Triangular Trade in Colonial America

The Triangular Trade was a Transatlantic network of trade routes that were used during the Colonial Era, to ship goods between England, Africa, and the Americas.

This illustration depicts a Sugar Plantation in the West Indies. Image Source: Library of Congress .

Triangular Trade Summary

Triangular Trade in Colonial America involved shipping commodities between three ports in a triangular sequence. The starting port was in West Africa, where manufactured goods were traded for captive Africans. The second port was the West Indies or the 13 Original Colonies , where Africans were traded for natural resources like rum, sugar, molasses, and cotton. The third port was England where raw materials were traded for manufactured goods. The first Triangular Trade journey was carried out by Sir John Hawkins in 1562 and the routes were shaped by geography and British economic policies.

Triangular Trade Facts

The Triangular Trade was a Transatlantic network of trade routes that were used during the Colonial Era, to ship goods between England, Africa, and the Americas. There were three main routes:

- England to Africa.

- Africa to the 13 Original Colonies and the British West Indies.

- The Americas back to England.

Goods were often traded, rather than purchased with specie — gold and silver. The goods that were traded typically included:

- Raw materials — rum, timber, sugar, tobacco, rice, and cotton — from the 13 Original Colonies and the British West Indies.

- Manufactured goods from England and Europe, such as guns, cloth, furniture, and jewelry.

- Captive people from West Africa, who were sold into slavery in South America, the West Indies, and the American Colonies.

Causes of the Triangular Trade Routes

Triangular Trade Routes were caused by three main factors:

- The Mercantile System

- The Navigation Acts

The trade routes were shaped by geography as much as anything because there was no easy route from the Americas or Europe to the Far East. Rrumors persisted of a legendary “Northwest Passage” to the Far East, which spurred many of the early expeditions during the Age of Exploration.

Triangular Trade routes were also shaped by England’s Mercantile System and the Navigation Acts, which placed significant restrictions on trade within the British Empire. Over time, more restrictions were added and a complex system emerged that was difficult to follow and to enforce.

The Mercantile System was an economic system that required England to maintain a positive trade balance, so it retained as much gold and silver as possible. In the system, colonies played an important role, because they provided raw materials. Because England controlled the colonies, it did not have to trade gold and silver for the raw materials. Further, the finished products had more value than the raw materials, which allowed England to maintain a favorable trade balance with its colonies.

The Navigation Acts required exports from the colonies to be transported on English ships, which had to pass through English ports, regardless of their final destination. When ships arrived in port, customs officials were required to check the shipments and collect customs duties.

Salutary Neglect

By the 1720s, Britain was caught up in European affairs and Prime Minister Robert Walpole encouraged a policy in which British customs officials neglected to enforce the Navigation Acts and collect customs duties.

The unwritten policy, which became known as “Salutary Neglect,” allowed American merchants to expand their markets and increase their profits. Despite this, the triangle-shaped routes continued to be used, primarily because the American Colonies and West Indies Colonies depended on slave labor from West Africa and manufactured products from England.

Although customs officials often looked the other way, they were also paid to do so through bribes. This led to an increase in bribery and smuggling, especially in the New England Colonies, where molasses from the West Indies was vital to the rum distilling industry.

Following the French and Indian War, Prime Minister George Grenville issued instructions for customs officials to enforce the Molasses Act , bringing Salutary Neglect to an end .

Transatlantic Slave Trade

Triangular Trade was closely associated with the Transatlantic Slave Trade . The capture of Africans for sale in slave markets was established by a network of African kingdoms, the Spanish , and the Portuguese. Over time, the Dutch and English became involved in the business.

The First Triangular Trade Voyage

The first expedition specifically to transport captive Africans to sell in the New World is believed to have been carried out by Sir John Hawkins, an English sea captain, in 1562. Hawkins captured and traded for captive Africans along the coast of Africa, and sailed to the Caribbean, where he traded them for pearls, animal hides, and sugar. The expedition was so lucrative that a coat of arms was designed for him, which included a crude drawing of an enslaved African. The first trip is considered by some to be the first implement and profit from the Triangular Trade Route.

The Cycle of Triangular Trade

Overall, the shipment of goods along the Triangular Trade routes moved in a fairly consistent manner:

- From England, Ships sailed to Africa, carrying manufactured goods and products, which were traded for captive Africans, gold, and spices.

- Leaving Africa, ships sailed to the West Indies and the American Colonies over the “Middle Passage.” Upon arrival, they traded slaves for raw materials.

- From the Americas, Ships transported raw materials back to England, where they were used to manufacture finished goods and products.

Chart of Exports Traded by the 13 Original Colonies

England established the colonies as a way to produce raw materials for British manufacturing companies, which was a key aspect of the Mercantile System. Another important part of the system was the restriction of manufacturing in the 13 Original Colonies. There were various acts passed that restricted manufacturing, ensuring British manufacturers received all the raw materials and natural resources. One important exception to the rules was shipbuilding, which was allowed.

New England Colonies Exports

- New Hampshire — Ships, Timber, Rum

- Massachusetts — Ships, Timber, Rum, Fish, Whale Products, Fur, Wool

- Rhode Island — Ships, Rum, Timber, Corn

- Connecticut — Ships, Timber, Flour, Fish, Rum

Middle Colonies Exports

- New York — Fur Trade, Flour, Timber, Iron Ore

- New Jersey — Agricultural Products, Iron Ore

- Pennsylvania — Grains and other Agricultural Products, Iron Ore

- Delaware — Fur, Timber, Iron Ore

Chesapeake Colonies Exports

- Maryland — Fish, Timber, Fur, Tobacco, Sugar

- Virginia — Corn, Flax, Tobacco, Sugar

Southern Colonies Exports

- North Carolina — Rice, Indigo, Tobacco, Sugar

- South Carolina — Indigo, Rice, Tobacco, Sugar

- Georgia — Tobacco, Cotton, Sugar

Triangular Trade Significance

Triangular Trade is significant to United States history because of the role it played in creating an economic system in the American Colonies.

Triangular Trade APUSH Review

Use the following links and videos to study Triangular Trade, the Mercantile System, and the Colonial Era for the AP US History Exam. Also, be sure to look at our Guide to the AP US History Exam .

Triangular Trade APUSH Definition and Significance

The definition of Triangular Trade for APUSH is a complex system of trade routes that developed during the Colonia Era. It involved three main legs: the first leg saw English goods, including firearms and textiles, shipped to Africa in exchange for enslaved Africans. The second leg consisted of the Middle Passage, where enslaved Africans were transported to the Americas. The third leg involved the transport of raw materials back to England. Triangular Trade played a significant role in shaping the economies of the 13 Original Colonies.

Triangular Trade Video for APUSH Notes

This video from Heimler’s History discusses the Triangular Trade system.

- Written by Randal Rust

The Triangular Trade

In the year 1730, in the region of present-day Senegal, a man named Ayuba Suleiman Diallo traveled down to an English port on the coast to purchase paper, likely manufactured in Europe, an important item for his Muslim cleric father. To purchase the paper, his father had given him a pair of slaves to trade, but on the way home, however, Ayuba encountered a roving band of Mandinka raiders who took him prisoner and sold him into slavery to an English captain in turn, making him one of the many millions who fell victim to the Atlantic Slave Trade. Ayuba’s account, written down years later as Some Memoirs of the Life of Job, the Son of Solomon…Who was a Slave About Two Years in Maryland…, does not describe the likely atrocious journey across the ocean to North America, where, on average, between 12% and 15% of slaves crossing the Atlantic died while in transit. The memoir is useful nonetheless for its brief glimpse into how the slave trade actually operated on the African continent. Far from existing in isolation, the Atlantic Slave Trade was interwoven into a vast, intercontinental mercantile system commonly called the Triangular Trade.

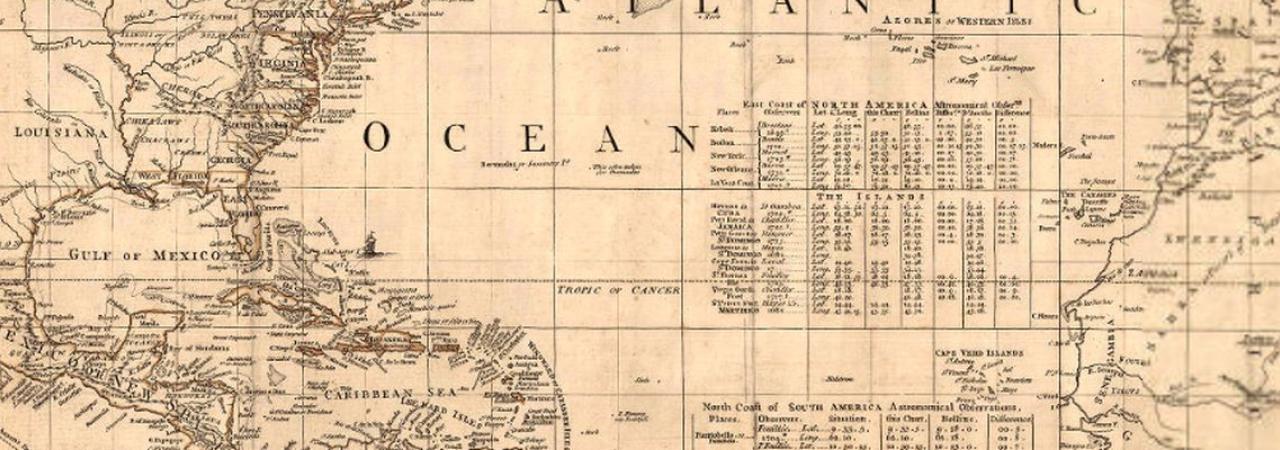

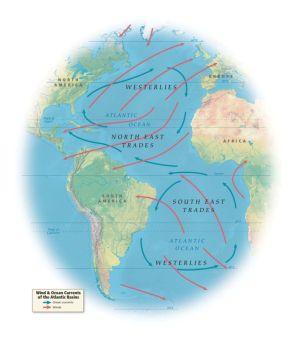

When Europeans began sailing further out onto the open ocean in the early-to-mid 15th century, they discovered that navigating the ocean required utilizing a series of perpetual wind cycles and ocean currents, such as the North Atlantic Gyre and the Gulf Stream. Portuguese navigators in particular established a kind of triangular route while exploring the western coast of Africa with the aid of the Northeast trade winds that dominate the tropics, returning to Europe not by reversing course, but sailing northwest to the Azores and catching the Southwest Westerlies home. Christopher Columbus himself became the first person to apply this principle to a transatlantic voyage, sailing north after making landfall in the Caribbean before returning to tell the world his discoveries. It is possible that Columbus also brought enslaved Africans with him on his first voyage, making him the first “triangle trader,” and as the various European powers began establishing their colonies in North and South America, introducing cash crops like sugarcane and adopting others like tobacco. In the meantime, the process of triangular maritime routes became the standard practice of transatlantic navigation.

As it happened, this process of navigation between Europe, Africa and the Americas fit in quite well with the prevailing economic theories on the purpose of colonies and international trade in the Early Modern Era. The overwhelming majority of colonies in the New World were not designed to exist as their own self-sustaining communities, but to act as production facilities for raw materials, particularly cash crops grown on massive plantations in hotter climates like cotton, sugarcane, chocolate, tobacco and coffee. Once harvested and processed, these crops were then sold and shipped to Europe where they were processed into finished goods. Often these goods were luxuries items made to be consumed by Europe’s elite classes, like chocolate which did not exist in a solid form yet, but as the continent inched towards the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century, lower class people began consuming sugar and coffee as useful stimulants: “fuel for the labor,” as one historian put it. Finished products that went unconsumed, however, were shipped South to Africa in order to purchase slaves, which then were carried back to the New World colonies to continue the harvesting of cotton, sugarcane, chocolate, tobacco and coffee.

But why all the way to Europe as the designated end point and as the center of production for finished goods? And why only to their own home countries? Surely wealthy individuals in Williamsburg, Vera Cruz, or Saint-Domingue enjoyed chocolate and coffee just as much as in London, Madrid or Paris. What prevented an English merchant from buying sugar in Dutch-ruled Aruba and selling it in Portuguese Brazil? The reason is that any of those practices ran up against the economic theory of Mercantilism, which in its simplest terms advocated the accumulation and circulation of precious metals (or bullion) within a single country’s market but taken to its logical extreme believed that countries should maximize exports and minimize imports under the assumption of international trade as a zero-sum game. Using policies such as high tariffs on imported finished products, and sometimes simple bans on certain exports, the European powers saw any gain their neighbors made in trade to be their loss, and they applied this principle to their colonies as well.

Most European colonies in the New World, especially cash crop producers, were completely banned from trading with either their colonial neighbors or European ports that did not belong to their mother countries. In Britain, this was done through legislation such as the Navigation Acts of 1660, which completely banned foreign merchants from purchasing or selling goods in any English port. Customers gained access (legally) to foreign products solely through English merchants setting forth and purchasing those items themselves. France committed itself and its colonies to similar principles, called Exclusif (exclusive) by King Louis XIV’s Minister of Finance Jean-Baptiste Colbert, who also forbade the colonies from developing any kind of local manufacturing to protect industries in the metropole. Colbert’s policies of protecting domestic manufacturing later had a major influence on Alexander Hamilton. That said, one of the major weaknesses of Mercantilist thought was the sheer difficulty in enforcing the proposed policies, the large area of open ocean necessary to crack down on smuggling made it a profitable though risky enterprise, and that is assuming that customs officials were not nearly as vulnerable to bribery as they probably were. Still, the most reliable way for a country to gain access to a particular resource was to hold a colony that produced it. Because of this, the trade wars waged between the colonial powers often spun into actual wars over colonial holdings, and the acquisition and annexation of various colonies became a repeated trend in multiple 17th and 18th conflicts, even those that began in Europe.

The Mercantilist nature of the Triangular Trade also had a major impact on the function of the slave trade, in Africa, the New World, and in between. From their small enclaves in Africa, colonial powers worked hard to maintain a favorable balance of trade with the local African elites as with their European neighbors. As mentioned before, the usual items traded for slaves were finished products, to avoid spending as much gold or silver as possible. These could include the same luxury items consumed by European elites, but also products like rum, paper and cotton cloth worked just as well, as demonstrated by Ayuba’s testimony. European weapons and munitions, too, were highly prized by the local kings and other rulers hoping to gain a military and political advantage over their rivals, as well as take new slaves as a result of the fighting.

Enslavement was hardly a new concept to Africa when Europeans began exploring the region, mostly done to criminals and war captives. Increased European demand for slave labor, however, increased the number of people captured and sold whole sale to the slave ships. Ultimately, modern estimates place the number of people taken from Africa in chains between nine and twelve million between the 16th and 19th centuries. The finance ministers of Europe also subjected the slave trade to the same Exclusif-style regulations as their colonies. All major colonial powers in the Americas participated in the trade to some extent, but when looking at the records, slave traders overwhelmingly disembark at ports owned by the nation whose flag whose flag they flew. As the records show, however, there were many exceptions to this rule. Around 39% of slaves brought to Spanish America were brought over by non-Spanish ships, British and Portuguese in particular. The vast majority of these voyages disembarked at Caribbean, Central or South American ports. If one gets the sense that North America was something of an afterthought in the entire process, they would be correct, as only 3% of slaves from Africa were sold in North America for a number of reasons. The first is that while cotton and tobacco were profitable, crops like sugarcane can only be grown in tropical climates, which North American colonies lacked. The other reason is that slaves in North America did not die as often. As an economic practice, human misery drove slavery and saying that does more than make a moral point. Sugarcane farming in the Caribbean and South America was extraordinarily deadly for slaves, and plantation owners considered importing new slaves a cheaper option than properly maintaining their current workforce, creating a constant demand for new workers and perpetuating the cycle of the triangular trade.

As the 18th century progressed, Mercantilism eventually fell into disuse, especially with the 1776 publication of The Wealth of Nations by Scottish philosopher Adam Smith, the first major work of modern capitalist theory. Smith argued against the high tariffs, government intervention in industries, and other barriers to free trade that defined earlier economic thought, and the rapidly industrializing Europe soon came around to his way of thinking. The slave trade also went into decline in the 19th century, as abolitionism took hold in Britain and France, though obviously, slavery continued in the United States and Brazil. Combined with the collapse of Spain’s Latin American empire, these factors all contributed to the Triangular Trade system falling into irrelevancy. It did not, however, cause the end of colonization, which began again in Asia and Africa itself in the coming decades.

Further Reading:

- The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation By: Daina Ramey Berry

- Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade By: David Eltis and David Richardson

- The French Atlantic Triangle: Literature and Culture of the Slave Trade By: Christopher L. Miller

- www.slavevoyages.com sponsored by Emory University

"Negro, Mulatto, or Indian man slave[s]": African Americans in the Rhode Island Regiments, 1775-1783

Boone Hall Plantation & Gardens

African Americans at Antietam

You may also like.

- Connect with us

- 2024 Tour Complete Rules

2024 Tour FAQs

- Springs Preserve — May 1

- Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art — May 14

- Denver Botanic Gardens Chatfield Farms — May 29

- Living History Farms — June 10

- Maryland Zoo — June 18

2024 Tour Rules

- Watch Episodes Online

- TV Schedule

- Best Moments of Season 27

- Best Moments of Season 26

- Best Moments of Season 25

- Best Moments of Season 24

- Best Moments of Season 23

- Cities from Past Seasons

- About Executive Producer Marsha Bemko

- Roadshow's Editorial Policy

Watch | Chicago, Hour 1

Watch | Chicago, Hour 2

Watch | Chicago, Hour 3

- Detours Podcast

- Video "RoadShorts"

- Roadshow Topics — Endangered Species

- Roadshow Topics — Sports Appraisals

- Roadshow Topics — Best Moments

- Roadshow Topics — Staff Picks

- For Teachers

- AR "Extras" Newsletter Sign-up

Article | What Became of the Chicago Seven?

Article | Psychedelic Style at the Apple Boutique

Owner Interview | Playboy Bunny Group

Explainer: What Was the Triangular Trade?

By ben phelan.

During the June 2015 ROADSHOW in Spokane, Washington, a guest brought in a small table, dating from the early years of the 19th century. From the runnel around its edge, seemingly designed to catch liquid and prevent it from spilling onto the floor, the table seemed to have played a food-serving role of some kind. The owner conjectured it was intended to hold a joint of meat while it was being carved and served. Not so, said appraiser Karen Keane . Rather, it was designed for mixing alcoholic drinks, and with its original top, it may have commanded $5,000 at auction. Without it, given the otherwise good condition, Keane estimates an auction value between $2,000 and $3,000.

The table’s mahogany veneer, said Keane, probably derived from three-legged trade routes between Africa, New England, and the lands of Central America and the Caribbean, generally referred to as the triangular trade. The “triangular trade” was not a specific trade route, but a model for economic exchange among three markets.

A triangular trade among Europe, West Africa and the New World is probably the best known. Following the colonization of the New World by European powers, Europe experienced a prolonged economic boom for reasons that are, from the economist’s perspective, self-evident. Suddenly, the world was a much bigger place. Novel and instantly prized goods that only existed in the New World seemed to blink into existence: sugar, tobacco, hemp. European merchants could command high prices for selling these goods to other Europeans, just as New World merchants could command high prices from their customers for manufactured items from Europe. But a direct exchange of these goods, between Europe and the colonizers in the New World, required start-up money. Transporting goods by sea was not cheap.

A solution to this economic problem appeared in the form of the transatlantic slave trade, which began operating as early as the 15th century, at the very beginning of the colonial period. European ships would travel to West Africa carrying manufactured goods to which Africans had no access: worked metal, certain types of clothing, weapons. Once there, as payment they would demand people captured for slavery, who would be loaded onto crowded ships and transported to the Americas. (This leg of the trade scheme is usually called the "Middle Passage," a term that has become a byword for suffering.) Upon arrival, the enslaved Africans who survived the voyage were sold to landowners looking for cheap labor. With the money derived from these slave sales, European merchants would then purchase the cotton, sugar and tobacco their customers back home were demanding, and the cycle continued.

(It’s important to note that single ships did not necessarily make all three legs of this voyage. The triangular trade was not a route, but a strategy for making trade among distant markets easier and more profitable.)

At the same time, a different triangular trade route arose between New England, West Africa, and Central America and the Caribbean islands that lay east of it.

The islands of the Caribbean Sea served as sources for cane sugar and molasses, which New World merchants would distill into rum, while the mahogany veneer on the mixing table probably came from Guatemala or Honduras.

Rum and manufactured goods taken by New World merchants to Africa were sold in exchange for enslaved people. These slaves were taken to the New World and sold. Slavers used the proceeds to buy mahogany and molasses, and the cycle continued onward.

It is obviously not necessary that one leg of a triangular trade route should consist of enslaved people. Triangular trade routes still exist today, although globalization and air travel have made international trade much more efficient. But during the colonial period in the New World and, indeed, well beyond the 1808 Act of Congress that sought to end the import of slaves, the triangular route between New England, West Africa, and the lands of the Caribbean ran on slavery. When the Civil War decided America's slavery question for good, enslaved people finally disappeared from the structure of international trade destined for America. In the meantime, untold millions had suffered and died in bondage.

Disco: Soundtrack of a Revolution

Discover the origins, fall, and legacy of disco.

Great American Recipe

Follow a competition among talented home cooks.

Pride Month

Stream PBS's collection of videos featuring LGBTQIA voices.

"I know there's a lot of envious people hearing that story..." Antiques Roadshow on Facebook

What’s inside the case?

William Austin Burt patented the U.S.'s first "typographer” on July 23 in 1829. 110 year later came this "The Gold Royal" typewriter… @RoadshowPBS

We're soaking up the story behind this @LeslieKeno appraisal! #antiquesroadshow @RoadshowPBS

A weekly collection of previews, videos, articles, interviews, and more!

- Earth and Environment

- Literature and the Arts

- Philosophy and Religion

- Plants and Animals

- Science and Technology

- Social Sciences and the Law

- Sports and Everyday Life

- Additional References

- Encyclopedias almanacs transcripts and maps

Triangular Trade Pattern

Triangular trade pattern.

TRIANGULAR TRADE PATTERN. The transatlantic slave trade involved more than the European purchase of slaves in Africa and their sale in the New World. Historians have identified as a triangular trade pattern a typical voyage of a slave ship consisting of three distinct legs: in the first, the ship would sail from a European port to coastal Africa and exchange its goods for slaves, who were then taken to the New World and sold for colonial produce. The ship then returned home to Europe laden with colonial cash crops, completing the triangle. The triangular trade found its classic, although not its original, expression in Eric Williams 's seminal Capitalism and Slavery (1944). Williams argued that the triangular trade was Great Britain 's primary trade in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and gave a triple stimulus to British industry. British manufactures were used to buy slaves in Africa, and once the slaves were put to work on American plantations, they were dressed — along with their owners — by British industries and fed by New England agriculture and Newfoundland fisheries. Finally, the New World commodities that the slaves produced were processed in Britain , thus giving rise to new industries.

Williams went on to suggest that this multiple stimulus was so significant that the British triangular trade paved the way for the industrial revolution. There was a link, he argued, between the capital accumulated in the slave trade of Liverpool, Britain's largest slave-trading port, and the emergence of manufactures in Manchester. Up to 1770, one-third of Manchester's textiles exports went via Liverpool to the African coast, and one-half to the American and West Indian colonies. Other historians have pointed out that long-term credits from Manchester manufacturers were used to finance Liverpool's trade. However, it has not been possible to determine the extent to which industrial development was linked directly to the slave trade.

Africa was always the first stop in the triangular trade, and the Europeans quickly learned that they needed a variety of goods in order to do business there. The specific merchandise brought to barter differed according to the place of trade, and it was important for slaver merchants to keep up with local demand. European goods were highly valued in the local African economies, both for their usefulness and their exchange value. Cloth, for example, was popular in Senegambia (the area of modern day Senegal and Gambia ), because it could serve as a kind of money or be made into clothes. The same was true of iron, which had a high exchange value but could also be made into tools, utensils, and weapons.

For lack of facilities to intern the slaves on the coast, the European purchase of slaves could take a long time. The average slaving vessel spent several months in Africa, the captain sailing up and down the coast or traveling inland until the ship's hold was filled. Once the so-called Middle Passage (the Africa-Americas run) had been completed, the slaves were sold. Payments were a perennial problem in the New World, since ships often arrived outside of the harvest season and, even when they arrived at the opportune time, most of their customers were heavily indebted planters. Due to the delay of payments, slave merchants were frequently compelled to advance credit to the planters, the interest for which was credited to the slave trader. Under this system, slave factors — traders in the employ of European merchant houses — served as intermediaries between the trader and the planter by arranging for the sale of slaves. In the British slave trade, the debt problem led to the adoption of a new system of remitting the proceeds of slave sales to England . This system, first introduced in the Caribbean in the 1730s, forced the slave factors to pay outstanding debts at specific times and to remit the proceeds of the slave sales in either cash, produce, or bills of exchange, effectively shifting the burden of supplying credit from the trader to the planter. If the factor cleared a debt with a bill of exchange, it had to be drawn against a British mercantile firm or guarantor.

Slave traders relied increasingly on these bills of exchange, as well as on the transport of produce on board ships other than slavers. The third leg of the triangular trade thus deviated from the model in that slave vessels did not usually carry large amounts of slave-produced goods from America to Europe. Many of the ships returning to the United Provinces from Suriname sailed in ballast, weighed down by sand and water. On the other hand, it was exceptional for slave vessels returning to British ports from Virginia and Jamaica to sail in ballast. Overall, it is hard to establish what percentage of the goods carried back represented payment for the slaves, although it is clear that the volume of goods that slavers transported from the New World to Europe was relatively small.

SHUTTLE OR ROUND-TRIP VOYAGES

In Atlantic trade generally, it was actually not the triangular trade that predominated, but the shuttle (also called round-trip) voyage, which did not include the New World – Europe leg of the triangle trip. Round-trip voyages produced experienced captains and increased the chance of a punctual delivery and of a landing around harvest time. By the last quarter of the seventeenth century, the transport of African slaves in the South Atlantic was partially a shuttle trade, in which the tobacco planters near Brazil 's capital of Bahia exchanged their crop for bonded Africans on the Gold Coast . A similar bilateral trade developed between Rio de Janeiro and Angola . The largest of all slave trades, that of Brazil, was therefore not triangular at all.

Nevertheless, although the African slave trade was often conducted separately from the trade between Europe and the Americas, the services it supplied to the latter were indispensable. And while doubt has been cast on the overall effect of the triangular model on British industrialization, the triangular trade pattern forms part of the web of dependence that connected Europe, Africa, and the New World in the age of the slave trade.

See also British Colonies: North America ; Commerce and Markets ; Slavery and the Slave Trade .

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Klein, Herbert S. The Atlantic Slave Trade . Cambridge, U.K., 1999.

Minchinton, Walter E. "The Triangular Trade Revisited." In The Uncommon Market: Essays in the Economic History of the Atlantic Slave Trade, edited by Henry A. Gemery and Jan S. Hogendorn, pp. 331 – 352. New York , 1979.

Richardson, David. "The British Slave Trade to Colonial South Carolina ." Slavery & Abolition 12, no. 3 (December 1991): 125 – 172.

Searing, James F. West African Slavery and Atlantic Commerce: The Senegal River Valley, 1700 – 1860. Cambridge, U.K., 1993.

Williams, Eric. Capitalism and Slavery. Chapel Hill, N.C., 1944.

Wim Klooster

Cite this article Pick a style below, and copy the text for your bibliography.

" Triangular Trade Pattern . " Europe, 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World . . Encyclopedia.com. 15 May. 2024 < https://www.encyclopedia.com > .

"Triangular Trade Pattern ." Europe, 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World . . Encyclopedia.com. (May 15, 2024). https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/triangular-trade-pattern

"Triangular Trade Pattern ." Europe, 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World . . Retrieved May 15, 2024 from Encyclopedia.com: https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/triangular-trade-pattern

Citation styles

Encyclopedia.com gives you the ability to cite reference entries and articles according to common styles from the Modern Language Association (MLA), The Chicago Manual of Style, and the American Psychological Association (APA).

Within the “Cite this article” tool, pick a style to see how all available information looks when formatted according to that style. Then, copy and paste the text into your bibliography or works cited list.

Because each style has its own formatting nuances that evolve over time and not all information is available for every reference entry or article, Encyclopedia.com cannot guarantee each citation it generates. Therefore, it’s best to use Encyclopedia.com citations as a starting point before checking the style against your school or publication’s requirements and the most-recent information available at these sites:

Modern Language Association

http://www.mla.org/style

The Chicago Manual of Style

http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html

American Psychological Association

http://apastyle.apa.org/

- Most online reference entries and articles do not have page numbers. Therefore, that information is unavailable for most Encyclopedia.com content. However, the date of retrieval is often important. Refer to each style’s convention regarding the best way to format page numbers and retrieval dates.

- In addition to the MLA, Chicago, and APA styles, your school, university, publication, or institution may have its own requirements for citations. Therefore, be sure to refer to those guidelines when editing your bibliography or works cited list.

More From encyclopedia.com

About this article, you might also like.

- Atlantic Slave Trade

- Slavery and the African Slave Trade

- Liverpool Slave Trade

- Slave Trade, Atlantic

- Interstate Slave Trade

- The Slave Trade

- The Slave Trade: An Overview

- Slave Trade, Domestic

NEARBY TERMS

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Historyplex

Triangular Trade

One of the most notorious concepts in the history of the world, the Triangular Trade played an important role in the incessant spread of slavery in the New World.

Did you know?

The name Triangular Trade or Triangle Trade was derived from the fact that its route roughly resembled a triangle on the map.

The term ‘Triangular Trade’ was used to refer to the slave trade which played a significant role in the American history. This trade, which was carried out between England, Africa, and North America, flourished throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. Its astounding success can be attributed to the fact that merchants involved in it garnered huge profits at each of the three phases of the trade.

Trans-Atlantic Triangular Trade

In general, the term ‘triangular trade’ can be used to refer to any trade carried out between three points. In this case, the three points were Europe, Africa, and North America. The concept implies trading of commodities that are not required in the particular region, in lieu of the required commodities available in other regions. In the ancient world, wherein barter services were in practice and sea route was the only mode of transport, this concept had several benefits.

The 3 Phases

Basically, this trade had three phases: Europe to Africa, Africa to North America, and North America to Europe, with each of these phases having peculiar characteristics. Given below are the details of each of these three phases.

The First Phase: The first phase of the trade was the journey from Europe to Africa. In this phase, manufactured goods were loaded onto the ship at the European ports and taken to Africa, where they were exchanged for slaves. The goods in question included cloth, metal goods, spirit, cooking utensils, beads, etc. Of the various finished products, arms and ammunition were important, as they were used by salve traders for their territorial expansion, which, in turn, meant access to more slaves. All these goods were exchanged for slaves in Africa, and these slaves were put on the ships and taken to the American slave market.

The Second Phase: The journey of ships laden with slaves from Africa was the second phase of the Triangular Trade, known as the ‘middle passage’. A single ship was packed with slaves beyond its capacity, as a result of which they were subjected to terrible conditions on board, with minimal food and water. The conditions were so harsh that approximately 13 percent slaves died in course of the journey. These slaves fetched a decent sum in the American market, so the merchants were not concerned about a few deaths that occurred during the journey. As the ships anchored on the American ports, these slaves were exchanged for raw goods, which were then taken to Europe.

The Third Phase: The third and the final phase of the Triangular Trade was the shipment of raw goods from the American plantations, where they were produced, to the European industries, where they were required to manufacture finished goods. These included cotton, sugar, molasses, tobacco, etc., which were used to produce finished goods. Molasses, for instance, was an important requirement for the European distilleries. As the ships docked at the ports in Europe, raw material was unloaded and finished goods were loaded. Thus started the cycle, all over again.

The plantation owners in the European colonies in America required slave laborers from Africa, the European industries needed raw material, which was produced in the New World colonies, and the African merchants wanted manufactured goods from Europe, which had a decent market share in Africa. The Trade ensured that all these requirements were met and helped maintain the balance.

Eventually, the role of Europe in the Triangular Trade was taken over by developing region of New England, as the merchants there started to produce finished goods from the raw material readily available in the New World. These goods were exported to Africa in lieu of slaves required at the plantations and also circulated within the New World itself.

Everything was going on in a smooth manner until the beginning of the 19th century, when Great Britain outlawed slave trade. The United States followed in the following year and thus, came to an end the age-old practice of slave trade. The British naval forces were ordered to monitor the Triangular Trade routes in order to curb this illegal practice.

Like it? Share it!

Get Updates Right to Your Inbox

Further insights.

Privacy Overview

- Yale University

- About Yale Insights

- Privacy Policy

- Accessibility

How has trade shaped the world?

Moving goods around the globe is such an everyday phenomenon that it has become almost invisible. But the business, policy, technology, and politics of trade have been powerful forces throughout history. William J. Bernstein, author of A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World, talked with Qn about both the sweep and the intricacies of the endeavor through history.

- William J. Bernstein William J. Bernstein, author of A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World

Q: What are the key threads to follow in understanding how trade has shaped the world? First, trade almost always benefits the nations that engage in it, but only when averaged over the entire national economy. Second, there is always a minority that is hurt by evolving trade patterns, and they will always call for protection. As early as the sixteenth century, Madeiran sugar growers demanded, and obtained, prohibitions against cheaper sugar from Brazil. Going back even further, by the third millennium BC, there was a vigorous trade between grain-rich Mesopotamia with mineral-rich Magan (modern Oman), and Dilmun (modern Bahrain) was the focal transshipment point for this operation. Although we have no record of it, you can bet that Dilmun's farmers were not happy with the cheap barley and wheat arriving on that city's wharves. Q: What did you discover about trade through looking at it with a long historical lens? The urge to trade is hard-wired into our DNA, and new patterns of trade always produce stresses, strains, cracks, and discontents. If you look at the historical record, you see that this process has been going on for centuries. For example, "tea parties" protesting taxes have been much in the news lately. This is beyond irony. The historical Boston Tea Party had almost nothing to do with taxes; rather, it was a protectionist backlash by middlemen and smugglers cut out of the tea trade by the decision to allow the East India Company to directly market its products in the colonies. Good for tea consumers, bad for those who had previously controlled the trade. Q: How has the role of the trader changed? How much has business changed? In the pre-modern world, the trader was a solitary, self-sufficient figure who more often than not sat and slept on his cargo and endured discomforts and dangers we cannot even begin to imagine. Today, the highest-value cargoes whip around the world at nearly the speed of sound on aircraft piloted by skilled specialists who end their workdays in taxis and four-star hotels. Lower-value cargoes travel on reasonably comfortable and safe vessels with well-stocked pantries and video collections, and both the aircraft and ship's crews are nearly always the employees of very large corporations. Q: Did your understanding of globalization change in doing the book? It could not help but do so. First, before I began the process, I hadn't realized just how relevant historical trade was to the modern story. As Harry Truman famously said, the only thing that's new in the world is the history we haven't read. You can take the stories of the opening up of the Manila Galleon route or the 1697 riots by London weavers displaced by Indian calicoes, change a few of the proper nouns and modernize the grammar, and you're reading James Fallows on the dumping of Chinese textiles or the AP coverage of the 1999 Seattle disturbances. Second, I hadn't realized what an intrinsic part of human behavior trade was. About 50,000–100,000 years ago, a small group of our ancestors in northeast Africa acquired the genetic endowment that gave them the language, social, and, intellectual skills that enabled them to break out of that continent through a barrier of their hominid competitors and go on to dominate the six habitable continents. The desire to trade — of which there is ample evidence in the prehistoric record — was part of that repertoire. Finally, I hadn't realized that trade's economic benefits pale in comparison to its intangible ones. In fact, you can make a pretty good case that before the mid-twentieth century, trade was not that much of an economic boon, although the post-1950 data leave little question of trade's material value. By contrast, trade's intangible benefits are enormous and indisputable: the desire to do business with your neighbors rather than to annihilate them. To convince yourself of that, look at the twentieth century: the Smoot-Hawley Tariff probably triggered the Second World War by embittering the Germans with their inability to recover and pay the Versailles reparations. No Smoot-Hawley, no Hitler chancellorship; no Hitler chancellorship, no World War II. By contrast, European free trade has made a major party conflict among western and central European powers unthinkable for the first time in history. Q: How important has technology been in shaping trade? Obviously, transport and communications technology played an enormously important role. Rather than mention the obvious advances — the steam engine, telegraph, aircraft, and computer — I'll focus here on a few less obvious ones that were just as important. The first of these more subtle technologies was the decoding of the planet's wind system. One great advance was the discovery of the Indian Ocean monsoon system by mariners around the dawn of the Common Era, which transformed the cities ringing it into prosperous trading states. The second great advance was the exploitation of the prevailing "trade winds" by European sailors in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which gave birth to the first flush of true "globalization" by about 1600. Another subtle but great advance in trade history was the invention of a process for mass producing inexpensive high-quality steel by Bessemer, Siemens, and Martin in the mid-nineteenth century. Prior to that, the soft iron rails and low-pressure iron boilers of the early steam age were not up to carrying very large volumes of grain. The new blast steel process yielded high-tensile strength rails and high-pressure boilers, which made possible, for the first time, an efficient global trade in bulk commodities, particularly grain, which would in turn ignite a protectionist backlash by European farmers that endures to this day. Finally, I can't resist mentioning the refrigerator. It's not commonly realized that by the early nineteenth century massive amounts of ice, and with it, chilled perishables, were being shipped around the world. Unfortunately, this was a one-way affair, and could originate only in places, such as New England, that had a reliable supply of it. If you were trying to ship beef from Argentina or Australia, you were out of luck. The invention of mechanical refrigeration around 1880 ignited a worldwide revolution in the growing of beef and pork for consumption halfway around the world. Q: Did the importance of policy, regulation, and finance as supports for successful trade change at some point? Trade has always required, and always will require, capital, which is why the Dutch were able to control it for much of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and why global trade volume has suffered a steep decline in the past year. The essence of free trade is the very absence of regulation. Unfortunately, as we've already seen, free trade always produces losers, who must of necessity be bought off, lest they clog up the works. As John Stuart Mill first pointed out, and as Paul Samuelson and Wolfgang Stolper have reiterated, the benefits of free trade will always be sufficient to "bribe the suffering factor." As a practical matter, free trade is joined at the hip with a generous social welfare system. When a worker loses his or her job to a better and/or cheaper foreign product, he or she not only deserves retraining, but should also not lose their health care coverage and all their income. Reasonable people can argue over the ethics of a generous social welfare policy, but there's no arguing over its political economy: if you don't compensate the losers, they wreck the system. Q: Is there anything distinctive about cities that are defined by trade? Sea transport has always been cheaper and more efficient than land transport. This was especially true in the pre-rail era. Genoa was the quintessential example of this. Hemmed in by mountains and facing the sea, it was easier to get to Lisbon or even London than to Milan or Geneva. A Genoese was more a citizen of the world than Italian, and it was perfectly natural for him to make his career abroad. Christopher Columbus, for example, spent most of his adult life in Portugal, Spain, and on the high seas. The same was also true of all of the great medieval Indian Ocean emporium ports, tied together by the monsoons and the institutional power of Islam. The commercial upper crusts of Cambay, Malacca, Calicut, and Mombasa had more in common with each other than with their fellow countrymen. Q: What are the relationships between legal and illicit trade? First, where there are tariffs, there is also smuggling; this is particularly true of high-value goods, whether licit or illicit: tea in the eighteenth century, heroin and cocaine today. Second, throughout most of history, the central calculus facing most leaders in the pre-modern era was the trilemma of whether to trade, raid, or protect. Today, we take the first as a given, but as we have recently learned off the Somali coast, the latter two options are still around. Read the introduction to the A Splendid Exchange on William J. Bernstein's website . Interview conducted and edited by Ted O’Callahan.

- Global Business

- Key Stage 3 & 4

- Video drama

- Small text size

- Regular text size

- Large text size

- High Contrast

How much did Manchester profit from slavery? Have your say

Revealing Histories: Remembering Slavery

A partnership project from eight museums in Greater Manchester

In Greater Manchester

- How money from slavery made Greater Manchester

- The importance of cotton in north west England

- The Lancashire cotton famine

- Smoking, drinking and the British sweet tooth

- Black presence in Britain and north west England

- Resistance and campaigns for abolition

- The bicentenary of British abolition

- Africa and the workings of the slave trade

- Colonialism and the expansion of empires

- Stereotypes, racism and civil rights

- Introduction

Africa, the arrival of Europeans and the transatlantic slave trade

- Triangular trade and multiple profits

Enlarge image

by Dr Alan Rice

'To put the matter simply, African slavery worked, it provided labour at a price Europeans could afford, in numbers they required and all to profitable economic use. Thus it was that Africans were quickly reduced from humanity to inanimate objects of trade and economic calculation.' James Walvin

The world economy was growing rapidly. More goods were being made and traded than ever before. Slavery was essential to this growth. Slaves were the 'human lubricant of the whole system', James Walvin.

Transatlantic slavery was basically triangular. At one point on the triangle was Europe. Manufactured and luxury goods from Europe such as textiles, guns (and gunpowder), knives, copper kettles, mirrors and beads were taken across to the west African coast. This coast was the second point of the triangle. On the west African coast, the goods from Europe were exchanged for enslaved Africans. Ships forcibly transported enslaved Africans to the Americas – the third point of the triangle. Upon a slaving ship’s arrival in the Americas, the enslaved Africans were landed and exchanged for goods such as sugar, tobacco, rice, cotton, mahogany and indigo. The ship then returned to Europe.

Increasingly slaving ships were not involved in the final journey of the triangular trade. Merchants found it more profitable to trade directly with the Americas using ships more suited to carrying goods. So, from the simple routes of its beginning, the triangular trade became a complex network of different trade routes. This network included important direct trades between Europe and the Americas, North America and the Caribbean and between Africa and Brazil. These routes were additional to the key trade between Europe and Asia developed since the sixteenth century in fine Indian textiles that were produced specifically for African and slave trade markets and were known as the Guinea cloths. Central to all the routes was the development of the plantation system and its dependence on an enslaved African workforce.

Tropical goods

European consumers loved goods from tropical countries. By the 1770s the British alone were consuming an average of six kilos of sugar per head annually. This addiction to sweetness was at the expense of Africans worked to an early death on the plantations of the Americas. The trade developed was massive: £2.75m (£275m in current prices) worth of British exports was shipped to the slave trade colonies annually and £3.15m (£315m) goods imported.

Banking and investment

Big profits were made not just by those directly involved in slaving or plantation economies, but also by banks. These banks were most often based in cities such as Liverpool and London. The foundation of the Bank of England in 1694 in London was crucial to trade regulation and the securing of profits. As trade profits grew, so did the banks and other financial institutions.

From the late 1600s to the 1800s, the providing of insurance, loans and other more complex trading instruments created massive new opportunities for making money. All this helped create modern capitalism. Indeed, it is one of the great ironies of history that a crude labour system like slavery was at the heart of the development of the modern global economy.

'To give just one example, by the late seventeenth century, the New England merchant, the Barbadian planter, the English manufacturer, the English slave trader and the African slave traders (and merchants) were joined in an intricate web of interdependent economic activity.' Barbara Solow

Related items

- Ibeji figures

- Slavery over time and the abuse of human rights

- The economic basis of the slave trade

- Mug, An East View of Liverpool Lighthouse & Signals

- The underdevelopment of Africa by Europe

- Barbados penny

- The National Lottery

- Heritage Lottery Fund

- Renaissance North West

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 1

- Motivation for European conquest of the New World

- Origins of European exploration in the Americas

- Christopher Columbus

- Consequences of Columbus's voyage on the Tainos and Europe

- Christopher Columbus and motivations for European conquest

- The Columbian Exchange

- Environmental and health effects of European contact with the New World

Lesson summary: The Columbian Exchange

- The impact of contact on the New World

- The Columbian Exchange, Spanish exploration, and conquest

Triangle trade of the Columbian Exchange

Review questions.

- What were the goals of Spanish colonization?

- How did technology help fuel European colonization?

- Can you name two positive and two negative effects of the Columbian Exchange?

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

COMMENTS

The Triangular Trade was a Transatlantic network of trade routes that were used during the Colonial Era, to ship goods between England, Africa, and the Americas. There were three main routes: England to Africa. Africa to the 13 Original Colonies and the British West Indies. The Americas back to England. Goods were often traded, rather than ...

triangular trade, three-legged economic model and trade route that was predicated on the transatlantic trade of enslaved people. It flourished from roughly the early 16th century to the mid-19th century during the era of Western colonialism. The three markets among which the trade was conducted were Europe, western Africa, and the New World.

Depiction of the classical model of the triangular trade Depiction of the triangular trade of slaves, sugar, and rum with New England instead of Europe as the third corner. Triangular trade or triangle trade is a historical term indicating trade among three ports or regions. Triangular trade usually evolves when a region has export commodities that are not required in the region from which its ...

During the colonial era, Britain and its colonies engaged in a " triangular trade ," shipping natural resources, goods, and people across the Atlantic Ocean in an effort to enrich the mother country. Trade with Europeans led to far-reaching consequences among Native American communities, including warfare, cultural change, and disease.

The Mercantilist nature of the Triangular Trade also had a major impact on the function of the slave trade, in Africa, the New World, and in between. From their small enclaves in Africa, colonial powers worked hard to maintain a favorable balance of trade with the local African elites as with their European neighbors.

The "triangular trade" was not a specific trade route, but a model for economic exchange among three markets. A triangular trade among Europe, West Africa and the New World is probably the ...

The Columbian Exchange is a term coined by Alfred Crosby Jr. in 1972 that is traditionally defined as the transfer of plants, animals, and diseases between the Old World of Europe and Africa and the New World of the Americas. The exchange began in the aftermath of Christopher Columbus' voyages in 1492, later accelerating with the European colonization of the Americas.

The Columbian Exchange: goods introduced by Europe, produced in New World. As Europeans traversed the Atlantic, they brought with them plants, animals, and diseases that changed lives and landscapes on both sides of the ocean. These two-way exchanges between the Americas and Europe/Africa are known collectively as the Columbian Exchange.

Triangular trade refers to the various navigation routes that emerged during the colonial period. There were numerous triangular paths that ships made to ferry people, goods (both raw and finished), and livestock. The most traveled triangular route began on Africa's west coast where ships picked up slaves.

TRIANGULAR TRADE PATTERN TRIANGULAR TRADE PATTERN. The transatlantic slave trade involved more than the European purchase of slaves in Africa and their sale in the New World. Historians have identified as a triangular trade pattern a typical voyage of a slave ship consisting of three distinct legs: in the first, the ship would sail from a European port to coastal Africa and exchange its goods ...

The name Triangular Trade or Triangle Trade was derived from the fact that its route roughly resembled a triangle on the map. The term 'Triangular Trade' was used to refer to the slave trade which played a significant role in the American history. This trade, which was carried out between England, Africa, and North America, flourished ...

The human story was dramatically reshaped by the Columbian Exchange, the Great Dying, and the Atlantic Slave Trade. It was also significantly changed by the growing global power of western Europe. Around the world, farming, mining, and deforestation led to increased energy production. But they also altered the world's physical landscape.

transatlantic slave trade, segment of the global slave trade that transported between 10 million and 12 million enslaved Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas from the 16th to the 19th century. It was the second of three stages of the so-called triangular trade, in which arms, textiles, and wine were shipped from Europe to Africa, enslaved people from Africa to the Americas, and ...

A triangle shaped series of Atlantic trade routes linking Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Describe the triangular trade route. On the first leg, merchant ships brought European goods to Africa. In Africa, the merchants traded these goods for slaves. On the second leg, known as the Middle Passage, the slaves were transported to the Americas.

The Triangular Trade The triangular trade was the trade between Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Raw materials like precious metals (gold and silver), tobacco, sugar and cotton went from the Americas to Europe. Manufactured goods like cloth and metal items went to Africa and the Americas. Finally, slaves went from Africa to the Americas to work.

Moving goods around the globe is such an everyday phenomenon that it has become almost invisible. But the business, policy, technology, and politics of trade have been powerful forces throughout history. William J. Bernstein, author of A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World, talked with Qn about both the sweep and the intricacies of the endeavor through history.

The foundation of the Bank of England in 1694 in London was crucial to trade regulation and the securing of profits. As trade profits grew, so did the banks and other financial institutions. From the late 1600s to the 1800s, the providing of insurance, loans and other more complex trading instruments created massive new opportunities for making ...

The spread of a disease to a large group of people within a population in a short period of time. An economic theory that was designed to maximize trade for a nation and especially maximize the amount of gold and silver a country had. The process by which commodities (horses, tomatoes, sugar, etc.), people, and diseases crossed the Atlantic.

A segment of the global slave trade, the transatlantic slave trade transported between 10 million and 12 million enslaved Black Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas from the 16th to the 19th century. The transatlantic slave trade was the second of three stages of the so-called triangular trade, in which arms, textiles, and wine ...

This period of industrialization led to the development of new technologies and innovations, such as the steam engine and the railway. Today, trade and travel continue to play a significant role in shaping the world. They continue to facilitate the sharing of knowledge and ideas, and they continue to lead to the exchange of goods and services.

Winds, Currents and Triangular Trade: In the early modern era (circa 1491- early 1800s) the global movement of goods and people relied upon winds and currents. Ships sailed across oceans only in ways that the natural movement of air and water allowed. The triangular trade between Europe, Africa and the Americas is indicative of this fact.

The transatlantic slave trade generated great wealth for many individuals, companies, and countries, but the brutal trafficking in human beings and the large numbers of deaths that resulted eventually sparked well-organized opposition to the trade. In 1807 the British abolished the slave trade. Another law passed in 1833 freed enslaved people ...

The Middle Passage involved shipping slaves from ____ to ____. Africa to America. The First Stage of Triangular Trade. Taking manufactured good from Europe to Africa: cloth, spirit, tobacco, beads, cowrie shells, metal goods, and guns. Guns were used to expand empires and get more slaves. (These goods were exchanged for slaves) The Middle Passage.