Clinical Researcher

Clinical Study Reports 101: Tips and Tricks for the Novice

Clinical Researcher September 15, 2020

Clinical Researcher—September 2020 (Volume 34, Issue 8)

PEER REVIEWED

Sheryl Stewart, MCR, CCRP

The tenets of Good Clinical Practice (GCP), promulgated by the International Council for Harmonization (ICH), require that investigator-initiated trials (IITs), especially those involving an Investigational New Drug application to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), have the principal investigator (PI), the institution, and the study team assume roles of both the sponsor (ICH GCP E6(R2), Section 5) and of the PI (ICH GCP E6(R2), Section 4).{1} If you are part of an IIT team, whether you are the investigator, a clinical research coordinator, or someone working in any of the many other important roles within the team, you may be tasked with authoring a clinical study report (CSR) at one time or another within the course of the study. At the very least, you may be asked to contribute to, or provide peer review of the document before it is submitted for its intended purpose.

The purpose of this review is to provide a framework for study team members, whether it’s for a large team that includes regulatory and administrative support or for smaller teams with only one or two members, for writing and organizing the CSR.

First, is important to understand the definition, requirements, and potential uses of a CSR. The report is a comprehensive look at all the data produced in a clinical study, presented in text, tables, and figure formats. It will often include discussions and conclusions that provide context to the findings regarding the drug, device, biological product, surgical method, counseling practice, or any other type of therapeutic product or practice under study and where it may contribute to an improvement on the state of the art for treating or preventing a particular health condition.

If a study has prespecified endpoints or parameters, the CSR will report the current outcomes and statistical parameters for these endpoints. Key messages will be referred to and highlighted throughout. Key messages are important study findings that support the prespecified endpoints, supply proof of the justification of clinical benefit, or differentiate the study product from others in the therapeutic space.

Most likely you already appreciate the ethical responsibility a clinical study team has to clinical study data transparency, which for that reason alone would make the production of some sort of CSR necessary. Indeed, the preparation and representation of study progress is prescribed in the aforementioned ICH GCP E6(R2) guideline,{1} which states that study sponsors should ensure that clinical trial reports are prepared and provided to regulatory agencies as they are required.

Further, the guideline recommends study sponsors to rely on a subsequent guideline on Structure and Content of Clinical Study Reports (ICH E3).{2} Lastly, adhering to this ethical responsibility and following GCP have become mandated both in the U.S. and in Europe, where study data are expected to be recorded on ClinicalTrials.gov and the EudraCT database, respectively, for the sake of transparency and in support of further scientific inquiry, thus making the organization and preparation of study data in a prespecified format necessary.{3,4}

There are a few different uses for a CSR, though primarily it is utilized either to summarize the data and outcomes at the end of the study, or for marketing authorization. Those two purposes are specifically outlined in ICH E3 and ICH E6.{1,2} However, a CSR may also be written for third-party payer reimbursement purposes, providing details in support of clinical benefit. Because in most cases CSRs will ultimately have a regulatory reviewer, authoring a report that is consistent in formatting and content with what is expected will hopefully not only enable a smooth review, but also will facilitate proper data cleaning, presentation, and timeliness that make the document fit for purpose.

ICH E3 offers a CSR template to guide you in terms of providing the proper data and content in a specified order and format. This guideline can be found either on the ICH website or the FDA website.{2,5}

It is important to note that there are no requirements to follow the template precisely. Not every section is appropriate for every study, and because the overarching purpose of a CSR is to provide proper representation of the study data and any key messages you want to report, flexibility is allowed and encouraged in order to meet those important goals. However, for anyone new to the process of crafting a CSR, this template is a helpful starting point.

Transcelerate Biopharma, a nonprofit organization involved in researching means to increase efficiency and innovation in the pharmaceutical research sciences, also has interpreted the ICH template and has produced a useful tool to improve this reporting.{6} If the instruction and guidance in the ICH or Transcelerate templates do not meet your needs, or you have further questions as to how to properly represent the study data, the CORE reference manual (Clarity and Openness in Reporting E3-based) is another resource. It was produced in 2016 in response to regulatory changes for public disclosure of clinical study data, and can provide direction and interpretation of the ICH E3 template.{7}

For the novice author of a CSR, however, the ICH E3 template, coupled with the Transcelerate template, should provide a strong starting point for the project planning of the report, as well as the document formatting.

Sidebar: Tips and Tricks for Getting Started

Determining Stakeholders

Once you’ve reviewed the template and created a draft outline of the project, determine the key stakeholders with whom you’ll need to partner to complete this project. Likely you will need input from your clinical study management team, teammates responsible for data entering and cleaning, a biostatistician, any teammate or organization member able to perform literature reviews, those staff qualified to compose patient or adverse event narratives, and those team members who can help determine key messaging in this report. Lastly you will want to determine the group of key stakeholders who will be your final review team for the document—those who will help you finalize the document prior to submission.

Sidebar: Tips and Tricks for Stakeholder and Project Management

Determining Timelines

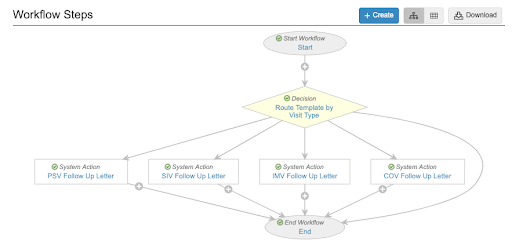

Once you have determined your key stakeholders, you will want to determine timelines to ensure steady progress continues to be made on the document. If you’ve chosen to utilize a scope document, you’ll want to include these timelines in it, so the entire team is aware of the project process, the timing requirements, and each gating item (key gating items are summarized in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Preparing, Writing, and Review of the Clinical Study Report—Key Gating Items

Time management is paramount for clinical trial submissions to regulatory authorities. Attendees at medical writing conferences over the course of a five-year period (2008 to 2013, n=78) were surveyed to determine to how long each step of the CSR process can typically require.{8}

To complete a “moderately complex” CSR for a Phase III study with 200 to 400 participants, the surveyed medical writers responded with a mean answer of 16.9 days from the receipt of the final tables, listings, and figures (TLFs) to delivery of the first draft of the CSR. They estimated a mean of 25.7 days from the first draft to the final draft routed for review. The time from database lock to completion was reported to be on average 83 days.

While there was a wide range for the timelines reported, these data provide the novice CSR author a basic reference point for how long the individual processes can expect to take with experienced medical writers. Fortunately, while TLFs are being crafted, multiple other “Writing and Document Review” tasks from Table 1 can be performed simultaneously.

At Last…the Writing!

Typically, the flow of your CSR will progress under six primary headings or sections, not unlike those used in a research manuscript. On the front end, even before the background and introduction, the document will include a title page, synopsis, table of contents, list of abbreviations, ethics statements, and details on the study’s administrative structure. The primary sections to come after that are highlighted in Figure 2 and summarized in turn below.

Figure 2: Primary Sections

Background, Intro. > Non-Results > Results > Discussion > Conclusion > Exec. Summary

Background and Introduction

When available, utilize any state-of-the-art analysis of the product/therapy from the protocol for your CSR introduction. If not available, you can briefly summarize the study design, objectives, and population and then you’ll need to craft a novel but brief state-of-the-art analysis based on literature review.

Be sure to align with the key messaging of your study and the indications of your study drug, device, or other type of therapeutic product or method. Utilize good literature review practices, such as choosing peer-reviewed publications, editorials from key opinion leaders in the therapeutic area, and studies with large or randomized cohorts, for support. This section will likely be no longer than one page.

Non-Results Section

Whether to cut and paste the procedures and assessments, primary and secondary endpoints, parameters or hypotheses, planned statistical analyses, monitoring plans, adverse event definitions, and assessment rules directly from the protocol or to simply refer to the protocol and the other study documents in an appendix is a topic of debate amongst medical writers of CSRs. Keep in mind that the CSR should be able to stand alone as a document, and thus while it is important to keep the document concise, it must be comprehensive enough for the reader to understand the study design, objectives, endpoints, processes, and intended analyses without having to refer constantly to the protocol. Regardless, in any summary of the study design, processes, and endpoints, be sure to align with any previously utilized language for consistency across study documents.

Results Section

Using the template and your tables as your structure, summarize the data and pull out any signals and trends, aligning with key messaging where possible. Start with patient disposition and demographics as per the template. Note any protocol deviations that may or may not have impacted patient safety or the evaluation of the outcomes.

Assess and evaluate the study outcome results against primary endpoints and secondary endpoints before discussing any additional secondary outcomes. You should not simply restate the data in the tables; however, refer to specifics in the tables when summarizing.

If you find that you cannot make a statement or conclusion given the TLFs you have, or you are consistently having to perform your own math to support your statements, consider asking your biostatistician to create the tables that will represent the data in a way that will better support your statement. For instance, it is acceptable to state that “most” of the patients responded to the study drug if more than 50% did so; however, if you are having to consistently add up percentages in a table to be able to state, for example, that 77% of the patients responded in a certain way and 33% responded in another, then you should have the biostatistician reformat the data output so it represents the percentages you want to report.

Patient narratives are an important source of context for the reader of the CSR. Depending on your study, you may need to collaborate with either your teammates responsible for assessment of adverse events or the study database administrator to help generate patient and/or event narratives for the CSR. If tasked with compiling or editing patient narratives yourself, the ICH E3 guideline prescribes the necessary components of a comprehensive patient safety narrative (Section 12).{2}

Narrative writing advice has also been previously published and would be a helpful source of direction for the novice narrative writer.{9,10} Narratives are suggested for every patient who experienced a safety endpoint event or death during the course of the study. Tie in patient narratives where appropriate when discussing safety events or refer to the patient narrative section when highlighting a particular patient’s data.

Discussions and Conclusions

Discussion and conclusion sections can either be placed after each section or placed at the end of the document. They should not simply restate the previous table summaries, but provide context and align the results with key messaging. Use an evidence-based approach, including literature references to provide more context as to the nature of the study outcomes with respect to the state of the art for the product/therapy, outcomes from alternate approaches, or further justification of clinical benefit with regard to potential disease progression. The conclusion section at the end of the document is often in bulleted format—not only for ease of the reader, but also to clearly highlight the key messaging and important outcomes you wish to impart.

Executive Summary

The executive summary, while placed at the front of the document prior to the introduction, is often easiest to construct last, as an overall summary of the entire document. The key elements of this summary should briefly recap the study design and objectives. Most likely only the primary and secondary endpoints should be included, unless additional outcomes proved compelling and important within the course of the study. Refer to any important literature comparisons as they relate to any conclusions made about the success or outcomes of the trials. Conclude the executive summary in a similar fashion to the overall study conclusion.

Sidebar: Tips and Tricks for the CSR Writing Process

Review Process

The review process can either facilitate a better document or it can slow down the entire process. The purpose of a cross functional review of a CSR is to confirm accurate key study messaging and data; allow medical review of the patient narratives, outcomes, and conclusionary statements; review the logical flow of ideas; and ensure that the CSR language is consistent across any other study document (i.e., the protocol, statistical analysis plan, etc.).

Sidebar: Tips and Tricks for an Efficient Review Process

CSRs are required by regulatory authorities to report and summarize the outcomes of a clinical study. Pre-project stakeholder determination and timeline planning can help with project management. Templates contained with the ICH E3 guideline can help organize the project as well as help create and finalize a document that is fit for purpose and meets the content expectations of the regulatory reviewer.

- ICH Working Group. 2016. ICH HARMONISED GUIDELINE INTEGRATED ADDENDUM TO ICH E6(R1): GUIDELINE FOR GOOD CLINICAL PRACTICE E6(R2).

- ICH Working Group. 1995. ICH HARMONISED TRIPARTITE GUIDELINE: Structure and Content of Clinical Study Reports E3 .

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2016. Clinical Trials Registration and Results Information Submission, 42 CFR Part 11. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/09/21/2016-22129/clinical-trials-registration-and-results-information-submission

- European Commission. 2001. Letter to Stakeholders Regarding the Requirements to provide results for Authortied clinical trials in EUDRACT. In: Article 57(2) Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 and Article 41(2) of Regulation (EC) No 1901/2006. https://eudract.ema.europa.eu/

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2018. ICH Guidance Documents . https://www.fda.gov/science-research/guidance-documents-including-information-sheets-and-notices/ich-guidance-documents

- Transcelerate Biopharma Inc. Clinical Template Suite (CTS), Template, Resources, and Use Guidance. https://transceleratebiopharmainc.com/assets/clinical-content-reuse-assets/

- Hamilton S, Bernstein AB, Blakey G, et al. 2016. Developing the Clarity and Openness in Reporting: E3-based (CORE) Reference user manual for creation of clinical study reports in the era of clinical trial transparency. Research integrity and peer review. 1:4.

- Hamilton S. 2014. Effective authoring of clinical study reports. Medical Writing 23(2).

- Nambiar I. 2018. Analysis of serious adverse event: Writing a narrative. Perspect Clin Res 9(2):103–6.

- Ledade SD, Jain SN, Darji AA, Gupta VH. 2017. Narrative writing: Effective ways and best practices. Perspect Clin Res 8(2):58–62.

Sheryl Stewart, MCR, CCRP, ( [email protected] ) is a Medical Writer working in the medical device industry in southern California.

Sorry, we couldn't find any jobs that match your criteria.

Barriers to Clinical Trial Enrollment: Focus on Underrepresented Populations

Using Simulation to Teach Research

An Approach to a Benefit-Risk Framework

Trip: Overview

- Get Individual Help

Trip Overview

Trip is a clinical search engine designed to allow users to quickly and easily find a variety of high-quality research evidence to support their practice and/or care. Results provided can be sorted by quality, relevance, date or popularity and organized by the type of evidence via a pyramid graphic under the title of each article.

The library provides the free version of Trip. We do not have an institutional subscription to this product. There is a pro version of Trip that can be purchased which allows more full text results and additional tools if you wish to subscribe on your own. The personal subscription has an annual cost of $55 + tax.

For a comparison of free versus paid features see: Trip Feature Comparison

Special Features

- Trip provides a graphic next to each result to inform you about level of evidence it qualifies as. The hierarchy is shown above.

- Filtering options are provided to focus on the kind of evidence (systematic reviews, primary research, regulatory guidance, etc.) desired.

- Search results can be ranked by quality, relevance, date or popularity.

- Patient/population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcomes ( PICO) searching is available allowing you to focus in on your research question.

- Trip provides a large collection of clinical guidelines and thousands of systematic reviews.

- The SmartSearch feature displays three related articles.

- If you sign up with your email to Trip, you can receive alerts about newly added sources regarding topics of interest to you at no charge.

Trip has a blog and the most recent posts are shown here. Click on the website link below to see the rest.

- Next: Tutorials >>

- Last Updated: Sep 8, 2023 8:01 AM

- URL: https://library.aah.org/guides/trip

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 7, Issue 4

TRIP database

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Victor M Montori , MD, MSc ,

- Jon O Ebbert , MD

- Mayo Clinic Rochester, Minnesota, USA

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebm.7.4.104

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

TRIP is easy to use, with a simple web page design that provides quick downloads even with slow internet connections. TRIP organises the links in its database into clinical areas (eg, cancer, cardiovascular, pregnancy and childbirth, and mental health) and features a self directed learning area that offers online continuing medical education based on systematic reviews. A user-friendly search engine is also available on the site. The user can enter a word or phrase (searched exactly as typed) or a simple Boolean expression into a query box. The search is limited to the title of the link or to the title and text that were captured in the database when the hit was first identified by TRIP (this text could include the executive summary of a guideline or the abstract of a manuscript). A helpful troubleshooting guide to improve searching is a click away. Users can store their search terms to be run periodically and can have the results emailed.

The search results are organised into colour coded categories. The categories include evidence-based resources (including links to ACP Journal Club and Evidence Based Medicine and links to databanks of critically appraised topics); query-answering services (mainly the Ask TRIP to Rapidly Alleviate Confused Thoughts [ATTRACT] service, www.attract.wales.nhs.uk ); peer reviewed journals (including the journals published by the BMJ Publishing Group, JAMA , Annals of Internal Medicine , and the New England Journal of Medicine ); guidelines; electronic textbooks (including the Merck Manual and emedicine.com); and links to the Clinical Queries feature of PubMed ( www.pubmed.gov .). Within each of these categories the links are listed by date of publication and include the name of the host website.

To evaluate TRIP, we completed a series of searches using questions that arose during our clinical practice. A search that used the simple Boolean expression “diabetes AND smoking” and that was restricted to “titles” identified 6 hits: 5 articles in peer reviewed journals and 1 guideline from the American Diabetes Association Practice Recommendations. When we completed the search using “titles and text,” it took longer, and most of the 387 resulting hits were not relevant.

A search for “vitamin E” in “titles” led to 19 hits. The results included critically appraised topics of several randomised trials of vitamin E and 3 Cochrane reviews. The hits also included ATTRACT’s answer to a question about the effectiveness of vitamin E in dementia. The peer reviewed journal hits included abstracts to 3 important clinical trials. The electronic textbook hits offered links to narrative reviews of vitamin E toxicity and deficiency.

Unfortunately, the search engine does not enhance the search terms entered by users who type in synonyms or medical subject headings. We found that searching by title and text yielded too many irrelevant hits, but this finding may represent our lack of experience with the search engine. Performance of quick searches on specific topics using TRIP can be hit or miss because success is dependent on the content of the database. We feel that the inclusion of textbooks delays the search and provides information of limited validity and clinical usefulness.

TRIP offers a friendly interface and quick access to the evidence (particularly if the search is limited to titles) with user friendly organisation of search results. We recommend this resource for those seeking pre-appraised evidence, reviews, and guidelines. Those seeking the original studies may be better off using the Clinical Queries and Related Articles functions in PubMed.

Methods/Quality:★☆☆☆☆

The website can be found at http://www.userguides.org

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Trip Database Blog

Liberating the literature, latest evidence from trip.

At Trip, we continuously update our database with thousands of new articles each month, prioritizing the inclusion of high-quality evidence such as guidelines and systematic reviews. Our ‘Latest’ feature is designed to present these recent additions in a user-centric manner, tailored according to individual profiles. This customization occurs in two primary ways:

- Clinical area: For users with specific clinical interests noted in their profiles, such as Gastroenterology, we curate and list the most recent, relevant evidence in that field. ( Click here to explore the latest articles in Gastroenterology).

- Personalised Topics: Users have the option to highlight particular topics of interest within their profiles. Based on these selections, we actively search for and recommend new articles that align with these specified interests, such as research on bipolar .

To ensure our users remain informed of the latest evidence, we distribute a monthly email containing a direct link to these updated resources. This link is accessible at any time, allowing users the flexibility to explore the latest findings at their convenience. While this feature is frequently utilized and appreciated by our community, we believe there are opportunities for enhancement to further enrich user engagement and satisfaction.

At the top is a list of 5 ‘key’ documents and below that a list of recorded search terms and/or clinical areas of interest. If you click on a link it takes you to a page of search results – the results being a search for the topic for content added that month:

Recognizing the current approach as ‘sub-optimal’—a diplomatic term for inadequate—we are in the process of re-evaluating this feature. It’s evident that users have a strong desire to access the most recent evidence related to their specific areas of interest, and we acknowledge the need for improvement in meeting this demand. We highly value your feedback and encourage you to share your insights and suggestions either through the comments section or by directly emailing me at [email protected] . This initiative is part of our ongoing commitment to enhance user experience and optimize our services for better search engine visibility and user satisfaction.

Share this:

- Uncategorized

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Recent posts.

- Relevancy – a big change

- We’ve moved

- Using document clustering to show evolution of a topic area

- Clustering search results using Carrot2

- Moving to the cloud

Recent Comments

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- February 2006

- Advanced search

- answer engine

- binary clock

- broken links

- clickstream

- clinical areas

- clinical decisions

- clinical trials

- communication

- critical friend

- development

- evidence hierarchy

- evidence live

- evidence service

- excluding results

- filter bubbles

- flibanserin

- google maps

- half man half biscuit

- http://schemas.google.com/blogger/2008/kind#post

- Iain Chalmers

- improved search

- institutions

- machine learning

- medical images

- multi-lingual

- new features

- nhs choices

- open access

- open medicine

- osteoporosis

- peer-review

- personalised search

- professions

- publication

- publication bias

- question analysis

- rapid reviews

- registration

- search algorithm

- search refinement

- search safety net

- search terms

- semantic annotation

- sentiment analysis

- serendipity

- strange results

- systematic review methods

- systematic reviews

- top articles

- trial registries

- TRIP Evidence Reviews

- trip profile

- uncertainties

- user-added content

Blog at WordPress.com.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Preparing Monitors for Tomorrow’s Clinical Trials

In the first blog in our series, we discussed how the global pandemic facilitated the need for the industry to change the way clinical trials are run. In this blog, we’ll explore the role of the CRA in a post-COVID era.

Monitoring Challenges

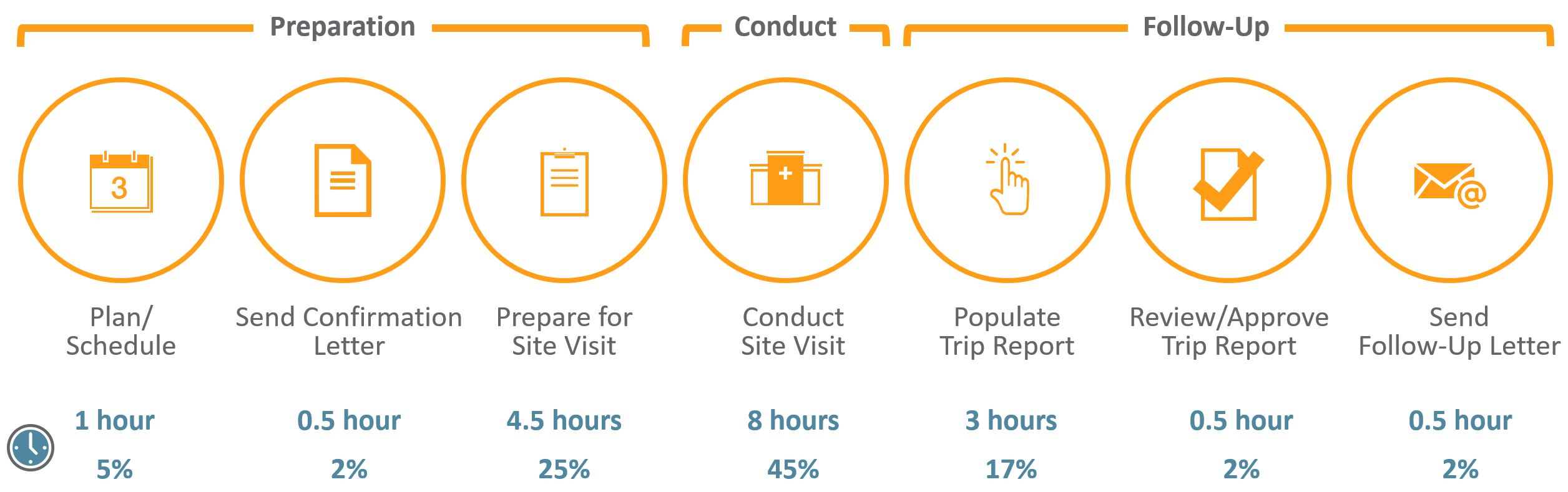

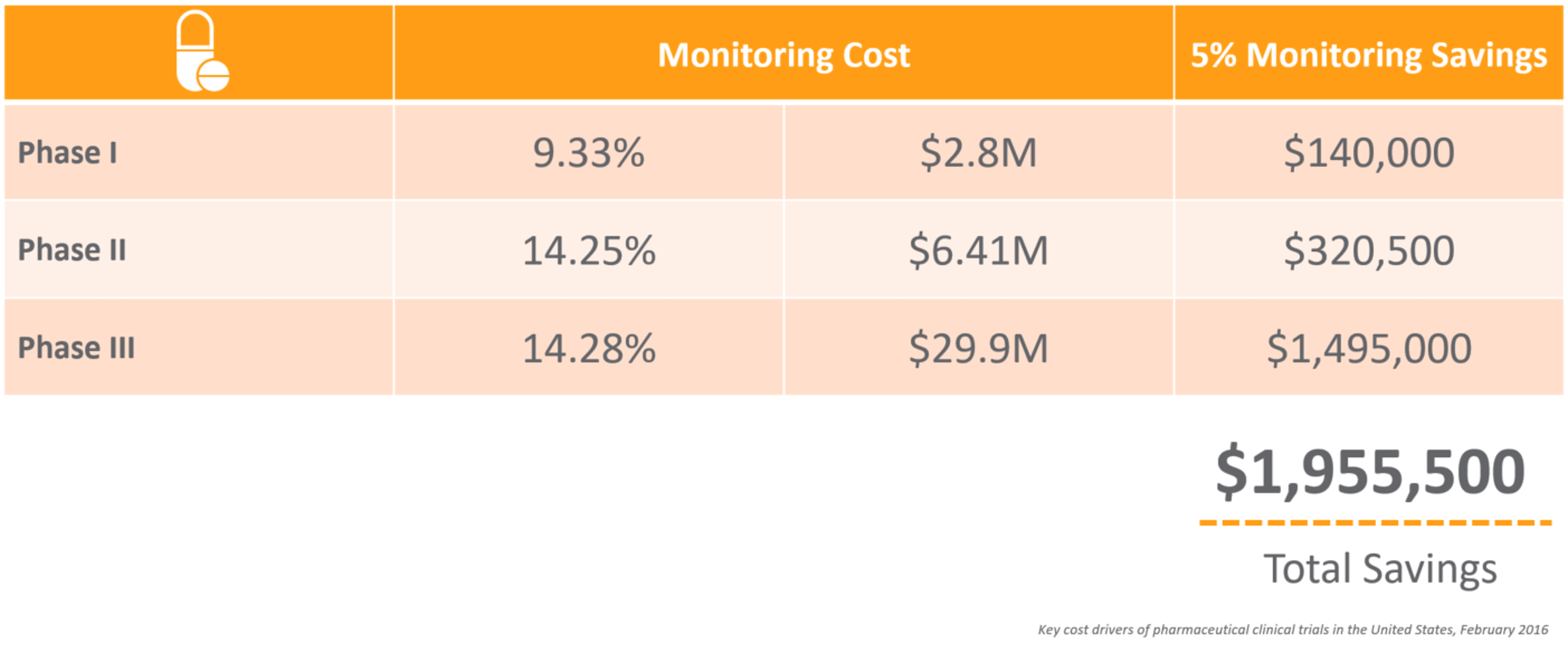

CRAs have a difficult job – from the extensive travel to the tedious time spent preparing for onsite visits and completing trip reports. For an average phase III trial for large pharma, monitors can spend up to 18 hours on just this task alone. With many top 20 pharma averaging over 40,000 monitoring trip reports per year, 1 it’s not surprising that 25%-30% of total clinical trial costs are attributed to site monitoring. 2

The time spent on monitoring visits is compounded by the reality that many CRAs work across 10+ systems, which are often siloed, adding effort and complexity to an already tough job.

Monitoring is an area ripe for optimization. Suppose you could reduce the time, effort, and cost of monitoring by 5%. What impact would that have on your clinical development costs and time to market?

Streamlining Clinical Trials: Adopting a Risk-Based Approach

One way to achieve significant time and cost savings, and increase study quality, is a sound RBM strategy that incorporates quality by design and centralized remote monitoring. Focusing on risks specific to a study’s critical data allows sponsors and CROs to be more productive and allocate resources more effectively. This risk-based approach also conforms with ICH GCP guidelines, enabling faster processes and workflows, and improving study quality.

By identifying critical data, performing risk assessments, and providing a more targeted SDV and remote monitoring strategy, clinical operations leaders can better mitigate risks and optimize trial outcomes.

The Shift in the Monitor’s Role

COVID has demonstrated just how much work CRAs can do offsite, such as reviewing regulatory documents and statistical reports. Armed with highly focused reports if they must go onsite, monitors can dedicate their time to value-add activities – ensuring drug storage procedures align with the protocol, supporting sites by creating an enrollment strategy, fixing known issues, and building stronger relationships with site personnel.

If there is a silver lining to this unprecedented global event, it’s that the industry has proven we can execute remote trials without 100% SDV, while upholding the same stringent efficacy, data quality, and data integrity standards. This approach has resulted in the first COVID vaccines being developed and delivered at record speeds. It will be interesting to see if the learnings we gained during this unprecedented time carry forward into normal monitoring processes post-COVID.

Check out the next blog in our series, where we dive into how to garner internal support for an RBM initiative and steps you can take to ensure a successful deployment and adoption.

1 De-identified average from Veeva customers. 2 Branch, E. (2016, April 30). Ways to Lower Costs of Clinical Trials and How CROs Help. Retrieved January 21, 2019, from https://www.americanpharmaceuticalreview.com/Featured-Articles/185929-Ways-to-Lower-Costs-of-Clinical-Trials-and-How-CROs-Help/

Interested in learning more about how Veeva can help?

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.15(2); 2023 Feb

- PMC10023071

Clinical Trials and Clinical Research: A Comprehensive Review

Venkataramana kandi.

1 Clinical Microbiology, Prathima Institute of Medical Sciences, Karimnagar, IND

Sabitha Vadakedath

2 Biochemistry, Prathima Institute of Medical Sciences, Karimnagar, IND

Clinical research is an alternative terminology used to describe medical research. Clinical research involves people, and it is generally carried out to evaluate the efficacy of a therapeutic drug, a medical/surgical procedure, or a device as a part of treatment and patient management. Moreover, any research that evaluates the aspects of a disease like the symptoms, risk factors, and pathophysiology, among others may be termed clinical research. However, clinical trials are those studies that assess the potential of a therapeutic drug/device in the management, control, and prevention of disease. In view of the increasing incidences of both communicable and non-communicable diseases, and especially after the effects that Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) had on public health worldwide, the emphasis on clinical research assumes extremely essential. The knowledge of clinical research will facilitate the discovery of drugs, devices, and vaccines, thereby improving preparedness during public health emergencies. Therefore, in this review, we comprehensively describe the critical elements of clinical research that include clinical trial phases, types, and designs of clinical trials, operations of trial, audit, and management, and ethical concerns.

Introduction and background

A clinical trial is a systematic process that is intended to find out the safety and efficacy of a drug/device in treating/preventing/diagnosing a disease or a medical condition [ 1 , 2 ]. Clinical trial includes various phases that include phase 0 (micro-dosing studies), phase 1, phase 2, phase 3, and phase 4 [ 3 ]. Phase 0 and phase 2 are called exploratory trial phases, phase 1 is termed the non-therapeutic phase, phase 3 is known as the therapeutic confirmatory phase, and phase 4 is called the post-approval or the post-marketing surveillance phase. Phase 0, also called the micro-dosing phase, was previously done in animals but now it is carried out in human volunteers to understand the dose tolerability (pharmacokinetics) before being administered as a part of the phase 1 trial among healthy individuals. The details of the clinical trial phases are shown in Table Table1 1 .

This table has been created by the authors.

MTD: maximum tolerated dose; SAD: single ascending dose; MAD: multiple ascending doses; NDA: new drug application; FDA: food and drug administration

Clinical research design has two major types that include non-interventional/observational and interventional/experimental studies. The non-interventional studies may have a comparator group (analytical studies like case-control and cohort studies), or without it (descriptive study). The experimental studies may be either randomized or non-randomized. Clinical trial designs are of several types that include parallel design, crossover design, factorial design, randomized withdrawal approach, adaptive design, superiority design, and non-inferiority design. The advantages and disadvantages of clinical trial designs are depicted in Table Table2 2 .

There are different types of clinical trials that include those which are conducted for treatment, prevention, early detection/screening, and diagnosis. These studies address the activities of an investigational drug on a disease and its outcomes [ 4 ]. They assess whether the drug is able to prevent the disease/condition, the ability of a device to detect/screen the disease, and the efficacy of a medical test to diagnose the disease/condition. The pictorial representation of a disease diagnosis, treatment, and prevention is depicted in Figure Figure1 1 .

This figure has been created by the authors.

The clinical trial designs could be improvised to make sure that the study's validity is maintained/retained. The adaptive designs facilitate researchers to improvise during the clinical trial without interfering with the integrity and validity of the results. Moreover, it allows flexibility during the conduction of trials and the collection of data. Despite these advantages, adaptive designs have not been universally accepted among clinical researchers. This could be attributed to the low familiarity of such designs in the research community. The adaptive designs have been applied during various phases of clinical trials and for different clinical conditions [ 5 , 6 ]. The adaptive designs applied during different phases are depicted in Figure Figure2 2 .

The Bayesian adaptive trial design has gained popularity, especially during the Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic. Such designs could operate under a single master protocol. It operates as a platform trial wherein multiple treatments can be tested on different patient groups suffering from disease [ 7 ].

In this review, we comprehensively discuss the essential elements of clinical research that include the principles of clinical research, planning clinical trials, practical aspects of clinical trial operations, essentials of clinical trial applications, monitoring, and audit, clinical trial data analysis, regulatory audits, and project management, clinical trial operations at the investigation site, the essentials of clinical trial experiments involving epidemiological, and genetic studies, and ethical considerations in clinical research/trials.

A clinical trial involves the study of the effect of an investigational drug/any other intervention in a defined population/participant. The clinical research includes a treatment group and a placebo wherein each group is evaluated for the efficacy of the intervention (improved/not improved) [ 8 ].

Clinical trials are broadly classified into controlled and uncontrolled trials. The uncontrolled trials are potentially biased, and the results of such research are not considered as equally as the controlled studies. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are considered the most effective clinical trials wherein the bias is minimized, and the results are considered reliable. There are different types of randomizations and each one has clearly defined functions as elaborated in Table Table3 3 .

Principles of clinical trial/research

Clinical trials or clinical research are conducted to improve the understanding of the unknown, test a hypothesis, and perform public health-related research [ 2 , 3 ]. This is majorly carried out by collecting the data and analyzing it to derive conclusions. There are various types of clinical trials that are majorly grouped as analytical, observational, and experimental research. Clinical research can also be classified into non-directed data capture, directed data capture, and drug trials. Clinical research could be prospective or retrospective. It may also be a case-control study or a cohort study. Clinical trials may be initiated to find treatment, prevent, observe, and diagnose a disease or a medical condition.

Among the various types of clinical research, observational research using a cross-sectional study design is the most frequently performed clinical research. This type of research is undertaken to analyze the presence or absence of a disease/condition, potential risk factors, and prevalence and incidence rates in a defined population. Clinical trials may be therapeutic or non-therapeutic type depending on the type of intervention. The therapeutic type of clinical trial uses a drug that may be beneficial to the patient. Whereas in a non-therapeutic clinical trial, the participant does not benefit from the drug. The non-therapeutic trials provide additional knowledge of the drug for future improvements. Different terminologies of clinical trials are delineated in Table Table4 4 .

In view of the increased cost of the drug discovery process, developing, and low-income countries depend on the production of generic drugs. The generic drugs are similar in composition to the patented/branded drug. Once the patent period is expired generic drugs can be manufactured which have a similar quality, strength, and safety as the patented drug [ 9 ]. The regulatory requirements and the drug production process are almost the same for the branded and the generic drug according to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), United States of America (USA).

The bioequivalence (BE) studies review the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of the generic drug. These studies compare the concentration of the drug at the desired location in the human body, called the peak concentration of the drug (Cmax). The extent of absorption of the drug is measured using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), wherein the generic drug is supposed to demonstrate similar ADME activities as the branded drug. The BE studies may be undertaken in vitro (fasting, non-fasting, sprinkled fasting) or in vivo studies (clinical, bioanalytical, and statistical) [ 9 ].

Planning clinical trial/research

The clinical trial process involves protocol development, designing a case record/report form (CRF), and functioning of institutional review boards (IRBs). It also includes data management and the monitoring of clinical trial site activities. The CRF is the most significant document in a clinical study. It contains the information collected by the investigator about each subject participating in a clinical study/trial. According to the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), the CRF can be printed, optical, or an electronic document that is used to record the safety and efficacy of the pharmaceutical drug/product in the test subjects. This information is intended for the sponsor who initiates the clinical study [ 10 ].

The CRF is designed as per the protocol and later it is thoroughly reviewed for its correctness (appropriate and structured questions) and finalized. The CRF then proceeds toward the print taking the language of the participating subjects into consideration. Once the CRF is printed, it is distributed to the investigation sites where it is filled with the details of the participating subjects by the investigator/nurse/subject/guardian of the subject/technician/consultant/monitors/pharmacist/pharmacokinetics/contract house staff. The filled CRFs are checked for their completeness and transported to the sponsor [ 11 ].

Effective planning and implementation of a clinical study/trial will influence its success. The clinical study majorly includes the collection and distribution of the trial data, which is done by the clinical data management section. The project manager is crucial to effectively plan, organize, and use the best processes to control and monitor the clinical study [ 10 , 11 ].

The clinical study is conducted by a sponsor or a clinical research organization (CRO). A perfect protocol, time limits, and regulatory requirements assume significance while planning a clinical trial. What, when, how, and who are clearly planned before the initiation of a study trial. Regular review of the project using the bar and Gantt charts, and maintaining the timelines assume increased significance for success with the product (study report, statistical report, database) [ 10 , 11 ].

The steps critical to planning a clinical trial include the idea, review of the available literature, identifying a problem, formulating the hypothesis, writing a synopsis, identifying the investigators, writing a protocol, finding a source of funding, designing a patient consent form, forming ethics boards, identifying an organization, preparing manuals for procedures, quality assurance, investigator training and initiation of the trial by recruiting the participants [ 10 ].

The two most important points to consider before the initiation of the clinical trial include whether there is a need for a clinical trial, if there is a need, then one must make sure that the study design and methodology are strong for the results to be reliable to the people [ 11 ].

For clinical research to envisage high-quality results, the study design, implementation of the study, quality assurance in data collection, and alleviation of bias and confounding factors must be robust [ 12 ]. Another important aspect of conducting a clinical trial is improved management of various elements of clinical research that include human and financial resources. The role of a trial manager to make a successful clinical trial was previously reported. The trial manager could play a key role in planning, coordinating, and successfully executing the trial. Some qualities of a trial manager include better communication and motivation, leadership, and strategic, tactical, and operational skills [ 13 ].

Practical aspects of a clinical trial operations

There are different types of clinical research. Research in the development of a novel drug could be initiated by nationally funded research, industry-sponsored research, and clinical research initiated by individuals/investigators. According to the documents 21 code of federal regulations (CFR) 312.3 and ICH E-6 Good Clinical Practice (GCP) 1.54, an investigator is an individual who initiates and conducts clinical research [ 14 ]. The investigator plan, design, conduct, monitor, manage data, compile reports, and supervise research-related regulatory and ethical issues. To manage a successful clinical trial project, it is essential for an investigator to give the letter of intent, write a proposal, set a timeline, develop a protocol and related documents like the case record forms, define the budget, and identify the funding sources.

Other major steps of clinical research include the approval of IRBs, conduction and supervision of the research, data review, and analysis. Successful clinical research includes various essential elements like a letter of intent which is the evidence that supports the interest of the researcher to conduct drug research, timeline, funding source, supplier, and participant characters.

Quality assurance, according to the ICH and GCP guidelines, is necessary to be implemented during clinical research to generate quality and accurate data. Each element of the clinical research must have been carried out according to the standard operating procedure (SOP), which is written/determined before the initiation of the study and during the preparation of the protocol [ 15 ].

The audit team (quality assurance group) is instrumental in determining the authenticity of the clinical research. The audit, according to the ICH and GCP, is an independent and external team that examines the process (recording the CRF, analysis of data, and interpretation of data) of clinical research. The quality assurance personnel are adequately trained, become trainers if needed, should be good communicators, and must handle any kind of situation. The audits can be at the investigator sites evaluating the CRF data, the protocol, and the personnel involved in clinical research (source data verification, monitors) [ 16 ].

Clinical trial operations are governed by legal and regulatory requirements, based on GCPs, and the application of science, technology, and interpersonal skills [ 17 ]. Clinical trial operations are complex, time and resource-specific that requires extensive planning and coordination, especially for the research which is conducted at multiple trial centers [ 18 ].

Recruiting the clinical trial participants/subjects is the most significant aspect of clinical trial operations. Previous research had noted that most clinical trials do not meet the participant numbers as decided in the protocol. Therefore, it is important to identify the potential barriers to patient recruitment [ 19 ].

Most clinical trials demand huge costs, increased timelines, and resources. Randomized clinical trial studies from Switzerland were analyzed for their costs which revealed approximately 72000 USD for a clinical trial to be completed. This study emphasized the need for increased transparency with respect to the costs associated with the clinical trial and improved collaboration between collaborators and stakeholders [ 20 ].

Clinical trial applications, monitoring, and audit

Among the most significant aspects of a clinical trial is the audit. An audit is a systematic process of evaluating the clinical trial operations at the site. The audit ensures that the clinical trial process is conducted according to the protocol, and predefined quality system procedures, following GCP guidelines, and according to the requirements of regulatory authorities [ 21 ].

The auditors are supposed to be independent and work without the involvement of the sponsors, CROs, or personnel at the trial site. The auditors ensure that the trial is conducted by designated professionally qualified, adequately trained personnel, with predefined responsibilities. The auditors also ensure the validity of the investigational drug, and the composition, and functioning of institutional review/ethics committees. The availability and correctness of the documents like the investigational broacher, informed consent forms, CRFs, approval letters of the regulatory authorities, and accreditation of the trial labs/sites [ 21 ].

The data management systems, the data collection software, data backup, recovery, and contingency plans, alternative data recording methods, security of the data, personnel training in data entry, and the statistical methods used to analyze the results of the trial are other important responsibilities of the auditor [ 21 , 22 ].

According to the ICH-GCP Sec 1.29 guidelines the inspection may be described as an act by the regulatory authorities to conduct an official review of the clinical trial-related documents, personnel (sponsor, investigator), and the trial site [ 21 , 22 ]. The summary report of the observations of the inspectors is performed using various forms as listed in Table Table5 5 .

FDA: Food and Drug Administration; IND: investigational new drug; NDA: new drug application; IRB: institutional review board; CFR: code of federal regulations

Because protecting data integrity, the rights, safety, and well-being of the study participants are more significant while conducting a clinical trial, regular monitoring and audit of the process appear crucial. Also, the quality of the clinical trial greatly depends on the approach of the trial personnel which includes the sponsors and investigators [ 21 ].

The responsibility of monitoring lies in different hands, and it depends on the clinical trial site. When the trial is initiated by a pharmaceutical industry, the responsibility of trial monitoring depends on the company or the sponsor, and when the trial is conducted by an academic organization, the responsibility lies with the principal investigator [ 21 ].

An audit is a process conducted by an independent body to ensure the quality of the study. Basically, an audit is a quality assurance process that determines if a study is carried out by following the SPOs, in compliance with the GCPs recommended by regulatory bodies like the ICH, FDA, and other local bodies [ 21 ].

An audit is performed to review all the available documents related to the IRB approval, investigational drug, and the documents related to the patient care/case record forms. Other documents that are audited include the protocol (date, sign, treatment, compliance), informed consent form, treatment response/outcome, toxic response/adverse event recording, and the accuracy of data entry [ 22 ].

Clinical trial data analysis, regulatory audits, and project management

The essential elements of clinical trial management systems (CDMS) include the management of the study, the site, staff, subject, contracts, data, and document management, patient diary integration, medical coding, monitoring, adverse event reporting, supplier management, lab data, external interfaces, and randomization. The CDMS involves setting a defined start and finishing time, defining study objectives, setting enrolment and termination criteria, commenting, and managing the study design [ 23 ].

Among the various key application areas of clinical trial systems, the data analysis assumes increased significance. The clinical trial data collected at the site in the form of case record form is stored in the CDMS ensuring the errors with respect to the double data entry are minimized.

Clinical trial data management uses medical coding, which uses terminologies with respect to the medications and adverse events/serious adverse events that need to be entered into the CDMS. The project undertaken to conduct the clinical trial must be predetermined with timelines and milestones. Timelines are usually set for the preparation of protocol, designing the CRF, planning the project, identifying the first subject, and timelines for recording the patient’s data for the first visit.

The timelines also are set for the last subject to be recruited in the study, the CRF of the last subject, and the locked period after the last subject entry. The planning of the project also includes the modes of collection of the data, the methods of the transport of the CRFs, patient diaries, and records of severe adverse events, to the central data management sites (fax, scan, courier, etc.) [ 24 ].

The preparation of SOPs and the type and timing of the quality control (QC) procedures are also included in the project planning before the start of a clinical study. Review (budget, resources, quality of process, assessment), measure (turnaround times, training issues), and control (CRF collection and delivery, incentives, revising the process) are the three important aspects of the implementation of a clinical research project.

In view of the increasing complexity related to the conduct of clinical trials, it is important to perform a clinical quality assurance (CQA) audit. The CQA audit process consists of a detailed plan for conducting audits, points of improvement, generating meaningful audit results, verifying SOP, and regulatory compliance, and promoting improvement in clinical trial research [ 25 ]. All the components of a CQA audit are delineated in Table Table6 6 .

CRF: case report form; CSR: clinical study report; IC: informed consent; PV: pharmacovigilance; SAE: serious adverse event

Clinical trial operations at the investigator's site

The selection of an investigation site is important before starting a clinical trial. It is essential that the individuals recruited for the study meet the inclusion criteria of the trial, and the investigator's and patient's willingness to accept the protocol design and the timelines set by the regulatory authorities including the IRBs.

Before conducting clinical research, it is important for an investigator to agree to the terms and conditions of the agreement and maintain the confidentiality of the protocol. Evaluation of the protocol for the feasibility of its practices with respect to the resources, infrastructure, qualified and trained personnel available, availability of the study subjects, and benefit to the institution and the investigator is done by the sponsor during the site selection visit.

The standards of a clinical research trial are ensured by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), National Bioethics Advisory Commission (NBAC), United Nations Programme on Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) (UNAIDS), and World Medical Association (WMA) [ 26 ].

Recommendations for conducting clinical research based on the WMA support the slogan that says, “The health of my patient will be my first consideration.” According to the International Code of Medical Ethics (ICME), no human should be physically or mentally harmed during the clinical trial, and the study should be conducted in the best interest of the person [ 26 ].

Basic principles recommended by the Helsinki declaration include the conduction of clinical research only after the prior proof of the safety of the drug in animal and lab experiments. The clinical trials must be performed by scientifically, and medically qualified and well-trained personnel. Also, it is important to analyze the benefit of research over harm to the participants before initiating the drug trials.

The doctors may prescribe a drug to alleviate the suffering of the patient, save the patient from death, and gain additional knowledge of the drug only after obtaining informed consent. Under the equipoise principle, the investigators must be able to justify the treatment provided as a part of the clinical trial, wherein the patient in the placebo arm may be harmed due to the unavailability of the therapeutic/trial drug.

Clinical trial operations greatly depend on the environmental conditions and geographical attributes of the trial site. It may influence the costs and targets defined by the project before the initiation. It was noted that one-fourth of the clinical trial project proposals/applications submit critical data on the investigational drug from outside the country. Also, it was noted that almost 35% of delays in clinical trials owing to patient recruitment with one-third of studies enrolling only 5% of the participants [ 27 ].

It was suggested that clinical trial feasibility assessment in a defined geographical region may be undertaken for improved chances of success. Points to be considered under the feasibility assessment program include if the disease under the study is related to the population of the geographical region, appropriateness of the study design, patient, and comparator group, visit intervals, potential regulatory and ethical challenges, and commitments of the study partners, CROs in respective countries (multi-centric studies) [ 27 ].

Feasibility assessments may be undertaken at the program level (ethics, regulatory, and medical preparedness), study level (clinical, regulatory, technical, and operational aspects), and at the investigation site (investigational drug, competency of personnel, participant recruitment, and retention, quality systems, and infrastructural aspects) [ 27 ].

Clinical trials: true experiments

In accordance with the revised schedule "Y" of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act (DCA) (2005), a drug trial may be defined as a systematic study of a novel drug component. The clinical trials aim to evaluate the pharmacodynamic, and pharmacokinetic properties including ADME, efficacy, and safety of new drugs.

According to the drug and cosmetic rules (DCR), 1945, a new chemical entity (NCE) may be defined as a novel drug approved for a disease/condition, in a specified route, and at a particular dosage. It also may be a new drug combination, of previously approved drugs.

A clinical trial may be performed in three types; one that is done to find the efficacy of an NCE, a comparison study of two drugs against a medical condition, and the clinical research of approved drugs on a disease/condition. Also, studies of the bioavailability and BE studies of the generic drugs, and the drugs already approved in other countries are done to establish the efficacy of new drugs [ 28 ].

Apart from the discovery of a novel drug, clinical trials are also conducted to approve novel medical devices for public use. A medical device is defined as any instrument, apparatus, appliance, software, and any other material used for diagnostic/therapeutic purposes. The medical devices may be divided into three classes wherein class I uses general controls; class II uses general and special controls, and class III uses general, special controls, and premarket approvals [ 28 ].

The premarket approval applications ensure the safety and effectiveness, and confirmation of the activities from bench to animal to human clinical studies. The FDA approval for investigational device exemption (IDE) for a device not approved for a new indication/disease/condition. There are two types of IDE studies that include the feasibility study (basic safety and potential effectiveness) and the pivotal study (trial endpoints, randomization, monitoring, and statistical analysis plan) [ 28 ].

As evidenced by the available literature, there are two types of research that include observational and experimental research. Experimental research is alternatively known as the true type of research wherein the research is conducted by the intervention of a new drug/device/method (educational research). Most true experiments use randomized control trials that remove bias and neutralize the confounding variables that may interfere with the results of research [ 28 ].

The variables that may interfere with the study results are independent variables also called prediction variables (the intervention), dependent variables (the outcome), and extraneous variables (other confounding factors that could influence the outside). True experiments have three basic elements that include manipulation (that influence independent variables), control (over extraneous influencers), and randomization (unbiased grouping) [ 29 ].

Experiments can also be grouped as true, quasi-experimental, and non-experimental studies depending on the presence of specific characteristic features. True experiments have all three elements of study design (manipulation, control, randomization), and prospective, and have great scientific validity. Quasi-experiments generally have two elements of design (manipulation and control), are prospective, and have moderate scientific validity. The non-experimental studies lack manipulation, control, and randomization, are generally retrospective, and have low scientific validity [ 29 ].

Clinical trials: epidemiological and human genetics study

Epidemiological studies are intended to control health issues by understanding the distribution, determinants, incidence, prevalence, and impact on health among a defined population. Such studies are attempted to perceive the status of infectious diseases as well as non-communicable diseases [ 30 ].

Experimental studies are of two types that include observational (cross-sectional studies (surveys), case-control studies, and cohort studies) and experimental studies (randomized control studies) [ 3 , 31 ]. Such research may pose challenges related to ethics in relation to the social and cultural milieu.

Biomedical research related to human genetics and transplantation research poses an increased threat to ethical concerns, especially after the success of the human genome project (HGP) in the year 2000. The benefits of human genetic studies are innumerable that include the identification of genetic diseases, in vitro fertilization, and regeneration therapy. Research related to human genetics poses ethical, legal, and social issues (ELSI) that need to be appropriately addressed. Most importantly, these genetic research studies use advanced technologies which should be equally available to both economically well-placed and financially deprived people [ 32 ].

Gene therapy and genetic manipulations may potentially precipitate conflict of interest among the family members. The research on genetics may be of various types that include pedigree studies (identifying abnormal gene carriers), genetic screening (for diseases that may be heritable by the children), gene therapeutics (gene replacement therapy, gene construct administration), HGP (sequencing the whole human genome/deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fingerprinting), and DNA, cell-line banking/repository [ 33 ]. The biobanks are established to collect and store human tissue samples like umbilical tissue, cord blood, and others [ 34 ].

Epidemiological studies on genetics are attempts to understand the prevalence of diseases that may be transmitted among families. The classical epidemiological studies may include single case observations (one individual), case series (< 10 individuals), ecological studies (population/large group of people), cross-sectional studies (defined number of individuals), case-control studies (defined number of individuals), cohort (defined number of individuals), and interventional studies (defined number of individuals) [ 35 ].

Genetic studies are of different types that include familial aggregation (case-parent, case-parent-grandparent), heritability (study of twins), segregation (pedigree study), linkage study (case-control), association, linkage, disequilibrium, cohort case-only studies (related case-control, unrelated case-control, exposure, non-exposure group, case group), cross-sectional studies, association cohort (related case-control, familial cohort), and experimental retrospective cohort (clinical trial, exposure, and non-exposure group) [ 35 ].

Ethics and concerns in clinical trial/research

Because clinical research involves animals and human participants, adhering to ethics and ethical practices assumes increased significance [ 36 ]. In view of the unethical research conducted on war soldiers after the Second World War, the Nuremberg code was introduced in 1947, which promulgated rules for permissible medical experiments on humans. The Nuremberg code suggests that informed consent is mandatory for all the participants in a clinical trial, and the study subjects must be made aware of the nature, duration, and purpose of the study, and potential health hazards (foreseen and unforeseen). The study subjects should have the liberty to withdraw at any time during the trial and to choose a physician upon medical emergency. The other essential principles of clinical research involving human subjects as suggested by the Nuremberg code included benefit to the society, justification of study as noted by the results of the drug experiments on animals, avoiding even minimal suffering to the study participants, and making sure that the participants don’t have life risk, humanity first, improved medical facilities for participants, and suitably qualified investigators [ 37 ].

During the 18th world medical assembly meeting in the year 1964, in Helsinki, Finland, ethical principles for doctors practicing research were proposed. Declaration of Helsinki, as it is known made sure that the interests and concerns of the human participants will always prevail over the interests of the society. Later in 1974, the National Research Act was proposed which made sure that the research proposals are thoroughly screened by the Institutional ethics/Review Board. In 1979, the April 18th Belmont report was proposed by the national commission for the protection of human rights during biomedical and behavioral research. The Belmont report proposed three core principles during research involving human participants that include respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. The ICH laid down GCP guidelines [ 38 ]. These guidelines are universally followed throughout the world during the conduction of clinical research involving human participants.

ICH was first founded in 1991, in Brussels, under the umbrella of the USA, Japan, and European countries. The ICH conference is conducted once every two years with the participation from the member countries, observers from the regulatory agencies, like the World Health Organization (WHO), European Free Trade Association (EFTA), and the Canadian Health Protection Branch, and other interested stakeholders from the academia and the industry. The expert working groups of the ICH ensure the quality, efficacy, and safety of the medicinal product (drug/device). Despite the availability of the Nuremberg code, the Belmont Report, and the ICH-GCP guidelines, in the year 1982, International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects was proposed by the CIOMS in association with WHO [ 39 ]. The CIOMS protects the rights of the vulnerable population, and ensures ethical practices during clinical research, especially in underdeveloped countries [ 40 ]. In India, the ethical principles for biomedical research involving human subjects were introduced by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) in the year 2000 and were later amended in the year 2006 [ 41 ]. Clinical trial approvals can only be done by the IRB approved by the Drug Controller General of India (DGCI) as proposed in the year 2013 [ 42 ].

Current perspectives and future implications

A recent study attempted to evaluate the efficacy of adaptive clinical trials in predicting the success of a clinical trial drug that entered phase 3 and minimizing the time and cost of drug development. This study highlighted the drawbacks of such clinical trial designs that include the possibility of type 1 (false positive) and type 2 (false negative) errors [ 43 ].

The usefulness of animal studies during the preclinical phases of a clinical trial was evaluated in a previous study which concluded that animal studies may not completely guarantee the safety of the investigational drug. This is noted by the fact that many drugs which passed toxicity tests in animals produced adverse reactions in humans [ 44 ].

The significance of BE studies to compare branded and generic drugs was reported previously. The pharmacokinetic BE studies of Amoxycillin comparing branded and generic drugs were carried out among a group of healthy participants. The study results have demonstrated that the generic drug had lower Cmax as compared to the branded drug [ 45 ].

To establish the BE of the generic drugs, randomized crossover trials are carried out to assess the Cmax and the AUC. The ratio of each pharmacokinetic characteristic must match the ratio of AUC and/or Cmax, 1:1=1 for a generic drug to be considered as a bioequivalent to a branded drug [ 46 ].

Although the generic drug development is comparatively more beneficial than the branded drugs, synthesis of extended-release formulations of the generic drug appears to be complex. Since the extended-release formulations remain for longer periods in the stomach, they may be influenced by gastric acidity and interact with the food. A recent study suggested the use of bio-relevant dissolution tests to increase the successful production of generic extended-release drug formulations [ 47 ].

Although RCTs are considered the best designs, which rule out bias and the data/results obtained from such clinical research are the most reliable, RCTs may be plagued by miscalculation of the treatment outcomes/bias, problems of cointerventions, and contaminations [ 48 ].

The perception of healthcare providers regarding branded drugs and their view about the generic equivalents was recently analyzed and reported. It was noted that such a perception may be attributed to the flexible regulatory requirements for the approval of a generic drug as compared to a branded drug. Also, could be because a switch from a branded drug to a generic drug in patients may precipitate adverse events as evidenced by previous reports [ 49 ].

Because the vulnerable population like drug/alcohol addicts, mentally challenged people, children, geriatric age people, military persons, ethnic minorities, people suffering from incurable diseases, students, employees, and pregnant women cannot make decisions with respect to participating in a clinical trial, ethical concerns, and legal issues may prop up, that may be appropriately addressed before drug trials which include such groups [ 50 ].

Conclusions

Clinical research and clinical trials are important from the public health perspective. Clinical research facilitates scientists, public health administrations, and people to increase their understanding and improve preparedness with reference to the diseases prevalent in different geographical regions of the world. Moreover, clinical research helps in mitigating health-related problems as evidenced by the current Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic and other emerging and re-emerging microbial infections. Clinical trials are crucial to the development of drugs, devices, and vaccines. Therefore, scientists are required to be up to date with the process and procedures of clinical research and trials as discussed comprehensively in this review.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Clinical Trial Monitoring Reports and How to Write Them

Among the most important aspects of study is observation. Overseeing the advancement of any stage, measure, process, and procedure in real time is essential to the accurate conclusion of any clinical trial undertaking. Normal monitoring actions are needed to guarantee caliber, efficiency, compliance within predefined and regulations fundamentals. In addition, it guarantees comprehensiveness, and precision within clinical investigation. Such actions also ensure that the trial isn't just conducted in compliance with Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). They must also function to validate it is correctly reported and recorded. Consider enrolling in the Clinical Research Coordinator course or the CRA training provided by CCRPS.

There demands something vital as a part in the execution of trials. And this thing is known as trial development reports.

Such a report ought to be carefully prepared and it must summarize the means that a study is done. It also ought to point out recruiting progress and procedures; should emphasize and clarify adjustments to the analysis, and ought to point security issues. If you're involved in such reporting or need an in-depth understanding of the procedures, the Advanced Clinical Research Project Manager Certification might be of interest.

Aside from the ethics committee, researchers could also need to present yearly improvement reports of an investigation (such as any applicable alterations or dangers) to spouses, encouraging associations, and/or organizations, along with other interested parties if needed. To understand more about these requirements and get certified, the ICH-GCP course is an excellent resource.

If you're thinking about getting important skills on GCP or you also would like to upgrade your own know-how, subscribe to our comprehensive Good Clinical Practice class here .

In summary, tracking and reporting processes is an incredibly significant function in clinical trials. The right conduct of these procedures ensure compliance with legislation, regulations, and predetermined conditions. In addition, they make certain that the study doesn't pose any dangers to wellbeing. Progress reports, subsequently, empower practitioners, specialists, researchers, ethics committees, as well as others involved to keep a tab on the trial and its own advancement. Clinical professionals need to signal any alterations or risks to react to them timely, correctly, and efficiently. For further training, consider the Pharmacovigilance Certification to deepen your knowledge in monitoring drug safety.

The objective of progress reports would be to accumulate and outline upgrades, key facets, along with summaries of a continuing trial. It's very crucial to be aware that progress reports must be filed to institutional evaluation board/independent integrity questionnaire (IRB/IEC), following a trial that has obtained positive opinion.

One other important issue to mention is there are many different forms and when it comes to submitting progress reports that researchers must take into consideration before proceeding.

Precisely, these kinds are:

Printing name and date of entry ought to be composed also. A digital copy is also needed to be delivered to the interested websites and committees inside a 30-day interval following the reporting procedure was completed.