- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Patient Perspectives

- Methods Corner

- Science for Patients

- Invited Commentaries

- ESC Content Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Instructions for reviewers

- Submission Site

- Why publish with EJCN?

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Read & Publish

- About European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing

- About ACNAP

- About European Society of Cardiology

- ESC Publications

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- War in Ukraine

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, why patient journey mapping, how is patient journey mapping conducted, use of technology in patient journey mapping, future implications for patient journey mapping, conclusions.

- < Previous

Patient journey mapping: emerging methods for understanding and improving patient experiences of health systems and services

Lemma N Bulto and Ellen Davies Shared first authorship.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Lemma N Bulto, Ellen Davies, Janet Kelly, Jeroen M Hendriks, Patient journey mapping: emerging methods for understanding and improving patient experiences of health systems and services, European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing , Volume 23, Issue 4, May 2024, Pages 429–433, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvae012

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Patient journey mapping is an emerging field of research that uses various methods to map and report evidence relating to patient experiences and interactions with healthcare providers, services, and systems. This research often involves the development of visual, narrative, and descriptive maps or tables, which describe patient journeys and transitions into, through, and out of health services. This methods corner paper presents an overview of how patient journey mapping has been conducted within the health sector, providing cardiovascular examples. It introduces six key steps for conducting patient journey mapping and describes the opportunities and benefits of using patient journey mapping and future implications of using this approach.

Acquire an understanding of patient journey mapping and the methods and steps employed.

Examine practical and clinical examples in which patient journey mapping has been adopted in cardiac care to explore the perspectives and experiences of patients, family members, and healthcare professionals.

Quality and safety guidelines in healthcare services are increasingly encouraging and mandating engagement of patients, clients, and consumers in partnerships. 1 The aim of many of these partnerships is to consider how health services can be improved, in relation to accessibility, service delivery, discharge, and referral. 2 , 3 Patient journey mapping is a research approach increasingly being adopted to explore these experiences in healthcare. 3

a patient-oriented project that has been undertaken to better understand barriers, facilitators, experiences, interactions with services and/or outcomes for individuals and/or their carers, and family members as they enter, navigate, experience and exit one or more services in a health system by documenting elements of the journey to produce a visual or descriptive map. 3

It is an emerging field with a clear patient-centred focus, as opposed to studies that track patient flow, demand, and movement. As a general principle, patient journey mapping projects will provide evidence of patient perspectives and highlight experiences through the patient and consumer lens.

Patient journey mapping can provide significant insights that enable responsive and context-specific strategies for improving patient healthcare experiences and outcomes to be designed and implemented. 3–6 These improvements can occur at the individual patient, model of care, and/or health system level. As with other emerging methodologies, questions have been raised regarding exactly how patient journey mapping projects can best be designed, conducted, and reported. 3

In this methods paper, we provide an overview of patient journey mapping as an emergent field of research, including reasons that mapping patient journeys might be considered, methods that can be adopted, the principles that can guide patient journey mapping data collection and analysis, and considerations for reporting findings and recognizing the implications of findings. We summarize and draw on five cardiovascular patient journey mapping projects, as examples.

One of the most appealing elements of the patient journey mapping field of research is its focus on illuminating the lived experiences of patients and/or their family members, and the health professionals caring for them, methodically and purposefully. Patient journey mapping has an ability to provide detailed information about patient experiences, gaps in health services, and barriers and facilitators for access to health services. This information can be used independently, or alongside information from larger data sets, to adapt and improve models of care relevant to the population that is being investigated. 3

To date, the most frequent reason for adopting this approach is to inform health service redesign and improvement. 3 , 7 , 8 Other reasons have included: (i) to develop a deeper understanding of a person’s entire journey through health systems; 3 (ii) to identify delays in diagnosis or treatment (often described as bottlenecks); 9 (iii) to identify gaps in care and unmet needs; (iv) to evaluate continuity of care across health services and regions; 10 (v) to understand and evaluate the comprehensiveness of care; 11 (vi) to understand how people are navigating health systems and services; and (vii) to compare patient experiences with practice guidelines and standards of care.

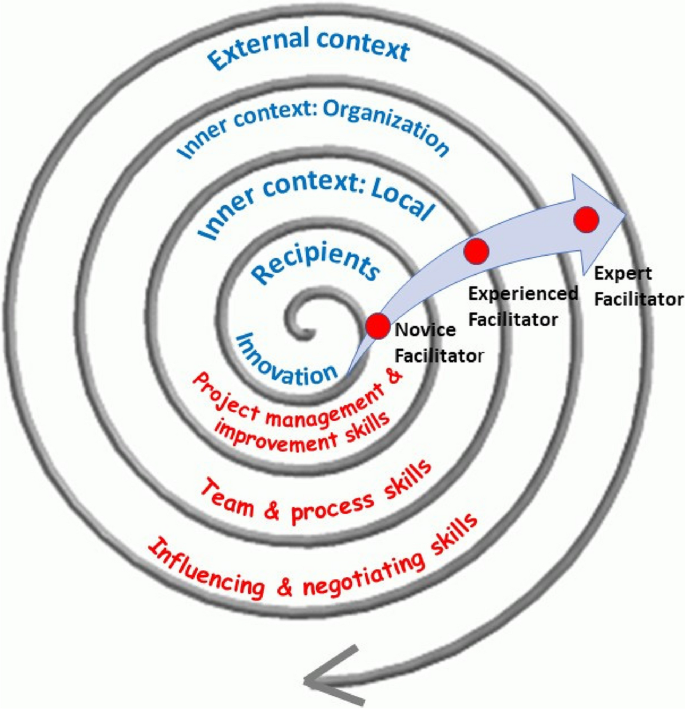

Patient journey mapping approaches frequently use six broad steps that help facilitate the preparation and execution of research projects. These are outlined in the Central illustration . We acknowledge that not all patient journey mapping approaches will follow the order outlined in the Central illustration , but all steps need to be considered at some point throughout each project to ensure that research is undertaken rigorously, appropriately, and in alignment with best practice research principles.

Steps for conducing patient journey mapping.

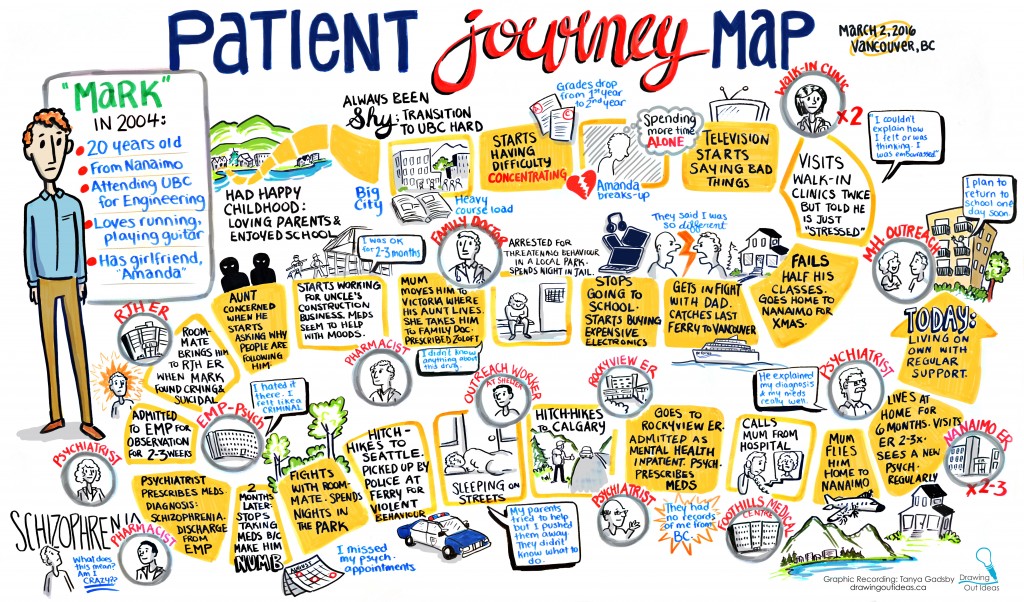

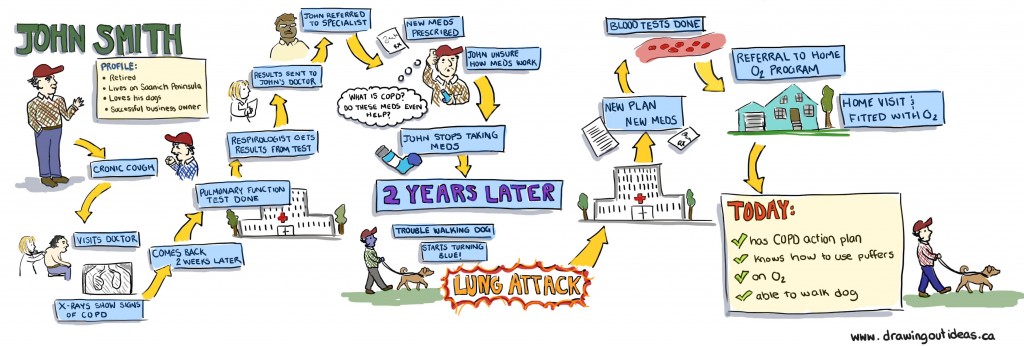

Five cardiovascular patient journey mapping research examples have been included in Figure 1 , 12–16 to provide specific context and illustrate these six steps. For each of these examples, the problem or gap in practice or research, consultation processes, research question or aim, type of mapping, methods, and reporting of findings have been extracted. Each of these steps is then discussed, using these cardiovascular examples.

Examples of patient journey mapping projects.

Define the problem or gap in practice or research

Developing an understanding of a problem or gap in practice is essential for facilitating the design and development of quality research projects. In the examples outlined in Figure 1 , it is evident that clinical variation or system gaps have been explored using patient journey mapping. In the first two examples, populations known to have health vulnerabilities were explored—in Example 1, this related to comorbid substance use and physical illness, 13 and in Example 2, this related to geographical location. 13 Broader systems and societal gaps were explored in Examples 4 and 5, respectively, 15 , 16 and in Example 3, a new technologically driven solution for an existing model of care was tested for its ability to improve patient outcomes relating to hypertension. 14

Consultation, engagement, and partnership

Ideally, consultation with heathcare providers and/or patients would occur when the problem or gap in practice or research is being defined. This is a key principle of co-designed research. 17 Numerous existing frameworks for supporting patient involvement in research have been designed and were recently documented and explored in a systematic review by Greenhalgh et al . 18 While none of the five example studies included this step in the initial phase of the project, it is increasingly being undertaken in patient partnership projects internationally (e.g. in renal care). 17 If not in the project conceptualization phase, consultation may occur during the data collection or analysis phase, as demonstrated in Example 3, where a care pathway was co-created with participants. 14 We refer readers to Greenhalgh’s systematic review as a starting point for considering suitable frameworks for engaging participants in consultation, partnership, and co-design of patient journey mapping projects. 18

Design the research question/project aim

Conducting patient journey mapping research requires a thoughtful and systematic approach to adequately capture the complexity of the healthcare experience. First, the research objectives and questions should be clearly defined. Aspects of the patient journey that will be explored need to be identified. Then, a robust approach must be developed, taking into account whether qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods are more appropriate for the objectives of the study.

For example, in the cardiac examples in Figure 1 , the broad aims included mapping existing pathways through health services where there were known problems 12 , 13 , 15 , 16 and documenting the co-creation of a new care pathway using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. 14

In traditional studies, questions that might be addressed in the area of patient movement in health systems include data collected through the health systems databases, such as ‘What is the length of stay for x population’, or ‘What is the door to balloon time in this hospital?’ In contrast, patient mapping journey studies will approach asking questions about experiences that require data from patients and their family members, e.g. ‘What is the impact on you of your length of stay?’, ‘What was your experience in being assessed and undergoing treatment for your chest pain?’, ‘What was your experience supporting this patient during their cardiac admission and discharge?’

Select appropriate type of mapping

The methods chosen for mapping need to align with the identified purpose for mapping and the aim or question that was designed in Step 3. A range of research methods have been used in patient journey mapping projects involving various qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods techniques and tools. 4 Some approaches use traditional forms of data collection, such as short-form and long-form patient interviews, focus groups, and direct patient observations. 18 , 19 Other approaches use patient journey mapping tools, designed and used with specific cultural groups, such as First Nations peoples using artwork, paintings, sand trays, and photovoice. 17 , 20 In the cardiovascular examples presented in Figure 1 , both qualitative and quantitative methods have been used, with interviews, patient record reviews, and observational techniques adopted to map patient journeys.

In a recent scoping review investigating patient journey mapping across all health care settings and specialities, six types of patient journey mapping were identified. 3 These included (i) mapping key experiences throughout a period of illness; (ii) mapping by location of health service; (iii) mapping by events that occurred throughout a period of illness; (iv) mapping roles, input, and experiences of key stakeholders throughout patient journeys; (v) mapping a journey from multiple perspectives; and (vi) mapping a timeline of events. 3 Combinations or variations of these may be used in cardiovascular settings in the future, depending on the research question, and the reasons mapping is being undertaken.

Recruit, collect data, and analyse data

The majority of health-focused patient journey mapping projects published to date have recruited <50 participants. 3 Projects with fewer participants tend to be qualitative in nature. In the cardiovascular examples provided in Figure 1 , participant numbers range from 7 14 to 260. 15 The 3 studies with <20 participants were qualitative, 12 , 14 , 16 and the 2 with 95 and 260 participants, respectively, were quantitative. 13 , 15 As seen in these and wider patient journey mapping examples, 3 participants may include patients, relatives, carers, healthcare professionals, or other stakeholders, as required, to meet the study objectives. These different participant perspectives may be analysed within each participant group and/or across the wider cohort to provide insights into experiences, and the contextual factors that shape these experiences.

The approach chosen for data collection and analysis will vary and depends on the research question. What differentiates data analysis in patient journey mapping studies from other qualitative or quantitative studies is the focus on describing, defining, or exploring the journey from a patient’s, rather than a health service, perspective. Dimensions that may, therefore, be highlighted in the analysis include timing of service access, duration of delays to service access, physical location of services relative to a patient’s home, comparison of care received vs. benchmarked care, placing focus on the patient perspective.

The mapping of individual patient journeys may take place during data collection with the use of mapping templates (tables, diagrams, and figures) and/or later in the analysis phase with the use of inductive or deductive analysis, mapping tables, or frameworks. These have been characterized and visually represented in a recent scoping review. 3 Representations of patient journeys can also be constructed through a secondary analysis of previously collected data. In these instances, qualitative data (i.e. interviews and focus group transcripts) have been re-analysed to understand whether a patient journey narrative can be extracted and reported. Undertaking these projects triggers a new research cycle involving the six steps outlined in the Central illustration . The difference in these instances is that the data are already collected for Step 5.

Report findings, disseminate findings, and take action on findings

A standardized, formal reporting guideline for patient journey mapping research does not currently exist. As argued in Davies et al ., 3 a dedicated reporting guide for patient journey mapping would be ill-advised, given the diversity of approaches and methods that have been adopted in this field. Our recommendation is for projects to be reported in accordance with formal guidelines that best align with the research methods that have been adopted. For example, COREQ may be used for patient journey mapping where qualitative methods have been used. 20 STROBE may be used for patient journey mapping where quantitative methods have been used. 21 Whichever methods have been adopted, reporting of projects should be transparent, rigorous, and contain enough detail to the extent that the principles of transparency, trustworthiness, and reproducibility are upheld. 3

Dissemination of research findings needs to include the research, healthcare, and broader communities. Dissemination methods may include academic publications, conference presentations, and communication with relevant stakeholders including healthcare professionals, policymakers, and patient advocacy groups. Based on the findings and identified insights, stakeholders can collaboratively design and implement interventions, programmes, or improvements in healthcare delivery that overcome the identified challenges directly and address and improve the overall patient experience. This cyclical process can hopefully produce research that not only informs but also leads to tangible improvements in healthcare practice and policy.

Patient journey mapping is typically a hands-on process, relying on surveys, interviews, and observational research. The technology that supports this research has, to date, included word processing software, and data analysis packages, such as NVivo, SPSS, and Stata. With the advent of more sophisticated technological tools, such as electronic health records, data analytics programmes, and patient tracking systems, healthcare providers and researchers can potentially use this technology to complement and enhance patient journey mapping research. 19 , 20 , 22 There are existing examples where technology has been harnessed in patient journey. Lee et al . used patient journey mapping to verify disease treatment data from the perspective of the patient, and then the authors developed a mobile prototype that organizes and visualizes personal health information according to the patient-centred journey map. They used a visualization approach for analysing medical information in personal health management and examined the medical information representation of seven mobile health apps that were used by patients and individuals. The apps provide easy access to patient health information; they primarily import data from the hospital database, without the need for patients to create their own medical records and information. 23

In another example, Wauben et al. 19 used radio frequency identification technology (a wireless system that is able to track a patient journey), as a component of their patient journey mapping project, to track surgical day care patients to increase patient flow, reduce wait times, and improve patient and staff satisfaction.

Patient journey mapping has emerged as a valuable research methodology in healthcare, providing a comprehensive and patient-centric approach to understanding the entire spectrum of a patient’s experience within the healthcare system. Future implications of this methodology are promising, particularly for transforming and redesigning healthcare delivery and improving patient outcomes. The impact may be most profound in the following key areas:

Personalized, patient-centred care : The methodology allows healthcare providers to gain deep insights into individual patient experiences. This information can be leveraged to deliver personalized, patient-centric care, based on the needs, values, and preferences of each patient, and aligned with guideline recommendations, healthcare professionals can tailor interventions and treatment plans to optimize patient and clinical outcomes.

Enhanced communication, collaboration, and co-design : Mapping patient interactions with health professionals and journeys within and across health services enables specific gaps in communication and collaboration to be highlighted and potentially informs responsive strategies for improvement. Ideally, these strategies would be co-designed with patients and health professionals, leading to improved care co-ordination and healthcare experience and outcomes.

Patient engagement and empowerment : When patients are invited to share their health journey experiences, and see visual or written representations of their journeys, they may come to understand their own health situation more deeply. Potentially, this may lead to increased health literacy, renewed adherence to treatment plans, and/or self-management of chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease. Given these benefits, we recommend that patients be provided with the findings of research and quality improvement projects with which they are involved, to close the loop, and to ensure that the findings are appropriately disseminated.

Patient journey mapping is an emerging field of research. Methods used in patient journey mapping projects have varied quite significantly; however, there are common research processes that can be followed to produce high-quality, insightful, and valuable research outputs. Insights gained from patient journey mapping can facilitate the identification of areas for enhancement within healthcare systems and inform the design of patient-centric solutions that prioritize the quality of care and patient outcomes, and patient satisfaction. Using patient journey mapping research can enable healthcare providers to forge stronger patient–provider relationships and co-design improved health service quality, patient experiences, and outcomes.

None declared.

Farmer J , Bigby C , Davis H , Carlisle K , Kenny A , Huysmans R , et al. The state of health services partnering with consumers: evidence from an online survey of Australian health services . BMC Health Serv Res 2018 ; 18 : 628 .

Google Scholar

Kelly J , Dwyer J , Mackean T , O’Donnell K , Willis E . Coproducing Aboriginal patient journey mapping tools for improved quality and coordination of care . Aust J Prim Health 2017 ; 23 : 536 – 542 .

Davies EL , Bulto LN , Walsh A , Pollock D , Langton VM , Laing RE , et al. Reporting and conducting patient journey mapping research in healthcare: a scoping review . J Adv Nurs 2023 ; 79 : 83 – 100 .

Ly S , Runacres F , Poon P . Journey mapping as a novel approach to healthcare: a qualitative mixed methods study in palliative care . BMC Health Serv Res 2021 ; 21 : 915 .

Arias M , Rojas E , Aguirre S , Cornejo F , Munoz-Gama J , Sepúlveda M , et al. Mapping the patient’s journey in healthcare through process mining . Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020 ; 17 : 6586 .

Natale V , Pruette C , Gerohristodoulos K , Scheimann A , Allen L , Kim JM , et al. Journey mapping to improve patient-family experience and teamwork: applying a systems thinking tool to a pediatric ambulatory clinic . Qual Manag Health Care 2023 ; 32 : 61 – 64 .

Cherif E , Martin-Verdier E , Rochette C . Investigating the healthcare pathway through patients’ experience and profiles: implications for breast cancer healthcare providers . BMC Health Serv Res 2020 ; 20 : 735 .

Gilburt H , Drummond C , Sinclair J . Navigating the alcohol treatment pathway: a qualitative study from the service users’ perspective . Alcohol Alcohol 2015 ; 50 : 444 – 450 .

Gichuhi S , Kabiru J , M’Bongo Zindamoyen A , Rono H , Ollando E , Wachira J , et al. Delay along the care-seeking journey of patients with ocular surface squamous neoplasia in Kenya . BMC Health Serv Res 2017 ; 17 : 485 .

Borycki EM , Kushniruk AW , Wagner E , Kletke R . Patient journey mapping: integrating digital technologies into the journey . Knowl Manag E-Learn 2020 ; 12 : 521 – 535 .

Barton E , Freeman T , Baum F , Javanparast S , Lawless A . The feasibility and potential use of case-tracked client journeys in primary healthcare: a pilot study . BMJ Open 2019 ; 9 : e024419 .

Bearnot B , Mitton JA . “You’re always jumping through hoops”: journey mapping the care experiences of individuals with opioid use disorder-associated endocarditis . J Addict Med 2020 ; 14 : 494 – 501 .

Cunnington MS , Plummer CJ , McDiarmid AK , McComb JM . The patient journey from symptom onset to pacemaker implantation . QJM 2008 ; 101 : 955 – 960 .

Geerse C , van Slobbe C , van Triet E , Simonse L . Design of a care pathway for preventive blood pressure monitoring: qualitative study . JMIR Cardio 2019 ; 3 : e13048 .

Laveau F , Hammoudi N , Berthelot E , Belmin J , Assayag P , Cohen A , et al. Patient journey in decompensated heart failure: an analysis in departments of cardiology and geriatrics in the Greater Paris University Hospitals . Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2017 ; 110 : 42 – 50 .

Naheed A , Haldane V , Jafar TH , Chakma N , Legido-Quigley H . Patient pathways and perceptions of treatment, management, and control Bangladesh: a qualitative study . Patient Prefer Adherence 2018 ; 12 : 1437 – 1449 .

Bateman S , Arnold-Chamney M , Jesudason S , Lester R , McDonald S , O’Donnell K , et al. Real ways of working together: co-creating meaningful Aboriginal community consultations to advance kidney care . Aust N Z J Public Health 2022 ; 46 : 614 – 621 .

Greenhalgh T , Hinton L , Finlay T , Macfarlane A , Fahy N , Clyde B , et al. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: systematic review and co-design pilot . Health Expect 2019 ; 22 : 785 – 801 .

Wauben LSGL , Guédon ACP , de Korne DF , van den Dobbelsteen JJ . Tracking surgical day care patients using RFID technology . BMJ Innov 2015 ; 1 : 59 – 66 .

Tong A , Sainsbury P , Craig J . Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups . Int J Qual Health Care 2007 ; 19 : 349 – 357 .

von Elm E , Altman DG , Egger M , Pocock SJ , Gøtzsche PC , Vandenbroucke JP , et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies . Lancet 2007 ; 370 (9596): 1453 – 1457 .

Wilson A , Mackean T , Withall L , Willis EM , Pearson O , Hayes C , et al. Protocols for an Aboriginal-led, multi-methods study of the role of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers, practitioners and Liaison officers in quality acute health care . J Aust Indigenous HealthInfoNet 2022 ; 3 : 1 – 15 .

Lee B , Lee J , Cho Y , Shin Y , Oh C , Park H , et al. Visualisation of information using patient journey maps for a mobile health application . Appl Sci 2023 ; 13 : 6067 .

Author notes

- cardiovascular system

- health personnel

- health services

- health care systems

- narrative discourse

Email alerts

Related articles in pubmed, citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1873-1953

- Print ISSN 1474-5151

- Copyright © 2024 European Society of Cardiology

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimise digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered straight to teams on the ground

Know exactly how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Meet the operating system for experience management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Employee Exit Interviews

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

- Artificial Intelligence

- Market Research

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Industry Specific

- Patient Journey Mapping

Your complete guide to patient journey mapping

15 min read Healthcare organisations can increase patient retention and improve patient satisfaction with patient journey mapping. Discover how to create a patient journey map and how you can use it to improve your organisation’s bottom line.

What is the patient journey?

The patient journey is the sequence of events that begins when a patient first develops a need for care. Rather than focusing on service delivery, the patient journey encompasses all touchpoints of a patient’s healthcare experience–from locating healthcare providers and scheduling appointments, to paying the bill and continuing their care after treatment.

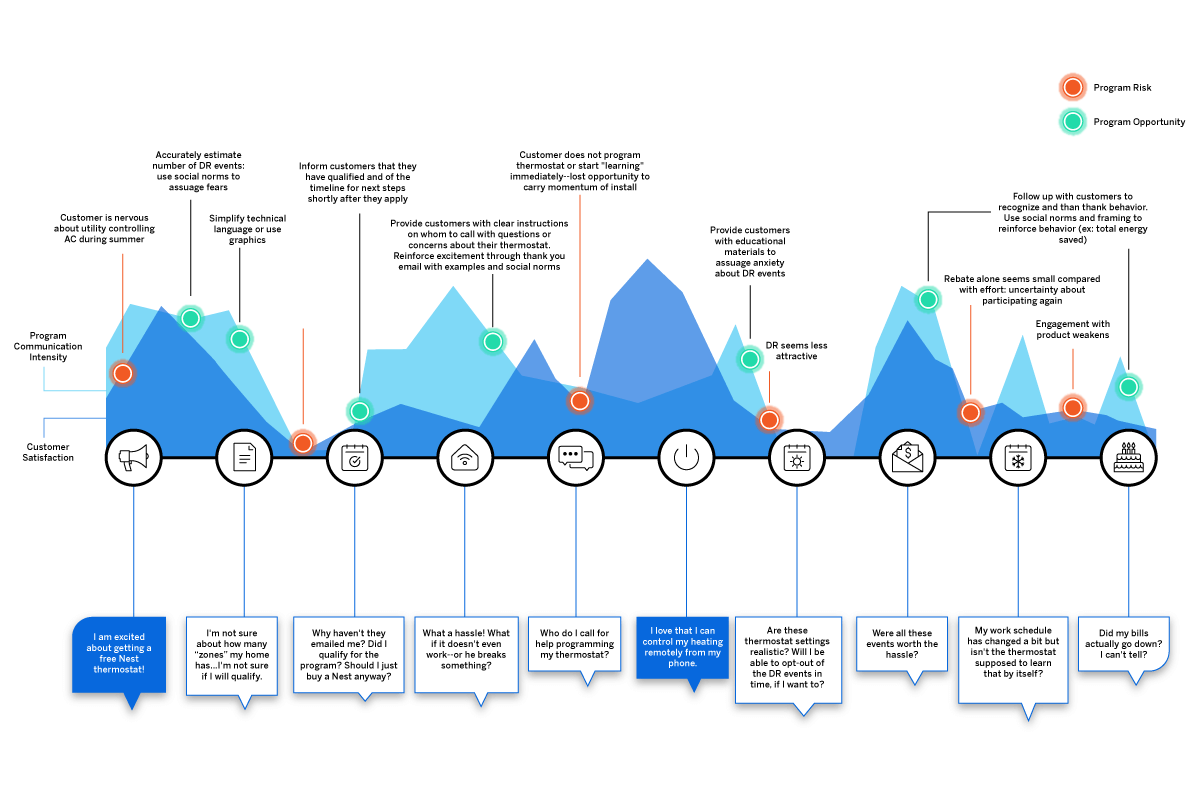

Examining the patient journey is essential to improving the patient experience. Not all interactions a patient has with your organisation are weighted the same. Gathering patient feedback and understanding perceptions all along the patient journey can help you to identify moments of truth : the touchpoints that have the biggest impact on patient loyalty.

Discover how Qualtrics can enhance the healthcare industry

The patient journey vs. the patient experience

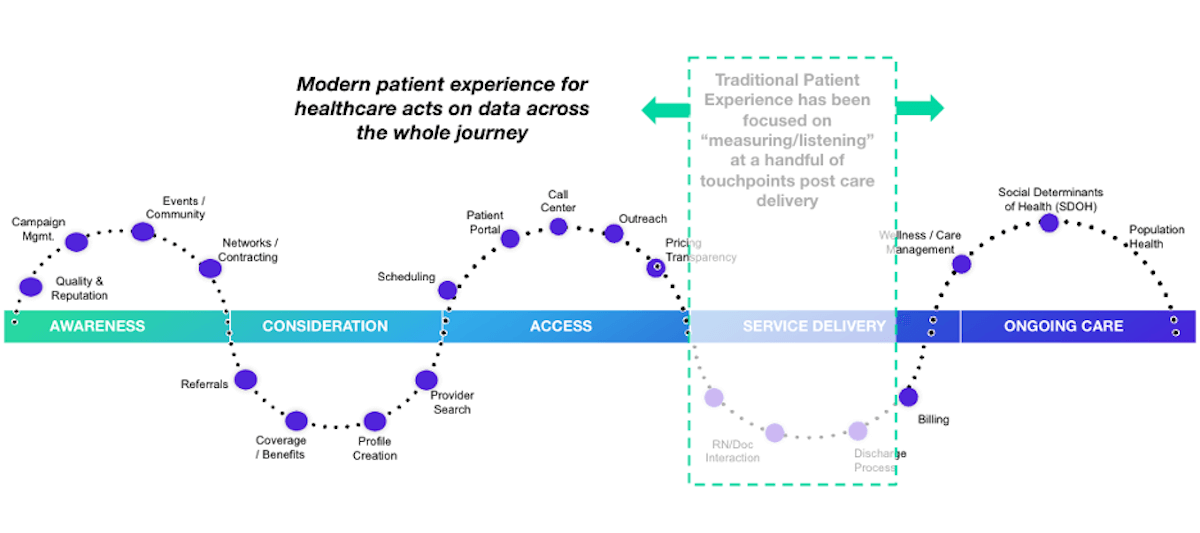

Unlike traditional patient experience measurement, the patient journey looks not only at service delivery but also at the steps the patient takes before and after they engage directly with your organisation. It recognises that patient interactions with a healthcare system go well beyond the walls of the medical facility itself.

What are the stages of the patient journey?

There are several stages along the patient journey. When gathering patient feedback, you should make sure to capture insights at each of these stages.

Stage 1: Awareness

The patient journey starts with awareness. In this stage, the patient identifies a need for care and begins searching for care providers. Examples of how patients learn about healthcare providers include online searches, review sites, marketing campaigns, networking, and community involvement.

Stage 2: Consideration

In the consideration stage, the patient weighs their options to determine if your health system can meet their needs. Factors patients consider include referrals, coverage and benefits, recommendations, access, and ratings and reviews. Often in this stage, patients interact with your website or social media pages or contact you via phone or email during this stage.

Stage 3: Access

The access stage is where the patient decides to schedule services with your healthcare organisation. Direct patient engagement with your organisation increases during this stage. You’ll engage with patients in a variety of ways including phone calls, the patient portal, text messages, and emails as part of the scheduling and new patient acquisition process.

Stage 4: Service delivery

The service delivery stage relates to the clinical care provided to your patients. Encompassed in this stage are the clinical visit itself, check-in and check-out, admission and discharge, and billing. Traditional patient satisfaction measurement centres around this stage of the patient journey.

Stage 5: Ongoing care

The ongoing care stage of the patient journey involves patient engagement that occurs after the interactions directly related to service delivery. In addition to wellness and care management, this stage may address social determinants of health and population health.

What is a patient journey map?

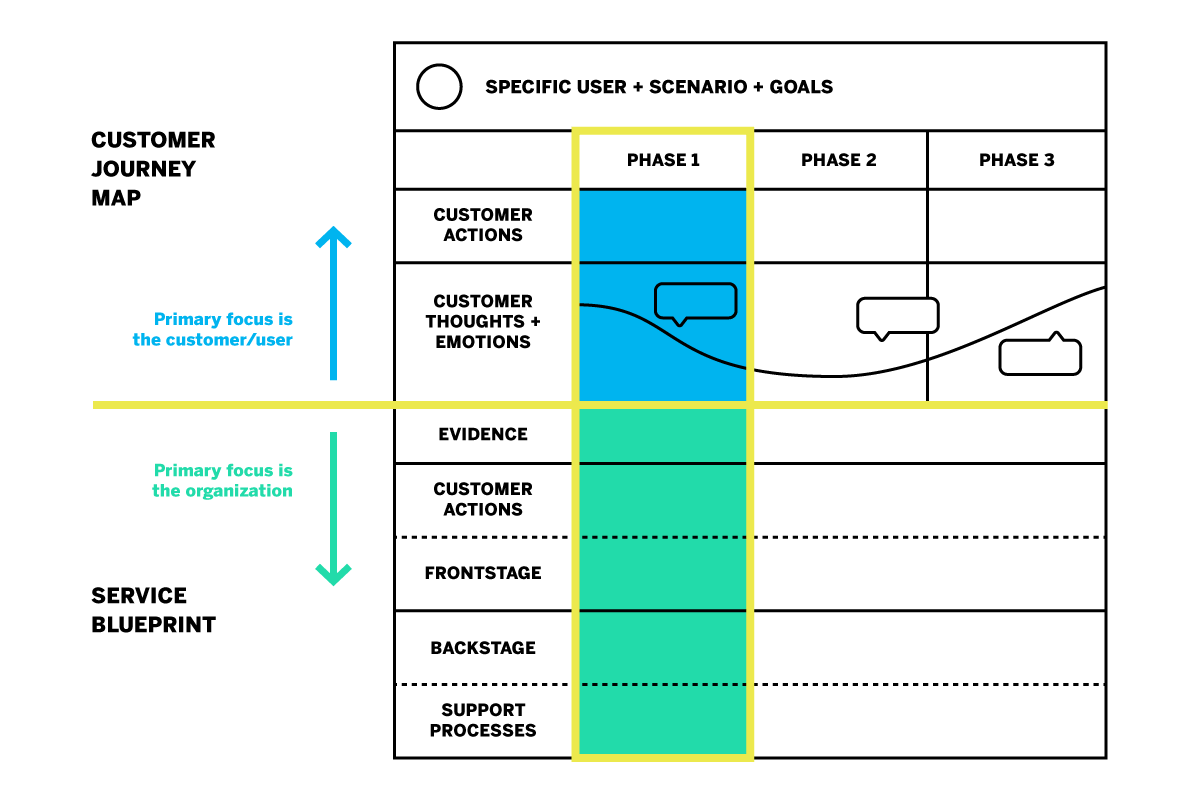

The best way to utilise the patient journey to enhance patient experiences is by journey mapping. A patient journey map is a visual tool that illustrates the relationship a patient has with a healthcare organisation over time.

Patient journey mapping helps stakeholders to assess the patient experience from multiple perspectives. Journey maps provide a way to visualise the internal and external factors affecting patient flow and the different paths patients must take in order to reach their care goals.

What are the benefits of patient journey mapping?

Patient journey mapping can help you to visualise all of the steps patients take throughout the entire process of seeking, receiving, and continuing care. Creating a patient journey map is useful to identify pain points and gaps in care. Mapping the patient journey makes it easier to develop solutions that make a more seamless experience within your healthcare system.

Patient journey mapping benefits include:

- Creating shared ownership of the patient experience

- Refining your patient listening strategy

- Aligning your organisation with a common view of the patient experience

- Measuring gaps between the intended experience for your patients versus the actual experience

- Identifying and resolving common pain points for your patients

Four types of patient journey maps

When creating a patient journey map, there are four types to consider. Each type of map has an intended purpose. You might start your patient journey mapping with only one type and incorporate the others as your efforts progress.

Current state

A current state journey map tells the story of what patients do, think, and feel as they interact with your organisation today. This type of patient journey map is ideally created using patient data and observational data.

The current state journey map is best for driving incremental improvements to enhance the patient experience.

Future state

A future state patient journey map tells the story of what you want your patients to do, think, and feel as they interact with your organisation in the future. This type of map should capture the ideal journey you’d like to see for your patients.

The future state journey map is an effective tool to drive strategy, align teams, and communicate your visions for new services, processes, and experiences.

Day in the life

A day in the life patient journey map illustrates what your patients do, think, and feel today, within a specific area of focus. Patient personas are particularly useful when creating day in the life maps; these are discussed in greater detail below.

This type of patient journey map is intended to capture what your patients experience both inside and outside of the healthcare system. Day in the life maps are valuable to address unmet needs and determine how and when you can better engage your patients.

Service blueprint

A service blueprint is a simplified diagram of a current state or future state patient journey map. In the service blueprint, you add layers to illustrate the systems of people, processes, policies, and technologies surrounding each patient touchpoint.

For current state patient journey maps, the service blueprint can help to identify root causes of pain points. For future state, the service blueprint is helpful to visualize the systems or processes that can be put in place to support the intended patient experience.

How do you create a patient journey map?

Now that you know about the different types of patient journey maps and their roles in driving patient experience improvement, how do you get started on creating your own?

The most useful maps are those which can expound upon each touchpoint of the healthcare journey with operational data, such as patient demographics, as well as real patient insights and perspectives. Using a platform that can capture this data will aid significantly in your patient journey mapping process.

Patient journey mapping: getting started

Before you get started, it’s a good idea to engage individuals across all departments and include input from multiple stakeholders. Once you’re ready, follow these steps to begin creating an effective patient journey map.

Identify your target audience

What type of patient journey will you be mapping? There may be varying patient journeys within your organisation; for instance, an oncology patient’s journey will look very different from that of an expectant mother. The journey of a patient with health insurance will differ from that of a patient without insurance. To map the patient journey, you’ll want to create robust patient profiles you can use to segment and track like-populations throughout the healthcare experience.

Establishing patient personas and segments

Not every patient will have the same healthcare goals. Creating patient personas based on behaviours and preferences is a good way to differentiate the needs and more clearly understand the perspectives of the unique populations you serve.

- Demographic information such as age group, gender, or location

- Healthcare-specific goals, conditions, and treatments

- Healthcare-specific challenges/pain points

- Engagement patterns and expressed feedback

- How your services fit into their life

- Barriers to care

Specify a goal for the patient’s journey

The patient personas you create will all have unique goals within the care journey. The patient has a specific goal in mind when they initiate contact with your organisation, whether it is treatment of symptoms, a diagnosis for chronic issues, or surgery.

Every interaction along the patient journey influences how successful the patient feels about achieving this goal. When mapping the patient journey, you’ll want to consider how the various touchpoints affect the patient’s ability to meet this goal.

Identify the patient’s steps to accomplish their target goal

This step is about how the patient views their care journey within your health system–not about the actual processes and systems your organisation has in place. Effective patient journey mapping requires you to see how the patient navigates the journey through their point of view.

Omni-channel listening is a valuable strategy in this step of journey mapping. Listening to your patients across all the channels can provide a clearer picture of their perceptions and behaviours as they engage with your organisation.

Some steps the patient takes may not even include your organisation, but might still affect how they are interacting with you directly. For example, if a patient logs into their health insurance portal to check coverage for healthcare services, they are not engaging with your organisation but this is still a part of their care journey that may feed into their interactions with your organisation later on.

Uncover perceptions along the journey

Gather patient feedback along the touchpoints of the care journey to identify key emotional moments that may disproportionately shape attitudes. These insights shed light on what’s working and what’s not; they can also be used to highlight the moments of truth that contribute to patient loyalty.

Patient perceptions are an important piece of patient journey mapping; it will be difficult to drive action without them.

Additional tips for creating the ideal patient journey map

Patient journey mapping is a continuous process. Creating the map is the first step, but the true value is dependent upon maintaining the map as you continue to gather insights and refine processes.

This leads to the second tip: be ready to take action! You can use a patient journey map to draw conclusions about your patients’ experiences within your organisation, but awareness alone will yield no benefits. The journey map is a valuable tool to be used in your wider improvement efforts.

How do you drive action using a patient journey map?

Once your patient journey mapping is complete, it’s time to put it to good use. Here are five ways patient journey maps can be used to drive action.

Identify and fix problems

The visual layout of a journey map makes it ideal to identify gaps and potential pain points in your patient journeys. This will give you a better understanding of what’s working and what’s not. It will also help you to visualise where and how improvements can be made.

Build a patient mindset

Patient journey mapping enables you to incorporate more patient-centric thinking into your processes and systems. Use your map to challenge internal ideas of what patients want or need. Invite stakeholders to navigate the touchpoints along the healthcare journey to gain perspective.

Uncover unmet patient needs

By mapping the patient journey, you can build stronger patient relationships by listening across all channels to determine where experiences are falling short or where unmet needs emerge. This enables you to look for opportunities to expand alternatives, streamline initiatives, and create new, engaging ways for your patients to share feedback.

Create strategic alignment

Utilise your patient journey map to prioritise projects or improvement efforts. It can also help you to better engage interdepartmental staff to better understand policies and work together toward patient experience goals.

Refine measurement

Patient journey mapping is a great resource to use when defining patient satisfaction metrics and identifying gaps in how you currently gather insights.

How does patient journey mapping increase your bottom line?

Patient journey mapping can increase your bottom line by laying the foundation for improved patient satisfaction and higher retention.

Organisations across all industries are looking to understand customer journeys in order to attract and retain customers by gaining deeper insights into what drives the consumer experience.

As healthcare becomes more consumer-driven, health systems must similarly map the patient journey to improve the patient experience and boost retention. The cost of patient acquisition, combined with the fact that patients are willing to shop around for the best healthcare experience, means success depends on creating the most seamless patient journey possible.

The tools for success

For the most impactful patient journey mapping experience, you’ll want the ability to link your operational and experience data to your journey map’s touchpoints. Insights about what has happened at each touchpoint, as well as why it is happening, empower you to create experiences that meet patient expectations and drive up satisfaction.

Here are some best practice considerations as you develop your patient journey mapping strategy:

- Create a shared understanding throughout your health system of how your patients interact with your organisation, and you’ll know the roles and responsibilities of your different teams

- Design a unique patient journey based on multichannel, real-time feedback from the patient

- Consider the frequency with which topics emerge in feedback, as well as the emotional intensity behind them to zero in on what improvements can drive the greatest impact

- Develop empathy and collaboration between teams, working together to achieve the same outcome

- Drive a patient-centric culture by developing a shared sense of ownership of the patient experience

- Connect your operational patient data with your patient experience feedback in one system

- Leverage a closed-loop feedback system that triggers actions for immediate responses to patient concerns

Qualtrics’ XM Platform™ is designed to support all of these actions throughout the journey mapping process.

Related resources

Nursing shortages 13 min read, healthcare branding 13 min read, patient feedback 13 min read, patient experience: your complete guide 12 min read, symptoms survey 10 min read, quality improvement in healthcare 11 min read, nurse satisfaction survey 11 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

The 1-2-3 Guide to Patient Journey Mapping [Template Inside]

by Gaine Solutions | Feb 28, 2024 | Healthcare , Life Sciences , Master Data Management

Patient journeys in today’s healthcare landscape are complex, spanning a number of platforms, systems, touchpoints, and interactions. As patients engage with healthcare providers through diverse channels, both digital and physical, the need for a structured and comprehensive approach to managing the patient journeys is evident. Patient journey mapping is the solution.

Patient journey mapping creates a high-level and holistic view of the patient journey that empowers healthcare providers to make the most informed and impactful decisions possible about how to enhance operations and care.

In this guide, we’ll walk step-by-step through the process of creating and implementing a patient journey map that drives better performance results and patient outcomes for your healthcare organization.

Key Takeaways:

- Patient journey mapping is crucial for understanding and enhancing the patient experience.

- Patient journey mapping leads to improved patient satisfaction, better clinical outcomes, and increased operational efficiency.

- Developing a patient journey map requires clear objectives, a cross-functional team, and data-driven approaches to gaining insight.

- Improvement strategies should be developed for each critical moment and touchpoint, with changes implemented and continuously monitored for effectiveness over time.

What is Patient Journey Mapping and Why Is It Important?

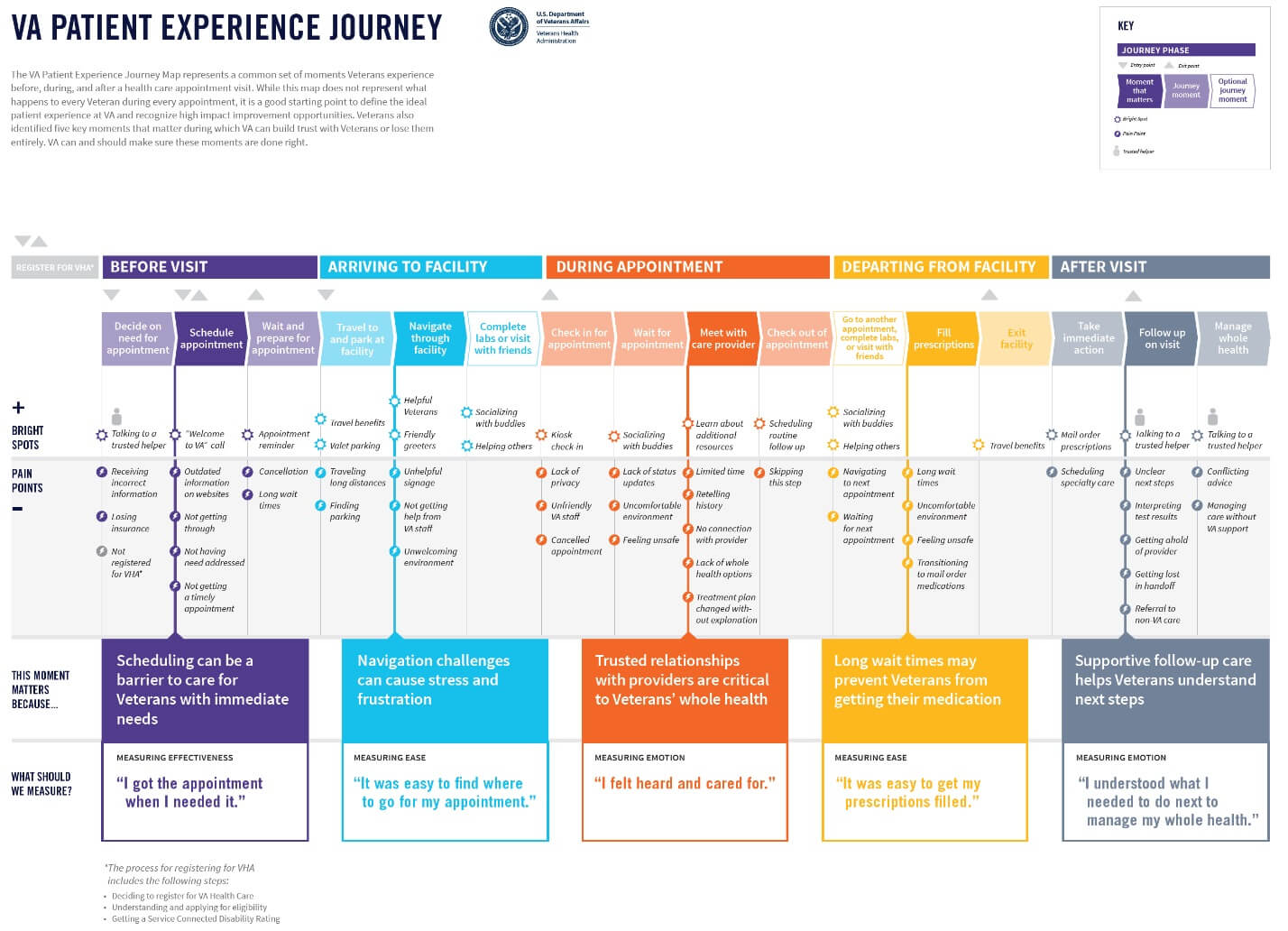

Patient journey mapping is the process of creating a detailed visualization of a patient’s healthcare journey, from initial contact through treatment and follow-up care, identifying every touchpoint along the way. This methodical approach helps healthcare providers see the care process from the patient perspective, including the highs, lows, and gaps in the patient experience.

The example below is from the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, and shows how intricate and complex the patient journey is once it’s mapped completely. This drives home the importance of documenting the journey visually in order to see it in a holistic way.

Image Source

When done effectively, patient journey mapping is a valuable tool driving more seamless, integrated, and patient-centered care. Journey mapping also helps healthcare organizations make informed decisions about where to allocate resources, how to streamline operations, and ways to personalize care to meet the unique needs of each patient.

In the end, the benefits of patient journey mapping are threefold:

- Improved Patient Satisfaction : Enhances the overall patient experience by addressing specific needs and preferences, leading to higher satisfaction rates.

- Better Clinical Outcomes : Identifies opportunities for early intervention and personalized care plans, contributing to improved health results.

- Increased Operational Efficiency : Streamlines healthcare processes by pinpointing inefficiencies and redundancies, leading to more effective use of resources.

It leads to 360-degree improvements that enhance clinical, administrative, and operational aspects of both the healthcare system and the patient experience. In the next section, we’ll walk through the steps you can take to develop a patient journey map for your organization.

Your Step-by-Step Patient Journey Mapping Template

1. identify the goals and scope of your map.

Begin by d eve loping a clear vision of what you aim to achieve through patient journey mapping. Whether it’s to enhance patient satisfaction, streamline healthcare delivery, or identify gaps in service, setting specific objectives will direct your mapping efforts. During this step, you should also determine the scope of your map (i.e. whether it focuses on a particular service line or the entire healthcare experience).

2. Gather a Cross-Functional Team

Assemble a team that represents a broad spectrum of roles within your organization, including clinicians, administrative staff, IT professionals, and cust ome r service representatives. Diverse perspectives ensure a holistic view of the patient journey, capturing insights from every facet of patient interaction.

3. Map the Patient Touchpoints

Systematically list every interaction point between the patient and your healthcare system. This includes digital touchpoints like website visits, appointment scheduling portals, and social media interactions, as well as physical touchpoints like clinic visits, phone calls, and direct mail communication. Mapping these touchpoints requires a detailed understanding of the patient’s path through your system, from initial awareness through treatment and follow-up care.

4. Collect and Analyze Data

Leverage diverse data sources to understand patient experiences at each touchpoint. Collect patient feedback through cha nne ls like surveys, interviews, and comment cards. Analyze staff insights and review operational data. Look for patterns in behavior and satisfaction levels, and identify bottlenecks or pain points in the patient journey.

Having a centralized data management platform in place is crucial for this step—it provides a central repository for the data you collect as part of your patient journey mapping exercise, while also giving you seamless access to historical data in one location.

5. Visualize the Journey

Develop a visual representation of the patient journey. Use flowcharts, storyboards, or diagrams to depict the sequence of touchpoints and the patient’s experience at each stage. This visualization should be from the patient’s perspective, highlighting critical interactions, emotions, and decision points.

Tools like customer journey mapping software can facilitate this process, but even simple graphical tools or whiteboards can be effective.

6. Identify Moments of Truth

Highlight key moments in the journey that significantly impact the patient’s perception of care—things like first contact, diagnosis communication, wait times, and billing support. These are opportunities to make a lasting impression on the patient, and identifying them allows your team to prioritize areas for immediate improvement or innovation.

7. Develop Improvement Strategies

For each critical moment and touchpoint, evaluate what’s working effectively as well as areas for potential improvements. Call out specific gaps and pain points that may exist for the patient at every stage on your journey map. Then, brainstorm how to resolve them.

This may happen by introducing new technologies, optimizing existing processes, providing additional training for your staff, enhancing communication strategies, and more.

8. Implement Changes

Prioritize the identified improvements based on their potential impact and feasibility. Create a detailed implementation plan, assigning clear responsibilities and deadlines. Ensure there is a mechanism for tracking progress and measuring the impact of these changes on the patient experience and other goals and objectives you set at the start of the process.

9. Monitor and Adjust

Establish a continuous feedback loop to monitor the effectiveness of implemented changes. Use patient feedback, staff input, and performance metrics to assess progress. Be prepared to make iterative adjustments to your strategies based on this feedback, fostering a culture of continuous improvement.

Putting it All Together

Embarking on patient journey mapping is more than a strategic exercise—it’s a commitment to elevating the standard of care through a deep understanding of the patient’s experience. It represents a pivotal shift toward a more empathetic, patient-centric approach in healthcare, where decisions are informed by the nuanced needs and experiences of those we serve.

Gaine’s Coperor platform is a scalable, ecosystem-wide master data management solution designed for the unique challenges of the healthcare and life sciences industries. It creates a single source of data truth within an organization that makes initiatives like journey mapping possible. Learn more here or start your real-time Coperer demo today.

Opt-in with Gaine for More Insight

Great welcome to the mdm a-team you may unsubscribe at any time., more articles like this.

- Case Studies

- Contracting

- Credentialing

- Data Governance

- Data Quality

- Data Science

- Health Plans

- Interoperability

- Life Sciences

- Master Data Management

- Network Adequacy

- Network Management

- Next-Gen MDM

- Provider Data Management

- Provider Groups

- Provider Network

- Provider Network Management

- Uncategorized

Understanding the Coperor™ Health Data Management Platform

Data-Driven Healthcare: Unveiling the Path to Enhanced HEDIS and Star Quality Metrics

Demystifying HEDIS and Star Ratings: Challenges & Best Practices for Providers.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Process mapping the...

Process mapping the patient journey: an introduction

- Related content

- Peer review

- Timothy M Trebble , consultant gastroenterologist 1 ,

- Navjyot Hansi , CMT 2 1 ,

- Theresa Hydes , CMT 1 1 ,

- Melissa A Smith , specialist registrar 2 ,

- Marc Baker , senior faculty member 3

- 1 Department of Gastroenterology, Portsmouth Hospitals Trust, Portsmouth PO6 3LY

- 2 Department of Gastroenterology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London

- 3 Lean Enterprise Academy, Ross-on-Wye, Hertfordshire

- Correspondence to: T M Trebble tim.trebble{at}porthosp.nhs.uk

- Accepted 15 July 2010

Process mapping enables the reconfiguring of the patient journey from the patient’s perspective in order to improve quality of care and release resources. This paper provides a practical framework for using this versatile and simple technique in hospital.

Healthcare process mapping is a new and important form of clinical audit that examines how we manage the patient journey, using the patient’s perspective to identify problems and suggest improvements. 1 2 We outline the steps involved in mapping the patient’s journey, as we believe that a basic understanding of this versatile and simple technique, and when and how to use it, is valuable to clinicians who are developing clinical services.

What information does process mapping provide and what is it used for?

Process mapping allows us to “see” and understand the patient’s experience 3 by separating the management of a specific condition or treatment into a series of consecutive events or steps (activities, interventions, or staff interactions, for example). The sequence of these steps between two points (from admission to the accident and emergency department to discharge from the ward) can be viewed as a patient pathway or process of care. 4

Improving the patient pathway involves the coordination of multidisciplinary practice, aiming to maximise clinical efficacy and efficiency by eliminating ineffective and unnecessary care. 5 The data provided by process mapping can be used to redesign the patient pathway 4 6 to improve the quality or efficiency of clinical management and to alter the focus of care towards activities most valued by the patient.

Process mapping has shown clinical benefit across a variety of specialties, multidisciplinary teams, and healthcare systems. 7 8 9 The NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement proposes a range of practical benefits using this approach (box 1). 6

Box 1 Benefits of process mapping 6

A starting point for an improvement project specific for your own place of work

Creating a culture of ownership, responsibility and accountability for your team

Illustrates a patient pathway or process, understanding it from a patient’s perspective

An aid to plan changes more effectively

Collecting ideas, often from staff who understand the system but who rarely contribute to change

An interactive event that engages staff

An end product (a process map) that is easy to understand and highly visual

Several management systems are available to support process mapping and pathway redesign. 10 11 A common technique, derived originally from the Japanese car maker Toyota, is known as lean thinking transformation. 3 12 This considers each step in a patient pathway in terms of the relative contribution towards the patient’s outcome, taken from the patient’s perspective: it improves the patient’s health, wellbeing, and experience (value adding) or it does not (non-value or “waste”) (box 2). 14 15 16

Box 2 The eight types of waste in health care 13

Defects —Drug prescription errors; incomplete surgical equipment

Overproduction —Inappropriate scheduling

Transportation —Distance between related departments

Waiting —By patients or staff

Inventory —Excess stores, that expire

Motion —Poor ergonomics

Overprocessing —A sledgehammer to crack a nut

Human potential —Not making the most of staff skills

Process mapping can be used to identify and characterise value and non-value steps in the patient pathway (also known as value stream mapping). Using lean thinking transformation to redesign the pathway aims to enhance the contribution of value steps and remove non-value steps. 17 In most processes, non-value steps account for nine times more effort than steps that add value. 18

Reviewing the patient journey is always beneficial, and therefore a process mapping exercise can be undertaken at any time. However, common indications include a need to improve patients’ satisfaction or quality or financial aspects of a particular clinical service.

How to organise a process mapping exercise

Process mapping requires a planned approach, as even apparently straightforward patient journeys can be complex, with many interdependent steps. 4 A process mapping exercise should be an enjoyable and creative experience for staff. In common with other audit techniques, it must avoid being confrontational or judgmental or used to “name, shame, and blame.” 8 19

Preparation and planning

A good first step is to form a team of four or five key staff, ideally including a member with previous experience of lean thinking transformation. The group should decide on a plan for the project and its scope; this can be visualised by using a flow diagram (fig 1 ⇓ ). Producing a rough initial draft of the patient journey can be useful for providing an overview of the exercise.

Fig 1 Steps involved in a process mapping exercise

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

The medical literature or questionnaire studies of patients’ expectations and outcomes should be reviewed to identify value adding steps involved in the management of the clinical condition or intervention from the patient’s perspective. 1 3

Data collection

Data collection should include information on each step under routine clinical circumstances in the usual clinical environment. Information is needed on waiting episodes and bottlenecks (any step within the patient pathway that slows the overall rate of a patient’s progress, normally through reduced capacity or availability 20 ). Using estimates of minimum and maximum time for each step reduces the influence of day to day variations that may skew the data. Limiting the number of steps (to below 60) aids subsequent analysis.

The techniques used for data collection (table 1 ⇓ ) each have advantages and disadvantages; a combination of approaches can be applied, contributing different qualitative or quantitative information. The commonly used technique of walking the patient journey includes interviews with patients and staff and direct observation of the patient journey and clinical environment. It allows the investigator to “see” the patient journey at first hand. Involving junior (or student) doctors or nurses as interviewers may increase the openness of opinions from staff, and time needed for data collection can be reduced by allotting members of the team to investigate different stages in the patient’s journey.

Data collection in process mapping

- View inline

Mapping the information

The process map should comprehensively represent the patient journey. It is common practice to draw the map by hand onto paper (often several metres long), either directly or on repositionable notes (fig 2 ⇓ ).

Fig 2 Section of a current state map of the endoscopy patient journey

Information relating to the steps or representing movement of information (request forms, results, etc) can be added. It is useful to obtain any missing information at this stage, either from staff within the meeting or by revisiting the clinical environment.

Analysing the data and problem solving

The map can be analysed by using a series of simple questions (box 3). The additional information can be added to the process map for visual representation. This can be helped by producing a workflow diagram—a map of the clinical environment, including information on patient, staff, and information movement (fig 3 ⇓ ). 18

Box 3 How to analyse a process map 6

How many steps are involved?

How many staff-staff interactions (handoffs)?

What is the time for each step and between each step?

What is the total time between start and finish (lead time)?

When does a patient join a queue, and is it a regular occurrence?

How many non-value steps are there?

What do patients complain about?

What are the problems for staff?

Fig 3 Workflow diagram of current state endoscopy pathway

Redesigning the patient journey

Lean thinking transformation involves redesigning the patient journey. 21 22 This will eliminate, combine and simplify non-value steps, 23 limit the impact of rate limiting steps (such as bottlenecks), and emphasise the value adding steps, making the process more patient-centred. 6 It is often useful to trial the new pathway and review its effect on patient management and satisfaction before attempting more sustained implementation.

Worked example: How to undertake a process mapping exercise

South Coast NHS Trust, a large district general hospital, plans to improve patient access to local services by offering unsedated endoscopy in two peripheral units. A consultant gastroenterologist has been asked to lead a process mapping exercise of the current patient journey to develop a fast track, high quality patient pathway.

In the absence of local data, he reviews the published literature and identifies key factors to the patient experience that include levels of discomfort during the procedure, time to discuss the findings with the endoscopist, and time spent waiting. 24 25 26 27 He recruits a team: an experienced performance manager, a sister from the endoscopy department, and two junior doctors.

The team drafts a map of the current endoscopy journey, using repositionable notes on the wall. This allows team members to identify the start (admission to the unit) and completion (discharge) points and the locations thought to be involved in the patient journey.

They decide to use a “walk the journey” format, interviewing staff in their clinical environments and allowing direct observation of the patient’s management.

The junior doctors visit the endoscopy unit over two days, building up rapport with the staff to ensure that they feel comfortable with being observed and interviewed (on a semistructured but informal basis). On each day they start at the point of admission at the reception office and follow the patient journey to completion.

They observe the process from staff and patient’s perspectives, sitting in on the booking process and the endoscopy procedure. They identify the sequence of steps and assess each for its duration (minimum and maximum times) and the factors that influence this. For some of the steps, they use a digital watch and notepad to check and record times. They also note staff-patient and staff-staff interactions and their function, and the recording and movement of relevant information.

Details for each step are entered into a simple table (table 2 ⇓ ), with relevant notes and symbols for bottlenecks and patients’ waits.

Patient journey for non-sedated upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

When data collection is complete, the doctor organises a meeting with the team. The individual steps of the patient journey are mapped on a single long section of paper with coloured temporary markers (fig 2 ⇑ ); additional information is added in different colours. A workflow diagram is drawn to show the physical route of the patient journey (fig 3 ⇑ ).

The performance manager calculates that the total patient journey takes a minimum of 50 minutes to a maximum of 345 minutes. This variation mainly reflects waiting times before a number of bottleneck steps.

Only five steps (14 to 17 and 22, table 2 ⇑ ) are considered both to add value and needed on the day of the procedure (providing patient information and consent can be obtained before the patient attends the department). These represent from 13 to 47 minutes. At its least efficient, therefore, only 4% of the patient journey (13 of 345 minutes) is spent in activities that contribute directly towards the patient’s outcome.

The team redesigns the patient journey (fig 4 ⇓ ) to increase time spent on value adding aspects but reduce waiting times, bottlenecks, and travelling distances. For example, time for discussing the results of the procedure is increased but the location is moved from the end of the journey (a bottleneck) to shortly after the procedure in the anteroom, reducing the patient’s waiting time and staff’s travelling distances.

Fig 4 Workflow diagram of future state endoscopy pathway

Implementing changes and sustaining improvements

The endoscopy staff are consulted on the new patient pathway, which is then piloted. After successful review two months later, including a patient satisfaction questionnaire, the new patient pathway is formally adopted in the peripheral units.

Further reading

Practical applications.

NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement ( https://www.institute.nhs.uk )—comprehensive online resource providing practical guidance on process mapping and service improvement

Lean Enterprise Academy ( http://www.leanuk.org )—independent body dedicated to lean thinking in industry and healthcare, through training and academic discussion; its publication, Making Hospitals Work 23 is a practical guide to lean transformation in the hospital environment

Manufacturing Institute ( http://www.manufacturinginstitute.co.uk )—undertakes courses on process mapping and lean thinking transformation within health care and industrial practice

Theoretical basis

Bircheno J. The new lean toolbox . 4th ed. Buckingham: PICSIE Books, 2008

Mould G, Bowers J, Ghattas M. The evolution of the pathway and its role in improving patient care. Qual Saf Health Care 2010 [online publication 29 April]

Layton A, Moss F, Morgan G. Mapping out the patient’s journey: experiences of developing pathways of care. Qual Health Care 1998; 7 (suppl):S30-6

Graban M. Lean hospitals, improving quality, patient safety and employee satisfaction . New York: Taylor & Francis, 2009

Womack JP, Jones DT. Lean thinking . 2nd ed. London: Simon & Schuster, 2003

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;341:c4078

Contributors: TMT designed the protocol and drafted the manuscript; TMT, MB, JH, and TH collected and analysed the data; all authors critically reviewed and contributed towards revision and production of the manuscript. TMT is guarantor.

Competing interests: MB is a senior faculty member carrying out research for the Lean Enterprise Academy and undertakes paid consultancies both individually and from Lean Enterprise Academy, and training fees for providing lean thinking in healthcare.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- ↵ Kollberg B, Dahlgaard JJ, Brehmer P. Measuring lean initiatives in health care services: issues and findings. Int J Productivity Perform Manage 2007 ; 56 : 7 -24. OpenUrl CrossRef

- ↵ Bevan H, Lendon R. Improving performance by improving processes and systems. In: Walburg J, Bevan H, Wilderspin J, Lemmens K, eds. Performance management in health care. Abingdon: Routeledge, 2006:75-85.

- ↵ Kim CS, Spahlinger DA, Kin JM, Billi JE. Lean health care: what can hospitals learn from a world-class automaker? J Hosp Med 2006 ; 1 : 191 -9. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Layton A, Moss F, Morgan G. Mapping out the patient’s journey: experiences of developing pathways of care. Qual Health Care 1998 ; 7 (suppl): S30 -6. OpenUrl

- ↵ Peterson KM, Kane DP. Beyond disease management: population-based health management. Disease management. Chicago: American Hospital Publishing, 1996.

- ↵ NHS Modernisation Agency. Process mapping, analysis and redesign. London: Department of Health, 2005;1-40.

- ↵ Taylor AJ, Randall C. Process mapping: enhancing the implementation of the Liverpool care pathway. Int J Palliat Nurs 2007 ; 13 : 163 -7. OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Ben-Tovim DI, Dougherty ML, O’Connell TJ, McGrath KM. Patient journeys: the process of clinical redesign. Med J Aust 2008 ; 188 (suppl 6): S14 -7. OpenUrl PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ King DL, Ben-Tovim DI, Bassham J. Redesigning emergency department patient flows: application of lean thinking to health care. Emerg Med Australas 2006 ; 18 : 391 -7. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Mould G, Bowers J, Ghattas M. The evolution of the pathway and its role in improving patient care. Qual Saf Health Care 2010 ; published online 29 April.

- ↵ Rath F. Tools for developing a quality management program: proactive tools (process mapping, value stream mapping, fault tree analysis, and failure mode and effects analysis). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008 ; 71 (suppl): S187 -90. OpenUrl PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Womack JP, Jones DT. Lean thinking. 2nd ed. London: Simon & Schuster, 2003.

- ↵ Graban M. Value and waste. In: Lean hospitals. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2009;35-56.

- ↵ Westwood N, James-Moore M, Cooke M. Going lean in the NHS. London: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2007.

- ↵ Liker JK. The heart of the Toyota production system: eliminating waste. The Toyota way. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004;27-34.

- ↵ Womack JP, Jones DT. Introduction: Lean thinking versus Muda. In: Lean thinking. 2nd ed. London: Simon & Schuster, 2003:15-28.

- ↵ George ML, Rowlands D, Price M, Maxey J. Value stream mapping and process flow tools. Lean six sigma pocket toolbook. New York: McGraw Hill, 2005:33-54.

- ↵ Fillingham D. Can lean save lives. Leadership Health Serv 2007 ; 20 : 231 -41. OpenUrl CrossRef

- ↵ Benjamin A. Audit: how to do it in practice. BMJ 2008 ; 336 : 1241 -5. OpenUrl FREE Full Text

- ↵ Vissers J. Unit Logistics. In: Vissers J, Beech R, eds. Health operations management patient flow logistics in health care. Oxford: Routledge, 2005:51-69.

- ↵ Graban M. Overview of lean for hospital. Lean hospitals. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2009;19-33.

- ↵ Eaton M. The key lean concepts. Lean for practitioners. Penryn, Cornwall: Academy Press, 2008:13-28.

- ↵ Baker M, Taylor I, Mitchell A. Analysing the situation: learning to think differently. In: Making hospitals work. Ross-on-Wye: Lean Enterprise Academy, 2009:51-70.

- ↵ Ko HH, Zhang H, Telford JJ, Enns R. Factors influencing patient satisfaction when undergoing endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 2009 ; 69 : 883 -91. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Del Rio AS, Baudet JS, Fernandez OA, Morales I, Socas MR. Evaluation of patient satisfaction in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007 ; 19 : 896 -900. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Seip B, Huppertz-Hauss G, Sauar J, Bretthauer M, Hoff G. Patients’ satisfaction: an important factor in quality control of gastroscopies. Scand J Gastroenterol 2008 ; 43 : 1004 -11. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Yanai H, Schushan-Eisen I, Neuman S, Novis B. Patient satisfaction with endoscopy measurement and assessment. Dig Dis 2008 ; 26 : 75 -9. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

Nursing and the Patient Journey

- First Online: 22 September 2023

Cite this chapter

- Barbara Sassen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8354-7885 2

557 Accesses

Patient mapping or patient journey, a tool used to visualize the patient journey, is beneficial in understanding the patient’s experience with healthcare. It highlights what contributes to good care and what does not from the patient’s perspective.

Additionally, the concept of the patient journey is used in the context of quality of care to refer to the path a patient takes through the healthcare system. By viewing the journey from the patient’s perspective, the effectiveness and efficiency of care can be improved by eliminating ineffective or unnecessary treatments. This can lead to a redesign of the patient’s journey with the goal of increasing patient satisfaction and improving the quality of care. Achieving this requires healthcare providers to align care with the patient’s perceptions, preferences, and expectations.

Understanding the patient experience within the healthcare system is important particularly using patient journey mapping. This involves mapping out the process a patient goes through, from diagnosis to discharge, to identify areas for improvement and to make care more efficient and effective. The focus should be on activities valued by patients to improve patient satisfaction. Process mapping is also used to optimize care processes, but it often lacks a patient-centered approach. The text emphasizes the importance of incorporating patient satisfaction into medical protocols, guidelines, and ethical standards. A care continuum is also preferable from a patient perspective, where care providers maintain continuous contact with their patients to avoid gaps in care and ensure effective care outcomes.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bate P, Robert G. Experience-based design: from redesigning the system around the patient to co-designing services with the patient. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:307–10. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2005.016527 . (This is based on mapping a consecutive series of ‘touch points’ between the patient and the service where patient experience is actively shaped).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Elliss-Brookes L, McPhail S, Ives A, Greenslade M, Shelton J, Hiom S, et al. Routes to diagnosis for cancer—determining the patient journey using multiple routine data sets. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1220–6.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gregory M. A possible patient journey: a tool to facilitate patient-centered care. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2012.

Google Scholar

McCarthy S, O’Raghallaigh P, Woodworth S, Lin Lim Y, Kenny LC, Adam F. An integrated patient journey mapping tool for embedding quality in healthcare service reform. J Decis Syst. 2016;25:354–68. Published online: 16 Jun 2016. https://doi.org/10.1080/12460125.2016.1187394 .

Article Google Scholar

Trebble TM, Hansi N, Hydes T, Smith MA, Baker M. Process mapping the patient journey: an introduction. BMJ. 2010;341:c4078. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c4078 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Applied Sciences, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Barbara Sassen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Barbara Sassen .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Sassen, B. (2023). Nursing and the Patient Journey. In: Improving Person-Centered Innovation of Nursing Care. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35048-1_26

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35048-1_26

Published : 22 September 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-35047-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-35048-1

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 20 October 2023

Navigating the facilitation journey: a qualitative, longitudinal evaluation of ‘Eat Walk Engage’ novice and experienced facilitators

- Gillian Harvey 1 , 2 ,

- Sarah Collyer 1 ,

- Prue McRae 3 , 4 ,

- Sally E. Barrimore 5 ,

- Camey Demmitt 6 ,

- Karen Lee-Steere 3 , 7 ,

- Bernadette Nolan 8 &

- Alison M. Mudge 3 , 9

BMC Health Services Research volume 23 , Article number: 1132 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

932 Accesses

7 Altmetric

Metrics details