'12 Monkeys' Ending Explained: How That Time-Travel Twist Worked

One of the more perplexing elements of the film is its ending, which provides a fair share of ambiguity even to viewers paying careful attention.

Terry Gilliam 's 12 Monkeys remains one of the director's most compelling films, packed to the gills with bizarre scenery, narrative switchbacks, and fascinating performances. One of the more perplexing elements of the film is its ending, which provides a fair share of ambiguity even to viewers paying careful attention. For those confounded by the sudden delivery of the gun or the role of the scientist on the plane, let this article serve as an explanation of the time travel in 12 Monkeys and its role in this film's gripping conclusion.

What Is 12 Monkeys About?

One of the reasons that 12 Monkeys is interesting to revisit with a modern lens is its post-apocalyptic future. The film begins with James Cole ( Bruce Willis ) imprisoned in a bleak looking cell within an underground prison in the year 2035. James is forced into "volunteer duty," which requires him to brave the planet's surface. After the outbreak of a virus in 1996, living above ground is no longer safe for humankind, though it is apparently quite hospitable for fearsome creatures like bears and lions, both of which James encounters on his visit to the surface. Because of his reliability, James is chosen by a bizarre group of scientists for a special mission: he will travel back in time to the year 1996 and locate a group known as The Army of the 12 Monkeys, who are believed to be responsible for releasing the virus. The scientists' overall goal is to pinpoint the location of the virus in its purest form so that they can study a sample and thereby devise a cure for the people of 2035.

RELATED: '12 Monkeys' Gets 4K Ultra HD SteelBook Release

Unfortunately for Cole the time travel device that the scientists use is a bit imprecise, resulting in him occasionally being sent to the wrong year. At one point he even finds himself in the middle of a World War I battlefield, thereby ensuring his place in history books as an example of what psychiatrist Dr. Kathryn Railly ( Madeleine Stowe ) dubs "Cassandra syndrome," a reference to the Trojan priestess of Greek myth whose doomsaying was never taken seriously. Cole also has the habit of suddenly disappearing whenever the scientists of the future decide that he needs to return, bewildering the people of the past in the process. Cole is drugged and flung across time and space, often reducing him to a drooling, erratic mess. It should be unsurprising that, like Cole, many viewers of 12 Monkeys have struggled to keep track of what exactly happened, which events (if any) were pre-destined, and how many of these misadventures were figments of Cole's imagination.

Understanding How 12 Monkeys Ends Is All About Remembering How it Begins

In order to understand the ending of 12 Monkeys, it is important to keep Cole's dream from the beginning of the movie in mind. While asleep in his prison cell in 2035, Cole dreams of a scene at an airport in the 1990s. The dream begins with the sound of a gunshot. A young boy watches a bloodied long-haired man fall to the ground. A woman shouts, "No!" and charges toward the long-haired man, cradling him. The film cuts from a shot of the boy watching the shooting to Bruce Willis's adult Cole asleep in his cell, implying that Cole was the child in the dream and that the dream is based on his memories. Thanks to the time travel complexity in 12 Monkeys , it turns out that Cole is both the child watching the shooting at the airport and the long-haired man gunned down by airport security. In attempting to elope with Dr. Railly, his newfound lover and former psychiatrist / kidnapping victim, Cole dons a wig and Hawaiian shirt, thereby disguising himself from the police as well as the viewers, who might have otherwise recognized him in the dream at the movie's beginning. Dr. Railly is likewise wearing a blonde wig in the dream, her face only shown briefly before being partially blocked by Cole's hand. In this way Gilliam cleverly foreshadows the film's ending in a way that prevents the audience from understanding its full impact.

Even though the film forms a bit of a narrative ouroboros, there are clues that in spite of adult Cole's demise, there is still hope for ending the virus's reign of terror in the future. One of those clues comes in the form of the Astrophysicist ( Carol Florence ), one of the scientists from 2035 who appears on the plane next to the villainous Dr. Peters ( David Morse ), the virologist responsible for releasing the deadly plague. The Astrophysicist introduces herself as Jones and says that her business is "insurance." Her lack of animosity toward the man who doomed the world suggests that her presence was meant as insurance for the virus to be released. After all, the scientists' goal is not to prevent the release of the deadly virus but simply to locate a sample of its purest form so that a cure can be made for the people of the future. Though their motivation for wanting to ensure the pandemic rather than prevent it is never explained, the Astrophysicist's final scene confirms that this is indeed their goal.

When Cole and Dr. Railly arrive at the airport, their plan is to slip away together and enjoy a new romantic life. This changes when Dr. Railly spots Dr. Peters at the airport, recognizing him as both a creepy attendant of the Cassandra syndrome lecture she gave and a prominent virologist featured on the cover of a nearby USA Today newspaper. She determines that Dr. Peters is the person planning to release the deadly virus, and so she rushes to find Cole and tell him. Meanwhile, Cole has been contacted by a friend of his from the prison in 2035, Jose ( Jon Seda ), who tells Cole that the scientists want him to follow orders and outfits Cole with a handgun. Though Cole is mystified by who exactly the scientists want him to shoot, the scientists' plot becomes a bit clearer once Cole charges through airport security with a gun in his hand.

Dr. Peters makes a break for his boarding gate and Cole runs after him, aiming to kill him. Dr. Railly shouts, "No!", giving Cole pause. When he turns to look at her, he is immediately gunned down by airport security and falls bloodied to the floor while another airport visitor, young Cole, watches, thereby creating the exact situation from the dream at the beginning. If the viewer takes this sequence of events into consideration along with the Astrophysicist's mention of "insurance," it seems likely that the scientists gave Cole a gun so that Cole would be treated as a threat by security, thereby ensuring that the virus would be released worldwide. Again, the movie never explains why the scientists prefer this outcome to potentially preventing the pandemic altogether, but it makes things abundantly clear that given the choice between preventing the virus or releasing it, they desire the latter outcome at any cost.

Was the Ending of 12 Monkeys an Inescapable Fate?

Some interpretations of 12 Monkeys suggest that the events at the end of the movie were inescapable, that they were set in stone by fate and that the movie's characters could never have prevented the release of the virus. If one takes into account the Astrophysicist's mention of insurance and the fact that the scientists gave Cole the gun, one may arrive at an alternate conclusion. Had Cole and Reilly merely been fulfilling their destiny, acting as helpless pawns doomed to repeat a vicious cycle of violence and disease, the scientists never would have needed to intervene in the airport. Though it could be argued that the scientists themselves are at the mercy of fate and had no agency of their own in these matters, the fact that the Astrophysicist says she works in "insurance" suggests the exact opposite: her presence on the plane was to ensure that the virus was released worldwide whether by Dr. Peters or herself.

When Cole and Dr. Reilly decide to run away together, Cole removes some of his teeth, having been told previously that the scientists use his teeth to track him. This is confirmed when Jose appears at the airport to deliver the gun to Cole. Jose chastises Cole for removing his teeth, suggesting that the scientists had difficulty finding Cole as a result of that decision. The scientists were only able to find Cole because he called them and left a voicemail before entering airport security, a mistake that allowed them to send Jose through time to his location and outfit Cole with the weapon that would lead to Cole's death. It is evident from their behavior that the scientists believe that changing the past is possible. The unpredictability of Cole's behavior made them worry that history might be rewritten. If deviation from history was impossible, the scientists never would have needed to send anyone to ensure the virus's release, let alone send the Astrophysicist as "insurance."

In 12 Monkeys, How Does Changing the Past Impact the Future?

What is unclear in 12 Monkeys (among other things) is whether changing the past would have a direct result on the future inhabited by the scientists, i.e., following Back to the Future rules, or instead if changing the past would create a new, distinct timeline in a potentially infinite sea of parallel universes with various differentiating outcomes. As much of this movie's charm is its assortment of mysteries, misdirects, and red herrings (like the titular 12 Monkeys themselves, who turn out to be nothing more than a slapdash animal rights brigade hellbent on releasing zoo animals), it is unlikely that Gilliam wanted to make such things explicit. What is clear is that 12 Monkeys depicts a time travel cycle in which it may be possible to change the past but that the scientists are continually conspiring to ensure that things play out exactly as they wish, likely for their own benefit. That being said, if the scientists were at least honest about their end goals, it is possible that they might use their newfound knowledge to concoct a cure and save the underground people of 2035. The same cannot be said for James Cole, who is apparently doomed to be a sacrifice, at least so long as the will of the scientists is fulfilled.

The oral history of 12 Monkeys , Terry Gilliam's time travel masterpiece

Inverse speaks with director Terry Gilliam and nine other people involved in the making of this 1996 sci-fi cult classic.

A quarter of a century after its release, Terry Gilliam still can’t believe anyone let him make 12 Monkeys . “You have your moment when you’re a golden boy and they listen to you,” the director tells Inverse .

The 1996 sci-fi classic about time travel, death, and madness was Gilliam’s sixth project as a solo director (following 1975’s Monty Python and the Holy Grail and his 1985 dystopian cult classic, Brazil ) and is regarded as one of his finest pieces of work. Though such a complex and ambitious film was fraught with drama — from asbestos to a knife-wielding prostitute — a number of stars aligned to ensure its commercial and critical success is remembered fondly 25 years on.

The opaque tagline, “the future is history,” is as much of an absurd paradox as the story within. A dense and destabilizing film, 12 Monkeys was unusual in being unapologetically weird while starring two of Hollywood's hottest names, Bruce Willis and Brad Pitt, in lead roles.

Given that Willis was synonymous with Die Hard in the mid-’90s, it came as a surprise when one of his next movies was a Gilliam mind-bender based on a dystopian black-and-white French arthouse film , but casting John McClane as a confused time traveler turned out to be sci-fi cinema’s best idea until Keanu Reeves said “ whoa ” three years later . (Though the casting what-ifs will make you wish you could travel back in time and change Gilliam’s mind.)

“I had never been a great fan of Bruce's before,” Gilliam says, revealing that he passed on Nicolas Cage and Tom Cruise before coming around to Willis.

As James Cole, Willis travels back and forth through time in an attempt to prevent the release of a virus he believes to have killed almost everyone on the planet. Dr. Kathryn Railly (Madeleine Stowe) diagnoses him as mentally ill, sending Cole to a mental institution where he meets Jeffrey Goines (Brad Pitt). But after encountering him again and again, Railly comes to realize Cole may be sane after all.

Confusing, amusing, and a Gilliam film through and through, 12 Monkeys is the definition of a movie that rewards repeat viewing. Twenty-five years after its January 5 wide release (following a limited premiere in late December of '95), Inverse spoke to 10 of the film's key players to piece together how such an ambitious project came to be.

The beginning

"We had an image of a city with no people and just animals roaming around, totally out of place."

Charles Roven (producer): I was given the short film La Jetée by Chris Marker by a gentleman by the name of Robert Kosberg. I then gave that to Dave and Jan [Peoples].

David Peoples (screenwriter): We had missed seeing La Jetée in the ‘60s when we should have seen it. They sent us a terrible video of it, but in spite of the fact that it was an awful video, it really was such a wonderful movie. We said, “We'll spend a weekend on it and see if there's anything we can come up with that would be interesting.” It did come to us that people hadn't been doing a lot of stuff with the threat of germs – man-made germs or germs from nature. We had an image of a city with no people and just animals roaming around, totally out of place. Chris [Marker] hadn't said it was OK to make a movie out of his movie. He hated all Hollywood movies except Vertigo .

Janet Peoples (screenwriter): We bumped into a friend of ours from Berkeley: Tom Luddy. Tom laughed and said, “Oh, I know Chris. You know, Chris loves Francis Coppola. And Francis is in town.” So we all met at a Chinese restaurant – writers and a couple of directors; no producers, no suits – and Chris Marker at one end of the table and Francis at the other. Francis looks up and says, “Chris!?” and Chris says, “Yes, Francis?” and Francis says, “Jan and Dave want to make this movie. They're good people; I think you oughta let them do it.” And Chris says, “Oh, OK, Francis.”

“I will die to make this film.”

Mick Audsley (editor): About two years before Terry [Gilliam] contacted me, Dave and Jan sent me a very early draft of Monkeys . I thought, I will die to make this film. If I have to lose my arm or sell my children, I want to make this film. They said, “Is it comprehensible in any way?” to which I replied, “Not at all, which is why I want to do it.”

Charles Roven: We were talking about directors to give it to. We all agreed that Terry would be a great choice.

David Peoples: Terry read it and liked it a lot, but he was totally devoted to a long-time project to make A Tale of Two Cities for Warner Brothers. So he had to say no to 12 Monkeys, at which point Chuck [Charles Roven] had us do another rewrite which he thought would make it appealing to other people. In the meantime, something went wrong with A Tale of Two Cities and suddenly Terry's available again. So we gave him the rewrite we'd done for Chuck and he said, “How come you ruined the script?”

Terry Gilliam (director): I was told by Chuck that it had been read by many different directors and nobody knew what to do with it. That's what excited me about it. The complexity was one thing that was intriguing. Who is the mad person in here? Is it Madeleine [Stowe]'s character or is it Bruce [Willis]'s character?

Janet Peoples: Both David and I worked in state hospital mental institutions when we were really very young.

David Peoples: We both remembered instances of sitting in staff meetings with the doctors all there and the patient not in yet, and one doctor would say something like, “Oh, by the way, what's the date today?” Then when the patient came in and they started asking him, “Do you know what the date today is?” it would be a big deal if they knew that stuff. That's what Terry likes, because Terry has this sense of absurdity that is just wonderful.

Terry Gilliam: The pressure was to get a movie star in. That was at a time when I was still a hot director, so people wanted to come near me and touch me. So they were coming up with all these names. And I just kept saying no. Tom Cruise, Nic Cage, they were all being thrown at me.

Margery Simkin (casting director): Terry called. Whatever he does, I will always be willing and able to come play. After all these years he trusts me a lot. It's like, I imagine when you're dealing at a restaurant and people are developing dishes. You're looking for various flavorings that will spice something up and make it special.

Terry Gilliam: I had never been a great fan of Bruce's before, but I liked talking to him, and I thought, OK, this guy's smart; he's funny. I explained to him my concerns about him as an actor. I hated that moue [pursed-lip expression] he does in his films when he gets a bit nervous. I thought, 'God, that's horrible.' He does a moue with his mouth; it's a Trumpian mouth. For a moment it goes all Trumpian. Rectal. It's like I'm looking at somebody's asshole."

Margery Simkin: Bruce was perfectly willing to leave the entourage behind.

“It's like I’m looking at somebody's asshole .”

Terry Gilliam: Brad [Pitt] came to London, and we had dinner because he was keen to get on board to play the part that I had already given to Bruce. I was actually scared shitless that Brad might not be able to do the character because up to then we'd never seen him as a motormouth.

Charles Roven: We were lucky that the actors fell in love with it and that they were willing to do the movie for not their established prices.

Margery Simkin: It seemed that they both wanted to be involved because it was an opportunity for both of them to stretch.

Terry Gilliam: I put [Brad] together with Stephen Bridgewater, who had worked with Jeff Bridges on The Fisher King . Stephen's first meetings with Brad — he liked pot too much, he had a lazy tongue. But he worked his ass off; he really did.

Charles Roven: To prepare for the movie, he checked himself into a mental ward. And he spent a few days there, just to get the feel of it.

Margery Simkin: With Brad at the time, it was a failure of people's imagination about him. And also the curse of the pretty boy, that people don't believe God gives with both hands or something.

Jon Seda (Jose): Once I got the script, I had to read it probably at least five times in a week, and I was still lost. I was trying so hard to make sense of it.

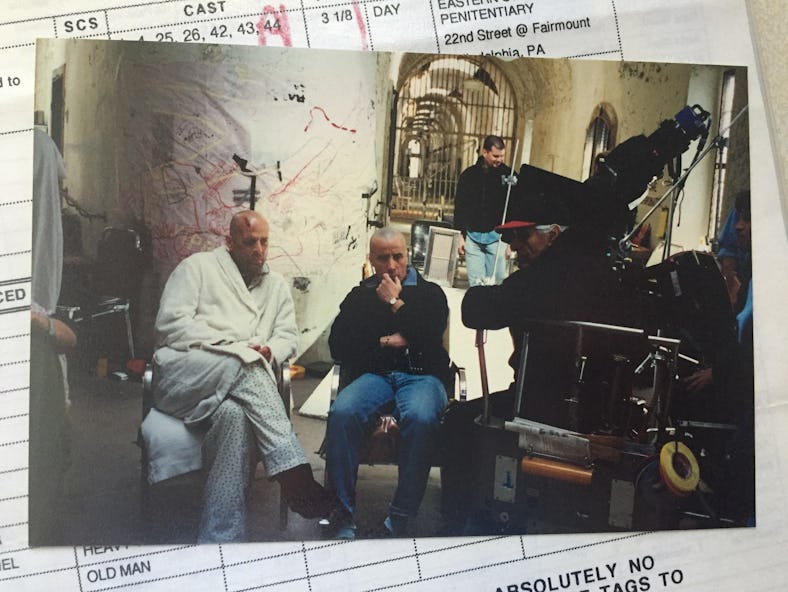

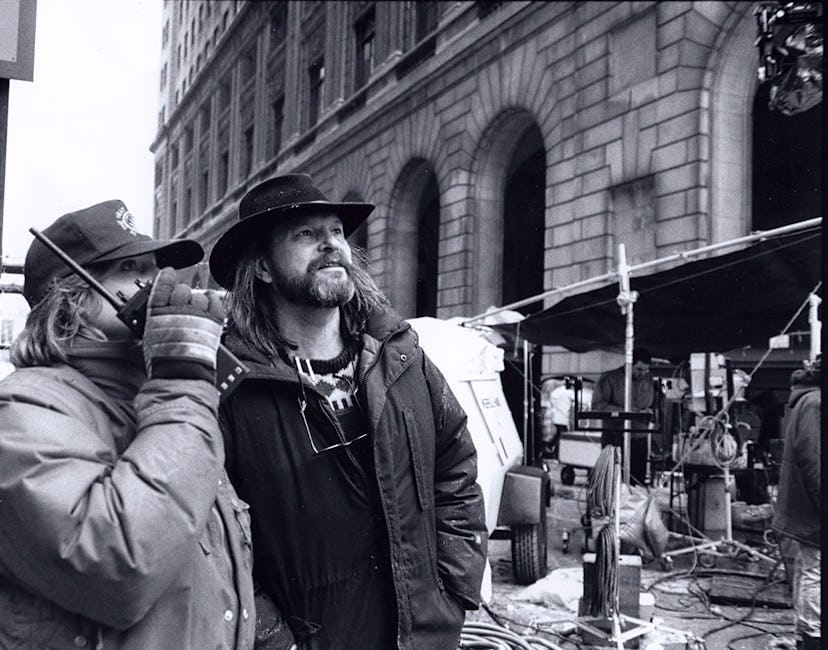

Terry Gilliam on the set of 12 Monkeys .

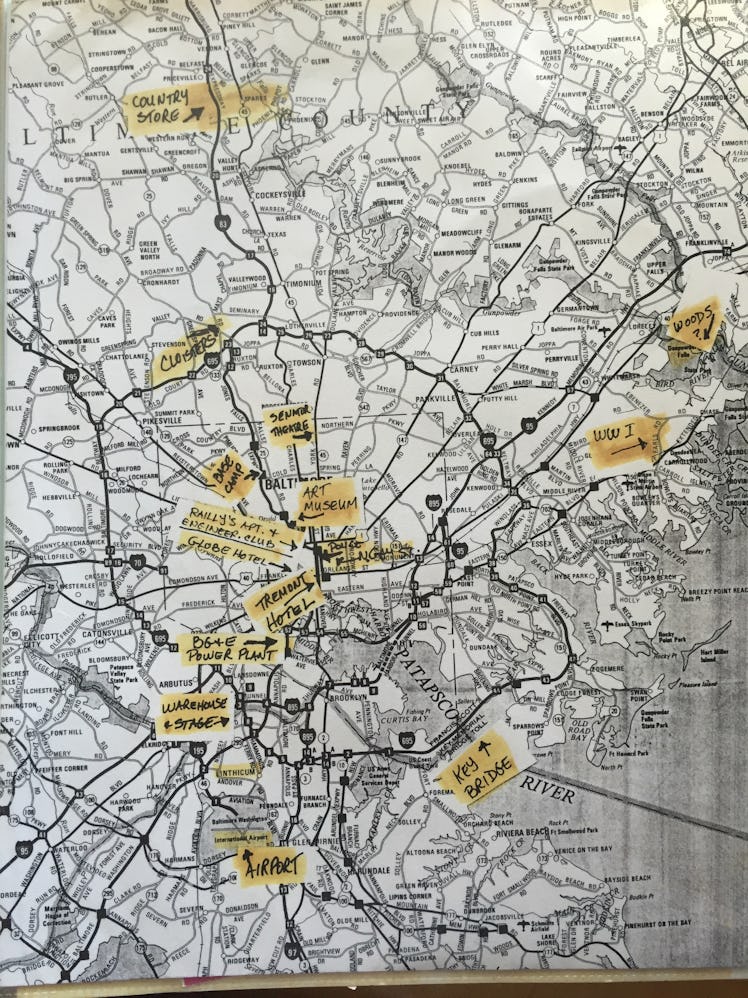

Scott Elias (location manager): I had just returned from doing something or other and had been away for quite some time and really didn't want to do another project right away. But then I got a call from Lloyd Phillips, who was a really interesting guy; he was the co-producer of the film. The moment he said, “Terry Gilliam,” I said, “Gee, I think I'm in, no matter what.” He said, “We need you here right away; we're on the verge of losing a location that Terry wants very badly.” I dropped everything and just ran over to Philadelphia.

Margery Simkin: Their downtown hadn't been torn down and rebuilt like many other American cities, so it still had all of these amazingly stunning old buildings downtown. There was something about that energy – of this beautiful, slightly crumbling place that was being energized.

Charles Roven: There were these amazing old 19th-century generator plants, which served as the locations for the subterranean areas where Cole was in the future.

Terry Gilliam: Having used Croydon power station for Brazil , I was obsessed with power stations and the technology within them.

“I learned more about asbestos abatement than I ever thought I would have to know.”

Scott Elias: Terry was enamored very much with a closed power plant on a Delaware river. It was maybe the biggest building in all of Philadelphia. We were maybe 30 feet inside this place and a huge chunk of the ceiling fell directly in front of me. Honest to God, had it hit me, it would have been the end of me. I looked up and in the distance on the ceiling it was just crumbling; all this concrete barely hanging there. I remember driving to the office, and I met with Lloyd Phillips and Chuck Roven. I said, “I can't take two people in there, let alone 200.” It took a pretty solid three months to make it safe.

Anthony Simonaitis (special effects on-set supervisor): The thing that we would do CG now, we wouldn't shoot in a power plant. We'd shoot on a stage and they would do CG set extensions, do blue screens. We'd be on a stage with a heater; it wouldn't be 15 degrees in there with 100 years of toxic residue and mold and asbestos and bird poop and all the other stuff that's in a 100-year-old industrial building.

Anna M. Elias (assistant location manager) : I learned more about asbestos abatement than I ever thought I would have to know. One of the things that was unique to these power plants was they were freezing inside, and we were filming in the winter in Philly. They had their own weather patterns. And we had Bruce Willis in next to nothing, so we had a tent for him that we'd have to haul up these steps.

"We used a penitentiary for the psychiatric asylum, which was the first real penitentiary in the world."

Scott Elias: We did shoot one scene in Camden, New Jersey. At the time it was really rough and tumble. I looked everywhere for a motel. It was a freezing cold day and I'm taking photographs of this motel, and a knife suddenly comes across my throat from behind. It was a hooker. It turns out that this was a hooker motel and she thought I was some kind of a policeman. And she actually stole my video camera, and she took my money as well.

Anna M. Elias: In the movie, we depict a World War I trench that we had to create from scratch in this quarry-type place in Chase, Maryland. Our art department had to go in and build World War I trenches. At some point, this wind arrived — like a tornado. It was strong enough to lift the tents out of the ground. I just remember lunging and grabbing the side of the tent and hanging on for dear life.

Jon Seda: I remember I could barely keep my eyes open because of all the stuff from the bombs going off and the dirt was flying down from the sky. They had to keep plucking pieces of rocks and sticks out of my eyes so we could get the take.

Scott Elias: We used a penitentiary for the psychiatric asylum, which was the first real penitentiary in the world. I think Charles Dickens even toured the place when it first opened, and Al Capone was housed there for a while. It was supposedly haunted, which I wouldn't doubt. They had a central rotunda and then various cell blocks pin-wheeled out from that center. The whole idea was that the guards could be in that center and could see everything that was going on.

The... issues

Charles Roven: Terry and I had a very interesting give-and-take relationship. We had some pretty nice arguments, but we also had some pretty nice times where we really agreed.

Anthony Simonaitis: It's the one movie I point to where the grey started to show up in my beard.

Margery Simkin: It wasn't easy, and Chuck really produced the film. He wrestled that film into being.

Anthony Simonaitis: I remember some pretty contentious budget meetings about the snow and some stand-offs on the set. There's a technique where we use a soap solution and compressed air and water. You aerate this material and you create a foam. You spray it on the ground, you spray it through hoses; you can cover large areas quickly, and it creates this white, soft blanket of snow. But at first, it looks like shaving cream. Terry was not happy with it when we first put it out.

Terry Gilliam: Bruce was trying incredibly hard to just be an actor at work, but he had been spoiled by success for so long. So he was in many ways like a kid who was pushing the limits constantly and then coming up with stupid excuses for being late on the set. There was one point he had something that looked like a note from his mother. We let Bruce go away for a long weekend and he came back and suddenly he was Bruce Willis Superstar again.

“There was one point he had something that looked like a note from his mother .”

Mick Audsley: He became the Die Hard man with his pouty mouth. Then we decided to see if we could rescue our Bruce, which we couldn't. He got re-molded back to the character.

Charles Roven: I would say that those were tense conversations, but ultimately it all worked out, clearly.

Terry Gilliam: Stephen Bridgewater was working with Brad daily. He was like a coach. And I think at a certain point, he decided that day he didn't need Stephen. It was a terrible day because Brad was not getting it right, and he knew it, which made it worse. Bruce became fantastic; he was like a father figure to Brad. I said, “Brad, you've got to call the studio and ask for another day.”

Anna M. Elias: Brad had just been Sexiest Man of the Universe.

Terry Gilliam: Legends of the Fall did it. It just changed everything. Girls were threatening to throw themselves off Philadelphian bridges.

Anna M. Elias: That penitentiary… I don't know how she did it, but somehow a girl got in and hid overnight. The next day, when we showed up to continue filming, she came out in the middle of things and wanted Brad.

Scott Elias: Sasha the Siberian tiger was a particular favorite because we housed her at the armory where our office was located. It had huge walls everywhere. And don't you know, a couple of teenage gang members decided that that was a good night to climb over the walls with ladders. So they crept up to this fancy-looking trailer that housed Sasha and they broke into it. And they were stealing a radio out of the cab of the truck, and the window was open between the cab of the truck and the trailer. I get a call from the security people, saying, “You need to come down to the armory, there's been a break-in.” So I just throw on some clothes and run down there as fast as I can to find these two 15/16-year-old kids literally weeping, one having wet himself – no kidding. What I discovered was, as they were breaking into the cab and they were stealing this radio, Sasha's paw comes through and she growls at them, and it scared them out of their wits.

The focus groups

Terry Gilliam: People don't understand the test screening aspect of filmmaking, which is possibly the most critical. You've made the film, you've done the work, and now you're surrounded by all these studio executives who are shitting themselves with nerves, worrying that they might have their name on a failure of a movie.

Mick Audsley: It was Georgetown. It was an educated audience. You felt this sparkle, and we thought, “Wow, they're loving it as much as I do,” only to get comments like, “I can't rate it, I'm too confused.” The one that I shall never forget: A man stood up and said, “This film is predictable.”

David Peoples: We did go to a screening where we were sitting in the back of the theatre. And some guy in the back of the theatre, as everybody was filing out, said, “They oughta shoot the writer!” We were a little panicked that people weren't being that entertained by the movie, but Mick and Terry are tough as nails. They just refused to make stupid changes.

Jon Seda: At the wrap party, Bruce was DJing the party. I went over and I joked, “Hey, where's the Latin music?” And he joked back, “You're the only Puerto Rican here.” Then he put on some salsa music.

The premiere

Bruce Willis at the premiere of 12 Monkeys .

Terry Gilliam: Getting to the premiere was a nightmare. It took place in New York in December and there was a huge blizzard. The whole thing was apocalyptic.

Jon Seda: I was so excited and eager to see it, and when I saw it the first time, I was blown away. Terry knew the story so well. He was the captain of the ship.

Anna M. Elias: He achieved a vision that probably none of us saw going in.

Terry Gilliam: I thought a [limited] release date of December 27 was a stupid idea, but it turned out to be brilliant. Boom, we went to number one.

Charles Roven: I had done some well-reviewed movies and had some commercial success, but this was by far my biggest hit. For a $30 million movie to do $180 million [$168.8 million] in worldwide box office at that time, that was quite significant.

Mick Audsley: People were going to see the film more than once. There were things to reveal on a second viewing, which for cinema was quite unusual.

Margery Simkin: I saw it again a couple of years ago. And I gotta say, there were a few things I didn't understand to begin with in the script and that were not illuminated on reviewing it.

Janet Peoples: We were lucky because it did well in our hometown and it didn't embarrass our children. We enjoyed it. We thought that Terry did a fantastic job.

Jon Seda: Sometimes we don't realize the significant moments in our lives as they're happening. It's years later when we look back and go, “Wow, I was a part of that. ” This was one of those. If someone else brings it up and says, “Hey man, you were in 12 Monkeys ,” I stop and I go, “You know what? Yeah! I was in 12 Monkeys !”

Update 1/11/2021: At Terry Gilliam's request, we've added the full version of his quote about a certain Bruce Willis facial expression to provide additional context.

This article was originally published on Jan. 5, 2021

- Science Fiction

- Cast & crew

- User reviews

Retroactive

A psychiatrist makes multiple trips through time to save a woman that was murdered by her brutal husband. A psychiatrist makes multiple trips through time to save a woman that was murdered by her brutal husband. A psychiatrist makes multiple trips through time to save a woman that was murdered by her brutal husband.

- Louis Morneau

- Michael Hamilton-Wright

- Robert Strauss

- Phillip Badger

- Jim Belushi

- Kylie Travis

- Shannon Whirry

- 73 User reviews

- 28 Critic reviews

- 6 wins & 4 nominations

- (as James Belushi)

- Truck Driver

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

More like this

Did you know

- Trivia Kylie Travis first came to the attention of the film's producers after she auditioned for another movie made by the same production company.

- Goofs The gun Frank takes from Jesse's truck is an old-fashioned six shooter, yet he fires off at least 20 rounds without reloading during the shootout at the gas station.

Frank : Women. Can't live with them, can't blow their heads off.

- Connections Features RoboCop (1987)

- Soundtracks 52 Pick-Up Written and Performed by Marcus Barone Courtesy of MPCA Pub. Grp., Inc. (ASCAP)

Technical specs

- Runtime 1 hour 31 minutes

- Dolby Digital

Related news

Contribute to this page.

- See more gaps

- Learn more about contributing

More to explore

Recently viewed

- The Best Time Travel Books of the 1990's

- Risingshadow

- Advanced Search

- Time travel

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Time Travel

There is an extensive literature on time travel in both philosophy and physics. Part of the great interest of the topic stems from the fact that reasons have been given both for thinking that time travel is physically possible—and for thinking that it is logically impossible! This entry deals primarily with philosophical issues; issues related to the physics of time travel are covered in the separate entries on time travel and modern physics and time machines . We begin with the definitional question: what is time travel? We then turn to the major objection to the possibility of backwards time travel: the Grandfather paradox. Next, issues concerning causation are discussed—and then, issues in the metaphysics of time and change. We end with a discussion of the question why, if backwards time travel will ever occur, we have not been visited by time travellers from the future.

1.1 Time Discrepancy

1.2 changing the past, 2.1 can and cannot, 2.2 improbable coincidences, 2.3 inexplicable occurrences, 3.1 backwards causation, 3.2 causal loops, 4.1 time travel and time, 4.2 time travel and change, 5. where are the time travellers, other internet resources, related entries, 1. what is time travel.

There is a number of rather different scenarios which would seem, intuitively, to count as ‘time travel’—and a number of scenarios which, while sharing certain features with some of the time travel cases, seem nevertheless not to count as genuine time travel: [ 1 ]

Time travel Doctor . Doctor Who steps into a machine in 2024. Observers outside the machine see it disappear. Inside the machine, time seems to Doctor Who to pass for ten minutes. Observers in 1984 (or 3072) see the machine appear out of nowhere. Doctor Who steps out. [ 2 ] Leap . The time traveller takes hold of a special device (or steps into a machine) and suddenly disappears; she appears at an earlier (or later) time. Unlike in Doctor , the time traveller experiences no lapse of time between her departure and arrival: from her point of view, she instantaneously appears at the destination time. [ 3 ] Putnam . Oscar Smith steps into a machine in 2024. From his point of view, things proceed much as in Doctor : time seems to Oscar Smith to pass for a while; then he steps out in 1984. For observers outside the machine, things proceed differently. Observers of Oscar’s arrival in the past see a time machine suddenly appear out of nowhere and immediately divide into two copies of itself: Oscar Smith steps out of one; and (through the window) they see inside the other something that looks just like what they would see if a film of Oscar Smith were played backwards (his hair gets shorter; food comes out of his mouth and goes back into his lunch box in a pristine, uneaten state; etc.). Observers of Oscar’s departure from the future do not simply see his time machine disappear after he gets into it: they see it collide with the apparently backwards-running machine just described, in such a way that both are simultaneously annihilated. [ 4 ] Gödel . The time traveller steps into an ordinary rocket ship (not a special time machine) and flies off on a certain course. At no point does she disappear (as in Leap ) or ‘turn back in time’ (as in Putnam )—yet thanks to the overall structure of spacetime (as conceived in the General Theory of Relativity), the traveller arrives at a point in the past (or future) of her departure. (Compare the way in which someone can travel continuously westwards, and arrive to the east of her departure point, thanks to the overall curved structure of the surface of the earth.) [ 5 ] Einstein . The time traveller steps into an ordinary rocket ship and flies off at high speed on a round trip. When he returns to Earth, thanks to certain effects predicted by the Special Theory of Relativity, only a very small amount of time has elapsed for him—he has aged only a few months—while a great deal of time has passed on Earth: it is now hundreds of years in the future of his time of departure. [ 6 ] Not time travel Sleep . One is very tired, and falls into a deep sleep. When one awakes twelve hours later, it seems from one’s own point of view that hardly any time has passed. Coma . One is in a coma for a number of years and then awakes, at which point it seems from one’s own point of view that hardly any time has passed. Cryogenics . One is cryogenically frozen for hundreds of years. Upon being woken, it seems from one’s own point of view that hardly any time has passed. Virtual . One enters a highly realistic, interactive virtual reality simulator in which some past era has been recreated down to the finest detail. Crystal . One looks into a crystal ball and sees what happened at some past time, or will happen at some future time. (Imagine that the crystal ball really works—like a closed-circuit security monitor, except that the vision genuinely comes from some past or future time. Even so, the person looking at the crystal ball is not thereby a time traveller.) Waiting . One enters one’s closet and stays there for seven hours. When one emerges, one has ‘arrived’ seven hours in the future of one’s ‘departure’. Dateline . One departs at 8pm on Monday, flies for fourteen hours, and arrives at 10pm on Monday.

A satisfactory definition of time travel would, at least, need to classify the cases in the right way. There might be some surprises—perhaps, on the best definition of ‘time travel’, Cryogenics turns out to be time travel after all—but it should certainly be the case, for example, that Gödel counts as time travel and that Sleep and Waiting do not. [ 7 ]

In fact there is no entirely satisfactory definition of ‘time travel’ in the literature. The most popular definition is the one given by Lewis (1976, 145–6):

What is time travel? Inevitably, it involves a discrepancy between time and time. Any traveller departs and then arrives at his destination; the time elapsed from departure to arrival…is the duration of the journey. But if he is a time traveller, the separation in time between departure and arrival does not equal the duration of his journey.…How can it be that the same two events, his departure and his arrival, are separated by two unequal amounts of time?…I reply by distinguishing time itself, external time as I shall also call it, from the personal time of a particular time traveller: roughly, that which is measured by his wristwatch. His journey takes an hour of his personal time, let us say…But the arrival is more than an hour after the departure in external time, if he travels toward the future; or the arrival is before the departure in external time…if he travels toward the past.

This correctly excludes Waiting —where the length of the ‘journey’ precisely matches the separation between ‘arrival’ and ‘departure’—and Crystal , where there is no journey at all—and it includes Doctor . It has trouble with Gödel , however—because when the overall structure of spacetime is as twisted as it is in the sort of case Gödel imagined, the notion of external time (“time itself”) loses its grip.

Another definition of time travel that one sometimes encounters in the literature (Arntzenius, 2006, 602) (Smeenk and Wüthrich, 2011, 5, 26) equates time travel with the existence of CTC’s: closed timelike curves. A curve in this context is a line in spacetime; it is timelike if it could represent the career of a material object; and it is closed if it returns to its starting point (i.e. in spacetime—not merely in space). This now includes Gödel —but it excludes Einstein .

The lack of an adequate definition of ‘time travel’ does not matter for our purposes here. [ 8 ] It suffices that we have clear cases of (what would count as) time travel—and that these cases give rise to all the problems that we shall wish to discuss.

Some authors (in philosophy, physics and science fiction) consider ‘time travel’ scenarios in which there are two temporal dimensions (e.g. Meiland (1974)), and others consider scenarios in which there are multiple ‘parallel’ universes—each one with its own four-dimensional spacetime (e.g. Deutsch and Lockwood (1994)). There is a question whether travelling to another version of 2001 (i.e. not the very same version one experienced in the past)—a version at a different point on the second time dimension, or in a different parallel universe—is really time travel, or whether it is more akin to Virtual . In any case, this kind of scenario does not give rise to many of the problems thrown up by the idea of travelling to the very same past one experienced in one’s younger days. It is these problems that form the primary focus of the present entry, and so we shall not have much to say about other kinds of ‘time travel’ scenario in what follows.

One objection to the possibility of time travel flows directly from attempts to define it in anything like Lewis’s way. The worry is that because time travel involves “a discrepancy between time and time”, time travel scenarios are simply incoherent. The time traveller traverses thirty years in one year; she is 51 years old 21 years after her birth; she dies at the age of 100, 200 years before her birth; and so on. The objection is that these are straightforward contradictions: the basic description of what time travel involves is inconsistent; therefore time travel is logically impossible. [ 9 ]

There must be something wrong with this objection, because it would show Einstein to be logically impossible—whereas this sort of future-directed time travel has actually been observed (albeit on a much smaller scale—but that does not affect the present point) (Hafele and Keating, 1972b,a). The most common response to the objection is that there is no contradiction because the interval of time traversed by the time traveller and the duration of her journey are measured with respect to different frames of reference: there is thus no reason why they should coincide. A similar point applies to the discrepancy between the time elapsed since the time traveller’s birth and her age upon arrival. There is no more of a contradiction here than in the fact that Melbourne is both 800 kilometres away from Sydney—along the main highway—and 1200 kilometres away—along the coast road. [ 10 ]

Before leaving the question ‘What is time travel?’ we should note the crucial distinction between changing the past and participating in (aka affecting or influencing) the past. [ 11 ] In the popular imagination, backwards time travel would allow one to change the past: to right the wrongs of history, to prevent one’s younger self doing things one later regretted, and so on. In a model with a single past, however, this idea is incoherent: the very description of the case involves a contradiction (e.g. the time traveller burns all her diaries at midnight on her fortieth birthday in 1976, and does not burn all her diaries at midnight on her fortieth birthday in 1976). It is not as if there are two versions of the past: the original one, without the time traveller present, and then a second version, with the time traveller playing a role. There is just one past—and two perspectives on it: the perspective of the younger self, and the perspective of the older time travelling self. If these perspectives are inconsistent (e.g. an event occurs in one but not the other) then the time travel scenario is incoherent.

This means that time travellers can do less than we might have hoped: they cannot right the wrongs of history; they cannot even stir a speck of dust on a certain day in the past if, on that day, the speck was in fact unmoved. But this does not mean that time travellers must be entirely powerless in the past: while they cannot do anything that did not actually happen, they can (in principle) do anything that did happen. Time travellers cannot change the past: they cannot make it different from the way it was—but they can participate in it: they can be amongst the people who did make the past the way it was. [ 12 ]

What about models involving two temporal dimensions, or parallel universes—do they allow for coherent scenarios in which the past is changed? [ 13 ] There is certainly no contradiction in saying that the time traveller burns all her diaries at midnight on her fortieth birthday in 1976 in universe 1 (or at hypertime A ), and does not burn all her diaries at midnight on her fortieth birthday in 1976 in universe 2 (or at hypertime B ). The question is whether this kind of story involves changing the past in the sense originally envisaged: righting the wrongs of history, preventing subsequently regretted actions, and so on. Goddu (2003) and van Inwagen (2010) argue that it does (in the context of particular hypertime models), while Smith (1997, 365–6; 2015) argues that it does not: that it involves avoiding the past—leaving it untouched while travelling to a different version of the past in which things proceed differently.

2. The Grandfather Paradox

The most important objection to the logical possibility of backwards time travel is the so-called Grandfather paradox. This paradox has actually convinced many people that backwards time travel is impossible:

The dead giveaway that true time-travel is flatly impossible arises from the well-known “paradoxes” it entails. The classic example is “What if you go back into the past and kill your grandfather when he was still a little boy?”…So complex and hopeless are the paradoxes…that the easiest way out of the irrational chaos that results is to suppose that true time-travel is, and forever will be, impossible. (Asimov 1995 [2003, 276–7]) travel into one’s past…would seem to give rise to all sorts of logical problems, if you were able to change history. For example, what would happen if you killed your parents before you were born. It might be that one could avoid such paradoxes by some modification of the concept of free will. But this will not be necessary if what I call the chronology protection conjecture is correct: The laws of physics prevent closed timelike curves from appearing . (Hawking, 1992, 604) [ 14 ]

The paradox comes in different forms. Here’s one version:

If time travel was logically possible then the time traveller could return to the past and in a suicidal rage destroy his time machine before it was completed and murder his younger self. But if this was so a necessary condition for the time trip to have occurred at all is removed, and we should then conclude that the time trip did not occur. Hence if the time trip did occur, then it did not occur. Hence it did not occur, and it is necessary that it did not occur. To reply, as it is standardly done, that our time traveller cannot change the past in this way, is a petitio principii . Why is it that the time traveller is constrained in this way? What mysterious force stills his sudden suicidal rage? (Smith, 1985, 58)

The idea is that backwards time travel is impossible because if it occurred, time travellers would attempt to do things such as kill their younger selves (or their grandfathers etc.). We know that doing these things—indeed, changing the past in any way—is impossible. But were there time travel, there would then be nothing left to stop these things happening. If we let things get to the stage where the time traveller is facing Grandfather with a loaded weapon, then there is nothing left to prevent the impossible from occurring. So we must draw the line earlier: it must be impossible for someone to get into this situation at all; that is, backwards time travel must be impossible.

In order to defend the possibility of time travel in the face of this argument we need to show that time travel is not a sure route to doing the impossible. So, given that a time traveller has gone to the past and is facing Grandfather, what could stop her killing Grandfather? Some science fiction authors resort to the idea of chaperones or time guardians who prevent time travellers from changing the past—or to mysterious forces of logic. But it is hard to take these ideas seriously—and more importantly, it is hard to make them work in detail when we remember that changing the past is impossible. (The chaperone is acting to ensure that the past remains as it was—but the only reason it ever was that way is because of his very actions.) [ 15 ] Fortunately there is a better response—also to be found in the science fiction literature, and brought to the attention of philosophers by Lewis (1976). What would stop the time traveller doing the impossible? She would fail “for some commonplace reason”, as Lewis (1976, 150) puts it. Her gun might jam, a noise might distract her, she might slip on a banana peel, etc. Nothing more than such ordinary occurrences is required to stop the time traveller killing Grandfather. Hence backwards time travel does not entail the occurrence of impossible events—and so the above objection is defused.

A problem remains. Suppose Tim, a time-traveller, is facing his grandfather with a loaded gun. Can Tim kill Grandfather? On the one hand, yes he can. He is an excellent shot; there is no chaperone to stop him; the laws of logic will not magically stay his hand; he hates Grandfather and will not hesitate to pull the trigger; etc. On the other hand, no he can’t. To kill Grandfather would be to change the past, and no-one can do that (not to mention the fact that if Grandfather died, then Tim would not have been born). So we have a contradiction: Tim can kill Grandfather and Tim cannot kill Grandfather. Time travel thus leads to a contradiction: so it is impossible.

Note the difference between this version of the Grandfather paradox and the version considered above. In the earlier version, the contradiction happens if Tim kills Grandfather. The solution was to say that Tim can go into the past without killing Grandfather—hence time travel does not entail a contradiction. In the new version, the contradiction happens as soon as Tim gets to the past. Of course Tim does not kill Grandfather—but we still have a contradiction anyway: for he both can do it, and cannot do it. As Lewis puts it:

Could a time traveler change the past? It seems not: the events of a past moment could no more change than numbers could. Yet it seems that he would be as able as anyone to do things that would change the past if he did them. If a time traveler visiting the past both could and couldn’t do something that would change it, then there cannot possibly be such a time traveler. (Lewis, 1976, 149)

Lewis’s own solution to this problem has been widely accepted. [ 16 ] It turns on the idea that to say that something can happen is to say that its occurrence is compossible with certain facts, where context determines (more or less) which facts are the relevant ones. Tim’s killing Grandfather in 1921 is compossible with the facts about his weapon, training, state of mind, and so on. It is not compossible with further facts, such as the fact that Grandfather did not die in 1921. Thus ‘Tim can kill Grandfather’ is true in one sense (relative to one set of facts) and false in another sense (relative to another set of facts)—but there is no single sense in which it is both true and false. So there is no contradiction here—merely an equivocation.

Another response is that of Vihvelin (1996), who argues that there is no contradiction here because ‘Tim can kill Grandfather’ is simply false (i.e. contra Lewis, there is no legitimate sense in which it is true). According to Vihvelin, for ‘Tim can kill Grandfather’ to be true, there must be at least some occasions on which ‘If Tim had tried to kill Grandfather, he would or at least might have succeeded’ is true—but, Vihvelin argues, at any world remotely like ours, the latter counterfactual is always false. [ 17 ]

Return to the original version of the Grandfather paradox and Lewis’s ‘commonplace reasons’ response to it. This response engenders a new objection—due to Horwich (1987)—not to the possibility but to the probability of backwards time travel.

Think about correlated events in general. Whenever we see two things frequently occurring together, this is because one of them causes the other, or some third thing causes both. Horwich calls this the Principle of V-Correlation:

if events of type A and B are associated with one another, then either there is always a chain of events between them…or else we find an earlier event of type C that links up with A and B by two such chains of events. What we do not see is…an inverse fork—in which A and B are connected only with a characteristic subsequent event, but no preceding one. (Horwich, 1987, 97–8)

For example, suppose that two students turn up to class wearing the same outfits. That could just be a coincidence (i.e. there is no common cause, and no direct causal link between the two events). If it happens every week for the whole semester, it is possible that it is a coincidence, but this is extremely unlikely . Normally, we see this sort of extensive correlation only if either there is a common cause (e.g. both students have product endorsement deals with the same clothing company, or both slavishly copy the same influencer) or a direct causal link (e.g. one student is copying the other).

Now consider the time traveller setting off to kill her younger self. As discussed, no contradiction need ensue—this is prevented not by chaperones or mysterious forces, but by a run of ordinary occurrences in which the trigger falls off the time traveller’s gun, a gust of wind pushes her bullet off course, she slips on a banana peel, and so on. But now consider this run of ordinary occurrences. Whenever the time traveller contemplates auto-infanticide, someone nearby will drop a banana peel ready for her to slip on, or a bird will begin to fly so that it will be in the path of the time traveller’s bullet by the time she fires, and so on. In general, there will be a correlation between auto-infanticide attempts and foiling occurrences such as the presence of banana peels—and this correlation will be of the type that does not involve a direct causal connection between the correlated events or a common cause of both. But extensive correlations of this sort are, as we saw, extremely rare—so backwards time travel will happen about as often as you will see two people wear the same outfits to class every day of semester, without there being any causal connection between what one wears and what the other wears.

We can set out Horwich’s argument this way:

- If time travel were ever to occur, we should see extensive uncaused correlations.

- It is extremely unlikely that we should ever see extensive uncaused correlations.

- Therefore time travel is extremely unlikely to occur.

The conclusion is not that time travel is impossible, but that we should treat it the way we treat the possibility of, say, tossing a fair coin and getting heads one thousand times in a row. As Price (1996, 278 n.7) puts it—in the context of endorsing Horwich’s conclusion: “the hypothesis of time travel can be made to imply propositions of arbitrarily low probability. This is not a classical reductio, but it is as close as science ever gets.”

Smith (1997) attacks both premisses of Horwich’s argument. Against the first premise, he argues that backwards time travel, in itself, does not entail extensive uncaused correlations. Rather, when we look more closely, we see that time travel scenarios involving extensive uncaused correlations always build in prior coincidences which are themselves highly unlikely. Against the second premise, he argues that, from the fact that we have never seen extensive uncaused correlations, it does not follow that we never shall. This is not inductive scepticism: let us assume (contra the inductive sceptic) that in the absence of any specific reason for thinking things should be different in the future, we are entitled to assume they will continue being the same; still we cannot dismiss a specific reason for thinking the future will be a certain way simply on the basis that things have never been that way in the past. You might reassure an anxious friend that the sun will certainly rise tomorrow because it always has in the past—but you cannot similarly refute an astronomer who claims to have discovered a specific reason for thinking that the earth will stop rotating overnight.

Sider (2002, 119–20) endorses Smith’s second objection. Dowe (2003) criticises Smith’s first objection, but agrees with the second, concluding overall that time travel has not been shown to be improbable. Ismael (2003) reaches a similar conclusion. Goddu (2007) criticises Smith’s first objection to Horwich. Further contributions to the debate include Arntzenius (2006), Smeenk and Wüthrich (2011, §2.2) and Elliott (2018). For other arguments to the same conclusion as Horwich’s—that time travel is improbable—see Ney (2000) and Effingham (2020).

Return again to the original version of the Grandfather paradox and Lewis’s ‘commonplace reasons’ response to it. This response engenders a further objection. The autoinfanticidal time traveller is attempting to do something impossible (render herself permanently dead from an age younger than her age at the time of the attempts). Suppose we accept that she will not succeed and that what will stop her is a succession of commonplace occurrences. The previous objection was that such a succession is improbable . The new objection is that the exclusion of the time traveler from successfully committing auto-infanticide is mysteriously inexplicable . The worry is as follows. Each particular event that foils the time traveller is explicable in a perfectly ordinary way; but the inevitable combination of these events amounts to a ring-fencing of the forbidden zone of autoinfanticide—and this ring-fencing is mystifying. It’s like a grand conspiracy to stop the time traveler from doing what she wants to do—and yet there are no conspirators: no time lords, no magical forces of logic. This is profoundly perplexing. Riggs (1997, 52) writes: “Lewis’s account may do for a once only attempt, but is untenable as a general explanation of Tim’s continual lack of success if he keeps on trying.” Ismael (2003, 308) writes: “Considered individually, there will be nothing anomalous in the explanations…It is almost irresistible to suppose, however, that there is something anomalous in the cases considered collectively, i.e., in our unfailing lack of success.” See also Gorovitz (1964, 366–7), Horwich (1987, 119–21) and Carroll (2010, 86).

There have been two different kinds of defense of time travel against the objection that it involves mysteriously inexplicable occurrences. Baron and Colyvan (2016, 70) agree with the objectors that a purely causal explanation of failure—e.g. Tim fails to kill Grandfather because first he slips on a banana peel, then his gun jams, and so on—is insufficient. However they argue that, in addition, Lewis offers a non-causal—a logical —explanation of failure: “What explains Tim’s failure to kill his grandfather, then, is something about logic; specifically: Tim fails to kill his grandfather because the law of non-contradiction holds.” Smith (2017) argues that the appearance of inexplicability is illusory. There are no scenarios satisfying the description ‘a time traveller commits autoinfanticide’ (or changes the past in any other way) because the description is self-contradictory (e.g. it involves the time traveller permanently dying at 20 and also being alive at 40). So whatever happens it will not be ‘that’. There is literally no way for the time traveller not to fail. Hence there is no need for—or even possibility of—a substantive explanation of why failure invariably occurs, and such failure is not perplexing.

3. Causation

Backwards time travel scenarios give rise to interesting issues concerning causation. In this section we examine two such issues.

Earlier we distinguished changing the past and affecting the past, and argued that while the former is impossible, backwards time travel need involve only the latter. Affecting the past would be an example of backwards causation (i.e. causation where the effect precedes its cause)—and it has been argued that this too is impossible, or at least problematic. [ 18 ] The classic argument against backwards causation is the bilking argument . [ 19 ] Faced with the claim that some event A causes an earlier event B , the proponent of the bilking objection recommends an attempt to decorrelate A and B —that is, to bring about A in cases in which B has not occurred, and to prevent A in cases in which B has occurred. If the attempt is successful, then B often occurs despite the subsequent nonoccurrence of A , and A often occurs without B occurring, and so A cannot be the cause of B . If, on the other hand, the attempt is unsuccessful—if, that is, A cannot be prevented when B has occurred, nor brought about when B has not occurred—then, it is argued, it must be B that is the cause of A , rather than vice versa.

The bilking procedure requires repeated manipulation of event A . Thus, it cannot get under way in cases in which A is either unrepeatable or unmanipulable. Furthermore, the procedure requires us to know whether or not B has occurred, prior to manipulating A —and thus, it cannot get under way in cases in which it cannot be known whether or not B has occurred until after the occurrence or nonoccurrence of A (Dummett, 1964). These three loopholes allow room for many claims of backwards causation that cannot be touched by the bilking argument, because the bilking procedure cannot be performed at all. But what about those cases in which it can be performed? If the procedure succeeds—that is, A and B are decorrelated—then the claim that A causes B is refuted, or at least weakened (depending upon the details of the case). But if the bilking attempt fails, it does not follow that it must be B that is the cause of A , rather than vice versa. Depending upon the situation, that B causes A might become a viable alternative to the hypothesis that A causes B —but there is no reason to think that this alternative must always be the superior one. For example, suppose that I see a photo of you in a paper dated well before your birth, accompanied by a report of your arrival from the future. I now try to bilk your upcoming time trip—but I slip on a banana peel while rushing to push you away from your time machine, my time travel horror stories only inspire you further, and so on. Or again, suppose that I know that you were not in Sydney yesterday. I now try to get you to go there in your time machine—but first I am struck by lightning, then I fall down a manhole, and so on. What does all this prove? Surely not that your arrival in the past causes your departure from the future. Depending upon the details of the case, it seems that we might well be entitled to describe it as involving backwards time travel and backwards causation. At least, if we are not so entitled, this must be because of other facts about the case: it would not follow simply from the repeated coincidental failures of my bilking attempts.

Backwards time travel would apparently allow for the possibility of causal loops, in which things come from nowhere. The things in question might be objects—imagine a time traveller who steals a time machine from the local museum in order to make his time trip and then donates the time machine to the same museum at the end of the trip (i.e. in the past). In this case the machine itself is never built by anyone—it simply exists. The things in question might be information—imagine a time traveller who explains the theory behind time travel to her younger self: theory that she herself knows only because it was explained to her in her youth by her time travelling older self. The things in question might be actions. Imagine a time traveller who visits his younger self. When he encounters his younger self, he suddenly has a vivid memory of being punched on the nose by a strange visitor. He realises that this is that very encounter—and resignedly proceeds to punch his younger self. Why did he do it? Because he knew that it would happen and so felt that he had to do it—but he only knew it would happen because he in fact did it. [ 20 ]

One might think that causal loops are impossible—and hence that insofar as backwards time travel entails such loops, it too is impossible. [ 21 ] There are two issues to consider here. First, does backwards time travel entail causal loops? Lewis (1976, 148) raises the question whether there must be causal loops whenever there is backwards causation; in response to the question, he says simply “I am not sure.” Mellor (1998, 131) appears to claim a positive answer to the question. [ 22 ] Hanley (2004, 130) defends a negative answer by telling a time travel story in which there is backwards time travel and backwards causation, but no causal loops. [ 23 ] Monton (2009) criticises Hanley’s counterexample, but also defends a negative answer via different counterexamples. Effingham (2020) too argues for a negative answer.

Second, are causal loops impossible, or in some other way objectionable? One objection is that causal loops are inexplicable . There have been two main kinds of response to this objection. One is to agree but deny that this is a problem. Lewis (1976, 149) accepts that a loop (as a whole) would be inexplicable—but thinks that this inexplicability (like that of the Big Bang or the decay of a tritium atom) is merely strange, not impossible. In a similar vein, Meyer (2012, 263) argues that if someone asked for an explanation of a loop (as a whole), “the blame would fall on the person asking the question, not on our inability to answer it.” The second kind of response (Hanley, 2004, §5) is to deny that (all) causal loops are inexplicable. A second objection to causal loops, due to Mellor (1998, ch.12), is that in such loops the chances of events would fail to be related to their frequencies in accordance with the law of large numbers. Berkovitz (2001) and Dowe (2001) both argue that Mellor’s objection fails to establish the impossibility of causal loops. [ 24 ] Effingham (2020) considers—and rebuts—some additional objections to the possibility of causal loops.

4. Time and Change

Gödel (1949a [1990a])—in which Gödel presents models of Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity in which there exist CTC’s—can well be regarded as initiating the modern academic literature on time travel, in both philosophy and physics. In a companion paper, Gödel discusses the significance of his results for more general issues in the philosophy of time (Gödel 1949b [1990b]). For the succeeding half century, the time travel literature focussed predominantly on objections to the possibility (or probability) of time travel. More recently, however, there has been renewed interest in the connections between time travel and more general issues in the metaphysics of time and change. We examine some of these in the present section. [ 25 ]

The first thing that we need to do is set up the various metaphysical positions whose relationships with time travel will then be discussed. Consider two metaphysical questions:

- Are the past, present and future equally real?

- Is there an objective flow or passage of time, and an objective now?

We can label some views on the first question as follows. Eternalism is the view that past and future times, objects and events are just as real as the present time and present events and objects. Nowism is the view that only the present time and present events and objects exist. Now-and-then-ism is the view that the past and present exist but the future does not. We can also label some views on the second question. The A-theory answers in the affirmative: the flow of time and division of events into past (before now), present (now) and future (after now) are objective features of reality (as opposed to mere features of our experience). Furthermore, they are linked: the objective flow of time arises from the movement, through time, of the objective now (from the past towards the future). The B-theory answers in the negative: while we certainly experience now as special, and time as flowing, the B-theory denies that what is going on here is that we are detecting objective features of reality in a way that corresponds transparently to how those features are in themselves. The flow of time and the now are not objective features of reality; they are merely features of our experience. By combining answers to our first and second questions we arrive at positions on the metaphysics of time such as: [ 26 ]

- the block universe view: eternalism + B-theory

- the moving spotlight view: eternalism + A-theory

- the presentist view: nowism + A-theory

- the growing block view: now-and-then-ism + A-theory.

So much for positions on time itself. Now for some views on temporal objects: objects that exist in (and, in general, change over) time. Three-dimensionalism is the view that persons, tables and other temporal objects are three-dimensional entities. On this view, what you see in the mirror is a whole person. [ 27 ] Tomorrow, when you look again, you will see the whole person again. On this view, persons and other temporal objects are wholly present at every time at which they exist. Four-dimensionalism is the view that persons, tables and other temporal objects are four-dimensional entities, extending through three dimensions of space and one dimension of time. On this view, what you see in the mirror is not a whole person: it is just a three-dimensional temporal part of a person. Tomorrow, when you look again, you will see a different such temporal part. Say that an object persists through time if it is around at some time and still around at a later time. Three- and four-dimensionalists agree that (some) objects persist, but they differ over how objects persist. According to three-dimensionalists, objects persist by enduring : an object persists from t 1 to t 2 by being wholly present at t 1 and t 2 and every instant in between. According to four-dimensionalists, objects persist by perduring : an object persists from t 1 to t 2 by having temporal parts at t 1 and t 2 and every instant in between. Perduring can be usefully compared with being extended in space: a road extends from Melbourne to Sydney not by being wholly located at every point in between, but by having a spatial part at every point in between.

It is natural to combine three-dimensionalism with presentism and four-dimensionalism with the block universe view—but other combinations of views are certainly possible.

Gödel (1949b [1990b]) argues from the possibility of time travel (more precisely, from the existence of solutions to the field equations of General Relativity in which there exist CTC’s) to the B-theory: that is, to the conclusion that there is no objective flow or passage of time and no objective now. Gödel begins by reviewing an argument from Special Relativity to the B-theory: because the notion of simultaneity becomes a relative one in Special Relativity, there is no room for the idea of an objective succession of “nows”. He then notes that this argument is disrupted in the context of General Relativity, because in models of the latter theory to date, the presence of matter does allow recovery of an objectively distinguished series of “nows”. Gödel then proposes a new model (Gödel 1949a [1990a]) in which no such recovery is possible. (This is the model that contains CTC’s.) Finally, he addresses the issue of how one can infer anything about the nonexistence of an objective flow of time in our universe from the existence of a merely possible universe in which there is no objectively distinguished series of “nows”. His main response is that while it would not be straightforwardly contradictory to suppose that the existence of an objective flow of time depends on the particular, contingent arrangement and motion of matter in the world, this would nevertheless be unsatisfactory. Responses to Gödel have been of two main kinds. Some have objected to the claim that there is no objective flow of time in his model universe (e.g. Savitt (2005); see also Savitt (1994)). Others have objected to the attempt to transfer conclusions about that model universe to our own universe (e.g. Earman (1995, 197–200); for a partial response to Earman see Belot (2005, §3.4)). [ 28 ]

Earlier we posed two questions:

Gödel’s argument is related to the second question. Let’s turn now to the first question. Godfrey-Smith (1980, 72) writes “The metaphysical picture which underlies time travel talk is that of the block universe [i.e. eternalism, in the terminology of the present entry], in which the world is conceived as extended in time as it is in space.” In his report on the Analysis problem to which Godfrey-Smith’s paper is a response, Harrison (1980, 67) replies that he would like an argument in support of this assertion. Here is an argument: [ 29 ]

A fundamental requirement for the possibility of time travel is the existence of the destination of the journey. That is, a journey into the past or the future would have to presuppose that the past or future were somehow real. (Grey, 1999, 56)

Dowe (2000, 442–5) responds that the destination does not have to exist at the time of departure: it only has to exist at the time of arrival—and this is quite compatible with non-eternalist views. And Keller and Nelson (2001, 338) argue that time travel is compatible with presentism:

There is four-dimensional [i.e. eternalist, in the terminology of the present entry] time-travel if the appropriate sorts of events occur at the appropriate sorts of times; events like people hopping into time-machines and disappearing, people reappearing with the right sorts of memories, and so on. But the presentist can have just the same patterns of events happening at just the same times. Or at least, it can be the case on the presentist model that the right sorts of events will happen, or did happen, or are happening, at the rights sorts of times. If it suffices for four-dimensionalist time-travel that Jennifer disappears in 2054 and appears in 1985 with the right sorts of memories, then why shouldn’t it suffice for presentist time-travel that Jennifer will disappear in 2054, and that she did appear in 1985 with the right sorts of memories?

Sider (2005) responds that there is still a problem reconciling presentism with time travel conceived in Lewis’s way: that conception of time travel requires that personal time is similar to external time—but presentists have trouble allowing this. Further contributions to the debate whether presentism—and other versions of the A-theory—are compatible with time travel include Monton (2003), Daniels (2012), Hall (2014) and Wasserman (2018) on the side of compatibility, and Miller (2005), Slater (2005), Miller (2008), Hales (2010) and Markosian (2020) on the side of incompatibility.

Leibniz’s Law says that if x = y (i.e. x and y are identical—one and the same entity) then x and y have exactly the same properties. There is a superficial conflict between this principle of logic and the fact that things change. If Bill is at one time thin and at another time not so—and yet it is the very same person both times—it looks as though the very same entity (Bill) both possesses and fails to possess the property of being thin. Three-dimensionalists and four-dimensionalists respond to this problem in different ways. According to the four-dimensionalist, what is thin is not Bill (who is a four-dimensional entity) but certain temporal parts of Bill; and what is not thin are other temporal parts of Bill. So there is no single entity that both possesses and fails to possess the property of being thin. Three-dimensionalists have several options. One is to deny that there are such properties as ‘thin’ (simpliciter): there are only temporally relativised properties such as ‘thin at time t ’. In that case, while Bill at t 1 and Bill at t 2 are the very same entity—Bill is wholly present at each time—there is no single property that this one entity both possesses and fails to possess: Bill possesses the property ‘thin at t 1 ’ and lacks the property ‘thin at t 2 ’. [ 30 ]

Now consider the case of a time traveller Ben who encounters his younger self at time t . Suppose that the younger self is thin and the older self not so. The four-dimensionalist can accommodate this scenario easily. Just as before, what we have are two different three-dimensional parts of the same four-dimensional entity, one of which possesses the property ‘thin’ and the other of which does not. The three-dimensionalist, however, faces a problem. Even if we relativise properties to times, we still get the contradiction that Ben possesses the property ‘thin at t ’ and also lacks that very same property. [ 31 ] There are several possible options for the three-dimensionalist here. One is to relativise properties not to external times but to personal times (Horwich, 1975, 434–5); another is to relativise properties to spatial locations as well as to times (or simply to spacetime points). Sider (2001, 101–6) criticises both options (and others besides), concluding that time travel is incompatible with three-dimensionalism. Markosian (2004) responds to Sider’s argument; [ 32 ] Miller (2006) also responds to Sider and argues for the compatibility of time travel and endurantism; Gilmore (2007) seeks to weaken the case against endurantism by constructing analogous arguments against perdurantism. Simon (2005) finds problems with Sider’s arguments, but presents different arguments for the same conclusion; Effingham and Robson (2007) and Benovsky (2011) also offer new arguments for this conclusion. For further discussion see Wasserman (2018) and Effingham (2020). [ 33 ]

We have seen arguments to the conclusions that time travel is impossible, improbable and inexplicable. Here’s an argument to the conclusion that backwards time travel simply will not occur. If backwards time travel is ever going to occur, we would already have seen the time travellers—but we have seen none such. [ 34 ] The argument is a weak one. [ 35 ] For a start, it is perhaps conceivable that time travellers have already visited the Earth [ 36 ] —but even granting that they have not, this is still compatible with the future actuality of backwards time travel. First, it may be that time travel is very expensive, difficult or dangerous—or for some other reason quite rare—and that by the time it is available, our present period of history is insufficiently high on the list of interesting destinations. Second, it may be—and indeed existing proposals in the physics literature have this feature—that backwards time travel works by creating a CTC that lies entirely in the future: in this case, backwards time travel becomes possible after the creation of the CTC, but travel to a time earlier than the time at which the CTC is created is not possible. [ 37 ]

- Adams, Robert Merrihew, 1997, “Thisness and time travel”, Philosophia , 25: 407–15.