- location of the visitor¡¦s home ¡¦ how far they traveled to the site

- how many times they visited the site in the past year or season

- the length of the trip

- the amount of time spent at the site

- travel expenses

- the person¡¦s income or other information on the value of their time

- other socioeconomic characteristics of the visitor

- other locations visited during the same trip, and amount of time spent at each

- other reasons for the trip (is the trip only to visit the site, or for several purposes)

- fishing success at the site (how many fish caught on each trip)

- perceptions of environmental quality or quality of fishing at the site

- substitute sites that the person might visit instead of this site

- The value of improvements in water quality was only shown to increase the value of current beach use. However, improved water quality can also be expected to increase overall beach use.

- Estimates ignore visitors from outside the Baltimore-Washington statistical metropolitan sampling area.

- The population and incomes in origin zones near the Chesapeake Bay beach areas are increasing, which is likely to increase visitor-days and thus total willingness to pay.

- changes in access costs for a recreational site

- elimination of an existing recreational site

- addition of a new recreational site

- changes in environmental quality at a recreational site

- number of visits from each origin zone (usually defined by zipcode)

- demographic information about people from each zone

- round-trip mileage from each zone

- travel costs per mile

- the value of time spent traveling, or the opportunity cost of travel time

- exact distance that each individual traveled to the site

- exact travel expenses

- substitute sites that the person might visit instead of this site, and the travel distance to each

- quality of the recreational experience at the site, and at other similar sites (e.g., fishing success)

- perceptions of environmental quality at the site

- characteristics of the site and other, substitute, sites

- The travel cost method closely mimics the more conventional empirical techniques used by economists to estimate economic values based on market prices.

- The method is based on actual behavior¡¦what people actually do¡¦rather than stated willingness to pay¡¦what people say they would do in a hypothetical situation.

- The method is relatively inexpensive to apply.

- On-site surveys provide opportunities for large sample sizes, as visitors tend to be interested in participating.

- The results are relatively easy to interpret and explain.

- The travel cost method assumes that people perceive and respond to changes in travel costs the same way that they would respond to changes in admission price.

- The most simple models assume that individuals take a trip for a single purpose ¡¦ to visit a specific recreational site. Thus, if a trip has more than one purpose, the value of the site may be overestimated. It can be difficult to apportion the travel costs among the various purposes.

- Defining and measuring the opportunity cost of time, or the value of time spent traveling, can be problematic. Because the time spent traveling could have been used in other ways, it has an "opportunity cost." This should be added to the travel cost, or the value of the site will be underestimated. However, there is no strong consensus on the appropriate measure¡¦the person¡¦s wage rate, or some fraction of the wage rate¡¦and the value chosen can have a large effect on benefit estimates. In addition, if people enjoy the travel itself, then travel time becomes a benefit, not a cost, and the value of the site will be overestimated.

- The availability of substitute sites will affect values. For example, if two people travel the same distance, they are assumed to have the same value. However, if one person has several substitutes available but travels to this site because it is preferred, this person¡¦s value is actually higher. Some of the more complicated models account for the availability of substitutes.

- Those who value certain sites may choose to live nearby. If this is the case, they will have low travel costs, but high values for the site that are not captured by the method.

- Interviewing visitors on site can introduce sampling biases to the analysis.

- Measuring recreational quality, and relating recreational quality to environmental quality can be difficult.

- Standard travel cost approaches provides information about current conditions, but not about gains or losses from anticipated changes in resource conditions.

- In order to estimate the demand function, there needs to be enough difference between distances traveled to affect travel costs and for differences in travel costs to affect the number of trips made. Thus, it is not well suited for sites near major population centers where many visitations may be from "origin zones" that are quite close to one another.

- The travel cost method is limited in its scope of application because it requires user participation. It cannot be used to assign values to on-site environmental features and functions that users of the site do not find valuable. It cannot be used to value off-site values supported by the site. Most importantly, it cannot be used to measure nonuse values. Thus, sites that have unique qualities that are valued by non-users will be undervalued.

- As in all statistical methods, certain statistical problems can affect the results. These include choice of the functional form used to estimate the demand curve, choice of the estimating method, and choice of variables included in the model.

- GolfSW.com - Golf Southwest tips and reviews.

- VivEcuador.com - Ecuador travel information.

- TheChicagoTraveler.com - Explore Chicago.

- FarmingtonValleyVisit.com - Discover Connecticut's Farmington Valley.

- View source

- View history

- Community portal

- Recent changes

- Random page

- Featured content

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

- Browse properties

Travel cost method

This article deals with the Travel Cost Method, which is often used in evaluating the economic value of recreational sites. This is particularly important in the coastal zone because of the level of use and the potential values that can be attached to the natural coastal and marine environment.

The Travel Cost Method (TCM) is one of the most frequently used approaches to estimating the use values of recreational sites. The TCM was initially suggested by Hotelling [1] and subsequently developed by Clawson [2] in order to estimate the benefits from recreation at natural sites. The method is based on the premise that the recreational benefits at a specific site can be derived from the demand function that relates observed users’ behaviour (i.e., the number of trips to the site) to the cost of a visit. One of the most important issues in the TCM is the choice of the costs to be taken into account. The literature usually suggests considering direct variable costs and the opportunity cost of time spent travelling to and at the site. The classical model derived from the economic theory of consumer behaviour postulates that a consumer’s choice is based on all the sacrifices made to obtain the benefits generated by a good or service. If the price ( [math]p[/math] ) is the only sacrifice made by a consumer, the demand function for a good with no substitutes is [math]x=f(p)[/math] , given income and preferences. However, the consumer often incurs other costs ( [math]c[/math] ) in addition to the out-of-pocket price, such as travel expenses, and loss of time and stress from congestion. In this case, the demand function is expressed as [math]x = f(p, c)[/math] . In other words, the price is an imperfect measure of the full cost incurred by the purchaser. Under these conditions, the utility maximising consumer’s behaviour should be reformulated in order to take such costs into account. Given two goods or services [math]x_1, x_2[/math] , their prices [math]p_1, p_2[/math] , the access costs [math]c_1, c_2[/math] and income [math]R[/math] , the utility maximising choice of the consumer is:

[math]max \, U = u(x_1,x_2) \quad subject \, to \quad (p_1+c_1)x_1+(p_2+c_2)x_2=R . \qquad (1)[/math]

Now, let [math]x_1[/math] denote the aggregate of priced goods and services, [math]x_2[/math] the number of annual visits to a recreational site, and assume for the sake of simplicity that the cost of access to the market goods is negligible ( [math]c_1 \approx 0[/math] ) and that the recreational site is free ( [math]p_2=0[/math] ). Under these assumptions, equation (1) can be written as:

[math]max \, U = u(x_1,x_2) \quad subject \, to \quad p_1x_1+c_2x_2=R . \qquad (2)[/math]

Under these conditions, the utility maximising behaviour of the consumer depends on:

The TCM is based on the assumption that changes in the costs of access to the recreational site [math]c_2[/math] have the same effect as a change in price: the number of visits to a site decreases as the cost per visit increases. Under this assumption, the demand function for visits to the recreational site is [math]x_2=f(c_2)[/math] and can be estimated using the number of annual visits as long as it is possible to observe different costs per visit. The basic TCM model is completed by the weak complementarity assumption, which states that trips are a non-decreasing function of the quality of the site, and that the individual forgoes trips to the recreational site when the quality is the lowest possible [3] , [4] . There are two basic approaches to the TCM: the Zonal approach (ZTCM) and the Individual approach (ITCM). The two approaches share the same theoretical premises, but differ from the operational point of view. The original ZTCM takes into account the visitation rate of users coming from different zones with increasing travel costs. By contrast, ITCM, developed by Brown and Nawas [5] and Gum and Martin [6] , estimates the consumer surplus by analysing the individual visitors’ behaviour and the cost sustained for the recreational activity. These are used to estimate the relationship between the number of individual visits in a given time period, usually a year, the cost per visit and other relevant socio-economic variables. The ITCM approach can be considered a refinement or a generalisation of ZTCM [7] .

[math]x_2 = g(c_2) . \qquad (3)[/math]

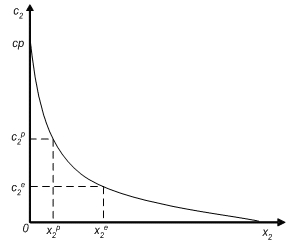

The demand function can also be estimated for non-homogeneous sub-samples introducing among the independent variables income and socio-economic variables representing individual characteristics [8] . Therefore, if an individual incurs [math]c_2^e[/math] per visit, he chooses to do [math]x_2^e[/math] visits a year, while if the cost per visit increases to [math]c_2^p[/math] the number of visits will decrease to [math]x_2^p[/math] . The cost [math]cp[/math] is the choke price, that is the cost per visit that results in zero visits. The annual user surplus (the use value of the recreational site) is easily obtained by integrating the demand function from zero to the current number of annual visits, and subtracting the total expenditures on visits.

Related articles

- ↑ Hotelling, H. (1949), Letter, In: An Economic Study of the Monetary Evaluation of Recreation in the National Parks , Washington, DC: National Park Service.

- ↑ Clawson, M. (1959), Method for Measuring the Demand for, and Value of, Outdoor Recreation . Resources for the Future, 10, Washington, DC.

- ↑ Freeman, A.M. III. (1993). The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values: Theory and Method , Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

- ↑ Herriges, J.A., C. Kling and D.J. Phaneuf (2004), 'What’s the Use? Welfare Estimates from Revealed Preference Models when Weak Complementarity Does Not Hold', Journal of Environmental Economics and Management , 47 (1), pp. 53-68.

- ↑ Brown, W.G. and F. Nawas (1973), 'Impact of Aggregation on the Estimation of Outdoor Recreation Demand Functions', American Journal of Agricultural Economics , 55, 246-249.

- ↑ Gum, R.L. and W.E.Martin (1974), 'Problems and Solutions in Estimating the Demand for and Value of Rural Outdoor Recreation', American Journal of Agricultural Economics , 56, 558-566.

- ↑ Ward, F.A. and D. Beal (2000), Valuing Nature with Travel Cost Method: A Manual , Northampton: Edward Elgar.

- ↑ Hanley, N. and C.L. Spash (1993), Cost Benefit Analysis and the Environment , Aldershot, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Definitions

- Articles by Paolo Rosato

- Integrated coastal zone management

- Evaluation and assessment in coastal management

- This page was last edited on 3 March 2022, at 21:18.

- Privacy policy

- About Coastal Wiki

- Disclaimers

Environmental Justice Organisations, Liabilities and Trade

Mapping environmental justice.

- Nuclear Energy

- Oil and Gas and Climate Justice

- Biomass and Land Conflicts

- Mining and Ship Breaking

- Environmental Health and Risk Assessment

- Liabilities and Valuation

- Law and Institutions

- Consumption, Ecologically Unequal Exchange and Ecological Debt

Travel-cost method

The travel-cost method (TCM) is used for calculating economic values of environmental goods. Unlike the contingent valuation method, TCM can only estimate use value of an environmental good or service. It is mainly applied for determining economic values of sites that are used for recreation, such as national parks. For example, TCM can estimate part of economic benefits of coral reefs, beaches or wetlands stemming from their use for recreational activities (diving and snorkelling/swimming and sunbathing/bird watching). It can also serve for evaluating how an increased entrance fee a nature park would affect the number of visitors and total park revenues from the fee. However, it cannot estimate benefits of providing habitat for endemic species.

TCM is based on the assumption that travel costs represent the price of access to a recreational site. Peoples’ willingness to pay for visiting a site is thus estimated based on the number of trips that they make at different travel costs. This is called a revealed preference technique, because it ‘reveals’ willingness to pay based on consumption behaviour of visitors.

The information is collected by conducting a survey among the visitors of a site being valued. The survey should include questions on the number of visits made to the site over some period (usually during the last 12 months), distance travelled from visitor’s home to the site, mode of travel (car, plane, bus, train, etc.), time spent travelling to the site, respondents’ income, and other socio-economic characteristics (gender, age, degree of education, etc). The researcher uses the information on distance and mode of travel to calculate travel costs. Alternatively, visitors can be asked directly in a survey to state their travel costs, although this information tends to be somewhat less reliable. Time spent travelling is considered as part of the travel costs, because this time has an opportunity cost. It could have been used for doing other activities (e.g. working, spending time with friends or enjoying a hobby). The value of time is determined based on the income of each respondent. Time spent at the site is for the same reason also considered as part of travel costs. For example, if respondents visit three different sites in 10 days and spend only 1 day at the site being valued, then only fraction of their travel costs should be assigned to this site (e.g. 1/10). Depending on the fraction used, the final benefit estimates can differ considerably.

Two approaches of TCM are distinguished – individual and zonal. Individual TCM calculates travel costs separately for each individual and requires a more detailed survey of visitors. In zonal TCM, the area surrounding the site is divided into zones, which can be either concentric circles or administrative districts. In this case, the number of visits from each zone is counted. This information is sometimes available (e.g. from the site management), which makes data collection from the visitors simpler and less expensive.

The relationship between travel costs and number of trips (the higher the travel costs, the fewer trips visitors will take) shows us the demand function for the average visitor to the site, from which one can derive the average visitor’s willingness to pay. This average value is then multiplied by the total relevant population in order to estimate the total economic value of a recreational resource.

TCM is based on the behaviour of people who actually use an environmental good and therefore cannot measure non-use values. This method is thus inappropriate for sites with unique characteristics which have a large non-use economic value component (because many people would be willing to pay for its preservation just to know that it exists, although they do not plan to visit the site in the future).

The travel-cost method might also be combined with contingent valuation to estimate an economic value of a change (either enhancement or deterioration) in environmental quality of the NP by asking the same tourists how many trips they would make in the case of a certain quality change. This information could help in estimating the effects that a particular policy causing an environmental quality change would have on the number of visitors and on the economic use value of the NP.

For further reading:

Ward, F.A., Beal, D. (2000) Valuing nature with travel cost models. A manual. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

Ecosystem valuation [ www.ecosystemvaluation.org/travel_costs.htm ]

This glossary entry is based on a contribution by Ivana Logar

EJOLT glossary editors: Hali Healy, Sylvia Lorek and Beatriz Rodríguez-Labajos

One comment

I quite like reading a post that will make people think. Also, thanks for allowing me to comment!

Browse by Theme

Browse by type.

- Presentations

- Press Releases

- Scientific Papers

Online course

Online course on ecological economics: http://www.ejolt.org/2013/10/online-course-ecological-economics-and-activism/

Privacy Policy | Credits

- No results found

The Travel Cost Model

Chapter 3. non-market valuation techniques, 3.4 the travel cost method (tcm), 3.4.1 the travel cost model.

The travel cost method is one of the oldest non-market valuation techniques used to value environmental goods and services (English & Bowker, 1996) and has been used extensively in the valuation of recreational sites (Seller, Stoll, & Chavas, 1985; Smith, Desvousges, & Fisher, 1986). The original theoretical foundation of the Travel Cost Method is attributed to Hottelling’s (1947) suggestion, in a two-page letter to the US National Park Service, that the benefits from outdoor recreation sites could be estimated by calculating individual recreationists’ cost of travel to the site (Smith, 1989; Kahn, 2005; Yao & Kaval, 2007). Hottelling’s theory was first applied in TCM studies involving water-based recreation by Trice and Wood (1958), and Clawson (1959).

The TC technique involves using travel cost as a proxy for the price of visiting outdoor recreational sites (Trice and Wood, 1958; Perman et al ., 2003). The rational is that, a recreationist undertakes a visit to a recreational site if the recreational benefits or utility from such a visit is at least equal to the cost of the visit to that site i.e. marginal benefit is at least equal to marginal cost. Travel cost is therefore used as a proxy for the price of the recreational experience on the visit since most recreational sites have zero (or nominal) entry fees (Smith, Desvousges, & Fisher, 1986). In this case, the cost (associated with the trip) incurred in the private goods and services market is used to infer the per-trip value (WTP) for the site visited. The visit to the site is treated as a single transaction and travel cost as the price for that transaction (Wilson & Carpenter, 1999) just like what happens in a market for a private good. When travel costs to a site change, economic theory predicts that individuals or households respond to this change by either increasing (for a reduction in travel cost or entrance fees) or reducing (for an increase in travel cost or entrance fees) the number of trips to the site until the marginal value of the last trip is just equal to travel cost.11

This follows from the assumption of a rational economic agent and constrained optimization (utility maximization).

A statistical relationship (trip generating function - TGF) between the observed visits and the cost of visiting is derived and used as a surrogate demand curve from which consumers’ surplus per visit- day can be measured by integrating under this curve (Ribaudo & Epp, 1984; Bowker,

English, & Donovan, 1996).

Data on distances travelled to site, mode of transport, travel time, costs directly related to the trip; socio-economic and demographic factors such as household income, age and education; site characteristics; and individual attitudes towards the environment may be collected through carefully designed questionnaires (Champ, Boyle & Brown, 2003). The most popular method of collecting this data is through on-site surveys where a random sample of site users is taken and the questionnaire administered through personal interviews or the individuals may be allowed to take the questionnaire away for completion later. On-site sampling introduces endogenous stratification, truncation, and over-dispersion in travel cost analysis (Shaw, 1988; Smith, 1989; Martinez- Espineira & Amoako-Tuffour, 2005). These concepts will be defined later.

The TC technique assumes weak complementarity between the non-market good or service and consumption expenditure on a complementary market good (Ribaudo & Epp, 1984; Perman et al ., 2003). This implies that, when consumption expenditure on the market good is zero, the marginal utility of the non-market good or service is also zero (Cocheba & Langford, 1978; Bouwes & Schneider, 1979). Cocheba and Langford assert that the TCM is only useful for measuring consumers’ surplus when the theoretically correct welfare measure is the Hicksian compensating variation or WTP. Seller, Stoll, and Chavas (1985) correctly point out that the TCM provides estimates of the Marshallian consumer surplus. If the correct welfare measure is the Hicksian equivalent variation or willingness to sell (WTA), the TCM would yield underestimates of value (Hammack & Brown, 1974 as cited by Cocheba & Langford, 1978 p. 494).

Since the Travel Cost Method is based on ex-post travel cost, it cannot be used to estimate values where very little or no travel cost is involved, implying that it cannot be used to estimate non-use values (Krutilla, 1967; Smith, 1989) such as option, existence and bequest values. The value of a recreational activity at a particular site is produced by a set of attributes associated with the site. For example the value of a recreational experience of an individual at the site may depend on a combination of scenic beauty, air quality, diversity of wildlife and fauna. The basic TCM may not effectively isolate the value of, say, wildlife from the value of the other inputs which are combined to produce the recreational experience (Cocheba & Langford, 1978). In other words the

basic TCM is unable to isolate the value of an ecosystem service from the ecosystem functions and other services. However advanced models of the TCM are now able to isolate and measure the importance of individual site attributes in terms of site choice (Smith 1989).

The travel cost method has been used to estimate non-market values of goods and services of a number of ecosystems. For example, Everitt (1983) used the TCM to estimate the value of recreational benefits of a forest ecosystem - the Coromandel State Forest Park in New Zealand. Smith, Desvousges and Fisher (1986) estimated the value of recreational benefits from increased water quality of a freshwater ecosystem. Wilson and Carpenter (1999) reviewed TCM valuation studies of fresh water ecosystem services in the US during the period 1971 and 1997 and observed that the studies focused on recreation demand as a proxy for non-market demand for water quality or water level of lakes, reservoirs and rivers.

3.4.2 Theoretical Illustration of Welfare Changes Associated with an

- Models for Analyzing Contingent Valuation Responses

- Issues Surrounding the Use of the CVM

- The Travel Cost Model (You are here)

- Key Design Issues

- The Survey Instrument

- Survey Procedure

- Fitting a linear multivariate model with alpha set at 0.05 (Model D

Related documents

Define Travel Cost Model

Explanation.

Use this activity to define a travel cost model. The Travel Cost Model ID can be connected to a resource or a resource type in Service and Maintenance/Scheduling/Basic Data/Scheduling Basic Data

To set up and to utilize the travel cost model a corresponding travel cost model with the same ID needs to be setup in the scheduling workbench. The definition of the travel cost model is set up in the Scheduling Workbench in Service and Maintenance/Scheduling/Scheduling Workbench - Planning - Data Management - Travel Cost Models. The travel cost model is used to set advanced rules to limit the amount of travel scheduled to a resource. Travel can be limited by individual journey time, by travel time from the shift start location and by total shift travel time. The limitation can either be a hard constraint, or be in the form of penalties and additional costs once the travel exceeds a certain threshold.

Prerequisites

System effects.

As a result of this activity, travel cost models can be used when defining resource and resource type in Scheduling Basic Data .

Travel Cost Model

Activity Diagrams

BDR for Scheduling Integration

Kia EV9: How Much Does It Cost To Charge It?

An awd kia telluride costs about 2 and a half times as much in gas to travel the same distance as the electric ev9..

E Vs have made a lot of inroads. But one vehicle the market needed for true mass adoption in America was an affordable, family-sized three-row SUV. That vehicle finally arrived in 2024 with the Kia EV9 . The EV9 took home this year’s World Car of the Year award . It has the potential to be Kia’s Telluride for the EV space. And if you hop on one of Kia’s current lease offers, it may be even cheaper than its popular combustion cousin.

One of the main benefits of going EV with your family hauler is not having to pay for gas on inefficient school runs and trips to the grocery store. But how much are you really saving with a Kia EV9, and how much does it cost to charge one? The answer depends on how and where you decide to charge it.

More On Charging Costs

- Ford Mustang Mach-E: How Much Does It Cost To Charge It?

- Hyundai Ioniq 5: How Much Does It Cost To Charge It?

- Tesla Model Y: How Much Does It Cost To Charge It?

- How Much Does It Cost To Charge An Electric Car?

How much does it cost to charge a Kia EV9?

Kia sells the EV9 with two battery pack options: a Standard Range with 76.1 kWh and a Long Range with 99.8 kWh. The national average rate for household electricity is 16.68 cents/kWh (as of this writing). At that rate, a 10-80% full charge of the Kia EV9 would cost about $8.88 for the Standard Range EV9 and $11.65 for the Extended Range EV9.

How much does it cost to charge a Kia EV9 at home?

Charging a Kia EV9 on a Level 2 unit at home should deliver the cheapest rate. However, that rate will vary from the national average due to several factors. Location matters. Some states are much more affordable or more expensive than others.

In North Dakota, where energy costs average just 10.44 cents/kWh, a full charge of the Kia EV9’s Extended Range pack would cost just $7.29. In California, where energy costs average 32.47 cents/kWh, the same full charge would cost about $22.68.

Wherever a Kia EV9 owner is, time will matter. It’s much cheaper to charge an EV9 during off-peak hours (often after 11 p.m.) than during peak hours in the afternoon and early evening. Utility companies may meter a home Level 2 charger separately with a discounted rate to charge at night during off-peak hours. For instance, my home provider DTE offers a discounted rate of 12 cents/kWh on my Level 2 charger.

Though home is often the cheapest place to charge, the cost of installing a Level 2 charger can negate a lot of the savings. A popular Level 2 unit, like a Chargepoint Home Flex , can cost more than $500. The cost can run into the thousands with a licensed electrician and permits.

How much does it cost to charge a Kia EV9 at a DC fast charger?

Charging the Kia EV9 on a Level 3 fast charger can be free initially when an owner buys a Kia EV9. Under Kia’s agreement with Electrify America , EV9 owners can get their first 1,000 kWh of fast charging free. It’s not two years unlimited like the Hyundai Ioniq 5 . But that’s enough to cover the first 14 full 10-80% charges to the EV9’s Extended Range battery pack.

Outside of that arrangement, fast-charging a Kia EV9 will typically be much more expensive than home charging. Precise rates will vary with the electricity price and can be more than twice the going local rate. Charging providers also add taxes and additional fees. For example, charging rates at my local EVgo charger in the northern Detroit suburbs typically run above 50 cents/kWh during the day.

How much cheaper is an EV9 to charge than a gas car?

The Kia EV9 is not the most efficient EV on the road, but it can still be much cheaper to charge than it would cost to fill up a comparable combustion SUV. The best comparison for the EV9 is its popular three-row counterpart, the Kia Telluride.

As of this writing, the average national price for a gallon of gas is $3.46. According to the EPA, an AWD Telluride requires five gallons of gas to travel 100 miles, costing $17.30. The EPA rates the AWD EV9 to use 41 kWh of electricity to travel the same 100 miles. At the national rate, that electricity would cost $6.84.

An exception may be if an EV9 owner is on a road trip and beholden to the fast-charging options en route. Rates exceeding 50 cents/kWh in that scenario could see the cost approach or even surpass that of filling up a Telluride, depending on the cost of gasoline in the area.

For more information, read our

Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

- Your Profile

- Your Subscriptions

- Your Business

- Support Local News

- Payment History

- Sign up for Daily Headlines

- Sign up for Notifications

Are all Canadian airlines adopting an 'ultra-low-cost' model?

- Share by Email

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share via Text Message

Metro Vancouverites looking to book flights across Canada shouldn't count on free seat selection or carry-on luggage even with the country's largest airlines.

Air Canada and WestJet have taken a nod from ultra-low-cost carriers and started implementing fares with less flexible re-booking policies and fewer inclusions, such as free seat selection and carry-on bags.

Air Canada received widespread backlash after announcing it would remove the free seat selection during the 24-hour check-in before flights. The airline tells V.I.A. that it has "not made any changes" but will "monitor competitive offerings regularly."

Travellers also spoke out after WestJet implemented its new UltraBasic fare that doesn't include a carry-on bag.

What are the options for flying in Canada on a budget right now?

Budget airlines, including Lynx Air, Swoop, and Canada Jetlines, have stopped providing service to travellers based in the Lower Mainland or shut down operations completely.

Lynx Air unexpectedly shut down operations on Feb. 25, citing fierce market competition, surging fuel prices, exchange rates, and increasing airport charges. In the fall of 2023, WestJet ended operations on its budget brand, Swoop , citing similar reasons.

Canada Jetlines, rebranded Jetlines, quietly ended its twice-weekly service connecting Vancouver International Airport (YVR) with Toronto Lester B. Pearson International Airport (YYZ); it has shifted its focus to Toronto, providing service to popular sun destinations including Miami, Montego Bay, Orlando, and Cancun.

In March 2023, the Government of Canada gave the green light to WestJet's merger with Sunwing Airlines . The airline plans to wind down the Sunwing brand by 2025.

Flair Airlines, Canada's only ultra-low-cost carrier, has a similar policy to WestJet's new UltraBasic option for travellers flying in its lowest fare class. They may bring a small personal item but carry-on or checked luggage costs an additional fee. The prices vary depending on the length of the route.

What should I keep in mind when selecting fares with Canadian airlines?

Chris Lynes, Managing Director for Flight Centre Travel Group, including global brands Flight Centre and Corporate Traveller , said Canada's largest airlines have adopted policies that align with global trends, catering to diverse needs and budgets.

"The trend, known as 'unbundling,' allows consumers to choose how they travel based on their personal preferences for cost, convenience, and comfort, presenting opportunities for savings," he told V.I.A.

Lynes pointed to WestJet's new UltraBasic fare class that doesn't include a carry-on bag but offers a cheaper ticket for budget-conscious travellers. These fares feature "transparent pricing," allowing customers to tailor their trips to suit their budgets and needs.

But travellers need to understand the details of the fare class they purchase.

"When evaluating airfare options, it is crucial to match the fare to your needs. For example, a non-refundable, non-changeable fare generally does not offer additional perks and may not suit everyone," he noted.

Business travellers require flexibility since their plans may change frequently and should purchase a "fully bundled fare that covers seat selection, upgrades and meals to accommodate any changes," he added.

Travellers on holiday who want to save money and don't anticipate plans changing can benefit from low-cost options.

"This is where the expertise of a travel advisor can be invaluable, providing insights into the specifics of various fare categories across different airlines—what's included and what's not—to avoid unexpected costs or disruptions," Lynes said.

What are some important considerations with Air Canada and WestJet?

Canada's biggest airlines have drastically different pricing for carry-on and checked luggage.

WestJet's UltraBasic ticket-holders may only bring a personal item, such as a purse, backpack, or another small personal item that travellers can store under the seat in front of them. They don't have access to the overhead bins for larger luggage. They must also board the plane last.

Air Canada's lowest fare class, Basic, includes a piece of carry-on luggage but does not allow changes to the ticket and customers must also board last. Travellers in this fare class must also pay to select a seat until the 24-hour check-in (until the new rule is implemented).

Related : Flair Airlines pokes fun at WestJet's new UltraBasic fare

Air Canada told V.I.A. its "range of fares enable customers to choose the products and services that each fare type offers to suit their travel plans."

But customers should look at the inclusions for each fare since the airlines offer similarly-priced flights, including on popular trips to destinations like Hawaii.

For example, WestJet and Air Canada typically offer the best prices on the route from YVR to Kahului Airport (OGG) but their inclusions vary dramatically.

Travellers can get the best deals on one-way, direct flights from YVR to OGG starting in October and continuing through November. Prices start at $216 on multiple dates with Air Canada and WestJet (see slide two).

But travellers who don't need to check a bag and can get away with carry-on luggage and a personal item may want to book with Air Canada. Canada's largest airline includes a free carry-on bag with a checked one for $35 (see slide three).

WestJet's lowest fare does not include a carry-on bag and the first piece of checked luggage costs $65 (see slide four).

Find more information about exciting destinations in B.C. and across the globe, as well as travel deals and tips, by signing up for V.I.A.'s weekly travel newsletter The Wanderer . Since travel deals can sell out, find out the day they are posted by signing up for our daily Travel Deals newsletter.

Want to learn more about a specific destination or have a travel concern or idea you would like V.I.A. to write about? Email us at [email protected] . Send us stories about recent holidays that you've been on, or if you have any tips you think our readers should know about.

- Oldest Newest

This has been shared 0 times

Featured Flyer

The Travel Cost Approach to Recreation Demand Modeling: An Introduction

Cite this chapter.

- V. Kerry Smith 4 &

- William H. Desvousges 5

Part of the book series: International Series in Economic Modeling ((INSEM,volume 3))

61 Accesses

The travel cost approach offers some of the most widely used demand models for valuing recreation sites. Originally suggested in a letter from Harold Hotelling to the director of the National Park Service, the approach’s basic idea—i.e., that the distances recreationists travel to the sites they visit indicate the implicit prices they are willing to pay for using these sites—has spawned an extensive literature.* Drawing on this literature, this chapter introduces and develops our indirect approach for measuring households’ valuation of water quality changes. In particular, we generalize the travel cost model to reflect the role of recreation sites’ characteristics on households’ demands for the services of these sites.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Becker, Gary S., 1965, “A Theory of the Allocation of Time,” Economic Journal , Vol. 75, September 1965, pp. 493–517.

Article Google Scholar

Becker, Gary S., 1974, “A Theory of Social Interactions,” Journal of Political Economy , Vol. 82, 1974, pp. 1063–93.

Berndt, Ernst, R., 1983, “Quality Adjustment in Empirical Demand Analysis,” Working Paper 1397–83, Sloan Schools, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, January 1983.

Google Scholar

Bockstael, Nancy E., W. Michael Hanemann, and Catherine L. Kling, 1985, “Modeling Recreational Demand in a Multiple Site Framework,” paper presented at AERE Workshop on Recreational Demand Modelings, Boulder, Colorado, May 1985.

Bockstael, Nancy E., and Kenneth E. McConnell, 1981, “Theory and Estimation of the Household Production Function for Wildlife Recreation,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management , Vol. 8, No. 3, September 1981, pp. 199–214.

Bockstael, Nancy E., and Kenneth E. Monnell, 1983, “Welfare Measurement in the Household Production Framework,” American Economic Review , Vol. 73, No. 4, September 1983, pp. 806–14.

Bockstael, Nancy E., Ivar E. Strand. Jr. and W. Michael Hanemann, 1984, “Time and Income Constraints in Recreation Demand Analysis,” unpublished paper, Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland, March 1984.

Brown, Gardner. Jr. and Robert Mendelsohn, 1984, “The Hedonic Travel Cost Method,” Review of Economics and Statistics , Vol. 66, No. 3, August 1984, pp. 427–33.

Burt, O. R., and D. Brewer, 1971, “Estimation of Net Social Benefits from Outdoor Recreation,” Econometrica , Vol. 39, October 1971, pp. 813–27.

Cesario, Frank J., 1976, “Value of Time in Recreation Benefit Studies,” Land Economics , Vol. 52, No. 1, February 1976, pp. 32–41.

Cesario, Frank J., and Jack L. Knetsch, 1970, “Time Bias in Recreation Benefit Estimates,” Water Resources Research , Vol. 6, No. 3, June 1970, pp. 700–04.

Cesario, Frank J., and Jack L. Knetsch, 1976, “A Recreation Site Demand and Benefit Estimation Model,” Regional Studies , Vol. 10, pp. 97–104.

Cicchetti, Charles J., Anthony C. Fisher, and V. Kerry Smith, 1976, “An Econometric Evaluation of a Generalized Consumer Surplus Measure: The Mineral King Controversy,” Econometrica , Vol. 44, No. 6, November 1976, pp. 1259–76.

Clawson, M., 1959, “Methods of Measuring the Demand for and Value of Outdoor Recreation,” Reprint No. 10, Resources for the Future, Inc., Washington, D.C., 1959.

Clawson, M., and J. L. Knetsch, 1966, Economics of Outdoor Recreation , Washington, D.C.: Resources for the Future, Inc., 1966.

Desvousges, William H., V. Kerry Smith, and Matthew McGivney, 1983, A Comparison of Alternative Approaches for Estimating Recreation and Related Benefits of Water Quality Improvements , Environmental Benefits Analysis Series, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, March 1983.

Deyak, Timothy A., and V. Kerry Smith, 1978, “Congestion and Participation in Outdoor Recreation: A Household Production Approach,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management , Vol. 5, March 1978, pp. 63–80.

Dwyer, John F., John R. Kelly, and Michael D. Bowes, 1977, Improved Procedures for Valuation of the Contribution of Recreation to National Economic Development , Research Report No. 128, Water Resources Center, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1977.

Fisher, Franklin M., and Karl Shell, 1968, “Taste and Quality Changes in the Pure Theory of the True Cost-of-Living Index,” in J. N. Wolfe, ed., Value, Capital, and Growth: Papers in Honour of Sir John Hicks , Chicago: Aldine Publishing Co., 1968.

Freeman, A. Myrick III, 1979, The Benefits of Environmental Improvement: Theory and Practice , Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press for Resources for the Future, Inc., 1979.

Hausman, Jerry A., 1978, “Specification Error Tests in Econometrics,” Econometrica , Vol. 46, November 1978, pp. 1251–72.

Lau, Lawrence J., 1982, “A Note on the Fundamental Theorem of Exact Aggregation,” Economic Letters , Vol. 9, 1982, pp. 119–26.

McConnell, Kenneth E., and Ivar Strand, 1981, “Measuring the Cost of Time in Recreation Demand Analysis: An Application to Sport Fishing,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics , Vol. 63, No. 1, February 1981, pp. 153–56.

Mendelsohn, Robert, 1984, “An Application of the Hedonic Travel Cost Framework for Recreation Modeling to the Valuation of Deer" in V. Kerry Smith and Ann D. Witte, eds., Advances in Applied Micro-Economics , Greenwich: JAI Press, 1984.

Morey, Edward R., 1981, “The Demand for Site-Specific Recreational Activities: A Characteristics Approach,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management , Vol. 8, No. 4, December 1981, pp. 345–71.

Morey, Edward R., 1984, “Confuser Surplus,” American Economic Review , Vol. 74, No. 1, March 1984, pp. 163–73.

Morey, Edward R., 1985, “Characteristics, Consumer Surplus and New Activities: A Proposed Ski Area,” Journal of Public Economics , Vol. 26, March 1985, pp. 221–36.

Muellbauer, John, 1974, “Household Production Theory, Quality and the ’Hedonic Technique,” American Economic Review , Vol. 64, No. 6, December 1974, pp. 977–94.

Pollak, Robert A., and Michael L. Wachter, 1975, “The Relevance of the Household Production Function and Its Implications for the Allocation of Time,” Journal of Political Economy , Vol. 83, April 1975, pp. 255–77.

Ravenscraft, David J., and John F. Dwyer, 1978, “Reflecting Site Attractiveness in Travel Cost-Based Models for Recreation Benefit Estimation,” Forestry Research Report 78–6, Department of Forestry, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois, July 1978.

Shephard, Ronald W., 1953, Cost and Production Functions , Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953.

Smith, V. Kerry, 1975, “Travel Cost Demand Models for Wilderness Recreation: A Problem of Non-Nested Hypotheses,” Land Economics , Vol. 51, May 1975, pp. 103–11.

Smith, V. Kerry, William H. Desvousges, and Matthew P. Mivney, 1983a, “An Econometric Analysis of Water Quality Improvement Benefits,” Southern Economic Journal , Vol. 50, No. 2, October 1983, pp. 422–37.

Smith, V. Kerry, William H. Desvousges, and Matthew P. Mivney, 1983b, “The Opportunity Cost of Travel Time in Recreation Demand Models,” Land Economics , Vol. 59, No. 3, August 1983, pp. 259–78.

Smith, V. Kerry, and Yoshiaki Kaoru, 1985. "The Hedonic Travel Cost Model: A View from the Trenches,” unpublished paper, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, September 1985.

Talhelm, Daniel R., 1978, “A General Theory of Supply and Demand for Outdoor Recreation in Recreation Systems,” unpublished manuscript, Department of Agricultural Economics, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, July 1, 1978.

Vaughan, William J., Clifford S. Russell, and Jule A. Hewitt, 1984, “Measuring the Benefits of Recreation Related Resource Enhancement: A Caution,” unpublished working paper, Resources for the Future, April 1984.

Wilman, Elizabeth A., 1980, “The Value of Time in Recreation Benefit Studies,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management , Vol. 7, No. 3, September 1980, pp. 272–86.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA

V. Kerry Smith

Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA

William H. Desvousges

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 1986 Kluwer-Nijhoff Publishing, Boston

About this chapter

Smith, V.K., Desvousges, W.H. (1986). The Travel Cost Approach to Recreation Demand Modeling: An Introduction. In: Measuring Water Quality Benefits. International Series in Economic Modeling, vol 3. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-4223-3_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-4223-3_7

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-94-010-8374-4

Online ISBN : 978-94-009-4223-3

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The travel cost method is used to estimate economic use values associated with ecosystems or sites that are used for recreation. The method can be used to estimate the economic benefits or costs resulting from: changes in access costs for a recreational site. elimination of an existing recreational site. addition of a new recreational site.

The travel cost model (TCM) is the revealed preference method used in this context. The basic insight underlying the TCM is that an individual's "price" for recre-ation at a site, such as hiking in a park or fishing at a lake, is his or her trip cost of reaching the site. Viewed in this way, individuals reveal their willingness to pay for

The travel cost model (TCM) is the revealed preference method used in this context. ... Site definition (Step 3) is obviously only for one site, and site characteristic data (Step 6) are typically not gathered. In instances where several single-site models are being "stacked" in estimation, analysts will often gather site characteristic ...

taxes). 2 If gas mileage is 25 miles to the gallon—at an assumed average speed of 50 miles per. hour —and if the individual lives 50 miles away from the recreational site, the cost of the ...

The travel cost model is used to value recreational uses of the environment. For example, it may be used to value the recreation loss associated with a beach closure due to an oil spill or to value the recreation gain associated with improved water quality on a river. The model is commonly applied in benefit-cost analyses and in natural ...

Definition of Travel cost method: A Surrogate Market Approach technique for valuing ecosystems or environmental resources that takes the costs people pay to visit an ecosystem as an expression of its recreational value. This is the common definition for Travel cost method, other definitions can be discussed in the article.

The travel cost model (TCM) of recreation demand is a survey-based method that was developed to estimate the recreation-based use value of natural resource systems. The TCM may be used to estimate the value of. changes in the quality of recreation sites or natural resources systems (Freeman 2003).

The travel cost method of economic valuation, travel cost analysis, or Clawson method is a revealed preference method of economic valuation used in cost-benefit analysis to calculate the value of something that cannot be obtained through market prices (i.e. national parks, beaches, ecosystems). The aim of the method is to calculate ...

The travel cost model is used to value recreational uses of the environment. For example, it may be used to value the recreation loss associated with a beach closure due to an oil spill or to ...

This chapter provides an introduction to Travel Cost Models used to estimate recreation demand and value recreational uses of the environment such as fishing, rock climbing, hunting, boating, etc ...

The travel-cost method (TCM) is used for calculating economic values of environmental goods. Unlike the contingent valuation method, TCM can only estimate use value of an environmental good or service. It is mainly applied for determining economic values of sites that are used for recreation, such as national parks.

3.4 The Travel Cost Method (TCM) 3.4.1 The Travel Cost Model. The travel cost method is one of the oldest non-market valuation techniques used to value environmental goods and services (English & Bowker, 1996) and has been used extensively in the valuation of recreational sites (Seller, Stoll, & Chavas, 1985; Smith, Desvousges, & Fisher, 1986).

This chapter provides an introduction to Travel Cost Models used to estimate recreation demand and value recreational uses of the environment such as fishing, rock climbing, hunting, boating, etc, and covers single-site and random-utility-based models. This chapter provides an introduction to Travel Cost Models used to estimate recreation demand and value recreational uses of the environment ...

TCM is used to value recreational uses of the environment. It is commonly applied in benefit cost analyses (BCA) and in natural resource damage assessments. It is based on „observed behaviour‟, thus is used to estimate use values only. TCM is a demand-based model for use of a recreation site or sites. A site: a river for fishing, a trail ...

The new variable is called TCM (1) if the travel cost is US$0.1004 per mile, and TCM (2) if the travel cost is US$0.2627 per mile. The use of TCM (1) in conjunction with the total expenses model generates the annual consumer surplus of US$285.47 million dollars per annum listed in Table 4. The per mile travel cost value for TCM (2) generates an ...

The travel cost model is used to value recreational uses of the environment. For example, it may be used to value the recreation loss associated with a beach closure due to an oil spill or to value the recreation gain associated with improved water quality on a river. The model is commonly applied in benefit-cost analyses and in natural resource damage assessments where recreation values play ...

The travel-cost method is used to evaluate the demand for hunting trips in Kansas. In contrast to earlier studies, time spent on-site for other recreational activities is explicitly included in the empirical analysis. The demand for hunting trips falls as cost rises.

This chapter describes the data used to estimate the generalized travel cost model. In effect, it forms a bridge between the previous chapter, which uses the household production framework to develop the generalized travel cost model and the following chapter, which describes the model's empirical results.

The travel cost method. A method used to estimate the economic use values associated with ecosystems or sites that are used for recreation based on the assumption that time and travel cost expenses that people incur to visit a site represent the "price" of access to the site. Travel cost method underlying assumptions.

The travel cost model is used to set advanced rules to limit the amount of travel scheduled to a resource. Travel can be limited by individual journey time, by travel time from the shift start location and by total shift travel time.

A travel cost method is an approach that indirectly values environmental goods, and this is usually done by conducting a willingness to pay for related goods and services. The method is used to ...

An AWD Kia Telluride costs about 2 and a half times as much in gas to travel the same distance as the electric EV9. E Vs have made a lot of inroads. But one vehicle the market needed for true mass ...

The treatment of the opportunity cost of travel time in travel cost models has been an area of research interest for many decades. Our analysis develops a methodology to combine the travel distance and travel time data with respondent-specific estimates of the value of travel time savings (VTTS). The individual VTTS are elicited with the use of discrete choice stated preference methods. The ...

Find more information about exciting destinations in B.C. and across the globe, as well as travel deals and tips, by signing up for V.I.A.'s weekly travel newsletter The Wanderer.Since travel deals can sell out, find out the day they are posted by signing up for our daily Travel Deals newsletter.. Want to learn more about a specific destination or have a travel concern or idea you would like V ...

10XTravel: Helps people get more out of their travel and finances, enabling them to travel more while paying less.

The travel cost approach offers some of the most widely used demand models for valuing recreation sites. Originally suggested in a letter from Harold Hotelling to the director of the National Park Service, the approach's basic idea—i.e., that the distances recreationists travel to the sites they visit indicate the implicit prices they are willing to pay for using these sites—has spawned ...