The Center for Global Studies

Understand haiku, haiku structure, know the sound structure of haiku.

Japanese Haiku traditionally consist of 17 on , or sounds, divided into three phrases: 5 sounds, 7 sounds, and 5 sounds. English poets interpreted on as syllables. Haiku poetry has evolved over time, and most poets no longer adhere to this structure, in either Japanese or English; modern Haiku may have more than 17 sounds or as few as one. [1]

- English syllables vary greatly in length, while Japanese on are uniformly short. For this reason, a 17-syllable English poem can be much longer than a traditional 17- on Japanese poem, straying from the concept that Haiku are meant to distill an image using few sounds. Although using 5-7- 5 is no longer considered to be the rule for Haiku in English, it is still often taught that way to children in school.

- Snow in my shoe

- Sparrow’s nest

Use Haiku to juxtapose two ideas

The Japanese word kiru , which means “cutting,” expresses the notion that Haiku should always contain two juxtaposed ideas. The two parts are grammatically independent, and they are usually imagistically distinct as well.

- how cool the feeling of a wall against the feet — siesta

- fresh scent—

- the labrador’s muzzle

- deeper into snow

- In either case, the idea is to create a leap between the two parts, and to heighten the meaning of the poem by bringing about what has been called an “internal comparison.” Creating this two- part structure effectively can be the hardest part of writing a haiku, because it can be very difficult to avoid too obvious a connection between the two parts, yet also avoid too great a distance between them.

Choose a Haiku Subject

Distill a poignant experience.

Haiku is traditionally focused on details of one’s environment that relate to the human condition. Think of a haiku as a meditation of sorts that conveys an objective image or feeling without employing subjective judgment and analysis. When you see or notice something that makes you want to say to others, “Look at that,” the experience may well be suitable for a haiku.

- Japanese poets traditionally used haiku to capture and distill a fleeting natural image, such as a frog jumping into a pond, rain falling onto leaves, or a flower bending in the wind. Many people go for walks just to find new inspiration for their poetry, known in Japan as ginkgo walks.

- Contemporary haiku may stray from nature as a subject. Urban environments, emotions, relationships and even humorous topics may be haiku subjects.

Include a seasonal reference

A reference to the season or changing of the seasons, referred to in Japanese as kigo , is an essential element of haiku. [4] The reference may be obvious, as in using a word like “spring” or “autumn” to indicate the season, or it might be subtler. For example, mentioning wisteria, which flower during the summer, can act as less obvious reference. Note the kigo in this poem by Fukuda Chiyo-ni:

- morning glory!

- the well bucket-entangled

- I ask for water

Create a subject shift

In keeping with the idea that haiku should contain two juxtaposed ideas, shift the perspective on your chosen subject so that your poem has two parts. For example, you could focus on the detail of an ant crawling on a log, then juxtapose that image with an expansive view of the whole forest, or the season the ant is currently inhabiting. The juxtaposition gives the poem a deeper metaphorical meaning than it would have if it were a simple, single-planed description. Take this poem by Richard Wright:

- Whitecaps on the bay:

- A broken signboard banging

- In the April wind.

Use Sensory Language

Describe the details.

Call the subject to mind and explore these questions:

- What did you notice about the subject? What colors, textures, and contrasts did you observe?

- How did the subject sound? What was the tenor and volume of the event that took place?

- Did it have a smell, or a taste? How can you accurately describe the way it felt?

Show, don’t tell

Haiku are about moments of objective experience, not subjective interpretation or analysis of those events. It’s important to show the reader something true about the moment’s existence, rather than telling the reader what emotions it conjured in you. [5] Let the reader feel his or her own emotions in reaction to the image.

- Use understated, subtle imagery. For instance, instead of saying it’s summer, focus on the slant of the sun or the heavy air.

- Don’t use cliches. Lines that readers recognize, such as “dark, stormy night,” tend to lose their power over time. Think through the image you want to describe and use inventive, original language to convey meaning. This doesn’t mean you should use a thesaurus to find words that aren’t commonly used; rather, simply write about what you saw and want to express in the truest language you know.

Become a Haiku Writer

Be inspired.

In the tradition of the great haiku poets, go outside for inspiration. Take a walk and tune in to your surroundings. Which details in your environment speak to you? What makes them stand out?

- Read other haiku writers. The beauty and simplicity of the haiku form has inspired thousands of writers in many different languages. Reading other haiku can help spur your own imagination into motion.

Like any other art, haiku takes practice. Bashō, who is considered to be the greatest haiku poet of all time, said that each haiku should be a thousand times on the tongue. Draft and redraft every poem until the meaning is perfectly expressed. Remember that you don’t have to adhere to the 5-7-5 syllable pattern, and that a true literary haiku includes a kigo , a two-part juxtapositional structure, and primarily objective sensory imagery.

Nature Haiku

- An afternoon breeze

- expels cold air, along with

- the fallen brown leaves.

- Cherry blossoms bloom,

- softly falling from the tree,

- explode into night.

- The warmth on my skin.

- Fire falls beneath the trees.

- I see the sun set.

- Summer here again.

- Music plays sweetly, drifting.

- And life is renewed.

- A winter blanket

- covers the Earth in repose

- but only a dream.

- An ocean voyage.

- As waves break over the bow,

- the sea welcomes me.

- Refreshing and cool,

- love is a sweet summer rain

- that washes the world.

- Love is like winter

- Warm breaths thaw cold hearts until

- one day the spring comes.

- A bird flies sweetly

- on paper wings. Telling all

- of my love for you.

- Every day I will

- love you more than you could know.

- We are here as one.

- The softest whisper

- beckons me closer to you.

- I love you, dearest.

- Vast as a mountain,

- my love for you shines through for

- all the world to see.

- The Serene Power of Haiku Poems: Capturing the Essence of Waves

In the realm of poetry, few forms are as revered and cherished as the haiku. Originating from Japan, haiku is a concise and evocative form of poetry that encapsulates a profound moment or observation in just three lines. With its strict syllable count of 5-7-5, this ancient art form has been celebrated for centuries, allowing poets to distill the essence of the natural world into a few carefully chosen words. Today, we dive into the mesmerizing world of haiku poems, specifically exploring the captivating theme of waves.

Examples of Haiku Poems about Waves:

A haiku's essence: simplicity and depth, the zen connection, the allure of waves in haiku.

Waves, with their rhythmic ebb and flow, have captivated poets for generations. They embody a sense of power, serenity, and constant change, making them an ideal subject for haiku poems. The brevity of haiku allows poets to capture the essence of waves, evoking emotions, painting vivid images, and provoking contemplation in just a few short lines.

1. The wave crashes in Foaming white against the shore— Nature's symphony.

2. Crests rise and fall fast, Whispers of the ocean's dance— Timeless rhythm flows.

3. Ocean's vast canvas, Brushstrokes of blue and silver— Waves paint the sunset.

At first glance, haiku poems may appear deceptively simple. However, their true power lies in their ability to convey depth and complexity within their concise structure. Through carefully chosen words, haiku poets can transport readers to the shoreline, allowing them to hear the crashing waves, feel the salty mist, and witness the eternal dance between land and sea.

The 5-7-5 syllable structure of haiku adds an additional layer of beauty to these poems. The rigid syllable count forces poets to carefully select their words, making each one count. This constraint encourages a sense of economy, distilling the poet's thoughts and observations into their purest form.

Haiku poems are deeply rooted in the concept of Zen Buddhism, emphasizing the present moment and the beauty of the natural world. As waves are in constant motion, they symbolize the impermanence and transience of life, a fundamental principle in Zen philosophy. By contemplating the waves through haiku, poets and readers alike can find solace, peace, and a connection to the profound forces of nature.

Haiku poems about waves hold a unique allure, allowing us to experience the vastness and power of the ocean within just a few lines. Through their concise structure, carefully chosen words, and adherence to the syllable count, these poems capture the essence of waves, transporting us to the shoreline and inviting us to contemplate the beauty and impermanence of life. So next time you gaze upon the ocean, take a moment to let the waves inspire your own haiku, and let your words flow like the eternal rhythm of the sea.

- The Power of Long Poems: Exploring Sadness

- Poems About Emotions: Unlocking the Inner World of KS2 Students

Entradas Relacionadas

Short Poems about Ireland: Capturing the Emerald Isle in Verse

Spanish Poems About Flowers: Celebrating the Beauty of Nature

Zen Poems About Life: Finding Serenity in Simplicity

Poetry Buzz: Exploring Bees through Kindergarten Verse

Ocean Poems: Capturing the Essence of Life's Journey

Simile Poems About Nature: Capturing the Beauty of the Natural World

Haiku: A Whole Lot More Than 5-7-5 And the 5-7-5 rule doesn't work the way you think

October 10, 2017 • words written by Jack • Art by Aya Francisco

In the spring of 1686, Matsuo Bashō wrote one of the world's best known poems:

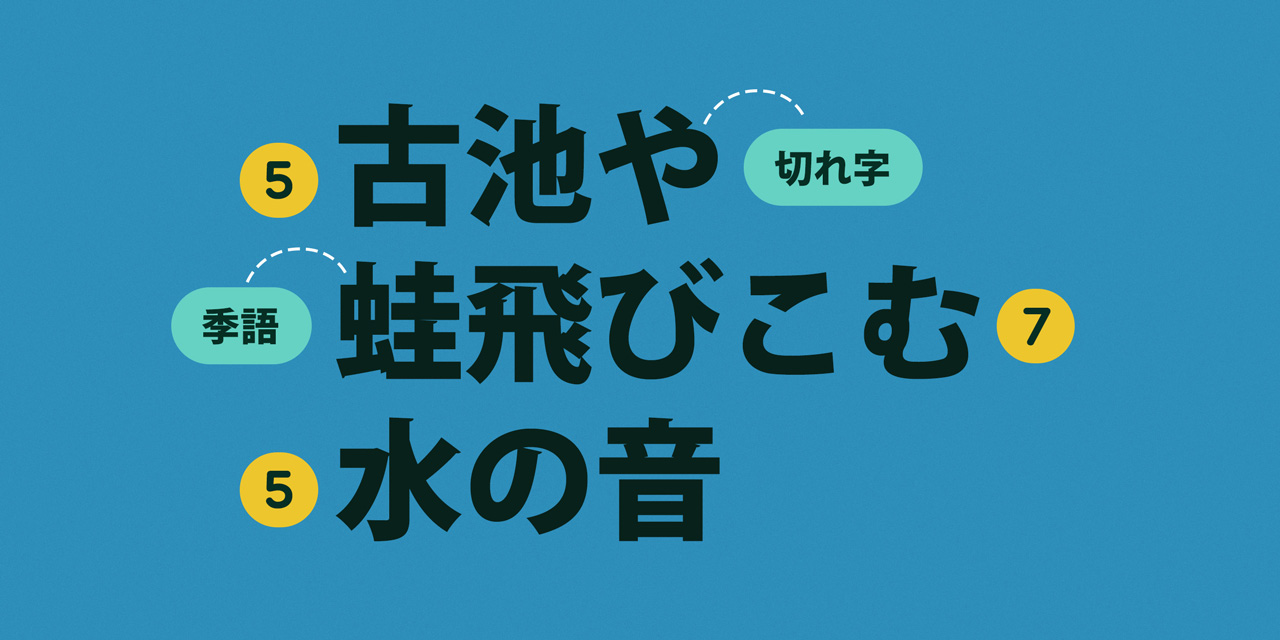

古池や蛙飛びこむ水の音 — 松尾芭蕉 Old pond Frog jumps in Sound of water 1 — Matsuo Bashō

This was a haiku 俳句 ( はいく ) , a short Japanese poem that presents the world objectively and contrasts two different images.

While Bashō wasn't the first to write haiku, this poem became the model that all haiku would be compared against and defined the form as we know it today.

But a haiku is more than just a poem that follows the skeleton of Old Pond. Let's start with a simple definition of what exactly a haiku is and go from there.

Prerequisite: This article is going to use hiragana, one of Japan's two phonetic alphabets, so if you don't know it yet, or just need a review, take a look at our hiragana guide !

What is Haiku?

5-7-5 structure, blurring of subject and object.

- Genuine feeling

- Egolessness

- Before Bashō

- Matsuo Bashō

- Kobayashi Issa

- Masaoka Shiki

- After Shiki

- What is the Future of Haiku?

The definition of a haiku in English is usually something similar to this: a poem that has three lines with a 5-7-5 syllable pattern.

But there's much more than that, especially in the syllable department. Let's make it easier by breaking the actual features of haiku into two groups:

Rules are what a poem needs to be considered a haiku. But as with all forms of art, these rules can be bent and sometimes broken for artistic effect.

Qualities are what separate a "good" haiku from a "bad" haiku. It's how you know who's a pro and who's a haiku scrub.

These are just my personal haiku definitions, so it's very likely you'll come across different distinctions and opinions on what makes or breaks haiku. It's a big topic, with a gargantuan history, so there's plenty of room to debate.

Let's begin by looking at the first feature: rules.

The Rules of Haiku

There are three basic rules for writing haiku:

- Seasonal Elements

- A "Cutting" Word

Each has its own important place in the anatomy of haiku.

The 5-7-5 structure is definitely the most well known characteristic of haiku. It's also the one that's broken the most. In fact, a scholar named Harold Gould Henderson (founder of the Haiku Society of America) estimated that about one in twenty classical haiku actually break the 5-7-5 rule. 2

Now, most English speakers learn that this structure refers to syllables. Letting you create cute a little haiku like:

Every day I wake And review WaniKani I know kanji now

But the English concept of syllables doesn't exist in the same way in Japanese.

Instead of a "syllable," which is usually based around a vowel, Japanese has a slightly different concept called on 音 ( おん ) . Linguists refer to this in English as "mora" or "morae" (if there's more than one) and モーラ in Japanese.

In Japanese outside of haiku you may see these on referred to as haku 拍 ( はく ) . But for our poetic purposes, we're going to stick with on .

Similar to the English syllable, a Japanese on measures a chunk of sound . And thanks to the way the Japanese writing systems work ( thank you kana ), these are very easy to understand once you know the rules.

- Each kana character is one on . This includes vowels.

- Contractions containing small kana count as one on .

Let's look at some examples:

A kana character like こ counts as just one on . Then when you add う to it to make it こう it becomes two on . In English, even though this is two kana characters and two on , we wouldn't distinguish the long こう sound as more than one syllable. To us, it's just a long vowel. So we think of it as just one syllable.

A kana contraction like きょ counts as just one on . That's because in Japanese, we think of small ゃゅょ as a part of the character that comes before it. Then when you add う to it to make きょう it becomes two on . In English, this is still just one syllable because to us きょう sounds like one long vowel after a consonant.

However the small っ does not get included in the on that comes before it. So やった has three on and, in English, two syllables.

The ん also counts as one on , if you were wondering. Which would seem very strange in English considering it's just the nasal n sound. But it's a kana in its own right, so it gets to count as one.

Below are a few real word examples, showing how sometimes the number of on and the number of syllables can be the same, and sometimes they don't match at all.

This would be cut and dry if haiku wasn't poetry and poetry wasn't art. Because there is always room for stylistic diversion and change, people can (and do) choose whether or not they count small kana (ゃゅょっ) as on . And just like English poetry, these don't always match with the style.

This can also be heard in Japanese music. Singers typically sing out the "extra" kana that you normally wouldn't hear if someone was just reading the lyrics out loud. But not always. It all depends on how it fits in the song.

However, in general, haiku should be three lines of 5-7-5 on . Let's take a look at a real haiku poem by Tagami Kikusha (田上菊舎), translated by former European haiku expert, Reginald Horace Blyth (R. H. Blyth), broken up into this on versus syllable style.

Remember, the syllables are counting the Japanese poem by English syllable standards, not the English translation.

Anyway, by Japanese standards this is a perfectly straightforward, well-structured haiku, but from the English syllable perspective it's not. So saying haiku is a 5-7-5 syllable structure just isn't true.

And because on are easy to see and count, Japanese haiku are generally written on a single line, rather than broken up into three, which means it's up to the reader to decide where those line "divisions" actually are. It's usually pretty clear, but this also opens up more formatting possibilities.

The 5-7-5 pattern underpins a lot of Japanese poetry. It's like iambic pentameter in English; the language naturally falls into this pattern, so verse was based on it for centuries before haiku existed.

However, as I said earlier, this rule is often broken (in English and Japanese). Here's an example from one of Matsuo Bashō's most famous haiku:

枯枝に烏のとまりけり秋の暮 — 松尾芭蕉 On a withered branch A crow has stopped Autumn evening — Matsuo Bashō

This poem was the first of Bashō's "new style" and it's 5-9-5. Even he broke the rule!

However, I still count this as a rule, not simply a quality of haiku, because it is obeyed most of the time. And when it's broken, it's usually for artistic effect, rather than incompetence.

Haiku are often considered nature poems. Look at any classical haiku and you'll usually see some kind of natural imagery like wildlife or weather. This is more formal than something like a sonnet, that should be about love but isn't always—haiku have specific words you have to use .

These are called kigo 季語 ( きご ) , or seasonal words. In our Bashō example, the kigo is the frog, which represents spring. Some kigo may seem more obvious than others, but they are all rooted deeply in Japanese culture. It isn't as simple as thinking about spring and writing it all down.

Another important mechanic of kigo is that they can be modified. For example, tsuki 月 ( つき ) (moon) is normally an autumn kigo , like in Takarai Kikaku's poem:

蜻蛉や狂ひしつまる三日の月 — 宝井其角 The dragonflies Cease their mad flight As the crescent moon rises. — Takarai Kikaku (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

But, you could write kangetsu 寒月 ( かんげつ ) (winter moon) to make a winter haiku. Yosa Buson does this:

寒月に木を割る寺の男かな — 与謝蕪村 The old man of the temple, Splitting wood In the winter moonlight. — Yosa Buson (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

So there are many, many kigo and they can be altered in many, many ways as long as they follow the rules of appearing where and when they're supposed to.

But how do you know what image goes with what season? There are tons of kigo, so even professionals need some help. All kigo are formally recorded in a saijiki 歳時記 ( さいじき ) , a book used by haiku writers to find the right seasonal word they want to use. These anthologies are often divided into five seasons: spring, summer, autumn, winter, and New Year.

Let's look at some examples to see what we might expect from each season.

繰り返し麦の畝縫ふ胡蝶哉 — 河合曾良 Weaving back and forth Through the lines of wheat A butterfly — Kawai Sora

Many spring haiku treat this time with lightness, joy, and comfort.

Spring is the season of new beginnings. The New Year has passed and plants and animals awaken to fill the world with noise, color, and smells. The days are still hazy, especially in early spring, but we haven't yet hit the oppressive summer heat.

Many spring haiku treat this time with lightness, joy, and comfort—in Sora's haiku, farming mirrors the movement of a butterfly as both begin life anew.

Other things to expect in spring are frogs (as in Bashō's poem), the uguisu 鶯 ( うぐいす ) (Japanese bush warbler), and of course plenty of flowers. Spring is the time for cherry blossoms, plum blossoms, and camellia flowers.

Also, spring is when cats get it on. There are a lot of humorous haiku about noisy felines shamelessly enjoying the season outside a poet's window.

夕立にうたるゝ鯉のあたまかな — 正岡子規 Summer shower Beats the heads Of carp — Masaoka Shiki

Summer opens with thumping rain at the beginning of June and it hits everything, even the water dwelling carp.

Summer weather also means hot days and cool nights. Daytime laziness and nighttime activity are often front and center in summer haiku.

Blyth says, "fields and mountains have in summer a vast, overarching meaning, something of infinity and eternity in them that no other season bestows."

Summer also welcomes the migration of the hototogisu 不如帰 ( ほととぎす ) (Japanese cuckoo), that sings a melancholy tune at night in the mountains.

Insects make appearances in summer haiku as well, and not just fireflies and cicadas either. Mosquitoes, fleas, and lice are all featured. It's common for haiku to treat insects with Buddha-like compassion rather than the annoyance that many of us feel.

砕けても砕けてもあり水の月 — 上田聴秋 The moon in the water; Broken and broken again, Still it is there — Ueda Chōshū (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

Autumn is the perfect time of year for Japanese art – it's excellent at capturing the melancholic beauty of things fading away.

For me, autumn is the perfect time of year for Japanese art—it's excellent at capturing the melancholic beauty of things fading away. Death isn't often featured in haiku, but autumn evenings are used to reflect on the mortality or flaws of man.

It's not all sitting alone feeling glum though. The Milky Way is most visible in autumn. The moon is the clearest symbol of the season, ever present in the haiku tradition as it is in Chōshū's poem above.

Both Chinese and Japanese poetry discuss the sounds of insects in autumn evenings. Haiku adds scarecrows and many flowers, most notably chrysanthemums, to the kigo list.

冬川や家鴨四五羽に足らぬ水 — 正岡子規 The winter river: Not enough water For four or five ducks. — Masaoka Shiki (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

Winter is, of course, a cold season. Even where it doesn't snow, everything becomes more monochromatic and flat. Snow is like winter's cherry blossoms, ever-present and flexible. It covers everything; though pine trees are less affected by the cold than others.

Expect to see tangled twigs and empty fields, with few signs of life beyond fish, owls, eagles, and water birds.

In the lunar calendar, winter is the end of the year, and this sense of finality will sometimes make its way into haiku written for the season.

元朝の見るものにせむ富士の山 — 山崎宗鑑 New Year's Morning The best sight shall be Mount Fuji — Yamazaki Sōkan

Before the Meiji Restoration , the Japanese calendar followed the Chinese lunar year rather than the Western Gregorian calendar. This meant the New Year fell right at the overlap between winter and spring, generally in early February. Plums are beginning to bloom and the sky is turning blue.

In particular, New Year's Morning is considered the beginning of the year—the first experiences of familiar things like the wind, running water, and clouds have a special significance on this day. A view of Mt. Fuji is like this; something seen every day but made more special thanks to the circumstances.

Alternative Kigo

Like 5-7-5, the kigo rule can be broken. Bashō wrote this season-less haiku about the Musashi Plain, now part of the present-day Tokyo Metropolis. In his time it was a vast wilderness.

武蔵野やさわるものなき君の笠 — 松尾芭蕉 The Great Musashi Plain; There is nothing To touch your kasa — Matsuo Bashō (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

The size and desolation of the plain was likely the reason for this haiku's lack of kigo. Regardless of when you walk through it, it will be the same huge, empty place.

Bashō's Musashi Plain haiku is a good example of how the form can be used to encapsulate places. Bashō was known for his travel journals and took many journeys across Japan. Many others followed his lead, and because of this haiku has become associated with travel writing.

Traveling poets weren't just wandering though. They had specific places they wanted to visit, and would write haiku about their experience of that place. It's partially a case of recording their own feelings, but it's also a link between different poets. Writing a poem, following the same themes as those that came before, added that poet to a long tradition.

And just like seasons have kigo, places have seasons you should visit them in and certain aspects you should write about when you're there.

Bashō turned this on its head when visiting the famous islands of Matsushima with his haiku:

松島や ああ、松島や 松島や — 松尾芭蕉 Matsushima… Ah! Matsushima… Matsushima… — Matsuo Bashō

This poem is often read as a refusal to engage in tired representations of the famously beautiful place, but probably shouldn't be taken too seriously—it's also suggested that Bashō just couldn't find the words to express what he'd seen.

In a sense, then, places and place names can act like a kind of kigo in that they link poems together across time and space.

The use of a cutting word, called kireji 切れ字 ( き じ ) is the final "rule" of haiku writing. It's also one of the hardest to translate because there's no direct equivalent in English, or most other languages.

Kireji act like punctuation in haiku. Classical Japanese , like Chinese, uses almost no punctuation beyond a full stop, so haiku use words to do this job instead. More specifically, they use particles.

Some of these are used in standard spoken Japanese, but in haiku their meanings are often quite different. Particularly with common ones, like や and かな , they've actually lost meaning, or rather become undefinable because they're so common.

Here's the most common kireji to look out for:

Meaning is more difficult with kireji, especially because many of them are simply used to add emphasis. Most will be translated in English as:

So if kireji are like punctuation, what exactly are they punctuating? Well, one of the foundations of haiku is juxtaposition. This is the act of taking different things (often visual images in haiku) and placing them close together. This divides and unites at the same time. Let's look at my personal favorite haiku, by Issa:

遠山や目玉に写るとんぼかな — 小林一茶 Distant mountains Reflected in the eyes Of a dragonfly — Kobayashi Issa

Issa creates a dizzying effect of space using the difference in scale between the mountains and how they appear in the dragonfly's compound eyes. This is juxtaposition, and it's fundamental for haiku.

Here the kireji is either や at the end of the first line or かな at the end of the third. や emphasizes the mountain, while かな emphasizes the dragonfly. This means that the two main elements sit at either end of the poem. In the middle is 目玉 ( めだま ) に 写る ( うつ ) , the reflection literally sits between and joins the two images.

Kireji mark emphasis and juxtaposition and the cut (切れ) is the change in focus from one thing to another. Your choice of kireji and where you put it can affect how this cut works. Haiku relies on creating associations, and the best are often interesting or powerful.

For Bashō's frog haiku, the kireji や is at the end of the first section. So we might split the poem into two parts:

古池や 蛙飛び込む水の音 — 松尾芭蕉 Old pond Frog jumps in, sound of water — Matsuo Bashō

Putting the や there marks the old pond as the setting for the action of the frog. We move from ancient stillness to movement as we cross the や cut.

An interesting side note: Bashō reportedly wrote the second part of this poem first, and went through numerous revisions before setting on 古池や. For this haiku, at least, the two-part structure was fundamental.

Issa's dragonfly haiku uses a different cutting technique. Placing かな at the end of the poem creates a cyclical effect, but also means the poem's cut is between its end and its beginning.

Because of this, the two images of the mountains, even though their sizes are very different, are unified by the かな, that also cuts off the end of the poem. Combine that with the linking we discussed above and you can see how full of connections Issa's poem is.

Kireji and juxtaposition are arguably the most important aspect of haiku, especially today. Even though they can't really be translated, the effect is essential in any language. It's also notable that while modern gendai haiku 現代俳句 ( げんだいはいく ) tend to ignore 5-7-5 and kigo rules, it's rare to see them without kireji or at least the cutting feeling.

Qualities of Haiku

So those are the rules that all haiku must at least be conscious of. But like I said, not all haiku have to follow them, and when they don't it's always a purposeful decision.

But there is more to haiku than just following rules. Good haiku are thought to be made up of qualities, and we'll be going through those next. Those qualities are:

- A blurring of subject and object

Just like we did with the rules, let's tackle these one at a time.

This quality is so common it's arguably a rule. Haiku is often critiqued along the line of subject (the thing doing) and object (the thing being done to). To understand why, we'll need some history.

Haiku as we know it is a reaction to the waka 和歌 ( わか ) poetry of the medieval Japanese court. At that time, poetry was often an exercise in wit rather than emotion. Juxtapositions could get tired, or even silly, as more and more people used them as a way to show off.

By Bashō's time, the "show off" poem had reached a fever pitch, and Bashō's insistence on objective presentation was an attempt at fighting back. We'll see later, he wasn't the first to do this, but he definitely became the most influential.

Join Discovery, the new community for book lovers

Trust book recommendations from real people, not robots 🤓

Blog – Posted on Wednesday, Sep 14

40 haiku poem examples everyone should know about.

Haiku is a form of traditional Japanese poetry, renowned for its simple yet hard-hitting style. They often take inspiration from nature and capture brief moments in time via effective imagery. Here are 40 Haiku poems that ought to leave you in wonder.

1. “The Old Pond” by Matsuo Bash ō

2. “The light of a candle” by Yosa Buson

The light of a candle

Is transferred to another candle —

spring twilight.

Another of haiku’s Great Masters, Yosa Buson is known for bringing in a certain sensuality to his poems (perhaps owing to his training as a painter). In this haiku, his image of a single lit candle against the twilight artfully depicts how one candle can light another without being diminished — until you have a star-filled sky.

3. “Haiku Ambulance” by Richard Brautigan

A piece of green pepper

off the wooden salad bowl:

For an example of a haiku that doesn’t adhere to traditional conventions, look no further than Richard Brautigan’s cheeky “Haiku Ambulance”. Eagle-eyed readers will notice that the syllable count doesn’t fall into the 5-7-5 pattern, and the lines are off-balance, too. So what? Appropriately, this poem suggests that nothing means anything at all — in a pepper’s exile from a salad bowl, in the rules of a poem, or even (dare we say) life.

4. “A World of Dew” by Kobayashi Issa

This world of dew

is a world of dew,

and yet, and yet.

The third master of Japanese haiku, Kobayashi Issa, grew up in poverty. From this humble background emerged beautiful poetry that expressed empathy for the less fortunate, capturing daily hardships faced by common people. This particularly emotionally stirring haiku was written a month after the passing of Issa’s daughter.

5. “A Poppy Blooms” by Katsushika Hokusai

I write, erase, rewrite

Erase again, and then

A poppy blooms.

In this piece, Katsushika Hokusai draws similarities between life and his writing — both processes of repetitive creation and destruction. Neither are linear or smooth, and both demand constant work and perseverance. However, the reward of his perseverance is something undeniably beautiful.

6. “In the moonlight” by Yosa Buson

In pale moonlight

the wisteria’s scent

comes from far away.

Buson invites the reader to share in his nostalgia with elements from nature such as ‘pale moonlight’ and the ‘wisteria’s scent’ triggering the our visual and olfactory senses — the fact that the scent is coming from far away adds a transportive element to the poem, asking us to imagine the unseen beauty of this tree.

7. “The earth shakes” by Steve Sanfield

The earth shakes

just enough

to remind us.

Penned in English, poet Steve Sanfield’s only haiku is a quiet reminder of our mortality, inviting us to consider what may be important to us before it’s too late.

8. “In a Station of the Metro” by Ezra Pound

The apparition of these faces

in the crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough.

All imagery with zero verbs, Ezra Pound delicately captures a still moment in time. The first image entirely comprises humans (faces in the crowd), while the second only shows nature (petals). By likening the two, the poet highlights the fleeting nature of life — be it the people we encounter every day or the wilting petals.

9. “The Taste of Rain” by Jack Kerouac

— Why kneel?

Yep, the iconoclastic author behind On the Road also wrote haikus! As one of the Beat Generation’s leading figures, he was part of a movement that produced some of the 20th century’s influential poems. This particular haiku has many interpretations — with many assuming this to be Kerouac’s take on religion and God.

10. “Haiku [for you]” by Sonia Sanchez

love between us is

speech and breath. loving you is

a long river running.

“Haiku [for you]” acts as a warm, comforting hug. The poet draws similarities between the nature of their love and that of ‘speech’ and ‘breath’ — natural and unforced. If someone whispered this to you, wouldn’t you feel love, too?

11. “Lines on a Skull” by Ravi Shankar

life’s little, our heads

sad. Redeemed and wasting clay

this chance. Be of use.

While many haiku have focused on the brevity of life, this entry from Ravi Shankar (no relation to the sitar player) takes a slightly darker approach. Using clay as a metaphor, Shankar reminds us that we have this one chance to shape our life — to either waste it away or be of use.

12. “O snail” by Kobayashi Issa

Climb Mount Fuji,

But slowly, slowly!

Aside from his pessimistic worldview, Issa was also renowned for shining a spotlight on smaller, less-than-glamorous creatures like grasshoppers, bugs, and sparrows. In “O snail”, he gently reminds the determined snail that while there are important things to do in life (like climbing mountains), there’s more to life than speed! The mountain isn’t going to go anywhere, is it?

13. “I want to sleep” by Masaoka Shiki

I want to sleep

Swat the flies

Softly, please.

The last of the Four Great Masters of haiku, Masaoka Shiki had a very direct writing style. Suffering tuberculosis for much of his life, his poetry was an outlet for his isolation. He would often focus on the trivial details of sick-room life, and in this haiku, his sadness and fatigue are almost palpable.

14. “JANUARY” by Paul Holmes

Delightful display

Snowdrops bow their pure white heads

To the sun's glory.

This haiku is a part of Paul Holmes’ A Year in Haiku Poem, where he attempts to capture the essence of each month of the year. Holmes does so fittingly, using vivid imagery to depict the seamless changing of the seasons— as the snowdrops bow their ‘white heads’ to make way for the sun’s glory.

15. “[snowmelt— ]” by Penny Harter

on the banks of the torrent

small flowers

By placing the river’s powerful torrent next to a delicate flower, Harter captures how all of nature’s diverse elements coexist beautifully. While the torrent certainly paints a more aggressive image than most haiku, it's balanced by the idea of the snow melting and the delicacy of the flowers emerging from spring.

16. [meteor shower] by Michael Dylan Welch

meteor shower

a gentle wave

wets our sandals

Another non-traditional haiku that eschews the 5-7-5, Welch’s entry here is a snapshot of a rare moment shared between the speaker and someone else. The order of the three images creates a sense of the poet lowering their eyes from shooting stars in the sky, before settling on a strangely intimate image of sitting on the beach. With all the wonders of the universe, nothing compares to a moment shared with someone close to you.

17. “[The west wind whispered]” by R.M. Hansard

The west wind whispered,

And touched the eyelids of spring:

Her eyes, Primroses.

By personifying the whispering ‘west wind’, R.M. Hansard gives life and agency to the natural world. Add in a second protagonist, the primrose-eye’d spirit of spring, and there we have it: a sensual dance that ushers in the changing of the seasons.

18. “After Killing a Spider” by Masaoka Shiki

After killing

a spider, how lonely I feel

in the cold of night!

Masaoka Shiki’s “After Killing a Spider” is a prime example of haiku’s ability to capture the minutiae of life. Filled with loneliness and regret, After Killing a Spider depicts exactly what it says on the tin. But then it goes further into the speaker’s emotions after the incident — for after killing his only companion, the speaker is left alone in the cold of the night. What’s also interesting is that the first break comes after the word ‘killing’, emphasizing the brutality the speaker felt on performing the act, even if it was just a spider.

19. “[I kill an ant]” by Kato Shuson

I kill an ant

and realize my three children

have been watching.

If you haven't had your fill of bug-killing action, here’s a haiku from Kato Shuson. As with “After killing a spider”, the speaker doesn’t feel remorse at having ended a life — but perhaps regrets allowing their kids to see their savage tendencies. Though short in length, this haiku imparts a powerful message: be the person that you want your children to see.

20. “Over The Wintry” by Natsume Sōse

Over the wintry

forest, winds howl in rage

with no leaves to blow.

One can easily imagine the person represented by the metaphorical wind in this haiku: someone in their winter years, who has spent the year railing against the world, only to be left with no one left to listen. While spring often represents the idea of hope in poetry, winter surely is the season of regret.

21. “[cherry blossoms]” by Kobayashi Issa

cherry blossoms

fall! fall!

enough to fill my belly

Cherry blossoms are a big deal in Japan, so it’s no surprise that they often turn up in haiku. In this poem, the cherry blossom festival must be in full swing, and the speaker can barely control their excitement, wishing for more — an excess of it that, surfeiting, the appetite might sicken and so die (as Shakespeare might say). It’s enough to make you want to book the next available flight to Tokyo.

22. “[The lamp once out]” by Natsume Soseki

The lamp once out

Cool stars enter

The window frame.

This is a classic by Natsume Soseki, a widely respected novelist and haiku writer. You might read it literally, thinking that one can marvel at the night sky in all of its wonder as soon as the light of the lamp on the street goes out, or you can also interpret the lamp as an active mind 一 only when we manage to quiet it can we access a deeper, wiser source of light, represented by the stars.

23. “[The snow of yesterday]” by Gozan

The snow of yesterday

That fell like cherry blossoms

Is water once again

As you might have noticed, the art of writing haiku demands an almost superhuman level of observation. Aida Bunnosuke, also known as Gozan, speaks about the impermanence of our surroundings by noticing how snowflakes turn into water in very little time. This theme of the ephemeral nature of life is again emphasized by the cherry blossoms, which only last for about a week after peak bloom.

24. “[First autumn morning]” by Murakami Kijo

First autumn morning

the mirror I stare into

shows my father's face.

Born in Tokyo in 1865, Murakami Kijo helped with the founding of Hototogisu, a literary magazine responsible for popularizing the modern haiku in Japan. In this particular piece, Kijo uses the simple act of looking into the mirror to convey one’s struggle with mortality.

25. “[Just friends:]” by Alexis Rotella

Just friends:

he watches my gauze dress

blowing on the line.

Contemporary poet Alexis Rotella knows how to tap into common human experiences — like, for instance, a friendship that gets in the way of love. In an instant, we can feel the frustration for a potential that won’t be expressed, and a desire that won’t be satisfied.

26. “[What is it but a dream?]” by Hakuen Ekaku

What is it but a dream?

The blooming as well

Lasts only seven cycles

This pensive haiku by Hakuen Ekaku broodingly reflects on the theme of death. As haiku writers like to remind us, the blooming of the most beautiful of nature’s occurrences like spring cherry blossom are always temporary. Coincidentally, Hakuen’s life also spanned seven cycles, as he died at the age of sixty-six.

27. “[Even in Kyoto,]” by Kobayashi Issa

Even in Kyoto,

Hearing the cuckoo’s cry,

I long for Kyoto

In this classic piece by Kobayashi Issa, a bird’s call brings him back to his early days as a student in Kyoto. The poem exudes a certain nostalgia and longing for that time in his life which is now lost 一 something we can all relate to, in our own ways.

28. “[The crow has flown away:]” by Natsume Soseki

The crow has flown away:

Swaying in the evening sun,

A leafless tree

The changing of the seasons is a theme common to Zen Buddhist philosophy, and its influence can be felt in many haiku. Through a series of simple yet provocative images, Natsume Soseki captures the seamless shift as the summer sun sets to make way for the ‘leafless’ fall.

29. “[The neighing horses]” by Richard Wright

The neighing horses

are causing echoing neighs

in neighboring barns

African American novelist and poet Richard Wright often used the ‘haiku round’, a technique where the reader can go back to the first line from the third, as if repeating the poem in endless loops. Try it with this one! Fun fact: according to his daughter, he would draft his poems on disposable napkins before transferring them to paper.

30. “[Lily:]” by Nick Virgilio

out of the water

out of itself

One of the most celebrated English-language haiku, this poem from Nick Virgilio demonstrates the effectiveness of the kireji, or the cutting word which helps the haiku ‘cut’ through space and time. Here, the abrupt colon after “Lily” allows the reader to fill in the gaps in search of the deeper meaning implied.

31. “Childless woman” by Hattori Ransetsu

The childless woman,

how tenderly she caresses

homeless dolls …

An Edo-period samurai who became a poet under the tutelage of Matsuo Bashō, Ransetsu is not usually considered a heavy-hitter in the history of the haiku. He did, however, have his moments, including this piece — a melancholy portrait that is very much the For sale: baby shoes, never worn of its era.

32. “[A raindrop from]” by Jack Kerouac

A raindrop from

Fell in my beer

While most Japanese haiku poems speak of humankind’s harmonious relationship with nature, Jack Kerouac’s contributions to the oeuvre put man and nature on opposing sides. After sketching an image that could easily have come from a pastoral scene — a raindrop fall from a roof — Keruoac pulls back to reveal the modern context. Representative of Kerouac’s caustic writing style, we find that nature disrupts — rather than soothes — the speaker.

33. “[I was in that fire]” by Andrew Mancinelli

I was in that fire,

The room was dark and somber.

I sleep peacefully.

The first line of Andrew Mancinelli’s haiku certainly packs a powerful punch. Was it a real ‘fire’ that our speaker was in, or a metaphorical one in their life? Have they overcome a tragedy and learned that all things must pass — or do they now “sleep,” perchance to dream, in a place beyond that mortal coil? In either case, it’s chilling stuff!

34. “[Plum flower temple:]” by Natsume Soseki

Plum flower temple:

Voices rise

From the foothills

Natsume Soseki was known for weaving fairy tales into his haikus, and this work is a perfect example. Through the myth-like depiction of the ‘plum flower temple’ or the unknown voices rising from the foothills, he creates a sense of wonder for the enigmas hidden in the world around us.

35. “[The first soft snow:]” by Matsuo Bashō

The first soft snow:

leaves of the awed jonquil

This piece by Matsuo Bashō is another ode to the power of nature. You almost sense a certain reverence in the ‘awed’ jonquil leaves that ‘bow low’ to the snow — a reminder that all life, however beautiful, eventually gives way to nature.

36. “[A caterpillar,]” by Matsuo Bashō

A caterpillar,

this deep in fall –

still not a butterfly.

Matsuo Bashō’s brilliance is captured in this simple haiku, which fully immerses you into the perspective of a caterpillar In just three lines. The way in which Bashō depicts the impatient caterpillar conveys a feeling of frustration and desire for growth. In doing so, we realize the angst of unrealized potential.

37. “[On the one-ton temple bell]” by Taniguchi Buson

On the one-ton temple bell

A moonmoth, folded into sleep,

Sits still.

Consider the sound that a ‘one-ton temple bell’ might make if it were to ring. That’s what Taniguchi Buson urges us to imagine, juxtaposing this deep bell against the silent moonmoth, unaware that it might be violently distrubed at any possible moment.

38. “[losing its name]” by John Sandbach

losing its name

enters the sea

As the river gives up its very identity to contribute to the sea, it reminds us of the importance of selflessness. After all, “no man is an island” and we are all parts of a bigger whole, aren’t we?

39. “[Grasses wilt:]” by Yamaguchi Seishi

Grasses wilt:

the braking locomotive

grinds to a halt.

A wilting grass and a braking locomotive: by juxtaposing the two, the poet has created a power dynamic between the images 一 one natural and one man-made. As the grass by the side of the tracks have wilted into the path of the locomotive, the poem suggests that even the mightiest of technological innovations must yield to nature.

40. “[Everything I touch]” by Kobayashi Issa

Everything I touch

with tenderness, alas,

pricks like a bramble

No, not the Britney Spears song! Instead, the author Everything I touch speaks about the tangible pain he feels every time he seeks a kindred contact. Through only three lines, he conveys the wounds of love — and the unforgiving ache of connection.

If these haikus have unlocked the deep thinker and poet in you, you can learn how to write a haiku yourself, or turn to our post on 40 Transformative Poems About Life.

Continue reading

More posts from across the blog.

The 25 Best Romance Authors (And Their Most Swoonworthy Reads)

Romance is one of the most popular genres in literature today, both for readers and writers of romance novels. And it’s no wonder why: romance is exciting, sexy, ...

Stranger Things Book Bag: 12 Must-Read Novels If You Love the Hit Show

If you’re as obsessed with Stranger Things as we are, you’ll know that the long wait for season 4 is finally over! Time to gleefully gobble up the next installment in the adventures of Mike, Eleven, Steve Harrington, Chief Hopper, and all the other resid...

70 Best Coming-of-Age Books of All Time

Everybody has to grow up sometime — and the books on this list show that it can happen in surprising ways. We’ve hand-picked the very best of the genre to bring you seventy must-read coming-of-age books.

Heard about Reedsy Discovery?

Trust real people, not robots, to give you book recommendations.

Or sign up with an

Or sign up with your social account

- Submit your book

- Reviewer directory

We made a writing app for you

Yes, you! Write. Format. Export for ebook and print. 100% free, always.

What is haiku poetry: format, rules and history

Table of Contents

Format, rule, seasonal words, and famous poets of haiku poetry

The rules of haiku is so simple. But do you know how to write haiku poems is different between Japanese and English?

What is a “haiku”? The structure in Japanese and in English.

The format of Japanese

- 5-7-5 syllables ( 17 syllables in all)

- Must use a seasonally word(phrase), “ kigo “(read below)

The strucure of haiku is basically 5-7-5, 15 syllables. It is a poem that place value on the rhythm of sound, so it is better to keep 5-7-5 as possible. It is like a samba rhythm for Brazilians. The Japanese settle down somehow by listening to this syllable.

However, as an exception, there are also haiku such as an extra syllable “ziamari” or conversely less “zitarazu”.

In addition, Taneda Santoka(1882-1940) is a poet who dared to begin haiku poems free from 5-7-5 structure.

Related Post

Differences between Haiku and Tanka poetry

The format of English

- Three lines and a preferably 5-7-5 syllables

- Kigo is unnecessary. It’s okay to have just sense of season

- Using a mark of dash(-) or colon(,) as “kireji”(read below)

- A theme is not a thought or concept but a matter

- Avoiding a description and prose

What does haiku mean?

The haiku’s history started from “haikai”(俳諧) which focused on funny themes. Haikai and “renga”(連歌, more elegan than haikai) started with “hokku”(発句), 5,7,5 syllables and next person consider another 7,7 syllables like fit to hokku, then the third person thinks 5,7,5 syllables for following.

So haiku originally meant a hokku(start) of haikai and the words joined.

First person(hokku): 5,7,5

Second person:7,7

Third person:5,7,5

Forth person:7,7

Comparing to haikai, people enjoyed sensibility and feelings in renga. Renga and haiku were played by two or more performers unlike tanka, 5-7-5-7-7 or 7-7-5-7-5 syllables by a single person. Hokku literally means starting phrase and is a part of kaminoku(the first part of a poem) in tanka.

Then, people in Edo Period made hokku independent and that is the style of haiku, 5-7-5 syllables.

Format of tanka poetry

t is said that 5-7-5 or 5-7-5-7-7 syllables are the most suitable rhythms for Japanese. And the other reason that English haiku doesn’t have 5-7-5 syllables, is the issue of languages. English syllable may have one vowel with some consonants. But Japanese syllable doesn’t have plural consonant. So it’s difficult to apply Japanese to English.

Seasonally word:kigo

Types of kigo widely cover the range of plants and animals, time of year, events, astronomy, life.

Also about kigo, the weather of Japan has clear four seasons and each kigo stir imagination of Japanese who live there. The countries have their own condition of the climate and the culture. It is impossible to compel kigo to others.

spring moon, spring dark, spring rain, spring river, spring sky, warm, tranquil, be perfectly clear, thin ice, laughing mountain, soap bubble, turban shell, the first day of spring, the vernal equinox, cherry-blossom viewing, the Dall’s Festival, swallow, silkworm, kitten, ume (plum blossoms), cherry blossoms, Japanese butterbur scape…

hot, cool, summer rain, summer sky, summer mountain, summer Fuji, ice cream, iced coffee, iced tea, rice‐planting, early summer rain, rainy season, early summer, morning cloud, firefly, cicada, cicada born, catfish, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, the summer solstice, carnation, young leaves, crape myrtlean, green chili…

fresh, chilly, autumn pond, autumn river, autumn rain, autumn day, autumn mountain, dewdrop, moon, the Milky Way, crescent, midnight moon, fireflower, the lingering summer heat, locust, bell cricket, good harvest, bad harvest, rice harvesting, autumn leaves, the autumnal equinox, autumn eggplant, gentian, orchid…

winter water, winter sea, winter field, oden, yakitori, fire, stove, catch a cold, north wind, sleeping mountain, snow, Orionthe Hunter, jacket, coat, globefish, yellowtail, rabitt, fox, mandarin orange, carrot, daikon(Japanese white radish)…

Pause:kire(切れ), kugire(区切れ)

Japanese haiku has two types of the pause in its short 17 syllables. When you want to emphasize the touched feeling and use a technique of “kire”. Using “kireji”(切れ字) including, ya, kana, and keri, you can express your delight or sadness strongly in same way of exclamation mark. It also has an effect of omitting the words and leaving the readers with an allusive feeling.

On the other side, “kugire” is a break of meaning in a haiku poem. There are four kinds of the pause, first line break(shoku-gire 初句切れ), second line break(niku-gire 二句切れ), no break(kugire-nashi 句切れなし), and mid-flow break(chukan-gire 中間切れ).

Examples of haiku poems

Matsuo basho.

- 10 Famous haiku poems of Matsuo Basho

Four seasons haiku

- Haiku poems of spring. The examples by Matsuo Basho

- Haiku poems of summer. The examples by Matsuo Basho

- Haiku poems of autumn. The examples by Matsuo Basho

- Haiku poems of winter. The examples by Matsuo Basho

Famous Poets

- Kobayashi Issa

- Masaoka Shiki

- Takahama Kyoshi

- Kawahigashi Hekigoto

- Japanese traditional haiku poems about nature

- 10 Haiku love poems

- Haiku poems about death and rip

- Haiku poems about Christmas

- The examples of haiku poems about flowers

- The spring haiku poem examples by Japanese famous poets

- The summer haiku poem examples by Japanese famous poets

- The autumn haiku poem examples by Japanese famous poets

- The winter haiku poem examples by Japanese famous poets

There were three famous poet of haiku in Edo Period, Matsuo Basho(松尾芭蕉), Yosa Buson(与謝蕪村), and Kobayashi Issa(小林一茶)

<English>

Even in profusion

I prefer the first cherry blossoms

Rather than peach

<Japanese>

咲き乱す 桃の花より 初桜

Sakimidasu/ Momo no hanayori/Hatsuzakura

The mayfly land

On the paper jacket

Of my shoulder

かげろうの わが肩に立つ 紙子かな

Kagerou no/ Waga kata ni tatsu/ Kamiko kana

Yosa Buson <English>

Spring ocean

Swaying gently

All day long.

Translated by Miura Diane and Miura Seiichiro

春の海 ひねもすのたり のたりかな

Haruno-umi Hinemosu-Notari Notarikana

Kobayashi Issa <English>

“Gimme that harvest moon!”

Cries the crying

Translated by David G. Lanoue

名月を 取ってくれろと 泣く子哉

Meigetsu-wo Tottekurero-to Nakuko-kana

Related posts:

- THF in the News

- THF Volunteer Appreciation

- Policies & Code of Conduct

- New to Haiku? Intro

- New to the Haiku Foundation?

- Haiku of the Day Archive

- Haiku Outside the Box

- Digital Library

- Publications

- HaikuLife: THF's Video Project

- Haiku Around the World

- THF Haiku App

- THF YouTube Channel

- Site Archive

- New to Haiku? Posts

- Contemporary Haiku

- Education Resources

- Haiku Dialogue

- Haiga Galleries

- Monthly Kukai

- Renku Sessions

- Haiku Registry

- Ways to Donate to THF

HAIKU DIALOGUE – A Good Wander: The Art of Pilgrimage – Obstacles and Trials

- October 26, 2022

A Good Wander: The Art of Pilgrimage with Guest Editor P. H. Fischer

“Every day is a journey, and the journey itself is home.” – Basho (translated by Sam Hamill, The Essential Bashō , Shambhala, 1999)

Ready to lose yourself in the wonder of wandering? If so, grab your rucksack, water bottle (filled with a bit of sake perhaps), a pair of good trail shoes, a sturdy walking stick, and, of course, your favourite notebook and pen.

Over these next two months, I’ll share brief reflections and photo prompts from my Camino pilgrimage. This 900 km trek, from France across the Iberian Peninsula to Santiago de Compostela and beyond to the Atlantic Ocean, reignited a passion in me for haiku. I committed to composing at least one poem per day as a practice of being present to the moments unfolding along the way.

I’m not the first to scribble haiku while sojourning through villages, cities, mountains, plains, and sacred sites. Beginning with Basho (his Narrow Road to a Far Province remains the classic haiku travelogue), many poets including Santoka, Ryokan, and Kerouac, have taken to the open road to wander lonely as clouds, sing songs of nature (and themselves), and return to inspire others to join in on the chorus.

I invite you, likewise, to heed the poet’s instinct to get outside to go within; to ramble with intent, to write, and to return from your journey renewed, perhaps even transformed. You don’t need to go to Santiago, Jerusalem, Stonehenge, Graceland, Burning Man, or Matsuyama to accomplish this. Even a walk to the corner store can be a pilgrimage if experienced with our haiku senses attuned. Through the wonders of technology, we can journey from the comforts of our home if a physical jaunt is not possible. And I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that perhaps the most fascinating journey – navigating our interior landscape – can happen while sitting quietly on our meditation cushion.

It may be true, as J.R.R. Tolkien attested that “not all who wander are lost,” but let’s have fun trying. Isn’t that the goal of both pilgrimage and art – to lose oneself utterly in the present moment? To experience the ineffable/transcendent/divine (pick your term), and at least try to transmute our experience through a creative medium like haiku?

Alright, enough talk! Let’s get out wandering and writing. I look forward to reading your poems about real, imagined, imminent, interrupted, or eventual journeys. May the wind be always at your back!

next week’s theme : Carpe Diem!

In Los Arcos, a week into my pilgrimage, and a day after the famed wine fountain at Irache, I paused at the cemetery on the edge of town to decipher an odd message written for all passersby. Inscribed over the gate of the burial ground was a proclamation by those who lived, toiled, and now rested in the earth of this old town.

As I watched fellow pilgrims walk past the inscription without as much as a glance, I was grateful for having seen it, and for Google’s ability to translate the message for me:

I once was what you are. You will be as I am.

A tingle shot up my spine; my brush with mortality in the Pyrenees still sending out aftershocks. I recalled an Ash Wednesday service I attended years ago, presided over by my clergy friend who first planted the idea of the Camino in me. Full of compassion, he looked into my eyes, loaded his thumb from a small bowl filled with palm ashes from the previous Easter, smudged a cross on my forehead, and spoke this strangely comforting blessing: “Remember, you are dust, and to dust you will return.”

I also thought of the Dead Poets Society and the fictional Professor Keating whispering to his students as they leaned in to view old photographs of deceased alumni: If you listen real close, you can hear them whisper their legacy to you… do you hear it? Carpe… carpe… carpe diem. Seize the day!

As we walk our own journeys this week, reflecting on the temporality of all things (including ourselves), let’s write a haiku/senryu inspired and encouraged by those gone before, by the great cloud of witnesses, by the communion of life. During this coming week of celebrating Halloween and All Souls, I look forward to your poems that seize the haiku moments within your day, considering the end we will all inevitably face (hopefully many more miles down the road).

The deadline is midnight Pacific Daylight Time, Saturday October 29, 2022.

Haiku Dialogue submission

- Name * First Last

- Place of Residence *

below is Peter’s commentary for obstacles and trials:

Friends, I’m playing hurt this week. Ironically, as our writing prompt recalls my last brush with mortality up in the French Pyrenees, I am now writing from a hospital bed. This has given me pause (again) to reflect on what is most important in my life journey. For that, I’m grateful. I’m staying positive and hopeful. In the meantime, your haiku submissions have been a tonic for me – a delightful diversion and sense of commiseration while waiting for the next steps.

Whether it was walking on thin ice, huddled in mountain caves, searching for sign posts buried in the snow, travelling to the roof of the world (the Himalayas), the English Channel, or the Australian outback, it wasn’t just my illness that took my breath away this week! I’ve picked out a handful of poems to comment on. Please share some of the heavy lifting and provide your own notes of appreciation for other fine haiku/senryu that speak to you in the selections.

A couple of housekeeping items before we dive in: Please remember to only submit two poems before the deadline per week. To honour the integrity of the submission process and to be fair to other poets, I will not select a poem if the poet has submitted more than the maximum limit of two. Hope that’s understandable. Another thing that would be really, really helpful for guest editors is for you to include your name and location underneath your poem(s) within the same cell that contains your poem. Even though the form asks for your name and location again in another cell, the happy result would mean one copy and paste instead of three, which adds up to a good chunk of time for the guest editor. Several of you are doing this already. Much appreciated!

Finally, while I covet your good vibes for my recovery (thank-you!), let’s keep the focus of our comments on the poems selected this week. There are some great ones, beginning with what follows.

Ultreia! Peter

looking beyond beyond Roberta Beach Jacobson Indianola, Iowa, USA

At first glance – and that’s all it took – this poem caught this “looker” like an image reflected in an infinity mirror. It’s fun, yet profound. For me, it raises the question: can we transcend our limited perspectives? Or can we let go of the desire to do so? Perhaps we’d be wise, as Antoine de Saint-Exupery once suggested, to close our eyes and open our hearts, which can “see” the essence of reality. Another way to view this poem (there are many) is to accept its implicit invitation to move past the question “is there life after death?” to a more important one. With the eyes of the heart opened, the question turns back around; reclaimed for the present moment: “Is there life before death?” As haiku poets, we know the answer to that question.

in the mud on the wrong side of the río one shoe Peggy Hale Bilbro Alabama

A single shoe in the mud on the banks of the Rio Bravo. Such powerful, evocative, and disturbing imagery! That said, it’s the phrase “wrong side” that haunts and keeps me coming back to this poem. Which side of the river is the “wrong” side? Can there be such a discrimination? Yes, unfortunately. If we follow some blow-hard politicians mischaracterizing their neighbours across the border, we may adopt an “us versus them” ideology that cages (literally sometimes) the other should they dare try to seek a better life on “our” side. From another perspective, the affluent, corporate-dominated, imperialistic, and domineering side of the divide may appear to be the “wrong side” for anyone with more compassionate, egalitarian, and inclusive values. Thankfully, Peggy doesn’t steer into didacticism but skillfully focuses the lens of the poem onto an image planted in the mud, a symbol of how entrenched we can be in nationalism instead of embracing our common humanity.

sundown the dog’s hips stuck in the squeeze stile simonj UK

Another trap! This time, as the day draws to a close, the poet describes “man’s best friend” stuck in a squeeze stile, the English invention farmers have used for centuries to allow humans to traverse boundaries while preventing livestock from doing the same. It’s not just human beings who encounter obstacles and trials along life’s path. The dog’s predicament freezes time for the reader as we’re left wondering if someone will save the poor pooch. The poem, with its liberal use of alliteration, assonance, and consonance, is euphonically pleasing. As is the freedom the dog in question experiences as we, the reader, finish the tale in the white space beyond the poem’s last syllable. It’s there that the poem takes a turn and man becomes the “dog’s best friend.”

closing my eyes to the memory balut ( balut = 18-day old incubated duck egg, eaten in the shell; street food in the Philippines) Jonathan Epstein USA

We expect to see haiku written in the present tense. In Jonathan’s delicious poem (the balut notwithstanding!), we meet someone in the present moment, closing their eyes. That’s all that’s happening here. Or is it? Whether the person’s at their writing desk, in transit on the subway, or pausing in front of a just-served balut in a Filipino restaurant in their American city, there’s a lot going on behind those eyelids! They transport back to another time, another place, another moment that, in recollection, becomes so perfectly present that we can taste it. They delight or cringe at the past, made present again through the superpower of imagination. As a vegan, I will not be ordering balut any day soon, but I’ll take a second helping of poems like this anytime!

monkey bite— I pretend Hanuman favors me Pippa Phillips Kansas City

Shit happens. Undeniably. A bird poops on your head, a car breaks down in the desert, a morning starts with coffee and Wordle and ends with half your ass hanging out of a hospital gown. A monkey may bite the hand that feeds. How to read this? How to read life? Why not mythologically, poetically, imaginatively? Pippa’s poem, alluding to the great Hindu Monkey King myth of Hanuman, invites us to reframe our maladies and misfortunes. What happens is often out of our control. Our response to what happens is up to us. Is it possible to see points of light in times of darkness? While I’d love to hear more of the subject’s encounter with a monkey, what I really need is a similar spirit of resilience to enliven my view of life’s obstacles and setbacks.

and here are the rest of the selections:

inside every heart the lonely traveler beside the wild lake Deborah Bennett Carbondale, Illinois USA 91st birthday climbing out of bed her Everest Nick T Somerset, UK repeat dream a leopard crouches low, leaps on a lowing calf Neera Kashyap Delhi, India weather forecast I pack my pilgrim bag I unpack my pilgrim bag Minal Sarosh Ahmedabad, India our luggage carrier saturated with cat piss Julie Bloss Kelsey Germantown, Maryland, USA hypertension as the red line picks up speed to the airport Srinivasa Rao Sambangi Hyderabad, India cancelled flight above the airport a flock of cranes Florin C. Ciobica Romania missed flight— breathless, I see the takeoff Neena Singh India meeting the One while stuck at the airport … changed route Natalia Kuznetsova Russia our lost tickets at the feet of Hermes Athens Airport Victor Ortiz Bellingham, WA TSA checkpoint stepping aside to air my dirty laundry Sharon Martina Warrenville, IL lost passport briefly freed from my karma Laurie Greer Washington, DC wrong train seeing another side of myself petro c. k. Seattle, Washington cruise of a lifetime in cabin lockdown Caroline Giles Banks Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA early morning bush walk clearing the cobwebs Carol Reynolds Australia road trip chatter turning out of the driveway we break down Marion Clarke Warrenpoint, Northern Ireland hard rain my mountain bike’s tyre exhales Ravi Kiran India mind the gap tripping and falling into the tube Nancy Brady Huron, Ohio Dover to Calais roll, pitch and heave ad nauseam Maxianne Berger Outremont, Quebec missing my bus the long, waterless, walk from Uluru Tracy Davidson Warwickshire, UK didgeridoo voice the wallet-less way home from the outback Richard L. Matta San Diego, California, USA growth strategy the great march forward leading backward John Hawkhead The Shambles, UK endless journey around the grindstone a blindfolded camel Ingrid Baluchi U.K./North Macedonia ramblers’ footpath I yield my right of way to the bull Ruth Holzer Herndon, Virginia the newborn’s discharge rescinded— incubator Stephen J. DeGuire Los Angeles, CA the son he imagined walks alongside the son that he has Colette Kern Southold, NY under the bridge never acknowledging the thin ice Lynne Jambor Vancouver BC Canada coyote call between the boulders my boot marilyn ashbaugh edwardsburg, michigan ancient forest bear and bear cub among the raspberries Stoianka Boianova Bulgaria detour – a field of wildflowers Dan Campbell Virginia beautiful the weeds in my garden Tiffany Shaw-Diaz United States dandelion through a crack loneliness escaping me Richa Sharma India songs of a thrush – ancestral messages from beyond Minko Tanev Bulgaria another uphill the rock in my shoe Lorraine A Padden San Diego, CA USA mountain climb I keep my balance with a selfie stick Maya Daneva The Netherlands halfway up the temple stairs . . . breathing meditation Kimberly Kuchar Austin, Texas wave of mist – climbing up from cloud to cloud Piyal Ranasinghe Colombo, Sri Lanka trudging up a crooked trail. . . the whole Himalayas Meera Rehm UK gravel mountain road flooring the supermini and praying Kerry J Heckman Seattle, WA Khardung La the next turn turns rain into snow (Khardung La is a mountain pass in the Leh district of Indian union territory of Ladakh. It is the highest motorable pass in the world.) Vandana Parashar India hairpin curves the illusion of new beginnings Daya Bhat India Koya mountain path in the blizzard barely visible signpost Teiichi Suzuki Japan pace of the wind I too change direction C.X.Turner United Kingdom stuck in the storm strangers telling each other their name Deborah Karl-Brandt Bonn, Germany mountain cave our embrace outlasts the snowstorm Subir Ningthouja Imphal, India camino pilgrims twisting in a cold wind… pink scallop shells Marilyn Ward Lincolnshire, UK mountain pilgrimage in my footsteps the questions I need to answer Stephen A. Peters Bellingham, WA stalemate the war with myself Tim Cremin Massachusetts walking in the fog I don’t get lost I’m already lost Luciana Moretto Treviso Italy seeking the big Buddha lost in the smog… Adele Evershed Wilton, Connecticut electrolyte deficit my wobble at high altitude Cynthia Anderson Yucca Valley, California slurred words I keep my own counsel Luciana Moretto Treviso Italy

Himalayan trek … he teaches us to climb down ……………………………. s …………………………. i ……………………. d ………………… e …………… w ………. a ….. y s Sushama Kapur India hitchhiker in a snowstorm the long night Richard Straw Cary, North Carolina arthritis— the haiku in my mind stays in my mind Mona Bedi Delhi, India withering winds… finally finding Ms. Right MD Keiko Izawa Japan side by side in the hotel in the hospital Maurice Nevile Canberra, Australia cut flowers – no one in his place on the return journey fiori recisi – nessuno al suo posto nel viaggio di ritorno Maria Teresa Piras Sardinia – Italy tenth wedding anniversary she takes off her ring Vicki Vogt Watertown, MA United States …………… ety …………….. ety bump ………. bump ………. long-haul Covid Valentina Ranaldi-Adams Fairlawn, Ohio USA glimpses of azure ocean from my bungalow porch covid iso Louise Hopewell Australia ocean voyage — waves lift and drop us in midnight’s black Pris Campbell U.S.A. baggage claim the wrong name on my suitcase Baisali Chatterjee Dutt Kolkata, India forgotten toothbrush our good morning air kiss Bryan Rickert Belleville, Illinois USA swim-up bar my underpants still flying elsewhere Alan Peat Biddulph, United Kingdom why can’t I go in? Buckingham Palace guards will not say a word Margie Gustafson Lombard, IL USA how lucky to find a waterside tent pitch — Alligator Lake (Arriving at night, we saw the warning sign only next morning) Keith Evetts Thames Ditton UK unprepared camper at the next site a bear eats his birthday cake Deborah P Kolodji Temple City, CA fear of heights left behind hot air balloons Geoff Pope Paducah, Kentucky windy riverside discovering a shrine between street arts Anna Yin Ontario, Canada retracing the path back home Hurricane Ophelia Lori Kiefer London UK the strait fills with fog no puffins today Susan Farner USA hearing aids— still can’t hear the rain pummeling the roof Terry Macrae Roseburg, OR, USA rising above negative self-talk erect lotus Amoolya Kamalnath India Cruz de Fierro the paraplegic on hands and knees (The Cruz de Fierro (cross of iron) on the Camino de Santiago is atop a large pile of stones that pilgrims have carried and deposited over the years as penance.) Helen Ogden Pacific Grove, CA climbing the last hill engine fire Pamela Jeanne Yukon, Canada overnight snow … in the silence nothing is certain Annie Wilson Shropshire, UK

Guest Editor P. H. Fischer (Peter) lives, works and plays in Vancouver, Canada, on the traditional, unceded territories of the Coast Salish peoples. He is the winner of the Vancouver category of the 2022 Haiku Invitational of the Vancouver Cherry Blossom Festival, and is grateful to see his poetry published in a growing list of haiku journals including The Heron’s Nest , Modern Haiku , Frogpond , Presence , First Frost , Whiptail , Kingfisher , Prune Juice , Haiku Canada Review and others. His top passions (besides family) are walking and writing haiku. If he could, he’d leave on another 900 km ginko today!

Lori Zajkowski is the Post Manager for Haiku Dialogue . A novice haiku poet, she lives in New York City.

Managing Editor Katherine Munro lives in Whitehorse, Yukon Territory, and publishes under the name kjmunro. She is Membership Secretary for Haiku Canada, and her debut poetry collection is contractions (Red Moon Press, 2019). Find her at: kjmunro1560.wordpress.com .

The Haiku Foundation reminds you that participation in our offerings assumes respectful and appropriate behavior from all parties. Please see our Code of Conduct policy .

Please note that all poems & images appearing in Haiku Dialogue may not be used elsewhere without express permission – copyright is retained by the creators. Please see our Copyright Policies .

This Post Has 31 Comments

Glad to hear you’re back home Peter. Prayers for a speedy recovery. With minimal access to the internet for the last week while traveling, I’ve been unable to make comments. So many great haiku submissions this week. Your introductions alone provide considerable inspiration. I’m enjoying this haiku journey with you. Thanks for including my airport debacle with TSA haiku.

Wow, Keith! Elephant at reception, lol. You should compile these stories in a book! :)

If I post a concrete haiku, will the formatting be lost in transit? Thank you for your reply.

Yes, most likely the submission form will not play nice with the special formatting. Please leave a note with formatting instructions. If needed, the team will connect with you to ensure proper formatting should the poem be selected. Hope this helps.

Good and speedy recovery, Peter!

Thank-you, Maria Teresa! :)

Thanks for including my haiku in this collection, Peter. I was struck by all the haiku, in particular, straight to the heart of Mona Bedi’s haiku.

arthritis— the haiku in my mind stays in my mind

It happens that physical difficulties prevent the expression of a thought. It evoked situations like this in me and involved me very much.

Peter, best wishes for a speedy recovery and thanks to all who contributed verses.

Thanks, Dan! :)

Thank you very much dear Peter Two Haiku of mine…so stunning?!? Never mind. Wednesday is a really exciting day, we can enjoy challenging prompts and masterly commentaries. Dear Peter I do hope you get well soon: all together we must resume our journey Thanks again Luciana Moretto

Oh my, Luciana! You’re very welcome. I enjoyed both of your poems but that was my mistake/oversight. I should have chosen only one, oops! I have been a bit off my game this week.

I am home from the hospital now and slowly recovering. Indeed, I’m still on the journey with all of you! Haiku Dialogue has been a welcome diversion for me. I am already enjoying this week’s submissions.

Thanks, Peter

don’t worry dear Peter, it’s all clear. A nice stroll and everything will be perfect. My warmest wishes

arthritis— the haiku in my mind stays in my mind / Mona Bedi Delhi, India / Arthritis happens to many people as they age. As the condition becomes more severe, more activities can no longer be performed. This haiku does a good job of describing this.

Thank-you P. H. for selecting mine. Best wishes on your recovery. Thank-you Kathy, Lori, and the Haiku Foundation

Welcome, Valentina! And thank-you for the well wishes. Like your poem, it’s been a bit bumpety bumpety but I’ve got good wheels to keep the cart rollin’ for now :)

I so enjoyed all of these, and there were so many that fed me humorously. But I wanted to highlight this favorite:

halfway up the temple stairs . . . breathing meditation

Kimberly Kuchar

As someone who has a terrible time with stairs and meditation, this one hit home. ?

My journey with Covid often leaves me breathless lately, too.

Sorry to read of your hospitalisation, Peter. Hope all will be well, soon. Housekeeping rules, my apologies.

Another delightful line-up of verses, congratulations to all poets.

early morning bush walk clearing the cobwebs – Carol Reynolds Australia

Not only clearing the cobwebs from the mind, but also the webs interlaced between plants. A lovely visual, Carol. I do try and avoid the cobwebs when out and about in the field, not always possible, though.

Thank you Carol. It seems we align not just with our names. This haiku has been waiting it’s opportunity on my list for a while. I am slowly realising the concept of less is more in my writing and rewriting some earlier ones. I am so enjoying Peter’s inspirational themes.

Thanks for the reply, Carol. And, a timely reminder to go look at verses I have stashed away and haven’t looked at for some time. Happy writing :)