rafael Cartay can be found on Amazon.com

English version translator/proofreader

Related Posts

November 27, 2019

13 Typical dances of the Amazon (videos, music and movements)

Daniel Osorio

November 25, 2019

Amazonian Languages

November 7, 2019

Deforestation in the Amazon Rainforest

October 5, 2019

1001 Animals in the Amazon Rainforest

🥇 Amazon Rainforest Plants: 1001 species, names, photos and uses!

Amazon Rainforest Culture: Peoples, Cosmovision, Languages, Myths, and More

Búsqueda amazónica

Visiting an Indigenous Tribe in the Amazon, Brazil

One of the reasons that I came to the Amazon was to visit an indigenous tribe. Another was Swimming with the pink dolphin .

I grew up watching so many programs about indigenous people, specially the ones in the Amazon, that I was very curious to have at least a minimum contact with them. In Brazil we even have one day to celebrate the indigenous culture.

There are around 400 indigenous tribes in the Amazon, each of them with its own language, culture and territory.

Some of the largest tribes in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest are Yanomami and Xingu. They live in an area of approximately 96,650Km 2 and 26,420Km 2 , and have a population of 35,000 and 7,000 indigenous people respectively.

Many indigenous tribes have had contact with outsiders for almost 500 years, while others ‘uncontacted’ tribes have had a minimum contact or no contact at all.

While visiting the most well-known Amazonian tribes can be hard, you can visit others when you’re in Manaus, Amazona’s capital.

This was exactly what I did, and in this post I’m going to share my experience with you.

* Affiliate disclosure : Some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning I earn a small fee if you click through and make a purchase. There is never any additional cost to you, and I use some of these earnings for my monthly charitable donations.

Table of Contents

Visiting Aldeia Cipiá, an Indigenous Tribe in the Amazon

The indigenous tribe that I visit while touring in Manaus , Aldeia Cipiá, lives around 80Km of the city. But despite its proximity to a big metropolis, they still preserves its old habits.

When the boat arrived we were welcomed in a big hangar made of wood and fibres, decorated with indigenous paintings, by the shaman (the chief of the tribe). A man in his 60’s, with the face partially painted, wearing a swimming suit covered with a piece of a painted sheet on the front and leaf on the back, a beautiful necklace made of jaguar teeth, and a crow adorned with colorful feathers.

I sat down close to some members of the indigenous tribe and started to talk to a good-looking one by my side. But he was so shy that the dialogue was very short…

They all had gorgeous necklaces made of seeds, feathers and shells. Their faces were painted, the men had awesome crows and women ravishing earrings.

The Rituals

The xamã started the presentation of the rituals to receive visitors.

The first was Jurupari’s dance, a supernatural god’s dance. Because of that there is no participation of the indigenous women and children and they never saw the instrument.

The teenagers guys took their big blower wood instruments and started making an interesting sound out of it, and moving it up and down.

The rituals were just starting and I was exhilarating!

The next was Japurutú’s dance executed only by the men and means offer of fruit, fishes, meat or crafts.

They made a big circle, put their left arm on the right shoulder of the person in front, started to sing on their on language and make sounds with their instruments.

One by one, women lined up in the middle of the circle and then every woman held every other man to do the Capiwayá’s dance. This dance means “serve me” and was created to socialize and mix the languages and races, as in the beginning they were all brothers and sisters and no one could get married.

They continued to sing and spin around the hangar using bamboos, rattles, clappers and wands.

I was in awe witnessing an indigenous ritual for the first time in my life!

In the end the started to play a very festive song with their flutes for the Reunion dance. The men invited visitors women and the women invited visitors men to join them.

It was a big celebration of the indigenous culture and heritage that is becoming very rare to preserve.

Everyone of us, Brazilians and foreigners were moved in the end of the presentation.

Their habitat

We had some free time to visit the village and also to by handicrafts.

They leave in a very simple way, in few houses similar to the hangar in the middle of the forest, and sleep in hammocks.

I took the opportunity to talk to a teenager girl who spoke perfect Portuguese and the indigenous tribe dialect and she told me that she goes to a school close by.

I also spoke with the shaman, who told me that they also receive overnight visitors and that the daily activities are fishing and hiking in the forest.

I left the indigenous tribe very happy to see that they still preserve their culture, which is also my own culture that was lost after generations of generations of my family.

I felt also proud of the miscegenation of the Brazilian population, because in the end we are all indigenous.

Safe travels and have fun in the Amazon.

- You can book this tour to visit Aldeia Cipiá here , or if you want to witness a Tucandeira Ants Tribe Ritual, a male initiation, book this one .

Watch video : Visiting an indigenous tribe in the Amazon.

Tips for Visiting Manaus

Where is manaus.

Manaus, capital of Amazonas state, northwestern Brazil lies along the north bank of the Negro River, 11 miles (18Km) above that river’s influx into the Amazon River (see exact location here ).

How to get there?

Manaus is surrounded by rivers and the best way to get there is by boat or airplane.

By airplane

Sadly there aren’t many international companies flying direct to Manaus. Some of them companies are: American Airlines , Copa Airlines and TAP .

Although there are plenty of flights from several cities in Brazil, specially from São Paulo and Brasília. The companies that fly frequently to Manaus are: TAM , Gol , Azul and Passaredo .

Book your flights with Skyscanner , that is the website that I use and trust .

There are many boats connecting Manaus with other cities in the North of Brazil, and also with Colombia and Peru. Those boats are huge and you sleep in a hammock.

To Colombia and Peru it takes in general one week.

One of the most common trips is from Manaus to Belem (Pará’s capital). It takes 5 days and you can book it online in advance here .

Best time to visit Manaus?

There are basically two seasons in Manaus: the rainy and high humidity season (from December to April), and the dry and very hot season (from July to September).

So, the best time to go is the shoulder season: May/June and October/November.

I was there for seven days in the beginning of April of 2016 and four days the weather was sunny and hot, one cloudy day, and two days with heavy rain.

Where to stay?

I stayed at Local Hostel Manaus and I loved it.

If you’re looking for another kind of accommodation, I suggest:

- Great value for money : Hotel Adrianópolis All Suites and Intercity Manaus .

- Luxury : Juma Ópera and Hotel Vila Amazônia .

Travel costs

- Flight from São Paulo to Manaus: R$ 349 (US$ 100).

- Five nights at Local Hostel Manaus : R$ 235 (US$ 67).

- Tour with Amazing Tours : R$ 300 (US$ 86).

* Prices of 2016.

- For more information about Manaus visit: www.visitamazonastour.com

- To check boat schedules and prices visit: www.portodemanaus.com.br

P.S.: Don’t forget to take the yellow fever vaccine at least ten days prior to arrival.

Other Tours in Manaus

∗ I was invited by Amazing Tours and all the opinions here are on my own and unbiased.

- Book Your Flight Find deals on airlines on my favorite search engine: Skyscanner . Be sure to read my How to find cheap flights article.

- Rent A Car Rental Cars is a great site for comparing car prices to find the best deal.

- Book Accommodation Booking.com is my favorite hotel search engine. But Hotels.com and Hilton Hotels have very interesting reward programs.

- Protect Your Trip Don’t forget travel insurance! I always use World Nomads for short-term trips and SafetyWing for long-term ones. Find out why Travel Insurance: Much More Than a Precaution, a Necessity .

- Book Tours in Advance Book unforgettable experiences and skip-the-line tickets with GetYourGuide or Viator .

- Book Ground Transportation BookaWay offers a stress-free experience with secure payments and no hidden fees. You pay online and receive your itinerary by email.

- Luggage Solutions Rent your luggage with Cargo or if you need to drop off your own luggage and enjoy your time without dragging it all over a city, find a LuggageHero shop here.

- Get a Travel Card Revolut Card is a pre-paid debit card that enables cash machine withdrawals in 120 countries. I’ve been using my Revolut Card for over a year and never paid foreign-transaction fees again. Get your Revolut Card with free shipping here .

- Packing Guide Check out my How to Pack a Carry-on Luggage For a Five-month Trip to help you start packing for your trip. Don’t forget your camera, chargers and other useful travel accessories.

1 thought on “Visiting an Indigenous Tribe in the Amazon, Brazil”

- Pingback: When things go wrong... - 7 Continents 1 Passport

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Everything you need to know about visiting the Amazon

Spanning a mind-blowing 5.5 million square kilometres, the Amazon is the largest rain forest on the face of the Earth.

This untamed wilderness is home to as many as 40,000 species of plant, several thousand species of birds, over four hundred mammals and 2.5 million different insects.

That handful of numbers alone is probably enough to make you feel overwhelmed! To help ease your mind, I’ve compiled all the information you need so that you can start planning your Amazon trip today.

The best time to go

Fotos593/Shutterstock

In truth, the Amazon jungle can be explored all year round. Even in spite of its enormity, the weather conditions here don’t really vary between seasons – expect it to be warm, rainy and humid.

January to June marks the wet season, with temperatures sitting between 23 and 30ºC (that’s 73 to 86ºF). Throughout this half of the year, daily showers are common and can sometimes be heavy. Increased rainfall makes the rain forest feel cooler and the river levels higher. This makes accessing the river easier and swimming more plausible. It’s also worth mentioning that the greater humidity means there are more mosquitos about.

The second half of the year, July to December, marks the dry season. During this time temperatures average around 26 to 40ºC (or 78 to 104ºF) and although there’s less rain, heavy showers are still not unheard of. Decreased rainfall makes jungle feel drier and the river levels lower. This makes exploring on foot easier and offers a great opportunity to spot caimans as they compete for shorter food supplies.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER FOR OUR LATEST NEWS, OFFERS AND COMPETITIONS

Getting there

Photo captured by Eduardo Mora

The vast rainforest spans nine different South American countries including Peru , Colombia , Ecuador and Bolivia – although it’s most prominent in Brazil .

Planning to visit the Peruvian Amazon? Flights can be arranged into Iquitos, Puerto Maldonado from Cusco. Hoping to experience the Brazilian Amazon? Flying into Manaus in the north is your best option. If it’s the Ecuadorian Amazon you’re after, then you can take a bus from Quito into Tena City (five hours) where you can hop in a pickup truck. Or, if you’re eager to explore the Bolivian Amazon, fly from La Paz to Rurrenabaque (around 45 minutes) and then ride a motor-boat upriver to Madidi.

Joining a short, escorted, group tour is an easy way to escape the trouble of organisation!

Intrepid trips to the Amazon:

- 4-day Peru Amazon

- 4-day Ecuador Amazon Jungle

- 12-day Inca Trail & Amazon

What you can see

Will Howe/Shutterstock

The Amazon Rainforest houses 10% of the planet’s known species, so there’s plenty for wildlife enthusiasts to get excited about. Hiding high in the canopy you might spot slow-moving sloths and all manner of monkeys including howler, spider, tamarin, capuchin and squirrel – to name but a few. Bring along your binoculars too for a closer look at brightly-billed toucans and scarlet macaws.

Lurking on the rainforest floor and on the leaves of lower lying plants you might see sinister-looking snakes such as green anacondas, boa constrictors and eyelash vipers. Also, look out for tiny poisonous dart frogs and cleverly camouflaged insects like the leaf-mimic katydid and moss-mimic stick insect.

Living on the river banks you might find capybara families playing, caimans looking for their next meal and tapirs nibbling on low-hanging branches. Whilst in its murky waters, you may see pink river dolphins coming up for air and giant otters tucking into their fish suppers.

LOVE WILDLIFE? CHECK OUT INTREPID TRAVEL’S FULL RANGE OF ANIMAL-FILLED TOURS

Nowaczyk/Shutterstock

If you’re more of a plant person, the Amazon offers up lots for green-fingered explorers too. Some of the most fascinating and unusual species include giant water lilies (or Victoria Amazonica), spaghetti passion flowers and monkey brush vines. It’s a brilliant destination for tree lovers too. You won’t be able to walk through the jungle without coming across the humungous roots of the kapok tree. These giants can reach over 60 metres in height!

And, for the foodies amongst us, you’ll also be able to spot the plants that some of our favourite foodstuffs come from including coffee, cacao and bananas.

Where you’ll stay

Photo captured by Barbara Glanz

The most prominent style of accommodation you’ll come across in the Amazon is jungle lodges, regardless of which section you’re visiting. And whilst you can get some incredibly luxury or extremely basic ones, most sit around the 3-star mark. In these lodges, you’ll usually stay in a comfortable twin share or double cabin with an ensuite bathroom. Rooms will be kitted out with mosquito nets and a fan to keep you cool and protected at night.

READ MORE: 5 AMAZON LODGE PHOTOS THAT WILL HAVE YOU PACKING YOUR BAGS IMMEDIATELY

Activities on offer

Photo captured by Stephen Parry

During your time in the Amazon, the days will be filled by jungle walks and river cruises. These will likely happen at varying times each day to give you an insight into how your surroundings can change. On some nights you’ll have the option to take part in an after-dark jungle walk, offering you the opportunity to spot some nocturnal animals. But if you’re not keen, no worries, you can choose to simply kick back in a hammock. Bear in mind that the day’s schedule can change depending on the weather. Other activities that are sometimes available include rafting, canoeing and swimming.

BOOK NOW: CHOOSE FROM 30+ INTREPID TRAVEL ITINERARIES FEATURING THE AMAZON

Packing essentials

Aside from lightweight, waterproof and moisture-wicking clothing, here are a few more items to pop on your packing list:

- A head torch for night walks through the jungle.

- A pair of binoculars so you can get a closer look at the amazing Amazonian animals.

- Mosquito spray regardless of whether you’re travelling in the wet or dry season.

- Sensible walking shoes, although rubber boots will be provided in most cases.

- A hat to protect your head from the sun when cruising down the river.

- High factor sun cream as you don’t want sunburn putting a downer on your experience.

- A camera as you’ll be presented with an abundance of photo opportunities.

READ MORE: 10 EASY WAYS TO BE A RESPONSIBLE TRAVELLER

5 tips for exploring the Amazon responsibly

RPBaiao/Shutterstock

1. Adopt a ‘take in, take back out approach’ with your rubbish when exploring the jungle.

2. Keep a respectful distance from the local wildlife, particularly those species that are poisonous.

3. Choose a lodge that invests money back into the local community.

4. Carry a reusable water bottle so that you’re able to refill it from the larger water bottles at the lodge.

5. Listen to your guide and follow the routes they lay out for you.

LEARN MORE ABOUT RESPONSIBLE TRAVEL

What to do in the Amazon Rainforest?

- Enjoy a Junge walk through the world’s biggest Rainforest, the amazon rainforest, discovering the unique and vibrant wildlife, as well as the abundance of amazing plant species on offer.

- Kayak down the Amazon River, exploring the remote, hard to reach areas. Spot the amazing marine life as you navigate down the river and through the dense jungle.

- Get up high and amongst the 70% of the Amazon wildlife which live in the canopy. The Canopy bridge walk is a fantastic way to explore the jungle and must for your Amazon trip.

I'm a firm believer in the saying: "you'll always regret what you didn't do, not what you did". So, even after people told me I'd never get a job again if I left London to travel, I did it anyway. 29 countries later, and it will always be one of the best decisions I've ever made (corny maybe, but true). Life's short, the time to get out there and see the world is now!

You might also like

All aboard the rail renaissance: 7 reasons to..., explore these 7 tea rituals from around the..., why travellers are choosing the galapagos off-season, tips and hacks for train travel in europe, why train travel is the one experience you..., everything you need to know about a night..., mind your manners: dining etiquette around the world, 5 places to escape the crowds in italy..., is australia safe everything you need to know, 10 fun facts you might not know about..., 12 facts you probably don’t know about guatemala.

The Lost Tribes of the Amazon

Often described as “uncontacted,” isolated groups living deep in the South American forest resist the ways of the modern world—at least for now

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

Joshua Hammer

Contributing writer

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Lost-Tribes-of-the-Amazon-jungle-631.jpg)

On a cloudless afternoon in the foothills of the Andes, Eliana Martínez took off for the Amazon jungle in a single-engine Cessna 172K from an airstrip near Colombia’s capital, Bogotá. Squeezed with her in the tiny four-seat compartment were Roberto Franco, a Colombian expert on Amazon Indians; Cristóbal von Rothkirch, a Colombian photographer; and a veteran pilot. Martínez and Franco carried a large topographical map of Río Puré National Park, 2.47 million acres of dense jungle intersected by muddy rivers and creeks and inhabited by jaguars and wild peccaries—and, they believed, several isolated groups of Indians. “We didn’t have a lot of expectation that we’d find anything,” Martínez, 44, told me, as thunder rumbled from the jungle. A deluge began to pound the tin roof of the headquarters of Amacayacu National Park, beside the Amazon River, where she now serves as administrator. “It was like searching for the needle in the haystack.”

Martínez and Franco had embarked that day on a rescue mission. For decades, adventurers and hunters had provided tantalizing reports that an “uncontacted tribe” was hidden in the rainforest between the Caquetá and Putumayo rivers in the heart of Colombia’s Amazon. Colombia had set up Río Puré National Park in 2002 partly as a means of safeguarding these Indians, but because their exact whereabouts were unknown, the protection that the government could offer was strictly theoretical. Gold miners, loggers, settlers, narcotics traffickers and Marxist guerrillas had been invading the territory with impunity, putting anyone dwelling in the jungle at risk. Now, after two years’ preparation, Martínez and Franco were venturing into the skies to confirm the tribe’s existence—and pinpoint its exact location. “You can’t protect their territory if you don’t know where they are,” said Martínez, an intense woman with fine lines around her eyes and long black hair pulled into a ponytail.

Descending from the Andes, the team reached the park’s western perimeter after four hours and flew low over primary rainforest. They ticked off a series of GPS points marking likely Indian habitation zones. Most of them were located at the headwaters for tributaries of the Caquetá and the Putumayo, flowing to the north and south, respectively, of the park. “It was just green, green, green. You didn’t see any clearing,” she recalled. They had covered 13 points without success, when, near a creek called the Río Bernardo, Franco shouted a single word: “Maloca!”

Martínez leaned over Franco.

" Donde? Donde? ”—Where? Where? she yelled excitedly.

Directly below, Franco pointed out a traditional longhouse, constructed of palm leaves and open at one end, standing in a clearing deep in the jungle. Surrounding the house were plots of plantains and peach palms, a thin-trunked tree that produces a nutritious fruit. The vast wilderness seemed to press in on this island of human habitation, emphasizing its solitude. The pilot dipped the Cessna to just several hundred feet above the maloca in the hope of spotting its occupants. But nobody was visible. “We made two circles around, and then took off so as not to disturb them,” says Martínez. “We came back to earth very content.”

Back in Bogotá, the team employed advanced digital technology to enhance photos of the maloca. It was then that they got incontrovertible evidence of what they had been looking for. Standing near the maloca, looking up at the plane, was an Indian woman wearing a breechcloth, her face and upper body smeared with paint.

Franco and Martínez believe that the maloca they spotted, along with four more they discovered the next day, belong to two indigenous groups, the Yuri and the Passé—perhaps the last isolated tribes in the Colombian Amazon. Often described, misleadingly, as “uncontacted Indians,” these groups, in fact, retreated from major rivers and ventured deeper into the jungle at the height of the South American rubber boom a century ago. They were on the run from massacres, enslavement and infections against which their bodies had no defenses. For the past century, they have lived with an awareness—and fear—of the outside world, anthropologists say, and have made the choice to avoid contact. Vestiges of the Stone Age in the 21st century, these people serve as a living reminder of the resilience—and fragility—of ancient cultures in the face of a developmental onslaught.

For decades, the governments of Amazon nations showed little interest in protecting these groups; they often viewed them as unwanted remnants of backwardness. In the 1960s and ’70s Brazil tried, unsuccessfully, to assimilate, pacify and relocate Indians who stood in the way of commercial exploitation of the Amazon. Finally, in 1987, it set up the Department of Isolated Indians inside FUNAI (Fundação Nacional do Índio), Brazil’s Indian agency. The department’s visionary director, Sydney Possuelo, secured the creation of a Maine-size tract of Amazonian rainforest called the Javari Valley Indigenous Land, which would be sealed off to outsiders in perpetuity. In 2002, Possuelo led a three-month expedition by dugout canoe and on foot to verify the presence in the reserve of the Flecheiros, or Arrow People, known to repel intruders with a shower of curare-tipped arrows. The U.S. journalist Scott Wallace chronicled the expedition in his 2011 book, The Unconquered , which drew international attention to Possuelo’s efforts. Today, the Javari reserve, says FUNAI’s regional coordinator Fabricio Amorim, is home to “the greatest concentration of isolated groups in the Amazon and the world.”

Other Amazon nations, too, have taken measures to protect their indigenous peoples. Peru’s Manú National Park contains some of the greatest biodiversity of any nature reserve in the world; permanent human habitation is restricted to several tribes. Colombia has turned almost 82 million acres of Amazon jungle, nearly half its Amazon region, into 14.8 million acres of national parks, where all development is prohibited, and resguardos , 66.7 million acres of private reserves owned by indigenous peoples. In 2011 Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos signed legislation that guaranteed “the rights of uncontacted indigenous peoples...to remain in that condition and live freely according to their cultures on their ancestral lands.”

The reality, however, has fallen short of the promises. Conservation groups have criticized Peru for winking at “ecotourism” companies that take visitors to gape at isolated Indians. Last year, timber companies working illegally inside Manú National Park drove a group of isolated Mashco-Piro Indians from their forest sanctuary.

Colombia, beset by cocaine traffickers and the hemisphere’s longest Marxist-Leninist insurgency, hasn’t always succeeded in policing its rainforests effectively either. Several groups of Indians have been forcibly assimilated and dispersed in recent years.

Today, however, Colombia continues to move into the vanguard of protecting indigenous peoples and their land. In December, the government announced a bold new plan to double the size of remote Chiribiquete Park, currently 3.2 million acres in southern Colombia; the biodiversity sanctuary is home to two isolated tribes.

Franco believes that governments must increase efforts to preserve indigenous cultures. “The Indians represent a special culture, and resistance to the world,” argues the historian, who has spent three decades researching isolated tribes in Colombia. Martínez says that the Indians have a unique view of the cosmos, stressing “the unity of human beings with nature, the interconnectedness of all things.” It is a philosophy that makes them natural environmentalists, since damage to the forest or to members of one tribe, the Indians believe, can reverberate across society and history with lasting consequences. “They are protecting the jungle by chasing off gold miners and whoever else goes in there,” Franco says. He adds: “We must respect their decision not to be our friends—even to hate us.”

Especially since the alternatives to isolation are often so bleak. This became clear to me one June morning, when I traveled up the Amazon River from the Colombian border town of Leticia. I climbed into a motorboat at the ramshackle harbor of this lively port city, founded by Peru in 1867 and ceded to Colombia following a border war in 1922. Joining me were Franco, Daniel Matapi—an activist from Colombia’s Matapi and Yukuna tribes—and Mark Plotkin, director of the Amazon Conservation Team, the Virginia-based nonprofit that sponsored Franco’s overflight. We chugged down a muddy channel and emerged into the mile-wide river. The sun beat down ferociously as we passed thick jungle hugging both banks. Pink dolphins followed in our wake, leaping from the water in perfect arcs.

After two hours, we docked at a pier at the Maloca Barú, a traditional longhouse belonging to the 30,000-strong Ticuna tribe, whose acculturation into the modern world has been fraught with difficulties. A dozen tourists sat on benches, while three elderly Indian women in traditional costume put on a desultory dance. “You have to sell yourself, make an exhibition of yourself. It’s not good,” Matapi muttered. Ticuna vendors beckoned us to tables covered with necklaces and other trinkets. In the 1960s, Colombia began luring the Ticuna from the jungle with schools and health clinics thrown up along the Amazon. But the population proved too large to sustain its subsistence agriculture-based economy, and “it was inevitable that they turned to tourism,” Franco said.

Not all Ticunas have embraced this way of life. In the nearby riverside settlement of Nazareth, the Ticuna voted in 2011 to ban tourism. Leaders cited the garbage left behind, the indignity of having cameras shoved in their faces, the prying questions of outsiders into the most secret aspects of Indian culture and heritage, and the uneven distribution of profits. “What we earn here is very little,” one Ticuna leader in Nazareth told the Agence France-Presse. “Tourists come here, they buy a few things, a few artisanal goods, and they go. It is the travel agencies that make the good money.” Foreigners can visit Nazareth on an invitation-only basis; guards armed with sticks chase away everyone else.

In contrast to the Ticuna, the Yuri and Passé tribes have been running from civilization since the first Europeans set foot in South America half a millennium ago. Franco theorizes that they originated near the Amazon River during pre-Columbian times. Spanish explorers in pursuit of El Dorado, such as Francisco de Orellana, recorded their encounters—sometimes hostile—with Yuri and Passé who dwelled in longhouses along the river. Later, most migrated 150 miles north to the Putumayo—the only fully navigable waterway in Colombia’s Amazon region—to escape Spanish and Portuguese slave traders.

Then, around 1900, came the rubber boom. Based in the port of Iquitos, a Peruvian company, Casa Arana, controlled much of what is now the Colombian Amazon region. Company representatives operating along the Putumayo press-ganged tens of thousands of Indians to gather rubber, or caucho , and flogged, starved and murdered those who resisted. Before the trade died out completely in the 1930s, the Uitoto tribe’s population fell from 40,000 to 10,000; the Andoke Indians dropped from 10,000 to 300. Other groups simply ceased to exist. “That was the time when most of the now-isolated groups opted for isolation,” says Franco. “The Yuri [and the Passé] moved a great distance to get away from the caucheros .” In 1905, Theodor Koch-Grünberg, a German ethnologist, traveled between the Caquetá and Putumayo rivers; he noted ominously the abandoned houses of Passé and Yuri along the Puré, a tributary of the Putumayo, evidence of a flight deeper into the rainforest to escape the depredations.

The Passé and Yuri peoples vanished, and many experts believed they had been driven into extinction. Then, in January 1969, a jaguar hunter and fur trader, Julian Gil, and his guide, Alberto Miraña, disappeared near the Río Bernardo, a tributary of the Caquetá. Two months later, the Colombian Navy organized a search party. Fifteen troops and 15 civilians traveled by canoes down the Caquetá, then hiked into the rainforest to the area where Gil and Miraña had last been seen.

Saul Polania was 17 when he participated in the search. As we ate river fish and drank açaí berry juice at an outdoor café in Leticia, the grizzled former soldier recalled stumbling upon “a huge longhouse” in a clearing. “I had never seen anything like it before. It was like a dream,” he told me. Soon, 100 Indian women and children emerged from the forest. “They were covered in body paint, like zebras,” Polania says.

The group spoke a language unknown to the search party’s Indian guides. Several Indian women wore buttons from Gil’s jacket on their necklaces; the hunter’s ax was found buried beneath a bed of leaves. “Once the Indians saw that, they began to cry, because they knew that they would be accused of killing him,” Polania told me. (No one knows the fate of Gil and Miraña. They may have been murdered by the Indians, although their bodies were never recovered.)

Afraid that the search party would be ambushed on its way back, the commander seized an Indian man and woman and four children as hostages and brought them back to the settlement of La Pedrera. The New York Times reported the discovery of a lost tribe in Colombia, and Robert Carneiro of the American Museum of Natural History in New York stated that based on a cursory study of the language spoken by the five hostages, the Indians could well be “survivors of the Yuri, a tribe thought to have become extinct for more than half a century.” The Indians were eventually escorted back home, and the tribe vanished into the mists of the forest—until Roberto Franco drew upon the memories of Polania in the months before his flyover in the jungle.

A couple of days after my boat journey, I’m hiking through the rainforest outside Leticia. I’m bound for a maloca belonging to the Uitoto tribe, one of many groups of Indians forced to abandon their territories in the Colombian Amazon during the rubber atrocities early in the past century. Unlike the Yuri and the Passé, however, who fled deeper into the forest, the Uitotos relocated to the Amazon River. Here, despite enormous pressure to give up their traditional ways or sell themselves as tourist attractions, a handful have managed, against the odds, to keep their ancient culture alive. They offer a glimpse of what life must look like deeper in the jungle, the domain of the isolated Yuri.

Half an hour from the main road, we reach a clearing. In front of us stands a handsome longhouse built of woven palm leaves. Four slender pillars in the center of the interior and a network of crossbeams support the A-frame roof. The house is empty, except for a middle-aged woman, peeling the fruits of the peach palm, and an elderly man wearing a soiled white shirt, ancient khaki pants and tattered Converse sneakers without shoelaces.

Jitoma Safiama, 70, is a shaman and chief of a small subtribe of Uitotos, descendants of those who were chased by the rubber barons from their original lands around 1925. Today, he and his wife eke out a living cultivating small plots of manioc, coca leaf and peach palms; Safiama also performs traditional healing ceremonies on locals who visit from Leticia. In the evenings, the family gathers inside the longhouse, with other Uitotos who live nearby, to chew coca and tell stories about the past. The aim is to conjure up a glorious time before the caucheros came, when 40,000 members of the tribe lived deep in the Colombian rainforest and the Uitotos believed that they dwelled at the center of the world. “After the big flooding of the world, the Indians who saved themselves built a maloca just like this one,” says Safiama. “The maloca symbolizes the warmth of the mother. Here we teach, we learn and we transmit our traditions.” Safiama claims that one isolated group of Uitotos remains in the forest near the former rubber outpost of El Encanto, on the Caraparaná River, a tributary of the Putumayo. “If an outsider sees them,” the shaman insists, “he will die.”

A torrential rain begins to fall, drumming on the roof and soaking the fields. Our guide from Leticia has equipped us with knee-high rubber boots, and Plotkin, Matapi and I embark on a hike deeper into the forest. We tread along the soggy path, balancing on splintered logs, sometimes slipping and plunging to our thighs in the muck. Plotkin and Matapi point out natural pharmaceuticals such as the golobi , a white fungus used to treat ear infections; er-re-ku-ku, a treelike herb that is the source of a snake-bite treatment; and a purple flower whose roots—soaked in water and drunk as a tea—induce powerful hallucinations. Aguaje palms sway above a second maloca tucked in a clearing about 45 minutes from the first one. Matapi says that the tree bark of the aguaje contains a female hormone to help certain males “go over to the other side.” The longhouse is deserted except for two napping children and a pair of scrawny dogs. We head back to the main road, trying to beat the advancing night, as vampire bats circle above our heads.

In the months before his reconnaissance mission over Río Puré National Park, Roberto Franco consulted diaries, indigenous oral histories, maps drawn by European adventurers from the 16th through 19th centuries, remote sensors, satellite photos, eyewitness accounts of threatening encounters with Indians, even a guerrilla from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia who had seen the Indians while on a jungle patrol. The overflights, says Franco, engendered mixed emotions. “I felt happy and I also felt sad, maybe because of the lonely existence these Indians had,” he told me on our last morning in Leticia. “The feelings were complicated.”

Franco’s next step is to use the photographs and GPS coordinates gathered on his flights to lobby the Colombian government to strengthen protection around the national park. He envisions round-the-clock surveillance by both semi-assimilated Indians who live on the park perimeter and rangers within the park boundaries, and an early warning system to keep out intruders. “We are just at the beginning of the process,” he says.

Franco cites the tragic recent history of the Nukak tribe, 1,200 isolated Indians who inhabited the forests northwest of Río Puré National Park. In 1981, a U.S. evangelical group, New Tribes Mission, penetrated their territory without permission and, with gifts of machetes and axes, lured some Nukak families to their jungle camp. This contact drove other Nukak to seek similar gifts from settlers at the edge of their territory. The Indians’ emergence from decades of isolation set in motion a downward spiral leading to the deaths of hundreds of Nukak from respiratory infections, violent clashes with land grabbers and narco-traffickers, and dispersal of the survivors. “Hundreds were forcibly displaced to [the town of] San José del Guaviare, where they are living—and dying—in terrible conditions,” says Rodrigo Botero García, technical coordinator of the Andean Amazon Project, a program established by Colombia’s national parks department to protect indigenous peoples. “They get fed, receive government money, but they’re living in squalor.” (The government has said it wants to repatriate the Nukak to a reserve created for them to the east of San José del Guaviare. And in December, Colombia’s National Heritage Council approved an urgent plan, with input from the Nukak, to safeguard their culture and language.) The Yuri and Passé live in far more remote areas of the rainforest, but “they are vulnerable,” Franco says.

Some anthropologists, conservationists and Indian leaders argue that there is a middle way between the Stone Age isolation of the Yuri and the abject assimilation of the Ticuna. The members of Daniel Matapi’s Yukuna tribe continue to live in malocas in the rainforest—30 hours by motorboat from Leticia—while integrating somewhat with the modern world. The Yukuna, who number fewer than 2,000, have access to health care facilities, trade with nearby settlers, and send their kids to missionary and government schools in the vicinity. Yukuna elders, says Matapi, who left the forest at age 7 but returns home often, “want the children to have more chances to study, to have a better life.” Yet the Yukuna still pass down oral traditions, hunt, fish and live closely attuned to their rainforest environment. For far too many Amazon Indians, however, assimilation has brought only poverty, alcoholism, unemployment or utter dependence on tourism.

It is a fate, Franco suspects, that the Yuri and Passé are desperate to avoid. On the second day of his aerial reconnaissance, Franco and his team took off from La Pedrera, near the eastern edge of Río Puré National Park. Thick drifting clouds made it impossible to get a prolonged view of the rainforest floor. Though the team spotted four malocas within an area of about five square miles, the dwellings never stayed visible long enough to photograph them. “We would see a maloca, and then the clouds would close in quickly,” Eliana Martínez says. The cloud cover, and a storm that sprang up out of nowhere and buffeted the tiny plane, left the team with one conclusion: The tribe had called upon its shamans to send the intruders a message. “We thought, ‘They are making us pay for this,’” Franco says.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

Joshua Hammer | READ MORE

Joshua Hammer is a contributing writer to Smithsonian magazine and the author of several books, including The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu: And Their Race to Save the World's Most Precious Manuscripts and The Falcon Thief: A True Tale of Adventure, Treachery, and the Hunt for the Perfect Bird .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Although the most remote and traditional tribes have not opened their homes to visitors, there are some interesting ethno-tours that can be experienced by the curious traveler. Read on to discover how to get a slice of traditional Amazonian culture on your next trip to Brazil.

Volunteer in the Amazon Rainforest. However, there are many tribes who welcome visitors, preferring to teach them about their culture. Visiting indigenous tribes of the Amazon is accessible to outsiders through volunteering, research and teaching opportunities.

Our ecological Jungle tours are designed to provide an immersive experience for all nature enthusiasts. Our knowledgeable guides will take you on a journey through the lush jungles, where you will have the opportunity to observe exotic wildlife, learn about different plant species, and appreciate the beauty of nature.

This article presents a list and description of the main tribes or peoples that inhabit the different countries of the Amazon jungle and basin, their history, origins, how many are left (population), and the dangers they face today.

While visiting the most well-known Amazonian tribes can be hard, you can visit others when you’re in Manaus, Amazona’s capital. This was exactly what I did, and in this post I’m going to share my experience with you.

Life's short, the time to get out there and see the world is now! Spanning 5.5 million square kilometres, the Amazon is the largest rainforest on the face of the Earth. Here's all the info you need to plan your trip.

These Amazon tours are owned and led by indigenous guides who focus on sustainability and culture. Find out how to ethically see the heart of the Amazon rainforest.

From Iquitos to the Madre de Dios, the Peruvian Amazon offers incredible wildlife, remote villages, and a huge range of adventures. Here's how to visit.

The Lost Tribes of the Amazon. Often described as “uncontacted,” isolated groups living deep in the South American forest resist the ways of the modern world—at least for now

About 400 tribes live in the Amazon. Spread out across 5.5 million kilometres and nine different countries, each have developed their own cultural identities. Travelers who would like to meet indigenous people can visit communities that make a living from tourism, or even stay overnight in a jungle hut.