Art & Culture Travel Blog

History of travelling: how people started to travel.

- Tea Gudek Šnajdar

- Cultural Tourism

Although we often have a feeling like people are travelling for the last few decades only, the truth is – people are travelling for centuries. Old Romans were travelling to relax in their Mediterranean villas. At the same time, people in Eastern Asia wandered for cultural experiences. I’ve got so fascinated with the history of travelling, that I did my own little research on how people started to travel. And here is what I’ve learned.

History of travelling

I was always curious about the reason people started to travel. Was it for pure leisure? To relax? Or to learn about new cultures, and find themselves along the way?

I wanted to chaise the reason all the way to its source – to the first travellers. And hopped to find out what was the initial motivation for people to travel.

According to linguists, the word ‘travel’ was first used in the 14th century. However, people started to travel much earlier.

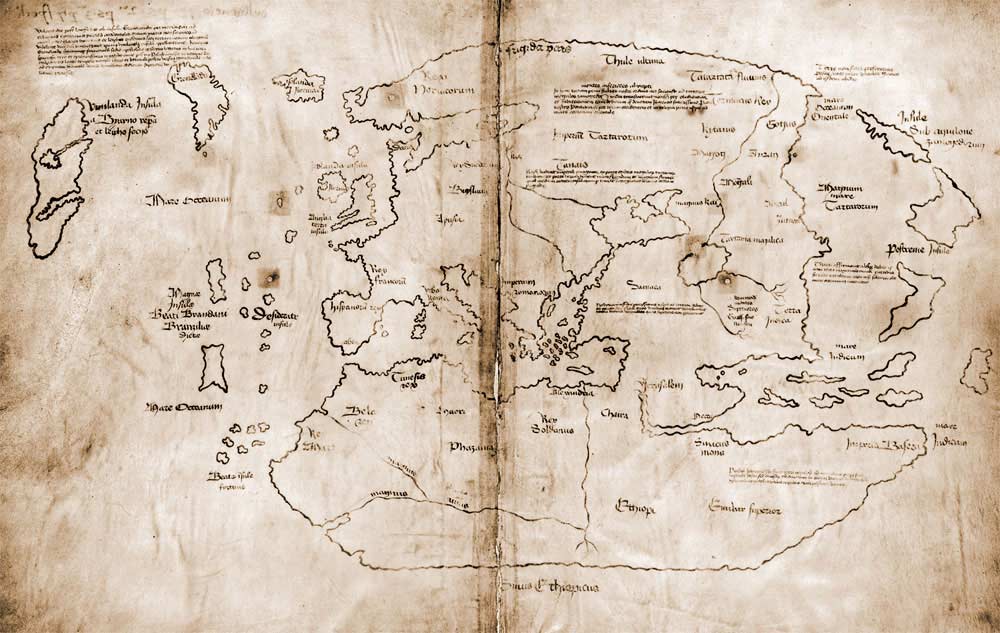

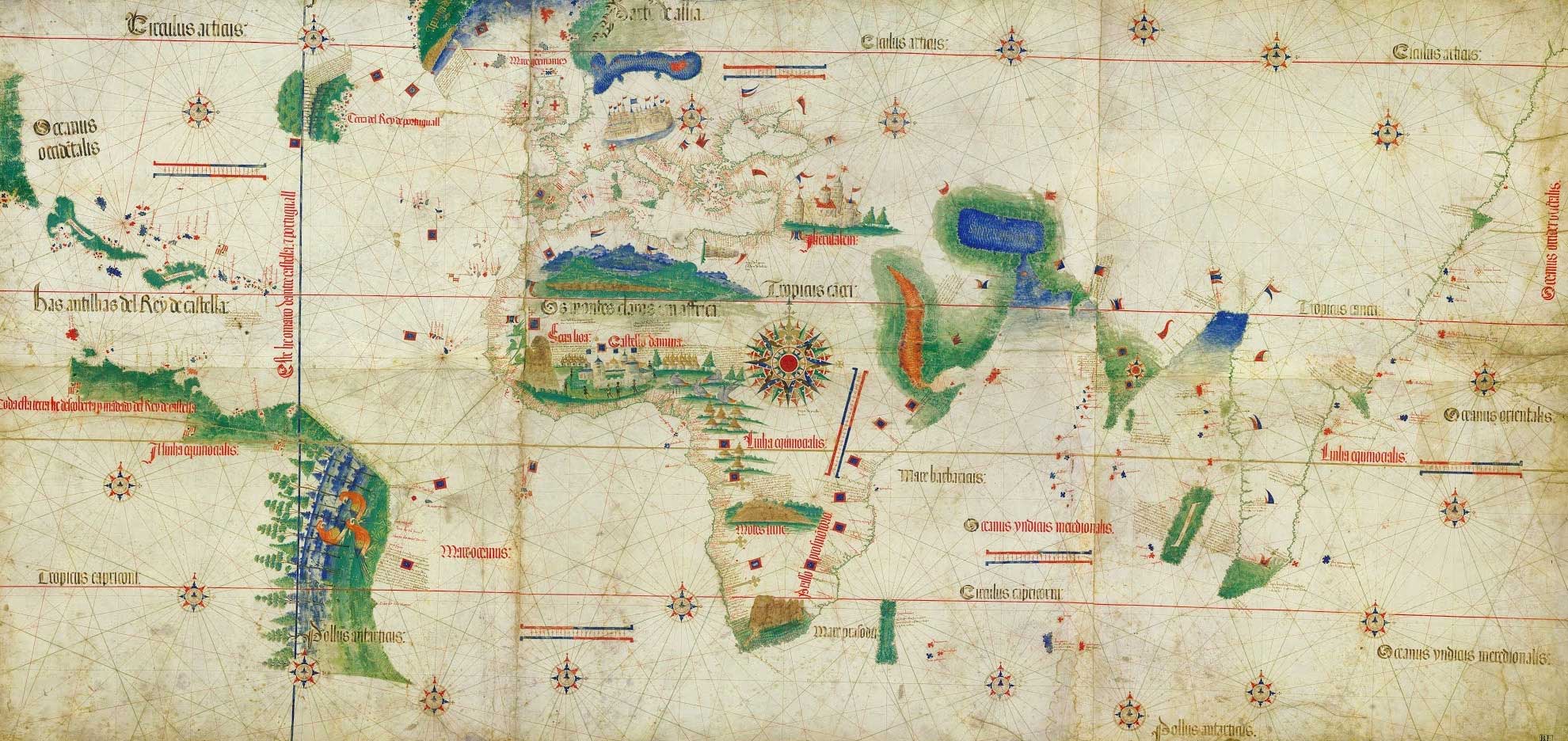

While looking at the history of travelling and the reasons people started to travel, I wanted to distinguish the difference between travellers and explorers. Most of the time, when thinking about travel in history, people like Marco Polo or Christopher Columbus are coming to mind. However, they weren’t really travellers in a modern sense. They were explorers and researchers. So, to really learn about how people started to travel, I wanted to focus on ordinary people. Travellers like you and me, if you wish.

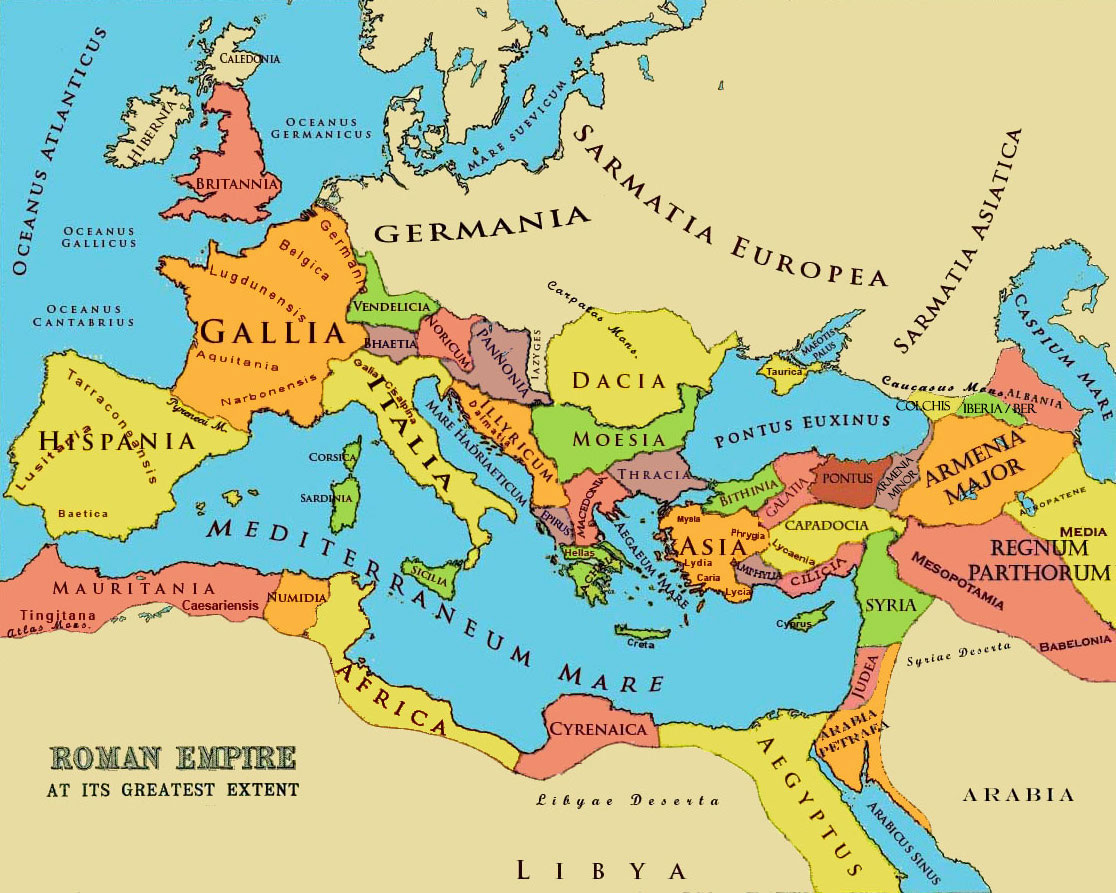

Romans and their roads

First people who started to travel for enjoyment only were, I’m sure you won’t be surprised, old Romans. Wealthy Romans would often go to their summer villas. And it was purely for leisure. They could, of course, start doing that because they invented something quite crucial for travelling – roads. Well developed network of roads was the reason they could travel safely and quickly.

However, there is another reason that motivated people in Antiquity to travel. And I was quite amazed when I learned about it.

It was a desire to learn. They believed travelling is an excellent way to learn about other cultures, by observing their art, architecture and listening to their languages.

Sounds familiar? It seems like Romans were the first culture tourists.

⤷ Read more : 20 Archaeological sites you have to visit in Europe

Travelling during the Middle Ages

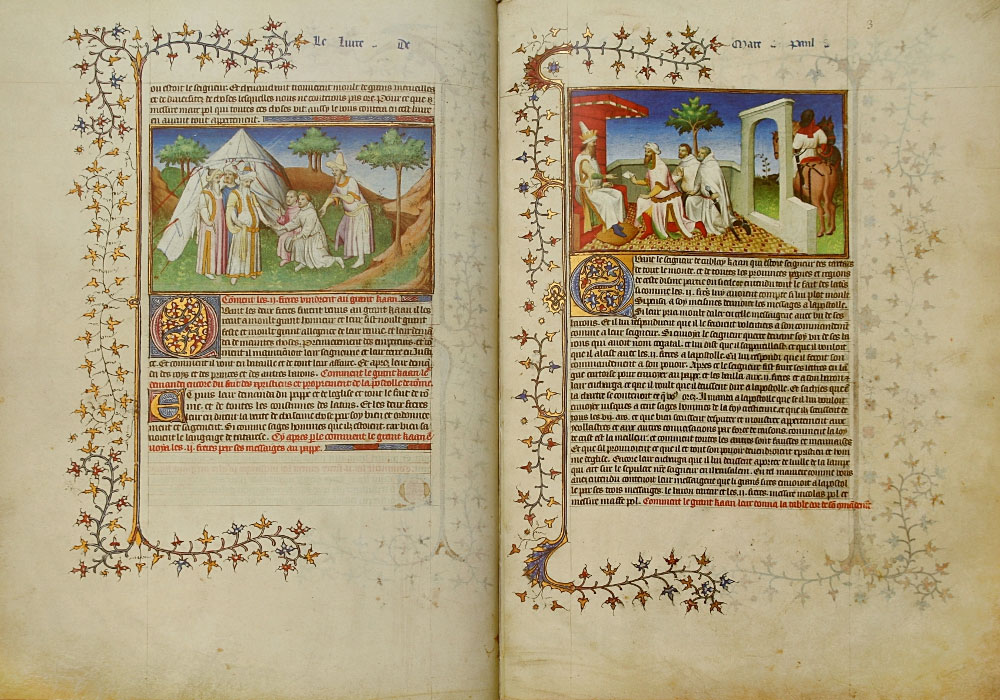

It may come by surprise, but people started to wander more during the Middle Ages. And most of those journeys were pilgrimages.

Religion was the centre of life back in the Middle Ages. And the only things that connected this world with the saints people were worshipping, were the relics of saints. Pilgrims would often travel to another part of the country, or even Europe to visit some of the sacred places.

The most popular destinations for all those pilgrims was Santiago de Compostela, located in northwest Spain. People would travel for thousands of kilometres to reach it. To make a journey a bit easier for them, and to earn money from the newly developed tourism, many guest houses opened along the way. Pilgrims would often visit different towns and churches on their way, and while earning a ticket to heaven, do some sightseeing, as well.

Wealthy people were travelling in the caravans or by using the waterways. What’s changing in the Middle Ages was that travel wasn’t reserved only for the rich anymore. Lower classes are starting to travel, as well. They were travelling on foot, sleeping next to the roads or at some affordable accommodations. And were motivated by religious purposes.

⤷ TIP : You can still find many of those old pilgrim’s routes in Europe. When in old parts of the cities (especially in Belgium and the Netherlands ), look for the scallop shells on the roads. They will lead you to the local Saint-Jacob’s churches. Places dedicated to that saint were always linked to pilgrims and served as stops on their long journeys. In some cities, like in Antwerp , you can follow the scallop shell trails even today.

Below you can see one of the scallop shells on a street and Saint-Jacques Church in Tournai , Belgium.

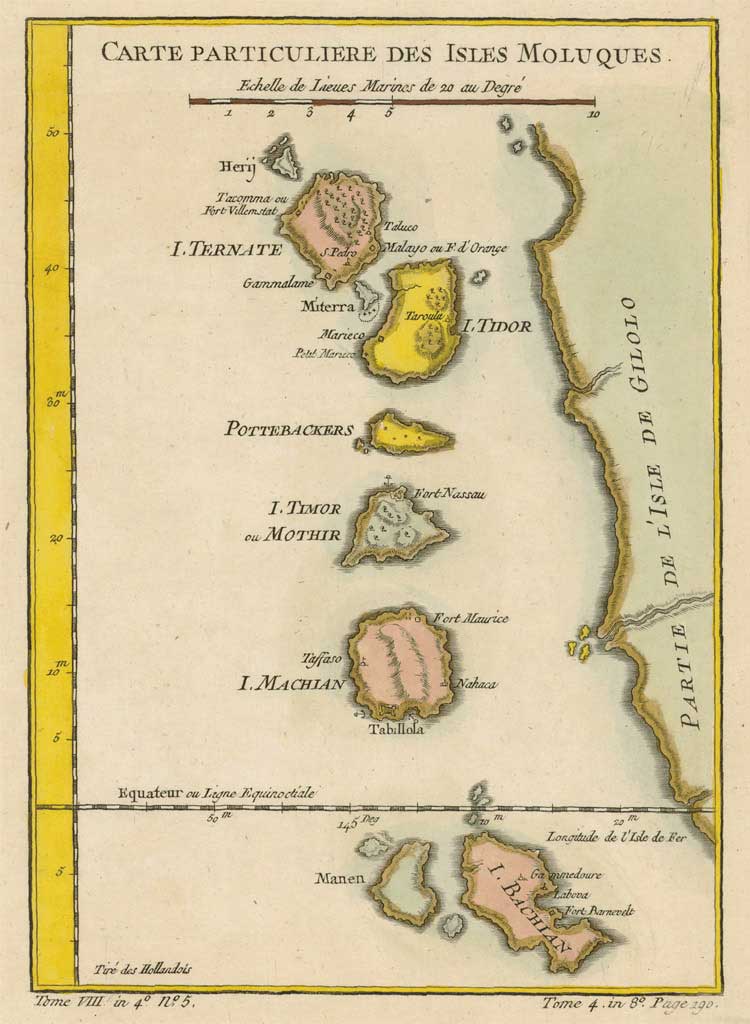

Grand Tours of the 17th century

More impoverished people continued to travel for religious reasons during the following centuries. However, a new way of travelling appeared among wealthy people in Europe.

Grand tours are becoming quite fashionable among the young aristocrats at the beginning of the 17th century. As a part of their education (hmmm… culture tourists, again?) they would go on a long journey during which they were visiting famous European cities. Such as London , Paris , Rome or Venice, and were learning about their art, history and architecture.

Later on, those grand tours became more structured, and they were following precisely the same route. Often, young students would be accompanied by an educational tutor. And just to make the things easier for them, they were allowed to have their servants with them, too.

One of those young aristocrats was a young emperor, Peter the Great of Russia. He travelled around western Europe and has spent a significant amount of his time in the Netherlands. The architecture of Amsterdam and other Dutch cities definitely inspired a layout of the new city he has built – Saint Petersburg . So, travelling definitely remains an essential part of education since Roman times.

⤷ Read more : 15 Best museums in Europe you have to visit this year

The railway system and beginning of modern travel in the 19th century

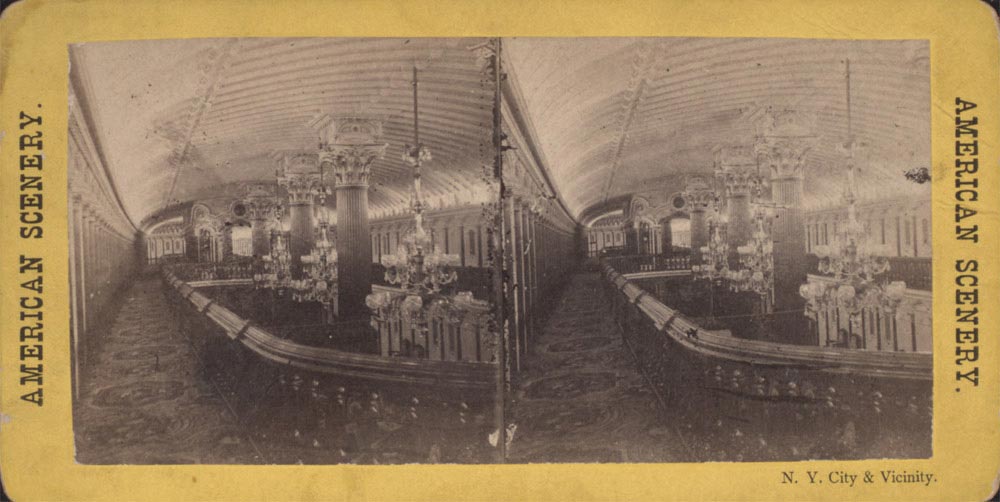

Before the railway system was invented, people mostly travelled on foot (budget travel) or by water (the first-class travel at that time). However, when in the 1840s, an extensive network of railways was built, people started to travel for fun.

Mid-19th century definitely marks a real beginning of modern tourism. It’s the time when the middle class started to grow. And they have found a way to travel easily around Europe.

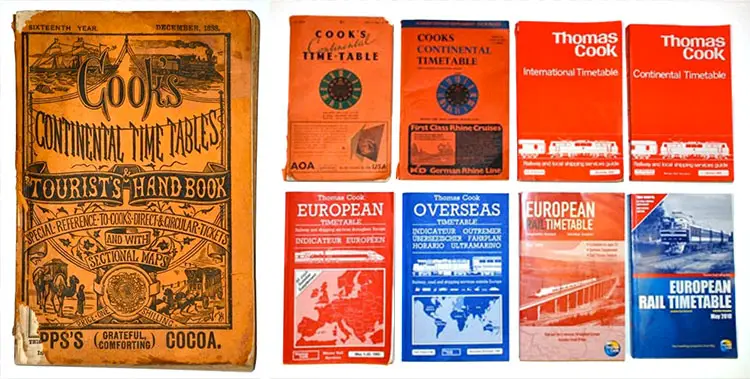

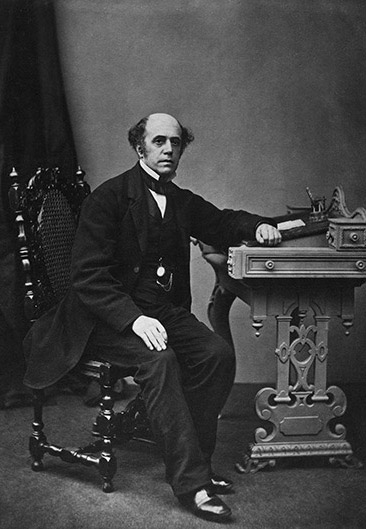

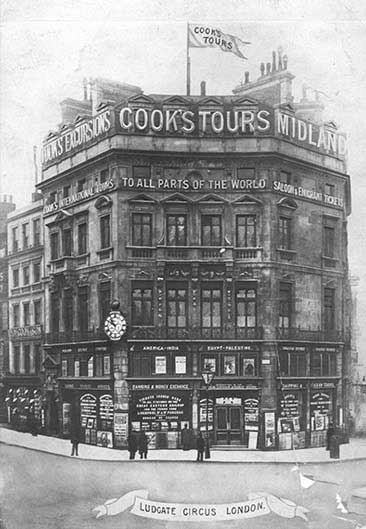

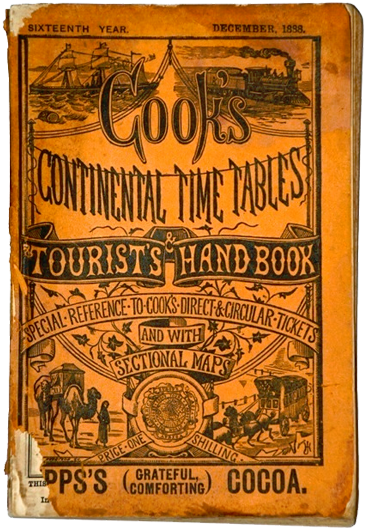

It’s coming by no surprise that the first travel agency, founded by Thomas Cook in England, was established at that time, too. He was using recently developed trains together with a network of hotels to organise his first group trips.

⤷ Read more : The most interesting European myths and legends

History of travelling in the 20th century

Since then, things started to move quickly. With the development of transportation, travelling became much more accessible. Dutch ships would need around a year to travel from Amsterdam to Indonesia. Today, for the same trip, we need less than a day on a plane.

After the Second World War, with the rise of air travel, people started to travel more and more. And with the internet and all the cool apps we have on our smartphones, it’s easier than ever to move and navigate your way in a new country. Mass tourism developed in the 1960s. But, with the new millennium, we started to face the over-tourism.

We can be anywhere in the world in less than two days. And although it’s a great privilege of our time, it also bears some responsibilities. However, maybe the key is to learn from history again and do what old Romans did so well. Travel to learn, explore local history and art, and be true culture tourists.

History of Travelling , How people started to travel , Travel

Join Us On YouTube!

Matsumoto Castle, Nagano, Japan

A Brief History of Travel and Tourism

Utilizing the widest definition of the word, human beings have been travelling since the dawn of time. No matter one’s beliefs about the creation of humans, everyone can agree our species began in some single locale, likely Africa or the Middle East , and ‘travelled’ outwards, settling new lands. However, most of this ‘travel’ was done out of necessity and war, often without the intent of return. It wouldn’t be until Antiquity, or the glory days of the Greek and Roman empires, that tourism, or leisure travel, would be introduced.

Aristocratic Tourism

In those days, tourism was a privilege almost entirely confined to the wealthy, who travelled largely for cultural exploration. One has to remember, the Greek and Roman upper classes were people who prided themselves on artistic, scientific, and philosophical pursuits. It follows, then, that these early travellers largely sought to learn the arts, languages, and cultures of their destinations.

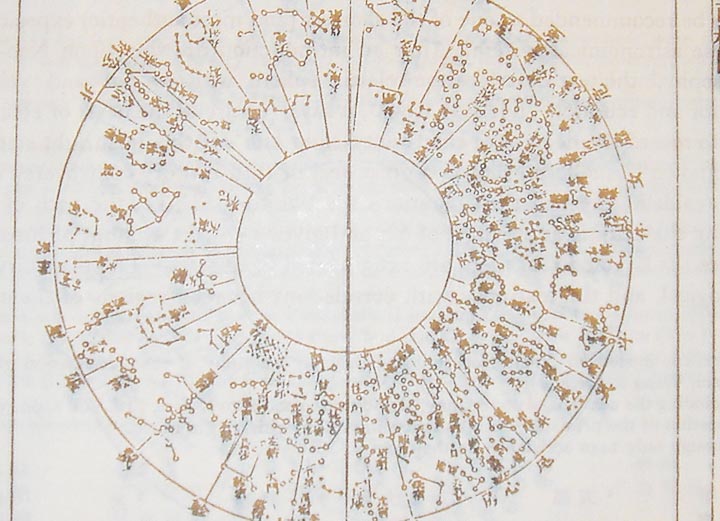

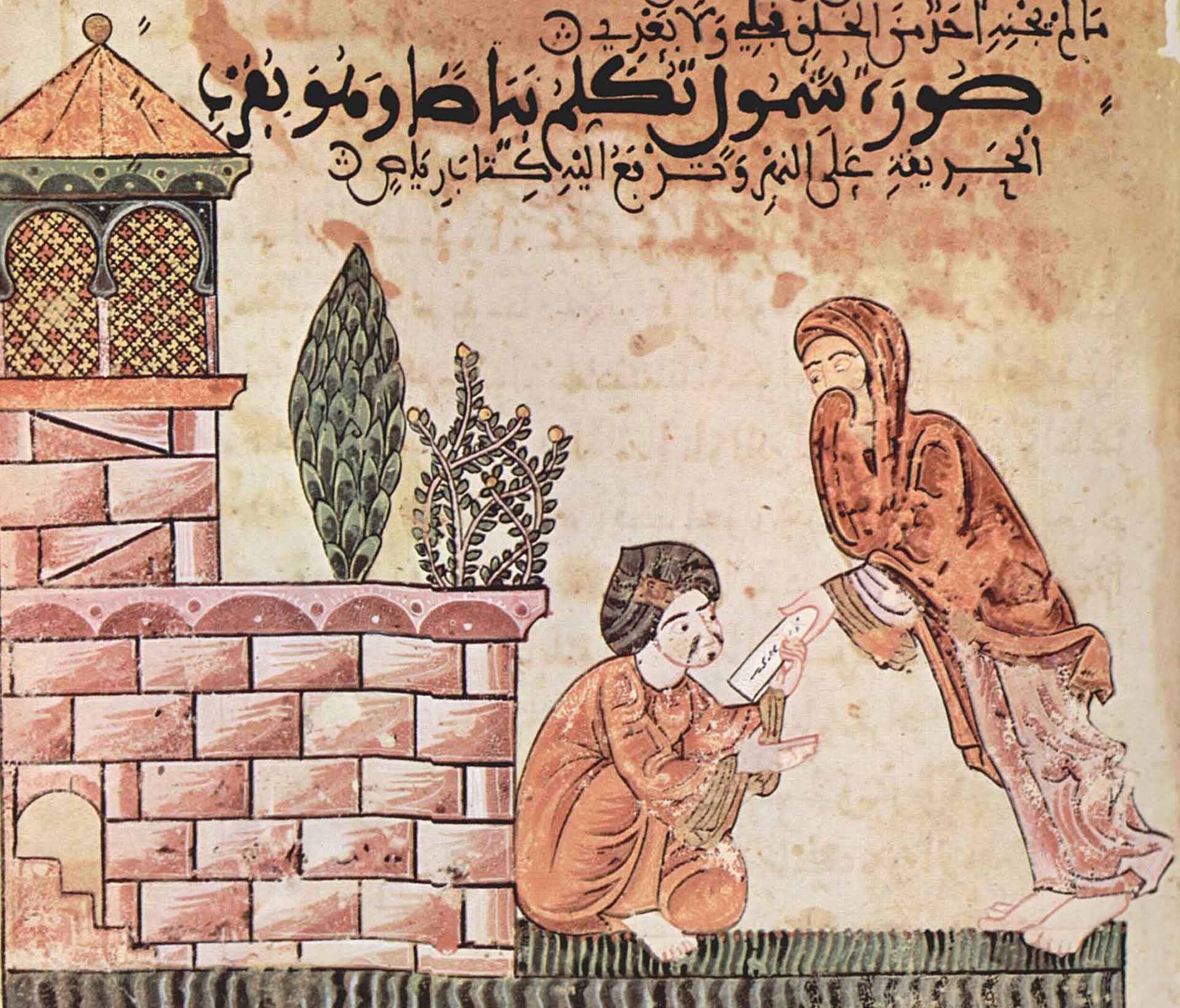

Soon enough, travelling for leisure’s sake began to gain popularity; from the Roman Empire arises some of the earliest examples of travel resorts and spas in the world. Though they documented their experiences most thoroughly, the elite Europeans were not the only ones travelling in ancient times. In eastern Asia , it was popular for nobles to travel across the countryside for the religious and cultural experience it offered, oftentimes stopping at temples and sacred sites during their travels.

Religious Tourism

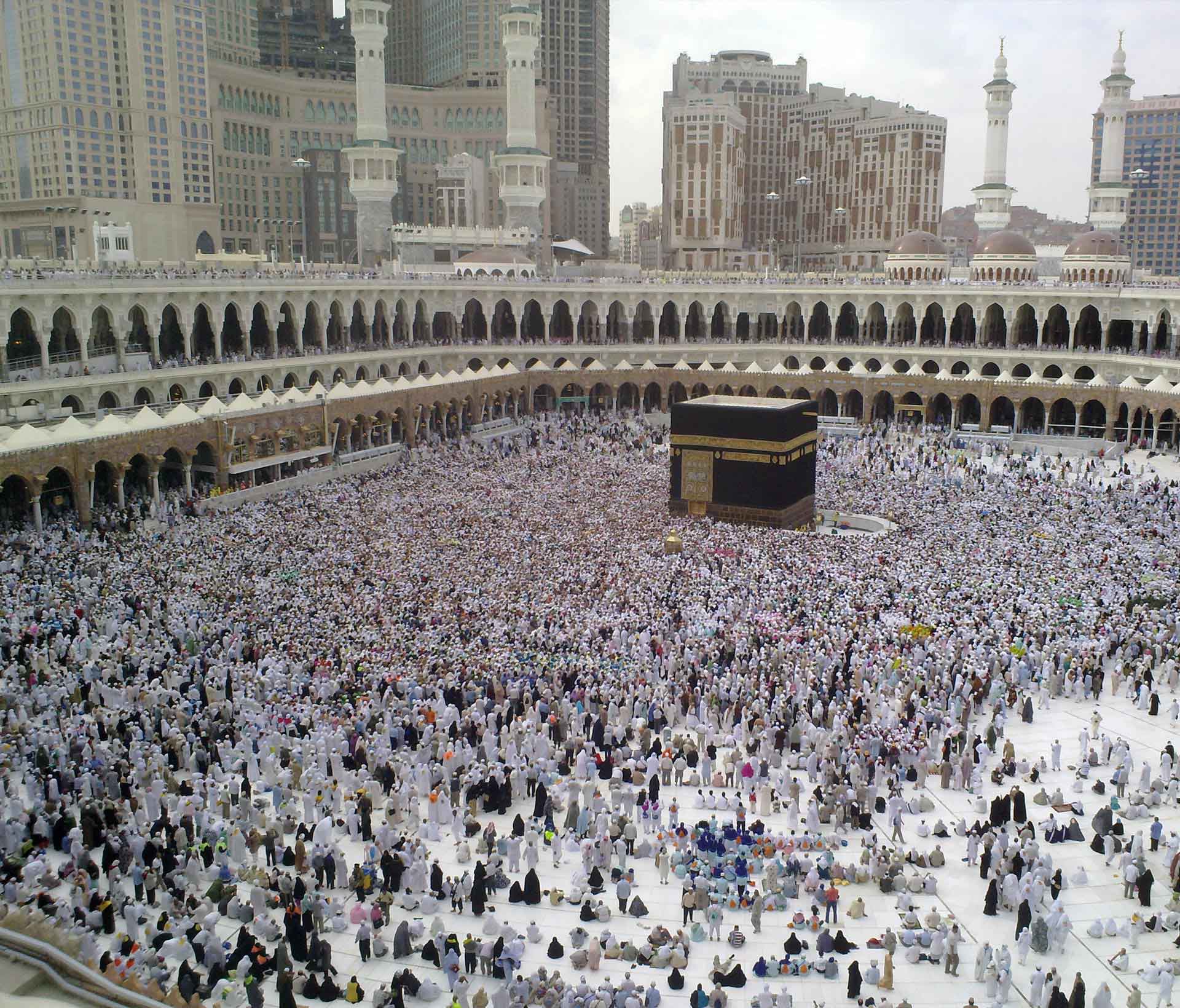

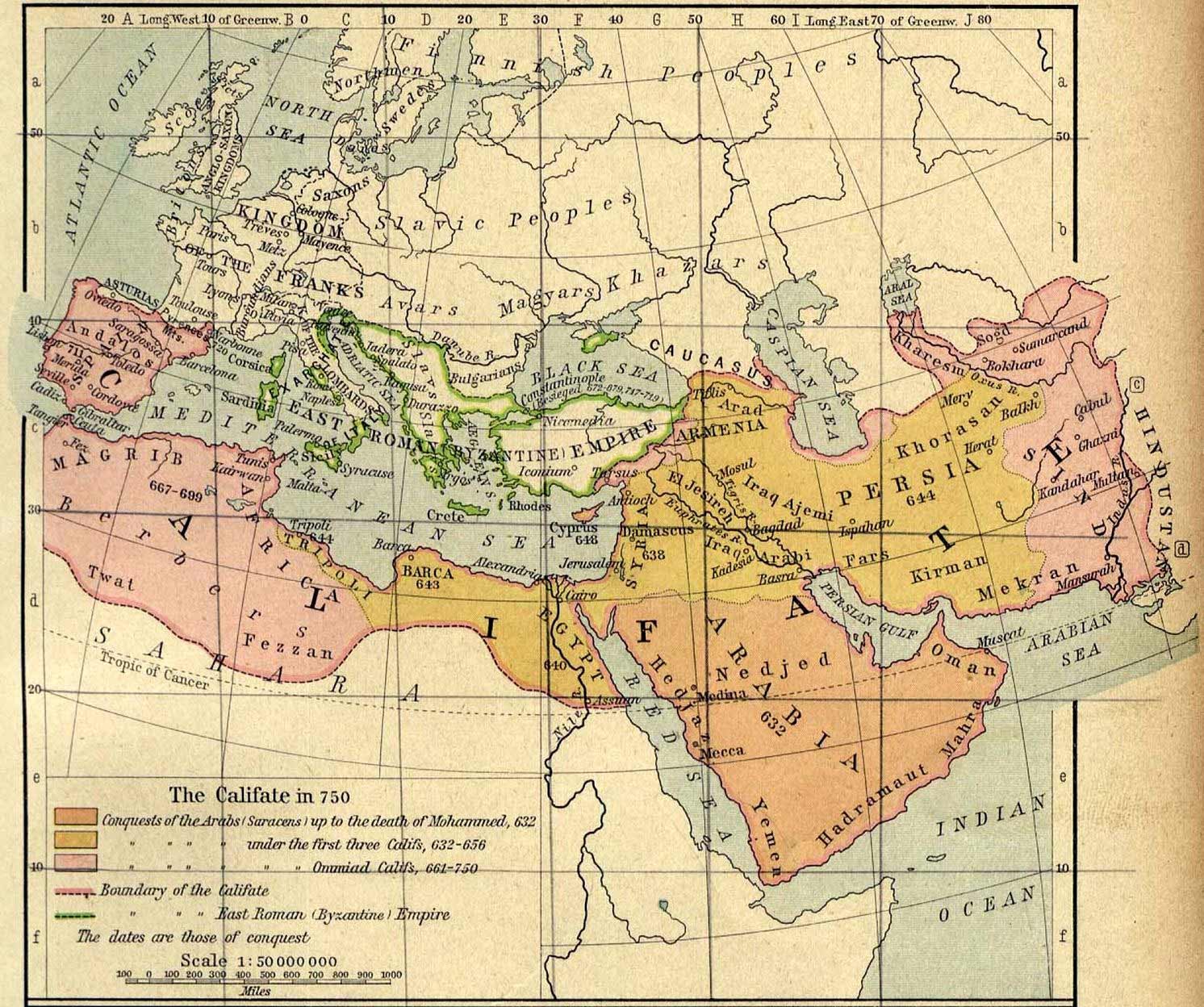

During the Middle Ages, travel took on a new meaning. Although leisurely travel was still reserved for the upper class, it became more and more common for members of the upper and even lower classes to embark on pilgrimages. Most of the major religions at the time, including the Islamic, Judaic, and Christian traditions, encouraged their practitioners to conduct pilgrimages.

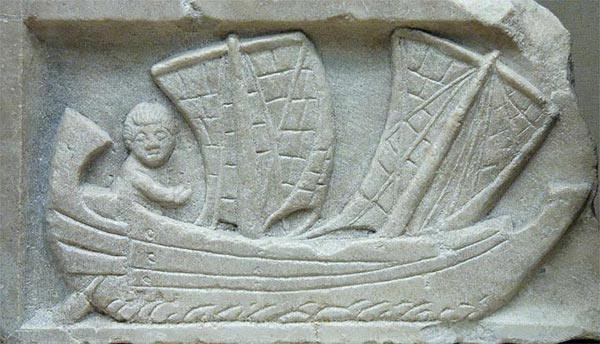

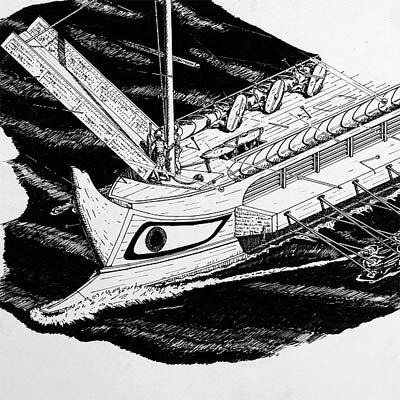

Largely unaided by technology, most of these journeys were done on foot, often occasionally with a beast of burden to carry supplies. The wealthy were able to afford other forms of travel including horseback and ship. Furthermore, the Middle Ages saw the emergence of connected shipping routes. As ports grew, travel opportunities increased, and the dock was typically the start of any long-distance travel during the Middle Ages.

The Grand Tour

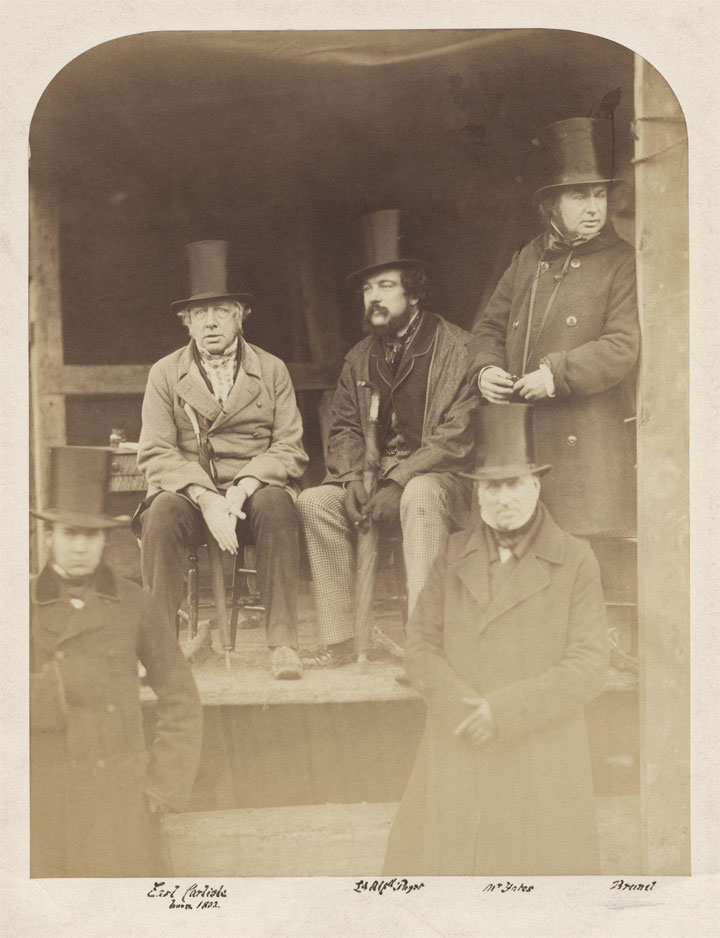

Travel continued to exist in this way for some time: the rich travelled primarily for cultural and leisure reasons, while the poor travelled largely for religious reasons, if at all. The next major development travel underwent was the establishment of the Grand Tour. Undertaken by the elite men of Western and Northern European countries , the Grand Tour took young travellers across Europe in a “rite of passage” meant to educate the wealthy after they finished their education but before adulthood. Historians cite this tradition as the origin of the modern tourism industry and indicate that the tradition had become well established in European culture by the 1660s.

Like many traditions, the Grand Tour eventually developed a rigid structure. Tourists were expected to follow a set itinerary and travelled with a tutor. The Grand Tour typically began in England, moved south through France into Switzerland and Italy. After spending a few months in Italy, the traveller and his tutor moved upwards through Germany and into Holland before returning to England. These trips utilized the most advanced travel technology of the day, including ships and collapsable coaches, and it wasn’t entirely uncommon for the traveller and tutor to be waited on by a handful of servants.

Tourism For The Masses

The Grand Tour remained a popular cultural phenomenon amongst the rich until the 1840s, which saw the advent of the first widespread railway system across system Europe. Immediately, this innovation opened the possibility of embarking on a Grand Tour to the middle classes, and soon it became more popular for middle and even working-class citizens to travel for leisure.

More importantly, the implementation of railway systems across Europe and the United States positioned the world for the Industrial Revolution. The United Kingdom is often cited as the first country to actively promote leisure time to its industrial class, and as a result, the country had a strong impact on the early development of the tourism industry. One hugely influential player in the history of travel and tourism was Englishmen Thomas Cook, who established the first-ever travel agency to provide ‘inclusive individual travel’ in the 1840s.

This means that travellers move independently in their travels, but all the food, lodging, and travel expenses were set at a fixed price for a predetermined length of time. This allowed travellers to take any route they fancied throughout Europe without having to ascertain food or lodging ahead of time. This fact, coupled with the falling ticket prices of railways, meant that long-distance travel was dramatically cheaper and faster than ever before. This not only further lowered the barriers to leisure travel but also drastically increased the incidences of business-related travel. As one can imagine, Cook’s Tours became massively popular, and the company remains successful today as the Thomas Cook Group.

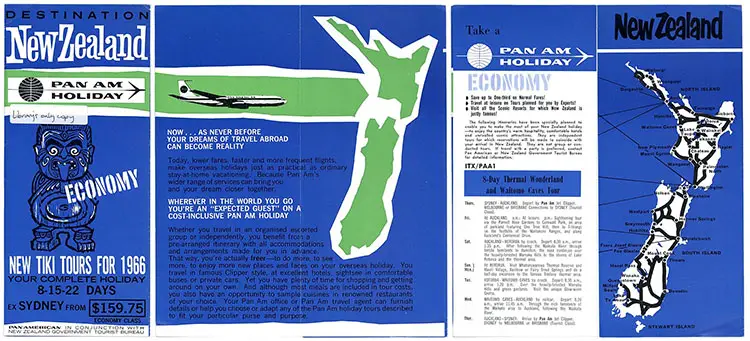

In short, the introduction of a widespread railway system gifted a massive boost to the tourism industry; this boon would largely reflect that the aeroplane would have in the early-20th century. More so than any other technological development, the aeroplane opened the floodgates of mass international tourism. Behemoth multinational airlines such as Pan Am, Delta, and American Airlines arose during the 1900s, and suddenly the physical boundaries between cities were rendered useless. It has become possible for a traveller to get nearly anywhere on the globe in less than 48 hours, for a price that most middle and working-class members can achieve.

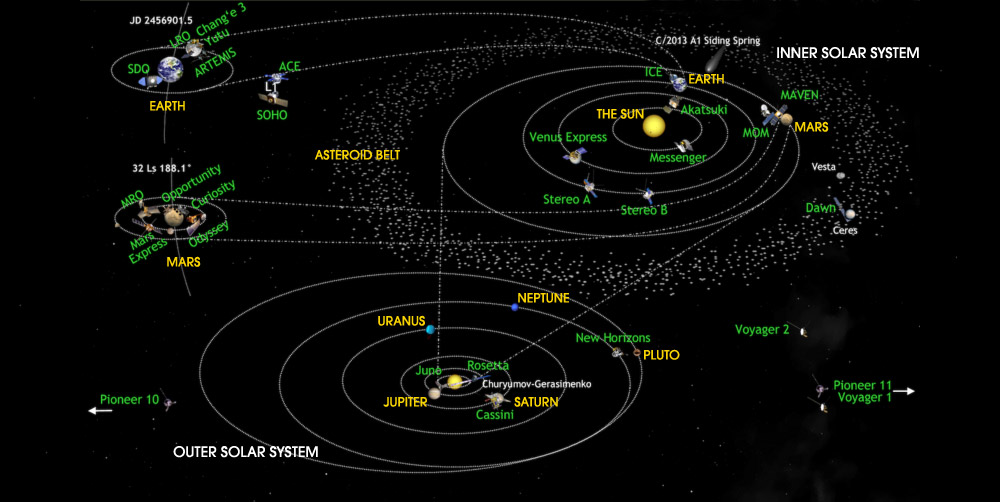

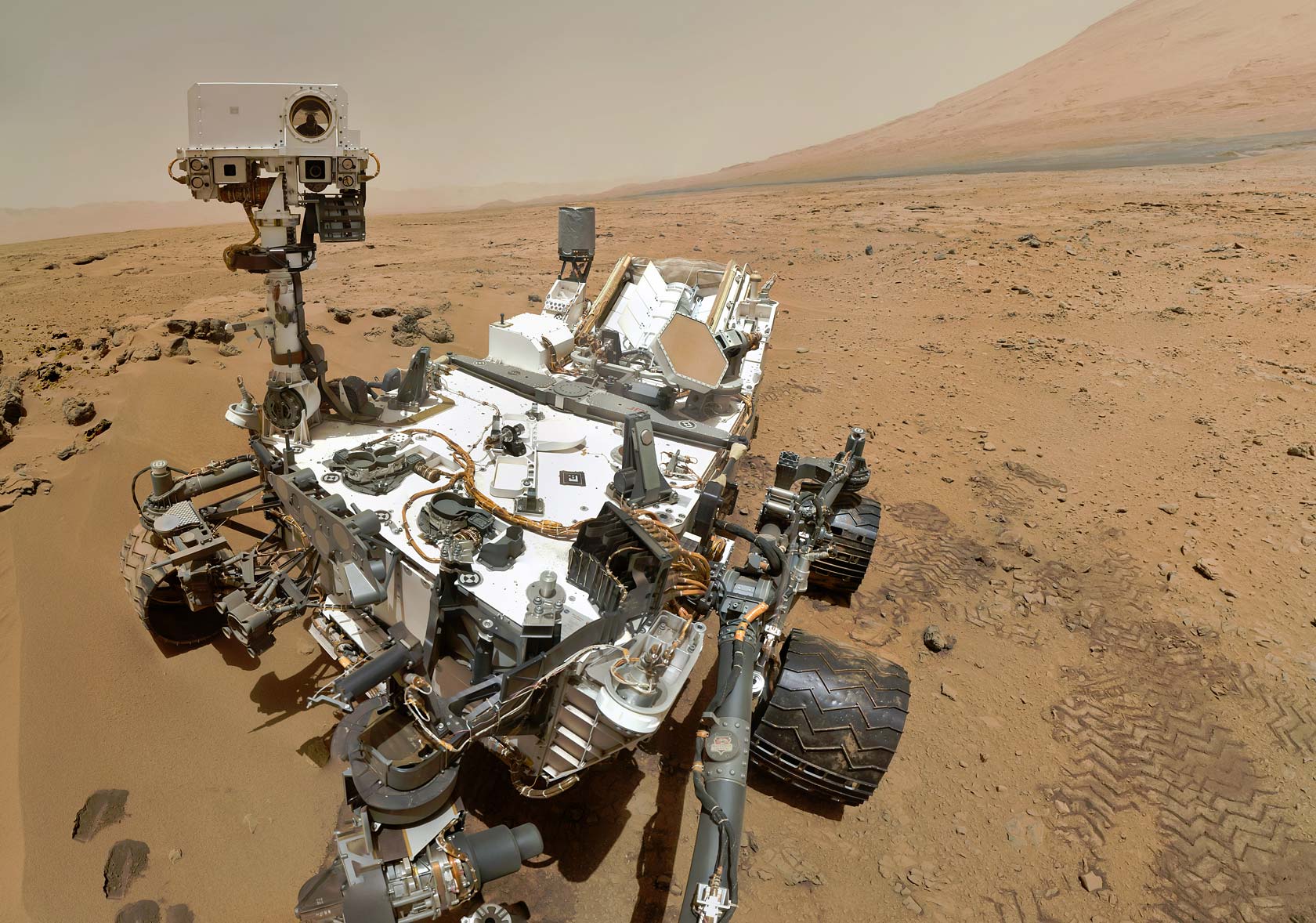

Today, travel stands as one of the most economically important leisure activities in the world. The tourism market is so large that it has split into an astounding number of niche markets, including ecotourism , backpacking, and historical tourism. As of the writing of this article, there have even been a handful of trips into orbit around Earth branded as “space tourism”, a new and exciting chapter in the history of travel and tourism. The story of tourism displays a remarkable connection to the technology that makes travel possible. Transportation innovations like the train and aeroplane have eliminated the difficulties and lowered the costs of long-distance travel, and planet Earth has truly become a smaller place because of it.

© Textbook Travel 2024 ⋅ View Privacy Policy

How and When Did Tourism Start?

Most of us love to travel and when we think about travelling, what we probably have in mind are the best two or three weeks of the year. Tourism has become a major industry and it creates around 100 million jobs worldwide.

Achim Riemann

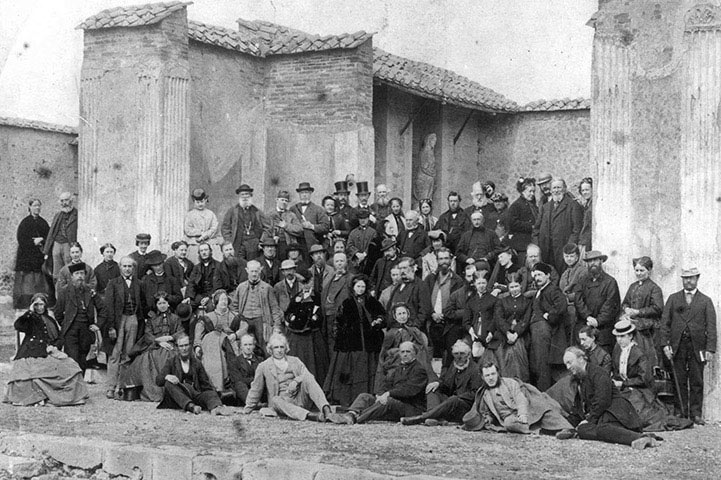

In 1854, the first travel agency opened. In 1869, one of the first group tours was launched. It included attendance at the opening of the Suez Canal in Egypt.

But how did it all start?

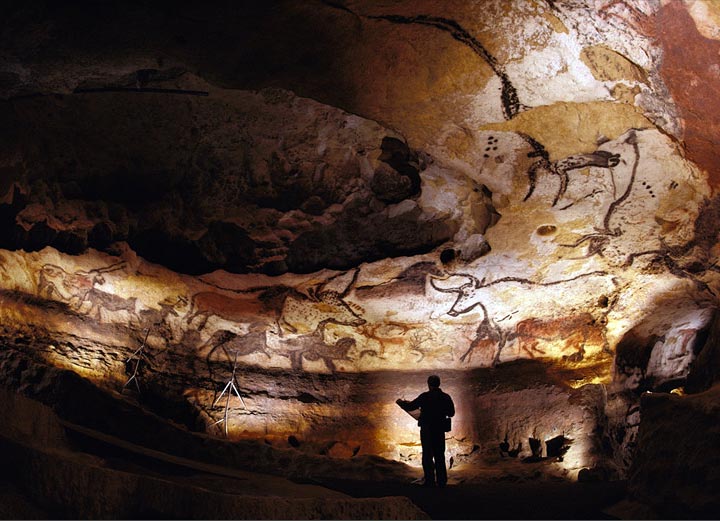

A long time ago, people initially moved around for practical reasons, such as looking for food or water, or fleeing natural disasters or enemies. But as early as ancient Egypt and in the other “high” cultures found throughout the continents at the time, people started to travel for religious reasons. They set out on pilgrimages, for example to Mecca, or on journeys to take a ritual bath in the Ganges River. That was the beginning of tourism.

What about modern tourism?

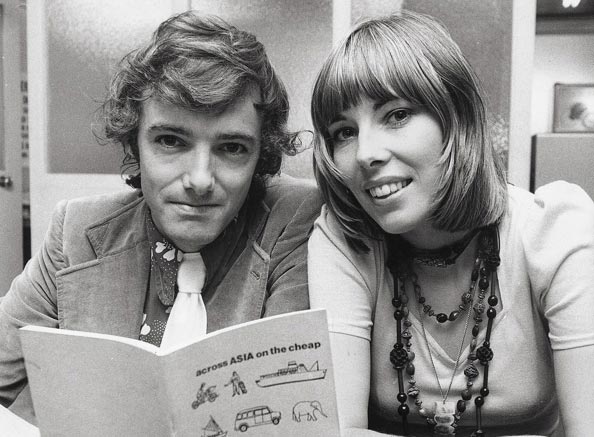

Modern tourism can be traced back to the so-called “Grand Tour”, which was an educational journey across Europe. One of the first who embarked on this journey was the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, Wladyslaw IV Vasa, also known as Wladislaus Sigismundus, Prince of Poland and Sweden. And yes, the grand tour was just for the super-rich. In 1624, Wladyslaw travelled to Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, France, Switzerland, Italy, Austria and the Czech Republic. (1)

Poor or even normal people had neither the money nor the time to go on a holiday. However, that started to change at the end of the 19th century. Around 1880, employees in Europe and North America were granted their first work-free days besides Sundays and the mostly Christian holidays, such as Easter or Christmas. These extra work-free days were usually unpaid in the beginning. Since most people couldn’t spare the money for travel, this led to excursions into the surroundings rather than travelling.

The founders of international “tourism” in Europe were the British

Thomas Cook is considered the founder of what is known as organized “package” holidays. In the last decades of the 19th century, the upper social classes in England were so wealthy due to the income from the British Empire that they were the first to be able to afford trips to far-flung areas. (1)

In 1854, the first travel agency opened. In 1869, one of the first group tours was launched. It included attendance at the opening of the Suez Canal in Egypt. From 1889, people took holiday cruises on steamships with musical performances. Seaside holidays became really popular around 1900 (and continue to be popular to this today). From the 1970s onwards, many in the industrialised countries could finally afford a holiday trip. The first criticism over this arose at the beginning of the 1970s: due to tourism, there were as many tourists in Spain in 1973 as there were inhabitants. (2)

In 2019, before the coronavirus pandemic, 1.5 billion tourist arrivals were recorded around the world, a 4% increase compared to 2018's figures. The most visited countries in 2019 were France with 89 million tourists, followed by Spain with 83 million tourists and the United States with 80 million tourists. China and Italy sit at fourth and fifth places, respectively, with 63 million tourists in China and 62 million tourists in Italy. (3)

And what are the most visited tourist attractions worldwide? According to a recent research from TripAdvisor, these are the top five: the Colosseum (Italy), the Louvre (France), the Vatican, the Statue of Liberty (USA), the Eiffel Tower (France) (4).

- Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tourismus , 12.03.2022

- Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Massentourismus , 12.03.2022

- TravelBook: https://www.travelbook.de/ziele/laender/die-meistbereisten-laender-der-welt

- Travel Wanderlust: https://www.travelwanderlust.co/articles/most-visited-tourist-attractions-in-the-world/ 12.03.2022

Subscribe to newsletter

Tourism Through the Ages: The Human Desire to Explore

- Read Later

Although taking a summer vacation is now a standard aspect of modern-day civilization for many, it wasn’t always that way. Tourism was far less common in ancient times than it is today, but that certainly doesn’t mean it didn’t occur at all. Even in ancient times, people had a natural curiosity about the world around them and yearned to explore.

However, tourism didn’t necessarily look the same then as it does now. So what did tourism look like, and where did ancient peoples like to travel the most? What was the perception of tourists in ancient times versus today?

What was Ancient Tourism Like?

Tourism as we think of it has not always existed. In fact, travel was not possible for most people in ancient times. Travel was often difficult and full of dangers such as disease , starvation, dehydration, or death by wild animals. Because of this, travel was often seen as too risky unless absolutely necessary, such as for relocation, or religious, political, or medical purposes.

However, travel did still happen. Armies would travel to take over new lands or conquer new cities. Tradesmen would travel to popular trade spots throughout their countries to sell goods for profits, while others would travel there to buy utilitarian or luxury items for their homes. Others would travel for important religious ceremonies that they were required to attend. Travel of this nature was considered a need within society, rather than a want, so not tourism as such.

Lydgate and Pilgrims to Canterbury. Early ‘tourism’ was frequently for religious ceremonies and pilgrimages. (Jim Forest / CC BY NC ND 2.0 )

As time went on, technology advanced. With the expansion of roads and the development of more efficient travel using boats , chariots , and carriages, travel for leisure, or tourism, became an intriguing possibility. However, many individuals struggled with the same tourism questions we do today: if they could even afford to travel, and if they could, where they would go.

Early tourists tended to avoid cities with political or civil unrest as it could be dangerous in the event of an uprising. It’s unsurprising these would be eliminated as tourism destinations . They would also avoid cities their own regions had hostility towards, as that was also considered risky business. They would instead choose regions that were not known to be dangerous, just to see what was out there.

Although technological advancements made travel easier than walking or horseback, it was still perilous and time-consuming. Travelers would often bring small weapons for protection, along with any money they planned to spend. Travel would take from a few days to a few weeks (or even a few months!), depending on how far they planned to venture out. This also meant having to take preserved food with them to last the journey, or knowing where to stop along the way to find food when hungry. There were few to no establish tourism ‘rest stops’ in ancient times.

- Colosseum Will Have a Floor For The First Time in 1500 Years!

- Ancient Journeys: What was Travel Like for the Romans?

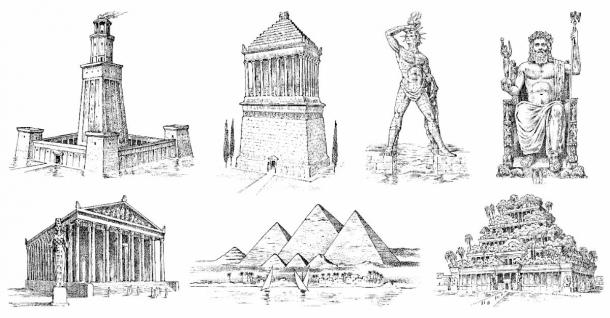

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World ( artbalitskiy / Adobe Stock)

Tourism Destinations of the Ancient World

There were many tourism destinations available in ancient times, but some were more popular than others. Particularly, ancient tourists enjoyed tourism spots that served multiple purposes. This started as early as the times of the ancient Egyptians , who often traveled for government activities but would stay in foreign areas longer than necessary to enjoy the local shops, restaurants, games, and other forms of entertainment.

This desire to stay abroad for entertainment continued with the Roman Empire. The Romans developed a system of roads that covered approximately 50,000 miles, in order to make travel easier. At the time, traveling 30 miles would take about a day, and they used that information to establish an inn system. Through this system, an inn would be placed approximately every 30 miles, so that you always knew you had a place to rest in the evenings as you traveled out.

With more tourism establishments like inns along the roads , travel felt safer as well. There would be more people present in case of an emergency, and a lower chance of running out of food or water. The risk of natural predators would be lower as well, since travel would no longer take place through endless plains or overgrown wilderness. The Roman system became so well-established that people from surrounding areas would visit Rome, just to see the roads, inns, and other established infrastructure.

Language and currency were an important part of tourism at this time as well. If your destination used a different currency or spoke a different language, you would likely be a bit reserved about spending much time there (if any time at all!). As a result, common tourism areas did business in several common languages, so they could be more inclusive of visitors and receive more tourism.

Tourism in the Middle Ages: Risky Business

After the fall of the Roman Empire , tourism was not the same. In fact, tourism hardly happened at all anymore because there was too much risk involved. Nations were at war with one another, and traveling to a new place meant inevitable danger for the traveler and their family. Lots of the efficient transportation infrastructure were now destroyed, and languages were more separated than ever.

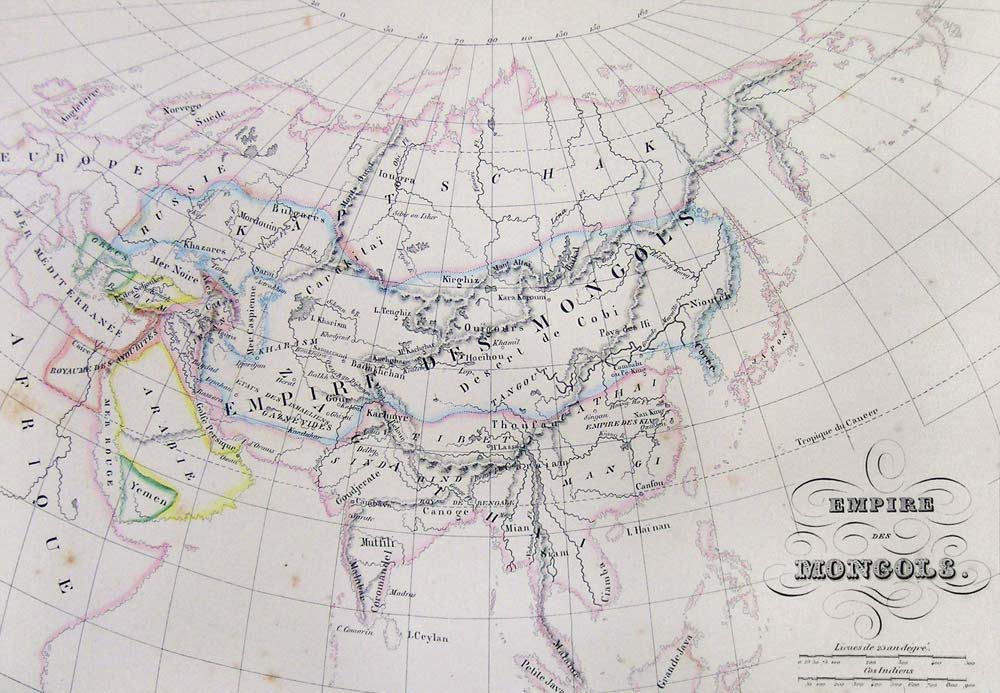

Travel returned to being a necessity rather than a vacation. Religious and political motives were the primary causes of any travel, as nations attempted to overtake one another. Trade routes had to be re-established, although many were still unwilling to risk the trek. It wasn’t until Marco Polo took the risk and began to write about his solo tourism in the 13th century that people began taking interest in exploration again.

By the Renaissance , trade began to take hold once more, and so merchants were willing to travel further than before. Additional trade and tourism businesses opened, and commercialism steadily increased, especially in Europe. People that would visit these trading posts to purchase new and luxury goods would wonder what the rest of the world was like, especially the sources of their favorite goods. This then ushered in the Grand Tour Era.

- Why Did Ancient People Travel Thousands of Kilometers for Incense?

- The Surprising and Iconic Bronze Age Egtved Girl: Teenage Remains Tell a Story of Trade and Travel

Exotic new products entering Renaissance markets fed a desire for tourism, Jan van Kessel the Elder 1650-1660 ( Public Domain )

The Grand Tour Era: Tourism for the Rich and Famous

The Grand Tour Era, as can be assumed by its name, was a major point in history for tourism. Between 1613 and 1785, the Grand Tour Era established tourism as a norm throughout many societies. However, it wasn’t always easy. Traveling at this time was mostly reserved for the upper classes, as travel and lodging had increased in price due to high demand. Rooms that could be provided for an average family were instead reserved for those able to pay the most.

Tourism was also held in high regard at this time because it was often used as a form of education. The children of the wealthy would travel abroad to gain an understanding of the world around them, making them more knowledgeable and well-rounded. Someone who’d had the opportunity to engage in tourism was seen as having a higher status than most, since they were perceived as more educated.

The most popular tourism regions at this time included Germany, Italy, France, and Switzerland. Europeans would often travel to these countries by carriage because it was more comfortable. Their carriage would be driven by an experienced chauffeur familiar with the routes, to make travel as efficient as possible. Tourists would frequently bring someone with them that would care for them, whether a servant or a more experienced traveler.

British Gentlemen in Rome, circa 1750 ( Public Domain )

Ushering in a New Era: The Industrial Revolution to Modern Times

Towards the end of the 18th century, tourism faced new challenges. The Industrial Revolution had changed tourism forever. Since people had more stable employment, they couldn’t take off for long periods of time to travel. Workers were stuck in their factories and businesses all week, unable to leave without jeopardizing the entire organization. Teamwork was essential and left no flexibility for vacationing.

However, the Industrial Revolution also helped people to travel more easily too. With new technology, travel became more efficient. Plus, for many workers, higher salaries contributed to their ability to go on a nice vacation. Additionally, business trips were increasing, to open more businesses and factories.

After several decades tied down to work and missing out on tourism experiences, workers began tiring of their overworked schedules. With more money came greater desire to expand one’s worldview. Planes, cars, and boats could be used to travel more quickly and comfortably than before. Office jobs also became more popular for their greater flexibility, and paychecks began to be used to see the world.

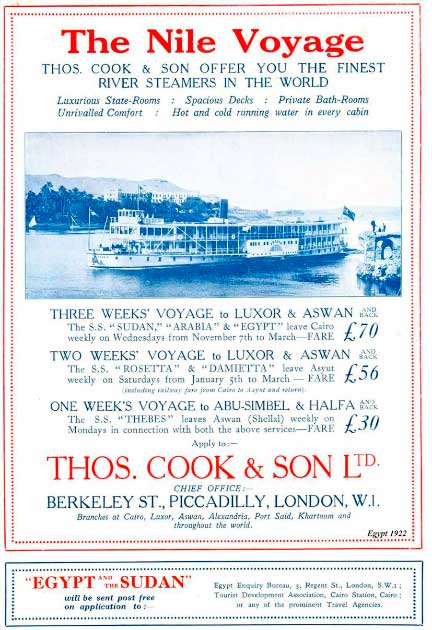

A 1922 Thomas Cook ad for a three-week trip on the Nile for £70 ($80) ( Public Domain )

At this point, tourism became an essential part of a fulfilling life. Countries such as France became hot spots for tourism because they had advanced technology and roads compared to other regions. Thomas Cook, an English businessman, inspired those without tourism experience to take a leap and go on an adventure. Later, paid work leave established for many in the 20th century ensured that more families could take the time to travel. It was the biggest increase in tourism since the Grand Tour Era.

Throughout the 20th century, hotels and motels became more common businesses worldwide, further fueling the tourism industry. Later, the development of credit cards helped lower-income families afford vacations more easily. Credit cards also helped universalize currency, so traveling between countries and buying necessities became more efficient. In the 21st century, traveling has become more accessible than ever.

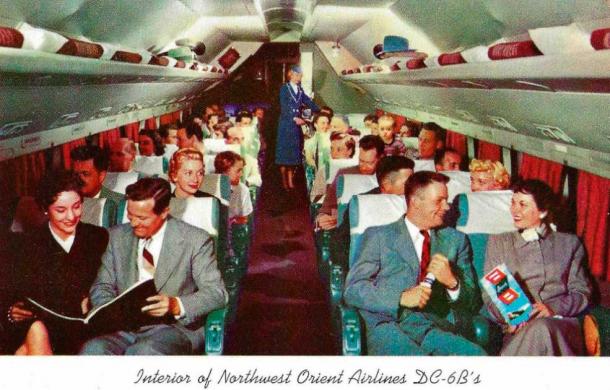

1957 postcard showing tourism airline interior (Joe Haupt / CC BY SA 2.0 )

Tourism Today: Roadside Attractions, Cruises, #VanLife, and more

Tourism in ancient times could be difficult, but those early tourists certainly made the most of it. Today, travel and tourism are certainly much simpler than they were back then. There is more available information about different countries that can be considered before taking a trip, and most frequent travelers are looking for more than just new scenery. Tourism agencies now seek to put together packages for those looking for adventure, romance, or knowledge.

The biggest difference between ancient and modern tourism is purpose. While ancient people traveled as a way to learn about the world around them, modern tourists seek to gather and savor experiences. Experiencing new places and cultures is more fulfilling than simply learning about the place online. If nothing else, travel nowadays is certainly much more efficient and luxurious than ever before. After all, aren’t you glad you don’t have to take a chariot everywhere?

Top image: Vintage postcard showing European tourism destinations. Source: Freesurf /Adobe Stock

By Lex Leigh

A Historical View of Tourism . Study.com. (n.d.). Available at: https://study.com/academy/lesson/a-historical-view-of-tourism.html

Gyr, U. (December 13, 2010). The History of Tourism: Structures on the Path to Modernity . EGO. Available at: http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/europe-on-the-road/the-history-of-tourism/ueli-gyr-the-history-of-tourism

Rodriguez, C. P. (June 16, 2020). Travelling for Pleasure: A Brief History of Tourism . Europeana. Available at: https://www.europeana.eu/en/blog/travelling-for-pleasure-a-brief-history-of-tourism

Stainton, H. (May 27, 2022). The Fascinating History of Tourism . Tourism Teacher. Available at: https://tourismteacher.com/history-of-tourism-2/

Tourism . (n.d.) Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/tourism

Lex Leigh is a former educator with several years of writing experience under her belt. She earned her BS in Microbiology with a minor in Psychology. Soon after this, she earned her MS in Education and worked as a secondary... Read More

Related Articles on Ancient-Origins

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- Why Publish with PQ?

- About The Philosophical Quarterly

- About the Scots Philosophical Association

- About the University of St. Andrews

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

The Meaning of Travel

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Pilar Lopez-Cantero, The Meaning of Travel, The Philosophical Quarterly , Volume 71, Issue 3, July 2021, Pages 655–658, https://doi.org/10.1093/pq/pqaa065

- Permissions Icon Permissions

A philosopher's inquiry on travel may take different paths. Emily Thomas follows several in The Meaning of Travel , where she uncovers novel philosophical debates such as the ontology of maps or the ethics of ‘doom tourism’. Perhaps unexpectedly for the reader, Thomas also offers accessible and engaging discussions on—mostly Early—Modern philosophy by connecting travel-related topics to the work of some well-known authors (René Descartes and Francis Bacon), some unjustly neglected ones (Margaret Cavendish) and some known mostly to specialists (Henry More). The result of this bric-a-brac approach is mostly positive: Thomas's work stands out as an entertaining, insightful read, suitable for a wide readership, whilst also having the potential to be a foundational text in the philosophy of travel. And I agree with Thomas: philosophy of travel ‘isn’t a thing, but it should be’ (p. 3).

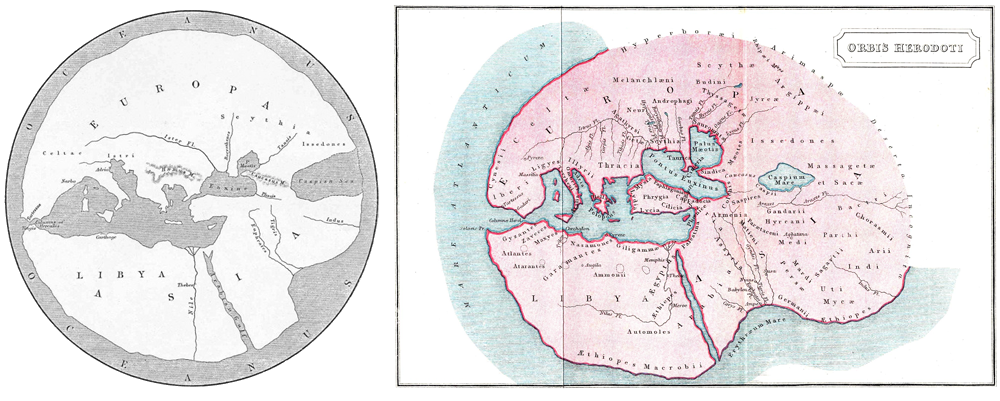

The book has twelve short, self-standing chapters that I divide here into two categories: chapters concerning the philosophy of travel and chapters attending to other philosophical themes that Thomas then connects with travel. Let us start with the first category. Chapter 1 convincingly states the case for the philosophical investigation of travel, and introduces the idea of travelling as the discovery of the unfamiliar, the exploration of ‘otherness’ (p. 3). In Chapter 2, on maps and cartography, Thomas impeccably combines a one-page, layperson-oriented definition of ontology with the launch of an intriguing question of concern to metaphysicians: Are maps things or processes? She believes they are the latter (p. 24), a point that is illustrated by the fact that we currently rely mostly on online maps—which, arguably, cannot be static things given their constant updating. This is an excellent chapter.

The following travel-focused discussion takes place in Chapter 5, on the origins of tourism. Tourism, says Thomas, was born when people started to travel by choice and for pleasure (p. 69). More recently, we travel to open up to the world by facing our fears (p. 84), to be able to brag to our friends (ibid.), and for ‘interior voyages’ of self-discovery (p. 85). This chapter contains a lot of historical trivia about the Grand Tour (the European adventure for young, wealthy British men in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries). It is both interesting and amusing, particularly the birth of the continental trope of debauchery-prone Brits abroad (pp. 78–9), which still pervades in some parts of Europe (the examples of Magaluf or Amsterdam come to mind, although the parallel with the present seems to have escaped Thomas).

Chapter 10 reveals the other side of the Grand Tour's story by launching the question of whether travel is a male concept. Whereas men were encouraged to embark in leisure travelling from its origin, women had to disguise themselves as men or use travel as a pretext for ‘ladylike pursuits’ such as painting (pp. 170–1). Again, the chapter is mostly historical, although Thomas also offers an explanation of the concept of gender for non-philosophers and highlights that in many cultures maleness is connected to adventure and exploration, while femaleness is usually tied to ‘home’ (p. 175).

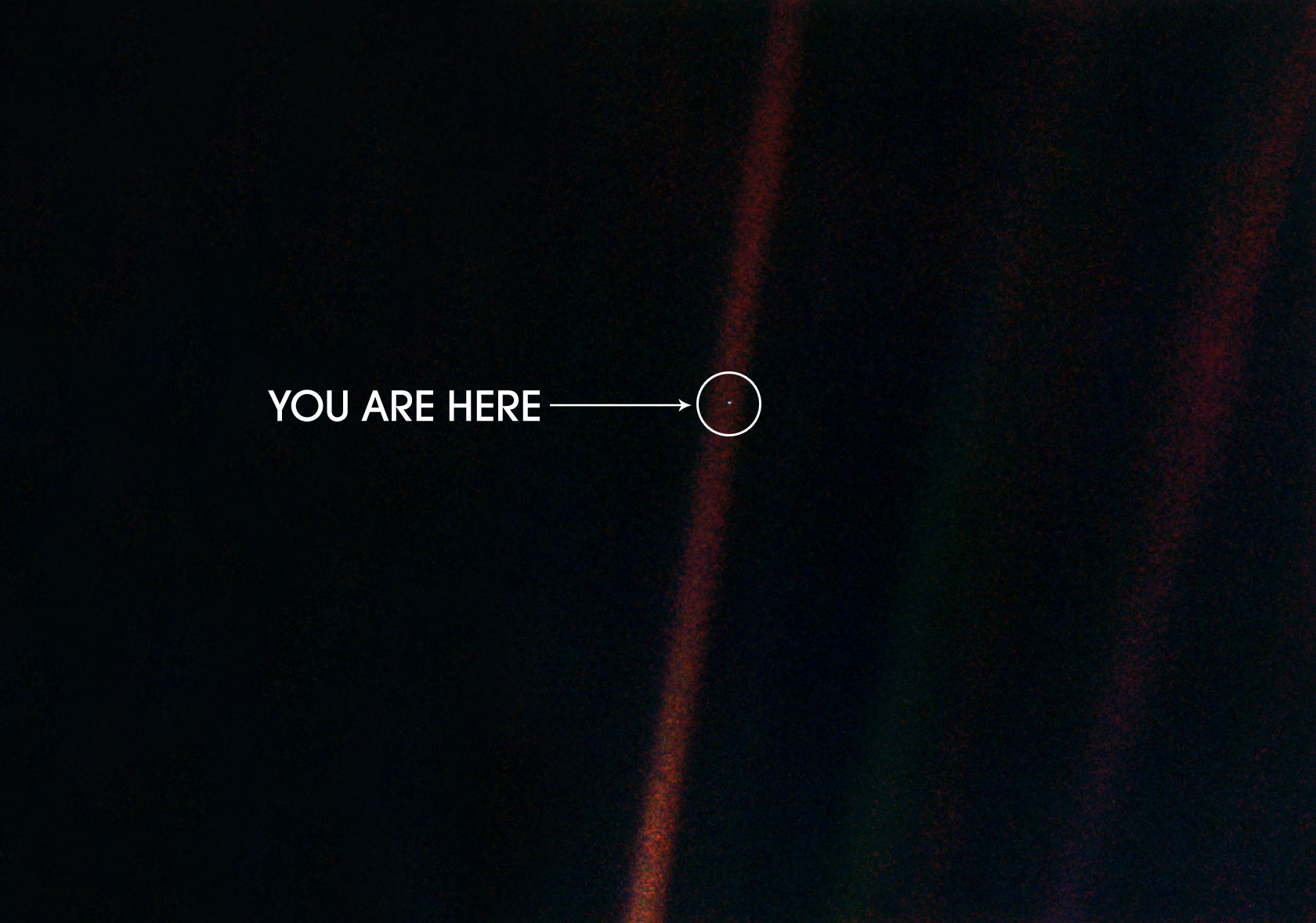

Finally, Chapter 11 explores the ethics of ‘doom tourism’, that is, travelling to places that are bound to disappear due to climate challenges. Thomas reveals a moral dilemma: while mass tourism may destroy these places faster, it may be that their precarious situation can only become known via the mouths of travellers (or ‘tourist ambassadors’, p. 183). This raises the question of what exactly it means to travel responsibly. Then, Chapter 12 delves on space tourism to reflect on the fact that travelling changes people, and specifically changes how they feel about their home places (pp. 190–1).

In the second group of chapters, Thomas connects travel to the work of several philosophers from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. This is the time of the explorers and the birth of tourism, which shape the structure of the book, and Thomas's works showcase how the work of philosophers reached beyond the armchair in the shape of Bacon's philosophy of science (Chapter 3), Locke's metaethics (Chapter 4), or More's philosophy of space (Chapter 7). Cavendish's account of matter in her fantasy short story Blazing World , which Thomas considers both a travel book and a thought experiment, receives long-deserved limelight in Chapter 6. There is also a place for discussing the sublime as an aesthetic concept (Chapter 8) and Thoreau influence on environmental thought (Chapter 9).

It is no minor feat to make the history of philosophy interesting for the non-specialist while trying to explain complex philosophical concepts in plain words. There aren’t either many philosophy books where one lifts one's head from the book to tell whomever is in the room yet another interesting anecdote (and does so often). However, the connection between travel and these authors (and, in turn, with chunks of the author's own travel diary) is not always done as seamlessly at it could be. These links often require stretches of thought, which Thomas, I believe, is too quick to endorse (More's influence on our view on mountains and Thoreau's link to the popularity of ‘cabin porn’ are two examples of this tendency).

I believe that the main strength of The Meaning of Travel is the chapters on the philosophy of travel, to the point of deserving a foundational status in the branch. Thomas launches more questions than she answers, but we must remember that this is not a book ‘for academic eyes only’. The type of answers a certain kind of philosopher may demand would have resulted in a completely different work—one with a way narrower reach. This book's academic value lies in the formulation of travel-focused questions on ontology (maps), ethics (responsible tourism), and political and social philosophy (personal change, gender), which by themselves deserve a philosophical branch of their own.

These questions that Thomas puts forward are not only of interest to people shielding in philosophy departments, but have a direct link to current affairs. I am referring specifically to the distinction between traveller and tourist, and to the notion of responsible travel (or responsible tourism, since these questions are related but independent of each other). Several local authorities (like those of Amsterdam, Barcelona, or Venice) have long raised the alarm regarding the effect mass tourism has on their homes. This is directly related to Thomas's doom tourism (in fact, Venice is in the list of disappearing destinations she reproduces in p. 181), but is put in slightly different terms by leaders in these mass destinations. Whereas travelling to environmentally challenged locations may be put in terms of responsibility, as Thomas does, the mayors of Amsterdam or Barcelona have been calling for quality tourism. But what is quality tourism? Is this a matter of the experiences travellers are seeking, of being more like those who embark on an interior voyage than the party-prone Grand Tourists? Thomas's book is definitely the place to begin with to answer this question, which I think will benefit from the input of political philosophers. After all, the lowering of the ‘quality’ of tourism seems to have followed the lowering of the cost of travelling, and hence opens a sub-debate on fairness and travelling as a human capability—this is an example of how Thomas's work opens a number of new, fascinating questions, which will shape the discipline of philosophy of travel in the coming years. (A side note here: at the time of publication of this review, the global health crisis has decimated international travel, but I believe that does not do away with these issues; if anything, it offers some space to have these debates.)

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Contact the University of St. Andrews

- Contact the Scots Philosophical Association

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1467-9213

- Print ISSN 0031-8094

- Copyright © 2024 Scots Philosophical Association and the University of St. Andrews

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Matador Original Series

A history of why people travel.

Ever notice how when you sit still for a few hours without moving, you suddenly get up and find your legs are cramped, or asleep, or feel tense?

That’s because they’re not meant to be still…at least not for long. We’re meant to move. Our limbs have to be in motion almost constantly.

Humans have always been on the move. Our skeletons and muscle structures have evolved to facilitate gathering our food, escaping from predators, and to satisfy our animal curiosity.

As our brains grew larger, so did our inquisitiveness, and driven by different reasons, humans began to travel.

The Early Explorers

In the Neolithic age we saw the first sailing vessels and the invention of the wheel, both designed to move us around in different ways.

Nomadic hunters and gatherers moved in search of food following seasonally available wild plants and game.

Then Ancient man began to build roads to facilitate the movement of troops through empires, and eventually civilians began to travel in caravans. Travel for the purpose of commerce and trade took explorers to strange lands to meet other people, and bring back riches of unfathomable value.

Wealthy Greeks and Romans began to travel for leisure to their summer homes and villas by the sea in cities like Pompeii and Baiae.

The freedom of travel in the Roman Empire brought many Jews to flourishing cities of the ancient world, and Jesus himself is thought to have traveled a great deal with his disciples.

We know that Vikings had a particular skill for sailing and a keen interest in exploring. Through perilous voyages they conquered areas such as Iceland and Greenland, and were even the first to accidentally discover America in 985 A.D, when a ship was blown off course on the way to Greenland.

In 1001, Leif Eriksson sailed back to explore it further and called it Vinland, or ‘land of pastures’.

Enter the Dark Ages

In Medieval times, the most notorious travelers were pilgrims and missionaries. Driven by their religious convictions, pilgrims made dangerous journeys to places like Santiago de Compostela, Canterbury, and Jerusalem while missionaries traveled to heathen areas to evangelize the people, such as the Celts in Ireland.

In the late 16th century it became fashionable for young aristocrats and wealthy upper class men to travel to important European cities as a crowning touch to their education in the arts and literature, designed to enlighten Europe’s young elite.

This was knows as the Grand Tour . London, Paris, Venice, Florence and Rome were visited by these grand tourists to expose themselves to the great masterpieces.

The French revolution marked the end of the Grand Tour as was known, and with the coming of rail transit in the early 19th century, travel was revolutionized.

Travel was no longer limited only to the privileged as it became cheaper, easier, and safer to travel. Young ladies began to travel too, chaperoned by an old spinster as was appropriate, as part of their education.

Steam and Steel

The Industrial Revolution brought leisure travel to Europe.

The new middle class, comprised of factory owners and managers, now had the time to travel thanks to industrialized production with efficient and faster machinery. They had more money and more time to relax and take part in recreational activities.

For the first time ever, traveling was done for the sole pleasure of it.

This was how Thomas Cook , in 1841, put together the first package holiday in history. He started off with tours in Britain but with his rapid success soon moved unto other European cities, where Paris and the Alps were the most popular destinations.

Thomas Cook pioneered all the common services that travel agencies undertake for the passenger today: accommodation, travel tickets, timetables, attractions, currency exchanges, travel guides and tours.

Air travel began after World War II, when a surplus of aeronautical technology and ex-military pilots who were more than ready to fly. Only the rich could afford holidays with air fare, whereby an all-inclusive two week holiday in Corsica cost around £32 in those days.

The Modern Age

Affordable air travel soon contributed to international mass tourism, pretty much as we know it today.

Over the years different developments in tourism have changed the way we travel, such as technology, safety and security, costs, social changes, etc.

The Grand Tourists of the 17th and 18th centuries echo today of the hoards of backpackers and gap-year students who, not content with traveling through one continent, do so throughout the entire world.

Much like the young European aristocrats of the time, we today also consider traveling as a rite of passage, an initiation, a transition, an opportunity for soul searching.

With tourism currents like Eco-travel, Ethical Travel, Volunteering, Mystical tourism, Dark Tourism, Pop-Culture tourism, Cosmetic Surgery tourism, and Independent traveling, the travel industry has reached an apogee never before seen.

So when we wonder why we travel, and where it all started, it might be comforting to think about our predecessors, and how they moved first out of necessity, then for religion, migration, emigration, commerce, enlightenment and finally for pleasure.

Today each of our personal reasons may vary, but one thing is certain: there will never be rest for a species that can only move, move and keep moving.

Trending Now

The most epic treehouses you can actually rent on airbnb, 21 of the coolest airbnbs near disney world, orlando, stay at these 13 haunted airbnbs for a truly terrifying halloween night, the top luxury forest getaways in the us, 13 la condesa airbnbs to settle into mexico city’s coolest neighborhood, discover matador, adventure travel, train travel, national parks, beaches and islands, ski and snow.

We use cookies for analytics tracking and advertising from our partners.

For more information read our privacy policy .

Matador's Newsletter

Subscribe for exclusive city guides, travel videos, trip giveaways and more!

You've been signed up!

Follow us on social media.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1. History and Overview

Learning Objectives

- Specify the commonly understood definitions of tourism and tourist

- Classify tourism into distinct industry groups using North American Industry Classification Standards (NAICS)

- Define hospitality

- Gain knowledge about the origins of the tourism industry

- Provide an overview of the economic, social, and environmental impacts of tourism worldwide

- Understand the history of tourism development in Canada and British Columbia

- Analyze the value of tourism in Canada and British Columbia

- Identify key industry associations and understand their mandates

What Is Tourism?

Before engaging in a study of tourism , let’s have a closer look at what this term means.

Definition of Tourism

There are a number of ways tourism can be defined, and for this reason, the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) embarked on a project from 2005 to 2007 to create a common glossary of terms for tourism. It defines tourism as follows:

Tourism is a social, cultural and economic phenomenon which entails the movement of people to countries or places outside their usual environment for personal or business/professional purposes. These people are called visitors (which may be either tourists or excursionists; residents or non-residents) and tourism has to do with their activities, some of which imply tourism expenditure ( United Nations World Tourism Organization , 2008).

Using this definition, we can see that tourism is the movement of people for a number of purposes (whether business or pleasure).

Definition of Tourist

Building on the definition of tourism, a commonly accepted description of a tourist is “someone who travels at least 80 km from his or her home for at least 24 hours, for business or leisure or other reasons” (LinkBC, 2008, p.8). The United Nations World Tourism Organization (1995) helps us break down this definition further by stating tourists can be:

- Domestic (residents of a given country travelling only within that country)

- Inbound (non-residents travelling in a given country)

- Outbound (residents of one country travelling in another country)

The scope of tourism, therefore, is broad and encompasses a number of activities.

Spotlight On: United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO)

UNWTO is the United Nations agency responsible “for the promotion of responsible, sustainable and universally accessible tourism” (UNWTO, 2014b). Its membership includes 156 countries and over 400 affiliates such as private companies and non-governmental organizations. It promotes tourism as a way of developing communities while encouraging ethical behaviour to mitigate negative impacts. For more information, visit the UNWTO website : http://www2.unwto.org/.

NAICS: The North American Industry Classification System

Given the sheer size of the tourism industry, it can be helpful to break it down into broad industry groups using a common classification system. The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) was jointly created by the Canadian, US, and Mexican governments to ensure common analysis across all three countries (British Columbia Ministry of Jobs, Tourism and Skills Training, 2013a). The tourism-related groupings created using NAICS are (in alphabetical order):

- Accommodation

- Food and beverage services (commonly known as “F & B”)

- Recreation and entertainment

- Transportation

- Travel services

These industry groups are based on the similarity of the “labour processes and inputs” used for each (Government of Canada, 2013). For instance, the types of employees and resources required to run an accommodation business — whether it be a hotel, motel, or even a campground — are quite similar. All these businesses need staff to check in guests, provide housekeeping, employ maintenance workers, and provide a place for people to sleep. As such, they can be grouped together under the heading of accommodation. The same is true of the other four groupings, and the rest of this text explores these industry groups, and other aspects of tourism, in more detail.

The Hospitality Industry

When looking at tourism it’s important to consider the term hospitality . Some define hospitality as “t he business of helping people to feel welcome and relaxed and to enjoy themselves” (Discover Hospitality, 2015, ¶ 3). Simply put, the hospitality industry is the combination of the accommodation and food and beverage groupings, collectively making up the largest segment of the industry. You’ll learn more about accommodations and F & B in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4, respectively.

Before we seek to understand the five industry groupings in more detail, it’s important to have an overview of the history and impacts of tourism to date.

Global Overview

Origins of tourism.

Travel for leisure purposes has evolved from an experience reserved for very few people into something enjoyed by many. Historically, the ability to travel was reserved for royalty and the upper classes. From ancient Roman times through to the 17th century, young men of high standing were encouraged to travel through Europe on a “grand tour” (Chaney, 2000). Through the Middle Ages, many societies encouraged the practice of religious pilgrimage, as reflected in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and other literature.

The word hospitality predates the use of the word tourism , and first appeared in the 14th century. It is derived from the Latin hospes , which encompasses the words guest, host , and foreigner (Latdict, 2014). The word tourist appeared in print much later, in 1772 (Griffiths and Griffiths, 1772). William Theobald suggests that the word tour comes from Greek and Latin words for circle and turn, and that tourism and tourist represent the activities of circling away from home, and then returning (Theobald, 1998).

Tourism Becomes Business

Cox & Kings, the first known travel agency, was founded in 1758 when Richard Cox became official travel agent of the British Royal Armed Forces (Cox & Kings, 2014). Almost 100 years later, in June 1841, Thomas Cook opened the first leisure travel agency, designed to help Britons improve their lives by seeing the world and participating in the temperance movement. In 1845, he ran his first commercial packaged tour, complete with cost-effective railway tickets and a printed guide (Thomas Cook, 2014).

The continued popularity of rail travel and the emergence of the automobile presented additional milestones in the development of tourism. In fact, a long journey taken by Karl Benz’s wife in 1886 served to kick off interest in auto travel and helped to publicize his budding car company, which would one day become Mercedes Benz (Auer, 2006). We take a closer look at the importance of car travel later this chapter, and of transportation to the tourism industry in Chapter 2.

Fast forward to 1952 with the first commercial air flights from London, England, to Johannesburg, South Africa, and Colombo, Sri Lanka (Flightglobal, 2002) and the dawn of the jet age, which many herald as the start of the modern tourism industry. The 1950s also saw the creation of Club Méditérannée (Gyr, 2010) and similar club holiday destinations, the precursor of today’s all-inclusive resorts.

The decade that followed is considered to have been a significant period in tourism development, as more travel companies came onto the scene, increasing competition for customers and moving toward “mass tourism, introducing new destinations and modes of holidaying” (Gyr, 2010, p. 32).

Industry growth has been interrupted at several key points in history, including World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II. At the start of this century, global events thrust international travel into decline including the September 11, 2001, attack on the World Trade Center in New York City (known as 9/11), the war in Iraq, perceived threat of future terrorist attacks, and health scares including SARS, BSE (bovine spongiform encephalopathy), and West Nile virus (Government of Canada, 2006).

At the same time, the industry began a massive technological shift as increased internet use revolutionized travel services. Through the 2000s, online travel bookings grew exponentially, and by 2014 global leader Expedia had expanded to include brands such as Hotels.com, the Hotwire Group, trivago, and Expedia CruiseShip Centers, earning revenues of over $4.7 million (Expedia Inc., 2013).

A more in-depth exploration of the impact of the online marketplace, and other trends in global tourism, is provided in Chapter 14. But as you can already see, the impacts of the global tourism industry today are impressive and far reaching. Let’s have a closer look at some of these outcomes.

Tourism Impacts

Tourism impacts can be grouped into three main categories: economic, social, and environmental. These impacts are analyzed using data gathered by businesses, governments, and industry organizations.

Economic Impacts

According to a UNWTO report, in 2011, “international tourism receipts exceeded US$1 trillion for the first time” (UNWTO, 2012). UNWTO Secretary-General Taleb Rifai stated this excess of $1 trillion was especially important news given the global economic crisis of 2008, as tourism could help rebuild still-struggling economies, because it is a key export and labour intensive (UNWTO, 2012).

Tourism around the world is now worth over $1 trillion annually, and it’s a growing industry almost everywhere. Regions with the highest growth in terms of tourism dollars earned are the Americas, Europe, Asia and the Pacific, and Africa. Only the Middle East posted negative growth at the time of the report (UNWTO, 2012).

While North and South America are growing the fastest, Europe continues to lead the way in terms of overall percentage of dollars earned (UNWTO, 2012):

- Europe (45%)

- Asia and the Pacific (28%)

- North and South America (19%)

- Middle East (4%)

Global industry growth and high receipts are expected to continue. In its August 2014 expenditure barometer, the UNWTO found worldwide visitation had increased by 22 million people in the first half of the year over the previous year, to reach 517 million visits (UNWTO, 2014a). As well, the UNWTO’s Tourism 2020 Vision predicts that international arrivals will reach nearly 1.6 billion by 2020 . Read more about the Tourism 2020 Vision : http://www.e-unwto.org/doi/abs/10.18111/9789284403394

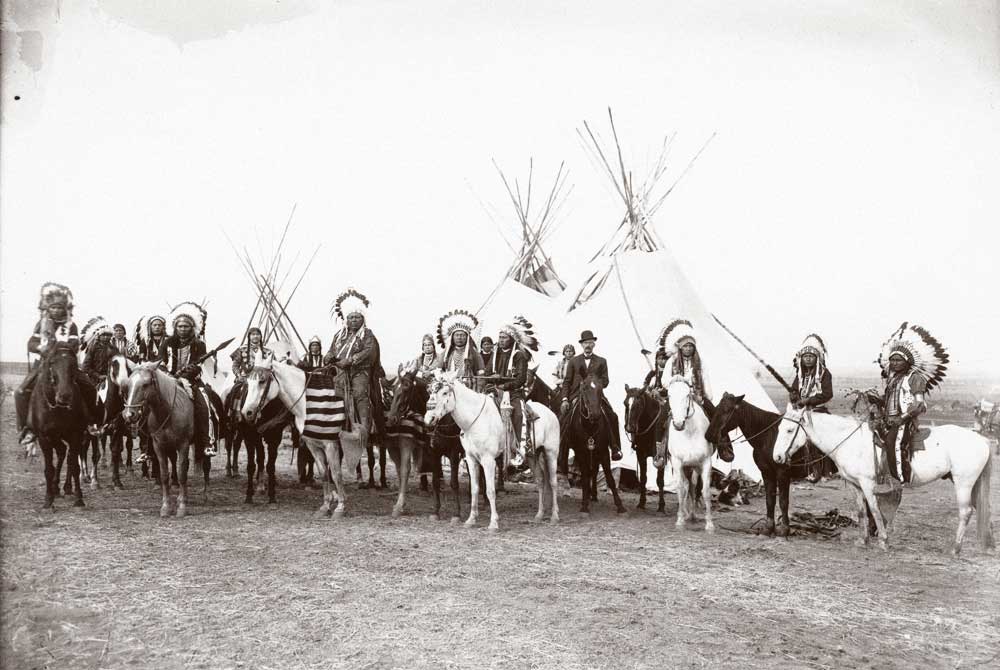

Social Impacts

In addition to the economic benefits of tourism development, positive social impacts include an increase in amenities (e.g., parks, recreation facilities), investment in arts and culture, celebration of First Nations people, and community pride. When developed conscientiously, tourism can, and does, contribute to a positive quality of life for residents.

However, as identified by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP, 2003a), negative social impacts of tourism can include:

- Change or loss of indigenous identity and values

- Culture clashes

- Physical causes of social stress (increased demand for resources)

- Ethical issues (such as an increase in sex tourism or the exploitation of child workers)

Some of these issues are explored in further detail in Chapter 12, which examines the development of Aboriginal tourism in British Columbia.

Environmental Impacts

Tourism relies on, and greatly impacts, the natural environment in which it operates. Even though many areas of the world are conserved in the form of parks and protected areas, tourism development can have severe negative impacts. According to UNEP (2003b), these can include:

- Depletion of natural resources (water, forests, etc.)

- Pollution (air pollution, noise, sewage, waste and littering)

- Physical impacts (construction activities, marina development, trampling, loss of biodiversity)

The environmental impacts of tourism can reach outside local areas and have an effect on the global ecosystem. One example is increased air travel, which is a major contributor to climate change. Chapter 10 looks at the environmental impacts of tourism in more detail.

Whether positive or negative, tourism is a force for change around the world, and the industry is transforming at a staggering rate. But before we delve deeper into our understanding of tourism, let’s take a look at the development of the sector in our own backyard.

Canada Overview

Origins of tourism in canada.

Tourism has long been a source of economic development for our country. Some argue that as early as 1534 the explorers of the day, such as Jacques Cartier, were Canada’s first tourists (Dawson, 2004), but most agree the major developments in Canada’s tourism industry followed milestones in the transportation sector: by rail, by car, and eventually, in the skies.

Railway Travel: The Ties That Bind

The dawn of the railway age in Canada came midway through the 19th century. The first railway was launched in 1836 (Library and Archives Canada, n.d.), and by the onset of World War I in 1914, four railways dominated the Canadian landscape: Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), Canadian Northern Railway (CNOR), the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR), and the Grand Trunk Pacific (GTP). Unfortunately, their rapid expansion soon brought the last three into near bankruptcy (Library and Archives Canada, n.d.).

In 1923, these three rail companies were amalgamated into the Canadian National Railway (CNR), and together with the CPR, these trans-continentals dominated the Canadian travel landscape until other forms of transportation became more popular. In 1978, with declining interest in rail travel, the CPR and CNR were forced to combine their passenger services to form VIA Rail (Library and Archives Canada, n.d.).

The Rise of the Automobile

The rising popularity of car travel was partially to blame for the decline in rail travel, although it took time to develop. When the first cross-country road trip took place in 1912, there were only 16 kilometres of paved road across Canada (MacEachern, 2012). Cars were initially considered a nuisance, and the National Parks Branch banned entry to automobiles, but later slowly began to embrace them. By the 1930s, some parks, such as Cape Breton Highlands National Park, were actually created to provide visitors with scenic drives (MacEachern, 2012).

It would take decades before a coast-to-coast highway was created, with the Trans-Canada Highway officially opening in Revelstoke in 1962. When it was fully completed in 1970, it was the longest national highway in the world, spanning one-fifth of the globe (MacEachern, 2012).

Early Tourism Promotion

As early as 1892, enterprising Canadians like the Brewsters became the country’s first tour operators, leading guests through areas such as Banff National Park (Brewster Travel Canada, 2014). Communities across Canada developed their own marketing strategies as transportation development took hold. For instance, the town of Maisonneuve in Quebec launched a campaign from 1907 to 1915 calling itself “Le Pittsburg du Canada.” And by 1935 Quebec was spending $250,000 promoting tourism, with Ontario, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia also enjoying established provincial tourism bureaus (Dawson, 2004).

National Airlines

Our national airline, Air Canada, was formed in 1937 as Trans-Canada Air Lines. In many ways, Air Canada was a world leader in passenger aviation, introducing the world’s first computerized reservations system in 1963 ( Globe and Mail , 2014). Through the 1950s and 1960s, reduced airfares saw increased mass travel. Competitors including Canadian Pacific (which became Canadian Airlines in 1987) began to launch international flights during this time to Australia, Japan, and South America ( Canadian Geographic, 2000). By 2000, Air Canada was facing financial peril and forced to restructure. A numbered company, owned in part by Air Canada, purchased 82% of Canadian Airline’s shares, with the result of Air Canada becoming the country’s only national airline ( Canadian Geographic, 2000).

Parks and Protected Areas

A look at the evolution of tourism in Canada would be incomplete without a quick study of our national parks and protected areas. The official conserving of our natural spaces began around the same time as the railway boom, and in 1885 Banff was established as Canada’s first national park. By 1911, the Dominion Forest Reserves and Parks Act created the Dominion Parks Branch, the first of its kind in the world (Shoalts, 2011).

The systemic conservation and celebration of Canada’s parks over the next century would help shape Canada’s identity, both at home and abroad. Through the 1930s, conservation officers and interpreters were hired to enhance visitor experiences. By 1970, the National Park System Plan divided Canada into 39 regions, with the goal of preserving each distinct ecosystem for future generations. In 1987, the country’s first national marine park was established in Ontario, and in the 20 years that followed, 10 new national parks and marine conservation areas were created (Shoalts, 2011).

The role of parks and protected areas in tourism is explored in greater detail in Chapter 5 (recreation) and Chapter 10 (environmental stewardship).

Global Shock and Industry Decline

As with the global industry, Canada’s tourism industry was impacted by world events such as the Great Depression and the World Wars.

More recently, global events such as 9/11, the SARS outbreak, and the war in Iraq took their toll on tourism receipts. Worldwide arrivals to Canada dropped 1% to 694 million in 2003, after three years of stagnant growth. In 2005, spending reached $61.4 billion with domestic travel accounting for 71% (Government of Canada, 2006).

Tourism in Canada Today

In 2011, tourism created $78.8 billion in total economic activity and 603,400 jobs. Tourism accounted for more of Canada’s gross domestic product (GDP) than agriculture, forestry, and fisheries combined (Tourism Industry Association of Canada, 2014).

Spotlight On: The Tourism Industry Association of Canada (TIAC)

Founded in 1930 and based in Ottawa, the Tourism Industry Association of Canada (TIAC) is the national private-sector advocate for the industry. Its goal is to support policies and programs that help the industry grow, while representing over 400 members including airports, concert halls, festivals and events, travel services providers, and businesses of all sizes. For more information, visit the Tourism Industry Association of Canada’s website : http://tiac.travel/About.html

Unfortunately, while overall receipts from tourism appear healthy, and globally the industry is growing, according to a recent report, Canada’s historic reliance on the US market (which traditionally accounts for 75% of our market) is troubling. Because three out of every four international visitors to Canada originates in the United States, the 55% decline in that market since 2000 is being very strongly felt here. Many feel the decline in American visitors to Canada can be attributed to tighter passport and border regulations, the economic downturn (including the 2008 global economic crisis), and a stronger Canadian dollar (TIAC, 2014).

Despite disappointing numbers from the United States, Canada continues to see strong visitation from the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Australia, and China. In 2011, we welcomed 3,180,262 tourists from our top 15 inbound countries (excluding the United States). Canadians travelling domestically accounted for 80% of tourism revenues in the country, and TIAC suggested that a focus on rebounding US visitation would help grow the industry (TIAC, 2014).

Spotlight On: The Canadian Tourism Commission

Housed in Vancouver, Destination Canada , previously the Canadian Tourism Commission (CTC), is responsible for promoting Canada in several foreign markets: Australia, Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Japan, Mexico, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States. It works with private companies, travel services providers, meeting professionals, and government organizations to help leverage Canada’s tourism brand, Canada. Keep Exploring . It also conducts research and has a significant image library (Canadian Tourism Commission, 2014). For more information, visit Destination Canada website : http://en.destinationcanada.com/about-ctc.

As organizations like TIAC work to confront barriers to travel, the Canadian Tourism Commission (CTC) is active abroad, encouraging more visitors to explore our country. In Chapter 8, we’ll delve more into the challenges and triumphs of selling tourism at home and abroad.

The great news for British Columbia is that once in Canada, most international visitors tend to remain in the province they landed in, and BC is one of three provinces that receives the bulk of this traffic (TIAC, 2012). In fact, BC’s tourism industry is one of the healthiest in Canada today. Let’s have a look at how our provincial industry was established and where it stands now.

British Columbia Overview

Origins of tourism in bc.

As with the history of tourism in Canada, it’s often stated that the first tourists to BC were explorers. In 1778, Captain James Cook touched down on Vancouver Island, followed by James Douglas in 1842, a British agent who had been sent to find new headquarters for the Hudson’s Bay Company, ultimately choosing Victoria. Through the 1860s, BC’s gold rush attracted prospectors from around the world, with towns and economies springing up along the trail (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2009).

Railway Travel: Full Steam Ahead!

The development of BC’s tourism industry began in earnest in the late 1800s when the CPR built accommodation properties along itsnewly completed trans-Canada route, capturing revenues from overnight stays to help alleviate their increasing corporate debt. Following the 1886 construction of small lodges at stops in Field, Rogers Pass, and Fraser Canyon, the CPR opened the Hotel Vancouver in May 1887 (Dawson, 2004).

As opposed to Atlantic Canada, where tourism promotion centred around attracting hunters and fishermen for a temporary infusion of cash, in British Columbia tourism was seen as a way to lure farmers and settlers to stay in the new province. Industry associations began to form quickly: the Tourist Association of Victoria (TAV) in February 1902, and the Vancouver Tourist Association in June of the same year (Dawson, 2004).

Many of the campaigns struck by these and other organizations between 1890 and 1930 centred on the province’s natural assets, as people sought to escape modern convenience and enjoy the environment. A collaborative group called the Pacific Northwest Travel Association (BC, Washington, and Oregon) promoted “The Pacific Northwest: The World’s Greatest Out of Doors,” calling BC “The Switzerland of North America.” Promotions like these seemed to have had an effect: in 1928, over 370,000 tourists visited Victoria, spending over $3.5 million (Dawson, 2004).

The Great Depression and World War II

As the world’s economy was sent into peril during the Great Depression in the 1930s, tourism was seen as an economic solution. A newly renamed Greater Victoria Publicity Bureau touted a “100 for 1” multiplier effect of tourism spending, with visitor revenues accounting for around 13.5% of BC’s income in 1930. By 1935, an organization known as the TTDA (Tourist Trade Development Association of Victoria and Vancouver Island) looked to create a more stable industry through strategies to increase visitors’ length of stay (Dawson, 2004).

In 1937, the provincial Bureau of Industrial and Tourist Development (BITD) was formed through special legislation with a goal of increasing tourist traffic. By 1938, the organization changed its name to the British Columbia Government Travel Bureau (BCGTB) and was granted a budget increase to $105,000. This was soon followed by an expansion of the BC Tourist Council designed to solicit input from across the province. And in 1939, Vancouver welcomed the King and Queen of England and celebrated the opening of the Lions Gate Bridge, activities that reportedly bolstered tourism numbers (Dawson, 2004).

The December 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii had negative repercussions for tourism on the Pacific Rim and was responsible for an era of decreased visitation to British Columbia, despite attempts by some to market the region as exciting. From 1939 to 1943, US visits to Vancouver (measured at the border) dropped from over 307,000 to approximately 183,600. Just two years later, however, that number jumped to 369,250, the result of campaigns like the 1943 initiative aimed at Americans that marketed BC as “comrades in war” (Dawson, 2004).

Post-War Rebound

We, with all due modesty, cannot help but claim that we are entering British Columbia’s half-century, and cannot help but observe that B.C. also stands for BOOM COUNTRY. – Phil Gagliardi, BC Minister of Highways, 1955 (Dawson, 2004, p.190)

A burst of post-war spending began in 1946, and although short-lived, was supported by steady government investment in marketing throughout the 1950s. As tourism grew in BC, however, so did competition for US dollars from Mexico, the Caribbean, and Europe. The decade that followed saw an emphasis on promoting BC’s history, its “Britishness,” and a commodification of Aboriginal culture. The BCGTB began marketing efforts to extend the travel season, encouraging travel in September, prime fishing season. It also tried to push visitors to specific areas, including the Lower Fraser Valley, the Okanagan-Fraser Canyon Loop, and the Kamloops-Cariboo region (Dawson, 2004).

In 1954, Vancouver hosted the British Empire Games, investing in the construction of Empire Stadium. A few years later, an increased emphasis on events and convention business saw the Greater Vancouver Tourist Association change its name in 1962 to the Greater Vancouver Visitors and Convention Bureau (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2009).

The ski industry was also on the rise: in 1961, the lodge and chairlift on Tod Mountain (now Sun Peaks) opened, and Whistler followed suit five years later (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2009). Ski partners became pioneers of collaborative marketing in the province with the foundation of the Ski Marketing Advisory Committee (SMAC) supported by Tod Mountain and Big White, evolving into today’s Canada’s West Ski Area Association (Magnes, 2010). This pioneer spirit was evident across the ski sector: the entire sport of heliskiing was invented by Hans Gosmer of BC’s Canadian Mountain Holidays, and today the province holds 90% of the world’s heliskiing market share (McLeish, 2014).

The concept of collaboration extended throughout the province as innovative funding structures saw the cost of marketing programs shared between government and industry in BC. These programs were distributed through regional channels (originally eight regions in the province), and considered “the most constructive and forward looking plan of its kind in Canada” (Dawson 2004, p.194).

Tourism in BC continued to grow through the 1970s. In 1971, the Hotel Room Tax Act was introduced, allowing for a 5% tax to be collected on room nights with the funds collected to be put toward marketing and development. By 1978, construction had begun on Whistler Village, with Blackcomb Mountain opening two years later (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2009). Funding programs in the late 1970s and early 1980s such as the Canada BC Tourism Agreement (CBCTA) and Travel Industry Development Subsidiary Agreement (TIDSA) allowed communities to invest in projects that would make them more attractive tourism destinations. In the mountain community of Kimberley, for instance, the following improvements were implemented through a $3.1 million forgivable loan: a new road to the ski resort, a covered tennis court, a mountain lodge, an alpine slide, and nine more holes for the golf course (e-Know, 2011).

Around the same time, the “Super, Natural British Columbia” brand was introduced, and a formal bid was approved for Vancouver to host a fair then known as Transpo 86 (later Expo 86). Tourism in the province was about to truly take off.

Expo 86 and Beyond

By the time the world fair Expo 86 came to a close in October 1986, it had played host to 20,111,578 guests. Infrastructure developments, including rapid rail, airport improvements, a new trade and convention centre at Canada Place (with a cruise ship terminal), and hotel construction, had positioned the city and the province for further growth (PricewaterhouseCooopers, 2009). The construction and opening of the Coquihalla Highway through to 1990 enhanced the travel experience and reduced travel times to vast sections of the province (Magnes, 2010).

Take a Closer Look: The Value of Tourism

Tourism Vancouver Island, with the support of many partners, has created a website that directly addresses the value of tourism in the region. The site looks at the economics of tourism, social benefits of tourism, and a “what’s your role?” feature that helps users understand where they fit in. Explore the Tourism Vancouver Island website : http://valueoftourism.ca/.

By 2000, Vancouver International Airport (YVR) was named number one in the world by the International Air Transport Association’s survey of international passengers. Five years later, the airport welcomed a record 16.4 million passengers (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2009).

Going for Gold

In 2003, the International Olympic Committee named Vancouver/Whistler as the host city for the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games. Infrastructure development followed, including the expansion of the Sea-to-Sky Highway, the creation of Vancouver Convention Centre West, and the construction of the Canada Line, a rapid transport line connecting the airport with the city’s downtown.

As BC prepared to host the Games, its international reputation continued to grow. Vancouver was voted “Best City in the Americas” by Condé Nast Traveller magazine three years in a row. Kelowna was named “Best Canadian Golf City” by Canada’s largest golf magazine, and BC was named the “Best Golf Destination in North America” by the International Association of Golf Tour Operators. Kamloops, known as Canada’s Tournament City, hosted over 100 sports tournaments that same year, and nearby Sun Peaks Resort was named the “Best Family Resort in North America” by the Great Skiing and Snowboarding Guide in 2008 (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2009).

By the time the Vancouver 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Games took place, over 80 participating countries, 6,000 athletes, and 3 billion viewers put British Columbia on centre stage.

Spotlight On: Destination British Columbia

Destination BC is a Crown corporation founded in November 2012 by the Government of British Columbia. Its mandate includes marketing the province as a tourist destination (at home and around the world), promoting the development and growth of the industry, providing advice and recommendations to the tourism minister on related matters, and enhancing public awareness of tourism and its economic value to British Columbia (Province of British Columbia, 2013b).

Tourism in BC Today

Building on the momentum generated by hosting the 2010 Winter Olympic Games, tourism in BC remains big business. In 2012, the industry generated $13.5 billion in revenue.