- Employee Center

- Commercial Site

The True Story of Flying Tiger 923’s Miraculous Water Landing

Eric Lindner’s Tiger in the Sea: The Ditching of Flying Tiger 923 and the Desperate Struggle for Survival tells the story of pilot John Murray’s 1962 life-saving “ditch” of an L-1049H Super Constellation in the North Atlantic ocean, a barely controlled water landing with 76 passengers and crew members onboard. The effort captivated the world at the height of the Cold War. Newspapers from London to Los Angeles ran breaking updates of the crash’s aftermath, and President Kennedy received hourly updates concerning the fates of all involved.

Lindner conducted dozens of interviews with survivors and eyewitnesses to write Tiger in the Sea. His account is definitive, unearthing details and insights from Murray and others that reveal the full extent of the event’s unprecedented danger, as well as Murray and his crew’s miraculous airmanship and extraordinary ingenuity.

Here, read an exclusive excerpt from Tiger in the Sea.

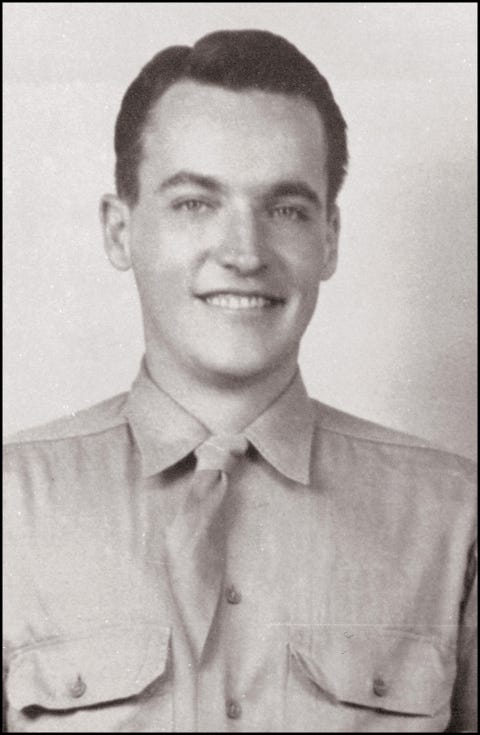

As Flying Tiger 923 sliced through the dark sky over the Atlantic, a thousand miles from land on the way to Frankfurt from Newfoundland, a red flash on the instrument panel caught Captain John Murray’s eye: Fire in engine no. 3; inboard, right side. The 73-ton Lockheed 1049H Super Constellation had 76 people onboard, but the 44-year-old pilot from Oyster Bay, Long Island, wasn’t rattled. He’d survived back-to-back plane crashes as a flight instructor in Detroit, Egyptian anti-aircraft as a black ops freelancer, and several overwater engine failures as a commercial pilot. Murray knew the most likely explanation for the signal was a transient electrical malfunction—the aircraft’s fire detection system was notoriously finicky—but still, Murray was puzzled: There was no alarm bell to go along with the flash. His log books accounted for 20 years of fire warnings, but zero entries spoke of a transient flash without an accompanying alarm.

Murray sat in the left cockpit seat, beside first officer Bob Parker. Navigator Sam “Hard Luck” Nicholson and flight engineer Jim Garrett sat behind them. The flight deck was a claustrophobic clutter of manuals, personal belongings, floor-to-ceiling electronics, and cigarette smoke. To eliminate the potential for lethal drag, Murray instructed Garrett to feather engine no. 3, then stand by to discharge fire suppressant.

Courtesy Flying Tigers Club Archives

Garrett pulled the throttle back to idle and feathered the engine’s propellor blades so they were parallel to the slipstream, then he cut off the fuel-air mixture control to disable the troubled engine. A bell clanged, and slumbering passengers jolted awake—it was a fire. Outside, crewmembers and passengers could see the flaming engine oil and white hot steel fragments shooting from the no. 3 engine’s exhaust stacks. The pyrotechnics lit up the sky.Garrett raised his voice above the alarm bell: “Ready to discharge, Captain.”

“Fire one bottle,” Murray said.

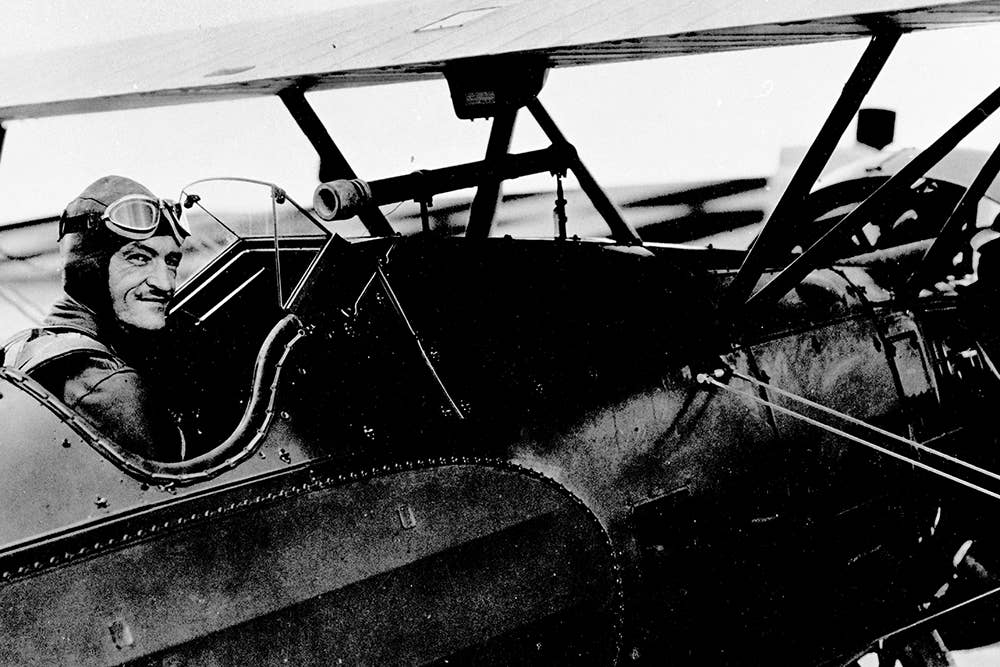

Captain John Murray

Courtesy John P. Murray

“Copy that.” Garrett lifted the small red spring-loaded aluminum cover labeled eng. fire dhg., moved the switch to the discharge position, and shot an extinguishing agent into the no. 3 engine. The alarm stopped. The fire light on the control panel went dark.

According to Aviation Safety Network statistics, which standardize accidents by passenger miles flown, when Flying Tiger 923 took off on September 23, 1962, air travel was 100 times more dangerous than it is today. As for the Constellation (“Connie”) series, nearly one of every five built between 1950 and 1958 had crashed or was otherwise out of commission. In March 1962, two Connies met ill-fated ends within hours of one another: one crashed in Alaska; the other disappeared somewhere over the Pacific.

Murray’s Connie had rolled off a Burbank assembly line on February 20, 1958, but Howard Hughes had conceived the plane all the way back in 1937. Because Connie used the same basic piston technology that powered wagons in 1844 (as opposed to the jet turbine first used in 1939), and because its Wright reciprocating engine wasn’t as reliable as its chief competitor’s Pratt & Whitney, Lockheed stopped producing Constellations a few months after Murray’s plane was manufactured. Yet Murray himself still found a lot to like in his plane. He liked her range, ruggedness, and versatility, as well as her unique triple tail fins. He’d flown her 4,300 hours, often in dire conditions. She’d never let him down.

Soldiers boarding the Flying Tiger Lockheed Super H Constellation on March 15,1962, which disappeared over the Pacific. Another Connie flight crashed in Alaska within hours of this one. Courtesy Flying Tigers Club Archives

The crisis seemed over by 8:11 p.m, three hours after takeoff. The fire was out, and any damage seemed contained within the exhaust stacks. Murray decided against shooting a second bottle of suppressant.

But flight engineer Garrett, a recent hire, had forgotten to close the no. 3 engine firewall. Moments after he closed the no. 1 firewall—on the left outboard engine—by mistake, his colleagues heard what they described as “a shrill obscene snarl” from the left side of the aircraft. “Runaway on number one!” Parker yelled.

The error had triggered a chain reaction: When the left outboard’s hydraulic subsystem stopped pumping, blast air stopped cooling the generator, and fuel and oil stopped flowing to the motor and governor. This caused the propellor to spin out of control at close to the speed of sound. If the 13-foot blades were to break free, the projectiles could down the plane.

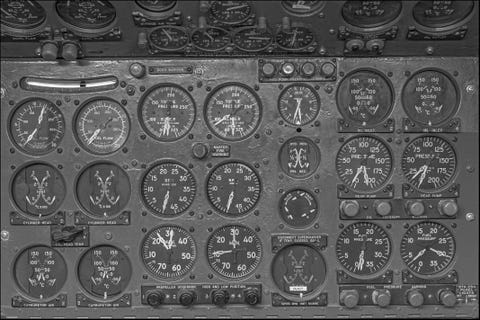

Courtesy Urs Mattle and Ernst Frei

The interior of a circa 1962 era Super H Constellation cockpit: pre-computer, pre–Black Box, pre-GPS (visible device retrofitted in 1980s). Courtesy Urs Mattle and Ernst Frei

Murray muscled all the throttles back and decelerated Connie to 210 mph. Then he began easing her nose up, leveraging the air current into a makeshift brake. The blades slowed enough to allow Garrett to feather the no. 1. Disaster was averted again.

But the plane had lost two of its four engines in seven minutes. Connie was 972 miles from land, hundreds from the nearest ship. Murray knew he shouldn’t try to make it all the way to Frankfurt, so he laid out three alternatives: pull up short at Shannon Airport, about 1,000 miles closer; divert north to Keflavik Airport, closer still; or, the worst case scenario, attempt a ditching, what the FAA referred to as a “controlled water landing.” Parker worked the radio, trying to keep the main rescue control center in Cornwall apprised of Flying Tiger 923’s coordinates and altitude, but he was struggling to communicate over the narrow, mid-oceanic high-frequency band. Garrett checked the performance charts to determine the cruising altitude that would cause the least strain per the current engine configuration and weight: 5,000 feet. They had enough fuel to reach Ireland.

But at 9:12 p.m. another red light flashed in the cockpit: fire in engine no. 2. Murray reduced power, Garrett feathered no. 2, the light went out, and the nerve-fraying alarm fell silent, but now the plane was flying on one engine. It couldn’t do so for long, so Garrett reversed the feather on no. 2. The props realigned, and Flying Tiger 923 was back to two engines; thankfully, one on each wing.

After Hard Luck plotted a course for Ireland, Murray led a discussion on whether to deviate so as to overfly Britain’s Ocean Station Juliett or America’s Ocean Station Charlie. If ditching proved necessary it would be much better to do so near one of the floating, well-provisioned outposts rather than in the middle of the open, frigid sea.

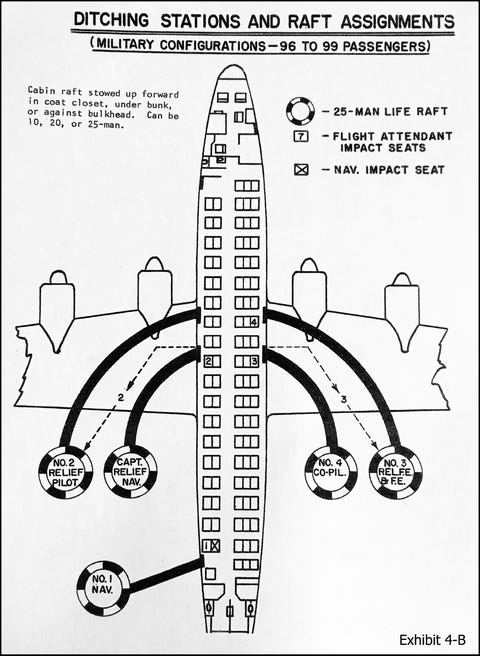

The thousands of exhibit pages entered into evidence during the U.S. Civil Aeronautics Board’s hearing into Flying Tiger 923, November 14-16, 1962, included this diagram showing where the 8 crew members were supposed to exit and which rafts they were supposed to occupy. But things didn’t go as planned. Courtesy U.S. Department of Transportation

Deviating wasn’t a straightforward proposition, however. First, while the British weather station was 100 miles closer (250 miles away versus 350 miles for the American station), the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Owasco was moored beside Charlie; it could travel to the crash site faster than either outpost in the event people needed rescue. Second, overflying either station could add another 175 miles of engine strain. Murray directed Parker to establish contact with the Owasco, then asked the chief stewardess to lead her three colleagues in a ditching drill. Passengers handed over their pens, pocketknives, reading glasses, dentures, belts, and anything else that might injure them on impact, or puncture their life jackets or rafts.

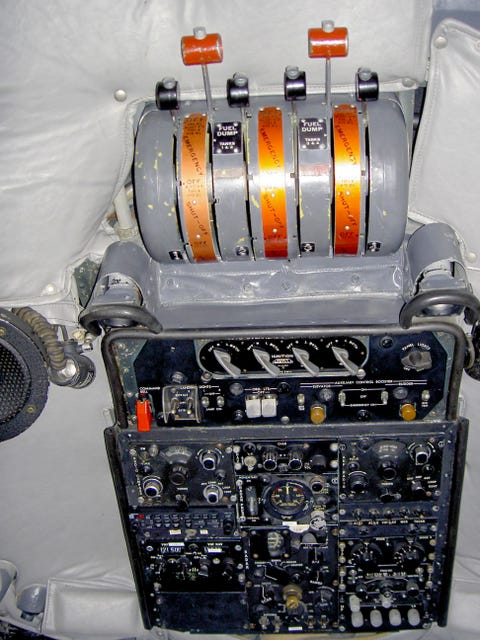

The flight deck was hot, humid, and hectic. As the plane descended and settled into a cruising speed of 168 mph, the uneven thrust from the full-powered right outboard and hobbled left inboard, coupled with the tacky altimeter and jumpy rpm, told Murray he wasn’t out of the woods. The pilot considered dumping fuel to trim the plane’s weight—the excess fuel beyond what they needed to reach Shannon was 5 percent of the load—but the added buoyancy of an empty tank wasn’t worth losing the cushion. He kept the fuel.

A circa 1962 Super H Constellation fuel dumping and firewall junction box (located at flight engineer’s workstation). Courtesy Peter W. Frey

Yet another bell rang at 9:27 p.m. A metallic grinding and screeching could be heard from the left side of the plane. Out the windows, a shower of sparks lit up the moonless sky. It seemed the no. 2 engine might explode any second.

Murray throttled back on no. 2. The plane slowed, its nose lifted, the bell stopped ringing, and the fire light went out. But the pilot knew if he kept throttling back he’d never reach Ireland. He’d exhausted all his options.

Circa 1962, the U.S. Coast Guard defined a “successful ditching” to mean (i) the aircraft didn’t sink immediately, (ii) it remained mostly intact, and (iii) a majority onboard survived impact. No pilot had ever successfully ditched in such brutal conditions: a pitch-black night, winds gusting to 65 mph, 20-foot seas. The North Atlantic seabed was a mausoleum for the remains of countless planes and ships, including the Titanic and dozens of Spanish galleons. For those aboard, hitting the water would feel like crashing onto a cement runway. Murray, a husband and father of five, knew his aluminum plane would most likely break apart on impact or sink in seconds. Land was 650 miles away.

A circa 1962 Super H Constellation cabin with Flying Tiger Line’s “Always Prepared” ditching pamphlet and life vests in seat backs. Courtesy Flying Tigers Club Archives

At 9:42, another alarm bell rang out. The left inboard engine began shooting fiery blue-black carbonized fuel globules the size of a fist past the windows. Murray silenced the alarm but told his crew: “Ditching seems probable now.”

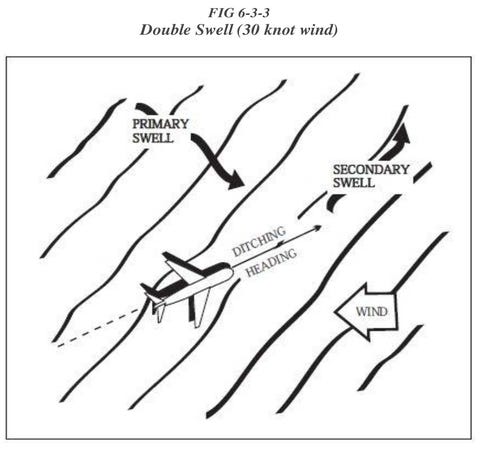

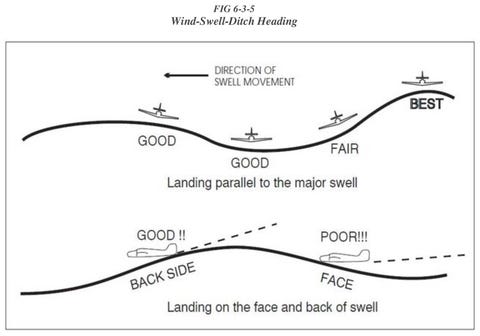

Absent a significant change in the swells’ direction, velocity, or height, Murray said he intended to fly into the wind, toward the swells, and touch down between two of them. His colleagues were perplexed. The manual read: “Never land into the face of a swell or within 45 degrees of it.” These same instructions were also in all the Navy tip sheets, Flight Safety Foundation bulletins, Air Line Pilots Association newsletters, and Civil Aeronautics Board accident reports. Murray explained: “In almost every ditching training session, after a discussion of why it’s better to land parallel to the swells, there’d always be an old-time flying boat captain who landed his Sikorsky or Boeing into the swells.” The Coast Guard’s instructions were “sensible in theory,” he added, but they didn’t apply to Connie’s unprecedented situation. Because Murray felt the stiff winds at sea level would cut his speed and minimize sideways drift, the Flying Tiger captain said he intended to ditch like the flying boat captains.

Capt. Murray’s insight led the U.S. Coast Guard and Federal Aviation Administration to change the official “Ditching Procedures,” as depicted in the FAA’s 2021 “Aeronautical Information Manual,” that shows how pilots shouldn’t just focus on primary swells, but instead weigh and balance a complex set of variables. COURTESY U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION

Just five jetliners have ditched in 60 years. On July 2, 2021, after its two engines had overheated and failed, a 45-year old Boeing 737-200 ditched 4 miles off the coast of Oahu, in 5-foot swells and 17-mph winds; it split in two on impact. Murray successfully ditched his Lockheed L-1049H prop 560 miles off the coast of Ireland, in 20-foot swells and gusts up to 65 mph. This diagram shows another facet of their shared predicament.

COURTESY U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION

Where to touch down was the next question, but a “height perception illusion,” unique to ditching, hindered Murray’s vision. For the human eye to process inputs, it needs a canvas of crisp, discrete focal points on which to paint a comprehensible picture. Seldom is this a problem when landing at an airport, since the trees, telephone poles, and air traffic control towers create a concrete referential pointillism easily processed by the eye. But during a ditching over active water, the sky merges into the sea, bleeds into the horizon, and plays tricks on a pilot’s eyes, wreaking havoc with their depth perception. Illusions lead pilots to hit the water at the wrong spot or angle; too soon or too late; too slow or too fast.

As he dipped Connie below 2,000 feet, Murray could discern the direction of the swells. He estimated their height to be between 15 and 20 feet, the interval separating them 150 to 175 feet. Were he to hit a swell, it would act as a ferocious impact force-multiplier against the aircraft. At best, he had 12 feet of wiggle room to lay down the 163-foot plane. With winds buffeting Connie 15 to 25 feet in every direction, and the possibility of hidden secondary swells beneath the whitecaps below, he’d have to perfectly calibrate the point and manner of impact.

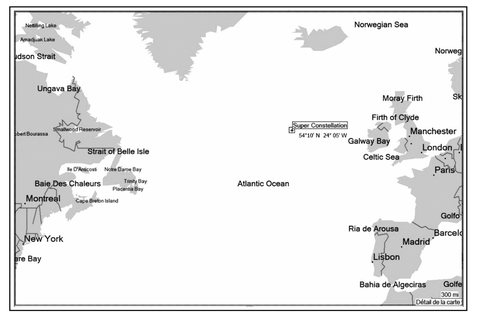

Map showing the precise ditching coordinates, drawn by deckhand (and, later, marine architect) of Flying Tiger 923’s rescue ship, Pierre-André Reymond. Courtesy Pierre-André Reymond

Then, it started to rain like mad. But as the moon emerged from hiding and lightened the sky, Murray’s height-perception illusion dissipated and he could more clearly make out the distance between swells: about 200 feet, crest to crest. That gave him a 37-foot margin of error—for a plane traveling 176 feet per second. The waves were high and powerful enough to snap Connie’s wings off and send the four life rafts tucked in their bays to the bottom of the sea.

The optimal descent slope was 25 feet per second, but Flying Tiger 923 was heading towards the sea at 34 fps. Murray fought to flatten the grade, but gravity was tugging Connie toward the ocean. If he didn’t elevate fast, they’d hit the water at a catastrophic angle and velocity.

He wrestled against the opposing winds, struggling to maintain an even keel. Were either wing to clip one of the powerful swells, Connie would flip into a horrifying cartwheel, breaking apart, sinking, and likely killing everyone. The lone working engine—the right outboard, no. 4—billowed angry blue flames as it tried to do the work of four. No. 2’s unfeathered prop rotated erratically at the mercy of the wind. As the landing lights illuminated his point of impact, Murray called out over the 121.5 frequency: “Mayday. About to ditch. Position at 2212 Zulu Fifty-Four North, Twenty-Four West. One engine serviceable. Souls on board seventy-six. Request shipping in area prepare to search. Over.”

The plane hit the water at 120 miles per hour—560 miles from land.

All 76 passengers and crew members survived the impact and evacuated the wreck. However, after seven nightmarish hours in the rough, bitterly cold North Atlantic, only 48 survivors boarded the first ship on the scene, a Swiss grain freighter. The remaining 28 died from drowning: many during a frantic, futile search to find the four missing life rafts.

Https://www.popularmechanics.com/flight/a37047867/the-true-story-of-the-miracle-pilot-and-his-120-mph-water-landing/

Adapted from Tiger in the Sea: The Ditching of Flying Tiger 923 and the Desperate Struggle for Survival (Lyons Press; May 14, 2021).

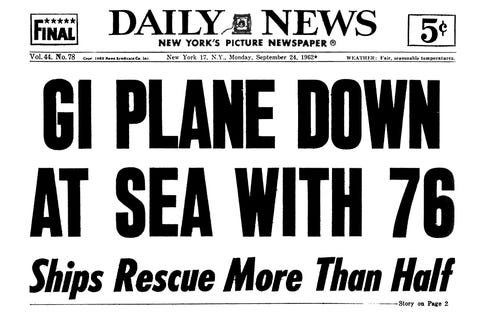

The Daily News front page on September 24, 1962, the day after Flying Tiger 923 went down. NY Daily News via Getty Images

Flying Tiger 923’s sea crash was the world’s top story for a week. In the U.S., news bulletins interrupted the massively popular Bonanza to give updates on the crash, rescuers appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show before an at-home audience of 40 million viewers, and in terms of column inches, the story received more newspaper coverage than astronaut John Glenn’s Florida splash-down earlier that year. Anchors and aviators alike hailed “the miracle pilot,” but how was John Murray able to overcome so many mechanical problems, manage so many simultaneous crises, and do what most experts said was impossible?

First, 85 percent of Murray’s piloting since 1957 came at the helm of a Super Constellation, but he also effected water landings on seaplanes and amphibians (he held ratings in both). Second, his engineering training primed his decision-making to be anchored in physics, not convention. Third, he was a precise delegator and leader, with a clarity of purpose and serenity fostered by a deep personal faith. He didn’t make reactive, survival-motivated decisions, but decisions based on a personal sense of responsibility for the 75 other lives onboard. A pilot colleague once said about him, “John knew he was expendable. It was the definition of what being a captain is all about: going down with your ship.”

80 Years Later, the Legacy of the Flying Tigers Endures

Kimberly johnson.

Captain Claire Chennault at the Air Corps Tactical School, Maxwell Field, Montgomery, AL, in 1932. [Courtesy: National Museum of the U.S. Air Force]

On December 20, 1941, an all-volunteer group of American mercenary pilots took on Japanese bombers in their first air combat mission to protect China.

By day’s end, the American Volunteer Group (AVG)—better known as the “Flying Tigers”—would go on to down nine out of 10 Japanese bombers in the first of many air battles in a seven-month campaign that helped block Japanese expansion into China.

The Flying Tigers’ legend is one that continues to represent military cunning and a special brand of American grit. It is a story of how an irascible commander trained a group of U.S. volunteer military pilots to beat an adversary that was better trained and outfitted through exploiting weakness, all while wearing the patch of another country.

Here are five things you should know about the Flying Tigers:

1. One man was behind the genius of the AVG’s winning air strategy: Claire Chennault.

U.S. Army Air Corps aviator Claire Chennault is remembered for many things, among them being opinionated and more than a little daring.

“Captain Chennault was known to fly his P-12 upside down under the Highway 31 bridge on his way home for lunch,” Fred Schramm, Air University History Office historian, once said. “He would also take his P-12 to Louisiana for the weekend on hunting expeditions,” he added. “He would load his dogs in the cargo section of the plane and fly home with his game strapped to the wing of his plane.”

Chennault was also not known to have an agreeable relationship with his superiors in the Army Air Corps. As he exited military service on a medical discharge in 1937, the Chinese government recruited him as an adviser for its air force.

“The day after he left the Air Corps as a captain, he was on his way to the West Coast to head to China and to become their air adviser,” said Tripp Alyn, chair of the Historical & Museums Committee AVG Flying Tigers Association. “They gave him the title of the rank in China of colonel, so an American captain suddenly becomes a colonel in the Chinese Air Force.”

When he arrived in China, Chennault was given a Curtiss P-36 Hawk, which he flew during reconnaissance missions observing Japanese air operations.

“In this aircraft, he went up and he observed the Japanese, and made copious notes,” Alyn said. “He observed their formations and their attack doctrine,” including their altitude, airspeed, direction, and how they attacked. “The Japanese were true to their doctrine, and they were very consistent and very predictable.”

The experience led to Chennault’s theories of defensive pursuit.

2. The AVG was created to defend China.

In the late 1930s, Japan’s expansion campaign in China raged on. Japanese bombers attacked Chinese cities, killing civilians indiscriminantly.

“Japan always thought they were invincible,” Alyn said. “They flew against the old aircraft of China with impunity.”

Chennault and a delegation of Chinese officials turned to the U.S. to ask for help.

“They reached out to us for help, but we couldn’t send them our units or we’d be at war,” said Bob van der Linden, a curator at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. “The United States was desperately trying to stay neutral, and stay out of wars, but also … trying to keep the Nazis at bay and trying to keep the aggression of Imperial Japan at bay,” he said. “[President] Roosevelt understood that Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan were a threat. But he also knew we could not declare war.”

- PHOTO GALLERY: The Flying Tigers

Roosevelt could, however, support the Chinese government in its defense against Japan in another way that would also help keep China in the war. The U.S. would support the creation of the American Volunteer Group, an all volunteer unit of 100 reserve military pilots who would be allowed to resign their commissions to travel to China to serve.

“At the time, the American public was quite pacifist and non-interventionist through the late ’30s,” said Gene Pfeifer, curator and historian at the National Museum of World War II Aviation. “It was very difficult for [Roosevelt] to see a way where he could meaningfully help the Chinese before we got into the war with the Japanese attacking Pearl Harbor. And this was one way that he felt he could make a meaningful contribution to checking Japanese expansionism in the Pacific.”

By the summer of 1941, the AVG began to mobilize in Burma as Japan launched a massive bombing campaign against Chinese cities. One such bombing occurred on December 19, 1941.

The next day, on December 20, the AVG received an alert that 10 Japanese bombers were en route. Information relayed by spotters confirmed their course toward Kunming. Recognizing the play, Chennault sent two squadrons up—one orbiting over the city of Kunming at an altitude that could be seen by the Japanese pilots, and the second ready to pounce.

“What he did was ingenious,” Alyn said. “They knew that an attack was eminent on them,” and they jettisoned their bombs as they turned to return to their home base.

“Because of the note locations, Chennault knew where they would be jettisoning their bombs,” as well as the course they would take and the altitude.

A squadron was ready for them, attacking from out of the sun so that the Japanese bombers would never know what hit them.

“Chennault taught the AVG to use a diving attack, to dive, shoot, then dive away,” Alyn said. The strategy maximized the rugged speed of the P-40s while limiting the time an adversary could fire back.

At the end of the day, only one of the 10 Japanese bombers made it back to their base.

“When the Americans returned to Kunming, the Chinese people were so thrilled. For the first time the Japanese had been shot down,” Alyn said. “The newspapers reported, ‘They’re fighting like tigers—Flying Tigers.’”

3. The AVG operated for only about seven months.

By July 1942, the AVG reportedly shot down or destroyed 297 enemy aircraft for a ratio of 20-to-1 and produced 20 ace pilots who shot down five or more. The Flying Tigers, which was composed of 311 pilots, ground crew and trainers, suffered 23 losses, including 22 pilots.

“It’s only seven months, but that was perhaps the most precarious seven months of the war in the Pacific,” van der Linden said. The U.S. had suffered an attack at Pearl Harbor and lost the Philippines. The U.S. Navy had been “knocked back on its heels,” and the Japanese Navy was operating unopposed in much of the Pacific.

The Flying Tigers turned the tide.

“Yes, they were fighting for nationalist China, but national China was our ally. And that was just fine. And they were striking blows against the Japanese,” van der Linden said. “America was still fighting back, and that was an extraordinary morale booster at home.”

4. The P-40 and AVG helped prove Chennault's theories of defensive pursuit.

On paper, the deck was stacked against the AVG. They were going up against Japanese Navy fighter pilots flying Mitsubishi A6M2 Zeros, a fast and nimble single-seater monoplane.

The AVG, by contrast, had Curtiss P-40 Warhawks, a ground-attack aircraft that was plentiful, but flirting with obsolescence.

“The United States was desperately trying to stay neutral, and stay out of wars, but also … trying to keep the Nazis at bay and trying to keep the aggression of Imperial Japan at bay.” Bob van der Linden, curator, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

“It performed very well throughout the war, but most of the aircraft it went up against were better either in terms of visibility or firepower,” and were slower than other fighter aircraft, van der Linden said. The P-40 couldn't turn with the Zero. What it did have, however, was a good range, coordinated controls and flew well.

The P-40 was “very much a pilot’s airplane,” he said.

“What the tactics of the Flying Tigers under Claire Chennault showed was that yes, the Zero is a better fighter than the P-40, but if you use the P-40s advantage in terms of speed, diving ability, and firepower and don’t turn with them, you can defeat them,” van der Linden said.

The AVG turned into a living laboratory for Chennault’s theories on defensive pursuit, which ran counter to the more prevalent offensive strategies centered on heavy bombers. Despite the success of the strategies, defensive pursuit wasn't readily embraced by military leaders back in the U.S.

“The rise of really fast and well-armed bombers in a world that had emerged from the First World War with a certain set of experiences and beliefs and so on, meant that the Second World War started with those beliefs being carried over,” said Doug Lantry, chief historian of the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

“[There was] a real faith among many powerful leaders that these new fast bombers would always get through to the target and that they were invulnerable. And they just couldn’t be stopped,” Lantry said. “And so pursuit aviation was, in a lot of cases, just put on the back shelf and ignored.”

5. Let’s talk about that iconic aircraft nose art.

The Flying Tigers began with 100 P-40 aircraft supplied by the Curtiss-Wright Corporation's plant in Buffalo, New York.

“They had to be taken from the plant down to Brooklyn and put aboard ships,” Alyn said. “Three different ships sailed for Rangoon, Burma with 100 aircraft destined for the AVG.” Their arrival in the capital of what is now Myanmar took an ominous turn when a crane unloading a ship dropped one of the aircraft in the harbor, instantly reducing the fleet to 99 aircraft before operations began, he said.

The iconic shark’s mouth paint scheme came later. According to Alyn, the idea for the fierce face came after AVG pilots were visiting with friends and spotted a photo of an airplane painted in the scheme on the cover of Illustrated Weekly of India sitting on the coffee table. They took the idea back to Chennault, who gave them permission to do it.

“He liked it so much that he said he wanted all their aircraft painted that way,” Alyn said.

For today’s military, the legend of the bravery and effectiveness of the AVG underdogs endures.

“What they did show was that you need to be open-minded and ready to adapt to the circumstances. And Chennault was very smart in this, like, you take what you have–in this case a P-40–and you emphasize its strengths and minimize its weaknesses,” van der Linden said.

Then there was the role they played in lifting the spirits of the U.S. in the dark months following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“They were honestly no more than a pinprick in the side of the Japanese but let them know that they weren’t going to get away with it without some payback,” van der Linden said. “The real importance was for the folks back home.”

“They came together in a very cohesive and very effective flying force that served as the model for what we continued to do in China after their service was over,” Pfeifer said.

Mostly, the AVG was an opportunity for an aviator from rural Louisiana who dared to challenge established military thinking to be proven right, historians say.

“The bottom line is that over time [Chennault] was proved correct,” Lantry said. “He was proved correct that bombers needed long range escort. And he was proved correct that a wide and continuous early warning network was vital for pursuit aviation. And he was proved correct that operating as tactical teams instead of individuals yielded better results,” he said.

“Here’s a few people as volunteers who have shed rigid military authority in favor of this kind of informal adherence to a charismatic, but demanding teacher and leader. And the legend is that they really did more with less,” Lantry said. “They really achieved a lot in a short period of time, against really huge odds. They could not have been favored in that fight, and yet they came out of it winners.”

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox

Subscribe to our newsletter

MilitaryHistoryNow.com

The Premier Online Military History Magazine

The Flying Tigers — 12 Facts About America’s Legendary Volunteer Fighter Squadron

“The victories of these Americans over the rice paddies of Burma are comparable in character, if not in scope, with those won by the RAF over the hop fields of Kent in the Battle of Britain.”

— winston churchill.

By Bill Yenne

FOR AMERICA, the final days of 1941 were among the darkest of World War Two. Pearl Harbor was in flames, the Philippines were in the crosshairs and Wake Island and was under siege. The Japanese were on the march everywhere, it seemed, and hope was in short supply. America desperately needed heroes — it would find them in the Flying Tigers.

The small group volunteer pilots from the United States seemed to be the only ones striking back against Japan, sweeping enemy bombers from the skies in far-away China. Until that moment, few at home had ever heard their name, but suddenly, everyone was asking: Who are these Flying Tigers?

Lust like the Royal Air Force pilots who saved the United Kingdom during the Battle of Britain , the Flying Tigers became a heroic symbol for America when it seemed all might be lost.

Today, the Flying Tigers are perhaps the best known American fighter aircraft group in history. Their name still resonates, just as the image of their shark-faced P-40s has become an icon of American airpower.

Here are a dozen things you probably never knew about the these incredible aviators.

1. The Flying Tigers were not part of the U.S. military

Because of their place in the pantheon of great American military organizations, it’s hard to imagine that the Flying Tigers didn’t wear their country’s uniform. In fact, they weren’t even professional soldiers, but soldiers of fortune employed by a mysterious shell company. While the pilots who were part of the American Volunteer Group had all previously served in the U.S. Army, Navy or Marine Corps, each one had resigned from the service to volunteer as civilian contractors with the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company (CAMCO), a Chinese firm that started out in the 1930s as a joint venture between that country’s national government and Curtiss-Wright , an American aircraft manufacturer doing business in China. CAMCO itself was under contract with an entity called China Defense Supplies, Inc., which had been set up in Washington, D.C. by Tommy Corcoran , a close advisor to President Franklin D. Roosevelt , and T.V. Soong the brother-in-law of Chinese leader Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek . It functioned as a mechanism for funneling money into the defense of China, and to process the acquisitions made possible by cash and carry financing, and later by Lend Lease .

2. They were actually bounty hunters

The pilots and support personnel of the American Volunteer Group who were hired as CAMCO “employees” received monthly salaries — ranging from $250 for ground crewmen to $750 for flight leaders — plus expenses routed though a Chinese bank account. In addition, the pilots were verbally promised a $500 “bonus” — equal roughly to about $7,000 in 2016 currency — for every Japanese plane they destroyed. This promise was not in writing. The volunteers were told simply that there was a “rumor” that the Chinese government would pay the bonus. Ultimately it did. A total of 296 were eventually paid to 67 pilots, most of whom shot down multiple Japanese aircraft.

3. The Flying Tigers never lost an air battle

Like Alexander the Great and a mere handful of heroes and heroic units throughout military history, the Flying Tigers were never defeated in combat. The pilots of the American Volunteer Group fought around 50 major aerial battles and never lost one. In their various engagements, they were almost always outnumbered by a factor of two-to-one, and usually by more than four-to-one, but they always prevailed. Radio Tokyo estimated that AVG combat strength was around 300 aircraft. In fact, the average rarely exceeded 36 available, with more than a dozen in the air at any given moment. The Japanese knew they substantially outnumbered the AVG, but but never imagined by just how much. A good laugh was had by the men when they tuned in to Radio Tokyo’s English language broadcasts to listen to the enemy report on their exploits. Only ten Flying Tigers were killed in action; seven of which perished in aircraft accidents. A full 19 of the unit’s pilots achieved the status of “ace,” which denotes five confirmed kills. Nine Flying Tigers topped 10 aerial victories, and Robert Neale exceeded 15.

4. They were in action for only seven months

Though their legacy looms large, making it seem as though their combat career must have spanned most of World War Two, the “undefeated season” of the American Volunteer Group lasted only from mid-December 1941 through mid-July 1942. The effective date of their contracts was July 4, 1941, but because of the logistical issues related to transporting the men and aircraft to the Far East, they did not fight their first aerial battle until Dec. 20 of that year. The contracts officially expired on July 4, 1942, but 55 AVG pilots and ground crewmen agreed to stay on for an additional two weeks until July 18. After that, the American Volunteer Group faded into history.

5. A civilian farmer led the contingent

Claire Lee Chennault was a chain-smoking former U.S. Army flyer with a face that seemed like it had been cut from worn leather with a dull knife. Nearly deaf and suffering from chronic bronchitis, he spent his last months in the service lying in a hospital bed. He entered civilian life in 1937 at age 43 at which point he planned to retire to his Louisiana farm. The ink was barely dry on his discharge when Chennault received an intriguing job offer — come to China job and serve as the chief military aviation advisor to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek! On the first day of May, 1937, just 24 hours after his retirement became effective, Chennault departed for for the Far East. He figured he’d give the new job three months; he ended up staying for eight years. As a farm owner, his passport identified him as a “farmer,” though officially, he was an “advisor” to the Central Bank of China. He was never to be offered a rank of any level in the Chinese Air Force, though he was always referred to informally in China — and later by all of the American flyers who served under him — as “Colonel Chennault.” In turn, he became the civilian leader of the Flying Tigers in 1941 when he convinced President Roosevelt to go along with his crazy idea for an “aerial foreign legion.”

6. The Flying Tigers weren’t allowed to refer to themselves ‘pilots’

Just like Chennault, the aviators of the American Volunteer Group carried passports that did not list them as flyers. In the new passports handed to them by CAMCO in the summer of 1941, each man’s alternate occupation was listed: banker, clerk, musician, student, etc. Ironically, the hard-drinking, barroom brawling, womanizing Greg Boyington was listed as a member of the clergy ! An American missionary who was traveling on the same ship with Boyington as the Flying Tigers sailed across the Pacific saw through the cover story almost immediately. When he asked Boyington whether he would like to deliver the sermon at the services on the upcoming Sunday, the red-faced former Marine Corps pilot declined.

7. The White House disavowed involvement in the Flying Tigers

It is widely believed that President Franklin Roosevelt authorized the American Volunteer Group through an executive order, but this is not true. In fact, the outfit’s very existence teetered on the edge of noncompliance with existing neutrality laws. Roosevelt anxiously wanted to help China save itself from the Japanese war machine, which was infamous for its “ Rape of Nanking .” He got his chance when Chennault came to him with daring a scheme for an “aerial foreign legion.” However, Roosevelt did it off the books to avoid legal inconveniences. As such, there was no executive order. Within the numbered, consecutive list of 381 executive orders issued by the president in 1941 and contained in the Federal Register, nothing remotely like the American Volunteer Group is mentioned. In fact, the dubious legality of the Fliying Tigers greatly disturbed many in the corridors of power, like Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau. Others, from Air Corps chief general Hap Arnold to Secretary of War Henry Stimson also harboured concerns.

8. The Flying Tigers struck America’s first blow against Japan

On Jan. 3, 1942, four American Volunteer Group pilots, Jack Newkirk, Jim Howard, Tex Hill, and Bert Christman, decided — partly to break the tension and partly out of sheer cockiness — to “take the war to the enemy” and stage a dawn raid on the Japanese base at Tak Airport near Raheng, north of Bangkok. Christman had to turn back early in the mission because of engine trouble, but the other three carried out the strike. Historian C. Douglas Sterner, the curator of the Military Times “Hall of Valor” has proposed that this spur-of-the-moment and ultimately successful mission was the first pre-planned American offensive action of World War Two. Of course, the three pilots were all civilian soldiers of fortune, and not active duty military personnel.

9. The Flying Tigers altered the course of the war in China

Though often overlooked in the history books, the actions of the American Volunteer Group at the Salween River Gorge probably altered the course of Chinese history by halting a Japanese offensive that might not have otherwise been stopped. By May 1942, the gorge was the only natural obstacle for the Japanese 56th Division marching into China from Burma. Had they crossed the Salween River, there would have been little to stop their march to Kunming , the headquarters of the Flying Tigers or even Chongqing , China’s wartime capital. Rather than dropping their few bombs directly on the Japanese column, the Tigers targetted the steep banks of the gorge, across which snaked the road in a long series of switchbacks. As the ordnance exploded, the road avalanched. Tons of falling rock and dirt snowballed into tens of tons of sliding gorge face dropping away from the cliff face like a calving glacier. Hundreds of troops and dozens of vehicles were swept downhill along with the plunging rocks and gravel to be buried in a massive, dust-billowing heap at the bottom. Without a route to advance, the 56th Division was forced to withdraw into Burma. They never threatened China from that direction again.

10. One of the flyers was a famous cartoonist

When he joined the Flying Tigers, Bert Christman ’s name was already a household word. During the 1930s, he had been the illustrator for the Scorchy Smith comic strip about a crime-fighting freelance pilot, and he was the artist and co-creator of the Sandman series for DC Comics . Anxious for adventure himself, Christman became a naval aviator, flying SB2U Vindicators off the USS Ranger — while continuing his career as a cartoonist in off hours. Craving something even more exciting, he resigned in 1941 to join the Flying Tigers. As a real life Scorchy Smith, he found the adventure he sought, and his fellow pilots found an illustrator who could create fantastic nose art for their aircraft. During an immense aerial battle over Rangoon, Burma on Jan. 23, 1942, Christman attacked a formation of enemy bombers but was jumped by several Japanese fighters. He managed to bail out of his burning aircraft, but was shot dead by Japanese pilots who fired at him as he hung helpless beneath his parachute. His comic strip would survive, in the hands of several other artists, until 1961. T he Sandman , has enjoyed various revivals and continues to make occasional cameo appearances, featured in retro settings, in DC Comics.

11. The Flying Tigers who were captured made dramatic escapes

Only three American Volunteer Group pilots are known to have been captured in action. Arnold Shamblin is believed to have bailed out of his plane, but never came back and is presumed to have been killed by his captors. Lew Bishop and William “Mac” McGarry both became prisoners — and then escaped . Bishop, who had been picked up by the Vichy French in Vietnam, was eventually turned over to the Japanese. Amazingly, he broke out of a prison train headed from Shanghai to Manchuria one night in early 1945. He managed to work himself free of his leg restraints in the dark without his captors noticing. While his train moved across the open country, he just stood up, hopped over the side of the car and rolled into a gully. Shots were fired but the engine did not stop. Bishop eventually made contact with an English-speaking Chinese man who was connected to the underground resistance and was smuggled to safety. Captured by Thai police after being downed over northern Thailand, Mac McGarry was handed over to the Japanese for interrogation, but when they were finished with him, they handed him back . The Thai authorities then jailed him in Bangkok. Enlisting the aid of an inside man, the U.S. Office of Strategic Services forged a death certificate so that McGarry could be successfully spirited out of the prison and out of the country in a coffin !

12. One of the Flying Tigers’s greatest heroes became an ace in Europe

When Flying Tiger Jim Howard returned home in 1942 after the American Volunteer Group was dissolved, he found invitations from both the USAAF and the U.S. Navy to enlist as an officer. A former navy aviator, he tired to return to North Island Naval Air Station in San Diego where he had served before the war. He still had his old pass and was waved through the front gate. When he went to call on the station commandant, the heavy-set captain became enraged and threatened to have Howard, an ace with six Japanese aircraft to his credit, arrested for illegal entry. He soon joined the USAAF and was overseas again, this time to serve with the 354th Fighter Group , where he piloted P-51 Mustangs with the Eighth Air Force out of England. He scored six aerial victories against the Luftwaffe , and on Jan. 11, 1944, he single-handedly engaged around 30 German fighters that were attacking American bombers over snow-covered Germany. Using tricks learned over the steamy jungles of the Far East, he downed three enemy aircraft that day, and continued to distract the Germans even after running out of ammunition. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for this action.

(Originally published in MilitaryHistoryNow.com on July 6, 2016)

Help spread the word. Share this article with your friends.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

21 thoughts on “ The Flying Tigers — 12 Facts About America’s Legendary Volunteer Fighter Squadron ”

I remember the Flying Tigers exploits and there was a member from my home town of Spartanburg S.C. I think his name was Mathias, He attended Wofford College there and was on their “track team. He was killed in ’42 I think in China..

Cool beans.

Man you must be old, old farts these days.

Mr. Powell that is very cool. And dang Mr. Brown what a rude thing to say? The other Mr. Brown (Kevin) was much nicer.

My father worked on The Flying Tigers aircraft in the Pacific and knew Pappy Boyington. Fantastic pilots…..I’m glad I listened to his stories.

Met one of the Flying Tigers today. What an honor.

My father was one of the flying tigers. I have all the letters he wrote to his mother and father and all his flight logs. The GREATEST GENERATION. We’ll never see another generation like it. Incredibly PROUD!!!!!

I had the great fortune of meeting ‘Pappy’ @ an airshow in 1984 – he autographed his book for me – what a great read and a interesting man! ‘Kudos’ to China for constructing a truly beautiful museum to the “AVG” in Kunming. You are so right on about that generation Betty – my Pops served in the Pacific (USMC) radio operator aboard AGC-1 ’43 – ’45; our cousin Don flew w/ the ‘Eagle’ squadrons then w/ the 4th FG in ETO. They all grew up in the ‘Depression’ and had nothing but gave everything.

George m. Bayone I was one of the Flying Tigers employee from 1973 to1987 very proud. we need to start a new airline called the Flying Tigers again.

how can I find out if my grandfather was part of this unit? He said he flew with the Flying Tigers, I have a photo of him next to a plane with the shark mouth paint job, and Green Hornet painted on the side. But I can find any mention of him on line.

Chris, email me your grandfather’s name, I have the tiger’s roster. [email protected] Reid

Was your grandfather AVG or 14th USAAF?

I have turned my 2000 Chevy S – 10 into a rolling tribute to the Flying Tigers ! I wish I could post pics here.

Where can I post pics ?

Can you tweet them to us? @milhistnow?

- Pingback: MOVIE REVIEW: Flying Tigers – Reformed Perspective

My grandfather (not a pilot) was part of the Flying tigers. Elliot Knecht. Why do some planes have star and some have a sun?

- Pingback: Wildcat vs. Zero – How America’s Grumman F4F Outfought ‘Superior’ Japanese Warplanes – MilitaryHistoryNow.com

I am wondering why there is no mention of Major Frank Schiel, Jr. who flew over 200 reconnaissance missions while a member of the AVG, China Task Force, 14th Air Force and was the last flying tiger still serving with Gen. Chennault. He was a flying tiger ace. He brought back very valuable photos of Japanese aerodromes — so valuable he was presented with the Silver Star for one of his missions. He also was the recipient of 2 Distinguish Flying Crosses, a British Distinguished Flying Cross and two of China military decorations – the Cloud and Banner and a 4 star wing medal. He was from Prescott. Arizona and if you believe it he has never been honored or remembered here.

From 1998 I created a Descent gaming group in honor of these heroes. Still going strong today 2023. Descent is a 360 degree first person shooter game flight simulator. One the greatest games ever produced for PC.

My father, Capt. Thomas O. Hunter was attached to the Flying Tigers and was their weather prognosticator. Dad was in the Army Air Corps, CBI Theater, but worked hand in hand with the pilots. He knew them all.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

From the MHN Archives

Top Posts & Pages

© COPYRIGHT MilitaryHistoryNow.com

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

THE TYGER VOYAGE

by Richard Adams illustrated by Nicola Bayley ‧ RELEASE DATE: Sept. 1, 1976

Though their spoofy intent doesn't entirely redeem the stultifying preciosity of Bayley's fussy Victorian interiors and surreal landscapes, the paintings do complement Adams' mock-heroic rhymed tale of the human narrator's "tyger" neighbors, Ezekiel and Raphael Dubb. Much to the consternation of the narrator's father, the Dubbs go off in a boat, land on a jungle island, climb a mountain that erupts while they're on it, are healed by a band of gypsies whom they join in their travels, and are at last found and sent home by "father." There's not a snag or a hint of strain in Adams' old-style verse and tongue-in-cheek decorum, but we found the whole performance as inconsequential as it is impeccable.

Pub Date: Sept. 1, 1976

ISBN: 978-1-56792-491-6

Page Count: 32

Publisher: Knopf

Review Posted Online: April 10, 2013

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Sept. 1, 1976

CHILDREN'S GENERAL CHILDREN'S

Share your opinion of this book

More by Richard Adams

BOOK REVIEW

by Richard Adams ; illustrated by Alex T. Smith

I WISH YOU MORE

by Amy Krouse Rosenthal ; illustrated by Tom Lichtenheld ‧ RELEASE DATE: April 1, 2015

Although the love comes shining through, the text often confuses in straining for patterned simplicity.

A collection of parental wishes for a child.

It starts out simply enough: two children run pell-mell across an open field, one holding a high-flying kite with the line “I wish you more ups than downs.” But on subsequent pages, some of the analogous concepts are confusing or ambiguous. The line “I wish you more tippy-toes than deep” accompanies a picture of a boy happily swimming in a pool. His feet are visible, but it's not clear whether he's floating in the deep end or standing in the shallow. Then there's a picture of a boy on a beach, his pockets bulging with driftwood and colorful shells, looking frustrated that his pockets won't hold the rest of his beachcombing treasures, which lie tantalizingly before him on the sand. The line reads: “I wish you more treasures than pockets.” Most children will feel the better wish would be that he had just the right amount of pockets for his treasures. Some of the wordplay, such as “more can than knot” and “more pause than fast-forward,” will tickle older readers with their accompanying, comical illustrations. The beautifully simple pictures are a sweet, kid- and parent-appealing blend of comic-strip style and fine art; the cast of children depicted is commendably multiethnic.

Pub Date: April 1, 2015

ISBN: 978-1-4521-2699-9

Page Count: 40

Publisher: Chronicle Books

Review Posted Online: Feb. 15, 2015

Kirkus Reviews Issue: March 1, 2015

More by Amy Krouse Rosenthal

by Amy Krouse Rosenthal & Christy Webster ; illustrated by Brigette Barrager & Chiara Fiorentino

by Tom Lichtenheld & Amy Krouse Rosenthal ; illustrated by Tom Lichtenheld

by Amy Krouse Rosenthal ; illustrated by Mike Yamada

STINK AND THE MIDNIGHT ZOMBIE WALK

From the stink series.

by Megan McDonald & illustrated by Peter H. Reynolds ‧ RELEASE DATE: March 13, 2012

This story covers the few days preceding the much-anticipated Midnight Zombie Walk, when Stink and company will take to the...

An all-zombie-all-the-time zombiefest, featuring a bunch of grade-school kids, including protagonist Stink and his happy comrades.

Pub Date: March 13, 2012

ISBN: 978-0-7636-5692-8

Page Count: 160

Publisher: Candlewick

Review Posted Online: Dec. 13, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Jan. 1, 2012

More In The Series

by Megan McDonald ; illustrated by Peter H. Reynolds

by Megan McDonald & illustrated by Peter H. Reynolds

More by Megan McDonald

by Megan McDonald ; illustrated by Scott Nash

by Megan McDonald ; illustrated by Katherine Tillotson

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

Do you want to stay on Global website or go to the UAE website?

Group Your bag is empty!

Everyday essentials

Tax included and shipping calculated at checkout

UK orders above £115 may be subject to additional import duties and taxes

Country & currency

- Austria EUR (€)

- Belgium EUR (€)

- Czechia EUR (€)

- Denmark DKK (kr.)

- Estonia EUR (€)

- Finland EUR (€)

- France EUR (€)

- Germany EUR (€)

- Greece EUR (€)

- Hungary EUR (€)

- Ireland EUR (€)

- Italy EUR (€)

- Latvia EUR (€)

- Lithuania EUR (€)

- Netherlands EUR (€)

- Norway NOK (kr.)

- Poland PLN (zł)

- Portugal EUR (€)

- Slovakia EUR (€)

- Spain EUR (€)

- Sweden SEK (kr.)

- United Kingdom GBP (£)

Account My account

Free shipping on orders above £40

Delivery fee of £5

New products every other week

- Did you know?

- Sustainability

Lemon serving plate

Lemon drinking glass. 220 ml

Lemon jug. 1.1 L

Strawberry serving dish

Lemon bowl. Small

Smartphone projector

Strawberry serving bowl. 3 pcs

Lemon napkins. 16 pcs

Picnic rug with carry handle

Lemon fabric napkins. 2 pcs

Lemon tablecloth. 220x140 cm

Bowl. Large

Storage box. Large

Foldable flamingo fan

Clam serving bowls. 2 pcs

Mist spray fan

Lemon tea towels. 2 pcs

Face and body paint. No perfume

Bead set. Incl. string

Lemon mug. 240 ml

Rainbow picnic blanket. 220x150 cm

Reusable water balloons. 5 pcs

Lemon snack box. Large

Snack box. Small

Picnic basket

Catch ball game

Laundry bag. For your luggage

Magnetic picture frames

Flower hairband. For adults

Sea shells drinking glass. 220 ml

Foldable fan

Red and pink glass beads box with...

Strawberry glass jar. 500 ml

Bowl. Small

Decorative Pride flag. 110x80 cm

Sticker book. Animals

Organiser bag

Portable cup with light

Inspiration from us and you

Tag @flyingtiger and join the fun. Explore a blend of our ideas and your creativity. Shop your favourites now.

See all the posts here

See all our inspiring minds here .

Things you didn't know existed

Table runner. 25 x 75 cm

Sweet vending machine

My little candy shop

Excavation kit

Winner trophy

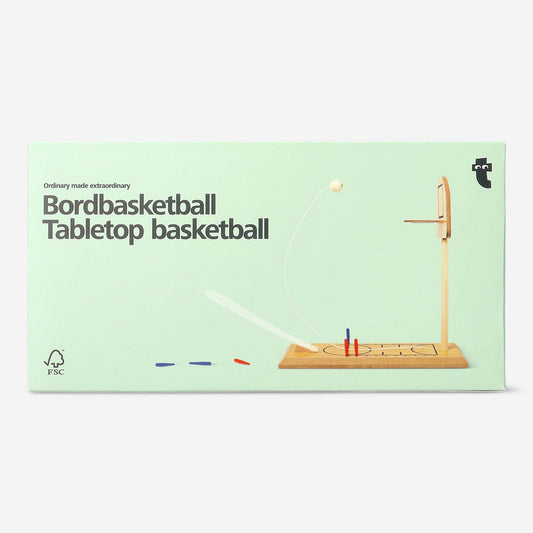

Tabletop basketball

Smartphone TV

Pink makeup sponge washing machine

Board game picnic blanket. 4 games

Travel bag for wardrobe. Foldable

Glowing drawing board

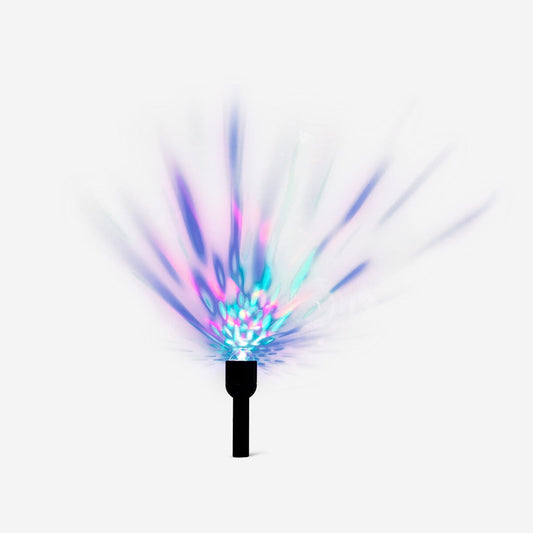

Handheld disco light

Candy bracelet

Dizzy glasses

Trending now, don't forget us.

Sustainable forests

When you choose FSC®-certified goods, you support the responsible use of the world's forests, and you help to take care of the animals and people who live in them. Look for the FSC mark on our products and read more at flyingtiger.com/fsc

You have {{X}} items in your basket.

Items in your basket are not reserved and may go out of stock. get them now before they go.

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Opens in a new window.

Please select your shipping country.

Buy from the country of your choice. Remember that we can only ship your order to addresses located in the chosen country.

- Austria / Österreich

- Czech Republic

- Eesti / Estonia

- Deutschland / Germany

- Greece / Ελλαδα

- Hungary / Hungary

- Italia / Italy

- Latvija / Latvia

- Lietuva / Lithuania

- Nederland / Netherlands

- Norway / Norge

- Polska / Poland

- Slovensko / Slovakia

- Sverige / Sweden

- United Kingdom

- Português (portugal)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Delivery details. Delivery from €5. Free on orders over €35. Delivery in 2-4 working days. Bottles with two different types of lids. Pack of 4 (60 ml). Flying Tiger Copenhagen.

Flying Tiger Copenhagen. Ignorer et passer au contenu Il semble que vous naviguiez depuis les Émirats arabes unis Voulez-vous rester sur le site Global ou aller sur le site des Émirats arabes unis ? ... Voyage Animaux domestiques Lunettes de lecture ...

Flying Tiger boats for sale on YachtWorld are offered at a range of prices from $21,823 on the lower-cost segment, with costs up to $49,500 for the most expensive, custom yachts. What Flying Tiger model is the best? Some of the most iconic Flying Tiger models currently listed include: 10M, FT 10 and FT10M. Specialized yacht brokers, dealers ...

Vessel FLYING TIGER is a Pleasure Craft, Registered in USA. Discover the vessel's particulars, including capacity, machinery, photos and ownership. Get the details of the current Voyage of FLYING TIGER including Position, Port Calls, Destination, ETA and Distance travelled - IMO 0, MMSI 368011240, Call sign WDJ7907

Following is a complete list of American Volunteer Group (Flying Tigers) pilots. The AVG was operational from December 20, 1941, to July 14, 1942. The press continued to apply the Flying Tigers name to later units, but pilots of those organizations are not included. ... On the ocean voyage to China, Petach became acquainted with Emma Jane ...

US Air Forces video: Flying Tigers Bite Back The First American Volunteer Group (AVG) of the Republic of China Air Force, nicknamed the Flying Tigers, was formed to help oppose the Japanese invasion of China.Operating in 1941-1942, it was composed of pilots from the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC), Navy (USN), and Marine Corps (USMC), and was commanded by Claire Lee Chennault.

Eric Lindner's Tiger in the Sea: The Ditching of Flying Tiger 923 and the Desperate Struggle for Survival tells the story of pilot John Murray's 1962 life-saving "ditch" of an L-1049H Super Constellation in the North Atlantic ocean, a barely controlled water landing with 76 passengers and crew members onboard. The effort captivated the world at the height of the Cold War.

The Last Voyage of the Flying Tiger Sunday, January 10, 2016. A 1600-mile trip with an old boat, from Kodiak, ... The 60' Flying Tiger, built in 1947, was the workhorse of a remote salmon cannery located deep in the fiord-like Uganik bay on the west side of Kodiak Island. This cannery-owned boat had a daily route around the outer bay stopping ...

Flying Tiger Line. Flying Tiger Line, also known as Flying Tigers, was the first scheduled cargo airline in the United States and a major military charter operator during the Cold War era for both cargo and personnel (the latter with leased aircraft). The airline was bought by Federal Express in 1989.

Flying Tiger Copenhagen (formerly Tiger) is a Danish variety store chain. Its first shop opened in Copenhagen in 1995 and the chain now has nearly 1000 shops. Its largest markets are Denmark, the UK, Italy, and Spain.Before June 2016, it operated as Tiger (or Tiger Copenhagen) in most markets, as T·G·R in Sweden and Norway, as Flying Tiger Copenhagen (or just Tiger Copenhagen) in Ireland ...

Here are five things you should know about the Flying Tigers: 1. One man was behind the genius of the AVG's winning air strategy: Claire Chennault. U.S. Army Air Corps aviator Claire Chennault ...

Flying Tigers wore these famous "blood chits" pinned to the back of their jackets. It reads: "This foreign person has come to China to help in the war effort. Soldiers and civilians, one and all, should rescue and protect him." (Image source: WikiCommons) 11. The Flying Tigers who were captured made dramatic escapes

Flying Tiger Copenhagen. 1.3M likes · 26 were here. Halløj! We love design, creativity and fun. Follow us and get inspired for home, office and play! #flyingtiger

Get the details of the current Voyage of FEI PENG including Position, Port Calls, Destination, ETA and Distance travelled - IMO 9610286, MMSI 414689000, Call sign BPDQ5. Vessel FEI PENG is a Bulk Carrier, Registered in China. Discover the vessel's particulars, including capacity, machinery, photos and ownership. Get the details of the current ...

At Flying Tiger Copenhagen, we design products to make you feel good - Find inspirational products in our new webshop. Flying Tiger Copenhagen - Shop Online Discover unique items that spark joy at Flying Tiger Copenhagen's webshop - Treat yourself to something special today!

After the Northern Expedition, Chiang Kai-shek began to expand his air force through purchasing U.S. aircraft and recruiting U.S. advisers. On February 22, 1932, Robert M. Short, a demonstration ...

Vessel FLYING TIGER is a Pleasure Craft, Registered in USA. Discover the vessel's particulars, including capacity, machinery, photos and ownership. Get the details of the current Voyage of FLYING TIGER including Position, Port Calls, Destination, ETA and Distance travelled - IMO 0, MMSI 338112876, Call sign

California. $23,900. Description: We have done much cursing and day sailing with her, mainly with children and young adults- she has a large cockpit. Two large Pt. & Stb. berth two smaller, V-berth. She sails faster than most catamarans, S.A. / Displ/ is 32 (above 20 is good below not) O.B.O. Equipment: Potty, 2x Anchors, chain & rode, Carbon ...

THE TYGER VOYAGE. by ... It starts out simply enough: two children run pell-mell across an open field, one holding a high-flying kite with the line "I wish you more ups than downs." But on subsequent pages, some of the analogous concepts are confusing or ambiguous. The line "I wish you more tippy-toes than deep" accompanies a picture of ...

Vessel FLYING TIGER is a Pleasure Craft, Registered in USA. Discover the vessel's particulars, including capacity, machinery, photos and ownership. Get the details of the current Voyage of FLYING TIGER including Position, Port Calls, Destination, ETA and Distance travelled - IMO 0, MMSI 338182957, Call sign

Flying Tiger Philippines. 4.6K likes · 867 talking about this. Halløj! We love design, creativity and fun. Follow us and get inspired for home, office and play!

LENGTH: Traditionally, LOA (length over all) equaled hull length. Today, many builders use LOA to include rail overhangs, bowsprits, etc. and LOD (length on deck) for hull length. That said, LOA may still mean LOD if the builder is being honest and using accepted industry standards developed by groups like the ABYC (American Boat and Yacht Council).

At Flying Tiger Copenhagen, we design products to make you feel good - Find inspirational products in our new webshop.