The Ultimate Guide To Driving The Pan-American Highway

The scenic Pan-American Highway is the longest road in the world stretching around 15,000 miles from Alaska in North America all the way down to Argentina in South America.

When we finally ditched our comfortable lives in LA and set out on a journey of a lifetime to travel across the Pan-American Highway for 15 months, we had no idea what to expect.

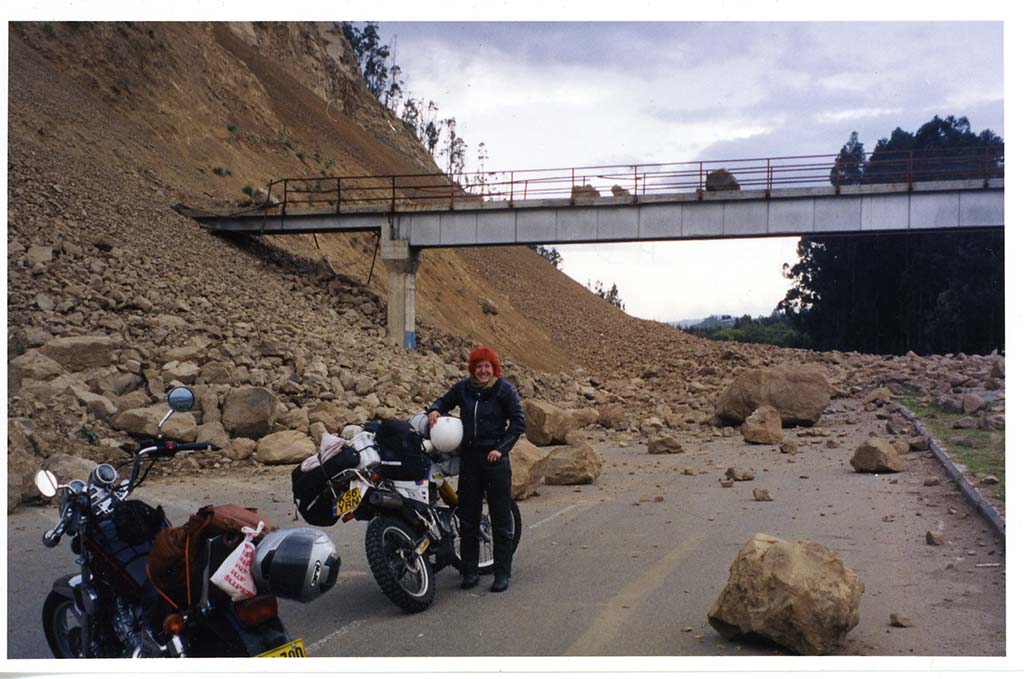

We learned so much along the way about things that can help make this trip easy ( and things that can go horribly wrong ).

Our Pan American Highway guide is here to help you plan an epic road trip and answer any questions you may have – from our personal experience!

If you are thinking about driving the famous Pan-American Highway, here are some tips and things that you should know before heading out on the Pan-American road trip:

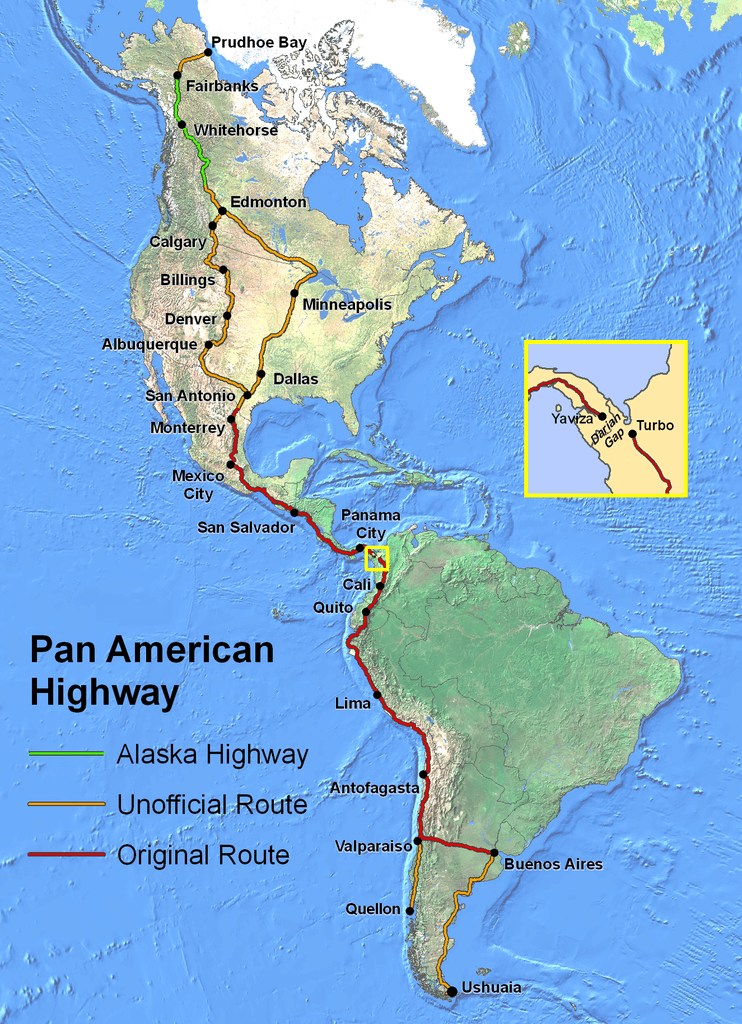

Pan-American Route & Map

How long does it take, how much does it cost, crossing the darien gap, best vehicle for pan-american, do you need a 4×4, highlights of the trip, pan-american dangers, what to bring, car insurance, currency & credit cards, must-have phone apps, cell service, traveling with pets, other pan american highway tips.

The Pan-American route is a network of roads that start in Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, and from there travel south through both North America and South America until its ending point in Ushuaia, Argentina. It’s known as the longest road in the world because it connects two continents north to south.

The Pan-American Highway is approximately 15,000 miles long and passes through 14 countries along the way.

In North America, the Pan-American Highway passes through : the US , Canada , Mexico , Guatemala , El Salvador , Honduras , Nicaragua , Costa Rica , and Panama .

In South America, the Pan-American Highway passes through: Colombia , Ecuador , Peru , Chile, and Argentina .

Although the actual Pan-American route mapped out is around 15,000 miles long, nobody does the exact route without venturing into many detours and side roads. On average, most people end up driving around 30,000 miles during their Pan-American road trip.

In fact, during our trip across the Americas, we spent very little time driving the actual Pan-American Highway because most of the time we were crisscrossing into various attractions along the way. Some of those side destinations often include Belize in Central America and Bolivia in South America.

While some people try to start off their Pan-American road trip in Alaska, it’s so remote and far out of the way that most people start their trip in Canada or the US .

When we set out to venture down the Pan-American highway, we started off in California. We had already spent considerable time exploring Canada and US and we wanted to venture into some new countries starting with Mexico.

A trip across the Pan-American highway can really take as long as you have time ( or money ) for it. Most people that we met traveling along the Pan-American highway do it anywhere from 9 months to 2 years. We ended up spending 15 months on the road traveling from California to Southern Argentina.

If you are short on time , it’s best to plan the route ahead of time and focus on seeing the main highlights. On the other hand, if you have all the time in the world, you’ll probably find yourself venturing into lesser-known areas and going more “off the beaten path”.

We tried to take it slow and see everything under the sun during the first 9 months of our trip but traveling in this style started wearing on us after a while . We felt like we spent more time “living” in these countries and trying to stretch every last penny than seeing all of the best highlights and enjoying the destinations like we would have if we were on a vacation.

When we got to South America, we switched up our approach and only traveled to the main highlights. It worked better for us since we spent less time exhausting ourselves driving to random little towns and we spent more time exploring the top locations.

Again, this just depends on your travel style . We just wanted to see all the top highlights and sooner than later return back home to our old lives in the US.

The cost of driving the Pan-American Highway is highly dependent on your comfort level while traveling. While we try to travel pretty cheaply, we always leave a little room and budget to splurge on things that we love ( like cheese and wine ).

On average, we spent around $2200 in travel expenses per month between the both of us. The biggest expense for us is typically food followed closely by gas.

We cook most of the meals in our campervan and seldom splurge on restaurants but we also don’t eat ramen noodles like college kids. Eating healthy and yummy food to us is a priority but that often comes with a steep price.

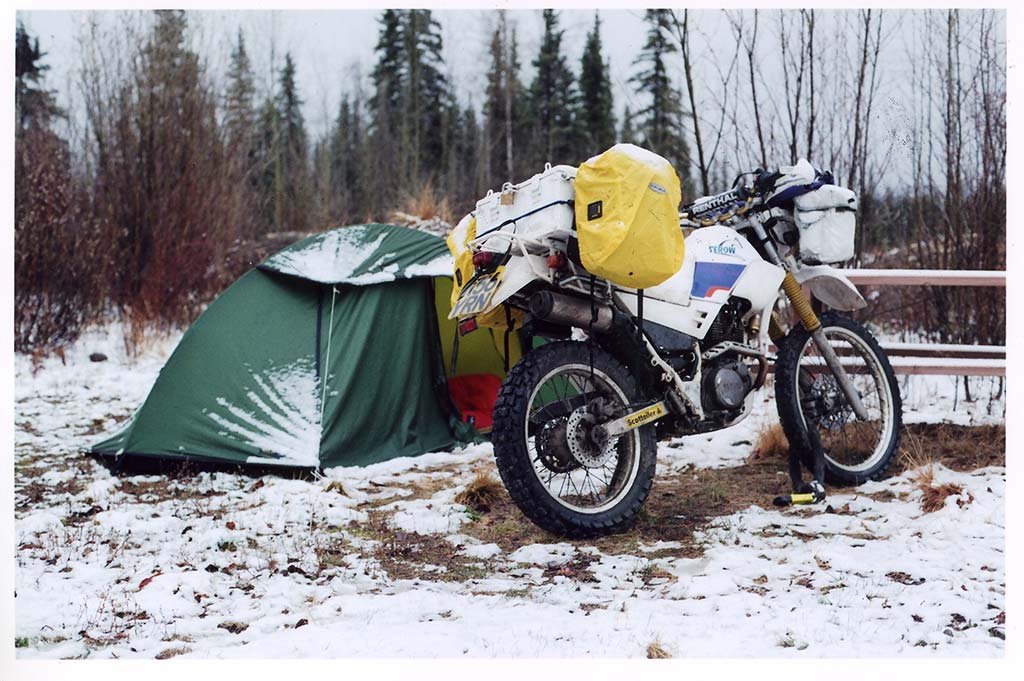

Since we travel in a van we rarely pay for campsites or hotels , only on special occasions when we feel like taking a break from van life or when our families come to visit.

The biggest one-off expense of the Pan-American highway for us was shipping our van across the Darien Gap which cost us $1100.

The most expensive single activity of this entire trip was visiting Machu Picchu in Peru. The cost to visit the Machu Picchu ruins is around $250 per person covering a train ticket, a bus ticket, and an entry ticket to get into the ruins. The good news is that we found a cheap workaround from a back entrance that can save you a lot of money. To read more on that check out our Machu Picchu Travel Guide here .

Read Next: VAN LIFE – How Much Does It Really Cost?

Although the Pan-American highway is known as the longest road in the world, there is a section between Panama and Colombia that is not drivable . This section is called The Darien Gap .

For environmental and political reasons, visitors are not allowed to travel into this section. The only way to get your car across the Darien Gap is on a ship. This ship typically takes a few days to get your car across from Panama into Colombia ( or vice versa ) and costs anywhere from $1000 to a few thousand depending on your car size.

There are a few ways to ship a car across the Darien Gap: RORO (roll on/roll off), container, and LOLO (lift on/lift off).

We chose to go with a container because it’s the most secure way to ship. We heard a lot of theft happens during the RORO shipping since you have to give your keys to the port staff and the cars are left unattended.

When you choose container shipping, you drive your own car into a container that gets sealed before getting loaded on a ship. You get to keep the keys and the car is completely locked up until you go to pick it up on the arriving side.

If you decide to ship in a container, first you will need to find a shipping partner to share a container with in order to split the cost in half. We used the Pan-American Travelers Association Facebook group and Container Buddies to see if anyone was shipping at the same time as us. We ended up shipping in a 40 ft High Cube container with another car and paid around $1100 each.

Once you find a shipping partner you will need to arrange a shipping agent who will coordinate everything for you . We shipped our van from Panama City to Cartagena and the two main agents for this route are Boris Jaramillo and Tea Kalalback.

We had originally contacted Tea and everything seemed ready to go when last minute she emailed us saying that we did NOT have a spot on the ship and we ended up losing the non-refundable flights that we had booked from Panama to Colombia.

We then contacted Boris with Ever Logistics and he was super helpful and got us a spot on the next outgoing boat a few days later. His contact email is [email protected].

Passengers are not allowed on this ship so you will need to arrange a flight into Colombia and a hotel while your car ships across. Once your car arrives in Cartagena, you will need to go down to the dock in Cartagena and get it out. This requires 2 days of running around Cartagena to pay various fees and get paperwork signed.

You don’t need an agent on the Colombia side, just a lot of patience while you run around the city getting paperwork done.

You May Also Like: 50 Van Life Tips For Living On The Road

During our trip along the Pan-American Highway, we met people traveling in all types of vehicles – small sedans, SUVs, motorcycles, vans, trucks with pop-up tents, huge motorhomes, bikes, Unimogs, old and new, you name it . There really is no best vehicle and it really just depends on your travel style and personal comfort level .

We had originally planned to do this trip in our Honda Element SUV. We even converted our Honda Element by adding a bed, solar shower, fan, and fridge. But after a trial month of traveling through the US and Canada, we realized that it was just too tight and crammed for us to enjoy a long-term trip.

Instead, we got a Promaster van and spent 3 months converting it into a campervan . It has made our traveling so much more comfortable and we rarely splurge on hostels or Airbnb’s, saving us a ton of money.

Having a midsize van on this trip also helps us stealth camp just about anywhere. It’s especially helpful in cities where the cops are a little stricter about camping on the streets. Most people just think we’re a working van.

Many people choose to go with smaller vehicles that may be more nimble or get better fuel mileage, but you’re likely to end up spending just as much in monthly expenses since you will need to pay for campsites, hostels, hotels, and Airbnb’s more often.

If you’re worried about having car issues and not finding parts, you might want to look for cars that are sold throughout Latin America . These would include any car or SUV sold by Kia or Hyundai, Ford Explorer, Mercedes Sprinter, Suzuki Grand Vitara, Toyota 4Runner, or Jeep Wrangler.

There are many others sold in North America that are also sold in Latin America, like Toyota Land Cruiser, Ram Promaster (Fiat Ducato/Citroen Relay/Peugeot Boxer/Renault Master), Land Rover Discovery, and Mitsubishi Montero, to name a few, but all of these are sold in North America with gasoline engines whereas in Latin America they are only sold with diesel engines. If something goes wrong and you have to find parts for the engine/tranny of these cars, you’re probably going to have to ship the parts in from another country ( speaking from our personal experience ).

If you have a right-hand drive vehicle, note that you may have some difficulty traveling through Central America, especially in Costa Rica. It is illegal to drive RHD vehicles in Costa Rica so many people end up shipping their vans from Guatemala into Colombia, skipping most of Central America for this reason.

A lot of people think that you need a 4×4 van to do this trip. Although there are roads along the Pan-American highway where having a 4×4 is helpful, it is not a necessity .

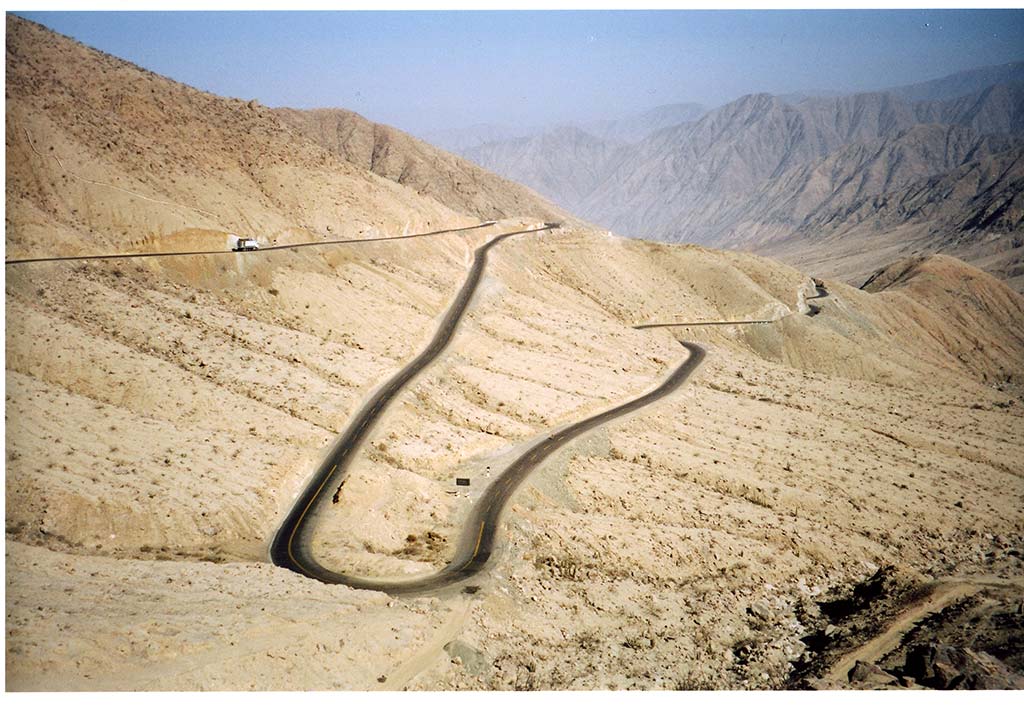

Our Promaster van is a front-wheel drive. We have driven across some of the most rugged roads in Guatemala and through the sketchiest mountain passes in Peru with no issues.

We did get stuck in a swamp once and had to get pulled out… but that was 100% our own fault .

Instead, what’s really essential in choosing the right vehicle for the Pan-American Highway is getting one that has high clearance, weighs as little as possible, has a good set of all-terrain tires, and isn’t oversized . This combination will get you to 90-95% of the places you want to go.

We’ve seen some really cool 4x4s that can’t go off the paved roads because they’re so overloaded and top-heavy. We’ve also seen many Unimogs that can’t go off the main highways because they don’t fit in any of the side roads or campgrounds, so having a 4×4 doesn’t always help.

Personally, we find it almost impossible to provide one single answer when someone asks us what our favorite country or place has been on this trip. However, there certainly are some places that stand out more than others. Here are some of our top highlights from 15 months of traveling along the Pan-American highway .

We started our trip in Mexico and our plan was to spend 2 months there, at the most. After realizing how much cool stuff there is to see and do, we threw that plan out the window and we ended up spending 5 months traveling through all of Mexico.

We swam in turquoise waterfalls in La Huasteca Potosina , snorkeled in underground cenotes in the Yucatan Peninsula , and drove through remote mountain roads to get to some unreal hillside thermal pools , all for only a few bucks each at the most. Thinking of countries that left a lasting impression on us, Mexico is definitely on top of that list.

Central America

After leaving Mexico we ventured into Belize which offers some of the best snorkeling in the world. Although Belize technically is not part of the Pan-American Highway, we just had to visit it.

Our main mission in Belize was to find the top snorkeling sites. While Caye Caulker is the “go to” fun party island that offers tours to some really amazing snorkeling sites ( and unlimited rum after ), our personal favorite was Silk Caye, a tiny island off the southern coast in Belize. Here we swam with sharks, eagle rays, octopus, and other incredible sea creatures for half the price and half the crowds.

We continued along into Guatemala , one of Joel’s favorite locations. Guatemala is one of the least developed countries in Central America which means rugged jungle adventures, erupting volcanoes, and remote pyramids along with some of the friendliest people we’ve met on this journey. Guatemala is also known for beautiful markets filled with colorful textiles. We have 5 blankets to prove it.

Another one of our favorites was Costa Rica . Costa Rica is known for its beaches, surfing and some unreal wildlife that looks like a scene from The Jungle Book come alive. While we certainly enjoyed searching for waterfalls in the jungle, our favorite part was seeing all the monkeys, sloths, and macaw birds along the trails.

Overall we loved Central America , but at the same time, the heat and humidity were making sleeping and cooking in our van almost impossible. In our opinion, this is a region that’s best explored in short traditional vacations while going on adventures during the day and recharging at a hotel pool or room at night.

South America

After crossing into South America, we didn’t really know what to expect of Colombia (it probably didn’t help that we just finished watching Narcos).

Colombia turned out to be one of the most diverse South American destinations with colorful colonial towns, lots of history, culture, amazing coffee, and unique adventures. After spending 2 months traveling through Colombia, here are 15 of our top Colombia destinations that we highly recommend for Overlanding .

One of my personal favorites of our time in South America was Peru ( okay, so maybe I DO have a favorite after all ). Besides visiting the world-famous Machu Picchu ruins , Peru is home to one of the tallest waterfalls in the world, incredible mountain hikes, and a cool oasis city Huacachina hidden between giant sand dunes in the Peruvian desert.

Last ( but not least ) there is the Carretera Austral Highway in Chile , the southern region of the continent. Known for turquoise blue lakes, unique caves, and endless glaciers I couldn’t think of a better way to finish up a trip through the Americas .

We could really go on forever sharing all about our favorite Pan-American destinations, but if you want to read more about our trip highlights, check out our Destinations page here .

This is one of the topics that we get asked about the most and something that our friends and family were really concerned about when we started the trip.

And I’m not gonna lie… we were pretty nervous too .

While I can’t speak for everyone because sometimes unfortunate things happen, during our 15 months of traveling the Pan-American highway we had no major issues and we felt relatively safe.

One of the worst things that happened to us was getting my backpack stolen in Colombia at a Starbucks ( from all places ) while I was working on my laptop and not paying attention.

There are some areas, however, that are known to be more prone to crime along the Pan-American highway and travelers should use more caution while driving through:

- Chiapas, Mexico . We always hear about the crime issues in Mexico due to the drug cartels, but neither we nor any of the hundreds of people we know who went through Mexico ever encountered an issue with cartel violence. Instead, it’s Chiapas, the southernmost state in Mexico, where people have the most issues. This region has long been anti-government, anti-establishment, very poor, and many of the villages thrive on violently extorting money from anybody who passes through. We were held up by angry mobs demanding money for driving on the roads and asked for a “security payment” by an armed “neighborhood watch”. Our friends had their tires slashed and chased by locals demanding money at the threat of violence, and another overlander was attacked with wooden boards with nails. And the saddest of all, two European bikers were found dead with their belongings missing while passing through this region. The cops and military don’t really go into this area so it’s sort of the Wild West down there.

- Peru Coast . We heard there are a lot of car break-ins, armed robberies, and well-organized scams along the Peruvian coast. It’s also one of the poorest areas that we saw along this trip so people are a bit more desperate. While traveling along the Peruvian coast we watched for any warnings left on the iOverlander app and we never left the van completely unattended. We personally had no issues but unfortunately, our friends were not so lucky and had a break into their van and had all of their electronics stolen.

- Costa Rica . This one was really surprising since Costa Rica is basically the 51 st state of the US these days, but Costa Rica is currently a hot spot for thieves and car break-ins. There are thousands of American tourists around every corner, and locals know that tourists carry nice, often expensive things in their cars as they move around the country. Many of the people we know had their cars broken into in Costa Rica, but they weren’t always necessarily only after nice things – our friend’s well-used swimming shorts were stolen right off his side mirror as he made dinner just a few feet away.

- Northern South America . From Colombia through the northern metros of Argentina and Chile, pickpocketing and petty theft are very common in cities. This is why you’ll see many people walking with their backpacks worn on their chest, and sitting at coffee shops with their bags held under their arms. While traveling in this area, just try not to walk on empty streets at night and never put anything into pockets that can’t be zipped or closed somehow. Since we spent very little time in the cities of South America and opted instead for the mountains and more remote areas, we mostly avoided these issues.

Most people who start the Pan-American road trip will pack their cars to the max with emergency and “just in case” items but in reality, you don’t need that much .

Personally, we don’t have a whole lot of stuff to begin with and we also like to keep our living space uncluttered. We decided to only bring the bare necessities which helped us keep the van light for better gas mileage.

Along with everyday necessities like clothing and kitchen utensils, here are some things that you should bring along on the Pan-American road trip :

- Two water tanks . We keep one water tank for filtered drinking water and one for everything else like doing dishes and brushing our teeth that we fill up at gas stations. You could use filtered water for everything but it would be quite costly.

- One spare tire . We actually didn’t even use our spare tire once during our 15 months of driving down the PanAm road so you don’t need more than one.

- Basic tools . Flat/Phillips screwdrivers , an adjustable wrench , duct tape , a flashlight , and pliers – the bare minimum in case you break down in the middle of nowhere. Otherwise, mechanics are everywhere and other overlanders usually carry a ton of tools in case you need to borrow one.

- Fire extinguisher . If you have a stove in your vehicle, you’ll be cooking in small quarters or outside and things can easily tip over and catch on fire. Our friends’ stove actually caught on fire but they were able to safely toss it out and put the fire out before it did any damage. Better to be prepared and keep a small fire extinguisher at hand reach.

- Tow strap . In case you push the limits of your car like we constantly do and need someone to pull you out. They’re super cheap and don’t take up much room.

- Headlamp . 95% of the time, we’re sleeping in places that don’t have much light. Look for one that is dimmable and preferably one that has a red light setting, which helps keep your night vision and doesn’t travel as far so you can be more incognito.

Read More: 85 Van Life Essentials That You Should Be Packing

There are a few countries along the Pan-American highway that require vehicle insurance for international drivers.

In North America, the countries requiring car insurance are: Canada, the US, Mexico, Costa Rica, and Panama .

US and Canada have reciprocal car insurance laws so if you have insurance in either country, you can use it in the other as well.

In South America, the countries requiring car insurance are: Colombia, Peru, Chile, and Argentina .

In the US, Mexico, and Chile we purchased our vehicle insurance online, but most of the time you can purchase car insurance right at the border. Peru was the only country where we had to cross the border and drive into the next town to purchase it.

Related Post: DIY Promaster Campervan Conversion Guide

Most of the small businesses in Central and South America operate on a cash basis so for this trip, it’s very important to have a good debit card that won’t charge you crazy ATM fees . We love the Schwab Debit Card because it is free, charges no overseas withdrawal fees, and refunds any ATM fees that we were charged by other banks at the end of the month.

The Schwab Debit card comes with the Schwab Bank High Yield Investor Checking Account – you can read more about it on the Schwab website.

At some ATMs we have been charged up to a $10 fee to take out the money in a single transaction. Getting this money back at the end of the month has been pretty sweet.

For this trip, you will also need a VISA credit card. Most businesses in Central & South America only accept VISA or Mastercard , but some countries like Peru only accept VISA (when they accept credit cards at all).

We really couldn’t have done this trip without our favorite phone app iOverlander . For us, this app was a total lifesaver.

The iOverlander app was created by other Pan-American overlanders as a place to note all the best campsites, attractions, gas stations, laundry spots, and other useful places while traveling. Over the years it has grown extremely popular and is based solely on reviews left by other travelers. iOverlander is our go-to source to find cheap (or free) camping spots and anything else we may need along the way.

There are also a couple of map apps that can make life on the road so much easier. Google Maps is great because the roads are pretty up-to-date, it gives you accurate driving time estimates, and you can download the map sections ahead of time to use when you’re offline. We also like using the Maps. me app which is amazing for finding hiking trails and figuring out their distance and elevation but is not so great for driving because it likes to give extremely optimistic time estimates and can sometimes lead you down dirt roads that shouldn’t even be on the map.

We also recently found out about the app WiFi Map . WiFi Map lists tons of open WiFi networks in the surrounding areas and for someone like me who works a lot online, this app is super helpful.

A few years ago I signed up for Google’s Project Fi cell phone service and it has been a total game changer for traveling. Instead of purchasing local cell phone chips in each new country, Google Fi automatically connects your cell phone to the local cell providers so you never lose reception while traveling, all at full LTE when available.

We pay around $80 per month for Google Fi service that includes “unlimited” data up to 15 GB for the two of us. The data is still unlimited after 15 GB but it’s much slower.

We use just about all of 15 GB of available data every month. But we also work online, stream shows and slightly obsess over Instagram so most people tend to use a lot less than that. It actually says on their website that less than 1% of users use all 15 GB of the available data so THAT makes me sort of question my life choices.

If you have a pet, you may be wondering if it’s possible to do this trip with your furry little friend.

During our trip along the Pan-American highway, we brought along our indoor cat Minka. We made some special arrangements for her in the van but overall we found that traveling with a pet through Central and South America is very easy .

It took her a couple of months to get used to being in new environments every day but now she absolutely loves it. As soon as we stop she hops out of the van, runs around a bit, eats some grass, and looks at the farm animals from the distance but mostly just naps. She has traveled through 15 countries in our van and every new place is like a new adventure for her.

Many of the people we’ve met during our Pan-American road trip travel with pets – mostly dogs, some cats, and even a couple of guinea pigs – and everyone manages just fine. There are some restrictions on dogs in many of the national parks of South America so it does limit you a tiny bit, but overall it’s not that difficult.

While most countries don’t really care that we have a cat at the border crossings, some countries are tougher than others. The hardest countries for crossing with pets are Belize, Panama, Colombia, and Chile, where they want some kind of paperwork to be done before entering and/or charge a fee for entering with a pet.

Before crossing any borders check iOverlander for any requirements. All of the information in iOverlander gets constantly updated by other travelers so this has been our best resource for border crossings with pets.

I also joined a Facebook group called Animal Travelers specifically created for people who travel with pets. It’s a great place to ask questions about traveling with pets, especially for flying and specific border crossings.

Read Next: 10 Tips & Tricks To Get Ready For Van Life With A Cat

Here are a few tips that we learned ( sometimes the hard way ) that can really help make life easier on this trip:

- Make copies of car registration, passports, driver’s licenses , and any other important documents before tucking them away somewhere safe. Also, make sure to scan and keep a backup online like on Google Drive.

- Apply for an extra license before leaving . This was a big one for us that we easily overlooked. After my wallet was stolen in Colombia and Joel lost his wallet in Ecuador, we were stuck without driver’s licenses which we needed to drive, pay for groceries, and cross borders. We didn’t have any extras so we ended up making laminated copies out of the scans that we had backed up. Thankfully they’ve worked so far at every border and checkpoint!

- Join the Pan-American Travelers Association Facebook Group . This is a public group with thousands of members who are traveling the Pan-American highway, have done it in the past, or plan to do it. If we have any concerns or questions that we can’t find answers to anywhere else, a lot of times we find them by searching this group or by posting a question in it.

The idea of traveling in a car through 14+ foreign countries can seem pretty intimidating ( at least it did for us ), but during our trip, we met so many amazing travelers and overlanders who helped us out with questions and tips along the way.

We hope this guide can do the same for you but if we didn’t cover something fully or if you still have any questions on traveling the Pan-American highway, don’t hesitate to ask us in the comments below!

Looking for more van life inspiration? Here are a few other helpful resources and blog posts that you may like:

- 16 Best Sprinter Conversions For Van Life

- 30 Must-Have Campervan Accessories For Van Life

- 10 Amazing Ford Transit Conversions For Inspiration

- How To Make Money While Living In A Van

- The Ultimate Solo Female Van Life Guide

This post is written by Laura Sausina. Hi, I’m the founder of the Fun Life Crisis travel blog and I’ve been traveling full-time for the past 7 years. Here I share my experiences and tips to help 100,000 people a month plan their adventures around the world! Read more about me here .

Some of the links used in this blog may be affiliate links. At no extra cost to you, I may earn a small commission when you book through these links which helps support this blog! Thank you!

Related Posts

10 Unique Places You Should Visit In Mexico

15 Best Things To See & Do In Colombia

10 Unreal Places Along Carretera Austral Highway

136 thoughts on “The Ultimate Guide To Driving The Pan-American Highway”

Very helpful, thank you. I’m a 58 year old (spiritually about 28!) Brit going to do the journey. No mention of buying US 3rd party insurance here though, any ideas? Thanks Andy

Personally, we have not used travel insurance and have gotten pretty lucky with never having any issues on our travels so far. But it is something that I am looking info for future travels and I have heard that the World Nomad insurance is a pretty popular choice. Here is a link to their UK website: https://www.worldnomads.co.uk/

Cheers, Laura & Joel

3rd party insurance is compulsory in US and most South American countries, I believe, isn’t it ?

Hey Andy, sorry I misread your comment. I thought you were asking about travel health insurance.

In US it’s easy to get car insurance as long as the car is registered in the US. There are tons of companies offering car insurance online such as Geiko, AAA, Progressive, State Farm, All State, Liberty Mutual etc.

In North America, the countries requiring car insurance are: Canada, US, Mexico, Costa Rica, and Panama. In South America, the countries requiring car insurance are: Colombia, Peru, Chile, and Argentina.

In the US, Mexico, and Chile we purchased our vehicle insurance online, but most of the time you can purchase the car insurance right at the border. Peru was the only country where we had to cross the border and drive into the next town to purchase it.

Hope this helps clarify things.

Hello! First of all, thanks a lot for this great info! It’s truly appreciated and useful. I’m a 30-year-old Argentine national but have lived in Florida for 19 years. I’m planning to tackle this road next year. I have the following questions, any info would be greatly appreciated!

1. Do you think is doable in 3-4 months starting from Florida? I have time constraints due to work/studies.

2. How much did it cost to ship the car from Ushuaia back home? (or perhaps from Buenos Aires or Valparaiso?)

3. Approximately how much did you spend in gas? food? paperwork/documentation?

4. How was your experience during border crossings? Was it expensive?

Thanks a lot in advance! I truly appreciate it.

1. I really don’t think you can do it in that short of time. In 3-4 months you could do the US through Panama, or part of South America, but I don’t think shipping the car to South America and back would be worth the hassle for that short of a trip. There are many overlanders selling their cars in South America for cheap after they finish their trip, maybe buying one of those and doing a few months in SA would be a good idea. 2. It all depends on the size, but from Valparaiso or BA/Montevideo to the US/Mexico, you’re looking at $2k-5k and takes a few weeks to coordinate. There are no shipping options south of that. 3. Our costs were about $1200 (Mexico) to $2500 (South America) per month for two people. This is highly dependent on where you stay, what you eat, and your fuel efficiency. We very rarely paid for places to sleep, cooked 95% of our own meals, and drove a van that got 16 mpg on average. 4. Border crossings are all over the place but usually not bad. Nicaragua was the worst by far because they were so slow, unorganized, and inspected everything, but the other ones were quick and we rarely got inspected or questioned. Usually, borders take 1-2 hours but some were as quick as 20 minutes. Having pets is probably the biggest hurdle because sometimes they want extra paperwork. Entering Mexico is the most expensive at around $100, the rest are usually free or a couple of dollars.

Hope that helps!

Nicolas have you considered shipping to Ushuania and driving back? I am from the UK and looking at riding a vespa scooter the whole route from south to north in early 2022.

There is no place to ship a vehicle south of Santiago, Chile or Buenos Aires, Argentina

Hi! Is shipping your van back to the states from Argentina best or is it easy to sell your van at the end of the trip? Thanks!!

It really depends on the vehicle, timing, and a bit of luck. For us, we tried to sell the van at a huge discount down in Argentina but couldn’t find the right buyer since it’s all about timing. I’ve heard of some people that sell their vehicles for next to nothing to avoid the shipping costs, and have known some people that paid a huge premium to get an expedition ready vehicle that was at the right place at the right time. In general, I noticed that vans were in high demand but only on the very low end of pricing, like under $5k.

Thanks for your response! Thought – what if we started in Patagonia/Argentina and tried to find a van down there to drive back north? Might be luck/timing but maybe could find someone selling in advance…? Not sure how popular the van life culture is down there / enough supply and demand. Mil gracias!

It’s pretty rare for people to sell their vehicles in Patagonia since it’s so far south and there’s so little transportation from down there. Most people sell around Santiago, Chile or Buenos Aires, Argentina since that’s where most international flights land and leave from. Buying a local vehicle with Chile or Argentina plates is super expensive because of their crazy import tax laws, so the best bet is to find another overlander who’s done with their trip.

This is what Ewan McGregor and Charlie Boorman did for Long Way Up. You should be able to ship a scooter or motorcycle (motorbike) in the cargo hold of an airplane.

Awee , I lived in Florida , was going through the whole process of traveling on the pan America highway , We shipped our Toyota truck in our country in Guyana and we went through Guyana interior , throughout to lethem into Brazil, , into Venezuela Columbia Ecuador Peru Chile Argentina and Brazil back into my country Guyana,Took us three months of nonstop driving, except in the night, We slept in a our truck. every night it was just me and my husband, that’for me was a life time adventure I will never forgot , the sceneries was breathtaking, there is so much to see, but we had to come back because we had four kids so so a good vehicle , know language,, and I have all your documents insurance and everything passport everything in order before traveling,,you would love the trip enjoy , it cost us around 12thousand dollars , and the year 1996 , the road driving is unbelievable ?????

Found your site and have enjoyed our reading so far. We are leaving after next year for 12-15 months like you to go to South America. Our big thing is we will have our two dogs (lab & husky) and the gap is our biggest concern right now. Can we go on any boat with our van? Flying with dogs is not an option (unless emergency). It does not have to be comfortable and we would pay extra for this want but seek beta from those who potentially have made the journey. Thoughts? Thanks for sharing

The only way to ship the car is on a cargo ship but they don’t allow passengers since they’re only for cargo. To get across the Darien Gap, you can either fly or take a sail boat that goes through the San Blas islands. We’ve heard numerous people go on those sail boats with animals, you just have to find the right captain that allows pets. What most people with pets do is get an ESA letter and fly with your pets onboard instead of in a kennel in the storage area. That’s what we did and it was really easy, you just need any ESA letter, a vet letter, and a pet document from Panama – the details of how to get that document is on iOverlander.

great article. I plan to make the drive from Costa Rica to the states. I have a vw wagon which I converted into a camper…I am not into outdoor life, however, I would like to do some sightseeing and take my time…I am retired and time is on my side. I was wondering if I can sleep in my wagon and relax….

That sounds like a very relaxing trip! We spent quite a bit of time in Central America and there is just so much to see and do. Hope you have a great time on your trip!

Is it possible to drive around Chiapas

Yes, you can stick to the northern coast of Mexico as you enter the Yucatan peninsula and enter Belize on your way south, skipping Chiapas altogether.

Always dreamed of driving through the Pan American Highway (Mexico to Argentina and then circle back from Brazil to French Guiana (Circle around the entire continent of South America). I now live in Europe, so I’m not sure when I’d be able to do it. Though I’ve already been to Peru, many other countries all over Latin America have intrigued me (Costa Rica, Panama, Belize, Colombia, Ecuador, Uruguay, Chile, Argentina, Brazil). Hopefully, I’ll be able to fulfill the dream soon, but I prefer to see countries by seeing them one at a time.

hi, am looking to start this journey soon…will be travelling south to north (peru to canada/alaska) any links for insurance please?

Insurance is usually bought on-site at or near the borders at every border you’ll be crossing. The only exception is Mexico through Canada where it’s done online. For Mexico, try Baja Bound insurance. I don’t know about US & CA insurance since we’re from the US and never had to deal with that part

What kind of insurance is he talking about? Car insurance? Health insurance? I never considered insurance…

Car insurance is mandatory in many countries, most can be bought at the borders but some you need to buy online. In some countries they won’t give you a car permit at the border without it, and in some they set up police checkpoints where they check your insurance. It sounds more complicated than it is, you figure it out pretty quickly once you hit the road get a few border crossings under your belt.

Your blog is great! My boyfriend and I are saving to drive from Canada to Argentina, your posts are so helpful! Thanks

Hi Marsha Do share your experience; I am in Toronto and planning to do an Arctic to Argentina trip myself. Thanks,,, Max

Thank you so much for the information. We are saving money for this trip and we want to go when we have enough money. But because of the wet season we don’t know when it is the best time to go. How did you plan that part?

We just went whenever our van was ready. Mexico is nice in October-March, central is good in December-July, the northern part of SA is good in May-September, and the southern part of SA is good in November-March. So it depends on how long you want to go but if you want to do it in about 15 months you could start in Mexico in the fall and hit every place in their ideal time. As for the rainy season, we kept hearing about the rain in Central America but we thought it was blown way out of proportion. CA did not have a bad rainy season since it’s always hot and humid anyway. The rainy season you should really watch out for is in the northern part of SA (Colombia-Peru) where you really can’t do anything between October-April. Many roads are impassable and most hikes are closed or impossible to do.

Hi there. We have been traveling back and forth from Mexico to Canada and have made three trips. We have a 29′ RV (I want to downsize) something missing in your posts was getting an import permit for any foreign vehicles traveling into Mexico. With the RV we could get a 6 month or a 10 year permit. If you are caught without a permit they will impound your vehicle. We paid around 450 pesos for a 10 year permit. The Permits are available at most border crossings in a separate building than Customs. We are enjoying the information you have shared here. Thank you and take care.

Thank you for this bit of info but I wonder if you could clarify what a foreign vehicle really means: one registered in another country (US/CAD) I presume? Also, wouldn’t customs inform people of this import permit? From what you say, it sounds as though it’s not nearly as obvious as it should be. True?

What Peter is trying to say is that Mexico’s border is pretty relaxed and for the most part, they just let you in without really stopping you. They do this because so many people cross the border daily that they can’t stop everybody and check for vehicle permits, it’s up to the driver to stop and get the appropriate vehicle permit to drive in the country. Also, you’re allowed to drive a foreign vehicle without a permit as long as you stay within 26 km of the border. If you just cross without stopping to get the permit, then later on you’ll get to a checkpoint where they’ll ask for your vehicle permit and you’ll have to drive back to the border to get the permit. This is very different from any country south of Mexico where they don’t have these agreements in place to let people roam freely, and in those borders they make you get all the appropriate permits before crossing.

I want to travel via sub or truck from Texas to Costa Rica. Any advice is cc’d welcome and appreciated.

Do you have to go both ways, can you sell your vehicle at the south end of the trip and fly back? If people are selling their vehicle at the south end, is it possible to buy it and drive back north? thanks

Hey Cornelius,

Most people go one way and either ship or sell their vehicles at the end of the trip. We drove from the US to Chile and shipped our van back to the US when we reached the end of the Pan-American Highway.

A lot of people do end up selling their vehicles at the south end because shipping them back costs around $3000-$5000. For that you can check out the PanAmerican Travelers Association Facebook group . A lot of people post their cars for sale on there.

Cheers, Laura

I have a house in Panama and I’m planning on driving down this time what does it cost and what kind of paperwork do you need to cross ryukahr does it need to be translated in Spanish

Hey Steven,

Are you referring to the Darien Gap? It costs around $1000 to ship a van across the Darien Gap. You will need the vehicle title to arrange shipping through an agent on the Panama side.

I’ve seen a lot of mention shipping one’s vehicle FROM Darien Gap but what about in reverse? Is it the same process? And is it possible to catch a sailboat with one’s dogs (flying isn’t an option) to get back to Panama? Also, no one’s mentioned how people get around once their vehicle’s been freighted. Is it easy to rent a car for a day or so?

Yes, plenty of people do it in reverse and it’s the same process. I’ve heard of people going on sailboats with their dogs to do the Panama-Colombia crossing which would be cool since they go through the San Blas islands. We originally wanted to do this but it takes a lot of planning to coordinate the crossings just right. We did the ESA thing for our cat, nobody hassled us and pets fly free in the cabin if they’re an ESA. Cartagena is really easy to get around in a taxis, Panama is a little more difficult because things are more spread out so a rental car would help there.

How much do you have to pay at each countries border crossing to get your car across and does the paperwork needs to be translated from English to Spanish notarized

Usually, you don’t have to pay for border crossings. When you do, it’s only a couple of dollars. You can check the iOverlander app where people leave notes for each border crossing.

The paperwork can be in English, it doesn’t have to be translated into Spanish.

This is Harold and Eva 66 and 67. If we ever would travel S.America, we would like to do this with some other party with similar interests. Anyone out there ?? Greetings, Harold

Yes. We are interested Brian & Shelly [email protected]

Great post. Love the fact you stated all the important details. Thanks

Your trip struck me as “the trip of a lifetime.” Hey, I get lost in my backyard, would my car navigation work out there in the towns and main highways. You guys are fantastic inspirations. Rick

Take a look at Itchyboots’ YouTube channel. She uses a nav system everywhere (South America, Africa, the Middle East) on her motorcycle. Very inspirational!

This post is so inspiring and informative!! Thank you so much!! I’m looking forward to taking more road trips after the pandemic and would love to convert a van.

That is very good.

Thanks for your post. My wife and I are considering driving from Florida to Panama City in a 4X4 pickup with my motorcycle in the bed. Looking to be expats moving to Panama. Will we incur any problems with this? Luggage will be minimal.

In some countries you’re only allowed one vehicle per person so make sure you have the vehicles titled to both names, that way if they say anything you can just do the paperwork under the other person’s name.

Advice: If you’re traveling on a right hand drive vehicle, note that in 2018 Guatemala passed a law that made right hand drive vehicles illegal (as in Costa Rica). Should you get caught driving on the right you could get fined and your car can even be consigned by law enforcment so don’t take that chance.

I’m putting together my 1949 F1 ,with a 2003 Lincoln avaitor drivetrain, what kind of documentation is needed for the vehicle to ship to Colombia, I’m in the US right now.

You just need the car title and registration along with a driver’s license and passport. They’ll ask for Colombian car insurance but you can easily get it in Cartagena if that’s where you’re shipping to.

Hi Laura and Joel I enjoyed reading about your trans-American Highway adventure. It is so informative and current. Thank you very much. I am planning to do this big driving trip. As I am not handy with car repairs, could I ask if the car does break down esp. in SA, are there mechanics available to help with repairs? Once again, thanks Peter

There are plenty of mechanics everywhere but the big problems with breakdowns are finding parts and getting towed anywhere. Unless you drive one of the few vehicles that are sold unchanged throughout the world, you’ll likely have to ship in parts if something goes wrong. Also, our overlanding rigs are usually too big to get towed since they’re used to dealing with much smaller cars in Latin America. Lastly, if you’re in a small town or in the middle of nowhere, there’s pretty much 0% chance you’ll find either of those two things without getting to a major city first. Best thing I can say is if you’re not very familiar with your vehicle and know how to fix things, buy the newest car you can afford for the trip since that’ll give you the best chance of making it without a breakdown

I saw a reference to RHD vehicles in both the article as well as the comments. Am I missing something?

Many people drive Delicas and other cool imported 4x4s that are perfect for a trip like this and are mostly found as RHD. Many people who do the trip also come from RHD countries.

Did you carry much cash or use it in transactions. How is the gas quality?

We hid some cash in our van’s walls in case we needed it but never did. Other than that, we carried very little cash on hand and used our Schwab account to take out money from ATMs anywhere for free. We never had issues with gas quality but we have a gasoline engine, those with modern diesel engines could have issues since they don’t sell ULSD between Mexico and Chile.

2 Questions… Did your van get searched at border crossings and can you carry a weapon for protection?

Our van got searched a few times (maybe 5) but usually not very thoroughly. We did not have weapons other than knives and wouldn’t risk bringing a firearm along as it’s illegal to cross borders with them and they’re illegal in many countries.

Great story and comments! Very intrigued by the prospect of doing this trip as we’re approaching retirement and would like to do it before we’re too old. I noticed that you made no comment as to currency types used. Was the US Dollar good everywhere? Or were you making currency changes in each country you passed through. Thanks in advance for the info and safe travels in the future!

We used our credit card almost everywhere since CCs actually give you pretty good conversion rates. We just made sure to use CCs that don’t have foreign transaction fees. When we needed cash, we took out local currency from the ATMs using our Schwab account which gives us free ATM withdrawals anywhere in the world and refunds us any fees the ATM charges. We never used USD except for El Salvador, Panama, and Ecuador where the dollar is used as their national currency.

I love this! It’s a perfect starting point to plan a trip

I’m hoping to start a big South American road trip in about a year if covid has finally settled down

Any advice on buying a car when you get to SA rather than shipping one? I’m trying to decide between buying a car in the Southern US and shipping it across the Darién gap when I get there or just backpacking Mexico/Central America and then buying a car in Colombia to drive South with.

I speak Spanish reasonably well and have a few close Colombian friends in Bogota and Medellin which should help with the paper work I think.

Buying a car in South America is a great way to do it because most people finish their trip down there and don’t want to deal with the expense or hassle of shipping their vehicle back home. The problem is you have to be pretty flexible as far as timing and what kind of vehicle you buy, but if you’re flexible, you can get some great deals. For instance, we were willing to sell our van for $10k less when it was down there but we didn’t find the right buyer at the right time. There are a few facebook groups dedicated to buying/selling overland vehicles in South America, check those out as they’re the best resources. The best place to find American titled vehicles is around Santiago and Buenos Aires as most people end their trips there and there are people that will title your car in Washington without being there.

I had heard that you can’t have any liens on your vehicle before entering mexico. ie fully own it with no payments.

Is that true?

I’m not sure about Mexico, plenty of people take new cars down there and I doubt they all own their vehicles outright. I know a lot of people take their cars to Mexico with just a registration so I don’t think Mexico cares about ownership. Once you keep going south, many of the other countries ask for the title but let’s just say they don’t know what a US car title looks like or have any way of verifying whether it’s real

Hello, I am Brazilian and I am currently in the USA, I want to drive from Las Vegas to Brazil, my question is regarding the documents to cross the borders, I have a car, insurance and driver license here from the USA all in my name, but my passport is from Brazil. do you believe this is a problem?

No, won’t be a problem anywhere except for maybe in Brazil. A lot of people drive cars titled in countries other than where they’re from.

Do you have to have a drivers license in all of the countries you travel through?

For clarification, I am an US citizen. I have a Utah drivers license. Will I need to get a new license in Mexico, Peru, etc. to drive in those countries?

No, any license will work

If you’re driving then yes you’ll need a license in case you get pulled over and to get the car permit at the borders

Do you have any interest in selling your van to us for the trip?

Hey Matthew,

Yes, we are looking to sell it soon. You can email us at [email protected] to chat more.

I just wanted to thank you for sharing your grand adventure, and all the most valuable information on traveling “do’s and don’ts”.

Thank you, Mike! We’re glad that our post was helpful : )

Hi , thanks for taking all the time to share your fantastic experiences. I’m from Australia. I would start the journey in the US. can I buy a car in the US as a tourist – or do I need a residential address in my name? I encountered this in Holland : There-was-no-way I could register a car in my name unless I was properly registered in a town’s citizens register, for which I needed proof of registered house ownership or … proof of registered house rental for which the waiting lists are so long one just as well books a burial lot.

You need some kind of address to write on the registration papers and get the registration and title sent to, but don’t necessarily have to prove residency. It also depends on the state, I know many foreigners go to the state of Washington since their rules are much more relaxed whereas in Oregon they wanted me to have an Oregon driver’s license to register a car. There are people who offer a service on the panamerican travel association group on facebook where for a small fee they’ll take care of everything and you don’t even have to be there. Otherwise, you can rent a virtual mailbox in a state to use as your home address and register the vehicle there then cancel the service once you get the registration and title delivered.

I’m really interested in knowing how you handled the problem in Chiapas and the right-hand drive issue at the Costa Rica border. Thanks

Chiapas has a deep history of anti-government activities and issues, and as a result it can be kind of lawless at times. Looking back at it now, the best outcome would be to approach that area with caution, stay and park only in secure areas, and be prepared to pay the locals when they violently demand money for no reason. Travel in groups when possible and don’t let your guard down. As for Costa Rica, we don’t have right-hand drive but the common things people do to get through if you do have right-hand drive is to either 1) stop in Nicaragua and head back to ship south from Guatemala or Mexico, or 2) cross the border at night, hide the wheel with stuff, and create a dummy steering wheel on the left side, or 3) pay someone a lot of money to tow your vehicle through the entire country. In my opinion, option 1 is best because once you’ve seen the jungles of southern Mexico through Nicaragua, there’s not much else to see in Costa Rica and Panama and you’ll save yourself from the torture of the never ending heat of Central America.

Holà, looking at driving home to Canada from Costa Rica, the winds seems favourable. This plan is in its early stages so I might add that I am not rushed at all, and that I’m very much looking into networking, forums, and tips that could help over the next months. I am planning the purchase of the vehicle in Costa Rica but so far my biggest barrier in preliminary research is the Insurance situation from Mexico-North…Tips, forum links, experienced persons would be hugely appreciated. Another import question I have is: tent & bnbs, or camper? Is camping more liberating than a well planned route with safe campsites/bnbs?

(i’ve emailed you as well btw)just in case

The best forum for information and questions is the Facebook group “Panamerican Travelers Association”. Most people who are traveling the panam are part of that group so it’s a great place to get updates on traveling conditions or to just connect with others who are also on the trip. The sleeping situation is probably one of the most varied in everyone’s approach. It’s hard to reliably find places to tent camp so that would be hard to do. It’s also hard to consistently find good hotels/hostels/whatever. The more set up your are to sleep in your own vehicle comfortably with some amenities, the easier the journey without having a need to constantly plan ahead or spend half the day looking for a hotel or campsite every time you move.

Hi there, Enjoyed everything you guys posted. One thing nobody bothered to ask was since your trip was going over 12 months how did you get your renewal tags for the following year since you were out of the country? Did you have a friend with access to your mailbox which then mailed them to your current location?

Thank you for your response!

We have permanent plates from Oregon but if we didn’t then I probably would have registered the vehicle as non-operational during the entire trip. That way you don’t have to keep paying for US insurance and the DMV won’t ask for smog checks. As far as the actual paperwork and mail, we had that delivered to our parents while we were gone. And as far as tags go, nobody outside the US knows what kind of tags your plates are supposed to have so nobody will ever notice or care that your tags are expired.

Hi Joel, Thanks for responding. Is there a difference between Oregon and California (This is where my car is registered) when it comes to plate assignment? So none of the countries you guys drove in bothered you guys at all if the car was current or not on its registration? And what I mean by that when you guys crossed the border, if you were pulled over or not by the police, or especially, when you shipped you van from Panama to Colombia? Because that’s kind of risky. I know for a fact in Chile and Argentina they will expect your car to be up to date on its registration year because that comes up when you need to obtain an car insurance policy in either of those counties. If you guys made it all the way down there without a hiccup you guys were incredibly lucky. But then again you guys had backup because your tags were mailed to your parents house so in the event that something were to happen they can easily fed-ex it to you guys.

Once you venture below the US you realize that for the most part, laws are at most a guideline that very few follow. Nobody ever bothered to look closely at any documents, even Chile and Argentina. In Chile their main concern at the border is pets and food, and Argentina didn’t really care about anything including so called mandatory insurance which most overlanders buy from some guy through Whatsapp and is probably fake. The brand Ram and the vehicle Promaster don’t exist south of the US and not a single country cared, they just marked us down as a Dodge Ram pickup truck which is close enough. It’s intimidating at first when planning ahead but once you hit the road and cross a few borders it all becomes much easier.

Hi there, Three of us are thinking of taking our Sprinter Vans along the Pan-American Hwy with our motorcycles on the back to get to those out of the way places our vans won’t go. Do you know if it is impossible to ‘import’ the 2nd vehicle (motorcycle) into some countries as they only allow one vehicle per person?

Like you said, some countries only allow one vehicle per person so it would probably be doable if there were two people per van and each person had their name on at least one of the titles. The other thing would be that you’ll have to do all the paperwork twice, get double the insurances, and in some countries pay fees for each (although it’s never much). What I would probably do is take something that doesn’t fit their bill of what a “vehicle” is and it wouldn’t trigger a need for an import permit. I’m thinking moped, electric bike, pocket bike, maybe even a Honda Ruckus with the plates removed… anything that doesn’t fit their idea of what a motorcycle should look like.

Hi there. Thanks for the info. I am wondering if there are people who want to make the trip south but don’t really want to turn around and do the trip north. Is there any group…. where I might be able to find a vehicle that wants to come back north?

I’ve never heard of anyone that has done the trip both ways. Most people start at the north, head south to the end, then travel back up to Buenos Aires or Santiago and ship their car back home from there. Europeans do it in reverse order quite often, shipping to Buenos Aires, heading south, then north to Canada before shipping back to Europe. Many people decide to sell their vehicles after doing the trip one way and is a great way to get into a vehicle that’s been prepared for overlanding but are typically in immediate need of maintenance.

Don’t you need a permit to take your car into each country? For example, I know when driving to Mexico you pay a fee and then it’s refunded (partially refunded) once you return. Any insight on this? I don’t plan on returning to the US though; I’m moving to Ecaudor.

Yes, you get a permit in each country as you enter, usually called a TIP. Mexico is the only one that actually charges you, the rest are free except for some spare change to make photocopies of documents. When you leave each country, the TIP is cancelled.

How did you get the van back from Argentina!!

We shipped our van from Buenos Aires to Houston via RORO ship (roll-on, roll-off)

can make this trip with a motorhome? (Buss). because of the roads

Absolutely, lots of people do the trip in Class A RVs, converted school busses, and Unimogs. The bigger the vehicle the more restricted you are in cities and remote locations but your comfort level increases drastically. We found that a van was probably the sweet spot between between comfort and access, with anything too much bigger or smaller requiring a lot more planning ahead for sleeping arrangements or road access.

me and my girlfriend were looking to drive the South America portion of the trip with our two cats. What did you guys do with your cat if you wanted to go off for the day exploring? Did you do any hiking in Patagonia?

we’re trying to be as realistic as possible.

The cat was perfectly fine throughout the trip, in fact she actually liked it more than being at a home. At home she just hides all the time, during the trip we was always trying to explore outside the van every time we stopped and wasn’t scared at all. We always made sure we left the exhaust fan on and a window cracked if we left her. We did a lot of hiking in Patagonia and would leave her in the van with extra food and water, she was always fine. Central America was actually the toughest region for her (and us) because it’s so hot and wet so there’s little you can do to cool the car down. All of South America, outside of the northern coast, had pretty cool weather so it was easy to leave her in the car.

Hey Joel, Laura Thank you for this blog! It is very well written and touches all the necessary aspects of Pan American travel. I am thinking of making this trip from Canada to Argentina solo in a 2-DR Jeep Wrangler. Good idea? Bad Idea? How long will it take (3-6 months?) and how much will it cost in total (USD 20,000?) I was wondering if I can may be get in touch with you at a regular basis for some guidance? Max

You can do it in any vehicle including the 2-door Jeep Wrangler but it’ll be a little harder with that car because you can’t sleep in it. It’s a decent choice, it’ll just take a little more planning because every day you’ll have to plan on where you’ll pitch a tent or rent a room to sleep in. If you can afford a roof top tent and have a way of putting it on, that would be a pretty ideal setup. The fastest we heard of people doing it and still having time to see things was about 8-9 months, anything less and you’re really having to skip too many things and spending most of your days driving. If you get a roof top tent, you should be able to do it quickly and cheaply since you can go faster without spending too much time trying to find the right sleeping place and you’ll rarely have to pay for campgrounds so it would very quickly pay for itself. Email us anytime for more

Hi, one of my fantasies has been doing this trip from US all the way until Chile. Every once in a while I do a search on how to do so and today I found your article and got me exited about trying to make it happen. One question, and of course safety is one of my biggest fears for doing the trip, but how you handled Chiapas people trying to bribe you?

Safety’s a big concern for everybody on the trip but once you get going you learn how to stay alert and avoid bad situations, for the most part. Out of all the people we met, we rarely heard of anybody getting into big trouble other than the occasional small theft. As for Chiapas, it’s pretty well known that certain areas are unstable and should be avoided so most people take a different route to avoid that bad area. When we couldn’t avoid it, it sucked paying an angry mob demanding money but there’s little we could do so we just bargained for the three vans we were traveling with and paid.

Hi, I’m curious how you paid the angry mobs when they demanded money. You mentioned you had cash hidden in the van’s walls, but that you never needed to use it. How then did you pay the angry mobs and how much did they demand vs. how much you actually had to pay? Thanks!

They usually had roadblocks set up and you couldn’t get through unless you paid. Every roadblock was different, some wanted $5, others $20. Sometimes we passed through multiple ones on the same day. I don’t know if the situation is still the same there.

Thanks for the info. We are planning Colombia to Argentina in Jan. Just a small point – in some of these countries you legally have to carry a kit in the car, for example in Colombia you must carry a fire extinguisher that is in date, and various tools.

Did you obtain visiting visa for each country you entered prior to your trip or the visas were obtained on arrival at the borders? (Not sure, to enter some of the latin American countries you don’t visas if you have USA passport).

If you are American, you don’t need a visa to enter most countries in Central and South America. The only country that might require a visa is Brazil (or at least they used to, not sure about it now) which is why we skipped it.

I am starting our trip very soon and I live in Colombia. I am a teacher and also plan on continuing teaching on the road through online classes. How reliable is the internet signal with the Google Fi service in countries like Peru and Bolivia?

Having Google Fi service was definitely the easiest option vs buying a SIM card in every new country like many of our friends did. Internet in bigger cities is pretty decent and you can also find a lot of coffee shops and cafes that offer internet. In smaller towns, it’s a bit more challenging so it just depends where you’re planning on traveling to.

Can you bring weapons for just incase purposes?

We personally did not. Every country has different rules and your van gets searched a lot, especially at the borders, so we didn’t risk it by bringing any weapons.

Did the national parks offer cabins as well as campsites?

It depends on each country and National Park. We visited several on our trip and some offered rustic accommodations, others campsites. Which park are you interested in?

Hi guys! I’ve been reading this article over an over. I’m hoping to do it soon. So, here is my thing. I’m living in the US, and anytime soon i want to go back home in Argentina. I have a dog, and a car so I thought driving back would be a great experience. I’m just interested in going back, so if we don’t do anything just driving and sleeping (on what would cost money), and some food and water, how much would you think it gonna cost? Do you pay a fee in every border you cross or some? I have an Argentinian passport so latin america should be easy to navigate. I have a regular suv car, so not like a ban or big car, will it cost about 1000$ to ship it to colombia? (From panama) -approximately- What expenses did you face only from easy food, gas and some campsites to sleep? Thank you!

How much you spend really depends on you. Our average was $2200 per month for two people but it’s hard to say what you would spend. Some quick math: Assuming you drive straight there without too many side trips, it’s about 20,000 miles. Most SUV’s get around 15 miles per gallon, so that would be 1,333 gallons of fuel, and at $5USD per gallon, that’s $6,700USD on fuel total. You could do that trip as fast as 3 months if you didn’t stop much, so $10 a day on food/water/basic necessities would be $900USD. Add in $2000 to ship your car plus flights, plus an extra $1000 for random expenses or emergencies. Add it all together and with minimal stops, driving fairly straight, not accounting for any entertainment or restaurant meals, and assuming you sleep in your car at free spots every night (easy to do 95% of the time), you’re looking at $10,600.

Do you have route coordinates you could share or a resource to pop into mapping software like GAIAGPS?

100% awesome usual information. Gracias! I’m planning to travel in my electric vehicle. I’ve done a lot of research and have discovered that there are more chargers than people might think. But I’ll also carry a range of adapter so I can plug into anything from a regular outlet (SLOW charging) to dryer, welder, and other outlets. Let me know if you know of any resources about EV traveling on the Pan American.

Thanks for your post and the pictures look incredible. Just added this to my bucket list. I do have some questions: 1. Did you have any issues with fuel? I have had issues using mexican gas back in the ’90’s. 2. Could a car be rented at each country to avoid all wear and tear on personal vehicles? 3. Can this be extended by driving back up on the east side of south america?

1. No issues with fuel since we used a gasoline engine, modern diesel engines that use DEF need some modifications to work with the dirty diesel 2. Probably not, the borders aren’t always by big cities so not sure how you’d get into a rental after crossing and how you would turn it in before crossing unless you took a taxi from the nearest city 3. Most people stick to the west side on the way down. You have to go back north because there aren’t any ports to ship from down south, so some people go on the east side on the way up. We did this to save time but the east was very boring, just long stretches on grasslands with very little to see. The northeastern countries are a bit tough to travel though, both physically and politically, so most people stop in Buenos Aires on the East.

How was the gas situation? Were there areas were it was difficult to find fuel?

We brought a 5-gallon gas can and didn’t use it once along our entire trip. It’s good to have as an emergency but the reality is that there’s gas everywhere. I’ve heard sometimes certain places like Patagonia’s route 40 will run out of fuel but we never experienced this. It could also be that we did the trip in a vehicle that can go 350+ miles on a single tank so maybe if you were going to do it in an older vehicle that doesn’t have a good range, then maybe you’d actually put the 5-gallon jerry can to use.

Wow, alot of great information. I’m retiring and hitting the road to live the nomad life.

I have considered travel outside if the states and the Pan American by highway trip interests me. Googling the trip your site came up. I am so glad to find it. Your article lets me I’m know that its not only possible but doable.

Hi, that’s really an amazing article and your effort and time to write it and post it is much appreciated. My wife and I are planning to do half of the trip. Would love to know your thoughts bout it. Planing to ship a 4×4 or a van from Florida to Columbia Cartagena and drive all the way down to Ushuaia Argentina and then Buenos Aries and ship it back (passing by Peru Chile etc.). or we can ship it to Uruguay, then go Buenos Aries, Ushuaia, and then all the way to Columbia and then ship it back to Florida. which one would you recommend? Second, how much would you think it takes to do the trip starting from Columbia or Argentina, the Southern part only and what would be the best time to do it? Countries we are planning to visit ( Columbia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Argentina, and maybe Uruguay to Sao Paolo) Thanks again and happy new year .

Hi Sam, the order you do it in is more dependent on when you do the trip. Ideally, you’d like to time it so you end up in Patagonia in their summer (December-February) and northern South America during the dry season (May-September). North Americans tend to go Colombia>Patagonia>BA since they come from the north, whereas many Europeans go BA>Patagonia>Colombia since they ship to BA. We know people that did all of South America in 3 months and others that took a year or more, it just depends on how many stops you make and how much you want to drive each day. I would plan for at least 6 months if you have the time and no faster than 3 months if you stick to only the highlights.

Thank You Joel & Laura Is it possible to make the trip without being fluent in spanish?

Hi Michael,

While Joel does speak fluent Spanish and it did help us a lot during the trip, there are plenty of people traveling the Pan-American Highway that don’t speak Spanish. I do recommend learning a few basics so you can purchase food at markets, buy entrance tickets and arrange campsites along the way. There are a lot of great free apps like Duolingo that make learning Spanish fun and easy! Cheers, Laura

Hi there I’m looking for a partner to make this adventure trip, by Chrisler Pacifica or eventually by motorcycle, Super Tenere 1250. [email protected]

This post is so helpful! Thank you! Not sure if you are still monitoring comments – but I just wondered what month you left in? We are trying to plan when to leave for a 12-14 Month trip and will be starting in Vancouver driving straight to Mexico (so leaving out alaska part and quickly through US)

Its hard trying to work a time so that we get to avoid rainy season in Central, but still get the Salt Flats drive in Bolivia – and Patagonia in Summer!

Hey Melissa! We started our trip in Mexico in December where we spent 6 months. Then we crossed into Central America for 4 months and then spent 5 months in South America. If I remember correctly, we finished the trip in March around 15 months later.

HI! First of all thanks for publishing this article. I’m an american living in Argentina looking to make the trip between Ushuaia and Alaska through December 2024 and Febuary 2025. My friends and I will be 21 during this timeframe and are concerned with the cost of insurance due to our age. Do you have any suggestions regarding this issue? Furthermore, we will drive one way and fly back the other, where would you recommend we start? Lastly, is there any page where we could contact other Overlanders looking to sell an American vehicle in Argentina or sell an argentine vehicle in the US or Canada? Kind regards, Dante

Hi Dante, if you’re talking about car insurance, it depends on each country but overall it was really cheap. We didn’t get medical insurance but that’s a bit of a gamble and completely up to you. Most people start in Canada or US but it’s cheaper to start in South America because a lot of people make it down there and sell their overlanding vehicles cheap which are already prepared for the drive. There is a facebook group called Overlanding Buy & Sell – Americas which will be your best bet for buying something, while the group Panamerican Travelers Association is a great place to get info and connect with others doing the drive. Good luck!

Thank you for this article! I’m in a corporate job i’m sick of & would like to quit and do some traveling before my next chapter in life.

1. I’m wondering how much money did you guys have saved up before leaving on this adventure? I have about $25k USD saved right now but not sure how long I can realistically make it. I live in Colorado & think I would go up to Canada first and adventure around there to get used to life on the road and avoid some culture shock as it would just be me.

2. Did you come across very many people doing this solo?

3. Ideally it would be great to document my trip on the various social media platforms and gain a following. I followed your IG and saw you have a pretty large following. Did you guys have that before your trip?

I may have more questions but that’s all i can think of for now. Just concerned doing it solo & how much i need to be able to do this.

1. We had saved up a good amount before traveling the PanAmerican Highway. We averaged $2200 in monthly costs for two people over the course of 15 months. This came out to around $33K for the entire trip. Canada is very expensive for traveling, but Mexico and south of US is much cheaper. 2. We came across solo travelers, couples, people with kids, retired people…it’s really a mix. There are people traveling the PanAmerican solo although they do it in much shorter trips. 3. We had a social media following before the trip but my blog is where I spend my focus on. If you want to grow an IG following for income reasons, making money on the road with brands through IG is nearly impossible as there is nowhere to send products to. Many people start YouTube channels documenting their trips and growing a following on there to make money from video ads.

Hope this helps! Good luck!

Hi, I am wondering if I would need a title for my vehicle to do all the border crossings. I am financing my van so I don’t have it. Is it possible to do a trip like yours without a title?