- Documentary

- Entertainment

- Discovery x Huawei

- Building Big

- How It’s Made

- Military History

- Monarchs and Rulers

- Travel & Exploration

Ibn Battuta: Journey of a Lifetime

Ibn Battuta is arguably the world’s greatest explorer. A fourteenth century pilgrimage to Mecca ended up as a thirty-year, 120,000-kilometre wanderlust which culminated in one of the world’s great travel diaries, but could he possibly have travelled that far? Read on to discover the remarkable story of the travels of Ibn Battutah.

In an age when few dared to travel beyond known boundaries, Ibn Battuta’s journey started as a pilgrimage to Mecca. It became an astonishing three decade quest to the depths of the unknown and ended with a monumental travelogue.

Dubbed by many as the world’s greatest traveller, the travels of Ibn Battutah surpassed those of his near-contemporary Marco Polo in both distance and duration. While Polo’s travels were primarily through Asia and the court of Kublai Khan, Ibn Battuta encompassed not only Asia but also North and West Africa, Southern and Eastern Europe, the Arabian Peninsula, Central and Southeast Asia, India and China.

This distinction often draws comparisons and links between Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo, highlighting their unique contributions to the understanding of the mediaeval world. Battuta’s travels were driven by both religious devotion and an insatiable curiosity about the cultures, peoples, and governance systems he encountered.

However, Ibn Battuta’s accounts have not been without their critics. Some modern historians have raised doubts about the authenticity and accuracy of his descriptions, questioning whether he could have possibly visited all the places he claimed.

Let’s step back in time to the fourteenth century in an attempt to shed light on the remarkable footsteps of Ibn Battuta.

The Early Life of Ibn e Batuta

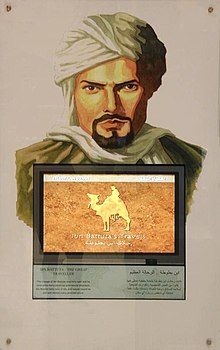

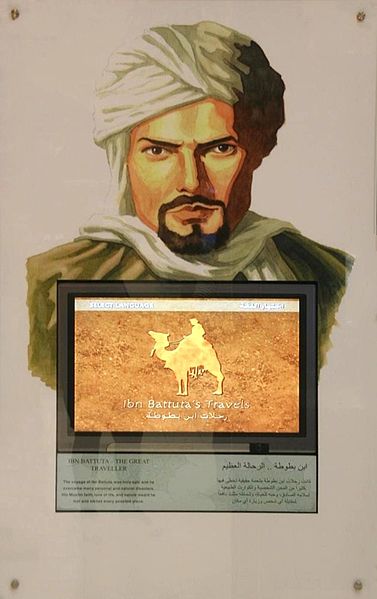

Portrait of Ibn Battuta (Credit: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Very little is known about the early life of Ibn Battuta, sometimes known as Ibn e Batuta or Ibn Battutah.

It’s believed he was born in Tangier – modern-day Morocco – in February 1304 into a Muslim Berber family of legal scholars known as qadis. It’s likely he studied at a school of Islamic jurisprudence, but in 1325 at the age of twenty-one he set out on a pilgrimage – hajj – to Mecca. It seems his original intention was to fulfil his religious duty, study under a number of eminent scholars and then return home, but it didn’t quite work out like that.

A passion for travel overtook him and he started to wander the Earth. Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo – albeit Marco Polo travelled thirty or so years before – were similar but different. Both extraordinary explorers, but the Venetian travelled for trade and education. Ibn Battuta travelled not to fulfil an obligation or mission, nor to reach a specific destination. He arguably travelled for the pure joy it gave him.

The Travels of Ibn Battutah - The First Itinerary

Ibn Battuta in Egypt. (Credit: Heritage Images / Contributor via Getty Images)

Ibn Battuta’s journey is generally broken up into three itineraries. The first, from 1325 until 1332 took him through North Africa, Iraq, Iran and elsewhere in the Arabian Peninsula, and down Africa’s east coast.

His first journey to Mecca, of which there were many, took him to Algeria and onto Tunisia. Here he got married, but soon left his new wife due to a dispute with her father. He then went to Alexandria in Egypt and then, on arriving in Cairo, he called it ‘peerless in beauty and splendour’.

Ibn Battuta then joined a caravan which took him as far as Medina. From there he completed his pilgrimage to Mecca. He was supposed to go home at this point, but decided instead to continue on. He travelled to Iraq and Iran in the summer of 1327 and sometime around September or October of that year, he went back to Mecca performing his second hajj.

It’s not clear in his chronicle but he either left Mecca in 1328, or stayed three years and left in 1330, but his next stops took him to Jeddah in Saudi Arabia. From there he took a series of boats south to Yemen and then down the eastern coast of Africa to Mogadishu in Somalia, a place he described as ‘an exceedingly large city’ known as Balad al-Barbar, or the ‘Land of the Berbers’.

From there, he went back to Mecca to perform a third hajj, either in 1330, or as the timeline suggests, most likely in 1332.

Ibn Battuta’s Journey - The Second Itinerary

The second itinerary, from 1332 until 1347 saw him travel across the Black Sea area, through Central Asia, India, Southeast Asia and China.

This period of Ibn Battuta’s journey is particularly challenging to detail accurately due to the mix of eyewitness accounts and second-hand information in his book. Some scholars suggest the confusion in the timeline could be due to the way Ibn Battuta recounted his stories to his scribe, Ibn Juzayy, years after the actual events. Despite these uncertainties, his account provides a rich and vivid picture of the mediaeval world.

After his third pilgrimage to Mecca, Ibn e Batuta travelled north to the Black Sea region, visiting Anatolia (present-day Turkey). He may have also journeyed to Crimea and the Golden Horde region along the Volga River. He returned to Mecca briefly and then set off for a long journey towards India. This journey led him across Persia (Iran) and Afghanistan. He likely travelled through cities like Shiraz, Herat, and Kabul.

Ibn Battuta arrived in India and spent an extended period in the Delhi Sultanate, under the patronage of Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq. He travelled extensively across the Indian subcontinent, visiting places like Bengal and the Malabar Coast.

It’s believed he spent as many as six years in India and, in around 1341, he was sent as an ambassador to China by the Sultan of Delhi. However, his journey was interrupted by pirates where he was almost killed. He went back to India and from there to the Maldives, where he stayed for about a year working as a judge and marrying into the royal family.

From the Maldives to Sri Lanka and from there the travels of Ibn Battutah took him to Bengal and Sumatra, eventually reaching the Chinese port of Quanzhou in the Fujian province around 1345. His descriptions of China include visits to Guangzhou, Hangzhou – which he described as one of the biggest cities he’d ever seen- and possibly even Beijing, although the exact details and sequence of these visits are uncertain.

The Return to Morocco

A tiled fountain on Mosque Hassan in Rabat, Morocco. (Credit: Richard Sharrocks via Getty Images)

Ibn Battuta’s return journey from China to Morocco, marking the final leg of his extensive travels, is a fascinating segment of his adventures, however it’s the aspect of his journey that is the most debated by academics and historians. Although the exact route and timeline are somewhat unclear due to inconsistencies in his accounts, the general outline of his journey effectively retraced his steps through Southeast Asia, back through Persia and the Middle East.

He then travelled across the North African coast and back to Morocco. At some point after his return it’s said he was sent by the Sultan of Morocco to Granada, the heartland of Muslim Spain.

Close-up of an old opened book in a historic library. (Credit: Westend61 via Getty Images)

There is one single account for the travels of Ibn Battutah, the book called A Masterpiece to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling, otherwise known as Rihla, or The Travels.

It was said he made no notes in the thirty years he was on the road and the book was dictated to a scholar he met in Granada named Ibn Juzayy. He relied on memory as well as manuscripts written by travellers who went before him. This has led scholars to have raised several specific issues regarding the authenticity of all the places Ibn Battuta claims to have visited.

Chronological and Geographical Inconsistencies

Some parts of the narrative contain chronological and geographical inconsistencies. For instance, the timeline of his travels in certain regions appears compressed or extended in a way that seems unrealistic. Additionally, the sequence of visits to some places does not align logically with the travel times and routes known from that period.

Second-Hand Information & Hearsay

There are suspicions that Ibn Battuta included accounts of places and events that he heard about from others but did not experience firsthand. This is particularly suspected in the sections about China and parts of Central Asia, where his descriptions sometimes seem more like compilations of other travellers’ tales rather than his own observations. For example, the descriptions of a number of locations in the Middle East are remarkably similar versions of accounts by Ibn Jubayr and Muhammad al-Abdari who travelled in the late thirteenth century.

Lack of Detailed Descriptions

In some instances, Ibn Battuta provides only vague or generic descriptions of certain places, lacking specific details that would indicate a personal visit. This has led some scholars to question whether he actually visited these locations. In addition, some descriptions of customs, cultures, and societal structures in various regions occasionally contain inaccuracies or exaggerations. These anomalies raise doubts about whether Ibn e Batuta fully understood or directly experienced these aspects.

Despite these issues, it’s important to note that many historians and scholars still regard Ibn Battuta’s Rihla as a valuable and accurate historical document. While there may be embellishments or occasional inaccuracies, the work provides an important perspective on the fourteenth century world, especially in relation to the Islamic societies and cultures he encountered. The Rihla remains a vitally important source for understanding the history, geography, and cultural and religious landscape of the mediaeval period.

Like his early years, very little is known of his life after the Rihla was finished around 1355. It’s believed he was made a judge in his home country of Morocco and died around 1369, aged 64 or 65.

The 75,000 Mile Man: The Travels of Ibn Battuta

Illustration of Ibn Battuta (Credit: Dorling Kindersley via Getty Images)

Ibn Battuta’s extraordinary journey encompassing vast swathes of the mediaeval world, stands as a remarkable testament to human curiosity and resilience. Despite the debates surrounding the veracity of his accounts, his narrative in the Rihla offers an invaluable window into the diverse cultures, societies, and landscapes of the fourteenth century.

His travels surpass mere physical exploration, delving into the realms of cultural exchange, religious devotion, and intellectual curiosity. The legacy of men like Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo endure through centuries and continue to inspire and educate, embodying the spirit of exploration and the timeless quest for knowledge and understanding of the world beyond one’s own horizons.

You May Also Like

The kecksburg ufo incident: a cold war mystery, the bell island boom: mystery explosion in newfoundland, carroll a. deering: lost ghost ship, awilda: tale of a pirate queen, explore more, cynocephaly: the legend of dog-headed man, understanding the roman dodecahedron: ancient artefact mystery, the legend of mokele-mbembe: africa’s hidden dinosaur, is the loch ness monster real, which nostradamus predictions came true, the story of valiant thor: visitor from venus.

Journey to Mecca: In the Footsteps of Ibn Battuta

It would take Ibn Battuta 18 months to travel the 5,000-mile route to Mecca. Battuta, who would eventually become the best-travelled person in antiquity, would not return home for 30 years. His journeys total three times those of Marco Polo. He would visit 40 countries and revisited Mecca five more times to perform the Hajj. Ibn Battuta sought out knowledge in his breathtaking journeys and eventually compiled his experiences in The Rihla , one of the most significant travel books ever written.

Ibn Battuta did not join a caravan, which was the normal way to perform pilgrimage 700 hundred years ago. At that time, there weren’t cars, airplanes, hotels, and air conditioning, luxuries afforded to today’s Hajj pilgrim. It was only you, the desert, and the sky above you.

Ibn Battuta decided to take the most difficult path to Mecca, as he had seen it in a dream. The voyage was not an easy one. Battuta sets out alone and is soon set upon by bandits who rob and almost kill him, until their leader recognizes his quest. “Pilgrim,” he says, “you may go.” He even offered to protect Ibn Battuta from additional bandits, however, for a fee. During his travels, the main character is attacked by bandits, dehydrated by thirst, rescued by Bedouins, and forced to retrace his route by a war-locked Red Sea.

As a viewer you will find yourself thrilled and enchanted by this beautiful piece of art. The detail, in everything from clothing to architecture, is meticulously researched. The re-creation of the storied Damascus camel caravan that took pilgrims across the desert to Mecca for centuries is so well researched that for a moment, it feels as if we too are there. The film runs for about 45 minutes, so don’t expect it to provide some groundbreaking insight into Islam; however, religious consultants ensured that the filmmakers accurately represented the Muslim faith.

In one of the final scenes, a close-up view of millions of pilgrims performing this year’s Hajj appears to be something similar to a human whirlpool so amazing and yet so intense. It’s at this moment we come to realize how much Journey to Mecca succeeds in capturing the everlasting wonder, pageantry, and beauty that are the symbols of any religion’s rituals and events. The true achievement of this film is that it takes us from the 14th century and ends up in modern times. The audience is able to live through his dream in a relatively short film, thanks to the aerial filming and profound dedication of the cast and crew of this film.

Islamic Insights Recommendation: This is a great movie that everyone regardless of his/her faith must see. The film’s main actor Chems Eddine Zinoun died in a car accident before the film was released, and in honor of his fantastic work, we should all see this film. The only complaint is that the film is too short and leaves you hungry for wanting more. Both history enthusiasts and your everyday popcorn lovers will enjoy this film.

Sign up for our Biweekly Newsletter

Subscribe to our mailing list to get updates.

Insightful reads to help you get through life's challenges!

Is the "New Middle East" Off the Table?

Related articles.

From Cemetery to a Holy Sanctuary

Lady Khadija, the Esteemed Wife of the Prophet

The Believer of Quraysh: Abu Talib

The Obesity Within Us

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Why Moroccan Scholar Ibn Battuta May Be the Greatest Explorer of all Time

By: Evan Andrews

Updated: September 11, 2023 | Original: July 20, 2017

The title of “history’s most famous traveler” usually goes to Marco Polo, the great Venetian wayfarer who visited China in the 13th century. For sheer distance covered, however, Polo trails far behind the Muslim scholar Ibn Battuta. Though little known outside the Islamic world, Battuta spent half his life tramping across vast swaths of the Eastern Hemisphere.

Moving by sea, by camel caravan and on foot, he ventured into over 40 modern day nations, often putting himself in extreme danger just to satisfy his wanderlust. When he finally returned home after 29 years, he recorded his escapades in a hulking travelogue known as the Rihla . Though modern scholars often question the veracity of Battuta's writings—he may never have visited China, for example, and many of his accounts of foreign lands appear to have been plagiarized from other authors' works—the Rihla is a fascinating look into the world of a 14th-century vagabond.

Born in Tangier, Morocco, Ibn Battuta came of age in a family of Islamic judges. In 1325, at age 21, he left his homeland for the Middle East. He intended to complete his hajj—the Muslim pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca—but he also wished to study Islamic law along the way. “I set out alone,” he later remembered, “having neither fellow-traveler in whose companionship I might find cheer, nor caravan whose party I might join, but swayed by an overmastering impulse within me and a desire long-cherished in my bosom to visit these illustrious sanctuaries.”

Battuta began his journey riding solo on a donkey, but soon linked up with a pilgrim caravan as it snaked its way east across North Africa. The route was rugged and bandit infested, and the young traveler soon developed a fever so severe that he was forced to tie himself to his saddle to avoid collapsing. Nevertheless, he still found time during one stopover to wed a young woman—the first of some 10 wives he would eventually marry and then divorce during his travels.

9 Intrepid Women Explorers

From a Viking 'far traveler' to a Soviet cosmonaut, these fearless women blazed daring new trails.

The Viking Explorer Who Beat Columbus to America

Leif Eriksson Day commemorates the Norse explorer believed to have led the first European expedition to North America.

6 Explorers Who Disappeared

These famous explorers journeyed to the far reaches of the earth, only to never be seen again.

In Egypt, Battuta studied Islamic law and toured Alexandria and the metropolis of Cairo, which he called “peerless in beauty and splendor.” He then continued on to Mecca, where he took part in the hajj. His travels might have ended there, but having completed his pilgrimage, he decided to continue wandering the Muslim world, or “Dar al-Islam.” Battuta claimed to be driven by a dream in which a large bird took him on its wing and “made a long flight towards the east…and left me there.” A holy man had interpreted the dream to mean that Battuta would roam across the earth, and the young Moroccan intended to fulfill the prophecy.

Battuta’s next few years were a whirlwind of travel. He joined a caravan and toured Persia and Iraq, and later ventured north to what is now Azerbaijan. Following a sojourn in Mecca, he trekked across Yemen and made a sea voyage to the Horn of Africa. From there, he visited the Somali city of Mogadishu before dipping below the equator and exploring the coasts of Kenya and Tanzania.

Upon leaving Africa, Battuta hatched a plan to travel to India, where he hoped to secure a lucrative post as a “qadi,” or Islamic judge. He followed a winding route east, first cutting through Egypt and Syria before sailing for Turkey. As he always did in Muslim-controlled lands, he relied on his status as an Islamic scholar to win hospitality from locals. At many points in his travels, he was showered with gifts of fine clothes, horses and even concubines and slaves.

From Turkey, Battuta crossed the Black Sea and entered the domain of a Golden Horde Khan known as Uzbeg. He was welcomed at Uzbeg’s court, and later accompanied one of the Khan’s wives to Constantinople. Battuta stayed in the Byzantine city for a month, visiting the Hagia Sophia and even receiving a brief audience with the emperor. Having never ventured to a large non-Muslim city, he was stunned by the “almost innumerable” collection of Christian churches within its walls.

Battuta next traveled east across the Eurasian steppe before entering India via Afghanistan and the Hindu Kush. Arriving in the city of Delhi in 1334, he won employment as a judge under Muhammad Tughluq, a powerful Islamic sultan. Battuta passed several years in the cushy job and even married and fathered children, but he eventually grew wary of the mercurial sultan, who was known to maim and kill his enemies—sometimes by tossing them to elephants with swords attached to their tusks. A chance to escape finally presented itself in 1341, when the sultan selected Battuta as his envoy to the Mongol court of China. Still thirsty for adventure, the Moroccan set out at the head of a large caravan brimming with gifts and slaves.

The trip to the Orient would prove to be the most harrowing chapter of Battuta’s odyssey. Hindu rebels harassed his group during their journey to the Indian coast, and Battuta was later kidnapped and robbed of everything but his pants. He managed to make it to the port of Calicut, but on the eve of an ocean voyage, his ships blew out to sea in a storm and sank, killing many in his party.

The string of disasters left Battuta stranded and disgraced. He was loath to return to Delhi and face the sultan, however, so he elected to make a sea voyage south to the Indian Ocean archipelago of the Maldives. He remained in the idyllic islands for the next year, gorging on coconuts, taking several wives and once again serving as an Islamic judge. Battuta might have stayed in the Maldives even longer, but following a falling out with its rulers, he resumed his journey to China. After making a stopover in Sri Lanka, he rode merchant vessels through Southeast Asia. In 1345, four years after first leaving India, he arrived at the bustling Chinese port of Quanzhou.

Battuta described Mongol China as “the safest and best country for the traveler” and praised its natural beauty, but he also branded its inhabitants “pagans” and “infidels.” Distressed by the unfamiliar customs on display, the pious traveler stuck close to the country’s Muslim communities and offered only vague accounts of metropolises such as Hangzhou, which he called “the biggest city I have seen on the face of the earth.” Historians still debate just how far he went, but he claimed to have roamed as far north as Beijing and crossed through the famous Grand Canal.

China marked the beginning of the end of Battuta’s travels. Having reached the edge of the known world, he finally turned around and journeyed home to Morocco, arriving back in Tangier in 1349. Both of Battuta’s parents had died by then, so he only remained for a short while before making a jaunt to Spain. He then embarked on a multi-year excursion across the Sahara to the Mali Empire, where he visited Timbuktu.

Battuta had never kept journals during his adventures, but when he returned to Morocco for good in 1354, the country’s sultan ordered him to compile a travelogue. He spent the next year dictating his story to a writer named Ibn Juzayy. The result was an oral history called A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling , better known as the Rihla (or “travels”). Though not particularly popular in its day, the book now stands as one of the most vivid and wide-ranging accounts of the 14th century Islamic world.

Following the completion of the Rihla , Ibn Battuta all but vanished from the historical record. He is believed to have worked as a judge in Morocco and died sometime around 1368, but little else is known about him. It appears that after a lifetime spent on the road, the great wanderer was finally content to stay in one place.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Voyages of Ibn Battuta

- 1 Understand

- 2.1 Across North Africa

- 2.2 Cairo to Mecca

- 2.3 Mesopotamia and Persia

- 2.4 East Africa

- 2.5 Anatolia

- 2.6 The Mongol lands

- 2.8 The Maldives and Sri Lanka

- 2.9 Toward China

- 2.11 Homeward bound

- 2.12 Iberia and West Africa

- 3 The Rihla

<a href=\"https://tools.wmflabs.org/wikivoyage/w/poi2gpx.php?print=gpx&lang=en&name=Voyages_of_Ibn_Battuta\" title=\"Download GPX file for this article\" data-parsoid=\"{}\"><img alt=\"Download GPX file for this article\" resource=\"./File:GPX_Document_rev3-20x20.png\" src=\"//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f7/GPX_Document_rev3-20x20.png\" decoding=\"async\" data-file-width=\"20\" data-file-height=\"20\" data-file-type=\"bitmap\" height=\"20\" width=\"20\" class=\"mw-file-element\" data-parsoid='{\"a\":{\"resource\":\"./File:GPX_Document_rev3-20x20.png\",\"height\":\"20\",\"width\":\"20\"},\"sa\":{\"resource\":\"File:GPX Document rev3-20x20.png\"}}'/></a></span>"}'/> Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah , commonly known as Ibn Battuta (1304–1368/1369) was a Berber explorer and scholar, and among the most well-travelled people of his time, reaching further than Marco Polo had a few decades earlier. His journeys were a showcase of the Islamic Golden Age .

Ibn Battuta came from a family of legal scholars, and he was trained in that field. At age 21, he set out from Tangier for his hajj , the pilgrimage to Mecca , and continued travelling until his forties, mostly in the Islamic world, India and imperial China .

He documented his journeys in the Rihla – always with the definite article, because rihla is a generic Arabic word for a travelogue. However, many scholars are uncertain if he visited all of the places mentioned in the Rihla or whether he based some of his descriptions on hearsay, and whether he visited them in the order provided in the book.

The University of California Berkeley has a good online account of Ibn Battuta's travels. Our text below is based on that.

Destinations

The Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca was Ibn Battuta's first long journey, starting in 1325. He travelled overland, at first alone but later joining various pilgrim caravans.

Across North Africa

Cairo to Mecca

There were several routes from Cairo to Mecca, and he chose what was then usually the safest — south along the Nile in territory controlled by the Mamluk rulers of Egypt, then across the Red Sea to Jeddah . However, as he approached the Red Sea port involved, he found out that its ruler was in revolt against the Mamluks and there was fighting nearby, so he turned back to Cairo.

From there he took another route to Mecca, first going to Damascus via Gaza , Hebron and Jerusalem .

Mesopotamia and Persia

After his year in Mecca, he visited what are now Iraq and Iran , which were then parts of the Mongol-ruled Ilkhanate .

East Africa

He returned to Mecca, then travelled by sea along the coast of East Africa , visiting Aden , Mogadishu , Malindi , Mombasa and Zanzibar .

After returning to Yemen, he went east on foot to Oman (which proved to be a difficult journey), by boat up the Persian Gulf , then overland back to Mecca.

After some time recovering in Mecca, he was ready to continue his journey east. In nearby Jeddah , he spent several months while looking for a ship that would take him to India, but to no avail.

He figured he might be able to join a Turkish trade caravan heading east, so he set off north toward Anatolia , travelling via Egypt and Damascus. He left Syria on a Genoese galley which took 10 days to cross the Mediterranean to arrive at Alanya, on the southern coast of Anatolia.

Ibn Battuta praised "the land of the Turks" for its beauty, delicious cuisine, and its people's hospitality, but was surprised by the Turks' less than perfect compliance with Islamic norms.

Ibn Battuta extensively travelled the land, and was hosted by an Islamic fraternity in most towns. He eventually made his way to Konya, the capital of the Mevlevi Sufi order.

At the time of Ibn Battuta's visit, there was no central authority in Anatolia, as the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum collapsed following the Mongol invasion, and numerous petty kingdoms known as beylik s had emerged in the power vacuum left behind. Ibn Battuta visited several of the local rulers, including Orhan, the chief of the nascent statelet that was to become the Ottoman Empire .

In November 1331, he started his trek north, which proved to be full of trouble. His progress was cut off by a raging river, then a guide got them lost (apparently on purpose as the guide later demanded a ransom ), and as the winter approached he almost froze to death, but he eventually managed to get to Sinop on the Black Sea coast.

The Mongol lands

From there he went into Mongol territory, first that of the Golden Horde . His boat struggled through the severe storms common in the Black Sea , and finally reached Caffa, present-day Feodosiya in Crimea, several days later.

He visited many Black Sea ports, inhabited by a multinational merchant population and receiving the rich produce of the steppe as well as that brought over via the Silk Road. He departed from Azov to catch up with the travelling court of Uzbeg Khan of the Golden Horde, whom he learned was a few days ahead.

At the time, the area was inhabited by Turkic and Mongolian nomads. He described their cuisine based on horse meat (still a delicacy in some of the modern nations in the wider region such as Kazakhstan ) and how they let their horses and other livestock free range on the open steppe. He also mentioned the nomad drinks of kumis, fermented mare's milk still popular in Turkic Central Asia and in Mongolia , and boza, a thick malt drink now common in Turkey and the Balkans .

Ibn Battuta met the khan's court, which he likened to an entire city on the move, near Beshtau, in what is now Stavropol Krai north of the Caucasus Mountains. From there, he went north to Bolghar, although some modern historians dispute this. If it's true that he had been there, that was the northernmost point he ever set foot in — indeed he noted that the summer nights that far north were unusually short to him.

While in Bolghar, Ibn Battuta thought about venturing further north into the "land of darkness", likely somewhere deep inside Siberia , which could only be reached by a dog sled and was said to be inhabited by a mysterious group of people. But such a trip never materialized.

From Bolghar, he returned to the khan's court, and they moved to Astrakhan together.

At Astrakhan, he heard the khan's wife, a Byzantine princess by birth, was about to leave for her father's realm to give birth to her baby there. So in July 1332 Ibn Battuta joined her party for a 75-day trip back along the Black Sea to Constantinople, where he stayed for more than a month.

As he went back to Astrakhan, it was already winter, brutal in the Eurasian steppe. He approached Sarai on the frozen Volga River.

From Sarai, his route trended south, into the Chagatai Khanate .

Leaving Mongol lands, he continued to the Indian subcontinent .

Eventually, the Sultan decided to use him as an envoy to China and put him in command of an expedition that included 15 Chinese envoys returning home. They went off toward the coast with a rich and well-guarded caravan, but had some serious trouble with rebels and bandits; at one point Ibn Battuta became separated from the caravan and was robbed of everything but his trousers. However, they did make it to the fortress of Daulatabad where they rested up for a few days before continuing to Cambay , then along the coast to Gandhar where they boarded four ships.

A severe storm came up, the junks put to sea (without Ibn Battuta) to ride it out, and two of them were sunk. The third ship set off for China, without Ibn Battuta; he pursued briefly, but gave up. That ship made it as far as Sumatra , but then was seized by a local king.

Left penniless, and afraid of what the Sultan might do if he returned to Delhi a failure, he found employment with one of the southern Muslin sultans for a while, then did some more travelling.

The Maldives and Sri Lanka

Leaving Sri Lanka, he had more bad luck. One ship was sunk by a storm, but he was rescued and boarded another ship; that one was taken by pirates and again he was robbed of everything except his trousers. However, the pirates put the passengers ashore unharmed and they made their way back to Calicut.

Toward China

From Calicut he decided to continue toward China; he returned to Malé and got on an eastbound ship.

The Sultan owned ships which traded with China, and sent Ibn Battuta off on one.

He landed in China at Quanzhou, then travelled by land to other cities.

Homeward bound

Returning to Quanzhou, he found a junk owned by the Sultan of Samudra in port, and boarded it to begin his three-year journey home. After a stop in Samudra he sailed to India, landing at Quilon then returning to Calicut where he boarded a westbound ship.

When Ibn Battuta had visited 11 years before, the Ilkhanate had been peaceful under a strong sultan. However, that sultan had died and the region was now chaotic as various generals and nobles vied for power. Ibn Battuta left Persia quickly, going west via Baghdad and Damascus.

He went back to Palestine , Cairo, Jeddah and Mecca, then returned to Egypt to take a ship west.

Iberia and West Africa

By now, Ibn Battuta had visited most of the Muslim world ( dar al Islam ), as well as areas beyond it. His last major journey was to Islamic kingdoms he had not yet seen.

After the West African journey, he settled in Tangier, worked as a judge, and wrote a book:

The work became well-known in the Muslim world, but was not much known in the West until the early 1800s.

- Has default banner

- Has mapframe

- Has map markers

- Listing with Wikipedia link but not Wikidata link

- In the footsteps of explorers

- Itineraries

- Outline itineraries

- Outline articles

- Pages using the Kartographer extension

Navigation menu

- College of Arts & Sciences

- Graduate Division

- College of Liberal and Professional Studies

Journey to Mecca: In the Footsteps of Ibn Battuta

(45 minutes) Journey to Mecca tells the story of Ibn Battuta (played by Chems Eddine Zinoun), a young scholar who leaves Tangier in 1325 on an epic and perilous journey, traveling alone from his home in Morocco to reach Mecca, some 3,000 miles to the east. Ibn Battuta is besieged by countless obstacles as he makes his way across the North African desert to Mecca. Along the route he meets an unlikely stranger, the Highwayman (played by Hassam Ghancy) who becomes his paid protector and eventual friend. During his travels he is attacked by bandits, dehydrated by thirst, rescued by Bedouins, and forced to retrace his route by a war-locked Red Sea. Ibn Battuta finally joins the legendary Damascus Caravan with thousands of pilgrims bound for Mecca for the final leg of what would become his 5,000 mile, 18 month long journey to Mecca. When he arrives in Mecca, he is a man transformed. We then experience the Hajj as he did over 700 years ago, and, in recognition of its timelessness, we dissolve to the Hajj as it is still performed today, by millions of pilgrims, in some of the most extraordinary and moving IMAX® footage ever presented. Ibn Battuta would not return home for almost 30 years, reaching over 40 countries and revisiting Mecca five more times to perform the Hajj. He would travel three times farther then Marco Polo. His legacy is one of the greatest travel journals ever recorded. A crater on the moon is named in his honour.

The Ages of Exploration

Ibn battuta.

Quick Facts:

He was a Muslim explorer who made a series of journeys that spanned nearly three decades. He traveled throughout almost the entire Islamic world, and went as far as India and China.

Name : Abu Abdullah Muhammad Ibn Battuta [ah-boo] [ahb-doo-luh] [moo-hah-muhd ] [ib-uhn] [buh-too-tuh]

Birth/Death : 1304 CE - 1368 CE

Nationality : Moroccan

Birthplace : Tangier

Ibn Battuta Portrait

Portrait of Ibn Battuta on an interactive display in Ibn Battuta Mall in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. (Credit: Imre Solt)

Introduction Abu Abdullah Muhammad Ibn Battuta, better known by his surname Ibn Battuta, was a great Medieval traveler and explorer. He is often compared to Marco Polo, who died a year before Ibn Battuta left home. But unlike Polo, Ibn Battuta traveled mostly to and within Muslim regions. This network of Muslim kingdoms is called the Dar al-Islam, or “Abode of Islam.” His book, or rihla in Arabic, helped shed light on many aspects of the social, cultural, and political history of a great part of the Muslim world.

Biography Early Life Abu Abdullah Muhammad Ibn Battuta was born on February 25, 1304 in the city of Tangier, Morocco in Northern Africa. Little is known about his early childhood. But we know much about his travels because he had them written. Several members of his family were legal scholars and judges. Ibn Battuta received a good education because he came from an elite family. Most boys of this time and place would have received a basic education of writing, grammar, and basic math until the age of twelve. Because Ibn Battuta’s family had status, he would also have had an advanced study of the Koran (also spelled Qur’an): the Sacred Book of the Islamic religion. 1 Ibn Battuta went on to study law to become a qadi . Qadi are the judges in Islamic society who have control over matters of religion. This is an important area within Islam.

In 1325, at the age of 21, he left his home to make the traditional pilgrimage, or hajj , to the sacred Muslim city of Mecca in Arabia (today called Saudi Arabia). He joined a caravan with about 20,000 other travelers. 2 The hajj would expand Ibn Battuta’s education for his office as qadi . During his year and a half journey, he traveled by sea and over land, often through rough deserts and mountains. He visited North Africa, Egypt, Palestine, and Syria. He wrote how the great port in Alexandria Egypt had two harbors – one for Christian merchant ships and one for Muslim ships. 3 He met many people along the way and studied with famous scholars from all over the Islamic world. He became a well liked man. He completed his pilgrimage in 1326, and studied in Mecca for many months. But Ibn Battuta had gained a love for travel. In late 1326, he joined a caravan of travelers heading for Mesopotamia (modern Iraq). 4 He would spend the next thirty years exploring the lands of Islamic culture.

Voyages Principal Voyage Much of Ibn Battuta’s journeys would take him in part by land, but mostly by water. He first left Mecca in in November 1326 and headed toward Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq). The new Mongol ruler declared that instead of Christianity, Islam would be the main religion of the area. The fact that Ibn Battuta could read and speak Arabic quickly made him a popular visitor among the leaders. His first journey took him to Baghdad in Iraq; Persia (modern Iran); and to Tabriz in Azerbaijan. He completed his journey by boat up the Tigris River to Mosul, Iraq, and then went back to Mecca in 1327. 5 His entire journey covered more than 4000 miles. Along the way, he mentions the merchants he met, the gardens in Iraq, and riches such as gold and silver offered to him. He did not stay in Mecca long. In 1328, he took a sea voyage down the eastern coast of Africa to Tanzania; then visited Oman and the Persian Gulf before once more returning to Mecca. 6

In 1330, Ibn Battuta left Mecca to head to Yemen and then India. His plan was to go to India, and work for the Sultan of Delhi and Indian government. 7 The areas traveled would have had him sailing on the Persian Gulf, Arabian Peninsula and the Red Sea. He would also travel by land through Egypt, Syria and to Asia Minor (part of modern day Turkey). From here he crossed the Black Sea to West Central Asia, and then to the Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire. Today, Constantinople is named Istanbul and is the capital city of Turkey. He continued east, until reaching India in September 1333. 8 He spent about eight years as qadi for the ruler of India and wrote about his time there. He mentioned that Indians mostly ate rice and green vegetables, that they were religious people, and even how a thief would be put to death for stealing a single nut. 9 In 1345, he decided to travel to China. He sailed along the coast of Burma, to the island of Sumatra, and then Guangzhou, China. He then returned to Mecca once more in 1346.

Subsequent Voyages Ibn Battuta soon headed for home, and arrived in the Moroccan capital of Fez in 1349. The next year he made a brief trip across the Strait of Gibraltar to Granada. His final journey came in 1353 when he traveled by land across the Sahara Desert to the Kingdom of Mali in the West African Sudan. 10 He returned to Morocco in 1355 where he would remain. During his thirty years of travel, he explored much of the eastern hemisphere and almost all of the Islamic world. From each place he visited, Ibn Battuta tells of his experiences. He wrote about the people, places, animals, and treasures he saw or was given. Overall, he traveled about 73,000 miles total, and visited about 40 countries. 11

Later Years and Death Ibn Battuta made many journeys in his life. In 1356, the ruler of Morocco asked a young scholar named Ibn Juzayy to write down Ibn Battuta’s explorations. They would work for two years. This book of travel is called a rihla . It means “journey” in Arabic. After completing the book, Ibn Battuta continued his role as judge in a small Moroccan town. He died around 1368 or 1369. His incredible story became very popular, especially among the Islamic world.

Legacy Ibn Battuta is celebrated as one one of the most famous Muslim explorers in history, and one of the great travelers of all time. His sea voyages and references to shipping show that the Muslims were very much involved in trading, commerce, and maritime activity of the Red Sea, the Arabian Sea, and Indian Ocean. Almost everything we know of his travels is known because he told his story and had it written down later in his life. His rihla offers a unique account on Islamic and medieval history.

- Ross E. Dunn, The Adventures of Ibn Battuta: A Muslim Traveler of the Fourteenth Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 19-20.

- Dunn, The Adventures of Ibn Battuta , 65.

- Fergus Fleming, Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration (New York: Grove Press, 2004), 19.

- Fleming, Off the Map, 19 .

- Fleming, Off the Map , 21

- Dunn, The Adventures of Ibn Battuta , 1.

- Fleming, Off the Map , 24

- Ibn Batuta and Oriental Translation Fund, The Travels of Ibn Batūta, trans. Samuel Lee (London: Oriental Translation Committee, 1829), 165.

- Dunn, The Adventures of Ibn Battuta , 3.

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

- Bibliography

Ibn Battuta and the Marvels of Traveling the Medieval World

Ibn Battuta (1304-68/69, An illustration from Jules Verne’s book “Découverte de la terre” (“Discovery of the Earth”) drawn by Léon Benett

On 24 February 1304, Muslim Berber Moroccan scholar, and explorer Ibn Battuta was born. Over a period of thirty years, Ibn Battuta visited most of the Islamic world and many non-Muslim lands, including Central Asia, Southeast Asia, India and China. Near the end of his life, he dictated an account of his journeys, titled A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling .

“I arrived at length at Cairo, mother of cities and seat of Pharaoh the tyrant, mistress of broad regions and fruitful lands, boundless in multitude of buildings, peerless in beauty and splendour, the meeting-place of comer and goer, the halting-place of feeble and mighty, whose throngs surge as the waves of the sea, and can scarce be contained in her for all her size and capacity.” – Ibn Battuta, Travels in Asia and Africa (Rehalã of Ibn Battûta)

Early Life and Pilgrimage to Mecca

All that is known about Ibn Battuta’s life comes from the autobiographical information included in the account of his travels, which records that he was of Berber descent, born into a family of Islamic legal scholars in Tangier , Morocco, on 25 February 1304, during the reign of the Marinid dynasty . At the age of 21, Battūta went on a Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca . This took place by land along the North African coast until Battūta reached Cairo via Alexandria . Here he was on relatively safe Mamluk territory and made his first detour from the path. At that time there were three common stages: a trip up the Nile, then east to the port city of Aidhab on the Red Sea. But there he had to turn back because of a local uprising. Back in Cairo, he made a second detour to Damascus (also under Mamluk control at that time), having previously met a “holy man” who had prophesied that he would reach Mecca only after a journey through Syria. Another advantage of his detour was that other holy places were along the way – such as Hebron , Jerusalem and Bethlehem – and the Mamluk authorities made special efforts to secure this pilgrimage route.

Along the Silk Road

After spending the month of fasting Ramadan in Damascus, Ibn Battuta joined a caravan that made the journey from Damascus to Medina , the burial place of the Prophet Mohammed. In order to keep up his strength, Battuta ate the young of his camel, as he could not use offspring. After four days there, he traveled on to Mecca. He completed the rituals necessary to attain his new status as a hadj, and now he had his way home. After a short consideration he decided to continue his journey. His next destination was the empire of the Mongolian Ilkhane , which lies in the territory of today’s Iran/Iraq. He again joined a caravan and crossed with it the border to Mesopotamia, where he visited Najaf , the burial place of the fourth Caliph Ali. From here he travelled to Basra , then to Isfahan , which was to be almost completely destroyed only a few decades later by the Turkmen conqueror Timur . Ibn Battuta’s next stops were Shiraz and Baghdad , which was in poor condition after it was taken by Hülegü.

Along the Coast of Africa

After this journey Ibn Battuta returned to Mecca with a second hadj and lived there for a year, before embarking on a second great journey, this time down the Red Sea along the East African coast. His first major stop was Aden , where he planned to make a fortune by trading goods that came to the Arabian Peninsula from the Indian Ocean. Before he put these plans into action, he decided to embark on one last adventure, and in the spring of 1331 he volunteered for a journey south along the African coast. He spent about one week each in Ethiopia, Mogadishu, Mombasa, Zanzibar , Kilwa and other places. With the change of the monsoon wind his ship returned to South Arabia. After completing this last journey before settling down, he decided to visit Oman and the Strait of Hormus directly.

Ibn Battuta Itinerary 1325-1332 (North Africa, Iraq, Persia, the Arabian Peninsula, Somalia, Swahili Coast)

From Mecca to Dehli

He then travelled once again to Mecca, where he spent another year and then decided to seek employment with the Muslim Sultan of Delhi . To find a guide and translator for his journey, he went to Anatolia, which was under the control of the Seljuk Turks, and joined a caravan to India. A sea voyage from Damascus on a Genoese ship brought him to Alanya on the south coast of what is now Turkey. From there he travelled overland to Konya and Sinope on the Black Sea coast. He crossed the Black Sea and landed at Kaffa in Crimea, entering the territory of the Golden Horde. On his journey through the country, he happened to meet the caravan of Özbeg , the khan of the Golden Horde, and joined its journey, which took him along the Volga to Astrakhan . Arriving in Astrakhan, the Khan allowed one of his wives, who was pregnant, to have her child in her home town – Constantinople. It is not surprising that Ibn Battuta persuaded the Khan to let him take part in this journey – the first to take him beyond the borders of the Islamic world.

On to the Maldives and towards China

The Sultanate of Delhi had become Islamic only shortly before, and the Sultan wanted to employ as many Islamic scholars and officials as possible to strengthen his power. Due to Ibn Battuta’s studies in Mecca, he was appointed as Qādī (“Judge”) by Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq. On the way to the coast his travel group was attacked by Hindu rebels – he was separated from his companions, robbed and almost killed. Nevertheless, after two days he caught up with his group and continued his journey to Cambay . From there he sailed to Calicut in southwest India. He decided to continue his journey to the Empire of China, but right at the beginning with a detour via the Maldives. He stayed on the archipelago for much more time than intended, namely nine months. He turned to Ceylon to visit the religious sanctuary of Sri Pada (Adam’s Peak). When he set sail from Ceylon, his ship almost sank in a storm – after another ship saved him, it was attacked by pirates. Stranded on the shore, Ibn Battuta once again made his way to Calicut, from where he sailed back to the Maldives before trying again to reach China aboard a Chinese junk. This time the attempt was successful – he quickly reached Chittagong, Sumatra, Vietnam and finally Quanzhou in Fujian province. From there he turned north towards Hangzhou, not far from today’s Shanghai. Ibn Battuta also claimed to have travelled even further north, through the Great Canal (Da Yunhe) to Beijing , but this is generally considered an invention.

Ibn Battuta Itinerary 1332-1346 (Black Sea Region, Central Asia, India, South East Asia and China)

Back to Mecca and the Plague

On his return to Quanzhou Ibn Battuta decided to return home – although he did not really know where his home was. Back in Calicut, India, he briefly considered surrendering to the grace of Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq, but changed his mind and returned to Mecca. When he arrived in Damascus to make his first pilgrimage to Mecca, he learned of his father’s death. The death continued to be his companion that year, because the plague had broken out and Ibn Battuta witnessed the spread of the Black Death over Syria, Palestine and Arabia. After reaching Mecca, he decided to return to Morocco, almost a quarter of a century after his departure from there. On his way home, he made a final detour via Sardinia and then returned to Tangiers – only to learn that his mother had also died a few months earlier.

El Andalus and back to North Africa

But even in Tangier he did not stay long – he set off for Al-Andalus – the Islamic Spain. Alfonso XI of Castile threatened to conquer Gibraltar , and Ibn Battuta left Tangier together with a group of Muslims – with the intention of defending the port city. When he arrived there, Alfonso had fallen victim to the plague and Gibraltar was no longer threatened; Ibn Battuta continued his journey for pleasure. He travelled through Valencia and reached Granada. A part of the Islamic world that Ibn Battuta had never explored was Morocco itself. On his return from Spain, he made a short stop in Marrakech, which had almost died out after the plague epidemic and the capital’s move to Fez. In the autumn of 1351, Ibn Battuta left Fez and a week later reached Sijilmasa , the last Moroccan city on his route. He joined one of the first winter caravans a few months later, and a month later he found himself in the middle of the Sahara in the city of Taghaza . A centre of the salt trade, it was flooded with salt and Malian gold – yet the treeless city did not make a favourable impression on Ibn Battuta. He travelled 500 kilometres further through the worst part of the desert to Oualata , then part of the Mali empire, now Mauritania.

Ibn Battuta Itinerary 1349-1354 (North Africa, Spain and West Africa)

Retirement and Travellog

On his onward journey to the southwest he thought he was on the Nile (in fact it was the Niger) until he reached the capital of the Malian Empire. There he met Mansa Suleyman, who had been king since 1341. Although he was suspicious of his stingy hospitality, Ibn Battuta stayed there for eight months before heading down the Niger to Timbuktu . At the end of December 1353 he returned to Morocco from this last journey. At the instigation of the Sultan Abū Inān Fāris Ibn Battuta dictated his travel experiences to the poet Mohammed Ibn Dschuzaj (died 1357), who elaborately embellished the simple prose style of Ibn Battuta and provided it with poetic additions. Although some of the places in the resulting work “Rihla” ( A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling ) were obviously the product of his imagination, it is one of the most accurate existing descriptions of some parts of the world in the 14th century. He travelled more than any other explorer in distance, totaling around 117,000 km, surpassing Zheng He with about 50,000 km and Marco Polo with 12,000 km.[ 4 ]

After he published “ Rihla “, Ibn Battuta lived in his homeland for 22 years, until he died in 1368 or 1377. You can learn more about Ibn Battuta in the video lecture of Paul Cobb, Professor, Islamic History, University of Pennsylvania presenting Traveler’s Tips from the 14th Century: The Detours of Ibn Battuta. The 14th century offered a different world of travel than the one that confronts us today—or did it? What advice can Ibn Battuta provide the globe-trotting public of the 21st century?

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Ibn Battuta, Travels In Asia And Africa 1325–1354 — Gibb’s 1929 translation from the Internet Archive

- [2] The Longest Hajj: The Journeys of Ibn Battuta — Saudi Aramco World article by Douglas Bullis (July/August 2000).

- [3] Works by Ibn Battuta at LibriVox

- [4] Marco Polo – The Great Traveler and Merchant , SciHi Blog

- [5] Paul Cobb, Great Voyages: Traveler’s Tips from the 14th Century: The Detours of Ibn Battuta

- [6] Ibn Battuta at Wikidata

- [7] Paul Cobb, Great Voyages: Traveler’s Tips from the 14th Century: The Detours of Ibn Battuta , Penn Museum @ youtube

- [8] Timeline of Medieval Travel Writers , via DBpedia and Wikidata

Harald Sack

Related posts, the adventures of sir richard francis burton in africa, carsten niebuhr and the decipherment of cuneiform, henry the navigator and the age of discoveries, gustav nachtigal and the explorations in africa, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Further Projects

- February (28)

- January (30)

- December (30)

- November (29)

- October (31)

- September (30)

- August (30)

- January (31)

- December (31)

- November (30)

- August (31)

- February (29)

- February (19)

- January (18)

- October (29)

- September (29)

- February (5)

- January (5)

- December (14)

- November (9)

- October (13)

- September (6)

- August (13)

- December (3)

- November (5)

- October (1)

- September (3)

- November (2)

- September (2)

Legal Notice

- Privacy Statement

- Course Information

- Medieval Travels

- Readings and Schedule

The Travels of Ibn Battutah: Alexandria

During Ibn Battutah’s pilgrimage to the Holy House in Mecca, he spent a considerable amount of time in Alexandria (al-Iskandariyah), Egypt, to explore the city and its culture. Battutah arrived on April 5, 1326, via a travel caravan from Tunis, and he stayed in Alexandria for several weeks. This section of Battutah’s travel narrative reflects his interest in the city’s culture, both via descriptions of cultural monuments as well as descriptions of the individuals with whom he interacted. He frequently expresses extreme awe towards the city from a visual, economic, and social perspective, and relays several positive experiences during his time there.

Battutah’s positive attitude towards Alexandria is first shaped by its beautiful and practical visual features. He specifically focuses on the city’s architecture, as it is not only visually appealing but also has aspects of functionality. The city includes a large citadel, secular buildings, religious edifices, and an impressive sea port. While describing the various structures in the city, he claims that they are built “in the way of embellishment and embattlement” that reflect “architectural perfection”(6). Battutah’s use of the word “embellishment” refers to the physical beauty of the city’s structures, while “embattlement” focuses on their strength and functionality. With his word choice, Battutah does not appreciate outward beauty without simultaneously considering its rational purpose. This reflects Battutah’s cultural values as a practicing Muslim; members of the Islamic faith express disdain towards waste and extravagance, so it makes sense for Battutah to justify Alexandria’s outward beauty and extravagance with its practicality and purpose.

While describing the city’s architecture, Battutah goes on to explain the structure and purpose of the city’s port. He credits some of the port’s success to its well-built structure, but also considers Alexandria’s geographic location as a key factor to its success. He refers to the city and its port as a mediator between the East and the West, indicating its vital role in the world of trade, communication, and travel. When describing the city as a whole, Battutah focuses on the man-made features; when describing the port, however, he references the man-made features as well as the geographical features in relation to the city’s success. The narrator’s shift in description shows that Alexandria’s success, especially in regards to trade, communication, and travel, relies on civilization competence just as much as geographic luck. For cities to thrive, they need to be in an economically beneficial location; this was especially true in the medieval ages because limited knowledge and resources made it more difficult to overcome limiting geographic features.

Battutah’s narrative also describes his interactions with the citizens of Alexandria. He considers all of the city’s people to be friendly and hospitable, but mainly interacts and describes his time spent with other educated, religious individuals such as Burhan al-Din the Lame and Shaikh Yaqut al-Habashi. In his narrative, Battutah describes these two individuals based on those with whom they interact. For example, he explains how Burhan al-Din the Lame has family in India and China, and mentions that Shaikh Yaqut al-Habashi has relations with a famous saint named Abul Hasan al-Shadhili (9). Describing people based on their relation to other people supports the trend of network communication via word of mouth. The limited nature of medieval travel and communication made it so that networks of “people who know people who know people” could be used to communicate. So, while interacting with Burhan al-Din the Lame and Shaikh Yaqut al-Habashi, Battutah also learns about other people and places to visit. This information is incredibly influential, as it actually leads Battutah to alter the trajectory of his journey to visit a pious figure known by Shaikh Yaqut al-Habashi. Because all of this information is delivered via word of mouth, though, its accuracy and truthfulness inherently comes into question. Errors can easily occur when people speak to each other, yet Battutah does not address this potential issue. It remains unclear whether this is due to ignorance or acceptance of his inability to solve the issue.

Ibn-Baṭṭūṭa Muḥammad Ibn-ʿAbdallāh, and Tim Mackintosh-Smith. The Travels of Ibn Battutah . Translated by Gibb Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen, Picador, 2002.

- Ibn Battutah

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Benjamin of Tudela

- Felix Fabri

- John Mandeville

- Margery Kempe

- Uncategorized

- February 2022

- February 2018

- August 2017

© 2024 Mapping the Global Middle Ages Academic Technology services: GIS | Media Center | Language Exchange

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

Riding a bike to China: Moroccan cyclist commemorates Ibn Battuta's journey to China

Karim Mosta, the 70-year-old renowned Moroccan cyclist, embarked on a journey by bicycle from Casablanca, traveling for eight months across 15 countries before arriving in Beijing. Mosta said he wanted to commemorate the Ibn Battuta story with his bicycle.

- Learn Chinese

EXPLORE MORE

DOWNLOAD OUR APP

Copyright © 2024 CGTN. 京ICP备20000184号

Disinformation report hotline: 010-85061466

- Terms of use

- Privacy policy

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Ibn Battuta started on his travels in 1325, when he was 20 years old. His main reason to travel was to go on a Hajj, or a Pilgrimage to Mecca, to fulfill the fifth pillar of Isla.. But his traveling went on for around 29 years and he covered about 75,000 miles visiting the equivalent of 44 modern countries which were then mostly under the ...

Ibn Battuta (born February 24, 1304, Tangier, Morocco—died 1368/69 or 1377, Morocco) was the greatest medieval Muslim traveler and the author of one of the most famous travel books, the Riḥlah (Travels). His great work describes his extensive travels covering some 75,000 miles (120,000 km) in trips to almost all of the Muslim countries and ...

Abū Abd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Abd Allāh Al-Lawātī (/ ˌ ɪ b ən b æ t ˈ t uː t ɑː /; 24 February 1304 - 1368/1369), [a] commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Maghrebi traveller, explorer and scholar. [7] Over a period of thirty years from 1325 to 1354, Ibn Battuta visited most of North Africa, the Middle East, East Africa, Central Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, China, the Iberian ...

The 20-year-old Muslim religious law student Ibn Battuta (1304-1368), [3] set out from Tangier, a city in northern Morocco, in 1325, on a pilgrimage to Mecca, some 3,000 miles (over 4,800 km) to the East.The journey took him 18 months to complete and along the way he met with misfortune and adversity, including attack by bandits, rescue by Bedouins, [4] fierce sand storms [5] and dehydration.

Without any serious incidents, the caravan arrived at Medina, City of the Apostle of God - a little island of fertility in the desert.In 622 A.D. Muhammad and a small group of followers retreated from a hostile Mecca.His flight to Medina - the Hijira - would mark the beginning of the Muslim calendar. When the Prophet died in 632, his grave in Medina became a site of pilgrimage second only to ...

Western North Africa (The Mahgrib) Ibn Battuta was born in Tangier, Morocco into a family of Muslim legal scholars in 1304. He studied Muslim law as a young man. Then in 1325, he left Tangier to make a pilgrimage to Mecca (in Islam this pilgrimage is called the "hajj.") He was 21 years old and eager for more learning and more adventure.

In the year 1325 CE, he decided to make the 3000 miles journey from Tangiers, Morocco, to Mecca. In Cairo, Ibn Battuta told Ibn Muzaffar his intention to move onward after his Hajj pilgrimage. Ibn Muzaffar talked to him about his journey and said, "Our Prophet Muhammad had said, 'Go in search of knowledge, even if your journey takes you to China.'.

—Ibn Battuta, 1355 C.E. Journey to Mecca: In the footsteps of Ibn Battuta 2 Journey to Mecca Educator's Guide ©2009 SK Films Inc. "The genesis of the film was to tell the remarkable story of Ibn Battuta, promote a better understanding of Islam in the West, and to present the heart of Islam to the Muslim world." The Producers of Journey ...

Ibn Battuta's journey is generally broken up into three itineraries. The first, from 1325 until 1332 took him through North Africa, Iraq, Iran and elsewhere in the Arabian Peninsula, and down Africa's east coast. His first journey to Mecca, of which there were many, took him to Algeria and onto Tunisia. Here he got married, but soon left ...

It would take Ibn Battuta 18 months to travel the 5,000-mile route to Mecca. Battuta, who would eventually become the best-travelled person in antiquity, would not return home for 30 years. His journeys total three times those of Marco Polo. He would visit 40 countries and revisited Mecca five more times to perform the Hajj.

China marked the beginning of the end of Battuta's travels. Having reached the edge of the known world, he finally turned around and journeyed home to Morocco, arriving back in Tangier in 1349 ...

Ibn Battuta came from a family of legal scholars, and he was trained in that field. At age 21, he set out from Tangier for his hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca, and continued travelling until his forties, mostly in the Islamic world, India and imperial China.. He documented his journeys in the Rihla - always with the definite article, because rihla is a generic Arabic word for a travelogue.

Ibn Battuta (l. 1304-1368/69) was a Moroccan explorer from Tangier whose expeditions took him further than any other traveler of his time and resulted in his famous work, The Rihla of Ibn Battuta.Scholar Douglas Bullis notes that "rihla" is not the book's title, but genre, rihla being Arabic for journey and a rihla, travel literature. The book's actual title is A Gift to Those Who ...

English. (45 minutes) Journey to Mecca tells the story of Ibn Battuta (played by Chems Eddine Zinoun), a young scholar who leaves Tangier in 1325 on an epic and perilous journey, traveling alone from his home in Morocco to reach Mecca, some 3,000 miles to the east.Ibn Battuta is besieged by countless obstacles as he makes his way across the ...

He completed his pilgrimage in 1326, and studied in Mecca for many months. But Ibn Battuta had gained a love for travel. In late 1326, he joined a caravan of travelers heading for Mesopotamia (modern Iraq). 4 He would spend the next thirty years exploring the lands of Islamic culture. ... Ibn Battuta left Mecca to head to Yemen and then India.

Journey to Mecca: In the Footsteps of Ibn Battuta is an IMAX dramatised documentary film charting the first real-life journey made by the Islamic scholar Ibn...

Had Ibn Battuta's work received the same attention, his name would rank alongside Marco Polo's as a synonym for world travel. Watch Journey to Mecca an IMAX dramatic and documentary feature that tells the amazing story of Ibn Battuta, the greatest explorer of the Old World, following his first pilgrimage between 1325 and 1326 from Tangier to Mecca.

Ibn Battuta was thinking about a return trip to Mecca - his third visit. Traveling mostly by land now, he reached Mecca in the winter of 1330. After tiring sea voyages, climbing high mountains in Yemen, traveling across the equator and through the hottest places on earth, and almost losing his life, he was looking forward to a long rest with ...

Due to Ibn Battuta's studies in Mecca, he was appointed as Qādī ("Judge") by Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq. On the way to the coast his travel group was attacked by Hindu rebels - he was separated from his companions, robbed and almost killed. ... At the instigation of the Sultan Abū Inān Fāris Ibn Battuta dictated his travel ...

Journey to Mecca is an IMAX® dramatic and documentary feature that tells the amazing story of Ibn Battuta, the greatest explorer of the Old World, following ...

The Travels of Ibn Battutah: Alexandria. During Ibn Battutah's pilgrimage to the Holy House in Mecca, he spent a considerable amount of time in Alexandria (al-Iskandariyah), Egypt, to explore the city and its culture. Battutah arrived on April 5, 1326, via a travel caravan from Tunis, and he stayed in Alexandria for several weeks.

The silver-domed Al-Aqsa Mosque was built in 691 across from the Dome of the Rock. Ibn Battuta stayed in Jerusalem for about one week. Because the Hajj season would begin soon, he continued on to Damascus and arrived there during the Holy Month of Ramadan, 1326. From Damascus he could join a hajj caravan going to Mecca.

Karim Mosta, the 70-year-old renowned Moroccan cyclist, embarked on a journey by bicycle from Casablanca, traveling for eight months across 15 countries before arriving in Beijing. Mosta said he wanted to commemorate the Ibn Battuta story with his bicycle.