Where did Columbus actually go on his first voyage in 1492?

As an Ecotourism Specialist, I am fascinated by the history of exploration and the impact it has had on the world. One of the most well-known explorers is Christopher Columbus, who embarked on his first voyage in 1492 with the goal of finding an all-water route to Asia. But where did Columbus actually go on his first voyage?

According to historical records, Columbus set sail from Spain on August 3, 1492. After more than two months at sea, he finally landed on an island in the Bahamas on October 12. This island, which Columbus named San Salvador, was called Guanahani by the native inhabitants. It was during this voyage that Columbus made the first known European contact with the Americas.

While Columbus is often credited with discovering America, it is important to note that he never actually set foot on North America. Instead, he explored various islands in the Caribbean and later reached present-day Venezuela on his fourth voyage. So, if Columbus didn’t discover America, who did?

The Vikings, led by Leif Erikson, were the first Europeans to reach North America. Around the year 1000 A.D., Erikson sailed to a place he called “Vinland,” which is now known as the Canadian province of Newfoundland. These early expeditions by the Vikings are well-documented and accepted as historical fact.

Columbus’s subsequent voyages took him to different parts of Central and South America, including Trinidad and Jamaica. He never did find the all-water route to Asia that he had been searching for, but his voyages had a profound impact on world history.

But did Columbus have a map to guide him on his voyages? Recently, a 1491 map was uncovered, which is believed to be the best surviving map of the world as Columbus knew it. It is believed that Columbus likely used a copy of this map in planning his journey.

Now, let’s address some frequently asked questions about Columbus and his voyages:

1. Did Columbus discover America? No, Columbus never discovered North America. He landed on various islands in the Caribbean and later reached parts of Central and South America.

2. Did Columbus have a map? Yes, Columbus likely used a map from 1491 in planning his voyages.

3. What land did Columbus actually sail to? Columbus landed on an island in the Bahamas, which he named San Salvador. He also explored other islands in the Caribbean and reached parts of Central and South America.

4. Where did Columbus start his second voyage? Columbus set sail from Cádiz, Spain on his second voyage in 1493.

5. Why did Christopher Columbus go on his third voyage? Columbus organized a third voyage to resupply the colonists and continue the search for a new trade route to the Orient.

6. How long did it take Columbus to cross the Atlantic? Columbus’s first voyage took a grueling two months and nine days. The first steamship to cross the Atlantic did so in 207 hours in 1819.

7. Who lived in America first? The first known inhabitants of North America were the Clovis people, who crossed a corridor between giant ice sheets covering what is now Alaska and Alberta.

8. Who discovered America for England? John Cabot and his expedition are credited with discovering America for England.

In conclusion, although Christopher Columbus is often associated with the discovery of America, he actually never set foot on North America. His first voyage in 1492 led him to the Bahamas, and subsequent voyages took him to different parts of the Caribbean and Central and South America. The Vikings, led by Leif Erikson, were the first Europeans to reach North America. However, Columbus’s voyages had a significant impact on world history and opened the way for further exploration and colonization of the Americas.

About The Author

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

By AD. F. Bandelier Transcribed by Janet van Heyst Dedicated in honor of Fr. Moses M. Nagy, O. Cist.

(Italian CRISTOFORO COLOMBO; Spanish CRISTOVAL COLON.) Born at Genoa, or on Genoese territory, probably 1451; died at Valladolid, Spain, 20 May 1506.

The early age at which he began his career as a sailor is not surprising for a native of Genoa, as the Genoese were most enterprising and daring seamen. Columbus is said in his early days to have been a corsair, especially in the war against the Moors, themselves merciless pirates. He is also supposed to have sailed as far south as the coast of Guinea before he was sixteen years of age. Certain it is that while quite young he became a thorough and practical navigator, and later acquired a fair knowledge of astronomy. He also gained a wide acquaintance with works on cosmography such as Ptolemy and the “Imago Mundi” of Cardinal d’Ailly, besides entering into communication with the cosmographers of his time. The fragment of a treatise written by him and called by his son Fernando “The Five Habitable Zones of the Earth” shows a degree of information unusual for a sailor of his day. As in the case of most of the documents relating to the life of Columbus the genuineness of the letters written in 1474 by Paolo Toscanelli, a renowned physicist of Florence, to Columbus and a member of the household of King Alfonso V of Portugal, has been attacked on the ground of the youth of Columbus, although they bears signs of authenticity. The experiences and researches referred to fit in satisfactorily with the subsequent achievements of Columbus. For the rest, the early part of Columbus’s life is interwoven with incidents, most of which are unsupported by evidence, though quite possible. His marriage about 1475 to a Portuguese lady whose name is given sometimes as Doña Felipa Moniz and sometimes as Doña Felipa Perestrella seems certain.

Columbus seems to have arrived in Portugal about 1471, although 1474 is also mentioned and supported by certain indications. He vainly tried to obtain the support of the King of Portugal for his scheme to discover the Far East by sailing westward, a scheme supposed to have been suggested by his brother Bartholomew, who is said to have been earning a livelihood at Lisbon by designing marine charts. Columbus went to Spain in 1485, and probably the first assistance he obtained there was from the Duke of Medina Celi, Don Luis de la Cerda, for whom he performed some services that brought him a compensation of 3000 maravedis in May, 1487. He lived about two years at the home of the duke and made unsuccessful endeavors to interest him in his scheme of maritime exploration. His attempts to secure the help of the Duke of Medina Sidonia were equally unproductive of results. No blame attaches to the noblemen for declining to undertake an enterprise which only rulers of nations could properly carry out. Between 1485 and 1488 Columbus began his relations with Doña Beatriz Enriquez de Arana, or Harana, of a good family of the city of Cordova, from which sprang his much beloved son Fernando, next to Christopher and his brother Bartholomew the most gifted of the Colombos.

Late in 1485 or early in 1486, Columbus appeared twice before the court to submit his plans and while the Duke of Medina Celi may have assisted him to some extent, the chief support came from the royal treasurer, Alonzo de Quintanilla, Friar Antonio de Marchena (confounded by Irving with Father Perez of La Rábida), and Diego de Deza, Bishop of Placencia. Columbus himself declared that these two priests were always his faithful friends. Marchena also obtained for him the valuable sympathy of Cardinal Gonzalez de Mendoza. Through the influence of these men the Government appointed a junta or commission of ecclesiastics that met at Salamanca late in 1486 or early in 1487, in the Dominican convent of San Esteban to investigate the scheme, which they finally rejected. The commission had no connection with the celebrated University of Salamanca, but was under the guidance of the prior of Prado. It seems that Columbus gave but scant and unsatisfactory information to the commission, probably through fear that his ideas might be improperly made use of and he be robbed of the glory and advantages that he expected to derive from his project. This may account for the rejection of his proposals. The prior of Prado was a Hieronymite, while Columbus was under the especial protection of the Dominicans. Among his early friends in Spain was Luis de Santangel, whom Irving calls “receiver of the ecclesiastical revenues of Aragon”, and who afterwards advanced to the queen the funds necessary for the first voyage. If Santangel was receiver of the church revenues and probably treasurer and administrator, it was the Church that furnished the means (17,000 ducats) for the admiral’s first voyage.

It would be unjust to blame King Ferdinand for declining the proposals of Columbus after the adverse report of the Salamanca commission, which was based upon objections drawn from Seneca and Ptolemy rather than upon the opinion of St. Augustine in the “De Civitate Dei”. The king was then preparing to deal the final blow to Moorish domination in Spain after the struggle of seven centuries, and his financial resources were taxed to the utmost. Moreover, he was not easily carried away by enthusiasm and, though we now recognize the practical value of the plans of Columbus, at the close of the fifteenth century it seemed dubious, to say the least, to a cool-headed ruler, wont to attend first to immediate necessities. The crushing of the Moorish power in the peninsula was then of greater moment than the search after distant lands for which, furthermore, there were not the means in the royal treasury. Under these conditions Columbus, always in financial straits himself and supported by the liberality of friends, bethought himself of the rulers of France and England. In 1488 his brother Bartholomew, as faithful as sagacious, tried to induce one or the other of them to accept the plans of Christopher, but failed. The idea was too novel to appeal to either. Henry VII of England was too cautious to entertain proposals from a comparatively unknown seafarer of a foreign nation, and Charles VIII of France was too much involved in Italian affairs. The prospect was disheartening. Nevertheless, Columbus, with the assistance of his friends, concluded to make another attempt in Spain. He proceeded to court again in 1491, taking with him his son Diego. The court being then in camp before Granada, the last Moorish stronghold, the time could not have been more inopportune. Another junta was called before Granada while the siege was going on, but the commission again reported unfavourably. This is not surprising, as Ferdinand of Aragon could not undertake schemes that would involve a great outlay, and divert his attention from the momentous task he was engaged in. Columbus always directed his proposals to the king and as yet the queen had taken no official notice of them, as she too was heart and soul in the enterprise destined to restore Spain wholly to Christian rule.

The junta before Granada took place towards the end of 1491, and its decision was such a blow to Columbus that he left the court and wandered away with his boy. Before leaving, however, he witnessed the fall of Granada, 2 January, 1492. His intention was to return to Cordova and then, perhaps, to go to France. On foot and reduced almost to beggary, he reached the Dominican convent of La Rábida probably in January, 1492. The prior was Father Juan Perez, the confessor of the queen, frequently confounded with Fray Antonio Marchena by historians of the nineteenth century, who also erroneously place the arrival of Columbus at La Rábida in the early part of his sojourn in Spain. Columbus begged the friar who acted as door-keeper to let his tired son rest at the convent over night. While he was pleading his cause the prior was standing near by and listening. Something struck him in the appearance of this man, with a foreign accent, who appeared to be superior to his actual condition. After providing for his immediate wants Father Perez took him to his cell, where Columbus told him all his aspirations and blighted hopes. The result was that Columbus and his son stayed at the convent as guests and Father Perez hurried to Santa Fe near Granada, for the purpose of inducing the queen to take a personal interest in the proposed undertaking of the Italian navigator.

Circumstances had changed with the fall of Granada, and the Dominican’s appeal was favourably received by Isabella who, in turn, influenced her husband. Columbus was called to court at once, and 20,000 maravedis were assigned him out of the queen’s private resources that he might appear in proper condition before the monarch. Some historians assert that Luis de Santangel decided the queen to espouse the cause of Columbus, but the credit seems rather to belong to the prior of La Rábida. The way had been well prepared by the other steadfast friends of Columbus, not improbably Cardinal Mendoza among others. At all events negotiations progressed so rapidly that on 17 April the first agreement with the Crown was signed, and on 30 April the second. Both show an unwise liberality on the part of the monarchs, who made the highest office in what was afterwards the West Indies hereditary in the family of Columbus. Preparations were immediately begun for the equipment of the expedition. The squadron with which Columbus set out on his first voyage consisted of three vessels–the Santa Maria, completely decked, which carried the flag of Columbus as admiral, the Pinta, and the Niña, both caravels, i.e. undecked, with cabins and forecastles. These three ships carried altogether 120 men. Two seamen of repute, Martín Alonso Pinzon and his brother Vicente Yanez Pinzon, well-to-do-residents of Palos commanded, the former the Pinta. the latter the Niña, and experienced pilots were placed on both ships. Before leaving, Columbus received the Sacraments of Penance and Holy Eucharist, at the hands (it is stated) of Father Juan Perez, the officers and crews of the little squadron following his example. On 3 August, 1492, the people of Palos with heavy hearts saw them depart on an expedition regarded by many as foolhardy.

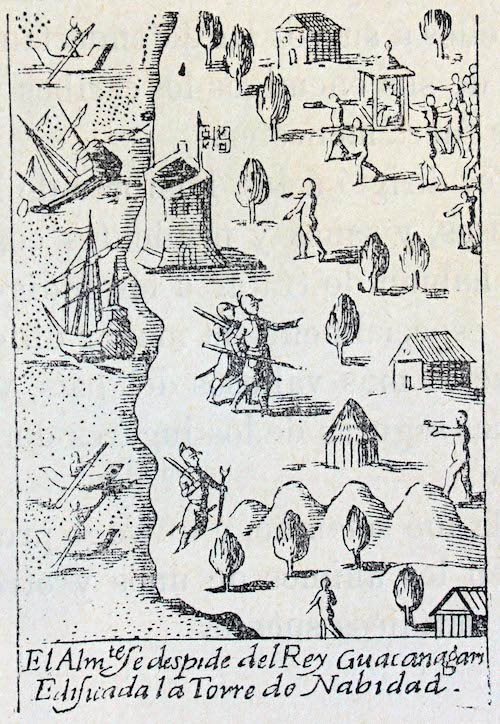

Las Casas claims to have used the journal of Columbus’s first voyage, but he admits that he made an abridged copy of it. What and how much he left out, of course, is not known. But it is well to bear in mind that the journal, as published, is not the original in its entirety. The vessels touched at the Canaries, and then proceeded on the voyage. Conditions were most favourable. Hardly a wind ruffled the waters of the ocean. The dramatic incident of the mutiny, in which the discouragement of the crews is said to have culminated before land was discovered, is a pure invention. That there was dissatisfaction and grumbling at the failure to reach land seems to be certain, but no acts of insubordination are mentioned either by Columbus, his commentator Las Casas, or his son Fernando. Perhaps the most important event during the voyage was the observation, 17 September, by Columbus himself, of the declination of the magnetic needle, which Las Casas attributes to a motion of the polar star. The same author intimates that two distinct journals were kept by the admiral, “because he always represented [feigned] to the people that he was making little headway in order that the voyage should not seem long to them, so that he kept a record by two routes, the shorter being the fictitious one, and the longer the true one”. He must therefore either have kept two log-books, or he must have made two different entries in the same book. At any rate Las Casas seems to have had at his command both sets of data, since he gives them almost from day to day. This precautionary measure indicates that Columbus feared insubordination and even revolt on the part of the crews, but there is no evidence that any mutiny really broke out. Finally, at ten o’clock, p.m., 11 October, Columbus himself described a light which indicated land and was so recognized by the crew of his vessel. It reappeared several times, and Columbus felt sure that the shores so eagerly expected were near. At 2 a.m. on 12 October the land was seen plainly by one of the Pinta’s crew, and in the forenoon Columbus landed on what is now called Watling’s Island in the Bahama group, West Indies. The discoverers named the island San Salvador. The Indians inhabiting it belonged to the widespread Arawak stock and are said to have called the island Guanahani. Immediately after landing Columbus took possession of the island for the Spanish sovereigns.

The results of the first voyage, aside from the discovery of what the admiral regarded as being approaches to India and China, may be summed up as follows: partial recognition of the Bahamas; the discovery and exploration of a part of Cuba, and the establishment of a Spanish settlement on the coast of what is now the Island of Haiti or Santo Domingo. Cuba Columbus named Juana, and Santo Domingo, Hispaniola.

It was on the northern coast of the large island of Santo Domingo that Columbus met with the only serious mishap of the first voyage. Having established the nucleus of the first permanent Spanish settlement in the Indies, he left about three score men to hold it. The vicinity was comparatively well peopled by natives, Arawaks like those of the Bahamas, but slightly more advanced in culture. A few days previous to the foundation Martin Alonso Pinzon disappeared with the caravel Pinta which he commanded and only rejoined the admiral on 6 January, 1493, an act, to say the least, of disobedience, if not of treachery. The first settlement was officially established on Christmas Day, 1492, and hence christened “La Navidad”. On the same day the admiral’s ship ran aground. It was a total loss, and Columbus was reduced for the time being to the Niña, as the Pinta had temporarily deserted. Happily the natives were friendly. After ensuring, as well as he might, the safety of the little colony by the establishment of friendly relations with the Indians, Columbus left for Spain, where, after weathering a frightful storm during which he was again separated from the Pinta, he arrived at Palos, 15 March, 1493.

From the journal mentioned we also gather (what is not stated in the letters of Columbus) that while on the northern shores of Santo Domingo (Hispaniola) the admiral “learned that behind the Island Juana [Cuba] towards the South, there is another large island in which there is much more gold. They call that island Yamaye. . . . And that the island Española or the other island Yamaye was near the mainland, ten days distant by canoe, which might be sixty or seventy leagues, and that there the people were clothed [dressed]”. Yamaye is Jamaica, and the mainland alluded to as sixty or seventy leagues distant to the south (by south the west is meant), or 150 to 175 English miles (the league, at that time, being counted at four millas of 3000 Spanish feet), was either Yucatan or Honduras. Hence the admiral brought the news of the existence of the American continent to Europe as early as 1493. That he believed the continent to be Eastern Asia does not diminish the importance of his information.

Columbus had been careful to load his ship with all manner of products of the newly discovered countries and he also took some of the natives. Whether, among the samples of the vegetable kingdom, tobacco was included, is not yet satisfactorily ascertained. Nor is it certain that, when upon his return he presented himself to the monarchs at Barcelona, an imposing public demonstration took place in his honour. That he was received with due distinction at court and that he displayed the proofs of his discovery can not be doubted. The best evidence of the high appreciation of the King and Queen of Spain is the fact, that the prerogatives granted to him were confirmed, and everything possible was done to enable him to continue his explorations. The fact that Columbus had found a country that appeared to be rich in precious metals was of the utmost importance. Spain was poor, having been robbed, ages before, of its metallic wealth by the Romans. As gold was needed the discovery of a new source of that precious metal made a strong impression on the people of Spain, and a rush to the new regions was inevitable.

Columbus started on his second voyage to the Indies from Cadiz, 25 September, 1493, with three large vessels and thirteen caravels, carrying in all about 1500 men. On his first trip, he had heard about other, smaller islands lying some distance south of Hispaniola, and said to be inhabited by ferocious tribes who had the advantage over the Arawaks of being intrepid seafarers, and who made constant war upon the inhabitants of the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas, carrying off women and children into captivity. They were believed to practice cannibalism. These were the Caribs and the reports about them were true, outside of some exaggerations and fables like the story of the Amazons. Previous to the arrival of Columbus the Caribs had driven the Arawaks steadily north, depopulated some of the smaller islands, and were sorely pressing the people of Hispaniola, parts of Cuba, Porto Rico, and even Jamaica. Columbus wished to learn more about these people. The helpless condition of the Arawaks made him eager to protect them against their enemies. The first land sighted, 3 November, was the island now known as Dominica, and almost at the same time that of Marie Galante was discovered. Geographically the second voyage resulted in the discovery of the Caribbean Islands (including the French Antilles), Jamaica, and minor groups. Columbus having obtained conclusive evidence of the ferocious customs of the Caribs, regarded them as dangerous to the settlements he proposed to make among the Arawaks and as obstacles to the Christianization and civilization of these Indians. The latter he intended to make use of as labourers, as he soon perceived that for some time to come European settlers would be too few in numbers and too new to the climate to take advantage of the resources of the island. The Caribs he purposed to convert eventually, but for the time being they must be considered as enemies, and according to the customs of the age, their captors had the right to reduce them to slavery. The Arawaks were to be treated in a conciliatory manner, as long as they did not show open hostility. Before long, however, there was a change in these relations.

After a rapid survey of Jamaica, Columbus hastened to the northern coast of Haiti, where he had planted the colony of La Navidad. To his surprise the little fort had disappeared. There were to be seen only smouldering ruins and some corpses which were identified as Spanish. The natives, previously so friendly, were shy, and upon being questioned were either mute or contradictory in their replies. It was finally ascertained that another tribe, living farther inland and hostile to those on the coast, had fallen upon the fort, killed most of the inmates and burnt most of the buildings. Those who escaped had perished in their flight. But it also transpired that the coast people themselves had taken part in the massacre. Columbus, while outwardly on good terms with them, was on his guard and, in consequence of the aversion of his people to a site where only disaster had befallen them, moved some distance farther east and established on the coast the larger settlement of Isabella. This stood ten leagues to the east of Cape Monte Cristo, where the ruins are still to be seen.

The existence of gold on Haiti having been amply demonstrated on the first voyage, Columbus inaugurated a diligent search for places where it might be found. The gold trinkets worn by the Indians were washings or placeres, but mention is also made, on the first voyage, of quartz rock containing the precious metal. But it is likely that the yellow mineral was iron pyrites, probably gold-bearing but, in the backward state of metallurgy, worthless at the time. Soon after the settlement was made at Isabella the colonists began to complain that the mineral wealth of the newly discovered lands had been vastly exaggerated and one, who accompanied the expedition as expert in metallurgy, claimed that the larger nuggets held by the natives had been accumulated in the course of a long period of time. This very sensible supposition was unjustly criticized by Irving, for since Irving’s time it has been clearly proved that pieces of metal of unusual size and shape were often kept for generations by the Indians as fetishes.

A more important factor which disturbed the Spanish was the unhealthiness of the climate. The settlers had to go through the slow and often fatal process of acclimatization. Columbus himself suffered considerably from ill-health. Again, the island was not well provided with food suitable for the newcomers. The population, notwithstanding the exaggerations of Las Casas and others, was sparse. Isabella with its fifteen hundred Spanish immigrants was certainly the most populous settlement. At first there was no clash with the natives, but parties sent by Columbus into the interior came in contact with hostile tribes. For the protection of the colonists Columbus built in the interior a little fort called Santo Tomas. He also sent West Indian products and some Carib prisoners back to Spain in a vessel under the command of Antonio de Torres. Columbus suggested that the Caribs be sold as slaves in order that they might be instructed in the Christian Faith. This suggestion was not adopted by the Spanish monarchs, and the prisoners were treated as kindly in Spain as the friendly Arawaks who had been sent over.

The condition of affairs on Hispaniola (Haiti) was not promising. At Isabella and on the coast there was grumbling against the admiral, in which the Benedictine Father Buil (Boil) and the other priests joined, or which, at least, they did not discourage. In the interior there was trouble with the natives. The commander at Santo Tomas, Pedro Margarite, is usually accused of cruelty to the Indians, but Columbus himself in his Memorial of 30 January, 1494, commends the conduct of that officer. However, he had to send him reinforcements, which were commanded by Alonzo de Ojeda.

Anxiously following up his theory that the newly discovered islands were but outlying posts of Eastern Asia and that further explorations would soon lead him to the coast of China or to the Moluccas, Columbus, notwithstanding the precarious condition of the colony, left it in charge of his brother Diego and four counsellors (one of whom was Father Buil), and with three vessels set sail towards Cuba. During his absence of five months he explored parts of Cuba, discovered the Isle of Pines and several groups of smaller islands, and made the circuit of Jamaica, landing there almost every day. When he returned to Isabella (29 September, 1494), he was dangerously ill and in a stupor. Meanwhile his brother Bartholomew had arrived from Spain with a small squadron and supplies. He proved a welcome auxiliary to the weak Diego, but could not prevent serious trouble. Margarite, angered by interference with his administration in the interior, returned to the coast, and there was joined by Father Buil and other malcontents. They seized the three caravels that had arrived under the command of Bartholomew Columbus, and set sail in them for Spain to lay before the Government what they considered their grievances against Columbus and his administration.

That there was cause for complaint there seems to be no doubt, but it is almost impossible now to determine who was most at fault, Columbus or his accusers. He was certainly not as able an administrator as he was a navigator. Still, taking into consideration the difficulties, the novelty of the conditions, and the class of men Columbus had to handle, and placing over against this what he had already achieved on Haiti, there is not so much ground for criticism. The charges of cruelty against the natives are based upon rather suspicious authority, Las Casas being the principal source. There were errors and misdeeds on both sides, which, however, might not have brought about a crisis had not disappointment angered the settlers, who had based their expectations on the glowing reports of Columbus himself, and disposed them to attribute all their troubles to their opponents.

TBC – Before the return of Columbus to Isabella, Ojeda had repulsed an attempt of the natives to surprise Santo Tomas. Thereupon the Indians of various tribes of the interior now formed a confederation and threatened Isabella. Columbus, however, on his return, with the aid of firearms, sixteen horses, and about twenty blood-hounds easily broke up the Indian league. Ojeda captured the leader, and the policy of kindness hitherto pursued towards the natives was replaced by repression and chastisement. According to the customs of the times the prisoners of war were regarded as rebels, reduced to slavery, and five hundred of these were sent to Spain to be sold. It is certain that the condition of the Indians became much worse thereafter, that they were forced into unaccustomed labours, and that their numbers began to diminish rapidly. That these harsh measures were authorized by Columbus there can be no doubt.

While the Spanish monarchs in their dispatches to Columbus continued to show the same confidence and friendliness they could not help hearing the accusations made against him by Father Buil, Pedro Margarite, and the other malcontents, upon their return to Spain. It was clear that there were two factions among the Spaniards in Haiti, one headed by the admiral, the other composed of perhaps a majority of the settlers including ecclesiastics. Still the monarchs enjoined the colonists by letter to obey Columbus in everything and confirmed his authority and privileges. The incriminations, however, continued, and charges were made of nepotism and spoliation if royal revenue. There was probably some foundation for these charges, though also much wilful misrepresentation. Unable to ascertain the true condition of affairs, the sovereigns finally decided to send to the Indies a special commissioner to investigate and report. Their choice fell upon Juan de Aguado who had gone with Columbus on his first voyage and with whom he had always been on friendly terms. Aguado arrived at Isabella in October, 1495, while Columbus was absent on a journey of exploration across the island. No clash appears to have occurred between Aguado and Bartholomew Columbus, who was in charge of the colony during his brother’s absence, much less with the admiral himself upon the latter’s return. Soon after, reports of important gold discoveries came from a remote quarter of the island accompanied by specimens. The arrival of Aguado convinced Columbus of the necessity for his appearance in Spain and that new discoveries of gold would strengthen his position there. So he fitted out two ships, one for himself and one for Aguado, placing in them two hundred dissatisfied colonists, a captive Indian chief (who died on the voyage), and thirty Indian prisoners, and set sail for Spain on 10 March, 1496, leaving his brother Bartholomew at Isabella as temporary governor. As intercourse between Spain and the Indies was now carried on at almost regular intervals. Bartholomew was in communication with the mother country and was at least tacitly recognized as his brother’s substitute in the government of the Indies. Columbus reached Cadiz 11 June, 1496.

The story of his landing is quite dramatic. He is reported to have gone ashore, clothed in the Franciscan garb, and to have manifested a dejection which was wholly uncalled for. His health, it is true, was greatly impaired, and his companions bore the marks of great physical suffering. The impression created by their appearance was of course not favourable and tended to confirm the reports of the opponents of Columbus about the nature of the new country. This, as well as the disappointing results of the search for precious metals, did not fail to have its influence. The monarchs saw that the first enthusiastic reports had been exaggerated, and that the enterprise while possibly lucrative in the end, would entail large expenditures for some time to come. Bishop Fonseca, who was at the head of colonial affairs, urged that great caution should be exercised. What was imputed to Bishop Fonseca as jealousy was only the sincere desire of an honest functionary to guard the interests of the Crown without blocking the way of an enthusiastic but somewhat visionary genius who had been unsuccessful as an administrator. Later expressions (1505) of Columbus indicate that the personal relations to Fonseca were at the time far from unfriendly. But the fact that Columbus had proposed the enslaving of American natives and actually sent a number of them over to Spain had alienated the sympathy of the queen to a certain degree, and thus weakened his position at court.

Nevertheless, it was not difficult for Columbus to organize a third expedition. Columbus started on his third voyage from Seville with six vessels on 30 May, 1498. He directed his course more southward than before, owing to reports of a great land lying west and south of the Antilles and his belief that it was the continent of Asia. He touched at the Island of Madeira, and later at Gomera, one of the Canary Islands, whence he sent to Haiti three vessels. Sailing southward, he went to the Cape Verde Islands and, turning thence almost due west, arrived on 31 July 1498, in sight of what is now the Island of Trinidad which was so named by him. Opposite, on the other side of a turbulent channel, lay the lowlands of north-eastern South America. Alarmed by the turmoil caused by the meeting of the waters of the Orinoco (which empties through several channels into the Atlantic opposite Trinidad) with the Guiana current, Columbus kept close to the southern shore of Trinidad as far as its south-western extremity, where he found the water still more turbulent. He therefore gave that place the name of Boca del Drago, or Dragon’s Mouth. Before venturing into the seething waters Columbus crossed over to the mainland and cast anchor. He was under the impression that this was an island, but a vast stream of fresh water gave evidence of a continent. Columbus landed, he and his crew being thus the first Europeans to set foot on South American soil. The natives were friendly and gladly exchanged pearls for European trinkets. The discovery of pearls in American waters was important and very welcome.

A few days later, the admiral, setting sail again, was borne by the currents safely to the Island of Margarita, where he found the natives fishing for pearls, of which he obtained three bags by barter.

Some of the letters of Columbus concerning his third voyage are written in a tone of despondency. Owing to his physical condition, he viewed things with a discontent far from justifiable. And, as already said, his views of the geographical situation were somewhat fanciful. The great outpour opposite Trinidad he justly attributed to the emptying of a mighty river coming from the west, a river, so large that only a continent could afford its space. In this he was right, but in his eyes that continent was Asia, and the sources of that river must be on the highest point of the globe. He was confirmed in this idea by his belief that Trinidad wasnearer the Equator than it actually is and that near the Equator the highest land on earth should be found. He thought also that the sources of the Orinoco lay in the Earthly Paradise and that the great river was one of the four streams that according to Scripture flowed from the Garden of Eden. He had no accurate knowledge of the form of the earth, and conjectured that it was pear-shaped.

On 15 August, fearing a lack of supplies, and suffering severely from what his biographers call gout and from impaired eyesight, he left his new discoveries and steered for Haiti. On 19 August he sighted that island some distance west of where the present capital of the Republic of Santo Domingo now stands. During his absence his brother Bartholomew had abandoned Isabella and established his head-quarters at Santo Domingo so called after his father Domenico. During the absence of Columbus events on Haiti had been far from satisfactory. His brother Bartholomew, who was then known as the adelantado, had to contend with several Indian outbreaks, which he subdued partly by force, partly by wise temporizing. These outbreaks were, at least in part, due to a change in the class of settlers by whom the colony was reinforced. The results of the first settlement far from justified the buoyant hopes based on the exaggerated reports of the first voyage, and the pendulum of public opinion swung back to the opposite extreme. The clamour of opposition to Columbus in the colonies and the discouraging reports greatly increased in Spain the disappointment with the new territorial acquisitions. That the climate was not healthful seemed proved by the appearance of Columbus and his companions on his return from the second voyage. Hence no one was willing to go to the newly discovered country, and convicts, suspects, and doubtful characters in general who were glad to escape the regulations of justice were the only reinforcements that could be obtained for the colony on Hispaniola. As a result there were conflicts with the aborigines, sedition in the colony, and finally open rebellion against the authority of the adelantado and his brother Diego. Columbus and his brothers were Italians, and this fact told against them among the malcontents and lower officials, but that it influenced the monarchs and the court authorities is a gratuitous charge.

As long as they had not a common leader Bartholomew had little to fear from the malcontents, who separated from the rest of the colony, and formed a settlement apart. They abused the Indians, thus causing almost uninterrupted trouble. However, they soon found a leader in the person of one Roldan, to whom the admiral had entrusted a prominent office in the colony. There must have been some cause for complaint against the government of Bartholomew and Diego, else Roldan could not have so increased the number of his followers as to make himself formidable to the brothers, undermining their authority at their own head-quarters and even among the garrison of Santo Domingo. Bartholomew was forced to compromise on unfavourable terms. So, when the admiral arrived from Spain he found the Spanish settlers on Haiti divided into two camps, the stronger of which, headed by Roldan, was hostile to his authority. That Roldan was an utterly unprincipled man, but energetic and above all, shrewd and artful, appears from the following incident. Soon after the arrival of Columbus the three caravels he had sent from Gomera with stores and ammunition struck the Haitian coast where Roldan had established himself. The latter represented to the commanders of the vessels that he was there by Columbus’s authority and easily obtained from them military stores as well as reinforcements in men. On their arrival shortly afterward at Santo Domingo the caravels were sent back to Spain by Columbus. Alarmed at the condition of affairs and his own importance, he informed the monarchs of his critical situation and asked for immediate help. Then he entered into negotiations with Roldan. The latter not only held full control in the settlement which he commanded, but had the sympathy of most of the military garrisons that Columbus and his brothers relied upon as well as the majority of the colonists. How Columbus and his brother could have made themselves so unpopular is explained in various ways. There was certainly much unjustifiable ill will against them, but there was also legitimate cause for discontent, which was adroitly exploited by Roldan and his followers.

Seeing himself almost powerless against his opponents on the island, the admiral stooped to a compromise. Roldan finally imposed his own conditions. He was reinstated in his office and all offenders were pardoned; and a number of them returned to Santo Domingo. Columbus also freed many of the Indian tribes from tribute, but in order still further to appease the former mutineers, he instituted the system of repartimientos, by which not only grants of land were made to the whites, but the Indians holding these lands or living on them were made perpetual serfs to the new owners, and full jurisdiction over life and property of these Indians became vested in the white settlers. This measure had the most disastrous effect on the aborigines, and Columbus has been severely blamed for it, but he was then in such straits that he had to go to any extreme to pacify his opponents until assistance could reach him from Spain. By the middle of the year 1500 peace apparently reigned again in the colony, though largely at the expense of the prestige and authority of Columbus.

Meanwhile reports and accusations had reached the court of Spain from both parties in Haiti. It became constantly more evident that Columbus was no longer master of the situation in the Indies, and that some steps were necessary to save the situation. It might be said that the Court had merely to support Columbus whether right or wrong. But the West Indian colony had grown, and its settlers had their connections and supporters in Spain, who claimed some attention and prudent consideration. The clergy who were familiar with the circumstances through personal experience for the most part disapproved of the management of affairs by Columbus and his brothers. Queen Isabella’s irritation at the sending of Indian captives for sale as slaves had by this time been allayed by a reminder of the custom then in vogue of enslaving captive rebels or prisoners of war addicted to specially inhuman customs, as was the case with the Caribs. Anxious to be just, the monarchs decided upon sending to Haiti an officer to investigate and to punish all offenders. This visitador was invested with full power, and was to have the same authority as the monarchs themselves for the time being, superseding Columbus himself, though the latter was the Viceroy of the Indies. The visita was a mode of procedure employed by the Spanish monarchs for the adjustment of critical matters, chiefly in the colonies. The visitador was selected irrespective of rank or office, solely from the standpoint of fitness, and not infrequently his mission was kept secret from the viceroy or other high official whose conduct he was sent to investigate; there are indications that sometimes he had summary power over life and death. A visita was a much dreaded measure, and for very good reasons.

The investigation in the West Indies was not called a visita at the time, but such it was in fact. The visitador chosen was Francisco de Bobadilla, of whom both Las Casas and Oviedo (friends and admirers of Columbus) speak in favourable terms. His instructions were, as his office required, general and his faculties, of course, discretionary; there is no need of supposing secret orders inimical to Columbus to explain what afterwards happened. The admiral was directed, in a letter addressed to him and entrusted to Bobadilla, to turn over to the latter, at least temporarily, the forts and all public property on the island. No blame can be attached to the monarchs for this measure. After an experiment of five years the administrative capacity of Columbus had failed to prove satisfactory. Yet, the vice-regal power had been vested in him as an hereditary right. To continue adhering to that clause of the original contract was impracticable, since the colony refused to pay heed to Columbus and his orders. Hence the suspension of the viceregal authority of Columbus was indefinitely prolonged, so that the office was reduced to a mere title and finally fell into disuse. The curtailment of revenue resulting from it was comparatively small, as all the emoluments proceeding from his other titles and prerogatives were left untouched. The tale of his being reduced to indigence is a baseless fabrication.

A man suddenly clothed with unusual and discretionary faculties is liable to be led astray by unexpected circumstances and tempted to go to extremes. Bobadilla had a right to expect implicit obedience to royal orders on the part of all and, above all, from Columbus as the chief servant of the Crown. When on 24 August, 1500, Bobadilla landed at Santo Domingo and demanded of Diego Columbus compliance with the royal orders, the latter declined to obey until directed by the admiral who was then absent. Bobadilla, possibly predisposed against Columbus and his brothers by the reports of others and by the sight of the bodies of Spaniards dangling from gibbets in full view of the port, considered the refusal of Diego as an act of direct insubordination. The action of Diego was certainly unwise and gave colour to an assumption that Columbus and his brothers considered themselves masters of the country. This implied rebellion and furnished a pretext to Bobadilla for measures unjustifiably harsh. As visitador he had absolute authority to do as he thought best, especially against the rebels, of whom Columbus appeared in his eyes as the chief.

Within a few days after the landing of Bobadilla, Diego and Bartholomew Columbus were imprisoned and put in irons. The admiral himself, who returned with the greatest possible speed, shared their fate. The three brothers were separated and kept in close confinement, but they could hear from their cells the imprecations of the people against their rule. Bobadilla charged them with being rebellious subjects and seized their private property to pay their personal debts. He liberated prisoners, reduced or abolished imposts, in short did all he could to place the new order of things in favourable contrast to the previous management. No explanation was offered to Columbus for the harsh treatment to which he was subjected, for a visitador had only to render account to the king or according to his special orders. Early in October, 1500, the three brothers, still in fetters, were placed on board ship, and sent to Spain, arriving at Cadiz at the end of the month. Their treatment while aboard seems to have been considerate; Villejo, the commander, offered to remove the manacles from Columbus’s hands and relieve him from the chains, an offer, however, which Columbus refused to accept. It seems, nevertheless, that he did not remain manacled, else he could not have written the long and piteous letter to the nurse of Prince Juan, recounting his misfortunes on the vessel. He dispatched this letter to the court at Granada before the reports of Bobadilla were sent.

The news of the arrival of Columbus as a prisoner was received with unfeigned indignation by the monarchs, who saw that their agent Bobadilla had abused the trust placed in him. The people also saw the injustice, and everything was done to relieve Columbus from his humiliating condition and assure him of the royal favour, that is, everything except to reinstate him as Governor of the Indies. This fact is mainly responsible for the accusation of duplicity and treachery which is made against King Ferdinand. Critics overlook the fact that in addition to the reasons already mentioned no new colonists could be obtained from Spain, if Columbus were to continue in office, and that the expedient of sending convicts to Haiti had failed disastrously. Moreover, the removal of Columbus was practically implied in the instructions and powers given to Bobadilla, and the conduct of the admiral during Aguado’s mission left no room for doubt that he would submit to the second investigation. He would have done so, but Bobadilla, anxious to make a display and angered at the delay of Diego Columbus, exceeded the spirit of his instructions, expecting thereby to rise in royal as well as in popular favour.

In regard to the former he soon found out his mistake. His successor in the governorship of Haiti was soon appointed in the person of Nicolas de Ovando. Bobadilla was condemned to restore to Columbus the property he had sequestered, and was recalled. The largest fleet sent to the Indies up to that time sailed under Ovando on 13 February, 1502. It is not without significance that 2500 people, some of high rank, flocked to the vessels that were to transport the new governor to the Indies. This shows that with the change in the administration of the colony faith in its future was restored among the Spanish people. By this time the mental condition of Columbus had become greatly impaired. While at court for eighteen months vainly attempting to obtain the restoration to a position for which he was becoming more and more unfitted, he was planning new schemes. Convinced that his third voyage had brought him nearer to Asia, he proposed to the monarchs a project to recover the Holy Sepulchre by the western route, that would have led him across South America to the Pacific Ocean. He fancied that the large river he had discovered west of Trinidad flowed in a direction opposite to its real course, and thought that by following it he could reach the Red Sea and thence cross over to Jerusalem. So preoccupied was he with these ideas that he made arrangements for depositing part of his revenue with the bank of Genoa to be used in the reconquest of the Holy Land. This alone disposes of the allegations that Columbus was left without resources after his liberation from captivity. He was enabled to maintain a position at court corresponding to his exalted rank, and favours and privileges were bestowed on both of his sons. The project of testing the views of Columbus in regard to direct communication with Asia was seriously considered, and finally a fourth voyage of exploration at the expense of the Spanish Government was conceded to Columbus. That there were some misgivings in regard to his physical and mental condition is intimated by the fact that he was given as companions his brother Bartholomew, who had great influence with him, and his favourite son Fernando. Four vessels carrying, besides these three and a representative of the Crown to receive any treasure that might be found, about 150 men, set sail from San Lucar early in May, 1502. Columbus was enjoined not to stop at Haiti, a wise measure, for had the admiral landed there so soon after the arrival of Ovando, there would have been danger of new disturbances. Disobeying these instructions, Columbus attempted to enter the port of Santo Domingo, but was refused admission. He gave proof of his knowledge and experience as a mariner by warning Ovando of an approaching hurricane, but was not listened to. He himself sheltered his vessels at some distance from the harbour. The punishment for disregarding the friendly warning came swiftly; the large fleet which had brought Ovando over was, on sailing for Spain, overtaken by the tempest, and twenty ships were lost, with them Bobadillo, Roldan, and the gold destined for the Crown. The admiral’s share of the gold obtained on Haiti, four thousand pieces directly sent to him by his representative on the island, was not lost, and on being delivered in Spain, was not confiscated. Hence it is difficult to see how Columbus could have been in need during the last years of his life.

The vessels of Columbus having suffered comparatively little from the tempest, he left the coast of Haiti in July, 1502, and was carried by wind and current to the coast of Honduras. From 30 July, 1502, to the end of the following April he coasted Central America beyond Colon to Cape Tiburon on the South American Continent. On his frequent landings he found traces of gold, heard reports of more civilized tribes of natives farther inland, and persistent statements about another ocean lying west and south of the land he was coasting, the latter being represented to him as a narrow strip dividing two vast seas. The mental condition of Columbus, coupled with his physical disabilities, prevented him from interpreting these important indications otherwise than as confirmations of his vague theories and fatal visions. Instead of sending an exploring party across the isthmus to satisfy himself of the truth of these reports, he accepted this testimony to the existence of a sea beyond, which he firmly believed to be the Indian Ocean, basing his confidence on a dream in which he had seen a strait he supposed to be the Strait of Malacca. As his crews were exasperated by the hardships and deceptions, his ships worn-eaten, and he himself emaciated, he turned back towards Haiti with what he thought to be the tidings of a near approach to the Asiatic continent. It had been a disastrous voyage; violent storms continually harassed the little squadron, two ships had been lost, and the treasure obtained far from compensated for the toil and the suffering endured. This was all the more exasperating when it became evident that a much richer reward could be obtained by penetrating inland, to which, however, Columbus would not or perhaps could not consent.

On 23 June, 1503, Columbus and his men, crowded on two almost sinking caravels, finally landed on the inhospitable coast of Jamaica. After dismantling his useless craft, and using the material for temporary shelter, he sent a boat to Haiti to ask for assistance and to dispatch thence to Spain a vessel with a pitiful letter giving a fantastic account of his sufferings which in itself gave evidence of an over-excited and disordered mind.

Ovando to whom Columbus’s request for help was delivered at Jaragua (Haiti) cannot be acquitted of unjustifiable delay in sending assistance to the shipwrecked and forsaken admiral. There is no foundation for assuming that he acted under the orders or in accordance with the wishes of the sovereigns. Columbus had become useless, the colonists in Haiti would not tolerate his presence there. The only practical course was to take him back to Spain directly and remove him forever from the lands the discovery of which had made him immortal. In spite of his many sufferings, Columbus was not utterly helpless. His greatest trouble came from the mutinous spirit of his men who roamed about, plundering and maltreating the natives, who, in consequence, became hostile and refused to furnish supplies. An eclipse of the moon predicted by Columbus finally brought them to terms and thus prevented starvation. Ovando, though informed of the admiral’s critical condition, did nothing for his relief except to permit Columbus’s representative in Haiti to fit out a caravel with stores at the admiral’s expense and send it to Jamaica; but even this tardy relief did not reach Columbus until June, 1504. He also permitted Mendez, who had been the chief messenger of Columbus to Haiti, to take passage for Spain, where he was to inform the sovereigns of the admiral’s forlorn condition. There seems to be no excuse for the conduct of Ovando on this occasion. The relief expedition finally organized in Haiti, after a tedious and somewhat dangerous voyage, landed the admiral and his companions in Spain, 7 November, 1504.

A few weeks later Queen Isabella died, and grave difficulties beset the king. Columbus, now in very feeble health, remained at Seville until May, 1505, when he was at last able to attend court at Valladolid. His reception by the king was decorous, but without warmth. His importunities to be restored to his position as governor were put off with future promises of redress, but no immediate steps were taken. The story of the utter destitution in which the admiral is said to have died is one of the many legends with which his biography has been distorted. Columbus is said to have been buried at Valladolid. His son Diego is authority for the statement that his remains were buried in the Carthusian Convent of Las Cuevas, Seville, within three years after his death. According to the records of the convent, the remains were given up for transportation to Haiti in 1536, though other documents placed this event in 1537. It is conjectured, however, that the removal did not take place till 1541, when the Cathedral of Santo Domingo was completed, though there are no records of this entombment. When, in 1795, Haiti passed under French control, Spanish authorities removed the supposed remains of Columbus to Havana. On the occupation of Cuba by the United States they were once more removed to Seville (1898).

Columbus was unquestionably a man of genius. He was a bold, skilful navigator, better acquainted with the principles of cosmography and astronomy than the average skipper of his time, a man of original ideas, fertile in his plans, and persistent in carrying them into execution. The impression he made on those with whom he came in contact even in the days of his poverty, such as Fray Juan Perez, the treasurer Luis de Santangel, the Duke of Medina Sidonia, and Queen Isabella herself, shows that he had great powers of persuasion and was possessed of personal magnetism. His success in overcoming the obstacles to his expeditions and surmounting the difficulties of his voyages exhibit him as a man of unusual resources and of unflinching determination.

Columbus was also of a deeply religious nature. Whatever influence scientific theories and the ambition for fame and wealth may have had over him, in advocating his enterprise he never failed to insist on the conversion of the pagan peoples that he would discover as one of the primary objects of his undertaking. Even when clouds had settled over his career, after his return as a prisoner from the lands he had discovered, he was ready to devote all his possessions and the remaining years of his life to set sail again for the purpose of rescuing Christ’s Sepulchro from the hands of the infidel.

OTHER MEMBERS OF THE COLUMBUS FAMILY

Other members of the Columbus family also acquired fame:

Diego, the first son of Christopher and heir to his titles and prerogatives, was born at Lisbon, 1476, and died at Montalvan, near Toledo, 23 February, 1526. He was made a page to Queen Isabella in 1492, and remained at court until 1508. Having obtained confirmation of the privileges originally conceded to his father (the title of viceroy of the newly discovered countries excepted) he went to Santo Domingo in 1509 as Admiral of the Indies and Governor of Hispaniola. The authority of Diego Velazquez as governor, however, had become too firmly established, and Diego was met by open and secret opposition, especially from the royal Audiencia. Visiting Spain in 1520 he was favourably received and new honours bestowed upon him. However, in 1523, he had to return again to Spain to answer charges against him. The remainder of his life was taken up by the suit of the heirs of Columbus against the royal treasury, a memorable legal contest only terminated in 1564. Diego seems to have been a man of no extraordinary attainments, but of considerable tenacity of character.

Ferdinand, better known as Fernando Colon, second son of Christopher, by Doña Beatriz Enriquez, a lady of a noble family of Cordova in Spain, was born at Cordova, 15 August, 1488; died at Seville, 12 July 1539. As he was naturally far more gifted than his half-brother Diego, he was a favourite with his father, whom he accompanied on the last voyage. As early as 1498 Queen Isabella had made him one of her pages and Columbus in his will (1505) left him an ample income, which was subsequently increased by royal grants. Fernando had decided literary tastes and wrote well in Spanish. While it is stated that he wrote a history of the West Indies, there are now extant only two works by him: “Descripción y cosmografía de España”, a detailed geographical itinerary begun in 1517, published at Madrid in the “Boletin de la Real Sociedad geográfica” (1906-07); and the life of the admiral, his father, written about 1534, the Spanish original of which has been lost. It was published in an Italian translation by Ulloa in 1571 as “Vita dell’ ammiraglio”, and re-translated into Spanish by Barcia. “Historiadores primitivos de Indias” (Madrid, 1749). As might be expected this biography is sometimes partial, though Fernando often sides with the Spanish monarchs against his father. Of the highest value is the report by Fray Roman Pane on the customs of the Haitian Indians which is incorporated into the text. (See ARAWAKS.) Fernando left to the cathedral chapter of Seville a library of 20,000 volumes, a part of which still exists and is known as the Biblioteca Columbina.

Bartholomew

Bartholomew, elder brother of Christopher, born possibly in 1445 at Genoa; died at Santo Domingo, May, 1515. Like Christopher he became a seafarer at an early age. After his attempts to interest the Kings of France and England in his brother’s projects, his life was bound up with that of his brother. It was during his time that bloodhounds were introduced into the West Indies. He was a man of great energy and some military talent, and during Christopher’s last voyage took the leadership at critical moments. After 1506 he probably went to Rome and in 1509 back to the West Indies with his nephew Diego.

Diego, younger brother of Christopher and his companion on the second voyage, born probably at Genoa; died at Santo Domingo after 1509. After his release from chains in Spain (1500) he became a priest and returned to the West Indies in 1509.

The tract of CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS, De prima in mari Indico lustratione, was published with the Bellum Christianorum principum of ROBERT ABBOT OF SAINT-REMI (Basle, 1533).–Codice diplomatico-Colombo-Americano, ossia Raccolia di documenti spettanti a Cr. Col., etc. (Genoa, 1823); ANON., Cr. Col. aiutato dei minorite nella scoperta del nuovo mondo (Genoa, 1846); SANGUINETTI, Vita di Colombo (Genoa, 1846); BOSSI, Vita di Cr. Col. (Milan, 1818); SPOTORNO, Della origine e della patria di Cr. Col. (Geonoa, 1819); NAVARRETE, Coleccion de los viajes y descubrimientas. . .desde fines del siglo XV (Madrid, 1825), I, II; AVEZAC-MACAYA, Annee veritable de la naissance de Chr. Col. (Paris, 1873); ROSELLY DE LORGNES, Vie et voyages de Chr. Col. (Paris, 1804), from which was compiled by BARRY, Life of Chr. Col. (New York, 1869); COLUMBUS, FERDINAND, French tr. by MULLER, Hist. de la vie et des decouvertes de Chr. Col. (Paris, s.d.); MAJOR (tr.), Select Letters of Chr. Col. (London, 1847 and 1870); HARRISSE, Fernando Colon historiador de du padre (Seville, 1871); VIGNAUD, La maison d’Alba et les archives colombiennes (Paris, 1901); l’HAGON, La Patria dr Colon segun los documentos de las ordenes militares (Madrid, 1892); UZIELLO in Congresso geografico italiano; Atti for April, 1901, Tascanelli, Colombo e Vespucci (Milan, 1902); WINSOR, Christopher Columbus (Boston, 1891); ADAMS, Christopher Columbus, in Makers of America (New York, 1892); DURO, Colon y la Historia Postuma (Madrid, 1885); THACHER, Christopher Columbus: His Life, His Work, His Remains (3 vols., New York, 1903-1904); IRVING, Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus (3 vols., New York, 1868); PETER MARTYR, Dr orbe nova (Alcala, 1530); LAS CASAS, Historia de las Indias in Documentas para la historia de Espana; OVIEDO, Hist. general (Madrid, 1850). The last three authors had personal intercourse with Columbus, and their works are the chief source of information concerning him. CLARKE, Christopher Columbus in The Am. Cath. Quart. Rev. (1892); SHEA, Columbus, This Century’s Estimate of His Life and Work (ibid.); U.S. CATH. HIST. SOC., The Cosmographier Introductio of Martin Waldseemuller (New York, 1908).

The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume IV Copyright © 1908 by Robert Appleton Company Online Edition Copyright © 1999 by Kevin Knight Nihil Obstat. Remy Lafort, Censor Imprimatur. +John M. Farley, Archbishop of New York

- The Columbian Exchange

De Las Casas and the Conquistadors

- Early Visual Representations of the New World

- Failed European Colonies in the New World

- Successful European Colonies in the New World

- A Model of Christian Charity

- Benjamin Franklin’s Satire of Witch Hunting

- The American Revolution as Civil War

- Patrick Henry and “Give Me Liberty!”

- Lexington & Concord: Tipping Point of the Revolution

- Abigail Adams and “Remember the Ladies”

- Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense,” 1776

- Citizen Leadership in the Young Republic

- After Shays’ Rebellion

- James Madison Debates a Bill of Rights

- America, the Creeks, and Other Southeastern Tribes

- America and the Six Nations: Native Americans After the Revolution

- The Revolution of 1800

- Jefferson and the Louisiana Purchase

- The Expansion of Democracy During the Jacksonian Era

- The Religious Roots of Abolition

- Individualism in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Self-Reliance”

- Aylmer’s Motivation in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “The Birthmark”

- Thoreau’s Critique of Democracy in “Civil Disobedience”

- Hester’s A: The Red Badge of Wisdom

- “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?”

- The Cult of Domesticity

- The Family Life of the Enslaved

- A Pro-Slavery Argument, 1857

- The Underground Railroad

- The Enslaved and the Civil War

- Women, Temperance, and Domesticity

- “The Chinese Question from a Chinese Standpoint,” 1873

- “To Build a Fire”: An Environmentalist Interpretation

- Progressivism in the Factory

- Progressivism in the Home

- The “Aeroplane” as a Symbol of Modernism

- The “Phenomenon of Lindbergh”

- The Radio as New Technology: Blessing or Curse? A 1929 Debate

- The Marshall Plan Speech: Rhetoric and Diplomacy

- NSC 68: America’s Cold War Blueprint

- The Moral Vision of Atticus Finch

Copyright National Humanities Center, 2015

Lesson Contents

Teacher’s note.

- Text Analysis & Close Reading Questions

Follow-Up Assignment

- Student Version PDF

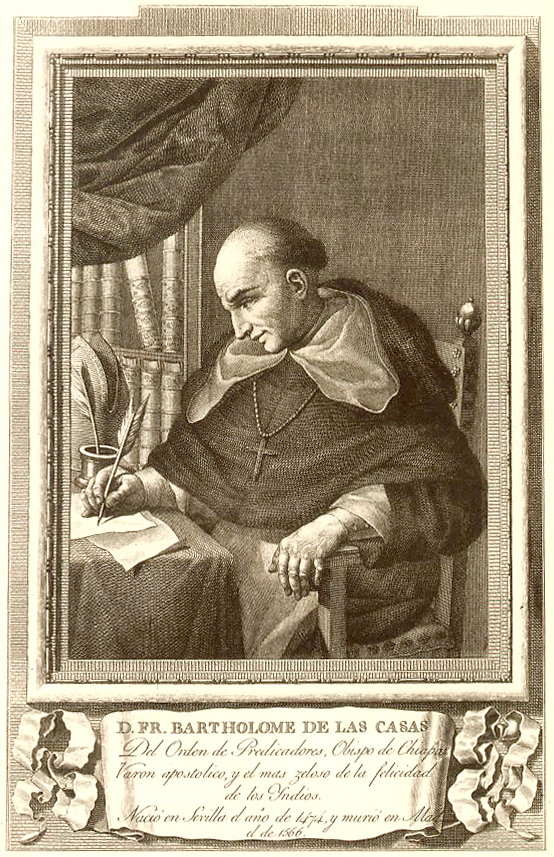

What arguments did Bartolome de Las Casas make in favor of more humane treatment of Native Americans as he exposed the atrocities of the Spanish conquistadors in Hispaniola?

Understanding.

First contact experiences on Hispaniola included brutal interactions between the Spanish and the Native Americans. Conquistadors subjugated populations primarily to garner personal economic wealth, and Natives little understood the nature of the conquest. As early as 1522 Bartolome de Las Casas worked to denounce these activities on political, economic, moral, and religious grounds by chronicling the actions of the conquistadors for the Spanish court.

Bartolome de Las Casas, A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies .

Book excerpt, Literary nonfiction.

Text Complexity

Grade 11-CCR complexity band.

For more information on text complexity see these resources from achievethecore.org .

In the Text Analysis section, Tier 2 vocabulary words are defined in pop-ups, and Tier 3 words are explained in brackets.

Click here for standards and skills for this lesson.

Common Core State Standards

- ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.1 (cite evidence to analyze specifically and by inference)

- ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.6 (determine author’s point of view)

Advanced Placement US History

- Key Concept 1.2 (IIB) (Spanish colonial economies marshaled Native American labor…)

Using excerpts from A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies , published in 1552, students will explore in this lesson how Bartolome de Las Casas (1484–1566) argued for more humane treatment of Native Americans in the Spanish New World colonies. In the first excerpt students will look at the author’s general description of the actions of the Spanish on Hispaniola, home to the Taino Indians. In the next three excerpts students will investigate the Spanish presence in a specific Hispaniola kingdom, Magua. De Las Casas argued to the Spanish King that his agents, the conquistadors, were brutalizing native peoples and that those actions were destroying the Spanish as well as the natives. A Brief Account details extremely graphic interactions between the Taino and the Spanish, but by strategic excerption this lesson works to temper the more sensational descriptions of atrocities while remaining true to the tone of the original text.

This lesson approaches American first contacts by reminding students that the exploration of the Americas involved brutal invasions with economic rather than religious objectives uppermost in the minds of the conquistadors. The New World inhabitants little understood the goals of the invaders and were not able to launch a successful defense.

The events related in this lesson occurred mainly during the reigns of Ferdinand II of Aragon (1452–1516) and Isabella I of Castile (1451–1504). Their marriage in 1469 marked the uniting of Spain through a joint reign, although both Aragon and Castile maintained independent political, economic and social identities. De Las Casas occasionally refers to the Spanish as “Castilian.”

This lesson is divided into two parts, both accessible below. In addition to close reading questions, interactive exercises and an optional followup lesson accompany the text. The teacher’s guide includes a background note, the text analysis with responses to the close reading questions, access to the interactive exercises, and the follow-up assignment. The student’s version, an interactive PDF, contains all of the above except the responses to the close reading questions and the follow-up assignment.

Teacher’s Guide

Background questions.

- What kind of text are we dealing with?

- When was it written?

- Who wrote it?

- For what audience was it intended?

- For what purpose was it written?

In this lesson you will explore excerpts from one of the first written accounts of interactions between Spanish conquistadors and Native Americans. The first passage describes Hispaniola, the Caribbean island that today includes Haiti and the Dominican Republic. One of the islands explored during his first voyage in 1492, Columbus found there the self-sufficient Taino tribe, numbering up to 3 million people by some estimates. The following passages detail interactions between Spanish conquistadors and the Taino.

Why did the Spanish land in Hispaniola? In brief, they explored for “God, Gold, and Glory.” King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, known as the “Catholic Monarchs,” sought to centralize Spain as a Catholic stronghold. Religious passions spread widely after Spain had driven Moors and Jews out of the Iberian Peninsula in 1492, and the Pope issued a decree in 1493 exhorting Spain to spread the Catholic faith into new lands. In addition, Pope Alexander VI granted to Spain any new world territory not already claimed by a Christian prince, and these newly discovered lands offered wide opportunities to convert to Christianity large numbers of “heathens.”

In order to understand the Spanish hunger for gold in the 16th century, one must recognize the Spanish treasure fleet system. Spain at this time had a strong navy but no real industry within the country, and so she had to buy all her goods from other nations, making gold and silver very important. To help fund their naval and colonial activities in the midst of competition with Portugal, the Spanish King and Queen financed Columbus’s voyages to search for trade routes and fresh sources of gold and silver through new colonies. The New World gold and silver mines became the largest source of precious metals in the world, and Spain passed laws that colonists could trade only with Spanish ships in order to keep the gold and silver flowing through Spain. The large flow of treasure to Spain from the capture of the Aztecs (1517), the Incas (1534), and Mexico (1545) sharpened the appetite for gold and silver in Hispaniola.

Columbus was soon followed by other explorers seeking glory for themselves as well as for Spain, including Bartolome de Las Casas (1484–1566), author of this text. Las Casas knew Christopher Columbus — his father and brother went with Columbus on his second voyage, and Bartolome edited Columbus’s travel journals. The Spanish King awarded de Las Casas and his family an encomienda, a plantation that included the slave labor of the Indians who lived on it, but after witnessing the brutality of other Spanish explorers to the local tribes, Bartolome gave it up. He became a Dominican priest, spending the rest of his life writing, speaking and encouraging the Christian conversion of the North American natives by peaceful rather than military means. De Las Casas started a mission in Guatemala and wrote several accounts, aimed at the king and queen and members of the royal court, that sought to expose the brutal methods of the conquistadors and persuade Spanish officials to protect the Indians. The excerpts in this lesson are from probably the best known of those accounts, A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies , published in 1552.

What were the effects of his work? While the Pope had granted Spain sovereignty over the New World, de Las Casas argued that the property rights and rights to their own labor still belonged to the native peoples. Natives were subjects of the Spanish crown, and to treat them as less than human violated the laws of God, nature, and Spain. He told King Ferdinand that in 1515 scores of natives were being slaughtered by avaricious conquistadors without having been converted. He sought to protect the souls of Spain and the conquistadors against divine retribution for the destruction of the native populations by awakening the moral indignation of Christian men to counter the growing tide of barbarism. Between 1513 and 1543 Spain issued several laws attempting to regulate the encomienda system and protect native populations, but enforcement was haphazard and the subjugation of the native populations was already a fact. Nonetheless, through his self-proclaimed goal of bearing witness to the savagery of the Europeans against the simply civility of the indigenous peoples, de Las Casas became characterized as the conscience of Spanish exploration.

If the immediate impact of his work was marginal, the long-term influence would be substantial. In the passages excerpted here and throughout A Brief Account , de Las Casas repeatedly asserts that he witnessed the events he is describing and thus bases his argument on the authority of his first-hand testimony. This practice makes his work an early example of empiricism, the idea that arguments and conclusions should be based upon observable fact. Unquestioned today, in the 1500s this was a new concept, for at that time people held that the proof of an argument should be based on the interpretation of texts rather than the concrete experience of an eye witness.

De Las Casas’ book describes events he witnessed on the island of Hispaniola. As your read these excerpts think about what the Indian kingdoms were like when the Spanish arrived. How did the Indians initially respond to the Spanish? How did the Spanish respond to the Indians? How does the fact that de Las Casas was an eyewitness to these events lend authority to this account?

Text Analysis

Close reading questions.

1. What did the Spanish do to the Natives? They enslaved them and took their food.

2. How would you characterize the Spanish treatment of the natives? It was very violent. The author describes the capture as “bloody slaughter and destruction.”

3. How did the Natives come to characterize the Spanish? Why? The Natives came to believe that the Spanish “had not their Mission from Heaven” because the Spanish so cruelly treated the Indians. The Indians saw them as evil.

4. What does this characterization tell us about the original perception of the Natives regarding the Spanish? They originally perceived them to be from heaven and believed that they had come for positive purposes.

5. How did the Natives respond to the Spanish cruelty? They hid their food from the Spanish and hid their wives and children in “lurking holes” [caves]. Some of them ran away to the mountains to escape punishment by the Spanish.

6. How did the Natives respond to the Spanish violence against them? What were the results? The Indians “immediately took up Arms.” However, the author describes the native weapons as those that boys play with rather than real weapons. They had very little effect.

7. Once the Spaniards realized that the Indians were resisting, what did they do? The Spaniards mounted their horses and attacked cities and towns, killing everyone.

8. What tone does de Las Casas create in this excerpt? How does he create that tone? Cite evidence from the text. De Las Casas uses diction (word choice) to create a tone of outrage. He is angry at the injustices being done to the Natives. He uses phrases such as “the bloody slaughter and destruction of men,” “making them slaves, and ill-treating them,” “laid violent hands on the Governours,” and “exercise the bloody butcheries.” De Las Casas conveys immediate physical violence through words like “bloody,” “destruction,” “violent,” and “butcheries.” He conveys short and long-term violence, including the losses of liberty and culture, through words like “slaves” and “ill-treating.”

9. How does de Las Casas portray the natives in this passage? Cite evidence from the text. He portrays them as naïve, innocent children. It apparently took them a while to figure out that the Spanish were not on a “Mission from Heaven.” The Indians are essentially defenseless against the Spanish, and when they do take up arms, their weapons resemble those of boys.

10. How does this portrayal advance de Las Casas’s argument? It establishes the vulnerability of the Indians and illustrates why they need the protection of the Spanish king.