Project News · 16 February 2022

Unlocking sustainable tourism

A challenge for our times.

The past couple of years have delivered a blow to the global travel and tourism industries unlike any in recent memory, impacting communities and livelihoods around the world. As some of our key coral reef sites experience a dramatic decline in visitor numbers, both challenges and opportunities are emerging.

In November 2021, the Great Barrier Reef Foundation brought together our partners, leading experts and our teams from the Resilient Reefs pilot sites (Palau, New Caledonia, Belize and Ningaloo) to hold a Solution Exchange on Sustainable Tourism. Together, the participants explored how World Heritage Marine sites can make their local tourism industry more sustainable for both people and the environment and build resilience to events such as the COVID-19 pandemic and reduce pressure on natural resources in the face of climate change.

The challenge

In COVID-free times, the travel and tourism sectors usually contribute around 10.4% to the global economy each year. Global coral reef tourism (pre-COVID) is a heavy hitting contributor to this, with an annual worth of $36 million. The industry can bring great economic benefits to the people who call World Heritage Marines sites home, but it can also prove unsustainable and put significant stress on local communities and the environment.

The scale of the global coral reef tourism industry itself also presents challenges for the coral reef ecosystems and people that depend on them, with some communities being ill-equipped to cope with tourist volumes. The extent of the impact this has on local communities and the environment is influenced by factors such as the infrastructure and processes in place to support tourist numbers, the behaviour of the tourists themselves and the governance communities have in place to manage all of this.

Tourists flock to coastal communities in COVID-free times. Credit: Michaela Hampi. (Top) Belize's tourism industry has suffered a downturn during COVID-19. Credit: Meritt Thomas

The current tourism hiatus provides us with an opportunity to look at ways to create more sustainable tourism practices to support the ongoing health and longevity of our reefs and the communities that depend on them.

So how do we support local coral reef communities to survive and thrive when many of their livelihoods have been decimated? And how do we foster alternative income streams while also ensuring their resilience in the face of unknown future challenges?

To begin to understand the path to sustainable tourism, the Solution Exchange focused on exploring tourism carrying capacity at sites, how to shift tourist behaviour to support local resilience goals and opportunities to diversity local livelihoods.

Tourists take part in scuba training in the Turks and Caicos Islands. Credit: The Ocean Agency, XL Catlin Seaview Survey

We need to better identify and manage tourism carrying capacity at sites

One way we can aid sustainable tourism is to understand and monitor the carrying capacity of tourist destinations; the maximum number of tourists that can visit a location at the same time without destroying the ecological, social and economic environment.

Impacts caused by exceeding carrying capacities at tourist destinations include:

Ecological - damage to corals, coastal vegetation and dune systems by tourists; disturbance of wildlife

Social - reduced amenity and perceptions of overcrowding for locals or visitors; potential loss of core community values; loss of cultural values

Economic - impacts (over the long term) on economic activity and tourism revenue from environmental degradation or overcrowding; over-utilisation of critical infrastructure and utilities

What we learned in the Solution Exchange, is that “carrying capacities” are rarely defined and managed by local partners – they often come as an informal response to hotel or transport capacities being stretched to the limit. Coming together with key partners to identify carrying capacity proactively instead of reactively, seeking alignment on key values and gaining shared understanding of risks, are all essential steps to support sustainable tourism at coral reef sites.

Two volunteers clean the beach in Indonesia. Credit: Ocean Cleanup Group

We need to shift tourist behaviour to better meet local resilience goals

The behaviour of tourists can have a negative impact on both coral reefs and communities. Impacts include physical damage to reefs and coral from boats, trampling and snorkelling, pollution from rubbish and human waste, wildlife disturbance where tourists aren’t maintaining a respectful distance and increased pressure from recreational fishing.

During the Solution Exchange, we explored ways to persuade, motivate or enable tourists to change their behaviour and minimise negative impacts on reefs and local communities. Key approaches to changing behaviour include:

Developing simple messaging that focuses on outcomes instead of complex science, such as Hawaii’s “Take what you need, not what you can” campaign

Using local champions to get communities on board, such as a well-known person from the country or a local church leader

Using pledges to make the message mainstream, gain broad support and inspire action

Eco-volunteers in Komodo National Park, Indonesia. Credit: Martin Colognoli, Ocean Image Bank.

We need to support opportunities for diversifying local livelihoods

The Solution Exchange explored ways to both improve access to tourism jobs for First Nations Peoples and communities, as well as opportunities to diversify local livelihoods so they are not solely reliant on reef assets.

Key to diversifying livelihoods is creating opportunities that remove pressure on natural resources and instead develop new, sustainable income streams independent from reef ecosystems. An unexpected, positive outcome of COVID-19 for some tourist destinations was how it ignited local entrepreneurship. Although COVID-19 had a devastating impact on the tourism industry in Belize, the pause in tourism created a surge in local entrepreneurship, especially among local women who are now making Belize-based products and selling them online.

While it is not always possible to completely move away from reef-based livelihoods, there are still opportunities to reduce pressure on reefs by developing low-impact, high-value tourist activities. Tourists could pay to take part in cultural experiences such as joining local community members for a home-cooked meal, for example.

Where to from here?

At the core of the Resilient Reefs Initiative is a drive to design innovative responses to common resilience challenges and to share and scale what works with reef managers globally. Our Solution Exchanges are intended to do just that: help catalyse action on the ground across our network and facilitate knowledge exchange well beyond.

This Solution Exchange raised the need to provide assistance to World Heritage Marine sites to develop integrated carrying capacity studies, as well as the potential to create sustainable tourism frameworks for reef sites – something that does not currently exist. Ningaloo has already begun scoping a local carrying capacity study and has connected with a range of global experts.

The Exchange once again highlighted how common the challenges were across the sites and the opportunity we have for collective action, problem solving and messaging. Key findings from the Exchange are available to be shared with reef managers worldwide on the Reef Resilience Network website .

Project News · 24 June 2024

Sharing costs to improve farming practices

Project News · 11 June 2024

Celebrating grazing land management successes in the Fitzroy

Project News · 29 May 2024

Supporting water quality monitoring for sugar cane farming

Project News · 22 May 2024

Organic farmers take on innovative technology for precision agriculture

Climate change, tourism and the Great Barrier Reef: what we know

Lecturer in tourism planning and development, CQUniversity Australia

Disclosure statement

Allison Anderson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

CQUniversity Australia provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

The removal of an entire section on the Great Barrier Reef from an international report on World Heritage and climate change has been justified by the Australian government because of the impact on tourism.

The Guardian reported that all mention of Australia has been removed from the report released on Friday. An Environment Department spokesperson was quoted as saying that “recent experience in Australia had shown that negative commentary about the status of World Heritage properties impacted on tourism”.

Australia is the only populated continent that was not mentioned in the report, which was produced by UNESCO , UNEP , and the Union of Concerned Scientists . It comes in the wake of one of the Great Barrier Reef’s most significant coral bleaching events – one widely attributed to climate change .

What’s to hide?

In its purest sense, it could be argued that it is important for the world to know about the impacts climate change is having on some of its most famous natural wonders. This has the potential to precipitate national and global policy change that might ultimately help the reef.

It could also be argued that much of the damage to perceptions of people around the world has already been done. The final episode of David Attenborough’s documentary on the Great Barrier Reef – which discusses the widespread bleaching in detail – arguably has far more potential to influence would-be tourists contemplating a visit to the reef.

News coverage of the events has reached audiences as far afield as the United States and Britain . And a recent picture essay on The Conversation provides evidence of the bleaching, observing the phenomenon as “a huge blow to all Australians who cherish this natural wonder and to the tourists who flock here to see the reef”.

The impact on tourism

Given that the issues on the reef are well known and widely covered, would the UNESCO report really have had an impact?

The Cairns tourism industry is a vital export earner, not only for the region but for the nation. The region has more than 2.4 million visitors per year, contributing A$3.1 billion to the economy , with the Great Barrier Reef as its anchor attraction.

Adding complexity to the issue, there is debate locally as to how widespread the coral bleaching reported by scientists really is.

The tourism industry in Cairns has been quick to counter scientists’ claims with its own. Tour operator Quicksilver has responded with Reef Health Updates featuring a marine biologist who claims that as the water cools through winter, many of the coral are likely to regain their colour.

Tourists have also been interviewed for the campaign, emerging from the water amazed and astounded at the diversity of colour and marine life they have seen.

Regional tourism organisation Tourism Tropical North Queensland has also begun a campaign to showcase undamaged parts of the reef.

Tourism is a perception-based activity. Expectations of pristine waters and diverse marine life on a World Heritage-listed reef are what drives the Cairns and North Queensland tourism industry in Australia.

We know from past research that perceptions of damage to the natural environment from events such as cyclones do influence travel decisions, but we do not yet know how this translates to coral bleaching events.

Researchers in the region are working to collect data from tourists about how their pre-existing perceptions of coral cover and colour match their actual experiences.

This will provide evidence of the impacts of the bleaching event on the tourist experience and also shed light on what has shaped tourists’ perceptions prior to visiting. Currently, we only have anecdotal evidence from operators and the tourist interviews in the Quicksilver video on what these impacts really are.

What impact could this have on the reef?

From another perspective, tourism is particularly valuable to the reef because it is a relatively clean industry that relies on the preservation, rather than depletion, of the resource for its own survival.

The Great Barrier Reef is a resource of value to both tourism and other industries. In the past, the reef has narrowly escaped gas mining, oil spill disasters and overfishing, not to mention the ongoing impacts of land-based industries along the coast that drains to it.

It is important to remember that the original World Heritage listing was “ born out of a 12-year popular struggle to prevent the most wondrous coral reef in the world from being destroyed by uncontrolled mining ”. This raises questions about whether the comparative economic importance of mining and other industries could increase if tourism declines.

The message about the threats to the Great Barrier Reef is already in the public domain. Research is still being done on the true impact of the bleaching event and associated perceptions on the tourism industry, and the results are not yet conclusive.

Rather than bury information that many people globally already have access to, perhaps the Australian government could think more creatively about how it is addressing the issues and promoting this as a positive campaign for “one of the best managed marine areas in the world” .

- Great Barrier Reef

- Coral bleaching

- Great Barrier Reef Marine Park

- UNESCO World Heritage sites

- 2016 coral bleaching event

Research Fellow – Magnetic Refrigeration

Centre Director, Transformative Media Technologies

Postdoctoral Research Fellowship

Social Media Producer

Dean (Head of School), Indigenous Knowledges

Advertisement

The Future of the Great Barrier Reef series in partnership with

How climate change impacts the Great Barrier Reef tourism industry

Climate change is hitting the corals of the Great Barrier reef hard. But what about the people whose livelihoods depend on a healthy reef?

9 October 2020

Great Barrier Reef Mass Coral Bleaching event, Port Douglas, Queensland

Dean Miller / Greenpeace

This article was written and sponsored by Greenpeace Australia Pacific

The appeal of swimming, snorkelling, diving and sailing in the Reef is dependent on healthy marine life and rich, multi-coloured corals. Climate change is posing a potentially catastrophic threat to not only the Reef but also its $6 billion tourism industry, and the 64,000 jobs that rely on a healthy reef.

Year after year, millions of tourists flock to Queensland’s coast to catch a glimpse of the stunning Great Barrier Reef. The largest living coral reef system in the world is a place of rich biodiversity and deep spiritual significance to Indigenous and non-Indigenous people alike. Beneath the glassy turquoise-waters, thousands of marine species live in perfect symbiosis; creating a colourful underwater city that teems with life.

In the past five years, we’ve witnessed three major mass-bleaching events as a result of climate change; the frequency and severity of which has damaged both the Reef and the livelihoods of 64,000 people .

Our escalating climate emergency has caused a 54 per cent increase in the number of marine heatwave days each year ; making it difficult for damaged corals to sufficiently recover. These dramatic changes to the once-thriving underwater ecosystem is causing a sense of apprehension among tourism operators.

“What you’ll find is that some tourism operators are a bit wary about talking about the problems that the Reef faces. Obviously, they don’t want people to know that the Reef is compromised; it’s bad for business,” says diving operator Tony Fontes.

“If we do talk about it, then the public starts to think: ‘well, there’s no Reef, so we’ll have to visit somewhere else’. It’s a fine line,” he says.

With 40 years of diving experience under his belt, Fontes has witnessed both the decimation and revival of corals, along with the changes to the Reef’s tourism industry.

“The Reef has had significant bleaching events, particularly in the past five years. But there’s still a lot of good coral out there. When bleaching occurs, or cyclones — you have to move. That’s practically what everyone has done”.

Coral bleaching occurs when zooxanthellae – the colourful, microscopic algae that live within the coral – is expelled due to environmental stressors like marine heatwaves caused by climate change. The absence of zooxanthellae gives the coral a faded, bleached appearance. If temperatures fail to return to normal, the coral eventually dies. It can take decades for coral reefs to recover from a single bleaching event.

“What I’ve seen happen now, in terms of adaption, is more non-underwater activities like sailing, bushwalking and jet-skiing. Many operators are looking at activities that don’t require you to get in the water and look at coral — which, to me is incredibly sad — but they’ve got no choice,” says Fontes.

At 1.5°C of global warming above pre-industrial levels, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts a loss of 70-90 per cent of the world’s coral reefs. At 2°C, that number increases to 99 per cent .

Dr Nikola Casule, Head of Research & Investigations at Greenpeace Australia Pacific, says that the harm inflicted upon the Reef is happening because humans have tampered with the natural mechanisms of the planet. Burning fossil fuels releases carbon emissions, which exacerbates the greenhouse effect and increases the temperature of our oceans.

“Corals are very sensitive to the particular ecosystems that they live in; they can only survive within a small temperature range. Climate change really is the biggest threat to the Reef, overwhelmingly because of the harmful effect that warming conditions have on corals,” says Dr Casule.

Queensland’s tourism industry is wholly dependent on the survival of the Great Barrier Reef, but Australian Marine Conservation Society’s (AMCS) David Cazzulino believes the reputation of the Reef has taken a hit in recent years.

“A lot of tourism operators feel frustrated with questions like: ‘wow, I heard the Reef is dying — do I bother coming to see it?’”

“There is a concern, if we don’t take action, what will happen to regional centres like Cairns and the Whitsunday’s — all those places where tourism relies heavily on the Great Barrier Reef”.

“That’s been the core of our work at the AMCS — so far, over thirty tourism operators have signed the Reef Climate Declaration which calls for action on climate change to keep global warming below 1.5°C. That timeline depends on what we do now,” says Cazzulino.

Fontes, having worked on the Reef for much of his lifetime, says that he’s both optimistic and realistic about the future of the Reef’s tourism industry.

“Future generations will have a Great Barrier Reef if we get on top of things soon. But if you want to have an impact and make people do something, you can’t just talk about nature and its beauty – you also have to talk about jobs and money,” says Fontes.

Keeping fossil fuels in the ground is essential to preserving the future of the Great Barrier Reef and its tourism industry. Dr Casule says there’s absolutely no time to waste. “The best time to have taken this seriously was 30 years ago, the next best time is now”.

“The question facing Australia, and the Federal Government in particular, is — do we want coral, or do we want coal? Because we can’t have both. The survival of the Reef is incompatible with continuing to burn coal,” says Dr Casule.

“As long as we’re doing our part, raising our voice for the Reef, and working together to push for bolder climate action – I think there is hope to protect our iconic reef,” Cazzulino concludes.

By Olivia Nankivell, a journalist, freelance writer and copywriter based in Adelaide, South Australia.

For more in this series, visit The Future of the Great Barrier Reef hub.

Sign up to our weekly newsletter

Receive a weekly dose of discovery in your inbox! We'll also keep you up to date with New Scientist events and special offers.

More from New Scientist

Explore the latest news, articles and features

$1m prize for AI that can solve puzzles that are simple for humans

Subscriber-only

Why our location in the Milky Way is perfect for finding alien life

Dangerous mpox strain spreading in Democratic Republic of the Congo

AI can turn text into sign language – but it’s often unintelligible

Popular articles.

Trending New Scientist articles

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 24 June 2019

Shifts in tourists’ sentiments and climate risk perceptions following mass coral bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef

- Matthew I. Curnock ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2365-810X 1 ,

- Nadine A. Marshall 1 ,

- Lauric Thiault ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5572-7632 2 , 3 ,

- Scott F. Heron ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5262-6978 1 , 4 , 5 ,

- Jessica Hoey 6 ,

- Genevieve Williams 1 , 6 ,

- Bruce Taylor 7 ,

- Petina L. Pert ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7738-7691 1 &

- Jeremy Goldberg 1 , 8

Nature Climate Change volume 9 , pages 535–541 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

56 Citations

53 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Climate-change impacts

- Psychology and behaviour

Iconic places, including World Heritage areas, are symbolic and synonymous with national and cultural identities. Recognition of an existential threat to an icon may therefore arouse public concern and protective sentiment. Here we test this assumption by comparing sentiments, threat perceptions and values associated with the Great Barrier Reef and climate change attitudes among 4,681 Australian and international tourists visiting the Great Barrier Reef region before and after mass coral bleaching in 2016 and 2017. There was an increase in grief-related responses and decline in self-efficacy, which could inhibit individual action. However, there was also an increase in protective sentiments, ratings of place values and the proportion of respondents who viewed climate change as an immediate threat. These results suggest that imperilled icons have potential to mobilize public support around addressing the wider threat of climate change but that achieving and sustaining engagement will require a strategic approach to overcome self-efficacy barriers.

Similar content being viewed by others

When, where, and which climate activists have vandalized museums

Pope Francis the Roman Catholic Church and citizen attitudes towards climate change in Latin America

Experience exceeds awareness of anthropogenic climate change in Greenland

Global warming threatens ecosystems and societies globally. However, in many countries public attitudes and perceptions of climate risks have lagged behind the accumulation of scientific evidence and assessments, contributing to inadequate political support for mitigation or adaptation 1 , 2 , 3 . As the risks and costs of climate change will increase the longer mitigation is delayed 4 , there is a need to understand barriers to public engagement with the issue and support for public action, including drivers of risk perceptions.

Many contextual and cultural factors can influence individuals’ climate change beliefs and attitudes, including value orientations, social identity and group norms 5 . While acceptance of the scientific consensus on human-induced climate change has been identified as an important ‘gateway belief’ to increased support for climate actions 6 , simply presenting more scientific facts to a sceptical or unengaged audience can be ineffective and even counterproductive 7 . Changing attitudes, beliefs and value orientations requires both cognitive and affective engagement (that is, reasoned understanding combined with emotional consequence), with emotion regarded to have the greater influence 3 , 8 , 9 . Yet failure to elicit an affective response to the threat of climate change is common among climate and behaviour change campaigns 10 . Part of this problem is a widespread perception that climate change is an abstract threat, with distant impacts that are presumed to affect other people, in other places at a future time 11 , 12 , 13 .

Research that seeks to understand the processes by which climate change risks become more salient to people has become an important field of enquiry. Climate change awareness and risk perceptions can be influenced through affective stimuli and the emotional responses associated with the perceived threat of loss or harm to oneself and/or things that are valued 5 , 14 . The effectiveness of emotional appeals and of evoking specific emotions to promote public engagement in environmental issues and behaviour change is an ongoing subject of scholarly debates 15 . Discrete emotions that have been identified as strongly associated with increased support for climate change policy include worry, interest and hope 14 . Eliciting fear can result in attitudinal changes and motivate new behaviours in response to a perceived threat 15 , 16 ; however, fear has also been shown to negatively influence engagement with the climate change issue and is considered detrimental to self-efficacy (the belief in one’s ability to affect change) 9 , 14 , 17 .

One approach to fostering improved engagement with climate change is the use and portrayal of icons. Icons are potent in their appeal to personal values and emotions; as such, they play an important role in representing climate change 18 , 19 . Iconic entities, including various animals, plants, natural and human-made landmarks, landscapes and ecosystems are symbolic, highly valued in numerous ways, and are synonymous with national and cultural identities 20 . Climate icons have been defined as “tangible entities which will be impacted by climate change, which the viewer considers worthy of respect, and to which the viewer can relate and feel empathy” 17 . Studies on the affective appeal of climate icons have used focus groups and workshops to identify characteristics that contribute to higher engagement 9 , 17 , 18 . However, affective responses associated with a large-scale climate impact to an iconic entity have not previously been documented.

In addition, an emerging body of literature on the ‘science of loss’ has highlighted an increasing need for research that explains the range of human values associated with the natural world, and how these values are endangered by a changing climate 21 , 22 . While the prospect of icons becoming damaged or degraded might prompt evaluations of tangible and direct economic losses, there are many intangible and non-economic values for icons that are likely to remain insufficiently accounted for (for example, cultural, lifestyle, health and identity values) 22 . The incomplete recognition of these intangible values, and of how heterogeneous communities will be affected by an icon’s loss or damage, increases the risk of failure to anticipate limits to adaptation, and to distinguish between acceptable, tolerable and intolerable outcomes 22 , 23 .

The Great Barrier Reef (GBR) is an iconic ecosystem and is regarded as Australia’s ‘most inspiring’ icon 24 . It is part of the national cultural identity and its UNESCO World Heritage status is a source of pride for most Australians 24 , 25 . Place attachment, pride and place values (for example, aesthetic, biodiversity, scientific heritage and lifestyle values) for the GBR extend to communities of stakeholders internationally 26 , 27 and contribute to the GBR’s appeal as an international tourism attraction 28 . Physical and aesthetic attributes of the GBR that motivate tourists to visit and that contribute to their satisfaction with reef-based activities (for example, snorkelling, scuba diving and wildlife watching), include the perception of healthy corals, abundant fish and clear water 29 . Tourism has become the GBR’s largest direct economic contributor, providing more than 58,000 sectoral jobs (full-time equivalent) and generating an estimated AUD$5.7 billion annually; the GBR’s total economic, social and icon asset value has been estimated at AUD$56 billion 30 .

However, the GBR faces multiple, cumulative threats, including climate change, and its long-term outlook has been assessed as poor and getting worse 31 . The 2016 marine heatwave caused the most intense coral bleaching observed on the GBR and resulted in an estimated 29–30% loss of shallow coral cover 32 . The following summer, unprecedented back-to-back coral bleaching caused an estimated 20% of additional coral mortality 33 . Most of the severe bleaching occurred in the northern half of the GBR Marine Park, affecting many tourism sites in the Cairns region 34 . Additionally, in March 2017, a severe tropical cyclone damaged reef and island tourism sites in the Whitsundays region 35 . Future projections of heat stress under a business-as-usual scenario (representative concentration pathway RCP 8.5) represent an existential threat to the GBR and to coral reefs globally, with severe coral bleaching expected to occur annually from the mid-2040s (ref. 36 ).

News of impacts to the GBR over 2016–2017 were reported internationally and a large proportion of those media stories were sensationalized and fatalistic in their messaging 37 . There were concerns that this negative media coverage would lead to a decline in tourist visits to the region 38 and propagate perceptions that no effective action to save the GBR is possible 37 . Records of visits to the GBR indicate that general decline in tourist visits has not yet occurred 39 ; instead, there has been an increase in ‘last chance tourism’, characterized by the motivation to see an iconic place (or species) before it is gone or permanently changed 40 .

In this study, we present results from surveys of 4,681 tourists (53% Australian and 47% international) who visited the GBR region before and after the events of 2016–2017 described above (see Methods ). We show that imperilled icons can contribute to proximizing the climate change issue across scales by comparing tourists’ affective responses and place values associated with an icon, their perceptions of threats to those values and their protective sentiment and self-efficacy, before (2013, n = 2,877) and after (2017, n = 1,804) the icon was subjected to a large-scale climatic impact.

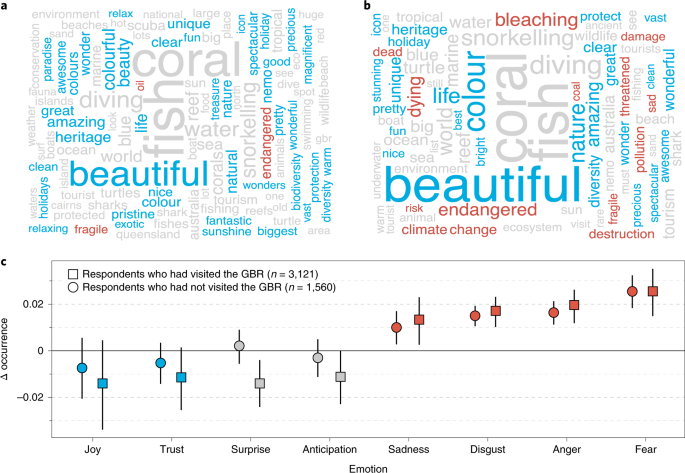

Emotional responses to the GBR

We found a significant increase in the use of negatively valenced emotional words from 2013 to 2017 in response to the open-ended question, “what are the first words that come to mind when you think about the GBR?” (Fig. 1a,b ). In particular, words associated with sadness (for example, ‘fragile’ and ‘disappointing’), disgust (for example, ‘pollution’ and ‘ruined’), anger (for example, ‘destruction’ and ‘damage’) and fear (for example, ‘change’ and ‘danger’) increased significantly, while words evoking neutral or positive emotions did not change (Fig. 1c ). We compared the use of emotive words provided by tourists who had visited the GBR ( n = 3,121) with words of those who had not visited the GBR at the time they were surveyed ( n = 1,560). There was no difference in the use of such words between the two groups (Fig. 1c ), suggesting that the emotive response was not dependent on personal experience and observation of GBR impacts.

a , b , Visual comparisons of “the first words that come to mind when you think of the GBR” among tourists in the GBR region in 2013 ( n = 2,877) ( a ) and 2017 ( n = 1,804) ( b ). The size of words represents the relative frequency of responses. Words with positive and negative valence are coloured in blue and red, respectively. Neutral words are shown in grey. Words occurring fewer than three times are omitted. c , Mean change in occurrence of positive (blue), negative (red) and neutral (grey) emotions associated with responses from 2013 to 2017 in respondents who had visited the GBR ( n = 3,121) compared with those who had not ( n = 1,560). Error bars show 95% confidence intervals. Changes in the occurrence of specific emotions are significant if the confidence interval does not overlap with the 2013 (zero) baseline.

Elements of the negative emotional content of responses in 2017 (Fig. 1b,c ) were consistent with ‘ecological grief’, characterized as “the grief felt in relation to experienced or anticipated ecological losses, including the loss of species, ecosystems and meaningful landscapes due to acute or chronic environmental change” 41 . Sadness, anger and fear are common emotional reactions to many different types of loss, contributing to diverse grief responses 42 . Disgust is a primitive behaviour-influencing emotion that also occurs in a variety of contexts, including in response to politically oriented stimuli 43 . Ecological grief is increasingly being recognized among the unquantified and intangible costs of ecological losses associated with the Anthropocene 41 , 44 , 45 . A related study reported ‘reef grief’ as a response to the 2016–2017 GBR coral bleaching event among local coastal residents and tourists, and found that ratings of place attachment, place identity, place-based pride, lifestyle dependence and derived wellbeing are associated with stronger expressions of ecological grief 46 . Our results here (Fig. 1 ) provide further insights into the emotional manifestation of ecological grief in this context. As non-local actors, tourists would not normally be considered to have strong lifestyle dependence on the destinations and attractions they visit; however, their place attachment for an icon such as the GBR can still be strong 25 , 26 and they are vulnerable to experiencing grief in response to the icon’s loss or damage.

Threat perceptions and climate change attitudes

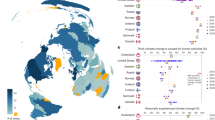

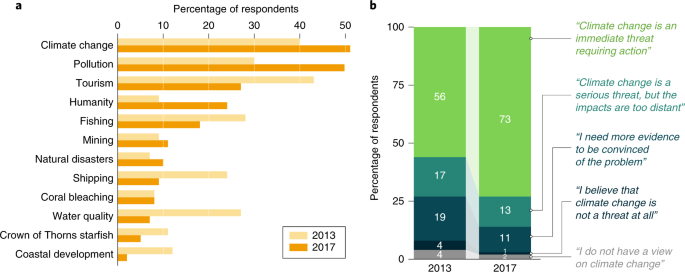

In short, open-ended responses to the question “what do you think are the three most serious threats to the GBR?”, the proportion of respondents identifying climate change increased from 40% of respondents in 2013 to 51% in 2017, making climate change the most frequently cited threat overall in 2017 (Fig. 2a ). In comparison, in 2013 the most commonly identified threat to the GBR was tourism (43% of respondents), which dropped to third-ranked in 2017 (27% of respondents). The pollution category included a wide range of responses (for example, litter, marine debris and urban pollutants) and was identified in 2017 by 50% of respondents. In 2017, pollution ranked second: up from being ranked third in 2013 at 30%, potentially reflecting an increased awareness of the threat of marine debris. The other category that displayed a notable increase was effects of humanity (9% in 2013 to 24% in 2017), which included responses such as overpopulation, human activity and anthropogenic threats. Coral bleaching was cited by 8% of respondents in both years; however, its ranking relative to other perceived threats increased from eleventh in 2013 to ninth in 2017.

a , The percentages of tourists in 2013 ( n = 2,877) and 2017 ( n = 1,804) who identified specific threats among their perceived “three most serious threats to the GBR”. The top 12 response themes are shown for each group. b , The percentages of tourists in 2013 ( n = 2,877) and 2017 ( n = 1,804) choosing each of five statements to represent their awareness and attitude towards climate change.

Public perceptions of environmental risks and threats are shaped by social, cultural and psychological processes, and the exchange of information about ‘risk events’ can amplify (or attenuate) public responses to a risk or threat 47 . Symbols and imagery portraying risk events further interact with these processes in ways that can intensify risk perceptions 48 . Public awareness and perceptions of threats facing the GBR have evolved in recent decades and media representations of threats and risk events are considered to have had influence 37 , 49 . Ironically, tourists perceive their own activities as a dominant impact at ecologically sensitive sites 50 . The presence of other tourists, associated infrastructure and localized site degradation are often the only pressures and impacts readily visible and identifiable at tourist sites, thus influencing visitors’ wider threat perceptions 51 . While tourism has not been recognized in any recent scientific literature as among the most serious threats to the GBR, our results suggest that in 2013 many GBR tourists were probably unaware of the level of risk associated with other, scientifically recognized, threats such as climate change; and that any effects that could be attributed to such threats were less (or were not) visible to GBR tourists at that time.

There was a marked increase from 2013 to 2017 in the proportion of tourists who reported their acceptance that “climate change is an immediate threat requiring action” (56 to 73%; Fig. 2b ). While this proportion for international tourists (increasing from 64% in 2013 to 78% in 2017) was higher than that for Australians (increasing from 50% in 2013 to 67% in 2017), the magnitude of this increase in both groups towards recognition of the climate change threat, its immediacy and the need for action, represents a substantial shift in normative attitudes toward climate change at a scale and in a timeframe not reported in previous studies. Previous annual surveys of Australian attitudes towards climate change, over the period from 2010 to 2014, showed that while the attitudes of individuals fluctuated, the aggregate levels of opinion remained stable over that time 52 . Whether the observed changes in 2017 represent a reaction at a moment in time or a lasting change in attitudes is uncertain and further work is needed to determine whether these perceptions have become normalized in the wider population.

While we cannot conclusively attribute the cause of this attitudinal change to the GBR coral bleaching events, we believe that a strong influence and ‘risk amplification’ was likely, considering the scale of the event, its extensive media coverage that explicitly attributed the events to climate change 37 , associated imagery, as well as the direct observation of affected reef sites by many tourists who visited the GBR over this time. While the more sensationalized and fatalistic media stories of the coral bleaching events and the GBR’s imperilled status have been criticized for their potential to cause public disengagement and a loss of hope in mitigation actions 37 , the broader exchange of information precipitated by this risk event may have had positive outcomes on public threat awareness (Fig. 2a ) and support for mitigative action (Fig. 2b ).

Personal experience and perceptions

We found significant declines in tourists’ perceptions of the GBR’s aesthetic beauty, their overall satisfaction with their experience of the GBR (among those who had visited) and in their ratings of the quality of reef tourism activities (among those who had participated; Table 1a ). While the 2017 mean scores remained relatively high on a 10-point scale (ranging between 7.46 and 8.52), there is an inherent positivity bias associated with tourist satisfaction ratings and relatively small changes can signal a qualitative distinction 53 .

The aesthetic appreciation of natural settings is a fundamental way in which people relate to the environment, and aesthetic perceptions play a critical role in the satisfaction that tourists derive from places 54 . In a coral reef setting, physical attributes that have been correlated quantitatively with non-expert ratings of aesthetic beauty include water clarity, fish abundance and ‘coral topography’ (the complexity of coral formations and features); however, many more visual and sensory attributes contribute to people’s overall aesthetic appraisal 54 . Imagery associated with the mass coral bleaching events was widely featured in media articles, in which aerial and underwater scenes of white, pale and fluorescent corals were often depicted (for example, see the March 2017 cover of Nature 55 ). Such imagery is visually striking, and scenes of bleached coral gardens can even be considered beautiful 56 . Such scenes are typically short-lived: once mortality occurs, brown algae quickly smothers coral skeletons 57 . While the biological process of coral bleaching is complex and its explanation is technical, the imagery from the event may have been highly engaging to non-expert audiences, overcoming barriers that have been associated with ‘expert’ conceptualizations of climate change threats and impacts 18 .

At the time of the 2017 tourist survey (July–August), bleached coral was still present in low levels; however, mortality associated with the 2016 coral bleaching event had already occurred from Cairns to the far north of the GBR, and cyclone-damaged reefs and islands in the Whitsundays region had not recovered 58 . We therefore consider that a substantial proportion of the 1,076 respondents who had visited the GBR when surveyed in 2017 probably had personally experienced and observed affected areas, influencing their aesthetic perceptions and satisfaction. However, as noted above, the personal observation of impacts on the GBR was not a requisite for recalling a negative emotional response to the GBR (Fig. 1c ).

Effects on place values, pride and identity

Understanding place values, which represent the estimated worth and meaning of a place, is important for environmental management and decision making 59 , 60 . We found that strong, shared values for an icon are responsive to ecosystem disturbances and threats. In contrast with the declines in ratings of GBR perceptions and the tourist experience reported above, we found small but significant increases from 2013 to 2017 in ratings of values attributed to the GBR, including its biodiversity value, scientific and education value, lifestyle value and international icon value. Similarly, pride and identity associated with the GBR were significantly higher in 2017 (Table 1b ). Pride in the GBR and GBR identity were positively correlated with these cultural values attributed to the GBR (see Table 2 ). Place values, such as those recorded for the GBR’s biodiversity, scientific heritage and lifestyle values, are consistently strong among diverse stakeholder groups (geographically proximate and distal alike), whereas greater variability is expressed for pride and identity 27 , consistent with the lower mean scores for GBR identity among tourists (Table 1b ).

We propose that these increased ratings for (or expressions of) place values, identity and pride are complementary to the expression of ecological grief (representing ‘ecological empathy’), and form part of the holistic affective response to an imperilled climate icon. Empathy for nature stems from a recognition of its intrinsic value and a feeling of connectedness to it (for example, pride and identity) 61 and the desire to protect the environment has been proposed as an extension of Maslow’s ‘values of being’ in the self-actualization process 61 . Knowing that such values can change in response to environmental change highlights a need for their continued assessment. As loss and ecological grief are expected to become increasingly common responses to climate impacts 21 , 41 , the health literature on cumulative trauma suggests that ‘compassion fatigue’ 62 and the erosion of ecological empathy (or ‘environmental numbness’) 63 may occur.

Protective sentiment and self-efficacy

While protective sentiment associated with the GBR increased significantly in 2017, including tourists’ willingness to act and willingness to learn (Table 1c ), there was a corresponding decline in self-efficacy, represented here by capacity to act and optimism for the future of the GBR. The slight increase in ratings for sense of agency and opportunity to act indicates some self-awareness of the individual’s role in mitigating threats. However, the corresponding decline in sense of individual responsibility suggests that community expectations of responsibility and capacity for addressing great threats such as climate change are located in the actions of governments and corporations, rather than their own actions.

Conclusions

Our study identified a clear affective response amongst tourists, whose protective sentiment for the GBR became heightened after a notable climate impact, while their sense of self-efficacy diminished. Concomitant with grief-associated emotive responses (sadness, anger and fear; Fig. 1c ), respondents expressed empathy for the icon through increased ratings of place values, identity and protective sentiment (Table 1a,b ).

While our study is limited to tourists, we note that they represent diverse national and international stakeholder interests, attitudes and values, from widespread places of origin. Their affective responses in this case were not dependent on visits to the GBR and personal experience of impacts (Fig. 1c ), indicating other contributing influences; for example, sensationalized media representations 37 and imagery of the coral bleaching event. This suggests that representations of icons like the GBR, when subject to a high-profile risk event, can elicit wide-reaching affective responses, amplify risks and proximize the climate change issue. However, like other examples of the iconic approach for representing climate change 9 , 18 , the observed decline in self-efficacy represents a barrier to productive engagement in mitigative actions. In particular, the expression of fear (Fig. 1c ) and the observed decline in individual sense of responsibility (Table 1c ) may be indicative of the perceived scale of the climate threat and the intractability of the problem through individual efforts alone. Nonetheless, the expressions of protective sentiment in this context suggest a significant potential to mobilize public support around addressing threats to icons, like the GBR, where opportunities for individual action are linked to a broader, collective response.

From an action perspective, our findings can be considered both potentially constraining (due to reduced self-efficacy) and enabling (due to increased protective sentiment). Management, scientific or conservation agencies that seek to engage communities in climate mitigation and adaptation may arouse high levels of interest and empathy by using evocative imagery of icons during crises or high-profile events. However, achieving and sustaining engagement in collective action will require a more strategic and thoughtful approach to overcome efficacy barriers. Prevailing over such barriers can potentially be achieved by drawing on lessons from health and psychology literature, including, for example, the ‘small changes’ approach 64 , positive affirmation and promotion of incremental successes 65 , and fostering pride in pro-environmental behaviours 66 . Maintaining hope, balanced with clear and accessible actions linked to attainable goals, also remains critical to motivating people and sustaining their engagement in collective efforts to restore, mitigate and adapt 63 , 67 .

Engaging with loss and grief represents an additional challenge that requires sensitivity. An understanding of shared place values provides an important basis for constructive engagement with the possibility of loss, and appealing to such values can empower communities and motivate cooperation to offset potentially harmful outcomes 21 , 22 . However, it is important to recognize that wider place values are heterogeneous, that some may be in conflict, and that respectful, transparent dialogue provides the best avenue to negotiate areas of contention 68 .

Our study provides insights into some of the shared place values assigned to the GBR among one, albeit diverse, non-local stakeholder group. As a multiple-use marine park and World Heritage area, with adjacent coastal communities dependent on tourism, fishing, agriculture and mining (among other industries), and with cross-scale communities deriving wellbeing from a broad range of cultural and ecosystem services, the GBR represents an important example among climate icons that encapsulates a multiplex of human values that are challenged by climate change. Like other natural World Heritage-listed sites, the full extent of cultural and other intangible values that are at stake in the GBR remains poorly understood 31 . Research to describe the diversity and importance of human values associated with iconic places that are vulnerable to loss is needed, as a precursor to predicting how such values might respond to future losses, to guide coordinated responses to the climate threat and to mitigate potential suffering from future impacts 21 , 22 .

Survey design

To measure and compare tourists’ perceptions and values of the GBR and protective sentiments for the GBR, we used a series of statements from an established framework for monitoring human–environment cultural and place values 27 and asked survey respondents to indicate their level of agreement/disagreement on a 10-point scale (1 = very strongly disagree; 10 = very strongly agree). Similarly, we asked respondents who had visited the GBR to provide ratings of their satisfaction (1 = extremely dissatisfied; 10 = extremely satisfied) and the quality of popular reef-based activities (1 = very low quality; 10 = very high quality) if they had undertaken them during their visit. Climate change threat awareness and perceptions were elicited by asking respondents to select one statement from five options that best reflected their viewpoint: (1) “climate change is an immediate threat requiring action”, (2) “climate change is a serious threat but the impacts are too distant for immediate concern”, (3) “I need more evidence to be convinced of the problem”, (4) “I believe that climate change is not a threat at all” and (5) “I do not have a view on climate change”. To elicit threat perceptions, respondents were asked to list what they thought were the “three most serious threats to the GBR” in a short, open-ended format. While some minor changes were made to the overall survey instrument between 2013 and 2017, the questions used for our analyses in this study remained identical.

Data collection

Tourists in the GBR region (defined as the GBR catchment, bounded by Cape York in the north, Bundaberg in the south and the Great Dividing Range in the west) were surveyed using face-to-face interviews between June and August in both 2013 and 2017 (ref. 69 ). For the purposes of this study we defined tourists broadly as non-resident visitors to the GBR region. The surveys were conducted at 14 regional population centres along the coast, in public locations such as beaches, boat ramps, parks, shopping centres and markets, and on a limited number of GBR tourism vessels. Interviews were conducted by trained survey staff, and responses were entered in situ into tablet computers, using the iSurvey application. In 2013, we achieved a sample of 2,877 tourists (1,557 of whom were Australian, 1,286 from overseas and 34 respondents who did not provide their place of origin), followed by a sample of 1,804 tourists in 2017 (831 Australian, 805 from overseas and 168 respondents who did not provide their place of origin). Our sampling strategy used a combination of convenience and quota sampling 70 , to minimize potential biases for gender, age and nationality. However, a limitation of the study was its availability in English only, and we acknowledge that some non-English-speaking tourist market segments are under-represented (for example, tourists from China). This research involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the CSIRO Social Science Human Research Ethics Committee and was conducted in accordance with the Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007). All respondents gave informed consent to participate in the voluntary survey.

Description of sample

The demography and location of origin for both domestic and international tourists was comparable between years; however, in 2017, the mean age of domestic tourists was lower than that for 2013 (43.5 ± 0.45 yr compared with 48.9 ± 0.64 yr respectively). A higher proportion of females was represented among the international tourists in both years (55% of our sample in 2013 and 57% in 2017). Overseas respondents came from 54 countries in our 2013 sample and 35 countries in our 2017 sample. Most international respondents came from Europe and North America, with the largest proportions originating from the United Kingdom (25% in 2013 and 19% in 2017), Germany (18% in 2013 and 19% in 2017), France (12% in 2013 and 11% in 2017) and the United States (8% in 2013 and 11% in 2017). Most domestic tourists were repeat visitors to the GBR region (77% in both years), while most international tourists were first-time visitors to the region (84% in 2013 and 86% in 2017). Among domestic tourists, 58% in both years had visited the GBR during their stay in the region; among international tourists, 85% had visited the GBR in 2013 and 67% had visited the GBR in 2017. The number of responses ( n ) varied for some of the survey questions (for example, ratings of the quality of scuba diving, snorkelling and wildlife watching were limited to respondents who had participated in those activities); where relevant, these differing sample sizes are shown (Table 1 ), with accompanying standard errors for mean scores.

Statistical analyses of numeric data

We used MS Excel and SPSS (v.22) software for analyses of numeric data (providing means and comparing the distribution of rating scores for a range of 10-point scaled response questions, as described above). Non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-tests (Table 1 ) and Spearman’s rho correlation tests (Table 2 ) were used, as the appropriate statistical tools for ordinal (10-point rating scale) data 71 . Effect sizes ( r ) were calculated manually from the SPSS output z value using: \(r = \frac{z}{{\sqrt {\mit{n}} }}\) .

Word–emotion analysis and word clouds

Our first question in the survey asked, in an open-ended short response format: “what are the first words that come to mind when you think about the GBR?” Responses were cleaned (correcting spelling, removing punctuation and stop words) and their association with eight core emotions theorized by R. Plutchik (fear, anger, joy, sadness, trust, disgust, anticipation and surprise) 72 were scored on a binary scale (0 = not associated, 1 = associated) using the National Research Council of Canada Word–Emotion Association Lexicon (EmoLex) 73 . EmoLex is a large, high-quality, word–emotion lexicon in which more than 14,000 English unigrams (nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs) and 25,000 word senses were manually annotated by crowdsourcing 74 , noting that multiple emotions can be evoked simultaneously by the same word. We then calculated, for each emotion, the difference in average occurrence (±95% confidence interval) between 2017 and 2013.

To produce the word-cloud visualizations showing basic emotional valence/sentiment associated with words/terms (positive or negative valence shown in blue and red, respectively; Fig. 1a,b ), we adapted EmoLex to account for the contextual relevance of particular words used when referring to a coral reef ecosystem. We removed words that otherwise would have been identified as negatively valenced (for example ‘cold’, ‘sharks’ and ‘wild’) or positively valenced (for example ‘hot’ and ‘warm’) outside this context. New words that we categorized as positively valanced included ‘diversity’, ‘life’, ‘icon’, ‘pristine’, ‘heritage’, ‘colours’, ‘relaxing’, ‘sunshine’, ‘biggest’, ‘vast’, ‘biodiversity’, ‘natural’, ‘nature’, ‘colourful’, ‘unique’, ‘holiday’, ‘holidays’ and ‘relax’. New words/terms that we identified as negatively valanced included ‘bleaching’, ‘bleached’, ‘climate change’, ‘coal’, ‘endangered’, ‘oil’, ‘pollution’ and ‘threatened’. Analyses were done using the {tm} and {syuzhet} packages (for text mining and cleaning and for the word–emotion and word cloud/sentiment analyses, respectively) in R.

Coding of threats

Respondents were asked “what do you think are the three most serious threats to the GBR” in a short open-ended response format. Ranking of the listed threats by respondents was not taken into account. Responses were cleaned and then sorted into main categories, using MS Excel, with coding checked by at least two researchers. Responses in the pollution category included marine debris, beach litter and a range of other contributors, as well as the generic term ‘pollution’. The water quality category included agricultural as well as urban and industrial runoff, sediments and pesticides, while coastal development encompassed port developments, dredging and other industrial activities. The fishing category included all extractive activities, commercial and recreational, illegal foreign fishing and ‘overfishing’ in general. The shipping category included oil spills and ballast water/pollution from shipping. The natural disasters category included responses such as storm damage, cyclones, floods, tsunamis and earthquakes. The climate change category included global warming, rising temperatures (sea and air) and sea level rise. Coral bleaching was coded separately, as was ocean acidification. While climate change, coral bleaching and ocean acidification are related, separate coding of the three terms was considered appropriate. Broad-scale (‘mass’) coral bleaching events result from heat stress, including the recent GBR events, and have been attributed scientifically to climate change 58 , 75 . However, coral bleaching can occur as a result of multiple non-climate change pressures, such as fresh-water inundation and overexposure to direct sunlight 57 . Further to this, heat-stress-induced coral bleaching is only one potential effect (or ‘symptom’) of climate change. Increased storm intensity and/or frequency (physical damage) and sea-level rise (reduced water quality and reef drowning) are other pressures affecting coral reefs that are linked to climate change 76 . Acidification, while associated with climate change as another consequence of increased atmospheric CO 2 absorbed by the ocean, is regarded as a separate driver of many (different) pressures affecting marine ecosystems 76 .

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study (SELTMP 2013; 2017) 69 are publicly available from the CSIRO online data access portal at https://doi.org/10.25919/5c74c7a7965dc . The R code used in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Lee, T. M., Markowitz, E. M., Howe, P. D., Ko, C. & Leiserowitz, A. A. Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nat. Clim. Change 5 , 1014–1020 (2015).

Article Google Scholar

Lacey, J., Howden, M., Cvitanovic, C. & Colvin, R. M. Understanding and managing trust at the climate science–policy interface. Nat. Clim. Change 8 , 22–28 (2018).

Lorenzoni, I., Nicholson-Cole, S. & Whitmarsh, L. Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Glob. Environ. Change 17 , 445–459 (2007).

Rogelj, J., McCollum, D. L., Reisinger, A., Meinshausen, M. & Riahi, K. Probabilistic cost estimates for climate change mitigation. Nature 493 , 79–83 (2013).

van der Linden, S. L. The social–psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: towards a comprehensive model. J. Environ. Psychol. 41 , 112–124 (2015).

van der Linden, S. L., Leiserowitz, A. A., Feinberg, G. D. & Maibach, E. W. The scientific consensus on climate change as a gateway belief: experimental evidence. PLoS ONE 10 , e0118489 (2015).

Wynne, B. Creating public alienation: expert cultures of risk and ethics on GMOs. Sci. Cult. 10 , 445–481 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Wood, W. Attitude change: persuasion and social influence. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 51 , 539–570 (2000).

O’Neill, S., Boykoff, M., Neimeyer, S. & Day, S. A. On the use of imagery for climate change engagement. Glob. Environ. Change 23 , 413–421 (2013).

Ockwell, D., Whitmarsh, L. & O’Neill, S. Reorienting climate change communication for effective mitigation: forcing people to be green or fostering grass-roots engagement? Sci. Commun. 30 , 305–327 (2009).

Myers, T. A., Maibach, E. W., Roser-Renouf, C., Akerlof, K. & Leiserowitz, A. A. The relationship between personal experience and belief in the reality of global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 3 , 343–347 (2013).

Singh, A. S., Zwickle, A., Bruskotter, J. T. & Wilson, R. The perceived psychological distance of climate change impacts and its influence on support for adaptation policy. Environ. Sci. Policy 73 , 93–99 (2017).

Scannell, L. & Gifford, R. Personally relevant climate change: the role of place attachment and local versus global message framing in engagement. Environ. Behav. 45 , 60–85 (2013).

Smith, N. & Leiserowitz, A. The role of emotion in global warming policy support and opposition. Risk Anal. 34 , 937–948 (2014).

Skurka, C., Niederdeppe, J., Romero-Canyas, R. & Acup, D. Pathways of influence in emotional appeals: benefits and tradeoffs of using fear or humor to promote climate change-related intentions and risk perceptions. J. Commun. 68 , 169–193 (2018).

Milne, S., Sheeran, P. & Orbell, S. Prediction and intervention in health-related behaviour: a meta-analytic review of protection motivation theory. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 30 , 106–143 (2000).

O’Neill, S. & Nicholson-Cole, S. “Fear Won’t Do It”: promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations. Sci. Commun. 30 , 355–379 (2009).

O’Neill, S. J. & Hulme, M. An iconic approach for representing climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 19 , 402–410 (2009).

Höijer, B. Emotional anchoring and objectification in the media reporting on climate change. Public Underst. Sci. 19 , 717–731 (2010).

Edensor, T. National Identity, Popular Culture and Everyday Life (Bloomsbury, 2002).

Barnett, J., Tschakert, P., Head, L. & Adger, W. N. A science of loss. Nat. Clim. Change 6 , 976–978 (2016).

Tschakert, P. et al. Climate change and loss, as if people mattered: values, places, and experiences. WIREs Clim. Change 8 , e476 (2017).

Dow, K. et al. Limits to adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 3 , 305–307 (2013).

Goldberg, J. et al. Climate Change, the Great Barrier Reef and the response of Australians. Palgrave Commun. 2 , 15046 (2016).

Marshall, N. A. et al. The dependency of people on the Great Garrier Reef, Australia. Coast. Manag. 45 , 505–518 (2017).

Gurney, G. G. et al. Redefining community based on place attachment in a connected world. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114 , 10077–10082 (2017).

Marshall, N. et al. Measuring what matters in the Great Barrier Reef. Front. Ecol. Environ. 16 , 271–277 (2018).

Coghlan, A. Linking natural resource management to tourist satisfaction: a study of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. J. Sustain. Tour. 20 , 41–58 (2012).

Esparon, M., Stoeckl, N., Farr, M. & Larson, S. The significance of environmental values for destination competitiveness and sustainable tourism strategy making: insights from Australia’s Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area. J. Sustain. Tour. 23 , 706–725 (2015).

At What Price? The Economic, Social and Icon Value of the Great Barrier Reef (Great Barrier Reef Foundation, 2017).

Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2014 (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, 2014).

Final Report: 2016 Coral Bleaching Event on the Great Barrier Reef (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, 2017).

James, L. E. Half the Great Barrier Reef is dead. National Geographic Magazine (August 2018); https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2018/08/explore-atlas-great-barrier-reef-coral-bleaching-map-climate-change/

Reef Health (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, 2019); http://www.gbrmpa.gov.au/the-reef/reef-health

Chen, D. Cyclone Debbie leaves Whitsunday Islands reefs in ruins. ABC News (9 April 2017); https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-04-09/cyclone-debbie-leaves-whitsundays-reefs-in-ruins/8428866

Heron, S. F. et al. Impacts of Climate Change on World Heritage Coral Reefs: A First Scientific Assessment (UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2017); https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1676/

Eagle, L., Hay, R. & Low, D. R. Competing and conflicting messages via online new media: potential impacts of claims that the Great Barrier Reef is dying. Ocean Coast. Manag. 158 , 154–163 (2018).

Willacy, M. Great Barrier Reef coral bleaching could cost $1b in lost tourism, research suggests. ABC News (21 June 2016); https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-06-21/reef-bleaching-could-cost-billion-in-lost-tourism/7526166

Annual Report 2017–2018 (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, 2018).

Piggott-McKellar, A. E. & McNamara, K. E. Last chance tourism and the Great Barrier Reef. J. Sustain. Tour. 25 , 397–415 (2016).

Cunsolo, A. & Ellis, N. R. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat. Clim. Change 8 , 275–281 (2018).

Archer, J. The Nature of Grief (Routledge, 1999).

Smith, K. B., Oxley, D., Hibbing, M. V., Alford, J. R. & Hibbin, J. R. Disgust sensitivity and the neurophysiology of left-right political orientations. PLoS ONE 6 , e25552 (2011).

Head, L. The Anthropoceneans. Geogr. Res. 53 , 313–320 (2015).

Adger, W. N., Barnett, J., Brown, K., Marshall, N. & O’Brien, K. Cultural dimensions of climate change impacts and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 3 , 112–117 (2013).

Marshall, N. et al. Reef grief: investigating the relationship between place meanings and place change on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Sustain. Sci. 14 , 579–587 (2019).

Kasperson, R. E. et al. The social amplification of risk: a conceptual framework. Risk Anal. 8 , 177–187 (1988).

Kasperson, J. X., Kasperson, R. E., Pidgeon, N. & Slovic, P. in The Social Amplification of Risk (eds Pidgeon, N. et al.) Ch. 1 (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Lankester, A. J., Bohensky, E. & Newlands, M. Media representations of risk: the reporting of dredge spoil disposal in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park at Abbot Point. Mar. Policy 60 , 149–161 (2015).

Prideaux, B., McNamara, K. E. & Thompson, M. The irony of tourism: visitor reflections of their impacts on Australia’s World Heritage rainforest. J. Ecotourism 11 , 102–117 (2012).

Hillery, M., Nancarrow, B., Griffin, G. & Syme, G. Tourist perception of environmental impact. Ann. Tour. Res. 28 , 853–867 (2001).

Leviston, Z., Greenhill, M. & Walker, I. Australian Attitudes to Climate Change and Adaptation: 2010–2014 (CSIRO, 2015).

Pearce, P. L. in Managing Tourism and Hospitality Services: Theory and International Applications (eds Prideaux, B. et al.) Ch. 25 (CABI, 2006).

Marshall, N. et al. Identifying indicators of aesthetics in the Great Barrier Reef for the purposes of management. PLoS ONE 14 , e0210196 (2019).

Nature 543 , 7645 (2017).

Pocock, C. Sense matters: aesthetic values of the Great Barrier Reef. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 8 , 365–381 (2002).

Brown, B. E. Coral bleaching: causes and consequences. Coral Reefs 16 , S129–S138 (1997).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming transforms coral reef assemblages. Nature 556 , 492–496 (2018).

Ives, C. D. & Kendal, D. The role of social values in the management of ecological systems. J. Environ. Manag. 144 , 67–72 (2014).

Kenter, J. O. et al. What are shared and social values of ecosystems? Ecol. Econ. 111 , 86–99 (2015).

Kuhn, J. L. Toward and ecological humanistic psychology. J. Humanist. Psychol. 41 , 9–24 (2001).

Figley, C. R. (ed.) Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in Those Who Treat the Traumatized (Routledge, 1995).

Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 66 , 290–302 (2011).

Hill, J. O., Wyatt, H. R., Reed, G. W. & Peters, J. C. Obesity and the environment: where do we go from here? Science 299 , 853–855 (2003).

Epton, T. & Harris, P. R. Self-affirmation promotes health behaviour change. Health Psychol. 27 , 746–752 (2008).

Harth, N. S., Leach, C. W. & Kessler, T. Guilt, anger, and pride about in-group environmental behaviour: different emotions predict distinct intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 34 , 18–26 (2013).

Hobbs, R. J. Grieving for the past and hoping for the future: balancing polarizing perspectives in conservation and restoration. Restor. Ecol. 21 , 145–148 (2013).

Chapin, F. S. & Knapp, C. N. Sense of place: a process for identifying and negotiating potentially contested visions of sustainability. Environ. Sci. Policy 53 , 38–46 (2015).

Marshall, N., et al. Social and Economic Long Term Monitoring Program (SELTMP) for the Great Barrier Reef Data. v1 (CSIRO, 2019); https://doi.org/10.25919/5c74c7a7965dc .

Bryman, A. Social Research Methods 4th edn (Oxford Univ. Press, 2012).

Fritz, C. O., Morris, P. E. & Richler, J. J. Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. 141 , 2–18 (2012).

Plutchik, R. A psychoevolutionary theory of emotions. Soc. Sci. Inf. 21 , 529–553 (1982).

Mohammad, S. M. & Turney, P. D. Emotions evoked by common words and phrases: using Mechanical Turk to create an emotion lexicon. In Proc. NAACL HLT 2010 Workshop on Computational Approaches to Analysis and Generation of Emotion in Text , 26–34 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2010).

Mohammad, S. M. & Turney, P. D. Crowdsourcing a word–emotion association lexicon. Comput. Intell. 29 , 436–465 (2012).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature 543 , 373–377 (2017).

Spillman, C. M., Heron, S. F., Jury, M. R. & Anthony, K. R. N. Climate change and carbon threats to coral reefs. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 92 , 1581–1586 (2011).

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted using data from the Social and Economic Long-Term Monitoring Program for the Great Barrier Reef (SELTMP: https://research.csiro.au/seltmp/ ) with funding provided by the Australian and Queensland Governments as part of the Reef 2050 Integrated Monitoring and Reporting Program (2017–2019) and the Australian Government’s National Environmental Research Program, Tropical Ecosystems Hub (2011–2015). S.F.H. was supported by National Oceanic and Atmospheric (NOAA) grant (no. NA14NES4320003) (Cooperative Institute for Climate and Satellites) at the University of Maryland/ESSIC. The scientific results and conclusions, as well as any views or opinions expressed herein, are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australian Government, the Minister for the Environment, the Queensland Government, NOAA or the US Department of Commerce.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

CSIRO Land and Water, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland, Australia

Matthew I. Curnock, Nadine A. Marshall, Scott F. Heron, Genevieve Williams, Petina L. Pert & Jeremy Goldberg

National Center for Scientific Research, PSL Université Paris, CRIOBE USR3278 CNRS-EPHE-UPVD, Paris, France

Lauric Thiault

Laboratoire d’Excellence CORAIL, Papetoai Moorea, French Polynesia

Coral Reef Watch, US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, College Park, MD, USA

Scott F. Heron

Marine Geophysical Laboratory, Physics, College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland, Australia

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Townsville, Queensland, Australia

Jessica Hoey & Genevieve Williams

CSIRO Land and Water, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

Bruce Taylor

College of Business, Law and Governance, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland, Australia

Jeremy Goldberg

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

N.A.M., M.I.C., P.L.P., J.G. and others designed the research and collected data. M.I.C., L.T., G.W. and N.A.M. analysed the data. M.I.C., N.A.M., L.T., S.F.H., J.H., B.T., P.L.P. and J.G. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Matthew I. Curnock .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information: Nature Climate Change thanks Karen McNamara, Nick Pidgeon and other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Curnock, M.I., Marshall, N.A., Thiault, L. et al. Shifts in tourists’ sentiments and climate risk perceptions following mass coral bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9 , 535–541 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0504-y

Download citation

Received : 11 December 2018

Accepted : 10 May 2019

Published : 24 June 2019

Issue Date : July 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0504-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Broad values as the basis for understanding deliberation about protected area management.

- Devin J. Goodson

- Carena J. van Riper

- Christopher M. Raymond

Sustainability Science (2024)

Climate Change and Travel: Harmonizing to Abate Impact

- Aisha N. Khatib

Current Infectious Disease Reports (2023)

Public perceptions of marine environmental issues: A case study of coastal recreational users in Italy

- Serena Lucrezi

Journal of Coastal Conservation (2022)

Ocean Warming Will Reduce Standing Biomass in a Tropical Western Atlantic Reef Ecosystem

- Leonardo Capitani

- Júlio Neves de Araujo

- Guilherme O. Longo

Ecosystems (2022)

Ecosystem response persists after a prolonged marine heatwave

- Robert M. Suryan

- Mayumi L. Arimitsu

- Stephani G. Zador

Scientific Reports (2021)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Sustainable tourism management in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park: a collective effort

A guest blog by Josh Thomas – CEO, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority

Josh Thomas

CEO, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority

The Great Barrier Reef is a global treasure. It is one of the world’s most remarkable natural wonders, a complex ecosystem that supports immense biodiversity and an iconic destination for global tourism. However, the reef, like other reefs worldwide, is under pressure. While the single greatest threat to the reef is climate change, it faces a range of other pressures, including impacts on water quality from catchment runoff, coastal development, fishing, and outbreaks of coral-eating crown-of-thorns starfish.

Given these pressures, it is vital to strike the right balance between protection and access—with an emphasis on developing and supporting responsible, sustainable tourism management and practices. At the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority we play a pivotal role in ensuring that future generations will have the opportunity to experience this unique natural wonder. We do this by fostering collaboration, implementing zoning and regulations, promoting education, monitoring, and conducting research. We work alongside the reef Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander traditional owners and high-standard tourism operators (ones that operate to a higher standard than required by legislation as part of their commitment to ecologically sustainable use), to contribute to the preservation of this unique ecosystem.

Minimising the impact of visitor activities on the reef ensures we can maximise the tourist experience and tourism’s significant contribution to local communities. Our purpose is to provide for the long-term protection, ecologically sustainable use, understanding and enjoyment of the Great Barrier Reef.

To protect the most vulnerable areas of the reef and mitigate impacts, the Reef Authority has developed and implemented a comprehensive zoning plan for the marine park. Each zone is tailored to preserve and support its unique ecological and recreational values. This includes designated no-entry zones to protect sensitive habitats, and zones that enable regulated tourism activities. The plan helps us to minimise disturbances to the reef’s fragile ecosystems, while also sharing its immense beauty with the world.

There are 60,000 people employed in reef-related industries, and strong industry support for a well-managed reef. A stringent permit system requires tourism operators in the marine park to obtain permits and adhere to strict guidelines on waste management, vessel operation, management of structures and wildlife interactions. Tourism activities are monitored and responsible practices enforced to ensure compliance with the regulations.