- A Brief History Of Irish...

A Brief History of Irish Travellers, Ireland’s Only Indigenous Minority

After a long battle, Irish Travellers were finally officially recognised as an indigenous ethnic minority by Ireland’s government in early March 2017. Here, Culture Trip takes a look at the origins of the Irish Travelling community and how the historic ruling came about. At the time of the 2011 census , there were around 29,500 Irish Travellers in the Irish Republic , making up 0.6% of the population. The community was found to be unevenly distributed across the country, with the highest number living in County Galway and South Dublin. Although – as the name suggests – Irish Travellers have historically been a nomadic people, the census showed a majority living in private dwellings.

Throughout Irish history, the Travelling community has been markedly separated from the general Irish population, resulting in widespread stereotyping and discrimination. The same year as the census, a survey conducted by Ireland’s Economic and Social Research Institute found that Irish Travellers suffer widespread ostracism; this and other factors have been shown to contribute to high levels of mental health problems among Irish Travellers. Indeed, the 2010 All Ireland Traveller Health Study found their suicide rate to be six times the national average, accounting for a shocking 11% of Traveller deaths.

Through the 2011 census, members of the Travelling community were also found to have poorer general health, higher rates of disability and significantly lower levels of education as compared to the general population, with seven out of 10 Irish Travellers educated only to primary level or lower.

Because of a lack of written history, the exact origins of the Irish Travelling Community have been difficult to clarify. Although it had been hypothesised, until relatively recently, that Irish Travellers may be linked to the Romani people, a genetic study released in February of this year revealed this connection to be false.

The study found that Travellers are of Irish ancestral origin, but split off from the general population sometime around the mid-1600s – much earlier than had been thought previously. In one widely quoted finding, the DNA comparisons conducted in the course of the research found that while Irish Travellers originated in Ireland, they are genetically different from ‘settled’ Irish people, to the same degree as people from Spain.

The results of the study, conducted by the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, University College Dublin, the University of Edinburgh and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, contributed significantly to Irish Travellers being officially designated an ethnic minority, defined as a group within a community with different national or cultural traditions from the main population.

Speaking to RTE on the day of the ruling, former director of the Irish Traveller Movement Brigid Quilligan said, ‘We want every Traveller in Ireland to be proud of who they are and to say that we’re not a failed set of people. We have our own unique identity, and we shouldn’t take on all of the negative aspects of what people think about us. We should be able to be proud and for that to happen our State needed to acknowledge our identity and our ethnicity, and they’re doing that today.’

Culture Trips launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes places and communities so special.

Our immersive trips , led by Local Insiders, are once-in-a-lifetime experiences and an invitation to travel the world with like-minded explorers. Our Travel Experts are on hand to help you make perfect memories. All our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.?>

All our travel guides are curated by the Culture Trip team working in tandem with local experts. From unique experiences to essential tips on how to make the most of your future travels, we’ve got you covered.

Places to Stay

The best cheap hotels to book in killarney, ireland.

Guides & Tips

These are the places you need to go on st patrick’s day .

The Best Hotels to Book in Ireland

The Best Coastal Walks in the World

Top Tips for Travelling in Ireland

The Best Hotels to Book in Killarney, Ireland, for Every Traveller

See & Do

24 hours in ireland’s second cities.

Somewhere Wonderful in Ireland Is Waiting

The Best Private Trips to Book For Your English Class

History and Culture on an Ireland Road Trip

Food & Drink

Combining ireland’s finest whiskey with sustainable forestry.

Tourism Ireland Promotion Terms & Conditions Culture Trip Ltd (Culture Trip)

Culture trip spring sale, save up to $1,100 on our unique small-group trips limited spots..

- Post ID: 1176219

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

- Schools & departments

Gene study reveals Irish Travellers' ancestry

Irish Travellers are of Irish ancestral origin and have no particular genetic ties to European Roma groups, a DNA study has found.

The research offers the first estimates of when the community split from the settled Irish population, giving a rare glimpse into their history and heritage.

Researchers led by the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) and the University of Edinburgh analysed genetic information from 42 people who identified as Irish Travellers.

The team compared variations in their DNA code with that of 143 European Roma, 2,232 settled Irish, 2,039 British and 6,255 European or worldwide individuals.

Irish ancestry

They found that Travellers are of Irish ancestral origin but have significant differences in their genetic make-up compared with the settled community.

These differences have arisen because of hundreds of years of isolation combined with a decreasing Traveller population, the researchers say.

The findings confirm that the Irish Traveller population has an Irish ancestry and this comes at a time where the ethnicity of Travellers is being considered by the Irish State. Professor Gianpiero Cavalleri Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland

The team estimates the group began to separate from the settled population at least 360 years ago.

Their findings dispute the theory that Travellers were displaced by the Great Famine, which struck Ireland in 1845.

It is exciting to find that the Irish Travellers have been genetically isolated for such a considerable time. They hold great potential for understanding common diseases, not just within their own community but also more generally. I hope very much that further funding will allow us to study the genetics of the Travellers in more detail. Professor Jim Wilson Usher Institute for Population Health Sciences and Informatics

Tight community

There are estimated to be up to 40,000 Travellers living in Ireland, which represents less than one per cent of the population.

Little is known about the group's heritage and there is scant documentary evidence of their history.

The study is published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Related links

Journal article in Scientific Reports

RCSI press release

Jim Wilson's profile on Edinburgh Research Explorer

Gianpiero Cavalleri's profile at RSCI

- PHOTOGRAPHY

Life With the Irish Travellers Reveals a Bygone World

One photographer spent four years gaining unprecedented access to this close-knit community.

When Birte Kaufmann first encountered Irish Travellers, she was on a trip with friends in the Irish countryside and saw a girl and her little brother running toward a roadside camp. The caravans and horses reminded Kaufmannn, who is German, of the Romany camps she had seen elsewhere in Europe, but the people looked intriguingly different.

Who were they, she wondered, and how could she delve deeper into their culture?

"People said, You'll never get an insight into that community—forget about it," Kaufmann recalls of sharing with Irish friends her burgeoning plans to photograph the close-knit Travellers.

An ethnic minority in Ireland , the Travellers have lived on the margins of mainstream Irish society for centuries. Efforts have been made to incorporate the nomadic group into mainstream culture by settling them into government housing and enforcing school attendance. But even living among "settled people," they face ongoing discrimination.

Kaufmann describes theirs as a parallel world, where deeply-rooted gender roles and an itinerant lifestyle have kept them apart from the broader Irish community even as their freedom to roam has become increasingly curtailed.

To gain access to the community, Kaufmann first attempted to engage through human rights groups that work with them—to no avail. So she decided to do it "the hard way," she says. She had heard about a “halting site”—walled areas on the outskirts of large towns that contain houses as well as spaces for caravan parking—and on her next trip to Ireland, she simply showed up.

She was met by barking dogs, one of which bit her. A young woman approached, speaking English with an accent so thick that Kaufmann had trouble comprehending. Undeterred, she decided to lay her cards on the table. "I was really honest. I told [her] I was coming from Germany , where we don't have our own traveling community, [that] I knew who they were and was interested in how [they live]," Kaufmann recalls.

The young woman "was totally surprised, but finally they invited me for a cup of tea. I was sitting in a caravan with her grandfather. I asked them if I could come back and stay with them." Kaufmann says they chortled, as if to say, Yeah, right.

When she next returned from Germany, it was with a camper van of her own, so that she could stay alongside the extended family clan that would become the focus of her project. "I knew it was a high risk," she says, “but I gave them some pictures I had taken in the caravan of the grandfather. And they said, 'Ok. Now you're here. We have the images. One cup of tea. Now go. We are busy.'"

You May Also Like

Barbie’s signature pink may be Earth’s oldest color. Here’s how it took over the world.

Meet the 5 iconic women being honored on new quarters in 2024

Does this ‘secret room’ contain Michelangelo’s lost artwork? See for yourself.

As a photographer, and especially as a woman, Kaufmann was something of a novelty given the strictly defined gender roles of the Traveller community—men tend to the horses and livestock, women to home and family. Girls marry young and only with the blessing of their parents. Men don’t typically speak to women in public.

She slowly gained their trust to the point that one of the family members—a young mother who took a particular shine to her and was perhaps even amused at her struggle to understand what they were saying—began teaching her Gammon, their unwritten language.

"She tried to teach me words to say if the guys are being rude," she says. "And then the father started telling me what I should say. [They] tried to make me feel more comfortable." Her knowledge of words selectively and seldom shared with outsiders demonstrated to other Travellers that one of their own had trusted her enough to share.

And in turn, understanding how they communicate with each other helped her get past the sense of feeling unwelcome and deepened her appreciation of their differences. "At first [the talk] sounds really rough," she says. "Then there was this point at which I realized it was their language. They don't really call anyone by name. It's 'the woman over there,' 'the man over there,' 'the child,'" she explains. "It's not personal, [but] at first it sounds very rude.”

Kaufmann made multiple visits to the family over the course of four years, eventually living with them. The men gradually accepted her and allowed her to photograph them hunting and trading horses at a fair. She was able to blend into the background and photograph them as an unobtrusive observer of their everyday lives—lives, she says, that are filled with a lot of idle time. As Ireland becomes less agrarian, the Travellers’ traditional work as horse traders, farm laborers, tinsmiths, and entertainers has become more scarce.

"The older generations can't read or write," Kaufmann says, "but they have their own intelligence. On the one hand life was so sad and boring because everything their lives were stemming from wasn't there anymore. On the other hand there was this freedom—they live their lives in their own way."

And then, she says, she found herself taking no photographs at all. "One of the boys who really didn't like to be photographed said, 'Do you know what's really strange with Birte now? She's here and she's not really photographing anymore.'"

And that's when she knew her project was done.

Birte Kaufmann's project on the Travellers is now available as a book . You may also see more of Birte Kaufmann's photographs on her website .

Related Topics

- PEOPLE AND CULTURE

- FAMILY LIFE

- PHOTOGRAPHERS

Just one pregnancy can add months to your biological age

Dementia has no cure. But there’s hope for better care.

IVF revolutionized fertility. Will these new methods do the same?

These Black transgender activists are fighting to ‘simply be’

Revealing the hidden lives of ancient Greek women

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 16 February 2017

Genomic insights into the population structure and history of the Irish Travellers

- Edmund Gilbert 1 ,

- Shai Carmi 2 ,

- Sean Ennis 3 ,

- James F. Wilson 4 , 5 na1 &

- Gianpiero L. Cavalleri 1 na1

Scientific Reports volume 7 , Article number: 42187 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

35k Accesses

24 Citations

119 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Consanguinity

- Population genetics

The Irish Travellers are a population with a history of nomadism; consanguineous unions are common and they are socially isolated from the surrounding, ‘settled’ Irish people. Low-resolution genetic analysis suggests a common Irish origin between the settled and the Traveller populations. What is not known, however, is the extent of population structure within the Irish Travellers, the time of divergence from the general Irish population, or the extent of autozygosity. Using a sample of 50 Irish Travellers, 143 European Roma, 2232 settled Irish, 2039 British and 6255 European or world-wide individuals, we demonstrate evidence for population substructure within the Irish Traveller population, and estimate a time of divergence before the Great Famine of 1845–1852. We quantify the high levels of autozygosity, which are comparable to levels previously described in Orcadian 1 st /2 nd cousin offspring, and finally show the Irish Traveller population has no particular genetic links to the European Roma. The levels of autozygosity and distinct Irish origins have implications for disease mapping within Ireland, while the population structure and divergence inform on social history.

Similar content being viewed by others

Genome-wide association studies

Analysis of somatic mutations in whole blood from 200,618 individuals identifies pervasive positive selection and novel drivers of clonal hematopoiesis

Leveraging functional genomic annotations and genome coverage to improve polygenic prediction of complex traits within and between ancestries

Introduction.

The Irish Travellers are a community within Ireland, consisting of between 29,000–40,000 individuals, representing 0.6% of the Irish population as a whole 1 . They are traditionally nomadic, moving around rural Ireland and providing seasonal labour, as well as participating in horse-trading and tin-smithing 2 . Since the 1950’s the need for such traditional services has declined 3 , and the population has become increasingly urban, with the majority living within a fixed abode 1 . Despite this change in lifestyle, the Traveller community remains tight-knit but also socially isolated. The population has its own language 4 , known as Shelta, of which Cant and Gammon are dialects.

There is a lack of documentary evidence informing on the history of the Irish Traveller population 5 , 6 . As a result, their origins are a source of considerable debate, with no single origin explanation being widely accepted. It has been suggested that the Irish Travellers are a hybrid population between settled Irish and Romani gypsies, due to the similarities in their nomadic lifestyle. Other, “Irish Origin”, hypothesised sources of the Irish Travellers include; displacement from times of famine (such as between 1740–1741, or the Great Famine of 1845–1852), or displacement from the time of Cromwellian (1649–53) or the Anglo-Norman conquests (1169 to 1240). The Irish Traveller population may even pre-date these events, and represent Celtic or pre-Celtic isolates 4 . These models of ethnogenesis are not necessarily mutually exclusive, and the Irish Traveller population may have multiple sources of origin with a shared culture.

Consanguineous marriages are common within the Irish Traveller community 7 , 8 . Small, isolated and endogamous populations such as the Travellers are also more prone to the effects of genetic drift. The isolation and consanguinity have in turn led to an increased prevalence of recessive diseases 7 , 9 , 10 , with higher incidences of diseases such as transferase-deficient galactosaemia 11 , 12 , and Hurler syndrome 13 observed in the Traveller population relative to the settled Irish. However, the extent of autozygosity within the population has yet to be quantified; as a result it is unknown how homozygous the population is compared to other, better-studied, isolated European populations.

Previous work into the genetics of the Irish Traveller population has been conducted on datasets of relatively low genetic resolution. A recent study used blood groups to investigate the population history of the Irish Travellers 2 . Multivariate analysis of genotype data across 12 red blood cell loci in 119 Irish Travellers suggested that the population clustered closely with the settled Irish to the exclusion of the Roma. They did, however, appear divergent from the settled Irish. The authors attributed the source of such divergence to genetic drift - but were unable to determine whether any such drift was due to a founder effect, or sustained endogamy. Studies of Mendelian diseases suggest that pathogenic mutations in the settled Irish population are often the same as those observed in the Traveller population such is the case for tranferase-deficient galactosaemia (Q118R in the GALT gene 11 ) and Hurlers Syndrome (W402X, in the α-l-iduronidase gene 13 ).

Using dense, genome-wide, SNP datasets which provide much greater resolution than genetic systems studied in the Travellers to date, we set out to i) describe the genetic structure within the Traveller population, ii) the relationship between the Irish Travellers and other European populations, iii) estimate the time of divergence between the Travellers and settled Irish, and iv) the levels of autozygosity within the Irish Traveller population.

Population Structure of the Irish Travellers

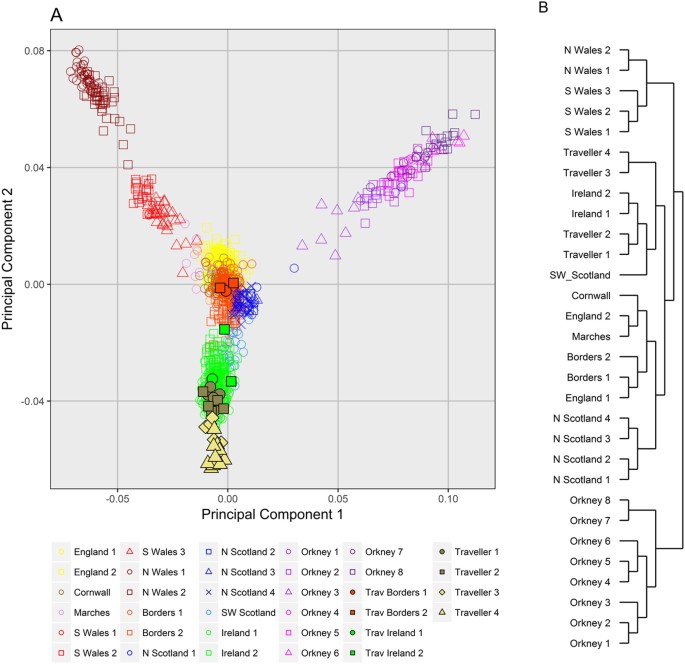

In order to investigate the genetic relationship between the Irish Travellers and neighbouring populations we performed fineStructure analysis on Irish Travellers, settled Irish from a subset of the Trinity Student dataset 14 , and British from a subset of the POBI dataset 15 . A subset of the datasets were used in this analysis as we were primarily interested in the placing of the Irish Travellers within the context of Britain and Ireland, not the full structure found within Britain and Ireland. The results are presented in Fig. 1 in the form of a principal component analysis of fineStructure’s haplotype-based co-ancestry matrix (1A) and a dendrogram of the fineStructure clusters (1B).

( A ) The first and second components of principal component analysis of the haplotype-based co-ancestry matrix produced by fineStructure analysis. Individual clusters are indicated by colour and shape. Individual Irish Travellers are indicated with black bordered shapes, with cluster shown in Legend. ( B ) The full fineStructure tree with the highest posterior probability, with cluster size and name, and broad branches shown.

We observe that 31 of 34 of the Irish Travellers cluster on the Irish branch, indicating a strong affinity with an Irish population ancestral to the current day “Traveller” and “settled” populations ( Fig. 1B ). One “Irish Traveller” is found within the Borders 1 cluster, and two are found within the Borders 2 cluster. These three individuals report full, or partial, English gypsie ancestry, a distinct and separate travelling population in Britain. One individual is found within the Ireland 1 cluster, and two are found within the Ireland 2 cluster. Traveller individuals within the Ireland 2 cluster report recent settled ancestry, and we have no such genealogical data on the individual grouped within the Ireland 1 cluster. Given their mixed ancestry, these individuals were excluded from subsequent F st , f 3 , and divergence estimate work.

The remaining 28 Irish Travellers in the fineStructure analysis were arranged into four clusters. These clusters were grouped on two separate branches ( Fig. 1B ), with Traveller 1 (n = 7) and Traveller 2 (n = 5) on the same branch, and Traveller 3 (n = 5) and Traveller 4 (n = 11) on a separate branch. The branch with clusters Traveller 3 and 4 , forms an outgroup to the rest of the settled Irish and Irish Traveller clusters. These two branches of Irish Traveller clusters align closely with the split of Irish Travellers observed through PCA ( Fig. S1 ). All the individuals who separate on the first principal component (henceforth “PCA group B”) are found in clusters Traveller 3 and 4 ( Fig. S2A ), and nearly all the individuals who remain grouped with the settled Irish on principle component 1 (henceforth “PCA group A”) are found in clusters Traveller 1 and 2 ( Fig. S2A ). The remaining PCA group A individuals are those Irish Travellers found in the aforementioned settled Irish or British clusters. This pattern is also repeated in the PCA ( Fig. 1A ), where members of Traveller 1 and 2 cluster with the settled Irish, where Traveller 3 and 4 individuals cluster separately.

Having identified distinct genetic groups of Irish Travellers, we investigated the correlation with Irish Traveller sociolinguistic features, specifically Shelta dialect, and Rathkeale residence ( Fig. S2B ,C, respectively). The majority of the Gammon speakers were members of clusters Traveller 1 and 2. All of Traveller 1 consisted of Gammon speakers. The majority of clusters Traveller 3 and 4 consisted of Cant speakers, where all but one individual, for whom language identity is unknown, of Traveller 4 were Cant speakers. We found that only clusters Traveller 1 and 2 contain any Rathkeale Travellers, where 4 out of 5 individuals in Traveller 2 are Rathkeale Travellers.

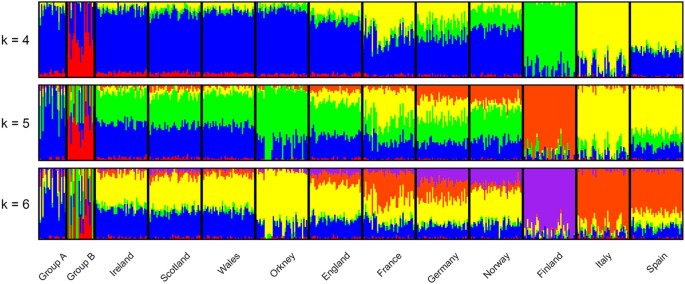

We next investigated population structure using the maximum-likelihood estimation of individual ancestries using ADMIXTURE ( Figs 2 and S3). For this analysis we used a subset of the European Multiple Sclerosis dataset consisting of three northern European (Norway, Finland and Germany), two southern European (Italy and Spain), and a neighbouring population (France). We categorised the POBI British as English, Scottish, Welsh, and Orcadian. We further separated out the Irish Travellers to those in PCA group A and those in PCA group B.

Shown are the ancestry components per individual for the two groups of Irish Travellers (Group A and Group B), settled Irish, British, and European populations; modelling for 4 to 6 ancestral populations.

At k = 4–6 ( Fig. 2 ), we observe the well-described north-south divide in the European populations ( k = 4), as well as Finland and Orkney ( k = 5) differentiating due to their respective populations’ bottleneck and isolation. Although at lower values of k the Irish Travellers generally resemble the settled Irish profile ( Fig. S3 ), at higher values of k two components are found to be enriched within the population. Each of these components is enriched in one of the two Irish Traveller PCA groups. Individuals with more than 20% of the “red” component when k = 5 belong to PCA group B and individuals with near 100% of “blue” component all belong to PCA group A ( Fig. 2 ). The fact that even at k = 3 PCA group B gains its own ancestral component ( Fig. S3 ) suggests strong group-specific genetic drift.

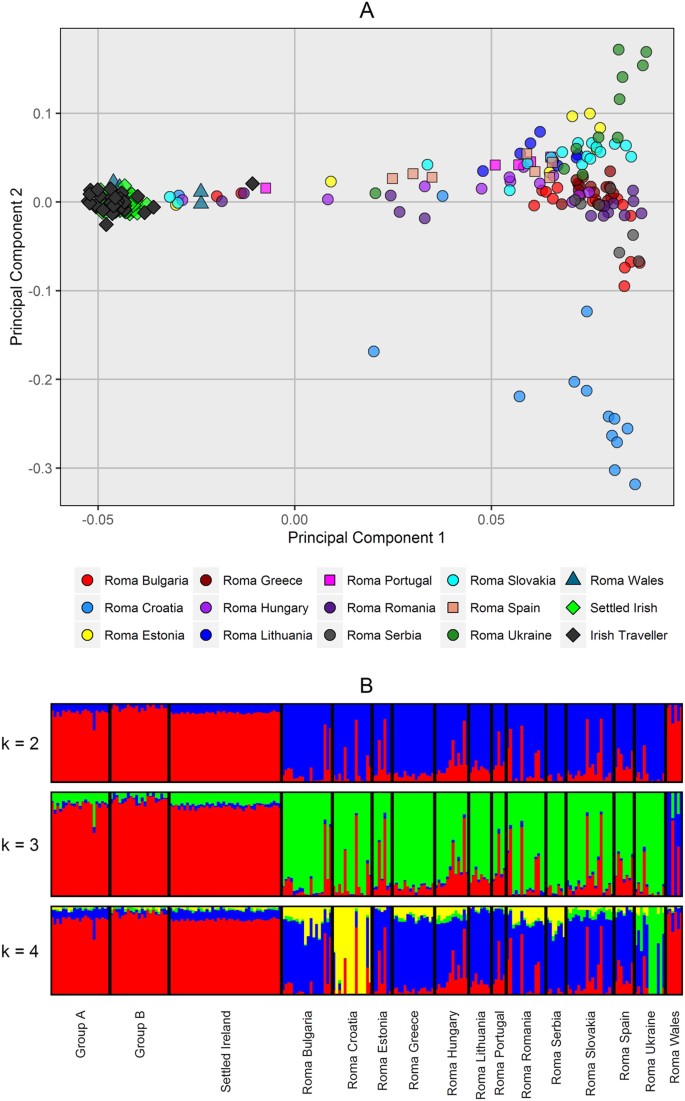

In order to investigate a possible Roma Gyspie origin of the Irish Travellers, we compared the Irish Travellers, and settled Irish to a dataset of Roma populations found within Europe 16 using PCA and ADMIXTURE. The results broadly agree, with the Irish Travellers clustering with the settled Irish in the PCA plot, and resembling the settled Irish profile in ADMIXTURE analysis (see Fig. 3 ). There was no evidence for a recent ancestral component between the Irish Traveller and Roma populations. In addition, we formally tested evidence of admixture with f 3 statistics in the form of f 3 (Irish Traveller; Settled Irish, Roma). We found no evidence of admixture either when considering all the Roma as one population, or in each individual Roma population’s case (all f3 estimates were positive).

( A ) The first and second components from principal component analysis using gcta64. ( B ) The ancestry profiles using ADMIXTURE, assuming 2 to 4 ancestral populations.

Given the apparent structure between the Travellers and the settled Irish populations, we quantified genetic distance using F st and “outgroup” f 3 statistics. F st analysis reveals a considerable genetic distance between the settled Irish and the Irish Traveller population (F st = 0.0034, Table S1 ) which is comparable to values observed between German and Italian, or Scotland and Spain.

In order to further investigate sub-structure within the Irish Travellers, we performed F st analysis on the Irish Traveller PCA (n = 2) and fineStructure (n = 4) groups, comparing them to the settled Irish (see also Table S1 ). The individuals belonging to cluster PCA group B are considerably more genetically distant from the settled Irish (F st = 0.0086), relative to PCA group A (F st = 0.0036). This could be explained by distinct founder events for PCA groups A and B, or that PCA group B has experienced greater genetic drift. The F st estimates of the Irish Traveller clusters are higher than the PCA groups. The estimates of clusters Traveller 1, 2 , and 3 range from 0.0052 to 0.0054. However, Traveller 4 shows the highest F st value (F st = 0.0104), suggesting this cluster of individuals is responsible for the inflation of the PCA group B’s estimate. Generally, however, these results suggest that the general Irish Traveller population does not have a very recent source, i.e. within 5 generations or so. If we perform the same F st analysis on two random groups of settled Irish see observe a F st value < 1∙10 −5 .

To inform on whether lineage-specific drift is influencing the observed genetic distances between the Irish Travellers, the settled Irish and other neighbouring populations, we performed outgroup f 3 analysis, using HGDP Yorubans as the outgroup. Such analysis can inform on whether PCA group B and Traveller 4 do indeed represent an older Irish Traveller group, or a sub-group that has experienced more intense drift. When we compare PCA groups A/B to the settled Irish we see no significant difference between the two groups (see Table S2 , A:settled f 3 = 0.1694 (stderr = 0.0013), B:settled f 3 = 0.1698 (stdrr = 0.0013), A:B f 3 = 0.1700 (stderr = 0.0013)); with similar results for the fineStructure clusters ( Table S2 ). These results suggest that PCA group B has experienced more drift than PCA group A, inflating the F st statistic, which in turn has inflated the Irish Traveller population F st . We note however that f 3 statistics may not be sensitive enough to detect differences from settled Irish to Traveller PCA groups A and B should the difference between A and B be a relatively limited number of generations.

A key question in the history of the Travellers is the period of time for which the population has been isolated from the settled Irish. In order to address this we utilized two methods, one based on linkage disequilibrium patterns and F st (which we call T F ), and one based on Identity-by-Descent (IBD) patterns (which we call T IBD ).

The T F method estimates the divergence to be 40 (±2 std.dev – obtained via bootstrapping) generations. Assuming an average generation time of 30 years the T F method estimates that the divergence occurred 1200 (±60 – std.dev) years ago. The method also estimates the harmonic mean N e for the two populations over the last 2000 years. The Irish Traveller estimate (1395, std.dev = 16 – obtained via bootstrapping) is considerably lower than the settled Irish estimate (6162, std.err = 122 – obtained via bootstrapping). However, the isolation of the Irish Travellers will artificially increase the F st value and consequently inflate the T F divergence estimate. We therefore estimated the divergence time with a different IBD-based method; as such an approach can accommodate genetic drift.

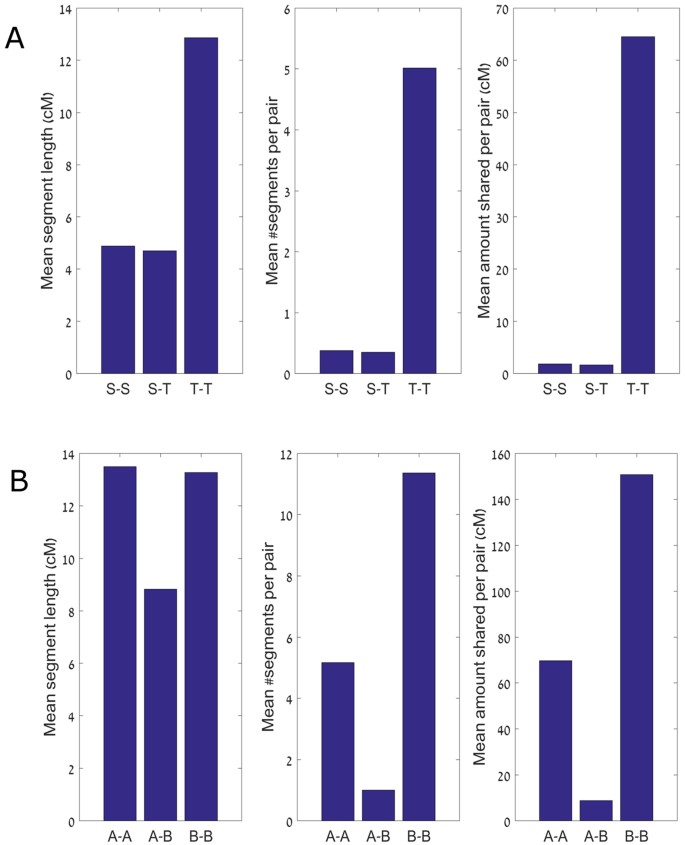

We first identified IBD segment sharing within and between the Irish Travellers and our settled Irish subset. The Irish Travellers were found to share 35-fold more genetic material IBD (in cM per pair) than the settled population ( Fig. 4A ). Specifically, a pair of Travellers share, on average, 5.0 segments of mean length 12.9 cM, compared to 0.4 segments of mean length 4.9 cM for the settled population ( Fig. 4A ; segments with length >3 cM). Additionally we compared IBD sharing within and between the two PCA groups; A and B ( Fig. 4B ). We observe a greater amount of IBD segments shared within PCA group B than PCA group A. These sharing patterns are not due to familial sharing, as we have previously removed individuals with close kinship (see Supplementary Methods 1.3 ). Sharing between settled and Traveller Irish was of similar extent to that within the settled group ( Fig. 4A ), with no significant difference between the PCA groups A and B (p = 0.12, using permutations, for the difference in the number of segments shared with the settled) ( Fig. S4 ). We used the number and lengths of segments shared within settled, within Travellers, and between the groups to estimate the demographic history of those populations, and in particular, the split time between these two groups.

( A ) The number and lengths of shared segments within Settled Irish, within Traveller Irish, and between the groups. Left panel: The mean segment length; middle panel: the mean number of shared segments; right panel: the mean total sequence length (in cM) shared between each pair of individuals. ( B ) The number and lengths of shared segments within Traveller Group A, Traveller Group B, and between the groups. The format of the figure is as in ( A ).

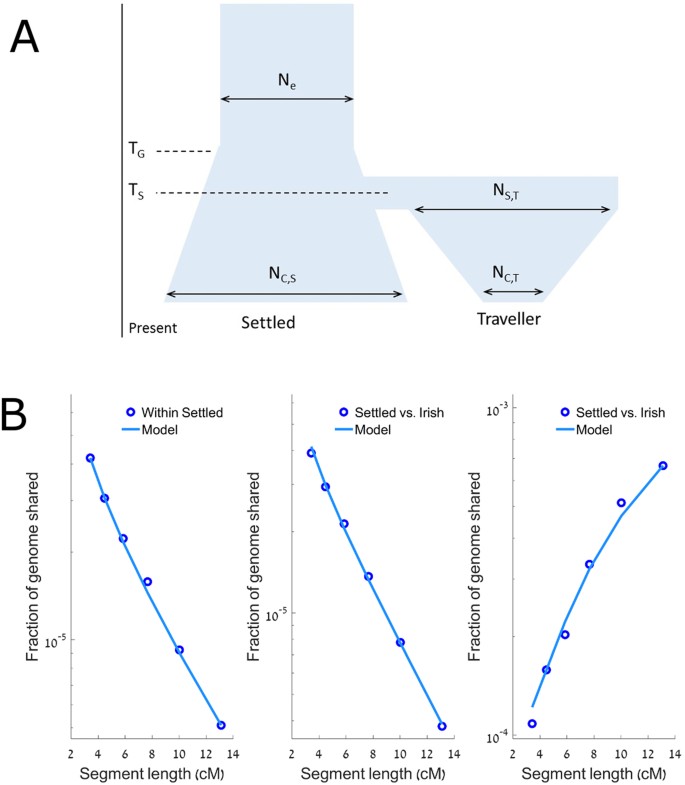

Briefly, we used the method developed in Palamara et al . 17 (see also Zidan et al . 18 ). We assumed a demographic model for the two populations ( Fig. 5A ), in which an ancestral Irish population has entered a period of exponential expansion before the ancestors of the present day settled Irish and Irish Travellers split. After this split, the settled Irish continued the exponential expansion, whilst the Irish Travellers experienced an exponential population contraction. We then computed the expected proportion of the genome found in shared segments of different length intervals using the theory of ref. 17 , and found the parameters of the demographic model that best fitted the data (see Supplementary Data 1.3 , Fig. 5B , and Table 1 ).

( A ) The model used for demographic inference. The two populations were one ancestral population, with size N e , T G generations ago. At this point the ancestral population started to grow exponentially until T S generations ago, where the ancestral Traveller and settled populations split from each other, with N S,T being the initial starting population size of the Traveller population. The settled population experienced continued exponential growth until the present, with a population size of N C,S . The Traveller population experienced a period of exponential contraction until the present, with a population of N C,T . ( B ) The proportion of the genome in IBD segments vs the IBD segments length. The total genome size and the sum of segment lengths were computed in cM. Left: sharing between pairs of settled Irish; middle: sharing between pairs of one settled and one Traveller individuals; right: sharing between pairs of Traveller Irish. Each data point is located at the harmonic mean of the boundaries of the length interval it represents.

The results of the model suggest the Irish Travellers and settled Irish separation occurred 12 generations ago (95% CI: 8–14). The results also support opposite trends in the effective population sizes (N e ) of the settled and Traveller Irish since that split: while the settled population has expanded rapidly, the Irish Travellers have contracted (see Table 1 ). When restricting to the 12 members of PCA group A, the split time was estimated to be 15 generations ago (95% CI: 13–18) ( Table 2 ). When restricting to the 16 members of PCA group B, the split time was 10 generations ago (95% CI: 3–14). We stress these results should be seen as the best fitting projection of the true history into a simplified demographic model, in particular given the limited sample sizes.

Runs of Homozygosity

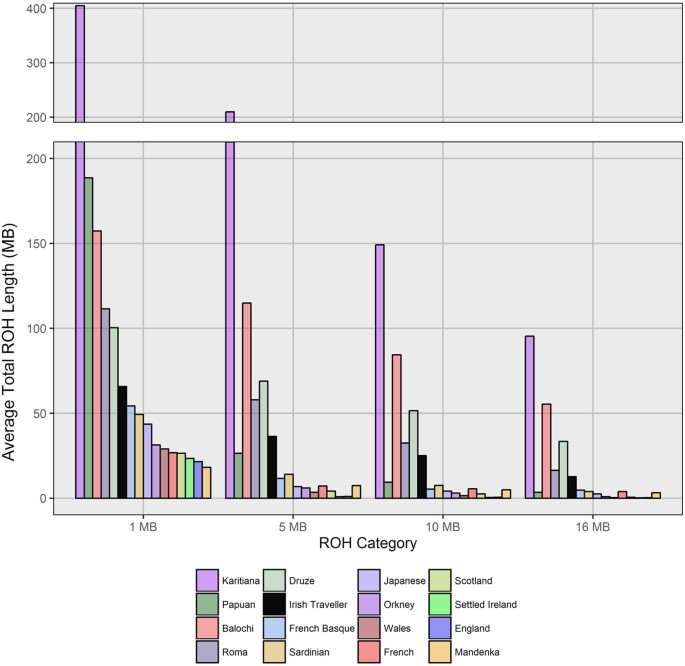

Consanguinity is common within the Irish Traveller population, and in this context we quantified the levels of homozygosity compared to settled Irish and world-wide populations 19 . We calculated the average total extent of homozygosity of each population using four categories of minimum length of Runs of Homozygosity (ROH) (1/5/10/16 Mb). Elevated ROH levels between 1 and 5 Mb are indicative of a historical smaller population size. Elevated ROH levels over 10 Mb, on the other hand, are reflective of more recent consanguinity in an individuals’ ancestry 10 . We also include average figures for the European Roma in the Irish Traveller – European analysis. Full European Roma ROH profiles are shown in Figure S5 .

As expected, the Irish Travellers present a significantly higher amount of homozygosity compared to the other outbred populations and to the European isolates the French Basque and Sardinian, which is sustained through to the larger cutoff categories of 10–16 Mb (see Fig. 6 ). Our results for the other world-wide populations agree with previous estimates 10 , with the Native American Karitiana showing the most autozygosity, and the Papuan population showing an excess of short ROHs. Two other consanguineous populations, the Balochi and Druze show slightly more homozygosity than the Irish Travellers, and the European Roma are most similar to the Travellers for both shorter and longer ROH.

Shown, across four minimum lengths of runs of homozygosity (ROH), are the average lengths of ROH in each population. The average ROH burdens for the European Roma are the mean of means across the 13 Roma populations studied. These values are from a separate analysis, and collated with the wider European ROH values for reasons of SNP coverage between the different datasets.

These results indicate a higher level of background relatedness in the Irish Traveller population history. The high levels of ROH larger than 10 Mb in length reflect recent parental relatedness within the population. This is supported by the average F ROH5 in the Irish Travellers (F ROH5 = 0.015), which is slightly lower but comparable to the F ROH5 score found among Orcadian offspring of 1 st /2 nd cousins (F ROH5 = 0.017) 20 .

Finally, in order to explore the potential of the Irish Traveller population for studying rare, functional variation for disease purposes, we tested minor allele frequency (MAF) differences between the settled Irish and the Irish Travellers from a common dataset of 560,256 common SNPs for 36 Traveller, and 2232 settled Irish individuals. We observed 24,670 SNPs with a MAF between 0.02–0.05 in the settled Irish population. We found that 3.29% of these SNPs had a MAF >0.1 in the Irish Traveller population. We tested the significance of this observation by calculating the same percentage, but taking a random 36 settled Irish sample instead of 36 Irish Travellers. We repeated this 1000 times and found no samples (p =< 0.001) with a greater percentage than 3.29 (mean = 1.3, std.dev = 0.11). This has additional implications for disease mapping within Ireland, as a proportion of the functional variants in the settled Irish population will be observed at a higher frequency in the Traveller population.

We have, using high-density genome-wide SNP data on 42 Irish Traveller individuals, investigated the genetic relationship between the Travellers and neighbouring populations and another nomadic European population, the Roma. For the first time we have estimated a time of divergence of the Irish Travellers from the general Irish population, and have also quantified the extent of autozygosity within the population.

We report that the Irish Traveller population has an ancestral Irish origin, closely resembling the wider Irish population in the context of other European cohorts. This is consistent with previous observations made using a limited number of classical markers 2 , 4 . In both our fineStructure and ADMIXTURE analyses, the Traveller population clusters predominantly with the settled Irish. Our fineStructure tree qualitatively agrees with the topology presented by Leslie et al . 21 , although there are some differences. For example, in the tree presented here, the Irish and individuals from south-west Scotland are grouped on one branch, with the rest of Scotland and England placed on a separate branch. fineStructure tree building is sensitive to the sample size, and due to the larger proportion of Irish genomes in our analysis, compared to Leslie et al .’s analysis (300 versus 44), it is not surprising that the Irish branch is placed differently.

We observe substructure within the Irish Traveller population, identifying (via fineStructure) four genetic clusters occupied only by Irish Travellers ( Fig. 1B ). These clusters align with the broad two way split in the Irish Traveller population we observe via allele frequency based PCA ( Fig. S1 ). In addition, our fineStructure clusters reflect sociolinguistic affinities of the population, membership of the Rathkeale group ( Traveller 2), and speakers of the Cant ( Traveller 4 ) or Gammon ( Traveller1 ) dialects of Shelta ( Fig. S2 ). Our results, therefore, suggest that these groups represent genuine structure within the Irish Traveller population, rather than having by chance sampled broad family groups.

Several Irish Traveller individuals in the fineStructure analysis show an affinity either with British or settled Irish, demonstrating some genetic heterogeneity within the Irish Traveller population. This heterogeneity can be explained by recent settled ancestry or ancestry with other Travelling groups within Britain and Ireland. However, the existence of sole Irish Traveller genetic clusters suggest that there is some sub-structure within the population, and a larger follow up study is warranted to elucidate the extent of this structure, and the representative nature of the observed clusters.

It appears that the Traveller population has experienced lineage-specific drift, as demonstrated by the discordant F st and f 3 estimates between the Travellers and the settled Irish. F st estimates of Traveller to Settled Irish genetic distance are comparable to that we observed between the Ireland and Spain ( Table S1 ). However, when we estimate using f 3 statistics (which is less sensitive to lineage-specific drift) the genetic distance, is reduced, and comparable to that observed between Irish and Scots. The theory of lineage-specific drift is also supported by the IBD analysis, which demonstrates very high levels of haplotype sharing within the Traveller population. Indeed, much of the overall genetic differentiation of the Travellers from the settled Irish is driven by the high F st distance between the Irish Traveller PCA group B (specifically the Traveller 4 cluster), and the settled Irish. This suggests that some subgroups within the Irish Travellers may have experienced greater genetic drift than others.

The dating of the origin of the Irish Travellers is of considerable interest, but this is distinct from the origins of each population. We have estimated the point of divergence between the Traveller and the settled Irish population using two different methods. Our LD-based (T F ) method estimates a split 40 (±2 std.err) generations ago, or 1200 (±60 – std.err) years ago (assuming a generation time of 30 years). Our IBD-based method (T IBD ) estimates 12 (8–14) generations, or 360 (240–420) years ago. However both estimates suggest that the Irish Travellers split from the settled population at least 200 years ago. The Irish Great Famine (1845–1852) is often proposed as a/the source of the Irish Traveller population, but results presented here are not supportive of this particular interpretation. The T IBD method suggested differences between the PCA groups; whilst PCA group A seems to have split relatively early and remained relatively large, PCA group B seems to have split off more recently and quickly decline in size ( Table 2 ). This might explain the higher degrees of genetic differentiation we see in PCA group B in our F st and f 3 analyses.

An important limitation of our dating analysis is that both the T IBD and T F approaches assume a single origin source, but there may have been multiple founding events contributing to the population present today. Both methods are further limited in that they do not model for subsequent gene flow in to the population. We would also consider the T F date to be inflated, given the lineage-specific drift we and others have illustrated in the Traveller population, and its corresponding impact on F st calculation. In the case of the T IBD method, the sample size of the Irish Traveller cohort was too small to infer more complex demographic models (e.g. post-split gene flow or multiple epochs of growth/contraction for each group), due to the risk of over-fitting. A larger dataset is required to explore the possibility of dating distinct events for the Traveller clusters our analysis has resolved.

One of the hypothesised sources of the Irish Travellers is that they are a hybrid population between the settled Irish and the Roma. The results of our ADMIXTURE analysis would not support such a hypothesis, with none of the self-identified Irish Travellers showing ancestry components specific to the Roma populations. We did however detect one individual showing a significant proportion of a Roma-specific ancestral component. This individual self-reported Gypsie ancestry, and did not cluster with the clusters of sole Irish Traveller membership.

We have presented the first population-based assessment of autozygosity within the Irish Traveller population. Compared to other cosmopolitan populations, we observe within the Irish Travellers an excess of ROH and IBD segments. The ROH profile of the Irish Travellers is comparable to other consanguineous populations such as the Balochi of Pakistan and Druze of the Levant. However, of the populations we tested for ROH, the Irish Travellers were most similar to the European Roma, who are also an endogamous nomadic community. This, and the F ROH5 statistic for the Irish Travellers, agrees with previous observations of endogamy within the Irish Travellers 7 , 8 . Our homozygosity results would account for the well-documented higher prevalence of recessive disease within the Irish Traveller community 11 , 13 , 22 . The levels of homozygosity have clear importance in the medical genetics of the Irish Traveller population and together with the drift of rarer variants to higher frequencies in the Irish Travellers may greatly aid in the identification of rarer variants contributing to the risk of common disease within Ireland 23 , both for the settled and the travelling populations.

In summary, we confirm an ancestral Irish origin for the Irish Traveller population, and describe for the first time the genetics of the population using high-density genome-wide genotype data. We observe substructure within the population, a high degree of homozygosity and evidence of the “jackpot effect” of otherwise rare variants drifting to higher frequencies, both of which are of interest to disease mapping and complex trait genetics in Ireland. Finally we provide important insight to the demographic history of the Irish Traveller population, where we have estimated a divergence time for the Irish Travellers from the settled Irish to be at least 8 generations ago.

Materials and Methods

Study populations.

We assembled five distinct datasets; the Irish Travellers (n = 50), the Irish Trinity Student Controls 14 (n = 2232), the People of the British Isles dataset 15 (n = 2039), a dataset of individuals with European ancestry 24 (n = 5964), individuals with Roma ancestry 16 (n = 143), and a dataset of world-wide populations 19 (n = 931). For more details of each dataset, see Supplementary Data 1.1 .

The Irish Traveller cohort and data presented here were analysed within the guidelines and regulations put forward by the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland Research Committee, and approved by the same Committee (reference number REC 1069). A waive of informed consent was granted by this Committee under an amendment of the same ethics reference number.

Quality Control of Genotype Data

Each of the five cohorts was individually processed through a number of quality control steps using the software PLINK 1.9 25 , 26 . Only autosomal SNPs were included in the analysis. Individuals or SNPs that had >5% missing genotypes, SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) <2%, and SNPs failing the HWE at significance of <0.001 were discounted from further analysis. Identity-by-Descent (IBD) was calculated between all pairs of individuals in each of the five datasets using the—genome function in plink, and one individual from any pairs that showed 3 rd degree kinship or closer (a pihat score ≥0.09) was removed from further analysis. Amongst the Irish Traveller cohort eight cryptic pairings closer than second-degree cousins were found, leaving 42 individuals for further analysis.

Individuals included from the European ancestry dataset 24 were genotyped as part of a study of multiple sclerosis (MS), which included cases. As the HLA region contains loci strongly associated with multiple sclerosis (MS) 24 , for any analyses that included the European individuals from this MS study we omitted SNPs from a 15 Mb region around the HLA gene region, starting at 22,915,594 to 37,945,593. In order to restrict the MS cohort to individuals of European ancestry, we conducted principal component analysis (PCA) with gcta64 (v1.24.1) 27 and outliers from each of the MS populations were also removed. This left the final 5964 individuals included in the MS European Cohort.

Population Structure

FineStructure 28 analysis was carried out on a combined dataset of Irish Travellers, Trinity Student Irish, and POBI British. As fineStructure is more sensitive to relatedness, instead of the previously described IBD threshold we removed one from each pair with a pihat score >0.06. Additionally we removed SNPs that were either A/T or G/C. This left a combined dataset of 34 Irish Travellers, 300 randomly chosen Irish from the Trinity Student dataset, and 828 British from the POBI dataset. The POBI samples were selected as follows; 500 individuals were chosen from England, and all 131 from Wales, 101 from Scotland, and 96 from Orkney. In order for the English individuals to be as representative as possible of English clusters identified previously 21 , the 500 consisted of; 200 randomly chosen from Central/South England, 50 randomly chosen from each of Devon and Cornwall, and 200 randomly chosen from the north of England. This final combined dataset had a total coverage of 431,048 common SNPs. Further details of the fineStructure analysis pipeline and its parameters are described in Supplementary Data 1.2 .

In order to compare to other population structure visualisation methods we also performed allele frequency-based PCA using the software gcta64 (v1.24.1) 27 . Detailed methods are provided in Supplementary Data 3 . This was applied to the same dataset as the fineStructure analysis, with the exception that we first pruned the dataset with regards to LD using plink 1.9 25 , 26 with the—indep-pairwise command, using a window of 1000 SNPs moving every 50 SNPs, with an r 2 threshold of 0.2. We also removed common SNPs that were either A/T or G/C, leaving 75,214 common SNPs.

Maximum likelihood estimation of individual ancestries was carried out using ADMIXTURE version 1.23 29 and a dataset that had been pruned with respect to LD, as recommended by the authors 29 . This was achieved using plink 1.9 25 , 26 with the—indep-pairwise command, using a window of 1000 SNPs moving every 50 SNPs, with an r 2 threshold of 0.2. For this analysis we used a combined dataset of 42 Irish Travellers, 40 randomly selected Irish individuals from the Trinity Irish cohort, 160 individuals from the POBI dataset (40 randomly chosen English, Welsh, Orcadian, and Scottish individuals), and 40 random individuals from each of the following populations within the MS European dataset; France, Germany, Italy, Norway, Finland, and Spain. The combined dataset consisted of 83,759 SNPs (after the removal of A/T or G/C variants), and 476 individuals.

ADMIXTURE analysis was carried out on k = 2–7 populations, with 50 iterations of each k value. The iteration with the highest log-likelihood and lowest cross validation score was used for further analysis.

Inter-population fixation indexes between the populations were studied using the Weir and Cockerham method 30 and the combined dataset used in ADMIXTURE analysis. The dataset was pruned with respect to LD using the same parameters as described above, leaving 83,759 common SNPs.

Due to the suspected lineage-specific drift in the Irish Traveller population history, we additionally calculated genetic distance using “outgroup” f 3 -statistics 31 , an extension of the f-statistics framework 32 . f 3 is proportional to the shared genetic drift between two test populations and an outgroup population, and should therefore be less sensitive to the Irish Travellers lineage-specific drift than the F st statistic. We performed this analysis on the same combined dataset used in F st analysis, with the additional inclusion of 21 Yorubans from the HGDP dataset in order to act as an outgroup to the pair-wise comparisons. The combined dataset consisted of 245,594 common SNPs (after the removal of A/T or G/C variants). The outgroup f 3 statistic was calculated using the software within the admixtools package 32 using default settings.

In order to estimate a time of divergence between the Irish Travellers and the settled Irish we utilised two methods. The first, the T F method, is based on a method first described by McEvoy et al . 33 and uses linkage disequilibrium patterns between markers in discrete bins of recombination distances, and genetic distance measured by F st in order to estimate a divergence time. The second, the T IBD method, uses the sharing of Identical by Descent (IBD) segments and demographic modelling using this sharing data to estimate a time of divergence and is based on the methodology previously described in Palamara et al . 17 and applied in Zidan et al . 18 . For more details of both methods, see Supplementary Data 1.3 .

Runs of Homozygosity Analysis

ROH analysis was carried out on a merged dataset of all individuals within the Irish Traveller, Trinity Student, and POBI cohorts, and a subset of the populations found within the Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP) dataset. The HGDP populations were chosen to be i) representative of world-wide diversity of autozygosity, and ii) to compare the levels of autozygosity of the Irish Travellers to known endogamous populations such as the Balochi and Karitiana. The combined dataset had an overlap of 193,508 common markers.

With the exception of one parameter (the gap between consecutive SNPs, see below), we followed McQuillan et al .’s methodology 20 for the ROH analysis; the window was defined as 1000 kb, moving every 50 SNPs, with 1 heterozygous position allowed and 5 missing positions allowed within the window. The run of homozygosity call criteria were defined as; 1/5/10/16 Mb minimum in length, 100 SNPs minimum within the window, the minimum marker density greater than 50 Kb/SNP. Due to the reduced SNP coverage in this dataset compared to previous analyses 10 , 20 the largest gap between consecutive SNPs before ending a run of homozygosity call was changed to 500 Kb. We calculated F ROH5 as it had previously been shown to strongly correlate with the inbreeding coefficient F PED 20 . F ROH5 was estimated for the 17 populations, as per the equation below.

where S ROH5 is the total length of ROH found in an individual where runs are >5 Mb and L auto is the total length of the autosomal genome (called as 2,673,768 kb here). The F ROH5 was averaged across the individuals to find the population mean of F ROH5 .

Relationship to European Roma

We performed several analyses in order to investigate the relationship between Irish Travellers and European Roma. Firstly, we assembled a merged dataset that included the full Irish Traveller, Trinity Student, and European Roma datasets. We additionally removed any variants that were A/T or G/C. For subsequent PCA and ADMIXTURE analysis the combined Roma dataset was pruned for LD, using a window of 1000 SNPs, moving every 50 SNPs with a r 2 inclusion threshold of 0.2 in PLINK, leaving 66,099 common SNPs.

Secondly, PCA was performed using gcta64 v1.24.1 27 , creating a genetic relationship matrix, and then generating the first 10 principal components. Thirdly we applied ADMIXTURE on a reduced combined dataset that included all Irish Traveller and European Roma individuals, but only 40 of the Trinity Student Irish. ADMIXTURE was used with the same parameters as above, modelling for 2–4 ancestral populations. Finally, we compared the levels of homozygosity between the Irish Travellers, Trinity Student Irish, and European Roma - using the full combined Roma dataset, with 148,362 common SNPs and using the parameters described above.

Thirdly, we formally tested evidence for admixture using admixture f 3 statistics 32 in the form f 3 (Traveller; Settled, Roma) using the full Trinity Irish dataset, a reduced European Roma dataset excluding the Welsh Roma (due to their outlier status in the rest of the dataset 16 ), and a reduced dataset of Irish Travellers belonging to Irish Traveller clusters identified in fineStructure analysis (see Results). This combined dataset consisted of 148,914 SNPs.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Gilbert, E. et al . Genomic insights into the population structure and history of the Irish Travellers. Sci. Rep. 7 , 42187; doi: 10.1038/srep42187 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abdalla S. et al. Summary of the findings of the All Ireland Traveller Health Study . School of Public Health and Population Science, University College Dublin (2010).

Relethford, J. & M. Crawford Genetic drift and the population history of the Irish travellers. American Journal of Physical Anthropology , 150 (2), 184–189 (2013).

Article Google Scholar

Commission of Itinerancy 1963, Report of the Commission of Itinerancy 1963. Stationery Office, Government Publication: Dublin (1963).

North, K. E., Martin, L. J. & Crawford, M. H. The origins of the Irish travellers and the genetic structure of Ireland. Annals of Human Biology , 27 (5), 453–66 (2000).

Article CAS Google Scholar

McCann, M., Síocháin, S. Ó. & Ruane, J. Irish Travellers: Culture and ethnicity . Institute of Irish Studies, Queens University of Belfast: Belfast (1994).

Equality Authority. Traveller ethnicity: an Equality Authority report . Brunswick Press Ltd: Dublin (2006).

Barry, J. & Kirke, P. Congenital Anomalies in the Irish Traveller Community. Irish Medical Journal . 90 (6), 233–7 (1997).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Flynn, M. Mortality, morbidity and marital features of travellers in the Irish Midlands. Ir Med J . 79 (11), 308–10 (1986).

Woods, C. et al. Quantification of homozygosity in consanguineous individuals with autosomal recessive disease. Am J Hum Genet 78 (5), 889–96 (2006).

Kirin, M. et al. Genomic runs of homozygosity record population history and consanguinity. PLoS One . 5 (11), e13996 (2010).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Murphy, M. et al. Genetic basis of transferase-deficient galactosaemia in Ireland and the population history of the Irish Travellers. European Journal of Human Genetics . 7 (5), 549–55 (1999).

Flanagan, J. et al. The role of human demographic history in determining the distribution and frequency of transferase-deficient galactosaemia mutations. Heredity . 104 , 148–55 (2010).

Murphy, A. et al. Incidence and prevalence of mucopolysaccharidosis type 1 in the Irish republic. Arch Dis Child . 94 (1), 82–4 (2009).

Desch, K. et al. Linkage analysis identifies a locus for plasma von Willebrand factor undetected by genome-wide association. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110 (2), 588–93 (2013).

Article CAS ADS Google Scholar

Winney, B. et al. People of the British Isles: preliminary analysis of genotypes and surnames in a UK-control population. Eur J Hum Genet . 20 (2), 203–10 (2012).

Mendizabal, I. et al. Reconstructing the Population History of European Romani form Genome-wide Data. Curr Biol . 22 (24), 2342–9 (2012).

Palamara, P. et al. Length distributions of identity by descent reveal fine-scale demographic history. Am J Hum Genet . 91 (5), 809–22 (2012).

Zidan, J. et al. Genotyping of geographically diverse Druze trios reveals substructure and a recent bottleneck. Eur J Hum Genet , 23 (8), 1093–9 (2015).

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Li, J. et al. Worldwide human relationships inferred from genome-wide patterns of variation. Science 319 (5866), 1100–4 (2008).

McQuillan, R. et al. Runs of Homozygosity in European Populations. Am J Hum Genet . 83 (3), 359–72 (2008).

Leslie, S. et al. The fine-scale population structure of the British population. Nature . 519 , 309–14 (2015).

Hamid, N. et al. Rare metabolic diseases among the Irish travellers: results from the All Ireland Traveller Health Study census and birth cohort (2007–2011). Rare Diseases and Orphan Drugs 1 (2), 35–43 (2014).

Google Scholar

Zuk, O. et al. Searching for missing heritability: designing rare variant association studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111 (4), E455–64 (2014).

IMSGC and WTCCC2. Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature . 476 (7359), 214–219 (2011).

Chang, C. et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience . 4 , 7 (2015).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet . 81 (3), 559–75 (2007).

Yang, J. et al. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis . Am J Hum Genet . 88 (1), 76–82 (2011).

Lawson, D. et al. Inference of population structure using dense haplotype data. PLoS Genet . 8 (1), e1002453 (2012).

Alexander, D. H., Novermbre, J. & Lange, K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Research 19 (9), 1655–1664 (2009).

Weir, B. & Cockerham, C. Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution . 38 , 1358–70 (1984).

CAS Google Scholar

Raghavan, M. et al. Upper Palaeolithic Siberian genome reveals dual ancestry of Native Americans. Nature . 505 (7481), 87–91 (2014).

Patterson, N. et al. Ancient admixture in human history. Genetics . 192 (3), 1065–93 (2012).

McEvoy, B. et al. Human population dispersal “Out of Africa” estimated from linkage disequilibrium and allele frequencies of SNPs. Genome Research 21 (6), 821–9 (2011).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the Irish Traveller population who participated in this study. The work was part funded by a Career Development Award (13/CDA/2223) from Science Foundation Ireland. We would also like to thank, Eoghan O’Halloran for help with data formatting, the Irish Center for High-End Computing (ICHEC) for the provision of computing facilities and support, Dan Lawson for advice and help with fineStructure, Michael McDonagh for helpful comments and insights into linguistic groups with the Irish Travellers, and Sinead Ní Shuinéar for inquiries on groups within the Irish Travellers. SC thanks a private donation from the Barouh and Channah Berkovits Foundation. We thank Liam McGrath and Scratch Films for their support in developing this project. We thank the reviewers for their helpful comments. This study makes use of data 24 generated by the Wellcome Trust Case-Control Consortium. A full list of the investigators who contributed to the generation of the data is available from www.wtccc.org.uk . Funding for the project was provided by the Wellcome Trust under award 76113, 085475 and 090355.

Author information

James F. Wilson and Gianpiero L. Cavalleri: These authors contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Molecular and Cellular Therapeutics, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, St Stephen’s Green, Dublin, 2, Ireland

Edmund Gilbert & Gianpiero L. Cavalleri

Braun School of Public Health and Community Medicine, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel

School of Medicine and Medical Science, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

Centre for Global Health Research, Usher Institute for Population Health Sciences and Informatics, University of Edinburgh, Teviot Place, Edinburgh, Scotland

- James F. Wilson

MRC Human Genetics Unit, Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Western General Hospital, Crewe Road, Edinburgh, Scotland

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

E.G., S.C., J.F.W., and G.L.C., wrote the main manuscript, E.G. ran the analysis, with exception of TIBD, which was run by S.C. S.E. contributed to supervision of E.G. J.F.W. and G.L.C. designed the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gianpiero L. Cavalleri .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary data (pdf 1190 kb), rights and permissions.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gilbert, E., Carmi, S., Ennis, S. et al. Genomic insights into the population structure and history of the Irish Travellers. Sci Rep 7 , 42187 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42187

Download citation

Received : 23 August 2016

Accepted : 04 January 2017

Published : 16 February 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42187

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

The newfoundland and labrador mosaic founder population descends from an irish and british diaspora from 300 years ago.

- Edmund Gilbert

- Heather Zurel

- Michael S. Phillips

Communications Biology (2023)

Presentations of self-harm and suicide-related ideation among the Irish Traveller indigenous population to hospital emergency departments: evidence from the National Clinical Programme for self-harm

- Katerina Kavalidou

- Caroline Daly

- Paul Corcoran

Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology (2023)

The genetic landscape of polycystic kidney disease in Ireland

- Katherine A. Benson

- Susan L. Murray

- Peter Conlon

European Journal of Human Genetics (2021)

Microbiome and health implications for ethnic minorities after enforced lifestyle changes

- David M. Keohane

- Tarini Shankar Ghosh

- Fergus Shanahan

Nature Medicine (2020)

Runs of homozygosity: windows into population history and trait architecture

- Francisco C. Ceballos

- Peter K. Joshi

Nature Reviews Genetics (2018)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Nomadism and Equality: The Irish Traveller and Gypsy Women

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 01 September 2020

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Madalina Armie 7 &

- Verónica Membrive 7

Part of the book series: Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals ((ENUNSDG))

38 Accesses

Itinerants ; Knackers ; Tinkers ; Pikeys

Definitions

When writing the story of the Irish Traveller and Gypsy women is important to specify that in the Irish Republic, the Irish Travellers, New Age Travellers, Irish Romani Gypsies, and Roma from Central and Eastern Europe minorities present broad internal subdivisions. Each of these groups attain different cultural traits and behavioral patterns, although it is true that they have more things in common – and this is one of the reasons why they are frequently and erroneously confused – rather than characteristics which distinguish them. The overlapping of experiences of Roma and Traveller minorities, then, would make impossible at times to treat them as separate cases of study. The Travellers are Ireland’s native ethnic minority. The New Age Travellers, on the other hand, do not form a distinct ethnic group according to the Irish law, and the creation of this nomadic group has as a backdrop the free festivals, therefore their...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Armie M (2019) The Irish contemporary short story at the turn of the 21st century: tradition, society and modernity. Dissertation, University of Almería

Google Scholar

Bohn Gmelch S, Gmelch G (2014) Irish Travellers: the unsettled life. Indiana University Press, Indiana

Book Google Scholar

Borrow G (2019) Romano Lavo-Lil: word book of the Romany; or, English gypsy language. Good Press, Glasgow

Braidotti R (1994) Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory. Columbia University Press, New York

Central Statistics Office (2007) Census 2006 reports. https://www.cso.ie/en/census/census2006reports/ . Accessed 1 June 2020

Central Statistics Office (2012) Census 2011 Reports. https://www.cso.ie/en/census/census2011reports/ . Accessed 1 June 2020

Central Statistics Office (2014) Population and Migration Estimates. https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/er/pme/populationandmigrationestimatesapril2013/ . Accessed 1 June 2020

Central Statistics Office (2017) Census 2016 reports. https://www.cso.ie/en/csolatestnews/presspages/2017/census2016summaryresults-part1/ . Accessed 1 June 2020

Crawford MH et al (2000) The origins of the Irish Travellers and the genetic structure of Ireland. Dig Annal Hum Biol 27(5):453–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/030144600419297

Article Google Scholar

de Beauvoir S (2011) The second sex (trans: Borde C and Malovany-Chevallier S). Vintage Books, London

Egan C (2020) “Who Are the Irish Travellers in the US?” In: IrishCentral.com. www.irishcentral.com/culture/who-are-irish-travellers-us . Accessed 11 Jul 2020

Equality and Human Rights Commission (2009) Inequality Experienced by Gypsy and Traveller Communities. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/publication-download/research-report-12-inequalities-experienced-gypsy-and-traveller-communities . Accessed 10 May 2020

European Commission (2010) Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions The social and economic integration of the Roma in Europe /* COM/2010/0133 final */ https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:0133:FIN:EN:HTML . Accessed 30 May 2020

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2016) Second European Union minorities and discrimination Survey-Roma https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2016/second-european-union-minorities-and-discrimination-survey-roma-selected-findings . Accessed 15 May 2020

Griffin C (2008) Nomads under the Westway: Irish Travellers, gypsies and other traders in West London. University of Hertfordshire Press, Hatfield

Hayes M (2006) Indigenous otherness: some aspects of Irish Traveller social history. Éire-Ireland 41(3):133–161

Helleiner J (1997) Women of the itinerant class: gender and anti-Traveller racism in Ireland. Women’s Stud Int Forum 20(2):275–278

Helleiner J (2000) Irish Travellers: racism and the politics of culture. University of Toronto Press, Toronto

Hetherington K (2000) New age Travellers: vanloads of uproarious humanity. Cassell, London/New York

Holst Petersen K, Rutherford A (1986) A double colonization: colonial and post-colonial women’s writing. Dangaroo Press, Oxford

Irish Department of Justice and Equality (2017) National Traveller and Roma Inclusion Strategy 2017-2021. http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/National%20Traveller%20and%20Roma%20Inclusion%20Strategy,%202017-2021.pdf/Files/National%20Traveller%20and%20Roma%20Inclusion%20Strategy,%202017-2021.pdf . Accessed 20 May 2020

Irish Statute Book (2000) Equal Status Act 2000. http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2000/act/8/enacted/en/html . Accessed 3 June 2020

Irwin A (2006) Stall Anoishe! Minceris Whiden, Stop Here! Travellers Talinking: Analysing the reality for Travellers in Galway city. http://gtmtrav.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Stall-Anoishe-Analysing-the-reality-for-Travellers-in-Galway-City.pdf

Kendall S (1999) Sites of resistance: places on the margin – the traveller homeplace. In: Acton AA (ed) Gypsy politics and Traveller identity: a companion volume to Romani culture and gypsy identity. University of Hertfordshire Press, Hertfordshire, pp 70–90

Lentin R (1998) ‘Irishness’, the 1937 constitution, and citizenship: a gender and ethnicity view. Ir J Sociol 8:5–24

Mac Gréil M (2011) Pluralism and diversity in Ireland: prejudice and related issues in early 21st century Ireland. The Columba Press, Dublin

Marcus G (2019) Gypsy and Traveller girls: silence, agency and power. Palgrave Macmillan, Glasgow

Mayall D (1988) Gypsy-Travellers in nineteenth-century society. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

McDonagh M (2000) Nomadism. In: Sheehan E (ed) Travellers: citizens of Ireland. The Parish of the Travelling People, Dublin, pp 33–46

Mckinley R (2011) Gypsy Girl: a life on the road. A journey to freedom. Hodder & Stoughton, London

Moane G (2002) Colonialism and the Celtic Tiger: legacies of history and the quest for vision. In: Kirby P et al (eds) Reinventing Ireland: culture, society, and the global economy. Pluto Press, London, pp 109–123

Murray C (2014) A minority within a minority? Social justice for Traveller and Roma children in ECEC. Dig ITB J 15(1):89–102. https://doi.org/10.21427/D75X6B

National Traveller Women’s Forum (2020) History. https://www.ntwf.net/about/history/ . Accessed 1 June 2020

Okley J (1983) The Traveller-gypsies. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Richardson J, Ryder A (eds) (2012) Gypsies and Travellers: empowerment and inclusion in British society. The Policy Press, Bristol

Rieder M (2018) Irish Traveller language: an ethnographic and folk-linguistic exploration. Palgrave Macmillan, Limerick

Tovey H, Share P (2003) A sociology of Ireland. Gill & Macmillan, Dublin, Ireland

United Kingdom Legislation (2010) Equality act 2010. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents . Accessed 4 June 2020

Van Hout M, Staniewicz T (2012) Roma and Irish Traveller housing and health: a public health concern. J Crit Public Health 22(2):193–207

Watson D, Kenny O, McGinnity F (2017) A social portrait of Travellers in Ireland. The Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Modern Languages, University of Almería, Almería, Spain

Madalina Armie & Verónica Membrive

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Madalina Armie .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

European School of Sustainability, Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

Walter Leal Filho

Center for Neuroscience & Cell Biology, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

Anabela Marisa Azul

Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Passo Fundo University Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Passo Fundo, Brazil

Luciana Brandli

HAW Hamburg, Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

Amanda Lange Salvia

International Centre for Thriving, University of Chester, Chester, UK

Section Editor information

Council for Scientific and Industrial Research - Natural Resources and Environment, Johannesburg, South Africa

Julia Mambo

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Armie, M., Membrive, V. (2020). Nomadism and Equality: The Irish Traveller and Gypsy Women. In: Leal Filho, W., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Wall, T. (eds) Gender Equality. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70060-1_131-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70060-1_131-1

Received : 04 June 2020

Accepted : 26 June 2020

Published : 01 September 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-70060-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-70060-1

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Earth and Environm. Science Reference Module Physical and Materials Science Reference Module Earth and Environmental Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

The long road towards acceptance for Irish Travellers

The Irish Traveller community is fighting for official recognition of its ethnic identity and for a way of life.

Avila Park, Dublin, Ireland – In a wooden shed in his back garden, James Collins sits on a low stool hammering out the final touches on a billy can. At 68, he is one of only two remaining traveller tinsmiths in Ireland.

Above the clutter of well-worn tools and scrap sheet metal hang a dozen or so other cans. Nowadays, he says, there’s precious little demand for his trade, and he largely continues it as a hobby, occasionally selling some of his work at vintage craft fairs.

Since the introduction of plastic homeware in the 1960s and 1970s, tinsmithing – traditionally dominated by the historically nomadic community known as Travellers – has effectively died out. Even the block tin, James originally used, is no longer available.

“It’s more difficult to work with,” he says, holding up a gleaming aluminium can. “You can’t make what you want to make out of it because you have to use solder and that won’t take solder.”