An archive of Star Trek News

Trek Composers: Twenty-Six Seasons Of Star Trek Music

- Cast & Crew

During the fifty plus years of scoring music for various Star Trek shows, four composers are primarily responsible for the different show themes and music.

The composers include Ron Jones, Dennis McCarthy, Jay Chattaway , and Jeff Russo .

The composers had a tricky assignment, enticing original series fans. Jones addressed this by adding something familiar at the beginning of the TNG theme. “What I was told by Robert Justman is that Paramount was worried that everyone who was used to the original Star Trek was used to Shatner and Spock and the look and the feel of that show,” he said. “And now here’s this new one with a British captain with a bald head, and there’s a Klingon there — it was a weird cast! It was like a nightclub in Denmark. It was a weird group of people. And Paramount was worried about that. That’s why they used Jerry Goldsmith ‘s familiar theme at the beginning.”

“I never questioned it,” said McCarthy. “They wanted Jerry, so if that’s what they want, that’s what they’ll get. I did write a theme — I called it the Picard Theme — because I thought they might want one. I had done Dynasty and other shows that were heavily motif-driven, so I thought it might be nice to have a motif for Patrick Stewart . So I wrote this theme that’s floating around on a CD somewhere, and I used it and they liked it. And then about three shows later, I used it again. But they stopped and said, ‘Wait a minute. We’ve already heard that. Don’t do that again.'”

Deep Space Nine was “challenging because it was claustrophobic,” said Chattaway, “but in some ways that made it more interesting. And I think viewers now are coming back to that show and saying, ‘Wait a minute. This is pretty amazing.’ I found it more interesting because it wasn’t about going out to blow up some planet. We had to develop some personal connections and write more personal music. Like the quirky Quark music. It was fun. It wasn’t your typical genre of what space was all about. It was fun. It wasn’t your typical genre of what space was all about.”

Working on Voyager was “like backing into the Next Generation again,” said McCarthy. “It was closer in attitude to The Next Generation and the original series than Deep Space Nine . By that time, we were given permission to be a little bolder. It was a good experience.

McCarthy wrote the music for the first and the last episodes of The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine , and Enterprise . “It’s very satisfying,” he said. “There’s sadness, of course, because you hate to see the series end. And with Enterprise , it was really sad because we were hoping to go longer. That was also the last I’d see of that giant orchestra. I’d have fifty to sixty people per episode. It was a wonderful, wonderful experience.”

Star Trek music is “an adventure,” said Russo. “You never know where it’s going to take you. The thing that I’ve enjoyed injecting into Star Trek music is trying to also find an emotionality to it. Telling the story from a character perspective and be able to connect those things thematically.”

About The Author

T'Bonz

See author's posts

More Stories

Cruz Supports Rapp’s SAG-AFTRA Candidacy

- Star Trek: Discovery

Jones: Creating Your Own Family

Burton Hosts Jeopardy! This Week

You may have missed.

Several S&S Trek Books On Sale For $1 This Month

- Star Trek: Lower Decks

Another Classic Trek Actor On Lower Decks This Week

Classic Trek Games Now On GOG

- Star Trek: Prodigy

Star Trek: Prodigy Opening Credits Released

List of Star Trek composers and music

This is a list of composers of music for the series Star Trek , and other articles about music associated with the franchise.

Film soundtracks overview

The original series, the next generation, reboot cast, television soundtracks overview, special instruments, concert tours, external links.

The following individuals wrote movie scores, theme music, or incidental music for several episodes and/or installments of the Star Trek franchise.

Other composers who contributed music to at least one episode include Don Davis , John Debney , Brian Tyler , George Romanis, Sahil Jindal, Andrea Datzman, and Kris Bowers.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979)

The score for Star Trek: The Motion Picture was written by Jerry Goldsmith , who would later compose the scores Star Trek V: The Final Frontier , Star Trek: First Contact , Star Trek: Insurrection , and Star Trek: Nemesis , as well as the themes to the television series Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Voyager . [3] [4] Gene Roddenberry had originally wanted Goldsmith to score Star Trek ' s pilot episode, " The Cage ", but the composer was unavailable. [5] When Robert Wise signed on to direct the film, Paramount asked the director if he had any objection to using Goldsmith. Wise, who had worked with the composer for The Sand Pebbles , replied "Hell, no. He's great!" Wise would later consider his work with Goldsmith one of the best relationships he ever had with a composer. [6]

Goldsmith was influenced by the style of the romantic, sweeping music of Star Wars . "When you stop and think about it, space is a very romantic thought. It is, to me, like the Old West, we’re up in the universe. It’s about discovery and new life [...] it’s really the basic premise of Star Trek ," he said. Goldsmith's initial bombastic main theme reminded Ramsay and Wise of sailing ships. Unable to articulate what he felt was wrong with the piece, Wise recommended writing an entirely different piece. Although irked by the rejection, Goldsmith consented to re-work his initial ideas. [5] The rewriting of the theme required changes to several sequences Goldsmith had scored without writing the main title piece. The approach of Kirk and Scott to the drydocked Enterprise by shuttle lasted a ponderous five minutes due to the effect shots coming in late and unedited, requiring Goldsmith to maintain interest with a revised and developed cue. [7] : 88 Star Trek: The Motion Picture is the only Star Trek film to have a true overture , using "Ilia's Theme" in this role. Star Trek and The Black Hole would be the only feature films to use an overture from the end of 1979 until the year 2000 (with the movie Dancer in the Dark ). [8]

Much of the recording equipment used to create the movie's intricately complicated sound effects was, at the time, extremely cutting edge. Among these pieces of equipment was the ADS ( Advanced Digital Synthesizer ) 11, manufactured by Pasadena, California custom synthesizer manufacturer Con Brio, Inc. The movie provided major publicity and was used to advertise the synthesizer, though no price was given. [9] The film's soundtrack also provided a debut for the Blaster Beam , an electronic instrument 12 to 15 feet (3.7 to 4.6 m) long. [10] [11] It was created by musician Craig Huxley , who played a small role in two episodes of the original television series. [7] : 89 [12] The Blaster had steel wires connected to amplifiers fitted to the main piece of aluminum; the device was played with an artillery shell. Goldsmith heard it and immediately decided to use it for V'ger's cues. [5] An enormous pipe organ first plays the V'ger theme on the Enterprise ' s approach, a literal indication of the machine's power. [7] : 89

Goldsmith scored The Motion Picture over three to four months, a relatively relaxed schedule compared to typical production, but time pressures resulted in Goldsmith bringing on colleagues to assist in the work. Alexander Courage , composer of the original Star Trek theme, provided arrangements to accompany Kirk's log entries, while Fred Steiner wrote the music to accompany the Enterprise achieving warp speed and first meeting V'ger. [7] : 90 The rush to finish the rest of the film impacted the score. [7] : 89 The final recording session finished at 2:00am on December 1, [5] only five days before the film's release. [13]

A soundtrack featuring the film's music was released in 1979 together with the film debut and was one of Goldsmith's best-selling scores. [7] : 90 Sony's Legacy Recordings released an expanded two-disc edition of the soundtrack on November 10, 1998. The album added 21 minutes of music to supplement the original tracklist, and was resequenced to reflect the storyline of the film. The first disc features the expanded score, while the sequence disc contains "Inside Star Trek", a spoken word documentary. [14] In 2012, La-La Land Records released a comprehensive 3 CD special edition which includes the complete score along with alternates and outtakes remastered from restored original 16 track masters, the original digital album master, and popular cover versions of the film's love theme.

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982)

While Jerry Goldsmith had composed the music for The Motion Picture , he was not an option for The Wrath of Khan due to a budget reduction; director Nicholas Meyer 's composer for Time After Time , Miklós Rózsa , was likewise prohibitively expensive. [7] : 105 Meyer and producer Harve Bennett wanted the music for the sequel to go in a different direction but had not decided on a composer by the time filming began. Initially, Meyer hoped to hire an associate named John Morgan, but Morgan lacked film experience, which would have troubled the studio. [7] : 5

Paramount's vice-president of music Joel Sill took a liking to a 28-year-old composer named James Horner , feeling that his demo tapes stood out from generic film music. [7] : 6 Horner was introduced to Bennett, Meyer, and Salin. [15] Horner said that "[The producers] did not want the kind of score they had gotten before. They did not want a John Williams score, per se . They wanted something different, more modern." [16] When asked about how he landed the assignment, the composer replied that "the producers loved my work for Wolfen , and had heard my music for several other projects, and I think, so far as I've been told, they liked my versatility very much. I wanted the assignment, and I met with them, we all got along well, they were impressed with my music, and that's how it happened." [17] Horner agreed with the producers' expectations and agreed to begin work in mid-January 1982. [15]

In keeping with the nautical tone, Meyer wanted music evocative of seafaring and swashbuckling, and the director and composer worked together closely, becoming friends in the process. [7] : 6 As a classical music fan, Meyer was able to describe the effects and sounds he wanted in the music. [16] While Horner's style was described as "echoing both the bombastic and elegiac elements of John Williams' Star Wars and Jerry Goldsmith 's original Star Trek (The Motion Picture) scores," [18] Horner was expressly told not to use any of Goldsmith's score. Instead, Horner adapted the opening fanfare of Alexander Courage 's Star Trek television theme. "The fanfare draws you in immediately—you know you're going to get a good movie," Horner said. [7] : 9

In comparison to the flowing main theme, Khan's leitmotif was designed as a percussive texture that could be overlaid with other music and emphasized the character's insanity. [19] The seven-note brass theme was echoplexed to emphasize the character's ruminations about the past while on Ceti Alpha V, but does not play fully until Reliant ' s attack on the Enterprise . Many elements drew from Horner's previous work (a rhythm that accompanies Khan's theme during the surprise attack borrows from an attack theme from Wolfen , in turn influenced by Goldsmith's score for Alien . Musical moments from the original television series are also heard during investigation of the Regula space station and elsewhere. [7] : 106–107

To Horner, the "stuff underneath" the main story was what needed to be addressed by the score; in The Wrath of Khan , this was the relationship between Kirk and Spock. The main theme serves as Kirk's theme, with a mellower section following that is the theme for the Starship Enterprise . [7] : 8 Horner also wrote a motif for Spock, to emphasize the character's depth: "By putting a theme over Spock, it warms him and he becomes three-dimensional rather than a collection of schticks." [19] The difference in the short, French horn-based cues for the villain and longer melodies for the heroes helped to differentiate characters and ships during the battle sequences. [7] : 9

The soundtrack was Horner's first major film score, [18] and was written in four and a half weeks. The resulting 72 minutes of music was then performed by a 91-piece orchestra. [16] Recording sessions took place April 12–15 at the Warner Brothers lot, The Burbank Studios. [7] : 9 A pickup session was held on April 30 to record music for the Mutara nebula battle, while another session held on May 3 was used to cover the recently changed epilogue. [7] : 10 Horner used synthesizers for ancillary effects; at the time, science-fiction films such as E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and The Thing were eschewing the synthesizer in favor of more traditional orchestras. [20] Craig Huxley performed his invented instrument—the Blaster Beam —during recording, as well as composing and performing electronic music for the Genesis Project video. [7] : 17 While most of the film was "locked-in" by the time Horner had begun composing music, he had to change musical cue orchestration after the integration of special effects caused changes in scene durations. [16]

Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1984)

Composer James Horner returned to score The Search for Spock , fulfilling a promise he had made to Bennett on The Wrath of Khan . Much like the content of the film, Horner's music was a direct continuation of the score he wrote for the previous film. When writing music for The Wrath of Khan , Horner was aware he would reuse certain cues for an impending sequel; two major themes he reworked were for Genesis and Spock. While the Genesis theme supplants the title music Horner wrote for The Wrath of Khan , the end credits were quoted "almost verbatim". [21]

In hours-long discussions with Bennett and Nimoy, Horner agreed with the director that the "romantic and more sensitive" cues were more important than the "bombastic" ones. [21] Horner had written Spock's theme to give the character more dimension: "By putting a theme over Spock, it warms him and he becomes three-dimensional rather than a collection of schticks," he said. [22] The theme was expanded in The Search for Spock to represent the ancient alien mysticism and culture of Spock and Vulcan. [21]

Among the new cues Horner wrote was a "percussive and atonal" theme for the Klingons which is represented heavily in the film. [21] Jeff Bond described the cue as a compromise between music from Horner's earlier film Wolfen , Khan's motif from The Wrath of Khan , and Jerry Goldsmith 's Klingon music from The Motion Picture . [7] : 113 Horner also adapted music from Sergei Prokofiev 's Romeo and Juliet for part of the Enterprise theft sequence and its destruction, while the scoring to Spock's resurrection on Vulcan draws similarities to Horner's Brainstorm ending. [7] : 114

Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986)

James Horner , composer for The Wrath of Khan and The Search for Spock , declined to return for The Voyage Home . Because of this Nimoy turned to his friend Leonard Rosenman , who had written the music to, among other films, Fantastic Voyage , Ralph Bakshi 's The Lord of the Rings , and two Planet of the Apes sequels. [7] : 119 [23] Rosenman wrote an arrangement of Alexander Courage 's Star Trek television theme as the title music for The Voyage Home , but Nimoy suggested that he write his own instead. As music critic Jeff Bond writes, "The final result was one of the most unusual Star Trek movie themes," consisting of a six note theme and variations set against a repetitious four note brass motif; the theme's bridge is reminiscent of material in Rosenman's "Frodo March" for The Lord of the Rings . [7] : 119 The melody makes appearances in the beginning of the film at Vulcan as well as when Taylor seeks Kirk's help finding her whales. [7] : 120

The Earth-based setting of the filming gave Rosenman leeway to write a variety of music in different styles. Nimoy intended the crew's introduction to the streets of San Francisco to be accompanied by something reminiscent of George Gershwin , but Rosenman changed the director's mind [7] : 131 and the scene was scored with a contemporary jazz fusion piece by Yellowjackets . When Chekov flees detention aboard the aircraft carrier, Rosenman wrote a bright cue that incorporated classical Russian compositions, while the escape from the hospital was done in a baroque style. More familiar Rosenman compositions included the action music as the Bird of Prey and a whaling ship face off in open water, while the whale's communication with the probe used atmospheric music reminiscent of the composer's work in Fantastic Voyage . After the probe leaves, the music turns into a Vivaldiesque "whale fugue". The first sighting of the Enterprise -A uses the Alexander Courage theme before the end title music. [7] : 120

Mark Mangini served as The Voyage Home ' s sound designer. He described it as different from working on many other films because Nimoy appreciated the role of sound effects and made sure that they were prominent in the film. Since many sounds familiar to Star Trek had already been established—the Bird of Prey's cloaking device, the transporter beam, et al.—Mangini focused on making only small changes to them. The most important sounds were those created by the whales and the probe. Mangini's brother lived close to Roger Payne , a biologist who had many recordings of whale song. Mangini went through the tapes and chose sounds that could be mixed to suggest a sort of language and conversation. The probe's screeching calls were the whale song in distorted form. The humpback's communication with the probe at the climax of the film contained no dramatic music, meaning that Mangini's sounds had to stand alone. He recalled that he had some difficulty with envisioning how the scene would unfold, leading Bennett to perform a puppet show to explain. Nimoy and the other producers were unhappy with Mangini's attempts to create the probe's droning operating noise; after 18 attempts, the sound designer finally asked Nimoy what he thought the probe should sound like, and recorded Nimoy's response. Nimoy's voice was distorted with "just the tiniest bit of dressing" and used as the final sound. [24]

The punk music that blares during the bus scene was written by Thatcher after he learned that the audio to be added to the scene would be " Duran Duran , or whoever" and not "raw" and authentic punk. [25] Thatcher collaborated with Mangini and two sound editors (who were in punk bands) to create their own music. They decided that punk distilled down to the sentiment of "I hate you", and wrote a sound to match. Recording in the sound studio as originally planned produced too clean a sound, so they moved to the outside hallway and recorded the entire band in one take using cheap microphones to create the distorted sound intended. [26] The song was later used for Paramount's " Back to the Beach ". [25]

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989)

Music critic Jeff Bond wrote that Shatner made "at least two wise decisions" in making The Final Frontier ; he chose Laurence Luckinbill to play the role of Sybok, and he hired Jerry Goldsmith to compose the film's score. Goldsmith had written the Academy Award-nominated score for Star Trek: The Motion Picture , and the new Trek film was an opportunity to craft music with a similar level of ambition while adding action and character—two elements largely missing from The Motion Picture . [7] : 133

Goldsmith's main theme begins with the traditional opening notes from Alexander Courage 's original television series theme; an ascending string and electronic bridge leads to a rendition of the march from The Motion Picture . According to Jeff Bond, Goldsmith's use of The Motion Picture ' s march led to some confusion among Star Trek: The Next Generation fans, as they were unfamiliar with the music's origins and believed that Goldsmith was stealing the theme to The Next Generation , which was itself The Motion Picture march. [7] : 133 Another theme from The Motion Picture that makes a return appearance is the Klingon theme from the 1979 film's opening scene. Here, the theme is treated in what Bond termed a "Prokofiev-like style as opposed to the avant-garde counterpoint" as seen in The Motion Picture . Goldsmith also added a crying ram's horn. [7] : 134

The breadth of The Final Frontier ' s locations led Goldsmith to eschew the two-themed approach of The Motion Picture in favor of leitmotifs , recurring music used for locations and characters. Sybok is introduced with a synthesized motif in the opening scene of the film, while when Kirk and Spock discuss him en route to Nimbus III it is rendered in a more mysterious fashion. The motif also appears in the action cue as Kirk and company land on Nimbus III and try to free the hostages. [7] : 133 When Sybok boards the Enterprise , a new four-note motif played by low brass highlights the character's obsession. The Sybok theme from then on is used in either a benevolent sense or a more percussive, dark rendition. Arriving at Sha-ka-ree, the planet's five-note theme bears resemblance to Goldsmith's unicorn theme from Legend ; "...the two melodies represent very similar ideas: lost innocence and the tragic impossibility of recapturing paradise," writes Bond. The music features cellos conveying a pious quality, while the appearance of "God" begins with string glissandos but turns to a dark rendition of Sybok's theme as its true nature is exposed. [7] : 134 As the creature attacks Kirk, Spock and McCoy, the more aggressive Sybok theme takes on an attacking rhythm. When Spock appeals to the Klingons for help, the theme takes on a sensitive character before returning to a powerful sequence as the ship destroys the god-creature. [7] : 135

Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991)

Director Nicholas Meyer's original plan for the score of The Undiscovered Country was to adapt Gustav Holst 's orchestral suite The Planets . The plan proved unfeasibly expensive, so Meyer began listening to demo tapes submitted by composers. [27] Meyer described most of the demos as generic "movie music", but was intrigued by one tape by a young composer named Cliff Eidelman . Eidelman, then 26, had made a career in composing for ballets, television, and film, but despite work on fourteen features, no film had been the hit needed to propel Eidelman to greater fame. [28]

In conversations with Eidelman, Meyer mentioned that since the marches that accompanied the main titles for other Star Trek films were so good, he had no desire to compete with them by composing a bombastic opening. He also felt that since the film was darker than its predecessors, it demanded something different musically as a result. He mentioned the opening to Igor Stravinsky 's The Firebird as similar to the foreboding sound he wanted. Two days later Eidelman produced a tape of his idea for the main theme, played on a synthesizer. Meyer was impressed by the speed of the work and the close fit to his vision. [27] Meyer approached producer Steven Charles-Jaffe with Eidelman's CD, which reminded Jaffe of Bernard Herrmann ; Eidelman was given the task of composing the score. [29]

Eidelman's previous project had been creating a compilation of music from the past five Star Trek films, and he consciously avoided taking inspiration from those scores. "[The compilation] showed me what to stay away from, because I couldn't do James Horner [composer for The Wrath of Khan and The Search for Spock ] as well as James Horner," he said. [30] Since he was hired early on in production, Eidelman had an unusually long time to develop his ideas, and he was able to visit the sets during filming. While the film was in early production Eidelman worked on electronic drafts of the final score, to placate executives who were unsure about using a relatively unknown composer. [30]

Eidelman stated that he finds science fiction the most interesting and exciting genre to compose for, and that Meyer told him to treat the film as a fresh start, rather than drawing on old Star Trek themes. [29] Eidelman wanted the music to aid the visuals; for Rura Penthe, he strove to create an atmosphere that reflected the alien and dangerous setting, introducing exotic instruments for color. Besides using percussion from around the world, Eidelman treated the choir as percussion, with the Klingon language translation for " to be, or not to be " (" taH pagh, taHbe ") being repeated in the background. Spock's theme was designed to be an ethereal counterpart to the motif for Kirk and the Enterprise , aimed at capturing "the emotional gleam in the captain's eye". [31] Kirk's internal dilemma about what the future holds was echoed in the main theme: "It's Kirk taking control one last time and as he looks out into the stars he has the spark again [...] But there's an unresolved note, because it's very important that he doesn't trust the Klingons. He doesn't want to go on this trip even though the spark is there that overtook him." [32] For the climactic battle, Eidelman starts the music quietly, building the intensity as the battle progresses. [29]

Star Trek Generations (1994)

Dennis McCarthy , a composer who had worked on The Next Generation , was given the task of composing for Star Trek Generations . Critic Jeff Bond wrote that while McCarthy's score was "tasked with straddling the styles of both series", it also offered the opportunity for the composer to produce stronger dramatic writing. His opening music was an ethereal choral piece that plays while a floating champagne bottle tumbles through space. For the action scenes with the Enterprise -B, McCarthy used low brass chords and touches. Kirk was given a brass motif accented by snare drums (a touch verboten during The Next Generation ), while the scene ends with a dissonant note as Scott and Chekov discover Kirk has been blown into space. [7] : 152

McCarthy expanded his brassy style for the film's action sequences, such as the battle over Veridian III and the crash-landing of the Enterprise . For Picard's trip to the Nexus, more choral music and synthesizers accompany Picard's discovery of his family. The film's only distinct theme, a broad fanfare, first plays when Picard and Kirk meet. The theme blends McCarthy's theme for Picard from The Next Generation ' s first season, notes from the theme for Star Trek: Deep Space Nine , and Alexander Courage 's classic Star Trek fanfare. [7] : 152

Star Trek: First Contact (1996)

Film composer Jerry Goldsmith scored First Contact , his third Star Trek feature. Goldsmith wrote a sweeping main title which begins with Alexander Courage 's classic Star Trek fanfare . [33] Instead of composing a menacing theme to underscore the Borg, Goldsmith wrote a pastoral theme linked to humanity's hopeful first contact. The theme uses a four-note motif used in Goldsmith's Star Trek V: The Final Frontier score, which is used in First Contact as a friendship theme and general thematic link. [7] : 155–156 A menacing march with touches of synthesizers was used to represent the Borg. In addition to composing new music, Goldsmith used music from his previous Star Trek scores, including his theme from The Motion Picture . [33] The Klingon theme from the same film is used to represent Worf. [34]

Because of delays with Paramount's The Ghost and the Darkness , the already-short four-week production schedule was cut to just three weeks. While Berman was concerned about the move, [7] : 158 Goldsmith hired his son, Joel , to assist. [7] : 155 The young composer provided additional music for the film, writing three cues based on his father's motifs [34] and a total of 22 minutes of music. [33] Joel used variations of his father's Borg music and the Klingon theme as Worf fights hand-to-hand [7] : 156 (Joel said that he and his father decided to use the theme for Worf separately). [7] : 159 When the Borg invade sickbay and the medical hologram distracts them, Joel wrote what critic Jeff Bond termed "almost Coplandesque " material of tuning strings and clarinet, but the cue was unused. While Joel composed many of the film's action cues, his father contributed to the spacewalk and Phoenix flight sequences. During the fight on the deflector dish, Goldsmith used low-register electronics punctuated by stabs of violent, dissonant strings. [7] : 156

In a break with Star Trek film tradition, the soundtrack incorporated two licensed songs: Roy Orbison 's "Ooby Dooby" and Steppenwolf 's "Magic Carpet Ride". GNP Crescendo president Neil Norman explained that the decision to include the tracks was controversial, but said that "Frakes did the most amazing job of integrating those songs into the story that we had to use them". [35]

GNP released the First Contact soundtrack on December 2, 1996. [35] The album contained 51 minutes of music, with 35 minutes of Jerry Goldsmith's score, 10 minutes of additional music by Joel Goldsmith, "Ooby Dooby" and "Magic Carpet Ride". The compact disc shipped with CD-ROM features only accessible if played on a personal computer, [36] including interviews with Berman, Frakes, and Goldsmith. [35]

Star Trek: Insurrection (1998)

Insurrection was composer Jerry Goldsmith 's fourth film score for the franchise. [7] : 163 Goldsmith continued using the march and Klingon themes he crafted for Star Trek: The Motion Picture in 1979, with adding new themes and variations. Insurrection opens with Alexander Courage 's Star Trek: The Original Series fanfare, also introducing a six-note motif used in many of the film's action sequences. The Ba'ku are scored with a pastoral theme, repeating harps, string sections, and a woodwind solo. The Ba'ku's ability to slow time uses a variation of this music. [7] : 164

Goldsmith approached starship sequences with quick bursts of brass music. While observers are watching the Ba'ku unseen, Goldsmith employed a "spying theme". Composed of a piano, timpani percussion, and brass, the theme builds until interrupted by the action theme as Data opens fire. Goldsmith did not write a motif for the Son'a, choosing to score the action sequence without designating the Son'a as an antagonist (suggesting the film's revelation that the Son'a and Ba'ku are related.) The film's climax is scored with the active material, balanced by "sense of wonder" music similar to cues from The Motion Picture . [7] : 164

Star Trek: Nemesis (2002)

The music to Nemesis was the final Star Trek score and penultimate film score composed and conducted by Jerry Goldsmith before his death in 2004 (not including his music for the 2003 film Timeline , which was rejected due to a complicated post-production process). The score opens with Alexander Courage 's Star Trek: The Original Series fanfare, but quickly transitions into a much darker theme to accompany the conflict between the Reman and Romulan empires. Goldsmith also composed a new 5-note theme to accompany the character Shinzon and the Scimitar , which is manipulated throughout the score to reflect the multiple dimensions of the character. Goldsmith also incorporated several zipping, swooshing synthesizers into the conventional orchestra to illustrate the suspenseful and horrific elements of the story. The score is book-ended with Goldsmith's theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture , following a brief excerpt from the popular 1929 song " Blue Skies " by Irving Berlin . [37] [38]

Star Trek (2009)

Michael Giacchino , Abrams' most frequent collaborator, composed the music for Star Trek . He kept the original theme by Alexander Courage for the end credits, which Abrams said symbolized the momentum of the crew coming together. [39] Giacchino admitted personal pressure in scoring the film, as "I grew up listening to all of that great [Trek] music, and that's part of what inspired me to do what I'm doing [...] You just go in scared. You just hope you do your best. It's one of those things where the film will tell me what to do." [40] Scoring took place at the Sony Scoring Stage with a 107-piece orchestra and 40-person choir. An erhu , performed by Karen Han , was used for the Vulcan themes. A distorted recording was used for the Romulans. [41] Varèse Sarabande , the record label responsible for releasing albums of Giacchino's previous scores for Alias , Lost , Mission: Impossible III , and Speed Racer , released the soundtrack for the film on May 5. [42]

Star Trek Into Darkness (2013)

Before the beginning of principal photography, Michael Giacchino announced that he would compose the score to Star Trek Into Darkness . Just as with the previous installment, Giacchino kept the original theme by Alexander Courage for the end credits, allowing for his newer themes for the various young members of Enterprise to evolve.

Star Trek Beyond (2016)

As with the previous two films, Michael Giacchino composed the score to Star Trek Beyond .

- Blaster Beam

- Ressikan flute

- " Star Trekkin' "

- " Banned from Argo "

- Star Trek: The Music

- Star Trek: The Ultimate Voyage

- List of Star Trek production staff

- William Shatner's musical career

- Leonard Nimoy discography

Related Research Articles

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan is a 1982 American science fiction film directed by Nicholas Meyer and based on the television series Star Trek . It is the second film in the Star Trek film series following Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), and is a sequel to the television episode "Space Seed" (1967). The plot features Admiral James T. Kirk and the crew of the starship USS Enterprise facing off against the genetically engineered tyrant Khan Noonien Singh. When Khan escapes from a 15-year exile to exact revenge on Kirk, the crew of the Enterprise must stop him from acquiring a powerful terraforming device named Genesis. The film is the beginning of a three-film story arc that continues with the film Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1984) and concludes with the film Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986).

Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home is a 1986 American science fiction film, the fourth installment in the Star Trek film franchise based on the television series Star Trek . The second film directed by Leonard Nimoy, it completes the story arc begun in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982), and continued in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1984). Intent on returning home to Earth to face trial for their actions in the previous film, the former crew of the USS Enterprise finds the planet in grave danger from an alien probe attempting to contact now-extinct humpback whales. The crew travel to Earth's past to find whales who can answer the probe's call.

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier is a 1989 American science fiction film directed by William Shatner and based on the television series Star Trek created by Gene Roddenberry. It is the fifth installment in the Star Trek film series , and takes place shortly after the events of Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986). Its plot follows the crew of the USS Enterprise -A as they confront renegade Vulcan Sybok, who is searching for God at the center of the galaxy.

Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country is a 1991 American science fiction film directed by Nicholas Meyer, who also directed the second Star Trek film, The Wrath of Khan . It is the sixth feature film based on the 1966–1969 Star Trek television series. Taking place after the events of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier , it is the final film featuring the entire main cast of the original television series. The destruction of the Klingon moon Praxis leads the Klingon Empire to pursue peace with their longtime adversary, the Federation; the crew of the Federation starship USS Enterprise must race against unseen conspirators with a militaristic agenda.

A film score is original music written specifically to accompany a film. The score comprises a number of orchestral, instrumental, or choral pieces called cues, which are timed to begin and end at specific points during the film in order to enhance the dramatic narrative and the emotional impact of the scene in question. Scores are written by one or more composers under the guidance of or in collaboration with the film's director or producer and are then most often performed by an ensemble of musicians – usually including an orchestra or band, instrumental soloists, and choir or vocalists – known as playback singers – and recorded by a sound engineer. The term is less frequently applied to music written for media such as live theatre, television and radio programs, and video games, and said music is typically referred to as either the soundtrack or incidental music.

Star Trek III: The Search for Spock is a 1984 American science fiction film, written and produced by Harve Bennett, directed by Leonard Nimoy, and based on the television series Star Trek . It is the third film in the Star Trek franchise and is the second part of a three-film story arc that begins with Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982) and concludes with Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986). After the death of Spock (Nimoy), the crew of the USS Enterprise return to Earth. When James T. Kirk learns that Spock's spirit, or katra, is held in the mind of Dr. Leonard "Bones" McCoy, Kirk and company steal the decommissioned USS Enterprise to return Spock's body to his homeworld. The crew must also contend with hostile Klingons, led by Kruge, who are bent on stealing the secrets of the powerful terraforming device, Genesis.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture is a 1979 American science fiction film directed by Robert Wise. The Motion Picture is based on and stars the cast of the 1966–1969 television series Star Trek created by Gene Roddenberry, who serves as producer. In the film, set in the 2270s, a mysterious and powerful alien cloud known as V'Ger approaches Earth, destroying everything in its path. Admiral James T. Kirk assumes command of the recently refitted Starship Enterprise to lead it on a mission to determine V ' Ger ' s origins and save the planet.

Jerrald King Goldsmith was an American composer known for his work in film and television scoring. He composed scores for five films in the Star Trek franchise and three in the Rambo franchise , as well as for films including Logan's Run , Planet of the Apes , Tora! Tora! Tora! , Patton , Papillon , Chinatown , The Omen , Alien , Poltergeist , The Secret of NIMH , Medicine Man , Gremlins , Hoosiers , Total Recall , Basic Instinct , Air Force One , L.A. Confidential , Mulan , and The Mummy . He also composed the fanfares accompanying the production logos used by multiple major film studios, and music for the Disney attraction Soarin' .

James Roy Horner was an American film composer. He worked on more than 160 film and television productions between 1978 and 2015. He was known for the integration of choral and electronic elements alongside traditional orchestrations, and for his use of motifs associated with Celtic music.

Alexander Mair Courage Jr. familiarly known as "Sandy" Courage, was an American orchestrator, arranger, and composer of music, primarily for television and film. He is best known as the composer of the theme music for the original Star Trek series .

Star Trek is a 2009 American science fiction action film directed by J. J. Abrams and written by Roberto Orci and Alex Kurtzman. It is the 11th film in the Star Trek franchise, and is also a reboot that features the main characters of the original Star Trek television series portrayed by a new cast, as the first in the rebooted film series. The film follows James T. Kirk and Spock aboard the USS Enterprise as they combat Nero, a Romulan from their future who threatens the United Federation of Planets. The story takes place in an alternate reality that features both an alternate birth location for James T. Kirk and further alterations in history stemming from the time travel of both Nero and the original series Spock. The alternate reality was created in an attempt to free the film and the franchise from established continuity constraints while simultaneously preserving original story elements.

The " Theme from Star Trek " is an instrumental musical piece composed by Alexander Courage for Star Trek, the science fiction television series created by Gene Roddenberry that originally aired between September 8, 1966, and June 3, 1969.

Star Trek: The Music is conducted by Erich Kunzel of the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra, and hosted/narrated by John de Lancie and Robert Picardo.

Star Trek: Music from the Motion Picture is a soundtrack album for the 2009 film Star Trek , composed by Michael Giacchino. The score was recorded in October 2008 since the film was originally scheduled to be released the following December. It was performed by the Hollywood Studio Symphony and Page LA Studio Voices at the Sony Scoring Stage in Culver City, California. The score incorporates the " Theme from Star Trek " by Alexander Courage and Gene Roddenberry.

Star Trek Into Darkness: Music from the Motion Picture is a soundtrack album for the 2013 film, Star Trek Into Darkness , composed by Michael Giacchino. The score was recorded over seven sessions at the Sony Scoring Stage in Culver City, California, on March 5–9 and April 2 and 3, 2013. It was performed by the Hollywood Studio Symphony in conjuncture with Page LA Studio Voices. The soundtrack album was released in physical form on May 21, 2013, through Varèse Sarabande, as the follow-up to the critically successful 2009 soundtrack album Star Trek .

Star Trek: Nemesis – Music from the Original Motion Picture Soundtrack is a soundtrack album for the 2002 film, Star Trek: Nemesis , composed by Jerry Goldsmith. Released on December 10, 2002 through Varèse Sarabande, the soundtrack features fourteen tracks of score at a running time just over forty-eight minutes, though bootleg versions containing the entire score have since been released. A deluxe edition soundtrack limited to 5000 copies was released on January 6, 2014 by Varèse Sarabande.

Jurassic World: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack is the film score to Jurassic World composed by Michael Giacchino. The album was released digitally and physically on June 9, 2015 by Back Lot Music.

Star Trek: The Ultimate Voyage is a multimedia concert experience featuring music and video footage from Star Trek motion pictures, television series, and video games in honor of franchise's 50th anniversary. The initial concert tour from 2015 to 2016 performed in 100 cities in North America and Europe and generally received positive reviews. The concerts series was produced by CineConcerts, a production company specializing in live music experiences performed with visual media.

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) is the score album to the 2014 film of the same name. Directed by Matt Reeves, the film is a sequel to Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) and the second installment in the Planet of the Apes reboot franchise . Reeves' frequent collaborator Michael Giacchino, who previously worked in Cloverfield (2008) and Let Me In (2010), composed the film's score. He significantly created themes deriving his own compositions from Lost (2004–2010) and Super 8 , and had referenced Jerry Goldsmith's themes from the original 1968 film. The soundtrack was released by Sony Classical Records on July 7, 2014, and received polarising reviews with praise over the score's integration and criticism directed on the album length and lack of significant themes, with some comparing it as inferior to Giacchino's compositions.

The music to the 1979 American science fiction film Star Trek: The Motion Picture featured musical score composed by Jerry Goldsmith, beginning his long association with the Star Trek film and television. Influenced by the romantic, sweeping music of Star Wars by John Williams, Goldsmith created a similar score, with extreme cutting-edge technologies being used for recording and creating the sound effects. The score received critical acclaim and has been considered one of Goldsmith's best scores in his career.

- ↑ 'Star Trek' boldly going symphonic [usurped] , Canadian Online Explorer . Retrieved 2010-08-23

- ↑ Music makes movies memorable [usurped] , Canadian Online Explorer , June 11, 2000. Retrieved 2010-08-23

- ↑ King, Susan; John Thurber (2004-07-23). "Jerry Goldsmith, 75, prolific film composer" . The Boston Globe . Retrieved 2009-03-01 .

- 1 2 3 4 Goldsmith, Jerry. Star Trek: The Motion Picture Directors Edition [Disc 2]. Special features: Commentary.

- ↑ Roberts, Jerry (1995-09-08). "Tapping a rich vein of gold; Jerry Goldsmith's music is as varied as the films he's scored". Daily Variety .

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 The Music of Star Trek at Google Books . Lone Eagle Publishing Co., 1999. ISBN 978-1-58065-012-0

- ↑ Dochterman, Darren; David C. Fein; Michael Matessino. Star Trek: The Motion Picture - The Director's Edition: Audio Commentary . Paramount . Retrieved 2009-04-03 .

- ↑ Vail, Mark (2000). Keyboard Magazine Presents Vintage Synthesizers: Pioneering Designers, Groundbreaking Instruments, Collecting Tips, Mutants of Technology . Backbeat Books. p. 85. ISBN 0-87930-603-3 .

- ↑ Staff (2004-07-24). "Jerry Goldsmith, Composer for such films as Chinatown and The Omen". The Daily Telegraph . p. 27.

- ↑ Morrison, Mairi (1987-01-04). "Otherworldly Sounds". The Washington Post . p. G3.

- ↑ Craig Hundley at IMDb

- ↑ Elley, Derek (2001-12-24). "Star Trek: The Motion Picture: The Directors' Edition". Variety . p. 21.

- ↑ Olson, Cathrine (1998-09-26). "Soundtrack and Filmscore News". Billboard .

- 1 2 Anderson, 71.

- 1 2 3 4 Larson, Randall (Fall 1982). "Interview: James Horner and Star Trek II". CinemaScore (10).

- ↑ Larson, Randall (Fall–Winter 1982). "A Conversation with James Horner". CinemaScore (11–12 (Double Issue)).

- 1 2 Harrington, Richard (1982-07-25). "Sounds Of the Summer Screen". The Washington Post . p. L1.

- 1 2 Anderson, 72.

- ↑ Sterritt, David (1982-08-17). "Films: zing go the strings of a polymoog". Christian Science Monitor . p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 Simak.

- ↑ Anderson, Kay (1982). " 'Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan': How the TV series became a hit movie, at last". Cinefantastique . 12 (5–6): 72. ISSN 0145-6032 .

- ↑ Breyer.

- ↑ Special features, "Below-the-Line: Sound Design".

- 1 2 Plume, Kenneth (2000-02-10). "Interview with Kirk Thatcher (Part 1 of 2)" . IGN . Retrieved 2009-12-08 .

- ↑ Special features: "On Location".

- 1 2 Meyer, Nicholas (1991). "Director's notes". Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (Media notes). Famous Music Corporation. pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Schweiger, 8.

- 1 2 3 Special Features, "Six Stories from Star Trek VI".

- 1 2 Schweiger, 9.

- ↑ Schweiger, 10.

- ↑ Altman, 46.

- 1 2 3 Norman.

- 1 2 Larson.

- 1 2 3 Sprague, David (1996-12-14). "Nothing like the reel thing; Soundtrack and film score news". Billboard .

- ↑ Herries, Iain (March–April 1997). "Score; the latest in soundtrack releases". Film Score Monthly . 2 (2): 34–35.

- ↑ Clemmensen, Christian. Star Trek: Nemesis soundtrack review at Filmtracks.com . Retrieved 2011-04-18.

- ↑ Peterson, Matt. "Taking the Trek Once More: Star Trek Nemesis by Jerry Goldsmith" soundtrack review at Tracksounds.com. Retrieved 2011-04-18.

- ↑ Christina Radish (2009-04-26). "Interview: J.J. Abrams on Star Trek" . IESB . Archived from the original on 2009-04-30 . Retrieved 2009-04-27 .

- ↑ Cindy White (2007-11-01). "Trek Score Will Keep Theme" . Sci Fi Wire . Archived from the original on 2008-02-02 . Retrieved 2007-11-03 .

- ↑ Dan Goldwasser (2009-04-21). "Michael Giacchino hits warp speed with his score to Star Trek " . ScoringSessions.com . Retrieved 2009-04-21 .

- ↑ Anthony Pascale (2008-03-23). "Giacchino's Star Trek Soundtrack Announced - Available For Pre-order" . TrekMovie.com . Retrieved 2008-03-25 .

- Composers at Memory Alpha , a Star Trek wiki

- List of staff

- Gene Roddenberry

- Norway Corporation

- musical theme

- " Where no man has gone before "

- " Beam me up, Scotty "

- Accolades (film franchise)

- The God Thing

- Planet of the Titans

- Star Trek 4

- Reference books

- A Klingon Christmas Carol

- Klingon opera

- Very Short Treks

- The Ready Room

- How William Shatner Changed the World

- Beyond the Final Frontier

- The Captains

- Trek Nation

- For the Love of Spock

- What We Left Behind

- Kirk and Uhura's kiss

- Comparison to Star Wars

- productions

- Memory Alpha

- Shakespeare and Star Trek

- The Exhibition

- The Experience

- " The Last Voyage of the Starship Enterprise " (1976 SNL sketch)

- Free Enterprise (1999 film)

- Galaxy Quest (1999 film)

- " Where No Fan Has Gone Before " (2002 Futurama episode)

- The Orville (2017 television series)

- Please Stand By (2017 film)

- " USS Callister " (2017 Black Mirror episode)

- More to Explore

- Series & Movies

The Music of Star Trek: Strange New Worlds

Meet the composers!

A behind-the-scenes look at how composer Nami Melumad and main title theme composer Jeff Russo created the music of Star Trek: Strange New Worlds .

Star Trek: Strange New Worlds streams exclusively on Paramount+ in the U.S., U.K., Australia, Latin America, Brazil, South Korea, France, Italy, Germany, Switzerland and Austria. In addition, the series airs on Bell Media’s CTV Sci-Fi Channel and streams on Crave in Canada and on SkyShowtime in the Nordics, the Netherlands, Spain, Portugal and Central and Eastern Europe. Star Trek: Strange New Worlds is distributed by Paramount Global Content Distribution.

- The Original Series

- The Animated Series

- The Next Generation

- Deep Space Nine

- Strange New Worlds

- Lower Decks

- Star Trek Movies

- TrekCore on Twitter

- TrekCore on Facebook

The Israeli-born composer first shared how she came to Star Trek through its music, as a young girl the English-language program was indecipherable to her.

“My I was a kid in the 90s, and I think it was TNG playing in the background at my family’s house — and I did not understand any of it. There were people with pointed ears and everyone was wearing different uniforms… I did not really get any of it. And it was in English, so I didn’t understand most of it! Later, I kind of came to ‘Star Trek’ because of the music, to be honest, like Jerry Goldsmith’s theme, and then I heard the Alexander Courage theme, and I thought it was so, so incredible. So what really drew me was the music, and it’s kind of like a circle back for me, to be working on this amazing franchise — especially one that features Janeway, because ‘Voyager’ is my favorite ‘Trek.'”

She also shared how her time scoring the Short Trek “Q & A” came to pass, the story which showed Ensign Spock’s first day aboard the USS Enterprise .

“The [‘Short Trek’] was the call of my dreams! I started working with Michael Giacchino, who we all know as an incredibly amazing composer. We did ‘American Pickle’ together, and during that time he connected me with Alex Kurtzman, and they offered me that short, and I got so, so, so excited. It was the legendary characters, you know? Spock! I just love Spock, so much. It was also such a big responsibility too, you know, his first day on the Enterprise. I’m trusted with this? It was an unbelievable moment for me. Luckily it happened very quickly, so I didn’t have time to process — and I’m very grateful for that! So I wrote the score; we did a couple of passes with feedback, and there were some really great ideas that the producers gave me. We recorded it at Warner Brothers, and I think we had 40 or 45 musicians — which was really cool — and then we mixed it. The whole thing was pretty quick, maybe three or four weeks… and then it aired!”

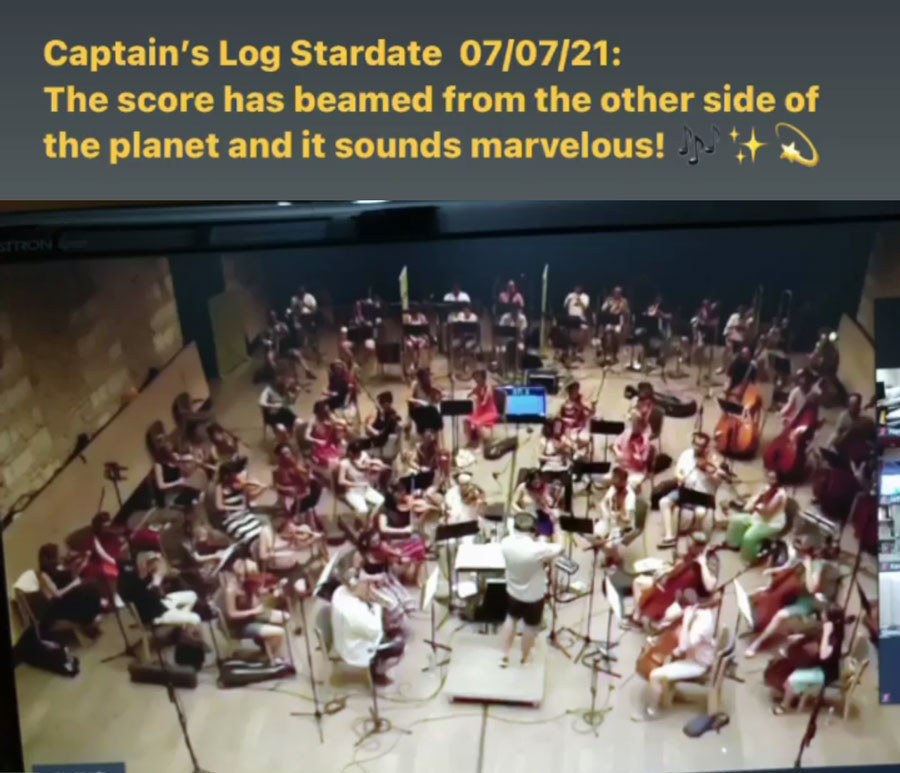

Speaking more directly about her work on Star Trek: Prodigy , Melumad — who will be the first female ‘primary’ composer for a Star Trek production — explained how the Budapest-based orchestra behind the animated series’ music is recording the score all in one place, rather than as individual artists (a challenge Discovery has been facing due to pandemic restrictions).

“For the first episode we had 64 musicians, and we stayed around those numbers. Sometimes bigger, sometimes smaller…. depending on the episode and budget. We started recording once things kind of settled [regarding] COVID procedures; we’re recording in Europe, and the players are together in the actual studio. I’m very glad we’re not doing it [individually] because recording every player separately in their home studio is a mess to edit all those recordings, and they’re not in the same space so there’s way more mixing [required], in terms of getting everyone into that same [sound] space with the mix. It’s also very time-consuming for the musicians, because they have to operate their own [software]… it’s just a lot, technically. So we got very lucky. [I’m remote, and they’re] in Budapest, and they’re amazing, amazing players. I’m in awe of how they read everything the first time they see it. We do a first take, obviously there’s little mistakes, you know, but usually it’s good! And then, second take, wow! Third take, we’re fixing some stuff, maybe changing a few dynamics or articulations, but after 10 or 12 minutes or so, the cue is magnificent.”

She also talked about how the character and story drive the musical intent behind each composition.

“It’s very character based… we’re [going with] motifs for these characters, so musically I’m kind of tying it together. [Musically, characters and story] go together, because if you have a moment that is more about Jankom, or a moment that is more about Zero…. it will be story based, for me, music is always story based. You want to address what’s happening on screen, especially with animation music is such an integral part of moving forward, adding pace and drama and pace and shape to every scene. But it’s also about the characters, and you have to tie it in a certain way that works for that character in the scenario they’re at, whether its danger, or a comedy moment, or hope, or fear — you can play around with those themes to fit that particular emotion. The thing with animation, especially on this show, it moves very fast. Where you were 20 seconds ago is not where you’re at now! It moves very quickly, and it’s great. It provides you so much opportunity for [different] colors, and the characters are so different — they all come from different places. I get to really play with the orchestra, and some synth stuff… it’s very fun to make each of them distinct. […] There’s one episode where I’m using a duduk … but you want to do those things only when they’re justified, you know, when you have a specific character, or a strange planet, or whatever fits. I do like using vocals, so there is quite a lot of that in the score, in several styles… for ‘Q & A,’ there’s a choir in the background at the end, and that’s me [singing]! There’s occasionally a guitar, which is not exactly what you would expect; a little bit of jazzy stuff, too, but of course there is also a large variety of synths which can all be very different.”

Finally, Melumad was asked if music from the legacy Star Trek shows might be included in the episodic score for Prodigy , especially considering the inclusion of a version of Star Trek: Voyager’s Captain Janeway among the series’ cast.

“I am quoting, occasionally, the original fanfare from Alexander Courage; that’s pretty much it. But, I mean, this is about licensing rights and I wish I could quote more, where it fits, but unfortunately we’re not allowed to do that. There’s no ‘Voyager’ music [with Janeway]; there’s some stuff that resembles it, or something that sounds of a memory to it, but it’s definitely not [from] ‘Voyager,’ no. But we’re doing something else, something new — not just in ‘Star Trek,’ but in other cinematic universes, you don’t want to overuse things. You would want to do it really delicately, and when it’s the most impactful, you know? If you get that theme all the time, it’s just not exciting anymore. If it was earned by the characters, that’s when you’d want to use the theme, to get the most emotional impact for the viewer. You’d want to be very particular on your choice when to use the theme.”

You can check out the entire hour-long interview with Nami Melumad — where she discusses her education and early musical experience, other professional projects, service in the IDF, the challenges of scoring for film and television, and more — at The Scotch Trekker’s YouTube channel.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D5Yn_W4mZjg

In addition, Rylee Alazraqui — who plays the massive Brikar girl Rok-Tahk on Prodigy — appeared on the Catalina Stars: Young and Famous podcast, where she spoke a little bit about her Star Trek: Prodigy experience so far, and how she brings the large alien character to life.

“When I’m voicing Rok-Tahk, I’m kind of just myself. Her character is a very friendly person; she loves animals, and she’s really kind. She’s also really sensitive, and when I’m acting [as] her, being myself is just really easy. How I came up with the character [voice] for her, I was just myself and they liked it! I started recording the show when I was eight or nine years old, and my voice was definitely very high-pitched in the show [when] we recorded the first episodes…. My voice hasn’t really changed since when I was eight, well, a little bit; it’s gotten deeper I guess. [Laughs] But I kind of listen, and I watched the trailer recently. I kind of memorized how her voice was, and I just make my voice as high as when I originally did the character.”

With SUCH a warm welcome, we decided to ride that energy and spread the Prodigy word to my elementary school this morning! Happy Friday! #startrekprodigy #ParamountPlus #nickelodeon #nickanimation #startrek pic.twitter.com/HHA7tTxnSS — Rylee Alazraqui (@rylee_alazraqui) September 3, 2021

She also described her audition for the role:

“I remember that the other people who went in [to audition] were in for like 15 minutes, and then I came out within like 5 minutes… I know that my mom and I were both thinking I probably didn’t get [the job], but then I got a callback and it just went from there! I was really excited. I didn’t know what ‘Star Trek’ was at the time, so I had to kind of research about it and watch a little bit of it.”

The Diviner isn't SO bad… #startrekprodigy #nickelodeon #startrekonpplus pic.twitter.com/Hmwu4DnAtQ — Rylee Alazraqui (@rylee_alazraqui) September 28, 2021

Finally, as the show has been entirely recorded during the COVID-19 pandemic, Alazraqui shared that to date she has only met one of her Star Trek: Prodigy castmates in real life.

“ I’ve met [the other actors] on Zoom for Comic Con, but that’s the only time! I met The Diviner [John Noble] just yesterday actually, while I was filming something; so that was really fun. He’s actually very, very nice in real life! The other cast I have not met, but I really like working with the writers and the director, they’re really nice. But in October, I’ll be going to New York for an in-person Comic Con!”

Star Trek: Prodigy premieres October 28 on Paramount+ in the United States (and CTV Sci Fi Channel in Canada), with a one-hour opening episode to kick of the show’s first season; it will premiere on Paramount+ in Australia on October 29.

Additional international premiere dates have not yet been announced.

- Behind The Scenes

- Nami Melumad

- PRO Season 1

- Rylee Alazraqui

- Star Trek: Prodigy

Related Stories

Paul giamatti joins star trek: starfleet academy as season 1’s recurring villain, wizkids announces new star trek: captain’s chair strategy card game, the final days of star trek starship sales at master replicas have arrived, search news archives, new & upcoming releases, featured stories, lost-for-decades original star trek uss enterprise model returned to roddenberry family, star trek: lower decks cancelled; strange new worlds renewed for season 4, our star trek: discovery season 5 spoiler-free review.

TrekCore.com is not endorsed, sponsored or affiliated with Paramount, CBS Studios, or the Star Trek franchise. All Star Trek images, trademarks and logos are owned by CBS Studios Inc. and/or Paramount. All original TrekCore.com content and the WeeklyTrek podcast (c) 2024 Trapezoid Media, LLC. · Terms & Conditions

- Film performers

- IFMCA Award nominees

James Horner

He also appeared in a small cameo role in The Wrath of Khan as an enlisted trainee .

Horner is best known for his scores for Braveheart (1995), Titanic (1997) and Avatar (2009).

His work on The Wrath of Khan earned Horner in retrospect an IFMCA Award nomination in the category Best New Release/Re-Release of an Existing Score on the occasion of the 2009 release of the remastered version of the movie, which he shared with Producer Lukas Kendall .

His music from The Wrath of Khan can also be heard in the US theatrical trailer for Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home , as well as in the Star Trek: Lower Decks episodes " Crisis Point " and " Crisis Point 2: Paradoxus ".

Horner was asked by director Nicholas Meyer to write the music score for Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country , however, he turned down the offer, claiming his career has "moved past Star Trek ".

Career outside Star Trek [ ]

Born in Los Angeles, California, Horner studied at the prestigious Royal Academy of Music in London, England. He went on to receive a bachelor's degree in music from the University of Southern California, followed by a masters degree and a doctorate from UCLA. After scoring student films for the American Film Institute, Horner entered a career in film scoring.

Horner began his career composing film scores for several B-movie pictures produced by Roger Corman including Battle Beyond the Stars (1980, with Morgan Woodward , Earl Boen , and Jeff Corey ), as well as low-profile horror movies such as The Hand (1981, with Bruce McGill and Tracey Walter ), Wolfen (1981, with Roy Brocksmith ), and Deadly Blessing (1981, with Michael Berryman , Lawrence Montaigne , and Percy Rodriguez ). His breakthrough work was his score for Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan , which opened whole new opportunities for the budding film composer. In the years to follow, Horner was assigned to work on films with a wider mass appeal. Since then, Horner collaborated primarily with acclaimed directors Ron Howard (brother of Clint Howard ) and James Cameron .

In 1987, Horner earned his first of many Oscar nominations in the category Best Music, Original Score for his work on Aliens (1981, featuring Jenette Goldstein , Mark Rolston , and Daniel Kash ). He also shared a nomination in the Original Song category that same year for co-writing "Somewhere Out There", the theme for An American Tail (which featured the voices of Christopher Plummer , Nehemiah Persoff , and a young Phillip Glasser ). Horner went on to earn an Oscar nomination for his scoring of the 1989 film Field of Dreams .

In 1996, he was nominated twice in the same category (Best Music, Original Dramatic Score) for his work on Apollo 13 (with Clint Howard, Max Grodénchik , Brian Markinson , Steve Rankin , and John Wheeler ) and Braveheart . In 1998, he received two more Oscar nominations for scoring Titanic (1997, with David Warner , Victor Garber , Michael Ensign , Jenette Goldstein, Shay Duffin , and Greg Ellis ) and writing the music for the film's song "My Heart Will Go On" – winning both. He went on to earn Oscar nominations for his work on Ron Howard's A Beautiful Mind (2001, with Christopher Plummer and Anthony Rapp , written by Akiva Goldsman ), and House of Sand and Fog (2003, with Shohreh Aghdashloo , Al Rodrigo , Spencer Garrett , Bonita Friedericy , and Michael Papajohn ).

Among the many other film scores which Horner composed are 48 Hrs. (1982, with Jonathan Banks , Margot Rose , Denise Crosby , and Nick Dimitri ), Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983, with Vidal Peterson ), Krull (1983, starring Kenneth Marshall ), Brainstorm (1983, with Louise Fletcher , directed and produced by Douglas Trumbull ), Cocoon (1985, with Herta Ware and Clint Howard), Willow (1988), The Land Before Time (1988, with the voices of Bill Erwin and Frank Welker ), Glory (1989, with Bob Gunton , Cliff DeYoung , Richard Riehle , Ethan Phillips , and Mark Margolis ), Honey, I Shrunk the Kids (1989, starring Matt Frewer and Amy O'Neill , with Mark L. Taylor , Carl Steven , and Frank Welker, photographed by Hiro Narita ), The Rocketeer (1991, with Paul Sorvino , Terry O'Quinn , Ed Lauter , Max Grodénchik, Clint Howard, William Boyett , Darryl Henriques , and Merritt Yohnka ), An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (1991, with the voices of Nehemiah Persoff and Ralph Maurer ), Patriot Games (1992, with Bob Gunton), The Pelican Brief (1993, with James B. Sikking , Jake Weber , and Casey Biggs ), Legends of the Fall (1994, with Kenneth Welsh ), Clear and Present Danger (1994, with Harris Yulin , Raymond Cruz , Ann Magnuson , Reg E. Cathey , Vaughn Armstrong , Michael Jace , and Cameron Thor ), Ransom (1996, with Paul Guilfoyle and Henry Kingi, Jr. ), Courage Under Fire (1996, with Tim Ransom , Ken Jenkins , and Bruce McGill), The Mask of Zorro (1998, with Tony Amendola and Victor Rivers ), Deep Impact (1998, with James Cromwell , Mark Moses , Denise Crosby, Tucker Smallwood , Ellen Bry , Kurtwood Smith , and Concetta Tomei ), The Perfect Storm (2000, with Bob Gunton and Christopher McDonald ), How the Grinch Stole Christmas (2000, with Bill Irwin , Clint Howard, Deep Roy , Landry Allbright , and Frank Welker), Enemy at the Gates (2001), The Missing (2003, with Clint Howard), Troy (2004, starring Eric Bana ), Flightplan (2005, with Lois Hall ), The New World (2005, starring Christopher Plummer, with John Savage ), Apocalypto (2006), and The Spiderwick Chronicles (2008, with the voice of Ron Perlman ).

In 2009 , Horner earned two Golden Globe Award nominations for Best Original Score – Motion Picture and for Best Original Song – Motion Picture ("I See You"), both for his work on Avatar , which starred Zoë Saldana . [1] In 2010, he received a Saturn Award nomination for Best Music for Avatar . [2]

Horner died when his small plane crashed on 22 June 2015. [3]

External links [ ]

- James Horner at the Internet Movie Database

- James Horner at Wikipedia

- 1 Daniels (Crewman)

- June 14, 2024 | Podcast: All Access Shares Its Pain With Laurence Luckinbill From ‘Star Trek V: The Final Frontier’

- June 13, 2024 | ‘Star Trek: Section 31’ Actor Teases His “Very Intense” Character, Praises “Hero” Michelle Yeoh

- June 13, 2024 | Everything Must Go In Final Master Replicas Sale Of Eaglemoss Star Trek Ship Models

- June 12, 2024 | Alex Kurtzman Talks Avoiding Star Trek Fan Service And Explaining Floating Nacelles In ‘Starfleet Academy’

- June 12, 2024 | Anson Mount Says ‘Star Trek: Strange New Worlds’ Season 3 Takes “Bigger Swings” Than Musical Episode

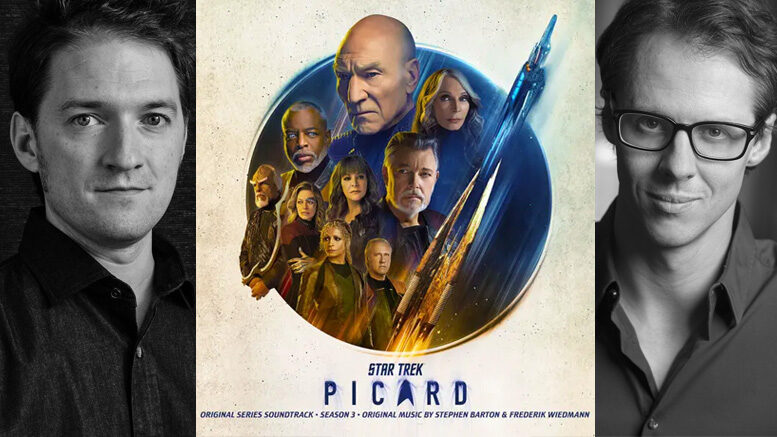

Interview: ‘Picard’ Season 3 Composers On How They Are Reviving Classic Star Trek Music

| March 29, 2023 | By: Jeff Bond 50 comments so far

Paramount+’s recent Star Trek series Discovery and Picard have employed composer Jeff Russo to bring a modern edge to the shows while occasionally tipping a hat toward the thematic material of earlier Trek composers. But for Picard’s third season, showrunner Terry Matalas recruited British composer Stephen Barton, who worked with Matalas on SyFy’s 12 Monkeys , and Frederik Wiedmann (who’s scored everything from numerous DC animated movies to children’s TV shows and video games). The pair were given a specific mission: resurrect the bold, in-your-face orchestral style of the classic Star Trek movies, with major callouts to themes by Jerry Goldsmith, James Horner, Cliff Eidelmann, and even Leonard Rosenman. The result is some of the most exciting Star Trek scoring in years, music that has fans fired up for the imminent soundtrack release. TrekMovie sat down with the composers for an extensive discussion to talk about this classic musical approach and how they tackled it.

Who do you guys answer to on Picard in terms of scoring? And what was the brief, just in general, when you started?

Stephen Barton: Terry Matalas and I had talked about Trek for a long time, actually, particularly when 12 Monkeys was going on. He’s a veteran of Star Trek —he was a PA on Voyager and then worked as a writer on Enterprise . So he’s kind of come up through the ranks on the Star Trek side. And when I first started working with him, five, six years ago, it was something we chatted about quite early on. I think even when I first met him for lunch on the Paramount lot it was one of the things we chatted about. And add the fact we had a shared past in that sense, in terms of what Trek we had grown up with, which was for both of us a case of parents having seen the original series, but the first time we got a series of our own was really Next Generation and watching it as kids. He’s a little bit older, but I was watching it when I was like five or six. I think for both of us it was very much a defining point in our relationship with television and with media in general. Akiva Goldsman was still very much running Picard season two and Terry was very much involved at the beginning of the season as a writer but about three or four episodes in he split off to really look after season three, which was always going to be his baby.

Terry very much pitched it to us as this idea of, let’s look back to the whole of the franchise and let’s look back, really in-depth at the Horner and the Goldsmith scores. Let’s look back at Dennis McCarthy’s work. Let’s look back at Ron Jones’ work, Cliff Eidelman, and Leonard Rosenman, looking back at all of it, let’s take a step back and look at what it means. And because the other thing was, obviously with Trek there’s been so many iterations and things used from one version into another, sometimes without a sense necessarily of what specifically something means. Even the Alexander Courage theme, this is a general Trek theme now and even was, I think, by the third movie, with the idea that this isn’t a specific thing; this is a wider theme. So, I think that was always what we were talking about.

And then as we got through the season, we were about six episodes in and one of the things we set out to do at the very outset was score it all. We weren’t going to do the typical TV thing of tracking, but the problem is, the shortest episode is 50-something minutes. So it’s 500 and something minutes of television. To most TV shows it would just be, we’re going to track half of this, or track a third of this or have three episodes in the middle which are just edited with some interstitials and things like that. And he was like, “No, no, I want to treat every scene of this like one of the scenes in the feature films.” And so, there are two ways to do that. Either you write a ton of music or… well, that’s basically the only way of doing it, really. So that was kind of the genesis of it. And we got about episode six, and I think I’d been on it for three months, I’d written about five hours of music, and was just dead, and we got to this point where we’re like, do we sacrifice the vision? Do we sacrifice that? Or do we get some help? And mercifully, episode seven to nine had a ton of Freddie’s music in the temp track. Because I think that’s one of the things that Drew Nichols, our editor, tried to do-he tried to temp with not Star Trek music, just to be able to get a lens on it, that was different to just putting Trek music wall to wall, which is obviously incredibly easy to do, because there’s so much of it. So Freddie came in and saved the day and took two episodes over and knocked them out of the park, and actually really allowed me to do what I want to do, which is to land the last 30 minutes of the final episode.

Frederik Wiedmann: I was just looking at the minutes for the final episode and I’m counting 55 minutes of music. In one episode of TV.

Frederik Wiedmann, Drew Nichols, Terry Matalas, and Stephen Barton (center four L-R) during Picard scoring session at WB Eastwood scoring stage

Since you mentioned Ron Jones, did you discuss the whole Rick Berman aesthetic versus what Matalas wanted? Because even though the scoring is different for the first two seasons of Picard , there’s a lot of active music, but this in particular, it’s very upfront in the mix and hits things. It is more of a movie aesthetic or a Ron Jones Next Generation aesthetic, as opposed to what the TNG music turned into by season four or five.

Barton: Yes, we discussed this at length. It wasn’t necessarily always even with the Ron Jones stuff what the music was doing in terms of harmonically or thematically, it was just in the way it’s paced and the way it’s scored. And I went back and watched what for me is the pinnacle of season three of Next Generation —at the end of “Best of Both Worlds, Part One,” the end of season three, which for me was ingrained in my mind in the summer of 1990. You have music that’s very overtly scored, it goes right for the jugular, it’s not holding back at all, but it works and it’s not full of music that you separate from the picture, it just is part of it. And so, scoring like that, that it’s okay to be big and it’s okay to go off to moments. And funny enough, I think in episode three, we had a big homage—there’s a big sequence with the first time Vatic fires the weapon, that’s very much an homage to Ron Jones throughout that whole sequence. It just goes there and it says, let’s turn the burner up to 10 and go maximum in terms of the way it’s scored. It’s okay to be big and it’s okay to make bold statements and okay to play melody. And I think that was very much the focus, because that’s what we loved from the Trek both Terry and I remember; that’s kind of a hallmark of it. And Freddy has a number of massive moments in episode seven that are very, very similar, that were just moments where you play it.

Wiedmann: It’s funny, when I watch old movies, including all Star Trek , I’m always baffled by how little music there is actually, in an episode or a movie, how much space there was back then, that was okay. Even when you watch a James Bond movie from the Sean Connery-era Bond, there is so little score in the entire movie. And when it comes, it’s big. It’s bold, and it has a very distinct purpose. I think the aesthetics have changed a lot over the past 20 years in terms of scoring movies, especially in the sci-fi genre, where there’s a lot more music now, and a lot more subtle stuff in between. What used to be just empty space and ambiance now has something like a little pulse or something going on to keep the tension going, that we just didn’t do back then. And I think one of the big challenges in this particular Trek was how do we make it feel like the old ideas, and the old sonic templates for Star Trek while taking it into this current time of scoring? And I think that the response so far has been fans have absolutely noticed how much we go back to the roots of Star Trek sounds while also kind of giving it this modern edge I think it needed.

You have, I think, at least five or six themes that are preexisting, very specific melodies. And then you provide one major new one, I know that there are other pieces of new material, too, that you guys develop, but you have a theme for the Titan that is in the end title. So first, tell me a little bit about developing that. I was talking to someone who’d seen the early episodes before I had and he said, “They’re playing James Horner music.” And when I heard this theme, I realized the theme is not James Horner’s, but the setting it’s in is very evocative of Horner.

Barton: Yeah, that was 1,000% the goal with that. I think the thing that Horner brought to Trek , which I think some people would say is not in the Goldsmith scores—but I think it is, it’s just a lot more buried—is that kind of nautical thing, the militaristic feeling, but it is a very specific, militaristic thing of very much feeling that these ships are just boats in space. Everything from the very classical horn kind of harmonic series, like we’ve got two horns in pairs going up and down the harmonic series, those sorts of motifs, they have a very English feel, and that was something that Horner was very interested in. He was obviously an anglophile and I had the pleasure of meeting him once, actually, only at Abbey Road one time, but I think that that part of Trek was something we felt had been put aside a little bit. It wasn’t that we wanted to necessarily turn it back to being Wrath of Khan but it’s just acknowledging the fact that whilst this is a ship of exploration, it’s still a military command structure, there’s still danger, and I think that the Horner scores for me (danger being one of his motifs, literally , but we then do use his danger motif), it was one where we talked at length about it as, “This is the strongest of spices,” in terms of its musical presence, and I think that’s why James Horner liked it. It’s just such a bold statement, that to not use it to us was almost disrespectful. We’re not going to plaster it everywhere, but I think when we’re in the nebula, there is obviously a bit of a callback to the Mutara Nebula cues.