Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

The grand tour.

Marble sarcophagus with the Triumph of Dionysos and the Seasons

Piazza San Marco

Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal)

Autre Vue Particulière de Paris depuis Nôtre Dame, Jusques au Pont de la Tournelle

Jacques Rigaud

Imaginary View of Venice, houses at left with figures on terraces, a domed church at center in the background, boats and boat-sheds below, and a seated man observing from a wall at right in the foreground, from 'Views' (Vedute altre prese da i luoghi altre ideate da Antonio Canal)

The Piazza del Popolo (Veduta della Piazza del Popolo), from "Vedute di Roma"

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Vue de la Grande Façade du Vieux Louvre

View of St. Peter's and the Vatican from the Janiculum

Richard Wilson

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768)

Anton Raphael Mengs

Modern Rome

Giovanni Paolo Panini

Ancient Rome

Portrait of a Young Man

Pompeo Batoni

Gardens of the Villa d'Este at Tivoli

Charles Joseph Natoire

Veduta dell'Anfiteatro Flavio detto il Colosseo, from: 'Vedute di Roma' (Views of Rome)

View of the Villa Lante on the Janiculum in Rome

John Robert Cozens

The Girandola at the Castel Sant'Angelo

Designed and hand colored by Louis Jean Desprez

Dining room from Lansdowne House

After a design by Robert Adam

The Burial of Punchinello

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo

Portland vase

Josiah Wedgwood and Sons

Jean Sorabella Independent Scholar

October 2003

Beginning in the late sixteenth century, it became fashionable for young aristocrats to visit Paris, Venice, Florence, and above all Rome, as the culmination of their classical education. Thus was born the idea of the Grand Tour, a practice that introduced Englishmen, Germans, Scandinavians, and also Americans to the art and culture of France and Italy for the next 300 years. Travel was arduous and costly throughout the period, possible only for a privileged class—the same that produced gentleman scientists, authors, antiquaries, and patrons of the arts.

The Objectives of the Grand Tour The Grand Tourist was typically a young man with a thorough grounding in Greek and Latin literature as well as some leisure time, some means, and some interest in art. The German traveler Johann Joachim Winckelmann pioneered the field of art history with his comprehensive study of Greek and Roman sculpture ; he was portrayed by his friend Anton Raphael Mengs at the beginning of his long residence in Rome ( 48.141 ). Most Grand Tourists, however, stayed for briefer periods and set out with less scholarly intentions, accompanied by a teacher or guardian, and expected to return home with souvenirs of their travels as well as an understanding of art and architecture formed by exposure to great masterpieces.

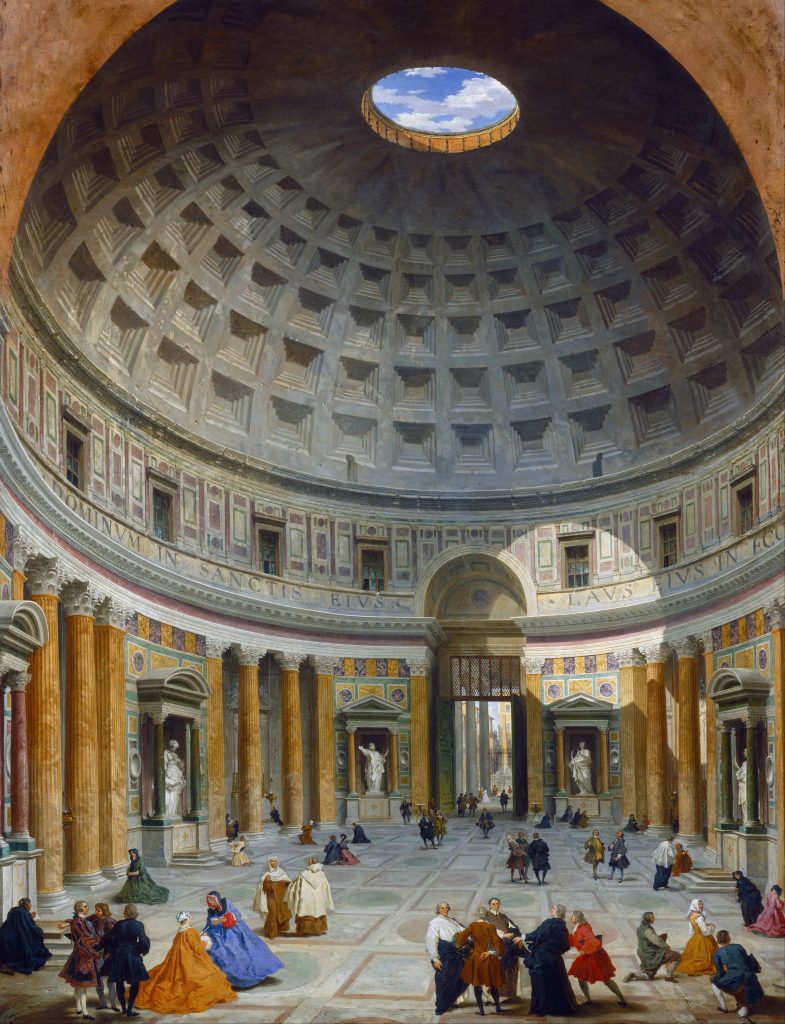

London was a frequent starting point for Grand Tourists, and Paris a compulsory destination; many traveled to the Netherlands, some to Switzerland and Germany, and a very few adventurers to Spain, Greece, or Turkey. The essential place to visit, however, was Italy. The British traveler Charles Thompson spoke for many Grand Tourists when in 1744 he described himself as “being impatiently desirous of viewing a country so famous in history, which once gave laws to the world; which is at present the greatest school of music and painting, contains the noblest productions of statuary and architecture, and abounds with cabinets of rarities , and collections of all kinds of antiquities.” Within Italy, the great focus was Rome, whose ancient ruins and more recent achievements were shown to every Grand Tourist. Panini’s Ancient Rome ( 52.63.1 ) and Modern Rome ( 52.63.2 ) represent the sights most prized, including celebrated Greco-Roman statues and views of famous ruins, fountains, and churches. Since there were few museums anywhere in Europe before the close of the eighteenth century, Grand Tourists often saw paintings and sculptures by gaining admission to private collections, and many were eager to acquire examples of Greco-Roman and Italian art for their own collections. In England, where architecture was increasingly seen as an aristocratic pursuit, noblemen often applied what they learned from the villas of Palladio in the Veneto and the evocative ruins of Rome to their own country houses and gardens .

The Grand Tour and the Arts Many artists benefited from the patronage of Grand Tourists eager to procure mementos of their travels. Pompeo Batoni painted portraits of aristocrats in Rome surrounded by classical staffage ( 03.37.1 ), and many travelers bought Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s prints of Roman views, including ancient structures like the Colosseum ( 59.570.426 ) and more recent monuments like the Piazza del Popolo ( 37.45.3[49] ), the dazzling Baroque entryway to Rome. Some Grand Tourists invited artists from home to accompany them throughout their travels, making views specific to their own itineraries; the British artist Richard Wilson, for example, made drawings of Italian places while traveling with the earl of Dartmouth in the mid-eighteenth century ( 1972.118.294 ).

Classical taste and an interest in exotic customs shaped travelers’ itineraries as well as their reactions. Gothic buildings , not much esteemed before the late eighteenth century, were seldom cause for long excursions, while monuments of Greco-Roman antiquity, the Italian Renaissance, and the classical Baroque tradition received praise and admiration. Jacques Rigaud’s views of Paris were well suited to the interests of Grand Tourists, displaying, for example, the architectural grandeur of the Louvre, still a royal palace, and the bustle of life along the Seine ( 53.600.1191 ; 53.600.1175 ). Canaletto’s views of Venice ( 1973.634 ; 1988.162 ) were much prized, and other works appealed to Northern travelers’ interest in exceptional fêtes and customs: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo ‘s Burial of Punchinello ( 1975.1.473 ), for instance, is peopled with characters from the Venetian carnival, and a print by Francesco Piranesi and Louis Jean Desprez depicts the Girandola, a spectacular fireworks display held at the Castel Sant’Angelo ( 69.510 ).

The Grand Tour and Neoclassical Taste The Grand Tour gave concrete form to northern Europeans’ ideas about the Greco-Roman world and helped foster Neoclassical ideals . The most ambitious tourists visited excavations at such sites as Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Tivoli, and purchased antiquities to decorate their homes. The third duke of Beaufort brought from Rome the third-century work named the Badminton Sarcophagus ( 55.11.5 ) after the house where he proudly installed it in Gloucestershire. The dining rooms of Robert Adam’s interiors typically incorporated classical statuary; the nine lifesized figures set in niches in the Lansdowne dining room ( 32.12 ) were among the many antiquities acquired by the second earl of Shelburne, whose collecting activities accelerated after 1771, when he visited Italy and met Gavin Hamilton, a noted antiquary and one of the first dealers to take an interest in Attic ceramics, then known as “Etruscan vases.” Early entrepreneurs recognized opportunities created by the culture of the Grand Tour: when the second duchess of Portland obtained a Roman cameo glass vase in a much-publicized sale, Josiah Wedgwood profited from the manufacture of jasper reproductions ( 94.4.172 ).

Sorabella, Jean. “The Grand Tour.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grtr/hd_grtr.htm (October 2003)

Further Reading

Black, Jeremy. The British and the Grand Tour . London: Croom Helm, 1985.

Black, Jeremy. Italy and the Grand Tour . New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

Black, Jeremy. France and the Grand Tour . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Haskell, Francis, and Nicholas Penny. Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500–1900 . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

Wilton, Andrew, and Ilaria Bignamini, eds. The Grand Tour: The Lure of Italy in the Eighteenth Century . Exhibition catalogue. London: Tate Gallery Publishing, 1996.

Additional Essays by Jean Sorabella

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Pilgrimage in Medieval Europe .” (April 2011)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Portraiture in Renaissance and Baroque Europe .” (August 2007)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Venetian Color and Florentine Design .” (October 2002)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Art of the Roman Provinces, 1–500 A.D. .” (May 2010)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in Baroque and Later Art .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in Western Art and Its Beginnings in Antiquity .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Monasticism in Western Medieval Europe .” (originally published October 2001, last revised March 2013)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Interior Design in England, 1600–1800 .” (October 2003)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Vikings (780–1100) .” (October 2002)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Painting the Life of Christ in Medieval and Renaissance Italy .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Birth and Infancy of Christ in Italian Painting .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Crucifixion and Passion of Christ in Italian Painting .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Carolingian Art .” (December 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Ottonian Art .” (September 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Ballet .” (October 2004)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Baroque Rome .” (October 2003)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Opera .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- American Neoclassical Sculptors Abroad

- Baroque Rome

- The Idea and Invention of the Villa

- Neoclassicism

- The Rediscovery of Classical Antiquity

- Antonio Canova (1757–1822)

- Architecture in Renaissance Italy

- Athenian Vase Painting: Black- and Red-Figure Techniques

- The Augustan Villa at Boscotrecase

- Collecting for the Kunstkammer

- Commedia dell’arte

- The Eighteenth-Century Pastel Portrait

- Exoticism in the Decorative Arts

- Gardens in the French Renaissance

- Gardens of Western Europe, 1600–1800

- George Inness (1825–1894)

- Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778)

- Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770)

- Images of Antiquity in Limoges Enamels in the French Renaissance

- James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

- Joachim Tielke (1641–1719)

- John Frederick Kensett (1816–1872)

- Photographers in Egypt

- The Printed Image in the West: Etching

- Roman Copies of Greek Statues

- Theater and Amphitheater in the Roman World

- Anatolia and the Caucasus, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Balkan Peninsula, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1600–1800 A.D.

- Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Florence and Central Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- France, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Low Countries, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Rome and Southern Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- The United States, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- 17th Century A.D.

- 18th Century A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- Ancient Roman Art

- Baroque Art

- Central Europe

- Central Italy

- Classical Ruins

- Great Britain and Ireland

- Greek and Roman Mythology

- The Netherlands

- Palladianism

- Period Room

- Southern Italy

- Switzerland

Artist or Maker

- Adam, Robert

- Batoni, Pompeo

- Cozens, John Robert

- Desprez, Louis Jean

- Mengs, Anton Raphael

- Natoire, Charles Joseph

- Panini, Giovanni Paolo

- Permoser, Balthasar

- Piranesi, Francesco

- Piranesi, Giovanni Battista

- Rigaud, Jacques

- Tiepolo, Giovanni Battista

- Tiepolo, Giovanni Domenico

- Wedgwood, Josiah

- Wilson, Richard

Online Features

- Connections: “Flux” by Annie Labatt

- Connections: “Genoa” by Xavier Salomon

- Collectibles

The Grand Tour: Shaping the European Mind and Imagination

- by history tools

- May 26, 2024

For nearly 200 years, the Grand Tour of Europe served as a moveable feast of culture for young elites. From the Enlightenment salons of Paris to the Classical ruins of Rome, these epic journeys lasted months or years and traversed thousands of miles. More than just a glamorous gap year, the Grand Tour aimed to steep aristocratic scions in art, history, languages, and worldly experience in preparation for leadership roles at home.

The tradition emerged in the late 17th century and reached its height from about 1760 to 1820. The typical tourist was British, male, and moneyed, "with a good deal more money than brains, and a good deal more flesh than spirit," as one contemporary put it. But women, Americans, Germans, and others also embarked as continental travel became more common.

Origins and Evolution

The Grand Tour had roots in the Renaissance, when travel to Italy blossomed among artists, scholars, and aristocrats. "The idea was to go and see the marvelous buildings of antiquity and the Renaissance, and travel for the sake of curiosity and learning," explains historian Jeremy Black. Key early figures included the poet John Milton and essayist Michel de Montaigne in the 1500s.

Over the 1600s, a more structured itinerary developed as the Enlightenment sparked new interest in the classical world. The English gentry in particular began sending sons to Europe "to rub off their provincial awkwardness, to learn some languages, and to acquire a little of that social polish which alone can complete a gentleman," wrote one observer. By 1700, "making the Grand Tour" was a recognized rite of passage.

The Typical Tourist

Most Grand Tourists were the sons of nobles, gentry, and wealthy professionals. James Boswell, Edward Gibbon, and Horace Walpole were among the luminaries who made the trip. Some brought along an entourage of servants, tutors, and "bear-leaders" to manage the logistics and their charges‘ behavior. Later, more women participated, like the art historian Anna Jameson and novelist Ann Radcliffe.

A key goal was gaining social polish and connections. Grand Tourists were expected to hobnob with European elites, often bearing letters of introduction. "The Englishman‘s Grand Tour was often a Pleasant Grand Detour to the gaming tables and fleshpots," notes historian Tony Perrottet. Many had flings with local women or fellow travelers of both sexes.

The Classic Itinerary

The standard route varied over time but focused on France and Italy. Here is an outline of the classic itinerary at its 18th century height:

- London – Gathering point and channel crossing to Calais/Ostend

- Paris – Cultural capital and social whirl of salons, theaters, shops

- Geneva – Key intellectual hub and gateway to the Alps

- Turin – First major city in Italy, known for royal court

- Milan – Economic and cultural powerhouse of Northern Italy

- Venice – Mecca of art, Carnival, and courtesans

- Florence – Cradle of the Renaissance with legendary art collections

- Rome – Ultimate goal with layers of Classical and Baroque wonders

- Naples – Scenic beauty, Roman sites, and a wilder side

Some ventured on to Sicily and Greece, while others headed home via Germany or Austria. The full circuit could take two to four years, with long stays in major cities. Art, architecture, music, and antiquities were key draws. "In the 18th century, Italy still shone as the supreme beacon of European civilization," Perrottet notes.

Impact on Art and Learning

The Grand Tour fueled a golden age of cultural exchange between Britain and the Continent. Tourists snapped up Old Masters, sculptures, books, gems, and more in a spending spree that reshaped British collections. The 2nd Earl of Petworth amassed over 200 paintings and 70 statues on his trips, while the Duke of Bedford bought so much he had to build a new wing on his country house.

Italy in turn enjoyed an economic and creative renaissance as artists, dealers, hoteliers and more catered to the tourist trade. "The English are numbered, and they are all very rich…they will take our pictures, our statues, our curiosities," exulted one Roman. Cultural sites like the Uffizi and Pompeii became major attractions.

The Tour also shaped intellectual life as Neoclassicism and Romanticism took hold. Artists from Piranesi to Turner found inspiration in Roman ruins and the Italian landscape. "Rome…appears to me like some mighty ruin of an angelic mind," marveled the poet Robert Lowell. The diaries of Boswell, Goethe, and others became celebrated travelogues in their own right.

Disruption and Decline

The French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars brought the Grand Tour‘s golden age to an end. France and Italy became perilous for Britons as the two nations warred from 1793 to 1815. Many of Italy‘s artistic treasures were carted off by Napoleon. A generation of young elites had their travels curtailed or spent them on the battlefield instead of the opera house.

As peace returned, so did tourists, but in a different form. The spread of rail and steamships made the Continent accessible to a rising middle class by the 1840s. Thomas Cook launched his famous package tours in the 1860s, offering an affordable taste of the Grand Tour to the masses.

For elite travelers, Europe no longer seemed so rare and wondrous compared to more far-flung destinations. "The idea of the Grand Tour as an aristocratic male preserve was exploded," Black notes. Intrepid Victorians increasingly set their sights on the Middle East, India, and beyond.

A Lasting Legacy

Though the classic Grand Tour faded by the late 1800s, it cast a long shadow over European travel and culture. Its ideals of edification and exoticism still shape study abroad programs, cultural tourism, and creative pilgrimages today. The letters, art, and souvenirs it generated provide a vivid window into the lives and mores of a bygone elite.

The Tour also had a formative impact on the collections that fill Europe‘s great museums, the English country house, and the imaginations of generations of artists and writers. From Keats swooning over a Greek urn to Henry James dissecting the ex-pat scene in Rome, its influence permeates Western culture.

Perhaps most of all, the Grand Tour instilled a sense of Europe as a shared cultural hearth with a deep, living heritage to be explored. At a time of rising nationalism, it emphasized what Europeans held in common and how the Classical world still spoke to the present. It made the Continent smaller and grander at the same time, a tension still at the heart of the European project today.

Key Facts and Figures

The term "Grand Tour" was coined by the Catholic priest Richard Lassels in his 1670 book Voyage to Italy .

From 1764-1796, the British took out 6,000 passports for travel abroad, and at least half of those were for the Grand Tour. In the same period, they were granted 40% of the 3,200 export licenses for art from Rome.

Popular guides included Thomas Nugent‘s The Grand Tour (1749) and Mariana Starke‘s Travels in Italy (1800s). The poet Lord Byron‘s letters home were another hit.

The average age of the British Grand Tourist was 22. Most were the sons of peers (30%), gentry (35%), or professionals (29%).

Grand Tourists were among the leading buyers in Italy‘s booming art market. British collectors accounted for 60% of ancient sculpture exports from Rome in the late 1700s.

Top destinations saw huge upticks in visitors: Venice went from about 10,000 tourists per year in 1700 to over 40,000 per year by 1800. Italy received an estimated £15 million from tourists over the 18th century (over £1 billion today).

Sources and Further Reading

Black, Jeremy. The British Abroad: The Grand Tour in the Eighteenth Century . Sutton, 2003.

Black, Jeremy. Italy and the Grand Tour . Yale University Press, 2003.

Bohls, Elizabeth A. and Ian Duncan (eds.). Travel Writing 1700-1830: An Anthology . Oxford University Press, 2008.

Chaney, Edward. The Evolution of the Grand Tour: Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations since the Renaissance . Routledge, 2000.

Hornsby, Clare. The Impact of Italy: The Grand Tour and Beyond . British School at Rome, 2000.

Perrottet, Tony. "The Grand Tour." Smithsonian Magazine , April 2009, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/the-grand-tour-142368742/

Redford, Bruce. Venice and the Grand Tour . Yale University Press, 1996.

Wilton, Andrew and Ilaria Bignamini (eds.). Grand Tour: The Lure of Italy in the Eighteenth-century . Tate Gallery Publishing, 1996.

Related posts:

- Unveiling the Timeless Majesty: 12 Remarkable Facts About Paris‘ Notre Dame Cathedral

- Tracing the Imperial Roots of the A10: Ermine Street and the Legacy of Roman Roads in Britain

- Uncover Istanbul‘s Magnificent Monuments: A Historian‘s Guide

- 12 Magnificent Churches and Cathedrals to Visit in London

- Thomas Cook: The Baptist Preacher Who Invented Modern Tourism

- Sun, Sea, and Spectacle: The Rise and Legacy of the Victorian Seaside Holiday

- Unveiling the Mysteries of Victorian Bathing Machines: A Peek into the Past

- Unraveling the Mysteries of China‘s Forbidden City: A Historian‘s Perspective

What was the Grand Tour?

Find out about the travel phenomenon that became popular amongst the young nobility of England

Art, antiquity and architecture: the Grand Tour provided an opportunity to discover the cultural wonders of Europe and beyond.

Popular throughout the 18th century, this extended journey was seen as a rite of passage for mainly young, aristocratic English men.

As well as marvelling at artistic masterpieces, Grand Tourists brought back souvenirs to commemorate and display their journeys at home.

One exceptional example forms the subject of a new exhibition at the National Maritime Museum. Canaletto’s Venice Revisited brings together 24 of Canaletto’s Venetian views, commissioned in 1731 by Lord John Russell following his visit to Venice.

Find out more about this travel phenomenon – and uncover its rich cultural legacy.

Canaletto's Venice Revisited

The origins of the Grand Tour

The development of the Grand Tour dates back to the 16th century.

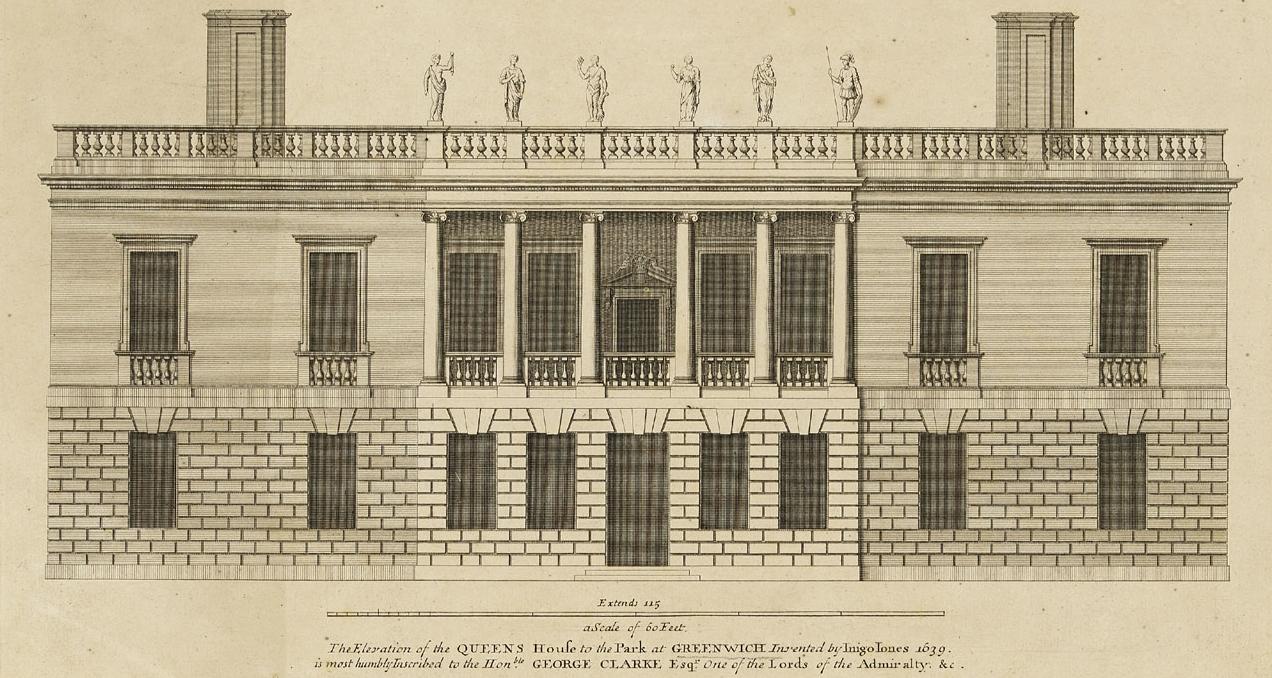

One of the earliest Grand Tourists was the architect Inigo Jones , who embarked on a tour of Italy in 1613-14 with his patron Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel.

Jones visited cities such as Parma, Venice and Rome. However, it was Naples that proved the high point of his travels.

Jones was particularly fascinated by the San Paolo Maggiore, describing the church as “one of the best things that I have ever seen.”

Jones’s time in Italy shaped his architectural style. In 1616, Jones was commissioned to design the Queen’s House in Greenwich for Queen Anne of Denmark , the wife of King James I. Completed in around 1636, the house was the first classical building in England.

The expression ‘Grand Tour’ itself comes from 17th century travel writer and Roman Catholic priest Richard Lassels, who used it in his guidebook The Voyage of Italy, published in 1670.

By the 18th century, the Grand Tour had reached its zenith. Despite Anglo-French wars in 1689-97 and 1702-13, this was a time of relative stability in Europe, which made travelling across the continent easier.

The Grand Tour route

For young English aristocrats, embarking on the Grand Tour was seen as an important rite of passage.

Accompanied by a tutor, a Grand Tourist’s route typically involved taking a ship across the English Channel before travelling in a carriage through France, stopping at Paris and other major cities.

Italy was also a popular destination thanks to the art and architecture of places such as Venice, Florence, Rome, Milan and Naples. More adventurous travellers ventured to Sicily or even sailed across to Greece. The average Grand Tour lasted for at least a year.

As Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art at Royal Museums Greenwich explains, this extended journey marked the culmination of a Grand Tourist’s education.

“The Grand Tourists would have received an education that was grounded in the Classics,” she says. “During their travels to the continent, they would have seen classical ruins and read Latin and Greek texts. The Grand Tour was also an opportunity to take in more recent culture, such as Renaissance paintings, and see contemporary artists at work.”

As well as educational opportunities, the Grand Tour was linked with independence. Places such as Venice were popular with pleasure seekers, boasting gambling houses and occasions for drinking and partying.

“On the Grand Tour, there’s a sense that travellers are gaining some of their independence and having a lesson in the ways of the world,” Gazzard explains. “For visitors to Venice, there were opportunities to behave beyond the social norms, with the masquerade and the carnival.”

Art and the Grand Tour

Bound up with the idea of independence was the need to collect souvenirs, which the Grand Tourists could display in their homes.

“The ownership of property was tied to status, so creating a material legacy was really important for the Grand Tourists in order to solidify their social standing amongst their peers,” says Gazzard. “They were looking to spend money and buy mementos to prove they went on the trip.”

The works of artists such as those of the 18th century view painter Giovanni Antonio Canal (known as Canaletto ) were especially popular with Grand Tourists. Prized for their detail, Canaletto’s artworks captured the landmarks and scenes of everyday Venetian life, from festive scenes to bustling traffic on the Grand Canal .

In 1731, Lord John Russell, the future 4th Duke of Bedford, commissioned Canaletto to create 24 Venetian views following his visit to the city.

Lord John Russell is known to have paid at least £188 for the set – over five times the annual earnings of a skilled tradesperson at the time.

“Canaletto’s work was portable and collectible,” says Gazzard. “He adopted a smaller size for his canvases so they could be rolled up and shipped easily.”

These detailed works, now part of the world famous collection at Woburn Abbey, form the centrepiece of Canaletto’s Venice Revisited at the National Maritime Museum .

Who was Canaletto?

The legacy of the Grand Tour

The start of the French Revolution in 1789 marked the end of the Grand Tour. However, its legacy is still keenly felt.

The desire to explore and learn about different places and cultures through travel continues to endure. The legacy of the Grand Tour can also be seen in the artworks and objects that adorn the walls of stately homes and museums, and the many cultural influences that travellers brought back to Britain.

Canaletto's Venice Revisited

Main image: The Piazza San Marco looking towards the Basilica San Marco and the Campanile by Canaletto . From the Woburn Abbey Collection . Canaletto painting in body copy: Regatta on Grand Canal by Canaletto From the Woburn Abbey Collection

The Grand Tour

Englishmen abroad.

At its height, from around 1660–1820, the Grand Tour was considered to be the best way to complete a gentleman’s education. After leaving school or university, young noblemen from northern Europe left for France to start the tour.

After acquiring a coach in Calais, they would ride on to Paris – their first major stop. From there they would head south to Italy or Spain, carting all their possessions and servants with them.

Their most popular destinations were the great towns and cities of the Renaissance, along with the remains of ancient Roman and Greek civilisation.

Their souvenirs were rather more durable than holiday snaps, replica Eiffel Towers or t-shirts – they filled crates with paintings, sculptures and fine clothes.

Travel was somewhat more of an ordeal than today (even accounting for the worst airport queues and hold-ups). However rich these young men were, there was no hot shower after a day on the road, no credit card to get them out of a tight spot, and no mobile phone to ring people for help.

Furthermore transport was slow. Instead of taking a 12-month trip, some went away for many years. Most went for at least two, spending months in essential spots along the way.

The plan was to set young noblemen up to manage their estates, furnish their houses and prepare for conversation in polite society. But did the Grand Tour turn them into gentlemen? Sometimes a taste for vice got in the way.

Next: A moral education

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

What Was the Grand Tour of Europe?

Lucy Davidson

26 jan 2022, @lucejuiceluce.

In the 18th century, a ‘Grand Tour’ became a rite of passage for wealthy young men. Essentially an elaborate form of finishing school, the tradition saw aristocrats travel across Europe to take in Greek and Roman history, language and literature, art, architecture and antiquity, while a paid ‘cicerone’ acted as both a chaperone and teacher.

Grand Tours were particularly popular amongst the British from 1764-1796, owing to the swathes of travellers and painters who flocked to Europe, the large number of export licenses granted to the British from Rome and a general period of peace and prosperity in Europe.

However, this wasn’t forever: Grand Tours waned in popularity from the 1870s with the advent of accessible rail and steamship travel and the popularity of Thomas Cook’s affordable ‘Cook’s Tour’, which made mass tourism possible and traditional Grand Tours less fashionable.

Here’s the history of the Grand Tour of Europe.

Who went on the Grand Tour?

In his 1670 guidebook The Voyage of Italy , Catholic priest and travel writer Richard Lassells coined the term ‘Grand Tour’ to describe young lords travelling abroad to learn about art, culture and history. The primary demographic of Grand Tour travellers changed little over the years, though primarily upper-class men of sufficient means and rank embarked upon the journey when they had ‘come of age’ at around 21.

‘Goethe in the Roman Campagna’ by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein. Rome 1787.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Grand Tours also became fashionable for women who might be accompanied by a spinster aunt as a chaperone. Novels such as E. M. Forster’s A Room With a View reflected the role of the Grand Tour as an important part of a woman’s education and entrance into elite society.

Increasing wealth, stability and political importance led to a more broad church of characters undertaking the journey. Prolonged trips were also taken by artists, designers, collectors, art trade agents and large numbers of the educated public.

What was the route?

The Grand Tour could last anything from several months to many years, depending on an individual’s interests and finances, and tended to shift across generations. The average British tourist would start in Dover before crossing the English Channel to Ostend in Belgium or Le Havre and Calais in France. From there the traveller (and if wealthy enough, group of servants) would hire a French-speaking guide before renting or acquiring a coach that could be both sold on or disassembled. Alternatively, they would take the riverboat as far as the Alps or up the Seine to Paris .

Map of grand tour taken by William Thomas Beckford in 1780.

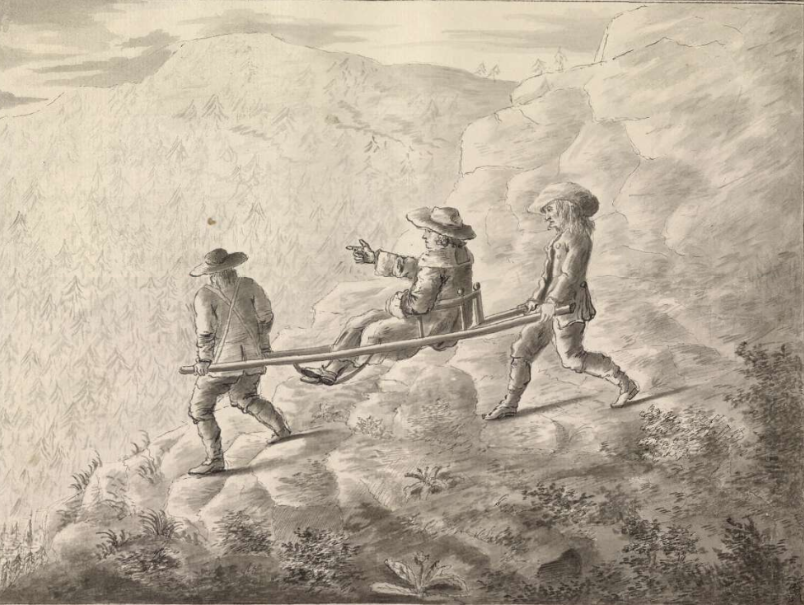

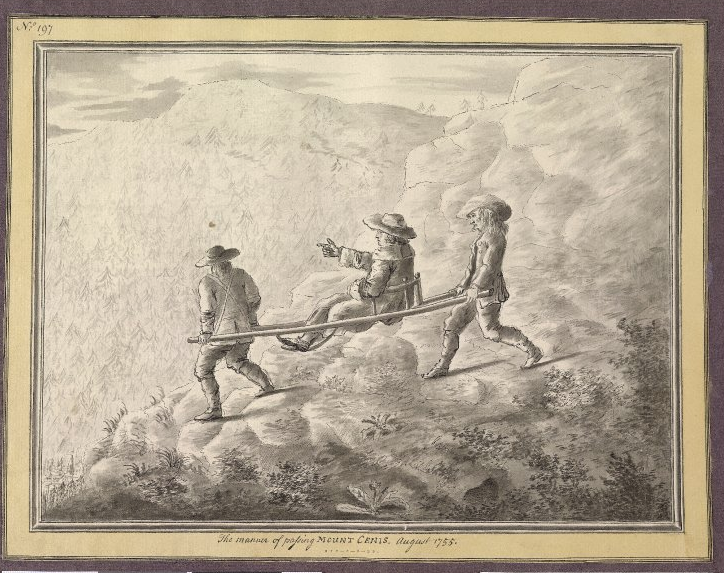

From Paris, travellers would normally cross the Alps – the particularly wealthy would be carried in a chair – with the aim of reaching festivals such as the Carnival in Venice or Holy Week in Rome. From there, Lucca, Florence, Siena and Rome or Naples were popular, as were Venice, Verona, Mantua, Bologna, Modena, Parma, Milan, Turin and Mont Cenis.

What did people do on the Grand Tour?

A Grand Tour was both an educational trip and an indulgent holiday. The primary attraction of the tour lay in its exposure of the cultural legacy of classical antiquity and the Renaissance, such as the excavations at Herculaneum and Pompeii, as well as the chance to enter fashionable and aristocratic European society.

Johann Zoffany: The Gore Family with George, third Earl Cowper, c. 1775.

In addition, many accounts wrote of the sexual freedom that came with being on the continent and away from society at home. Travel abroad also provided the only opportunity to view certain works of art and potentially the only chance to hear certain music.

The antiques market also thrived as lots of Britons, in particular, took priceless antiquities from abroad back with them, or commissioned copies to be made. One of the most famous of these collectors was the 2nd Earl of Petworth, who gathered or commissioned some 200 paintings and 70 statues and busts – mainly copies of Greek originals or Greco-Roman pieces – between 1750 and 1760.

It was also fashionable to have your portrait painted towards the end of the trip. Pompeo Batoni painted over 175 portraits of travellers in Rome during the 18th century.

Others would also undertake formal study in universities, or write detailed diaries or accounts of their experiences. One of the most famous of these accounts is that of US author and humourist Mark Twain, whose satirical account of his Grand Tour in Innocents Abroad became both his best selling work in his own lifetime and one of the best-selling travel books of the age.

Why did the popularity of the Grand Tour decline?

A Thomas Cook flyer from 1922 advertising cruises down the Nile. This mode of tourism has been immortalised in works such as Death on the Nile by Agatha Christie.

The popularity of the Grand Tour declined for a number of reasons. The Napoleonic Wars from 1803-1815 marked the end of the heyday of the Grand Tour, since the conflict made travel difficult at best and dangerous at worst.

The Grand Tour finally came to an end with the advent of accessible rail and steamship travel as a result of Thomas Cook’s ‘Cook’s Tour’, a byword of early mass tourism, which started in the 1870s. Cook first made mass tourism popular in Italy, with his train tickets allowing travel over a number of days and destinations. He also introduced travel-specific currencies and coupons which could be exchanged at hotels, banks and ticket agencies which made travelling easier and also stabilised the new Italian currency, the lira.

As a result of the sudden potential for mass tourism, the Grand Tour’s heyday as a rare experience reserved for the wealthy came to a close.

Can you go on a Grand Tour today?

Echoes of the Grand Tour exist today in a variety of forms. For a budget, multi-destination travel experience, interrailing is your best bet; much like Thomas Cook’s early train tickets, travel is permitted along many routes and tickets are valid for a certain number of days or stops.

For a more upmarket experience, cruising is a popular choice, transporting tourists to a number of different destinations where you can disembark to enjoy the local culture and cuisine.

Though the days of wealthy nobles enjoying exclusive travel around continental Europe and dancing with European royalty might be over, the cultural and artistic imprint of a bygone Grand Tour era is very much alive.

To plan your own Grand Tour of Europe, take a look at History Hit’s guides to the most unmissable heritage sites in Paris , Austria and, of course, Italy .

You May Also Like

The Royal Mint: Oliver Cromwell’s Depiction as a Roman Emperor

The Royal Mint: Edward VIII’s Unreleased Coins

A Timeline of Feudal Japan’s ‘Nanban’ Trade with Europeans

Mac and Cheese in 1736? The Stories of Kensington Palace’s Servants

The Peasants’ Revolt: Rise of the Rebels

10 Myths About Winston Churchill

Medusa: What Was a Gorgon?

10 Facts About the Battle of Shrewsbury

5 of Our Top Podcasts About the Norman Conquest of 1066

How Did 3 People Seemingly Escape From Alcatraz?

5 of Our Top Documentaries About the Norman Conquest of 1066

1848: The Year of Revolutions

The Grand Tour Of The 18th Century

In the eighteenth century, the Grand Tour was an obligatory part of a young nobleman’s artistic, intellectual and sentimental education.

The ‘Grand Tour’, that extended journey to Italy undertaken mainly by British but also French and German aristocrats in the eighteenth century, is not only the stuff of legend, but meant as many different things as there were tourists; each came back with a particular and personal view of the experience.

The Grand Tour evolved during the seventeenth century to become a formative experience for the leaders of British society. Princes, nobles, aristocrats, landed gentry, and politicians—with courtiers, retinues, scholars, tutors, advisors and servants—all made the journey across France. Crossing the Alps at Mont Cenis (usually carried in a chair), they descended into Italy at Turin, or, taking a felucca from Marseilles, they landed at Genoa.

Italy was seen as the cradle of Western civilisation, the source and home of all that was reckoned to be significant historically, aesthetically, politically, religiously and, above all, for collecting: antique sculpture, Old Master paintings, furniture, textiles, objets de vertu, jewellery, contemporary sculpture and painting.

In the latter category, most highly prized were portraits of the tourists themselves by masters such as Pompeo Batoni and ‘vedute’, views of the sites visited as presented in Canaletto’s paintings or Piranesi’s prints. Moreover, Italy was the textbook for students of architecture, with ancient and modern buildings not only to be studied but imitated back home. The British stately home is almost by definition the result of the Grand Tour in both its architecture and its contents.

Earlier this year, the ‘Italy Observed’ exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum in New York showcased a fine selection of Italian vedute, from paintings of Venetian life by Luca Carlevaris to a Neapolitan album of gouache drawings documenting the eruption of Vesuvius in 1794 to sketches and watercolours of Italian antiquities, capturing the artist’s romantic attraction to Italy and its irresistible Roman heritage.

The places to visit included most of the sites still popular with less grand tourists today: Florence, with untold riches held by the Grand-Ducal Medicis in their several city palaces, as well as works of art in the churches and monasteries; Venice, which combined artistic and mercantile wealth; Genoa, which had artistic links with Britain due to the visits of Rubens and Van Dyck whose works adorned that city; and Naples, the capital of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, an outpost of the Habsburg empire with a glamorous court and the place where in the later part of the eighteenth century Sir William Hamilton and his wife, Emma—later to achieve fame as Nelson’s lover—held cultural sway.

Later in the century the archaeological excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum put these on the tourist trail, as sites for the study of the ancient world, sources for yet more riches to be brought home, and templates for decoration and decorative art works in the Neo-classical style that emerged partly as a result of these finds. At the same time, Southern Italy and Sicily were added to the Tour as interest grew in classical Greek architecture, the temples at Paestum and Segesta being among the finest examples.

Above all others, the destination of the Grand Tour was Rome—the crossroads of the ancient and the Christian worlds—and the place that epitomised Western civilisation. The site of the vestiges of the Roman Republic and Empire, those sources of European law and administration, and of the noble examples of pagan virtue and rectitude that inspired the classical ideals of the Augustan gentleman, Rome was also the heart of European Christianity: for Catholics the very heart of the religion; for Protestants, although historically important if doctrinally suspect or downright repugnant, a power to be known and reckoned with.

However, the Grand Tourists were not pilgrims, but came with other motives—often mixed, but principally to drink from the source of civilisation, to undertake a Bildungsreise, the journey of a life time (often lasting several years), an experience that would form an aristocrat’s life-long attitudes, tastes, intellectual habits and manners. It was also a major shopping expedition intended to provide the nobility with objects to furnish their newly built Neo-classical houses.

Grand Tourists can be seen in works of art such as the portraits of Lord Mountstuart and John Talbot painted respectively by Jean-Étienne Liotard in 1763 and Pompeo Batoni, ten years later. Talbot is shown as the consummate Grand Tourist: elegant, poised, nonchalant, surrounded by the signs of his Roman sojourn—a broken capital at his feet, a Grecian urn at his elbow and the Ludovisi Ares in the background.

Tourists who had not done their homework before setting off were ably assisted by their tutors, the ubiquitous and often ill-used ‘bear leaders’, who were also meant to oversee their charges’ moral integrity, a fruitless task more often honoured in the breach.

In fact, the Grand Tourists’ less high-minded behaviour and interests were frequently remarked on—pointedly, in one instance by Alexander Pope who satirised the twin aspects of the Grand Tourist’s agenda: ‘… he sauntered Europe round, / And gather’d ev’ry Vice on Christian ground; / Saw ev’ry Court, heard ev’ry King declare / His royal Sense of Op’ra’s or the Fair; / The Stews and Palace equally explor’d / Intrigu’d with glory, and with spirit whor’d.’

But the Grand Tourist whose budget did not stretch to having a personal tutor was responsible for the invention of what has become an indispensable item of tourism: the guidebook, with foldout maps and panoramic views marked with the not-to-be-missed monuments and sites.

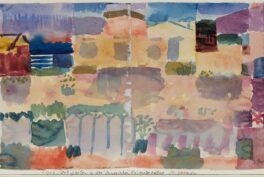

The beautiful red chalk drawing of an antique monument in a landscape by Marie-Joseph Peyre from about 1753-85 is an example that serves as reminder that many Grand Tourists were taught, on the spot, to draw, sketch and paint. The Grand Tourists’ collecting activities promoted the revival of ancient art forms, creating a taste for architecture and sculpture in a Neo-classical or Greek style, and in the manufacture of objects such as Wedgwood cameo wares.

The publication in 1755 of Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s Reflections on the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks influenced European taste for the next half-century. Greek sculpture was (as it still is) known almost exclusively through Roman copies, and the striving for the cool, serene and noble sentiments that art seemed to embody is exemplified most of all by the work of Antonio Canova, represented by his marble statue of Apollo crowning himself.

Ancient carved gemstones and cameos, cameo casts, contemporary gemstones carved in the manner of ancient ones, prints, and a painting by Canaletto, The Arch of Constantine with the Colosseum in the background, show how works of art served as souvenirs and aide-memoires for returning visitors. Ultimately, their patronage and spending was the driving force behind Neo-classicism, the international style that wedded the principles of ancient art to modern individual inventiveness.

Collecting of an entirely different sort and on an entirely different scale marked the end of the Grand Tour and of aristocratic classical taste. Napoleon’s invasion of Italy signaled the beginning of the end of the aristocratic age for which Italy was both the goal and the source.

See also: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Years in Vienna

- the Grand Tour

Austerity Measures And a Vintage Celebrity

Unmissable events—eccentric, regal and random.

Related Posts

18th Century Grand Tour of Europe

The Travels of European Twenty-Somethings

Print Collector/Getty Images

- Key Figures & Milestones

- Physical Geography

- Political Geography

- Country Information

- Urban Geography

- M.A., Geography, California State University - Northridge

- B.A., Geography, University of California - Davis

The French Revolution marked the end of a spectacular period of travel and enlightenment for European youth, particularly from England. Young English elites of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries often spent two to four years touring around Europe in an effort to broaden their horizons and learn about language , architecture , geography, and culture in an experience known as the Grand Tour.

The Grand Tour, which didn't come to an end until the close of the eighteenth century, began in the sixteenth century and gained popularity during the seventeenth century. Read to find out what started this event and what the typical Tour entailed.

Origins of the Grand Tour

Privileged young graduates of sixteenth-century Europe pioneered a trend wherein they traveled across the continent in search of art and cultural experiences upon their graduation. This practice, which grew to be wildly popular, became known as the Grand Tour, a term introduced by Richard Lassels in his 1670 book Voyage to Italy . Specialty guidebooks, tour guides, and other aspects of the tourist industry were developed during this time to meet the needs of wealthy 20-something male and female travelers and their tutors as they explored the European continent.

These young, classically-educated Tourists were affluent enough to fund multiple years abroad for themselves and they took full advantage of this. They carried letters of reference and introduction with them as they departed from southern England in order to communicate with and learn from people they met in other countries. Some Tourists sought to continue their education and broaden their horizons while abroad, some were just after fun and leisurely travels, but most desired a combination of both.

Navigating Europe

A typical journey through Europe was long and winding with many stops along the way. London was commonly used as a starting point and the Tour was usually kicked off with a difficult trip across the English Channel.

Crossing the English Channel

The most common route across the English Channel, La Manche, was made from Dover to Calais, France—this is now the path of the Channel Tunnel. A trip from Dover across the Channel to Calais and finally into Paris customarily took three days. After all, crossing the wide channel was and is not easy. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Tourists risked seasickness, illness, and even shipwreck on this first leg of travel.

Compulsory Stops

Grand Tourists were primarily interested in visiting cities that were considered major centers of culture at the time, so Paris, Rome, and Venice were not to be missed. Florence and Naples were also popular destinations but were regarded as more optional than the aforementioned cities.

The average Grand Tourist traveled from city to city, usually spending weeks in smaller cities and up to several months in the three major ones. Paris, France was the most popular stop of the Grand Tour for its cultural, architectural, and political influence. It was also popular because most young British elite already spoke French, a prominent language in classical literature and other studies, and travel through and to this city was relatively easy. For many English citizens, Paris was the most impressive place visited.

Getting to Italy

From Paris, many Tourists proceeded across the Alps or took a boat on the Mediterranean Sea to get to Italy, another essential stopping point. For those who made their way across the Alps, Turin was the first Italian city they'd come to and some remained here while others simply passed through on their way to Rome or Venice.

Rome was initially the southernmost point of travel. However, when excavations of Herculaneum (1738) and Pompeii (1748) began, these two sites were added as major destinations on the Grand Tour.

Features of the Grand Tour

The vast majority of Tourists took part in similar activities during their exploration with art at the center of it all. Once a Tourist arrived at a destination, they would seek housing and settle in for anywhere from weeks to months, even years. Though certainly not an overly trying experience for most, the Grand Tour presented a unique set of challenges for travelers to overcome.

While the original purpose of the Grand Tour was educational, a great deal of time was spent on much more frivolous pursuits. Among these were drinking, gambling, and intimate encounters—some Tourists regarded their travels as an opportunity to indulge in promiscuity with little consequence. Journals and sketches that were supposed to be completed during the Tour were left blank more often than not.

Visiting French and Italian royalty as well as British diplomats was a common recreation during the Tour. The young men and women that participated wanted to return home with stories to tell and meeting famous or otherwise influential people made for great stories.

The study and collection of art became almost a nonoptional engagement for Grand Tourists. Many returned home with bounties of paintings, antiques, and handmade items from various countries. Those that could afford to purchase lavish souvenirs did so in the extreme.

Arriving in Paris, one of the first destinations for most, a Tourist would usually rent an apartment for several weeks or months. Day trips from Paris to the French countryside or to Versailles (the home of the French monarchy) were common for less wealthy travelers that couldn't pay for longer outings.

The homes of envoys were often utilized as hotels and food pantries. This annoyed envoys but there wasn't much they could do about such inconveniences caused by their citizens. Nice apartments tended to be accessible only in major cities, with harsh and dirty inns the only options in smaller ones.

Trials and Challenges

A Tourist would not carry much money on their person during their expeditions due to the risk of highway robberies. Instead, letters of credit from reputable London banks were presented at major cities of the Grand Tour in order to make purchases. In this way, tourists spent a great deal of money abroad.

Because these expenditures were made outside of England and therefore did not bolster England's economy, some English politicians were very much against the institution of the Grand Tour and did not approve of this rite of passage. This played minimally into the average person's decision to travel.

Returning to England

Upon returning to England, tourists were meant to be ready to assume the responsibilities of an aristocrat. The Grand Tour was ultimately worthwhile as it has been credited with spurring dramatic developments in British architecture and culture, but many viewed it as a waste of time during this period because many Tourists did not come home more mature than when they had left.

The French Revolution in 1789 halted the Grand Tour—in the early nineteenth century, railroads forever changed the face of tourism and foreign travel.

- Burk, Kathleen. "The Grand Tour of Europe". Gresham College, 6 Apr. 2005.

- Knowles, Rachel. “The Grand Tour.” Regency History , 30 Apr. 2013.

- Sorabella, Jean. “The Grand Tour.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History , The Met Museum, Oct. 2003.

- What Are Word Blends?

- A Beginner's Guide to the Enlightenment

- Architecture in France: A Guide For Travelers

- The History of Venice

- A Brief History of Rome

- The Best Books on Early Modern European History (1500 to 1700)

- A Beginner's Guide to the Renaissance

- The Top 10 Major Cities in France

- Renaissance Architecture and Its Influence

- William Turner, English Romantic Landscape Painter

- What Is a Monarchy?

- Architecture in Italy for the Lifelong Learner

- Female European Historical Figures: 1500 - 1945

- Hispanic Surnames: Meanings, Origins and Naming Practices

- Biography of Harriet Quimby

- 8 Major Events in European History

The Grand Tour: Everything You Need to Know

Gokce Dyson 28 November 2022 min Read

Carl Spitzweg, Englishmen in Campania , ca. 1835, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany.

Recommended

Art Travels

On the Road: Best Traveling Paintings

Artists’ Beloved Travel Destinations as Seen Through Their Art

How to Do a 21st-Century Grand Tour According to Mr. Bacchus

Nowadays, it is very common to take a gap year before or after university studies to travel and expand your horizons. Dedicating a year or two before committing to a full-time job means you can experience different cultures, learn languages, and enjoy having a bit of fun before settling down. Back in the day, with similar objectives, many noblemen embarked on a journey across Europe before entering adulthood. It was called the Grand Tour.

The Grand Tour evolved between the 17th and 18th centuries as a custom of a traditional trip. The purpose of the Grand Tour was to provide male members of upper-class families with a formative experience. The term was first used by the Catholic priest and travel writer Richard Lassels in his guidebook The Voyage of Italy . The book came out in 1670 and described young lords traveling to Italy to see art, architecture, and antiquity. Lassels completed the Grand Tour five times during his lifetime.

In England, for example, the general view held by the aristocrats was that foreign travel completed the education of an English gentleman. However, some people were also quite skeptical about the tour. They feared the amount of money spent to make the Grand Tour possible could ruin the young nobility.

Although the Grand Tour was largely associated with English travelers, they were far from being the only ones on the road. On the contrary, wealthy families in France, Germany, Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark also saw traveling as an ideal way to finish the education of their societies’ future leaders.

Itinerary of the Grand Tour

The traditional route of the Grand Tour usually began in Dover, England. Grand tourists would cross the English Channel to Le Havre in France. Upon arrival in Paris , the young men tended to hire a French-speaking guide as French was the dominant language of the elite during the 17th and 18th centuries. In Paris, they spent some time taking lessons in fencing, riding, and perhaps dancing. There, they became accustomed to the sophisticated manners of French society in courtly behavior and fashion. Paris was a crucial step in preparing for their positions to be fulfilled in government or diplomacy waiting back in England.

From there, tourists would buy transport, and if they were prosperous enough, they would hire a tutor to accompany them. The travelers would then get back on the road and cross the Alps, carried in a chair at Mont Cenis before moving on to Turin.

Italy was exceedingly the most traveled country on the Grand Tour. A Grand tourist’s list of must-see cities in Italy included Florence , Venice , and Naples . And then, there was Rome . Each Italian city offered immense importance in experiencing art and architecture, and Rome had it all.

Touring Italy

Once arriving in Italy, noblemen traveled to Florence followed by Venice, Rome, and Naples. Florence was popular for its Renaissance art, magnificent country villas, and beautiful gardens. Young aristocrats were able to gain entry to private collections where they could observe the legacy of the Medici family. Venice , on the other hand, was the party city. There was, however, a second reason to visit Venice. During their travels, grand tourists often commissioned art to take back home with them. Wealthy ones brought sketch artists along with them. Others purchased ready-made artworks instead. Giovanni Battista Piranesi created numerous prints and sketches depicting the ancient ruins in Rome. The works of the Venetian artist were popular among noblemen.

Rome was considered the ultimate stop during the Grand Tour. The city had a harmonious mixture of past and present. One could experience modern-day Baroque art and architecture and ancient ruins , dating back thousands of years at the same time. It was lauded as home to Michelangelo’s and Bernini’s most prized works. Gentlemen visited spots like the Pantheon, the Colosseum, and Porta del Popolo. William Beckford described his feelings in a letter when he was on his Grand Tour:

Shall I ever forget the sensations I experienced upon slowly descending the hills, and crossing the bridge over the Tiber; when I entered an avenue between terraces and ornamented gates of villas, which leads to the Porto del Popolo… William Beckford, letter from the Grand Tour, 1780.

The next stop on the route was Naples. When Italian authorities began excavations in Herculaneum and Pompeii in the 1730s, grand tourists flocked there to delve into the mysteries of the ancient past. Naples became a popular retreat for the British who wanted to enjoy the coastal sun. Travelers such as J. W. Goethe praised the city’s glories:

Naples is a Paradise: everyone lives in a state of intoxicated self-forgetfulness, myself included. I seem to be a completely different person whom I hardly recognize. Yesterday I thought to myself: Either you were mad before, or you are mad now. J. W. Goethe, Google Arts& Culture .

Returning home, young gentlemen crossed the Alps to the German-speaking parts of Europe and visited Innsbruck, Vienna , Dresden, and Berlin . From there, they stopped in Holland and Flanders before returning to England.

With the introduction of steam railways in Europe around 1825, travel became safer, cheaper, and easier to undertake. The Grand Tour custom continued; however, it was not limited to the members of wealthy families. During the 19th century, many educated men had undertaken the Grand Tour. It also became more popular for women to travel across Europe with chaperones. A Room with A View, written by English novelist E. M. Forster, tells the story of a young woman who embarks on a journey to Italy in the 1900s.

Legacy of the Grand Tour

Grand tourists would return with crates full of books, oil paintings, medals, coins, and antique artifacts to be displayed in libraries, cabinets, drawing rooms, and galleries built for that purpose. The marble sarcophagus shown above was brought back from Italy to England by the third duke of Beaufort who found this item during his Grand Tour stop in Pompeii. Impressed by the European art academies on his Grand Tour, Joshua Reynolds founded the Royal Academy of Arts in London upon his return in 1768. The Grand Tour inspired many travelers to take a greater interest in ancient art. The British School in Rome was established to learn more about the Roman ruins and it still exists today.

Get your daily dose of art

Click and follow us on Google News to stay updated all the time

We love art history and writing about it. Your support helps us to sustain DailyArt Magazine and keep it running.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!

Gokce Dyson

Based in Canterbury, Gokce holds a bachelor's degree in History and Archaeological Studies and a master's degree in Museum and Gallery Studies. She firmly believes that art enables us to find ourselves and lose ourselves at the same time. If Gokce is not tucked into a cosy corner with a medieval history book, she can be found spending her evenings doing jigsaw puzzles.

5 Artsy Things to do in Tórshavn, Faroe Islands

You might find yourself wanting to travel to the Faroe Islands because you saw photographs of their spectacular bird cliffs and green mountainsides,...

Theresa Kohlbeck Jakobsen 23 May 2024

Top 5 Artsy Travel Destinations in 2024 Through Paintings

We suggest you a selection of the best tourist destinations and festivals by the hand of great artists!

Andra Patricia Ritisan 11 March 2024

Art Travels: Golden Temple of Amritsar

Nestled in the city of Amritsar in Northwestern India is the iconic Harmandir Sahib or Darbar Sahib, better known as the Golden Temple. This sublime...

Maya M. Tola 8 January 2024

Art and Sports: En Route to the Paris 2024 Olympics

The forthcoming Paris 2024 Summer Olympics will bridge the worlds of art and sport, with equestrian competitions at the Palace of Versailles, fencing...

Ledys Chemin 9 April 2024

Never miss DailyArt Magazine's stories. Sign up and get your dose of art history delivered straight to your inbox!

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.3 The Grand Tour

Read the following excerpt from Sarah Goldsmith’s book, Masculinity and Danger on the Eighteenth-Century Grand Tour .

Introduction

Eighteenth-century Britain was a society in constant motion. As the country’s trading empire grew, vessels set sail to explore and trade around the globe. Within the British Isles, aristocratic households moved regularly between the town and country, labouring communities migrated for work, and domestic tourism was on the rise. Between the extremities of global and domestic travel lay the destination of continental Europe. Diplomatic, military, trade, intellectual and artistic networks facilitated travel across the channel at almost every level of society. These occupational travellers frequently took the opportunity to enact the role of tourist and were joined by a growing body of travellers from elite and middling backgrounds whose purpose for going abroad rested entirely on reasons of pleasure, curiosity and health. This nascent culture of tourism could result in short week- or month-long trips or in years spent in expatriate communities. It was stimulated by a developing genre of travel writing, which was also highly influential in the diffusion of key cultural trends, including the novel, sentimentalism, the sublime and picturesque, and Romanticism.

In the midst of this was the Grand Tour, a well-established educational practice undertaken by the sons of many eighteenth-century aristocratic and gentry families. The Tour, which dates back to the Elizabethan era, had its roots in a long tradition of travel as a means of male formation, which included the medieval practice of raising young boys in noble households and the Renaissance custom of peregrination. Its participants were young elite men in their late teens and early twenties, often travelling after school, home tutoring or university but before the responsibilities of adult life. As this was the most expensive, time-consuming and socially exclusive of the early modern options of educational travel, a Grand Tourist was typically the family heir, often with companions. These were mostly tutors (part companion, part in loco parentis) and servants, but could also include younger brothers, friends of a lesser rank and older male companions. These groups embarked on journeys that typically lasted between three to four years, although they could be as long as five years or as short as several months. During this time, Grand Tourists received a formal education, through tutors, academies and universities, and an experiential one, via encounters with a wide variety of European countries, societies and cultures. Key destinations included the cities, courts and environs of France, the Netherlands and Low Countries, the German principalities, Austria, Switzerland and Italy, with occasional excursions further afield.

As a practice of travel that catered exclusively to the young, elite and male, the Grand Tour had a distinctly educational purpose that distinguished it from other cultures of eighteenth-century travel. The Tour was understood as a finishing school of masculinity, a coming-of- age process, and an important rite of passage that was intended to form young men in their adult masculine identities by endowing them with the skills and virtues most highly prized by the elite. [1] ¹ As a cornerstone of elite masculine education, it was a vital part of this social group’s understanding, practice and construction of masculinity, and of their wider strategies of self-fashioning and power.² This intrinsic relationship between the Grand Tour and elite masculinity is at the heart of Masculinity and Danger on the Eighteenth-Century Grand Tour .

Studies of the Grand Tour have typically focused on the destinations of Italy and France, and asserted that the Tour’s itinerary and goals prioritized polite accomplishments, classical republican virtue and an aesthetic appreciation of the antique. On the Grand Tour, elite young men were supposedly taught to wield power and social superiority primarily through cultural means. Through this, it is argued, male tourists were formed in a code of masculinity that was singularly polite and civil. This conclusion is influenced by the history of masculinity’s early theory – adapted from the sociologist R. W. Connell – which argued that historical understandings of maleness were dominated by a succession of hegemonic expressions of masculinity. As a cultural institution exclusively associated with the polite man, the Grand Tour has been viewed as a tool used to propagate and enforce a hegemonic norm. It is a principal contention of this book that these approaches have masked the full depth, breadth and complexity of the Grand Tour and, correspondingly, of eighteenth-century elite masculinity. As the book’s title suggests, it offers a reassessment of the Tour’s significance for the history of elite masculinity by investigating its aims, agendas and itineraries through bringing together archival evidence around the theme of danger.

The Grand Tour was an institution of elite masculine formation that took place in numerous environs across Europe, resulted in myriad experiences, and imparted a host of skills and knowledge. In his memoirs, published after his death in 1794, the historian and MP Edward Gibbon reflected on the ideal capacities of a Grand Tourist. Alongside ‘an active indefatigable vigour of mind and body’ and ‘careless smile’ for the hardships of travel, the Tourist, or traveller, required a ‘fearless’, ‘restless curiosity’ that would drive him to encounter floods, mountains and mines in pursuit of ‘the most doubtful promise of entertainment or instruction’. The Tourist must also gain ‘the practical knowledge of husbandry and manufactures … be a chemist, a botanist, and a master of mechanics’. He must develop a ‘musical ear’, dexterous pencil, and a ‘correct and exquisite eye’ that could discern the merits of landscapes, pictures and buildings. Finally, the young man should have a ‘flexible temper which can assimilate itself to every tone of society, from the court to the cottage’. In a line later edited out, he concluded that this was a ‘sketch of ideal perfection’.³

Gibbon’s list was wide-ranging, but even so he included only some of the Tour’s agenda. He made no mention of one of the most common expectations surrounding the Tour: that young men would gain an insight into the politics, military establishment, economy, industries and, increasingly, the manners and customs of other nations. The impressive diversity of the Tour’s agenda was intentionally ambitious and unified by a single aim: to demonstrate, preserve and reinforce elite male power on an individual, familial, national and international level. Acknowledging the full breadth of the Grand Tour’s ambition allows one to consider how this goal was achieved through a complex, calculated use of practice, performance, place, and narrative. This book starts the process of unpacking the full extent of the Tour’s diversity by offering an in-depth examination of its provision of military education and engagement with war; the Tour as a health regime; Tourists’ participation in physical exercises, sports and the hardships of travel; and their physical, scientific and aesthetic engagement with the natural phenomena of the Alps and Vesuvius. Each episode in this agenda is united by two factors: it was understood to harbour elements of physical risk, and it has been largely neglected by existing scholarship. During these activities, encounters with danger were often idealized and used as important and formative opportunities that assisted young men in cultivating physical health, ‘hardy’ martial masculine virtues of courage, self-control, daring, curiosity and endurance, and an identity that was simultaneously British, elite and cosmopolitan.

In identifying the significance of ‘hardy’, martial masculinities to eighteenth-century elite culture, this book is not arguing that the masculinities of polite connoisseurship were any less important. Rather, it contends that the Grand Tour’s diversity of aims, locations and itineraries was intentionally used to form men in multiple codes of elite masculine identity. To have a ‘flexible temper’ that could be assimilated in ‘every company and situation’ was not simply a hallmark of polite sociability.4 It was evidence of a masculine trait of adaptability. Acknowledging that adaptability and multiplicity were crucial components to elite masculinity as a whole is central to moving the history of masculinity beyond the search for a hegemonic norm. Examining these issues through the theme of danger and hardy masculinity adds another degree of complexity to understanding the types of men that the eighteenth-century elite wished the next generation of British political, military and social leaders to be.

The itineraries, agendas and mentalities explored throughout this book are not easily visible in the contemporary published literature surrounding the Grand Tour and have, for the most part, been recovered through an analysis of archival sources. The Tour’s highly prized status has meant that related correspondence, journals, tutor reports and financial records were often carefully preserved. This book draws on research into more than thirty Grand Tours, taking place between 1700 and 1780, and closely follows the experiences and writings of these gentry and aristocratic Grand Tourists, their tutors, companions, servants and dogs. These men exchanged correspondence with a wider range of male and female family members, friends, diplomats and members of a continental elite befriended during their travels; they also wrote diaries and memoirs, commissioned and purchased portraits, artwork and mementos and, in the case of some tutors, published literature based on their travels. Recovering an individual and familial perspective allows one to delve beyond the cultural representation of the Tour into richly textured accounts of lived experience in all its complexity. Probing the differences between published and archival accounts enables a fuller, nuanced understanding of how the British elite as a community understood the Grand Tour, the masculinities that families hoped to cultivate in their sons and that these sons desired for themselves, and the ways in which this cultivation was undertaken. By investigating the priorities, agendas and beliefs evident in these sources, a collective elite agenda can be distilled while still allowing for individual approaches, divergences and disagreements.

- For scholarly discussions of the Grand Tour as a form of initiation, see B. Redford, Venice and the Grand Tour (New Haven, Conn. and London, 1996), pp. 7–9, 14–15; M. Cohen, Fashioning Masculinity: National Identity and Language in the Eighteenth Century (London, 1996), pp. 54–63; R. Sweet, Cities and the Grand Tour: the British in Italy, c.1690– 1820 (Cambridge, 2012), pp. 23–5.

- H. Greig, The Beau Monde: Fashionable Society in Georgian London (Oxford, 2013), pp. 24–5; S. Conway, England, Ireland and Continental Europe in the Eighteenth Century (Oxford, 2011), ch. 7.

- British Library (Brit. Libr.)., Add. MS. 34874 C, ‘Memoirs of the life and writings of Edward Gibbon, written c.1789–90’, fos. 29–30.

- Brit. Libr., Add. MS. 34874 C, ‘Memoirs of the life and writings of Edward Gibbon, written c.1789–90’, fos. 29–30.

Attribution

“Introduction” in Masculinity and Danger on the Eighteenth-Century Grand Tour by Sarah Goldsmith published by University of London Press, Institute of Historical Research is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

- For scholarly discussions of the Grand Tour as a form of initiation, see B. Redford, Venice and the Grand Tour (New Haven, Conn. and London, 1996), pp. 7–9, 14–15; M. Cohen, Fashioning Masculinity: National Identity and Language in the Eighteenth Century (London, 1996), pp. 54–63; R. Sweet, Cities and the Grand Tour: the British in Italy, c.1690– 1820 (Cambridge, 2012), pp. 23–5. ↵

Origins of Contemporary Art, Design, and Interiors Copyright © by Jennifer Lorraine Fraser is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- What Was The Grand Tour...

What Was the Grand Tour and Where Did People Go?

Freelance Travel and Music Writer

Nowadays, it’s so easy to pack a bag and hop on a flight or interrail across Europe’s railway at your own leisure. But what if it was known as a right of passage, made no easier by the fact that there was no such modern luxury? Welcome to the Grand Tour – and we’re not talking about Jeremy Clarkson’s TV series …

What was the grand tour all about.

The Grand Tour was a trip of Europe, typically undertaken by young men, which begun in the 17th century and went through to the mid-19th. Women over the age of 21 would occasionally partake, providing they were accompanied by a chaperone from their family. The Grand Tour was seen as an educational trip across Europe, usually starting in Dover, and would see young, wealthy travellers search for arts and culture. Though travelling was not as easy back then, mostly thanks to no rail routes like today, those on The Grand Tour would often have a healthy supply of funds in order to enjoy themselves freely.

What did travellers get up to?

Just like us today, explorers travelled to discover and experience all kinds of different cultures. With their near-unlimited funds, travellers would often head off for months – or even years – in search of Western civilisation, perfecting their language skills and even commissioning paintings in the process.

Of course, in the 17th century, there was no such thing as the internet, making discovering things while sat on the other side of the world near impossible. Cultural integration was not yet fully-fledged and nothing like we experience today, so the only way to understand different ways of life was to experience them yourself. Hence why so many people set off for the Grand Tour – the ultimate trip across Europe!

Typical routes taken on the Grand Tour

Travellers (occompanied by a tutor) would often start around the South East region and head in to France, where a coach would often be rented should the party be wealthy enough. Occasionally, the coaches would need to be disassembled in order to cross difficult terrain such as the Alps.

Once passing through Calais and Paris, a typical journey would include a stop-off in Switzerland before crossing the Alps in to Northern Italy. Here’s where the wealth really comes in to play – as luggage and methods of transport would need to be dismantled and carried manually – as really rich travellers would often employ servants to carry everything for them.

Of course, Italy is a highly cultural country and famous for its art and historic buildings, so travellers would spend longer here. Turin, Florence, Rome, Pompeii and Venice would be amongst the cities visited, generally enticing those in to extended stays.

Become a Culture Tripper!

Sign up to our newsletter to save up to $1,395 on our unique trips..

See privacy policy .

On the return leg, travellers would visit Germany and occasionally Austria, including study time at universities such as Munich, before heading to Holland and Flanders, ahead of crossing the Channel back to Dover.

Culture Trips launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes places and communities so special.

Our immersive trips , led by Local Insiders, are once-in-a-lifetime experiences and an invitation to travel the world with like-minded explorers. Our Travel Experts are on hand to help you make perfect memories. All our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.

All our travel guides are curated by the Culture Trip team working in tandem with local experts. From unique experiences to essential tips on how to make the most of your future travels, we’ve got you covered.

Guides & Tips

The best private trips to book in southern europe.

The Best Private Trips to Book in Europe

Places to Stay

The best private trips to book for your classical studies class.

The Best Places in Europe to Visit in 2024

The Best Places to Travel in May 2024

The Best Private Trips to Book With Your Support Group

The Best Rail Trips to Take in Europe

The Best European Trips for Foodies

Five Places That Look Even More Beautiful Covered in Snow

The Best Trips for Sampling Amazing Mediterranean Food

The Best Private Trips to Book for Your Religious Studies Class

The Best Places to Travel in August 2024

Culture Trip Summer Sale