Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 10 September 2024

When urban poverty becomes a tourist attraction: a systematic review of slum tourism research

- Tianhan Gui ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6069-3046 1 &

- Wei Zhong 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 1178 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Business and management

Over the last two decades, the phenomenon of “slum tourism” and its academic exploration have seen considerable growth. This study presents a systematic literature review of 122 peer-reviewed journal articles, employing a combined approach of bibliometric and content analysis. Our review highlights prominent authors and journals in this domain, revealing that the most cited journals usually focus on tourism studies or geography/urban studies. This reflects a confluence of travel motivations and urban complexities within slum tourism. Through keyword co-occurrence analysis, we identified three primary research areas: the touristic transformation of urban informal settlements, the depiction and valorization of urban poverty, and the socio-economic impacts of slum tourism. This study not only maps the current landscape of research in this area but also identifies existing gaps. It suggests that the economic, social, and cultural effects of slum tourism are areas that require more in-depth investigation in future research endeavors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Knowledge mapping of relative deprivation theory and its applicability in tourism research

Bibliometric analysis of trends in COVID-19 and tourism

A ten-year review analysis of the impact of digitization on tourism development (2012–2022)

Introduction.

“Slums” are defined by UN-Habitat ( 2006 ) as underdeveloped urban areas lacking in a durable housing, adequate living space, safe water access, sanitation, and tenure security. Emerging from urban growth disparities, these informal settlements have proliferated since the latter half of the 20th century, especially in the Global South’s cities. Despite progress in urban planning and poverty reduction, UN-Habitat ( 2020 ) reports that over a billion people, with 80% in developing regions, still live in such conditions.

Slums undeniably “represent one of the most enduring faces of poverty, inequality, exclusion and deprivation” (UN-Habitat, 2020 , p. 25), necessitating policy intervention. However, the term “slum” is controversial among scholars as it often carries negative connotations, conflating poor housing conditions with the identities of residents (Gilbert, 2007 ). Beyond poverty and disease, it suggests crime and immorality, contributing to a narrative of fear and fascination (Davis, 2006 ; Mayne, 2017 ).

Recent decades have seen a surge in “slum tours” in the Global South, attracting tourists from the affluent North. Driven by complex motives that “consist of a mix of adventurous inquiry and humanitarian ambitions” (Dürr, 2012b , p. 707), tourists from the affluent North desire to glimpse “the other side of the world” (Steinbrink, 2012 , p. 232). This trend has turned guided tours in informal settlements into a booming business in cities like Mumbai, Rio de Janeiro, Cape Town, and Nairobi, drawing approximately one million tourists annually (Frenzel, 2016 ).

Modern slum tourism has deep historical roots, originating as “slumming” in Victorian England and early 20th-century America. Rapid urbanization in cities like London and New York created neglected areas, which, to middle and upper-class observers, represented a mysterious and chaotic “other world” (Steinbrink, 2012 ). This perception of danger and uncivilization paradoxically attracted bourgeois curiosity (Frenzel et al. 2015 ).

By the late 1970s, with the surge in international tourism, this localized “slumming” transformed into a global phenomenon. Affluent residents from the Global North began exploring underprivileged urban pockets in the Global South, making these areas tourism hotspots (Freire-Medeiros, 2009 ; Iqani, 2016 ). This trend marked the beginning of modern slum tourism, a practice that took a significant turn in the 1990s in South Africa. Initially focusing on anti-apartheid landmarks in townships like Soweto, Johannesburg (Steinbrink, 2012 ), these tours diversified to other cities, including Rio de Janeiro, Mumbai, and Manila (Frenzel et al. 2015 ). The once sporadic visits to informal settlements have now metamorphosed into well-orchestrated tours, often recommended by travel guidebooks. Today’s travelers can dine at local eateries, visit schools, interact with residents, or even step inside their homes (Frenzel, 2017 ; Frenzel and Blakeman, 2015 ). The industry has professionalized, with cities in the Global South attracting tourists mainly from the United Kingdom, United States, Germany, and Scandinavia (Frenzel, 2012 ; Frenzel and Blakeman, 2015 ; Steinbrink, 2012 ).

The burgeoning interest in slum tourism has sparked significant scholarly discourse, particularly in the new millennium. Research in this realm predominantly orbits around the ethical implications of such tourism, its role in mitigating poverty, and the duties of governing bodies in these scenarios. Slum tourism research encompasses various disciplines, including urban studies, tourism and hospitality, and human geography, with a significant proliferation of publications in recent years.

The surge in research has also led to several evaluative studies scrutinizing the breadth and depth of the subject. Frenzel’s ( 2013 ) thematic review, for instance, probed the nexus between slum tourism and poverty alleviation. Given that most slum tours proclaim poverty alleviation as their core intent, Frenzel’s inquiry into the intersection of this mission with tourism was insightful. He also championed the need for a rigorous exploration of the multifaceted valorization of poverty within tourism dynamics. A more expansive review by Frenzel et al. ( 2015 ) delved into various research focuses like the evolution of slum tourism, tourist experiences, operational aspects, economic implications, and so on. Their assessment underscored existing research voids, emphasizing the necessity for more nuanced, comparative studies. Tzanelli ( 2018 ) examined the socio-cultural and political drivers behind tourists’ inclinations towards informal settlements, critically analyzing the epistemological frameworks employed by scholars.

While these reviews have significantly sketched the contours of the discipline, many leaned heavily on conventional literature review techniques—predicated on selected, and at times, circumscribed resources (Petticrew and Roberts, 2008 ). Such manual methodologies, albeit insightful, are prone to biases “during the identification, selection, and synthesis of included studies” (Haddaway et al. 2015 , p. 1956). A systematic literature review, which adheres to rigorous protocols and curtails subjective inclinations, would be more enriching. Such a methodological shift not only offers a panoramic view of pivotal research arguments and deliberations but also illuminates evolving trends and perspectives. The surge in slum tourism literature recently underscores its dynamic nature, necessitating a renewed scrutiny of nascent discussions eluding preceding reviews.

Addressing this research exigency, our current endeavor undertakes a comprehensive examination of a gamut of articles illuminating diverse research angles on slum tourism. Employing both bibliometric and qualitative content analysis techniques, our study dissects 122 journal articles published over the past twenty years. We endeavor to spotlight seminal authors and journals, delineate prevailing themes in slum tourism studies, and carve out prospective trajectories for forthcoming research endeavors.

Methodology

Search process and sample selection.

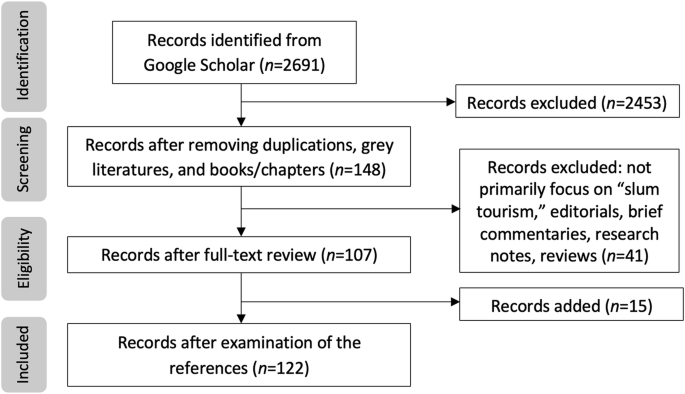

A systematic review requires researchers to thoroughly examine all existing studies in a certain research area. This ensures a replicable, scientific, and transparent approach with minimal bias (Denyer and Tranfield, 2009 ). We adopt the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis” (PRISMA) guideline (Moher et al. 2009 ) to identify eligible articles. The screening process is presented in Fig. 1 . We consulted an advanced keyword search on Google Scholar to retrieve literature on slum tourism. We chose Google Scholar because it provides broader access to a diverse range of scholarly articles, including those from various regions and disciplines that may not be indexed in databases like Web of Science or Scopus. Furthermore, since this study aims to review research articles on slum tourism, which is pertinent in the Global South, many journals or articles published or authored in the Global South are not indexed in Web of Science or Scopus but can be found on Google Scholar. This accessibility is vital for ensuring the inclusion of relevant studies that reflect the diverse contexts of slum tourism.

The systematic workflow and results.

For our subject search, we used the keywords “slum tourism.” We consciously omitted country-specific terms like barrios, township, and favela to prevent a regional bias (Baffoe and Kintrea, 2023 ). Google Scholar Advanced Search provides the choice to locate keywords either “in the title of the article” or “anywhere in the article.” We chose the latter, ensuring the inclusion of articles that might employ regional terms synonymous with “slum” in their titles. This approach also considered the potential cross-referencing of slum tourism literature in these articles. Conducted in August 2023 without time constraints, our search yielded 2690 materials.

To uphold the literature’s quality, only peer-reviewed scientific articles were chosen, excluding “grey literatures” such as reports, theses, conference proceedings, and other similar outputs. Books and book chapters were not incorporated into our review because our focus extended to trends in slum tourism research. The accelerated pace of academic publishing in journals, as compared to the longer timelines associated with books, means they often house the most current findings and trends. Utilizing a bibliometric analysis approach, we found the standardized structure of journal articles particularly beneficial, allowing for a more straightforward process in extracting, comparing, and synthesizing data. Books and their chapters, given their varied formats, might not always provide this level of consistency. Recognizing that a systematic review cannot encompass all languages, we confined our study to English-written articles.

After the initial screening, 148 articles closely related to slum tourism were identified. Our perspective on slum tourism aligns with Frenzel’s ( 2018 , p. 51) definition, describing it as “tourism where poverty and associated signifiers become central themes and (part of the) attraction of the visited destination.” Upon a thorough review of the full texts, it became apparent that some articles, while mentioning “slum tourism,” did not primarily focus on it. For instance, the work of Jones and Sanyal ( 2015 ) discusses the portrayal of Dharavi—India and Asia’s largest informal settlement—in slum tours, arts, and documentaries. Although their article addresses how Dharavi is represented in slum tours, its primary focus is on the depiction of informal settlements and urban poverty across various media, not slum tourism per se. Consequently, this article was excluded from our dataset. We also eliminated editorials, short commentaries, research notes, and prior literature reviews. This filtering narrowed our selection to 107 peer-reviewed articles. An exhaustive examination of their references added another 15 articles, giving a total of 122 articles. Figure 1 visualizes the selection process.

Data analysis

This study utilized both bibliometric and qualitative content analyses. Bibliometric analysis is crucial for identifying both established and emerging research themes as well as influential authors, key studies, and prominent journals (Hajek et al. 2022 ). We employed VOSviewer, a leading bibliometric analysis software, to undertake co-citation and keyword co-occurrence analyses, examining slum tourism research. Co-citation analysis pinpoints influential authors, studies, and journals, leveraging citations as pivotal indicators of scientific impact (De Bellis, 2009 ). Meanwhile, keyword co-occurrence analysis highlights prominent keywords and their relationships, signposting research field hotspots (Wang and Yang, 2019 ).

Augmenting the bibliometric approach, our qualitative content analysis delved deeper into the primary themes of slum tourism research. The keyword co-occurrence analysis supplied a broad view of research themes and trending topics. Emerging nodes and clusters helped pinpoint dominant research themes. By meticulously analyzing each article’s content, we executed a critical review of every theme. We also broached prospective research trajectories in the article’s conclusion.

Overview of slum tourism research

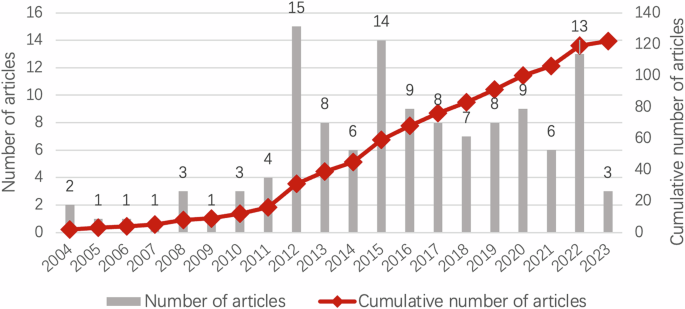

Figure 2 illustrates the evolving research landscape of slum tourism. The journey began in 2004 with two seminal papers by Kaplan ( 2004 ) and Rogerson ( 2004 ). Both delved into Johannesburg’s township tourism, emphasizing tourism’s potential in poverty mitigation and the region’s economic upliftment. Post-2004, the domain attracted escalating scholarly interest, evidenced by a notable publication upswing from 2012 onward.

Publishing trends of slum tourism research.

Two pivotal discursive events in Bristol (2010) and Potsdam (2014) further catalyzed the field’s evolution. Gathering global experts on slum tourism, these events spurred foundational texts that have since informed the discipline. The post-Bristol momentum produced a special Tourism Geographies issue in 2012, curated by Frenzel and Koens. Successive publications, like the “Slum Tourism” special issue of Die Erde 144 (2) in 2013, and the themed “Slum Tourism” issue of Tourism Review International in 2015, further cemented the field’s prominence. Undoubtedly, these seminal conferences and publications have been instrumental in surging scholarly endeavors in slum tourism research.

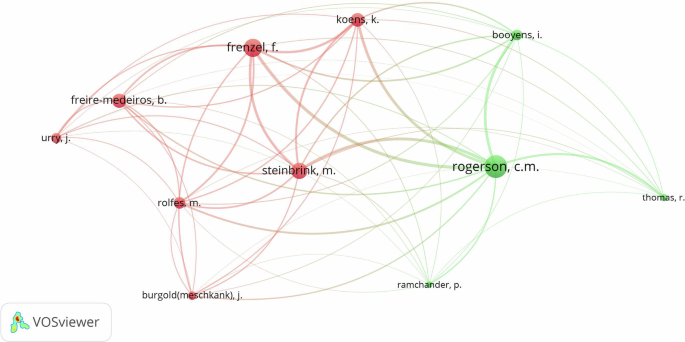

We conducted a co-citation analysis to pinpoint the leading authors and journals in the realm of slum tourism research. A co-citation refers to the simultaneous citation of two documents (Small, 1973 ). Such analysis aids scholars in organizing scientific literature and grasping the evolution of specific research domains (Surwase et al. 2011 ).

Figure 3 illustrates the outcomes of our author co-citation analysis. We established a threshold of 40 citations to identify the most influential authors within our dataset of 4229 authors. Only 11 authors met this threshold, allowing for a focused examination of the core contributors in the field. Their significant scholarly impact is reflected by their extensive citations, with node size in the visualization representing co-citation strength. Rogerson, Frenzel, and Steinbrink emerged as the most frequently cited authors, with the highest link strengths of 3978, 3173, and 2734, respectively. Rogerson’s work delved into the economic ramifications of tourism in South African townships, highlighting the part slum tourism plays in poverty reduction and sustainable community economic growth (Booyens and Rogerson, 2019 a, 2019b ; Rogerson, 2014 ). He also discussed urban tourism’s influence on small and medium-sized enterprises (Rogerson, 2004 , 2008 ). In contrast, Frenzel and Steinbrink examined the commercialization of urban informal settlements and the portrayal and appreciation of poverty (Frenzel, 2017 ; Frenzel and Blakeman, 2015 ; Steinbrink, 2012 , 2013 ).

Author co-citation network.

Other notable authors in this field include Freire-Medeiros, who discussed the transformation of Brazilian favelas into tourist attractions (Freire-Medeiros et al. 2013 ; Freire-Medeiros, 2007 , 2009 , 2011 ), Koens, who probed the growth of small and medium-sized businesses in South African townships (Koens and Thomas, 2015 , 2016 ) and local perceptions of slum tourism in India (Slikker and Koens, 2015 ), and Booyens, who primarily focused on responsible tourism in South African townships (Booyens, 2010 ; Booyens and Rogerson, 2019b , 2018). Rolfes also made a significant contribution by studying the ethical aspects of slum tourism (Burgold and Rolfes, 2013 ; Rolfes, 2010 ).

Intriguingly, although not a slum tourism specialist, Urry stands among the eleven most-cited authors. He is renowned for introducing “the tourist gaze” concept (Urry, 1990 ), suggesting that tourist experiences and choices are more influenced by the tourism industry, societal norms, and cultural factors than by personal autonomy. This theory offers a crucial framework for understanding how poverty is portrayed in slum tourism and the dynamics between tourists and local residents.

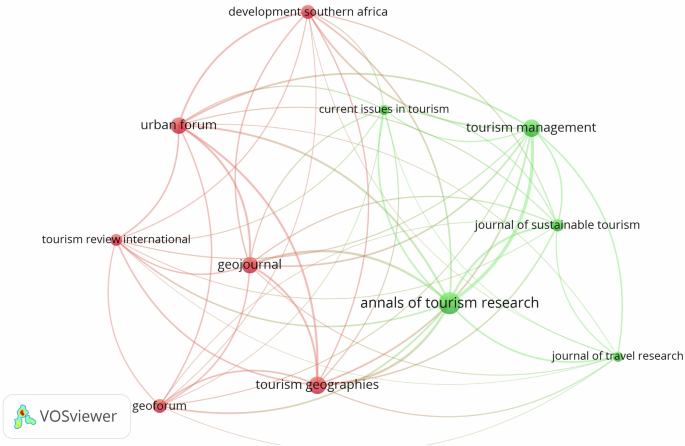

Figure 4 presents the map of journal co-citations, illuminating the academic areas focused on the topic of “slum tourism.” A journal co-citation analysis, conducted with a threshold of 40 citations, identified 11 key journals from a pool of 3013 in our dataset, underscoring their central roles in the discourse of the field. Notably, the Annals of Tourism Research occupies a central position on the map with the highest link strength of 2608, highlighting its prominence as the most-cited journal in slum tourism research. These journals are categorized into two primary clusters: tourism studies and geography/urban studies. This categorization reflects the dual scholarly interest in slum tourism, which intertwines travel motivations with the complexities of urban environments. On one hand, tourism researchers probe the allure of these regions, the ensuing cultural interactions, and the ethical debates surrounding poverty as an attraction. Conversely, geography and urban studies scholars explore the spatial structures of informal settlements, underlying socio-economic drivers, and the reciprocal impact between tourism and urban evolution. Collectively, these disciplines provide a nuanced view of slum tourism’s multifaceted nature. Notably, Development Southern Africa does not align strictly with these categories, but as a multidisciplinary journal emphasizing policy and practice in Southern Africa—a hub for modern slum tourism—it garners frequent citations.

Journal co-citation network.

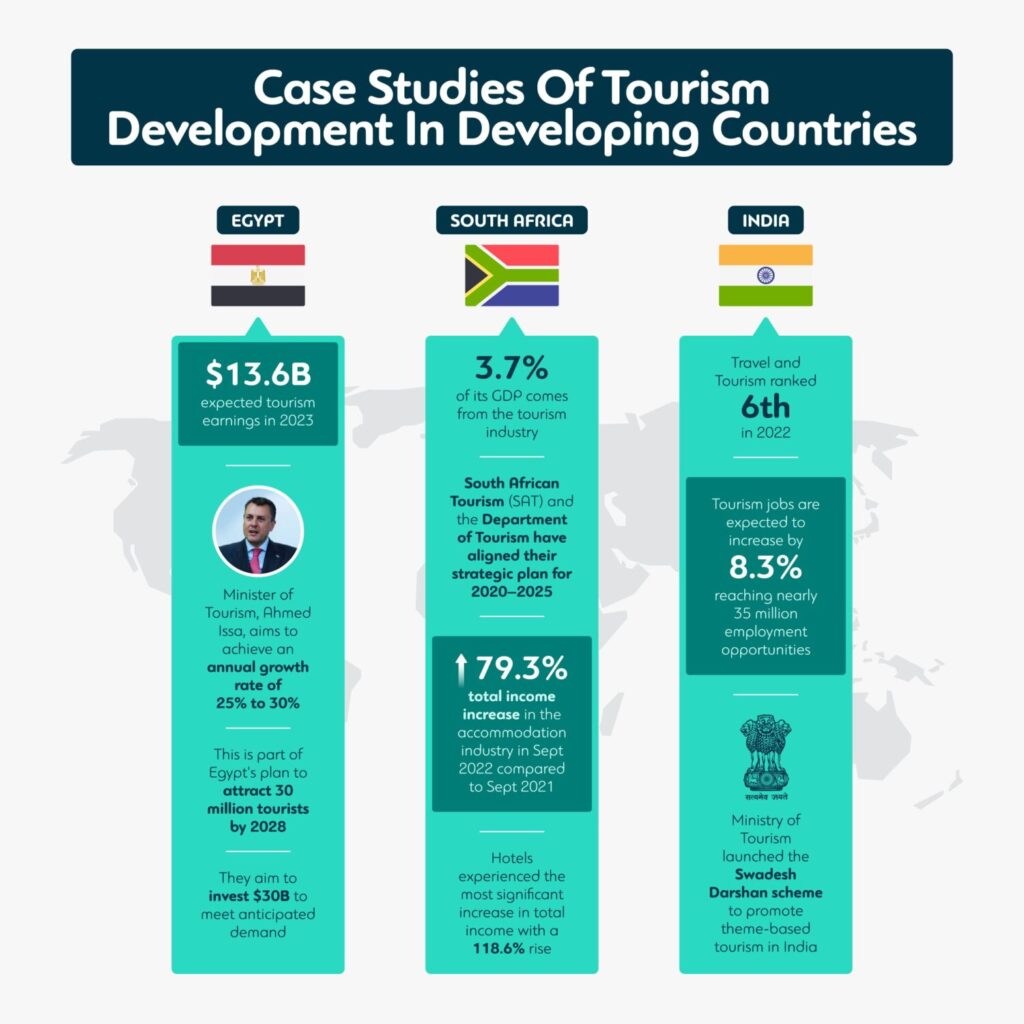

After meticulously reviewing the 122 publications, we pinpointed the locations that are focal points for slum tourism research. As presented in Table 1 , South Africa, India, and Brazil emerge as the most extensively researched countries in this domain. They are closely followed by Kenya, Mexico, Colombia, Egypt, and Indonesia.

Township tourism in South Africa, deeply rooted in the country’s complex history, is a significant topic in slum tourism research. This form of tourism, which emerged in post-apartheid South Africa (Steinbrink, 2012 ), focuses on areas historically designated as “black only” zones, where disparities still exist (Iqani, 2016 ). Originating in Soweto, Johannesburg, it has since spread to other major cities. The 2010 FIFA World Cup, hosted by South Africa, notably boosted its popularity (Marschall, 2013 ). Today, Cape Town is a key destination for township tourism, with townships like Langa and Khayelitsha attracting tourists due to their historical significance (Rolfes, 2010 ).

Similar to South Africa, favela tourism in Brazil has political roots. These favelas, initially informal settlements for the formerly enslaved (Iqani, 2016 ), gained international attention after the 1992 Earth Summit, when delegates visited Rio de Janeiro’s favelas (Frenzel, 2012 ). Their prominence increased further during the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Olympics (Steinbrink, 2013 ). Despite their cultural richness, favelas face challenges like crime and drug trafficking (Freire-Medeiros, 2009 ). Rio’s favelas, especially Rocinha and Santa Marta, attract numerous tourists each year (Frenzel and Blakeman, 2015 ).

In India, the scenario of slum tourism is notably different, with Mumbai’s Dharavi, one of the world’s largest informal settlement, being a key focus of India-specific studies. Other informal settlements in cities like Kolkata and Delhi have also attracted scholarly attention (Holst, 2015 ; Sen, 2008 ). These informal settlements are characterized by their micro-industries and recycling efforts, showcasing the resilience and entrepreneurial spirit of the residents (Gupta, 2016 ). Although a relatively new trend compared to its counterparts, India’s slum tourism industry has burgeoned, spawning numerous tour operators (Frenzel and Blakeman, 2015 ).

Over time, slum tourism has gained traction, spreading to nations across the Global South, including Kenya, Colombia, Mexico, Egypt, and the Philippines. In our study, while most articles were location-specific, ten adopted a holistic approach, discussing the overarching theme of slum tourism.

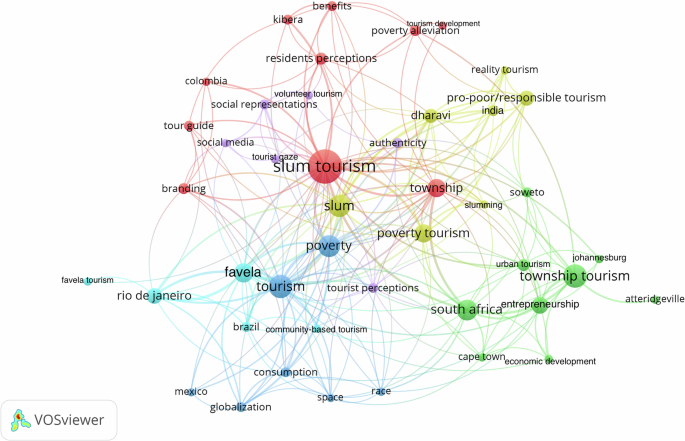

Prominent areas of slum tourism research

We conducted a keyword co-occurrence analysis on our slum tourism research dataset to identify and visualize the most significant themes by examining the frequency and relationships of keywords. This method facilitated the identification of central research clusters and thematic hotspots within the topic. Figure 5 illustrates the network of keywords that frequently co-occur in slum tourism studies. To refine our data, we consolidated similar keywords, for example, pairing “township” with “townships” and “developing countries” with “developing world.” For this analysis, we set a threshold to include keywords that appeared at least three times, leading to the selection of 44 out of 322 keywords, thereby emphasizing their significance within the field. In the network, each node represents a keyword; larger nodes indicate higher frequencies of occurrence. Our analysis revealed six distinct clusters, each differentiated by a unique color.

Network visualization of the keywords co-occurrence.

The red cluster focuses on “slum tourism,” examining the development of tourism in informal settlements and its wide-ranging socio-economic impacts. This cluster covers aspects such as “branding” and the role of “tour guides,” and emphasizes key socio-economic factors including “residents’ perceptions” and “poverty alleviation.” Simultaneously, the green cluster, highlighting terms such as “township tourism” and “economic development,” shifts focus to the growth of local, often small-to-medium-sized, tourism businesses, particularly spotlighting township tourism in South Africa. Meanwhile, the light blue cluster examines the impact of slum tourism on local communities, with a special focus on “community-based tourism” and favela tourism in Brazil. The yellow cluster delves into the portrayal of poverty as a key draw in slum tourism, questioning its classification as “poverty tourism” and exploring the shift towards more ethical, “pro-poor,” and responsible tourism practices. Concurrently, the purple cluster critically examines the portrayal and perception of poverty in slum tourism, focusing on tourist perspectives influenced by the “tourist gaze” and social media. Lastly, the dark blue cluster analyzes how globalization and rising consumer culture have spurred the growth of slum tourism, integrating themes like “globalization,” “space,” and “consumption,” and underscoring poverty’s central role in this phenomenon.

In our thematic analysis of publications, we integrated clusters with similar themes. The red, green, yellow, and light blue clusters, which focus on the socio-economic impacts of slum tourism on local communities, were merged. The red and dark blue clusters, addressing the transformation of urban informal settlements into tourist destinations and their driving factors, were also combined into a single theme. Furthermore, the purple and yellow clusters, centered on the portrayal and perception of poverty in slum tourism, were grouped together. Our review systematically examines these unified themes, as illustrated in Table 2 .

Touristic transformation of urban informal settlements

The transformation of urban informal settlements into tourist destinations has been extensively discussed in earlier literature on slum tourism. This transformation hinges significantly on cultural and historical heritage. As previously mentioned, Brazil’s favelas and South Africa’s townships attracted visitors with political and cultural interests (Frenzel, 2012 ; Steinbrink, 2012 ). Gradually, with the globalization that stimulated global mobility and the rise of consumer culture, these locales became spaces of interaction, juxtaposing mobility and immobility on a global scale (Dürr, 2012a ). As many informal settlements in the Global South were represented in global media, they gained increasing touristic attention. For instance, after the success of the film “The City of God” in 2003, the number of foreign visitors to favelas in Rio grew significantly (Freire-Medeiros, 2011 ). As Freire-Medeiros ( 2009 , p. 582) mentioned in another article that tours in these informal settlements “are equally indebted to the phenomenon of circulation and consumption, at a global level, of the favela as a trademark.”

In the touristic transformation of informal settlements, policy plays a pivotal role. For instance, local governments in South Africa actively encouraged township tourism by creating museums, developing historical and political heritage sites, and promoting township upgrading programs (Booyens, 2010 ; Booyens and Rogerson, 2019b ; Marschall, 2013 ). In Brazil, favela tourism served as a means to enhance its image in the context of preparations for mega-events in Rio, a strategy dubbed “Festifavelasation” (Steinbrink, 2013 ). South Africa pursued a similar path after securing the 2010 FIFA World Cup (Marschall, 2013 ). In Colombia, a policy known as “social urbanism” led Medellin, previously known for its drug barons and criminal activities, to undergo social and economic transformation, attracting both interest and tourists (Hernandez‐Garcia, 2013 ).

In analyzing our dataset’s articles, it is evident that slum tours primarily occur in well-known informal settlements of the Global South, such as Mumbai’s Dharavi, Rio de Janeiro’s Rocinha, and Johannesburg’s Soweto. These locations are preferred due to the factors previously mentioned. However, this growing industry often overlooks numerous lesser-known and more impoverished communities (Koens, 2012 ). Issues such as insufficient infrastructure, the absence of tourist attractions, and poor security hinder the growth of tourism in informal urban settlements. This situation is clearly seen in areas like Harare, Zimbabwe (Mukoroverwa and Chiutsi, 2018 ), and certain townships in Durban, South Africa (Chili, 2015 ).

A significant barrier is also the lack of awareness of pro-poor tourism in these lesser-known areas. Munyanyiwa et al.’s ( 2014 ) research in Harare’s townships revealed that many residents were unaware of township tourism, compounded by insufficient infrastructure and community involvement to support it. Moreover, residents were unsure of how to benefit from such initiatives, with historical tourism activities largely unknown to them. Similarly, Attaalla’s ( 2016 ) study in Egypt highlighted the minimal awareness of pro-poor tourism, the absence of a comprehensive government policy to develop this tourism type, and the scarcity of specialized Egyptian tour operators and travel agencies in the pro-poor tourism market. For successful tourism in these areas, it’s vital to enhance infrastructure, safety, and offer innovative tourism experiences (Mukoroverwa and Chiutsi, 2018 ). Additionally, improved information dissemination and increased stakeholder engagement are essential (Munyanyiwa et al. 2014 ).

The transition of informal settlements into tourist destinations brings several challenges. Notably, the commercialization of these marginalized areas can aestheticize deprivation and social inequality, turning them into themed spaces that reinforce stereotypes and maintain informal settlements as attractions shaped by tourist expectations (e.g. Altamirano, 2022b ; Dürr, 2012a ). Building on this point, Dürr et al. ( 2020 ) highlighted that marketing urban poverty and violence as a city brand could exacerbate existing inequalities. Research also shows that in many touristic informal settlements, local residents often do not fully engage with or benefit from tourism (Koens and Thomas, 2015 ; Marschall, 2013 ). Furthermore, public policies aimed at transforming these settlements sometimes lack consistency, creating insecurity among locals (Altamirano, 2022b ). Addressing these issues requires enhanced policies and increased community involvement in tourism, posing significant challenges for local governments.

Valorization and representation of urban poverty

In 2010, the term “poverty tourism” was recognized in slum tourism research, casting a spotlight on the intricate connection between poverty and this type of tourism (Rolfes, 2010 ). This tourism variant is not without controversy, interrogating the confluence of poverty, power, and ethical dilemmas (see Chhabra and Chowdhury, 2012 ; Korstanje, 2016 ; Outterson et al. 2011 ). This dynamic between the commodification of impoverished settlements and their portrayal within the tourism spectrum has ignited fervent academic debate.

Frenzel ( 2014 ) critically observed that within the paradigm of slum tourism, poverty transcends its role as a mere backdrop, ascending to the primary spectacle. Consequently, this leads to the commodification of urban impoverishment, turning it into a tourism commodity with tangible monetary value (Rolfes, 2010 ). Scholars have extensively dissected this juxtaposition. While some examine the framing, representation, and marketing dimensions (Dürr et al. 2020 ; Meschkank, 2011 ; Rolfes, 2010 ), others argued that poverty becomes romanticized, perceived more as a cultural artifact rather than an urgent societal issue (Crossley, 2012 ; Huysamen et al. 2020 ; Nisbett, 2017 ).

In this tapestry, both tourists and tour operators play pivotal roles in framing the narrative. Operators, tapping into the tourists’ quest for the “authenticity” embedded in the narratives of global urbanization, exert significant influence in shaping perceptions (Meschkank, 2012 ; Rolfes, 2010 ). Studies have observed that in an attempt to counteract the inherently negative perceptions surrounding informal settlements (Dyson, 2012 ), operators often position these spaces as beacons of hope, underlining the tenacity, optimism, and aspirations of the residents (Crossley, 2012 ; Dürr et al. 2020 ; Huysamen et al. 2020 ; Meschkank, 2011 ). Moreover, to navigate the moral complexities that tourists might grapple with, operators design their offerings as ethical enterprises, promising both enlightenment for the tourists and tangible economic upliftment for the communities (Muldoon and Mair, 2016 ; Nisbett, 2017 ).

However, such strategies face intellectual scrutiny for their potential to obfuscate the palpable suffering that underpins these urban landscapes. Several studies affirm that poverty dominates the observational narratives across tours in global cities from Mumbai to Rio de Janeiro (Crossley, 2012 ; Dürr et al. 2020 ; Meschkank, 2012 ). As Clini and Valančiūnas ( 2023 ) observed, such sanitized representations, while better than negative stereotypes, could unintentionally normalize the systemic inequalities associated with poverty. This approach not only risks reducing the perceived need for urgent poverty alleviation efforts but also may leave existing societal inequalities unchallenged. This has prompted critiques that label the phenomenon as commercial “voyeurism, and exploitation for commercial ends” (Burgold and Rolfes, 2013 , p. 162).

For tourists, their motivation often orbits around the pursuit of “authenticity” when they consider visiting informal settlements (see Clini and Valančiūnas, 2023 ; Crossley, 2012 ; Gupta, 2016 ; Meschkank, 2011 ; Steinbrink, 2012 ). Marketed as unvarnished encounters with reality, informal settlements are often depicted as bastions of culture, diversity, and authenticity (Frenzel et al. 2015 ). This category of slum tourism is, thus, situated within the broader realm of “reality tourism,” promising participatory experiences in socio-economically challenged urban landscapes (Wise et al. 2019 ). However, this approach, despite aligning with general tourism patterns, is not devoid of problems. The very essence of this touristic venture, which is to experience urban impoverishment, inherently establishes an imbalanced dynamic between tourists and inhabitants, leading to its characterization as a form of voyeurism. (Dürr et al. 2020 ; Meschkank, 2011 ).

In the last decade, slum tourism has diversified with new tours offered by locals and NGOs, aiming to challenge stereotypes and present a more complex picture of informal settlements. Frenzel ( 2014 ) noted that guides can empower communities by focusing on often-ignored aspects of these areas. While motivations vary, with some guides driven by profit and others by community welfare and resisting gentrification effects, the role of guides is crucial. Angelini’s ( 2020 ) examination of favela tours accentuated the nuanced challenges faced by these guides, as they attempt to strike a balance between authentic representation and the commodification of their environments. Further, Dürr et al. ( 2021 ) in their ethnographic study in Mexico City’s Tepito, showed how guides can positively portray deprived areas without depoliticizing them, contextualizing local achievements within city politics and using historical narratives to emphasize the area’s significance.

In the digital era, social media significantly influences the slum tourism narrative (Sarrica et al. 2021 ). The Internet is vital for operators to market and sell tours and provide information to potential travelers (Privitera, 2015 ). Many studies have analyzed slum tourism portrayals in online reviews and media, exploring how these areas and experiences are represented (Huysamen et al. 2020 ; Nisbett, 2017 ; Sarrica et al. 2021 ; Shang et al. 2022 ; Wise et al. 2019 ). For instance, Nisbett ( 2017 ) highlighted concerns about reviews that often gloss over poverty’s complexities, focusing instead on the tours’ economic aspects. Similarly, Huysamen et al. ( 2020 ) observed that tourist narratives tend to paint these areas as “slums of hope,” ignoring the disparity between wealthy tourists and impoverished locals. Ekdale and Tuwei ( 2016 ) studied texts from Kibera visitors, noting that while tourists claim to gain authentic understanding of global inequality, their privileged perspective remains unexamined. These “ironic encounters” often reinforce global inequalities, serving more as self-validation for tourists than a true engagement with local challenges.

On the flip side, social media’s role in depicting informal settlements is not always reductive. Some academics posit that these platforms can provide a counter-narrative to skewed representations by offering avenues to disseminate a diverse array of authentic stories and perspectives (Sarrica et al. 2021 ). Crucially, social media can amplify local residents’ voices, allowing them to share concerns about slum tourism, including privacy, potential exploitation, and daily life disruptions (Crapolicchio et al. 2022 ). The digital era thus presents both opportunities and challenges for slum tourism, underscoring the need for ethical and respectful interactions that honor and authentically represent these communities’ narratives.

Social and economic impact of slum tourism to local communities

The economic and social impacts of tourism in these informal settlements are prominent themes in slum tourism research. Across various countries, including Egypt, South Africa, Brazil, and Indonesia, tourism has spurred urban development and improved living conditions in informal settlements (Anyumba, 2017 ; Booyens and Rogerson, 2019a ; Mekawy, 2012 ; Sulistyaningsih et al. 2022 ; Torres, 2012 ). Developments like aerial cable cars in Brazil’s favelas and minibus-taxis in South African townships have evolved local transportation systems (Freire-Medeiros and Name, 2017 ; Rietjens et al. 2006 ). These advancements facilitate social transformation, such as increased security investments in Brazilian favelas (Freire-Medeiros et al. 2013 ) and “social urbanism” in Colombian barrios, integrating marginalized communities and improving education and security (Hernandez‐Garcia, 2013 ). A comparative study of the touristification of Gamcheon Culture Village (Busan, South Korea) and Comuna 13 (Medellin, Colombia) highlighted that effective governance can create community networks and stakeholder partnerships, fostering entrepreneurial opportunities (Escalona and Oh, 2022 ).

Tourism holds potential as a means to reduce poverty by creating employment opportunities in impoverished urban areas (Aseye and Opoku, 2015 ; Cardoso et al. 2022 ; Paul, 2016 ). Slum tourism, in particular, fosters entrepreneurship, allowing residents to start their own tour companies or bed and breakfasts. However, challenges for local entrepreneurs include limited market access, stiff competition, low marketing budgets, poor business locations, and lack of support from established firms, often leading to the marginalization of smaller operators in a market dominated by larger companies (see Chili, 2018 ; Hikido, 2018 ; Mokoena and Liambo, 2023 ; Mtshali et al. 2017 ; Nemasetoni and Rogerson, 2005 ). Further, small business owners frequently lack essential education and marketing skills (see Leonard and Dladla, 2020 ; Letuka and Lebambo, 2022 ; Rogerson, 2004 ). Mokoena and Liambo ( 2023 ) observed that only a minority of entrepreneurs adopt competitive strategies in their businesses.

Scholars have also observed that the profits from slum tourism are insufficient for significant poverty alleviation (Freire-Medeiros, 2009 , 2012 ). Koen and Thomas’ study of South Africa townships ( 2015 ) highlighted the challenge to the idea that small business owners reinvest their profits locally for economic development. Successful entrepreneurs often leave their townships due to a lack of local ties, leading to economic benefits being concentrated among a small, predominantly male, privileged group, while marginalized groups’ businesses yield lower gains. Moreover, most slum tour companies depend heavily on foreign support, resulting in substantial economic leakage (Frenzel and Blakeman, 2015 ; Meschkank, 2012 ; Rolfes, 2010 ).

The social implications of slum tourism form a major focus in recent academic studies, particularly regarding how local residents perceive this tourism form. Surveys and interviews with inhabitants of informal settlements have uncovered a range of reactions, including positive, negative, skeptical, and indifferent attitudes toward slum tourism (Amo et al. 2019 ; Auala et al. 2019 ; Freire-Medeiros, 2012 ; Marschall, 2013 ; Slikker and Koens, 2015 ).

In Rio, Mumbai, and Nairobi, some studies reveal that residents feel embarrassed by slum tourism, as certain operators emphasize negative community aspects to cater to tourists seeking “real” poverty experiences, leading to privacy issues (Freire-Medeiros, 2012 ; Kieti and Magio, 2013 ; Slikker and Koens, 2015 ). Conversely, slum tourism is also viewed positively in many areas. Slikker and Koens’ ( 2015 ) study in Mumbai and Amo et al. ( 2019 ) research in Medellin found residents believe it counters negative stereotypes and raises community visibility. In Nairobi and Cape Town, locals welcome it as a source of income and jobs (Chege and Mwisukha, 2013 ; Potgieter et al. 2019 ). Additionally, Muldoon et al.’s South African studies suggest slum tourism empowers residents by bringing international attention to townships, giving them more control over their narratives and a sense of importance (Muldoon, 2020 ; Muldoon and Mair, 2022 ).

Indeed, the social impact of tourism is dualistic. As Altamirano ( 2022a ) pointed out, while tourism can establish new material and symbolic frameworks, providing residents with chances for counter-hegemonic actions, it does not uniformly support the cultural empowerment of impoverished communities. Instead, it can result in neoliberal development and increased surveillance. This underscores the necessity for thoughtful policymaking in slum tourism, advocating for policies that prioritize the well-being and cultural richness of communities over mere profit generation, particularly in environments marked by urban disparities and complex power dynamics.

Booyens and Rogerson ( 2019 b) suggested that slum tourism ought to function as a type of “creative tourism,” fostering solidarity and mutual understanding between tourists and local residents, stimulating economic growth in communities, and increasing awareness of the North-South disparity in the postcolonial context. The transition to pro-poor tourism heavily relies on effective policy implementation. Therefore, numerous scholars have advocated for policy instruments to enhance safety and infrastructure, and to facilitate effective coordination among various stakeholders, alongside strengthening institutional frameworks (e.g. Aseye and Opoku, 2015 ; Booyens, 2010 ; Chege and Mwisukha, 2013 ; Rusata et al. 2023 ).

Furthermore, the success of slum tourism largely depends on local community engagement (Duarte and Peters, 2012 ). Yet, in many cases, such as in India (Slikker and Koens, 2015 ), Kenya (Kieti and Magio, 2013 ), Brazil (Freire-Medeiros, 2012 ), and elsewhere, local residents’ participation is limited. Various factors contribute to this, including inadequate business knowledge and skills, and social and financial barriers (Dzikiti and Leonard, 2016 ; Hammad, 2021 ; Leonard and Dladla, 2020 ). Addressing this, researchers emphasize the need for tourism-specific training and resources for local entrepreneurs, particularly focusing on youth (Dzikiti and Leonard, 2016 ; Mbane and Ezeuduji, 2022 ; Nkemngu, 2014 ). To leverage slum tourism for community development, equipping locals with the skills and tools for effective tourism participation is crucial, though it remains a challenging goal.

Conclusion and future research agenda

Over the past two decades, “slum tourism” and its academic study have expanded significantly. Our systematic review of 122 peer-reviewed journal articles sheds light on key authors and journals in this field. The most cited journals typically specialize in tourism studies or geography/urban studies, underscoring the blend of travel motivations and urban complexities in slum tourism. Our findings show that South Africa, India, and Brazil are the most researched countries, with others like Kenya, Mexico, Colombia, Egypt, and Indonesia also being significant. The keyword co-occurrence analysis identified three primary research areas: the touristic transformation of urban informal settlements, the portrayal and valorization of urban poverty, and the socio-economic impacts of slum tourism. This study not only outlines the scope of current research but also points out gaps, suggesting that the economic, social, and cultural effects of slum tourism warrant further exploration in future studies.

The economic aspects of slum tourism, widely debated in academic circles, pose unanswered questions about the actual financial benefits for local residents and communities. Frenzel and Koens ( 2012 ) noted a lack of quantitative evaluations, leaving the impact of slum tours on poverty reduction and urban development uncertain. Existing research, primarily qualitative involving interviews, ethnography, media content analysis, and stakeholder surveys, fails to adequately measure the economic impact on informal settlements. Although studies like those by Chege and Mwisukha ( 2013 ) and Potgieter et al. ( 2019 ) indicated resident perceptions of slum tourism as a source of income and employment, these lack concrete statistical backing. The financial dynamics of slum tourism, including the economic leakage stemming from reliance on external and foreign support (Frenzel and Blakeman, 2015 ; Meschkank, 2012 ; Rolfes, 2010 ), warrant more in-depth investigation. Future research should focus on tracing profit distribution in slum tourism and assessing its real effects on the communities, considering the prominent role of local guides and their relationships with tour operators.

The intangible impacts of slum tourism, including social, political, and cultural aspects, are a fertile area for future research. Shifting focus to local residents’ views, recent studies have shown slum tourism’s broad influence beyond just economic factors, notably in changing perceptions of poverty. However, as Koens ( 2012 ) pointed out, evaluating these impacts is complex due to the deep social and historical contexts within these communities. Advocates for authentic local engagement, like Slikker and Koens ( 2015 ) and Freire-Medeiros ( 2012 ), emphasized the importance of giving local residents a voice. Muldoon’s research ( 2020 ; Muldoon and Mair, 2022 ) in South Africa demonstrates how township tourism allows locals to redefine their identities and interactions with tourists. On the other hand, Freire-Medeiros ( 2012 ) noted in Brazil’s Rocinha the possibility of residents altering narratives for tourist appeal. This highlights the need to integrate the genuine experiences of locals into slum tourism research to fully grasp its diverse impacts.

The potential for slum tourism to either reinforce or challenge existing power dynamics and stereotypes represents a dynamic area of ongoing debate, ripe for further theoretical exploration. Slum tourism is emblematic of neoliberal capitalist practices, where the lived experiences of marginalized communities are commodified and consumed predominantly by Western tourists. This pattern aligns with David Harvey’s concept of “accumulation by dispossession,” where the exploitation and aestheticization of poverty serve to reinforce global economic disparities (Harvey, 2003 ). By transforming informal settlements into tourist attractions, slum tourism becomes a mechanism of cultural commodification, packaging poverty-stricken environments for sale and perpetuating a global hierarchy that privileges affluent tourists while marginalizing local residents.

The representation of informal settlements within this tourism framework often involves selective storytelling, echoing Edward Said’s notion of “Orientalism.” This process portrays the “Other” in ways that reinforce Western superiority and exoticize non-Western realities, contributing to the perpetuation of stereotypes and obscuring the systemic causes of poverty (Said, 2003 ). Such portrayals often sanitize the harsh realities of poverty, presenting informal settlements as exotic and intriguing destinations, thus skewing the understanding of global inequalities and framing poverty more as a cultural artifact than an urgent social issue.

Conversely, slum tourism holds potential to challenge and subvert these entrenched power dynamics and stereotypes. When approached through the lens of ethical representation, it becomes a platform that amplifies marginalized voices and promotes more equitable narratives. This approach is deeply rooted in theories of participatory development and empowerment, which argue that local communities should be active agents in shaping their own narratives, rather than passive subjects (Dürr et al. 2021 ; Frenzel, 2014 ). Employing local guides and focusing on authentic narratives that highlight both the challenges and resilience of informal settlement residents can provide a counter-narrative to dominant discourses, promoting a more nuanced and respectful understanding of these communities.

The role of social media in slum tourism highlights the significance of digital globalization in shaping narratives. Social media platforms provide avenues for local residents to share their perspectives, thereby democratizing the discourse and challenging stereotypical representations (Sarrica et al. 2021 ). This aligns with the ethics of representation, advocating for portrayals that respect the dignity and agency of marginalized communities (Crapolicchio et al. 2022 ). By enabling a more participatory and inclusive approach, social media can help mitigate the voyeuristic tendencies of slum tourism and foster a more ethical engagement with these communities.

Another prominent takeaway from this systematic literature review is the observation that the practice, perception, and success of slum tourism vary significantly across different cultural and geographical contexts. In Brazil, for instance, the favelas of Rio de Janeiro have been transformed into tourist destinations, influenced not only by their portrayal in internationally acclaimed films but also by the mega-events hosted in the city. This phenomenon has led to a form of tourism that often celebrates the cultural vibrancy of these areas, despite underlying issues of poverty and inequality. Conversely, in India, Mumbai’s Dharavi is marketed as a hub of entrepreneurship and industry, attracting tourists more interested in the economic dynamics of informal settlement life than in cultural spectacle alone. These differences illustrate how local contexts shape the thematic emphasis of slum tours.

However, the ability to develop slum or pro-poor tourism is not uniformly distributed. Many areas lack the necessary infrastructure, adequate security, or appealing tourist attractions, which impedes their ability to attract and sustain tourism. For instance, some townships in Durban, South Africa, and informal settlements in Harare, Zimbabwe, contend with issues such as poor security and insufficient infrastructure, making them less appealing to tourists and challenging to market as destinations (Chili, 2015 ; Mukoroverwa and Chiutsi, 2018 ). This disparity highlights the uneven impacts of global tourism trends on local communities and points to the necessity for ethical and sustainable tourism practices in urban settings marked by significant socio-economic divides.

To enhance our understanding of slum tourism dynamics and to devise more effective interventions, it is crucial to undertake further comparative studies. These studies should delve into why certain areas are successful in developing tourism that benefits local communities while others falter, considering both global influences and local conditions. Such research is imperative for uncovering the potential of tourism as a tool for social and economic improvement in marginalized urban areas and contributes significantly to the broader discourse on globalization, urban inequality, and sustainable development.

In this vein, a pivotal area for future research is transforming “slum tourism” into a form of responsible tourism that transcends the poverty-centric narrative often associated with terms like “slum,” “township,” and “favela” (Burgold and Rolfes, 2013 ; Rolfes, 2010 ; Steinbrink et al. 2012 ). While it is valuable to highlight the cultural and historical aspects of these communities, such portrayals frequently overlook the entrenched structural inequality and violence that pervade these areas. Furthermore, tourism often concentrates only on well-known locations, ignoring the most impoverished and lesser-known settlements, thus raising questions about the applicability of sustainable development strategies in these marginalized areas (Frenzel, 2013 ). It is essential that future research explores how slum tourism can truly benefit residents and address broader socio-economic challenges, ensuring it evolves into a form of responsible tourism.

This shift towards responsible slum tourism necessitates a comprehensive emphasis on ethical considerations, community involvement, and sustainable economic benefits for local residents. Ethical considerations must encompass respect for the dignity and agency of the communities involved, eschewing exploitative practices that commodify poverty for tourist consumption. Community involvement is imperative, as it enables residents to influence how their neighborhoods are portrayed and ensure their central participation in both managing and benefiting from tourism initiatives. This might include training local guides, engaging residents in creating tour content, and allocating a substantial share of tourism revenues back into the community.

Furthermore, ensuring sustainable economic benefits for residents is fundamental to responsible slum tourism. This involves fostering tourism that generates reliable income opportunities for locals, such as through establishing small businesses or cooperative ventures tailored to the tourism industry. Potential enterprises could include local eateries, souvenir shops, and accommodation services, all managed and operated by community members. Investment in infrastructure improvements that support tourism activities and simultaneously enhance resident quality of life is also crucial. Additionally, it is essential to implement mechanisms to track the flow of financial benefits to ensure that the revenue generated by tourism is indeed benefiting the local communities as intended.

The data collection for this study, completed in August 2023, revealed a notable gap: the lack of research on the impact of the COVID pandemic on slum tourism, despite the pandemic lasting three years. The pandemic has disproportionately affected informal settlement dwellers, as evidenced by Seddiky et al. ( 2023 ). For instance, Bangkok’s informal settlement residents have suffered significant economic hardships (Pongutta et al. 2021 ), and containment measures have led to widespread business closures, impacting low-income, daily wage earners in impoverished communities (Solymári et al. 2022 ). This absence of academic focus on COVID’s specific impact on slum tourism marks a limitation in current literature. The pandemic’s disruption of travel presents an opportunity to reassess and develop more sustainable tourism practices that could benefit residents in impoverished areas.

Additionally, this study’s focus on slum tourism in the Global South overlooks the re-emerging field of slum or poverty tourism in the Global North. For instance, Burgold ( 2014 ) explored guided walking tours in Berlin-Neukölln, an area known for poverty and social issues, contrasting them with traditional tourism and highlighting their role in changing perceptions and aiding local residents’ societal integration. Similarly, “homeless experience” tours in cities like Toronto, London, Amsterdam, and Seattle offer insights into the lives of homeless individuals (Haven Toronto, 2018 ; Kassam, 2013 ). These tours, as controversial in the Global North as in the South, raise ethical concerns about commodifying poverty. Proponents see them as empathy-building, while critics view them as exploitative. The dynamics of poverty tours vary between developed and less developed countries, presenting a potential area for future comparative research.

“Slum tourism,” a relatively new research field, reflects the complexities of rapid urbanization and the North-South power dynamics in a globalized era. The current study offers a comprehensive, longitudinal perspective on slum tourism research, charting future directions for scholarly inquiry. It also provides valuable insights for practitioners to reassess the role of tourism in poverty alleviation within urban informal settlements in the Global South. For public policy, this research is instrumental in shaping strategies for urban development, poverty alleviation, and sustainable tourism, advocating for the integration of informal settlements into wider economic frameworks. Academically, it enriches the existing body of knowledge, spurring interdisciplinary research and delving into lesser-explored aspects of slum tourism. Additionally, by shedding light on the effects of tourism in these communities, the study promotes more informed, respectful, and responsible tourist behavior, encouraging travelers to adopt a more empathetic and culturally sensitive approach.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available in an uploaded CSV file.

Altamirano ME (2022a) Legitimizing discourses within favela tourism. Tour Geogr 25(7):1–18

Google Scholar

Altamirano ME (2022b) Overcoming urban frontiers: Ordering Favela tourism actor-networks. Tour Stud 22(2):200–222

Article Google Scholar

Amo MDH, Jayawardena CC, Gaultier SL (2019) What is the host community perception of slum tourism in Colombia? Worldw Hosp Tour Themes 11(2):140–146

Angelini A (2020) A Favela that yields fruit: community-based tour guides as brokers in the political economy of cultural difference. Space Cult 23(1):15–33

Article ADS Google Scholar

Anyumba G (2017) Planning for a Township Tourism destination: Considering red flags from experiences in Atteridgeville, South Africa. Afr J Hosp Tour Leis 6(2):1–22

Aseye FK, Opoku M (2015) Potential of slum tourism in urban Ghana: A case study of Old Fadama (Sodom and Gomorra) slum in Accra. J Soc Dev Sci 6(1):39–45

Attaalla FAH (2016) Pro-poor tourism as a panacea for slums in Egypt. Int J Tour Hosp Rev 3(1):30–44

Auala LSN, van Zyl SR, Ferreira IW (2019) Township tourism as an agent for the socio-economic well-being of residents. African Journal of Hospitality . Tour Leis 8(2):1–11

Baffoe G, Kintrea K (2023) Neighbourhood research in the Global South: What do we know so far? Cities 132:104077

Booyens I (2010) Rethinking township tourism: Towards responsible tourism development in South African townships. Dev South Afr 27(2):273–287

Booyens I, Rogerson C (2019a) Creative tourism: South African township explorations. Tour Rev 74(2):256–267

Booyens I, Rogerson C (2019b) Re-creating slum tourism: Perspectives from South Africa. Urban Izziv 30(supple):52–63

Burgold J (2014) Slumming the Global North? Überlegungen zur organisierten Besichtigung gesellschaftlicher Problemlagen in den Metropolen des Globalen Nordens. Z F ür Tour 6(2):273–280

Burgold J, Rolfes M (2013) Of voyeuristic safari tours and responsible tourism with educational value: Observing moral communication in slum and township tourism in Cape Town and Mumbai. Erde 144(2):161–174

Cardoso A, da Silva A, Pereira MS, Sinha N, Figueiredo J, Oliveira I (2022) Attitudes towards slum tourism in Mumbai, India: analysis of positive and negative impacts. Sustainability 14(17):10801

Chege PW, Mwisukha A (2013) Benefits of slum tourism in Kibera slum in Nairobi, Kenya. Int J Arts Commer 2(4):94–102

Chhabra D, Chowdhury A (2012) Slum tourism: Ethical or voyeuristic. Tour Rev Int 16(1):69–73

Chili NS (2015) Township Tourism: The politics and socio-economic dynamics of tourism in the South African township: Umlazi, Durban. J Econ Behav Stud 7(4):14–21

Chili NS (2018) Constrictions of emerging tourism entrepreneurship in the townships of South Africa. Afr J Hosp Tour Leis 7(4):1–10

Clini C, Valančiūnas D (2023) Bollywood and slum tours: poverty tourism and the Indian cultural industry. Cult Trends 32(4):366–382

Crapolicchio E, Sarrica M, Rega I, Norton LS, Vezzali L (2022) Social representations and images of slum tourism: Effects on stereotyping. Int J Intercult Relat 90:97–107

Crossley É (2012) Poor but Happy: Volunteer Tourists’ Encounters with Poverty. Tour Geogr 14(2):235–253

Davis M (2006) Planet of Slums. Verso

De Bellis N (2009) Bibliometrics and citation analysis: from the science citation index to cybermetrics. Scarecrow Press

Denyer D Tranfield D (2009) Producing a systematic review. In D Buchanan & A Bryman (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational research methods (pp. 671–689). Sage Publications Ltd

Duarte R, Peters K (2012) Exploring the other side of Favela tourism. an insight into the residents’ view. Rev Tur Desenvolv 2(17/18):1123–1131

Dürr E (2012a) Encounters over garbage: Tourists and lifestyle migrants in Mexico. Tour Geogr 14(2):339–355

Dürr E (2012b) Urban poverty, spatial representation and mobility: Touring a slum in Mexico. Int J Urban Reg Res 36(4):706–724

Dürr E, Acosta R, Vodopivec B (2021) Recasting urban imaginaries: politicized temporalities and the touristification of a notorious Mexico City barrio. Int J Tour Cities 7(3):783–798

Dürr E, Jaffe R, Jones GA (2020) Brokers and tours: selling urban poverty and violence in Latin America and the Caribbean. Space Cult 23(1):4–14

Dyson P (2012) Slum tourism: representing and interpreting “Reality” in Dharavi, Mumbai. Tour Geog 14(2):254–274

Dzikiti LG, Leonard L (2016) Barriers towards African youth participation in domestic tourism in post-apartheid South Africa: The case of Alexandra Township, Johannesburg. Afr J HospTour Leis 5(3):1–17

Ekdale B, Tuwei D (2016) Ironic encounters: Posthumanitarian storytelling in slum tourist media. Commun Cult Crit 9(1):49–67

Escalona M, Oh D (2022) Efficacy of Governance in Sustainable Slum Regeneration: Assessment framework for effective governance in sustainable slum tourism regeneration. Rev de Urban 46:131–151

Freire-Medeiros B (2007) Selling the favela: thoughts and polemics about a tourist destination. Rev Bras Ciências Soc 22(65):61–72

Freire-Medeiros B (2009) The favela and its touristic transits. Geoforum 40(4):580–588

Freire-Medeiros B (2011) I went to the city of god’: Gringos, guns and the touristic favela. J Lat Am Cultural Stud 20(1):21–34

Freire-Medeiros B (2012) Favela tourism: Listening to local voices. In F Frenzel, K Koens, & M Steinbrink (Eds.), Slum Tourism: Poverty, Power and Ethics (pp. 175–192). Routledge

Freire-Medeiros B, Name L (2017) Does the future of the favela fit in an aerial cable car? Examining tourism mobilities and urban inequalities through a decolonial lens. Can J Lat Am Caribb Stud 42(1):1–16

Freire-Medeiros B, Vilarouca MG, Menezes P (2013) International tourists in a “pacified” favela: Profiles and attitudes. the case of santa marta. Rio de Jan Erde 144(2):147–159

Frenzel F (2012) Beyond ‘Othering’: The political roots of slum tourism. In F Frenzel, K Koens, & M Steinbrink (Eds.), Slum Tourism: Poverty, Power and Ethics (pp. 32–49). Routledge

Frenzel F (2013) Slum tourism in the context of the tourism and poverty (relief) debate. DIE ERDE – J Geogr Soc Berl 144(2):117–128

Frenzel F (2014) Slum Tourism and Urban Regeneration: Touring Inner Johannesburg. Urban Forum 25(4):431–447

Frenzel, F (2016). Slumming it: The tourist valorization of urban poverty. Zed Books Ltd

Frenzel F (2017) Tourist agency as valorisation: Making Dharavi into a tourist attraction. Ann Tour Res 66:159–169

Frenzel F (2018) On the question of using the concept ‘Slum Tourism’ for urban tourism in stigmatised neighbourhoods in Inner City Johannesburg. Urban Forum 29(1):51–62

Frenzel F, Blakeman S (2015) Making slums into attractions: The role of tour guiding in the slum tourism development in Kibera and Dharavi. Tour Rev Int 19(1–2):87–100

Frenzel F, Koens K (2012) Slum tourism: developments in a young field of interdisciplinary tourism research. Tour Geogr 14(2):195–212

Frenzel F, Koens K, Steinbrink M, Rogerson CM (2015) Slum tourism: State of the art. Tour Rev Int 18(4):237–252

Gilbert A (2007) The return of the slum: does language matter? Int J Urban Reg Res 31(4):697–713

Gupta V (2016) Indian reality tourism-a critical perspective. Tour Hosp Manag 22(2):111–133

Haddaway NR, Woodcock P, Macura B, Collins A (2015) Making literature reviews more reliable through application of lessons from systematic reviews. Conserv Biol 29(6):1596–1605

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Hajek P, Youssef A, Hajkova V (2022) Recent developments in smart city assessment: A bibliometric and content analysis-based literature review. Cities 126:103709

Hammad AA (2021) Exploring the Role of Slum Tourism in Developing Slums in Egypt. J Assoc Arab Univ Tour Hosp 20(1):58–77

Harvey D (2003) The New Imperialism . Oxford University Press

Haven Toronto (2018) Poverty tourism: Take a homeless holiday . Haven Toronto

Hernandez‐Garcia J (2013) Slum tourism, city branding and social urbanism: the case of Medellin, Colombia. J Place Manag Dev 6(1):43–51

Hikido A (2018) Entrepreneurship in South African township tourism: The impact of interracial social capital. Ethn Racial Stud 41(14):2580–2598

Holst T (2015) Touring the Demolished Slum? Slum Tourism in the Face of Delhi’s Gentrification. Tour Rev Int 18(4):283–294

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Huysamen M, Barnett J, Fraser DS (2020) Slums of hope: Sanitising silences within township tour reviews. Geoforum 110(March)):87–96

Iqani M (2016) Slum tourism and the consumption of poverty in TripAdvisor reviews: The cases of Langa, Dharavi and Santa Marta. In Consumption, media and the global south: Aspiration contested (pp. 51–86). Springer

Jones GA, Sanyal R (2015) Spectacle and suffering: The Mumbai slum as a worlded space. Geoforum 65:431–439

Kaplan L (2004) Skills development for tourism in Alexandra township, Johannesburg. Urban Forum 15(4):380–398

Kassam A (2013) Poorism, the new tourism . Maclean’s

Kieti DM, Magio KO (2013) The ethical and local resident perspectives of slum tourism in Kenya. Adv Hosp Tour Res (AHTR) 1(1):37–57

Koens K (2012) Competition, cooperation and collaboration: business relations and power in township tourism. In F Frenzel, K Koens, & M Steinbrink (Eds.), Slum tourism (pp. 101–118). Routledge

Koens K, Thomas R (2015) Is small beautiful? Understanding the contribution of small businesses in township tourism to economic development. Dev South Afr 32(3):320–332

Koens K, Thomas R (2016) “You know that’s a rip-off”: policies and practices surrounding micro-enterprises and poverty alleviation in South African township tourism. J Sustain Tour 24(12):1641–1654

Korstanje ME (2016) The ethical borders of slum tourism in the mobile capitalism: A conceptual discussion. Rev de Tur -Stud Si Cercetari Tur 21:22–32

Leonard L, Dladla A (2020) Obstacles to and suggestions for successful township tourism in Alexandra township. South Africa . e-Rev Tour Res (ERTR) 17(6):900–920

Letuka P, Lebambo M (2022) A typology of challenges facing township micro-tour operators in Soweto, South Africa. Afr J Sci, Technol, Innov Dev 14(7):1829–1838

Marschall S (2013) Woza eNanda: perceptions of and attitudes towards heritage and tourism in a South African township. Transform: Crit Perspect South Afr 83(1):32–55

Mayne A (2017) Slums: The history of a global injustice. Reaktion Books

Mbane TL, Ezeuduji IO (2022) Stakeholder perceptions of crime and security in township tourism development. Afr J Hosp Tour Leis 11(3):1128–1142

Mekawy MA (2012) Responsible slum tourism: Egyptian experience. Ann Tour Res 39(4):2092–2113

Meschkank J (2011) Investigations into slum tourism in Mumbai: Poverty tourism and the tensions between different constructions of reality. GeoJournal 76(1):47–62

Meschkank J (2012) Negotiating poverty: the interplay between Dharavi’s production and consumption as a tourist destination. In F Frenzel, K Koens, & M Steinbrink (Eds.), Slum Tourism (pp. 162–176). Routledge

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group*, P. (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151(4):264–269

Mokoena SL, Liambo TF (2023) The sustainability of township tourism SMMEs. Int J Res Bus Soc Sci 12(1):341–349

Mtshali M, Mtapuri O, Shamase SP (2017) Experiences of black-owned Small Medium and Micro Enterprises in the accommodation tourism-sub sector in selected Durban townships, Kwazulu-Natal. Afr J HospTour Leis 6(3):130–141

Mukoroverwa M, Chiutsi S (2018) Prospects and challenges of positioning Harare as an urban township tourism destination. Afr J Hosp Tour Leis 7(4):1–11

Muldoon ML (2020) South African township residents describe the liminal potentialities of tourism. Tour Geogr 22(2):338–353

Muldoon ML, Mair HL (2016) Blogging slum tourism: A critical discourse analysis of travel blogs. Tour Anal 21(5):465–479

Muldoon ML, Mair HL (2022) Disrupting structural violence in South Africa through township tourism. J Sustain Tour 30(2–3):444–460

Munyanyiwa T, Mhizha A, Mandebvu G (2014) Views and perceptions of residents on township tourism development: Empirical evidence from Epworth, Highfields and Mbare. Int J Innov Res Dev 3(10):184–194

Nemasetoni I, Rogerson CM (2005) Developing small firms in township tourism: Emerging tour operators in Gauteng, South Africa. Urban Forum 16(2–3):196–213

Nisbett M (2017) Empowering the empowered? Slum tourism and the depoliticization of poverty. Geoforum 85(July):37–45

Nkemngu AP (2014) Stakeholder’s participation in township tourism planning and development: The case of business managers in Shoshanguve. Afr J Hosp Tour Leis 3(1):1–10

Outterson K, Selinger E, Whyte K (2011) Poverty Tourism, Justice, and Policy: Can Ethical Ideals Form the Basis of New Regulations? Public Integr 14(1):39–50

Paul NIJ (2016) Critical analysis of slum tourism: A retrospective on Bangalore. ATNA J Tour Stud 11(2):95–113

Petticrew M Roberts H (2008) Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. John Wiley & Sons

Pongutta S, Kantamaturapoj K, Phakdeesettakun K, Phonsuk P (2021) The social impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on urban slums and the response of civil society organisations: A case study in Bangkok, Thailand. Heliyon 7(5):E07161

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Potgieter A, Berman GK, Verity JM (2019) The relationship between socio-cultural impacts of a township tour and the overall life satisfaction of residents in townships in the Western Cape, South Africa. Afr J Hosp Tour Leis 8(4):1–17

Privitera D (2015) Tourist valorisation of urban poverty: an empirical study on the web. Urban Forum 26(4):373–390

Rietjens S, Makoriwa C, de Boer S (2006) Utilising excess minibus-taxi capacity for South African townships tours. Anatolia 17(1):75–92

Rogerson C (2004) Urban tourism and small tourism enterprise development in Johannesburg: The case of township tourism. GeoJournal 60(3):249–257

Rogerson C (2014) Rethinking slum tourism: Tourism in South Africa’s rural slumlands. Bull Geogr 26(26):19–34

Rogerson C (2008) Shared growth in urban tourism: evidence from Soweto, South Africa. Urban Forum 19(4):395–411

Rolfes M (2010) Poverty tourism: Theoretical reflections and empirical findings regarding an extraordinary form of tourism. GeoJournal 75(5):421–442

Rusata T, Atmadiredja G, Kornita A (2023) Slum tourism: representing and interpreting reality in city. Indones J Tour Leis 4(1):55–64

Said EW (2003) Orientalism. Penguin

Sarrica M, Rega I, Inversini A, Norton LS (2021) Slumming on social media? E-mediated tourist gaze and social representations of indian, south African, and Brazilian slum tourism destinations. Societies 11(3):106

Seddiky MA, Chowdhury NM, Ara E (2023) Satisfaction level of slum dwellers with the assistance of the city corporation during COVID 19: the Bangladesh Context. Soc Sci 12(9):520

Sen A (2008) Sex, sleaze, slaughter, and salvation: phoren tourists and slum tours in Calcutta (India). Journeys 9(2):55–75

Shang Y, Li FS, Ma J (2022) Tourist gaze upon a slum tourism destination: a case study of Dharavi, India. J Hosp Tour Manag 52(September):478–486

Slikker N, Koens K (2015) Breaking the silence”: Local perceptions of slum tourism in Dharavi. Tour Rev Int 19(1):75–86

Small H (1973) Co‐citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the relationship between two documents. J Am Soc Inf Sci 24(4):265–269

Solymári D, Kairu E, Czirják R, Tarrósy I (2022) The impact of COVID-19 on the livelihoods of Kenyan slum dwellers and the need for an integrated policy approach. PloS One 17(8):e0271196

Steinbrink M (2012) We did the Slum!’—Urban poverty tourism in historical perspective. Tour Geogr 14(2):213–234

Steinbrink M (2013) Festifavelisation: Mega-events, slums and strategic city-staging - The example of Rio de Janeiro. Erde 144(2):129–145

Steinbrink M, Frenzel F, Koens K (2012) Development and globalization of a new trend in tourism. In F. Frenzel, K. Koens, & M. Steinbrink (Eds.), Slum Tourism (pp. 19–36). Routledge

Sulistyaningsih T, Jainuri J, Salahudin S, Jovita HD, Nurmandi A (2022) Can combined marketing and planning-oriented of community-based social marketing (CBSM) project successfully transform the slum area to tourism village? A case study of the Jodipan colorful urban village, Malang, Indonesia. J Nonprofit Public Sect Mark 34(4):421–450

Surwase G, Sagar A, Kademani BS, Bhanumurthy K (2011) Co-citation analysis: An overview. BEYOND LIBRARIANSHIP: Creativity, Innovation and Discovery (BOSLA National Conference Proceedings) , 179–185

Torres I (2012) Branding slums: A community-driven strategy for urban inclusion in Rio de Janeiro. J Place Manag Dev 5(3):198–211

Tzanelli R (2018) Slum tourism: A review of state-of-the-art scholarship. Tour Cult Commun 18(2):149–155

UN-Habitat. (2006) State of the World’s Cities 2006/7

UN-Habitat (2020) World Cities Report 2020: The Value of Sustainable Urbanization

Urry J (1990) Tourist Gaze: Travel, Leisure and Society. In Tourist gaze: travel, leisure and society . Sage Publications Ltd

Wang H, Yang Y (2019) Neighbourhood walkability: A review and bibliometric analysis. Cities 93:43–61

Wise N, Polidoro M, Hall G, Uvinha RR (2019) User-generated insight of Rio’s Rocinha favela tour: Authentic attraction or vulnerable living environment? Local Econ 34(7):680–698

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Public Policy and Management, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China

Tianhan Gui & Wei Zhong

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Tianhan Gui spearheaded the conceptual background, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript writing. Wei Zhong directed the methodology, supervised the data analysis, and also contributed to the manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Wei Zhong .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gui, T., Zhong, W. When urban poverty becomes a tourist attraction: a systematic review of slum tourism research. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11 , 1178 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03696-w

Download citation

Received : 22 March 2024

Accepted : 30 August 2024

Published : 10 September 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03696-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Open access

- Published: 05 January 2021

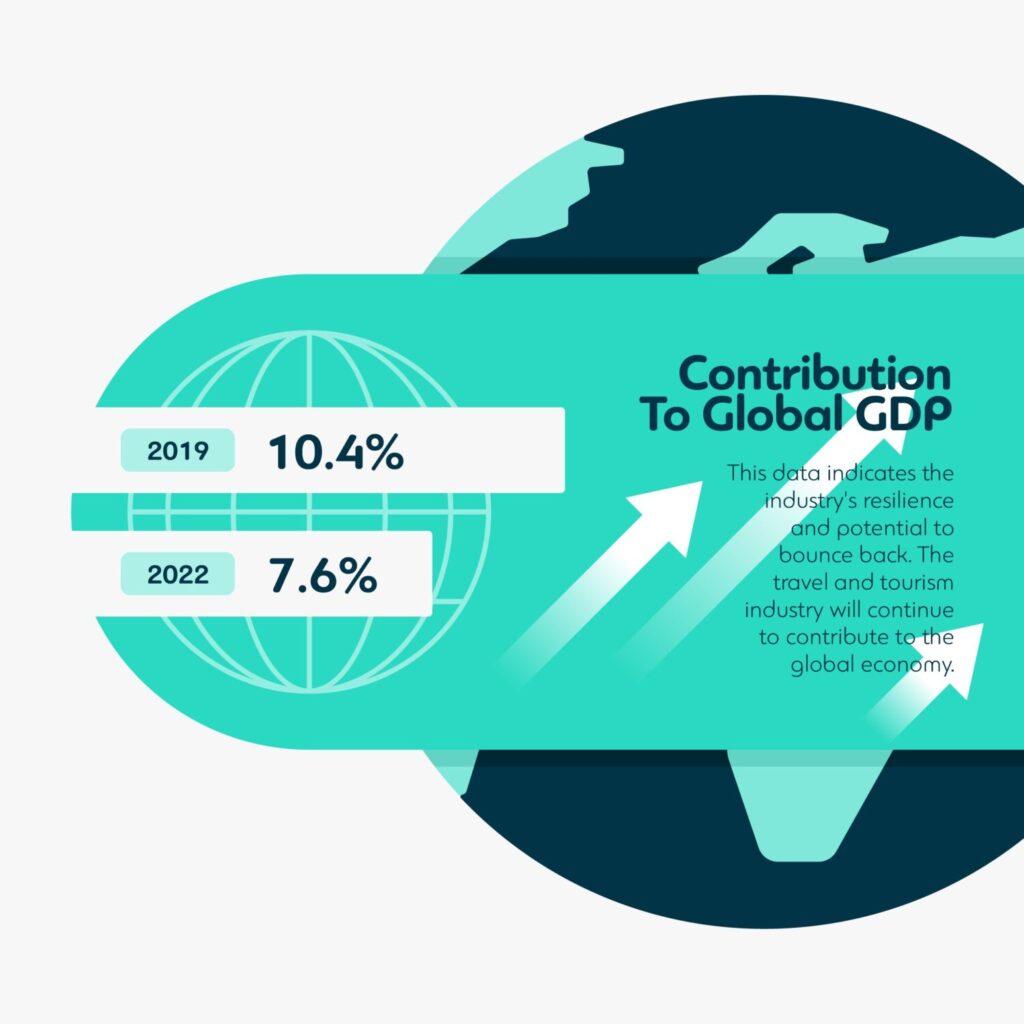

The relationship between tourism and economic growth among BRICS countries: a panel cointegration analysis

- Haroon Rasool ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0083-4553 1 ,

- Shafat Maqbool 2 &

- Md. Tarique 1

Future Business Journal volume 7 , Article number: 1 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

127k Accesses

122 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details