- Collectibles

The Extraordinary Voyages of the Viking Age: A Historian‘s Perspective

- by history tools

- May 26, 2024

Introduction

The Vikings were the greatest explorers and travelers of the Medieval world. From the late 8th to the 11th centuries AD, these intrepid Scandinavians journeyed far beyond their Nordic homelands, leaving an indelible mark on the history and culture of Europe and beyond.

While popular culture often depicts the Vikings primarily as bloodthirsty raiders and warriors, this is only part of their story. They were also skilled craftsmen, merchants, and above all, masterful seafarers whose advanced ships and navigation techniques allowed them to voyage further than any of their contemporaries.

Just how far did the Vikings travel? From the icy shores of Greenland to the sun-baked coast of Italy, from the streets of Constantinople to the markets of Baghdad, Viking expeditions spanned thousands of miles and forever changed the course of world history. Let us embark on a journey to explore the full extent of their extraordinary travels.

The Viking Diaspora

Scandinavia and the north atlantic.

The Viking Age began in the late 8th century AD, as Scandinavians began to venture beyond their homelands in present-day Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. Overpopulation, scarcity of good farmland, and political strife may have driven many to seek their fortunes elsewhere.

Some of the earliest recorded Viking attacks struck the British Isles, with the infamous raid on the monastery of Lindisfarne in 793 AD sending shockwaves through Christian Europe. Over the next few centuries, Vikings continued to stage hit-and-run raids, but also established permanent settlements and trading posts.

The Vikings soon pushed even further west into the uncharted waters of the North Atlantic. They settled the Faroe Islands in the 9th century, and shortly thereafter discovered Iceland, which was permanently colonized around 874 AD. Within 60 years, the population of Iceland had swelled to over 10,000 Norse settlers [1].

Greenland was settled in 985 AD by Erik the Red, who named the ice-covered island after its few pockets of lush green valleys. At their peak, the Viking colonies in Greenland numbered around 5000 inhabitants and lasted for over 400 years [2].

The British Isles and Ireland

Viking raids on England began in earnest in the 830s AD. By 865, the Great Heathen Army invaded, conquering the kingdoms of Northumbria, East Anglia, and Mercia. In 878, Alfred the Great of Wessex made peace with the Viking leader Guthrum, partitioning England into the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex and the Danelaw, where Viking laws and customs held sway.

In Ireland, Vikings founded the city of Dublin in 841 and established a thriving slave trade. Other important Viking towns included Wexford, Waterford, Cork, and Limerick. Over time, many Vikings intermarried with the native Irish, giving rise to a people known as the Norse-Gaels.

Scotland and its islands also fell victim to extensive Viking raids and settlement beginning in the 790s. Shetland, Orkney, the Hebrides, and the Isle of Man came under Norse control and would remain Scandinavian in language and culture for centuries. The legacy of the Vikings in Scotland lives on in placenames and archaeological sites like the Brough of Birsay in Orkney.

Normandy and France

In 911, a band of Vikings led by Rollo besieged Paris. Defeated, the French king offered the Vikings a swath of territory in northwest France in exchange for halting their attacks. Rollo and his followers settled this region, which became known as Normandy (from "Northmen").

The Normans, as they came to be known, swiftly adopted the French language and culture. In 1066, the Norman duke William the Conqueror launched his own conquest of England, defeating the Anglo-Saxons at the Battle of Hastings – arguably the Vikings‘ greatest lasting political impact on European history.

Italy and the Mediterranean

The Vikings even left their mark on the warm waters of the Mediterranean Sea. Viking fleets sacked Moorish Seville in 844 and raided Pisa, Lucca, and Fiesole in Italy in 860. In 911, a Viking fleet attacked Piombino in Tuscany [3].

Some Vikings chose to settle in southern Italy and Sicily, where they served the Lombards, Byzantines, and Arabs as mercenaries before assimilating into the local population. Runestones in Scandinavia boast of the exploits of Vikings who guarded the Strait of Messina.

To the East: Russia, Byzantium, and the Islamic World

Not all Viking expeditions headed west. Swedish Vikings known as the Rus‘ (from which Russia takes its name) sailed down the great rivers of Eastern Europe, trading and raiding as they went.

Viking goods including furs, honey, amber, and slaves flowed south and east along trade routes like the Volga, while Islamic silver coins found their way back to Scandinavia. In 921, Ibn Fadlan, an Arab diplomatic envoy, gave a detailed description of a Rus‘ trading party on the Volga, including their funeral customs [4].

The Rus‘ founded the city of Kiev in the 9th century, which became the capital of the first East Slavic state, Kievan Rus‘. From there, these Viking-descended rulers presided over a vast territory encompassing parts of modern-day Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus.

Some Vikings – known to the Greeks as Varangians – traveled even further south to Constantinople, the capital of the mighty Byzantine Empire. They served as mercenaries in the emperor‘s elite Varangian Guard and even left runic graffiti in the Hagia Sophia cathedral.

Across the Atlantic: The Norse Discovery of North America

Perhaps the most extraordinary Viking voyage was also one of the last. Around 985 AD, the Icelandic explorer Bjarni Herjólfsson was blown off course while sailing from Iceland to Greenland. He sighted an unknown forested coast, but did not make landfall.

Inspired by Bjarni‘s tale, Leif Erikson organized an expedition around 1000 AD to the land he called "Vinland" for its wild grapes. The Norse sagas record that Leif set up a small encampment, possibly at L‘Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada. In 1960, archaeologists discovered the remains of a Viking outpost there, confirming that Columbus was not in fact the first European to reach the New World.

Tantalizing clues hint that the Norse may have explored even further south. Butternuts, which grow as far north as New Brunswick, have been found at Viking sites in Greenland [5]. An 11th-century Norwegian coin was discovered in Maine in 1957. However, the true extent of Viking exploration in North America remains one of history‘s greatest mysteries.

Technological Triumphs: Viking Ships and Navigation

None of the Vikings‘ epic voyages would have been possible without their state-of-the-art ships and advanced navigation skills. Viking shipwrights pioneered the clinker method, overlapping planks riveted together to create sleek, durable longships.

These vessels were wider, shallower, and more flexible than earlier ships, capable of crossing open oceans but also sailing up rivers [6]. A typical longship featured both sails and oars for maximum speed and maneuverability. Special ships like the snekkja and skeid were even faster assault craft.

The Vikings‘ understanding of coastal geography was second to none. They could read wave patterns, tides, and the color of the water to deduce their position and avoid hazards. Migratory birds and the behavior of sea mammals also provided vital clues. By combining technology and lore, Vikings could confidently venture far out of sight of land.

The Viking Legacy: Trade, Settlement, and Cultural Exchange

The popular image of Vikings as mere marauders is wildly incomplete. To be sure, the Vikings could be brutal raiders who did not hesitate to loot, burn, and enslave. But they were also canny traders who forged economic links between Northern Europe and the wider world.

Viking towns like Hedeby in Denmark and Birka in Sweden became thriving commercial hubs, exporting furs, walrus ivory, amber, and slaves in exchange for luxury goods like silk, glass, and silver. Viking craftsmen were renowned for their intricate metalwork, jewelry, and shipbuilding.

Everywhere they went, Vikings left a lasting cultural and genetic imprint. Up to 60% of the population of Iceland can trace its ancestry back to Norse settlers [8]. Names, placenames, and loanwords across Europe attest to centuries of Viking influence. The Althing, Iceland‘s national parliament, was established by Viking settlers in 930 AD and is the oldest legislature in the world.

The Viking Age drew to a close in the 11th century as Scandinavia converted to Christianity and centralized kingdoms emerged. But the Viking spirit of exploration and adventure lived on, inspiring daring voyages like those of Columbus and Magellan centuries later.

Today, interest in Viking history and culture is experiencing a revival, fueled by archaeological discoveries, popular media, and the enduring fascination with these medieval trailblazers. While much about their world remains cloaked in mystery, one thing is certain – the intrepid Norsemen will continue to capture our imaginations for generations to come.

Related posts:

- The Stone of Scone: A Legendary Symbol of Scottish Sovereignty

- Illuminating the Past: The Art of Medieval Historical Illustration

- Thor, Odin and Loki: Exploring the Legacy of the Most Influential Norse Gods

- Decoding the Troston Demon: A Window into the Medieval Mind

- Resurrecting an Anglo-Saxon King: The Glittering Treasures of Sutton Hoo

- Crossbow vs. Longbow: The Defining Ranged Weapons of Medieval Warfare

- The Viking Attack on Lindisfarne: A Turning Point in European History

- Aethelflaed: Lady of the Mercians and Architect of an English Kingdom

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: May 18, 2023 | Original: November 4, 2009

From around A.D. 800 to the 11th century, a vast number of Scandinavians left their homelands to seek their fortunes elsewhere. These seafaring warriors–known collectively as Vikings or Norsemen (“Northmen”)–began by raiding coastal sites, especially undefended monasteries, in the British Isles. Over the next three centuries, they would leave their mark as pirates, raiders, traders and settlers on much of Britain and the European continent, as well as parts of modern-day Russia, Iceland, Greenland and Newfoundland.

Who Were the Vikings?

Contrary to some popular conceptions of the Vikings, they were not a “race” linked by ties of common ancestry or patriotism, and could not be defined by any particular sense of “Viking-ness.” Most of the Vikings whose activities are best known come from the areas now known as Denmark, Norway and Sweden, though there are mentions in historical records of Finnish, Estonian and Saami Vikings as well. Their common ground–and what made them different from the European peoples they confronted–was that they came from a foreign land, they were not “civilized” in the local understanding of the word and–most importantly–they were not Christian.

The exact reasons for Vikings venturing out from their homeland are uncertain; some have suggested it was due to overpopulation of their homeland, but the earliest Vikings were looking for riches, not land. In the eighth century A.D., Europe was growing richer, fueling the growth of trading centers such as Dorestad and Quentovic on the Continent and Hamwic (now Southampton), London, Ipswich and York in England. Scandinavian furs were highly prized in the new trading markets; from their trade with the Europeans, Scandinavians learned about new sailing technology as well as about the growing wealth and accompanying inner conflicts between European kingdoms. The Viking predecessors–pirates who preyed on merchant ships in the Baltic Sea–would use this knowledge to expand their fortune-seeking activities into the North Sea and beyond.

Early Viking Raids

In A.D. 793, an attack on the Lindisfarne monastery off the coast of Northumberland in northeastern England marked the beginning of the Viking Age. The culprits–probably Norwegians who sailed directly across the North Sea–did not destroy the monastery completely, but the attack shook the European religious world to its core. Unlike other groups, these strange new invaders had no respect for religious institutions such as the monasteries, which were often left unguarded and vulnerable near the shore. Two years later, Viking raids struck the undefended island monasteries of Skye and Iona (in the Hebrides) as well as Rathlin (off the northeast coast of Ireland). The first recorded raid in continental Europe came in 799, at the island monastery of St Philibert’s on Noirmoutier, near the estuary of the Loire River.

For several decades, the Vikings confined themselves to hit-and-run raids against coastal targets in the British Isles (particularly Ireland) and Europe (the trading center of Dorestad, 80 kilometers from the North Sea, became a frequent target after 830). They then took advantage of internal conflicts in Europe to extend their activity further inland: after the death of Louis the Pious, emperor of Frankia (modern-day France and Germany), in 840, his son Lothar actually invited the support of a Viking fleet in a power struggle with brothers. Before long other Vikings realized that Frankish rulers were willing to pay them rich sums to prevent them from attacking their subjects, making Frankia an irresistible target for further Viking activity.

Did you know? The name Viking came from the Scandinavians themselves, from the Old Norse word "vik" (bay or creek) which formed the root of "vikingr" (pirate).

Conquests in the British Isles

By the mid-ninth century, Ireland, Scotland and England had become major targets for Viking settlement as well as raids. Vikings gained control of the Northern Isles of Scotland (Shetland and the Orkneys), the Hebrides and much of mainland Scotland. They founded Ireland’s first trading towns: Dublin, Waterford, Wexford, Wicklow and Limerick, and used their base on the Irish coast to launch attacks within Ireland and across the Irish Sea to England. When King Charles the Bald began defending West Frankia more energetically in 862, fortifying towns, abbeys, rivers and coastal areas, Viking forces began to concentrate more on England than Frankia.

In the wave of Viking attacks in England after 851, only one kingdom–Wessex–was able to successfully resist. Viking armies (mostly Danish) conquered East Anglia and Northumberland and dismantled Mercia, while in 871 King Alfred the Great of Wessex became the only king to decisively defeat a Danish army in England. Leaving Wessex, the Danes settled to the north, in an area known as “Danelaw.” Many of them became farmers and traders and established York as a leading mercantile city. In the first half of the 10th century, English armies led by the descendants of Alfred of Wessex began reconquering Scandinavian areas of England; the last Scandinavian king, Erik Bloodaxe, was expelled and killed around 952, permanently uniting English into one kingdom.

Viking Settlements: Europe and Beyond

Meanwhile, Viking armies remained active on the European continent throughout the ninth century, brutally sacking Nantes (on the French coast) in 842 and attacking towns as far inland as Paris, Limoges, Orleans, Tours and Nimes. In 844, Vikings stormed Seville (then controlled by the Arabs); in 859, they plundered Pisa, though an Arab fleet battered them on the way back north. In 911, the West Frankish king granted Rouen and the surrounding territory by treaty to a Viking chief called Rollo in exchange for the latter’s denying passage to the Seine to other raiders. This region of northern France is now known as Normandy, or “land of the Northmen.”

In the ninth century, Scandinavians (mainly Norwegians) began to colonize Iceland, an island in the North Atlantic where no one had yet settled in large numbers. By the late 10th century, some Vikings (including the famous Erik the Red) moved even further westward, to Greenland. According to later Icelandic histories, some of the early Viking settlers in Greenland (supposedly led by the Viking hero Leif Eriksson , son of Erik the Red) may have become the first Europeans to discover and explore North America. Calling their landing place Vinland (Wine-land), they built a temporary settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows in modern-day Newfoundland. Beyond that, there is little evidence of Viking presence in the New World, and they didn’t form permanent settlements.

Danish Dominance

The mid-10th-century reign of Harald Bluetooth as king of a newly unified, powerful and Christianized Denmark marked the beginning of a second Viking age. Large-scale raids, often organized by royal leaders, hit the coasts of Europe and especially England, where the line of kings descended from Alfred the Great was faltering. Harald’s rebellious son, Sven Forkbeard, led Viking raids on England beginning in 991 and conquered the entire kingdom in 1013, sending King Ethelred into exile. Sven died the following year, leaving his son Knut (or Canute) to rule a Scandinavian empire (comprising England, Denmark, and Norway) on the North Sea.

After Knut’s death, his two sons succeeded him, but both were dead by 1042 and Edward the Confessor, son of the previous (non-Danish) king, returned from exile and regained the English throne from the Danes. Upon his death (without heirs) in 1066, Harold Godwinesson, the son of Edward’s most powerful noble, laid claim to the throne. Harold’s army was able to defeat an invasion led by the last great Viking king–Harald Hardrada of Norway–at Stamford Bridge, near York, but fell to the forces of William, Duke of Normandy (himself a descendant of Scandinavian settlers in northern France) just weeks later. Crowned king of England on Christmas Day in 1066, William managed to retain the crown against further Danish challenges.

End of the Viking Age

The events of 1066 in England effectively marked the end of the Viking Age. By that time, all of the Scandinavian kingdoms were Christian, and what remained of Viking “culture” was being absorbed into the culture of Christian Europe. Today, signs of the Viking legacy can be found mostly in the Scandinavian origins of some vocabulary and place-names in the areas in which they settled, including northern England, Scotland and Russia. In Iceland, the Vikings left an extensive body of literature, the Icelandic sagas, in which they celebrated the greatest victories of their glorious past.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Wallace, Birgitta. "Norse Voyages". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 04 March 2015, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/norse-voyages. Accessed 22 June 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 04 March 2015, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/norse-voyages. Accessed 22 June 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Wallace, B. (2015). Norse Voyages. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/norse-voyages

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/norse-voyages" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Wallace, Birgitta. "Norse Voyages." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published February 07, 2006; Last Edited March 04, 2015.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published February 07, 2006; Last Edited March 04, 2015." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Norse Voyages," by Birgitta Wallace, Accessed June 22, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/norse-voyages

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Norse Voyages," by Birgitta Wallace, Accessed June 22, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/norse-voyages" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Norse Voyages

Article by Birgitta Wallace

Published Online February 7, 2006

Last Edited March 4, 2015

In mid-985 or mid-986 an Icelandic flotilla led by Eric the Red set out to colonize southwest Greenland. Near summer's end Bjarni Herjolfsson , a trader, belatedly sailed to join them but was blown far off course. He coasted north to the latitude of southern Greenland, then turned east to complete his intended voyage, becoming the first European of certain record to have reached the American mainland. His first sighting of land was probably of Newfoundland, from which he coasted north at least to the termination of Labrador. The more southerly lands he found were well forested. About the turn of the century Eric's eldest son, Leif Ericsson , decided to exploit Bjarni's discovery.

Retracing Bjarni's route in reverse, Leif explored three distinct regions. In the north was Helluland, Land of Stone Slabs, an area that had nothing but glaciers, mountains and rock. This must be the area from the Torngat Mountains to Baffin Island. Farther south was Markland, Land of Forests, probably a large region around Hamilton Inlet in central Labrador. South of there was Vinland. Here Leif established a base camp from which he launched a systematic exploration of neighbouring areas. During his explorations he came upon wild-growing grapes wound around tall trees. Enchanted, he name the area Vinland, Land of Wine, and brought both wine and lumber back to Greenland.

Leif's voyage was followed by further expeditions, all led by members of Leif's family. The first was headed by his brother Thorvald, who was killed in a skirmish with aboriginal people. The second was by his brother Thorstein, who remained storm-tossed all summer and never reached land. A third expedition was under the command of Thorfinn Karlsefni , married to Gudrid, the widow of Thorstein. Karlsefni's expedition has been vastly glorified and magnified in the Eric's Saga version of the Vinland Sagas. The last recorded expedition was led by Leif's sister Freydis in partnership with two Icelandic traders. This expedition ended in disaster when Freydis had her people brutally slaughter her Icelandic partners and their crew.

Although distorted and incorporating elements from the Greenlanders' Saga, Eric's Saga and the Greenlanders' Saga complement each other with regard to details of the various expeditions. The base camp was called Straumfjord, meaning Current Fjord, and was located in the northern part of Vinland, probably in the Strait of Belle Isle area, at Epaves Bay on the northern tip of Newfoundland ( see L'Anse aux Meadows ). Another camp, used only in the summer, was Hop, meaning Lagoon, and located in southern Vinland. It was here that grapes and good timber were harvested for shipment back to Greenland. It was also here that the Norse encountered aboriginal people, with whom they had skirmishes sufficiently severe to make the Norse leave. Winters were spent at Current Fjord; summers were spent in reconnaissance and exploitation of resources to be shipped back to Greenland. A third location, mentioned only in the Greenlanders' Saga, is Leifsbuxir, or Leif's Camp. Leif's camp encompasses elements from both Hop and Straumfjord but is in essence synonymous with Straumfjord.

The Norse voyages to Vinland lasted only a few years, probably because the fledgeling new colony in Greenland, numbering only a few hundred, had no need for additional land. The resources of Vinland were too distant to be useful. Vinland was as distant from Greenland as was Norway, and the same products could be obtained in Europe where other necessities such as iron, grain, salt, and spices were also available. However, knowledge of the New World persisted among the Norse in Greenland, and there were occasional visits to Markland (Labrador) for lumber.

Indigenous Perspectives Education Guide

Further Reading

Helge Ingstad, Westward to Vinland (1969); Gwyn Jones, The Norse Atlantic Saga (1986).

External Links

Vikings Watch the Heritage Minute about evidence of Viking visits to Canadian territory from Historica Canada. See also related online learning resources.

The Norse in the North Atlantic About early Viking voyages to North America. Includes photos of L'anse aux Meadows. A Memorial University of Newfoundland website.

Recommended

Qitdlarssuaq, eenoolooapik.

A Guide to the Viking Language

Old Norse Vocabulary: The 246 Most Common Words

“The total vocabulary of the sagas is surprisingly small. There are only 12,400 different words in the corpus of the family sagas out of a total word count of almost 750,000. The 70 most frequently used words account for nearly 450,000 or 60% of the total word count… the greatest benefit is found in learning the top 246 words.” – Jesse L. Byock, Viking Language 1

The Old Norse vocabulary below compiles the 246 most common Old Norse words that appear in the family sagas. A more extensive dictionary can be found here.

Additional grammars, and vocabularies can be found as part of the Viking Language Series .

Bolded Old Norse words are among the 70 most frequent words in the sagas.

— A/Á —

— b —, — d —, — e —, — f —, — g —, — h —, — i/í/j —, — k —, — l —, — m —, — n —, — o/ó —, — r —, — s —, — t —, — u/ú —, — v —, — y —, — þ —, — æ —, share this:, published by jules william press.

Jules William Press is a small press devoted to publishing the best about the Viking Age, Old Norse, and the Atlantic and Northern European regions. Jules William Press was founded in 2013 to address the needs of modern students, teachers, and self-learners for accessible and affordable Old Norse texts. JWP began by publishing our Viking Language Series, which provides a modern course in Old Norse, with exercises and grammar that anyone can understand. This spirit motivates all of our publications, as we expand our catalogue to include Viking archaeology and history, as well as Scandinavian historical fiction and our Saga Series. View more posts

7 thoughts on “ Old Norse Vocabulary: The 246 Most Common Words ”

- Pingback: The Word Tate In Italian Means Cheese – Neveazzurra

- Pingback: 190+ Beautiful & Strong Viking Names for Dogs - FireSwirl

- Pingback: The Socio-linguistic Context Of Old English

- Pingback: Tips For Learning The Ancient Language From Eragon

- Pingback: Nord: The North Wind And Direction – Neveazzurra

- Pingback: The Old Norse Dictionary: The Language of the Sagas - Homepage

- Pingback: Closest Language to English And Notable Facts About Them - Daily Guide

Comments are closed.

You can now buy the audio pronunciation albums for Viking Language 1 in our store! Dismiss

Discover more from Homepage

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Privacy & disclosure policy

- Portfolio & Press

- NORWAY ITINERARIES

Nordic Symbols and Meanings: 12 Must-Know Viking Symbols + Runes

Psst! Some links in my posts may be affiliate links, which means that I get paid a fee if you chose to purchase something through it. This doesn't cost you anything, but makes a huge difference for me! Thanks for your support!

As a Norwegian, I’ve grown up hearing countless tales about our Viking ancestors, their fascinating Nordic symbols and meanings. We learned about the Vikings and Norse mythology in school, as an important part of our own history and heritage.

But the Norsemen are not only fascinating to us, but for the rest of the world too! And so are their symbols.

This is not just because they make for killer tattoo ideas (though, they really do!), but also because the symbols and runes used by the Vikings were an integral part of their culture.

These Nordic symbols and runes were essentially the Vikings’ emojis, used for everything from protection against mischievous trolls to attracting good luck.

The Vikings are amongst the things Norway is most famous for , and I often get asked by visitors about their significance in Norway today. If you are planning a trip to Norway , knowledge about the Vikings and their signs and symbols isn’t really important, but it’s always fun to dive deep into a country’s heritage before you travel!

In this article, I’ll dive into the most famous Viking symbols and the meaning behind them. I will also share a little bit about the difference between runes, and other symbols used by the vikings.

In short, this post is for anyone who is curious about Nordic/Norse symbols and meanings, perhaps because you want to learn more about Viking history, you’re considering getting a symbol as a tattoo, or you’re just a history buff (like me)!

So buckle up, and let’s set sail on this exciting voyage into the mysterious world of Norse symbols and runes!

Is Norse and Viking the same?

It’s quite a common mistake to think that Norse and Vikings are the same, but in reality, they’re as different as mead and ale!

Let’s clear this up: the term ‘Norse’ actually refers to the language spoken by the folks in the Nordics during the Viking Age (and before). It’s like the ancient cousin of modern Scandinavian languages.

Within the language, there are some Nordic symbols that were used to make sense of it all, called Runes, and some symbols that had a greater meaning. But more on that below.

Currently, it is Icelandic that is the closest equivalent to the Norse language. However, Norwegian (and especially the western Norwegian dialects like the one I speak) come in as a close second.

Side note : Some people also refer to the people of the Nordic during Medieval times as Norse. So, it covers not only the language, but also a culture found across the Scandinavian and Nordic countries.

For example, Norse mythology was believed and practiced as the main religion across Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark and Iceland during the Viking age.

Now then, what about the Vikings?

Who were the Vikings?

The Vikings were obviously not a language, but did you know it was a profession .

These were the seafaring Norse folks who got a kick out of exploring, trading, and sometimes – let’s be honest – a bit of raiding.

Most people believe that Viking was the name of the entire people alive in Scandinavia during the Viking age, but in fact, most of them were farmers. Only some (the brave, explorer-types) were actually Vikings.

So, can you be a Viking without being Norse? Nope. But if you spoke Norse, did that make you a Viking? Not necessarily. It’s like owning a ship doesn’t necessarily make you a sailor, right?

I hope this makes sense!

To dive more into the Vikings and who they were, check out my guide to the most famous Vikings in history next!

Runes, Symbols and More

Now that we’ve cleared up the difference between Norse and Vikings, let’s talk about runes and symbols of the time.

Both were used by the Vikings, but had different purposes. Runes were an alphabet used for writing , while the other Nordic symbols had a more visual meaning.

Below, I have split this guide into Norse Symbols and their meanings, and then covered Runes separately.

What are runes?

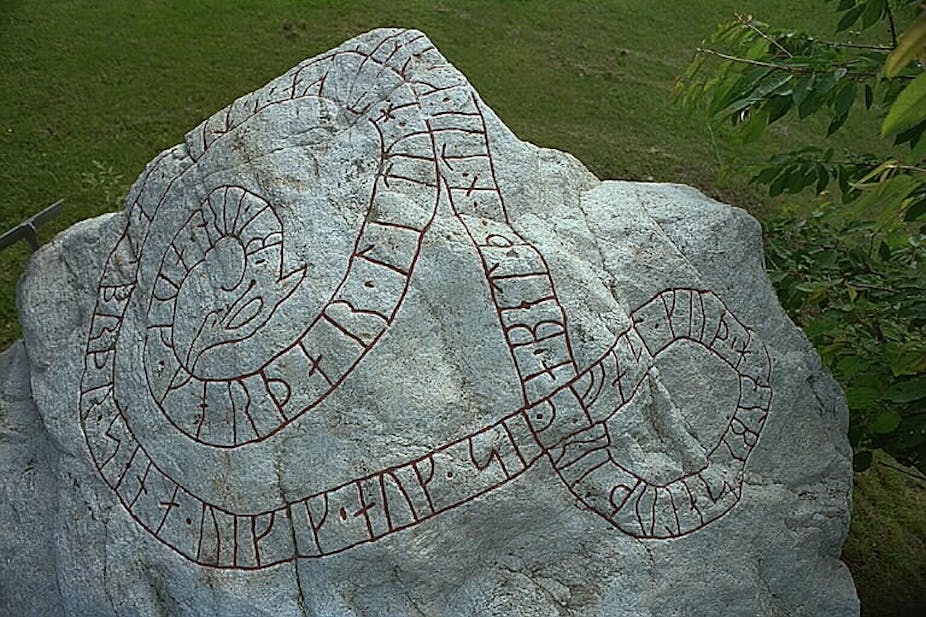

Runes aren’t just pretty etchings on stones or ancient Viking graffiti (or tattoos on guys who think they are Vikings).

They were the real deal – the ABCs of the Norse world. Runes are letters in alphabet sets known as runic alphabets. They were the literal letters of the time.

You have probably seen runes before, either as symbols on someone’s necklace, or even on a Scandinavian-inspired TV show.

Each rune had its own distinct meaning and was used to communicate something specific. They were etched onto various materials like stone, wood, and metal to serve numerous purposes.

From commemorating feats of bravery to leaving directions for fellow travelers, runes were the Norse folks’ go-to method for written communication.

In addition to being the letters of the time, the runes also had their own symbolic meaning separately. Some of the runes were the Norse symbol for protection, luck and balance, for example.

Basically, when a Rune stood on its own, it could mean more than just being a sound to tell you how to pronounce a word (like a letter).

The difference between runes and Viking symbols

So, what separates a rune from other Nordic symbols?

Well, it’s like comparing apples to oranges… (or should we say, runes to symbols?)!

Runes, being the alphabetic system of the Norse, were primarily used to represent sounds and form words.

On the other hand, the other Viking symbols, while being just as cool as runes, were more like visual metaphors.

They were used for their symbolic value, representing a wide array of ideas, from courage to fate to gods. Think of it this way: if the Norse world was a comic book, runes would be the dialogue and other symbols would be the super cool artwork!

I know it is a little confusing, since I just said that runes could also have a symbolic meaning. However, this was only when they stood on their own.

12 Must-Know Nordic Symbols and meanings

Below I have outlined the 12 most famous Nordic symbols and their meanings. Note that these are not runes , but symbols used during the Viking age to symbolise certain feats and wishes.

I have covered runes and their meanings further down in this article.

Most of these are symbols that were actually worn by people during the Viking age, such as Thor’s hammer. We know this, because necklaces with the hammer have been dug up near graves from the Middle ages across Scandinavia.

A few are also symbols from Norse mythology that have been given meaning through their stories, without necessarily being something the Vikings (or Norsemen) carried around physically. For example, the Fenrir wolf.

#1 Thor’s Hammer (Mjølner/Mjolnir)

Ever heard of Mjolnir? I’m sure you have, as it’s probably the most famous of all the Viking symbols that is still being used today.

Mjolnir was the mighty hammer wielded by none other than Thor, the Norse god of thunder. He would ride around the skies on his chariot pulled by goats (yes), setting of thunder and lightning using his hammer.

Mjolnir was a symbol of protection and power , capable of leveling mountains with a single blow.

When the Vikings weren’t busy navigating the high seas or raiding (they weren’t just about that, you know), they would wear amulets in the shape of Mjolnir for good luck and protection.

So, think twice the next time you casually pick up a hammer. You might just be holding a symbol of ancient strength and power!

#2 Valknut (Odin’s Knot)

Okay, so let’s move onto a more geometric symbol called the Valknut – Val translates to choice , and knut translates to knot . Yet, instead of calling it a “choice not”, it has been dubbed Odin’s Knot in English.

This symbol is a set of three interlocking triangles, kind of like a Viking version of a Venn diagram. It was found on items onboard the famous Oseberg ship, so we know the old Norse folks thought it was pretty important.

The Valknut is often called Odin’s Knot because it’s associated with the Allfather himself, Odin, the god of war, wisdom, and poetry.

Whilst the experts aren’t in complete agreement about its meaning, the symbol is believed to represent the transition between life and death.

#3 Yggdrasil (the Tree of life)

Next up on our Viking symbol tour is the big one, the epicenter, the “root” of it all – the Yggdrasil, otherwise endearingly known as the Tree of Life.

Now, imagine a tree so huge that it makes your favorite oak tree look like a bonsai. Yggdrasil, this cosmic ash tree, has its branches reaching out to touch the heavens and the roots digging deep down into the underworld.

Yggdrasil is the ultimate symbol of interconnectedness, linking the realms of the Norse goddesses and gods, men, and the dead.

If you ever feel a bit lost, just remember – we’re all just hanging out somewhere on Yggdrasil’s branches, navigating through this vast cosmos together. Pretty cool, huh?

Therefore, it’s pretty obvious that the symbol of Yggdrasil (whether you want it as a tattoo or a necklace), is a reminder that you are part of something greater.

#4 Vegvisir (the Viking compass)

I love how these Norse words and expressions are so similar to words we use in Norway today. “Vegvisir” sounds a lot like the word “Vegvisar” (or “veiviser” if you are from eastern Norway), which means “ pathfinder ” in Norwegian.

This Viking compass symbol was said to protect travelers from getting lost in unfamiliar territories. Shaped like an eight-pointed star, with different rune-like symbols on each point, Vegvisir was believed to guide the bearer through rough waters and bring them safely home.

Nowadays, you might not find a compass like this on your GPS, but rest assured that wherever you go, Vegvisir has got your back!

#5 Hugin and Munin (Odin’s ravens)

Hugin and Munin, the winged companions of Odin, are more than just a couple of ravens with cool names.

In Old Norse, Hugin translates to ‘thought’ and Munin to ‘memory’.

These ravens weren’t just Odin’s pets; they were his eyes and ears in the world. Every day, they’d fly across the realms, observing everything, and at dusk, they’d return to whisper all they’d seen and heard into Odin’s ears.

Imagine having an X (formerly Twitter) feed directly wired into your brain, except every tweet is a meaningful update about the state of the universe.

So, the symbol of Hugin and Munin is a powerful reminder to us all, to use our thoughts and memories wisely as we navigate life’s challenges. Norse symbols always have a way of bringing profound life lessons to the front, don’t they?

#6 The Fenrir Wolf (Fenrisulven)

The Fenrir Wolf, or Fenrisulven as we affectionately call it in Norway, is another gripping symbol from the Norse mythology.

This monstrous wolf is actually the child of Loki, and let’s just say, the apple didn’t fall far from the tree! Fenrir was prophesied to cause mayhem during Ragnarok, the end of the world. So, the gods decided to play it safe and keep him chained up.

Today, Fenrir serves as a potent symbol of destructive forces that are difficult to control, but also of the courage to face our deepest fears.

So next time you come across this symbol, remember, it’s not just about the fear of the wolf; it’s about the courage in facing it.

#7 The Helm of Awe (Oegishjalmr, Norse symbol for protection)

The Helm of Awe, or Oegishjalmr as it’s known in the old tongue, is a real head-turner in the world of Viking symbols. It’s the Norse equivalent of a security blanket.

This symbol, often depicted as an eight-armed figure radiating from a central point, was believed to provide protection and the power to strike fear in one’s enemies.

The Helm of Awe is more than just a tool for intimidation; it’s a reminder of our inner strength and resilience, and the lengths we’ll go to protect what’s important to us.

So, when life feels like a Viking raid, remember the Helm of Awe – you’re stronger than you think!

#8 Skuld’s Net (Net of Wyrd)

Skuld’s Net is also known as the Net of Wyrd.

This intriguing piece of Viking symbolism is like the ancient Norse version of the world wide web. Instead of cat videos and memes, it represents the interconnectedness of past, present, and future.

Picture it as a complex web, where each intersection is an event in time, linked to every other event – a reminder that our actions today ripple through time, impacting our tomorrows.

So, why was it important to our seafaring predecessors?

Well, the Vikings believed that destiny was a powerful force but not unalterable. The Net of Wyrd symbolized their understanding of shaping their own fate.

So next time you’re faced with a tough decision, remember the Net of Wyrd. It’s not just about accepting our fate; it’s about weaving it.

#9 Gungnir (Odin’s mighty spear)

Gungnir, the notorious spear of the All-father Odin, is another fascinating symbol in the Viking lexicon.

As the stories go, this was no ordinary spear. Crafted by the dwarves – the master smiths of Norse mythology – Gungnir never missed its target and always drew blood when thrown.

But what’s the deeper significance and the meaning here? To the Vikings, Gungnir symbolized the unerring pursuit of knowledge, the relentless quest for wisdom, much like Odin himself who was known for his wisdom.

So, the next time you’re in a tight spot, remember Gungnir. Take aim, trust your intuition, and let fly! After all, who doesn’t want to channel a bit of Odin’s unstoppable spirit in their everyday life?

#10 Hraethigaldur and Ottastafur

Moving onto yet another intriguing piece of Viking symbolism, let’s dive into Hraethigaldur and Ottastafur.

Not as famous as our friend Gungnir, but equally fascinating, these two are Norse stave symbols often intertwined with magic and protection.

Hraethigaldur , or the “Rune of Rabbits,” is believed to help one become elusive and quick, just like a bunny hopping away from danger.

On the other hand, Ottastafur is your go-to symbol for causing fear and panic among enemies.

So, whether you’re channeling your inner Bugs Bunny or want to ward off that particularly pesky co-worker, these symbols got your back.

#11 The Midgard Serpent (Jörmungandr, the Norse Ouroboros)

Heard of the Midgard Serpent? No, it’s not the latest character in a Marvel comic, but a powerful creature from Norse mythology.

All though, to be fair, I would love for Midgardsormen to show up in the next Thor movie.

Born from the union of the trickster god Loki and the giantess Angrboda, the Midgard Serpent was so enormous that he could encircle the entire world, Midgard, and grasp his own tail in his mouth.

But what does Midgardsormen (Norwegian) / Jörmungandr (Old Norse) symbolize, you ask?

Well, it’s all about the eternal cycle of life, death, and rebirth – quite deep for a giant mythical snake, right?

This massive serpent biting its own tail represents the concept of the Ouroboros, a symbol of eternal cyclic renewal.

#12 Vatnahlífir (norse symbol for protection from water)

Vatnahlífir was a stave often tattooed on a Viking’s underarm as they sailed across difficult oceans and rivers. It was the Norse symbol to protect you from drowning, and was believed to be very important to the Vikings.

The Vikings also believed that the Vatnahlifir helped guide you through rough waters. So, when they were rowing across the seas in their longships (pictured below), they usually had some version of the Vatnahlifir on their person.

Now that we’ve covered the 12 most famous Nordic symbols and their meaning, it’s time to move on to the other form of symbol from the Vikings: runes!

The Runes (Viking symbols) and their meaning

Let’s quickly recap what runes are.

These were the Viking’s version of an alphabet , called the Futhark , and they’re chock-full of mystery and magic.

Each rune was not only a letter in their written language but also held a special meaning as a standalone symbol (talk about multitasking).

They were used in everything from everyday writing to divination and were a significant part of Norse culture.

The oldest form of the Scandinavian runic alphabeth is the Elder Futhark. There are 24 signs, or letters, in this alphabet.

The Runic Alphabet

Below I have listed each of the runes, and their individual meaning.

- Algiz: The rune of protection and defense

- Ansuz: Considered the rune of Odin himself, and communication

- Berkana: The rune of birth, femininity and fertility

- Dagaz: The rune of dawn, awakening, awareness and hope

- Ehwaz: The rune of transportation and movement (and as a result, progress)

- Eihwaz: The rune of reliability, dependability and balance

- Fehu: The rune of success, wealth and abundance

- Gebo : The rune of balance, generosity and gift (Elhwas is also the rune of balance)

- Hagalaz: The rune relating to the wrath of nature and being tested

- Inguz: The rune og growth, change and common sense

- Isa: The rune of clarity, watching and waiting (being introspective)

- Jera: T his rune represents the harvest, a time of peace and happiness, and a fruitful season

- Kennaz: The rune of vision, knowledge and creativity

- Laguz: The water rune, and the rune of flow, intuition and emotions

- Mannaz: The rune of humanity, friendship and collaboration, but also of individuality

- Nauthiz: The rune of need, restriction, conflict, willpower and endurance

- Othila: The rune of ancestry, heritage and inheritance

- Perthro: The rune of fate, mystery and secrets

- Raidho: The rune of travel, rhythm and spontaneity

- Sowilo: The rune of the sun, success and goals achieved

- Thurisaz: The rune of brute force/power, warrior, and the symbol of Thor (it looks the most like a modern T)

- Tiwaz: The rune of masculinity, leadership and justice

- Uruz: The rune of strength of will

- Wunjo: The rune of comfort, pleasure, joy and also success

Wondering how to pronounce the runic alphabet? Watch the video below!

Norwegian souvenirs with Nordic Symbols and runes

If you found this post because you want to find a Viking-themed necklace or gift for someone you know, you’ve come to the right place!

Now that we have covered some of the most famous Nordic symbols and runes, I want to share some of my favorite types of Viking-themed souvenirs and jewelry, where the ancient symbols of the Nordic warriors meet modern style!

From the helm of awe or terror, known as Oegishjalmr, a symbol of protection and might, to other significant Norse symbols, each piece tells a unique tale of Viking valor.

For the vikings, these symbols were more than just decorative motifs; they represented the beliefs, values, and way of life of the Norse people. For instance, Oegishjalmr was believed to instill fear in enemies while protecting its wearer from harm. Other popular symbols include Thor’s hammer, Mjolnir, symbolizing strength and power, and Yggdrasil, the tree of life.

Whether you are looking for a meaningful gift or want to add a touch of Viking heritage to your own style, there are plenty of options to choose from.

Another great Scandinavian gift is a knitted Nordic sweater !

Below I have hand-picked a range of gifts with Viking symbols on them, mostly necklaces and jewelry (it’s the most common). Amazon especially has a lot to choose from, from $300 gold pieces necklaces to more affordable ones.

Nordic Symbols and Meanings FAQ

Below you will find the most frequently asked questions about nordic symbols and their meaning. I have done my best to answer all. If you have a question that is missing, comment below so I can add it to the FAQ.

The most powerful Norse symbol is the Valknut. It is a symbol of power, strength and courage. It was believed to be a magical symbol capable of connecting with the gods and spirits of the Norse pantheon. The Valknut was associated with Odin, who was the most powerful god in Norse mythology.

Thor’s hammer, known as Mjölnir, is the most famous Viking symbol. It was used by the Norse God Thor to protect Asgard, the home of the gods, from their enemies. The hammer was said to be able to deliver lightning and thunder and could level mountains with one blow. In Norse culture, it is a symbol of protection, strength, and courage.

Norse runes were the alphabet of the Viking age, used to form words and sentences. The runes also had meaning on their own, and could represent protection, love, strength and more.

Runes were the nordic alphabet. Other Nordic symbols include Thor’s hammer, the Tree of Life (Yggdrasil) and Valknut (Odin’s know).

The rune Ehwaz is the most commonly known Viking symbol for loyalty.

Mount Ulriken, Bergen: Complete Hiking Guide, Map & Video!

The 10 best cafes in bergen, norway [by a local], you may also like, how to be a tourist in norway, 10 ridiculous questions tourists in norway have *actually*..., how to plan a trip to norway [a..., 5 fun things to do in oslo with..., top things to do in oslo, norway [a..., 15 free attractions in oslo [a local’s guide], the best museums in oslo, norway [a local’s..., the best hotels in oslo, norway [budget to..., 5 best fjord cruises from bergen, norway [a..., how to get from bergen airport to the..., leave a comment.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

What does the word ‘Viking’ really mean?

Professor of Viking Studies, University of Nottingham

Disclosure statement

Judith Jesch receives funding from AHRC for a project 'Bringing Vikings Back to the East Midlands' (1 February 2017-31 March 2018).

University of Nottingham provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

We all know about the Vikings. Those hairy warriors from Scandinavia who raided and pillaged, and slashed and burned their way across Europe, leaving behind fear and destruction, but also their genes, and some good stories about Thor and Odin .

The stereotypes about Vikings can partly be blamed on Hollywood, or the History Channel. But there is also a stereotype hidden in the word “Viking”. Respectable books and websites will confidently tell you that the Old Norse word “Viking” means “pirate” or “raider”, but is this the case? What does the word really mean, and how should we use it?

There are actually two, or even three, different words that such explanations could refer to. “Viking” in present-day English can be used as a noun (“a Viking”) or an adjective (“a Viking raid”). Ultimately, it derives from a word in Old Norse, but not directly. The English word “Viking” was revived in the 19th century (an early adopter was Sir Walter Scott) and borrowed from the Scandinavian languages of that time. In Old Norse, there are two words, both nouns: a víkingr is a person, while víking is an activity. Although the English word is ultimately linked to the Old Norse words, they should not be assumed to have the same meanings .

Víkingr and Víking

The etymology of víkingr and víking is hotly debated by scholars, but needn’t detain us because etymology only tells us what the word originally meant when coined, and not necessarily how it was used or what it means now. We don’t know what víkingr and víking meant before the Viking Age (roughly 750-1100AD), but in that period there is evidence of its use by Scandinavians speaking Old Norse.

The laconic but contemporary evidence of runic inscriptions and skaldic verse (Viking Age praise poetry) provides some clues. A víkingr was someone who went on expeditions, usually abroad, usually by sea, and usually in a group with other víkingar (the plural). Víkingr did not imply any particular ethnicity and it was a fairly neutral term, which could be used of one’s own group or another group. The activity of víking is not specified further, either. It could certainly include raiding, but was not restricted to that.

A pejorative meaning of the word began to develop in the Viking Age, but is clearest in the medieval Icelandic sagas, written two or three centuries later – in the 1300s and 1400s. In them, víkingar were generally ill-intentioned, piratical predators, in the waters around Scandinavia, the Baltic and the British Isles, who needed to be suppressed by Scandinavian kings and other saga heroes. The Icelandic sagas went on to have an enormous influence on our perceptions of what came to be called the Viking Age, and “Viking” in present-day English is influenced by this pejorative and restricted meaning.

How to use it

The debate between those who would see the Vikings primarily as predatory warriors and those who draw attention to their more constructive activities in exploration, trade and settlement, then, largely boils down to how we understand and use the word Viking. Restricting it to those who raided and pillaged outside Scandinavia merely perpetuates the pejorative meaning and marks out the Scandinavians as uniquely violent in what was in fact a universally violent world.

A more inclusive meaning acknowledges that raiding and pillaging were just one aspect of the Viking Age, with the mobile Vikings central to the expansive, complex and multicultural activities of the time.

In the academic world, “Viking” is used for people of Scandinavian origin or with Scandinavian connections who were active in trading and settlement as well as piracy and raiding, both within and outside Scandinavia in the period 750-1100. The Viking Age was a large and complex phenomenon which went far beyond the purely military, and also absorbed people who were not originally of Scandinavian ethnicity.

As a result, the English word has usefully expanded and developed to give a name to this phenomenon and its Age, and that is how we should use it, without regard either to its etymology, or to its narrower meanings in the distant past.

- Scandinavia

Postdoctoral Research Fellowship

Health Safety and Wellbeing Advisor

Social Media Producer

Dean (Head of School), Indigenous Knowledges

Senior Research Fellow - Curtin Institute for Energy Transition (CIET)

Crewmembers in the Viking Age

In addition to entertaining guests in the King's hall the scald probably also took part in longer expeditions. It was therefore important for him to be able to improvise and conjure up verses about heroes and battles won whenever the King or the chieftain wished – for example before an important battle: In AD 1230 Snorre Sturlasson wrote in Olav the Holy's Saga that early one morning, just before the battle of Stiklestad in AD 1030, scald Thormod Kolbrunsskjald narrated the Eddic poem Bjarkemål . The poem was about the brave, legendary king Rolf Krake and his men's many battles, and it was intended to give courage to Olav's warriors before the battle.

"Long swords

sing strangely

split axles

and tear open chests".

The contents of the poems

Several poems contain kenninger , which gave them their exciting and dramatic style, often by supplying bloody details. Kenninger consist of two words: a main word and a qualifying word. Some examples of kenninger are: " the wound's sea" or " the sword's sweat", which refer to the blood flowing from a battle wound, " horse of the waves" where horse means a ship, and " flame of the Rhine" which means the Rhine's gold.

Several poems also contained myths and legends about the Nordic gods, as the Vikings were of the opinion that the gods had a great influence on the outcome of a battle.

» Egil Skallagrimson's " The Head Ransom"

» Make your own epic poem

The ordinary crew members on board warships in the Viking Age were called holumenn and their most important task was to sail the ship.

The Norwegian Gulating Law, dating from the 12th and 13th century, relates that the King would appoint a coxswain. The coxswain would then select the crew – as a rule these were young, unmarried men. If they did not turn up, of if they refused to sail with the ship, they were issued with a fine. In cases where there were not enough young farm hands, the farmers who employed the workmen had to join the ship for the voyage. Everybody was paid and, according to the Norwegian law text, the payment was 1 øre per month.

Watches on board

The crew formed watches. The watchs Bergvordr by the oars, Rávordr by the sail, Festavordr by the mooring on land and Strengvordr by the cable when the ship lay at anchor. All of the watches were to be manned day and night.

The tasks were to trim the sail, to keep the ship empty of water, to keep watch and steer the rudder. The helmsman was also called Stjórnari.

There was also a lookout in the bow section of the vessel. In Viking times he was called Stafnbúar or Sundvordr. Together with the skipper and the coxswains the lookout had a responsible position on board, especially when sailing along the coast where it was important to keep an eye out for distinctive landmarks. The lookout had to have a strong voice so that he could shout his observations to the rest of the ship and to the skipper, who stood either by the mast or at the stern of the ship. According to Helge Hundingsbane's story warships had a special watch for looking out for the enemy.

Personal equipment

Icelandic sources indicate that the crew brought along some kind of sleeping bag. There were no berths – instead the spaces between each thwart constituted their sleeping places. The sleeping bag was called a Húdfat; it was a large hide stitched together along the sides and with room for two persons.

Sea chests were part of the general equipment on warships and these could probably be moved around. E yrbyggernes Saga relates that the men occupying a rum (or section of the ship) had to share a chest for storing their supplies, clothes and weapons .

Women on board

Normally there were no women on board ships in the Viking Age. But sometimes there were women slaves or prisoners of war on board, or women of high rank were carried as passengers. The fact that the presence on the ships of women was quite exceptional is evident from a few written sources. These recount that the women had to be protected against various dangers and from rain.

Fact: The Icelandic Flateyjarbok from the 14th century relates how Leif and his men, during a voyage to Østerø on the Faroe Islands, all were soaked because they had to make sure that Thora remained dry.

Life on board

Today it is hard to tell what the crew did on board the ships when not on duty. In the rich ship burial of Oseberg and on a reused deck plank found in Aarhus a gaming board has been found which could be used for the games of morris and nefatavl . Many graves also contain gaming pieces and dice made of glass, bone, antler, tooth or horn. On the Isle of Lewis 93 chessmen mede of walrus ivory were found in 1831. The sagas speak of games such as halatavl , nefatavl and chess. Though not stating the rules of the games the sagas indicate that the ability to play, for example, chess was part of a noble education. For example a certain man Grymer who was courting a beautiful maid had to prove his worth through weapons exercises, climbing of icebergs, performing trials of strength, play chess well, interpret the stars and other sports.

» Games

» Stories on board

Weapons and Equipment

In the Viking Age, the weapons to be carried on board a warship were decreed by law. Norwegian laws relates that it was the crew’s task to provide weapons for the ship.

On board the smaller warships each free man of age was to present a broad-axe, a sword, a spear and a shield, and he would be fined 3 øre for each missing weapon. The farmers were to bring two quivers of arrows and a bow for each thwart in the ship, and they also paid 3 øre per missing bow. Helmets and chain mail are not mentioned.

Fact : The law texts also recount that it was the coxswain’s job to bring the ship’s rudder.

For chieftains’ ships, such as Skuldelev 2 with a crew of 60-70 men, the equipment was more comprehensive and more defensive/protective equipment was taken along.

A ship of Skuldelev 2’s size would presumably have had:

- 34 bows, with 48 arrows per bow

- 60 light axes

- 30 battle axes

- as well as throwing stones and slings.

Further to this, the warriors protected themselves with:

- 20 sets of chain mail

- 20 helmets

- 60 sets of leather armour

- 60 leather hoods

- 80 round shields

- as well as shin and wrist guards.

» Warrior and warfare

» Make your own sword

» Read more about the crew members today...

About cookies.

This website uses cookies. Those have two functions: On the one hand they are providing basic functionality for this website. On the other hand they allow us to improve our content for you by saving and analyzing anonymized user data. You can redraw your consent to using these cookies at any time. Find more information regarding cookies on our Data Protection Declaration and regarding us on the Imprint .

These cookies are needed for a smooth operation of our website.

With the help of these cookies we strive to improve our offer for our users. By means of anonymized data of website users we can optimize the user flow. This enables us to improve ads and website content.

- Beard Beads

- Hair Accessories

- Street Clothing

- Historic Clothing

- Drinking Horns

- Decor, Games & More

Viking History

Viking Symbols and Meanings

Posted by sons of vikings on january 14, 2018.

- Viking Symbols

Last updated on 1/30/2023:

A quick note about Viking Symbols It is helpful to understand the true origin and background of each symbol. Some of these iconic images were primarily used before or not until well after the Viking age. As well, the original true meaning of these symbols are simply educated guesses by archaeologists, anthropologists, and historians. A few symbols that are often considered 'Viking' actually have no proof of ever being used during the Viking age, such as the the Elder Futhark runes which most scholars believe were replaced by the Younger Futhark runes around the beginning of the Viking Age. But of course, just as we can still interpret these runes a thousand years later, it makes sense that many of the Vikings were able to do so as well. Also, we would add that many of our customers are not just fans of what happened during "the Viking Age" but the entire history of our Nordic ancestors. Two other very popular symbols known as the ' Viking Compass ' (Vegvisir) and the ' Helm of Awe ' (Ægishjálmur) which were both first found in Icelandic magic books from the 19th century (roughly 800 years after the Viking Age ended). We offer an entire separate article discussing the controversy of their origin. Other examples of non-Viking aged symbols include the Troll Cross (not shown) which is based on later Swedish folklore.

Why include Celtic symbols?

By the end of the Viking age, Vikings were already beginning to blend with the cultures they settled in. Many of the last few generations of these Vikings were often the children of a Celtic mother ...or Slavic, English, etc. The National Museum of Ireland stated the following:

"By the end of the 10th century the Vikings in Ireland had adopted Christianity, and with the fusion of cultures it is often difficult to distinguish between Viking and Irish artifacts at this time."

Article continued below.

Brief Overview of Viking Symbols

Symbols and Motifs

Following is a brief introduction to some common Norse symbols and motifs. The list is not all-inclusive, nor is it meant to be exhaustive but rather just a basic starting point. Remember, a picture is worth a thousand words.

Return to the menu

Runes (Norse Alphabet)

View our collection of: Rune Necklaces Rune Rings Rune Beard Beads Rune Shirts

Valknut (Knot of the Slain)

View our collection of: Valknut Necklaces Valknut Rings Valknut Beard Beads Valknut Drinking Horns

Ægishjálmr (Helm of Awe)

Return to the menu

View our collection of: Helm of Awe Necklaces Helm of Awe Rings Helm of Awe Home Decor

Vegvisir (Viking Compass)

View our collection of: Viking Compass Necklaces Viking Compass Rings Viking Compass Home Decor

Triskele (Horns of Odin)

View our collection of: Triskele Necklaces Triskele Rings Triskele Beard Beads

Triquetra (Celtic Knot)

View our collection of: Triquetra Necklaces Triquetra Rings Triquetra Earrings

The origin of Mjölnir is found in Skáldskaparmál from Snorri's Edda. Loki made a bet with two dwarves, Brokkr and Sindri (or Eitri) that they could not make something better than the items created by the Sons of Ivaldi (the dwarves who created Odin's spear Gungnir and Freyr's foldable boat skioblaonir). The result was the magical hammer that was then presented to Thor as described in the following:

Then he gave the hammer to Thor, and said that Thor might smite as hard as he desired, whatsoever might be before him, and the hammer would not fail; and if he threw it at anything, it would never miss, and never fly so far as not to return to his hand; and if be desired, he might keep it in his sark, it was so small; but indeed it was a flaw in the hammer that the fore-haft (handle) was somewhat short. — The Prose Edda

Return to the menu

View our collection of: Thor's Hammer Necklaces Thor's Hammer Rings Thor's Hammer Beard Beads Thor's Hammer Earrings

View our collection of: Viking Axe Necklaces

Yggdrasil (Tree of Life or World Tree)

As Dan McCoy of Norse-mythology.org points out, “Yggdrasil and the Well of Urd weren’t thought of as existing in a single physical location, but rather dwell within the invisible heart of anything and everything.” Yggdrasil is a distinctive and unique Norse-Germanic concept; but at the same time, it is similar conceptually to other “trees of life” in ancient shamanism and other religions. As a symbol, Yggdrasil represents the cosmos, the relationship between time and destiny, harmony, the cycles of creation, and the essence of nature.

View our collection of: Tree of Life Necklaces Tree of Life Rings Tree of Life Earrings Tree of LIfe Home Decor

View our collection of: Viking Ship Necklaces Viking Ship Rings Viking Ship T-Shirts Viking Ship Home Decor

Web of Wyrd

View our collection of: Gungnir Items

View our collection of: Raven Necklaces Raven Bracelets Raven Rings Raven Earrings

View our collection of: Wolf Necklaces Wolf Bracelets Wolf Rings Wolf Earrings Wolf T-Shirts

8-Legged Horse

View our collection of: Sleipnir Related Items

Dragons (and Serpents)

Though the Norse did not equate dragons with the Devil, as Christians do (remember, the Norse did not have a Devil), dragons like Fáfnir can sometimes represent spiritual corruption or the darker side of human nature. Most of all, dragons embody the destructive phase of the creation-destruction cycle. This means that they represent chaos and cataclysm, but also change and renewal.

View our collection of: Dragon Necklaces Dragon Rings Dragon Bracelets

Boars (Nordic and Celtic)

View our collection of: Boar Related Items

Cats, Bears (and other animals)

Text References

- McCoy, D. The Viking Spirit: An Introduction to Norse Mythology and Religion. Columbia. 2016

- McCoy, D. Norse Mythology for Smart People . Norse Mythology Accessed January 9, 2018. Norse-mythology.org

- Zolfagharifard, E. Hammer of Thor' unearthed: Runes on 1,000-year-old amulet solve mystery of why Viking charms were worn for protection. Daily Mail. Published July 1, 2014. Accessed January 9, 2018 http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2676386/Hammer-Thor-unearthed-Runes-1-000-year-old-amulet-solve-mystery-Viking-charms-worn-protection.html

- Howell, E. Parallel Universes: Theories and Evidence . Space. Published April 28, 2016. Accessed January 9, 2018. https://www.space.com/32728-parallel-universes.html

- Lonegren, S. Runes: Alphabets of Mystery . Accessed January 9, 2018. http://www.sunnyway.com/runes/runecasting.html

- Hauge, A. The History of the Runes . 2002. Accessed January 9, 2018. http://www.arild-hauge.com/history.htm

- Viking Age Runes. Viking Archeology . Accessed January 9, 2018, http://viking.archeurope.info/index.php?page=runes

- Kernell, M.H. Gotland’s Picture Stones: Bearers of an Enigmatic Legacy . Gotland Museum, 2012. Accessed January 9, 2018, http://uni.hi.is/adalh/files/2013/02/Hildr-Eng.pdf

- Odin’s Horn . Symbolic Dictionary. Accessed January 9, 2018. http://symboldictionary.net/?p=714

- Flowers, S. The Galdrabok: An Icelandic Grimoire. Samuel Wiser, Inc. New York. 1989.

- Briggs, K. (1976). An Encyclopedia of Fairies, Hobgoblins, Brownies, Bogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures . Pantheon Books, New York.

- Lindhall, C., MacNamara, J., & Lindow, J. (2002) Medieval Folklore . Oxford University Press, New York

- Siegfried, K. Odin and the Runes part 2. The Norse Mythology Blog . Published March 26, 2010. Accessed January 11, 2018 http://www.norsemyth.org/2010/03/odin-runes-part-two.html

- Hrafnsmerki - the Raven Banner. Geni . Accessed January 11, 2018 https://www.geni.com/projects/hrafnsmerki-the-Raven-Banner/29520

- Mastgrave, T. Demons, Monsters, and Ghosts, Oh No! Part XIX: Norwegian Dragons. Broken Mirrors. Published January 26, 2012. Accessed January 11, 2018 https://tobiasmastgrave.wordpress.com/tag/norse-dragons/

- About Sleipnir the Eight-Legged Horse. Geni . Accessed January 11, 2018 https://www.geni.com/people/Sleipnir-the-eight-legged-horse/6000000003935159261

- So the Horse has Eight Legs! The Mindful Horse . Published 2014. Accessed January 11, 2018 https://themindfulhorse.wordpress.com/a-mindful-blog/so-the-horse-has-eight-legs/

- Brownworth, L. The Sea Wolves: A History of the Vikings. Crux Publishing, Ltd. United Kingdom. 2014

- Saxo Grammaticus. The Danish History, Book Nine. Circa 12th century. Accessed November 10, 2017. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1150/1150-h/1150-h.htm

- Saxo Grammaticus. The Danish History, Book Nine. Circa 12th century. Accessed November 10, 2017. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1150/1150-h/1150-h.htm

- Crawford, J. (2017). The Saga of the Volsungs, with the Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok. Hacket Publishing, Indianapolis.

- Groeneveld, E. (2018, February 19). Freyja. Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.ancient.eu/Freyja/

Image References Viking symbols stone - https://www.pinterest.com/pin/500110733594231549/ Rune Stone - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Runestone Yggdrasil - http://www.germanicmythology.com/original/cosmology3.html Valknut - https://norse-mythology.org/symbols/the-valknut/ Helm of Awe - https://norse-mythology.org/symbols/helm-of-awe/ Vegvisir - http://spiritslip.blogspot.com/2013/10/travel-well.html Horns of Odin - http://www.vikingrune.com/2009/01/viking-symbol-three-horns/ Horns of Odin - http://symboldictionary.net/?p=714 Triquetra - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triquetra Tree of Life - https://spiritualray.com/celtic-tree-of-life-meaning Raven - https://www.pinterest.com/pin/367817494547305175/ Longship Stone - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hja%C3%B0ningav%C3%ADg Dragon Head Viking Ship - http://www.bbc.co.uk/guides/zy9j2hv Runes Stone - http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ancient/viking-runes-through-time.html Raven Stone Carving - http://www.odinsvolk.ca/raven.htm Viking Axe Artifact - http://www.shadowedrealm.com/medieval-forum/gallery/image/48-viking-battle-axejpg/ Viking Animals Carving - http://norseandviking.blogspot.com/2011/09/viking-cats-and-kittens-ii.html Dragon Stone - http://users.stlcc.edu/mfuller/NovgorodMetalp.html Sleipnir Carving - https://norse-mythology.org/gods-and-creatures/others/sleipnir/ Bronze Dragon Carving - https://www.pinterest.com/pin/268456827765461653/ Niohoggr - http://mythology.wikia.com/wiki/N%C3%AD%C3%B0h%C3%B6ggr Bronze Ravens with Odin - https://fi.pinterest.com/pin/398709373239383493/ Viking Ship Stone - http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/primaryhistory/anglo_saxons/anglo-saxons_at_war/teachers_resources.shtml Raven triskele broach - https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/384494886917515740/ Raven coin - https://oldcurrencyexchange.com/2016/05/18/irish-coin-daily-silver-penny-of-anlaf-guthfrithsson-hiberno-norse-king-of-northumbria/ Danish mjolnir - https://mikkybobceramics.wordpress.com/2014/10/28/norseviking-artifacts/

About Sons of Vikings

If you appreciate free articles like this, please support us by visiting our online Viking store and follow us on Facebook and Instagram .

Share this article on social media:

← Older Post

Newer post →, quick links.

- Our Warranty

- Viking Newsletter

- Viking History Blog

- Norse Mythology Blog

- Viking Festivals

- Customer Reviews

- Celtic Jewelry

- Privacy Policy

- Viking Coffee

Contact Us:

(757) 652-1366

Storefront: 801 Volvo Parkway Chesapeake, VA 23320

Mailing Address: 1108 Fairway Drive Chesapeake, VA 23320

Sign up to our mailing list

Connect with us.

COMMENTS

Across the Atlantic: The Norse Discovery of North America. Perhaps the most extraordinary Viking voyage was also one of the last. Around 985 AD, the Icelandic explorer Bjarni Herjólfsson was blown off course while sailing from Iceland to Greenland. He sighted an unknown forested coast, but did not make landfall.

Viking Words and Their Meanings. The Vikings, often remembered as fearsome conquerors and explorers, left an indelible mark on history that extends far beyond their legendary raids and settlements. While their physical journeys are well-documented, their linguistic voyage is an equally fascinating aspect of their legacy.

Schematic drawing of the longship type. Longships were a type of specialised Scandinavian warships that have a long history in Scandinavia, with their existence being archaeologically proven and documented from at least the fourth century BC. Originally invented and used by the Norsemen (commonly known as the Vikings) for commerce, exploration, and warfare during the Viking Age, many of the ...

The Vikings used the word themselves to refer to the activity of armed raids on other lands for the purpose of plunder. The Old Norse phrase fara i viking ("to go on expedition") had a distinctly different meaning than going on a sea voyage for the purposes of legitimate trade. When one decided to "go Viking" one was announcing one's ...

Viking armies (mostly Danish) conquered East Anglia and Northumberland and dismantled Mercia, while in 871 King Alfred the Great of Wessex became the only king to decisively defeat a Danish army ...

A viking, meanwhile, is a sea voyage. Often, but not always, it refers to a voyage with raiding elements, usually in the compound fara i viking - "to travel on a voyage." If you ever hear someone online say that "going Viking" was a verb in Old Norse, that phrase is actually what they're referring to.

This dictionary, in both Old Norse to English and English to Old Norse versions, is derived from the sources listed at bottom. Some liberties have been taken with the English definitions to facilitate sorting them in a usable order. This is a work of data transcription, conversion, combination and formatting, with only a minor amount of ...

The Viking Age (793-1066 CE) was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonising, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. It followed the Migration Period and the Germanic Iron Age. The Viking Age applies not only to their homeland of Scandinavia but also to any place significantly settled by Scandinavians ...

Norse Voyages. Article by Birgitta Wallace. Published Online February 7, 2006. Last Edited March 4, 2015. Retracing Bjarni s route in reverse, Leif explored three distinct regions. In the north was Helluland, Land of Stone Slabs, an area that had nothing but glaciers, mountains and rock. This must be the area from the Torngat Mountains to ...

Old Norse Vocabulary: The 246 Most Common Words. "The total vocabulary of the sagas is surprisingly small. There are only 12,400 different words in the corpus of the family sagas out of a total word count of almost 750,000. The 70 most frequently used words account for nearly 450,000 or 60% of the total word count… the greatest benefit is ...

Jera: T his rune represents the harvest, a time of peace and happiness, and a fruitful season. Kennaz: The rune of vision, knowledge and creativity. Laguz: The water rune, and the rune of flow, intuition and emotions. Mannaz: The rune of humanity, friendship and collaboration, but also of individuality.

A pejorative meaning of the word began to develop in the Viking Age, but is clearest in the medieval Icelandic sagas, written two or three centuries later - in the 1300s and 1400s.

The Viking ship has become synonymous with Norse culture and for good reason: the ship was a potent symbol of life, livelihood, one's journey through life, and the afterlife, and was used by the Norse for transport, in trade, in warfare, and as a burial vessel for centuries. The oldest Nordic boat is the Als Boat (also known as Hjortspring Boat ...

Original meaning and derivation of the word Viking Runestone raised in memory of Gunnarr by Tóki the Viking. ... The purpose of the voyage was to test and document the seaworthiness, speed, and manoeuvrability of the ship on the rough open sea and in coastal waters with treacherous currents. The crew tested how the long, narrow, flexible hull ...