- More to Explore

- Series & Movies

Published Nov 20, 2013

One Trek Mind: Deciphering "Darmok"

Arguments about what is the best Star Trek episode can get heated and go on late into the night - I should know, I've been there. Moreover, I can be easily swayed. “ The City on the Edge of Forever ?” “ The Inner Light ?” “ Mirror Mirror ?” “ Yesterday's Enterprise ?” Yes, yes, yes! They're all the best episode. But when it comes time to discuss what is the most profound episode, I think I have a clear pick.

“ Darmok ,” from The Next Generation 's fifth season, edges out some of the competition (like TOS' fiercely pacifist “ Day of the Dove ” or “ A Taste of Armageddon ”) with its odd specificity. In other words, a message about the futility of war isn't something you'll only get from Trek . But “Darmok”'s story about a group or an individual so determined to communicate with others that they are willing to sacrifice themselves to make that contact – that's something more unusual, even if it isn't any less universal.

“Darmok,” of course, is the episode where a Tamarian (also known as the Children of Tama) named Dathon realizes that great risks must be taken if his people are ever going to reach outside their own clan. Because of their unique fashion of speech which used metaphoric descriptions based on their own mythology, the universal translator is unable to make the usual connections. We'll eventually realize that “Shaka, when the walls fell” means “failure,” but with no reference to Shaka (or his wall-falling misfortune) the UT program is unable to do so.

But Dathon perseveres. Lucky for him he's going head-to-head with Captain Picard, a man with an almost fanatical devotion to understanding and learning. It reaches its climax when Picard, our most cultured of all Captains, engaged in conversation with a man who can't really understand him, but yearns for that outreach. He tells him a story – the first story – the Epic of Gilgamesh. Perfectly, the tale of Gilgamesh mirrors the current life-or-death struggles of our two poet-warriors on the dangerous planet of El-Adrel.

But this is even luckier for us. This is just the sort of thing Patrick Stewart can sink his teeth into in ways other actors wouldn't dare. His recounting of Gilgamesh's tale is some of his most basso profundo moments in all of TNG , but that ain't nothing compared to the big finale when Picard runs to the bridge, olive branch extended, to face forward and intone the now meaningful words “Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra” and “Darmok and Jalad on the ocean.”

Yet there's one annoying thing about “Darmok.” If the Tamarians only speak in these metaphors, how did they ever learn the words that later came to be used in the phrases? How did they know that walls fell around Shaka if they need a phrase to symbolize the word “wall?” Or, at the finish, when Dathon's first officer concludes “Picard and Dathon at El-Adrel,” how did they know the planet was called El-Ardel?

There are a few possible answers. The first one, as always, is “shut up!” (More so than usual, the choice to just suspend disbelief offers great pleasure – the cathartic final beat should swell up emotion in just about anyone, as success at communication is a very basic human trait.) The other suggestion I've heard is that the Tamarians speak with partial telepathy, and the verbal aspect is merely flourish – like an emotional tint that comes from inflection. Or it could just be that the instigating words are somehow just lost in the mists of time.

We do get a very quick peek at Dathon's log and its strange notation that appears to have graphs as well as glyphs. They look neat, but no amount of scrutiny will ever make them mean anything. Repeat viewings of “Darmok,” however, will give you a few key Tamarian phrases you can keep in your back pocket. Among them:

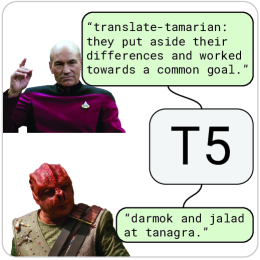

“Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra.” This most famous phrase (which appears on some hilarious T-shirts) means, basically, “working together.”

“Darmok and Jalad on the ocean.” Building on the last one, this is when two strangers, or foes, work together against a threat and succeed.

“The beast at Tanagra.” This is the foe that Darmok and Jalad fought, but has grown to represent any problem that needs to be solved. The lack of communication between Dathon and Picard is a “beast at Tanagra” of its own.

“Temba, his arms open.” This means “take or use this.” A gift.

“Temba, at rest.” When a gift has been rebuffed.

“Zinda, his face black, his eyes red.” Hearing this means bad news. Something one says when in great pain or very angry.

“Kiazi's children, their faces wet.” This also means pain, but also sadness or frustration. It may also mean “oh, leave me alone!”

“Shaka, when the walls fell.” Failure. I've decided to start saying this when anything doesn't go my way. Works just as well as “oy vey.”

“Mirab, with sails unfurled.” This means travel or departure.

“Uzani, his army with fists open.” A tactical move to lure your enemy closer by spreading out.

“Uzani, his army with fists closed.” A tactical move to close-in on an enemy after luring him in.

“The river Temarc, in winter.” Be quiet. Possibly based on “freeze,” as in “freeze your thoughts/mouth.”

“Sokath, his eyes open.” To translate this to TOS, this means “We Reach!”

I've left a few out. Frankly, I'm not sure I've nailed them all yet. However, my favorite one is “Picard and Dathon at El-Adrel.” It doesn't just mean two strangers come and make a connection. That's what “Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra” and “Darmok and Jalad on the ocean” mean. No, this one is something totally new. This one means “first contact.”

Did your first viewing of “Darmok” blow your mind like it did mine? If so, leave your metaphorical description below.

__________________

Jordan Hoffman is a writer, critic and lapsed filmmaker living in New York City. His work can also be seen on Film.com , ScreenCrush and Badass Digest . On his BLOG , Jordan has reviewed all 727 Trek episodes and films, most of the comics and some of the novels.

Get Updates By Email

Search this site

Star Trek: The Next Generation

“Darmok”

Air date: 9/30/1991 Teleplay by Joe Menosky Story by Philip Lazebnik and Joe Menosky Directed by Winrich Kolbe

Review by Jamahl Epsicokhan

Review Text

An alien race called the Tamarians meets the Enterprise in orbit of a planet to establish first diplomatic relations, where initial communications prove frustrating and bizarre because of the Tamarians' incomprehensible language, which when translated results only in phrases like "Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra." The Tamarian captain, Dathon (Paul Winfield), kidnaps Picard to the planet surface where the two attempt to come to some sort of understanding while a strange creature lurks on the other side of the rocks.

It's fascinating, how these Tamarian words, initially so nonsensical, ultimately end up taking on so much meaning. "Darmok" might be the ultimate Joe Menosky episode — one deeply rooted in ancient legends and strange cultures, and a story that's far more conceptual than your average storytelling fare. Essentially, you have a story that's being told through snippets of other stories that the characters are telling each other. In this vein of unique Menosky-scripted myths within myths, see also TNG 's "Masks" (which I'll deal with down the road), DS9 's "Dramatis Personae," and Voyager 's "Muse." Granted, the level of success varied greatly among these episodes, but there's a kindred thematic current running through them all.

All of which means that it kind of pains me to say that I like, but do not love, "Darmok." I admire it more than I enjoy it, because to a certain degree this episode keeps itself at arm's length with all of its legends and metaphors and its striving to reach this conceptually ambitious place. The Tamarians, you see, have a language based completely on metaphors and storytelling, so in order to know what "Darmok, his arms wide" actually means, you need to know who and what Darmok himself represents.

That's a fascinating concept, but not one that's easy to convey on screen — or without a certain level of (granted, perfectly TNG -appropriate) exposition. The story frequently cuts back to the Enterprise , where sometimes too much is made of dealing with the procedural details of Riker trying to get past the Tamarians' energy field in the attempts to rescue Picard. And at times the story stalls dramatically; for stretches it's just two guys sitting on a rock trying patiently to break through the wall of confusion that stands between them. But in this conviction is also the story's strength. What I really like about "Darmok" is Picard's willingness to listen — really listen — and try to figure out what all of this means. (I think it takes a little too long for Picard to initially realize that this encounter is in fact not a death match, but once he gets over that misconception, the story demonstrates Picard's gifts for digging in for the long haul and fighting for diplomacy.)

Ultimately, Picard reaches that epiphany. The entire meeting was set up by Dathon in order to reenact an ancient Tamarian tale in which Darmok and Jalad fought together in much the same way Picard and Dathon do here. That's a neat narrative trick, but not one that completely makes me a die-hard advocate of this episode. Sometimes the experience of watching "Darmok" is as slow going as the process of Picard learning about it. But when you finally get to the end, you see how that patience pays off.

Previous episode: Redemption, Part II Next episode: Ensign Ro

Like this site? Support it by buying Jammer a coffee .

◄ Season Index

Comment Section

199 comments on this post, startrekwatcher.

I do agree Darmok is overrated by the fan community and is more of a 2.5-3 star episode. The scenes back on the ship do seem like padding and a lot of the scenes on the ground are routine. The alien threat was a macguffin and reminded me of the Gorn. Sure the ending was poignant but that doesn't make a 4 star episode. The episode isn't that entertaining--the episode is more of an academic exercise.

"Darmok" is no more overrated by its fanbase than DS9 (as a whole) is by its fanbase

philosopher-animal

I'd put Darmok higher because of how it can be sort of twisted to apply to itself -think of TNG itself as a legend ... Also, as someone who wonders about such things as the nature of communications and concepts I do find the "crazy premise" wonderful, even if absurd if taken literally.

Giving this particular episode only a 3 star rating, much like DS9's "Sacrifice of Angels" (another vastly underrated episode reviewed), is one I strongly have to disagree with. Granted I haven't watched Darmok in a few years, I do remember it as one of the stand out episodes of the entire series. Even after re-watching it in my adulthood. The fact that it was just essentially two guys talking and trying to understand each other--in ways beyond just language, is what gave it its strength and uniqueness. I did not find it dull in the least, even stripped of all the usual sci-fi and action. Maybe it was just the way Patrick Stewart and the other actor portrayed it, but this wasn't another average fare episode (which is what 3 stars suggests). I think at very least it deserves 3.5 stars. Sacrifice of Angels though, that I'll always be of the opinion it deserved a full 4. :)

I agree with Mitch (on both counts!) and I don't think either "Damok" or DS9 are overrated by their fan bases :) As a translator, I have always found it laughable how easy it is for alien species to understand each other through the miracle of technology. But then here comes an episode whose whole point is about two very different peole who have to learn to understand each other's language. Never has that idea been more compelling to me than in this episode.

It was Temba whose arms were wide, not Darmok. I'm not going to try to persuade you of this episode's brilliance, since your comment that it pains you to give this a good-not-great review indicates that you've probably heard them all before (besides, Mitch and Nic seem to have covered all the bases regardless). All I can say is that this is by far my favorite TNG episode and that it has moved me in ways that Trek would not do again until DS9's "The Visitor." I absolutely adore the small morsels of the Tamarian language that we are given here and wish that Menosky were able to give us further insights in subsequent episodes (I've been known, on very rare occasions, to use, "Sokath, his eyes uncovered!" as a cry of victory). Beyond that, there are just so many little things that I love about this episode - the slightly exaggerated, theatrical mannerisms of the Tamarians (e.g., the way the first officer hangs his head after being chastised by Dathon), the way Dathon chuckles, "Gilgamesh," during Picard's story. It is, to me, a very rich, vibrant episode that gives a fascinating peek into such a thoroughly alien culture, and one of the sorts of things that made me a Trekkie in the first place. (Okay, so maybe that had more of a persuasive edge than I'd intended.)

For my part, I always rated this episode highly because it was the debut of Picard's bitchin' jacket. To follow up on my comment to "Redemption II" regarding my perception of Ron Moore as a writer -- I had a sense of Joe Menosky as a writer at the time, simply because of his focus on anthropological themes.

I'll admit that I've bought into the love this episode gets. It's been so long since it first aired it's impossible to recall what it was like after first viewing. But I think it's a brilliant idea, greatly executed. It's so much what Voyager could have been. SO many episodes had those great one-liner ideas, but they were usually botched beyond measure. TNG shows almost always -- if nothing else -- managed to live up to the premise.

Latex Zebra

I'm not even going to jusify it. I love this episode, one of my all time favourites of any Trek series.

karatasiospa

If anyome would ever ask me to use an episode to describe why i love TNG and why i hate the reboot movie then Darmok would be one of the first that would come to my mind, 4 stars from me.

Nick Poliskey

I think I am can sum up the problem with this episode. I call it the "Star Trek VI" problem. This episode is PHENOMENAL, when you first see it. No argument at all there. But I agree with most here (who aren't lignuists), that once you have seen it and "get it", it really is dull on the re-watch. I don't think it is truly a bad thing, there are lots of episodes and movies of all genres like this. I think the reason we are so critical is because we know that Dathon is a good dude, but when I first so the episode, you do not have the slightest idea what is going on. So I would agree with the 3 star review. I think 4 star episodes should be enjoyable viewing past the 1st time.

I guess to each their own, but to my mind this is one of the best that Star Trek has to offer. I've watched it many times and always enjoy it.

This was one of those episodes that I knew as I was going in for the revisit it had much love in the TNG fandom circles. But I just couldn't muster more than three stars. I like it, but it just doesn't go beyond like for me. It's nice, it's original, but it's also kind of a dramatically repetitive show. Mitch, I will officially announce here that I underrated "Sacrifice of Angels." I've watched that many times on DVD over the years and found it constantly rewatchable and just a plain great hour of TV. The three stars should probably be four. (I'm not going to officially change the rating, because I could probably change dozens of ratings on this site, and there's just no point.) Nick Poliskey, I disagree on the "Star Trek VI" comparison. If anything, "Star Trek VI" remains just as entertaining when rewatching. The same flaws are evident, but it's a definitely rewatchable and entertaining movie.

grumpy_otter

I love this episode, but when I rewatch it, I only watch the Picard and Dathon parts and fast-forward through all the on-ship stuff. But as much as I love the idea of their metaphor language, how could it possibly work in practical terms? How, for example, do they potty train their children? Mirab, with sails unfurled.

I've never liked this episode, despite wanting to. Can someone please explain to me how it makes any sense? I mean are we supposed to believe that the Universal Translator knows enough to translate this alien language into English words, but can't figure out these metaphors? This is the Magic Trek Universal Translator we're talking about here. A device that's so good that it even makes the aliens lips appear to move in English. And also has been shown to work many times without ever having encountered a language before. I really want to figure this out! Or maybe we're supposed to believe that all these aliens just speak English?

I must admit on first viewing of this episode many years ago I experienced two WTF moments that caused me to lose focus on the episode. First, Picard's uniform. There was no explanation, it had two layers with the primary shirt being blue, his pants were tucked into his boots. Why? What was the reason? No one else had it and no one else ever would in the Star Trek universe. I seriously thought I must have missed an episode or something. Second - when phaser fire started blasting out of the photon launcher. I was totally confused, literally said "what the hell?" and was pulled out of the action. I thought to myself "could the FX department had screwed up that bad? Where's quality control?"

to Angel, let me paraphrase the Big Lebowski, " What does DS9 have to do with anything????" good enough, had to be very patient at the time reminds me of Alien Mine movie

Harsh rating. You've given plenty of inferior Voyager and Enterprise episodes higher ratings. Realistically if Darmok is only 3 stars, no Voyager or Enterprise episode deserves 4 stars. Perhaps you should go through your old reviews and apply your new harsh standards.

Ian Whitcombe

MadBaggins, not only are Jammer's scores relative between series, season and year of review, but he was also quite clear that he didn't think VOY or ENT were successful series as a whole. So, those four-star reviews you deride are only in the relative scale of being above average for some very flawed series'.

I love the relationship between Picard and Dathon, but I could never buy into either the impossibility of communication with the aliens, or the likelihood of their language being so based on metaphor. In the first case, I know that I - as a child, on first viewing - understood that their language was metaphor-based from the beginning. Guy mouthing off, other guy yells "The river in winter", and the first guy shuts up. Child Me says, "Oh, I get it: he meant shut up, be still, i.e. like a frozen river". If I got it, then why does it take the Predator to hammer the point home to Picard? And more importantly, how could these people have developed their language in the first place if it was only ever based on something else? If I make a reference to Romeo & Juliet, then Shakespeare had to have written the play in the first place for my metaphor to make any sense. These people had to have had a non-metaphorical language in the first place to have written (or read) the stories their metaphors refer to. And how the hell does one construct a starship when one's language is entirely metaphorical? How would you go about discussing mechanical engineering or complex computer programming in terms of Greek myth?! So, nice acting, nice Trekian philosophy, but zero logic.

Both the review and comments which follow offer me the knowledge that Star Trek is truly lost on most people, even those who like it. Star Trek is a MYTH. The science fiction aspect to the drama serve the same function as magic or divine powers in ancient stories. Has anyone here even read Gilgamesh? Geez. This is the absolute best episode of the season....in fact its existence alone justifies the season as a whole. Enough quibbling over the technologies, the fireside scenes are completely captivating and emotionally resonant. The story is not a "conceptual one" at all. It's rooted in the very legend it names; love, trust and loyalty to one principles transcends any kind of cultural or technological barrier (as it did between Gilgamesh and Enkidu) and the bonds our shared adventures create, the dreams we whisper to one another change us more than "event" could ever hope to. Four stars without question. THIS is the essence of Star Trek in every way...and it's executed extremely well by the actors and director.

To Noxex regarding the universal translator- If you had a term you used to describe waking up because of an experience. Say a cat sitting on your head (I'm sure cat owners will gt that one). You could say 'A cat sitting on my head' to a Russian, in Russian and they would understand the words, but not the meaning behind it.

To Elliot, You are absolutely wrong about that. That is not a view shared by casual fans, obsessive fans, or even the producers or creators. The show went out of its way to hire very smart people with PHD in physics, chemistry, etc.. to be part of the show (Sternbach, Okuda, etc...) Now I think you could make a strong argument this episode was meant as myth, but I would disagree with you even on that one. This was a genuine attempt at something, and when you read what the writer and producers were aiming for you have to take them at their word. Part of the reason people get so jazzed up is becuase STTNG was generally so straight forward in its' presentation of science, that when there are some irregularities, they are that much more noticeable. Obviously this is a TV show, but it is not "meant" as a myth anymore than any other TV show, and I think people are quite justified in their complaints on this particular hour.

to Weiss, I'm just sick of people who think that the ONLY possible way to give DS9 the love & attention it didn't get during its run is to take pot shots at TNG, the show which made DS9 possible, & the way Jammer (and some others) basically drool over that show by giving too many of its episodes 4 stars, while short-changing TNG classics such as this one, "Family," & "The Drumhead" in the same way suggests they are doing just that. Read any interview with the irascible Ira Behr and he basically says: "TNG sucks, watch our show instead." Hardly a way to draw viewers! He comes across as bitchy as Kevin Sorbo does when anyone brings up Xena.

@ Nick P : Intent does not account for content. I understand and appreciate that there is a real science aspect to the show; and much of it is there (whether or not this was anyone's intention) as a means for social commentary ON technology itself and our use of it. The fact is in all the incarnations of Trek (some more than others) the core of characterisations come from archetypes, the building-blocks of myth. The references in the show to our own poetic heritage (here and elsewhere) is part of the message here. Many will label such devices as "derivative," thereby demonstrating their severe lack of creative energy. Science fiction is a 200-year-old genre, but the power of Star Trek as compared to the myriad of other sci-fi is its durability. That durability comes from its mythical power. Myths are older than civilisation itself and will never decay. When Star Trek is at its best (as it is in "Darmok"), it captures that timeless quality as well as any TV show ever has. You say people are justified in their complaints, but such complaints stem from an emotional vacancy in the fans--they are looking for something superficial because the true content of the show is lost on them.

@ angel : couldn't agree with you more. I can't help but feel a sneaking suspicion that the DS9 "droolers" never really appreciated their Trek for what it was, being possessed of some other Sehnsucht which DS9 offered them.

Elliott, in your arguments you have concluded what Star Trek is and have also decided that those fans who haven't reached the same conclusions as you must therefore not understand what Star Trek is. I find that position awfully myopic.

Armed with a working definition of what myth is and multiple viewings of every episode and movie of the franchise (well, I admit, I couldn't bring myself to multiple viewings of many ENT episodes), I reached a conclusion. When an episode can fundamentally exist as only Trek and not any other subgenre of Sci-fi, I take that to define its essence. While there are numerous good episodes which don't necessarily make the most of this core, that doesn't change the fact that it's what makes Star Trek special. Tell me that the archetypal image of a ship on an idealistic adventure meeting aliens which personify various archetypes and allegories is anything but the stuff of myth? A thing is what it is. It may mean nothing to some, everything to others, but it exists as itself on some fundamental, platonic level. Is it myopic to hold a thing accountable to its essence?

@Grumpy I vividly remember 20 years ago watching the coming attractions for this episode at the end of "Redemption II" and thinking that perhaps they were going to change the uniforms. I always loved that bitchin' jacket too - I think it was called the "light duty uniform" on the packaging for the Picard action figure that was released the following year. I remember reading that Patrick Stewart simply wanted a more comfortable costume and that's what Robert Blackman came up with. In fact as I recall it was Stewart who got the uniforms changed to the two piece design in Season Three because the jumpsuits were giving him back trouble. Perhaps they decided it would be more cost effective this time to just give Picard a special outfit rather than make new ones for the whole cast. @Don It wasn't unprecedented in "Trek" for the captain to have his own uniform variant. On "TOS" Kirk sometimes wore that cool green tunic instead of the usual yellow shirt and that was never explained either. Much more annoying to me was that until Captain Jellico came along in Season Six Deanna Troi was allowed to run around in all sorts of silly outfits. And I thought she was sexier in a Starfleet uniform than in any of those costumes! (Well... that low cut teal number was pretty hot.) LIke many Trekkies I've always counted "Darmok" as a favorite for all the reasons that the other posters have said. But I think my favorite part of the show is at the end when Picard returns to the bridge and hails the Tamarian ship. He just strides on the bridge with his ripped up uniform with such authority and takes control and saves the day. For me it was one of his coolest moments. Maybe because he was wearing the bitchin' jacket!

@Jammer: "...the show's Prime Directive--not to interfere with the normal development of other civilisations--has appealed to millions. It has also inspired each series to reflect the moods and concerns of the times in which it was made. It IS our own 20th-century mythology, and there's NOTHING else out there like it." --Majel Barrett Roddenberry, aired on Sci Fi, January 12, 1995 You or anyone may argue if you wish the definition of mythology or its applicability, but to deny that it provides the essence if not the entire Universe of possibilities for Star Trek is naïve and self-defeating.

Elliot, that was beautifully put. I never really thought of it that way. I personally don't really care for the prime directive, but it is as much the core of Star Trek as Spock is. It IS Star Trek, philosophically.

Jeff O'Connor

One day, somehow, the TNG-versus-DS9 wars shall end. For my money, "Darmok" is three-and-a-half stars. I like it a lot but I don't quite love it. Everything about the episode is wonderful high-concept science fiction but there was a bit of a pacing issue as far as Riker's scenes were concerned. When an episode isn't just as comfortable a fit no matter which set is being filmed I tend to subtract a bit of the score. Riker's scenario wasn't intended to be quite as compelling as Picard's, I'd imagine... but every time I saw the bridge I just desperately wanted to see the planet again.

Good to see new TNG posts (ok, I'm a bit behind noticing, but still nice). Also a plus to see more 'full' reviews. Sorry to hear you didn't get more work done on these during the summer. I'm in the camp of people who would rate this episode at 3.5 or 4 stars. I respect your opinion on this one, but for me the Picard/Dathon scenes more than make up for any on-ship scenes that drag. I noticed that one commenter mentioned the Gorn. Funnily, I had a Gorn thought while reading your review as well. My thought was that this episode acts as a sort of anti-‘Arena’. In this episode, everyone assumes that this is a deathmatch a-la Gorn. However, it turns out to be the opposite. The thing is that the episode also serves to highlight the differences between Riker and Picard and what makes Picard a true diplomat. Only Picard ever realizes that Dathon is seeking friendship. Riker continues to be aggressive and assume hostile intent because he doesn’t understand. I wonder if there was any intent to make a comment to the point that people assume the worst of someone who speaks differently than themselves (though in this case, they do seem to “attack” the Enterprise). In any event, the relationship that builds between Picard and Dathon is the gem of the episode. Stewart and Winfield turn in fantastic performances of frustration, anger and ultimately friendship and understanding. I usually get a tear or two when Dathon ultimately dies. Picard almost seems to realize that had they just understood each other in the first place, it might not have been necessary, making it truly tragic. The only other pieces of Trek that really give me that emotional reaction are the eulogy in ST:II, and when Jake reveals his plan in The Visitor. Ultimately instead of trying to outwit and defeat the Gorn, Picard has to learn to communicate and work together with Dathon, which makes this a standout “see how Trek has evolved since TOS” episode. I understand that there’s a lot of exposition or stalling on the ship, but it doesn’t seem terribly forced to me. It seems like Data and Troi trying to genuinely figure out the issue of communicating with this culture, and it goes to show again that not everything can be solved via the computer and databank research. This problem was solved by Picard’s communication skills and intuition.

Jeff O'Connor, The TNG vs. DS9 wars can only end when those who obsessively drool over DS9 can see reason by not taking pot shots at TNG whenever they praise 'their' show. If someone likes DS9 better than TNG that's fine, but what bugs the crap out of me is how they basically dismiss TNG as a bland abomination for no good reason.

@tony "The TNG vs. DS9 wars can only end when those who obsessively drool over DS9 can see reason by not taking pot shots at TNG whenever they praise 'their' show." Well, not saying your experience is my experience, but I haven't really seen this. DS9 fans are in large part people who have come to Trek through TNG. Most of them, as far as I know, hold both TNG and DS9 in high regard. Now Voyager is a completely different matter :)

I'm with Paul - I've known TNG fans who didn't care for DS9. Either because they bailed early on when the show was still finding its voice or because they had very narrow definitions of what "Trek" should be - namely one hour isolated stories featuring a ship and its crew. However I don't recall ever meeting a DS9 fan who didn't like TNG let alone dismiss it as a "bland abomination". Now Voyager, as Paul puts it, is indeed a completely different matter.

@Tony & Phil : Well, it's been my experience that most of DS9's fans liked or even loved TNG but found it rather childish in comparison to the former--which, as this episode should demonstrate--is utter rubbish. In other words, I'm convinced that DS9 was the non-trek that bribed fandom through references and continuity to TNG.

"Can someone please explain to me how it makes any sense? I mean are we supposed to believe that the Universal Translator knows enough to translate this alien language into English words, but can't figure out these metaphors?" I gave this a bit of thought and came up with one possible solution: the Tamarians split from another race that speaks more normally and that the Federation has dealings with, so the ordinary words can be translated but the metaphors cannot. The name "Children of Tama" suggests a cult that left the home planet. Of course this isn't stated in the episode, but it could be added without changing anything, so I'm willing to let it slide. That said, I do think this episode is a bit overrated. Good but not excellent.

Captain Tripps

Always loved this episode, in a way it's almost like we're seeing a mirror image of Picard in the Temarian, that culture's version of the captain dedicated to meeting new life and establishing communication. Nitpicking the chosen language conceit, and the translation difficulties, is an old past time. It makes sense to me that the Universal translator would fail with idiom and metaphor, it does the same with curse words, in a more literal fashion. People who speak different languages on Earth today face the same difficulties, heck even English causes some confusion, with the various dialects and whatever it is they speak across the pond. As to the great Trek debate, I'll weigh in by saying that the usual suspects complaining above are guilty of the exact thing they lament, namely dismissing DS9 and insulting it's fans in a lame attempt to prop up (uneedlessly, IMO) TNG. I'll say this, DS9 is my favorite Trek. It's the most consistently well written from the 1st season onward, the characters are so diverse in temperament, the setting unique in the franchise, so and and so forth. However, TNG defines Trek, even more so than TOS. That obviously doesn't make it a better series, since not everything about Trek is necessarily a positive, but even the excessive technobabble and bumpy forehead aliens are part of the formula. TNG isn't diminished because someone likes another series more. I expect that kind of defensiveness from Voyager fans (smile).

@Tripps "I'll say this, DS9 is my favorite Trek. It's the most consistently well written from the 1st season onward, the characters are so diverse in temperament, the setting unique in the franchise" I am currently rewatching DS9 after many years. It's interesting how solid that series is, and I think characters are the main "culprits"; even a stupid episode is often saved by all those wonderful characters. Sisko&Co, not to forget the huge support cast, in my opinion, have a... I don't know, vibrancy, radiance, life to them that really set DS9 apart from other Trek series. Of all the Treks, they are the most lifelike and, well, in the words of James T. Kirk, human.

Great reviews Jammer, and glad to see you were able to post some new stuff. Skip to 3:02 for some Darmok-related goodness. Heck, the whole thing is hilarious: http: //www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=X6oUz1v17Uo @MadBaggins - dig the name. It's also the name of my (conceptual) stoner rock band. If only I could learn to appear on stage with a flash and a bang.

My opinion of the great TNG/DS9 Debate. OK, I feel torn here. I will go on a limb and say that DS9 is a better series. That is really hard to argue against. It is tighter, better written, better characters, and way better actors, overall. that being said, I am a purist, DS9 is NOT Star Trek. I am firmly in the camp that Gene Roddenberry would have hated calling this star trek. This is not drama. It is a war story in Space. People forget that Gene had a vision, and I disagree with his vision in many ways, but he still had a vision, and TOS and TNG was it. It was not people hating each other and religious nonsense being "respected", that was in no way roddenberry. He would have hated DS9 I have no doubt. It is much close to BSG than ST.

People argue way too much over this one. This episode relies almost purely on how far one is willing to suspend their disbelief. The concept itself is great, but there's an "uncanny valley" effect introduced by the execution. It's not really worth debating whether it's 3 or 4 stars.. the concept is 4-star, the execution is what people tend to harp on and that's less important to most sci-fi viewers. You can rationalize away the "speaking with metaphors" thing either as "there's more (non-verbal) communication we don't see or hear" or "it's just artistic license" (etc), but it still comes down to how much you like the idea and want to see it work. For my money, the execution was sub-optimal, but it deserves props for the concept and the fact that such a silly episode actually worked. As cheesy as the metaphor idea was, it did give us some memorable quotes.

A great story, but the brief battle at the end where the Tamarians totally outclassed the Enterprise tactically seems a contrivance.

"Darmok" is far more fitting 25th Anniversary episode for Trek than the "Unification" 2-parter. Gene Roddenberry's memorial card (which was at the beginning of both parts of "Unification" should have been for this show.

Hear! Hear! Patrick! Every truly great work of art is rooted in myth. This must be true because myth is the most original expression of the human subconscious, the nouminal and the metaphysical, and because only art can express these things in a coherent way. This inevitable truth is recognised in the review to BSG's "Mælstrom," also an excellent episode of myth-oriented television. Mythology and religion are, of course, intertwined, but not inexorably. Star Trek is the demonstration to the 20th/21st centuries that science fiction is a means by which myth and religion can be separated WITHOUT sacrificing the power of mythical insight. In the 19th century, it was Wagnerian opera, in the 18th it was poetry of Goethe... This episode is the pinnacle of that realisation and is supplied with pitch-perfect performances and just a hint of self-awareness that make it unquestionably great. Yes, unquestionably. That is the price one pays sometimes when dealing with things as potent as myth; they simply are or are not, like the will of a deity and do not succumb to the opinions of critics. I can understand that this is a problem for many in our democratic and atheistic zeitgeist (I believe in democracy and am an atheist) but without that un-questionability, Star Trek would not be the phenomenon it is. As a television show, it could stoop to the lows of "Spock's Brain" or the highs of "Far Beyond the Stars" and "The Inner Light", but as an idea, it is impenetrable. "Darmok" is the sacred altar of the myth that is Star Trek, which is why awarding it anything other than 4 stars is * irreverent* if tolerable.

I really liked this episode. When I was 13. 3 stars is about right.

I went into this episode hating the first 20-25 minutes of it. I found the language unbelievable, the Enterprise scenes tedious, and the phrases repetitive and annoying. All of that changed at the end, when the writers managed to pull off a sudden understanding that made most of the language hang together, as well as the telling of the story of Gilgamesh, which had some seriously stunning emotion, and Picard's final delivery to the Temarians, more or less, made the beginning of the episode worth it.

This is a fantastic episode, maybe in the top 5. It is very deep and is similar to the way humans have difficulty communicating ideas that are not tangible, and more spiritual. The acting is amazing and Picard is flawless as usual. I do not think it is as touching as "The Inner Light" or "Tapestry" nor as exciting as "Yesterday's Enterprise" or "Best of Both Worlds", but it is right up there with them. Also, I'm really tired of hearing the negative comments with regard to Voyager. Some of the episodes on Voyager were right up there with the very best of ANY Star Trek from any of the series. Anyone who says there were no four star episodes has obviously never seen masterpieces such as "Distant Origin", "Timeless", "Living Witness", "Blink of An Eye" - not to mention some incredibly fun episodes such as "Pathfinder", "Scorpion", and "Year of Hell" (Red Foreman people, come on!) On the whole, TNG might have been a little better (thanks to Patrick Stewart), but Voyager was Star Trek at its best once again. I do not think people open their minds enough to even give it a chance. The acting on the whole is better than ANY of the series (other than Patrick Stewart). Robert Picardo (Doctor) is an unbelievable actor, as well as Robert Beltran, Ethan Phillips, Tim Russ, and of course Janeway. I'm also tired or hearing that DS9 is far superior to Voyager. Baloney! It is still great Trek, but talk about overrated, please! Voyager is so much more interesting, not to mention the acting is far superior, and the screenplays are more diverse and thought provoking, especially the aforementioned episodes.

To weigh in on the TNG/DS9 wars, I am someone who came to DS9 via TNG, love TNG, but still find DS9 to be the "better" series. I don't feel that it takes a pot shot at TNG to say so either. If you look at TNG->DS9 as a whole entity that spans a 12 year period DS9 just simply benefited from being second. The writers were able to push into a more serial direction where actions have consequences because TV was evolving and this is where it was going. My favorite "arcs" from TNG involve Data's growth and Worf's family/Klingon drama. They were TNG's best attempts at having actions with consequences and real character development. If you look at Worf in TNG S1 and see what they did to him by the end.... well THATS why DS9 wanted him. TNG took a 2 dimentional character and made him really interesting. And after the writer's learned you could do stuff like this on television they applied that standard to DS9 and doubled up on it, make even the minor characters like Nog/Garak be fully realized and interesting. I don't know why saying these things (which I basically take as facts) diminishes TNG in ANY way. TNG laid the foundation for amazing Trek and DS9 kept building on it. Saying these things does diminish Voyager, since they decided to take the things that TNG and DS9 built up and knock them down, going back to what TV was like a decade before Voyager was on. There was a time when DVDs weren't around and shows weren't watched in marathon style bursts. Back then it was more important that you put out an hour of awesome television. The world is changed now and DS9, taken as a whole product, is simply more satisfying than TNG. However I love TNG and I think that if I was being really fair and grading on the exact same curve TNG (with episodes like Inner Light, Measure of a Man, Darmok, Best of Both Worlds, Yesterday's Enterprise, Drumhead and All Good Things) would likely have the same number of 4 star episodes as DS9. When I say DS9 is better I mean as an entire 7 season product, not necessarily which has more 4 star episodes. As for Voyager... I watched it all and will concede that there are some really amazing stand out episodes. What hurts Voyager is looking at the interesting premise and how far DS9 had come with compelling character studies by then and knowing what Voyager could have been and chose not to. TNG evolved the franchise from its 1st year attempt to emulating TOS badly to being an amazing show in its own right. DS9 learned from TNG and pushed the envelope further to fully realize its own premise. Voyager dropped the ball. It will always stand for me as a show that could have been more.

@Robert I think the whole TNG vs DS9 thing boils down to a kid who had his entire education paid for by his father who busted his rear and innovated to make sure his kid had a first class schooling. And the kid, now fully educated, thinks he's not just smarter, but better than his old man. As you say, TNG evolved. Boy howdy! It went from episodes like "Skin of Evil" to episodes like "Chain of Command" in less than six years. (I think the key catalyst of this was the late, great Michael Piller, who was a co-creater of DS9, but anyway) DS9 was a terrific show, but it was standing on the shoulder of a couple of giants.

@Patrick I pretty much agree. As I said, I don't feel that saying DS9 is better takes away anything from TNG. DS9 climbed a little higher because its standing on TNGs shoulders. I take this as a fact, you'll get no argument from me. TNG was groundbreaking, it was amazing and it put out many hours of excellent television. It also probably has the best actor in the entire franchise. But it didn't have the benefit of the hard working father to teach it (the way that DS9 did). As to DS9 fans, who I assume are like the kid who thinks hes not only smarter but also better... I am not one of those. I think the show is better (as I said, from the perspective of watching it as a 7 year product) but that doesn't in any way imply that I think TNG wasn't as great for its time or as groundbreaking. And it certaintly doesn't mean that, as a fan who thinks DS9 is better I still don't look up to the old man (continuing your metaphor). Because I do, and he is a great man.

Have to agree with Elliott on this one. For me, this is a straight 4 star episode. The basic premise is excellent- a race who as Picard says'are extending a hand' encounters the Enterprise but is unable to communicate, as although the Translator makes their language comprehensible to the Enterprise crew - the ideas are couched in a form which is incomprehensible. This was, and still is, one of the best episodes of this or any season. Guest star The late Paul Winfield, superb in Star Trek 2, is pitch perfect here as Captain Dathon, the Alien willing to sacrifice himself for the sake of greater understanding between the two elope, and Patrick Stewart gives his customary excellent performance, thriving on having such a strong guest star. A must watch for anyone seeing TNG or indeed any Star Trek incarnation for the first time. As I say, Elliott and I haven't always seen eye to eye on some episodes but here he is spot on.

The way they outclassed the Federation flagship, it would have been nice to see these guys as allies during the Dominion War..

Mephyve and pillow when the sun falls , ie, snoozefest.

Why is it that people think that serial television automatically is better than episodic television??? For an extreme example, I don't think anyone would ever argue that Days of Our Lives is superior writing to Seinfeld. And Days of Our Lives, SOAP OPERA, is indeed where all serial television really evolved from. For my money, TNG accomplishes far smarter and more philosophically challenging concepts in its best hour long stand alone episodes (like this one) than DS9 does in all its melodramatic, angsty soap opera.

@Patrick: I don't know that I "automatically" think that serial television is better. It IS a fact that there is only so deep as single hour can go when the goal of that hour is to ensure that the status quo is maintained at the end. TNG has a lot of great episodes. A LOT. I doubt anybody on these boards would argue it. But that still doesn't change the fact that having your characters change and grow makes for a deeper experience. Look at early episodes with Beverly and Picard. Then look 7 years later. It just went NOWHERE. That doesn't make for a satisfying experience. Say what you will about DS9, but stuff happened and consequences for actions were felt. Did they press the reset button too? Yes. Less than TNG though. And they ALL pressed it less than Voyager. I guess THAT'S what's nice about serialized TV. The reset button is just a amateur writer's plot device. In serialized TV it gets pressed less (on average). But that doesn't have to be the case. In soap operas they constantly bring back dead characters years later with ridiculous reasons. Doesn't get more reset buttony than that. TNG occasionally didn't press it (or only pressed it halfway). Then you get brilliant episodes with great fallout like S4's Family.

@Robert : I think it's fine to speak of being "satisfied" with story arcs and continuity, lack of reset, etc. In-Universe continuity is always fun for the viewer, it rewards him for having paid attention to what happened before, to care about it episode to episode. However, saying that it is "a fact" that serialised television goes "deeper" is, I think, erroneous. If that were the case, we could say that "Atlas Shrugged" is factually deeper than "Dubliners" or that a 4-hour Händel opera is deeper than a Beethoven string quartet, or that "Avatar" is deeper than "Run, Lola, Run"--you get my point, I believe. Yes, it is perhaps unfortunate the TNG (and especially VOY) writers did not take advantage more fully of the fact they had so many episodes to work with--that they could have been as broad as they were deep, but DS9's serialised nature does not make its content deeper or even more interesting. As I said, it simply rewards the viewer for his loyalty and attention.

I think I agree with... Elliott. But I also agree with Robert. Therefore, by the Transitive Property of Grumpy, Elliott and Robert agree with each other.

P.S. I disagree with Patrick's choice of Seinfeld as an example of non-serialized TV. Its peak episode, "The Pilot," built on a season's worth of continuity. Subsequent seasons each had their own long-term arcs, too. So, bad example. Of course, now we all want to know: Jammer, when will you start posting reviews if Seinfeld?? And Days of Our Lives???

@Grumpy : LOL! Although, I think your transitive property works (at least on my side). Robert does agree with Elliott. When I said deeper I believe I was not necessarily referring to deeper content. It is a fact that, unless a person is deeply broken they should be much less affected by me killing a character on a TV show that they met an hour ago than killing their best friend that they've known for 30 years. In that regard all I'm trying to say is that serialized TV offers the possibility (but not the guarantee) of a deeper, more meaningful and emotional connection with the characters and the setting. I did not mean that one show was intellectually deeper than the other. When you look at shows like Inner Light, Measure of a Man, The Offspring, Tapestry and Darmok.... even if you consider that DS9 has it's own powerful stories I wouldn't claim that DS9's powerful stories were intellectually deeper than TNG's. All I'm trying to say is that when things happen to your characters and you don't reset button them away.... it makes for deeper emotions. When Vedek Bareil died I imagine most people felt for Kira harder than when Dax lost Deral in Meridian... because Bareil had been around for 3 years and you've seen their relationship grow. TNG understood this too though. Worf's loss of K'Ehleyr was made deeper by their history on and off screen. If she had been a one episode wonder you wouldn't have cared as much. So in closing, while I can't say for certain that Elliott agrees with me, I mostly agree with him. Serialization doesn't necessarily make content deeper or more interesting, but I DO think it connects you more deeply to the characters. Most people seem drawn to the TNG characters that had the largest arcs (Data for instance has at least 20 episodes where we explore his history, family, friendships, growth and his quest to become human). The kind of continuity and growth we see from Data connects us to him in a way that causes us to be more invested in his episodes from the start. Let's take an episode I really love... VOY's "Blink of an Eye". It was great sci fi, and interesting concept and I even especially connected with the guest character that visited the "sky ship" in the end. But the depth of my emotional attachment to him just can't compare to an old friend I've seen grow over 7 years... no matter how much I love that episode.

I think this was a really good episode. I'm not sure I'd give it four stars, but it's definitely in my list of personal favorites. It took some getting into initially, but overall, it was very, very good. Great performances by the two captains. Very touching ending. As someone further above said, the ending was so brilliant, it made the first 25 minutes "worth it".

Watched this again last night and nothing changes. Solid 4/4 and this is the epitome of what TNG was about is about. DS9 could never have done an episode like this because that wasn't what DS9 was about. Would have been nice to see Voyager take on more stories like this. That's not a Voyager slag off by the way. Just a want for a little more.

SkepticalMI

Shahryar, his ears perked. Scheherazade, surviving the night. Keanu, saying "whoa". Siskel and Ebert, their thumbs skyward. Mona Lisa in the Louvre. [Translated: The story was quite interesting and had me engaged. I would highly recommend it, and think it stands as a true classic.] See, their language isn't hard to understand! In all seriousness, I think I consider this episode the quintessential TNG episode. Or, more accurately, the best possible episode to introduce others to TNG. It's not the best; far from it! But BBW and YE aren't exactly typical of TNG. Likewise, they both require a bit of background and a bit of time spent with the characters in order to fully appreciate them. On the other hand, Darmok requires no previous knowledge of any of the characters, and no previous knowledge of Trek in general. And it also seems to be a summation, really, of what TNG is all about. For one, it has all the flaws that people tend to use to denigrate TNG. There's technobabble here. It's slow and talky. It involves one interesting story and one not quite as interesting. It has the silly fake ship in peril scenes at the end. It has bad special effects. Yes, these are all here. If you can't look past them, then what can I say? TNG is not the show for you, and we can all move on. But if you do think these are only minor issues, if you can tolerate them and focus on the larger picture, if you can enjoy the show despite these flaws, then you will probably enjoy all of TNG. Because what does it have going for you? A truly unique and interesting story that you most likely will not find anywhere else. An interesting science fiction story, discovering with Picard a bizarre yet still recognizable society. A story that draws you in at a leisurely pace, allowing it to grow naturally. A touching, emotional story with engaging characters. A story that makes you care for these people, and hope for a positive resolution. A story that makes you feel a loss, saddened when one of the characters dies. Yet you still feel relief knowing he did not die in vain. A story told by brilliant actors. A story told with excellent direction. TNG, at its best, could tell these stories. Exploring the potential of humanity and the unknown possibilities of existence, all with a positive outlook and a sense of both awe and determination. And when looking at all the diverse stories it told, flowing easily from deep philosophical discussions to defining character moments to political intrigue to high drama to bizarre tech to intense personal stories. Not just any stories, but stories with an impact, stories that stay with you. Darmok is a near perfect example of this. As for a few of the complaints: 1) How did they get their stories in the first place??? Actually, this is shown clearly. Picard is seen flipping through Dathon's logbook, which has some sort of symbolic language that seemed to map out ideas visually (at least that was my impression). Picard offers it to the first officer, who glances at it and says "Picard and Dathon at El Adrel". Clearly, that log will be circulated to provide a new story for the Children of Tama to reference. 2) The language was so simple!!! We know that this is not the first time the Children of Tama attempted to communicate with the Federation. So they knew it was a difficult test. It's quite possible that they were attempting to "dumb down" their language to make it easier for the Federation to understand. For example, maybe they have a dozen different metaphors for giving that would work in different circumstances, just as we have many different words (giving, donating, sharing, etc). But perhaps Temba is the most basic one and thus the only one Dathon used. It was like he was trying to teach a child to talk; why would he complicate things? 3) This is so ridiculous, how would a culture like that exist??? Actually, I find this pretty interesting. There was a line by Data that I don't remember exactly, but he said something along the lines of "Tamarians have an unusually low sense of ego". I think that's the root of it, and that that lack of ego, lack of self, is the dominant trait in the Children of Tama. They see themselves, not as an internal reference, but seemingly as an external reference. Almost like they are performing in a drama, performing for others. They see themselves as parts of an overall story. While they probably recognize the concept of free will, and certainly act on their own volition, they may not necessarily do it from a selfish perspective. Obviously this is hard to tell from just one episode. But we saw quite a bit of ritualistic behavior from the First Officer. Rituals deny the importance of the self in favor of the continuity of a community, and thus strengthening my thesis here. When you are performing a ritual, you are acting the part expected of you. But more importantly is Dathon's actions. Seriously, do they make sense to you? You're having trouble connecting with someone. So you think, "hey, I read a story in which two strangers fought side by side in a battle to the death with a common enemy, and left as friends. Maybe if I set a similar scenario up with this guy and risk both of our lives, the same thing will happen!" No, that would be crazy. But that's what Dathon does. So to him, it can't be crazy. And thus Data's statement makes sense. I wouldn't risk my life on a crazy scheme like that. And I wouldn't think it would work, because I know I wouldn't want someone to do that to me. But if I have no ego? If I think I'm just a character in a story? Then maybe it makes sense. They were at an impasse, and needed to do something to move the plot along. Dathon thought this might work. His own mortality was not a concern, because the story is immortal. If the plot follows how he thinks it will go, then the story ends happily. If it veers in a different direction, then at least he creates a new story that others can follow. And if the self isn't important but the narrative is, then it becomes a sane conclusion to risk your life in this way.

OtherRobert

I used to post under the name of Robert, but that was before I realized that there was someone else who posted under the name of Robert. So now I'm "OtherRobert". Anyways. Just wanted to register my "votes", not to persuade/dissuade anyone, but just to go on the record. As in, -I really love this episode: four stars for me, one of my favourite Trek episodes. -I luv the Picard bitch' jacket -I like all the characters, including the "beast" -I thought the space battle scene was cool -even on initial viewing I did squirm at the idea that the aliens could communicate solely through metaphor. But that doesn't change how I feel about the episode. On a separate note, I do get a kick out of the passionate debates on all Star Trek. What number of stars rating is correct? TNG vs. DS9. The castigating of VOY and ENT. And on and on... Really enjoy reading everyone's reviews, even the ones I can't stand. :-)

Great thoughts, SkepticalMI. The part about Tamarians' lack of ego and acting as players in a 'story' reminds me a bit of Julian Jaynes' theory of the bicameral mind. You might want to track down his book.

FlyingSquirrel

I sort of agree that it seems implausible that a language would really develop like this, especially since, as several people have noted, the stories would have to be written before they could be used as metaphor for future communication. I guess one possibility is that the Tamarians keep written records of their stories and myths that are in more literal form, and that perhaps it's more of a cultural standard that they don't *speak* literally even if they can still understand more literal forms of communication. If that's the case, then perhaps Picard and company have simply encountered them at a stage of cultural development where this is their preferred method of verbal communication. It does seem unlikely that they've communicated exclusively through metaphors throughout their entire history. The question that I guess that leaves unanswered is why it might not occur to them to try a different method of communicating with the Enterprise crew. They're smart enough to have developed a rich mythology and to have constructed starships, so wouldn't they realize that other species might have different cultural standards of communication? On the other hand, I sometimes think that science fiction fails to deal adequately with the possibility of aliens who are very different from us psychologically. For example, the question is sometimes raised as to why, if there is alien life in the galaxy, there's no trace of their existence through stray radio communications or even a long-term galactic colonization project. I sometimes wonder if there might be advanced species who simply don't care what might lie outside their own solar systems and just haven't made the effort to communicate or explore even if they could theoretically do so. So perhaps it's understandable that the Tamarians fail to account for cultural differences despite their apparently considerable scientific advancement.

I'm fairly certain that the Tamarians are just what happens after 3 centuries of lolcats and internet memes. People don't remember how to say "I'm disappointed" and just say "McKayla after the vault". Picard his face in his hand. Fry, his brow furrowed. Could we ever end up like this? Only ceiling cat knows....

Interesting suggestion, Robert. It would be kind of cool if the standard response to faux-macho behavior became, "Degrasse Tyson, his arms raised!"

The conceit with this race is the same as with Vulcans, Romulans and Mentakans being "related" yet evolving on different worlds before the advent of space travel, or probe from The Inner Light being built by a pre-warp civilisation--it's not meant to be an extrapolation of a plausible race, but a means to an end for us the viewers. The Tamarians represent an important if overlooked truth about ourselves: the power of our own metaphorical mythology (including Star Trek itself).

@Squirrel - :) @Elliott - Of course, but what kind of Star Trek fans would we be if we couldn't fanwank an explanation for how they got that way!!

@Robert: I see your point of course, but I've always viewed Trek as mythology. I don't try to explain every thunderbolt hurled by Zeus or how mermaids reproduce either. What matters to me is why the Tamarians got to be this way, not how. Maybe that's just me.

@Elliott - I do get your point but I think there's more meat in imagining how a civilization created a language based on metaphors than how the Q can teleport by snapping his fingers. Obviously the alien races are supposed to be us painted through a fun house mirror, but it's still fun to imagine how the Tamarians got to be that way.

They fixed the Phaser FX mistake in the Blu-Ray Remastered edition. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=awhS30Ln7Gw

Note this is the first appearance of Robin Lefler (played by Ashley Judd), helping Geordi try to break through the ionospheric scattering field to try and beam up Picard. She'd later play opposite Wesley in The Game.

@Robert. I would really like an article now extrapolating memes as a fully functional language like these Tamarian guys. I've never seen this episode.

@Matrix - h t t p://www.lbgale.com/2012/07/29/the-tamarian-takeover-memes-and-language/#.VFEHRldsL4c Wish granted. Now as payment, go watch the episode.

@Robert Cheers for that! I have read it and will probablybe thinking about this for a long time now and it seems a lot of other people will too. There's a passage on a reddit page linked there that I love: PICARD: "I don't understand you! Return me to my ship!" DARMOK: "Not sure if serious." PICARD: "Wait. Are you saying that this is a complex bonding ritual in which we strand ourselves on a planet with a partially invisible monster?" DARMOK: "Shut up and take my money!" PICARD: "We shall be fast friends until the end of the episode." DARMOK: "HA! HA! I'm using Forbes' insoluble dry plates!" at the very least it makes you think and for that reason alone it's a valuable episode. i will be checking it out very soon.

I appreciate your take on this episode, Jammer, but think it's a bit misguided. This story is what Trek is all about, an alien race with whom we've struggled to make a connection, any connection for that matter. All of the crew, not just Picard, trying to figure out the problem. A courageous sacrifice by the Tamarian captain all in the name of trying to understand one another... Not sure why you feel the pace is too slow, as I thought those slower parts were necessary to get us to the payoff at the end... The "fans" rate this in the top 5 consistently for good reason, and I would easily rate this as a 4-star episode. It's great stuff that you can't find anywhere else on television.

I liked this episode on the whole... It was a nice tale. It is one of those episodes where you have to throw science and logic out the window, though (as with much of Trek and its "science"), but if you can ignore that (and with this episode I could), then you will find it enjoyable. It's these kind of episodes that I like, but at the same time cause me to see Trek as entertainment and sci-fantasy, rather than sci-fi. Too many conflicts to be taken seriously, but some very fun episodes nonetheless.

Scott from Detroit

I'd give this episode 1.5 to 2 out of 4. It has several fatal flaws. - Pacing: This would be a much better plot if the show was only 30 minutes long - Believably: So this alien race is advanced enough to build ships, transporters, and everything else that they'd have leading up to space travel, but they only have a couple handful of phrases they can say that are metaphors for large ideas? I simply don't believe that this race has made it to space. - Repeated phrases: They simply just say the same jibberish too much in the episode, to the point that it becomes annoying. Nonetheless, this is still an episode that I cherish, because it is a very unique TNG episode.

I had no idea who the actor who played the captain was until I rewatched this last night and checked imdb. Talk about escaping into your role! I literally had no idea it was THAT guy playing the alien captain. Talk about acting range!!!! I do enjoy the episode a lot, although the premise of the Tamar language is really really distracting. For the umpteenth time watching this, I wondered how it could be possible for the Tamarians to speak in metaphor, yet still have myths that were told in a straight-forward manner. (Data and Troi had no problem reading the historical legends of the Tamarians). Shouldn't all their myths be written the same way they speak? And furthermore, even if they use metaphor, they still construct the phrases in those metaphors with nouns and verbs. But yeah, if you ignore the linguistic rabbit hole, there's a lot here to be enjoyed. Picard and the alien captain bonding is a masterclass in understated portrayal. Data and Troi using logic and reason to investigate the issue is nice to see. Really, the only negative to this episode (other than the language) is the boring musical underscore. So underwhelming it almost detracts from what is onscreen. *** three stars

As a writer and a lifelong fan of mythology, this episode really appealed to me. I'd give it 4 stars. Good acting, a tense and well-paced plot, and even a brief appearance by Ashley Judd as a crew member. The linguistic concept of a language based so heavily on imagery, metaphor and shared myths was sort of intellectual candy. The fact that some Star Trek episodes are thought-provoking is one of the main reasons it's such a great show. My only quibbles were that it struck me as unlikely that a species whose language was structured that way would ever become so technologically advanced as to achieve interstellar travel. At least in our world, engineers tend to be extremely literal minded, and perhaps there's a reason for that. I also failed to see why Picard could not initially communicate more through gestures, body language and facial expressions. That would not work with a non-humanoid, but the Tamarians seemed to be sufficiently similar to humans for some non-verbal communication to be possible.

OmicronThetaDeltaPhi

@Elliott I agree that Star Trek is a mythology, but curiosity and logic and the-quest-for-explanations are core values of this mythology. So in my opinion, the view of "don't bother to explain away inconsistencies, because Trek is just a myth" doesn't jive too well with the spirit of Star Trek Mythos.

I'm in the "overrated" camp on this one. The linguistic barrier seems cool at first, but if you think about it, it really makes no sense. I mean, after all, how do these people even know their own myths if they don't have the words to tell them? Presumably these stories involve descriptions, scenarios, dialogue; so why can't they use those words in the same way? They're using words normally to paint these images: "his arms wide," for instance. Why can they only use those words to recite images from stories? It just makes no sense. I mean, how do these people actually communicate in detail? They're flying spaceships, for Pete's sake. How do you build a spaceship communicating only in mythic imagery? How do you order a pizza? Say one of these guys' air conditioner breaks at home. How do they schedule a repair? Call the guy, then what? "Darmok, his air conditioner broken." "Timpek, his schedule full until Tuesday at eleven-thirty." Makes no sense. The whole idea is a house of cards. I can't even watch this episode because this is all I can think about the whole time and I just feel like it's too silly to even try to care about it. Not to mention the very idea that these people make first contact by kidnapping Picard and yelling stuff at him while an invisible space monster tries to kill them. Seriously, WTF is this?

Turin at Nargothrond. Luthien in the forest. The river Sirion, Ulmo not hearing. Beleg, his bow taut. Turambar, his face aghast. Maeglin in Gondolin. Thingol, his caverns rich. Maedhros upon Thangorodrim. Does anybody have the vaguest idea what I'm talking about? Unless you're a fan of J.R.R. Tolkien and have a fairly good memory for his book "The Silmarillion," I doubt you do. Every single one of those statements I just made is a reference to the stories in that book. Now imagine, if you will, that a whole civilization had based its entire language around that. Sound absurd? That's because it is. And that's the problem with "Darmok." How in the world can anybody take the Tamarian language even remotely seriously? How can these people communicate with themselves, let alone an alien species? The fact that it is all based on metaphor and citation of example makes it virtually unworkable as a functioning language. It would necessitate that every single Tamarian be 100% instantly familiar with the entirety of Tamarian mythology. With my Tolkien idea, that would require everyone to be intimately familiar with "The Silmarillion." See the problem? That isn't going to (I would argue it can't) happen. And that's just one book of pseudo-mythology written within the last century. Now imagine every human being having perfect memory recall of every single myth humanity has had throughout recorded history. Again, see the problem? The base assumption this episode asks the viewers to make is absurd on its face. And that's sad because "Darmok" does have a lot of good points. Picard's willingness to dig in an find a common ground between him and Captain Dathon, a rather nice tech plot on-board the Enterprise, the use of diplomacy to solve the crisis and the final scene of Picard reading the Homeric Hymns (I like that the episode takes the time to encourage viewers to read actual mythology). If they had done something similar to the DS9 episode "Sanctuary" where the problem was that the alien language's syntax and grammar structure were simply so different from anything on file, I wouldn't have a single problem with the episode. So, as it sits, count me in the "like but not love" camp. 8/10

Luke, I agree 100%. Without an underlying language for sharing the metaphors the metaphors would be totally meaningless to eveyone with the exception of those who witnessed the actual events the metaphors were based upon. This was one of the most absurd and illogical ideas in Trek history, even sillier than Paris and Janeway evolving into lizards and mating.

Luke, First, I just wanted to say I've enjoyed reading your reviews of TNG, even though I have close to the opposite opinion of yours of what makes Trek special. Anyways, I think you're a bit harsh on the premise of this episode. You claim the idea would require the entire Tamarian race to be familiar with precisely the same stories. But perhaps other Tamarians exist who are not familiar with these stories. They just couldn't communicate as easily with the Tamarians we meet. But even though Picard has no idea about the specific stories, once he understands the concept, he is able to communicate simply enough. Perhaps all Tamarians descended from a single community that never split off in ways similar to humanity. Perhaps their 'scientific' communication (to build a ship, etc) is handled purely symbolically/mathematically. We even see a hint of this when Picard looks at Dathon's record book. None of this makes real sense when you probe for the details. But in my opinion, that's true of the vast majority of Trek. At the very least, the idea of the Universal Translator itself is far more difficult to swallow to me. But we allow it because it allows compelling stories to be told. Same with the political and military structure/scale of basically any of the 'majors' (Federation, Klingons, Romulans, etc). In general, I think good fantasy/scifi fiction needs a premise. I think most fans of these genres have to be lenient on the premise. Then good stories feel as though they flow naturally/logically from said premise. I think this episode takes an admittedly absurd premise and runs with it in the best possible way. Even in the small details that remain unexplained, like Dathon's nighttime ritual. All that said, I suppose 8/10 is a fair score to someone who values the 'world-building' of vast political/cultural landscapes over the concept of seeking out and trying to understand the unknown.

At the risk of getting flagged for preaching or whatever nonsensical insult one wants to hurl, I believe that faulting this episode based on the plausibility or workability of the Tamarian "language" is missing entirely the point of the episode. When Data and Troi are searching through the databanks to try and figure it out, do they at any point discuss grammar, semantics or etymology? No, they discuss history and mythology. The Tamarian language does not make sense in a *literal* sense, but in a metaphorical sense, just like our own mythologies don't make literal sense, but metaphorical sense. The Tamarian language and culture are themselves metaphors for our own connection to the primitive sources of our own culture. The language is not meant to be plausible, it's meant to be representative; to cause us to reflect on our cultural history and value of stories like "Gilgamesh." That said, if you absolutely must find the apologist's answer to the Tamarian dilemma, don't forget that they have a written language as well. Their written language may be able to convey non-metaphorical ideas like mathematics. They did after all make contact with the Federation by sending out mathematical sequences. If you need a little bit of filling in the blanks to get at the heart of this episode, then fine, they aren't difficult to concoct, but I would beg you not to allow those blanks to obfuscate the incredible depth and power of this episode.

"Without an underlying language for sharing the metaphors the metaphors would be totally meaningless to eveyone with the exception of those who witnessed the actual events the metaphors were based upon." Why do you assume there is no underlying language? I'm assuming the universal translator is translating the language. Furthermore, at the end they create a new phrase. Picard and Dathon at El-Adrel. Mirab, with sails unfurled. They clearly have words equivalent to "and" and "to". I think the real point is that they don't THINK like this anymore. The truth is that we speak in metaphors all the time, they just do so more. In Japanese the word for tornado basically translates into "rolling dragon". In English we use Nazi to indicate extreme oppression. We may not be so "flowery" about it... but is feminazi as an insult so different from invoking a short phrase about "Hitler, his wrath absolute"? And Luke, you invoke Tolkien but why should you do that? There may be a great overlap between Tolkien readers and Star Trek fans (at least greater than the average population most likely) but why can there be nothing shared culturally? Memes for instance. Would most of you understand what I meant if I said of your argument that this cannot be "McKayla at the medal ceremony"? Now what if everyone spoke that way? I don't personally think that way, so I have issues with the nuance... but as Elliott said, they have math. I go into a store and pick up a widget. Me : "Spock, his eyebrow raised" Shopkeeper : "Baby, his fist pumped" Me : "Bob Barker waiting in anticipation" Shopkeeper : 35 Darmoks Me : "Fry, his eyes narrowed" Shopkeeper : 30 Darmoks Me : 20 Shopkeeper : "Picard, his arm held outward"! Me : ::Shrugging:: 25? Shopkeeper : 28 Me : "Picard, his face in his hand"! Shopkeeper : 26? Me : "Happy Cat is happy" ::hands over cash:: How many of you understood 90% of that?

Just to say one more thing... I think the charm of the episode was to explore a situation where the universal translator fails NOT because it doesn't understand the aliens (which is a stupid cop out) but because it DOES understand the aliens and they think so differently than we do that we can't figure each other out.