Travel Vaccines and Advice for Sierra Leone

Despite its beauty, Sierra Leone has remained mostly uninfluenced by tourist activities. Much of the country is still undiscovered.

The country’s coastline, is only one of its many attractive landscapes. The Loma Mountains in the north have dense rain forests and volcanoes nestled in rolling hills.

In Freetown vibrant houses perched on stilts remain from when freed slaves relocated to the country’s Western shores.

On This Page: Do I Need Vaccines for Sierra Leone? Other Ways to Stay Healthy in Sierra Leone Do I Need a Visa or Passport for Sierra Leone? What Is the Climate Like in Sierra Leone? How Safe Is Sierra Leone? Is the Food Safe in Sierra Leone? Going to Banana Island What Should I Take to Sierra Leone? U.S. Embassy in Sierra Leone

Do I Need Vaccines for Sierra Leone?

Yes, some vaccines are recommended or required for Sierra Leone. The CDC and WHO recommend the following vaccinations for Sierra Leone: typhoid , hepatitis A , polio , yellow fever , chikungunya , rabies , hepatitis B , influenza , COVID-19 , pneumonia , meningitis , chickenpox , shingles , Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis) and measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) .

See the bullets below to learn more about some of these key immunizations:

- Typhoid – Food & Water – Shot lasts 2 years. Oral vaccine lasts 5 years, must be able to swallow pills. Oral doses must be kept in refrigerator.

- Hepatitis A – Food & Water – Recommended for most travelers.

- Polio – Food & Water – While there is no active polio transmission in Sierra Leone, it is vulnerable for outbreaks. Considered a routine vaccination for most travel itineraries. Single adult booster recommended.

- Yellow Fever – Mosquito – Required for arriving travelers from ALL countries. Recommended for all travelers over 9 months of age.

- Chikungunya – Mosquito – Few cases reported since 2016. Increased risk for those who may be in more rural areas.

- Rabies – Saliva of Infected Animals – High risk country. Vaccine recommended for long-term travelers and those who may come in contact with animals.

- Hepatitis B – Blood & Body Fluids – Recommended for travelers to most regions.

- Influenza – Airborne – Vaccine components change annually.

- COVID-19 – Airborne – Recommended for travel to all regions, both foreign and domestic.

- Pneumonia – Airborne – Two vaccines given separately. All 65+ or immunocompromised should receive both.

- Meningitis – Direct Contact & Airborne – Given to anyone unvaccinated or at an increased risk, especially students.

- Chickenpox – Direct Contact & Airborne – Given to those unvaccinated that did not have chickenpox.

- Shingles – Direct Contact – Vaccine can still be given if you have had shingles.

- Polio – Food & Water – Considered a routine vaccination for most travel itineraries. Single adult booster recommended.

- TDAP (Tetanus, Diphtheria & Pertussis) – Wounds & Airborne – Only one adult booster of pertussis required.

- Measles Mumps Rubella (MMR) – Various Vectors – Given to anyone unvaccinated and/or born after 1957. One time adult booster recommended.

See the table below for more information:

Specific Vaccine Information

- Typhoid – Typhoid, caused by Salmonella Typhi, spreads via contaminated food and water, especially in areas with poor sanitation. Protect yourself by practicing good hygiene and safe food habits. Vaccination can significantly reduce the risk of typhoid infection, especially when traveling to endemic areas.

- Hepatitis A – Hepatitis A is a highly contagious liver infection caused by the hepatitis A virus, typically spreading through contaminated food or water, or close contact with an infected person. Symptoms can include fatigue, nausea, stomach pain, and jaundice. The hepatitis A vaccine is a safe and effective shot that provides immunity against the virus, usually given in two doses.

- Yellow Fever – Yellow fever is a serious, potentially fatal viral disease transmitted by mosquitoes, characterized by fever, jaundice, and bleeding. The yellow fever vaccine, given as a single injection, offers effective, long-lasting immunity against the virus and is crucial for travelers to and residents of endemic areas in Africa and South America.

- Chikungunya – Chikungunya, spread by infected mosquitoes, can be prevented through mosquito bite prevention and vaccination. The chikungunya vaccine is considered the best form of protection.

- Rabies – The rabies virus is a deadly threat that spreads through bites and scratches from infected animals. Preventing rabies involves timely vaccination, avoiding contact with wildlife and seeking immediate medical attention if bitten. The rabies vaccine is instrumental in developing immunity and safeguarding against this fatal disease.

- Hepatitis B – Hepatitis B, a liver infection spread through bodily fluids, poses a significant health risk. Safe practices help, but vaccination is the ultimate safeguard. It prompts the immune system to produce antibodies, ensuring strong and persistent protection.

- Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR) – Measles, mumps, and rubella are contagious viral infections, causing various symptoms and complications. To prevent them, vaccination is key. The MMR vaccine, given in two doses, safeguards against all three diseases and helps establish herd immunity, reducing the risk of outbreaks.

Yellow Fever in Sierra Leone

Yellow fever vaccination is required for entry to Sierra Leone. All travelers over the age of nine months must show proof of vaccination upon arriving in the country. Vaccination is also recommended by the CDC and WHO to keep travelers protected against the virus.

Malaria in Sierra Leone

Malaria is widespread in Sierra Leone. Antimalarials are recommended for all travelers to the country. Atovaquone, doxycycline, mefloquine and tafenoquine are often given to travelers to Sierra Leone. Malaria parasite are resistant to chloroquine in the region. Be sure to consult with a travel health specialist on which antimalarials are best for your itinerary and health situation.

Proof of yellow fever vaccination is required for entry to Sierra Leone.

The CDC also says that the Zika virus is a risk in Sierra Leone. This virus can cause serious birth defects. It is recommended that pregnant women, or women planning to become pregnant, should not travel to Sierra Leone.

Typhoid vaccination is highly recommended for travelers to Sierra Leone. Individuals who visit friends or relatives or go to rural areas are at greater risk and should be immunized.

Ebola struck Sierra Leone in July of 2014. The outbreak claimed more than 700 lives.

In March 2016, the World Health Organization declared Sierra Leone Ebola-free.

To find out more about these vaccines, see our vaccinations page. Ready to travel safely? Book your appointment either call or start booking online now.

Other Ways to Stay Healthy in Sierra Leone

Prevent bug bites in sierra leone.

To ward off bug bites, follow CDC advice: wear long clothing, use screens, and remove standing water. Opt for EPA-registered repellents with DEET, picaridin, or OLE for protection. If bitten, wash the area, avoid scratching, and apply remedies. Seek medical help for severe reactions.

Food and Water Safety in Sierra Leone

Abroad, practice food safety by avoiding street vendors, washing hands thoroughly, and choosing well-cooked meals. Opt for bottled or canned drinks with unbroken seals. Prevent travelers’ diarrhea by practicing hand hygiene, skipping raw foods, and dining at reputable establishments.

Infections To Be Aware of in Sierra Leone

- African Tick-Bite Fever – ATBF, transmitted by ticks in sub-Saharan Africa, can be prevented by wearing protective clothing, using insect repellent, and checking for ticks. For additional protection, inquire about available options from healthcare experts before traveling to affected areas.

- Dengue – Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne illness with symptoms ranging from mild to severe, including high fever and pain. The CDC emphasizes prevention through avoiding mosquito bites by using repellents and removing standing water. Treatment focuses on symptom relief and hydration, avoiding certain pain relievers that can worsen bleeding risks.

- Ebola – Ebola, a deadly virus, can be prevented through rigorous hand hygiene and avoiding infected individuals, both are crucial in halting its transmission.

- Lassa Fever – Lassa fever, caused by the Lassa virus, spreads via rodents and human-to-human transmission. Although no vaccine is licensed yet, prevention entails strict hygiene, rodent control, and healthcare safety measures.

- Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever – Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever (MHF) spreads through contact with infected animals and individuals, necessitating stringent protective measures. Safe burial practices, healthcare infection control, and community education are pivotal in reducing MHF transmission risks.

- Schistosomiasis – Schistosomiasis is a parasitic infection transmitted through contaminated water. Avoiding contact with infected water sources and using protective clothing can reduce the risk of infection. Seeking medical evaluation promptly if symptoms such as fever and fatigue manifest enables timely diagnosis and treatment, preventing complications and promoting recovery.

- Zika – Zika, a mosquito-borne virus, spreads through mosquito bites, sexual contact, and from mother to child during pregnancy. Preventive measures include using repellent, practicing safe sex, and removing mosquito breeding sites.

Do I Need a Visa or Passport for Sierra Leone?

All U.S. citizens must have a visa before visiting Sierra Leone. If you do not have a visa, you will be denied entry.

Sources: Embassy of Sierra Leone and U.S. State Department

Your passport must be valid for at least 6 months following your expected date of arrival. Proof of yellow fever immunization is also required for entry.

What Is the Climate Like in Sierra Leone?

Sierra Leone is, for the most part, humid year-round. The country’s hottest season is from November through around April. During this time, travelers can expect a slight drop in humidity, but a spike in temperatures. Near the coast, breezes from the Atlantic offer a slight drop in temperature. March is considered the peak of the dry, hot season.

From December to January, dry dust storms from the Sahara blow through most of the country.

November and May are considered “wet months.” Travelers should expect a moderate amount of rainfall during this time.

- Freetown – In this coastal town, the temperatures tend to be relatively cooler than other major cities in Sierra Leone. Freetown experiences frequent rainfall.

- Kenema – Located in the South Sierra Leone, the climate is tropical and rainfall is present for most of the year. The dry season here has little impact on the climate.

- Makeni – Located in the center of Sierra Leone, this city experiences weather like Kenema to the South and Freetown to the West. But, this area experiences less rainfall.

How Safe Is Sierra Leone?

Sierra Leone is widely regarded as one of the poorest countries in the world. With this poverty comes an increase in crime rates.

Freetown is seen as the safest destination in the country. But, even in Freetown, night time wandering is not recommended. If you decide to travel from Freetown, the trip should be made in the daylight as run-ins with bandits are not uncommon.

If you are headed to border areas pay attention to your surroundings and never travel alone if you can help it. For instance, the border to Liberia is considered unstable.

Is the Food Safe in Sierra Leone?

Most dishes in Sierra Leone are spicy, plant-based and served with rice. Vegetable, meat and nut stews are common. Local dishes include: okra stew, cassava bread, coconut cake and pepper soup.

More impoverished areas in the country will have poor hygiene practices. It is best to stick to restaurants that are recommended for serving quality food on a consistent basis.

Although street food may smell tempting, cooking food outdoors increases the likelihood of your meal becoming contaminated.

All travelers to Sierra Leone should bring a travelers’ diarrhea kit , typhoid and hepatitis A vaccinations.

Going to Banana Island

Avoid an embarrassing stop, over 70% of travelers will have diarrhea., get protected with passport health’s travelers’ diarrhea kit .

Banana Island is a beautiful place in Sierra Leone that tourists like to visit because of its clear waters and white sandy beaches. People can do fun activities there, like swimming, snorkeling, and diving to see different types of colorful fish and sea animals. They can also go fishing with local fishermen, who use traditional methods to catch fish.

Banana Island is also a good place to relax and unwind because it is a quiet and peaceful island. Visitors can take a guided tour to learn about the island’s history and culture, or walk around and explore. There are also small guesthouses and lodges on the island where people can stay and experience island life.

Banana Island is a great place to visit if you like being near the ocean, want to try new things or want to relax in a beautiful setting.

What Should I Take to Sierra Leone?

Consider packing the following items, regardless what time of year you plan on traveling to Sierra Leone:

- Either a rain poncho or a light rain jacket – Prepare for any expected or unexpected rainfall.

- Bug spray or insect repellent – The high level of humidity across the country attracts mosquitoes, among other insects.

- Long sleeved shirts and pants – Coverage of the arms and legs further reduces your chances of being bitten by mosquitoes.

- Light and airy, yet relatively conservative clothing – The temperatures are manageable, but humidity can make it feel much warmer than it is.

U.S. Embassy in Sierra Leone

The U.S. Embassy urges travelers to register with the State Department before traveling to Sierra Leone.

Travelers also must make an appointment at the embassy for all non-emergency services including: routine passport application and renewals and notary signings.

U.S. Embassy Freetown Southridge, Hill Station Freetown, Sierra Leone Tel: (232) 99-105-000 Emergency after hours: (232) 99-905-029 Email: [email protected]

Ready to start your next journey? Call us at or book online now !

Customer Reviews

Passport health – travel vaccines for sierra leone.

- Records Requests

- Passport Health App

- Privacy Center

- Online Store

Security Alert May 17, 2024

Worldwide caution, update may 10, 2024, information for u.s. citizens in the middle east.

- Travel Advisories |

- Contact Us |

- MyTravelGov |

Find U.S. Embassies & Consulates

Travel.state.gov, congressional liaison, special issuance agency, u.s. passports, international travel, intercountry adoption, international parental child abduction, records and authentications, popular links, travel advisories, mytravelgov, stay connected, legal resources, legal information, info for u.s. law enforcement, replace or certify documents.

Before You Go

Learn About Your Destination

While Abroad

Emergencies

Share this page:

Sierra Leone

Travel Advisory July 31, 2023

Sierra leone - level 2: exercise increased caution.

Reissued with obsolete COVID-19 page links removed.

Exercise increased caution in Sierra Leone due to crime and civil unrest .

Country Summary: Violent crimes, such as robbery and assault, occur frequently in Sierra Leone, especially in Freetown. Local police often lack the resources to deal effectively with serious criminal incidents.

Demonstrations and protests occur in Sierra Leone and on occasion have resulted in violence.

If traveling outside the Freetown peninsula, make all efforts to complete your travel during daylight hours due to increased safety hazards at night. The U.S. Embassy is unable to provide emergency services to U.S. citizens outside of Freetown at night as U.S. government employees are prohibited from traveling outside the capital after dark.

Read the country information page for additional information about travel to Sierra Leone.

If you decide to travel to Sierra Leone:

- Do not physically resist any robbery attempt.

- Do not display signs of wealth, such as expensive watches or jewelry.

- Use caution when walking or driving at night.

- Always carry a copy of your U.S. passport and visa (if applicable). Keep original documents in a secure location.

- Enroll in the Smart Traveler Enrollment Program ( STEP ) to receive Alerts and make it easier to locate you in an emergency.

- Follow the Department of State on Facebook and Twitter .

- Review the Country Security Report for Sierra Leone.

- Prepare a contingency plan for emergency situations. Review the Traveler’s Checklist .

- Visit the CDC page for the latest Travel Health Information related to your travel.

Embassy Messages

View Alerts and Messages Archive

Quick Facts

1 page per stamp.

Yellow Fever.

Embassies and Consulates

U.S. Embassy Freetown Southridge, Hill Station Freetown, Sierra Leone Telephone: (+232) 99-105-000 Emergency after-hours telephone: (+232) 99-905-029 Email: [email protected]

Destination Description

Learn about the U.S. relationship to countries around the world.

Entry, Exit and Visa Requirements

A valid passport and visa are required for travel to Sierra Leone. Visitors to Sierra Leone are required to show their International Certificates of Vaccination (yellow card) upon arrival at the airport with a record of vaccination against yellow fever.

Visit the Embassy of the Republic of Sierra Leone’s website for the most current visa information.

The U.S. Department of State is unaware of any HIV/AIDS entry restrictions for visitors to or foreign residents of Sierra Leone.

Find information on dual nationality , prevention of international child abduction and customs regulations on our websites.

Safety and Security

Areas outside Freetown lack basic services. Travel outside the capital after dark is not allowed for U.S. Embassy officials and should be avoided by all travelers. Emergency response to vehicular and other accidents ranges from slow to nonexistent.

Crime: Crime is widespread in Sierra Leone. U.S. citizens have experienced armed mugging, assault, and burglary. Petty crime and pick pocketing of wallets, cell phones, and passports are very common, especially on the ferry to and from Lungi International Airport, as well as in bars, restaurants, and nightclubs in the Lumley Beach and Aberdeen areas of Freetown.

Demonstrations occur frequently. They may take place in response to political or economic issues, on politically significant holidays, and during international events.

- Even demonstrations intended to be peaceful can turn confrontational and possibly become violent.

- Avoid areas around protests and demonstrations.

- Check local media for updates and traffic advisories.

International Financial Scams: See the Department of State and the FBI pages for information on scams.

Internet romance and financial scams are prevalent in Sierra Leone. Scams are often initiated through Internet postings or profiles, or by unsolicited emails and letters. Scammers almost always pose as U.S. citizens who have no one else to turn to for help. Common scams include:

- Romance/Online dating

- Money transfers

- Lucrative sales

- Gold purchase

- Contracts with promises of large commissions

- Grandparent/Relative targeting

- Free Trip/Luggage

- Inheritance notices

- Work permits/job offers

- Bank overpayments

Victims of Crime: U.S. citizen victims of sexual assault should first contact the U.S. Embassy at (232) (99) 105 500. Report crimes to the local police at (232) (76) 692 830.

Remember that local authorities are responsible for investigating and prosecuting the crime.

See our webpage on help for U.S. victims of crime overseas.

- help you find appropriate medical care

- assist you in reporting a crime to the police

- contact relatives or friends with your written consent

- explain the local criminal justice process in general terms

- provide a list of local attorneys

- provide our information on victim’s compensation programs in the U.S.

- provide an emergency loan for repatriation to the United States and/or limited medical support in cases of destitution

- help you find accommodation and arrange flights home

- replace a stolen or lost passport

Domestic Violence: U.S. citizen victims of domestic violence are encouraged to contact the Embassy for assistance.

Tourism: The tourism industry is unevenly regulated, and safety inspections for equipment and facilities do not commonly occur. Hazardous areas and activities are not always identified with appropriate signage, and staff may not be trained or certified either by the host government or by recognized authorities in the field. In the event of an injury, medical treatment is typically available only in or near major cities and there are few medical specialists in country able to treat complicated medical conditions. First responders are generally unable to access areas outside of major cities and are not trained to provide urgent medical treatment. U.S. citizens are encouraged to purchase medical evacuation insurance .

Local Laws & Special Circumstances

Criminal Penalties: You are subject to local laws. If you violate local laws, even unknowingly, you may be expelled, arrested, or imprisoned.

Furthermore, some laws are also prosecutable in the United States, regardless of local law. For examples, see our website on crimes against minors abroad and the Department of Justice website .

Arrest Notification: If you are arrested or detained, ask police or prison officials to notify the U.S. Embassy immediately. See our webpage for further information.

Exports: Sierra Leone's customs authorities enforce strict regulations concerning the export of gems and precious minerals, such as diamonds and gold. All mineral resources, including gold and diamonds, belong to the State, and only the Government of Sierra Leone can issue mining and export licenses. The National Minerals Agency (NMA) can provide licenses for export, while the agency’s Directorate of Precious Minerals Trading is responsible for Kimberly Process certification of diamonds. For further information on mining activities in Sierra Leone, contact the Ministry of Mines and Mineral Resources , or see the Department of State’s annual Investment Climate Statement .

The Embassy has received reports in recent years of U.S. citizens investing in Sierra Leone who have been victims of fraud, often in the mining industry. Examples of fraud include advance-fee schemes where individuals have approached U.S. citizens urging them to purchase diamonds directly from Sierra Leone. The U.S. Embassy cannot interfere or intervene in any legal disputes, including those related to precious minerals. Please be aware that the U.S. Embassy cannot conduct checks on potential local partners.

Photography: Travelers must obtain official permission to photograph government buildings, airports, bridges, or official facilities including the Special Court for Sierra Leone and the U.S. Embassy.

Dual Nationals: U.S. citizens who are also Sierra Leonean nationals must provide proof of payment of taxes on revenue earned in Sierra Leone before being granted clearance to depart the country.

Faith-Based Travelers: See our following webpages for details:

- Faith-Based Travel Information

- International Religious Freedom Report – see country reports

- Human Rights Repor t – see country reports

- Hajj Fact Sheet for Travelers

- Best Practices for Volunteering Abroad

LGBTI Travelers: Consensual sexual relations between men are criminalized in Sierra Leone. Although the U.S. Embassy is not aware of any recent prosecutions for consensual sexual activity between men, such activity is illegal and penalties can include imprisonment. While there is no explicit legal prohibition against sexual relations between women, lesbians of all ages can be victims of “planned rapes” initiated by family members in an effort to change their sexual orientation.

See our LGBTI Travel Information page and section 6 of our Human Rights report for further details.

Travelers with Disabilities: The law in Sierra Leone does not prohibit discrimination against persons with disabilities and offers no specific protections for such persons. Social acceptance of persons with disabilities in public is as prevalent as in the United States. Expect accessibility to be limited in public transportation, lodging, communication/information, and general infrastructure throughout the country. Rental, repair, replacement parts for aids/equipment/devices, and service providers, such as sign language interpreters, are not available.

Students: See our Students Abroad page and FBI travel tips.

Women Travelers: Rape, including spousal rape, is illegal in Sierra Leone and punishable by up to 15 years in prison. However, rape is common and indictments are rare. Domestic violence is illegal and punishable by a fine of up to five (5) million leones ($943) and up to two years in prison. However, domestic violence is common and police are unlikely to intervene.

Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) is widespread in Sierra Leone. The government imposed a moratorium on practicing FGM/C as an emergency health response to the Ebola outbreak, and the moratorium remains in place, but the prohibition is not actively enforced.

See our travel tips for Women Travelers.

Please visit the Embassy’s COVID-19 page for more information about COVID-19 in Sierra Leone.

Medical facilities and services in Sierra Leone are severely limited. The standard of care, including basic medical services such as imaging or blood tests, is much lower than that of the United States.

For emergency services in Sierra Leone, dial 117.

Ambulance services are:

- not widely available and training and availability of emergency responders may be below U.S. standards.

- not present throughout the country or are unreliable in most areas.

- not equipped with state-of-the-art medical equipment.

- not staffed with trained paramedics and often have little or no medical equipment.

Injured or seriously ill travelers may prefer to take a taxi or private vehicle to the nearest major hospital rather than wait for an ambulance.

We do not pay medical bills. Be aware that U.S. Medicare/Medicaid does not apply overseas. Most hospitals and doctors overseas do not accept U.S. health insurance.

Medical Insurance: Make sure your health insurance plan provides coverage overseas. Most care providers overseas only accept cash payments. See our webpage for more information on insurance providers for overseas coverage. Visit the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for more information on type of insurance you should consider before you travel overseas.

We strongly recommend supplemental insurance to cover medical evacuation.

Always carry your prescription medication in original packaging, along with your doctor’s prescription. Check with the Sierra Leone’s Federal Office of Public Health to ensure the medication is legal in Sierra Leone.

Vaccinations: Be up-to-date on all vaccinations recommended by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Further health information:

- World Health Organization

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Air Quality: Visit AirNow Department of State for information on air quality at U.S. Embassies and Consulates.

The U.S. Embassy maintains a list of doctors and hospitals . We do not endorse or recommend any specific medical provider or clinic.

Water Quality:

- In many areas, tap water is not potable. Bottled water and beverages are generally safe, although you should be aware that many restaurants and hotels serve tap water unless bottled water is specifically requested. Be aware that ice for drinks may be made using tap water.

- Many cities in Sierra Leone, such as Kabala, are at high altitude. Be aware of the symptoms of altitude sickness and take precautions before you travel. Visit the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website for more information about Travel to High Altitudes.

Adventure Travel:

- Visit the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website for more information about Adventure Travel.

General Health:

The following diseases are prevalent:

- Yellow Fever

- Travelers’ Diarrhea

Use the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended mosquito repellents and sleep under insecticide-impregnated mosquito nets. Chemoprophylaxis is recommended for all travelers even for short stays.

Visit the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website for more information regarding specific issues in Sierra Leone.

Air Quality:

- Air pollution is a significant problem in several major cities in Sierra Leone. Consider the impact seasonal smog and heavy particulate pollution may have on you and consult your doctor before traveling if necessary.

- Infants, children, and teens

- People over 65 years of age

- People with lung disease such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which includes chronic bronchitis and emphysema;

- People with heart disease or diabetes

Travel and Transportation

Road Conditions and Safety: Most main roads in Freetown are navigable, but narrow and often have potholes. There is limited roadside assistance in-country and it is often difficult to find adequate fuel for longer journeys. Serious accidents are common, especially outside of Freetown, where the relative lack of traffic allows for greater speeds. Nighttime travel should be avoided.

Traffic Laws: International road signs and protocols are not routinely observed in Sierra Leone. In the event of a traffic accident, you should follow all police instructions. Large mobs often form at the scene of an accident and threaten the safety of the driver. You should go to the nearest police station for safety, even in the smallest of accidents.

Public Transportation: Public transport (bus or group taxi) is erratic, unsafe, and not recommended. U.S. Embassy officials are prohibited from using public transportation or taxis.

Motorcycle taxis are ubiquitous in Freetown and are often the cause of serious accidents. The U.S. Embassy strongly advises against utilizing these motorcycles. Pick pocketing is common in public taxis and mini-buses.

See our Road Safety page for more information.

Visit the website of Sierra Leone’s national tourist office and national authority responsible for road safety.

Aviation Safety Oversight: As there is no direct commercial air service to the United States by carriers registered in Sierra Leone, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has not assessed the government of Sierra Leone’s Civil Aviation Authority for compliance with International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) aviation safety standards. Further information may be found on the FAA’s safety assessment page.

Maritime Travel: Mariners planning travel to Sierra Leone should also check for U.S. maritime advisories and alerts. Information may also be posted to the U.S. Coast Guard homeport website , and the NGA broadcast warnings.

For additional travel information

- Enroll in the Smart Traveler Enrollment Program (STEP) to receive security messages and make it easier to locate you in an emergency.

- Call us in Washington, D.C. at 1-888-407-4747 (toll-free in the United States and Canada) or 1-202-501-4444 (from all other countries) from 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m., Eastern Standard Time, Monday through Friday (except U.S. federal holidays).

- See the State Department’s travel website for the Worldwide Caution and Travel Advisories .

- Follow us on Twitter and Facebook .

- See traveling safely abroad for useful travel tips.

For additional IPCA-related information, please see the International Child Abduction Prevention and Return Act (ICAPRA) report.

Travel Advisory Levels

Assistance for u.s. citizens, sierra leone map, learn about your destination, enroll in step.

Subscribe to get up-to-date safety and security information and help us reach you in an emergency abroad.

Recommended Web Browsers: Microsoft Edge or Google Chrome.

Check passport expiration dates carefully for all travelers! Children’s passports are issued for 5 years, adult passports for 10 years.

Afghanistan

Antigua and Barbuda

Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, and Saba

Bosnia and Herzegovina

British Virgin Islands

Burkina Faso

Burma (Myanmar)

Cayman Islands

Central African Republic

Cote d Ivoire

Curaçao

Czech Republic

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Dominican Republic

El Salvador

Equatorial Guinea

Eswatini (Swaziland)

Falkland Islands

France (includes Monaco)

French Guiana

French Polynesia

French West Indies

Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Martin, and Saint Barthélemy (French West Indies)

Guinea-Bissau

Isle of Man

Israel, The West Bank and Gaza

Liechtenstein

Marshall Islands

Netherlands

New Caledonia

New Zealand

North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea)

Papua New Guinea

Philippines

Republic of North Macedonia

Republic of the Congo

Saint Kitts and Nevis

Saint Lucia

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Sao Tome and Principe

Saudi Arabia

Sint Maarten

Solomon Islands

South Africa

South Korea

South Sudan

Switzerland

The Bahamas

Timor-Leste

Trinidad and Tobago

Turkmenistan

Turks and Caicos Islands

United Arab Emirates

United Kingdom

Vatican City (Holy See)

External Link

You are about to leave travel.state.gov for an external website that is not maintained by the U.S. Department of State.

Links to external websites are provided as a convenience and should not be construed as an endorsement by the U.S. Department of State of the views or products contained therein. If you wish to remain on travel.state.gov, click the "cancel" message.

You are about to visit:

- Company History

- Mission Statement

- Philippines

- South Africa

- Afghanistan

- American Samoa

- Antigua and Barbuda

- British Virgin Islands

- Burkina Faso

- Canary Islands

- Cayman Islands

- Central African Republic

- Christmas Island

- Cocos (Keeling) Islands

- Cook Islands

- Cote d'Ivoire

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Dominican Republic

- Easter Island

- El Salvador

- Equatorial Guinea

- Falkland Islands

- Faroe Islands

- French Guiana

- French Polynesia

- Guinea-Bissau

- Liechtenstein

- Madeira Islands

- Marshall Islands

- Netherlands

- New Caledonia

- New Zealand

- Norfolk Island

- North Korea

- North Macedonia

- Northern Mariana Islands

- Palestinian Territories

- Papua New Guinea

- Pitcairn Islands

- Puerto Rico

- Republic of the Congo

- Saint Barthelemy

- Saint Helena

- Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- Saint Martin

- Saint Pierre-et-Miquelon

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Sao Tome and Principe

- Saudi Arabia

- Sierra Leone

- Sint Eustatius

- Solomon Islands

- South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

- South Korea

- South Sudan

- Switzerland

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Turkmenistan

- Turks and Caicos Islands

- U.S. Virgin Islands

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Wake Island

- Western Sahara

- Travel Vaccines

- Travel Health Consultations

- Travellers’ Diarrhea Kits

- Dengue Fever Prevention

- Malaria Prevention

- Chikungunya Prevention

- Zika Prevention

- Ebola Virus

- Yellow Fever

- Hepatitis A

- Japanese Encephalitis

- Hepatitis B

- Tickborne Encephalitis (TBE)

- Tetanus-Diphtheria-Pertussis

- Measles-Mumps-Rubella

- Influenza (Flu)

- Blood Tests

- Vitamin Injections

- Physician Referral Program

- London Bridge Clinic

- London – Euston Travel Clinic

Travel Vaccines and Advice for Sierra Leone

Despite its beauty, Sierra Leone has remained mostly uninfluenced by tourist activities. Much of the country is still undiscovered.

The country’s coastline, is only one of its many attractive landscapes. The Loma Mountains in the north have dense rainforests and volcanoes nestled in rolling downs.

In Freetown vibrant houses perched on stilts remain from when freed slaves relocated to the country’s Western shores.

Do I Need Vaccines for Sierra Leone?

Yes, some vaccines are recommended or required for Sierra Leone. The National Travel Health Network and Centre and WHO recommend the following vaccinations for Sierra Leone: COVID-19 , hepatitis A , hepatitis B , typhoid , cholera , yellow fever , rabies , polio and tetanus .

See the bullets below to learn more about some of these key immunisations:

- COVID-19 – Airborne – Recommended for all travellers

- Hepatitis A – Food & Water – Recommended for most travellers to the region, especially if unvaccinated.

- Hepatitis B – Blood & Body Fluids – Recommended for travellers to most regions.

- Tetanus – Wounds or Breaks in Skin – Recommended for travelers to most regions, especially if not previously vaccinated.

- Typhoid – Food & Water – Jab lasts 3 years. Oral vaccine lasts 5 years, must be able to swallow pills. Oral doses must be kept in refrigerator.

- Cholera – Food & Water – Recommended for travel to most regions.

- Yellow Fever – Mosquito – Required for arriving travellers from ALL countries. Recommended for all travellers over 9 months of age.

- Rabies – Saliva of Infected Animals – High risk country. Vaccine recommended for long-stay travellers and those who may come in contact with animals.

- Polio – Food & Water – Recommended for travel to some regions. Single adult booster recommended.

See the tables below for more information:

Proof of yellow fever vaccination is required for entry to Sierra Leone.

The NaTHNaC also says that the Zika virus is a risk in Sierra Leone. This virus can cause serious birth defects. It is recommended that pregnant women, or women planning to become pregnant, should not travel to Sierra Leone.

Ebola struck Sierra Leone in July of 2014. The outbreak claimed more than 700 lives.

In March 2016, the World Health organisation declared Sierra Leone Ebola-free.

To find out more about these vaccines, see our vaccinations page. Ready to travel safely? Book your appointment either ring or start booking online now .

Do I Need a Visa or Passport for Sierra Leone?

A visa is required for all travel to Sierra Leone. Passports must have at least six months validity. Proof of yellow fever vaccination is required to enter the country. If you do not have proof of vaccination, you may be vaccinated on site, quarantined or returned to your previous location.

Sources: Embassy of Sierra Leone and GOV.UK

What is the Climate Like in Sierra Leone?

Sierra Leone is, for the most part, humid year-round. The country’s hottest season is from November through around April. During this time, travellers can expect a slight drop in humidity, but a spike in temperatures. Near the coast, breezes from the Atlantic offer a slight drop in temperature. March is considered the peak of the dry, hot season.

From December to January, dry dust storms from the Sahara blow through most of the country.

November and May are considered wet months. Travellers should expect a moderate amount of rainfall during this time.

- Freetown – In this coastal town, the temperatures tend to be relatively cooler than other major cities in Sierra Leone. Freetown experiences frequent rainfall.

- Kenema – Located in the South Sierra Leone, the climate is tropical and rainfall is present for most of the year. The dry season here has little impact on the climate.

- Makeni – Located in the centre of Sierra Leone, this city experiences weather like Kenema to the South and Freetown to the West. But, this area experiences less rainfall.

How Safe Is Sierra Leone?

Sierra Leone is widely regarded as one of the poorest countries in the world. With this poverty comes an increase in crime rates.

Freetown is seen as the safest destination in the country. But, even in Freetown, night time wandering is not recommended. If you decide to travel from Freetown, the trip should be made in the daylight as run-ins with bandits are not uncommon.

If you are headed to border areas pay attention to your surroundings and never travel alone if you can help it. For instance, the border to Liberia is considered unstable.

Is the Food Safe In Sierra Leone?

Most dishes in Sierra Leone are spicy, plant-based and served with rice. Vegetable, meat and nut stews are common. Local dishes include: okra stew, cassava bread, coconut cake and pepper soup.

More impoverished areas in the country will have poor hygiene practices. It is best to stick to restaurants that are recommended for serving quality food on a consistent basis.

Although street food may smell tempting, cooking food outdoors increases the likelihood of your meal becoming contaminated.

All travellers to Sierra Leone should bring a traveller’s diarrhoea kit and receive cholera , typhoid and hepatitis A vaccinations.

Camping With the Wildlife of Tiwai Island

Gola Forest National Park is the best opportunity to get up close with wildlife. At one point of entry to the park sits Tiwai Island, where 11 primate species, exotic butterflies and pygmy hippos live.

Local groups offer weekend excursions that involves canoeing, hiking, animal tracking and visits to local communities for a full cultural experience.

What Should I Take to Sierra Leone?

Consider packing the following items, regardless what time of year you plan on travelling to Sierra Leone:

- Either a rain kagoul or a light rain jacket – Prepare for any expected or unexpected rainfall.

- Insect spray or insect repellent – The high level of humidity across the country attracts mosquitoes, among other insects.

- Long sleeved shirts and trousers – Coverage of the arms and legs further reduces your chances of being bitten by mosquitoes

- Light and airy, yet relatively conservative clothing – The temperatures are manageable, but humidity can make it feel much warmer than it is.

Embassy of the United Kingdom in Sierra Leone

If you are in Sierra Leone and have an emergency (for example, been attacked, arrested or someone has died) contact the nearest consular services. Contact the embassy before arrival if you have additional questions on entry requirements, safety concerns or are in need of assistance.

British High Commission Freetown 6 Spur Road Freetown Freetown Sierra Leone Telephone: +232 (0) 78200190 Emergency Phone: +232 (0) 76780713 Email: [email protected]

Ready to start your next journey? Ring us up at or book online now !

On This Page: Do I Need Vaccines for Sierra Leone? Do I Need a Visa or Passport for Sierra Leone? What Is the Climate Like In Sierra Leone? How Safe Is Sierra Leone? Is the Food Safe In Sierra Leone? Camping With the Wildlife of Tiwai Island What Should I Take to Sierra Leone? Embassy of the United Kingdom in Sierra Leone

- Privacy Policy

- Automatic Data Collection Statement

Sierra Leone Travel Restrictions

Traveler's COVID-19 vaccination status

Traveling from the United States to Sierra Leone

Open for vaccinated visitors

COVID-19 testing

Not required

Not required for vaccinated visitors

Restaurants

Not required in public spaces.

Sierra Leone entry details and exceptions

Documents & additional resources, ready to travel, find flights to sierra leone, find stays in sierra leone, explore more countries on travel restrictions map, destinations you can travel to now, dominican republic, netherlands, philippines, puerto rico, switzerland, united arab emirates, united kingdom, know when to go.

Sign up for email alerts as countries begin to open - choose the destinations you're interested in so you're in the know.

Can I travel to Sierra Leone from the United States?

Most visitors from the United States, regardless of vaccination status, can enter Sierra Leone.

Can I travel to Sierra Leone if I am vaccinated?

Fully vaccinated visitors from the United States can enter Sierra Leone without restrictions.

Can I travel to Sierra Leone without being vaccinated?

Unvaccinated visitors from the United States can enter Sierra Leone without restrictions.

Do I need a COVID test to enter Sierra Leone?

Visitors from the United States are not required to present a negative COVID-19 PCR test or antigen result upon entering Sierra Leone.

Can I travel to Sierra Leone without quarantine?

Travelers from the United States are not required to quarantine.

Do I need to wear a mask in Sierra Leone?

Mask usage in Sierra Leone is not required in public spaces.

Are the restaurants and bars open in Sierra Leone?

Restaurants in Sierra Leone are open. Bars in Sierra Leone are .

Sierra Leone launches Online Travel Portal to Manage Passenger

by dsti_v2 | Jul 5, 2023 | COVID19 | 0 comments

Travel.Gov.Sl is Sierra Leone’s official travel registration portal for passengers arriving at or departing from Freetown International Airport. The ICT Covid-19 Response PIllar manages the site which processes travel authorisation and assists the Surveillance Pillar with contact tracing during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Government of Sierra Leone has reopened its national airspace to commercial flights after air, land, and sea borders were closed on March 22, 2020. Public health and aviation officials agree that one key way to build traveler confidence and continue to flatten the coronavirus curve is with increased testing.

Sierra Leone’s travel protocols effective July 22, 2020, require all passengers to apply for a travel permit from Travel.Gov.Sl . To receive permission to travel in or out of the country, each passenger must provide the following: A negative COVID-19 PCR lab test result issued no longer than 72hours before departure, proof of payment for a COVID-19 PCR test in Sierra Leone, and a completed public health locator form. Children ages two years old and younger are exempt from testing. Travel.Gov.Sl is the one-stop-shop that will process all requirements and issue travel authorizations.

Travel.Gov.Sl is available 24/7. Passengers can register and pay for their tests online and through mobile money. They can order a regular or premium test, with the latter offering appointment flexibility.

Since the COVID-19 outbreak in Sierra Leone the Directorate of Science, Technology, and Innovation as the lead of the ICT Pillar of the National Covid-19 Emergency Response has worked with various Ministries, Departments, and Agencies, Local ICT experts and development partners to deploy digital tools to improve the fight against the coronavirus. Fix Solutions , a technology company has played a leading role in the design and deployment of the travel web application.

From drones for surveillance during lockdowns to an e-pass solution to ease travel restrictions , and a COVID-19 Self-Check SMS and USSD Mobile Application ; DSTI continues to champion Sierra Leone’s commitment to national innovation.

#TECHAGAINSTCOVID19 COVID-19 COVID-19 E-PASS FOR ESSENTIAL TRAVEL DSTI SIERRA LEONE

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Recent Posts

- Forging Future Frontiers: UNICEF Sierra Leone Country Rep, Rudolf Schwenk Visits DSTI Sierra Leone

- General Procurement Notice: Digital Connectivity in Schools

- Bridging Digital Divides: ISDB, Unicefsl and Sierra Leone’s Bold Stride To Connect 11,000 Schools to The Internet

- Sierra Leone Joins Global Digital Public Infrastructure Ecosystem For The Launch Of The 50in5 Campaign

- Sierra Leone Joins Global Dpi Ecosystem For The Launch Of The 50in5 Campaign

Recent Comments

We’re sorry, this site is currently experiencing technical difficulties. Please try again in a few moments. Exception: request blocked

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 13 March 2024

Last-mile delivery increases vaccine uptake in Sierra Leone

- Niccolò F. Meriggi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6757-1284 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Maarten Voors ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5907-3253 2 ,

- Madison Levine 4 ,

- Vasudha Ramakrishna 5 ,

- Desmond Maada Kangbai 6 ,

- Michael Rozelle 2 ,

- Ella Tyler 2 ,

- Sellu Kallon 2 , 7 ,

- Junisa Nabieu 2 ,

- Sarah Cundy 8 &

- Ahmed Mushfiq Mobarak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1916-3438 9

Nature volume 627 , pages 612–619 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

4739 Accesses

2 Citations

159 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Developing world

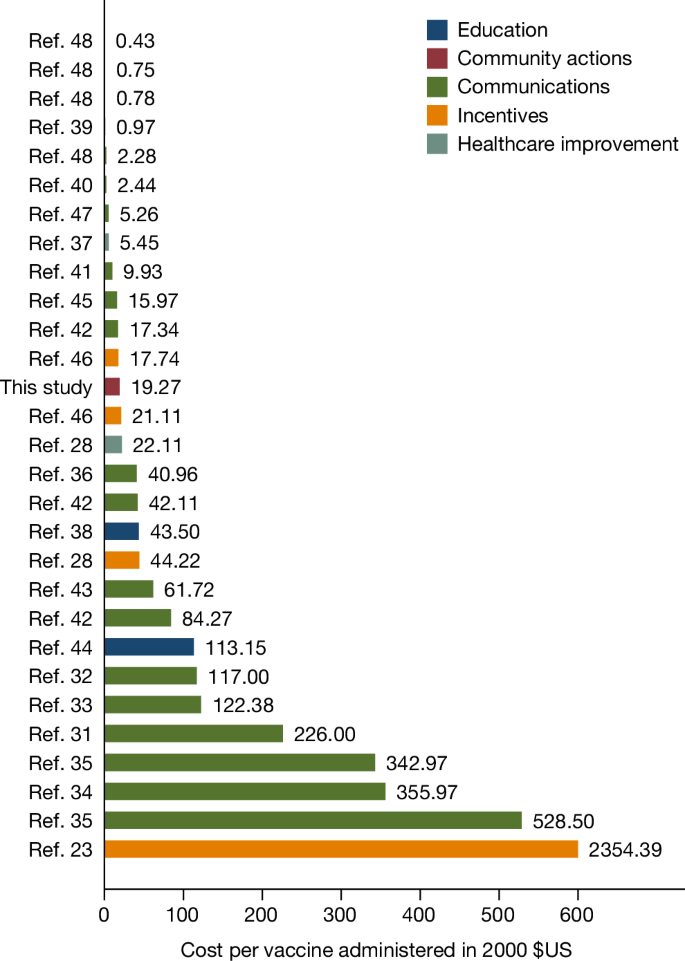

Less than 30% of people in Africa received a dose of the COVID-19 vaccine even 18 months after vaccine development 1 . Here, motivated by the observation that residents of remote, rural areas of Sierra Leone faced severe access difficulties 2 , we conducted an intervention with last-mile delivery of doses and health professionals to the most inaccessible areas, along with community mobilization. A cluster randomized controlled trial in 150 communities showed that this intervention with mobile vaccination teams increased the immunization rate by about 26 percentage points within 48–72 h. Moreover, auxiliary populations visited our community vaccination points, which more than doubled the number of inoculations administered. The additional people vaccinated per intervention site translated to an implementation cost of US $33 per person vaccinated. Transportation to reach remote villages accounted for a large share of total intervention costs. Therefore, bundling multiple maternal and child health interventions in the same visit would further reduce costs per person treated. Current research on vaccine delivery maintains a large focus on individual behavioural issues such as hesitancy. Our study demonstrates that prioritizing mobile services to overcome access difficulties faced by remote populations in developing countries can generate increased returns in terms of uptake of health services 3 .

Similar content being viewed by others

Safety outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination and infection in 5.1 million children in England

A meta-analysis on global change drivers and the risk of infectious disease

Post-COVID conditions following COVID-19 vaccination: a retrospective matched cohort study of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection

By 10 March 2022, more than a year after COVID-19 vaccines arrived on the market, 80% of the populations living in high-income countries had received at least one dose compared with only 15% of the people in low-income countries. As of 20 November 2023, only 33% of the population in Africa had received at least the first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine 1 . Low rates of vaccination keep many countries in Africa vulnerable to the threat of disease recurrence and a renewed possibility of costly lockdowns capable of undermining employment, income generation and food security 4 . Low vaccination coverage also raises the hazard of new subvariants emerging that puts the entire world at risk 5 .

To understand why vaccination rates remain low, we assembled data on vaccination beliefs, hesitancy and access from several countries in late 2021 (ref. 6 ). Nationally representative data from Sierra Leone revealed that obtaining access to a COVID-19 vaccine required the average person in Sierra Leone to travel three and a half hours each way to the nearest vaccination centre at a cost that exceeds 1 week of wages 2 . This finding motivated the design of an intervention we implemented in March–April 2022 in partnership with the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MoHS) and the international non-governmental organization (NGO) Concern Worldwide. The primary aim of this intervention was to take vaccine doses and nurses to administer vaccines to remote, rural communities, preceded by seeking permission and community mobilization. A cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) across 150 communities showed that the vaccination rate in treatment villages increased by about 26 percentage points in response to this intervention. In addition, large numbers of people from neighbouring communities showed up to receive vaccines at our temporary clinics. In villages that received the intervention, the average number of people vaccinated increased from about 9 people pre-intervention to 55 people within the intervention period of about 2–3 days, at a cost of $33 per person vaccinated.

These results suggest that low vaccination rates are related to deficiencies in access and that a cost-effective intervention is capable of overcoming that deficiency. The Sierra Leone MoHS operates a network of peripheral health units (PHUs), but a significant proportion of people in Sierra Leone—particularly those in inaccessible rural areas—live outside the 5-km catchment area of any PHU. As such, interventions such as the one we conducted in communities outside PHU catchment areas are necessary to ease the burden of access.

This result carries broader implications for global public health. The child mortality rate in Sierra Leone was 10.5% in 2021 (ref. 7 ), as many children die from preventable diseases that immunizations and other simple interventions could address. The situation is almost as acute in neighbouring Guinea and Liberia. By contrast, efforts at community engagement in Bangladesh, including simple acts of taking maternal and child health interventions to rural populations, contributed to increasing the infant vaccination rate from 1% in the early 1980s to more than 70% within 10 years 8 . Populations in remote areas of West Africa have proven more challenging to reach, but our intervention with COVID-19 vaccination serves as a proof of concept that it may be similarly possible to tackle the high rates of child mortality in West Africa by cost-effectively delivering simple health interventions to rural populations. In fact, bundling multiple health interventions together would further reduce the cost of delivery per person treated given the high fixed transportation costs of reaching each remote community.

These results are relevant for donors and international pharmaceutical companies who have cited cases of unused vaccines in Africa reaching expiration dates 9 to explain why low-income countries did not receive adequate supplies of vaccine doses early in the pandemic 10 , 11 . Our implementation efforts taught us that the Sierra Leone MoHS needed to engage in ‘learning by doing’ to develop new distribution systems to reach remote populations with those doses. But it is a catch-22 situation: the required experimentation is only possible once a steady and dependable supply of vaccine doses is made available.

To benchmark our results against other vaccination strategies, we conducted a comprehensive literature review that identified 235 distinct interventions in 144 RCT studies that used information, nudges, community engagement, social signalling and non-financial and financial incentives to increase vaccination rates across many settings around the world. More than one third of these interventions produced null effects. Here our access intervention produced a larger percentage point effect size than 223 (95%) of the treatments reviewed. This result is not surprising because vaccinating the first 50% of the population in remote parts of low-income countries requires solving the fundamental problem of access, which we address. Once access issues are addressed, misinformation and hesitancy may loom large in the effort to vaccinate the last 20% of the population of high-income countries who stubbornly hold out, and this is the target of the bulk of the literature. Even in high-income settings, access constraints were relevant in the earliest phase of COVID-19 vaccine delivery 12 .

This finding implies that we may need to further emphasize access interventions if we are to increase the global vaccination rate and improve vaccine equity. Guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and the World Health Organization (WHO) highlight the importance of ‘bringing services closer to the people’, and our RCT is a proof of concept that such approaches can increase vaccination rates rapidly and cost-effectively, even under difficult circumstances in the most remote communities. The mobile delivery concept has produced large effects in HIV testing 13 . Rigorously demonstrating effectiveness in vaccine delivery is crucial given the persistent low rates of vaccination in low-income countries. Our literature review revealed thousands of studies on vaccine hesitancy and misinformation, but only a handful on vaccine supply and access, with a clear bias in favour of high-income contexts. This imbalance is emblematic of a wider debate on the relative importance of individual-specific behavioural factors versus systemic deficiencies in limiting the diffusion of welfare-improving technologies among low-income populations 14 . Prominent behavioural scientists have recently acknowledged our excessive focus on individual behavioural peculiarities (‘i-frame’) at the expense of systemic solutions (‘s-frame’) 15 .

Context and research design

We conducted a pre-registered cluster RCT in 150 rural villages in Sierra Leone. We first mapped all PHUs where the MoHS was offering COVID-19 vaccines together with the catchment areas of a PHU, which is defined by the MoHS as the 5-mile (about 8-km) radius around each PHU. We then compiled a list of all communities situated outside these catchment areas and randomly selected 150 communities from this list. Overall, 100 communities were randomly assigned to receive the intervention and the other 50 were assigned to the control group. During March and April 2022, a research team first visited all communities to conduct a village population listing and a baseline survey. Immediately afterwards, mobile vaccination teams coordinated by the MoHS visited the 100 villages assigned to the intervention for 2–3 days per village (Supplementary Fig. 1 ).

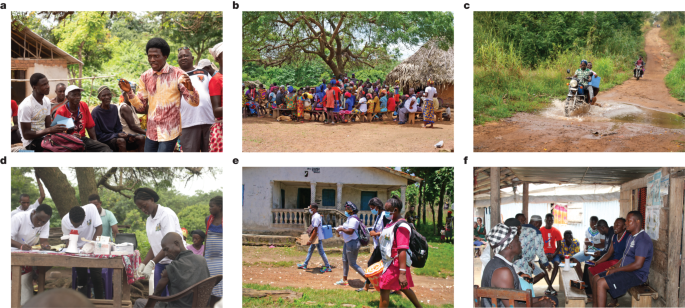

On the first day of the intervention, a social mobilization team—trained and supervised by the MoHS—organized a conversation with all village leaders, including the town chief, mammy queen, town elders, the youth leaders and religious leaders, and any other important stakeholders including the paramount and section chiefs if they were available (step 1; Fig. 1a ). Members of the social mobilization team we employed were previously vetted and trained by ministry staff and commonly engaged for short-term projects such as vaccination campaigns. This cadre is referred to as MoHS volunteers because they are paid per-diem against project work and not a regular salary per a civil servant. The mobilization team explained the purpose of the visit, answered questions about the available vaccines and asked leaders for their cooperation in encouraging eligible community members to take the COVID-19 vaccine.

a – f , Representative photographs of the steps taken by the vaccination teams in each village for the mobile vaccination clinic. a , Step 1. A social mobilization team from the MoHS organizes a meeting with village leaders. b , Step 2. Social mobilizers convene a community meeting to talk directly with all village residents about vaccine efficacy and safety, the importance of getting vaccinated, address villagers’ questions and concerns, and the location and timing of the mobile vaccination site. c , Step 3. MoHS staff bring vaccine doses and staff to the village. d , Step 4. MoHS staff set up a 48–72 h mobile vaccine clinic in a central location in the village. e , Step 5a. Social mobilizers provide vaccine information to community members in private during door-to-door visits. f , Step 5b. Social mobilizers target social groups at fixed spots in and around the villages. Photographs in a – f reproduced with permission from Concern Worldwide.

Social mobilizers then asked leaders to convene a community meeting that same evening (when people return home from farms) to allow mobilizers to talk directly with all village residents about vaccine efficacy and safety, the importance of getting vaccinated, and to address villagers’ questions and concerns. This process (step 2; Fig. 1b ) ended with social mobilizers explaining the location and timing of the mobile vaccination site that they were about to set up.

Vaccine doses, nurses to administer vaccines and MoHS staff who could register the vaccinated were brought into the community either the same evening or early the next morning (step 3; Fig. 1c ). The vaccine doses and staff often travelled on motorbikes or on boats given the difficult terrain they had to traverse to reach these remote communities. Once the team was in place, the temporary vaccination site started operating in a central location in the village (step 4; Fig. 1d ). Villages in our sample were small, with houses closely clustered; therefore, walking distances to the vaccination site were short. The vaccination site remained operational from sunrise to sunset over the next 2–3 days, which enabled people to visit when convenient. Nurses and registration staff remained stationed at the temporary clinic while the mobilizers continued to provide vaccine information to various community members (step 5).

We randomized the exact nature of these additional step-5 mobilization activities. Half the treatment villages were randomized into an individualized door-to-door campaign (step 5a; Fig. 1e ), whereby social mobilizers went to 20 randomly selected structures to privately discuss any concerns about that vaccine that the household residents had and to encourage them to visit the vaccination site. The other 50 treatment communities were randomized into small-group outreach (step 5b; Fig. 1f ), whereby mobilizers targeted social groups who gathered at fixed spots in and around the villages (for example, groups of farmers in fields, mosque attendees or women collecting water). Social mobilizers engaged the group to have joint conversations about the vaccines. There was equipoise about whether individualized or small-group outreach would be more successful in persuading people to get vaccinated, so we tested both strategies.

Effects on COVID-19 vaccination rate

Our primary outcome was verified adult vaccine uptake, which was measured using a respondent-level question on whether the person took a COVID-19 vaccine of any type, checked against their vaccination card (if consented). This measure provided us with a site-level count of vaccine doses administered.

To calculate a village-level vaccination rate, we first enumerated the population in all 150 treatment and control villages. Such community census lists typically do not exist in Sierra Leone. Our research team therefore walked to all structures in every village to tally the number of households (39 on average, s.d. = 23), and the number of individuals living in those households (29,588 individuals across the 150 villages, or about 197 people per village).

The population of these villages was on average 22.3 years old, 26.5% of households were headed by women and 64.5% of people lived in a household of 6 or fewer people. Only 20.1% lived in a household where the household head had any form of formal schooling, and about 86.1% lived in a household where the head was primarily engaged in farming. Respondent characteristics were well balanced across the treatment groups (Extended Data Table 2 ) except for the following: the baseline vaccination rate; the proportion of households employed in agriculture; the proportion of households that own a radio; the proportion of women breastfeeding; and the proportion that owns land. Although an overall F -test did not reject the equality of means across the full set of outcomes, we added these covariates in part of our analysis below.

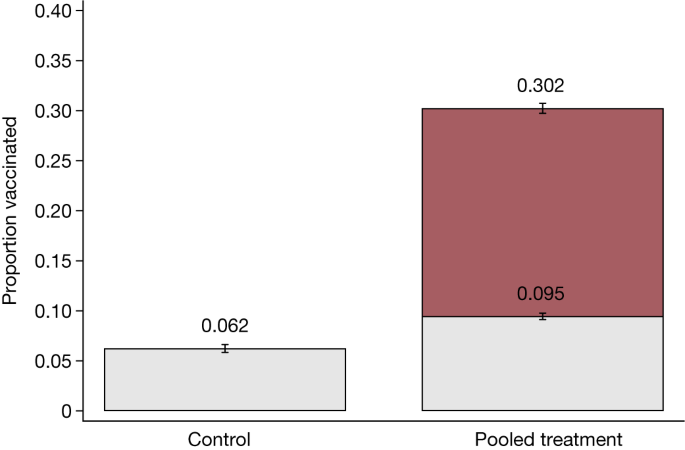

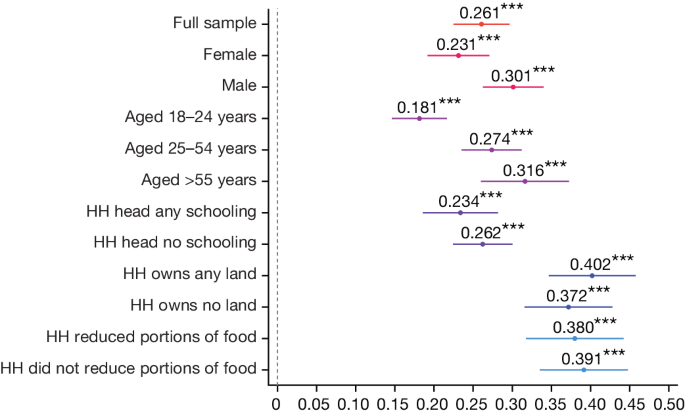

Figure 2 shows that at baseline, the average vaccination rate in villages assigned to the control group (control villages) was 6.2% compared with 9.5% in villages that received treatment (treatment villages) (ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, difference = 0.035, s.e. = 0.014, P = 0.015, n = 12,096). After intervention, the vaccination rate increased to 30.2% in treatment villages. We report effects from linear regression specifications of the intent-to-treat effect with randomization fixed effects and heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors clustered at the village level in Extended Data Table 3 (see the section ‘Statistical analysis’ in the Methods ). The intent-to-treat effect was 26 percentage points (OLS regression, s.e. = 0.018, P < 0.001, n = 12,096). The results remained qualitatively similar (OLS regression, 25 percentage points, s.e. = 0.019, P < 0.001, n = 12,096) when covariates for respondent characteristics were added that were imbalanced at baseline (such as vaccination status) or when we aggregated the data up to the village level (OLS regression, 28 percentage points, s.e. = 0.025, P < 0.001, n = 150).

The proportion of vaccinated adults that were enumerated during the census before and at the end of the study in control villages and pooled treatment villages. The analysis includes the 12,096 people (aged >18 years) in 150 villages. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. In the control group, 6% were vaccinated at baseline, whereas 9.5% were vaccinated in treatment groups. At endline, 30% were vaccinated. The intent-to-treat treatment effects estimated using OLS and including randomization block fixed effects and heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors clustered at the village level are provided in Extended Data Table 3 .

This increase in the vaccination rate is an underestimate of the total number of vaccines administered over those 2–3 days, as it does not include vaccines given to migrant returnees and others from nearby villages. The average uptake also masks considerable heterogeneity among villages. In 2 out of the 100 treatment villages, there was no increase in vaccination rate because the village authorities either dissuaded villagers from getting vaccinated or refused permission for the intervention to take place, which causing the intervention to essentially fail at step 1 (Fig. 1a ). By contrast, the full distribution of vaccination rates displayed in Supplementary Fig. 2 shows that in 5 villages, more than 50% of adults enumerated in the community census were vaccinated during the course of our intervention. A similar large degree of variation was evident from the total count of immunizations set per village (Supplementary Fig. 3 ).

Effects on total vaccination count

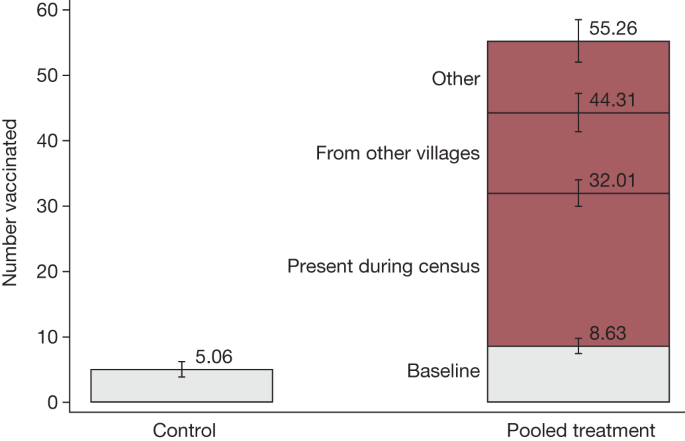

Many of the people who attended our temporary clinics to receive a vaccine were not enumerated during the community census. These additional people fell into one of three categories: residents of other nearby villages (who heard about the clinic and were interested in taking advantage of the easy access to a vaccine); recent migrant returnees who were not present during the village listing; and others—such as high-frequency commuters—not captured in the census. For these auxiliary populations, we do not have a denominator and can therefore not estimate a vaccination rate. We can, however, provide results on vaccination counts.

At baseline, there were on average about 5 people vaccinated in control villages and about 9 people in treatment villages (OLS regression, difference = 3.57, s.e. = 1.51, P < 0.021, n = 150). Figure 3 shows that after the intervention was implemented over the subsequent 2–3 days, the number of vaccinated individuals increased to about 55 people on average per treatment site, which is a 6-fold increase. This is the full effect of our mobile vaccination drive. Among individuals vaccinated who were not enumerated in the census, 53% (12–13 people per treatment community) were visitors who came from nearby villages to get vaccinated, whereas the remaining 47% (11–12 people) included short-term, circular commuters or migrant returnees who were not present on the day of the census and could not be matched to our listing records, as well as individuals whose ‘community of origin’ was unknown. The intent-to-treat regression estimates with heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors and additional covariates are included in Extended Data Table 4 . In total, the teams vaccinated 4,771 people aged 12 years or above. Of these, 39% received a Johnson & Johnson vaccine, 29% Pfizer, 17% Sinopharm and 16% received AstraZeneca. A variety of vaccine types was administered because there was no steady supply of any specific type of vaccine dose in Sierra Leone when this intervention was conducted. Therefore, we had to make use of the vaccines available in the Ministry of Health stocks in any given week.

The number of the people vaccinated before and by the end of the study. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. The analysis includes 150 villages. In the control group, on average five people were vaccinated, whereas in treatment villages, this was nine people. Treatment increased the count to 55 people, including 22–23 individuals who were enumerated during the census group, 12–13 people from nearby villages and 11–12 short-term, circular commuters or migrant returnees who were not present on the day of the census and could not be matched to our listing records, as well as individuals whose community of origin was unknown. The intent-to-treat treatment effects estimated using OLS and including randomization block fixed effects and heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors are provided in Extended Data Table 4 .

Effects of home visits

Both types of mobilization activities implemented in step 5 had similar effects on the vaccination rate. The evidence on whether the door-to-door or small-group activities were more effective was mixed. When we compared across communities, the door-to-door programme increased the adult vaccination rate by about 29 percentage points compared with 23 percentage points in villages assigned to the small-group mobilization activities ( t -test, difference = 6 percentage points, P = 0.014, n = 12,096; see column 1 in Extended Data Table 1 ). However, when we studied individual households randomly assigned to a visit against those who are not within door-to-door villages, we did not detect any differential uptake. In these 50 villages, up to 20 randomly selected structures were visited for a private or semi-private conversation with residents about the vaccine and to encourage them to visit the temporary clinic. The random selection of structures enabled us to report experimental results on the effects of receiving this extra nudge on the propensity to receive a vaccine. We interpret this activity as a ‘demand-side treatment’, in that the visit and conversation provides that resident an opportunity to discuss their concerns or questions about vaccines in private, which could be useful to overcome potential hesitancy. Column 3 in Extended Data Table 1 shows that this extra effort did not generate additional demand beyond the effect of our ‘supply side’ activities to enhance vaccine access. The adult vaccination rate at the end of the vaccination programme among those who received the home visit by mobilizers was not different from those who did not receive the extra nudge points (OLS regression, difference = –0.01, s.e. = 0.019, P = 0.543, n = 3,760). Social mobilizers received extensive training and close supervision, but the lack of impact from this additional demand-generating activity on vaccine uptake may reflect low effort by social mobilizers. Within-village spillovers may also dampen these individual treatment effects. Unfortunately, we lack data on distances and other channels of interactions among households to formally test this measure. However, this type of spillover may be small owing to the relatively short time interval between the home visits and the vaccine drive.

We do not have an equivalent analysis of the individual effect of the small-group treatment because that was not randomized within villages. Moreover, the enumerators were not able to exactly track which households participated in the small-group sessions.

Although our vaccine access intervention significantly raised the vaccination rate, it was also clear that we remained far short of reaching the WHO goal of near-universal uptake. We collected individual-level data in all treatment villages after the intervention from both vaccine takers and non-takers. These data can shed some light on why and how our access intervention was more or less successful for certain types of people.

Meeting attendance

Step 2 of our intervention (Fig. 1b ) was to organize a community-wide meeting to inform all village residents about the vaccine clinic. The field team registered which community members attended that meeting, and 41% of households participated in these meetings. Overall, 44% of those who chose to attend the meeting subsequently chose to get vaccinated. One cannot impose any causal interpretation to this correlation because people who were already interested in getting vaccinated may have been the ones who chose to attend the meeting.

We can make a slightly stronger inference by examining the subset of people who stated in our baseline survey that they were unwilling to receive a vaccine (Extended Data Table 5 ). Within this subgroup, 53.8% of those who attended meetings ultimately took the vaccine, whereas the vaccination rate was only 14.4% among those who did not attend. Even within the converse subgroup (those who stated at baseline that they were willing to take the vaccine), meeting attendance was strongly predictive of subsequent vaccine uptake: 64.6% vaccination rate among attendees and 39.4% among non-attendees.

These are not causal estimates, but the size and direction of these correlations suggest that the information shared in the meeting, and the answers that were provided to the community’s questions, are unlikely to have dissuaded people from getting vaccinated. These correlations—combined with our team’s on-field experience—suggest that holding these meetings was helpful and form a necessary part of any access intervention. Encouraging greater attendance in meetings in any future replications would probably be a good idea.

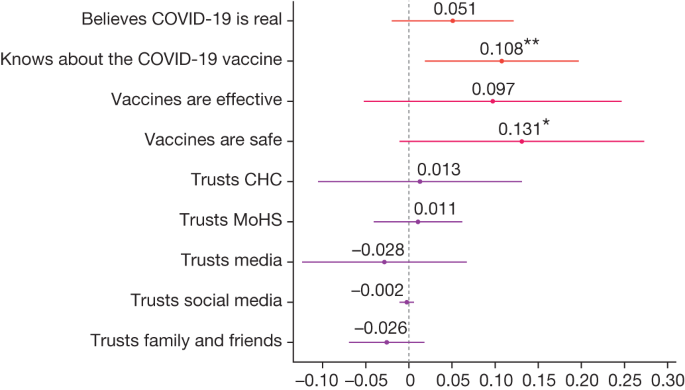

Vaccination knowledge and trust

We also collected data on another intermediate outcome in a subset of villages: people’s knowledge and attitudes regarding the COVID-19 vaccine. Figure 4 shows that the treatment improved people’s knowledge about vaccines (OLS regression, difference = 0.11 points, s.e. = 0.044, P = 0.019, n = 817). The change in knowledge implies that our intervention was not solely about improving access. That is, the community interactions and the information we shared were also relevant parts of the intervention package. However, there was no significant change in people’s beliefs about vaccine efficacy (OLS regression, difference = 0.097, s.e. = 0.074, P = 0.197, n = 686). Using a 95% confidence interval (CI), we can reject that our treatment increased beliefs about vaccine efficacy by more than 12 percentage points. The effect on beliefs about the safety of vaccines is not statistically precise (OLS regression, difference = 0.131 points, s.e. = 0.070, P = 0.069, n = 686)—we can neither rule out a null effect nor a 27 percentage point effect. The null effects in OLS regressions on the sources that people trust the most for receiving health information were more precisely estimated: community health clinics (OLS regression, difference = 0.013, s.e. = 0.059, P = 0.828, n = 817, 95% CI upper bound = 0.13); the MoHS (difference = 0.011, s.e. = 0.025, P = 0.682, n = 817, 95% CI upper bound = 0.06); media (OLS regression, difference = –0.028, s.e. = 0.047, P = 0.553, n = 817, 95% CI upper bound = 0.07); social media (OLS regression, difference = –0.002, s.e. = 0.004, P = 0.555, n = 817, 95% CI upper bound = 0.006); or family and friends (OLS regression, difference = –0.026, s.e. = 0.022, P = 0.242, n = 817, 95% CI upper bound = 0.018). Extended Data Tables 6 and 7 provide the associated regression estimates. Note that because this is an exploratory exercise in which we test treatment effects across several outcomes, the tables report the false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted q values to adjust for multiple hypothesis testing.