- Kidney stone treatment typically would be covered by health insurance. For patients covered by health insurance, out-of-pocket costs typically would consist of a doctor visit specialist copay, prescription drug copays, possibly a hospital copay of $100 or more, and coinsurance of 10% to 50% for the procedure, which could reach the yearly out-of-pocket maximum. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation[ 1 ] , the average hospital copay for outpatient surgery is $132 and for inpatient surgery is $232 .The average coinsurance rate is 17% to 18%.

- For patients not covered by health insurance, kidney stone treatment typically costs less than $500 to allow the stone to pass naturally with monitoring from a doctor, and possibly prescription medication. For example, at Southern Illinois Urology, the cost of a doctor consultation is $150 . One medicine sometimes prescribed to patients with kidney stones, Urocit-K, costs about $65 for a one-month supply at Drugstore.com. Another, Zyloprim, costs about $80 . Generic versions of some of the drugs are available for less than $20 ; for example, Drugstore.com sells 100 tablets of Allopurinol (generic Zyloprim) for $13.99 .

- Kidney stone treatment can cost from just under $10,000 to $20,000 or more for surgical removal or extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL). For example, at Saint Elizabeth Regional Medical Center[ 2 ] , in Lincoln, NE, a cystourethroscopy -- a kind of examination of the urinary tract using a long, flexible tube -- with removal of a kidney stone typically costs about $7,400-$12,200, not including doctor fee. At Garden City Hospital[ 3 ] , in Michigan, the full price of a surgical kidney stone removal via cystoscopy is about $8,700 -- but the hospital offers it at a discounted price of about $2,500 for uninsured patients. Fragmenting a kidney stone using ESWL typically costs about $10,700-$16,700 or more. At Baptist Memorial Health Care, in Memphis, ESWL costs about $9,870 not including the doctor fee. According to NewChoiceHealth.com[ 4 ] , the national average cost for ESWL is $17,400 -- with range from $8,300 to $35,800 .

- Some smaller kidney stones can pass naturally. After first seeking the advice of a doctor, the patient would drink at least six glasses of water per day, and use over-the-counter pain relievers -- and possibly prescription medications -- while waiting for the stone to pass. WebMD has information[ 5 ] on medications for kidney stones.

- For ESWL, the most common method of treatment for stones that are actually in the kidney (rather than the ureters or bladder), the patient is placed under local or general anesthesia and lies in either a tub of warm water or on a special cushion on a table. X-rays or ultrasound are used to locate the kidney stone, then up to 2,000 shock waves are passed through the patient to crush the stone. Typically, a day or two of hospitalization is required, and there might be pain or bleeding as fragments are passed.

- In ureteroscopy, which is often used for stones in the ureters (the tubes connecting the bladder to the kidneys), the doctor passes a flexible scope with a basket on it through the urethra, and bladder, into the ureters. The doctor grabs the stone with the basket and removes it. This typically is an outpatient procedure.

- In percutaneous nephrolithotomy/percutaneous nephrolithotripsy, which might be used for stones of a size or shape that make them impossible to remove through other methods, the patient is placed under general anesthesia. The doctor makes a small incision in the back and inserts instruments to either remove or break up the stone. A few days of hospitalization and about a week off work are required.

- The National Kidney Foundation offers overviews of ESWL[ 6 ] , ureteroscopy[ 7 ] and percutaneous nephrolithotomy/nephrolithotripsy[ 8 ] .

- Depending on the type of kidney stone, a dietician might recommend a kidney stone prevention diet[ 9 ] . Many hospitals have dieticians available, and an initial consultation can cost $100-$200 .

- Some clinics, such as the NYC Free Clinic[ 10 ] and the Clinic at Brackenridge[ 11 ] in Austin, TX, offer access to specialist care. The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services offers a tool[ 12 ] to find a federally funded health clinic.

- The American Urological Association offers a urologist locator[ 13 ] by zip code. It is important to check to make sure the doctor is board-certified by the American Board of Urology[ 14 ] .

- It is important to discuss risks with the doctor. Risks vary, depending on the treatment but can include reaction to anesthesia, infection and bleeding.

- kff.org/health-costs/report/employer-health-benefits-2012-annual-survey/

- tp.chi.acelogicus.net/nese/Default.aspx

- www.gch.org/Home.aspx?id=219&sid=1

- www.newchoicehealth.com/Directory/Procedure/136/Lithotripsy%20(Kidney%20Stone%20Re...

- www.webmd.com/kidney-stones/kidney-stones-medications

- www.kidney.org/atoz/content/lithotripsy.cfm

- www.kidney.org/atoz/content/kidneystones_Ureteroscopy.cfm

- www.kidney.org/atoz/content/kidneystones_PNN.cfm

- kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/kidneystonediet/

- nycfreeclinic.med.nyu.edu/information-for-patients/schedule-appointment

- www.seton.net/locations/brackenridge/services

- bphc.hrsa.gov/technicalassistance/taresources/slidingscale.html

- www.urologyhealth.org/urology/findurologist.cfm

- www.abu.org/

About Virtucare

- Hospital Partnerships

- Our Doctors

What Will the ER Do For My Kidney Stones?

If you’ve ever had a kidney stone, then you know how painful they can be. Although you may decide to head to the emergency room (ER) for kidney stone relief, your experience can be more painful than the kidney stone. Long wait times, overcrowded waiting rooms and chaos. This is not what you need right now.

Before you call an ambulance for kidney stones or yell at your spouse to drive you to the ER, you should have a reasonable expectation of “what will the ER do for my kidney stones?”

As board-certified urologists who’ve been on call for the ER, allow VirtuCare experts to guide you. You don’t have to go through this painful experience alone.

Why do kidney stones hurt?

Before we discuss going to the ER for kidney stones, it helps to understand why stones hurt so much in the first place.

Kidney stones cause pain when they cause a blockage of urine in the ureter (the tube connecting your kidney to your bladder). When a stone is stuck in the ureter, it blocks the flow of urine. This causes a backflow of pressure that distends or stretches out the plumbing system of the kidneys.

Internal organ pain due to lack of blood flow, blockage or severe trauma is known as visceral pain. This is the most severe type of pain because our body is notifying us that a vital organ is “in trouble and you better get help!”

When should you go to the ER for kidney stones?

If you are experiencing any of the following symptoms, GO IMMEDIATELY TO THE EMERGENCY ROOM:

- Intolerable kidney stone pain despite prescription pain medications

- Fever > 101 F

- Mental status changes (passing out, not able to hold a conversation)

These can be signs of a urinary tract infection along with a kidney stone blockage. A kidney infection at the time of a kidney stone requires emergent drainage of your kidney (usually with a stent) to prevent sepsis or even death.

Should you go to the ER or urgent care for kidney stones?

There are situations when a kidney stone can be managed without needing a trip to the ER.

Urgent care clinics are convenient care clinics which usually accept walk-in or same day appointments. However, they are more similar to your primary care provider’s office than an ER. Provider’s can prescribe medications and order tests like your regular doctor. But, expect to have to make a separate trip elsewhere for anything other than lab tests.

So how do you decide on an urgent care vs. an ER for your kidney stone pain? It depends on how bad of shape you’re in. Again if you’re having fevers, vomiting, or intolerable pain then the ER should be your first choice for kidney stones.

As long as you’re not having any of the above serious symptoms, then an urgent care provider may be able to help you. However, realize that you’ll likely be seeing a nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant with a primary care background. You typically won’t have immediate access to a specialist if a procedure or further advice is needed.

What tests will the ER do for kidney stones?

If a kidney stone is suspected based on your history, then the ER provider will often start with blood and urine samples. They will look for microscopic blood in the urine which is a sign of a kidney stone (although blood in the urine is absent in 10% of patients). A blood count will evaluate for signs of an infection. Kidney function tests (creatinine or GFR) will make sure your kidneys are working properly.

The best imaging test is a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis without any contrast. This is 99% accurate for detecting kidney stones. If a kidney stone is present it will be important to know the following:

- Is the kidney stone causing an obstruction or blockage?

- What size is the stone?

- Where is the stone located?

Based on these factors the ER doctor can help make a determination if you need a urology consultation now or if the evaluation can wait.

What medications will help my kidney stone pain?

A variety of intravenous medications are used for kidney stone pain. The most commonly used is ketorolac (Toradol). This is a strong NSAID (similar to ibuprofen) that is more effective than most opioids. It should be used with caution if you have acid reflux, ulcers, or kidney dysfunction.

Opioids or narcotics (hydrocodone, oxycodone, morphine, hydromorphone) are often used in combination with NSAIDS. These medications are very effective for pain relief but are also associated with nausea, vomiting and constipation.

Additionally there is an opioid epidemic in our country due to heroin and prescription pain medications. The medical community is being asked to be very cautious with the amount and frequency with which we prescribe these medications.

A safe, prescription medication called tamsulosin (Flomax) has been shown to decrease kidney stone pain and increase the likelihood of stone passage. This is a prostate medication but has been used “off-label” for years in kidney stone patients (don’t worry ladies, you won’t grow a mustache on this pill. It’s not a hormone.)

Can you use telemedicine for kidney stones?

At VirtuCare we certainly appreciate the desire to avoid the ER for kidney stones. If you are interested in using telemedicine for kidney stones here’s how we can help:

- Direct access to a specialist

Why not skip the middle-man and go right to the expert?! As board-certified urologists, managing kidney stones is our specialty. You’ll have the best counseling and care from the comfort of your home.

- Prescribe medications

Non-narcotic pain medications can be called in to the local pharmacy of your choice. Due to federal and state laws, we are unable to prescribe narcotics or opioids. So if you need oxycodone you’ll unfortunately have to go see someone in person.

The good news is that often tamsulosin and ketorolac will be enough to relieve your pain.

- Order imaging and labs

After a thorough history via telemedicine, our VirtuCare experts can send orders for labs or imaging to a local facility. We can even receive the results and follow up with you to discuss the next steps.

- Refer to surgeon

If we find a stone that is unlikely to pass (usually >5 mm in size) then we can help you find the closest and best urologist to discuss a stone removal or lithotripsy.

- Follow up visits for kidney stone prevention

Once you’ve recovered from this terrible episode, make sure to schedule a follow up visit with your VirtuCare urologist to discuss stone prevention. We will cover the latest dietary recommendations for a kidney stone diet. If necessary then a 24 hour urine collection can be ordered to perform a deep dive analysis of why you’re forming kidney stones.

With VirtuCare we offer discounted follow-up visits and annual membership plans so you can continue seeing the same urologist.

We are there for you in the moments when you need help the most!

Dr. Joe Pazona

We’re here to help..

At VirtuCare, we believe that patients deserve direct access to the experts. There should be no gatekeeper standing between you and a healthcare specialist. VirtuCare puts you in control.

Related Posts

Cremaster muscle pain: the likely cause of your achy balls, when should a woman see a urologist, how to get a telemedicine prescription, interested in learning more about a partnership with virtucare hear from one of our partners..

When to Go to the ER for Kidney Stones

When to Go to the ER

Mar 1, 2024

Kidney stones are a common and painful condition that affects millions of people each and every year. While kidney stones can often be treated at home, there are times when knowing when to go to the ER for kidney stones is necessary.

The emergency medical experts from Complete Care are here to discuss when you should go to the ER or urgent care for kidney stones and what the kidney stone ER protocol is, so you can know what to expect during your visit.

Before we go deeper on the subject, if you suspect that you have kidney stones, you should head to the ER if you have any of the following symptoms:

- Abdominal pain

- bloody urine

- Pain when urinating

- Severe pain

What is the main cause of kidney stones?

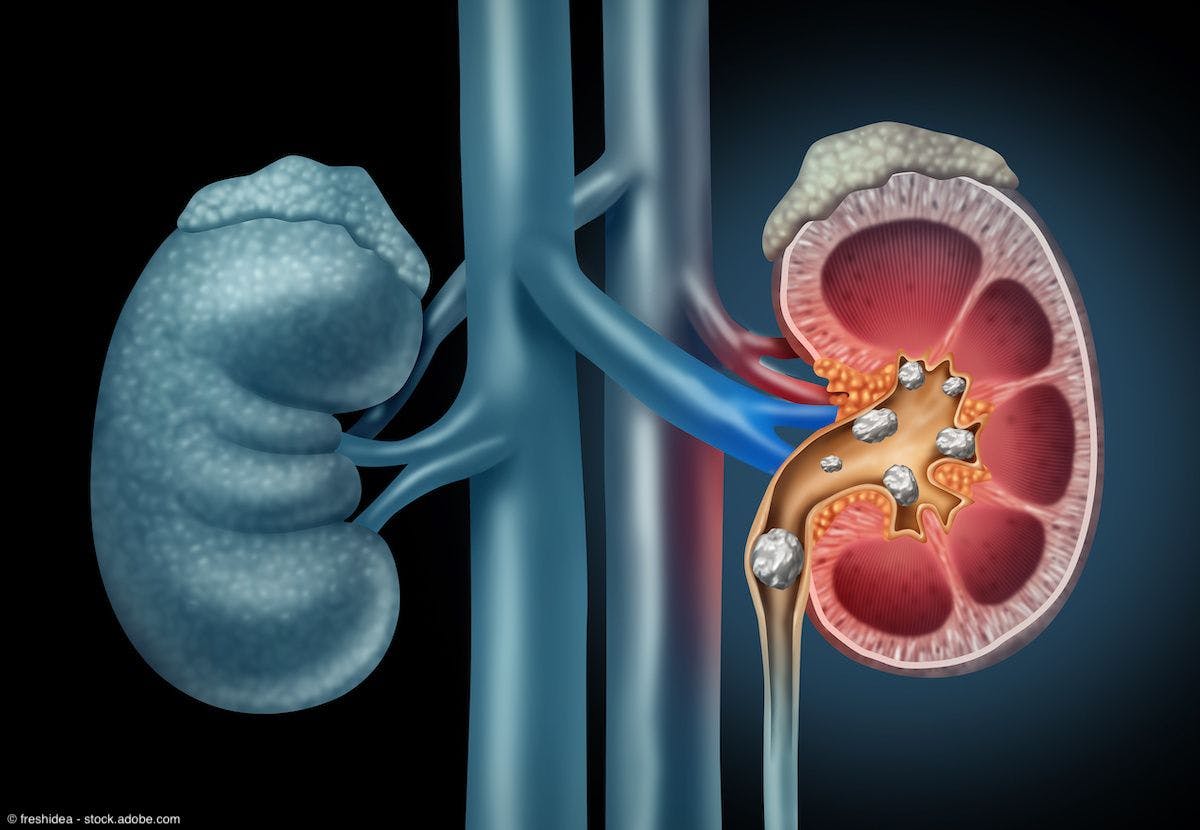

Kidney stones are hard deposits of minerals and salts that can form in the kidneys when there is an imbalance of water, salt, and mineral water in your urine. As the stones grow in size, they can lead to severe pain and other symptoms.

Kidney stones typically occur when you’re drinking less water than what your body needs, which is something many of us are guilty of. People in warmer climates who sweat more are often more susceptible as they require more water to stay hydrated. However, there are many other factors that can increase your risk of developing kidney stones, including:

- High blood pressure

- Eating a diet high in salt and sugar

- Family history

The most common type of kidney stone is made of calcium oxalate, but it can also be made of other substances such as uric acid or struvite. Kidney stones, depending on their cause and make-up, can develop over weeks or months.

Symptoms of kidney stones

How can I check myself for kidney stones? Symptoms of kidney stones most often include:

- Severe abdominal, back, or left side pain

- Severe pain in the groin or genitals

- Painful urination

- Blood in urine

- Fever and chills

- Nausea or vomiting

It’s important to note that small kidney stones can pass on their own without medical intervention, but it will not be pleasant. Passing a kidney stone can be extremely painful, even if your symptoms are mild.

How long should I wait for a kidney stone to pass?

How long a kidney stone takes to pass varies from person to person and depends on factors such as the stone’s size and location. While some stones may pass within a few days with adequate hydration and pain management, others may require medical intervention. If left untreated for too long, kidney stones can enlarge and become infected, which can pose a number of dangerous health issues.

How do you know when a kidney stone is serious?

When should you go to the ER for kidney stones? In addition to the symptoms above, you should visit the emergency room immediately if you have:

- A fever higher than 101.5 degrees Fahrenheit, as a high fever coupled with chills can be a clear sign of infection (keep reading: How does the ER treat high fever? ).

- A burning sensation when you urinate , are having difficulty urinating, or are unable to urinate at all, as this could be a sign of a blockage caused by a kidney stone.

- Cloudy, pink, or foul-smelling urine, which can be a sign that there is blood or bacteria in your urine.

- Intolerable or severe pain in your abdomen that is not relieved by over-the-counter pain medication, as this could be a sign of a larger or more complicated kidney stone that may require medical intervention (keep reading: When to go to ER for stomach pain ).

- Certain medical conditions that make passing a stone more dangerous, such as diabetes or decreased kidney function.

- A history of kidney stones and have experienced complications in the past.

If you’re unsure of whether you should go to the ER or urgent care for kidney stones, an urgent care will be able to help you manage pain and mild symptoms, whereas an emergency room will be able to handle more severe symptoms and will likely have the equipment available to provide you with a more accurate diagnosis.

Can the ER do anything for kidney stones?

Absolutely! Once you get to the emergency room, a healthcare professional will evaluate your symptoms and medical history. Kidney stone ER protocol will likely include a physical exam, blood work, and imaging tests to determine the size and location of the kidney stone, which may include an X-ray and/or a CT scan of your abdomen and pelvis. Once confirmed, you’ll be prescribed medications to help alleviate the pain and manage your symptoms as the stone passes.

In some cases where the kidney stone has grown too large, surgery may be required. When this is the case, you can be administered a non-invasive shockwave treatment procedure (lithotripsy) to remove the enlarged kidney stone or a ureteroscopy, where a small scope is used to remove the stone.

How do you prevent kidney stones from forming?

To lower your risk of kidney stones, you should drink the suggested amount of water per day. For the average adult, this should be eight 8-ounce glasses of water each day. If you live in a warmer climate or exercise often you should increase your daily water intake to stay hydrated. You can also be mindful of your salt intake and choose foods and beverages that have lower sodium levels to further reduce your risk for kidney stones.

Obesity can also raise your risk of kidney stones. If your BMI is within the obese range, you can talk to your doctor about making the changes necessary to achieve a healthy weight for your body type and lower your risk.

Experiencing painful kidney stones? Complete Care has got you covered.

Kidney stones can be a painful and uncomfortable experience, that in most cases can be treated at home. However, it’s important to know when to go to the ER for kidney stones in case you experience symptoms that are more severe. If you experience severe pain, difficulty urinating, or signs of infection, come to a Complete Care emergency room as soon as possible.

Our freestanding emergency rooms are fully equipped with digital imaging services such as X-rays and CT scans that may be necessary for determining your treatment. With our low wait times, you won’t have to deal with severe pain for long — we will get you in, out, and on the mend as soon as possible.

We have multiple locations in Texas ( Austin , Corpus Christi , Dallas/Fort Worth , East Texas , Lubbock , and San Antonio ) and in Colorado Springs that are open 24/7 to care for you and help alleviate your kidney stone symptoms. Passing a kidney stone is never fun, but it can be a lot more manageable (and a lot less scary) when you’re in our capable hands.

The BEST experience I’ve ever had medically. Hands down. I have severe anxiety when it comes to needles and came in with kidney stone pain which is spooky enough. Dr. King and her staff were so kind and patient, and got me all the scans and blood work needed while comforting me through my phobia. I’m on my second visit here, and couldn’t for better. The facility is extremely clean, quiet, and it’s a very fast trip! Little to no wait time! Front desk is extremely welcoming and did a great job! Bri N. | Satisfied Patient

More Helpful Articles by Complete Care:

- When to Go to the ER for Knee Pain

- When to Go to the ER for Sciatica Pain

- Is My Thumb Broken or Sprained?

- Exercise Safety Tips to Remember in the New Year

- Why Patients Say Complete Care is the Best Emergency Room

Share this on

- How is a ureteral stent placed?

- How is a ureteral stent removed?

- Kidney Stones FAQ

- Kidney stone myths

- Dietary prevention of kidney stones

- Letting a kidney stone pass

- Medications to help pass kidney stones

- Ureteroscopy

- Shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL)

- Percutaneous nephrolithotripsy

- Comparing ureteroscopy, shockwave lithotripsy, and percutaneous nephrolithotripsy

A reliable source of information for kidney stone patients.

The Healthcare Costs of Kidney Stones

With the increased attention on the rapidly increasing cost of healthcare , we decided to take a closer look at how much kidney stone disease costs in the United States.

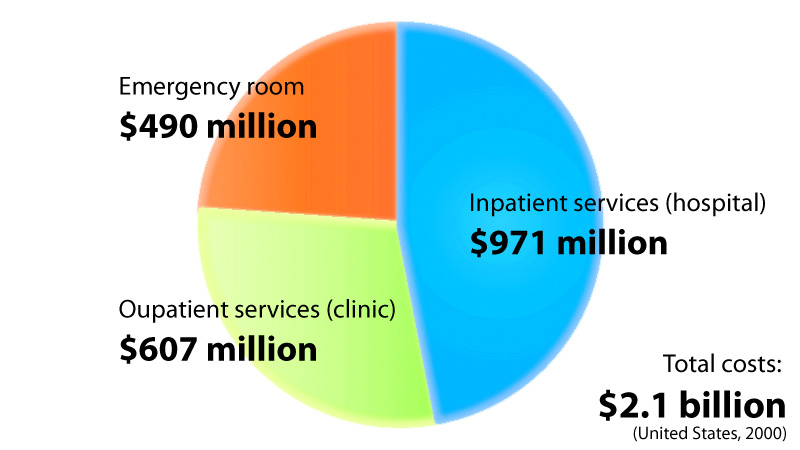

United States healthcare expenditures for kidney stone disease for the year 2000 (most recent available published data).

Underlying the costs for kidney stone treatment is how common stone disease is, with about 1 in 10 Americans experiencing a stone during their lifetime . That results in a lot of clinic and emergency room visits, trips to the operating room, and prescriptions for pain control medication. Additionally, because stone disease often afflicts working aged adults, there are also large costs incurred due to lost work hours.

Where is the money going?

About half of the healthcare expenditures for stone disease was due to inpatient hospital costs , which includes surgeries requiring hospitalizations and admissions to the hospital for stone related problems. Other costs included clinic visits, outpatient procedures, emergency room visits, radiology examinations, and prescription drugs. The estimated average healthcare cost for each stone patient for the year amounted to $6,532 dollars. This is considerably higher than the average healthcare cost of $3,308 for non-stone formers during the same year. Note that these figures refer to costs for health insurers. The “out-of-pocket” costs for an uninsured individual will be higher, sometimes significantly more.

Average cost per stone former:

$6,532 of which

18% were for prescription drugs

Cost of surgeries

About 25% of stone patients require surgical treatment each year . Of the surgical options available, percutaneous nephrolithotripsy was the most expensive approach, as measured by cost by procedure, with shockwave lithotripsy and ureteroscopy coming in second and third. The dollars figures shown below were for the year 2000 and reflects expenditures by insurance companies. Out-of-pocket costs for an uninsured patient will be higher.

Average cost of stone surgeries:

PCNL: $3,624

ESWL: $2,295

Ureteroscopy: $1,425

Costs due to lost work:

In 2000, 1% of all working age adults missed work due to a stone episode. When focusing on just stone formers, 30% of them missed work due to a stone episode, with each worker losing an average of 19 work hours over the year , or 3.1 million lost workdays for the entire working population. Estimating an average U.S. hourly wage of $24 an hour, that equates to $456 of wages lost per worker. From an employer’s standpoint, the estimated indirect costs due to stone disease was $775 million dollars a year. Unmeasured here are other potential costs, such as childcare, transportation, and lost work by family members that might be incurred during trips to the emergency room, clinic, or operating room.

Lost hours of work:

19 hours per worker

Lost wages per worker:

$456 dollars

Saigal et al, “Direct and indirect costs of nephrolithiasis in an employed population: Opportunity for disease management?” Kidney International, 2005.

Lotan and Pearle, “Economics of Stone Management”, Urologic Clinics of North America, 2007.

If you have experienced kidney stones, let us and other readers know how costs for stone treatment have personally impacted you by commenting below.

2 Leave a Reply

[…] nerkowe dotykają około 10% ludzi w świecie zachodnim, a roczne koszty opieki zdrowotnej związane z kamieniami nerkowymi w samych Stanach Zjednoczonych wynoszą ponad 2 miliardy […]

Is there anyone in the Southern Ontario area with Medullary Sponge Kidneys. I am interested in knowing if they encountered the same medical roadblocks that I have. There is a doctor in Michigan who performs a surgery that helps eleveate problems associated with MSK. Of course they do not cover the procedure in Ontario and I am not financially able to afford to pay to see this doctor on my own, or I would immediately. I just want to be able to live my life, work and be a mother who is active and able to do my daily duties. It is very frustrated to suffer and feel there is no end in sight and no way to be treated for this debilatating condition.

Find Urgent Care today

Find and book appointments for:, urgent care.

- Pediatric Urgent Care

- COVID Testing

- COVID Vaccine

Navigating Urgent Care for Kidney Stones: What to Expect and Aftercare Tips

- Kidney stones are hardened mineral deposits that can cause severe pain and complications.

- Urgent care provides prompt medical attention, diagnosis, and treatment for kidney stones.

- Aftercare and preventive measures are essential to manage kidney stones effectively.

Causes, Types, and Risk Factors of Kidney Stones

Getting diagnosed with kidney stones, treatment options, complications and emotional impact of kidney stones, when to seek urgent care for kidney stones, what to do after visiting urgent care for kidney stones, finding an urgent care for kidney stones.

- Frequently Asked Questions

Urination is the way that many minerals and salts get transported out of your body. In some cases, however, a buildup of these minerals can form stones—known as kidney stones. Anyone who has ever dealt with a kidney stone probably describes it as one of the most painful experiences of their life. This is usually because the stones became large and irritating as they traveled from the kidneys through the ureters, bladder, and urethra, reports the Kidney Foundation.

If you’re dealing with what you think could be kidney stones, urgent care can be a great option for getting a diagnosis and treatment.

At urgent care, you can expect to receive prompt medical attention from experienced healthcare professionals. They will assess your symptoms, give you pain medication if indicated, perform diagnostic tests if necessary, and determine the best course of treatment for your kidney stones. Aftercare is also an important part of managing kidney stones, and your urgent healthcare provider will be able to give you instructions on how to care for yourself at home and when to follow up with your primary care physician or urologist. If you’re not sure if you’re experiencing kidney stones, continue reading for more about the causes, symptoms, and treatment options.

Kidney stones are hardened mineral deposits that form in the kidneys and then can make their way down the ureters, into the bladder, and then out the urethra with your urine. Occasionally, a kidney stone may be too large to pass and end up getting stuck in the kidney or ureter. They can be caused by a variety of factors, according to the Kidney Foundation. Some of these factors include:

- Dehydration

- Eating a diet high in sodium, animal protein, or sugar

- Certain medical conditions, such as gout or inflammatory bowel disease

Types of Kidney Stones

There are five main types of kidney stones, according to the Urology Care Foundation. Genetics and lifestyle habits influence which type of kidney stone develops.

- Calcium oxalate stones: These are the most common type of kidney stone and are caused by a buildup of calcium and oxalate in the urine.

- Calcium phosphate stones: These stones are commonly caused by abnormalities in the urinary system.

- Cystine stones: This type of kidney stone is caused by a hereditary disorder called cystinuria. This genetic disorder causes excessive amounts of the amino acid cystine to collect in the urine.

- Uric acid stones: These stones are caused by a buildup of uric acid in the urine and are more common in people with gout.

- Struvite stones: These stones are caused by a bacterial infection in the urinary tract and can grow quickly and become quite large.

Risk Factors for Kidney Stones

Many risk factors for developing kidney stones are unavoidable. However, understanding risk factors will help you determine if your symptoms could be related to kidney stones, according to the Kidney Foundation. The largest risk factors for kidney stones include:

- Age - People between the ages of 30 and 50 are more likely to develop kidney stones according to the Urology Foundation.

- Gender - Men are more likely to develop kidney stones than women, according to the Mayo Clinic.

- Certain medical conditions - Conditions like High blood pressure and diabetes can increase the risk of kidney stones according to the Mayo Clinic.

- Family history - If someone in your family has had kidney stones, you are more likely to develop them as well, according to the Kidney Foundation.

Chances are, you may be in a great deal of pain when you arrive at the doctor's office if you suspect you have kidney stones. For this reason, a quick evaluation is necessary to get you the proper treatment. The staff at urgent care understands this and will work efficiently to determine the likelihood of kidney stones while also ruling out other potential causes of your symptoms. The Mayo Clinic outlines the most common strategies used to diagnose kidney stones, starting with a physical exam.

Physical examination and medical history

The staff at an urgent care clinic will usually start their investigation of your symptoms by doing a physical examination. This will likely involve palpating your abdomen and checking for tenderness or pain in your stomach, back, and flank areas. They will also check your vital signs, including your blood pressure, heart rate, and temperature. This will help them rule out more serious conditions while also evaluating if you have an infection.

Alongside the physical exam, the healthcare providers will also gather information from your medical history. This will include asking you questions about your symptoms—including when the symptoms began, how severe they are, and whether you have experienced similar symptoms in the past. They will also ask about any pre-existing conditions and medications you are taking.

Imaging tests (X-ray, CT scan, ultrasound)

Imaging tests are commonly used to diagnose kidney stones. X-rays are one way to detect the presence of stones—but some stones may not be visible on an X-ray. For this reason, a CT scan or ultrasound may be ordered to get a better view of the kidneys and urinary tract.

Urine and blood tests

Urine and blood tests can also help diagnose kidney stones. A urine test can detect the presence of blood or minerals that may indicate the presence of stones, according to the Mayo Clinic. Blood tests can also be used to check for signs of infection or other conditions that may be causing your symptoms.

Once a diagnosis is made, your healthcare provider can begin providing the appropriate treatment and aftercare tips to manage your symptoms and prevent future kidney stones.

There are several options available for treating kidney stones, according to the Kidney Foundation and Mayo Clinic. Your doctor will recommend the best treatment option for your specific case based on the size and location of your kidney stones, as well as your overall health.

Pain management for kidney stones

Kidney stones can be extremely painful, and managing your pain is often a top priority for both you and your medical provider. In the appropriate clinical setting, strong pain medications may be given, sometimes intravenously. Upon discharge, your doctor may recommend over-the-counter pain relievers such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen, or prescribe stronger pain medications if necessary.

Medications for kidney stones

There are several medications available that can help kidney stones pass more easily or prevent them from forming in the first place.

- Alpha-blockers (such as Alfuzosin, Doxazosin, and Terazosin) are one class of medications that can relax the muscles in the ureter, making it easier for the stone to pass.

- Diuretics are used to help flush out the stone. Your doctor may recommend purchasing these over the counter or may prescribe them to you.

- Antibiotics are also used in some cases if your healthcare provider believes that an infection is present.

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) for kidney stones

ESWL is a non-invasive procedure that uses shock waves to break up the kidney stone into smaller pieces—thus making it easier to pass. This procedure does not require an incision and is typically performed on an outpatient basis, according to the Urology Foundation.

Ureteroscopy for kidney stones

Ureteroscopy involves inserting a small scope into the ureter to locate and manually remove the kidney stone. This procedure may be necessary for larger stones or stones that are located in a difficult-to-reach area. This procedure is also used when other techniques fail to relieve you of kidney stones, according to the Kidney Foundation.

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL)

PCNL is a surgical procedure that involves making a small incision in the back and using a scope to locate and remove the kidney stone. Much like ureteroscopy, the Urology Foundation notes that this procedure is typically reserved for larger stones or stones that cannot be removed using other methods.

Non-urgent Treatment Options for Kidney Stones

The Mayo Clinic and the Kidney Foundation both note that drinking plenty of water and making dietary changes can help prevent kidney stones from forming and help them pass more easily if they do form. Your doctor may also recommend limiting your intake of certain foods (like processed meats, red meats, and foods high in salt, as well as alcohol, and soda) or increasing your intake of others (water, low-sodium foods, fruits, vegetables, and legumes).

Kidney stones can lead to various complications, including kidney damage and infection, according to the Mayo Clinic. If a kidney stone blocks the flow of urine, it can cause pressure to build up in the affected kidney, leading to swelling and damage. The risk of kidney damage increases if the stone is left untreated for a long time.

In some cases, kidney stones can also cause urinary tract infections (UTIs). UTIs can cause additional symptoms such as pain and burning during urination, frequent urination, and fever . If left untreated, UTIs can spread to the kidneys, leading to more severe complications.

The impact of kidney stones on patients and their families

Kidney stones can have a significant emotional and psychological impact on patients and even their families, notes the Mayo Clinic . The discomfort caused by kidney stones can be intense and debilitating, making it difficult to carry out daily activities. This can lead to feelings of frustration, helplessness, and anxiety—especially when kidney stones are recurring.

Kidney stones can also cause a financial strain , as medical bills and time off work can quickly add up. Patients may worry about the possibility of future kidney stones and the impact this can have on their quality of life and long-term finances.

Family members and caregivers also experience emotional stress as they support their loved ones through the kidney stone experience. They may feel helpless or overwhelmed by their loved one’s pain and have to adjust their life schedule to handle additional responsibilities or medical visits.

All of this underscores the importance of seeking prompt medical attention and following up with appropriate aftercare to minimize the risk of complications and support a full recovery.

In some cases, kidney stones can cause severe pain and other complications that require immediate medical attention. If you suspect that you have kidney stones, it is important to seek medical attention as soon as possible. Here are some signs to look out for, as outlined by the Mayo Clinic, that should prompt you to seek medical care immediately.

- Severe pain - Especially in your back, side, or lower abdomen. The pain may come and go in waves and may be accompanied by nausea or vomiting .

- Blood in your urine - This could be a sign that you have a kidney stone that is causing damage to your urinary tract. Blood in urine can also be a sign of a UTI or other serious conditions, so it is important to seek medical attention right away.

- The inability to urinate - This could be a sign that a kidney stone is blocking your urinary tract. If left untreated, this can lead to serious complications, including kidney damage, according to the Mayo Clinic.

- Fever - If you have a fever (above 100.4°F), along with any other symptoms of kidney stones, you should seek urgent care. A fever could be a sign that you have an infection, which can be a complication of kidney stones.

What to expect at urgent care

When you arrive at the urgent care facility for kidney stone symptoms, you can expect a prompt and thorough evaluation of your condition. The urgent care staff will evaluate you by performing a physical examination while assessing your symptoms and medical history. They then will order diagnostic tests to help ensure the proper diagnosis. Testing may include X-rays, urine tests, blood tests, ultrasounds, or CT scans. Based on the results of the examination and diagnostic testing, your urgent care staff will recommend the appropriate treatment options. Treatment options may include:

- Pain management

- Medication to help pass the stones

- Procedures to remove the stones in some cases

Your medical provider will also determine if you need referral to a specialist, such as a urologist or nephrologist. This referral may be to continue treatment or to follow up.

Insurance coverage and costs associated with urgent care for kidney stones

Urgent care costs can vary depending on your insurance coverage and what specific services are provided to you. You can check with your insurance provider to understand your coverage and any associated costs. It is important to note that you should not delay seeking medical attention if you are unsure of your insurance coverage. Some urgent care facilities may offer self-pay options or payment plans.

After receiving treatment for kidney stones at urgent care, it's important to follow any home instructions that your healthcare provider gives you. The home instructions may include instructions on how to take prescribed and over-the-counter medication, foods and drinks to avoid, how much water to drink, and when to follow up with your primary care physician or urologist. You may also be asked to filter your urine in order to capture and identify the type of stone. Follow-up evaluations are recommended by the Kidney Foundation to monitor your condition and determine if additional treatment is necessary.

Your doctor may also recommend that you undergo follow-up testing, (such as a CT scan or ultrasound) to check for any remaining stones or kidney damage.

Lifestyle Changes to Help Prevent Kidney Stones

If you have experienced kidney stones, you are probably wondering what you can do to avoid ever having them again. Although there is no guarantee that you won’t develop them again, there are some lifestyle changes you can make that can help lower your chances. The Kidney Foundation recommends:

- Drinking plenty of water to stay hydrated

- Reducing your intake of sodium and animal protein

- Increasing your intake of fruits and vegetables

Additionally, your doctor may recommend that you take calcium and vitamin D supplements, as these can help prevent the formation of kidney stones.

When to Seek Further Medical Attention

While most kidney stones can be treated at urgent care, there are some cases where further medical attention may be necessary. The Urology Foundation lists symptoms that may indicate a severe case as:

- Severe pain that is not relieved by medication

- Blood in your urine

- Difficulty urinating

- Fever and chills

- Nausea and vomiting

If you suspect that you have kidney stones, it's important to seek medical care right away. An urgent care clinic is a great option for getting fast, cost-efficient medical care. If you are experiencing any of the symptoms of kidney stones, according to the Mayo Clinic including:

- Pain or discomfort in your abdomen, back, or sides

- Painful urination

- Nausea, or vomiting

Use Solv to find an urgent care near you, by searching our directory. We can help you find an urgent care client with skilled medical providers and the testing capabilities necessary to diagnose and treat kidney stones. Once you have received care at urgent care, you can continue using Solv to book your follow-up appointments or find specialists in your area who can help you prevent future kidney stones from developing.

Frequently asked questions

What are kidney stones and how do they form, what are the types of kidney stones, what are the risk factors for developing kidney stones, how are kidney stones diagnosed, what are the treatment options for kidney stones, can lifestyle changes help prevent kidney stones, when should i seek urgent care for kidney stones, what should i do after visiting urgent care for kidney stones.

Michael is an experienced healthcare marketer, husband and father of three. He has worked alongside healthcare leaders at Johns Hopkins, Cleveland Clinic, St. Luke's, Baylor Scott and White, HCA, and many more, and currently leads strategic growth at Solv.

Dr. Rob Rohatsch leverages his vast experience in ambulatory medicine, on-demand healthcare, and consumerism to spearhead strategic initiatives. With expertise in operations, revenue cycle management, and clinical practices, he also contributes his knowledge to the academic world, having served in the US Air Force and earned an MD from Jefferson Medical College. Presently, he is part of the faculty at the University of Tennessee's Haslam School of Business, teaching in the Executive MBA Program, and holds positions on various boards, including chairing The TJ Lobraico Foundation.

Solv has strict sourcing guidelines and relies on peer-reviewed studies, academic research institutions, and medical associations. We avoid using tertiary references.

- Kidney stones. (April 30, 2023) https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/kidney-stones/symptoms-causes/syc-20355755

- Kidney Stones. (April 30, 2023) https://www.urologyhealth.org/urology-a-z/k/kidney-stones

- Kidney stones. (April 30, 2023) https://www.kidney.org/atoz/content/kidneystones

- Kidney stones. (April 30, 2023) https://www.kidneyfund.org/all-about-kidneys/other-kidney-problems/kidney-stones

- Kidney stones. (April 30, 2023) https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/urologic-diseases/kidney-stones

- Kidney stones. (April 30, 2023) https://medlineplus.gov/kidneystones.html

- Alpha-blockers: Types & Usage (April 30, 2023) https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/22321-alpha-blockers

- medical imaging

- urgent care

Quality healthcare is just a click away with the Solv App

Book same-day care for you and your family

Find top providers near you

Choose in-person or video visits, manage visits on-the-go, related articles.

How to Treat Gout: 7 Things You Can Do to Relieve Your Gout Flare-up

Gout is a type of arthritis that happens when uric acid builds up in the blood and forms crystals in the...

UTIs and Urgent Care: Understanding the Risks, Costs, and Complicat...

A urinary tract infection (also called a “bladder infection” or “UTI”) is a common bacterial infection that can...

Plantar Warts: Why Urgent Care is a Great Option for Plantar Wart R...

Plantar warts are a common type of wart that affects the feet, and they can be painful at times, according to...

The Role of Urgent Care in Early Diagnosis and Management of Hernia...

A hernia occurs when an internal organ pushes through a weakened area of muscle. While a hernia can occur in...

Urgent Care for Knee Pain: When to Seek Medical Attention

If you're experiencing knee pain, you're not alone. Knee pain is a common issue that affects people of all ages,...

Debunking Migraine Myths: The Importance of Seeking Urgent Care for...

Migraines are recurring headaches that cause moderate to severe pain. According to the Mayo Clinic, some...

Don't Ignore the Signs: Urgent Care Options for High Blood Pressure

High blood pressure (also called hypertension) is a common condition that affects millions of people...

Don't Wait: The Importance of Urgent Care for Hemorrhoids

Hemorrhoids are a common condition that affects nearly three out of every four people, according to the Mayo...

Shedding Light On Melanoma

Melanoma is the most dangerous form of skin cancer—and it's on the rise in younger people. The Melanoma...

At-home Tips for Diabetes Self-Care

Diabetes is a chronic condition that requires careful management to prevent complications including kidney...

Related Health Concerns

Abdominal Pain

Antihistamines

Athlete's Foot

COVID-19 Vaccine

Cataract Surgery

Pinched Nerve

Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Tonsil Stones

This site uses cookies to provide you with a great user experience. By using Solv, you accept our use of cookies.

- Quick Links

- Make An Appointment

- Our Services

- Price Estimate

- Price Transparency

- Pay Your Bill

- Patient Experience

- Careers at UH

Schedule an appointment today

Comprehensive Kidney Stone Relief, Treatment & Prevention Services

Kidney stones send more than one million Americans to the emergency room every year. That doesn’t need to happen to you. If you have a kidney stone , let the experienced urology team at University Hospitals develop a personalized care path for immediate relief and help you prevent new stones from forming.

Our urologists and other kidney stone experts have many different non-invasive and minimally invasive treatment options to remove your kidney stone based on its size, location and your other health conditions. Throughout your care, our team strives to ensure your complete comfort and successful recovery.

Find Complete Relief from Your Kidney Stones

If you think you may have a kidney stone, or have suffered from them in the past, please contact the UH urology team to schedule an appointment at 216-844-3009 .

Find a Doctor

What are Kidney Stones?

Kidney stones are made of dissolved minerals, such as calcium, that crystalize in the kidney. These stones either stay in the kidney or travel down through the ureters, which are tubes that connect your kidneys with your bladder. Sometimes, if the stone is large enough, it gets stuck in the ureter and blocks urine, causing great pain. If the stone passes into the bladder, expelling it during urination can also be quite uncomfortable. Other kidney stone symptoms may include:

- Pain in the side, back and may radiate to the belly or groin

- Blood in the urine

- Cloudy or odorous urine

- Fever and chills

- Frequent urination

- Nausea and vomiting

With the advanced diagnostics needed, our urology experts conduct blood, urine and imaging tests — such as an X-ray, ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scan — to determine the type of stone you have, its location and its size.

Based on the test results and a full medical evaluation, our specialized team of kidney stone experts will recommend kidney stone treatment options based on your unique health needs to provide the best treatment for your kidney stones and kidney stone pain.

UH Offers Unique Metabolic Evaluations for Stone Prevention

Removing stones and ensuring your comfort is our most immediate concern. However, the experts at University Hospitals conduct a complete metabolic evaluation to find out why your stone formed and how to prevent others from occurring.

A metabolic evaluation includes an analysis of the passed stone, as well as 24-hour urine collection and dietary log. In the vast majority of cases, by analyzing urine over a 24-hour period and conducting a complete health assessment, our specialists can pinpoint the cause of kidney stone formation.

Not all healthcare organizations perform a metabolic evaluation, but our team is committed to helping you avoid another painful kidney stone experience. Our specialists are highly experienced in performing metabolic evaluations, and recommend them for all our patients with kidney stones.

Improved Outcomes from Specialized Urologist Care

More than 80 percent of kidney stones pass on their own. In these situations, our primary goal is to reduce your kidney stone pain and discomfort and help it pass quickly and without injury. For more complex or larger stones, there are numerous non-invasive and minimally invasive treatments available, including:

- Cystolitholapaxy: This procedure uses a laser or other modalities to break up bladder or kidney stones.

- Shock waves or extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL): A non-invasive procedure, we use shock waves to break stones into smaller pieces, so they can be passed through the urine.

- Ureteroscopy: A kidney stone surgery using a tiny camera, or scope, through the urethra, our team is able to precisely locate the stone while a surgeon removes or breaks the stone into smaller pieces.

- Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL): Reserved for larger stones, this procedure to remove kidney stones uses a small incision in the back with a tube inserted to the kidney stone location. The urologist will then insert the tools through the tube to remove the stone.

- Percutaneous nephrolithotripsy (PCNL): Using the same technique as percutaneous nephrolithotomy, our urologists treat larger kidney stones, usually 2 cm or larger, by inserting tools through a tube inserted in a small incision in the back. Stones are broken up and the small fragments are then removed through the tube.

At University Hospitals, our skilled urology team operates the scopes and is responsible for every step of the process. This typically results in the faster and more precise identification of the stone, a more efficient overall procedure and better results.

Sign up for our free newsletters!

- Consumer updates newsletter

- Industry insider newsletter

ClearHealthCosts

Bringing transparency to the health care marketplace.

Kidney stone removal or lithotripsy: How much does it cost?

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

(Updated 2022) Kidney stone removal, or lithotripsy , uses shock waves or lasers to break down stones in the kidney, gallbladder, or ureters. Kidney stone removal costs can vary. One of our community members shared several prices for treatment via our site , and we started a conversation focusing on both his experience and his kidney stone removal cost. Let’s call the community member Michael from the Louisville, Ky. area.

Before we start, though, I want to note that a system requiring someone like Michael to go to these lengths while he’s worrying about a serious health problem is unusual throughout the developed world. It’s pretty much only here in the United States that he would have to do this. The prices varied widely: $16,177, $9,773 or $7,642?

Also, he noted the pushback he got from seeking these prices, and adds that he succeeded this way: “I have successfully communicated to them through the analogy of having a car delivered to your house and being told that you must pay for it, but no one can tell you how much until after its delivered… and there are no returns.”

We plan to follow his journey, so check back for updates.

Michael’s experience with kidney stones

I am self-employed and my choice was down to paying for insurance or doctor bills. So I chose to forgo insurance to make sure I could afford to see my doctors.

Since that decision was made, I have had a bout of kidney stones (4 separate stones) and two surgeries… one left to go.

I told them I needed it all done before my insurance expired, but the doctors couldn’t make that happen.

I was admitted through the E.R. of a local hospital late in September and had Laser Lithotripsy done for two stones in my left kidney, the largest of which was 11mm. The approach was, I later learned, a “dusting” approach usually done for “softer” stones. I was informed only recently that the collections of stone fragments from that surgery were too small to collect. I suspect, however that they were either lost, discarded or unable to be collected as I understand that using a laser on a stone, even a soft one, breaks it into fragments. In any case, there is no analysis on record as to the actual composition of the stones.

In late December, I had another stone attack which landed me back in the E.R. with the right kidney this time having two stones, one lodged in the ureter (5mm) and one at the entrance to the ureter in the kidney (7mm). The stone pain had subsided thanks to the miracle of modern pain relief and I was able to clear-headedly discuss the plan and options with the urologist on call.

As is usual these days, the urologists are not employees of the hospital. I discussed with him the plan for treatment and together we decided to use shock wave lithotripsy which was not available in that hospital. I decided that if it was simply a matter of where I was bedded that was keeping me from the treatment that could potentially get at both stones at once (as apposed to lasering which would not allow access to both stones), then a transfer was preferable to multiple surgeries which would definitely land outside of my covered period as my insurance expired at the end of the month.

One stone left after the lithotripsy procedure

My shock wave lithotripsy (SWL) was performed and a stent was put in while I was under on the last day of the month (the soonest it could be performed) as an outpatient surgery. Unfortunately, my bones were placed in such a way that the SWL could not get past my pelvic bone to access the larger stone in my kidney. I am now left with a stone at the entrance to my right kidney that hangs like the sword of Damocles.

I had not received detailed information from my providers on these upcoming procedures that would allow me to ascertain costs. When I requested this information prior to undergoing each of the previous procedures I was told that it was impossible to know.

So, now without the excuse of “I can’t tell you how much it costs because of insurance variability”, I demanded to know the price tags… prior to getting anything done. I have had to cancel surgeries twice in order to get the information.

I am still in that process. The facilities charges are astronomical and are built around the codes that the doctors determine they will need for their surgery. Each separate code brings with it well over $1,000. So when the doctor ordered an additional code for my second operation (after I canceled the first), I started to question everything.

talk to hospital operators to find lithotripsy specialists

Here’s what I have found: Each facility has a specialist hidden within the phone system tree, and it is best to talk to the operator to find them. They are called Insurance Verification, Cost Evaluators, Financial Counselors, Cost Estimators, and possibly more as there seems to be no consistency in the industry.

If the doctors office had already scheduled you at the facility, they will have the codes the doctor sent over. If you have not been scheduled, you must get the codes from the scheduling person for your doctor. If they haven’t decided to schedule you yet, you can ask for the codes that the doctor will be using and why each code is necessary during your visit. They will likely not know, but they can get them for you… this will likely take a willingness to be persistent. I am going back to my doctor to discuss the codes chosen and exactly why each was chosen. This will cost me a doctors visit ($125), but I think it’s worth my time and $.

BTW, I found one facility that charges $2,000 less for the exact same codes… but my doctor’s office said that they don’t work at that hospital even though it is only about 6 miles away. That’s okay, because I can use another urologist in the same medical group who will, once I have squared away all of the information…. for $2k, it’s worth it.

I had trouble getting prices out of the urologists office for just their work, and finally got hold of someone in billing while on site who gave me the extension of the one person (and only one person) who does pricing. They aren’t in the phone tree, so it was a bit of a bear.

Funny thing was, their prices are very much in line with Medicaid pricing, so it’s not like they had anything to hide… they just made it difficult.

The medical codes that govern pricing

The codes that I received from talking to the scheduling nurse were the items I used to get pricing. Each code is a universal number that is applicable across all the medical universe. These are called CPT codes or “Current Procedural Terminology”. Think of them like a standard that is used so that different offices can talk to each other and be more precise. For more in-depth information about CPT codes you can find websites that discuss CPT coding as it is the basis of billing for hospitals and insurance (e.g. https://www.medicalbillingandcoding.org/intro-to-cpt/ ).[Editor’s note: Here’s our handy guide to coding .]

Strangely, the codes that I was given were all procedures that could be performed individually, but not usually together (according to the cost evaluations person at one of the hospitals that I was doing the pricing). While this was probably done so that the doctor could cover their bases in case they had to switch from one kind of procedure to another without having to request the hardware from the facility, each additional code added $1,200 – $1,800 on the low side. I determined that I would need to be very specific with my doctor and get more information on why each of these codes were necessary. Since this is an ongoing journey, I have not yet spoken with my urologist regarding the necessity of these codes.

I will include my spreadsheet. The totals given here are facility charge plus doctor charge plus $500 predicted anesthesia charge. The highlighted cells are changes that were made after initial information was given either due to the doctor adding a code (ergggh) or the facility changing their cost estimates:

I have not found a way, yet, to get prices for anesthesiologists. I have an estimate from the scheduling nurse, but I think I will have to contact the facility, find out who works there, and then call the individual offices to get prices.

My methodology for surgery pricing:

1) Get codes from doctors office… not easy, but necessary. 2) Get pricing from that office’s doctor’s billing department for the doctor’s work – get itemized pricing for each code. 3) Get pricing from facilities based off of codes from the doctor’s office – get itemized pricing for each code.

That’s it. It makes it sound easy, but the facilities do not want to give you an itemized list and in one case quoted $2K more once the codes were listed out. That same facility then quoted me regular prices and then (when pressed) gave me a 50% discount for self pay which brought it back down to the first quoted price.

I have made a list of the people I talked to at each location… none of which readily gave me a last name or a direct number to call back.

Non-surgery-related charges, and a mystery

Testing and diagnostics are sent from the doctors office to whoever it is easiest for them to send to… normally a large chain like Labcorp. When you ask how much a diagnostic or analysis will be the doctor’s office simply doesn’t know. When pressing for codes or numbers to order, they usually don’t have that either.

I was able to get into Labcorp’s public-facing website and look up tests. This allowed me to determine the limited number of tests that it could be and then a phone call to Labcorp narrowed it further to the single test for (in this case) stone analysis.

I got the CPT code from their website and I contacted a well-established lab I had run across doing my own research on kidney stones. I called them and asked for a price on that CPT code and they offered me a price of less than half the cost of Labcorp. This is where things get interesting.

I called my doctors office and let them know that I wanted my stones sent to this other lab for analysis. Gave them the address and let them know that I had already made arrangements for payment to the lab so all they had to do was send it and the order for the test.

trying to use the lower-priced provider

A day later I got a call from my doctor’s office letting me know that they can’t do that. They have a policy to only work with Labcorp (meaning they won’t do that). In the U.S., labs are not allowed to take a sample from an individual and return it to the individual under federal law. Sending my sample out of the states to a friend overseas who then submits my sample to the lab is a valid work-around, as the federal laws no longer apply.

I have recently shopped around for X-rays as well. As far as I know there isn’t the convenience of a CPT Code, but instead the designation of the area to be X-rayed. This does not correspond to the same verbiage as a CT Scan which has it’s own set of designations:

X-RAY: K.U.B (Kidneys Urinary Tract, Bladder) CT-Scan: Abdomen Pelvis

A facility again, not on my initial calling list, was half the cost.

The list is more of an assumption than a physical list that I was able to locate. “The list” was comprised of the places at which that the scheduling team at my urologists had scheduled me. I suppose I could call and ask them at which facilities they would be willing to perform surgeries or scans and I would get a pretty short list.

When it came time to do X-Ray and diagnostics pricing, I first had to get the terminology from the nurse at the doctor’s office for what kind of X-ray (or CT scan) they wanted to perform. X-rays are pretty straightforward, but CT scans can be done with or without contrast. You will need to find out if it is necessary to have contrast from your Doctor’s office, and you must get an order from them.

using the internet to find THE BEST kidney stone removal COST

Once armed with that information, I turned to the trusty Interwebs. I did a Google search for locations that are in the metropolitan area of the closest major city (which seemed like the best bet to find stand-alone centers) that performed X-ray or radiology services. This resulted in a few places to call, and so I did. I asked to speak with someone who could get me a price on an X-ray and/or CT scan. They seemed to be a lot easier to deal with than the surgery facilities when getting this information.

Thanks for being interested in my journey.

I am a self-employed computer consultant who does more research than the average person, so this isn’t totally outside of my wheelhouse. What is the most difficult is wading through the reticence I receive from these businesses to give me actual pricing _before_ they do the work.

I have successfully communicated to them through the analogy of having a car delivered to your house and being told that you must pay for it, but no one can tell you how much until after its delivered… and there are no returns.

I hope your journeys are fruitful.

Market forces simply cannot exist where there is no functioning market.

Jeanne Pinder

Jeanne Pinder is the founder and CEO of ClearHealthCosts. She worked at The New York Times for almost 25 years as a reporter, editor and human resources executive, then volunteered for a buyout and founded... More by Jeanne Pinder

- Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

- Hormone Therapy

- Genomic Testing

- Next-Generation Imaging

- OAB and Incontinence

- Genitourinary Cancers

- Kidney Cancer

- Men's Health

- Female Urology

- Sexual Dysfunction

- Kidney Stones

- Urologic Surgery

- Bladder Cancer

- Benign Conditions

- Prostate Cancer

ER costs for treating stones, UTI vary widely

A recent study highlights huge price swings in patient charges for the 10 most common outpatient conditions-including kidney stones and urinary tract infection-in emergency rooms across the country.

The study, representing an estimated 76 million emergency department visits between 2006 and 2008, used data from the 2006-2008 Medical Expenditures Panel Survey from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Researchers focused on adults 18 to 64 years of age, the demographic at the highest risk of facing the largest out-of-pocket charges. It excluded people 65 years of age or older because most such patients are covered by Medicare. Visits resulting in hospital admission were also excluded.

Altogether, the authors, who published their findings online in PLOS ONE (Feb. 27, 2013), looked at the total charges-medical care, tests, and treatment-for 8,303 patients, nearly half of them privately insured. The charges do not represent the amount patients or insurers reimburse providers, but rather the total charge that patients or their insurance providers are billed. Because of the complex survey design, the number of patients analyzed in the sample was weighted to provide the total estimated number of ER visits during the study time frame.

The authors found that out-of-pocket patient charges ranged from $128 to $39,408 for kidney stones and $50 to $73,502 for urinary tract infections. Of all the conditions studied, which also included sprains and strains, headache treatment, and intestinal infections, kidney stone treatment had the highest median price at $3,437.

"Our study shows unpredictable and wide differences in health care costs for patients," said senior author Renee Y. Hsia, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco.

Related Content

ER data: Urolithiasis, stone-related infection rising

Analysis bolsters expulsive therapy's cost-effectiveness

Data support shock wave lithotripsy for pediatric patients with kidney stones

Regarding patient-reported outcomes, those who underwent URS showed higher urinary symptoms, greater pain intensity, and greater pain interference at 1 week following surgery compared with those who underwent SWL.

Why kidney stones will become more prevalent over time

“The prevalence of kidney stones has increased over 80% over the last 30 years, and the epidemiology has changed such that it's beginning at a younger age now,” says Gregory Tasian, MD, MSc, MSCE.

Combo of burst wave lithotripsy and ultrasonic propulsion feasible for kidney stones

Combination treatment with burst wave lithotripsy and ultrasonic propulsion for small, asymptomatic renal stones is feasible.

Dr. Krambeck investigates efficacy of Trilogy and ShockPulse-SE lithotripters

“You have tradeoffs with every device that you use,” says Amy E. Krambeck, MD.

FDA grants orphan drug designation to ADV7103 for cystinuria

ADV7103 is currently being studied in the phase 2/3 CORAL-1 study, enrolling patients with cystinuria across centers in France and Belgium.

Alkaline water unlikely to prevent kidney stones, study finds

"While alkaline water products have a higher pH than regular water, they have a negligible alkali content–which suggests that they can't raise urine pH enough to affect the development of kidney and other urinary stones," says Roshan M. Patel, MD.

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

Kidney Stone Symptoms and When to See a Doctor

Are you experiencing severe pain in your lower back? Is there blood in your urine? Do you have difficulty urinating? You may have a kidney stone, a rock-like deposit created from high levels of minerals and other substances in the urine. ( 1 , 2 ) Kidney stones can form in one or both of your kidneys, organs that remove waste from the blood and excrete urine. ( 3 )

While kidney stones have become increasingly common, with 1 in 11 people in the United States developing them, the important message is that they are treatable — and easily treated if caught early. ( 4 ) Untreated kidney stones that grow and cause complications, such as infection, fever, or blood in the urine, can be particularly dangerous.

Recognizing the symptoms associated with kidney stones is the first step to getting proper and timely care if and when you do have a stone.

You’ll Likely Feel Pain When You Have a Kidney Stone

Kidney stones can grow quietly within the kidney without causing any symptoms for months or even years, says John C. Lieske, MD , a consultant in the division of nephrology and hypertension at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. However, when a stone breaks loose, it can block the ureter (the small tube that drains urine from the kidney and transports it to the bladder) and start causing a lot of pain.

The pain can be so severe that many people end up in the emergency room (ER), says Dr. Lieske, with one study finding more than one million visits to the ER in a year because of kidney stones. ( 5 )

Pain occurs because the stone is blocking the flow of urine, explains Daniel Marchalik, MD , a urologist and director of the kidney stone program at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington, DC. The backup of urine makes the kidney swell, causing discomfort. “The size of the stone isn’t always important,” he says. “Even small stones can become lodged in the ureter and cause a backup of urine and severe pain.”

As the stone travels through the urinary tract, pain can shift from either side of the lower back to the abdomen and the groin, says Dr. Marchalik. Sharp, stabbing pain that comes in waves is common.

“Some women say the pain is worse than childbirth,” adds Naim Maalouf, MD , an associate professor of internal medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Overall, symptoms tend to be similar in men and women. However, men can sometimes experience pain radiating to the tip of their penis when the stone is low in the ureter, says Marchalik.

Other Kidney Stone Symptoms, From Nausea to Cloudy Urine

In addition to pain, kidney stones can cause other symptoms: ( 6 , 7 , 8 )

- Nausea and vomiting

- A strong need to urinate

- Urinating more frequently

- Urinating small amounts

- A burning sensation or pain while urinating

- Blood in the urine — the urine will look brown, pink, or red

- Cloudy urine

- Gravel (or tiny kidney stones) in the urine

- Urine that smells bad

- Fever and chills, if you also have an infection

When and How Soon to See a Doctor if You Suspect a Stone

At the time of a first kidney stone attack, people often aren’t sure what is going on and need to be seen by a doctor to make sure the symptoms aren’t the result of a more serious problem, such as appendicitis, says Lieske.

As a general rule, you need to seek medical attention if you experience any of the following symptoms:

- Severe pain that makes sitting still or getting comfortable impossible

- Pain with nausea and vomiting

- Pain with fever and chills

- Blood in the urine

- Difficulty passing urine

- A burning sensation while urinating

If you can’t see your doctor that day, head to the ER.

“If stone pain and fever develop, go directly to the ER,” says Timothy F. Lesser, MD , a urologist at Torrance Memorial Medical Center in Torrance, California. A kidney stone with a urinary tract infection (UTI) may cause sepsis and must be treated immediately. ( 9 )

If urine is trapped behind a kidney stone that is blocking the ureter, the urine can become infected, says Seth K. Bechis, MD , a urologist at UC San Diego Health. This, in turn, can cause an infection of the kidney tissue or result in the infection spreading to the bloodstream, causing sepsis, he explains.

Additionally, over time stones can become infected and harbor bacteria, causing urinary tract infections, adds Dr. Bechis. Some people who have a history of recurrent UTIs are found to have a large stone that continuously sheds bacteria into the urine. When doctors suspect that someone has a kidney stone with a UTI, they place a tube in the ureter or kidney to drain the backed up, infected urine, says Bechis. In addition, antibiotics are given to treat infection. ( 10 )

While men are more prone to kidney stones than women, women are more likely to get UTIs, says Lieske. “So it’s not surprising that women are also more likely to get a urinary infection associated with their kidney stones,” he says.

People With a History of Kidney Stones May Sometimes Forgo the Doctor

While infection with kidney stones is a medical emergency, some people with a history of kidney stones may not always need to see a doctor, says Lieske. After an initial consultation with their physician, people who recognize their symptoms may be able to have pain medication on hand, so they can try passing the stone at home, he explains. Your doctor will likely have you drink plenty of water to help flush the stone out of your urinary tract.

Whether to use this approach “really depends on how severe the pain is and how comfortable people are with this strategy,” says Lieske. “Anecdotally, it seems that patients may have less severe pain the more kidney stone attacks they have had over the years, although this is certainly not universally true.”

Ibuprofen (Advil) can help with kidney stone pain , while a drug called tamsulosin (Flomax) may help relieve discomfort and enable you to pass the stone, notes Marchalik.

Fortunately, doctors can help you make prevention plans so you can avoid repeatedly developing stones.

Editorial Sources and Fact-Checking

Everyday Health follows strict sourcing guidelines to ensure the accuracy of its content, outlined in our editorial policy . We use only trustworthy sources, including peer-reviewed studies, board-certified medical experts, patients with lived experience, and information from top institutions.

- Kidney Stones: Symptoms and Causes. Mayo Clinic . June 3, 2022.

- Definition and Facts for Kidney Stones. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases . May 2017.

- How Your Kidneys Work. National Kidney Foundation .

- About USDRN. Urinary Stone Disease Research Network .

- Foster G, Stocks C, Borofsky MS. Emergency Department Visits and Hospital Admissions for Kidney Stone Disease, 2009. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Statistical Briefs . July 2012.

- What Are Kidney Stones? Urology Care Foundation .

- Kidney Stones. National Kidney Foundation .

- Patient Education: Kidney Stones in Adults (Beyond the Basics). UpToDate . July 2022.

- Kidney Stones. Sepsis Alliance . February 10, 2022.

- Treatment. Sepsis Alliance . March 25, 2021.

How Much Does It Cost to Go to the ER?

Treating a UTI costs $2,598, on average -- and we needed a study to tell us this.

"The health care market is not a market at all. It's a crapshoot." That's where, over 30 pages later, Time magazine's longest-ever article ended. It asked, in the course of its investigation into the industry, "Why should a trip to the emergency room for chest pains that turn out to be indigestion bring a bill that can exceed the cost of a semester of college?"

Such astronomical prices are indeed seen, according to a NIH-funded study published today in PLOS ONE: The median ER visit costs 40 percent more than what the average American pays in monthly rent. But the discrepancy in ER charges is so great, according to the study's authors , that patients have no way of knowing how much they can expect to be billed.

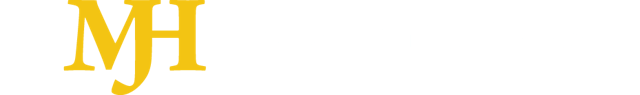

The average cost of a visit to the ER for over 8,000 patients across the U.S. was $2,168. But the interquartile range (IQR), which represents the difference between the 25th and 75th percentile of charges, was $1,957 -- meaning many patients were paying a lot more or a lot less than that. Of the top ten most common reasons for ER visits, treating kidney stones was most expensive, on average. But it was also the most variable. All of the charges -- which represent the total bill for adults 18 to 64 years old who, for simplicity's sake, came in with a single outpatient diagnosis -- followed similar patterns:

These numbers don't represent how much of the charges were ultimately covered by insurers. The researchers, did, however, also find that uninsured patients are typically charged the least, followed by privately insured patients, and finally by those on Medicaid, who saw the highest bills.

- Browse Topics

- Earn CME Credits Stroke Cardiac Trauma Pediatric Trauma Urgent Care All CME Tests

- Pathways New!

- Resources For Emergency Physicians Urgent Care Clinicians Emergency PAs & NPs Residents Groups & Hospitals

Renal Calculi: Emergency Department Diagnosis And Treatment

*new* quick search this issue.