Destination

Active travel & language agence de séjours linguistiques en angleterre et dans de nombreux pays.

Depuis plus de 50 ans, ACTIVE TRAVEL & LANGUAGE propose des séjours linguistiques ado , enfants et adultes. Notre organisme, labellisé UNOSEL (Union Nationale des Organisations de Séjours Éducatifs, Linguistiques et de Formation en langues), est au service des jeunes, des étudiants et des adultes souhaitant apprendre ou améliorer leur niveau en anglais, en espagnol, en allemand, en italien, en japonais, tout en voyageant.

Nous vous proposons des summer camps , des séjours à thèmes, des séjours Classes Prépa, etc. Vous vivrez une expérience unique à travers nos programmes d’immersion linguistique adaptés à vos besoins, et à votre niveau.

Embarquez pour un séjour linguistique en Angleterre, Irlande, Malte, Espagne, Allemagne, États-Unis, Canada, Australie, Italie, Écosse, Afrique du Sud, Japon, à Londres, Cambridge, Dublin, Barcelone, Berlin…

NOS PRESTATIONS

ACTIVE TRAVEL & LANGUAGE vous propose des programmes riches et variés.

Séjours linguistiques

Outre l’apprentissage de la langue, nos séjours linguistiques permettent aux jeunes de découvrir une autre culture et un nouveau mode de vie.

Summer camps

Nous proposons des summer camps aux enfants et adolescents souhaitant perfectionner leur anglais, au contact de jeunes anglophones.

Séjours académiques

Pendant vos études, optez pour un séjour académique pour approfondir vos connaissances tout en améliorant votre niveau en anglais.

Nos Points Forts

Nos programmes sont adaptés aux enfants, aux adolescents et aux adultes.

Nos Valeurs

Toutes nos équipes partagent des valeurs de voyage responsable.

NOS GARANTIES

AVIS DE NOS CLIENTS

Nous faisons tout pour satisfaire nos clients. Découvrez leur avis.

Suivez-nous sur Instagram

Pour découvrir toutes nos actualités, nous vous invitons à visiter notre page Instagram.

Contactez-nous

Pour réserver ou recevoir plus d’informations sur nos séjours linguistiques , contactez-nous.

Veuillez laisser ce champ vide. Veuillez laisser ce champ vide.

En soumettant ce formulaire, j'accepte la politique de confidentialité

Ce site est protégé par reCAPTCHA. les règles de confidentialité et les conditions d'utilisation de Google s'appliquent.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

What Are the Health Benefits of Active Travel? A Systematic Review of Trials and Cohort Studies

Affiliation Faculty of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation General and Adolescent Paediatrics Unit, UCL Institute of Child Health, London, United Kingdom

- Lucinda E. Saunders,

- Judith M. Green,

- Mark P. Petticrew,

- Rebecca Steinbach,

- Helen Roberts

- Published: August 15, 2013

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912

- Reader Comments

Increasing active travel (primarily walking and cycling) has been widely advocated for reducing obesity levels and achieving other population health benefits. However, the strength of evidence underpinning this strategy is unclear. This study aimed to assess the evidence that active travel has significant health benefits.

The study design was a systematic review of (i) non-randomised and randomised controlled trials, and (ii) prospective observational studies examining either (a) the effects of interventions to promote active travel or (b) the association between active travel and health outcomes. Reports of studies were identified by searching 11 electronic databases, websites, reference lists and papers identified by experts in the field. Prospective observational and intervention studies measuring any health outcome of active travel in the general population were included. Studies of patient groups were excluded.

Twenty-four studies from 12 countries were included, of which six were studies conducted with children. Five studies evaluated active travel interventions. Nineteen were prospective cohort studies which did not evaluate the impact of a specific intervention. No studies were identified with obesity as an outcome in adults; one of five prospective cohort studies in children found an association between obesity and active travel. Small positive effects on other health outcomes were found in five intervention studies, but these were all at risk of selection bias. Modest benefits for other health outcomes were identified in five prospective studies. There is suggestive evidence that active travel may have a positive effect on diabetes prevention, which may be an important area for future research.

Conclusions

Active travel may have positive effects on health outcomes, but there is little robust evidence to date of the effectiveness of active transport interventions for reducing obesity. Future evaluations of such interventions should include an assessment of their impacts on obesity and other health outcomes.

Citation: Saunders LE, Green JM, Petticrew MP, Steinbach R, Roberts H (2013) What Are the Health Benefits of Active Travel? A Systematic Review of Trials and Cohort Studies. PLoS ONE 8(8): e69912. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912

Editor: Jonatan R. Ruiz, University of Granada, Spain

Received: January 31, 2013; Accepted: June 13, 2013; Published: August 15, 2013

Copyright: © 2013 Saunders et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Public Health Research programme (project number 09/3001/13). The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Health. The funders had no role in the design, conduct or reporting of project findings.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

The link between physical activity and health has long been known, with the scientific link established in Jerry Morris' seminal study of London bus drivers in the 1950s [1] . There is also good ecological evidence that obesity rates are increasing in countries and settings in which ‘active travel’ (primarily walking and cycling for the purpose of functional rather than leisure travel) is declining [2] , [3] . Given that transport is normally a necessity of everyday life, whereas leisure exercise such as going to a gym may be an additional burden, and is difficult to sustain long term, [4] , [5] encouraging ‘active travel’ may be a feasible approach to increasing levels of physical activity [6] . It is therefore plausible to assume that interventions aimed at increasing the amount of active travel within a population may have a positive impact on health. This has been the underlying rationale for recent public health interest in transport interventions aiming to address the obesity epidemic and a range of other health and social problems [7] ; for example, “For most people, the easiest and most acceptable forms of physical activity are those that can be incorporated into everyday life. Examples include walking or cycling instead of travelling by car, bus or train” [8] . Active travel is seen by policy makers and practitioners as not only an important part of the solution to obesity, but also for achieving a range of other health and social goals, including reducing traffic congestion and carbon emissions [9] .

It has been recommended that the public health community should advocate effective policies that reduce car use and increase active travel [10] . One recent overview concluded that active travel policies have the potential to generate large population health benefits through increasing population physical activity levels, and smaller health benefits through reductions in exposures to air pollution in the general population [6] . However, while a systematic review [11] has found that non-vigorous physical activity reduces all-cause mortality, the two studies which looked at active commuting alone [12] , [13] found no evidence of a positive effect. There are a number of reasons why active travel may not contribute to overall physical activity levels. Some studies of young children have found no differences in overall physical activity levels for active and non-active commuters [14] , [15] , [16] , perhaps because the distance walked to school may simply be too short to make a significant contribution. For both children and adults, it is unclear how far individuals may offset the extra effort of cycling or walking with additional food intake, or by reducing physical activity in other areas of everyday life. Additionally, there is evidence that the health benefits of exercise are not shared equally across populations, with the cultural and psychological meanings of activities such as walking or cycling potentially influencing their physiological effects [17] , [18] .

A reliable overview of the strength of the scientific evidence is therefore needed because the causal pathways between active travel and health outcomes such as obesity are likely to be complex, and promoting active travel may have unintended adverse consequences [19] , for example by reducing leisure activity.

Existing studies show a mixed picture on the relationship between active travel and health outcomes including obesity [20] . Recent systematic reviews have focussed almost exclusively on cross-sectional studies [20] , [22] , [23] , or one narrow health outcome [24] or on combined leisure and transport activity [25] . Obesity is a particular focus because the rise in the prevalence of obesity over the past 30–40 years has occurred in tandem with the decline of active travel, and overweight and obesity are now the fifth leading risk for death globally as well as being responsible for significant proportions of the disease burden of diabetes (44%), ischaemic heart disease (23%) and some cancers (7–41%) [21] .

Given the widespread promotion of active travel for reducing obesity in particular, and improving the public health in general, it is perhaps surprising that is, to date, no clear evidence on its effectiveness. To address this gap, a systematic review of evidence from empirical studies was carried out with the objective of assessing the health effects of active travel specifically (rather than of physical activity in general, where the evidence is already well-established). This review was undertaken to identify and synthesise the relevant empirical evidence from intervention studies and cohort studies in which health outcomes of active travel have been purposively or opportunistically measured to assess the impact of active travel on obesity and other health outcomes.

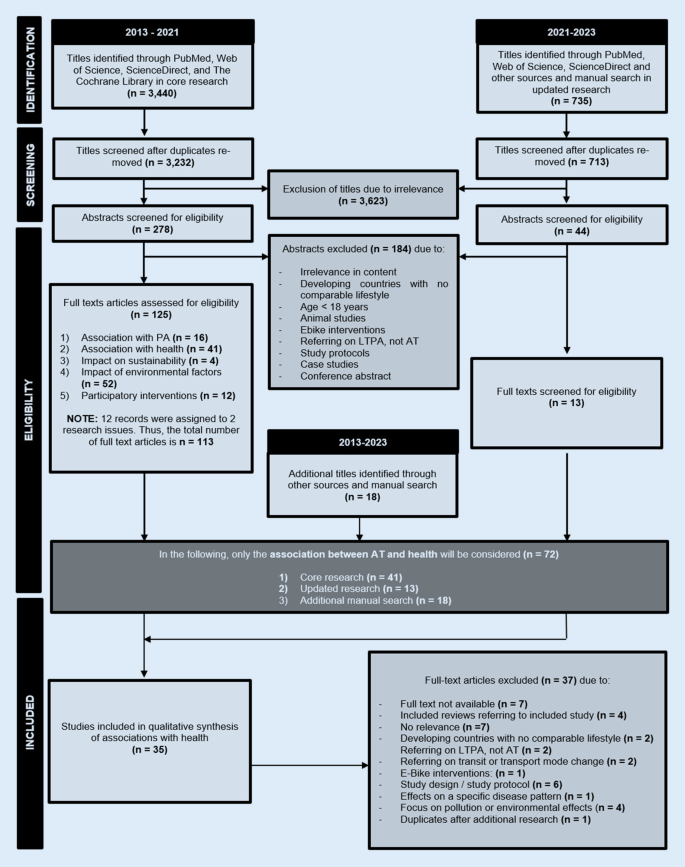

Eleven databases were searched for prospective and intervention studies of any design (Cochrane Library, CINAHL Plus, Embase, Global Health, Google Scholar, IBSS, Medline, PsychInfo, Social Policy and Practice, TRIS/TRID, Web of science – full details in Table 1 ). The review protocol is available on request from the authors. The search strategy adapted the search terms developed by Hoskings et al. [26] (2010 Cochrane Review) and Bunn et al. [27] (2003) to create a master search strategy for Medline (see Appendix S3 ) which was then adapted as needed to fit each database (The exact search strategy used in each database is available from the corresponding author). No time, topic or language exclusions or limits were applied. Hand-searching of relevant studies was also conducted, and bibliographies of identified papers were checked along with those of papers already known to the researchers. The PRISMA flow chart, PRISMA checklist and search strategy are included in Appendices S1, S2, and S3 respectively.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912.t001

Two reviewers independently identified potentially relevant prospective studies. If it was not clear from the title and abstract whether the article was relevant to active travel, then the paper was reviewed in detail. Non-English language studies were eligible for inclusion, though no relevant studies were identified. One reviewer then screened the articles using the following inclusion criteria:

- Prospective study examining relationship between active travel and health outcomes; or study evaluating the effect of an active travel intervention; and

- Active travel (walking or cycling for transport rather than work or leisure) measured in a healthy population (e.g. using self report measures, or use of pedometers); and

- Health outcome included.

Retrospective and single cross-sectional studies (e.g. one-off surveys) were excluded.

One reviewer extracted data including information on methods, outcomes (as adjusted relative risks, or hazard ratios; if these were not available or calculable, other effect measures were extracted – e.g. mean changes), populations and setting for each study. The quality assessment was conducted using a standardized evaluation framework, the ‘Evaluation of Public Health Practice Projects Quality Assessment Tool’ (EPHPP) al. [28] [29] . Two reviewers independently reviewed each study and discussed any differences to produce consensus scores for each study against each quality criterion (see Table 4 ).

Twenty-four studies reported in thirty-one papers were included (see Tables 2 and 3 ). Five were prospective cohort studies with obesity-related outcomes, all in children; fifteen were prospective cohort studies with other health outcomes; and five were intervention studies with other health outcomes (details of excluded studies available on request from the authors). For the prospective cohort studies the results are presented adjusted for covariates. There was variation in what adjustments were made by different studies but the adjustments did not have large impacts on effect size. Details of the methodological assessment of each paper are included in Table 4 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912.t002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912.t003

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912.t004

1. Studies in adults

Eighteen studies in adults were identified; five intervention studies and thirteen prospective cohort studies.

1.1 Intervention studies.

The intervention studies included adults in north-west Europe and measured multiple health outcomes including fitness, blood pressure, cholesterol, oxygen uptake, and body weight [30] , [31] , [32] , [33] , [34] , [35] , [36] ; none measured obesity directly. Three studies found improvements in fitness measures in the intervention group compared with the control group [30] , [33] , [35] , [36] , one found increased physical activity levels [31] , [32] , [37] but one did not [35] , [36] , two found no significant change in body weight [31] , [32] , [35] , [36] and one found significantly higher scores for 3 of the 8 domains of the SF-36 in the intervention group [34] . All these studies were at risk of selection bias and none reported baseline differences between intervention and control groups for potential confounders [30] , [31] , [32] , [33] , [34] , [35] , [36] , [37] . However, all five studies were rated moderately overall. All but one [30] were controlled with appropriate statistical analyses. All but one [34] had low levels of drop-out and ensured that the intervention was consistently applied.

1.2. Prospective Cohort Studies.

The 13 prospective cohort studies of adults (described below) [12] , [13] , [38] , [39] , [40] , [41] , [42] , [43] , [44] , [45] , [46] , [47] , [48] , [49] , [50] , [51] covered a range of health outcomes. Eight were conducted in Scandinavia [12] , [38] , [39] , [40] , [42] , [43] , [44] , [45] , [46] , [47] . This may reflect the longer history of higher population levels of active travel, as a result of which questions on active travel have been included in population surveys over recent decades. Overall, these studies reported conflicting findings when measuring similar mortality and cardiovascular outcomes, with the exception of diabetes where the 2 studies both found statistically significant positive results for active travellers compared with non-active travellers and hint at a dose-response relationship [43] [52] .

Five studies investigated all cause mortality. One study in Denmark [38] found a significantly lower all-cause risk of mortality in cycle-commuters compared with non-cyclists - this was not found in a second such study in Finland [12] . Batty et al. (2001) [13] also found no statistically significant differences for 12 mortality endpoints between men in London, UK who actively travelled more or less than 20 minutes on their journey to work. Matthews et al. (2007) [48] studied women in China and found no significant relationship between walking and cycling for transport and all cause mortality [48] . Besson et al (2008) [53] studied men and women in Norfolk, UK and found a non-significant reduced risk of all cause mortality in those who travelled actively (measured as more than 8 metabolic equivalent task values (MET.h.wk −1 )). None of these studies were rated consistently strong or moderate across all quality criteria. However they did all measure different levels of active travel among participants, which was a strength.

Five studies reported on cardiovascular outcomes. Besson et al.(2008) [53] found no significant reduction in cardiovascular mortality risk among active travellers whereas Barengo (2004) [12] in Finland found it to be significantly lower (adjusted hazard ratio 0.78 [CI: 0.62–0.97]) only among women actively travelling 15–29 minutes each way to work compared with those travelling less than 15 minutes each way but not in those travelling more than 30 minutes each way, and not in men. Hu et al (2005, 2007, 2007) [42] , [44] , [45] , also measured Coronary Heart Disease and found a significant relationship in women who travelled 30+ minutes per day (0.80 [CI:0.69–0.92]) compared with those who did not travel actively at all. Like Barengo (2004) [12] , they found no relationship between active travel and Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) in men. Barengo (2005) [39] found no difference in hypertension risk between those travelling more or less than 15 minutes each way to work. Hayashi et al. (1999) [41] found a statistically significant reduced risk of hypertension in those men in Osaka, Japan who walked 21 minutes or more to work compared with men who walked less than 10 minutes (adjusted relative risk 0.70 [CI: 0.59–0.95]). However, it was not clear from either of these papers how frequently the active travellers walked to work. Wagner et al. (2001, 2002, 2003) [49] , [50] , [51] found a statistically non-significant increase in risk of CHD events in men walking and cycling to work, although the amount of exercise taken while actively commuting was not recorded.

Four studies examined health outcomes other than all cause mortality or cardiovascular disease. Two studies found significant benefits of active travel for reducing diabetes risk. A study in Japan by Sato et al found a 27% reduced odds of type 2 diabetes among men who walked more than 21 minutes to work compared with those who walked less than 10 minutes (CI:0.58–0.92) [52] . A study in Finland [43] found the relative risk for Type 2 diabetes to be 34% lower among active travellers travelling 30 minutes or more per day compared with those not travelling actively (CI: 0.45–0.92). Luoto et al. 2000 [47] reported a non-significant reduction in relative breast cancer risk at 15 years follow-up of 0.87 (CI: 0.62–1.24) in women who actively travelled more than 30 minutes each day. Moayyeri et al. (2010) found no significant association between active travel and bone strength and fracture risk, but the numbers of study participants who travelled actively were extremely small [54] .

2. Studies in children

No intervention studies in children were identified. Four prospective cohort studies were identified with obesity outcomes and two with other health outcomes.

2.1 Obesity.

One prospective cohort study measured the BMI of children aged 13 and again two years later in the Netherlands and Norway [55] . This study found that those children who continued to cycle to school throughout the study period were less likely (OR 0.44, 95% confidence interval 0.21,0.88) to be overweight than those who did not cycle to school, those who took up cycling and those who stopped cycling to school. Also those who stopped cycling to school during the study were more likely to be overweight than the other groups combined (OR 3.19, 95% confidence interval 1.41, 7.24). However the authors acknowledged that there were some limitations to this study including uncontrolled confounding variables and a relatively high dropout of 56% of participants between baseline and follow-up measurements. A study in Denmark and Sweden with six year follow-up of children from aged nine found no significant association between the obesity measures (BMI, skin-folds and waist circumference) and travel mode [56] [29] . Three other prospective cohort studies with obesity outcomes were all conducted in North America and included children aged ten years or younger at baseline who were followed up for between six months and two years [57] , [58] , [59] . BMI measurements were taken in all three studies and skinfold measurements were taken in two of the studies. There was no significant association between active travel and the obesity outcome measures in any of the studies. All three studies were rated low on the quality assessment measure as no data on baseline differences between groups were presented.

2.2 Other health outcomes.

Two studies examined health outcomes other than obesity. One study conducted in Denmark and Sweden found that children who cycled to school in Denmark had significantly better cardio-respiratory fitness [40] and cardiovascular risk markers than those who did not [56] . This study took a range of measures of school children aged 9 and repeated the measurements after six years. In Sweden, children who cycled to school increased their fitness 13% more than those who used passive modes and 20% more than those who walked during the six year period. Children who took up cycling during the follow up period increased their fitness by 14% compared with those who did no t [29] . However, no significant association between travel mode to school and cardiovascular risk factors was found in the Swedish arm of the study. Interestingly, the Danish arm of the study found that walkers had the same fitness levels as those who travelled by ‘passive’ modes [56] . While the study scored moderately well for selection bias (76% participation in Denmark), drop out from this study was 60% in Sweden and 43% in Denmark. This study, as was the case for many of the prospective cohort studies, may have been at risk of contamination or co-intervention as monitoring during the follow-up period was not reported. Lofgren et al. (2010) [46] also studied children actively travelling to school in Malmö, Sweden and measured a range of bone health indicators but found no significant relationship. This study scored relatively well in the quality assessment, with good controlling of confounders and high participation levels, although as with all the prospective cohort studies scored weak on study design.

This is the first review to bring together all prospective observational and intervention studies to give an overview of the evidence on health effects of active travel in general. Previous systematic reviews of health outcomes of active travel have included primarily cross-sectional studies from which reliable inferences about causality cannot easily be drawn, or have relied on indirect evidence on the effects of physical activity on health, as opposed to the effects of active travel. Although we found no prospective studies of active travel with obesity as a primary outcome in adults, and no significant associations between obesity and active travel in studies which included children, for other health outcomes small positive health effects were found in groups who actively travelled longer distances including reductions in risk of all cause mortality [38] , hypertension [41] , and in particular Type 2 diabetes [43] , [52] .

One challenge to synthesising and using this evidence is that “active travel” is not defined consistently across studies, and the definition is dependent on what is considered normal in a particular setting. For example Luoto (2000) [47] , and Barengo (2004, 2005) [12] , [39] considered active travel to be more than 30 minutes per day and inactive travel to be less than 30 minutes per day. Batty (2001) [13] , Sato (2007) [52] and Hayashi (1999) [41] however considered active travel to be more than 20 minutes per day. Differences in health outcomes between people who actively travel 29 minutes per day and those who travel 31 minutes per day are unlikely, so differences between active and sedentary populations may be masked by the methods by which active travel is defined and reported. Meanwhile Besson (2008) [53] and Moayyeri (2010) [54] considered active travel to be more than 8 metabolic equivalent task (MET) hours per week while Matthews (2007) [48] considered it to be more than 3.5 metabolic equivalent task hours per day which may reflect differences in norms between UK and China in terms of active travel.

In light of this, users of the findings of this and similar reviews need to consider the extent to which we can generalise between studies conducted in different countries or settings. In particular, the amount of exertion required to travel actively may be greater in some settings than others for the same journey time, due to differences in congestion, terrain and climate. In countries where current levels of physical activity are low (such as the UK, where only 39% of men and 29% of women achieve 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity of any type five times a week [60] [61] ) adding 30 minutes of active travel per day might well produce much larger changes in health at a population level than were measured in non-UK studies. The prospective cohort studies also tended to focus on travel to work or school rather than active travel for general transportation, which again may limit generalisability.

The study by Cooper et al. (2008) [40] of school children in Odense, Denmark found that 65% of boys and girls walked or cycled to school, a much higher proportion than is currently found in the UK. However, journey times were less than 15 minutes for the majority of active travellers so the health effects of active travel for such short periods are difficult to measure in isolation. This highlights one of the difficulties of assuming active travel to school in young people to be a major source of physical activity, as it is common for children only to walk or cycle to school when the journey time is relatively short. In adults as little as 10 minutes of physical activity are acceptable to contribute to their weekly physical activity target of minimum 150 minutes. However children aged five – 18 are expected to be physically active for a minimum of 420 minutes per week [8] so a short active commute to school will not make a significant contribution to their overall physical activity requirements. The study by Lofgren et al. [46] included a study population with fairly high levels of physical activity overall and half the participants were active travellers, which makes it difficult to attribute health outcomes to active travel alone, as active travel may not contribute significantly to participants overall physical activity levels.

De Geus et al. (2007) [30] highlighted one of the difficulties of measuring active travel in intervention studies as they found that study participants cycled 13% faster when their fitness was being measured compared to their usual speed on their daily cycle commute. The process of measuring active travel can therefore result in an over-estimate of the health benefits conferred by active travel. It is also not clear whether levels of active travel impact on levels of other types of physical activity such as sport and leisure. This relationship has been explored by, among others, Dombois et al who found no relationship between levels of sports activity and mode of travel in adults in the Swiss Alps [62] , and also by Santos et al who found a more complex relationship between different types of activity in children in Portugal [63] . Thus issues including type of terrain, problems of definition, study design and the difficulty of disentangling the effects of active travel from more general physical activity make synthesis difficult.

There is a particular challenge in measuring health outcomes in children because some health outcomes relating to physical activity can take many years to develop. For example an intervention study by Sirard et al. involving children in the USA measured moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) in a randomised controlled trial with 12 participants and a two week duration [37] . However, it could not be included in this review because it did not measure a health outcome.

This review also highlights the difficulty in measuring health outcomes of active travel in the general population. In prospective cohort studies if the follow-up period is short then it may not be possible to measure health effects that take many years to appear. Conversely in those studies which do have long follow-up periods of many years there is the risk that active travel has not been consistently adhered to throughout the follow up period.

The likelihood of health outcomes will depend on the context within which individuals are travelling – length of journey, frequency of travel, nature of the terrain, risk of injury, levels of air pollution and so on as well as other aspects of the lifestyles of the participants. For example travelling actively may mean that the individual is more or less likely to be physically active at other times, or they may modify their diet. It may mean that they are more or less likely to strengthen social networks. It is also important to note that active travel not only potentially benefits health by way of physical activity but may also off-set air pollution from motorised vehicles and contribute to social and environmental goals such as improving social cohesion and reducing CO 2 emissions. These combined benefits are a potent argument for promoting active travel, and emphasise the importance of models which incorporate both health and non-health benefits [64] , [65] such as carbon dioxide emissions.

Finally, designing searches which are both sensitive and specific is a challenge for public health systematic reviews. It is interesting to note that over 70% of the studies we identified were initially found through hand-searching, although some subsequently appeared in the database searches, which highlights the importance of a broad search not confined to electronic sources. While it is possible that studies may have been missed, our comprehensive search for studies makes it unlikely that a significant body of work has been excluded.

While the studies identified in this review do not enable us to draw strong conclusions about the health effects of active travel, this systematic review of intervention and prospective studies found consistent support for the positive effects on health of active travel over longer periods and perhaps distances, and it is of interest that there is some evidence that active travel may reduce risk of diabetes. This may be an important area for future research.

These cautious conclusions on the health impact of active travel do not, of course, mean that now is the time to confine active travel to the walk from the front door to the car door. The evidence on the effect of physical activity is sufficiently strong to suggest that the part played by active travel is well worth maintaining. Other aspects of active travel, including a reduction in pollution, and in carbon footprint are clear potential co-benefits and likely to become even more so.

Supporting Information

Appendix s1..

PRISMA flowchart.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912.s001

Appendix S2.

PRISMA checklist.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912.s002

Appendix S3.

Search strategy.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912.s003

Acknowledgments

We thank the other members of the project team (Phil Edwards, Paul Wilkinson, Alasdair Jones, Anna Goodman, John Nellthorpe and Charlotte Kelly) for their advice.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: LS JG MP RS HR. Performed the experiments: LS JG MP RS HR. Analyzed the data: LS JG MP RS HR. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: LS JG MP RS HR. Wrote the paper: LS JG MP RS HR.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 7. Wanless D, Treasury H (2004) Securing good health for the whole population: final report. London: HM Treasury. 1–222 p.

- 8. Department of Health (2011) Start active, stay active: A report on physical activity from the four home countries' Chief Medical Officers. Department of Health, Physical Activity, Health Improvement and Protection.

- 21. World Health Organization (2011) Obesity and overweight.

- 28. Effective Public Health Practice Project (2009) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies.

- 60. Health Survey for England (2009) Health Survey for England 2008. The Health and Social Care Information Centre.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

What Are the Health Benefits of Active Travel? A Systematic Review of Trials and Cohort Studies

Lucinda e. saunders.

1 Faculty of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom

Judith M. Green

Mark p. petticrew, rebecca steinbach, helen roberts.

2 General and Adolescent Paediatrics Unit, UCL Institute of Child Health, London, United Kingdom

Conceived and designed the experiments: LS JG MP RS HR. Performed the experiments: LS JG MP RS HR. Analyzed the data: LS JG MP RS HR. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: LS JG MP RS HR. Wrote the paper: LS JG MP RS HR.

Associated Data

Increasing active travel (primarily walking and cycling) has been widely advocated for reducing obesity levels and achieving other population health benefits. However, the strength of evidence underpinning this strategy is unclear. This study aimed to assess the evidence that active travel has significant health benefits.

The study design was a systematic review of (i) non-randomised and randomised controlled trials, and (ii) prospective observational studies examining either (a) the effects of interventions to promote active travel or (b) the association between active travel and health outcomes. Reports of studies were identified by searching 11 electronic databases, websites, reference lists and papers identified by experts in the field. Prospective observational and intervention studies measuring any health outcome of active travel in the general population were included. Studies of patient groups were excluded.

Twenty-four studies from 12 countries were included, of which six were studies conducted with children. Five studies evaluated active travel interventions. Nineteen were prospective cohort studies which did not evaluate the impact of a specific intervention. No studies were identified with obesity as an outcome in adults; one of five prospective cohort studies in children found an association between obesity and active travel. Small positive effects on other health outcomes were found in five intervention studies, but these were all at risk of selection bias. Modest benefits for other health outcomes were identified in five prospective studies. There is suggestive evidence that active travel may have a positive effect on diabetes prevention, which may be an important area for future research.

Conclusions

Active travel may have positive effects on health outcomes, but there is little robust evidence to date of the effectiveness of active transport interventions for reducing obesity. Future evaluations of such interventions should include an assessment of their impacts on obesity and other health outcomes.

The link between physical activity and health has long been known, with the scientific link established in Jerry Morris' seminal study of London bus drivers in the 1950s [1] . There is also good ecological evidence that obesity rates are increasing in countries and settings in which ‘active travel’ (primarily walking and cycling for the purpose of functional rather than leisure travel) is declining [2] , [3] . Given that transport is normally a necessity of everyday life, whereas leisure exercise such as going to a gym may be an additional burden, and is difficult to sustain long term, [4] , [5] encouraging ‘active travel’ may be a feasible approach to increasing levels of physical activity [6] . It is therefore plausible to assume that interventions aimed at increasing the amount of active travel within a population may have a positive impact on health. This has been the underlying rationale for recent public health interest in transport interventions aiming to address the obesity epidemic and a range of other health and social problems [7] ; for example, “For most people, the easiest and most acceptable forms of physical activity are those that can be incorporated into everyday life. Examples include walking or cycling instead of travelling by car, bus or train” [8] . Active travel is seen by policy makers and practitioners as not only an important part of the solution to obesity, but also for achieving a range of other health and social goals, including reducing traffic congestion and carbon emissions [9] .

It has been recommended that the public health community should advocate effective policies that reduce car use and increase active travel [10] . One recent overview concluded that active travel policies have the potential to generate large population health benefits through increasing population physical activity levels, and smaller health benefits through reductions in exposures to air pollution in the general population [6] . However, while a systematic review [11] has found that non-vigorous physical activity reduces all-cause mortality, the two studies which looked at active commuting alone [12] , [13] found no evidence of a positive effect. There are a number of reasons why active travel may not contribute to overall physical activity levels. Some studies of young children have found no differences in overall physical activity levels for active and non-active commuters [14] , [15] , [16] , perhaps because the distance walked to school may simply be too short to make a significant contribution. For both children and adults, it is unclear how far individuals may offset the extra effort of cycling or walking with additional food intake, or by reducing physical activity in other areas of everyday life. Additionally, there is evidence that the health benefits of exercise are not shared equally across populations, with the cultural and psychological meanings of activities such as walking or cycling potentially influencing their physiological effects [17] , [18] .

A reliable overview of the strength of the scientific evidence is therefore needed because the causal pathways between active travel and health outcomes such as obesity are likely to be complex, and promoting active travel may have unintended adverse consequences [19] , for example by reducing leisure activity.

Existing studies show a mixed picture on the relationship between active travel and health outcomes including obesity [20] . Recent systematic reviews have focussed almost exclusively on cross-sectional studies [20] , [22] , [23] , or one narrow health outcome [24] or on combined leisure and transport activity [25] . Obesity is a particular focus because the rise in the prevalence of obesity over the past 30–40 years has occurred in tandem with the decline of active travel, and overweight and obesity are now the fifth leading risk for death globally as well as being responsible for significant proportions of the disease burden of diabetes (44%), ischaemic heart disease (23%) and some cancers (7–41%) [21] .

Given the widespread promotion of active travel for reducing obesity in particular, and improving the public health in general, it is perhaps surprising that is, to date, no clear evidence on its effectiveness. To address this gap, a systematic review of evidence from empirical studies was carried out with the objective of assessing the health effects of active travel specifically (rather than of physical activity in general, where the evidence is already well-established). This review was undertaken to identify and synthesise the relevant empirical evidence from intervention studies and cohort studies in which health outcomes of active travel have been purposively or opportunistically measured to assess the impact of active travel on obesity and other health outcomes.

Eleven databases were searched for prospective and intervention studies of any design (Cochrane Library, CINAHL Plus, Embase, Global Health, Google Scholar, IBSS, Medline, PsychInfo, Social Policy and Practice, TRIS/TRID, Web of science – full details in Table 1 ). The review protocol is available on request from the authors. The search strategy adapted the search terms developed by Hoskings et al. [26] (2010 Cochrane Review) and Bunn et al. [27] (2003) to create a master search strategy for Medline (see Appendix S3 ) which was then adapted as needed to fit each database (The exact search strategy used in each database is available from the corresponding author). No time, topic or language exclusions or limits were applied. Hand-searching of relevant studies was also conducted, and bibliographies of identified papers were checked along with those of papers already known to the researchers. The PRISMA flow chart, PRISMA checklist and search strategy are included in Appendices S1, S2, and S3 respectively.

Two reviewers independently identified potentially relevant prospective studies. If it was not clear from the title and abstract whether the article was relevant to active travel, then the paper was reviewed in detail. Non-English language studies were eligible for inclusion, though no relevant studies were identified. One reviewer then screened the articles using the following inclusion criteria:

- Prospective study examining relationship between active travel and health outcomes; or study evaluating the effect of an active travel intervention; and

- Active travel (walking or cycling for transport rather than work or leisure) measured in a healthy population (e.g. using self report measures, or use of pedometers); and

- Health outcome included.

Retrospective and single cross-sectional studies (e.g. one-off surveys) were excluded.

One reviewer extracted data including information on methods, outcomes (as adjusted relative risks, or hazard ratios; if these were not available or calculable, other effect measures were extracted – e.g. mean changes), populations and setting for each study. The quality assessment was conducted using a standardized evaluation framework, the ‘Evaluation of Public Health Practice Projects Quality Assessment Tool’ (EPHPP) al. [28] [29] . Two reviewers independently reviewed each study and discussed any differences to produce consensus scores for each study against each quality criterion (see Table 4 ).

Twenty-four studies reported in thirty-one papers were included (see Tables 2 and and3). 3 ). Five were prospective cohort studies with obesity-related outcomes, all in children; fifteen were prospective cohort studies with other health outcomes; and five were intervention studies with other health outcomes (details of excluded studies available on request from the authors). For the prospective cohort studies the results are presented adjusted for covariates. There was variation in what adjustments were made by different studies but the adjustments did not have large impacts on effect size. Details of the methodological assessment of each paper are included in Table 4 .

1. Studies in adults

Eighteen studies in adults were identified; five intervention studies and thirteen prospective cohort studies.

1.1 Intervention studies

The intervention studies included adults in north-west Europe and measured multiple health outcomes including fitness, blood pressure, cholesterol, oxygen uptake, and body weight [30] , [31] , [32] , [33] , [34] , [35] , [36] ; none measured obesity directly. Three studies found improvements in fitness measures in the intervention group compared with the control group [30] , [33] , [35] , [36] , one found increased physical activity levels [31] , [32] , [37] but one did not [35] , [36] , two found no significant change in body weight [31] , [32] , [35] , [36] and one found significantly higher scores for 3 of the 8 domains of the SF-36 in the intervention group [34] . All these studies were at risk of selection bias and none reported baseline differences between intervention and control groups for potential confounders [30] , [31] , [32] , [33] , [34] , [35] , [36] , [37] . However, all five studies were rated moderately overall. All but one [30] were controlled with appropriate statistical analyses. All but one [34] had low levels of drop-out and ensured that the intervention was consistently applied.

1.2. Prospective Cohort Studies

The 13 prospective cohort studies of adults (described below) [12] , [13] , [38] , [39] , [40] , [41] , [42] , [43] , [44] , [45] , [46] , [47] , [48] , [49] , [50] , [51] covered a range of health outcomes. Eight were conducted in Scandinavia [12] , [38] , [39] , [40] , [42] , [43] , [44] , [45] , [46] , [47] . This may reflect the longer history of higher population levels of active travel, as a result of which questions on active travel have been included in population surveys over recent decades. Overall, these studies reported conflicting findings when measuring similar mortality and cardiovascular outcomes, with the exception of diabetes where the 2 studies both found statistically significant positive results for active travellers compared with non-active travellers and hint at a dose-response relationship [43] [52] .

Five studies investigated all cause mortality. One study in Denmark [38] found a significantly lower all-cause risk of mortality in cycle-commuters compared with non-cyclists - this was not found in a second such study in Finland [12] . Batty et al. (2001) [13] also found no statistically significant differences for 12 mortality endpoints between men in London, UK who actively travelled more or less than 20 minutes on their journey to work. Matthews et al. (2007) [48] studied women in China and found no significant relationship between walking and cycling for transport and all cause mortality [48] . Besson et al (2008) [53] studied men and women in Norfolk, UK and found a non-significant reduced risk of all cause mortality in those who travelled actively (measured as more than 8 metabolic equivalent task values (MET.h.wk −1 )). None of these studies were rated consistently strong or moderate across all quality criteria. However they did all measure different levels of active travel among participants, which was a strength.

Five studies reported on cardiovascular outcomes. Besson et al.(2008) [53] found no significant reduction in cardiovascular mortality risk among active travellers whereas Barengo (2004) [12] in Finland found it to be significantly lower (adjusted hazard ratio 0.78 [CI: 0.62–0.97]) only among women actively travelling 15–29 minutes each way to work compared with those travelling less than 15 minutes each way but not in those travelling more than 30 minutes each way, and not in men. Hu et al (2005, 2007, 2007) [42] , [44] , [45] , also measured Coronary Heart Disease and found a significant relationship in women who travelled 30+ minutes per day (0.80 [CI:0.69–0.92]) compared with those who did not travel actively at all. Like Barengo (2004) [12] , they found no relationship between active travel and Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) in men. Barengo (2005) [39] found no difference in hypertension risk between those travelling more or less than 15 minutes each way to work. Hayashi et al. (1999) [41] found a statistically significant reduced risk of hypertension in those men in Osaka, Japan who walked 21 minutes or more to work compared with men who walked less than 10 minutes (adjusted relative risk 0.70 [CI: 0.59–0.95]). However, it was not clear from either of these papers how frequently the active travellers walked to work. Wagner et al. (2001, 2002, 2003) [49] , [50] , [51] found a statistically non-significant increase in risk of CHD events in men walking and cycling to work, although the amount of exercise taken while actively commuting was not recorded.

Four studies examined health outcomes other than all cause mortality or cardiovascular disease. Two studies found significant benefits of active travel for reducing diabetes risk. A study in Japan by Sato et al found a 27% reduced odds of type 2 diabetes among men who walked more than 21 minutes to work compared with those who walked less than 10 minutes (CI:0.58–0.92) [52] . A study in Finland [43] found the relative risk for Type 2 diabetes to be 34% lower among active travellers travelling 30 minutes or more per day compared with those not travelling actively (CI: 0.45–0.92). Luoto et al. 2000 [47] reported a non-significant reduction in relative breast cancer risk at 15 years follow-up of 0.87 (CI: 0.62–1.24) in women who actively travelled more than 30 minutes each day. Moayyeri et al. (2010) found no significant association between active travel and bone strength and fracture risk, but the numbers of study participants who travelled actively were extremely small [54] .

2. Studies in children

No intervention studies in children were identified. Four prospective cohort studies were identified with obesity outcomes and two with other health outcomes.

2.1 Obesity

One prospective cohort study measured the BMI of children aged 13 and again two years later in the Netherlands and Norway [55] . This study found that those children who continued to cycle to school throughout the study period were less likely (OR 0.44, 95% confidence interval 0.21,0.88) to be overweight than those who did not cycle to school, those who took up cycling and those who stopped cycling to school. Also those who stopped cycling to school during the study were more likely to be overweight than the other groups combined (OR 3.19, 95% confidence interval 1.41, 7.24). However the authors acknowledged that there were some limitations to this study including uncontrolled confounding variables and a relatively high dropout of 56% of participants between baseline and follow-up measurements. A study in Denmark and Sweden with six year follow-up of children from aged nine found no significant association between the obesity measures (BMI, skin-folds and waist circumference) and travel mode [56] [29] . Three other prospective cohort studies with obesity outcomes were all conducted in North America and included children aged ten years or younger at baseline who were followed up for between six months and two years [57] , [58] , [59] . BMI measurements were taken in all three studies and skinfold measurements were taken in two of the studies. There was no significant association between active travel and the obesity outcome measures in any of the studies. All three studies were rated low on the quality assessment measure as no data on baseline differences between groups were presented.

2.2 Other health outcomes

Two studies examined health outcomes other than obesity. One study conducted in Denmark and Sweden found that children who cycled to school in Denmark had significantly better cardio-respiratory fitness [40] and cardiovascular risk markers than those who did not [56] . This study took a range of measures of school children aged 9 and repeated the measurements after six years. In Sweden, children who cycled to school increased their fitness 13% more than those who used passive modes and 20% more than those who walked during the six year period. Children who took up cycling during the follow up period increased their fitness by 14% compared with those who did no t [29] . However, no significant association between travel mode to school and cardiovascular risk factors was found in the Swedish arm of the study. Interestingly, the Danish arm of the study found that walkers had the same fitness levels as those who travelled by ‘passive’ modes [56] . While the study scored moderately well for selection bias (76% participation in Denmark), drop out from this study was 60% in Sweden and 43% in Denmark. This study, as was the case for many of the prospective cohort studies, may have been at risk of contamination or co-intervention as monitoring during the follow-up period was not reported. Lofgren et al. (2010) [46] also studied children actively travelling to school in Malmö, Sweden and measured a range of bone health indicators but found no significant relationship. This study scored relatively well in the quality assessment, with good controlling of confounders and high participation levels, although as with all the prospective cohort studies scored weak on study design.

This is the first review to bring together all prospective observational and intervention studies to give an overview of the evidence on health effects of active travel in general. Previous systematic reviews of health outcomes of active travel have included primarily cross-sectional studies from which reliable inferences about causality cannot easily be drawn, or have relied on indirect evidence on the effects of physical activity on health, as opposed to the effects of active travel. Although we found no prospective studies of active travel with obesity as a primary outcome in adults, and no significant associations between obesity and active travel in studies which included children, for other health outcomes small positive health effects were found in groups who actively travelled longer distances including reductions in risk of all cause mortality [38] , hypertension [41] , and in particular Type 2 diabetes [43] , [52] .

One challenge to synthesising and using this evidence is that “active travel” is not defined consistently across studies, and the definition is dependent on what is considered normal in a particular setting. For example Luoto (2000) [47] , and Barengo (2004, 2005) [12] , [39] considered active travel to be more than 30 minutes per day and inactive travel to be less than 30 minutes per day. Batty (2001) [13] , Sato (2007) [52] and Hayashi (1999) [41] however considered active travel to be more than 20 minutes per day. Differences in health outcomes between people who actively travel 29 minutes per day and those who travel 31 minutes per day are unlikely, so differences between active and sedentary populations may be masked by the methods by which active travel is defined and reported. Meanwhile Besson (2008) [53] and Moayyeri (2010) [54] considered active travel to be more than 8 metabolic equivalent task (MET) hours per week while Matthews (2007) [48] considered it to be more than 3.5 metabolic equivalent task hours per day which may reflect differences in norms between UK and China in terms of active travel.

In light of this, users of the findings of this and similar reviews need to consider the extent to which we can generalise between studies conducted in different countries or settings. In particular, the amount of exertion required to travel actively may be greater in some settings than others for the same journey time, due to differences in congestion, terrain and climate. In countries where current levels of physical activity are low (such as the UK, where only 39% of men and 29% of women achieve 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity of any type five times a week [60] [61] ) adding 30 minutes of active travel per day might well produce much larger changes in health at a population level than were measured in non-UK studies. The prospective cohort studies also tended to focus on travel to work or school rather than active travel for general transportation, which again may limit generalisability.

The study by Cooper et al. (2008) [40] of school children in Odense, Denmark found that 65% of boys and girls walked or cycled to school, a much higher proportion than is currently found in the UK. However, journey times were less than 15 minutes for the majority of active travellers so the health effects of active travel for such short periods are difficult to measure in isolation. This highlights one of the difficulties of assuming active travel to school in young people to be a major source of physical activity, as it is common for children only to walk or cycle to school when the journey time is relatively short. In adults as little as 10 minutes of physical activity are acceptable to contribute to their weekly physical activity target of minimum 150 minutes. However children aged five – 18 are expected to be physically active for a minimum of 420 minutes per week [8] so a short active commute to school will not make a significant contribution to their overall physical activity requirements. The study by Lofgren et al. [46] included a study population with fairly high levels of physical activity overall and half the participants were active travellers, which makes it difficult to attribute health outcomes to active travel alone, as active travel may not contribute significantly to participants overall physical activity levels.

De Geus et al. (2007) [30] highlighted one of the difficulties of measuring active travel in intervention studies as they found that study participants cycled 13% faster when their fitness was being measured compared to their usual speed on their daily cycle commute. The process of measuring active travel can therefore result in an over-estimate of the health benefits conferred by active travel. It is also not clear whether levels of active travel impact on levels of other types of physical activity such as sport and leisure. This relationship has been explored by, among others, Dombois et al who found no relationship between levels of sports activity and mode of travel in adults in the Swiss Alps [62] , and also by Santos et al who found a more complex relationship between different types of activity in children in Portugal [63] . Thus issues including type of terrain, problems of definition, study design and the difficulty of disentangling the effects of active travel from more general physical activity make synthesis difficult.

There is a particular challenge in measuring health outcomes in children because some health outcomes relating to physical activity can take many years to develop. For example an intervention study by Sirard et al. involving children in the USA measured moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) in a randomised controlled trial with 12 participants and a two week duration [37] . However, it could not be included in this review because it did not measure a health outcome.

This review also highlights the difficulty in measuring health outcomes of active travel in the general population. In prospective cohort studies if the follow-up period is short then it may not be possible to measure health effects that take many years to appear. Conversely in those studies which do have long follow-up periods of many years there is the risk that active travel has not been consistently adhered to throughout the follow up period.

The likelihood of health outcomes will depend on the context within which individuals are travelling – length of journey, frequency of travel, nature of the terrain, risk of injury, levels of air pollution and so on as well as other aspects of the lifestyles of the participants. For example travelling actively may mean that the individual is more or less likely to be physically active at other times, or they may modify their diet. It may mean that they are more or less likely to strengthen social networks. It is also important to note that active travel not only potentially benefits health by way of physical activity but may also off-set air pollution from motorised vehicles and contribute to social and environmental goals such as improving social cohesion and reducing CO 2 emissions. These combined benefits are a potent argument for promoting active travel, and emphasise the importance of models which incorporate both health and non-health benefits [64] , [65] such as carbon dioxide emissions.

Finally, designing searches which are both sensitive and specific is a challenge for public health systematic reviews. It is interesting to note that over 70% of the studies we identified were initially found through hand-searching, although some subsequently appeared in the database searches, which highlights the importance of a broad search not confined to electronic sources. While it is possible that studies may have been missed, our comprehensive search for studies makes it unlikely that a significant body of work has been excluded.

While the studies identified in this review do not enable us to draw strong conclusions about the health effects of active travel, this systematic review of intervention and prospective studies found consistent support for the positive effects on health of active travel over longer periods and perhaps distances, and it is of interest that there is some evidence that active travel may reduce risk of diabetes. This may be an important area for future research.

These cautious conclusions on the health impact of active travel do not, of course, mean that now is the time to confine active travel to the walk from the front door to the car door. The evidence on the effect of physical activity is sufficiently strong to suggest that the part played by active travel is well worth maintaining. Other aspects of active travel, including a reduction in pollution, and in carbon footprint are clear potential co-benefits and likely to become even more so.

Supporting Information

Appendix s1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Appendix S2

PRISMA checklist.

Appendix S3

Search strategy.

Acknowledgments

We thank the other members of the project team (Phil Edwards, Paul Wilkinson, Alasdair Jones, Anna Goodman, John Nellthorpe and Charlotte Kelly) for their advice.

Funding Statement

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Public Health Research programme (project number 09/3001/13). The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Health. The funders had no role in the design, conduct or reporting of project findings.

- Press Releases

- Images and Media

- At ISPO Munich

- At OutDoor by ISPO

- Press Contact

- Sustainability

- Connective Consultancy

- 50 years of tomorrow

- Advertise on ISPO.com

- Exhibition areas

- List of exhibitors

- Exhibitor statements

- Opening hours

- Directions & Accomodation

- Application

- Participation opportunities

- Services around the trade fair appearance

- Program 2024

- Trader & Exhibitor Statements

- Exhibitor shop

- Directions & Visa

- Exhibitor Manual

- ISPO Academy International conferences and trainings for your edge of knowledge

- Events All events at a glance

- Innovation Labs

- Award Our quality seal for outstanding products

- Judging & Criteria

- Application Process

- Awardees Textrends Fall/Winter

- Awardees ISPO Spring/Summer

- Collaborators Club We connect brands with consumer experts

- Sports Business

- Product Reviews

- Challenges of a CEO

- Heroes and Athletes

- To the newsletter registration

- About All about the ISPO Collaborators Club

- For business members Benefits and successes

Active Travel: How sport is revitalizing tourism

This feature is only available when corresponding consent is given. Please read the details and accept the service to enable rating function.

After the bitter years of the pandemic, the tourism industry is expecting record sales again in 2024. The sports industry can also benefit from this - through partnerships, communities and many other ideas for active vacations.

- Sports Business Green fashion trend: how preloved sportswear is conquering the market

- Sustainability Green change in Europe: What the new rules mean for sport and the outdoors, part 1

- Sustainability 5 fabrics for climate change: stay chilled in the heat with these textiles

- All about Sports Business

All insights at a glance

How partnerships can inspire vacation regions, sweating for rewards, hotels are increasingly adapting to trends and movements.

- Tour of the Alps: Three regions, one destination

Climate change, rising prices, dwindling young talent: Alpine skiing put to the test

The world is becoming entangled in polycrises. As a result, many people are longing for positive personal experiences. Sport and travel are very popular as a balance and distraction from everyday life - especially after the years of privation and isolation caused by the pandemic. Now the opposite is happening: communities are in demand and sport in the community. Many need variety, want to discover new things and experience "once in a lifetime" moments: Adventure trips, caravanning, bikepacking and long-distance hikes are very popular. At the Sports Travel Hub at ISPO Munich 2023, these trends were lectured on and discussed for three days - and the meaningful synergies between the sports industry and tourism were considered. This is because brands can benefit massively from the increasing popularity of combining sport and travel, as consultant Maurici Carbó reports. He expects an average annual growth rate of 17.5% from 2023 to 2030. Europe is the largest market in terms of revenue share with 38%. "People want to actively shape their vacations - whether young or old," says Carbó. We present future-oriented partnerships, show how hotels are adapting to some sports trends and which tourism sectors have a long-term agenda.

Many brands from the endurance sector have recognized how important and essential partnerships are. For the success of the companies themselves, but also for the experience of the community. The US manufacturer of running shoes and running apparel Brooks is a player in the market that doesn't stand still. Otherwise, it would certainly not be able to look back on 110 years of company history today. Brooks has been cooperating with Strava - a fitness tracking app for runners and cyclists - for some time now. The reason is simple. "We monitor around one million active runners every month in the Brooks community alone. That's huge potential," emphasizes Evelina Jarbin, responsible for brand partnerships at Strava. "It is therefore a matter of course for us to be active there and offer something to the athletes," explains Lara Hasagic, Marketing Director (DACH) at Brooks.

The running product manufacturer succeeded in doing just that with the market launch of its Run Visible collection. Via Strava, wildcards gave them the chance to take part in this launch event on the island of Usedom together with over 30 influencers and brand ambassadors from Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Good for the sporting goods manufacturer, as the running-enthusiastic influencers reported on the campaign and the new products on their social media accounts with a wide reach and high visibility. The island of Usedom also benefited from the cooperation, as together with the Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Tourist Board, it was able to present itself as a running paradise and bring the island's diverse charm to life. Engagement with Strava, greater awareness of Brooks and an increase in bed bookings on Usedom - a win-win situation for all three players.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Brooks Running 🇩🇪🇦🇹🇨🇭 (@brooksrunningde)

In the cycling community, Strava partnerships with brands from the clothing industry have been working successfully for many years. Rewards and vouchers are unlocked by uploading activities. The British label Rapha and Maap from Australia began intensifying their community relationship years ago. Cycling for discounts! This even works virtually. True to the motto "Performance pays off", you can have your virtual jersey unlocked using an indoor smart trainer on Zwift and show the community the reward for past efforts. After all, recognition is also important in sport. And just like in the running community , travel regions are now also discovering this partnership potential. "Becoming a Flandrien" is the name of a creative project from Belgium, presented by Dries Verclyte, Product Manager at Visit Flanders. Anyone who conquers the famous 59 iconic mountain and cobblestone passages in Flanders within 72 hours will become part of the cycling legend. Strava segments as travel inspiration. The reward is a cobblestone engraved with your name, which is given a place on the real Wall of Fame in the Ronde Van Vlaanderen Center in Oudenaarde. All the more reason to travel to the place dedicated to the gods of cycling .

- These are the best free bike apps

View this post on Instagram A post shared by VISITFLANDERS (@visitflanders)

Resorts and hotels are currently paying more attention to the yoga sector and are responding to the increasing demand. A fitness room with mostly outdated equipment is no longer enough. People also want space for meditation, yoga and stretching. Roll out the mat and say "Namaste"! Another remarkable development is the spillover from the padel scene into tourism. Padel is growing incredibly fast. There are currently more padel players in Spain than in tennis. The hotel industry has not missed the boom either and is adapting to it. New padel courts are being built or existing tennis courts are being converted. This is because the padel community is staying longer, traveling in larger groups and venues for tournaments are gaining in importance. The signs are pointing to growth.

Tour of the Alps: three regions, one destination

In the Alpine region, new growth opportunities are being seen in destination management. The fact that vacation regions work together with various sports associations and present their presence at competitions on television in a way that is suitable for the masses is nothing new. Working with ambassadors to highlight the benefits of a region has also been common practice for a number of years. What is new, however, is that otherwise competing vacation regions are joining forces. In Tyrol, South Tyrol and Trentino, this works very well with the UCI professional cycling race Tour of the Alps. Until 2016, this cycling race was still called the Giro del Trentino, but it was then decided to expand it with new stages and routes in South Tyrol and beyond the main Alpine ridge in Tyrol. The three regions are closely linked by their identity and share common values. With the same vision and idea of cycling, they have created the Tour of the Alps. The race in April is seen as a good preparation for the Giro d'Italia - with a clear concept: short but challenging stages and as few transfers as possible. David Evangelista, Head of Communication for the Tour of the Alps, explains the advantages: "The start and finish are in one place for many stages. This means fewer emissions, less travel stress for the riders and more time for recovery. This benefits everyone, the professionals and the spectators."

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Tour of the Alps (@tourof_thealps)

- Overtourism: Are the mountains running out of steam?

These examples show how tourism regions can benefit from sport through innovative marketing. Other traditional sports regions, on the other hand, are struggling to attract guests. Some winter sports resorts are worried and in some cases are already under enormous pressure. Customers are staying away, everything is becoming more expensive and the season is being shortened due to climate change. Winter sports enthusiasts who can afford it are traveling to more expensive, snow-sure areas.

However, price points and accessibility are aspects that increasingly speak against practicing winter sports . This is the result of a recent study presented in part by Prof. Dr. Ralf Roth from the German Sport University at the Sports Travel Hub of ISPO Munich 2023. There has been a decline on the slopes, particularly among 25 to 35-year-olds, compared to the demographic age distribution. Skiing has always been expensive, but prices have continued to skyrocket in recent years. Rath warns: "You have to be seriously careful here that you don't end up losing the next generation. Why can't every child have access to cross-country and alpine skiing in the Allgäu, for example?"

The rising prices are also a reason why more and more winter sports enthusiasts are turning to other activities during their vacation. Ski tours, tobogganing or snow hikes - 7 days of skiing in a row are no longer a matter of course. There is no shortage of alternatives here. The situation is quite different when it comes to travel, which still accounts for the largest share of CO 2 -footprint that most ski tourists leave behind in the snow. There is often a lack of seriously attractive public transport options that connect the cities with the ski resorts as an alternative to traveling by car. Cooperation and partnerships between ski resorts, local and long-distance public transport, cities and municipalities are major tasks for the coming years. This could also improve the image of ski tourism in the long term.

Why is the connection between sports and tourism significant?

The connection between sports and tourism provides a welcome break and distraction from everyday life, especially after the isolating pandemic years. People seek positive experiences and new adventures, leading to the popularity of trends like adventure travel, caravanning, and long-distance hiking.

How can businesses benefit from partnerships in tourism?

Partnerships, such as the one between Brooks and Strava, allow businesses to increase their brand presence and actively engage with their target audience. By collaborating with travel destinations, companies like Brooks can promote both their products and the holiday destination, thus benefiting from the growing popularity of active vacations.

What role do rewards play in the sports community?

Rewards, such as discounts and vouchers, are used in the sports community as incentives for activities. Platforms like Strava offer rewards for athletic achievements, increasing community motivation and fostering cohesion.

How are hotels adapting to sports and wellness trends?

Hotels are responding to the growing demand for sports activities and wellness offerings by adapting their facilities accordingly. In addition to fitness rooms, they now also provide space for yoga, meditation, and other activities. Furthermore, hotels recognize the trend towards sports like paddle tennis and are expanding their facilities accordingly.

What are the benefits of joint events by tourism regions?

Joint events, such as the Tour of the Alps, offer tourism regions the opportunity to strengthen their identity and attractiveness. Through collaboration, they can reach a larger audience and benefit from joint marketing efforts, leading to growth in tourism for the region.

- Action Sports

- Mountain sports

- ISPO Munich

- Water sports

- Winter sports

- OutDoor by ISPO

- Transformation

- Urban Culture

- Trade fairs

- Find the Balance

- Product reviews

- Use ISPO.com for marketing

- Individual consultancy

- Contact the editorial team

- Help & FAQ

Where does active travel fit within local community narratives of mobility space and place?

- Civil and Environmental Engineering

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review