Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Office of Undergraduate Research

My first research experience: being open to the unexpected, by claire fresher, peer research ambassador.

Many things surprised me when I started my first research opportunity. I didn’t know what to expect. I had heard a few things from upperclassmen about their own experiences and had attended a couple presentations from OUR, which is what got me interested in research in the first place, but I had no idea what my personal research experience was going to be like.

Something I hadn’t expected was how many people there are in a research group to support you and how willing people are to help. When I started my research position, I was introduced to a graduate student that worked in the lab station right next to mine. She showed me around the lab space and set me up on my computer. She was always there to ask quick questions or help me with any problems I encountered, as were the other people using the lab space, even if they weren’t in my specific lab group.

After a few weeks, I was given a partner who was also an undergraduate and I was introduced to the other undergraduates in the lab who I met at our weekly lab meetings where I got to hear what everyone was working on. I personally loved having a partner who could help me on the specific project I was assigned since I didn’t want to interrupt the other people in the lab with every question I had when they had other similar projects they were working on.

There was definitely a learning curve when I first started since I had never seen anything like this before. I started with basic literature research and began getting a better look into the broad topic which made it easier to really dive into the specific project that I was working on. In the beginning the work seemed a little intimidating but once I got comfortable in the lab space and knew I had people that could help me it was a lot easier to really get going and get into the really interesting parts, which is actually discovering new and exciting things!

I think the most important thing that I went into research with was being open to anything, and not being set on one way of learning or doing things. This was beneficial since it allowed me to be able to learn something completely new and be open to doing things differently than I had done before.

Throughout the course of my research experience, I know that I have changed in many ways. I learned how to work independently, how to be more analytical in my work, and how to ask the important questions that led to new discoveries. Research really has taught me to be open to the unexpected, and even welcome it, since being open has made me into a better researcher and student.

Claire is a junior majoring in Mechanical Engineering and minoring in Mathematics. Click here to learn more about Claire.

Important Addresses

Harvard College

University Hall Cambridge, MA 02138

Harvard College Admissions Office and Griffin Financial Aid Office

86 Brattle Street Cambridge, MA 02138

Social Links

If you are located in the European Union, Iceland, Liechtenstein or Norway (the “European Economic Area”), please click here for additional information about ways that certain Harvard University Schools, Centers, units and controlled entities, including this one, may collect, use, and share information about you.

- Application Tips

- Navigating Campus

- Preparing for College

- How to Complete the FAFSA

- What to Expect After You Apply

- View All Guides

- Parents & Families

- School Counselors

- Información en Español

- Undergraduate Viewbook

- View All Resources

Search and Useful Links

Search the site, search suggestions, my unusual path to neuroscience, and research.

I remember having a conversation with my mom where I essentially regurgitated my desire to research plants and plant medicine in college.

I've loved plants for as long as I've known. I've had plants like this one in my room since I first got my own room.

As a kid, I knew little about research, but I knew I wanted to be part of it when I grew older. Fast forward a few years, and I’m now working in the Faja Lab at the Boston Children’s Hospital as a student intern.

What happened in between? A lot!

Since I was little, I’ve always wanted to do research. As a kid, I thought scientists looked so cool with their bottles, lab coats, and bubbling chemicals. Later, I realized research was about so much more than that. In high school, I studied genetics through fruit fly experiments, learned about the lens through dissecting cow eyes, and wrote papers upon papers about literature and how the disconnect between agricultural science and farmers contributed to the Great American Dust Bowl.

In high school, I realized research was a limitless adventure where I could explore just about anything. It’s a curious kid’s playground, a skeptic’s dreamland. When I realized I had a passion for plants, chemicals, and psychology, I thought, “Why not research all of these?”

I was (and still am) particularly interested in terpenes and terpenoids in herbs like lavender.

So, I came into college ready to take on a unique branch of science: plant chemistry. But, when I arrived, I realized there were few labs studying plants, and no labs studying plant chemistry. My passion was a unique one at best.

It took a while to realize that my passions were not what I had thought they were. Through the past few years, I’ve learned so much about myself and what I am interested in. In this blog, I’d like to share my journey to choosing Neuroscience and working in a research lab.

An Unexpected Path to Neuroscience

Interested in plants and their chemicals, I came into college with one concentration (Harvard’s word for major) in mind: Molecular and Cellular Biology (MCB). There are around 9 life sciences concentrations at Harvard, but I just knew I wanted to do MCB. I’d done my research. I’d get the chance to study how chemicals interact with the body and brain, I thought. I’d learn about how individual cells might interact with different compounds, I thought.

Well, I was wrong—in two ways. First, despite thinking I knew everything about MCB, MCB was not the only concentration that studied those interactions. If anything, Chemical and Physical Biology (or just Chemistry) might be better suited to studying those relationships. Second, after taking a few classes on molecular biology, I realized that MCB was awesome, but it wasn’t the only subject that interested me.

During sophomore year, I decided to take an intro neuroscience class called Neuro 80, one of the foundational MCB classes that double counts as a neuroscience class. I loved it! I realized I was fascinated by the brain and how it worked. My journey in neuroscience began with learning about neurons and the history of neuroscience and evolved into studying the molecular basis of behavior. I found myself drawn to the inner workings of the mind and brain. I took a psychology class, and since then, I’ve taken four more. By the time I realized I was interested in the mind and brain, I had already declared Neuroscience on the Mind, Brain, and Behavior (MBB) track as my concentration.

Brains are cool!

Then, this year, I realized that my passion for plants and plant science had never disappeared. I took an MBB seminar called “Drug Use in Nature” (one of the best classes I’ve taken at Harvard!) where we learned about bugs that can sense chemicals released by rotting wood to find homes, cardiac glycosides and why monarch butterflies are resistant to them, and the role of terpenes and terpenoids in plant survival. The class was eye-opening. Somehow, it brought together everything I was interested in—plants, chemistry, psychology, the brain, and medicine. After junior fall, I realized my “passion” was not one thing, but rather a conglomerate of many things. Realizing that opened up my eyes to so many new possibilities, perspectives, and opportunities.

Like "Tree," a class on trees that I took my first year, this class brought me a new appreciation of plants and how they work.

A winding road to research.

I’d always wanted to do research, but I came into college set on doing one thing: plants. I realized later on that there were other interesting topics, too—like behavioral and developmental neuroscience! At the beginning of my junior year, I’d been thinking about joining a lab when, one day, I got an email about an opportunity at the Boston Children’s Hospital. The Faja Lab was a clinical psychology and cognitive neuroscience lab studying individual differences observed in autistic children. I was fascinated by psychiatry, developmental psychology, and cognitive neuroscience, so this lab felt like the perfect match. I applied with great hopes, and was invited to join the team!

However, my journey to this point took a while. When I came in as a first-year, I was intimidated by research. After attending the annual Harvard Undergraduate Research Opportunities in Science (HUROS) fair, I realized research was far more complex than I had thought. Without any previous research experience, I didn’t feel ready. However, the fair seeded in me a hope to learn more.

By the end of my first year, I had reached out to several labs, but I realized that many of them weren’t the right fit for me. So, I waited. During sophomore year, I had found a few cool plant science labs, but, unfortunately, I was busy during the school year and already had summer plans, so the timing didn’t work out. Some of the labs were also at capacity, so I would have to wait. When my junior year began, I had started thinking more about ways to explore the intersection between psychology and neuroscience. That’s when I came across the Faja Lab!

A picture I took the first time I visited the Boston Children's Hospital to get my badge.

I will never forget the first day I went to Boston Children’s Hospital. I was excited to work with children, and everyone on the team was incredibly kind, fun, and supportive. I feel incredibly lucky to be a part of the team!

Meet Pompom, our lab mascot!

Reflections.

I remember receiving a letter that I wrote for myself last year. “Are you still studying neuroscience on MBB—are you now working in a lab?” Yes, and yes! It’s been a crazy ride, but I’m so happy about where I've ended up. I could never have imagined that after a few years, I’d be working in an awesome lab studying something I love. I’m excited for this summer and upcoming year when I’ll be working on a project exploring the relationship between executive function and play that will (hopefully!) culminate in a senior thesis. Here’s to a new beginning!

A picture I drew in one of my psychology classes. Somehow, "Braintree" sums up what I'm interested in.

I’d like to shout out everyone at my lab and Ryan, my Neuroscience concentration advisor, for making my experience in research so great! I’m looking forward to this upcoming year and am excited about this summer.

- Student Activities

- Student Life

Raymond Class of '25

Hey everyone! My name is Raymond, and I’m a junior at Harvard College studying Neuroscience on the Mind, Brain, and Behavior track. I live in Currier House—objectively the best house at the College!

Student Voices

From campus to the coast: my journey to gloucester.

Hana Rehman Class of '25

Student Employment on Campus

Janaysa Class of '27

NSA: The Best Org on Campus

Faith Class of '27

Logo Left Content

Logo Right Content

Stanford University School of Medicine blog

How a Nobel laureate’s life story and encouraging words inspire my scientific journey

Editor's update: Emily Ashkin is featured in a podcast from The Lasker Foundation.

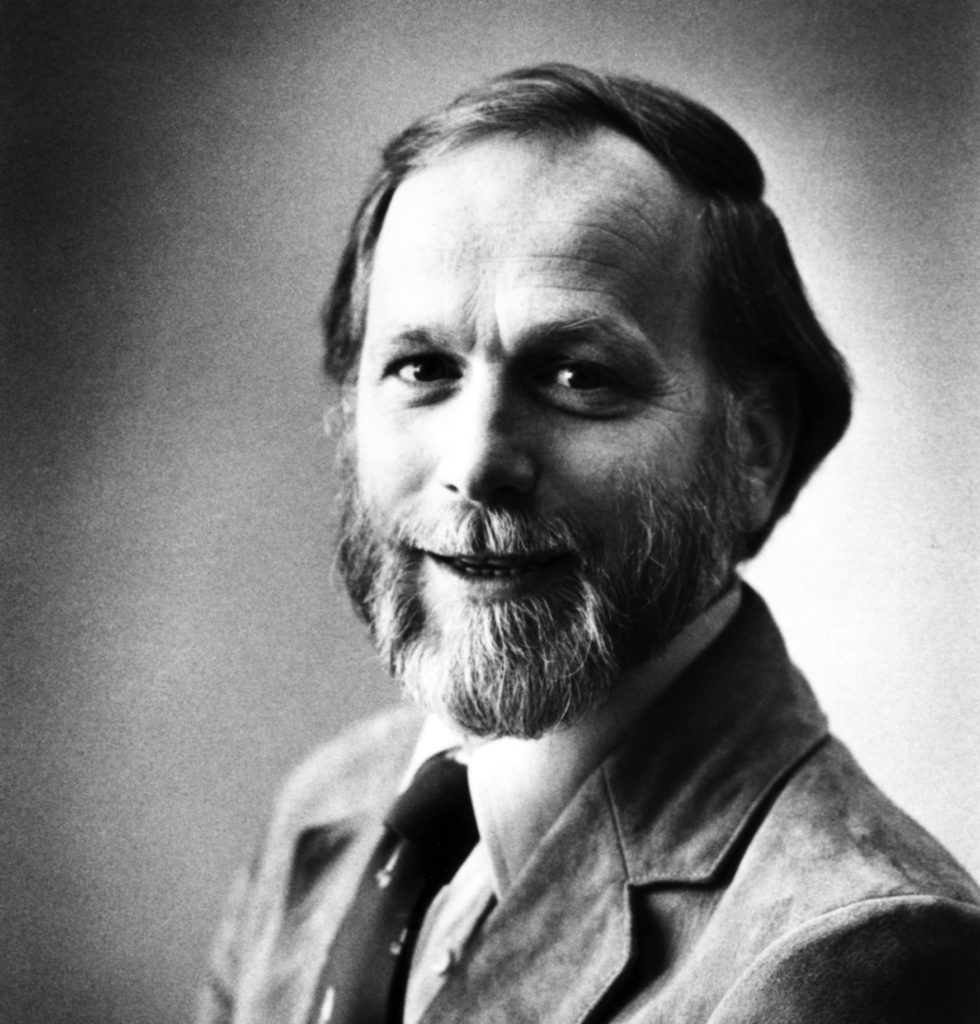

My legs were starting to ache from standing by my research poster for nearly ten hours. At 15, I was anxiously awaiting the possibility to speak to my biggest role model, J. Michael Bishop , MD.

I'd heard rumors from other students who had previously participated in the International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF) that the Nobel Laureate walks around from poster to poster to speak with students during the Public Showcase Day. However, they said he usually only goes up to posters of students who scored highest the previous day of judging.

I did not believe that I had done well during the judging sessions, and was disheartened at the thought that I might not have the opportunity to meet my scientific hero.

I first learned Dr. Bishop's story at the age of 11. This was around the same time a family member was diagnosed with cancer, and I had made it my life goal to study the disease.

However, I had no means to pursue a career in science. As a Latina, with neither of my parents as scientists, I had no one to pave a path for me to follow.

Contributions that extend beyond science

With encouragement from my mom's doctors, I started learning the basics and foundations of cancer biology. And that was where I came across Dr. Bishop's paradigm-shifting scientific discoveries. Very quickly, I learned that Dr. Bishop's contributions to science extended far beyond his discoveries in the lab. Every year, Dr. Bishop serves as a mentor and speaks as part of a panel at the ISEF poster session.

He speaks about his childhood and how he had hardly been exposed to science. Throughout his college education, he never imagined himself as a scientist. He had even been denied entry into countless labs due to a lack of prior experience. He had an ambition to become a scientist, but lacked the guidance to visualize his future career. Over time, he developed relationships with mentors who believed in him. More importantly, he learned how to believe in himself.

I found inspiration in Dr. Bishop's goal of becoming a scientist and his willingness to be open and vulnerable -- he often gave talks about experiencing self-doubt. Dr. Bishop is a role model for anyone who -- like me -- comes from an unconventional background, inspiring us to persevere and work through self-doubt to pursue a career in science.

Talking with my hero

After learning Dr. Bishop's story, I realized that there is no exact mold that dictates the development of a scientist, and I became more determined to continue studying cancer biology. I also became determined to keep sharing his message with the generations of scientists who will follow me.

All of this weighed heavily on my mind as I looked up and realized that Dr. Bishop was inches away from the aisle of posters nearest to mine. I ran up to my hero and asked him to come to my poster even if I wasn't on his list. He was kind enough to spend almost an hour with me, discussing my research and ultimately my goal to pursue a PhD.

I conveyed to him my self-doubt, given my background, and how learning about his story of discovering that science was right for him gave me direction.

Dr. Bishop looked me in the eyes and made it clear to me that my background was a strength, something that I hold onto to this day.

Continuing to draw inspiration

I continue to draw inspiration from him throughout my scientific journey, especially when I face obstacles, such as difficult classes or failed experiments.

Seven years after meeting Dr. Bishop, I have the privilege of pursuing a PhD in cancer biology, and my path continues to mirror his. I find guidance in how he handled the uncertainty he faced, but also the value he places on mentoring young minds.

I am devoting my graduate and scientific career to mentoring students from underrepresented backgrounds through teaching, guiding them through their own research projects, and openly sharing my own story, just as Dr. Bishop has.

I aspire to keep paving new paths and to become a role model to other young minds. I want to inspire them to turn to science and critical thinking to solve problems affecting themselves, their families and their communities.

This piece, originally in a longer form , was among 11 winners of the 2020 Lasker Essay Contest , which recognizes writing by young scientists from around the world. It first appeared on Scope in the summer of 2020.

Emily Ashkin is a PhD candidate in the lab of Monte Winslow , PhD, and part of Stanford Medicine's Cancer Biology Program . Emily has a strong passion for inclusivity in science and science communication. Feel free to communicate at [email protected] .

Top photo courtesy of Emily Ashkin. Photo of Bishop by General Motors Cancer Research Foundation .

Related posts

A winning essayist’s tips for keeping track of scientific facts

Brother’s brain surgery inspires Stanford MD-PhD student

Popular posts.

Addictive potential of social media, explained

Padded helmet cover shows little protection for football players

- Posted on October 3, 2020

- In About innovation ecosystems

PhD reflections – What worked, what I would do differently

I hunkered down to complete my PhD around the time that COVID-19 hit in Australia. My initial thought was that lockdown would be a perfect opportunity to finish the thesis. I was mistaken.

The pandemic proved an ‘all hands on deck’ moment for anyone involved in economic and community development work. I found myself busier than ever even as I read stories about people learning to bake bread and being bored in lockdown

COVID-19 also became the dominant distraction. A PhD is already an exercise in disciplined procrastination avoidance. The pandemic combined with a pervasive media cycle has proven virulent in consuming any available attention.

So my 2020 PhD completion plan of two weeks became four, then a two month plan extended to six. We are now in October, the chapters have gone through multiple supervisor reviews, and I am in the final revision and submission process. Between external reviewers and admin, I am looking at a March 2021 completion date.

Now that I am coming up for air, I wanted to take a moment to reflect and learn before my own revisionist history gets the better of me. Writing provides benchmarks in our lives. Reading my original PhD post from 2016 , I smile at who I was, my optimistic two-year prediction, and who I thought I might be when I finished.

I share so that perhaps others may learn for their future journey, that those who have been down the path might reflect and compare, and those who are considering the PhD path may learn as careers and professions continue to be disrupted. Like any personal narrative, take and apply what adds value, leave the rest. Below are some brief reflections on what I found helpful and what I would do different.

The PhD process

Some people do a PhD through coursework, others through submitting multiple journal submissions, still others with one main thesis. I did one thesis, but I recommend submitting articles as you go. PhDs will also be different based on the domain – medicine, business, sociology, psychology, manufacturing, etc. The steps below are based on my own experience at the cross-section of business and community.

STEP 1: Apply

The first step is to apply . I have heard of people having a few attempts as they find the right fit with their question, one or more supervisors with interest and capacity to support the topic, and a primary university in which they will be based. Universities are also often looking for people to research a particular field and scholarships are available if your interests align with desired outcomes.

I was was working as a community manager in an innovation hub in 2016 when I started asking questions about the impact the hub was having on the wider community. This aligned with a focus area for the local university (University of Southern Queensland) and availability of supervisors including one who with a focus on social enterprise and another who was developing an innovation program for women in regional and rural communities. I later added another supervisor from the Queensland University of Technology who specialised in regional innovation-related entrepreneurship and data.

STEP 2: Proposal

The second stage of a PhD is to refine the question and develop the research proposal . This involves a review of research that has gone before and conversations with your supervisor to focus your question.

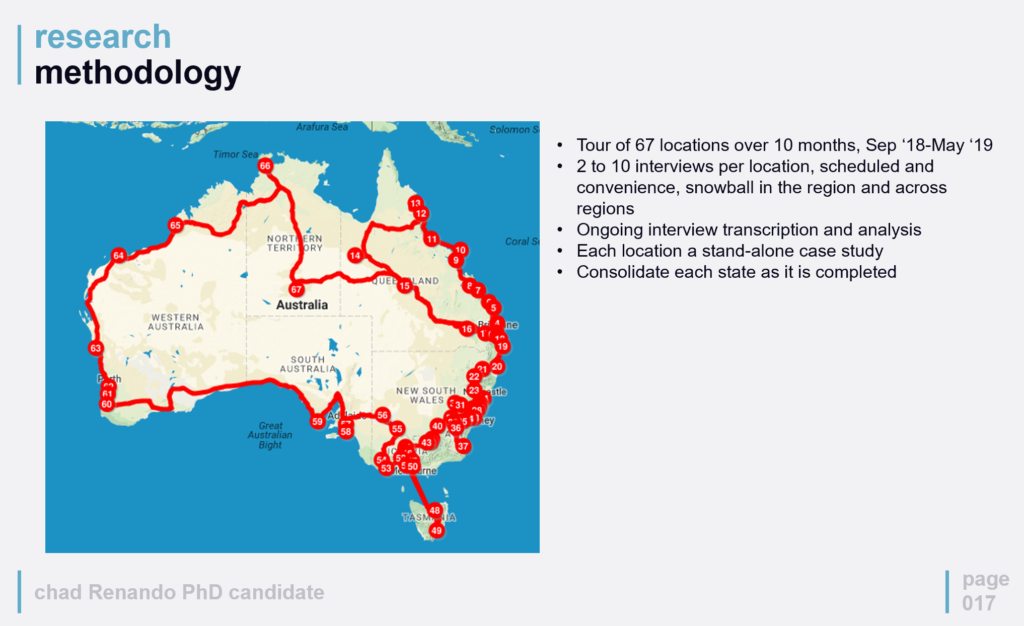

I was too broad in so many areas, asking about the role of the innovation hub, ways to measure the impact, innovation hub sustainability, regional comparisons and statistical data, and all this across all of Australia with global comparisons. I developed a software platform to measure innovation hub impact, mapped the ecosystem across Australia, and planned to physically interview every innovation ecosystem in Australia. I was grossly over-ambitious.

I am grateful for the feedback of those who helped me focus my attention. This process of refinement is natural and not unexpected. In startup terms, this is similar to the process of customer validation. Like many startups, there is a risk of trying to solve to many problems, addressing issues that aren’t really an issue, and not identifying the gap where others have not already addressed the issue or opportunity.

STEP 3: Confirmation

The third stage is presenting the research proposal and being confirmed . This is like pitching your idea.

I was humbled to present my proposal for confirmation to a panel that included leaders whose work inspired me to pursue my topic. I remember the chuckles as I shared my plan for a national driving tour over 10 months. I am glad I took their feedback on board to limit the scope to Queensland. Otherwise I might still be on the road.

Through the proposal and confirmation process, I also met the tribe of like-minded researchers, policy-makers, and practitioners who were interested in similar outcomes. This process was valuable to connect with many who I now call colleagues, mentors, advisors, and friends.

STEP 4: Research

The fourth stage is conducting the research . This may be collecting new data from surveys, interviews, or workshops, or collating existing data sets in new ways. My research involved driving across Queensland for almost three months conducting over 180 interviews, as well as fly-in visits to centres in each state and territory.

A key take away was to do one thing and do it well. My intent was to focus on research outcomes while at the same time promoting regional innovation and supporting local leaders through sharing stories. After over 60 days of AirBNBs, going through two drones, five hard drives of data, two laptops, and navigating a summer of record heat and fires, my priority focused exclusively on capturing the stories and data. I still have the content for a potential documentary, but the research became a priority.

STEP 5: Analysis and writing

Once you have the data, it is time to analyse and write up the results. I found this a process of learning how to write as much as writing itself. My document ballooned to over 250,000 words before settling on the current 120,000 words over nine chapters.

Written and read is better than perfect. I held on to my work for too long before getting it reviewed and in front of my supervisors early and often. I ended up with significant rewrites having followed a few literature rabbit trails and mixing method with theory. Earlier reviews would have minimised the rework.

The writing also did not flow like I thought it would. I would stare at the screen for days with only one or two pages to show for it. Then re-reading a week later, I would move entire lines of thought to the appendix as they were not contributing to the original question.

I ended up taking breaks and engaging regions to break the blocks. It was necessary to reconnect with the original passion that inspired my journey in the first place.

STEP 6: Review, submission, and defence

I am now in the final stage of review and submission and expect to defend my position with external reviewers by early 2021. Given the past reviews and refinement, I am fairly confident in the next steps. I will keep you updated as I go.

Four reflections

The PhD process is one of ups and downs. There are Twitter communities dedicated to the journey at #phdlife and #phdchat . Anyone doing a PhD will quickly stumble across the disturbingly accurate Piled higher and Deeper comic strip . These streams of thought have been very helpful to normalise my experience versus to my own preconceived view of my PhD journey.

The tweets below remind me I am not alone in my thinking…

What I thought:

I’m done writing, my thesis is awesome, after a brief review I should be done in two weeks!

The reality:

I can write, I’ve done a Masters, and have you seen my blog posts?

I’ll drive around and collect data across Australia, film and edit a documentary, make a significant contribution to literature, and build a software business in on the side.

I could go on, but you get the idea. Part of my desire to write this post is to now contribute for those in the midst of the PhD to know that what they are experiencing is OK. With that in mind, here are some top of mind reflections.

Reflection 1: A lot of life happens in a PhD

My first reflection is an acknowledgment that life happens around a PhD. A full-time PhD is scheduled at three years. My own journey will clock in at five years and includes a leave of absence and three extensions. A lot of life happens in five years.

From when I started my PhD to now, I:

- created three businesses,

- was contracted or employed in seven positions,

- completed regional consultancy engagements across Australia,

- toured North America,

- visited every state and territory in Australia,

- divorced, and

- re-married.

Not to mention the pandemic.

Who I am now is different than who I was. I have had successes, made mistakes, and learned lessons along the way.

Through it all the PhD has been a constant. My starting question has not changed, but the personal and global context in which the question is asked has. The PhD has been a constant interaction between self and the environment.

Rather than detract, these changes and challenges have made the process all the richer. It has allowed me to explore personal, organisation, and community resilience in the midst of disruption.

A PhD is a marathon. Marathons are about the journey, not the finish line.

Reflection 2: The guilt

My second reflection is about something I read a lot about in PhD conversations – the guilt. At some point, my life became a constant state of either working on the thesis or not working on the thesis. Everything else – sleep, family, eating, work – was framed as a decision to not work on the thesis. You would think this would be motivating to finish the thesis, but the self-imposed pressure inhibited creativity and the words stopped flowing.

I also found it difficult to justify writing the thesis with so many immediate needs to be addressed, particularly in the middle of a pandemic. Social media feeds became a vicious cycle of procrastination and guilt. The inner monologue was that others were making a difference while I stared at the screen willing my paragraphs to rewrite themselves.

A few perspectives helped with this process. First, everyone is in different stages and seasons in life. I have had times of building companies and communities, working in agencies, and studying. This was a season of study. It was just taking a bit longer than I expected.

Second, I kept reminding myself of the reason I started the journey in the first place. I believe the challenges we face are complex and systemic. These challenges require solutions that have rigour and address systemic and embedded barriers. I believe my research is contributing to this solution.

Finally, the guilt is a feeling that passes. The way out is the way through, appreciating what the guilt was saying, applying what is mine to own, leaving what is not, and continuing with the work regardless. Once I was able to observe the guilt for what it was, I was able to lean into it and continue writing.

Reflection 3: This is not your life’s work

The third reflection is that the PhD is only the beginning. When I started the PhD process, I felt it would be the pinnacle of academic achievement and the consolidation of my experiences. One of my supervisors gave me great advice – the PhD is not my life’s work, but a starting point. This was confronting and humbling to realise that what I thought was the finish line is actually the starting block.

Every day of research is an awareness of how little I know and how much there is to learn. The PhD will not be a culmination of knowledge but joining a group of those on a life journey of sharing knowledge with others.

Reflection 4: The support of others

My last reflection (for now) is the value of support from others. I started the PhD as a solo effort. It was not until much later that I leaned more on my supervisors and colleagues for input, feedback, and support. Having been a mentor and coach for others, I found it difficult to raise my hand and ask for help or even be aware that help was needed.

I would not be where I am if not for the last six months of weekly submissions and daily catch ups with a few people who have provided advice or simply a sanity check. I am very grateful and look forward to returning the favour for others. If I were to do it again, I would get this routine in earlier.

Which brings me to where to from here. I am working through the backlog of projects and reports queued up as I worked on the thesis. I am fortunate to have two Research Fellow roles that allow me to apply my research, and there are about six papers to be delivered off the back of my thesis. There is also ongoing regional work and mapping to be done across Australia through the Universities as well as my not-for-profit Startup Status .

One of the things I am most looking forward to is the ability to be a supervisor for others on the PhD journey. I am keen to pass on lessons and walk with others so they can go even further and faster.

I am also excited about making my research operational. I expect I will turn my thesis into a book and integrate the models into platforms so leaders in the field can benefit more broadly. Finally, I look forward to reconnecting with everyone I interviewed and repay them for the time they so graciously provided.

Thanks to those who have been on the journey with me. I look forward to continuing the conversation.

My Research Journey

- First Online: 18 October 2019

Cite this chapter

- Diane Charleson 2

204 Accesses

Filmmaking as research has emerged recently as a subset of the broader category of research that has practice at its core. In this chapter, I contextualize the historical emergence of such research and the various definitions that have been proffered to define this. Practitioners have increasingly found themselves working in a university setting where they need to produce impact research and in so doing need to define their work in this context. The rigor around such definitions has resulted from a need by practitioners to position their practical research outputs in relation to more traditional research outputs. In light of this, I proceed to discuss how I have journeyed through this process as a filmmaking researcher and investigate the reasons I have come to adopt the methodologies that I use, particularly, autoethnography. In order to do this, I explore my journey from practitioner to researcher and how this has emerged and developed.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bibliography

Anderson, Leon. “Analytic Autoethnography.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35, no. 4 (2006): 373–395.

Article Google Scholar

Argyris, Chris, and Donald Schön. Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness , 224. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1974.

Google Scholar

Batty, Craig, and Marsha Berry. “Constellations and Connections: The Playful Space of the Creative Practice Research Degree.” Journal of Media Practice 16, no. 3 (2015): 181–194.

Batty, Craig, and Susan Kerrigan. Screen Production Research: Creative Practice as a Mode of Enquiry. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Berry, Marsha. Creating with Mobile Media. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, Imprint: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Brabazon, Tara, and Zeynep Dagli. “Putting the Doctorate into Practice, and the Practice into Doctorates: Creating a New Space for Quality Scholarship Through Creativity (Report).” Nebula 7, no. 1–2 (2010): 23.

Candy, Linda. Practice Based Research: A Guide. Sydney: Creativity and Cognition Studios Report. Sydney: University of Sydney, 2006.

Clandinin, D. Jean. Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2000.

Denzin, Norman K., and Michael D. Giardina. Qualitative Inquiry and the Conservative Challenge . Walnut Creek, CA and London: Troika Distributor, 2006.

Eaves, Sally. “From Art for Arts Sake to Art as Means of Knowing: A Rationale for Advancing Arts-Based Methods.” ISSUU . Accessed November 10, 2018. https://issuu.com/academic-conferences.org/docs/ejbrm-volume12-issue2-article388 .

Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 575–599.

Harris, Anne. Writing for Performance. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2016.

Haseman, Bradley C. “A Manifesto for Performative Research.” Media International Australia Incorporating Culture and Policy 118, no. 1 (2016): 98–106.

Holman Jones, Stacy. Handbook of Autoethnography. London, UK and New York, NY: Routledge, 2016.

Holman Jones, Stacy. “Creative Selves/Creative Cultures: Critical Autoethnography, Performance, and Pedagogy.” In Creative Selves/Creative Cultures: Critical Autoethnography, Performance, and Pedagogy , edited by Stacy Holman Jones and Marc Pruyn, 3–20. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018.

Kerrigan, Susan. “A ‘Logical’ Explanation of Screen Production as Method-Led Research.” In Screen Production Research: Creative Practice as a Mode of Enquiry , edited by Craig Batty and Susan Kerrigan, 11–27. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018.

Lillis, Theresa, Jennifer McMullan, and Jackie Tuck. “Gender and Academic Writing.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 32 (2018): 1–8.

Mansfield, Nick. Subjectivity: Theories of the Self from Freud to Haraway. St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2000.

Milech, Barbara H., and Ann Schilo. “‘Exit Jesus’: Relating the Exegesis and Creative/Production Components of a Research Thesis.” Text . http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue3/milechschilo.htm .

Richardson, Laurel. Writing Strategies Reaching Diverse Audiences. Newbury Park: Sage, 1990.

Scrivener, Stephen. The Art Does Not Embody a Form of Knowledge . UAL. Accessed December 10, 2018. http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/783/ .

Schön, Donald. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books, 1983.

Smith, Hazel, and Rogert T. Dean. Practice-Led Research, Research-Led Practice in the Creative Arts . Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009.

Tripp, David. Critical Incidents in Teaching: Developing Professional Judgement. Milton Park, UK: Routledge, 2012.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Arts (Media), Australian Catholic University, Fitzroy, VIC, Australia

Diane Charleson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Diane Charleson .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Charleson, D. (2019). My Research Journey. In: Filmmaking as Research. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24635-8_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24635-8_2

Published : 18 October 2019

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-24634-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-24635-8

eBook Packages : Literature, Cultural and Media Studies Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Research really has taught me to be open to the unexpected, and even welcome it, since being open has made me into a better researcher and student. Claire is a junior majoring in Mechanical Engineering and minoring in Mathematics. Click here to learn more about Claire. This entry was posted in Peer Research Ambassadors, Student Research Blog.

However, my journey to this point took a while. When I came in as a first-year, I was intimidated by research. After attending the annual Harvard Undergraduate Research Opportunities in Science (HUROS) fair, I realized research was far more complex than I had thought. Without any previous research experience, I didn't feel ready.

Xiaolin Xu Ph.D. Student Faculty of Edu. ation, Memorial University of [email protected] passionate, positive, and perseve. e. This is what I have learned through my research journey as an international graduate student. I believe being passionate about your research project is the most important thing, and that is the reason my ...

Editor's update: Emily Ashkin is featured in a podcast from The Lasker Foundation.. My legs were starting to ache from standing by my research poster for nearly ten hours. At 15, I was anxiously awaiting the possibility to speak to my biggest role model, J. Michael Bishop, MD. I'd heard rumors from other students who had previously participated in the International Science and Engineering Fair ...

Books and newspapers became my good friends on this path, and I made it to college in Beijing. I struggled but managed to graduate, though without a sense of academic fulfillment in my field of engineering. Still, my goal to become a scientist remained alive, and I decided to pursue a master's degree in a new field, meteorology.

In my life's journey as a researcher, I have followed my passions and charted new territory, sometimes inadvertently. Research has been for me a life-long journey of discovery--of who I am, of ...

A full-time PhD is scheduled at three years. My own journey will clock in at five years and includes a leave of absence and three extensions. A lot of life happens in five years. ... I believe my research is contributing to this solution. Finally, the guilt is a feeling that passes. The way out is the way through, appreciating what the guilt ...

My research journey began in the mid-1990s when I was undertaking a Masters of Education and I came upon reflective practice for the first time. Until this time, I had successfully completed two bachelor's degrees and. an honors degree which required me to use conventional academic writing and methodologies.

3.5 Key Recommendations. Your research journal can record the entire story of your research journey, including all of the ups, downs, and complexities. Remember that your journal is a personal record of your journey, so make it fit your needs. All we have done here is illustrate some possibilities.

This paper is my analysis and reflection of more than three years of experience as a doctoral student. I maintained a reflective diary throughout the research journey as it enabled me not only to learn, recognise and reflect the effect of my own experience as a researcher on the research process (Jootun et al., 2009; Rice and Ezzy, 1999), but also to gain a better understanding of dynamics of ...

My research journey began in the mid-1990s when I was undertaking a Masters of Education and I came upon reflective practice for the first time. Until this time, I had successfully completed two bachelor's degrees and an honors degree which required me to use conventional academic writing and methodologies. As a practitioner I had always ...

Reflexivity is a vital part of qualitative research, as it is an important concept in discussions on subjectivity, objectivity and social science knowledge and research. 294. (Hsiung, 2008). One of the most important aspects of reflexivity is that it highlights possible researcher bias in qualitative research (Pillow, 2003; Pullen, 2006) which ...

10 Strategies for a Successful Research Journey. Here are some important strategies for successfully completing a thesis, so you can be productive and happy while writing your thesis. Be proactive - Your thesis is your responsibility to complete: it has your name on it! Get support. There will be ups and downs - it is not always a smooth ...

These are some of the questions I want to explore in this chapter as I reflect upon my life history as a reader, as a teacher of reading and as a researcher of children's and teachers' identities as readers. Whilst this is of necessity a personal journey, I trust there will be connections for you. Others' life stories can enable us to ...

Abstract. My journey in the field of stress and coping began in the mid 1980s when I was researching the rather new field of childhood depression. It was a relatively under-explored field, and as a clinical and educational psychologist it was becoming increasingly apparent that there were concerns of young people, with some of these reflected ...

I am motivated to continue my research in this space to help improve and advance patient care. Tell us about a surprise in your research journey. When I joined the Ryan Immunology Lab, I was immediately surprised by the wealth of knowledge present within the research space. It is nearly impossible to know everything in any given field, and I ...

gn and methodology was provided. In Chapter 3, I include a more personal account of what I call my research journey, ba. ed in part on my research diary. I cannot describe every detail of my journey, but I attempt to point out all the major decisions made - all the m. jor cities visited, so to speak. In addition, it is important to note that ...

Plan the research steps: Where possible, plan the research journey from inception to publication, and consider the routes for dissemination at various stages of the project. For 'Blue Sky' research consider the potential broader applications of the results and where these would be best placed to be most accessible to others.

My Research Journey in Self-Publishing. In this article, Alison Baverstock reflects on her research into self-publishing: its methods, its impact, and the motivation and demographics of those involved. She considers its initial frosty reception and its new position at the core of an area of great significance to the publishing industry, the ...

"Talking about motivation, my journey into the medical laboratory science profession began in an unexpected way. Like many high school students, I thought the only paths to helping sick people ...

This reprinted article originally appeared in Psychoanalytic Psychology, 2014, 31(1), 4-25. (The following abstract of the original article appeared in record 2014-05396-002). Video microanalysis taught me to see how the intricate process of mother-infant moment-to-moment communication works. It is a powerful research, treatment, and training tool. I owe my love of video microanalysis to Dan ...

Research has shown that those with strong social support tend to cope better with their cancer diagnosis (National Cancer Institute, 2022). These conversations helped me process the diagnosis, and sharing my fears made them feel less isolating. ... One of the most important lessons I learned during my journey was the power of self-acceptance ...