Voyager 1: Facts about Earth's farthest spacecraft

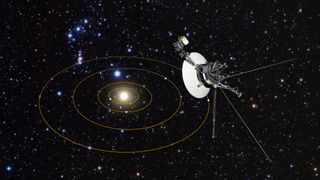

Voyager 1 continues to explore the cosmos along with its twin probe, Voyager 2.

The Grand Tour

Voyager 1 jupiter flyby, voyager 1 visits saturn and its moons, voyager 1 enters interstellar space, voyager 1's interstellar adventures, additional resources.

Voyager 1 is the first spacecraft to travel beyond the solar system and reach interstellar space .

The probe launched on Sept. 5, 1977 — about two weeks after its twin Voyager 2 — and as of August 2022 is approximately 14.6 billion miles (23.5 billion kilometers) away from our planet, making it Earth 's farthest spacecraft. Voyager 1 is currently zipping through space at around 38,000 mph (17 kilometers per second), according to NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory .

When Voyager 1 launched a mission to explore the outer planets in our solar system nobody knew how important the probe would still be 45 years later The probe has remained operational long past expectations and continues to send information about its journeys back to Earth.

Related: Celebrate 45 years of Voyager with these amazing images of our solar system (gallery)

Elizabeth Howell, Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before that, since 2012. Elizabeth's on-site reporting includes two human spaceflight launches from Kazakhstan, three space shuttle missions in Florida, and embedded reporting from a simulated Mars mission in Utah.

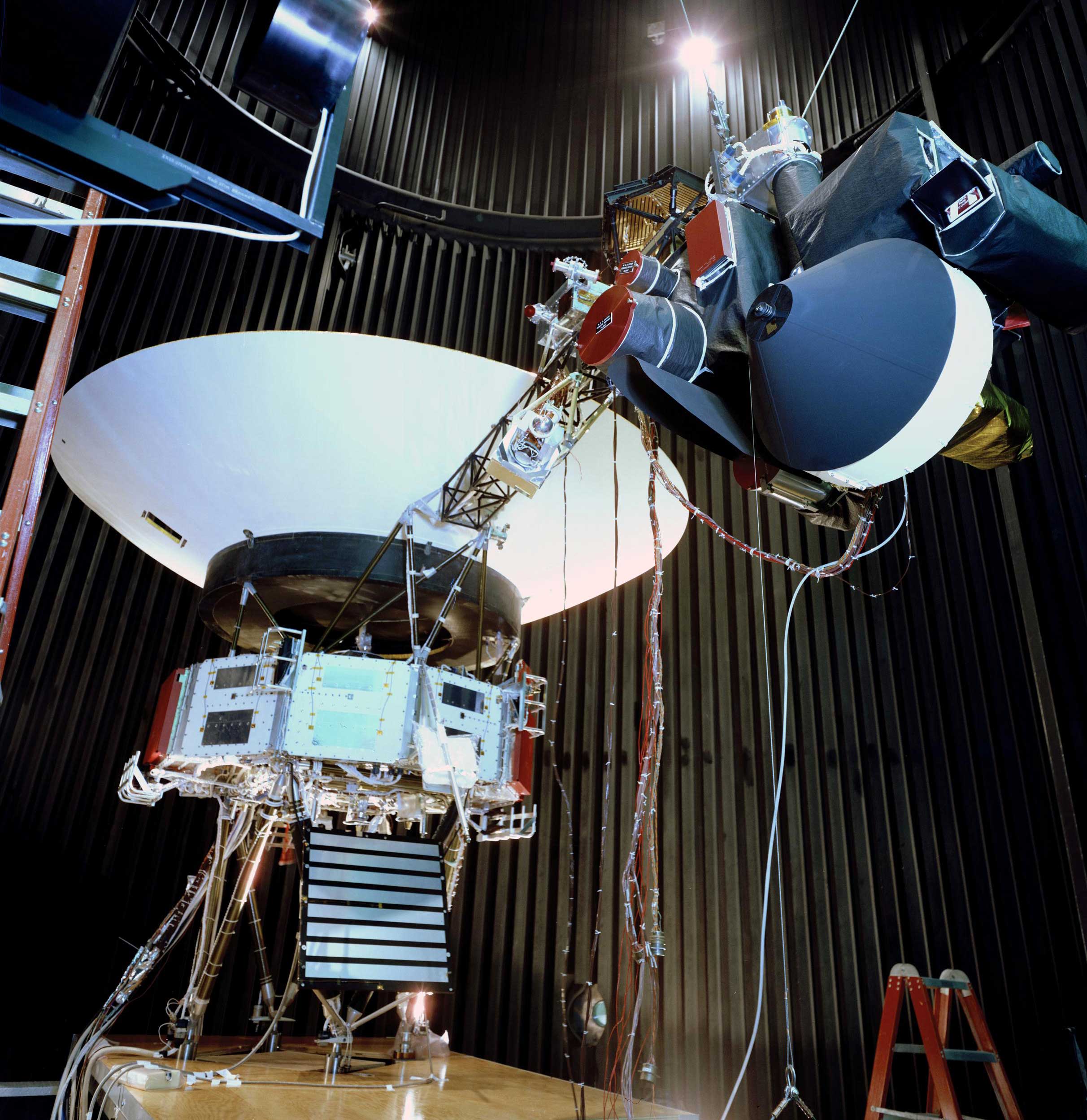

Size: Voyager 1's body is about the size of a subcompact car. The boom for its magnetometer instrument extends 42.7 feet (13 meters). Weight (at launch): 1,797 pounds (815 kilograms). Launch date: Sept. 5, 1977

Jupiter flyby date: March 5, 1979

Saturn flyby date: Nov. 12, 1980.

Entered interstellar space: Aug. 25, 2012.

The spacecraft entered interstellar space in August 2012, almost 35 years after its voyage began. The discovery wasn't made official until 2013, however, when scientists had time to review the data sent back from Voyager 1.

Voyager 1 was the second of the twin spacecraft to launch, but it was the first to race by Jupiter and Saturn . The images Voyager 1 sent back have been used in schoolbooks and by many media outlets for a generation. The spacecraft also carries a special record — The Golden Record — that's designed to carry voices and music from Earth out into the cosmos.

According to NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) , Voyager 1 has enough fuel to keep its instruments running until at least 2025. By then, the spacecraft will be approximately 13.8 billion miles (22.1 billion kilometers) away from the sun.

The Voyager missions took advantage of a special alignment of the outer planets that happens just once every 176 years. This alignment allows spacecraft to gravitationally "slingshot" from one planet to the next, making the most efficient use of their limited fuel.

NASA originally planned to send two spacecraft past Jupiter, Saturn and Pluto and two other probes past Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune . Budgetary reasons forced the agency to scale back its plans, but NASA still got a lot out of the two Voyagers it launched.

Voyager 2 flew past Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune , while Voyager 1 focused on Jupiter and Saturn.

Recognizing that the Voyagers would eventually fly to interstellar space, NASA authorized the production of two Golden Records to be placed on board the spacecraft. Sounds ranging from whale calls to the music of Chuck Berry were placed on board, as well as spoken greetings in 55 languages.

The 12-inch-wide (30 centimeters), gold-plated copper disks also included pictorials showing how to operate them and the position of the sun among nearby pulsars (a type of fast-spinning stellar corpse known as a neutron star ), in case extraterrestrials someday stumbled onto the spacecraft and wondered where they came from.

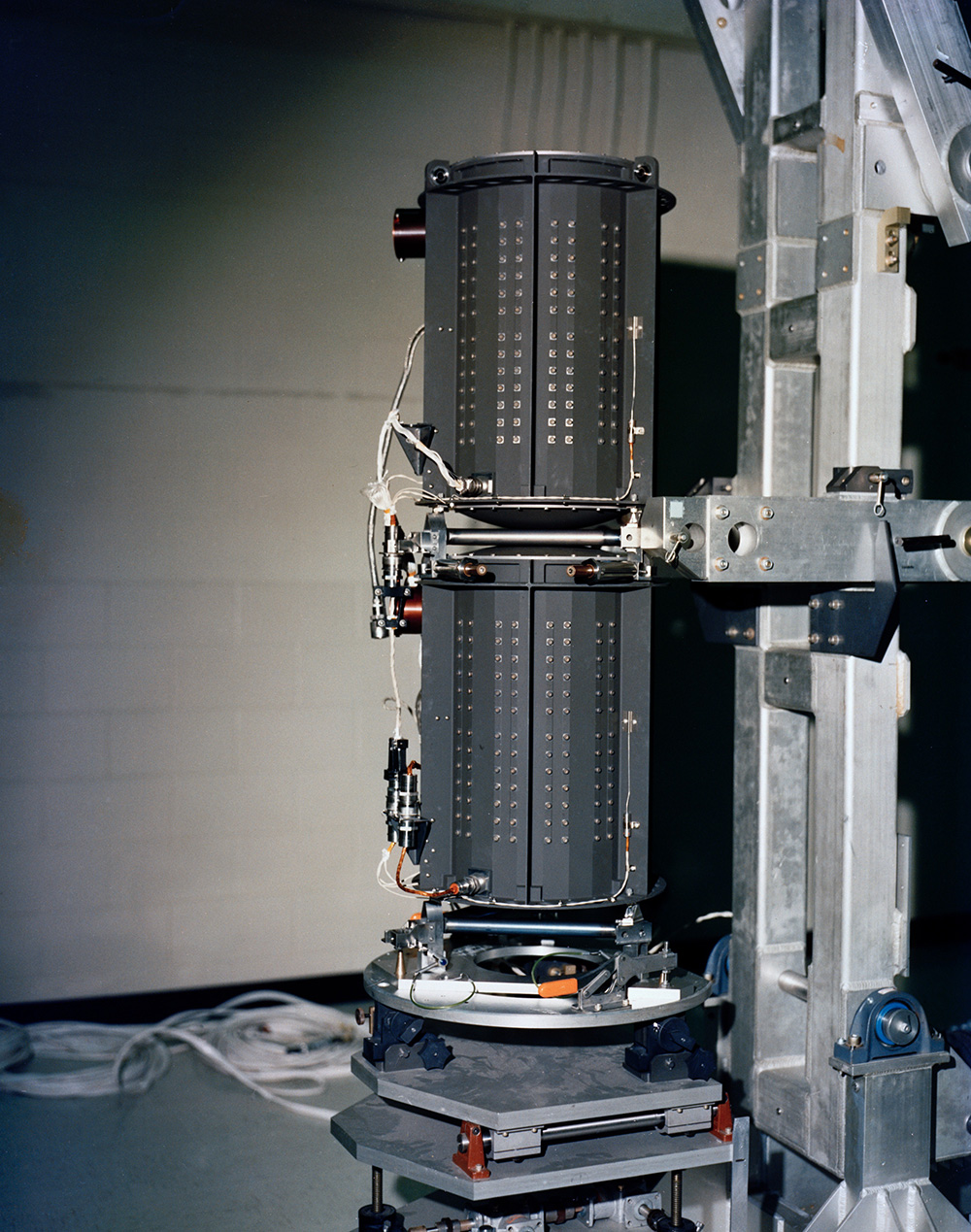

Both spacecraft are powered by three radioisotope thermoelectric generators , devices that convert the heat released by the radioactive decay of plutonium to electricity. Both probes were outfitted with 10 scientific instruments, including a two-camera imaging system, multiple spectrometers, a magnetometer and gear that detects low-energy charged particles and high-energy cosmic rays . Mission team members have also used the Voyagers' communications system to help them study planets and moons, bringing the total number of scientific investigations on each craft to 11.

Voyager 1 almost didn't get off the ground at its launch , as its rocket came within 3.5 seconds of running out of fuel on Sept. 5, 1977.

But the probe made it safely to space and raced past its twin after launch, getting beyond the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter before Voyager 2 did. Voyager 1's first pictures of Jupiter beamed back to Earth in April 1978, when the probe was 165 million miles (266 million kilometers) from home.

According to NASA , each voyager probe has about 3 million times less memory than a mobile phone and transmits data approximately 38,000 times slower than a 5g internet connection.

To NASA's surprise, in March 1979 Voyager 1 spotted a thin ring circling the giant planet. It found two new moons as well — Thebe and Metis. Additionally, Voyager 1 sent back detailed pictures of Jupiter's big Galilean moons ( Io , Europa , Ganymede and Callisto ) as well as Amalthea .

Like the Pioneer spacecraft before it , Voyager's look at Jupiter's moons revealed them to be active worlds of their own. And Voyager 1 made some intriguing discoveries about these natural satellites. For example, Io's many volcanoes and mottled yellow-brown-orange surface showed that, like planets, moons can have active interiors.

Additionally, Voyager 1 sent back photos of Europa showing a relatively smooth surface broken up by lines, hinting at ice and maybe even an ocean underneath. (Subsequent observations and analyses have revealed that Europa likely harbors a huge subsurface ocean of liquid water, which may even be able to support Earth-like life .)

Voyager 1's closest approach to Jupiter was on March 5, 1979, when it came within 174,000 miles (280,000 km) of the turbulent cloud tops. Then it was time for the probe to aim for Saturn.

Scientists only had to wait about a year, until 1980, to get close-up pictures of Saturn. Like Jupiter, the ringed planet turned out to be full of surprises.

One of Voyager 1's targets was the F ring, a thin structure discovered only the year previously by NASA's Pioneer 11 probe. Voyager's higher-resolution camera spotted two new moons, Prometheus and Pandora, whose orbits keep the icy material in the F ring in a defined orbit. It also discovered Atlas and a new ring, the G ring, and took images of several other Saturn moons.

One puzzle for astronomers was Titan , the second-largest moon in the solar system (after Jupiter's Ganymede). Close-up pictures of Titan showed nothing but orange haze, leading to years of speculation about what it was like underneath. It wouldn't be until the mid-2000s that humanity would find out, thanks to photos snapped from beneath the haze by the European Space Agency's Huygens atmospheric probe .

The Saturn encounter marked the end of Voyager 1's primary mission. The focus then shifted to tracking the 1,590-pound (720 kg) craft as it sped toward interstellar space.

Two decades before it notched that milestone, however, Voyager 1 took one of the most iconic photos in spaceflight history. On Feb. 14, 1990, the probe turned back toward Earth and snapped an image of its home planet from 3.7 billion miles (6 billion km) away. The photo shows Earth as a tiny dot suspended in a ray of sunlight.

Voyager 1 took dozens of other photos that day, capturing five other planets and the sun in a multi-image "solar system family portrait." But the Pale Blue Dot picture stands out, reminding us that Earth is a small outpost of life in an incomprehensibly vast universe.

Voyager 1 left the heliosphere — the giant bubble of charged particles that the sun blows around itself — in August 2012, popping free into interstellar space. The discovery was made public in a study published in the journal Science the following year.

The results came to light after a powerful solar eruption was recorded by Voyager 1's plasma wave instrument between April 9 and May 22, 2013. The eruption caused electrons near Voyager 1 to vibrate. From the oscillations, researchers discovered that Voyager 1's surroundings had a higher density than what is found just inside the heliosphere.

It seems contradictory that electron density is higher in interstellar space than it is in the sun's neighborhood. But researchers explained that, at the edge of the heliosphere, the electron density is dramatically low compared with locations near Earth.

Researchers then backtracked through Voyager 1's data and nailed down the official departure date to Aug. 25, 2012. The date was fixed not only by the electron oscillations but also by the spacecraft's measurements of charged solar particles.

On that fateful day — which was the same day that Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong died — the probe saw a 1,000-fold drop in these particles and a 9% increase in galactic cosmic rays that come from outside the solar system . At that point, Voyager 1 was 11.25 billion miles (18.11 billion km) from the sun, or about 121 astronomical units (AU).

One AU is the average Earth-sun distance — about 93 million miles (150 million km).

You can keep tabs on the Voyager 1's current distance and mission status on this NASA website .

Since flying into interstellar space, Voyager 1 has sent back a variety of valuable information about conditions in this zone of the universe . Its discoveries include showing that cosmic radiation out there is very intense, and demonstrating how charged particles from the sun interact with those emitted by other stars , mission project scientist Ed Stone, of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, told Space.com in September 2017 .

The spacecraft's capabilities continue to astound engineers. In December 2017, for example, NASA announced that Voyager 1 successfully used its backup thrusters to orient itself to "talk" with Earth . The trajectory correction maneuver (TCM) thrusters hadn't been used since November 1980, during Voyager 1's flyby of Saturn. Since then, the spacecraft had primarily used its standard attitude-control thrusters to swing the spacecraft in the right orientation to communicate with Earth.

As the performance of the attitude-control thrusters began to deteriorate, however, NASA decided to test the TCM thrusters — an idea that could extend Voyager 1's operational life. That test ultimately succeeded.

"With these thrusters that are still functional after 37 years without use, we will be able to extend the life of the Voyager 1 spacecraft by two to three years," Voyager project manager Suzanne Dodd, of NASA's Jet Propulsion, Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California, said in a statement in December 2017 .

Mission team members have taken other measures to extend Voyager 1's life as well. For example, they turned off the spacecraft's cameras shortly after the Pale Blue Dot photo was taken to help conserve Voyager 1's limited power supply. (The cameras wouldn't pick up much in the darkness of deep space anyway.) Over the years, the mission team has turned off five other scientific instruments as well, leaving Voyager 1 with four that are still functioning — the Cosmic Ray Subsystem, the Low-Energy Charged Particles instrument, the Magnetometer and the Plasma Wave Subsystem. (Similar measures have been taken with Voyager 2, which currently has five operational instruments .)

The Voyager spacecraft each celebrated 45 years in space in 2022, a monumental milestone for the twin probes.

"Over the last 45 years, the Voyager missions have been integral in providing this knowledge and have helped change our understanding of the sun and its influence in ways no other spacecraft can," says Nicola Fox, director of the Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington, in a NASA statement .

"Today, as both Voyagers explore interstellar space, they are providing humanity with observations of uncharted territory," said Linda Spilker, Voyager's deputy project scientist at JPL in the same NASA statement.

"This is the first time we've been able to directly study how a star, our Sun, interacts with the particles and magnetic fields outside our heliosphere, helping scientists understand the local neighborhood between the stars, upending some of the theories about this region, and providing key information for future missions." Spilker continues.

Voyager 1's next big encounter will take place in 40,000 years when the probe comes within 1.7 light-years of the star AC +79 3888. (The star is roughly 17.5 light-years from Earth.) However, Voyager 1's falling power supply means it will probably stop collecting scientific data around 2025.

You can learn much more about both Voyagers' design, scientific instruments and mission goals at JPL's Voyager site . NASA has lots of in-depth information about the Pale Blue Dot photo, including Carl Sagan's large role in making it happen, here . And if you're interested in the Golden Record, check out this detailed New Yorker piece by Timothy Ferris, who produced the historic artifact. Explore the history of Voyager with this interactive timeline courtesy of NASA.

Bibliography

- Bell, Jim. " The Interstellar Age: Inside the Forty-Year Voyager Mission ," Dutton, 2015.

- Landau, Elizabeth. "The Voyagers in popular culture," Dec. 1, 2017. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/jpl/the-voyagers-in-popular-culture

- PBS, "Voyager: A history in photos." https://www.pbs.org/the-farthest/mission/voyager-history-photos/

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, " Why Am I Taller ?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace

- Daisy Dobrijevic Reference Editor

Boeing's 1st Starliner astronaut mission extended through June 18

At long last: Europe's new Ariane 6 rocket set to debut on July 9

'Star Trek V: The Final Frontier' at 35: Did William Shatner direct the cheesiest chapter in the franchise?

Most Popular

- 2 Solar flare blasts out strongest radiation storm since 2017

- 3 Take a video tour of Boeing’s Starliner with its 2 NASA astronauts

- 4 A 'new star' could appear in the sky any night now. Here's how to see the Blaze Star ignite

- 5 Astrophotographer gets close-up look at monster sunspot that led to May's global auroras

We have completed maintenance on Astronomy.com and action may be required on your account. Learn More

- Login/Register

- Solar System

- Exotic Objects

- Upcoming Events

- Deep-Sky Objects

- Observing Basics

- Telescopes and Equipment

- Astrophotography

- Space Exploration

- Human Spaceflight

- Robotic Spaceflight

- The Magazine

How Voyager opened the door to the ice giants

Voyager 2 flew past Uranus on January 24, 1986, more than four years after the probe visited Saturn. Following the excitement at that ringed world (and Jupiter before it), scientists were eager to see what Voyager would reveal at the more distant and enigmatic uranian system.

Suzy Dodd, the project manager for Voyager’s interstellar mission, worked on the sequencing teams for Uranus and Neptune. The group determined exactly when Voyager’s instruments should take data in order to return the information the science team wanted. This meant understanding in minute detail how the planets and their moons moved. The sequencing team orchestrated the various instruments to use every second of the precious flyby windows to image the most valuable targets: the limb or edge of the planets, the terminators where day and night meet, the moons in their orbits, and the planets’ own broad faces.

After the rich and complex atmospheres of Jupiter and Saturn, Uranus seemed pretty bland, Dodd recalls. “You didn’t get all the great storms you got at the other planets,” she says. Instead, Uranus “looked like a fuzzy, blue tennis ball.”

Voyager did reveal a previously undetected magnetic field around Uranus, comparable in strength to Earth’s. Due to its nearly 90° axial tilt, Uranus rolls around its orbit like a ball. And while Earth’s orbital and magnetic fields are offset by roughly 12°, Uranus’ are 60° apart. This results in a corkscrewing magnetic field trailing millions of miles behind the planet.

What’s more, scientists still aren’t sure why the magnetic field exists at all, since Uranus lacks the standard liquid metallic inner layer that powers such fields on other planets. Voyager also revealed intense radiation belts around the planet, similar to those seen at Saturn.

Astronomers at Cornell University discovered Uranus’ ring system in early 1977, just before Voyager’s launch. The sighting was a happy accident, when a chance alignment carried Uranus in front of a distant star. Scientists had planned to use the occultation to study Uranus’ atmosphere, but the star’s repeated appearance and disappearance before it slid out of view behind the planet made astronomers realize that a series of rings surrounded our far-off neighbor. The flyby was a chance to investigate them up close.

Voyager imaged the ring system for the first time, informing astronomers of its detailed structure. The spacecraft also discovered two entirely new rings. The close-up views confirmed that Uranus’ subtle bands are not like Saturn’s bright icy rings; they are dark and reflect little light, making them difficult to see. Scientists think the rings are probably made mostly of ice, like Saturn’s, but covered in organic material such as methane, and then baked dark by the planet’s radiation belts.

Uranus’ moons, too, camouflage well against the dark of space. When Voyager left Earth, astronomers knew of only five satellites around the planet. From observations during its brief visit, the spacecraft tripled that number, yielding 10 new moons. “I really think the satellites were the highlight of Uranus,” says Dodd. Voyager images lent the five larger known moons detail and character, telling varied stories of violent pasts.

Two of the new moons, Cordelia and Ophelia, were identified as shepherd moons. They orbit on either side of Uranus’ outer Epsilon ring, and their gravitational pull herds the small particles in that ring along their orbital path and keeps them from dissipating into space. Uranus’ rings are uncommonly narrow; without shepherd moons, the small particles would disperse over long timescales.

Last year, astronomers from the University of Idaho revisited the Voyager data. Thirty years after the flyby, they found evidence for two more tiny moonlets shaping Uranus’ rings. “Nobody — or not many people — had looked at this in a very long time,” says Robert Chancia, who led the investigation. In fact, the Voyager data were taken before he was born. Chancia and his adviser, Matthew Hedman, usually study Saturn’s rings. But recent discoveries by the Cassini spacecraft have added greatly to astronomers’ understanding of planetary rings. So Chancia and Hedman decided to take another look at the Voyager findings, applying new theories to old data.

“There are several narrow ringlets within the rings of Saturn” that provide reasonable proxies for Uranus’ system, Chancia explains. So he and Hedman adopted techniques that planetary scientist Mark Showalter used to find the moonlet Pan in Voyager 2’s observations of Saturn’s ring system.

They found distinct patterns in Uranus’ rings consistent with “wakes” carved by moonlets circling a planet within a ring system. The predicted moonlets are tiny, only 2 to 9 miles (4 to 14 kilometers) across. And they are likely dark, like the rest of the moons and ring system. Confirming the moonlets will be a challenge. But even 30 years later, Voyager is still helping to crack Uranus’ secrets.

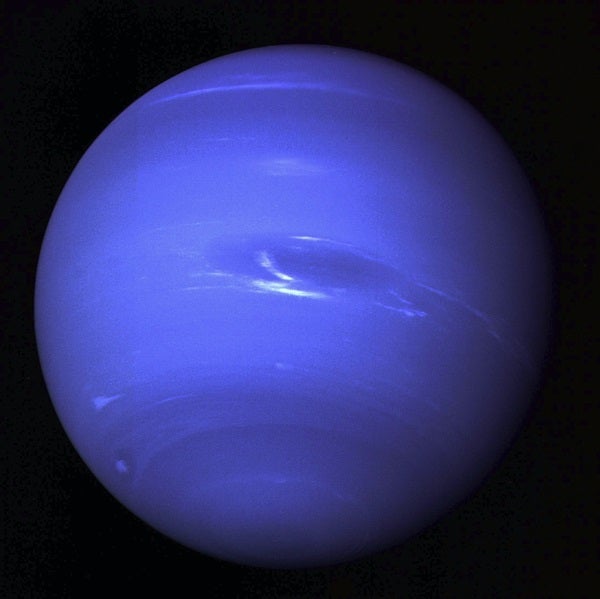

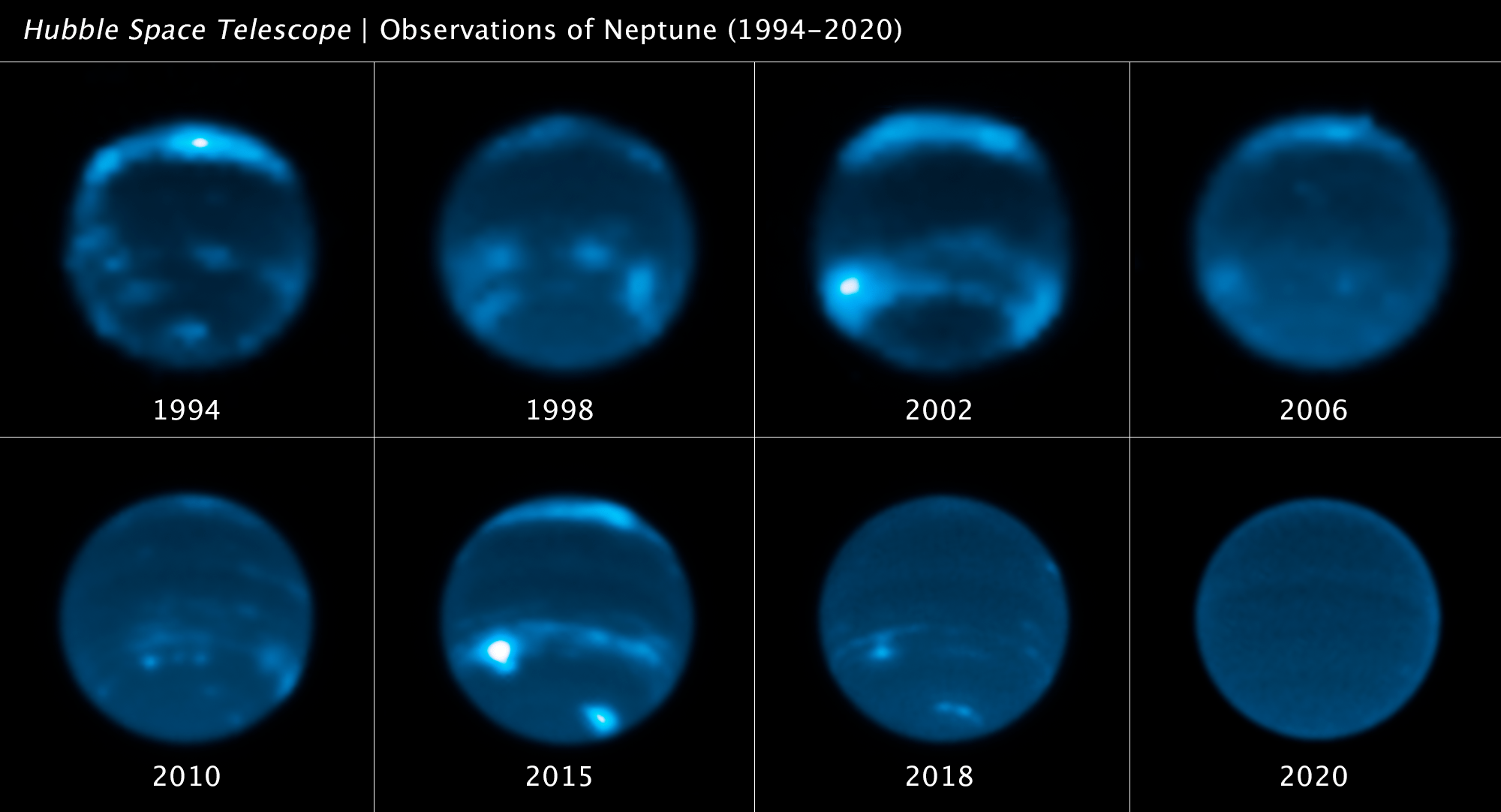

Voyager’s last planetary encounter came August 24, 1989. Far from Uranus’ “fuzzy tennis ball,” Neptune was alive with storms and bright, quick-moving clouds, delighting unsuspecting astronomers. Clouds not only appeared clearly in Voyager images, but they also cast shadows on deeper cloud layers, allowing scientists to measure the planet’s atmosphere in great detail. The “Great Dark Spot,” as astronomers termed the largest tempest, was as big as Earth, swirling in Neptune’s southern hemisphere and boasting wind speeds as high as 750 mph (1,200 km/h). In the decades since, that storm has died, while new storms have risen in its place.

“That was a bit of a surprise to me when you consider the Great Red Spot on Jupiter has been going on for 400 years,” Dodd says.

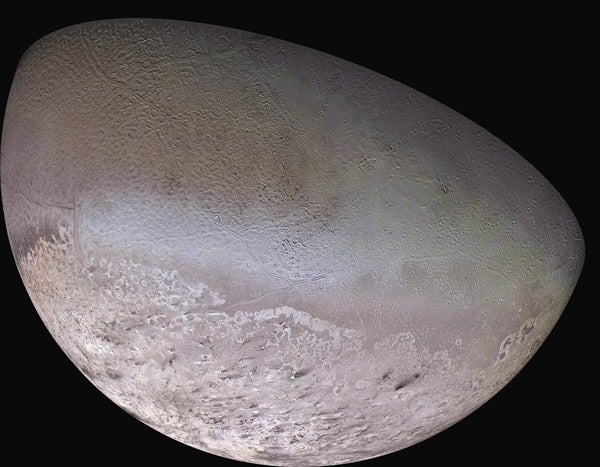

More surprises waited on Triton, Neptune’s biggest moon. Triton was already a hotbed of intrigue; it’s by far the solar system’s largest retrograde satellite, meaning it orbits in the direction opposite to its planet’s rotation. This is usually a sign of a captured object, but most other retrograde moons are small, misshapen asteroids. Triton is three-quarters the size of our Moon, and survived its capture intact. Scientists wanted close-up views of the satellite, and since it was the last target, they were free to adjust Voyager’s trajectory as needed. So the spacecraft swooped only 3,075 miles (4,950km) above Neptune’s north pole — its closest approach to any object during the mission — and flew toward its encounter with Triton.

The last world Voyager 2 visited stunned scientists. The moon boasted a thin atmosphere, polar caps, and active geysers that spewed icy material miles high. The active cryovolcanism puts Triton in a select group of satellites, in the company of other dynamic moons such as Europa and Enceladus.

Voyager also discovered six new moons orbiting Neptune and delivered clear pictures of its ring system for the first time, revealing the rings to be clumpy but complete, unlike those at Uranus.

And as it did at Uranus, Voyager discovered that Neptune’s magnetic pole is misaligned from its rotational pole, causing extreme variations in its magnetic field as the planet rotates. Furthermore, both planets’ magnetospheres are offset from center by a large fraction: about one-third the planet’s radius for Uranus, and nearly half a radius for Neptune. Both planets could have oceans of conductive icy slush that perform the work of the liquid metallic cores at Earth and Jupiter, but inconclusive models and observations have left scientists with little more than guesswork as to what exactly drives the magnetic fields that Voyager observed.

Voyager also detected aurorae on Neptune. Due to the strange and complex nature of the planet’s magnetic field, these aurorae don’t occur only at the poles; instead they are scattered across Neptune’s upper atmosphere.

Voyager also closed a contentious chapter in astronomy history by revising Neptune’s mass downward by around half a percent — or roughly the mass of Mars. This miscalculation had sent astronomers on a wild goose chase through the years as they tried to make sense of Uranus’ and Neptune’s orbits, usually by invoking the existence of a mysterious Planet X tugging on both of them. (Pluto was found as a direct result of this hunt, but its small size was never enough to resolve the initial problem.) Voyager settled the issue, as Neptune’s smaller mass means it and Uranus orbit just as they should.

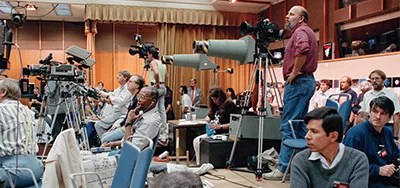

To mark the final flyby, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory hosted a special event celebrating Voyager’s journey and accomplishments. Scientists shared images with the public, and rock-’n’-roll legend Chuck Berry, whose music lives on as part of Voyager’s Golden Record, played in a special concert.

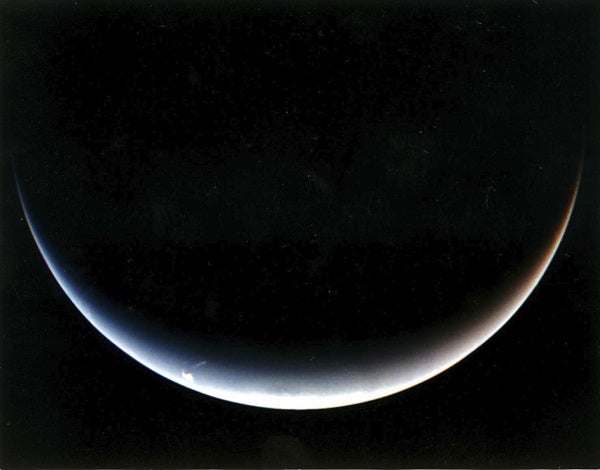

At the edge of our planetary system, 2.75 billion miles (4.43 billion km) from Earth, Voyager turned its cameras back for a last look, imaging farewell shots of a crescent Neptune. Dodd recalls her reaction to the images: “Wow. The planetary mission is done. We’re going off into the deep dark and cold realms of space. Who knows how long the mission will last?”

When she left her position with the Neptune team, Dodd says, no one then imagined Voyager would continue as long as it has. She returned to Voyager’s interstellar mission in 2010, 21 years after she left the project. In many ways, she admits that the spacecraft is an artifact — memory and power limited, with many of its specialists long since retired or passed on. Since Voyager’s departure from Neptune, many of its instruments have gone quiet. There is no need for imaging cameras in the dark void of space. But that does not mean the project is defunct.

Voyager continues to measure magnetic fields, charged particles, plasma density, and more as it cruises the solar system’s hinterlands, teaching scientists about the subtle edges of the solar system’s boundaries. Voyager 1 has passed beyond the reach of the solar wind, and thus is sampling aspects of interstellar space, though it still lies well within the Sun’s gravitational influence. Voyager 2, following a slower trajectory from its two-planet detour, tags behind, still sampling the solar wind. From their distance, it takes more than 15 hours for their signals to reach Earth.

Sometime in the next decade, the spacecraft will lose power and begin to shut down. Dodd’s team will turn the Voyagers’ heaters off first, and one by one, the science instruments will succumb to the cold of space. But the spacecraft themselves and their Golden Records will journey on, carrying humanity’s imprint into the cosmos.

It will be years before any spacecraft retreads Voyager’s path to Uranus or Neptune. With at least half a century of technological advances behind it, any future craft will undoubtedly revolutionize our understanding of the ice giants all over again. But it’s safe to say that nothing will match Voyager for sheer adventure and scope. Decades after its primary mission, Voyager continues to teach, to inspire, and to explore.

Starmus spotlights planet Earth: This Week in Astronomy with Dave Eicher

NASA’s asteroid Bennu sample return mission was a prime time to study an artificial meteor

The People’s Spaceship: NASA, the Shuttle Program, and Public Engagement after Apollo

Amateur astronomers help ID a ‘warm Jupiter’ exoplanet

Edmond Halley: The man behind the comet

The most common planets in the universe might be rich in carbon

The aging Hubble Space Telescope is not finished quite yet

Hubble finds signature of water vapor in exoplanet GJ 9827d’s atmosphere

Volcanic moon Io gets close-up look from Earth observatory

25 Years After Neptune: Reflections on Voyager

Members of the Voyager team reflect on the mission's Neptune encounter, 25 years later.

August 25, 1989: Neptune is in view. It is the middle of the night and everything is happening fast at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Voyager team members have had little or no sleep. Vice President Dan Quayle is on the scene and Chuck Berry, of "Johnny B. Goode" fame, is prepping for an outdoor party. This will be "the last picture show" of the grand tour of the solar system by NASA's Voyager mission.

Fast forward to August 25, 2014: New Horizons, the first mission sent to explore dwarf planet Pluto and other icy objects within the Kuiper Belt, is less than one year away from its arrival. And today, New Horizons will cross Neptune's orbit -- the very day that Voyager 2 flew past Neptune 25 years ago.

In celebration of this anniversary, scientists from both missions reflected on Voyager 2's Neptune encounter.

The Encounter -- Coming in Close

The Voyager team remembers how extraordinary it was to visit Neptune.

"We had been lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time with the right team, and this was the first and only opportunity we would have for a long time for an up-close and personal view with Neptune and the outer parts of our solar system," said Ralph McNutt, a member of the New Horizons science team who was a plasma data team member on Voyager 2.

New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern, now based at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, was a graduate student at the University of Colorado, Boulder, at the time of the encounter.

"As much as anything, just seeing this world unfold from the point of light it had been to become a real place was just enthralling," Stern said.

The Exhilaration at JPL

JPL, which manages the Voyager mission, was an exciting place to be in 1989.

Tom Spilker, who was a member of the Voyager 2 radio science team and who has since moved on from JPL, recalls: "I got this overwhelming feeling inside, as if I was standing in the bow of Captain Cook's expedition into the Gulf of Alaska for the very first time. We were going to places where no one had ever gone before -- we were explorers."

Stern describes JPL as the place where "all the action was" in August of 1989.

"I do remember Carl Sagan calling me at the Goddard Space Flight Center, while I was making collaborative measurements of Neptune's moon Triton with the International Ultraviolet Explorer satellite to say, 'Hey, you're not in the thick of it, but let me tell you what the press doesn't know yet.' He did this so I would feel like an insider," Stern said.

Discoveries

As the spacecraft delivered images of Neptune, scientists uncovered some unexpected findings.

"The Voyager 2 flyby of Neptune was just another example of the surprises we had time after time as Voyager was flying by each of the outer planets," said Ed Stone, project scientist for Voyager at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

The "Great Dark Spot" on Neptune was the first big surprise.

"This dark spot is very similar to the Great Red Spot on our solar system's largest planet, Jupiter, which is a very large storm," Stone said. Because Neptune is six times farther from the sun than Jupiter, it receives a fraction of the energy that Jupiter does -- this dark spot was a complete surprise.

Voyager scientists were also amazed to see that Triton, a moon of Neptune, has active geysers.

"The Triton flyby was my favorite moment partly because it was a bookend. The journey really started with the discovery of volcanoes on Io with Voyager 1, 10 years earlier -- the first bookend. We finished the planetary part of the mission with another bookend, the flyby of Triton, where we discovered a much colder, smaller world that was also geologically active," Stone said.

In the spirit of the Voyager 2 missions to Uranus and Neptune, New Horizons is going where no spacecraft has gone before.

"New Horizons will certainly provide us with new and exciting discoveries, just as Voyager did with its planetary flybys," said Suzanne Dodd of JPL, project manager for Voyager.

Stern summed up the two missions nicely: "The Voyager and New Horizons missions have very important similarities. They are both historic missions of exploration to the very frontier of human knowledge: Voyager with the middle zone of the solar system and the giant planets, and New Horizons with the Kuiper Belt and Pluto. Both excite the public about not only the field of planetary science, but also about exploration and some of the things that our nation and NASA do that really do go down in the history books."

Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, were launched 16 days apart in 1977. The Voyager spacecraft were built and continue to be operated by JPL. Caltech manages JPL for NASA. The Voyager missions are a part of NASA's Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

For more information about Voyager, visit:

http://www.nasa.gov/voyager

http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov

New Horizons was designed, built and is operated by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. New Horizons, which launched in 2006, is the first mission in NASA's New Frontiers Program of medium-class spacecraft exploration projects.

For more information about New Horizons, visit:

http://www.nasa.gov/newhorizons

http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/

News Media Contact

Written by Autumn Burdick

Elizabeth Landau/Preston Dyches

818-354-6425 / 354-7013

[email protected] / [email protected]

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Voyager 1, First Craft in Interstellar Space, May Have Gone Dark

The 46-year-old probe, which flew by Jupiter and Saturn in its youth and inspired earthlings with images of the planet as a “Pale Blue Dot,” hasn’t sent usable data from interstellar space in months.

By Orlando Mayorquin

When Voyager 1 launched in 1977, scientists hoped it could do what it was built to do and take up-close images of Jupiter and Saturn. It did that — and much more.

Voyager 1 discovered active volcanoes, moons and planetary rings, proving along the way that Earth and all of humanity could be squished into a single pixel in a photograph, a “ pale blue dot, ” as the astronomer Carl Sagan called it. It stretched a four-year mission into the present day, embarking on the deepest journey ever into space.

Now, it may have bid its final farewell to that faraway dot.

Voyager 1 , the farthest man-made object in space, hasn’t sent coherent data to Earth since November. NASA has been trying to diagnose what the Voyager mission’s project manager, Suzanne Dodd, called the “most serious issue” the robotic probe has faced since she took the job in 2010.

The spacecraft encountered a glitch in one of its computers that has eliminated its ability to send engineering and science data back to Earth.

The loss of Voyager 1 would cap decades of scientific breakthroughs and signal the beginning of the end for a mission that has given shape to humanity’s most distant ambition and inspired generations to look to the skies.

“Scientifically, it’s a big loss,” Ms. Dodd said. “I think — emotionally — it’s maybe even a bigger loss.”

Voyager 1 is one half of the Voyager mission. It has a twin spacecraft, Voyager 2.

Launched in 1977, they were primarily built for a four-year trip to Jupiter and Saturn , expanding on earlier flybys by the Pioneer 10 and 11 probes.

The Voyager mission capitalized on a rare alignment of the outer planets — once every 175 years — allowing the probes to visit all four.

Using the gravity of each planet, the Voyager spacecraft could swing onto the next, according to NASA .

The mission to Jupiter and Saturn was a success.

The 1980s flybys yielded several new discoveries, including new insights about the so-called great red spot on Jupiter, the rings around Saturn and the many moons of each planet.

Voyager 2 also explored Uranus and Neptune , becoming in 1989 the only spacecraft to explore all four outer planets.

Voyager 1, meanwhile, had set a course for deep space, using its camera to photograph the planets it was leaving behind along the way. Voyager 2 would later begin its own trek into deep space.

“Anybody who is interested in space is interested in the things Voyager discovered about the outer planets and their moons,” said Kate Howells, the public education specialist at the Planetary Society, an organization co-founded by Dr. Sagan to promote space exploration.

“But I think the pale blue dot was one of those things that was sort of more poetic and touching,” she added.

On Valentine’s Day 1990, Voyager 1, darting 3.7 billion miles away from the sun toward the outer reaches of the solar system, turned around and snapped a photo of Earth that Dr. Sagan and others understood to be a humbling self-portrait of humanity.

“It’s known the world over, and it does connect humanity to the stars,” Ms. Dodd said of the mission.

She added: “I’ve had many, many many people come up to me and say: ‘Wow, I love Voyager. It’s what got me excited about space. It’s what got me thinking about our place here on Earth and what that means.’”

Ms. Howells, 35, counts herself among those people.

About 10 years ago, to celebrate the beginning of her space career, Ms. Howells spent her first paycheck from the Planetary Society to get a Voyager tattoo.

Though spacecraft “all kind of look the same,” she said, more people recognize the tattoo than she anticipated.

“I think that speaks to how famous Voyager is,” she said.

The Voyagers made their mark on popular culture , inspiring a highly intelligent “Voyager 6” in “Star Trek: The Motion Picture” and references on “The X Files” and “The West Wing.”

Even as more advanced probes were launched from Earth, Voyager 1 continued to reliably enrich our understanding of space.

In 2012, it became the first man-made object to exit the heliosphere, the space around the solar system directly influenced by the sun. There is a technical debate among scientists around whether Voyager 1 has actually left the solar system, but, nonetheless, it became interstellar — traversing the space between stars.

That charted a new path for heliophysics, which looks at how the sun influences the space around it. In 2018, Voyager 2 followed its twin between the stars.

Before Voyager 1, scientific data on the sun’s gases and material came only from within the heliosphere’s confines, according to Dr. Jamie Rankin, Voyager’s deputy project scientist.

“And so now we can for the first time kind of connect the inside-out view from the outside-in,” Dr. Rankin said, “That’s a big part of it,” she added. “But the other half is simply that a lot of this material can’t be measured any other way than sending a spacecraft out there.”

Voyager 1 and 2 are the only such spacecraft. Before it went offline, Voyager 1 had been studying an anomalous disturbance in the magnetic field and plasma particles in interstellar space.

“Nothing else is getting launched to go out there,” Ms. Dodd said. “So that’s why we’re spending the time and being careful about trying to recover this spacecraft — because the science is so valuable.”

But recovery means getting under the hood of an aging spacecraft more than 15 billion miles away, equipped with the technology of yesteryear. It takes 45 hours to exchange information with the craft.

It has been repeated over the years that a smartphone has hundreds of thousands of times Voyager 1’s memory — and that the radio transmitter emits as many watts as a refrigerator lightbulb.

“There was one analogy given that is it’s like trying to figure out where your cursor is on your laptop screen when your laptop screen doesn’t work,” Ms. Dodd said.

Her team is still holding out hope, she said, especially as the tantalizing 50th launch anniversary in 2027 approaches. Voyager 1 has survived glitches before, though none as serious.

Voyager 2 is still operational, but aging. It has faced its own technical difficulties too.

NASA had already estimated that the nuclear-powered generators of both spacecrafts would likely die around 2025.

Even if the Voyager interstellar mission is near its end, the voyage still has far to go.

Voyager 1 and its twin, each 40,000 years away from the next closest star, will arguably remain on an indefinite mission.

“If Voyager should sometime in its distant future encounter beings from some other civilization in space, it bears a message,” Dr. Sagan said in a 1980 interview .

Each spacecraft carries a gold-plated phonograph record loaded with an array of sound recordings and images representing humanity’s richness, its diverse cultures and life on Earth.

“A gift across the cosmic ocean from one island of civilization to another,” Dr. Sagan said.

Orlando Mayorquin is a general assignment and breaking news reporter based in New York. More about Orlando Mayorquin

What’s Up in Space and Astronomy

Keep track of things going on in our solar system and all around the universe..

Never miss an eclipse, a meteor shower, a rocket launch or any other 2024 event that’s out of this world with our space and astronomy calendar .

The company SpaceX achieved a key set of ambitious goals on the fourth test flight of a vehicle that is central to Elon Musk’s vision of sending people to Mars.

Euclid, a European Space Agency telescope launched into space last summer, finally showed off what it’s capable of with a batch of breathtaking images and early science results.

A dramatic blast from the sun set off the highest-level geomagnetic storm in Earth’s atmosphere, making the northern lights visible around the world .

With the help of Google Cloud, scientists who hunt killer asteroids churned through hundreds of thousands of images of the night sky to reveal 27,500 overlooked space rocks in the solar system .

Is Pluto a planet? And what is a planet, anyway? Test your knowledge here .

May 30, 2024

Voyager 1’s Revival Offers Inspiration for Everyone on Earth

Instruments may fail, but humanity’s most distant sentinel will keep exploring, and inspiring us all

By Saswato R. Das

Artist's rendering of a Voyager spacecraft in deep space.

Dotted Zebra/Alamy Stock Photo

Amid April’s litany of bad news—war in Gaza, protests on American campuses, an impasse in Ukraine—a little uplift came for science buffs.

NASA has reestablished touch with Voyager 1 , the most distant thing built by our species, now hurtling through interstellar space far beyond the orbit of Pluto. The extraordinarily durable spacecraft had stopped transmitting data in November, but NASA engineers managed a very clever work-around, and it is sending data again. Now more than 15 billion miles away, Voyager 1 is the farthest human object, and continues to speed away from us at approximately 38,000 miles per hour.

Like an old car that continues to run, or an uncle blessed with an uncommonly long life, the robotic spacecraft is a super ager that goes on and on—and, in doing so, has captivated space buffs everywhere.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Launched on September 5, 1977, the one-ton Voyager 1 was meant to chart the outer solar system, in particular the gas giant planets Jupiter and Saturn, and Saturn’s moon, Titan. Its twin, Voyager 2 , launched the same year, followed a different trajectory with a slightly different mission to explore the outer planets before heading to the solar system’s edge.

Those were NASA’s glory days. A few years earlier, NASA had successfully landed men on the moon—and won the space race for the U.S. NASA’s engineers were the envy of the world.

To get to Jupiter and Saturn, both Voyagers had to traverse the asteroid belt, which is full of rocks and debris orbiting the sun. They had to survive cosmic rays, intense radiation from Jupiter and other perils of space. But the two spacecraft made it without a hitch.

President Jimmy Carter held office when Voyager 1 was launched from Cape Canaveral; Elvis Presley had died just three weeks before; gas was about 60 cents a gallon; and, like now, the Middle East was in crisis, with Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat trying to find peace.

Voyager 1 sent back spectacular photos of Jupiter and its giant red spot. It showed how dynamic the Jovian atmosphere was, with clouds and storms. It also took pictures of Jupiter’s moon Io, with its volcanoes, and Saturn’s moon Titan , which astronomers think has an atmosphere similar to the primordial Earth’s. The spacecraft discovered a thin ring around Jupiter and two new Jovian moons, which were named Thebe and Metis. On reaching Saturn, it discovered five new moons as well as a new ring.

And then Voyager 1 continued on its journey and sent images back from the edge of the solar system. Many of us remember the Pale Blue Dot , a haunting picture of the Earth it took on Feb 14, 1990, when it was a distance of 3.7 billion miles from the sun. The astronomer Carl Sagan wrote:

“There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we've ever known.”

By then Voyager 1 had long outlived its planetary mission but kept faithfully calling home as it traveled beyond the solar system into the realm of the stars. By 2012 Voyager 1 had reached the heliosphere , the farthest edge of the solar system. There, it penetrated the heliopause, where the solar wind ends, stopped by particles coming from the interstellar medium, the vast space between the stars. (Astronomers know that the space between the stars is not totally empty but permeated by a rarefied gas .)

From Voyager 1, scientists learned that the heliopause is quite dynamic and first measured the magnetic field of the Milky Way beyond the solar system. And its instruments kept sending data as it traveled through the interstellar medium.

On hearing that Voyager 1 had gone dark, I had checked in with Louis Lanzerotti , a former Bell Labs planetary scientist who did the calibrations for the Voyager 1 spacecraft and was a principal investigator on many experiments. He told me that a NASA manager in the 1970s had doubted that the spacecraft’s mechanical scan platform, which pointed instruments at targets, and very thin solid state detectors, which took those edge of the solar system readings, on the spacecraft would survive. They not only survived but worked flawlessly for all this time, Lanzerotti said, providing excellent data for decades. He was overjoyed on hearing the news that Voyager 1 was still alive.

Voyager 1 instruments have power until 2025 . After that, they will shut off, one by one. But there is nothing to stop the spacecraft as it speeds away from us in the vast emptiness of space.

Thousands of years from now, maybe when the human race has left this planet, Voyager 1, the tiny little spacecraft that could, will still continue its inexorable journey to the stars.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

25 Years After Neptune: Reflections on Voyager

August 25, 1989: Neptune is in view. It is the middle of the night and everything is happening fast at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Voyager team members have had little or no sleep. Vice President Dan Quayle is on the scene and Chuck Berry, of "Johnny B. Goode" fame, is prepping for an outdoor party. This will be "the last picture show" of the grand tour of the solar system by NASA's Voyager mission.

Fast forward to August 25, 2014: New Horizons, the first mission sent to explore dwarf planet Pluto and other icy objects within the Kuiper Belt, is less than one year away from its arrival. And today, New Horizons will cross Neptune's orbit -- the very day that Voyager 2 flew past Neptune 25 years ago.

In celebration of this anniversary, scientists from both missions reflected on Voyager 2's Neptune encounter.

The Encounter - Coming in Close

The Voyager team remembers how extraordinary it was to visit Neptune.

"We had been lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time with the right team, and this was the first and only opportunity we would have for a long time for an up-close and personal view with Neptune and the outer parts of our solar system," said Ralph McNutt, a member of the New Horizons science team who was a plasma data team member on Voyager 2.

New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern, now based at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, was a graduate student at the University of Colorado, Boulder, at the time of the encounter.

"As much as anything, just seeing this world unfold from the point of light it had been to become a real place was just enthralling," Stern said.

The Exhilaration at JPL

JPL, which manages the Voyager mission, was an exciting place to be in 1989.

Tom Spilker, who was a member of the Voyager 2 radio science team and who has since moved on from JPL, recalls: "I got this overwhelming feeling inside, as if I was standing in the bow of Captain Cook's expedition into the Gulf of Alaska for the very first time. We were going to places where no one had ever gone before -- we were explorers."

Stern describes JPL as the place where "all the action was" in August of 1989.

"I do remember Carl Sagan calling me at the Goddard Space Flight Center, while I was making collaborative measurements of Neptune's moon Triton with the International Ultraviolet Explorer satellite to say, 'Hey, you're not in the thick of it, but let me tell you what the press doesn't know yet.' He did this so I would feel like an insider," Stern said.

Discoveries

As the spacecraft delivered images of Neptune, scientists uncovered some unexpected findings.

"The Voyager 2 flyby of Neptune was just another example of the surprises we had time after time as Voyager was flying by each of the outer planets," said Ed Stone, project scientist for Voyager at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

The "Great Dark Spot" on Neptune was the first big surprise.

"This dark spot is very similar to the Great Red Spot on our solar system's largest planet, Jupiter, which is a very large storm," Stone said. Because Neptune is six times farther from the sun than Jupiter, it receives a fraction of the energy that Jupiter does -- this dark spot was a complete surprise.

Voyager scientists were also amazed to see that Triton, a moon of Neptune, has active geysers.

"The Triton flyby was my favorite moment partly because it was a bookend. The journey really started with the discovery of volcanoes on Io with Voyager 1, 10 years earlier -- the first bookend. We finished the planetary part of the mission with another bookend, the flyby of Triton, where we discovered a much colder, smaller world that was also geologically active," Stone said.

In the spirit of the Voyager 2 missions to Uranus and Neptune, New Horizons is going where no spacecraft has gone before.

"New Horizons will certainly provide us with new and exciting discoveries, just as Voyager did with its planetary flybys," said Suzanne Dodd of JPL, project manager for Voyager.

Stern summed up the two missions nicely: "The Voyager and New Horizons missions have very important similarities. They are both historic missions of exploration to the very frontier of human knowledge: Voyager with the middle zone of the solar system and the giant planets, and New Horizons with the Kuiper Belt and Pluto. Both excite the public about not only the field of planetary science, but also about exploration and some of the things that our nation and NASA do that really do go down in the history books."

Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, were launched 16 days apart in 1977. The Voyager spacecraft were built and continue to be operated by JPL. Caltech manages JPL for NASA. The Voyager missions are a part of NASA's Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

For more information about Voyager, visit:

http://www.nasa.gov/voyager

Http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov.

New Horizons was designed, built and is operated by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. New Horizons, which launched in 2006, is the first mission in NASA's New Frontiers Program of medium-class spacecraft exploration projects.

For more information about New Horizons, visit:

http://www.nasa.gov/newhorizons

Http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/, related terms, explore more.

NASA’s Voyager Team Focuses on Software Patch, Thrusters

The efforts should help extend the lifetimes of the agency’s interstellar explorers. Engineers for NASA’s Voyager mission are taking steps to help make sure both spacecraft, launched in 1977, continue to explore interstellar space for years to come. One effort addresses fuel residue that seems to be accumulating inside narrow tubes in some of the […]

Neptune’s Disappearing Clouds Linked to the Solar Cycle

Astronomers have uncovered a link between Neptune's shifting cloud abundance and the 11-year solar cycle, in which the waxing and waning of the Sun's entangled magnetic fields drives solar activity.

All Eyes on the Ice Giants

NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft plans to observe Uranus and Neptune from its location far out in the outer solar system this fall, and the mission team is inviting the global amateur astronomy community to come along for the ride – and make a real contribution to space science – by observing both ice giants at the same time.

Discover More Topics From NASA

Facts About Earth

Asteroids, Comets & Meteors

Kuiper Belt

Why is Voyager 1 sending Gibberish after 47 Years?

Data classification and risk assessment: foundations for effective data protection, 9 new ways to power data centers: the unthinkable to the absurd.

Active for almost 50 years since its launch in 1977, Voyager 1 – the first spacecraft to cross into interstellar space – is not doing well. Adarsh explains what’s going on….

NASA launched Voyager 1 from the Kennedy Space Cater in Florida in 1977, along with its sister craft Voyager 2. These two are the longest-serving, nonpassive spacecrafts in existence. They are part of an elite fleet of five probes that are on trajectories that will take them out of the solar system, never to return.

But since November of 2023, Voyager 1 has been sending incomprehensible messages back to Earth and that has got the engineers at NASA really worried. Suzanne Dodd, a part of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said “”It basically stopped talking to us in a coherent manner.”

So, is the Voyager 1’s near-50-year journey about to end?

The History of the Voyagers

Voyagers 1 and 2 were initially on a four-year mission to study Jupiter, Saturn and the larger moons of the two planets over a period of five years. But they have managed to outlast their original mission lifespan by more than 35 years and are both currently 130 times farther away from Earth than our planet is from the Sun.

The twin spacecraft made a string of discoveries on and around Jupiter and Saturn, like the intricacies of Saturn’s rings and the presence of active volcanoes on Jupiter’s moon Io. Voyager 2 went on to explore Uranus and Neptune and is still the only spacecraft to have visited those planets.

Apart from its scientific impact, Voyager 1 also clicked the famous “Pale Blue Dot” image of Earth, which American astronomer Carl Sagan interpreted as a representation of how small humanity is in the grand scale of the cosmos.

What seems to be the Problem

Voyager 1 started facing a critical computer glitch in November last year. Instead of the expected data, Mission Control was receiving gibberish from the craft, indicating a malfunction in its flight data subsystem (FDS).

With Voyager 1’s software and documentation dating back to the 1970s, troubleshooting was proving to be a challenge. Most of the scientists who worked on the old code have retired by now and the documentation itself is aging, adding to the complexity of the situation.

Mission Control suspected corrupted code and began sending commands to bypass the issue. A breakthrough came on March 1, this year, when a command successfully reached Voyager 1, although it took nearly two days for a response due to the immense distance. Upon decoding the response, engineers realized it contained the entire FDS memory, providing a comprehensive record of the craft’s data and operations.

This discovery serves as a cosmic Rosetta Stone, allowing NASA to compare current and past data to pinpoint the malfunction’s cause and hopefully extend Voyager 1’s mission.

The Last Word

Regardless of this issue, Voyager 1 has been showing its age and isn’t anticipated to last more than a few more years as its radio-thermal generators run down.

But if the engineers at NASA don’t manage to overcome the computer glitch completely, that journey could end a lot sooner. Whether they are able to solve it, remains to be seen.

In case you missed:

- Presenting the Matsya 6000 – India’s First Manned Submersible

- Exploring ISRO’s Ambitious Plans for 2024

Are you ready for the Apple Flip Phone? Get Ready for the Foldable iPhone!

- Einstein’s 100-Year-Old Prediction about the Universe Proven!

- How AI is transforming the Way We Work!

- The Pros & Cons of Facial Recognition

- All You Need to Know about Gemini, Google’s Response to ChatGPT

- Introducing Universal AI Employee being built by Ema AI

- Work Video Calls are having an Adverse Effect on our Brains!

Elon Musk says X will now be payable for New Users

Adarsh hates personal bios, Chelsea football club and Oxford commas. When he's not writing, he's busy playing FIFA on his PlayStation.

Leave A Reply Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Latest Posts

How ai helped us find plato’s burial site, presenting claude, chatgpt’s competitor which is apparently better, 5 free ai assistants to make your life easier, will ai eat up more it jobs in 2024.

- Buy Domains

- Cloud Services

- Digital Services

- Data Center Services

- Networks Services

- Integration Services

- Security Services

- Sify Marketplace

- Privacy Policy

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.

- The Contents

- The Making of

- Where Are They Now

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Q & A with Ed Stone

golden record

Where are they now.

- frequently asked questions

- Q&A with Ed Stone

News | April 27, 2023

Nasa's voyager will do more science with new power strategy.

Editor's note: Language was added in the second paragraph on May 1 to underscore that the mission will continue even after a science instrument is retired.

The plan will keep Voyager 2's science instruments turned on a few years longer than previously anticipated, enabling yet more revelations from interstellar space.

Launched in 1977, the Voyager 2 spacecraft is more than 12 billion miles (20 billion kilometers) from Earth, using five science instruments to study interstellar space. To help keep those instruments operating despite a diminishing power supply, the aging spacecraft has begun using a small reservoir of backup power set aside as part of an onboard safety mechanism. The move will enable the mission to postpone shutting down a science instrument until 2026, rather than this year.

Switching off a science instrument will not end the mission. After shutting off the one instrument in 2026, the probe will continue to operate four science instruments until the declining power supply requires another to be turned off. If Voyager 2 remains healthy, the engineering team anticipates the mission could potentially continue for years to come.

Voyager 2 and its twin Voyager 1 are the only spacecraft ever to operate outside the heliosphere, the protective bubble of particles and magnetic fields generated by the Sun. The probes are helping scientists answer questions about the shape of the heliosphere and its role in protecting Earth from the energetic particles and other radiation found in the interstellar environment.

“The science data that the Voyagers are returning gets more valuable the farther away from the Sun they go, so we are definitely interested in keeping as many science instruments operating as long as possible,” said Linda Spilker, Voyager's project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, which manages the mission for NASA.

Power to the Probes

Both Voyager probes power themselves with radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), which convert heat from decaying plutonium into electricity. The continual decay process means the generator produces slightly less power each year. So far, the declining power supply hasn't impacted the mission's science output, but to compensate for the loss, engineers have turned off heaters and other systems that are not essential to keeping the spacecraft flying.

Each of NASA's Voyager probes are equipped with three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), including the one shown here. The RTGs provide power for the spacecraft by converting the heat generated by the decay of plutonium-238 into electricity. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

With those options now exhausted on Voyager 2, one of the spacecraft's five science instruments was next on their list. (Voyager 1 is operating one less science instrument than its twin because an instrument failed early in the mission. As a result, the decision about whether to turn off an instrument on Voyager 1 won't come until sometime next year.)

In search of a way to avoid shutting down a Voyager 2 science instrument, the team took a closer look at a safety mechanism designed to protect the instruments in case the spacecraft's voltage – the flow of electricity – changes significantly. Because a fluctuation in voltage could damage the instruments, Voyager is equipped with a voltage regulator that triggers a backup circuit in such an event. The circuit can access a small amount of power from the RTG that's set aside for this purpose. Instead of reserving that power, the mission will now be using it to keep the science instruments operating.

Although the spacecraft's voltage will not be tightly regulated as a result, even after more than 45 years in flight, the electrical systems on both probes remain relatively stable, minimizing the need for a safety net. The engineering team is also able to monitor the voltage and respond if it fluctuates too much. If the new approach works well for Voyager 2, the team may implement it on Voyager 1 as well.

“Variable voltages pose a risk to the instruments, but we've determined that it's a small risk, and the alternative offers a big reward of being able to keep the science instruments turned on longer,” said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager's project manager at JPL. “We've been monitoring the spacecraft for a few weeks, and it seems like this new approach is working.”

The Voyager mission was originally scheduled to last only four years, sending both probes past Saturn and Jupiter. NASA extended the mission so that Voyager 2 could visit Neptune and Uranus; it is still the only spacecraft ever to have encountered the ice giants. In 1990, NASA extended the mission again, this time with the goal of sending the probes outside the heliosphere. Voyager 1 reached the boundary in 2012, while Voyager 2 (traveling slower and in a different direction than its twin) reached it in 2018.

More About the Mission

A division of Caltech in Pasadena, JPL built and operates the Voyager spacecraft. The Voyager missions are a part of the NASA Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of the Science Mission Directorate in Washington.

For more information about the Voyager spacecraft, visit:

https://www.nasa.gov/voyager

News Media Contact

Calla Cofield Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. 626-808-2469 [email protected] 2023-059

COMMENTS

Voyager 1, launched September 5, 1977, visited Jupiter in 1979 and Saturn in 1980. It is now leaving the solar system, rising above the ecliptic plane at an angle of about 35 degrees, at a rate of about 520 million kilometers a year. ... Voyager observed Neptune almost continuously from June to October 1989. Now Voyager 2 is also headed out of ...

Today, 45 years after its launch and 14.6 billion miles from Earth, four of Voyager 1's 11 instruments continue to return useful data, having now spent 10 years in interstellar space. Signals from the spacecraft take nearly 22 hours to reach Earth, and 22 hours for Earth-based signals to reach the spacecraft.

Voyager 2 and its twin, Voyager 1 (which had also flown by Jupiter and Saturn), continue to send back dispatches from the outer reaches of our solar system. At the time of the Neptune encounter, Voyager 2 was about 2.9 billion miles (4.7 billion kilometers) from Earth; today it is 11 billion miles (18 billion kilometers) from us.

Voyager 1 was part of a twin-spacecraft mission with Voyager 2. The twin-spacecraft mission took advantage of a rare orbital positioning of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune that permitted a multiplanet tour with relatively low fuel requirements and flight time. The alignment allowed each spacecraft, following a particular trajectory, to use its fall into a planet's gravitational field to ...

The probe launched on Sept. 5, 1977 — about two weeks after its twin Voyager 2 — and as of August 2022 is approximately 14.6 billion miles (23.5 billion kilometers) away from our planet ...

Voyager 1 is a space probe launched by NASA on September 5, 1977, as part of the Voyager program to study the outer Solar System and the interstellar space beyond the Sun's heliosphere. ... The trajectory Voyager 1 was launched into would not have allowed it to continue on to Uranus and Neptune, ...

Neptune - Moons, Rings, Orbit: Voyager 2 is the only spacecraft to have encountered the Neptunian system. It and its twin, Voyager 1—both launched in 1977—originally were slated to visit only Jupiter and Saturn, but the timing of Voyager 2's launch gave its trajectory the leeway needed for the spacecraft to be redirected, with a gravity assist from Saturn, on extended missions to Uranus ...

Neptune has been directly explored by one space probe, Voyager 2, in 1989. As of 2024, there are no confirmed future missions to visit the Neptunian system, although a tentative Chinese mission has been planned for launch in 2024. [1] NASA, ESA, and independent academic groups have proposed future scientific missions to visit Neptune.

As Voyager 1 raced out of the solar system, Voyager 2 struck out on its own toward the last two unvisited giant planets: Uranus and Neptune. Smaller and more distant than Jupiter and Saturn, these ...

Members of the Voyager team reflect on the mission's Neptune encounter, 25 years later. August 25, 1989: Neptune is in view. It is the middle of the night and everything is happening fast at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Voyager team members have had little or no sleep.

In the summer of 1989, NASA's Voyager 2 became the first spacecraft to fly by Neptune, its final planetary encounter. Managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, Voyagers 1 and 2 were a pair of spacecraft launched in 1977 to explore the outer planets. Initially targeted only to visit Jupiter and Saturn, Voyager 2 took ...

Voyager's fuel efficiency (in terms of mpg) is quite impressive. Even though most of the launch vehicle's 700 ton weight is due to rocket fuel, Voyager 2's great travel distance of 7.1 billion km (4.4 billion mi) from launch to Neptune resultsed in a fuel economy of about 13,000 km per liter (30,000 mi per gallon).

It did that — and much more. Voyager 1 discovered active volcanoes, ... Voyager 2 also explored Uranus and Neptune, ... the voyage still has far to go. Voyager 1 and its twin, each 40,000 years ...

Early Voyager 2 images of Uranus and Neptune. Back in 1986 and 1989, NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft flew past Uranus and Neptune, respectively. Those images showed the two planets looking ...

Voyager. 2023 Technology Showcase for Planetary Science. Hubble Space Telescope. avatars. In the summer of 1989, NASA's Voyager 2 became the first spacecraft to observe the planet Neptune up close, its final planetary target.

On hearing that Voyager 1 had gone dark, I had checked in with Louis Lanzerotti, a former Bell Labs planetary scientist who did the calibrations for the Voyager 1 spacecraft and was a principal ...

It was the ultimate remote IT service, spanning 24 billion kilometers of space to fix an antiquated, hobbled computer built in the 1970s. Voyager 1, one of the celebrated twin spacecraft that was the first to reach interstellar space, has finally resumed beaming science data back to Earth after a 6-month communications blackout, NASA announced this week.

Fast forward to August 25, 2014: New Horizons, the first mission sent to explore dwarf planet Pluto and other icy objects within the Kuiper Belt, is less than one year away from its arrival. And today, New Horizons will cross Neptune's orbit -- the very day that Voyager 2 flew past Neptune 25 years ago. In celebration of this anniversary ...

Voyager 1 was launched in September 1977 and flew by Jupiter and Saturn. Voyager 2 was launched in August 1977 and flew by Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. Both spacecraft are now headed out of the solar system into interstellar space. › read more Related Links. Glossary of Abbreviations; Interstellar Mission; Planetary Voyage

Voyager 2 went on to explore Uranus and Neptune and is still the only spacecraft to have visited those planets. ... The image of earth clicked by Voyager 1 which Carl Sagan called the 'Pale Blue ...

Note: Because Earth moves around the sun faster than Voyager 1 is speeding away from the inner solar system, the distance between Earth and the spacecraft actually decreases at certain times of year. Distance from Sun: This is a real-time indicator of Voyagers' straight-line distance from the sun in astronomical units (AU) and either miles (mi ...

NASA extended the mission so that Voyager 2 could visit Neptune and Uranus; it is still the only spacecraft ever to have encountered the ice giants. In 1990, NASA extended the mission again, this time with the goal of sending the probes outside the heliosphere.