- Accessories

- Maintenance

- Used Aircraft Guide

- Industry News

- Free Newsletter

- Digital Issues

- Reset Password

- Customer Service

- Free Enewsletter

- Pay My Bill

Cessna 177RG

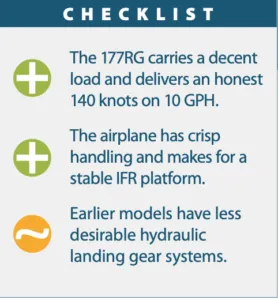

The retractable-gear cardinal is a compelling used-market buy. it’s stable, reasonably fast and an easy step-up single..

We’ve seen it plenty of times. A buyer on a budget has the heart set on a Cessna 210, but a closer look at market asking prices and operating costs squashes the idea. Luckily there’s an alternative in the Cessna Cardinal RG. And overall there’s a lot to like about life in a retrac Cardinal.

It has a strong, strutless wing and wide cabin doors that make getting in and out the 48-inch-wide cabin easy. As far as four-place retractables go, the airplane won’t win any speed records, but it’s easy to fly and makes for a stable IFR platform. Plus, what shop can’t work on the familiar and reliable 200-HP Lycoming IO-360 engine?

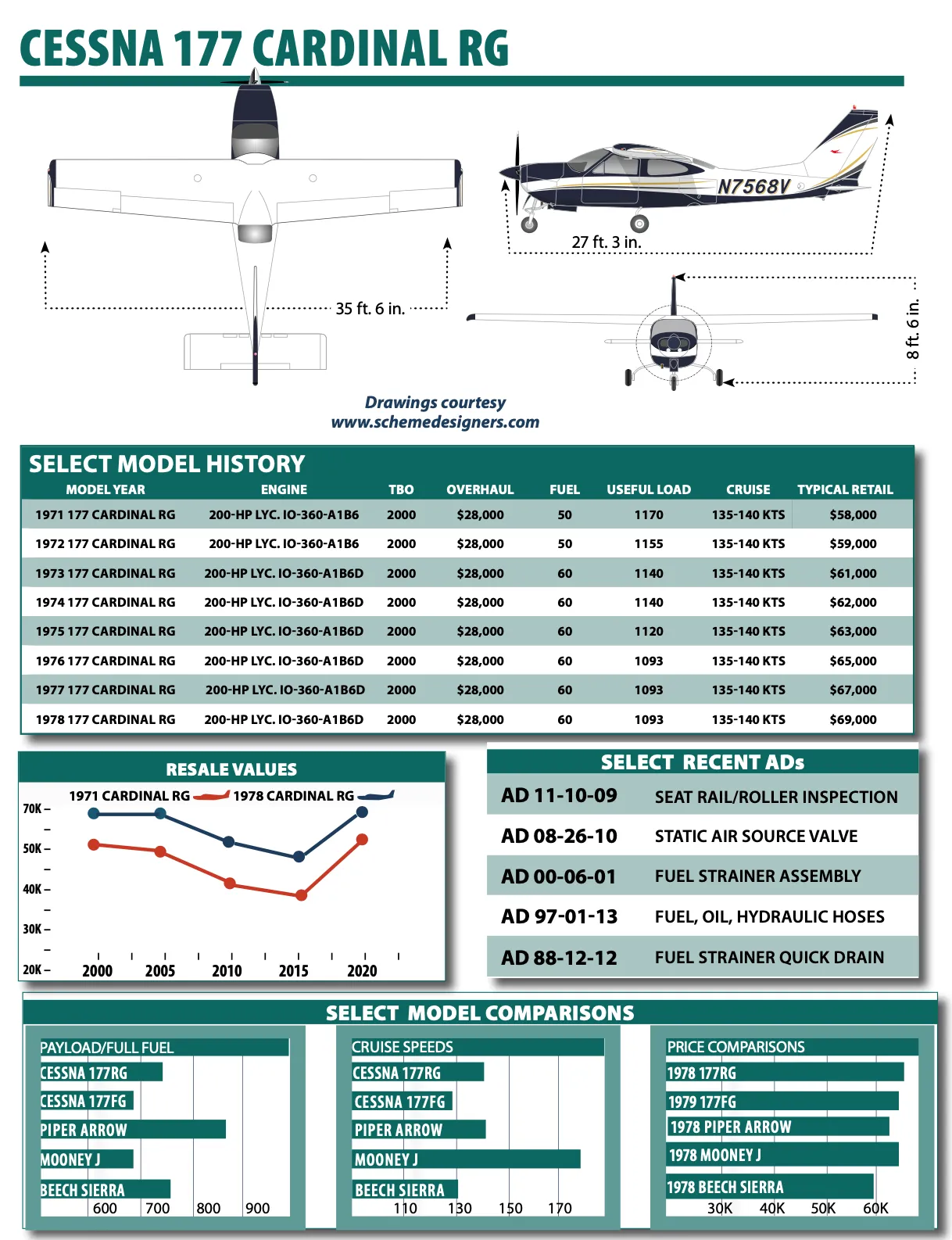

As with most sought-after singles, a well-cared-for 177RG fetches good money—especially later-model airplanes with modern interior, nice paint and the latest avionics.

Among entry-level four-place retracs, it’s faster than all but the Mooney, roomier than all but the Beech Sierra and has better useful load than any of the others. It’s also hard to load out of CG.

The Cardinal RG is basically the same airframe as the fixed-gear Cardinal. This may not have been a favor to the RG, since the fixed-gear model, introduced in 1968, had a number of well-publicized problems that took a couple of years to sort out. The lack of power in the original FG Cardinal (150 HP) was fixed with an upgrade to 180 HP. Pulsing in the yoke during a full-flap slip was fixed with leading-edge slots in the control surface. The RG, however, started and stayed with a fuel-injected 200-HP Lycoming IO-360 engine and had the leading-edge slots in the stabilator from the get-go.

The larger engine gives the Cardinal RG a welcome boost in gross weight compared to the fixed-gear airplane (2800 vs. 2500 pounds). Although empty weights are higher, the net gain in useful load is about 100 pounds.

The competition in 200-HP four-seat retractables at the time of the Cardinal RG’s introduction in 1971 was fierce. Piper had been building its successful Arrow for four years, Mooney was we’ll established with various flavors of the M20 and Beech had just started selling the Sierra. It was a lucrative market segment, attracting buyers wanting a high-performance single but without the means to afford a more powerful airplane like the Debonair. Cessna didn’t help itself with a base price on the RG of $24,795—several thousand more than the Mooneys of the time.

The original fuel system was an unusual (for Cessna) design that had only on and off settings. This occasionally caused problems, since it’s possible for one tank to empty more quickly than the other. But ingenious Cardinal RG owners have found that this can be resolved in flight with a short but healthy sideslip. The tanks then feed equally for the remainder of the flight. The problem also occurs in later models with left-both-right-off fuel selectors, but here, the fix is simply to switch to the fuller tank for a few minutes.

There were several minor improvements to the Cardinal RG during its production run. The 1972 model gained a few knots in cruise and a slightly better climb rate thanks to a new prop. The gear system also gained some improvements, with mechanical switches moving to a more trouble-free magnetic setup. Both the hydraulic and electrical control systems changed, each step a small improvement. Also, the fixed cabin steps were dropped. They tended to expose the bottom of the fuselage to even more grief if the aircraft landed with the gear up. Instead, small foot pads were placed on the main gear struts.

In addition, landing and taxi lights were moved from the wing to the nose, a feature that many feel wasn’t an improvement because the higher vibration levels in the cowl shorten the life of cowl-mounted landing lights

Prior to 1976, the instrument panel was higher in front of the pilot than the right-seat passenger. This was nice for the passenger but limited panel space for added avionics. In 1976, the instrument panel was redesigned and enlarged and a simplified landing gear hydraulic system was offered. This gear configuration was maintained through the end of production except for the powerpack change in 1978. For the 1977 model, the aircraft received a fuel selector that gave it commonality with other Cessna singles, had a more positive detent and was supposed to be more easily maintainable. And finally, in 1978, the aircraft got a 28-volt electrical system and an improved gear retraction power pack that cut retraction time in half, to six seconds.

Production of the Cardinal RG ended after the 1978 model year, with 1366 aircraft built. Unlike many designs, the 177RG didn’t linger on with production trailing off to a trickle; about 100 airplanes were built that last year. However, in 1978, Cessna introduced the larger, more powerful Skylane RG and it’s likely the manufacturer didn’t want to wind up competing with itself. Interestingly, 177 Cardinals were also built in France under contract and these occasionally turn up in the U.S. These were internally corrosion proofed with zinc chromate.

SPACIOUS CABIN

Cessnas are big favorites with passengers, for several reasons. The cabins are generally quite roomy and the high wing makes for a cool, shady ride as we’ll as a better view. The Cardinal adds to this with a wider cabin than the 172 or 182, low sill height and wide doors.

But those big doors—four feet wide—can be a problem on windy days. They’re fairly light and can fly right out of your hand if they get caught by a gust, causing damage to the hinge or the skin ahead of the door, or both. The doors also have proved to be leak-prone. Some of the doors fit too tightly, others too loosely, due to either poor quality control in production, subsequent wind damage or both.

Air leaks mean cold air, and some Cardinal owners report that the back seat gets pretty chilly despite Cessna’s attempts to warm things up with heater ducts. Careful sealing of potential air leaks in the cabin can bring some improvement, but a lap blanket for back-seat passengers is useful when the ambient temperature falls below zero.

Many owners assume that if the door leaks air, it also leaks water. The windshield has also been implicated in water leaks. But water leaks, for the most part, seem to come from the fairing joint at the wing root and owners and mechanics have come up with a fix for this leak that owners can do easily. Still, many owners find a hand towel is a useful checklist item for IFR flight.

As noted earlier, visibility from the front seats is among the best in any Cessna. With the seats forward in flight position, the pilot sits about even with the wing’s leading edge. This allows a view around the wing during maneuvering. The seats themselves could be ordered with vertical height adjusters—a boon to both short and tall pilots.

At the other end of the cabin, the baggage compartment is, to put it mildly, oddly shaped. Cessna had to put the wheels somewhere and they wound up in the baggage bay. The usual Cessna cavern has a big hump in the middle of it, right next to the baggage door. This sounds worse than it is in practice. The baggage compartment holds a huge volume and Cardinal RG owners use the hump as a divider. The baggage door is wide, but what won’t fit through the baggage door will go in over the back seats.

One owner commented: “We had occasion to stuff the entire contents of a freshman girl’s dorm room into the baggage compartment one time. we’ll OK, her trunk had to go into the back seat, but everything else went into the baggage compartment. Try that in your Mooney.”

An interesting exercise is to try to load a Cardinal RG out of CG. It’s tough to do. You are more likely to go out the front end of the envelope than the back, especially with a heavy pilot and instructor and no baggage. In the Cardinal RG, at least, the 25 to 50 pounds of undefined “stuff” most of us leave in the baggage compartment becomes useful to counteract forward-CG problems.

DECENT PERFORMANCE

Pilots say that the Cardinal RG makes for a good, stable instrument platform, but it’s still nimble. “Compared to a Skylane RG,” said one, “it’s like a sports car.” As noted above, the speed is good in its class, although not up to that of the Mooney. Owners report cruise of about 140 to 145 knots at 11 to 12 GPH, or about 135 knots at 9 to 10 GPH. The RG doesn’t get its speed from raw power, so proper rigging is important in obtaining book speeds.

Cessna’s flaps are among the biggest in the business and the Cardinal RG uses them to get respectable short-field performance for a four-place retractable. Landing distance over a 50-foot obstacle is a claimed 1220 feet, shortest in its class.

Despite the higher horsepower, the Cardinal RG’s takeoff performance (takeoff roll: 890 feet, and 1585 feet over an obstacle) falls short of the later fixed-gear Cardinals (750 feet and 1400 feet over the obstacle). While some of this is due to the higher gross weight, another factor is the large nosegear door that sits immediately behind the propeller when the gear is down. Cardinal RG pilots say they can tell if the nosegear is down without looking at the gear lights simply by the vibration the gear door induces. This vibration also means that the nosegear door hinge is an item to watch for wear.

Because all three gear legs retract aft, there is a noticeable pitch-trim change during both extension and retraction. On takeoff, experienced owners take advantage of this by letting the aircraft accelerate to the target climb speed and then retracting the gear. The change in CG brings the aircraft into climb attitude with almost no pilot input.

The pitch change during gear extension is easily canceled by lowering 10 degrees of flaps at the same time. In IMC, some pilots like to take advantage of the gear’s drag and pitch change by lowering it right at the outer marker. If you set up your speed carefully in advance, you will find that only slight power adjustments are necessary to maintain a stabilized descent on a 3-degree glideslope.

The stabilator in the Cardinal RG has been the subject of a lot of discussion. While it’s less sensitive than some other stabilator-equipped aircraft, it’s much more sensitive than the stabilizer/elevator combination that most Cessna pilots know and love. More than a few folks transitioning from the 172 or 182 to the Cardinal RG have embarrassed themselves by crow-hopping down the runway. A good checkout with careful attention to the special needs of the stabilator is a must, but once mastered it becomes a non-issue.

LANDING GEAR TWEAKS

Through the eight years of its production, the Cardinal had four different landing gear systems, as Cessna strived to correct all its quirks. Major components remained the same but plumbing and controls evolved. The first, most problem-plagued one on the 1971 and 1972 Cardinal RGs was a Rube Goldberg combination of electrical and hydraulic components. Its weakest links were electrically actuated main gear downlocks and mechanical position switches.

The 1973 Cardinals got magnetic position sensing switches, which held up better to the elements, hydraulic downlock actuators that improved reliability and direct control of the gear movement through a hydraulic valve rather than an electric switch. By 1974, the hydraulic system was almost completely in control of the gear, although a complex electrical control system remained. There are many stories told about Cardinal gear issues, most of them inaccurate, but perhaps more than any other Cessna, the early Cardinal gear systems benefit from a mechanic with prior Cardinal knowledge.

In 1976, Cessna finally got it right, removing all of the electrics from the gear system in favor of fully hydraulic gear using only two switches: a pressure switch to control the hydroelectric gear pump and a squat switch to keep the gear down while on the ground. While any of these gear systems are dependable if properly maintained, 1976 and later Cardinal owners are most likely to report a fully trouble-free ownership experience.

Finally, with the 1978 models, the 12-volt Prestolite hydraulic power packs were eliminated in favor of a 24-volt power pack of Cessna’s design. This has proved to be the most satisfactory of all the gear systems and, of course, would be the one to choose if cost considerations and availability permit—only 100 RGs were built in 1978.

There are other landing gear issues too, not related to the hydraulics. The most serious is the main gear actuating cylinder rod ends, which had a nasty habit of breaking off at inopportune moments, rendering the main gear inoperative. Actually, the main gear dropped to in-trail position and for a while, there was talk about carrying boathooks to reach down and pull it into the locks. But replacing the rod ends is a more permanent solution. Have your mechanic check for grease zerk fittings on the rod ends. If they are there, you have the old rod ends.

At any rate, buyers should check to see which, if any, of Cessna’s recommended service instructions have been applied to the model being considered. There are at least eight of them that come to mind, including numbers 71-41, 72-26, 73-28, 74-26, 75-25, 76-4, 76-7 and 77-20.

The landing gear raises the issue of proper maintenance. Experienced Cardinal RG owners will tell you that properly maintained, the landing gear is every bit as reliable as the gear on any other aircraft. The problem is finding a mechanic who really understands the landing gear, as we’ll as the rest of the airplane. Proper rigging of the gear is set forth in great detail in the maintenance manual and careful adherence to these procedures usually results in a reliable landing gear system. This is where the owner organization proves its worth, with a lot of useful and detailed advice as we’ll as referrals to knowledgeable Cardinal mechanics.

MAINTENANCE ISSUES

The Lycoming IO-360-A1B6D engine in the 1973 to 1978 Cardinal RGs has a couple of notable idiosyncrasies. One is that it uses the infamous Bendix dual magneto that puts two magnetos on a single shaft, making the shaft a potential single-point failure item that can rob you of all engine power instantly if it fails.

The Cardinal RG is not the only aircraft using a dual-magneto engine—some Mooney models and Beech Duchess models do also. The 1971 Cardinal RG used the IO-360-A1B6 engine, with separate magnetos. This engine is approved for all Cardinal RGs, but getting an exchange at overhaul time can be costly. The dual-magneto engines were recently a subject of Special Airworthiness Information Bulletin NE-06-08, which alerted owners and mechanics to a prop governor hazard that “could result in loss of engine oil leading to engine failure.”

Not only could it, it has. The oil loss results from omission of a plate between the prop governor drive pad and the prop governor itself. The plate is between two gaskets and is often thrown away with the gaskets when the old governor is removed. Unfortunately, the gasket without the plate often takes 15 minutes or so to fail, setting up the pilot for an off-airport landing.

SUPPORT ORGANIZATION

We think one of top selling points for all Cardinals is Cardinal Flyers Online (CFO). This model-specific organization with over 2000 members maintains a large and complete website ( www.cardinalflyers.com ) that is a treasure trove of data and advice on Cardinals. Much has been contributed by members, but the operators of the site, Keith Peterson and Paul Millner, have become experts in every detail of Cardinals. CFO was the first organization to call attention to the prop governor plate problem and was instrumental in getting the recent SAIB published. Most of the fixes or techniques noted in this article have been documented on the CFO website.

In addition to the website, CFO sends out an almost daily email digest containing messages from members, replies from other members and comments from both Millner and Peterson. Past digests are maintained on the site, with a search facility that lets you search all the digests from the most recent (#5122 at this writing) to the earliest digest in March 1997. Membership in CFO is $34 a year.

You can turn the airplane into a fast flight level flyer with a turbonormalizing system from Tornado Alley Turbo at www.taturbo.com . When we reviewed the mod in a flight trial way back in the May 2009 Aviation Consumer we saw 177 knots (cool coincidence) at 17,500 feet. North of $40,000, the mod won’t be worth it to many for a four-place single in this price segment, but it will for some and we think they won’t be disappointed.

Speed modifications of various kinds are available from several sources, including wingtip mods and fairings for the exhaust pipe, and Maple Leaf Aviation is a popular go-to. Contact them through www.aircraftspeedmods.ca . Vortex generators are available for the Cardinal from Micro Aerodynamics at www.microaero.com .

Hartzell and McCauley continue to offer three-blade prop conversions. Contact www.hartztellprop.com and McCauley at www.mccauley.txtav.com .

CURRENT MARKET

According to Aircraft Bluebook , retail prices for the 177RG have been on an upward trend. While the latest models of the 177RG (1978) have a typical retail value of around $69,000 (per Aircraft Bluebook ) we found asking prices to be higher for models with new paint and fresh avionics upgrades.

We found one offered by Van Bortel Aircraft in Texas for a whopping $109,500. It had 1151 hours on the engine since overhaul, but older avionics and decent paint. Another 1977 model was listed on an FBO bulletin board for $90,000. It had new Garmin avionics, including a primary flight display and custom panel, new paint, newer interior and 500 hours on the engine since factory new. Use the pricing in the data sheet on page 25 as a starting point, but expect to pay more.

OWNER COMMENTS

I own a 1975 177RG and have been very happy with it. I purchased it in 2001 and it took several years to get it to where I want it, doing gradual updates and new paint in 2015.

The panel is a bit outdated with a Garmin-AT GNS 480 GPS navigator, MX20 multifunction display, SL30 navcomm radio, a King HSI system and an all-electric Kelly Manufactuing RCA2610 digital attitude indicator with battery backup. A Garmin GTX 345 transponder meets the Mode-S, ATCRBS and ADS-B Out requirements. There are better panels out there, for sure, but this one does provide for a very capable IFR platform.

The Cardinal RG is a comfortable plane with plenty of room for four people. The large doors allow easy access for passengers. On the down-side, the landing gear hump makes loading the baggage compartment a bit annoying with larger-sized carry-on bags.

Currently configured with all seats in, it has a useful load of a bit over 1000 pounds and the airplane has a 60-gallon fuel capacity. So legal max gross weight is easy to hit with full fuel and American-sized passengers. I do have an extended-range fuel tank (60 gallons) via an STC that includes a letter from Cessna for adding another 700 pounds to its max gross weight. But I’ve only used that for one flight.

The airplane handles most runway surfaces very well. I have landed on sand in Copalis, Washington, grass in Center Island, Washington, and delivered supplies to an island rocky runway in La Gonave, Haiti, for the 2010 earthquake recovery efforts.

One downside is the small wheels. I have skipped landing on some grass/dirt fields because I wasn’t sure I could handle what I thought were some surface irregularities (difficult to tell from the air), and it would be a bit too late when landing to find out my wheels weren’t large enough. It would be nicer to have C210-size wheels, but I guess one can’t have everything; plus the baggage compartment would be inaccessible with any larger wheels.

I have flown it across the country many times both alone and with passengers. The passengers have all commented positively on its comfort. I have also used it for delivering hurricane supplies in the U.S.

With the rear seats out it has a large storage capacity, and for the Haiti mission I also removed the copilot seat for even more storage space.

With some aftermarket fairings (from Maple Leaf Aviation), I consistently cruise at 150 knots true between 5000 and 8000 feet on 10.5 GPH with a light to medium load, including me, a passenger and fuel tanks at three-quarters full.

Running lean of peak, I burn between 8 and 9 GPH and cruise at 140 KTAS. With the extended fuel range, its endurance now outlasts my bladder (I’ve gotten older and it has, apparently, shrunk with age along with the rest of me).

Sherif Sirageldin – via email

When I owned my Cessna T210 Centurion my flying mission was much different than today. With its great range, awesome payload and predictable Cessna handling, this wonderful high-flyer took myself and my family, the dog—and just about whatever we could fit—anywhere we needed to go in air-conditioned, above-the-weather comfort. That was then.

With flying about recreation these days, I said goodbye to the Centurion but kept I kept the skills up by flying the venerable Cessna 182. But for my next airplane I wanted economy and some degree of speed performance. Two cabin doors and retractable landing gear was a must. Enter my new Cardinal RG with its roomy cabin, decent speed and impressive economy thanks to its fuel-sipping, fuel-injected 200-HP Lycoming IO-360.

Easy to fly, easy to get in and out of and with pleasant flying manners it’s been an easy transition from my beloved T210. Memorize a few V-speeds and it’s an absolute pleasure to fly. With a few checkout hours with a very knowledgeable CFI, I had no trouble ferrying this machine from Wisconsin to my home field in Connecticut.

With six weeks of flying the 177RG under my belt, it’s been a great transition so far and I look forward to many years of use. With my high-performance retrac time, insurance is around $1800 per year.

My Cardinal cruises at around 130 to 140 true on 8.5 GPH. It’s a high flyer, but I fly the East Coast. There’s a great community with Cardinal Flyers Online owner’s group.

Mark Hagopian – via email

We purchased our Cardinal in 1987 after two years of Cessna 152 ownership. It was the perfect step-up family aircraft for us, offering excellent cross-country speed and range in true comfort. The four-cylinder engine brings an economy of operation and maintenance, and systems like rudder trim and bullet air vents provide the capabilities of fancier airplanes.

It has provided decades of safe and comfortable travel for our family of four, making countless trips to grandparents and around the country. With upgrades like paint, interior and a glass panel across the years, our Cardinal remains an outstanding balance of ability and affordability. We greatly enjoy being in the community with other Cardinal owners through the Cardinal Flyers.

Cardinal Flyers Online was founded in 1997 with the purpose of bringing Cardinal owners together for safety, savings and fun. We have enjoyed over 20 years of providing technical knowledge, sharing experience and providing social interaction, events and gatherings. Cardinals are usually personal aircraft and seem to be more pampered and upgraded than other models. Cardinal Flyers members possess a remarkable depth of knowledge and a willingness to share that knowledge while welcoming new owners. We have been proud to provide the organization within which so many owners have made good friends and receive enduring value.

Cardinal Inspections ( www.cardinalinspections.com ) leverages over 30 years of experience with an exclusive focus on Cardinals to provide services to buyers, sellers and owners. Services include in-depth Cardinal inspections at any location, buyer assistance with shopping, evaluating and transacting, and seller assistance with listing, pricing and negotiating. Cardinal Inspections helped over 70 clients in 2019 and aspires to be the best path to Cardinal ownership.

Keith and Debbie Peterson – via email

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Cessna Cardinal RG

Cirrus SR20

Piper Twin Comanche

Featured video.

Garmin GNS 430: Throwaway or Keeper?

- Online Account Activation

- Privacy Policy

- Aircraft For Sale

- Browse by Topic

- Magazine & Index

- For Members

- Business Directory

- Join / Renew

Select Page

177RG Cardinal: Cessna’s “Airplane of the ‘70s”

Posted by Bill Cox | Jul 13, 2015 | Featured Plane

Living proof that if it looks good, it’ll fly well!

There are a few airplanes that are nothing less than beautiful in flight. Never mind the paint job; any airplane can benefit from an artistically designed paint scheme. Instead, silhouette the airplane against a near-sunset sky, and you’re treated to a work of art.

In general aviation ranks, the V-tail Bonanza qualifies as an outstanding aesthetic design and is one of the few airplanes that look good from the rear. The venerable Cub may be another winner. Then, there’s the remarkable Wing Derringer twin, the slick Meyers 200, the muscular Beech Staggerwing biplane, the speed demon Aerostar, and the Cessna Cardinal RG.

That’s pretty august company for the little Cardinal RG. From its very inception, the Cessna model 177RG was a conscious attempt to create something unseen up to that time – a sporty Cessna, or, if you will, a Corvette to the company’s Chevy-sedan Skyhawk and Buick-solid Skylane.

The basic Cardinal was designed in 1967 to be a futuristic, innovative airplane—built low to the ground, swept, slick, and faired to the wind. Indeed, Cessna was so impressed with its handiwork, they labeled the model 177 Cardinal the “Airplane of the ‘70s” when it was introduced in the late ‘60s. The 177’s immediate follow-on, the Cardinal RG, was an even more striking design, possessed of racehorse lines and an indefinable appeal that transcended considerations of performance, utility, and economy.

Creating a new retractable to compete in the crowded 200 hp, high-performance class was a risky venture. There were already a number of airplanes with four seats, wheels that went to bed, and 200 hp, all produced by well-established manufacturers. Beech had the Sierra, Piper offered the very popular Arrow, Rockwell Commander was about to enter the fray with the Commander 112, and Mooney, the long-time sales and performance leader, had the Executive, Chaparral, and Ranger.

You might notice that all the airplanes mentioned above are low-wings. On the surface, a high-wing retractable poses some interesting engineering challenges—most importantly, where to hide the wheels. You can’t very well tuck them up into the wings, unless you utilize thick, draggy airfoils, long, complex struts, and a truly stout (read “heavy”) retraction system. Long legs just beg to be side-loaded in crosswinds, are bound to demand more maintenance, may not allow much prop clearance, add to empty weight, and could compromise fuel tank location and quantity. But, what if you were to retract the gear into the airplane’s belly instead?

Cessna, long a proponent of high-wing single design, demonstrated a long time ago that such tricks are possible. The 1959 Cessna 210 was the Wichita manufacturer’s first retractable single that folded its feet awkwardly (but effectively) down, back, and up into the bottom/aft fuselage.

Eleven years later when it came time to hide the wheels on the swept Cardinal, Cessna adapted the 210’s basic electro-hydraulic gear system to the Cardinal—sans the troublesome main gear doors. Later, Cessna was to discard the Centurion’s pesky gear doors and their complex sequencing mechanism altogether.

By sweeping up the wheels and adding a mere 20 hp, Cessna claimed an increased cruise of 24 knots, from 120 to a theoretical 144 knots. Hmmm. This made the Cardinal RG second only to the Mooneys in cruise velocity. Perhaps more importantly, however, the Cardinal RG expanded on a basic design concept Cessna hoped would become their pre-eminent, single-engine airplane, supplanting even the Skyhawk. In addition to offering the initial stiff-legged version and the basic retractable model, Cessna had also hoped to introduce a turbocharged 177 and a higher horsepower variation (240 hp). However, the company abandoned the idea of additional Cardinal models in 1978 in favor of a pair of retractable 182s—the Skylane RG and Turbo Skylane RG. Cessna built an average of 170 Cardinal RGs during the type’s comparatively short eight-year production run. By today’s standards, 170 airplanes a year of any given model would be a roaring success—not so in the early ‘70s.

The Cardinal RG incorporated a number of features not seen on previous Cessna models. The airplane was built low to the ground, with doors that opened a full 90 degrees. This was great for entry/egress, but not so wonderful when strong winds were blowing and could potentially warp the doors. Cardinals also employed an all-flying stabilator for pitch control, another mixed blessing that offered greater pitch sensitivity—perhaps a little too much response for some pilots. Early Cardinals were prone to porpoise on landing, so Cessna toned down pitch response with slots in the stabilator.

Performance was typically good for a 200 hp retractable. That is, once you got the wheels stored in the aft fuselage recesses, a process that could take as long as 15-20 seconds on some airplanes. Standard climb was 800-900 fpm from sea level and cruise registered 142-143 knots at 7500 feet. With 60 gallons aboard and a burn of 10.5 gph, the Cardinal RG could endure for four hours plus IFR reserves, worth 550 nm between pit stops.

Whatever your perspective on the success of the model, we’re left today with a group of airplanes that can represent excellent used buys. The 177RG is certainly among the most efficient of light, production retractables, and nearly every pilot would agree the shape is among the most recognizable in the sky.

The Lopresti Cardinal RG

The late Roy Lopresti was one of those engineers who were constantly looking for ways to make a good airplane even better. The Cardinal RG became one of his targets a few years ago. The engineer traced his credentials all the way back to the ‘50s when man was first considering reaching for the moon, and yes, Lopresti WAS a rocket scientist!

Roy worked for Grumman (a contractor to NASA) on the Apollo program, helping to design the lunar lander. He created the Grumman Cheetah and Tiger, went on to reshape the Mooney Executive into the remarkably efficient Mooney 201, then helped guide the Beech Starship through certification.

In his later years, the elder Lopresti founded a company in Vero Beach that designed and fabricated more efficient cowlings for a variety of airplanes and created other speed mods. Lopresti’s overriding project was the Fury, a beautiful, slippery, two-seat sport plane with the handling of a fighter and the economy of a trainer. Sadly, brilliant design can’t trump a recession. Only one Fury prototype was ever built, and it’ll probably remain an orphan forever unless someone in the Lopresti family wins a really big lotto.

In Florida, Lopresti also began modifying and improving cowlings on a variety of airplanes. One of those was Lopresti’s own Mooney 201. When he supervised the redesign of the Mooney Executive in the mid-70s, Lopresti was never totally happy with the cowling shape and function, but the need to “freeze” the design for production required him to stop experimenting with speed mods. Then, when he established his own company, Speed Merchants, he became the only arbiter of when a product was “ready.” As a result, Lopresti and his sons, Curt, David, and Jim, set about designing a series of cowlings for aircraft ranging from the Grumman-American Tiger to most Mooneys, Piper Arrows, Lances, Saratogas, and Comanches to the Seneca, Twin Comanche, and a half-dozen other designs, the latter including the Cessna Cardinal RG.

In keeping with the company name, the primary goal on every model the family addressed was to decrease drag and improve speed. A secondary goal was to enhance engine cooling both during climb and in cruise.

On the 177RG, the Loprestis found the Cardinal RG cowling was similar to that of the earlier, modified Mooney cowl. Both models used virtually the same engine, the 200 hp Lycoming IO-360-A1B6D/A3B6D, so the external cowling design could be nearly identical.

Curt Lopresti:

“Just as on the 201, our goal on the Cardinal RG was six-to-seven knots of speed increase, hopefully with an improvement in cooling. We replaced all baffling with more durable material that tends to retain its shape. The new, carbon fiber cowling utilized oven-cured, fire-retardant, epoxy resin and incorporated a SCRAM (Super Clean Ram Air Module) feature similar to that used on the Mooney cowl. SCRAM delivers between ¾ and 1 ¼ inches of additional manifold pressure, depending upon altitude.

“Inlets for cooling air were extended forward to come as close as possible to the back of the prop arc…and the contour and diameter of the inlets themselves were shaped to improve airflow thru the cowl. We were especially concerned with controlling cylinder head temperatures. Reducing drag doesn’t mean much if you’re compromising reliability by running the engine too hot.

“Along the top of the new cowl, we installed large access doors that allowed better access to the top of the engine, and we lowered the cowling trim line, so it was only necessary to remove the top cowl for access to both the top and bottom spark plugs. We also installed a new nose gear door, a larger, 13-fin, oil cooler, and a new spinner. The result was a more aerodynamically-efficient cowling that’s also more esthetic and functional.”

Retired Western/Delta Airlines Captain, Jim Honeycutt, of Mallards Landing, Georgia, lives the dream that so many of us would love to emulate. Jim and his wife, Sandy, also a pilot, live on an airpark and fly a Cardinal RG, the latest in a series of at least a dozen airplanes he’s owned in his 30-year flying career. Honeycutt purchased his RG slightly damaged in the mid ‘90s after a wood hangar collapsed on top of it. He and his friends rebuilt the airplane to near-showroom condition and decided to add the Lopresti cowling and Power Flow exhaust two years ago. In fact, Honeycutt was the launch customer for the Loprestis’ new Cardinal RG cowling.

“Lopresti had an excellent reputation as a mod manufacturer, and I decided to try his cowling to see if it really would improve cruise performance and reduce cylinder head temperatures,” said Honeycutt. “I flew my airplane into the company’s Melbourne, Florida, facility, had them do all the work, and sure enough, the cowling did everything the company claimed. I saw a significant speed benefit from the combination of the cowling and the Power Flow tuned exhaust. Lopresti claims six-to-seven knots from the cowling, and that’s probably about right, as Power Flow delivers three knots more, and I saw a total of 10 knots cruise improvement with both mods installed.” Honeycutt explains.

With the help of the Lopresti cowling, Honeycutt can outrun the majority of other Cardinal RGs, though he recognizes the universal rule of TINSTAAFL (There Is No Such Thing As A Free Lunch). “The Power Flow exhaust adds about eight to ten percent to cruise power,” he said. “But, of course, that means it adds the same percentage to fuel burn.”

Sadly, Cessna’s “Airplane of the ‘70s” catchphrase for the Cardinal turned out to be a little too prophetic. The Cardinal design lasted just under a decade before Cessna phased it out to make room for the retractable Skylanes. In total, Cessna constructed some 1,350 Cardinal RGs and terminated production with the 1978 model.

Today, Aircraft Bluebook Price Digest suggests you can find used 177RGs for prices starting at $41,000 for the first 1971 models and peaking at $50,000 for one of the last 1978 airplanes in good condition.

Don’t even consider snagging a primo example such as Jim and Sandy Honeycutt’s retractable Cardinal for that money, however. With an updated panel and all the mods, especially the Lopresti cowling, you’d probably have to pay at least $15,000-$20,000 more for a copy of Honeycutt’s airplane. But, consider for a moment what that’ll buy. You’d have the distinction of aviating in an aircraft that, at least, resembles a sport plane—even if it isn’t one. Plus, you might even be able to give Jim Honeycutt a run for the money!

Specifications & Performance – Cessna Cardinal RG

All specifications and performance figures are drawn from official sources, often the aircraft flight manual or the manufacturer’s website. Another reliable source of information is Jane’s All-the-World’s Aircraft. Specifications on older aircraft will not always agree, as different sources may publish different numbers.

Specifications

Engine(s) – make/model: Lycoming IO-360-A1B6D

Hp: 200

Fuel type: 100LL

Landing gear type: Tri/retr

Max TO weight (lbs): 2800

Empty weight (lbs): 1768

Useful load–std (lbs): 1032

Usable fuel–std (gal/lbs): 60

Payload–full std fuel (lbs): 672

Wingspan: 35’ 6”

Overall length: 27’ 3”

Height: 8’ 7”

Wing area (sq ft): 174

Wing loading (lbs/sq ft): 16.1

Power loading (lbs/hp): 14.0

Seating capacity: 4

Cabin doors: 2

Cabin width (in): 43

Cabin height (in): 43

Performance

Cruise speed (kts–75%): 144

Cruise Fuel Burn (gph/lbs): 10.5

Best rate of climb, SL (fpm): 925

Service Ceiling (ft): 17,100

Stall (Vso – kts): 50

TO over 50 ft (ft): 1645

Ldg over 50 ft (ft): 1370

About The Author

Bill Cox took his first flight in a Piper J-3 Cub in 1953 and has logged some 15,000 hours in 311 different types of aircraft since. He has authored more than 2,200 magazine articles and was the on-camera host of the 1980s TV series “ ABC’s Wide World of Flying.” Bill is currently rated Commercial/Multi/Instrument/Seaplane/Glider/Helicopter. He can be contacted via email at [email protected]. Learn About Bill's Book Here

Related Posts

April 2, 2021

Cessna 182 Turbo Skylane: Business Turbo for the Family Man

May 27, 2015

Owner’s Perspective: Skylark

May 7, 2020

Cessna 172 Market Report & Tips

February 14, 2023

Box A Zone 1

Box b zone 2, box c zone 3, box d zone 4, free digital magazine & newsletters.

Click HERE to choose your FREE download: 172 Owners Guide, 182 Owners Guide, or Digital Magazine.

You have successfully subscribed.

You are here

Cessna 177rg cardinal rg.

The final aircraft in the 177 line was the retractable-gear 177RG Cardinal RG, which Cessna began producing in 1971 as a direct competitor to the Piper PA-28-200R Cherokee Arrow and Beechcraft Sierra . The RG had a 150 kW engine to offset the 136 kg increase in maximum weight, much of which was from the electrically-powered hydraulic gear mechanism. The additional power and cleaner lines of the 177RG resulted in a cruise speed of 146 knots, 22 knots faster than the 177B . 1,543 177RG's were delivered including those built in France by Reims, as the Reims F177RG.

1 x Lycoming IO-360-A1B6D, 200 hp (150 kW).

SKYbrary Partners:

Safety knowledge contributed by:

Join SKYbrary

If you wish to contribute or participate in the discussions about articles you are invited to join SKYbrary as a registered user

Message to the Editor

About SKYbrary

What is SKYbrary

Copyright © SKYbrary Aviation Safety, 2021-2024. All rights reserved.

- Forgot your password?

- Forgot your username?

Cessna Cardinal – The Cardinal’s Sins

October 2004

In 1965, Cessna had already been the industry leader for two decades, building more than half of the world’s GA products. In the ten years since they had introduced the 172 Skyhawk, about 9,000 of the four-place singles had been built—it was already the world’s most popular airplane.

But the title of No. 1 came with certain obligations, and assurance of continued business through R&D was one. There had been new features added to the 172, like the Omni-Vision rear window, aerodynamic clean-up, one-piece windshield and the like, but both management and engineering were interested in the business an advanced design (or at least the perception of one) could generate. After all, the original 172 fuselage design was based on the 120/140 of 1946 and its wing originated on the 1949 170A.

Why new designs are as rare as a tailwind

The average customer may not comprehend the reason aircraft designers and manufacturers recycle their basic designs. There are manufacturing considerations, of course: the longer tooling can be used, the less the unit cost, but the principal reason is that basic engineering, testing and use history has proved a structure to be of a predictable strength and performance.

That having been (hopefully) explained may help you understand some of the problems created by the inevitable compromises that surround the introduction of a totally new airplane like the Cardinal.

In reaction to customer demand and a desire for higher performance, Cessna engineers had become intrigued with the NACA series of laminar flow airfoils. Data showed extraordinarily low drag coefficients if precise wing smoothness could be achieved. At the same time, it appeared that higher cruising speeds could be achieved by eliminating the wing struts then in use on all Cessna singles.

The high-performance 210 Centurion was the logical candidate. Design work began on the new wing in 1964. First off, the proposed location of the main spar didn’t match the door posts on the existing 210, so a heavy supporting structure had to be added—but that lessened headroom, which required another compromise.

The next obstacle was that because a cantilever wing is inherently heavier than a strut-braced wing, it normally requires a heavier main spar. Cessna was able to breach the problem (at great expense) by machining a tapered spar. Next, the wing was moved 4½ inches aft for better visibility, but that created a nose-heavy condition and stability problems, the solution of which was a higher-dihedral wing.

Dozens of other compromises had to be made before it was test flown in mid-1965. That was when it was evident that more elevator power was needed, and six sq. ft. was added to the horizontal tail (a fully articulated tail had been considered, but was abandoned after testing). The cantilever laminar flow wing debuted on the 1967 210H/T210H.

Gross weight had, of necessity, grown 100 pounds, and cruise speed increases were a modest two to three mph, although ongoing refinements over the next 15 years would eventually net an additional 20-30 mph.

Even though Cessna had spent millions in development, the 1967 models were priced virtually the same as the year before. It would take a long time to recoup the investment. But one way to get the best value for money spent was to spread the expense across several models, and the venerable 172 seemed to be a good place to start.

The J-bird and its flying tail

Planning for a 1968 introduction, work was started on the 172J in 1965. It was referred to internally as the “J-bird,” and security was tight. The new 172 would have a large, spacious cabin, better pilot visibility, more speed, easy entrance and exit through 47½” wide doors, better flying qualities, tubular steel landing gear and a modern, streamlined appearance. And, by management decree, it had to use a 150 hp engine for cruise efficiency.

All previous flat-engine Cessnas had been powered by Continental, and the 172 had used the 145 hp six-cylinder O-300 model since its 1956 introduction. However, for some reason Continental was abandoning its lower-power engines. Lycoming had a perfect candidate. Cessna was so confident that it ordered 2,000 four-cylinder, 150 hp O-320s before the 172J flight testing was finished, and they took an option on 2,000 more: there was much joy in Williamsport.

To start with, engineers used the new cantilever wing design that was being introduced on the ’67 Centurion, built with scaled-down component thicknesses for the lower target gross weight of 2,350 lb. The wing skins would be thin, but the plan was to machine-rivet the sections that would form the leading edges. However, factory manufacturing engineers rejected the scheme as too expensive, so even thinner aluminum was specified.

The problem was that if the leading edge developed any dimples or waves, it would nullify the low-drag potential of the laminar flow airfoil. The next decision was to place the wing further aft than normal on the fuselage for better visibility. That, of course, produced a nose-heavy condition and aggravated the pitch-down forces caused by wing flaps. In turn, a tremendous amount of elevator power would be needed for tail-low touchdown. At that point, an all-moveable horizontal tail (stabilator) was specified.

The maiden flight was made by test pilot Bill Robinson on July 15, 1966, and it showed that a great deal of development work was needed on the stabilator. Piper had been using the stabilator for quite a few years and knew its idiosyncrasies, but it was new to Cessna. Wind tunnel and flight testing showed that they had over-engineered it, and trim and anti-servo forces were excessive.

In addition, the original 40 degree setting of the wide-span flaps produced a high rate of sink on final, so the maximum deflection was reduced to 30 degrees; the stall penalty was only one mph and landing distance over the 50-foot obstacle increased about 50 feet.

Despite its other good characteristics, the 172J wanted to drop a wing at stall. A high-camber airfoil section at the tip and a 3° twist hadn’t cured the problem, so 12-inch stall strips were installed on the leading edge, placed at a point on the wing that corresponded to the outer end of the horizontal tail. Flaps-retracted stall speed was six knots higher than on the 172H at the same weight. At maximum flap deflection, the increase was only three knots.

The biggest problem showed up in an accelerated 1,000-hour service test, which included 5,000 landings flown by a number of pilots of different experience levels, and engineers found out that many were approaching with excessive speed and over-controlling and porpoising in the landing flare, often resulting in nosewheel landings and wrinkled firewalls. It might prove to be a problem for owners to make the transition from elevator (slow pitch response) to stabilator (quick pitch response).

The Goose that laid the Golden Egg

As changes and improvements were made, the weight of the prototype began to grow. One cure was reduction in wing skin thickness (which some wags were already referring to as Spearmint gum wrapper) and shaving excess thickness of other parts.

Eventually, empty weight came down to an average of 1,350 pounds, about 75 pounds. higher than the 172. Time was running out. Early in 1967, a date was set for the introduction of the sleek new design in late summer, soon after it was scheduled to receive its Type Certificate.

As the prototypes flew nearly every day, keeping them a secret became an obsession. No pilot was allowed to land at public airports or even fly low enough to be identified. But for all intents and purposes, the company did a good job of keeping it a secret from the public—and especially from the dealers and potential customers, who might postpone a purchase until the sleek newcomer was available.

Manufacturing began early, and plans for a lavish introduction were underway. Then someone asked a very good question. “Let me get this straight,” a brave but anonymous marketer said. “We’re going to drop our best-selling model—the goose that laid the golden egg, so to speak—and replace it with a radically new airplane that’s untried?”

The topic had already been discussed and the motives questioned over lunch pails among the rank and file—who obviously didn’t understand the intricate overview afforded those behind the ivy-covered walls, but nonetheless, a period of extremely uncomfortable silence ensued.

Finally, someone in charge broke the silence with an expletive that communicated the very same lack of foresight. Then with an inspired expression, he presented Plan B. “Okay. How many 172s did we sell last year—sixteen hundred? We have 2,000 engines on order to cover this year’s production and another 2,000 for next year, right? What say we build the new airplane, recertify it as the 172½ or something and keep the old Hawk in the line—powered with those other 2,000 Lycomings?”

That’s not exactly how it happened, but that is what they did.

Everyone got busy. Deadlines were met. Overnight, the 172J became the 177 Cardinal and the 172 continued its charmed life as the 172I.

About 1,100 Cardinals were sold at the gala world introduction in Wichita, where dealers were able to take same-day delivery on their new airplane and fly it home to show to customers. There was just one problem. As nearly every airplane took off from Cessna’s Delivery Center, it popped into the air, then dipped back toward the runway and continued to porpoise over the horizon toward an uncertain fate.

Not surprisingly, it was the same problem that had confronted service test pilots that was now being experienced by the people who were ultimately responsible for selling the airplane. A stabilator replacement program ensued, whereby a unit with leading edge slots was installed to increase landing authority, but the damage had been done.

The Cardinal had the sleek look of a crouching panther, but the speed and strength of a four-week-old kitten, and the typical blanket damnation from pilots was, “It doesn’t fly like a Cessna.”

The net result of the Year of the Cardinal was that, after the deliveries of those first 1,100 aircraft, less than 100 re-orders were booked. Cessna faced the reality that 150 hp was marginal, and immediately set to work on the 177A with a 180 hp Lycoming O-360-E2D engine. It debuted in 1969 and furnished a modest gain in performance—four knots at cruise, 90 fpm more climb and a much higher service ceiling.

Everyone agreed it should have been the engine for the original Cardinal, but the cavalry had arrived too late to save the wagon train. Dealers still trusted the 172I, however. They bought 649 of them in 1968 and more than 2,000 over the next two model years.

While the fixed-gear 177 suffered through another 10 years of mediocre sales, the retractable version (RG) may actually have made the whole program worthwhile. As it became obvious that the 177 was catering to an upscale market, engineers borrowed the technology from the 210.

Using an electro-hydraulic system like the Centurion’s, but with rear-retracting nosegear, the 177RG filled a vacant niche in the Cessna lineup. Gross weight was upped to 2,800 lb. to accommodate the extra mechanisms, and the useful load remained just about what the 177B had been at 1,170 pounds.

The RG was first flown in February 1970 and went to market as a ’71 model. The sleek and modern shape of the basic Cardinal had been seemingly marred only by its “down-and-welded” landing gear, and the RG exercise produced a model that was competitive with the Piper Arrow and Mooney Ranger.

With a 200 hp IO-360 engine, the RG could cruise 80 percent as fast as the 210 for 60 percent of its purchase price, and of all the Cardinal models sold from 1968 through 1978, half were RGs.

The 177 saga provides a short course in not only the engineering, but the psychology of building a new design. While marketing furnishes valuable input on a program, it should be up to the slide rule crowd to determine if it can become a reality.

The Cardinal’s fate was sealed the first time the first dealer struggled off the ground on that 90-degree day in Wichita and porpoised over the horizon. By the time he got home, he had found all of its real or imagined problems and unconsciously conveyed a distrust to his customers. As TV’s Dr. Phil puts it, “There is no such thing as reality; there’s only perception.”

Daryl Murphy and the Super Skymaster both started flying in 1965. As part of the Cessna marketing team that introduced the 177 Cardinal to the world, he offers an insider’s view of the airplane’s short life. Murphy’s work also appears regularly in GA News and Aviation International News.

- Brands/Models

- Buyer’s Guide

- Glass Cockpits

- Auto-Pilots

- Legacy Instruments

- Instruments

- Safety Systems

- Portable Electronics

- Modifications

- Maintenance

- Partnerships

- Pilot Courses

- Plane & Pilot 2024 Photo Contest

- Past Contests

- Aviation Education Training

- Proficiency

- Free Newsletter

Cessna 177 Cardinal

When Cessna brought back its greatly abbreviated lineup of single-engine planes in the mid-1990s after a 10-year hiatus, perhaps the omission that most grieved enthusiasts was that of the Cardinal, which is arguably one of the, if not the , most beautiful Cessnas ever built. Introduced in the late ’60s, the Cardinal was intended by Cessna as a replacement for the 172, which sounds like a bad joke today. It didn’t work, and Cessna built many thousands of 172s after that, but by gum, the Cardinal was much beloved by those who owned and flew them. Don’t get the wrong idea. It was far from a niche offering. Cessna built more than 4,000 in the decade following the type’s introduction in 1968. And it was cool, with its two major features being the cantilever high wing and the setback of said wing, both of which allowed easy access to the seating area. And Cessna did a great job with the interior as well. It was comfortable and had terrific visibility, but it wasn’t fast, with a cruise speed of around 120-125 knots. Even the retractable-gear 177RG isn’t much faster than that. And if you note the Cardinal’s passing from production in 1978, seven years before the company pulled the plug on the rest of its singles, you might get the idea that it wasn’t selling well. Correct. Though Cessna did, indeed, get a lot of low-pressure urging to put the plane back into production, the all-metal model wasn’t cheap to build—cantilever-wing designs tend to require lots of production hours compared to their strut-braced brethren. And in a way, Cessna almost did bring back the Cardinal, or at least a Cardinal wannabe, when it floated the idea of a high-winged, no-strut, all-composite plane it called the Next Generation Piston (NGP). It never took off, production-wise, and as far as beauty is concerned, it couldn’t hold a candle to its sheet-metal inspiration.

Stay in touch with Plane & Pilot

America’s owner-flown aircraft enthusiasts and active-pilot resource, delivered to your inbox!

Save Your Favorites

Already have an account? Sign in

Save This Article

- Manufacturers

- CESSNA 177RG Cardinal

What feature of our site is most important to you?

- Aircraft for sale

- Operating Costs

- Performance Specs

- Used Aircraft Values

- Aircraft Sales and Accident History

1972 - 1978 CESSNA 177RG Cardinal

Log in to compare." data-placement="left" data-activity="click on '+ add to compare cessna 177rg cardinal'" > view comparison.

Single engine piston aircraft with retractable landing gear. The 177RG Cardinal seats up to 3 passengers plus 1 pilot.

View 59 CESSNA 177 For Sale

PAPI™ Price Estimate

Market stats.

Performance specifications

Horsepower:

Best Cruise Speed:

Best Range (i):

Fuel Burn @ 75%:

Stall Speed:

Rate of climb:

Takeoff distance:

Landing distance:

Takeoff distance over 50ft obstacle:

Landing distance over 50ft obstacle:

Gross Weight:

Empty Weight:

Maximum Payload:

Fuel capacity:

Ownership Costs 1972

Total cost of ownership:.

Total Fixed Cost:

Total Variable Cost:

Total Fixed Cost

Annual inspection cost:

Weather service:

Refurbishing and modernization:

Depreciation:

Total Variable Cost ( 107.4 Hrs ) Cost Per Hour = $97.37 Cost Per Mile = $0.65

Fuel cost per hour: (10.5 gallons/hr @ $5.40/gal)

Oil cost per hour:

Overhaul reserves:

Hourly maintenance:

Misc: landing, parking, supplies, catering, etc

Engine (x1)

Manufacturer:

IO-360-A1B6D

Overhaul (HT):

Years before overhaul:

Also Consider

Cessna 177rg cardinal (1971 - 1971).

Typical Price: $127,829.00 Total Cost of Ownership: $19,773.99 Best Cruise: 144 KIAS ( 5 ) Best Range: 506 NM ( 6 ) Fuelburn: 10.5 GPH ( 0.0 )

Adjust ownership costs parameters

- Cost Per Mile

- Cost Per Hour

Leave Us Feedback PlanePhD is only as good as its community. Everyone wins if you share.

Please tell us: - Features that would be useful to you. - Aircraft data that you believe is inaccurate or have specific experiences. - Aircraft specific reviews and articles. Please send us your experiences on your aircraft. - Send us pictures of your plane. - Use this form or email to reach out to us: [email protected]

Thank you for contacting us!

One of our Planephd Experts will be in touch with you shortly.

Cessna Cardinal 177 AB Series Data, History, & More

Cessna By Textron Aviation

Before creating his own initial aircraft, Cessna’s founder Clyde V. Cessna made his first appearance at an airshow in 1911. It was there that he quickly became interested in designing and producing aircraft. With experience as a mechanic and auto salesman, Clyde put together his aircraft with a kit from Queens Airplane Company in the Bronx. Over time, Clyde became a fairly good pilot.

In 1916, Clyde got the opportunity to use a space for his aircraft dreams rent-free on one condition – any new aircraft he made had to have the name of a particular car model called “Jones-Six” painted on the underside of its wings.

In 1917, he built the Comet. However, World War I impacted his vision, halting sales and production altogether as most critical parts and supplies became essential for war use. After coming to terms with his failed venture, he returned to farming.

Years later, in 1925, wealthy businessmen Walter Beech and Lloyd Stearman offered Cessna an opportunity to build and produce more aircraft. After teaming up, they created Travel Air Manufacturing Company with Cessna as its president. But Cessna didn’t enjoy his role as president and missed being heavily involved with aircraft design and production. So two years later, Cessna teamed up with Victor Roos to create the Cessna-Roos Company. His partner Roos left the business shortly after for another job.

Cessna had successful sales through the business’s A and D series, but tough times were still ahead. After private aircraft sales fell to an all-time low in 1931, Cessna closed his company again.

By 1933, Cessna’s nephew Dwane Wallace obtained his degree in Aeronautical Engineering from Wichita University. He eventually worked for Beech Aircraft Company, where he convinced executives to allow his uncle to reopen his shop and continue making aircraft. At the time, Beech occupied a small section of Cessna’s former factory.

After Cessna’s retirement in 1936, he allowed the sale of all of his shares to his nephews, Dwane and Dwight Wallace. Under the Wallace Brothers’ leadership, Cessna designed and built its first twin-engine aircraft in 1938. Before World War II started, government demands from the U.S. and Canada poured in for aircraft to be used for military training. From there, Cessna’s business expanded quickly, embracing its newfound success.

Creating The Cardinal

Driven by a need to create a higher-performing 172, Cessna’s engineers began working on the 177 in the 1960s, later producing the first 177. While it had a sleek new look, aviation enthusiasts and pilots had issues with its speed and strength. Additionally, nearly every aircraft that launched at Cessna’s Delivery Center showed signs of stability issues right away. Even though the issue was solved later, the massive error wouldn’t soon be forgotten. In fact, of the initial 1,100 aircraft sold, less than 100 were reordered.

Cessna began working on a faster, improved 177 with the 177A in 1969. Powered with a 180-horsepower Lycoming O-360-E2D engine, the 177A still spent the next 10 years struggling with sales from and beyond the release of the 177B. However, Cessna’s development of the 177RG redeemed its namesake by increasing its speed with a 200-horsepower IO-360 engine, with the ability to rival the Piper Arrow and Mooney Ranger in the early 1970s.

Country of Origin: America

Cessna Cardinal 177 A/B

Below are the average statistics for the latest Cessna Cardinal 177 A and 177 B models. Find more information on Cessna’s Cardinal series by joining VREF Online .

Cessna Cardinal 177 A Statistics

Cessna cardinal 177 b statistics, operational resources, operations manual, maintenance document.

- 177A and 177B Service Manual

Local Resources

- Textron Aviation Inc. (Domestic and International Service Centers)

- Cessna Flyer Association

Manufacturer

- AOPA Insurance

- BWI Aviation Insurance

- Falcon Aviation Insurance

- Travers Aviation Insurance

- USAA Aircraft Insurance For Pilots

Cessna Cardinal 177 A/B Details

The following is information about the latest Cessna Cardinal 177 A/B.

Cessna’s 177A features a spacious back seat, more headroom, cigarette lighters, and signature red-accented panel control. It has a distinctly modern style called “fastback”, which Cessna’s marketing used in attention-grabbing headlines like “The Fastback Revolution”.

Cessna’s 177B features built-in lumbar seating designed with its contouring suspension system and optional adjustability features. This variation also has a separate baggage compartment and a T-style avionics panel.

This variation showcases a 180 horsepower increase while slots were added to the stabilator to improve landing. This variation is known for its wraparound windshields for ideal visibility, sharp leading-edge wings, and heavier nose design.

Wings on the later 177 series include a more blunt design to improve takeoff. This variation also has improved door sealing, optional 60-gallon fuel tanks, a 28-volt electrical system, a D-engine model update, and upgraded prop for higher continuous revolutions per minute (rpm).

- PS Engineering PMA 7000B-T Audio Panel/Intercom System (Bluetooth)

- Dual King KX 170B Navigation/Communications

- Dual Glideslopes

- King KCS 55A Compass System

- L3 Lynx NGT-9000 Multilink ADS-B In/Out Transponder with traffic display

- Northstar GPS-60 Navigator

- Davtron digital clock

- King KR 87 ADF

- King KN 64 DME

- Cessna 300 A Autopilot with ST-60 Altitude Hold, Vertical Speed, and Glideslope Coupling

- Eventide Argus 5000 Moving Map

- WX-10A Stormscope

- Shadin Digital Fuel Flow/Totalizer

- Electronics International UBG-16 Engine Analyzer with Burst Recorder

- Precise Flight Standby Vacuum System

- Pulselight Landing and Taxi Light System

- Garmin 3X GDU PFD Touch

- Garmin G-5 Standby

- Garmin GTN-750Txi

- Garmin GTR 225 Navigation/Communications

- Garmin GNX375 GPS WAAS ADS-B in and out

- Garmin GAD 29B

- Garmin GSU 25D ADAHRS

- Garmin GMA 340 Audio Panel

- Garmin GFC 500 Autopilot System

Specifications

- Take Off Run (50 ft.): 1,575 ft.

- Configuration: Single Engine, Piston, Fixed Gear

- Max Seats: 4

- Max Take-Off Weight: 2,500 lbs.

- Cruise: 130 kts

- Range: 535 nm

- Take Off Run: 750 ft.

- Landing Roll: 600 ft.

- Wing Span: 35 ft. 6 in.

- Length: 27 ft. 3 in.

- Height: 8 ft. 7 in.

Cessna Cardinal Models

In the mid-1960s, Cessna engineers sought to create a more modern version of the ever-famous 172. As a result, the original 177 went into production as a high-wing single-engine aircraft in late 1967 with a horsepower of 150.

Because the 177 was deemed an “underpowered” model, Cessna made adjustments. And in 1969, Cessna’s 177A appeared with an all-inclusive price of $16,995 and a power increase to 180 horsepower. This variation has a four-cylinder Lycoming O-360 engine with an improved cruise speed of 11 knots.

In 1970, Cessna welcomed the 177B into its 177 series. Major updates include a refreshed wing airfoil and a new constant-speed propeller. Cessna introduces a luxury version of the 177B in 1978 with leather upholstery, a table for the rear passengers, and a 28-volt electrical system.

The final 177 of the series introduced in 1970 is a retractable-gear 177RG Cardinal RG. Major changes from the 177B include a retractable nose-wheel and main wheels, with the nose-wheel enclosed by doors when pulled in. This variation is powered by a 200-horsepower Lycoming IO-360 engine and increased in maximum weight by 300 lbs. Cruise speed increased from the 177B by 148 knots.

Top Cessna Cardinal Questions

Check out FAQs about Cessna’s Cardinal.

Is Cessna Cardinal A Good Plane?

Cessna’s first of the 177 Cardinal series is known to be a slower aircraft with a decent but not tremendously exceptional range. After fixing notable issues, Cessna ended up with a decent plane in the 177RG. Outside of the 177, Cessna continues to see tremendous success selling its 172 and newer aircraft models.

How Much Is A Cessna Cardinal?

The cost of a Cessna Cardinal depends on the version. The estimated price for the 177 series according to its latest variation:

- 177 – $101,060

- 177A – $82,407

- 177B – $156,073

- 177RG – $153,266

Join VREF Online to keep an eye on future estimated aircraft prices.

How Fast Is A Cessna Cardinal RG?

A Cardinal RG has a maximum cruise speed of 180 mph or 156 kts. However, the recommended cruise speed is 171 mph or 148 kts.

Are There Any Incidents On The Cardinal’s Record?

According to the Aviation Safety Network’s database, 554 occurrences are on record. Of these incidents, 4 are notable – taking place from 1968 to 2003.

The grandson of a former U.S. Vice President, Alben Truitt, hijacked a 177 from Key West to Cuba in 1968, returning the aircraft nearly 4 months later. He was then charged with 40 combined years in prison for aircraft piracy and kidnapping.

In 1996, 7-year-old Jessica Dubroff, her certified flight instructor and father, took off in a 177B in an attempt to set a cross-country record for young pilots. However, the plane crashed after takeoff in Cheyenne, Wyoming killing everyone on board.

In 1998, a single pilot was flying a 177RG when it collided with another aircraft that had traveled off course with 14 people on board. Both aircraft crashed into Quiberon Bay off the coast of France, resulting in complete fatalities for everyone on board.

The young author of Wonder When You’ll Miss Me , Amanda Davis, and her parents crashed in a 177 shortly after takeoff. Amanda’s father, who was also chairman of the neurology department at Long Island’s Stony Brook University, was piloting the plane. According to news outlets, he lost control of the aircraft after he reported bad weather. This caused the 177 to crash into the mountainside, killing all on board.

Why Was The First Cardinal Engine A Failure?

The AOPA cites the Cardinal’s first engine as a misstep in design and manufacturing. The engine for this aircraft was too slow, which caused problems during takeoff and landing. One more specific problem initially reported is pilot-induced oscillation (PIO) or porpoising, which causes the aircraft to switch between upper and lower movements. It’s a control issue that Cessna fixed quickly with the launch of the 177A model.

Does Cessna Still Make The Cardinal?

Cessna ceased producing the Cardinal in 1978. While it was intended to replace the Cessna 172 Skyhawk, it was not successful. Even with its latest 177RG variation, sales slowed significantly. Only about 100 177s were made within its last year of production.

Join VREF Online For More About Cessna’s Cardinal Series

Join VREF Online for real-time data on thousands of single-engine aircraft, their turbocharged counterparts, and much more.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Related posts.

Women In Aviation: Breaking Barriers And Making Strides

Implications Of AI In Aviation: The Good, Bad, & Ugly

Piper Comanche PA-24-250

- AVwebFlash Current Issue

- AVwebFlash Archives

- Aviation Consumer

- Aviation Safety

- IFR Refresher

- Inside Aviation Podcast

- Business & Military

- eVTOLs/Urban Mobility

- Experimentals

- Spaceflight

- Unmanned Vehicles

- Who’s Who

- Video of the Week

- Adventure Flying

- AVWeb Classics

- CEO of the Cockpit

- Eye of Experience

- From The CFI

- Leading Edge

- Pelican’s Perch

- The Pilot’s Lounge

- Brainteasers

- Company Profile

- Flying Media Offers

- Question of the Week

- Reader Mail

- Short Final

- This Month In Aviation Consumer Magazine

- This Month In IFR Magazine

- Farnborough

- HAI Heli Expo

- Social Flight

- Sun ‘N Fun

- Women in Aviation

- Accidents/NTSB

- Aeromedical

- FAA and Regs

- Flight Planning

- Flight Schools

- Flight Tracking

- Flight Training

- Flight Universities

- Instrument Flight

- Learn to Fly

- Probable Cause

- Proficiency

- Risk Management

- Accessories and Consummables

- Aircraft Upgrades

- Equipment Reviews

- Maintenance

- Refurb of the Month

- The Savvy Aviator

- Tires/Brakes

- Used Aircraft Guide Digest

- Electronic Flight Bag

- Engine Monitors

- Portable Nav/Comm

- Specifications

- Sign in / Join

- Register Now

- Customer Service

- Reset Password

- Sign up for AVweb Flash

- Read AVweb Flash

- Aviation Publications

- Contact AVweb

‘Midnight’ Developer Archer Achieves FAA Part 135 Certification

Starliner Crewed Launch Scrubbed

Joby Completes Pre-Production Flight Testing, Eyes Air Certification For Electric Air…

LSA-Based Exploding Drones Used In Attacks On Russia

In Wine And Journalism, Context Is Everything

Whitecaps On Their Martinis

Blog: Remembrances Of Triple-Ace Bud Anderson

Blog: V-Tail Myths And The Truth, As We Know It, So…

Talk Like A Pirate Pilot

Best Of The Web: Snowflakes In The Air

Picture Of The Week: June 7, 2024

Best Of The Web: Super 18 Jump

Short Final: Watch Your Language

Short Final: Happy Landings

Short Final: An Abundance Of Caution

Short Final: Seeing The Light

RAF Pilot Dies In Spitfire Crash

NTSB: Rule Violation Contributed To Fatal Midair Collision At EAA AirVenture

Alaskan Instructor Wins Martha King Scholarship

Sun ‘n Fun 2024: Bose A30 Headset

Controller Warned Floatplane Pilot Of Boat Before Collision

Airline Floatplane And Boat Collide In Vancouver Harbor (Updated)

Owner’s Fatal Crash Forces Flight School Closure, Students Left In Limbo

NTSB Cites Lack Of Safety Technology And Controller Error For Near…

VP Racing Responds To Fuel Suitability Comments

California Pilots Urged To Contact Senators Over Leaded Fuel Ban

Citizens Group Targets EAGLE Co-Chair And NATA Head Castagna

Court Action Looms Over California Unleaded Fuel Availability

Unjammable ‘Quantum Navigation’ Tested in U.K.

ForeFlight Introduces Reported Turbulence Map

uAvionix Gets FAA Airport Surface Situational Awareness Contract

Sun ‘n Fun 2024: Garmin VHF Radios

- features_old

Cessna 177 Cardinal

An economical cruiser that looks more modern than a skyhawk, the fixed-gear cessna 177 cardinal is a good choice for performance-seekers on a budget..

Although the design is more than four decades old, the Cessna 177 Cardinal—with its racy sloped windshield, wide doors and strutless wings—looks more modern than the newest Skyhawks coming out of Cessna’s Independence, Kansas, plant. Yet, sadly, the Cardinal is a poster child for why innovation and audacity in general aviation development has often met dismal results in the market. Despite high expectations for a design that would usher in new thinking in light aircraft, the Cardinal had a rocky start and was gone from Cessna’s inventory a decade after it emerged.

Although Cessna’s 177 Cardinal was intended to be a Skyhawk killer, the venerable 172 outlasted it and continues to be a mainstay in Cessna’s current piston aircraft line. Still, the Cardinal enjoys enthusiastic support among owners for many of the reasons that Cessna thought it would become a hit. And despite its warts and shortfalls, many of which have been rectified, the Cessna Cardinal is an excellent choice for owners who want a bit more performance than the Skyhawk offers without stepping up to the 182 Skylane.

Cessna 177 Cardinal Model History

By the time the Cessna 177 Cardinal appeared, the Cessna 172 was long in the tooth, having been on the market for 12 years. It was time for something new. When the first Cardinals hit dealers in 1967, buyers were clearly confronted with just that.

Besides being sleeker and strutless, the new model had a stabilator, just like Piper’s competing Cherokees did. With the wings placed aft of the main part of the cabin, the pilot sat ahead of the leading edge, which produced better inflight visibility than any of the previous Cessnas had.

The 1968 Cardinal had a fixed-pitch prop and a Lycoming O-320-E2D. The airplane was designed with the 180-HP engine in mind, but Cessna had ordered 2000 150-HP engines from Lycoming—its first purchase from the company.

Cessna was so confident that the Cardinal would succeed that the Skyhawk production line was actually shut down in anticipation of the Hawk’s planned demise. Things didn’t work out that way, however.

The 150-HP, fixed-pitch prop Cardinal looked great, but gained a reputation for lethargic climb performance. In reality, it took some time for Cessna to figure out that pilots were loading and flying the Cardinal as if it were a 172—which meant they were often over gross weight—since it carried 10 more gallons of fuel and had a heavier empty weight. Worse, Cessna discovered that pilots were climbing the aircraft well below Vy (Vy in the 172 was 10 MPH slower than it was for the Cardinal). When flown and maintained properly, the 150-HP Cardinal actually outclimbed and outran the 150-HP 172.

Cessna produced 1164 Cardinals that first year, but word got around about the airplane’s performance. The following year, sales slumped, while other models were selling well. In fact, no more than 250 Cardinals were built in any single year after the airplane’s introduction. (A total of 2752 were built, eventually.)

The Cessna Cardinal’s wing was a high-performance NACA 6400 series airfoil, the same one used in the Aerostar and Learjet. But that airfoil tends to build up drag quickly at high angles of attack and low speeds, which isn’t a good trait for an airplane flown by low-time, step-up pilots. The stall speed was higher than the Skyhawk’s, too.

In the late 1970s, an accident involving an original model 150-HP Cardinal prompted a series of test flights (performed by an expert test pilot working for plaintiffs’ attorneys) in an attempt to prove that the 177 Cardinal didn’t live up to its performance figures. The accident in question involved a pilot who supposedly had operated the airplane as described in the manual and wound up clipping the trees at the end of the runway. But because these trials weren’t conducted by the FAA or Cessna, no official action was taken against Cessna. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that the expert test pilot was proven wrong in court about his claims of the Cardinal’s short field takeoff performance.

Touchy Controls for the Cessna 177 Cardinal?

The 1968 Cardinal as originally delivered was quite sensitive on the controls, particularly in the pitch mode. In crosswinds, the stabilator could stall in the landing flare, resulting in a sudden loss of tail power and an unexpected plunge of the nosewheel onto the runway.

Porpoising and bounced landings were commonplace. Various studies showed a disproportionately high rate of hard landings and takeoff stall-mush accidents for the early models.

Cessna realized it had made a major gaffe with the Cardinal. It restarted the Skyhawk production line (using the 150-HP engines that had been purchased for the Cardinal) and set to work fixing the Cardinal’s problems. Under the “Cardinal Rule” program, it retrofitted leading edge slots to stabilators on all Cardinals already in the field and made them standard in new production machines. This fixed the stabilator-stalling problem, although pitch forces remained lighter than average for a Cessna.

The 1969 model (177A) had a 180-HP Lycoming engine, plus there was a 150-pound increase in gross weight to compensate for both the engine’s increased mass and some shortcomings in the original airplane’s useful load. The stabilator-to-wheel control linkage ratio was changed to slow the response in pitch slightly. The nosegear/firewall area was also beefed up to prevent bent metal from bounced landings. This fix was offered as a retrofit to 1968 models via an early bulletin.

Despite the improvements, 1969 sales nose-dived to about 200 units, while Skyhawk sales rebounded to their former league-leading levels. In 1970, Cessna made more major improvements, yielding the 177B Cardinal. The 6400 series airfoil was changed to a more conventional 2400-series similar to the Skyhawk’s, plus a constant-speed propeller was added for better takeoff and climb performance.