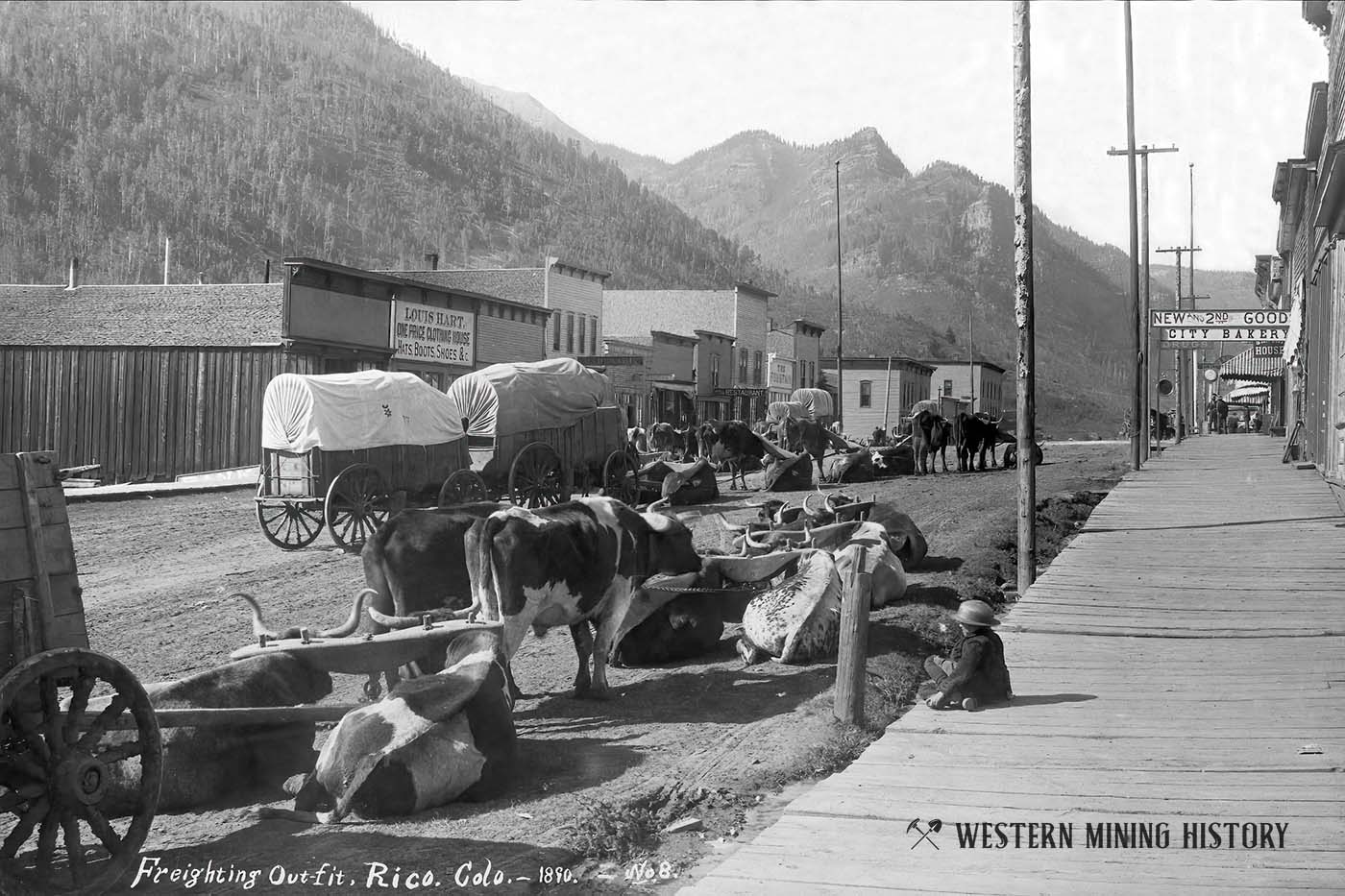

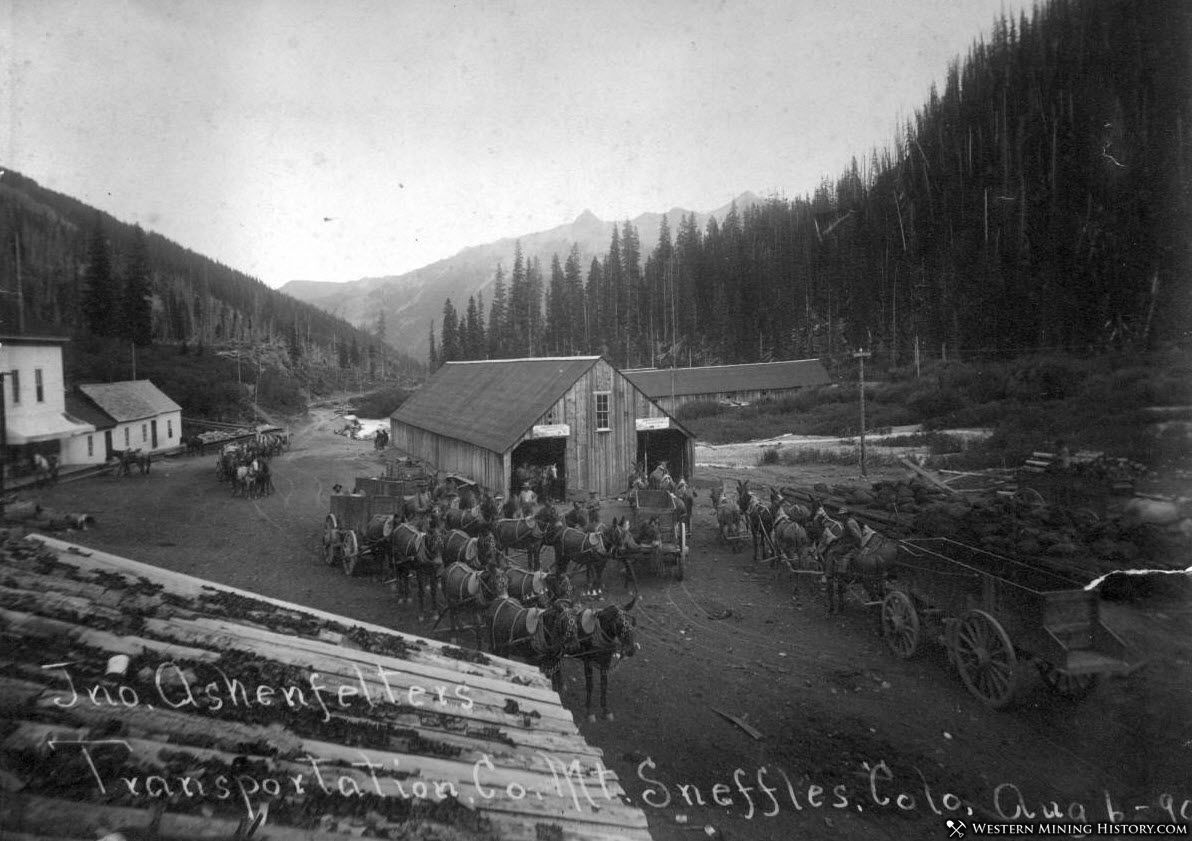

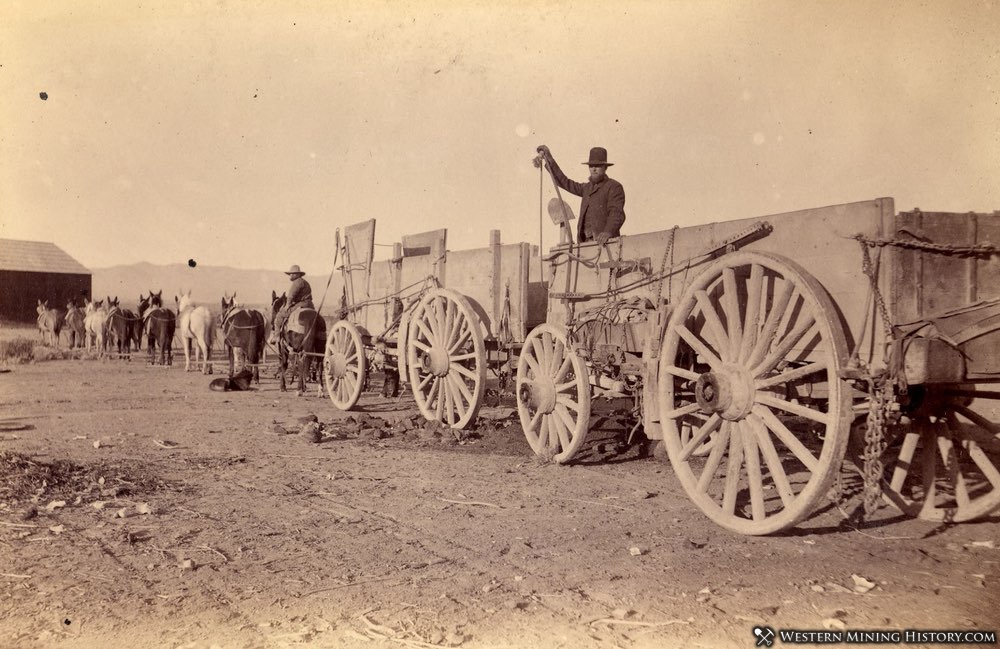

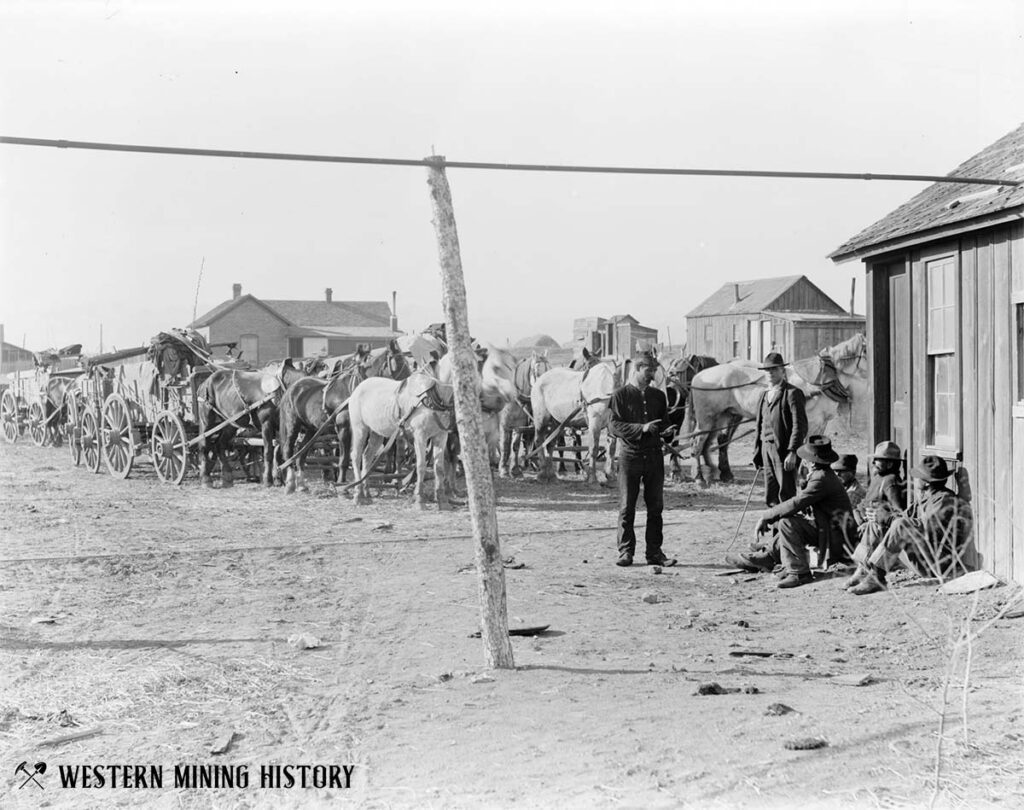

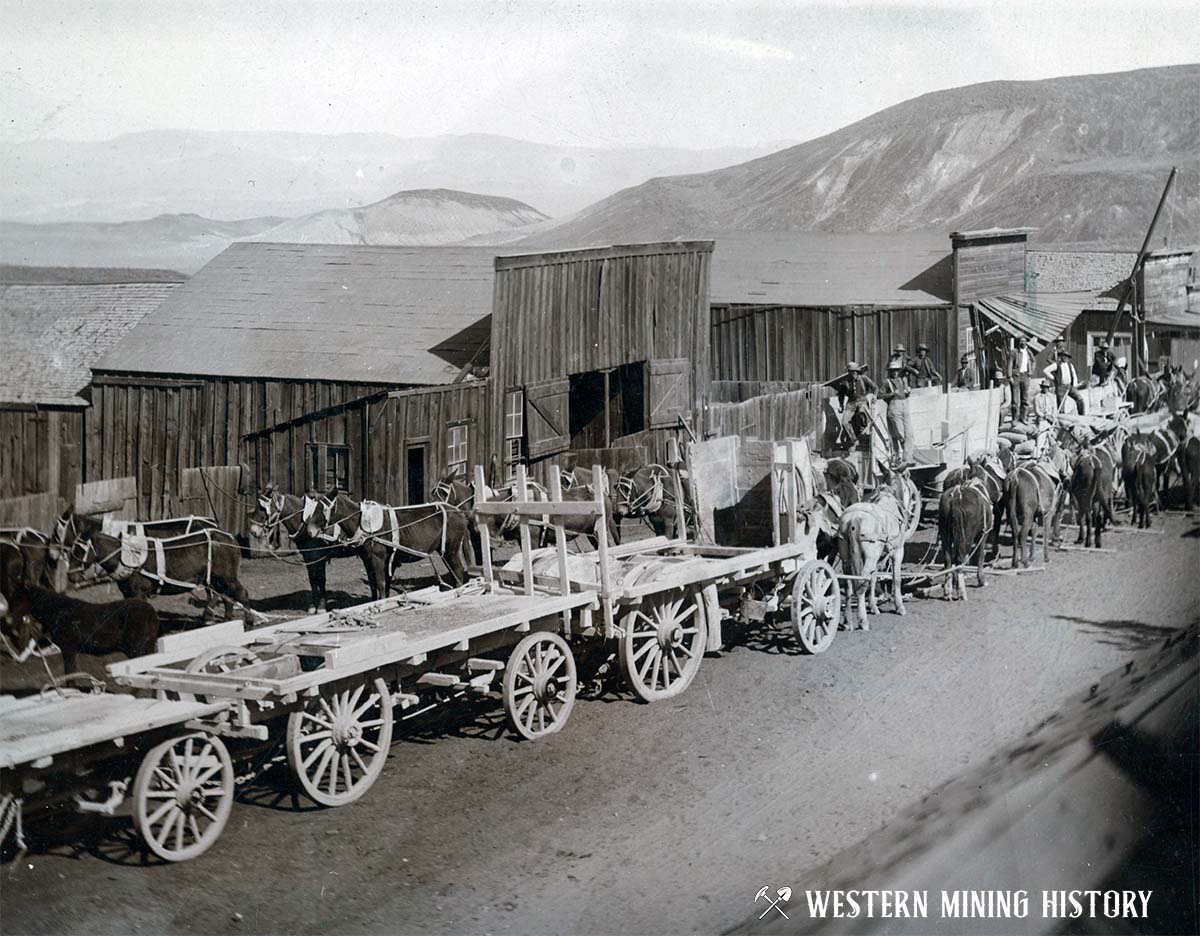

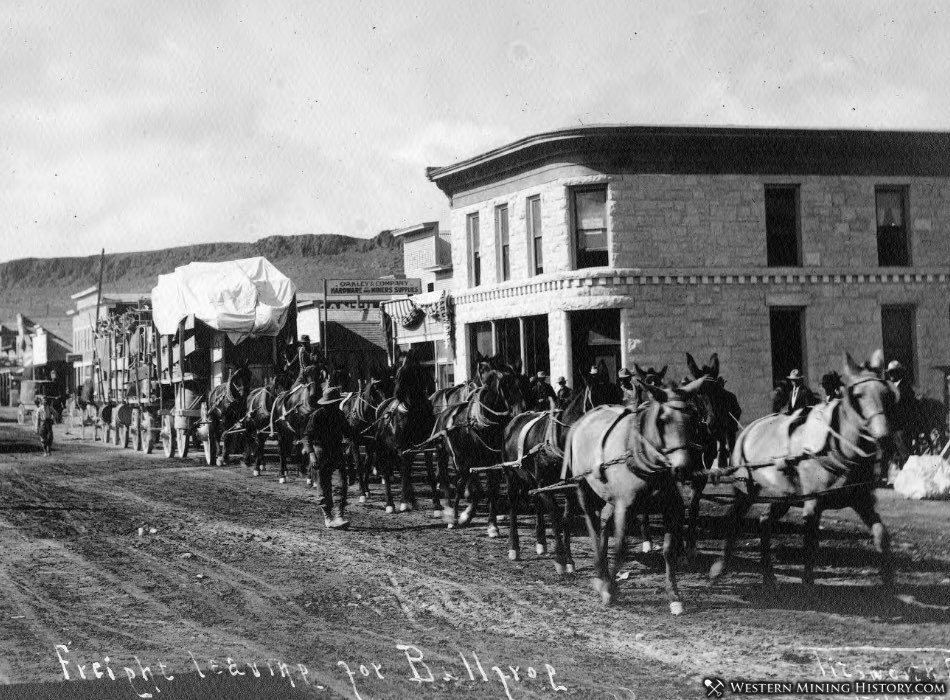

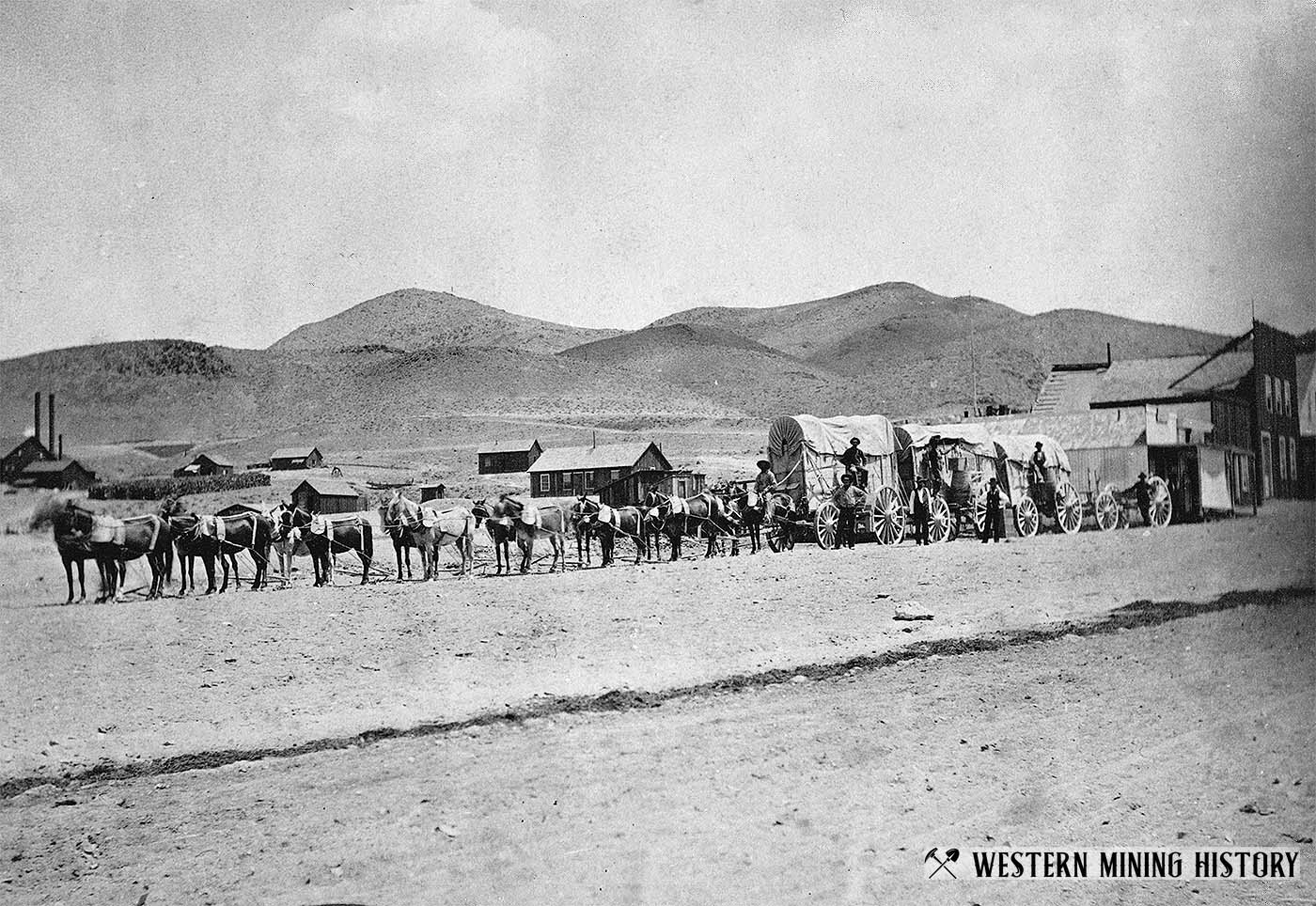

Heavy Freight Wagons of the American West

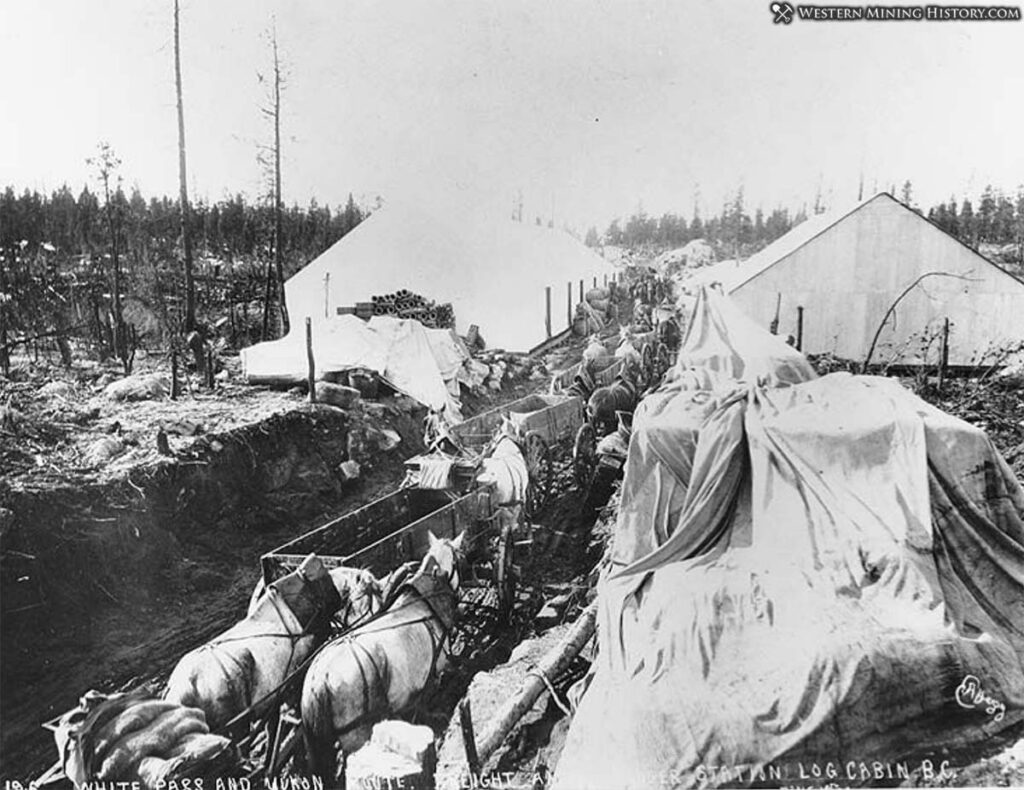

Text By Gary Carter

Photos sourced by Western Mining History from various archives.

Author`s Note

Twelve billion tons of freight were transported by truck in the United States last year. The skilled drivers have CB contact, radio, headphones, paved roads, power steering, sleeper cabs, and comfortable seats. Truck stops provide food, showers, and fuel.

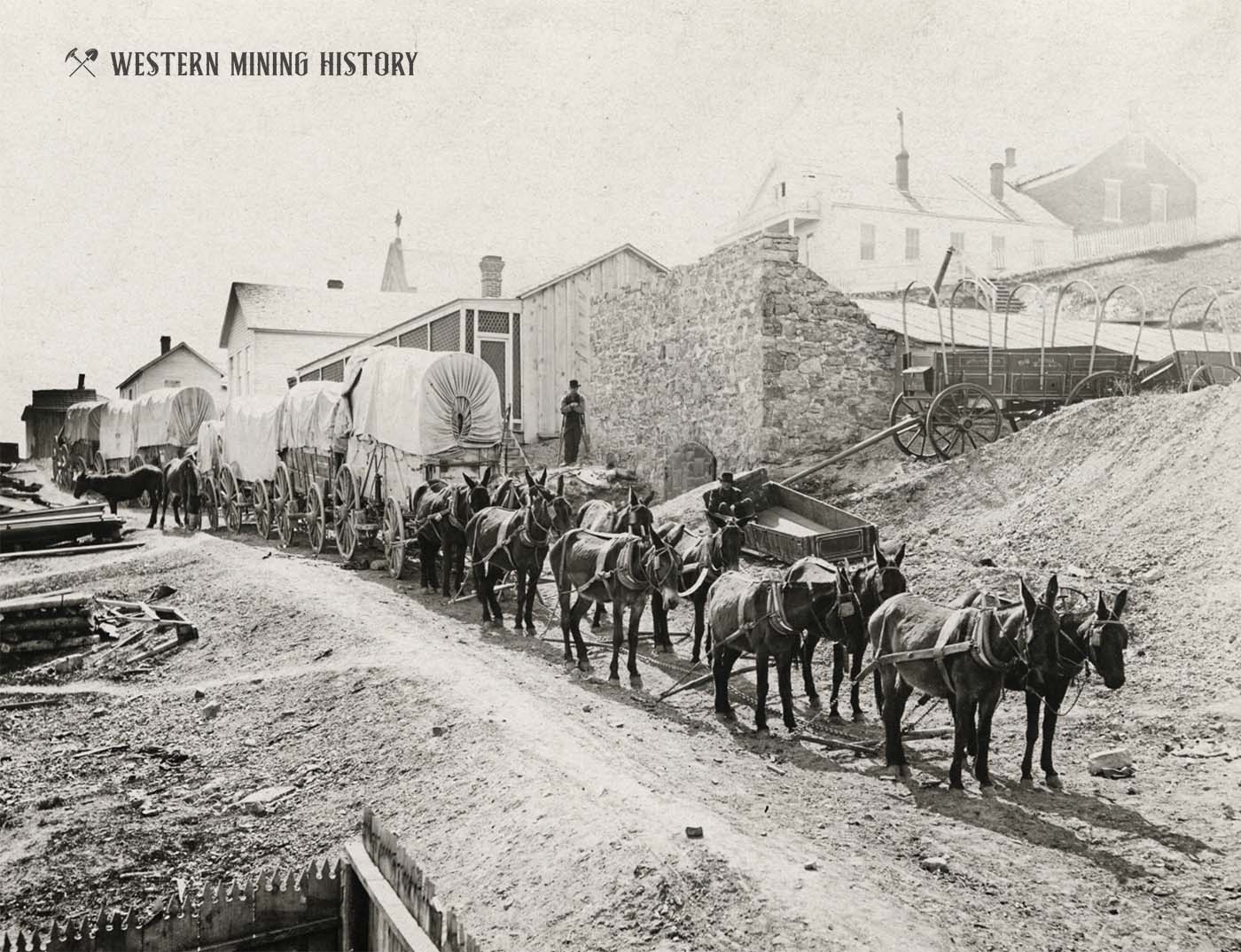

One of the least appreciated but important jobs during the era of the western expansion was moving freight to provide everything from food to machinery, household goods, ore, and needed equipment for the rancher, miner, farmer, households, and storekeeper. Yet the “mule skinner” or “bull whacker” ranked near, if not at the bottom, on the scale of importance in stories about the old West, and even during their time they were looked down upon.

This article will provide a snapshot of the operation and men (mostly) of early freighting in the period before wheeled vehicles. The use of steamboats on navigable waters in the west, and the steady growth of railroads from the 1840’s well into the latter part of the century provided a huge slice of the freight transporting business, but those modes generally reached cities and large towns, off loaded and needed to be transported.

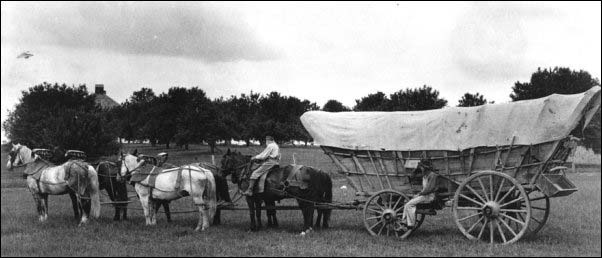

The focus of this article is on heavy duty freight wagons. Light weight express wagons, farm wagons, “Prairie Schooners“ and Conestoga wagons typically used along the trails heading West, military supply/escort wagons, and stage coaches will not be addressed. I hope readers will be as surprised, interested and entertained as I was doing the research.

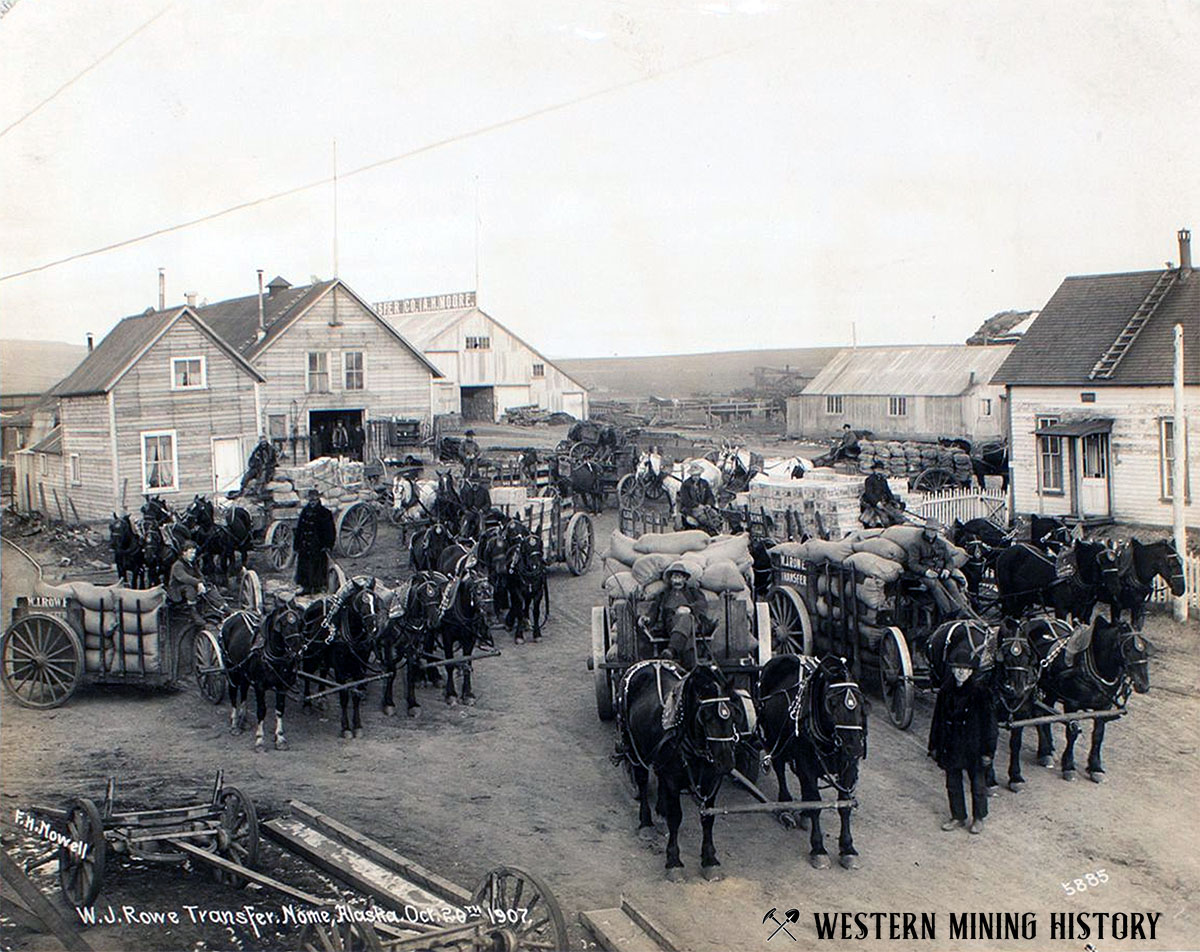

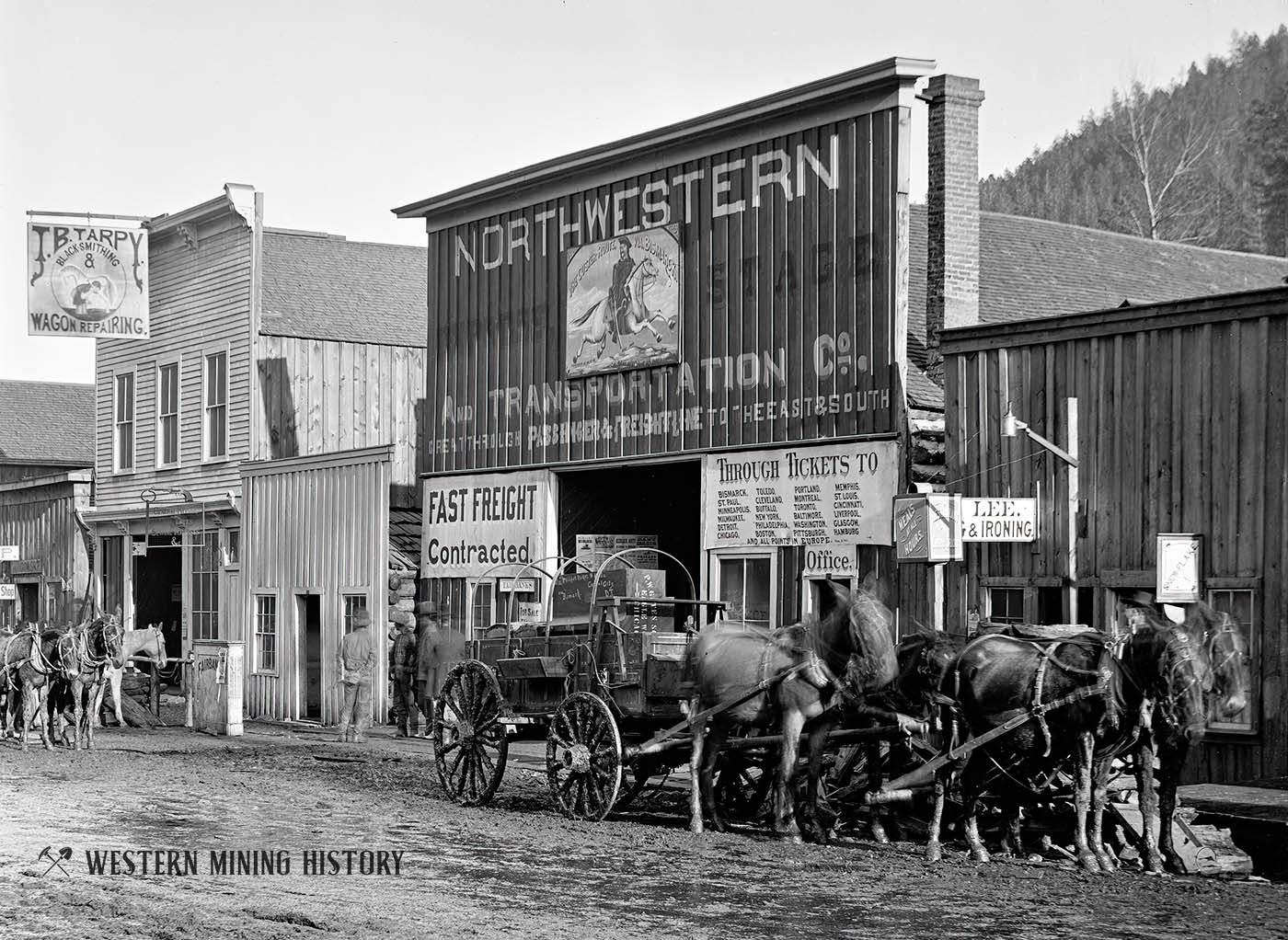

The Freight Companies

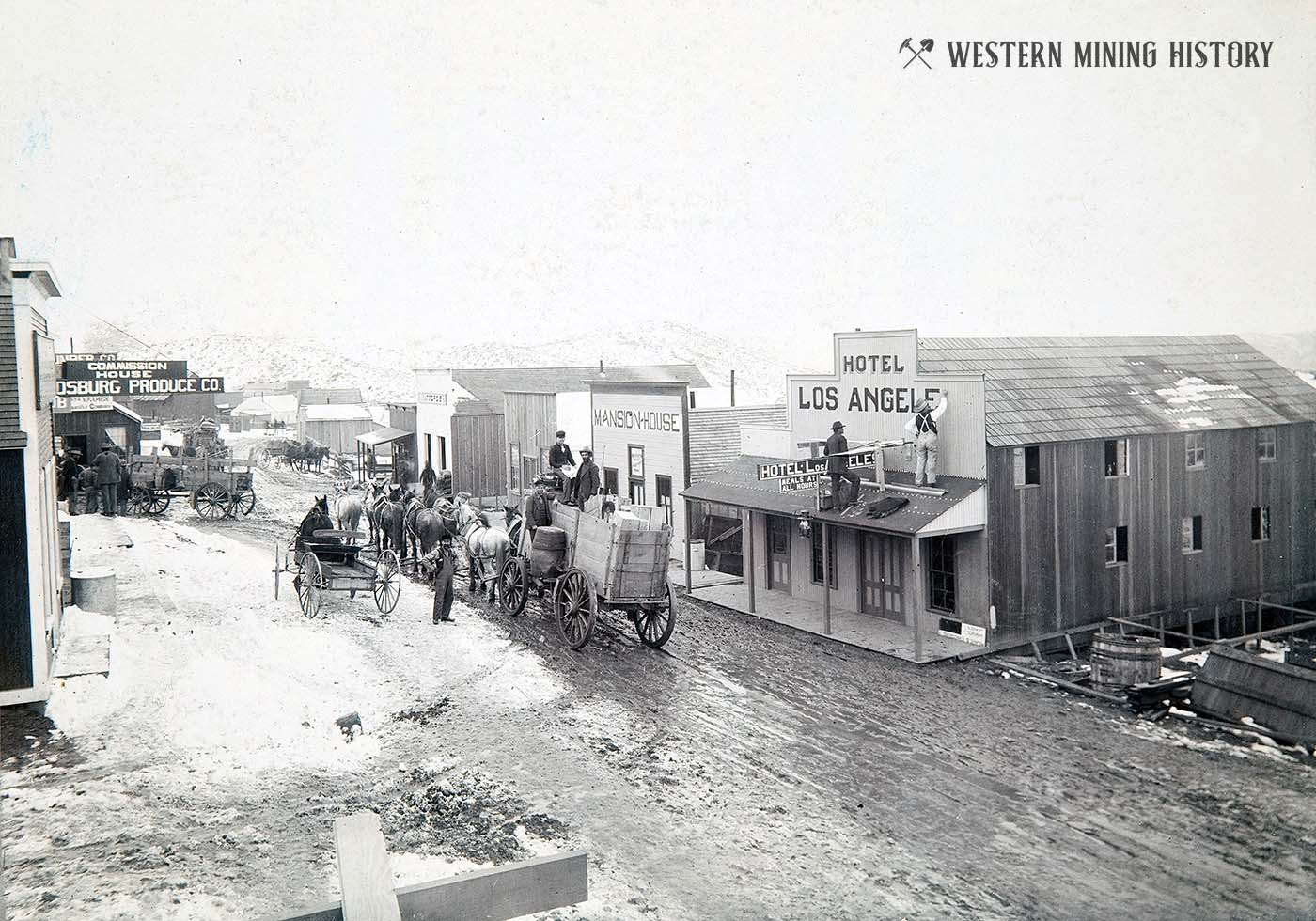

Sometimes the scope of things really doesn’t change that much. Just as today, in the early days (up to 1900), there were large freight companies and plenty of independent operators who saw a need to earn a living transporting goods.

Some of the larger companies in the Western States were: The Miller Brothers Freight Company in Arizona, Charles T. Hayden’s Freight company, which had a wide range of coverage. Russell, Majors, and Waddell, while starting in the Great Plains eventually grew to ship goods throughout the west via Santa Fe. Ketchum’s Fast Freight Line served most places in Idaho.

Frank Shaw had a large freight operation that supplied many towns and mines in eastern California and western Nevada and hauled out the first Twenty Mule Team borax wagon load from Death Valley.

Remi Nadeau was known as the king of the Desert Freighters and his company regularly moved goods from Los Angeles to Salt Lake City and Virginia City, Montana. In the late 1860’s Remi Nadeau and Mortimer Belshaw, part owner of the famous Cerro Gordo silver mine, combined to operate the famed Cerro Gordo Freight Company which served most of California and clear into New Mexico.

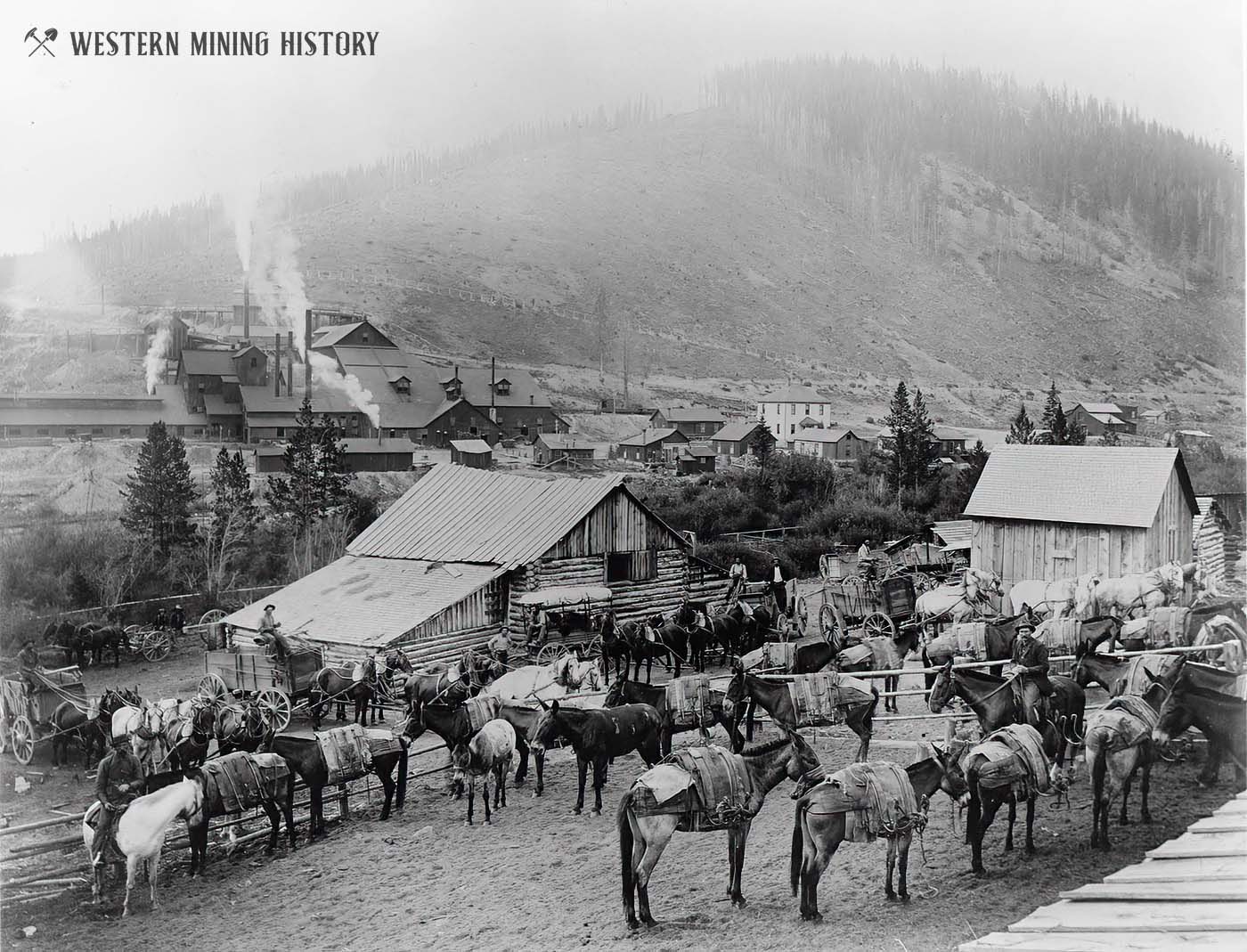

During the California Gold Rush, mining camps were often so remote and difficult to reach that pack trains of mules carried supplies and much of this was done by individuals. By the mid 1850’s some trails were sufficient to be attempted by wagons, and Phineas Banning and David Alexander formed a freight company which supplied many camps. Their livestock included over 500 mules and horses capable of hitching to forty or more wagons.

In Colorado, especially in the rich San Juan Mining District, John Ashenfelter ran a large pack train and freighting company that supplied the towns and mining camps, and along with Dave Wood were the largest freighters into Southwestern Colorado towns and mining districts.

These are just a few of the larger freight companies. On a smaller scale were the independent and often lone teamsters who took on the contracts too small, dangerous, or remote for the larger outfits to bother with.

Mule Skinners and Bull Whackers

Depending on your team of animals those who drove the freight wagons were called mule skinners or bull whackers. The mules, of course were not skinned, but the “bull whackers” did have long whips with which to “urge the oxen along”.

Typically drivers were loners, and might go days without seeing another human, a bath, decent food, or necessities. They slept in the open or under the wagons and most often the larger wagons, especially the ore wagons, had no place to sit, so the freighter rode on the last animal that was in harness or yoke. Some of the wagons had wooden bench seats but men often walked since it was easier on the body than the bouncing of the wagon.

There were often no way stations, no pull offs, no places to safely seek shelter. Up until around the mid 1880, Indians were a menace and quite eager to attack a lone freight wagon and take the animals and goods.

The teamsters usually traveled light carrying a hat, knife, rifle, and the clothes they wore including heavy boots. A rough and ready group, full of profanities and lack of social etiquette, their work day began early and ended late – taking care of the animals and feeding themselves. John Bratt, a bull whacker, said he only ever knew one who did not chew tobacco, swear or drink.

Their life on the trail and vices generally meant most were single and when they did have free time it was often spent on booze, gambling, and soiled doves. The pay of around $70-$80 a month for an experience hand was above that of common laborers or miners who generally got from $2.00-$3.50 a day. To put that in perspective, before the Civil War soldiers (privates) stationed in the West received no more than $15 a month.

A typical charge to haul freight might be $8 to $10 per one hundred pounds but also depended on distance, dangers and difficulty. Large companies with many outfits on the road could do quite well. Russell, Majors and Waddell wagons once made $300,000 on one trip carrying supplies for the army.

The Earp brothers were often engaged in the freight trade, taking turns as “swampers” (helpers who generally assisted in loading and unloading) and drivers.

In deliveries to towns of any size there often was an area of town where the needs of the freighters, such as reshoeing and repairs, could be obtained. More often, especially on lonely, isolated stretches, the swamper and driver performed the chores. Fortunately the wagons were so carefully and sturdily built that despite the difficult conditions serious breakdowns were infrequent.

The Animals

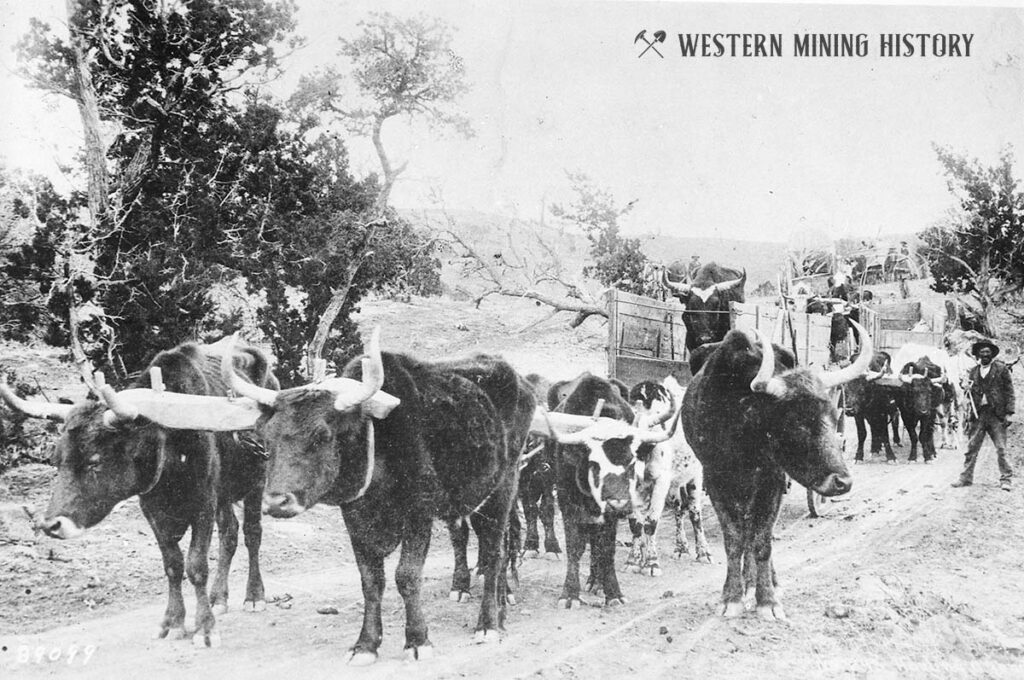

As you might imagine the most important aspect of the trade were the animals. Oxen, mules, and horse were all put in harness and each contributed their own advantages and disadvantages.

Oxen were much cheaper to buy (a pair for about $65 in the mid-1880’s) and could pull considerable weight. They needed less water and feed and often foraged off the land but were much slower than horses and mules. Travel by oxen was at an average of about two miles per hour, which was one-half to two-thirds the speed of a horse or mule.

Big steers with horns were generally the choice for “oxen” with Texas “long horns” or big Durham’s often used. Horns helped to brace the steer on both the up and down hill. The bull whacker chose his stock with care and an experienced eye, not only because of cost but his safety and livelihood often depended on it.

Horses and Mules were expected to pull their weight, thus the etymology of the phrase – “to pull your own weight”. A large mule or horse was typically judged to be able to pull one ton.

Wagons were loaded according to the number of horse or mules needed. A big mule could pull more than a ton and more than the average size horse. Mules and horses were more expensive than oxen with a pair of mules costing about $50 more than the average price for two horses (about $100-$150 in the mid 1800’s).

These animals could cover more ground than an oxen team but needed good feed and more water, which was not always available, especially in the Southwest. Mules and oxen were sure footed and often used over rugged and narrow terrain.

The Wagons and Freight

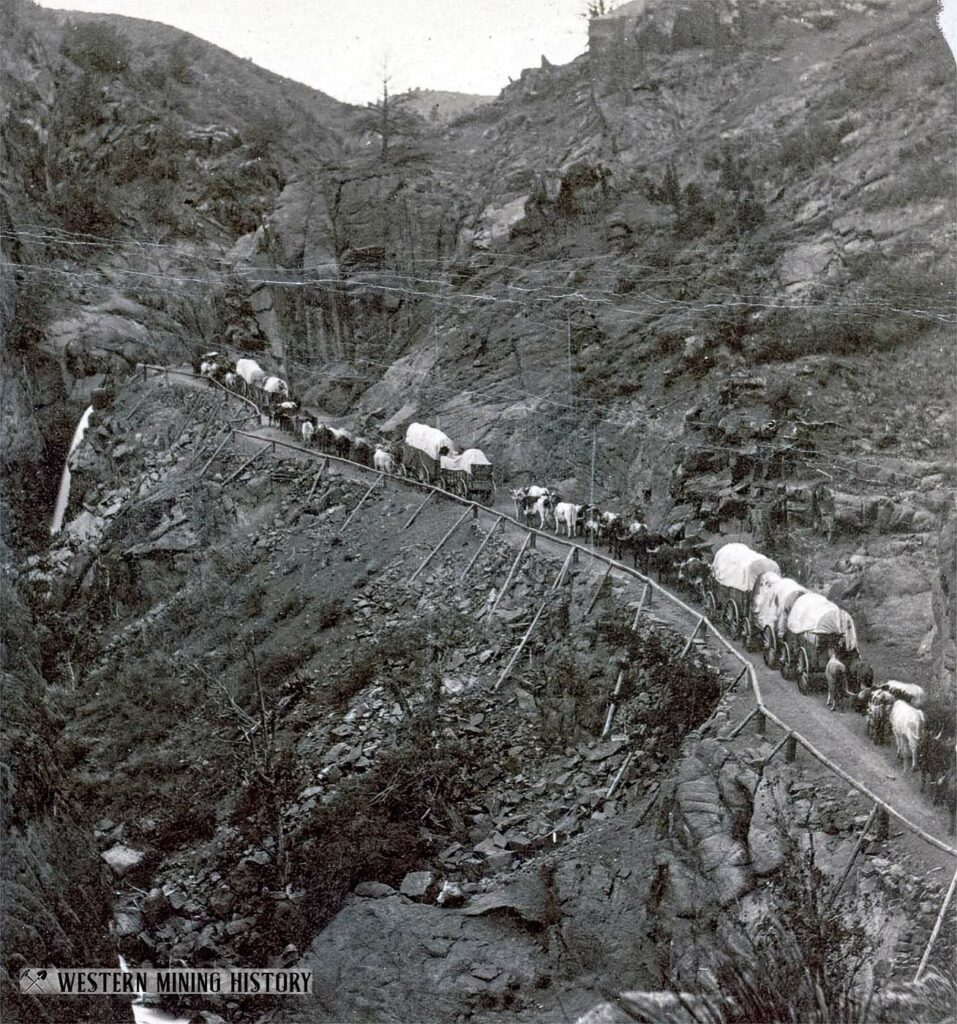

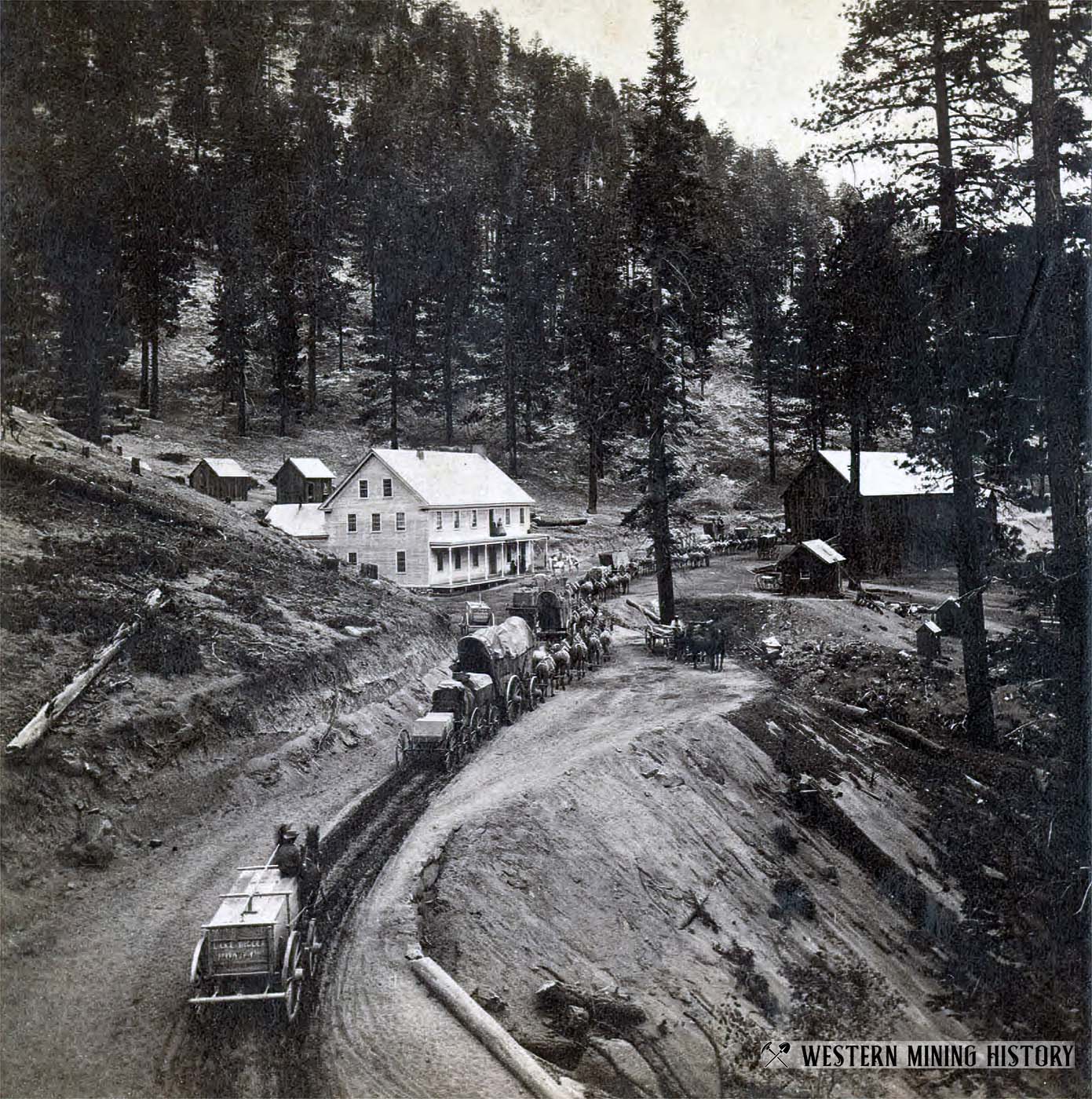

The immediate challenge was terrain, and the word “path” really speaks to the early routes covered by the big freight wagons more than calling them roads.

Rocks, washes, drop offs, mud during rainy weather, slides, dust, steep, treacherous climbs, narrow one-way paths and brake burning descents were the conditions that the driver and wagon needed to negotiate. Usually the only “road maintenance” was continued use which often rutted the trail.

Today it often takes an all-terrain vehicle to reach some of the abandoned towns and old mining camps that were serviced by pioneer freight wagons.

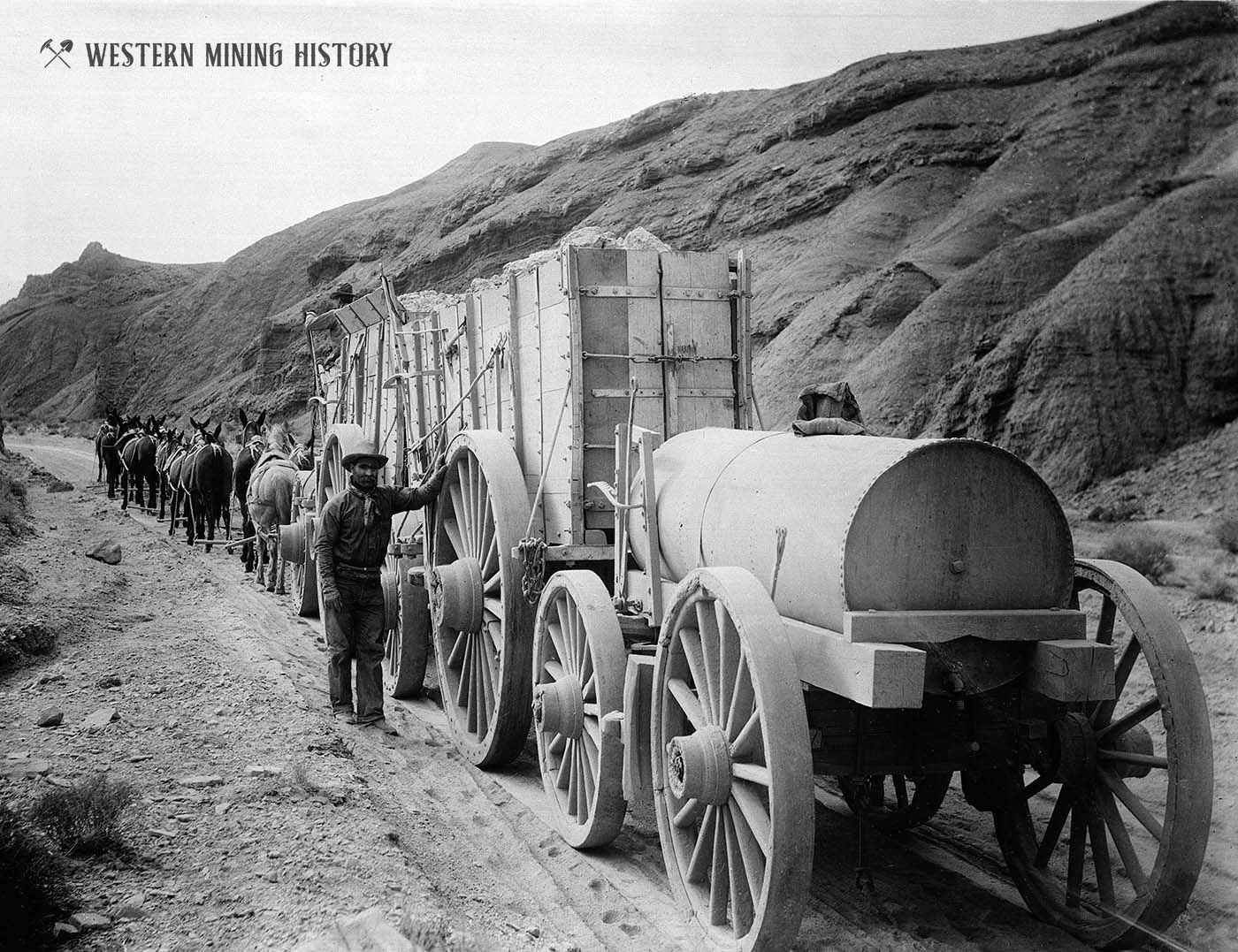

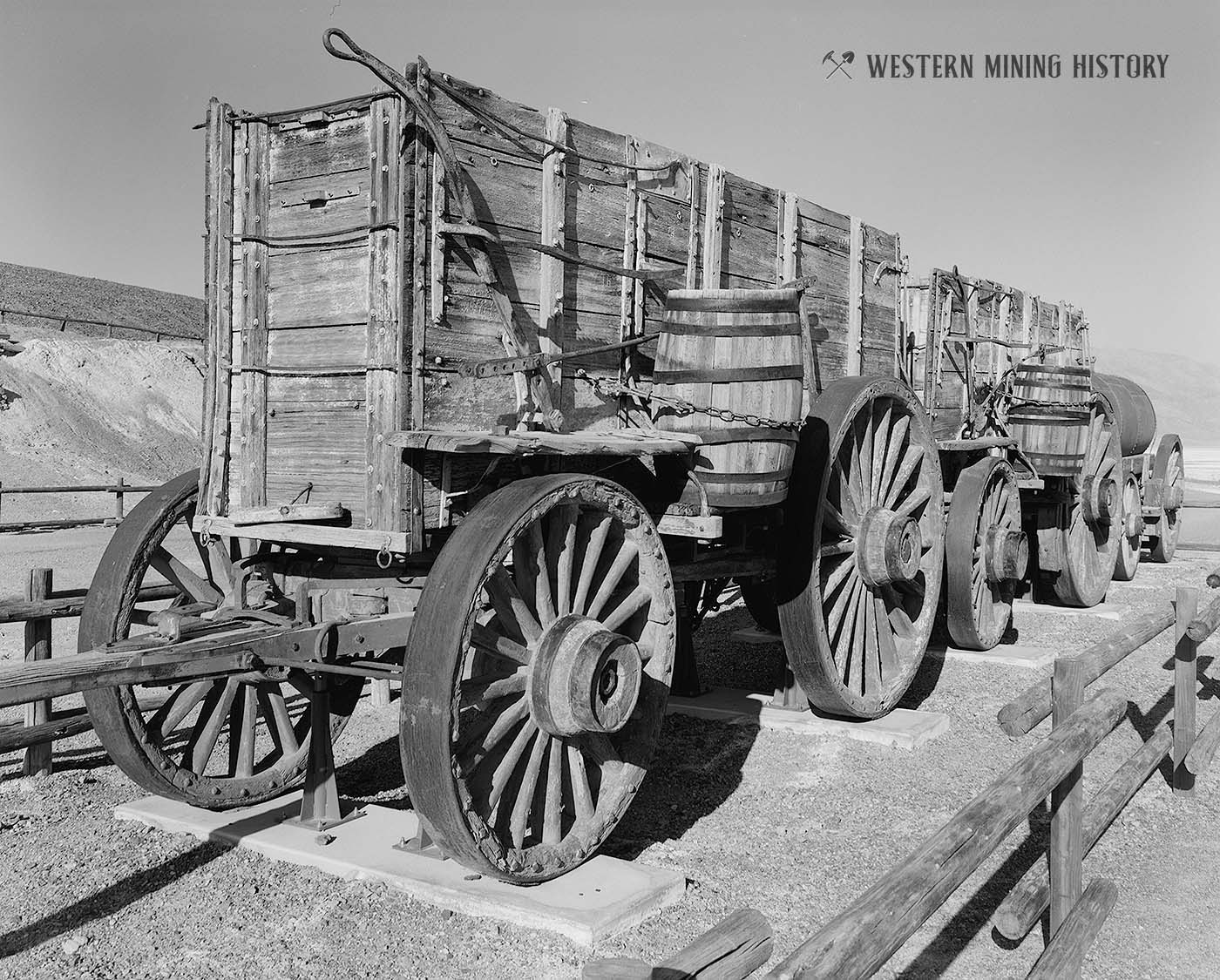

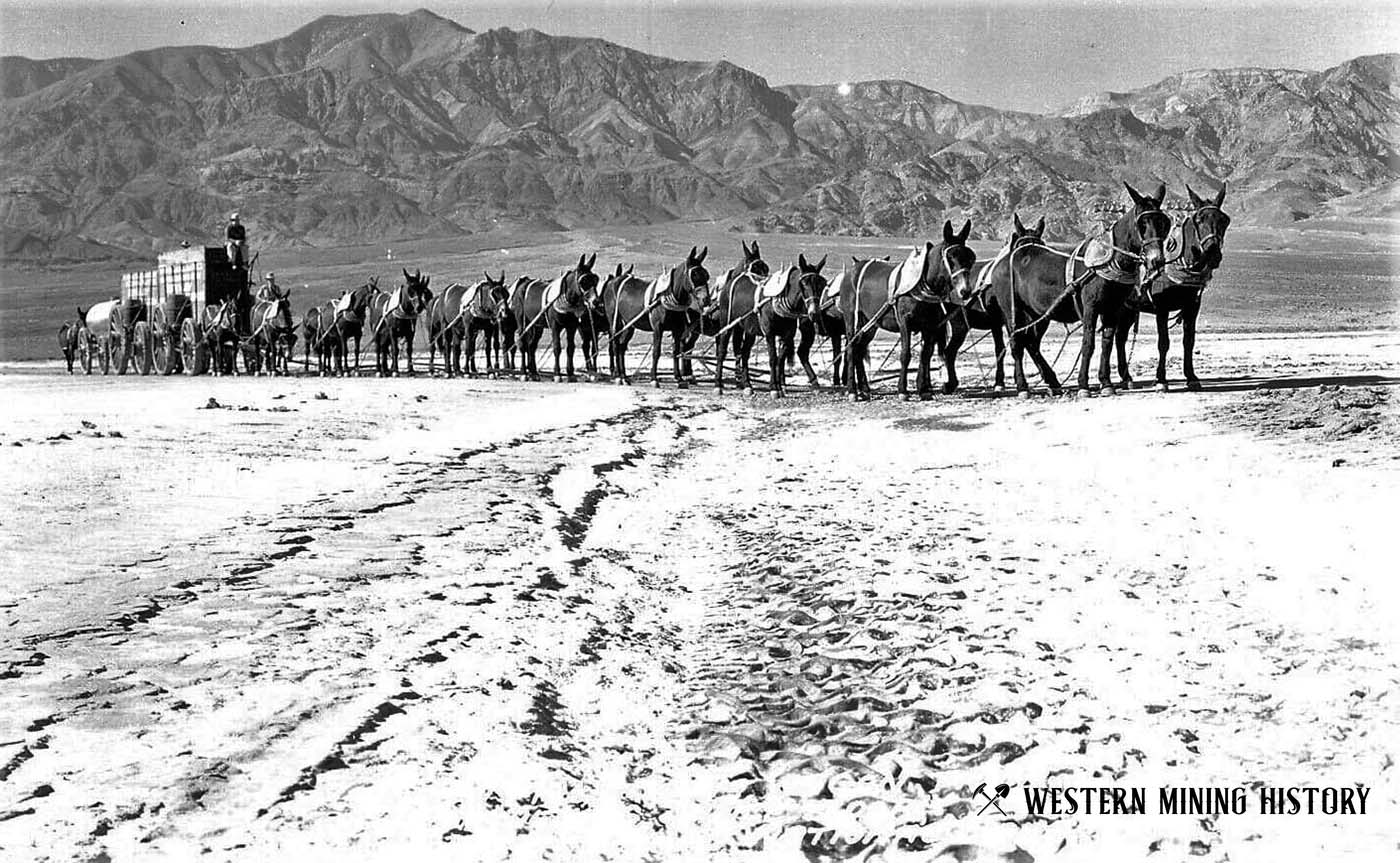

Of necessity, the wagons were built for endurance, durability and carrying capacity. Under carriages were made of iron and the beds and wheels of oak or other durable wood. Dimensions varied, but empty wagons weighed from one ton up to the nearly 8,000 pounds for the big 20 Mule team Borax wagons which operated out of Death Valley.

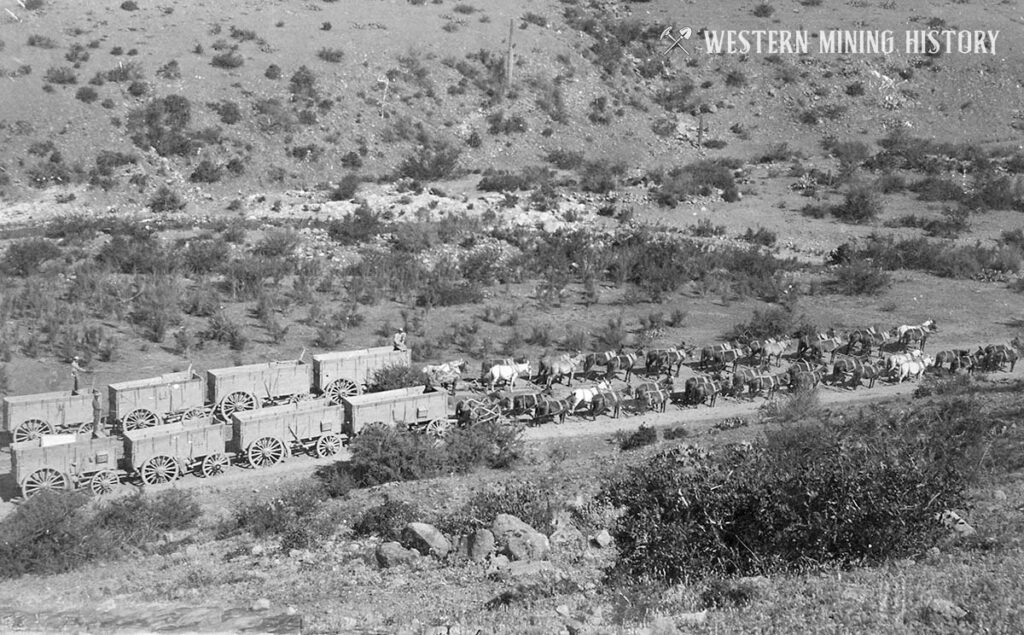

Freighters, depending on size and need usually hauled from three up to thirty plus tons of cargo.

The big Twenty Mule Team borax wagons that operated out of Death Valley were some of the largest at Sixteen feet long, four feet wide and six feet deep. They carried over thirty-five tons when loaded and had seven foot high rear wheels. Their customary route was from what is now the Furnace Creek Ranch area to the railhead at Mohave, some one hundred and sixty miles through the desert. It was generally a ten day trip.

Overnight travel required the teamster to make provisions to carry water for himself and animals and perhaps feed as well. On long trips in dry areas or places with few streams, it was impossible to carry enough water so drivers needed to be aware of and plans stops at known springs and water holes.

Stream crossings, especially in the spring, were traversed with great caution as unseen rocks, deep spots or an eroded soft bottom could cause problems for the animals and wagons. Likewise steep uphill grades often required the unhitching of one team and using it to help the other ascend and then repeating the process for the other wagon.

On one trip from Prescott to the Pima Villages in Arizona, the driver waited several days for the Gila River to recede and when it did not he built a raft, unloaded the goods, poled them over piecemeal and then drove the team and wagon across, reloaded and was on his way.

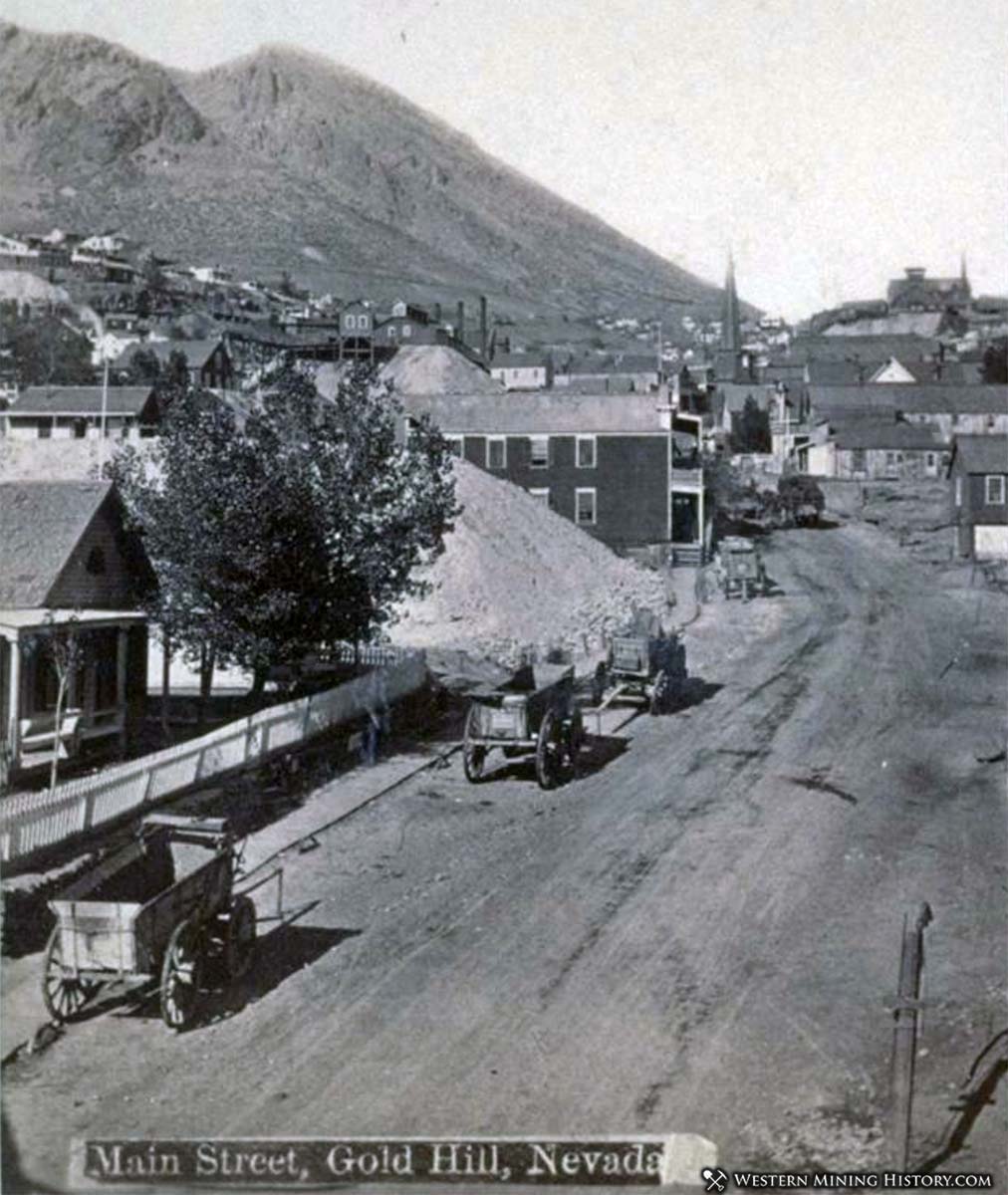

The freighters generally got their loads from the mines, in the form or ore to deliver, from steamboats that carried cargo, from big towns and manufacturers, or from the railroads delivering goods to towns like Denver, San Francisco, or other major stops throughout the West.

It was big business and newspapers were always reporting the arrival of freight – the “West Wind” made our landing last evening, loaded to her guards with a large quantity of freight and two crushers for the mine.

The arrival of a railroad provided not only an impetus for the growth of small towns but new ones often sprang up. There were plenty of spur lines (especially to mining centers) delivering and obtaining materials. The increased need for supplies resulted in fierce competition between freight companies.

Military Contracts were some of the most sought after jobs. Once forts became more numerous, and many were in isolated areas, the army needed to be regularly resupplied. This created a consistent source of work and income and Army contracts often spanned a year.

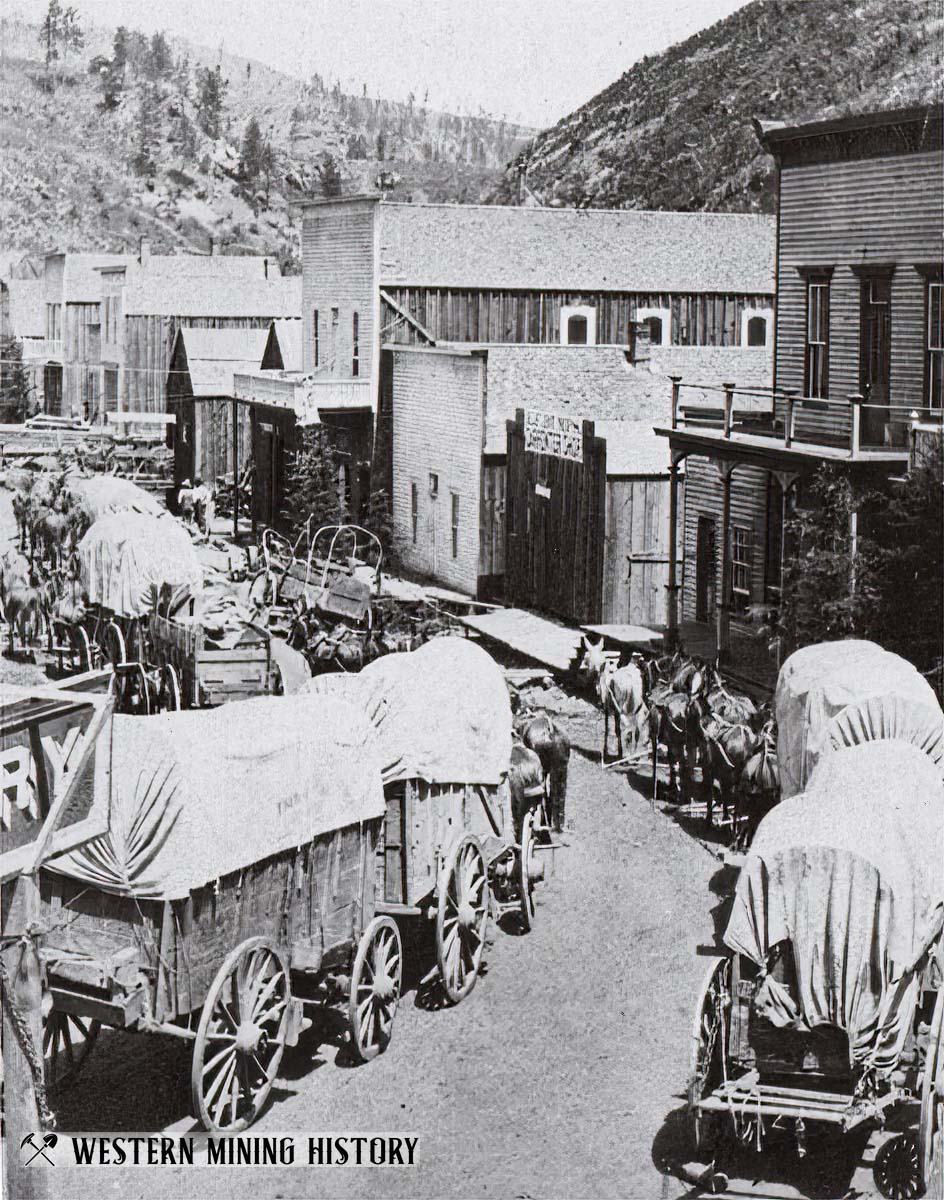

It is hard to envision the number of departures and arrivals of large freight wagons. One paper stated that “the large freight wagons are constantly clogging the streets and last week 110 passed through, each one carrying an average of five thousand pounds.”

Large outfits generally had the larger contracts which called for a string of wagons, a dozen or more in line were not uncommon, this alignment worked best on well traveled roads as a breakdown in one of the front wagons on a rocky or narrow route could cause major problems. Large outfits traveling together provided much more protection and assistance for one another.

Weather might cause delays but was no deterrent when goods were needed or contracts were on the line.

End of The Road

Large freight wagons gradually became victims of progress. Trucks, better and more roads, an increase in rail lines and service to smaller towns lessened the need for many of the big wagons.

As motorized vehicles became less expensive, more reliable, and plentiful, many companies, mining operations, and businesses acquired their own fleet of trucks for delivery. Smaller and more manageable wagons still worked the farms and delivered goods but as the road systems improved and reached more isolated spots, the large freighters became less seen and not needed.

Trucking grew and slowly replaced wagons as the automobile replaced stages and carriages. By 1910 there were still only about ten thousand trucks in the entire country but by World War I and certainly by 1920 the proliferation of paved roads and trucks changed the freight industry.

The speed and service improvements meant the utilization of trucks to carry everything from gasoline to hay, which were more cost effective, quicker, more sanitary, and less cumbersome than using wagons.

Now one can find trucks to fit every need and service –from the giant Belazarus mining truck which can carry 450 tons at once to the small U. S P.S. truck that delivers your mail.

More Freight Wagons

There are many amazing photos of freight wagons at work hidden in various archives. As I run across them, I will add them here, so remember to check back to see how this collection grows over time.

Related Articles

The following articles from Western Mining History explore more on the topics of freighting and transportation in the West.

The Twenty Mule Teams of Death Valley

The Twenty Mule Teams of Death Valley presents text and diagrams from a series of reports by the Historic American Engineering Record. Included are historical images of these iconic western wagon teams.

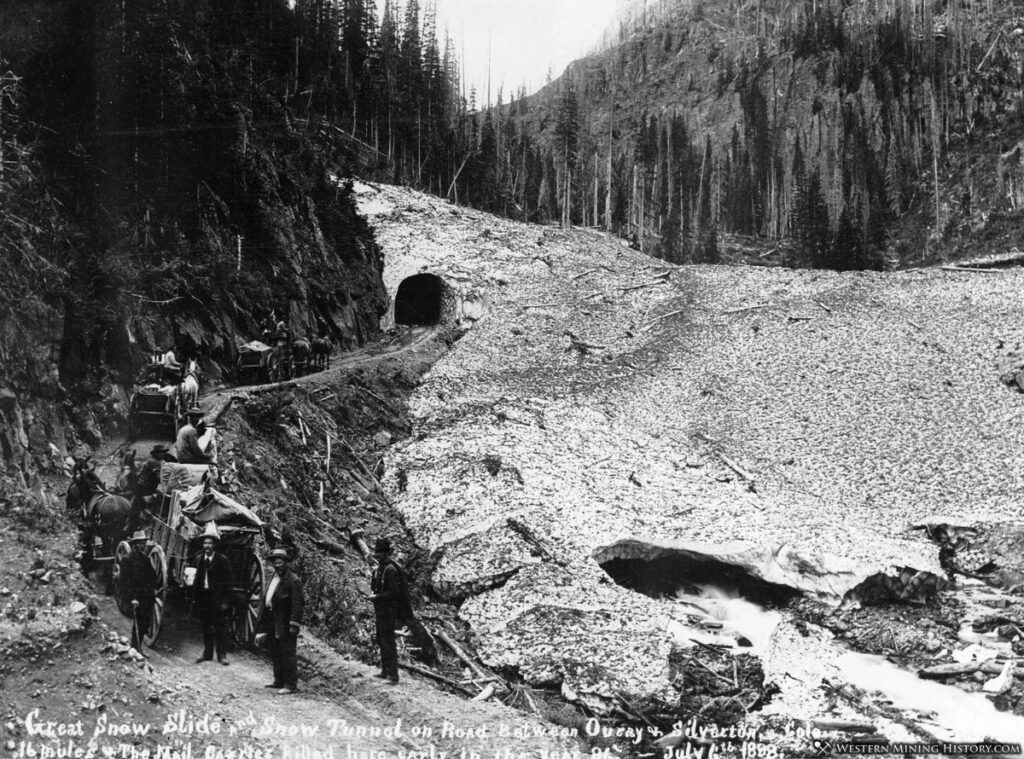

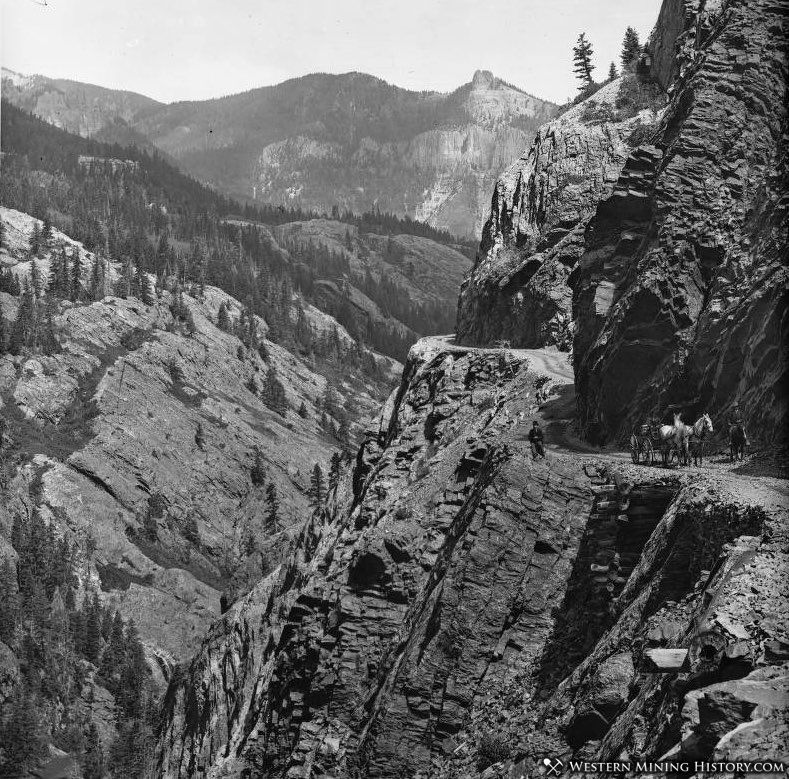

The Impossible Road

For years attempts were made at building a road between Ouray and Silverton, but these attempts were always a failure. Building the road was thought to be impossible by some, but by the mid 1880s Otto Mears, premier road builder of the region, was able to complete the job.

The Impossible Road: Incredible Photos of the Otto Mears Toll Road

Bibliography

GENi-Old West Teamsters and Freighters

History Net-“Though Bullwhackers often swore-etc”.-John Koster

HistoryTrailsWest.com—“Our Wagons”

Legends of America-Russell, Majors and Waddell

mulemuseum.org-Mule Teams and Freight Wagons

ouraynews.com—From Wagons to Apples-etc.,June 17,2020

Overland Freighting in the Platte Valley-1937-U. of NebraskaFloyd Bresee

The Story Behind Ketchum’s Famous Ore Wagons

Wagons on the Santa Fe Trail-Nat. Park Service-1997-Mark L. Gardner

Wheels that Won the West.com

National Parks Service – Twenty Mule Teams

Western Mining History is the work of Aaron Walton. About Western Mining History

Western Mining History needs you! Please consider becoming a member.

Western Mining History Memberships

Covered Wagons Heading West: Life on the Oregon Trail

Catherine Lugo

Amelia Stewart Knight knew the cross-country journey west would be a rough one; it was not for the weak or timid. The trip to Oregon would take at least four months; there were barren landscapes and tricky mountain passes to get through. As it turned out, that spring was especially rainy and the heavy wagon wheels kept bogging down in the many soft mudholes along the way. In her diary she recorded her daily events in an unadorned fashion, describing what it was like to travel the Oregon Trial:

(April 23, 1853) “Still in camp, it rained hard all night, and blew a hurricane almost, all the tents were blown down, and some wagons capsized, Evening it has been raining hard all day, everything is wet and muddy, One of the oxen missing, the boys have been hunting him all day. Dreary times, wet and muddy, and crowded in the tent, cold and wet and uncomfortable in the wagon no place for the poor children …”

Sometimes Amelia Stewart Knight and her family had to sleep “in wet beds, with their wet clothes on, without supper.”

Sick or well, Amelia had chores to do; and they were endless. Scrubbing and mending clothes, keeping watch over her seven children, preparing meals for her family of eight, (soon to be nine), and the five hired hands that traveled with them. Yes, she was pregnant with her eighth child during her time on the Oregon Trail. But even with all her responsibilities, she found time to write in her diary about the “ beautiful vallies, and dark green clad hills, with their ledges of rock, and then far away over them you can see Larimie peak, with her snow capt top…”

Even with all the hardships, Amelia’s story wasn’t much different from most of the folks traveling the Oregon Trail. Long wagon trains of families trekked across the plains, doing all they could to stay together in order to help each other. Struggling over treacherous mountain passes and parched deserts, the pioneers inched their way west in long, snaking wagon trains. The forerunners of the American dream lived through hail storms, pelting rain, muddy trails, lost livestock, and dreaded diseases like cholera, which caused excruciatingly painful death within hours.

Nowhere was the human struggle more poignantly played out than in the migration of settlers to the western United States in the 1800s. They came from Ohio, Illinois, Kentucky, and Tennessee, looking for the land of plenty in Oregon that they had heard about. They braved all that Mother Nature and life could throw at them; illness, accidents, and unthinkable hardships were just par for the course. Broken down wagons, scarce food and water, barren landscapes to trudge across, and hostile Natives were just some of the challenges they faced. Despite all this hardship and misery, new births , gorgeous scenery, weddings, and campfire dances were also part of their trek across the plains. Such things were recorded in the diaries of the women of the wagon as they inched across the new frontier; they were determined to outlast the Oregon Trail.

Their mode of transportation was the renowned covered wagon; the pickup truck of its day. What gave them the strength to carry on? It was the promise of fertile land and a new-found freedom. For some, it was the call of the wild, the promise of independence and a fresh start. This was their chance to forge new paths and create the original American dream. For others it was the lure of the California gold rush of 1848; gold fever was already at epidemic proportions by the time the pioneers began heading west. The Oregon Trail was a route blazed by fur traders. It went west along the Platte River in Nebraska, through the Rocky Mountains via the South Pass in Wyoming and then northwest to the Columbia River; the largest river in the Pacific Northwest.

Prairie Schooners

German immigrants built the first covered wagons around the year 1717 in the area near the Conestoga River in Pennsylvania, thus the name Conestoga Wagon. These wagons, also called “prairie schooners” were built extra sturdy and were able to haul up to six tons of freight. They were designed like a boat with both ends of the floor of the wagon curved up to prevent goods from falling out as the wagon bumped along rocky roads and through mountain passes. Thus, the name prairie schooner. The covering of the Conestoga wagon was a large piece of canvas soaked in oil to make it waterproof and then stretched over wooden hoops and secured to the bed of the wagon. Pioneer women spun the linen for the covers of the wagons themselves; they called the covers bonnets.

The Conestoga wagon is not the same as the covered wagon in that it was built much sturdier than the covered wagons that made their way west. Conestoga wagons were used mainly in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Ohio, and Virginia. The covered wagons that most folks went west in did not have the curved floors nor could they haul as much freight as the sturdy Conestoga’s. Still, the wagons that went west were built tough. The wagon wheels were made of hickory or oak and had rims of iron. The wagons had no brakes or springs, so the pioneers tied chains around the rear wheels to lock them or provide a drag whenever they had to go down steep hills; which they often did.

These sturdy wagons carried pioneer families and all their worldly goods across the uncharted terrain of America. Standing 7-8 feet tall and 10-15 feet long, the covered wagons of yesteryear were symbols of freedom. They were the vehicle that would carry the pioneers across the rugged terrain on their way to the building of America; and they had to be as tough as the pioneers who drove them.

Life on the Oregon Trail: Not Your Average Camping Trip

Traveling west in a covered wagon was truly one bold, daring and extraordinary journey for the pioneers of the 1800s. It was a grand life but a tough one. The promise of a better life drove them onward mile after grueling mile. At times, the trip probably seemed as impossible as the terrain was impassible. As they surveyed the lay of the land they must have felt overwhelmed; but their pioneer spirit pushed them to forge ahead. If it rained, they might only be able to travel one or two miles a day, due to washed-out trails.

Most covered wagon families could travel about 10-15 miles a day; carrying all that weight, it must have been agonizingly slow at times. Amelia Stewart Knight wrote in her diary on September 8, 1853, at the end of a long and treacherous day:

“ Traveled 14 miles over the worst road that was ever made, up and down very steep rough and rocky hills, through mud holes, twisting and winding round stumps, logs, and fallen trees. Now we are on the end of a log, now bounce down in a mud hole , now over a big root of a tree, or rock, then bang goes the other side of the wagon and woe to be whatever is inside .”

Families sometimes had to abandon their covered wagons along the way due to the roughness of the roads and make the rest of the trip on foot. Oxen were often chosen to pull the wagons because they were the strongest animals around. The oxen were controlled by an ox yoke; a curved wooden beam fitted to a pair of oxen so that they could work together pulling the covered wagons. Today, ox yokes are collected as primitive pieces of Americana. Oxen also had to be shod if they were to make it across the new frontier; so special shoes were forged of iron and carefully fitted to each ox. These shoes played an important role in the pioneer’s expansion of the new frontier; making it more likely that the pioneers would reach their destination.

Fields of magnificent wildflowers , rushing rivers, and breathtaking views awaited them along the way to the new land. But many times, the pioneer families had to go for days without water while traveling through open, often hostile, territory. Mothers gave their last swallow of water to their children; fathers worried as parched oxen trudged ahead. But the pioneers were hardy people and most of them persevered until water was found. They often had to lighten the load of the wagon by discarding items along the road or getting out of the wagon and walking along beside it. It’s said that the Oregon Trail was littered with the clothes, dishes, and furniture the pioneers had to leave behind to lighten the load as the trail became rougher and the oxen wearier for lack of water or food.

Keturah Belknap wrote in her diary along the trail: “Will start with some old clothes on and when we can’t wear them any longer will leave them on the road.”

“Use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without.”

This was the motto that dictated the lives of the people traveling west to the new frontier. The pioneers had to be very careful how they packed their wagons. They didn’t want to overload them and make it impossible for the oxen to pull the wagon; the maximum weight the wagons could hold was 2,000 to 2,500 pounds. A well-stocked wagon could mean the difference between life and death as they traveled through stark and unfamiliar lands. The typical journey lasted four to six months and the wagons had to hold enough provisions for the entire family for the long trip.

Some of the things the pioneers had to carry included tools like shovels, hammers, axes, rope and grinding stones. Personal items would include clothing, rifles, knives , toys, and of course the family Bible. Food may have been the thing that took up the most weight. A large amount of flour was required, at least 200 pounds for each person of the family, and each family carried at least 50 gallons of water. Other necessities were bacon, rice, coffee, sugar, salt, beans, and cornmeal. Food had to be rationed very carefully along the way, as did the water; they never knew when they would find a lake or spring along the way. In addition to all the above, the pioneers carried household goods like coffee grinders, butter churns, bedding, spinning wheels, rocking chairs, cradles, buckets, Dutch ovens , and eating utensils. Wisely making use of every square inch of space, they attached hooks to the hoops inside the wagon to hold clothes, buckets, weapons, etc.

Pioneer woman Margaret Frink wrote in her diary: “The wagon was lined with green cloth, to make it pleasant and soft for the eye, with three or four large pockets on each side, to hold many little conveniences–looking glasses, combs, brushes, and so on.” So, as you can see, the pioneers were experts at making use of every little bit of space; they made their supplies last and they were also tough enough to outlast the Oregon Trail. They kept their eyes on the prize all the way across the country through countless, unthinkable trials and tribulations; and they laid the groundwork for the American dream; for the generations of Americans and immigrants that would one day follow in their footsteps.

Check out another pioneer woman: Matilda Jackson: Making a Home on the Last Frontier

Mollie Dorsey Sanford: Frontier Wife, Frontier Life

https://www.homestead.org/homesteading-history/mountain-men/

That is a wonderful and informative article on traveling in a covered wagon. Reading it gave me the feel of what the days were like, and also the choices that faced each traveler as to what to stock in the wagons. A portrait of the strong stock and dedication is also seen. Pioneers faced horrible weather on trails through the wilderness, not roads of any type. I wonder how they crossed the mountains. Was there a pass that let them through and how treacherous the journey must have been. What great dedication and also a great fellowship to accomplish the journey seems to have been the thread of success. Thank you so much for this article.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me via e-mail if anyone answers my comment.

I consent to Homestead.org collecting and storing the data I submit in this form. (Privacy Policy) *

Notify me by email when the comment gets approved.

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail. You can also subscribe without commenting.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Why did so many Western-bound wagon trains use oxen instead or horses of mules?

by Marshall Trimble | Aug 1, 2001 | Inside History

Joshua Young Star Valley, Arizona

Oxen were slower than mules or horses, but they had their advantages, such as they ate less, required less care, and they could pull heavier loads. And while a mule or horse could cost $90, an ox could be bought for about $50.

Related Articles

Why did Mountain Men prefer riding mules over horses? And how come the Indians never…

Stephen W. Kearny played a big role in the conquest and settlement of the West.…

Chester A. Arthur is the only U.S. president to make an extensive overland march, mostly…

In This Issue:

- Discover the West!

- Tom Mix’s Last Sundown

- A Deadly Duel at 500 Yards

- The Last Hurrah

- Custer Almost Kills Curtis

- Bass Reeves Finally Gets His Due

Western Books & Movies

- In Search of the Real Bass Reeves

- Tucson Book Festival

- Grit and Grace

To The Point

- Brothers From Another Mother

More In This Issue

- What History Has Taught Me with Terrence Moore

- Doc Holliday, Reward Money and Fast-Draw

- Jerome, Arizona

- Rebel Yankees: The McCulloch Colts

- Rolling the Dice!

- Shooting Back

- Truth Be Known

Subscribe to the True West Newsletter

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Wagons on the emigrant trails.

Minivan of the Emigrant Trails

Murphy Wagon

Studebaker Wagon

Conestoga Wagon

NPS/Eric Grunwald

Mormon Handcart

Part of a series of articles titled The Emigrant Experience .

Previous: Traveling the Emigrant Trails

Next: Death and Danger on the Emigrant Trails

You Might Also Like

- california national historic trail

- mormon pioneer national historic trail

- oregon national historic trail

- scotts bluff national monument

- emigrant trails

- covered wagons

California National Historic Trail , Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail , Oregon National Historic Trail , Scotts Bluff National Monument

Last updated: November 9, 2021

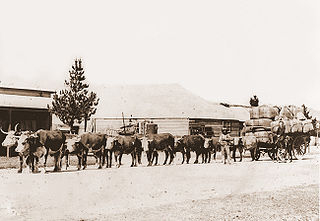

An ox-wagon or bullock wagon is a four-wheeled vehicle pulled by oxen (draught cattle). It was a traditional form of transport , especially in Southern Africa but also in New Zealand and Australia . Ox-wagons were also used in the United States . The first recorded use of an ox-wagon was around 1670, [ citation needed ] but they continue to be used in some areas up to modern times.

South Africa

Afrikaner symbolism.

Ox-wagons are typically drawn by teams of oxen, harnessed in pairs. This gave them a very wide turning circle , the legacy of which are the broad, pleasant boulevards of cities such as Bulawayo , Zimbabwe , which are 120 feet (37 m) wide, [1] and Grahamstown , South Africa , which are "wide enough to turn an ox-wagon".

The wagon itself is made of various kinds of wood, with the rims of the wheels being covered with tyres of iron , and since the middle of the 19th century the axles have also been made of iron. The back wheels are usually substantially larger than the front ones and rigidly connected to the tray of the vehicle. The front wheels are usually greater in diameter than the clearance under the tray of the vehicle so that the steering axle could not turn far under the tray. This makes little difference to the turning circle of the wagon because of the oxen drawing it (see above) and it makes the front of the wagon much more stable because the track is never much less than the width of the tray. It also allowed a much more robust connection between the hauling traces of the oxen and the rear axle of the wagon (usually iron chain or rods) that is necessary for heavy haulage.

Most of the load-carrying area was covered in canvas supported by wooden arches; the driver sat in the open on a wooden chest (Afrikaans: wakis ).

- Examples of ox-wagons

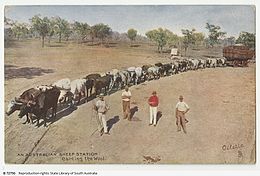

Bullock wagons were important in the colonial history of Australia. [2] Olaf Ruhen, in his book Bullock Teams remarks on how bullock teams "shaped and built the colony. They carved the roads and built the rail; their tractive power made populating the interior possible; their contributions to the harvesting of timber opened the bush; they offered a start in life to the enterprising youngster". Bullocks were preferred by many explorers and teamsters because they were cheaper, quieter, tougher and more easily maintained than horses therefore making them more popular for draught work. [3] Frequently comprising long trains of bullocks, yoked in pairs, they were used for hauling drays, wagon or jinker loads of goods and lumber prior to the construction of railways and the formation of roads. In early days the flexible two-wheeled dray, with a centre pole and narrow 3-inch (8 cm) iron tyres was commonly used. The four-wheeled dray or box wagon came into use after about 1860 for loads of 6 to 8 long tons (6.7 to 9.0 short tons; 6.1 to 8.1 t) and was drawn by 16 to 18 bullocks. A bullock team was led by a pair of well trained leaders who responded to verbal commands as they did not have reins or a bridle. [4] The bullock team driver was called a bullocky , bullock puncher or teamster .

Many Australian country towns owe their origin to the bullock teams, having grown from a store or shanty where teams rested or crossed a stream. These shanties were spaced at about 12-mile (19 km) intervals, which was the usual distance for a team to travel in a day. [5]

The Voortrekkers used ox-wagons ( Afrikaans : Ossewa ) during the Great Trek north and north-east from the Cape Colony in the 1830s and 1840s. An ox-wagon traditionally made with the sides rising toward the rear of the wagon to resemble the lower jaw-bone of an animal is also known as a kakebeenwa (jaw-bone wagon). South Africa has 800 varieties of wood of which 17 varieties were used for wagon building. South African wood varieties are regarded as the best for wagon building. Wood varieties used for wagon making ranged from hard yellowwood to Boekenhout, is a softer wood and was used as a shock absorber but still stayed firmly in place. The iron rim around the wheel was burnt onto the wheel, the charcoal would protect the iron rim from rust and rot, making it easy to cross rivers. The ox-wagon could be pulled by 12-16 oxen. [6]

The ox-wagon could also be disassembled in five minutes by hitting out four pegs on the wheels, then lifting the top of the wagon in seven pieces and carried by four people over rough terrain or across rivers. The ox-wagon could also twist 40 degrees which made it ideal for traversing difficult surface areas. The wheels of the ox-wagon were painted in red lead paint which acted as an excellent water repellant. Various flower and ornament designs were also painted on the wagons and the chests the wagons carried, making them look very colourful. [7]

Often the wagons were employed as a mobile fortification called a laager , such as was the case at the Battle of Blood River .

After the discovery of gold in the Barberton area in 1881, ox-wagons were used to bring in supplies from former Lourenço Marques . James Percy FitzPatrick worked on those ox-wagons and described them in his famous 1907 book Jock of the Bushveld .

In South Africa , the ox-wagon was adopted as an Afrikaner cultural icon. The ossewa is mentioned in the first verse of " Die Stem ", the Afrikaans poem which became South Africa's national anthem from 1957 to 1994. When a pro- German Afrikaner nationalist organisation formed in 1939, to oppose South Africa's entry into World War II on the British side, it called itself the Ossewabrandwag (Ox-wagon Sentinel). [8]

- South African cultural heritage

- Bullock cart (ox-cart)

- Conestoga wagon

Related Research Articles

A wheel is a rotating component that is intended to turn on an axle bearing. The wheel is one of the key components of the wheel and axle which is one of the six simple machines. Wheels, in conjunction with axles, allow heavy objects to be moved easily facilitating movement or transportation while supporting a load, or performing labor in machines. Wheels are also used for other purposes, such as a ship's wheel, steering wheel, potter's wheel, and flywheel.

A cart or dray is a vehicle designed for transport, using two wheels and normally pulled by draught animals such as horses, donkeys, mules and oxen, or even smaller animals such as goats or large dogs.

The Great Trek (Afrikaans: Die Groot Trek was a northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyond the Cape's British colonial administration. The Great Trek resulted from the culmination of tensions between rural descendants of the Cape's original European settlers, known collectively as Boers , and the British Empire. It was also reflective of an increasingly common trend among individual Boer communities to pursue an isolationist and semi-nomadic lifestyle away from the developing administrative complexities in Cape Town. Boers who took part in the Great Trek identified themselves as voortrekkers , meaning "pioneers", "pathfinders" in Dutch and Afrikaans.

A carriage is a private four-wheeled vehicle for people and is most commonly horse-drawn. Second-hand private carriages were common public transport, the equivalent of modern cars used as taxis. Carriage suspensions are by leather strapping or, on those made in recent centuries, steel springs. Two-wheeled carriages are informal and usually owner-driven.

The Ossewabrandwag (OB) was an Afrikaner nationalist organization with strong ties to national socialism, founded in South Africa in Bloemfontein on 4 February 1939. The organization was strongly opposed to South African participation in World War II, and vocally supportive of Nazi Germany. OB carried out a campaign of sabotage against state infrastructure, resulting in a government crackdown. The unpopularity of that crackdown has been proposed as a contributing factor to the victory of the National Party in the 1948 South African general election and the rise of Apartheid.

A wagon or waggon is a heavy four-wheeled vehicle pulled by draught animals or on occasion by humans, used for transporting goods, commodities, agricultural materials, supplies and sometimes people.

The Battle of Blood River was fought on the bank of the Ncome River, in what is today KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa between 464 Voortrekkers ("Pioneers"), led by Andries Pretorius, and an estimated 25,000 to 30,000 Zulu. Estimations of casualties amounted to over 3,000 of King Dingane's soldiers dead, including two Zulu princes competing with Prince Mpande for the Zulu throne. Three Voortrekker commando members were lightly wounded, including Pretorius.

The year 1838 was the most difficult period for the Voortrekkers from when they left the Cape Colony, till the end of the Great Trek. They faced many difficulties and much bloodshed before they found freedom and a safe homeland in their Republic of Natalia. This was only achieved after defeating the Zulu Kingdom, at the Battle of Blood River, which took place on Sunday 16 December 1838. This battle would not have taken place if the Zulu King had honoured the agreement that he had made with the Voortrekkers to live together peacefully. The Zulu king knew that they outnumbered the Voortrekkers and decided to overthrow them and that led to the Battle of Blood river.

The Voortrekker Monument is located just south of Pretoria in South Africa. The granite structure is located on a hilltop, and was raised to commemorate the Voortrekkers who left the Cape Colony between 1835 and 1854. It was designed by the architect Gerard Moerdijk.

A teamster in American English is a truck driver; a person who drives teams of draft animals; or a member of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, a labor union. In some places, a teamster was called a carter, the name referring to the bullock cart.

The Conestoga wagon is a specific design of heavy covered wagon that was used extensively during the late eighteenth century and the nineteenth century in the eastern United States and Canada. It was large enough to transport loads up to six short tons, and was drawn by horses, mules, or oxen. It was designed to help keep its contents from moving about when in motion and to aid it in crossing rivers and streams, though it sometimes leaked unless caulked.

A covered wagon , also called a prairie wagon , whitetop , or prairie schooner , is a horse-drawn or ox-drawn wagon with a canvas top used for transportation or hauling. The covered wagon has become a cultural icon of the American West.

An ox OKS , also known as a bullock , is a bovine, trained and used as a draft animal. Oxen are commonly castrated adult male cattle; castration inhibits testosterone and aggression, which makes the males docile and safer to work with. Cows or bulls may also be used in some areas.

A bullock cart or ox cart is a two-wheeled or four-wheeled vehicle pulled by oxen. It is a means of transportation used since ancient times in many parts of the world. They are still used today where modern vehicles are too expensive or the infrastructure favor them.

A horse-drawn vehicle is a piece of equipment pulled by one or more horses. These vehicles typically have two or four wheels and were used to carry passengers or a load. They were once common worldwide, but they have mostly been replaced by automobiles and other forms of self-propelled transport but are still in use today.

A bullocky is an Australian English term for the driver of a bullock team. The American term is bullwhacker . Bullock drivers were also known as teamsters or carriers.

A wagon fort , wagon fortress , wagenburg or corral , often referred to as circling the wagons, is a temporary fortification made of wagons arranged into a rectangle, circle, or other shape and possibly joined with each other to produce an improvised military camp. It is also known as a laager , especially in historical African contexts, and a tabor among the Cossacks.

The Afrikaans Language and Culture Association , ATKV , is a society that aims to promote the Afrikaans language and culture. The association was founded in 1930 in Cape Town. Since its inception and up to the end of Apartheid in 1994, membership was only open to members of the Afrikaner Christian community. Membership was thereafter opened to include people of all ethnicities, sharing the same values as the ATKV.

Hoërskool Voortrekker is a public Afrikaans medium co-educational high school situated in the municipality of Boksburg in the city of Ekurhuleni in the Gauteng province of South Africa. The academic school was established in 1920.

The Battle of Vegkop , alternatively spelt as Vechtkop , took place on 16 October 1836 near the present day town of Heilbron, Free State, South Africa. After an impi of about 600 Matebele murdered 15 to 17 Afrikaner voortrekkers on the Vaal River, abducting three children, King Mzilikazi ordered another attack. The voortrekkers, under the command of Andries Potgieter, repulsed them, but at the cost of abandoning their livestock.

Henning Johannes Klopper (1895–1985) was a South African politician who served as Speaker of the National Assembly, and the first chairman of the Afrikaner Broederbond. He is known for promoting Afrikaans and fighting White Afrikaner poverty in South Africa.

- ↑ The Australian Encyclopaedia . The Grolier Society. Halstead Press, Sydney. {{ cite book }} : CS1 maint: others ( link )

- ↑ "Annual Berry Show" . www.berryalliance.org.au . Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2012 . Retrieved 3 February 2022 .

- ↑ Beattie, William A. (1990). Beef Cattle Breeding & Management . Popular Books, Frenchs Forest. ISBN 0-7301-0040-5 .

- ↑ "Chisholm, Alec H.". The Australian Encyclopaedia . Vol. 2. Sydney: Halstead Press. 1963. p. 181. Bullock-driving.

- ↑ Davie, Lucille. "Step into a wagon and go back 200 years" . The Heritage Portal . Retrieved 9 October 2018 .

- ↑ Davie, Lucille. "Step into a wagon and go back 200 years" . The Heritage Portal .

- ↑ Williams, Basil (1946). Botha Smuts And South Africa . London: Hodder And Stoughton. pp. 160–161.

EVOLUTION OF WAGONS

By: Judas Makwela, Junior Curator – DITSONG: National Museum of Cultural History

The history of transport includes the era of the ox wagon. The DITSONG: National Museum of Cultural History (DNMCH) is proudly home to diverse heritage assets. Amongst them that caught my attention and interest is the Museum’s wagon collection and specifically the development of the ox wagon, of which there are various types that were used for different reasons.

Figure 1. An open ox-drawn or transport wagon such as this example was used by different cultures to load, and transport goods such as farming produce and other large loads.

Figure. 2 Ox-drawn traveling wagon covered with a canvas tent for protection.

Wagons were built in different sizes according to the purpose for which they were used. In South Africa, 17 varieties of wood were used for wagon building. South African wood varieties are regarded as the best for wagon building.

Some wagons were used to travel long distances to other towns or farms. Most of the load-carrying area was covered in canvas, supported by wooden arches, and protected the travellers from rain and the hot sun. They could also sleep in their wagons. Larger wagons were built for transporting goods and large raw materials.

Figure 3. Ox-drawn transport wagon.

This article addressed some aspects in the development of the ox wagon. They were initially used by Europeans for transporting goods or when taking long journeys/ trekking . African people managed to acquire these ox wagons and utilize them. Even after automobiles were introduced in South Africa (1896), it still took many decades to completely phase them out and replace them by cars. Even today, in some rural areas, ox wagons are still in use as an alternative means of transport or for leisure purposes.

Rosenthal, Eric. 1975. Victorian South Africa . Tafelberg: Cape Town.

DITSONG: National Museum of Cultural History, “Transport Collection. Accession Number: L 2311 (Figure 2).

Wagons in history: the bokwa : Figures 01 and 03.

Photographs by Judas Makwela (Junior Curator), DNMCH.

Related Posts

THE CARVED KRAG JÖRGENSON RIFLE OF CHRISTIAAN BEYERS, ASSISTANT COMMANDANT-GENERAL DURING THE ANGLO-BOER WAR OF 1899-1902

THE TIMELINE OF MONEY DESIGN CHANGES IN SOUTH AFRICA BETWEEN 1652 AND 2023

THE CARVED MAUSER OF LOUIS BOTHA, ONE OF THE YOUNGEST BOER GENERALS IN THE ANGLO-BOER WAR OF 1899-1902

THE MIGHT OF FIJIAN WAR CLUBS

Mules, Horses or Oxen

Historical trails, trail basics - mules, horses or oxen.

Early Wagon Train

Which would be best to pull your heavy wagons? Mules are strong, can go faster, but are often tricky to handle. Mules also had tendencies to bolt and become unruly. Oxen are slower, but more reliable and tougher than mules. They will eat poor grass. Oxen were very strong and could haul fully-loaded wagons up ravines or drag them out of mudholes. A large wagon needed at least three pairs of oxen to pull it.

Scholars put the percentage of pioneer wagons pulled by oxen at one-half to three-quarters. The cost of a yoke of oxen during the last half of the 1840s varied from a low of $25 to a high of $65.

The three main parts of a prairie wagon were the bed, the undercarriage, and the cover. BED = was a rectangular wooden box, usually 4 feet wide by 10 feet long. At its front end was a jockey box to hold tools. UNDERCARRIAGE = was composed of the wheels, axle assemblies, the reach (which connected the two axle assemblies), the hounds (which fastened the rear axle to the reach and the front axle to the wagon tongue) and the bolsters (which supported the wagon bed). Dangling from the rear axle was a bucket containing a mixture of tar and tallow to lubricate the wheels. COVER = was made of canvas or cotton and was supported by a frame of hickory bows and tied to the sides of the bed. It was closed by a drawstring. The cover served the purpose of shielding the wagon from rain and dust, but when the summer heat became stifling the cover could be rolled back and bunched to let fresh air in.

Wagons being pulled by horses and mules

Double Wooden Ox Bow

Notes From The Frontier

- Oct 21, 2019

What Pioneers Packed to Go West

Updated: May 11, 2023

Pioneers packed like their lives depended on it, because they did!

Westering pioneers had many routes to choose from but the main ones were the Oregon, California, Sante Fe, and Mormon Trails. Whatever route they chose, many read guidebooks like Landsford Hastings’ 1845 “The Emigrant’s Guide to Oregon and California” or Captain Randolph Marcy’s 1859 “The Prairie Traveler: A Hand-Book for Overland Expeditions.” They offered advice on what and how to pack, what draft animals to buy, distances, water, grass, terrain, weather, firearms and ammunition, tools, wagon parts, how to make repairs, and what hardships they might meet along the way.

Two primary types of wagons were used on wagon trails going west. The Conestoga wagon was named for Conestoga Township in Pennsylvania where many German pioneers in the 1750s first started West on the Appalachian Trail to settle land east of the Mississippi. It was a huge and very heavy wagon, 28 feet long with wheels five feet tall and, loaded, could weigh as much as six tons and took three pair of oxen to pull. (Like pulling a semi!)

Later, the much smaller Prairie Schooner became most common on the Oregon, California and Sante Fe Trails to the Western frontier. It was usually built in the Midwest for the departure points in Missouri, where all three trails started. The prairie schooner was half the size of the Conestoga, 12-13 feet long, and weighed 1,300 pounds empty and as much as two tons loaded. It required less animals to pull and to feed on the trail and could move faster (20 miles a day vs. 13-15 for the Conestoga wagon).

The sides of the wagons were waterproofed with tar, so they could ford rivers and keep the cargo dry. A thoroughly water-proofed wagon would also float in high water, making the crossing much easier. The canvas tops were oiled to keep out the rain. Wooden wheels had iron rims to prevent wear.

The Oregon Trail took roughly four to six months to complete. Packing could mean the difference between life and death on the trail and varied wildly depending upon the sensibilities (and sometimes the sense!) of the travelers. James Miller’s 1848 diary entry describes what they packed for food: “We had… 200 lbs. flour for each person, 100 lbs. bacon, corn meal, dried apples and peaches, beans, salt, pepper, rice, tea, coffee, sugar, and many smaller articles for such a trip.” Pioneers also commonly packed 80 lbs. lard, 20 lbs. sugar, 10 lbs. each of coffee and salt per person, yeast, hardtack and crackers.

A wagon was filled with essentials, so travelers usually walked alongside the wagons. This also saved the energy of the oxen, mules or horses pulling the wagons. Teams grazed at night for grass.

Some travelers brought cattle to butcher along the way. Many brought a milk cow and a chicken or two for eggs. Each morning, after milking the cow, the buckets of milk were covered and hung under the wagon. The jarring of the unsprung axle would churn the milk! At night, the fresh butter would be skimmed off. A Dutch oven was the standard cooking container because it was versatile and could be used to bake bread, cook soups, grill meat, and make oatmeal in the morning.

Most wagons had a “chuck box” at the back of the wagon that consisted of a fold-down table surface in front of a cabinet that contained food stuffs, utensils, plates and basics needed to prepare a meal. Shelving below the axle contained larger Dutch ovens, bowls for making bread dough, tubs for washing, or even bottles of a more sundry nature.

Large wooden water kegs were carried on the sides of the wagons. Water would be resupplied from rivers along the way. However, there were some dry stretches and water was carefully preserved. Cholera epidemics were most common along the Platte River and were caused by contaminated water from the massive numbers of travelers that bivouacked there.

Medical and surgical supplies were essential: bandages, ointment, laudanum, cough syrups that contained cocaine, painkillers that contained opium, and of course alcohol for drinking. (Alcohol as an antiseptic was not commonly used until the 1890s.) Surgical instruments for suturing wounds, pulling teeth, lancing boils, extracting bullets or arrowheads, and a bone saw for amputating were commonly packed as well.

Tools for repairing or rebuilding wheels, axles, wagons, ox bows, and harnesses were heavy but crucial to have. The basics were hammers, saws, augers and gimlets. Prudent planners would also pack heavy rope, chains, spare parts, axle grease, and even pulleys. Oil and candle lanterns were essential since work and repairs often had to be done at night, so all would be ready when the wagon train left in the morning.

Warm clothing for rain and cold was packed, as was bedding. Although bedding took up space, it was crucial to get as much sleep as possible. Travelers walked about 20 miles a day over often rough terrain, or in prairie grass as tall as they were, and were exhausted at the end of each day.

Those who insisted on packing iron stoves, heavy furniture, pianos, sewing machines, iron plows, kegs of whiskey, blacksmith anvils, or other weighty items usually discarded them on the side of the trail as the grazing and water ran out. Fort Laramie in Wyoming became known as “Camp Sacrifice” because it was so littered with jettisoned cargo, antique furniture and family heirlooms, chests of silver and china, stoves, and pianos, broken wagons, and dead animals.

Most wagon trains had at least 25 wagons. Perhaps the largest wagon train to travel on the Oregon Trail left Missouri in 1843 with over 100 wagons, 1,000 men, women and children, and 5,000 head of oxen and cattle. The train was led by a Methodist missionary named Dr. Elijah White. But wagon trains became so common on the trail that processions seemed to have no beginning or end. Diaries told of hundreds of wagons passing by Fort Laramie in a single day in the 1850s. Foraging for the teams became a serious challenge because grazing near the trail had been exhausted.

Two posts from the pioneer diary of Elizabeth J. Goltra provide a glimpse of traveling on the trail:

September 20, 1853: Two of our horses are missing this morning. Bought 30 pounds of beef and some other eatables… found plenty of wood and water and grass one mile south. We are now at the foot of the Cascades, in heavy timber. Bought 80 pounds of flour off an emigrant at 10¢ per pound. We now have plenty of provisions to last us through. We guard our cattle very closely or we would lose them in the timber. Rest the remainder of the day to let the cattle eat plenty for feed is scarce in the mountains.

September 24, 1853: This is a very rainy morning. The roads are very bad. Fearful of being caught in a snowstorm… This is the roughest and steepest hill on the road. Got down all safe by cutting and chaining a tree behind the wagon 100 feet long. Camped at the foot of the hill and tied our stock up with nothing to eat but a little grass we carried along with us.

PHOTOS: (1) Conestoga wagons were used early in pioneer history to travel on the Appalachian Trail and east of the Mississippi. But they were extremely heavy—up to six tons loaded--and required up to six animals, usually oxen, to pull. (2) The smaller Prairie Schooner started to replace the larger Connestoga wagons and were often built in the Midwest near the starting point of the Oregon Trail. (3) Two families rest at the end of the day on the trail at the foothills of the Rockies in northern Utah,1870. Photograph by Henry Martinean. Denver Public Library. (4) A very rare photograph of the inside of a covered wagon packed for the Oregon Trail shows the crowded quarters. (5) Custer’s Black Hills Expedition of 1874 included 110 covered wagons, 1,200 men, artillery and food supply for two months. This expedition was about the same size as the largest wagon train ever to travel the Oregon Trail.

You may also enjoy these related posts:

-What Pioneers Ate

https://www.notesfromthefrontier.com/post/what-pioneers-ate

-Pioneer Survival Guides

https://www.notesfromthefrontier.com/post/pioneer-survival-guides-in-the-1800s

"What Pioneers Packed" was originally posted on Facebook and NotesfromtheFrontier.com on June 24, 2019

513,667 views / 23,754 likes / 14,767 shares / 676 comments

© 2021 NOTES FROM THE FRONTIER

- Homesteading Life

- Most Popular

Thank you for this wonderful and detailed post. the photos and drawings are awesome and so helpful in research.

Thank you, Gini❣️

I really enjoyed this article! I’m always fascinated with American pioneer history!!

Great article and photos. Much appreciated. Really brought out what hardships they faced and what was needed to survive them. Interesting re: food supplies.

Thanks for your question, Jim. I can’t answer your question off the top of my head, but I do know that reliable wagon masters were a rare breed and a very valuable commodity! Many had worked the fur trade or been Indian scouts. This would make an excellent post in the future! Look for it. Thanks again.

Any recollection of a Peter Purrier as a wagon master? Approximately how many “reliable” wagon masters were there. Thanks Jim Wheeler

Deborah Hufford

Author, Notes from the Frontier

Deborah Hufford is an award-winning author and magazine editor with a passion for history. Her popular NotesfromtheFrontier.com blog with 100,000+ readers has led to an upcoming novel ! Growing up as an Iowa farmgirl, rodeo queen and voracious reader, her love of land, lore and literature fired her writing muse. With a Bachelor's in English and Master's in Journalism from the University of Iowa , she taught students of Iowa's Writer's Workshop , then at Northwestern University , Marquette and Mount Mary . Her extensive publishing career began at Better Homes & Gardens , includes credits in New York Times Magazine , New York Times , Connoisseur , many other titles, and serving as publisher of The Writer's Handbook .

Deeply devoted to social justice, especially for veterans, women, and Native Americans, she has served on boards and donated her fundraising skills to Chief Joseph Foundation , Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women ( MMIW ), Homeless Veterans Initiative , Humane Society , and other nonprofits.

Deborah's soon-to-be released historical novel, BLOOD TO RUBIES weaves indigenous and pioneer history, strong women and clashing worlds into a sweeping saga praised by NYT bestselling authors as "crushing," "rhapsodic," "gritty," and "sensuous." Purchase BLOOD TO RUBIES online beginning June 9. Connect with Deborah on DeborahHufford.com , Facebook , and Instagram .

- Travel Website

- Travel trade website

- Business events website

- Corporate & media website

- Welcome to South Africa

- What you need to know

- Things to do

- Places to go

- Get in touch

Choose your country and language:

- South Africa

Asia Pacific

- South Korea

- Netherlands

- United Kingdom

By creating an account, I agree to the Terms of service and Privacy policy

Vibrant culture

Become an oxwagon pioneer – clarens oxwagon camp.

O O xwagons – South Africa’s Voortrekker pioneers rode in them, blazed trails in them, sometimes gave birth in them and died in them. Relive those days when you sleep out at the Clarens Oxwagon Camp. Dine out beside a crackling camp fire before bedding down in a comfortable old-time oxwagon .

The Clarens Oxwagon Camp is a living reminder of those feisty, Dutch-speaking Voortrekkers (literally 'one who goes before') who left the British-ruled Cape Colony in the 1830s and 40s to forge independence and a new life for themselves in the vast, largely unexplored interior of South Africa.

Oxwagons carried these pioneer families, their worldly possessions and their dreams of a place where they could live in freedom , unfettered by British rule.

Tucked away in a tall poplar grove surrounded by golden sandstone mountains on St Fort farm just outside Clarens , off one of the most beautiful scenic roads in the e astern Free State, is Clarens Oxwagon Camp.

St Fort farm is known for its views of the aptly named Mushroom Rock , the nearby San rock paintings and the excellent fly-fishing.

Inside the sturdy wooden walls encircling the open-air camp you'll find the wagons. There are 14 of them, each authentic and restored, furnished with 4 single bunk beds , sleeping up to 8 people .

The camp is self-catering , so bring all your own food and drink. There's a kitchen with a kettle, a two-plate stove, a washing up area and an undercover braai area. Most importantly, however, there's a campfire where you can sit late into the night and swap tales with the other guests.

At the end of the evening as the stars blaze over the mountains, climb into your white canvas oxwagon with its cheerful red wheels, curl up in a comfortable bunk and dream of those long - ago days.

The area around Clarens is one of the loveliest in the whole country – expect soaring red mountains, clear mountain streams, winding roads lined with poplars and panoramic views.

T T ravel tips & planning info

Who to contact

Clarens Oxwagon Camp

Tel: +27 (0) 58 256 1 260

How to get here

Take the N3 west from Johannesburg. Then the R26 to Bethlehem and follow the signs for Clarens . The Oxwagon Camp is 7 km from Clarens on the Fouriesburg Road.

Best time to visit

It can get very hot in summer and bitterly cold in winter, so spring and autumn are best.

Things to do

The Golden Gate Highlands National Park is a short drive away , as is the arty town of Clarens .

What will it cost?

Please enquire directly about rates .

Length of stay

One night is sufficient for the oxwagon experience. But if you are using the camp as a base for exploring the area, then 2 or 3 nights.

What to pack

The Clarens Oxwagon Camp is self-catering , so bring all your food and drink ( Clarens has a number of excellent supermarkets, butcheries, delis and liquor stores) , as well as cooking utensils.

What's happening

Among the most popular events in the area are the Clarens Craft Beer Festival in February and the Cherry Festival in November.

Best buys

Clarens is a shopping mecca. Find African crafts and curios, art galleries, handcrafted leather, pottery, handmade quilts, jewellery , jams and preserves, freshly baked bread and pastries… and lots more.

Related links

- Clarens Destination s

- Clarens Oxwagon Camp

- Clarens Craft Beer Fes t ival

- Eastern Free State Oxw a gon

South Africa on social media

The BMW International Open has made us excited for the BMW Golf Cup World Final to be hosted in SA. We caught up wi… https://t.co/XiU3waBo1T

Always a pleasure partnering with local businesses to promote SA on the global stage. Warren Weitsz, Co-Founder of… https://t.co/YRxoX6Jdtx

To say the players are bringing their A-game is an under statement! Round 2 has given us many unforgettable moments… https://t.co/4bBdAuXMUL

"...Patrons have been keen and interested in engaging on where the best fairways in SA are. Paired with some of our… https://t.co/tIoXM2uUrh

Our stand at the BMW International Open has been drawing a lot of attention – and rightfully so! “We are proud and… https://t.co/ulYSTje4CB

Clear skies, rolling greens, supportive crowds – the conditions couldn’t be better for a day at Golfclub München Ei… https://t.co/3TMmUxsN0m

What happens when an amateur and pro hit the fairway together? Find out in the Pro-Am Tournament, where 3 amateurs… https://t.co/hkvHUw0H0E

Ready to get into the swing of things? The Pro-Am Tournament of the 2023 BMW International Open starts today in Mün… https://t.co/WqLU7FshdH

South Africa has many exquisite golf courses. As we gear up for The BMW International Open in Germany, we hope to s… https://t.co/vTFwgOa78W

South African Tourism will be showcasing our beautiful country's offerings in Germany! We have so much to offer glo… https://t.co/O1m4yVy491

#DidYouKnow South Africa has produced some of the top golfers in the world. As we gear up for the BMW International… https://t.co/E1GsW6z1Fy

#DidYouKnow ? #VisitSouthAfrica ❤️🇿🇦 https://t.co/Y4zWjb8xIz

RT @Roberto_EUBXL: Amazing #YouthDay2023 long weekend in @MidlandsMeander ! Another 💎 of multifaceted #SouthAfrica : touches of 🇬🇧 🇧🇪 🇱🇺 co…

What does golf, South Africa, BMW and Germany have in common? The 34th staging of the BMW International Open in Ger… https://t.co/YdvuWOjs8O

Golf was first played in South Africa in 1885, in Cape Town. Now we are taking our love of golf to the world, as we… https://t.co/dXc5uIyGxI

RT @PublicSectorMan: Today marks 47 years since the youth uprising of 16 June 1976. Deputy President Paul Mashatile will lead the commemor…

We look forward to showcasing South Africa’s abundant tourism offerings to a global audience while reminding them a… https://t.co/yVz97hDGaa

A dynamic collaboration between SA Tourism and the iconic BMW Group is set to supercharge the country’s efforts tow… https://t.co/JhLDwHlLix

50 days until the kick-off – or shall we say the tip-off – of the Vitality #NWC2023 in SA! Excitement levels are at… https://t.co/Ni2fHwh2NJ

#VisitSouthAfrica ❤️🇿🇦 https://t.co/ApcA6wNNop

- Useful links

- Travel partners

- Business events

- Travel trade

- Accommodation

- Useful contacts

- Visa & entry info

- Digital Assets Library

- Image Library

What You Probably Didn't Know About Covered Wagons

Safety in numbers. Or, if you prefer, misery loves company. Either way, the great Western Migration of the 19th Century was largely accomplished by people crossing the Great Plains, bound from the East, or even what's now the Midwest, en route to the lush lands of Oregon and California, there for the taking, there for the settling — if you survived the trip.

There was no easy way to make a new life for yourself in the 1800s. Not if you wanted to move, and not if you wanted to move a family. Passage by ship around the tip of South America was an expensive and dangerous option. Railroads? The transcontinental railroad wasn't completed until 1869, according to History . Stagecoach? Impractical for families, plus what they might need when you got where you were going — tools, household goods.

Not that the alternative was a whole lot better. While many of the Latter-day Saints made the trip to Utah using handcarts (and walking), relates Historynet , many others would invest in a covered wagon of some kind. There were various sizes available, and of course in this case, size actually mattered — because you had to take into consideration how you were going to move that wagon, loaded up with supplies, tools, and household goods with which to make your new start in a new land.

Most people walked most of the way

They would travel in packs — wagon trains, a collective of like-minded folk, guided by someone who claimed to know where they were going and the best way to get there (though that didn't always work out — ask the Donner Party ). Migration began in earnest with the opening of the Santa Fe Trail in the 1820s, then picked up considerably with wagons headed for Oregon and California in the 1840s, writes Marshall Trimble in True West Magazine . The first wagons generally measured about 10 feet long, four feet wide, and two feet deep, writes Jana Bommersbach, also for True West . Arches over the top of the wagon were covered by heavy canvas. The incredible weight being moved required significant animal power, and so most often, wagons were pulled by teams of oxen, though occasionally mules or horses were utilized instead. Added benefit: an ox wasn't a very attractive target for thieves — they moved slowly, you couldn't ride them, and not particularly tasty. As the trip wore on, and the oxen wore out, it was not unusual for families to start abandoning the things that seemed so important before they left.

The so-called Conestoga wagon was extremely popular until the 1850s — as popular as something as primitive as this could be, anyway — rugged, dependable, and incredibly uncomfortable. One advantage of using oxen was that the family could walk alongside at a relaxed pace.

Wagons were built to endure

On a good day, a wagon train might cover 20 miles — seven days a week, with no holidays, trying to take advantage of good weather before autumn and winter struck, trying to cover some 2,000 miles in about five months. There was a break for lunch, then the evening stop for the night, with beds unrolled underneath the wagon — there wasn't room within for people. Repairs had to be done on the road. The wagons had springs, but if you did try to ride, it was a bone-jarring trip and most people didn't bother. Advancements in wagon design — it's probably a stretch to call it "technology" — resulted in the slightly smaller, perhaps faster, "prairie schooner," replacing the Conestoga in the middle of the century.

Wagon trains, especially the larger groups, were rarely attacked by Native Americans. More problematic was the weather. A swollen river could prove impossible to cross, causing days, even weeks, of waiting. Muddy ground could slow progress. And if the guide was inexperienced, there was always the nightmare of getting lost, losing time, and getting stuck. (Donners, anyone?)

The voyage completed, the wagon often served as temporary shelter

Once arrived in the new territory, the wagon would provide the first shelter for the family, until something a little more permanent could be built, whether of timber or simply prairie sod. The vehicle itself would continue to be used to move what needed moving as the family settled in.

Texas rancher Charles Goodnight is credited (by some) with inventing another form of Old West wagon: the chuckwagon , a rolling kitchen serving the needs of cattle drives. The cook would drive the wagon ahead of the herd during the day, meet up to serve hot food, move ahead again to prepare for the evening, while gathering firewood and perhaps fresh game or even wild bird eggs along the way. It was smaller than the prairie schooner or the Conestoga, and would feature fold-down work spaces, maximized storage for cooking equipment, and no matter who invented it, was generally an ingenious piece of American engineering.

Search form

How the ox-wagon and transport-rider opened up this country.

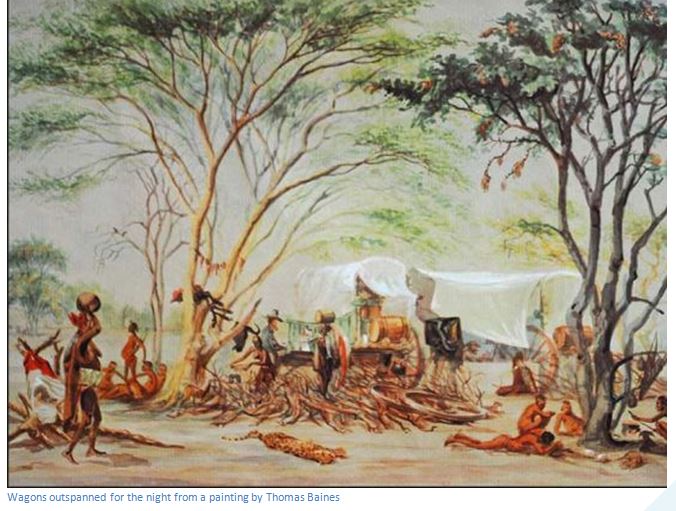

Hans Sauer says the trek ox is the real pioneer of the southern African sub-continent. They dragged the wagons across the whole of South Africa and crossed the Limpopo and Shashe Rivers and then across the Lundi (Runde) to Victoria and finally Salisbury.

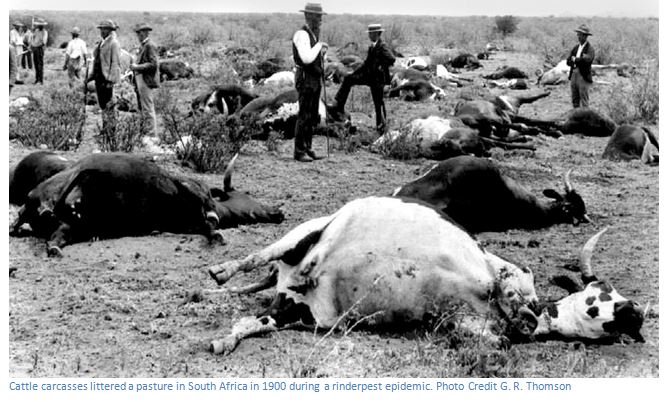

Before the coming of the railways it was the trek ox that provided all the transport leading to the development of the diamond fields at Kimberley and the goldfields of the Witwatersrand and finally the occupation of Mashonaland and conquest of Matabeleland.

The trek ox brought from the coast into the interior all the food, furniture, clothing, household utensils, corrugated sheeting, timber, heavy machinery required for mining, the portable steam engines that provided power and permitted the development of the towns at Victoria (Masvingo) Salisbury (Harare) Gwelo (Gweru) and Bulawayo.

To the transport-riders the road had huge appeal. Stanley Hyatt says to him, the road was what the sea is to other born wanderers. He had already sailed around the world in a wind-jammer, but this was nothing in comparison to the dusty, narrow track which ran from the railhead towards the heart of Africa.

To see examples of wagons, visit the excellent Mutare Museum, which specializes in transport, and has some excellent wagons and carts donated by the Strickland family, or see the article under Manicaland Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

So quickly did land transport develop – the railway reaching Bulawayo in 1897 and Salisbury from Beira in 1899 and from Bulawayo in 1902, that the era of the ox wagon and the transport –rider was a short one and their significant part in the opening up of the country is largely forgotten.

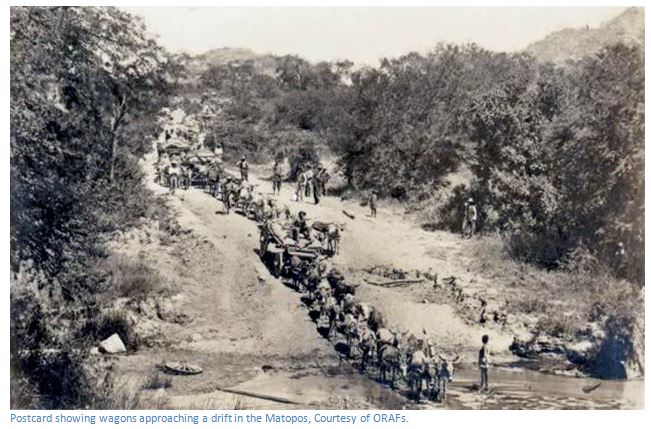

Louis Bolze reminds us in the Foreword to The Old Transport Road by Stanley Portal Hyatt that wagons plying the route between the railhead at Vryburg and Bulawayo took two months to complete the 840 kilometre route; in 1895 the Bulawayo Chamber of Commerce reported over 2,000 ox wagons had arrived in Bulawayo and in the same year a passenger on a Zeederberg coach counted over 100 ox wagons between Palapye and Bulawayo.

Stanley Hyatt, born in 1877, felt great pride and affection for his trek oxen, their individual characters and positions in the span, their care and training, the driver skills and resourcefulness called for to keep an ox-wagon on the road, from repairing a broken wheel in the bush, righting a capsized wagon with an 3,600 kilogram load, to looking after a sick ox.

For Hyatt who came to Matabeleland when he was 19 the fascination of the transport road was immense. He says it did not lead to places, to Palapye, to Bulawayo, to the Victoria Falls. It led through them, past them. It went on; it was always going on, into the very heart of the Dark Continent. One year a District would be a blank on the map, a mere name at best; the next year you would find that the road had reached it, had passed through it, and in the new edition of the map there would be scores of names of mountains, rivers and townships even, on that space.

In 1891 the only route from Fort Tuli to Salisbury was along the route cut by the Pioneer Column between July and September of the previous year. In their hurried march during the previous year Dr Hans Sauer says the worst obstacles they left behind were the many foot-high tree stumps as, unlike stone boulders which the wagon wheels climbed over, they produced a dead shock followed by a violent swerve which could result in the dϋsselboom , or wagon pole snapping. When this happened, everyone looked for a suitable shaped tree to replace the broken dϋsselboom which often had to be cut down by starlight.

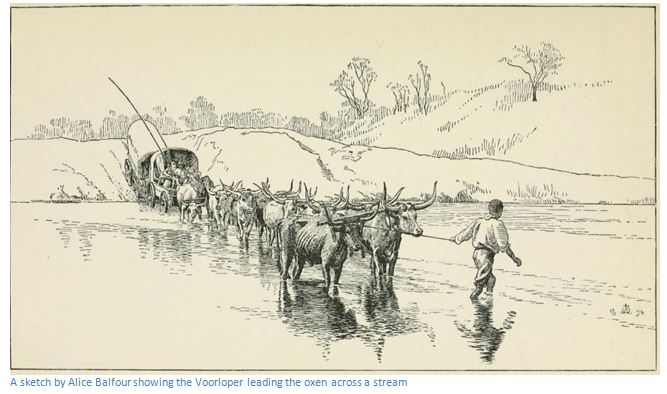

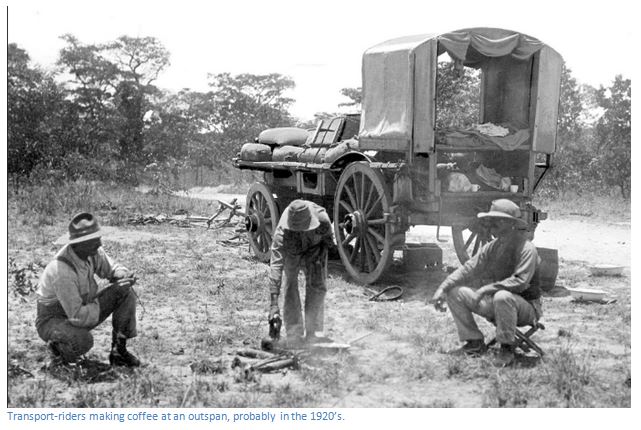

On his journey Sauer followed the routine of the Afrikaner transport riders, which was the tried and tested method for oxen when long distances were being traversed. Two treks were made every 24 hours. The first began about 4pm when the voorloper would crack his whip and bring the oxen back to the wagon for in- spanning. The trek began at 5pm and lasted until 9pm when the oxen were unyoked and tied to the trek chain to lie down and chew the cud. Two or three fires were lit around the camp to scare off lions and for the evening meal. Dry firewood was collected and stacked for use during the night. After supper everyone slept, rising about 2am when the second trek began and ended just after sunrise at 5am.

During the day the oxen were let out to graze with a herder, and the wagon conductor or driver, the voorlooper and other assistants would take long naps, just waking to check on the oxen. All passengers followed their example as it was difficult to sleep whilst the waggons were trekking due to the wheels constantly bumping against boulders and stumps.

The only exception to this routine was in the rainy season when the roads washed out, every rut became a river and scooped out the road into trenches up to three feet deep and travelling by night became dangerous; the Selukwe-Victoria road was notorious for wash-outs.

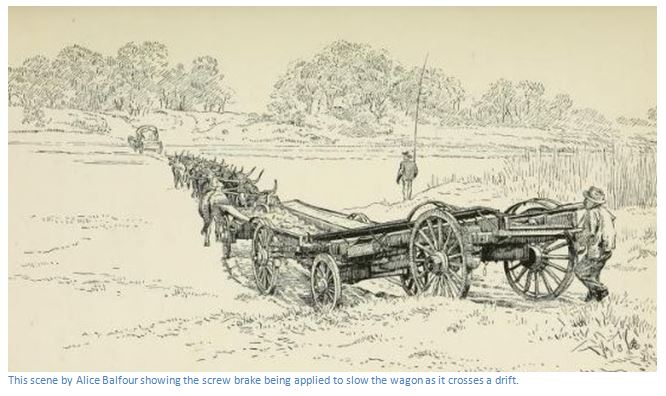

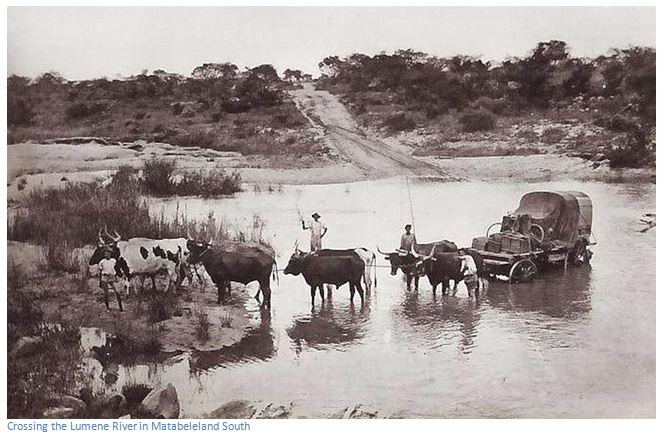

Approaches to drifts across rivers were always taken cautiously especially if the pull-out was steep or narrow, often just a cutting in the river bank. It was always difficult to get the span to begin a heavy pull with a dead-straight chain, they preferred a swing and often at drifts two spans would be used as the wheels would get caught in a wash-out into which they sank.

On flat ground the driver had an easy time sitting on the front box with his helper smoking endless pipes of Boer tobacco. Trekking by night in broken country intersected by dongas and small streams could be very difficult. The driver would be on foot beside the oxen, shouting their individual names and cracking the whip in the air when they were not doing their fair share of pulling, touching an ox with his whip on occasion when it refused to obey an instruction and prodding the wheeler in the ribs with the whip butt end to make him swerve and miss a stump or boulder on the road.

When the voorloper shouted they were approaching a steep stream bank, the driver would rush to the rear of the wagon to screw the brake onto the two rear wheels to prevent the wagon gaining speed and injuring, and even killing the two hind oxen, or wheelers. The constant braking and then loosening the brake when negotiating difficult ground was hard work and a great test of the driver’s ability; demanding strength and stamina and quick thinking. Hans Sauer says he tried it and found seven or eight kilometres of bad road quite exhausting work.

Accidents were common. Lord Randolph Churchill does not mention this happening in his book Men, Mines and Animals in South Africa to one of his ox-wagons when crossing the Lundi River (Runde) on his grand tour of Rhodesia in 1891. The slope leading down to the river was very steep and the driver too slow in applying the brakes so that the wagon rushed down on the team of oxen, killing both wheelers and injuring others. A little later, voorloper was killed by a crocodile, another incident which also goes unmentioned, but is recounted by Hans Sauer, who was crossing the Lundi River at the same time.

Trekking was a noisy affair; the driver shouting out the names of the oxen if he considered they were not pulling their weight. “Englishman” or “ Rooinek ” was the name usually given to the worst in the span and was an old-standing joke with Boers. Other common names were Bandom, Biffel, Jackalass, Jonkman, Sixpence, Fransman, Witkop, Blom, Appel, Basket, Scotchman, Swartland and Dudmaaker.

Biffel, the left hind bullock of the Stanley Hyatt’s black span was his favourite. Like all true Mashona cattle he was short in the legs and long in the body with a beautiful head, short flat horns and the kindest, wisest eyes. He was fond of strolling up to strangers in the mining camps and would stand still as they scratched his ears, or put an arm around his great neck.