Arctic Tourism - More than an Industry?

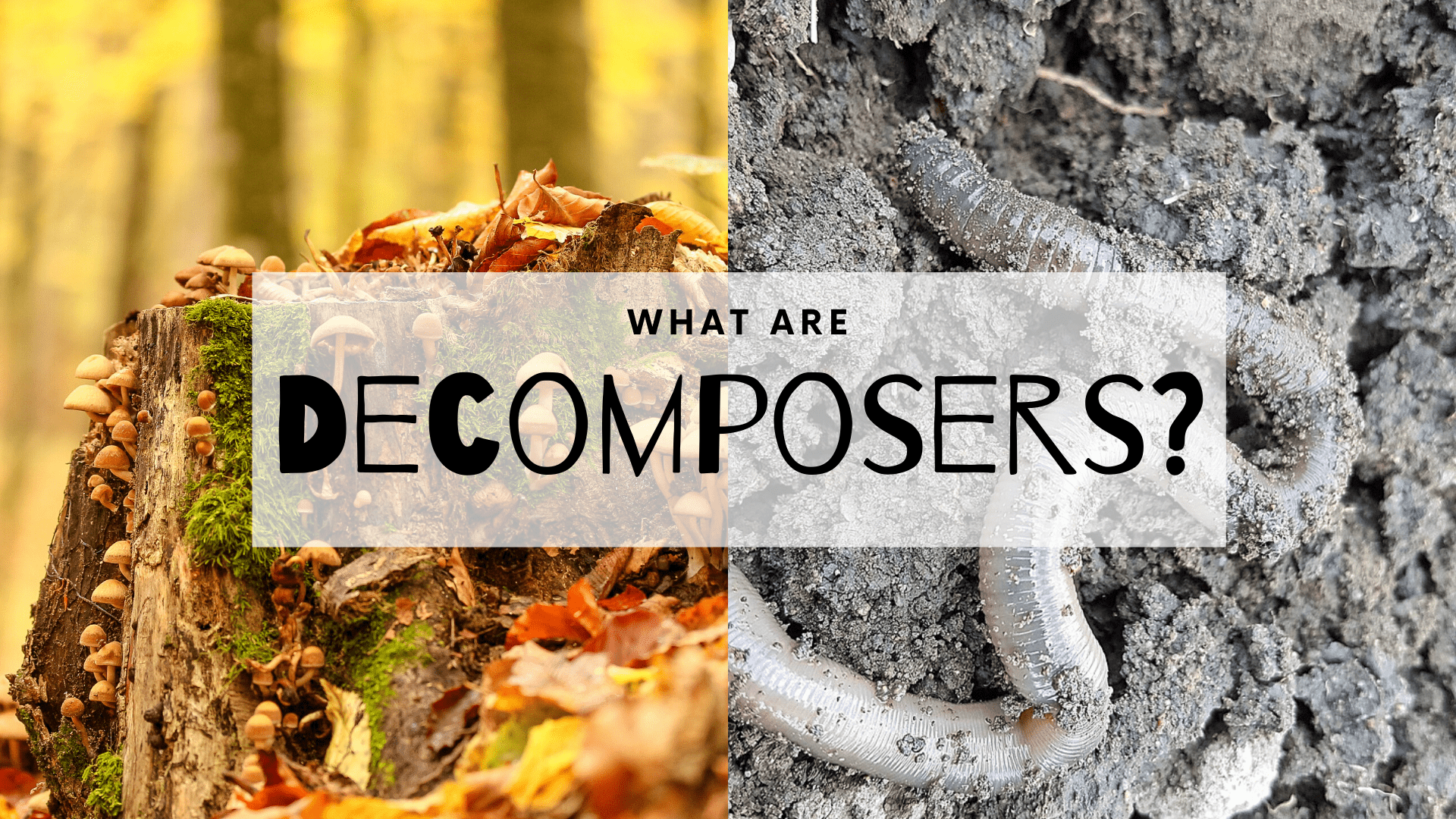

Overseeing Kangerlussuaq Airport, Greenland. Three more international airports are currently being planned in Greenland, partially to accommodate for more tourism. Photo: Carina Ren

In Greenland, politicians and businesses are hoping and planning for substantial growth in tourism. As the construction of three transatlantic airports draws closer, a broader societal discussion of how (much) tourism should be developed, in what ways, and by whom, is lacking. In this article, we show how tourism practitioners in Greenland perceive the challenges and potential posed by tourism and discuss how its development could be linked to other spheres of society—turning tourism from an industry into a potential catalyst for social change.

Arctic Tourism on the Rise

While tourist numbers in the Arctic are still relatively low in comparison to other parts of the world, 1) Mason P, Johnston M & Twynam D (2000) The World Wide Fund for Nature Arctic Tourism Project. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 8(4): 305-323 tourism is currently experiencing unprecedented attention in Arctic regions. Greenland is no exception to this trend. Successful marketing combined with a growing global interest in the Arctic has led to an increasing amount of tourists and; unsurprisingly, to a coinciding rise in political and societal interest in tourism.

Today, tourism is proposed as one of Greenland’s three economic pillars, next to fishing and mining, and as a promising lever for the Arctic nation’s future economic development. 2) Bjørst L R & Ren C (2015) Steaming Up or Staying Cool? Tourism Development and Greenlandic Futures in the Light of Climate Change. Arctic Anthropology 52(1): 91-101 Its successful development could potentially help pave the way for the Arctic nation’s independence from the Danish Commonwealth.

In the coming years, large infrastructure projects—partially triggered by a wish to facilitate transatlantic tourism—will require large-scale investments. While there is a continuous public debate about the location, building, and enlargement of the proposed three airports and several harbors, very little attention is given in public discourse to broader questions of tourism development.

For a community with less than 60.000 inhabitants, living conditions in Greenland are due to become affected as tourism numbers swell. In a research project conducted by Aalborg University mapping the current tourism landscape in Greenland, one of the interlocutors from a major travel agency voiced his concern: “Nobody has tried to sit down and to find out how we want it [tourism]. On what kinds of conditions and terms do we want this development?”.

Despite significant changes on the horizon, a discussion of how tourism should be developed, how much is desired, in what ways, and by whom, has until now remained absent.

A Fish called Tourism? Lessons from Iceland

This lack of concern about the impacts of tourism is surprising considering the proximity to Iceland, currently witnessing an explosive intake of tourists. While the two destinations are hardly comparable in terms of what they offer , their infrastructure, and their capacity, seeing the massive impacts that tourism has created on the neighboring nation could trigger some reflections. One could look to Iceland, for example, on how to understand the role and transformative capacity of tourism in society.

In his 2015 article “A Fish Called Tourism”, Icelandic tourism researcher Gunnar Thór Jóhannesson prophetically warned a euphoric Icelandic tourism industry on the dangers of thinking about tourism as yet another business opportunity. 3) Jóhannesson G T (2016). A Fish Called Tourism: Emergent Realities of Tourism Policy in Iceland. In van der Duim, R T, Ren, C & Jóhannesson, G T (eds.) Tourism Encounters and Controversies: Ontological Politics of Tourism Development. Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 181-200 In his account of how tourism evolved to be taken seriously as “a real business”, Jóhannesson describes how tourism was gradually taken up during the late 1990s as a solution to the continual crisis in the agricultural sector with farmers being offered financial support to turn from farming sheep and cows to “herding” tourists. Similar to the situation in Greenland today, tourism in Iceland seemed to offer a beam of hope as the traditional staples of the economy were in crisis.

Parallel to this development, the Icelandic Tourist Board convincingly transferred important vocabulary of fishery management to tourism, equating the export value of each tourist to a ton of cod, talking of “tourist stock” and depicting the airplanes of Icelandair as “trawlers”. This, Jóhannesson argued, helped position tourism in the discourse on the national economy as similar to and on par with fisheries and heavy industries.

While such an approach helps policy makers and investors to recognize tourism as a ‘real business’, the problem is that a narrative framing the tourism sector in terms of fisheries hides its complexity. Unlike fish, tourists do not stay in the oceans around Iceland, but interfere in good and bad ways with life on shore. In the context of tourism policy making, it is important to acknowledge the ways in which tourism activities are connected to the environment and visited societies and to view tourism as more than just another industry, similar to that of mining and fisheries.

Tourism: more than an Industry?

A similar argument can be found in the article “More than an ‘industry’: The forgotten power of tourism as a social force”. Based on historical document studies from international tourism organizations and councils, Australian tourism researcher Freya Higgins-Desbiolles depicts how tourism from its very early proliferation was seen as a way to facilitate social change and further intercultural understanding. 4) Higgins-Desbiolles F (2006) More than an “industry”: The forgotten power of tourism as a social force. Tourism Management 27(6): 1192–1208 As economic and industrial discourses continually exposed tourism to market forces from the mid-1900s, the dominant perception of tourism was successfully transformed into that of an industry.

As a result, tourism research and policy making are today overwhelmingly dedicated to the business side of tourism, viewing tourism as a strictly economic endeavor. However, as argued by Higgins-Desbiolles, tourism is not merely an industry but rather a social force with deep transformative capacities for societies, cultures, and the environment.

Jóhannessons’s and Higgins-Desbiolles’ attempt to revive and reinforce a wider vision of the role of tourism in local and global communities lead us back to the initial questions of how tourism as a social force could work as a catalyst for change in Arctic communities. How could tourism be mobilized in meaningful ways to help engage with local challenges in the Arctic? As discussions about sustainability unsurprisingly continue to grow in an Arctic context—and there is a push to incorporate society and the environment into economic development—planning for tourism in Arctic communities could be guided by more than market forces.

We turn to Greenland to exemplify how tourism is connected to societal challenges in the Arctic and how this might offer ways to rethinking tourism as something more than an industry in a Greenlandic context. We discuss three ways in which the development of tourism is linked to societal challenges: in the field of cultural heritage, within education, and in the area of entrepreneurship.

The examples are drawn from the research project “Tourism Development in Greenland – Identification and Inspiration” where Greenlandic tourism stakeholders in Kangerlussuaq, Sisimiut, Ilulissat, and Nuuk shared insights on how they work with and envision tourism. 5) Ren C & Chimirri D (2017) Turismeudvikling i Grønland: Afdækning og inspiration (Tourism Development in Greenland – Identification and Inspiration). Denmark: Aalborg University. Retrieved from: https://www.inside.aau.dk/digitalAssets/282/282589_turismeudvikling-i-groenland-rapport_endelig.pdf . Accessed on 17 January 2018

Cultural Heritage and Local Knowledge—New Possibilities in Tourism?

We find a powerful example of how tourism is connected to current societal challenges in the area of cultural heritage. While kayaks are less and less used for their original hunting purpose, local knowledge about them is still present and the tourist interest in kayak touring and building is increasing. By becoming part of tourism activities and a potential business, local knowledge is not only mobilized, but also contributes to the sustaining—and reconceptualization—of cultural heritage. This illustrates how tourism can play a crucial part in Arctic societies today in potentially re-activating local knowledge.

Tourism and community stakeholders work together; for instance, in integrating cultural heritage and local knowledge into local tourism products and experiences. At a visit to the UNESCO site Ilulissat Icefjord, its site manager noted the raising interest in Greenlandic kayaks: “There are people who travel from all over the world and want to do workshops on how to build a Greenlandic kayak. The interest in building Greenlandic kayaks is so high.[…] we can use this interest in building your own kayak and do offers here in Greenland”.

However, questions of risk, safety, and certification prevail: “[Locals] are more than qualified to take people out but the problem is they are not certified as sea kayak instructors, even though they know more about the kayak”. While official certification might function to assure the tourist of the highest degree of safety, integrating local knowledge, which has been passed down from generation to generation as informal non-certified skills, through certification is highly complex.

This raises the question of how to create a certification framework which acknowledges local knowledge and it’s anchoring in local cultural heritage, but also responds to standardized requirements. In this work to connect local knowledge and experience to the development of tourism products, tourism actors point to collaboration as central to their work. Collaboration offers them the possibility to build capacity and share knowledge. Collaborative activities also highlight the potential and value of informal knowledge based on acquired everyday skills.

The challenge of certification intersects with general concerns regarding the educational sector in Greenland. According to one tourism stakeholder, “one of the toughest social challenges in Greenland is education. We definitely need to have more people educated. Education is our guiding star right now. It has been for years and it will be for years. We have to do that in collaboration with companies and municipalities, with everybody”.

Another tourism actor supports this by saying that education “is the main challenge of all. We have been talking about tourism and the overall infrastructure, but one of the biggest challenges is education. That is something we can agree upon in the whole of the country”. So while education is crucial for developing stronger and more innovative tourism services and experiences, the specificities of tourism also calls for specific skills.

Good language skills are quintessential to operate successfully: “If you have problems with speaking English and Danish, it’s really difficult to operate a tourism business”. This rudimentary demand is paired with the expressed need for raising service levels and thus calls for improving the relatively low educational level in Greenland, where only ¼ of the population graduates from high school and little over 10% receive a college degree. 6) Naatsorsueqqissaartarfik/Greenland Statistics (2015) Befolknings uddannelsesprofil 2015 (Educational profile of the population). Retrieved from https://stat.gl/publ/da/UD/201604/pdf/2015%20Befolkningens%20uddannelsesprofil.pdf . Accessed on 17 January 2018

Campus Kujalleq, located in South Greenland, has developed new educational programs in Arctic tourist guiding, adventure guiding, and in hospitality and tourism management. Several informants from the public and private sector point to a climbing number of graduates as an example showcasing the interest in this field. According to a teacher it is also “a very popular education, attracting quite many and they all go out and find a job in tourism after [they have finished their studies]”.

By combining a tourism workforce training with a raising awareness of the role and (re)activation of local knowledge and informally acquired skills, 7) Kleist K V & Knudsen R J (2016) Sitting on gold: a report on the use of informally acquired skills in Greenland, Retrieved from: https://backend.orbit.dtu.dk/ws/files/126842966/Sitting_on_Gold_25._maj_2016.pdf . Accessed on 10 January 2018 tourism contributes to crafting new educational offers and an increasing interest in attaining post-secondary education.

Seeing and talking of tourism as an industry easily overlooks the clear connections between developing tourism, raising the educational level at a national level, and providing attractive educational and training opportunities. By linking the development of tourism to issues of education, we see its ability to supplement existing educational offerings for the young generation and contribute to future educational groundings as new career opportunities and paths in tourism open itself to new groups of young people.

Entrepreneurship

A representative from Corporate Social Responsibility Greenland raised concerns about the need to build local capacity in tourism by including new, younger actors: “If we want to develop tourism, it does not only happen with the people that are already involved. We also need to involve more young people. That way we can develop our own community in a sustainable way”. This touches upon a similar issue, entrepreneurship, which has so far received very little governmental attention.

Entrepreneurship is increasingly recognized on a global scale as an important factor in changing and developing societies. The last decade has witnessed an increasing focus on developing strategies for entrepreneurship education in a Nordic context. In Greenland however, limited experience has been made in this area. As stated in the report Nordic Entrepreneurship Islands, published by the Danish Foundation for entrepreneurship, the country has no national strategy or goals for entrepreneurship education, no ministry involvement or any national definition. 8) Reffstrup T & Christiansen S K (2017) Nordic Entrepreneurship Islands : Status and potential Mapping and forecasting Entrepreneurship Education on seven selected Nordic Islands. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers In spite of any governmental strategy, Greenlandic tourism actors at a local level point to an increased interest in entrepreneurship and link this to new opportunities created through the intensification of tourism. In the words of one: “Especially in tourism now, you can see a potential. It’s really moving forward. And people see that potential and start new things towards exploiting it”.

Tourism entrepreneurs in Greenland are typically small, often seasonal initiatives, offering services or products such as equipment, souvenirs, food products, or excursions. Their businesses are often characterized by collaboration. As stated by a tourism actor in West Greenland, this collaboration creates benefits beyond the often small business themselves: “When you have small entrepreneurs in a small community, everyone relies on the others, and we all take a little share of the cake”.

Tourism actors identify entrepreneurship in tourism as a potential lever to lifting Greenlandic businesses and communities. As stated by a tourism actor in Greenland, “we see more and more people getting into the tourism business, taking the guide education and we hear about people who are thinking of starting something new in Greenland, which is very positive”.

The tourism product is often composed of many different ‘subservices’ such as transportation, accommodation and catering to mention the most basic. In order to create and deliver tourism products, tourism actors therefore rely on each other and need to work together. An example on how entrepreneurial activities and collaboration emerge on a community scale comes from cruise tourism, where smaller villages in Northern Greenland often have the whole village involved. According to a cruise operator: “now when the cruise ships come in, the locals are all in their national costumes and everybody is selling small things, souvenirs. This is what they are doing now. That is what is needed. It’s not one or two operators in a small town; it needs to be the whole community”.

Developed collaboratively, tourism holds the potential to inspire new ways of thinking about and engage with local challenge. Emerging local tourism initiates show that education, entrepreneurship and community development are not issues separate from tourism, but are rather—as shown in these examples—intrinsically linked to them and that new opportunities in each of these areas could be developed together, rather than separately.

Expanding the Values of Arctic Tourism Development

Insights from tourism actors in Greenland display that tourism, as argued by Jóhannesson and Higgins-Desbiolles, is not merely an industry but a social force. Tourism is increasingly recognized as significant for the future economic development of Arctic communities, 9) Hall C M & Saarinen J (2010) Tourism and Change in Polar Regions: Climate, environments and experiences. Abingdon: Routledge but this should be accompanied by careful preparation. If planned with local challenges and resources in mind, tourism has much to offer to local communities, for instance in revaluing and activating cultural heritage, in assisting in recognizing and certifying local (informal) knowledge, raising the level of education, and stimulating and facilitating entrepreneurial activities.

The hands-on challenges and concerns of tourism stakeholders in Greenland display the acute need for strategic calls to action grounded in public involvement. Arctic tourism is not merely a fish-like resource to be “trawled” or mined but a powerful societal force to be carefully managed. Public discussion is needed on where tourism development is currently heading, how it could be planned and developed in the future, and how it might also be connected to other societal challenges as “more than an industry”.

Carina Ren is Associate Professor in Tourism and Cultural Innovation at the Tourism Research Unit at Aalborg University, Denmark, and is affiliated to AAU Arctic in connection to her current research on Arctic tourism development, in particular in Greenland. Daniela Chimirri is a PhD student on community-based tourism and collaboration in Greenland and is jointly affiliated to the Tourism Research Unit and the Center for Innovation and Research in Culture and Living in the Arctic at Aalborg University, Denmark.

References [ + ]

- NOEP Overview

- Research Team

- Privacy Policy

- NOEP History

Arctic Menu

- Shipping Data

- Fisheries Data

- Arctic Extractives

- Oil & Gas Data

- Minerals Data

- Aggregates Data

- Arctic Ecosystems

- Tourism Data

- Non-Market Studies

- Subsistence Economy

- Glossary of Terms

- Data Sources

- Ocean Economy

- Ocean Economy Statistics

- Coastal Economy

- Living Marine Resources

- Offshore Minerals

- Valuation Studies

- Value Estimates

- References & Tools

- Ports & Cargo Data

- About the Data

Demographics Menu

- Data Search

- Coastal Vulnerability Data

Offshore Menu

- Offshore Wind

- Ocean Hydrokinetic

- Costs and Impacts

- Database Search

- Links to Resources

- Papers & Reports

- OMB Ocean Budgets

- Ocean Time Series

Arctic Tourism

As sea ice has declined as much as 40% since satellite observation began in 1979, Arctic tourism has been increasing dramatically. Due to the harsh winter climates in the Arctic, tourism is currently only feasible during the summer months. During these months, visitors can explore endless days and a long list of outdoor activities. Nature based activities are most popular for international travelers. Visitors engage in self-guided tours, ship cruises, and eco-tours.

There is a wide range of activities for individuals to explore the spectacular landscapes and wildlife— skiing, kayaking, diving, dog-sledding, mountaineering, boating. While the increase in tourism will increase revenues to local Arctic economies, the dramatic increases of these activities may also cause some negative externalities to these pristine environments. With increased use we will see increases in development of infrastructure, increased pollution and waste, and harm to ecosystems.

Many organizations such as the Sustainable Arctic Tourism Association, the Arctic Council, and conservation groups are working to urge both governments and the tourism industry to insure that these touristic activities take into account the already fragile ecosystems of the Arctic in order to best protect it.

updated 29-Mar-2017

- Web Use Policy

© Copyright 2022, National Ocean Economics Program

Mar 31, 2022 Tourism in the Arctic: A Catalyst for Good or Bad?

The Arctic, a region extending from the North Pole into Canada, Greenland, the Faroe Islands, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States, has experienced global warming at twice the rate of the rest of the planet. The likely cause of such higher temperatures? Loss of sea ice. “When bright and reflective ice melts, it gives way to a darker ocean; this amplifies the warming trend because the ocean surface absorbs more heat from the Sun than the surface of snow and ice.” ( NASA ).

This year, the Arctic sea ice reached its seasonal peak growth on February 25 th , according to provisional satellite data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center , making it the tenth lowest in the 44-year history of recording such data. This year’s data continues a 15-year trend . At this rate, some modelers forecast that the Arctic could be ice-free part of the year before the end of this century .

Meanwhile, travelers flock to the Arctic for its nature and outdoor activities. A 2020 study examining social media data showed that summer tourism quadrupled, and winter tourism in the Arctic increased by an astronomic 600% between 2006 and 2016. The Arctic as a tourist destination is expected to continue an upward trajectory, with one article estimating 8.3 million tourists annually . These numbers will only increase as melting ice opens the waters during more months of the year to more passenger vessels, the number of which has already seen a 35% increase from 2103 to 2019 .

Polar bear with her yearling cubs against Arctic sunset

Traveling to destinations such as the Arctic to see the ice shelves or polar bears before they “disappear,” so-called “last chance tourism” by the media, may only intensify that demand. So how does this growing demand for travel to the Arctic impact an already fragile environment?

- Access to these areas by plane, cruise ship, car, mainly by international travelers, contributes to greenhouse gas emissions. A study of the 2018 polar bear viewing season in Churchill, Manitoba , estimated that tourism produced 23,017 t/CO2 in emissions, a sizeable increase from 2008.

- The popularity of specific destinations leads to crowding and trampling. Littering of natural sites, termed “overtourism,” diminishes tourists’ quality of experience. Quality of life for residents is reduced as well. The pandemic only exacerbated these issues. Iceland has become the poster child for “overtourism,” attracting millions of visitors annually , significantly exceeding its national population.

- While there are economic upsides to increased tourism across the Arctic, the impact on residents, particularly Indigenous Peoples, can be harmful – housing shortages, inflated property values, infringement on property and food resources, and more.

Can tourism and sustainability co-exist? Indeed, tourists are starting to demand this. In a recent study , 72% of people surveyed said that travel should “support local communities and economies, preserve destinations’ cultural heritage and protect the planet.”

Many tour companies operating throughout the Arctic now voluntarily comply with the WWF’s 10 Principles for Arctic tourism . Organizations such as the Arctic Council and its research organization, the University of the Arctic (UArctic), facilitate collaborative processes among the several Arctic States, Indigenous Peoples, and other varied regional interests to tackle sustainable tourism.

Photo by SeppFriedhuber

Despite these and other efforts to protect the Arctic, much more is needed to be done. We need to look no further than the other pole – the Antarctic, to focus on a very successful international treaty. There are few places in the world where there has never been war, where the environment is fully protected, and where research and scientific discovery have priority. The Antarctic Treaty has successfully protected the Antarctic and resolved international disputes since it was opened for signature in 1961. The Treaty provided that any party could call for a review conference after thirty years. But no party has called for such a review. All parties recognize the continuing strength and relevance of the original Treaty that established” a natural reserve, devoted to peace and science .” We now need an Arctic Treaty protecting the other pole for people, animals, and the environment.

The final frontier: how Arctic ice melting is opening up trade opportunities

With financial gains to be exploited, will the world have enough restraint to resist damaging this landscape? Image: Unsplash/Valeriia Bugaiova

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Nicolas LePan

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Arctic is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

- As Arctic ice melts, sea routes will stay navigable for longer periods, which could drastically change international trade and shipping.

- This chart shows the location of major oil and gas fields in the Arctic and the possible new trade routes through this frontier.

The Arctic is changing. As retreating ice cover makes this region more accessible, nations with Arctic real estate are thinking of developing these subzero landscapes and the resources below.

As the Arctic evolves, a vast amount of resources will become more accessible and longer shipping seasons will improve Arctic logistics. But with a changing climate and increased public pressure to limit resource development in environmentally sensitive regions, the future of northern economic activity is far from certain.

This week’s Chart of the Week shows the location of major oil and gas fields in the Arctic and the possible new trade routes through this frontier.

Have you read?

The arctic is now expected to be ice-free by 2040, battling arctic invaders may sound like a game, but it's one of the biggest threats to our environment, how vulnerable are arctic populations.

A final frontier for undiscovered resources?

Underneath the Arctic Circle lies massive oil and natural gas formations. The United States Geological Survey estimates that the Arctic contains approximately 13% of the world’s undiscovered oil resources and about 30% of its undiscovered natural gas resources.

So far, most exploration in the Arctic has occurred on land. This work produced the Prudhoe Bay Oil Field in Alaska, the Tazovskoye Field in Russia, and hundreds of smaller fields, many of which are on Alaska’s North Slope, an area now under environmental protection.

Land accounts for about 1/3 of the Arctic’s area and is thought to hold about 16% of the Arctic’s remaining undiscovered oil and gas resources. A further 1/3 of the Arctic area is comprised of offshore continental shelves, which are thought to contain enormous amounts of resources but remain largely unexplored by geologists.

The remaining 1/3 of the Arctic is deep ocean waters measuring thousands of feet in depth.

The Arctic circle is about the same geographic size as the African continent─about 6% of Earth’s surface area─yet it holds an estimated 22% of Earth’s oil and natural gas resources. This paints a target on the Arctic for exploration and development, especially with shorter seasons of ice coverage improving ocean access.

Thawing ice cover: improved ocean access, new trading routes

As Arctic ice melts, sea routes will stay navigable for longer periods, which could drastically change international trade and shipping. September ice coverage has decreased by more than 25% since 1979, although the area within the Arctic Circle is still almost entirely covered with ice from November to July.

Typically shipping to Japan from Rotterdam would use the Suez Canal and take about 30 days, whereas a route from New York would use the Panama Canal and take about 25 days.

But if the Europe-Asia trip used the Northern Sea Route along the northern coast of Russia, the trip would last 18 days and the distance would shrink from ~11,500 nautical miles to ~6,900 nautical miles. For the U.S.-Asia trip through the Northwest Passage, it would take 21 days, rather than 25.

Control of these routes could bring significant advantages to countries and corporations looking for a competitive edge.

Competing interests: Arctic neighbors

Eight countries lay claim to land that lies within the Arctic Circle: Canada, Denmark (through its administration of Greenland), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States.

There is no consistent agreement among these nations regarding the claims to oil and gas beneath the Arctic Ocean seafloor. However, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea provides each country an exclusive economic zone extending 200 miles out from its shoreline and up to 350 miles, under certain geological conditions.

Uncertain geology and politics has led to overlapping territorial disputes over how each nation defines and maps its claims based on the edge of continental margins. For example, Russia claims that their continental margin follows the Lomonosov Ridge all the way to the North Pole. In another, both the U.S. and Canada claim a portion of the Beaufort Sea, which is thought to contain significant oil and natural gas resources.

To develop or not to develop

Just because the resources are there does not mean humans have to exploit them, especially given oil’s environmental impacts. Canada’s federal government has already returned security deposits that oil majors had paid to drill in Canadian Arctic waters, which are currently off limits until at least 2021.

In total, the Government of Canada returned US$327 million worth of security deposits, or 25% of the money oil companies pledged to spend on exploration in the Beaufort Sea. In addition, Goldman Sachs announced that it would not finance any projects in the U.S.’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

The retreat of Western economic interests in the Arctic may leave the region to Russia and China , countries with less strict environmental regulations.

Russia has launched an ambitious plan to remilitarize the Arctic. Specifically, Russia is searching for evidence to prove its territorial claims to additional portions of the Arctic, so that it can move its Arctic borderline — which currently measures over 14,000 miles in length — further north.

In a changing Arctic, this potentially resource-rich region could become another venue for geopolitical tensions, again testing whether humans can be proper stewards of the natural world.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Nature and Biodiversity .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How nature positive start-ups are helping China build a carbon neutral economy

Yangjie (JoJo) Zheng and John Dutton

June 26, 2024

The world has a water pollution problem. Here’s how innovation can help solve it

Tania Strauss and Sundararajan Mahalingam

How can offshore wind be a nature-positive climate solution?

Xi Xie and Qin Haiyan

June 24, 2024

AMNC24: What to know about climate, nature and energy

Spencer Feingold

June 23, 2024

4 steps to jumpstart your mangrove investment journey

Whitney Johnston and Estelle Winkleman

June 20, 2024

Richer nations divided over climate crisis funding for poor countries, and other nature and climate stories you need to read this week

Michael Purton

June 19, 2024

March 13, 2015

Future Arctic: More Mining, More Shipping and More Tourists

As the Arctic thaws, northern nations dream of a new economy

By Benjamin Hulac & ClimateWire

ROVANIEMI, Finland—In one of this nation's northernmost cities and at the close of a winter that citizens here have called unusually mild, foreign ambassadors spoke of their nations' hope to do business in the Arctic, Finnish spokesmen outlined their plans to attract international money, and business owners burnished their cases for investment in the polar north.

"Nordic lights is a good example of business actually nowadays," Juha Mäkimattila, the chairman of the Lapland Chamber of Conference, said at a dinner for foreign guests Wednesday, with a slideshow of aurora borealis photographs thrumming behind him. "We can actually make money on the northern lights from people from new parts of the world."

At the two-day Arctic Business Forum, hosted by the Lapland chamber, delegations from more than 20 nations, most which do not border the Arctic Circle, said the tone reflected a robust appetite for economic expansion, natural resource extraction and an optimistic prognosis for strong tourist spending.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Meeting in a city that advertises itself on its website as "The Official Hometown of Santa Claus," most speakers alluded to environmental management but didn't get into the problems of melting permafrost or the additional threats of future oil spills or the loss of species.

On both days, the tone was bullish. Diplomats from global trade and economic powers signaled their governments' growing interest in Arctic transit and heavy shipping in the Arctic Ocean.

Business sugarplums Dorothee Janetzke-Wenzel, the German ambassador, said global coordination on trade, international politics and environmental maintenance is important for the Arctic's future.

She said Germany views the Arctic Eight—the five Nordic nations plus Canada, Russia and the United States—as the "main guardians of Arctic policy," and Arctic nations should create a "disaster response mechanism"—an international plan to respond to oil spills and other crises.

"What happens in the Arctic affects far more than the Arctic," she said. "We can work on the assumption that there will be new opportunities." But, she added, "there are also new challenges as the Arctic is growing in strategic and geopolitical challenges."

Pacing on a stage behind flags of several European countries (Italy, Germany, Poland, Ukraine, Great Britain and others), East and Southeast Asian nations (China, Japan, South Korea and Vietnam), and all eight Arctic nations and Australia, the Dutch ambassador said most of the Netherlands' business in the Arctic is coastal.

"We are not doing enough business here," said Ambassador Henk Swarttouw of inland Finland. "The Arctic is a very important strategy area and only becoming more so."

Due to climate change, he said, the Northwest Passage will become easier to navigate.

"There are also of course opportunities [that are] going to be opened by climate change," he said, adding that "there are more opportunities there than threats" regarding global climate impacts to the Arctic.

"We are working with our large companies," said Swarttouw, singling out Royal Dutch Shell PLC, "to increase fossil fuel extraction in the Arctic" in an environmentally friendly way.

'Opportunities' with LNG And Kenji Shinoda, the Japanese ambassador to Finland, said the "Arctic is becoming more and more promising for collaboration" between the two nations. The growth of shipping liquefied natural gas (LNG) through the Northern Sea route from Scandinavia to Japanese ports has been "impressive," and the Barents Sea, which cradles Scandinavia and Northwest Russia, is an "active and enticing region for various sectors."

"Now is not too early to start looking vigorously for these opportunities," Shinoda said.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development forecast in January says international freight movement will be 4.3 times larger in 2050 than it is today. Freight shipments will replace passenger transportation as the sector's top carbon emission source, according to the report.

Consumers in Asia, and China in particularly, are driving this demand.

Half of the world's busiest ports by volume are in China, Taiwan or Hong Kong, according to the International Association of Ports and Harbors. Import-export volume coming to and from Chinese shores has multiplied in recent years, too—skyrocketing from about 41,000 20-foot equivalent units (TEUs) in 2003 to more than 150,000 in 2012. (Shipping traffic for the world's ports is measured in TEUs, the industry standard. A 20-foot cargo container is 1 TEU, and a 40-foot container, the more common variety, represents 2 TEUs).

Malte Humpert, the director of the Arctic Institute and a maritime shipping expert, said shipping will play an outsized role in the region's future. However, he tempered notions that the Northern Sea Route—which connects Europe and Asia by wrapping around Russia's north—could soon replace more established routes.

"We have not yet seen a real container ship go through the Arctic," Humpert said. Lacking cargo, westbound container ships carry 52 percent ballast on their returns from Asia to Europe, he added, and harsh winter weather can damage cargo such as electronics. "That definitely raises some questions."

By comparison, 95 and 99 percent of traffic through the Suez and Panama canals is not ballast. And both traditional canals are being expanded for larger vessels—workers are deepening the Suez Canal and widening the Panama Canal, Humpert said—while the Northern Sea path can stifle ships with icy conditions.

"In general" in the Arctic regions, Humpert said, "it's very hard right now to build infrastructure."

Anchored to the falling Russian ruble Timo Rautajoki, the Lapland chamber's chief executive, conceded that worldwide economic trends—such as oil price shocks and a slowing domestic economy, which has been hamstrung by the decline of the Russian ruble and a slowing tourism industry from across the Russian border—have dragged down Finnish business.

"We've gone from Arctic idealism to Arctic realism" in the past three years, Rautajoki said.

By developing LNG as a fuel, mining in Sweden, tourism in Finland and tapping "know-how" about conducting business in cold climates, Finland and its neighbors can bring capital to the Nordic region, said Risto Penttilä, president and chief executive of Finland's Chamber of Commerce.

The Lapland Chamber of Commerce dismissed military conflict in Eastern Europe and economic instability in the eurozone as a long-term concern.

"The continuing financial crisis in Europe and the political tension caused by Ukraine have not impacted the development of the investment potential," Rautajoki said in a distributed statement.

"There is room enough for all businesses here," Rautajoki said. But he acknowledged the crises have "clearly postponed the start of projects."

Investment targets in northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Murmansk and Arkhangelsk areas of Russia are worth €197 billion ($208 billion), €50 billion more than 2014, according to the Lapland chamber.

Pekka Suomela, a spokesman for FinnMin, the Finnish Mining Association, said financial instability in the region has hurt the sector's bottom line. "We are suffering of the European economy and its developments," Suomela said of Finnish mining firms. It will take two to three years for the sector to recover from the condition, he estimated.

Construction at a 20-year low The director of the Confederation of Finnish Construction Industries also told listeners his industry's business has reached a 20-year low within the country but is more robust in other E.U. markets. Inflation for Finland year over year at the start of 2015 was minus 0.2 and minus 0.7 from December to January.

Government approval for extraction firms appears to have slowed mining plans nationwide. "The share price is always going down as we are waiting for permits," said Noora Raasakka, the environmental leader in Mawson Resources Inc., a Canadian mining company.

Since 1900, atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations have risen an average of 2.6 percent annually, though emission levels have ramped up significantly in recent decades. Arctic sea ice has steadily retreated since the 1970s, and some climate scientists project the Arctic may be ice-free in the summer within 20 to 30 years.

The limits of Arctic sea ice may reach an all-time low this winter, according to an analysis released February by the National Snow and Ice Data Center. Winter sea ice in February covered the smallest swath of territory since record keeping started in 1979, according to the NSIDC.

Asked about the potential environmental and financial risks to northern Finland and adjacent communities if the Arctic melted and threatened tourism, Penttilä, the Finland Chamber of Commerce president and chief executive, said the future is too unpredictable to make estimates.

"It's impossible to say," he told reporters at a lunch here. "Climate change may lead to more snow. There's such uncertainty regarding the outcome of climate change in this region."

Reprinted from Climatewire with permission from Environment & Energy Publishing, LLC. www.eenews.net , 202-628-6500

Arctic Marine Tourism: Development in the Arctic and enabling real change

Analyzing and promoting sustainable tourism across the circumpolar Arctic.

As Arctic marine tourism increases, how can we ensure it’s sustainable?

Project details, lead working groups, lead arctic states & permanent participants, engaged observers, start - end, circumpolar seabird expert group (cbird), marine protected areas (mpa) network toolbox, kola waste project.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Quantifying tourism booms and the increasing footprint in the Arctic with social media data

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected] , twitter@Claire_Runge

Affiliation Arctic Sustainability Lab, Department of Arctic and Marine Biology, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway

Roles Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Département de biologie, 'Université Laval, Québec, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing

- Claire A. Runge,

- Remi M. Daigle,

- Vera H. Hausner

- Published: January 16, 2020

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227189

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Arctic tourism has rapidly increased in the past two decades. We used social media data to examine localized tourism booms and quantify the spatial expansion of the Arctic tourism footprint. We extracted geotagged locations from over 800,000 photos on Flickr and mapped these across space and time. We critically examine the use of social media as a data source in data-poor regions, and find that while social media data is not suitable as an early warning system of tourism growth in less visited parts of the world, it can be used to map changes at large spatial scales. Our results show that the footprint of summer tourism quadrupled and winter tourism increased by over 600% between 2006 and 2016, although large areas of the Arctic remain untouched by tourism. This rapid increase in the tourism footprint raises concerns about the impacts and sustainability of tourism on Arctic ecosystems and communities. This boom is set to continue, as new parts of the Arctic are being opened to tourism by melting sea ice, new airports and continued promotion of the Arctic as a ‘last chance to see’ destination. Arctic societies face complex decisions about whether this ongoing growth is socially and environmentally sustainable.

Citation: Runge CA, Daigle RM, Hausner VH (2020) Quantifying tourism booms and the increasing footprint in the Arctic with social media data. PLoS ONE 15(1): e0227189. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227189

Editor: Wenwu Tang, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, UNITED STATES

Received: June 14, 2019; Accepted: December 9, 2019; Published: January 16, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Runge et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data underlying the results presented in the study are available from Flickr ( www.flickr.com ). To aid decision-making we have made the code, rasters and maps of tourism intensity across the Arctic and tables of the footprint across time publicly and freely available for download at doi: 10.18710/QEOFPY .

Funding: The work was funded by grants awarded to VHH from FRAM - High North Research Centre for Climate and the Environment through the Flagship MIKON (Project RConnected; https://www.framcentre.com/ ) and the Arctic Belmont Forum Arctic Observing and Research for Sustainability (Project CONNECT; https://www.belmontforum.org/ ). The Norwegian collaboration was financed by Norwegian Research Council grant 247474 ( https://www.forskningsradet.no/en ). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The number of tourists visiting the Arctic has increased dramatically over the past two decades [ 1 , 2 ], reflecting a rise in tourism globally over the past 50 years [ 3 ]. While this could bring alternative livelihoods to Arctic communities, concerns over the social and environmental sustainability of the rate and scale of the tourism boom are growing across the Arctic [ 4 – 6 ]. Tourism can have both positive and negative impacts on the natural environment and on host communities. Direct effects of tourism (e.g. transporting, accommodating, and feeding tourists) and the indirect socioeconomic change brought about by the tourism industry (e.g. influx of seasonal workers) drive increased habitat loss [ 7 ], resource use, and carbon emissions [ 8 ] across the world, in addition to the localized consequences of nature-based tourism and recreation activities on the natural environment, such as injury, death, or disturbance of wildlife or damage to vegetation [ 9 ]. Understanding, at a local scale, how and where tourism booms are distributed across landscapes is crucial for conserving Arctic environments and for managing impacts on host communities.

A major challenge for planning and managing sustainable tourism growth in the Arctic lies in the difficulties of mapping where tourists go and how they use landscapes and ecosystems. Data on spatial visitation and trends is sparse in the Arctic. While statistics on hotel stays and transport use are now commonly collected by government and tourism management organizations, data on where tourists go during the day and what they do there is rarely collected.

Social media provides a useful source of information on tourist visitation patterns to better pinpoint the needs of tourists and target actions to manage tourism impacts [ 10 ]. Passively crowdsourced and high resolution information from social media (volunteered geographic information; VGI) can be used to rapidly generate maps of the multiple destinations visited by tourists across large areas and over time [ 11 ]. Social media data has been well demonstrated to be useful for mapping and monitoring at a range of spatial scales across the world. Such data has been used to map the distribution of tourists in protected areas [ 12 – 14 ], and within cities [ 11 ] and can be used to inform a variety of aspects of tourism and landscape management, including to identify peaks of visitation to attractions [ 15 , 16 ], map environmental impacts [ 17 ] and to estimate the landscape values, nature-based experiences and ecosystem services appreciated by tourists [ 18 – 20 ]. Most of these studies use the social media platform, Flickr, which has been shown to correlate well with visitor statistics at different scales [ 12 , 15 , 16 , 21 ].

Similar to many nature-based tourism destinations in developing countries, parts of the Arctic in Scandinavia, Iceland, Faroe Islands and Alaska have experienced unprecedented growth in the number of tourists in recent years, and Greenland, Canada and the Russian Arctic are likely to be the next tourism frontiers [ 22 , 23 ]. Rapid and localized booms in tourism can overwhelm local capacity (and desire) to host visitors, particularly in small, remote communities such as those found in the Arctic and many parts of the developing world [ 23 – 26 ]. The ability to rapidly identify sites in the early stages of a boom would support better adaptation and planning to pre-emptively address many of the sustainability challenges brought about by rapid increases in nature-based tourism. It would allow local communities and national tourism organizations to proactively direct resources to sites where special management such as provisioning of restrooms and waste disposal, better signage, safety and disaster management, parking, and trail maintenance may be required. Social media data has been demonstrated as an early-warning system for rapidly detecting booms and busts in such diverse applications as disaster management [ 27 , 28 ] and disease control [ 29 ]. Methods for such ‘event detection’ are rapidly evolving [ 30 , 31 ]. These methods rely on large amounts of high temporal resolution data (‘big data’). The suitability and limitations of social media data for detecting events in data-sparse regions has yet to be tested. We investigate whether Flickr data can be used as an early warning system to detect localized booms in tourism in the Arctic and similar data-deficient regions.

Tourism growth can influence the spatial use of landscapes in various ways. Here, we demonstrate how the tourist footprint on Arctic landscapes has changed over the past 14 years at a pan-Arctic scale, and examine the management implications of those changes. We test two hypotheses drawn from theories of tourism and economic geography [ 32 , 33 ] 1) that tourists visit the same sites through time (overall footprint is unchanged but magnitude of use at each site has increased) 2) that tourists have spread throughout the landscape (overall footprint increased but magnitude of use at any one site is constant). These two patterns of tourism growth have very different implications for both the social and environmental sustainability of tourism and the satisfaction of the tourist experience. For instance, if tourists avoid busy areas and self-segregate across landscapes [ 34 ], environmental and social impacts will be more widespread but lower intensity. Alternately, the negative impacts of tourism can be localized by channeling tourists into high use sites and away from sensitive communities and ecosystems. We examine seasonal differences in the spatial patterns of Arctic visitation, and explore how infrastructure such as roads, airports and ports influences these patterns, with a view to informing how upcoming infrastructure development could contribute to tourist growth.

Materials and methods

Extraction of data from flickr.

We first extracted geotagged and publicly shared photo metadata for over 2 million photos from Flickr ( www.flickr.com ) for the region north of latitude 60°N. Photo metadata included location and date that each photo was taken, user id (key coded by Flickr), image URL, Flickr- and user- generated image tags, and user-generated image title. Data was extracted from the Flickr API ( https://www.flickr.com/services/api/ ) on 4 December 2017. Due to an issue with the data download we re-extracted photos for Iceland (bounded by -27° to -12° longitude and 62° to 68° latitude) on 11 January 2018. Hourly metrics of the number of photos uploaded to Flickr globally between to January 1 2004 and December 31 2017 were obtained from the Flickr API on 07 May 2018. We used the R package ‘flickRgeo’ [ 35 ] which provides an R wrapper for the Flickr API.

For the purposes of this study we define our study region, ‘Arctic’, as the region bounded by the Arctic Council AMAP boundaries [ 36 ] and confined to areas north of latitude 60°N. We constrain the study region using an environmental rather than political definition as the study is focused primarily on impacts on Arctic landscapes. We excluded photos from the extracted dataset that were taken outside this study region. We also excluded photos that were missing urls or geotag coordinates, had null coordinates (0,0), and photos taken prior to January 1 2004, or after December 31 2017. We excluded photos by users with only 1 or 2 photos within the study region as they are likely to represent people who are just trialing Flickr by uploading a random photo rather than a photo representing a genuine tourist. These ‘test users’ account for approximately 36% of users in the Flickr dataset but just 0.95% of photos. Further details on the choice of 2 photos as a threshold for exclusion are included in S1 Appendix . The final dataset contained a total of 805,684 geotagged photos with metadata from 13,596 unique users.

Mapping the seasonal distribution of Arctic tourism

To map the relative intensity of visitation across the Arctic in summer and winter, we first created square spatial grids (rasters) at 10km and 100km resolutions. We then calculated the photo-unit-days in each grid cell for summer and for winter aggregating data for each season across all years (2004–2017). We defined the months of May to October as ‘summer’ and November through April (of the following year) as ‘winter’ (e.g. “winter 2016” includes the months November and December in 2016 and January through April in 2017). Photo-unit-days (PUD) is an established metric of tourism visitation [ 15 ] that accounts for the biases in social media data introduced by differences in the number of photographs uploaded by different users. For example, three PUD can represent either a site visited on three separate days throughout the year by a single person, or by three separate people on a single day. This is the conventional approach for working with this type of social media data because it corresponds to empirical user data collected by tourism sites that are often based on daily user access fees. For example, if three users access a park with daily user access fees on the same day, or a single user accesses that park on 3 separate days, both visitation scenarios appear identical in terms of empirical visitation rates (i.e. fees collected) as well as PUD.

Pan-Arctic trends in the footprint of Arctic tourism over time

To quantify the ‘footprint’ of Arctic tourism (the percentage of the Arctic visited by tourists), we created a hexagonal spatial grid covering the entire Arctic with a 5km diameter resolution. We chose this resolution after examining the trade-off between commission errors and computing efficiency ( S2 Appendix ). We allocated each cell a value of 1 (visited) if any user had taken a photograph in that cell in a given year (2004–2017) and season (summer, winter), and 0 (unvisited) if not. The number of people using Flickr globally changed over time as the popularity of the platform waxed and waned. Relying on raw metrics of the number of Arctic Flickr users, photographs or photo-unit-days will thus result in biased estimates of tourism trends across time. The global and Arctic trends in Flickr use across time and the number of photos sampled in each year can be found in S3 Appendix . We calculated the footprint in three ways. Firstly, the Uncorrected Arctic footprint uses all available Flickr records (566205 summer; 228667 winter) and shows the full extent of Flickr users’ footprint, but includes the bias from the global change in Flickr usage between 2004 and 2017. The Global-bias corrected subsample removes the global pattern of Flickr usage to represent a less source-biased view of the rise in the footprint of tourism in the Arctic. This was done by selecting a random sample of Arctic photos based on the change in number of photos submitted to Flickr globally using 2004 values as a baseline. For example, the year with the lowest global usage (2004), we kept all the photo records. If the global Flickr usage doubled in a particular year relative to 2004, we sampled half of the available records for that particular year. The number of records sampled for each month can be found in Table S3 Appendix (total 36546 summer records, 12262 winter). Finally, the Equal sample size also removes the global bias and provides a measure of the change in the relative footprint per-tourist across time. This was done by randomly selecting an equal number of photographs for each year from which to calculate the footprint (total 15652 records summer, 4018 records winter). Numbers for 2017 should be treated with caution and are likely underestimates as we extracted data from the Flickr API on 4 December 2017 and the average lag time between photos being taken and uploaded is 2 weeks, but can be longer [ 13 ].

Modelling the influence of accessibility on seasonal patterns of Arctic landscape use

The location of airports, ports and populated areas, and country boundaries were extracted from Natural Earth ( www.naturalearthdata.com ) using the R package ‘rnaturalearth’ [ 37 ]. Roads were extracted from Global Roads Inventory Project [ 38 ]. Protected area boundaries were drawn from CAFF [ 39 ] and supplemented with data from Protected Planet [ 40 ]. We ran separate models for summer and winter as the presence of snow and ice limits access to rural areas in winter. The summer model had 90,750 cells with no photos, and 6,554 with photos. The winter model had 93,990 cells with no photos, and 3,314 with photos.

Local trends (booms and busts) in Arctic tourism

We investigated the suitability of Flickr data to be used to identify local booms and busts in tourism in the Arctic, a data deficient region. We first divided the landscape into a square grid cells and calculated the photo-unit-days in each cell for each year. We then performed linear regression modelling to identify trends in PUD in each cell between 2012 and 2017 and test their statistical significance. We ran models for cell diameters ranging from 500m to 100km to examine the effect of data availability on trend detection. We modelled only cells that were visited in at least two of the six years between 2012 and 2017. This timeframe was chosen as global Flickr usage remained reasonably constant during this period (Fig A in S3 Appendix ).

Unless otherwise stated, all analysis was conducted in R version 3.4.2 [ 41 ] using the ‘tidyverse’ [ 42 ], ‘sf’ [ 43 ], and ‘mgcv’ [ 44 ] packages. All spatial data was projected to North Pole Azimuthal Lambert equal area (EPSG:102017) for analysis. Code associated with the project is available at doi: 10.18710/QEOFPY .

Increase in Arctic summer and winter tourism footprint

We find that the overall footprint of tourism and area used per tourist has increased since 2004 ( Fig 1 ). In the 10 years between 2006 and 2016, the uncorrected footprint increased from 0.066% to 0.385% of the Arctic in summer and 0.015% to 0.173% in winter. After correcting these figures to account for the increased proportion of tourists captured in the analysis over that time (i.e. accounting for the rise in Flickr use globally), the footprint increased by 374% in summer (0.029% of Arctic in 2006, 0.109% in 2016) and 634% in winter (0.006% of Arctic in 2006, 0.036% in 2016). The relative-footprint-per-tourist also increased over that period (summer: 0.028% of Arctic in 2006 to 0.043% in 2016; winter: 0.007% in 2006 to 0.012% in 2016). We caution that this metric is not the absolute per-tourist footprint, rather it should be interpreted as a relative indication of how the footprint of a fixed (and unquantified) number of tourists has changed across time. These estimates are robust to uncertainty introduced by random sampling in the Global-bias corrected and Equal sample size methods ( S4 Appendix ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

The total footprint of Arctic tourism measured from Flickr data increased between 2004 and 2017 ( Uncorrected Arctic footprint , darker blue), even after adjusting for the global rise in Flickr use during this period ( Global-bias corrected , green). The relative footprint per tourist ( Equal sample size , pale blue) also increased slightly over this time. Similar trends are seen in summer and winter, though the tourism footprint in winter is approximately half the magnitude of that in summer. The footprint is defined as the percentage of 5 km hexagonal grid cells within the Arctic region visited by at least one Flickr user per year. The 2017 decline should be interpreted with caution as it may in part be an artefact of the timing of our data download and the lag between photos being taken and their being uploaded to Flickr.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227189.g001

Growth in Arctic visitation over time

The total number of photos on Flickr increased between 2004 and 2017, both globally and in the Arctic. Global uploads of photos to Flickr steadily increased between 2004 and 2008, slowed between 2008 and 2012 before a slight upsurge in 2012, plateaued between 2013 and 2015 and has declined slightly since then (Fig A in S3 Appendix ). The Arctic represents an increasing share of Flickr’s yearly photo traffic (Table in S3 Appendix ). The number of photos uploaded in the Arctic shows an exponential growth between 2004 and 2013, and has remained roughly steady since then (Fig B in S3 Appendix ), with this trend overlaid on a seasonal trend in visitation (Fig C in S3 Appendix ). Across the Arctic, July and August were the most popular months to photograph the Arctic (Fig D in S3 Appendix ). Nonetheless, a large number of users visited during the Arctic winter ( Table 1 ; 29.8% of all photos; 40,272 photo-unit-days, 53.3% of summer PUD). At the extreme, visitation in Greenland is concentrated in the summer months (91% of photos). In contrast to the rest of the Arctic, visitation in northern Finland peaks in winter (61.3% of photos). Winter and Christmas are a key part of the branding of tourism to northern Finland, and places such as ‘Santa Claus’s village’ in Rovaniemi, Lappland, attract the majority of the visitors to the region ( Fig 2 ). These metrics of Arctic visitation derived from Flickr show good agreement with official metrics of tourism visitation ( S1 Table ), consistent with previous research on social media data [ 12 , 15 , 21 ].

The guide maps (right) are displayed at 100km resolution. Spatial patterns of tourism are strongly governed by air, road and sea access, with few tourists venturing far from populated areas in winter. A photo-unit-day value of 14 corresponds to one Flickr user visiting the cell per year. Country borders are modified from Natural Earth CC PD.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227189.g002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227189.t001

Flickr data not suitable as early-warning system

We investigated the potential for Flickr data to be used to identify local trends in tourism over time. The Arctic is a data-poor region and we found that only a small number of places were photographed more than once per year (Fig in S2 Appendix ). Only 22 10km grid cells were visited by Flickr users more than 50 times (i.e. once a week) in 2017. Although annual tourism growth is documented as ranging from 5–20% across the Arctic, due to these data limitations regression models of trends in visitation between 2012 and 2017 were able to detect significant trends at just a handful of sites ( S1 Fig ). Most sites lacked sufficient data to detect trends even when aggregated to 10km grid cells, a relatively large scale compared to the scale required for management decisions.

Spatial patterns of Arctic visitation change across the seasons

The spatial pattern of tourists’ landscape use differed between summer and winter. Flickr users ventured further north and into marine areas to a greater extent during the summer months ( Fig 2 ). Visitation was influenced by access and often, though not always, concentrated in recognized tourism hotspots ( Fig 2 ). The main hotspots of tourism fall along coastal roads in Iceland, in the fjords and islands of northern Norway, and in protected areas and along roads in North America ( Fig 2 ). We note that although the size of the Alaskan tourism market eclipses that of the rest of the Arctic, including Iceland, few cruises travel further north than Anchorage (61.2°N), and the majority of this tourism thus falls outside our study region which is bounded to the south at 60°N.

Accessibility drives Arctic visitation

We found that accessibility has a significant effect on the distribution of Flickr users throughout the Arctic, with the presence of tourists decreasing rapidly as distance from transport infrastructure and populated areas increases, and increasing with the length of road in a given cell ( Table 2 ). The summer accessibility model explained 47.3% of the deviance in the presence of tourists (adjusted R 2 0.448, AIC 25347). The winter accessibility model explained 51.4% of the deviance in the presence of tourists (adjusted R 2 = 0.436, AIC of 14117). The variable square root of length of road in cell had the largest explanatory power of the accessibility variables (model without this variable had adjusted R 2 0.409 summer, 0.393 winter, deviance explained 44.7% summer, 48.8% winter). The protected area term of the winter model was significant (p = 0.000670) in the full model, but not significant in more parsimonious models. Removal of this term only slightly decreased the deviance explained (ΔAIC = 9, Δdf = -1.0239, Δdeviance = -10.706, Pr(>Chi) = 0.001117), indicating that tourists were no more or less likely to visit protected areas than non-protected areas in winter. All other terms were significant in both models. We removed the variable that had the least explanatory power, log distance to port , from the summer model, and the winter model without the protected area term. This reduced the model fit of the summer model (ΔAIC = 145, Δdf = -1.0881, Δdeviance = -146.57, Pr(>Chi) = 2.066x10 -16 ) but had minimal effect on the winter model (ΔAIC = 25, Δdf = -1.1028, Δdeviance = -27.406), though the large number of data points in the model meant that this variable was significant at 95% confidence (2.02x10 -7 ). Removal of all other terms substantially decreased the deviance explained by the models. Visual examination of model residuals did not reveal any residual spatial autocorrelation in any of the models. Plots of model fit and partial plots of model variables are included in S5 Appendix .

The intercept represents Norway, unprotected. The protected area term was not included in the winter model.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227189.t002

The footprint of tourism on the Arctic environment has almost quadrupled over the past decade, from 0.03% of the Arctic in summer 2006 to 0.11% of the Arctic in summer 2016 ( Fig 1 ), and the winter footprint has increased by over 600%. Despite this dramatic expansion, large areas of the Arctic still remain free from tourists ( Fig 2 ). Arctic tourists tend to congregate in a handful of highly visited sites ( Fig 2 ) with a long tail of places that are visited only occasionally, following the power law seen in other parts of the world [ 45 ]. The recent tourism boom across the Arctic has led to widespread concerns over the effects of tourism on Arctic ecosystems and communities, and the sustainability of Arctic tourism [ 4 , 5 ]. Arctic tourism is often marketed around ideas of pristine, untouched nature, and the overall growth in tourist numbers and the concurrent increase in infrastructure to support that growth presents challenges for maintaining environmental and social sustainability. There are indications that many popular sites are reaching capacity, and that tourists are beginning to experience disappointment and frustration around the large number of visitors present [ 46 ]. The footprint per tourist has also increased ( Fig 1 ), indicating that tourists are now visiting a wider variety of places. This may be either due to self-segregation by tourists seeking an undisturbed experience [ 46 ], or the marketing of a wider variety of tourist attractions and nature-based activities as Arctic tourism matured over the past decade [ 47 ].

These patterns of visitation present both advantages for the management of tourists and challenges for the sharing of the economic benefits of the recent and ongoing Arctic tourism boom. Management of tourists and their impacts is often easier where they congregate in a few small areas as resources can be allocated to these high priority areas bringing economies of scale. This is particularly important in small, rural communities where both human and financial capacity to manage tourist impacts can be limited [ 24 ]. Though environmental impacts can be locally high in these well-visited areas, requiring thoughtful management, aggregation of tourists in a few small areas can reduce the impacts of tourism across the wider landscape and channel resources into efficient management at the high use sites to sustain tourist satisfaction despite crowding. Channeling visitors into such ‘sacrificial sites’ may have net benefits at the landscape scale in places like the Arctic, where wildlife and vegetation are highly sensitive to disturbance and take a long time to recover from human impacts.

The tourism footprint is strongly associated with access, and is particularly dependent on the presence of roads and airports. This is not surprising, but important to keep in mind when planning for growth in tourism. The proposed construction of three transatlantic airports in Greenland has a high potential of boosting tourism in host communities that do not have sufficient capacity to sustainably manage this growth. The sustainability of tourism in Greenland, and similar developing places around the world depends heavily on building community capacity that sustains natural resources and local culture, and that protects vulnerable sites and species from the expansion of tourists into new locations [ 6 ]. The spatial extent of the winter footprint of tourism is about 40% lower than that in summer, with tourists gathering closer to airports and towns. Managers therefore need to be especially aware of the expansion of tourists into vulnerable sites and the greater use of protected areas in the summer season. Ports have only minimal influence on the presence of tourists on land.

While social media data may be useful for rapidly detecting localized booms in tourism in highly visited regions [ 48 ], our analysis indicates that Flickr data is of limited use for identifying local tourism booms in data deficient regions such as in the Arctic. Low rates of visitation across most of the Arctic combined with the small proportion of visitors that use Flickr [ 15 ] means that just a handful of Arctic locations are visited by Flickr users more than once a month (Fig C in S1 Fig ). One of the few regions where we detected statistically significant increases in visitation was the Lofoten islands of northern Norway. There, our analysis confirmed qualitative trends already noticed by tourism agencies in the region. Twitter has a higher user base and may be a better source of fine-scale temporal data in the parts of the Arctic with high-speed mobile data coverage [ 18 , 49 , 50 ]. Changes in ownership of the social media platforms and changes to data access rules means social media data from other suitable platforms such as Panoramio and Instagram were no longer freely available to academic researchers at the time of analysis. Quantitative analysis of social media data requires specialized computing and technical skills that are not normally available to local tourism management agencies. Maintaining dialogue between tourism management bodies and local communities and tour operators remains the most pragmatic way to detect and respond to fine-scale tourism trends in areas where data and technical capacity are limited.

Conclusions

The recent and rapid increase in the footprint of tourists on the Arctic that we document here is concerning. Upcoming investments in transport infrastructure in places like Greenland and the promotion of remote areas of the Arctic as tourist destinations, such as Franz Josef in Russia, will drive a further expansion of the tourist footprint in this unique part of the world. Destinations are also increasingly been marketed as ‘last chance tourism’ attracting visitors to venture into previously unexplored areas to experience Arctic ecosystems and species at risk of disappearing [ 4 , 51 ]. For instance, in Hudson Bay in Canada the small community of Churchill where polar bears spend increasingly more time on shore due to climate change, have experienced a rapid influx of tourists [ 4 ]. Wildlife viewing of vulnerable species, such as polar bears, narwhals and beluga whales, is putting additional pressure on species threatened by climate change [ 52 , 53 ]. Our high resolution and seasonal maps of Arctic tourism allow tourist management bodies and environmental organizations to pinpoint the places visited by tourists and the relative magnitude of visitation across the Arctic and to detect landscape-wide trends in visitation that need to be managed. Strategic and thoughtful assessment of whether this ongoing growth in Arctic tourism is sustainable or desirable for Arctic ecosystems and communities is urgently required.

Supporting information

S1 appendix. sensitivity analysis of photo exclusion threshold..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227189.s001

S2 Appendix. Sensitivity analysis of resolution.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227189.s002

S3 Appendix. Global and Arctic Flickr trends.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227189.s003

S4 Appendix. Uncertainty around footprint estimates.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227189.s004

S5 Appendix. GAM model performance.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227189.s005

S1 Fig. Annual maps of tourism growth.