Journey Pursuits

Why Islam Promotes Travel & Exploration: 5 Reasons

The significance of travel in islam.

Islam is a religion that promotes travel and exploration. For Muslims, traveling is not only a way to see the world, but it is also a way to connect with God, learn new things, and expand their knowledge. Muslims are encouraged to travel and explore the world, and there are many reasons why Islam promotes travel and exploration. In this article, we will discuss five reasons why Islam encourages Muslims to travel and explore the world.

Incentive to Seek Knowledge

One of the main reasons why Islam promotes travel and exploration is the incentive to seek knowledge. Muslims are encouraged to seek knowledge and explore the world in order to learn and gain a better understanding of the world around them. Traveling is a great way to learn about new cultures, languages, and customs. When Muslims travel, they are exposed to different ways of life, and they can learn from the people they meet along the way.

The Quran encourages Muslims to seek knowledge and explore the world. In Surah Al-Mujadilah, Allah says, “And Allah has made the earth a wide expanse for you, that you may follow therein roads of guidance.” This verse emphasizes the importance of exploring the world and learning from it. Muslims are encouraged to travel and explore the world in order to gain knowledge and wisdom.

Encouragement to Expand Horizons

Another reason why Islam promotes travel and exploration is the encouragement to expand horizons. Traveling allows Muslims to see the world from a different perspective and experience new things. It helps them break out of their comfort zones and explore new opportunities. Muslims are encouraged to expand their horizons and challenge themselves in order to grow and develop as individuals.

The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) encouraged Muslims to travel and explore the world. He said, “Travel and explore the world, for the earth is God’s mosque.” This hadith emphasizes the importance of traveling and exploring the world. Muslims are encouraged to see the world as a place of worship and to use their travels as a way to connect with God.

Emphasis on Unity and Brotherhood

Islam promotes unity and brotherhood among Muslims. One of the ways to promote unity and brotherhood is through travel and exploration. When Muslims travel, they meet people from different backgrounds and cultures, and they can learn to appreciate their differences. Traveling can also help break down barriers and promote understanding between people of different faiths and cultures.

The Quran emphasizes the importance of unity and brotherhood. In Surah Al-Hujurat, Allah says, “O mankind, indeed We have created you from male and female and made you peoples and tribes that you may know one another. Indeed, the most noble of you in the sight of Allah is the most righteous of you. Indeed, Allah is Knowing and Acquainted.” Muslims are encouraged to appreciate the diversity of the world and to use their travels as a way to connect with people of different backgrounds and cultures.

Appreciation for Diversity and Culture

Another reason why Islam promotes travel and exploration is the appreciation for diversity and culture. Muslims are encouraged to appreciate the diversity of the world and to learn about different cultures and customs. Traveling allows Muslims to experience different cultures firsthand and gain a better understanding of the world around them.

The Quran emphasizes the importance of diversity and culture. In Surah Al-Ankabut, Allah says, “And of His signs is the creation of the heavens and the earth and the diversity of your languages and your colors. Indeed, in that are signs for those of knowledge.” Muslims are encouraged to appreciate the diversity of the world and to use their travels as a way to learn about different cultures and customs.

Spiritual and Personal Growth

Finally, Islam promotes travel and exploration as a way to promote spiritual and personal growth. Traveling can be a transformative experience that can help Muslims grow and develop as individuals. It can help them gain a better understanding of themselves and their place in the world.

The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) said, “Whoever travels to seek knowledge, Allah will facilitate for him the way to Paradise.” This hadith emphasizes the importance of seeking knowledge through travel and exploration. Muslims are encouraged to use their travels as a way to connect with God and to grow and develop as individuals.

In conclusion, Islam promotes travel and exploration for many reasons. Muslims are encouraged to seek knowledge, expand their horizons, promote unity and brotherhood, appreciate diversity and culture, and promote spiritual and personal growth. Traveling is not only a way to see the world, but it is also a way to connect with God and grow as individuals. Muslims should embrace travel and use it as a way to learn and grow.

Similar Posts

October weather in madrid, spain: a comprehensive guide., expat life in manila: a comprehensive guide, idaho to wyoming: discovering the boise to jackson hole route, air canada vs westjet: a traveler’s guide, discover expat life in senegal: a guide, expert expat guide: essential tips for travelers.

About Islam

- # Quran 382 Articles

- # Spirituality 382 Articles

- # Discovering Islam 382 Articles

- # Shariah 382 Articles

- # Videos 382 Articles

- # Family & Life 382 Articles

- # Fatwa & Counseling 382 Articles

- # Muslim News 382 Articles

- # Youth Q & A 382 Articles

- # Donate 382 Articles

- Family & Life

- Culture & Entertainment

10 Reasons Why Muslims Should Travel

Traveling is healthy for the body, mind, and spirit; Islam prescribes these exact reasons to why Muslims should travel.

If you’re looking for encouragement to plan your next adventure , here are eight wonderful benefits of traveling to help you decide.

1 – Create Meaningful Relationships

Knowing and learning about others is part of our deen. Allah says in the Qur’an,

“O mankind, indeed we have created you from male and female and made you peoples and tribes that you may know one another […]” (Al-Hujurat 49:13)

Visiting, experiencing, and relating to new people and cultures helps improve both your social and communication skills. You’re always likely to make some new friends along the journey. Traveling to new places allows you to build new relationships .

You can also use the challenges, experiences, and new knowledge about yourself to strengthen existing relationships .

" title="Advertise and Market to Muslims" target="_blank">Ads by Muslim Ad Network

2 – Shake Things Up

Travel keeps things interesting! If you are feeling confused, stagnant, or just plain bored in your life, taking a break from the ordinary can help you move forward . New experiences help you process old ones to make fresh, interesting connections in your brain.

Traveling can also act as a muse to your creativity . It helps you gather and assimilate new, original, and creative thoughts. Anytime you are feeling stuck or need a change of pace, travel is the perfect solution.

Travel also enhances and grows the amount of uncertainty you’re able to tolerate. And tolerance to change is a great skill to have when you head back to a more stable and settled life . Because no matter where you are, your days will always have unexpected challenges and hiccups: that’s life!

3 – Prove Dreams Come True

The whole experience of travel involves both planning and achieving your dreams . There is goal setting, itineraries, mapping out your experience, and waiting for the date. Travel is a new experience in space and time that usually requires both money-saving and pining for the experience.

There is a deep sense of accomplishment during and after travel. You’ve proven to yourself that you can achieve any dreams and goals when you apply yourself to them.

4 – Gain Peace of Mind

While some people use travel as a temporary (or semi-permanent) escape. It can also give you a renewed sense of peace with yourself and your “regular” living environment.

Travel — especially to drastically different cultures and faraway lands — can help you gain gratitude and appreciation for what you already have in your life. Travel inspires you to make peace with what you have and be grateful for your many privileges and blessings.

5 – Broaden Your Horizons

This travel reason is cliché but true. You don’t understand all that you don’t know until you’re exposed to it. Traveling helps you understand and see that you have a lot to learn .

There is a mystery to unlock about you, others, and the world we all live in. Traveling throughout the land gives you a chance to expand your maps of how you move in the world and gain new perspectives. Travel can also help you connect to God, His creation, nature, and the universe in ways that you can’t when locked in a box of your own making.

Islam doesn’t want us to stay blind to the ways and cultures of others. In fact, quite the opposite. Allah commands us to travel:

“Say, [O Muhammad], ‘Travel through the land and observe how He began creation. Then Allah will produce the final creation. Indeed, Allah, over all things, is competent.’” ( Al-`Ankabut 29:20)

6 – Collect Cool Stories

Travel gives you a wealth of memories to last you a lifetime. While there will be some fun (and some harrowing) experiences, no matter what happens, it will always be an adventure. Traveling helps you loosen up and have a good time experiencing new places, cultures, and people. Travel creates feel-good memories that you can share with your friends and family, or recall whenever you need to go back to a “happy place.”

7 – Challenge Yourself

If you feel you’re stuck in a rut in your daily life, travel can help you break free. Travel pushes you to the limits of what you can tolerate and master. This helps you get to know yourself better . Getting in touch with yourself, your essence, and your uniqueness are some of the greatest gifts travel gives you.

8 – Gain a Real-life Education

When you are on the ground in a new place, there is much learning to do in a short amount of time. You must work through puzzles and challenges on the fly. Traveling pushes you to develop new skills — even learn new languages — to both survive and thrive.

9 – Boost Your Confidence

Traveling, especially solo traveling, makes you trust yourself and become more self-reliant . It gives you a chance to understand and use your unique gifts to conquer new challenges. The more you practice traveling, the more your confidence builds and the easier it gets. This means that over time it will become easier to identify your fears and overcome them in new situations.

10 – Food! (For Thought)

Last but not least, let’s not forget the new foods. We tie so much of our cultures into the foods we eat. The spices, the preparation, the ceremony of serving: food is a powerful way to understand others.

When you understand the foods others eat and why they eat them, you get to know them on one of their most primal levels. We also can’t deny that most of the new foods you’ll taste on your travels are delicious!

Remember, you don’t have to go far to experience all these benefits of travel. Even a few hundred miles (or kilometers) out of your hometown can expose you to all the challenges, situations, and people who will help you grow.

Where have you always wanted to visit? What’s stopping you other than yourself? Enough with the excuses: take the leap and start planning your next trip today.

Privacy Overview

11 Reasons Why Muslims Should Travel in 2023!

With there being limited or no travel restrictions since Covid-19 measures were lifted, it’s time for Muslims to take up travelling! Here are 11 reasons why.

Advertise on TMV

With Covid-19 restrictions more or less lifted everywhere, I highly recommend Muslims make the habit of travelling!

I take off at every opportunity I can, be it with family, friends or alone, exploring, photographing and documenting interesting stuff in exotic destinations and taking the odd selfie to make friends jealous along the way (actually I rarely go to exotic destinations and am still struggling to work the ‘selfie’ feature on my phone – although my wife and daughters are usually on hand should the need arise!).

But as a Muslim Travel Writer living in challenging times, I’ve come to see travel in a completely different light; as an education and spiritually transformative experience. I also now understand why travel is encouraged by Islam – why else would we be able to collapse our prayers? But what I don’t understand is the lack of Muslims willing to travel. And before you bombard me with your messages and selfies from Dubai and Sharm, let’s just make clear that a package holiday to a touristic location geared to all your expectations and creature comforts is not ‘travel’. That would be a holiday. I believe all Muslims should really travel, the proper independent stuff and here are eleven reasons why (beyond just being able to collapse our daily prayers – so technically that’s 12!):

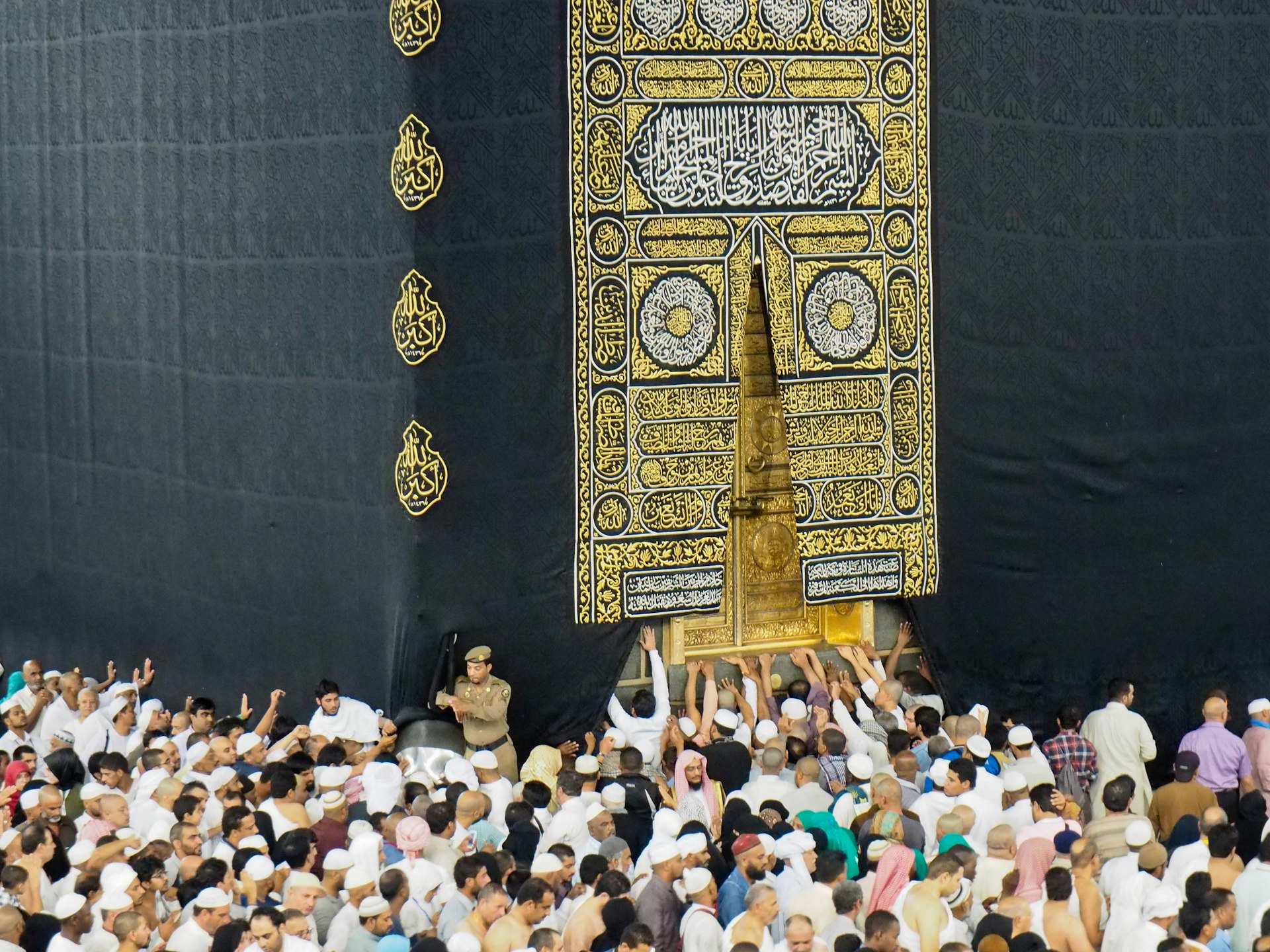

1. The Hajj (or Umrah)

Travel is integral to many ‘spiritual’ aspects of Islam. Most notably the pilgrimages of Hajj or Umrah, both of which require Muslims to travel to Makkah, a journey that has always been viewed as much a transformative experience as the Hajj or Umrah itself – something great Muslim travellers like Ibn Battuta and the Victorian explorer Richard Burton have testified in their memoirs. On top of this both the Hajj and Umrah involve numerous rituals of motion and travel, such as the tawafs (initial and farewell) around the Ka’ba, the walk between Saf’a and Mar’wah, and the (Hajj only) journeys to Mina, Mount Arafat and Muzdalifah. Each of these demands the pilgrim meditates and reflects whilst moving.

2. The Prophet

Travel was openly encouraged by the Prophet Muhammad who saw it as an essential way to seek knowledge. Preserved narrations such as the oft-cited “seek knowledge even unto China” support this. Then there is the Prophet’s highly spiritual experience, the ‘night journey’ or Meraj in which he ascends through the Seven Heavens, meets the prophets of before and receives instructions from God about the daily prayers. This journey, which most scholars believe happened before his emigration to Medina, was intended to strengthen his resolve and inner belief about his own prophethood. Finally, much of the Prophet’s formative years were spent travelling with his family’s business caravans all over the Middle East. These travels later had a profound impact on his ability to respect difference and empathise with different cultures.

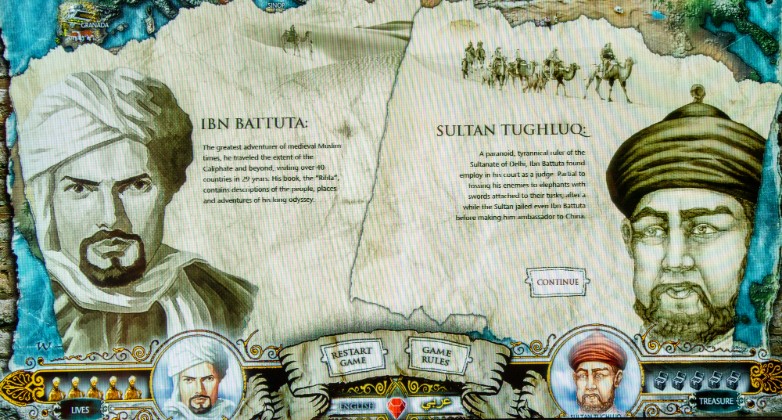

3. A Travelling Tradition

Muslims come from a long line of famous travellers who were transformed irreversibly by their experiences. This includes the world’s most travelled man, Ibn Battuta who was born in Tangier, Morocco and travelled for 30 years after setting off for the Hajj in 1325 aged only 21 (one might say he was the first ‘gap’ year student!). Muslims scholars also deemed it important to travel and often covered great distances to acquire knowledge like the Sunni Muhaddith, Muhammad al-Bukhari. Finally there are many prophets who embarked on monumental spiritual journeys that transformed their character and strengthened their inner resolve. The most famous of these is Musa’s journey (Moses) alongside al-Khidr.

4. The Spirituality of Travel

“Be in this world as if you were a stranger or a traveler along a path”, this is a popular hadith about attachment to the material world and it is therefore no surprise that every spiritual tradition in Islam (and most other faiths) incorporates ‘wandering’ or ‘travel’ as part of the soul’s training. The wisdom behind this is to encourage detachment to the dunya (material world), i.e. make it ‘strange’ to the spirit, and thereby develop a greater appreciation of the hereafter. Following his spiritual crisis, the great medieval theologian Abu Hamed Muhammad ibn Muhammad al Ghazali – often called the ‘Proof of Islam’ – embarked on just such a journey.

5. Love of God

Through travel we get to know God better, it’s that simple. I have had some of my most spiritual moments staring out across a mountain range, a desert, lake or even just humanity going about its daily existence. Travel makes the familiar unfamiliar to us and in doing so we come to better appreciate God’s creation. Throughout the Qur’an verses ask man to reflect on what has been created on earth and in the heavens – what better way to do that then through travel?

6. The Death of Ignorance and Birth of Humility

Nothing quite extinguishes ignorance like real life experiences. In an increasingly global world saturated by media, we find it easy to sit on one side of the world and judge people on the other. Using video, news articles and pictures it is easy to arrogantly believe we know a people or a place just by how media has represented them. Yet the very meaning of ‘media’ is that it is in the middle of reality and a mere representation of it. It is not the reality. Travelling to places we have judged or thought we knew is the best way to realise this, because it teaches us just how wrong we can be and addresses our ignorance. Travel makes us see that actually we know very little.

7. Know Thyself

Talk to anyone who has ‘travelled’, especially solo travellers and you will be blown away by their self-confidence, open-mindedness and how well they seem to know themselves. Travel creates a better you, because it takes you out of your comfort zone and forces you to ask questions about who you are, why you are and what you are. As Muslims we believe there will come a time when we have to stand alone in front of our Creator and be cross examined. Travel allows you to cross examine yourself without the expectations of society, culture, religion and family. Those who have done this will tell you that nothing is more liberating than having only your own expectations. But be aware this can be quite scary the first time because you might suddenly realise that actually you don’t have that many expectations of your own .

8. Experience Something ‘New’

The world is an amazing place full of amazing experiences waiting to be had. To not enjoy any of them whilst you’re here seems such a waste. In an age where travel is becoming increasingly cheap and methods of income ‘on the road’ to fund those travels, increasingly flexible, few excuses remain to not go off and try to see the world at least once. Those who don’t will never see a sunrise over an ancient man-made masterpiece like Macchu Picchu; they won’t ever listen to the silence of a natural wonder like the Sahara desert; nor will they taste the sweetness of a star fruit freshly shaken from its tree by Bangladeshi village children, and they certainly won’t experience the joyous smells of a thousand spices as they stroll through a real Arabian bazaar .

9. Appreciate What and Who You Have

W e always take our parents, brothers, sisters and homes for granted but spend a few months on the road and then taste your mother’s home cooking or listen to your father’s boring stories of old. Come back after a month euro railing and see if your sister is actually as annoying as you thought or your older brother as overbearing as he seemed. ‘Absence makes the heart fond’ they say, but what that really means is you finally see what God has blessed you with.

10. Regain your Faith in Humanity

One day I am going to write a book about the kindness of strangers on my travels for those people who were also born into a ‘world’ that seemed difficult to trust. It was travel that regained my faith in humanity.

From the gypsies in the hills of Tuscany who drove my family and I up a mountain to catch the last bus to Omar, the Turkish man who we fell in love with after he spontaneously took us on a road trip through rural Turkey, I have had beautiful encounters with strangers all over the world and come to realise that actually people are amazing. Growing up in 1980s inner city London, that was difficult to imagine. I now know that the vast majority of human beings in the world are caring, wonderful and respectful people – the very embodiment of what it means to be ‘human’.

11. Islamic History

Head to my blog and check out the previously unheard of Islamic stories of Europe uncovered on my travels, like the discovery of a Muslim Dracula; the Christian island where the lingua franca is Arabic or the story of the Christian boy who grew up to rule the Ottoman empire and you will appreciate the vast amount of heritage just waiting to be unearthed (and this is just the tip of the iceberg). By travelling to places significant in Islamic history, whether it be Medina or Cordoba in Spain, we come closer to our roots, our past and our heritage. It is only by knowing where we came from, can we truly know where we are travelling to.

12 inspiring and applicable excerpts from the ‘Treatise on Rights’ by Imam Zain Al-Abideen

Five Reasons We Need More Female Entrepreneurs!

5 Mistakes You Might Be Making In Your Prayers

Creation’s Reality: A Personal Journey Through The Quran

Congregational Prayers and the Community in the Prophet’s Sirah

Self-Care Does Not Have to be Self-Obsession: We Can All Help

11 Reasons Why Muslims Should Travel

I take off at every opportunity I can, be it with family, friends or alone, exploring, photographing and documenting interesting stuff in exotic destinations and taking the odd selfie to make friends jealous along the way (actually I rarely go to exotic destinations and am still struggling to work the ‘selfie’ feature on my phone – although my wife and daughters are usually on hand should the need arise!).

But as a Muslim Travel Writer living in challenging times, I’ve come to see travel in a completely different light; as an education and spiritually transformative experience. I also now understand why travel is encouraged by Islam – why else would we be able to collapse our prayers? But what I don’t understand is the lack of Muslims willing to travel. And before you bombard me with your messages and selfies from Dubai and Sharm, let’s make clear that a package holiday in a touristic location where all your expectations and creature comforts are met is not ‘travel’. That would be a holiday. I believe all Muslims should really travel, the proper independent stuff and here are eleven reasons why (beyond just being able to collapse our daily prayers – so technically that’s 12!):

1. The Hajj (or Umrah)

Travel is integral to many ‘spiritual’ aspects of Islam. Most notably the pilgrimage of Hajj, which is one of the five fundamental pillars of the faith. Then there is also the recommended smaller pilgrimage Umrah, both require Muslims to travel to Makkah, a journey that is viewed as much a transformative experience as the actual pilgrimage itself – something Muslim traveller Ibn Battuta and even Victorian explorer Richard Burton wrote about in their memoirs. The Hajj and Umrah also involve numerous rituals of motion and travel, such as the tawafs (initial and farewell) around the Ka’ba, the walk between Saf’a and Mar’wah, and the (Hajj only) journeys to Mina, Mount Arafat and Muzdalifah. Each of these demands the pilgrim meditates and reflects whilst moving.

2. The Prophet (peace be upon him)

Travel was openly encouraged by the Prophet Muhammad who, amongst other things, saw it as an essential way to seek knowledge. The Prophet experienced highly spiritual journeys himself such as the mystical ‘night journey’ or Meraj in which he ascends through the Seven Heavens, meets the prophets of before and receives instruction from God about the daily prayers. This journey, which most scholars believe happened before his emigration to Medina, was intended to strengthen his resolve and inner belief about his own prophethood. Finally, much of the Prophet’s formative years were spent travelling with his family’s business caravans all over the Middle East. These travels later had a profound impact on his ability to respect difference and empathise with other cultures.

3. A travelling tradition

Related: Fascinating Photos of Pilgrims from 10 Countries During Hajj in 1880

Muslims come from a long line of famous travellers transformed irreversibly by their experiences. This includes the world’s most travelled man, Ibn Battuta who was born in Tangier, Morocco and travelled for 30 years after setting off for the Hajj in 1325 aged only 21 (one might say he was the first ‘gap’ year student!). Muslim scholars also deemed it important to travel and often covered great distances to acquire knowledge like the Sunni Muhaddith, Muhammad al-Bukhari. Finally there are many prophets who embarked on monumental spiritual journeys that transformed their character and strengthened their inner resolve. The most famous of these is Musa’s journey (Moses) alongside al-Khidr.

4. The spirituality of Travel

“Be in this world as if you were a stranger or a traveller along a path”,

This is a popular hadith about attachment to the material world and it is therefore no surprise that every spiritual tradition in Islam (and most other faiths) incorporates ‘wandering’ or ‘travel’ as part of the soul’s training. The wisdom behind this is to encourage detachment to the dunya (material world), i.e. make it ‘strange’ to the spirit, and thereby develop a greater appreciation of the hereafter. Following his spiritual crisis, the great medieval theologian Abu Hamed Muhammad ibn Muhammad al Ghazali – often called the ‘Proof of Islam’ – embarked on just such a journey.

5. Love of God

Through travel we get to know God better, it’s that simple. I have had some of my most spiritual moments staring out across a mountain range, a desert, lake, or even just humanity going about its daily existence. Travel makes the familiar unfamiliar to us and in doing so we come to better appreciate God’s creation. Throughout the Qur’an verses ask man to reflect on what has been created on earth and in the heavens – what better way to do that than through travel?

6. The death of ignorance and birth of humility

Nothing quite extinguishes ignorance like real life experiences. In an increasingly global world saturated by media, we find it easy to sit on one side of the world and judge people on the other. Using video, news articles and pictures it is easy to arrogantly believe we know a people or a place just by how media has represented them. Yet the very meaning of ‘media’ is that it is in the middle of reality and a mere representation of it. It is not the reality. Travelling to places we have judged or thought we knew is the best way to realise this, because it teaches us just how wrong we can be and addresses our ignorance. Travel makes us see that actually we know very little.

7. Know thyself

Talk to anyone who has ‘travelled’, especially solo travellers and you will be blown away by their self-confidence, open-mindedness and how well they seem to know themselves. Travel creates a better you, because it takes you out of your comfort zone and forces you to ask questions about who you are, why you are and what you are. As Muslims we believe there will come a time when we have to stand alone in front of our Creator and be cross examined. Travel allows you to cross examine yourself without the expectations of society, culture, religion and family. Those who have done this will tell you that nothing is more liberating than having only your own expectations. But be aware this can be quite scary the first time as you might suddenly realise that actually you don’t have that many expectations of your own.

8. Experience something ‘new’

The world is an amazing place full of amazing experiences waiting to be had. To not enjoy some of these whilst you’re here seems such a waste. In an age where travel is becoming increasingly cheap and methods of income ‘on the road’ to fund those travels, increasingly flexible, few excuses remain to not go and see the world at least once. Those who don’t will never see a sunrise over an ancient man-made masterpiece like Macchu Picchu; they won’t ever listen to the silence of a natural wonder like the Sahara desert; nor will they taste the sweetness of a star fruit freshly shaken from its tree by Bangladeshi village children.

9. Appreciate what and who you have

We always take our parents, brothers, sisters and homes for granted but spend a few months on the road and then taste your mother’s home cooking or listen to your father’s boring stories of old. Come back after a month Euro-railing and see if your sister is actually as annoying as you thought or your older brother as overbearing as he seemed. ‘Absence makes the heart fond’ they say, but what that really means is you finally see what God has blessed you with.

10. Regain your faith in humanity

One day I am going to write a book about the kindness of strangers on my travels for those who were also born into a ‘world’ that seemed difficult to trust. It was travel that regained my faith in humanity. From the gypsies in the hills of Tuscany who drove my family and I up a mountain to catch the last bus to Omar, the Turkish man who we fell in love with after he spontaneously took us on a road trip through rural Turkey, I have had beautiful encounters with strangers all over the world and come to realise that actually people are amazing. Growing up in 1980s inner city London, that was difficult to imagine. I now know that the vast majority of human beings in the world are caring, wonderful and respectful people – the very embodiment of what it means to be ‘human’.

11. Islamic history

There is so much Islamic history just waiting to be unearthed by travelling. Most of you know I am on my own journey doing just that and have already posted previously unheard of tales about Europe’s forgotten Muslim heritage, like the discovery of a Muslim Dracula and the Latin island where the lingua franca is Arabic or the story of the Christian boy who grew up to rule the Ottoman empire (and these are just the tip of a huge iceberg I am sifting through). By travelling to places significant in Islamic history, whether it be Medina or Cordoba in Spain, we come closer to our roots, our past and our heritage. It is only by knowing where we came from, can we truly know where we are travelling to.

Source: The Wandering Musulman

Tharik Hussain is a freelance Travel Writer, Photographer and Blogger. He has a Masters in Islamic tradition, culture and history and a Bachelors in Media and Cultural Studies. He has also been a News Journalist for Asian tabloid Eastern Eye as well as a Copyeditor for the Saudi Gazette.

Written by Tharik Hussain

Tharik is a freelance journalist, travel writer, photographer and broadcaster specialising in the Islamic stories of Europe and the West, and Muslim ('Halal') travel.

5 Steps to Reconnect With Your Wife

8 Steps to Reconnect With Your Husband

Copyright © IlmFeed 2018

TRAVEL GUIDES

Popular cities, explore by region, featured guide.

Japan Travel Guide

Destinations.

A Creative’s Guide to Thailand

Creative resources, photography, videography, art & design.

7 Tips to Spice up Your Photography Using Geometry

GET INVOLVED

EXPERIENCES

#PPImagineAZ Enter to Win a trip to Arizona!

The journal, get inspired, sustainability.

How to Be a More Responsible Traveler in 2021

Egypt , jordan , middle east , morocco , travel stories , turkey, why we travel: lessons from the islamic world.

- Published March 30, 2017

For me, travel is not solely about beautiful beaches, luxurious poolsides, or warmer climates. It’s about gaining a greater sense of the world; it’s about learning and understanding. As fear has driven Western tourists out of the Islamic world, I only grew more fascinated by these countries — and by the Islamic community I’d grown so familiar with during my childhood.

I was 21 when I ventured back to the Middle East and Turkey — where I watched the balloons rise in Cappadocia, swam in the warm seas of the Turquoise Coast, and fell in love with one of the world’s most incredible, contrasting cities; Istanbul. I strolled between sacks of colored spices in the markets, drank black tea from ornate glass cups, and admired views across the Bosphorus. It was a short introduction to the city, but one that left me craving more.

Egypt was next, and I was blown away by the warmth and openness of the local people. ‘Welcome’ followed me everywhere. I realized how much the tourism industry was suffering because of ongoing conflicts in nearby countries, and as a result of the Arab Spring. Boats along the Nile sat immobile, and visiting the Pyramids of Giza, one of the world’s greatest and most famous sites, as the only tourist in sight was surreal. Cairo glowed in golden layers, and I met incredibly strong and modern women who were kind enough to show me the city through their eyes. Out on the edge of the Western Desert at the Birqash Camel Market, I saw a timeless world in reverse, but it was clear that in Cairo, there was a conflicting desire to modernize and develop while still holding on to Egypt’s rich cultural past.

In Jordan, I drove through the Wadi Rum desert to Bedouin camps which sat in a moon-like landscape. Our dinner was cooked underground, a delicious feast of roasted vegetables, tabbouleh, hummus, and tea stuffed with fresh mint leaves. Songs were played on traditional instruments as we ate and the rich melodies filled the tent. Bedouin hospitality is like no other, as is the rich Arabic coffee served after meals.

As a traveler, there are few places I find more exciting than the vibrancy of the Islamic world. Everywhere, the call to prayer followed me, singing from rooftops in the early morning as the sun rose into the sky. Everywhere, the sunsets were magnetic, the food delicious, and the people unforgettable.

As a photographer and writer, there’s nothing more rewarding than changing other people’s perspectives of a place. I hope I can change someone else’s mind about these countries, and encourage them to book a plane ticket and see for themselves.

Fear is one thing, but misunderstanding based on misinformation is another, and unfortunately these lines have been blurred in recent years. The word which followed me around Egypt was ‘Welcome,’ and I felt it in each of these places.

Now more than ever, travelers are needed in these countries, not only to support the tourism industries which have been hugely affected by conflicts in these regions, but also so we can be the ones to return home and share our experiences of these countries and their people in a positive light.

Trending Stories

The pursuit of self on south africa’s spectacular otter trail, two hours from: reykjavic, from the arabian sea to your plate: seafood in varkala , explore by region, explore by map.

SIGN UP TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Get your weekly dose of armchair travelling, straight to your inbox.

© Passion Passport 2024

- Utility Menu

GA4 tracking code

- For Educators

- For Professionals

- For Students

dbe16fc7006472b870d854a97130f146

Muslims in outer space, islam case study - technology | 2018.

PDF Case File

Download Case

Note on This Case Study

New technologies present both opportunities and challenges to religious communities. Throughout history, many religious people have created and used new technologies on behalf of their religious traditions. At times, religious needs have driven technological innovation. Yet many religious people have also tried to limit the use of certain technologies that they felt violated principles of their tradition. The relationship between religion and technology is complex and highly dependent on context. As you read these case studies, pay attention to that context: Who are the groups involved? What else is happening in their context? Who benefits from new technologies? Who gets to decide if they are legitimate or not?

As always, when thinking about religion and technology, maintain a focus on how religion is internally diverse, always evolving and changing, and always embedded in specific cultures.

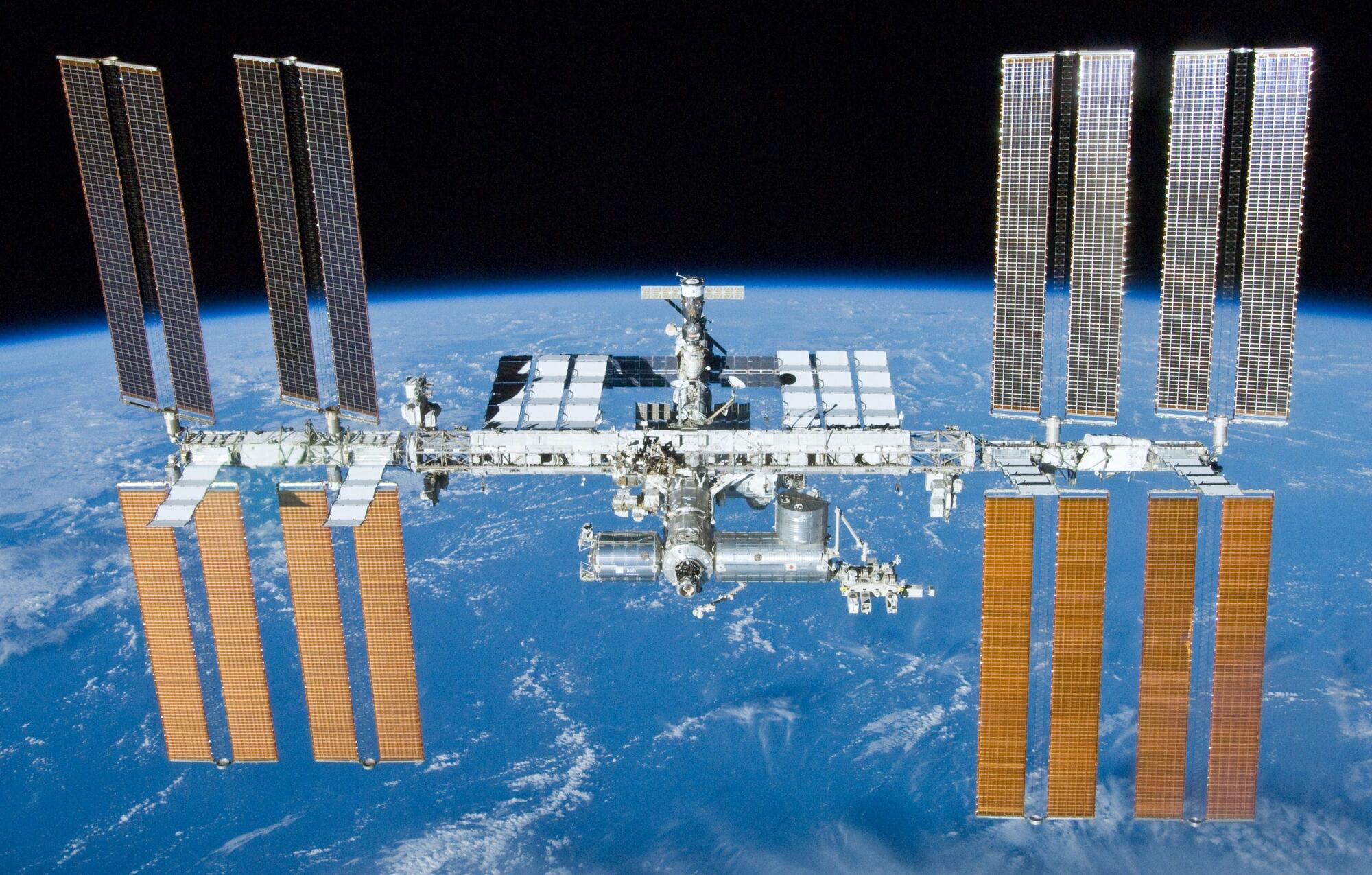

In the last century, advances in science, engineering, and technology have allowed humans to travel to space.

Over five hundred people have gone to space since 1961, and at least nine of them have been Muslim. Though Muslims make up approximately one quarter of the global population, they make up less than 2% of astronauts to date, in part because of the hiring practices of the historically dominant US and USSR space programs. The US initially only recruited white, Christian males, and the USSR initially only hired ethnic Russians and Slavs, who were also more likely to be Christian. However, as these space programs have diversified to reflect their populations, and as other countries have developed their own space programs, Muslim astronauts have become more common.

Space travel can create several interesting challenges for Muslims, because some common Islamic practices are tied to geography on Earth or the orbits of celestial bodies. For example, many Muslims pray by facing Mecca, but when orbiting Earth at 17,400 miles per hour, Mecca moves rapidly below the spacecraft. In addition, many Muslims pray five times a day, but astronauts experience sunrise and sunset every ninety minutes while they orbit Earth. These quick sunrises and sunsets can cause confusion about when to pray, as well as when to fast during the holy month of Ramadan when many Muslims fast during the day. Many Muslims also prostrate during prayer, but this is nearly impossible in space due to the lack of gravity.

The first Muslim to encounter these challenges in space was Sultan bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Al-Saud, a fighter pilot and a prince of Saudi Arabia. In 1985, he was a Payload Specialist for the US’s National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) mission STS-51G, using space shuttle Discovery to launch three satellites. Sultan chose not to fast for Ramadan while he was training and in space, but he brought a small Qur’an into space with him, along with a prayer from his mother asking God to protect travelers. He also told reporters that he tied his feet to the shuttle floor to allow himself to perform the motions of prostration to the best of his ability.

Later Muslims in space were cosmonauts from the Soviet Union, and there is no evidence that their religious practices impacted their travel in space. It is likely that these Muslims found their scientific mission to be more pressing than their religious practice, particularly in the officially atheist USSR. Similarly, Anousheh Ansari, the first Muslim woman in space, made few public statements about whether her religious tradition affected her flight on Russia’s Soyuz rocket to the International Space Station (ISS) in 2006. Ansari, a multimillionaire, paid an undisclosed sum—some sources say $20 million—to go to the ISS. While the Iranian-American pointed out that she views faith and science as “very complementary,” she did not note any particular religious plans for her space travel, instead focusing on her scientific goals.

Other Muslim astronauts have been more outspoken about their religious obligations. In 2007, Malaysia sent its first astronaut to the ISS as part of a $900 million deal to buy fighter jets from Russia. The astronaut was Sheikh Muszaphar Shukor, a Muslim doctor who launched aboard Russia’s Soyuz TMA-11. Before liftoff, Dr. Shukor said that while his “main priority is more of conducting experiments,” he was concerned about maintaining his Islamic practices in space. In response, the Malaysian government called a gathering of 150 Islamic legal scholars, scientists, and astronauts to create guidelines for Dr. Shukor. The scholars produced a fatwa, or non-binding Islamic legal opinion, intended to help future Muslim astronauts, which they translated into both Arabic and English. They wrote that in order to pray, Muslims in space should face Mecca if possible; but if not, they could face the Earth generally, or just face “wherever.” To decide when to pray and fast during Ramadan, the scholars wrote, Muslims should follow the time zone of the place they left on Earth, which in Dr. Shukor’s case was Kazakhstan. To prostrate during prayer in zero gravity, the scholars stated that the astronaut could make appropriate motions with their head, or simply imagine the common earthly motions.

Despite issuing guidelines, the scholars agreed with Dr. Shukor that his priority was conducting experiments. A minister of religious affairs in Malaysia noted the fatwa was created, “to ensure our astronaut could fully concentrate on his mission, without having to worry about… his religious obligations in space.” Along with the guidelines for religious practice, the conference approved space travel generally: “according to Islam, traveling to space is encouraged.” Other Muslims have pointed to a Qur’anic verse to back up this claim: “O assembly of Jinn and men! If you can pass beyond the zones of the heavens and the earth, then pass!” (Q. 55:33).

However, some Muslims see religious limitations to space travel. In 2014, after thousands of Muslims applied for a one-way trip to Mars through the Mars One organization, a fatwa council in the United Arab Emirates issued a ruling that condemned promoting or being involved with Mars One. These Islamic legal scholars argued that the risks of the trip were tantamount to suicide. Citing verse 4:29 of the Qur’an which states: “do not kill yourselves or one another,” they asserted that a Mars mission would pose a “real risk to life.” Mars One disagreed, noting that the crew would only liftoff after a livable Martian habitat was completed, and asked that the fatwa be rescinded. Some Islamic legal scholars also decried the fatwa. Khaleel Mohammad, an expert in Islamic Law in the US, called it “extremist nonsense.” Regardless, Muslim communities will continue to grapple with celestial questions as more Muslims travel to space. Islam Case Study – Technology 2018

Additional Resources

Primary sources.

• Malaysian fatwa “A Guideline of Performing Ibadah at the International Space Station (ISS)” (2007): https://bit.ly/2MTgrvp • NPR interview with Prince Sultan on his space travel (2011): https://n.pr/2vRqoTq • Video of Dr. Shukor praying in the ISS in 2007: https://bit.ly/2KXjTn1 • Speech by Dr. Shukor on his mission, in the US in 2008: https://bit.ly/2Mm5MNw • Muslim author Farah Rishi writes about the importance of outer space in Islamic science fiction (2016): https://bit.ly/2MV8Kol

Secondary Sources:

• Article from Wired magazine exploring the intersection of Islam and space travel (2007): https://bit.ly/2w8G7wY • Documentary from Journeyman Pictures about Dr. Shukor: https://bit.ly/2MzcwqD • Article from Christian Science Monitor on the Mars One fatwa (2014): https://bit.ly/2PoHJv5

Discussion Questions

• What prevented Muslims from going to space in the early decades of space travel? What has changed that allows or restricts Muslims’ space travel today? • Why might some Muslims feel it is important for religious scholars to address space travel? Why might others feel it is unimportant? • How do the different responses of Prince Sultan, Soviet cosmonauts, Ansari, and Dr. Shukor to their religious tradition in a new context show how Islam is internally diverse? Why might they hold these different positions? • Read the Malaysian fatwa in the primary source list. What is something that surprised you? Why? How do you think this fatwa’s rulings might change if it was written in a different country? • Read Rishi’s piece about Muslims in space in science fiction in the primary sources. What does her perspective on Muslims in space add to our understanding of Islam? • The fatwas mentioned in this case study are written by those in power in Malaysia and in the United Arab Emirates. How do you think this influences what the texts say?

This case study was created by Kristofer Rhude, MDiv ’18, under the editorial direction of Dr. Diane L. Moore, faculty director of Religion and Public Life.

- 1. Cathleen S. Lewis, “Muslims in Space: Observing Religious Rites in a New Environment,” Astropolitics 11, no. 1-2 (2013): 109-10.

- 2. Bettina Gartner, “How Does an Islamic Astronaut Face Mecca in Orbit?” Christian Science Monitor, Oct. 10, 2007. https://bit.ly/2L8hRAm

- 3. Lewis, “Muslims in Space,” 110; Sultan Bin Salman Bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, “Praying Toward Mecca… In Outer Space,” interview by Michel Martin, Tell Me More, NPR, July 12, 2011, audio, 4:30. https://n.pr/2vRqoTq

- 4. Lewis, “Muslims in Space,” 110-113.

- 5. Department of Islamic Development Malaysia, “A Guideline for Performing Ibadah at the ISS,” (2006): 5-6. https://bit.ly/2MTgrvp .

- 6. Lewis, “Muslims in Space,” 114.

- 7. Department of Islamic Development Malaysia, “A Guideline,” 7.

- 8. Farah Rishi, “Why Sci-Fi Gives Me Hope for the Future as a Muslim,” Vice, Nov. 15, 2016. https://bit.ly/2MV8Kol .

- 9. Ahmed Shaaban, “One-way Trip to Mars Prohibited in Islam,” Khaleej Times, Feb. 20, 2014. https://bit.ly/2L6D91r ; Sudeshna Chowdhury, “Can A Muslim Take a One-way Trip to Mars?” Christian Science Monitor, Feb. 21, 2014. https://bit.ly/2PoHJv5.

- See more Islam case studies

- See more technology studies

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Agriculture

- Sustainability

- Architecture

- World Events

- Manuscripts

Travellers and Explorers from a Golden Age

By salim al-hassani - 1001 book chief editor published on: 1st august 2020.

5 / 5. Votes 2

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Since the Quran said every able-bodied person should make a pilgrimage, or hajj, to Mecca at least once in their lifetime, thousands travelled from the farthest reaches of the Islamic empire to Mecca, beginning in the seventh century. As they travelled, they made descriptions of the lands that they passed through. Some of the most famous include...

From left. Imaginary potrait of Zheng He, Ibn Battuta and Ibn Majid from 1001 Inventions’ ‘Journeys from a Golden Age’ ( Source )

Editorial Note: Extracted from “1001 Inventions: The Enduring Legacy of Muslim Civilization Reference (4th Edition) Annotated”. First published in 1001 Inventions website – www.1001inventions.com/travellers

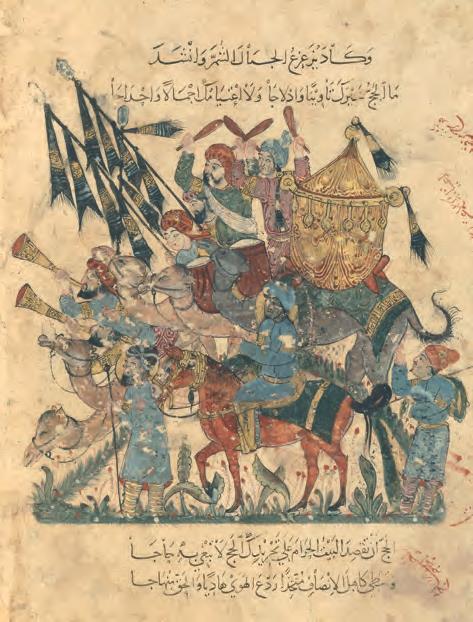

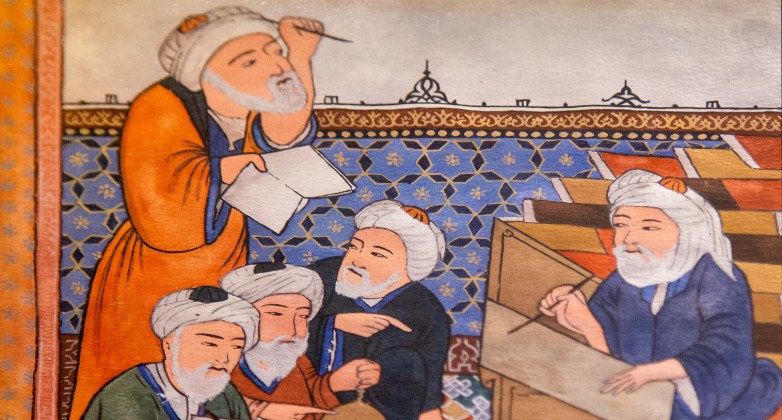

A 13th-century manuscript shows a caravan en route (Source: 1001 Inventions: The Enduring Legacy of Muslim Civilization, 3rd edition, page 247)

Al-Biruni, in the 11th century, wrote in his book the Dema r cation o f the L imits o f the A r eas that Islam has already penetrated from the Eastern countries of the earth to the Western.

It spread westward to Spain [Al-Andalus], eastward to the borderland of China and to the middle of India, southward to Abyssinia and the countries of Zanj Zanj [meaning black Africa from Mali to Kilwa (Tanzania) and Mauritania to Ghana], eastward to the Malay Archipelago and Java, and northward to the countries of the Turks and Slavs. Individual Muslim sultans ruled, and although there was conflict at times between them, an ordinary traveller could pass through the various regions.

Since the Quran said every able-bodied person should make a pilgrimage, or hajj, to Mecca at least once in their lifetime, thousands travelled from the farthest reaches of the Islamic empire to Mecca, beginning in the seventh century.

As they travelled, they made descriptions of the lands that they passed through. Some of the most famous include:

Al – Y a ’ q u bi , 8 th Century

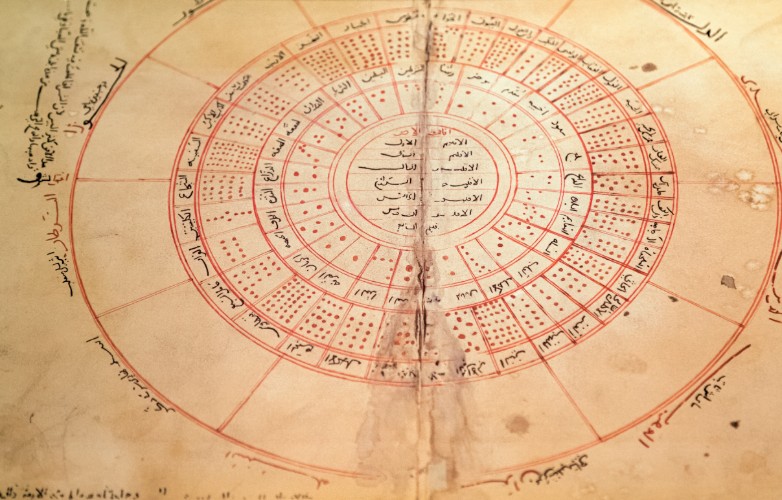

A 13th-century miniature depicts an eastern Muslim boat from the classical Arabic work of literature Maqamat al- Hariri. The Arabic writing refers to a sea voyage, and mentions a verse from the Quran referring to Noah’s ark. This is usually used as a blessing: “In the name of Allah, the one who protects the ship’s sailing, seafaring and berthing.” (Source: 1001 Inventions: The Enduring Legacy of Muslim Civilization, 3rd edition, page 248)

He wrote the Book of C o untries, which he completed in 891 after a long time spent traveling, and he gave the names of towns and countries, their people, rulers, distances between cities and towns, taxes, topography, and water resources. [1]

Al-Ya’qubi wrote that “China is an immense country that can be reached by crossing seven seas; each of these with its own color, wind, fish, and breeze, which could not be found in another, the seventh of such, the Sea of Cankhay [which surrounds the Malay Archipelago] only sailable by a southern wind.”

Ab u Z ay d H a san, 9 th Century

He was a Muslim from Siraf, and told about boats that were sailing for China from Basra in Iraq and from Siraf on the Gulf. Chinese boats, much larger than Muslim boats, also visited Siraf, where they loaded merchandise bought from Basra. Abu Zayd also deals with the Khmer land and its vast population, a land in which indecency, he notes, is absent.

I bn W a h ha b, 9 th Century

He was a trader from Basra who sailed to China and described the Chinese capital as divided into two halves, separated by a long, wide road. On one side the emperor, his entourage, and administration resided, and on the other lived the merchants and ordinary people. Early in the day, officials and servants from the emperor’s side entered the other, bought goods, left, and did not mingle again. [2]

Al – Muq a d da s i, ( ca 9 45 – 100 0 )

He was a geographer who set off from his home in Jerusalem many centuries before Ibn Battuta. He also visited nearly every part of the Muslim world and wrote a book called Best Divisions for K n o wle dg e of the Regions , completed around 985. [3]

One of the accurate drawing based on personal observation is the sketch of the famous Lighthouse of Alexandria by the Andalusian traveller, Abu Hamid Al-Gharnati . He visited Alexandria first in 1110 and again in 1117. ( Source )

I bn Khur r adadh bih, 10 th Century

He wrote the Book of Roads an d P r o vinces , which gave a description of the main trade routes of the Muslim world, referring to China, Korea, and Japan, and describing the southern Asian coast as far as the Brahmaputra River, the Andaman Islands, Malaya, and Java. [4] Ibn Khurradadhabih died in 912.

Ibn Fadlan, 10 th Century

Ibn Fadlan was an Arab chronicler, and in 921 the caliph of Baghdad sent him with a diplomatic mission to the king of the Bulgars of the Middle Volga. He wrote an account of his journey, and this was called R i s alah . Like Ibn Battuta’s R ihla , the R i s alah is of great value because it describes the places and people of northern Europe, in particular a people called the Rus from Sweden. [5]

Yaqut a l- H a m a wi, 13 th C entur y

He was a geographer who wrote the Dictionary o f C o untries about countries, regions, towns, and cities that he visited, all in alphabetical order, giving their exact location, and describing monuments, resources, history, population, and leading figures. [6]

Z ak ar i y a ’ i b n Mu h am ma d a l- Q a z wini, 13 th C entur y

He left accounts of the marvellous creatures that thrive in the China Sea, notably very large fish (possibly whales), giant tortoises, and monstrous snakes, which land on the shores to swallow whole buffaloes and elephants. [7]

I bn S a’id a l- Ma ghr i bi, 13 th C entur y

He gave the latitude and longitude of each place he visited, and wrote much on the Indian Ocean islands and Indian coastal towns and cities.

Al-Di ma s h qi , A 14 th C entur y

He gives very detailed accounts of the island of Al-Qumr, also called Malay Island or Malay Archipelago. He says there are many towns and cities; rich, dense forests with huge, tall trees; and white elephants. Also there lives the giant bird called the Rukh , a bird whose eggs are like cupolas. The Rukh is featured in a story about some sailors breaking and eating the contents of its egg; the giant bird chased after them on the sea, carrying huge rocks, which it hurled at them relentlessly. The sailors only escaped with their lives under the cover of night. [8]

This story, like other accounts by travellers, formed the basis of many of the tales that enrich Islamic literature, such as The A dventures of S inbad the S ailor and The Th o u s and and One Nights . The richness of these thousand-year-old accounts has inspired many writers and filmmakers.

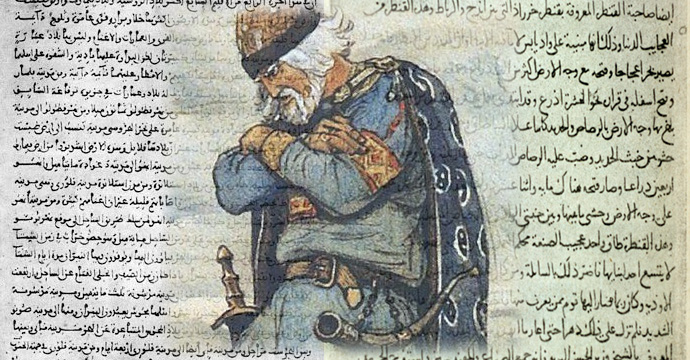

Ibn Battuta, 14 th Century

Imaginary Painting of Ibn Battuta

Ibn Battuta was only 21 on June 13, 1325, when he set out alone on his donkey at the beginning of a 3,000-mile overland journey to Mecca from Tangier in Morocco. He left his family, friends, and hometown, and would not see them again for 29 years. Some he never saw, because the plague reached them before he returned. He journeyed by walking, riding, and sailing more than 75,000 miles, through more than 40 modern countries.. [9]

His accounts have placed the medieval world before us, so we know that gold traveled from south of the African Sahara into Egypt and Syria; pilgrims continuously flowed to and from Mecca; shells from the Maldives went to West Africa; pottery and paper money came west from China. Ibn Battuta also flowed along with the wool and the wax, gold and melons, ivory and silk, sheikhs and sultans, wise men and fellow pilgrims. [10] He worked as a qadi , a judge, for sultans and emperors, his journey a grand tour, mixing prayer, business, adventure, and the pursuit of knowledge. He returned to his native city three decades later and recounted stories of distant, exotic lands. [11] The sultan of Fez (Fes), Abu ’Inan, asked him to write down his experiences in a Rihla , a travel book, and with a royal scribe, Ibn Juzayy, he completed the task in two years. His account of medieval Mali in West Africa is the only record we have of it today. [12]

The Traveling Man: the Journey of Ibn Battuta, 1325-1354 by James Rumford (Houghton Mifflin, 2001). ( Source )

Other travellers from the ninth and tenth centuries include Ibn al-Faqih, who compares the customs, food diets, codes of dress, rituals, and also some of the flora and fauna of China and India. [13] Ibn Rustah focuses on a Khmer king, surrounded by 80 judges, and his ferocious treatment of his subjects while indulging himself in drinking alcohol and wine, but also his kind and generous treatment of the Muslim. [14] Abu al-Faraj dwells on India and its people, customs, and religious observations. He also talks of China, saying it has 300 cities, and that whoever travels in China has to register his name, the date of his journey, his genealogy, his description, age, what he carries with him, and his attendants. Such a register is kept until the journey is safely completed. The reasoning behind this was a fear that something might harm the traveller and thereby bring shame to the ruler.

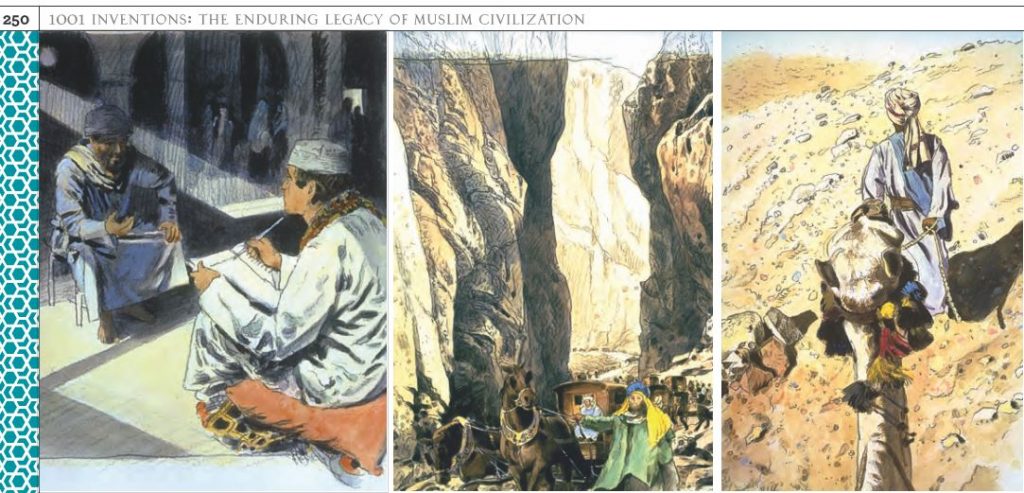

An artist’s rendering shows Ibn Battuta dictating his Rihla, passing through a dangerous gorge, and walking with his camel. (Source: 1001 Inventions: The Enduring Legacy of Muslim Civilization, 3rd edition, page 250)

Get the full story from 1001 Inventions: The Enduring Legacy of Muslim Civilization Reference (4 th Edition) Annotated. www.amazon.co.uk/1001-Inventions-Civilization-Reference-Annotated-ebook/dp/B0775TFKVY/

[1] The Kitab al-buldan appears in Bibliotheca ceocraphorum arabicorum Vll, M. J. de Goeje, ed. (1892); ed and trans into French by G. Wiet, Les Pays (1937). [2] Carra de Vaux, Les Penseurs, op. cit., 57-58. [3] Al Muqadassi, op. cit. [4] S. M. Z. Alavi, Arabic Geography, op. cit., 27. [5] On Muslim accounts of Scandinavia, see Harris Birkeland, Nordens hidstorie I middelalderen etter arabiskenkilder, Norske Videnskaps-Akademi i Oslo, Skrifter, Hist.-Filos. Klasse, 2 Scriffer, 1954, 2 (1954). [6] Ibn Abd Allah al-Hamawi Yaqut, Jacut’s Geographisches Worterbuch, F. Wustenfeld, ed., 6 Vols. (Leipzig, 1866-70). -C. Bouamrane and L. Gardet, Panorama de la Pensee Islamique (Paris: Sindbad, 1984), 260. [7] Ibid, 302-04. [8] The work was edited by A. F. Mehren, Quarto (St. Petersburg, 1866), 375 pages. – G. Sarton, Introduction, op. cit., Vol. 3, 800. – G. Ferrand, Relations de Voyages, 363-93. [9] Ibn Battuta, Voyages d’Ibn Battuta, Arabic text accompanied by French trans. by C. Defremery and B. R. Sanguinetti, preface and notes by Vincent Monteil, I-IV (Paris, 1968, reprint of the 1854 ed.). [10] Ibn Battuta, Travels in Asia and Africa, trans. and selected by H. A. R. Gibb (London: Routledge, 1929). [11] F. Rosenthal, Ibn Battuta, Dictionary of Scientific Biography, op. cit., Vol. 1, 517. – R. B. Winder, Ibn Battuta, in The Genius of Arab Civilisation, J. R. Hayes, ed., op. cit., 210. [12] Ibn Battuta, Travels in Asia and Africa, Gibb, op cit. [13] Ibn al-Faqih al-Hamadhani, auctore, Kitab al-buldan, M. J. De Goeje, ed., Bibliotheca geographorum arabicorum, 5 (Leiden, 1885). [14] G. Sarton, Introduction, op. cit., Vol. 1, 635. – G. Ferrand, Relations de Voyages, op. cit., 54-66.

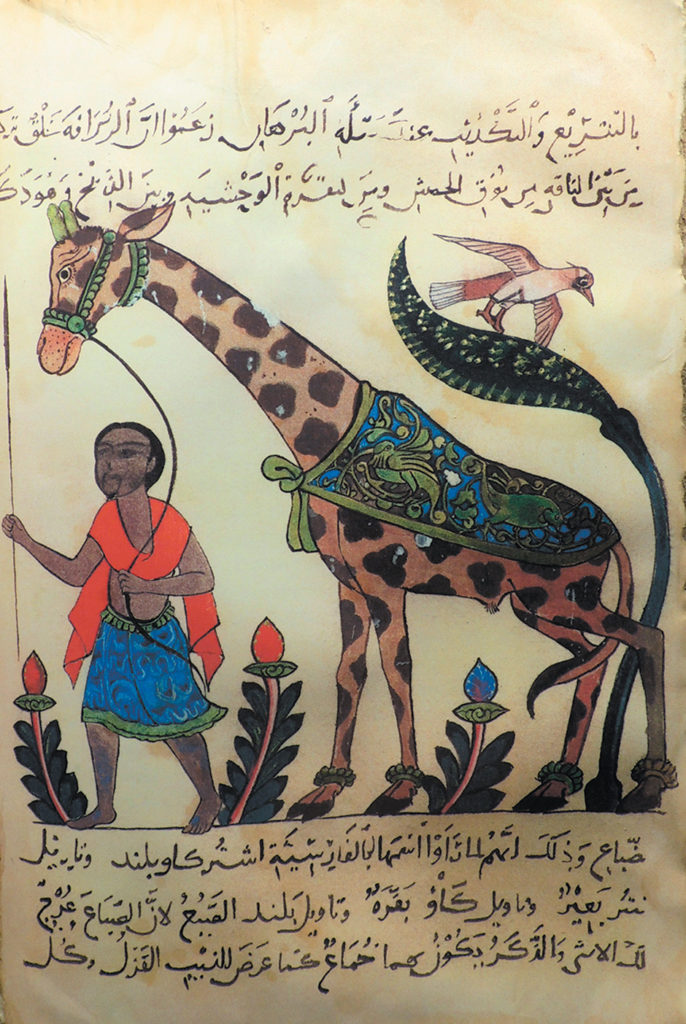

Al-Ǧāḥiẓ/Jahiz, Kitāb al-ḥayawān (Book of the animals), Syria, 15th C. Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Ms. arab. B 54, f. 36 (Source)

Cem Nizamoglu

Related articles.

Video Message by Professor Salim Al-Hassani to the“Science and Technology in Islamic Civilization” conference

The Levantine Hajj route and the ruins of the people of Lut: A study of the Islamic geographical sources

Video: What did Medieval Muslims Think of Ancient Egypt | Al Muqaddimah

Forward by HRH Prince Charles, now HM King Charles III, to the 1001 Inventions Book

Fine Dining

Arabic Mission to the Volga

An Ottoman Cosmography: Translation of Katib Celebi’s Cihannuma

Video: Al Idrissi – The Muslim Geographer

1001 Inventions – Home

Celebrate Chemistry Week with 1001 Inventions in Manchester

The Story Begins – The Golden Age

The Ottoman Mosque Fallacy: Places of Worship Facing the Kaaba or “Monuments of Jihad”?

Overland Hajj Route Darb Zubayda

Hospital Development In Muslim Civilisation

The Petra Fallacy: Early Mosques do face the Sacred Kaaba in Mecca

The Mystery of Hayy Ibn Yaqzan

Memory and Erasure in the Story of the West: Or, Where have All the Muslims Gone?

Shining light upon light

Peregrination and Ceremonial in the Almohad Mosque of Tinmal

Turkish Medical History of the Seljuk Era

Keep your distance – health lessons from the history of pandemics

From this author.

On the Coffee Trail

New Annotated Reference (Text Only) Edition of 1001 Inventions Book

The Birth of Modern Astronomy

Muslim Heritage: Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

- International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

- World Water Day

- Flowing Through History: Water Management in Muslim Civilization

- International Women’s Day

- Ibn al-Zarqalluh’s discovery of the annual equation of the Moon

- News Desk - 1,907,546 views

- FSTC - 1,828,510 views

- Lectures on Islamic Medicine at RCP, London - 993,786 views

- FSTC Activity Report 2015 - 368,155 views

- 1001 Inventions - 205,384 views

- Media Desk - 164,141 views

- What does Islam say about the Flat earth?- Sabreen Syeed - 113,524 views

- Libraries of the Muslim World (859-2000) - 94,104 views

- Muslim Founders of Mathematics - 90,228 views

- Contact - 64,881 views

Discover the golden age of Muslim civilisation.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

Privacy Overview

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

The Rise of Halal Tourism

Muslims now make up one of the fastest-growing segments of the global travel industry. In response, hotels and tour operators are increasingly trying to meet their dietary and religious needs.

By Debra Kamin

For one of the fastest-growing sectors of the global travel industry, there is no pork on the hotel dinner menus. There are flights with no alcohol on the drink carts, resorts with separate swimming pools for men and women, and daily itineraries with built-in break times for the five daily calls to prayer.

Since 2016, the number of Muslim travelers has grown nearly 30 percent, and a recent joint study by Mastercard and Crescent Rating , a research group that tracks halal-friendly travel, projects that over the next decade that sector’s contribution to the global economy will jump to $300 billion from $180 billion. With a population that is disproportionately young, educated and upwardly mobile, they are one of the fastest-growing demographics on the global tourism scene.

But this wasn’t always the case.

In 2015 , Soumaya Hamdi went roadtripping through Asia with her husband and her then 4-month-old baby. The trio visited Singapore and Malaysia, and then caught a flight to South Korea and on to Japan. The trip was thrilling, but Ms. Hamdi and her husband, who are both observant Muslims, found the daily search for halal-certified food a difficult one.

Ms. Hamdi, who is based in London, began blogging about the best Muslim-friendly restaurants she found, as well as prayer facilities and sites that were particularly welcoming for a family with a young baby. Those musings turned into Halal Travel Guide , an online platform offering tips, recommendations and curated itineraries for Muslim travelers.

Her timing was right.

“In Europe the Muslim community is now in its third or fourth generation. They are educated and have good paying jobs,” said Ufuk Secgin, chief marketing officer for Halal Booking , a Muslim-focused vacation search engine. “For the first generation, their idea of a holiday was visiting the family in the home country. This has changed.”

At ITB Asia this October, a leading travel show held in Singapore, organizers partnered with two halal travel authorities, Crescent Rating and Halal Trip , to offer specialized panel discussions and showcases targeting the estimated 156 million Muslims who will book travel between now and 2020.

At the heart of much of the discussion was matters of the belly. For Muslim travelers, “the number one factor is good quality halal food,” Ms. Hamdi said in an email exchange. “I’m not talking about curry or biryani — I’m talking about authentic local food that is halal. After that, it’s usually prayer facilities.”

Tourists’ global demand for halal food has grown so much, in fact, that Have Halal Will Travel , a Singapore-based online community for Muslim travelers, has also partnered with ITB Asia with a three-hour conference and special booth space focusing on foodie-centric outreach to the Muslim tourism sector.

Like Halal Travel Guide , Have Halal Will Travel was founded in 2015. Today, their content reaches 9.1 million users each month, according to their founder, Mikhael Goh. Mr. Goh dreamed up the site with three friends while studying abroad in Seoul; he found himself frustrated on a daily basis with a lack of information about where to find quality halal food.

“We were thinking, why is it in 2015, when there is Yelp and TripAdvisor and so many popular apps and services to tell you where to eat and where to travel, why on earth is there so little information for Muslims?” Mr. Goh said in a phone interview. “Not just about food — yes, halal food is the basis of a lot of things, but also about safety and prayer. There was a general lack of information out there and the information that did exist was so fragmented.”

Only a handful of years later, that gap in the market is now teeming with niche sites, many of them written specifically for young Muslim women. At Passport and Plates , the Los Angeles-based blogger Sally Elbassir chronicles her global foodie adventures where pork and alcohol are always off the menu; at Arabian Wanderess , Esra Alhamal writes about traveling as a female, Muslim millennial on a budget; and at the popular Muslim Travel Girl , run by the Bulgaria-born, Britain-based Elena Nikolova, readers can learn about Muslim-friendly honeymoon resorts with private pools and get tips for a D.I.Y. Umrah (Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca).

Many of the bloggers interviewed for this article echoed the same sentiment: Their goal is not just to make it easier for Muslim travelers to find food, prayer spaces and alcohol-free activities that appeal to them. It’s also to support those travelers to branch out of their comfort zones and feel empowered exploring the world.

“We specialize in pushing people to non-Muslim majority countries,” said Mr. Goh. “The most popular destinations we work on are Japan and Korea. Our audience is young — 25 to 30 years old — and very influenced by K-pop and Instagram, so we write a lot about how welcoming those places are.”

Ms. Hamdi of Halal Travel Guide agreed. “We encourage Muslims to seek culturally immersive travel experiences outside of the traditional Muslim-friendly destinations such as Dubai and Morocco,” she said. “Muslims are looking for added value to their trips — from private beaches where women can bathe without men to disturb them, and more than this, trips that offer the Muslim traveler the chance to experience something completely different.”

Follow NY Times Travel on Twitter , Instagram and Facebook . Get weekly updates from our Travel Dispatch newsletter, with tips on traveling smarter, destination coverage and photos from all over the world.

- Albalagh.net

- AnswersToFatawa

- Arij Canada

- Askimam.org

- Askmufti.co.za

- AskOurImam.com

- CouncilofUlama.co.za

- Darulfiqh.com

- Darulifta Azaadville

- Darulifta Deoband Waqf

- Darulifta-Deoband.com

- Daruliftaa.com

- DaruliftaaMW.com

- DaruliftaaZambia.com

- DarulIftaBirmingham

- Darulihsan.com

- DarulUloomTT.net

- Fatwa-TT.com

- Fatwa.org.au

- FatwaCentre.org

- HadithAnswers.com

- IslamicPortal.co.uk

- IslamicSolutions.org

- Jamia Binoria

- Mahmoodiyah

- Mathabah.org

- Muftionline.co.za

- Muftisays.com

- MuslimaCoaching.com

- Seekersguidance.org

- ShariahBoard.org

- Tafseer Raheemi

- TheMufti.com

- ZamzamAcademy.com

- BinBayyah.net

- Darul Iftaa Jordan

- Shafiifiqh.com

- HanbaliDisciples.com

- TheHanbaliMadhhab.com

- Ask Question

- Lailatul Qadr

Home » Hanafi Fiqh » DarulIftaBirmingham » Tourism in Islam

Related Q&A

- What subjects are permissible to study at college or university and what are strictly not permissible?

- Is it halal to provide services to Sikh Yatris visiting Pakistan?

- What is the Ruling on Having a Baby Shower?

- I am very curious about the ruling of smoking weed (marijuana) in Islam.

- Ruling on Using the Concessions Granted to a Picnic Traveler

- Ruling on good deeds done before Islam

Tourism in Islam

Answered by Molana Muhammad Adnan

Question:

I wanted to know the ruling of tourism in Islam as I’ve heard from some brothers that its haraam. I would like some clarification in regards to the matter please.

Answer:

The concept of travel/tourism in Islam is referred to as siyaahah. The ruling on siyaahah depends a lot on situations which vary from person to person, but as a general guide it needs to be understood that if there is anything impermissible attached to the siyaahah then its blameworthy. A few examples would be, a woman travelling without a mahram, over expenditure, travelling to places that are known for immorality and strife etc.

If there is no element of impermissibility then tourism is permitted, with the intention that it is to see the wonders and blessings of Allah (The most glorified, the most high) and to seek reminders of the doom of the predecessors.

[al-Naml 27:69]

Only Allah Knows Best

Written by Molana Muhammad Adnan

Checked and approved by Mufti Mohammed Tosir Miah

Darul Ifta Birmingham

This answer was collected from DarulIftaBirmingham.co.uk , which is run under the supervision of Mufti Mohammed Tosir Miah from the United Kingdom.

Read answers with similar topics:

Random Q&A

Is it acceptable to believe in horoscopes or are they just predetermined destiny, forex trading in islamic account: swap-free and leverage-free, status of a partnership after a partner passes away, doubts regarding washing the hands after istinja, is it permissible for muslims to keep certain animals such as fish at home provided we take great care of them & respect them, sharing one’s room with one’s co-wife, more answers….

- What Is the Ruling of Putting Names With Allah on Grave Boards

- Who are the Munafiqs?

- Does a Madrasah student shorten his prayer when he is at home for his holidays

- Can I Take a Conventional Mortgage To Buy a House Where Rent Prices Are High?

- Authenticity of Durud Tunjinaa

- Missing Jummah Salah due to working in restaurants?

Latest Q&A

- Is Makeup Allowed During Iḥrām?

- Do These Actions Formulate Disbelief?

- The Status of a Job Acquired with False Certification

- Can a Ḥanafī Resident Pray Behind a Shāfi’īe Traveller?

- Is it Permissible to Allow Wheelchairs in a Masjid?

- Is an Entry Fee at a Charity Event Considered Charity?

Indexed Websites

Privacy overview.

Trade and Travel

Contact between China and the Near East predates the advent of Islam in the seventh century; sea and land routes connected the two regions as early as the third century B.C. The main route was the Silk Road , named after the most important commodity that was traded along it—Chinese silk ( see map ). The ease of travel across Asia and the Middle East was facilitated in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries by the Pax Mongolica (literally, " Mongol peace")—the unification under the Mongol conquerors, who swept through Asia establishing control over territories stretching from East Asia to eastern Europe ( see map ).

In addition to traveling by land routes, merchants also traded via sea routes, carrying luxury commodities such as ceramics, carpets, rice wine, musk, perfumes, paper, dyestuffs, pearls, ink, and ivory in great quantities.

During the reign of the Abbasids (750–1258) there was remarkable expansion in international trade. Sea routes stretched all the way from Iraq to Indonesia, and ships traveling back and forth would stop at many ports along the way to buy and sell goods. Abbasid merchants returned home with finished goods (such as ceramics, paper, silk, and ink from China) as well as raw materials (like spices from India and teakwood from Southeast Asia). This boom in trade transformed Iraq into an international marketplace in which prized Chinese and Southeast Asian imports such as silk, paper, tea, and ceramics were sold.

RELATED AUDIO FROM THE GALLERY GUIDE

Please enable flash to view this media. Download the flash player.

Denise Leidy: The term "Silk Road" is, of course, a metaphor for a series of overland trade routes, some of which ran north and south, but the two biggest of which ran from east—so, technically from China—all the way through what we often refer to as central Asia and into the Islamic world, and, ultimately, of course, from the Islamic world into the European world. So it was probably the first great global highway in world history. If silk and a certain kind of luxury textile went from east to west, then a taste for luxury metalwork clearly went from west—in which case, I mean the ancient Near East and the Islamic world—to east, because the Chinese prior to the sixth century or so really didn't have gold and silver very much.

Maryam Ekhtiar: Another material that was brought into the Islamic world from China is paper.

Denise Leidy: That's a very good point. You know, it's one of these commonplace things that we take for granted but in fact it changed how the world wrote, and how they recorded things. In museums, we tend to end up focusing on things that are very tangible—ceramics or textiles or even paper—but in fact so much more was traded.

Maryam Ekhtiar: That's right.

Denise Leidy: Spices.

Maryam Ekhtiar: Spices and pearls and ivory and incense.

Denise Leidy: And so it's, I think, very interesting to look at all the great objects in a museum and imagine them moving with all these other things as people discovered each other through their visual and material cultures.

From DIY pilgrimages to halal restaurant tips: how this travel blogger built a community of Muslim travelers

Jan 21, 2022 • 6 min read

Elena Nikolova (pictured) has spent years building a resource for Muslim travelers who are looking for relevant information and good deals.

Elena Nikolova converted to Islam in 2009. Four years later, she channeled her wanderlust into a new endeavor: helping other Muslims travel the world.

On one of Elena Nikolova’s first trips as a Muslim, she realized travel for her had changed forever. Visiting Bulgaria from the United Kingdom , she saw how her new halal diet was at odds with her pork-heavy, Bulgarian-Greek upbringing. It wasn’t long before Nikolova also noticed she was getting extra checks at the airport and more attention once she landed because of her hijab.

“I realized that whether we wanted it or not, there is prejudice against those who wear a hijab,” Nikolova said. “I realized that kind of puts Muslims off traveling.”

Since she converted to Islam in 2009, Nikolova has worked to make travel more accessible and comfortable for Muslims. A lover of deals, she began to share cheap fares and travel hacks on social media to encourage others in her new community to travel too. As a student in the UK, she often booked the longest layovers possible on her way back home to Greece just so she could explore new places.

An online forum for advocating Muslim travel

Upon the urging of a friend, Nikolova transformed her expertise into the blog Muslim Travel Girl in 2013, with the goal of helping Muslims travel while being confident in their identities and without breaking the bank. Right away, she started receiving questions related to airport security and whether certain countries were welcoming to Muslims. Her readers, mostly based in North America and Europe , were apprehensive. One of Muslim Travel Girl’s most popular videos , for example, is on navigating airports as a hijab-wearing Muslim woman.

Building a comfort zone

“Throughout the past seven years, we've gone through [issues with] the media and Muslims, and the hijab and problems with women traveling,” she said. “The whole point of a Muslim travel blog is to help and encourage those people, to give them the resources to actually find destination information.”

While other resources exist, Nikolova says it was especially hard to find information that spoke directly to the experience of traveling as a Muslim when she started the blog. “Even though travel [for Muslims] in general is not so different, we have some differences, like [needing] places to pray or [specific] food to eat,” she said. “Not every Muslim needs these, but it should be there.”

A recent survey found the availability of halal food and prayer facilities among the most cited faith-based needs of Muslim travelers. Since 9/11, many Muslim travelers say they’ve faced discrimination at airports and on airplanes, ranging from extra security searches and intense questioning by airport staff to unexplainable visa troubles and hostility from fellow passengers.

The 'halal tourism' boom

At the same time, the Muslim-friendly travel market, or “halal tourism” as some call it, has been booming. The industry caters to Muslim travelers looking for destinations that meet their faith-based needs, be it a place to pray, alcohol-free hotels or women-only pools and spas. Before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, it was estimated that by 2026, 230 million Muslim tourists would travel, locally and abroad, up from 98 million in 2010. By that time, Muslim travelers were expected to inject $300 billion into the global economy. With COVID-19, it’s now estimated it will take until 2023 to return to the same levels of Muslim tourists seen in 2019.

Nikolova attributes this increase in Muslim travelers to the global aspirations of younger Muslims, more disposable income and the persuasive power of social media. With more travelers, she says, has also come more blogs on Muslim-friendly travel, more interest from big brands and companies, conferences on the topic, and travel agencies like Halalbooking.com .

From credit card rewards to dinner recommendations

As the demographic makeup of Muslim travelers has changed, so has what Nikolova’s readers want. While initially some of Muslim Travel Girl’s most popular and requested posts were on the practicalities of traveling as a Muslim, she says now that more Muslims are traveling, the interest has shifted to what destinations to visit, insider travel tips and halal food recommendations in those places. One of their most popular topics is advice on DIY Umrah , so travelers can take the Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca without using a travel agent or expensive tour package.

Bassam Ansari, who is based in Saudi Arabia , first discovered Muslim Travel Girl in 2013 through a friend. He says he often visits the site for its hotel and flight deals and has saved significant money through the site’s advice, which he finds to be personable and genuine.

“Using her reviews and travel advice I have found the best possible hotel options in quite a few different destinations,” he said. For example, Ansari says he saved 70 percent on the cost of a standard hotel room in Mecca during Ramadan, finding a room for $300 instead of the usual $1,000, because of Nikolova’s advice on how to effectively buy and use hotel reward points.

Small changes that make a big difference