Appointments at Mayo Clinic

Foot swelling during air travel: a concern, what causes leg and foot swelling during air travel.

Leg and foot swelling during air travel is common. It's usually harmless. The most likely reason for it is sitting for a long time without moving during a flight.

Sitting with the feet on the floor for a long time causes blood to pool in the leg veins. The position of the legs while seated also increases pressure in the leg veins. This plays a role in swelling by causing fluid to leave the blood and move into the surrounding soft tissues.

A dangerous blood clot called deep vein thrombosis (DVT) sometimes causes leg swelling. But the risk of getting DVT on an airplane is very low for healthy people, especially on flights that last under four hours. In general, the chance of getting DVT starts to rise on flights over 12 hours.

You can reduce foot and leg swelling, and lower your risk of blood clots, by wearing compression stockings on a long flight. The stockings apply pressure to the lower legs.

If you notice swelling in one leg that doesn't go away or starts within two weeks of a long flight, get a health care checkup right away. The swelling might be a symptom of DVT or another condition that needs treatment. If you have a higher risk of blood clots, talk with a member of your health care team before you fly.

John M. Wilkinson, M.D.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Hand swelling during exercise: A concern?

- Clarke MJ, et al. Compression stockings for preventing deep vein thrombosis in airline passengers (review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021; doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004002.pub4.

- Douketis JD, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in adult travelers. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed June 27, 2023.

- Blood clots and travel: What you need to know. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/travel.html. Accessed June 27, 2023.

- AskMayoExpert. Health considerations for air travelers. Mayo Clinic; 2022.

- Jong EC. Jet health. Travel and Tropic Medicine Manual. Elsevier; 2017. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed June 27, 2023.

- Smith CC. Clinical manifestations and evaluation of edema in adults. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed June 27, 2023.

- The effect of compression stocking on leg edema and discomfort during a 3-hour flight: A randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2019; doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2019.01.013.

- Nishmura N, et al. Gravity-induced lower-leg swelling can be ameliorated by ingestion of α-glucosyl hesperidin beverage. Frontiers in Physiology. 2021; doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.670640.

- Wilkinson JM (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. July 4, 2023.

Products and Services

- Available Compression Products from Mayo Clinic Store

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Mitral valve clip to treat mitral regurgitation: Bob's story

- Mitral valve overview

- Chronic sinusitis

- Cold urticaria

- Compression bandaging

- Mitral valve regurgitation

- Myocarditis

- Robotic heart surgery treats mitral regurgitation: Ed's story

- Scleroderma

- Symptom Checker

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Foot swelling during air travel A concern

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

10 Ways to Avoid Swollen Feet and Ankles During Travel

Cramped seats, salty snacks, and long periods of sitting are a recipe for uncomfortable swelling. But these expert tips can help you prevent discomfort and deal if you experience the condition.

When you fly, you're trapped in a tiny seat in an enclosed area without much room to move — so it’s no wonder you may land with swollen feet. And although leg and foot swelling during air travel is common and typically harmless, per the Mayo Clinic , it can still put an uncomfortable damper on your travel plans.

Luckily, there are things you can do to prevent it. Here, three doctors share their tips on how to avoid swollen feet and ankles during air travel and what you can do if you do experience some swelling.

Why Do Your Feet Swell When You Fly?

It comes down to inactivity during flights, says Lauren Wurster, a doctor of podiatric medicine and an Arizona-based podiatrist and spokesperson for the American Podiatric Medical Association (APMA) . “The longer you are sitting still, the more gravity pulls fluid down to your feet and ankles,” she explains. “Also, the position you are sitting in, with your legs bent, increases the pressure on the veins and increases swelling.”

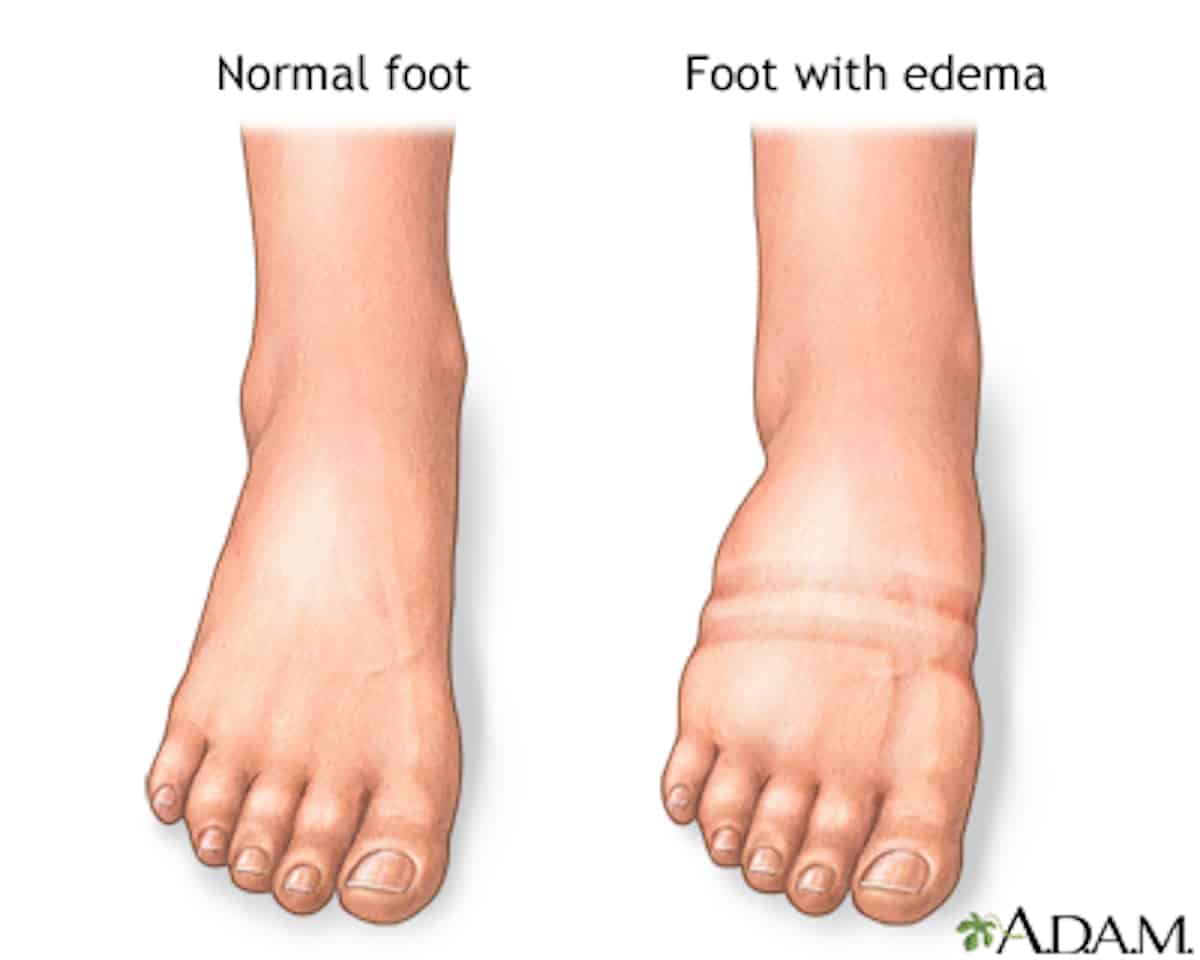

When sitting, the muscles that help pump fluid out of your legs are not active, says Timothy Ford , a doctor of podiatric medicine and an associate professor in the department of orthopedics at the University of Louisville School of Medicine. As a result, blood may pool in your feet, leading to swelling, medically known as edema.

Travel day habits can also contribute to feet swelling, says Todd Taylor, MD , an associate professor at Emory University’s department of emergency medicine. “As we travel, we tend to eat in restaurants, eat snacks, and consume other processed foods high in salt. This will raise our salt level in our body, increasing the fluid and again contributing to dependent edema [leg swelling].”

Finally, Dr. Wurster notes, there are certain health conditions that can cause swelling in your legs or feet regardless of your altitude, including heart, liver, thyroid, and kidney conditions; pregnancy; and venous insufficiency. (That said, if minor swelling occurs only during air travel, it’s more likely due to the lack of mobility in your legs than an underlying medical concern.)

Fortunately, there are steps you can take to reduce the likelihood of leg swelling during travel and potentially reduce swelling when it happens. Read on for the experts’ tips.

10 Ways to Prevent Swollen Feet During Travel

1. drink water throughout your travels.

Even though it might feel counterintuitive to add more fluids to your body when it’s retaining fluid, the Cleveland Clinic notes that drinking more water can help clear your system of excessive sodium, which contributes to fluid retention . Drink plenty of water the day before and the day of the trip so that you don't start out dehydrated. Bring a big bottle of water with you on the plane, and refill it as needed to stay hydrated. Another plus to drinking a lot of water: It’ll motivate you to get up and walk to the bathroom when nature calls.

2. Watch Your Diet and Avoid Salty Foods

Avoid salt as much as possible on the day of and even the day before. Salt can cause you to retain fluid, notes the Mayo Clinic , which can make your feet swell even more.

3. Reach for a Pair of Compression Socks

Your flight day outfit should include compression socks that reach up to your knees. “I really love this one as they are really effective,” says Dr. Taylor. And these days, they don’t have to be boring! Endurance athletes use compression socks during and after racing, so you can find cool colors and patterns. The APMA also offers a list of its approved socks and hosiery . “Avoid normal socks that constrict above the ankle," suggests Ford.

4. Stretch Your Legs on Long Flights

If possible, get up to walk the aisle every hour or so, especially on flights over two hours, recommends Dr. Ford. Standing or walking to the bathroom can get your blood flowing and help combat swelling.

5. Give Your Feet a Seated Workout

Even when you can't get up and walk around, you can work the muscles in your feet. Point your toes up and down, then side to side to get your feet moving. The focus here is flexing the muscles in your feet, calves, and legs to get them engaged after a long period of inactivity, says Wurster.

6. Stow Bags Overhead to Maximize Legroom

If your feet are fighting for space with your carry-on bags, they'll be cramped even more into awkward positions that cut off the blood supply. Store your bags overhead.

7. Don't Cross Your Legs

Your circulation is already slower when you're sitting for hours, so don't cut it off even more by crossing your legs. ( Past research has also suggested crossing the leg at the knee results in a significant increase in blood pressure for people with hypertension.)

8. Shift Positions Regularly While Seated

The position of your legs when you are seated increases pressure in your leg veins, explains the Mayo Clinic, so don’t stay locked in one position for too long. Wurster advises shifting your seated position frequently to avoid being in one position for too long.

9. Elevate Your Feet to Help Blood Flow Return

Keeping your legs raised can help improve circulation, per the Cleveland Clinic . Wherever possible, try to raise your legs and feet; if there's no one next to you, stretch out and prop your feet up across the seats.

10. Opt for Comfy and Practical Footwear

Ford recommends wearing slip-on shoes on travel days because “they can be removed easily and allow you to massage your feet or exercise your feet." A foot massage could help stimulate blood flow — just be conscious of your neighbors. (This might be one tip to save for a road trip rather than a crowded plane.)

How to Reduce Swelling in Feet After Travel

Once you’ve landed, you can use a lot of the same tools to reduce swelling after your travel: “Stay hydrated, move around, and wear compression socks,” says Wurster. “Also, be mindful of what you're eating and avoid foods too high in sodium because that can also add to further swelling.”

If you can’t move around, elevating your legs after traveling can also help, says Taylor. Use gravity to your advantage and prop your feet up to help your circulation move that blood around. For those who can manage it, the Cleveland Clinic recommends a yoga pose called Viparita Karani, where you lay with your back on the ground perpendicular to a wall and then press your legs up against the wall. (Steer clear of this pose if you’re living with uncontrolled high blood pressure, glaucoma , congestive heart failure , kidney failure, or liver failure, though.)

When Should You See a Doctor About Swollen Feet and Legs?

“Usually, the swelling isn't serious and will improve with activity after the flight lands,” says Wurster. “However, in long periods of travel and with people with certain risk factors, the swelling can be a sign of a blood clot in the calf, also known as a deep vein thrombosis . This can be very serious if not treated appropriately.”

Wurster and Taylor say any of these red flags would be a reason to go to the nearest emergency department for an evaluation:

- Severe leg swelling

- One leg bigger than the other

- Swelling, pain, redness, and warmth to one of the calves

- Shortness of breath

MORE TIME TO TRAVEL

Explore new places and savor new tastes

Swollen Ankles When Flying: 8 Questions and Answers

Have you ever gotten off a plane, looked down at your swollen legs after flying — and become alarmed at their size?

Rest assured. It’s usually not a serious problem if it is time-limited.

Swollen ankles, feet, and legs are common among travelers—especially older ones. With aging, many people tend to experience leg and foot swelling due to excess fluid buildup in the tissues.

“Edema” is the medical term for this condition. Colloquially, some people call them “flight feet.”

Although temporary, swollen legs can be more than unattractive.

Depending on the extent of the swelling, you may experience discomfort from the stretching of your skin, or have a tough time getting your shoes back on (if you’ve taken them off during a flight).

This post may contain affiliate links. This means that I may receive compensation if you click a link, at no additional cost to you. For more information, please read my privacy and disclosure policies at the end of this page.

Jump ahead to...

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS ABOUT SWOLLEN ANKLES WHEN FLYING

What causes leg swelling when you’re flying?

The amount of legroom on flights seems to be constantly shrinking.

And depending on the placement of your seat and the pattern of turbulence, it can be difficult to get up and stretch, especially on long-haul flights (four hours or more) or lights-out overnight flights across the ocean.

Being seated in one fixed position in a cramped space for a long period of time causes fluid to leave the blood and move into surrounding tissues.

Is swelling more prevalent with age?

Aging makes many things more complicated, including leg swelling.

Older people are prone to experience more significant swelling and tightness after long flights than younger people for a variety of age-related reasons.

For example, their veins don’t circulate blood as well as they used to, and they are more likely to be taking certain prescribed medications (e.g., blood pressure-lowering medications like calcium channel blockers).

What can you do to prevent swollen ankles when flying?

There are a number of common sense ways to prevent or reduce swollen legs and ankles on long flights:

- Maintain a healthy body weight,

- Seek out flights and seats with more legroom, when possible,

- Limit salt intake on the day of and during the flight (I always wonder why airlines offer pretzels and salted peanuts with drinks),

- Keep hydrated and avoid excessive alcohol intake,

- Avoid caffeine intake as well, and while it may seem counterintuitive, try to increase water intake,

- Opt for loose, non-binding clothing and shoes that easily slip off (I love this pair of Skechers because they are lightweight and easy to get on an off),

- Wear compression stockings (see below),

- Remove your shoes when it’s safe to do so,

- Avoid keeping your legs crossed for long periods of time,

- Wiggle your toes and move your legs in circles during the flight, and tighten and loosen your leg muscles,

- To improve blood flow, several airlines recommend pulling each knee to your chest and holding it there for 15 seconds, repeating this up to 10 times (CDC, Clots During Travel , accessed 10/17/23).

- Get up, move, and walk up and down the aisle several times during the flight (your bladder will thank you, too).

What do I need to know about compression socks for swollen ankles when flying?

A systematic Cochrane literature review looked at the effects of wearing compression socks on flights of at least four hours duration.

It concluded with high certainty that the use of compression socks had a substantial impact on lowering the incidence of symptomless DVT and lower certainty evidence that it reduced edema of the lower legs.

Healthline describes three different types of compression socks:

- Graduated compression socks, usually prescribed by a healthcare professional

- Nonmedical support hosiery (intended to provide support and improve circulation), widely available in stores and online

- Anti-embolism stockings , also prescribed by a professional, are intended to prevent DVT .

Although compression socks aren’t likely to pose problems for most individuals, wearers do need to be cautious of potential skin problems (burning, chafing, bruising, and broken skin) that can lead to infections and any signs of impaired circulation on a long flight.

Getting them on can be challenging too, but practice makes perfect. Doctors recommend getting used to them by wearing them for a few hours at first and gradually increasing the time you wear them.

We recently learned about zip-up compression socks that take the pain out of trying to get them on and off. Another alternative is to ask your spouse or travel companion for help.

Does recent surgery increase the risk of DVTs?

Evidence suggests that long-distance air travel post-surgery (e.g., hip and knee replacements) can increase the risk of leg blood clots.

Therefore, it is essential for travelers to consult their physician concerning how soon after surgery they can safely fly and what precautions they should take to minimize the risk of DVT when they do.

In general or orthopedic surgery settings, research on the efficacy of graduated compression socks has been shown to be a literal lifesaver.

A meta-analysis of 19 studies involving 1681 individuals found them effective in lowering the risk of DVT in hospitalized patients. More effectiveness research needs to be conducted on outpatients.

Is the use of aspirin recommended to prevent blood clots?

An article in AFAR notes that there is no available data to suggest that travelers take aspirins to prevent blood clots on long-haul flights.

However, taking into account an individual patient’s health history and risk factors (e.g., gastrointestinal bleeding), some doctors might recommend its use or prescribe an anticoagulant drug to prevent blood clots. As noted above, the risk of DVT may be elevated after recent surgery.

But it is always advisable to check with your physician before taking aspirin before flying.

If your legs swell after flying, what can you do afterward?

- If your legs, ankles or feet are swollen after getting off the plane, it’s wise to take off your shoes and elevate your legs (above your heart) to lessen the swelling.

- It also could be useful to soak your legs in lukewarm water, or gently massage them once you get to your destination.

- Try to minimize eating foods with excessive salt until you see the swelling of your ankles and/or legs go down.

Is leg swelling dangerous?

According to a recent publication from the Mayo Clinic , swelling caused by inactivity during travel (e.g. on planes or long car rides) is usually harmless .

When to seek medical attention for leg swelling

However, it is prudent to seek medical attention if you experience any of the following, especially if the swelling is frequent and persistent:

- Swelling that is red or warm to the touch (this could be a sign of a clot),

- Pain, tenderness or swelling only in one leg (as opposed to both),

- Any chest pain associated with swelling, and

- Swelling that doesn’t dissipate after several hours of activity.

- Mayo Clinic: What causes leg and foot swelling during travel?

- Healthy Advice: Preventing DVT when traveling

- Medline Plus: Foot, leg and ankle swelling

- PubMed: Prevention of edema, flight microangiopathy and venous thrombosis in long flights with elastic stockings

- Medical News Today: What can cause socks to leave marks on legs?

- Centers for Disease Control: Clots During Travel

A Mini-Guide to Compression Socks

What to look for when buying compression socks.

- Make sure they offer the correct amount of compression recommended by a healthcare professional

- Find your correct size to ensure a good fit (including calf width); most vendors provide sizing guides

- Choose breathable, moisture-wicking materials

- Read the return policy in case the compression socks don’t fit or aren’t comfortable

- To maintain them at their best, wash them in a mesh laundry bag and let them air-dry

- Remove them at bedtime and never weak them to sleep

Benefits of Compression Socks

- Reduce pain, swelling and inflammation

- Help prevent fluids from pooling in the feet and ankles

- Promote increased flow toward the heart

- Help prevent blood clots and embolisms

Lily Trotter Wide-Calf Compression Socks for Women

The Lily Trotter line of socks comes in a number of great looks and sizes.

The idea of designed compression socks may sound like an oxymoron but women no longer have to sacrifice fashion for fitness. These athletic support socks are made with graduated compression measured at 15-20 mmHg.

READ MORE OR PURCHASE

Hi Clasmix Medical Grade Compression Socks for Men & Women

These knee-highs offer graduated compression at 20-30 mmHg and come in a variety of sizes and colors.

With more than 40,000 ratings, they are a best seller on Amazon.

Jobst Unisex Relief Stockings

These medical grade 20-30 mmHg compression socks come with a closed-toe style that offers a roomy toe allowance for those who want extra wiggle room.

They also come in an open-toe version for even more toe room and in graduated compression at 30-40 mmHg.

Also on MoreTimeToTravel:

Ever find a rash around your ankles when traveling in warm climates or taking long walks? Read on:

Golfers Vasculitis: A Common But Often Misdiagnosed Boomer Travel Malady

Save to Pinterest!!

Similar Posts

The sharing economy has changed the face of travel

In a phenomenon dubbed the “sharing economy” or “peer-to-peer marketplace,” Americans are traveling in ways that were virtually unheard of a decade ago.

Traveling with Friends: Always popular but on the upswing

Traveling with friends is nothing new but because of the confluence of demographics and economics, it’s a phenomenon that appears to be gaining popularity across all age groups

Lounge Review: Airspace Lounge at JFK Terminal 5

You have to look hard to find the Airspace Lounge at JFK airport in NYC. The only lounge in Terminal 5 is tucked in a space at its far end, across from Gates 24 and 25.

How to tag your bag…and give it personality

I wrote this short piece about how to tag your bag a while ago for the Chicago Tribune that seems to have stood the test of time. It’s still important to tag it, especially if you are planning holiday travel! Fire-engine red and royal blue may be the new black, but it’s still pretty tough…

Foolproof Tips For Fighting Jet Lag

Experiencing jet lag is almost inevitable after most long haul flights but there are some simple ways to minimize the effects.

Take the MTA Bus: Best Senior Travel Bargain in NYC

You might have called me a bus snob. I hadn’t used an MTA bus in NYC since my college days. But after depending on city buses exclusively last week, I’ll tell you why I prefer them.

20 Comments

Excellent article! This just became an issue with me. Now I swear by compression socks and re-hydration products in addition to lots of water.

I’m curious…what kind of re-hydration products do you use?

Maintaining a healthy body weight is probably the one piece of advice that may be difficult to achieve on the fly—so to speak. 😉 I’ve definitely noticed that it’s harder to slip my shoes back on after a flight.

Yes, that’s a battle to be waged on the ground!:-)

Maintaining a healthy body weight is most important. My feet and ankles used to swell on long road trips, so I began stopping every hour or so to walk around to prevent this. Now I can do a 6 hour drive with one stop and my ankles don’t swell at all.

My doctor told me there’s usually no worry if both of your ankles swell. The time to be concerned is if only one side is swollen because it could be a sign of something else more serious like a blood clot.

Good advice from your doc! Congratulations on your weight loss. You’re more fit to travel!

Very helpful, thank you. It happened to me once on a cruise and just recently on a 4-hour fight. For me getting my feet above my heart always works. That and loads of water. –MaryGo

People make the mistake of thinking that cruises are sedentary but most travelers do far much more walking and standing than they usually do.

Your timing is epic. This has never happened to me before except just a few days ago. We took a red eye from Kauai (used miles, you take what you can) I noticed that both of my feet were swollen in the car on the way home. Kind of freaked me out! Since is was an overnight flight, I only got up once. I also crossed my legs a great deal. I won’t let this happen again.

You look like a leg-crosser!;-)

Great article Irene! I’m a huge believer in compression socks and wear them on all flights. I even use them for trade-shows or all day walking they make a big difference.

You are one of the few. Many people dread putting them on.

So far — knock on wood — I’ve been lucky and never had swollen ankles. I always drink a lot of water on flights, and, of course, that means I make multiple trips to the toilet, which lets me stretch a bit. And in most planes I’m too tall to be able to cross my legs, so I don’t do that either. Thanks for the tips, though. I suppose it’s just a matter of time till this starts happening to me too on long flights!

I think genetics makes some people more prone than others. You may be among one of the lucky ones!

What a great article people often avoid writing about these things as they think they are not interesting. Will bookmark for our next flight great tips to help stop the cursed swollen ankles.

Hope it helps!

My sister-in-law always gets swollen ankles on even a relatively short flight (3-1/2 hours) but not on much longer road trips of several hundred kilometres. She does everything possible – excercises; walking, elevation of legs, etc. – but nothing works. She said that as soon as she comes back home the swelling goes down. I was a bit dubious, until this happened to me also. Long car trips cause a little edema, but a 33-4 hour flight has my ankles and feet hugely swollen, and staying like that for days and days. When I came home, all of the swelling had gone by the next morning. So, I’m not sure that it has a great deal to do with inactivity.

“Being seated in one fixed position in a cramped space for a long period of time causes fluid to leave the blood and move into surrounding tissues.”

This is more likely to occur in a plane than a car because there is less space and opportunity to move around. It’s important to wiggle your toes, move your feet, and stand up and walk around, whenever possible.

How can you keep hydrated when every small bottle of water costs £2. You cannot take any water onto the plane for”security ” reasons

Most airlines provide beverage service with water. You can also purchase a large bottle of water after you pass through security.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Free shipping over $75 USD

Get the most effective travel essentials here.

Learn about our story and our products.

- Try FLIGHTFŪD We're currently experiencing turbulence

Your carry on baggage

Free US Shipping on Orders $39+

Before you take off, we think you may also love this.

Water Bottle

- Try FLIGHTFŪD

- Swelling When Traveling? Here’s Why It Happens + What to Do

Jet lag , bloating , and a reduced immune system are all unfortunate but well-known side effects of travel.

But there’s another common and equally annoying side effect: swelling.

If you’re a frequent flyer, you’ve likely been a victim of swelling at some point. Swollen feet after a long flight, swollen face after the loss of sleep , or swollen fingers from the heat of a tropical destination have probably happened to you before.

Swelling happens to us all differently, and it can be hard to predict when and where it will happen. This article will cover why swelling when traveling happens and 10 ways to prevent or treat it on your next trip.

Article Guide

Why does swelling happen when you travel, the effects of swelling on your body and your health, how to prevent swelling when traveling, where does swelling happen when traveling, the best ways to relieve swelling when traveling.

Swelling, also called edema, happens when fluids in the body pool in certain areas, causing them to become temporarily larger.

Sometimes swelling is mild and may go away on it’s own in a few hours. Other times it can be uncomfortable and lead to other problems.

While swelling can happen to the body anytime, traveling puts your body through specific conditions that trigger it.

To prevent swelling, we need to understand why it happens when we travel. These are the main travel related causes of swelling in the body.

#1. Swelling from Flying

Swelling is most common for travelers when they are flying.

Those long hours spent sitting in your cabin chair causes blood to pool into your feet and ankles, also known as gravitational edema.

It happens when you are in an upright position for a long time, but aren’t moving.

The result is swollen feet that may even make wearing shoes uncomfortable.

The lower air pressure and humidity inflight also promotes dehydration, which causes your body to retain water and swell.

Read More : Does Flying Dehydrate You? Your Guide to Air Travel Hydration

#2. Your Body Adjusting to a Sudden Change in Climate

Another common cause for swelling while traveling is that your body has to adjust to a sudden change in temperature and climate.

If you aren’t used to hot or humid climates, or you’re flying from winter into a tropical place, swelling in the limbs can happen.

It can affect any body part, from the face, hands, feet, arms or legs to your fingers and toes. This explains why so many travelers find it difficult to remove their rings during and after a trip to a warm-weather destination.

#3. Changes in Diet from Travel

One of the challenges of travel (and why FLIGHTFUD exists!) is that access to high-quality, healthy foods is so limited in airports and on most flights.

While most airlines are improving their food options, historically, airplane food is known to be sodium-filled and made from unhealthy ingredients that can make you bloated and feel swollen in both the face and tummy.

Most people eat more healthfully at home then they do when traveling partially because of the lack of access to nutrient-rich foods. So your diet when you’re going places tends to differ from your normal eating patterns.

This can cause swelling as your digestive system and cells attempt to deal with the onslaught of nutrient-depleted, carbohydrate-heavy travel options.

Plus, if the cuisine in your destination is saltier or heavier than your usual diet, your body will retain water and the dreaded face swelling can happen.

Generally, swelling is harmless and not life-threatening.

Most travelers and frequent flyers will experience mild swelling at some point on their travels. Once relieved, they can go on enjoying their trip as usual.

But sometimes swelling can lead to other issues.

Foot and ankle swelling can make wearing your shoes unbearable, and in some cases it can be uncomfortable to walk for days.

In extreme cases, the swelling can become a serious condition.

If swelling doesn’t go down within a few days after a flight, you seek medical attention. In rare cases, it can even lead to blood clotting. Thankfully, this is very rare and there are loads of ways you can prevent swelling from becoming serious, or from happening at all.

The best way to deal with swelling is to avoid it in the first place.

Here are some key tips on how to lower your chances of experiencing this unfavorable part of travel.

#1. Stay Hydrated

Cabin air on your flight is dryer than the Sahara desert, because it needs to be.

The dry air can lead to dehydration than you’d think.

Among keeping other crucial bodily processes running smoothly, water is vital to keeping your blood circulation from slowing, which is a culprit of swelling.

Since dehydration is such a prevalent travel side-effect that leads to so many other impaired bodily processes and symptoms, it’s crucial to stay hydrated and drink plenty of water before and during your flight.

This is why we developed Flight Elixir as a drink mix . We could have made it in any other form, but we wanted to encourage travelers to stay hydrated.

Ideally, you’ll drink the equivalent of 1, 8-oz glass of water for each in-flight hour.

Once at your destination, keep your Travel Water Bottle on hand so you can stay hydrated and can track how much water you’re drinking.

#2. Wear Loose Clothing

Besides being incredibly uncomfortable, wearing tight clothing, especially jeans or anything that constricts your mid-section, can impair blood circulation which is necessary for keeping fluids flowing in your body and preventing swelling.

This can lead to swelling in the lower body.

Skip the jeans and restrictive clothing and opt for joggers, leggings, or loose-fitting pants to avoid this. Tight shoes and socks should be avoided as well.

#3. Avoid Salty Food

Airplane food is notorious for being salty and just not very healthy overall.

You don’t have to go on a food strike while you fly, but it’s wise to avoid stopping at the convenience store on your way through the airport to grab even more salty snacks. In flight, this means avoiding the peanuts, chips, and pretzels that are commonly given on-board.

While in your destination, it may be harder to say no to the cuisine. After all, a big part of travel is trying new food! But it does pay to be mindful of what you eat, and try to avoid mindlessly snacking.

#4. Drink Alcohol Wisely

One of the best parts about flying is that you can sit back, relax, and order a drink. And we’re realistic. We’re not going to tell you to avoid the inflight indulgences.

Just be aware that alcohol dehydrates your body, which is the main reason you might experience a headache when you overindulge the night before. In response, your body may also react by retaining fluids.

Alcohol depresses the nervous system as well, which can make you more likely to fall asleep in a bad sitting position in-flight after a few drinks, which may cause ankle and foot swelling.

So while we’re not saying you have to skip the wine, definitely consume your spirits wisely inflight (and in general).

Drink in moderation, and drink an extra glass of water for each drink.

It doesn’t hurt to ensure you’re drinking your Flight Elixir as well; with coconut water crystals for electrolytes and vitamins to support your body while you travel, we’ve stacked it with the ingredients you need to help you balance your body.

#5. Come Prepared

Travel can be hard on the body . It promotes dehydration, impairs circulation and exposes you to pollutants which have negative health impacts.

Boost your body’s immunity and function by bringing your own micronutrient supplements.

We’ve created our own all-in-one Flight Elixir made to support the body’s specific needs during travel, with ingredients such as papaya for bloating and indigestion and goji berry, which dilate blood vessels promoting optimal circulation and blood flow.

Another supplement to consider bringing is probiotics, which promote gut health. This will help lessen the impacts of swelling from the foreign food. Omega-3 is also known to be an effective anti-inflammatory to reduce swelling and pain.

Swelling can happen anywhere on the body depending on the cause.

Flying usually leads to swelling in the ankles and feet, while a new travel diet can lead to swelling in the stomach and face. If the weather or change in climate is the cause of swelling, it can happen anywhere in the body, from the neck, limbs, or even hands.

If you do experience swelling during your travels, there are a few ways to find relief quickly. Here are some key tips on what to do if you start to swell.

#1. Stretch and Change Positions

If you feel your ankles and feet swelling in the airplane cabin, try to stretch it out before it gets worse.

Start by rolling your ankle around in a circular motion, extend your legs and stretch, then change positions.

It also helps to continue changing positions and stretching frequently until landing. This keeps blood circulation up, and prevents it from pooling into the lower body again.

#2. Go for Walks in the Airplane Cabin

If you feel the onset of swelling coming, get up and go for a walk.

Even in the flight cabin when there’s limited space, just going for a short walk to the bathroom or down the aisle and back will help.

Walking helps to bring back proper blood circulation, which stops the swelling from getting worse.

#3. Do Cardio

If you find yourself swelling during your trip because of hot weather or from the foreign cuisine, opt for some cardio.

Swimming is a great counter to swelling, so is hiking and jogging.

If the swelling is too painful to do those, going for a brisk walk also works. Exercise helps improve blood flow giving relief from swelling. Plus, the salt your body loses from sweating helps to release excess fluids your body may be holding onto.

#4. Elevate the Limbs

Elevating the swollen body parts will help drain the extra fluid pooled into that area.

If possible, elevate the swollen limb above the heart, on a chair or cushion in bed. If swelling persists, you can elevate the limb overnight while sleeping.

#5. Use Compression Socks

If you are a frequent flyer who often experiences swelling, it may be worth it to get compression socks.

These help to both prevent and relieve swelling. If you find your feet and ankle swelling mid-flight, slip on the compression socks and they’ll safely help to push the extra fluid out of the ankle and foot.

Sarah Peterson

Sarah Peterson is the co-founder and head of marketing at FLIGHTFŪD. She's a travel health expert and after having visited 20+ countries as a digital nomad and flying every 4-6 weeks for business, she became passionate about empowering others to protect their bodies on the go.

Hi Patrick! We discussed via email, but in case anybody else has experienced this problem, we definitely recommend visiting a doctor who specializes in circulatory issues. Circulation can become impaired when you fly and left unchecked, issues can become more serious.

Sounds more like a dvt / a blood clot. Get to a US doctor ASAP

Greetings, I just flew from Bali had a stop over in Istanbul went into Los Angeles and now into Puerto Vallarta. It’s been 5 days and I have my left arm swollen and dark blue as perhaps a capillary broke. I’ve gone to the doctor here in Puerto Vallarta and it seems my pulse and my blood flow is good and although the swelling has lessened it’s still numb tingly and discolored. I understand you’re not positions and not legally entitled to give that advice but what do you suggest I should do? Thank you for your time, Blessings to you and your loved ones sincerely Patrick

Leave a comment

Explore more.

- Healthy Travel

- things to do

- Travel Destinations

- travel essentials

- Where to eat

- where to stay

Popular posts

Featured product

FLIGHT CHECK IN

Check into the VIP News Room. Stay up to date on all flight changes.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Guidelines for Flying With Heart Disease

Air travel is generally safe for heart patients, with appropriate precautions

- Pre-Flight Evaluation

Planning and Prevention

During your flight.

If you have heart disease, you can fly safely as a passenger on an airplane, but you need to be aware of your risks and take necessary precautions.

Heart conditions that can lead to health emergencies when flying include coronary artery disease (CAD) , cardiac arrhythmia (irregular heart rate), recent heart surgery, an implanted heart device, heart failure , and pulmonary arterial disease.

When planning air travel, anxiety about the prevention and treatment of a heart attack on a plane or worrying about questions such as "can flying cause heart attacks" may give you the jitters. You can shrink your concern about things like fear of having a heart attack after flying by planning ahead.

Air travel does not pose major risks to most people with heart disease. But there are some aspects of flying that can be problematic when you have certain heart conditions.

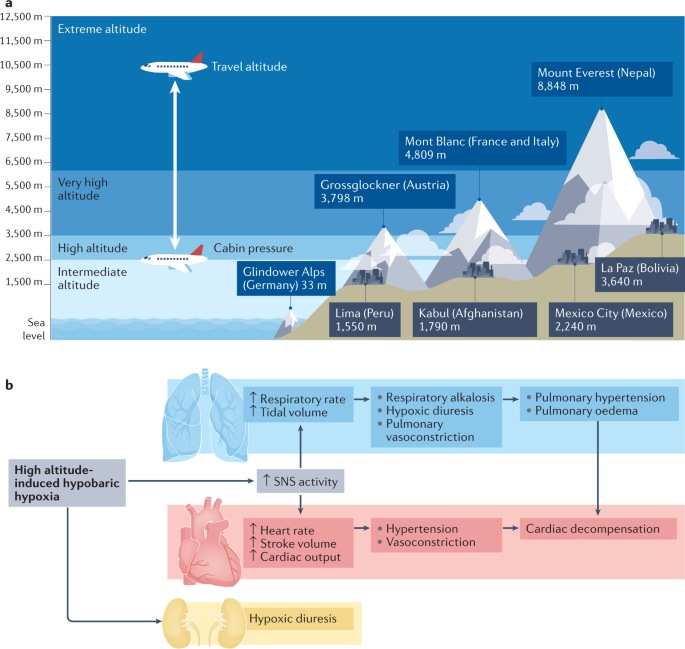

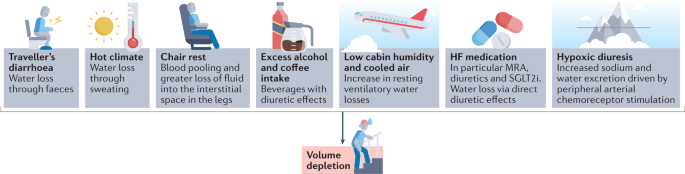

When you have heart disease, air flight can lead to problems due to the confined space, low oxygen concentration, dehydration, air pressure, high altitude, and the potential for increased stress. Keep in mind some of these issues compound each other's effects on your health.

Confined Space

The prolonged lack of physical movement and dehydration on an airplane may increase your risk of blood clots, including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) . One of the biggest risks for people with heart disease who are flying is developing venous thrombosis.

These risks are higher if you have CAD or an implanted heart device, such as an artificial heart valve or a coronary stent. And if you have an arrhythmia, a blood clot in your heart can lead to a stroke.

One of the biggest risks for people with heart disease who are flying is developing an arterial blood clot or venous thrombosis.

Low Oxygen and Air Pressure

The partial pressure of oxygen is slightly lower at high altitudes than at ground level. And, while this discrepancy on an airplane is typically inconsequential, the reduced oxygen pressure in airplane cabins can lead to less-than-optimal oxygen concentration in your body if you have heart disease.

This exacerbates the effects of pre-existing heart diseases such as CAD and pulmonary hypertension .

The changes in gas pressure in an airplane cabin can translate to changes in gas volume in the body. For some people, airplane cabin pressure causes air expansion in the lungs. This can lead to serious lung or heart damage if you are recovering from recent heart surgery.

Dehydration

Dehydration due to cabin pressure at high altitude can affect your blood pressure, causing exacerbation of heart disease. This is especially problematic if you have heart failure, CAD, or an arrhythmia.

If you experience stress due to generalized anxiety about traveling or sudden turbulence on your flight, you could have an exacerbation of your hypertension or CAD.

Pre-Flight Health Evaluation

Before you fly, talk to your healthcare provider about whether you need any pre-flight tests or medication adjustments. If your heart disease is stable and well-controlled, it is considered safe for you to travel on an airplane.

But, if you're very concerned about your health due to recent symptoms, it might be better for you to confirm that it's safe with your healthcare provider first before you book a ticket that you may have to cancel.

Indications that your heart condition is unstable include:

- Heart surgery within three months

- Chest pain or a heart attack within three months

- A stroke within six months

- Uncontrolled hypertension

- Very low blood pressure

- An irregular heart rhythm that isn't controlled

If you've had a recent heart attack, a cardiologist may suggest a stress test prior to flying.

Your healthcare provider might also check your oxygen blood saturation. Heart disease with lower than 91% O2 saturation may be associated with an increased risk of flying.

Unstable heart disease is associated with a higher risk of adverse events due to flying, and you may need to avoid flying, at least temporarily, until your condition is well controlled.

People with pacemakers or implantable defibrillators can fly safely.

As you plan your flight, you need to make sure that you do so with your heart condition in mind so you can pre-emptively minimize problems.

While it's safe for you to fly with a pacemaker or defibrillator, security equipment might interfere with your device function. Ask your healthcare provider or check with the manufacturer to see if it's safe for you to go through security.

If you need to carry any liquid medications or supplemental oxygen through security, ask your healthcare provider or pharmacist for a document explaining that you need to carry it on the plane with you.

Carry a copy of your medication list, allergies, your healthcare providers' contact information, and family members' contact information in case you have a health emergency.

To avoid unnecessary anxiety, get to the airport in plenty of time to avoid stressful rushing.

As you plan your time in-flight, be sure to take the following steps:

- Request an aisle seat if you tend to need to make frequent trips to the bathroom (a common effect of congestive heart failure ) and so you can get up and walk around periodically.

- Make sure you pack all your prescriptions within reach so you won't miss any of your scheduled doses, even if there's a delay in your flight or connections.

- Consider wearing compression socks, especially on a long trip, to help prevent blood clots in your legs.

If you have been cleared by your healthcare provider to fly, rest assured that you are at very low risk of developing a problem. You can relax and do whatever you like to do on flights—snack, read, rest, or enjoy entertainment or games.

Stay hydrated and avoid excessive alcohol and caffeine, which are both dehydrating. And, if possible, get up and walk for a few minutes every two hours on a long flight, or do leg exercises, such as pumping your calves up and down, to prevent DVT.

If you develop any concerning issues while flying, let your flight attendant know right away.

People with heart disease are at higher risk for developing severe complications from COVID-19, so it's especially important for those with heart disease to wear a mask and practice social distancing while traveling.

Warning Signs

Complications can manifest with a variety of symptoms. Many of these might not turn out to be dangerous, but getting prompt medical attention can prevent serious consequences.

Symptoms to watch for:

- Lightheadedness

- Dyspnea (shortness of breath)

- Angina (chest pain)

- Palpitations (rapid heart rate)

- Tachypnea (rapid breathing)

To prepare for health emergencies, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration mandates that supplemental oxygen and an automated external defibrillator (AED) is on board for passenger airplanes that carry 30 passengers or more. Flight crews receive training in the management of in-flight medical emergencies and there are protocols in place for flight diversions if necessary.

A Word From Verywell

For most people who have heart disease , it is possible to fly safely as long as precautions are taken. Only 8% percent of medical emergencies in the air are cardiac events, but cardiac events are the most common in-flight medical cause of death.

This means that you don't need to avoid air travel if you have stable heart disease, but you do need to take precautions and be aware of warning signs so you can get prompt attention if you start to develop any trouble.

Hammadah M, Kindya BR, Allard‐Ratick MP, et al. Navigating air travel and cardiovascular concerns: Is the sky the limit? Clinical Cardiology . 2017;40(9):660-666. doi:10.1002/clc.22741.

Greenleaf JE, Rehrer NJ, Mohler SR, Quach DT, Evans DG. Airline chair-rest deconditioning: induction of immobilisation thromboemboli? . Sports Med. 2004;34(11):705-25.doi:10.2165/00007256-200434110-00002

American Heart Association. Travel and heart disease .

Ruskin KJ, Hernandez KA, Barash PG. Management of in-flight medical emergencies . Anesthesiology. 2008;108(4):749-55.doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e31816725bc

Naqvi N, Doughty VL, Starling L, et al. Hypoxic challenge testing (fitness to fly) in children with complex congenital heart disease . Heart. 2018;104(16):1333-1338.doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312753

By Richard N. Fogoros, MD Richard N. Fogoros, MD, is a retired professor of medicine and board-certified in internal medicine, clinical cardiology, and clinical electrophysiology.

NICOLE POWELL-DUNFORD, MD, MPH, JOSEPH R. ADAMS, DO, MPH, AND CHRISTOPHER GRACE, DO, MPH

Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(4):403-410

Related Letter to the Editor: Helping Adults With Dementia Travel by Air

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Air travel is generally safe, but the flight environment poses unique physiologic challenges such as relative hypoxia that may trigger adverse myocardial or pulmonary outcomes. To optimize health outcomes, communication must take place between the traveler, family physician, and airline carrier when there is any doubt about fitness for air travel. Travelers should carry current medications in their original containers and a list of their medical conditions and allergies; they should adjust timing of medications as needed based on time zone changes. The Hypoxia Altitude Simulation Test can be used to determine specific in-flight oxygen requirements for patients who have pulmonary complications or for those for whom safe air travel remains in doubt. Patients with pulmonary conditions who are unable to walk 50 m or for those whose usual oxygen requirements exceed 4 L per minute should be advised not to fly. Trapped gases that expand at high altitude can cause problems for travelers with recent surgery; casting; ear, nose, and throat issues; or dental issues. Insulin requirements may change based on duration and direction of travel. Travelers can minimize risk for deep venous thrombosis by adequately hydrating, avoiding alcohol, walking for 10 to 15 minutes every two hours of travel time, and performing seated isometric exercises. Wearing compression stockings can prevent asymptomatic deep venous thrombosis and superficial venous thrombosis for flights five hours or longer in duration. Physicians and travelers can review relevant pretravel health information, including required and recommended immunizations, health concerns, and other travel resources appropriate for any destination worldwide on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention travel website.

Air travel has become increasingly popular over time, despite decreases during the COVID-19 pandemic, with 1.1 billion total passengers in 2019 and most Americans having flown at least once in the past three years. 1 Air travel is generally safe, but especially for the aging U.S. population, the flight environment poses unique physiologic challenges, particularly relative hypoxia, which may trigger adverse myocardial or pulmonary outcomes. To optimize health outcomes, communication must take place between the traveler, family physician, and airline carrier when any doubt occurs about fitness for air travel. Travelers should carry current medications in their original containers as well as a list of their medical conditions and allergies and should adjust timing of medications as needed based on time zone changes. Travelers should also consider available medical resources at their travel destinations and layover locations. Family physicians and travelers can review relevant pretravel health information, including required and recommended immunizations, health concerns, and other travel resources appropriate for any destination worldwide at https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/list .

Pulmonary Conditions

By law, U.S. commercial aircraft cannot exceed a relative cabin altitude of 8,000 feet (2,438 m) because of the potential for significant hypoxia above this altitude. 2 Most passengers exposed to this environment will have a partial pressure of arterial oxygen (Pao 2 ) of 60 to 65 mm Hg (7.98 to 8.64 kPa), corresponding to 89% to 94% peripheral oxygen saturation (Spo 2 ), which may compromise cardiovascular or pulmonary disease in affected travelers. 3 Neither reassuring pulse oximetry nor reassuring forced expiratory volume in one second has been found to predict hypoxemia or in-flight events for patients with pulmonary conditions. 3

The nonstandardized Hypoxia Altitude Simulation Test, administered and interpreted by pulmonologists, can be used to determine specific in-flight oxygen requirements for patients with pulmonary complications or those for whom safe air travel remains in doubt. Typically, the Hypoxia Altitude Simulation Test comprises breathing 15% fraction of inspired oxygen for 20 minutes, with pulse oximeter and blood gas measurements taken before and after testing. 4 – 6 Patients with a Hypoxia Altitude Simulation Test Pao 2 less than 50 mm Hg (6.65 kPa) at any point during the test require supplemental oxygen in flight, whereas those with a Pao 2 greater than 55 mm Hg (7.32 kPa) do not. Pao 2 measurements falling between 50 and 55 mm Hg are considered borderline and may necessitate further testing with activity. 5 Given that the test itself incurs some risk and may not be available to all travelers, family physicians can counsel patients who are unable to walk 50 m (164 ft) or those whose usual oxygen requirements exceed 4 L per minute not to fly. 3 , 4 , 7 , 8

Patients with oxygen requirements less than 4 L per minute can be counseled to double their usual flow rate while flying. 8

Commercial airline carriers usually permit the use of personal Federal Aviation Administration–approved portable oxygen compressors, but carriers require travelers to give from 48 hours to one month's notice before flight when they are requesting the use of compressed oxygen. 9

Table 1 lists indications for which further assessment (e.g., Hypoxia Altitude Simulation Test, ability to walk 50 m) is warranted, including previous respiratory difficulties while flying, severe lung disease, recent or active lung infections, any preexisting oxygen requirements or ventilatory support, or if less than six weeks have passed since hospital discharge for acute respiratory illness. 3 Patients who have undergone an open-chest lung procedure should defer travel for two to three weeks, must not have any recent or residual pneumothorax, and should be assessed for supplemental oxygen needs. 10

Cardiac Conditions

Travelers with underlying cardiac conditions should use airport assistance services such as wheelchairs and baggage trolleys to decrease myocardial oxygen demand. 9 Although most cardiac conditions are safe for flight, some require additional consideration. Travelers with minimally symptomatic, stable heart failure may safely fly, but medication adherence is critical. 9 , 11 Patients with stable angina should be assessed for oxygen needs if they become short of breath after walking 50 m , and they should not fly following any recent medication changes that have not demonstrated clinical stability beyond that medication's half-life. 7 , 11

Patients with unstable angina, new cardiac or pulmonary symptoms, or recent changes in medication without appropriate follow-up should not fly until stable, particularly for medication changes that could impact blood pressure or coronary reserve. 11 Travelers with recent myocardial infarction at low risk should defer air travel for three to 10 days postevent 11 – 15 ( Table 2 11 ) . Low-risk patients who required percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty may fly after three days as long as they are asymptomatic. 9 Travelers who have had coronary artery bypass grafting or an uncomplicated open-chest procedure should wait to fly until they are 10 days postprocedure. 7 , 11

Many implantable-cardioverter defibrillators are compatible with standard airport security. 9 The Transportation Security Administration recommends that travelers with pacemakers, defibrillators, or any other implanted metal device request pat-down screening instead of using a walk-through metal detector. 16 For travelers with pacemakers and implantable-cardioverter defibrillators, a two-day flight restriction following uncomplicated placement is appropriate. 11 It is prudent for all cardiac patients to travel with a copy of their most recent electrocardiography results and a preflight graded exercise test, which may aid in assessment and management in case of an event during flight. 9 In patients with hypertension, medication compliance is especially important because aircraft noise and other travel-related stress may provoke blood pressure elevations. 17 Travel in patients with moderately controlled hypertension is not a contraindication, but airline travel for those with uncontrolled hypertension requires shared decision-making and clinical judgment.

Ear, Nose, and Throat Conditions

Trapped gases and sinus air-fluid levels can cause significant pain for the patient with ear, nose, and/or throat conditions. Adult patients with symptomatic rhinosinusitis or allergic rhinitis may benefit from oxymetazoline (Afrin) and/or pseudoephedrine to prevent ear blockage during descent. 18 No evidence suggests that antihistamines or decongestants are beneficial in children with sinusitis, 19 and these medications should not be used to hasten an early clearance for flight in any age group. Flight within 36 hours of otitis media resolution is generally safe. 20 Equalizing pressure on descent can also be accomplished in adults with frequent swallowing, chewing gum or food, or by generating pressure against a closed mouth and glottis. In young children and infants, upright bottle feeding or pacifier use can achieve similar effects. 21

Patients who have undergone jaw fracture repair should defer flying for at least one to two weeks, and jaw wiring should be temporarily replaced with elastic bands in case of emesis. 18 Transdermal scopolamine is effective in preventing air sickness , 22 and alternatives such as first-generation antihistamines may also be useful. Patients who elect to take scopolamine should be counseled on adverse effects of drowsiness, blurry vision, dry mouth, or dizziness. 22 Individuals who are prone to air sickness should refrain from alcohol use during flight and in preflight and should eat smaller, lighter meals. 18 The expansion of trapped gas at altitude may cause severe tooth pain in patients with caries beneath fixed restorations. Travelers with hearing aids should bring extra batteries and all accessories and may need to adjust their volume levels to offset background noise.

Diabetes Mellitus

In addition to carrying all medications, travelers with diabetes requiring insulin should request appropriate meals and consider checking blood glucose levels at intervals during longer flights. 23 Bringing snacks or other food can assist those with tenuous diabetes management in the event of layovers or delays. Insulin requirements may change based on the direction of travel and crossing time zones, which may entail lost or gained hours. Even if it is not part of the patient's normal regimen, fast-acting insulin, ideally with a pen device, should be considered for all travelers during flight due to its flexibility and responsiveness. 23 When traveling east, if the day is shortened by two or more hours, it may be necessary to give less insulin on the first day at the destination. When traveling west, if the day is extended by two or more hours, it may be necessary to give more insulin on the first day at the destination. Blood glucose should be checked at least 10 hours after the first-day dose to allow for further adjustments. Travelers can return to their normal insulin regimen on day 2 at their destination. A comprehensive public access resource for medical professionals addressing insulin adjustment for the air traveler is available through the Aerospace Medical Association. 23

Gastrointestinal Conditions

For travelers with recent intra-abdominal procedures, trapped gas expansion could disrupt sutures and cause rebleeding. Travelers should wait until 24 hours have passed and any bloating has resolved following laparoscopic abdominal procedures or colonoscopy. 7 , 10 Travelers should wait one to two weeks after open abdominal surgery. 10 Patients with active gastrointestinal problems, including hematemesis, melena, or obstruction, should not fly. 24

Hematologic Conditions

A baseline anemia may predispose travelers to syncope given the relative hypoxia of the flight environment. Caution should be exercised for travelers with a hemoglobin level below 8.5 g per dL (85 g per L), and some authorities recommend not advising flight for any travelers with levels below 7.5 g per dL (75 g per L). 7 Young, otherwise healthy patients with chronic anemia may be more tolerant of relative hypoxia, especially if their hemoglobin level is greater than 7.5 g per dL. 24 For the traveler with sickle cell anemia, sickling crisis during flight is unlikely 24 ; however, flight should be delayed for 10 days following an acute crisis, and patients with sickle cell anemia who have received a recent transfusion should not fly if hemoglobin levels are less than 7.5 g per dL. 24

Although deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is not caused by the flight environment itself, DVT is a concern for people who sit for extended periods or have risk factors. 25 Incidence of DVT reaches up to 5.4% in high-risk groups flying an average of 12.4 hours. 26 Compression stockings can prevent asymptomatic DVT and superficial venous thrombosis in flights lasting five hours or longer. 27 Table 3 lists recommendations for DVT prophylaxis for travelers who are at low, moderate, and high risk for DVT. 11 The baseline recommendations for each group include staying hydrated, avoiding alcohol to prevent dehydration, walking at least 10 to 15 minutes in each two hours of travel time, and performing isometric exercises while seated. 11 When indicated for high-risk travelers, including those with reduced mobility, low-molecular-weight heparin (e.g., 40 mg of subcutaneous enoxaparin [Lovenox]) on the day of and day after travel is appropriate for anticoagulation. 28

Psychiatric and Intellectual Disability Conditions

Passengers with mental or intellectual disabilities often benefit from a traveling companion because physiologic stresses of flight and the chaotic nature of busy airports may be especially challenging aspects of travel for these groups. 9 Prescription anxiolytics may alleviate travel anxiety, but a test dose is highly encouraged before flight. 9 Service or emotional support animals can be used for a variety of mental health conditions; an article in American Family Physician provides information about considerations for documentation for emotional support animals. 29 See the U.S. Department of Transportation website for current guidelines regarding the use of these animals during air travel. 30

Neurologic Conditions

Passengers predisposed to stress-related headaches and severe migraines should always carry abortive medications. Travelers with uncontrolled vertigo are not good candidates for flight. Patients prone to syncope should remain well-hydrated and be cautioned to avoid alcohol or quickly standing from a seated position. One small study suggests that people who have epilepsy with a history of flight-related seizures and a high baseline seizure frequency are likely to have a seizure after flying. 31 The Aerospace Medical Association recommends that patients with uncontrolled or poorly controlled seizures should not fly. 32 A safe amount of time permitted before flight following a seizure has not been established, but clinical judgment and the presence of a knowledgeable chaperone should factor into any medical recommendation. Although some airline carriers allow patients to fly 72 hours after a stroke, 7 the Aerospace Medical Association recommends waiting one to two weeks. 32

Obstetric Conditions

Background radiation associated with the flight environment does not pose a special hazard for most pregnant air travelers; however, the Federal Aviation Administration recommends informing aircrew or frequent flyers about health risks of radiation exposure. 33 Because a lack of in-flight medical resources may jeopardize safety of the mother and neonate, patients with an uncomplicated singleton pregnancy should generally not fly beyond 36 weeks of estimated gestational age 7 , 24 , 33 , 34 and those with a multiple gestation not beyond 32 weeks . 7 , 34 Body imaging scanners are safe for security screening during pregnancy. 34 , 35 Postpartum travelers are at moderate risk for DVT and should wear compression stockings and perform isometric exercises during flight. 11 Travelers who have undergone an uncomplicated cesarean delivery are generally safe for flight within one to two weeks. 10

Ophthalmologic Conditions

Passengers with severe visual impairment may benefit from having a traveling companion. Xerophthalmia may be exacerbated in the low humidity of the airplane cabin, and lubricating eye drops are advisable. Cataracts and clinically stable glaucoma are not contraindications to flight; however, any retinal detachment interventions should restrict flight for at least two weeks. 36 Open-globe eye surgery should delay air travel for up to six weeks, and travel recommendations should be made in conjunction with an ophthalmologist. 36

Orthopedic Conditions

Because of expansion of trapped air at altitude, all fixed casts should be bivalved. 7 , 37 Some airlines do not permit air casts of any kind, but if they are used, a small amount of air should be released to prevent any limb compression that occurs as a result of trapped gas expansion. Elastic bandages can be added to a bivalved cast and can be loosened as tolerated. The Transportation Security Administration recommends that passengers with prosthetic limbs should avoid metal detector screening and should be screened with alternative measures. 16 Individuals with significantly decreased mobility should consider wheelchairs and the use of travel companions. Passengers with low back pain and other mobility-limiting conditions can request seating near the front to reduce walking; however, business and first-class seating is an additional cost.

Urologic Conditions

Foley catheters and other inflatable balloons are compatible with flight; however, they should be filled with liquid for air travel, given the previously described expansion of trapped gas at altitude.

Special Considerations for Children

Healthy, term neonates should not fly for at least 48 hours after birth but preferably one to two weeks. 21 Infants younger than one year with a history of chronic respiratory problems since birth should be evaluated by a pulmonologist before air travel. 3

Other Air Travel Considerations

Jet lag occurs as a result of desynchronization between an individual's internal circadian rhythm and the external environment's time zone. 38 , 39 Jet lag is worse for eastward rather than westward travel. 40 Measures for prevention include ensuring enough sleep before travel, timing light exposure using sunglasses, avoiding alcohol, and eating at appropriate times after arriving at the destination. Timed melatonin is highly effective at treating jet lag, 41 and prescription hypnotic-sedative medications may also work in controlling sleep loss. 38

Self-contained underwater breathing apparatus (SCUBA) divers should not fly within 12 hours of a dive because of the concern for decompression sickness or life-threatening arterial gas embolism. 42

The airplane cabin does not inherently pose greater risk for infection than any other close contact, but respiratory viral pathogens are the most commonly transmitted infections. 43 Because of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends delaying travel until the individual is fully vaccinated because traveling increases the chance of getting and spreading COVID-19. For patients not fully vaccinated who must travel, it is important to follow the CDC's recommendations for unvaccinated people. Check for evolving guidelines on the CDC's website. 44

Patients with breast cancer who have had surgery may fly without risking new or worsening lymphadenopathy. 45

A comprehensive discussion of in-flight emergencies is beyond the scope of this article. See the American Family Physician article on in-flight emergencies for more details. 46

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Bettes and McKenas . 37

Data Sources: A PubMed, Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, ACCESSSS, and ECRI search occurred in April and May 2020 and April and May 2021 using search terms aviation medicine, travel medicine, commercial flight, air travel, and fitness to fly. The Aerospace Medical Association's website resource, Medical Considerations for Airline Travel, was searched in its entirety. The Handbook of Aviation and Space Medicine, Fundamentals of Aerospace Medicine, and Aviation and Space Medicine were reviewed for clinically relevant chapters.

The authors acknowledge Rachel Kinsler, USAARL Research Engineer, for her thoughtful review of this manuscript.

The views, opinions, and/or findings contained in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed as an official Department of the Army position, policy, or decision, unless so designated by other official documentation. Citation of trade names in this report does not constitute an official Department of the Army endorsement or approval of the use of such commercial items.

Airlines for America. Air travelers in America: annual survey. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://www.airlines.org/dataset/air-travelers-in-america-annual-survey/#

14 Code of Federal Regulations §25.841—pressurized cabins. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/CFR-2012-title14-vol1/CFR-2012-title14-vol1-sec25-841

- Ahmedzai S, Balfour-Lynn IM, Bewick T, et al.; British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee. Managing passengers with stable respiratory disease planning air travel. Thorax. 2011;66(suppl 1):i1-i30.

Respiratory disease. In: Green N, Gaydos S, Hutchinson E, et al., eds. Handbook of Aviation and Space Medicine . CRC Press; 2019:329–333.

Dine CJ, Kreider ME. Hypoxia altitude simulation test. Chest. 2008;133(4):1002-1005.

- Matthys H. Fit for high altitude: are hypoxic challenge tests useful? Multidiscip Respir Med. 2011;6(1):38-46.

Bagshaw M. Commercial passenger fitness to fly. In: Gradwell DP, Rainford DJ, eds. Ernsting's Aviation and Space Medicine . 5th ed. CRC Press; 2016:631–640.

Josephs LK, Coker RK, Thomas M; BTS Air Travel Working Group; British Thoracic Society; Managing patients with stable respiratory disease planning air travel. Prim Care Respir J. 2013;22(2):234-238.

Rayman RB, Williams KA. The passenger and the patient inflight. In: DeHart RL, Davis JR, eds. Fundamentals of Aerospace Medicine . 3rd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:453–469.

Aerospace Medical Association. Surgical conditions. May 2003. Accessed May 1, 2021. http://www.asma.org/asma/media/asma/Travel-Publications/Medical%20Guidelines/Surgical-Conditions.pdf

- Smith D, Toff W, Joy M, et al. Fitness to fly for passengers with cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2010;96(suppl 2):ii1-ii16.

- Thomas MD, Hinds R, Walker C, et al. Safety of aeromedical repatriation after myocardial infarction: a retrospective study. Heart. 2006;92(12):1864-1865.

Roby H, Lee A, Hopkins A. Safety of air travel following acute myocardial infarction. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2002;73(2):91-96.

- Zahger D, Leibowitz D, Tabb IK, et al. Long-distance air travel soon after an acute coronary syndrome: a prospective evaluation of a triage protocol. Am Heart J. 2000;140(2):241-242.

- Cox GR, Peterson J, Bouchel L, et al. Safety of commercial air travel following myocardial infarction. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1996;67(10):976-982.

Transportation Security Administration. Frequently asked questions. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://tsa.gov/travel/frequently-asked-questions

- Steven S, Frenis K, Kalinovic S, et al. Exacerbation of adverse cardiovascular effects of aircraft noise in an animal model of arterial hypertension. Redox Biol. 2020;34:101515.

Aerospace Medical Association. Ear, nose, and throat. May 2003. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://www.asma.org/asma/media/asma/Travel-Publications/Medical%20Guidelines/Ear-Nose-and-Throat.pdf

Shaikh N, Wald ER, Pi M. Decongestants, antihistamines and nasal irrigation for acute sinusitis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(10):CD007909.

- Pinto JA, Dos Santos Sobreira Nunes H, Soeli Dos Santos R, et al. Otitis media with effusion in aircrew members. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2019;90(5):462-465.

Aerospace Medical Association. Travel with children. May 2003. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://www.asma.org/asma/media/asma/Travel-Publications/Medical%20Guidelines/Travel-With-Children.pdf

Spinks A, Wasiak J. Scopolamine (hyoscine) for preventing and treating motion sickness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):CD002851.

Aerospace Medical Association. Diabetes. May 2003. Accessed May 1, 2021. http://www.asma.org/asma/media/asma/Travel-Publications/Medical%20Guidelines/Diabetes.pdf

Passenger fitness to fly. In: Green N, Gaydos S, Hutchinson E, et al., eds. Handbook of Aviation and Space Medicine . CRC Press; 2019:263–266.

Watson HG, Baglin TP. Guidelines on travel-related venous thrombosis. Br J Haematol. 2011;152(1):31-34.

Possick SE, Barry M. Evaluation and management of the cardiovascular patient embarking on air travel. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(2):148-154.

- Clarke MJ, Broderick C, Hopewell S, et al. Compression stockings for preventing deep vein thrombosis in airline passengers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;(4):CD004002.

Gavish I, Brenner B. Air travel and the risk of thromboembolism. Intern Emerg Med. 2011;6(2):113-116.

Tin AH, Rabinowitz P, Fowler H. Emotional support animals: considerations for documentation. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(5):302-304. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2020/0301/p302.html

U.S. Department of Transportation. U.S. Department of Transportation announces final rule on traveling by air with service animals. December 2, 2020. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://www.transportation.gov/briefing-room/us-department-transportation-announces-final-rule-traveling-air-service-animals

Trevorrow T. Air travel and seizure frequency for individuals with epilepsy. Seizure. 2006;15(5):320-327.

Hastings, JD; Aerospace Medical Association. Medical guidelines for airline travel: air travel for passengers with neurological conditions. September 2014. Accessed May 1, 2021. http://www.asma.org/asma/media/asma/Travel-Publications/Medical%20Guidelines/Neurology-Sep-2014.pdf

ACOG Committee opinion no. 746: air travel during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(2):e64-e66.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Air travel and pregnancy: scientific impact paper no. 1. May 2013. Accessed May 1, 2021. http://www.asma.org/asma/media/asma/Travel-Publications/Medical%20Guidelines/RCOG-Pregnancy-and-Air-Travel-Scientific-Impact-Paper.pdf

Harvard Medical School. Are full-body airport scanners safe? June 2011. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/are-full-body-airport-scanners-safe#:~:text=he%20authors%20begin%20with%20an,the%20biological%20effects%20of%20radiation

Aerospace Medical Association. Ophthalmological conditions. May 2003. Accessed May 1, 2021. http://www.asma.org/asma/media/asma/Travel-Publications/Medical%20Guidelines/Ophthalmological-Conditions.pdf

Bettes TN, McKenas DK. Medical advice for commercial air travelers. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60(3):801-808. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/afp/1999/0901/p801.html

Aerospace Medical Association. Jet lag. May 2003. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://www.asma.org/asma/media/asma/Travel-Publications/Medical%20Guidelines/Jet-Lag.pdf

Choy M, Salbu RL. Jet lag: current and potential therapies. PT. 2011;36(4):221-231.

- Waterhouse J, Reilly T, Atkinson G, et al. Jet lag: trends and coping strategies. Lancet. 2007;369(9567):1117-1129.

Herxheimer A, Petrie KJ. Melatonin for the prevention and treatment of jet lag. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD001520.