— The End —

Field Trip to the Museum of Human History

Introduction.

🌟 Welcome to a Journey Through Time! 🌟

“Field Trip to the Museum of Human History” by Franny Choi is more than just a poem; it’s an expedition into the caverns of human experience and emotion. Franny Choi, a notable figure in contemporary poetry, uses her sharp, insightful words to sketch a world where history and personal narrative collide. This poem, like many of her works, falls under the genre of modern poetry, where traditional forms meet the urgent, often chaotic themes of today’s world.

In this particular piece, Choi imagines a future where humans look back at our current civilization much like how we view ancient exhibits in a museum. The poem is layered with rich imagery and poignant reflections, making it a compelling read for anyone intrigued by the complexities of human nature and history. 😌📜

Meaning of ‘Field Trip to the Museum of Human History’

Franny Choi’s poem unfolds in a structured yet reflective manner, mirroring the way a museum tour might progress from one exhibit to another. Let’s break down the meaning section by section:

Opening Section:

- The poem begins with an invitation into this museum, setting a tone of exploration and curiosity. The opening lines serve as a doorway into the past, inviting readers to witness human history as if they are seeing it for the first time through the eyes of the future. Choi uses this setup to challenge the reader’s perspective on what is considered ‘normal’ or ‘historical’.

Mid Section:

- In the middle of the poem, Choi dives deeper into specific “exhibits” that depict everyday aspects of human life but are framed as ancient artifacts. This part of the poem critically examines how mundane objects and actions will be perceived in the distant future. It’s a poignant reminder of the impermanence of our current culture and societal norms, encouraging readers to think about what legacy they are creating.

Concluding Section:

- The conclusion of the poem brings a reflective and somewhat melancholic tone , as the speaker in the poem contemplates the transient nature of human existence. Choi uses this section to pose questions about the relevance and weight of human endeavors, suggesting that what we value today might be just a curiosity for future generations.

Through these sections, Choi crafts a compelling narrative that uses the metaphor of a museum to explore themes of memory, history, and the human condition.

In-depth Analysis

Field Trip to the Museum of Human History by Franny Choi is meticulously crafted, with each stanza contributing to the overarching theme of examining human history through a futuristic lens. Here’s a detailed breakdown:

- Imagery and Setting : The poem opens by setting the scene of a museum, instantly transporting readers into a space that is familiar yet distant. The use of vivid imagery helps paint this museum not just as a place of history, but as a window into the soul of humanity.

- Syntax and Diction : The choice of words is deliberate, with terms that evoke a sense of antiquity and reverence, suggesting the depth of what is to be explored.

- Contrast and Irony : This stanza introduces everyday objects but places them in a context that feels alien and historical. The irony of seeing such mundane items in a museum exhibit highlights the transient nature of our current culture and technology.

- Figurative Language : Metaphors are used to liken modern objects to relics, suggesting a deep disconnect between the present and the future perceptions of our time.

- Tone and Mood : The mood shifts slightly here, becoming more introspective. The tone helps underscore the emotional weight of realizing that what is everyday for us will one day be history.

- Symbolism : Everyday actions and experiences are symbolized as artifacts, making readers question the importance and impermanence of their daily lives.

- Questioning and Reflection : Questions posed in this stanza invite the reader to think critically about the legacy of current human actions. It serves as a call to reflect on what will be left behind and how it will be interpreted.

- Philosophical Underpinning : This part of the poem delves deeper into philosophical questions about the meaning of progress and the role of humanity in the larger tapestry of time.

- Culmination and Conclusion : The final stanza wraps up the poem with a poignant conclusion, echoing the themes introduced earlier but with a more resolved tone . This stanza reinforces the inevitability of change and the passage of time.

- Allusion and Final Thought : There’s often a subtle allusion to historical cycles and possibly a nod to the cyclical nature of human history itself, suggesting a continuous loop of rise, fall, and rediscovery.

Each stanza of Choi’s poem is layered with complex literary techniques that require deep analysis to fully appreciate how they contribute to the poem’s thematic concerns.

Poetic Devices used in Field Trip to the Museum of Human History

Here’s a detailed table identifying the top 10 poetic devices used by Franny Choi in her poem “Field Trip to the Museum of Human History”. These devices enrich the poem’s texture and deepen its thematic resonance.

These devices are meticulously woven into the fabric of the poem, each adding a layer of meaning or emotional depth to the narrative .

Field Trip to the Museum of Human History – FAQs

Here are some frequently asked questions about Franny Choi’s “Field Trip to the Museum of Human History,” which might be particularly useful for students taking advanced placement language courses.

1. What is the primary theme of ‘Field Trip to the Museum of Human History’?

- The primary theme revolves around the impermanence and transience of human culture and technology. The poem explores how the future generations might view the everyday objects and activities of today, highlighting the fleeting nature of our current societal norms.

2. How does Franny Choi use irony in the poem?

- Choi employs irony by presenting mundane, contemporary objects as exhibits in a museum, thus inviting readers to view their everyday world through the lens of history and antiquity. This shift in perspective underscores the absurdity and temporality of what is often considered permanent.

3. What poetic techniques does Choi use to convey her themes?

- Choi uses a variety of poetic techniques including metaphor, symbolism, imagery, and irony. These techniques help to create a vivid picture of a museum that archives current human life, thereby reflecting on how the mundane might be perceived as historic or exotic in the future.

4. Can you explain the significance of the setting in the poem?

- The setting of a museum is crucial as it transforms the reader’s understanding of modern life by placing it within the context of an exhibit. This not only serves as a narrative tool but also as a metaphorical space where current human behaviors are critiqued and analyzed from a future perspective .

5. How does the structure of the poem enhance its message?

- The poem’s structure, resembling a guided tour through a museum, enhances its message by systematically breaking down aspects of human life and presenting them as exhibits. This mimics how a museum curates pieces from history, providing a structured yet reflective exploration of human culture.

6. What role does contrast play in the poem?

- Contrast is pivotal in highlighting the differences between current perceptions of normalcy and how these might be viewed as curious or outdated in the future. By contrasting modern life with its future museum depiction, Choi emphasizes the changing nature of societal values and technologies.

7. How does Choi handle the concept of time in her poem?

- Time is treated as a fluid, almost elastic concept in the poem. Choi plays with the notion of temporal relativity—how quickly the present becomes the past—and uses it to provoke thoughts about the legacy and permanence of our cultural practices.

8. What might students gain by studying this poem in an advanced placement course?

- Students can gain insights into how poetry can explore complex themes like time, culture, and the human condition in a compact form. They’ll learn to appreciate the use of literary devices to convey deep philosophical questions and reflect on the ephemeral nature of human achievements.

Field Trip to the Museum of Human History Study Guide

Here’s a practical exercise designed to help students delve deeper into the poetic devices used in Franny Choi’s “Field Trip to the Museum of Human History.” This exercise will enhance their analytical skills and appreciation of poetic techniques.

Exercise: Analyzing Poetic Devices

Instructions: Read the following verse from “Field Trip to the Museum of Human History.” List all the poetic devices you can identify. Explain how these devices contribute to the overall theme or mood of the poem.

Verse: “In the exhibit on extinct technologies, whirring softly, the last smartphone glows. Visitors marvel at its archaic form, pondering the quaintness of touchscreens.”

Answer Key:

- Imagery – The description of the smartphone and its gentle whirring creates a vivid picture in the reader’s mind, making the technology almost tangible despite its obsolescence.

- Metaphor – The smartphone is not just a device but a representative of all “extinct technologies,” suggesting broader themes of obsolescence and change over time.

- Irony – The idea that something as commonplace as a smartphone is now an exhibit in a museum highlights the irony of technological progress and its fleeting nature.

- Alliteration – “whirring softly,” enhances the auditory experience of the verse, adding to the sensory depth of the museum setting .

- Personification – The smartphone “glows” and “whirrs,” ascribing human-like qualities to the device, enhancing its role as a relic of a bygone era.

- Symbolism – The smartphone symbolizes broader ideas about human dependency on technology and the rapid pace of technological obsolescence.

By completing this exercise, students can practice identifying and analyzing poetic devices, which are crucial skills in understanding and interpreting poetry. This type of analysis not only aids in literary appreciation but also deepens critical thinking about the themes and techniques used by poets like Franny Choi.

About the Writer

Sharon korzelius.

Turn a Field Trip Into a Poetry Lesson

Any time is a good time to write a poem. students can become poets by participating in these poetry lessons..

By Cathy Neushul

Every year students visit the art museum, the zoo, or the aquarium. After the field trip students are usually asked to reflect on what they saw. They might be asked to write an essay, or participate in a discussion. Maybe, for a change of pace, you could ask your students to write a poem about the experience. It could be about a particular painting, the park where they ate lunch, or an experience of riding in a smelly school bus. Whatever they get excited about, should be what they write about.

Before students start complaining that they don’t remember anything that stood out, brainstorm some ideas, and share your own. For example, there was one thing that stood out for me on my most recent field trip. When I visited the local art museum, a docent showed us this enormous white canvas with what looked like a bunch of black dots. She told us that this was actually a picture of thousands of flies that had been carefully placed on photographic paper, I was amazed. By far, this was my favorite picture at the museum. The flies definitely inspire poetry.

As a poetry lover, I suggest teaching related lessons whenever you can, but definitely if you want students to write something after a particular field trip. Depending on your grade level, you can set the parameters for the assignment. Maybe four lines that rhyme for lower elementary, and a more difficult task for older students. Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken” is always a good one if you are going on an outdoor field trip. The descriptions of the woods, and his feelings can get students thinking about details. Another favorite of mine is William Wordsworth waxing poetic in “The Daffodils." If you want examples of some more modern poetry try Nikki Giovanni’s “My First Memory (of librarians)." You can almost feel the room she’s describing.

By letting students in on the secret that everyone is a poet, you can help them get turned on to this type of writing.

Elementary :

All Together Now: Collaborations in Poetry Writing

This lesson provides a long list of kid-friendly poems, and related activities. It also provides poem templates so you have everything you need to complete as many lessons as you want. I particularly liked the poetry suggestions. There was one by Judith Viorst, the author of Alexander and the Very Bad Day, called “Fifteen, Sixteen Things to Worry About," and another by Emily Dickinson called “I’m Nobody! Who are You?” The lesson even provides extension ideas to link the poems to ecology, or other subjects.

Elementary/Secondary :

The Imagine Poetry & Mural Lesson

This lesson uses John Lennon’s song “Imagine” as a way to discuss poetry, and have students create their own. For younger children they create a group poem, and mural. For older students they do a more in depth analysis of Lennon’s song and create individual poetry. A great way to infuse Rock and Roll music into the curriculum

“Take My Advice”: Poems with a voice

This lesson uses “Take My Advice," a poem by Langston Hughes as a way to talk about the tone, and voice of poems. Students discuss the poem, and then create their own poems in the advice format. I liked the poem used in this lesson. It could create a great way to discuss students’ views on success, and how to keep moving up.

Secondary :

Poetry of the Great War: From Darkness to Light

This lesson uses poetry written during World War I as a way to discuss both poems, and the history of the war. After reading one of the poems discussed in the lesson, Edgar A. Guest’s “The Things That Make A Soldier Great," I can see why this might stimulate some great class discussions. Guest explains why men would be willing to go fight in such a difficult, and deadly war. Students could analyze their own views on war.

Imagination and Words: The Power of Language – Nikki Giovanni

This lesson uses a poem by Nikki Giovanni to discuss voice and persona. Giovanni’s poem “Ego Tripping” is an interesting, and different way to look at self expression. Students can see the pride with which she views her past.

Our City, Our Words

This lesson uses Walt Whitman’s poem “Mannahatta” to give students an example of writing poetry about the city they live in. The poem itself if full of details, and images that are excellent examples for students. I would use Whitman’s poem as an example, but would have students write about their hometowns.

Start Your 10-Day Free Trial

- Search 350,000+ online teacher resources.

- Find lesson plans, worksheets, videos, and more.

- Inspire your students with great lessons.

Writing Guide

Cathy Neushul

Recent Writing Articles

- Five Benefits of Class Pen Pals

- Thursday Papers

- Achieve Writing Mastery

- How To Teach Writing—for the Non-English Teacher

- by Title, Form, Author

- Story Lists

- For Teachers

- For Students

- High School Contest

- Explore by Theme

- Theme-Based Reading Guide

- Recommended Reading

- Best Advice

- Writers & Mentors Videos

- Video Tutorials

- Writing Prompts

- Writers' Resources

- Board of Directors

- Friends & Patrons

- Narrative in the News

- Advertise in Narrative

- BY TITLE, FORM, AUTHOR

- STORY LISTS

- SUBMIT YOUR WORK

- BOARD & COUNCIL

- FRIENDS & PATRONS

- NARRATIVE IN THE NEWS

- ADVERTISE IN NARRATIVE

- ADVERTISING

- PRIVACY POLICY

- TERMS OF USE

What, though, could they learn here, Pennsylvania’s slate sky

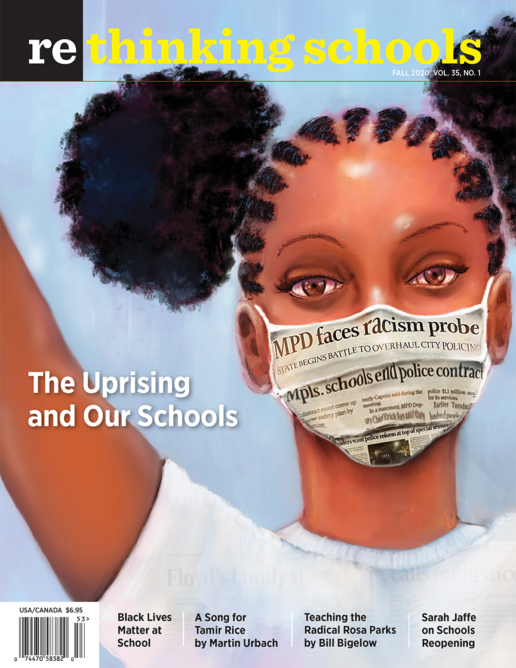

Rethinking Schools

Non-Restricted Content

A Field Trip to the Future

Helping students imagine a better world.

By Kurt David

Illustrator: Fabio Consoli

“What’s the point of museums?” I ask one day to kick off class.

I teach English at a public high school in Fall River, a deindustrialized city on Massachusetts’ southeastern coast. My racially diverse, largely working-class students generally have little firsthand experience with museums: a field trip to Battleship Cove in town or, back in elementary school, one to Boston’s Museum of Science. The truth, though, is that I worry Fall River can itself feel like a museum sometimes, its old mills and factories vivid proof of better days.

“So we can see what the past was like,” Lara suggests.

“Why do we care about the past?”

“It’s interesting?”

I look over at Justin, whose knee-jerk skepticism I can count on. “Is it?”

“Hell no!” he says, earning a class laugh.

“Why do we preserve history?” I push on, smiling. “Why study it?”

“To learn from it.”

“To not repeat the mistakes of history.”

“So we can understand why things are the way they are today — like, how we got here.”

“Yes to all of that.” I plant myself at the front of the room. “Today we’re going to visit a museum,” I announce, and then over their immediate groans, “but before you tell me you’re already bored, I promise you it’s not like any museum you’ve ever been to.”

“Today,” I say, “we’re taking a field trip to the ‘Museum of Human History.’”

Franny Choi wrote her poem “ Field Trip to the Museum of Human History ” back in 2015, a couple of years into the Black Lives Matter movement. I’ve been teaching it ever since.

In the poem, Choi boldly imagines a world without police, an institution she defamiliarizes by allowing us to see it through the eyes of children generations into the future. In an interview with PBS NewsHour , she explains that it grew out of her work organizing around issues of police accountability and racial profiling in Providence. I love the poem for its radical clairvoyance.

“[We] are focusing on such tiny concrete gains and victories that sometimes it’s hard to zoom out and think about what we’re actually working toward,” Choi said.

It’s intentionally hard for us to “zoom out.” Author Arundhati Roy makes clear that “empire . . . [is] selling — their ideas, their version of history, their wars, their weapons, their notion of inevitability.” In my classroom, I try to expose this false but pervasive “notion of inevitability.” I want my students to see the status quo as unnatural and therefore changeable. After all, I believe it’s my students who, with the proper tools, will struggle hardest and most effectively against “empire” and its systems of oppression.

“Field Trip to the Museum of Human History” issues the same challenge, exposing the police as anything but natural or inevitable. I teach the poem toward the end of my semester-long writing elective, in the middle of a short unit I call “Another World Is Possible.” The unit invites students to dream of a better society by having them emulate a series of rebellious mentor texts, such as Choi’s poem and Safia Elhillo’s “Self-Portrait with No Flag.” The unit serves as the fulcrum on which the course pivots: It comes after months of having written and shared stories about our lives and the world we have, but before we carry out our own local organizing campaign.

To launch the unit, we read and debate Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” (This coming year, I would like to couple it with N. K. Jemisin’s response: “The Ones Who Stay and Fight.”) We also define “utopia,” not in its pie-in-the-sky sense, but in Eduardo Galeano’s motivating one: “What, then, is the purpose of utopia?” he asks, if it’s always on the horizon. “To cause us to advance.”

After my students dream up their own utopias, we then start to work with mentor texts like “Field Trip to the Museum of Human History,” a poem that feels more relevant than ever. The twin pandemics of COVID-19 and unabated racist state violence lay bare the tragic inadequacy of accepting “the way things are” in our country, where free health care is not universally guaranteed, where Black Americans like George Floyd continue to be lynched.

Although the lesson I describe here took place before Floyd’s murder, I know that — in the wake of his murder and the national uprising it sparked — my students will be as fired up as ever for this field trip.

I pass out “Field Trip to the Museum of Human History” to the class. “We’re going to listen to Franny Choi read her own poem,” I say. “As we listen the first time, just try to get your bearings. Where are we? When are we?”

I pull up the poem online and turn the lights off. “It’s creepy,” I warn. “Get ready.” Choi’s voice hisses from the speakers as she introduces “the new exhibit, / recently unearthed artifacts from a time / no living hands remember.”

“What 12-year-old,” she asks, “doesn’t love a good scary story?”

We listen. I slip Khalil a granola bar when he puts his head down. I get Sierra a highlighter when she asks for one. I notice that she highlights the lines about an object in the “new exhibit:” “a ‘nightstick,’ so called for its use / in extinguishing the lights in one’s eyes.”

After our first read, I make sure we arrive at a shared understanding of the basics: In the poem, students are visiting a museum on a field trip. The poem takes place in the future. “Ancient American society” refers to us.

“As we listen a second time,” I say, “let’s focus on the exhibit they have come to see.” I project a set of questions on the board:

- What does this poem tell us about the future?

- What was Choi’s purpose?

While we listen to Choi again, I point out key words (“police,” for example) to a few students to help them concentrate on what’s most essential.

“I get it!” someone erupts halfway through the second listen.

I hush them. “Keep listening!”

Once we finish, I have students jot down quick answers to both questions before we talk together. I kneel beside a student who looks baffled and star a few central lines:

In place of modern-day accountability practices, / the institution known as “police” kept order / using intimidation, punishment, and force.

She attempts the first question. In my experience, many students have an automatic reaction to poetry that tells them it’s too hard — inaccessible and indecipherable. This poem, regardless of how much I try to hype it, is no different.

“OK,” I begin, “what do we know about this future?”

Justin pipes up: “They don’t have police anymore.”

“Yes!” I say. “How do you know?”

“The kids are learning about things like nightsticks and handcuffs for like the first time,” Ana answers. “They don’t get what those things are.”

“And how do the students in the future feel?”

“They’re scared,” Lara says.

“How do you know?”

Courtney looks at the poem, flips it over. “Well, the kids are ‘dry-mouthed’ and their palms are ‘slick.’ They’re nervous.”

“Team,” I say, “we’re on fire. Let’s move to the second question. I want to hear from Abraham first and then Sierra about why you think the poet, Franny Choi, wrote this poem.”

Abraham’s eyes go wide. “You got this,” I tell him.

We wait. After a beat, he ventures, “She doesn’t like police?”

“True! What makes you say that, Abraham?”

“It says they used ‘intimidation, punishment, and force.’ And ‘domination and control.’ Like all these bad words about them.”

“Perfect! Sierra, what else?”

“I think she’s trying to tell us something. Like that the police are bad, but we don’t see it because we’re so used to the police.”

Ana raises her hand. I nod her way. “I think it’s about police brutality,” she says.

“Yeah, and racism,” Lara adds.

“The police are killing Black people for no reason!” Justin says.

“You all nailed it. Franny Choi wrote this poem in 2015, following the high-profile murders of Black Americans — like who?”

“Trayvon Martin.”

“Michael Brown in Ferguson.”

“Right, and of course there were huge protests there and in other places, too, like Baltimore, where Freddie Gray was killed. Like the protesters, Choi is trying to help us see that we don’t have to accept things the way they are.” I hold still. “Take me to a line in the poem that highlights this.”

Some of my students look back at the poem. Others wait for their classmates to come up with an answer. I call on someone from the latter group: “Nicole,” I prompt, “in the poem, how do you see Choi trying to show us that what we have now, in the 21st century, is not OK?”

Nicole studies the front and back of the poem. “I guess it’s weird that she calls handcuffs an ‘ancient torture instrument’ — like, that’s not how we think of them.”

“Perfect! What else?”

Sierra calls our attention to the lines “assuming positions / of power were earned, or at least carved in steel, / that they couldn’t be torn down like musty curtains.”

I exhale deeply. “I love those lines, too, Sierra, and the phrase that follows: ‘obsolete artifacts.’” I call on a couple of students to make sure we all know that vocabulary. I explain, as clearly as I can, that I think Choi is exposing what we take for granted in present-day society as inconceivable, unintelligible, and unconscionable from a future utopian perspective.

“OK, you all know what comes next: We’re going to write our own pieces inspired by Franny Choi’s,” I offer. We start with a brainstorm.

“The last couple of days,” I remind them, “we’ve been working with the idea of utopia. You’ve already come up with what you’d want in a perfect society. Today, I want you to brainstorm everything you wouldn’t want, everything that wouldn’t exist there.” Because I want my students to have plenty of room to develop their own politics — not parrot mine — I add, “And maybe you disagree with Choi. Maybe you believe that police would exist in a perfect society. You get to decide what you are getting rid of, OK?”

I turn on a song and float around the room. A few minutes later, I offer even more specific instructions: “I’m seeing big, abstract ideas like war, racism, homophobia, and poverty. Excellent. Now, I want us to think about the concrete artifacts that we could link to each. Like, what objects do we associate with racism?”

“The Confederate flag.” “The KKK hood.” “The chain thingies that slaves wore on their feet.”

“Manacles,” I say. “Exactly — those are all things we can touch and would make sense in a museum exhibit about racism. Which is what you’re going to dream up today.” I project an example of an exhibit description I wrote as a model, a remix of Choi’s poem that I call a “wall label.” I describe it as something that might accompany an exhibit in Choi’s museum:

In Ancient American society, an institution known as “the police” kept order. If someone broke the law, police officers would “arrest” them, meaning they would lock their hands with “handcuffs,” an ancient torture instrument, a contraption of chain and bolt. The police kept order using intimidation, punishment, and force. This punishment disproportionately fell on people of color because, in Ancient American society, there were no greater protections from police than wealth and whiteness.

I walk us through the exemplar, noting how I defined terms that might be unfamiliar to people living in the better America of the future. “You are all going to write your own wall labels. They will describe something from our society today that you don’t want to exist in the future. I want to give you one more song to brainstorm. As you’re coming up with ideas, really try to think about what from our present you would relegate, what you would banish, to the Museum of Human History.”

I move from desk to desk, supporting the students with scant lists. I make sure everyone has at least one viable exhibit idea. When the song ends, I ask students to share them, many of which emerge from their own lived experiences: prisons, heroin, schools, zoos, money, homeless shelters, fossil fuels, scales. “Don’t be afraid to steal each other’s ideas,” I encourage. “It’s all part of the process.” When Nicole suggests “cultural appropriation,” a topic we’d discussed earlier in the year, I push us to identify an object we might see in that exhibit.

“A Native American Halloween costume,” someone suggests.

“Right. I’m loving these ideas. You all are just about ready to write your wall labels.”

“The key,” I reiterate, “is to make sure you describe this object from our present as if kids in the future would have no idea what you’re talking about. It’s unimaginable to them. Remember that, just as Choi does, the way you write should make us realize that it’s totally messed up that we ever allowed ourselves to tolerate whatever it is you describe in your exhibit.” I let this sink in.

“You don’t have to reinvent the wheel here either,” I say. “I lifted language right out of Choi’s poem. You can do the same. Start your own museum labels with ‘In Ancient American society’ if you want.” I notice a few students write down that line, a helpful scaffold.

After I answer clarifying questions, I set them to work: “You’ve got 15 minutes. Let’s get it.” I put on a chillhop playlist and wait to see which students don’t put pen to paper. I give them a minute or two before I wander over. As students write, I try to offer small suggestions on how they might more closely capture the poet’s style.

“Notice how Franny Choi doesn’t assume her audience will understand the word ‘handcuffs,’” I whisper to Nick. “Your audience has no idea what money is — what it looks or feels like.” He nods and adds in a few words without ever looking up from the page.

When the timer goes off, I ask for volunteers to share.

“I’ll go,” Ana offers right away, clearly proud of what she wrote:

In Ancient American society, dark stone walls restricted those who broke the law — or those who hadn’t really done anything at all. These walls were called prison, and the people were labeled prisoners. They were confined in small rooms with steel bars and were given beds hard as rock. . . . Some were sent there for the sole purpose of being killed. They would be strapped down to cold uncomfortable chairs, usually of iron, so that the electricity that passed through the prisoner’s body would kill them with complete accuracy.

We sit, stunned, before remembering to snap. “I love how you help us to see prison and the death penalty in a whole new way here. Thank you, Ana. Who’s next?”

Lara hesitates at first, then dives in:

Zoos took animals out of their natural habitat. They were then bred in captivity, so they no longer knew natural life. They only knew confinement and being controlled. Many families in Ancient America brought their drooling, ugly kids there to stick their noses and sticky hands on the glass. The animals looked sad. It was hot, and they were mopey, knowing they didn’t belong there. There was no instinct for those animals. They lived in their cages, got hand-fed. They didn’t get to hunt. They sat there as a show for those families — as entertainment.

We snap again. “You really came for those kids,” I joke.

Nick says, “These are fire. Mine sucks.”

“Oh, please. Just share what you have, Nick. You’re brilliant.”

So he does:

In Ancient American society, something called money, a small piece of green paper with a number on it, was everything in this society. This simple object could not be eaten. You could not wear it, and you could not build anything out of it that you could live inside. The truth is, it was only given and taken as a prize in exchange for the objects you actually needed or just desired. You want or need a house? You want to visit your family in another place? You needed that piece of green paper that could be ripped easily and lose its worth. Everything was about money.

“You thought that sucked?” Lara asked him. “That was so good.” We snap in agreement.

At the end of the unit, we head to the computer lab for students to revise and polish two of the pieces inspired by the mentor texts we studied, followed by a more formal read-around. For students who choose to turn their wall labels about obsolete artifacts into final drafts, I push them to grow their ideas of what replaced them. Lara, for example, will go on to mention “the Wildlife Preservations that we have today” and document the “Animal Liberation Movement [that] began in 2098” to abolish zoos.

I wrap up class by connecting the Museum of Human History back to our unit. Another world is possible, I say, so long as we have the imagination to dream it into being and the disciplined will to fight for it.

Franny Choi’s poem feels freshly necessary in 2020. The racist violence facing Black Americans — a knee on the neck always — was made horrifically real for George Floyd, who, like Eric Garner and others before him, cried out “I can’t breathe” as a white police officer suffocated him on film.

The national rebellion waged in response to Floyd’s murder (and the looting of Black life and livelihood that has always defined this country) opened space for more Americans to reach for Choi’s revolutionary future. Calls to defund the police and abolish prisons moved from the left-wing fringe to the political mainstream in the United States, and Americans of all parties have had to grapple with these institutions: where they come from, what function they serve, and whether we need them at all.

In “How We Save Ourselves,” a June opinion piece published by the New York Times , Roxane Gay confessed, “If you had asked me, before George Floyd’s killing, if I believed in police abolition I would have said that reform is desperately needed but that abolition was a bridge too far. I lacked imagination. I could not envision a world where we did not need law enforcement as it is presently configured. I am ashamed. Now I know we don’t need reform. We need something far more radical.”

I believe our classrooms must be sites of radical imagination in order to seed radical change. Arundhati Roy insists, “Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.” I keep my ear to the ground always for this breath — a gift stolen mercilessly, again and again, from Black Americans like Garner and Floyd. By being in conversation with revolutionary mentor texts, I hope my students have the quiet chance to hear her, too — to see her take shape.

Field Trip to the Museum of Human History By Franny Choi

Everyone had been talking about the new exhibit, recently unearthed artifacts from a time

no living hands remember. What twelve year old doesn’t love a good scary story? Doesn’t thrill

at rumors of her own darkness whispering from the canyon? We shuffled in the dim light

and gaped at the secrets buried in clay, reborn as warning signs:

a “nightstick,” so called for its use in extinguishing the lights in one’s eyes.

A machine used for scanning fingerprints like cattle ears, grain shipments. We shuddered,

shoved our fingers in our pockets, acted tough. Pretended not to listen as the guide said,

Ancient American society was built on competition and maintained through domination and control.

In place of modern-day accountability practices, the institution known as “police” kept order

using intimidation, punishment, and force. We pressed our noses to the glass,

strained to imagine strangers running into our homes, pointing guns in our faces because we’d hoarded

too much of the wrong kind of property. Jadera asked something about redistribution

and the guide spoke of safes, evidence rooms, more profit. Marian asked about raiding the rich,

and the guide said, In America, there were no greater protections from police than wealth and whiteness.

Finally, Zaki asked what we were all wondering: But what if you didn’t want to?

and the walls snickered and said, steel, padlock, stripsearch, hardstop.

Dry-mouthed, we came upon a contraption of chain and bolt, an ancient torture instrument

the guide called “handcuffs.” We stared at the diagrams and almost felt the cold metal

licking our wrists, almost tasted dirt, almost heard the siren and slammed door,

the cold-blooded click of the cocked-back pistol, and our palms were slick with some old recognition,

as if in some forgotten dream we did live this way, in submission, in fear, assuming positions

of power were earned, or at least carved in steel, that they couldn’t be torn down like musty curtains,

an old house cleared of its dust and obsolete artifacts. We threw open the doors to the museum,

shedding its nightmares on the marble steps, and bounded into the sun, toward the school buses

or toward home, or the forests, or the fields, or wherever our good legs could roam.

Franny Choi is author of the poetry collections Soft Science and Floating, Brilliant, Gone. She is a Bolin Fellow in English at Williams College. Visit her website at frannychoi.com . This poem originally appeared in a PBS NewsHour online feature.

Kurt David is a public high school English teacher and union leader in Fall River, Massachusetts. He is also a Macrorie Fellow at the Bread Loaf School of English.

Illustrator Fabio Consoli’s work can be seen at fabioconsoli.com .

Included in:

Volume 35, No. 1

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Rate the lesson plan, field trips, field trip: longfellow poetry workshop.

Longfellow House Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

- March-April

- Tuesdays & Wednesdays, 10:00-11:45 AM

- 3rd-5th grade classes

- Limit 24 students per group (at least 1 chaperone per 8 students)

- Reservations required

As a writer, famous poet Henry Longfellow took inspiration from many things – his children, people who lived in the house before him, his community, and his travels. During this creative 90-minute program, 3rd-5th grade students will explore literary history and use poetry as a tool to express their experiences and inspirations.

Students will consider the people, places, and ideas that inspired the work of famed 19th century poet Henry Longfellow. They will work together to analyze the structure and meaning of four of his poems: “The Children’s Hour,” “The Village Blacksmith,” “To a Child,” and “Travels by the Fireside.” The program includes a visit to Longfellow’s Study or Library, where students will undertake a sensory exploration of the historic space and analyze poetry. Finally, students will collaborate to write original poetry based on their own inspirations and experiences, and share it with their classmates in a fun and supportive environment.

This program consists of three parts (detailed itinary below under "Source Materials"):

Welcome, introduction and initial poem discussion (45 minutes)

Brief visit to the inside of the house (one group will visit the Study, the other the Library), second poem discussion and sensory exploration (30 minutes)

Create your own poem challenge, shareout (45 minutes)

Parts 1 and 3 take place outdoors (weather permitting) on the Longfellow House lawn. In the event of inclement weather, these will move inside the Carriage House.

How to Book Your Field Trip

We are no longer booking reservations for spring 2024. Please Email us with any questions.

Goals and itinerary for the 2023 Poetry Workshop field trip.

Download Longfellow Poetry Workshop Itinerary

Lesson Plans

Last updated: March 5, 2024

- Submissions

- Request Book Reviews

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Onkar Sharma

Literary Yard

Search for meaning

‘Field Trip’ and other poems

By: KJ Hannah Greenberg

Before masks and hand gel were commonplace, At a time when Internet was a science fiction trope, School districts chartered buses, bid kids to pack lunches, Sought “wild” adventures at free, public gathering places.

One such quest was the Fifth Grade rite of passage, Was that annual collection of peanut butter sandwich Students, to the city’s storage bin of historical, scientific, Cultural, and artistic artifacts. We best loved the dioramas.

Behind glass (since plastic was yet expensive), aboriginal People, both local and foreign, were placed with household Effects. Also, strange beast, all claws, fangs, stood perched As though prepared to attack. Some children sloughed tears.

The nylon bags in neon colors, filled with a species of air, Wagging like unstrung puppets, interested us for two entire Minutes, whereas the acrylic abstracts in hippie hues of green, Pink, blue, yellow, captured our attention for half that amount.

Confronted by towering sculptures, we pretended they Sheltered dragons. Sleepy security guards called for us To cease running around those priceless works constructed From soda cans, milk cartons, chicken wire, spit, clothes pins.

Dead citizens from outlying lands caught us staring at Their sarcophagi, inscribed with hieroglyphics, the nature Of which we’d only previously viewed in our comic books Full of caped heroes, select bad guys, enough buckshot to kill.

### The Colors of Noise

“Black noise’s” silence. “Pink noise,” though, is twitterpated with bass, Cranked past comfortable decibels. Similarly, “white noise” is obsessed With environmental sensitivity.

As per “blue noise,” those high-pitched sounds, similar to articulated Dithering, make peace among audible reverberations. Still, “green Noise,” ever balanced, stays in the background.

“Grey noise,” alternatively, weighted or not, calms psychotics, puts Murders and rapists to sleep, pacifies every robber, all manner of Gang bangers.

It’s “Brownian noise,” however, that aids ordinary folks, culls splashes Of ocean waves, booms of heavy wind, the inner peace concommitant To deliberation.

Omitting choice themes when communicating, Is all but supererogatory, maybe immoral, Perhaps, likewise, is the worst sort of caesura.

Eliding, whether mañana or else immediately, Breaks not only the flow of talk, but also The exchange of truths, similar importances.

Plainly, certain folks insinuate that asemic Writings, like toddlers’ scribbles, count Naught against malfunctioning discourse.

Such foolish sorts, ever quarrelsome when Enacting self-replicating insights, laugh At core attempts to fashion epistemologies.

Banners for Separating Idealized from Realized Meaning

Rhetorical analyses establish obscured discrepancies. Idealized vs. realized moral foundations of basic discourse, Contrary to social myths, contrary to equanimity, utilitarian, Individualistic, or expressive conventions, hardly ever buttress The importance of the combined creation/maintenance of our State, or else aid individuals’ singular, cognitive behaviors. Rather, these assessments bolster federal fashions for Conservation, empowerment, private somebodies.

Thus, the morality, which allegedly Undergirds public edification, differs from The principles used to mystify our population. Hence, citizens fail at voicing ideological conflict, Also, at challenging cultural norms. We cannot Discuss culpabilities no matter the dangers. So, our goals become circumscribed by “Evidence” about “shared values.”

This shortage of knowledge per accountability Deters our upkeep of civilization. To gain illumination, We must embrace nonuniversal, accepted conceptualizations Of beliefs such that dearths of literature on contexts surrounding Meaning making won’t upset politicians or social scientists. To clinch interdisciplinary perspectives & fundamentally Complex collective missions, we must thwart reliance On technical aptness, not yield sundry truths.

Share this:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Related posts.

- Kindertotenlieder *

‘Heinrich Böll, Group Portrait with Lady’ and other poems

‘One More Day’ and other poems

Type your email…

- Archaeology/History

- Books Reviews

- Content Marketing

- Global Politics

- Literary criticism

- LiteraryArt

- Non-Fiction

- Video Interviews

Recent Posts

- White Rose, Red Orchestra: the German Resistance to Hitler

- Recent Beauty Product Controversies Women Need to Know

- A Woman’s Coffin

Recent Comments

Related Categories

VFT Home | About | Field Trip List | Lounge | Standards

the software | the field trips | the book | the training Home | About Tramline | Support | Store | Contact

Moscow Bells

Edna dean proctor, moscow, russia.

Corinne Segal Corinne Segal

Leave your feedback

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/arts/poetry/poet-franny-choi-pictures-a-world-without-police

Poet Franny Choi pictures a world without police

What world a world without police look like?

Poet Franny Choi’s work attempts to answer that question, exploring the ways that power, specifically in the realms of race, class and gender, operate in U.S. systems and institutions.

Poetry is uniquely situated to expose what many people consider to be “unspeakable” forces of violence and erasure within those systems, Choi said.

“When people of color are being murdered by the police with impunity, and when queer and trans folks are being murdered and being incarcerated for trying to defend their own lives, and when immigrants are being deported at record high rates, and when there’s a presidential candidate who proposes having a national Muslim database, it seems like there are a lot of forces in the world that tell me, and people who are similarly outside the norm of a ‘default human,’ that we need to apologize for existing,” she said.

Those norms can also play an oppressive role in the world of poetry, she said. In a recent incident, poet Michael Derrick Hudson, a white man, was accepted into the prestigious “The Best American Poetry 2015” anthology under the Chinese female pseudonym “Yi-Fen Chou.” Hudson described the pseudonym as a tool he used to get published, prompting criticism and outrage from many in the poetry community.

“An Asian woman was basically erased and used as a mask for a white man to put on for his own personal gain,” Choi said. “It lit a fire under me to keep writing.”

That writing is heavily influenced by Choi’s work as a community organizer in Providence on issues of police accountability and racial profiling, she said. For Choi, that work has brought an urgency to imagining alternatives to the current police system, as well as questions about the specifics: “When [organizers] say we want abolition of prisons and cops, what do we envision in its place?” she said.

An answer began to take form for her after reading Ursula K. Le Guin’s novel “The Dispossessed,” which chronicles life in a utopic society. “I felt like it was a door in my brain opening up,” she said.

“Field Trip to the Museum of Human History” depicts part of that answer, showing a group of students who learn about the modern-day U.S. in a future where police have been abolished. To this group, police brutality and class inequality are antiquated horrors of the past.

“The idea of the children of my child looking at the messed-up things about this world from the other side of a glass was very appealing to me,” she said. “I thought of some of the youth organizers that I stand in solidarity with, and the idea of them and their future generations being able to do that was really exciting.”

The type of high-level view of police reform that the poem explores can be useful for activists facing the threat of burnout, she said. “We get bogged down, as organizers, [by] the details of the everyday,” she said. “[We] are focusing on such tiny concrete gains and victories that sometimes it’s hard to zoom out and think about what we’re actually working toward.”

Hear Choi read “Field Trip to the Museum of Human History,” or read the poem below.

Field Trip to the Museum of Human History

Everyone had been talking about the new exhibit, recently unearthed artifacts from a time

no living hands remember. What twelve year old doesn’t love a good scary story? Doesn’t thrill

at rumors of her own darkness whispering from the canyon? We shuffled in the dim light

and gaped at the secrets buried in clay, reborn as warning signs:

a “nightstick,” so called for its use in extinguishing the lights in one’s eyes.

A machine used for scanning fingerprints like cattle ears, grain shipments. We shuddered,

shoved our fingers in our pockets, acted tough. Pretended not to listen as the guide said,

Ancient American society was built on competition and maintained through domination and control.

In place of modern-day accountability practices, the institution known as “police” kept order

using intimidation, punishment, and force. We pressed our noses to the glass,

strained to imagine strangers running into our homes, pointing guns in our faces because we’d hoarded

too much of the wrong kind of property. Jadera asked something about redistribution

and the guide spoke of safes, evidence rooms, more profit. Marian asked about raiding the rich,

and the guide said, In America, there were no greater protections from police than wealth and whiteness.

Finally, Zaki asked what we were all wondering: But what if you didn’t want to?

and the walls snickered and said, steel, padlock, stripsearch, hardstop.

Dry-mouthed, we came upon a contraption of chain and bolt, an ancient torture instrument

the guide called “handcuffs.” We stared at the diagrams and almost felt the cold metal

licking our wrists, almost tasted dirt, almost heard the siren and slammed door,

the cold-blooded click of the cocked-back pistol, and our palms were slick with some old recognition,

as if in some forgotten dream we did live this way, in submission, in fear, assuming positions

of power were earned, or at least carved in steel, that they couldn’t be torn down like musty curtains,

an old house cleared of its dust and obsolete artifacts. We threw open the doors to the museum,

shedding its nightmares on the marble steps, and bounded into the sun, toward the school buses

or toward home, or the forests, or the fields, or wherever our good legs could roam.

Franny Choi is a writer, teaching artist, and the author of Floating, Brilliant, Gone (Write Bloody Publishing, 2014). She has received awards from the Poetry Foundation and the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Poetry Magazine, The Journal, Rattle, Indiana Review, and others. She is a VONA alumna, a Project VOICE teaching artist, and a member of the Dark Noise Collective. Audio edited by Brigid Choi.

Corinne is the Senior Multimedia Web Editor for NewsHour Weekend. She serves on the advisory board for VIDA: Women in Literary Arts.

Support Provided By: Learn more

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

Class Trips

Arrange a class trip.

Please contact Jade Mapp with any questions.

- Email * Enter Email Confirm Email

- Best time to call?

- School name *

- Grade level and/or age range *

- Number of students *

- Preferred dates / availability * Please note the following: Poets House typically schedules class visits from 10:00am-11:30am Tuesday and Friday, and 11:00am-12:30pm Thursdays. Our space can accommodate groups of up 30 individuals. If your party exceeds this number, we are happy to schedule multiple visits. For private schools, we suggest a donation of between $50-$250, though this is not required.

- For classes with older students, if applicable: What current literary coursework would you ideally like this visit to focus on or help develop further?

- Is there anything else you'd like our educators to know about your class?

Like this page? Share it.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share via Email

This One Guy Made the Washington DC Field Trip a Middle School Rite of Passage

No, not the cherry blossoms. It’s the middle school T-shirt, the unofficial signal that spring has sprung in the nation’s capital.

Every year, more than one million eighth graders—about one in every three —can be seen running up and down the National Mall in matching school-colored tees, pacing awkwardly in the Smithsonian , taking lunch at the L’Enfant Plaza and Pentagon City food courts, and racking up soda fountain tabs at the Hard Rock Cafe.

A field trip that started as a business idea has since evolved into a decades-long tradition, bolstering economies and creating entirely new ones . And while it’s become the subject of debate in school districts from Ohio to Massachusetts , in DC, it remains both a fact of life and a total vibe .

Filling the Void

It was quite a different experience from what you might expect of DC tourism these days. In the 1960s, due to political strife and moral resentment against America’s involvement in Vietnam, many young people didn’t have an interest in visiting the president’s house. Bus companies and airlines took note, leaving a void for trips centered around our nation’s history for younger generations. Moreover, Wendel tells me that during his initial trip, “I’m listening to some tour guide who’s probably been picked off the corner, and he’s lecturing kids.”

Convinced he could do better, Wendel coordinated the following year’s trip with a fellow teacher, attempting to give his students a more academically driven experience. The year after that, he founded Lakeland Tours solely to coordinate travel for eighth graders to DC Wendel sold Lakeland Tours in 1999, but he estimates the company helped bring a million students to DC overall; the company is now known as WorldStrides , one of the largest student tourism companies in the country.

All the while, much larger trends were emerging as well. One of the most important—beyond the rapid growth in air travel—was the evolving access to museums. In the early 20th century, museums were seen as bastions of elitism, a place where culture lived but only existed for those deemed worthy of entry. “Culture for culture’s sake was what the Smithsonian meant to its lay visitors,” wrote Louise Connolly in her 1914 book, The Educational Value of Museums . “Young people led through it contracted, not the museum habit, but museophobia, a horror of museums.”

But that sentiment began to change heading into World War II with the rise of the museum as an educational companion (the concept of “visual education,” i.e., using visual aids to enforce concepts , was introduced in the early 1920s). No longer were museums reserved just for the upper echelons; they were a place to engage, learn, and question, no matter who you were.

Today, museums welcome approximately 55 million students from school groups .

How Do You Do, Fellow Kids?

For three to five days—the usual length of the trip—students are whisked around the city from dawn until dusk. It’s not atypical for every day to last from 8:30 am to 10 pm, says Lindsay Hill, the associate director of visitor experience and group tours at Destination DC, where she helps tour groups coordinate with tour operators. She says the jam-packed days are a win-win for everyone involved: Students get to see as much of the city as possible, and there’s less time for them to get into trouble (more on that later.)

The usual stops are the usual suspects: the US Capitol, the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial, the MLK Jr. Memorial, several war memorials, the Smithsonian Museums, Arlington National Cemetery, the National Zoo, the Holocaust Museum, and the Ford Theater. (All of these landmarks are free to visit.) You might also have been lucky enough to get a tour of the White House (also free but more challenging to plan), meet your local congressperson, or travel by boat to Mount Vernon to tour George Washington’s landmark estate. Or better yet, maybe you were whisked around DC in an amphibious World War II vehicle — as part of a so-called “duck tour”—allowing you to view landmarks by land and water (a tour that, sadly, no longer operates).

Meanwhile, the Hard Rock Cafe serves as a beacon of sustenance that helps to fuel all that sight-seeing. The Hard Rock not only plans for these travelers—a student group-focused menu, including a soda, entree, and chocolate chip cookies for dessert, ensures that students are “in and out in about an hour,” says Sara Lester, a regional sales and marketing manager at Hard Rock Cafe—but it relies on them, too. Case in point: Through March and April of this year, they’ve welcomed a total of 25,000 eighth graders, putting them on pace to reach 50,000 students by the end of the field trip season.

Not to mention, the Hard Rock isn’t without some political significance. Among its many pieces of music-themed memorabilia, two, in particular, speak to our nation’s history/sense of patriotism: 1) a saxophone played by President Bill Clinton; and 2) a red, white, and blue outfit worn by Beyoncé.

Not-So-Unruly Behavior

“Eighth graders are in a unique position where they’re big enough to be self-reliant, but not so big that they’re going to run out and create havoc in the streets,” explains John Raymond, the vice president of sales and marketing of student tourism company Grand Classroom, which oversees the travel of some 20,000 students to Washington, D.C. annually.

Raymond estimates that over the course of three decades, there have been just five or six instances where students were sent home on a trip. If anything, such rarity speaks perfectly to the eighth-grade mindset. “You don’t want to be outside of the herd. You don’t want to draw unnecessary attention to yourself,” Raymond says.

It helps, too, that the trip isn’t cheap—prices average from $2,000 to $3,000 per student. Additionally, parents must sign a liability waiver that holds them responsible for any financial damages incurred by their child, and no kid wants to have that conversation with mom and dad.

That said, if there is a mischievous will, eighth graders will surely find a way, an attitude that prompted Wendel, while at Lakeland Tours, to hire enlisted military members to sit outside students’ hotel rooms to ensure they didn’t sneak out at night. “That isn’t to say that the kids didn’t win some of the battles,” Wendel says. “But once we had a lights out or a curfew, with about 99% certainty, we were able to keep the kids confined to their rooms.”

It’s worth noting, too, that any havoc the students create is often unintentional and harmless. Or, in true eighth-grade fashion, just plain awkward. “I was accidentally locked in my hotel bathroom during my eighth-grade field trip to DC,” recalls Dan Howie, now a recruiting manager from North Carolina. “Maintenance had to come in and drill through the lock. It took about two hours for them to get me out, and there was quite an audience waiting to see if I’d emerge. It certainly added to my eighth-grade cool-kid mystique.”

The Kids Are Alright

As a result, what may be thought of as a few days for students to get away from their parents and vice-versa—a pitch that Wendel used while working at Lakeland—has become an opportunity for personal growth and cultural exposure. “Getting outside of your home base and what’s comfortable for you is where the change in perspective and the ability to really understand different cultures and people’s backgrounds comes from,” Hill says.

For that alone, maybe it’s worth the trip—matching T-shirts and all. Want more Thrillist? Follow us on Instagram , TikTok , Twitter , Facebook , Pinterest , and YouTube .

Colin Hanner is a freelance writer based in Chicago. He writes about food, travel, and whatever else he’s interested in.

- My View My View

- Following Following

- Saved Saved

Lagging in polls, UK Conservatives pitch national service at 18

- Medium Text

Sign up here.

Editing by Elaine Hardcastle

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. New Tab , opens new tab

A British air force pilot has died after a Spitfire aircraft crashed on Saturday into a field in eastern England, police and the RAF said.

A professional horse rider has died from a fall when competing at an equestrian event in Britain, governing body British Eventing said.

World Chevron

Millions without power as cyclone Remal pounds Bangladesh and India

Strong winds and heavy rain pounded the coastal regions of Bangladesh and India as severe cyclone Remal made landfall late on Sunday, leaving millions without electricity after power poles fell and some trees were uprooted by gusty winds.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Field Trip Poems - Examples of all types of poems about field trip to share and read. This list of new poems is composed of the works of modern poets of PoetrySoup. Read short, long, best, and famous examples for field trip. Search Field Trip Poems: FBI ARLINGTON HEIGHTS ILLINOIS CIVIL RIGHTS DIVISION CRISIS TEAM OF CONFIDENTIAL HUMAN SOURCES ...

Poems about Field trip at the world's largest poetry site. Ranked poetry on Field trip, by famous & modern poets. Learn how to write a poem about Field trip and share it! Login Register Help . Poems Write Groups. All groups; Free writing courses; Famous poetry classics;

Part of this poem job Almost forgot thee 'Til student told me It's "morning glory"! A school property But not CapSU-D Also a public Bigger, more classic With BEEd 4 Wrote this night after Our fieldtrip venture Picked thee morning late On Feb. Twenty-Eight At about Twelve noon Meters from the gate West Visayas State University Next ...

"Field Trip to the Museum of Human History" by Franny Choi is more than just a poem; it's an expedition into the caverns of human experience and emotion. Franny Choi, a notable figure in contemporary poetry, uses her sharp, insightful words to sketch a world where history and personal narrative collide. This poem, like many of her works, falls under the genre of modern poetry, where ...

Field Trip. Bunnies take the backseat, flamingoes fill the front. Rhinos rest upon the roof, turtles swim inside the trunk. Weasel's ready at the wheel for adventure to ensue- Today's their day to visit wild humans at the zoo. This poem is copyright (©) Sharon Korzelius 2024.

Complexly, The Poetry Foundation, and curators Charlotte Abotsi and Sarah Kay. Natasha Huey (she/her/hers) reads the poem, "Field Trip to the Museum of Human History" by Franny Choi. Ours Poetica captures the intimate experience of holding a poem in your hands and listening as it's read by a distinctive voice.

Turn a Field Trip Into a Poetry Lesson. Any time is a good time to write a poem. Students can become poets by participating in these poetry lessons. By Cathy Neushul. Every year students visit the art museum, the zoo, or the aquarium. After the field trip students are usually asked to reflect on what they saw.

Corey Van Landingham, a finalist in Narrative's Fifth and Ninth Annual Poetry Contests, is the author of Antidote. She has also had work included in Best American Poems, 2014. Born in Ashland, Oregon, she received an MFA from Purdue University and was a Wallace Stegner Fellow in poetry. She lives in Cheviot, Ohio.

Hi friends! This is a set of 3 field trip poems: The Zoo, The Farm, The Aquarium!Each poem includes 3 b&w versions for differentiation and a pocket chart. They each include familiar sight words for easy reading!This is part of a money saving poems throughout the year GROWING Bundle! The growing bundle also includes a digital boom card version of this poem for distance learning!Thank you so ...

Franny Choi wrote her poem "Field Trip to the Museum of Human History" back in 2015, a couple of years into the Black Lives Matter movement. I've been teaching it ever since. In the poem, Choi boldly imagines a world without police, an institution she defamiliarizes by allowing us to see it through the eyes of children generations into ...

Create your own poem challenge, shareout (45 minutes) Parts 1 and 3 take place outdoors (weather permitting) on the Longfellow House lawn. In the event of inclement weather, these will move inside the Carriage House. How to Book Your Field Trip. We are no longer booking reservations for spring 2024. Please Email us with any questions. Materials

Field Trip. Sought "wild" adventures at free, public gathering places. Cultural, and artistic artifacts. We best loved the dioramas. Effects. Also, strange beast, all claws, fangs, stood perched. As though prepared to attack. Some children sloughed tears. Pink, blue, yellow, captured our attention for half that amount.

Teaching the Museum of Human History. "Field Trip to the Museum of Human History" is a poem I wrote in 2015, while living and organizing for police accountability in Providence, Rhode Island. The poem is inspired by a scene in Ursula K. LeGuin's novel The Dispossessed, in which a group of schoolchildren in an anarchist society is ...

49 Trip Poems ranked in order of popularity and relevancy. At PoemSearcher.com find thousands of poems categorized into thousands of categories. ... Field Trip Book of the Week: "Gary the Gorgeous Goat ... 826la.org. 826la.org. helpful non helpful. What I Got For Christmas..., Kevin & Amanda, Food ... kevinandamanda.com. kevinandamanda.com ...

By focusing on children's poetry that is less complex, this module attempts to spark interest in poetry and build student confidence in deciphering it. The student tour introduces students in grades 3-6 to different types of poetry and a few well-known poets and their work in a fun and enjoyable way—via the Internet!

The fields were green, and the sky was blue, Morbleu! Parbleu! What a pleasant excursion to Moscow! Four hundred thousand men and more. Must go with him to Moscow; There were marshals by the dozen, And dukes by the score; Princes a few, and kings one or two. While the fields are so green, and the sky so blue, Morbleu! Parbleu!

And while the rose-clouds with the breeze. Drift onward,—like a dream, High in the ether's pearly seas. Their radiant faces gleam. O, when some Merlin with his spells. A new delight would bring, Say: I will hear the Moscow bells. Across the moorland ring! The bells that rock the Kremlin tower.

Hear Choi read "Field Trip to the Museum of Human History," or read the poem below. ... She has received awards from the Poetry Foundation and the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts. Her ...

The pleasure of Juster's poems goes beyond their dead-pan humor; it hinges on his language, his use of every device, and his mastery of every form. Here is his "Round Trip," a rondeau that is also almost monorhyme, so that the repetitive form and the obsessive end-rhymes recreate the experience being conveyed: ROUND TRIP

Please note the following: Poets House typically schedules class visits from 10:00am-11:30am Tuesday and Friday, and 11:00am-12:30pm Thursdays. Our space can accommodate groups of up 30 individuals. If your party exceeds this number, we are happy to schedule multiple visits. For private schools, we suggest a donation of between $50-$250, though ...

Astronomers Tycho Brahe and Edmund Halley accompany modern scientists including Rebecca Elson, Alice Gorman on the first woman in space, and Yun Wang's space journal on travel to Andromeda. This collection reaches across time and cultures to illuminate how we think about outer space, and ourselves. Comprehensive: Gathers well-known and lesser ...

Filling the Void. In the fall of 1963, Phil Wendel began teaching at Northwood Junior High School in Highland Park, Illinois. Later that academic year, in the spring of 1964, he led his first ...

Putin arrives in Uzbekistan, third foreign trip since re-election World category · May 26, 2024 · 11:24 PM UTC · ago Putin has traveled abroad only infrequently since the start of Moscow's ...