What Is on Voyager’s Golden Record?

From a whale song to a kiss, the time capsule sent into space in 1977 had some interesting contents

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino

Senior Editor

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Voyager-records-631.jpg)

“I thought it was a brilliant idea from the beginning,” says Timothy Ferris. Produce a phonograph record containing the sounds and images of humankind and fling it out into the solar system.

By the 1970s, astronomers Carl Sagan and Frank Drake already had some experience with sending messages out into space. They had created two gold-anodized aluminum plaques that were affixed to the Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 spacecraft. Linda Salzman Sagan, an artist and Carl’s wife, etched an illustration onto them of a nude man and woman with an indication of the time and location of our civilization.

The “Golden Record” would be an upgrade to Pioneer’s plaques. Mounted on Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, twin probes launched in 1977, the two copies of the record would serve as time capsules and transmit much more information about life on Earth should extraterrestrials find it.

NASA approved the idea. So then it became a question of what should be on the record. What are humanity’s greatest hits? Curating the record’s contents was a gargantuan task, and one that fell to a team including the Sagans, Drake, author Ann Druyan, artist Jon Lomberg and Ferris, an esteemed science writer who was a friend of Sagan’s and a contributing editor to Rolling Stone .

The exercise, says Ferris, involved a considerable number of presuppositions about what aliens want to know about us and how they might interpret our selections. “I found myself increasingly playing the role of extraterrestrial,” recounts Lomberg in Murmurs of Earth , a 1978 book on the making of the record. When considering photographs to include, the panel was careful to try to eliminate those that could be misconstrued. Though war is a reality of human existence, images of it might send an aggressive message when the record was intended as a friendly gesture. The team veered from politics and religion in its efforts to be as inclusive as possible given a limited amount of space.

Over the course of ten months, a solid outline emerged. The Golden Record consists of 115 analog-encoded photographs, greetings in 55 languages, a 12-minute montage of sounds on Earth and 90 minutes of music. As producer of the record, Ferris was involved in each of its sections in some way. But his largest role was in selecting the musical tracks. “There are a thousand worthy pieces of music in the world for every one that is on the record,” says Ferris. I imagine the same could be said for the photographs and snippets of sounds.

The following is a selection of items on the record:

Silhouette of a Male and a Pregnant Female

The team felt it was important to convey information about human anatomy and culled diagrams from the 1978 edition of The World Book Encyclopedia. To explain reproduction, NASA approved a drawing of the human sex organs and images chronicling conception to birth. Photographer Wayne F. Miller’s famous photograph of his son’s birth, featured in Edward Steichen’s 1955 “Family of Man” exhibition, was used to depict childbirth. But as Lomberg notes in Murmurs of Earth , NASA vetoed a nude photograph of “a man and a pregnant woman quite unerotically holding hands.” The Golden Record experts and NASA struck a compromise that was less compromising— silhouettes of the two figures and the fetus positioned within the woman’s womb.

DNA Structure

At the risk of providing extraterrestrials, whose genetic material might well also be stored in DNA, with information they already knew, the experts mapped out DNA’s complex structure in a series of illustrations.

Demonstration of Eating, Licking and Drinking

When producers had trouble locating a specific image in picture libraries maintained by the National Geographic Society, the United Nations, NASA and Sports Illustrated , they composed their own. To show a mouth’s functions, for instance, they staged an odd but informative photograph of a woman licking an ice-cream cone, a man taking a bite out of a sandwich and a man drinking water cascading from a jug.

Olympic Sprinters

Images were selected for the record based not on aesthetics but on the amount of information they conveyed and the clarity with which they did so. It might seem strange, given the constraints on space, that a photograph of Olympic sprinters racing on a track made the cut. But the photograph shows various races of humans, the musculature of the human leg and a form of both competition and entertainment.

Photographs of huts, houses and cityscapes give an overview of the types of buildings seen on Earth. The Taj Mahal was chosen as an example of the more impressive architecture. The majestic mausoleum prevailed over cathedrals, Mayan pyramids and other structures in part because Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan built it in honor of his late wife, Mumtaz Mahal, and not a god.

Golden Gate Bridge

Three-quarters of the record was devoted to music, so visual art was less of a priority. A couple of photographs by the legendary landscape photographer Ansel Adams were selected, however, for the details captured within their frames. One, of the Golden Gate Bridge from nearby Baker Beach, was thought to clearly show how a suspension bridge connected two pieces of land separated by water. The hum of an automobile was included in the record’s sound montage, but the producers were not able to overlay the sounds and images.

A Page from a Book

An excerpt from a book would give extraterrestrials a glimpse of our written language, but deciding on a book and then a single page within that book was a massive task. For inspiration, Lomberg perused rare books, including a first-folio Shakespeare, an elaborate edition of Chaucer from the Renaissance and a centuries-old copy of Euclid’s Elements (on geometry), at the Cornell University Library. Ultimately, he took MIT astrophysicist Philip Morrison’s suggestion: a page from Sir Isaac Newton’s System of the World , where the means of launching an object into orbit is described for the very first time.

Greeting from Nick Sagan

To keep with the spirit of the project, says Ferris, the wordings of the 55 greetings were left up to the speakers of the languages. In Burmese , the message was a simple, “Are you well?” In Indonesian , it was, “Good night ladies and gentlemen. Goodbye and see you next time.” A woman speaking the Chinese dialect of Amoy uttered a welcoming, “Friends of space, how are you all? Have you eaten yet? Come visit us if you have time.” It is interesting to note that the final greeting, in English , came from then-6-year-old Nick Sagan, son of Carl and Linda Salzman Sagan. He said, “Hello from the children of planet Earth.”

Whale Greeting

Biologist Roger Payne provided a whale song (“the most beautiful whale greeting,” he said, and “the one that should last forever”) captured with hydrophones off the coast of Bermuda in 1970. Thinking that perhaps the whale song might make more sense to aliens than to humans, Ferris wanted to include more than a slice and so mixed some of the song behind the greetings in different languages. “That strikes some people as hilarious, but from a bandwidth standpoint, it worked quite well,” says Ferris. “It doesn’t interfere with the greetings, and if you are interested in the whale song, you can extract it.”

Reportedly, the trickiest sound to record was a kiss . Some were too quiet, others too loud, and at least one was too disingenuous for the team’s liking. Music producer Jimmy Iovine kissed his arm. In the end, the kiss that landed on the record was actually one that Ferris planted on Ann Druyan’s cheek.

Druyan had the idea to record a person’s brain waves, so that should extraterrestrials millions of years into the future have the technology, they could decode the individual’s thoughts. She was the guinea pig. In an hour-long session hooked to an EEG at New York University Medical Center, Druyan meditated on a series of prepared thoughts. In Murmurs of Earth , she admits that “a couple of irrepressible facts of my own life” slipped in. She and Carl Sagan had gotten engaged just days before, so a love story may very well be documented in her neurological signs. Compressed into a minute-long segment, the brain waves sound, writes Druyan, like a “string of exploding firecrackers.”

Georgian Chorus—“Tchakrulo”

The team discovered a beautiful recording of “Tchakrulo” by Radio Moscow and wanted to include it, particularly since Georgians are often credited with introducing polyphony, or music with two or more independent melodies, to the Western world. But before the team members signed off on the tune, they had the lyrics translated. “It was an old song, and for all we knew could have celebrated bear-baiting,” wrote Ferris in Murmurs of Earth . Sandro Baratheli, a Georgian speaker from Queens, came to the rescue. The word “tchakrulo” can mean either “bound up” or “hard” and “tough,” and the song’s narrative is about a peasant protest against a landowner.

Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode”

According to Ferris, Carl Sagan had to warm up to the idea of including Chuck Berry’s 1958 hit “Johnny B. Goode” on the record, but once he did, he defended it against others’ objections. Folklorist Alan Lomax was against it, arguing that rock music was adolescent. “And Carl’s brilliant response was, ‘There are a lot of adolescents on the planet,’” recalls Ferris.

On April 22, 1978, Saturday Night Live spoofed the Golden Record in a skit called “Next Week in Review.” Host Steve Martin played a psychic named Cocuwa, who predicted that Time magazine would reveal, on the following week’s cover, a four-word message from aliens. He held up a mock cover, which read, “Send More Chuck Berry.”

More than four decades later, Ferris has no regrets about what the team did or did not include on the record. “It means a lot to have had your hand in something that is going to last a billion years,” he says. “I recommend it to everybody. It is a healthy way of looking at the world.”

According to the writer, NASA approached him about producing another record but he declined. “I think we did a good job once, and it is better to let someone else take a shot,” he says.

So, what would you put on a record if one were being sent into space today?

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino | | READ MORE

Megan Gambino is a senior web editor for Smithsonian magazine.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How the Voyager Golden Record Was Made

By Timothy Ferris

We inhabit a small planet orbiting a medium-sized star about two-thirds of the way out from the center of the Milky Way galaxy—around where Track 2 on an LP record might begin. In cosmic terms, we are tiny: were the galaxy the size of a typical LP, the sun and all its planets would fit inside an atom’s width. Yet there is something in us so expansive that, four decades ago, we made a time capsule full of music and photographs from Earth and flung it out into the universe. Indeed, we made two of them.

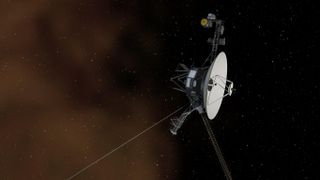

The time capsules, really a pair of phonograph records, were launched aboard the twin Voyager space probes in August and September of 1977. The craft spent thirteen years reconnoitering the sun’s outer planets, beaming back valuable data and images of incomparable beauty . In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first human-made object to leave the solar system, sailing through the doldrums where the stream of charged particles from our sun stalls against those of interstellar space. Today, the probes are so distant that their radio signals, travelling at the speed of light, take more than fifteen hours to reach Earth. They arrive with a strength of under a millionth of a billionth of a watt, so weak that the three dish antennas of the Deep Space Network’s interplanetary tracking system (in California, Spain, and Australia) had to be enlarged to stay in touch with them.

If you perched on Voyager 1 now—which would be possible, if uncomfortable; the spidery craft is about the size and mass of a subcompact car—you’d have no sense of motion. The brightest star in sight would be our sun, a glowing point of light below Orion’s foot, with Earth a dim blue dot lost in its glare. Remain patiently onboard for millions of years, and you’d notice that the positions of a few relatively nearby stars were slowly changing, but that would be about it. You’d find, in short, that you were not so much flying to the stars as swimming among them.

The Voyagers’ scientific mission will end when their plutonium-238 thermoelectric power generators fail, around the year 2030. After that, the two craft will drift endlessly among the stars of our galaxy—unless someone or something encounters them someday. With this prospect in mind, each was fitted with a copy of what has come to be called the Golden Record. Etched in copper, plated with gold, and sealed in aluminum cases, the records are expected to remain intelligible for more than a billion years, making them the longest-lasting objects ever crafted by human hands. We don’t know enough about extraterrestrial life, if it even exists, to state with any confidence whether the records will ever be found. They were a gift, proffered without hope of return.

I became friends with Carl Sagan, the astronomer who oversaw the creation of the Golden Record, in 1972. He’d sometimes stop by my place in New York, a high-ceilinged West Side apartment perched up amid Norway maples like a tree house, and we’d listen to records. Lots of great music was being released in those days, and there was something fascinating about LP technology itself. A diamond danced along the undulations of a groove, vibrating an attached crystal, which generated a flow of electricity that was amplified and sent to the speakers. At no point in this process was it possible to say with assurance just how much information the record contained or how accurately a given stereo had translated it. The open-endedness of the medium seemed akin to the process of scientific exploration: there was always more to learn.

In the winter of 1976, Carl was visiting with me and my fiancée at the time, Ann Druyan, and asked whether we’d help him create a plaque or something of the sort for Voyager. We immediately agreed. Soon, he and one of his colleagues at Cornell, Frank Drake, had decided on a record. By the time NASA approved the idea, we had less than six months to put it together, so we had to move fast. Ann began gathering material for a sonic description of Earth’s history. Linda Salzman Sagan, Carl’s wife at the time, went to work recording samples of human voices speaking in many different languages. The space artist Jon Lomberg rounded up photographs, a method having been found to encode them into the record’s grooves. I produced the record, which meant overseeing the technical side of things. We all worked on selecting the music.

I sought to recruit John Lennon, of the Beatles, for the project, but tax considerations obliged him to leave the country. Lennon did help us, though, in two ways. First, he recommended that we use his engineer, Jimmy Iovine, who brought energy and expertise to the studio. (Jimmy later became famous as a rock and hip-hop producer and record-company executive.) Second, Lennon’s trick of etching little messages into the blank spaces between the takeout grooves at the ends of his records inspired me to do the same on Voyager. I wrote a dedication: “To the makers of music—all worlds, all times.”

To our surprise, those nine words created a problem at NASA . An agency compliance officer, charged with making sure each of the probes’ sixty-five thousand parts were up to spec, reported that while everything else checked out—the records’ size, weight, composition, and magnetic properties—there was nothing in the blueprints about an inscription. The records were rejected, and NASA prepared to substitute blank discs in their place. Only after Carl appealed to the NASA administrator, arguing that the inscription would be the sole example of human handwriting aboard, did we get a waiver permitting the records to fly.

In those days, we had to obtain physical copies of every recording we hoped to listen to or include. This wasn’t such a challenge for, say, mainstream American music, but we aimed to cast a wide net, incorporating selections from places as disparate as Australia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, China, Congo, Japan, the Navajo Nation, Peru, and the Solomon Islands. Ann found an LP containing the Indian raga “Jaat Kahan Ho” in a carton under a card table in the back of an appliance store. At one point, the folklorist Alan Lomax pulled a Russian recording, said to be the sole copy of “Chakrulo” in North America, from a stack of lacquer demos and sailed it across the room to me like a Frisbee. We’d comb through all this music individually, then meet and go over our nominees in long discussions stretching into the night. It was exhausting, involving, utterly delightful work.

“Bhairavi: Jaat Kahan Ho,” by Kesarbai Kerkar

In selecting Western classical music, we sacrificed a measure of diversity to include three compositions by J. S. Bach and two by Ludwig van Beethoven. To understand why we did this, imagine that the record were being studied by extraterrestrials who lacked what we would call hearing, or whose hearing operated in a different frequency range than ours, or who hadn’t any musical tradition at all. Even they could learn from the music by applying mathematics, which really does seem to be the universal language that music is sometimes said to be. They’d look for symmetries—repetitions, inversions, mirror images, and other self-similarities—within or between compositions. We sought to facilitate the process by proffering Bach, whose works are full of symmetry, and Beethoven, who championed Bach’s music and borrowed from it.

I’m often asked whether we quarrelled over the selections. We didn’t, really; it was all quite civil. With a world full of music to choose from, there was little reason to protest if one wonderful track was replaced by another wonderful track. I recall championing Blind Willie Johnson’s “Dark Was the Night,” which, if memory serves, everyone liked from the outset. Ann stumped for Chuck Berry’s “ Johnny B. Goode ,” a somewhat harder sell, in that Carl, at first listening, called it “awful.” But Carl soon came around on that one, going so far as to politely remind Lomax, who derided Berry’s music as “adolescent,” that Earth is home to many adolescents. Rumors to the contrary, we did not strive to include the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun,” only to be disappointed when we couldn’t clear the rights. It’s not the Beatles’ strongest work, and the witticism of the title, if charming in the short run, seemed unlikely to remain funny for a billion years.

“Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground,” by Blind Willie Johnson

Ann’s sequence of natural sounds was organized chronologically, as an audio history of our planet, and compressed logarithmically so that the human story wouldn’t be limited to a little beep at the end. We mixed it on a thirty-two-track analog tape recorder the size of a steamer trunk, a process so involved that Jimmy jokingly accused me of being “one of those guys who has to use every piece of equipment in the studio.” With computerized boards still in the offing, the sequence’s dozens of tracks had to be mixed manually. Four of us huddled over the board like battlefield surgeons, struggling to keep our arms from getting tangled as we rode the faders by hand and got it done on the fly.

The sequence begins with an audio realization of the “music of the spheres,” in which the constantly changing orbital velocities of Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, and Jupiter are translated into sound, using equations derived by the astronomer Johannes Kepler in the sixteenth century. We then hear the volcanoes, earthquakes, thunderstorms, and bubbling mud of the early Earth. Wind, rain, and surf announce the advent of oceans, followed by living creatures—crickets, frogs, birds, chimpanzees, wolves—and the footsteps, heartbeats, and laughter of early humans. Sounds of fire, speech, tools, and the calls of wild dogs mark important steps in our species’ advancement, and Morse code announces the dawn of modern communications. (The message being transmitted is Ad astra per aspera , “To the stars through hard work.”) A brief sequence on modes of transportation runs from ships to jet airplanes to the launch of a Saturn V rocket. The final sounds begin with a kiss, then a mother and child, then an EEG recording of (Ann’s) brainwaves, and, finally, a pulsar—a rapidly spinning neutron star giving off radio noise—in a tip of the hat to the pulsar map etched into the records’ protective cases.

“The Sounds of Earth”

Ann had obtained beautiful recordings of whale songs, made with trailing hydrophones by the biologist Roger Payne, which didn’t fit into our rather anthropocentric sounds sequence. We also had a collection of loquacious greetings from United Nations representatives, edited down and cross-faded to make them more listenable. Rather than pass up the whales, I mixed them in with the diplomats. I’ll leave it to the extraterrestrials to decide which species they prefer.

“United Nations Greetings/Whale Songs”

Those of us who were involved in making the Golden Record assumed that it would soon be commercially released, but that didn’t happen. Carl repeatedly tried to get labels interested in the project, only to run afoul of what he termed, in a letter to me dated September 6, 1990, “internecine warfare in the record industry.” As a result, nobody heard the thing properly for nearly four decades. (Much of what was heard, on Internet snippets and in a short-lived commercial CD release made in 1992 without my participation, came from a set of analog tape dubs that I’d distributed to our team as keepsakes.) Then, in 2016, a former student of mine, David Pescovitz, and one of his colleagues, Tim Daly, approached me about putting together a reissue. They secured funding on Kickstarter , raising more than a million dollars in less than a month, and by that December we were back in the studio, ready to press play on the master tape for the first time since 1977.

Pescovitz and Daly took the trouble to contact artists who were represented on the record and send them what amounted to letters of authenticity—something we never had time to accomplish with the original project. (We disbanded soon after I delivered the metal master to Los Angeles, making ours a proud example of a federal project that evaporated once its mission was accomplished.) They also identified and corrected errors and omissions in the information that was provided to us by recordists and record companies. Track 3, for instance, which was listed by Lomax as “Senegal Percussion,” turns out instead to have been recorded in Benin and titled “Cengunmé”; and Track 24, the Navajo night chant, now carries the performers’ names. Forty years after launch, the Golden Record is finally being made available here on Earth. Were Carl alive today—he died in 1996 at the age of sixty-two—I think he’d be delighted.

This essay was adapted from the liner notes for the new edition of the Voyager Golden Record, recently released as a vinyl boxed set by Ozma Records .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Anthony Lydgate

By John McPhee

By Richard Brody

- Become A Member

- Gift Membership

- Kids Membership

- Other Ways to Give

- Explore Worlds

- Defend Earth

How We Work

- Education & Public Outreach

- Space Policy & Advocacy

- Science & Technology

- Global Collaboration

Our Results

Learn how our members and community are changing the worlds.

Our citizen-funded spacecraft successfully demonstrated solar sailing for CubeSats.

Space Topics

- Planets & Other Worlds

- Space Missions

- Space Policy

- Planetary Radio

- Space Images

The Planetary Report

The eclipse issue.

Science and splendor under the shadow.

Get Involved

Membership programs for explorers of all ages.

Get updates and weekly tools to learn, share, and advocate for space exploration.

Volunteer as a space advocate.

Support Our Mission

- Renew Membership

- Society Projects

The Planetary Fund

Accelerate progress in our three core enterprises — Explore Worlds, Find Life, and Defend Earth. You can support the entire fund, or designate a core enterprise of your choice.

- Strategic Framework

- News & Press

The Planetary Society

Know the cosmos and our place within it.

Our Mission

Empowering the world's citizens to advance space science and exploration.

- Explore Space

- Take Action

- Member Community

- Account Center

- “Exploration is in our nature.” - Carl Sagan

The Voyager Golden Record

For full functionality of this site it is necessary to enable JavaScript. Here are instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your web browser .

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Voyager Golden Record Finally Finds An Earthly Audience

Alexi Horowitz-Ghazi

The Voyager Golden Record remained mostly unavailable and unheard, until a Kickstarter campaign finally brought the sounds to human ears. Ozma Records/LADdesign hide caption

The Voyager Golden Record remained mostly unavailable and unheard, until a Kickstarter campaign finally brought the sounds to human ears.

The Golden Record is basically a 90-minute interstellar mixtape — a message of goodwill from the people of Earth to any extraterrestrial passersby who might stumble upon one of the two Voyager spaceships at some point over the next couple billion years.

But since it was made 40 years ago, the sounds etched into those golden grooves have gone mostly unheard, by alien audiences or those closer to home.

"The Voyager records are the farthest flung objects that humans have ever created," says Timothy Ferris, a veteran science and music journalist and the producer of the Golden Record. "And they're likely to be the longest lasting, at least in the 20th century."

In the late 1970s, Ferris was recruited by his friend, astronomer Carl Sagan, to join a team of scientists, artists and engineers to help create two engraved golden records to accompany NASA's Voyager mission — which would eventually send a pair of human spacecraft beyond the outer rings of the solar system for the first time in history.

Carl Sagan And Ann Druyan's Ultimate Mix Tape

Ferris was tasked with the technical aspects of getting the various media onto the physical LP, and with helping to select the music. In addition to greetings in dozens of languages and messages from leading statesmen, the records also contained a sonic history of planet Earth and photographs encoded into the record's grooves. But mostly, it was music.

"We were gathering a representation of the music of the entire earth," Ferris says. "That's an incredible wealth of great stuff."

Ferris and his colleagues worked together to sift through Earth's enormous discography to decide which pieces of sound would best represent our planet. They really only had two criteria: "One was: Let's cast a wide net. Let's try to get music from all over the planet," he says. "And secondly: Let's make a good record."

That meant late nights of listening sessions while "almost physically drowning in records," Ferris says.

The final selection, which was engraved in copper and plated in gold, included opera, rock 'n' roll, blues, classical music and field recordings selected by ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax .

When Voyager 1 and its identical sister craft Voyager 2 launched in 1977, each carried a gold record titled T he Sounds Of Earth that contained a selection of recordings of life and culture on Earth. The cover contains instructions for any extraterrestrial being wishing to play the record. NASA/Getty Images hide caption

When Voyager 1 and its identical sister craft Voyager 2 launched in 1977, each carried a gold record titled T he Sounds Of Earth that contained a selection of recordings of life and culture on Earth. The cover contains instructions for any extraterrestrial being wishing to play the record.

Ferris says that from the very start, many people on the production team expected and hoped for the record to be commercially released soon after the launch of Voyager.

"Carl Sagan tried to interest labels in releasing Voyager," Ferris says. "It never worked."

Ferris says that's likely because the music rights were owned by several different record labels who were hesitant to share the bill. So — except for a limited CD-ROM release in the early 1990s — the record went largely unheard by the wider world.

David Pescovitz, an editor at technology news website Boing Boing and a research director at the nonprofit Institute for the Future, was seven years old when the Voyager spacecraft launched.

"When you're seven years old and you hear that a group of people created a phonograph record as a message for possible extraterrestrials and launched it on a grand tour of the solar system," says Pescovitz, "it sparks the imagination."

A couple years ago, Pescovitz and his friend Tim Daly, a record store manager at Amoeba Music in San Francisco, decided to collaborate on bringing the Golden Record to an earthbound audience.

Pescovitz approached his former graduate school professor — none other than Ferris, the Golden Record's original producer — about the project, and Ferris gave his blessing, with one important caveat.

Voyagers' Records Wait for Alien Ears

"You can't release a record without remastering it," says Ferris. "And you can't remaster without locating the master."

That turned out to be a taller order than expected. The original records were mastered in a CBS studio, which was later acquired by Sony — and the master tapes had descended into Sony's vaults.

Pescovitz enlisted the company's help in searching for the master tapes; in the meantime, he and Daly got to work acquiring the rights for the music and photographs that comprised the original. They also reached out to surviving musicians whose work had been featured on the record to update incomplete track information.

Finally, Pescovitz and Daly got word that one of Sony's archivists had found the master tapes.

Pescovitz remembers the moment he, Daly and Ferris traveled to Sony's Battery Studios in New York City to hear the tapes for the first time.

"They hit play, and the sounds of the Solomon Islands pan pipes and Bach and Chuck Berry and the blues washed over us," Pescovitz says. "It was a very moving and sublime experience."

Daly says that, in remastering the album, the team decided not to clean up the analog artifacts that had made their way onto the original master tapes, in order to preserve the record's authenticity down to its imperfections.

"We wanted it to be a true representation of what went up," Daly says.

Pescovitz and Daly teamed up with Lawrence Azerrad, a graphic designer who has made record packaging for the likes of Sting and Wilco , to design a luxuriant box set, complete with a coffee table book of photographs and, of course, tinted vinyl.

"I mean, if you do a golden record box set, you have to do it on gold vinyl," Daly says.

They put the project on Kickstarter and expected to sell it mostly to vinyl collectors, space nerds and audiophiles — but they underestimated the appeal.

"The internet was just on fire, talking about this thing," Daly says.

They blew past their initial funding goal in two days, eventually raising more than $1.3 million dollars, making it the most successful musical Kickstarter campaign ever. Among the initial 11,000 contributors were family members of NASA's original Voyager mission team.

An Alien View Of Earth

Last week, Ferris got his box set in the mail. He says that his friend, the late Carl Sagan, would be delighted by what they made.

"I think this record exceeds Carl's — not only his expectations, but probably his highest hopes for a release of the Voyager record," Ferris says. "I'm glad these folks were finally able to make it happen."

Pescovitz says he's just glad to have returned the Golden Record to the world that created it.

At a moment of political division and media oversaturation, Pescovitz and Daly say they hope that their Golden Record can offer a chance for people to slow down for a moment; to gather around the turntable and bask in the crackly sounds of what Sagan called the "pale blue dot" that we call home.

"As much as it was a gift from humanity to the cosmos, it was really a gift to humanity as well," Pescovitz says. "It's a reminder of what we can accomplish when we're at our best."

The 116 photos NASA picked to explain our world to aliens

by Joss Fong

If any intelligent life in our galaxy intercepts the Voyager spacecraft, if they evolved the sense of vision, and if they can decode the instructions provided, these 116 images are all they will know about our species and our planet, which by then could be long gone:

When Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 launched into space in 1977, their mission was to explore the outer solar system, and over the following decade, they did so admirably.

With an 8-track tape memory system and onboard computers that are thousands of times weaker than the phone in your pocket, the two spacecraft sent back an immense amount of imagery and information about the four gas giants, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

But NASA knew that after the planetary tour was complete, the Voyagers would remain on a trajectory toward interstellar space, having gained enough velocity from Jupiter's gravity to eventually escape the grasp of the sun. Since they will orbit the Milky Way for the foreseeable future, the Voyagers should carry a message from their maker, NASA scientists decided.

The Voyager team tapped famous astronomer and science popularizer Carl Sagan to compose that message. Sagan's committee chose a copper phonograph LP as their medium, and over the course of six weeks they produced the "Golden Record": a collection of sounds and images that will probably outlast all human artifacts on Earth.

How would aliens know what to do with the Golden Record?

The records are mounted on the outside of Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 and protected by an aluminum case. Etched on the cover of that case are symbols explaining how to decode the record. Put yourself in an extraterrestrial's shoes and try to guess what the etchings seek to communicate. Stumped? Hover over or click on the yellow circles for the intended meaning of these interstellar brain teasers:

What else is on the Golden Record?

Any aliens who come across the Golden Record are in for a treat. It contains:

- 116 images encoded in analog form depicting scientific knowledge, human anatomy, human endeavors, and the terrestrial environment. (These images appear in color in the video above, but on the record, all but 20 are black and white.)

- Spoken greetings in more than 50 languages.

- A compilation of sounds from Earth.

- Nearly 90 minutes of music from around the world. Notably missing are the Beatles, who reportedly wanted to contribute "Here Comes the Sun" but couldn't secure permission from their record company. For the video above, I chose to include "Dark Was the Night" by Blind Willie Johnson, a 1927 track Sagan described as "haunting and expressive of a kind of cosmic loneliness."

The committee also made space for a message from the president of the United States:

Where are they now?

Incredibly, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are still communicating with Earth — they aren't expected to lose power until the 2020s. That's how NASA knew that Voyager 1 became the first ever spacecraft to enter interstellar space in 2012: The probe detected high-density plasma characteristic of the space beyond the heliosphere (the bubble of solar wind created by the sun).

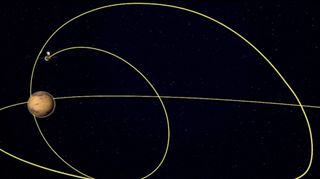

Voyager 2 is currently traveling through the outer layers of the heliosphere. It's moving southward relative to Earth's orbit, while Voyager 1 is moving northward. In more than 40,000 years, they will each pass closer to another star than they are to our sun. (Or, more accurately, stars will pass by them).

There are three other spacecraft headed toward interstellar space; two of them, Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11, are shown in this somewhat dated illustration:

NASA launched Pioneer 10 and 11 in 1972 and 1973, and has since lost communication with both. They aren't traveling as fast as the Voyagers, but they will eventually enter interstellar space as well.

They too, carry a message for extraterrestrial life, in the form of a 6-by-9-inch gold-anodized aluminum plaque, designed by Sagan and other members of the team that would go on to create the Voyager Golden Record five years later.

Like the Golden Record, the plaque features the pulsar map, uses hydrogen to define the binary units, and depicts humankind. NASA faced a backlash for the nudity of the human figures.

Another interstellar message

The fifth probe that will exit our solar system is New Horizons , the spacecraft that flew by Pluto in 2015. It is headed in a broadly similar direction as Voyager 2, but having launched in 2006, it's many years behind. It may not reach interstellar space for another 30 years.

New Horizons was sent into space without any message like the Golden Record, but it's not too late to add one. A group led by Jon Lomberg , a member of Sagan's Golden Record team, is trying to convince NASA to upload a crowdsourced message to the probe for any intelligent life that might come across it.

The spacecraft's memory system is similar to a flash drive, and it wouldn't be as durable as the copper records on Voyager. "The most conservative estimates are a lifetime of a few decades. Other physicists and engineers believe the message might remain for centuries or even millennia," says the website of the message initiative, adding, more hopefully, "Another unknown is the advanced technology possessed by any ETs who find the spacecraft. They might have ways of reading the faded memory we cannot yet imagine."

Most Popular

What to know about claudia sheinbaum, mexico’s likely next president, the best — and worst — criticisms of trump’s conviction, take a mental break with the newest vox crossword, billie eilish vs. taylor swift: is the feud real who’s dissing who, what trump really thinks about the war in gaza, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Video

How screens actually affect your sleep

Why can’t prices just stay the same?

Why does this forest look like a fingerprint?

How AI tells Israel who to bomb

Should humans get their own geologic era?

You need $500. How should you get it?

This changed everything

10 big things we think will happen in the next 10 years

Serial transformed true crime — and the way we think about criminal justice

The “racial reckoning” of 2020 set off an entirely new kind of backlash

The overlooked conflict that altered the nature of war in the 21st century

The last 10 years, explained

Scientists' predictions for the long-term future of the Voyager Golden Records will blow your mind

Buckle up, everyone, and let's take a ride on a universe-size time machine.

The future is a slippery thing, but sometimes physics can help. And while human destiny will remain ever unknown, the fate of two of our artifacts can be calculated in staggering detail.

Those artifacts are the engraved "Golden Records" strapped to NASA's twin Voyager spacecraft , which have passed into interstellar space. Although the spacecraft will likely fall silent in a few years, the records will remain. Nick Oberg, a doctoral candidate at the Kapteyn Astronomical Institute in the Netherlands, and a colleague wanted to calculate which (if any) stars the two Voyager spacecraft may encounter in the long future of our galaxy.

But the models let them forecast much, much farther into the future. Oberg presented their work at the 237th meeting of the American Astronomical Society , held virtually due to the coronavirus pandemic, on Jan. 12, where he spun a tale of the long future of the twin Voyagers and their Golden Records.

Related: Pale Blue Dot at 30: Voyager 1's iconic photo of Earth from space reveals our place in the universe

NASA launched Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 in 1977 to trek across the solar system. On each was a 12-inch (30 centimeters) large gold-plated copper disk. The brainchild of famed astronomer Carl Sagan, the Golden Records were engraved with music and photographs meant to represent Earth and its humans to any intelligent beings the spacecraft meet on their long journeys. Both spacecraft visited Jupiter and Saturn, then the twins parted ways: Voyager 1 studied Saturn's moon Titan while Voyager 2 swung past Uranus and Neptune.

In 2012, Voyager 1 passed through the heliopause that marks the edge of the sun's solar wind and entered interstellar space; in 2018, Voyager 2 did so as well. Now, the two spacecraft are chugging through the vast outer reaches of the solar system. They continue to send signals back to Earth, updating humans about their adventures far beyond the planets, although those bulletins may cease in a few years, as the spacecraft are both running low on power .

But their journeys are far from over.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Oberg and his colleague combined tracking the Voyagers' trajectories forward with studying the environments the spacecraft will fly through to estimate the odds of the Golden Records surviving their adventures while remaining legible. The result is a forecast that stretches beyond not just humanity's likely extinction, but also beyond the collision of the Milky Way with the neighboring Andromeda galaxy — beyond even the extinction of most stars.

Related: The Golden Record in pictures: Voyager probes' message to space explained

Milky Way sightseein

Unsurprisingly, the duo's research ambitions didn't start out quite so vast. The new research was inspired by the release of the second batch of data from the European Space Agency's spacecraft Gaia , which specializes in mapping more than a billion stars super precisely.

"Our original goal was to determine with a very high precision which stars the Voyagers might one day closely encounter using the at the time newly released Gaia catalog of stars," Oberg said during his presentation. So he and his co-author began by tracing the Voyagers' journeys to date and projecting their trajectories out into the future.

But don't get excited for any upcoming milestones. Not until about 20,000 years from now will the Voyagers pass through the Oort cloud — the shell of comets and icy rubble that orbits the sun at a distance of up to 100,000 astronomical units, or 100,000 times the average Earth-sun distance — finally waving goodbye to its solar system of origin.

"At that point for the first time the craft will begin to feel the gravitational pull of other stars more strongly than that of our own sun," Oberg said.

It's another 10,000 years before the spacecraft actually come near an alien star, specifically a red dwarf star called Ross 248. That flyby will occur about 30,000 years from now, Oberg said, although it might be a stretch to say that the spacecraft will pass by that star. "It's actually more like Ross 248 shooting past the nearly stationary Voyagers," he said.

By 500 million years from now, the solar system and the Voyagers alike will complete a full orbit through the Milky Way. There's no way to predict what will have happened on Earth's surface by then, but it's a timespan on the scale of the formation and destruction of Pangaea and other supercontinents, Oberg said.

Throughout this galactic orbit, the Voyager spacecraft will oscillate up and down, with Voyager 1 doing so more dramatically than its twin. According to these models, Voyager 1 will travel so far above the main disk of the galaxy that it will see stars at just half the density as we do.

Odds of destruction

The same difference in vertical motion will also shape the differing odds each spacecraft's Golden Record has of survival.

The records were designed to last, meant to survive perhaps a billion years in space : beneath the golden sheen is a protective aluminum casing and, below that, the engraved copper disks themselves. But to truly understand how long these objects may survive, you have to know what conditions they'll experience, and that means knowing where they will be.

Specifically, Oberg and his colleague needed to know how much time the spacecraft would spend swathed in the Milky Way's vast clouds of interstellar dust , which he called "one of the few phenomena that could actually act to damage the spacecraft."

It's a grim scenario, dust pounding into the Voyagers at a speed of a few miles or kilometers per second. "The grains will act as a steady rain that slowly chips away at the skin of the spacecraft," Oberg said. "A dust grain only one-thousandth of a millimeter across will still leave a small vaporized crater when it impacts."

Voyager 1's vertical oscillations mean that spacecraft will spend more time above and below the plane of the galaxy, where the clouds are thickest. Oberg and his colleague simulated thousands of times over the paths of the two spacecraft and their encounters with the dust clouds, modeling the damage the Golden Records would incur along the way.

That work also requires taking into consideration the possibility that a cloud's gravity might tug at one of the Voyagers' trajectories, Oberg said. "The clouds have so much mass concentrated in one place that they actually may act to bend the trajectory of the spacecraft and fling them into new orbits — sometimes much farther out, sometimes even deeper toward the galactic core."

Both Golden Records have good odds of remaining legible, since their engraved sides are tucked away against the spacecraft bodies. The outer surface of Voyager 1's record is more likely to erode away, but the information on Voyager 2's record is more likely to become illegible, Oberg said.

"The main reason for this is because the orbit that Voyager 2 is flung into is more chaotic, and it's significantly more difficult to predict with any certainty of exactly what sort of environment it's going to be flying through," he said.

But despite the onslaught and potential detours, "Both Golden Records are highly likely to survive at least partially intact for a span of over 5 billion years," Oberg said.

Related: Photos from NASA's Voyager 1 and 2 probes

After the Milky Way's end

After those 5 billion years, modeling is tricky. That's when the Milky Way is due to collide with its massive neighbor, the Andromeda galaxy , and things get messy. "The orderly spiral shape will be severely warped, and possibly destroyed entirely," Oberg said. The Voyagers will be caught up in the merger, with the details difficult to predict so far in advance.

Meanwhile, the vicarious sightseeing continues. Oberg and his colleague calculated that in this 5-billion-year model-friendly period, each of the Voyagers likely visits a star besides our sun within about 150 times the distance between Earth and the sun, or three times the distance between the sun and Pluto at the dwarf planet's most distant point.

Precisely which star that might be, however, is tricky — it may not even be a star we know today.

"While neither Voyager is likely to get particularly close to any star before the galaxies collide, the craft are likely to at least pass through the outskirts of some [star] system," Oberg said. "The very strange part is that that actually might be a system that does not yet exist, of a star that has yet to be born."

Such are the perils of working on a scale of billions of years.

From here, the Voyagers' fate depends on the conditions of the galactic merger , Oberg said.

The collision itself might kick a spacecraft out of the newly monstrous galaxy — a one in five chance, he said — although it would remain stuck in the neighborhood. If that occurs, the biggest threat to the Golden Records would become collisions with high-energy cosmic rays and the odd molecule of hot gas, Oberg said; these impacts would be rarer than the dust that characterized their damage inside the Milky Way.

Inside the combined galaxy, the Voyagers' fate would depend on how much dust is left behind by the merger; Oberg said that may well be minimal as star formation and explosion both slow, reducing the amount of dust flung into the galaxy.

Depending on their luck with this dust, the Voyagers may be able to ride out trillions of trillions of trillions of years, long enough to cruise through a truly alien cosmos, Oberg said.

"Such a distant time is far beyond the point where stars have exhausted their fuel and star formation has ceased in its entirety in the universe," he said. "The Voyagers will be drifting through what would be, to us, a completely unrecognizable galaxy, free of so-called main-sequence stars , populated almost exclusively by black holes and stellar remnants such as a white dwarfs and neutron stars."

It's a dark future, Oberg added. "The only source of significant illumination in this epoch will be supernovas that results from the once-in-a-trillion-year collision between these stellar remnants that still populate the galaxy," he said. "Our work, found on these records, thus may bear witness to these isolated flashes in the dark."

Email Meghan Bartels at [email protected] or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

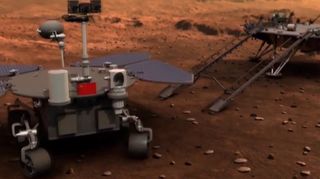

China has made it to Mars .

The nation's first fully homegrown Mars mission, Tianwen-1 , arrived in orbit around the Red Planet today (Feb. 10), according to Chinese media reports.

The milestone makes China the sixth entity to get a probe to Mars, joining the United States, the Soviet Union, the European Space Agency, India and the United Arab Emirates, whose Hope orbiter made it to the Red Planet just yesterday (Feb. 9).

And today's achievement sets the stage for something even more epic a few months from now — the touchdown of Tianwen-1's lander-rover pair on a large plain in Mars' northern hemisphere called Utopia Planitia , which is expected to take place this May. (China doesn't typically publicize details of its space missions in advance, so we don't know for sure exactly when that landing will occur.)

Related: Here's what China's Tianwen-1 Mars mission will do See more: China's Tianwen-1 Mars mission in photos

Book of Mars: $22.99 at Magazines Direct

Within 148 pages, explore the mysteries of Mars. With the latest generation of rovers, landers and orbiters heading to the Red Planet, we're discovering even more of this world's secrets than ever before. Find out about its landscape and formation, discover the truth about water on Mars and the search for life, and explore the possibility that the fourth rock from the sun may one day be our next home.

An ambitious mission

China took its first crack at Mars back in November 2011, with an orbiter called Yinghuo-1 that launched with Russia's Phobos-Grunt sample-return mission . But Phobos-Grunt never made it out of Earth orbit, and Yinghuo-1 crashed and burned with the Russian probe and another tagalong, the Planetary Society's Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment.

Tianwen-1 ( which means "Questioning the Heavens" ) is a big step up from Yinghuo-1, however. For starters, this current mission is an entirely China-led affair; it was developed by the China National Space Administration (with some international collaboration) and launched atop a Chinese Long March 5 rocket on July 23, 2020.

Tianwen-1 is also far more ambitious than the earlier orbiter, which weighed a scant 254 lbs. (115 kilograms). Tianwen-1 tipped the scales at about 11,000 lbs. (5,000 kg) at launch, and it consists of an orbiter and a lander-rover duo.

These craft will take Mars' measure in a variety of ways. The orbiter, for example, will study the planet from above using a high-resolution camera, a spectrometer, a magnetometer and an ice-mapping radar instrument, among other scientific gear.

The orbiter will also relay communications from the rover, which sports an impressive scientific suite of its own. Among the rover's gear are cameras, climate and geology instruments and ground-penetrating radar, which will hunt for pockets of water beneath Mars' red dirt.

Occupy Mars: History of robotic Red Planet missions (infographic)

"On Earth, these pockets can host thriving microbial communities, so detecting them on Mars would be an important step in our search for life on other worlds," the Planetary Society wrote in a description of the Tianwen-1 mission .

The lander, meanwhile, will serve as a platform for the rover, deploying a ramp that the wheeled vehicle will roll down onto the Martian surface. The setup is similar to the one China has used on the moon with its Chang'e 3 and Chang'e 4 rovers, the latter of which is still going strong on Earth's rocky satellite.

If the Tianwen-1 rover and lander touch down safely this May and get to work, China will become just the second nation, after the United States, to operate a spacecraft successfully on the Red Planet's surface for an appreciable amount of time. (The Soviet Union pulled off the first-ever soft touchdown on the Red Planet with its Mars 3 mission in 1971, but that lander died less than two minutes after hitting the red dirt.)

The Tianwen-1 orbiter is scheduled to operate for at least one Mars year (about 687 Earth days), and the rover's targeted lifetime is 90 Mars days, or sols (about 93 Earth days).

Bigger things to come?

Tianwen-1 will be just China's opening act at Mars, if all goes according to plan: The nation aims to haul pristine samples of Martian material back to Earth by 2030, where they can be examined in detail for potential signs of life and clues about Mars' long-ago transition from a relatively warm and wet planet to the cold desert world it is today.

NASA has similar ambitions, and the first stage of its Mars sample-return campaign is already underway. The agency's Perseverance rover will touch down inside the Red Planet's Jezero Crater next Thursday (Feb. 18), kicking off a surface mission whose top-level tasks include searching for signs of ancient Mars life and collecting and caching several dozen samples.

Perseverance's samples will be hauled home by a joint NASA-European Space Agency campaign, perhaps as early as 2031 .

So we have a lot to look forward to in the coming days and weeks, and many reasons to keep our fingers crossed for multiple successful Red Planet touchdowns.

"More countries exploring Mars and our solar system means more discoveries and opportunities for global collaboration," the Planetary Society wrote in its Tianwen-1 description. "Space exploration brings out the best in us all, and when nations work together everyone wins."

Mike Wall is the author of " Out There " (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.

SpaceX to launch 23 Starlink satellites from Florida tonight

Boeing's Starliner rolls out to pad for June 1 astronaut launch (photos)

Peru and Slovakia sign the Artemis Accords for peaceful moon exploration

Most Popular

- 2 Is 'Star Wars: The Acolyte' already canceled? Breaking down the rumors

- 3 SpaceX to launch 23 Starlink satellites from Florida tonight

- 4 Lego wants you to vote on a new color for its astronaut minifigures

- 5 Moon-mapping could level up for NASA's upcoming Artemis missions. Here's how

The remarkable engineering triumph of the Voyager program

In 1977, two spacecraft, Voyager 1 and 2, were launched on their mission from Cape Canaveral to explore Jupiter and Saturn. Not only did they accomplish those missions, but they also continued on to observe Uranus and Neptune, eventually reaching interstellar space, where they continue to operate and send back valuable information to scientists today. On this edition of "Weekend Insight," TPR's Jerry Clayton talks about this remarkable feat of engineering with Voyager project scientist Linda Spilker.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Clayton: Give us a quick overview of the Voyager project that started going on 47 years ago now.

Spilker: The two Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977, and their original mission was to visit the four outer planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, which Voyager 2 did, visiting all four planets. And then after that, continue to study the heliosphere. That's the bubble created by our sun crossing the heliopause. Voyager 1 crossed in 2012. Voyager 2 crossed the heliopause in 2018.

Clayton: Now, Voyager 1 is now the farthest manmade object away from Earth. Is that correct?

Spilker: That's right. Jerry. Voyager 1 is now about 15 billion miles away from the sun, and it's traveling about a million miles per day. So, getting farther away every day and it won't be coming back. It's going to continue in that space between the stars.

Clayton: That distance is mind-boggling. And what's more mind-boggling is that you're able to communicate back and forth with the spacecraft. Now, I know there have been a few communications issues over the years, but back in November of 2023, tell me what happened with Voyager 1? Did you guys think it was over with?

Spilker: Well, Voyager 1 went from one day sending back good science and engineering data until the next day just sending back a single tone, essentially like a dial tone from a phone. And there was no longer any information. And so, we were really worried that we had no information coming from the spacecraft, except we knew it was still there. And so, then the task began to figure out what had happened to Voyager 1.

Clayton: And how did you fix that problem?

Spilker: We tried a series of steps and finally identified that a chip in the flight data subsystem memory had failed, and it was stuck at a bit. And so, it was no longer working the way that it should. So we figured out we needed to move all of the computer programing the subroutines to a good portion of the memory, and then link it all back together and get it to run. And that's exactly what we did.

Clayton: How simple are these systems on board the spacecraft computer-wise compared to technology today?

Spilker: Oh, the Voyager computers are much simpler than the technology we have today. In fact, the total memory of the Voyager computers is about equivalent to what you have on your key fob. So, your cell phone is much more capable than the Voyager computers.

Clayton: So what's next for Voyager 1 and Voyager 2?

Spilker: Well, both Voyagers are going to continue to explore interstellar space. We think that they'll last it, barring any other anomalies out until about the 2030s, at which point the power will be too low to maintain operation of the spacecraft. Each of them carries a golden record , with the sights and sounds of the Earth moving out toward stars in the future. And so they'll become our silent ambassadors, carrying our message of hope and goodwill to the rest of the universe.

Is there a topic or person you'd like to hear featured on this program? Email us at [email protected]

- The Contents

- The Making of

- Where Are They Now

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Q & A with Ed Stone

golden record

Where are they now.

- frequently asked questions

- Q&A with Ed Stone

golden record / whats on the record

Music from earth.

The following music was included on the Voyager record.

- Bach, Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F. First Movement, Munich Bach Orchestra, Karl Richter, conductor. 4:40

- Java, court gamelan, "Kinds of Flowers," recorded by Robert Brown. 4:43

- Senegal, percussion, recorded by Charles Duvelle. 2:08

- Zaire, Pygmy girls' initiation song, recorded by Colin Turnbull. 0:56

- Australia, Aborigine songs, "Morning Star" and "Devil Bird," recorded by Sandra LeBrun Holmes. 1:26

- Mexico, "El Cascabel," performed by Lorenzo Barcelata and the Mariachi México. 3:14

- "Johnny B. Goode," written and performed by Chuck Berry. 2:38

- New Guinea, men's house song, recorded by Robert MacLennan. 1:20

- Japan, shakuhachi, "Tsuru No Sugomori" ("Crane's Nest,") performed by Goro Yamaguchi. 4:51

- Bach, "Gavotte en rondeaux" from the Partita No. 3 in E major for Violin, performed by Arthur Grumiaux. 2:55

- Mozart, The Magic Flute, Queen of the Night aria, no. 14. Edda Moser, soprano. Bavarian State Opera, Munich, Wolfgang Sawallisch, conductor. 2:55

- Georgian S.S.R., chorus, "Tchakrulo," collected by Radio Moscow. 2:18

- Peru, panpipes and drum, collected by Casa de la Cultura, Lima. 0:52

- "Melancholy Blues," performed by Louis Armstrong and his Hot Seven. 3:05

- Azerbaijan S.S.R., bagpipes, recorded by Radio Moscow. 2:30

- Stravinsky, Rite of Spring, Sacrificial Dance, Columbia Symphony Orchestra, Igor Stravinsky, conductor. 4:35

- Bach, The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 2, Prelude and Fugue in C, No.1. Glenn Gould, piano. 4:48

- Beethoven, Fifth Symphony, First Movement, the Philharmonia Orchestra, Otto Klemperer, conductor. 7:20

- Bulgaria, "Izlel je Delyo Hagdutin," sung by Valya Balkanska. 4:59

- Navajo Indians, Night Chant, recorded by Willard Rhodes. 0:57

- Holborne, Paueans, Galliards, Almains and Other Short Aeirs, "The Fairie Round," performed by David Munrow and the Early Music Consort of London. 1:17

- Solomon Islands, panpipes, collected by the Solomon Islands Broadcasting Service. 1:12

- Peru, wedding song, recorded by John Cohen. 0:38

- China, ch'in, "Flowing Streams," performed by Kuan P'ing-hu. 7:37

- India, raga, "Jaat Kahan Ho," sung by Surshri Kesar Bai Kerkar. 3:30

- "Dark Was the Night," written and performed by Blind Willie Johnson. 3:15

- Beethoven, String Quartet No. 13 in B flat, Opus 130, Cavatina, performed by Budapest String Quartet. 6:37

Voyager Golden Record

Golden Record Sounds and Music

Sounds of earth.

The following is a listing of sounds electronically placed onboard the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft.

Music from Earth

The following music was included on the Voyager record.

Discover More Topics From NASA

Our Solar System

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Learn about the Golden Record, a phonograph record carried by Voyager 1 and 2 to communicate a story of Earth to alien civilizations. Find out what's on the record, how it was made, and why it was created.

The golden record is attached to the spacecraft. Voyager 1 was launched in 1977, passed the orbit of Pluto in 1990, and left the Solar System (in the sense of passing the termination shock) in November 2004. It is now in the Kuiper belt.

Learn about the contents of the Golden Record, a phonograph record sent into space in 1977 by the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 probes. See the photographs, sounds, music and greetings that represent humanity to alien civilizations.

The Voyager Golden Record contains 116 images and a variety of sounds. The items for the record, which is carried on both the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft, were selected for NASA by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan of Cornell University.Included are natural sounds (including some made by animals), musical selections from different cultures and eras, spoken greetings in 59 languages ...

The contents of the record were selected for NASA by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan of Cornell University, et. al. Dr. Sagan and his associates assembled 115 images and a variety of natural sounds, such as those made by surf, wind and thunder, birds, whales, and other animals. To this they added musical selections from different cultures and ...

Images on the Golden Record. The following is a listing of pictures electronically placed on the phonograph records which are carried onboard the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft. The contents of the record were selected for NASA by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan of Cornell University, et. al. Dr. Sagan and his associates assembled 115 images and ...

This essay was adapted from the liner notes for the new edition of the Voyager Golden Record, recently released as a vinyl boxed set by Ozma Records. Timothy Ferris, the producer of the Golden ...

The Voyager Golden Record On board each Voyager spacecraft is a time capsule: a 12-inch, gold-plated copper disk carrying spoken greetings in 55 languages from Earth's peoples, along with 115 images and myriad sounds representing our home NASA/JPL. Most NASA images are in the public domain. Reuse of this image is governed by NASA's image use ...

Voyager 1, robotic U.S. interplanetary probe launched in 1977 that visited Jupiter and Saturn and was the first spacecraft to reach interstellar space. Voyager 1 swung by Jupiter on March 5, 1979, and then headed for Saturn, which it reached on November 12, 1980. ... Cover of Voyager golden record. Each Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977 ...

The Golden Record is basically a 90-minute interstellar mixtape — a message of goodwill from the people of Earth to any extraterrestrial passersby who might stumble upon one of the two Voyager ...

No spacecraft has gone farther than NASA's Voyager 1. Launched in 1977 to fly by Jupiter and Saturn, Voyager 1 crossed into interstellar space in August 2012 and continues to collect data. Mission Type. ... Engineers secure the cover over the Voyager 1 Golden Record in this archival image from 1977. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog ...

When Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 launched into space in 1977, their mission was to explore the outer solar system, ... and over the course of six weeks they produced the "Golden Record": a collection ...

NASA launched Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 in 1977 to trek across the solar system. On each was a 12-inch (30 centimeters) large gold-plated copper disk. On each was a 12-inch (30 centimeters) large ...

Voyager 1's magnetometer and plasma wave subsystem are now back to returning useful data. ... The Voyager spacecraft also both carry a copy of the Golden Record, a kind of time capsule with sounds and images from Earth for any would be alien salvagers that may come across the spacecraft.

In 1977, two spacecraft, Voyager 1 and 2, were launched on their mission from Cape Canaveral to explore Jupiter and Saturn. In 1977, two spacecraft, Voyager 1 and 2, were launched on their mission from Cape Canaveral to explore Jupiter and Saturn. ... Each of them carries a golden record, with the sights and sounds of the Earth moving out ...

Voyager Golden Record. December 4, 2017. Credit. NASA/JPL-Caltech. Language. english. Each Voyager spacecraft carries a copy of the Golden Record, which has been featured in several works of science fiction. The record's protective cover, with instructions for playing its contents, is shown at left.

Holborne, Paueans, Galliards, Almains and Other Short Aeirs, "The Fairie Round," performed by David Munrow and the Early Music Consort of London. 1:17; Solomon Islands, panpipes, collected by the Solomon Islands Broadcasting Service. 1:12; Peru, wedding song, recorded by John Cohen. 0:38; China, ch'in, "Flowing Streams," performed by Kuan P'ing ...

Voyager Golden Record. Share. Roberto Mario • 1 month ago. eu nao entendi merda nenhuma, e agora eu estou. genuinamente duvidando da minha capacidade. de interpretar uma simples história, por mais que. eu seja uma leitora desde de que me entendo por. gente, isso me fez um questionamento de até. quando isso importa, já que eu não consegui.

Sounds of Earth The following is a listing of sounds electronically placed onboard the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft. Music from Earth The following music was included on the Voyager record. Country of origin Composition Artist(s) Length Germany Bach, Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F. First Movement Munich Bach Orchestra, Karl Richter, conductor 4:40 Java […]