Guide to Conducting Healthcare Facility Visits

by Craig Zimring, Ph.D. Georgia Institute of Technology

Published by The Center for Health Design, 1994

INTRODUCTION

A major medical center is building a new diagnostic and treatment center that will include both inpatient services and expensive high technology outpatient services The center is considering whether to provide day surgery within the diagnostic and treatment center or in a freestanding outpatient facility. They are facing a dilemma. If they locate the day surgery center separately, they can use lower-cost construction. If they combine the functions, they can use the spare capacity that will likely become available in the inpatient operating rooms. This is especially important as outpatient procedures become increasingly complex. The center wishes to evaluate sites that currently operate in fully separate facilities versus ones that provide separate outpatient and inpatient reception and recovery facilities, but share operating rooms.

A large interiors firm has been contacted to conduct a visit of several new children’s hospitals in the Northwest. Eager to get the commission from this major hospital corporation to renovate the interior of a large children’s hospital, the firm arranges visits of hospitals it has designed as well as two designed by other firms.

An architecture firm is renovating a large medical laboratory in an existing building which has a minimal 11-foot-3-inch floor-to-floor height. Concerned that the client may not understand the implications of this tight dimension-which means that the fume hood ventilation system can not easily be installed within this space-the architects arrange visits of other labs with similar floor-to-floor heights, change in healthcare and society is rapid and increasingly unpredictable, bringing an unprecedented level of risk for healthcare organizations facing new projects. This guide discusses a specific tool that healthcare organizations and design professionals can use to help manage uncertainty: the facility visit. In almost every healthcare project someone-client, designer, or client-design team-visits other facilities to help them prepare for the project. A probing, well structured, and well run visit can highlight the range of possible design and operational alternatives, pinpoint potential problems, and build a design team that works together effectively over the course of a design project. It can help a team creatively break their existing paradigms for their current project and can provide a pool of experience that can inform other projects. All of these can help reduce risk for healthcare organizations.

However, current facility visits are often ineffective. They are frequently conducted quite casually, despite the rigor of much other healthcare planning and design. Visits are often costly—$40,000 or more-yet they often fall short of their potential. Sites are often chosen without careful consideration, little attention is given to clarifying the purpose or methods of visits, there is often little wrap-up, and frequently no final report is prepared. Not only is the money devoted to the visit frequently not used most effectively, the visit presents important opportunities to learn and to build a design team. These opportunities are too often squandered.

This guide focuses on what a facility field visit can accomplish and suggests ways to achieve these goals. Although a facility visit may occur in a variety of circumstances, including the redesign of the process of healthcare without any redesign of the physical setting, this guide focuses on situations in which architectural or interior design is being contemplated or is in process.

SCOPE OF THE RESEARCH

The goals of this project were to learn about the existing practice of conducting healthcare facility visits, to learn about the potential for extending their rigor and effectiveness, and to develop and test a new approach. We interviewed over 40 professionals in the fields of healthcare and design from every region of the US, including interior designers, architects, and clients who had participated in design projects, and healthcare professionals who conduct visits of their own facilities. We sampled professionals from large and small design firms, and from large and small medical organizations. To get a picture of both “average” and “excellent” practice we randomly selected members from professional organizations such as the AIA Academy on Architecture for Health and the American Society of Hospital Engineers, and augmented these with firms and individuals who were award winners or were recommended to us by top practitioners. We developed a multi-page questionnaire that probed the participants’ experiences with visits, including their reasons for participating, their methods, and how they used the information produced. We faxed each participant the questionnaire, then followed up with an interview on the phone or in person. The interviews averaged about one-and-a-half hours in length. Every person we initially contacted participated in an interview. Everyone in our sample had participated in some sort of visit of healthcare facilities within the past year.

After conducting the interviews we developed, field tested, and revised a new facility visit method, which is presented in this guide. Throughout this process we conferred with select members of the Research Committee of The Center for Health Design and the Project Advisory Board.

GOALS OF FACILITY VISITS

There are many reasons for doing a facility visit and many different kinds of visits. However, visits roughly fall into three categories: specific visits, departmental visits and general visits. Specific visits focus on particular issues such as the design of patient room headwalls, nursing stations, or gift shops; departmental visits focus on learning about the operations and design of whole departments such as outpatient imaging or neonatal intensive care; general visits are concerned with issues relevant to a whole institution, such as how to restructure operations to become patient-focused. Usually, departmental and general visits occur during programming or schematic design; specific visits often occur during design development, when decisions are being made about materials, finishes and equipment.

More broadly, there are several general reasons for conducting visits: learning about state-of-the art facilities; thinking about projects in new ways; and creating an effective design team.

LEARNING ABOUT STATE-OF-THE-ART FACILITIES

Visit participants want to learn what excellent organizations in their field, both competitors and other organizations, are doing. Participants are often particularly interested in learning how changes in business, technology or demographics, such as increased focus on outpatient facilities or increased criticality of inpatients, might affect their own operations and design. For example, in Story 1, below, a UK team was interested in grafting US experience onto a UK healthcare culture. In another example, hospital personnel at Georgia’s St. Joseph’s Hospital visited five emergency rooms over the course of several weeks before implementing an “express” service of their own. According to planner Greg Barker (Jay Farbstein & Associates, CA) they “use site visits as a method of exposing the clients to a broader range of operating philosophies and methods.” This gives the clients and design professionals a common frame of reference on which to base critical operational and design decisions.

William Headley, North Durham Acute Hospitals, UK

Traditionally, hospital design in the UK has been established centrally, with considerable emphasis placed on standard departmental areas and on a standardized planning format known as “Nucleus.” The 20-year-old Nucleus system is based on a standard cruciform template of approximately 1,000 square meters housing a multitude of departments, which can be interlinked to provide the nucleus of a District General Hospital.

Durham wished to develop a hospital that in its vision would meet the challenges of the 21st Century, and produce a custom-designed hospital solution built to suit the needs of the patient, not just individual departments.

The brief has, therefore, to be developed from a blank sheet of paper and not from standard guidelines. It is also the Trust’s objective to have the brief developed by staff from the bottom up. The purpose of the study tour was to allow frontline staff the opportunity to experience new ideas firsthand and talk to their medical counterparts about some of the philosophies of patient-focused care and to input their findings into the briefing process. We acknowledged the differences in the US and UK healthcare systems, but were interested in ensuring that best US practices, including the patient focused approach, facilities design, and the use of state of the art equipment, was studied and subsequently tailored to suit the new North Durham hospital.

THINKING ABOUT A PROJECT IN A NEW WAY

Participants who are currently engaged in a design or planning project are concerned with using visits to advance their own project. They use a visit to analyze innovative ideas and to help open the design team to new ideas. At the same time they are interested in building consensus on a preferred option. In Story 2, below, a hospital serves as a frequent visit host because it shows how special bay designs can be used in neonatal intensive care, and participants can consider how these designs apply to their current project. Other visit organizers see a visit as an opportunity for focusing the team on key decisions that need to be made, or to help the team focus in a systematic way on a range of strategic options and critical constraints. The visit exposes each team member to a variety of ways of accomplishing a similar program of requirements and thus starts the debate on how to achieve the best results for the facility being designed.

Georgia Brogdon, Vice President Operations, Gwinnett Women’s Pavilion, GA

We get visitors at our facility about once per month. Right now the NICU (neonatal intensive care unit) is the most frequently visited location. The main reason is that Ohmeda uses our unit as a showcase for a special design of NICU bays. People want to see it because most think that Hill Rom is the only vendor of this type of equipment.

Early on, we were also one of the only state-of-the-art LDR facilities around. So if people wanted to visit an LDR unit, they had little choice but to come here. Now, however, people come to see us because we are a freestanding yet still attached facility. Over time the visits have evolved away from the design of the facility and more into programming, services, and operational issues.

We give three types of visits: 1) overview visits for lay people who just want to come see the area; 2) functional visits for other hospital people or architects who want to see the LDR design, mother/baby floor, NICU design, etc.; 3) operational flow visits to learn how the LDR concept impacts operations. In general, we start the visitors wherever the patient would start in the facility.

To arrange a successful visit of our facility, we need to know the interests of the visitors; then we can focus the schedule on that. Also knowing who they are bringing is helpful. You need to have their counterparts available. The types of information needed to conduct facility visits are: 1) what specific operational information to ask for in advance-size, number of rooms, number of physicians, staffing, C-section rate, whether they are a trauma center; 2) how to prepare for the visit; 3) who to bring. We’ve found that periodically the visitors are disappointed because they didn’t bring enough people. Better to have too many than not enough.

CREATING AN EFFECTIVE DESIGN TEAM

Participants use visits as an opportunity for team building. Many visits are conducted early in a design project by a team who will work together for several years. The visit provides participants a useful opportunity to get to know each other and to build an effective team. As Story 3 illustrates, clients often look to a visit to see how well designers can understand their needs; designers use it as a way to learn about their clients and to mutually explore new ideas. A visit can also provide an opportunity for medical programmers to work with designers and clients. This is particularly important if programming and design are done by different firms.

Many visit participants focus on interpersonal issues: spending several days with someone helps build a personal relationship that one can rely on during a multi-year project. A visit also provides the opportunity to achieve other aspects of team building: clarifying values, goals, roles and expertise of individual participants; and identifying conflicts early so they can be resolved. One result for some teams is that it establishes a common vocabulary of operational and facility terms translated to the local healthcare facility.

Bing Zillmer, Director Engineering Services, Lutheran Hospital, La Crosse, WI

Conducting a facility field visit is an opportunity to have that one-on-one contact and find out if the architect “walks the talk or talks the walk.” The biggest benefit is in finding out how the visit team of the architectural firm has been assembled: to see their level of participation, and how they have interacted with and listened to the clients and the hosts. What we look for in a consultant is not a “yes man”; we look for someone who knows more about existing facilities than we do. Our key concerns are how the team worked together, how they listened.

Dennis C. Lagatta, Vice President, Ellerbe Becket, Washington, DC

The main reason for conducting a visit is to settle an issue with the client. The clients usually have only two frames of reference: the current facility and the one where they were trained. These two frames of reference are hard to overcome without a visit. We conduct visits to help settle an issue between various groups within the institution. The visit process tends to be a good political way to illustrate a problem or a solution to a problem. A good example is when you have a dispute between critical care physicians and surgeons. Both parties may be unwilling to compromise. Usually a visit will be a good way to defuse this conflict.

James W. Evans, Facilities Director, Heartland Health System, St. Louis, MO

Responding to the question, what kinds of team-building activities were conducted before the actual visit took place? The functional space program stage is where you start building a team. Functional space programming is a narrative of what you want to do. If the programming includes a laboratory or some other specialty area, you would also want to have the consultant (if you are using one) involved in this process. Between blocks and schematics is when you want to go on any visits. By working together and staying together through big and small projects, you develop a lot of rapport and credibility.

Les Saunders, Nix Mann And Associates, Architects, Atlanta, GA

In the case of marketing visits, we try and present our unique abilities to our clients and to get to know each other better, Our visits are generally tailored to what the client group is trying to accomplish. Our functional experts will go on the visit so they can get to know the client and try to enhance “bonding.”

Facility visits allow healthcare organizations and design professionals to address several important trends in healthcare.

- A visit allows a team to understand the experience of stakeholders who they do not currently serve, and to examine the design and operations of facilities that are more customer-oriented.

- Social changes are resulting in some stakeholder groups gaining importance, such as outpatients involved in more complex procedures, higher acuity inpatients, older people, or non-English speakers.

- A visit can provide quantitative and qualitative data that support future decision making.

- Tighter budgets, shorter design and construction schedules and more complex projects are requiring design teams to form more quickly and work more effectively.

- A visit can be an effective tool for building a design team early in a design project.

FALLING SHORT OF THEIR POTENTIAL

In a design project, the client healthcare organization generally pays for a visit, either directly or as a part of design fees. Do healthcare organizations usually get good value for their investment? Do visits generally achieve their ambitious goals of learning about competition and change, moving the design project along, and building teams? We found very different answers. Despite the usual rigor of healthcare planning and programming, many current visits are very casual. Whereas some planners of visits do careful searches of available facilities to fit specific criteria, most choose sites to visit in other ways— sites participants happen to already know because they have been written about in magazines, or sites where there is a contact that someone on the team knows. Though these ways of choosing sites may be appropriate, they raise a question as to whether most participants are visiting the best sites for their purposes.

In many cases visit teams simply do not spend much time structuring the visit. Most teams do not even meet in advance to decide the major foci of the visit. We did not find many groups who use checklists or sets of questions or criteria when they go into the field. Whereas some teams compile the participants’ notes, and one team actually created a videotape in a large project, most teams do not create any kind of written or visual record of their visit. Many teams hold no meeting at the end to discuss the implications of the visit, although many participants felt that they emerged in subsequent programming or design meetings.

Despite the apparent casualness of these visits, designers and clients alike almost without exception felt they were a valuable resource.

Simply visiting a well-run facility can be vivid and exciting. It is fascinating to see how excellent competitors operate, to talk to them and learn of their experience. (It is also an excellent opportunity for administrators and designers to get away from their daily routine and talk to professional counterparts.)

But there are large opportunity costs in the way most current visits are run, and they represent considerable lost value for the healthcare organization, designer, and design project.

COMMON PITFALLS

Opportunity costs of current visits come from several common pitfalls.

LOW EXPECTATIONS LEAD TO LIMITED BENEFITS

Often, participants see field visits as a way to get to know other team members and simply to see other sites, but have no clear idea about what information can be helpful to the project at hand. They don’t think through how the visit can help the goals of their project or organization.

TOO BUSY TO PLAN

The planner of a visit faces multiple problems. Often the visit is seen as a minor part of the job of most participants and doesn’t get much attention in advance; schedules and participants may change at the last minute. In many cases, no one is assigned to develop the overall plan of the visit, and to ask if the major components-choice of sites, choice of issues to investigate, methods for visits, ways of creating and disseminating a report-match the overall goals of the organization and project. This is especially ironic because participants are often advocates of careful planning in other areas.

TOO FOCUSED ON MARKETING

Many visits, and especially designer-client visits, are billed as data gathering but are in fact aimed at marketing. A design firm may literally be marketing services or may be trying to get a client to accept a solution that they have already developed: marketing an idea. This may lead to an attempt to create a perfect situation in the facility being visited, one without rush, bustle, or everyday users and the information they can provide. For designer-client teams, we heard many designers complain that they couldn’t control their clients, that they couldn’t keep them focused on prearranged ideas or keep them limited to prearranged routes. (This is often the result of not enough advance work aimed at understanding what interests the participants have and not enough time spent building common goals.)

CLOSING THE RANGE OF DESIGN OPTIONS TOO EARLY

Many visits occur early in the design process or when an organization is considering significant change, a perfect time to consider new possibilities or address issues and solutions not previously considered. This timing, and the chance to see and discuss new options in a visit, presents an opportunity for a design team to open its range of choices and consider novel or creative alternatives. However, many visit participants feel strong pressures to “already know the answer” when they start the visit. Many designers and consultants feel that their clients do not want them to genuinely explore a range of options, that they were hired because they know the solution. Similarly, some medical professionals establish positions early to avoid seeming foolish or uninformed. As a result, the team may choose sites that bring only confirmation, not surprise, and people will be interviewed who bring a viewpoint that is already well established. This is not simply a matter of the individual personalities of people who set up visits, but rather a problem of the design of teams and the context within which they operate. It is often important for a design firm to show a client the approach it is advocating and for them to jointly explore its suitability for the client’s project. However, if the client expects a designer to know the answer before the process starts, rather than developing it jointly with the client, the designer is forced to use the visit to exhort rather than to investigate.

TOO LITTLE STRUCTURE FOR THE VISIT

Whereas no one likes to be burdened with unnecessary paperwork before or during a visit, it is easy to miss key issues if there is not an effort to establish issues in advance, with a reminder during the visit. Seeing a new place, with lots of activity and complexity, makes it easy to miss some key features. Many team members come back from visits with a clear idea of some irrelevant unique feature such as the sculpture in the hallway, rather than the aspect of the site that was being investigated.

INTERVIEWING THE WRONG PEOPLE

Often, out of organizational procedure or courtesy, a site being visited will assign an administrator or person from public relations to be the primary guide. It is almost always preferable to interview people familiar with the daily operations of the department or site.

MISSING CRITICAL STAKEHOLDERS

Almost every healthcare facility is attempting to become more responsive to customers, both patients and “internal” customers such as staff. Patients often now have a choice of healthcare providers, and staff are costly to replace. Despite these trends, many visits miss some key customer groups such as inpatients, outpatients, visitors, line staff, and maintenance staff. It is very important that these groups or people who have close contact with them be represented in visits.

A DESIGNER PROVIDING TOO MUCH DIRECTION DURING A DESIGNERCLIENT VISIT

In an effort to control the outcome, a designer may attempt to ask most of the questions during interviews. In addition to the problem of focusing exclusively on “selling” ideas described above, clients do not like to feel that their role is usurped.

MISSING OPPORTUNITIES FOR TEAM BUILDING

Teams are most effective when everyone understands the values, goals, expertise and specific roles of others on the team. Teams are also most effective when the team understands the process and resources of the team, the nature of the final product, how the final product will be used: who will evaluate it, and by what criteria the success of the product will be evaluated. Although management consultants routinely recommend making such issues explicit at the beginning of team building, we found few visit teams that deal with these issues directly. Many teams do not even get together before a visit to discuss these issues.

NOT ATTENDING TO CREATING A COMMON LANGUAGE

Multidisciplinary design teams often speak different professional languages and have different interests and values. Designers are used to reading plans and thinking in terms of space and materials; healthcare administrators are used to thinking in terms of words and operational plans. Unless a field visit team is conscious about making links between space and operations, there can be little opportunity to establish agreement.

LACK OF AN ACCESSIBLE VISIT REPORT

Most current visits produce no report at all; some produce at least a compilation of handwritten notes. We heard a repeated problem: no one could remember where they saw a given feature.

CHAPTER 1: MAJOR TASKS

The healthcare facility visit process has three major phases, divided into specific team tasks that are conducted before, during, and after a visit. These phases, and the 13 major tasks that comprise them, are below. The process we propose is quite straightforward, but compared to most current visits it is more deliberate about defining goals, thinking through what will be observed, preparing a report, and being clear about the implications of the visit for the current design project.

PREPARATION

TASK 1. SUMMARIZE THE DESIGN PROJECT

In this task the project leader or others prepare a brief description of the goals, philosophy, scope, and major constraints overview of the design project that the visit is intended to aid. It should include the shortcomings that the design project is to resolve: space limitations, operational inefficiencies, deferred maintenance, etc.

The overview helps focus the facility visit, and can be provided to the host sites to help them understand the perspective of the visit. This summary should be brief, only a few pages of bulleted items, but should clearly identify the strategic decisions the team is facing. For example, a team may be considering whether to develop a freestanding or attached woman’s pavilion. It is also important to identify key operational questions in the project summary. Focusing on design solutions too early may distract the team from more fundamental questions that need to be resolved. The purpose of the summary is to establish a common understanding of goals, build a common understanding of constraints, and allow the visit hosts to prepare for the visit.

The summary of the design project may focus on several topics:

- How do these critical purposes link to key business imperatives, such as “broadening the base of patients” or “allowing nurses to spend more time delivering patient care”?

- What measurable or observable aspects of the design relate to these key purposes? For example, one team may be interested in whether carpeting leads to increased cleaning costs or increased infection rates; another team may be interested in visitor satisfaction with a self-service gift shop.

Key issues in summarizing the design project:

- It should identify the full range of stakeholders who affect the current design.

Note: Many visits ignore this critical up-front work. Depending on the schedule and scope, the summary can be circulated to the team in advance of the brainstorming meeting.

TASK 2. PREPARE BACKGROUND BRIEF

More than most building types, healthcare facilities have a large body of literature providing descriptions of new trends, research, design guidelines, and post-occupancy evaluations. Many design firms and healthcare organizations have this material in their library or can get it from local universities or medical schools. In this task the visit organizer creates a file of a few key articles or book chapters describing the issue or facility type being visited. These are then distributed to the team, allowing all team members to have at least a minimal current understanding of operations and design.

The team leader also prepares an Issues Worksheet. This is a one-page form that is distributed along with the Background Brief to all members of the visit team prior to their first meeting. (See Figure 2 for a sample Issues Worksheet.) It encourages them to jot down what is important to them, and to discuss issues with their coworkers. It works most effectively when the visit organizer adds some typical issues to help them think through the problem. Participants should be encouraged to bring the Worksheet with them to the team meetings.

Key issues in preparing the Background Brief:

- Providing a few current background articles on the kind of department, facility, or process being visited helps create at least a minimum level of competence for the team and helps establish a common vocabulary prior to the visit.

- The Issues Worksheet, along with the Project Summary and Background Brief, allows participants to develop a picture of the project and to brainstorm ideas.

TASK 3. PREPARE DRAFT WORK PLAN AND BUDGET

Once the team leader or others have summarized the design project and prepared the Background Brief, a draft work plan outlining the major components of the field visits can be prepared. At this stage, it is important to establish a tentative budget for the visit. It is also important to make sure that the major components of the draft work plan, such as choosing visit sites and developing critical issues, match the overall goals of the organization and project. The draft work plan provides a tentative structure for the field visits, which can be modified by other team members.

Key issues in preparing the draft work plan:

TASK 4. CHOOSE AND INVITE PARTICIPANTS

The effectiveness of the team is, of course, most directly related to the nature of the participants. Field visit teams are sometimes chosen for reasons such as politics, or as a reward for good service, rather than for their relevance to the project. For healthcare organizations field visit teams are usually most successful if they mix the decision makers who will be empowered to make design decisions with people who have direct experience in working in the area or department being studied. For design firms, teams are often most successful if they include a principal and the project staff. In both of these cases, the team combines an overall strategic view of the organization and project with an intimate knowledge of operational and design details.

Key issues in choosing participants:

- Participants should be chosen with a clear view of why they need to participate and what their responsibility is in planning, conducting and writing up the visit.

- Site hosts say that teams larger than about seven tend to disrupt their operations.

TASK 5. CONDUCT TEAM ISSUES SESSION

It is usually advisable to hold a team meeting early in the visit planning process to: 1) clarify the purposes and general methods of the field visit; 2) build an effective visit team by clarifying the perspective and role of each participant; 3) ‘identify potential sites, if the visit sites have not already been selected. Some resources and methods to select sites are discussed further in the next section, “Critical Issues in Conducting Facility Visits.”

The issues session is often a “structured brainstorming” meeting aimed at getting a large number of ideas on the table. (This is particularly important during departmental and general visits, and if team members don’t know each other.) The purpose is opening the range of possible issues rather than focusing on a single alternative.

This meeting is typically aimed at building a common sense of purpose for all team members, rather than marketing a preconceived idea. This meeting also serves the purpose of making critical decisions regarding the choice of sites and identifying who at the sites should be contacted.

Each participant should bring his or her Issues Worksheet along to the meeting. The initial task is to get all questions and information needs onto a flip chart pad or board before any prioritization goes on. Then the leader and group can sort these into categories and discuss priorities. These categories and priorities may be sorted in the form of lists which include: 1) a list of critical purposes of the departments or features being designed; 2) a list of critical purposes of the departments or features being evaluated at each facility during visits; 3) a list of existing and innovative design features relevant to these purposes. The critical purposes of the departments or design features at existing facilities can be charted at different spatial levels of the facilities, such as: site, entrance, public spaces, clinical spaces, administrative and support areas. Some typical architectural design issues are provided in the appendix.

The issues session may be run by the leader or the facilitator. Because one of the purposes of this meeting is to get balanced participation, it may be useful to have someone experienced in group process run the meeting, rather than the leader. His or her job is to make sure everyone participates, allowing the leader to focus on content.

This meeting may also provide an early opportunity to identify potential problems in conflicting goals, values or personalities on the team. For instance, a healthcare facility design project may have significant conflicts between departments, or between physicians and administrators. The meeting may also allow the team to agree on basic business imperatives and to be clear about the constraints that are of greatest importance to them, such as “never having radioactive materials cross the path of patients.”

Key points in running an issues session:

- Everyone should be able to participate without feeling “dumb.”

- The leader and group should try to understand the range of interests and priorities represented.

- Brief notes of the meeting should be distributed to all participants.

Note: This meeting is successful if participants feel they can express ideas, interests, and concerns without negative consequences from other members of the team. There is no such thing as a stupid question in this meeting.

TASK 6. IDENTIFY POTENTIAL SITES AND CONFIRM WITH THE TEAM

Based on the work plan which established the visit objectives and the desires, interests and budget of the team, the visit organizer chooses potential sites, and checks with the team. If possible, he or she provides some background information about each site to help the team make decisions.

The team may know of some sites they would like to visit, and these might have emerged in the issues session. Otherwise there are a range of sources for finding appropriate sites to visit: national organizations such as the American Hospital Association, as well as the American Institute of Architects Academy on Architecture for Health Facilities, and a range of magazines that discuss healthcare facilities. (See the section below entitled “Choosing Sites.“)

Different teams pick sites for different reasons. Some may pick a site because it is the best example of an operational approach such as “patient-focused care.” Others may look for diversity within a given set of constraints, such as different basic layouts of 250-bed inpatient facilities.

Many visit leaders complain that the team sometimes is distracted by features outside the focus of the tour, and particularly by poor maintenance. Wherever possible, it is advisable for the visit organizers to tour the site in advance of the group visit and to brief the hosts in person about the purposes of the visit. Although it is rare, some sites now charge for visits.

A key issue in choosing sites:

- The selection of sites should challenge the team to think in new ways.

Note: Sites are often chosen to provide a clear range of choices within a set of constraints provided by operations, budget, or existing conditions, such as “different layouts of express emergency departments” or “different designs of labor-delivery-post-partum-recovery rooms.”

TASK 7. SCHEDULE SITES AND CONFIRM AGENDA

The leader or facilitator calls a representative at each host site to schedule the visit. He or she confirms the purposes of the visit, confirms with the host sites the information needed before and during the field visit, and confirms who will be interviewed at the site. Healthcare facilities are sometimes more responsive to a request for a visit if they are called by a healthcare professional or administrator rather than a designer: if someone on the team knows someone at a site, he or she may want to make the first phone call. Many teams also find that if they arrange for a very brief visit, this may be extended a bit on site when the hosts become engaged with the team. When confirming the schedule for the visit with the host facilities, the visit organizer should specify that the visit team would prefer to interview people familiar with the daily operations of the department or site.

Key issues in scheduling sites:

Note: Sites are often proud of their facilities and often enjoy receiving distinguished visitors. However, they often find it difficult to arrange interviews or assemble detailed information on the spot.

TASK 8. PREPARE FIELD VISIT PACKAGE

Visits are more effective if participants are provided a package of information in advance: information about schedule, accommodations, and contact people; information about each site, including, where possible, brief background information and plans; a simple form for recording information; and a “tickler” list of questions and issues.

a) Prepare visit information package

The organizers should provide participants information about the logistics of the field visit: schedules, reservation confirmation numbers, phone numbers of sites and hotels.

b) Prepare site information package

The site information package orients participants to the site in advance of the visit. Depending on what information is available, it may include: plans and photos of each site; basic organizational information about the site (client name and address, mission statement, patient load, size, date, designers, etc.); description of special features or processes or other items of interest. Whereas measured plans are best, these are not often available. Fire evacuation plans can be used. A sample site information package is provided in the Appendix. Many teams find it useful to review job descriptions for the host site, and many organizations have these readily available.

c) Prepare Visit Worksheet

Facility visits are often overwhelming in the amount of information they present. It is useful for the organizers to provide the participants with a worksheet for taking notes. We have provided a sample worksheet as Figure 3 below, and blank forms are provided in the Appendix. The purpose of the checklist is to remind participants of the key issues and to provide a form that can easily be assembled into the trip report.

Note: A successful worksheet directs participants to the agreed-upon focal issues without burdening them with unnecessary paperwork. Participants should understand the relationship between filling out the checklist and filling out the final report.

FACILITY VISIT

TASK 9. CONDUCT FACILITY FIELD VISIT

The actual site visit typically includes: 1) an initial orientation interview with people at the site familiar with the department or setting being investigated; 2) a touring interview where the team, or part of it, visits the facility being investigated with someone familiar with daily operations, asking questions and observing operations; 3) recording the site; 4) conducting a wrap-up meeting at the site. (Each of these steps is discussed individually below.) The interview sessions are focused on helping the team understand a wider range of implications and possibilities. If appropriate, the wrap-up session may also be used for focusing on key issues that move the design along.

Note: Participants often like to speak to their counterparts: head nurse to head nurse, medical director to medical director, etc., although everyone seems to like to talk to people directly involved with running a facility such as a head nurse. People who know daily operations are often more useful than a high-level administrator or public relations staff member.

a) Conduct site orientation interview

During the orientation interview the visit team meets briefly with a representative of the site to get an overall orientation to the site: layout and general organization; mission and philosophy; brief history and strategic plans; patient load; treatment load; and other descriptions of the site. Many teams are also interested in learning about experiences the healthcare organization had with the process of planning, design, construction and facility management: What steps did they use? What innovations did they come up with? What problems did they encounter? What are they particularly proud of? What do they wish they had done differently?

b) Conduct a touring interview

The touring interview was developed by a building evaluation group in New Zealand and by several other post-occupancy evaluation researchers and practitioners. (See the post-occupancy evaluation section of the Bibliography.) In the touring interview, the team, or a portion of it, visits a portion of the site to understand the design and operations. Conducting an interview in the actual department being discussed often brings a vividness and specificity that may be lacking in an interview held in a meeting room or on the phone. One of the great strengths of the touring interview is the surprises it may bring, and the option it provides to consider new possibilities or to deal with unanticipated problems. As a result, it often works best to start with fairly open-ended questions:

- What works well here? What works less well?

- What are the major goals and operational philosophy of the department?

- What is the flow of patients, staff, visitors, meals, supplies, records, laundry, trash?

- Can they demonstrate a sample process or procedure, such as how a patient moves from the waiting room to gowning area to treatment area?

- What are they most proud of?

- What would they do differently if they could do it over?

These questions also provide a nonthreatening way to discuss shortcomings or issues that are potentially controversial. The team may then want to focus on the specific concerns that were raised in the issues session.

A difficult, but critically important, thing to avoid in a touring interview is to become distracted by idiosyncratic details of the site being visited. Often operational patterns or philosophy are more important than specific design features that will not be generalized to a new project: how equipment is allocated to labor-delivery-recovery-postpartum rooms in the site being visited may be more important than the color scheme, even though the color may be more striking.

Large multidisciplinary teams are particularly hard to manage during a touring interview. A given facility may have a state-of-the-art imaging department that is of great interest to the radiologists on the team but may have a mediocre rehabilitation department. In these cases, some of the touring interviews may be focused on “what the host would do differently next time.”

Key issues in conducting the touring interview:

Note: It is important to include people familiar with daily operations on the touring interview, both on the team side and on the side of the site being visited. A frequent problem is that some stakeholder groups such as patients or visitors are not represented; special efforts should be taken to understand the perspectives of these groups.

c) Document the visit

The goals of the visit dictate the kinds of documentation that are appropriate. However, most visits call for a visual record, sketches, and written notes.

In most cases it is useful to designate one or more “official” recorders who will assemble notes and be sure photos are taken, measurements made, plans and documents procured, etc. For designer-client visits, it is often useful to have at least two official recorders to look after both design and operational concerns. However, because a team often splits up, most or all participants may need to keep notes.

It is quite rare for teams to use video to record their visit, although this seems to be increasing in popularity. Editing videos can be very costly: it may take a staff member several person-days in a professional editing facility to edit several hours of raw video down to a 10- or 15- minute length. However, this time may be reduced with the increased availability of inexpensive microcomputer-based editing programs.

Key issues in recording the facility:

Many departmental and general visit teams find it useful to photographically record key flows, such as patients, staff and supplies, and location of waiting rooms and other patient amenities.

Note: If the method of creating the documentation is established in advance it can easily be assembled into a draft report.

d) Conduct on-site wrap-up meeting

Whereas the visit interview is focused on opening options for the team and identifying new problems and issues, the wrap-up meeting is often more focused on clarifying how lessons learned on the visit relate to the design project, and how they begin to answer the questions the team established. It is often useful to have a representative of the host site present at the wrap-up meeting to answer questions, if their time allows.

Key issues in conducting wrap-up meetings:

TASK 10. ASSEMBLE DRAFT VISIT REPORT

A draft visit report may take many different formats. The simplest is to photocopy and assemble all participants’ worksheets and notes, retyping where necessary. Alternatively, the organizers or a portion of the team may edit and synthesize the worksheets and notes. Though more time consuming, this usually results in a more readable report. A somewhat more sophisticated version is to establish a database record that resembles the form used to take notes on-site in a program such as FoxPro, Dbase, or FileMaker Pro. Participants’ comments can be typed into the database and sketches and graphics can be scanned in and attached.

These are then provided to all participants.

A key issue in assembling the draft report:

- Simplicity is often best; simply photocopying or retyping notes is often adequate, especially if photos and sketches are attached.

TASK 11. CONDUCT FOCUS MEETING

Upon returning home, the team conducts a meeting to review the draft trip report and to ask:

Unlike the issues session held early in the visit planning process, which was primarily concerned with bringing out a wide range of goals and options, this meeting is typically more aimed at establishing consensus about directions for the project.

A key issue in conducting the focus meeting:

- The purpose of the focus meeting is to establish the lessons learned for the design project.

Note: The leader should carefully consider who is invited to the focus meeting. This may include others from the design firm, consultants, healthcare organization, or even representatives from the site.

TASK 12. PREPARE FOCUS REPORT

The focus report briefly summarizes the key conclusions of the visit for the visit team and for later use by the entire design team. It is an executive summary of the visit report which may provide a number of pages of observations and interview notes.

Key issues in preparing the focus report:

- The focus report should be a clear, brief, jargon-free summary.

TASK 13. USE DATA TO INFORM DESIGN

The key purpose of a facility visit is to inform design. Whereas this can occur informally in subsequent conversations and team meetings, it is best achieved by also being proactive. For example, the team can:

Key issues in using data to inform design:

- Reports and materials collected on visits should be available to all participants in the design process and should be on hand during subsequent meetings. A central archive of materials should be available and should be indexed to allow easy access for people involved in future projects.

CHAPTER 2: TOOL KIT

TASK CHECKLIST

The team leader prepares a brief summary of the goals, philosophy, scope, and major constraints of the design project to help focus the field visit.

- Prepare a list of design or operational features related to these critical purposes.

The team leader prepares a file of a few key articles or book chapters that provide descriptions of new trends, research, design guidelines and post-occupancy evaluations of the facility type, department or issue being studied. He or she also prepares Issues Worksheets for team members to make notes on prior to the initial issues brainstorming session.

- Assemble current literature on existing facilities. Prepare the Issues Worksheet.

The draft work plan clarifies the values, goals, process, schedule and resources of the visits.

In this task the team leader builds a team. The ideal team combines a view of the overall strategic perspective of the organization and project with an intimate knowledge of daily operations.

The team issues session has three purposes: 1) clarify the purposes and general methods for the field visit; 2) build an effective team; 3) identify potential sites. The issues session is often a “structured brainstorming” meeting aimed at getting a large number of ideas on the table, and at understanding the various perspectives of the team.

- Clarify the resources available to the team and the use of the information collected.

TASK 6. IDENTIFY POTENTIAL SITES AND START FACILlTY VISIT PACKAGE

Based on visit objectives and the desires, interests and budget of the team, the visit organizers choose potential sites and check with the team. If possible they provide some background information about each site.

- If field investigation sites are already selected, provide fact sheets about each site to the participants.

In this task, the purposes and schedule of the visit are confirmed with the sites. This should occur at least two weeks before the visit.

The field investigation package includes the following components, which are used for conducting the visit:

- Tour information package (tour itineraries, transportation and accommodation details, list of contact people at each facility).

- Site information package (description of the sites, background information, facility plans).

- Site Visit Worksheets for notetaking.

TASK 9. CONDUCT FIELD VISIT

The interview sessions are focused on opening: helping the team understand a wider range of implications and possibilities. If appropriate, the wrap-up session may also be used for focusing on key issues that move the design along. Conduct site orientation interview.

- Collect any additional information from the host site.

- Conduct touring interview with people familiar with daily operations and a range of stakeholders.

- Document the visit through notes, sketches and photos.

- Conduct on-site wrap-up meeting with team members.

The draft report is a straightforward document allowing others to benefit from the investigation and providing the team a common document to work from.

The team conducts a focus meeting to ask: What are the major lessons of the investigation? What does it tell the team about the current project?

The Focus Report briefly summarizes the key conclusions of the visit for the visit team and for later use by the entire design team. It is an executive summary of the Visit Report which may provide a number of pages of observations and interview notes.

- Prepare and distribute a brief Focus Report.

The purpose of this document is to inform the design process.

- Write a brief newsletter about the design project that includes key findings from the visit.

SAMPLE FACILITY FACT SHEET (see PDF version)

CHAPTER 3: CRITICAL ISSUES IN CONDUCTING FACILITY VISITS

Selecting visit sites.

One of the most important steps in conducting healthcare facility visits is the selection of appropriate sites. However, there is no single source of information on healthcare facilities, and site selection is not an easy task. It is difficult to locate sites with comparable features in terms of workload, size, budget, operational facilities and physical features. Without this information, the tendency is to choose sites based on other criteria, such as location and proximity, or the presence of a friend or former coworker at specific host facilities.

However, depending on the nature of the facility visit, there are several resources that can be consulted for site selection. Some healthcare and design professional associations periodically publish guides and reference books which are helpful in selecting sites for facility visits. The following sources can be referred to before selecting specific facilities for field visits:

NATIONAL HEALTHCARE ASSOCIATIONS

American Hospital Association (AHA) AHA Resource Center, Chicago, (312) 280-6000

AHA database for healthcare facilities in the state of Missouri. : Missouri Hospitals Profile . Listed price: $27.50.

AHA Guide to locating healthcare facilities in the US . The listed facilities are classified according to the city/county with a coded format for the number of beds, admission fee, etc. Listed price: $195 for nonmembers and $75 for members.

AHA Health Care Construction Database Survey . Contact Robert Zank at the AHA Division of Health Facilities Management, (312) 280-5910.

Association of Health Facilities Survey Agency (AHFSA) Directory of the Association of Health Facilities Survey Agency. AHFSA, Springfield, IL.

National Association of Health Data Organizations (NAHDO) Some states collect detailed hospital-level data. To obtain information on states with legislative mandates to gather hospital-level data, contact Stacey Carman at 254 B N. Washington Street, Falls Church, VA 22046-4517, Telephone: (703) 532-3282, FAX: (703) 5323593.

NATIONAL ASSOCIATIONS FOR DESIGN PROFESSIONALS

American Institute of Architects (AIA) AIA Academy on Architecture for Health 1735 New York Avenue NW Washington, DC 20006

(202) 626-7493 or (202) 626-7366, FAX (202) 626-7587 To order AIA publications: (800) 365-2724

Hospital Interior Architect .

Hospital and Health Care Facilities, 1992. Listed price: $48.50 for nonmembers; 10% discount for members off listed price.

Hospitals and Health Systems Review, July 1994. Listed price: $12.95 for nonmembers; 30 % discount for members off listed price.

Hospital Planning . Listed price: $37.50 for nonmembers; 10% discount for members off listed price.

Hospital Special Care Facility , 1993.

Organizational Change: Transforming Today’s Hospitals, January 1995: Listed price: $36.00 for nonmembers; 30% discount for members off listed price.

Health Facilities Review (biannual), 1993. Listed price: $20 for nonmembers; $14 for members.

PERIODICALS DESCRIBING SPECIFIC HEALTHCARE FACILITIES

Modern Healthcare. This national weekly business news magazine for healthcare management is published by Crain Communication, and holds annual design awards. In conjunction with AIA Academy of Architecture for Health, this periodical announces annual competition and honors architectural projects that build on changes in healthcare delivery. Contact Joan Fitzgerald or Mary Chamberlain at 740 N. Rush Street, Chicago IL 60611-2590, (312) 649-5355.

American Hospital Association Exhibition of Architecture for Health , 1993.

For further information contact Robert Zank at the Division of Health Facilities Management, (312) 280-5910.

Journal of Healthcare Design . This journal illustrates 20-40 exemplary healthcare facilities in each

annual issue. Free list of previously-toured exemplary facilities (available by calling The Center).

Æsclepius . Æsclepius is a newsletter discussing a range of design issues relevant to healthcare facilities.

TEAMBUILDING

Many people who conduct healthcare facility field visits use them as a way to build an ongoing design team. This is particularly true of designer-client-consultant teams who conduct visits early in a design project. According to organizational researcher and consultant J. Richard Hackman, 1 teams often spend too much time worrying about the “feelgood” aspects of interpersonal relationships and not enough time focusing on other key issues such as choosing the right people for the team, making roles and resources clear, specifying final products, and clarifying how the final product will be used.

Participants are often chosen because they are upper-level administrators or because they deserve the perk. It may not be clear what their function is on the visit or how they would contribute to any later decision making about the design project. Likewise, visit teams often don’t know what resources are available to them: Can they visit national sites? Can they call on others to help prepare and distribute a visit report?

- Some key team building steps include:

- Select visit participants with a clear idea of why they are participating and how they can contribute.

- Keep the team small; visit teams of more than seven or eight people are hard to manage.

- Provide each participant a clear role before, during and after the actual site visit, and negotiate this role to fit their interests and skills. Roles should be clearly differentiated and clear to all participants.

- Make the final product clear: simple photocopying and assembly of notes and photos taken during the visit; brief illustrated written report; videotape, etc.

- Clarify how the visit findings are to be used: what key decisions are the major focus?

ROLES IN CONDUCTING FACILITY VISITS

There are several key roles in the process. Depending on the size of the team and the nature of the visit, each role may be taken on by a different person, or they may be combined.

LEADERSHIP TASKS:

- Restate current need and parameters of the design project.

- Develop some background information on the issues or setting types being investigated, and distribute to team members.

- Conduct a brainstorming meeting to understand the expertise, interests, values, and goals of each team member.

- Identify potential visit team members, and invite them.

- Summarize the goals of the design project, clarify how the field visit might advance these goals, and communicate these to the team.

- Identify roles for each team member.

- Develop a work plan and budget.

- Clarify the criteria for choosing sites.

- Prepare and/or review major documents: site-specific protocols; checklists and lists of questions and issues; information about each site being visited; overall plan for the visit; visit report; focus report.

- Conduct wrap-up meeting at each site.

- Conduct focus meeting on returning home.

SUPPORT TASKS:

- Assemble a few key articles or other documents to help the team understand the key issues in the setting types, processes or departments being visited.

- Identify potential sites, with some information about each site candidate so the leader and team can make final choices.

- Confirm with sites, and clarify what information the team will need in advance and what will be collected during the visit.

- Prepare draft materials (Background Brief, site information package, visit information, interview protocol) for review by the leader.

- Organize any trip logistics that are not done individually by participants: car rentals, hotel reservations, air tickets, etc.

- Write thank-you letters to site participants.

- Prepare a Draft Visit Report for review by the leader and team.

- Draft a Focus Report for review by the leader and the team.

FACILITATION TASKS:

When the team is attempting to get broad input into the process, such as when the team meets initially to set direction, it is often useful to have someone run the meeting who has the role of simply looking after the process of the meeting, rather than the content. He or she is charged with making sure that everyone is heard without prejudice, and that all positions are brought out. It often works poorly to have a senior manager in this role. Even if he or she has good facilitation skills, it is intimidating for many people to speak up in a meeting led by their boss.

Specific tasks:

- Conduct the initial brainstorming session that establishes the direction, issues and roles for the visit.

- Conduct any additional sessions where balanced participation is important to increasing the pool of ideas or getting “buy-in” from all team members.

RECORDER TASKS:

During the actual site visit, one or more people are typically charged with maintaining the “official” records of the visit (individuals may keep their own notes as well). This may include written notes, audio or video records, or photographs. If the team breaks up during the visit, a recorder should accompany each group.

Specific tasks include:

- Procure any required recording devices and supplies, such as cameras, tape recorders, paper forms, etc.

- Make records during the visit.

- Edit the record and assemble into a report.

TEAM PARTICIPANTS TASKS:

INTERVIEWING

Interviews vary greatly in the amount of control exercised by the interviewer in choosing the topic for discussion and in structuring the response. An intermediate level of control over topic and responses, often called a “structured interview,” is usually appropriate in a facility visit. In a structured interview, the interviewer has an interview schedule which is a detailed list of questions or issues which serves as a general map of the discussion. However, the interviewer allows the respondent to answer in his or her own words and to follow his or her own order of questioning if desired. The interview is usually aided by walking through the setting or by having plans or other visual aids during seated sessions.

The use of fixed responses, in which respondents have to choose a “best” alternative among several presented, allows rapid analysis of results and may be appropriate if a large number of people are interviewed during a visit. The cost-effectiveness of interviews needs to be considered by the architect or manager when designing the process. Individual interviews are useful because people being questioned may be more forthcoming than if friends or colleagues are present.

However, individual interviews are expensive. With scheduling, waiting time, running the interview, and coding, a brief individual interview may involve several hours or more of staff time.

In summary, interviews are valuable because people can directly communicate their feelings, motives and actions. However, interviews are limited by people’s desire to be socially desirable or by their faulty memories, although these problems may not be too serious unless the questions are very sensitive.

CHAPTER 4: CONCLUSIONS

Unfortunately, many design processes do not do a good job at controlling risks, costs, and inefficiencies. A design project may have a big influence on the future of an organization, but critical operational and design decisions often receive too little attention. And problems or new ideas are often discovered very late in a design process, when they are difficult and costly to accommodate. It is not hard to understand the source of these difficulties. The crises of everyday life go on unabated during design and distract people from design, short-term politics continue, and many people are comfortable with what they already know. Many design team participants representing healthcare organizations want to reproduce their existing operation, even if they can recognize its flaws.

A healthcare design team is too often more like a raucous international meeting than like an effective task-oriented organization. Participants speak different professional languages, have different experiences, have different short-term objectives, hold different motivations for participating, and hold different values about what constitutes a successful project. The team may be far into a project before it understands the different viewpoints represented on the team.

A facility visit is a unique opportunity to address some of these problems. It provides an extended opportunity for a design or planning team to get together outside the pressures of daily life, to critically examine the operations of an excellent facility, to rethink its own ideas, and to build the basis of a team that may function for several years. It is often the longest uninterrupted time a team ever spends together, and the best chance to think in new ways.

A visit has three goals: to establish a situation for effective critical examination of state-of-the-art operations and facilities; to think about the project in new ways; and building a team. These goals are intertwined. A well-structured facility visit may help build a team more effectively than an artificial “feel-good” exercise of mountain climbing or simulated war games. A team that looks at a facility from different perspectives, and in which participants forcefully argue their viewpoint based on evidence from a common visit, can learn each other’s strengths, preferences, and priorities quickly and in a way that builds a bond that is closely related to their own project.

Many teams, however, do not provide enough structure for either critical examination or team building. Critical examination requires an understanding of what key issues are to be examined and how they might apply to the current design problem. Team building requires that a team clearly establishes the role of each team member, makes the resources, process, and schedule clear, is explicit about the form and use of the final report, and establishes a common language.

Healthcare designers and consultants can develop better facility visits, but the responsibility for improving this practice rests with healthcare clients. For a visit to reach its potential, clients must demand an improved process, hold the organizer accountable-and be willing to pay for it. The healthcare client must see design and planning as a process open to mutual learning, and make it happen.

APPENDIX A: BIBLIOGRAPHY

See PDF version for bibliography.

APPENDIX B: EXEMPLARY MICRO-CASES

See PDF version for micro-cases.

Copyright © 1994 by The Center for Health Design, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced by any means or used in any form without written permission of the publisher.

The views and methods expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions of The Center for Health Design, or its Board, or staff.

Log in or register

You need to be logged in to continue with this action.

Please Log in or register to continue.

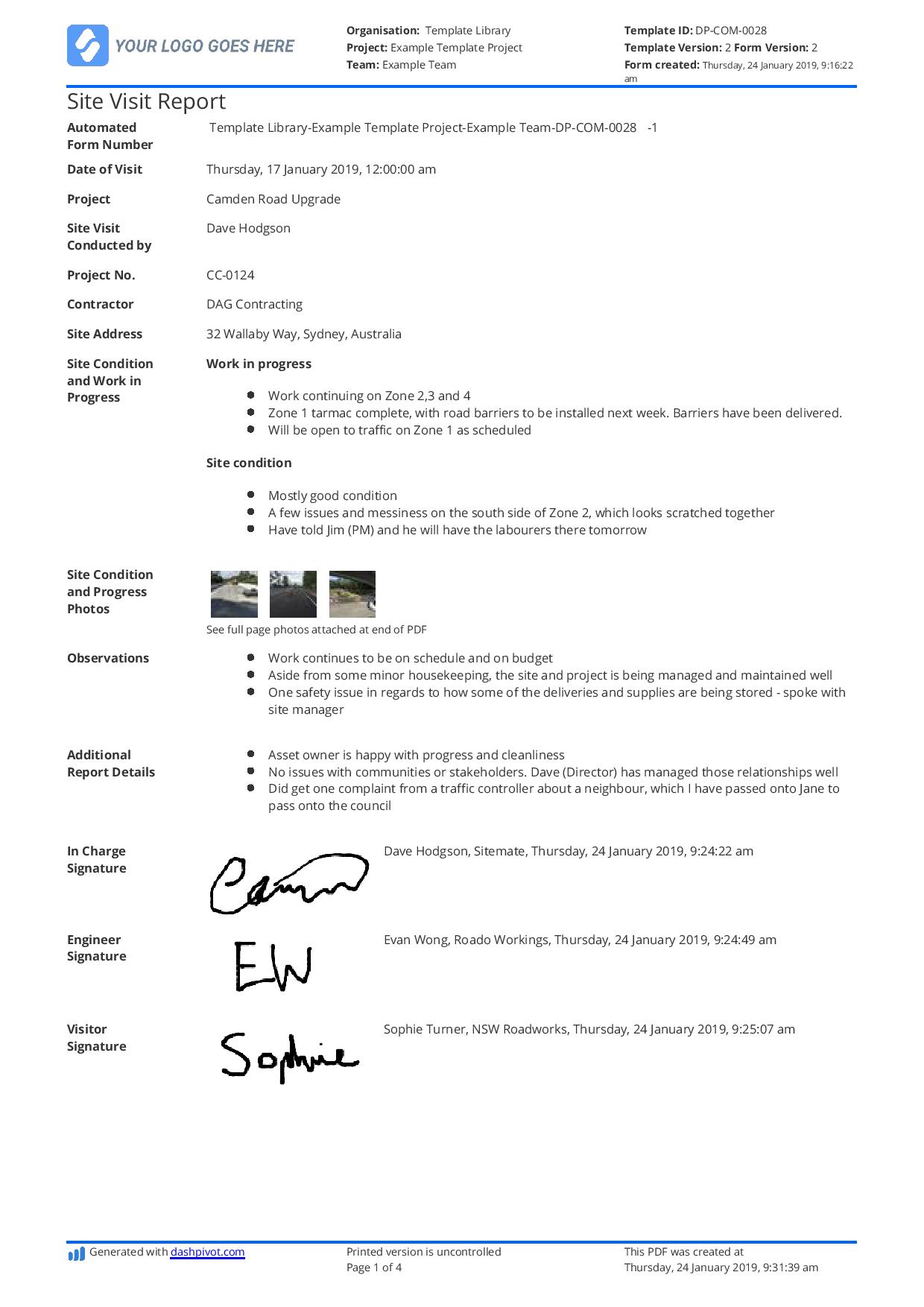

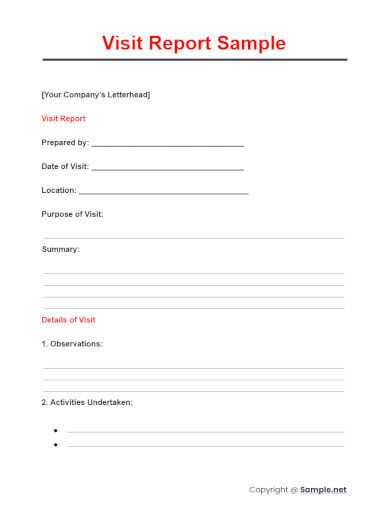

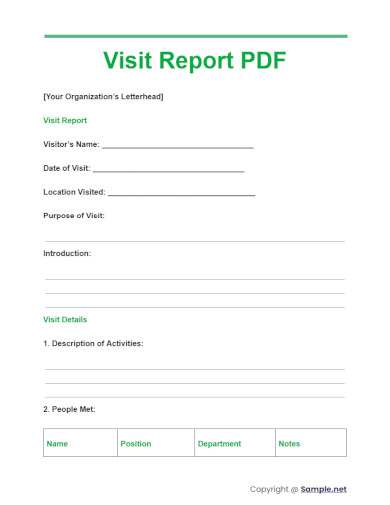

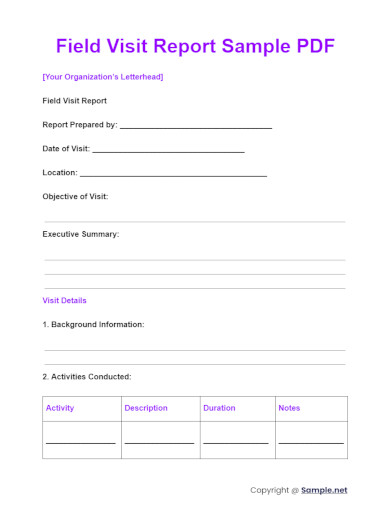

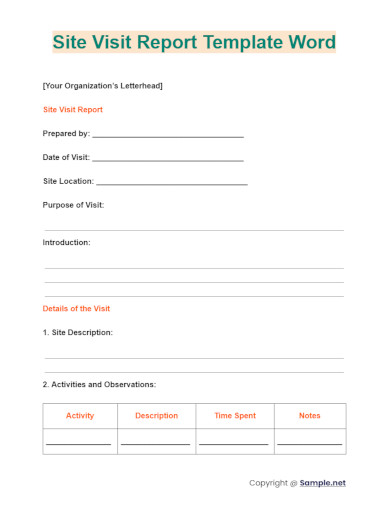

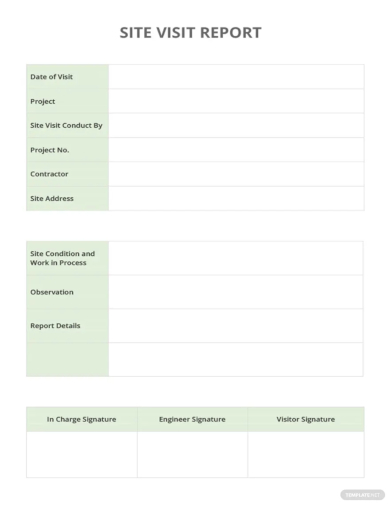

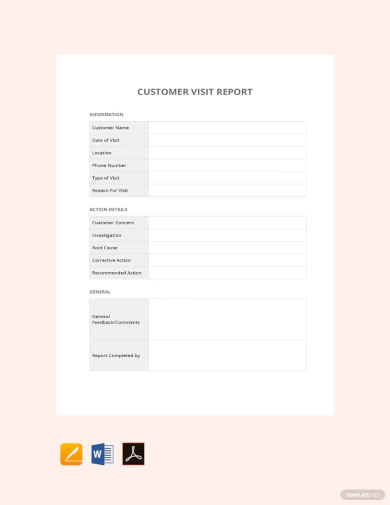

Dashpivot article – Site Visit Report example

Site Visit Report example

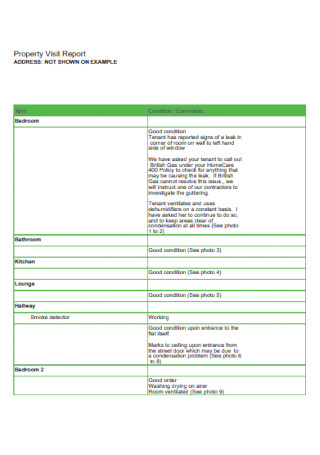

What is a site visit report.

A site visit report is a formal document that provides a detailed account of a visit to a particular location or project site.

It records the observations, activities, conditions, discussions, and any deviations or issues identified during the visit.

The report often includes recommendations or action items based on these findings.

It serves as an official record, aids in tracking progress or compliance, and can guide future decision-making.

What does the site visit report example cover?

Here's what's covered in the site visit report example:

- Report Title: Clearly indicating it's a "Site Visit Report."

- Project Name/Title: Name of the project or site.

- Location: Address or description of the site visited.

- Date of Visit: The exact date the visit took place.

- Prepared By: Name of the person or team who prepared the report.

- Introduction/Objective: A brief section detailing the purpose and objectives of the site visit.

- Attendees/Participants: A list of individuals present during the visit, including their roles or affiliations.

- Summary of Activities/Observations: A concise overview of what was done and seen during the visit.

- Project Progress: Status of ongoing work.

- Safety Measures: Observations related to safety precautions, PPE usage, and potential hazards.

- Quality of Work: Comments on the quality of work done so far.

- Equipment & Resources: Status and condition of machinery, tools, and other resources.

- Personnel: Feedback on staff performance, skill levels, or interactions.

- Issues or Concerns Identified: Any problems, discrepancies, or potential risks noticed during the visit.

- Recommendations: Based on observations and identified issues, suggest corrective actions, improvements, or next steps.

- Photos and Diagrams: Visual documentation can be invaluable in a site report. Include relevant photos with clear captions to illustrate points made in the report.

- Conclusion: Sum up the main findings and the overall impression from the site visit.

- Next Steps/Follow-Up Actions: Any scheduled follow-up visits, tasks to be done, or decisions to be made after the site visit.

- Attachments/Appendices: Additional materials, notes, or detailed data supporting the report's content.

- Signatures: Depending on the report's formality, it might be necessary for the person preparing the report and perhaps a superior or project stakeholder to sign off on its contents.

A well-prepared site visit report should be clear, concise, and structured. It provides a factual and objective account of the visit and serves as a vital tool for communication, decision-making, and record-keeping.

Site Visit Report example and sample

Below is an example of a site visit report in action. You can use this example in its entirety or sample it as needed.

Use a free Site Visit Report template based on this Site Visit Report example

Digitise this site visit report example.

Make it easy for your team to fill out site visit reports by using a standardised site visit report template .

The free digital site visit report comes pre-built with all the fields, section and information from the site visit report example above for your team to carry out detailed reports.

Customise the report with any extra information you need captured from your site visit reports with the drag and drop form builder.

Distribute your digital site visit report for your team on mobile or tablet so they can fill it out on site while the information is still fresh and at hand.

Create digital workflows for your site visit reports

Make it easy for your team to request, record and sign off on site visit reports by utilising a dedicated a site visit report app .

Automated workflows move a site visit request from planning to recording to signoff a smooth and simple process.

Quickly and easily share completed site visit reports as perfectly formatted PDF or CSV so your team is always across what's been recorded.

Take photos of site progress on site via your mobile or tablet, attach directly to your site visit reports with automatic timestamps, geotagging, photo markup and more.

Site diary template

Complete and organise your daily diaries more efficiently.

Meeting Minutes template

Capture, record and organise those meeting minutes.

Progress Claim template

Streamline and automate the progress claim process to get paid faster and look more professional.

Sitemate builds best in class tools for built world companies.

About Nick Chernih

Nick is the Senior Marketing Manager at Sitemate. He wants more people in the Built World to see the potential of doing things a different way - just because things are done one way doesn't mean it's the best way for you.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Official Writing

- Report Writing

How to Write a Visit Report

Last Updated: March 30, 2024 References

This article was co-authored by Madison Boehm . Madison Boehm is a Business Advisor and the Co-Founder of Jaxson Maximus, a men’s salon and custom clothiers based in southern Florida. She specializes in business development, operations, and finance. Additionally, she has experience in the salon, clothing, and retail sectors. Madison holds a BBA in Entrepreneurship and Marketing from The University of Houston. This article has been viewed 663,946 times.

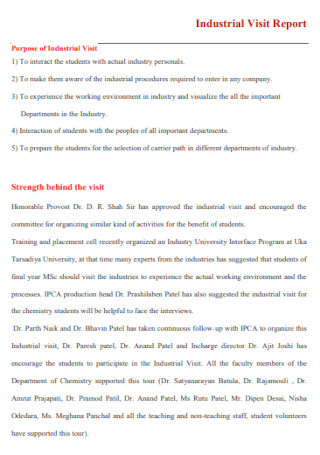

Whether you’re a student or a professional, a visit report helps you document the procedures and processes at an industrial or corporate location. These reports are fairly straightforward. Describe the site first and explain what you did while you were there. If required, reflect on what you learned during your visit. No additional research or information is needed.

Writing a Visit Report

Explain the site's purpose, operations, and what happened during the visit. Identify the site's strengths and weaknesses, along with your recommendations for improvement. Include relevant photos or diagrams to supplement your report.

Describing the Site

- Reports are usually only 2-3 pages long, but in some cases, these reports may be much longer.

- In some cases, you may be asked to give recommendations or opinions about the site. In other cases, you will be asked only to describe the site.

- Ask your boss or instructor for models of other visit reports. If you can't get a model, look up samples online.

- If you visited a factory, explain what it is producing and what equipment it uses.

- If you visited a construction site, describe what is being constructed and how far along the construction is. You should also describe the terrain of the site and the layout.

- If you’re visiting a business, describe what the business does. State which department or part of the business you visited.

- If you’re visiting a school, identify which grades they teach. Note how many students attend the school. Name the teachers whose classes you observed.

- Who did you talk to? What did they tell you?

- What did you see at the site?

- What events took place? Did you attend a seminar, Q&A session, or interview?

- Did you see any demonstrations of equipment or techniques?

- For example, at a car factory, describe whether the cars are made by robots or humans. Describe each step of the assembly line.

- If you're visiting a business, talk about different departments within the business. Describe their corporate structure and identify what programs they use to conduct their business.

Reflecting on Your Visit

- Is there something you didn’t realize before that you learned while at the site?

- Who at the site provided helpful information?

- What was your favorite part of the visit and why?

- For example, you might state that the factory uses the latest technology but point out that employees need more training to work with the new equipment.

- If there was anything important left out of the visit, state what it was. For example, maybe you were hoping to see the main factory floor or to talk to the manager.

- Tailor your recommendations to the organization or institution that owns the site. What is practical and reasonable for them to do to improve their site?

- Be specific. Don’t just say they need to improve infrastructure. State what type of equipment they need or give advice on how to improve employee morale.

Formatting Your Report

- If you are following a certain style guideline, like APA or Chicago style, make sure to format the title page according to the rules of the handbook.

- Don’t just say “the visit was interesting” or “I was bored.” Be specific when describing what you learned or saw.

Sample Visit Report

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://services.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/471286/Site_Reports_for_Engineers_Update_051112.pdf

- ↑ https://www.examples.com/business/visit-report.html

- ↑ https://www.thepensters.com/blog/industrial-visit-report-writing/

- ↑ https://eclass.aueb.gr/modules/document/file.php/ME342/Report%20Drafting.pdf

About This Article