- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

A Year Without Travel

For Planet Earth, No Tourism Is a Curse and a Blessing

From the rise in poaching to the waning of noise pollution, travel’s shutdown is having profound effects. Which will remain, and which will vanish?

By Lisa W. Foderaro

For the planet, the year without tourists was a curse and a blessing.

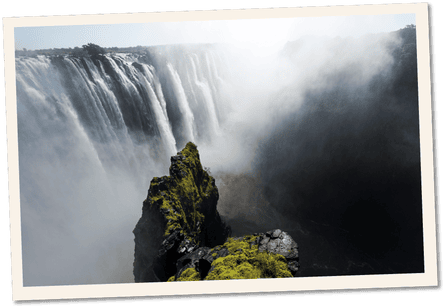

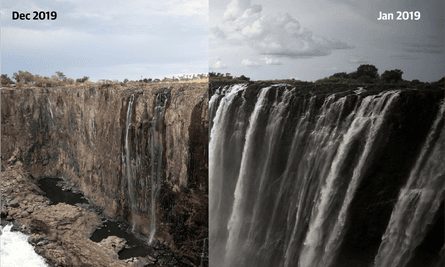

With flights canceled, cruise ships mothballed and vacations largely scrapped, carbon emissions plummeted. Wildlife that usually kept a low profile amid a crush of tourists in vacation hot spots suddenly emerged. And a lack of cruise ships in places like Alaska meant that humpback whales could hear each other’s calls without the din of engines.

That’s the good news. On the flip side, the disappearance of travelers wreaked its own strange havoc, not only on those who make their living in the tourism industry, but on wildlife itself, especially in developing countries. Many governments pay for conservation and enforcement through fees associated with tourism. As that revenue dried up, budgets were cut, resulting in increased poaching and illegal fishing in some areas. Illicit logging rose too, presenting a double-whammy for the environment. Because trees absorb and store carbon, cutting them down not only hurt wildlife habitats, but contributed to climate change.

“We have seen many financial hits to the protection of nature,” said Joe Walston, executive vice president of global conservation at the Wildlife Conservation Society. “But even where that hasn’t happened, in a lot of places people haven’t been able to get into the field to do their jobs because of Covid.”

From the rise in rhino poaching in Botswana to the waning of noise pollution in Alaska, the lack of tourism has had a profound effect around the world. The question moving forward is which impacts will remain, and which will vanish, in the recovery.

A change in the air

While the pandemic’s impact on wildlife has varied widely from continent to continent, and country to country, its effect on air quality was felt more broadly.

In the United States, greenhouse gas emissions last year fell more than 10 percent , as state and local governments imposed lockdowns and people stayed home, according to a report in January by the Rhodium Group, a research and consulting firm.

The most dramatic results came from the transportation sector, which posted a 14.7 percent decrease. It’s impossible to tease out how much of that drop is from lost tourism versus business travel. And there is every expectation that as the pandemic loosens its grip, tourism will resume — likely with a vengeance.

Still, the pandemic helped push American emissions below 1990 levels for the first time. Globally, carbon dioxide emissions fell 7 percent , or 2.6 billion metric tons, according to new data from international climate researchers. In terms of output, that is about double the annual emissions of Japan.

“It’s a lot and it’s a little,” said Jason Smerdon, a climate scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory . “Historically, it’s a lot. It’s the largest single reduction percent-wise over the last 100 years. But when you think about the 7 percent in the context of what we need to do to mitigate climate change, it’s a little.”

In late 2019, the United Nations Environment Program cautioned that global greenhouse gases would need to drop 7.6 percent every year between 2020 and 2030. That would keep the world on its trajectory of meeting the temperature goals set under the Paris Agreement, the 2016 accord signed by nearly 200 nations.

“The 7 percent drop last year is on par with what we would need to do year after year,” Dr. Smerdon said. “Of course we wouldn’t want to do it the same way. A global pandemic and locking ourselves in our apartments is not the way to go about this.”

Interestingly, the drop in other types of air pollution during the pandemic muddied the climate picture. Industrial aerosols, made up of soot, sulfates, nitrates and mineral dust, reflect sunlight back into space, thus cooling the planet. While their reduction was good for respiratory health, it had the effect of offsetting some of the climate benefits of cascading carbon emissions.

For the climate activist Bill McKibben , one of the first to sound the alarm about global warming in his 1989 book, “The End of Nature,” the pandemic underscored that the climate crisis won’t be averted one plane ride or gallon of gas at a time.

“We’ve come through this pandemic year when our lives changed more than any of us imagined they ever would,” Mr. McKibben said during a Zoom webinar hosted in February by the nonprofit Green Mountain Club of Vermont.

“Everybody stopped flying; everybody stopped commuting,” he added. “Everybody just stayed at home. And emissions did go down, but they didn’t go down that much, maybe 10 percent with that incredible shift in our lifestyles. It means that most of the damage is located in the guts of our systems and we need to reach in and rip out the coal and gas and oil and stick in the efficiency, conservation and sun and wind.”

Wildlife regroups

Just as the impact of the pandemic on air quality is peppered with caveats, so too is its influence on wildlife.

Animals slithered, crawled and stomped out of hiding across the globe, sometimes in farcical fashion. Last spring, a herd of Great Orme Kashmiri goats was spotted ambling through empty streets in Llandudno, a coastal town in northern Wales. And hundreds of monkeys — normally fed by tourists — were involved in a disturbing brawl outside of Bangkok, apparently fighting over food scraps.

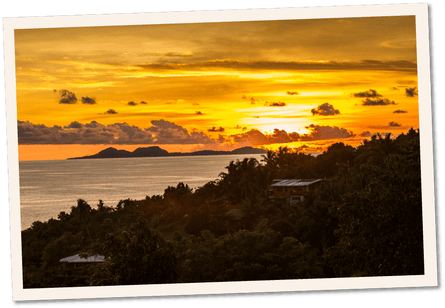

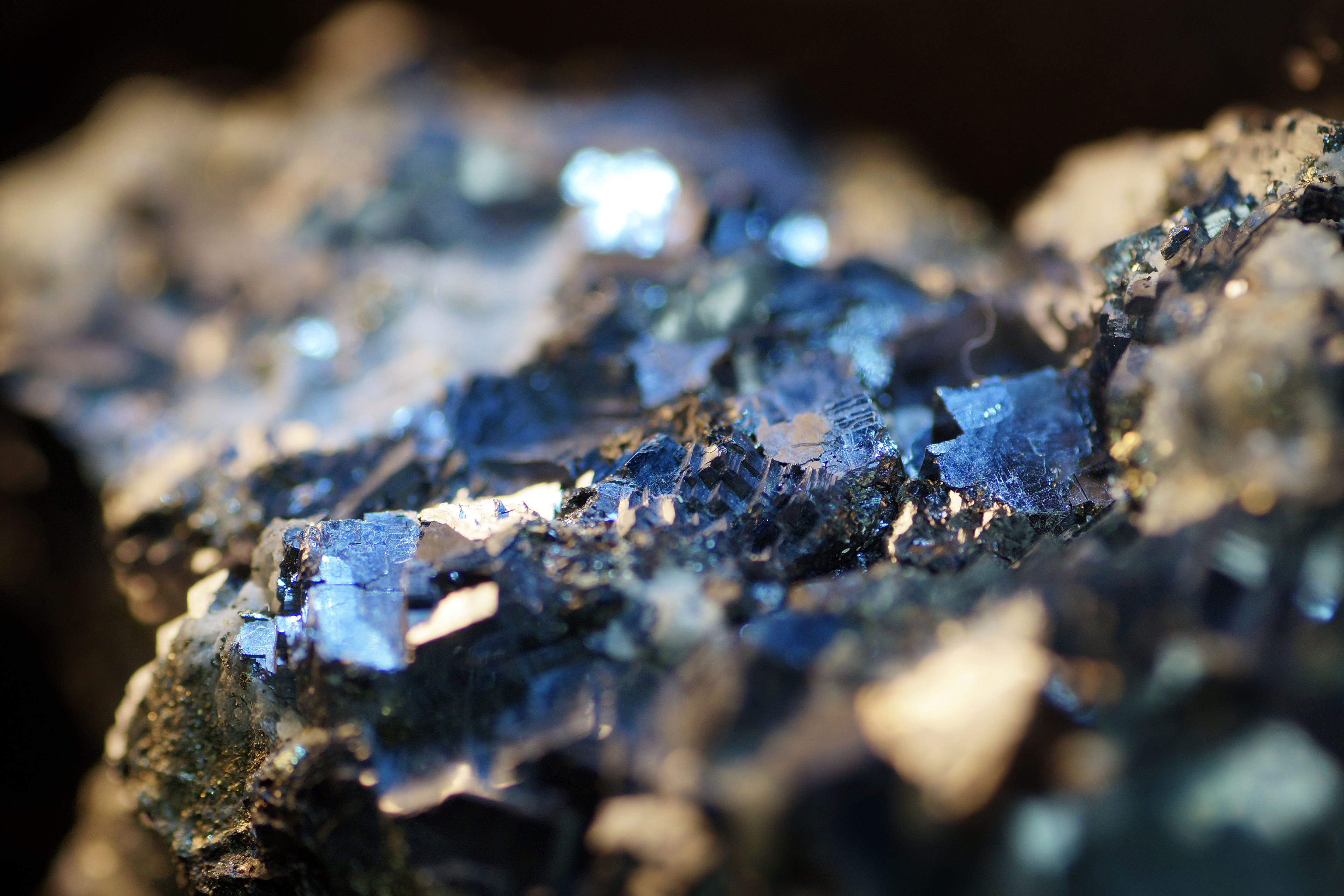

In meaningful ways, however, the pandemic revealed that wildlife will regroup if given the chance. In Thailand, where tourism plummeted after authorities banned international flights, leatherback turtles laid their eggs on the usually mobbed Phuket Beach. It was the first time nests were seen there in years, as the endangered sea turtles, the largest in the world, prefer to nest in seclusion.

Similarly, in Koh Samui, Thailand’s second largest island, hawksbill turtles took over beaches that in 2018 hosted nearly three million tourists. The hatchlings were documented emerging from their nests and furiously moving their flippers toward the sea.

For Petch Manopawitr, a marine conservation manager of the Wildlife Conservation Society Thailand, the sightings were proof that natural landscapes can recover quickly. “Both Ko Samui and Phuket have been overrun with tourists for so many years,” he said in a phone interview. “Many people had written off the turtles and thought they would not return. After Covid, there is talk about sustainability and how it needs to be embedded in tourism, and not just a niche market but all kinds of tourism.”

In addition to the sea turtles, elephants, leaf monkeys and dugongs (related to manatees) all made cameos in unlikely places in Thailand. “Dugongs are more visible because there is less boat traffic,” Mr. Manopawitr said. “The area that we were surprised to see dugongs was the eastern province of Bangkok. We didn’t know dugongs still existed there.”

He and other conservationists believe that countries in the cross hairs of international tourism need to mitigate the myriad effects on the natural world, from plastic pollution to trampled parks.

That message apparently reached the top levels of the Thai government. In September, the nation’s natural resources and environment minister, Varawut Silpa-archa, said he planned to shutter national parks in stages each year, from two to four months. The idea, he told Bloomberg News , is to set the stage so that “nature can rehabilitate itself.”

An increase in poaching

In other parts of Asia and across Africa, the disappearance of tourists has had nearly the opposite result. With safari tours scuttled and enforcement budgets decimated, poachers have plied their nefarious trade with impunity. At the same time, hungry villagers have streamed into protected areas to hunt and fish.

There were reports of increased poaching of leopards and tigers in India, an uptick in the smuggling of falcons in Pakistan, and a surge in trafficking of rhino horns in South Africa and Botswana.

Jim Sano, the World Wildlife Fund’s vice president for travel, tourism and conservation, said that in sub-Saharan Africa, the presence of tourists was a powerful deterrent. “It’s not only the game guards,” he said. “It’s the travelers wandering around with the guides that are omnipresent in these game areas. If the guides see poachers with automatic weapons, they report it.”

In the Republic of Congo, the Wildlife Conservation Society has noticed an increase in trapping and hunting in and around protected areas. Emma J. Stokes, regional director of the Central Africa program for the organization, said that in Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park, monkeys and forest antelopes were being targeted for bushmeat.

“It’s more expensive and difficult to get food during the pandemic and there is a lot of wildlife up there,” she said by phone. “We obviously want to deter people from hunting in the park, but we also have to understand what’s driving that because it’s more complex.”

The Society and the Congolese government jointly manage the park, which spans 1,544 square miles of lowland rainforest — larger than Rhode Island. Because of the virus, the government imposed a national lockdown, halting public transportation. But the organization was able to arrange rides to markets since the park is considered an essential service. “We have also kept all 300 of our park staff employed,” she added.

Largely absent: the whir of propellers, the hum of engines

While animals around the world were subject to rifles and snares during the pandemic, one thing was missing: noise. The whir of helicopters diminished as some air tours were suspended. And cruise ships from the Adriatic Sea to the Gulf of Mexico were largely absent. That meant marine mammals and fish had a break from the rumble of engines and propellers.

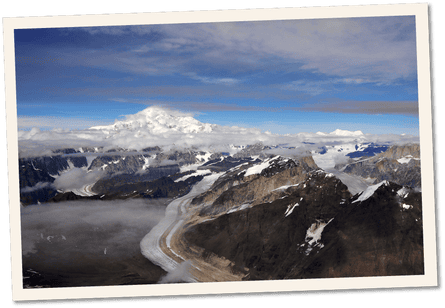

So did research scientists. Michelle Fournet is a marine ecologist who uses hydrophones (essentially aquatic microphones) to listen in on whales. Although the total number of cruise ships (a few hundred) pales in comparison to the total number of cargo ships (tens of thousands), Dr. Fournet says they have an outsize role in creating underwater racket. That is especially true in Alaska, a magnet for tourists in search of natural splendor.

“Cargo ships are trying to make the most efficient run from point A to point B and they are going across open ocean where any animal they encounter, they encounter for a matter of hours,” she said. “But when you think about the concentration of cruise ships along coastal areas, especially in southeast Alaska, you basically have five months of near-constant vessel noise. We have a population of whales listening to them all the time.”

Man-made noise during the pandemic dissipated in the waters near the capital of Juneau, as well as in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve . Dr. Fournet, a postdoctoral research associate at Cornell University, observed a threefold decrease in ambient noise in Glacier Bay between 2019 and 2020. “That’s a really big drop in noise,” she said, “and all of that is associated with the cessation of these cruise ships.”

Covid-19 opened a window onto whale sounds in Juneau as well. Last July, Dr. Fournet, who also directs the Sound Science Research Collective , a marine conservation nonprofit, had her team lower a hydrophone in the North Pass, a popular whale-watching destination. “In previous years,” she said, “you wouldn’t have been able to hear anything — just boats. This year we heard whales producing feeding calls, whales producing contact calls. We heard sound types that I have never heard before.”

Farther south in Puget Sound, near Seattle, whale-watching tours were down 75 percent last year. Tour operators like Jeff Friedman, owner of Maya’s Legacy Whale Watching , insist that their presence on the water benefits whales since the captains make recreational boaters aware of whale activity and radio them to slow down. Whale-watching companies also donate to conservation groups and report sightings to researchers.

“During the pandemic, there was a huge increase in the number of recreational boats out there,” said Mr. Friedman, who is also president of the Pacific Whale Watch Association . “It was similar to R.V.s. People decided to buy an R.V. or a boat. The majority of the time, boaters are not aware that the whales are present unless we let them know.”

Two years ago, in a move to protect Puget Sound’s tiny population of Southern Resident killer whales, which number just 75, Washington’s Gov. Jay Inslee signed a law reducing boat speeds to 7 knots within a half nautical mile of the whales and increasing a buffer zone around them, among other things.

Many cheered the protections. But environmental activists like Catherine W. Kilduff, a senior attorney in the oceans program at the Center for Biological Diversity, believe they did not go far enough. She wants the respite from noise that whales enjoyed during the pandemic to continue.

“The best tourism is whale-watching from shore,” she said.

Looking Ahead

Debates like this are likely to continue as the world emerges from the pandemic and leisure travel resumes. Already, conservationists and business leaders are sharing their visions for a more sustainable future.

Ed Bastian, Delta Air Lines’ chief executive, last year laid out a plan to become carbon neutral by spending $1 billion over 10 years on an assortment of strategies. Only 2.5 percent of global carbon emissions are traced to aviation, but a 2019 study suggested that could triple by midcentury.

In the meantime, climate change activists are calling on the flying public to use their carbon budgets judiciously.

Tom L. Green, a senior climate policy adviser with the David Suzuki Foundation , an environmental organization in Canada, said tourists might consider booking a flight only once every few years, saving their carbon footprint (and money) for a special journey. “Instead of taking many short trips, we could occasionally go away for a month or more and really get to know a place,” he said.

For Mr. Walston of the Wildlife Conservation Society, tourists would be wise to put more effort into booking their next resort or cruise, looking at the operator’s commitment to sustainability.

“My hope is not that we stop traveling to some of these wonderful places, because they will continue to inspire us to conserve nature globally,” he said. “But I would encourage anyone to do their homework. Spend as much time choosing a tour group or guide as a restaurant. The important thing is to build back the kind of tourism that supports nature.”

Lisa W. Foderaro is a former reporter for The New York Times whose work has also appeared in National Geographic and Audubon Magazine.

Follow New York Times Travel on Instagram , Twitter and Facebook . And sign up for our weekly Travel Dispatch newsletter to receive expert tips on traveling smarter and inspiration for your next vacation.

Come Sail Away

Love them or hate them, cruises can provide a unique perspective on travel..

Cruise Ship Surprises: Here are five unexpected features on ships , some of which you hopefully won’t discover on your own.

Icon of the Seas: Our reporter joined thousands of passengers on the inaugural sailing of Royal Caribbean’s Icon of the Seas . The most surprising thing she found? Some actual peace and quiet .

Th ree-Year Cruise, Unraveled: The Life at Sea cruise was supposed to be the ultimate bucket-list experience : 382 port calls over 1,095 days. Here’s why those who signed up are seeking fraud charges instead.

TikTok’s Favorite New ‘Reality Show’: People on social media have turned the unwitting passengers of a nine-month world cruise into “cast members” overnight.

Dipping Their Toes: Younger generations of travelers are venturing onto ships for the first time . Many are saving money.

Cult Cruisers: These devoted cruise fanatics, most of them retirees, have one main goal: to almost never touch dry land .

14 important environmental impacts of tourism + explanations + examples

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

The environmental impacts of tourism have gained increasing attention in recent years.

With the rise in sustainable tourism and an increased number of initiatives for being environmentally friendly, tourists and stakeholders alike are now recognising the importance of environmental management in the tourism industry.

In this post, I will explain why the environmental impacts of tourism are an important consideration and what the commonly noted positive and negative environmental impacts of tourism are.

Why the environment is so important to tourism

Positive environmental impacts of tourism, water resources, land degradation , local resources , air pollution and noise , solid waste and littering , aesthetic pollution, construction activities and infrastructure development, deforestation and intensified or unsustainable use of land , marina development, coral reefs, anchoring and other marine activities , alteration of ecosystems by tourist activities , environmental impacts of tourism: conclusion, environmental impacts of tourism reading list.

The quality of the environment, both natural and man-made, is essential to tourism. However, tourism’s relationship with the environment is complex and many activities can have adverse environmental effects if careful tourism planning and management is not undertaken.

It is ironic really, that tourism often destroys the very things that it relies on!

Many of the negative environmental impacts that result from tourism are linked with the construction of general infrastructure such as roads and airports, and of tourism facilities, including resorts, hotels, restaurants, shops, golf courses and marinas. The negative impacts of tourism development can gradually destroy the environmental resources on which it depends.

It’s not ALL negative, however!

Tourism has the potential to create beneficial effects on the environment by contributing to environmental protection and conservation. It is a way to raise awareness of environmental values and it can serve as a tool to finance protection of natural areas and increase their economic importance.

In this article I have outlined exactly how we can both protect and destroy the environment through tourism. I have also created a new YouTube video on the environmental impacts of tourism, you can see this below. (by the way- you can help me to be able to keep content like this free for everyone to access by subscribing to my YouTube channel! And don’t forget to leave me a comment to say hi too!).

Although there are not as many (far from it!) positive environmental impacts of tourism as there are negative, it is important to note that tourism CAN help preserve the environment!

The most commonly noted positive environmental impact of tourism is raised awareness. Many destinations promote ecotourism and sustainable tourism and this can help to educate people about the environmental impacts of tourism. Destinations such as Costa Rica and The Gambia have fantastic ecotourism initiatives that promote environmentally-friendly activities and resources. There are also many national parks, game reserves and conservation areas around the world that help to promote positive environmental impacts of tourism.

Positive environmental impacts can also be induced through the NEED for the environment. Tourism can often not succeed without the environment due the fact that it relies on it (after all we can’t go on a beach holiday without a beach or go skiing without a mountain, can we?).

In many destinations they have organised operations for tasks such as cleaning the beach in order to keep the destination aesthetically pleasant and thus keep the tourists happy. Some destinations have taken this further and put restrictions in place for the number of tourists that can visit at one time.

Not too long ago the island of Borocay in the Philippines was closed to tourists to allow time for it to recover from the negative environmental impacts that had resulted from large-scale tourism in recent years. Whilst inconvenient for tourists who had planned to travel here, this is a positive example of tourism environmental management and we are beginning to see more examples such as this around the world.

Negative environmental impacts of tourism

Negative environmental impacts of tourism occur when the level of visitor use is greater than the environment’s ability to cope with this use.

Uncontrolled conventional tourism poses potential threats to many natural areas around the world. It can put enormous pressure on an area and lead to impacts such as: soil erosion , increased pollution, discharges into the sea, natural habitat loss, increased pressure on endangered species and heightened vulnerability to forest fires. It often puts a strain on water resources, and it can force local populations to compete for the use of critical resources.

I will explain each of these negative environmental impacts of tourism below.

Depletion of natural resources

Tourism development can put pressure on natural resources when it increases consumption in areas where resources are already scarce. Some of the most common noted examples include using up water resources, land degradation and the depletion of other local resources.

The tourism industry generally overuses water resources for hotels, swimming pools, golf courses and personal use of water by tourists. This can result in water shortages and degradation of water supplies, as well as generating a greater volume of waste water.

In drier regions, like the Mediterranean, the issue of water scarcity is of particular concern. Because of the hot climate and the tendency for tourists to consume more water when on holiday than they do at home, the amount used can run up to 440 litres a day. This is almost double what the inhabitants of an average Spanish city use.

Golf course maintenance can also deplete fresh water resources.

In recent years golf tourism has increased in popularity and the number of golf courses has grown rapidly.

Golf courses require an enormous amount of water every day and this can result in water scarcity. Furthermore, golf resorts are more and more often situated in or near protected areas or areas where resources are limited, exacerbating their impacts.

An average golf course in a tropical country such as Thailand needs 1500kg of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides per year and uses as much water as 60,000 rural villagers.

Important land resources include fertile soil, forests , wetlands and wildlife. Unfortunately, tourism often contributes to the degradation of said resources. Increased construction of tourism facilities has increased the pressure on these resources and on scenic landscapes.

Animals are often displaced when their homes are destroyed or when they are disturbed by noise. This may result in increased animals deaths, for example road-kill deaths. It may also contribute to changes in behaviour.

Animals may become a nuisance, by entering areas that they wouldn’t (and shouldn’t) usually go into, such as people’s homes. It may also contribute towards aggressive behaviour when animals try to protect their young or savage for food that has become scarce as a result of tourism development.

Picturesque landscapes are often destroyed by tourism. Whilst many destinations nowadays have limits and restrictions on what development can occur and in what style, many do not impose any such rules. High rise hotels and buildings which are not in character with the surrounding architecture or landscape contribute to a lack of atheistic appeal.

Forests often suffer negative impacts of tourism in the form of deforestation caused by fuel wood collection and land clearing. For example, one trekking tourist in Nepal can use four to five kilograms of wood a day!

There are also many cases of erosion, whereby tourists may trek the same path or ski the same slope so frequently that it erodes the natural landscape. Sites such as Machu Pichu have been forced to introduce restrictions on tourist numbers to limit the damage caused.

Tourism can create great pressure on local resources like energy, food, and other raw materials that may already be in short supply. Greater extraction and transport of these resources exacerbates the physical impacts associated with their exploitation.

Because of the seasonal character of the industry, many destinations have ten times more inhabitants in the high season as in the low season.

A high demand is placed upon these resources to meet the high expectations tourists often have (proper heating, hot water, etc.). This can put significant pressure on the local resources and infrastructure, often resulting in the local people going without in order to feed the tourism industry.

Tourism can cause the same forms of pollution as any other industry: Air emissions; noise pollution; solid waste and littering; sewage; oil and chemicals. The tourism industry also contributes to forms of architectural/visual pollution.

Transport by air, road, and rail is continuously increasing in response to the rising number of tourists and their greater mobility. In fact, tourism accounts for more than 60% of all air travel.

One study estimated that a single transatlantic return flight emits almost half the CO2 emissions produced by all other sources (lighting, heating, car use, etc.) consumed by an average person yearly- that’s a pretty shocking statistic!

I remember asking my class to calculate their carbon footprint one lesson only to be very embarrassed that my emissions were A LOT higher than theirs due to the amount of flights I took each year compared to them. Point proven I guess….

Anyway, air pollution from tourist transportation has impacts on a global level, especially from CO2 emissions related to transportation energy use. This can contribute to severe local air pollution . It also contributes towards climate change.

Fortunately, technological advancements in aviation are seeing more environmentally friendly aircraft and fuels being used worldwide, although the problem is far from being cured. If you really want to help save the environment, the answer is to seek alternative methods of transportation and avoid flying.

You can also look at ways to offset your carbon footprint .

Noise pollution can also be a concern.

Noise pollution from aircraft, cars, buses, (+ snowmobiles and jet skis etc etc) can cause annoyance, stress, and even hearing loss for humans. It also causes distress to wildlife and can cause animals to alter their natural activity patterns. Having taught at a university near London Heathrow for several years, this was always a topic of interest to my students and made a popular choice of dissertation topic .

In areas with high concentrations of tourist activities and appealing natural attractions, waste disposal is a serious problem, contributing significantly to the environmental impacts of tourism.

Improper waste disposal can be a major despoiler of the natural environment. Rivers, scenic areas, and roadsides are areas that are commonly found littered with waste, ranging from plastic bottles to sewage.

Cruise tourism in the Caribbean, for example, is a major contributor to this negative environmental impact of tourism. Cruise ships are estimated to produce more than 70,000 tons of waste each year.

The Wider Caribbean Region, stretching from Florida to French Guiana, receives 63,000 port calls from ships each year, and they generate 82,000 tons of rubbish. About 77% of all ship waste comes from cruise vessels. On average, passengers on a cruise ship each account for 3.5 kilograms of rubbish daily – compared with the 0.8 kilograms each generated by the less well-endowed folk on shore.

Whilst it is generally an unwritten rule that you do not throw rubbish into the sea, this is difficult to enforce in the open ocean . In the past cruise ships would simply dump their waste while out at sea. Nowadays, fortunately, this is less commonly the case, however I am sure that there are still exceptions.

Solid waste and littering can degrade the physical appearance of the water and shoreline and cause the death of marine animals. Just take a look at the image below. This is a picture taken of the insides of a dead bird. Bird often mistake floating plastic for fish and eat it. They can not digest plastic so once their stomachs become full they starve to death. This is all but one sad example of the environmental impacts of tourism.

Mountain areas also commonly suffer at the hands of the tourism industry. In mountain regions, trekking tourists generate a great deal of waste. Tourists on expedition frequently leave behind their rubbish, oxygen cylinders and even camping equipment. I have heard many stories of this and I also witnessed it first hand when I climbed Mount Kilimanjaro .

The construction of hotels, recreation and other facilities often leads to increased sewage pollution.

Unfortunately, many destinations, particularly in the developing world, do not have strict law enrichments on sewage disposal. As a result, wastewater has polluted seas and lakes surrounding tourist attractions around the world. This damages the flora and fauna in the area and can cause serious damage to coral reefs.

Sewage pollution threatens the health of humans and animals.

I’ll never forget the time that I went on a school trip to climb Snowdonia in Wales. The water running down the streams was so clear and perfect that some of my friends had suggested we drink some. What’s purer than mountain fresh water right from the mountain, right?

A few minutes later we saw a huge pile of (human??) feaces in the water upstream!!

Often tourism fails to integrate its structures with the natural features and indigenous architecture of the destination. Large, dominating resorts of disparate design can look out of place in any natural environment and may clash with the indigenous structural design.

A lack of land-use planning and building regulations in many destinations has facilitated sprawling developments along coastlines, valleys and scenic routes. The sprawl includes tourism facilities themselves and supporting infrastructure such as roads, employee housing, parking, service areas, and waste disposal. This can make a tourist destination less appealing and can contribute to a loss of appeal.

Physical impacts of tourism development

Whilst the tourism industry itself has a number of negative environmental impacts. There are also a number of physical impacts that arise from the development of the tourism industry. This includes the construction of buildings, marinas, roads etc.

The development of tourism facilities can involve sand mining, beach and sand dune erosion and loss of wildlife habitats.

The tourist often will not see these side effects of tourism development, but they can have devastating consequences for the surrounding environment. Animals may displaced from their habitats and the noise from construction may upset them.

I remember reading a while ago (although I can’t seem to find where now) that in order to develop the resort of Kotu in The Gambia, a huge section of the coastline was demolished in order to be able to use the sand for building purposes. This would inevitably have had severe consequences for the wildlife living in the area.

Construction of ski resort accommodation and facilities frequently requires clearing forested land.

Land may also be cleared to obtain materials used to build tourism sites, such as wood.

I’ll never forget the site when I flew over the Amazon Rainforest only to see huge areas of forest cleared. That was a sad reality to see.

Likewise, coastal wetlands are often drained due to lack of more suitable sites. Areas that would be home to a wide array of flora and fauna are turned into hotels, car parks and swimming pools.

The building of marinas and ports can also contribute to the negative environmental impacts of tourism.

Development of marinas and breakwaters can cause changes in currents and coastlines.

These changes can have vast impacts ranging from changes in temperatures to erosion spots to the wider ecosystem.

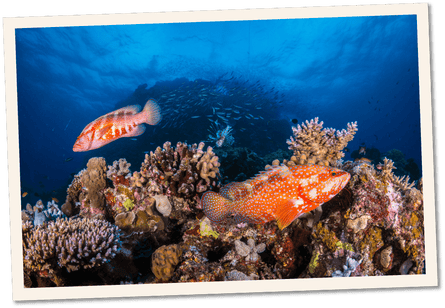

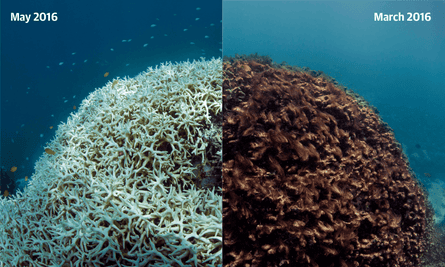

Coral reefs are especially fragile marine ecosystems. They suffer worldwide from reef-based tourism developments and from tourist activity.

Evidence suggests a variety of impacts to coral result from shoreline development. Increased sediments in the water can affect growth. Trampling by tourists can damage or even kill coral. Ship groundings can scrape the bottom of the sea bed and kill the coral. Pollution from sewage can have adverse effects.

All of these factors contribute to a decline and reduction in the size of coral reefs worldwide. This then has a wider impact on the global marine life and ecosystem, as many animals rely on the coral for as their habitat and food source.

Physical impacts from tourist activities

The last point worth mentioning when discussing the environmental impacts of tourism is the way in which physical impacts can occur as a result of tourist activities.

This includes tramping, anchoring, cruising and diving. The more this occurs, the more damage that is caused. Natural, this is worse in areas with mass tourism and overtourism .

Tourists using the same trail over and over again trample the vegetation and soil, eventually causing damage that can lead to loss of biodiversity and other impacts.

Such damage can be even more extensive when visitors frequently stray off established trails. This is evidenced in Machu Pichu as well as other well known destinations and attractions, as I discussed earlier in this post.

In marine areas many tourist activities occur in or around fragile ecosystems.

Anchoring, scuba diving, yachting and cruising are some of the activities that can cause direct degradation of marine ecosystems such as coral reefs. As I said previously, this can have a significant knock on effect on the surrounding ecosystem.

Habitats can be degraded by tourism leisure activities.

For example, wildlife viewing can bring about stress for the animals and alter their natural behaviour when tourists come too close.

As I have articulated throughout this post, there are a range of environmental impacts that result from tourism. Whilst some are good, the majority unfortunately are bad. The answer to many of these problems boils down to careful tourism planning and management and the adoption of sustainable tourism principles.

Did you find this article helpful? Take a look at my posts on the social impacts of tourism and the economic impacts of tourism too! Oh, and follow me on social media !

If you are studying the environmental impacts of tourism or if you are interested in learning more about the environmental impacts of tourism, I have compiled a short reading list for you below.

- The 3 types of travel and tourism organisations

- 150 types of tourism! The ultimate tourism glossary

- 50 fascinating facts about the travel and tourism industry

Liked this article? Click to share!

National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

What's the problem with overtourism?

With visitor numbers around the world increasing towards pre-pandemic levels, the issue of overtourism is once again rearing its head.

When locals in the charming Austrian lakeside village of Hallstatt staged a blockade of the main access tunnel, brandishing placards asking visitors to ‘think of the children’, it highlighted what can happen when places start to feel overrun by tourists. Hallstatt has just 800 residents but has opened its doors to around 10,000 visitors a day — a population increase of over 1,000%. And it’s just one of a growing number of places where residents are up in arms at the influx of travellers.

The term ‘overtourism’ is relatively new, having been coined over a decade ago to highlight the spiralling numbers of visitors taking a toll on cities, landmarks and landscapes. As tourist numbers worldwide return towards pre-pandemic levels, the debate around what constitutes ‘too many’ visitors continues. While many destinations, reliant on the income that tourism brings, are still keen for arrivals, a handful of major cities and sites are now imposing bans, fines, taxes and time-slot systems, and, in some cases, even launching campaigns of discouragement in a bid to curb tourist numbers.

What is overtourism?

In essence, overtourism is too many people in one place at any given time. While there isn’t a definitive figure stipulating the number of visitors allowed, an accumulation of economic, social and environmental factors determine if and how numbers are creeping up.

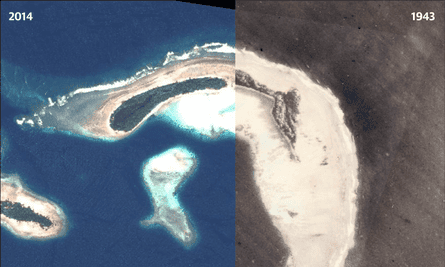

There are the wide-reaching effects, such as climate change. Coral reefs, like the Great Barrier Reef and Maya Bay, Thailand, made famous by the Leonardo DiCaprio film, The Beach , are being degraded from visitors snorkelling, diving and touching the corals, as well as tour boats anchoring in the waters. And 2030 transport-related carbon emissions from tourism are expected to grow 25% from 2016 levels, representing an increase from 5% to 5.3% of all man-made emissions, according to the United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO). More localised issues are affecting locals, too. Renters are being evicted by landlords in favour of turning properties into holiday lets, and house prices are escalating as a result. As visitors and rental properties outnumber local residents, communities are being lost. And, skyrocketing prices, excessive queues, crowded beaches, exorbitant noise levels, damage at historical sites and the ramifications to nature as people overwhelm or stray from official paths are also reasons the positives of tourism can have a negative impact.

Conversely, ‘undertourism’ is a term applied to less-frequented destinations, particularly in the aftermath of the pandemic. The economic, social and environmental benefits of tourism aren't always passed on to those with plenty of capacity and, while tourist boards are always keen for visitors to visit their lesser-known attractions, it’s a more sustainable and rewarding experience for both residents and visitors.

What’s the main problem with it?

Overcrowding is an issue for both locals and tourists. It can ruin the experience of sightseeing for those trapped in long queues, unable to visit museums, galleries and sites without advance booking, incurring escalating costs for basics like food, drink and hotels, and faced with the inability to experience the wonder of a place in relative solitude. The absence of any real regulations has seen places take it upon themselves to try and establish some form of crowd control, meaning no cohesion and no real solution.

Justin Francis, co-founder and CEO of Responsible Travel, a tour operator that focuses on more sustainable travel, says “Social media has concentrated tourism in hotspots and exacerbated the problem, and tourist numbers globally are increasing while destinations have a finite capacity. Until local people are properly consulted about what they want and don’t want from tourism, we’ll see more protests.”

A French start up, Murmuration, which monitors the environmental impact of tourism by using satellite data, states that 80% of travellers visit just 10% of the world's tourism destinations, meaning bigger crowds in fewer spots. And, the UNWTO predicts that by 2030, the number of worldwide tourists, which peaked at 1.5 billion in 2019, will reach 1.8 billion, likely leading to greater pressure on already popular spots and more objection from locals.

Who has been protesting?

Of the 800 residents in the UNESCO-listed village of Hallstatt, around 100 turned out in August to show their displeasure and to push for a cap on daily visitors and a curfew on tour coach arrivals.

Elsewhere, residents in Venice fought long and hard for a ban on cruise ships, with protest flags often draped from windows. In 2021, large cruise ships over 25,000 tonnes were banned from using the main Giudecca Canal, leaving only smaller passenger ferries and freight vessels able to dock.

In France, the Marseille Provence Cruise Club introduced a flow management system for cruise line passengers in 2020, easing congestion around the popular Notre-Dame-de-la-Garde Basilica. A Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA) spokesperson said, “Coaches are limited to four per ship during the morning or afternoon at the Basilica to ensure a good visitor experience and safety for residents and local businesses. This is a voluntary arrangement respected by cruise lines.”

While in Orkney, Scotland, residents have been up in arms at the number of cruise ships docking on its shores. At the beginning of 2023, the local council confirmed that 214 cruise ship calls were scheduled for the year, bringing around £15 million in revenue to the islands. Following backlash from locals, the council has since proposed a plan to restrict the number of ships on any day.

What steps are being taken?

City taxes have become increasingly popular, with Barcelona increasing its nightly levy in April 2023 — which was originally introduced in 2012 and varies depending on the type of accommodation — and Venice expects to charge day-trippers a €5 fee from 2024.

In Amsterdam this summer, the city council voted to ban cruise ships, while the mayor, Femke Halsema, commissioned a campaign of discouragement, asking young British men who planned to have a 'vacation from morals’ to stay away. In Rome, sitting at popular sites, such as the Trevi Fountain and the Spanish Steps, has been restricted by the authorities.

And in Kenya’s Maasai Mara, meanwhile, the Narok County governor has introduced on-the-spot fines for off-roading. He also plans to double nightly park fees in peak season.

What are the forecasts for global tourism?

During the Covid pandemic, tourism was one of the hardest-hit industries — according to UNWTO, international tourist arrivals dropped 72% in 2020. However, traveller numbers have since been rapidly increasing, with double the number of people venturing abroad in the first three months of 2023 than in the same period in 2022. And, according to the World Travel Tourism Council, the tourism sector is expected to reach £7.5 trillion this year, 95% of its pre-pandemic levels.

While the tourism industry is forecast to represent 11.6% of the global economy by 2033, it’s also predicted that an increasing number of people will show more interest in travelling more sustainably. In a 2022 survey by Booking.com, 64% of the people asked said they would be prepared to stay away from busy tourist sites to avoid adding to congestion.

Are there any solutions?

There are ways to better manage tourism by promoting more off-season travel, limiting numbers where possible and having greater regulation within the industry. Encouraging more sustainable travel and finding solutions to reduce friction between residents and tourists could also have positive impacts. Promoting alternative, less-visited spots to redirect travellers may also offer some benefits.

Harold Goodwin, emeritus professor at Manchester Metropolitan University, says, “Overtourism is a function of visitor volumes, but also of conflicting behaviours, crowding in inappropriate places and privacy. Social anthropologists talk about frontstage and backstage spaces. Tourists are rarely welcome in backstage spaces. To manage crowds, it’s first necessary to analyse and determine the causes of them.

Francis adds: “However, we must be careful not to just recreate the same problems elsewhere. The most important thing is to form a clear strategy, in consultation with local people about what a place wants or needs from tourism.”

As it stands, overtourism is a seasonal issue for a small number of destinations. While there is no one-size-fits-all solution, a range of measures are clearly an option depending on the scale of the problem. For the majority of the world, tourism remains a force for good with many benefits beyond simple economic growth.

Related Topics

- OVERTOURISM

- SUSTAINABLE TOURISM

You May Also Like

How can tourists help Maui recover? Here’s what locals say.

One of Italy’s most visited places is an under-appreciated wine capital

For hungry minds.

In this fragile landscape, Ladakh’s ecolodges help sustain a way of life

Cinque Terre’s iconic ‘path of love’ is back. Don’t love it to death

25 breathtaking places and experiences for 2023

See the relentless beauty of Bhutan—a kingdom that takes happiness seriously

Is World Heritage status enough to save endangered sites?

- Paid Content

- Environment

- Photography

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 31 May 2023

Eco-tourism, climate change, and environmental policies: empirical evidence from developing economies

- Yunfeng Shang 1 ,

- Chunyu Bi 2 ,

- Xinyu Wei 2 ,

- Dayang Jiang 2 ,

- Farhad Taghizadeh-Hesary ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5446-7093 3 , 4 &

- Ehsan Rasoulinezhad ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7726-1757 5

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 275 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

9210 Accesses

8 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Environmental studies

Developing ecotourism services is a suitable solution to help developing countries improve the status of sustainable development indicators and protect their environment. The primary purpose of this paper is to find out the effects of green governance variables and carbon dioxide emissions on ecotourism for 40 developing economies from 2010 to 2021. The results confirmed a uni-directional causal relationship between the green governance indicator and the inflation rate of the ecotourism indicator. In addition, with a 1% improvement in the green governance index of developing countries, the ecotourism of these countries will increase by 0.43%. In comparison, with a 1% increase in the globalization index of these countries, ecotourism will increase by 0.32%. Moreover, ecotourism in developing countries is more sensitive to macroeconomic variables changes than in developed economies. Geopolitical risk is an influential factor in the developing process of ecotourism. The practical policies recommended by this research are developing the green financing market, establishing virtual tourism, granting green loans to small and medium enterprises, and government incentives to motivate active businesses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Comprehensive green growth indicators across countries and territories

Role of foreign direct Investment and political openness in boosting the eco-tourism sector for achieving sustainability

Ways to bring private investment to the tourism industry for green growth

Introduction.

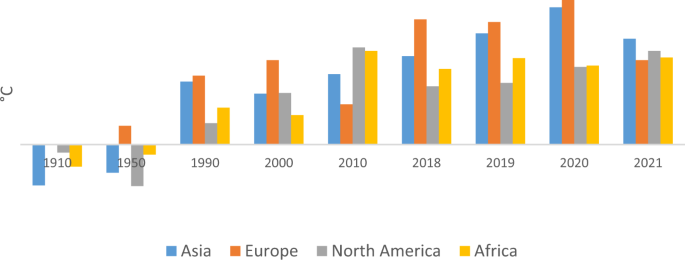

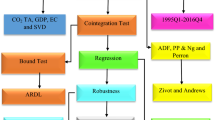

The challenge of climate change has become a primary threat to living on the Earth in the last centuries (Rasoulinzhad and Taghizadeh-Hesary, 2022 ). Many meetings of the countries at the regional and international level are held on the topics of environment and climate change. Regardless of environmental issues, population growth, and the lack of control of greenhouse gas emissions, industrialization has been the most crucial cause of the climate change crisis. Chao and Feng ( 2018 ) address human activity as the leading cause of climate change and express that this challenge is a potential threat to living on Earth. Woodward ( 2019 ) argued that climate change threats include the rise in global temperature, the melting of polar ice caps, and unprecedented disease outbreaks. Therefore, urgent policies and solutions are essential to control and lower the risk of global change. One of the signs of climate change is the increase in the average temperature of the Earth’s surface. Figure 1 shows the temperature data from 1910 to 2021 for the four continents of Asia, Europe, Africa, and North America.

Source: Authors from NOAA ( https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/climate-at-a-glance/global/time-series ).

The data in Fig. 1 shows that the air temperature has increased significantly over the past century, which has been more prominent in Asia and Europe. In 2021, we saw a decrease in temperature changes due to the spread of the Corona disease and a decrease in the rate of greenhouse gas emissions. However, the role of the Asian continent in increasing the global temperature has been more than other continents due to its large population and excessive consumption of fossil fuels.

During the past decades, the world’s countries have tried to formulate and implement various environmental policies collectively in the form of agreements or separately to fight environmental threats. Regarding international agreements, such things as the Paris Agreement of 2015, the Kyoto Protocol of 1997, the Montreal Protocol of 1987, and the Vienna Convention on the Protection of the Ozone Layer in 1985 can be addressed whose primary purpose is to integrate the goals and motivation of the international community to the world’s environmental threats. However, a group of earlier studies, such as Zheng et al. ( 2017 ), Takashima ( 2018 ), and Roelfsema et al. ( 2022 ), emphasized the inefficiency of these global agreements, especially after the left the USA from the Paris Agreement on 1 June 2017. The most important cause of this inefficiency has been the need for more motivation of countries to fulfill their international obligations towards environmental issues. However, many governments consider the threat of climate change only within their geographical boundaries and have tried to formulate and implement green policies to advance their environmental protection goals. These policies include green financial policies (green taxes, green subsidies), monetary policies (such as green loans and green financing), and cultural and social policies in line with sustainable development. The ultimate goal of these green policies is a green economy, an environmentally friendly economy, a zero carbon economy, or a sustainable economy. Lee et al. ( 2022 ) define the green economy as a broad concept comprising green industry, agriculture, and services. Centobelli et al. ( 2022 ) express that environmental sustainability should be more attention in the service sector owing to its penetration into social life and interactions.

Tourism and travel-related services are among countries’ main parts of the service sector. By creating the flow of tourists, tourism services can lead to capital transfer, job creation, cultural exchange (globalization), and increasing welfare in the country hosting the tours. According to the Yearbook of Tourism Statistics published by the World Tourism Organization, international tourism has increased from 522.2 billion US dollars in 1995 to nearly 1.86 trillion US dollars in 2019. This increase shows the importance of tourism services in generating income for countries, especially in the era of Corona and post-corona. Casado-Aranda et al. ( 2021 ) express that tourism services can be a central driver of economic growth recovery in post COVID era. Jeyacheya and Hampton ( 2022 ) argue that tourism can make high incomes for host countries leading to job creation and economic flourishing in destination cities for tourists.

An important issue mentioned in the corona era and relies on the post-corona era is the revitalizing of green economic growth. An important issue mentioned in the corona era and relying on the post-corona era is the revitalizing green economic growth (Bai et al., 2022 ; Werikhe, 2022 ), an opportunity that countries should pay more attention to in order to rebuild their economic activities. In other words, countries should plan their return to economic prosperity with environmental issues in mind. To this end, the issue of tourism finds a branch called Ecotourism or sustainable tourism which has environmental concerns and tries to help countries to improve environmental protection policies. Ecotourism is an approach based on environmental criteria, which is opposed to over-tourism (a type of tourism that disrupts the protection of the environment and destroys natural resources). The International Ecotourism Society defines Ecotourism as an efficient way to conserve the environment and improve local people’s well-being. It can be said that Ecotourism, along with various economic advantages (income generation, job creation, globalization, poverty alleviation), will bring environmental protection to the world’s countries, achieving the goals of green economic growth recovery and sustainable development. Xu et al. ( 2022 ) consider Ecotourism as one of the essential components of achieving sustainable development in the post-corona era.

Ecotourism in developing countries has more priorities compared to developed economies. Firstly, developing countries are often countries with financial problems of the government, and the governments in these countries need more capital to advance sustainable development goals. Therefore, developing ecotourism services can be a suitable solution to help these countries improve the status of sustainable development indicators and protect their environment. Second, due to the spread of the Corona disease, developing countries have experienced numerous bankruptcy in the tourism services sector. Therefore, promoting ecotourism in these countries is of great importance in the post-corona era. Third, developing countries have a high share in the emission of greenhouse gases in the world due to their high dependence on fossil fuels and the lack of advanced green technologies. Fourth, due to bureaucratic processes, high cost, and lack of market transparency, greenwashing may happen in developing economies’ ecotourism industry, meaning that a company serving ecotourism services makes its activities seem more sustainable and ethical than they are. The term “greenwashing” can harshly impact the future development path of the ecotourism industry in developing economies. According to the reasons mentioned above, developing ecotourism in developing countries can be an essential factor in controlling and reducing greenhouse gas emissions in these countries.

This paper tries to contribute to the existing literature from the following aspects:

Calculating the ecotourism index for selected countries based on the criteria for measuring sustainable tourism stated by the World Tourism Organization in the United Nations. Considering that there is no specific index for ecotourism, the calculation of ecotourism in this article will be innovative.

Measuring the green governance index as a proxy for environmental policies for selected countries based on the Environment Social and Governance (ESG) data.

Selecting a sample of 40 developing countries from different geographical regions to calculate the interconnections between ecotourism, green governance, and climate change

Making a further discussion to address the role of uncertainty and the developing level of countries in the relationship between ecotourism and explanatory variables.

The main results confirm the existence of a uni-directional causal relationship running from the green governance indicator and inflation rate to the ecotourism indicator. In addition, with a 1% improvement in the green governance index of developing countries, the ecotourism of these countries will increase by 0.43%. A 1% increase in the globalization index of these countries accelerates ecotourism by 0.32%.

Moreover, ecotourism in developing countries is more sensitive to macroeconomic variables changes than in developed economies. Geopolitical risk is an influential factor in the developing process of ecotourism. The practical policies recommended by this research are developing the green financing market, establishing virtual tourism, granting green loans to small and medium enterprises, and government incentives to motivate active businesses.

The paper in continue is organized as follows: section “Literature review” provides a short literature review to determine the gaps this research seeks to fill. Section “Data and model specification” argues data and model specification. The following section represents empirical results. Section “Discussion” expresses discussion, whereas the last section provides conclusions, policy implications, research limitations, and recommendations to research further.

Literature review

This part of the article analyzes and classifies the previous literature on ecotourism and sustainable development in a rational and structured way. The importance of tourism in economic growth and development has been discussed in previous studies. However, the study of the effect of tourism on climate change has received little attention. Especially the relationship between sustainable tourism, climate change, and environmental policies is a problem that has yet to receive the attention of academic experts.

A group of previous studies has focused on the place of tourism in economic development and growth. Holzner ( 2011 ) focused on the consequences of tourism development on the economic performance of 134 countries from 1970 to 2007. They found out that excessive dependence on tourism income leads to Dutch disease in the economy, and other economic sectors need to develop to the extent of the tourism sector. In another study, Sokhanvar et al. ( 2018 ) investigated the causal link between tourism and economic growth in emerging economies from 1995 to 2014. The main results confirmed that the linkage is country-dependent. Brida et al. ( 2020 ) studied 80 economies from 1995 to 2016 to determine how tourism and economic development are related. The paper’s conclusions highlighted tourism’s-positive role in economic activities.

Another group of previous studies has linked tourism to sustainability targets. Sorensen and Grindsted ( 2021 ) expressed that nature tourism development has a positive and direct impact on achieving sustainable development goals of countries. In a new study, Li et al. ( 2022 ) studied the impacts of tourism development on life quality (as one of the sustainable development goals defined by the UN in 2015) in the case of Japan. They found that tourism development positively impacts the quality of life of age groups in the country. Ahmad et al. ( 2022 ) explored the role of tourism in the sustainability of G7 economies from 2000–2019. The primary findings revealed the positive impact of tourism arrivals on sustainable economic development. Zekan et al. ( 2022 ) investigated the impact of tourism on regional sustainability in Europe. They concluded that tourism development increases transport, leading to increased carbon dioxide emissions. Therefore, tourism development causes environmental pollution.

Tourism that can pay attention to environmental issues is called “ecotourism.” Many new studies have studied different dimensions of ecotourism. Lu et al. ( 2021 ) expanded the concept of the ecotourism industry. The significant results expressed that smart tourist cities are essential for efficient ecotourism in countries. Thompson ( 2022 ) expressed the characteristics of ecotourism development through survey methodology. The results confirmed the importance of transparent regulations, government support, and social intention to promote ecotourism. In another study, Heshmati et al. ( 2022 ) employed the SWOT analysis method to explore the critical success factors of ecotourism development in Iran. They found that legal documentation and private participation are major influential factors in promoting ecotourism in Iran. In line with the previous research, Hosseini et al. ( 2021 ) tried to explore the influential factors in promoting ecotourism in Iran by employing a SWOT analysis. They depicted that attracting investors is essential to enhance ecotourism projects in Iran. Hasana et al. ( 2022 ) reviewed research to analyze the earlier studies about ecotourism. The conclusions expressed that ecotourism is necessary for environmental protection. However, it is a challenging plan for the government, and they should carry out various policies toward ecotourism development. Kunjuraman et al. ( 2022 ) studied the role of ecotourism on rural community development in Malaysia. The significant results confirmed that ecotourism could transfer-positive impacts.

Several earlier studies have concentrated on the characteristics of ecotourism in different developed and developing economies. For example, Ruhanen ( 2019 ) investigated the ecotourism status in Australia. The paper concluded that the country could potentially make a larger share of ecotourism to the entire local tourism industry. Jin et al. ( 2022 ) studied the role of local community power on green tourism in Japan. They concluded that the concept of agricultural village activity and regional support positively influences the development of green tourism in Japan as a developed economy. Choi et al. ( 2022 ) sought to find aspects of ecotourism development in South Korea. The preliminary results confirmed the importance of green governance and efficient regulation to promote a sustainable tourism industry. Baloch et al. ( 2022 ) explored the ecotourism specifications in the developing economy of Pakistan. They found that Pakistan’s ecotourism needs government support and the social well-being of the visited cities. Sun et al. ( 2022 ) studied ecotourism in China. They concluded that there is imbalanced development of ecotourism among Chinese provinces due to the need for more capital to invest in all ecotourism projects throughout the Chinese cities. Tajer and Demir ( 2022 ) analyzed the ecotourism strategy in Iran. They concluded that despite various potentials in the country, insufficient capital, lack of social awareness, and political tension are the major obstacles to promoting a sustainable tourism industry in Iran.

Another group of earlier studies has drawn attention to promoting eco-tourism in the post COVID era. They believe that the corona disease has created an excellent opportunity to pay more attention to environmental issues and that countries should move towards sustainable development concepts such as sustainable (eco) tourism in the post-corona era. Soliku et al. ( 2021 ) studied eco-tourism in Ghana during the pandemic. The findings depicted the vague impacts of a pandemic on eco-tourism. Despite the short-term negative consequence of the pandemic on eco-tourism, it provides various opportunities for developing this sector in Ghana. Hosseini et al. ( 2021 ) employed the Fuzzy Dematel technique to find solutions for promoting eco-tourism during COVID-19. They found out that planning to increase the capacity of eco-tourism and incentive policies by governments can help promote the eco-tourism aspect under the pandemic’s consequences. Abedin et al. ( 2022 ) studied the consequence of COVID-19 on coastal eco-tourism development. The primary findings confirmed the negative impacts of a pandemic on the development of eco-tourism.

A review of previous studies shows that tourism can positively impact green growth and sustainable development. Sustainable tourism can be used as a policy to deal with the threat of climate change. This issue needs more attention in the corona and post-corona eras. Because in the post-corona era, many countries have sought to revive green economic growth, and ecotourism can be one of the tools to achieve it. As observed, a detailed study of the relationship between climate change, ecotourism, and environmental policies has yet to be done. Therefore, this research will address and fill this literature gap.

Data and model specification

Data description.

The paper seeks to find the relationship between climate change, ecotourism, and environmental policy for the panel of 40 developing economies from different regions from 2010 to 2021 (480 observations). The sample size could have been more extensive due to the lack of information on some variables. However, there are 480 observations in the data analysis of the data panel; therefore, the number of samples selected is acceptable.

To determine the proxies for main variables, CO2 emissions per capita are selected as the proxy for climate change. Many earlier studies (e.g., Espoir et al., 2022 ) have employed this variable as an appropriate variable representing the status of climate change. Regarding ecotourism, the World Tourism Organization proposed some measurements of sustainable tourism, and also following Yusef et al. ( 2014 ), the entropy weight method is employed to calculate a multi-dimensional ecotourism indicator comprising per capita green park area (square meters), gross domestic tourism revenue (US dollars), the ratio of good air quality (%), green transport, renewable water resources (km3) and deforestation rate (%). It is a novel ecotourism indicator that can show the ecotourism status in countries.

In addition, the green governance index is calculated as a proxy for environmental policy. Principally, the Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG) data from World Bank are gathered to calculate this variable. With the improvement of the Green Governance Index, the quality of environmental policies will also increase, and vice versa. With the adverseness of the Green Governance Index, the efficiency of environmental policies will decrease.

Regarding control variables, the inflation rate as an influential factor in tourism flows is selected. The importance of this variable to promoting/declining tourism flows has been drawn to attention by some earlier studies, such as Liu et al. ( 2022 ). The inflation rate can raise the total cost of travel, causing a reduction in tourism flows, while any reduction in the inflation rate can increase the intention of tourists to travel. In addition, the KOF globalization index provided by the KOF Swiss Economic Institute is another control variable. A country with a higher degree of globalization means more readiness to accept tourists from countries with different cultures and religions.

Model specification

According to the variables mentioned above, 40 examined developing countries from 2010 to 2021, the panel co-integration model can be written as Eq. 1 :

ETOR indicates the ecotourism index, while CO2, GGI, INF, and GLOB denote Carbon dioxide emissions per capita, green governance index, inflation rate, and globalization index, respectively. i is 1,2,…,40 and shows examined developing economies, while t is time and contains 2010, 2011,..,2021.

Prior to the estimation of coefficients of Eq. 1 , the panel unit root tests are employed to find out whether the series is stationary. To this end, three tests of LLC (Levin et al., 2002 ), Breitung’s test ( 2000 ), and the PP-Fisher test (Philips and Perron, 1988 ). If all the variables are stationary at the first level of difference (I(1)), a panel co-integration test can be conducted to explore whether the model is spurious. To this end, Kao’s co-integration test ( 1999 ) and Pedroni’s residual co-integration test ( 2004 ) are conducted. If the co-integration relationship exists among variables, the panel causality test can be run to determine the causal linkages among variables. In this paper, the two steps of Engle and Granger (1987)‘s test, which is based on the error correction model (ECM) is used as Eqs. 2 – 6 :

In the above Equations, Δ is the first differences of variables, while θ and ECT represent the fixed country effect and error correction term.

The next step is the long-run panel co-integration estimations. To this end, Fully Modified OLS (FMOLS) and Dynamic OLS (DOLS) as robustness checks are conducted, which are two famous panel co-integration estimators (Rasoulinezhad, 2018 ). The FMOLS estimator has various advantages. It allows serial correlation, endogeneity, and cross-sectional heterogeneity (Erdal and Erdal, 2020 ).

Empirical results

In this section, we will implement the experimental research model. The purpose of implementing an econometric model based on panel data is to find the effects of green governance variables and carbon dioxide emissions on ecotourism. As the first step, the panel unit root tests are conducted. The results are reported in Table 1 as follows:

According to Table 1 , all three-panel unit root tests depict that all series are non-stationary at the level and become stationary after a first difference. Next, the panel co-integration tests are conducted, and their results are represented in Tables 2 and 3 :

The two-panel co-integration tests’ findings confirm the presence of co-integration linkages among variables.

The panel causality test studies the short-term and long-term causal relationship among variables. Table 4 reports the results of the panel causality check as follows:

According to Table 4 , there is a uni-directional causal relationship between the green governance indicator and the inflation rate of the ecotourism indicator. At the same time, there is a bi-directional causal relationship between carbon dioxide emissions and ecotourism indicators, confirming the existence of the feedback effect. In addition, there is only short-term causality from the green governance indicator to carbon dioxide emissions. In contrast, ecotourism and the globalization index have a uni-directional causal linkage. In the short term, improving ecotourism can cause globalization and reduce carbon emissions in developing economies. Regarding the long-term causality, it can be concluded that the ECT of ecotourism, green governance index, and globalization index are statistically significant. These three variables are major adjustment variables when the system departs from equilibrium.

In the last stage, the long-run estimations are done through FMOLS and DOLS estimators. Table 5 lists the results of the estimations by these two-panel co-integration estimators:

Based on FMOLS estimation, it can be concluded that the Green Governance index has a positive and significant coefficient in such a way that with a 1% improvement in the green governance index of developing countries, the ecotourism of these countries will increase by 0.43%. By improving the state of green governance, the quality of formulated and implemented green policies in these countries will increase, improving the conditions of ecotourism development. This finding aligns with Agrawal et al. ( 2022 ) and Debbarma and Choi ( 2022 ), who believe that green governance is essential to sustainable development. In the case of carbon dioxide emissions, the coefficient of this variable is not statistically significant. In other words, the variable of carbon dioxide emissions per capita has no significant effect on ecotourism in developing countries. The inflation rate has a significant negative effect on ecotourism. With a 1% increase in the general prices of goods and services in developing countries, ecotourism will decrease by 0.34%. This finding aligns with Rahman ( 2022 ), who showed a negative relationship between inflation and sustainable development in their research. An increase in inflation means an increase in the total cost of a tourist’s trip to the destination country, inhibiting the growth of tourist services.

Regarding the globalization variable, this variable has a significant positive effect on the ecotourism of developing countries. With a 1% increase in the globalization index of these countries, ecotourism will increase by 0.32%. Globalization means more interaction with the world’s countries, acceptance of different cultures and customs, more language learning in society, more acceptance of tourism, and development of tourist services in the country. This finding is consistent with the results of Akadiri et al. ( 2019 ), who confirmed that globalization is one of the crucial components in tourism development.

The DOLS estimator was also used to ensure the obtained findings’ validity. The results of this method are shown in Table 5 . The signs of the coefficients are consistent with the results obtained by the FMOLS method. Therefore, the validity and reliability of the obtained coefficients are confirmed.

In this section, we will briefly discuss the relationship between ecotourism and climate change and the environmental policy considering the uncertainty and the relationship between variables in developed and developing countries.

Consideration of uncertainty

Uncertainty as a primary reason for risk has become a research issue in recent decades. Uncertainty can make the future unpredictable and uncontrollable, affecting economic decision-making. Regarding tourism, the impacts of uncertainty have been drawn to attention by several earlier studies (e.g., Dutta et al., 2020 ; Das et al., 2020 ; and Balli et al., 2019 ; Balli et al., 2018 ). In general, uncertainty in the tourism industry reflects tourists’ concerns and consumption habits in the way that by increasing uncertainty, it is expected that tourists make sense of risks and postpone their tourism activities, and vice versa; in the sphere of certainties, the various risks are clear, and tourists can make rational decisions for their tourism plans and activities. In order to explore the impacts of uncertainties on eco-tourism of the examined developing economies, the geopolitical risk index (GPR) as a proxy for economic policy uncertainty index is gathered and added as a control variable to Eq. 1 . The estimations results by FMOLS are reported in Table 6 as follows.

According to Table 6 , the uncertainty (geopolitical risk) has a negative coefficient meaning that with a 1% increase in geopolitical risk, the eco-tourism industry in the examined developing countries decreases by approximately 0.69%. The signs of coefficients of other variables align with the earlier findings, represented in Table 5 . In addition, the magnitude of the impact of geopolitical risk is larger than the impacts of other variables highlighting the importance of lower geopolitical risk in these economies to reach sustainable tourism targets.

Difference in developed and developing economies

Considering the different structures and financial power of these two groups of countries, the relationship between the variables mentioned in these two groups is expected to be different. In the previous section, the results for the group of developing countries showed that the Green Governance index has a positive and significant coefficient. In the case of carbon dioxide emissions, the coefficient of this variable is not statistically significant. The inflation rate has a significant negative effect on ecotourism. Regarding the globalization variable, it can be mentioned that this variable has a significant positive effect on the ecotourism of developing countries. In order to analyze the relationship between variables in the developed countries, the top 10 countries with the highest HDI in 2021 are selected (Switzerland (0.962), Norway (0.961), Iceland (0.959), Hong Kong (0.952), Australia (0.951), Denmark (0.948), Sweden (0.947) and Ireland (0.945)). The selected variables, explained in section “Data and model specification”, are collected from 2010 to 2021. The panel unit root tests confirmed that all series are non-stationary at the level and become stationary after a first difference. In addition, the presence of co-integration linkages among variables is revealed by the panel co-integration test. The panel co-integration estimator of FMOLS is employed to study the long-term relationship among variables. The findings are reported in Table 7 as follows: