- FOR PROFESSIONALS

- PATIENT PORTAL

- TELETHERAPY

We have beds available!

How To Help Someone Having a Bad Trip, According to Medical Professionals

When someone takes a psychoactive substance like a hallucinogen or cannabis , they often experience a trip. A trip is a set of hallucinations and other psychological symptoms that come from using a substance. Some psychoactive trips can be pleasant, but others lead to troubling experiences and mental status changes. If a loved one uses a drug and has a bad trip, it’s important to know how to help the person through the ordeal.

What Are the Signs of a Bad Trip, and How Can They Be Avoided?

Signs of a bad trip are very subjective based on what the person is hallucinating and if they perceive it as concerning, scary, dangerous, or otherwise uncomfortable. Common signs of a trip, which may be bad for some, include :

- Hallucinations

- Intensified sensory experiences

- Changes in awareness of time

Risk factors have been identified for bad trips, especially those related to psilocybin (shrooms). Researchers have found that mental health symptoms like neurosis make a person more likely to have a bad trip.

When to Seek Medical Attention

If ever in doubt whether someone is having a bad trip, contact poison control at 1-800-222-1222 or by chat here .

However, some symptoms warrant a call to 911. If you or a loved one experience any of these symptoms, call 911 immediately. You will not get in trouble for saving someone’s life, even if you have been taking drugs yourself:

- Increased heart rate

- Increased blood pressure

- Increased breathing rate

- Excessive sweating

- Being a danger to oneself or others

Step-by-Step Instructions on How To Help Someone Experiencing a Bad Trip

The most important ways you can help someone overcome a bad trip are calmly supporting them throughout the trip and calling for help when necessary.

Step One: Recognize That the Person Is Having a Bad Trip

The first step in overcoming a problem is identifying it. If a person has a bad trip, having someone else there to realize there is a problem is vital.

Step Two: Make Sure the Person Is in a Safe Place

Having a bad trip can be very scary. The person may feel out of control physically and mentally. Ensure they are in a place where they can work through their trip safely.

Step Three: Calmly Explain to the Person Why They Are Feeling the Way They Do

A person having a bad trip may not remember taking a substance and be unaware they are on a trip. Calmly reminding the person that they took a drug and are in a safe place while going through its effects can help keep them calm.

Step Four: Stay With the Person During the Trip

Being a source of safety and staying with the person through their bad trip can help keep them physically and mentally safe during the experience.

Step Five: Protect Others

Upsetting hallucinations during trips can make a person a danger to themselves and others. Make sure the person experiencing the trip stays calm and stays away from others, for their safety.

Step Six: Seek Help if Needed

Despite your best efforts, sometimes a person having a bad trip may become a danger to themselves or others or have physical symptoms like a fever that require medical attention. The best thing you can do at that time is to call 911 and refer the person to medical experts who can help them through the rest of the trip.

How Long Will a Bad Trip Last (By Drug Type)?

An unpleasant experience with a drug usually lasts just as long as a good experience. However, a trip can last different lengths depending on the drug taken.

- What can happen during a bad trip? Many different things can happen during a bad trip. Often, the person has troubling hallucinations. However, other symptoms like fever, fast heart rate or panic can also occur.

- What to do if someone has a panic attack? If someone has a panic attack while on a bad trip, you should try your best to calm and reassure them that they are safe. If they remain agitated and you fear they are a danger to themselves or others, you should seek emergency medical attention and call 911.

- What to do if someone becomes overheated and dehydrated? If a person becomes overheated or dehydrated, you should call 911. The person may need intravenous fluids or medical assistance to get their temperature back to normal.

If you or someone you love struggles with substance misuse and has a bad trip, this may be a sign of addiction. Contact our intake experts at The Recovery Village today to learn how we can help.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. “ What are marijuana’s effects? ” July 2020. Accessed September 25, 2022.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. “ Hallucinogens .” November 2021. Accessed September 25, 2022.

Drugs.com. “ Ketamine .” Accessed September 25, 2022.

Drugs.com. “ Bath Salts .” Accessed September 25, 2022.

Drugs.com. “ Mescaline .” Accessed September 25, 2022.

Drugs.com. “ Synthetic Cannabinoids (Synthetic Marijuana, Spice, K2) .” Accessed September 25, 2022.

Drugs.com. “ MDMA (Ecstasy/Molly) .” Accessed September 25, 2022.

Drugs.com. “ Psilocybin (Magic Mushrooms) .” Accessed September 25, 2022.Barrett, Frederick S.; Johnson, Matthew W.; Griffiths, Roland R. “ Neuroticism is associated with challengi[…]psilocybin mushrooms .” Personality and Individual Differences, June 7, 2017. Accessed September 25, 2022.

The Recovery Village aims to improve the quality of life for people struggling with substance use or mental health disorder with fact-based content about the nature of behavioral health conditions, treatment options and their related outcomes. We publish material that is researched, cited, edited and reviewed by licensed medical professionals. The information we provide is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It should not be used in place of the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare providers.

We can help answer your questions and talk through any concerns.

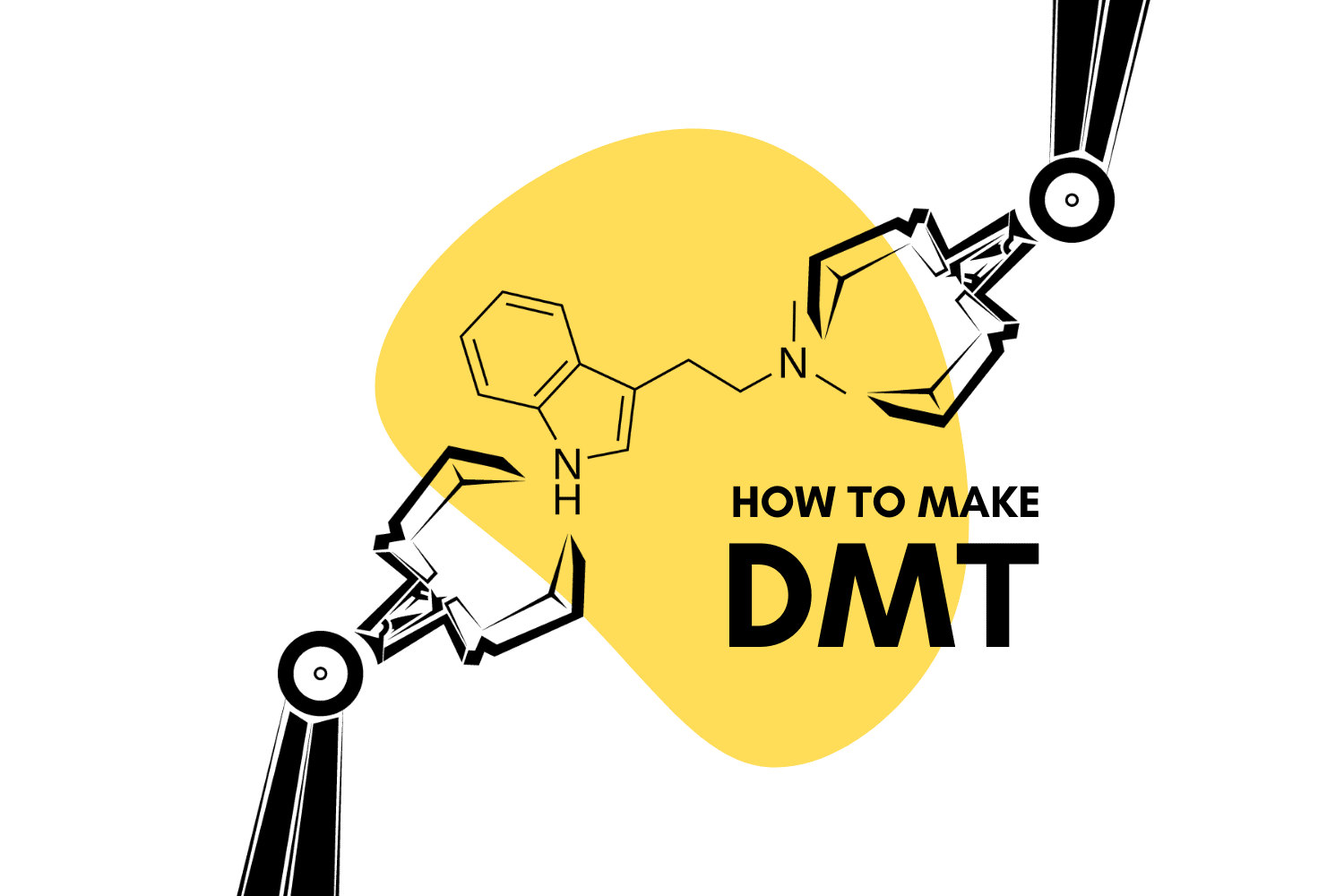

What It's Like to Trip on DMT

How to Set an Intention for Your Drug Trip

What is dmt, how do people make, buy, and use dmt, how mixing mushrooms and mdma affects your body and brain, what is it like to take dmt, some pointers for not overdoing it on party drugs if it’s been a while, can you use dmt for medical purposes, why and how does dmt naturally occur in our bodies, people are using ketamine at home to escape their pandemic reality, are there any new developments in the scientific study of dmt, one email. one story. every week. sign up for the vice newsletter..

By signing up, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy & to receive electronic communications from Vice Media Group, which may include marketing promotions, advertisements and sponsored content.

Using ‘trip killers’ to cut short bad drug trips is potentially dangerous

Professor of Neuropharmacology, University of Central Lancashire

Disclosure statement

Colin Davidson has previously received funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIH, USA) and the European Community for projects related to stimulant drug abuse and novel psychoactive compounds respectively. He is currently a paid consultant with the Defence Science Technology Laboratory (MOD) working on new psychoactive compounds.

University of Central Lancashire provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

As interest in psychedelics has grown, so has interest in ways to end a bad trip. Recent research reveals that people are giving potentially dangerous advice on social media on how to stop a trip that is less than pleasurable.

Psychedelics cause changes in a person’s perception of reality. One of the earliest descriptions of a psychedelic experience in western literature can be found in Aldous Huxley’s 1953 book The Doors of Perception . Huxley describes mostly beautiful visions while tripping on mescaline.

And then there were the Beatles seeing “tangerine trees” and “marmalade skies” and “a girl with kaleidoscope eyes”.

The last few years have seen a resurgence of illicit use, not only of established psychedelics, such as LSD and magic mushrooms (psilocybin), but also of the novel psychoactive substances that are psychedelics, such as AMT, 5-MeO-DALT, mCPP and methoxetamine.

There is also renewed interest in studying these drugs as treatments for mental health conditions, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression. Even a single dose of these drugs appears to have long-term therapeutic effects.

But not all trips are pleasurable. Research shows that if someone is in a bad mood or depressed then they are more likely to have a bad trip , as are people who take too high a dose.

This sort of experience might include extreme fear, time standing still and mood swings. Very high doses of LSD can also cause agitation, vomiting, high blood pressure, hyperthermia and other nasty side-effects. But at regular doses, psychedelics are relatively safe .

To mitigate against bad trips, people will often take the drug in a relaxing and safe environment, and they might include a friend, or “trip sitter” to look after them for the duration of the trip. This was a common practice in the 1960s among people taking psychedelics.

Trip killers

More recently, though, some psychedelic users have been turning to “trip killers” to end a bad trip. These are drugs that can either block the direct effects of the psychedelic or simply reduce the anxiety associated with a bad trip.

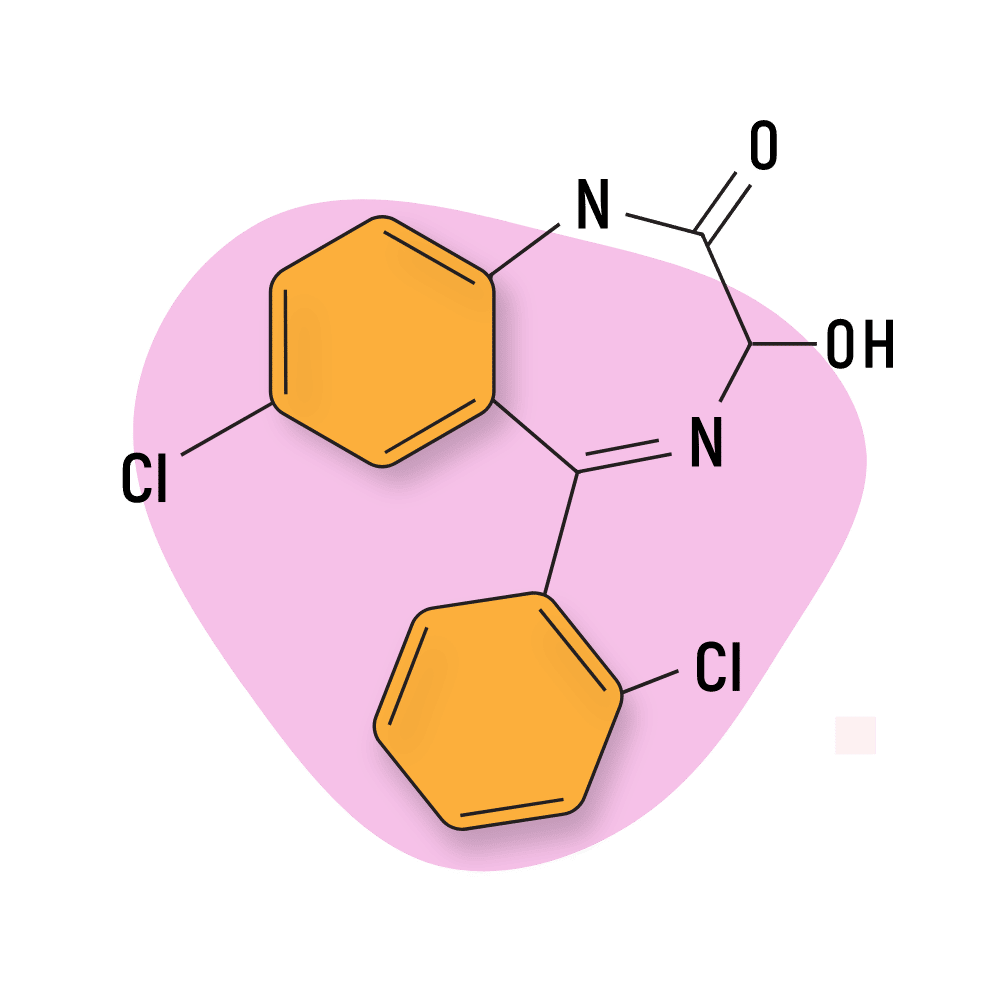

Few clinical studies have examined trip killers, but one has found that ketanserin – a drug used to treat high blood pressure – reverses the psychedelic effects of LSD.

A recent article in the Emergency Medical Journal analysed posts on Reddit about trip killers. The researchers found 128 threads with 709 posts from 2015 to 2023.

Trip killers were discussed most often for LSD (235 posts), magic mushrooms (143 posts) and MDMA (21 posts). The most commonly suggested trip killer was Xanax (an anxiolytic) followed by quetiapine (an antipsychotic), trazodone (an antidepressant) and diazepam (an anxiolytic). Alcohol, herbal remedies, opioids, antihistamines, sleep medication and cannabinoids were barely mentioned.

Receptor blocking

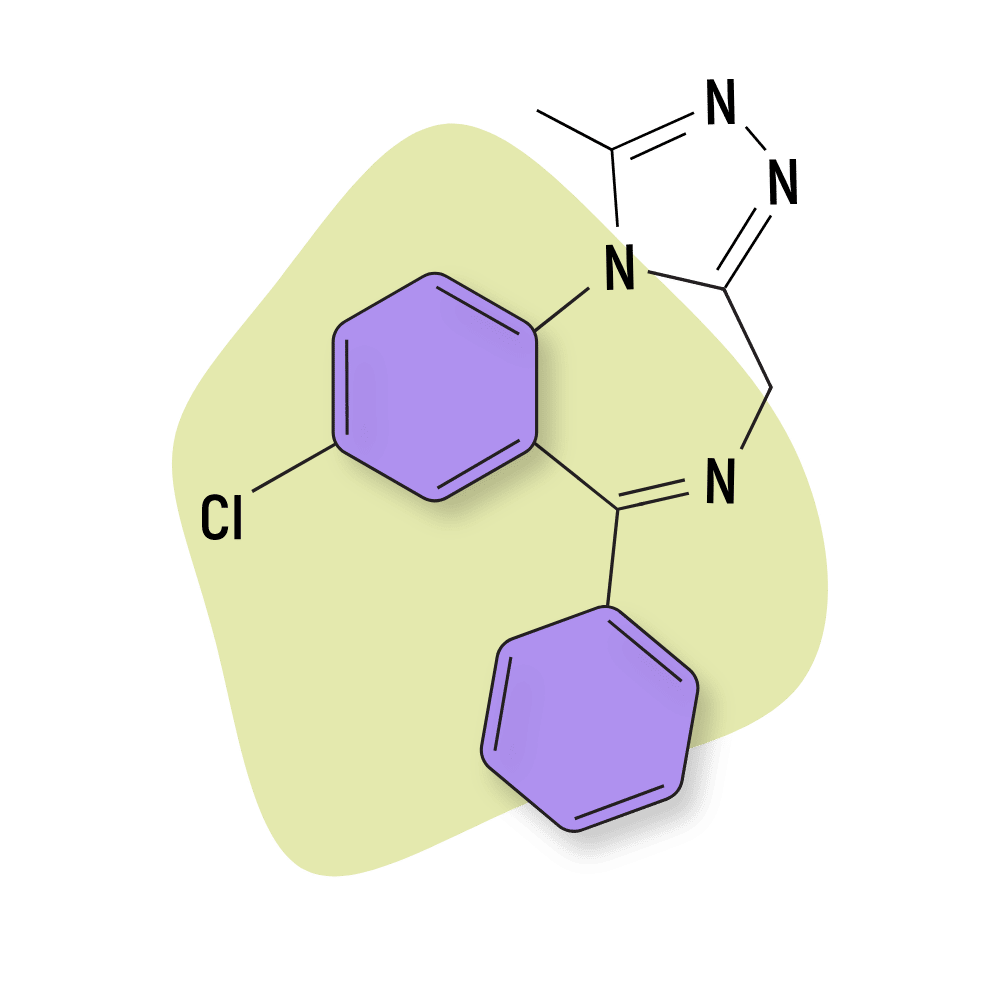

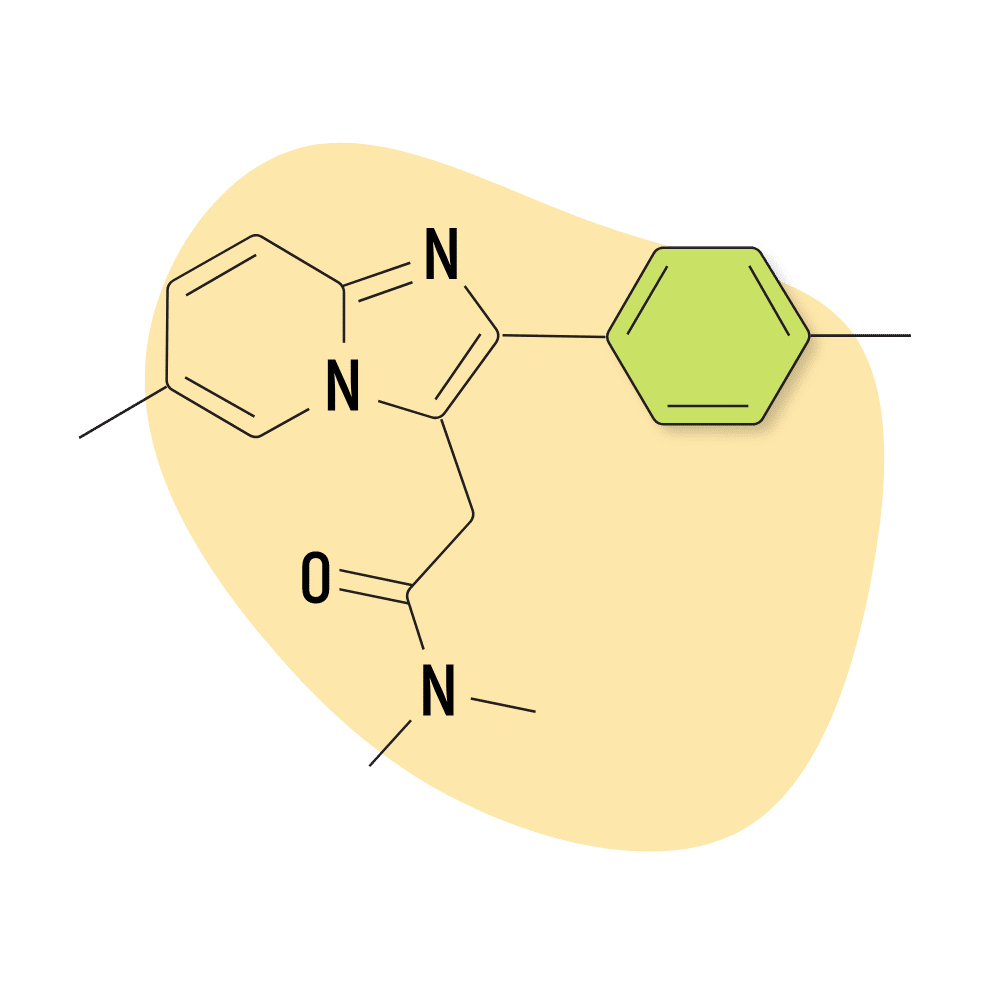

LSD and magic mushrooms create their effects by activating certain proteins in the brain. These are called 5-HT2A receptors and are usually activated by the neurotransmitter serotonin (5-HT). There are 14 known 5-HT receptors, but psychedelics have specific activity at only the 5-HT2A subtype.

To kill a trip then, one simply has to give the drug user another drug that blocks (rather than activates) the 5-HT2A receptor. Many prescription drugs can do this and they tend to be antipsychotic drugs .

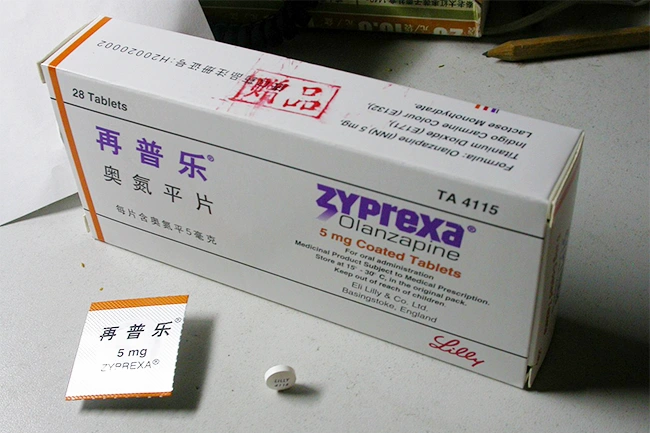

Quetiapine from the list above is one popular example, while another antipsychotic, olanzapine, was mentioned in 14 posts in that study. Similarly, the atypical antidepressants trazodone and mirtazapine also block the 5-HT2A receptor.

One can think of these trip killers as working in the same way that naloxone would be used for heroin or fentanyl overdose. These drugs activate mu opioid receptors in the brain, while naloxone blocks these receptors. Naloxone is therefore used to treat life-threatening respiratory depression from opioid overdose.

Another option for the psychedelics would be to decrease the anxiety associated with the trip by taking anxiolytics, such as benzodiazapines – alprazolam (Xanax) and diazepam (Valium) being the most popular in the posts analysed above. These would also help the drug taker to fall asleep.

Some of the trip-killing drug doses suggested in the Reddit posts were high. For example, quetiapine was suggested to be used at 25mg to 600mg, but clinical guidance for these drugs suggests a single dose of up to 225mg.

The doses suggested on Reddit for alprazolam are 0.5mg to 4mg but the clinically suggested maximum dose is usually 2mg to 3mg. Four milligrams could cause low blood pressure, oversedation and respiratory depression. Unfortunately, benzodiazepines are also highly addictive and can lead to overdose deaths.

People who turn up at A&E suffering from a bad trip or overdose of a psychedelic will be reassured in a calm environment. If that doesn’t work, they are likely to be given an antipsychotic or low-dose benzodiazepine, at a clinically advised dose.

Read more: A brief history of drug-fuelled combatants

- War on Drugs

- Psychedelics

- Richard Nixon

Research Fellow – Magnetic Refrigeration

Centre Director, Transformative Media Technologies

Postdoctoral Research Fellowship

Social Media Producer

Dean (Head of School), Indigenous Knowledges

Trip Killers: How To Stop an Acid Trip

Occasionally, a psychedelic trip can take a turn for the worse. This group of “trip killer” drugs are used by experienced trip sitters and medical professionals to stop the trip in its tracks.

What Are Trip Killers?

1. alprazolam (xanax), 2. lorazepam (ativan), 3. diazepam (valium), 4. clonazepam (klonopin), 5. zolpidem (ambien), 6. quetiapine (seroquel), 7. olanzapine (zyprexa) , how long do trip killers take to kick in, psychedelics that have trip killers, psychedelics that don’t have trip killers, 1. are you in over your head, 2. are you or those around you at risk, 3. do you need to sober up asap, who shouldn’t use benzodiazepine-based trip killers, 1. the “bad trip”, 2. you or your trip sitter realize it’s time for a trip killer, 3. you enter “the placebo effect”, 4. the trip killer begins to take effect, 5. the trip comes to an end , 6. you feel almost sober, 1. sourcing the trip killers responsibly, 2. get the dose right, set (mindset), final word: using trip killers .

In most cases, “a bad trip” is just your mind’s way of showing you factors in your past or present life that need to be confronted and dealt with. However, in some cases, a bad trip can become nightmarish to the point that it may put yourself or others in danger.

In these situations, it may be beneficial to have some form of a trip killer on hand to get you out of the negative headspace and effectively “kill” the trip.

Let’s delve into what trip killers are, when to use them, explore the risks, and discuss what to expect when you use one halfway through a psychedelic journey.

Trip killers are substances that help mellow out or block the effects of psychedelic substances. They “bring you back to reality” when a trip takes a dark turn.

Trip killers are taken with the intent to end a psychedelic trip. There is no one substance that will help end a psychedelic experience, and not all trip killers are effective for all psychedelics — you have to use the right trip killer depending on what substance you’re using.

The most common trip killers are benzodiazepines, but other drugs, such as certain antipsychotic medications, can also be effective.

Just as it’s important to know the right dose of the psychedelic you’re using, it’s important to take the right dose of trip killers too. Some of these substances are exceptionally potent and should be taken with great care.

Trip killers are a last resort and should only be used when the effects of a bad trip start to become dangerous to oneself or others.

Ideally, people who are at risk of such an experience will be under the supervision of a trained psychedelic facilitator who can help walk the user through the challenging visions they may be receiving. In many cases, the bad trips are where most of the benefits of psychedelics derive from — so stopping them in their tracks should be avoided if possible.

Top 7 Trip Killers

By far, the most effective and commonly used trip killers are benzodiazepine drugs . We’ll look at these substances first because they offer the strongest and fastest-acting way to end a psychedelic experience.

Benzodiazepines aren’t for everyone; some people should avoid them entirely. In these cases, there are other options available (keep reading).

It’s important to note that benzodiazepines can be dangerous, especially if mixed with other sedative drugs or alcohol. They’re also notoriously addictive. Taking benzos habitually doesn’t end well for anybody.

For now, let’s take a look at the most common trip killers:

Alprazolam is one of the fastest-acting trip killers in the benzodiazepine family — but it’s also one of the shortest-lasting. The effects of Xanax, although fast-acting, only last for around four to six hours.

Xanax is a favored trip killer among psychonauts purely because of its fast-acting nature. It’s designed for people to use at the first sign of an anxiety attack to stop it in its tracks.

The effects of alprazolam start to kick in within 15 minutes or so and reach peak effects in as little as 45 minutes.

Xanax does have a habit of wiping your memory, in a sense. When consumed with other substances or at too high a dose, it can make you black out and lose all memory of the previous night.

When you consume Xanax as a trip killer, you should be prepared to lie down and get some rest. When you awake, you may have an extremely blurry memory and struggle to recall anything about the experience. This can be a positive or negative point, depending on what you want to achieve from the psychedelic trip.

Lorazepam is considered an intermediate-acting benzodiazepine. This means it won’t kick in quite as fast as something like Xanax — but the effects last for over eight hours. This is a better option for long-lasting psychedelics, such as DOX compounds, 2CX compounds , or other amphetamine psychedelics .

Lorazepam is great for getting you out of a bad trip, but it may cause drowsiness to the point you fall asleep. This can be a plus since it allows you to rest easy after a bad experience, but it does put a complete halt on your psychedelic experience.

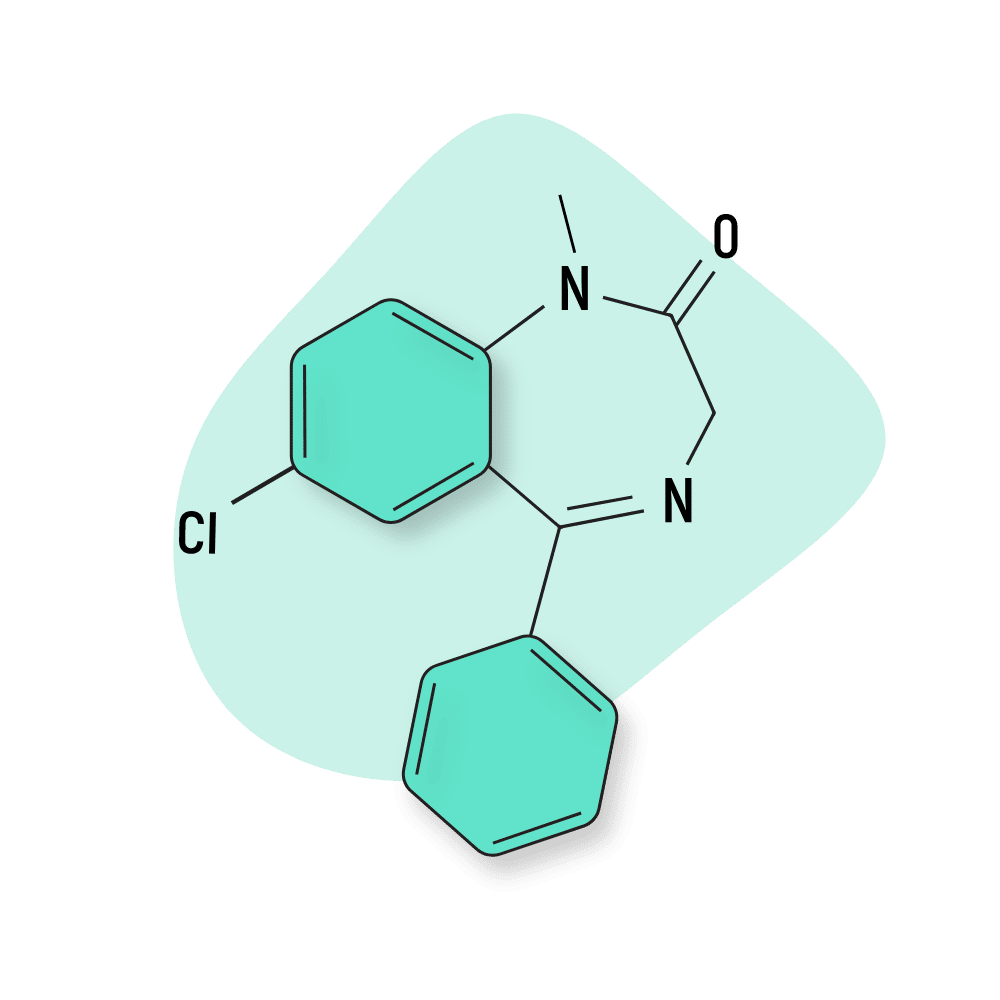

Diazepam isn’t as fast-acting as lorazepam and alprazolam, but it is one of the longest-lasting of the popular benzodiazepine trip killers. The effects of diazepam can last for over 12 hours.

It’s reported that this trip killer takes “too long” to take effect when swallowed in pill form. However, the onset of effects can be sped up significantly by chewing the drug, so it can be sublingually absorbed under the tongue.

Diazepam works great to get you out of a nightmarish thought loop, but it doesn’t have the same effect as lorazepam and alprazolam in the aspect of drowsiness. Many people report that taking diazepam during a bad trip helps them calm down without completely removing the psychedelic effects of the drug.

Clonazepam is considered the slowest-acting of the benzodiazepine trip killers. It can take between one and four hours after taking it to reach peak levels in the blood. Of course, this can be sped up by chewing the pill and allowing it to absorb sublingually.

Although clonazepam takes a long time to kick in, the effects can last up to 12 hours, and the half-life is also long, standing at around 40 hours — meaning it won’t be cleared from the body for a couple of days.

This is the least popular of the common benzodiazepine trip killers, but it’s often one of the easiest to get hold of (depending on where you live). Some like Klonopin for its euphoric nature, which many other benzodiazepines don’t have.

Zolpidem is classified as a Z-drug — which is a group of compounds that exert benzodiazepine-like effects but have an entirely different structure.

These drugs work in much the same way as benzos and are also considered useful as trip killers. But there’s one catch — these drugs tend to be much more sedative than their benzodiazepine cousins. People who take Ambien to stop a trip will almost always fall asleep shortly after. You may or may not remember the experience the following morning.

While Z-drugs carry a lower risk than most benzodiazepines, there’s still a great deal of risk associated with their use. Getting the dose right, avoiding mixing with other depressants, and only using if you’ve been approved by a doctor are still key elements for using these substances safely.

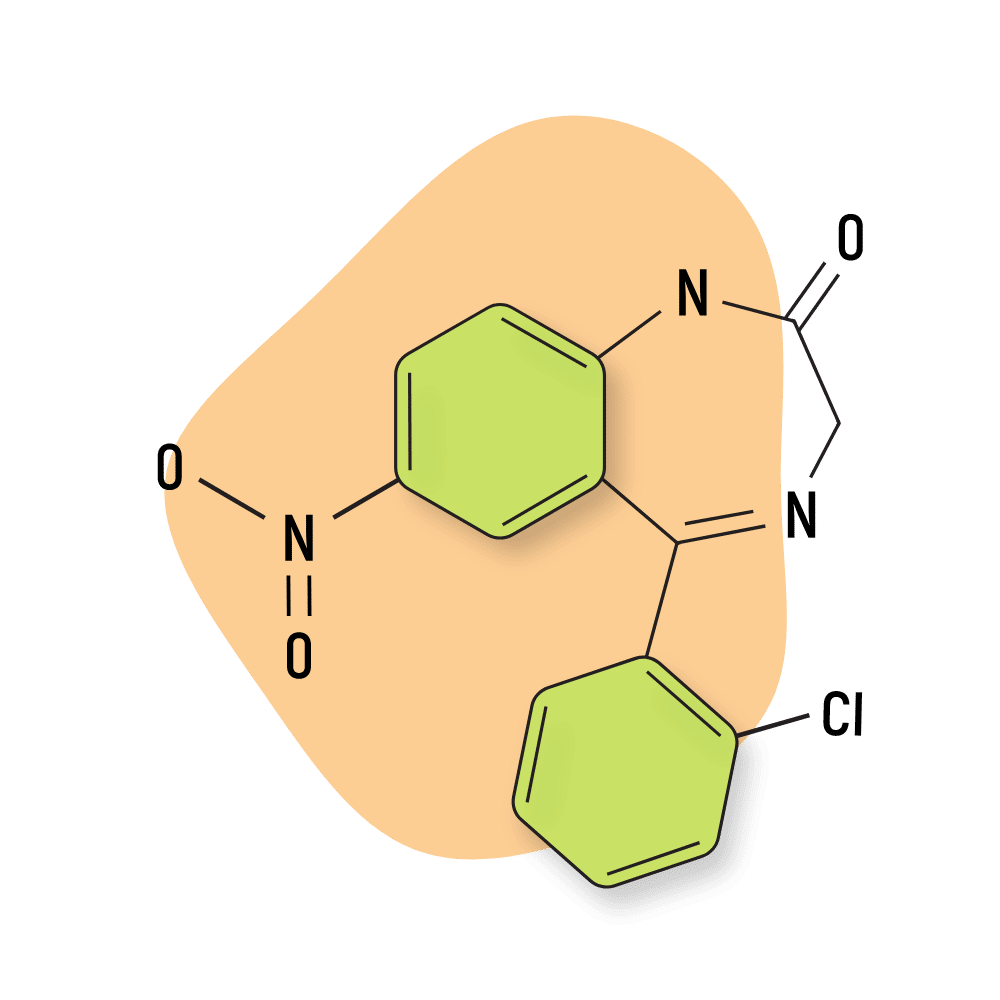

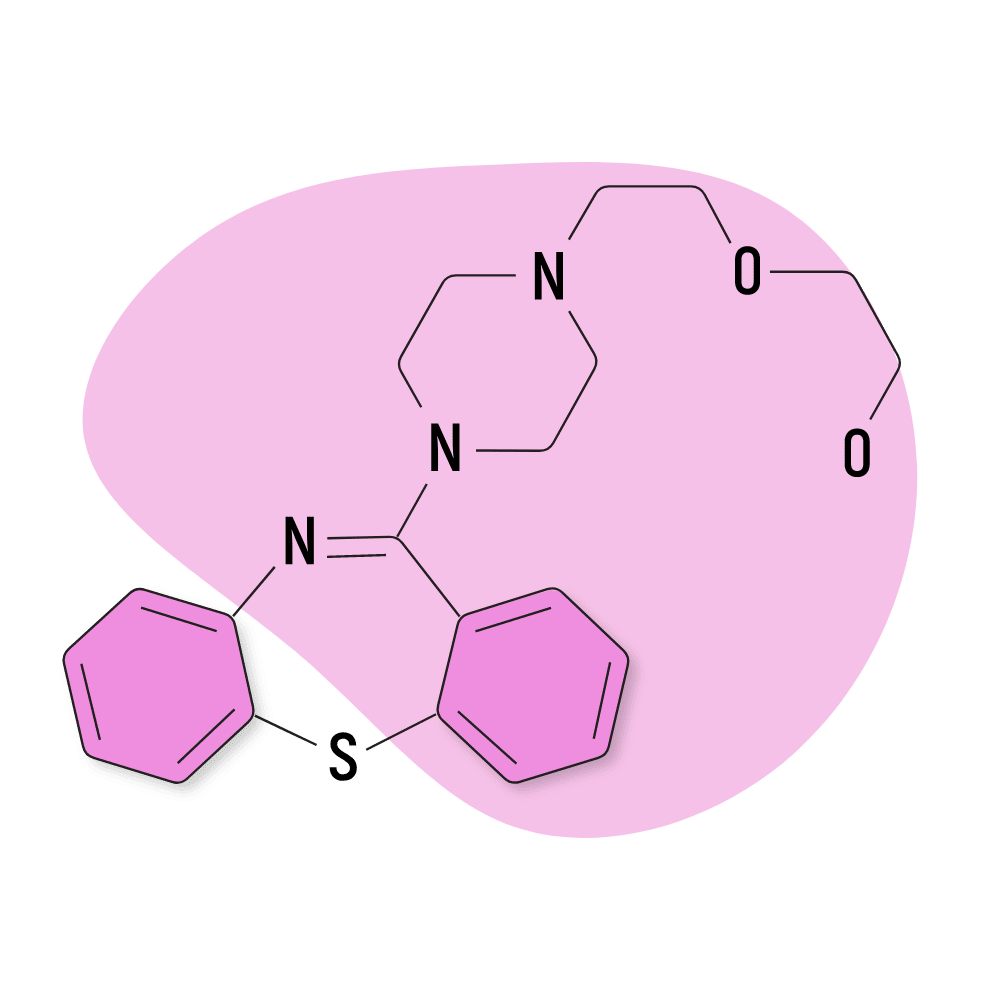

Although nowhere near as popular as benzos, another common option is antipsychotics like quetiapine (Seroquel).

Antipsychotic medications treat psychosis. People with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe depression, and Alzheimer’s are often prescribed these.

Quetiapine is classified as an atypical antipsychotic. It differs from typical antipsychotics because it produces fewer extrapyramidal symptoms and has a lower risk of tardive dyskinesia. In simpler terms, it produces fewer side effects than typical antipsychotics, such as the inability to sit still, muscle contractions, tremors, and stiff muscles.

Antipsychotics are the best trip killers for people that can’t use benzodiazepines or Z-drugs.

Seroquel typically takes 20 to 60 minutes to kick in when consumed sublingually at a dose of around 25–50 mg.

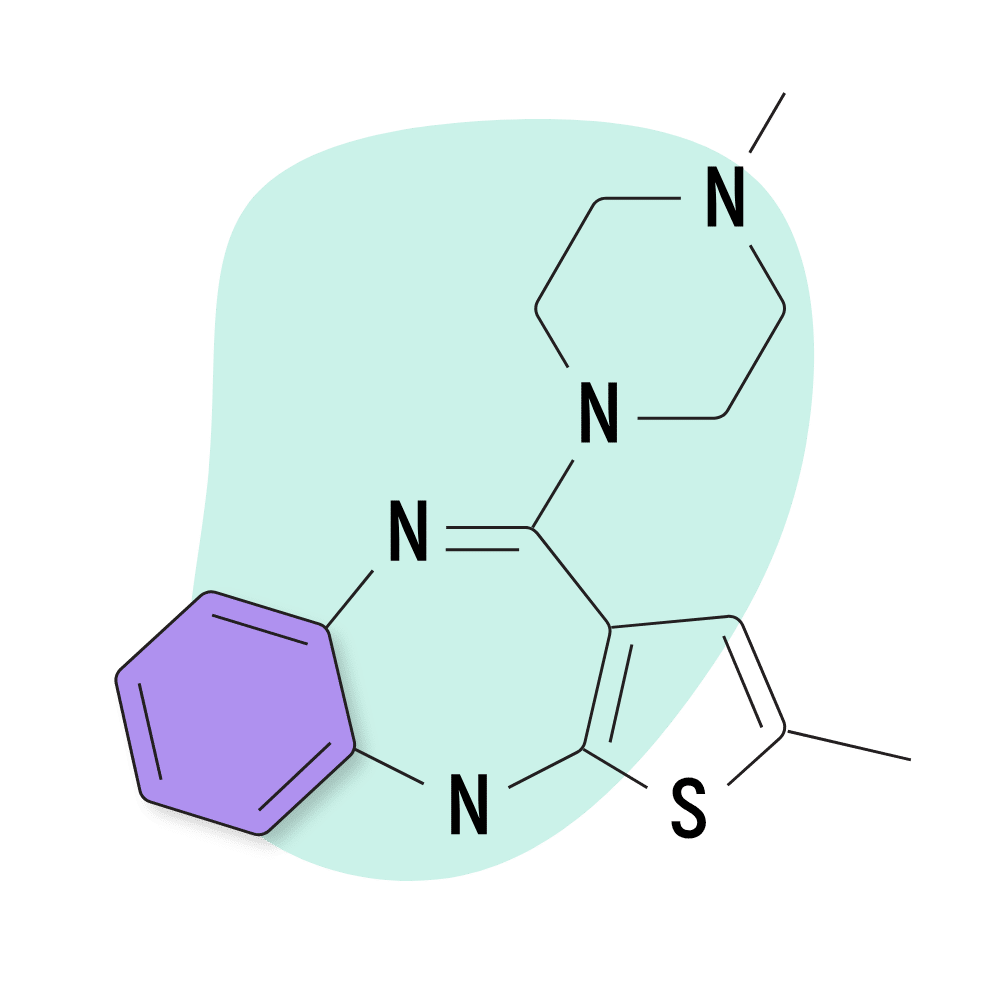

Olanzapine is another atypical antipsychotic reported to be effective in dulling the effects of psychedelics. This compound has a particularly high affinity for the 5HT2A receptor and is, therefore, better for killing the trips from tryptamine-based psychedelics like LSD, psilocybin, or DMT.

Zyprexa is less effective for dopaminergic or NMDA-based psychedelics such as the psychedelic amphetamines (MDMA, MDA, cathinones) or arylcyclohexylamines (PCP, ketamine, and others).

Olanzapine usually takes around 30 minutes to kick in at a 10–20 mg dose.

How Do Trip Killers Work?

Benzodiazepines such as diazepam or lorazepam (or other sedative anxiolytics) are usually the substances a doctor will administer if you’re submitted to the hospital due to signs of psychosis from consuming too much of a psychedelic substance.

These drugs work similarly to those for someone with a panic or anxiety attack. They have anxiolytic, sedative, and relaxant properties that all work to reduce anxiety levels and negative thought loops.

More specifically, benzodiazepines kill the trip by amplifying the activity of GABA in the brain. GABA is a neuroinhibitor — which means it reduces brain activity.

When we’re anxious, the inhibitory effects of GABA result in a dramatic reduction in anxiety levels. We think less, care less about our problems and feel more calm and relaxed. In higher doses, this causes full-on sedation.

The same concepts apply to psychedelic experiences. Paranoia, anxiety, and fear responses experienced during the psychedelic state can all be muted by dulling brain activity with GABA-boosting drugs.

Antipsychotic trip killers work a little bit differently. These drugs work as serotonin and dopamine antagonists (blockers). The exact mechanism is still not fully understood, but the leading theory is that certain antipsychotics reverse the effects of psychedelics by blocking the 5-HT2A receptors.

5-HT2A is one of the main receptor sites on which psychedelics such as LSD and psilocybin work. Some, but not all, psychedelic substances bind to these receptors to induce their psychedelic effects.

Every trip killer is different — some kick in quickly (10–20 minutes); others take an hour or more.

Here are some of the average onset times for the four most popular benzo-based trip killers listed above.

These refer to the oral onset time of these drugs. It’s not a good idea to smoke, inject, or snort benzodiazepines for any reason.

- Alprazolam (Xanax): 10–20 minutes

- Lorazepam (Ativan): 20–45 minutes

- Diazepam (Valium): 1–2 hours

- Clonazepam (Klonopin): 45–60 minutes

When Do Trip Killers NOT Work?

Trip killers don’t work on every psychedelic substance. Benzodiazepines and antipsychotic medications are effective for standard, serotonin-based psychedelics such as LSD and psilocybin. However, there are a few substances that don’t have any effective trip killers.

Always educate yourself on any substance before using it. You should know how much to take, what to expect during the trip, and onset times and duration. You should also know whether there’s an effective trip killer for it.

Psychedelic trips from some of the most commonly used psychedelics can be stopped by the use of benzodiazepines or antipsychotic medications.

These are the most prevalently used and have the most research surrounding them, though trip killers likely work on more substances than the ones listed below.

Here’s a list of commonly used psychedelic substances that do have effective trip killers:

- LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) (and other lysergamide psychedelics )

- Psilocybin (the active compound in magic mushrooms )

- 4-AcO-DMT (synthetic shrooms)

- 5-MeO-DMT (the active compound in bufo toad venom )

- N,N-DMT (the active ingredient in ayahuasca )

- 2C-B (and other 2C psychedelics )

- NBOMes (N-bombs)

- Synthetic Cathinones (Bath Salts)

- MDMA (and other MDXX psychedelics )

- Mescaline (the active compound in Peyote & San Pedro cactus)

Some psychedelic substances do not have trip killers. Not all psychedelics affect the brain in the same way; therefore, trip killers, such as benzodiazepines, will not end all psychedelic experiences.

For example, many dissociative drugs like PCP or ketamine work via the NMDA receptors in the brain. The psychedelic trips these drugs produce appear to be unaffected by benzodiazepines. Making matters worse, most dissociatives are also considered sedatives — which are notoriously dangerous to mix with benzodiazepines.

Other substances, such as salvinorin A from salvia or any of the deliriant hallucinogenics, don’t diminish after taking benzodiazepines or Z-drugs. There are no effective trip killers for these substances.

If you plan on consuming any of the substances listed below, be warned that you have no option but to ride the experience out naturally. Never consume a substance that you’re not comfortable with.

It’s a good idea to have a trip sitter around that you trust who can help you through a difficult experience should it arise.

Here are some of the more common psychedelic substances that do not have effective trip killers:

- Datura (a hallucinogenic flower from the nightshade family)

- Brugmansia (commonly known as angel’s trumpet)

- Phencyclidine (and other arylcyclohexylamines )

- Ketamine (and other dissociatives )

- Grayanotoxins (found in Rhododendron flowers)

- Xenon gas or nitrous oxide gas

- Salvia divinorum

When Should You Use a Trip Killer?

Preferably, you should never consume a trip killer. A “bad trip” can often unlock a door that will show you traits in our personality (our “ shadow ”) or traumas and aspects in life that we need to heal in order to live a better life.

A typical “bad trip” is often a lesson containing vital information we can use to work on ourselves and get over mental blocks that reduce our quality of life. Using a trip killer to end an experience like this may be counterintuitive. Doing so could close “the door” that leads to healing.

Many experienced psychonauts swear off ever needing to consume trip killers to end a trip because they believe every vision has value. However, trip killers definitely have their place. You should always be safe rather than sorry and never bite off more than you can chew in terms of set, setting, and dosage. End the trip if you feel you’re in over your head.

As long as you use psychedelics responsibly , you’ll likely never need a trip killer. Proper dosing is the best way to ensure this, but having your frame of mind and setting fit for a psychedelic trip is also important. This way, if a bad trip occurs, you have the strength to deal with it.

Sometimes, we don’t get it right. A “bad trip” can spiral out of control into a nightmarish event that can be truly traumatic. When this happens, you and the others around you could be at risk.

People who swear off trip killers may have experienced a challenging trip but may not have had a truly terrifying one. It may never happen, but it could occur at any time, so it’s always wise to have some form of trip killer available.

A nightmarish loop of events during a trip can seem to last forever, and in some, it can lead them to cause harm to themselves or others. This is rare but not unheard of. Trip killers can be a lifesaver for those who find themselves trapped in such a situation.

In our opinion, trip killers should be a part of every psychonaut’s tool kit. You should strive never to use them, but they should be readily available in case a trip takes a dark turn that you feel you can’t benefit from or work through without putting yourself or others at risk.

No matter how responsible you are when planning a psychedelic trip, there are times when circumstances come up that are outside your control. You think you have the day to sit and trip, but suddenly something comes up (family emergency, etc.), and you need to be sober ASAP.

Even though a trip killer won’t make you feel “normal,” it’ll speed up the process and make you more clear-headed than you would be without it.

Some people should avoid benzodiazepine-based trip killers at all costs . This section outlines who should not take these types of trip killers and what they can use instead.

Although most psychedelics aren’t addictive, benzos definitely are. Anyone with an addictive personality or who has had a past dependence on benzos or similar substances should avoid using these as trip killers.

Benzos have some of the longest-lasting, worst, and most savage withdrawals of any substance on the planet.

Withdrawal symptoms can last for months. If you become addicted and prolong the use of these substances, quitting cold turkey isn’t an option. Simply quitting after prolonged benzo abuse can be life-threatening due to the body seizing up.

In simple terms: don’t use benzo-based trip killers if there’s a chance you’ll get addicted to them.

What To Expect When You “Kill” a Trip

As I’ve mentioned, trip killers aren’t an instant solution. You’re not going to magically become sober as soon as the pill touches your tongue. The onset time and experience will vary depending on the type of trip killer consumed, the dosage taken, the psychedelic consumed, and how far into your trip you are.

That being said, I can give you a rough idea of what happens when consuming a benzodiazepine trip killer during a bad experience.

Let’s paint a hypothetical picture.

A few hours after consuming your chosen psychedelic, you enter an area of dark and disturbing thoughts somewhere in your subconscious mind. At first, tell yourself, “It’s okay; it’s just the psychedelic messing with my brain.”

After a while, you start to convince yourself that this is, in fact, real, and you begin to sink into nightmarish thought loops.

If the situation starts to get out of hand, a trip killer might be employed to bring you back to some semblance of reality.

You chew one milligram of Xanax in the hope that the sublingual absorption will allow it to take effect quickly.

Although unpleasant, the acrid taste of the trip killer in your mouth relieves you. You associate the taste with the trip coming to an end. When you swallow your saliva, you feel a wave of calm rush over you because you know that this nightmare will all be over soon.

About 15 to 30 minutes later (depending on the trip killer consumed), you notice a wave of relaxation come over you. Any feelings of anxiety and panic start to wash away as the drug begins to take effect.

Not only do the dark thought loops start to diminish, but you also start to feel as though you don’t care about much of anything at all. You become emotionless and calm. You may or may not continue to experience hallucinations, but none of them seem to steal your attention.

If you’re not laying down already, you’ll probably seek out somewhere to post up and relax for a while as your muscles start to feel weak.

One hour after taking the trip killer, your hallucinations have likely died down substantially, and you feel much more rational and level-headed. You may even regret taking the trip killer — if you were in this head space originally, perhaps you wouldn’t have had such a terrifying experience.

Two to three hours after ingesting the trip killer, you feel more or less sober (depending on the psychedelic you consumed). Most of the effects of the psychedelics have worn off, and if you’re not already asleep, you’re probably feeling pretty drained and ready for some zzz’s.

You’ll be emotionally and physically exhausted by this time, and you’ll likely reach for a bottle of water and a hefty snack to restore the energy lost throughout the ordeal.

Safety Aspects to Consider When Using Trip Killers

There are a few things to consider when purchasing and adding trip killers to your psychedelic tool kit. The most effective trip killers — benzodiazepines — are restricted in terms of sale and use. This can make it difficult to legally purchase these drugs, which is where our first safety aspect stems.

If you cannot obtain trip killers (benzos) in a legal way — via prescription from a doctor — the level of risk goes up substantially.

The most popular benzodiazepines for recreational use are Valium (diazepam) and Xanax (alprazolam). These can be obtained on the black market, but it’s not recommended.

Illegal vendors distributing Valium and Xanax don’t necessarily consider the consumer’s best interest. Several samples of these substances have contained drugs such as fentanyl (an extremely dangerous synthetic opioid).

Clandestine drug manufacturers use tablet molds that produce exact replicas of the prescribed Xanax and Valium tablets. Criminals produce pills with these molds that look the same but contain a cocktail of potentially life-threatening substances. Whether you’re tripping or not, taking one of these pills at any time may pose a serious health risk.

Basically, unless you’re getting your drugs from a pharmacy, you can never be sure the drugs you’re using are safe.

If you absolutely have to purchase “trip killers” from the black market, you must test them using — at the minimum — a fentanyl test kit. We cannot stress this enough.

You can also buy benzo test kits to help identify what adulterants may be contained in your pills.

You should check your benzos before you need them. You’re not going to have time to test them for safety if using them as a trip killer.

Another safety aspect to consider is, of course, dosage. Getting the correct dosages for each substance is critical to avoid overdosing . However, you also need to consume enough of the substance to kill a trip.

Several individual drugs fall under the benzodiazepine classification; although similar, the required dosage for each differs.

It’s important to note that your weight, gender, and familiarity with the drug will affect the exact dose. A heavier person that regularly consumes benzos will need a far larger dose than a small-framed person that has never tried the substance before.

Below I’ve listed the recommended dosages of the four most popular trip killers based on first-hand reports and prescribed dosage guides. However, you should take these numbers with a grain of salt and do your own research outside before consuming anything to kill a trip. These substances can be dangerous.

- Alprazolam (Xanax): 0.5 to 1 mg

- Lorazepam (Ativan): 0.5 to 1.5 mg

- Diazepam (Valium): 5 to 10 mg

- Clonazepam (Klonopin): 1 to 1.5 mg

As you can see, the recommended dosages for killing a trip vary and depends on where you are on your trip.

Again, I can’t stress this enough — everyone’s required dosage will be different because of a variety of factors. Unfortunately, your required dose will be something you’ll have to find out through experience. Just be aware that trip killers of this nature don’t work immediately, so don’t keep dosing if you don’t experience any trip-calming effects right away . This is how overdoses occur.

How To Minimize the Risk of a Bad Trip

Trip killers should only be used in an emergency when a trip takes a dark turn that could harm you or others around you. It’s best to avoid trip killers at all costs, and these steps can also help you have the best trip possible.

Preparation is key. If you’ve experimented with psychedelics before, you must have heard of set and setting.

The set is the frame of mind you’re in. When consuming psychedelic substances, you should never be in a negative, anxious, or unstable state of mind. Entering a trip with negative thoughts in your head is a surefire way to a nightmarish trip.

It’s important to relax your body and mind before entering a trip. This can be done by simply putting yourself in a good headspace by recalling a positive memory or experience. Practicing meditation and/or yoga can also help you relax into a positive state of mind.

The setting is the space you’ll experience the trip in. The setting is extremely important in psychedelics and will help you stay in the right “set.” Playing relaxing music, putting beautiful pictures around you, and lighting a few candles can make the setting more relaxed and inviting.

Many people also like to trip out in nature. This is a fantastic way to do it; however, several variables can affect your trip.

If you head out into nature for a psychedelic trip, ensure it’s in a safe area with no foot traffic. Make sure the weather is good, and there are no external factors that may “freak you out.” The last thing you want is bad weather (a storm, for example) or a stranger entering your space — this will likely lead to a bad experience.

Another way to ensure a smooth trip is to have an object nearby that means something to you. This object helps connect you to the physical world and can get you back on course if your trip dives into a dark place . Simply holding the object and looking at it may just be enough to snap you back to reality.

This technique is definitely something to try before resorting to the use of trip killers.

Trip killers may be an important part of the psychonaut’s tool kit. Hopefully, you will never need to use them, and you should strive to work through difficult experiences rather than chemically halt them.

However, if you have a truly terrifying psychedelic experience, they will help you get back to reality as quickly and safely as possible.

The most popular and effective trip killers are benzodiazepines or Z-drugs, but some antipsychotic medications are also effective and a good alternative for people with addictive personalities.

When sourcing trip killers, it’s important to test their purity. Several drugs on the black market are contaminated with fentanyl — an extremely dangerous synthetic opioid that’s similar to morphine but much stronger. This drug can be life-threatening, so it’s of paramount importance that any drug sourced on the black market is tested thoroughly.

Regardless of whether you have trip killers available, you should always practice safe psychedelic use. Ensuring that your set and setting are perfect before a trip helps mitigate the risk of a bad trip occurring. As we said, you should never need to use a trip killer, but they should be available as an absolute last resort.

How to Make DMT: 3 Separate Methods (N,N,DMT & 5-MeO-DMT)

Can Psychedelics Help With Problem Solving?

The Mind’s Theatre: Psychedelics & Dreams

What is the psilocybin cup (cup winners & strongest strains 2021 & 2022).

How to Make Ayahuasca: Step-by-Step Guide

Where Does Ketamine Come from?

Subscribe for more psychedelics 🍄🌵.

This will close in 20 seconds

How to cope with a ‘bad trip’ or high when using drugs

If you or a friend is experiencing a ‘bad trip’ you can use this advice to navigate the complex and distressing feelings it may bring up.

Written by spunout

Fact checked by experts and reviewed by young people.

People will often use drugs like mushrooms , LSD , MDMA , cannabis and ketamine to feel a sense of euphoria, excitement and wonder. Users will often report that they feel more sociable, find the world around them more fascinating and feel more connected to the universe and others around them when high on certain drugs.

But the feelings caused by recreational drug use are not always positive. The effect a drug will have on you can be difficult to predict, particularly when it comes to psychedelics. Sometimes, users may find themselves feeling panicked, depressed and paranoid during a drug high. This is often referred to as a ‘bad trip’.

What is a ‘bad trip’?

A ‘trip’ is a term used to refer to a drug high. It is most often associated with psychedelic drugs, such as mushrooms and LSD, and may include effects like visual hallucinations or ‘visuals’. The act of being on a trip is called ‘tripping’. Some users also report tripping while taking drugs such as MDMA and ketamine. These drugs can have some psychedelic properties, though they are not typically called psychedelics.

Bad trips are most often associated with psychedelics. It is possible to experience negative emotional side effects with a lot of drugs, even ones that aren’t typically considered to produce a ‘trip’. If you or someone you know is experiencing a bad trip, here are a few ways you can minimise how unpleasant the experience is.

Ensure the person tripping is physically safe

Before proceeding with harm reduction advice, it is important to make sure that the person in question is physically safe. You can use this guide to determine whether a person is experiencing a drug emergency .

When in doubt, it is always best to seek the advice of a medical professional, and to be totally honest with this professional about what the person has taken and how much they have taken.

Being high on drugs will often impair a person’s judgement. In some cases, drugs may also interfere with depth perception, making falls more likely. To minimise the chance of accident or injury, keep the person tripping away from high places, bodies of water, traffic or other physical dangers.

Take the person to a calm, safe environment

If the person experiencing a bad trip is not already in a safe, controlled environment, such as their home or the home of a friend, try to bring them to a place that is peaceful and quiet.

Loud, public settings such as festivals can be difficult to tolerate when under the influence of drugs such as psychedelics. If you are in a public place, you should bring the person tripping to a quieter spot to help them feel more calm. Try to avoid leaving the person on their own.

Some music festivals will have welfare tents or areas where you can bring people who are having a bad trip. The HSE operates welfare tents at some Irish music festivals with on-site volunteers, as do some harm reduction organisations such as Help Not Harm and PsyCare Ireland .

Stay hydrated

It is a good idea to get some water for a person experiencing a bad trip and advise them to take slow sips. They do not need to chug massive amounts of water in a short period of time, taking sips of water is best. Gentle hydration can help with feelings of nausea, and can help to rehydrate the person if they have vomited during the course of their high.

Talk about how you are feeling during your bad trip

If you are experiencing a bad trip, try to be as open as possible about how you are feeling with a trusted friend or loved one. Sharing your experiences can reduce the distress you may feel and may help pull you out of whatever emotional spiral you are experiencing.

If you are caring for someone having a bad trip, gently ask them how they are, and tell them it is okay for them to share and that you would be happy to listen to them. Telling them that it is okay and that you would be happy to listen may help them feel less self-conscious about opening up.

Equally, try not to push someone to speak if they don’t feel comfortable doing so. It is best to just let them know you are here for them and let them make their own choice.

All trips are temporary

It can be helpful to remember, or to remind someone you are caring for, that a drug high will eventually wear off. Drugs can influence the perception of time, so it is easy while experiencing a bad trip to worry that the trip will last an inordinately long time, or will never subside. Reassure the person you are taking care of that what they are feeling will not last forever and that the high will eventually wear off.

Avoid self-medicating

It may be tempting to use other drugs, such as cannabis or alcohol , while experiencing a bad trip, as you may assume that these substances will help you calm down. Introducing more drugs is risky, as how drugs interact with each other isn’t always very predictable, especially if the person having a bad trip has already taken multiple substances, such as mixing LSD and MDMA .

Benzodiazepines (better known by brand names such as Xanax or Valium) are not capable of stopping a psychedelic trip, despite what some myths may suggest. If you present to a doctor or paramedic, they may give you this kind of medication to help you calm down. Introducing prescription drugs should only be done under medical supervision. If you have been prescribed a drug such as a benzodiazepine, only ever use it as indicated by your prescribing physician.

Try some grounding techniques

If you find yourself distressed or panicking while high on drugs, using grounding techniques can help prevent you from getting too overwhelmed by your emotions.

One type of grounding technique called the 54321 technique and relates to the five senses. If you feel like you would not get distressed by thinking too much about your surroundings, you can try these steps:

- First, look around and pick out five things that you can see. In a living room, you might pick a carpet, a television, a mug, a gaming console and a plant. It can help to say each item out loud.

- Look for four things you can touch. This could be the feeling of clothes against your skin, or the grass under your feet, depending where you are. You can reach out and touch an object nearby and think about the sensation.

- Acknowledge three things you can hear. Try to focus on things outside of your body, such as the rumbling of a nearby train track, the sound of an extraction fan and the caw of a bird.

- Think of two things you can smell. If you are at home, you may be able to smell the scent of shampoo on your hair or the lingering smell of whatever you cooked for lunch. Outdoors or at a festival, you may smell grass or the smell of food being cooked at a food stall.

- Think of one thing you can taste; this could be the lingering taste of something you recently ate or drank. Alternatively, if you have a piece of gum, you could take the chance to chew a piece and focus on the taste and sensation

Use breathing exercises

There are also a number of breathing techniques that are useful for anxiety in general that may help a person experiencing a bad trip:

- ‘Box breathing’, or square breathing, involves taking deep breaths (that cause both your chest and stomach to move) and timing your breathing. To do this, inhale through your nose for four seconds, hold your breath for four seconds without exhaling, and then slowly exhale for four seconds. Repeat until you feel more centred.

- Another technique is the 4-7-8 technique. This involves inhaling through the nose for four seconds, holding your breath for seven seconds and then exhaling through the mouth for eight seconds.

Stick together and implement a buddy system

A person having a bad trip is in a vulnerable position and should not be left alone. The gentle presence of another person can help them feel less afraid, while they may be inclined to panic if left by themselves. If you are having a bad trip, it may be tempting to run off by yourself, but it is always better to let a friend know how you are feeling and ask them to come with you.

Can a bad trip be avoided?

It is impossible to guarantee that you will not have a bad trip or drug experience, but some pre-planning can minimise the likelihood of it happening.

Some people who use psychedelics report introspective experiences while tripping such as confronting a past trauma . A good thing to consider before taking psychedelics is whether you feel prepared to deal with something like this should it arise, and what supports you might turn to if it does. If you do not feel emotionally prepared for that possibility, or feel like you do not have a support system, it may be better to avoid taking psychedelics or drugs in general.

If you do decide to use drugs, it is always advised to take them in a safe and controlled environment such as your home, especially if you have never taken a certain drug before. It is likely better to take drugs with others you trust around you as opposed to alone, so that you can ask for help should you need it.

In the case of psychedelics, some people recommend taking them with a ‘trip sitter’, a person who has used psychedelics before and who will remain sober during the course of your trip to monitor you if anything should go wrong.

Planning a trip

There are some steps you can take to make your drug taking experience as safe and pleasant as possible:

- Reflect on your mindset at the time and make sure you are in the right headspace to take psychedelics.

- Choose a calm environment, such as your home or a wide open space such as a garden.

- Avoid taking drugs alone and instead do them with people you trust.

- If you are new to taking psychedelics, take a low dose so that you are not too overwhelmed by the intensity.

- Make a plan of how you might spend your time during your trip.

- Minimise the need to venture into busy areas; ensure you have adequate food and water before starting and try not to have any reason to leave the safe, familiar space you have decided to trip in. Having snacks, water, a colouring book or other supplies on hand before your trip can help with this.

- Figure out before your trip who you will call or what you will do in the event of an emergency. Find out more about how to cope with a drug emergency here .

Support services

- Drugs.ie : Online information and support for drug and alcohol use. Includes a national directory of drug and alcohol services

- HSE Drugs, Alcohol, HIV and Sexual Health Helpline: Freephone 1800 459 459

- You can contact Youth Information Chat , an online service that can put you in touch with Youth Information Officers based all around the country, for more general information

- You can also contact the HSE’s Drug and Alcohol Helpline on freephone at 1800 459 459 if you want to discuss your cocaine use

Feeling overwhelmed and want to talk to someone?

- Get anonymous support 24/7 with our text message support service

- Connect with a trained volunteer who will listen to you, and help you to move forward feeling better

- Free-text SPUNOUT to 50808 to begin

- Find out more about our text message support service

If you are a customer of the 48 or An Post network or cannot get through using the ‘50808’ short code please text HELLO to 086 1800 280 (standard message rates may apply). Some smaller networks do not support short codes like ‘50808’.

Related articles

Staying sesh safe with drug harm reduction

If you or those around you choose to use drugs, you should try to be aware of harm reduction advice.

Harm reduction advice for when you are using drugs

If you choose to use drugs, you can reduce the risks to your health by following simple harm reduction advice.

Signs that your relationship with drug use is problematic

People take drugs for many reasons, such as to relax or to socialise. However, sometimes drug use can become problematic.

Our work is supported by

Let’s Talk About Bad Trips: Separating Difficult from Traumatic

Bad trips are a polarizing concept in psychedelics. acknowledging that they exist - and knowing how to work with them - can be healing..

Want to start a war on social media? Post something like this: “Bad trips exist.”

As somebody who has worked in the psychedelic space for years now and has supported many, many people during their trips, it’s time to come out of the closet and say it: people can be harmed by psychedelics, and bad trips exist.

But allow me to define the term “ bad trip ,” because the vague phrase has become too polarized to be meaningful.

When I talk about bad trips, I’m not talking about the harrowing, painful journeys to the underworld from which we return raw and exhausted, with some important piece of our healing work having been catalyzed.

When I talk about bad trips, I mean the trips that register in the body as a trauma or injury to the nervous system. And that is not , in fact, the same thing as a difficult trip.

What happens when we deny this truth is that we inadvertently alienate those who have had traumatic or harmful experiences. These people have endured a trauma, and are now being told that they have not.

So let’s talk about traumatic trips: The psychedelic experiences that leave us injured. Thankfully, they are rare.

I’m not just speaking from my observations as a clinician, but also from personal experience: I had a traumatic psychedelic experience on ayahuasca many years ago. I was decidedly “not okay” afterwards and required much time and support to recover.

Despite the shock and injury to my nervous system, I eventually used psychedelics again. In fact, in the eight or so years that have passed since the traumatic trip, I have openly supported the legalization of psychedelics, and have built two businesses centered around empowering people to heal with psychedelics.

I have also taken sabbaticals from my practice to work in other countries as a psychedelic facilitator. I am now a lead educator in the country’s first training program for psilocybin facilitators to be licensed by Oregon’s Higher Education Coordinating Commission (HECC). I’m a ketamine prescriber, and I train other prescribers in the use of ketamine for treating chronic pain and mood disorders. I lead and run intensive healing retreats. I’ve also taken my own fair share of mind altering substances in a variety of sets, settings, and time zones.

All of which is to say: I am no newcomer to the world of psychedelics.

And yet I cannot swallow the field’s echo-chamber-like mantra that “there is no such thing as a bad trip .” In fact, I find the rabidity with which some of my fellow cosmonauts deny the existence of bad trips to be rather disconcerting. In the more-than-one heated debate I’ve had about this topic, I’ve noticed certain patterns – or myths, if you will – around the topic of traumatic trips. I address each one here.

Myth: Bad Trips Only Happen When the Set and Setting Are Improper

If the word “only” didn’t appear in the above sentence, it would be true. In my experience in working with hundreds of patients who have used psychedelics – and in administering psychedelics myself – I’ll say that the vast majority of traumatic trips happen when the environment is not safe, calm, and supportive.

When we talk about set and setting in psychedelic harm reduction , we mean two things: (1) the person’s mindset when they took the drug, and (2) their physical environment. If somebody had just had an argument with their spouse before taking LSD, for example, that’s their set. If they were at a noisy, crowded music festival, that’s the setting. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the majority of bad trips happen when individuals on drugs feel overwhelmed in a noisy, chaotic setting like that of a concert or party. Drug-drug interactions are also often at play during difficult trips, for example, when people combine alcohol with psychedelics.

When people insist a little too strongly that, “There’s no such thing as a bad trip, if the set and setting are right,” I feel uneasy. It’s perhaps like asking a rape survivor, “Yeah, but what were you wearing?” (If you think the analogy of a bad trip and rape is too far of a reach, you luckily have never had a traumatic trip.)

There are other factors in psychedelic harm reduction that influence the outcomes. These include the substance being used, the dosage taken, and the people you’re with.

The night of my traumatic trip was the third of a three-night ayahuasca ceremony. I was there with my then-partner. I liked the other people attending. I trusted the facilitators completely and knew they were well trained and highly esteemed by their colleagues. The medicine was pure. The environment was soothing and well contained. The music was beautiful. The first half of the third ceremony was trippy, strange, and lovely.

After I drank my second dose of the brew, however, I was decidedly NOT OKAY. I will not describe the experience here, but I will say two things about it: (1) I felt like my nervous system was being gang raped, repeatedly, and (2) I can now absolutely understand why people with psychosis sometimes choose to die by suicide.

The facilitators of the circle took care of me, pulling me out of the ceremony space and letting me try to calm down outside. Somebody stayed with me at all times until I vomited up the salt water they gave me to drink.

There’s one factor of harm reduction we don’t discuss enough: dose. It’s possible that the second cup of ayahuasca I drank that night contained more voltage than my nervous system could handle – that it was too much, too fast, and too hard for me.

The Influence of Neuroticism

Aside from the environment, another factor that can predict bad trip potential is neuroticism. Neuroticism is one of the “Big Five” traits thought to collectively form the full picture of personality.

People who score high on neuroticism tend to overthink things, typically have a hard time relaxing, and may feel irritated in noisy settings or stressful situations. These folks are often described as “high strung.”

At least two studies have shown that people who score high on neuroticism scales are more likely to have a challenging psychedelic trip than those who score lower. [1] , [2] The theory behind this is that if a neurotic’s negative thoughts or feelings arise during a psychedelic trip, the person might get pulled into an amplification spiral of their own negativity.

But does that mean it’s somebody’s fault that if they tend towards neurosis and they have a bad trip? Aren’t psychedelics supposed to help heal negativity? What does it mean that the same drugs that help soothe negative thoughts and feelings can also make us feel worse? (Let a neurotic chew on that one.)

Once again, we could very easily slip into the territory of victim blaming if we are not mindful.

While writing this article, I took the Big Five Personality Test online. I scored in a higher-than-average percentile for negative emotionality (neuroticism). That may explain why grumpy cat is one of my heroes and why my friend Greg refers to me as “a female Larry David.” It could also explain why I’m one of the unlucky few who have had a traumatic psychedelic trip. (Side note: I also scored pretty high on open mindedness, so that could explain why got into psychedelics in the first place.)

Myth: Bad Trips Are Actually Just Difficult Experiences That Haven’t Been Integrated

I continue to stay in this field because traumatic trips are, indeed, exceedingly rare, and because the healing gains people typically experience from psychedelics are unparalleled by any other intervention I’ve found.

Working regularly with patients in non-ordinary states of consciousness, I see that the most challenging experiences are often the most rewarding. Drawing from my previous experiences in volunteering with the Zendo Project and White Bird , I teach my students the tenants of “trip sitting.”

As one of the Zendo principles states: difficult is not necessarily bad. Note that the phrase is not “difficult is not bad,” but rather, “ difficult is not necessarily bad. ” In other words, difficult can sometimes be bad.

Another layer to this argument is that if you wait long enough, the bad experience will prove itself to be good. This does, indeed, happen to many people after their challenging journeys. Yet there is a difference between suggesting this to a bad trip survivor and insisting that “everyone gets the trip they need.”

Many of my new-age peers have become allergic to the word “bad,” especially within the context of bad trips. “Is anything really bad?” I’m often asked. The argument here, as I understand it, is that with every cloud there comes a silver lining, and that silver lining might just hold a very valuable teaching for us.

I admit that my own traumatic trip gave me a lesson: It taught me that there is indeed such a thing as a bad trip. Another gift was that my bad trip helped me to better understand, validate, and support others who have been harmed by psychedelics. Another lesson was this: my bad trip was an amplifier of the toxic positivity that I see running rampant in the psychedelic field.

In fact, a patient once confessed to me, “I’m just so mad at her” – her being ayahuasca – “but everyone in the group is so in love with Great Grandmother that if I say one bad thing about her, it’ll be like heresy.” I noticed that he was clenching his jaw and only breathing into the upper part of his chest. I leaned forward, looked him in the eye, and said: “Tell me exactly what you think about that bitch – you won’t offend me.”

By the end of the hour, he had raged, wept, and laughed. His breath was reaching his abdomen and his jaw was relaxed. The client messaged me some days later, saying, “That was so healing for me just to be heard, to be able to say mean things without being afraid somebody would cancel me. Thank you.”

Perhaps for this client, “the medicine” was to be heard without anybody trying to stop him from expressing anger. Maybe the bad trip was just part of the arc that took him to that finale. I don’t know.

Myth: There’s No Such Thing as Bad

There’s that old story about the Zen master, whose son got a new horse. “What good luck!” The neighbors said. “We’ll see,” said the master. One day the son was thrown from the horse and broke his leg. “How terrible!” Said the neighbors. “We’ll see,” said the master. Then the country went to war, and the army came to recruit soldiers. Because the young man’s leg was broken, they army didn’t take him to battle. “How good!” said the neighbors. “We’ll see,” said the Zen master. Perhaps there is no good or bad.

What I’ve always found lacking in this story about the Zen master was the voice of his son – the one who actually fell from the horse.

Is a bad trip like falling from a horse? It absolutely can be. Yet something about the “you just haven’t integrated it yet, there’s gold there” argument feels like a dismissive bypass. Let us consider other situations in which we could apply such a statement:

- After getting food poisoning and vomiting for hours

- After taking penicillin and breaking out in a full body rash

- After going on a horrible date

- After surviving a sexual assault

- After your child has been diagnosed with a life-threatening illness

- After losing a loved one to cancer

- After surviving a terrible accident that has resulted in disability

- After your cat has been run over by a car

- After losing a house to foreclosure

Would we really tell the people in the above hypothetical situations that there was no such thing as bad shellfish? No such thing as a bad drug reaction or a bad date? No such thing as rape? No such thing as a bad diagnosis, a bad prognosis? Or how about just a bad day? Or something as non-threatening as a bad movie, a bad haircut, or a bad parking job? Would we really tell somebody whose child just died to avoid using the word “bad” to describe her condition?

Perhaps it is true that none of these things are bad, and that all of them are blessings in disguise. But would we really get righteous about it on social media, the way some of us do about denying bad trips?

And what’s so bad about saying “bad,” anyway? Must everything truly be a blessing? (The neurotic writing this article needs to know.)

I’d also like to share the story of Becks. Becks was a 24-year-old female patient of mine with anorexia nervosa who did MDMA-assisted psychotherapy to heal from PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) rooted in childhood sexual abuse.

In a follow-up visit, Becks told me that the MDMA-assisted therapy session (done with an underground provider) had done wonders for her. She was getting much more mileage out of her weekly therapy sessions. She was now remembering things she had repressed previously, and she was able to stay present when the memories arose.

Becks had also forgiven herself. She explained that without realizing it, she had blamed herself for what happened to her when she was a child, punishing herself through self-denigrating thoughts, food restriction, and high-risk drinking. Her MDMA-assisted therapy session helped her identify this pattern and realize that she didn’t deserve the blame or the punishment. Having forgiven herself, Becks was now sleeping better at night, eating when she was hungry, and avoiding alcohol. Clearly, much healing had occurred for her.

Yet Becks felt discouraged and worried. “I don’t think I’m doing it right,” she told me while pulling at the rings on her fingers.

“Why’s that?” I asked.

“Well,” she explained, “I know I’m supposed to get to this place where I feel like the trauma was a blessing – and that hasn’t happened.”

“You think you’re supposed to get to a place where you think that being repeatedly molested as a child is a blessing? ” I asked her.

“Yes,” she said with a defeated sigh as she looked at her shoes.

“Where’d you get that idea?”

Her head snapped up to look at me, breathless, huge-eyed. And then she burst out laughing. The laughter turned to tears. She sobbed and babbled something about a podcast she’d heard. Then she laughed some more. Her face lit up and the color returned to her cheeks.

“Becks, was being molested by your stepbrother every night a blessing?” I asked her.

“No, it was a fucking horrible nightmare that I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy,” she declared.

“Okay,” I said, “and is it possible that it was a fucking horrible nightmare and that you still get to heal and have a happy adult life starting right now?” I asked.

“ Fuck yeah,” she said. And the look on her face told me she believed it.

(This, by the way, is what happens when you go to a doctor who scores high on neuroticism scales: We acknowledge and celebrate that life might be a fucked up mess sometimes, and that we can still heal even if we don’t buy into toxic positivity.)

(Also: I do have patients who come to see their traumas as gifts. It truly is a powerful and important step in their healing. But let’s not assume that healing cannot happen in other forms. Everyone’s path is different and valid.)

Myth: Talking About Bad Trips Is Going to Harm the Psychedelic Movement

On the day I graduated from medical school, I took an oath to First, Do No Harm . Sometimes, First, Do No Harm means doing the uncomfortable thing or saying what others don’t want to hear. In this case, it means acknowledging that there are risks to using psychedelic substances, and a traumatic trip is one of those risks.

Every therapy, every medicine, every experience comes with risks and benefits. One risk of taking vitamin C is that too much can cause diarrhea. One risk of antibiotics is that they can lead to vaginal yeast infections. One risk of using acetaminophen (paracetamol) is that it’s hard on the liver. One risk of eating a vegan diet is that it can deplete vitamin B12 stores and subsequently trigger depression. One risk of a life-saving surgery is that it can result in a lethal infection. And so forth.

Psychedelic medicines also come with their risks, and the risk of a traumatic trip should be on that list. Admittedly, it should be in small letters, towards the bottom of the list, next to the words “very rare when used in therapeutic contexts.” But traumatic trips are, in fact, “a thing.” They’re part of the fine print.

As far as I know, bad trips have not been reported in any of the clinical trials on psychedelics – but keep in mind that we haven’t had too many people go through the clinical trials as compared to the number of folks doing psychedelics “in the wild.” Bad trips may have also been down-played in the trials as “dysphoria” or “agitation” by the researchers.

Are the possible risks of psychedelic medicines worth wagering for the potential benefits? The answer to that question can only be answered on a case-by-case basis – as with any intervention.

For me personally: The healing engendered by psychedelics has far outweighed and more than redeemed the harm I’ve endured. Every time I take a psychedelic medicine now, I understand that I am taking a risk, and I make the clear, informed decision to proceed – or not to proceed, depending on the circumstance.

When I advocate for the destigmatization and legalization of psychedelics, furthermore, I don’t just act out of love for the movement: I act out of love for my patients.

What’s going to injure the psychedelic movement even more than a level-headed discussion about traumatic trips is the harm that may be caused by denying them.

How to Talk to a Bad Trip Survivor

So, what should we say to a survivor of a traumatic trip? Anything but: “There’s no such thing as a bad trip.”

If somebody tells you they’ve endured a bad trip, treat them as if they’d just told you that they survived an accident, an assault, or another kind of shock. Offer them comfort and support. Listen. Don’t ask them to prove the truth of what they say happened.

Essentially: treat them as you would treat the survivor of any kind of experience that was too much, too hard, and/or too fast for their mind, body, or spirit.

Remember that the word “trauma” does not refer to the distressing event itself, but rather to the resulting emotional and neurological response. Trauma can harm a person’s sense of Self, their sense of safety, their ability to navigate relationships, and their ability to regulate their emotions. Trauma, in other words, is injury to the nervous system that ripples outward. (To be clear: Trauma does not mean simply feeling uncomfortable or offended, as some people mistakenly use it.)

Even if integration of the experience would be helpful for the survivor – and might even help them stop using the term “bad trip” to describe it – that cannot happen at the beginning. The first thing the bad trip survivor likely needs is to know that they are safe now . The nightmare has ended, and they are loved and supported by trustworthy people who care.

How can we help others feel safe? By our presence. By regulating our own breath. By listening. By letting them know that we believe them. By showing empathy. By making them soup, gifting them a massage, or offering to pick their kids up from school. By being kind.

Even if the traumatic trip was the result of poor planning, improper set and setting, or other user error, hold your tongue for now. Think of how you might react if a friend was in a terrible car accident that resulted from driving when they were overly tired.

Think of how you might respond if a child dragged a chair to the kitchen counter and climbed atop it to try and reach the off-limits cookie jar sitting high up on a shelf – only to tumble backwards and slam onto the floor. Would you shout, “Well, that’s what you get for climbing on the chair!” while the poor kiddo cried on the linoleum? I hope not. I hope you would sit by their side, hug them, and stroke their hair. Once you felt their breathing return to normal and the smile return to their face – and not a second sooner – might you ask, “Honey, remember what we said about climbing on the furniture?”

Healing From My Bad Trip

It took me almost eight years to feel like I had fully integrated my bad trip. Curiously, what helped me complete the arc from wound to health was a peyote ceremony.

What prolonged my healing was people insisting that there was no such thing as a bad trip. I heard this line in my ayahuasca circle, at psychedelic conferences, on social media, on podcasts, and in books. The experience-denying and victim-blaming made me feel angry and alone.

Another factor that delayed my full recovery was peer pressure. Buckling to the well-intentioned insistence of friends, I returned to the ayahuasca circle (and other psychedelic circles) sooner than I truly wanted to. This meant that I was taking medicines with a mindset of doubt and fear, which resulted in several dysphoric, confusing, and terrifying journeys that only compounded the injury.

I was fortunate to find a healer who believed in bad trips and who confirmed that I was not fully in my body. Through regular sessions, I was able to return. While my therapist hadn’t had much psychedelic experience herself, she at least believed me. That allowed us to start from a place of trust and not from a place of defensiveness. I also took a break from psychedelics and instead cultivated gentler, more predictable health-affirming practices like singing and going to the gym.

Years after the experience, I read about the concept of “too much, too hard, too fast” in a book about psychedelic facilitation. I felt a surge of heat rush to my face as I read the words; hot tears filled my eyes. I hadn’t made it up. It had happened to me. I wasn’t weak, or stupid, or crazy. But why was the truth so hard for other people to accept?

I’m grateful to my own stubborn will to get better – to that spark within me that keeps me seeking out people, places, and things that can help me heal, grow, and learn.

There was, indeed, some good that came from my bad trip on ayahuasca all those years ago. The seams of that horrific shroud were sewn with golden thread. I am grateful for the blessings gleaned.

I am also grateful to my unconditionally supportive family, friends, and partner, and to Grandfather Peyote for helping me weave the blessings into my life and pull back the heavy curtain.

I had a bad trip, and that’s okay.

And you know? Considering that I’m a neurotic, I’m pretty proud of myself for saying so.

Follow your Curiosity

[1] Barrett FS, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Neuroticism is associated with challenging experiences with psilocybin mushrooms. Pers Individ Dif. 2017 Oct 15;117:155-160. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.004 .

[2] Petter Grahl Johnstad (2021) The Psychedelic Personality: Personality Structure and Associations in a Sample of Psychedelics Users, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 53:2, 97-103, DOI: 10.1080/02791072.2020.1842569

You may also be interested in:

Mental Health

Harm Reduction

Self-Discovery

What Exactly Is a “Bad Trip”? Dangers of Hallucinogens

A broad category of drugs used recreationally falls under the heading of hallucinogens. Most of these drugs can result in a pleasant experience of unusual perceptual and sensory experiences. Colloquially, taking hallucinogens is known as “tripping.” Taking these drugs regularly increases your risk of a bad trip.

What Is a Bad Trip?

A bad trip is an unpleasant experience while using hallucinogens, though some users even report bad trips when using marijuana, which is not typically categorized as a hallucinogen. During a bad trip, users may experience extreme psychological distress. Externally, a bad trip might look like someone destroying a room, crying for extended periods of time or seeming unresponsive to external stimuli.

Hallucinogens That Can Cause a Bad Trip

There are two basic categories of hallucinogens: classic and dissociative . Drugs in both categories can cause a bad trip at times. There’s no specific way to determine which way a trip will go, though there are risk factors that can make a trip more likely to go bad. If you want to avoid adverse reactions, you should avoid using:

- LSD: LSD , also known as acid, is a well-known and powerful hallucinogenic drug. Its psychedelic effects are often depicted in movies and media.

- DMT: Dimethyltryptamine, also known as psilocybin or magic mushrooms, is another powerful psychedelic. Many people report experiencing a bad trip while using mushrooms.

- MDMA: “Molly” or ecstasy is best known as a party drug. While bad trips are uncommon, they can occur on MDMA when paired with dehydration and too much partying.

- Salvia divanorum: Salvia, a plant commonly found throughout southern Mexico and in Central and South America, is a short-acting and potent psychedelic. Users often report feeling terrified when experiencing a bad trip on salvia due to the heightened experience.

- Peyote: A small, spineless cactus that contains mescaline, this drug is used in some indigenous practices in the United States. When brewed into a tea or other liquid, trips can last for 12 hours or more.

- Ketamine: Users may mention falling into a K-hole, which is a reference to a bad trip on ketamine and describes a near-complete disassociation from reality and a trance-like state.

- Marijuana: Paranoia and anxiety are often reported side effects of using weed , which can fall under the heading of a bad trip.

Studies are ongoing as to the efficacy of using psychedelics as part of a treatment plan for depression, anxiety and trauma. Talk to your mental health provider before you consider using any drug as a treatment option.

Signs and Symptoms of a Bad Trip

No two bad trips are the same, even when experienced by the same person taking the same drug. However, some of the most commonly reported bad trip symptoms include:

- Time dilation, or the sense that time isn’t passing

- Negative thought spirals

- Extreme paranoia and emotional distress

- Sudden mood swings with extreme responses