Is time travel even possible? An astrophysicist explains the science behind the science fiction

Assistant Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Disclosure statement

Adi Foord does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Maryland, Baltimore County provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to [email protected] .

Will it ever be possible for time travel to occur? – Alana C., age 12, Queens, New York

Have you ever dreamed of traveling through time, like characters do in science fiction movies? For centuries, the concept of time travel has captivated people’s imaginations. Time travel is the concept of moving between different points in time, just like you move between different places. In movies, you might have seen characters using special machines, magical devices or even hopping into a futuristic car to travel backward or forward in time.

But is this just a fun idea for movies, or could it really happen?

The question of whether time is reversible remains one of the biggest unresolved questions in science. If the universe follows the laws of thermodynamics , it may not be possible. The second law of thermodynamics states that things in the universe can either remain the same or become more disordered over time.

It’s a bit like saying you can’t unscramble eggs once they’ve been cooked. According to this law, the universe can never go back exactly to how it was before. Time can only go forward, like a one-way street.

Time is relative

However, physicist Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity suggests that time passes at different rates for different people. Someone speeding along on a spaceship moving close to the speed of light – 671 million miles per hour! – will experience time slower than a person on Earth.

People have yet to build spaceships that can move at speeds anywhere near as fast as light, but astronauts who visit the International Space Station orbit around the Earth at speeds close to 17,500 mph. Astronaut Scott Kelly has spent 520 days at the International Space Station, and as a result has aged a little more slowly than his twin brother – and fellow astronaut – Mark Kelly. Scott used to be 6 minutes younger than his twin brother. Now, because Scott was traveling so much faster than Mark and for so many days, he is 6 minutes and 5 milliseconds younger .

Some scientists are exploring other ideas that could theoretically allow time travel. One concept involves wormholes , or hypothetical tunnels in space that could create shortcuts for journeys across the universe. If someone could build a wormhole and then figure out a way to move one end at close to the speed of light – like the hypothetical spaceship mentioned above – the moving end would age more slowly than the stationary end. Someone who entered the moving end and exited the wormhole through the stationary end would come out in their past.

However, wormholes remain theoretical: Scientists have yet to spot one. It also looks like it would be incredibly challenging to send humans through a wormhole space tunnel.

Paradoxes and failed dinner parties

There are also paradoxes associated with time travel. The famous “ grandfather paradox ” is a hypothetical problem that could arise if someone traveled back in time and accidentally prevented their grandparents from meeting. This would create a paradox where you were never born, which raises the question: How could you have traveled back in time in the first place? It’s a mind-boggling puzzle that adds to the mystery of time travel.

Famously, physicist Stephen Hawking tested the possibility of time travel by throwing a dinner party where invitations noting the date, time and coordinates were not sent out until after it had happened. His hope was that his invitation would be read by someone living in the future, who had capabilities to travel back in time. But no one showed up.

As he pointed out : “The best evidence we have that time travel is not possible, and never will be, is that we have not been invaded by hordes of tourists from the future.”

Telescopes are time machines

Interestingly, astrophysicists armed with powerful telescopes possess a unique form of time travel. As they peer into the vast expanse of the cosmos, they gaze into the past universe. Light from all galaxies and stars takes time to travel, and these beams of light carry information from the distant past. When astrophysicists observe a star or a galaxy through a telescope, they are not seeing it as it is in the present, but as it existed when the light began its journey to Earth millions to billions of years ago.

NASA’s newest space telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope , is peering at galaxies that were formed at the very beginning of the Big Bang, about 13.7 billion years ago.

While we aren’t likely to have time machines like the ones in movies anytime soon, scientists are actively researching and exploring new ideas. But for now, we’ll have to enjoy the idea of time travel in our favorite books, movies and dreams.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to [email protected] . Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

- Time travel

- Special Relativity

- Thermodynamics

- Stephen Hawking

- Curious Kids

- Curious Kids US

- Time travel paradox

Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

- The Magazine

- Stay Curious

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Planet Earth

Is Time Travel Even Possible? An Astrophysicist Explains The Science Behind The Science Fiction

If traveling into the past is possible, one way to do it might be sending people through tunnels in space..

Have you ever dreamed of traveling through time, like characters do in science fiction movies? For centuries, the concept of time travel has captivated people’s imaginations. Time travel is the concept of moving between different points in time, just like you move between different places. In movies, you might have seen characters using special machines, magical devices or even hopping into a futuristic car to travel backward or forward in time.

But is this just a fun idea for movies, or could it really happen?

The question of whether time is reversible remains one of the biggest unresolved questions in science. If the universe follows the laws of thermodynamics , it may not be possible. The second law of thermodynamics states that things in the universe can either remain the same or become more disordered over time.

It’s a bit like saying you can’t unscramble eggs once they’ve been cooked. According to this law, the universe can never go back exactly to how it was before. Time can only go forward, like a one-way street.

Time is relative

However, physicist Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity suggests that time passes at different rates for different people. Someone speeding along on a spaceship moving close to the speed of light – 671 million miles per hour! – will experience time slower than a person on Earth.

People have yet to build spaceships that can move at speeds anywhere near as fast as light, but astronauts who visit the International Space Station orbit around the Earth at speeds close to 17,500 mph. Astronaut Scott Kelly has spent 520 days at the International Space Station, and as a result has aged a little more slowly than his twin brother – and fellow astronaut – Mark Kelly. Scott used to be 6 minutes younger than his twin brother. Now, because Scott was traveling so much faster than Mark and for so many days, he is 6 minutes and 5 milliseconds younger .

Time isn’t the same everywhere.

Some scientists are exploring other ideas that could theoretically allow time travel. One concept involves wormholes , or hypothetical tunnels in space that could create shortcuts for journeys across the universe. If someone could build a wormhole and then figure out a way to move one end at close to the speed of light – like the hypothetical spaceship mentioned above – the moving end would age more slowly than the stationary end. Someone who entered the moving end and exited the wormhole through the stationary end would come out in their past.

However, wormholes remain theoretical: Scientists have yet to spot one. It also looks like it would be incredibly challenging to send humans through a wormhole space tunnel.

Paradoxes and failed dinner parties

There are also paradoxes associated with time travel. The famous “ grandfather paradox ” is a hypothetical problem that could arise if someone traveled back in time and accidentally prevented their grandparents from meeting. This would create a paradox where you were never born, which raises the question: How could you have traveled back in time in the first place? It’s a mind-boggling puzzle that adds to the mystery of time travel.

Famously, physicist Stephen Hawking tested the possibility of time travel by throwing a dinner party where invitations noting the date, time and coordinates were not sent out until after it had happened. His hope was that his invitation would be read by someone living in the future, who had capabilities to travel back in time. But no one showed up.

As he pointed out : “The best evidence we have that time travel is not possible, and never will be, is that we have not been invaded by hordes of tourists from the future.”

Telescopes are time machines

Interestingly, astrophysicists armed with powerful telescopes possess a unique form of time travel. As they peer into the vast expanse of the cosmos, they gaze into the past universe. Light from all galaxies and stars takes time to travel, and these beams of light carry information from the distant past. When astrophysicists observe a star or a galaxy through a telescope, they are not seeing it as it is in the present, but as it existed when the light began its journey to Earth millions to billions of years ago.

NASA’s newest space telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope , is peering at galaxies that were formed at the very beginning of the Big Bang, about 13.7 billion years ago.

While we aren’t likely to have time machines like the ones in movies anytime soon, scientists are actively researching and exploring new ideas. But for now, we’ll have to enjoy the idea of time travel in our favorite books, movies and dreams.

Adi Foord is an Assistant Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license . Read the original article .

- engineering

- human spaceflight

Already a subscriber?

Register or Log In

Keep reading for as low as $1.99!

Sign up for our weekly science updates.

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Is time travel possible? Why one scientist says we 'cannot ignore the possibility.'

A common theme in science-fiction media , time travel is captivating. It’s defined by the late philosopher David Lewis in his essay “The Paradoxes of Time Travel” as “[involving] a discrepancy between time and space time. Any traveler departs and then arrives at his destination; the time elapsed from departure to arrival … is the duration of the journey.”

Time travel is usually understood by most as going back to a bygone era or jumping forward to a point far in the future . But how much of the idea is based in reality? Is it possible to travel through time?

Is time travel possible?

According to NASA, time travel is possible , just not in the way you might expect. Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity says time and motion are relative to each other, and nothing can go faster than the speed of light , which is 186,000 miles per second. Time travel happens through what’s called “time dilation.”

Time dilation , according to Live Science, is how one’s perception of time is different to another's, depending on their motion or where they are. Hence, time being relative.

Learn more: Best travel insurance

Dr. Ana Alonso-Serrano, a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Germany, explained the possibility of time travel and how researchers test theories.

Space and time are not absolute values, Alonso-Serrano said. And what makes this all more complex is that you are able to carve space-time .

“In the moment that you carve the space-time, you can play with that curvature to make the time come in a circle and make a time machine,” Alonso-Serrano told USA TODAY.

She explained how, theoretically, time travel is possible. The mathematics behind creating curvature of space-time are solid, but trying to re-create the strict physical conditions needed to prove these theories can be challenging.

“The tricky point of that is if you can find a physical, realistic, way to do it,” she said.

Alonso-Serrano said wormholes and warp drives are tools that are used to create this curvature. The matter needed to achieve curving space-time via a wormhole is exotic matter , which hasn’t been done successfully. Researchers don’t even know if this type of matter exists, she said.

“It's something that we work on because it's theoretically possible, and because it's a very nice way to test our theory, to look for possible paradoxes,” Alonso-Serrano added.

“I could not say that nothing is possible, but I cannot ignore the possibility,” she said.

She also mentioned the anecdote of Stephen Hawking’s Champagne party for time travelers . Hawking had a GPS-specific location for the party. He didn’t send out invites until the party had already happened, so only people who could travel to the past would be able to attend. No one showed up, and Hawking referred to this event as "experimental evidence" that time travel wasn't possible.

What did Albert Einstein invent?: Discoveries that changed the world

Just Curious for more? We've got you covered

USA TODAY is exploring the questions you and others ask every day. From "How to watch the Marvel movies in order" to "Why is Pluto not a planet?" to "What to do if your dog eats weed?" – we're striving to find answers to the most common questions you ask every day. Head to our Just Curious section to see what else we can answer for you.

Is Time Travel Possible?

We all travel in time! We travel one year in time between birthdays, for example. And we are all traveling in time at approximately the same speed: 1 second per second.

We typically experience time at one second per second. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA's space telescopes also give us a way to look back in time. Telescopes help us see stars and galaxies that are very far away . It takes a long time for the light from faraway galaxies to reach us. So, when we look into the sky with a telescope, we are seeing what those stars and galaxies looked like a very long time ago.

However, when we think of the phrase "time travel," we are usually thinking of traveling faster than 1 second per second. That kind of time travel sounds like something you'd only see in movies or science fiction books. Could it be real? Science says yes!

This image from the Hubble Space Telescope shows galaxies that are very far away as they existed a very long time ago. Credit: NASA, ESA and R. Thompson (Univ. Arizona)

How do we know that time travel is possible?

More than 100 years ago, a famous scientist named Albert Einstein came up with an idea about how time works. He called it relativity. This theory says that time and space are linked together. Einstein also said our universe has a speed limit: nothing can travel faster than the speed of light (186,000 miles per second).

Einstein's theory of relativity says that space and time are linked together. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

What does this mean for time travel? Well, according to this theory, the faster you travel, the slower you experience time. Scientists have done some experiments to show that this is true.

For example, there was an experiment that used two clocks set to the exact same time. One clock stayed on Earth, while the other flew in an airplane (going in the same direction Earth rotates).

After the airplane flew around the world, scientists compared the two clocks. The clock on the fast-moving airplane was slightly behind the clock on the ground. So, the clock on the airplane was traveling slightly slower in time than 1 second per second.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Can we use time travel in everyday life?

We can't use a time machine to travel hundreds of years into the past or future. That kind of time travel only happens in books and movies. But the math of time travel does affect the things we use every day.

For example, we use GPS satellites to help us figure out how to get to new places. (Check out our video about how GPS satellites work .) NASA scientists also use a high-accuracy version of GPS to keep track of where satellites are in space. But did you know that GPS relies on time-travel calculations to help you get around town?

GPS satellites orbit around Earth very quickly at about 8,700 miles (14,000 kilometers) per hour. This slows down GPS satellite clocks by a small fraction of a second (similar to the airplane example above).

GPS satellites orbit around Earth at about 8,700 miles (14,000 kilometers) per hour. Credit: GPS.gov

However, the satellites are also orbiting Earth about 12,550 miles (20,200 km) above the surface. This actually speeds up GPS satellite clocks by a slighter larger fraction of a second.

Here's how: Einstein's theory also says that gravity curves space and time, causing the passage of time to slow down. High up where the satellites orbit, Earth's gravity is much weaker. This causes the clocks on GPS satellites to run faster than clocks on the ground.

The combined result is that the clocks on GPS satellites experience time at a rate slightly faster than 1 second per second. Luckily, scientists can use math to correct these differences in time.

If scientists didn't correct the GPS clocks, there would be big problems. GPS satellites wouldn't be able to correctly calculate their position or yours. The errors would add up to a few miles each day, which is a big deal. GPS maps might think your home is nowhere near where it actually is!

In Summary:

Yes, time travel is indeed a real thing. But it's not quite what you've probably seen in the movies. Under certain conditions, it is possible to experience time passing at a different rate than 1 second per second. And there are important reasons why we need to understand this real-world form of time travel.

If you liked this, you may like:

Do you believe in time travel? I’m a skeptic myself — but if these people’s stories about time travel are to be believed, then I am apparently wrong. Who knows? Maybe one day I’ll have to eat my words. In all honesty, that might not be so bad — because the tradeoff for being wrong in that case would be that time travel is real . That would be pretty rad if it were true.

Technically speaking time travel does exist right now — just not in the sci fi kind of way you’re probably thinking. According to a TED-Ed video by Colin Stuart, Russian cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev actually traveled 0.02 seconds into his own future due to time dilation during the time he spent on the International Space Station. For the curious, Krikalev has spent a total of 803 days, nine hours, and 39 minutes in space over the course of his career.

That said, though, many are convinced that time dilation isn’t the only kind of time travel that’s possible; some folks do also believe in time travel as depicted by everything from H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine to Back to the Future . It’s difficult to find stories online that are actual accounts from real people — many of them are either urban legends ( hi there, Philadelphia Experiment ) or stories that center around people that I’ve been unable to verify actually exist — but if you dig hard enough, sincere accounts can be found.

Are the stories true? Are they false? Are they examples of people who believe with all their heart that they’re true, even if they might not actually be? You be the judge. These seven tales are all excellent yarns, at any rate.

The Moberly–Jourdain Incident

In 1901, two Englishwomen, Anne Moberly and Eleanor Jourdain , took a vacation to France. While they were there, they visited the Palace of Versailles (because, y’know, that’s what one does when one visits France ). And while they were at Versailles, they visited what’s known as the Petit Trianon — a little chateau on the palace grounds that Louis XVI gave to Marie Antoinette as a private space for her to hang out and do whatever it was that a teenaged queen did when she was relaxing back then.

But while they were there, they claimed, they saw some… odd occurrences. They said they spotted people wearing anachronistic clothing, heard mysterious voices, and saw buildings and other structures that were no longer present — and, indeed, hadn’t existed since the late 1700s. Finally, they said, they caught sight of Marie Antoinette herself , drawing in a sketchbook.

They claimed to have fallen into a “time slip” and been briefly transported back more than 100 years before being jolted back to the present by a tour guide.

Did they really travel back in time? Probably not; various explanations include everything from a folie a deux (basically a joint delusion) to a simple misinterpretation of what they actually saw. But for what it’s worth, in 1911 — roughly 10 years after what they said they had experienced occurred — the two women published a book about the whole thing under the names Elizabeth Morison and Frances Lamont simply called An Adventure. These days, it’s available as The Ghosts of Trianon ; check it out, if you like.

The Mystery Of John Titor

John Titor is perhaps the most famous person who claims he’s time traveled; trouble is, no one has heard from him for almost 17 years. Also, he claimed he came from the future.

The story is long and involved, but the short version is this: In a thread begun in the fall of 2000 about time travel paradoxes on the online forum the Time Travel Institute — now known as Curious Cosmos — a user responded to a comment about how a time machine could theoretically be built with the following message:

“Wow! Paul is right on the money. I was just about to give up hope on anyone knowing who Tipler or Kerr was on this worldline.

“By the way, #2 is the correct answer and the basics for time travel start at CERN in about a year and end in 2034 with the first ‘time machine’ built by GE. Too bad we can’t post pictures or I’d show it to you.”

The implication, of course, was that the user, who was going by the name TimeTravel_0, came from a point in the future during which such a machine had already been invented.

Over the course of many messages spanning from that first thread all the way through the early spring of 2001, the user, who became known as John Titor, told his story. He said that he had been sent back to 1975 in order to bring an IBM 5100 computer to his own time; he was just stopping in 2000 for a brief rest on his way back home. The computer, he said, was needed to debug “various legacy computer programs in 2036” in order to combat a known problem similar to Y2K called the Year 2038 Problem . (John didn’t refer to it as such, but he said that UNIX was going to have an issue in 2038 — which is what we thought was going to happen back when the calendar ticked over from 1999 to 2000.)

Opinions are divided on whether John Titor was real ; some folks think he was the only real example of time travel we’ve ever seen, while others think it’s one of the most enduring hoaxes we’ve ever seen. I fall on the side of hoax, but that’s just me.

Project Pegasus And The Chrononauts

In 2011, Andrew D. Basiago and William Stillings stepped forward, claiming that they were former “chrononauts” who had worked with an alleged DARPA program called Project Pegasus. Project Pegasus, they said, had been developed in the 1970s; in 1980, they were taking a “Mars training class” at a community college in California (the college presumably functioning as a cover for the alleged program) when they were picked to go to Mars. The mode of transport? Teleportation.

It gets better, too. Basiago and Stillings also said that the then- 19-year-old Barack Obama , whom they claimed was going by the name “Barry Soetero” at the time, was also one of the students chosen to go to Mars. They said the teleportation occurred via something called a “jump room.”

The White House has denied that Obama has ever been to Mars . “Only if you count watching Marvin the Martian,” Tommy Vietor, then the spokesman for the National Security Council, told Wired’s Danger Room in 2012.

Victor Goddard’s Airfield Time Slip

Like Anne Moberly and Eleanor Jourdain, senior Royal Air Force commander Sir Robert Victor Goddard — widely known as Victor Goddard — claimed to have experienced a time slip.

In 1935, Goddard flew over what had been the RAF station Drem in Scotland on his way from Edinburgh to Andover, England. The Drem station was no longer in use; after demobilization efforts following WWI, it had mostly been left to its own devices. And, indeed, that’s what Goddard said he saw as he flew over it: A largely abandoned airfield.

On his return trip, though, things got… weird. He followed the same route he had on the way there, but during the flight, he got waylaid by a storm. As he struggled to regain control of his plane, however, he spotted the Drem airfield through a break in the clouds — and when he got closer to it, the bad weather suddenly dissipated. But the airfield… wasn’t abandoned this time. It was busy, with several planes on the runway and mechanics scurrying about.

Within seconds, though, the storm reappeared, and Goddard had to fight to keep his plane aloft again. He made it home just fine, and went on to live another 50 years — but the incident stuck with him; indeed, in 1975, he wrote a book called Flight Towards Reality which included discussion of the whole thing.

Here’s the really weird bit: In 1939, the Drem airfield was brought back to life. Did Goddard see a peek into the airfield's future via a time slip back in 1935? Who knows.

Space Barbie

I’ll be honest: I’m not totally sure what to do with thisone — but I’ll present it to you here, and then you can decide for yourself what you think about it. Here it is:

Valeria Lukyanova has made a name for herself as a “human Barbie doll” (who also has kind of scary opinions about some things ) — but a 2012 short documentary for Vice’s My Life Online series also posits that she believes she’s a time traveling space alien whose purpose on Earth is to aid us in moving “from the role of the ‘human consumer’ to the role of ‘human demi-god.’”

What I can’t quite figure out is whether this whole time traveling space alien thing is, like a piece of performance art created specifically for this Vice doc, or whether it’s what she actually thinks. I don’t believe she’s referenced it in many (or maybe even any) other interviews she’s given; the items I’ve found discussing Lukyanova and time travel specifically all point back to this video.

But, well… do with it all as you will. That’s the documentary up there; give it a watch and see what you think.

The Hipster Time Traveler

In the early 2010s, a photograph depicting the 1941 reopening of the South Fork Bridge in Gold Bridge, British Columbia in Canada went viral for seemingly depicting a man that looked… just a bit too modern to have been photographed in 1941. He looks, in fact, like a time traveling hipster : Graphic t-shirt, textured sweater, sunglasses, the works. The photo hadn’t been manipulated; the original can be seen here . So what the heck was going on?

Well, Snopes has plenty of reasonable explanations for the man’s appearance; each item he’s wearing, for example, could very easily have been acquired in 1941. Others have also backed up those facts. But the bottom line is that it’s never been definitively debunked, so the idea that this photograph could depict a man from our time who had traveled back to 1941 persists. What do you think?

Father Ernetti’s Chronovisor

According to two at least two books — Catholic priest Father Francois Brune’s 2002 book Le nouveau mystère du Vatican (in English, The Vatican’s New Mystery ) and Peter Krassa’s 2000 book Father Ernetti's Chronovisor : The Creation and Disappearance of the World's First Time Machine — Father Pellegrino Ernetti, who was a Catholic priest like Brune, invented a machine called a “chronovisor” that allowed him to view the past. Ernetti was real; however, the existence of the machine, or even whether he actually claimed to have invented it, has never been proven. Alas, he died in 1994, so we can’t ask him, either. I mean, if we were ever able to find his chronovisor, maybe we could… but at that point, wouldn’t we already have the information we need?

(I’m extremely skeptical of this story, by the way, but both Brune’s and Krassa’s books swear up, down, left, and right that it’s true, so…you be the judge.)

Although I'm fairly certain that these accounts and stories are either misinterpreted information or straight-up falsehoods, they're still entertaining to read about; after all, if you had access to a time machine, wouldn't you at least want to take it for a spin? Here's hoping that one day, science takes the idea from theory to reality. It's a big ol' universe out there.

A beginner's guide to time travel

Learn exactly how Einstein's theory of relativity works, and discover how there's nothing in science that says time travel is impossible.

Everyone can travel in time . You do it whether you want to or not, at a steady rate of one second per second. You may think there's no similarity to traveling in one of the three spatial dimensions at, say, one foot per second. But according to Einstein 's theory of relativity , we live in a four-dimensional continuum — space-time — in which space and time are interchangeable.

Einstein found that the faster you move through space, the slower you move through time — you age more slowly, in other words. One of the key ideas in relativity is that nothing can travel faster than the speed of light — about 186,000 miles per second (300,000 kilometers per second), or one light-year per year). But you can get very close to it. If a spaceship were to fly at 99% of the speed of light, you'd see it travel a light-year of distance in just over a year of time.

That's obvious enough, but now comes the weird part. For astronauts onboard that spaceship, the journey would take a mere seven weeks. It's a consequence of relativity called time dilation , and in effect, it means the astronauts have jumped about 10 months into the future.

Traveling at high speed isn't the only way to produce time dilation. Einstein showed that gravitational fields produce a similar effect — even the relatively weak field here on the surface of Earth . We don't notice it, because we spend all our lives here, but more than 12,400 miles (20,000 kilometers) higher up gravity is measurably weaker— and time passes more quickly, by about 45 microseconds per day. That's more significant than you might think, because it's the altitude at which GPS satellites orbit Earth, and their clocks need to be precisely synchronized with ground-based ones for the system to work properly.

The satellites have to compensate for time dilation effects due both to their higher altitude and their faster speed. So whenever you use the GPS feature on your smartphone or your car's satnav, there's a tiny element of time travel involved. You and the satellites are traveling into the future at very slightly different rates.

But for more dramatic effects, we need to look at much stronger gravitational fields, such as those around black holes , which can distort space-time so much that it folds back on itself. The result is a so-called wormhole, a concept that's familiar from sci-fi movies, but actually originates in Einstein's theory of relativity. In effect, a wormhole is a shortcut from one point in space-time to another. You enter one black hole, and emerge from another one somewhere else. Unfortunately, it's not as practical a means of transport as Hollywood makes it look. That's because the black hole's gravity would tear you to pieces as you approached it, but it really is possible in theory. And because we're talking about space-time, not just space, the wormhole's exit could be at an earlier time than its entrance; that means you would end up in the past rather than the future.

Trajectories in space-time that loop back into the past are given the technical name "closed timelike curves." If you search through serious academic journals, you'll find plenty of references to them — far more than you'll find to "time travel." But in effect, that's exactly what closed timelike curves are all about — time travel

This article is brought to you by How It Works .

How It Works is the action-packed magazine that's bursting with exciting information about the latest advances in science and technology, featuring everything you need to know about how the world around you — and the universe — works.

There's another way to produce a closed timelike curve that doesn't involve anything quite so exotic as a black hole or wormhole: You just need a simple rotating cylinder made of super-dense material. This so-called Tipler cylinder is the closest that real-world physics can get to an actual, genuine time machine. But it will likely never be built in the real world, so like a wormhole, it's more of an academic curiosity than a viable engineering design.

Yet as far-fetched as these things are in practical terms, there's no fundamental scientific reason — that we currently know of — that says they are impossible. That's a thought-provoking situation, because as the physicist Michio Kaku is fond of saying, "Everything not forbidden is compulsory" (borrowed from T.H. White's novel, "The Once And Future King"). He doesn't mean time travel has to happen everywhere all the time, but Kaku is suggesting that the universe is so vast it ought to happen somewhere at least occasionally. Maybe some super-advanced civilization in another galaxy knows how to build a working time machine, or perhaps closed timelike curves can even occur naturally under certain rare conditions.

This raises problems of a different kind — not in science or engineering, but in basic logic. If time travel is allowed by the laws of physics, then it's possible to envision a whole range of paradoxical scenarios . Some of these appear so illogical that it's difficult to imagine that they could ever occur. But if they can't, what's stopping them?

Thoughts like these prompted Stephen Hawking , who was always skeptical about the idea of time travel into the past, to come up with his "chronology protection conjecture" — the notion that some as-yet-unknown law of physics prevents closed timelike curves from happening. But that conjecture is only an educated guess, and until it is supported by hard evidence, we can come to only one conclusion: Time travel is possible.

A party for time travelers

Hawking was skeptical about the feasibility of time travel into the past, not because he had disproved it, but because he was bothered by the logical paradoxes it created. In his chronology protection conjecture, he surmised that physicists would eventually discover a flaw in the theory of closed timelike curves that made them impossible.

In 2009, he came up with an amusing way to test this conjecture. Hawking held a champagne party (shown in his Discovery Channel program), but he only advertised it after it had happened. His reasoning was that, if time machines eventually become practical, someone in the future might read about the party and travel back to attend it. But no one did — Hawking sat through the whole evening on his own. This doesn't prove time travel is impossible, but it does suggest that it never becomes a commonplace occurrence here on Earth.

The arrow of time

One of the distinctive things about time is that it has a direction — from past to future. A cup of hot coffee left at room temperature always cools down; it never heats up. Your cellphone loses battery charge when you use it; it never gains charge. These are examples of entropy , essentially a measure of the amount of "useless" as opposed to "useful" energy. The entropy of a closed system always increases, and it's the key factor determining the arrow of time.

It turns out that entropy is the only thing that makes a distinction between past and future. In other branches of physics, like relativity or quantum theory, time doesn't have a preferred direction. No one knows where time's arrow comes from. It may be that it only applies to large, complex systems, in which case subatomic particles may not experience the arrow of time.

Time travel paradox

If it's possible to travel back into the past — even theoretically — it raises a number of brain-twisting paradoxes — such as the grandfather paradox — that even scientists and philosophers find extremely perplexing.

Killing Hitler

A time traveler might decide to go back and kill him in his infancy. If they succeeded, future history books wouldn't even mention Hitler — so what motivation would the time traveler have for going back in time and killing him?

Killing your grandfather

Instead of killing a young Hitler, you might, by accident, kill one of your own ancestors when they were very young. But then you would never be born, so you couldn't travel back in time to kill them, so you would be born after all, and so on …

A closed loop

Suppose the plans for a time machine suddenly appear from thin air on your desk. You spend a few days building it, then use it to send the plans back to your earlier self. But where did those plans originate? Nowhere — they are just looping round and round in time.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Andrew May holds a Ph.D. in astrophysics from Manchester University, U.K. For 30 years, he worked in the academic, government and private sectors, before becoming a science writer where he has written for Fortean Times, How It Works, All About Space, BBC Science Focus, among others. He has also written a selection of books including Cosmic Impact and Astrobiology: The Search for Life Elsewhere in the Universe, published by Icon Books.

Beginner-friendly Celestron StarSense Explorer telescope now under $200

Lost photos suggest Mars' mysterious moon Phobos may be a trapped comet in disguise

Metal detectorists unearth 300-year-old coin stash hidden by legendary Polish con man

Most Popular

- 2 James Webb telescope confirms there is something seriously wrong with our understanding of the universe

- 3 Some of the oldest stars in the universe found hiding near the Milky Way's edge — and they may not be alone

- 4 The mystery of the disappearing Neanderthal Y chromosome

- 5 Can a commercial airplane do a barrel roll?

- 2 In a 1st, HIV vaccine triggers rare and elusive antibodies in human patients

- 3 The same genetic mutations behind gorillas' small penises may hinder fertility in men

- 4 Scientists grow diamonds from scratch in 15 minutes thanks to groundbreaking new process

- 5 50,000-year-old Neanderthal bones harbor oldest-known human viruses

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Letter of Recommendation

How I Became Obsessed With Accidental Time Travel

The web is awash with ordinary peoples’ stories of “time slips.” Their real magic is what they can tell us about our relationship to time.

By Lucie Elven

This year, I turned 30, a development that came with a breathless sense of dread at time’s passing. It wakes me up in the early mornings: Nocturnal terror breaks through the surface of sleep like a whale breaching for air. My ambition and fear kick in together until I get up, pour myself some water and look out the window at the squid-ink sky and the string of lights along my neighbors’ houses. I lie down again after finding firmer mental ground, dry land.

So when a guy that my friend was seeing evangelized about “time slips” — a genre of urban legend in which people claim that, while walking in particular places, they accidentally traveled back, and sometimes forward, in time — I was a ripe target. Curious and increasingly existential, I Googled these supposed time slips. I found a global community of believers building an archive of temporal dislocations from the present. These congregants gathered in corners of the internet to testify about how, in the right conditions, the dusting of alienation that settles over the world as we age can crystallize into collective fiction.

I was initially skeptical of the vague language that time-slip writers employed to convey experiences I already found dubious: too many uses of foggy words like “blunder” and “sporting”; detail lavished on varieties of hats encountered. But I was drawn in by their secretive tone — I sensed that sharing these anecdotes was compromising, even shameful (“People would laugh at you,” one poster wrote). Disapproval became attraction, and I returned to the message boards throughout the summer.

Here’s a classic that, like the best of these stories, was related secondhand on a paranormal blog: In a Liverpudlian street in 1996, an off-duty policeman named Frank was going to meet his wife, Carol, in a bookshop called Dillons when “suddenly, a small box van that looked like something out of the 1950s sped across his path, honking its horn as it narrowly missed him.” More disorienting still, Frank “saw that Dillons book store now had ‘Cripps’ over its entrance” and that there were stands of shoes and handbags in the window instead of new fiction. The only other person not wearing midcentury dress was a girl in a lime green sleeveless top. As Frank followed her into the old women’s wear boutique, “the interior of the building completely changed in a flash”; it was once again a bookshop.

I found a global community of believers building an archive of temporal dislocations from the present.

As with a spell of déjà vu, the experience was short-lived, and time was regained. According to the blogger’s detective-like report, Cripps “was later determined” to have been a business in the 1950s. In response to Frank’s slip, posters have told their own or related accounts they’ve heard from others: “This happened to my ex-boss, Glyn Jackson in London, England,” one begins. “Glyn’s story is Highly believable as Glyn is person who lacks imagination on such a scale that he could not put together a grade one story for English to save his life.” And on it goes.

I have never appreciated stories about the passage of time. I resent that I won’t ever get back the hours of my life that Richard Linklater stole with “Boyhood” — his two-and-three-quarter-hour film, shot over a 12-year period in which time is the force that overwhelms everything, not least the idea that our own actions drive our life stories. There’s a whole lot of unwelcome profundity there.

Time-slip anecdotes, though fashioned out of the ambient dread of living with the ticking clock, are childlike in their sense of wonder. They are light, playful and irrational, as frivolous and folky as a ghost story if it were narrated by the confused ghost instead of the people it haunts. One poster, as a girl, used to see a woman in a blue bathrobe in her room: “Her hair was long and messy, a reddish brown. I didn’t see her face because she was usually turned away. I used to mistake her for my mom.” Years later, grown up, the poster’s daughter slept in her former bedroom. “One day I realized ... I was wearing the same blue bathrobe,” the mother writes. Paranormal trappings aside, this story speaks to the feeling of whiplash brought on by time’s passing.

Slipping can be significant, as any Freudian will tell you, and these narratives are riddles whose answers might tell us about our relationship to time. I have begun considering the message boards on which they are exchanged to be narrow but important release valves, allowing posters to talk about the feelings that arise from being time-bound: depression, midlife crises, the dysmorphia of living in a human body. What ailed Miss Smith, whose car slid into a ditch after a cocktail party, and who witnessed “groups of Pictish warriors of the late seventh century, ca. 685 AD,” if not an understanding of her smallness in history’s vast expanse? Why did two academics, famous in the time-slip community for writing a book about spotting Marie Antoinette in the Versailles grounds, encounter trees that looked lifeless, “like wood worked in tapestry”? Perhaps in that instant, like the last queen of France’s Ancien Régime, they felt radically out of joint with their present moment.

If you suspend disbelief, you’ll find these threads constitute a philosophical inquiry about the place of the spirit in our physical beings. They debate the merits of subjectivity and objectivity and question the idea that time is a one-lane highway to death. These writers argue that our past and future can suffuse our present, unveiling an epic dimension of our quotidian existences in moments when we slip and, like Frank, feel eternity.

Lucie Elven is a writer whose first book of fiction, “The Weak Spot,” was published this year in the United States by Soft Skull Press and in Britain by Prototype.

Background photograph: George Marks/Getty Images

Explore The New York Times Magazine

How Israeli Extremists Took Over : After 50 years of failure to stop violence and terrorism against Palestinians by Jewish ultranationalists, lawlessness has become the law .

The Interview : Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson talks about how to overcome the “soft” climate denial that keeps us buying junk.

The Dynamite Club : In early 20th-century America, political bombings by anarchists became a constant menace — but then they helped give rise to law enforcement as we know it.

Losing Your Native Tongue : After moving abroad, a writer found her English slowly eroding. It turns out our first languages aren’t as embedded as we think .

7 Americans’ Last Day : American culture has no set ritual to mark retirement. These new retirees created their own .

Time Travel Proof: The Mounting Evidence Of A Broken Timeline

Time traveling tourists & other things.

Evidence of time travel is not something to be ignored — these periodic blips of stories, pictures, and artifacts are nothing less than blatant signs that our universe is in peril. The space-time continuum is breaking apart!

Eight years ago, I shared the first batch of this evidence. A handful of photographs and video clips that many believed were proof that time travel not only existed, but that individuals from the future had already visited us. Some, it was claimed, had even journeyed back to ancient times.

But they left footprints. They dropped artifacts. They were mistakenly caught on camera. Others deliberately shared knowledge of their strange voyages.

Others, if their stories are to be believed, were not quite so deliberate — they were like you or me. Ordinary people caught in time slips, temporarily whisked away to other eras, or perhaps even other universes.

Who were these alleged time travelers? These are some of their stories…

- The 1917 Photograph

The Mummy’s Modern Boots

- Project Pegasus & Nikola Tesla’s Jump Room

- A Watch Found In A Chinese Tomb

- Time Traveler Bridge Photo

- Charlie Chaplin Time Traveler

- An 1800s CD Case

- The Time Slip Hotel

- A Mysterious Near-Miss

Time Traveler In 1917 Photograph

It’s an odd thing when something, or someone, doesn’t quite fit in. At first, you may not notice. But upon closer inspection, the anomaly becomes clear.

So is the case with this seemingly ordinary photograph taken in 1917 Canada, found in a 1974 book titled The Great History of Cape Scott . It shows a group of people sitting upon the rocks of a beach, but among the crowd is a man who appears suspiciously out of place.

Many believe his clothes do not match those of the other beach-goers. Wearing a tee shirt, shorts, and with a hair style that seems quite modern in comparison, the mysterious individual hits all the check boxes for a person displaced in time.

In the photo, others even appear to look at him, perhaps in confusion.

This particular time traveler is colloquially known as the “surfer dude.”

Others, however, raise incredible questions.

For some time now, many have wondered about the existence of the so-called “Adidas Mummy,” the preserved body of a 30 to 40-year-old woman discovered in the Altai mountains region of Mongolia in 2016. She had been buried there for about 1,100 years.

Those studying her found that she had likely died of a “blow to the head.” However, her feet drew the most attention.

She wore what looked uncannily like modern day shoes, perhaps resembling a pair of snowboarding boots, as the Daily Mail mused in 2017 . They were made of felt, with splashes of bright red, and “knee length” with leather soles.

Their unique design, likened to Adidas, led many to question if perhaps the ancient Mongolian woman was in fact a time traveler. Perhaps, even if the shoes themselves were not from current times, they were made, or possibly inspired, by someone from the future utilizing the same style.

Among her other belongings was what archaeologists described as a “beauty kit,” including a mirror, a comb, and a knife. However, scientists brushed off any claims that she was a time traveler, though they did say the style of the boots was “very modern.”

Nikola Tesla’s Jump Room

For years, Andrew Basiago has told the story of Project Pegasus, the alleged covert time travel initiative that was funded and maintained by the United States government throughout the 1960s and 70s. But perhaps the most interesting detail of his peculiar story is the existence of the so-called Jump Room.

It was in this room that Basiago claimed participants such as himself performed their secretive time travel experiments.

Built using designs by the late Nikola Tesla, recovered from his New York apartment shortly after his death, the room housed what some would call a teleportation machine. It consisted of a “shimmering curtain” made of “radiant energy,” a special, and allegedly as-yet-undisclosed, form of energy that is “latent and pervasive” throughout the cosmos. It is, if this story is to be believed, what makes time travel possible.

The curtain stood between two elliptical booms, and by passing through it, would-be travelers could journey across vast distances — and time itself. Basiago claims to have visited Gettysburg using the jump room, and that the experiments even took him as far as the planet Mars.

Beyond that, there are few other details about the mysterious Jump Room, and no physical proof remains. Did it really exist?

Evidence Of Time Travel In A Chinese Tomb?

A story from 2008, originally published by none other than the Daily Mail , claimed that Chinese archeologists found a watch in a 400-year-old Si Qing tomb in Shangsi County, China. This story then went extremely viral, after I shared my original article on it (“Are These Images Proof Of Real Time Travel,” published March 22, 2012). The images, which are still scattered around out there (source unknown), show a group of archeologists examining a stone block within a room, as well as the singular image of someone holding up a tiny piece of metal in the shape of a watch.

Allegedly, the timepiece was “frozen” at 10:06, with the word “Swiss” engraved on its back. However, the object looked much more like a sculpted piece of stone than an actual functioning watch, not to mention the fact that its circumference appeared smaller than that of a finger.

If I were charitable, I could say that perhaps 400 years ago some people carved this to look like a watch someone had seen, perhaps one worn by a visiting time traveler. That, or I’m incorrect and it is an actual watch and the time traveler was just very tiny. Maybe we all do shrink in the future, like the Shrinking Man Project suggests we should. You never know! Moving on!

Time Traveler Visits A Bridge?

A strange photo, once available at the Virtual Museum Of Canada (which has since been decommissioned), appeared to show a group of people attending the reopening of the South Fork Bridge in 1941. The bridge was located in Gold Bridge in British Columbia, Canada, and quite a few people showed up for it. But like the 1917 Canadian surfer dude mentioned earlier, someone in this photo seemingly doesn’t belong.

Who was this oddly out-of-place individual, wearing what looks like modern clothing all the way back in the 1940s? Who knows? The photo went absolutely viral some time around 2010, with the man in question becoming dubbed the “Time Traveling Hipster.”

What’s fun about this one is that, time traveler or not, it’s a real photo. The man certainly stands out from his cohorts – he’s wearing sunglasses, possibly a hoodie or light jacket, and what appears to be a branded t-shirt. He’s also holding a relatively small camera. Was he simply ahead of his time? Or out of it? We can’t be sure, but but the story of this photograph is one to remember. Next!

Lights! Camera! Action!

Next up we have two, count them two, short videos which many claim show time travelers unwittingly caught in the act of…talking on the phone!

Indeed, smartphones are the bane of any would-be time traveling tourist, as they seem like the most obvious thing to be spotted in photos, videos, and even paintings .

The above video, uploaded October 27, 2010, currently has over 4.3 million views, and contains a clip from a special feature found on the DVD edition of the Charlie Chaplin film The Circus. It’s of the movie’s premiere at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in 1928.

But what’s so special about it? What’s worth 4.3 million views on YouTube? Well, you see that woman in the dark coat walking behind zebra? What’s she holding up to their ear? Is it a cellphone? Or was she just scratching her head, like the rest of us?

Meanwhile, from over in 1938 Massachusetts, we have the following video that some also suggest proves the existence of smartphones long before their time (or have at least mused about the possibility). A crowd of people exit a DuPont factory, and one woman is seen holding something to her ear.

Smartphones, brushes, other handheld rectangular objects of a dubious nature. Our universe is one filled with mystery, and some questions may forever remain unanswered. Onward!

A Compact Disc Case In The 1800s?

A painting from the 1800s appears to show a man holding what some have described as a fancy CD box. You can see another man depicted to be lifting up what looks like a square plastic “sleeve” that you’d place individual CDs into. The earliest form of plastic didn’t exist until the mid-1800s, and Compact Discs wouldn’t arrive on the scene until the 1980s.

Of course, it’s possibly this is just an ordinary box made for ordinary 1800s-era items.

Safety Not Guaranteed?

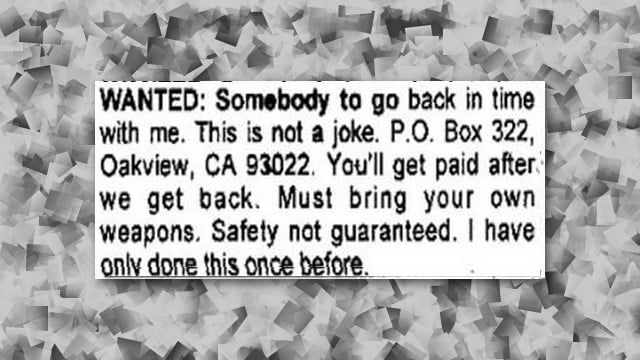

In 1997, an unusual classified ad appeared in Backwoods Home Magazine:

“WANTED: Somebody to go back in time with me. This is not a joke. P.O. Box 322, Oakview, CA 93022. You’ll get paid after we get back. Must bring your own weapons. Safety not guaranteed. I have only done this once before.”

As you can imagine, some people found that odd, and it naturally wound up on the Internet. In 2012, they even made a film based on it called, well, Safety Not Guaranteed .

The Time Slip Hotel: Proof That Even Buildings Time Travel?

It’s not unusual to, on occasion, find yourself at what you might describe as a “strange” place, especially if you happen to be in a country you’ve never visited before. Two couples who vacationed to Spain in the late 1970s know this all too well. In fact, their story has become something of a time slip legend.

In 1979, they were on their way to Spain, leaving England and venturing through France. While near Montelimar, they decided to stop and search for a hotel. Their original choices were packed, but eventually they did find one — an odd place, an old two-story building with the simple word “HOTEL” above the entrance.

They got a room, and stayed for the night, despite everything seeming particularly old-fashioned. The bed was hard, the place didn’t have a telephone, and there was no glass in the windows. Likely out of bemusement, they took a number of photographs.

When they went down to the dining room the next morning, they had a chance to see the hotel’s other customers. They too looked strangely out of place, dressed in outmoded clothing, two in old uniforms. Strangest of all was the bill for their stay — 19 francs, far less than they had anticipated.

All in all, it was a somewhat strange experience, but not unpleasant. They’d found a place to rest for the night, and continued on their way to Spain, where they presumably had a decent time. It wasn’t until they returned to France and looked for the hotel again that they knew something was truly amiss.

The hotel didn’t exist.

This wasn’t a matter of the hotel simply shutting down, or their being unable to find it again. It simply was not there. They even asked around in Montelimar, and no one had ever heard of it.

When they returned to England, the mystery deepened: Their photographs of the hotel were gone. Not only was there no proof that the hotel existed, but there was no proof that they’d ever been there at all.

Their odd tale was later featured on an episode of the television series Strange But True .

Is One Man’s Near Miss Proof of Time Travel?

In 2019, a very curious video from Turkey showed a man nearly meeting his fate, only to be saved in the strangest way by a mysterious passerby.

According to Demirören News Agency , the event happened in late February in the Turkish city of Adana. Serdar Binici was standing outside of his store when another man, who happened to be walking by, tapped his left shoulder.

Binici, for reasons even he claims to not understand, instinctively looked over to his right, and in that moment a truck drove by, and its rear metal door swung open toward his head. Binici was able to move out of the way just in time.

The story was featured by news outlets in Turkey, and was eventually shared on Reddit .

During a follow-up interview, Binici questioned how and why the events played out as they did. Why did he look over his opposite shoulder, and not the one he’d been tapped on? Why did the stranger tap his shoulder at all? Binici supposes the stranger may not, himself, know why any of this happened. Perhaps, he thinks, it was all some kind of divine intervention.

However, the peculiarity of this video has led many to speculate that the passing stranger wasn’t just some random person, but actually a time traveler — possibly one on a mission from the future, striving to put right what once went wrong. Could this incident be yet more proof of real time travel?

Somewhere In Time

Even if these stories and strange photographs are not evidence of anything, these tales are part of our shared paranormal folklore, and have become online urban legends. Some, like the tale of Rudolph Fentz, date back decades. And while others are easily disproved, they stand as fun little anecdotes that do make you wonder, what if?

At the end of the day, it’s all just a bunch of wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey…stuff. Best not to take it too seriously. Still, if you’re looking for more on possible time travelers, consider checking out the following:

- Rudolph Fentz , an accidental time traveler from a series of short stories

- John Titor , the alleged time traveler from 2036

- The HDR , an alleged time traveling device powered by crystals

- A Wormhole Under A Kitchen Sink?

Rob Schwarz

Pocket-lint

The best images of time travellers from throughout history.

Every now and then an image appears online which people claim shows a time traveller somewhere they shouldn't be. Are they real though?

Every now and then an image appears online which people claim shows a time traveller somewhere they shouldn't be. But are they just cases of people letting their imaginations run wild?

We've rounded up some of the best and most interesting images of time travellers throughout history. Some turned out to be plain fakes or cases of mistaken identities, but others are certainly intriguing.

Which have you seen before?

- The most famous ghost photographs ever taken

- 35 of the most famous alien, monster and unexplained photographs ever taken

The time travelling hipster

This photo was snapped in 1941 at the re-opening ceremony for the South Fork Bridge in British Columbia.

If you look carefully, on the right-hand side you can see an unusually dressed man in what appears to be modern clothing, sporting sunglasses at a time when most were wearing hats and smart jackets.

Many argue this is a time traveller, while others have countered that he's simply a man with a fashion sense ahead of his time. Snopes has shown his clothing is relevant to the time and the area, but it's still great to imagine.

World Cup celebrations

This photo comes from the 1962 World Cup and shows the celebrations as the Brazilian team lifts the trophy.

If you look closely though, you'll see in the bottom centre of the image what looks like someone with a mobile phone snapping a photo of the event.

Could this be a time traveller as well? A bit odd to think someone in the future might have a flip phone , but then they have been making a comeback recently and we know folding phones are about to be big too .

The time travelling sun seeker

This image from 1943 apparently shows British factory workers escaping to the seaside for a break during the midst of wartime. The clothes and beachwear of most people certainly fit the era, but in the centre of a frame appears to be a man dressed like Mr Bean checking his mobile phone.

Or maybe it's a time travel device? Likely a bit of a stretch or a case of overactive internet imagination, but we still enjoy the thought. Maybe there are no public beaches in the future?

Mohawk time traveller

This image from 1905 appears to show the usual happenings of the time - including workers and a banana boat delivering its goods.

However, if you look near the edge of the boat you can spy a man in a white shirt with what appears to be a Mohawk-style haircut. A very unusual haircut for the time and possible proof of a time traveller? Who can say?

Film footage captured during the recording of Charlie Chaplin's 1928 silent film "The Circus" appears to show a lady dressed all in black, wearing a hat and walking around the set talking on her mobile phone.

The footage is a little iffy as is the idea that anyone could be talking on a mobile device in the 1920s, but it's certainly got some suggesting it might be proof time travellers are among us.

The ancient astronaut sculpture

In Salamanca, Spain, there's a cathedral with multiple sculptures carved into its sides. One such sculpture appears to show the likeness of a modern-day (or perhaps futuristic) astronaut.

Considering the cathedral's construction dates back to 1513, people have taken this as proof that time travellers made their way back to that time. However, the truth is the astronaut is merely a modern addition to the artwork carried out by Jerónimo García de Quiñones during renovations in 1992.

Time travelling celebrities

There's an interesting trend of people who closely resemble folks from a bygone era. This could just be a spooky coincidence, but maybe it's proof that time travel is possible.

Perhaps these celebrities are living a double life in another century. Here, Marxist-Leninist Revolutionary Leader Mahir Cayan who was born in 1946 and died in 1972 is shown to bear a striking resemblance to TV star Jimmy Fallon. Is Jimmy Fallon living a double life as a revolutionary communist? Seems hilariously unlikely.

A man and his mobile phone

Some claim that this oil painting by Pieter de Hooch, which was lovingly crafted in 1670 appears to show a young man holding his mobile phone. In an age where such a thing would probably have seen him burnt at the stake, this one is hard to believe.

A description of the image also suggests the young man is a messenger and that's a letter in his hand, not a phone, but it's still nice to let your imagination run wild once in a while. We've often wondered what it would be like to be able to travel back to simpler times to see what life was like for ourselves.

The Adidas trainers mummy

A couple of years ago, an ancient mummy was unearthed by archaeologists digging in Mongolia. At the time, it was suggested the funky-looking footwear she was wearing bore a striking resemblance to Adidas trainers. More evidence of a time traveller visiting ancient times? Investigation of the body dated it around 1,100 years old. That's one heck of a blast through the past.

However, further unearthing showed the woman was more likely to have been a Turkic seamstress which might explain the fresh kicks. She was found with an ancient clutch bag, a mirror, a comb, a knife and more. But no mobile phone.

The time surfer

Another image of an out-of-place individual that people have latched on to as proof that time travel is a reality.

This image dates back over 100 years and shows some smartly dressed Canadians sitting on the side of a hill.

On the left-hand side though, sits a young man in what appears to be a t-shirt and shorts with ruffled hair. He was quickly referred to as the surfing time traveller due to how unusual his attire is. Others have suggested people in the photo appear shocked by his appearance, even pointing out the woman on the right who seems to be gesturing in his direction. Again, this a bit of a stretch as would a time traveller really go through time dressed like that?

A visitor to wartime Reykjavík

This photograph apparently shows a scene from downtown Reykjavík in 1943.

In the heart of wartime, soldiers and sailors can be seen everywhere in the streets among civilians. The man circled though, appears to be on a mobile phone.

We've really got a theme going with these smartphone using time travellers. Who is he calling? And how? And if he is a time traveller, why is he not in Berlin trying to assassinate Hitler?

The dabbing WWII soldier

There's an apparent theme to these time traveller photos that not only includes smartphone users, but also people visiting the second world war.

In this image, a young soldier is seen dabbing, a dance move that became popular around 2014, but certainly wasn't known in wartime.

Of course, it turns out this photo isn't an image of a time traveller, but rather just an image of some actors from 2017's blockbuster Dunkirk . The fact that most of the soldiers are smiling should also be a bit of a giveaway with this one.

Greta Thunberg

In 2019, the internet discovered a photograph from 1898 which showed three children working at a gold mine in Canada's Yukon territory.

The image seemed to show a girl with an incredible likeness to the young climate activist Greta Thunberg. Does this make Thunberg a time traveller who's come through time to save the planet? Weird year for her to choose, but it's a nice idea.

A woman clutching a smartphone (1860)

The painting " The expected one " from 1860, by Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller appears to show a woman walking along a rough path, about to be accosted by an adoring young man clutching a pink flower.

A close look though and you'll see she appears to have her attention firmly glued to a modern smartphone. Is this woman actually a time traveller?

Vladimir Putin

A few years back, a number of images surfaced online that seemingly showed Russian President Vladimir Putin snapped over various decades without ageing. Either proof that he's a time traveller or perhaps just immortal?

If true, he's incredibly patriotic, with each image showing him serving his country in one way or another. Though it's more likely to just be a strong likeness.

The AI time traveller

Here's a time traveller with a difference. Stelfie the Time Traveller has been using AI to travel through time. Or at least to give the illusion of doing so.

This creative individual has been using Stable Diffusion to insert the likeness of a modern man into ancient civilisations including Egypt when the pyramids were being constructed, Rome with the centurions and the land of the dinosaurs . It's fun to imagine these as being real, though if you look closely they're clearly AI-generated. As this artificial intelligence improves we'll no doubt get even better images like this. Interestingly even the character taking the selfies isn't real here, but is also made using AI.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Conversational time travel: evidence of a retrospective bias in real life conversations.

- 1 Department of Psychology, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

- 2 University Research Priority Program “Dynamics of Healthy Aging”, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

- 3 Department of Psychology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

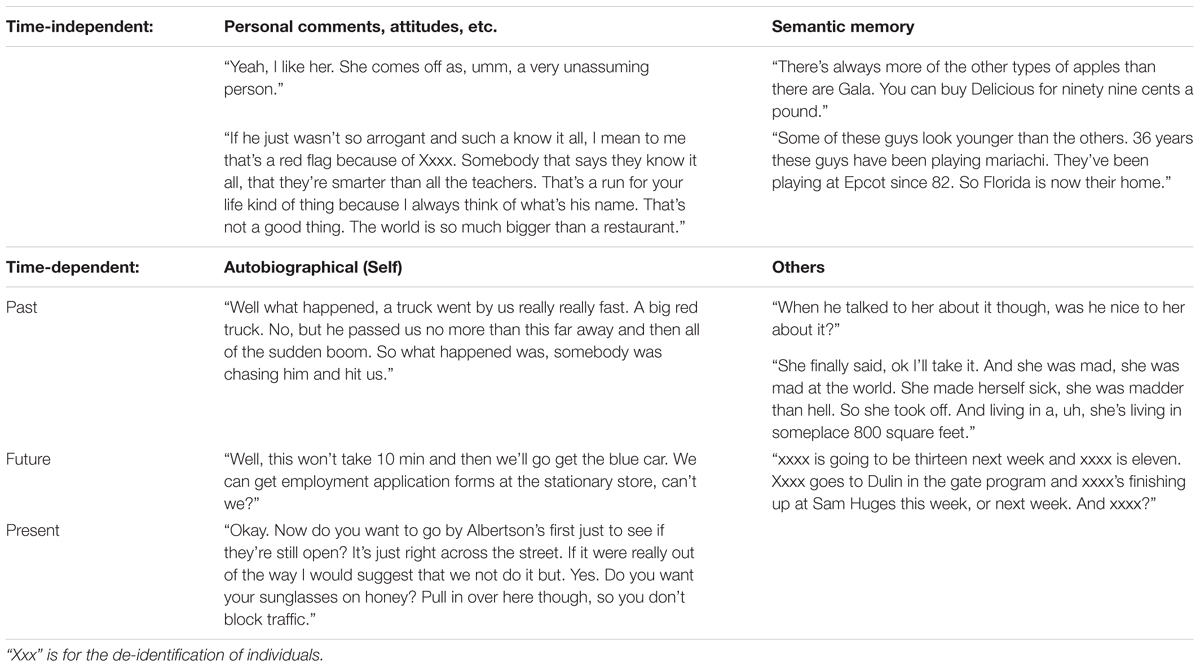

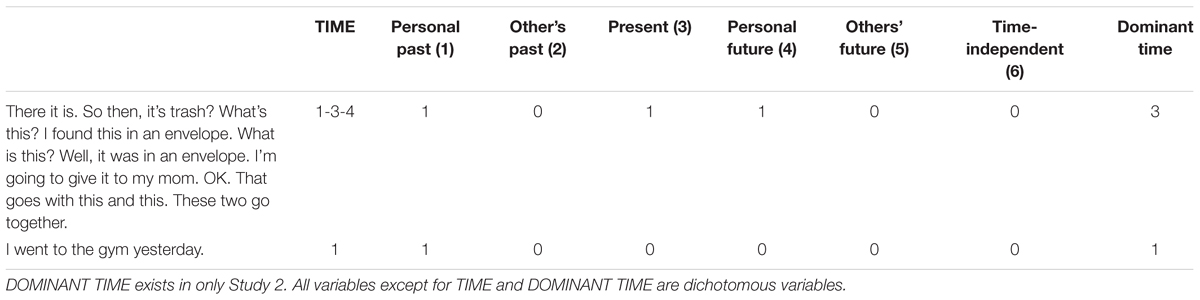

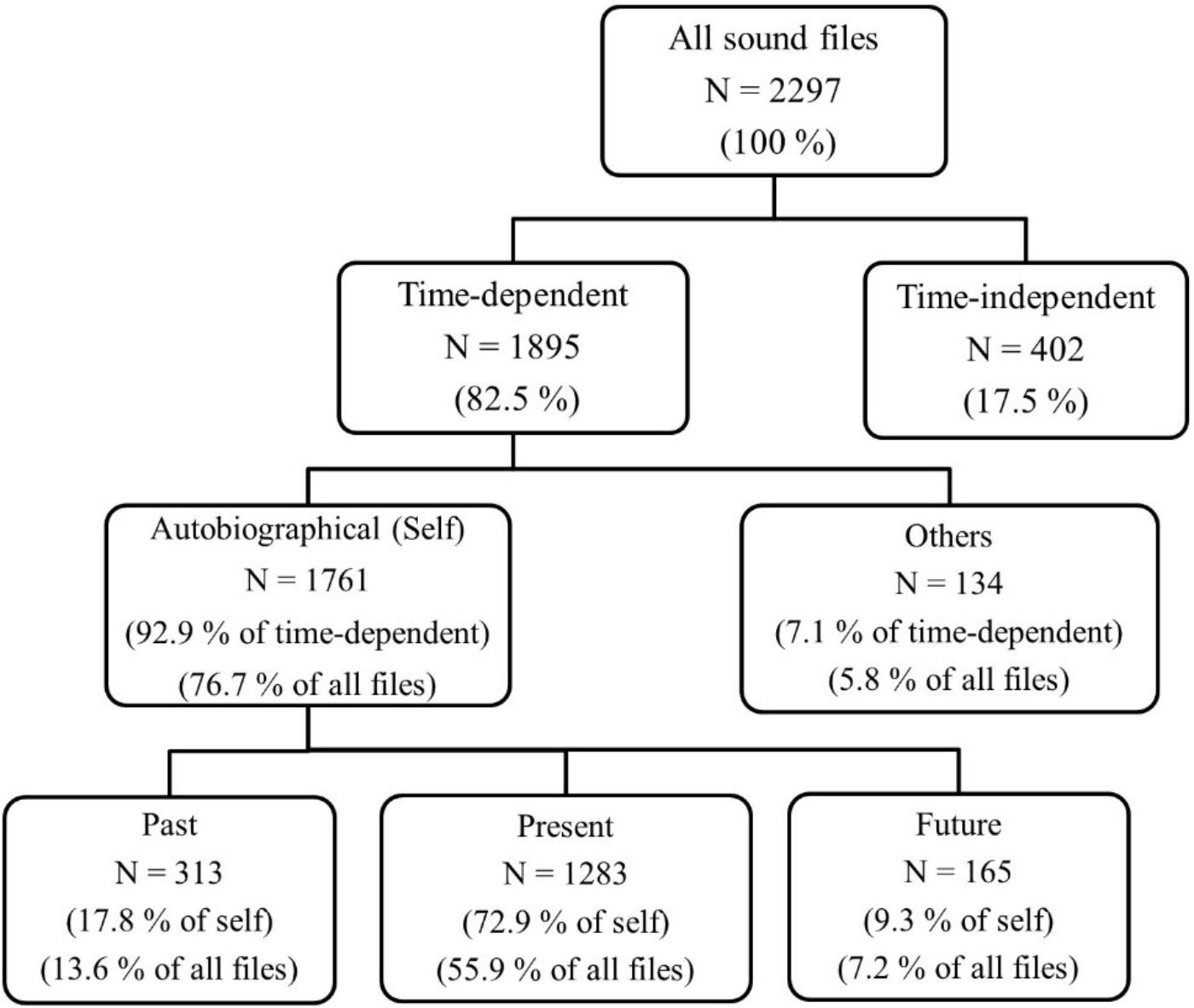

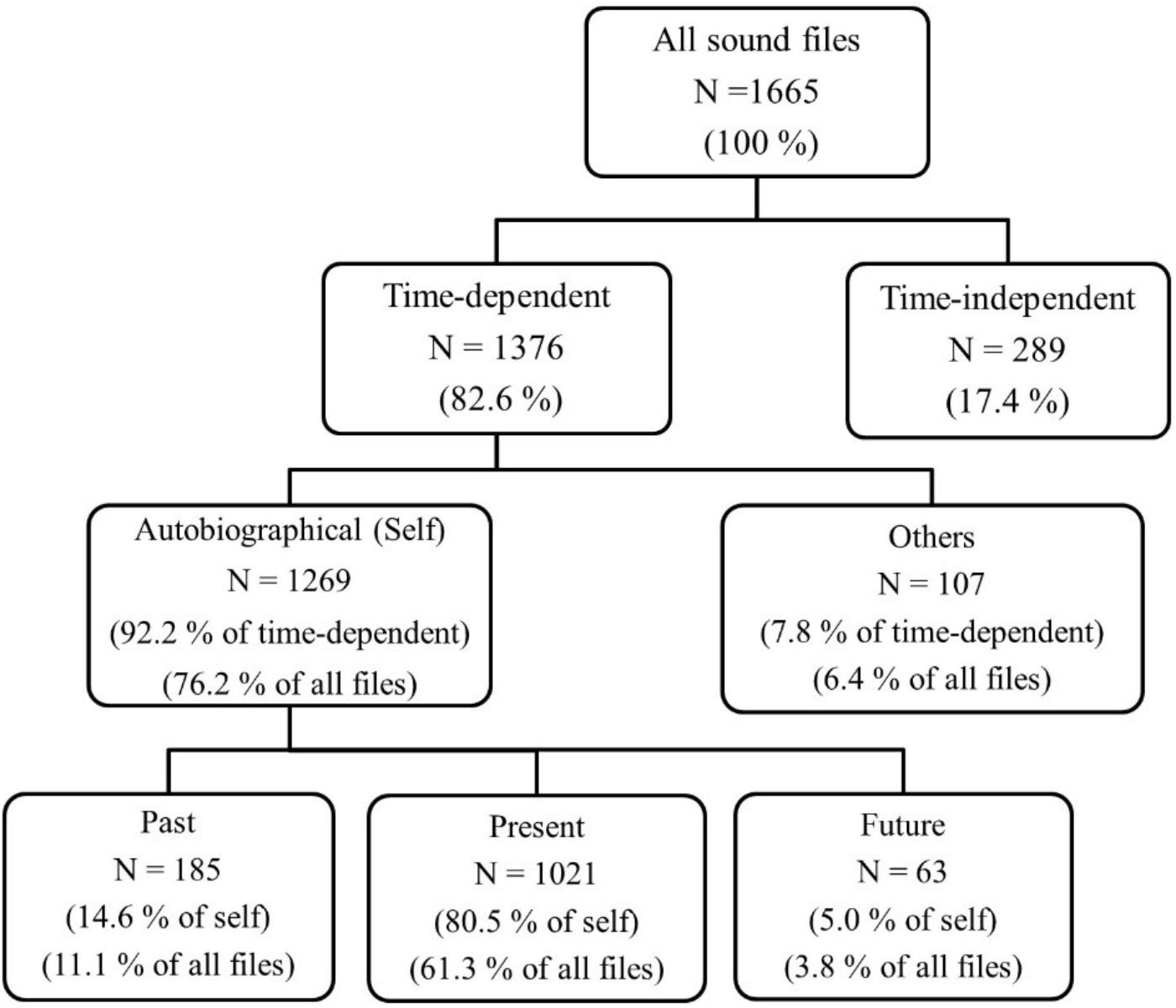

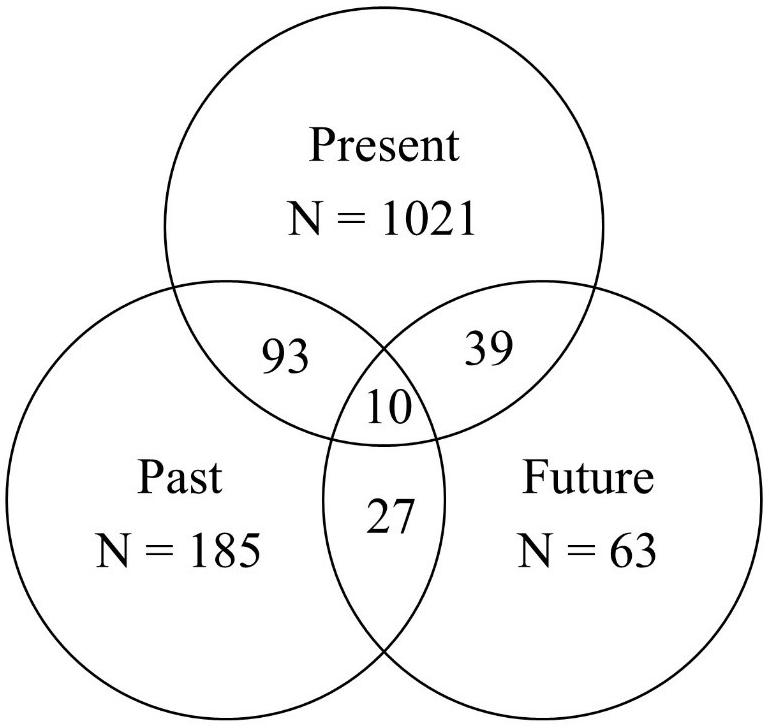

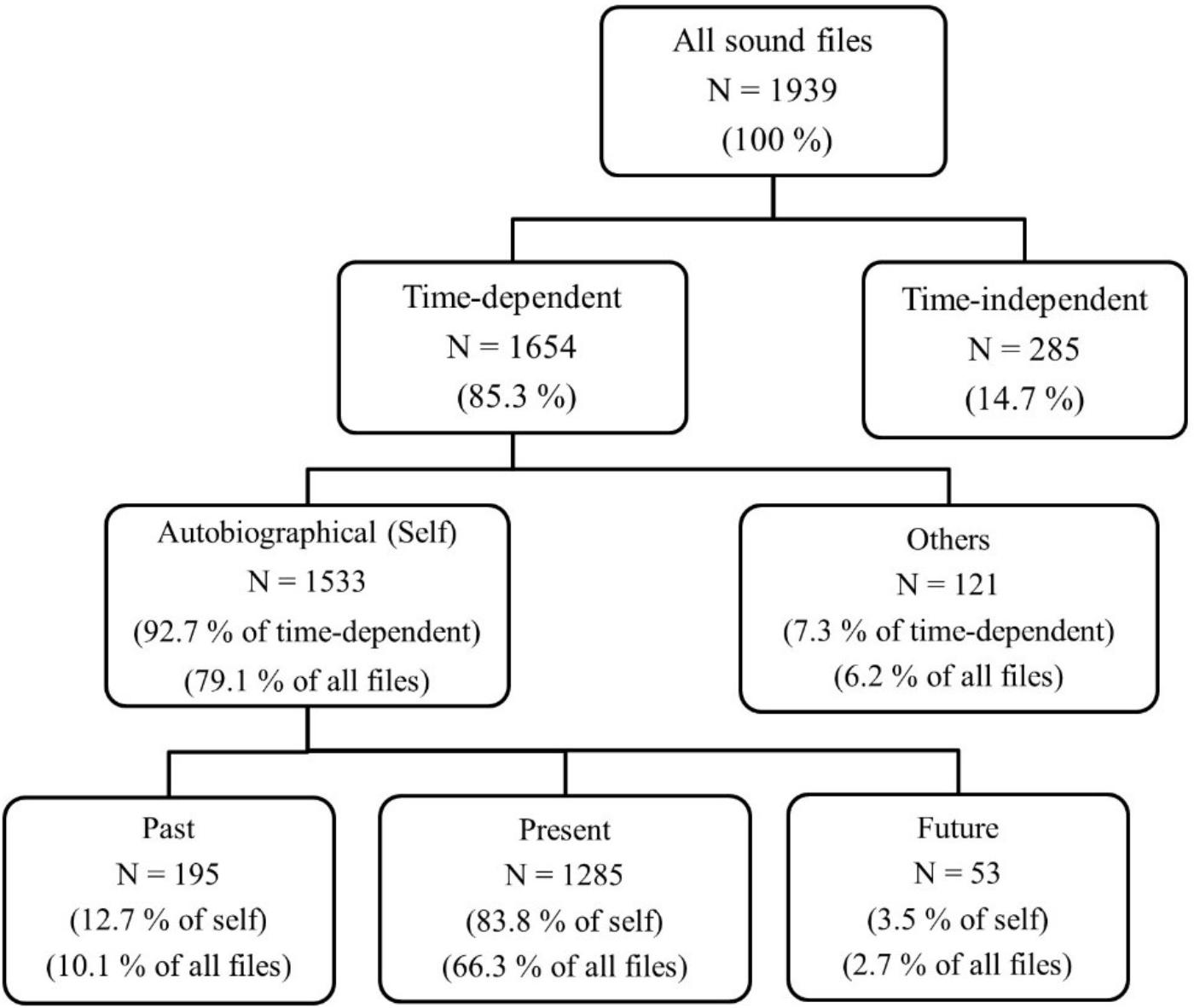

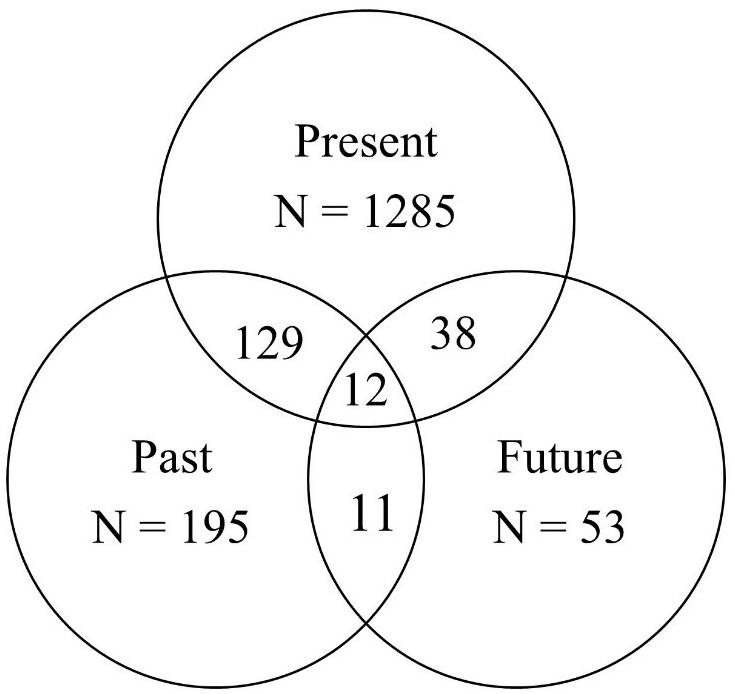

We examined mental time travel reflected onto individuals’ utterances in real-life conversations using a naturalistic observation method: Electronically Activated Recorder (EAR, a portable audio recorder that periodically and unobtrusively records snippets of ambient sounds and speech). We introduced the term conversational time travel and examined, for the first time, how much individuals talked about their personal past versus personal future in real life. Study 1 included 9,010 sound files collected from 51 American adults who carried the EAR over 1 weekend and were recorded every 9 min for 50 s. Study 2 included 23,103 sound files from 33 young and 48 healthy older adults from Switzerland who carried the EAR for 4 days (2 weekdays and 1 weekend, counterbalanced). 30-s recordings occurred randomly throughout the day. We developed a new coding scheme for conversational time travel: We listened to all sound files and coded each file for whether the participant was talking or not. Those sound files that included participant speech were also coded in terms of their temporal focus (e.g., past, future, present, time-independent) and autobiographical nature (i.e., about the self, about others). We, first, validated our coding scheme using the text analysis tool, Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count. Next, we compared the percentages of past- and future-oriented utterances about the self (to tap onto conversational time travel). Results were consistent across all samples and showed that participants talked about their personal past two to three times as much as their personal future (i.e., retrospective bias). This is in contrast to research showing a prospective bias in thinking behavior, based on self-report and experience-sampling methods. Findings are discussed in relation to the social functions of recalling the personal past (e.g., sharing memories to bond with others, to update each other, to teach, to give advice) and to the directive functions of future-oriented thought (e.g., planning, decision making, goal setting that are more likely to happen privately in the mind). In sum, the retrospective bias in conversational time travel seems to be a functional and universal phenomenon across persons and across real-life situations.

Introduction

Live in the here and now – so goes a common credo. However, one of the most remarkable skills of humans is not their ability to have their minds set on the present, but, rather, to engage in mental time travel. The human cognitive apparatus is a powerful time travel machine, allowing us to almost effortlessly project ourselves into the future to simulate possible future events, as well as put ourselves back into the past to relive our past experiences ( Suddendorf and Corballis, 2007 ). Recently, psychologists have started to emphasize that memory (e.g., autobiographical memory) and prospection (e.g., future-oriented thought) are closely related phenomena that share many common qualities (e.g., Schacter et al., 2012 ; Klein, 2013 ; Rasmussen and Berntsen, 2013 ). Thinking or talking about our past and future are such natural, moment-to-moment activities that we do not notice or wonder how often we recall our memories or imagine our future in everyday life. Psychologists have started to explore this prevalence question using a range of self-report methods (e.g., diary method, experience-sampling) with a focus on participants’ thoughts. Here, we used, for the first time, an ecological behavioral observation method that is free of self-report to examine the prevalence of mental time travel behavior in everyday conversations (i.e., conversational time travel). Using the Electronically Activated Recorder (EAR; Mehl et al., 2001 ), we unobtrusively and intermittently sampled snippets of ambient sounds and speech from participants’ natural lives, and extracted information about their moment-to-moment conversations.

The first goal of the current research was to develop and validate a new, naturalistic observation approach to studying mental time travel reflected in everyday conversations. We listened to and coded participants’ recorded utterances in terms of whether they (a) had a time reference or not and (b) were about the self versus others. We tapped onto mental time travel by focusing on those utterances that were about the self with a time reference. In two studies, we validated our coding scheme using a text analysis program and with adult samples representing different age groups and countries.

The second goal of the current research was to examine how often people engage in conversational time travel, and when they do, how often they talk about their past versus future. There is some work on how much people think about their personal past versus future in everyday life (e.g., Klinger and Cox, 1987 ; Berntsen and Jacobsen, 2008 ; Gardner and Ascoli, 2015 ), but no work on how much they talk about their past versus future. The solitary nature of thinking versus the social nature of talking should have different effects on mental time travel (e.g., Kulkofsky et al., 2010 ), which has methodological and theoretical implications. Humans spend 32–75% of their waking time with other people ( Mehl and Pennebaker, 2003 ). That is, much of human behavior occurs in a social context, therefore we examined, for the first time, mental time travel in the context of conversations. We unobtrusively observed and objectively coded the overt behavior of talking in everyday life to examine mental time travel reflected in people’s utterances.

Prevalence of Past- and Future-Oriented Thoughts in Everyday Life

Previous studies measuring the incidence of subjective thoughts and experiences have typically used variants of the original experience-sampling method (ESM; Csikszentmihalyi et al., 1977 ). One type of ESM is event-contingent sampling (e.g., diary method; Berntsen, 2007 ) in which diary entries are prompted by participants through introspection and detection of the occurrence of a target event. The second type is signal-contingent sampling , which requires people to evaluate the presence of a targeted experience when prompted by a randomly timed signal (e.g., Pasupathi and Carstensen, 2003 ). One important advantage of these methods is their high ecological validity.

Using the diary method, D’Argembeau et al. (2011) explored the frequency of thinking about the personal future in everyday life. They asked participants to report whenever they realized that they were thinking about their future and found that participants reported experiencing, on average, 59 future-oriented thoughts on a typical day. In contrast, Rasmussen and colleagues (i.e., Rasmussen and Berntsen, 2011 ; Rasmussen et al., 2015 ) examined the frequency of thinking about the personal past (i.e., autobiographical memories) using the diary method. They made a distinction between voluntarily thinking about memories versus involuntary memories (which spontaneously pop up without deliberate search) and compared their frequency. They showed that participants self-reported recalling on average 7–8 voluntary and 20–22 involuntary autobiographical memories per day. Taken together, these two studies suggest that young adults think about their personal future twice as much as their past. Berntsen and colleagues ( Berntsen and Jacobsen, 2008 ; Finnbogadottir and Berntsen, 2013 ), however, did not replicate this finding. They used the diary method to examine involuntary mental time travel and compared the frequency of involuntary memories and involuntary future-oriented thoughts. They found that involuntary memories were as frequent as involuntary future-oriented thoughts in daily life (around 22 per day).